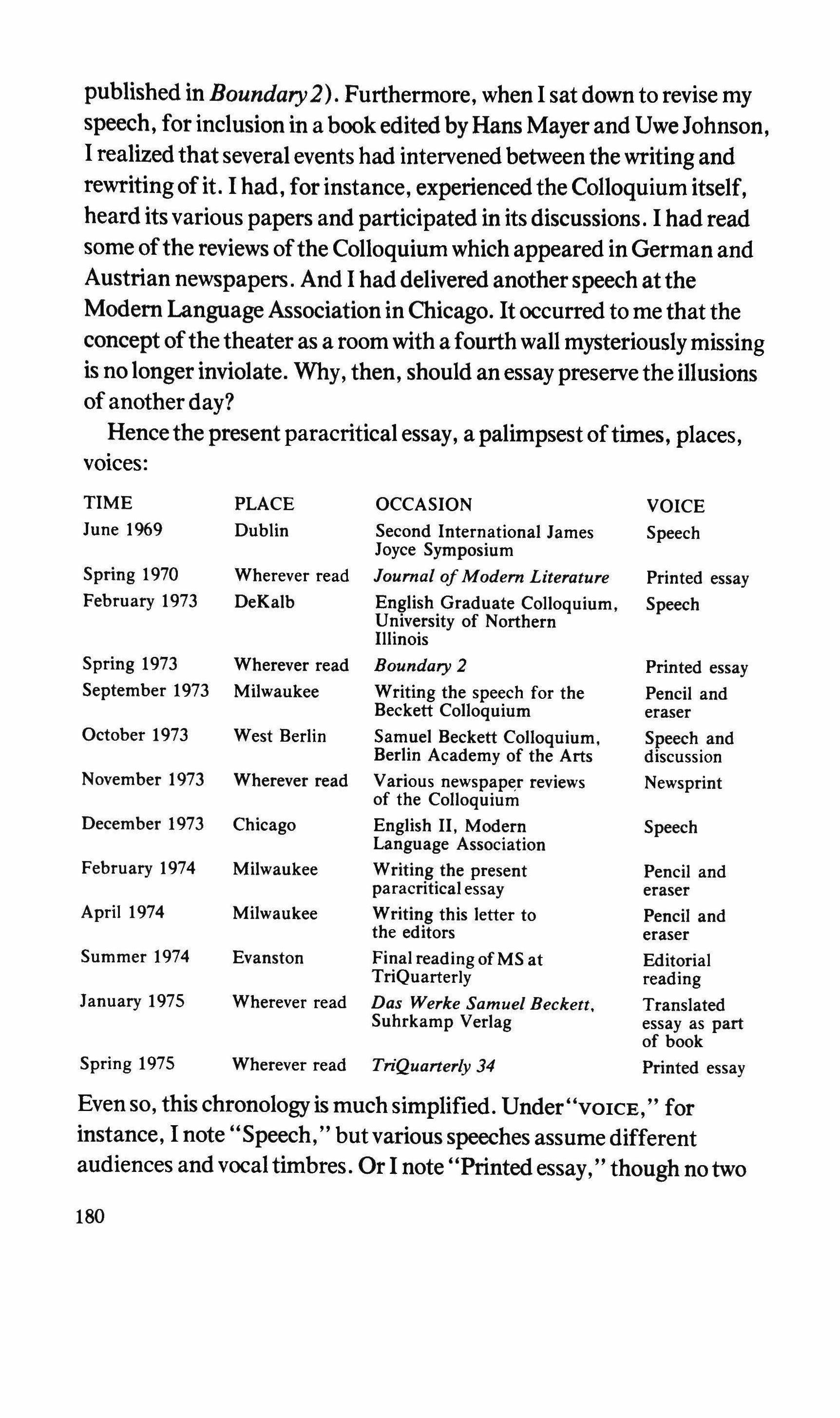

1 t I 1111

EDITOR Elliott Anderson

ART DIRECTOR ..•..•..••.. Lawrence Levy

MANAGING EDITOR .....•..• Theresa Maylone

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

ASSISTANT EDITORS

ADVISORY EDITORS

PRODUCTION

FULFll.LMENT .•...........

Michael McDonnell

Allan Gray

Lisa Freeman

George Mundstock

Debby Silverman

Mary Elinore Smith

Gerald Graff

Peter Michelson

Robert Onopa

Cynthia Anderson

MaryMargaret Zakrasek

TriQuarterly is an international journal of arts, letters, and opinion published in the fall, winter, and spring at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60201. Subscription rates: One year $10.00; two years $15.00; three years $20.00. Foreign subscriptions $1.00 per year additional. Single copies usually $3.SO. Back issue prices on request. Contributions, correspondence, and SUbscriptions should be addressed to TriQuartel'ly, University Hall 101, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60201. The editors invite submissions, but queries are strongly suggested. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuartel'ly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1975 by TriQuartel'ly. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America. Claims for missing numbers will be honored only within the four-month period after month of issue.

NATIONAL DISTRIBUTOR TO RETAIL TRADE: B. DEBOER, 188 mGH STREET, NUTLEY, NEW JERSEY 07110. DISTRIBUTOR FOR WEST COAST RETAIL TRADE: BOOK PEOPLE, 2940 7TH STREET, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA 94710. DISTRIBUTOR FOR GREAT BRITAIN AND EUROPE: B. F. STEVENS &: BROWN, LTD., ARDON HOUSE, MILL LANE, GODALMING, SURREY, ENGLAND.

REPRINTS OF BACK ISSUES OF TriQuarterly ARE NOW AVAILABLE IN FULL FORMAT FROM KRAUS REPRINT COMPANY, ROUTE 100, MILLWOOD, NEW YORK 10546, AND IN MICROFILM FROM UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS, A XEROX COMPANY, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN 48106.

1/ ?'

CHARLES NEWMAN

Wll..LlAM S. WILSON

IAN MCEWAN

RON SUKENICK

GENE Wll..DMAN

ALBERT GUERARD

ANDREI CODRESCU

MICHAEL BENEDIKT

ROBERT CREELEY

RUSSELL BANKS

GILBERT SORRENTINO

NATHANIEL TARN

ffiAB HASSAN

JOSEPH Me ELROY

JEROME KLINKOWITZ

ROBERT SCHOLES

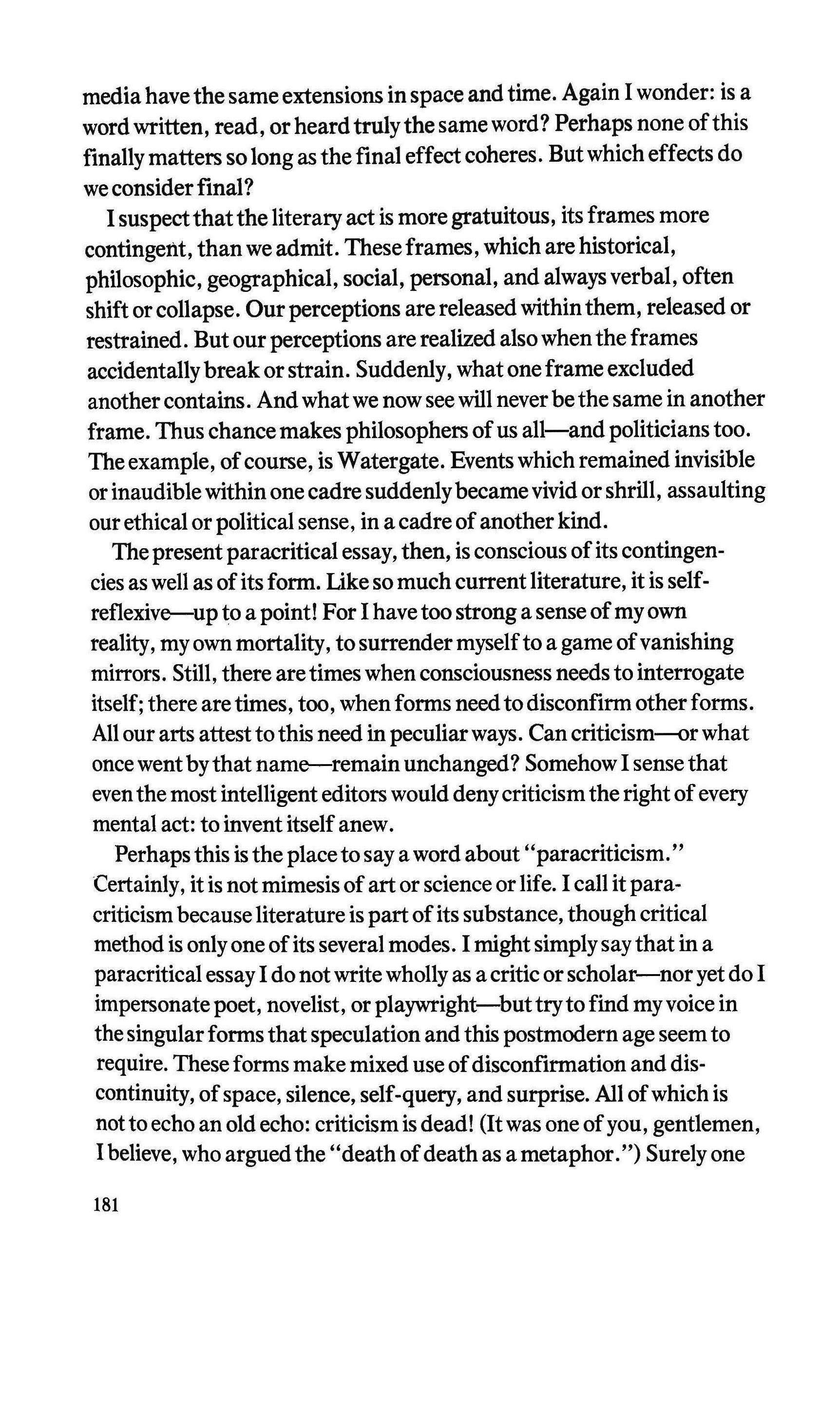

Fiction

A dolphin in the forest, a wild boar on the waves: A requiemforChristmasfuture 5

Desire 58

Intersection 63

The children ofFrankenstein from98.6 87

Miss Clarity and her unfortunate charisma 101 Bon Papa reviendra (suite et fin) 107

