EVANSTON, ILLINOIS

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

EDITOR ....••.••••••.•••• Charles Newman

EXECUTIVE EDITOR Elliott Anderson

MANAGING EDITOR .•••••••• Suzanne Kurman

ART DIRECTOR ...••..•••.• Lawrence Levy

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Timothy O'Grady

ASSISTANT EDITORS •..•.•.. Darcie Sanders

Mary Elinore Smith

ADVISORY EDITORS •...••..• Gerald Graff

Peter Michelson

FULFILLMENT

Lillian Kacyn

Angela Novak

Debbie Petranek

TriQuarterIy is an international journal of arts, letters, and opinion published in the fall, winter, and spring at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60201. Subscription rates: One year $7.00; two years $12.00; three years $17.00. Foreign subscriptions $.75 per year additional. Single copies usually $2.50. Back issue prices on request. Contributions, correspondence, and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterIy, University Hall 101, Northwestern University, Evanston, llIinois 60201. The editors invite submissions, but queries are strongly suggested. No manuscript will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TrlQuarterIy, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1973 by Northwestern University Press. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America. Claims for missing numbers will be honored only within the four-month period after month of issue.

NATIONAL DISTRmUTOR TO RETAIL TRADE: B. DEBOER, 188 HIGH STREET, NUTLEY, NEW JERSEY 07110. DISTRmUTOR FOR GREAT BRITAIN AND EUROPE: B. F. STEVENS,. BROWN, LTD., ARDON HOUSE, MILL LANE, GODALMING, SURREY, ENGLAND. DIsTRmUTOR FOR THE NETHERLANDS: M. VAN GELDERN ZOON, N,Vl, N. Z. VOORBUROWAL 140-142 AMSTERDAM, HOLLAND.

REPRINTS OF BACK ISSUES OF TriQuarterIy ARE NOW AVAILABLE IN FULL FORMAT FROM KRAUS REPRINT COMPANY, ROUTE 100, MILLWOOD, NEW YORK 10546, AND IN MICROFILM FROM UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS, A XEROX COMPANY, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN 48106.

CHARLES NEWMAN

STANLEY ELKIN

ALVIN GREENBERG

THOMAS MC GUANE

WARREN FINE

JONATHAN BAUMBACH

A. B. PAULSON

M. G. STEPHENS

HENRY H. ROTH

"HERB" JOHNSON

WALTER ABISH

PATRICK F. CAHILL

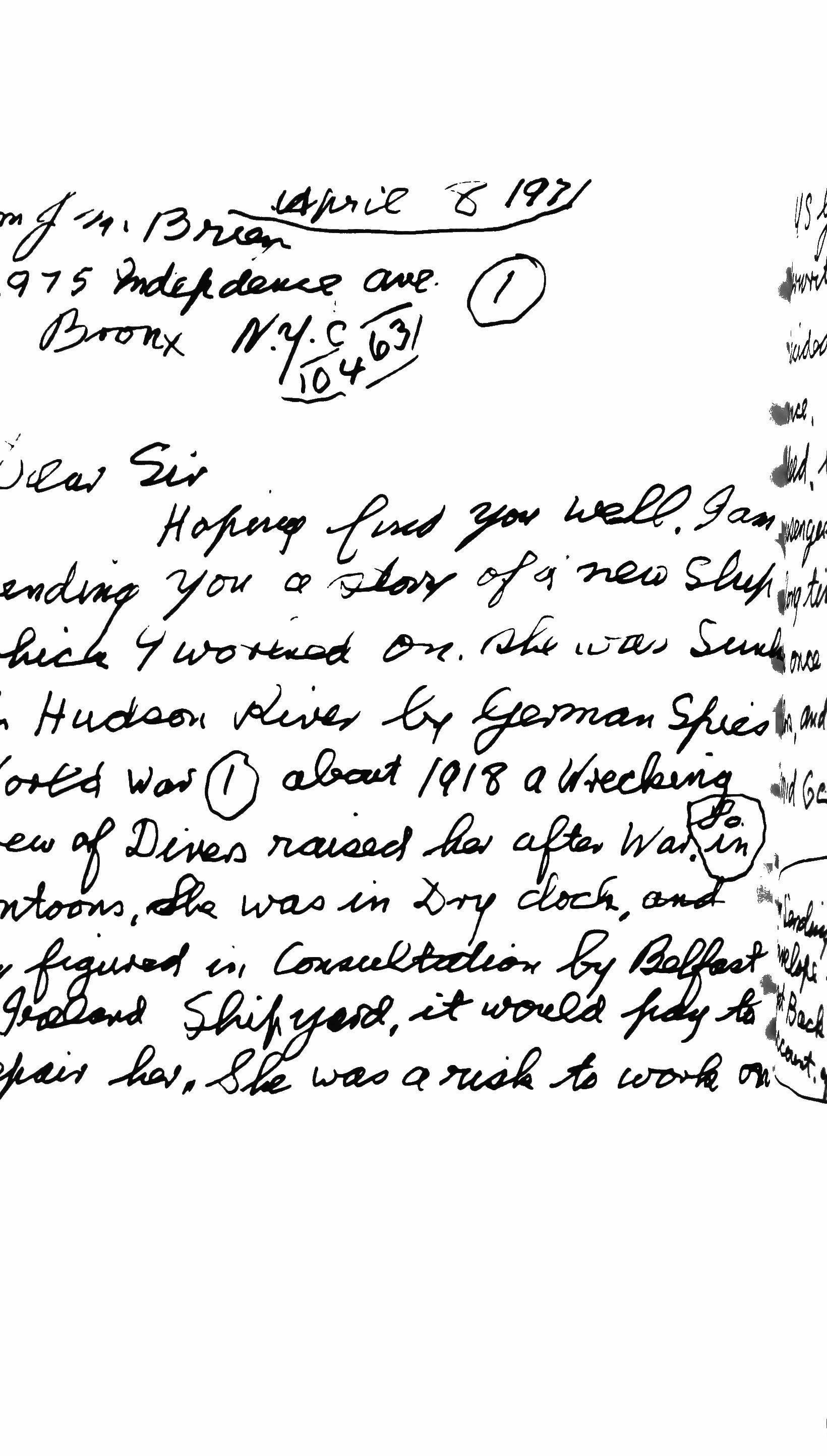

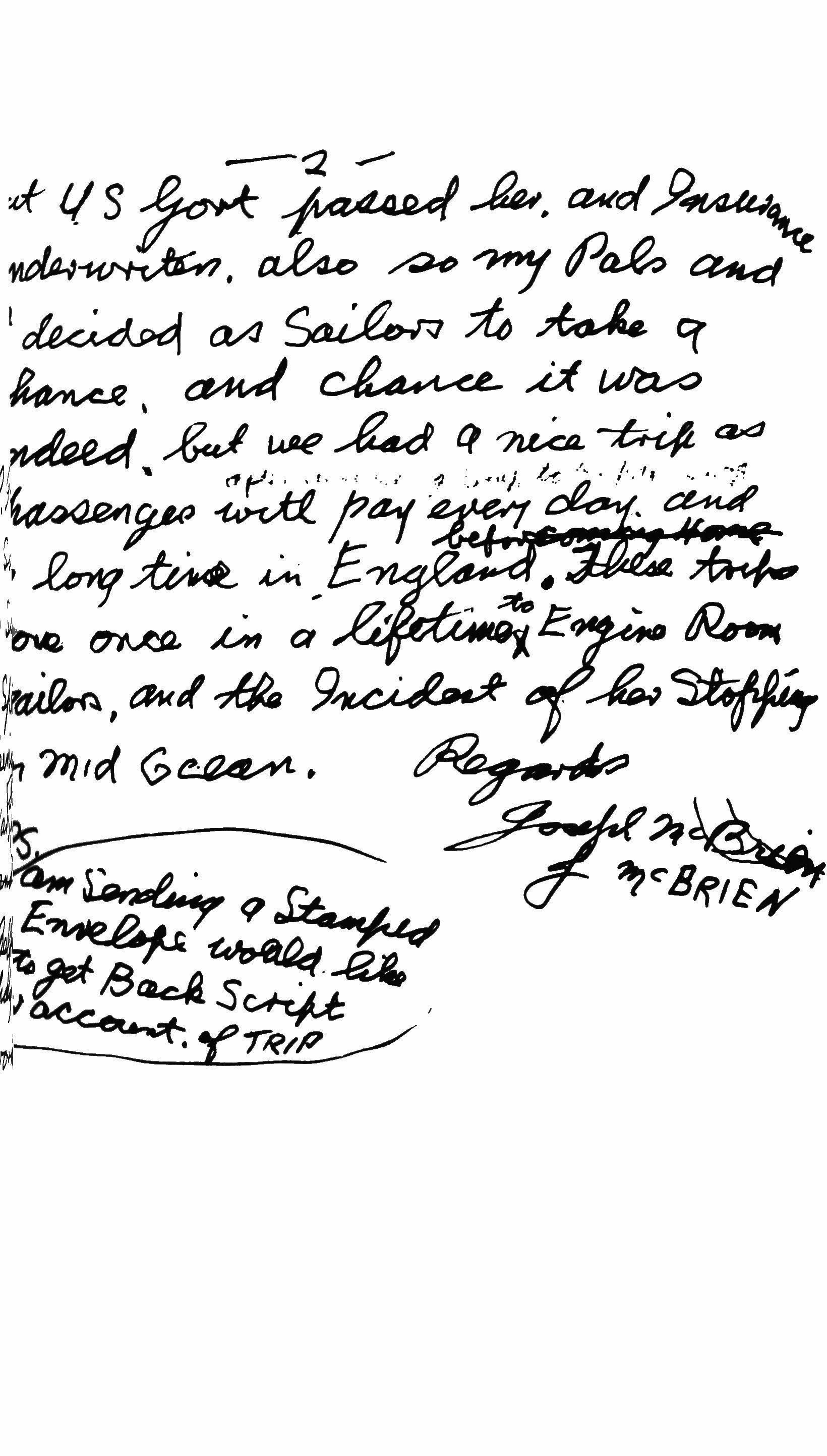

JOE MCBRIEN

ROBERT COOVER

JOYCE CAROL OATES

JERRY BUMPUS

RUSSELL EDSON

ALAIN ROBBE-GRILLET

PHILIP I>TEVICK

ROBERT ONOPA

GERALD C,RAFF

ELWOOD H. SMITH

Introduction

The uses and abuses of death: a little rumble through the remnants of literary culture 3

Fiction

The making of Ashenden 42 The discovery of America 104 Ninety-two in the shade 119 Margaret said: 173 The traditional story returns 184 "2" 192

The last poetry reading 193 from Love zap 202

A "Bob" Brown sampler:

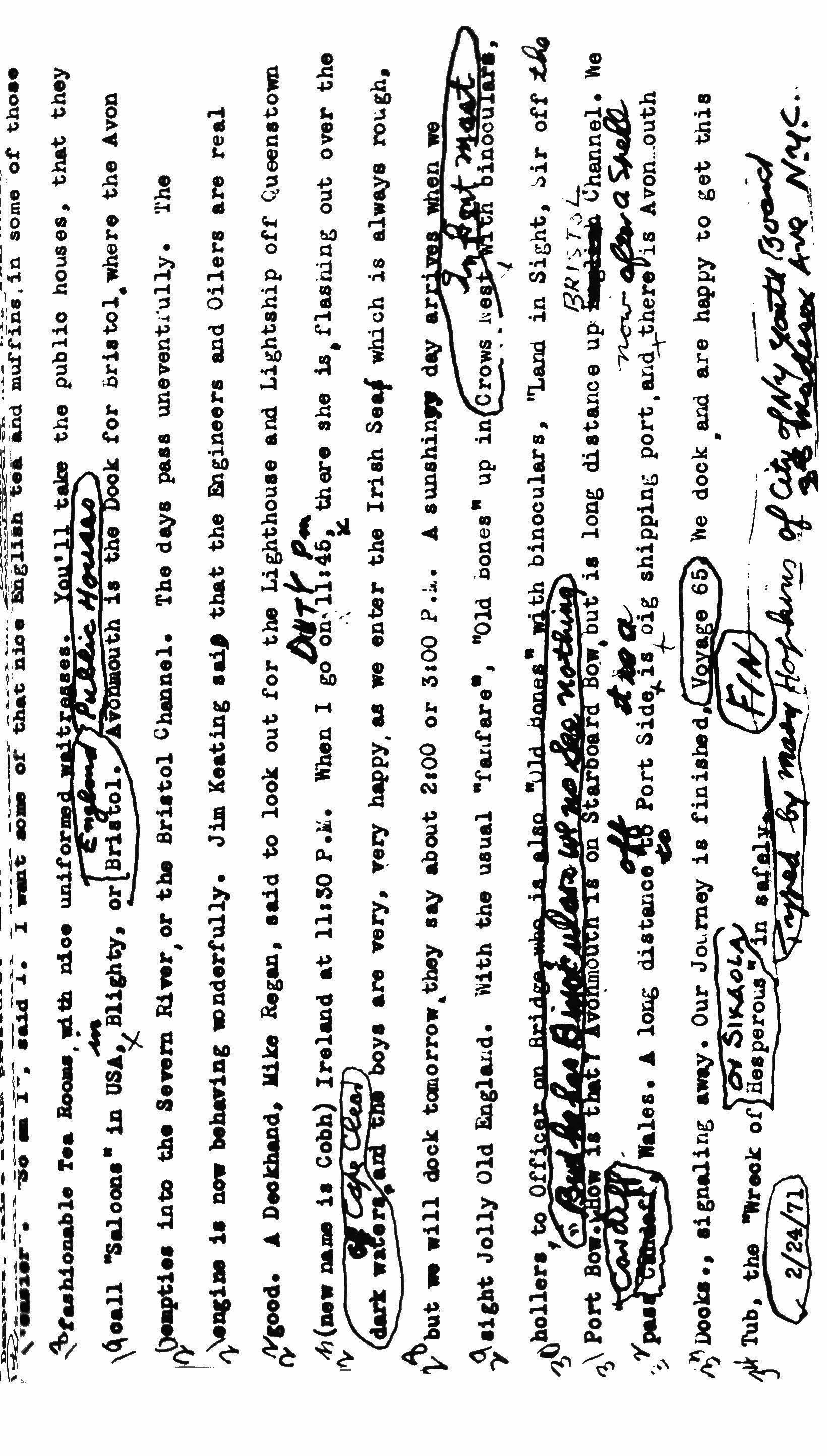

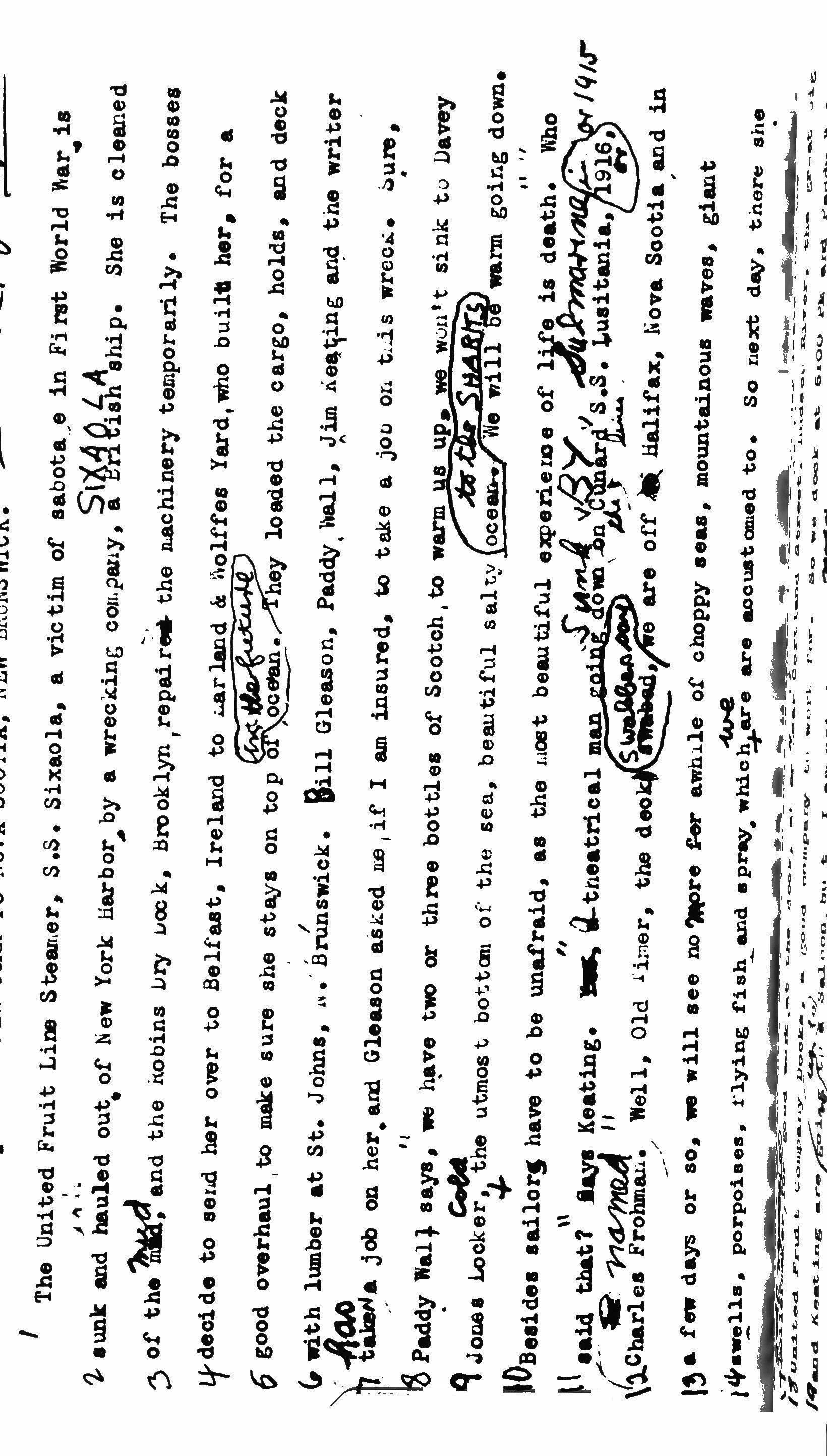

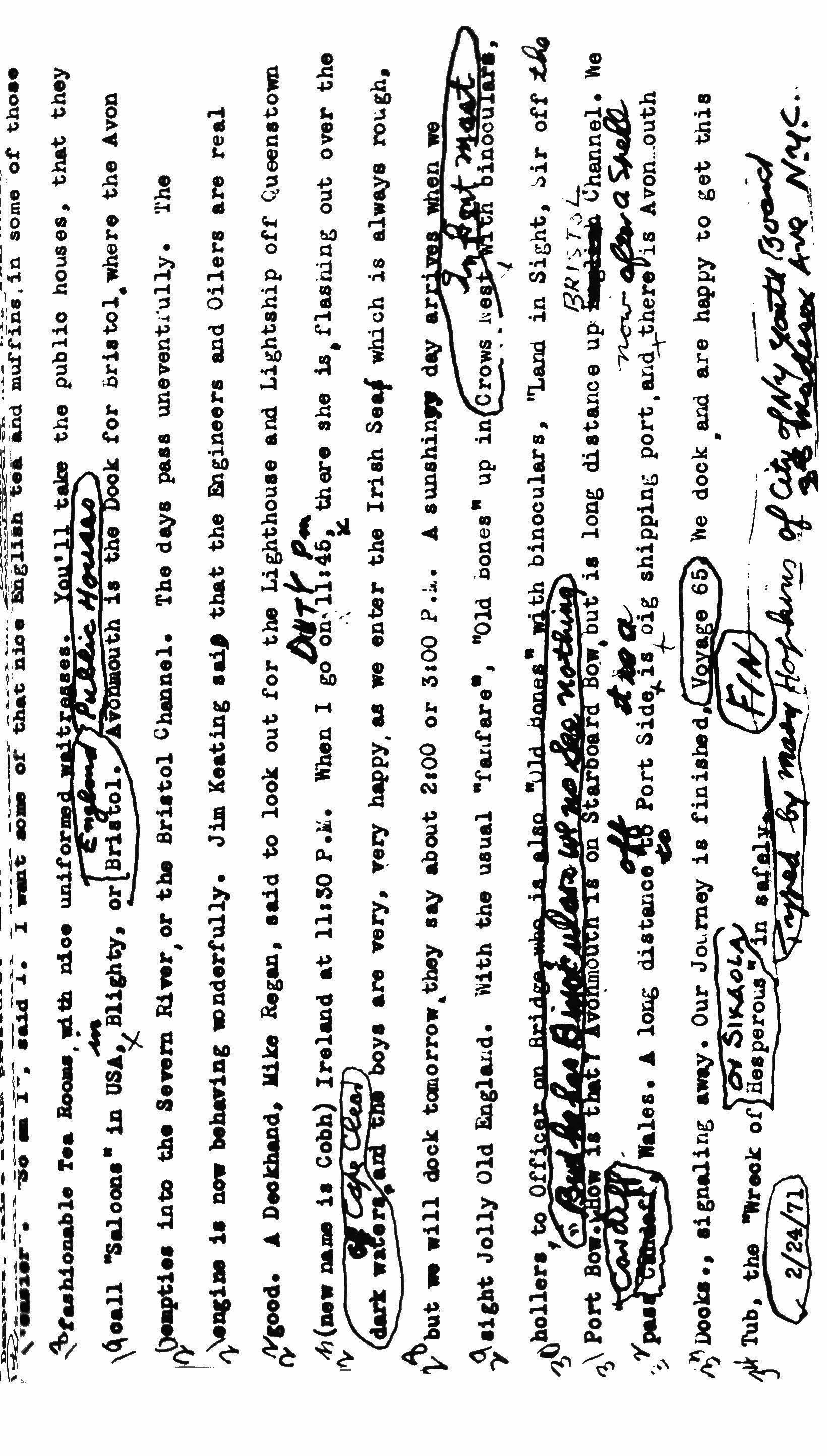

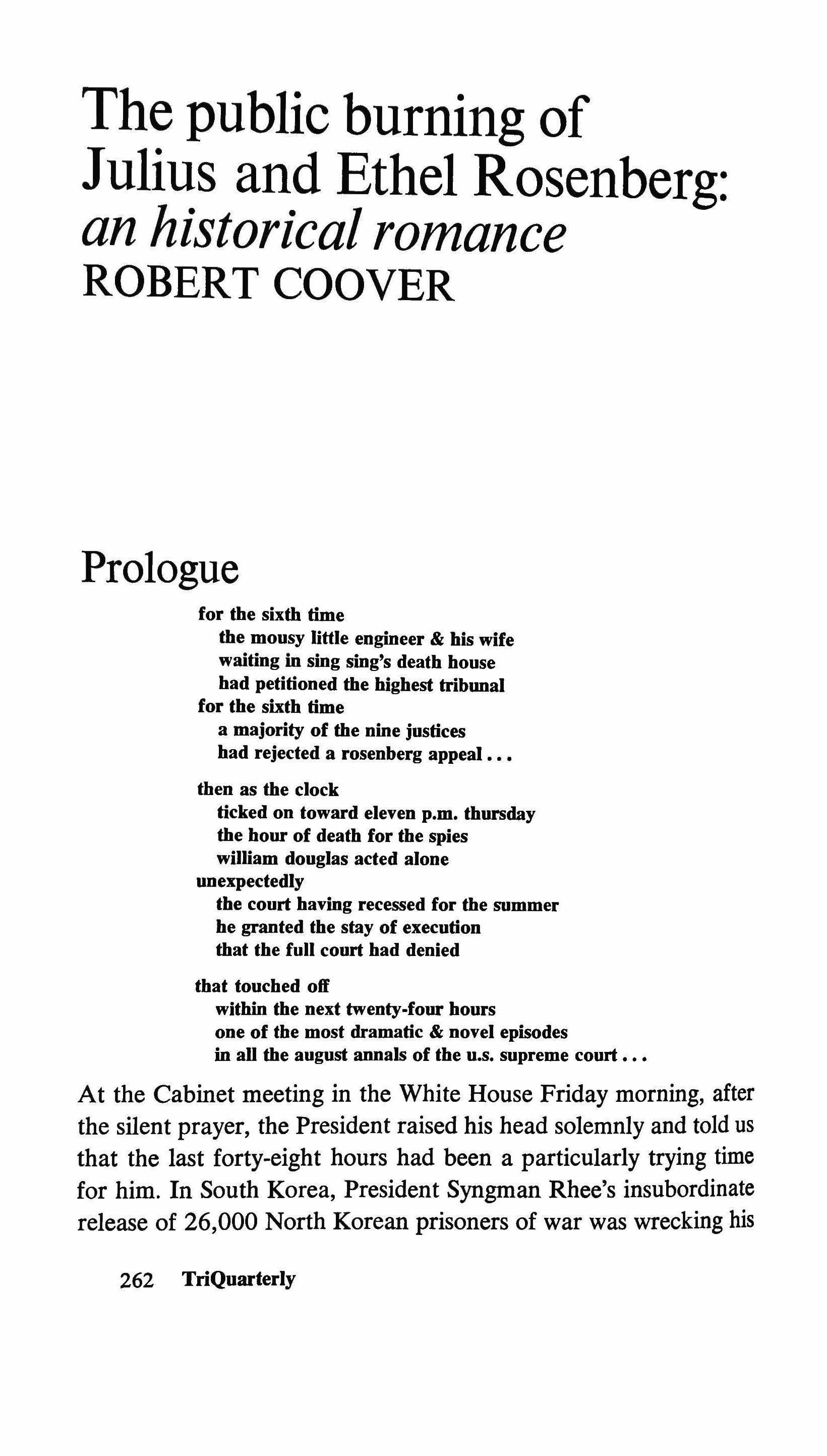

morceaux choisis from the novels 215 from Minds meet 232 from Harlequin's numbers 246 New York to Nova Scotia, New Brunswick 256 The public burning of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg: an historical romance 262 Meredith Dawe 282 Beginnings 299

Theater

The children 310

