Editor: Elliott Anderson

Guest Co-editor: Robert Coover

Executive Editor: Mary Kinzie

Art Director: Lawrence Levy

Managing Editor: Theresa Maylone

Associate Editors: Michael McDonnell, Allan Gray, Mary Elinore Smith

Advisory Editor: Charles Newman

Production: Cynthia Anderson

Fulfillment: Mary M. Zakrasek, Doris Grimes

Contributing Editors: Robert Alter, Joseph Epstein, Gerald Graff, John Hawkes, David Hayman, Lawrence Levy, Joseph McElroy, Peter Michelson, Robert Onopa, Tony Tanner, Nathaniel Tarn

TriQuarterly is an international journal of arts, letters, and opinion published in the fall, winter, and spring at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60201. Subscription rates: One year $10.00; two years $15.00; three years $20.00. Foreign subscriptions $1.00 per year additional. Single copies usually $3.50. Back issue prices on request. Contributions, correspondence, and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly, University Hall 101, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60201. The editors invite submissions, but queries are strongly suggested. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1976 by TriQuarterly. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America. Claims for missing numbers will be honored only within the fourmonth period after month of issue.

NATIONAL DISTRIBUTOR TO RETAIL TRADE: B. DEBOER, 188 HIGH STREET, NUTLEY, NEW JERSEY 07110. DISTRIBUTOR FOR WEST COAST RETAIL TRADE: BOOK PEOPLE, 2940 7TH STREET, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA 94710. DISTRIBUTOR FOR GREAT BRITAIN AND EUROPE: B. F. STEVENS & BROWN, LTD., ARDON HOUSE, MILL LANE, GODALMING, SURREY, ENGLAND.

REPRINTS OF BACK ISSUES OF TriQuarterly ARE NOW AVAILABLE IN FULL FORMAT FROM KRAUS REPRINT COMPANY, ROUTE 100, MILLWOOD, NEW YORK 10546, AND IN MICROFILM FROM UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS, A XEROX COMPANY, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN 48106.

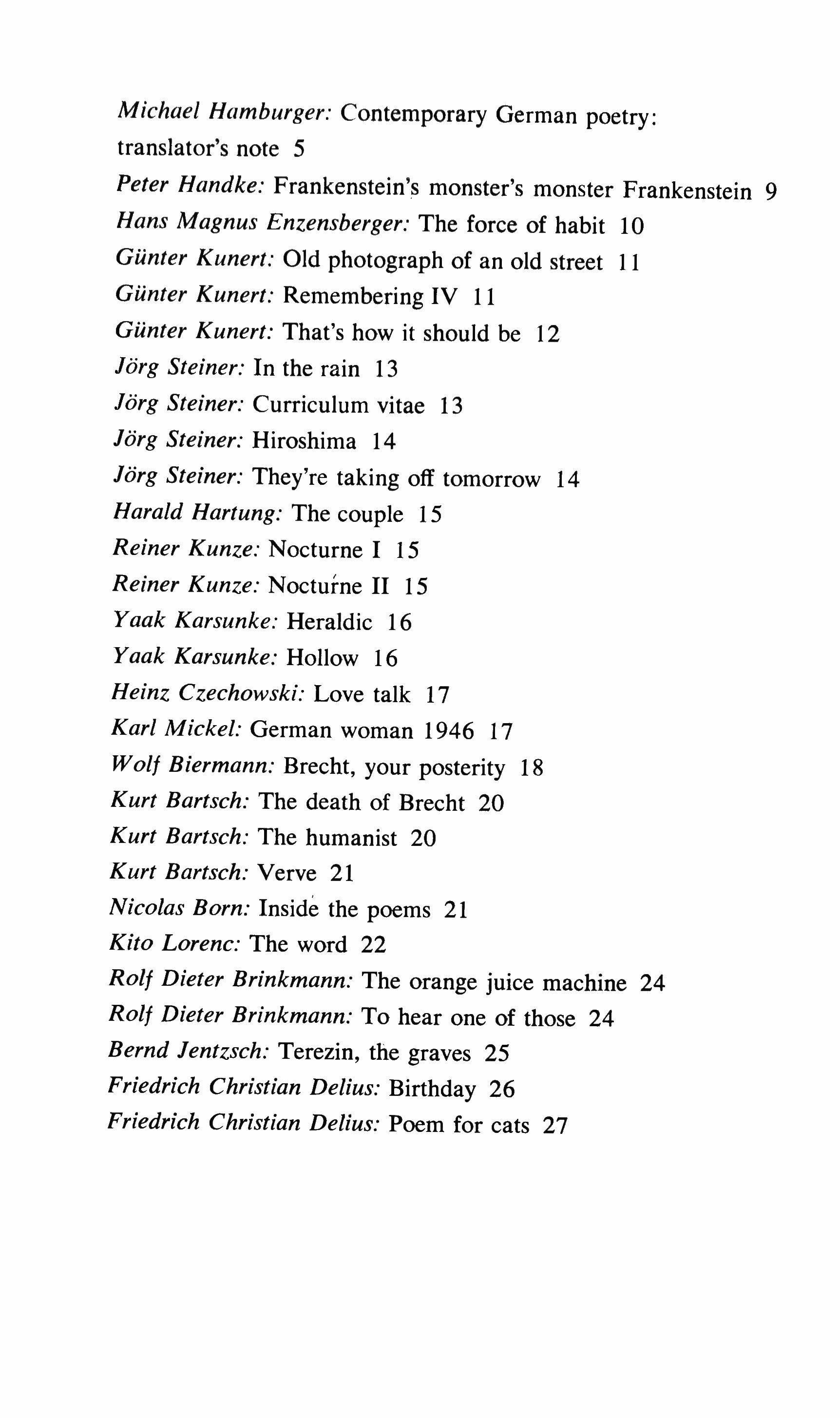

W. S. Merwin: Vanity 5

W. S. Merwin: The good-bye shirts 6

John Hawkes: Design and debris (from Travesty) 7

Margarita Karapanou: The honey 9

Margarita Karapanou: That afternoon a bee had stung her 10

Steve Katz: On hidden blessings 12

Steve Katz: On the difference between the 60's and 70's 13

Terry Stokes: Directions to a new town 14

Istvan Orkeny: Snowy landscape with two onion domes 14

Ursule Molinaro: Burial rites 16

Frederic Tuten: from The Tomkins Square Park Tales 17

J. G. Ballard: Queen Elizabeth's rhinoplasty 18

Max Apple: Heart attack 20

John Bdtki: The footnote as medium 22

John Bdtki: The mysterious cell count 22

Francis Ponge: Rain 23

Francis Ponge: Orange 24

Steve Schutzman: The bank robbery 25

Ira Sadoff: The romance of the radish 26

Ira Sadoff: The romance of the restless 27

Eugene Wildman: My Gringo 28

Leonard Michaels: 3. The words for penis 30

Sotere Torregian: Chateaubriand 31

Sotere Torregian: The Supermart 32

Gail Godwin: His house 32

Ian MacMillan: Berlin, 1945/Fallen pinup girl 35

Ian MacMillan: Messinghausen, 1945/The unknown soldier passes 36

Eugene K. Garber: Mannikin 37

David Ohle: The boy scout 39

David Ohle: The rules 41

2

Robert Onopa: Case 7/The compensatory use of confabulation 41

Ronald Sukenick: Endless short story [Aziff] 42

Alain Robbe-Grillet: Coda 42

Ben Birnbaum: The night they turned grandma upside down 45

Angela Carter: The dark tower 45

Randall Reid: Sea story 47

Robert Creeley : from Mabel!a story 48

John Lahr: The girl who danced with Fred Astaire 50

Russell Edson: Silly old funny uncle Lewis 52

Russell Edson: Dr. Nigel Bruce Watson counting 53

Silvina Ocampo: Report on Heaven and Hell 54

Susan Fromberg Schaeffer: The taxi 55

Bob Perelman: Her me them it 57

Charles Newman: A comprehensive development project for these United States in the last third of the twentieth century 57

