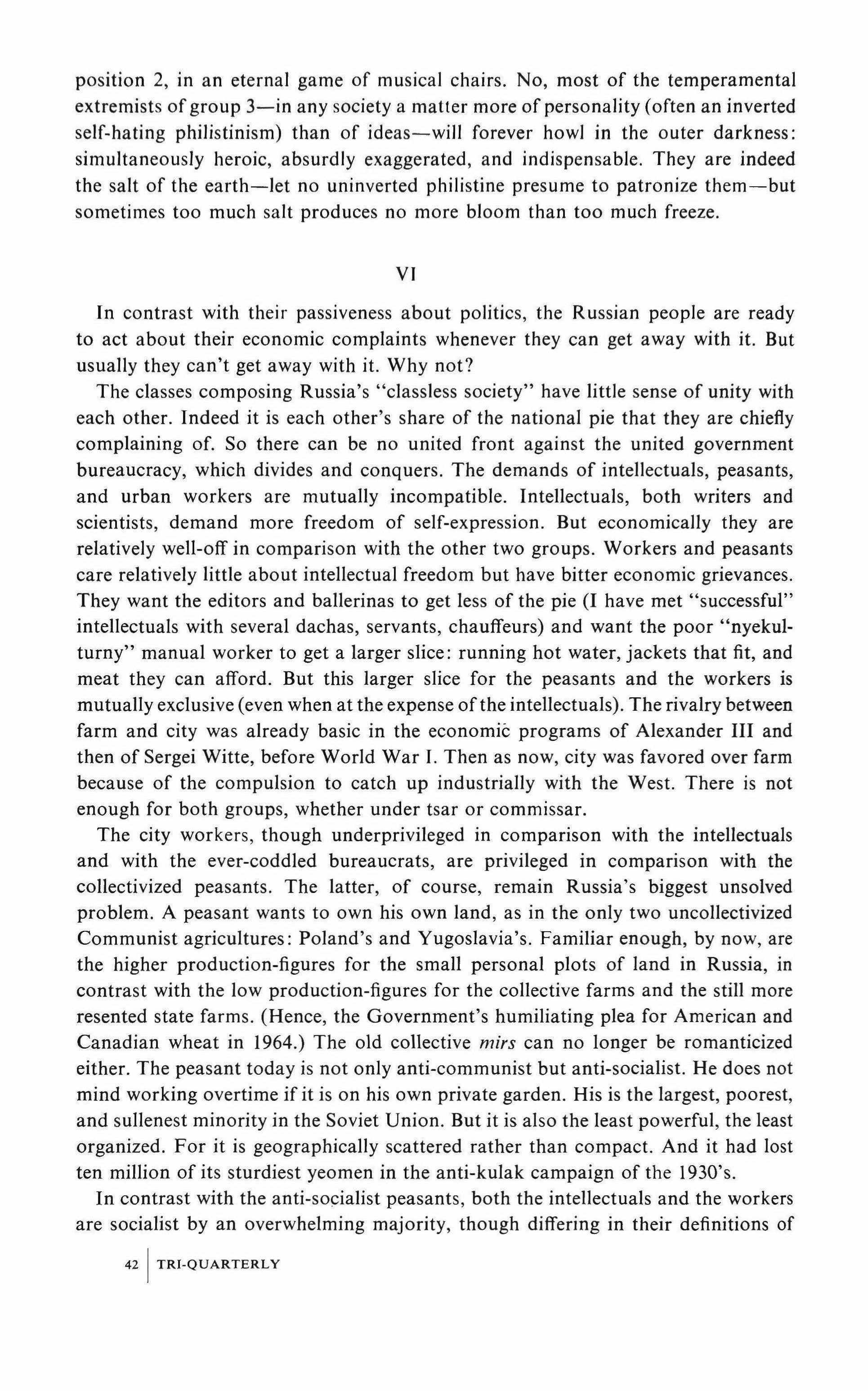

First published in part in The Kenyon Review

"A high-tension wire plugged into the sensibilities the narrator has sought and identified authentic love. It surpasses sex. It rises from time." - WEBSTER SCHOTT, N. Y. Times Book Review

"A perceptive, unique novel Carter has brought it off with compassion and power." - CHARLES NEWMAN, Chicago Tribune

The oldest publisher-sponsored award of its kind has introduced many of America's most distinguished authors, among them Dorothy Baker, Robert Penn Warren, Elizabeth Bishop, Eugene Burdick, Philip Roth.

