NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

EVANSTON, ILLINOIS

Charles Newman

EDITOR •.•••.••..••••.•..

GUEST CO-EDITORS

Simon Karlinsky

Alfred Appel, Jr.

EXECUTIVE EDITOR ........• Elliott Anderson

MANAGING EDITOR Suzanne Kurman

ART DIRECTOR Lawrence Levy

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

ASSISTANT EDITORS

FULFILLMENT

Timothy O'Grady

Barry Jordan

Darcie Sanders

Dave Sedgwick

Mary Elinore Smith

Debbie Petranek

TriQuarterly is an international journal of arts, letters, and opinion published in the fall, winter, and spring at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60201. Subscription rates: One year $7.00; two years $12.00; three years $17.00. Foreign subscriptions $.75 per year additional. Single copies usually $2.50. Back issue prices on request. Contributions, correspondence, and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly, University Hall 101, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60201. The editors invite submissions, but queries are strongly suggested. No manuscript will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1973 by Northwestern University Press. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America. Claims for missing numbers will be honored only within the four-month period after month of issue.

NATIONAL DISTRIBUTOR TO RETAIL TRADE: B. DEBOER, 188 HIGH STREET, NUTLEY, NEW JERSEY 07110. DISTRIBUTOR FOR GREAT BRITAIN AND EUROPE: B. F. STEVENS & BROWN, LTD., ARDON HOUSE, MILL LANE, GODALMING, SURREY, ENGLAND. DISTRIBUTOR FOR THE NETHERLANDS: M. VAN GELDERN & ZOON, N.Vl, N. Z. VOORBURGWAL 140-142 AMSTERDAM, HOLLAND.

REPRINTS OF BACK ISSUES OF TriQuarterly ARE NOW AVAILABLE IN FULL FORMAT FROM KRAUS REPRINT COMPANY, ROUTE 100, MILLWOOD, NEW YORK 10546, AND IN MICROFILM FROM UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS, A XEROX COMPANY, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN 48106.

Cover photos: front, Avenue de l'Observatoire, 1932, by Brassai; back, St. Petersburg, by Ernst A. Jahn

TriQmrWrJy

In the last issue, number twenty-seven, spring 1973

SIMON KARLINSKY

ALEX M. SHANE

ALEXEI REMIZOV

ROBERT P. HUGHES

VLADISLAV KHODASEVICH

Foreword: who are the emigre writers? 5

I: SIX MAJOR £MIGR£ WRITERS

Alexei Remizov (1877-1957)

An introduction to Alexei Remizov 10

Vedogon: a prose poem 17

Three dreams 19

Three apocrypha 22

The barber 28

Sleepwalkers 36

Mu'allaqAt 46

Vladislav Khodasevich (1866-1939)

Khodasevich: irony and dislocation:

a poet in exile 52

The monkey 67

Poem 69

Orpheus 69

Tolstoy's departure 71

On Khodasevich 83

VLADIMIR NABOKOV

D. S. MIRSKY

MARINA TSVETAEVA

VLADIMIR NABOKOV

GEORGY IVANOV

VLADIMIR NABOKOV

ALFRED APPEL, .JR.

VLADIMIR NABOKOV

ANTHONY OLCOTT

BORIS POPLAVSKY

SIMON KARLINSKY

Marina Tsvetaeva (1892-1941)

Marina Tsvetaeva 88

Three poems by Marina Tsvetaeva 94

A poet on criticism 103

A letter to Anna Teskova 135

Georgy Ivanov (1894-1958)

Georgy Ivanov: nihilist as light-bearer 139

Double vision: six poems 164

Esenin's fate 169

Vladimir Nabokov (1899Torpid smoke 188

Nabokov's dark cinema: a diptych 196

Solus rex 274

Boris Poplavsky (1903-1935)

Poplavsky: the heir presumptive of Montparnasse 305

Seven poems 320

A chapter from Homeward from Heaven 327

In search of Poplavsky: a collage 342

In this issue, number twenty-eight, fall 1973

II: MUSIC

PETER YATES

ANNA KISSELGOFF & JOHN MALMSTAD

VLADIMIR MARKOV

NIKOLAI MORSHEN

ANATOLY STEIGER

YURI ODARCHENKO

IGOR CIDNNOV

GAUNA KUZNETSOVA

CZESLAW MILOSZ

EDYTHE C. HABER

NADEZHDA TEFFI

HELEN ISWOLSKY

V. S. YANOVSKY

OLGA HUGHES

ALLA KTOROv'A

PARKER TYLER

TATIANA KUSUBOVA

KONSTANTIN KOROVIN

VALENTINE &

JEAN CLAUDE MARCADE

MIKHAIL ANDREENKO

ALFRED APPEL, JR.

Igor Stravinsky: the final maturity 365

Balanchine 380

Mozart: theme and variations 396

III: EMIGRE POETRY

Two poems 426

Ten poems 428

Three poems 431

Three poems 433

IV: EMIGRE PROSE AND PHILOSOPHY

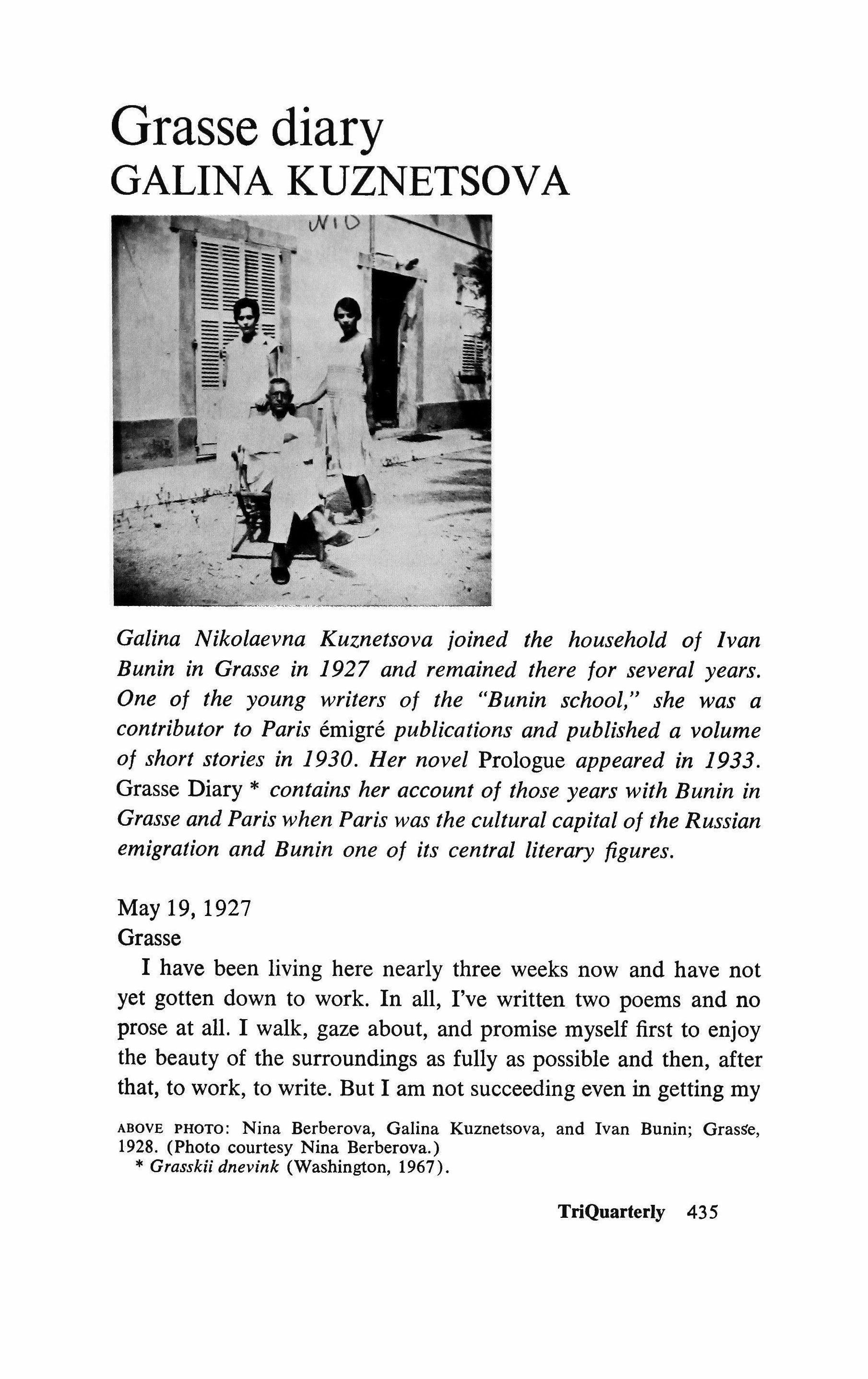

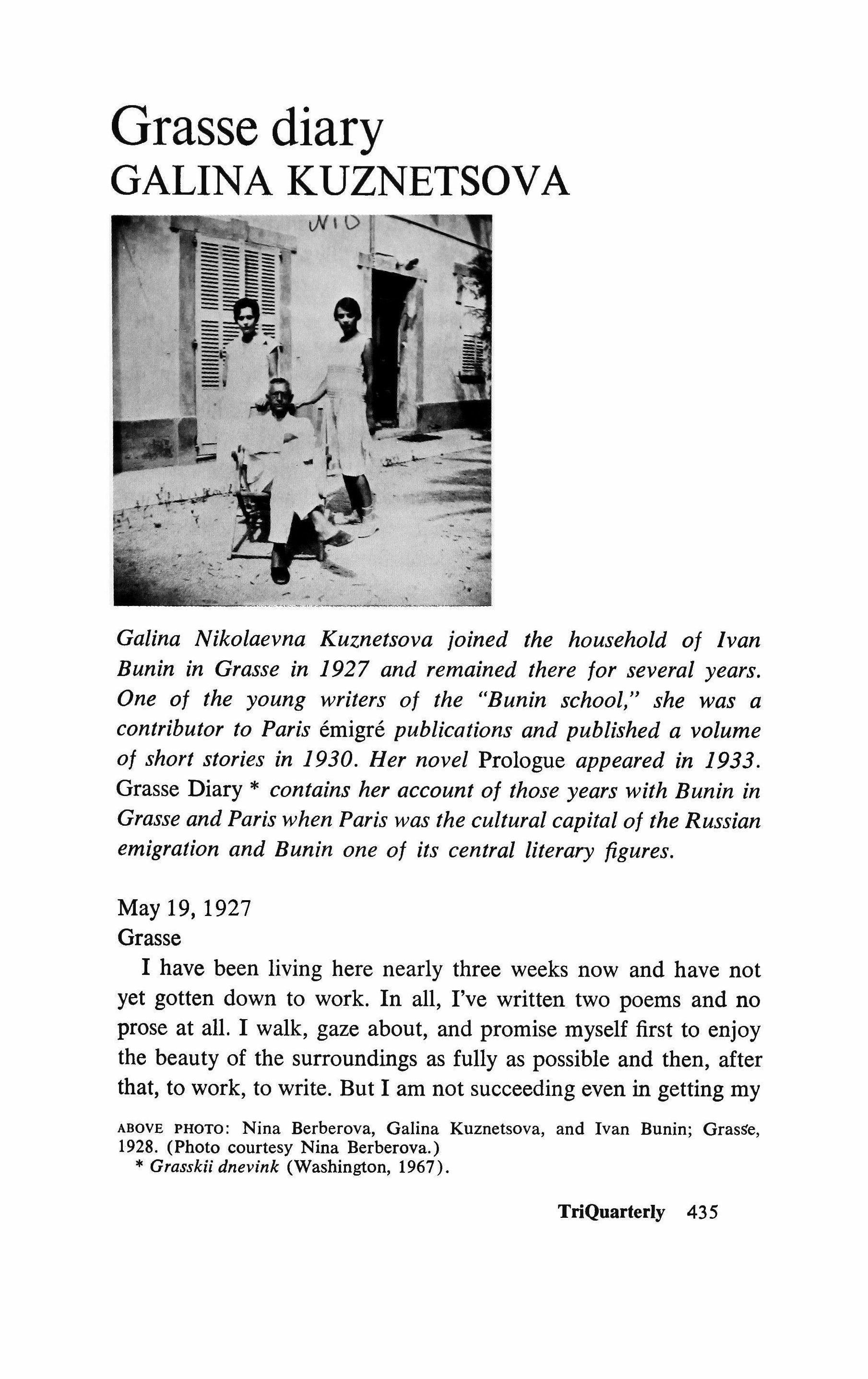

Grasse diary 435

Shestov, or the purity of despair 460

A note on Teffi 481

Time 483

V. S. Yanovsky: some thoughts and reminiscences 490 Struggle for perfection 492 from the novel American experience 500

AIla Ktorova: a new face 507 The face of Firebird: scraps of an unfinished anti-novel 521

V: PAINTING AND PAINTERS AS WRITERS

Tchelitchew as noble heir of exilic changes 542

A note on Konstantin Korovin (1860-1939) 558 My encounters with Chekhov 561

Andreenko's constructivist cubism 570 Mice 579

Exit smiling: an epilogue 608

A 3507

Source list

Nikolai Morshen poems from Punctuation: Colon iDvoetochle), Washington, 1967. Igor Chinnov's poems I and III from The [Musical] Score (Panitura), New York, 1970; poem II published in The NI'II' Review (Novyi zhurnal), New York, No. 100, September 1970. The Yuri Odarchenko poems from Quite a Day (1)('/1\'0/..), Paris, 1949. Anatoly Steiger's poem ("How can I shout ") from Two Times Two Makes Four (Dvazhdy Dva = Chetyre), 1950. All other Steiger poems from his collection Ingratitude iNebiagodarnost'Y, Paris, 1936. N. Teffi's "Time" from A II About Love ( V.I'Yo 0 Lyubvi), Paris, n.d. (ca. 1950). Georgy Ivanov: St. Petersburg Winters, originally Paris, 1928; the expanded section on Esenin from the second edition, New York, 1952. Ivanov's poems: "Thank god there is no tsar from Embarkation for Cythera, Paris, 1937; all others from Poems /9·U-1958, New York, 1958. Marina Tsvetaeva: "Poems grow ," originally in the journal Contemporary Annals, No. 52, Paris, 1933; "Psyche," originally in her collection Versts (Vyorsty), Moscow, 1922; "To Mayakovsky," originally in the journal Volya Rossii, XI-XII, Prague, 1930; "A Poet on Criticism," originally in Blagonamerennyi, II, Brussels, 1926. Letter to Anna Teskova from Marina Tsvetaeva's Letters to Anna Teskova, Prague, 1969. Boris Poplavsky: "In the Distance," "The Rose of Death," and "Rondeau Mystique III" from Flags, Paris, 1931; "Biography of a Clerk," "Rembrandt," and "Another Planet" from Dirigible of Unknown Destination, Paris, 1965; "How awful, getting tired from Snowy Hour, Paris, 1936. The chapter from Homeward from Heaven, originally in the collection Krug, Vol. 1-2, Paris, n.d. (ca. 1935). Vladimir Markov: "Mozart," originally in The New Review, New York, XLIV, 1956. Vladislav Khodasevich's essay on Tolstoy from his collected Literary Essays and Memoirs, New York, 1954. Mikhail Andreenko: "Mice," in The New Review, No. 99, New York, 1970. Konstantin Korovin's memoir on Chekhov originally published in Russia and Slavdom (Rossiya i slavianstvo), Paris, July 13, 1929; reprinted in Literary Heritage (Literatumoe nasledstvo); Vol. 68, Moscow, 1960. D. S. Mirsky's essay on Tsvetaeva originally in Contemporary Annals, No. 27, Paris, 1926.

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint the following materials: excerpts from Grasse Diary, by Galina Kuznetsova, and The Face of Firebird, by Alia Ktorova, reprinted by permission of Viktor Kamkin, Rockville, Maryland.

We would also like to thank the Center for Slavic and East European Studies, University of California, Berkeley, for its assistance in the preparation of this issue.

Photo credits

The Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archive: The Scarlet Empress; The Last Command; The North Star; You Can't Take It with You; Touch of E�'iI; Tarzan and the Apes; Safety Last; Brats. National Film Archives: The Hands of Orlac; Love; The Killers; The Last Command; I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang; The North Star; The Hitler Gang; Mission to Moscow; Song of Russia; Casablanca; A Night at the Opera; The Scarlet Empress, Buster Keaton. Doug Lemza and Films, Inc.: Fra Diavolo. The Bettmann Archive: Stravinsky and Debussy; Stravinsky and Nijinsky, Culver Pictures; Stravinsky et al. Kevin Brownlow: Surrender. Impact Films: Transport from Paradise.

Igor Stravinsky: the final maturity

PETER YATES

)l,f\Pb-nTHUl\ CKI\3KI\·bAJIETb 60 1)·110 KI'\I"THtlI'\Xb.

L'OISEJ-IO DE FEll,

C01'(Tf O.f\NS£ E."I 2 TI\BLf.1\(JX

Igor Strawlnsky.

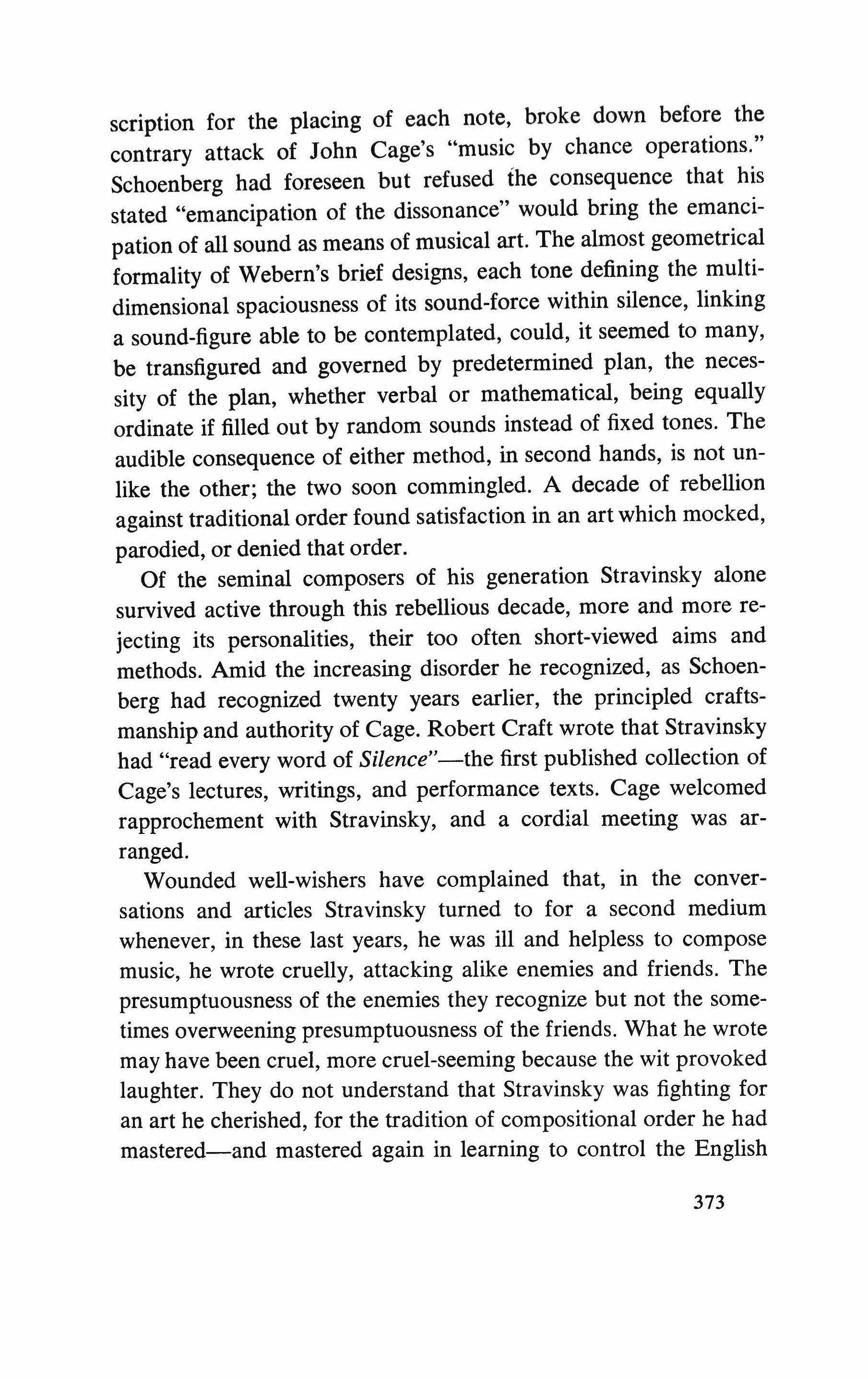

With the death of Igor Stravinsky and of Carl Ruggles, both in 1971, the generation that created 20th century music has ended. Ruggles, who lived the longest, wrote the least; a performance of his complete works at Bennington in 1968 filled so much less than one evening concert that his largest work, Sun Treader, was repeated. Stravinsky, the beloved Haydn of our era, poured out compositions almost without interruption lifelong, yet, as the intervening short life of Mozart was necessary to the final maturity of Haydn, so Stravinsky's belated discovery of Schoenberg opened for him a new potency. Whether this late product was a final maturity or a turning aside has been fiercely debated. Stravinsky himself seems never to have doubted that it was a step forward, although he was inclined in public utterance to give equal or more credit to his slightly later discovery of Webern. I would say that the revelation came through Schoenberg, the congeniality of the new