The women ofTransylvania 127

Getting a cup ofcoffee at the Orange CountyAirport 128

The queer poets' seance 129

The long opera 129

The wild wild west 130

The nipplewhip 131

Cirrhosis ofthe liver 131 from Mabel: a story 133

Remember me to Camelot from Family Life 139

The notebooks ofAnthony Lamont 146

Perspectives fromLyrics for the bride ofGod 158

Criticism

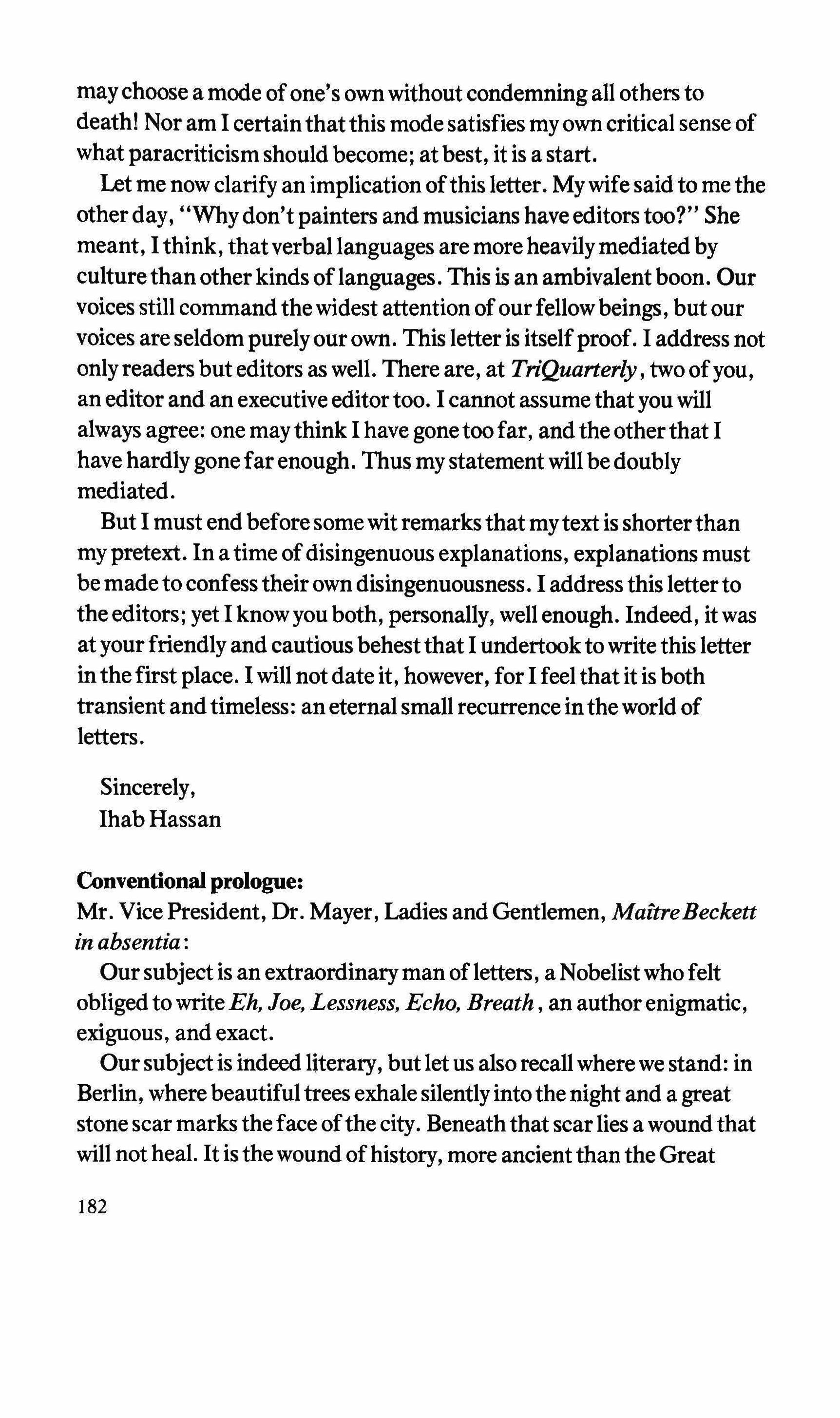

Joyce, Beckett, and the postmodern imagination 179

Neural neighborhoods and other concrete abstracts 201

Michael Stephens' superfiction 219 The fictional criticism ofthe the future 233

This issue ofTriQuarterly was illustratedby WilliamE. Biderbost

With issues33/34, CharlesNewman, Editorandfounderofthisjournal, resigned. He willcontinue to serve in an advisorycapacity.

ElliottAnderson, presentExecutive Editor, assumes editorship.

TheresaMaylone, ManagingEditor, andLawrenceLevy,'ArtDirector, willcontinue to have thingspretty much their own way.

A dolphin in the forest, a wild boar on the waves: A requiemfor Christmasfuture

Charles Newman

We must act as if we were lost, desperate beings - Van Gogh to his brother

We'll start with Moulton. He's mybrother and the important one inthe story, which is also about Mom and Dad and poor bigsister, Rita. I'm known as the genius ofthe family because I rememberwhat everybody else says. But I'm no genius. I never made up a thing in my life; I simply remember andwonder, like most people. Theythink 1'm brilliant because I can repeatwhat they say. Andrecitefor guests, of course. My teachers say I've got a photographic memory, but with all due respect that's a sloppyevaluation, since a camera can'thear. Certainly I can remember whole pages ofwhat theytell me to go read, and whenever anybodytalks, thewords go across my eyes like on a movie screen; so it's seeingwhat you hear and then repeatingitthat I'm reallygood at. Please rememberthatwhat I'm sayingis what other people saidsomething I'veread or heard somewhere-and a lotofthetime I honestlydon't understand itmyself. I'm justthirteen, after all, andjust because I gotstraight A's doesn't mean I knoweverything. Butdon't get me wrongeither. I do love all thosevoices inmyhead. It'sjustthat I don'tlove one more than another. The otherthingto knowis that people think I'm not onlysmart, but cute-and I havethe feelingthat I'm going to payforthat. Everyone I ever knewwho was cute, smart or not, has to.

S TriQuarterly

At any rate, when Moulton came home from college for Christmas this time, he was really sullen. Maybe that's all you reallyhave to know about him. There were some sporadic fires in the city, at leastthere were coils ofsmoke on thehorizon. The airlines were grounded, and Moulton had totake the overnight train, then hitch with a security patrol to the National Guard camp. Moulton has changed a lot since he has been to college, and because Mom and Dad never went away to school, they probablyexaggerate it. But having, as I do, a better memory, as well as less to remember, I think it's fairto saythat nobody can say just how Moulton has changed, and iftheytry, theygetpretty confused. Mom and Dad aren't againstchangeexactly,just any more change in their own lifetimes. And ifyou want to know, I don't blame them one bit.

Moulton always had to work forwhathe got. I don't mean in theway that Mom and Dad did, but he studied five times as long as I ever did for good grades, and made himself into a "competent," as coach says, football player. He was not big or particularlyagile, but was born to a certain leverage, an abilityto anticipate holes beforetheyopen, and in that he could usuallybeat a bigger man. His specialty was blocking extra points. Invariably, Moult could find the hole, breakthrough, and throw himself onto that foot. His fingers are all broken from it, the knuckles bend both ways. But each frottagedfinger can signal one less point for them-and gains these days are always, coach hassaid, a matter of inches! The defense catchinguptothe offense, ifyou need a handle forthe age.

Because of mytalent, my problem, this linotypeofwords slipping across my cute cobalt corneas, I have always divided people intothose who are able to write andthose who should bewritten about. Moulton, forbetter or worse, falls into the lattercategory You and I think more clearly, more demandingly, perhaps, than mybrother; but we think almost exclusively about people like him.

It could be argued that no man has been more generallydisappointing (and none, certainly, more forgiven), but Moulton gained his distinction from givingthe impressionthat he was lost in a world ofhis own making. He alone had no excuse but Providence itself. And no matter how maddeningly self-assured or curiouslyimpotent he might

6

seem at anyone moment, he always retained an almost ethereal balance. That, I suppose, is what our Founding Fathers were getting at in the Declaration when they gave equalweight to the dissonant voices ofjustice andconsanguinity.

When Moultwent away, he was wearing a lovetgreen suitand a yellow tie. His hair was carefullybrushed in front, but stood up inthe back. He was wearinghom-rims, black and amber like a coral snake, which occasionally, when you were talking, he'd remove and poke you. Girls tookthis forvanity, but gradually I saw what he was accomplishing. Not knowingwhether he was near- or far-sighted, you didn't know whether hewanted to see more or less ofyou. He was one up already. Hejust stood there, slouched inwhattheycalled"conceit" and he called "empiricism," beautifullytentative--thepioneer stance--a man who pays lip service to nature but finally stands in awe onlyofhis own will.

But when he came back, his hair was standing on end as if in thefirst moments after electrocution, his glasses were rose-tinted and rimmed with golden wire, he wore an old Prince Albert which he had once refused to wear to a debutantecotillion, its velvet lapels spattered with an undistinguished sauce, a $35 Viyellashirtwhich had been ruined after one washing(explicitlyagainst the instructions on the label, words in a red saddle-stitch which still move across mysomnambular gaze) and Lord, our Dad's old white buckswhich he could never bearto wear, too big for Moulton, naturally, for Dad is verylargeindeed, largerthan life as they say, but I'm afraid unSanforized. Beauty has gone out ofthe world, the poet says, andthe words come to the eye's mind:

The soft tartan will glimmer in the sunlight, but not ifyou wash it.

As I was saying, Moulton was more withdrawn each Christmas he came back: bittersweet, perspicacious, but reluctant to exercise his perfectcontrol. My own theory, havingbeen forcedbycircumstancesto scan much serious literature, was that hisfine preparation had merely begun to lose its dazzle, that his potential had become a cumbersome and slightly ridiculous bearward. He no longerfathomed eitherthe sources or the uses ofhis considerable power. He was becoming more invisible, or rather hazier, bythe day. I shall never have such power, but I will never be so alone.

"What are you goingto do now?" he was frequentlyasked, and this

7

was not simply a paternalistic question. It was asked bybadly acned sailors with whom hehad sat by chance on publictransportation, by girlswith a page boy's hair and functionwho at parties held him by a singlefinger of his hand like a child crossingthe street, bybusinessmen who slipped him their card, invited him to lunch, so that he might resist and confirm their lack ofprejudice. They all had highhopes for him. They all had their investments, had devised strategies for his better knowledge, and very soon, theyinsisted, any minute now, he would go andgetit.

So, as it happened, Moulton was the unacknowledged arbiter, the administrative cement forthe irregularshape of our family, and perhaps Mom and Dad secretlybelieved that hewould take care ofthem properly one day.