The awards are designed to help authors complete literary projects in fiction and non-fiction, but finished manuscripts are also eligible. The awards are $5,000, $3,000 of which is to be considered an advance against royalties. For complete information and application forms, write to:

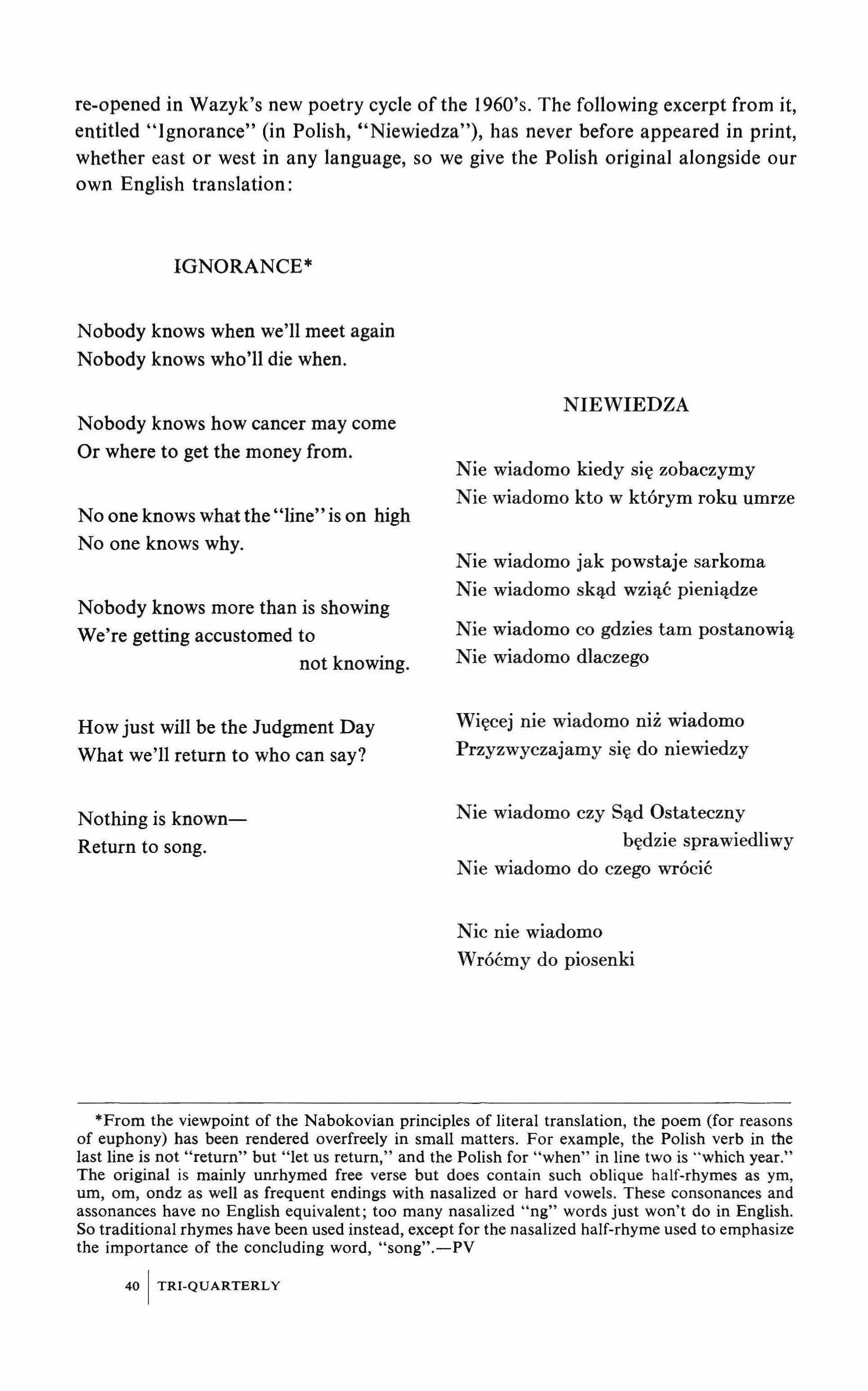

PETER VIERECK 7 The Mob Within the Heart: Russia's Rebel Writers

ANDREW FIELD 57 Marina Tsvetaeva's Poems to Blok

LT. KIJE 65 Creativity and Control in the Soviet Union

DEMING BROWN 75 Vasili Aksenov at 33

DAVID JORAVSKY 119 The Silences of Academician Prianishnikov

NORRIS HOUGHTON 139 Creativity and Control in the Soviet Theatre

Two Commentaries

PETER YAKOVLEVICH

YURI KAZAKOV 129 A Place to Spend the Night

GEORGE L. KLINE

ANDREI VOZNESENSKY

JOSEPH BRODSKY

LESLIE

The Unhappiness of Arthur MillerAfter The Fall, Incident at Vichy, and the Lincoln Center

EDITOR: Charles Newman. ART DIRECTOR: Lawrence Levy. ASSOCIATES: John Almquist, Colton Johnson, William A. Henkin, Jr. PRODUCTION: Lauretta Akkeron. CIRCULATION: Valerie Nelson. BUSINESS: Suzanne Berger, Judith Jay, Suzanne Kurman. ADVERTISING: Adele Wolfberg. STAFF: Arthur F. Gould, Richard Thieme, Joel Pondelik, Anne Campbell, Dan Conrad.

The Ttl-Quarterly is a national journal of arts, letters and opinion, published in the fall, winter and spring quarters at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. Subscription rates: $3.00 yearly within the United States; $3.25 Canada and Mexico; $3.75 Foreign. Single copies will be sold for $1.50. Contributions, correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to Tri-Quarterly, University Hall 101, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. Unsolicited manuscripts are welcome, but will not be returned unless accompanied by a self-addressed stamped envelope. Copyright © 1965 by Northwestern University Press. All rights reserved. The views expressed in the magazine, except for editorials. are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors.