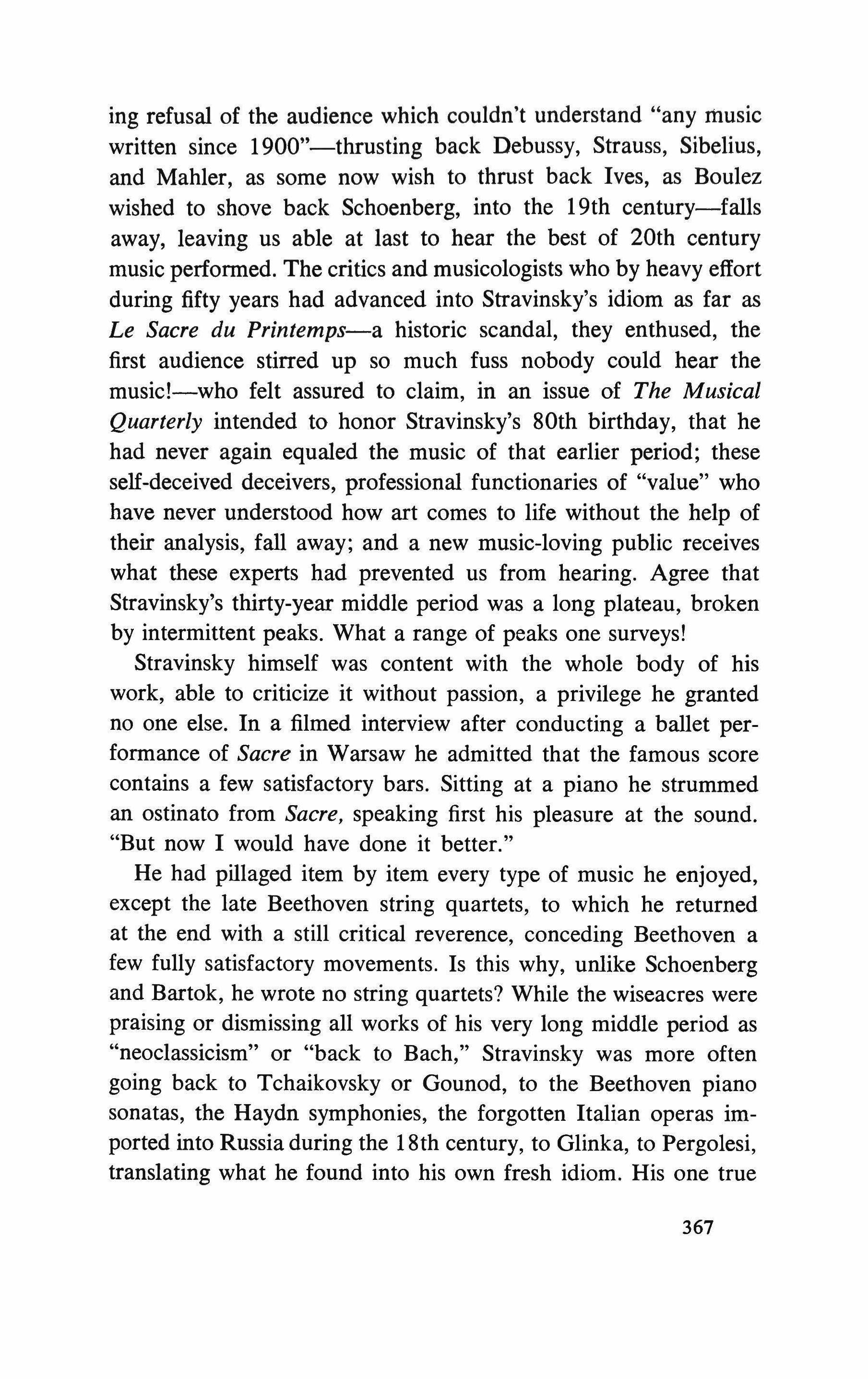

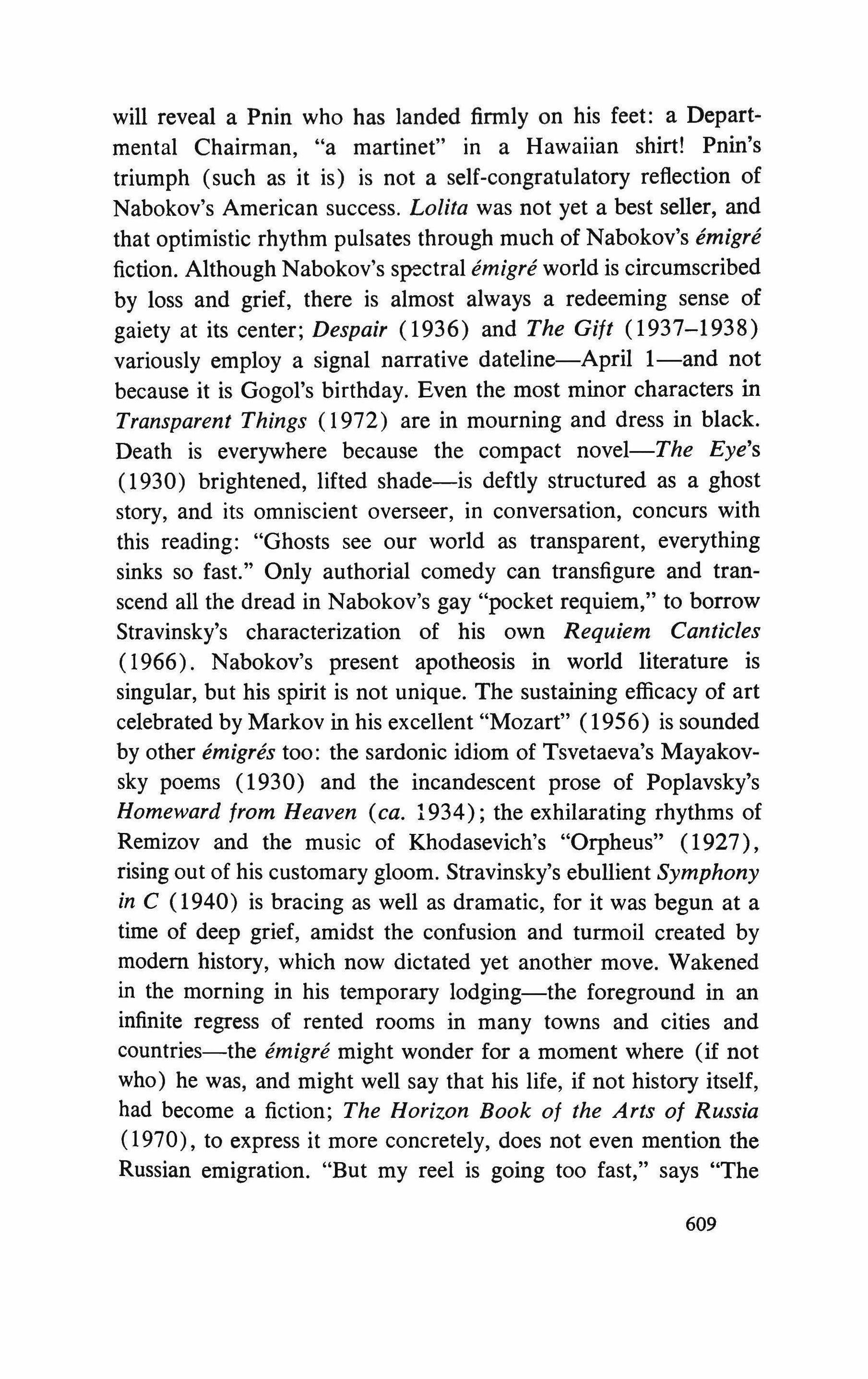

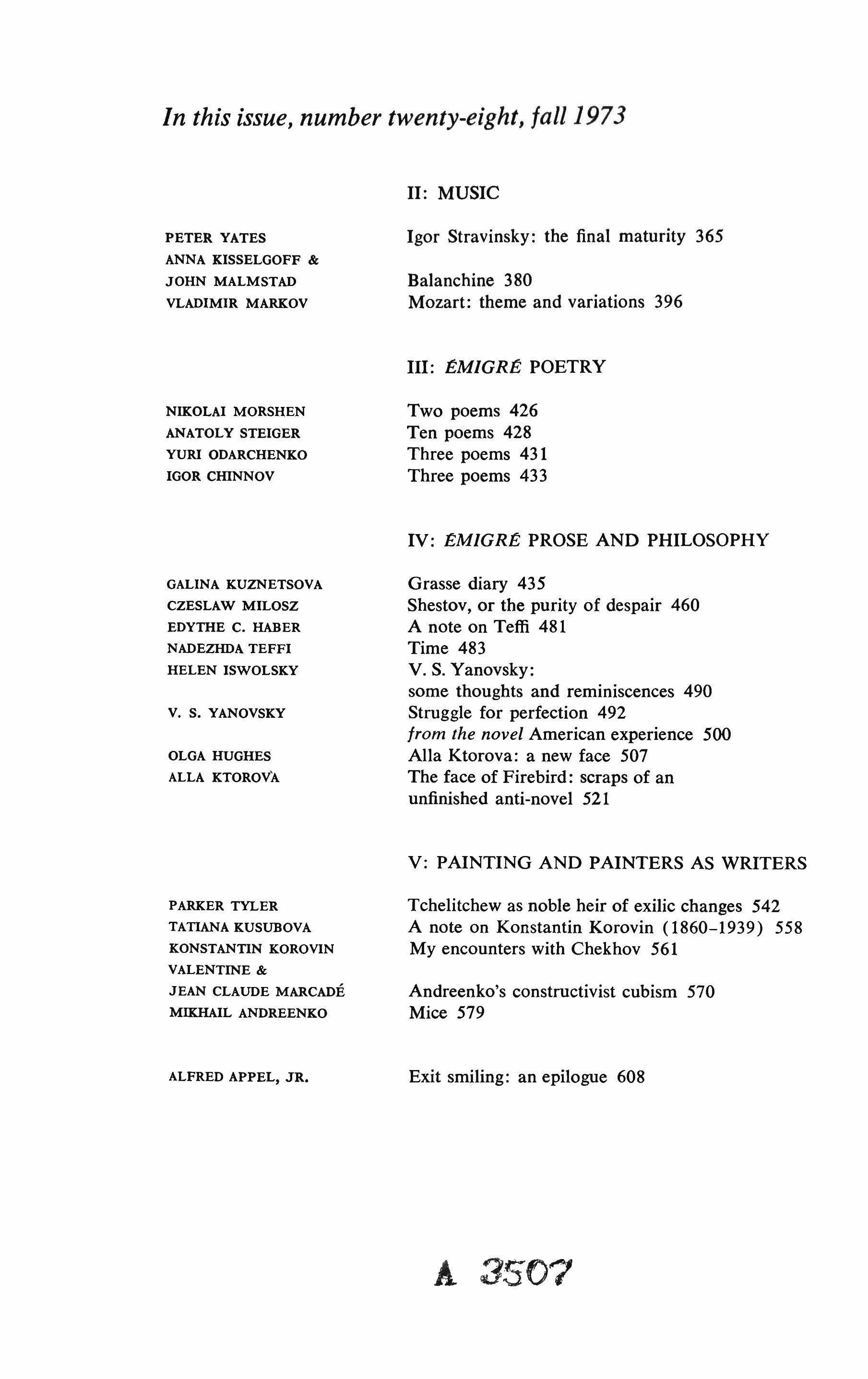

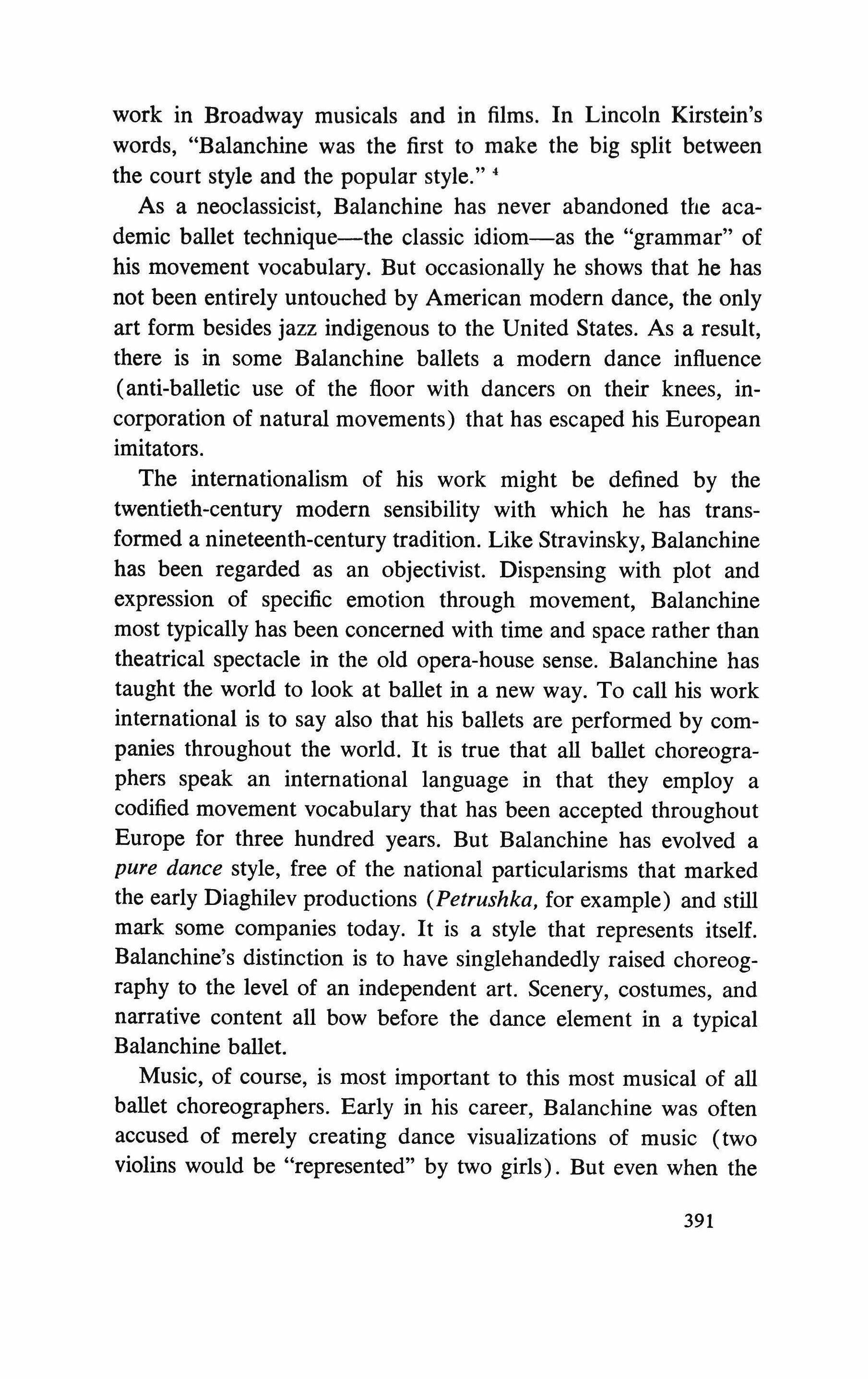

ABOVE PHOTO: The first edition of The Firebird score (1910), inscribed by Stravinsky "50 years later"(!) for James J, Fuld, author of The Book of WorldFamous Music. (Photo courtesy James J. Fuld.)

TrlQuarterly 365

�.----.-.....(/.�--,<',�,,/ Hropa c;���mmo.�T�';-j]--�? �(.>,L--7 "9 ..::..

�.r;:""

�'i

practice from Webern. Stravinsky's music of the last years was not a change of direction but a fulfillment.

The true change was internal. In Stravinsky'S statement: "Today harmonic novelty is at an end. As a means of musical instruction, harmony offers no further resources in which to inquire and from which to seek profit. The contemporary ear and brain require a completely different approach to music."

Simple enough! the innovators exclaim. Throw out tradition with harmony, throw out order with tradition. Destruction is not reconstitution; the fathers of 20th century musical freedom, with release, probed difficulty.

Ruggles vehemently condemned Stravinsky for writing other men's music. You couldn't argue the point with Carl; he was stone deaf. Carl held firmly to the belief that every note of every measure one wrote must be one's own original conception; in that granitic purpose he reworked and rewrote his few compositions. The polyglot Stravinsky appropriated whatever he came on in sound or organizing method that seemed appropriate to himself. "One does not borrow, one steals," he quoted to me. "One does not imitate, one makes one's own." The score of Threni brings together Monteverdi, the tone-row, and the choral speaking-singing of Schoenberg's Moses and Aron and De Profundis. "I like very much the speaking-singing of Schoenberg's later compositions," Stravinsky said to me. Yet anyone hearing Threni (1961) and The Wedding (1914-1923) in succession must agree that each measure of rhythm, each isolate timbral composite, Jeremiah or Muzhik, speak and sound the one Stravinsky.

So much for originality. There is only music fully made or insufficiently made-s-pastiche. Well-organized pastiche furnishes the 'Commonplace originality of every generation. The cluttering craftsmanship of the contemporaries falls away, and a younger generation inherits what remains, the essential workmanship of the generation preceding the last. Today the generation preceding the last is that of Schoenberg, Ruggles, Webem, and Stravinsky. Also Ives, on whose music Stravinsky'S highest praise lighted in the 1960's, to be afterwards characteristically qualified. The block-

366

ing refusal of the audience which couldn't understand "any music written since 1900"-thrusting back Debussy, Strauss, Sibelius, and Mahler, as some now wish to thrust back Ives, as Boulez wished to shove back Schoenberg, into the 19th century-falls away, leaving us able at last to hear the best of 20th century music performed. The critics and musicologists who by heavy effort during fifty years had advanced into Stravinsky's idiom as far as Le Sacre du Printemps-a historic scandal, they enthused, the first audience stirred up so much fuss nobody could hear the music!-who felt assured to claim, in an issue of The Musical Quarterly intended to honor Stravinsky's 80th birthday, that he had never again equaled the music of that earlier period; these self-deceived deceivers, professional functionaries of "value" who have never understood how art comes to life without the help of their analysis, fall away; and a new music-loving public receives what these experts had prevented us from hearing. Agree that Stravinsky's thirty-year middle period was a long plateau, broken by intermittent peaks. What a range of peaks one surveys!

Stravinsky himself was content with the whole body of his work, able to criticize it without passion, a privilege he granted no one else. In a filmed interview after conducting a ballet performance of Sacre in Warsaw he admitted that the famous score contains a few satisfactory bars. Sitting at a piano he strummed an ostinato from Sacre, speaking first his pleasure at the sound. "But now I would have done it better."

He had pillaged item by item every type of music he enjoyed, except the late Beethoven string quartets, to which he returned at the end with a still critical reverence, conceding Beethoven a few fully satisfactory movements. Is this why, unlike Schoenberg and Bartok, he wrote no string quartets? While the wiseacres were praising or dismissing all works of his very long middle period as "neoclassicism" or "back to Bach," Stravinsky was more often going back to Tchaikovsky or Gounod, to the Beethoven piano sonatas, the Haydn symphonies, the forgotten Italian operas imported into Russia during the 18th century, to Glinka, to Pergolesi, translating what he found into his own fresh idiom. His one true

367

"back to Bach" work came toward the end, his resetting with chorus and orchestra of Bach's Canonic Variations for organ. Even after his last official composition he was orchestrating Preludes and Fugues of the Well-Tempered Clavier. He did not permit himself the usual mistake of imitating masterpieces or try to put into effect "ideas" about music. He parodied and re-created what he heard. He wrote of Beethoven: "It is in the quality of his material and not in the nature of his ideas that his true greatness lies "--defying thus a century of Germanic-romantic scholarship. He sought material which had not been worked out, to give it in his own setting a fresh relevance.

How explain the imaginative discipline through which a group of small pieces by Pergolesi became Pulcinella-!he duet for trombone and contrabass? Echoed decades later by the little concerto for violin and three trombones in Agon. That's the fun of art.

I see him at the final rehearsal of that concert in the 1953-1954 season of Evenings on the Roof when Robert Craft directed nine works by Webem, several of them first performances, beginning the heroic effort which produced, with no financial backing, the album of the "Complete Works." While an audience of composers and musicians strolled the floor comparing opinions, Stravinsky sat at a table, the scores in front of him, his magnifying glass ready to be lifted for a quick analytic glance, his head bent to follow every gesture of the music he was hearing. In this self-concentrated self-oblivion he seemed a comic figure, adjusting two pairs of glasses up and down the narrow curve of bare forehead, glancing up through cherub-innocent eyes, face intent to hear what would be said to him, cheeks already quivering with the smile through which he would respond.

When others were borrowing shapeliness for their theories from Webem, professors explaining Webern's art by diagrams, and a new generation of composers stretching out Webern's renunciations to symphonic lengths, Stravinsky had already appropriated and made modestly his own what he had learned.

Stravinsky did not, like Beethoven or Schoenberg, explore the depths. His pleasure was ordonnance, the discipline of the ballet,

368

the precise movement, the illuminated stage, the gesture sufficient to itself, not caught up in the superreality of drama. Sacre had gone too far; he preferred not to go that way again. Only through the religious music did he a little reveal what was inward to him, and there too he preferred not the questioning of Schoenberg but a formality of ritual celebration. I believe that may have been why, during the later years, he so often performed the Symphony of Psalms. His Oedipus Rex is deliberately not a tragedy of human beings; he twice returned the libretto to Cocteau asking him to make it "more banal," and for that reason he had the text translated into the impersonality of Latin. At the first performance in Philadelphia nine-foot puppets slowly gestured the roles, while the singers, sitting around the great mound that was Matzenauer, performed as in an oratorio.

It was possible to guess before he said so that the Symphony in Three Movements responded to the Second World War, but it is not outwardly a battle symphony or expressive of the subjects he attributed to the three movements. From the Symphonies for Winds, in Memory of Claude Debussy, through the several brief elegiac works of his·later years, to Threni, and the utmost austerity of his own commitment to death, Requiem Canticles, there is a growing, sometimes embittered and defiant sadness. His great career ends in the Canticles; he added one little work, elusive as a smile and dedicated to his wife, Vera, a setting for voice and piano of Edward Lear's The Owl and the Pussycat.