Jack Matthews: The discovery of the Greenbrier River 58

Sydney Martin & James Mechem: Wichita daughter of the Manitou 60

Ian McEwan: Untitled 62

Paul West: The Paganini break 64

Leandro Urbina: Our father who art in heaven 65

Norman Lavers: The divorced mother to her son home on a visit 65

Michael Brownstein: Ninth Symphony 67

Michael Benedikt: Moral decisions 67

Hans Carl Artmann: The gypsy life 68

Hans Carl Artmann: Psychic state in a part of the harbor 70

Hans Carl Artmann: Thank you, signor Drapier 71

Jorge Luis Borges: Argumentum ornithologicum 73

Michael Anania: The Marble Faun 73 3

Michael Anania: The necklace 74

Charles Aukema: Environmental bath 75

Julio Cortdzar: Whatever he sees, he sees soft 75

Jonathan Baumbach: The frozen yak fields of Alaska 76

Carol Berge: The gifted 78

Robert Coover: The fallguy's faith 79

Andrei Codrescu: The hero plot 80

Andrei Codrescu: Oriental 81

Kenneth Bernard: Subway 1 81

T. Coraghessan Boyle: The See 82

George Chambers: Jirac and Sonya 84

Andrew Delbanco: Untitled 86

Kent H. Dixon: First spring fly 88

Richard Brautigan: Football 89

Bill Henkin: from Raw dog 89

Robert Kelly: Opera 90

Eduardo Gudino Kieffer: Fairy song 92

Elaine Kraj: Windows 93

Oakley Hall: How to make jimsonweed beer 95

M. F. Beal: Nail soup (a depression recipe) 96

Annie Dillard: Utah 96

Ron Loewinsohn: The statues 98

Ron Loewinsohn: In the woods 100

Stephen Kessler: It must have happened in my sleep 100

Stephen Kessler: Why is this night different from all other nights? 101

Vicente Aleixandre: Concerning the color of nothingness 102

R. D. Skillings: Dark Harbor, Dark Point 103

W. P. Kogut: Canada 106

Rikki: Natural history 107

Marilyn Krysl: The artichoke 109

Acknowledgments 111 4

One night we decided to camp in the hills beside a series of waterfalls, and had to speak a little louder than we usually did in the woods. It was later in the day than we would have liked it to be, when we got there. It had rained all day and the grass and bushes were dripping. Just up ahead of us there was a small bridge over the stream. When we had eaten we got ready to sleep in the car. It was going to rain some more.

When it was already night we heard voices. Deep resonant voices of men. The summer nights there are twilit for a long time. We could make out a big old truck parked a little behind us on the same small level patch, with its lights out. Some figures were using flashlights to get things out of the covered back of the truck. If they peered in on us, we said to each other, the tops of bottles glinting in the dim light looked like the ends of gun barrels. They would think we were armed. We laughed. We lay whispering about them, rehearsing what we had heard about local people, and describing the place to each other, the sound, the light, the colors, the past day, in which we had come a long way.

One of the men, who looked very large, in a long raincoat, came over toward us. He looked like a farmer. He wore a sweater and a knitted hat. A big crumpled and swollen face, a protruding chin. He put his face up near the window. After a while he must have seen us. He said Hello.

So we answered. We said Hello.

He said it looked as though we weren't from around there.

No, we said.

Well, he said, he wasn't either. He named a place he had come from, and asked whether we were acquainted with it, but neither of us had heard the name he had said, and so we answered no.

So he started to tell us about it. How far away it was. Its population. What the winters were like. What sort of people lived there. He shone his flashlight into the car and said it looked as though we really lived in there, and he admired that.

He asked us if we were going on in the morning, and we said yes.

So is we, he said. And he asked if we had heard of the Bible meeting at another town whose name he chewed and swallowed, and we answered no. So he started to tell us about that. The road

there, what it was like at different times of year. What an event it was for miles about. How they sang hymns he had never heard. He said he was going there to preach. He liked to preach there. He went every year.

He said he hoped we wouldn't mind their staying the night beside us there. He said he had a young man with him who was not right in the head but he wasn't no harm, nor nothing like that. Just so we wouldn't think anything wrong. They would just be getting ready for bed, he said.

He turned away, and took a few steps.

Then he came back.

He asked us whether we would be interested to know what text he was intending to preach on. So we said yes.

He raised his hand, and then bent down to the window to stare in at us.

From the Book of Ecclesiastes, he said. Two, five. He nodded his head. Do you remember that one?

So we answered no.

He shook his head, and gestured in the air, and rolled his words, and recited: I made myself gardens and parks and planted in them all kinds of fruit trees.

That's it, he said. All kinds of fruit trees.

Well, so good-night, he said.

So we said good-night, but he had already turned off the flashlight and was on his way back to the unlit truck and his companion.

So we laughed.

Daily the indispensable is taught to elude us, while we are furnished according to our wishes with armories of what we do not need. And like all armories, they wait. None of us needs a good-bye shirt. But which of us (if a man) is without one? The lack of one, to our eyes, would be a matter for pity ("Poor thing, not even a good-bye shirt") or for contempt ("Not even a good-bye shirt") or for the perfunctory expression of horror elicited by murders and grotesque accidents ("Not even a good-bye shirt") or for the prophylactic amusement used for saints ("Not even

a good-bye shirt"). So in each of our cupboards there it lies, no doubt, or will lie, and we do not even know-we may never know-which one it is, any more than we knew which would be the meeting shirt, though we may have tried and tried to choose it. And what guides our hand at last? If we could be said to know what we were choosing, would we ever put on the good-bye shirt at all? Or would we put it on at once? Have we in fact already worn it repeatedly, through the casual farewells of days that have faded out, one behind the other? Are we wearing it now? When two good-bye shirts meet each other, at the laundry, or on the bodies of their wearers, what lack of recognition (as far as we can tell) even at the moment and in the very gestures of routine parting! But then, are we ourselves prompt to recognize those who share our calling, our fate? And the shirts, the real good-bye shirts, can be certain of sharing only two things: they have owners; and they can be emptier when worn than when waiting in the cupboard or hanging on the line in the sunlight, .waving,

Do not be alarmed, cher ami. The matter at hand is not necessarily so very important. But we might as well spare ourselves whenever we can. The problem is that there is exactly time enough for me to forewarn you that in a few seconds we will be passing directly through the center of the only village that lies between the beginning of our trip tonight and its conclusion, and that mars an otherwise quite empty road. The little place is known for its 'ruined abbey, or perhaps it is a ruined mill. But believe me, please. This route was the most fortuitous I could select. I wished only for an unimpeded journey. However, the sore spot of this little village was unavoidable. At any rate, you deserve to know the worst and the best, and should be as clear as I am about our situation and hence be in a position to prepare yourself moment by moment to achieve understanding and avoid merely shocking or destructive surprises. So let me warn you that tonight we will encounter only three genuine points of danger, though unhappily the rain has become a kind of general hazard, albeit 7

one out of your hands and of little interest to me. But back to the three genuine points of danger. The final turnoff to the abandoned farm, the Roman aqueduct, and the village we are rapidly approaching-each of these will present us with grave danger, which I will not attempt to conceal, as I have said. However, I am confident about the aqueduct while our journey itself is preparation for the final turnoff, which, hopefully, by that time you will encounter as something quite beyond danger. So we may discount the final turnoff. I may even go so far right now as to guarantee you its serenity.

But to be perfectly honest, the village is something else again. It is careening toward us this very moment, only a few words or a few breaths away. Of course the little street through that village is short, hardly more than several lengths of the car or one of those sylvan paths that take you from the intersection of two dusty roads to the turnstile at the edge of the field. So it is a short village street but obstinate, and unlighted, and extremely narrow, and bordered for its entire length by a high, sinuous stone wall overtopped by the now wet tile roofs of the village houses and the limbs of an occasional dead tree. Throughout our passage through the wretched place the side of the car will be within touching distance of the heavy stone. If you insist on looking, you will see an infinite rapid shuffling of rock and wood; iron door handles and high broken shutters will fly in your face; our way shall consist of impossible angles, a near collision with the fountain in the central square, a terrible encounter with a low arch. We shall have become a locomotive in a maze, and the noise will be the worst of all. Our lights will be like searchlights swiveling in unimaginable confinement, and a forlorn, artificial rose and the granite foot of one of their crucified Christs and a sudden low chimney will all approach us like a handful of thrown stones. But the noise will be the worst. It will be as if we ourselves were a rocket firing in the caves and catacombs of history. Let us hope that the cats of the village are not as prevalent as the rabbits of our rural highway. Let us hope that we are not deflected by a shard of tile or little rusted iron key or the slick, white femur bone of some recently slaughtered' animal. Otherwise we shall brush the stone walls, swerve, bring down the entire village to a pile of rubble which we shall no doubt drag after us a hundred meters or more.

