Contributors:

Jonathan Williams

Eric Mottram

Jules Chametzky

Edward Keith Whittaker

Raymond Rosenthal

Anthony Burgess

Herbert Miller

Kay Boyle

ArnoKarlen

William O'Rourke

William M. Ryan

Adele Z. Silver

Donald J. Paquette

Gilbert Sorrentino

Ronald Johnson

Thomas Meyer

Guy Davenport

Josepbine Herbst

John Wain

Allen Tate

Paul Metcalf

Karl Shapiro

Hugh Kenner

IhabHassan

Frank Macshane

Fred Moramarco

Harold Billings

Kim Taylor

Robert Kelly

Arnold Gassan

Paul Carroll

August Derleth

Harold Rosenberg

Norman Holmes Pearson

Irving Rosenthal

Sid Chaplin CidCorman

Douglas Woolf

Edwin Seaver

Victor Weybright

James Laughlin

Theodore Wilentz Coburn Britton

Walter Lowenfels

James Broughton Muriel Rukeyser

Thomas Merton

Thomas McGrath

Joel Oppenheimer

Gus Blaisdell

Philip O'Connor

Gilbert Neiman

Jack Kerouac

Stanley Burnshaw

Christopher Middleton

Ronald Bayes

Philip Whalen

Anselm Hollo

Anthony Kerrigan

Frederick Eckmann

Keith Wilson

LarryEigner

Edward Dahlberg

R. B. Kitaj

AND OTHERS

EDITOR

MANAGING EDITOR

Charles Newman

Suzanne Kurman

ART DIRECTOR Lawrence Levy

SENIOR EDITOR Laurence Gonzales

BUSINESS MANAGER

ASSOCIATES

Dianne Wall

Mary Kinzie

Debbie Petranek

Christine Robinson

Mary Elinore Smith

Roberta Stein

TriQuarterly is a national journal of arts, letters and opinion published in the fall, winter and spring at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60201. Subscription rates: Individuals, $5.00 yearly within the United States; $5.25 Canada and Mexico; $5.75 Foreign. Libraries, $6.00, $6.25, $6.75. Single copies will usually be sold for $1.95. Contributions, correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TrlQuarterly, University Hall 101, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60201. But please, due to a massive backlog of manuscript, do not submit any material for publication until the fall of 1971 when we will, hopefully, have the space, time and money to give it careful consideration. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of the editors, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1971 by Northwestern University Press. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Claims for missing numbers will be honored only within the four-month period after date of issue.

NATIONAL DISTRIBUTOR TO RETAIL TRADE: B. DEBOER, 188 HIGH STREET, NUTLEY, NEW JERSEY 07110. DISTRIBUTOR FOR GREAT BRITAIN AND EUROPE: B. F. STEVENS & BROWN, LTD., ARDON HOUSE, MILL LANE, GODALMING, SURREY, ENGLAND.

