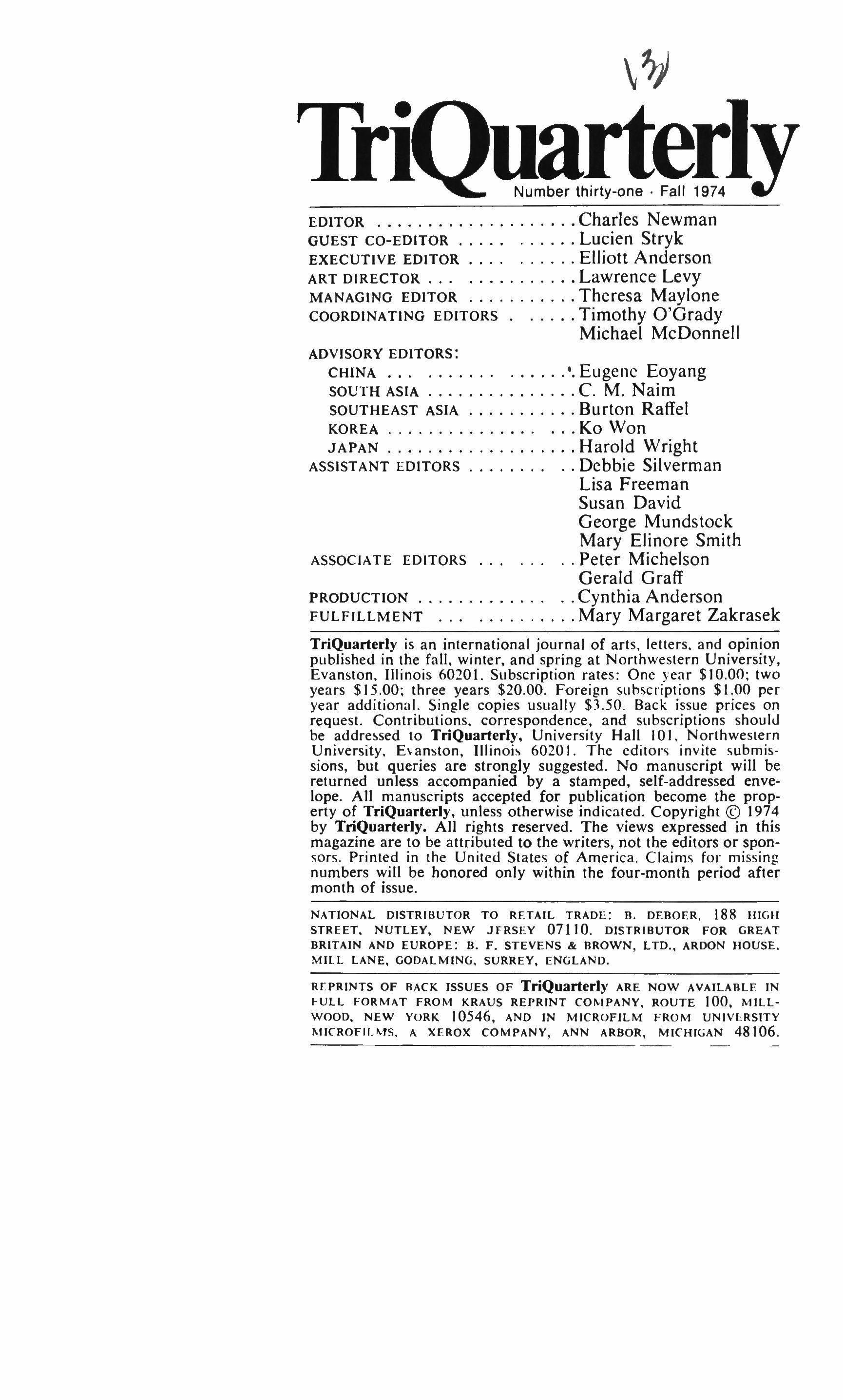

Charles Newman

EDITOR ..••..•..........•••

GUEST CO-EDITOR ....• Lucien Stryk

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

ART DIRECTOR

MANAGING EDITOR

COORDINATING EDITORS

ADVISORY EDITORS:

Elliott Anderson

Lawrence Levy

Theresa Maylone

Timothy O'Grady

Michael McDonnell

CHINA '. Eugene Eoyang

SOUTH ASIA

SOUTHEAST ASIA

KOREA

JAPAN

ASSISTANT EDITORS.

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

PRODUCTION

FULFILLMENT

C. M. Nairn

Burton Raffel

Ko Won

Harold Wright

Debbie Silverman

Lisa Freeman

Susan David

George Mundstock

Mary Elinore Smith

Peter Michelson

Gerald Graff

Cynthia Anderson

Mary Margaret Zakrasek

TriQuarterly is an international journal of arts. letters. and opinion published in the fall. winter, and spring at Northwestern University, Evanston. Illinois 60201. Subscription rates: One year $10.00; two years $15.00; three years $20.00. Foreign subscriptions $],00 per year additional. Single copies usually $3.50. Back issue prices on request. Contributions. correspondence. and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly, University Hall 101. Northwestern University. E\ anston, Illinois 6020 I. The editors invite submissions, but queries are strongly suggested. No manuscript will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1974 by TriQuarterly. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America. Claims for missing numbers will be honored only within the four-month period after month of issue.

NATIONAL DISTRIBUTOR TO RETAIL TRADE: B. DEBOER. 188 HIGH STREET. NUTLEY. NEW JFRSEY 07110. DISTRIBUTOR FOR GREAT BRITAIN AND EUROPE: B. F. STEVENS & BROWN, LTD ARDON nOUSE. MII.L LANE, GODALMING. SURREY, ENGLAND.

R[PRINTS OF RACK ISSUES OF TriQuarterly ARE NOW AVAILABLE IN �ULL FORMAT FROM KRAUS REPRINT COMPANY. ROUTE 100, MILLWOOD. NEW YORK 10546, AND IN MICROFILM FROM UNIV[,RSITY MICROFIL"S. A XEROX COMPANY, ANN ARBOR. MICHIGAN 48106.