There is nothing to be done about the sound. But you may well wish to close your eyes, or simply lean forward and bury your face in your hands. The entire deafening passage will last an eternity but also no time at all. Why see it? Why not leave the seeing as well as the driving to me? And you might amuse yourself by considering what the peasants will think when we shake their street and start them shuddering in their poor beds: that we are only an immoral man and his laughing mistress roaring through the rainy night on some devilish and frivolous escapade. Or consider what we shall leave in our wake: only an ominous trembling and a half-dozen falling tiles.

But do you see it ? Just there ? That huddled darkness f h bitati ? Th he rai ? H o a nation e stones m t e ram ere It IS.

Hold on

One night in summer, when Mother had kissed me on the left cheek and said goodnight, she turned the light off, and I was alone in the dark room. Singing to myself, I put my hand in my panties for a bit of company. But I went numb and furry; a sweetness wrapped right around me, and I wouldn't stop.

Faster and faster; I was going to burst. Kind of weights, like sugared almonds, came up from my soles to my belly, and I was filled with sugar. Thick honey trickled from everywhere, and I was drowning in sweetness.

Suddenly, when the sweetness had choked my throat, the house started to shake and rain began to fall from the sky. The earth opened up and swallowed up the houses all around, one by one. I pulled my hand out of my panties quickly.

"Little Jesus," I said, "forgive me. I'll never do it again. Don't cut my life off."

But the earth all around was still caving in. Little Jesus was really angry this time.

So I put my hand back in my panties, and the sweetness came back. I sang to myself too.

While the house was disappearing in the holed earth, the honey bathed me all over, and I died in sweetness. -translated by N. C. Germanacos

Margarita Karapanou: That afternoon a bee had stung her

"Does it hurt, Mother?"

That afternoon a bee had stung her under her nightgown, on her belly. Autumn had come. Elsewhere the leaves must have been falling from trees, the sun sad, the earth getting ready to sleep again. Here, on the bare island, only the sea had gone darker; it had become bad.

"Does it hurt, Mother?"

She took off her nightgown, went to the end of the garden, sat on a rock, naked, facing the sunset and stroking her swollen belly.

She gazed out to sea.

"Does it hurt, Mother?"

A lizard scurried into my bathing suit.

The sun poured over the sea like ink, the garden of our house was ablaze. Autumn had come, and we were alone on the island: Mother, Minos, and 1.

Minos was a father to me. He'd lift me up on his shoulders, and run deep into the sea, which was good to me, with me clinging to the back of his neck and laughing, because he was strong, and he was a man, with legs and arms. After that, we'd come home all covered with salt, Minos would close the wooden shutters and stretch himself out in the cool sheets, his eyes open, waiting for night to fall. Mother would stretch out beside him and tend him like a mermaid. I'd run off to chase lizards.

Autumn had come; only our house was still alive. Elsewhere children must have started school, with schoolbags and sharp pencils and angry and kind teachers.

The sun didn't burn any more; it went away early. I was afraid of the sea now. As soon as I touched it, it licked me, kissed me, ready to suck me in. I couldn't see the bottom any more; at noon the sky got cloudy. It was as if the sea was giving birth to autumn monsters in the depths, then hiding them down there. Its color grew darker and darker, its waves went dumb, huge. In the last few days it has become carnivorous too. Minos didn't lift me on his shoulders any more.

He took me by the hand instead, and we ran along the beach, stopping and looking at the water and shivering. When night fell, he caressed my hair and kissed me.

Yesterday, a wave like a mountain stopped at the window. It slid along the pane caressing itself, coaxing me to let it in.

"I must be dreaming," I thought.

I was. The wave looked at me, laughing. If I'd opened the pane, it would have swallowed me in, wandered with me far and wide, taken me down to the depths, and there it would have forgotten me.

I got scared. It was for real. I got so scared I opened the door. Mother was standing there, laughing.

"Come."

We both bent over Minos, who was sleeping like a baby. She took off her nightgown, became a bird on him, an octopus, arms and legs around him, her eyes on me.

Next day we went for a walk, Minos and I. He was crying.

"You're my daughter," he said thoughtfully, hopefully.

"You're my father."

He was crying.

The sun was shining very red, filling his face with such light I shut my eyes so as not to be blinded. I loved him so much I would have liked to turn him into a statue, kiss his feet, and light fires all around him and worship him.

On the way home, the beach was covered with seaweed; I almost choked with the smell; the house had gone green, it had become sealike.

"Minos."

I became a seashell in his arms. Our tears and mouths became sealike too.

"Minos."

"Goodbye," Minos said.

Mother was in the garden in her nightgown. She'd opened her legs to suck up the last rays of the sun, when a bee had stung her on the belly. Her face became a sting.

"Does it hurt, Mother?"

She took off her nightgown, stroked her swollen belly. Then she went to the end of the garden, sat on a rock, naked, facing the sunset. She gazed out to sea. Her eyes filled with seaweed.

Night.

"Come."

She took me by the hand. We bent over Minos, who was sleeping like a baby. She took off her nightgown.

I knew Minos was going to die. I danced. With my arms stretched forward, I became a woman; there was a tray in my hands, which I was going to pile with heads so she could eat them for dessert. I danced rhythmically, in a circle, sealike, around Minos, who was naked as a baby. I took my bathing suit off and stayed without a skin. "Caress him."

The command filled me. I took hold of Minos' strength: it swelled, stared up at the ceiling, crying, like sea without water, with brine only. Minos was Elsewhere, he was already Another. I caressed rhythmically. Minos sprouted thorns between his legs, like a rose, for protection. My hands bled. I bent lower and bit him, swallowed him whole, sucked him in like a jellyfish. I drank milk between his legs, drank his soul, thirstier than I had ever been before. I would not have quenched that thirst of mine if I'd swallowed the entire ocean. I had no legs any more, nor arms. I curled up. Mother, above me, groaned, contracted. I tried to howl, curled up, but my ears, eyes, nose, mouth were choked with juices.

Mother screamed. The juices fell away. I opened my eyes and howled.

Minos disappeared forever, running toward the sea, embracing it. A bee flew out of the window.

The swelling on Mother's belly went down. -translated by N. C. Germanacos

excuse me I was watching the stars I haven't had time yet to read your application or your manuscript I agree it's past noon but I watch them on my own schedule who are you why did you bring your matters here to my tent I'm in no position to recommend you for anything I can't comment on the quality of your soul let me look into your eyes you have a scummy soul your soul pisses in its own bed get up don't let your soul loose without a chaperon now here comes my soul look out soul let's watch them sh they are dancing no your 12

soul is fucking my soul no my soul cooks dinner for your soul no our souls have heated up this tent and now we're in this hot-air balloon we are drifting over Miami the people of Miami Beach are waving at us from their wheelchairs there's Cape Kennedy stay away from it too late here comes one of those motherfucking F-111's our souls have left us here to die you steer the tent I'll hit that plane with this axe hold her steady oof got it now ease her down you're doing great come to think of it our souls did okay too we make a good team now I know you well enough to help you out here's my advice settle down somewhere in the midwest but don't get married sell farm machinery or work for the liquor commission raise a fatherless child write a couple of books based on your childhood in Buffalo New York call them Frozen Steel and Fiddler on the Root publish the first one with Alfred Knopf this is the beginning of your second book YOlJ can have it free I don't need it your career can have my career I have spoken now I'm going to close my eyes again don't mention anything I have said or anything that has happened here don't tell anyone else where I am

Steve Katz: On the difference between the 60's and 70's somewhere else something wonderful has captured the imagination of the young I intend to go there and insist on their freedom I do not expect to use force or display my wicked arsenal of banality I will free them by persuasion and talent I will use all the money at my disposal come with me but bring your own poems perhaps we will find when we get there that the problem has already been solved in that case I shall have to wrap you in your poems and ship you home I don't relish that responsibility on second thought I would prefer that you stay here and keep my place in order here is lumber build whatever you please over my hole after I emerge there is grain & lentils & beans & rice & lentils eat them I'm leaving I wont be back this is tuesday this is wednesday this is saturday evening I have arrived in Pennsylvania the people are inhospitable and the city is crowded I have nowhere to go I have 13

to rent a cheap bed in a flophouse 0 I have no money I am going to sleep on the street I'm glad I brought this bundle Good Night

I am holding out for high wages. Once, I could have had any peat moss factory in the country. I could have had any peat moss factory in the city. Waterlogging is the name of the game. We hitch up the horses, & go after the ventricles first. We occasionally gather some bleeding-heart liberals. We let them bleed. WAIT A MINUTE! The factory, peat moss, Waterlogging. It is a card game played with 14 to 17 people sitting at opposite ends of the table from the pile of peat moss. The objective: to gather peat moss without anyone knowing how or why you are doing it. The uniforms are simple satin. No pockets. Waterlogging is considered de rigueur in most parts of the country where the game is played; it is like playing with your satin pants down. We do not allow Waterlogging in our closed circle. However, if you want to speed up the game, & it is a final competition, Waterlog, if you wish. I was, of course, quite successful at it.