Essays

J. M. G. LeCLEZIO

MAURICE MERLEAU-PONTY

EDWARDW. SAID

GEORGE STEINER

MICHEL BUTOR

TONY TANNER

MORSE PECKHAM

ANNE MANGEL

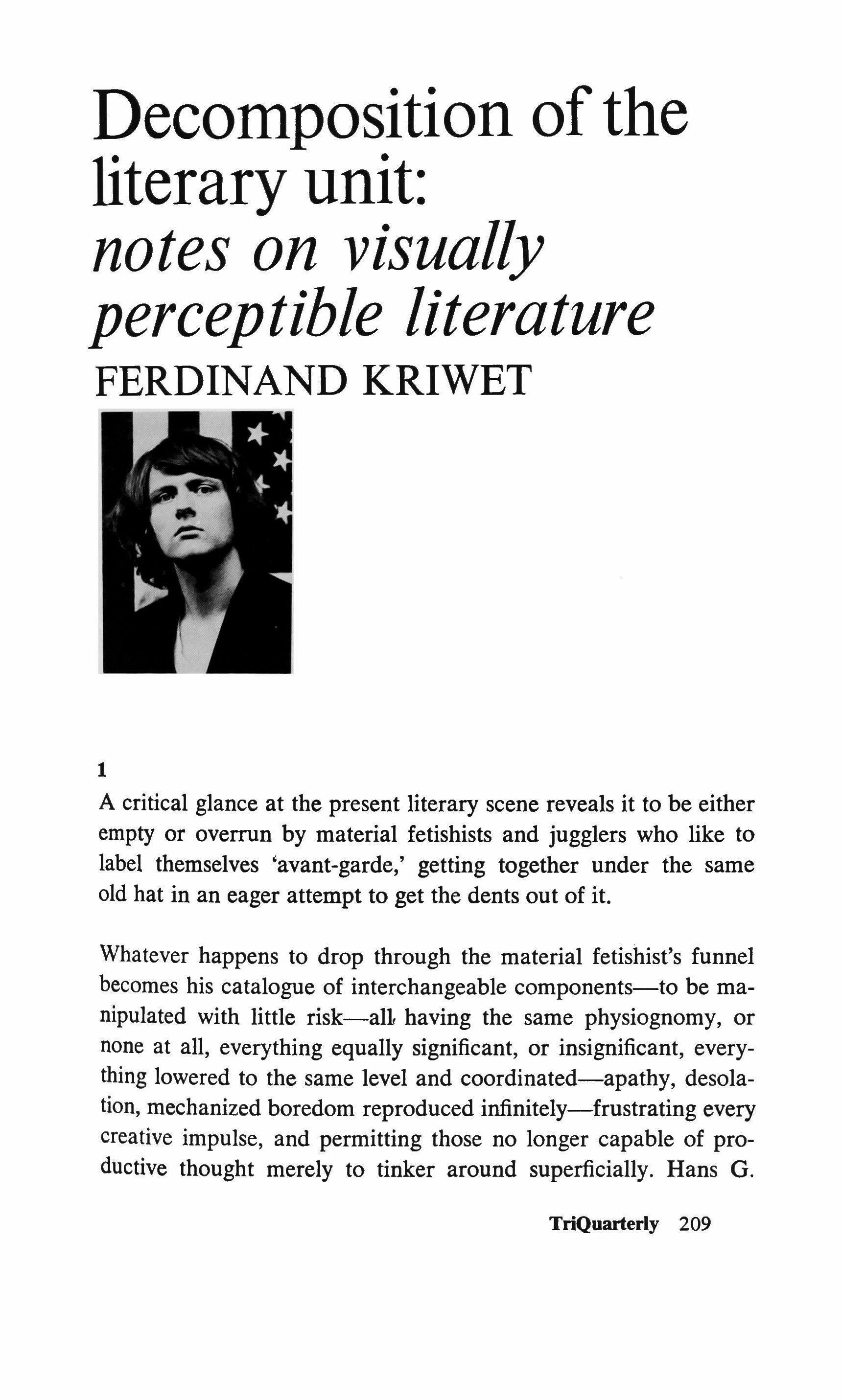

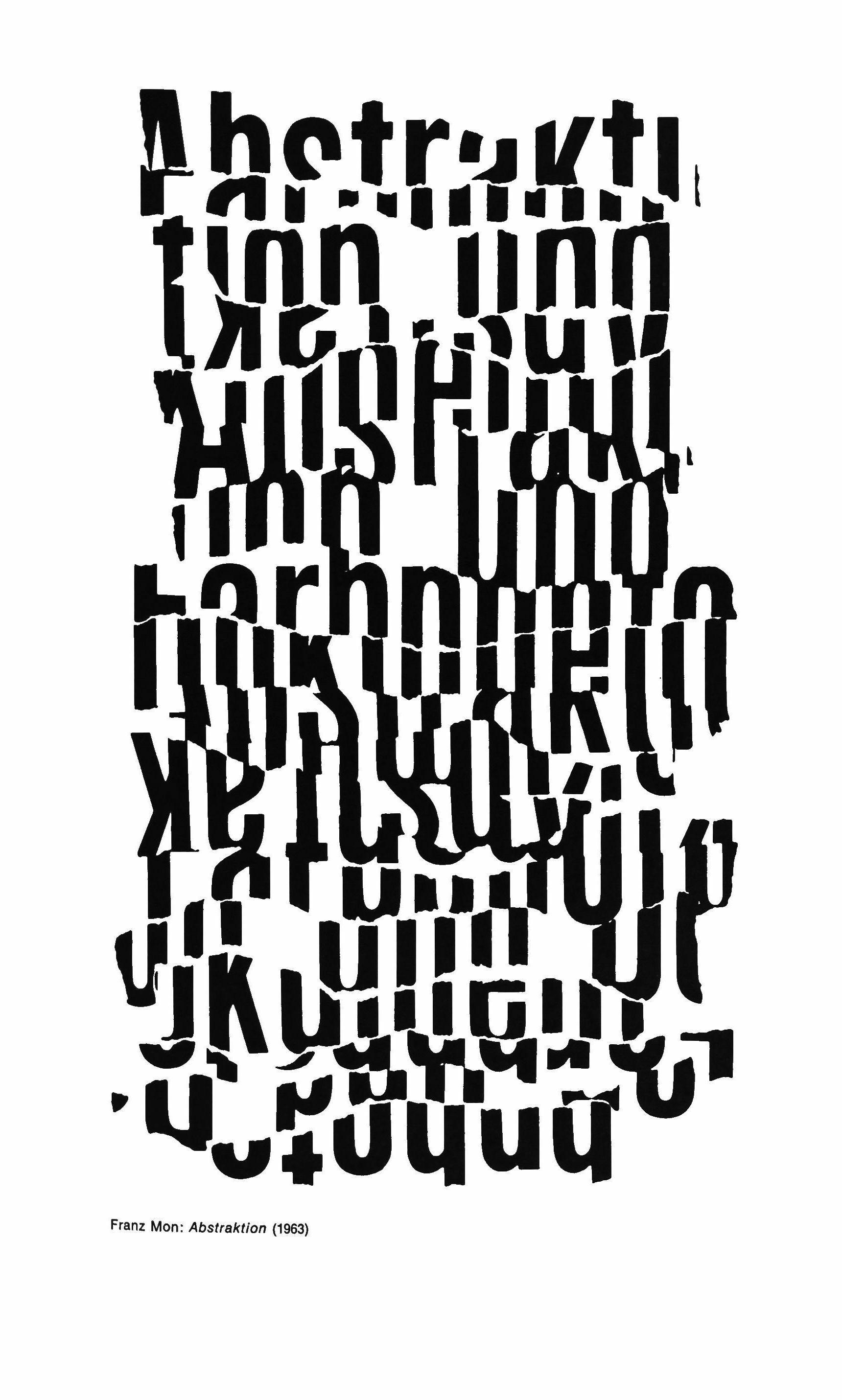

FERDINAND KRIWET

ALBERT J. GUERARD

E. M. CIORAN

CHARLES NEWMAN

The great city of literature translated by Richard Howard 5

The prose of the world translated and with an afterword by John O'Neill 9

Abecedarium culturae: structuralism, absence, writing 33

Linguistics & poetics 73

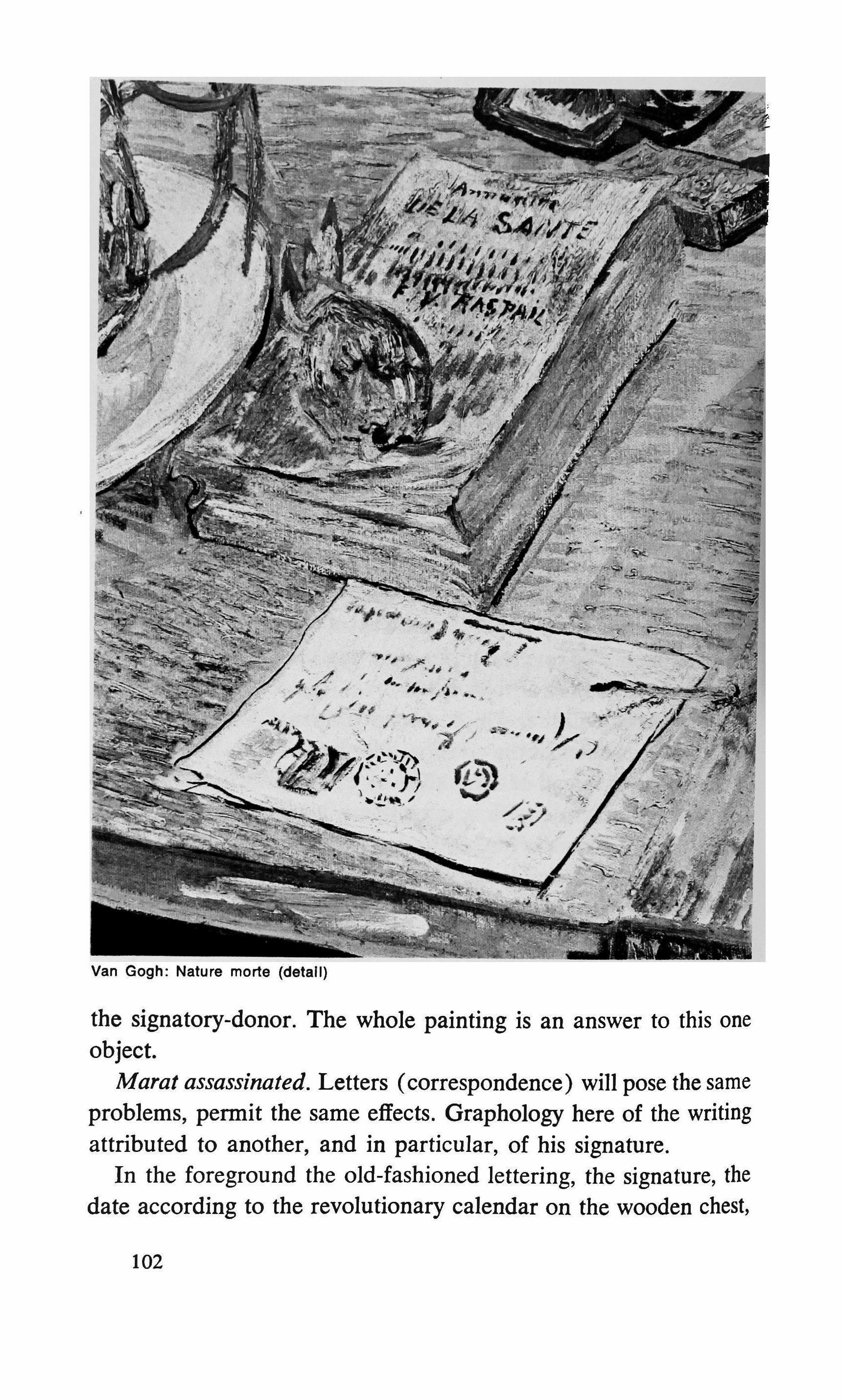

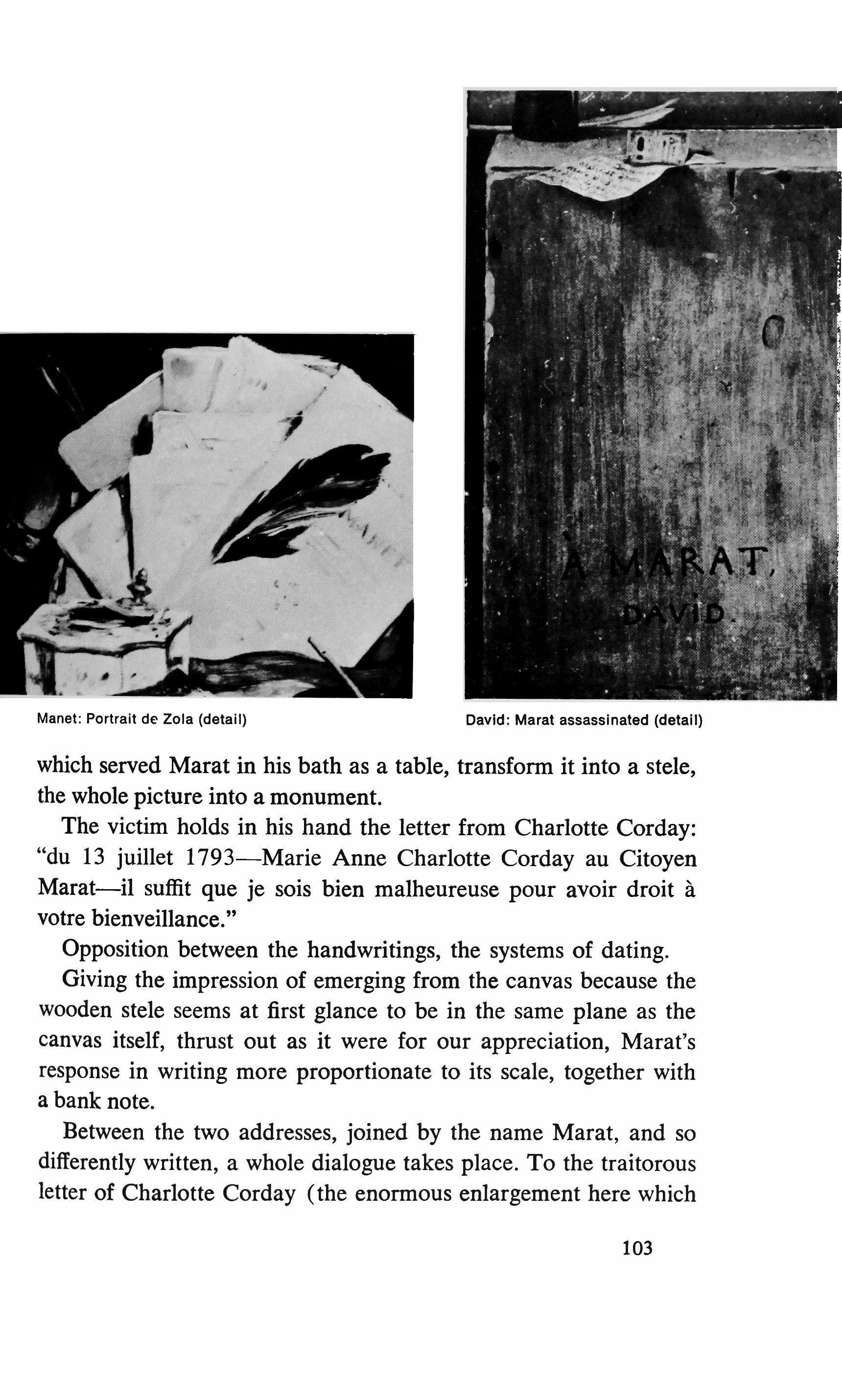