For Schoenberg the stage of the melodic drama was the mind in depth, not easily transferable to the visual stage: the idiom a ceaseless melodic interchange expressive of conflicting, arguingthe chief quality of the music, which is the passionate development of the argument Stravinsky wrote, mentioning also "the songfulness and the humor "-emotions unresolved, symbolic, dreamlike, conceptual, needing only a few registers on the organ of timbral color; the rhythm, at first hearing almost indeterminable, governed by the interweaving phrases. Schoenberg's intricate designing of melodic idiom had early rejected the metrical measure of accompaniment, so familiar in Stravinsky, the ostinati of the 369

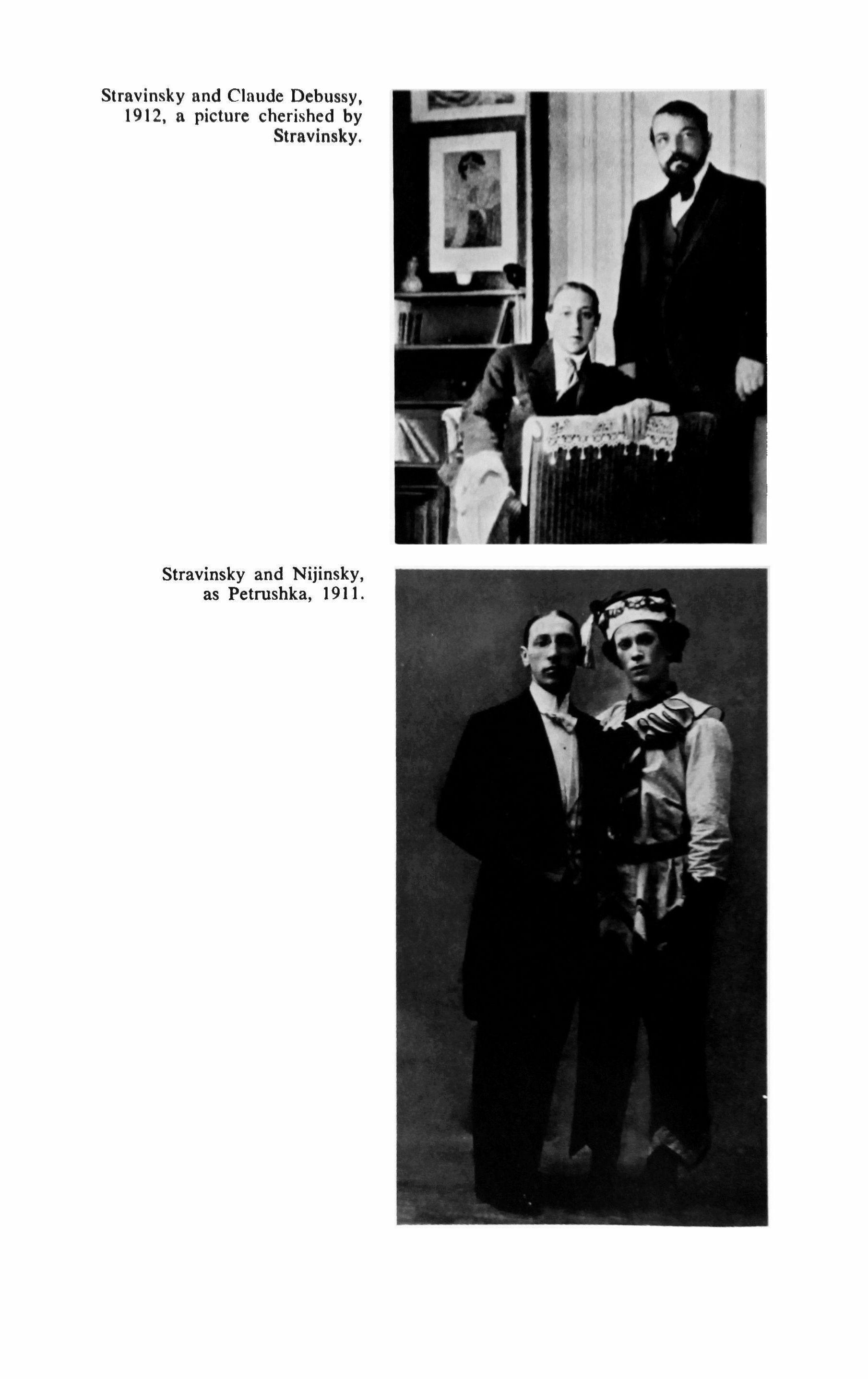

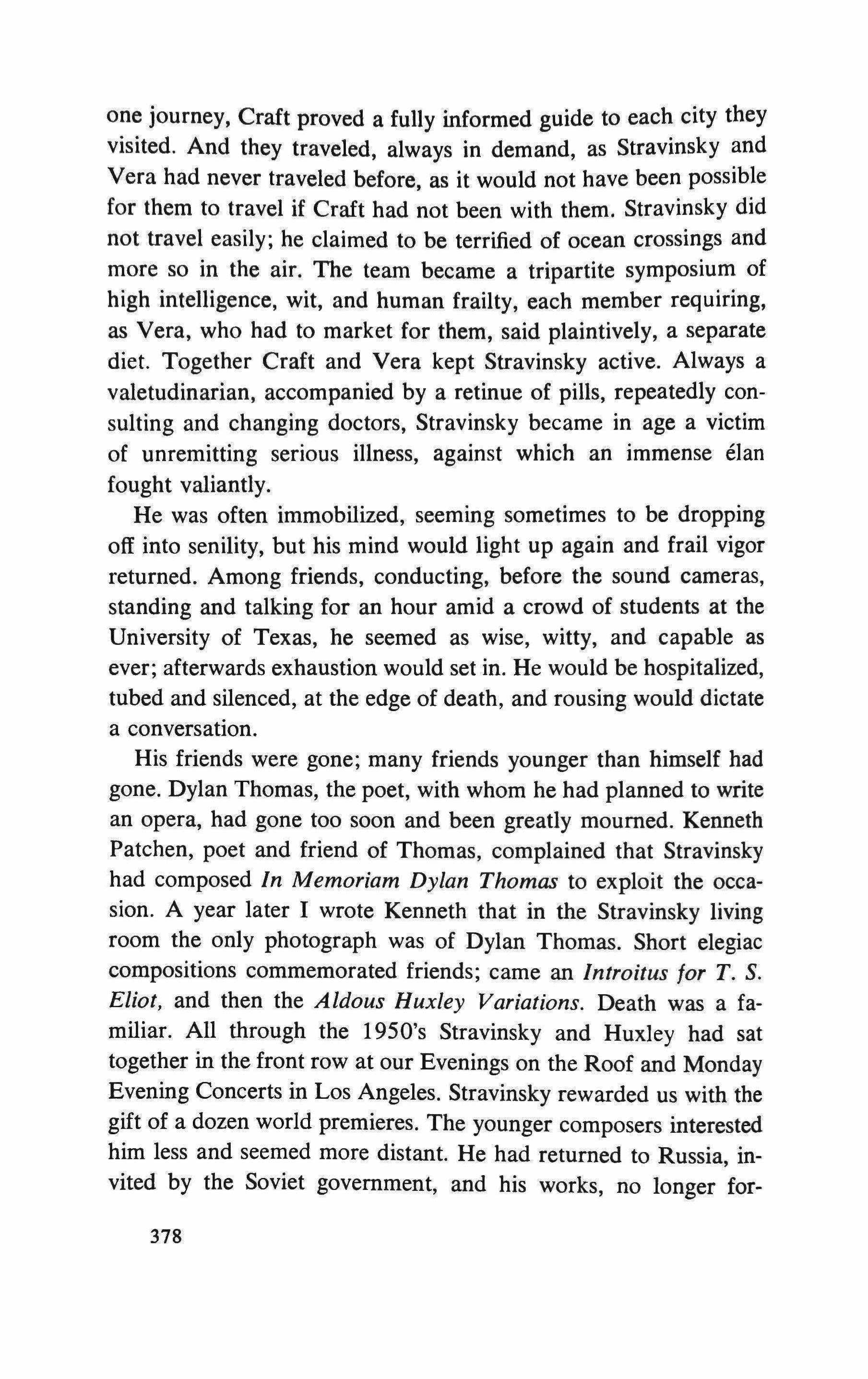

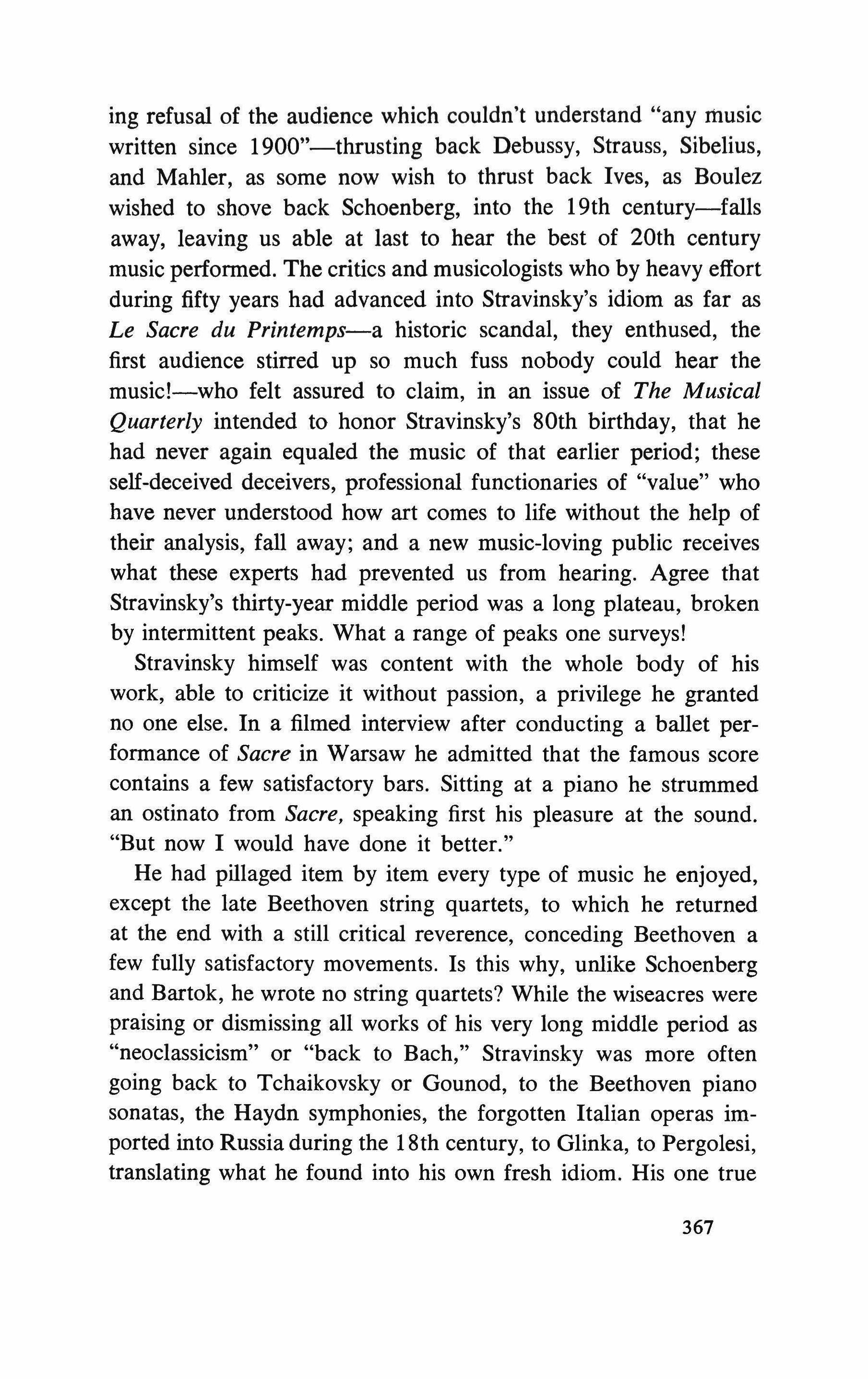

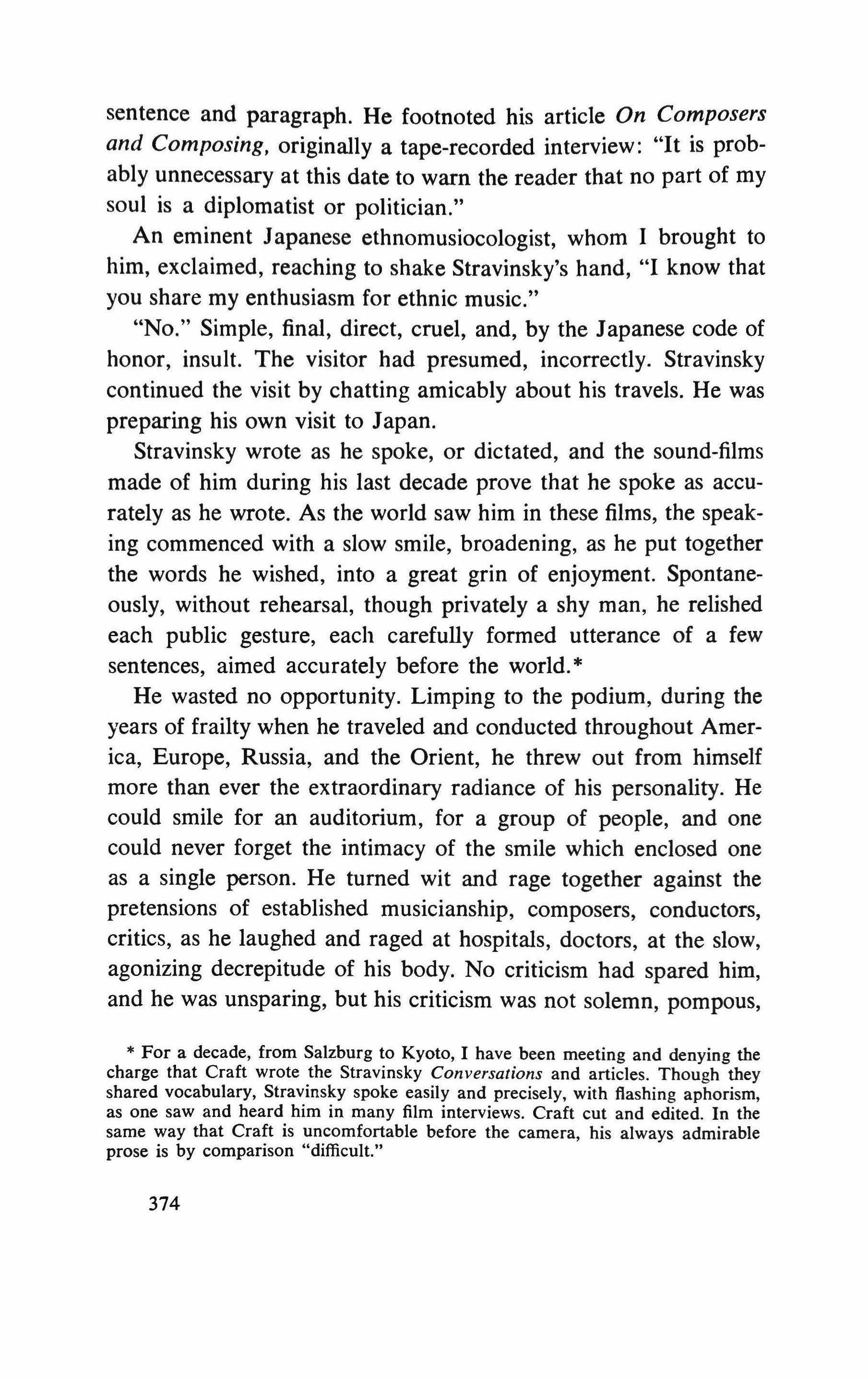

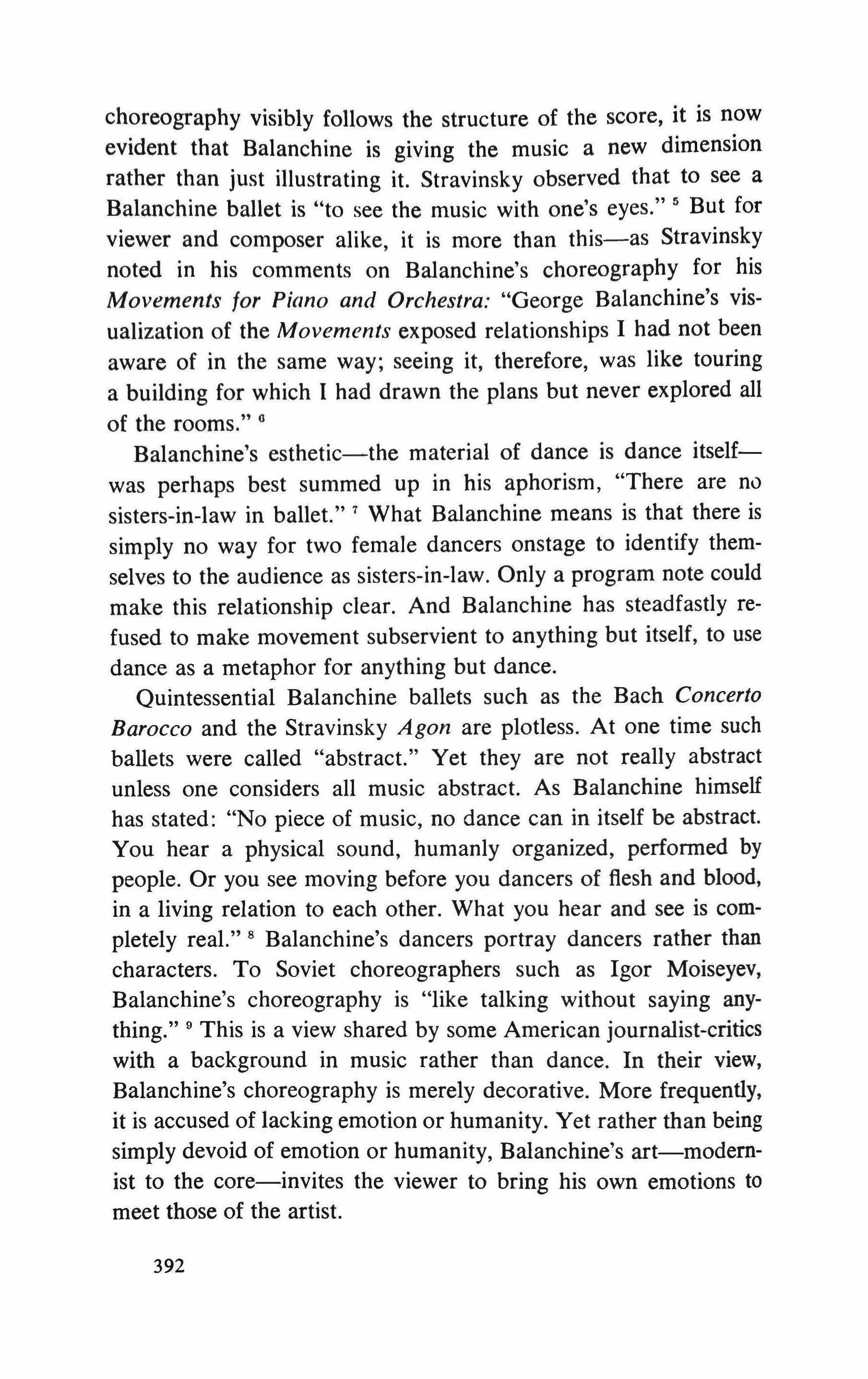

Stravinsky and Claude Debussy, 1912, a picture cherished by Stravinsky.