Actually all of Davidovka should have been out there; that is, not only our battalion but the local population as well. But that's not how it happened. Among our men, only the few usual losers showed up, along with some convalescents, clerks, quartermasters-in other words, people with something to lose, forty or fifty in all. And not even that many Russians. If the sergeant could flush you from the barracks, you were out there on the square milling around for a while before grabbing the first chance to escape back. Even more remarkable was the fact that Major Hollo, the battalion commander, was absent even though up till then he had attended every execution; he was careful about formalities. He did appear for a moment in front of headquarters, looked around the church square, said it was cold, went back in, and was seen no more. So that the only officials present in addition

to the doctor and the sergeant were the German truck driver and the NCO with the Leica around his neck. They had brought the condemned to Davidovka because this is where the sentence of the German court-martial was to be executed. Oh yes and this is where the driver named Ecetes was to be found, the man who said he would hang the woman for three liters of rum. Ecetes had already gone through the first liter and was somewhat uncertain on his feet.

The woman stood waiting under the tree, motionless as if her feet had frozen to the ground. There were no tears on her face. So far we had found that old people die easiest. They panic as if they don't know what is happening, but they do not plead, cry, or scream. This woman was fairly young, fairly good-looking, and fairly well dressed, yet she did not say a word. She just stood and stared with burning eyes at the little girl who had climbed under the truck and was peeking out from there. The girl was maybe four or five. She had a thin and dirty face but she too wore fairly good clothes: small sheepskin vest, quilted pants, thick cotton stockings, and rubber boots. When the rope was placed around the young woman's neck, the girl under the truck laughed out with a voice as light as if she had been tickled.

Three minutes later the medical officer verified that death had .taken place. A cold wind came and the young woman's body began to sway. The little girl crawled out from under the truck. For a while she followed the swinging movement with her eyes. Then, like someone who's had a good time but is beginning to tire of the joke, she yelled up at the tree.

"Mama!"

By then, no Russians were left on the square, and of ours, only the driver Marton Ecetes, the sergeant Elek Bir6, the medical officer Dr. Tibor Friedrich, and a corporal named Istvan Koszta, in civilian life a bartender at the Arany Bika Inn who had, because of his furuncles, several times requested to be transferred to a hospital behind the lines. Even now he stood so as to let the doctor see the reddening lumps on his neck. Dr. Friedrich, however, turned the other way and looked into the lens of the Leica. The German NCO motioned at the girl to step out of the picture but she did not budge from where she stood. With wide open shining eyes she stared at the Leica. Probably she had never seen a camera before. -translated by John Bdtki

Ursule Molinaro: Burial rites

Ursule Molinaro: Burial rites

She had agreed to have one last dinner with him: in honor of what is now over between them. (Can't be over between them: he thinks: or she wouldn't be here with him.) In the little Spanish restaurant where it had started between them. Where they had eaten five months of dinners. Every night, until a month ago.

The nun has come in.

Every night the same beautiful black nun, carrying a red plastic saucer. & every night he'd give her something. A quarter. Sometimes 50 cents.

Maybe she isn't a real nun : she says. Does it matter? To me, I mean. To my giving. It's the giving that counts. For me.

The nun is going from table to table.

Women: he says: Women should wear long black dresses

Men should wear codpieces: she says & live in the kitchen: he says: & come out

Codpieces, to show off their wares: she says: With rhinestones. & falsies & come out with something delicious: he says. & falsies: she says: when their sex is mostly in the head & take off their long black dresses, & serve: he says.

Why don't you marry the nun: she says: Like Martin Luther. Then you could playa real monk

His manicured right middle finger massages the dent in his right temple: I'm always right. My temple is always right. A thankless privilege. He'd enjoy being wrong for a change. In his judgment of her, for instance Has she come here without him?

He has ceased to exist for her. & is dead. She can see his manicured nail grow, against his temple. On his left hand, too. Doesn't he notice how his nails are growing around his fork?

Have you come here without me?

She shrugs. She is playing with the napkin in her lap. A snug white rabbit. She is pulling one of its ears.

The nun is heading for their table. He is feeling for change

Have you come here with somebody else?

Why don't you ask your nun: she says.

He looks at her. Not at the nun. Nor at the dollar bill he's dropping into the red plastic saucer.

God bless you: says the nun.

Wait a minute! She has caught the nun by a sleeve. I want to ask you something. Are you a real nun?

God bless you: says the nun, trying to get away.

His long-nailed hand is around her arm, & she is outside in the street. He is opening the door of a hearse. He shoves her in.

From the window she can see the impassive face of the beautiful black nun, who is holding out her saucer to a man at the bar.

There down by the river we waited a long time for you, sir; "and what is the upshot of this experiment?" you asked that day in the garden. Oh! that terrible voice of yours, we can remember it still and always, that voice calling to us down in the garden, "Is this the upshot of your experiment," you said; and what had we to say to that, sir? We were there among all the plants and shrubs all verdurous and thick and green. We were in that garden, we were there, and you too, the first time in a long time, and just before you came we asked, "Is he ever coming again, so that we can show him the pears and things we sprouted a season ago?" Moll said, "'course he'll come, sure as rain, as certain as the sun he'll be here again." And me and the Captain danced a jig for joy, one two three, one two three, step and turn again; "Moll," we asked, "when he comes will he bring the ?" "Sh, Sh!" Moll hushed us, "you better be still about that now. He'll come when he's ready, there's no rushing matters." So we leaned back and loafed looking up at the sky and the big clouds passing by, we lazed away the time, me and the Captain smoking cheroots and blowing ringlets right up to the leafy branches above, hanging down heavy with our pears and apples and mulberries and quinces.

The sky, etc., and the clouds, etc., too. And a lot of healthy sunshine warming us up: the catfish and cod and whales and muskrats and 'possoms and polar bears and bees and hawks and sparrows and quail and ducks and cats and dogs and fleas and amoebas and elephants and tigers and doves and lizards and lots of others, humming and prancing and joking each other, or

letting each other be, each minding his own business and doing no harm to man or self. Just one of those mellow days, waiting for him but not waiting too hard or too mindfully.

Moll rolled over on her belly and showed her naked pretty golden ass, the grass tickling her other side so that she wiggled and twisted 'bout, inching 'round me and the Capt'n, 'til I could see he had a stand-on, and I had one too, no use saying the contrary, Moll's ass on the green was something to see, after all.

A big bolt from the blue!

"Is this the upshot of your experiment ? Is this the fruit of all you have learned?" That luminous voice blasted at us 'til we was peeing in the grass, getting our feet wet, so that the next day we took sick with shiver chills and cold soles. Oh! what a time. What a time.

Many views were expressed as to what would be the ideal shape of the Queen's nose, and how it could best be obtained. Some of her surgeons favored the profilometer (Straith, 1938), by which Her Majesty's nose would emerge after operation with a standard height, tip angle, and bridge line. Other surgeons modeled the patient, trying out various patterns of the future nose in the attempt to obtain Her Majesty's approval for a particular one. The principle here was rather like that of trying out a new hat.

Unfortunately, human tissues are prone to thicken and behave in a way that is unpredictable. It was felt unwise, therefore, to lay too much emphasis with Her Majesty on exact details. Generalities were discussed, such as whether a straight or a hollowed-out bridge line was to be aimed at, whether her nose was to be retrousse or not, and whether the tip was to be narrowed or left alone.

Preoperative preparation. The Queen's nostril vibrissae were cut short and her nose packed with cocaine and adrenalin as for a submucous resection of the septum. General anesthesia was preferred, the Queen's trachea being intubated and the pharynx carefully packed off around the tube.

The incisions. Bilateral vestibular incisions were made through

the lining of the lateral wall, placed between the alar cartilage and the lateral cartilage. These incisions were carried forward over the apex of each of Her Majesty's nostrils and met centrally at another incision made by transfixing the septum just below the lower border of its cartilage.