Foreign perspectives

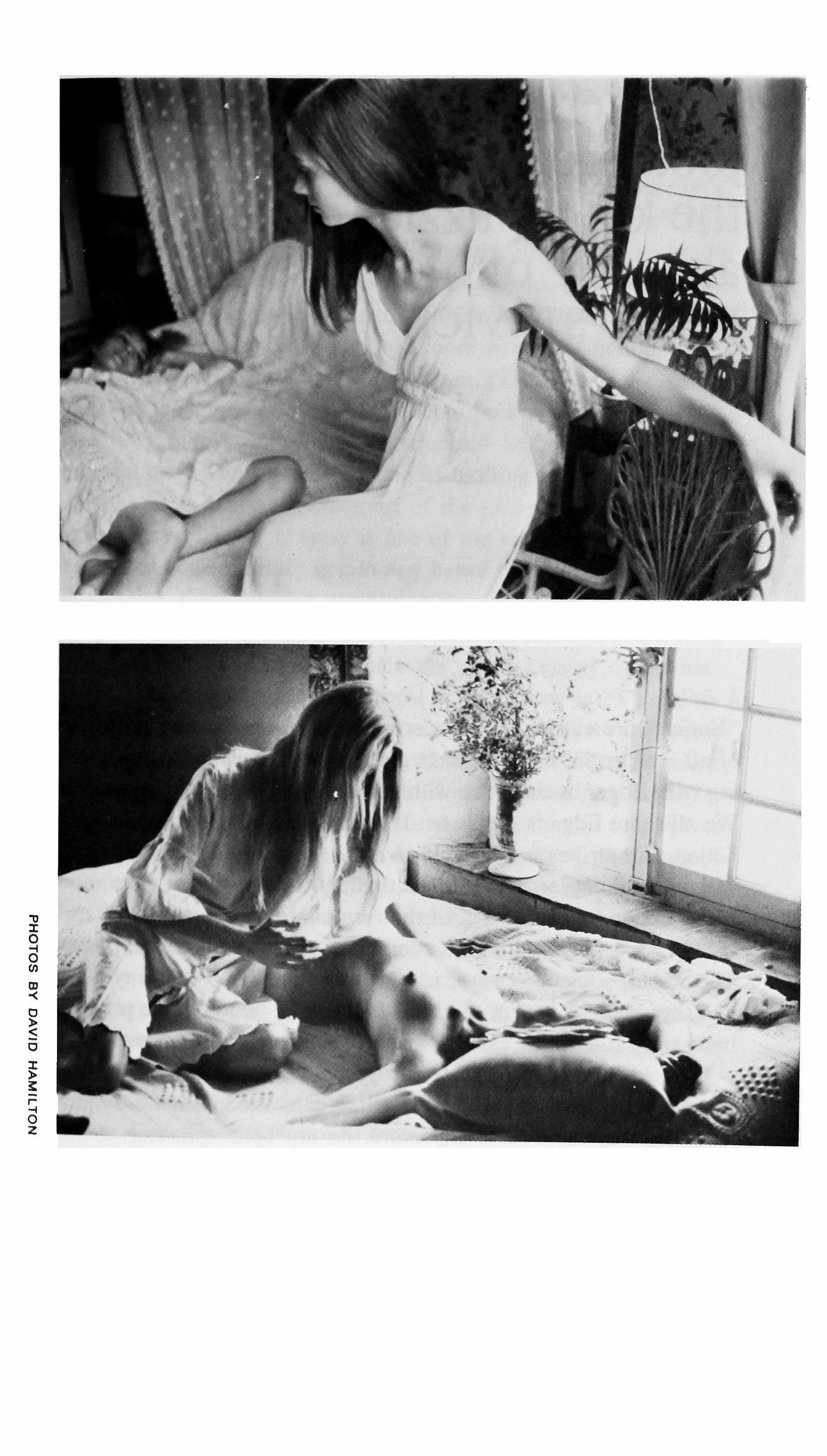

The still abode of David Hamilton 323

Criticism

Scherezade runs out of plots, goes on talking; the king, puzzled, listens: an essay on new fiction 332 The end of art as a spiritual project 363 The myth of the postmodernist breakthrough 383

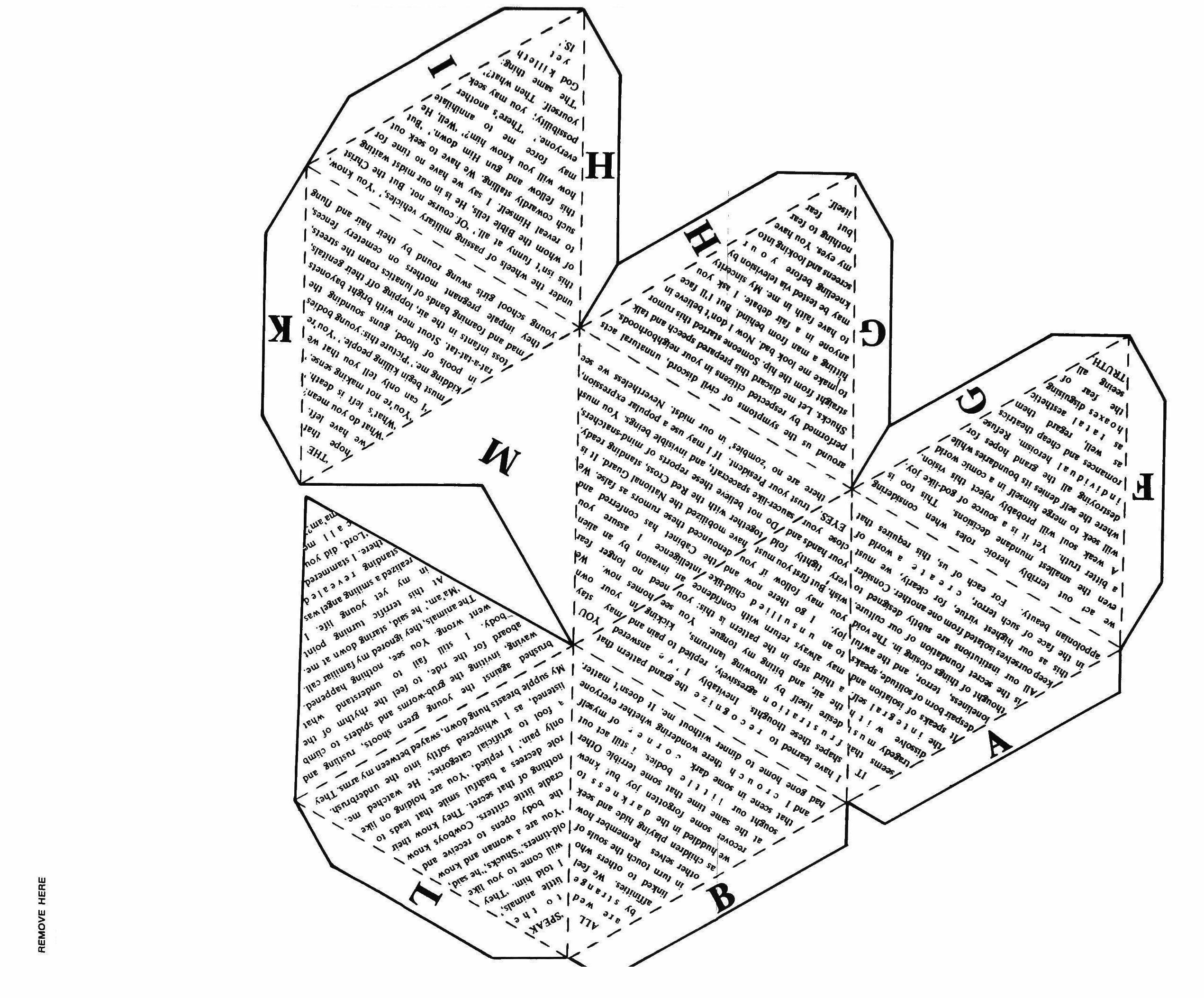

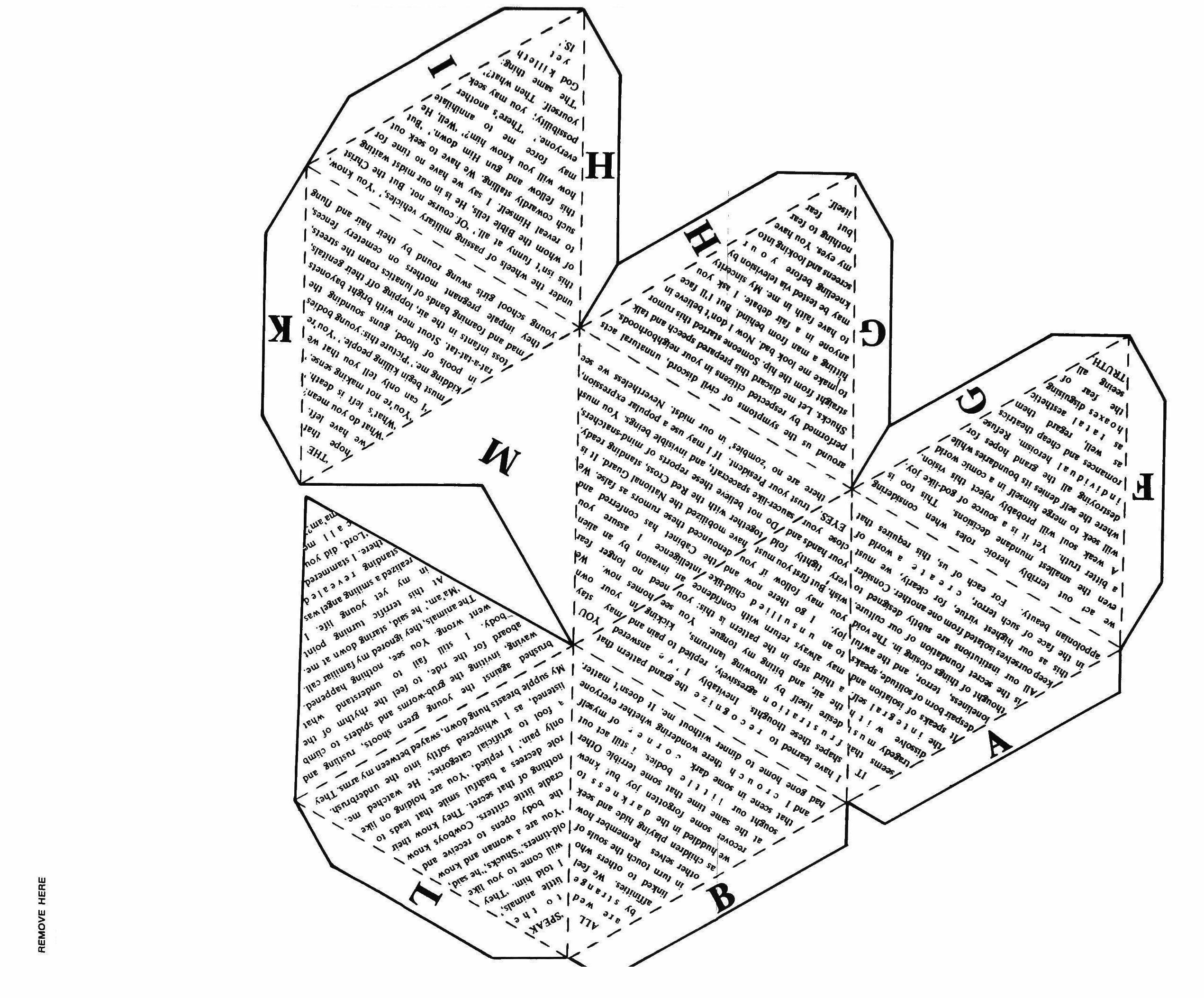

cover illustration

Text on cover from Walt Whitman's "Respondez"