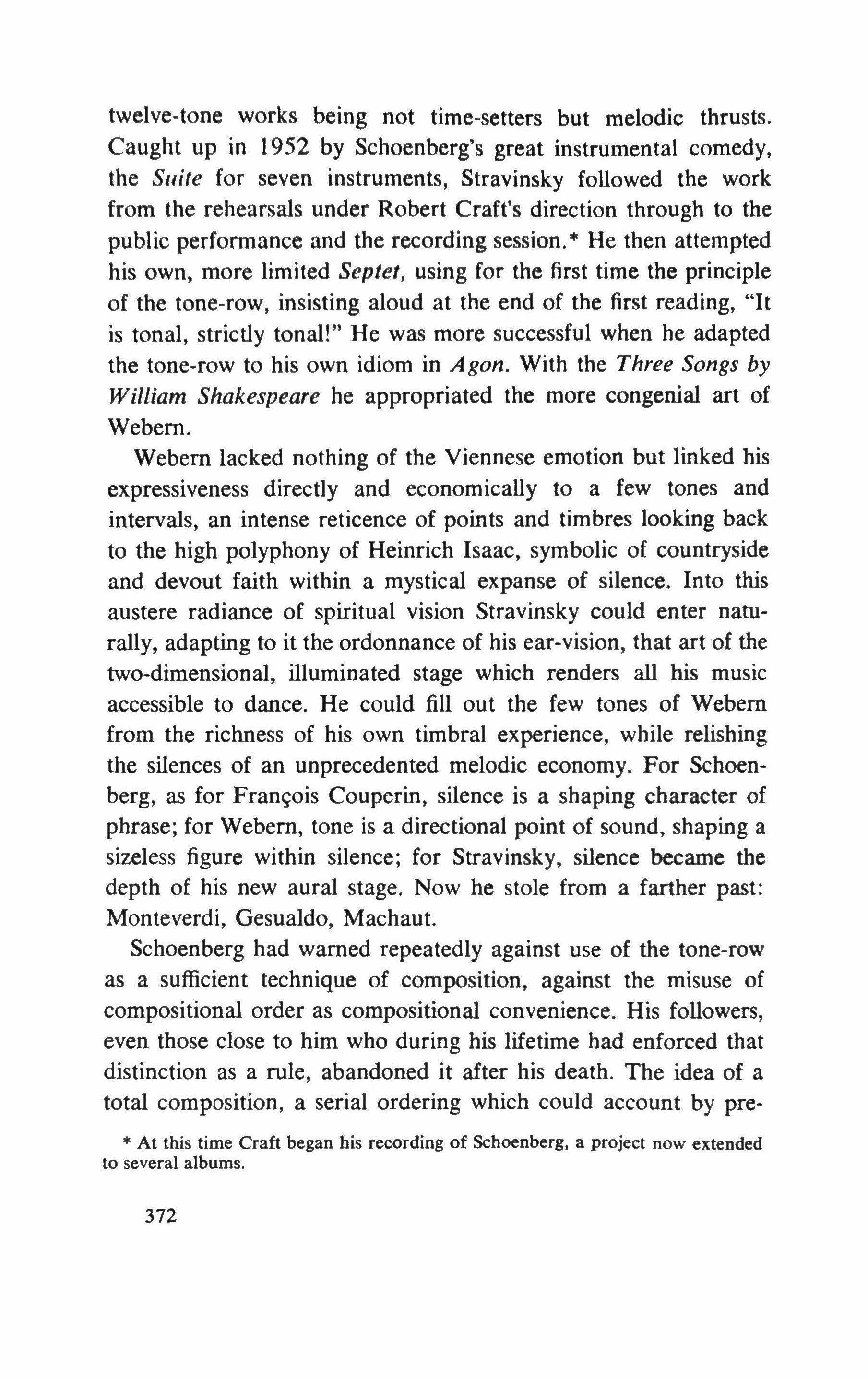

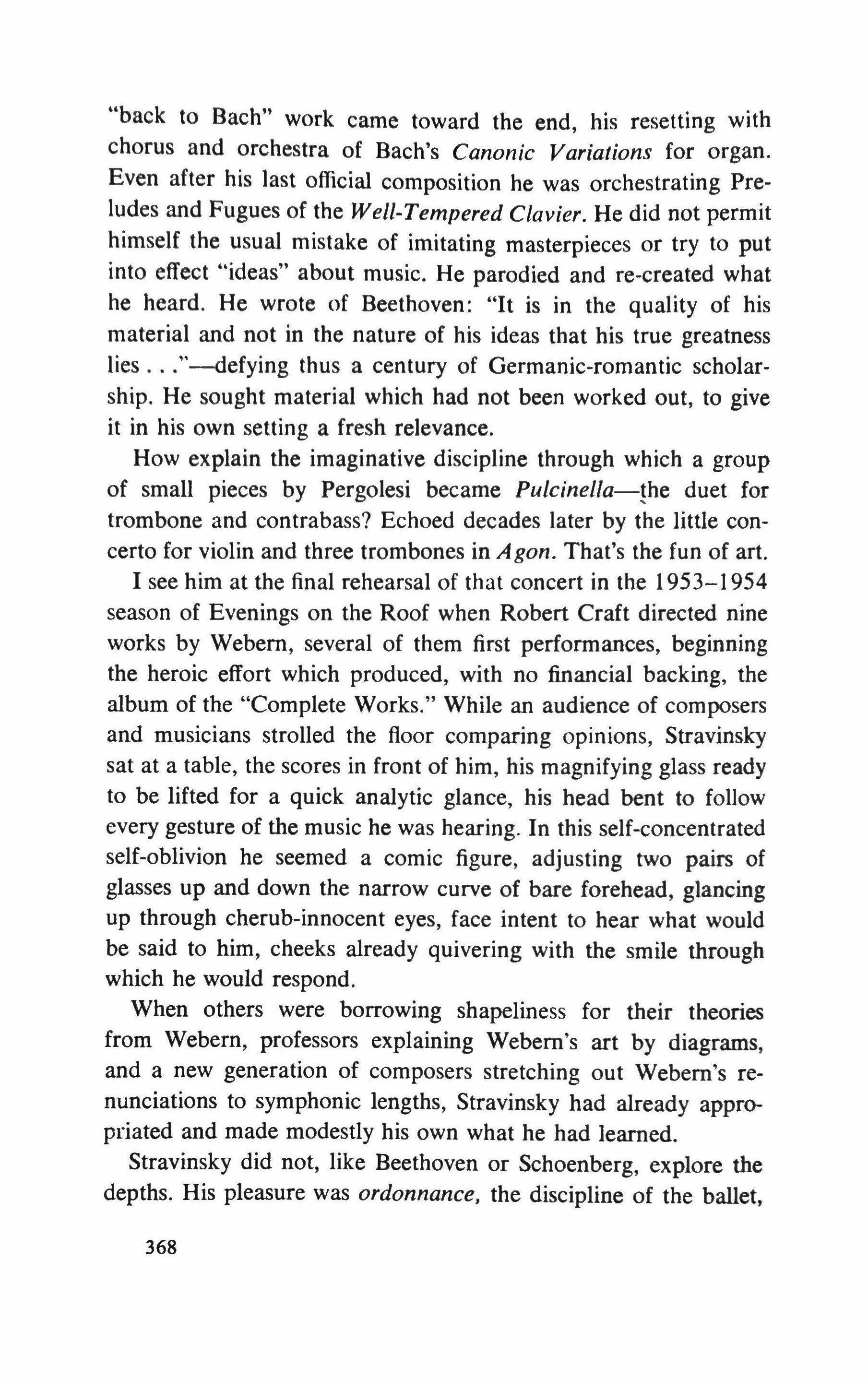

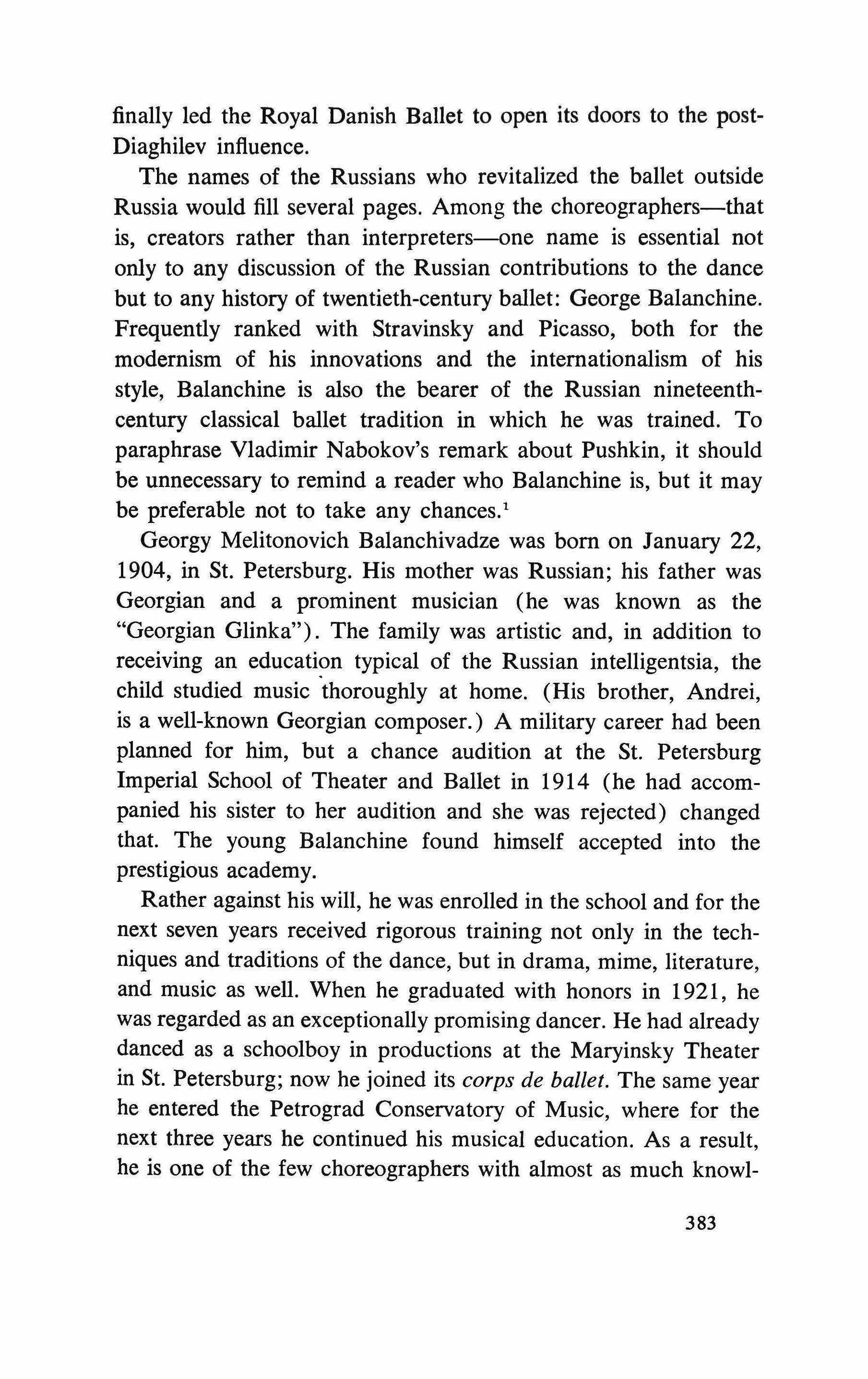

Stravinsky and Nijinsky, as Petrushka, 1911.