NATIONAL DISTRIBUTOR TO RETAIL TRADE: B. DEBOER, 188 HIGH STREET, NUTLEY, NEW JERSEY.

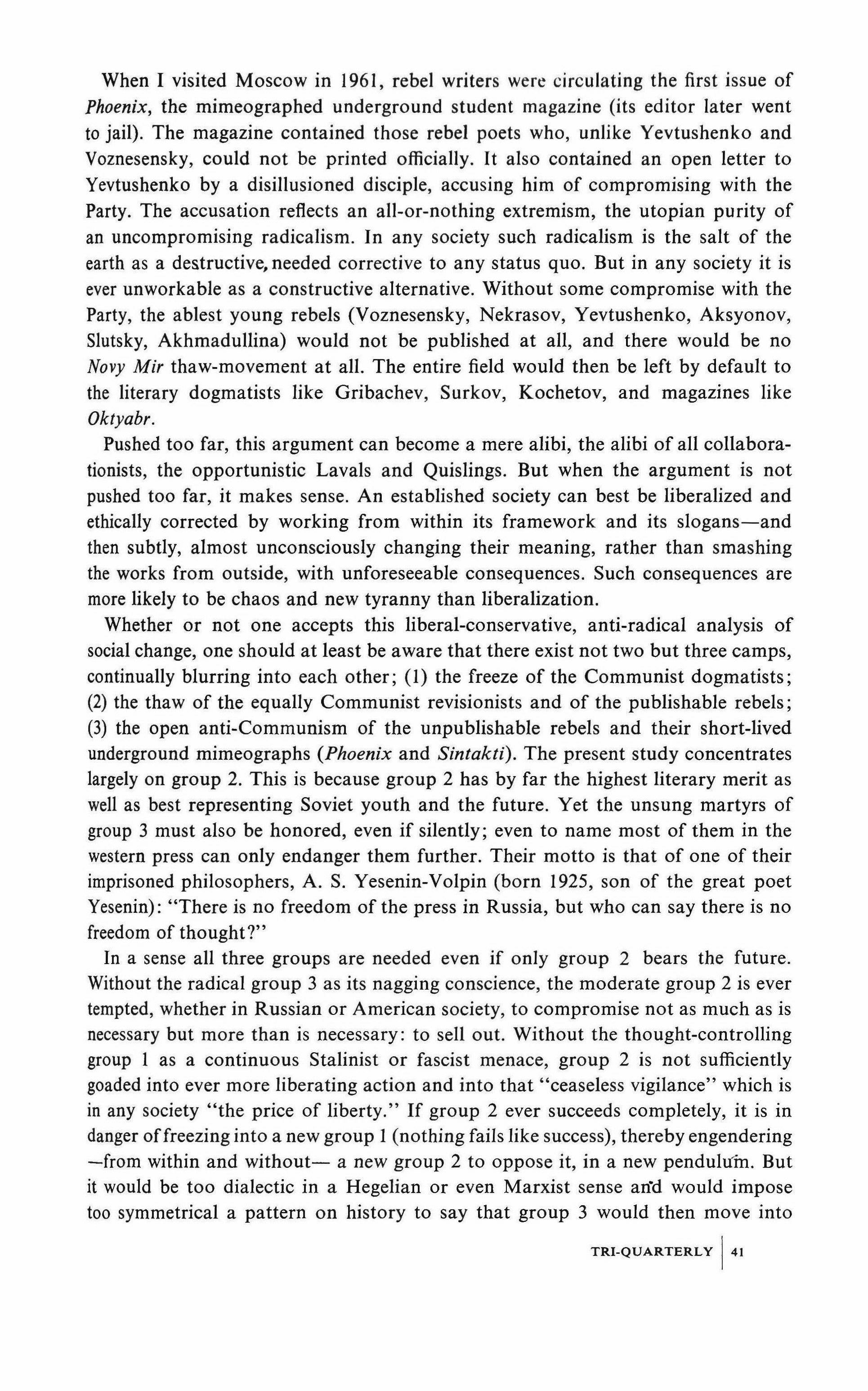

"The mob within the heart Police cannot supress"

EMILY DICKINSONAPENDULUM BETWEEN thaw and freeze characterizes not only Soviet society today but Russian society through the ages. Thus a reformist Alexander I seems forever alternating with a dogmatist Nicholas I, a reformist Alexander II with a dogmatist Alexander III, a reformist Kerensky with a dogmatist Lenin, the N. E. P. thaw of the mid-1920's with Stalin. And already before Alexander I, there was the pro-western "18th century enlightenment" of Catherine the Great alternating with the anti-western dogmatist Paul. The pendulum is not automatic. It is not swung by a capitalized attraction called "History" or by any other intellectual or economic determinism. It is swung only by concrete human beings, making efforts of will and conviction in either direction. Yet it is reasonable to assume that both directions will continue to be actively and effectively represented. For both directions have deep roots in Russia's past and present and are being personally passed on to the future.