The uses and abuses of death: a little rumble through the remnants ofliterary culture

CHARLES NEWMAN

"Do you know, Mr. Yule, that you have suggested a capital idea to me? If I were to take up your views, I think it isn't at all unlikely that I might make a good thing of writing against writing. It should be my literary specialty to rail against literature. The reading public should pay me for telling them that they oughtn't to read. I must think it over."

"Carlyle has anticipated you," threw in Alfred.

"Yes, but in an antiquated way. I would base my polemic on the newest philosophy."

-George Gissing, New Grub Street, 1891

"The only difference between writers and normal people," a pale student shouted at me some years ago after a lecture on Sylvia Plath, "is that writers watch themselves die, while we're dead before we know it!"

That was before that remarkable woman's tragic end had been totally confused with her last work, but the kid made me realize

[INTRODUCTION]

TriQuarterly 3

how facilely I had appropriated her deathly metaphor to give a handle to the age, and how, equally, he accepted it as an abstraction without personal or even philosophical consequences. I certainly didn't feel that I was dying, or even approaching extinction; in fact, at the very moment I felt most confident about my own work and was learning most from my contemporaries, when put in the position of an uneasy cultural critic, I invariably fell back on the terminology of despair. In other words, when I had to locate contemporary literature in recent history, provide some palatable generalization for the genre, the most assimilable rhetoric available was that which least touched my own working state of mind.

The upshot of this was a recurrent scheme for a story I shall never write, since the scenario is sufficient.

A sociologist is sitting in his study/basement writing an article on "the death of the modem nuclear family," while overhead, his wife, three planned children, and large spoiled dog patter unknowingly.

Take it from there.

It's easy enough to write off apocalyptic criticism as a self-contained enterprise with little relation to the energies which actually produce literature, and also fair enough to write off the decreasing market for serious literature to a conspiracy of greedy publishers and a distracted, mindless reading public. But those of us who have been preoccupied with minority publishing during the age of the Death of Language, and with fiction during the Death of the Novel, owe such categorizations a little scrutiny.

As any Trade Editor will corroborate, serious fiction, as a commercially viable item, is now undeniably moribund. To say, of course, that an art form which cannot pay its own way is also generically defunct is a respectable American argument; happily it is no longer applied to any other art form, from Grand Opera to aerial bombardment. It is somewhat closer to the truth to say

4

that it is almost impossible to raise money to subsidize literature, the most obvious reason being that literature is both produced and consumed in private, and thus it is difficult to involve patrons as, say, with the ballet, where an audience can, if not appreciate the production, at least get a sense of itself. What is worth pursuing is how the End-of-the-Genre Criticism dovetails nicely and so curiously with corporate apologetics about the lack of demand for fiction. To which we will return later.

Let us pursue three assertions. (1) At the moment when America has an unprecedented number of good fiction writers, and (2) the novel and short story are undergoing crucial innovation, (3) the response of the conventional market to fiction is as low as it ever has been-let's say since Melville, to certify it. Now (1) cannot be proven-only exemplified-and we offer in this issue a small if not precisely random sample of the rich variety of exciting fictions being written today. We take no credit for searching it out-it's available to any publisher who's willing to lose money. And (2) remains the domain of close textual analysis. But I want to examine (3) in a rather simple-minded way-literature as a commodity.

Let us first regard ourselves, not as artists engaged in some risky transcendental project, but rather as collective artisans who have absolutely no control over the forces which produce and distribute what we make.

Literary Law # 1: Literature is the only artjorm in our generation whose technology has not been recently and radically challenged by its practitioners.

Both the European tradition of art as a secular religion and the American predilection for artists as heroic or at least stoic isolatos have made it very difficult for American writers to question the means of book production-it seems, if not hopeless, then beneath them, a quarrelsomeness which no serious artist should permit himself. 1 his denies community, we know; it also denies what even most established American writers have only recently done 5

without: a sense of audience. I think it's fair to say that no serious fiction writer in America today can tell you who he is writing for. That is not death, but it is narcosis. It doesn't affect genius or human will, it can never be used as an excuse for failed experiments, but it does have serious cumulative effect on the development of the genre, as well as the health of a culture. It forces us to rely on either a pride or a cynicism which is not earned.

Over the last decade, our writers have become increasingly characterized by the extent of their brain damage-no accident that Barthelme is the Salinger of the sixties-and fiction writing itself has been described as a kind of timeworn self-indulgence in an increasingly nonverbal society, the last gasp of privatism and individualism in a world which can be saved only by destroying the last links to language, by a collective sensory experience beyond symbol and sign. At any rate, we have rarely viewed our writers as functional craftsmen, and the refusal to accept artists as anything but madmen or eremites is not exactly new. But the fashion to celebrate writers for the damage they do themselves, to see their power as commensurate with the pain they inflict, has reached a new intensity. No accident that the exemplary narrative voice of the decade is paranoia, or that, in a time when the most effective form of private politics is assassination, self-loathing should be the primary mode of our best poets.

Perhaps in the sixties our sense of self was so diminished that fiction-whose traditional domain is the relation of the private self to its public contexts-was preempted by the confessional shriek, a cry so intense and deafening that it hardly required narrative momentum.

It is a little nostalgic to recall that early on in the sixties, we were told what was "out there" was so fascinating that only documentary reportage could be equal to it, and this was cause enough for ignoring the fictional imagination which had somehow not kept pace with reality. But in the end, the decade was chronicled in poetic fragments, in suicide's dreams, not by our essayistes. If fiction could not keep pace with the relevance of the New

6

Journalism, neither, it would seem, could it be adequate for a "counter culture" in which Reality became totally privatized. Its middle distance strategy was not serviceable for either the Think Piece or the Hallucination. And being told one is anachronistic is, after all, better than being told one is untalented or unpopularit absolves everyone of responsibility. One could argue, as I have elsewhere, * that if the novel remains the unequaled medium for fusing the imaginary and analytical faculties, intuition with concrete social analysis, then given what we have recently lived through, fiction will reclaim its share of our attention. It would

certainly seem that the cultural antennae are increasingly to be found in prose, rather than poetry. But such speculations do not confront the argument which proposes an intrinsic devolution of a genre. And my point is, bluntly, that we are determined not by genre, but by a hopelessly anachronistic technology. In other words, the cost of producing and marketing what we make has simply exceeded the industry's profit margin, and this particular disease has been masked long enough by theories of dying forms and metaphors of terminal illness.

It doesn't take a Marxist to understand the effect of conglomerate mergers in trade publishing-it is the American fate of our time and I don't suppose that writers should be exempted from it more than anyone else. Nor am I complaining that the book business is a business; but that as long as we are so absorbed by the deaths of certain traditions, we must understand that businesses, like genres, have their own cycles of expiration. In other words, conglomerates, given their internal capitalization, their high salaries and wage scales, can compete only through constant expansion fueled by continuous breakthroughs in technology. This is not to suggest that corporate ownership automatically reduces the options of a publisher-indeed you could argue with some hopeful logic that working for RCA would allow one to take more

'" "Beyond Omniscience: Notes Toward a Future for the Novel," TriQuarterlv 10, 1967.

7

risks on marginal books-but there nonetheless seem to be some inexorable laws which operate with regard to what we call "serious literature.

1. A conglomerate's products are defined by their "spin-off value"-products which create other products within interlocking systems, and hence the book, and the novel in particular, is defined by its subsidiary functions almost totally-movie rights being the penultimate example. It is easy to put down Erich Segal's oeuvre, but the fact that the book of Love Story grew out of the movie is the key to understanding the technological determinants here.

Lit Law #2: The commercial success of a novel is exactly proportionate to the extent to which it is translated into media other than its own.

2. The flexibility as well as competitiveness of conglomerates is determined, in America particularly, by successive breakthroughs in technology, and as artisans, we have a situation where there has been no advance in the science of making books since offset printing. As always, the weakness of the system is revealed most clearly in a hiatus of growth. Given this, let me offer a simpleminded explanation of the death of the novel or the marginal book. The real costs to make this thing we call a book have more than doubled in a decade. Retail prices have almost tripled. There has been no advance in the distribution or promotion technology in at least a generation. Five years ago it took 2,500 copies of a first novel to break even. Today the figure is at least 5,000-and most trade publishers won't look at anything that doesn't have a chance to sell around 10,000. The paperback "revolution" obviously only increases the odds against a book with a limited audience. Is it not unreasonable to suppose that the audience for serious fiction should triple in less than a decade? The audience for serious fiction has not decreased-in fact, anyone who has been around a university lately knows that both in percentage of the population and in absolute numbers, it has increased.

Lit Law #3: This audience simply has not increased exponentially with the increase in cost to produce serious literature.

8

Literature, in more than one sense, is a handmade art in a massproduction economy.

This doesn't have the stink of a true conspiracy, only that of just another technological system which doesn't work under pressure. After all, is it outrageous to assume that perhaps one half of one per cent of the U.S. population is capable of reading a serious book? That's a million people. But the question is, obviously, not one of how many are actually out there, but how many of them have $7.95 to plunk down for somebody they don't know-assuming he's in stock. As usual, the burden of proof is thrown back on the consumer, and under present conditions, it will take a pretty hefty browser to save an author from his publisher.

It is interesting how rather simple economic priorities gather unto themselves the most metaphysical of justifications. We are, of course, no longer talking about books, but properties. But rarely do we hear this refreshing Philistinism any more. I have heard a vice-president of a large publishing house justify its reluctance to publish fiction by quoting George Steiner on the death of tragedy, Adorno on the impossibility of poetry in a world of concentration camps, McLuhan on the anality of print culture, and finally the crusher, that TV has preempted the function of fiction. Well, it's quite true that fiction has lost its monoply on middle-class consumer information-it lost that to the newspaper long before electricity-and so if TV has re-preempted that function, we can only wish them luck and go about our real business.

Mark it well. We are not being told that the function of books ought to be redefined or that fiction is trying to tell us something different than the Evening News. We are being told that fiction represents an insufficient profit for those who also own the Evening News, and that to survive at all it must be marketed like the Evening News.

Lit Law #4: It is perhaps a little early to pronounce on the death of literature. What is certain is that publishing as we have known it is dying.

While that may amount to the same thing, we cannot do much about our debilitated genius, but we can certainly demand institu9

tions which serve needs beyond those dictated by a corporate balance sheet.

I've deliberately avoided drawing some obvious political implications from this analysis because I want to suggest that these corporate decisions are not so much wrong in terms of some highflown aesthetic as confused within their own logic, and suffer from their own mythology of consumption.