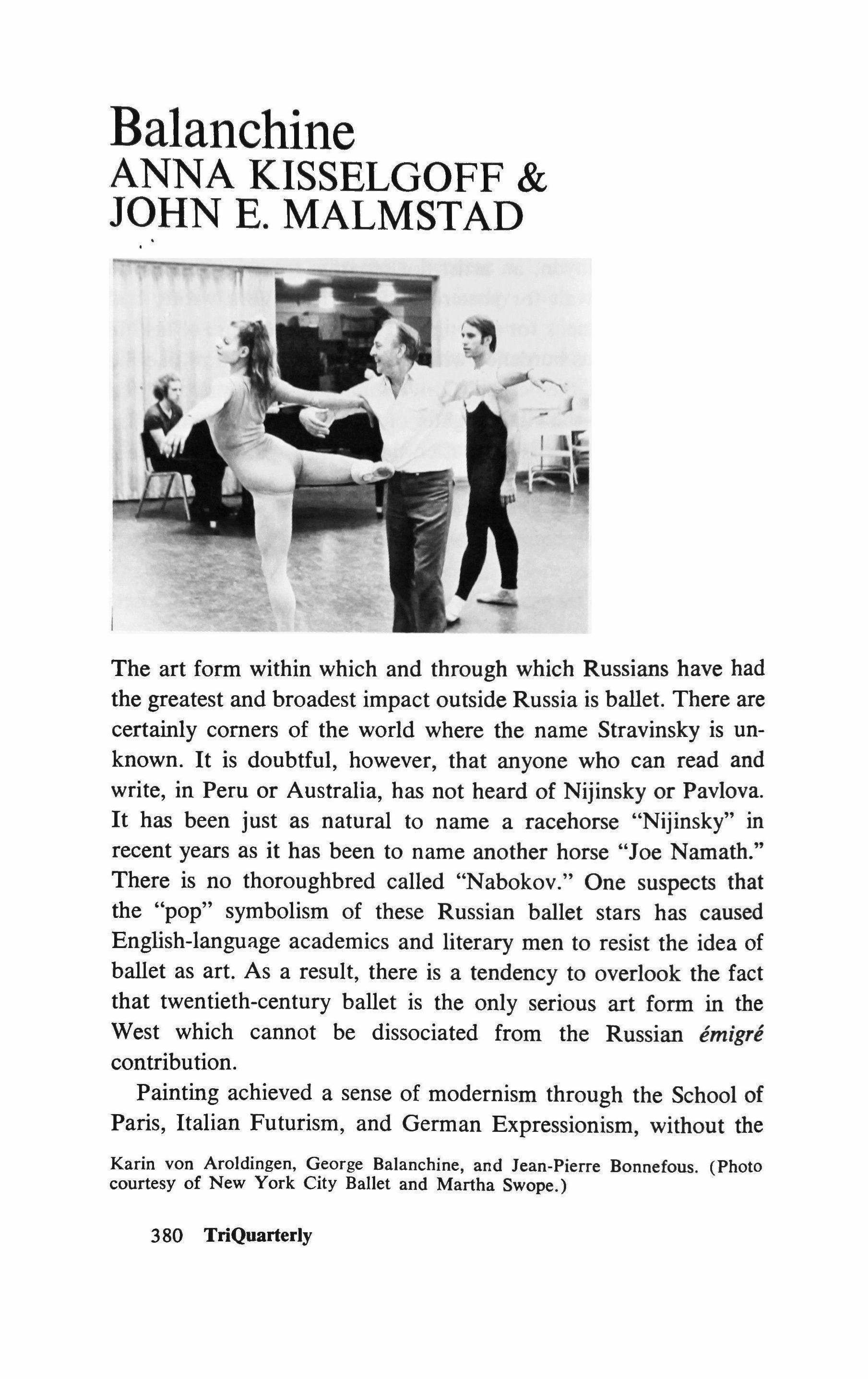

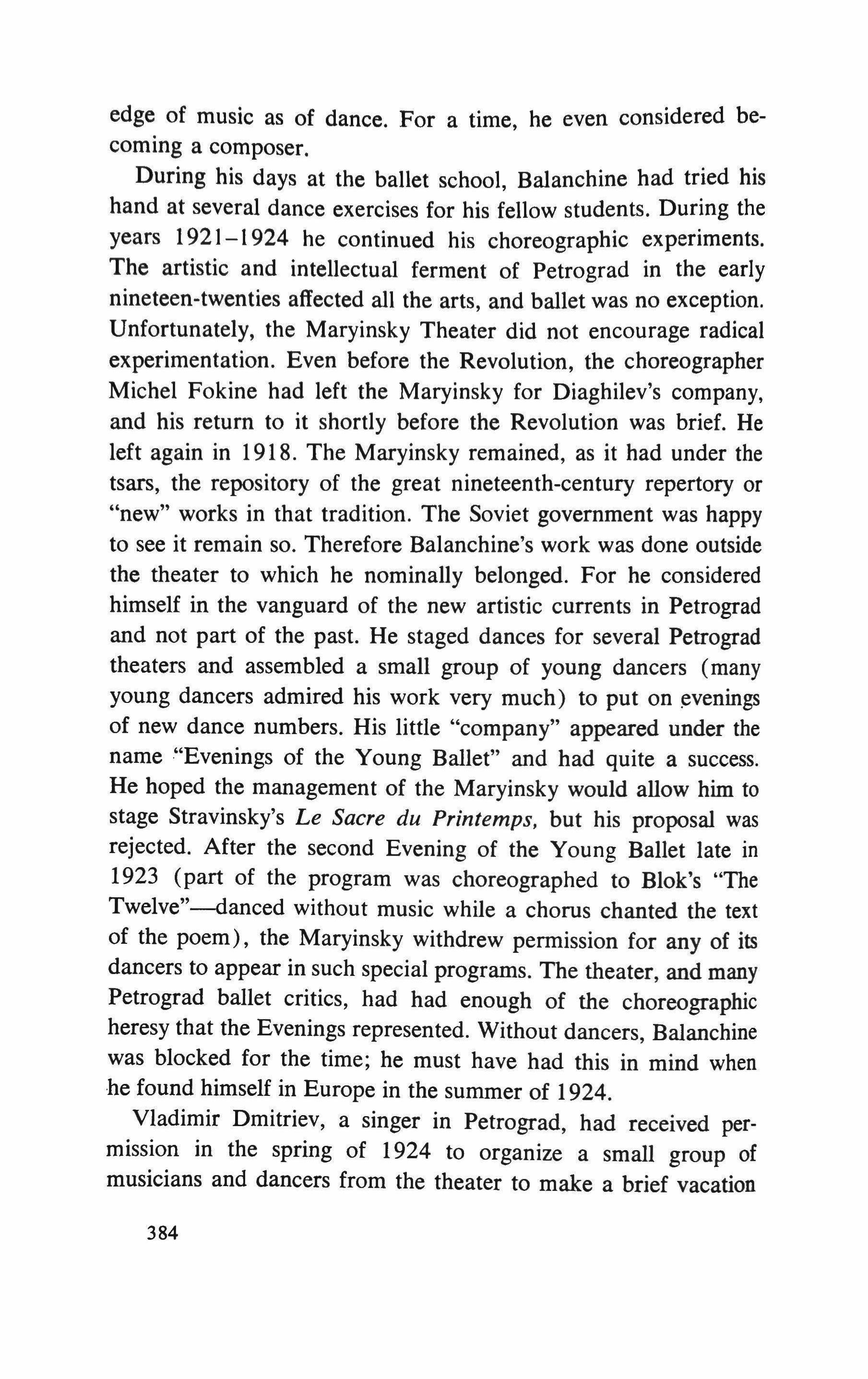

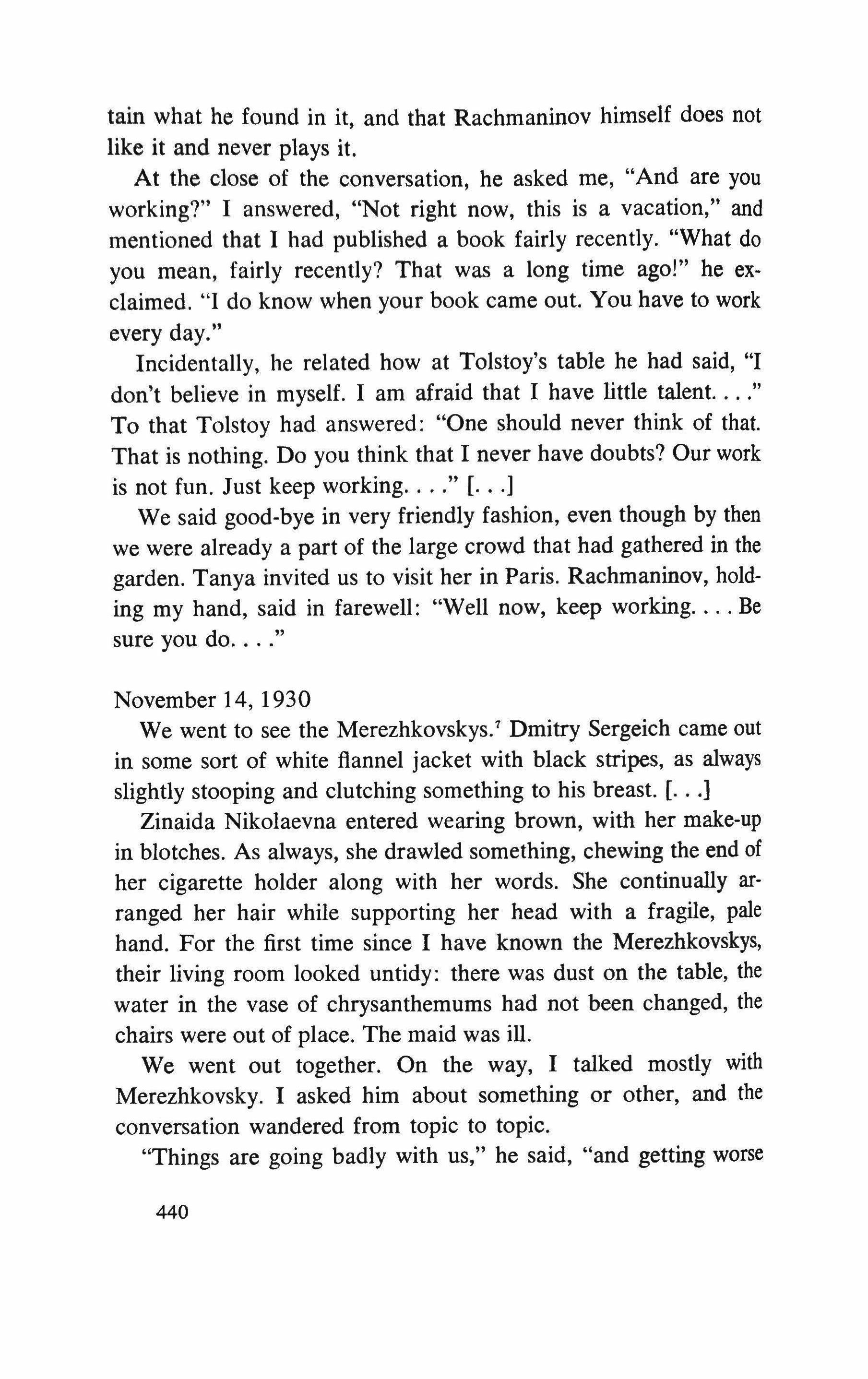

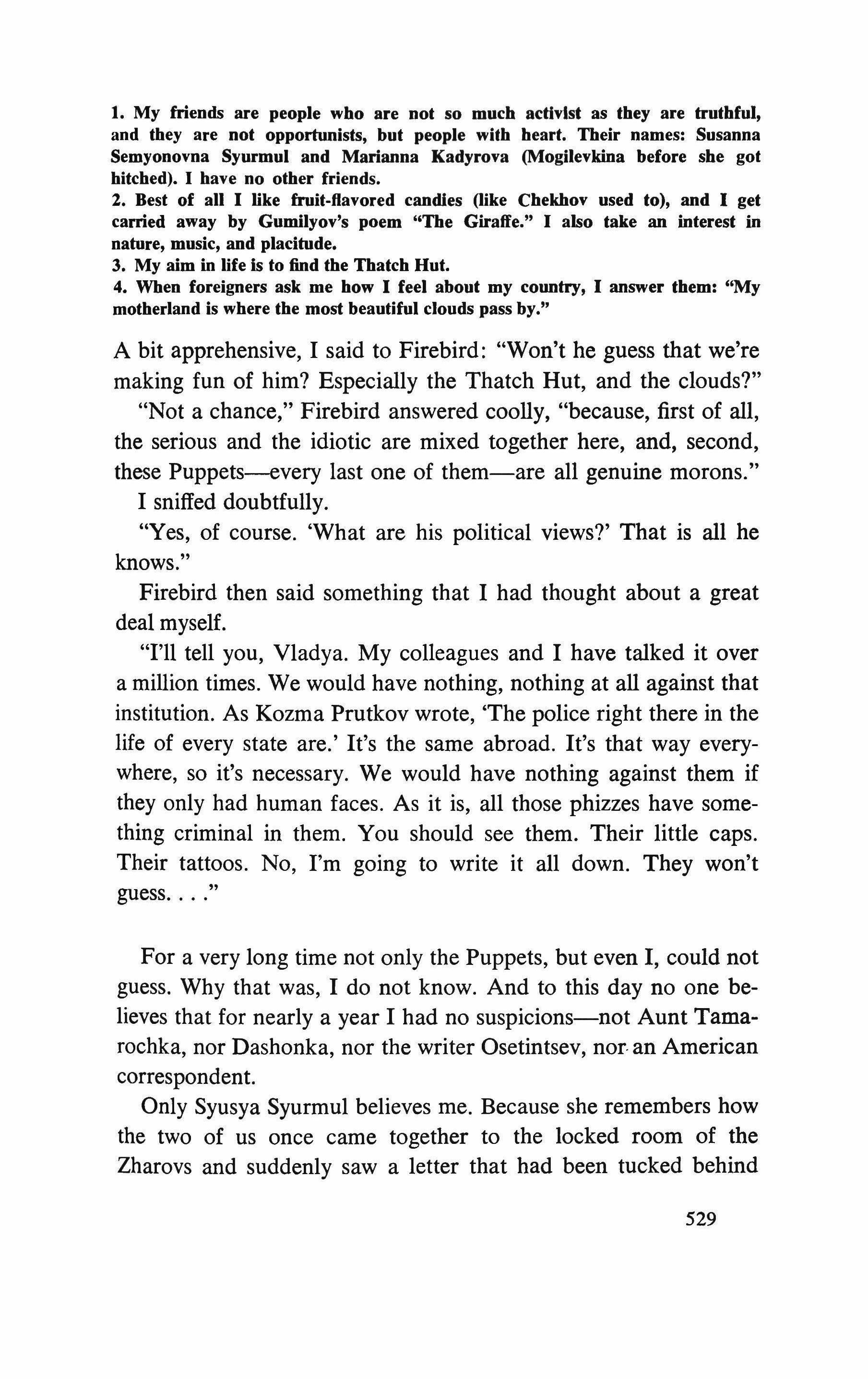

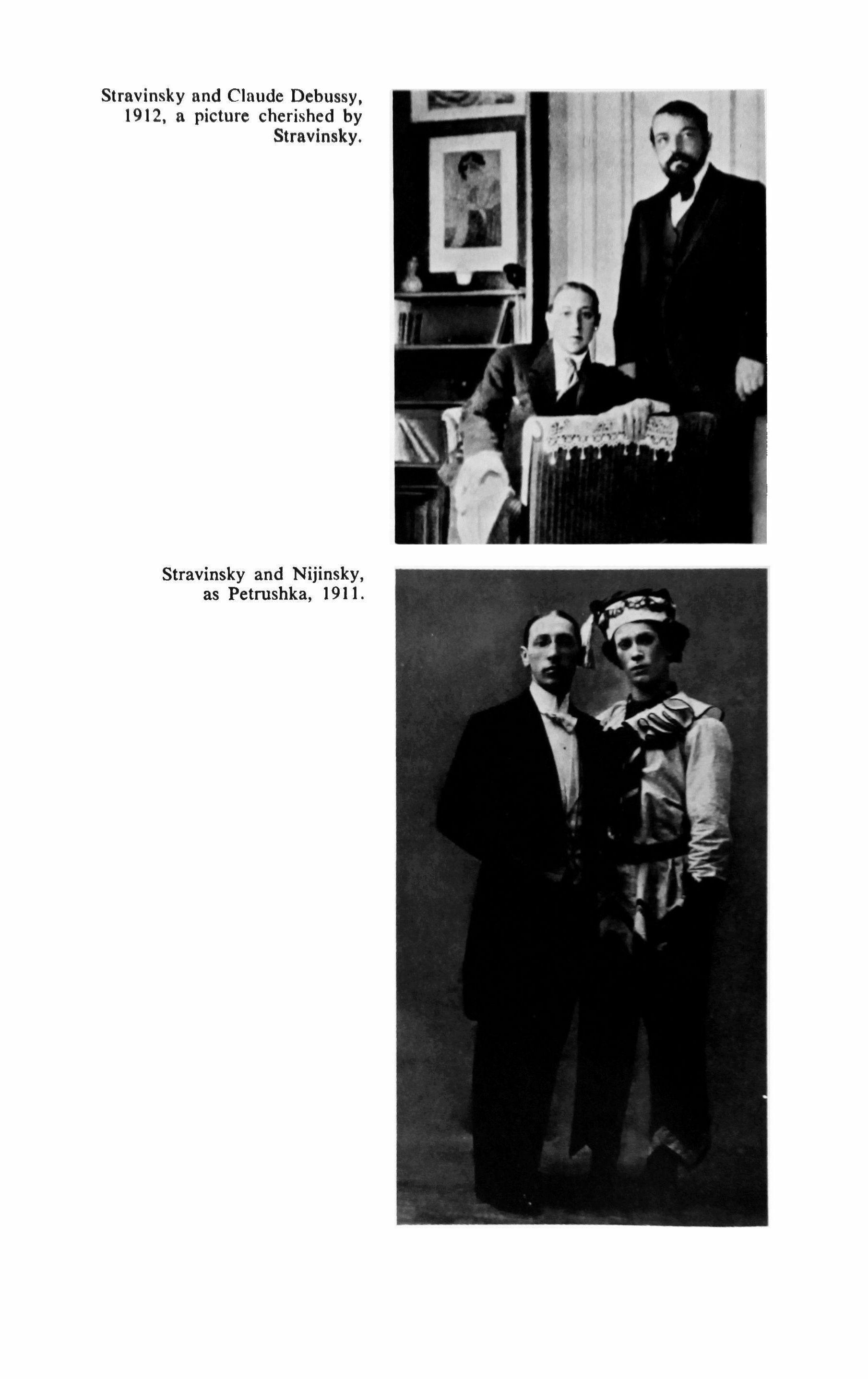

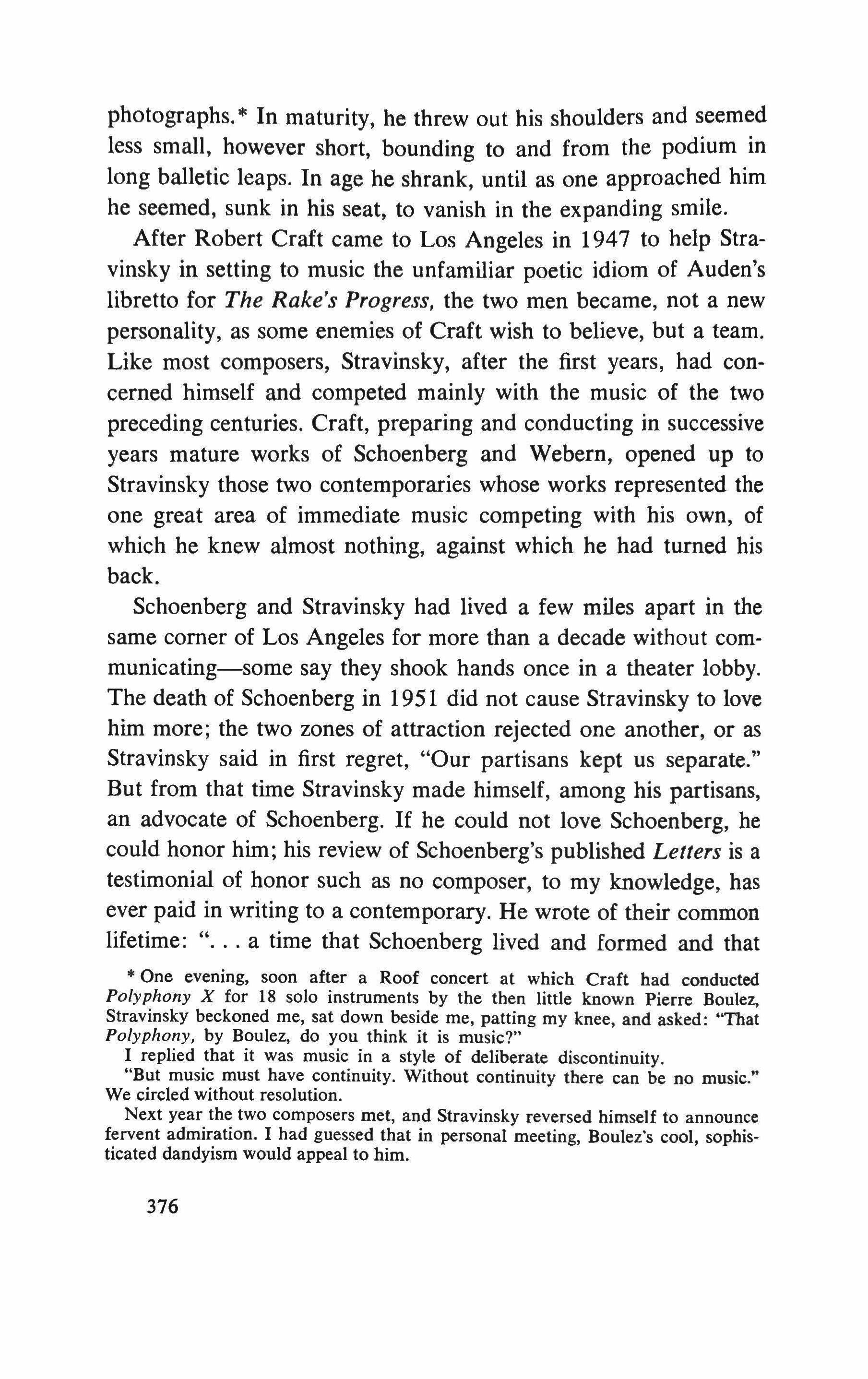

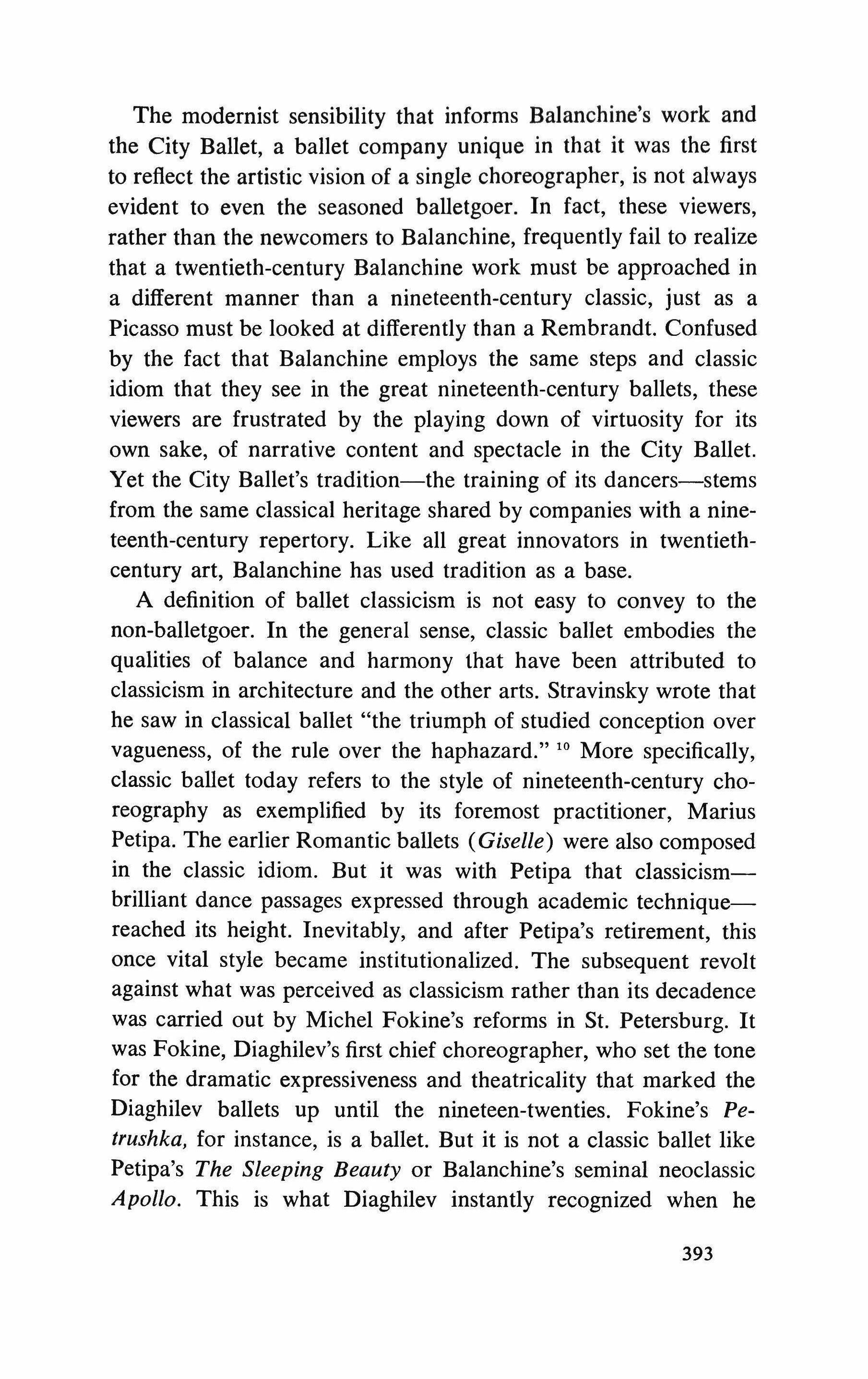

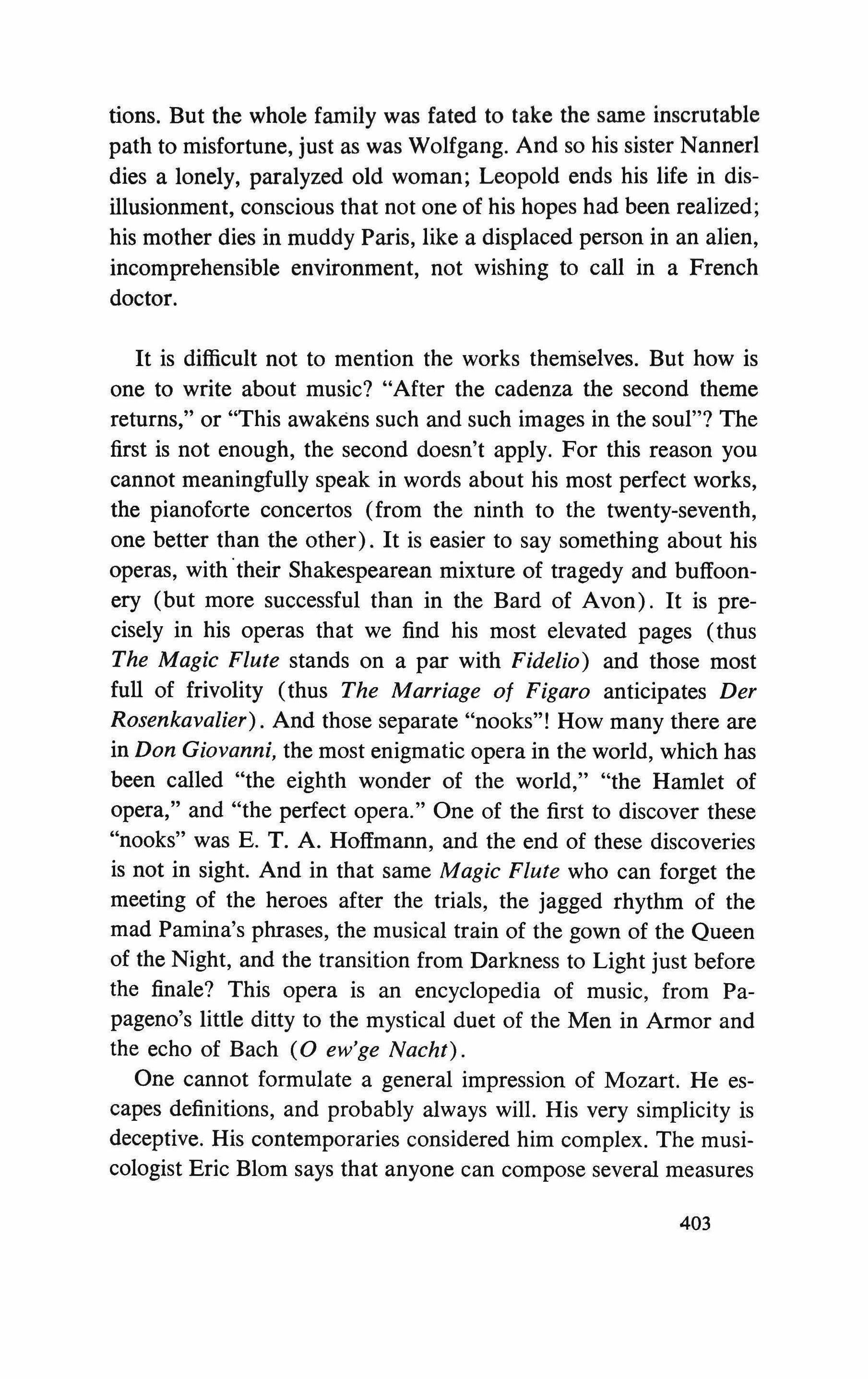

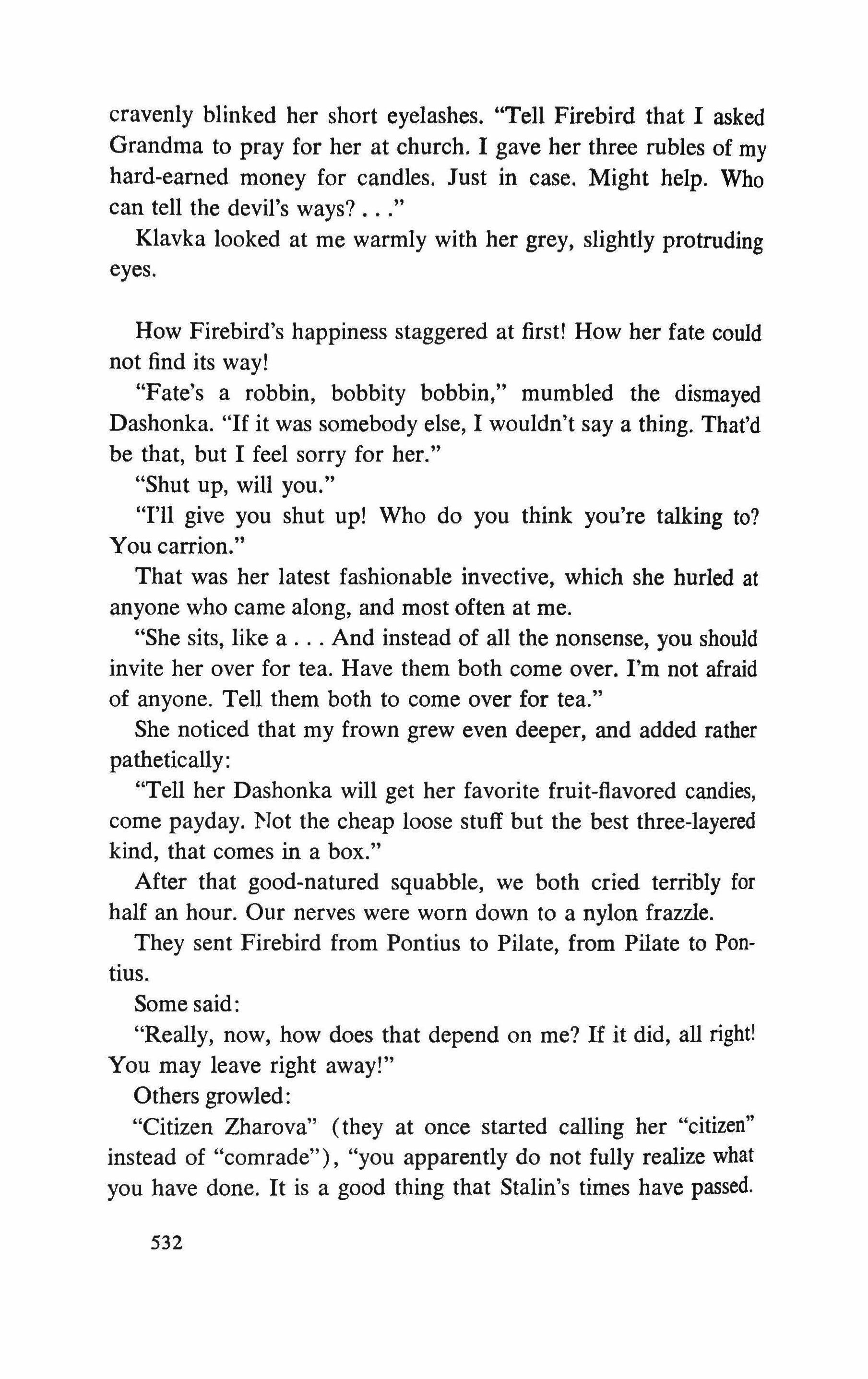

Manuscript work-sheet of "Full Fathom Five," second of the Three Songs by William Shakespeare (1953) dedicated to the Evenings on the Roof concerts. Inscribed with a couplet by Stravinsky to Peter Yates: "Who kindled this Roof in the Evenings/For listeners so cool in the day."

� I&J':-�) t'l'.r- l ,,_ "'�r s; ��I';;'I'.�.--t I'" t I tl,/!" :- if : / Ik, "" ", /,;:;,.., I� ; -1-'61' L�. 'f. j+tc��r ·'bL�) .!'-fc. /11 :§1{"_ 1111!; 11101/,'>', t'1'.-/�1 /./S,

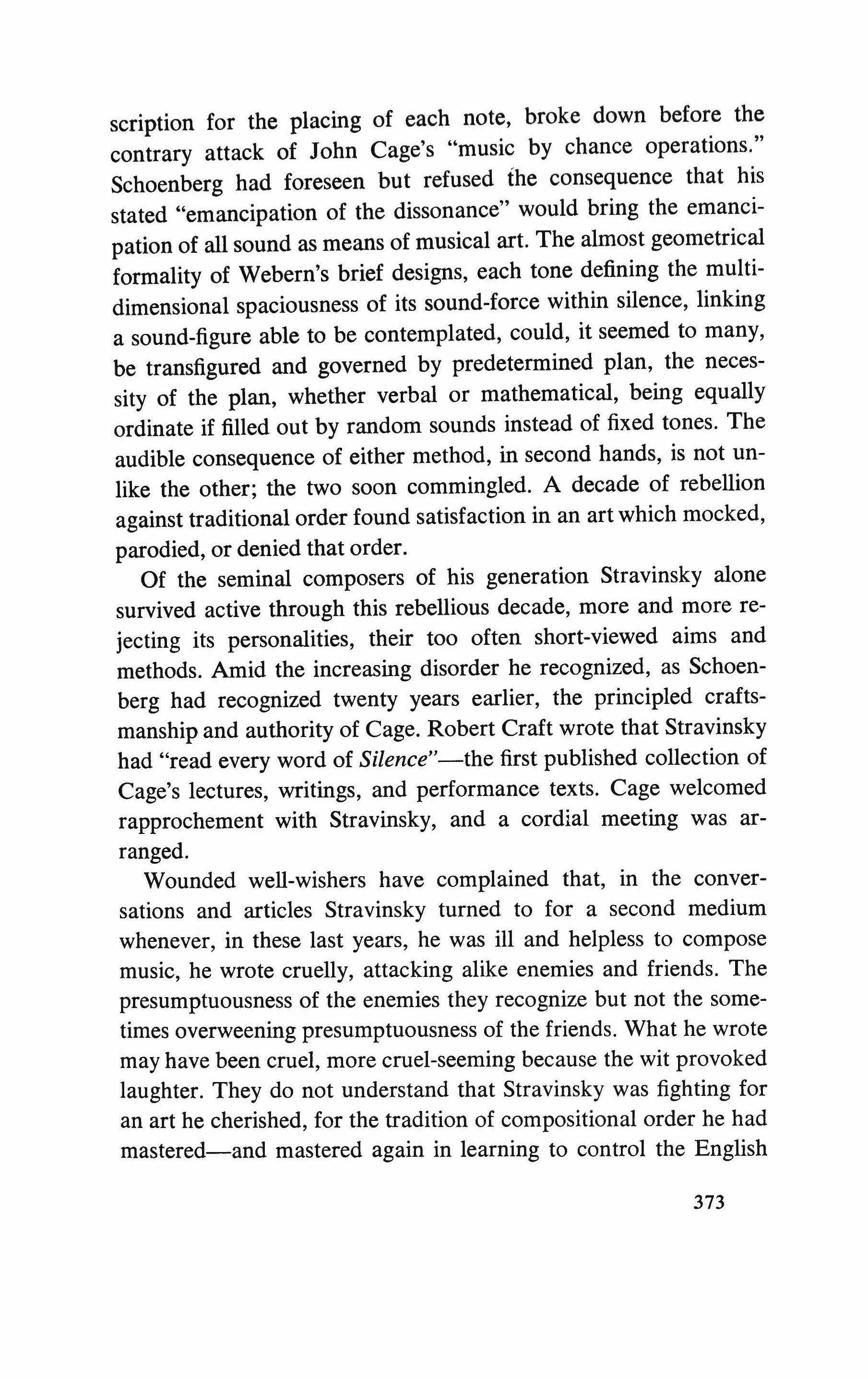

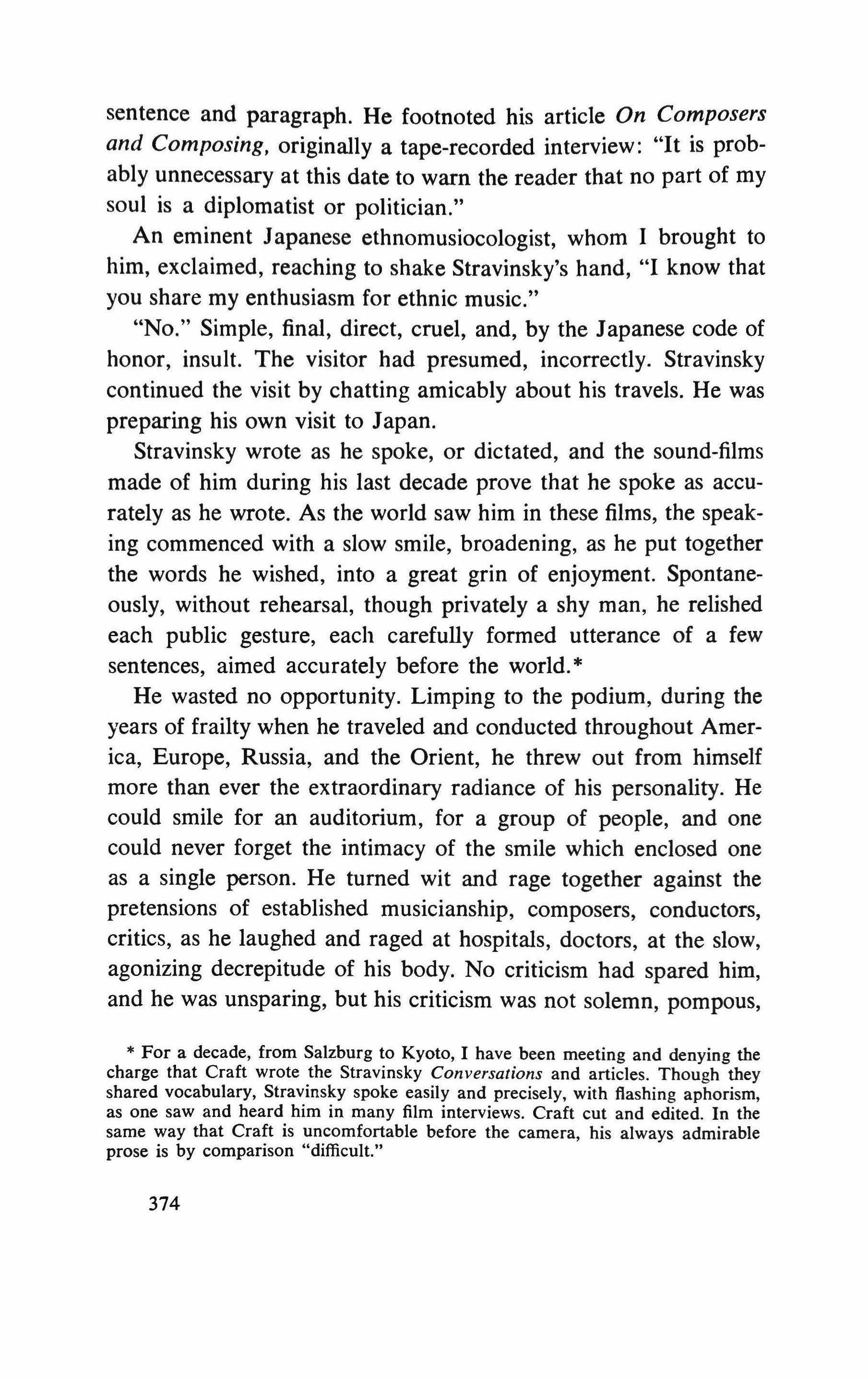

twelve-tone works being not time-setters but melodic thrusts. Caught up in 1952 by Schoenberg's great instrumental comedy, the Suite for seven instruments, Stravinsky followed the work from the rehearsals under Robert Craft's direction through to the public performance and the recording session." He then attempted his own, more limited Septet, using for the first time the principle of the tone-row, insisting aloud at the end of the first reading, "It is tonal, strictly tonal!" He was more successful when he adapted the tone-row to his own idiom in Agon. With the Three Songs by William Shakespeare he appropriated the more congenial art of Webern.