The dogmatist direction of Russian culture has been shaped for centuries by Byzantine and Greek Orthodox traditions. Their heritage, inherited unintentionally but almost totally by the dogmatist wing of communism, includes a Caesaro-papist identity of state with ideology (tsardom with theology) and an accompanying sense of Russia's world-saving mission, whether for Christian Orthodoxy with a capital "0" or for a Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy with a small "0". For example, the same Russian-messianic motif in the novels of the tsarist Dostoyevsky and the novels of his communist disciple, Leonid Leonov.! with whom in Moscow I discussed pre-

lWhen I told Leonov that I consider his Thief the greatest Communist novel ever written (it applies to a backsliding Soviet war-hero the Dostoyevsky gamut of sin-suffering-redemption) he told me how Stalin in person had underlined in red ink those passages he deemed heretical. Leonov's face lighted up with that quick-flashing sense of condensed history (a uniquely Russian look that I met in many tormented idealistic Communists) when I replied that, of course, Nicholas I had also underlined in person, and also with red ink, the Lermontov novel, A Hero of Our Time.

TRI-QUARTERLY

cisely this parallel. Equally deep (today even deeper because of anti-Stalinist revulsion, pro-Western nostalgia, and the spread of scientific education) is the anti-dogmatist, liberationist tradition of Russian writers, whether the old nineteenthcentury "Westernizers" or the current "revisionists". An example is the following parallel between a quotation of 1847 by the anti-tsarist rebel Belinsky and a quotation of 1963 by the anti-Stalinist rebel Yevtushenko. In a letter secretly circulated against the tyrant Nicholas I, the libertarian socialist Belinsky exulted:

"The public looks upon Russian writers as its only leaders, defenders, and saviors against Russian autocracy The title of poet and writer has eclipsed the tinsel of epaulettes and gaudy uniforms."

In 1963 the poet Yevtushenko, speaking for what he calls the "anti-dogmatist" Communist idealists, told the Paris L'Express (in an interview secretly circulated in Russia and denounced in person by Khrushchev):

"All the tyrants in Russia have taken the poets as their worst enemies. They feared Pushkin. They trembled before Lermontov. They were afraid of Nekrasov

Equally rejecting American pessimism (which expects "a new Stalinist terror" after Khrushchev's downfall) and American optimism (which expects "liberalism at last" after his downfall) here follow some of the reasons for a more balanced, cautious optimism. One is probably justified in expecting more cultural (but not political) liberty from Khrushchev's successors. The increase in cultural and intellectual liberty (Lysenko'S downfall, for example, followed Khrushchev's) seems inevitable not because of any sudden conversion to John Stuart Mill on the part of this tough, cynical new "collective leadership" but because of changes in Soviet society as a whole.

AUTHOR'S NOTES ON HIS SOVIET TRAVELS:

Of the nine months I spent in Communist countries during my three visits of 1961-63, over three months were in the Soviet Union: not only Moscow and Leningrad, but also Georgia, Armenia, Uzbekistan, the Ukraine, and the Crimea and Black Sea, everywhere meeting without undue difficulty (though admittedly not always unattended) the local poets, scholars, and Writers Unions of each area. Also more than three months in Poland: visiting the Writers Unions and the universities of over a dozen cities, invited by some of them to give lectures or readings of my poetry. Some two months of similar travels to every part of Rumania; also a brief passage through Hungary and two visits of about two weeks each to the universities and Writers Unions of Yugoslavia.

The presence of my wife, who speaks a completely fluent Russian and a partly-fluent Polish (my own halting, bookish Russian is merely the product of three years of study in graduate school), enabled us to dispense with official guides much of the time. We found it possible to talk alone with ordinary citizens in relaxed, informal, unsupervised circumstances (parks, stations, railways, airplanes, restaurants other than those of tourist hotels, and each local students' or writers' club) as well as meet the intellectuals and poets who were the purpose of the trip. These rebel writers are the main subject of this essay.

Politics aside, I learned to love and respect the peoples of eastern Europe; and any criticisms I venture (which in any case apply more to governments than peoples) will be seen as a kind of lovers' quarrel within the context of that mutual respect. The present essay is mainly confined to the prospects of-and differences between-cultural freedom and political freedom in the new communist world of the 1960's, above all Russia. But I have also acceded to the Editor's request to add-to what was originally an impersonal academic analysis-my citations from personal conversations with writers of interest as well as other firsthand references to them; these asides account for the veritable forest of parentheses.

TRI-QUARTERLY

What has saved the Soviet rebel writers of today from Stalin-style torture and death? No mere change of rulers. Khrushchev, Brezhnev, Kosygin (also Mikoyan, Suslov, Podgorny) all made their careers under Stalin; all had once actively helped his lethal purges. Yet Soviet writers have not been suffering in the 1960's, under Khrushchev-Brezhnev-Kosygin and their cultural watchdog Ilychev, the consequences they would have suffered in that earlier decade when the same Ilychev was still one of Stalin's favorite editors. In December 1962 and March 1963 the official language of Khrushchev and Ilychev, darkly threatening the experimental painters and revisionist poets, resembled the language of Stalin and Zhdanov in 1949. Yet the consequences for the victims have been incomparably less dire than under Stalin and Zhdanov.