I have no further comment on the matter.

Mom and Dad looked up from swabbing out theturkey and rifle, respectively. The air was flecked with beads ofoil. Moulton was stompingaround, cursingsilently. Then he went to the closet, slipped on his parka, flipped me mine, and thumbed me toward the back door.

"Takeyour gun," Dad said.

"Mind thefrostbite, hear!" Mom chorused.

One thing I have always admired about Mom and Dad is thatthey almost never scream for more than five or ten seconds. Moult slung a bandolier ofshells over one shoulder and strapped the .30-.30 across the other. My .32 was where it always was, in my parkapouch with the hand-warmer. The message across myeyes read: Get me out ofthis fucker house!

Out in theback yard, the wind had frozen the snow solid, and we walked upon itwithout sinking. It was so cold and clear thatyou noticed the sun onlywhen you lookedstraight into it. Mere light. The creek was inseparable from theland. That wind had fossiled everything.

We walked down themiddleofthecreektowardthe."Weeds," blitzingthe delicate sewing-machinetracks offey, lighthearted animals. Moult's heavierfeet kicked away more snow than mine, and in his footsteps I could see black water surgingbeneath the ice.

The Weeds are forty acres ofdespoiled copseboundedbythe creek

8

and a piquant railroad cut. We have lived near here all our short, totally recalledlife. The creek is lined with willow, clumps ofhemlock, and wild privet. This latter bush is always brittle from either fierce frost or malarial heat, shattering upon our thornytouch. It grows green and flexible only in ourforty-eight-hour springwhen the creekburgeons and makesthe copse impassable. Because oftheflooding we had always believed it safe fromdevelopment. But it was filled with homes now, longlowhomes oflannon stone and aluminum, sportingwrought-iron trellises, afleurdelis or American eagle on thefrontdoor, and garages with percale curtains inthewindows. It still floods over, nonetheless, and when the husbands come home on either of our springevenings, theirOldsmobiles throw a wake like Pfboats. The doors rise upon an electric signal, the curtained windows enfold and disappear into the roofline, the scarletbrake-lights reveal walls beadedwiththe sweat of the comatose. The housesjut from long,whiskey-darkpuddles-cork tile, bits ofcolloidal forest, and hundreds ofindestructible styrenetoys which spanthe generationsbobbingabout-toys older than mel Theystill have more moneythan we do.

Manyyears ago, once each week, before I could read, armed with ball bats andlengths ofpipe, Moult and I went to tearthe real estate signs down. It was rather stupid, as I remember, theclangingand fumeof sparks as we smashed them down. Thefirst signs were wood; we simply threw them in thecreek. Then theyerected stripsteel; we bentthem double. Finally,they set anodized aluminum poles in concrete; that was when we had to smash themdown.

I am not at all sure what we were up to.

What is certain is that they have relinquished what we would have prevented. The Californiaredwood oozes orangefrom their unmaintained casements. Their yards, slabs ofyellowmud, are inchingtheir way intothecreek. Moonbeams dive beneath rivulets ofmud inthe middle ofthenight. The mud suffers inthesunlightwhere quince once bloomed and wild iris prospered amongstgnarled roots. Through the word SPRING, lean seetheold creek runningto rise, and between the whiteeddies our heavenlydetritus: tires, cans, bricks, bottles, and great stationaryeels oftoilet paper.

The moss hung in thewillows alongthe creek has been cut away, and 9

floodlights installed so that lawns, once glazed white forguestarrivals, are now illumined forthe unprescientprowlerwho shall be blasted from the night.

Nobody outside today. The men are home, yes, all home. From each house, headlights peer out from the curtains; thick smiles of pumpkins, rushingthe season.

Moulton arched a snowball onto a front yard. I remember when he thought. not so long ago at all, that he was betterthan they were. I asked him about this. but he didn't answer. I am beginning to suspect that Moulton thinks too much about his life to think properly at all. Maybe that is his problem. The hardest thingto understand about this world is that nothingis true to the extent that it is widely understood. And I am developing a theory about people like Moulton. It's that everybody normal is born with this ribbon ofwords in their heads like I have, but theystop seeing it after a whilebecause theyworry aboutthemselves too much. Theystop seeingwhat they'relisteningto; sending or receiving. Maybe it's true that peopleget overwhelmed by their "feelings," but all the people I know have been worn out by"long-termplanning," as the President calls it. And I wouldn't have minded Moulton giving up so much; it was the self-important way in whichhe was doingitthat bothered me. The truth is, mister, you have to beloved or hated more than ordinarily to pay attention to that telltale tape. And I havebeen loved a-plenty. I suppose, eventually, it soon dissolves intothe redwebs ofone's eyes, and comes out, ifnot as tears, then as thatyellowstuff in the comer. Orsomewhere else. I don't know.

Whenyou're inthe Weeds at night now, and the headlights crash back fromthe picturewindows, I rememberthe only house I loved as a formerchild-before I learned what thewords meant on my "window to the world," as the newsmen say. It was just a white cement-block shoeboxof a house with windows running all the way around. Thepoorguy had put it up a yearbefore the expressway was built, and theyarched a cloverleaf rightthrough his front yard. Afterthat, everytime a car took a tum, its lights flared up in his living room. You would havethought he'd have thrown up a hedge, gotout, but he never plantedanything and stayed. He must have had a lot on his mind to dothat. He must havejust sat in his living room sippingbrandywith a bigdog at his feet,just leaning on backwith no book or fire, studyingthepatterns oflight

10

sweepingthe wall, and not a little warmed by the glare crackling through his glass.

And I wonderedwhat he did now with no traffic, no snarl and thud and haste and honk, no lights save the blue strobesofthe patrols. I rememberwatching Dad when you could go to work in the city, whenthe expressway hadjust been finished, watchinghimfromtheridge, his big puce car caughtbetween theothersealed and waxen commuters, exhaust fumes rising overthe splattered dogs, asphalt seams smacking, smooching, popping, as they went to get the money before it got too dark.

We're in the silenttrough of some gigantic wave.

We followed the creek until it dodged into a culvert beneath the expressway. Thetraffic was sparse; the orange lightfor generalsecurity was lit. Only an occasional coaltruck, weavingto avoid thepotholes. Pretty soon the old greenZenithwould be plowingalongthe median strip, her upper windows busted out for machine-guns, the bar car filled with monitoringequipment and a complement ofsecuritypatrol.

In thedark oftheculvert, Moulton againstomped and cursed. No ice here, the water coursing over myboots, and light, nothing save light, such blindinglight, at both ends.

As we emerged, Moulton reached back and took myhand, but instead ofcontinuinginto the PopularForest, he turned upthe embankment, backtowardthe expressway. Wecrawledbeneaththe barbwire and jumped the restrainingbarrier. The four lanes were badly buckled and faulted. I looked both ways out of redundanthabit, and then, as my brother againtook me bythe arm, I knewwhat was coming up. Chicken.

Chicken was a game. We had played itwiththe Zenithwhen she was still a commuter.

Moulton led me over thenorthbound restrainingrail and out onto the median strip. His hands were cold as thetracks we knelt over. I gave him one hard look and then laydown. I hadn'tforgotten how. The tape was wet and blurry. I was damned if I would cry. I knewthe rules. Moulton pressed myhead ontotherail and turned my face inthe direction oftheZenith. Then helaydown solemnlybehind.

I tucked myscarfin, the rail was cold, and I could hearthehum of

11

something not such a long way off after all. I wondered about the patrol and iftheymight take a pot-shot at us. I wondered whotheymight be carryingbesides the usual army officers, priests, doctors, and dreary journalists.

The humming became a dull recognizablebeat; then it began to syncopate. I looked down the rail like a rifle barrel and could see a bogglinglight. It was comingfast, this one. Maybe VIPs, or wounded. I was not yet either curious or scared, and this surelydidn't recall our good old times together. The waythings were now, it seemed a little, well, "self-indulgent," as Dad says sometimes, probablytoo often actually, and the othervoices in myhead were fogging over, diving under water and gurglingecholess.

That converted tank of a green streak was closingin, and the rail whanged my cheekbone. Whoevertook his ear offthe rail first was the Chicken, so I reached behind me to grab Moulton. But he was too far, I couldn't reach him.

"Moult," I muttered, but no answer. Bluffing, the son of a bitch. It was mean ofhim to pullthis. I hadn't survived all his pettybullyingfor nothing. So I stayed put, myjawaching, the snow soakingthrough my jeans. The light was in my eyes. I was the smallest ofhis lies. It was like lookingdown through the ocean at an old console TVwith plankton glowingwherethe picture was. It wasn't likeit was when Moulton used to lie on top of me until I gave; it was as ifhe were trying to punish himselfthrough me, his only brother. So I thoughtthen I would really scare the pee out ofhim and liethere right untilthe last moment, until he screamed and screamed.

But onlythe train and me were screaming. And that train wasn't socking on the brakes likeshedid inthe old days. If anything, she was speeding up. I still wasn't scared, mister. But I did feel a little stupid. That rail was shimmyingrightalongtheties now, and thenmylegs were scrambling even though mybrain was welded to thatsteel, and then I saw my cheek was frozen to therail, and I flashed on a newspaper clippingabout a dog that gothistonguefrozento a streetlight in Lebanon, Indiana, andthe wholetown gathered around him, and finally, they cut the streetlightdown and carried thedog and the streetlight, still connected, intothefiredepartment until theythawed. Moult!

The scream didn't come from my mouth. It came out ofmywhole

12

body, and that scared me. The Zenith wasn't twentyyards off now. My head was an inch offthe rail, my cheek skin ripping away, andthen a piece ofthe lower lip. Mytongue was thickwithblood. I had been waitingfor Moulton to be grabbing at me, to be screamingtoo, to be helping me, to be calling me chicken, you'rethe chicken, butthen my bodysaved my brain, popping me offthat steel like a bandageoff a wound, and my ears were full, thewordshad stopped, and I saw the scream as I rolled,

Er, Er, Er, Er, EEEE

And instead ofmylife all over, which, ofcourse, would havebeen so boring, brief, and inconsequential, there was time inthosefewseconds to run through the alphabet a fewtimes, as the carriages clacked monotonouslyalongthetracklets. I kept my eyes closed intheditch, but through theslits I saw the guards' helmeted heads goby me upside down. Theywouldn't waste a bullet on a corpse whenthere might be real trouble ahead. I spit out a lump ofsomething. Still no Moult. I waited untilthesound oftheZenith was gone, and thenthe funnything was I crawled up theembankment to look formyflesh on thetrack, but it was shiny, shiny as a gun barrel, "Clean as a whistle," as Dad says, a phrase which I have never understood.