Webern lacked nothing of the Viennese emotion but linked his expressiveness directly and economically to a few tones and intervals, an intense reticence of points and timbres looking back to the high polyphony of Heinrich Isaac, symbolic of countryside and devout faith within a mystical expanse of silence. Into this austere radiance of spiritual vision Stravinsky could enter naturally, adapting to it the ordonnance of his ear-vision, that art of the two-dimensional, illuminated stage which renders all his music accessible to dance. He could fill out the few tones of Webern from the richness of his own timbral experience, while relishing the silences of an unprecedented melodic economy. For Schoenberg, as for Francois Couperin, silence is a shaping character of phrase; for Webern, tone is a directional point of sound, shaping a sizeless figure within silence; for Stravinsky, silence became the depth of his new aural stage. Now he stole from a farther past: Monteverdi, Gesualdo, Machaut.

Schoenberg had warned repeatedly against use of the tone-row as a sufficient technique of composition, against the misuse of compositional order as compositional convenience. His followers, even those close to him who during his lifetime had enforced that distinction as a rule, abandoned it after his death. The idea of a total composition, a serial ordering which could account by pre-

At this time Craft began his recording of Schoenberg, a project now extended to several albums.

372

scription for the placing of each note, broke down before the contrary attack of John Cage's "music by chance operations." Schoenberg had foreseen but refused the consequence that his stated "emancipation of the dissonance" would bring the emancipation of all sound as means of musical art. The almost geometrical formality of Webern's brief designs, each tone defining the multidimensional spaciousness of its sound-force within silence, linking a sound-figure able to be contemplated, could, it seemed to many, be transfigured and governed by predetermined plan, the necessity of the plan, whether verbal or mathematical, being equally ordinate if filled out by random sounds instead of fixed tones. The audible consequence of either method, in second hands, is not unlike the other; the two soon commingled. A decade of rebellion against traditional order found satisfaction in an art which mocked, parodied, or denied that order.

Of the seminal composers of his generation Stravinsky alone survived active through this rebellious decade, more and more rejecting its personalities, their too often short-viewed aims and methods. Amid the increasing disorder he recognized, as Schoenberg had recognized twenty years earlier, the principled craftsmanship and authority of Cage. Robert Craft wrote that Stravinsky had "read every word of Silence"-the first published collection of Cage's lectures, writings, and performance texts. Cage welcomed rapprochement with Stravinsky, and a cordial meeting was arranged.

Wounded well-wishers have complained that, in the conversations and articles Stravinsky turned to for a second medium whenever, in these last years, he was ill and helpless to compose music, he wrote cruelly, attacking alike enemies and friends. The presumptuousness of the enemies they recognize but not the sometimes overweening presumptuousness of the friends. What he wrote may have been cruel, more cruel-seeming because the wit provoked laughter. They do not understand that Stravinsky was fighting for an art he cherished, for the tradition of compositional order he had mastered-and mastered again in learning to control the English

373

sentence and paragraph. He footnoted his article On Composers and Composing, originally a tape-recorded interview: "It is probably unnecessary at this date to warn the reader that no part of my soul is a diplomatist or politician."

An eminent Japanese ethnomusiocologist, whom I brought to him, exclaimed, reaching to shake Stravinsky's hand, "I know that you share my enthusiasm for ethnic music."

"No." Simple, final, direct, cruel, and, by the Japanese code of honor, insult. The visitor had presumed, incorrectly. Stravinsky continued the visit by chatting amicably about his travels. He was preparing his own visit to Japan.

Stravinsky wrote as he spoke, or dictated, and the sound-films made of him during his last decade prove that he spoke as accurately as he wrote. As the world saw him in these films, the speaking commenced with a slow smile, broadening, as he put together the words he wished, into a great grin of enjoyment. Spontaneously, without rehearsal, though privately a shy man, he relished each public gesture, each carefully formed utterance of a few sentences, aimed accurately before the world. *

He wasted no opportunity. Limping to the podium, during the years of frailty when he traveled and conducted throughout America, Europe, Russia, and the Orient, he threw out from himself more than ever the extraordinary radiance of his personality. He could smile for an auditorium, for a group of people, and one could never forget the intimacy of the smile which enclosed one as a single person. He turned wit and rage together against the pretensions of established musicianship, composers, conductors, critics, as he laughed and raged at hospitals, doctors, at the slow, agonizing decrepitude of his body. No criticism had spared him, and he was unsparing, but his criticism was not solemn, pompous,

* For a decade, from Salzburg to Kyoto, I have been meeting and denying the charge that Craft wrote the Stravinsky Conversations and articles. Though they shared vocabulary, Stravinsky spoke easily and precisely. with flashing aphorism, as one saw and heard him in many film interviews. Craft cut and edited. In the same way that Craft is uncomfortable before the camera, his always admirable prose is by comparison "difficult."

374

or cynical. Formerly, when his ripostes had been spoken, few heard them; when the ripostes commenced appearing in print they hurt.

He had been cut off from his origins, from his Russian past, from the common use of his own language, even from the royalties which signified that the enormously popular early works belonged to him. All through his life he was to see these early works performed instead of his newer compositions because orchestras could perform them without payment. What local of a musicians' union has ever gone on strike to demand fees for composers!

He rewrote his old works in new versions to bring them again under copyright into his possession, but, except when he conducted, orchestra managements chose to perform the works which cost them nothing. Among the critics each new work suffered similar fate: good enough, perhaps, but not another Petrushka. Critics and colleagues decided and agreed that he was not the best conductor of his music. He recorded each new work as rapidly as opportunity permitted and instructed other conductors to take his versions for a model; in a late writing he withdrew this instruction. He countered the critics by criticizing them.

He persisted until he had made himself financially independent, until the public demand to hear his newer works and to see him at least occasionally conduct them, and the recording of his music made him a millionaire. Towards the end of his life, when he was often sick and helpless, attempt was made to take control of his money and the ownership of his manuscripts.

He was one of those rare fortunates whose leisure is in the pursuit of their art. He was happiest when he was composing music; conversing with friends or dictating sentences came second. He preferred composing to hearing or performing his completed compositions. He was devoted to his friends and as grateful for anything they did as he was sharp when anyone presumed against him. Shorter in height than most men and even women around him, the very small, narrow head not homely or ugly, decisively lipped and beaked but certainly not handsome, he had made of his youthful appearance the dandy of the Parisian sketches and 375

photographs. * In maturity, he threw out his shoulders and seemed less small, however short, bounding to and from the podium in long balletic leaps. In age he shrank, until as one approached him he seemed, sunk in his seat, to vanish in the expanding smile.

After Robert Craft came to Los Angeles in 1947 to help Stravinsky in setting to music the unfamiliar poetic idiom of Auden's libretto for The Rake's Progress, the two men became, not a new personality, as some enemies of Craft wish to believe, but a team. Like most composers, Stravinsky, after the first years, had concerned himself and competed mainly with the music of the two preceding centuries. Craft, preparing and conducting in successive years mature works of Schoenberg and Webern, opened up to Stravinsky those two contemporaries whose works represented the one great area of immediate music competing with his own, of which he knew almost nothing, against which he had turned his back.

Schoenberg and Stravinsky had lived a few miles apart in the same corner of Los Angeles for more than a decade without communicating-some say they shook hands once in a theater lobby. The death of Schoenberg in 1951 did not cause Stravinsky to love him more; the two zones of attraction rejected one another, or as Stravinsky said in first regret, "Our partisans kept us separate." But from that time Stravinsky made himself, among his partisans, an advocate of Schoenberg. If he could not love Schoenberg, he could honor him; his review of Schoenberg's published Letters is a testimonial of honor such as no composer, to my knowledge, has ever paid in writing to a contemporary. He wrote of their common lifetime: " a time that Schoenberg lived and formed and that

* One evening, soon after a Roof concert at which Craft had conducted Polyphony X for 18 solo instruments by the then little known Pierre Boulez, Stravinsky beckoned me, sat down beside me, patting my knee, and asked: "That Polyphony, by Boulez, do you think it is music?"

I replied that it was music in a style of deliberate discontinuity.

"But music must have continuity. Without continuity there can be no music." We circled without resolution.

Next year the two composers met, and Stravinsky reversed himself to announce fervent admiration. I had guessed that in personal meeting, Boulez's cool, sophisticated dandyism would appeal to him.

376

now to some extent-for centripetal as he was, other developments were and are possible-lives and finds its form in him." And again: " the lenses of Schoenberg's conscience were the most powerful of the musicians of that era, and not only in music."

I believe it was the bitterness of the letters resulting from the avoidance of Schoenberg's music that most shocked Stravinsky. He himself had known neglect, yet nothing to compare with this. "But the nadir comes in a letter the seventy-year-old master addressed to the Guggenheim Foundation asking for assistance so that he could finish Moses and Aron. Though even a few measures of this opera would have been worth a whole catalogue of music the Guggenheim Foundation did sponsor, Schoenberg's request was denied."

Gertrud Schoenberg told me that before the book of Schoenberg's Letters appeared the Guggenheim Foundation wrote her asking to buy this letter.

I myself, as a "scout" for the Pulitzer committee, recommended for the Pulitzer award Schoenberg's A Survivor from Warsaw in the year of its world premiere by the Albuquerque Symphony. The prize went instead to a long-forgotten chamber work. Such are the rewards of genius in our society.

Describing the association of Craft with Stravinsky one cannot speak of Craft as "alter ego" or "amanuensis"; it was in fact a partnership. They shared ability and talents, as they shared the concerts for which Craft prepared the orchestra, while Stravinsky chose which works of the program he would direct. We owe to this partnership the many late recordings. Though they disagreed in interpretation, Craft being a strict Stravinskyite and Stravinsky increasingly and lovingly free of his own strictures, the difference did not part them. In conversation derived from wide reading and a happy tending of dictionaries, encyclopedias, vocabulary-Stravinsky noted that during the period he read much more than in the past-they shared criticism and amplified their mutual interests.

When traveling, as Elliott Carter told me after joining them for 377

one journey, Craft proved a fully informed guide to each city they visited. And they traveled, always in demand, as Stravinsky and Vera had never traveled before, as it would not have been possible for them to travel if Craft had not been with them. Stravinsky did not travel easily; he claimed to be terrified of ocean crossings and more so in the air. The team became a tripartite symposium of high intelligence, wit, and human frailty, each member requiring, as Vera, who had to market for them, said plaintively, a separate diet. Together Craft and Vera kept Stravinsky active. Always a valetudinarian, accompanied by a retinue of pills, repeatedly consulting and changing doctors, Stravinsky became in age a victim of unremitting serious illness, against which an immense elan fought valiantly.

He was often immobilized, seeming sometimes to be dropping off into senility, but his mind would light up again and frail vigor returned. Among friends, conducting, before the sound cameras, standing and talking for an hour amid a crowd of students at the University of Texas, he seemed as wise, witty, and capable as ever; afterwards exhaustion would set in. He would be hospitalized, tubed and silenced, at the edge of death, and rousing would dictate a conversation.

His friends were gone; many friends younger than himself had gone. Dylan Thomas, the poet, with whom he had planned to write an opera, had gone too soon and been greatly mourned. Kenneth Patchen, poet and friend of Thomas, complained that Stravinsky had composed In Memoriam Dylan Thomas to exploit the occasion. A year later I wrote Kenneth that in the Stravinsky living room the only photograph was of Dylan Thomas. Short elegiac compositions commemorated friends; came an Introitus for T. S. Eliot, and then the Aldous Huxley Variations. Death was a familiar. All through the 1950's Stravinsky and Huxley had sat together in the front row at our Evenings on the Roof and Monday Evening Concerts in Los Angeles. Stravinsky rewarded us with the gift of a dozen world premieres. The younger composers interested him less and seemed more distant. He had returned to Russia, invited by the Soviet government, and his works, no longer for-

378

bidden, were now performed in his homeland. He wrote of his childhood.

The last paragraph of his unfinished last article surveyed the current scene: "We live in a very exhilarating time, a little short of a Golden Age, perhaps and ended quoting Jimmy Durante.

He was, like Haydn, an artist not separate from his time, who did not need to wait for posterity. "Posterity," Vera wrote, had "hung around his neck for so long that for three-quarters of his life he must have felt as burdened with it as a belled cat." And like the reviews of G.B.S., the "cruel" Conversations of Stravinsky will be rousing laughter-the vital laughter of an inexhaustible craftsman, an unyielding courage-long after the victims' pain has passed.

379

Balanchine ANNA KISSELGOFF &

JOHN E. MALMSTAD

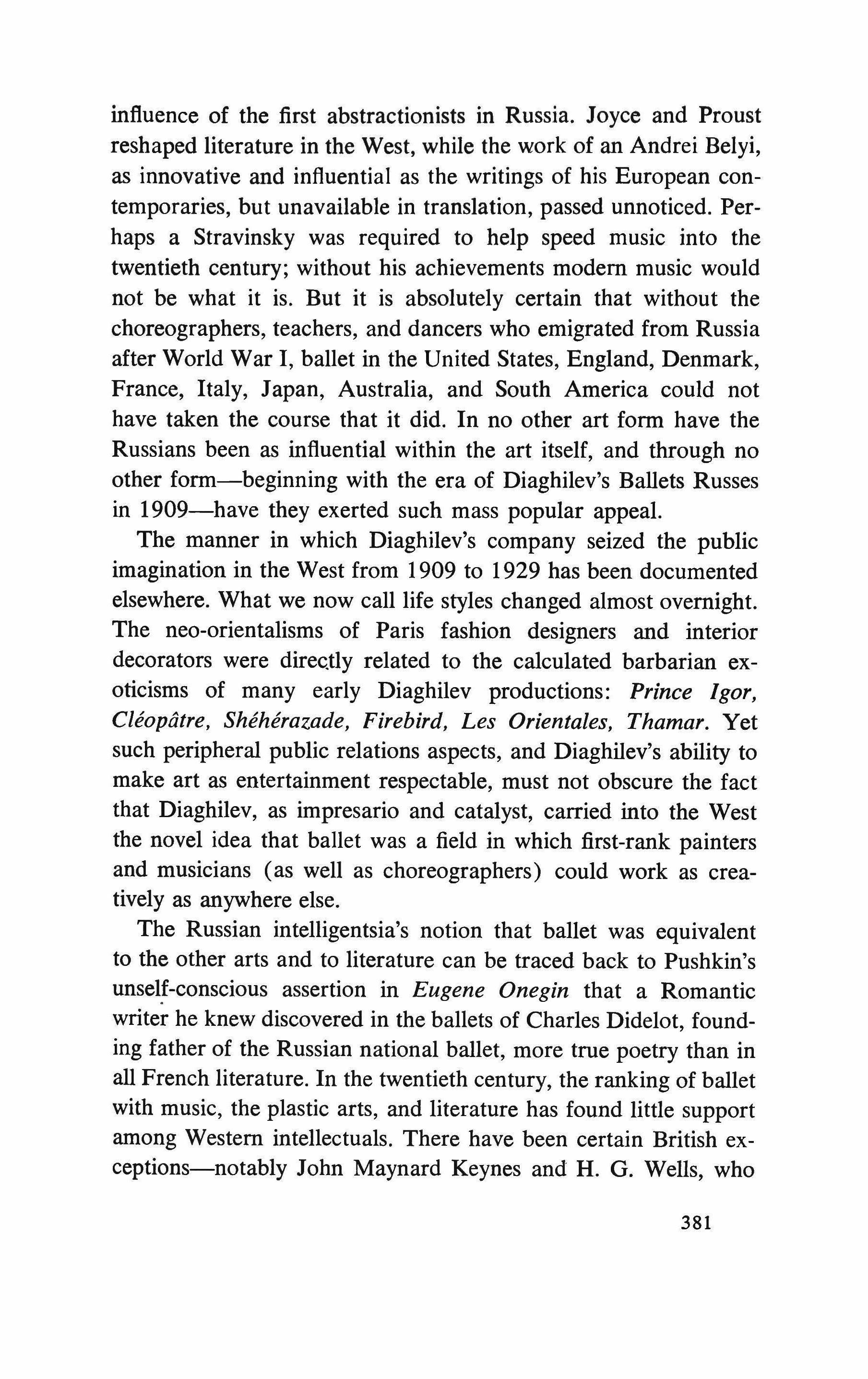

The art form within which and through which Russians have had the greatest and broadest impact outside Russia is ballet. There are certainly comers of the world where the name Stravinsky is unknown. It is doubtful, however, that anyone who can read and write, in Peru or Australia, has not heard of Nijinsky or Pavlova. It has been just as natural to name a racehorse "Nijinsky" in recent years as it has been to name another horse "Joe Namath." There is no thoroughbred called "Nabokov." One suspects that the "pop" symbolism of these Russian ballet stars has caused English-language academics and literary men to resist the idea of ballet as art. As a result, there is a tendency to overlook the fact that twentieth-century ballet is the only serious art form in the West which cannot be dissociated from the Russian emigre contribution.