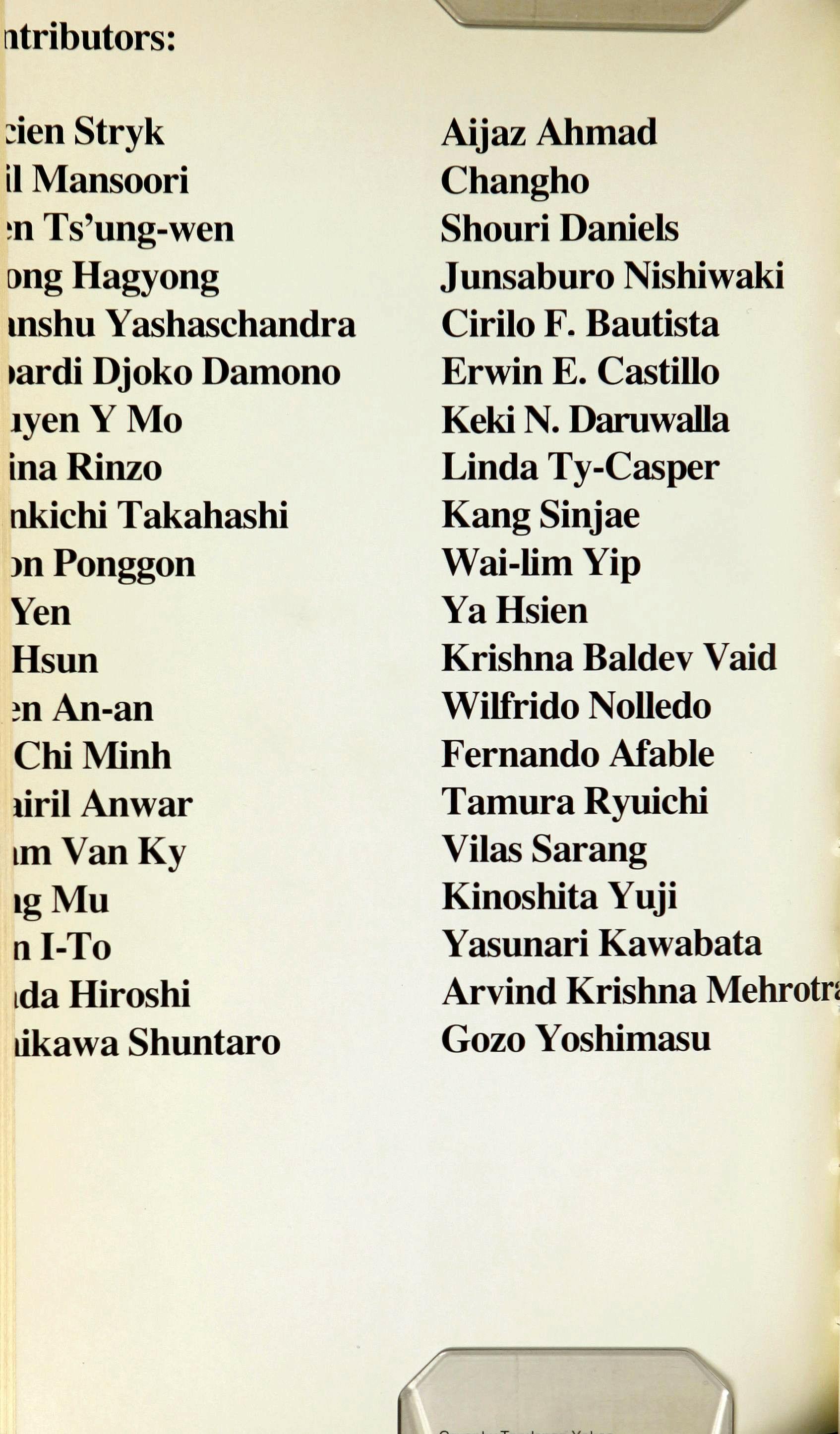

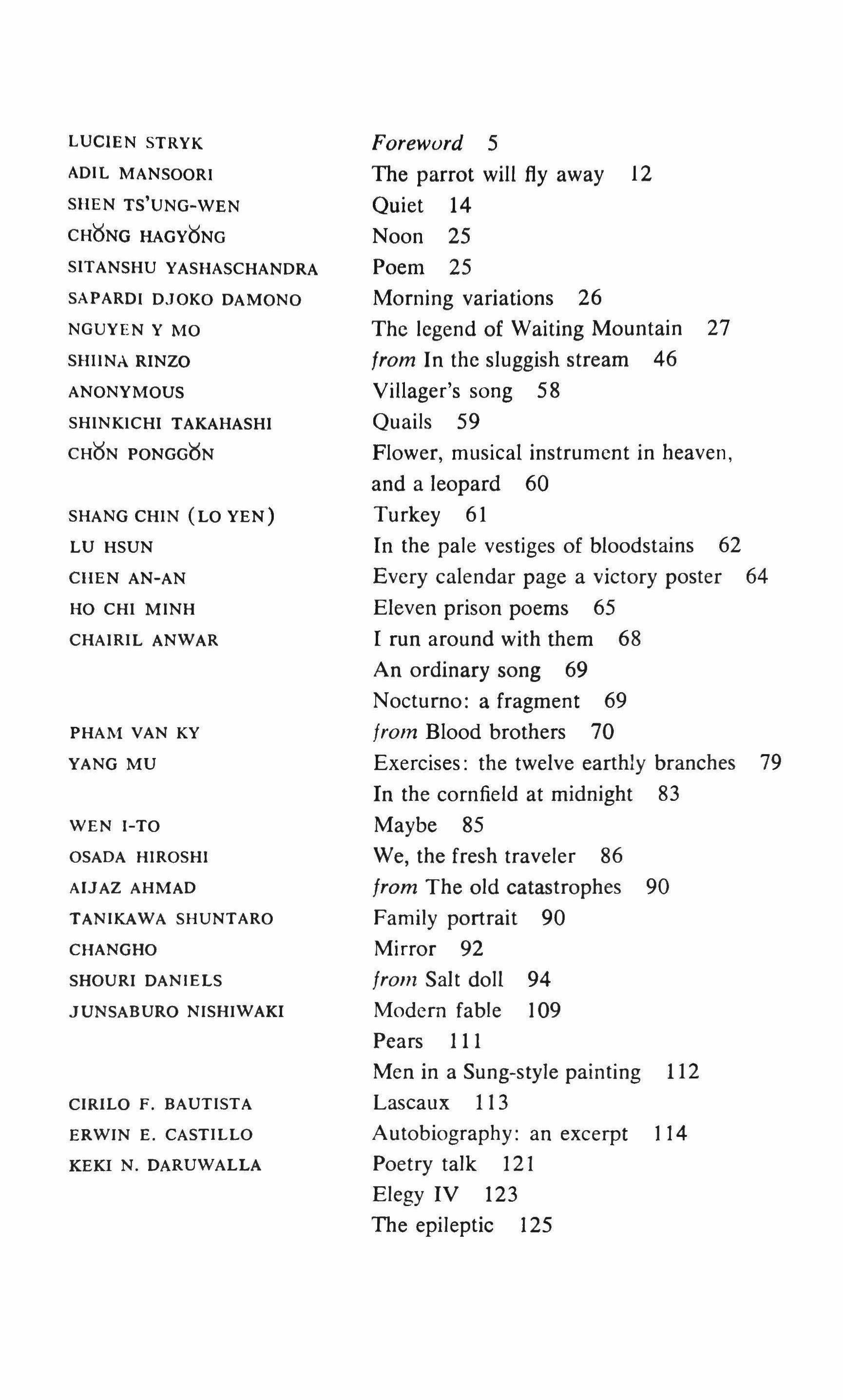

LUCIEN STRYK

ADIL MANSOORI

SHEN TS'UNG-WEN

CH�NG HAGY(:)NG

SITANSHU YASHASCHANDRA

SA PARDI DJOKO DAMONO

NGUYEN Y MO

SHIINA RINZO ANONYMOUS

SHINKICHI TAKAHASHI

CH�N PONGG�N

SHANG CHIN (LO YEN)

LU HSUN

CIlEN AN-AN

HO CHI MINH

CHAIRIL ANWAR

PHAM VAN KY

YANG MU

WEN I-TO

OSADA HIROSHI

AIJAZ AHMAD

TANIKAWA SHUNTARO

CHANGHO

SHOURI DANIELS

JUNSABURO NISHIWAKI

CIRILO F. BAUTISTA

ERWIN E. CASTILLO

KEKI N. DARUWALLA

Foreword 5

The parrot will flyaway 12

Quiet 14 Noon 25

Poem 25

Morning variations 26

The legend of Waiting Mountain 27

from In the sluggish stream 46

Villager's song 58

Quails 59

Flower, musical instrument in heaven, and a leopard 60 Turkey 61

In the pale vestiges of bloodstains 62

Every calendar page a victory poster 64

Eleven prison poems 65 I run around with them 68

An ordinary song 69

Nocturno: a fragment 69 from Blood brothers 70

Exercises: the twelve earthly branches 79 In the cornfield at midnight 83 Maybe 85

We, the fresh traveler 86 from The old catastrophes 90

Family portrait 90 Mirror 92 from Salt doll 94

Modern fable 109 Pears III

Men in a Sung-style painting 112 Lascaux 113

Autobiography: an excerpt 114 Poetry talk 121

Elegy IV 123

The epileptic 125

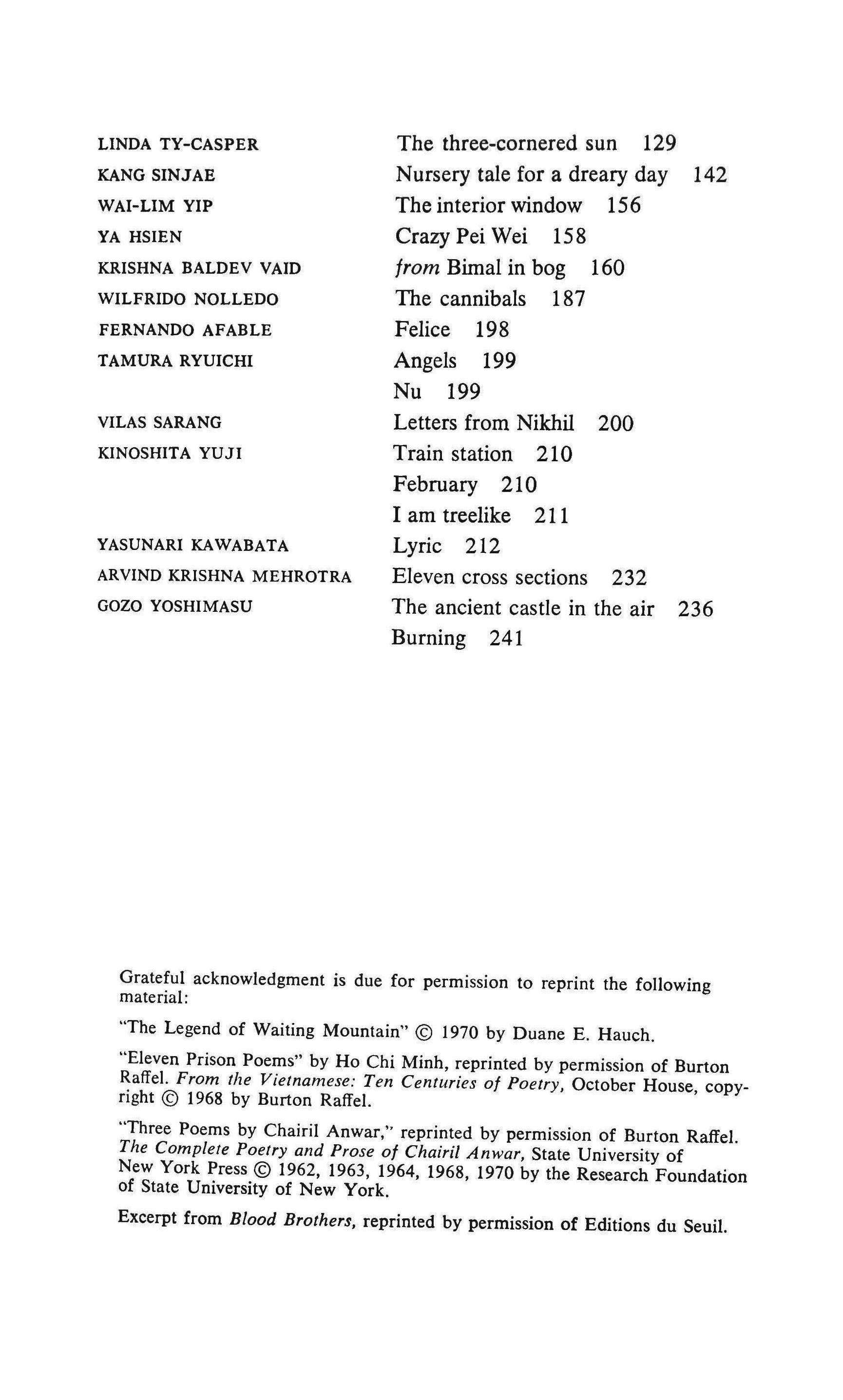

LINDA TY-CASPER

KANG SINJAE

WAI-LIM YIP

YA HSIEN

KRISHNA BALDEV VAID

WILFRIDO NOLLEDO

FERNANDO AFABLE

TAMURA RYUICHI

VILAS SARANG

KINOSHITA YU JI

YASUNARI KAWABATA

ARVIND KRISHNA MEHROTRA

GOZO YOSHIMASU

The three-cornered sun 129

Nursery tale for a dreary day 142

The interior window 156

Crazy Pei Wei 158

from Bimal in bog 160

The cannibals 187

Felice 198

Angels 199

Nu 199

Letters from Nikhil 200

Train station 210

February 210

I am treelike 211

Lyric 212

Eleven cross sections 232

The ancient castle in the air 236

Burning 241

Grateful acknowledgment is due for permission to reprint the following material:

"The Legend of Waiting Mountain" © 1970 by Duane E. Hauch.

"Eleven Prison Poems" by Ho Chi Minh, reprinted by permission of Burton Raffel. From the Vietnamese: Ten Centuries of Poetry, October House, copy right © 1968 by Burton Raffel.