The skin covering of the Queen's nose was freed on a deep subcutaneous plane right up to the glabella and well around to the sides. This was done with a pair of small curved scissors with blunt points. Where the saw cuts were to be made along the posterior margins of the Queen's nose, an elevator was introduced via the small lateral incisions. A pair of straight scissors carried up on either side of the cartilaginous septum now left this structure standing free and allowed the lateral cartilages to fall away on the sidewall of the nose, being carried in a mucosal flap. The septum was then trimmed along its anterior aspect to complete the reduction of the bridge line.

There were two schools of thought regarding the instrument to be used for the bone section. One favored the use of the osteome; the other preferred the saw. Much was made of the dangers of bone dust, and its part in producing thickening after operation. Joseph's nasal saws angled differently for left and right sides were good saws for the purpose. In the revision of the nose tip after previous unsatisfactory surgical intervention, asymmetrical alar cartilages presented special problems difficult of solution by the usual intranasal techniques. The so-called "flying-boat" approach was employed, as described by Rethi (quoted May 1951).

The radical operation on the Queen's nose carried with it a tendency to bleed. Hematoma formation would lead to excessive thickening, and possibly even to infection. Iced compresses during the first forty-eight hours diminished the edema that occurred in the Queen's eyelids and cheeks. Packs were removed after twentyfour hours. Her Majesty's nose was interfered with as little as possible during the next few days, the air way being cleaned with a pledget of cotton wool. The splint was removed after seven days and the Queen instructed in the digital pressure required to maintain the position of the nasal bones. A brisk reactionary hemorrhage was controlled by packing.

Her Majesty was warned that some bruising (black eyes) was likely up to three weeks after the operation, and that her social

activities would have to be curtailed. The Queen was also informed that she should not attempt to blow her nose until the intranasal incisions were soundly healed (two weeks).

During after-care, Her Majesty found it difficult to understand that her nose was swollen, and that such edema would settle down slowly and irregularly. Her Majesty was warned that her nose should not be operated upon for a further time within six months of the previous operation.

My sickness bothers me, though I persist in denying it. It is indigestion I think and eat no onions; gout and I order no liver or goose. The possibility of nervous exhaustion keeps me abed for three days, breathing deeply. I do yoga for anxiety. But, finally, here I am amid magazines awaiting, naked to the waist, cough at the balls, needle in the vein. From my viral pneumonia days, I remember his Sheaffers desk set and the 14kt gold point. It writes prescriptions without a scratch. In the time of the bad sunburn my damaged eyes scanned the walls reading degrees and being jealous of the good-looking woman, the three boys, the weeping willow in the back yard.

I have a choice of Sports Illustrated, Time, Boy's World, others. As if by design, I choose the free pamphlet on the wall. Fleischmann's Margarine gives me some straight talk about cholesterol. I remember the ten thousand eggs of my youth, those miracles of protein that have perhaps made my interior an artgum eraser. Two over easy in the morning, a hard one every night, poached, sometimes eviscerated by mayonnaise. In many ways I have been an egg man. The pamphlet shows my heart, a small pump the size of my fist. I make a fist and stare at knuckles, white as the eggshells I wish I had eaten instead. Where did I learn that your penis is the size of your middle finger plus the distance that finger can reach down your arm. Mine cannot make it to the wrist. My heart too must be a pea in this flimsy, hairless chest. From a door marked PRIVATE a nurse, all in white, comes to me. She sits very close on the couch and looks down at my pamphlet. She takes my damp hand in hers and tickles my palm.

Her soft lips against my ear whisper musically, "Every cloud has a silver lining

"But arteries," I respond, "my arteries are caked with the mistakes of my youth."

She points to the pamphlet. "Arteries should be lined only with their moist little selves. Be good to your arteries, be kind to your heart. It's the only one you'll ever have." She puts her tongue in my ear, and one arm reaches under my shirt. She sings, "A fella needs a girl.

"I need a doctor my arteries."

She points again to the pamphlet and reads, "Arteries, though similar to, are more important than girls in several ways. Look at this one pink and flexible as a Speidel band. Over there threatens cholesterol, dark as motor oil, thick as birthday cake. Cholesterol is the bully of the body. It picks on blood, good honest blood who bothers no one and goes happily between the races, creeds, and colors."

"I have pains," I tell her, "pains in my chest and my tongue feels fat and moss grows in my joints."

She unbuttons my shirt slowly. Her long cool fingers cup me as if I were all breasts. Her clever right hand is at my back counting vertebrae. She takes off the stiff nurse's cap and nuzzles my solar plexus. Into my middle she hums, "I'm as corny as Kansas in August " The vibrations go deep. She responds to me. "There," I gasp, "right there." I am overcome as if by Valium. As I moan she moves me down on the cracking vinyl couch. Her lips, teeth, and tongue fire between my ribs. She hums Muzak and the room spins until I sight the pamphlet clinging to a bobby pin. In my ecstasy, I see the diagram of cholesterol, in peaks and valleys, nipping at blood which makes its way, like a hero, through the narrow places.

When she lets me up, I am bruised but feeling wonderful. Her lips are colorless from the pressure she has exerted upon me. I start to take off my trousers. She stays my hand at the belt buckle, kisses me long. "The oath," she whispers.

"I'm cured," I say. "Forget him. Forget the urine and the blood. Look." I beat my chest like Tarzan, I spit across the room into a tiny bronze ashtray.

"I'll pack," she says, She goes into PRIVATE while I pick out a

few Reader's Digests for the road, Today's Health for the bathroom. She returns carrying a centrifuge and a rack of test tubes. We embrace, then I bend to help with her things.

"Don't be cruel," she whispers, "to a heart that's true

On the way out we throw a kiss to the pharmacist and my blood slips through.

Bdtki:

In the jungle of language iridescent parrots and stern anchorites flash through the visual screen of the observer out to divine the scientific laws of the organic continuum that speaks in an infinity of frequencies ranging from a strident Squawk! to the smoothly radiating ripples in a pool. If we now abandon the nineteenth century with its Dr.-Livingstone-I-presume attitudes and exchange its scary ontological pith helmet for the strictly functional threelegged collapsible chair or blowpipe of the native, we at once become aware of certain necessary adjustments. Having shed the honkiness and paranoia of our "protective-preventive" massproduced equipment together with the critical!evaluative guise that inspired it, we must now meet the facts of nature one at a time, with the wariness of twice-burned toucans suspiciously eyeing a Brazil nut on the jungle floor. For the deceptively exciting object is fully seen only in the context of its simultaneous and informative footnote: the native at the end of the string controlling the trapdoor to the cage that encloses the cleverly disguised bait.

Bdtki:

Chapter one. And so the Count was less and less pleased with the results of our work. We spent seven years and the better part of his inheritance without isolating the virus or even beginning to make headway toward the baffling mystery of man's origins.

Chapter two. For years, these organisms would insist on coming to the Restaurant every Friday night. It became one of our weekly 22

rituals to lie in wait for these persistent, sneaky fellows and prevent their entrance.

Chapter three. "This is the last installment," warned the Cell Count. "If you haven't got it together by now, you might as well forget about the Whole Thing. If you glance periodically at the table, you may wonder how come the total number of elements equals the number of beads on a Central Asian rosary."

The rain, in the courtyard where I watch it fall, descends with an alluring variety. In the center, it is a thin, discontinuous curtain (or net), a falling implacable but relatively slow, of drops that are doubtless light enough, a precipitation continual but without force, an intense fission of pure meteor. Near the walls, to the left and right, separate and heavier drops fall more noisily. Here, they seem about the size of a grain of wheat; there, the size of a pea, or a ball-bearing. On the rods which support the window, the rain runs horizontally, while underneath them it hangs in small convex panes. Along the entire surface of a small zinc roof overhanging the drain, rain streams in a narrow sheet fed by varied currents made by the invisible waves and valleys of the surface. From the waiting gutter, where it runs with the clamor of a hollow brook down a slight slope, it falls suddenly in a perfect vertical thread, coarsely braided, straight to the ground, where it breaks and splatters in glittering needles.

Each of its forms has a unique attraction, and makes a peculiar noise. The whole apparatus lives with intensity, like a complicated machine that is both precise and haphazard, like a clock whose spring is the weight of a mass of vapor in suspension.

The sound on the ground of its vertical threads, the gurgling of the gutters, the tiny gong strokes, multiply and reverberate, all at once, in a concert that is without monotony, but never without delicacy.