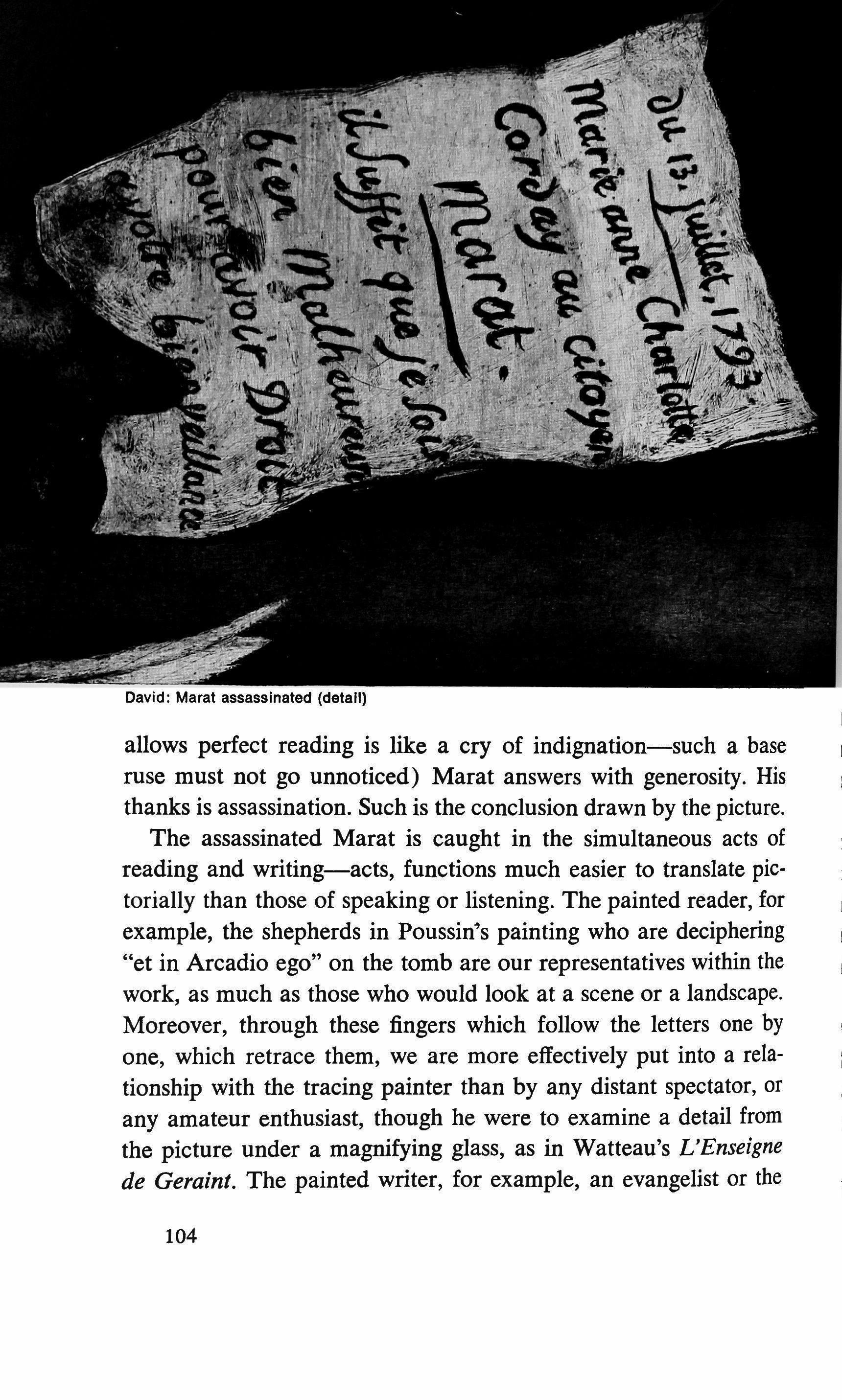

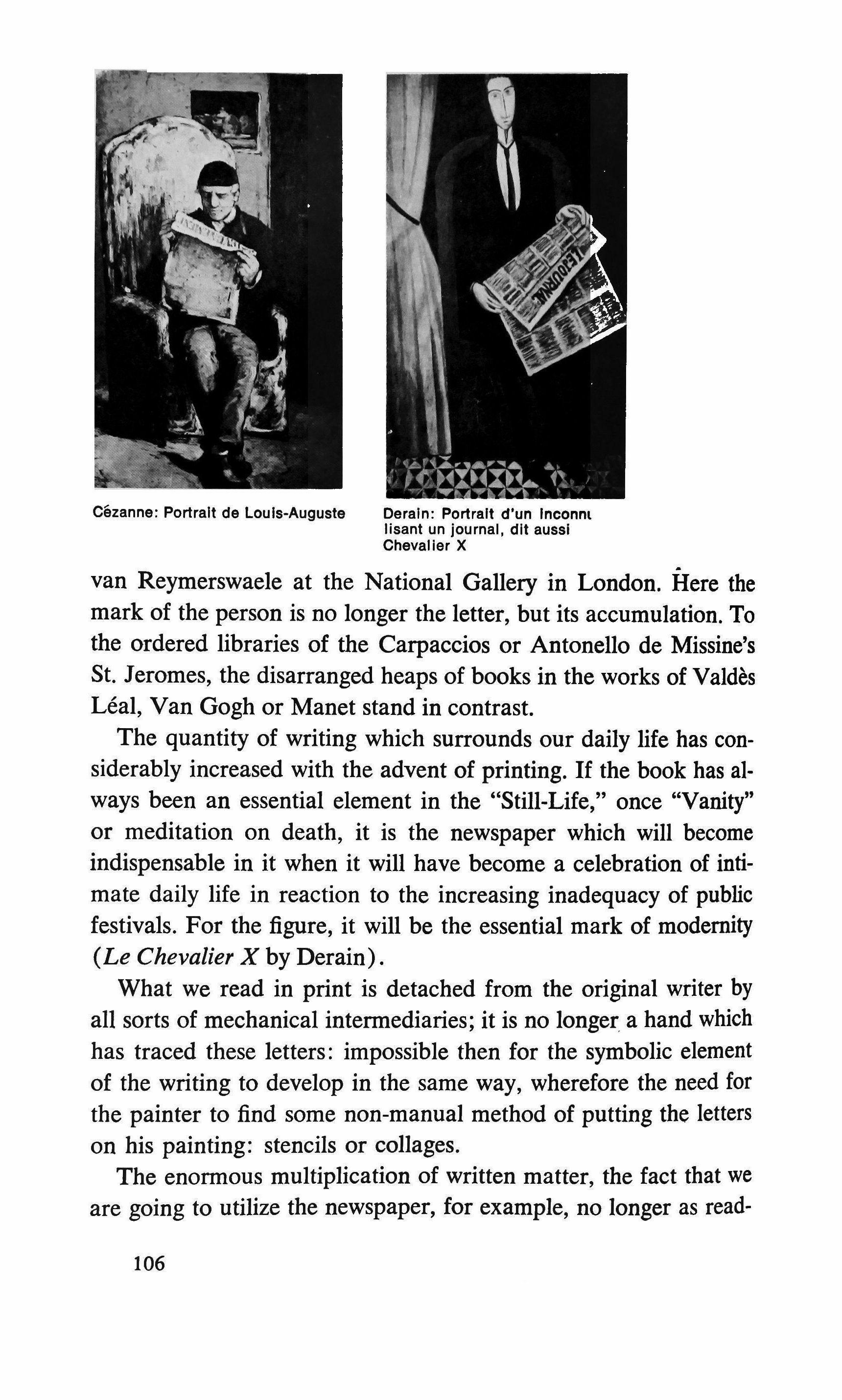

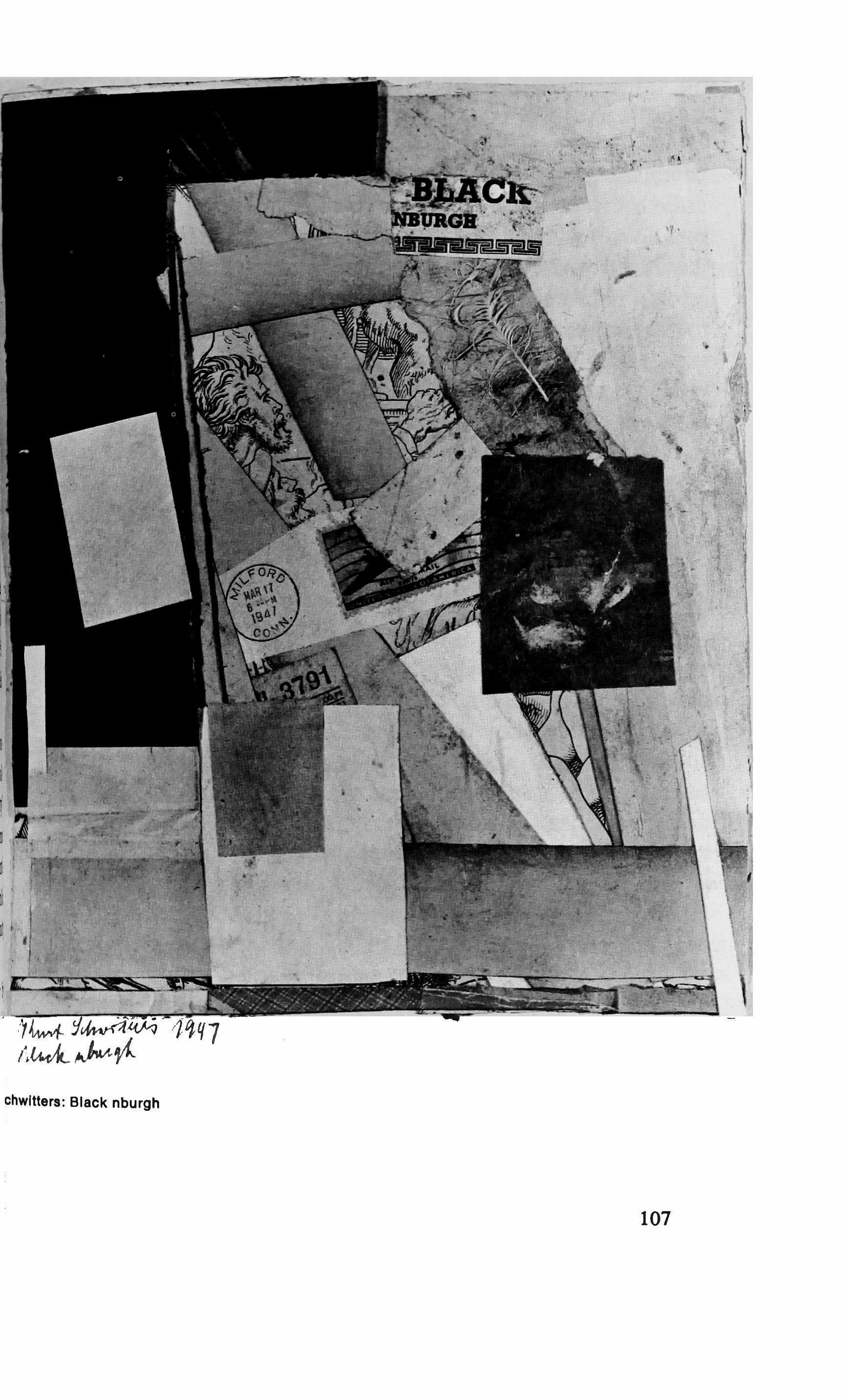

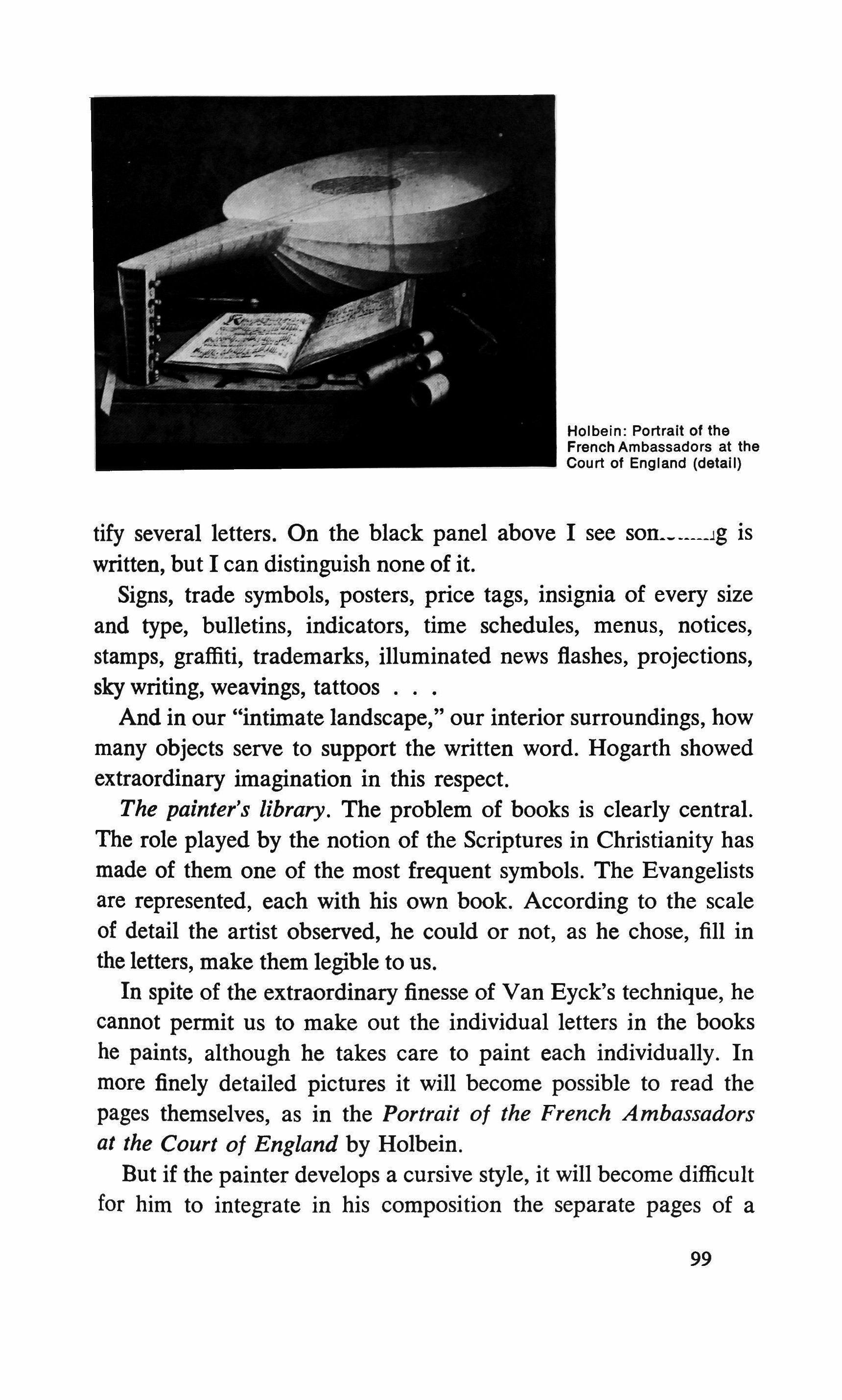

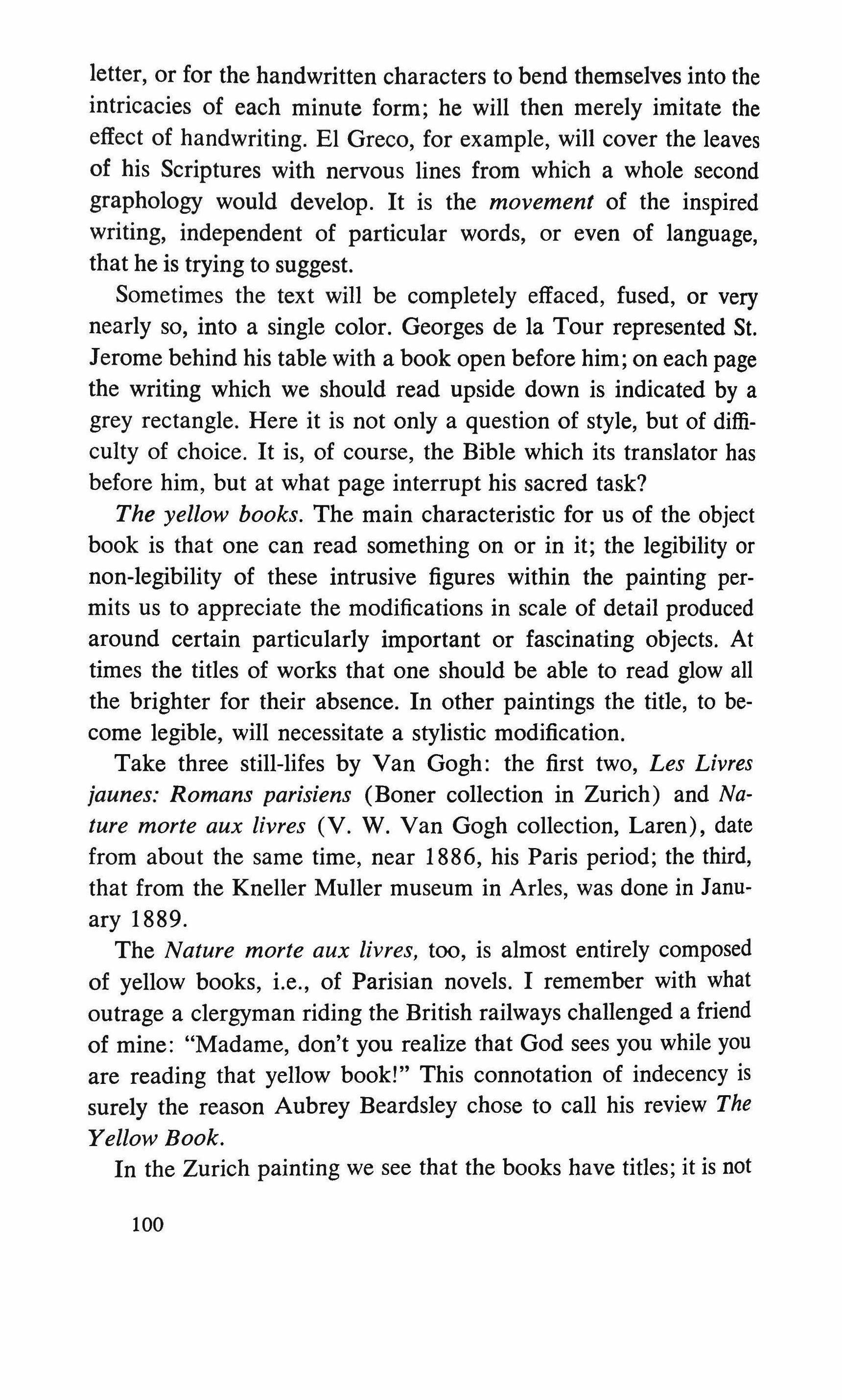

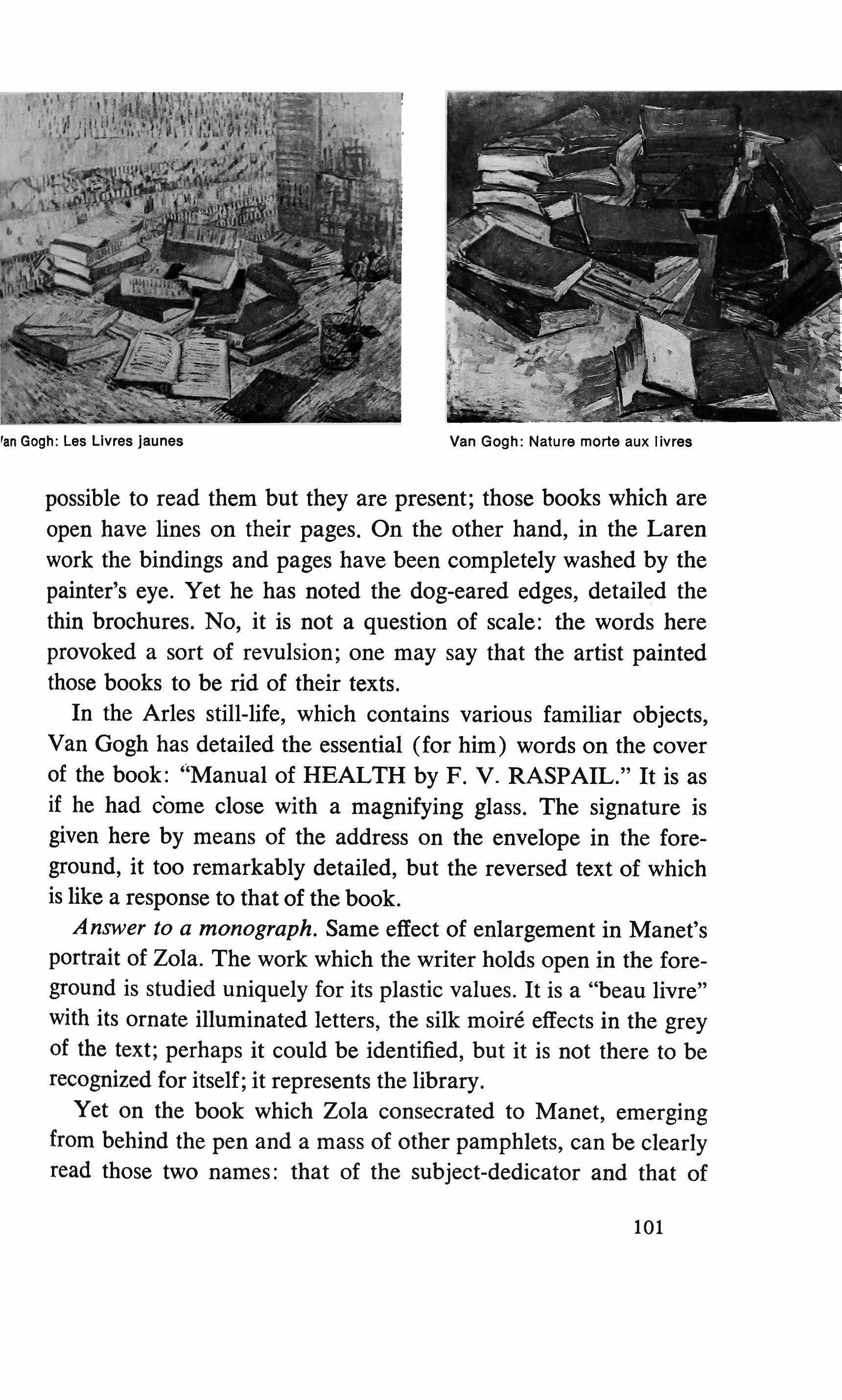

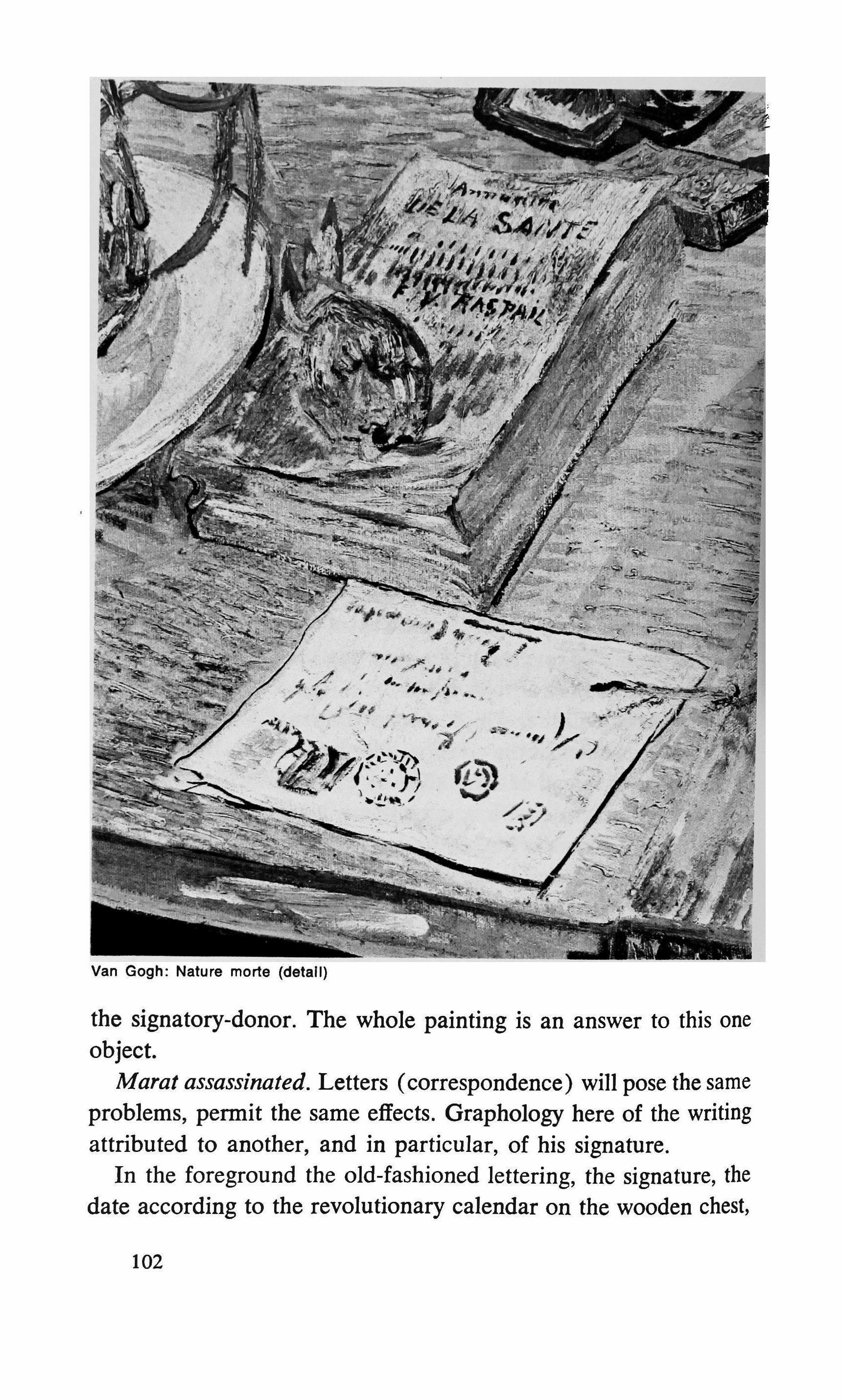

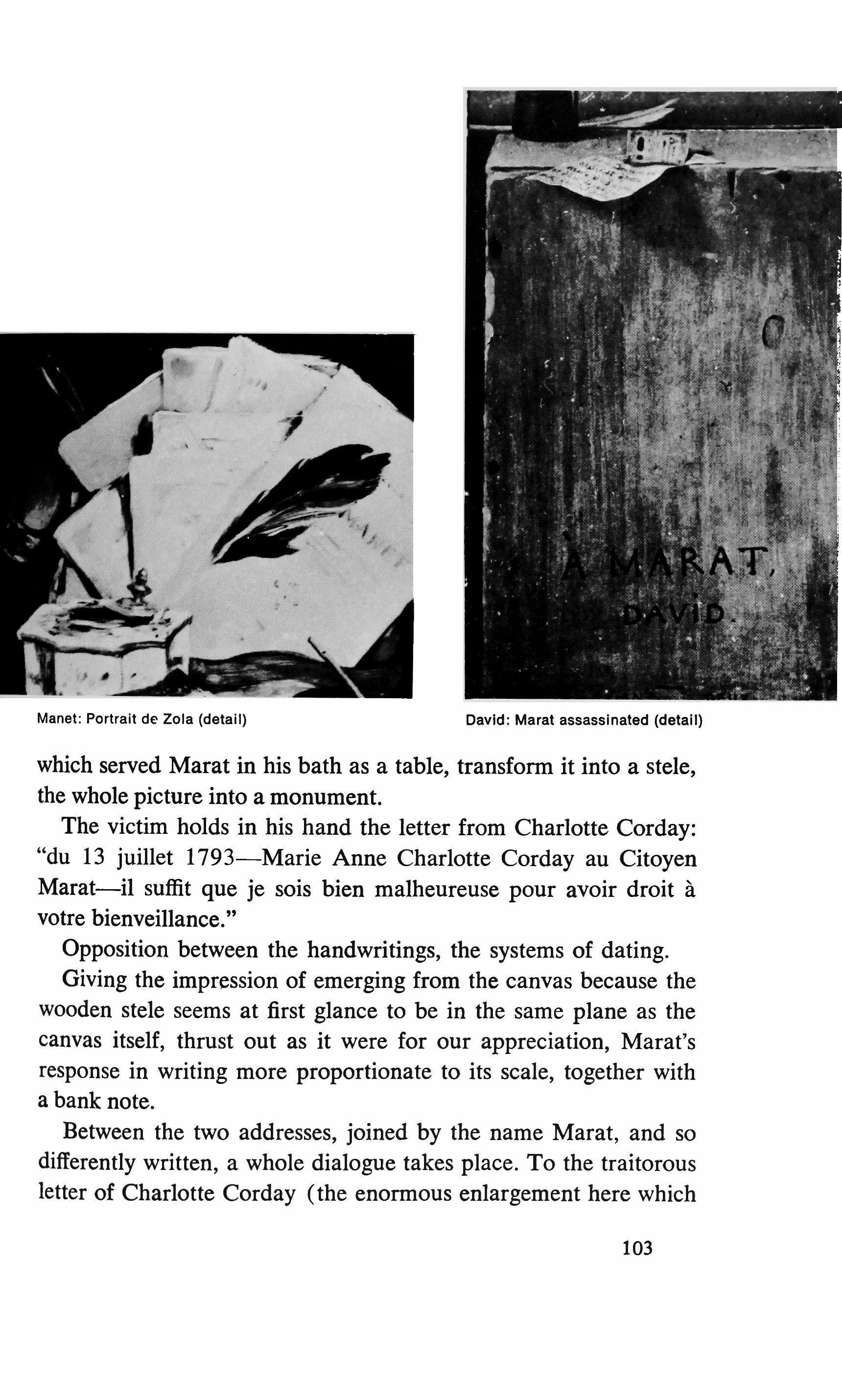

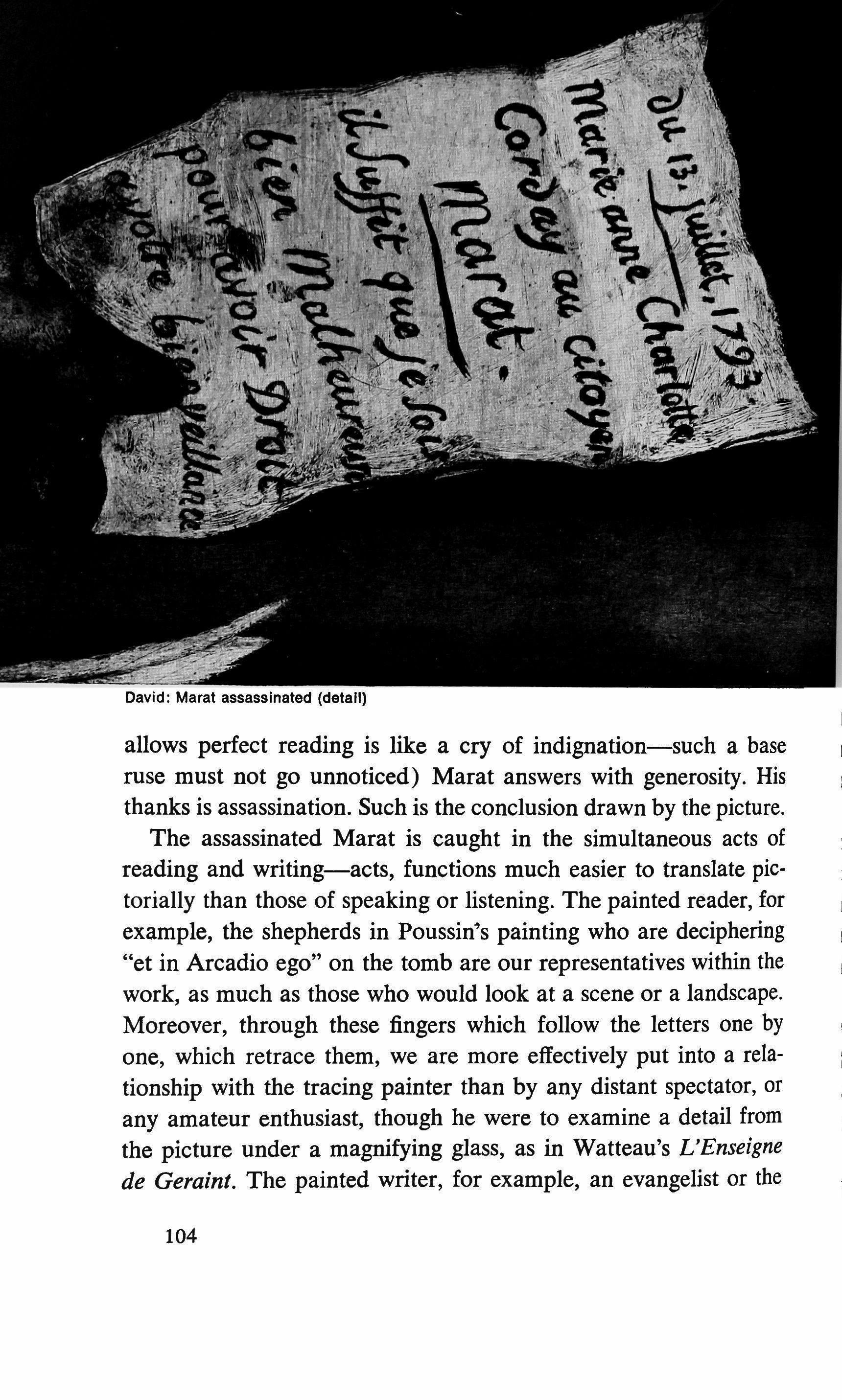

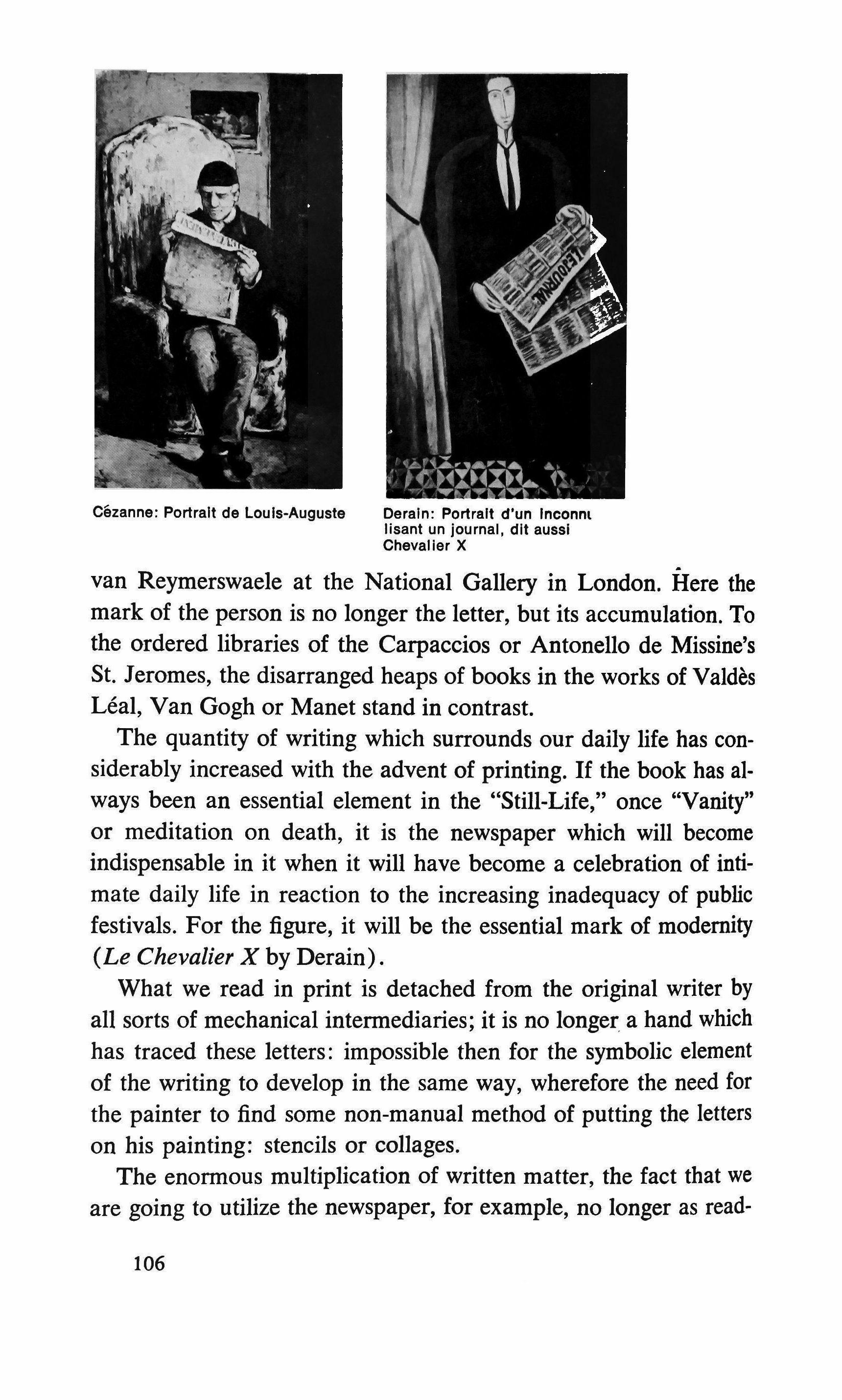

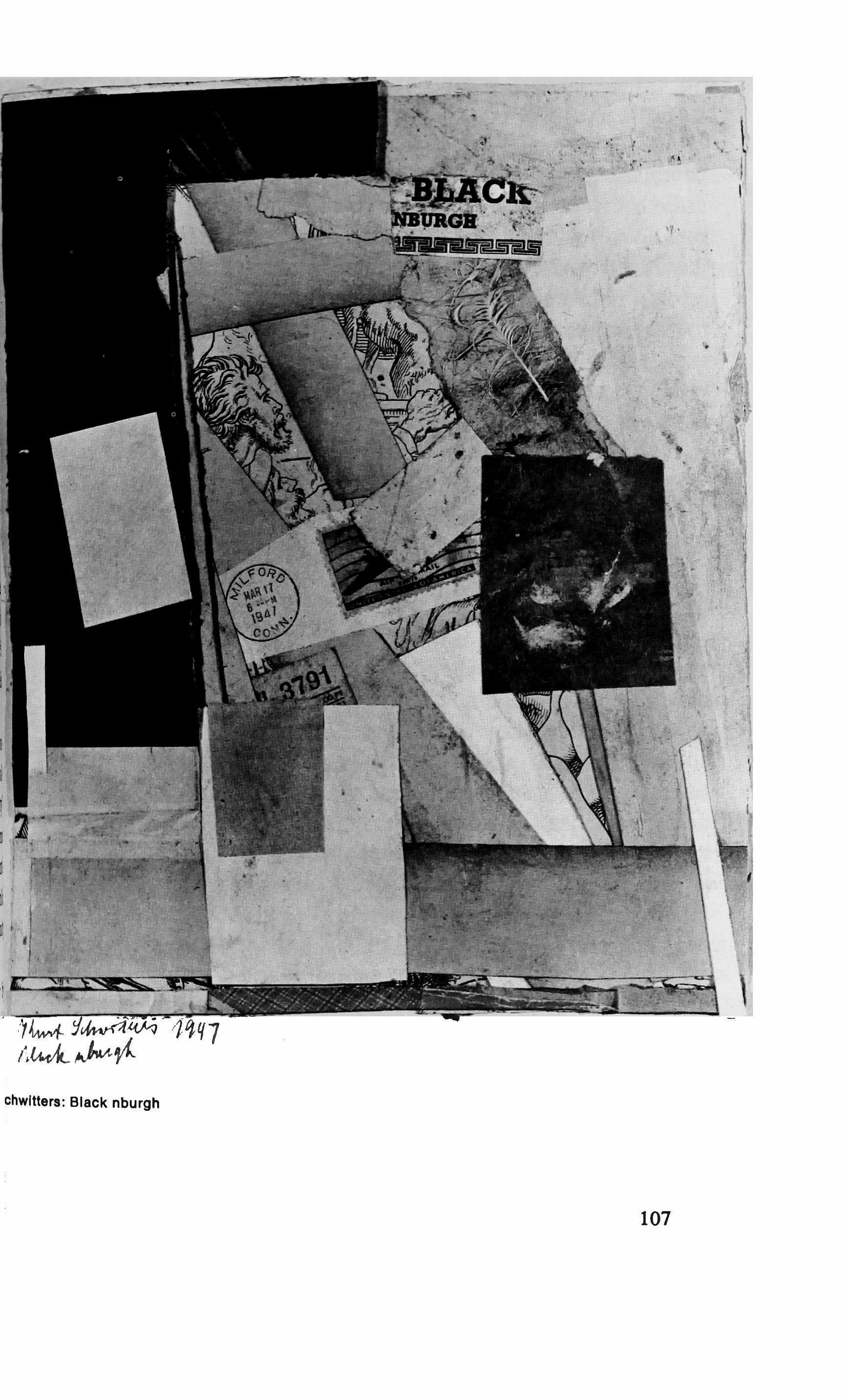

Painting words translated by Joy N. Humes 98

Necessary landscapes and luminous deteriorations: on Hawkes 145