I put myhand to myface, theonlymanlything to do. I covered one eyetotake my mind offmy bad lip. Andthen, somethinglike a pirate, I looked around forMoult. His tracks crossed the tracks and were headed across the southbound lanes towardthe Popular Forest.

Obviously I shouldhave gone home rightthen and told Mom and Dad, buttheywouldn't believe that my own brother was tryingto bump me off. For one thing, therehad been so much killinglately; easy, unpunished killing, alongwith what Dad calls "unjustified melancholia," that he didn't have to doitto me.

I followed Moult's tracks as they entered the PopularForest. A cut of trees had been taken out for a fire brake. Downthe cut, across ajunk pile ofold radios, the railroad and theexpressway, you could see straightthrough to town. Onthetop ofthebank was a signtellingthe time and theweather. No clock or thermometer, justnumbers changing everyminute with the new time and static cold. It was 10:46 and 9° when we went in.

13

The creek was tangled with dead vines in the forest, slow going. Besides, the cold air caught inyourlungs ifyou wenttoofast, and I needed to breathe easy. I went up to mycrotch in a snowbank and took the occasion to soak my mouth in clean crystal.

Then I saw him, about two hundred yards ahead wherethe bridle pathbegins, but suddenly Moult hit the ground, and I heard the .30-.30 speaktwice. At first I thought he might be goingfor me, and I froze, butthen I saw he'd fired twice and hit the bear in the throat and the nostrils. I had forgotten about the bear, that fine plywoodspringboard bearwith red pants, cowboyhat, and official badge who rears up, trippedby a laserbeam, at all entrances to the PopularForest; his lips are human and in his clawless, white-gloved, three-fingered hands he holds a sign, mulled with buckshot.

BE CONSIDERATE

BE CAREFUL

Moulton was up then, cruising at his old lope, frost trailingfrom his mouth as fromthe exhaust of a sports car. He'd lost some wind at school, but I still had trouble gaining on him.

It was hard going even on thebridle path. Ibroke through the snow into drainage ditches twice; Moult's path almost disappeared. The snow was pocked with pools ofsludge as if a herd offilthy animals had shaken themselves offthere.

I passed a largedriftfromwhich an arm and legprotruded. The sun remained an unlikely ornament inthe wet sky.

I clambered up an embankment, cleared the woods again. Graylinks oflake appeared between the trees. The top-heavyforest slanted toward me. Bristlylocust and splayedpine, stunted from sun bythe larger lumber long gone. I was feelingused up too.

It gotsteeper and slipperier near thebluffs. I was bent over fromthe cold and looking for hidden holes. I keptfoggingmysightwith my own deep breath. Then I heard them. Bells. Not churchlike, but electric. I scrambled up the rocks until I came to a plateau. Beneath the snow you could see theoutline of a softball diamond andthe stakes of a dozen horseshoe pits. A series ofslittrenches had been begun and lined with tanbark and brokencrockery. Moult's trail crossed the infield and ascended a rock garden. The dwarf evergreens had been uprooted and the imported stones piled incairns. Up inthetreetops on the edge ofthe

14

bluffnested an enormous egg. I yelled Moult's name intothewind. For a minute I thought I could hearhim crashingalong above me, butthen thebells blotted out everything. They were comingfrom thatbigegg, I knew. Mylegs ached andmyfeet were soaked. I wanted tobutt a tree in desperation. I was losinginterest as he lost me. I was tired and confused. I dismissedthe eggfrom mymind. The droneofthebells became absorbed intothe natural din oftheforest. Myheartbeat dropped a level and, warm forthe firsttimethatday, the perspiration tricklingdown theliningofmy parka, I headed forthe lake.

Thetrees ceased atthe bluffs, slate abutmentspermittingnothing butwinterlichen. Asimulated birch railinghad been erected bythe State, and I picked myway alongittotheendof a short promontory where there had been a picnic parapet. I pressed my stomach againstthe railing andleaned over the edge. The lake was frozen solid. It stretched away, angular and ribbed like a gull'swing. Atthebeach, deeper currents forced up geysers through thejagged ice. They came up inky, turned green at theirtopmostpoint, and thenfell backinvisible upon theice, amidst therusted turrets ofseveral coast guard chase boats.

Thebluffs were called OconomawakBluffs after an Indian chief, one ofthose Indians wholeapt into space ratherthan submit to our forefathers. They were lookingfortreasure (ourforefathers) and when they didn'tfind it,theydestroyed Oconomawak's village and chased him up here, where hejumped, or so thestorygoes. I don'tthink, myself, it was a very goodplaceto look fortreasure, butwhatever, on theparapetthere is a bronze plaquecommemoratingthe chase, and bearingthewords Lest WeForget. I have never understood exactlywhat it is we are not to forget, butwhatever it is, I wish I could. I have an idea, though, ofwhat wentthroughthe Chief's mind. There had been, from his point ofview, a terriblemisunderstanding. But I can't even imaginewhat went through our forefathers' minds as theychased the Chiefup there. Whateverdidtheythink when, after breakingbreathlesslythrough the foliage at the summit,theyfound no trace of an enemy-only a vast inland sea and the treasures ofthe empire still hypothetical upon the horizon? Nowondertheirportraits are so sullen and severe.

I satdownto wait for Moult. Somewhere downthebluffs the egg was blatant. Out ofbreath on the parapet, Iwondered ifMoult was running

15

away or searchingout. and figuredthat was probably our forefathers' problem too. We never did getthis straight. and now it's too late. Down in the Weeds. I could hear our most recent forefathers opening cans oftunafish and flushingthe oil down theirjohns. I did not want to be alone, not at all. Ijust didn't want to be alone with them. I wanted their fluorescent light offmy eyes. mywalls. But sitting like a stupe on the bluffs was also profitless. It was merelypreferable. And as any foreign person knows. that is not sufficient. I stared at my boots and gazed down at the Weeds. It would serve Moult right ifI showed up all a-whimper at their doors and begged them to organize a search partyfor my poor brother. onlyto find him warm at home whilethey were sloshing around with their guilt and guns. As a matteroffact, maybe those people in the Weeds. ifnot as smart or sensitive as Moult, were braver? They at least were putting up with things, keepingthe porch lights on. It was funny. Moultonstill felt above them yet hated himself at the same time.

Shit. I had begun to run again.

The bells increased their tempo and resonance. And then I found him about a hundred yards intothetrees, gripping a cyclone fence. His arms were stretched out above him, his fingersentangled inthe mesh. He was standing one foot uponthe other, as ifcaught inthemidstof a leap. Then I yelled. but Moult didn't move. I screamed falsetto. Not a flinch. I ran crazily toward him waving my arms. Butit was like he was in a movie and I was in a booklet. The wind burned in my nose and teeth. Slagheaps of ice roots and earth had been bulldozed against the fence. The great egg in thetreetops revolved imperceptiblybut constantly, its booby bells chatteringendlessly. Steam escapedfrom a small hooded funnel. Perhaps in my craze I had lost what Mom and Dad call perspective. I could not even rememberbeingthat close to carelessness before. Distant machinerydroned evenly, wearily, warily, wolverine. There were shouts, I thought, but I could not see what was said. Moulton's head had dropped back; his face impressed withthecrisscross pattern ofthe fence. The skyrolled back above me. I dropped to my knees, and graspingthe network ofsteel in one hand and Moult's calfwith the other, followed his gaze

It rose against theforest like a. like a. an icicle? A steeple? A totem pole? A fountain? A Louisville slugger? A naked ladyfrom a

16

cake? What can thecomparison matter? Ivory, finned, oblique, pert on a khaki crane, rusty, slightly arrested. The bells stopped abruptly, the machineryceased coaxing. Adull shadowmottled thetheradar's egg. It had started out as a secret, then graduallybecame an abstract idea, ifin factthere's any difference. Nobody knewwhattheyreallylooked like, even through the wars, untiltheywent, for some reason, for a brief time, to the moon. I have no idea howold this one was. Olderthan me, certainly, probablyolder than Moult, though not quite so old as Mom and Dad. What I rememberbest is notthe silhouette, which we still had to memorize in our civil defense course, butthat once you could signup for a four-yearhitch, playalotofsoftball and horseshoes, and come up from the underground with a four-yeareducation and a marketable career skill. I wonderwhat happened to those good old boys.

Moult was still gapingceremonially. I was getting more and more disappointed with him.

Therocket had now swung out ofthesilodoors, and it was going

They were automated before I was born and, shortlythereafter, disarmed after never beingused. "Ourholocaust was not collective," as my favorite teacher, Mr. Howe, says.

The governmenthad built ampitheaters around most ofthem, declaringthem national monuments, and ifthetruth betold, Mom and Dad had courted righthere, I think, or maybeit was the one down near thebreakwaterin thecity. Dad said once thatwatchingthem was the onlyfun thing he can remember aboutthattime, althoughtheir discussion since has spoiltmany a supper.

The radar egg revolved on its magnesiumspindles, our fathomer, listeningto everything in order to see, but understanding, remembering nothing. Slivers ofice cascaded down the concrete bunker. I don'tget mad easy, but I was fed up now. I put both arms around Moult's waist and yanked him from thefence. The steel nettingtwangedviolently against its posts. I felthis powerfulthighs contract. He was in whatthey call his prime. Sowhat. Whatdutiful enemycould he now brutalize? The Chiefhad leaptlong ago. And with the secret leverageof a diffident child, I soon had him pointed whereIwanted to go. I steered him from

errrerrrr

17

behind and stepped up the pace. He ran naturally once I got him started. We charged up the path and alongthe slope to the summit. I held fast to his belt so he wouldn't outdistance me again. I ratcheted my elbow against the birch fence to keep us on course. Soon we were back at the parapet, gasping for breath over the edge.

Out in the lake, a convoy of squattankers, bows aflamewith rust, bulled their waythrough the ice toward the reactor. More supplies, And down the shore, the Private Gun Club was in action. A man in a red jacketflung skeet with a hand trap. Another broke them consistently, dottingthe beach below with black and yellowclay. But because ofthe wind there was no report, only a cartoon puff at the end ofthe barrel. I gulped wind to kill the nausea, and Moult sucked too-long,deeper inhalations syncopated with mine. Moult was smirking.