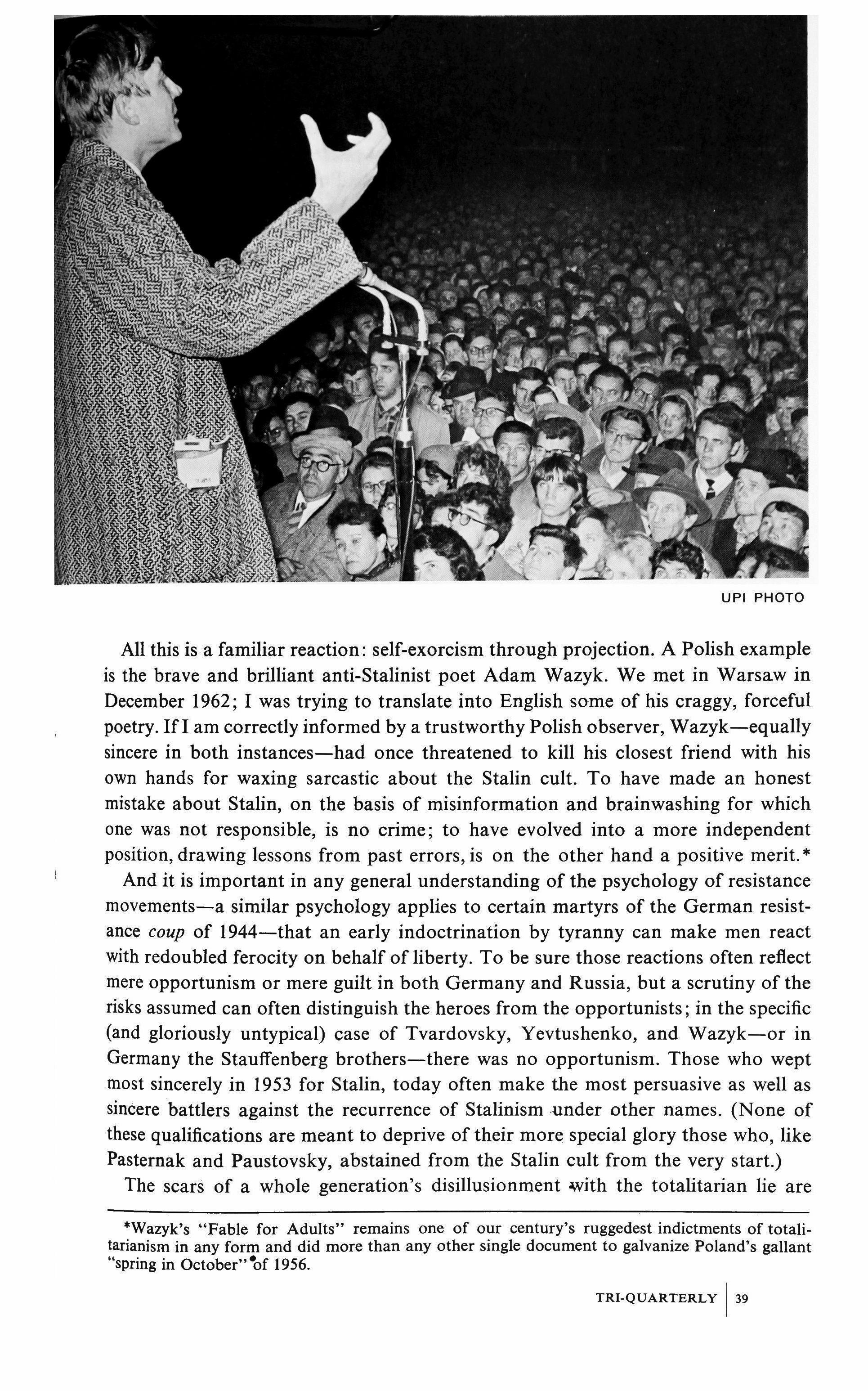

The most denounced of these victims-the poets Voznesensky and Yevtushenko, the prose writers Ehrenburg, Aksyonov, and Victor Nekrasov-are not only still alive but out of prison. They are still publishing widely without major concessions. So far, none has been expelled from the Writers Union, despite threats to that effect by Government leaders (notably against the unrecanting Nekrasov). It may be evidence for bad nerves among watchdogs that the vast public poetry readings in Moscow, which I witnessed in 1961, * 1962, and 1963, are no longer permitted. But smaller indoor readings by the denounced poets continue to express and fan the fervor of students for freer self-expression. Yevtushenko is still listed on the masthead of Yunost ("Youth"), from which the Party had threatened to oust him.

Since there have been no sweeping changes in Stalinist personnel nor in the official language and aim of ideological control and since, nevertheless, the Stalinist consequences no longer occur, the change must be in Soviet life itself. "Soviet life" is a vague phrase at best, a matter of atmosphere, and yet a real source of hope for Russia, for American relations with Russia, and for the cause of peace. The new atmosphere may be partly summarized by observing that Pavlov's dog never had an education. Therefore, he stayed conditioned. Not so the newly educated Russian of today. No longer can he be disregarded by the Party as a "dumb muzhik." No longer will he stand for what he had to endure in Stalin's day. A separate factor may be noted now but analyzed later: the feeling of guilt and atonement in a certain limited number of ex-Stalinists.