The virtues of superficialty 180

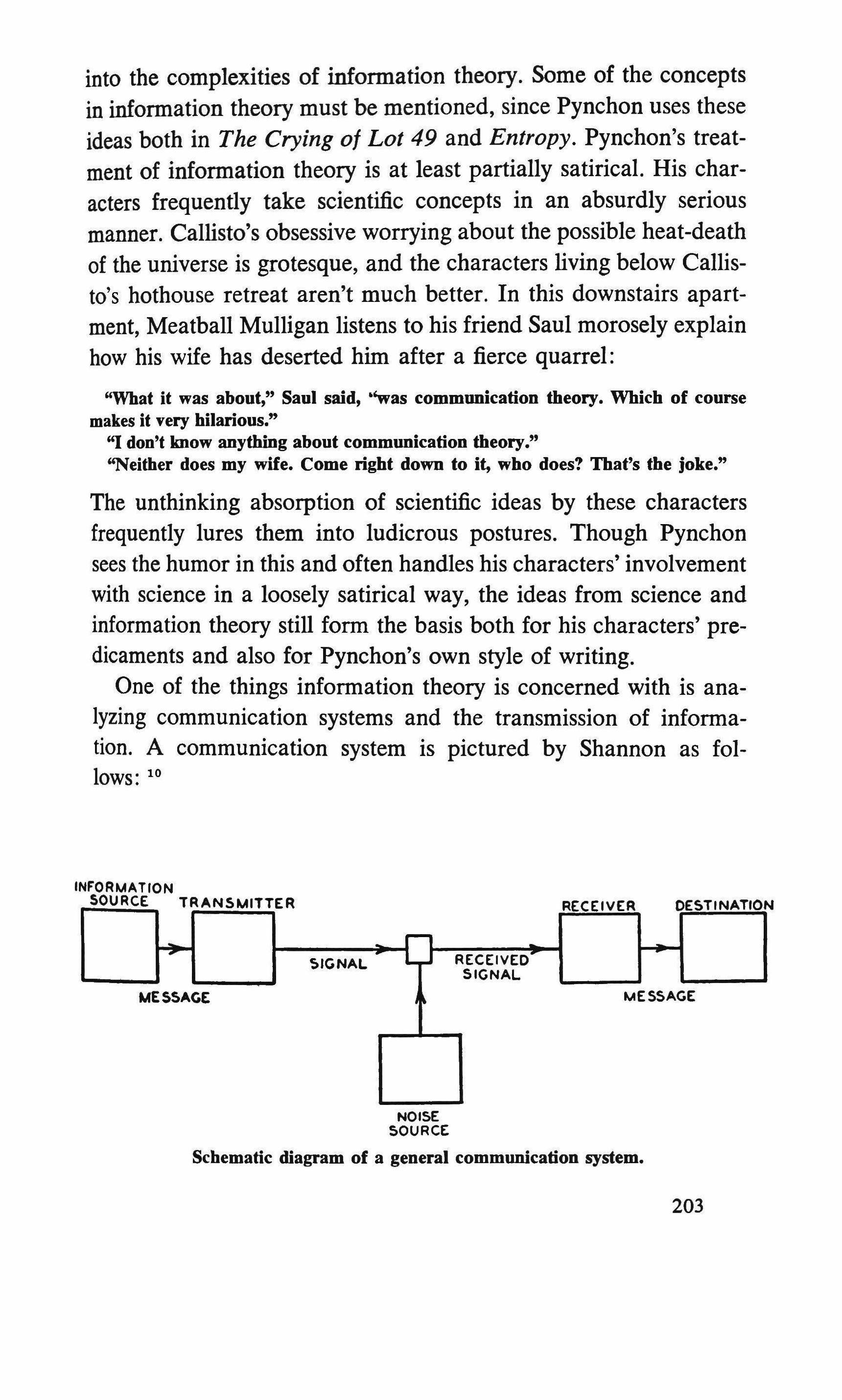

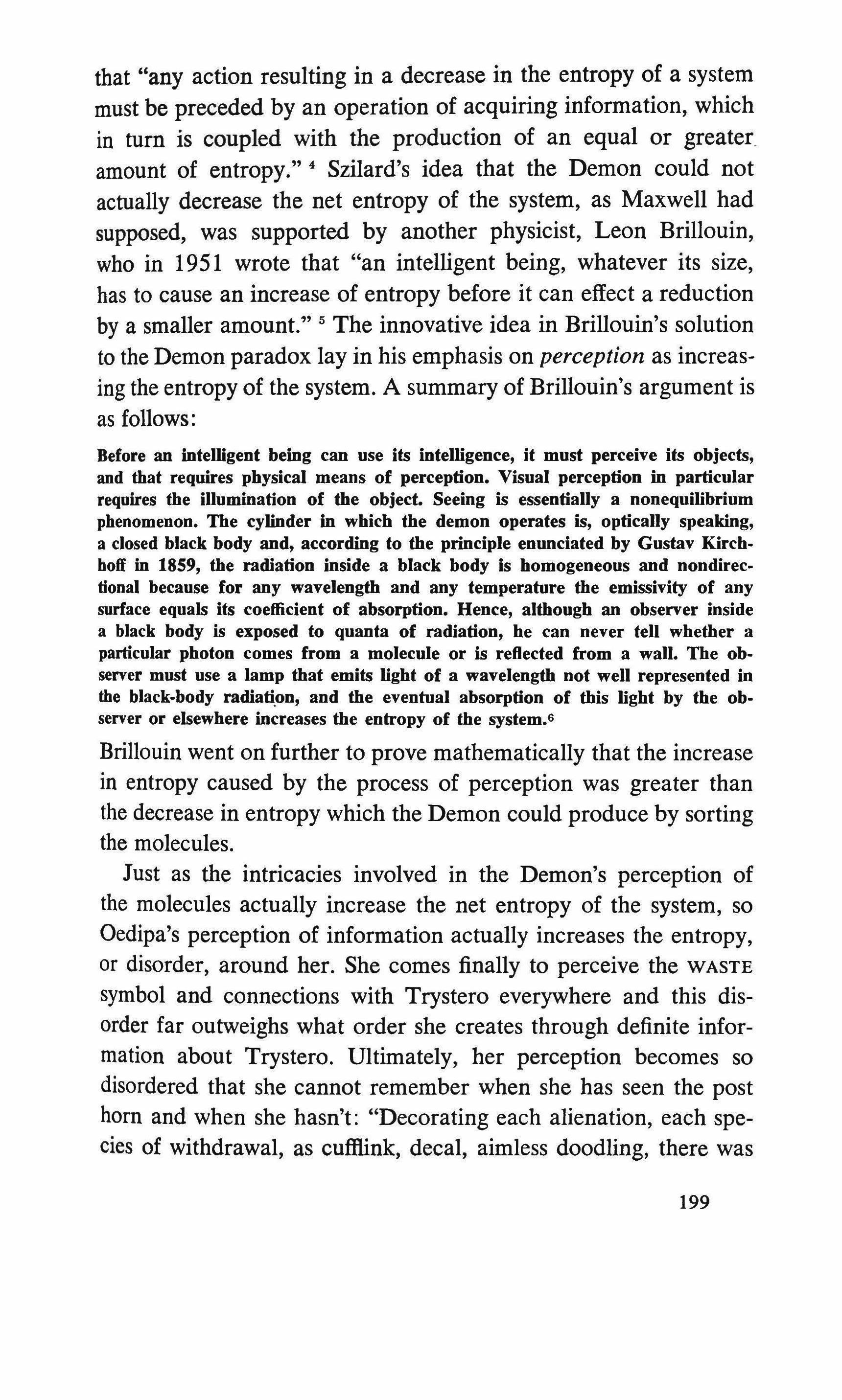

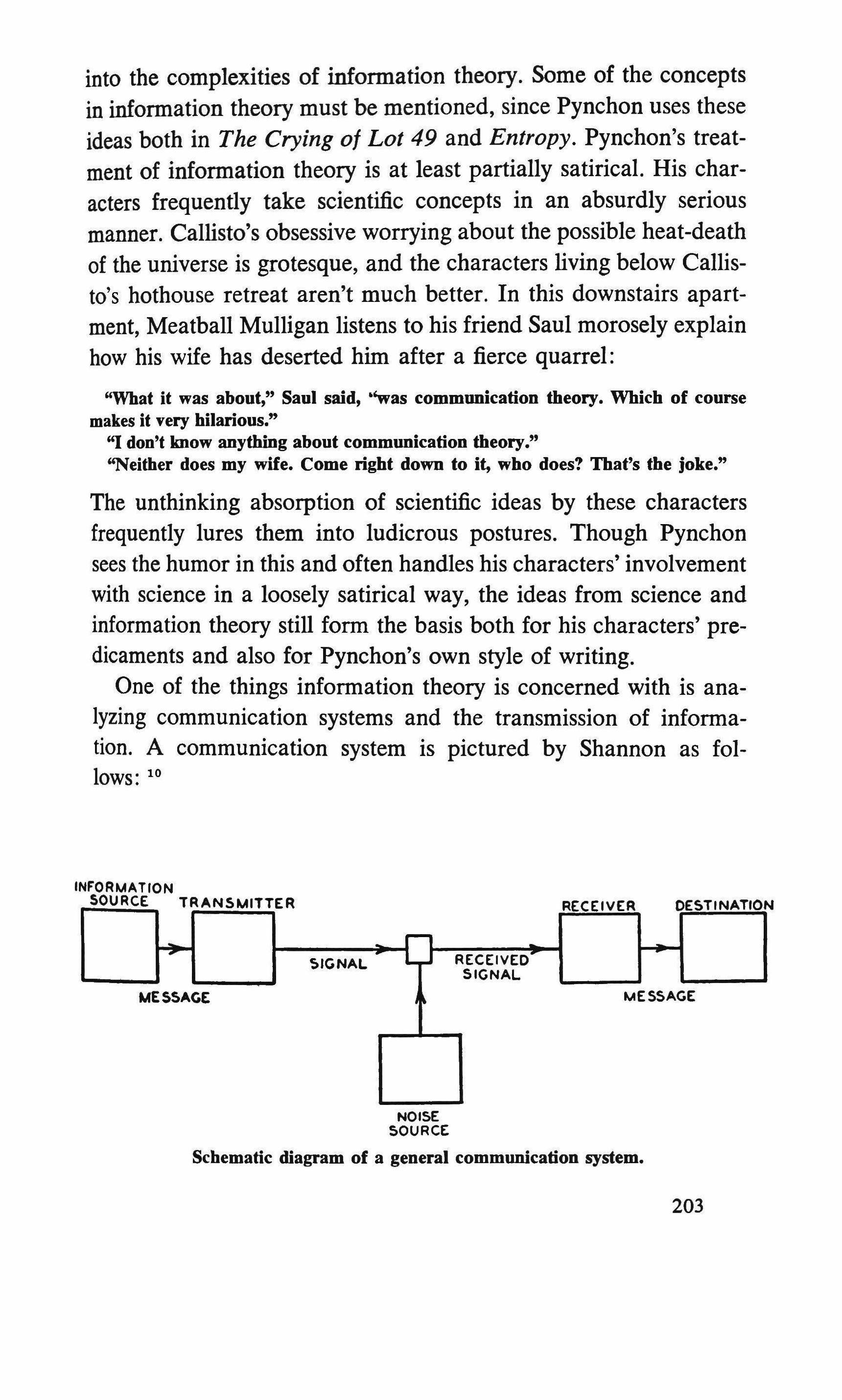

Maxwell's demon, entropy, information: the crying of lot 49 194

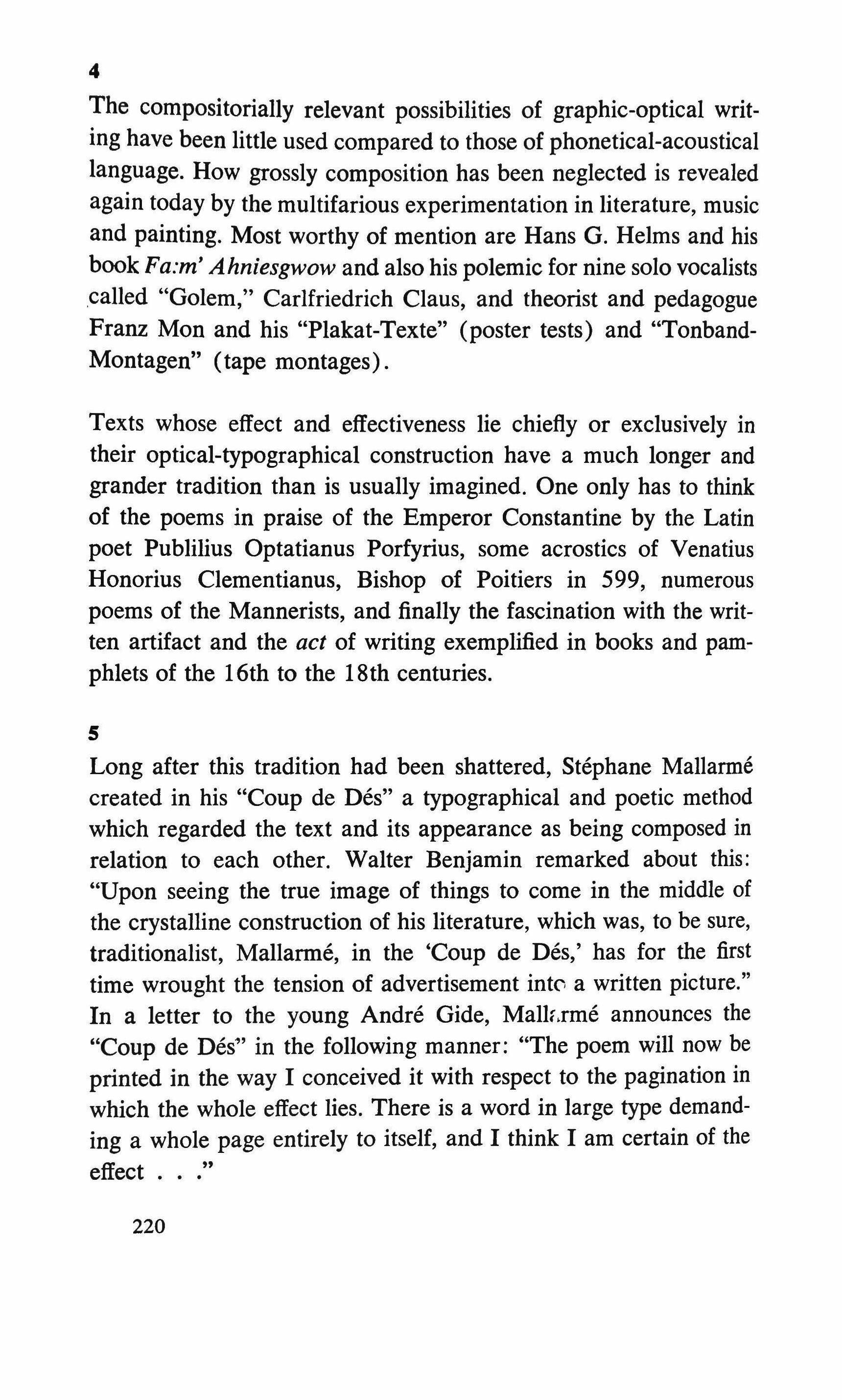

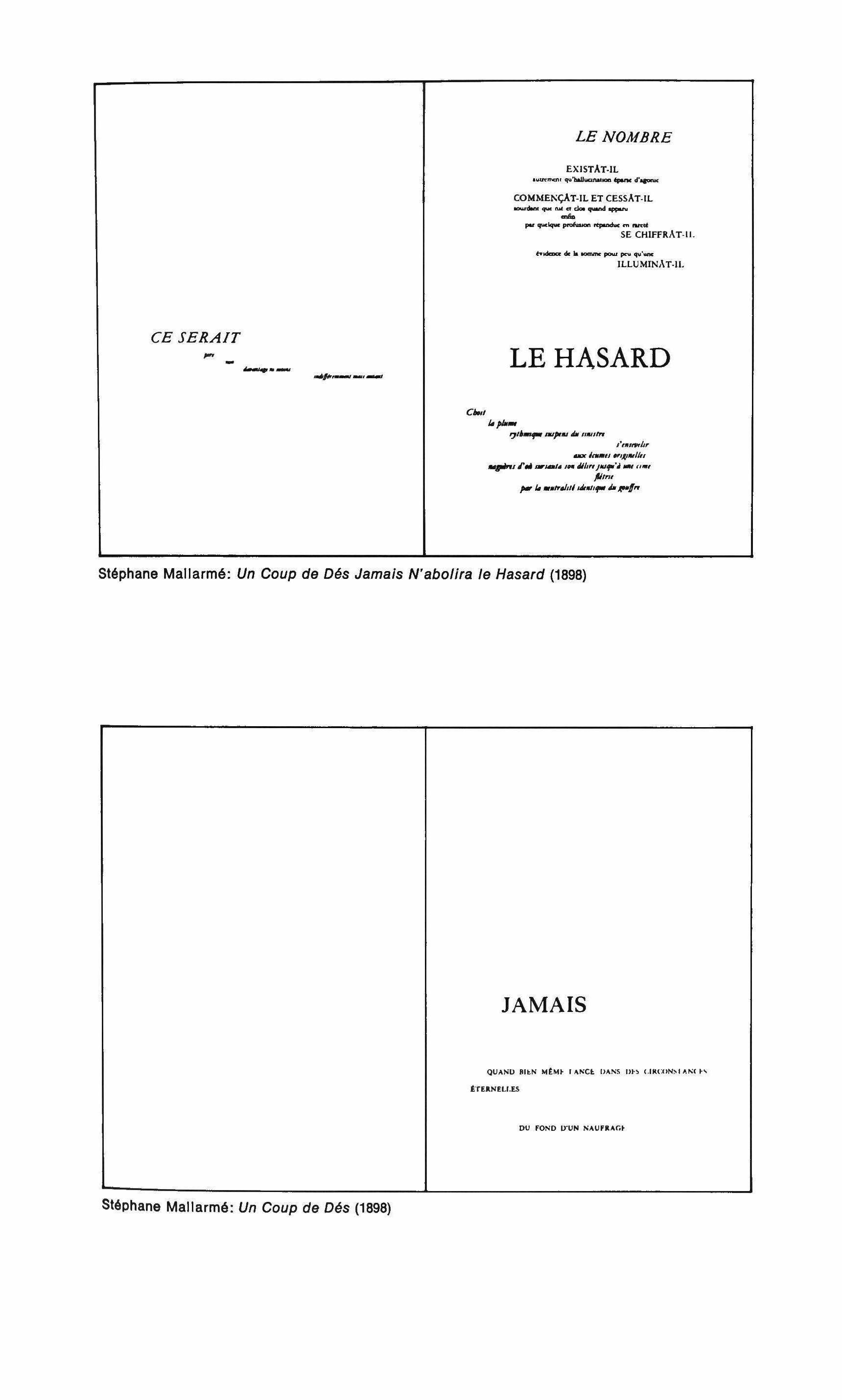

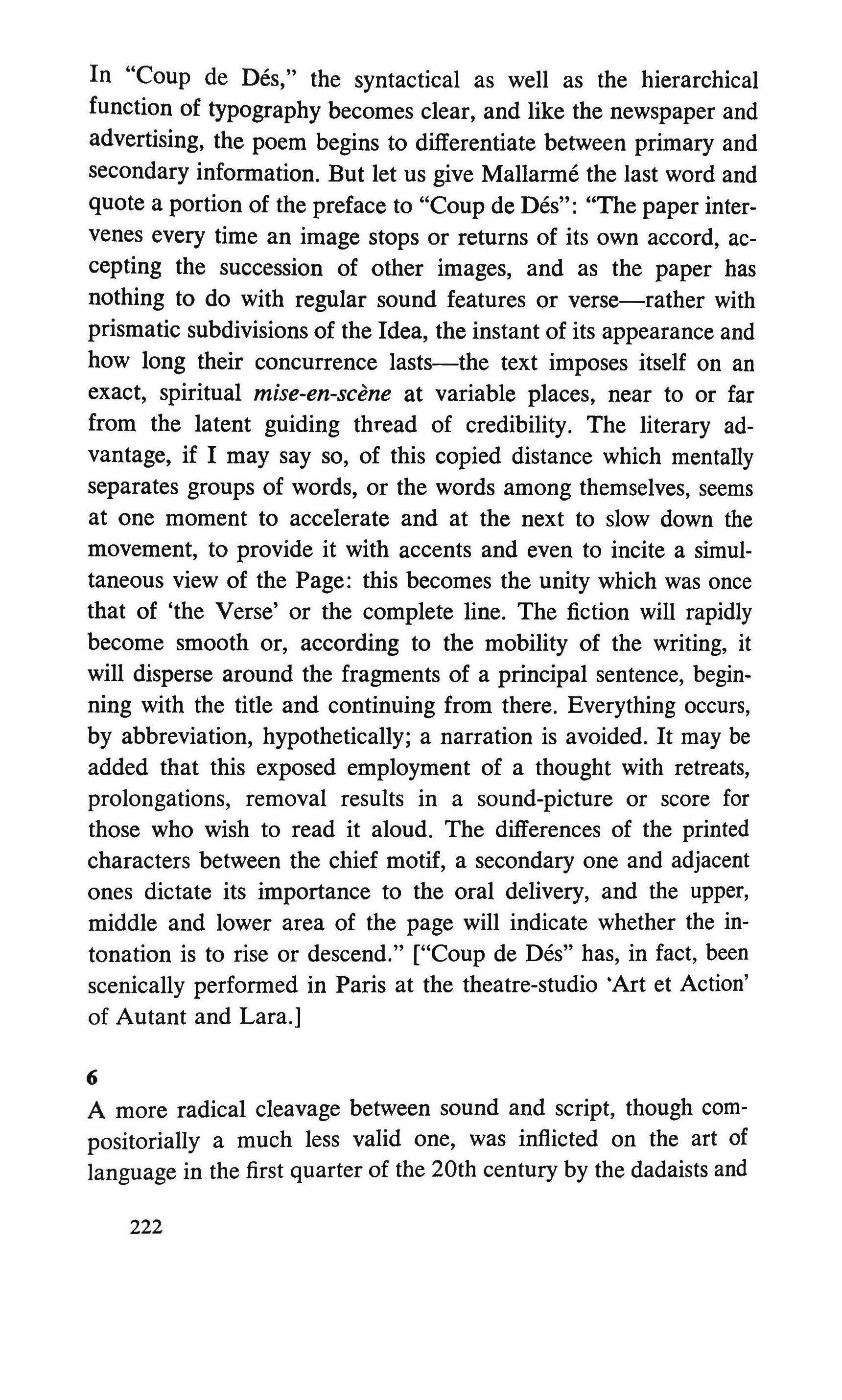

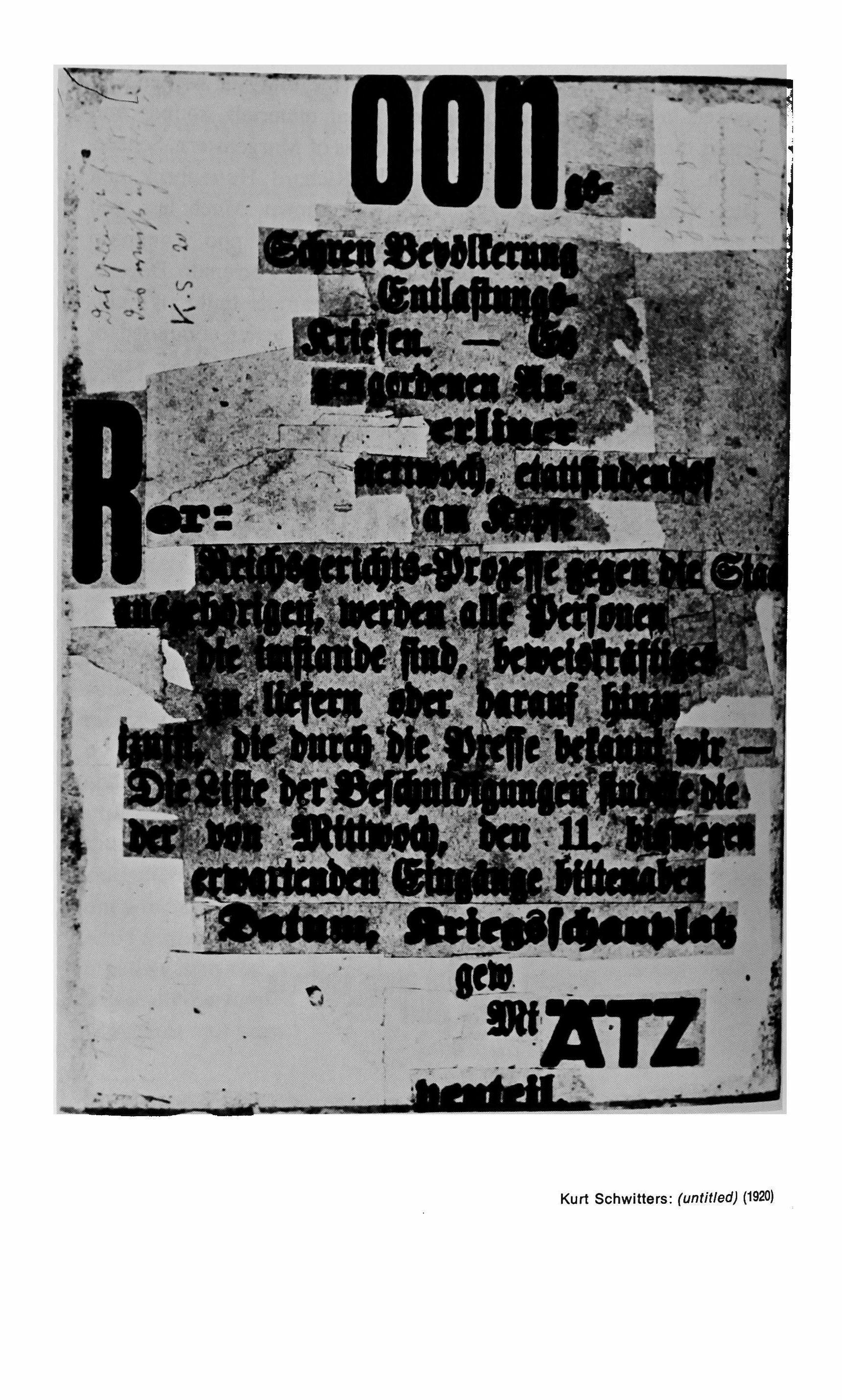

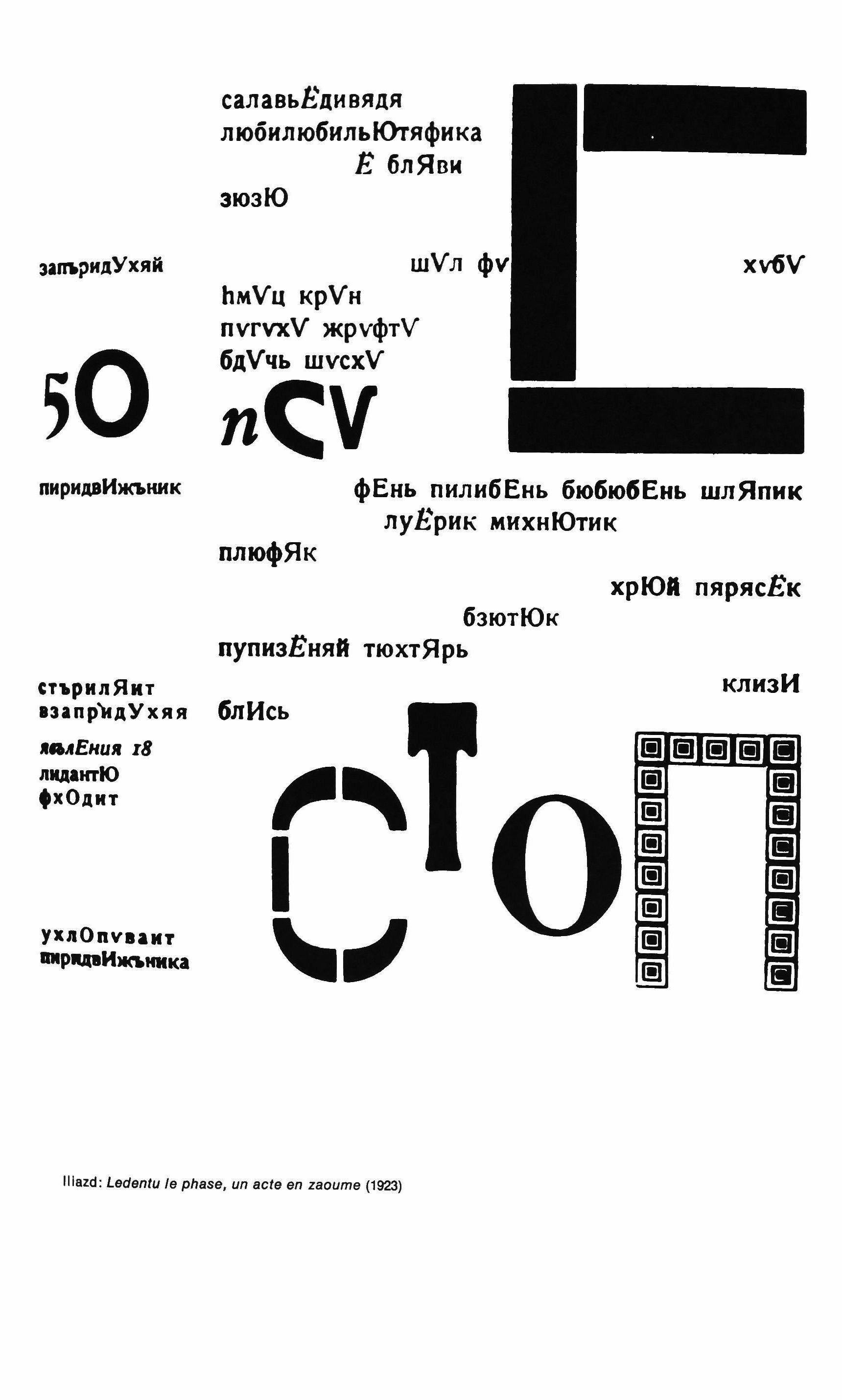

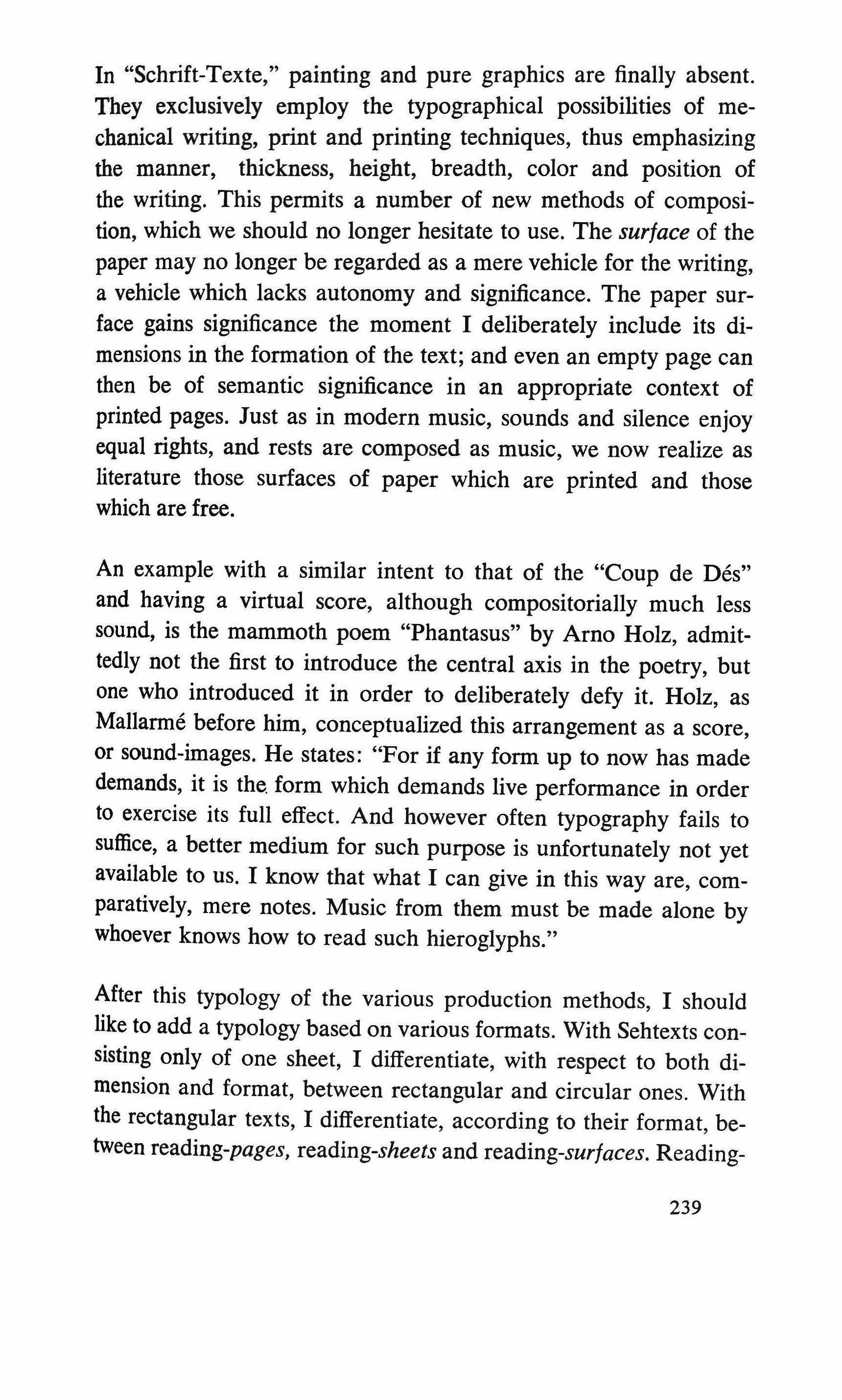

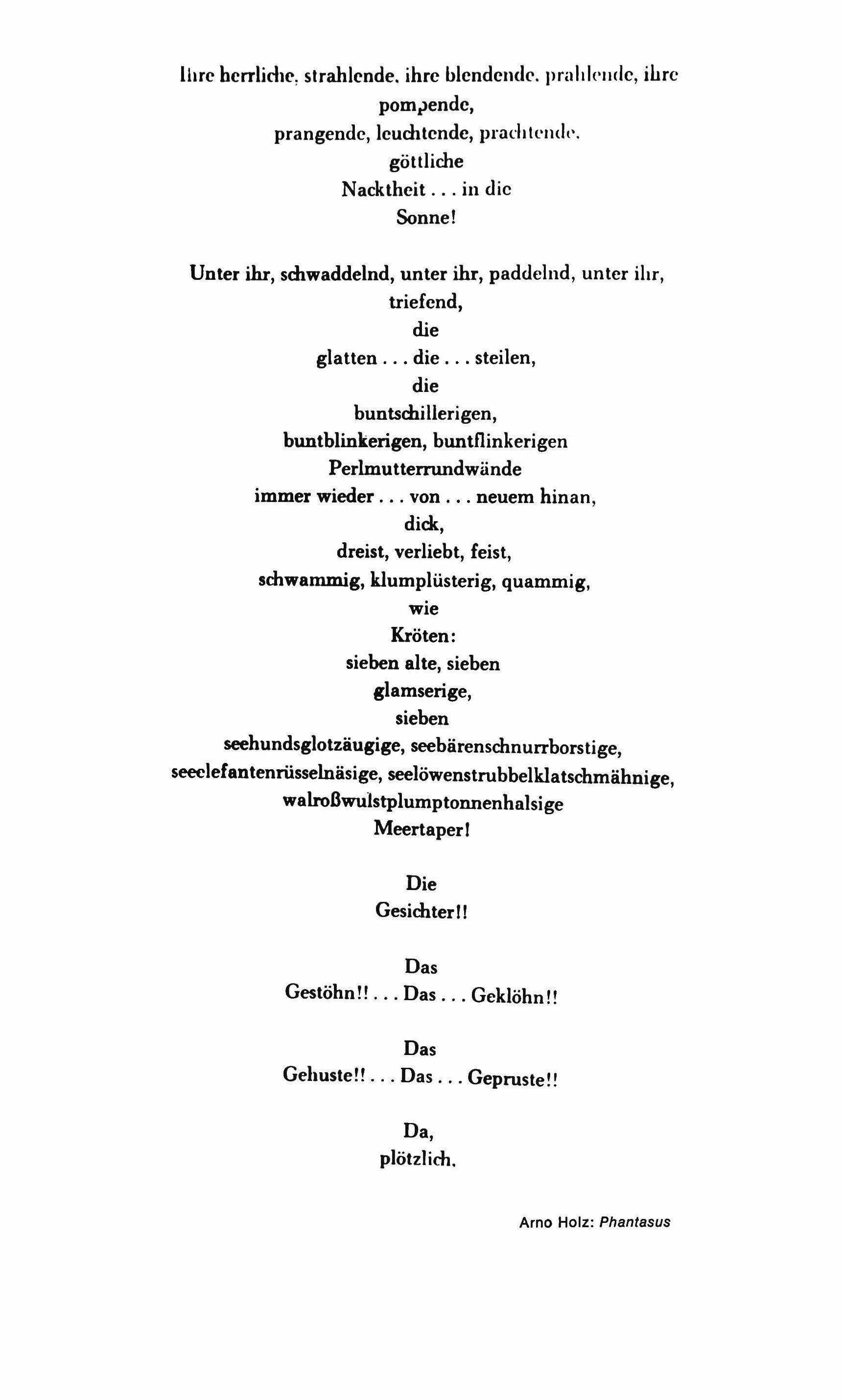

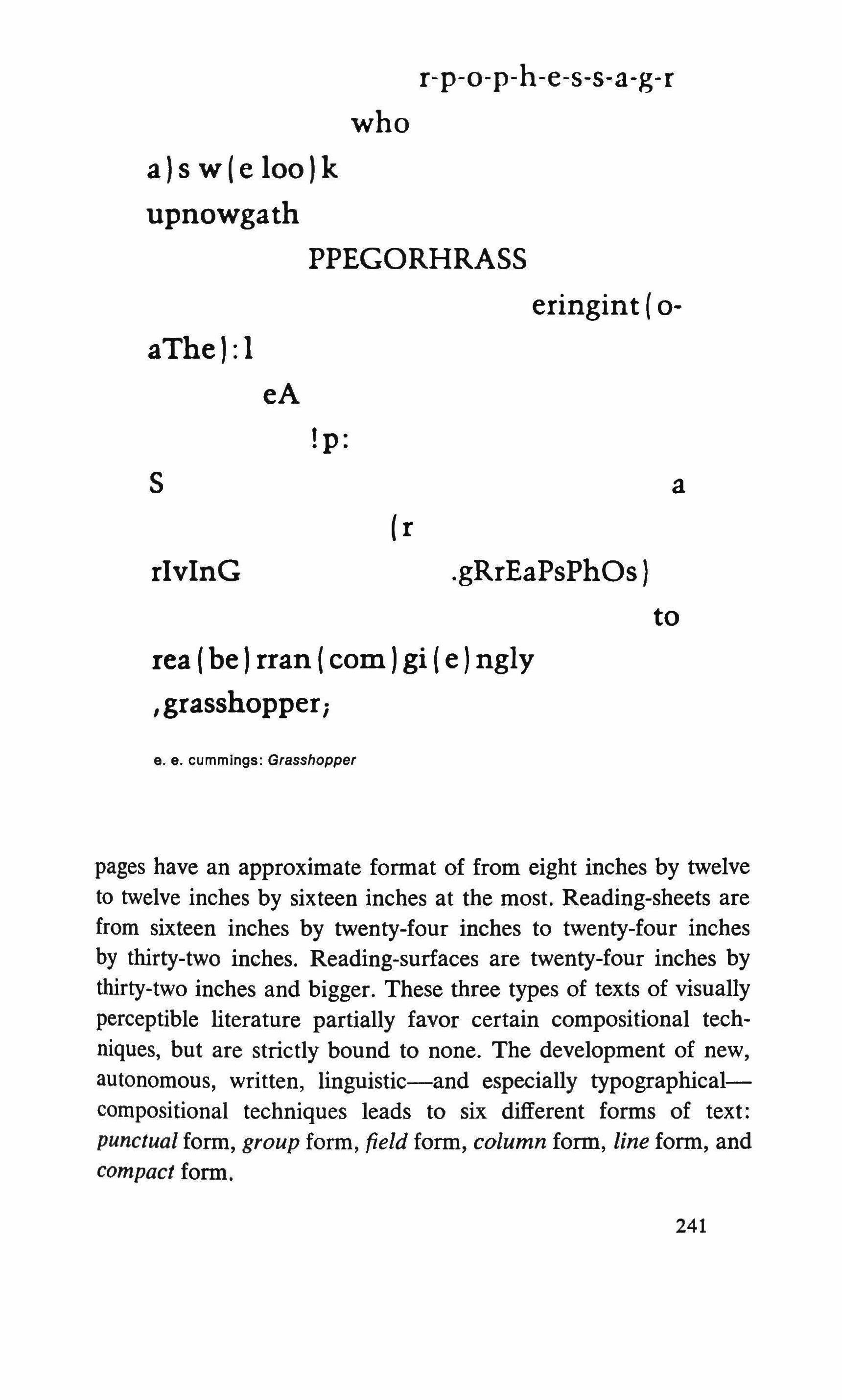