When the spring is unwound, certain wheels continue to revolve, more and more slowly; then all the machinery stops. Whereupon, if the sun reappears, all is soon dissolved, and the glistening machine vanishes: it has rained. -translated by William Pratt

Like the sponge, the orange has an instinctive yearning to regain its shape after it has been squeezed. But while the sponge always succeeds, the orange never does: for its cells are broken, its tissues torn. While the outer casing alone feebly recovers its shape, thanks to its elasticity, an amber liquid is dispensed, accompanied by a refreshing, soothing perfume-but often, as well, by a bitter smell resulting from a premature expulsion of seeds.

Should we choose sides in these two struggles against oppression?-The sponge is all muscle, and fills up again with air, with clean or even dirty water: its acrobatic ability is a trifle vulgar. The orange is more dignified, but it is a bit too passive-and its fragrant sacrifice gives its oppressor too rich a reward.

But we have not done justice to the orange, merely to take note of its special way of perfuming the air and rewarding its oppressor. Let us dwell on the marvelous color of the liquid it produces, which, even more than the juice of a lemon, makes our throat open to pronounce its name and drink its liquid, without causing our mouth to pucker or tingle too much inside.

And words can hardly express enough admiration for its outer shell, this tender, fragile, reddish oval balloon, with its thick, moist blotter, and its delicately thin but richly pigmented skin, so bitter to the taste, and just pebbled enough to catch and hold the light on the perfectly rounded fruit.

But we must come to the end of this all-too-brief study, and round it out as fully as possible-we must examine the seed. This granule, in the shape of a tiny lemon, offers, on the outside, the white color of lemon wood, and, on the inside, the green of a pea or a tender bulb. It is in it that we discover, after the sensational explosion of a Venetian lantern of flavors, odors, and colors that make up the fruit-balloon itself-the very hardness and vitality (nat entirely tasteless) of the wood, the branch, and the leaf: the small totality which is the very essence of the fruit. -translated by William Pratt

The bank robber told his story in little notes to the bank teller. He held the pistol in one hand and gave her the notes with the other. The first note said:

This is a bank holdup because money is just like time and I need more to keep on going, so keep your hands where I can see them and don't go pressing any alarm buttons or I'll blow your head off.

The teller, a young woman of about twenty-five, felt the lights which lined her streets go on for the first time in years. She kept her hands where he could see them and didn't press any alarm buttons. Ah danger, she said to herself, you are just like love. After she read the note, she gave it back to the gunman and said: "This note is far too abstract. I really can't respond to it."

The robber, a young man of about twenty-five, felt the electricity of his thoughts in his hand as he wrote the next note. Ah money, he said to himself, you are just like love. His next note said:

This is a bank holdup because there is only one clear rule around here and that is WHEN YOU RUN OUT OF MONEY

YOU SUFFER, so keep your hands where I can see them and don't go pressing any alarm buttons or I'll blow your head off.

The young woman took the note, touching lightly the gunless hand that had written it. The touch of the gunman's hand went immediately to her memory, growing its own life there. It became a constant light toward which she could move when she was lost. She felt that she could see everything clearly as if an unknown veil had just been lifted.

"I think I understand better now," she said to the thief, looking first in his eyes and then at the gun. "But all this money will not get you what you really want." She looked at him deeply, hoping that she was becoming rich before his eyes. Ah danger, she said to herself, you are the gold that wants to spend my life.

The robber was becoming sleepy. In the gun was the weight of his dreams about this moment when it was yet to come. The gun was like the heavy eyelids of someone who wants to sleep but is not allowed.

Ah money, he said to himself, I find little bits of you leading to more of you in greater little bits. You are promising endless amounts of yourself but others are coming. They are threatening our treasure together. I cannot pick you up fast enough as you lead into the great, huge quiet that you are. Oh money, please save me, for you are desire, pure desire, that wants only itself.

The gunman could feel his intervals, the spaces in himself, piling up so that he could not be sure of what he would do next. He began to write. His next note said:

Now is the film of my life, the film of my insomnia: an eerie bus ride, a trance in the night, from which I want to step down, whose light keeps me from sleeping. In the streets I will chase the wind-blown letter of love that will change my life. Give me the money, my Sister, so that I can run my hands through its hair.

This is the unfired gun of time, so keep your hands where I can see them and don't go pressing any alarm buttons or I'll blow your head off with it.

Reading, the young woman felt her inner hands grabbing and holding onto this moment of her life.

Ah danger, she said to herself, you are yourself with perfect clarity. Under your lens I know what I want.

The young man and woman stared into each other's eyes forming two paths between them. On one path his life, like little people, walked into her, and on the other hers walked into him. "This money is love," she said to him. "I'll do what you want." She began to put money into the huge satchel he had provided. As she emptied it of money, the bank filled with sleep. Everyone else in the bank slept the untroubled sleep of trees that would never be money. Finally she placed all the money in the bag.

The bank robber and the bank teller left together like hostages of each other. Though it was no longer necessary, he kept the gun on her, for it was becoming like a child between them.

This is what I learned from the art of gardening: the aphid leaves nothing to the leaves, the mole loves to possess by the roots, what you take from the earth you cannot get back. I met a man

in the garden once, he said he was without profession. Yet he was always giving advice: plant onions by the cabbage, don't sow the seeds too deep in the ground. In time he invited himself into my house, planted his feet next to mine, shoveled his tongue between my lips. At first I tried to ignore him, I asked him to leave. But something was growing between us: on days he did not come I became impatient with myself, I tore the marigolds up with the weeds. Insects were eating the tomatoes from the inside, I did not know how to save them. It turned out I needed his advice. It was months before he asked me for money, still later before he moved into my bed. Making love, he had the tongue of a chameleon, and afterward the voice of a cricket. He had an aversion to the personal: when I asked him how long he would stay, he said, "I will not leave you. I am a perennial, if I leave I'll come back-like the wild asparagus, I'll pop up where you least expect." I don't know how many times I threatened to leave him, but leaving him would mean leaving my own house, everything I owned.

He never thought me attractive: he loved to tell me how pale I looked, how I did not eat the proper foods. He'd laugh and say no one else would have me. In the winter, he would not see me at all. And in the spring, when the squash and spinach began to sprout, he wrote me letters from some place distant, told me to water every day and dust the tomatoes, make sure the men in my life would take care of me and get plenty of sun. But when the garden began to bear its full weight, I felt too weak to weed myself, I let the broccoli go to flower, I let everything else go to waste.

Ira Sadoff: The romance of the restless

Power that is not used is power abused.-Egil Krogh If you think that only men are studs, you're sadly mistaken. I've walked into bars, ordered myself a drink, harassed the man next to me, the short one with the glasses; I've rubbed my hand against his thigh. At first he was frightened and tried to pull away; he said he was married, he was waiting for someone who was on her way. I told him I'd slept with men lots uglier than he was, 27

that's how much I'd been around. If he were married, so much the better: fewer complications. Then, after I put my arm around him, made small circles in his ear with my tongue, got him all hot and bothered, I excused myself to go to the ladies' room and sneaked out the back door, never to come back.

At parties I can be very aggressive: I walk up to the handsomest man and strike up a conversation. If he wants to talk deep, the way most men think they do, I can talk deep. I can mention Kierkegaard, de Mandiargues, Wilhelm Reich, or Otto Rank. I can tell him my psychological problems, just to let him know I can be vulnerable. I tell him, "I'm just waiting for the man who can make me enjoy it." If he wants small talk, that's also in my repertoire; I can tell by his eyes when he's getting bored and that's when I rub my breast against his shoulder. I know everything about multiple orgasms, the size of men's organs. I can be cruel and I can be kind: whichever serves my purpose. If it was difficult at first, I'd just watch men in action, I could smell them a mile away. Their routines were like vaudeville acts at an underground nightclub, like men who still wear love beads and say, "Yeah man." I only wish I'd been in the war or could handle myself in a brawl. And as for those who think I secretly hate myself and can't look into a mirror, they're the ones who don't get much, who think the bedroom's for sleeping. To tell you the truth, if it weren't for the boredom, for the nonsense I have to put up with to get what I want, I'd have thought I was born into paradise, the place where everyone sits around without clothes, touching themselves, waiting for something to happen, hoping it won't.

We are sitting here Mrs. Capon the Capon's wife and I normally calmly talking as if nothing out of the most absolutely ordinary was going down. The tape recorder is getting it all this is it the last interview. So this is it the last time the Capon's wife says dismally. Everything is swirling around the whole thing is going down the tape recorder spins on the table. Till the next time I say some laugh some consolation so what if the venom effect so

what if it never ends if it's all the rest that's used up. The next time it will be the same Panama City 1938 Panama City on location all the time 1938 it's all that's left. Sitting there like that she is decidedly attractive sexy the feeling comes over me it is important to fuck the Capon's wife.