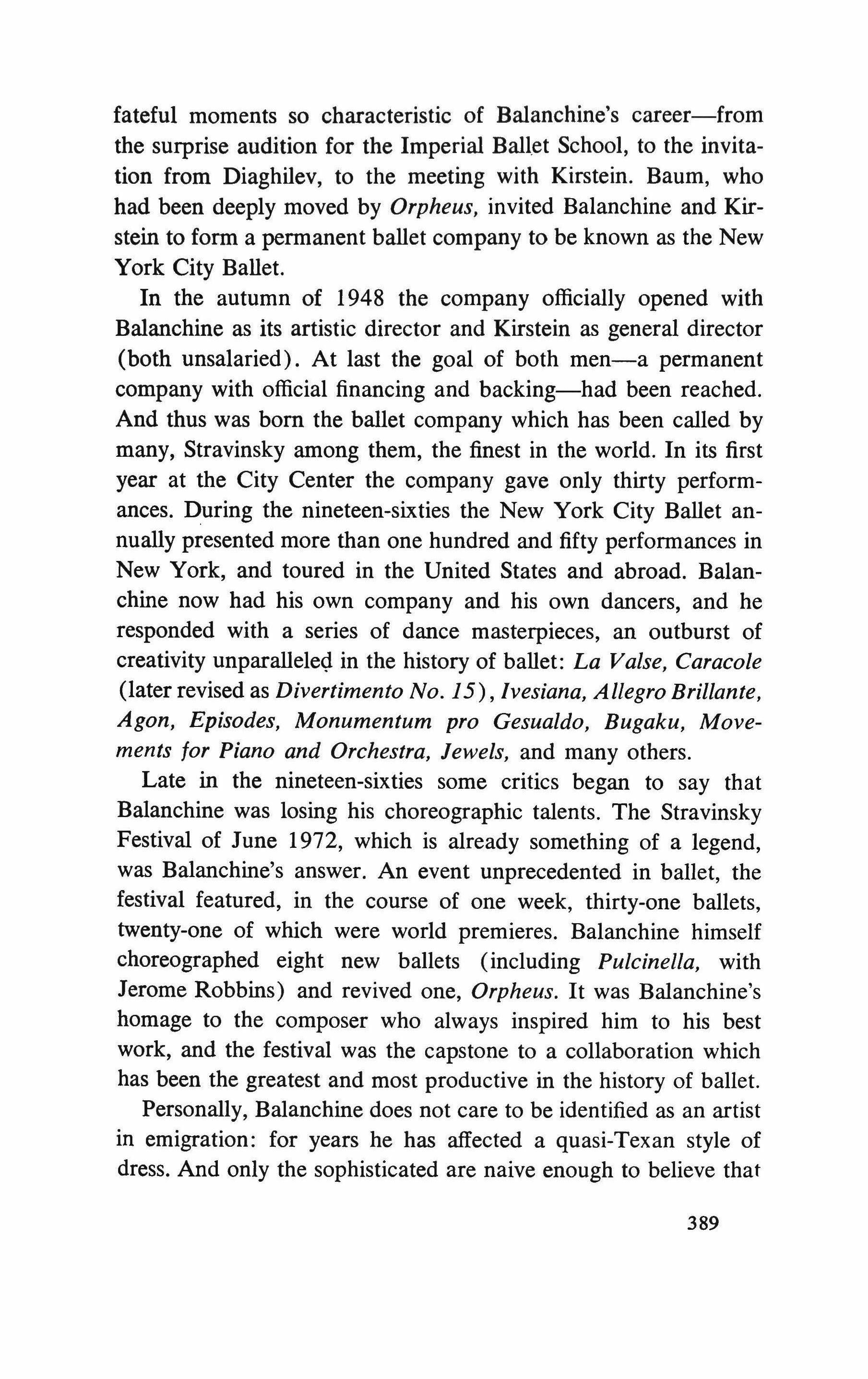

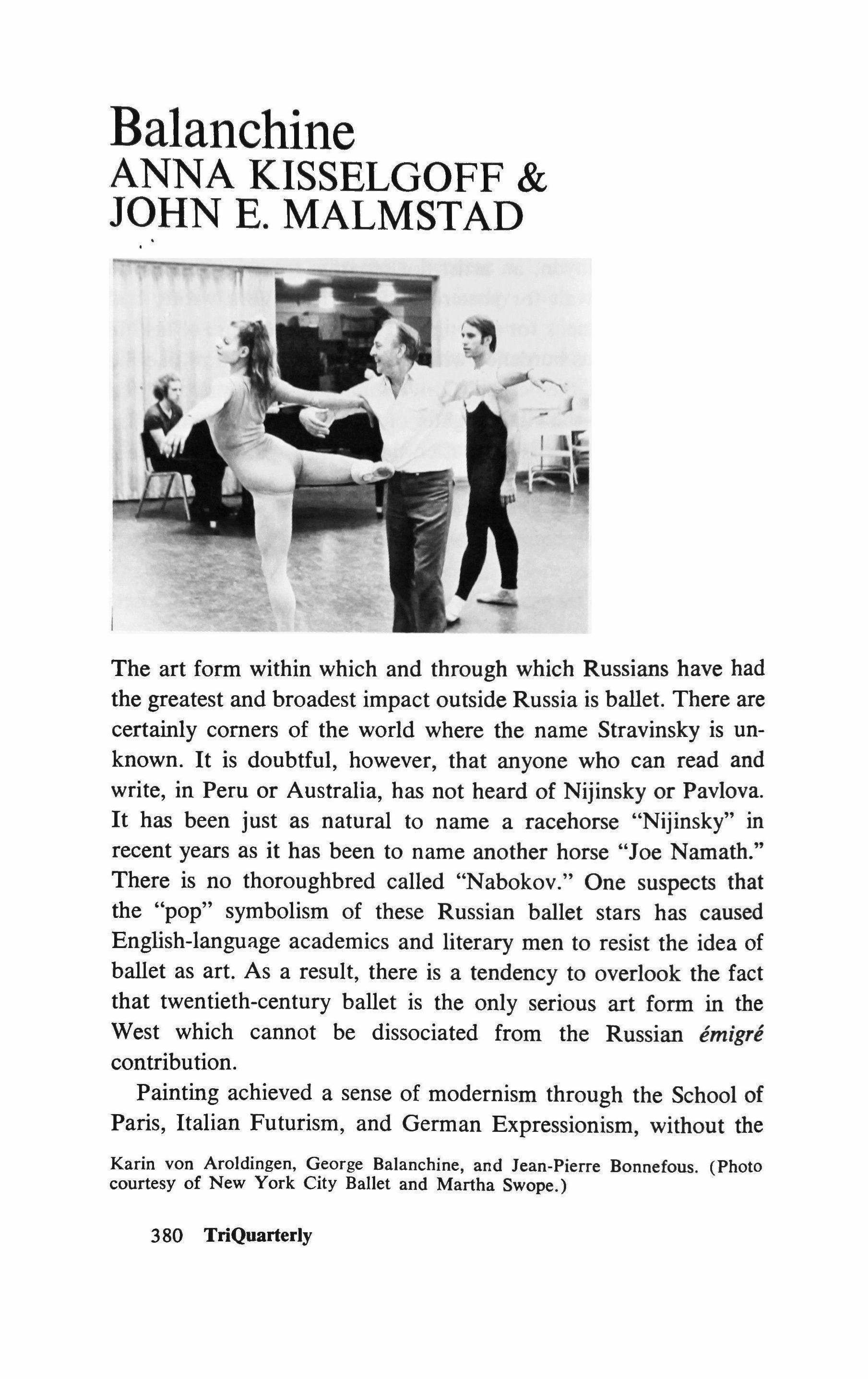

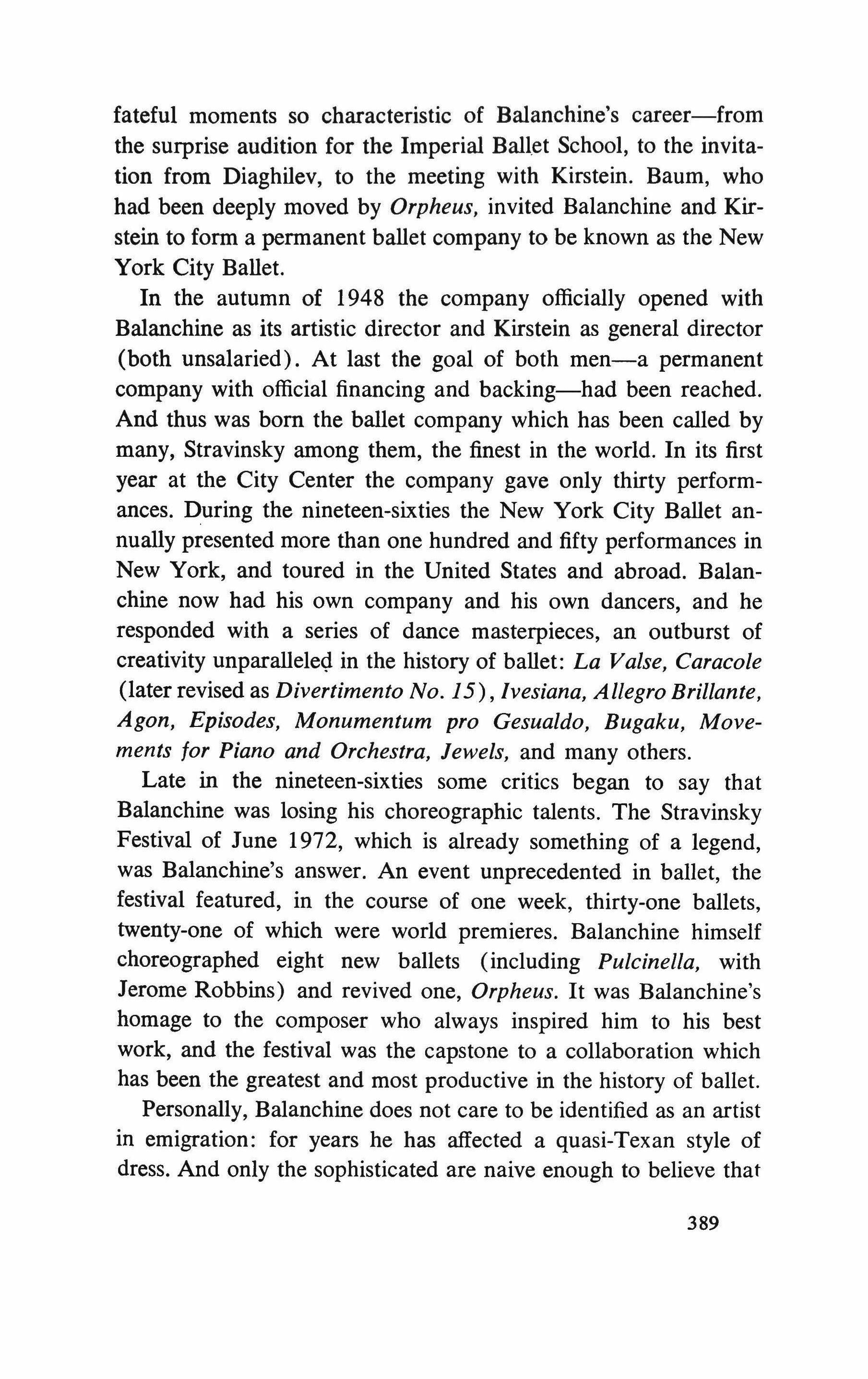

Painting achieved a sense of modernism through the School of Paris, Italian Futurism, and German Expressionism, without the Karin von Aroldingen, George Balanchine, and Jean-Pierre Bonnefous. (Photo courtesy of New York City Ballet and Martha Swope.)

380 TrlQuarterly

influence of the first abstractionists in Russia. Joyce and Proust reshaped literature in the West, while the work of an Andrei Belyi, as innovative and influential as the writings of his European contemporaries, but unavailable in translation, passed unnoticed. Perhaps a Stravinsky was required to help speed music into the twentieth century; without his achievements modem music would not be what it is. But it is absolutely certain that without the choreographers, teachers, and dancers who emigrated from Russia after World War I, ballet in the United States, England, Denmark, France, Italy, Japan, Australia, and South America could not have taken the course that it did. In no other art form have the Russians been as influential within the art itself, and through no other form-beginning with the era of Diaghilev's Ballets Russes in 1909-have they exerted such mass popular appeal.

The manner in which Diaghilev's company seized the public imagination in the West from 1909 to 1929 has been documented elsewhere. What we now call life styles changed almost overnight. The neo-orientalisms of Paris fashion designers and interior decorators were direc.tly related to the calculated barbarian exoticisms of many early Diaghilev productions: Prince Igor, Cleoptitre, Sheherazade, Firebird, Les Orientales, Thamar. Yet such peripheral public relations aspects, and Diaghilev's ability to make art as entertainment respectable, must not obscure the fact that Diaghilev, as impresario and catalyst, carried into the West the novel idea that ballet was a field in which first-rank painters and musicians (as well as choreographers) could work as creatively as anywhere else.

The Russian intelligentsia's notion that ballet was equivalent to the other arts and to literature can be traced back to Pushkin's unself-conscious assertion in Eugene Onegin that a Romantic writer he knew discovered in the ballets of Charles Didelot, founding father of the Russian national ballet, more true poetry than in all French literature. In the twentieth century, the ranking of ballet with music, the plastic arts, and literature has found little support among Western intellectuals. There have been certain British exceptions-notably John Maynard Keynes and H. G. Wells, who

381

actively, publicly supported ballet. But generally it is an idea that has encountered more resistance from nonartist intellectuals than from artists and writers themselves. Certainly this scorn was not shared by Picasso, Matisse, Braque, Derain, Gris, Utrillo, Ernst, Mira, Rouault; or Ravel, Debussy, Satie, de Falla, Poulenc, Auric, Milhaud, Sauguet-to name some non-Russians who did commissioned work for Diaghilev.

The willingness of the Russians themselves to collaborate on Diaghilev's ventures before and after he drew upon Western artists was less surprising. Stravinsky and Prokofiev, Bakst and Benois from the "World of Art" circle that had spawned Diaghilev himself, abstractionists like Goncharova and Larionov, constructivists like Gabo and Pevsner who had made their original reputations outside the field of stage design-all had been brought up in a country whose various elites paid homage to ballet. In 1909, ballet was still a vital art in Moscow and, particularly, in St. Petersburg.

This was hardly the case in the West, where ballet was dead, dying, or in decline. By the time Diaghilev came to Paris with a group of Russian dancers on summer holiday from the Imperial Theaters (most of whom emigrated after 1920), he was stepping into an artistic void that the Russians could fill only too easily. At the Paris Opera, until 1870 the center of the ballet world in the nineteenth century, ballet could be described only as decadent. In England and the United States, it could not even be described.' Foreign ballerinas, including a few native-born dancers, still made guest appearances, often in a music-hall format, but no national ballet existed. Italy, the birthplace of ballet, had turned to technique rather than creation, and by the late nineteenth century was busy exporting to Russia virtuoso ballerinas whose talent for spinning on one foot went unmatched until Mathilde Kchessinska, once mistress to Nicholas II, learned the secrets of the trade from an Italian teacher. Denmark alone continued to hand down the unbroken nineteenth-century tradition of its famous choreographer and ballet master August Bournonville. But the purity of this isolation held the danger of provincialism, which

382

finally led the Royal Danish Ballet to open its doors to the postDiaghilev influence.

The names of the Russians who revitalized the ballet outside Russia would fill several pages. Among the choreographers-that is, creators rather than interpreters-one name is essential not only to any discussion of the Russian contributions to the dance but to any history of twentieth-century ballet: George Balanchine. Frequently ranked with Stravinsky and Picasso, both for the modernism of his innovations and the internationalism of his style, Balanchine is also the bearer of the Russian nineteenthcentury classical ballet tradition in which he was trained. To paraphrase Vladimir Nabokov's remark about Pushkin, it should be unnecessary to remind a reader who Balanchine is, but it may be preferable not to take any chances.'

Georgy Melitonovich Balanchivadze was born on January 22, 1904, in St. Petersburg. His mother was Russian; his father was Georgian and a prominent musician (he was known as the "Georgian Glinka"). The family was artistic and, in addition to receiving an education typical of the Russian intelligentsia, the child studied music 'thoroughly at home. (His brother, Andrei, is a well-known Georgian composer.) A military career had been planned for him, but a chance audition at the S1. Petersburg Imperial School of Theater and Ballet in 1914 (he had accompanied his sister to her audition and she was rejected) changed that. The young Balanchine found himself accepted into the prestigious academy.

Rather against his will, he was enrolled in the school and for the next seven years received rigorous training not only in the techniques and traditions of the dance, but in drama, mime, literature, and music as well. When he graduated with honors in 1921, he was regarded as an exceptionally promising dancer, He had already danced as a schoolboy in productions at the Maryinsky Theater in S1. Petersburg; now he joined its corps de ballet. The same year he entered the Petrograd Conservatory of Music, where for the next three years he continued his musical education. As a result, he is one of the few choreographers with almost as much knowl-

383

edge of music as of dance. For a time, he even considered becoming a composer.

During his days at the ballet school, Balanchine had tried his hand at several dance exercises for his fellow students. During the years 1921-1924 he continued his choreographic experiments. The artistic and intellectual ferment of Petrograd in the early nineteen-twenties affected all the arts, and ballet was no exception. Unfortunately, the Maryinsky Theater did not encourage radical experimentation. Even before the Revolution, the choreographer Michel Fokine had left the Maryinsky for Diaghilev's company, and his return to it shortly before the Revolution was brief. He left again in 1918. The Maryinsky remained, as it had under the tsars, the repository of the great nineteenth-century repertory or "new" works in that tradition. The Soviet government was happy to see it remain so. Therefore Balanchine's work was done outside the theater to which he nominally belonged. For he considered himself in the vanguard of the new artistic currents in Petrograd and not part of the past. He staged dances for several Petrograd theaters and assembled a small group of young dancers (many young dancers admired his work very much) to put on evenings of new dance numbers. His little "company" appeared under the name "Evenings of the Young Ballet" and had quite a success. He hoped the management of the Maryinsky would allow him to stage Stravinsky's Le Sacre du Printemps, but his proposal was rejected. After the second Evening of the Young Ballet late in 1923 (part of the program was choreographed to Blok's "The Twelve"-danced without music while a chorus chanted the text of the poem), the Maryinsky withdrew permission for any of its dancers to appear in such special programs. The theater, and many Petrograd ballet critics, had had enough of the choreographic heresy that the Evenings represented. Without dancers, Balanchine was blocked for the time; he must have had this in mind when he found himself in Europe in the summer of 1924.

Vladimir Dmitriev, a singer in Petrograd, had received permission in the spring of 1924 to organize a small group of musicians and dancers from the theater to make a brief vacation

384

tour of Western Europe. Dmitriev selected Balanchine as one of his five dancers; among the others were Alexandra Danilova and Tamara Geva, Balanchine's first wife. The little group, known as the Soviet State Dancers, left for Germany in June 1924. Shortly'. after they arrived in Berlin, they were summoned back to Russia, but instead Dmitriev and the dancers decided to remain in the West. (Balanchine was not to return to Russia until 1962.) Their financial situation was desperate-a situation Balanchine was to know for many, many years-but they were able to arrange a very short German tour.

Fortunately, Diaghilev heard of the group and invited them to Paris to audition for his .Ballets Russes. The decision was a fateful one. Balanchine and the other dancers needed jobs; Diaghilev, then at odds with his current choreographer, Bronislava Nijinska, needed both new dancers and a new choreographer. After an audition in the famous Paris salon of Misia Sert, the young dancers were accepted into the company. Shortly afterward, when Nijinska left the company, the twenty-year-old Balanchivadzerenamed George Balanchine at Diaghilev's request-found himself chief choreographer and ballet master of the most famous ballet company in the world. He was to remain with the company for five years.

For several years the Ballets Russes, unable to recruit new dancers from Russia, had been relying on chic, reputation, and daring scenic innovations to hide the deterioration of its dancing. Balanchine, grounded in the great tradition of the Maryinsky and a master of ballet technique, soon had the company dancing at the levels which had made it famous years before. He was also required to supply several new ballets for each season. All were professionally done; some were memorable, such as the 1927 La Chatte, with sets and costumes by Gabo and Pevsner. But it was not until 1928, when he was asked to choreograph a new Stravinsky ballet, that the young choreographer truly found himself. His first piece for Diaghilev had been new choreography for the 1925 revival of Stravinsky's Le Chant du Rossignol. Now he was able to work intimately with Stravinsky himself, and the

385

result was a landmark in the history of ballet: Apollon Musagete (or Apollo, as it is now known). At the premiere, June 12,1928, in Paris at the Theatre Sarah-Bernhardt, Stravinsky conducted a cast which included Serge Lifar, Lubov Tchernicheva, Felia Doubrovska, Alice Nikitina, and Danilova.

Balanchine, then only twenty-four years old, recalls the work as the turning point in his life: "In its discipline and restraint, in its sustained oneness of tone and feeling, the score was a revelation. It seemed to tell me that I could dare not to use everything, that I, too, could eliminate I examined my own work in the light of this lesson It was in studying Apollon that I came first to understand how gestures, like tones in music and shades in painting, have certain family relations. As groups they impose their own laws. The more conscious an artist is, the more he comes to understand these laws, and to respond to them. Since this work, I have developed my choreography inside the framework such relations suggest." 2

In 1929 he choreographed The Prodigal Son to the music of Prokofiev and with sets by Georges Rouault, a work that is still in the repertory of the New York City Ballet. It is difficult to say how Balanchine might have continued with the company, but everything came to an abrupt end with the death of Diaghilev in August 1929. The years immediately following were rootless ones for Balanchine. He did work for the English showman Sir Charles Cochran and a brief stint as guest ballet master for the Royal Danish Ballet. But none of these jobs satisfied him or his employers, who were interested in restaging the Diaghilev repertory, not in new ballets. If there was one thing Balanchine would not tolerate then (or now), it was the notion of ballet as a museum. For a time (1932) he worked with Colonel W. de Basil's Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, but disagreements soon led to his dismissal. In January 1933, he formed his own small company and called it simply Les Ballets 1933. Stimulated by the new venture, Balanchine created six works for the company, but after a short summer season in Paris he was again without work and with few prospects for the future.

386

At this moment he met a young American, Lincoln Kirstein, a young Harvard intellectual with whom ballet had become an obsession. Excited by Apollo, which he had seen in the late twenties, Kirstein was determined that Balanchine was the man to bring to America if his plans to create a new American ballet company with its own classic repertory were to be realized. Fortunately, Balanchine had nothing to keep him in Europe, and he accepted Kirstein's offer, arriving in New York City on October 18, 1933. The first fruit of the Balanchine-Kirstein collaboration involved, quite logically, the founding of a ballet school to train American dancers for the future company. On January 1, 1934, the School of American Ballet opened its doors in New York City in a studio which Isadora Duncan had once used. There were soon twentyfive dancers in the School and with them Balanchine staged his first American ballet, Serenade, one of his most enduring works. By late 1934 Balanchine and Kirstein decided that the school's pupils were ready to perform publicly and the American Ballet was formed. The company' was essentially only a performing group from the school, and while it put on several programs it could not fully occupy Balanchine's time. It was far from being the permanent ballet company he and Kirstein, his patron, had in mind.

In 1935 Balanchine was invited to become ballet master of the ballet company of the Metropolitan Opera. He accepted and stayed longer than most people predicted, since there were serious disagreements between him and the management. He finally left angrily in 1938, but not until he had organized several successful programs. The most famous was the Stravinsky Festival in the spring of 1937, which featured a revival of Apollo and two new ballets, Le Baiser de la Fee and leu de Cartes (A Card Game: Ballet in Three Deals). By 1938 the financial situation of the American Ballet (supported by Kirstein and his friends) was desperate, and the little company closed. The school remained open, however. For about the next ten years Balanchine spent much of his time doing work on Broadway and in Hollywood (connoisseurs of his work will stay up to all hours to catch the television "late show" of the water ballet Balanchine did for his

387

wife Vera Zorina in The Goldwyn Follies). He worked on his first musical comedy in 1936 when he did the famous "Slaughter on Tenth Avenue" ballet for On Your Toes. This was a first in another way, too: for the first time in Broadway history a printed program read, not "dances by ," but "choreography by " In 1941 the American Ballet was revived for a special four-month tour of South America. Balanchine once again rose to the occasion and created two new ballets, both still in the repertory: Ballet Imperial to Tchaikovsky's Second Piano Concerto and Concerto Barocco to the music of Bach. When the company returned to the United States it was again forced to disband. In 1944 Balanchine began work with Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, an association that lasted for two years.

By this time Lincoln Kirstein had returned from military service with plans for a new ballet company, Ballet Society. Finances dictated that there be only four programs a year for a subscription audience, but once again Balanchine had a company of his own. The first "season" opened on November 20, 1946, in the auditorium of the Central High School of Needle Trades in New York City. It featured the premiere of yet another seminal Balanchine ballet, The Four Temperaments, danced to a specially commissioned score of Hindemith. In 1947 the Paris Opera invited Balanchine to be its guest ballet master. He accepted the offer, returned to Paris, and there choreographed Le Palais de Cristal (now known as Symphony in C) to the music of Bizet. Fortunately for the history of American ballet he was not invited to stay permanently.

Balanchine and Kirstein wanted new works for their Ballet Society. Both had long wanted Stravinsky to compose another "Greek" ballet, to be paired with the earlier Apollo. Stravinsky responded with the beautiful Orpheus, which premiered on April 28, 1949, in New York City, with the composer conducting. Ballet Society had booked itself for four performances into the New York City Center, and on the night of the Orpheus premiere Morton Baum, chairman of the City Center Finance Committee, was standing in the rear of the theater. Then came one of those

388

fateful moments so characteristic of Balanchine's career-from the surprise audition for the Imperial Ballet School, to the invitation from Diaghilev, to the meeting with Kirstein. Baum, who had been deeply moved by Orpheus, invited Balanchine and Kirstein to form a permanent ballet company to be known as the New York City Ballet.