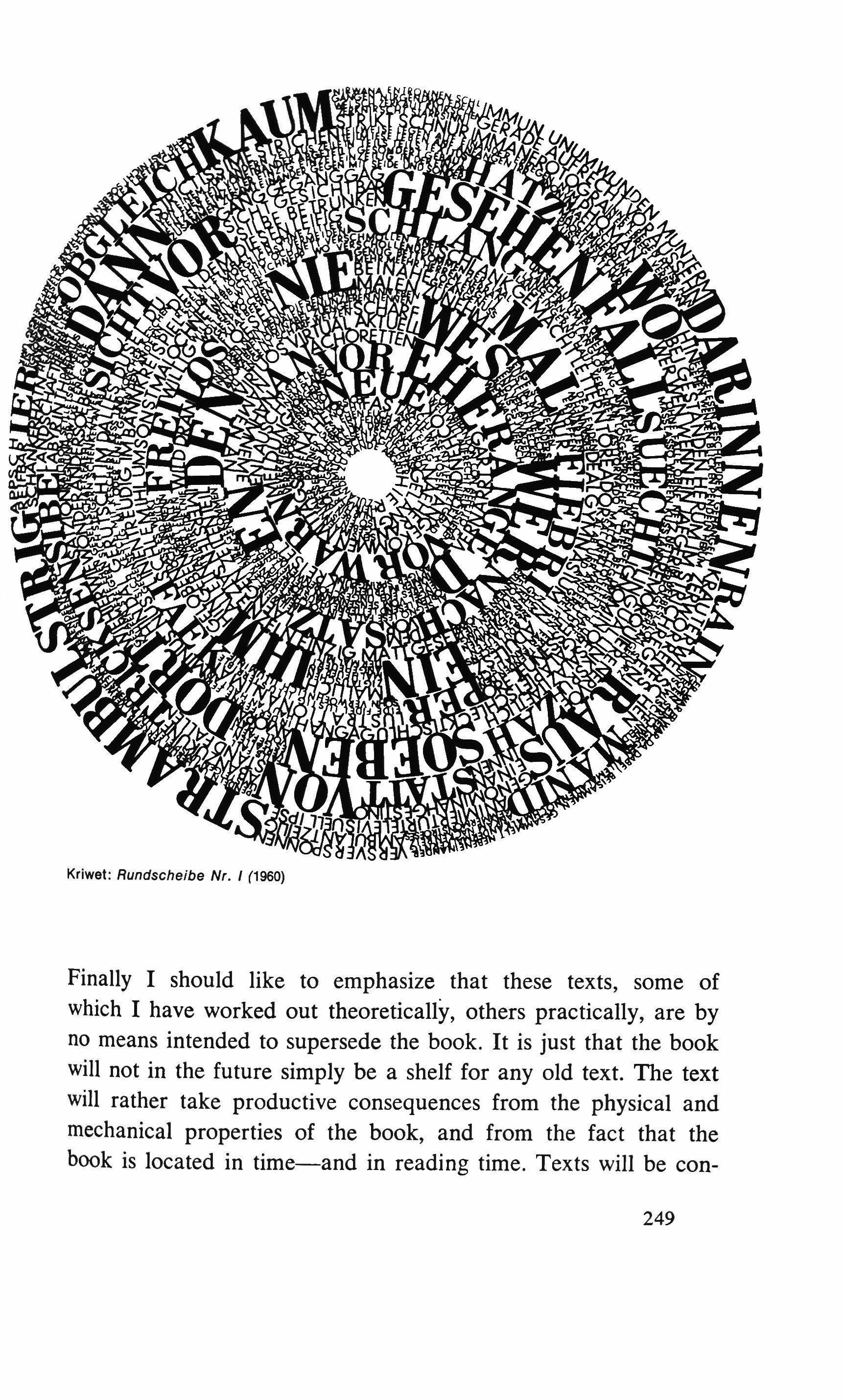

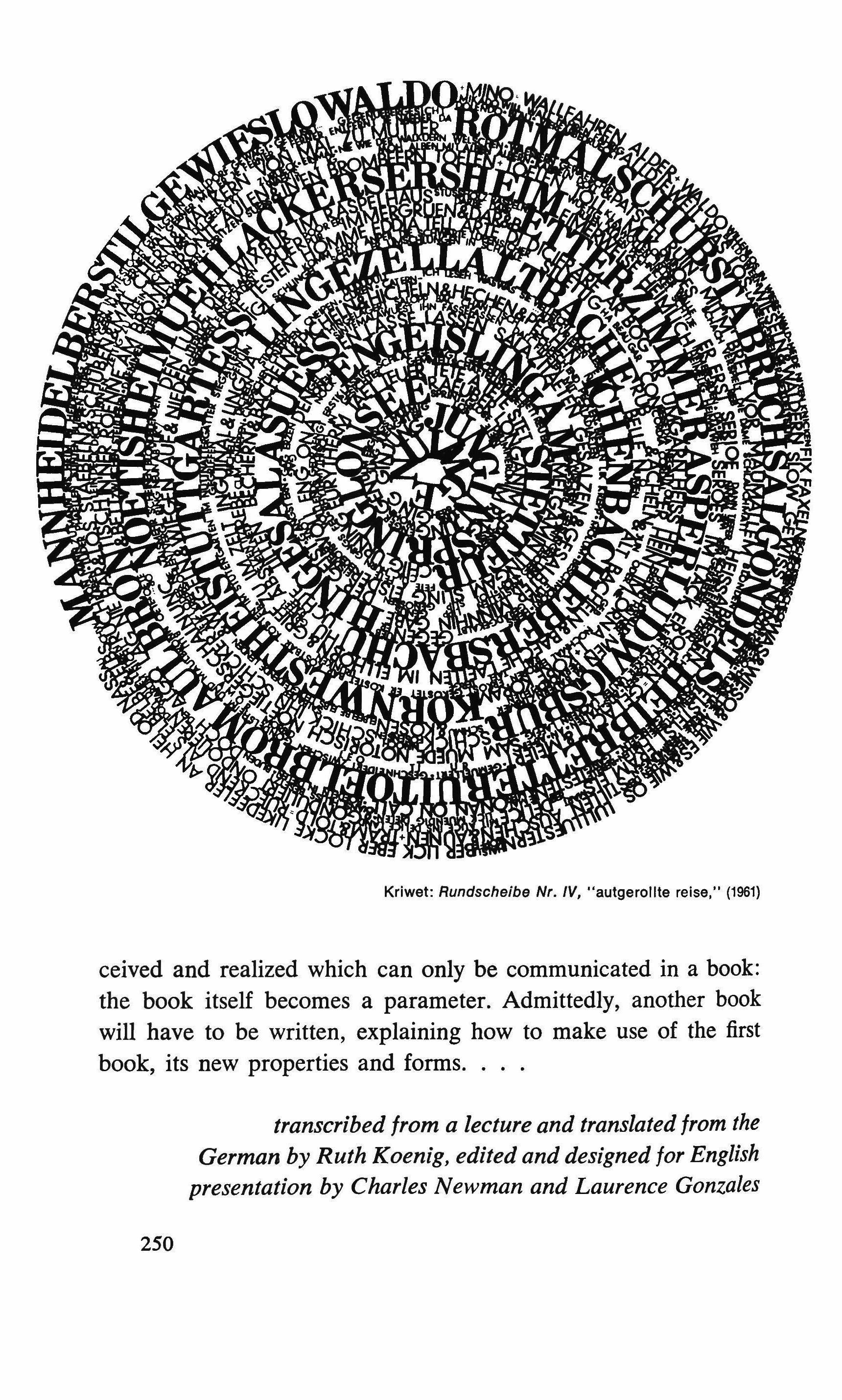

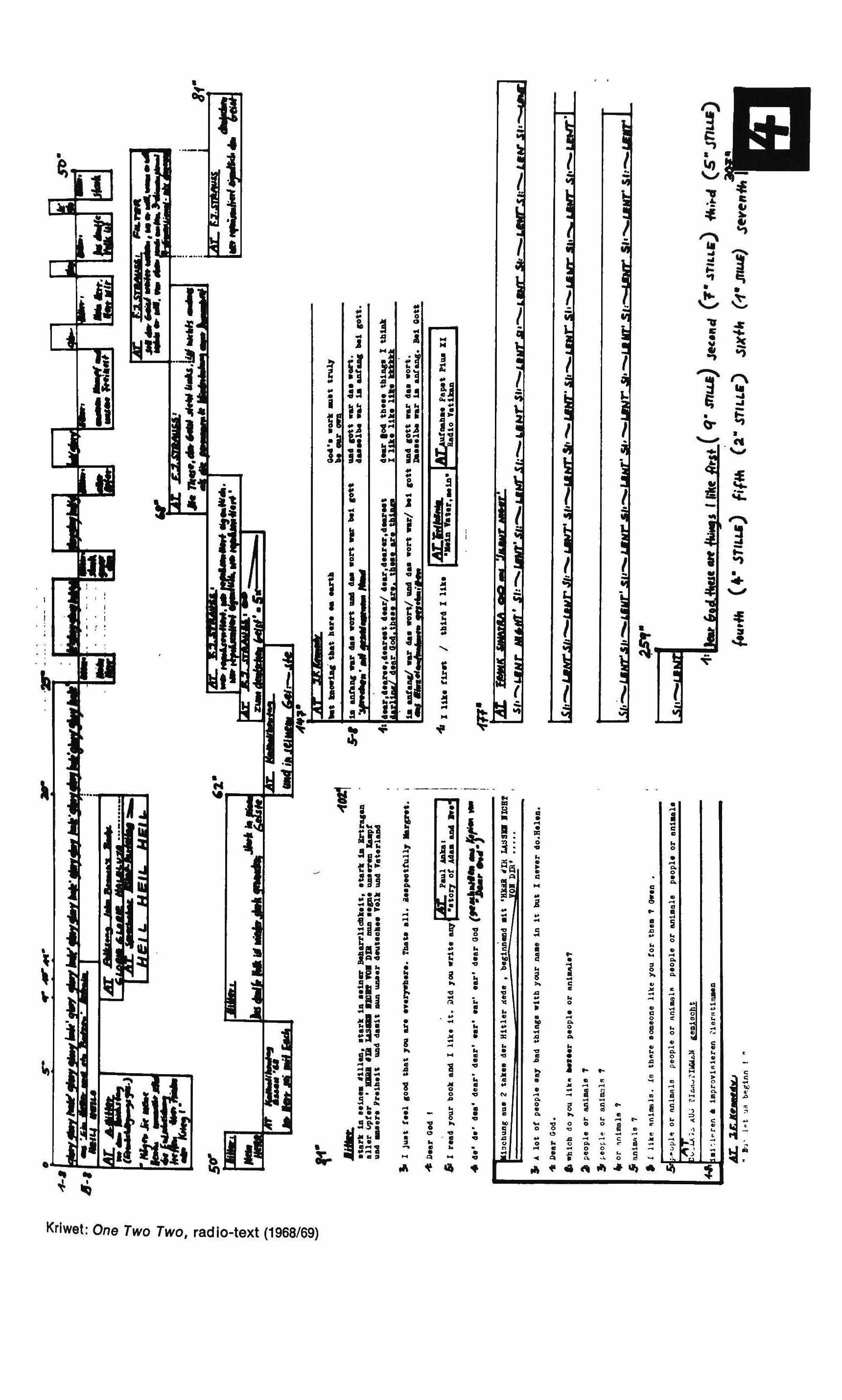

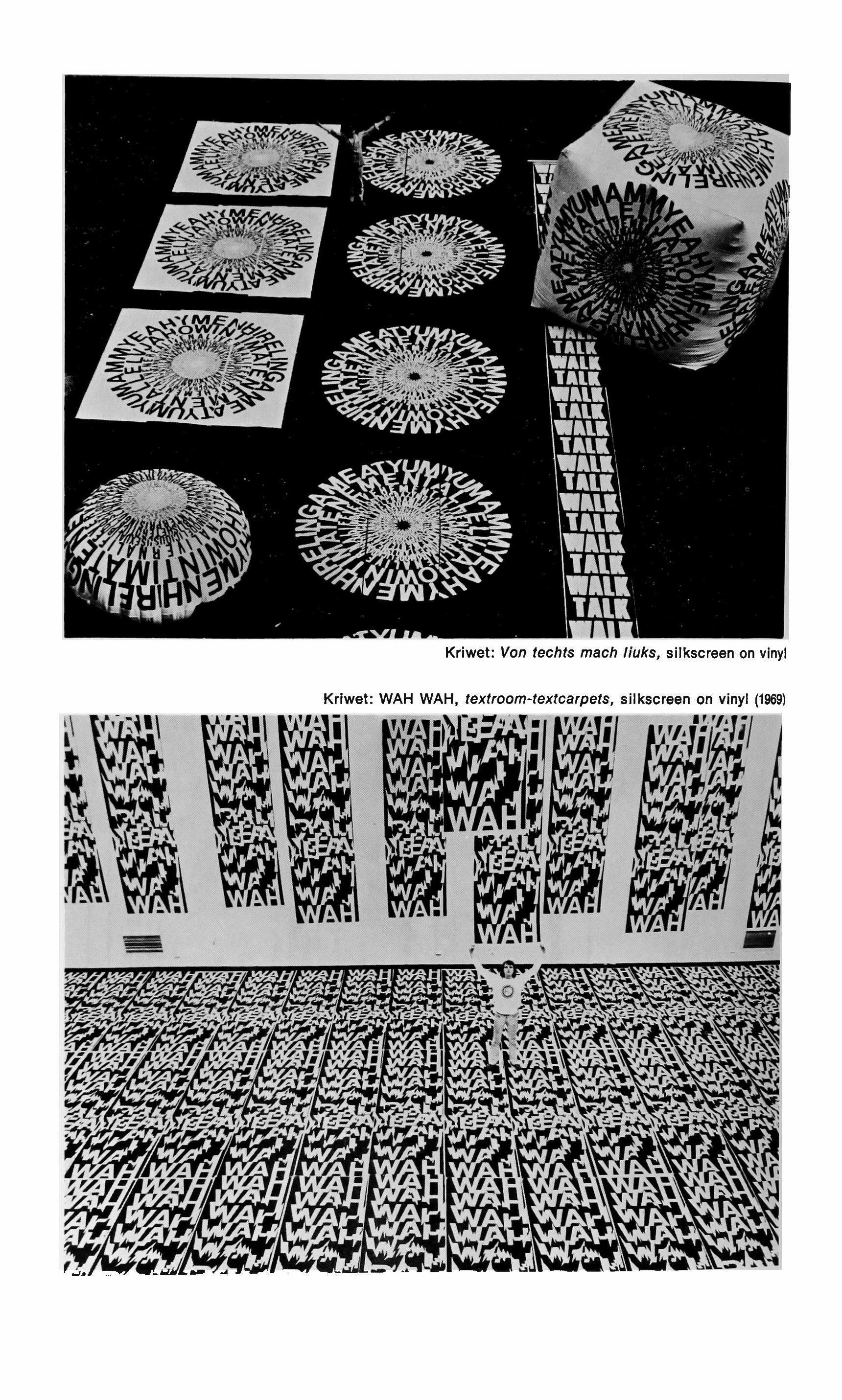

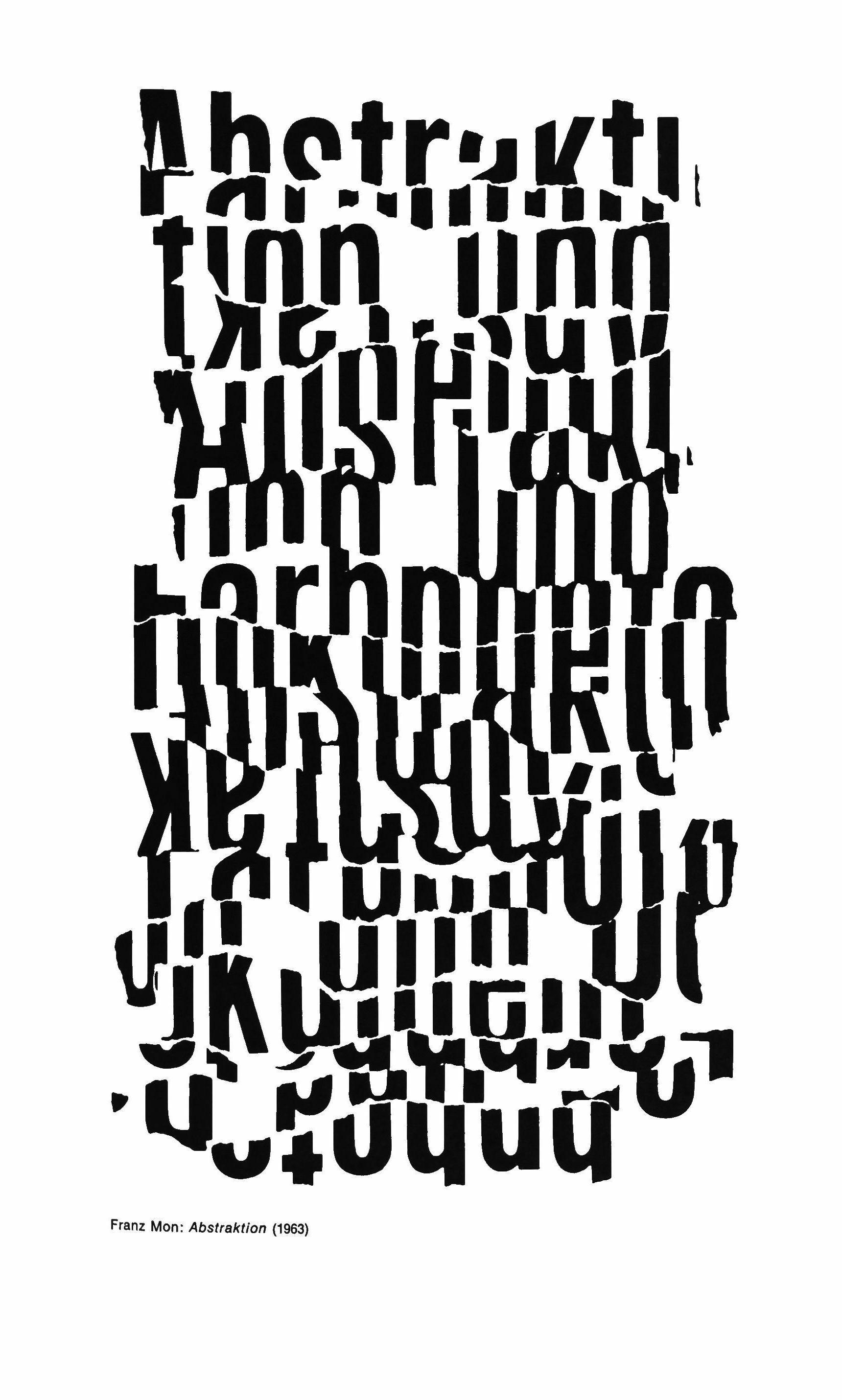

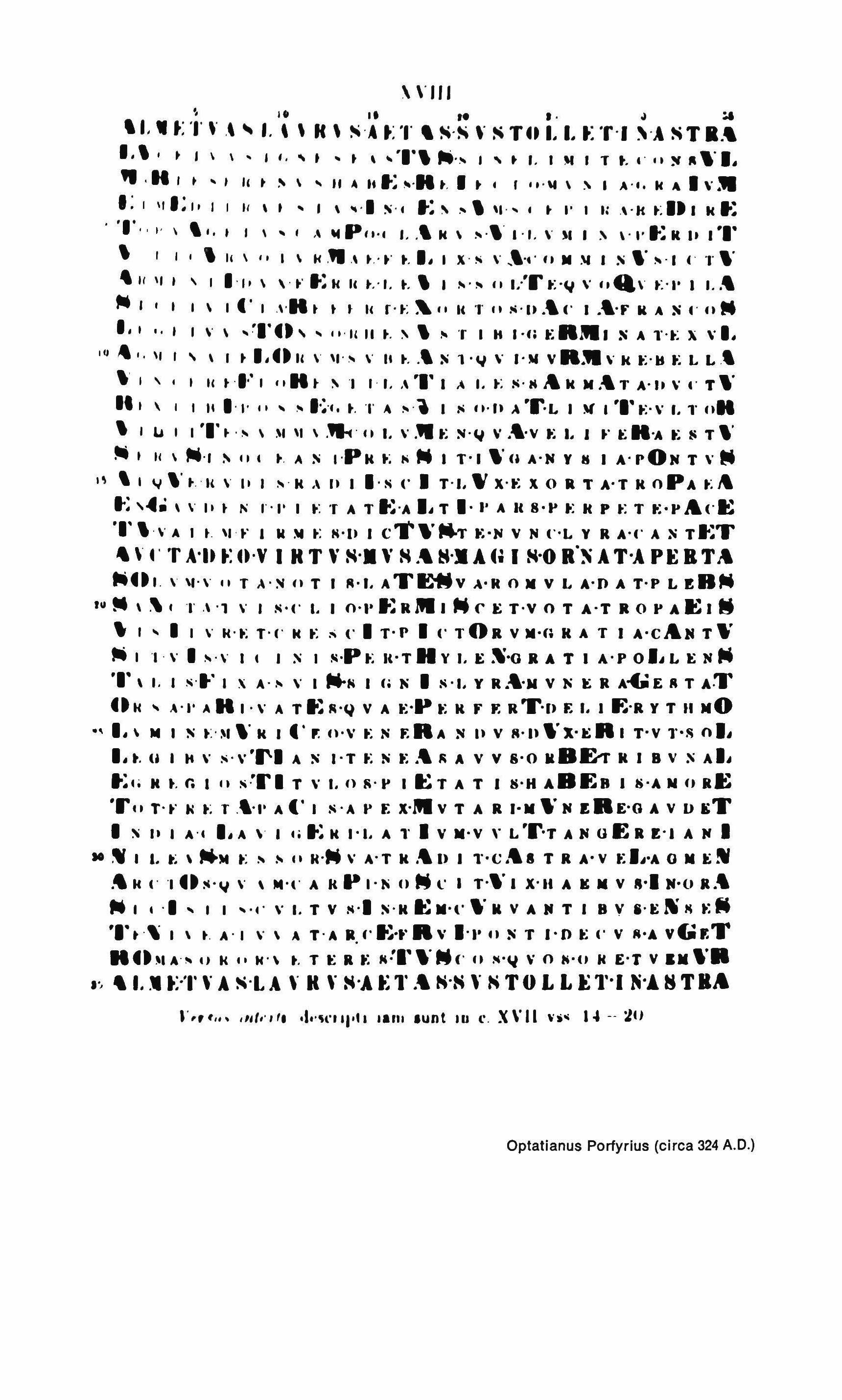

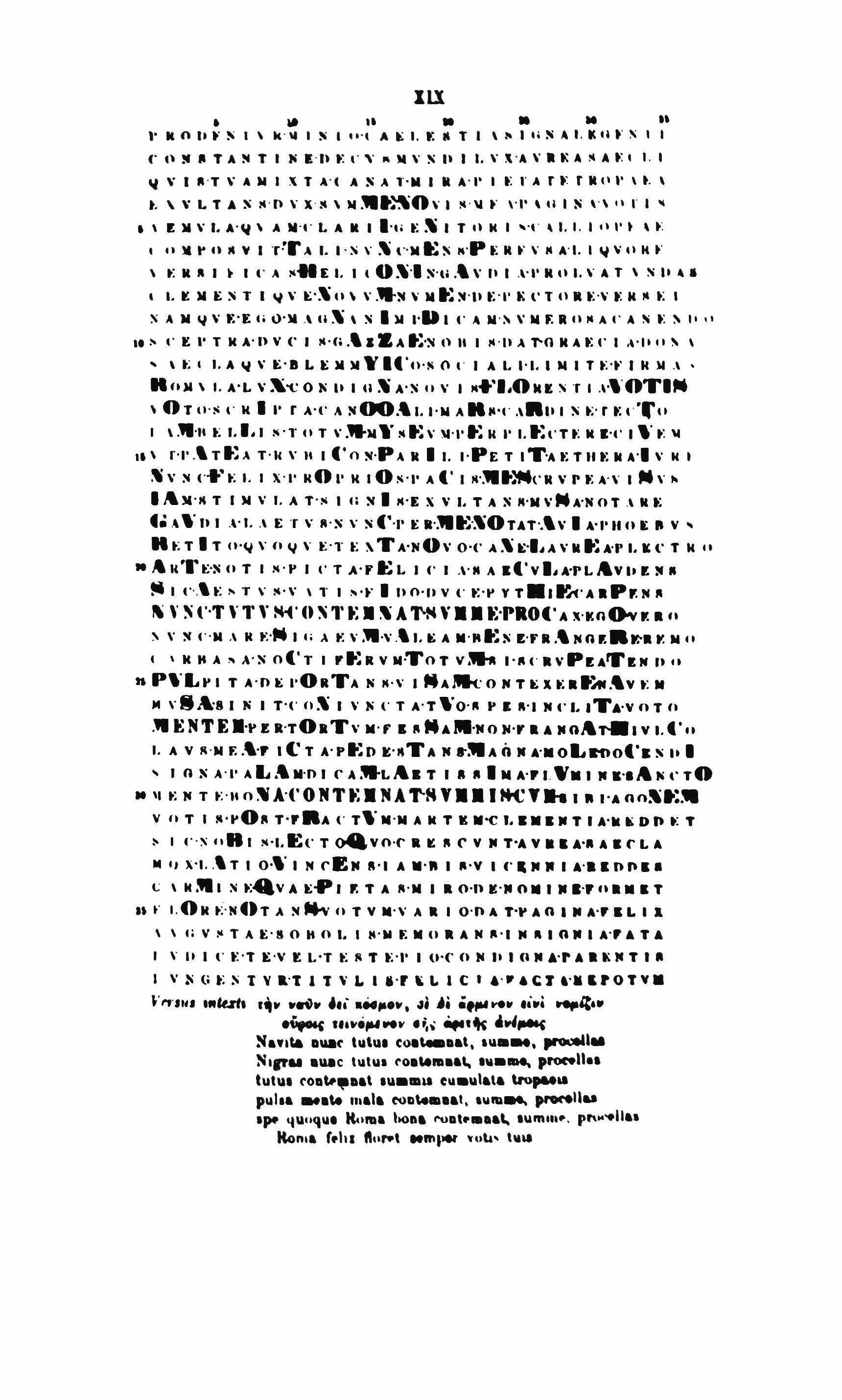

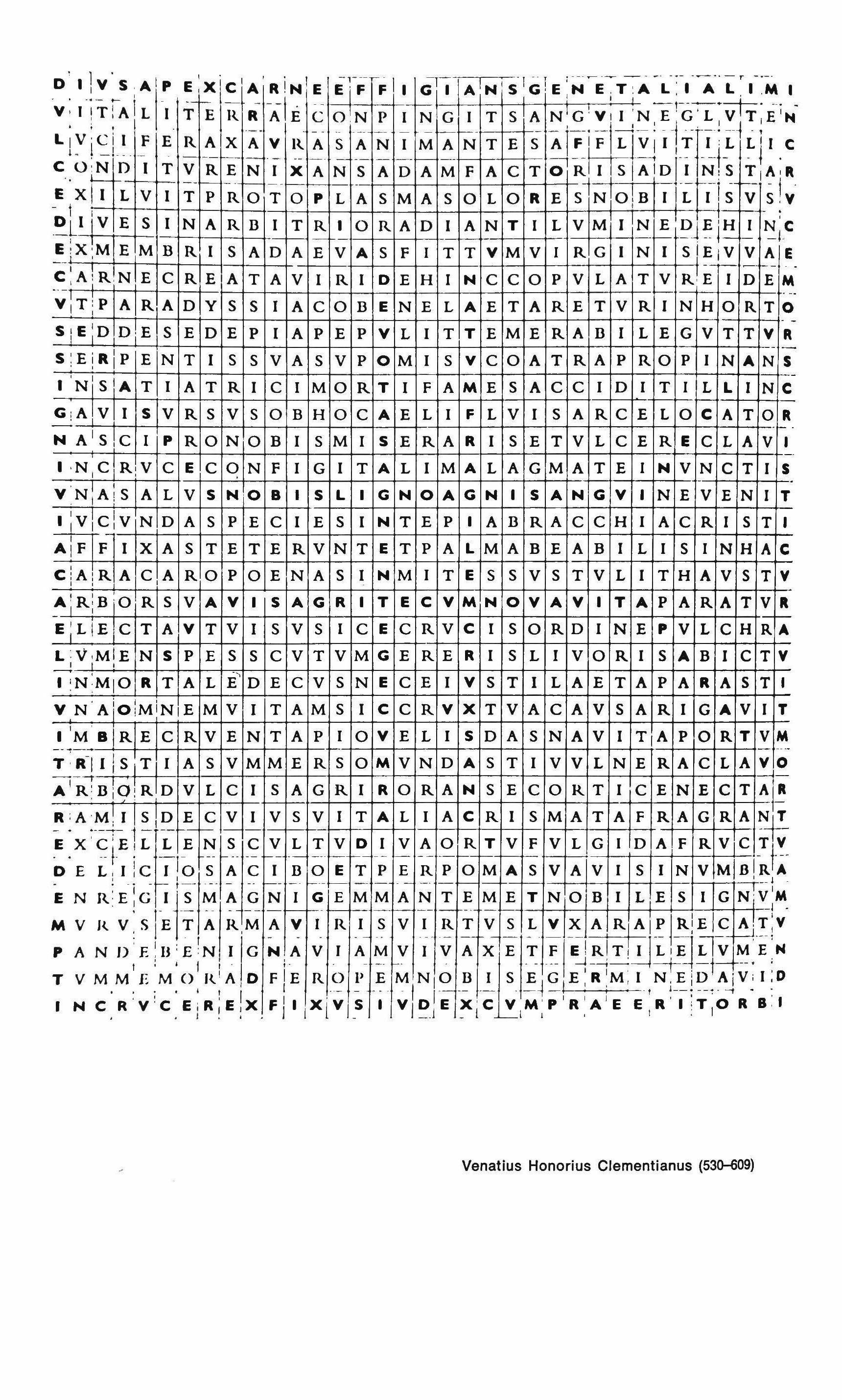

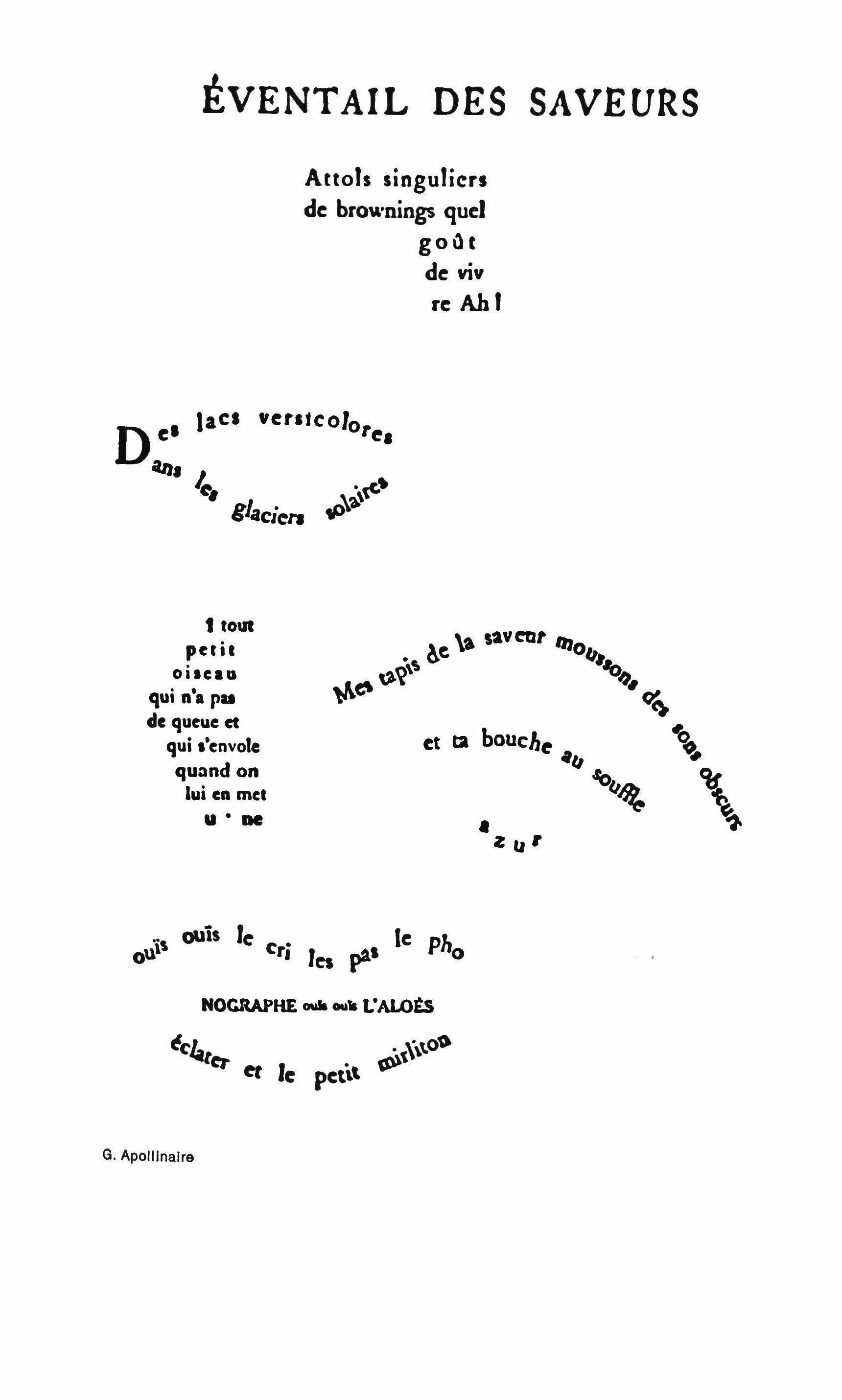

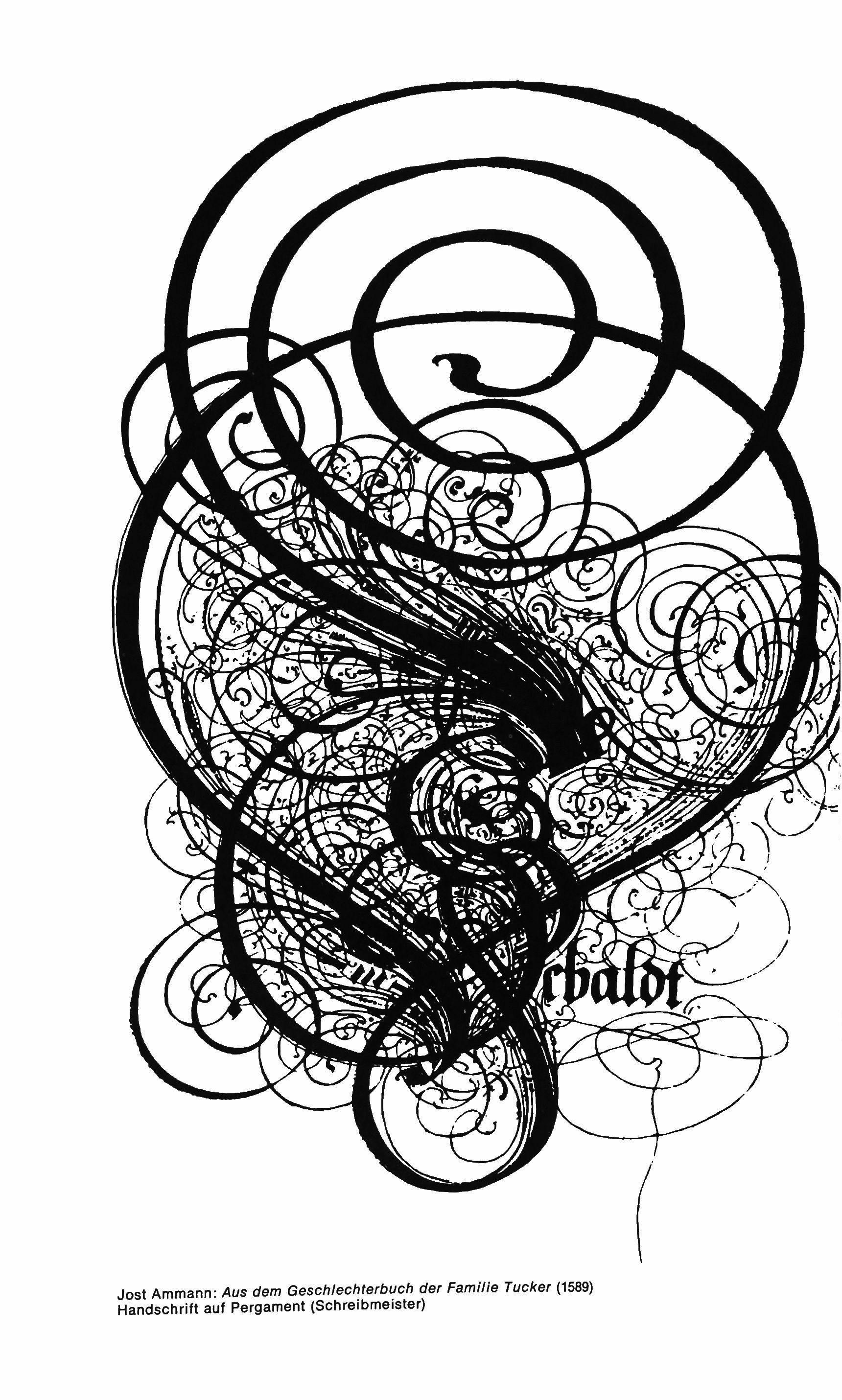

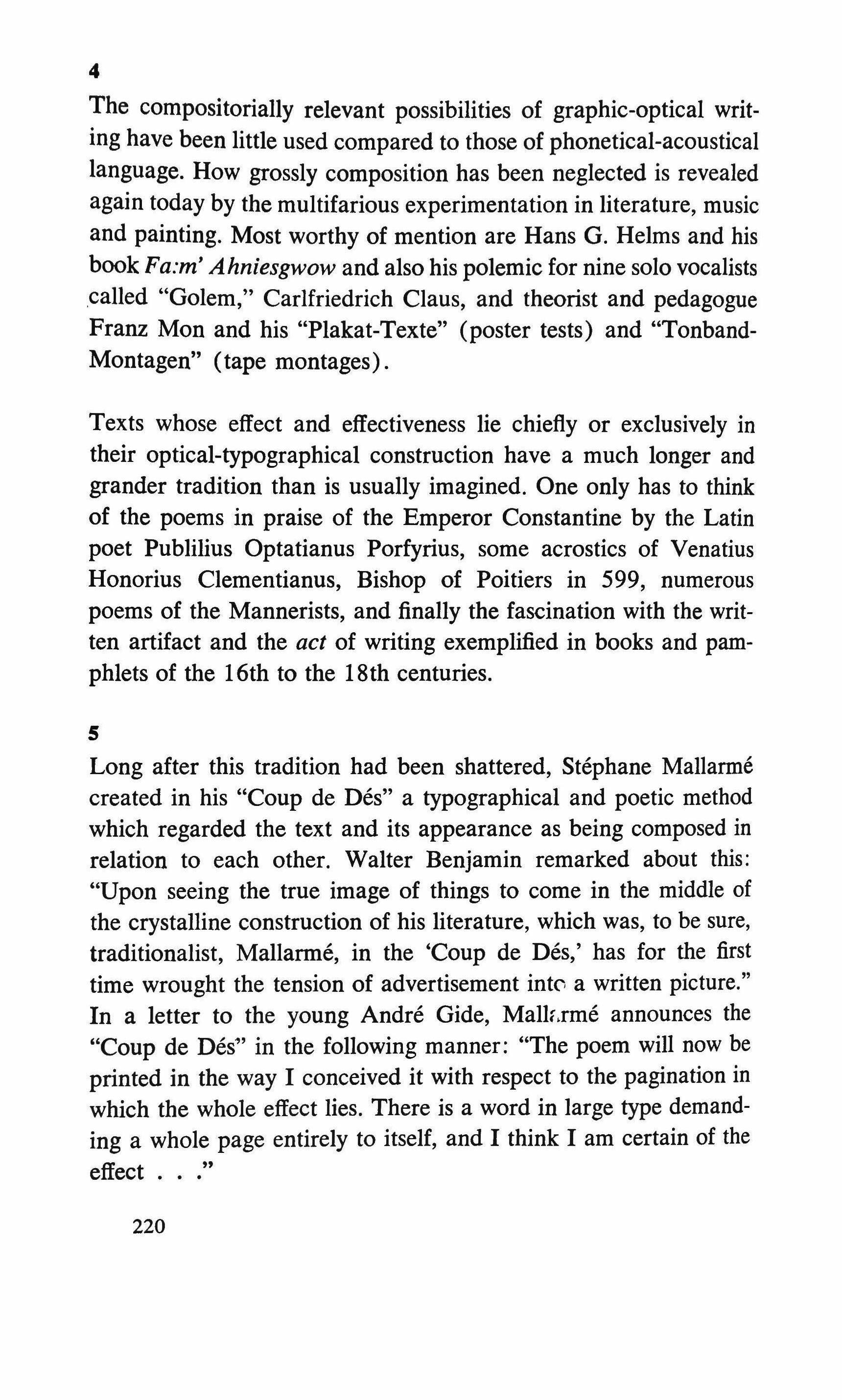

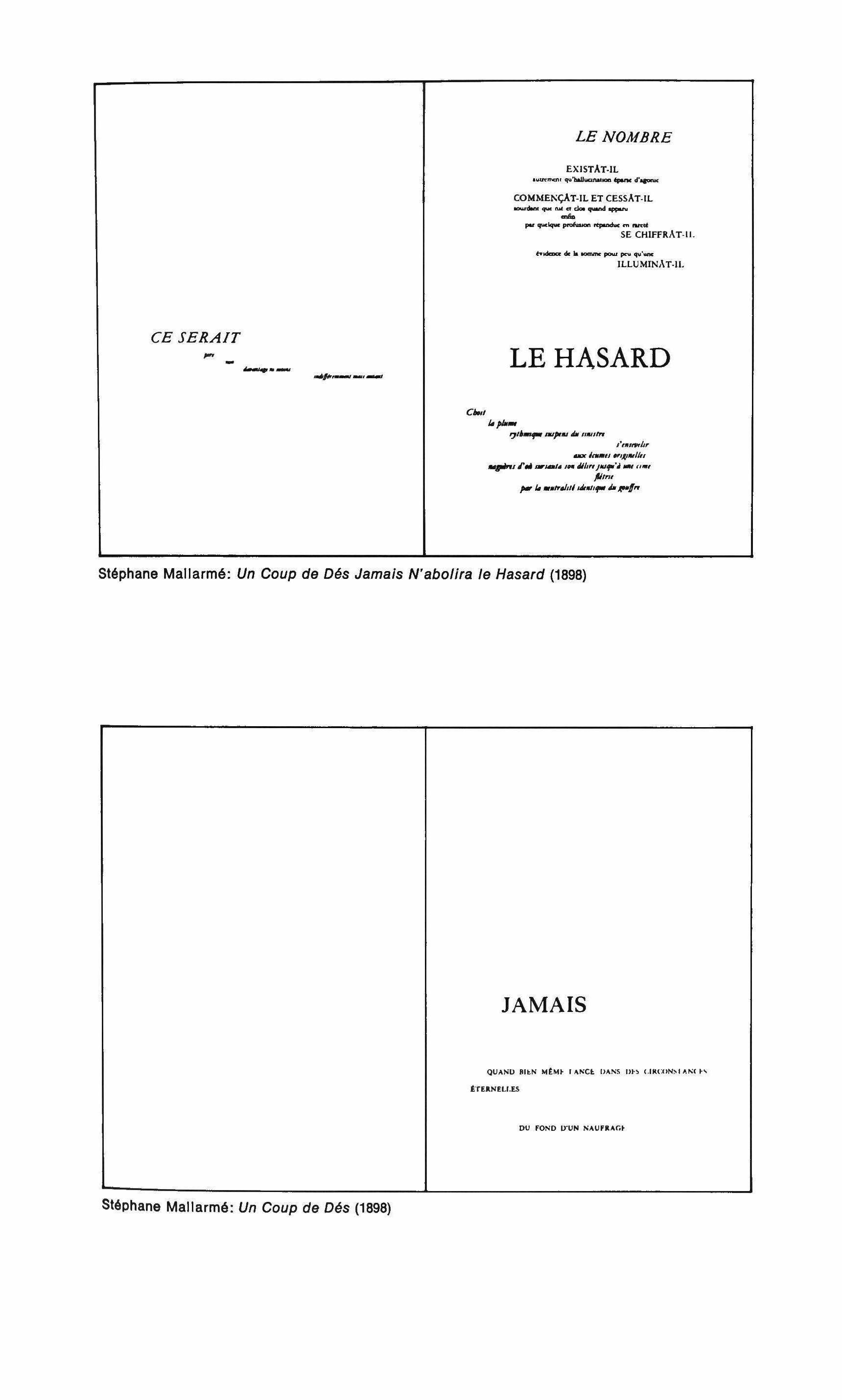

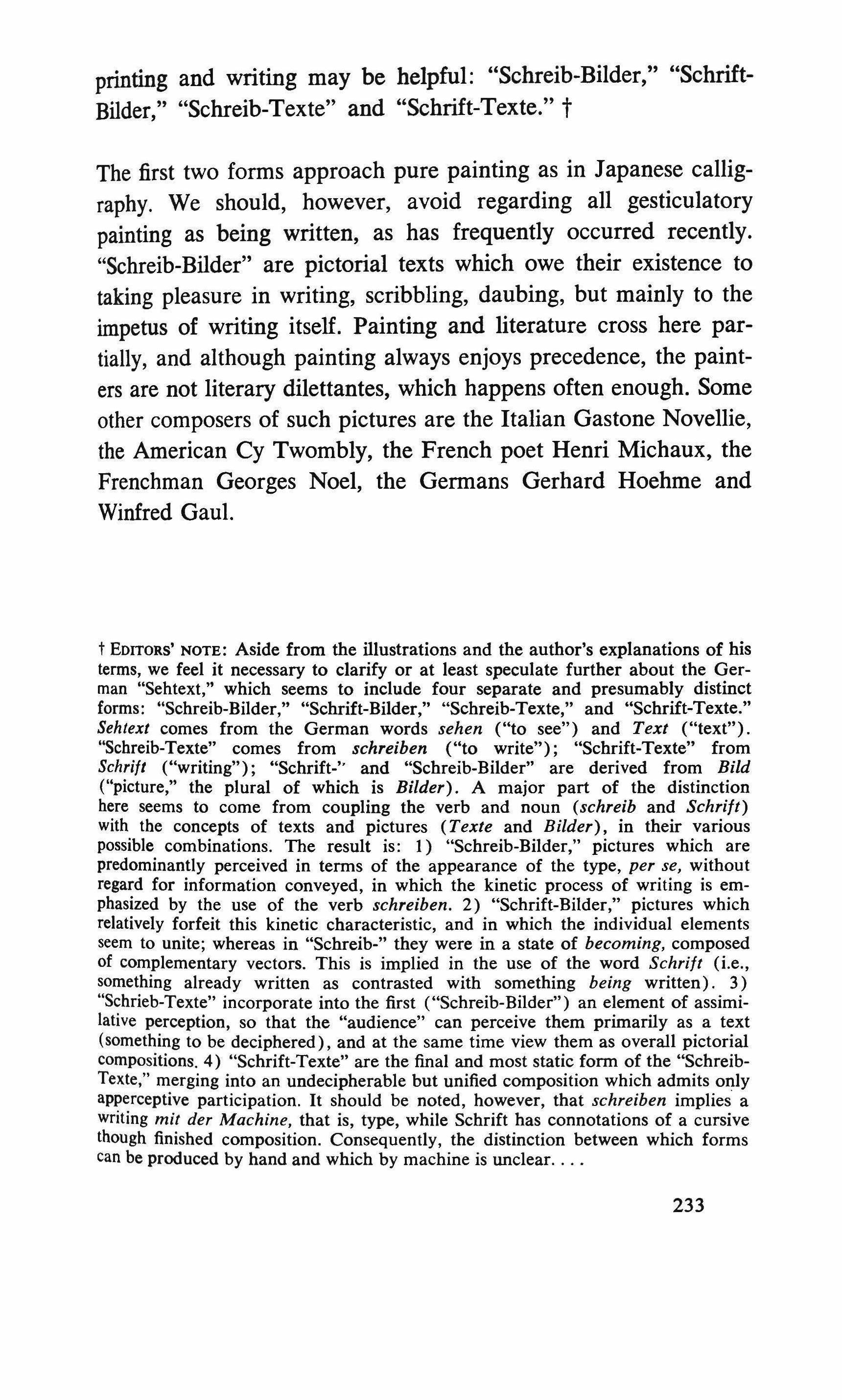

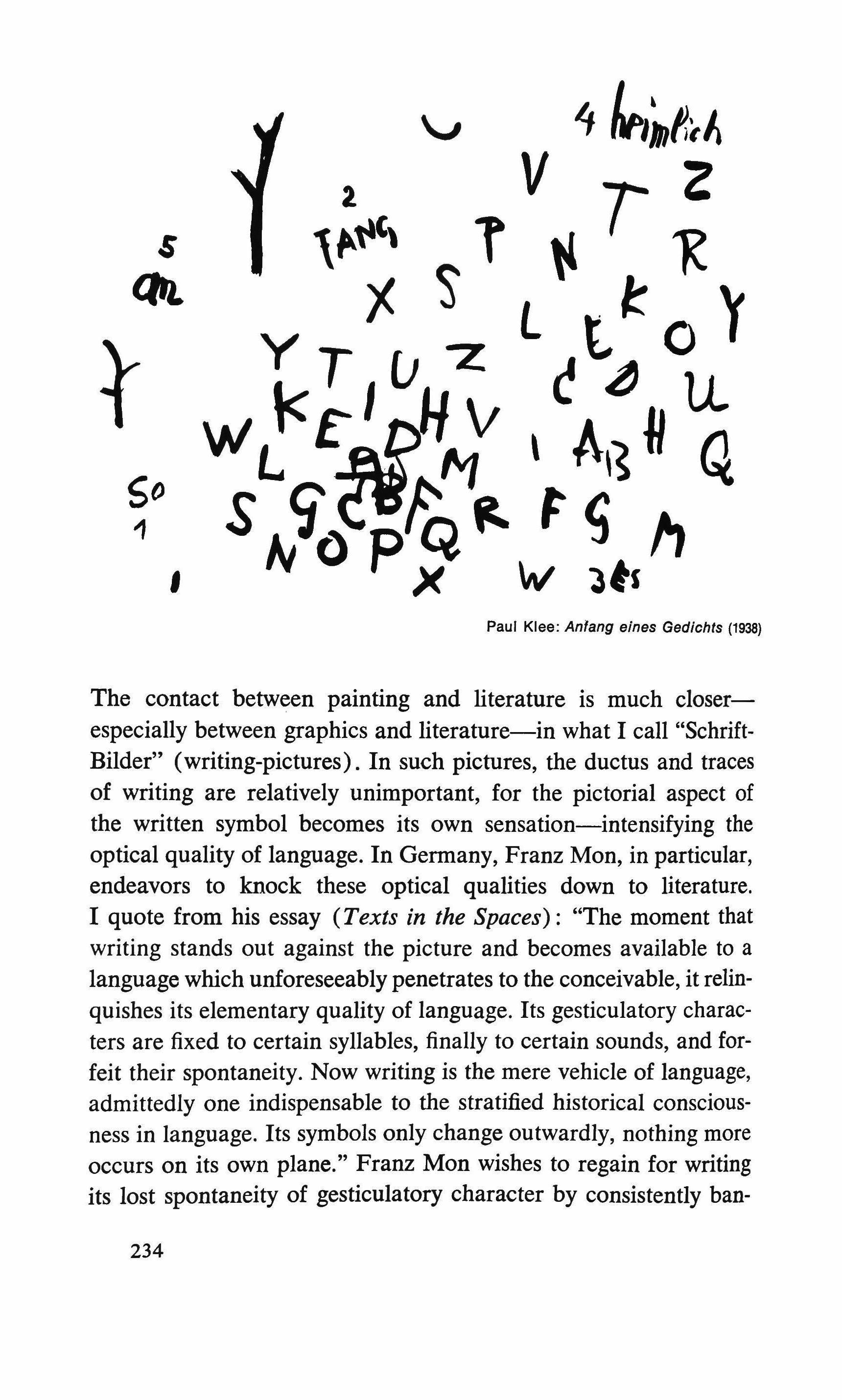