Let us not speak of minerals she says let us talk about history. Yes I agree it would be good to talk about history. Even though the tape is erasing all the time it is going down. But what do you call yourself como se llama one or the other it's all the same she says she smiles a trifle coquettish. Her face is something of a cross between Jeanette MacDonald and Eva Braun and it is making me horny for some reason I have this feeling I can't go on without fucking her. They call me the Hip Flask I say I am aching to put it to her. It is increasingly difficult to concentrate on the interview. Want a taste I say pulling it out the flask from my pocket and offering a swig of fly venom she takes it.

You know the last few years were terrible for him those dreadful vulgar impersonations she is saying I am supposed to be interviewing her about the Singing Capon. In rich sonorous voice she is explaining their life in 1938 her breasts are large and heavy larger and heavier than they were 15 seconds ago we are growing larger and heavier together you see she says he was a great man. My Gringo she says her eyes are closed and she is rocking back and forth. Am I my Gringo I ask myself am I.

In fact there were no Gringos in 1938. Not before time flies anyway. Time flies were discovered in 1971 venom produced commercially in 1973. Almost simultaneously in early 1974 the movies invented Gringos. Then they invented Nelson Eddy and a whole line of so-called two-timers. John F. Kennedy Abraham Lincoln Adolf Hitler and Mao Tse-tung all were invented after Gringos. The movies were invented in 1972.

The Capon's wife is making my head spin. There is nobody who doesn't want to fuck her. The same way everybody is dying to get inside Jackie Kennedy or the Lady in Red. Like I used to want to fuck Mrs. Neil Armstrong so I could close my eyes and come inside her like the prick that walked on the moon. The face is a cross between Jean Harlow and Hitler's mistress and it is driving me crazy.

In 1964 Einstein discovered television and later that year 29

Edward R. Murrow invented history. The moon was invented in 1962. President Willkie outlawed television and the movies assassinated him in 1973. Margaret Mead became the first woman President and sponsored the development of artificial fly venom. Just once I keep thinking if I could just fuck you once.

I try to imagine them living together the Singing Capon and this woman but the image will not work my mind draws a blank. The fact is she is a biddy a crone she could be 100 more maybe so what is it I want from her. And suddenly I understand it everybody wants a piece of history the room is spinning all around us even to him she was the Capon's wife even to him. To make a long story short she pulls me to her you don't want to fuck me she says my Gringo my Gringo even to her she wants it too as we tumble onto the rug.

I am as much with the Capon as with her I think as I feel myself sliding into her yes she gasps yes yes. Whispering in my ear she is Madame Nhu and Hedy Lamar and Carole Lombard. It is remarkable the way the venom works the bloating effect of time has had a firming effect the breasts are hard just this once I stammer the room is spinning faster we are grinding it out up and down in time together. We are in time together in time. She and I the Capon Madame Nhu Hedy Lamar Carole Lombard Jean Harlow Jeanette MacDonald Eva Braun John F. Kennedy Abraham Lincoln Adolph Hitler Mao Tse-tung we are all fucking together.

We are almost simultaneous almost superimposed we are moving in and out of each other so quickly it is something like an implosion that works backward outward time it makes me hot she is insatiable again she keeps saying again. I come not once but 6789 times 6789 and she is still not satisfied she will not let up her sighing and moans but history has not been invented yet if only I could pull my prick out.

Leonard Michaels: 3. The words for penis

Francis' older sister, age nine, began to menstruate. He rushed to see my son, his best friend. I heard my son hiss, "What's the symbol for it?" Francis twisted a couple of fingers into an arthritic

design. "Show me another symbol." Francis stuck an index finger through a circle formed by the index finger and thumb of his other hand. Shock flattened my son's face like a slap. He whispered, "Show me more. What's the symbol for shit?" Francis didn't know. They started to wrestle. Francis' plastic luger, in his back pocket, cracked. He went home crying. 1 approached. "Hey, man, you want to talk about something?" He said, "No." 1 said, "How about sex words?" He said, "I know the words for penis-dick, weenie, penis." "Good," 1 said. He shrugged, then studied the floor. I saw that he was proud to know the words for penis. He said, "Dick, weenie, penis, cock, tit." 1 said, "Yeah, good, but ." He said, "I have to go poo."

1. Heathcliff meets Chateaubriand on the golf course, however inadvertently.

Chateaubriand on the golf course, holding his dismembered penis in his hand. "These Americans are clods. They have looks but no charm. They can have only my Ha Ha ha."

An exquisite young woman in white shorts and wife of an Exec that was failing miserably in his practice strokes (in everything) came up converted her golf club into a firearm took aim & shot Chateaubriand dead in the chest right there

She then gave a discourse on St. Francis Xavier. After which "in heat" she licked the dials of the car radio that was playing Spanish music.

"Guttersnipes!" was the last thought of Chateaubriand. This was how the first flowers of May bloomed. And how the First of May got its "red."

2. "Remember," Heathcliff said to Athalee, "this is the way to free oneself for the purity of one's task."

He took her to the cheval mirror & drew her in naked outline there in soap and in ravishment. Then he said, "This woman will remain for eternity."

A little gold airplane from the lost planet of Mou happened to fall just then, off a tree, and as gracefully floated as a leaf to the ground.

Heathcliff was again on his seat on the wind ever traveling toward dream.

In the Supermart the music was first "tested" upon "contented cows." And then it assumed its aphrodisiac quality.

When Heathcliff went into the Supermart he was always a sitting duck because of this. He lackadaisically sat on his funereal barge of the South. And the Queen of Sheba always came up out of the pond with her French restoration fowling piece, tenderly took aim and shot him. Each time she shot him unintentionally he laid a fart and said the word "Dolphin." He made the motions of the Cumaean Dolphin. (With his hands behind his back and his fingers wriggling.)

He became the ace of spades of the Cumaean Night.

There is a house I know, he tells her. It has interested me for a long time. It is eloquent.

I'd like to see it now, she says, for she has begun to think of herself inside a house with this man.

We can go anytime you are ready. The house is always there. Are you sure you want to go now?

Now, she says, so he helps her on with her coat and leads her out into the smoky November night, walks her under a solsticedoomed sky, past amberlit pubs and the smell of coal fires, down bare-branched avenues of expensive terrace houses whose lamplit people can be seen yet can't see them. They go deeper now into an unfamiliar part of the city she thought she knew so well and come at last to a somber avenue which reverberates with the faint sound of smothered trains.

Soon now, he says softly, watching her attend with eagerness the stately houses.

This one? This? Which one is it? They are all fine houses, not elegant; they are highborn dowagers groomed but past their prime. Just down here, he says, gently pressing her on.

And then: that one. There. The one just like its neighbors on either side. The one between the two.

She stands beside him, her head just breaking the ridge of his shoulder. She's chilled but alert as she looks at his house and wonders what it means. She knows he is watching her, waiting for her to respond, and she wants to say the right thing. Again a train passes, underground beneath her feet. She waits for the noise to diminish and then says, I like the house, of course it is the same as the ones on either side, yet somehow it's also different.

How different? he asks, looking at her with interest.

She looks at the gray two-storied house, white molding under each tall window, dark door with polished brass knocker, manicured hedge on either side of a moon-pale walk. I don't know, she says, it has a feeling about it that the others don't have.

Go close, he says, and see if you can define that feeling. Go up to the door.

What if someone comes? Will you go with me? It's true, there are no lights in the house, but still

You go, I'll wait here, he says, and laughing a little he urges her forward, practically pushes her up the walk towards the silent house.

She goes by herself up that interminable aisle of a walk, feeling more alone than ever before in her life. He's behind her on the street, but only in the same way the streetlamp, clawed by blowing bare branches, is behind her, and when she at last stands uncertainly before the door she actually leaps inside her body she so expects that dark door to be flung open and someone, something, to shrill: WHAT ARE YOU DOING HERE!

But nobody comes, though they may be watching her, and she gathers courage, reaches out and touches with her fingers the brass knocker, presses her whole palm against the wood of the door. She listens, hears nothing but the sound of trains, turns back to look at him who is only a shadow in an overcoat on the street.