Within this improved way of life, the old historical pendulum continues to alternate, just as much as before. But now less murderously. And quicker, more deviously: for example, one could write whole books-and the best authorities do-tracing how Yevtushenko was ousted during the 1963 freeze from the governing board of the Moscow Writers Union but was re-elected to it in January 1965, or tracing how the last volume of Ehrenburg's memoirs was announced by the thaw magazine, Navy Mir, for 1964 publication and then mysteriously failed to appear, only to be re-announced all over again by Navy Mir for 1965. To become a virtuoso of"thawmanship" (a word we may coin to express in literature what "Kremlinology"

*In 1961, Richard Wilbur and I were officially appointed by the State Department to travel as guests of the Soviet Writer's Union in exchange for the earlier visit of Voznesensky and Yevtushenko as guest poets. My later visits were private, unofficial.

TRI-QUARTERLY

expresses in politics) one must ponder the secret meaning, ifany, ofwhy (for example) the January Yunost of 1965 failed to print a certain long-announced new poem of Yevtushenko's; does it perhaps mean a new reversal of that third rehabilitation which followed his third disgrace? But all such reversals can again be reversed, and every book and article of thawmanship must revise its galleyproofs frantically to be one-up on rival experts. No end to this; and up to a reasonable point, necessary. But at some point of diminishing returns, it becomes not only simpler but truer to utter instead the single word "pendulum."

More amusing as well as more revealing are the government attempts to by-pass pendularity toward these rebel writers by starting all over again with more docile specimens: the teacher's-pets of communism. In spring 1963 a Moscow conference of younger writers assembled 170 eager new apple-polishers from all over the USSR, hoping to substitute them in public affection for such youth-idols as Voznesensky, Yevtushenko, and the latter's ex-wife Akhmadullina. (A Polish poet, who had attended the well-directed Gorki Writers Institute with her, told meafter hearing I addressed a class there-that Akhmadullina was hounded out of the Institute by a Party hack, jealous of her proud creative individualism; "the Tartar princess," they nicknamed-for her pride-this best of Russia's younger woman-poets.) But despite Party funds and pressure, the above 1963 conference for "new youth" evoked little new talent. The 170 preening pets failed to catch on in terms of either sales or moral influence. The Party can do little to prevent or avenge this kind of increasingly typical fiasco. It can arrest citizens for any positive revolt but not for the negative, unprovable revolt of simply staying home from bad poetry readings and leaving unreadable books unread.

On April 19, 1963 the Komsomol leader Sergei Pavlov-no relation to the scientist-tried to reopen the March campaign against Yevtushenko. In his speech this lesser Pavlov alleged that Russian youth is still indignant against Yevtushenko for his arrogance, his insufficient recantation, and his publication abroad of his autobiography. Yet in the same speech Pavlov added that his Young Guard organization still desires to publish a new book of Yevtushenko's poems; what began as a threat ended as a whine, complaining that Yevtushenko "says he is too busy" to talk to this Komsomol publisher.

In the 1960's the key figure in Party control of the arts has been Leonid llychev. Not only for Khrushchev but also for the first half-year of the Brezhnev-Kosygin regime, university-trained ideologist Ilychev has been the nearest Soviet equivalent of a Minister of Propaganda. His official title during November 1962-March 1965: head of the Ideological Commission of the Central Committee. On March 23, 1965 the 58-year-old Ilychev became, instead, Deputy Foreign Minister (no very drastic demotion, as the Soviet press had already been featuring his consultations with Brezhnev and Kosygin on the 1965 Vietnam crisis). His replacement, the engineer Peter Demichev, has indicated no break with the cultural policy Ilychev carried out for Khrushchev and Brezhnev.

A basic continuity characterizes this cultural policy of the 1960's. In aim it is the old Stalin-Zhdanov policy of imposing ideology on intellectuals and artists. But in method it uses persuasion and relatively peaceful threats, with arrest as a

last resort and without shootings. Stalin used arrest as almost a first resort for literary deviators, and shootings as a norm.

As of 1965, what has been the upshot of this post-Stalin cultural policy? A small amount of arrests, notably of Brodsky and Yesenin-Volpin, and a large amount of suppressions, notably of the experimentalist painters. But no Stalin-style murders, no Zhdanov-style total suppressions. Nothing that can in all fairness be compared to the stultifying Stalinist terror to which the anti-Soviet western press sometimes draws analogies.

I do not mean to say sanctimoniously, heartlessly: the persecuted writers and artists in Russia "should be grateful" for not being tortured or killed. They have nothing to be grateful for; on the contrary, they have inherent human liberties to demand from their oppressors. But there is one historical and literary advantage in not being killed. This is the plain physical fact that the victims today can "sit out" the pendulum until the next swing in their favor. The Mandelstams and Babels and Tabidzes of the Stalin ear were not able to flower in the subsequent thaw; they were dead.

The difference is not only one of actions but of atmosphere. Despite the Government's intention to stultify, the atmosphere continues lively and rebellious; the persecution has only increased the popularity and the solidarity of the rebels. I can testify to this from personal experience because the Government crackdown was already in full swing during my third Russian visit, that ofJanuary and February 1963. By then, Khrushchev had made his December attack on the abstract painters; the Shostakovich performance of Yevtushenko's "Babi Yar" had been withdrawn and then resumed in censored form; and Izvestia was featuring its January attack on Nekrasov's favorable travelogue about America. With what results? A knowledgeable and well known figure in the Soviet world of the arts told me: "Everyone recalls the Nazi attack on abstract art. My friends and I, who have always disliked abstract painting, are now doing everything to defend it in response to the Government demand for mass meetings against it."