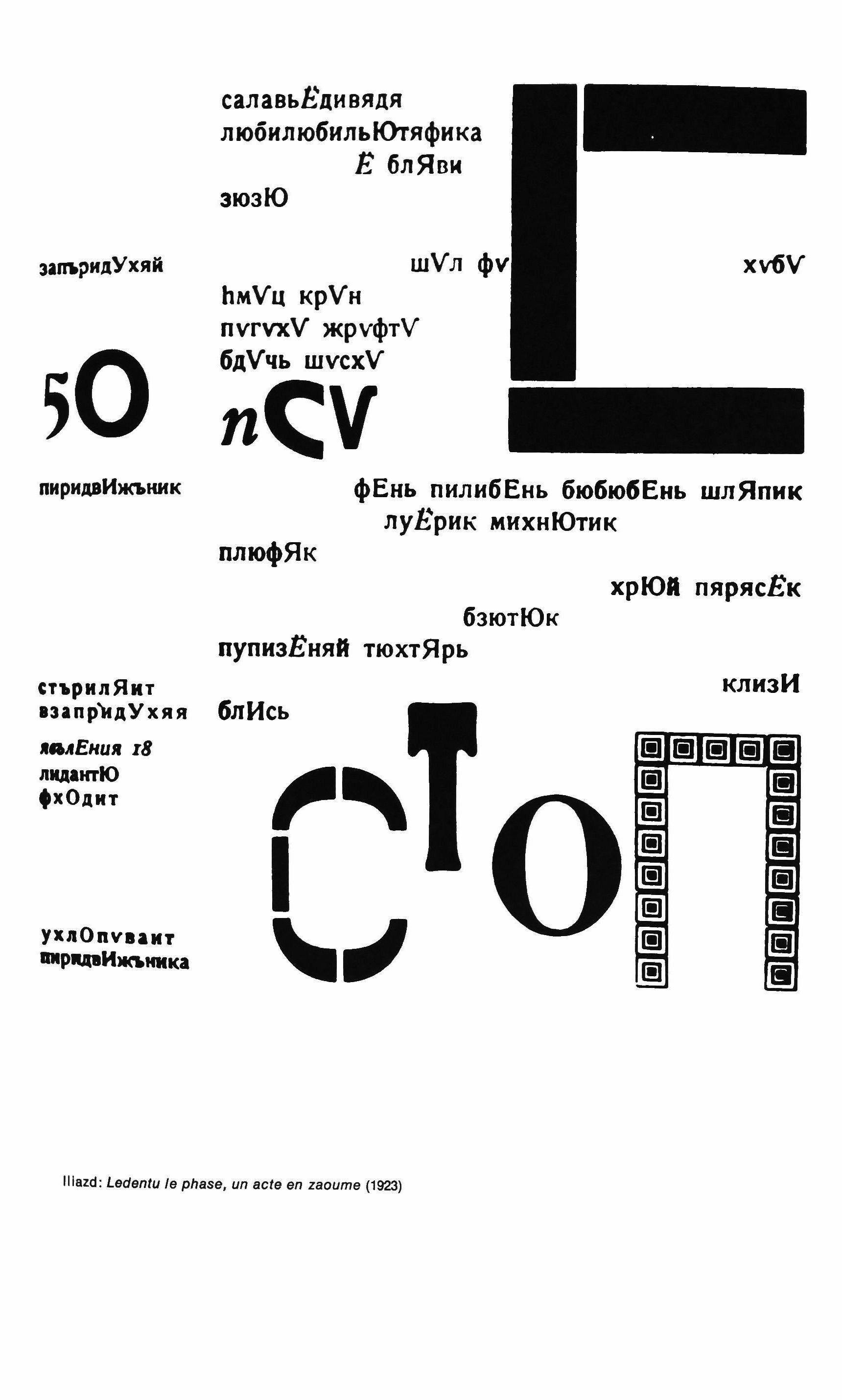

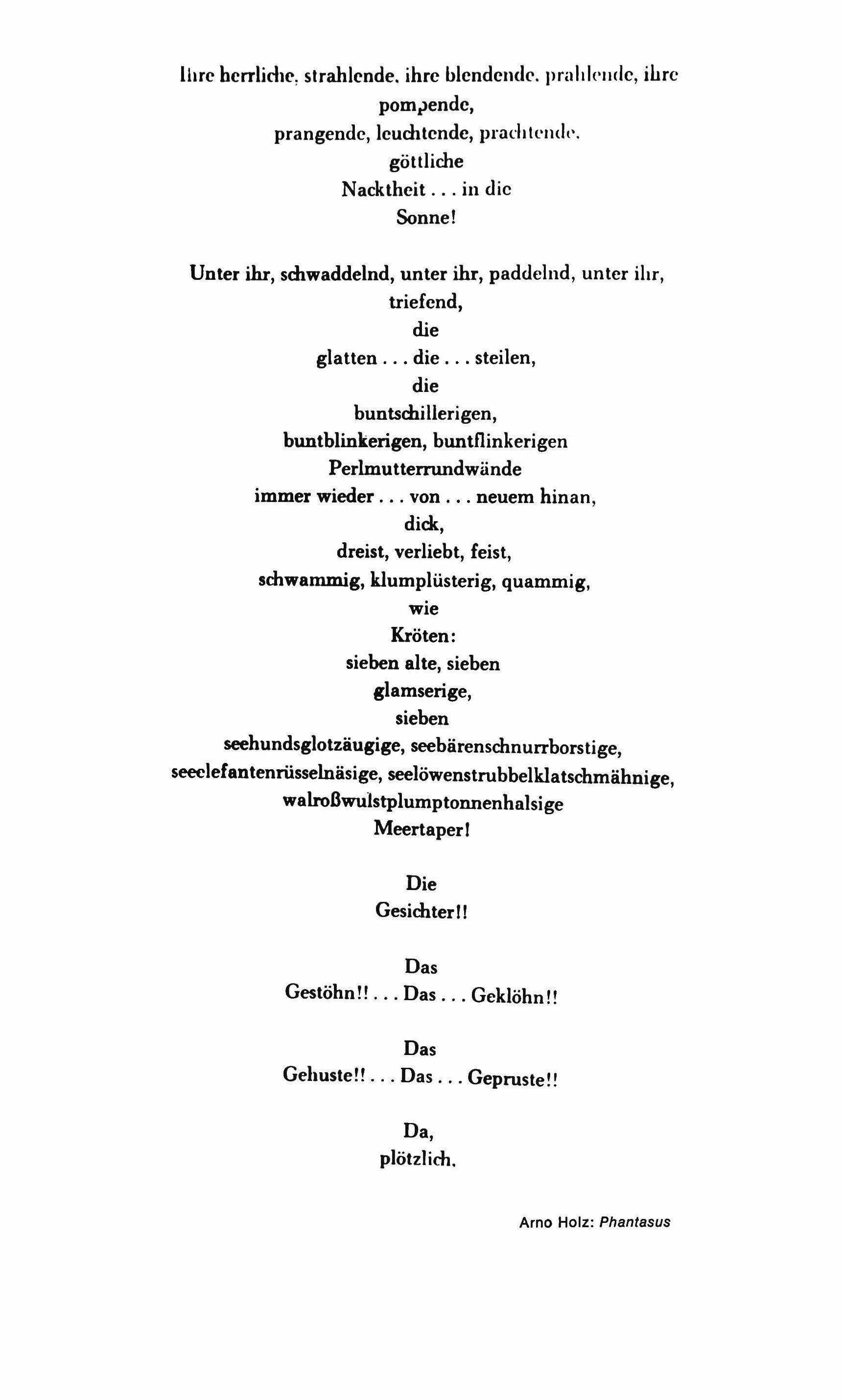

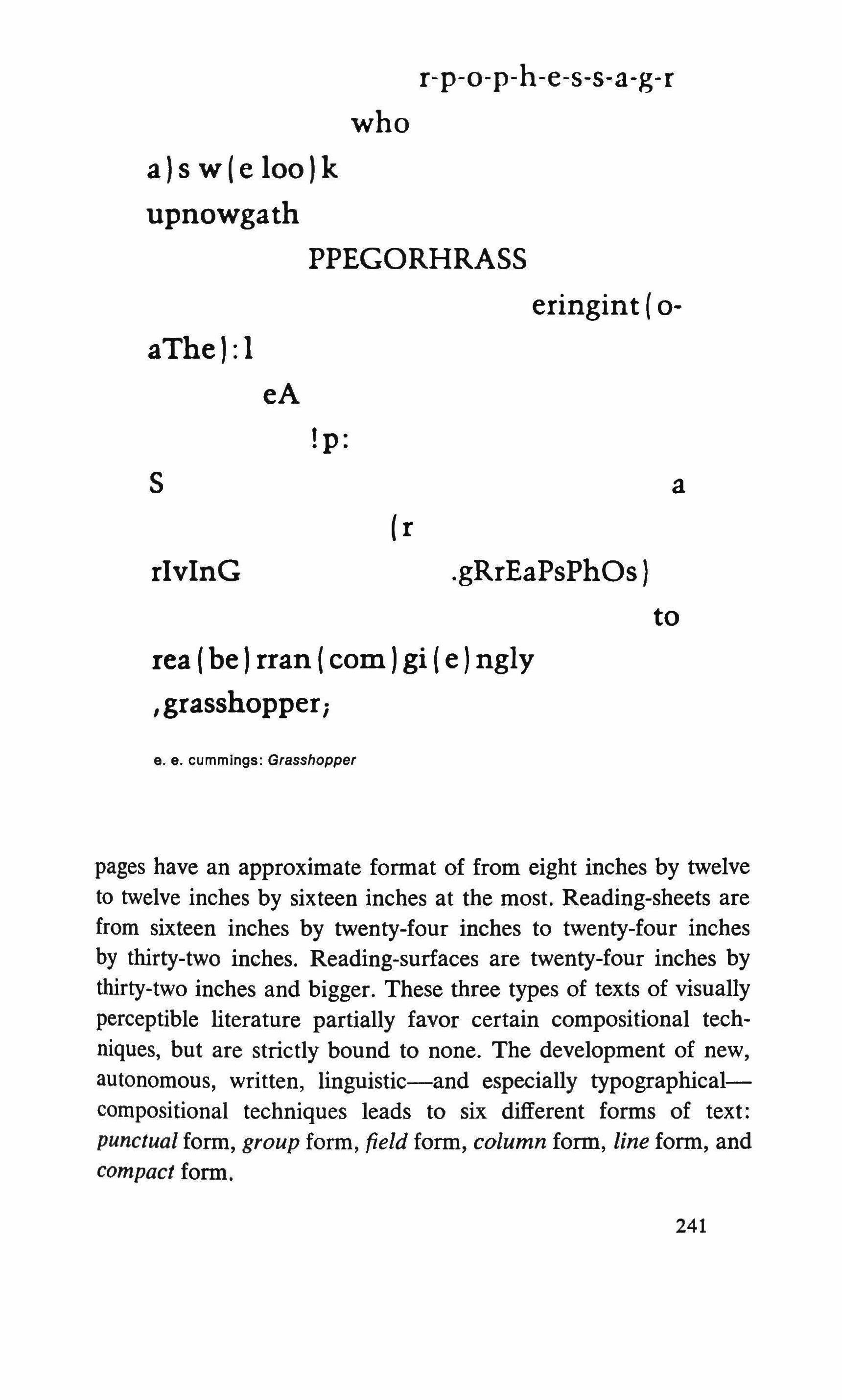

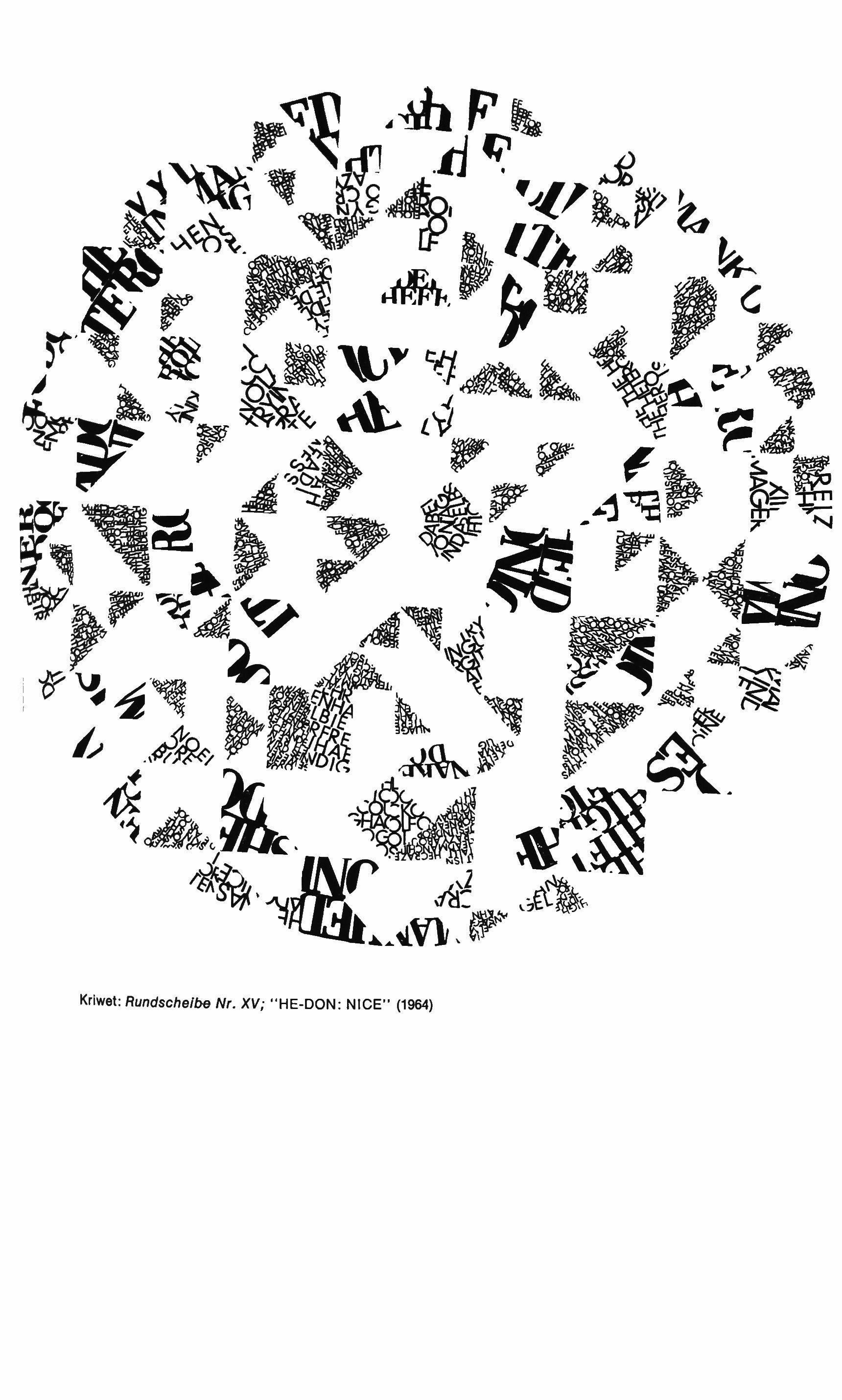

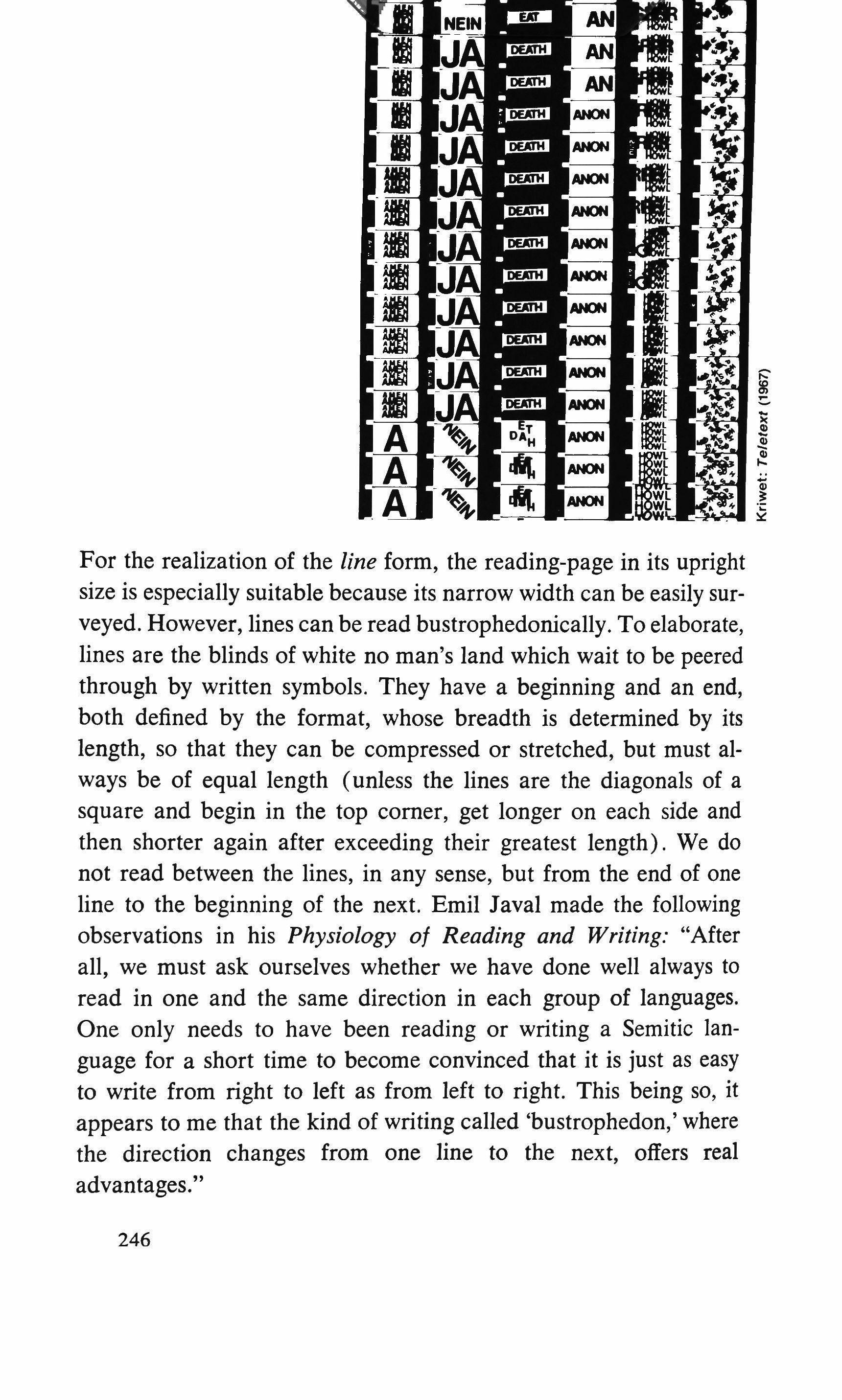

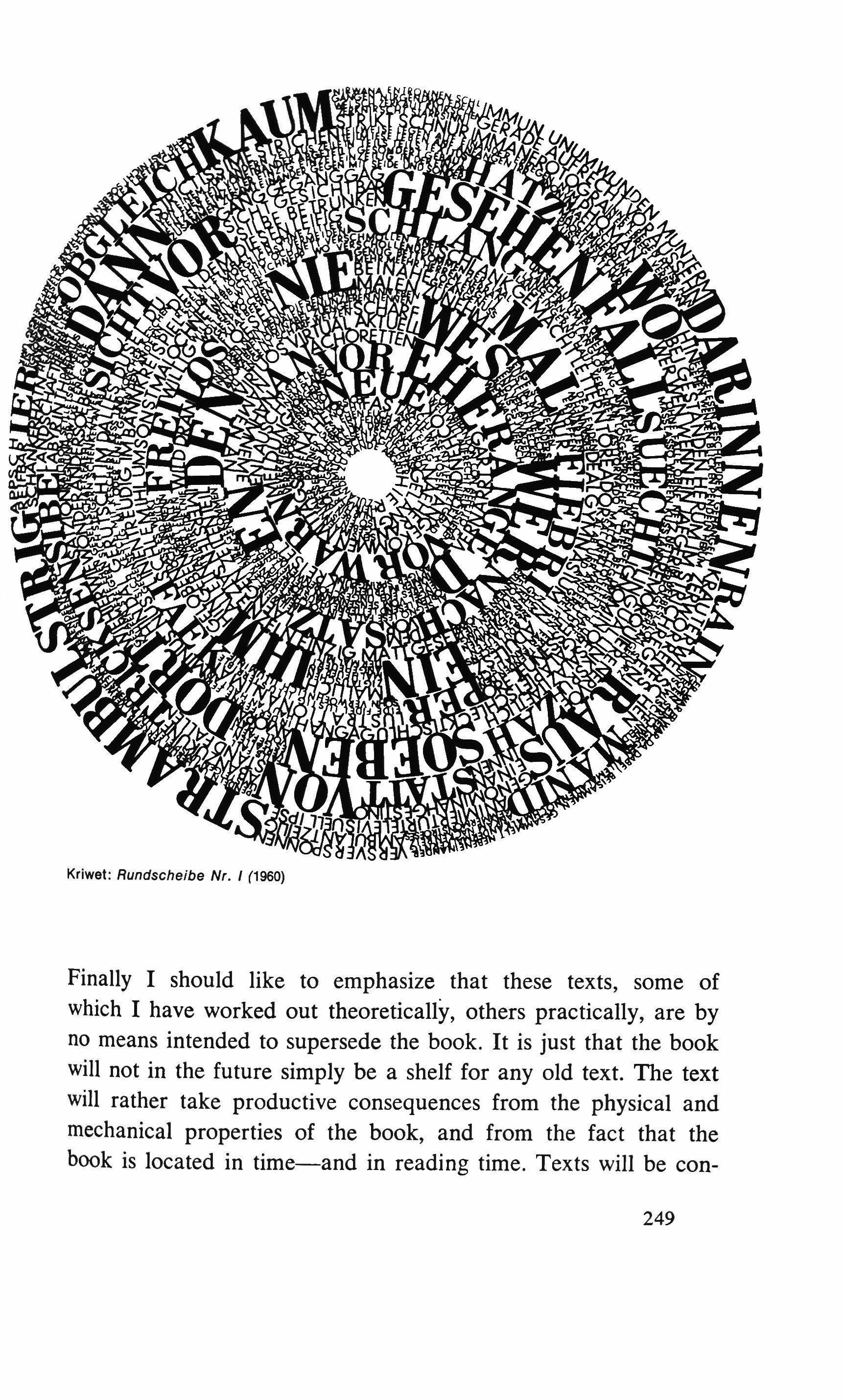

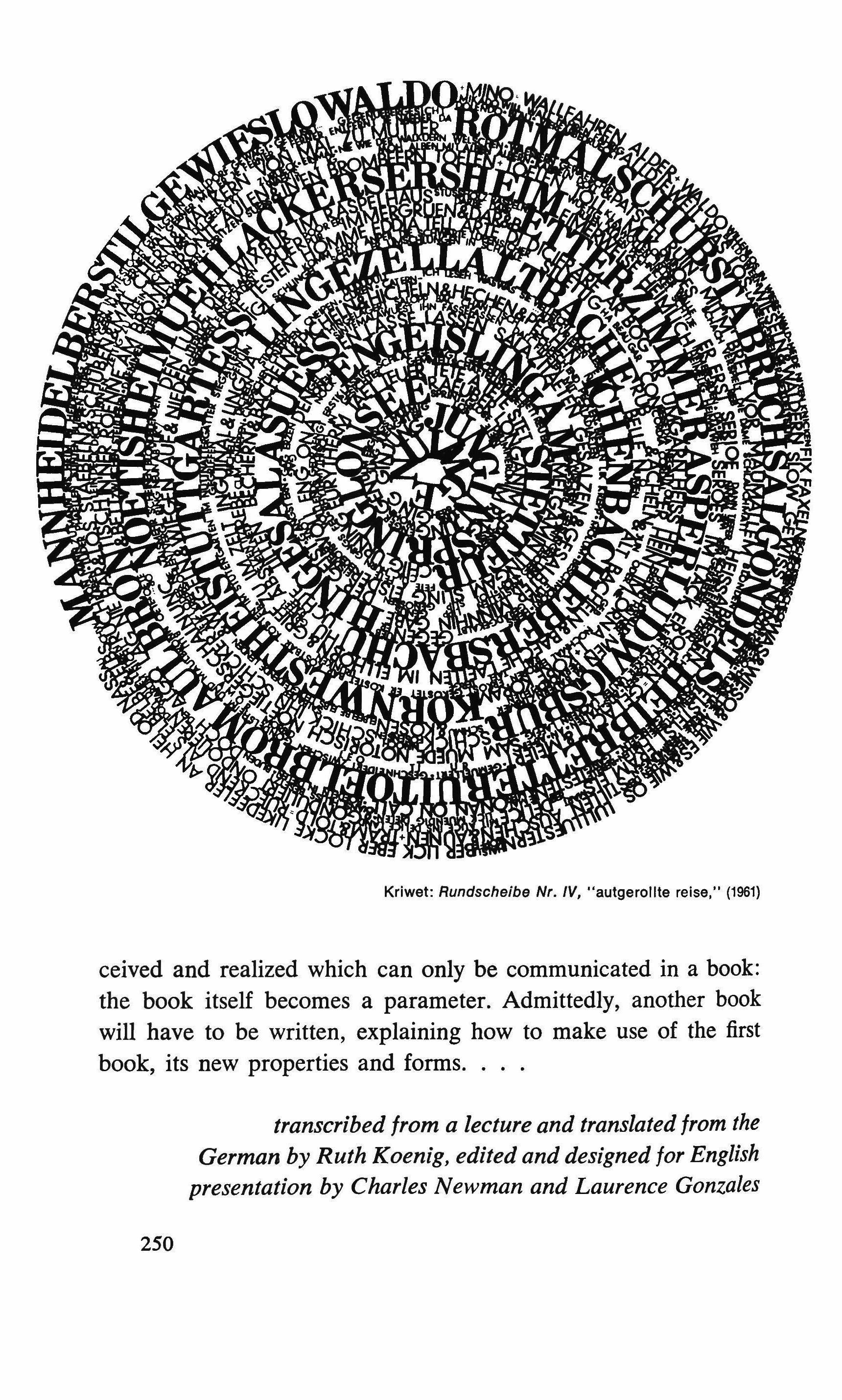

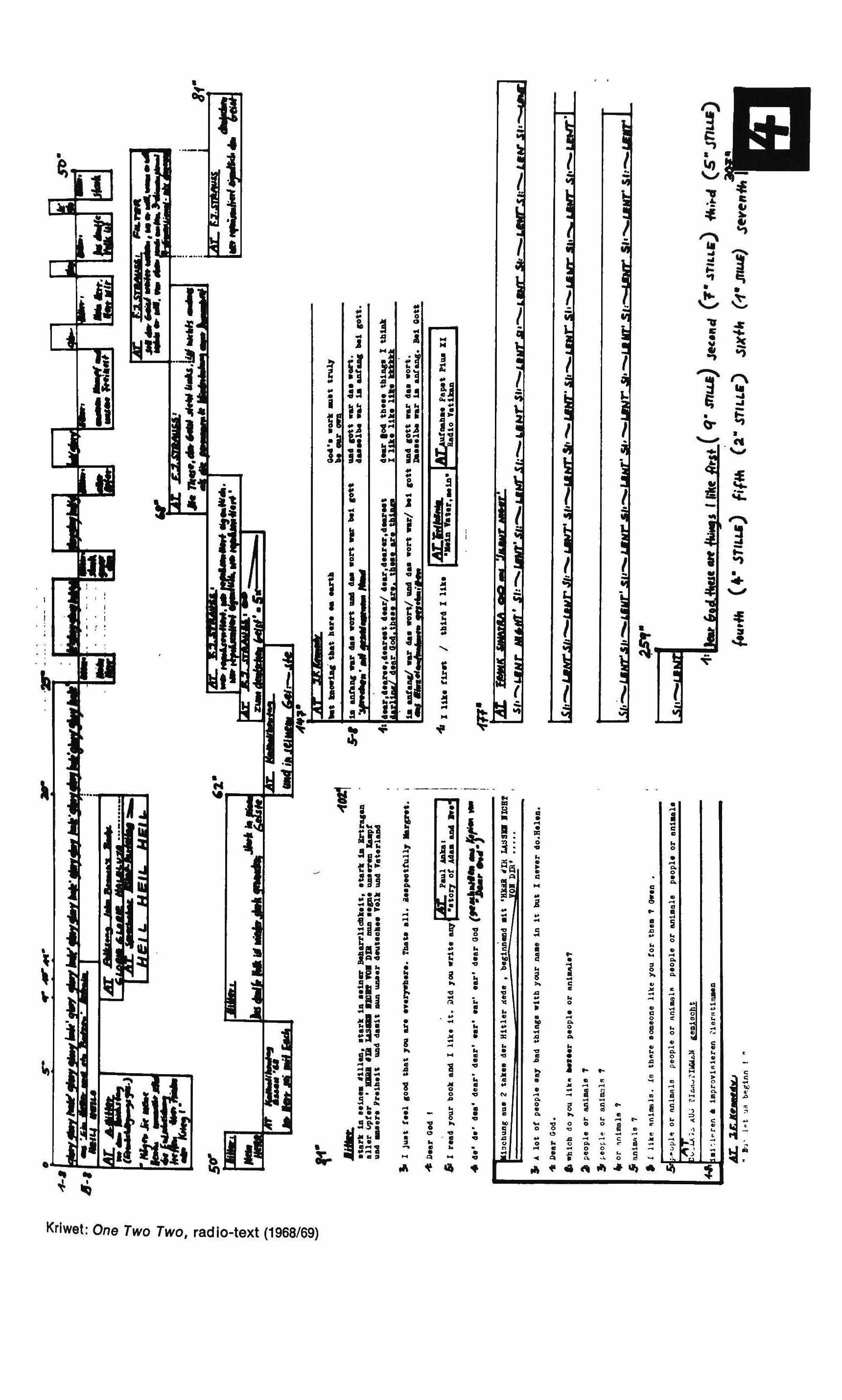

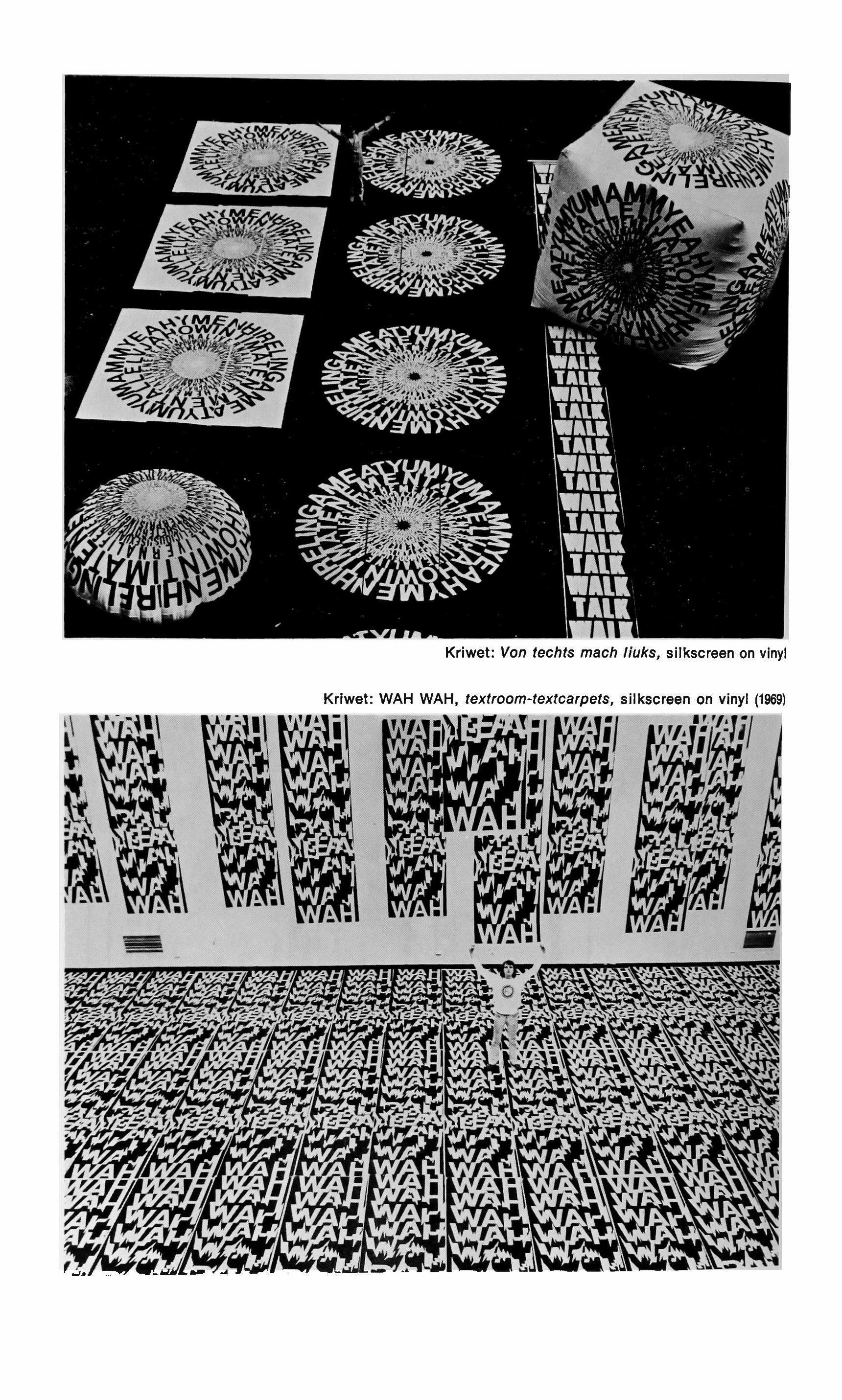

Decomposition of the literary unit: Notes on visually perceptible literature translated by Ruth Koenig 209 Was Lia de Putti dead at 22? 255 from "The fall into time": The tree of life