Listen, for example, to a Mr. Karl Fink before the American Institute of Graphic Arts:

There are many ways in which packaging could enhance the appeal of books-gift-wrapping keyed to special events, new types of groupings or sets, re-use features, user-oriented bindings and constructions, improved display of selling messages. But before such ideas can be tried on a realistic scale attitudes of publishers toward the design and manufacture of their books must change

They must learn to regard the book as a product to be packaged and sold as are other products, and they must develop, along with their manufacturers, a system of standardized alternatives to control today's undisciplined proliferation of physical variables.

In applying to publishing the types of packaging thinking that takes place in other industries, the book must be viewed crassly as a product to be sold. Much as I respect literary merit and fine bookmaking, as a packager I must evaluate books in much the same way I evaluate a can of soup or a bottle of wine--as items which vie for consumer acceptance in order to make it in the marketplace

There is, for instance, the matter of selling books in multiple units. I know that we have sets of Dickens or George Eliot or Winnie the Pooh, but what about grouping various books on one subject to develop multiple sales? Might not a travel guide to Spain be packaged with a road map, street maps of principal cities, a money changer, a tipping guide? Could simultaneous publishing dates on Civil War books from different publishers be turned into enticing offerings--through joint packaging-to Civil War buffs, instead of competitors for sales ?

And what about special-occasion packaging? We know that if you're looking for a Bible as a confirmation gift, there is a convenient choice between a white slipcover for girls and a simulated morocco for boys. But what about appealing covers encasing appropriate books for Mother's Day? Hearty barbecue books for Father's Day? Love poems for Valentine's Day? Graduation dictionaries?

Still another packaging design staple that might be adapted to specialized books is the re-use container. The package for a book on birds might ultimately convert into a bird feeder. A cookbook's binding might be doubled and hinged at the top to form its own easel.

We must find out more about people's attitudes toward books. Do they retain jackets or toss them away? If so, when? Do they dust books or leave them on

10

she es? Do they, in fact, keep them at all? Do they regard books as objects, as status symbols, or do they consider having read them the most important thing?

(PublilheJl, Weekly, March 6, 1972)

What's objectionable here is hardly Mr. Fink's indifference to intrinsic value. Indeed, he has struck an unwitting blow for concretism and paraliterature. The resistance of publishers to anything but the most standardized format has discouraged not only Mr. Fink, but a good deal of experimental fiction, in the same way that the format of commercial magazines has had an undeniable if yet unexamined effect not only on the content but the very structure of the American short story. (Ah, yet another death. Short Fiction abounds. But whatever happened to the magazines which printed it? Again, the genre's evolution/reconstitution is confused with the demise of its traditional package, or "vehicle," or whatever Mr. Fink wants to call it.) No, what is both saddening and hilarious is the desperate response to submit all problems to repackaging and mass market research. A Free Pocket Harpoon Gun with every copy of (abridged) Melville! The solution of every commercial magazine to its structural economic problems in the last few years has been: (1) redesign format, (2) reduce trimsize, (3) knock out fiction. My God, the power of literature! All those little stories dragging entire corporations to fiscal ruin. As long as the publishing industry subjects all of its products to the same promotional techniques, as long as serious books must compete not only with other books but TV and gimmicks, and fiction remains undifferentiated from Confirmation gifts, then of course, its piece-cost will continue to rise, and its claims on ordinary attention continue to decrease.

There are those who argue that corporate control, with its rational accounting, will eventually solve the problem of the marginal books by improving "seat-of-the-pants" marketing. This seems to me incredibly naive. The present anachronistic system at least allows for some personal taste to becloud a decision. More and better advertising will not sell books that won't sell-as long as sales are defined as a return sufficient to cover the absurdly high costs of space advertising. Further, even if publishers decided to

11

invest in market research, how would they persuade retail outlets of their newfound market? Mass marketing specializes in the selffulfilling prophecy, and to urge the corporations to identify a new audience is only to encourage them to bring more retail outlets under their own hegemony, in order to fully rationalize decisions made at the production point.

Lit Law #5: The audience for serious literature-while it can be statistically defined by traditional labels: geography, age, sex, income, profession, etc.-cannot be reached by traditional marketing devices, no matter how intensively applied.

In other words, the system does not cater to the reflective, selective buyer who is most likely to be primarily impressed by word of mouth, occasionally a review, and the actual physical presence of the book. The answer to this-as with all such problems of quality items in competition with the mass market-is selectivity, lower costs, and proximity to minority consumers. I will come back later to alternative possibilities for achieving this.

In such a situation, it is hardly enough to be anti-establishment. Those of us who have made our living on the periphery of universities, for example, are also accountable. For the university press, as a countervailing institution, has failed utterly to provide a genuine alternative press or distribution system. It has favored exegesis over art, and generally ignored the culture of its time. It has not created a single innovation in production or distribution technology, despite massive subsidy and proximity to all the research facilities necessary. It has been timid editorially, conservative politically and aesthetically. It has failed to serve even the day-to-day educational needs of its own community (except to certify certain academic hiring and promotion policies) and ignored any audience beyond its narrowest constituency. It has passed its costs, in the form of outrageous cover prices, on to its basic consumer, the library, which in turn has passed them on to the government. And when the economic crunch comes, for the same reasons it has come to its commercial counterpart, the university press-rather than addressing itself to areas in which com-

12

mercial publishers default, rather than acting like a subsidized countervailing institution-it too defines literature as marginal, and the first things to go are the poetry series, the literary reviews, the search for the unexpected imagination, all these "luxuries" whose constituency is never represented on policy-making boards. A strange situation-information which should be in retrieval systems, information which is of use only to a handful of specialists, is produced in twelve-dollar limited editions; while literature which not only has a wider minority audience, and whose only possible medium is the book, is ignored. The university press is as venally bound to a guaranteed library sale of specialist nonfiction as is a commercial publisher to the guaranteed sale on Greyhound bus station racks, and with the same result-the forfeiture of cultivating an audience.

The first university press which puts its dissertations and statistical abstracts on microfilm, rethinks what ought to be printed, and devotes itself to literature and the art of its time and place will make an indelible mark on this century, and perhaps even regain the respect for continuity and independent judgment which the university has forfeited.

There are, of course, a few exceptions in both academic and commercial publishing, and we have been fortunate enough to gain their .support. But our position as a kind of broker between the solitary writer and the institutions which alone can give him the audience he deserves, has forced home the less than perfect relationship between them. It's not much fun to be simply an exception which proves the rule. And while we have certainly been lucky to survive as long as we have, we have seen too much talent come our way in the last few years to believe, as we once did, that it will find its own level. It is harder to break in now than it ever was, and even established talents have minimal claims on their potential audience. We frankly think it's pathetic that an extract of a novel in small-fry TriQuarterly may well reach more active readers than the eventual casebound edition from a commercial publisher. Our purpose is not merely to indict, but to try

13

to see these as problems whose solutions are explicitly political and technological, and not caused by some vague, incurable cultural malaise.

II. Let's be clear on what we're complaining about. Any assessment of the present literary situation must begin with the redefinition of "censorship" and "relevance," those sub-indexes of free speech and intellectual freedom. It's quite clear, for example, that a commercial publisher can absorb such criticism by pointing out its youth list, its woman's list, its black list. Indeed, when social issues are most polarized, it is perhaps easiest for the establishment to compartmentalize its market and to diffuse criticism with an illusion of contemporaneity. But the alacrity to cash in the literary chips on issues pre-glamorized by the media in no sense represents a more venturesome commitment to serious analysis or to the issues-as Youth and Black culture are already finding out, as the returns start coming in. Nor does this, of course, have anything to do at all with either social relevance or literary innovation, which have only the most tenuous relationship, and that established by hindsight.

Further, literary freedom has become equated almost solely with the license to use explicit language to describe sexuality. And in this case, the increase in pornography is seen as the last breakthrough in the fight for freedom of expression. Again, to ignore the question of intrinsic merit, it should be understood that the freedom to say or read "fuck" is directed more at the engorgement of the volume market than the satisfaction of either erotic desire or the elimination of constraint. Alas, explicit politics or explicit sex has little to do with releasing the energies of serious literature. And such increased tolerance is no avant garde, only a middleclass acceptance of colloquial speech once limited to rare book and locker rooms.

In such a context, freedom of expression has come to mean little more than saying in public what was once formerly said or read in private, without unpleasant consequences. Most Americans under-

14

stand cultural censorship as nothing more than bleeping talk shows, and literary censorship as a fusty court battle won before they were born. (You don't, after all, need a Justice Black or a Brandeis when Playboy is apparently taking the fight right into the kitchenettes of America.)

Lit Law #6: It doesn't matter what you say, or how you say it, but where. A classical totalitarian society censors at the production point. An oligopolistic democracy censors at the distribution point.

A modem government can kill off objectionable ideas with prurience or sedition laws, just as commercial publishing companies, by setting advertising rates which only corporations can afford or piece costs justified only by volume printing and mass distribution, can limit minority reports. It is a sad fact that countries with much more rigid official censorship laws-France and England, say-offer a better selection of serious literature to their consumers than America. The idea is, you can go into a bookstore which doesn't depend on get-well cards for its profit, browse among some authors you haven't heard of, come out with a book, and still have money for lunch. This, friends, is what we're asking for.

What we are really talking about here are basic minority rights -the right to see our most serious efforts reach their widest audience. It is not a large constituency-perhaps 25,000 hard core to 100,000, but it is growing. It is a minority which is at present nameless, and cannot organize beyond its hunger for a vision of America beyond the ghostly images of electronic communication. Choice kinds without names," is what nurseries label plants which have lost their tags during a strong, wet growing season.

Censorship in our culture must be understood as a combination of both its Roman and Freudian definitions-as any object which prevents individual expression from entering a larger consciousness. If a book deserves to be printed and is refused because it won't sell 5,000, that is censorship. If a novel has a

15

potential audience of 20,000 and receives a quarter of that because it is not reviewed, promoted, or in stock, that is censorship. It hardly matters whether this is due to ideological opposition, official ignorance, a conspiracy of indifference, or the exigencies of a free market, it has the same effect-the denial of a rightful audience and the loss of community. If we were told, for example, that an anti-establishment novel in Poland was printed in a small edition, went unpromoted and unreviewed, and then was rapidly allowed to go out of print, we would know the reasons why. Here, it happens every day and we are not scandalized. There is no fundamental difference between initially restricting information and making utterly unreasonable demands on the consumer. In fact, where censorship has a more bureaucratic structure, in Central Europe for example, a controversial play may be allowed to be printed but not performed, a similar novel permitted to be read aloud at a club, but not printed and circulated. There, censorship works by denying the medium best suited to the form, and by delimiting the potential audience. It has a familiar ring.

There are several reasons why we have not been able to develop a significant theory of how (and why) America restricts literary as well as larger political options. The first is, of course, that we have relied on the European model of repression rather than really investigating the American tactic of absorption-the supermarket censors in its own way just as much as the ministry of culture. But even more importantly, the escalation of rhetoricall sides accusing each other of being "dead"-has so banalized polemic that it is a rarity not only to see a limited and telling attack upon the establishment, but even to recognize a true expression of agony. The "Grateful Dead" indeed. (As G. Graff says, it used to be that one tried to prove one's enemies wrong. But now that right and wrong are "meaningless" categories, it is better to identify the opposition as "dead." The Death Argument saves a lot of trouble because reasons are irrelevant; it is basically unanswerable, and it implies that the prosecutors are "the lively ones.")

To illustrate, look at this press release which recently came into the office-its heading:

16

In observance of International Book Year 1972 OBSERVATIONS of American Writers

prepared by the Publishers Publicity Association for reprint use in newspapers and magazines

In observance of International Book Year 1972, James Purdy, Author of ''Elijah Thrush" published by Doubleday & Company, has written this personal observation on the American literary scene.

In response to an invitation from this organization to write a piece on "The Joy of Writing," James Purdy came up with the following put-on, which he obviously believed would never see the light of day.