"Three Poems by Chairil Anwar," reprinted by permission of Burton Raffel. The Complete Poetry and Prose of Chairil Anwar, State University of New York Press © 1962, 1963, 1964, 1968, 1970 by the Research Foundation of State University of New York.

Excerpt from Blood Brothers, reprinted by permission of Editions du Seuil.

The preparation of this issue has required more than three years and engaged the various skills and interests of nine different editors. The result, as guest co-editor Lucien Stryk indicates in his Foreword, is a collection-more miscellany than anthology--of some of the most interesting contemporary Asian literature available in English. Our intention has been to select works for their excellence as English artifacts. Then rather than order the issue according to culture or chronology, which ought to have implied a representative, even comprehensive regard for the great diversity of Asian writing, we have proceeded loosely, by theme or aesthetic sensibility, from the traditional, through the socially and politically engaged, to the experimental and self-referential. This framework reflects our concern for a miscellany with a particular, formal coherence, a narrative of voices each deriving from its own circumstance. It is not intended to offer broad literary or cultural definitions.

We would like to thank the Asian Literature Program of the Asia Society in New York for its generous assistance in the preparation of this issue. We would also like to thank the translators and advisory editors Eugene Eoyang, C. M. Naim, Burton Raffel, Ko Won, and Harold Wright, who have given freely of their time and knowledge.

Charles Newman

Elliott Anderson

Timothy O'Grady

4

Much has been said since World War II about the need to see the world as one-about as much, and as eloquently stated, as after World War 1. The syncretist approach to the world's various cultures has, it has been claimed, favorable political implications -though it may be going too far to assert that everyone is convinced of the truth of the late W. H. Auden's verse/axiom, "We must love one another or die." Far, demonstrably, from it. Around the time of Auden's death in the fall of 1973 there was a savage coup in Chile and a breakout of war once again in the Middle East. The grim truth is, pace the poet's noble spirit, that politically man is a beast, incapable of the kind of love leading to universal harmony, yet individually he has it in him to become a saint. Literature, wherever it occurs in the world, is meant not for the political animal but for the human-mostly unhappy, sometimes well disposed, usually hoping for something slightly bigger than himself, the vision of which is offered by, among only a few other things, books. Which are valuable only to the rare, those able to experience in the way that all good things are experienced: with the senses and the engaged imagination.

This collection of modern Asian writing, drawn from five major cultures and a number of subcultures, some of which have

TriQuarterly S

been at each other's throats intermittently for centuries, unpacified by the most pacific religious and philosophical systems the world has known, should not, then, be seen as another futile attempt to bring East and West together. It has but one purpose, simple enough: to present in the most artistically crafted English translations some of the most interesting writing being produced by Asians. We say "some," meaning those often most fortuitously collected, for we could consider mainly only that work available for first publication in a magazine. (Many of the major Asian writers, old and young, have not been translated recently, or translated well, or the translations of their work could not be used for copyright or other reasons.) Though some of these writers are known to all literate men, they were not selected for their fame. If anything, an effort was made to unearth the best work of the newest and most experimental writers-when they have been well translated. Inevitably some of the translations read better than others. But given the incontestable fact that a foreign writer is only as good as his best translator, we offer translations that are, in our judgment, not only readable but, often enough, impressive.

Perhaps the greatest strength of the collection is to be found in its variety, as might be expected of one drawn from so wide and culturally dissimilar an area of the world. Indeed the differences between some of the selections-and our ordering of the material, not by culture but, loosely, by theme is meant to suggest such differences-as between, say, the South Asian and the Chinese, may be far greater than those between equally representative French and German works. In any case there was no attempt to shake the collection up into something homogeneous.

We who speak and write one of the world's dominant languages cannot possibly appreciate the very special difficulties and demoralizations faced by a gifted writer whose mother tongue is, in terms of international literature, a minor one. The excerpt from the novel Bimal in Bog, for example, originally written in Hindi, though not published (for obvious reasons?) in India, was translated by the author into English, and parts of it published here

and there. But few authors can translate their own works, and for the ambitious Indonesian poet, the Vietnamese playwright, the Korean short story writer, it takes much patience and considerable luck with translators to reach a wider audience. In the case of great writers like Yasunari Kawabata, there is of course no lack of translation, yet they too have to be fortunate, and for every admirer of their translators there are at least ten detractors; and denunciations of translations, from whatever language and whatever the reputations of their makers, are unusually vehement. As are, and for better reason, those "take-offs" on and "imitations" of original works-a species of writing that at its best can show little more than ingenuity and at its worst can be downright parasitical. To the best of our knowledge, and in the judgment of our advisory editors, each chosen in part for his knowledge of languages, there is none of that kind of writing in this collection. It will not go unnoticed that certain of the cultures represented are given considerably more space than others, and that there has been no attempt to afford equal space to each in the interest of literary harmony. Our selection reflects, as one might expect, the current importance of certain cultures internationally-and that is, in some ways, deeply to be regretted. Inevitably there is a very real danger that such judgments are made because of a special ambience. One's view of a Japanese story, say, might be strongly affected by a recent response to a Kurosawa film or an exhibition of contemporary woodcuts-and there's nothing shiftier than ambience-which creates, among other more genuine things, fads and advertising. The result is a very special kind of unfairness when it comes to cultural representation in a gathering of modern Asian writing-for the editorial mind is as susceptible as any to the subtle pressures which, in part, make up one's age. Also, an issue edited by a number of hands, however capable, is in danger of becoming a cook's broth, as much spoilt as made unusual by being so. In any case, mine was but one voice in the volume of praise and blame inspired by each work considered. Had it been stronger or more persuasive, there would have been a

more equal cultural representation-certainly more Chinese, Korean, and Southeast Asian works. But a guest editor is just that, and is expected to be on his good behavior. Is there anything convincing that one can say about the quality of Asian writing, whatever the cultural origin, or is every such statement, as I suspect, an insult to the reader's intelligence? When I arrived in Japan to take up my visiting lectureship there in 1956, I was told a story about William Faulkner. A year or two before, he had been the subject of the Nagano Conference, arranged in his honor and with his active participation by university English departments throughout the country. Subsequently he was very often referred to-for those who attended the conference, eminent then, became important members of their respective faculties. A day or two after his arrival in Japan, Faulkner was asked the standard question, "What was your first impression of Japan?" Now whenever that question is asked, in the usual way for the usual reasons, the answer invariably is redolent with cherry blossoms and tall as Mount Fuji. Faulkner's questioners, breathlessly recording the novelist's every word, expected naturally something a bit more original from him, and they were not disappointed (though to a man, it was reported, they were distinctly puzzled). Faulkner's answer: "The sound of running water."

Had the novelist been asked to give his first impression of Asia, there is a strong possibility that he would have remained silent. Had he been asked for his impression, first or otherwise, of Asian literature-of which as a richly informed artist he must have known something-his answer, if any were offered, would possibly have been unprintable. Writers do not think in cultural terms, moving if they must from the particular toward the general and always stopping short of it. Editors, on the other hand, are expected to find the atmosphere of generality bracing, their natural element. Well, there are editors and editors. To illustrate further the kind of difficulty I have in mind, I take the liberty of returning to my experience as a lecturer in Japan. For my course "Literature in English," required of all seniors majoring in English, I assigned, among other poetic texts, some by

Virginia Woolf. I had assumed, not without encouragement from colleagues, that work such as hers would appeal very strongly to students as sensitively cultivated as the Japanese. What could be closer, I reasoned, to the "Less is more" aesthetic associated with Zen Buddhism and the best known masterworks of Japanese art, in all media, than a passage like the following from Virginia Woolf's A Writer's Diary?

The idea has come to me that what I want now to do is to saturate every atom. I mean to eliminate all waste, deadness, superfluity: to give the moment whole; whatever it includes ; this appalling narrative business of the realist: getting on from lunch to dinner: it is false, unreal why admit anything to literature that is not poetry ••. ?

The very few women, and a couple of men, among the students admired Virginia Woolf's writing. Most, however, found it treasonably irrelevant to contemporary life and demanded, through the head of my department, that in the future I use as texts the works of writers like Upton Sinclair, regularly extolled in the socialist papers.

For every reader, in Japan, of Kawabata's "Lyric"-surely one of the finest stories in our collection-there will be a number of impassioned admirers of another selection, the excerpt from that realistic account of the life of an impoverished office worker, In the Sluggish Stream. Japan has an impressive proletarian fiction which, as might be expected, has been produced in the face of the "refined" tradition associated with writers like Kawabata. And she is not alone among the nations represented in our collection where such forces conflict, where-especially among the "emerging nations"-a man's literary allegiances, whether as author or reader, have political importance. There have been book-burnings in Asia; men have been condemned to execution because of compromising bookshelves.

Though this issue does not have as one of its intentions the putting to rest of certain misconceptions about the Asian mind, it should suggest through its presentation of a variety of stances (in the case of Chinese selections, for example, the contrast between the surrealistic "The Interior Window," by Wai-lim Yip

of Hong Kong, and the militant piece by the Shanghai poet Chen An-an) that all is far from being the travel brochure's tinkling of wind-bells in some fabulous Cathay.

As one who has taught three times in Asia, I can testify to the disconcerting fact that throughout that part of the world there are as many people hostile to the arts as elsewhere; that most of them aspire unashamedly, relentlessly to the higher material life, and couldn't care less about literature. Yet it is far from true, as some appear to feel, that the most honored elements of Asian culture are endangered by what is loosely called Westernization. Indeed there is strong likelihood that, so threatened, they will be held all the more precious and cultivated with greater zeal than ever before. That is certainly true for Zen Buddhism, and the arts associated with it, in Japan. There is little fear among those seriously involved in the discipline that it is, in any real sense, threatened by breakneck industrialization and the encouragement of essentially mercantile values.