The wind had become stronger, turning our sweat against us, so we left the parapet and returned to the woods, where we sat down at one of the picnic tables bythe defunct horseshoe pits. Moulton cocked the .30-.30 and pushed it butt forward across the table to me. We faced each other, hands on hips, our debate mere clots ofvaporwhich coalesced, then evaporated between us. I refused to take the gun.

Finally, Moulton folded his arms judiciously, elevated his gaze to a pointslightly above myforehead, and with greatsolemnity, put his index finger to his temple, cocked an arch thumb, and fired!

"It's as easy to smile as to scowl," I said, apropos ofnothing, and, withdrawing my curled hand from a parkapouch, forced myfingers into a mock pistol.

We played guns without our guns, but not forverylong. After a while you reach a point, the long, rich arc ofparalysis, when the bells stop ringing and you'vegot to go back to The-Hotel-in-the-Rain. You get tired ofasking, explaining, commiserating, making up sense. Quite frankly, I wished mybrotherdead.

And when somethinglike that happens, so deep, pathetic, and unspoken, pretty soon youjustget up and start walkingagain, not together but merelyproximate, nobodyleading, nobodyfollowing, letting the gaps inthe Popular Forestdecide, the course through a light and swirly snow.

18

Crossing the creek again, we followed it until it skippedthrough another culvert atthe main highway. The underbrush was coiled, twigs thickened with sheaths ofice. The water there was frozen solid but still stank oftankage. Then we took the cloverleafintotown. The sign on top ofthe bank said it was warmer and later than when we started.

We got some broth and bologna out ofthevendingmachine and took our lunch down to the park. In the parkthere was a tremendous rose garden with sixteen canopied trellises radiatingfrom a cupola. In the summer, it used to be that a helicopter would takeyou up for five dollars to get an aerial viewofthe pattern. There are supposed to be over three thousand different varieties ofroses, butthey're all red from up there. Each one, though, has its name written in Latin on a tonguedepressor stuck in at the proper root. We went to the cupola to sit where there would be less wind. The barevines twisted up into a turret, like a bombed cathedral, held up byitsverycracks. Through a hole in the floorboards, I could make out some rusted machinery. It was just possible we were on an old revolving bandstand.

Moult took the rinds offhis bologna. We ate for a while, passingthe soybroth back and forth. Throughthe ashes and snow, a milliontongue depressorspoked their sepulchral heads. A helicopter hovered over us for a while, then headed for some plumes of smoke on the western horizon.

When we finished lunch, a scruffysparrowcrawled intothecupola and toyed with a bolognarind. I peered down each ofthe archways. The arbors were swathed in plasticbunting, makingthe garden seem a machine wired for some immense computation. It was depressing, surrounded by all those names and not a single flower.

And that takes me backto my childhood and the laws ofthings. None of us enjoyed very much being a youngster, I think. That derives from havingparents who had nice childhoods and then a tough row to hoe, so theytend to link us with theirchildhoods ratherthan their adult lives, which no doubt are pretty messy, though it's truetheytryto spare us the details. Theygave up things for us, I guess, as no one will ever give them up again. But when a child is celebrated in such terms, all he can piece togetherlater is howcruel he was. I don't think all theloving in theworld is goingto make anydifference now. As Dad says, often and with a

19

strangeguttural accent, we're goingto have to be very, verysmart to get alongwithout him, implyingthat the future will require more than a sense ofhumor.

I didn't know what to say any more, or even how to stop, look, and listen, so I asked Moult ifhewanted to go over to Rita's and he nodded. And then it was my turn to take his hand.

Our sister Rita lives with the parents ofher husband. They are going to have a baby. I am going to be its uncle. I never visit them if I can help it. I fear for everychild added to this world, exceptional or no.

Drifts alongthe main road were piled high as the mailboxes and packed hard from manyplowings. We salked on topofthem, six feet above the road; our heads in the leafless trees, occasionallystriking a soft spot and goingdown to thecrotch in powdered ice. It was sheer luck that Mrs. Nadler came alongjustthen.

She was waving up at us, lookingbluethrough thetinted windshield ofthe last Cadillac, but smiling-and, boy, was I glad to see herllfthere was anybody leftwho could straighten Moulton out, it was Irma Nadler.

"And where are you going?" shethrobbed, "onthedaybefore Christmas? Do your parents knowyou're out?" Then she guffawed and her neckdisappeared into her shoulders.

Moult, staringdown, managed a lofty wave.

"Come," Mrs. Nadler sangout, "I am breakingthe lawbystopping for hitchhikers, but I will give myfavorite guy a lift."

I clambered downthe bank and Moult followed, scowlinglike a satyr.

As you may have guessed, Mrs. Irma Nadler was our Jew. I don't know whether she considered herselfthat before she came to livewith us, or ratherthe other way around, since Dr. Nadler had boughtthe firstland here when the monasterybegan to reduce its holdings, but now she knew, I guess.

Dr. Nadlerbought out here when it was still a horseradish farm and sold offpiecebypiece. He has four acres left, right inthe center of us, theonly house you can't see fromthe road. He's left all his trees standing and has neither lawn nor guns.

Irma Nadler was the only person inmylifewhom I liked more and more.

20

The last Caddyhad pearl-gray leather upholsteryfolded and stitched in contours likehuman brains. Explosions ofganglia ran throughthe polishedspaces where the Nadlers sat most often. From those, you couldtell that Mrs. Nadlerdrovewhenthey were togetherbecause the death seat was polishedby a tinypointedbehind, which sat very near the window and put all its weight on the armrest, like a puppy, and Mrs. Nadler's behind was not small at all and hardlypointed. She wore her hairpiled on top ofher head like a whetstone, and affected the usual formlessdresses and enormous brooches ofthosewho have learned to celebrate their own creased weight.

Moulton got in back, giving me bad-ass looks. I got up infrontwith Mrs. Nadler. She patted me on theknee and accelerated.

"Sowhere are you going, sonny? It's on my way."

"Going to see our dear sister," I said, "and youknowwhere that is."

"A lotof sufferingthere terrible suffering "

When Mrs. Nadler said "terriblesuffering," it sounded like "table soap-ring," andthat somehow authenticated itfor me.

"It sure makes Mom and Dad sad," I began.

"Theygot used to," shesnapped. "Nowit's foryou to."

Wedrove on in silencefor a while. Moult was fidgetingwith his gun in theback.

Mrs. Nadlertossed her massive head.

"Theworld has becomevery cruel," she said to me in a stage whisper. It was gettingveryuncomfortable inthe car because Mrs. Nadlerhad herfirst-class heater on wideopen.

"Say," I said, "do you mind if I turndown that heat a little?"

"Sure, sonny," she said, "third lever on the left, down and to the right about an inch and a half."

We went on in silence, gettingcooler. I was wonderingifI oughtto be keepingmyhand-warmer and pistol in the same pocket.

Mrs. Nadler swungthe heavy car from the road and banged over a curbingintotheparkinglot ofthePick'N' Save. She glided alongthe sea ofstalled and stripped autos for a goodfive minutes, the engine laboring at lowrpm. Atlast shefound a space and fell upon it. As she gotout, she half-turned tome, speakingsoftly.

"I noticeyou got a gunthere, youngfella. I'm hoping it's not greasing on the car." Then she slammedthe door.

21

We sat in the cooling Cadillac and watched the mothers on the ramp to the supermarket. Mrs. Nadler was slowlygrindingher way up, clingingto the rail, a mauve duck in a shootinggallery. The Pick'N' Save had had its windows shot out so oftentheyhad filled most ofthem in with cement block. Which isjust as well because flies had hatched in thethermopane and keptcrawling up and down the insidethe windows. Theycould never get out to bother anybody, but theystill could drive you crazy. And the stench from theoffal trucks was unimaginable. It was Christmastime, and thefood store shouldn't stink forChristmas. I held my nose and looked up at the Pick'N'Save sign. It was a bigwiener that touched ends, and right inthe curve ofthewiener was a man, and fromwhere I was, thewiener went inhis mouth and came out ofhis behind, and this was the least part ofthis gigantic wiener.

Now the"Jew Canoe," as Dad refers to it, was gettingcold. Mrs. N. had been gone almost half an hour. I didn't likethe look on Moulton's face. I saidwe'd better go get her.

We got out, lockedthe car up, and headed for the ramp. The Pick 'N'Save's doors were still glass and had pinkribbons across them so that customers would not walkthrough them before theyopened.

Most ofthe people inside were guards. Buttherewasn't much left to guard on thedaybefore Christmas. Theemptyproduce counters converged to a singlegleaming dot.

Suddenly Mrs. N. appeared before us, chargingdown an aisle, pretendingshe was goingto run over us with herbasket, thenswerving at the lastmoment, she drew to a stop, clutchingherbreast. She had picked up almost everythingthat was left, and I recall there was a time when Moulton would have called that gauche.

"MyGod, my what a place! It kills me everytime, butIloveit. Sonny, do a favor and get an old woman some grapefruit. I passed itbut I couldn't stop. Then to poor Rita."

Moult and she stalked one anotherwhile I went and gotthe grapefruit, and we met at the checkout counter. I gave the girlthe fruit, but Mrs. Nadlertook one look and snatched them away fromher.

"Not so fast forjust a minute," she snapped. "These are having rinds like cantaloupes. Where'd you findthese, sonny boy?"

"I never bought citrus before," I admitted, with a littlesnarl. The Nadlers always had more money than we did.

22

"Hoo! Never shopping his life. A man!"

We left thefreckled checker girl mulling over our produce as Mrs. Nadlertookthe lead again. She negotiated the corridors crabwise, her spectaclespropped back on herforehead like racinggoggles. When we arrived at thefruit bin, a goodthirty feet long, Mrs. N. flungthe rejects into a comer, and then started feeling over the side like a man searching for a plug in a soapytub. She never looked,justfelt, bringing out perhaps one ofeveryten she handled.

"Looks ruthless, " she grunted, "but it's onlysmart."

Soon she hadtwenty or thirtylined up on the edgeofthebin, ordered bytouch, ascendingin qualityfrom her tothe rear ofthe store. Then she took myhand firmly in hers.

"Nowfeel, young man," she commanded, "everyone."

Wewent downthe row, my hand on thefruit, Mrs. Nadler's on mine, me squeezingthefruitthe same as she squeezed me.

"The thickerthe rind, the less oflife," she pronounced, "you got to feeljuice. Whenitbounces back a littlein your hand, thenyou know that's health!"

We had reached theclimax ofthefruit arrangement; they were gettingjuicier, I could tellthat, and at last, we came upon two or three almost perfect ones, firm and buoyant as I imagine lemons used to bein Spain and figs in othercountries.