Then came the stronger guns of the IIychev and Khrushchev barrage of March 7-8, 1963 (against Ehrenburg, Nekrasov, Aksyonov, Yevtushenko, and other rebel poets and artists); the Writers Union meeting of March 26-28 in a similar vein; the Party meeting of June with its resolutions for imposing more ideology upon literature-and so on, with alternating temporary relaxations, right through today. The results of all these ear-splitting threats and pep-talks, though sometimes grim enough, show a downright sensational disproportion between bark and bite. Just before March 1963 the younger Russian writers and students were turning against Yevtushenko and Voznesensky because the two poets were becoming too official, were having too many trips abroad, trips allowed for not exactly aesthetic reasons by the Party. I even heard Yevgeny Yevtushenko nicknamed "Yevgeny Gapon" by a more bitter poet (after the Father Gapon who had led the protesting workers of Bloody Sunday, 1905, but turned out to be a secret government agent). But the rebel poets regained much of their lost popularity and influence because the Government then denounced them and cancelled their trips abroad. In retrospect, recalling my firsthand impressions oftheir public readings and their followers and discounting

TRI-QUARTERLY I"

their necessary concessions to official lines, I am convinced they are sincere, independent, and enormously influential voices of the thaw and not puppets of any communist-or, for that matter, anti-communist-government.

The confessions of the denounced writers of 1963, if one studies the texts carefully, confess very little. All Voznesensky promised the Party to do was "to work harder." And the bravest of the lot, the novelist Victor Nekrasov, refused to confess at all. Nekrasov is a veteran Communist hero of "the trenches of Stalingrad" (to quote the title of one of his novels). It is his Communist faith which sustains not only his refusal to confess and recant but those other positions for which Izvestia attacked him on January 17, 1963 and Khrushchev and Ilychev on March 7 and 8. These positions include his defense of experimentalism in the arts and cinema, his insistence on the good as well as bad side of the west, his demand that Russian tourists in America be allowed by their government to travel alone instead of in disciplined, shadowed groups. All the west knows Yevtushenko's poem of 1961, "Babi Yar"; it protests against anti-Semitism and the lack of Soviet memorials at the site of the biggest Nazi pogrom. Very few in the west realize that already two years earlier Nekrasov (by nationality a Ukrainian) had published an equally courageous protest against Soviet plans to build a sports stadium instead of a memorial there: "On the site of such a colossal tragedy to make merry and play football!" (Literaturnaya Gazeta, October 10, 1959).

Nekrasov, with whom I briefly corresponded after my 1963 visit to the Kiev Writers Union, does not take the above positions out of anti-Communism. He takes them in order to strengthen Russia's economic Communism by combining it with intellectual and artistic freedom and with its original Leninist freedom from anti-Semitism. This hope for intellectual freedom under economic Communism, a hope I found widely diffused in eastern Europe, may seem rash to an American. Rash but not ignoble. It is the hope and indeed the logic of that de-Stalinization which most Russians now want, non-writers as well as writers, and which the Government first triggered, for motives of its own, but tries to limit.

Will the Government's limited and manipulated de-Stalinization get out of hand and create an uncheckable thirst for freedom? Yes and no. Probably yes in regard to the broad-based demand of all classes for a freer private life. Probably no in regard to those basic democratic liberties which are taken for granted in much of the West but which have not yet become sufficiently rooted in modern Russia except for the 1905-17 Duma interlude) to produce a broad-based demand. Moreover, these democratic liberties are incompatible with the economic privileges of the one-party ruling class (as well as with its priestly psychological privileges as the official Caesaro-papist guardians of absolute truth) and will be ruthlessly restricted by any Communist government, no matter how anti-Stalinist, except for minor non-basic concessions.

I interpret the current unrest among Russian youth as no movement of ideas or blueprints but as a vague, explosive, non-rationalist "conspiracy of feelings". Fellow admirers of Yuri Olesha will, of course, recognize that we have taken this phrase from his suppressed story "Envy", 1927, which prophetically foresaw that Russia's rebellion against Communism would come not from any political or

economic revolt of any alien capitalism but from the protest of human feelings against a dry, inhuman technology and ideology. Russia's irresistible future expansion of the private life-that is, of cultural and human liberties-is partly compatible with one-party control of politics and economics; that is, with the present more authoritarian than totalitarian dictatorship. (Only Stalin and Hitler were true totalitarians; Mussolini, Franco, all the present Communist dictatorships except perhaps China, and most of South America are neither totalitarian nor free but authoritarian.) The partial compatibility between cultural freedom and complete Corrrmunist political dictatorship is proved by the current practice in Poland, Hungary, Yugoslavia. Inside those countries I found that their boast of having more cultural freedom than Russia is not a myth but a reality; visit their theaters and cafes or their very individualistic farmhouses, or pick up any of their magazines and newspapers, and the difference is self-evident. When these three Communist governments allow this greater cultural freedom (with which Russia will have to catch up), their motive is partly a yielding to the inevitable and partly an astute exploitation of the inevitable. Why exploitation? Because their partial cultural freedom, by serving as a safety valve for man's irrepressible individualism, often struck me as-in the short run-strengthening rather than weakening the Communist dictatorship in political and economic terms. So much for the short run. In the long run will the new cultural momentum for non-political liberty remain safety-valved-or canalized-within the Communist framework? (a framework sincerely accepted by Russia's literary rebels but not by Poland's). Or will such cultural momentum spill over into political momentum? It is easier to raise than to answer these questions. There are too many interacting factors (and we ourselves are part of the test tube we are trying to see from the outside) to enable us to answer these questions confidently. Or to enable the Communist leaders to answer them. Hence, the zigzag in the cultural policies of the various Communist dictatorships. Such a course is probably due not to diabolical master-plans but to genuine confusion, uncertainty, and inconsistency at the top about these unanswerable questions, which certainly confuse us as well.