That philosophy, like others in Asia, has for centuries shown itself capable of adapting to all kinds of social change, and the present age is no exception. It is one of the above-mentioned Western misconceptions that practitioners of disciplines like Zen are "quietists" who sit facing walls, with their backs to the world. So they do while in training, and are the better for the experience when fully turned around again, self-discovered and ready as never before to respond to the real world. One of the contributors to this collection, the greatest living Zen poet, Shinkichi Takahashi, was not facing a wall when he was moved to compassionate response by the news of a fellow Buddhist's self-sacrifice. In protest against the Vietnam war, he wrote "Burning Oneself to Death":

Tbat was the best moment of the monk's life.

Firm on a pile of firewood

With nothing more to say, bear, see, Smoke wrapped bim, bis folded bands blazed.

There was nothing more to do, the end Of everytbing. He remembered, as a cool breeze

Streamed through him, that one is always In the same place, and that there is no time.

Suddenly a whirling mushroom cloud rose Before his singed eyes, and he was a mass Of flame. Globes, one after another, rolled out, The delighted sparrows flew round like fire balls.

The reader with some awareness of the political realities of modern Asia may be puzzled to find that the "other side"mainland China, North Korea, North Vietnam-is given little more than token representation in our collection. He would be wrong to assume that it is due to political partiality. On the contrary, we urged our advisory editors to try to put us in touch with translators working on such material, and some was considered. That not much was used was of course not necessarily due to its poor quality in the original, however ideological its purpose, but very little of it was translated adequately. The trouble is not that the considerable difference between, say, mainland Chinese and Taiwanese writing is difficult to understand-or suggest through judicious selection. Rather, there appears to be a serious imbalance of creative energy expended on the translations. With all the good will in the world, the sophisticated reader would find it most difficult to warm to the productions, as Englished, emanating from behind the bamboo curtain. Perhaps one day translators with adequate skill and the appropriate political sympathies will emerge to do such works justice. Until that day, alas, much of the important literature of Asia will be missing from collections like this. With these lacks noted and disclaimers made, it is yet possible to claim something positive for our collection. We have fulfilled, I believe, our essential purpose: to bring together, without thought of the distinction of their makers, a large and varied group of works from the whole of Asia. The collection is, in our judgment, an exciting one which should go some way in establishing the importance of modem Asian literature in the English-speaking world.

Lucien Stryk

The parrot isn't hungry

The parrot isn't thirsty

The parrot sits on the mango tree

The parrot sits on the lake's edge

The parrot eats raw mangos

The parrot eats ripe mangos

The parrot hasn't a beak

The parrot hasn't eyes

The parrot hasn't wings

The parrot has no color

The parrot has no limbs

Nameless the parrot 0

Homeless the parrot 0

Unemployed the parrot 0

Godless the parrot 0

The parrot is brown

The parrot is red

The parrot is yellow

The parrot is black

The parrot is concave

The parrot is flat

o the parrot is round

o the parrot is square

The parrot is a well

The parrot is a whirlpool

The parrot is a boat

The parrot is a stool

Adjoining the village a lake

The parrot is moss spread over it 12

In the eyes of fishes

The parrot is enclosed

The parrot is seen

In the hollow of drops

The parrot sits in the palanquin

Let's go and see him

The palanquin sits in the parrot

Let's go and see him

Pluck the mangos

Or the parrot will flyaway

Pick chillies from the fields

Or the parrot will flyaway

Fetch Ganges water

Or the parrot will flyaway

Bring the brass chain

Bring the silver anklets

Tie the necklace of gold

Or the parrot will flyaway

Will flyaway

The parrot

Will flyaway

ADIL MANSOORI translated from the Gujarati by Arvil Krishna Mehrotra

In memory 01 my elder sister's deceased son, Pel-sheng, Shanghai, 30 March 1933. Revised, Kunmlng, 10 May 1942

The spring day was very long. During the long daylight hours in the little city, the old people sat in the sun enjoying the warmth or dozing; young people with nothing to do were out on the porches or in the empty fields flying kites. The white sun in the sky moved along slowly, the clouds moved along slowly. Someone's kite string broke, and everywhere people looked up searching the sky. Children made a great racket, jumping up and down and waving their arms as they watched the end of the ownerless kite string fall into someone's yard and catch on the end of a drying pole at the comer of the wall.

Yueh-min, a girl of about fourteen with a small, white, undernourished face and wearing a new blue dress which she would have to grow into, was just then on the drying porch behind the house. She watched the broken-stringed kite float at a slant over her head, the end of the string dragging over the roof tiles. Just as a fat woman on the porch of the neighboring house was awkwardly trying to catch the kite string with a clothespole, the girl heard a noise on the steps behind her. A little boy was climbing

14 TriQuarterly

up the stairs on his hands and knees, and after a short while a small forehead appeared at the head of the stairs. Nervously and stealthily, the child's lively eyes looked around and before he had reached the top step he called out softly, "Aunty, Aunty, Grandmother is asleep. Can I come up for a while?"

The girl heard his voice and quickly turned her head. She looked at the child and scolded him softly, "Pei-sheng, you should be spanked! Why did you come up here again? Your mother will be back soon. Aren't you afraid of a scolding?"

"Let me play a while, Aunty. Don't make any noise. Grandmother is asleep," the child repeated in a pleading tone. His voice was very weak and soft.

The girl frowned, scaring him a little, then went over and helped him up onto the porch.

This drying porch, like most of the drying porches in the little city, was made of wooden planks roughly arranged on a wooden frame-though most of the other porches were older. The two people stood on the porch leaning against the rotting, mosscovered railing, so rickety that it seemed about to collapse, and counted the kites in the sky. Beneath the porch was the slanting roof. Some tiles were missing, and green moss had grown in the places exposed to the spring rains. Roof touched roof, and on both sides of the porch were the porches of other houses. Clothing and sheets, drying on bamboo poles stuck up into the air, flapped like flags in the light breeze. Across from the porch was the stone city wall where the vines were putting out new shoots in the cracks between the stones. Behind the porch was a small river.

The gently flowing water was both clear and soft. Beyond the river was a large field which looked like a big green carpet embroidered with flowers of various colors. At the far end of the field were vegetable gardens and a small, red-walled convent. The peach trees beside the garden fence and inside the convent walls were just in bloom.

The sun was so warm and the scene so peaceful that the two children did not speak but looked now at the sky, now at the river. The river water was not the same shade of green as it was in the

morning and the evening: in some places it seemed blue and in some places there were flecks of silver where the sun was reflected. In the big field on the opposite bank, there were several patches of rape, the flowers a clear golden yellow. Elsewhere in the grassy field large pieces of white cloth were being dried by the people from the dye works in the city, and were lying stretched out, held down at the ends by large stones. Three people flying kites were sitting on a big rock in the field. One of them, a child, was playing tunes on a reed whistle. Some untended horses, three white and two brown, were casually eating grass, moving along with their heads down.

Pei-sheng saw two of the horses begin to run and shouted gleefully, "Look, Aunty. Look!" Aunty looked at him and pointed down. The child understood that she was afraid they would be heard downstairs. He quickly pressed his hand over his mouth, looked at his aunt, and shook his head as if to say, "Hush, hush! We don't want them to find out."

They watched the horses, looked at the grass, looked at everything. The boy was wildly happy, but the girl seemed to be thinking of something far away.

They were refugees. This was not their home, nor was it their destination. In the group of Yueh-min, her mother, sister-in-law, elder sister and her son Pei-sheng, and the little maid Ts'ui-yun, the five-year-old Pei-sheng was the only male. Confused, they had traveled for fourteen days in a small boat. After the boat had come this far, they were supposed to change to a river steamer; but when they inquired, they learned that Wuchang was still surrounded and that none of the boats or vehicles going to Shanghai or Nanking could get through. When they arrived, they found that the news they had heard farther up the river was not entirely accurate. They could not go on, and it would not be easy for them to go back either. It would be expensive and troublesome and, what was more, unsafe. On the mother's suggestion, they had hunted up this little house to live in for the time being. The soldier who had come with them they sent on to Yichang. They

also sent letters to Peking and Shanghai, and then waited for replies from all three places.

Mother and Sister-in-Law hoped someone would come from Yichang, Elder Sister hoped for a letter from Peking, and Yuehmin thought only of Shanghai. She hoped a letter would come from Shanghai first, so she could go to school there. If they went to Yichang to live with her father, who was a military attache (her elder brother was an army officer too), it would not be as nice as going to Shanghai to live with her second elder brother, who was a teacher. But Wuchang had been under siege for a month, and who could say for sure when they would be able to get through on the Yangtse River? They had already been here forty days.

Every day she and the little maid went to the local newspaper office to read the reports, and then hurried back to tell Mother and Elder Sister all the news. They either tried to find some comfort in the news, or they chatted until late about their good dreams, and from these dreams tried to divine all sorts of impossibly good omens. In the month and more that they had been here, there had been no letters from anywhere, and only a small part of their traveling expenses remained.

Mother had always been sickly. Since her condition had always been poor, the added hardships of travel quite naturally made it worse. Yueh-min often thought, "If nothing happens in a couple of weeks, perhaps it would be best if I just went to the Party school." There were probably a lot of fourteen-year-old girls attending the Party school. What was wrong with a colonel's daughter attending too? Once she had been accepted, they need not spend any more money on her, and after graduation in six months she would be assigned somewhere and, in addition, would be paid fifty dollars a month. She had read alL about this in the newspaper but she had kept it to herself, not yet daring to bring it up with her mother.

While she was standing there, thinking of the Party school and her own future, the little boy kept listening intently. He was afraid that when his grandmother woke up she would find out that he had

climbed up onto the porch by himself, and then she would say that he could have fallen into the yard and broken his arm. Just now he heard his grandmother coughing, and he pulled at the edge of the girl's dress. "Aunty, let me go down now. Grandmother's awake," he said softly. Though the child had climbed the steps by himself, he didn't quite know how to get down and had to have some help.

As Yueh-min took the child down the steps, she saw that the maid was in the yard washing clothes. She went over and squatted down beside the basin and scrubbed at a couple of things, but didn't find it to her liking.

"Ts'ui-yun, you're awful busy. I'll go up on the porch and hang the clothes up for you." She took some damp clothes that had been wrung out and went back up onto the porch. In a short while she had hung the clothes on bamboo poles.