"Makethemsay 'yes' to you," she said, and swept them into a sack. Thenshebattedthe rest back. "Ortheywill giveyou rind every time."

We took up our penultimates and marched back to the counter. The checkerette was awaiting us, saggingsarcasticallyagainstthe cash register. It was clear shefoundthewhole choosingbusiness pointless. I could well imagine whatshe would whisper to herpackingpartner as Mrs. Nadler left, and I was ashamed for knowingthis so well. It is clear that we are goingto haveto learn howtobe picky like Irma allover again.

When we gotback to the car, I saw that Moult had splurged on a big cigar. Alreadythe air smelled vaguelyof a stable. While Mrs. N. swatted atthe smoke, I putthe groceries inthe trunk. There were some small bullet holes and some funny-lookingcandelabras inthe back of the last Cadillac.

Then we got in and were off, teeteringalongthedrifted, salt-stained roads, Mrs. Nadler pounding out a rhythm, goingfrom braketo

23

accelerator to passing gearto brake as fromfruit to fruit. We passed through the town, spewingsludge up over the sidewalks, were waved through the barricades, and settled intothe auxiliaryhighwaywhere a convoy ofsupplytrucks flung waves ofoil and ice in our eyes.

"I wonder, " I said aloud but mostlyto myself, "if we shouldjustdrop in. like this. I mean after such a longtime. without warning

"You mean to say," Mrs. Nadlerbroke in, "you wanttomakethem think you didn't really want to see them, butit'sjust an accidentyou're here?"

"Ijust mean," I rejoined, "that if wejustshowup as a matter of curiosity, theymight take it as an insult."

"My God! So you can't be interested in your own family?"

"Nottoomuch no."

Mrs. Nadler repeated my words to herself, bitingthemoff, "not too much I shut and rubbed myeyes, the onlyway I have of resting from thewords; if I rub enough thelymphgoes bloody and blessedlyopaque. But my mouth was running on.

You got to be careful now about howyou care about. ."

"My God. The whole world is now doctors. I'mwonderingsometimes howtheymake a livingoffeach other."

Mrs. Nadler paused, thenflicked her eyes to the rear-viewmirror and gunned into passinggear. "You probably know my husband's a doctor,and you, sonny boy, remind me ofhim. Everynight he comes home from the hospital. 'It's very hard to maintain your objectivityin this profession, Irma,' he says, 'but you got to. You can'tgetyourself involved or your work suffers,' he says. 'Basically I'm a sirnple man. A medical man.' That's what hetells me. ."

"Well, anyway," I insisted, "could you stop sort of up the road from the house? We'll take it fromthere."

"You're hurtingme," shesaid.

"It's gotnothingto dowith you," I pleaded.

"Orthem," she snorted, braked, accelerated.

The auxiliaryhighway was badlyfissured; fragments ofmacadam protruded fromthe drifts. Enormous icicles grazed our top on turns, and the quaintbridges were choked with slush. A pond was fastened to theedge of a dam, where a silent opaquespout arced into a frozenpool

24

below, welded to its sources like a porcelainpitcher handle. Because of thelaw againstcutting inthe Popular Forest, most oftheorchards had been savaged back to rootstock.

Wetookthe hills and potholesindifferently; the heater induced sleep. The radiofaintly intonedthe old-timyfrenetic commuters' music.

Walk right in, sit right down Baby let your hair grow on

Everybody's talkin' bout a new way 0' walkin' Do you wanna lose your mine?

But you couldn't stop Mrs. N.

"I know you wantto do the rightthing. You're tryingto be neutral and that's nice. But maybeyou're hurting more than helping. Did you ever think ofthat?"

We both shrugged.

"Listen. I'mjust a fussyold woman whoshouldn't bother young people "

Moultonyawned audibly.

Listen. People now wantto cure all thetime, forwhat I don't know. It's a terriblething to say, but I'm so verytired ofcuring. You know what I mean? Everybodywants to be a professional. And theywant everybodyelse to be professional too, so theywon't feel guilty, Professional doctors want professional patients and the other waytoo. But you get down in with them and they are all tough like nuts. And then you got to be professionalyourself. To protectyourself. And you're supposed to saythank you forthat. Personally, Ijust like to grab. Butthey cure you ofthat. No promiscuous here. Plan. Plan. Plan. Plan. Plan!"

When Mrs. Nadler finished, I sawjust howuglyand flat the word plan is. Thenshe adjustedthevisor to keep the sun out ofher eyes and went on.

"I know aboutplanning from my Benjamin,boys. He is a wonderful man and husband and doctor, but he shows you still. In theold country, before, Benjamin could have done anything. He had a strong and beautiful head. His parents were rich. The burghers hated his family, but hedidn't care. He was always very gentle. Thenhe gotto planning, or inclinedthat way. He made up his mind in South France in the 2S

••.

middle of a hot summer. They used to go on bicyclingtrips, all the students, and thatyear they went to South France. It was the custom to split up and ride out, each on a differentroad, and then meet back at the innthat night to tell what they had seen and thoughtof in the day. One ofthedays, Benjamin rode out on his road. I don't know ifit was a fine day or not, but at any rate, near noon, he passed a highhedgealong the roadway. He had that urge to look through, my Benjamin's naturallycurious, and sohedid. He saw a beautiful walled garden with a pool right in the middle. Soon a lovelyyoung lady comes with a palette of paints and lays them out on a stone table. Then she goes back in the house and comes out with a big canvas and sets it on the easel. Someone is paintingwaterlilies! And soon, like a dream, comes the fabulous old master, all bent over and fat-what's-his-name! Benjamin said he didn't even mix his paints. They were all ready. Hejustlooked inthe pool, dabbed at the palette, dabbed at the canvas, looked back atthe lilies, putting in the sunlight like nothing at all. Then suddenly, terribly, a cloud came over the sun, and the old man stepped back, shakinghis brush atthe sky, yelling, 'Merde!Merdel'

Mrs. Nadler herselfgrimaced, shouted, shook her fist. Moulton and I were squirminglike kids.

Benjamin ran back to his bicycle and pedaled fastbacktotown. Right then, he said, he knewwhat hewanted to be. a doctor! He didn't even wait to tell his friends. Hetook thefirst train backto Vienna and started in. Now Benjamin tells me that story when we are courting, he tells it to a Belgian architect coming over on the boat, and he tells itto his classes at the medical college, and all the students think it is very beautiful. And you know, I did not understand it at first, or on theboat, and I do not understand now what it has to dowith anything! Except that it is part of a plan, and that men will do anythingto have one. So you can get off right here to sneak up and help yourfamity."

Mrs. Nadler slammed on the brakes, and I pitched forward intothe dashboard. Moult got out and slammed thedoor. I said "Thank you" and"Sorry" and "Goodbye" and"Sorry" again, and stumbled out after him. The last Caddyswiveled artlessly away on the ice. I didn't have the faintest ideawhat she was talkingabout, much less about Benjamin.

26

Waterlilies? The MayorofWho?

Shehad left us on theedgeof an oldtrash pit, which had come to light in one ofthe thaws; our heavenlybottles, cans, andjars had been coated, submerged, and regurgitated. Scavengers had alreadygotten most ofthe good stuff, but I chanced upon a small block ofmarbled ice, and through themilkyglaze a kindly old apronedladylooked back at me. She was cooking. Herlips were parted, she was sayingsomething, thewords frozen in a small balloon near hermouth. "I can't make all thecatsup on theworld, so Ijust makethebestofit," she was saying testily, and I thought I detected a trace ofhysteria inher eyes.

I dropped herto catch up with Moulton. I didn't want himstarting anything. Through a breakin thetrees I could make out an inoperative seesaw, a busted birdbath, and beyond, our destination. It was a nice house, but while itsthree stories remained the oldest, highest in the perimeter area, its striped awnings llOW hungtattered and sodden from theirframes. Their car was up on blocks, the surrounding snow well lubricated.

We approached the kitchen door; an electric fan spun warmth and odor outto us. Bread. There was a treebytheback stoop, its lowerlimbs severed and patched with tar. Strips ofsalt pork had been nailed tothe tree, and a rare cardinal busilygutted one. I could hearthe sow they were fattening, rooting about inthe garage. Theyhad always had less moneythan us.

The door was Dutch, andthe motherofmysister's husband opened thetop of itbefore we knocked. Aforlorn cadaverous cocker spaniel was squirming in her arms. Herhair was red like Rita's and our Mom's, but not so natural. Whatyou might call a flamingo red. But was she glad to see us! I know, becausehers was a veryslowsmile. Ifnot knowing, willing.

"I'mtryingto getthrough on thephone," she said. "Rita and Shel are inthe wreck room hownice to see you. Excuse me just a moment."

Shewaved us in, dropped thedoggie, and hurried away. The spaniel turned to go after her, but his claws did not hold on thelinoleum so he spun staticallyfor some time before pickingupthetrail again. Moulton and I stood in the emptykitchen waitingfor some signal. The basement door was closed. Itwas a new door ofcheap green slash pine, and you

27

could still smell the sap. In the next room, small foldingtables and chairs were set in a circle around the TV for supper. Overthe back of a wingchair I could see thetop ofthe man-of-the-house's head. Smoking. And then I realized I couldn't remember theirlast name.

Rita and our mother, Rose, are very sly and verybrave and, forthose two reasons primarily, very lonely. Theylive in a place which has not yet decided exactly what to dowith them, so inthe interim the people ofthe place have learned to say, "Do anything, it isyour right." They are not lonelybecause ofbeingsly and brave, but rathertheyhaveto be sly so they can avoid" doinganything," and brave as thosewho have so many "rights" must be. Theydon't want to be entitled to everythingbecause they don't want to havedo everything. They, perhaps more than anybodyelse in the world, would like one thing theycould dobetter than anyone else, and have absolutely no rights at all. Both ofthem are redheads.

When Rita was my age, she was just brave. Once we were walking about inthe Popular Forest, and one ofthose fellowsfromthe city, as is still their habit, was waitingfor us. He was sitting on a stumpbythe bridle path, and as we broke intothe sunlight around a tum, hegot up and started toward us. Whenhe was about a hundred yards away, he pulled his hat down over his eyes and opened his fly. Thenhe kept on walking.

I didn't know what to do. I knew he could outrun us, and I didn't want to turn my back on him. But Rita knew. Shejust walked over to the edge ofthe bridle path, picked up a stick, and ran straight at him. She ran as fast as shecould, holdingthe stick more like a baton than a weapon, her dress and red braids flying out behind her. The man stopped shortwhen she was fiftyyards away, and then as she closed the gap, turned and ran, losinghis hat, crashinglike a blind bearin theforest.