On sickness, Skeptic & barbarian translated by Richard Howard 369

On Cioran 406

JOHN HAWKES

WILLIAM H. GASS

Fiction

from "The blood oranges" 113 from "The tunnel"

Why windows are important to me 285

JOYCE CAROL OATES

YVESVELAN

CAROL EMSHWILLER

HERBERT GOLD

RICHARD HOWARD

An American adventure 312 Je 328

translated by Stanley E. Gray Lib 344

Song of the first and last beatnik 352

Poetry

November, 1899 131

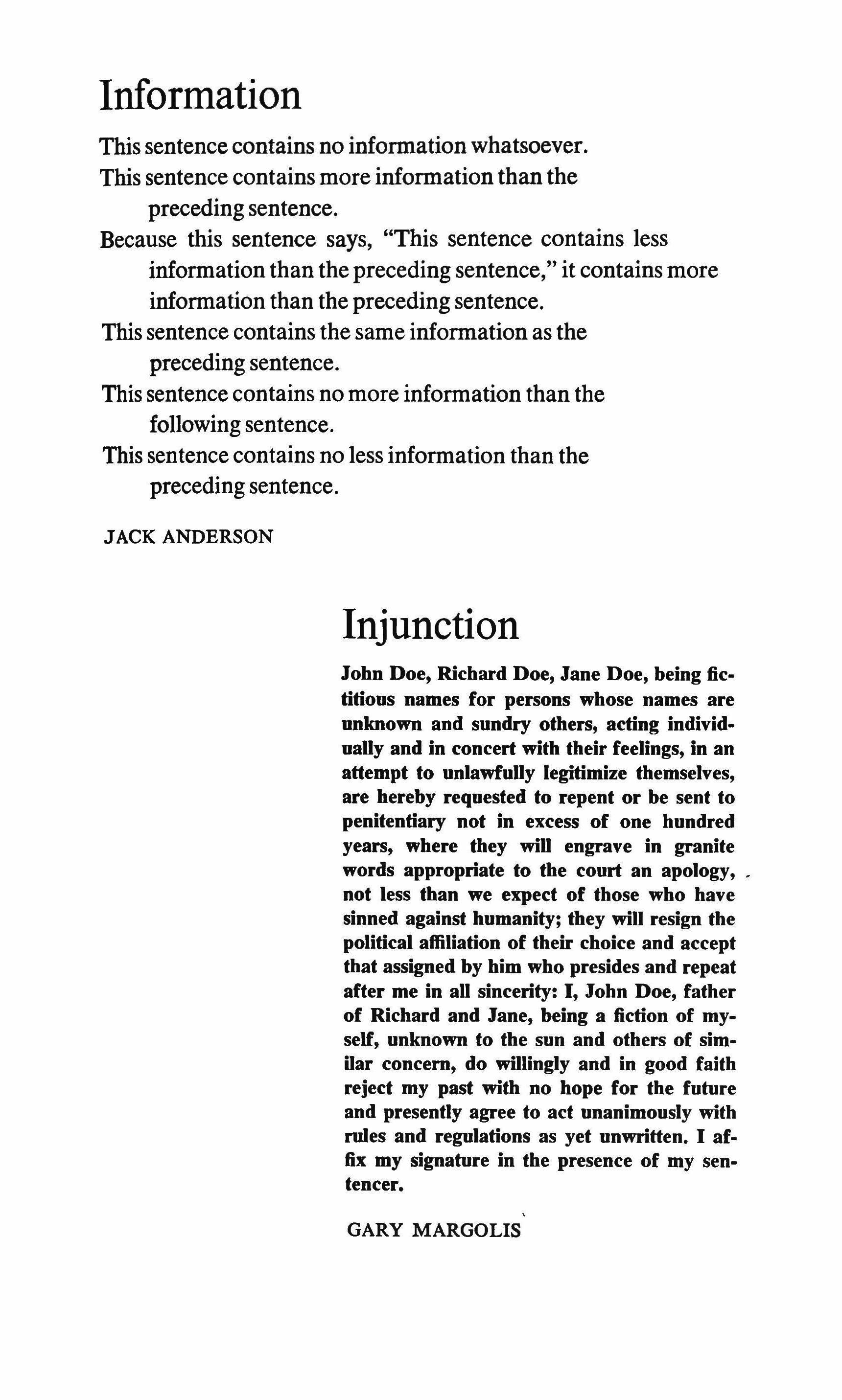

JACK ANDERSON Information 253

GARY MARGOLIS Injunction 253

LUCIEN STRYK

BOB RAINES

Letter to Jean-Paul Baudot, at Christmas 284

Epistemology love list 11 pm vision 308

SAPPHO 16, translated and with an afterword by John Frederick Nims 310

JOHN MATTHIAS

AIME CESAIRE

Three love songs for U.P.!' 325

The thunder's son 350 The wheel 351 translated by Michael Benedikt

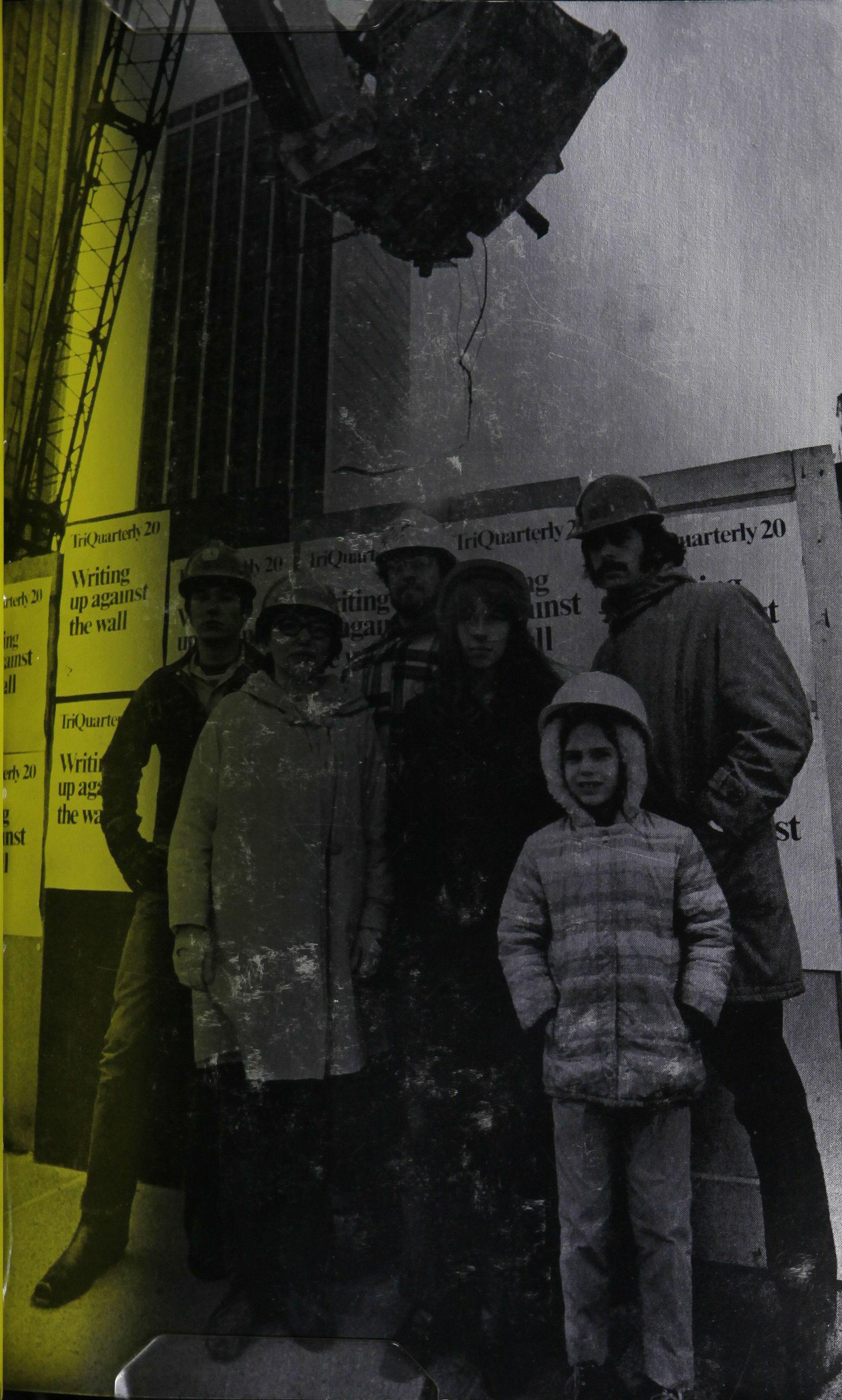

Cover TriQuarterly staff photo by Jonas Dovydenas, headgear by Tony Adams

The great city of literature

J. M. G. LeCLEZIO

If someday someone, leaving his fear behind and finishing Carroll's Through the Looking-Glass, were to ask, quite simply, what is the good of this book, what is the use of literature, the use of this series of words, this imagination, this language, these linked visions, it is really true that there would be nothing to answer.

If someone suddenly closed a book, and stubbed out his cigarette in a glass ashtray, and wanted to forget his feelings, or else wanted to think that he was the man who had written the book, the man who had been able to write all books, all sentences, all words, could you really say no to him, could you shove him back into his autonomy and close the door on him, jamming the keyhole?

In the name of what? To protect what so-called culture, to defend what pride, to justify what wretched notion of individual time? That's the way it is, the habit is formed now. The history of words

TriQuarterJy 5

has become, without our really knowing how, the history of men: the history of one man.

Each follows the next, each buries the next. There has been Greek thought, German mythology, Pali erudition, Mayan cosmogony, Chan, Zen, the Walam Olum of the Lenape Indians. There has been classicism, romanticism, realism. In the mind's carnival, the little booths are set up, one after the other, and each sells a better product than the next. Here I find Shakespeare hawking waiHes, there Dostoievsky, behind the cotton candy. Further down, Faulkner stands at the counter and waits for his customers. Or Joyce, Proust, Kafka, frozen in their attitudes, their products signed, sporting an inimitable label so that we recognize them at first glance. Everywhere, in the great carnival with its sparkling lights, is exhibited the merchandise with its loud colors, the words which echo oddly in the,silence of life, the signs, the quick and affecting movements, the statues with their deep faces, the hours of life, the blood, the intelligence, the power.

It is not life which is to be bought at the Gide stall, the T. S. Eliot stall, the Sartre stall. It is not truth shamelessly displayed here. It is not pure pain, nor love, advertised on the posters of the Cummings booth, the Aragon booth, the Stig Dagerman booth. Life is elsewhere, in the silhouette of that man wandering along, for instance, or in the vague ghost, a memory of certain moments of sunshine, of wind, of rain, which soars above the carnival of words. It is a city we see, but as though from the top of a high mountain, and each street bears the glorious name of the man who has decided to sell his thought to the rest. There is Dante Street, Hugo Street, Blake Street. Camus Boulevard, Baudelaire Avenue, Zola Square, Dos Passos Promenade, Hemingway Alley, Moravia Lane, Woolf Hill, Beckett Park. This enormous city-you can see it spread out, stretching over the ground, caught in a cloud of mist, or vanishing into the night's black light-shimmers and swarms with an incomprehensible life. It is the great city of dead culture, of imagined ventures, of words and cries addressed only to the past.

This unknown man leaning over it as though from high up on a balcony, and trying to understand, suddenly grows dizzy. He sees

6

the streets, the boulevards stretching out like tentacles, dividing, breaking off short. Along the creeping fissures, concrete cubes are being built, each lighting, within its dim cellar, a tiny trembling lamp. They appear, they are there, they grow. Their neighborhoods fill out, girdled with parks of skeletal trees, embellished with fountains which spit only dust. Each new district is handsomer, bigger, more secret than the last. There are the realists, the surrealists, the post-realists, and the new realists. There are the rich neighborhoods, with their huge shops selling useless words and sentences reserved for those who can afford them. There are the industrial districts, with their tragic, general cries, the red-light districts, with their obsessive, erotic images. And there are the poor neighborhoods, and their stories are always the same, stories of abandoned princesses and orphans as handsome as gods.

Above the buildings where the words are manufactured, the raw cries, the redolent thoughts which awaken hunger, thirst, which trouble the faint souls of men, up there the new signs are written in neon:

New Novel

The Style of Silence

Structuralism

ECRITURE

Psychology No-Myths Yes

Description of the Moment

Mechanisms Understood

Language System Language

Adventures of Consciousness

Authentic-Inauthentic

Representation

The Hygiene of Vision

Enumerations

Canned Culture

The words leap out, the fluttering of bright-bodied gnats which seek to populate the air: "blood," "cataract," "night," "birth," "anthill," "desire," "Chamomor," "spider," "woman," "pain," "hallucination," "song," "death." From all over the phantom city rise the shrieks, the imprecations, the endearments, laughter, invocations, rising, spreading in the air, forming above the ground a dome of heat and noise.

7

And suddenly the man overlooking the city notices the very place where his soul dwells. He recognizes the street, the house, the room where he was born, where he will die. He thought he was out of reach, 'yet he has become a vendor like the rest. He will take this from Tolstoy, that from Salinger. Then he will manufacture in the back of his shop the merchandise which will bear his name.

There is nothing new, nothing will ever be invented. Only this commerce, the true commerce of the language of men, which develops, parodies itself, lies or tells the truth of feeling, in order to conquer the silence of the other languages. He will discover nothing, will teach nothing to the rest. In the huge living-dead city, all the inhabitants are the same, no one knows more than the others.

In Tel Aviv, Canton, Djakarta, Marseilles, Chicago, the millions of hallucinated ants live together: the great city of literature has no other reasons.

Then, if someday someone finished the last page of Through the Looking-Glass wondering who wrote this book, and why, and where human thought is heading, we can always try to answer:

translated by Richard Howard

translated by Richard Howard

you fo, nothing nouihere

8

The prose of the world

MAURICE MERLEAU-PONTY

Here men have been talking for a long time on earth and yet three quarters of what they say goes unnoticed. A rose, it is raining, it is fine, man is mortal. These are paradigms of expression for us. We believe expression is most complete when it points unequivocally to events, to states of objects, to ideas or relations. For in these instances expression leaves nothing to desire, contains nothing which it does not reveal and thus sweeps us toward the object which it designates. In dialogue, narrative, word-plays, trust, promise, prayer, eloquence, literature, we possess a second-order language, where we only speak about objects and ideas in order to reach someone. The correspondences in this language are internal to its words; it achieves transcendence internally and thus constructs a buzzing and swarming kingdom over nature. Yet we still insist on I wish to acknowledge the kind permission of Madame Merleau-Ponty and the editors of the Revue de Metaphysique et de Morale to publish this extract from the unfinished work of Maurice Merleau-Ponty.

TriQuartedy 9

treating this language as a simple variety among the canonical forms used to enunciate some thing. On this view expression involves nothing more than replacing a perception or an idea with a conventional sign that announces, evokes, or abridges it. Of course, language contains more than just ready-made phrases and it can refer to what has never yet been seen. But how could language achieve this if what is new were not composed of old elements, already experienced, that is, if new relations were not entirely definable through the vocabulary and syntactical relations of the conventionallanguage? A language makes use of a certain number of basic signs, arbitrarily linked to certain key-significations; from the latter it can recompose any new signification and can thus express them in the same language. Finally, a language expresses something because it channels all our experiences into the system of initial correspondences between a particular sign and a particular signification which we acquired when learning the language. The language itself is absolutely clear because not a single thought is left hanging behind the words nor any word behind the pure thought of some object. We all secretly venerate the ideal of a language which in the last analysis would deliver us from language by delivering us to things. We regard language as a fabulous apparatus which makes possible the expression of an indefinite number of thoughts or objects through a finite number of signs so chosen as to recompose exactly everything new that one might wish to say and to bestow upon it the same evidence as the first names of things.

In view of the fact that one does in fact speak and write, it is thought that (like God's understanding) language contains the germs of every conceivable signification and that all our thoughts are destined to be expressed in language; or that every signification which enters man's experience carries within it its own formula, the way the sun, in the minds of Piaget's children, bears its name in its center. Our language recovers in the heart of things the word which made them.

These are not just common-sense attitudes. They predominate in the exact sciences (but not, as we shall see, in linguistics). It is fre-

10

quently repeated that science is a well-formed language. That is also to say that language is the beginning of science and that the algorithm is the mature form of language. Now science attaches to fixed signs clear and precise significations. It fixes a certain number of transparent relations, and to represent them it establishes symbols which in themselves are meaningless and can therefore never say more than they mean conventionally. Having thus protected itself from the shifts in meaning which create error, science is in principle assured at any moment of being able to completely justify its claims through appeal to its initial definitions. Should there ever be a question of expressing relations as a given algorithm not constructed for them, the so-called problems of "another form," it may be necessary to introduce new definitions and new symbols. But if the algorithm is to do its job, if it means to be a rigorous language and to control its moves at every moment, nothing implicit should be introduced into it; all new and all old relations should form one family derivable from a single system of possible relations so that one never means to say more than one does say and no more is said than one means; so that, finally, the sign remains a simple abbreviation of a thought which could at any moment clarify and explain itself. Thus the sole but decisive virtue of expression is to replace the confused allusions which each of our thoughts makes to all the others with precise significations for which we might truly be responsible because their exact sense is known to us. The virtue of expression is to recover for us the life of our thought. Likewise, the expressive value of the algorithm is entirely lodged in the unequivocal relations between the secondary and primitive significations and between the latter and signs that in themselves have no signification, where our thought discovers nothing but what it has put into them.

The algorithm, the project of a universal language, is a revolt against language in its existing state, and a refusal to depend upon the confusions of everyday language. The algorithm is an attempt to construct language according to the standard of truth, to redefine it to match the divine mind, and to return to the very,origin of the history of speech or, rather, to tear speech out of history.

11

The divine speech, or the language we always presuppose as prior to speech, is no longer to be found in present-day languages, scattered throughout history and the world. It is the spiritual word which is the standard of the incarnate word. In this sense, it is the very opposite of the magical belief which puts the word "sun" in the center of the sun. All the same, language was created by God at the beginning of the world; it was sent forth by Him and received by us as a prophecy. Prefigured in God's understanding by the system of possibles which preeminently contains our confused world, language is rediscovered in human thought which in the name of this spiritual model orders the chaos of historical languages. Thus language resembles in every instance the objects and ideas expressed in it. Language is the double of being, and no object or idea can be conceived coming into the world without words.

Mythical or intelligible, there is a place where everything that now exists, or will exist, prepares for being put into words.

In the writer this is a fixed belief. One should always go back to those astonishing words which Jean Paulhan cites from La Bruyere: "Of all the possible expressions which might render our thought there is only one which is the best. One does not always come upon it in writing or talking: it is nevertheless true that it exists." 1 How does he know this? All he knows is that the writer or speaker is first mute, straining toward what he wants to convey, toward what he is going to say. Then, suddenly, a flood of words comes to save this silence and give it an equivalent so exact and so capable of yielding the writer's own thought to him, where he might have forgotten it, that one can only believe it had already been expressed before the world began. Given that language is there, like an all-purpose tool, with its vocabulary, its turns of phrase and form which have been so useful, and that it always responds to our call, ready to express anything, language is regarded as the treasury of everything one might wish to say, as having all our future experience already written into it, just as the destiny of men is written in the stars. All that is required is to come upon the phrase readymade in the limbs of language, to recover the muted language in which being murmurs to us. It may seem that our friends, being

12

who they are, could not be called by any other name, that in naming them we simply deciphered what was called for by eyes of that color, a face like that, that walk-though some are misnamed and all their lives carry a false name or pseudonym (like a wig or mask) In the same way, expression and what is expressed strangely alternate and through a sort of false rebirth make us feel that the word had inhabited the thing from all eternity.

But if men unearth a prehistoric language spoken in things, or if beneath our stammerings there is a golden age of language in which words once adhered to the objects themselves, then communication involves no mystery. I point to a world around me which already speaks, just as I point my finger toward an object which was already in the visual field of others. It is said that physiognomic expressions are equivocal in themselves and that reddening in the face may be taken for pleasure, shame, anger, or passion, according to the context. In the same way, a linguistic expression may arouse nothing in the mind of an observer. For it shows him in silence things whose name he already knows because he is their name. But let us leave aside the myth of a language of things, or, rather, let us take it in its sublime form, as a universal language which contains in advance everything it might have to express because its words and syntax reflect the fundamental possibles and their articulations. The implications are the same. The word possesses no virtue of its own; there is no power hidden in it. It is a pure sign standing for a pure signification. The person speaking is coding his thought. He substitutes his thoughts with a visible or sonorous pattern which is nothing but sounds in the air or ink spots on the paper. Thought understands itself and is self-sufficient; it translates itself in a message which is not its vehicle and only conveys it unequivocally to another mind which can read the message because it habitually attaches the same signification to the respective signs, whether ruled by human conventions or by some divine institution. In any case, we never find among our words any that we have not put there ourselves. Communication is an appearance; it never brings us anything truly new. How could communication possibly carry us beyond our own powers of reflection since the

13

signs it employs could never tell us anything if in the background we did not already have the signification? It may be true that when we watch signals in the night like Fa15rice, or the fast and slow moving letters in a flashing neon sign, we feel we are watching the birth of the news. Something pulsates and comes alive: the thought of man shrouded somewhere in the distance. But, actually, this is only a mirage. If I were not present to perceive the rhythm and pick out the moving letters there would only be a meaningless clicking on and off, like the twinkling of the stars; there would be nothing but lights clicking on and off mechanically. Even the news of a death or a disaster brought to me by telegram is not entirely news; I only receive this news because I already know that deaths and disasters are possible. Certainly, there is something more than just this in the way men experience language. They cannot restrain themselves from a chat with a famous author; they visit him the way people visit Saint Peter's statue. They have a mute faith in the secret virtues of communication. They don't need to be told that news is news; they know that it is no help to have often thought of death so long as one has not learned of the death of a loved one. But the moment they begin to reflect upon language instead of living it they cannot see how one could accord language such power. After all, we understand what is said to us because we know in advance the meaning of the words spoken to us.j We only understand what we already know and never set ourselves any problem that we are not able to resolve. Consider the model of two thinking subjects closed in their signification-between them messages circulate which convey nothing and are only the occasion for each subject to observe what he already knew-and when the one speaks and the other listens their thoughts reproduce one another, but unwittingly and never face to face. Such a theory of language would result, ultimately (as Paulhan says), "in everything happening between them as though language had not existed." 2

II

Indeed, one of the effects of language is to efface itself to the t Marginal note: Describe the contrast between meaning which is at hand and meaning which is in the process of creation.

14

extent that expression comes across. As I become engrossed in a book I no longer see the letters on the page nor do I recall turning the page. Through all the letters and on every page I continually seek and find the same incidents, the same events even to the point of not noticing the light or perspective in which they are presented. Similarly, in naive perception I see a man over there who has a man's shape although I could only say what his "apparent size" was by closing one eye, fragmenting the visual field, destroying the background, and projecting the whole spectacle onto an illusory plane in which every fragment is compared to some close object such as my pencil and thus assigned a specific size. It is impossible to make the comparison with both eyes open. Then my pencil is a near object; things far away are far away and between them and my pencil there is no common reference. Or, rather, if I succeed in making the comparison for one object in the visual field I cannot manage it for the rest of them at the same time. The man over there is neither one inch nor five feet tall; he is a man in the distance. His height is there like a meaning which lies within him but not like an observable trait, for I am totally unaware of any signs by which I might spot it. In the same way, a great book, a play, or a poem is there in my memory en bloc. I can, of course, by recalling what I read or heard, remember a particular passage, word, situation, or shift in the action. But when I do this, I am dealing with a recollection which is unique and retains its evidence independently of these details; for it is as unique and as inexhaustible as the sight of an object. When a conversation involves me and, for once, gives me the feeling of really talking to someone, I forget none of it and the next day I could relate it to anyone interested in it. But if it really excites me like a book I do not have to recollect a series of quite distinct aspects of it. I still have it in my hands like something I hold, wrapped up in my memory; and all I have to do is to return to the incident for everything-the interlocutor's gestures, his smiles, his hesitations and his words-to reappear in their proper place. When someone-an author or a friend-succeeds in expressing himself, the signs are immediately forgotten; all that re-

15

mains is the meaning. The perfection of language lies in its capacity to pass unnoticed.

But therein lies the virtue of language: it is a language which throws us toward the things it signifies. In the way it works language hides itself from us. Its triumph is to efface itself and to take us beyond the words to the author's very thoughts so that we imagine we are engaged with him in a wordless meeting of minds. Once the words have congealed they remain fixed to the page as signs whose very power to project us far away from themselves makes it impossible for us to believe they are the source of so many thoughts. Nevertheless, while reading it is these signs on the page which speak to us, suspended in the movement of our eyes and our feelings which they in turn convey and project unerringly. Together with these signs we paired the blindman and the paralytic so that they, thanks to us, and we, thanks to them, became speech rather than language; we became at the same time a voice and its echo.

We might say that there are two languages. First, language as an afterthought, or language as an institution, which effaces itself in order to yield the meaning which it conveys. Second, the language which creates itself in its expressive acts, which sweeps me on from the signs toward meaning-prosaic language and poetic language (Ie langage parle et le langage parlant).

Once I have read the book it acquires a unique and undeniable existence quite apart from the words on the pages. It is with reference to the book that I discover the details I am looking for. One could even say that while I am reading it is always with reference to the whole, as I grasp it at any point, that I understand each phrase, each shift in the narrative or delay in the action, to the point that, as the reader, I feel, in Sartre's words, as though I could have written the book from start to finish." But, really, that is an afterthought. In reality, I could not have written the book which I love so much. In reality, one has to read first and then, as Sartre again puts it so well, it "catches" 4 like a fire. I bring the match near, I light a flimsy piece of paper, and, behold, my gesture receives inspired help from the things around, as if the chimney

16

and the dry wood had been waiting for me to set the light, or as though the match had been nothing but a magic incantation, a homeopathic call responded to beyond all imagination. In the same way, I start to read idly, giving it hardly any thought, when, suddenly, a few words move me, the fire catches, my thoughts are ablaze, there is nothing in the book which I can overlook, and the fire feeds off everything in my reading. I am receiving and giving in the same gesture. I have given my knowledge of the language; I brought along what I already knew about the meaning of the words, the phrases, and the syntax. I have also contributed my whole experience of others and everyday events, with all the questions it left in me, the situations left open and unsettled, as well as those with whose ordinary resolution I am all too familiar. But the book would not interest me so much if it only told me about things I already know. It makes use of everything I contributed in order to carry me beyond it. With the aid of signs agreed upon by the author and myself because we speak the same language, the book made me believe that we already shared a common stock of well-worn and readily available significations. Then, imperceptibly, it varied the ordinary meaning of the signs and like a whirlwind they swept me along toward the other meaning with which I was going to connect.

Before I read Stendhal, I already know what a rogue 'is and so I can understand what he means when he says that Rossi the revenue man is a rogue. But when Rossi the rogue begins to live, it is no longer he who is a rogue; it is a rogue who is the revenue man Rossi. I have access to Stendhal's story through the commonplace words he uses, but in his hands these words undergo a secret twist. The cross-references multiply and more and more arrows point in the direction of a thought I have never encountered before and perhaps never would have met without Stendhal. At the same time, the contexts in which Stendhal uses common words reveal even more majestically the new meaning with which he endows them. I get closer and closer to him until in the end I read his words with the very same intention that he gave to them. One cannot mimic a person's voice without assuming something

17

of his physiognomy and even his personal style. In the same way, the author's voice results in my assuming his thoughts. Common words and familiar events, like jealousy or a duel, which at first immerse us in the everyday world, suddenly function as emissaries from the world of Stendhal. Although the final effect is not for me to dwell within Stendhal's lived experience, it does at least bring me into the imaginary self and the internal dialogue Stendhal held with it for fifty years, while he was coining it in his works. It is only then that the reader or the author can say with Paulhan, "In this light at least, I have been you." 5

I create Stendhal; I am Stendhal while reading him. But that is because first of all he knew how to bring me to dwell within him. The reader's sovereignty is only imaginary, given that he draws all his force from that infernal machine called the book, the apparatus for making significations. The relations between the reader and the book are like those loves in which one partner dominates at first because he is more proud or more temperamental, and then that gives way, and it is the other, more wise and more silent, who rules. The expressive moment occurs where the relationship reverses itself, where the book takes possession of the reader.

Prosaic language is the language the reader brings with him; it is the stock of accepted relations between signs and familiar significations without which he could never have begun to read; it constitutes the literature of the language; thus it is also Stendhal's work once it has been understood and added to the cultural heritage.

But poetic language is the call of the book to the unprejudiced reader; it is the operation through which a conventional arrangement of signs and significations gets altered and in turn transfigures each internal element so that in the end a new signification is secreted. It is the effect through which Stendhal's own language comes to life in the reader's mind henceforth for his own use. Once I have acquired this language, I can easily delude myself that I could have understood it by myself. That is because it has transformed me and made me capable of understanding it.

18

In afterthought, everything happens as though in effect language had not existed. Moreover, I flatter myself with being able to understand Stendhal from my own thoughts and the most I do is grudgingly to concede him a part of the system, like those who repay old debts by borrowing from their creditor. Perhaps in the long run that will be true. Maybe, thanks to Stendhal, we shall transcend Stendhal. But that will be because he has ceased to speak to us; it will be because his writings have lost their power of expression for us. As long as language is functioning authentically it is not a simple invitation to the listener or reader to discover in himself significations that were already there. It is rather the trick whereby the writer or orator, touching on these significations already there in us, makes them yield strange sounds. At first these sounds seem false or dissonant. But because the writer is so successful in converting us to his system of harmony we adopt it henceforth as our own. From then on, between the writer and ourselves, there remain only the pure relations of spirit to spirit. But all this began through the complicity of speech and its echo, or, to use Husserl's lively phrase with regard to the perception of others, through the coupling of language.