Since the bridge over the middle part of the river was rather far away, for convenience there was a ferry boat, about as wide as a wooden bench, which was just now pulled to the shore. The ferry did not connect with the road, so often for long periods of time not a single person was seen riding it across the river, except for people from the dye works drying cloth and a few laborers carrying earth. At the moment, the ferryman was lying asleep on a big stone in the field. The boat was gray and worn, as though thoroughly bored and fatigued with being blown in the direction of the current by the gentle wind.

"Why is it so quiet?" Yueh-min wondered. On the opposite bank, some boat builders were hammering on the side of a boat. In the little village on the other side of the river, a peddler selling needles and thread was beating his small drum. The sounds floating on the air intensified the feeling of unusual quiet.

A little nun wearing a gray robe and black skullcap and carrying a new bamboo basket came out of the convent where the peach trees were. With broad steps she crossed the field and headed for the riverbank. She walked up to the bank a little above the ferry, stopped, then squatted down on a stone and slowly rolled up her

sleeves. She looked around, then looked up at the kites in the sky. Casually and unhurriedly, she took big bunches of vegetables from the basket, one by one set them in front of her, then she swished them around in the water. The water rippled and glistened.

Soon a woman came out on the city-side bank and called over to the ferryman. The ferryman got into his boat, picked up his long pole and pushed the boat across the river. Then he ferried the woman back to the other bank. For some reason the ferryman seemed upset about something and spoke in a loud voice, but the woman went away without saying a word. Not long after, three men carrying empty baskets called to the ferryman from the cityside bank and, as before, the ferryman slowly pushed the boat across. This time the three men were arguing with each other and the ferryman did not say a word. As soon as the ferry reached the bank, the ferryman stuck his pole into the sand, and before long the six baskets had formed into a line and disappeared at the far end of the field.

The little nun finished washing her vegetables and began beating a piece of cloth with a wooden mallet. After pounding it several times, she rinsed it in the water and then began pounding it again. The sound of the wooden mallet echoed from the city wall. Perhaps fascinated by the sound, the nun stopped pounding and shouted, "Ssu-lin! Ssu-lin!" and the wall answered "Ssu-lin! Ssulin!" Then someone from the convent also shouted "Ssu-lin! Ssu lin!"-then said something else, probably asking if her work were finished. The nun's name must be Ssu-lin! Her work was finished and she was tired of playing in the water, so the little nun picked up her basket and walked back to the convent, intentionally cutting across the white cloth, stepping in the empty places.

When the little nun had gone, Yueh-min watched some vegetable leaves floating on the river, and as they slowly moved closer to the ferry she thought of the happy appearance of the nun a moment before. "Now she must be in the convent hanging the clothes to dry on bamboo poles or she's under the peach trees pounding an old nun's back or she's reciting sutras and play-

ing with a kitten As she thought these things she felt them very amusing, and smiled and imitated the little nun in a low voice, "Ssu-lin, Ssu-lin."

A while passed. Thinking of the little nun, the river water, and the distant flowers, and the clouds in the sky, and her mother's illness, the girl began to feel a little lonely.

She remembered that in the morning a magpie sang for a long time on the porch, and then she remembered that every day at about this time the mailman came. Perhaps she should go downstairs to see if there was a letter from Shanghai. She went to the stairs and saw Pei-sheng climbing up onto the bottom step on his hands and knees. The child was lonely, too.

"Pei-sheng, you little scamp! You don't obey. Your mother will be home soon, don't come up again."

She went down the steps. Pei-sheng tugged at her, asking her to bend her head and put her ear next to his mouth. "Aunty," he whispered, "Grandmother spit.

When she got inside the house, she saw her mother lying on the bed as still as death, breathing very weakly and softly; her thin narrow face was marked with fatigue and anxiety. Her mother seemed to have been awake for a while, and she opened her eyes when she heard someone walk into the room.

"Min-min, take a look and see how much water is left in the thermos."

As the girl mixed some medicine with hot water for the invalid, she looked at her mother's face, which was growing thinner daily.

"The weather is nice, Mama," Yueh-min said. "And from the porch we can see the peach blossoms in the convent on the other side of the river. They're all open today."

The invalid smiled weakly. She thought of the blood she had just spit out and stretched out her thin hand to rub her forehead.

"I don't have a fever," she mumbled. As she spoke, she looked at the girl and smiled faintly. The smile was so pitifully gentle that it made the girl sigh.

"Is your cough a little better?"

"Yes, it's all right. It's not that bad. I was careless when I ate some :fish this morning. My throat burns a little, but it's not important."

During this exchange the girl tried to look into the small spit bowl next to the pillow, but the invalid anticipated her and repeated, "It's nothing." Then she added, "Min-min, stand there and don't move. I want to have a look at you. You've grown taller this month. You look just like a grownup."

The girl smiled in embarrassment. "But I'm like a bamboo, Mama. I'm so worried. It doesn't look good to be so tall at fifteen. If you grow too tall, people laugh at you."

It was quiet for a moment, then the mother remembered something. "Min-min, I had a good dream. I dreamed that we were already on the boat, but the third-class cabins were terribly crowded. I was worried, but I thought that in just three or four days we'll be there and then we can rest for a couple of weeks."

The invalid had made the dream up, and because her mind was confused this was the second time she had related it.

Yueh-min looked at her mother's waxy face and forced a smile.

"Last night I dreamed that we were on the boat and that cousin San-mao was a steward at the Fulu Hotel and came to meet us and gave each of us a guidebook. A magpie sang for a long time this morning, so I think a letter might come today."

"If one doesn't come today, one should come tomorrow."

"Maybe he'll even come himself."

"Didn't the paper say that the Thirteenth Division in Yichang was being transferred?"

"Perhaps Papa has already started out."

"If he's coming, he would send a telegram first."

They chatted optimistically, each deceiving the other. Though she joined the game, Yueh-min thought to herself, "Mama, what are we going to do about your illness?" and the mother thought, "If this illness continues, it will be terrible."·

Elder Sister and Sister-in-Law had returned from the fortuneteller's in the north part of the city and were standing in the yard talking quietly. Yueh-min went to the door and feigned a happy

voice. "Elder Sister, Sister-in-Law, a while ago a kite string broke and dragged across the tiles and the woman next door tried to catch it with a bamboo pole and broke a lot of tiles. It was really funny!"

"Pei-sheng, you've been up on the porch again with Aunty," Elder Sister said. "If you're not careful, you'll break a leg and become a cripple and then you'll have to become a beggar."

Pei-sheng was squatting beside Ts'ui-yun, who was washing vegetables. He heard his mother speak to him but did not bother to answer, just looked slyly at his aunt and smiled.

As she smiled at Pei-sheng, Yueh-min walked across the yard and pulled her sister toward the kitchen. "Sister, it looks like mother spit blood again," she said in a low voice.

"What are we going to do?" Elder Sister said. "A letter has just got to come from Peking."

"Did you draw lots?"

Elder Sister took out a copy of the characters which had been written on the lot and gave them to the girl, then beckoned to Peisheng, who was still squatting on the ground. The child came to her side and put his arms around her.

"Mama, Grandmother spit again. She put it under the pillow."

"Pei-sheng," Elder Sister said, "I've told you not to go into Grandmother's room and make a fuss, do you hear?"

"Yes," the child said, then asked, "Mama, the peach blossoms on the other side of the river are all open. Can Aunty take me up on the porch to play for a while? I won't make any noise."

Elder Sister pretended to be angry. "You're not to go up there. It's rained a lot and it's very slippery. You go to your room and play. If you go up on the porch, Grandmother will scold Aunty."

The child moved to his aunt's side, squeezed her hand, then obediently went to his room.

Ts'ui-yun had finished washing the clothes and was rinsing them. As she was wringing them out, Yueh-min said, "Ts'ui-yun, let's take them to the river the next time. It's lots easier. We can take the ferry to the other side of the river. There's no one there, so we don't have to be afraid of anything."

Ts'ui-yun said nothing, but her face reddened and she bowed her head and smiled.

The mother had a fit of coughing, and Elder Sister and Sisterin-Law went inside. Ts'ui-yun finished wringing out the clothes and prepared to take them up on the porch. Yueh-min stood in the yard and looked at the shadows, then went to the door of the sickroom and looked inside. All she could see was her sister-in-law cutting paper and her elder sister sitting on the edge of the bed trying to look into the small spit bowl. At first the mother would not allow it and covered the bowl with her hand, but finally Elder Sister managed to see and just shook her head. All three of them were smiling forcedly and trying to talk about other things to relieve the mournfulness of their situation a little. They began to talk of unrelated matters, but in the end they came back to discussing letters and telegrams. Yueh-min didn't know why, but her heart was full of sadness. She stood in the yard, her eyes red, biting her lip as though angry with someone. Some time passed, and she heard Ts'ui-yun call down from the porch, "Miss Min, Miss Min, come up and see the new bride on a horse! She's going to cross the river!"

Another while passed, and Ts'ui-yun said, "Oh look! Hurry! A big kite has got away. Hurry! It's right over us. Let's catch it!"

Yueh-min looked up. From the yard she too could see the kite up high, weaving back and forth like a drunken policeman, and she could faintly see the long, white kite string waving about in the air.

Yueh-min was not interested in seeing either the kite or the new bride. She waited until Ts'ui-yun had come down from the porch before she went up herself. She leaned against the railing and looked around. Her heart slowly became calmer. She watched the people from the dye works pick up their cloths in the big field They folded the white cloths into shapes like dried bean curd, then piled them on the grass one by one. She saw smoke above the roof tiles of the convent, and when there was smoke coming from most of the houses, she left the porch.

After she came down the steps she looked in at the door of the sickroom. Her mother and sisters were all asleep on the bed. She went to Pei-sheng's room. He was sound asleep on the floor with a little stuffed dog. She went to the kitchen, where she found Ts'uiyun sitting on a wooden bench by the stove stealthily whitening her face with tooth powder and water. Afraid that the maid would be embarrassed, Yueh-min quickly returned to the yard.

From the other side of the wall she heard someone knock at the door, then she heard voices. "Who are they looking for? Could it be that Papa and Brother have come and are asking for us?" she wondered. Her heart began to pound and she hurried to the front door. She waited for someone to knock or ring the bell. It must be someone from far away.

Soon everything was quiet again.