Writing from InRe1' Compulsion

I became a writer because there was no way for me to avoid writing, and I am in the same unchanged situation today. My early writings had to be privately printed because my work then as today violated the taboos and crotchets of the U.S. Publishing Monopoly (the taboos seem to change as the System goes on crumbling, but the main character of the monopoly remains-its outlawing of native vision and speech, its assassination of pure talent, and its denigration of integrity). Although over the years, beginning with my privately printed books on down to those of my writings which commercial publishers have condescended to publish, my readers may have increased by numbers, I am still writing from inner not outer compulsion, and my work is truly reaching only those few who can accept vision and voice unconnected with the dogmatism of the politicopomog'raphy which constitutes U.S. writing today.

I think that to be ignored by the vast collection of monopolies which today control publishing, criticism, reviewing, the book prizes, etc., to be swept, in fact, under the rug by this huge structure, to be denigrated and isolated as I have been by it, far from being "hard luck" is in the end the best thing that could happen to me or any other writer who has originality of vision and tongue. Either one is a success and a coprophagist in New York, or he is out of it, sweetbreathed, and whole.

If one writes from inner prompting and the instinct to put down his own voice on paper, he cannot expect rewards and accolades from the most meretricious and deceitful, the most shoddy and unreal civilization the world has ever seen.

It was of course printed and circulated as a fit "observation," despite its obvious disdain for the entire process. And perhaps the press release will reach a wider audience than Purdy's books. But there are several things in the text worth remarking on. First, it is

17

the writer placed in the position of "cultural critic" once again, and note the extremity and rigidity of the rhetoric-something Purdy would never permit himself in his own fiction. Also, whatever his indifference to "fame," note the underlying poignancy, the yearning for a knowable audience. He knows very well that what has happened to him is not the "best" thing; it is simply preferable to being a clique's cutie or a hack. Indeed, like many rebellious writers, he accepts the either/or criterion of success promulgated by the industry; he simply reverses their valuation. But much more significant than Purdy's contradictions is the incredible cynicism which would offer this wholesale condemnation of publishing as "publishers' publicity," complete with a phone number to TimeLife Books. What possible follow-up could they offer? What other culture in all history could so effortlessly absorb the most vitriolic attack by an ingenious and respected writer, repackage it, and throw it back in his face as an instance of their benign tolerance? You see, this sort of inaudible outrage is what is expected of us, this is what comes of writing froni "inner compulsion," this is our role because it can be written off to the rhetoric of the alienatedwe are specialists in the last gasp-and because Purdy has nothing to fall back on save the integrity of his isolation, the Publishers' Publicity Association knows that these words, no matter how hurtful, true, or indicative, are no threat to them. They lack power. And I am not talking about stylistics. Or perhaps-and this is the most terrifying aspect of this artifact-perhaps we are so accustomed to this rhetoric that it is impossible to give it any credence. It exists only as a mirror image of somnambular Timespeak; nil admirari, nil desperendum. At any rate, this is how we celebrate "International Book Year"-with such instances of "free speech."

If we are to be obsessed with relevance, perhaps we should pay more attention to a distribution system which hasn't changed much since Henry James. Aside from the question of efficiency, how can a presumably advanced society accept a system in which one or two estimable gentlemen of no particular credentials, and responsible

18

to absolutely no one, decide for example which paperbacks will be available to the populace of Chicago each month? If our drugs or underwear were rationed in such a way, we would be at the least incredulous. I live in a metropolitan area of eight and a half million people with the highest per capita wealth in the history of the world, and there is one outlet within that area which carries a representative selection of the magazines and periodicals in which most of the serious literature and criticism in America is published. Except for lower Manhattan, this is the situation throughout the rest of the country.

Lit Law #7: The dearth of quality is most apparent in those institutions which give the illusion of offering the greatest choice.

In this respect, the chain bookstore/newsstand is in no respect different from the drugstore which offers a "choice" between thirty toothpastes, and has to rely on either packaging or media exposure to create the very will to choose.

If we can have a civilian review board for our police, for our cinema, why not one for newsstands? I am almost serious about this. If space is the problem, then the polity ought to provide for those needs, for the same reason they provide drinking fountains and urinals. I would much rather take my chances with the sense of fairness of the average man than the exigencies of the "free market." You can educate a citizen; you can only outwit or overthrow a system. There are more independent bookstores in the city of Paris than in the whole of the United States, and in France, less than 1 percent of the population claims to have read a novel. This is a matter of economics, not taste.

There remain, of course, some economic advantages in being an American writer. We have not failed, as France has, to provide our writers jobs; and indeed, intellectuals as a class receive more abstract respect than they perhaps deserve. Writers have a way of destroying themselves in our culture, and one of the reasons is because they do not identify their enemy beyond whatever institution is paying them. In the thirties, it was Hollywood which killed us, now it is the academy. If contempt is this important to us, we

19

ought to make heavier use of it. The anti-intellectualism of the fifties is largely over, though it resurfaces periodically on the mystical left as it once did on the Philistine right. In many respects, the teaching of literature, and the health and honesty of high journalism, the opportunities for free-lancing, have never been better. The prose and editorial acuity of a Sports Illustrated, say, is of higher quality than in most literary magazines.

We have failed in what we presumably do best-to make our technology responsive to a pluralistic society, to pragmatically facilitate communication, to offer alternatives to a diverse public which we must respect as basically curious if easily distracted. The literary act is the most intense and private and individual transaction of a species which is defined, for better or worse, by language. And in our time, such an act becomes exemplary beyond its purely aesthetic function.

The most powerful idea to come out of the 20th century American experiment was the transfer of an Enlightenment view of political life to culture itself. For if our politics have been basically conservative, it is in the operation of our cultural and artistic life that our more radical ideals have had their greatest expression. Against the European notion of culture as standards enforced by an elite, we have come to see culture as a series of alternatives, and the greatest legacy of the otherwise dissipated radical politics of the sixties (as well as the greatest oversight of the liberal mind) was the realization that the communications structure must be changed before you can hope to alter, much less bind, thought and action. In this respect, the two cultures' debate, and the fifties' distinction between hi/Io mass/mid cult, are no longer appropriate analytical weapons. Mass Culture, in and of itself, is in no sense an enemy of serious literature, any more than a "classical" FM station is damaged by hard rock; our anger must be directed at proper objects, at those agencies which homogenize mass culture as well as ignoring "serious" art. Mass Culture provides about the only sense of past available to an average American; its health is contingent upon the health of innovation.

20

We ought to recognize, however, that the media have preempted the function of the writer as celebrity. We have many writers the equal of Hemingway and Fitzgerald, but no one equal to their public function-no one whom the public can either fear or heroize. And frankly, with whom would they identify? Mailer? Capote? (Mailer is most interesting, not for his boorish existential posturings, but for the way he has personally taken on, and overridden, the technological determinants of the industry. He remains the only serious writer who has managed to use the media faster than they have used him-though it seems a pretty close race at times.) The talk show is, after all, an attempt to create through form what was once content, to create through instantaneous exposure what was once mythology or at least romantic rumor. At least people could genuinely envy Hemingway or sympathize with Fitzgerald, for their self-promotion was related directly to the forces which produced their art; their posturing was a way of testing the reality of their audience, and there can be little such testing through the tube, even if Homer himself were MC. But we should suffer little nostalgia over this. After all, it's demonstrably destructive for writers to live out the fantasies of their public; they should rather be read than recognized. We have grown up to the extent that we can see that artists might have other serious social roles besides that of the celebrity. To this extent, literature has certainly become de-prophetized, and the only societies in which a writer can still claim this sort of charisma are those where the government either officially honors its writers or punishes them publicly. It is hard to imagine an American government getting around to doing either. This partly accounts for the non-polemical situation of literature at the moment-it is difficult, and appropriately so, to compete with athletes, activists and experts for public posture-but it is more than that. The left has been isolated so completely that we have a situation where almost all writers share roughly the same politics, while differing radically over aesthetic strategies. (Indeed, our time is marked by the confusion of the two.) There is a battle coming between the

21

new realists of "committed literature" and those who take a more philosophical and paralinguistic view of language. One hopes it will be more productive than the Beat vs. Academy skirmish of the fifties, and it should be, since it will concern other genres than poetry, and should not degenerate into a question of competing life styles. For the past ten years, however, these theoretical debates over means and materials have been increasingly subsumed by the political hopelessness which has been our common lot. Vietnam is after all the first war in which intellectuals, those who claim purchase on consciousness, have not been direct participants. And nothing cripples a writer more than an enforced sense of abstraction.

For some reason, there is a hopeful side to this. At the very moment the writer is in most serious doubt about his audience, there exists for the first time, at least in this generation, a sense of community among writers, of strength in numbers, of being on the verge of a collective breakthrough-not a break with the past but a conscious elaboration of a tradition, the shared feeling that our antecedents finally belong to us. The thrust is away from interlocking elites and self-protection. The exacerbated ideological temperament which made possible the Partisan of the forties, the Kenyon of the fifties is a redundant memory. And this is hardly Con III (if that still exists by the time this sees print), but a return to a belief in the possibility of literature having an instrumental relation to life. Of course, it could be argued that the colorful competition has diminished because the prize is such small potatoes. But I see it as a minority of competence too preoccupied with seeking its own concrete audience to take internecine warfare very seriously. This doesn't mean that younger writers are less interested in money or public leverage, but only more so in an audience which provides some kind of continuous feedback roughly coextensive with their production. The artist defined as neither prophet nor pariah, but as a functional artisan in a society unafraid to confront itself in all its contradictions.

Lit Law #8: Literature is not dead, nor new politics. What has died is literary politics, literary leftism.

22

ill. If I am right about both the anachronistic technology and the unprecedented talent of the moment, as well as the need to account for the latter by radically changing the former, then what are the alternatives for action? Here are a few that should, I think, be scrutinized but ultimately disregarded.

1. Cooperative effort: Even if writers were more temperamentally and geographically proximate than they are, it is unreasonable to think they could either capitalize or run a modern publishing venture. This does not mean that writers could not participate more in the decisions of who gets published, nor that this would drive a wedge between those whose books make a profit and those who don't-for, in fact, under the present system, the successful writer subsidizes the unknown, and the former might welcome a say in whom he is supporting. And fiction, as opposed to poetry, say, is too varied, too long, and too expensive for a cooperative to produce, except perhaps on some regional or socioethnic basis. In any case, our salons, like our restaurants and brothels, have always been mediocre. We must recognize that there are very few cultures in which writers, established or not, participate so peripherally in the engines which produce their work, as in ours. We must learn more about the machinery, and submit less to paternalism. The private form is gone forever, and the corporate form too much with us. We will not be driven back to the mimeograph machine, limited editions or underground cliques. We are not outcasts, and we must claim our share of democratic communications.

2. Taste tax: In some neo-Marxist societies, an attempt has been made to tax mass entertainment as a way of subsidizing a minority art; i.e., an Agatha Christie mystery will cost more than a Beckett, a ticket to Fiddler on the Roof will help pay for the production of a new playwright. The objectivity of this is appealing, but naturally the bureaucratic distribution of the subsidy remains the stumbling block-for at best, the result would be cheaper editions of Shakespeare and Balzac, and would leave more controversial and/or contemporary art in limbo. There is no reason, however, why municipalities, for example, could not

23

directly tax profit-making entertainment enterprises, and specifically earmark revenue for disbursement. If we rely too heavily on private endowment for literary art, the hardback novel, like a decent season ticket to the opera, will remain a prerogative of the rich.

3. Individual support: It is idle to suppose that we can expect much help for individual writers from corporate conglomerates, or from the "general interest" magazines now also accountable to their ledgers. But again, it is missing the point to blame those agencies whose avowed intention, after all, is to make money. The foundations have also admitted, by cutting back already meager support to creative writers, that they have no way of choosing between writers, or, for that matter, the literary magazines in which most of them publish. It is not surprising, then, that the few grants made to writers are in the form of rewards for a successful career, or that the only grant made to a literary magazine by a large private foundation in the last twenty years has been the recent Ford bequest of $50,000 to you guessed it-Encounter Magazine. In reply to a request for "clarification," a memo from W. McNeil Lowry, "Vice President in charge of Humanities and Arts," to President McGeorge Bundy is worth quoting in part, at least for unborn rhetoricians.