Now she puts her ear to the door, her eye to the keyhole, hears, sees nothing, tramps through the grass behind the neat hedge and peers shamelessly into one dark window, then another. Nothing. The curtains are drawn tight behind the glass panes, but she knows suddenly not from them, from the quality of the air itself? from the endless patience of her guide waiting out there on the street for her to know, that there is nobody available in that house. Angered, yet vitalized, she runs back, knocks boldly at the door, rattles the brass knocker, kicks the door, the molding, and the bland gray walls on either side, then tries the knob which doesn't turn at all. She goes back down the walk quicker than light, confronts the man who is smiling broadly now, and says: I know. But I want you to show me.

He leads her to the end of that street, turns her left at the corner. Down another short street, then left again into the street behind his house. The street becomes a bridge, with a high wall on its left side, just where they could have the best view of the back of his house. I'll have to lift you, he says, and she stands in front of him, her back to him, and with a leap helps him hoist her to a hold on top of the wall.

Tell me, says he, what you see.

I see the backs of-two houses, she says, and blackness in between. Directly beneath that blackness is a tunnel. In a minute a train will roar through the tunnel, between those two houses and under the facade.

And sure enough it does. She makes him keep holding her up that wall, the toes of her good shoes digging into the concrete, so she can savor to the dregs the destruction of her illusion. The black train hurtles from its hole, its lighted cubicles framing transient commuters bound for their respective stations. Her own walls shake and only the man's hands are impersonal, firm. Afterwards is the silence, black as the tomb, vastly, dreadfully generative.

He lifts her down. They walk back towards her city which will never be the same. His steps are the same as always. She feels cold, wise, lonely, old and clean. Why? she asks, not him but the blackness.

I didn't build it, he replies.

Ian MacMillan: Berlin, 1945

Hungerford sees him in there, sitting with his back against a wooden icebox under a section of corrugated roof. "Sind Sie Amerikaner oder Russe?'

"Out," Hungerford says, "uh, 'raus, schnell."

"Amerikaner-gut." He comes out. Still fat, Hungerford sees, bald, thin little mustache. The German bows slightly, squinting in the light. He looks around, sees their other refugee, an ancient man in a black suit made gray by plaster dust. The two Germans seem to recognize each other.

Kelly still looks down at the girl, who is untouched except for something which has nearly cut her in half at the waist. "Really looks a lot like Hayworth," Kelly says. "Ole Rita up and down."

The fat German looks at the blackened shells of the buildings, his eyes watering. "So viele," he says. "Es ist schlecht, schlecht." Up along the gutter are more corpses, pushed out of the way so that the trucks could pass.

"Hey Danny?" Kelly says. "Don't you think so? Like Hayworth?" The old German looks at the girl, and at the fat man.

"Hey Danny?" Kelly says.

"Sure," Hungerford says, "up and down."

The old German looks at the other bodies along the road. He becomes angry. He stumbles toward Hungerford and the fat one, gathering up his anger, and spits into the face of his countryman, who flushes and looks with shock at the aged face. The old man nods and turns away, muttering.

"What got into him?" Kelly says.

Hungerford shrugs and leads the fat German away. Wiping the spit from his face the German says, "Schlecht." He has trouble seeing where he places his feet. The soft wind moves the hair on the girl's forehead.

Irmhild Stauffer walks down the dusty Messinghausen street lugging in her right hand the heavy container of milk, seeing by her shadow that her body is offset by its weight, and it seems to her that she has passed the entire war listening to her own footfalls. Only once did she see troops passing. And to where? She could not remember the direction. Brilon, to the north, where nothing of any value could be contested? Niedermarsburg to the south, where nothing of any value existed either? So went the first war too. Her husband, children, all had gone off, the men to die in both, wars, and her daughter doubtless to a more sinful end in Duisburg. She walks against the direction of the current of the stream which runs along the rail tracks, through the gorge from Brilon. She sees the little crowd coming in her direction, pointing down at the water, the men talking, the women covering their faces and retreating to the other side of the road. Some object in the water draws them along, makes the crowd increase in size as it approaches her. Old Mueller, who forty years ago was almost her lover, maintains his stern gait in the effort of walking so fast, and gestures at the sky with his cane.

She puts the can down. The object, she sees now, is an arm, with a military sleeve tightly containing it, with a bloated hand traveling always palm up, whirling slowly in the gentle eddies like a small ship in a sea storm. She stands still and lets the crowd pass, streaming by her. Mueller's cane brushes against her skirt. They continue on, discussing the bloated arm as it goes on its southward journey. She picks up the can and continues toward her house. When she reaches it, aching from the effort, she stands on the porch and watches the crowd, which is nearly twice the size of the one which briefly engulfed her a minute ago. It follows the arm out the other end of town. She leaves the milk on the porch and goes into the house to look one by one, and with close attention, at the many photographs of her husband and sons.

Eugene K. Garber: Mannikin

Eugene K. Garber: Mannikin

Childhood, boyhood, youth I spent with my wealthy widowed mother in Taloosa. Now I live alone in the French Quarter, a quaint dapper little man. Nearby I hear the cocking of Father Levantine's high hom. This is the legend: that his trumpet has a fourth stop which on the precipice of perilous lyric he presses, that a drop of magic liquid slides into his mouth from which then issues such suaveness that the musiferous air floats trumpeter and listener alike in honeyed flight, that this is a concoction of his black mother witch now dead, that the final drops curl in a highshelved green bottle like a restive serpent, that when he has supped the last drop he will plunge down from his high horn as from the tower perilous.

Applesauce made by slow scraping of a spoon on the peeled flesh of the fruit, and fed tiny mound by mound from finger to tongue until there was only a blind mouth glutted with slaverous sauce, cooing and cocking. Until black seeds glistened on the bare core like windowlets upon a cavernous interior, which frightened me because I thought they might burst and jet black. My mother wiped my mouth. "You quaint little boy."

In the June garden behind the house of Ted Strand, prince of mischief, Aunt Cora hung wash and sang of troubles. Inside, Viola Strand, rich Yankee grass widow, priestess of afternoon cigarettes and sherry, led my mother through the antics of many men. (As once years later a delicately lascivious guide, inverse Ariadne, led mother and son down the crooked lanes of Pompeii, showed above cribs dim positional murals, and finally revealed triumphantly the famous Priapus, keeper of erect pride under centuries of volcanic dust. And what had they guessed, man and statue smiling identically?) In the greenhouse I, too, received instruction, stationed behind a vined trellis to witness the visit of Angie, Aunt Cora's twelve-year-old niece. Earlier Ted had furnished preparatory emblems: in a fine-meshed cage a big black snake under whose lassitudinous eye a white mouse happily nibbled small grain. "What's he waiting for?" I had asked. "For his juices to get going." So I witnessed from my leafy covert Ted's dramatic reversal-black mouse engorging white snake. Should 37

I have stoppered ears to which came such a rich slaverous yeasting that I almost fainted in that green bower?

This was the grandest mischief, to climb the water tower at dusk when it began to float like an aluminum moon tethered to the dark hill by cables of serpentine scintillance. On the flank of the dome were four huge characters painted in black: sncr. This was the legend: that a mad black boy mounted the tower at night intending to inscribe a giant obscenity on the face of the white world, that he plunged to his death, that the town elders preserved the inscription as a monument to black folly and ignorance. From the high catwalk I saw the brightening town pulse like a phosphorescent sea monster sucking up hapless fingerlings. Waiting for me at the foot of the ladder was the one who had dared and promised. "Did you let go?" "Yes." And I had, on the catwalk, until I saw the hill coil to spring at me. "How many seconds?" "Seven." So she pressed her lips over mine for seven seconds. Her tongue shot into my mouth, curled and searched until I gasped. She laughed and ran away. That night I dreamed about a thing my mother had told me. Any unfortunate black child, she said, who had a tapeworm was starved for a time. Then his tongue was tied and he was strapped down with his mouth next to a bowl of milk. The white worm crawled up his throat and was destroyed. I dreamed that the huge black sncr was the sound that came from the choking child. I awoke and vomited copiously.

So I have been choked by white worms, envenomed by black snakes, have plunged down from towers, a veritable chapbook of execrable emblems, and yet still live, albeit a quaint man. Yesterday I finished another's book, about an innocent old Jew all of whose latter days were empurpled by the pursuit of a black prince with a huge penis. I give you, old Jew, a kind smile, my hand. Come. We will go to Father Levantine's. From the singing horn we will sup the black mother witch's magic potion, surcease from this serpent world.

David Ohle: The boy scout

David Ohle: The boy scout