Yueh-min smiled faintly, she didn't know why. The slanting rays of the sun threw the shadows of the roof and the poles on the porch into a corner of the yard, just as in another place the little paper flags stood up on the grave of the Papa they were waiting for.

translated from the Chinese by W.

L. MacDonaldIn the blotchy shade of the green vineyard at high noon, Sleeping without a pillow, a naked child with a hand like a fern shoot. A dragonfly settles there and tickles the hand with its purple wings.

CHONG HAGYONG translated from the Korean by Richard Rutt

The night cow, large and black, wanders about the shores of things, with the hot headed bull of noon. She drinks from the pools of muddy eclipses, yet rivers holy as Ganga descend from her bladder.

SITANSHU YASHASCHANDRA translated from the Gujarati by the author

1

in the beginning was fog; and in the fog echoes of a bell, as a single leaf falls, and, half-asleep, edging to the sea, vanishes (can you hear it sighing, like a Voice)

2 and the light (which first bathed you) singing for a dragonfly, flowers, and two butterflies; the Light (laughing at a bird's song) suddenly retreating onto an old leaf, slowly burning, leaving no trace

3

turning into shadows, shadows which suddenly stir as the bird swoops down on the dragonfly (good morning, sun), shivering restlessly as the butterflies fall to the wet earth, fighting

1970

SAPARDI DJOKO DAMONO

translated from the Indonesian by Harry Aveling

Scene 1

NARRATOR: Once upon a time someone in the West wrote this poem.

Call not the wanderer home as yet, Though it be late. Now Is his first assailing of The invisible gate.

Be still through that light knocking: The hour is filled with fate.

To that first tapping at the invisible door, Fate answereth.

What shining image or voice, what sigh Or boneyed breath

Come forth-shall be Master of Life, Even to death.

Whether you know or do not know the author of this poem is of no importance. Some find it a little pompous. As for me, I find it sad. I first read it a long time ago. It seems to me I've been reading it since all eternity, across an infinity of lives. And it reminds me of a very old story of ours, a story which has also come across an infinity of lives. It's a legend handed down from no one knows what era, a legend of all eras, which is as sad as this poem.

TriQuarterly 27

But perhaps it's not so sad. Sadness is a very elastic thing, and at its limits one may find joy. I don't know. All this is very complicated.

My legend, on the contrary, is very simple. It's like one of those women of great age who are bent in half, with nothing more to do in this world, nothing more to say, nothing more to hope for-yet who preserve in their eyes a certain something: a glimpse, an expectation, a secret.

My legend also has its secret. It concerns a rock up on a mountaintop, all alone, facing the sea-a rock which has the form of a woman. She says nothing; she seems to have been there since the dawn of time, waiting for the coming of a man. And men have come to her and tried to understand her silence. And men have been very clever: they have guessed everything. They know her story now. They know where she came from and whom she is waiting for.

Here are the characters of the story:

The Husband and his Wife

The Old Man of the Moon and the Lady of the Moon

An old male domestic And a fortune-teller

And a fisherman

Well, ladies and gentlemen, here they are-the characters of our legend, behaving themselves quite well, as you can see. They are only waiting for me to give them the word to tell you their story.

Ah, what a sublime and anguishing moment for me! I could say to them, "Don't speak! Stay where you are!" for one second, then another, then still another-seconds which would extend into minutes, hours, days, weeks, years. And they would freeze on their chairs and say nothing. That would be logical. After all, why try to tell in words a story which is but silence?

But what's the use? They are already here to tell you the story. And the story has already been written. The cards of fortune have been laid out for a long time. They have been laid out from the very beginning.

The husband takes his wife's hand. Together, they walk very slowly toward the audience.

HUSBAND: (Very seriously.) This is my wife.

WIFE: (Very cheerjully.) And this is my husband.

HUSBAND: We've just gotten married.

WIFE: No, no, it's been a long time since we were married. (Counts on her fingers.) Exactly twelve months and nineteen days.

HUSBAND: That's true. You have a good memory. But to me it seems as if it were just yesterday. No-it's both very close and very far away (She smiles.) That's silly, isn't it? Yet I think one always says that when one's in love.

WIFE: (Affectionately.) And we have a boy.

HUSBAND: Who looks just like you.

WIFE: No, he looks just like you.

HUSBAND: He looks like both of us, then. Three drops of water falling from heaven! (Anxiously.) But where is he?

WIFE: He's asleep, darling. (Laughing.) You always seem to be afraid someone's going to steal something from you-either your wife or your child.

HUSBAND: That's true. I'm always afraid because I just can't explain this happiness. I used to be all alone in a world of blood, alone with my dreams, my past, my anxieties. And now here I am-three. And pretty soon, four and five, and six. I work, I eat, I sleep. Every day is like every other. There are no more days. I'm happy, and yet I'm frightened by this Present which doesn't end. This is too simple, you see, and I'm always expecting something to happen Oh, well, I suppose I'm just being foolish.

WIFE: It's probably all that war that's still inside you.

HUSBAND: Maybe The war. That long night-watch in company with Death. One endless day till victory came. There were no more nights, only halts where one could rest. We. didn't sleep, we just rested. And the horizon was always in flames. You opened your eyes and everything was red; you closed your eyes and everything was black. There were only two colors-

red and black. War makes you forget many things, things that return to mind once peace returns.

WIFE: (Closing his mouth.) Forget all that, darling. Forget all your past that I don't know about. Forget the war we've both known. Why always revive the dead? You were born the day we met. What happened before doesn't matter any more. We are happy; that's all I care about. Don't ask any more questions. Look at the sea, all still below our house, like glass beneath the sun. And look at those white sails way out there -they look like white pigeons on a mossy green roof We've won the war. I love you. All is well.

HUSBAND: (Dreaming.) Peace A woman under a roof covered with green moss. The poetic Chinese invented that. But inner peace is quite another thing. It's an agreement with the self which I don't have. That's why I'm always trying to find some reason for this happiness, which I feel unworthy of. The least thing frightens me. For instance, it's only since yesterday that I've known you are just your father's adopted daughter.

WIFE: (Laughing.) Is that why you've been moody with me all day long?

HUSBAND: But why didn't you tell me?

WIFE: My goodness! I didn't even remember it. And no one in Father's house even knows about it except our old servant. He must have been the one who told you about it. My father found me and adopted me during one of his journeys a long time ago. I was a tiny little thing then, and don't remember anything any more. (Teasing.) So you're not satisfied with having married a poor adopted girl, eh? Ah, if I'd only known

HUSBAND: (Pulling her toward him and looking at her pro[oundly.) I chose you among all women.

WIFE: And what about me? I didn't choose you? You just came to me, that's all?

HUSBAND: Isn't it strange-why you, and not someone else? And did I really make a choice? The moment I first saw you everything was accomplished. One might say the whole uni-

verse was made just so we two should meet. Fortune-tellers are all liars. They "predict" the future, but the future doesn't exist: it's we who make the future And yet, at times, one has the feeling that everything has been provided for in advance.

WIFE: When will you ever stop asking questions? Just imagine what it'll be like when our son starts talking. The two of you will flood me with questions! I think I'll run away

HUSBAND: (Sweetly.) My dear little wife (A baby cries.)

WIFE: I'd better go in now.

She leaves him and returns to her seat. He remains alone in the middle of the stage, arms crossed, eyes fixed dreamily on the distance.

Scene 3

We see the Old Man of the Moon and the Lady of the Moon.

OLD MAN: (Closing his book and stretching.) That's enough for today! Ah, my dear child, I'm getting old.

LADY: In the first place, I'm not your dear child. In the second place, you've always been old. And lastly, whether you're young or old doesn't concern me in the least.

OLD MAN: (Smiling.) I know, I know. I just wanted to hear somebody talk. You see, my dear, one always likes to have a little chat after one's work is done, and you're so miserly with words I've got to use a little trick every time I want you to open your mouth. The funny thing is, you always fall into the same trap.

LADY: You're impossible!

OLD MAN: I know, I know. But some day you'll have to make up your mind to put up with me. We're here to serve humanity till the end of the world, and the end of the world is a long way off. That's the Boss's concern, and he doesn't seem to have decided on it yet. (Pauses). Do you remember the good old days in the beginning, my dear, when there were just a few boys and girls on earth? What enthusiasm we had! I always remember my emotion each morning when I was about

to join two human destinies. The work was so light then! There were only a few names in the register of births. I had the time to choose well-matched couples and make beautiful marriages. But they began multiplying so fast they soon filled Up the earth, and from then on, no more breaks, no more poetry. I don't even have enough time to marry them all, and every year there are a lot of old maids and bachelors left over. What a pity!

LADY: (Dreaming and sad.) Yes, the good old times at the beginning. The first lovers used to stroll at night under my eyes. How beautiful they were! I used to be their sole confidante, the witness to all their promises, a mirror for them to contemplate together, fascinated And the trees and flowers surrounding them used to send their perfume up to me. The whole earth was nothing but tenderness. But now everything is ugly and the earth is sick. I'm the moon of lepers, criminals, beggars, the desperate, and dogs howl at me. It seems as if the earth itself is howling at me. There are a few lovers left, but they're lost, too. They have to work, and hardly ever look up at me. I'm the moon of carefree hours, yet down there anguish squeezes man's heart. I'm the moon of love, and down there love is gone. I was created for happiness, but down there happiness is no more. Oh, what a sad, forsaken earth! (Long silence.) All this is your fault, Old Man. Why did you make so many bad marriages?

OLD MAN: Ah, ah, not me, my dear! Why don't you blame the Boss instead? He could have given me a secretary. I've been asking him for one for centuries. But he seems to have been so busy and with all that bureaucracy of his Meanwhile, I assure you, I'm doing my best.

LADY: Huh, huh, that's what you think, Old Man. Look at that couple down there, at our feet. They look very happy, don't they? Especially the young wife. They're one of the last couples I've got left, and one of the most charming. A little hut and two hearts of gold. Ah, these are true Vietnamese! But look at the young man. He's upset. His eyes are looking

dreamily into the distance. He's asking himself a lot of questions. There must be something below the surface (loudly), something that I know, Old Man. You think you've done your best! You've made my lovers into criminals!