Later on, she gotvicious for a time and finallysly, even reasonable. But of course it is high time to be reasonable. We are franklyobsessed with it. After she graduated fromschool, she went offto the cityfor some job. Once in a while I'd get a letterfrom hersaying, "I'm waiting till we fall tobits," or things likethat. She used to send Moultonpoems. He never showed me any. But I stole one once, though I couldn't understand thewords. Itwent (and goes):

28

Death comes. I have come. To kiD my feathered fears And when I die A gift returned unwrapped Pinwheel in small mist

Then, atthe bottom ofthe typescript, in longhand: "Puttingthis in poetry seems tobe an excuse for gettingdown thoughts which are incomplete-butthere's a certain freedom to it. Iforgot to includethe usual grumblingnoises "

And then she got married. Vaguelybut not effortlessly, sort ofsecond nature. But what isthe nature ofsecond nature? Her husband, Sheldon, isn'ttelling.

Now theconception oftheirchild took placethis way. Rita was the daughterofRose. Rose was our mother, and Rose was thewife of our Dad. ThenRitamarried Sheldon, at thetimeofhis graduation, and he had two parents also, Michael and Elizabeth, and Rita was found to be with child. And theywentto live with Michael and Elizabeth.

I saw Rita's scrapbookonce-sneaked, of course. It was made from lumpy orange art paper and hadHIM-NAL written on the cover. It was the storyofher IDMS: photographs, trinkets, letters, corsages, ticket stubs glued to the pages. Another attempt to provecertain unallowable correspondencies. On thelast page was written, IDM OF IDMS, and it was Sheldon.

Sheldon was sensitive. He had become acquaintedwithZen in nonconceptual ways. When Sheldon sulked and was most silent, Rita was most moved. He alwaystalked as ifhe was inthemidstof a blizzard. He was plainlyoftwo minds aboutthis baby. His father, Michael, had a ferocious grinwhichwould have looked better on him ifhe were cool and swarthy. Sheldon is also an artist. Aflutist. Don't ask me why. What Sheldon liked best was to laytheresponsibility forthe war on his dad at dinner. I'm not sure ofwhich war, butthe last I heard Sheldon's dad had the blood of2SO,OOO Brazilians on his hands. Since herconception, Rita has rarelybeen moved, and never byhis silence.

I do not believe any sentence which begins, "Since thebaby" or "Since the war

Sheldon, I almostforgot, was known for his personaldiscoverythat success was rotten. Thesedays, the notion has not a little quaintness. Beingright, it appears, is no consolation, even to Sheldon.

29

Those were all the ideas he had.

I often wonderhow we got in this fix. You know, ifonly someone had just gone up to Christ and said, "Look, youjust listen to me for a minute. This cross isn't for you. Take myword for it. What are you trying to prove anyway? You don't need it, and you're not readyfor it. Maybe ifyou had reallydone somethingto be ashamed of. But notthis time. It's too much for you You want to make yourselfbetterby suffering? Okay. You wantto helpthese sons-of-bitches? Okay. We all do. But I tell you just rememberthe other guywhosuffers, all the time, and thatwill be enough. Get some education first. We'll get organized. We'll go underground. We need you. Don'tyou see that? You can't dothis now. They won't understand. They'll thinkyou were crazy. And some other guywill take uptheball and we'll never see it again. Look. You don'ttie your shoes in a melon patch. Right? Ifyou throw this thingdown right now andheadforthe desert, it'll accomplish much betterwhat you want to do. What we all wantto do. We'll get organized and come back. And you'll be even a greater man than ifyou quit on us now. It's worth a try, don't you think?"

Now, ifthat man had only come along and done hisjob, ifhe could have sold Him, he'd bethe one to celebrate. And I knowthis sounds pretentious-all right, sacrilegious, but I wish I could havebeen there.

Wheelwright, dammit, Wheelwright. That'stheir name! And I started for the basement, Moult in tow.

Mrs. Wheelwright had changed from her housecoat to a pantsuit. Her hair was braided and coiled on top ofherhead.

"Already Christmas and you haven't killed the pig?" I said cheerily. I could feel Moult a-hulked up behind me.

Mrs. Wheelwright seemed embarrassed. "There'll beother Christmases," she said, more mysteriouslythan nicely. "We're having fried egg sandwiches for dinner," she went on "Youstay now. What's Christmas without children?"

"Thanks anyway. Mom and Dad've gotsomethingplanned, I imagine."

Mrs. Wheelwright was thebest cook around, but I wasn't about to get into anythinglike dinnerwiththem.

30

The cocker spun out on the straightaway and crashed into a door jamb. Moulton laughed hugely. Mrs. Wheelwrightopened thewreck room door, and some music came upthe stairs which bewildered us. I searched out Mrs. Wheelwright's unremarkable eyes and she smiled again, a little faster this time. It makes peoplesuspicious eventually, that slow motion grin.

"Rita got a recorderfrom Sheldon forChristmas. She's done nothing elsefor a week."

The musicwelled up fromthebasement. It was "Good King Wenceslas." Slow, cerebral, but good for a beginner. Rita was playing a hymn for her Him of Hims. But her nonchalance frightened me. I looked over my shoulder at Moulton. He had stopped cold, cocked his head. He was licking his lips.

The music persisted, and we stoodbystupidly. Mrs. Wheelwright looked rightthrough us. Thecocker ran a wideningcircle at our feet. Then "Good KingWenceslas" was finished, and she started scales, up and down, gracefully, without a break. They were togetherdown there. She would be sittingcross-legged, performing, and Sheldonwould have his fat head in his hands. The scales expanded an octave, growingshrill at either pole. Mrs. Wheelwright was gettingfidgety. Moult was waiting for me. The musicdidn't stop for a minute. I could not break through that recorder. Whateverit was, escape or warmth, play or protest, I could nottake it. No one said anything. Across myeyes went the thought, Wegot no business here.

But Moulton was alreadypushing me down the stairs, and the door behind us closed to with a rush of compressed air.

Rita and Sheldon were sittingcross-legged on a bigpillow, and when Rita saw us she stopped in the middle of a rise and handed the recorder to Sheldon.

"Well, if it isn't Boy Wonder!" She was almost always shittylike that now.

"How's everythingwith you?" I said.

"What will be, is," Rita said, and got up. I noticedthat thechild had put a nasty little strain on herboyishhips! She was near due. And her face, iffuller, redder, was still beautiful.

"You can't stay for dinner," she whispered. "We've gotbarely enough as it is."

31

"Yourmother-in-law already invited us," I replied rather testily. "Then go eat with them," she flounced. "We don't go upstairs at all. We even have our own entrance now."

The wreck room was the basement ofthe Wheelwrighthouse, but it was another world. Shel and Rita had decorated itthemselves. There was no furniture at all, unless you count the lonelywhite commode in the comer. For chairs they had pigchopsacks, stuffed with buckwheat hulls; their bed frame, a garage door on cementblocks. From the bed her old menagerie ofstuffed animals eyed us warily. The colddamp of the floor was cured by a matting ofnewpaperthick as garden mulch, this in turn covered with straw. The walls were papered with Sheldon's old flute scores and Sundayeditions. So we faced each other, shuffling around the coal stove, us peers, our poorbroke-down family, Rita staring at her tummy, glaring at us. I thanked mystars that I was not that kid to come, and I saw the only reason we were together was that none of us wanted togoupstairs.

Moulton spit on the stove, and it sizzled orange. Rita looked up at him, as she alwaysdid, a pure wave of admiration flecked with envy. In the roseate fire ofthe stove, he was admittedly an incrediblyhandsome man. Ritatook his hand in hers, butspoke to me.

"How's Mom and Dad?"

"Nowthere's a question foryou."

Sheldon still sat half-turned away from us. I don'tthink he knew whether to be confused or angry.

"What'd you getfor Christmas?" Rita asked me.

"You know we don't open until Christmas day."

"Well I gotta recorder."

"So I heard. You and Shel can playduets now."

"Sheldonwon't play any more. He says he's got as good as he's going to get."

"Can't he get anybetter?"

"I'm goodenoughalready," Sheldon sulked.

"Rita, you playsomethingthen."

"You've heardwhat I know, honey. I might never be as good as Sheldon."

"You're betterthan all of us, except Sheldon I began, but then, above us, throughthe rafters, Mrs. Wheelwright's steps could be heard.

32

"I better fix Shel somethingto eat," Rita said immediately. Shetook a greasy pan out from underthe bed, set it on the stove and then went tothewindowsill, retumingwith two brown eggs. She dropped the eggs into the pan, chopping at theyolks with a fork, searing thewhite in a trice. Thenshe broke the mass apart with thefork and, scooping upthe glutinous flakes with a hamburgerbun, handed it in the general direction of Sheldon, who ate it in three not inconsiderable bites.

Bang! went Sheldon's teeth.

"Oneto provokeyou," Rita sang.

Bang!

"Oneto surround you."

Bang!

And one to break your heart!"

Rita caught me staring at her.

"I cooktoo much to be a goodcook," she said. "What happened to your face anyway?"

"Oh, fell."

Moultonhad gone over and flipped on theTV. I did not think I could take anothersplotch of news 'n' sports, the grim statistics which we have somehow outlived. Besides, I needed to crap, and I wasn't about to unload on that open commode. "Love your own best," as the President says.

Upstairsagain, the doorhissed to behind me. I wentto askthe Wheelwrights if I could use theirjohn. Butthey were justabout to eat, and I watched themfrom the hall through louvered doors. It was pretty obvious the orig�al decorofthewreck room had been moved upstairs to theliving room. Everything was so bright and polished it was almost scary. Thejauntyred and gold divan was covered with plastic so the cocker could sit on it, andthe floor was black and white linoleumtile that reflected thefamilybodies as theywalked. It was sort of nautical too, a globe and sailingship on thebookcase, a ship's wheel and captain'schairs, some fishnet and corks over thebar.

The Wheelwrights were watchingthe same news 'n' sports as we were downstairs, and Mrs. Wheelwright was making her famous fried egg sandwiches. She was kneelingbeforethefireplace with her condiments in a small red wagon, whileMr. Wheelwright'sblue pipe smoke turned

33

green inthe light ofthe TV, its statistics batteringlike sleet about his wife atwork.