Throughout its existence, the Division of the Foundation that has been most concerned with humanistic and artistic periodicals has not been able to adopt an open policy of potential support to all the important literary, artistic and scholarly journals or other periodicals. The fields covered by the Division of Humanities and the Arts range through all the humanistic, creative and performing arts. In all these fields, there are periodicals of varying quality but a large number which are outlets for creative writers. There are also possible gaps which need to be filled by publications concerning the arts which do not actually exist. [sic]

The Ford Foundation staff for many years have studied this question and in that study have drawn upon the experience of other publications. The staff has concluded that in most cases even a commitment of Ford Foundation support over periods as short as two or three years would not leave the publication in a sound position for permanent operations through other support or other income. We do not pretend that there is not more to do for the Ford Foundation in helping advance opportunities for creative writers. We have found, rightly or wrongly, that the way of direct subsidy of individual literary magazines or the field as a whole is a way fraught with too many difficulties.

24

The suppositions here are rather interesting:

( 1) The creative arts (one presumes this includes writing) are lumped with the performing arts and scholarship, though it would seem that the problems each encounters are utterly different. Accountability is the criterion here=-one funds a program, an operational procedure, an established voice, but not a potential community, a magazine, an idea.

(2) The Foundation will not fund projects which cannot become financially self-sustaining. (The assumption here is pretty clear. Legitimacy is defined by acceptance in the marketplace. Yet how does this justify the millions Ford poured into university presses and repertory theater in the fifties?) This ignores the fact that the average life of noncommercial magazines in the culture is about three years, and that their very obsolescence is precisely what has made them the most powerful force for innovation in American literary life. Their proliferation and constant renewal provide, in fact, the only continuity in American literary life. It is of course the continuity of an impulse, not an institution or name brand. The Foundation not only wants to avoid association with a loser, it wants immortality-of a modest capitalist sortthe balanced budget. Writers don't need posterity-they would be satisfied, I think, with surviving and publishing in increments of two or three years. And it would be interesting to know the reaction if the criterion of self-sustenance were applied to other popular Foundation programs-birth control in the Middle East, for example.

At any rate, after careful consideration, the Foundation has decided that the only publication which merits its support is a foreign journal with no particular relevance to American intellectual life, and minimal commitment to the arts, as well as the only magazine in our generation which has managed, quite unnecessarily, to disgrace all those who worked so hard to bring it to fruition.

Apart from the questionable suppositions above, the reasons fo: such official reluctance are not complex. I for one do not believe that the grant was made to Encounter because that magazine had 25

been relatively hospitable to our foreign policy, or because one of the architects of that policy now happens to run the Ford Foundation, or because 90 percent of the periodicals the Foundation has supported were formerly subsidized by the CIA. I believe it was a simple way of avoiding the political repercussions of choosing between American magazines. (And not only literary magazines. Think of all the good biweeklies which have gone under in the last few years. And come to think of it, what good independent magazine or periodical in this country isn't subsidized by somebody?) If a grant had been made to an American magazine it would have created an unheard-of precedent, inviting both abuse and, even worse, applications. There are, of course, many good pragmatic reasons why foundations should try to give direct grants to writers rather than help magazines, but to categorically write magazines off is a convenient way of isolating the only constituency that writers have ever had in this country. If Ford or others did make such a grant, they would have to face a problem of severe selectivity and independent judgment, and as everyone knows, in these days of death, there are just too damn many good writers and magazines in this country for a foundation to choose between them-to question their own procedures, make a critical choice, and take the political consequences. In such a situation, there is no alternative strategy except to encourage those who can to take the money and run. And in any case, we would be better off campaigning for a guaranteed annual wage, and/or tax help for artists, than complaining about the paucity of Guggenheims. Until we have a headier sense of ourselves as a community, perhaps we do not deserve better.

4. Appropriation of other media: One of the few salutary events of the sixties was the creation of the "counter culture" press and distribution service-a way of bypassing the conventional production and distribution costs with alternative information. Corresponding efforts were made to get literature into the schools, not only by visiting writers, but by use of tape cassettes and video tape -in other words, to use cheaper media for literature, as well as

26

to identify it as a living process created by human beings, rather than just part of an infinite abstract curriculum. Fiction, a magazine in tabloid format published three times a year and selling 50,000 in its first edition, is the most admirable example of this to date. When it can afford to come out monthly, can afford sufficient space to print more than extracts, and each city has its own variant, it will add immeasurably to our culture. Until then, it will survive as only another littlemag-a collectors' item dependent on the energies of a few unpaid enthusiasts. Furthermore, there is only so much we can learn from the methodology of the counter culture and more palatable media; even personal appearances are not going to alleviate the problem of genre. Our medium, both physical and intellectual, for better or worse, is the Book, a machine of pages. It is a fine thing for a poet to read to young people, as long as they have an odds-on chance of following him up on the page--otherwise, we have reverted to celebrity function. The "oral tradition" notwithstanding, literature is the aural written down, the aural become visual. We are not pedagogues, entertainers, therapists, magicians, shamans or ideologues. We are something less than each and something more than all of them together. However much the entire notion of the book is redefined, our parameters remain the printed page. The alternative press has prospered, not because it has discovered either a new consciousness or a new form, but because, like any profit-making operation, it has succeeded in selling basic consumer information to the new middle class. And if we did not survive between ads for Ford and Chanel, there is no reason to suppose that ads for herbs and stud service will carry us. Whatever else, the counter culture will not be remembered for its sentences. To take literature into the streets is a fine thing as long as it does not serve-like so much recent surrogate radicalism-as as shortlived flouting of an establishment which congratulates itself on being able to absorb such oblique challenges. Literature can create a community only by challenging that community's most deeply held notions about itself. And when all is said and done, we can-

27

not really appropriate other media--only know our own limitations better.

5. Self-support: There is a more drastic alternative, first suggested by Michael Anania of Swallow Press over a plate of Saltimboca Sicilia at his private literary haunt. Let all books of "literary value" be supplied with a coupon, and let all publishers and magazines require that each manuscript submitted for publication be accompanied by three such coupons. This alone would subsidize literature for a decade. (Thus qualifying the author, perhaps, for a Ford grant.) As Kenneth Patchen once said, "People who say they like poetry and don't buy any are a pack of cheap sons-ofbitches." This would also postpone the possibility of our becoming the first culture with more good writers than readers.

IV. All right, then. What in God's name do we have a right to expect? The following options seem to me minimal and practical, and could be accomplished at the cost of a few B-52 sorties:

1. An alternative distribution service: To cop a phrase, this has to do with the death of the library and the death of the independent bookstore. (And while we're on the subject, if youth has no interest in books, how do you account for the soaring theft rate? Does ripping off a book have to do with a lack of respect for literature or for the lubricant of the system?) The public library of Carnegie and its librarian, the bookstores with knowledgeable clerks-the visible proprietors-are doubtless finished. With any other commodity, specialization would be the obvious solution. We must create an institution which is something between a repository of all culture and a boutique. And this has to do with the basic needs of democracy and not some remaindered aesthetics. Such an alternative seems to me the only genuine way of ameliorating the present situation.

Lit Law #9: Literature is the last serious artform which has any pretensions about paying its own way in the marketplace. Literature requires, in short, what every other surviving mode of creative expression has had in any country under any system,

28

subsidy-its own house in which it can cultivate its audience without competing with bread and circuses. In a country as large and diverse as ours, where both talent and need are rarely concentrated, this would seem a necessity even if the economics were less deterministic and did not threaten to grow worse.

We begin with three pissed trade house editors, 25 discontented professors, 50 stoic teamsters, 100 graduate school dropouts, several hundred students who believe that literature is something more than a one-way ride into the middle class, and a lawyer without fee.

We begin with six regional warehouses and 100 retail outlets, near universities and other ghettos. Fifty universities, 30 colleges, three foundations, and a government matching grant underwrite a five-year pilot project. Small but significant standing orders are placed with commercial publishers for serious work, including first novels, poetry, etc. Similar orders are placed with periodicals, small and/or scholarly presses. These selected titles are prepacked in portable modules (otherwise known as bookcases) and trucked from the regional depots to selected outlets. These modules have their own centralized inventory and billing apparatus attached. The retail clerk simply files a copy of the receipt at sale. These are applied against returns and copies in stock when the truck returns the following month. Now, given this system-selective choice, centralized billing, and a delivery vehicle-let's see what we've got before we go any further. First of all, we make it possible for the commercial publisher to apply different accounting standards and overhead to a certain kind of book. He knows he has a small guaranteed sale for an otherwise unpromotable book. His unit cost and overhead are cut down, it doesn't prevent him from putting his promotional dollar on the fiction that does sell, and it allows him to begin thinking in terms of selective marketing. More importantly, such a minimal floor would make it possible for most periodicals and small presses to actually break even, in the same way Title II grants to libraries floated university presses for so many years. Most significantly, the possibility of reaching this

29

small but defined market would generate a whole new generation of small publishers, and it would increase the chances of "social issue" magazines surviving.

The retail outlets built on this substructure would vary widely. In those few towns which still have good independent bookstores, our representative might simply provide the modules to various stores-thus saving the bookseller billing, inventory, return, and display/space problems. In most areas, however, a physicallocation-a franchise-would be necessary. The owner would be allowed to pretty much give the store whatever character he wished -and to sell whatever books he could. Given the delivery system, he could probably make good money simply by giving some personal attention to special orders, but his profit from the "franchise" would be related to which books he sold as well as volume.

This would be a place of books where people would also talk to one another. Staffed by part-time people with special interests and expertise who are now typing dissertations and grading for World Literature I, it would be difficult to tell who is selling and who is buying. It would hardly be "free," but it would be inexpensive, proximate, and would cut across cultural lines: counter culture, professoriat, litterateurs, newsstand buffs, bibliophiles, the reading housewife, and the rest of us at our leisure. Its local forms would run the gamut from high entrepreneur to cooperative arrangements. It would cash in on fashions without being dependent on them. And once you have a clearinghouse, then the adjuncts of readings, local politics, tape libraries, tabloids begin to make sense. All great bookplaces, from the Widener periodical room to City Lights, gather to themselves a social function.

Lit Law #10: A book is something designed to be picked up.

Like any other public service institution, it would have to be endowed. And the literary infighting would be scandalous. It would be under attack from the General Accounting Office to the Journal of Psychedelic Anthropology. But until such an institution exists, any speculations on the function of literature and the future of literacy are premature. Such a national program could be started for a tenth of the cost of the Kennedy Center for the Per-

30

forming Arts. And the people wouldn't have to rip off the lavatory fixtures to feel part of it.

2. A national book review: Beyond this, we desperately need a national literary review (or several) the lack of which makes us unique in the civilized world. While such a paper would be free from the space and editorial restrictions of journalistic format, this doesn't mean that it couldn't be distributed with, say, the twenty largest Sunday editions in the country. It is absurd for the New York Times Book Review to carry the burden it has assumedthrough no old-boy conspiracy, but through default. No one else even tries. Recently the Times has bent over backward to be more serious as well as representative; in fact, giving major attention to books, which, to judge from its own editorials, are hardly the personal favorites of the staff. This has resulted in less genteel and more sophisticated reviewing, at some sacrifice of elan and coherence, but the harder they try, the more uncomfortable they seem with their own power. Literature-wise, they simply cannot print all the news that's fit. And why should they?

Obviously, nothing can be improved until writers themselves have a public medium in which to write at length about books they admire, in a context where they don't have to compete with best sellers, movie listings, children's books, and the cause of the day. It would seem to be to the advantage of major publishing houses to at least partially subsidize such a venture, particularly if its advertising rates were more in proportion to small promotion budgets. It could be argued that such an operation would inevitably be taken over by petty careerists of one stripe or another. To that objection one can only apply Lit Law # 11: A writer needs, after a sense of audience and selective distribution, an establishment coherent enough to attack.

The question of format cannot be en.phasized enough, and there has never been, to my knowledge, any serious inquiry into the effect of format upon the evolution of style. To put it another way, the essay review is the only intelligent way to discuss a book, a format in which the reviewer is not only free from conventional editorial and space limitations, but can speak of things other than

31

the book-the presumptions which inform his analysis, for example-and not worry much about coming up a box score. The discussion of a book, in particular a work of creative prose, must take place within a wider discourse, or it is nothing more than a hole in the air.