OLD MAN: Criminals? How do you mean?

LADY: Yes, criminals. I mean what I say. Oh, for heaven's sake, why give such a job to such an old man? Open your book to page 2980 and take a look at the names of the couple. You're the one who joined them, Old Man. (While she is talking, the Old Man digs nervously into his register, then jumps to his feet and clutches the Moon by the hand.)

OLD MAN: Heavens! Why did you let me commit such a blunder? You saw me do it, didn't you? (Shouting.) Why? (They look at one another a moment in silence.)

LADY: (Gently.) That wasn't my job, Old Man. I'm not supposed to check your work. I was created for lovers only.

The husband and the fortune-teller

HUSBAND: (As if he has just awakened from a long dream.) Impossible! The future it's we who make it!

FORTUNE-TELLER: (Having approached very slowly.) Is that right? If so, we'd better change our profession.

HUSBAND: Who are you? And what do you want with me?

FORTUNE-TELLER: I'm the fortune-teller of this town. I know the past, the present, and the future.

HUSBAND: (Taken aback, then angrily.) I hate all your kind. You live by your lies. Go away!

FORTUNE-TELLER: That's what everybody tells us. But that doesn't stop them from coming and begging for our help sooner or later. And when they don't come to us, we go to them out of compassion. Oh, what a crazy world!

HUSBAND: (With a hollow voice.) Once more, go away! It's because of a fellow of your kind that I (He stops, abashed.)

FORTUNE-TELLER: (Slowly.) That you did what?

HUSBAND: Nothing. Go away! (He turns away.)

FORTUNE-TELLER: I know the past, the present, the future-your past, your present, your future. They are written on your face, and destiny is implacable.

HUSBAND: (Grumbling.) What is destiny?

FORTUNE-TELLER: Everything goes as planned-all things are linked, and every man does exactly what's been planned for him to do. That's destiny.

HUSBAND: But there must be a beginning. Who decides when the beginning will begin?

FORTUNE TELLER: I don't know. All I know is that you're a criminal-at least what people consider a criminal.

HUSBAND: (Shouting.) Yes, I was a criminal.

FORTUNE-TELLER: No, you are a criminal.

HUSBAND: (Laughing nervously.) Yes, a criminal remains a criminal all his life, even if he wasn't responsible for his crime. That's the way life is. Twenty years ago, I killed my little sister after a fortune-teller had predicted that I'd have her as my wife one day. She was about two years old-a pretty little thing. I took her into the forest and cracked her head with a hammer. I was so scared! That was twenty years ago, yet that dreadful deed is still as fresh in my mind as the day it was done. (Silence.) There, are you satisfied now? Go ahead, tell the town I killed my little sister twenty years ago. It'll be a great triumph for you.

FORTUNE-TELLER: (Slowly.) Are you sure you killed her?

HUSBAND: (Rushing at the fortune-teller's throat.) Ah, I don't know why I haven't strangled all of your kind! Listen, old man, I know how to split a skull open and how dead a man is after that. And my little sister's skull-I have it right here, in my head. You understand? All because I was stupid enough to believe in your dirty prophesies. Now, go away. If I see you around my house just once more, I'll strangle youlike this. ( He grabs the fortune-teller by the throat.)

FORTUNE-TELLER: Are you sure you killed her? Let me go! Help!

WIFE: (Running up to them.) What's the matter? Who's this old

man? Let him go! You naughty old man, why did you make my husband angry? He's terrible when he's angry!

HUSBAND: Now, go away. I don't want to see any more of you.

FORTUNE-TELLER: All right, all right. But remember what I told you.

WIFE: What did he say?

HUSBAND: (Shuddering.) Oh, nothing He just got on my nerves. Let's go into the house. It's getting cold.

WIFE: (Clinging to his arm.) Tell me what he said. All at once I'm afraid.

HUSBAND: (Shouting.) Afraid of what?

WIFE: Please don't shout at me. I don't know why, but I'm just afraid. There's a strange presence around us, between ussomething I don't know about. Don't you feel anything? Look at the sea, all dark now, and chilly. And the fog, stealing softly in from the horizon. And the bits of night already clinging to the branches. I feel as if I were all by myself in some besieged castle. Listen to the howling of the wind coming in from the sea. Oh, darling, I'm suddenly scared to death!

HUSBAND: Stop it, will you? It's just that night's closing in, a night without moon or stars. Women are always afraid of nights like this. You march off to bed and hold the baby tight. I want to take a little walk yet About the. old man, it was nothing at all, so don't you worry. He just claimed I don't know how to kill-I who've cracked the heads of hundreds of men.

WIFE: Do you know him?

HUSBAND: He's the town fortune-teller, and a liar like all others of his kind. You're not scared any more now, are you, darling?

WIFE: No, not any more.

HUSBAND: You see? It's night that's won out. When it falls-after the battle with each day's light, and while the outcome is still uncertain-people are always afraid. But once it's fallen, everything returns to normal. We feel at ease in it, as if we were under a blanket. Good night, little sister.

WIFE: Good night, darling. Don't stay out too late.

HUSBAND: (Holding her back. squeezing her hand. and looking at her profoundly.) Woman, I want you to be happy-always.

WIFE: (Laughing.) You've said that to me a thousand times. I am happy!

HUSBAND: Forgive me for making you uneasy with all my doubts, my questions, my problems.

WIFE: All men have doubts, questions, problems.

HUSBAND: From now on you can be sure I'm happy. Good night, darling. (Wife exits.)

A pause. then the domestic servant enters.

HUSBAND: Who's there?

DOMESTIC: It's me, young master. How are you?

HUSBAND: Why are you here so late?

DOMESTIC: I don't know I was home when I suddenly got worried about you and the young mistress. I felt kind of scared-I don't know why. An old man's whim, I suppose. Anyway, I just came to see if everything is all right.

HUSBAND: You too-you were scared, too! Well, thanks for coming. We're all fine. My wife went to bed a while ago. She and the baby are probably asleep already.

DOMESTIC: SO much the better. You have to take very good care of her. You see, she used to have headaches when autumn came. When she was little, she'd cry each time, and I was the only one who could soothe her. I'd tell her fairy stories one after the other. I'd play the devil, the elephant, the hen, the pig, and make her laugh. Poor little sweetheart! Ah, you are lucky, master. She is a really nice girl, your wife is.

HUSBAND: You were afraid of something. That's a bad omen. Tomorrow maybe I won't have any courage left in me. Listen: stay with me tonight. I want you to tell me everything you know about her childhood. You've all been so quiet about that in her family. It wasn't until we'd been married more than a year that you even told me she'd been adopted.

DOMESTIC: Yes, but that was on account of the old master. He loved her so much he wouldn't let anyone remind him that

she'd been adopted. Since he came and settled in this new village, on account of the war, no one's ever known the story except me. I don't imagine the little mistress herself has any clear idea about it.

HUSBAND: (In a soft voice.) It was in the South that he found her, right?

DOMESTIC: No, master. It was in the North.

HUSBAND: But he's always been in the South.

DOMESTIC: That's right. But it was during a trip he made to the capital-oh, I don't remember on what sort of business. He was ever so busy, the old master

HUSBAND: Then, it was in the capital that he found her?

DOMESTIC: No, master. It was in a forest nearby.

HUSBAND: (Seizing him by the shirt.) Are you sure of what you are saying? There's only one forest near the capital, and I know it.

DOMESTIC: What's the matter with you, master?

HUSBAND: (Yelling.) Are you sure of what you just said?

DOMESTIC: What's come over you, master? I'm scared. This isn't the same fear I had a while ago. It's as if someone were standing right beside us and listening to us. What a black night! You scare me, master!

HUSBAND: (Letting him go, and speaking in a hollow voice.) I'm scared, too, and the night is dark But answer me, please: are you certain he found my wife in that forest?

DOMESTIC: How could I be wrong, master? I was there, and it was I who brought her to the old master She was ugly to look at. She'd almost starved to death, and had a big wound on her head. She was about two. The old master had to stay in the capital a whole month to take care of her But what's happened, master? (Yelling.) Master! What's happened?

HUSBAND: Nothing. I'm just surprised No, I'm not even surprised. Everything goes as planned; all things are linked together, and each man does exactly what's been ordained for him to do. You go and take your rest now, my dear old man.

DOMESTIC: Where are you going tomorrow?

HUSBAND: Oh, not very far. Before you came, a messenger brought me some bad news. An old friend, a man I went through the war with, is dying. I ought to be at his bedside. Since he lives a few miles from here on the coast, I'll take my boat. I'll leave quite early-maybe right now. Look, it's nearly daybreak!

DOMESTIC: Does the mistress know you're going?

HUSBAND: No, the message came after she'd gone to bed and I didn't want to wake her up.

DOMESTIC: But why not wait until she wakes, master? It's no good leaving without saying good-bye to one's own wife Ah, this younger generation seems to have lost all sense of politeness!

HUSBAND: I ought to be off right now. Otherwise, I may not see my old friend again. You tell my wife about it. It'll only be for a few days. While I'm gone, you stay here and take good care of her and the baby. She's to be happy-always. Is that understood, old man?

DOMESTIC: Oh, yes, yes! The poor sweetheart

HUSBAND: If she has a headache and cries, you lull her to sleep again, or play the devil, the elephant, the hen, the pig, and make her laugh. We want her to be happy, don't we, old man?

DOMESTIC: Oh, yes, master. You don't have to remind me of my duty. I promised the old master before he died to take good care of her, always.

HUSBAND: And if she wants to go and wait for me on the hilltop behind the house, as she used to do whenever I went somewhere, tell her not to wait for me. Tell her I'll be back just as soon as I'm finished at my friend's.

DOMESTIC: I'll certainly do that. Is it proper for a good woman to go and wait for her husband on top of a hill, where everyone in town can see? Our mothers had more modesty than that!

HUSBAND: And if something happens to me at sea, old man

DOMESTIC: Oh, you, master! If you were my son I'd give you a good spanking. Is it nice to say such things just before going to sea? That's not good. You young people who've been in the war don't seem to care about anything. But there are words one shouldn't say.

HUSBAND: One never knows, my good old man. Maybe a storm

DOMESTIC: Will you stop it, master?