Shetook a small marrow bone and and banged it gentlywith her little fist, disgorging a gelatinouspellet which liquefiedquickly in the pan. Then while still holdingthe pan above thecoals with herlefthand, the handle of a cuplooped about her rightthumb, with herfour freefingers she broke an egg intothe cup. Then she slid the eggintothe pan, where it congealed in an instant as shebasted it, withoutthefaintest trace of brown. She covered the panwhile she cut twothick slices ofdarkbread, brushing one with mayonnaise, theotherwith marrow and paprika, then slippedthe egg, its yolk now pink, between them. Finally, she added a sliverofhorseradish root, a halfmoon ofpimento, and the sandwich flew like an astonished finch intothechair.

I snuck off, for some reason embarrassed, to theirbathroom.

When I got back downstairs, they had alreadytakenthe pills and were lying around on thefloortogether, oohingand ahhing, earlierthan usual. Sheldon handedthe vial to me, but I refused as I alwaysdid, and Rita mumbled, "think you'rebetterthan us, kid?"

"No, honest, Rita "

"You were always an insufferable arrogant little snot."

"You ought to stopthis stuff at least until you have it," I said.

"I'd get even fatterifI did."

"You'll ruin your goddamtastebuds," I said.

I decided to snuffout the news'n' sports and put on some old videotapes, some history, or what I call" Pre-Me"; it's hard thesedays totrust a memorythat isn'tyours. I didn't care aboutthem takingthat stuff, but Ijust can'thack it. It's worse than TV, beingconked out likethat, and when I am, all Iget is advertisements on my eyes, personalized stuff with my name in computer italics.

Everybodyelse was now unconscious, and I picked out an old tape about howTarzan andJane met. It seems thatJane's parents, due to genteel naivete and general stuffiness, were killed bythe cannibals, and Jane, notyet oldenough to fight fortheempire or plumpenoughfor eating, is abducted. As a result ofbeingfattened up on nativegruel, however, her new charmsbecome apparent, and she is inturn spirited awayby, or soldto, it was never quiteclear, an Arab chieftain, Who'San, whotakes her to hispalacewhere the desert andjungle meet.

34

ThereJane is tenderlyraised bythe ladies ofthe harem, whojust naturallytake to her. Then one day, while swimmingin ajunglepool, she meets Tarzan. (Acrocodile attacks her and he breaks itsjaw.)

Who'San knows all about Tarzan. In fact, there is strongevidence thatthetwo control thejunglebetweenthem, an unspokenpact. Who'San considers him a rival, though Tarzancouldn't care less. That is why Tarzan is so effective. Hecouldn't care less. He takes what's offered, and fightsonlywhen it's necessary. He couldn'tverywelljust look on whileJanegot eatenby a crocodile, forexample, and, as Tolstoi pointed out, such thingshappenrarely. He's never surprisedby anythingbecause he never anticipates anything. He'sjust as loose as a goose and never loses.

At anyrate, Who'San sends out a battalion ofdervishes to get Tarzan, but naturallyTarzanis warned byhis manyanimal friends, and thedervishes are trampledby a premeditatedelephantstampede. GraduallyTarzan comes to realizethat Who'San is outto get him and becomes curious aboutthis strange white girlwhohas upsetthejungle balance ofterror. His fine-featheredlieutenants reportbackthat Who'San is keepingJanehigh in a palace minaret. Tarzan looks up "minaret" and sets off, breaststhe swollen river, and swings up onto the palace balustrade where he overpowersthe fagsentry, flinginghim to thepiranha fish. Nevertheless, hehas miscalculated and swung onto the terrace belowJane-theTerrace oftheTreasure Trove. Hewanders amongthe overflowingcaskets, fondlingcoins andjewelryuncomprehendingly. Suddenlyhe comes across a locketwith cameos ofJane's parents in it, and a lightignites between his eyes. Atthis moment of racial illumination, however, Who'San confronts him and, misunderstandingTarzan's motives, draws his scimitar. Atthat pointJane rushes in, and seeingthelocket in thesavage's hand, a locketshe herselfhas pondered over and fondled inthethepast, shetoo misunderstands Tarzan's motives. Throwingherselfat Who'San'sfeet, shebegs him not to kill JungleBoybecause "JungleBoy can tell me who I am."

Fade-out, wide angleofJungleBoy'sface, which expresses, in its absence of a single crease or tic, "I don't need this"-thevictor driving hencethe Spirit ofVictory.

I stoppedthe storythere and put on a real oldie, a familyseries probably, entitled MacArthurReturns. It starts outwiththis old guywadingashore to some island, his pants

3S

rolled up, and an eagle on his cap that looksjust like his face. Then he is driven around the island all alone, sittingin theback of a jeep in his gold braid and executivesunglasses. The natives are all laughinghysterically, jumping up and down, throwingflowers atthejeep, trying to run out to kiss him and gettingshoved awaybybigblack soldiers who look like Who'San. Then at the end ofthe route, in front ofthebombed-out capital, a little girl is pushedtoward himwith a box of soil andthe seed of a palm tree inherfist. He leans down, the Lof hisbody at rightangles but still at attention, and kisses her a bigsoldier-firm kiss, and she runs awayintothe crowd cryingforjoy.

I flicked that offtoo-for being even more ridiculous thanTarzan. Jesus, what will theytryto pass off on us next?

My peers were stirring now; Rita had rolled beside me. "Playa music, playsomethingnice," sheslurs, and I put a stack ofrecords on the changer.

"Ohh," she exclaims, " Malaguena.' " "Close," I said, " 'Clair de Lune.'

"Ooh," she was going on, "this is ludicrous ." Then she opened her eyes and brightened measurably. "Ludicrouse, lood-i-crush, my word forthe week. Then she flopped back, and with herfeet and fingers tried to tapalongwith Debussy.

I laydown infront ofthecoal stove totake a little nap. Above us I could hearthe hesitantbut all consumingstep ofMrs. Wheelwright, a perfectlycompensatory double limp, and I was goingto goupthere again to see iftheywetereally there; butjustbefore I dropped off, the words beganwhirring across myeyes:

is this the way it is stop is this theway it is

I dreamed Rita and I were walking inthe Popular Forest again, inthe late summer when everything is brittle, readyto catch on fire atthe slightestword, and the skyis a garishprairiepink all evening. Wewalk towherethebridle path ends with cement posts, wanderoff intothe slough, and return unwillingly,shakingwith chills as the skyconforms to night, knowing we have everythingto learn and nothingto lose.

I woke up later to a funnysound. It was startingto darken, andRita was sitting on her haunches brushingherhair with long, deliberate strokes. She was obviously in a racy mood, a sort of Spanish Provincial mood.

36

"Don'tbrusha now, Reet," 1 mumbled.

"It makes my facefeel lighter,"she crept out from under my logic, her grayeyes glowingfromthe corona of red hair.

"You know," she went on, "I think you're veryinsecure in a way."

1 didn't know how to answer that, andjust then Rita's fiery hair fell down over my stomach like a tent.

1 couldn't see what she was doingbut froze when 1 felt her undoing my pants. Rita was always clumsyfor a girl, but now she was so gentle I couldjust feel a thousand little caterpillars on mythighs and tummy, her hairswayingback andforth likethelinden treesjustbefore a storm, and hertonguepart, then all, of me. I was wet in my eyes too, all the words were foggyexcept forfor the easy low errr-er-er-er.

Then some new spurious words appeared, in capitals, IDS POOKE FLOTCHED and thenthewords began to dance to some exciting nonsense, words I didn't knowthe meaningof:

Beneath on earth pompe peJfe prase they pooke Her pat my hart in sick a flocht

I felt I had been droppedgentlyinto a warm and shallow sea, and the ripples from my splash were going out and out toward the horizon; my life was goingout of me, but I was not afraid at all, andthen I thought my back wouldbust as I screamedforjoy.

Moulton and Sheldon were up and groggylikesoldiers at reveille, and Rita was still on herknees, swaying, grinning, herface like a flowerwith petals blown off as I zipped up; I had read aboutthis at an airport newsstand once, and therefore knewwhat to expect, and howit was perfectly natural.

"Boy," she said, "doyour eyes ever go nutty."

I glanced at mytremblingwatch and gavethe sign to Moult to go "See," Rita went on nasally, "you'rejustlike the rest of us after all."

I was feelinggood but pointless. Sheldon was an artist, Moult an intellectual, Rita was pregnant, I was pooke-stupid, and everybody else was upstairs.

Rita escorted us to the landing, where she kissed me on the cheek and whispered in my ear, "Keep it in your knickers, fella."

I almost slipped on the linoleum as Mrs. Wheelwright came out of the

37

living room with her mouthfull. Myknees negotiated a separate peace. I got thetop halfofthe door open, and Mrs. Wheelwright reminded me, muffledly, "It's a Dutchdoor," and I gotthebottom halfopenwith my boot. I looked up at her; she was eating anothercookie and the crumbs stuck to herlips. We stood silently in thedoorway for some timewhile Moulton got his gun. Hertongue was feelingfor a crumb.

"Why are you staring at me, child?" Mrs. Wheelwright said.

"I had a very nice time, ma'am, thankyou," Icaughtmyself. The dog had stoppedfloundering and squinted up at me.

"Anytime," she said.

I concurred, and we headed down the road to the intersection, intent on catching a lift. Mrs. Wheelwrightpicked up the dog and stood in the rectangle ofthe half-light longafter we left, feedingher dyingcocker the remains ofherdessert.

"There has notbeen a fatalityforforty-eightdays," thesignsays fashioned in Olde Englisheexcept forthe numberwhich is handily chalked in. Erect atthe intersection fortheduration, ithas been upto over a hundred, down to zero. When I was little and had more timeto think about suchthings, I wondered whose office it isthatbelieves that o is more terrifyingthan 100; surelythehigherthe orderofaccidentless days, the more imminentthe catastrophe.

We passed the sign, Moult and I, took our timeand temperature from the bank, and, spying no traffic, struck outfor home and dinner. It was 5:28 and 23°.

Back in the Popular Forest, we floundered alongthebridle path, finding our previous tracks nearlyfilled in again. Moult's pants were wadded in frozen wrinkles; his white bucks hadturned black and were turned up at the toes like ajester's. He walked on theedge ofthe path wherethe crust had hardened, gazing at his frozen feet, out intothe trees, andback to his feet. Youcould tell fromthewayhe walked thatit was very painful.

Out ofcold and boredom I began to speculate on mymute brother, whom, ifyou didn't know him as I do, you mightsimplywrite off as a murderous shit. There was something in his forgetfulness, a "cruel indifference" as the old books say, "a menace to society" accordingto

38