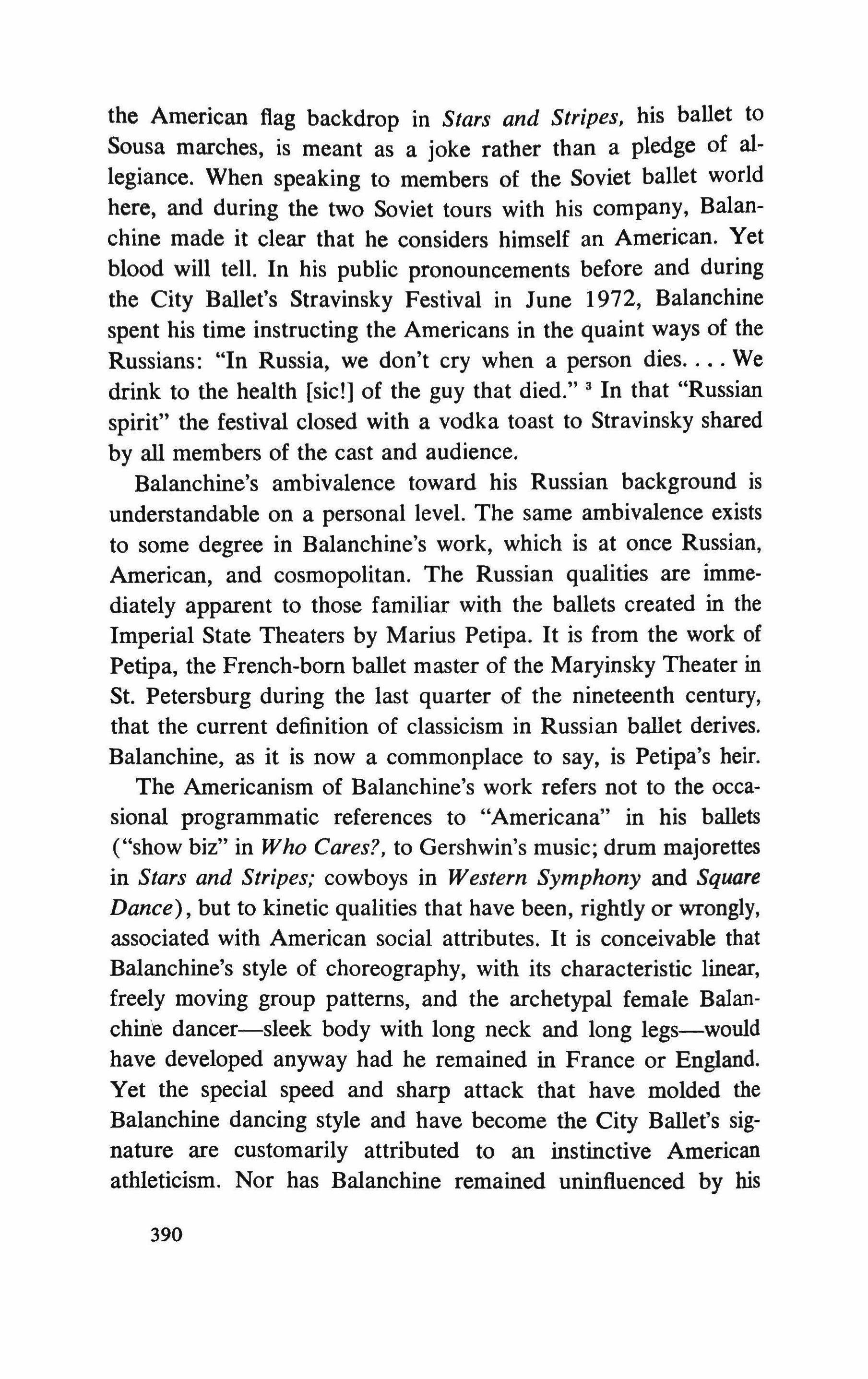

In the autumn of 1948 the company officially opened with Balanchine as its artistic director and Kirstein as general director (both unsalaried). At last the goal of both men-a permanent company with official financing and backing-had been reached. And thus was born the ballet company which has been called by many, Stravinsky among them, the finest in the world. In its first year at the City Center the company gave only thirty performances. During the nineteen-sixties the New York City Ballet annually presented more than one hundred and fifty performances in New York, and toured in the United States and abroad. Balanchine now had his own company and his own dancers, and he responded with a series of dance masterpieces, an outburst of creativity unparalleled in the history of ballet: La Valse, Caracole (later revised as Divertimento No. 15), /vesiana, Allegro Brillante, Agon, Episodes, Monumentum pro Gesualdo, Bugaku, Movements for Piano and Orchestra, Jewels, and many others.

Late in the nineteen-sixties some critics began to say that Balanchine was losing his choreographic talents. The Stravinsky Festival of June 1972, which is already something of a legend, was Balanchine's answer. An event unprecedented in ballet, the festival featured, in the course of one week, thirty-one ballets, twenty-one of which were world premieres. Balanchine himself choreographed eight new ballets (including Pulcinella, with Jerome Robbins) and revived one, Orpheus. It was Balanchine's homage to the composer who always inspired him to his best work, and the festival was the capstone to a collaboration which has been the greatest and most productive in the history of ballet.

Personally, Balanchine does not care to be identified as an artist in emigration: for years he has affected a quasi-Texan style of dress. And only the sophisticated are naive enough to believe that

389

the American flag backdrop in Stars and Stripes, his ballet to Sousa marches, is meant as a joke rather than a pledge of allegiance. When speaking to members of the Soviet ballet world here, and during the two Soviet tours with his company, Balanchine made it clear that he considers himself an American. Yet blood will tell. In his public pronouncements before and during the City Ballet's Stravinsky Festival in June 1972, Balanchine spent his time instructing the Americans in the quaint ways of the Russians: "In Russia, we don't cry when a person dies We drink to the health [sic!] of the guy that died." 3 In that "Russian spirit" the festival closed with a vodka toast to Stravinsky shared by all members of the cast and audience.

Balanchine's ambivalence toward his Russian background is understandable on a personal level. The same ambivalence exists to some degree in Balanchine's work, which is at once Russian, American, and cosmopolitan. The Russian qualities are immediately apparent to those familiar with the ballets created in the Imperial State Theaters by Marius Petipa. It is from the work of Petipa, the French-born ballet master of the Maryinsky Theater in St. Petersburg during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, that the current definition of classicism in Russian ballet derives.

Balanchine, as it is now a commonplace to say, is Petipa's heir.

The Americanism of Balanchine's work refers not to the occasional programmatic references to "Americana" in his ballets ("show biz" in Who Cares?, to Gershwin's music; drum majorettes in Stars and Stripes; cowboys in Western Symphony and Square Dance), but to kinetic qualities that have been, rightly or wrongly, associated with American social attributes. It is conceivable that Balanchine's style of choreography, with its characteristic linear, freely moving group patterns, and the archetypal female Balanchine dancer-sleek body with long neck and long legs-would have developed anyway had he remained in France or England. Yet the special speed and sharp attack that have molded the Balanchine dancing style and have become the City Ballet's signature are customarily attributed to an instinctive American athleticism. Nor has Balanchine remained uninfluenced by his

390

work in Broadway musicals and in films. In Lincoln Kirstein's words, "Balanchine was the first to make the big split between the court style and the popular style." 4

As a neoclassicist, Balanchine has never abandoned the academic ballet technique-the classic idiom-as the "grammar" of his movement vocabulary. But occasionally he shows that he has not been entirely untouched by American modern dance, the only art form besides jazz indigenous to the United States. As a result, there is in some Balanchine ballets a modern dance influence (anti-balletic use of the floor with dancers on their knees, incorporation of natural movements) that has escaped his European imitators.

The internationalism of his work might be defined by the twentieth-century modern sensibility with which he has transformed a nineteenth-century tradition. Like Stravinsky, Balanchine has been regarded as an objectivist. Dispensing with plot and expression of specific emotion through movement, Balanchine most typically has been concerned with time and space rather than theatrical spectacle in the old opera-house sense. Balanchine has taught the world to look at ballet in a new way. To call his work international is to say also that his ballets are performed by companies throughout the world. It is true that all ballet choreographers speak an international language in that they employ a codified movement vocabulary that has been accepted throughout Europe for three hundred years. But Balanchine has evolved a pure dance style, free of the national particularisms that marked the early Diaghilev productions (Petrushka, for example) and still mark some companies today. It is a style that represents itself. Balanchine's distinction is to have singlehandedly raised choreography to the level of an independent art. Scenery, costumes, and narrative content all bow before the dance element in a typical Balanchine ballet.

Music, of course, is most important to this most musical of all ballet choreographers. Early in his career, Balanchine was often accused of merely creating dance visualizations of music (two violins would be "represented" by two girls). But even when the 391

choreography visibly follows the structure of the score, it is now evident that Balanchine is giving the music a new dimension rather than just illustrating it. Stravinsky observed that to see a Balanchine ballet is "to see the music with one's eyes." 5 But for viewer and composer alike, it is more than this-as Stravinsky noted in his comments on Balanchine's choreography for his Movements for Piano and Orchestra: "George Balanchine's visualization of the Movements exposed relationships I had not been aware of in the same way; seeing it, therefore, was like touring a building for which I had drawn the plans but never explored all of the rooms." 6

Balanchine's esthetic-the material of dance is dance itselfwas perhaps best summed up in his aphorism, "There are no sisters-in-law in ballet." 7 What Balanchine means is that there is simply no way for two female dancers onstage to identify themselves to the audience as sisters-in-law. Only a program note could make this relationship clear. And Balanchine has steadfastly refused to make movement subservient to anything but itself, to use dance as a metaphor for anything but dance.

Quintessential Balanchine ballets such as the Bach Concerto Barocco and the Stravinsky Agon are plotless. At one time such ballets were called "abstract." Yet they are not really abstract unless one considers all music abstract. As Balanchine himself has stated: "No piece of music, no dance can in itself be abstract. You hear a physical sound, humanly organized, performed by people. Or you see moving before you dancers of flesh and blood, in a living relation to each other. What you hear and see is completely real." 8 Balanchine's dancers portray dancers rather than characters. To Soviet choreographers such as Igor Moiseyev, Balanchine's choreography is "like talking without saying anything."

9 This is a view shared by some American journalist-critics with a background in music rather than dance. In their view, Balanchine's choreography is merely decorative. More frequently, it is accused of lacking emotion or humanity. Yet rather than being simply devoid of emotion or humanity, Balanchine's art-modernist to the core-invites the viewer to bring his own emotions to meet those of the artist.

392

The modernist sensibility that informs Balanchine's work and the City Ballet, a ballet company unique in that it was the first to reflect the artistic vision of a single choreographer, is not always evident to even the seasoned balletgoer. In fact, these viewers, rather than the newcomers to Balanchine, frequently fail to realize that a twentieth-century Balanchine work must be approached in a different manner than a nineteenth-century classic, just as a Picasso must be looked at differently than a Rembrandt. Confused by the fact that Balanchine employs the same steps and classic idiom that they see in the great nineteenth-century ballets, these viewers are frustrated by the playing down of virtuosity for its own sake, of narrative content and spectacle in the City Ballet. Yet the City Ballet's tradition-the training of its dancers-stems from the same classical heritage shared by companies with a nineteenth-century repertory. Like all great innovators in twentiethcentury art, Balanchine has used tradition as a base.

A definition of ballet classicism is not easy to convey to the non-balletgoer. In the general sense, classic ballet embodies the qualities of balance and harmony that have been attributed to classicism in architecture and the other arts. Stravinsky wrote that he saw in classical ballet "the triumph of studied conception over vagueness, of the rule over the haphazard." 10 More specifically, classic ballet today refers to the style of nineteenth-century choreography as exemplified by its foremost practitioner, Marius Petipa. The earlier Romantic ballets (Giselle) were also composed in the classic idiom. But it was with Petipa that classicismbrilliant dance passages expressed through academic techniquereached its height. Inevitably, and after Petipa's retirement, this once vital style became institutionalized. The subsequent revolt against what was perceived as classicism rather than its decadence was carried out by Michel Fokine's reforms in St. Petersburg. It was Fokine, Diaghilev's first chief choreographer, who set the tone for the dramatic expressiveness and theatricality that marked the Diaghilev ballets up until the nineteen-twenties. Fokine's Petrushka, for instance, is a ballet. But it is not a classic ballet like Petipa's The Sleeping Beauty or Balanchine's seminal neoclassic Apollo. This is what Diaghilev instantly recognized when he

393

watched the young Balanchine creating Apollo in 1928. According to Nicholas Nabokov, Diaghilev's reaction to Balanchine was the following: "What he is doing is magnificent. It is pure classicism such as we have not seen since Petipa's." 11

Significantly, some of Balanchine's most revealing comments about himself are found in a discussion of Petipa with Lincoln Kirstein in Saratoga Springs, New York, in 1967. This brief but remarkable interview (never published in English) was contributed especially for a collection of articles about Petipa by choreographers in the East and West. Entitled Marius Petipa, the volume was published by "Iskusstvo" in Leningrad in 1971.

Calling Petipa "my spiritual father," Balanchine praises this "greatest master of them all" for his "combination of elegance and high professionalism." These are, in fact, the qualities that admirers of Balanchine would attribute to him as well. What Balanchine says of Petipa could be said of Balanchine himself. Petipa, says Balanchine, was a tireless worker. He did not wait for success or the whim of inspiration to create a ballet, just "as a chef does not wait to be pushed by his appetite into preparing a culinary masterpiece." Petipa was attracted to the very essence of dance: movement, steps, and the combinations of these steps. He used the individual capacities of his dancers and extended the vocabulary of ballet technique in trying to extend these dancers' capacities.

The above self-definition of Balanchine, through Petipa, concludes with the following pertinent statements: "The language of classic dance is unchanging, universal and eternal. Perhaps thanks to our efforts and the fact that the viewer now accepts what he previously rejected, that language has become more flexible and extensive but its base remains unchanged I personally believe that innovation is rarely new; usually it is merely the transformation of the old. Tradition is stronger than its negation. It can absorb the new with amazing speed."

If this sounds familiar it is not because the ideas are derivative; rather they are representative of the attitude of several generations of modern artists. This viewpoint received its most perfect critical expression in T. S. Eliot's seminal essay, "Tradition and the In-

394

dividual Talent" (1919), with its notions that "the historical sense involves a perception not only of the past but of its presence" and that "art never improves but the material of art is never quite the same." 12 Lincoln Kirstein has publicly acknowledged his debt to Eliot's essay (he says it became his "code and guide") 13 and his comments on Balanchine's Apollo show the impact clearly: "It [Apollo] demonstrated that tradition is not merely an anchorage to which one returns after eccentric deviations but the very floor which supports the artist, enabling him securely to build upon its elements which may seem at first revolutionary, ugly and new, both to him and the audience These innovations [in Apollo] horrified many people at first, but they were so logical an extension of the pure line of Saint-Leon, Petipa and Ivanov that they were almost immediately absorbed into the tradition of their craft." 14 For Balanchine, tradition in Eliot's ideal sense has been a liberation, not a constriction.

Notes

1. See Nabokov's biographical note on Pushkin in Three Russian Poets: Translations of Pushkin, Lermontov, and Tiutchev (Norfolk, Conn., 1944).

2. See Balanchine's "The Dance Element in Stravinsky's Music," in Stravinsky in the Theatre, ed. Minna Lederman (New York, 1949), pp. 81-82.

3. From a press conference in March 1972 (see New York Times, March 7, 1972); repeated in an opening-night speech at the Stravinsky Festival.

4. From an interview with Lincoln Kirstein by Anna Kisselgoff, New York Times, June 17, 1971.

5. Igor Stravinsky and Robert Craft, Themes and Episodes (New York, 1966), p. 24.

6. Quoted in the section "Movements for Piano and Orchestra" in the special supplement on Stravinsky prepared for the souvenir booklet sold during the Stravinsky Festival of the New York City Ballet in June 1972 (no pagination).

7. Quoted in Bernard Taper's Balanchine (New York, 1960), p. 260. This is the only biography of Balanchine.

8. Stravinsky in the Theatre, op. cit., p. 79.

9. From an interview with Igor Moiseyev by Anna Kisselgoff, New York Times, July 6, 1970.

10. Stravinsky in the Theatre, op. cit., p. 164.

11. Taper, op. cit., p. 103.

12. T. S. Eliot, Selected Essays (New York, 1950), pp. 4, 6.

13. See Lincoln Kirstein's "Apollo-Orpheus-Agon" in the Stravinsky souvenir booklet, op. cit. (no pagination).

14. Lincoln Kirstein, "Balanchine Musagete," Theatre Arts, November 1947.

395

Mozart: theme and variations VLADIMIR MARKOV

If only there could be found a spot here, where men had ears, a heart to feel, and at least a little understanding of music.

-from Mozart's letters

Two hundred years ago. The twenty-seventh of January, eight o'clock in the evening. Probably never among the "earth-born" (Tyutchev) has there been someone so uncommon.

Sequences of thirds were picked out on the harpsichord at the age of three; he composed his first minuet at five; as an eight-yearold-his first symphony; his first opera was written in his twelfth year. Europe was charmed by the child virtuoso, empresses kissed him on his chubby cheeks, learned Englishmen conducted scientific research on him. Then things got difficult, and they grew ever more difficult. Just when he ceased being a child prodigy and began to create true miracles. There were, of course, grand (if shortlived) successes: The Marriage of Figaro? the concertos for Vienna. A handful of connoisseurs always knew his worth. But, as his merry hero sings: "Molto onor, poco contante." And not 396 TriQuarterIy

always was there even much honor. It seemed that fate and men conspired to strike him down again and again. Metaphorical blows there were a-plenty; one was literal, when Count Arco kicked his behind down some stairs. Nor was this proud man and lover of the good life made for humiliation and poverty. Over a year before the end, he had come to wait for death. He died a beggar, in debt, a spiritual wreck, all his strength expended-feverishly, hurriedly finishing the composing of what he still could. He was buried in a common grave for paupers. No one has yet been able to find this grave.

Soon after his death, he became really famous. True, for his first love, Aloysia, Mozart remained merely "a nice little fellow." But his wife, Aloysia's sister, soon realized that Mozart was a great man (incidentally, she was a sweet but limited creature, who in her own way loved Mozart very much). She squandered his manuscripts, destroyed a great many letters, and crossed out lines in others: the nineteenth century was just beginning and had its own conception of morality and its own opinion about the relationship of that morality to greatness.

The nineteenth century revered Mozart. Whether it understood him is another question. He and Raphael were always referred to as the summit of perfection (only in our time has a different painter been found whose name goes incomparably better with Mozart's-Watteau). Schumann called Mendelssohn the Mozart of the nineteenth century (the way Ostrovsky is dubbed the Russian Moliere). Not that the century really knew Mozart well: only an insignificant portion of his works were performed, the "unquestionably great" works-that is, three of the forty symphonies, one or two of the more than twenty remarkable concertos for pianoforte. His operas were staged at times in an altogether outrageous manner: at the beginning of the century The Magic Flute was performed in Paris with music from various works, not only by Mozart, but by Haydn too. Tamino sang the Queen of the Night's first aria, and the Queen herself, on the other hand, sang Donna Anna's vengeance aria from Don Giovanni. Finally a shepherd (where did he come from?) and a totally unidentifiable

397

Mona sang a duet (!) to the music of Don Giovanni's "champagne" aria. In time this sort of thing came to an end, as a growing academic conscientiousness took over. They even began to attach the real finale to Don Giovanni-with no letup, it's true, in the complaining and lamenting that it "lowered the dramatic quality." The "amoral" and "preposterous" Cost fan tutte was barred from the stage. In short: there was no love for Mozart. And all through the nineteenth century there could be heard the strumming of thousands of poor little girls, whose feet did not reach the pedals, and who with no enthusiasm banged out the Sonata K. 545, secretly hating this Mozart, since at the mention of his name their music teachers invariably produced some sound resembling an exclamation point and an expression of sedate, stupid rapture.

There's no point in painting the picture too black. Many great composers were drawn to Mozart, among them such opposites as Chopin and Brahms, Wagner and Tchaikovsky, Rossini and Richard Strauss. And not only composers: Stendhal, Balzac, Ingres, Delacroix. Goethe understood Mozart, the way he understood everything; it was he who said that only Mozart could compose the music for his Faust. Let us not forget that Pushkin's tragedy and the story by Eduard Morike were written in the nineteenth century.

An unexpected discovery of Mozart is occurring in our time. A shift is taking place within the Bach-Mozart-Beethoven triad. The nineteenth century put Beethoven in first place; at the beginning of the twentieth century there was a tendency to reserve this place for Bach; and now Mozart is mentioned more and more as number one. But the triad itself is "eternal"; one can hardly speak seriously about a fourth candidate for this company. Perhaps it is still too early to analyze the meaning of the shift. Although it is possible to assert that if you are searching for man in music, then your composer is Beethoven; if music for you is a means of communion with God, you will hardly bypass Bach; but if you want music from music, then the name Mozart acquires for you a special significance.

This authentic musicality was our first and most important discovery in Mozart. We are speaking here, of course, not about "art

398

for art's sake," not about mathematics, not about abstraction, but about limits correctly divined. Musical meaning does not coincide with a "resume of content," whether of plots (in opera), or of "ideology" (in symphonies). From the point of view of "content," COSl fan tutte is an absurd anecdote, The Magic Flute a hodgepodge. But as soon as their music reaches you The musical meaning of Mozart is harbored not only in the change of keys and their selection, the type of modulations and so on, but in peculiar "nooks," which more often than not do not coincide with the main incidents of the plot. An example might be the Count asking the Countess' forgiveness in The Marriage of Figaro, or Fiordiligi's part in the farewell quartet. These "nooks" are especially numerous in Donna Anna's role.

The second thing that we discovered in Mozart is his true humanity. This does not contradict the fact that we linked the human with Beethoven. In Beethoven, man is a rebel and is alone, the favored hero of the Faustian age, Man with a capital M, the master of nature, which has a "proud sound," and so forth. In Mozart there is everything valuable that has been accumulated by the human community, man in his modest and disciplined communication with his own kind-of which life has actually consisted (not "ought to consist") from time immemorial. From this point of view there is no music more humane and more human. A French traveler through the jungles of the Amazon played for the most savage people on earth records of boogie-woogie and military marches, and did not make the slightest impression on them. A Mozart symphony "did not cover their faces with a mask of fear it revealed the inmost recesses of their hearts." We needed two hundred years to figure out Mozart. In spite of the established conception of the unclouded Olympian quality of Mozart, in our time drama was discovered in him (how could it have been missed earlier?). In this, our opinion coincided with that of his contemporaries, who considered his music passionate and melancholy. When the shadows were found, the light also began to sparkle in a new way. Here is one of the explanations of our gravitation toward Mozart, a gravitation toward the opposite: our horror has patches

399

of light, his light has dark "nooks." Verbal labels reveal little, and in the majority of cases one cannot even say whether he is joyful or sad: at times the one and the other are in inseparable conjunction. At any rate, the common misunderstanding-that Mozart is typical rococo-has come to an end. Goethe's words about Mozart's "demonic spirit" no longer sound like a paradox.