HUSBAND: Well, if something should happen to me, tell her that I love her

DOMESTIC: (Holding his ears.) I'm not listening to you any more.

HUSBAND: Keep an eye on the child. And take good care of yourself, my dear old man. Now, go to bed, I'm going down to the shore. Farewell. Remember what I've told you. (Pauses, then slowly moves away.)

So, it's all come to pass just as it was preordained. Are you satisfied, fortune-teller who predicted my future? Now you can congratulate yourself.

And you, you that I cannot see but who decides my destiny-who are you? What have I done to you to deserve such punishment? Are you the Old Man of the Moon who joins a boy to a girl at random? Are you that cruel, whimsical creature who builds up this world only to laugh at its misfortunes? What have I done? What have I ever done to you? My rescued sister is my wife. For twenty years you led us toward one another across a vast country and a terrible war. Ah, you are powerful! You hold us tight in your iron grip. How many times have I sought death on the battlefield, and death simply passed me by, unconcerned. You've given me plenty of time to build up our misfortunes, day by day. And day by day you've allowed both uncertainty and hope to remain within me-the miraculous water that keeps us alive.

But now it's all come to pass, and I'm free. I've come to the end of my uncertainty, to the end of my hope. The night may be dark, but everything is clear. I've nothing left, and now there's nothing more you can do to me.

Ah, how I'd like to see you and know who you are! I'll take my boat and sail away to the end of this sea, to where the waves go to lick the feet of heaven. Perhaps out there I'll find the way to you. Even if I die before I reach that terrible shore, it'll be a delight to make a journey with no return, a journey away from the realm of uncertainty and hope.

Old Man 0/ the Moon and the Lady 0/ the Moon

LADY: Do you realize, Old Man, the magnitude of your error?

OLD MAN: Oh, please. A misfortune is a misfortune, and a life is over so fast. If you rake me over the coals, I'll be likely to make other errors. This one, after all, may have some good effect on the Boss. I've just sent him a report that's certain to force him, for once, to look down on the poor world. For centuries now, I've been asking him for a secretary, but he never seems to remember.

LADY: You'd better ask for a small pension while you're at it, Old Man, and go live on some star where you'll be all alone.

OLD MAN: My dear child, as long as the administration says nothing, I'm supposed to be fit for service.

LADY: Oh, you're unbearable!

OLD MAN: Well, don't worry. The earth's too old and too sick to last much longer. I think the Boss has got a formidable plan up his sleeve, something sensational.

LADY: Whatever it is, it's about time it all ended. By the sun, I feel all tired out and as old as eternity.

OLD MAN: I'm sorry for that, my dear, but eternity is young. And for a woman to feel old, even though she be the moon, is the beginning of wisdom. Sh! Look at the young wife.

LADY: How does this story end?

OLD MAN: It will end the way it's supposed to end. From the moment I blundered, the whole thing has come to pass automatically, following its own internal logic. There lies our power, or lack of it. With women, however, one never knows.

We men are logical and go on to the end, but women-they always have some surprise to startle us with.

WIFE: Oh, old man, I'm frightened, I'm frightened!

DOMESTIC: I'd like to comfort you, but it's no use. I'm frightened myself.

WIFE: What did he say before he left?

DOMESTIC: •.. Oh, nothing out of the ordinary. He told me to take good care of you and the baby. But he was very careless-he said things that could bring him bad luck.

WIFE: No, it's impossible, dear old man. The sea's been calm all week. And you really don't know where he wanted to go?

DOMESTIC: I was a fool, dearest mistress. How could I be so stupid? But we might try guessing. He said to me, "A few miles from here." And he took his boat. The wind blows south, so he must have gone south. Doesn't he have a friend in that neighborhood? I've got it! It must be the young man who came here once to see him and who seemed to be so sick. I know his name and his village.

WIFE: I know him, too. Oh, good old man, would you hire a boat from a fisherman and go there? Why didn't we think of it before?

DOMESTIC: I'll go at once, mistress.

WIFE: Thank you, my dear old man. I'll wait here till night comes. Maybe your boat will meet his on the way.

DOMESTIC: No, no, my sweet lady! A woman shouldn't be all alone like this on top of a hill all day. And how are you going to eat?

WIFE: I'm not hungry. I'll go home when I get hungry, or buy something from a fisherman.

DOMESTIC: And what about the baby?

WIFE: The servant will take care of him for the day Oh, please, old man. I'll die at home! Besides, you'll be gone and

won't be here to scold me, anyway. Farewell, old man.

DOMESTIC: All right, all right.

WIFE: Good-bye, old man. I'm scared, I'm scared.

DOMESTIC: But everything's clear now. Surely he just went down there and his friend simply couldn't decide whether to diethat's all.

WIFE: But he should have sent us a message.

DOMESTIC: Oh, you know how absent-minded he is-and remember he's at the bedside of a dying man. It's his dearest friend, he said. Anyway, I'm leaving right now. So, farewell, dear mistress. And don't you worry. I'm not scared any more. I'll be back tonight-maybe with him, if his friend's made up his mind to die.

WIFE: Thank you, dear old man. Now hurry! (Domestic exits.)

His boat has a white sail and a green flag. He's always been proud of that flag, a flag he won during some battle. His boat has a white sail and a green flag. He'll be coming back soon with the old man. Or maybe the old man will come back alone and tell me he's at his friend's home, his dying friendthat he's well, that he thinks of us, that he'll return as soon as he can.

Yet somehow I'm scared-I don't know why. Why can't I get over this fear that's been torturing me since the night before he left? Who was the fortune-teller he nearly strangled? He didn't go to bed at all that night. That's happened many times before-but he was so sad. Why did he question the old man so closely about how I was adopted? Why did he leave so early, and in such a hurry, without seeing me?

(Slowly.) There's some terrible secret, and this is what I'm afraid of. I'm less afraid of his death than I am of this secret! (The fisherman enters.) Fisherman! Fisherman! Did you see a white sail and a green flag at sea, just a week ago?

FISHERMAN: Yes, my lady. It was very early in the morning while the sun was still sleeping beneath the waves. It was a beautiful boat with a young man in it, and the young man was dressed in black.

WIFE: Fisherman, fisherman. Describe him to me. Was he sad? Was he cheerful? Where was he bound for?

FISHERMAN: His face was as calm as an autumn sky. He stood erect in his boat, and his eyes never moved-they were fixed on the horizon. Only his smile was sad. He didn't seem to be aware of anything but himself. My boat crossed his quite close, but he didn't even see me. He was heading straight out into the open sea.

WIFE: Fisherman! Fisherman! (The fortune-teller enters.)

FORTUNE-TELLER: Why ask the fisherman, my lady? Fishermen are poets-they don't know anything. Me, I know everything. I know the past, present, future.

WIFE: Ah, it's you-the fortune-teller. I don't need you. I have no past and no future, only the present. I'm waiting for the man I love.

FORTUNE-TELLER: Very well said. It's plain to see that rich young girls nowadays learn their lessons well. This is progress But do you know, fair lady, who it is that you love?

WIFE: It doesn't matter to me who he is or what he is. If he were a criminal, I'd only love him more. So go away.

FORTUNE-TELLER: There are mysteries that are more dreadful than crimes

WIFE: Oh, leave me alone. Go away, will you?

FORTUNE-TELLER: But I have pity on you as I have pity on all men. I'm compelled to tell the truth that concerns each one of them. Because only the truth can cure them of hope. Don't waste your time waiting for your husband: he'll not be coming back today or tomorrow or the day after. He's dead.

WIFE: That isn't true. He's gone to see a friend who's dying, and our old domestic just left to look for him. Even if he doesn't find him, I'll be waiting for him right here for the rest of my life. So go away

FORTUNE-TELLER: Why fight the inevitable? You already believe what I said-but you're afraid of the truth. You're afraid to know who your husband really is-to know the terrible

secret he's taken with him forever. You want to hang on to your uncertainty, no matter how slight it is.

WIFE: (Shouting.) I'll have nothing to do with your truth. Go away. (Very rapidly.) My husband has a boat with a white sail and a green flag, the flag he won in battle. We love each other, and we have a baby boy. He'll come back tonight with the old man, and everything will be just as it was before. There's a sail!

FORTUNE-TELLER: That's the old man's sail, and he's all alone.

WIFE: Yes, but that means his friend hasn't died yet and my husband has to stay a little while longer.

FORTUNE-TELLER: Let me tell you once more: don't have illusions. I know all.

WIFE: (Very fast.) Help me, old man, help! Oh, you're still too far away, good old man, and can't do anything for me. Help me, my husband! Help! But where are you, darling? Where are you? Oh, heaven! How dark the night is, and how lonely I am!

FORTUNE-TELLER: All you have to do to get out of the night is listen to me.

WIFE: (Very slowly and softly.) Please, fortune-teller, please don't say anything more. Even if my husband really is dead, let me wait for him just the same. I have neither past nor future. My present is this waiting. Leave that to me at least. I don't want any of your certainty. I don't care what my husband is: he's my husband and I love him, and I don't want to know any more than that. So don't say another word. Because I won't listen to you. (Very slowly.) I'd rather turn into a statue of stone.

FORTUNE-TELLER: All the same, I'm going to tell you because it's my duty to tell you the truth. (Slowly.) Do you know why your husband's dead? He's dead because he learned that he was your. As he speaks, the young woman raises her eyes and stretches her arms heavenward in a gesture of supplication. She then joins her hands together and moves no more, eyes closed, facing the sea.

Scene 7

Old Man of the Moon and Lady of the Moon

OLD MAN: Didn't I tell you, dear child? Women always come up with some surprise. I've begun to admire them!

LADY: Look how beautiful she is with her expressive little face. When I come out tonight, I'll bathe her in my light, and she'll be even more beautiful. She'll stay there waiting to the end of time, and all the powers that be can do nothing against her. Nor can fortune-tellers, or dreadful nights, or storms. She's won, Old Man! She's triumphed over your fatal error, and the whole earth seems concentrated in her waiting. She didn't want to know, for she was stubborn, like stone, like the stone that she's become! She's defended her happiness as a lioness defends her offspring. How beautiful she is-the little girl of hope!