I bring up this obviety only to recall that literary reviews, as well as larger, middle-ground magazines, have failed utterly as an alternative reviewing medium. Not only because they are hopelessly behind schedule, but because they have adopted either the most truncated "books in brief" format-a plot summary in an incomplete sentence, aureoled by an adjective of praise or blame -or that penultimate absurdity of criticism, the omnibus review or "chronicle"-which is of course nothing but a collection of "books in brief" that tries to look like an essay, a consideration of books which have nothing in common save their date of publication. The "books in brief" format gives the illusion of "keeping up," the chronicle creates the illusion of synthesis. Both smack of desperation, in which commercial indifference and academic pretension are indistinguishable. Perhaps it should not be surprising that the most successful-and deservedly so-intellectual review of the decade, the New York Review of Books, treats fiction as an occasional brunch of leftovers, in which each paragraph is likely to begin, "This novel fails because

It is time to invoke the one man/one book rule. It is also time to rethink reviewing formats created in 18th century tabloid newspapers, and 19th century periodicals. It is useless to speculate on the life of a genre or bemoan the confusion of critical standards as long as there remain so few avenues for leisurely and intelligent discourse.

Lit Law #12: Suitable reviewing media must offer a combination of the amplitude of a periodical with a journalistic vehicle. So far, we have created only the silliest sort of compromises, and writers themselves must accept their share of blame.

3. Assistance to alternative magazines and publishers: What is obvious now is that an entirely new kind of magazine will have to come into existence: a kind of hybrid between the leisurely quar-

32

terly, the specialists' periodical, the general interest magazine, the politically oriented biweekly, and the underground press. (It is magazines, not genres, which face a common insuperable crisis that is more financial than cultural.) Such magazines could begin as a kind of clearinghouse for the thousands of "little magazines" and their coteries, and the hundreds of unfocused anthologies of the trade houses. They would be independent and personal, notable, above all, for the quality of their sentences. They would have low enough overheads so they would not have to depend on space advertising for the majority of their income, and their readership would be made up of that small but substantial band of patriots who prefer not to have their intelligence insulted every time they tum a page. The idea of a reader having a definable, personal relationship to what he reads is, unfortunately, a new idea -for example, the possibility of a reader's actually commissioning a writer, in the same way and for the same reasons he commissions a sculptor, remains only one of many fascinating possibilities. It would be a relatively simple matter-both economically and politically-to subsidize these modest ventures. If only half of the state and city libraries in the country could afford to expand their periodical subscriptions, and would make it a matter of policy to support new magazines on a trial basis at their inception, every literary magazine worth the name in America today and, more importantly, those which don't exist as yet, could be close to selfsupporting. Obviously, there would also be even more dreck than there already is, but that's an old American story. It is really only a matter of each library in the country expending $100 extra in a selective manner. (For example, if only half the members of the state library association in five midwestern states subscribed to TriQuarteriy, we would make a profit.) It is absolutely astonishing when you think that these magazines represent the most obvious basic resource for any university English curriculum and yet are unavailable even in most periodical rooms. The important thing here is to neither frame our complaints as insults to venal businessmen or limited critics, nor to be deluded that we have a situation amenable to a little good will and technical

33

correction. The question is how to reassert our pride, the pride of independent artisans, which has, up to now, been the pride of metaphysical isolation, and to demand some help without adopting some facile paranoia. This is asking, I realize, for a lot more sour grapes, but nothing could be worse than the present biformity of alienation and smugness which attends the activity of making books. It is about time the American writer, rather than confusing his peripherality with freedom of expression, began to find out where he fits into productive and social relations of the world which most affects him. (If man is a creature of print, Mr. McLuhan, what is he when he is not printed?) He will undoubtedly be told that the price of his concern will be his imagination; that his job is to stay in his room and write, write, write; that his "time will come." If a twelve-year-old Puerto Rican kid in a ghetto can question this brand of paternalism, you would think a literate adult might.

Let me sum up. The fictional imagination remains the most open-ended linguistic activity, and its only "form" can be said to be an arena where facticity and fantasy can synergize, where art creates an independent reality while still recognizing itself as art. But to realize the full aesthetic and physical possibilities of the medium, we must throw off both commercial and cultural definitions of genre. The vehicle of fiction is not genre but print technology itself-and it is our technology which must be reexamined, along with the book as material object and a commodity of history. Further, technology is not changed either by scientific priority or even aesthetic strategy; it is modified only by the larger politics which program it. If we can perceive this, even dimly, it will not only increase the number of voices, and audiences, available to the writer, but it will mean that we can begin again to return "communications" to the root of that word, and experience literature, not as form or content, not as material luxury or spiritual transcendence, but as what--despite the fact it is practiced and appreciated by a tiny minority-renews the human family. Literature as the energizer of Discourse.

34

The important point I tried to argue with Henry James was that the novel ofcompletely consistent characterization, arranged beautifully in a story and painted deep, round and solid, no more exhausts the possibilities of the novel than the art of Velasquez exhausts the possibilities of the paintedpicture.

-H.G. Wells

All of this does not, of course, answer the question which prompted this hysterical meditation. "If the word isn't dead," that student went on, "how come all these writers say so?!" If Barth, Beckett, or Barthelme really believe what they say, how can they possibly keep writing? (His parents would have asked, regarding Faulkner-how can he stand to write such sad stories?) The reader will always confuse his capacity to react with the writer's ability to explore. And happily, we will never resolve this.

But is it so difficult to understand this obsession with culmination, with self-parody, with the metaphors of exhaustion, with what I call the rhetoric of terminality?

Recall that while every American generation, from the midnineteenth century at least, has described itself by its peculiar myth of deprivation-war, the Depression, ennui, repression, the light that failed, nada, darkness at noon, the shining palace built upon the sand, silence, apathy, involution, apocalypse-the catalog is endless as it is banal-we should note how these were invariably united around a single recurrent theme-their existence between realities, a transitional age. As Whitman had it, echoing Matthew Arnold, "society waits unform'd, and is for a while between things ended and things begun," which is, after all, the quintessential American sense of history, Confirmation, and our dubious gift to the devolution of Western thought.

Is it really surprising, after a century of this metaphor of transition-whether in its optimistic or pessimistic form-after surviving innumerable redundant mock apocalypses, that we should seize upon such extreme rhetoric of dissonance? It was the bomb shelter mentality of the fifties which provided us with the 35

V.

fashionable Apocalypse, as well as the Black Humor whose central tactic was, after all, to ridicule the pretensions of existentialism by mocking the immensity of its own despair. In the sixties we hedged our bets with Entropy. Stasis seems to be in favor now. Only the degree of degradation here is different-they are all commencement exercises. "Universal history," Borges says somewhere, "is the history of the different intonations given a handful of metaphors." And now that we have scandalized ourselves in every possible way, inhabiting an incredulous world where the slightest slip of consumership can kill you, is it not appropriate to finish off these metaphors by literally beating them to death? The Apocalypse is over. Not because it didn't happen, but because it happens every day.

Fiction, after all, always exists in a double sense: as a report on changing patterns of behavior-paranoia/self-Ioathing for example-as well as an evolution of forms and language. With regard to the second sense, we should recall that Modernism held out the hope that while industrialism and science were increasingly out of control, we could nevertheless create an edifice of the imagination, and through art create a consciousness for a scientific age. As great as that literature is, it is hardly the last gasp of the narrative impulse, but a kind of magnificent holding action, and it is no less great for that. Once we begin to suspect our minds, our very aesthetic means and materials-to question them as much as we despised the world-then the mythology of transition will no longer do. To draw attention, as contemporary fiction has, to the problematical nature of art demeans neither the artist nor its function, but simply unburdens literature from having to function as a secular religion, a preserve within the ravages of technology, and the insanity of our politics. The general acceptance that art alone cannot give a complete image of man's self reaffirms both the richness of our humanity and the possibilities of artistic enterprise. And in an age when we have, at the same moment, dismissed both our utopian notions of the future, and any continuity with the past, the new mythology is that we have none. "I have killed the last myth"-that is the narrative imposture of our times.

36

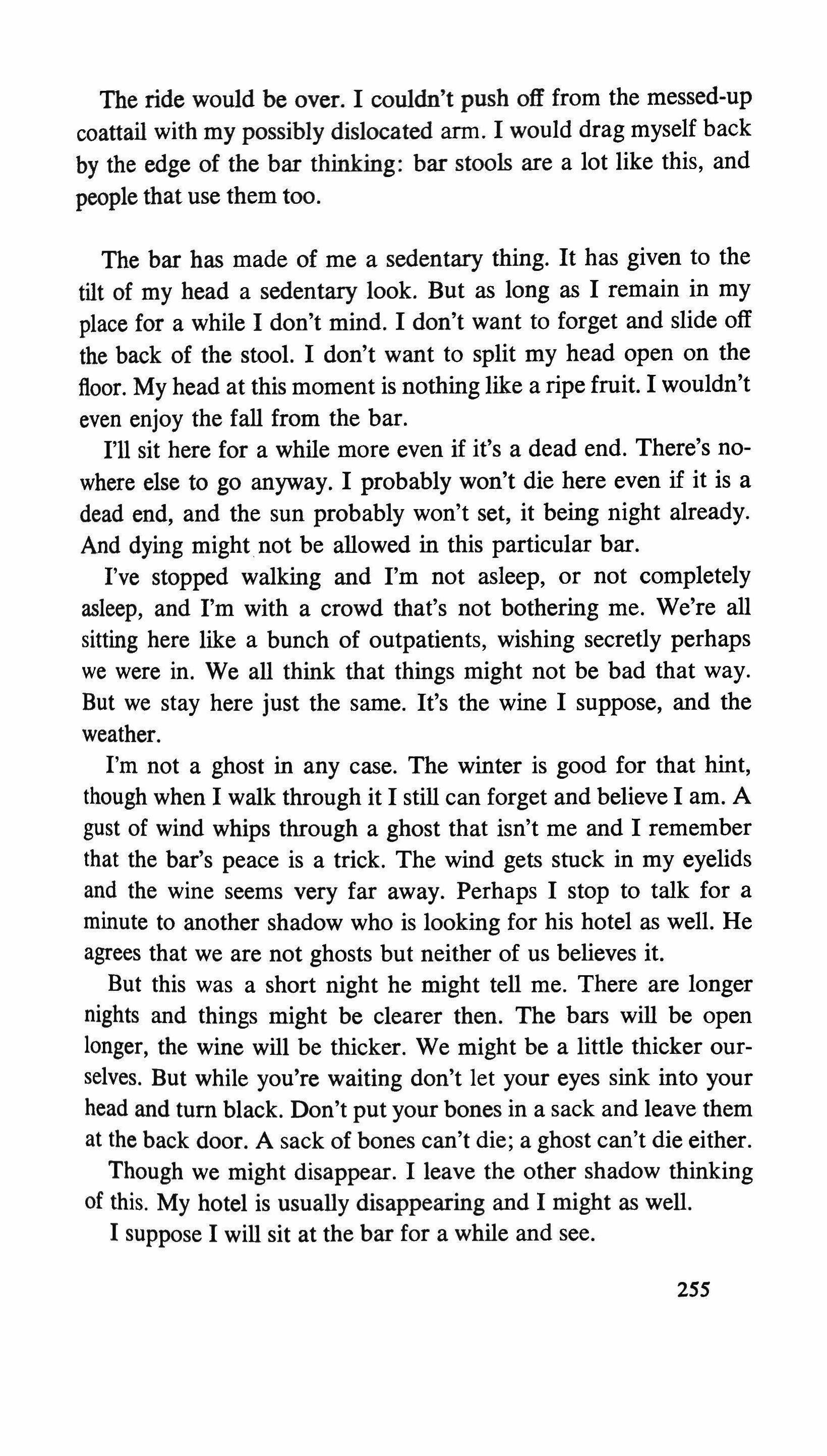

And it is important to see this as appropriate aesthetic strategy, not as divination or cosmic necessity. Literature is not religion, or philosophy, or psychology, it is not a political act, or intrinsically virtuous, neither weapon nor sanctuary, and least of all it is not therapy. Literature attends primarily to worn-out metaphors, and we are just beginning to discover that these metaphors are not national treasures or genre properties, but transcultural phenomena. Literature is in this sense "behind the times," for it has been the last artform to be internationalized.