Reading is an encounter between the glorious and impalpable incarnations of my own speech and the author's speech. As we said before, what happens is that reading projects us beyond our own thoughts toward the other person's intention and meaning, just as perception takes us to things themselves across a perspective of which we become aware only after the event. But my power of transcending myself through reading is mine in virtue of being a speaking subject, capable of linguistic gesticulation, just as my perception is possible only through my body. The patch of light which falls in two different points on both my retinas is seen by me as a single distant spot because I possess a look and a mobile body which confront external messages with a viewpoint in which the spectacle is organized, arrayed, and equilibrated. Similarly, I cut straight through the scribbling to the book because I have built up in myself this strange expressive organism which can not only interpret the conventional meaning of the book's words and 19

techniques but can even allow itself to be transformed by the book and endowed by it with new organs. One can have no idea of the power of language until one has taken stock of that working or constitutive language which emerges when the constituted language, suddenly off-center and out of equilibrium, reorganizes itself to teach the reader-and even the author-what he never knew how to think or say. Language leads us to the things themselves to the precise extent that it is signification before having a signification. If we concede language only its secondary function, it is because we presuppose the first as given. It is because we make it depend upon an awareness of truth whereas it is actually the vehicle of truth. In this way we are putting language before language.

We shall attempt elsewhere t to develop these remarks more fully in a theory of expression and truth. It will be necessary then to clarify or explicate the experience of speech in terms of what we know from the sciences of psychology, behavior disorders, and linguistics. It would also be necessary to consider those philosophical positions which claim to resolve the problem of expression by treating it as a species among the pure acts of signification which philosophical reflection makes perfectly clear to us. But that is not our task at present. We simply mean to initiate such a study by trying to illustrate the function of expression in literature. We reserve a more complete explanation for another work, as mentioned above. However, it is, of course, unusual to begin a study of expression with, say, its most complex function and to proceed from there to the simpler ones. We therefore have to justify the procedure by making it clear that the phenomenon of expression, as it appears in literary speech, is no curiosity or introspective fantasy marginal to the philosophy or science of language. It has to be shown that the phenomenon of expression belongs both to the scientific study of language and to literary experience and that these two studies overlap. How could there

t For references to Merleau-Ponty's projected writings see "An Unpublished Text by Maurice Merleau-Ponty: A Prospectus of His Work," in The Primacy of Perception, edited, with an Introduction, by James M. Edie, Evanston, Northwestern University Press, 1964. Translator.

20

be a division between the science of expression, provided it conceives its subject as broadly as it should, and the lived experience of expression, where it is lucid enough? Science is not devoted to another world, but to our own; in the end it refers to the same things that we experience in living. Science constructs everyday objects by combining pure ideas defined the same way that Galileo constructed the fall of a body on an inclined plane from the ideal case of free fall. Ultimately, however, ideas are always subject to the constraint of illuminating the opacity of objects, and the theory of language must gain access to the experience of speaking subjects. The idea of a possible language is shaped upon and assumes the actual language we speak and which we are. Linguistics is nothing but a rigorous and conceptual way of clarifying in terms of all the other facts of language the speech which declares itself in us and to which, even in the midst of our scientific work, we are still attached like an umbilical cord.

Some would like to break this tie. They would like to get away from the confused and annoying situation of a being who is what he is talking about. They would like to look at language and society as if they had never been caught up in it, to adopt a bird's-eye view or a divine understanding; in other words, they would like to be without a point of view. There are two ways, one Platonist and the other nominalist, of talking about a language without words, or at least so that the significations of the words used, once redefined, never exceed what one invests in them and expects from them. The first is Husserl's "eidetic of language" or "pure grammar," which he outlined in his early writings, and the other is a logic concerned only with the formal properties of significations and their rules of transformation. On this view, those words or formulae which resist analysis, by definition, have no meaning for us; furthermore, no problem is raised by what is non-sense, a question being merely the expectation of a yes or no which in either case results in a proposition. The proposal is to create a system of precise significations which would translate everything in a language that is clear and thus constitute a model to which language can add only error and confusion. Such a

21

standard would provide a measure of any individual's power of expression. In the end the sign would function purely as an index without any admixture of signification But no one dreams any more of a logic of invention, and even those who think it is possible to express by means of an arbitrary algorithm every well-formed proposition do not believe that this purified language would exhaust everyday language any more than the latter could absorb it. For how should we attribute to non-sense everything in everyday language which goes beyond the definitions of the algorithm or of a "pure grammar" when it is precisely in this alleged chaos that new relations will be found which make it both necessary and possible to introduce new symbols?

Once the new relation has been fitted in and order temporarily reestablished, there can be no question of making the system of pure logic and pure grammar self-subsistent. It is known that this system is always on the verge of signification. By itself it never signifies anything, since everything it expresses is already abstracted from a ready-made language and from an omnitudo realitas which in principle it cannot embrace. Reflection cannot close itself off from the significations it has recognized nor can it make them the standard of meaning. It cannot treat speech and everyday language as simple instances of itself because ultimately it is through them that the algorithm intends to say something. There is at least one question which is not merely a provisional form of the proposition-and it is this question which the algorithm tirelessly puts to factual thought. There is no special question about being for which there is not a corresponding yes or no in being which settles it. But the question of knowing why there are questions, and how there come to be those non-beings who do not know but would like to know, cannot find a response in being.

Philosophy is not the passage from a confused world to a universe of closed significations. On the contrary, philosophy begins with the awareness of a world which consumes and destroys our established significations but which also renews and purifies them. To say that self-sufficient thought always refers to a thought en-

22

meshed in language is not to say that thought is alienated or that language cuts off thought from truth and certainty. We must understand that language is not an impediment to thought and that there is no difference for it between self-destruction and selfexpression. In its live and creative state, language is the gesture of renewal and recovery which unites me with myself and others. We must learn to reflect on consciousness in the hazards of language as quite impossible without its opposite.

In the "I speak" psychology rediscovers for us an operation, a dimension, and relations which do not belong to thought in the ordinary sense. "I think" means there is a certain locus called "I" in which action and awareness of action are not different, in which being confounds itself with its own awareness of itself and thus no intrusion from outside is even conceivable. Such an "I" could not speak. He who speaks enters into a system of relations which presupposes his presence and at the same time makes him open and vulnerable. Certain patients believe that someone is talking inside their head or in their body, or that someone else is talking when it is themselves who are pronouncing or at least mouthing the words. Whatever one's view of the relation between healthy and pathological behavior, it is necessary that speech be such in its normal functioning that its maladies remain a permanent possibility. There must be something in the very heart of speech which makes it susceptible to these pathologies. If one says that the patient is experiencing bizarre or confused feelings in his body, or, as they say, "problems of coenesthesia," one is simply inventing an entity or phrase which instead of explaining the problem merely baptizes it. On closer inspection, the so-called "problems of coenesthesia" are seen to have widespread ramifications, and a change in them also involves a change in our relations with others. I am speaking and I think that it is my heart which is speaking; I am speaking and I think it is someone else speaking to me or in me, or even that someone knew before I said it what I was going to say-all these phenomena which are so often associated must have something in common. The psychologists discover the common factor in our relations with others. "The

23

patient feels as though there is no boundary between himself and others. This leads us to conclude that strictly speaking what is involved is the loss of the distinction between action and passivity, between the self and others." 6

These speech defects are thus related to disturbances of the lived body and interpersonal relations. How are we to understand this relationship? It arises because speech and understanding are moments in the unified system of self-other. The substratum of this system is not a pure "I" (which would never see anything more than an object of its own reflection placed before itself) but rather an "I" endowed with a body which reveals its thoughts sometimes to attribute them to itself and at other times to impute them to someone else. I accommodate to the other person through my language and my body. Even the distance which the normal subject puts between himself and others as well as the clear distinction between speaking and listening are modalities of the system of embodied subjects. Verbal hallucination is another modality of the same system. It can happen that the patient believes someone is speaking to him when in fact it is himself speaking because the principle underlying this aberration is part of the human situation. As an embodied subject I am exposed to the other person, just as he is to me, and I identify myself with the person speaking before me.

Speaking and listening, action and perception are only quite distinct operations for me when I reflect upon them. Then I analyze the spoken words into "motor influxes," or "articulated elements," understanding them as auditory "sensations and perceptions." When I am actually speaking I do not first figure the movements involved. My whole bodily system concentrates on finding and saying the word in the same way that my hand moves toward what is offered to me. What is more, it is not even the word or phrase that I have in mind but the person. I speak to him as I find him, with a certainty that at times is prodigious. I use words and phrases he can understand or to which he can react. If I have any tact, my words are both a means of action and feeling; there are eyes at the tips of my fingers. When I am listening, it is not necessary to say that I have an auditory perception of the articulated

24

sounds but that the conversation pronounces itself within me. It summons me and grips me; it develops and inhabits me to the point that I cannot tell what comes from me and what from it.

Whether speaking or listening, I project myself into the other person, I introduce him into my own self and our conversation resembles a struggle between two athletes in a tug-of-war. The speaking "I" abides in its body. Rather than imprisoning it, language is like a magic machine for transporting the "I" into the other person's perspective. "There is in language, a two-way action: one which is induced by our own presence and another which we bring about in the socius by regarding him as being outside ourselves." 7 Language continuously reminds me that the "incomparable monster" which I am when silent can, through speech, be brought into the presence of another myself who recreates every word I say and sustains me in reality as well. There can only be speech (and in the end personality) for an "I" which contains the germ of depersonalization. Speaking and listening not only presuppose thought but what is even more essential, for it is practically the foundation of thought-the capacity to allow ourselves to be pulled down and rebuilt again by the other person before us, by others who may come along, and in principle by anyone. The same transcendence which we found in the literary uses of speech can also be found in everyday language. This transcendence arises the moment I refuse to content myself with the established language, which in effect is a way of silencing me, and as soon as I truly speak to someone. Formerly, psychologists regarded language as merely a series of images, a verbal hallucination or a purely imaginary exuberance. Their critics regarded language as the simple product of a pure mental function. We now regard language as the reverberation of my relations with myself and with others.

It is natural, after all, that the psychologist's analysis of man's speech should emphasize the way we express ourselves in language. But that does not prove that that is the primary function of speech. If I am to communicate with another person I must first have available a language which names the things he and I can see. The

2S

psychologist's account takes this primordial function for granted. The psychologist's account, as well as a writer's reflections, would very likely seem superficial if instead of considering language as a medium of human relations, we looked at it as the expression of objects or in terms of its entire history, apart from its everyday uses, as though we could survey it the way a linguist does. It is here that we encounter one of the paradoxes of science, namely, that science itself is the surest road to the speaking subject.

Let us take as a text the famous page from Valery where he expresses so well what is overwhelming for man, whose thought is tied to history and to language. "What is reality?, the philosopher asks; and What is freedom? He puts himself in a state of ignorance concerning the origins of these nouns, which are indistinguishably metaphorical, social, and statistical, so that as they slide toward the undefinable the philosopher can produce the most profound and delicate compositions according to his fancy. The philosopher would not be satisfied to find his question answered simply by the history of a word through the ages. For the detailed story of the mistakes, the figurative uses, the number of incoherent and peculiar locations through which a poor word becomes as complex and mysterious as an individual and arouses the same almost anxious curiosity as the life of an individual. The word conceals itself from any precise analysis; it is an accidental creature with simple needs, an old makeshift invented in the mixing of peoples. Finally, it acquires the most noble destiny of arousing all the powers of interrogation and capacities for response in the wondrously attentive mind of the philosopher." 8

It is quite true that thought involves first of all thought about words. But Valery believed that words contain nothing but the sum of misunderstandings and misinterpretations which have brought them from their proper meaning to their figurative meaning. Thus he believed that man's philosophical questioning would cease once he took note of the hazards which have joined contradictory meanings to the same word. But that is again conceding too much to rationalism. It amounts to stopping halfway on the road to an understanding of contingency. Behind his nominalism, there is an

26

extreme confidence in knowledge. For Valery at least believed in the possibility of a history of words capable of completely analyzing their meaning and eliminating the problem raised by the ambiguity of words as a false problem. Yet the paradox is that even if the history of language contains too many hazards to permit a logical development, it nevertheless produces nothing for which there is not a reason. Even if every word, according to the dictionary, has a great number of meanings, we go straight to the one which fits a given sentence (and if there remains some ambiguity, we find a further expression for it). Finally, there is the paradox that there is meaning for us although we inherit words which are so worn and exposed by history to the most imperceptible changes of meaning. We speak and we understand one another, at least at the start. If we were enclosed in the contradictory meanings which words acquire historically, we would not even have the idea of speaking; the need for expression would be undermined. Thus language is not, while it is functioning, the simple product of the past it carries with it. The past history of language is the visible trace of a power of expression which it in no way invalidates. Moreover, since we have abandoned the fantasy of a pure language or an algorithm concentrating in itself the power of expression and only lending it to historical languages, we must find in history itself, with all its disorder, that which nevertheless makes possible the phenomenon of communication and meaning. Here the findings of the sciences of language are decisive. Valery restricted himself to the option of the philosopher who believes he can capture pure significations through reflection and so stumbles over the misinterpretations built up in the history of words. Nowadays psychology and linguistics are revealing that it is possible to forsake a timeless philosophy without falling into irrationalism.

translated by Iohn O'Neill

27

1. Jean Paulhan, Les Fleurs de Tarbes, Paris, N.R.F., 1942, p. 128.

2. Les Fleurs de Tarbes, p. 128.

3. Jean-Paul Sartre, What Is Literature? translated by Bernard Frechtman, New York, Harper and Row, 1965.

4. Ibld., p. 37.

5. Les Fleurs de Tarbes, p. 133.

6. Henri WaHon, Les origines du caractere chez l'enjant, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1962, pp. 135-136.

7. Daniel Lagache, Les hallucinations verbales et la parole, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1934, p. 139.

8. Paul Valery, Variete Ill, Paris, Gallimard, 1936, pp. 176-177.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961) was, together with Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, a founder of French existentialism after the Second World War. His chei d'oeuvre, The Phenomenology 01 Perception, influenced a generation of philosophers and acquainted French thinkers with the phenomenological method as it had been inaugurated by Husserl in pre-war Germany. The appearance of this book in 1945 marks what is now called the beginning of the "second" (or existential) school of phenomenology, and it earned its author the distinction of being the youngest man ever to be elected to the chair of philosophy at the College de France. He launched Les Temps Modernes together with Sartre as his co-editor and remained its political editor until his final break with Sartre in 1954. His final writings were concerned with the philosophy of language and literature, as well as the arts in general. La prose du monde, published posthumously in 1969 from notes left incomplete at his death, is the culmination of his later thought. It will appear in English translation by John O'Neill from the Northwestern University Press in the near future, in the Northwestern University Studies in Phenomenology and Existential Philosophy. The article in this issue represents approximately half the original text of the Introduction to La prose du monde.

Notes

28

Language and embodiment: an afterword JOHN O'NEILL

The remarks which follow are intended to provide some understanding of the philosophical background to Merleau-Ponty's thoughts on language in the unfinished essay, "The Prose of the World." This translation will be included in a forthcoming collection of essays by Merleau-Ponty, entitled The Prose of the World, to be published in the Northwestern University Studies in Phenomenology and Existential Philosophy.

Merleau-Ponty's approach to the phenomenology of language presupposes and illustrates his conceptions of intersubjectivity and rationality and the fundamentals of his philosophy of perception and embodiment.' The phenomenological approach to language is ultimately an introduction to the ontology, or to the poetry of the world. It is a reflection upon our being-in-the world through embodiment which is the mysterious action of a presence that can be elsewhere. The philosophical puzzles of how we are in the world (ontology) or how the world can be in us (epistemology), which have dictated quite particular analyses of the logic of language and thought, are transcended in the phenomenological conception of embodiment as a corporeal intentiality. I reach out to my pen when I am ready to write without consciously thematizing either the pen as something to write with or the distance

TriQuarterly 29

between myself and where the pen lies. My hand is already looking for something to write with and, as it were, scans the desk for a pen or pencil which is there "somewhere," where it usually is or where I just put it down, so that it too seems to guide my hand in its search. But I can only look for the pen because in some sense I have my hand on it. If writing were painful to me or if I were sensible of having to write to someone I did not care for, or for whom I had only bad news, I might "put off" writing because I do not "feel" like writing. In this case, my pen there on the desk does not invite me to pick it up except with a painful reminder of my relations with someone else. Thus the structure of the experience of writing is there in my fingers, in the pen and my relations to the person to whom I am writing. It is neither a structure which I "represent" to myself, which would neglect the knowledge in my fingers, nor is it a simple "reflex" stimulated by my pen, which would overlook my relations to the person I am writing. The structure of writing is an "ensemble" in which the elements function only together and whose expressive value for me plays upon my relation to myself and others.

In the same way, speech is a capacity I acquire for communication which arises not just from the expressive values of the words when joined with due respect for logic and syntax but also from my experience of the world, other persons, and the language I inhabit. Linguistics 2 as a science of language treats language as a natural object and logic treats it as an entirely artificial object. The linguistic conception of language presents language as a universe from which man is absent and with him the consequences of time and the disclosure of nature in magic, myth, and poetry. In logic man's power over language which is ignored in linguistics is raised above magic and poetry to the creation of a mathesis universalis which sloughs off all historical languages and purifies the word once and for all. The linguistic conception of the relation of language to meaning breaks down for the very reason that a language tells us nothing except about itself." The problems of discrimination, quantification, and predictability which concern the statistical treatment of language are independent of the semantic value of the information being processed. From the standpoint of semantics it is words not phonemes which carry meaning. Furthermore, words have meaning on their own account, especially such words as liberty or love, but also as elements in a whole which is not just the phrase or sentence but the entire "mother" language. To know the meaning of a word is not just a question of an appropriate phonetic motivation. It involves familiarity with an entire universe of meaning in which language and society interpenetrate the lived meaning of words.

30

Language like culture is often regarded as a tool or an instrument of thought. But then language is a tool which accomplishes far more and is far less logical than we might like it to be. It is full of ambiguity and in general far too luxuriant for the taste of positivist philosophers. As a tool language seems to use us as much as we use it; and in this it is more like the rest of our general culture, which we cannot use without inhabiting it. Ultimately, language like culture defeats any attempt to conceive it as a system capable of revealing the genesis of its own meaning. This is because we are the language we are talking about. That is to say, we are the material truth of language through our body, which is a natural language. It is through our body that we can speak of the world because the world in tum speaks to us through the body. "In my book the body lives in and moves through space and is the home of a full human personality. The words I write are adapted to express first one of its functions then another. In Lestrygonians the stomach dominates and the rhythm of the episode is that of the peristaltic movement." "But the minds, the thoughts of the characters," I began. "H they had no body they would have no mind," said Joyce. ''It's all one. Walking towards his lunch my hero, Leopold Bloom, thinks of his wife, and says to himself, 'Molly's legs are out of plumb.' At another time of day he might have expressed the same thought without any underthought of food. But I want the reader to understand always through suggestion rather than direct statement." 4

Since human perception falls upon a world in which we are enclosed our expression of the world in language and art can never be a simple introduction to the prose of the world apart from its poetry. We express the world through the poetics of our being-in-the world, beginning with the first act of perception which brings into being the perspective of form and ground through which the invisible and ineffable speaks and becomes visible in us. All other cultural gestures are continuous with the first institution of human labor, speech and art through which the world takes root in us. In this sense, we may consider talk, reading, writing, and love as institutions, that is to say, polarizations of the established and the new. We may, for example, distinguish between the institution of language as an objective structure studied by linguistics and speech, which is the use-value language acquires when turned toward expression and the institution of new meanings. We start by reading an author, leaning at first upon the common associations of his words until, gradually, the words begin to flow in us and to open us to an original sound which is the writer's voice borrowing from us an understanding that until then we did not know was ours to offer. Yet it comes only from what we ourselves brought to the book, our knowledge of the language, of ourselves, and life's questions which we share with the author. Once we have acquired the author's style of thinking

31

our lives interweave in a presence which is the anticipation of the whole of the author's intention and its simultaneous recovery which continues the understanding.' In talking and listening to one another we make an accommodation through language and the body in which we grow older together. We encroach upon one another from each other's time, words, and looks what we are looking for in ourselves. In this way our mind and self may be thought of as an institution which we inhabit with others in a system of presences which includes Socrates or Sartre just as much as our friends in the room.

"When I speak or understand, I experience that presence of others in myself or of myself in others which is the stumbling-block of the theory of intersubjectivity. I experience that presence of what is represented which is the stumbling-block of the theory of time, and I finally understand what is meant by Busserl's enigmatic statement, 'Transcendental subjectivity is intersubjectivity.' To the extent that what I say has meaning, I am a different 'other' for myself when I am speaking; and I understand, I no longer know who is speaking and who is listening." 6

Through language I discover myself and others, in talking, listening, reading, and writing. It is language which makes possible that aesthetic distance between myself and the world through which I can speak about the world and the world in tum speak in me. Our thoughts and purposes are embodied in bodily gestures which in the act of expression structure themselves toward habit and spontaneity, and thus we make our world.

Finally, what we may learn from Merleau-Ponty's approach to the phenomenology of language is that expression is always an act of selfimprovisation in which we borrow from the world, from others, and from our own past efforts. Language is the child in us which speaks of the world in order to know who he is.

Notes

1. John O'Neill, "Perception, Expression and History in the Philosophy of Maurice Merleau-Ponty," Social Research, Vol. 34, No.1, Spring 1967, pp. 47-66.

2. Merleau-Ponty's conception of linguistics depends very much upon his own interpretations of Husserl's views on the ontogenesis of speech and his interpolation of a social psychology to complement Saussure's linguistics. Cf. Maurice Lagueux, "MerIeau-Ponty et la linguistique de Saussure," Dialogue, Canadian Philosophical Review, Vol. IV, No.3, 1965, pp. 351-364.

3. For the relations between language, linguistics, logic, and semantics see Mikel Dufrenne, Language and Philosophy, translated by Henry B. Veatch with a Foreword by Paul Henle, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1963.

4. Frank Budgen, James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1960, p. 21.

5. Maurice MerIeau-Ponty, "On the Phenomenology of Language," Signs, translated by Richard C. McCleary, Evanston, Northwestern University Press, 1964.

6. Signs, p. 97.

32

Abecedarium culturae: structuralism, absence, writing

EDWARD w. SAID

Holoiemes: The deer was, as you know, sanguis, in blood; ripe as the pomewater, who now hangeth like a jewel in the ear of caelo, the sky, the welkin, the heaven, and anon falleth like a crab on the face of terra, the soil, the land, the earth. -Love's Labor's Lost, IV, ii

No reader of Paradise Lost is ever likely to have experiences of the kind undergone by Adam; which is why Dr. Johnson insisted on the poem's "inconvenience, that it comprises neither human actions nor human manners." Preeminently an imaginative vision, rather than a true record of actual events, Paradise Lost is conceded by Dr. Johnson to be the great poem of a man who "saw Nature, as Dryden expresses it, through the spectacles of books." Every inconvenience we normally feel when we find language wanting in its ability to convey direct experience directly, is, in such a poem as Milton's, especially acute. During Book VII, for example, Raphael is sent to inform Adam of the events in heaven, events that include the indescribable and "Immediate acts of God, more swift/Than time or motion." From the beginning, therefore, lan-

TriQuarterJy 33

guage is not adequate for its intention. Raphael continues to hedge his recital.

to recount almighty works

What words or tongue of seraph can suffice, Or heart of man suffice to comprehend?

He goes on, the difficulties notwithstanding, because such commission from above

I have received, to answer thy desire Of knowledge within bounds; beyond abstain

To ask, not let thine inventions hope Things not revealed, which the invisible king, Only omniscient, hath suppressed in night, To none communicable in earth or heaven: Enough is left besides to search and know.

The truth is at about five removes from the reader. Originally suppressed in night, suppressed once again by Raphael (who as an angel knows more than Adam), suppressed still further because Adam after all is the original man from whose priority we have all fallen, suppressed another time by Milton's use of English to convey the conversation in Eden, and finally suppressed by a poetic discourse to which we can attain only after a mediated act (of reading a seventeenth century epic)-the Truth is actually absent. Words represent words which represent other words, and so on. Whatever sense we make of Milton is provided by our use of accepted conventions, or codes, of meaning that allow us to sort out the words into coherent significance. We may take comfort in Raphael's assertion that there had been a Word, a primal unity of Truth, to which such puzzles as "meaning" and "reference" are impertinent. Yet, on the other hand, we have only his word for it; not a thing certainly, and not more than an assertion that depends on other words and an accepted sense-giving code for support.

Milton's theme is loss, or absence, and his whole poem represents and commemorates the loss at the most literal level. Thus Milton's anthropology is based on the very writing of his poem, for only because man has lost does he write about it, must write about it, can only write about it, "it" here being what he cannot really name except with the radical qualification that "it" is only a name, a word. To read Paradise Lost is to be convinced, in Rus-

34

kin's phrase, of the idea of power: by its sheer duration and presence, and by its capacity for making sense despite the absence at its center, Milton's verse seems to have overpowered the void within it. Only when one questions the writing literally does the obvious disjunction between words and reality become troublesome. Words are endless analogies for each other. Outside the monotonous sequence of analogies, we presume, is a primeval Origin, but that, like Paradise, is lost forever. Language is a sequel to or supplement of the beginning event, man's Fall: language is one of the actions that succeeds the lost Origin. Human discourse, like Paradise Lost, lives with the memory of origins long since violently cut off from it: having begun, discourse can never recover its origins in the unity and unspoken Word of God's Being. This, we know, is the human paradigm incarnated in Paradise Lost.

Dr. Johnson's reservations about the poem do not prevent him from reading it; the common-sense difficulties he experiences (the poem's length, the lack in it of human interest) are to him adjuncts to, examples of, Milton's intransigence that trouble Milton's poetic achievement. When, however, Milton's great poem is read with the disquieting sense that what we are watching in the poem is an "ontology of nothingness" l-an infinite regress of truths permanently hidden behind words-then we accept the governing awareness of French structuralism. For while it is, I think, inappropriate to force an ideological unity upon the structuralists, it is apt to see them the way they very often see others, as inhabiting and constituting a certain level of consciousness with its own sense of difference from others, its own idioms, patterns, ambitions, and narrative rhythm.

Of them all, it is Michel Foucault who has become, in Roland Barthes' words, the very thing his works describe: 2 a consciousness awakened to the troubled conditions of modern knowledge. 3 Foucault is, to use Blackmur's phrase, a technique of trouble. As history is gradually unveiled in Foucault's work, we do not watch an easy chronicle of events but a succession of functional conditions that enable the existence not only of knowledge, but of man himself: 4 hence the subtitle "an archaeology of human sciences" to 3S

Les Mots et les choses. Permanently hampered by language, which is the first, and in a sense the last, instrument at its disposal, Foucault's job of getting to the bottom yields only the repeated and much-modulated assertion that man is a temporary interruption, a figure of thought, of the already-begun (le deja commence). Any human investigation (and here the relevance of Wittgenstein's later work is crucial) is actually bound up in the nature of language. The interpretation of evidence, for example, is exegesis. But when we ask the question "exegesis of what?" we commit ourselves totally to a perpetual series of the preposition 0/; the modern form of criticism, according to Foucault, is philology as an analysis of what is being said in the depth of the discourse." Just as there is no beginning to the process of exegesis, there is also no end:

In the sixteenth century, interpretation went from the world (things and a text at the same time) to the divine Word which was deciphered in the world; our Interpretation, the one which in any case has been ours since the nineteenth century, goes from men, from God, from knowledge or chimeras, to the words that make them aU possible; and what is discovered is not the sovereignty of a primal dis· course but the fact that before the least of our utterances, we have already been dominated and paralyzed by language.s

The drama of Foucault's work is that he is always coming to terms with language as both the constricting horizon and the energizing atmosphere within and by which all human activity must be understood. Two of Foucault's major works (Histoire de fa folie a l'age classique and Les Mots et les chases) describe respectively how language has permitted the social discriminations of "otherness," and the cognitive connections between the orders of "sameness"; in the former work it is madness, isolated in a silence outside rational language, that is made by society to carry the weight of an alienated "otherness," and in the latter work it is through the powers of language that words are made into a universal collection of signs for everything. As with most of the structuralists Foucault must presume a conceptual unity-variously called an epistemological field, an epistemological unity, or episteme-that anchors and informs linguistic usage at any given time in history; yet to the structuralists' credit it must also be said that the presumption is often made with no attempt to palm it off as anything more than a

36

practical assertion, as a working hypothesis. Not in Foucault's case however. "In a culture, and at a given moment," he writes in Les Mots et les chases, "there is never more than one episteme that defines the conditions of possibility of all knowledge." 7 One of the various chores this univocal assertion is made to perform is, as Steven Marcus has remarked," that it gives license to Foucault's literal faith in an era before the modem dissociation of sensibility. For according to Foucault, language in the Renaissance was intimately connected with things; words were believed to be inherent in the script of an ontological discourse (God's Word) that only required reading for the guarantee of their meaning and truth. Words existed inside Being: they reduplicated it: they were its signature, and man's decipherment of language was a direct, whole perception of Being.

Foucault's brilliant analyses of Don Quixote and Velasquez' Las Meninas show how the intricate system of resemblances, by which things were ultimately linked to a divine Origin, began to break down: Don Quixote in his madness is unable to find the creatures of his reading in the world, Velasquez' magistral painting focuses outward and away from the canvas to a point its composition requires but does not contain. The representative space of language has become, by the eighteenth century, an ordered film, a transparency through which the continuity of Being can shine. Thus, "the essential problem for classical [or eighteenth century] thought is lodged in the rapports between the name and order: to discover a nomenclature that was also a taxonomy, or to establish a system of signs that were transparent to the continuity of Being." 9 When words lose the power to represent the connections between them-that is, the power to refer not only to the objects with which the words point, but also to the system that connects objects to each other in a universal taxonomy of existence-then we enter the modern period. Not only can the center not hold, but also the network around it begins to lose its cohesive power.

It is when, in his two major historical books and in his archaeology of clinical observation, Foucault embarks on a discussion of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that it becomes apparent

37

how much his vision of history preceding the modern age is projected back from his apprehension of the contemporary. For like every one of the structuralists, Foucault is obsessed with the inescapable fact of ontological discontinuity. In language, for example, "the thing being represented falls outside of the representation itself"; 10 thus the signifying power of language far exceeds, indeed overwhelms, what is being signified. Another example: the emergence of the idea of man (whose advent Foucault associates exclusively with the early nineteenth century) coincides with the breakdown in the representative power of language. Man therefore is what essentially resists language; he becomes what Foucault calls an "empirico-transcendent doublet," 11 two parallel zones of actual raw human experience on the one hand and human transcendence on the other, that together are alien to discourse. And discourse is the "analytic of finitude" which comprises modern knowledge and which is made possible by man's alienation from it, for, according to Foucault, the discourse of modern knowledge always hungers for what it cannot fully grasp or totally represent. Thus knowledge is perpetually in search of its elusive subject. Here again the fact of discontinuity--or difference, as it is also called-is paramount.

Finally, the densely and portentously argued theme of Les Mots et les choses (a book whose literary and philosophical implications are almost frighteningly vast) is occupied with the vacant spaces between things, words, ideas. In the eighteenth century the possibility of representing things in space-as in a painting--derived from the acceptance of temporal succession which thereby allowed the constitution of spatial simultaneity; the fact that objects could exist together in the privileged space of a painting depended upon an unquestioned belief in the continuing forward movement of time. Spatial togetherness was conceived to be an emanation out of temporal succession. Yet in the modern era the profound sense of spatial distance between things, that separates like things from each other, permits the modern mind to contemplate time as only a dream of succession, as a promise of unity or of a return to the Origin." Above all, time is the most tenuous of the spatial con-

38