Like Hitler's dictatorship and unlike Mussolini's and Khrushchev's, Stalin's dictatorship was "monolithic" (to use his own favorite term) in every sphere, from poetry and physics to politics and economics, from linguistics and genetics to secret police. Today there is more elbow-room for the private life, more free debate in certain vital though limited cultural areas and a lot less police terror for the average citizen; this post-totalitarian, post-Stalin Communism is a dictatorship not over the totality of a man's life but over the political and economic sectors. Are the latter sectors more important than the inner world of personal human contacts and of the creative imagination? The answer, if there is an answer, depends on the context. In the simple, urgent context of a Nazi or Stalinist menace, politics came first; the alternative was suicide. But today, in the more complex, less rigid context of a worldwide robotizing mechanization, the private, non-ideological

TRI-QUARTERLy 113

expression of the human personality has been too long ignored by the efficient bustling Organization Men of Russia and America alike.

Hence, in my 1961 verse play The Tree Witch (which a Soviet bureaucrat had seen while in America at Harvard's Loeb theater and had strongly condemned although an experimental theater in Poland hopes to stage it) the spokesmen of Russian and American robotry sing the following "Global Lobal Blues" together. Our song owes its moment of conception to the spectacle-that brotherhood, despite mutual denunciation, of all gadget worshippers-of Khrushchev and Richard Nixon exchanging Pepsi-Cola toasts at an industrial exhibit in Moscow 1959; at that touching moment the worldwide homogenization of all technocrats seemed inevitable:

Now when dacha nouveau-riche and hot-cha profit itch Merge brands, When brain-wash sociology and sublim-ad psychology Join hands,

When Pepsi-Cola toasts unite vulgarians of all LANDS And "peace" means the homogenizing global churn of kitsch, You'll be FORCED to croon the globallobal blues. First they toasted, THEN they tiffed; Yet-through summit OR through rift-

Here's a truth will never shift while any bureaucrat comMANDS: Human heads will get short shrift from RObot hands. So strike up all Rotarian proletarian pan-barbarian BANDS. Progress is a PLAStic bag; Come stick in your head and what AILS you will gag, Gasping the BLUE-in-the-face blues.

When our propaganda spasms turn your isms into wasms, We'll bag the earth in a PLAStic globe And disconnect your frontal lobe

With our gadget-pop Agitprop air-jet-hop think-no-more blues.

To this worldwide capitalist-plus-socialist technologizing of the 1960's, the ablest philosophers of Communist Europe are daringly reapplying Marx's once-neglected notes of 1844 about modern man's alienation from society. Since alienation is likewise the present theme of western poets, philosophers, and rebels, here is the point of unity between anti-robot individualists on both sides of the cold war. Assuming reader familiarity with Western examples, let us cite some Eastern ones. The fact that they are published at all is a measure of the very real progress toward cultural liberty under those rigid political dictatorships. The Kafka authority in Prague, Edward Goldstuecker, now free but in jail under Stalin, was allowed to publish in 1964 this almost Pasternakian appeal against materialism:

"Technical civilization, alone and of itself, produces antihumanism and dehumanizing pressure on every individual. Modern civilization draws the individual from the collective, even if it creates enormous new collectives, and makes the individual lonesome. I n a society where religion has ceased

to be the cement and connecting link creating ethical inhibitions, it must be replaced by something else; and this sornct hing is, in the first place, art."

Such sentiments are part of an unorganized worldwide movement to return to art and heart (in The Tree Witch we called it Aphrodite's underground movement against Hephaistos, the first technocrat). In a Belgrade philosophyjournal (Praxis, November 1964) Yugoslavia's Professor Mihajlo Markovic, while staunchly attackin the old capitalist alienation in Marxist terms, is now warning the Soviet bloc against the new kind of alienation caused by communism. He defines it as the alienation suffered when the individual is treated as a mere object by communist bureaucrats, dehumanized by what he calls their "cult of technology." Markovic sees these new "forms of alienation" threatening "those Socialist countries where the creation of new centers of enormous power-which are no longer based on economic wealth, as in capitalism, but on unlimited political authority-has been made possible."

Parallel sentiments were voiced in the Prague Kafka conference of May 1963. There, too, it was not anti-Communists but two Party members (one French, one Austrian) who with lasting effect told the Russian delegates that a Kafkaesque alienation is today inherent in all technocracies, not just those of capitalism and the west. With the 1964 publication of In the Penal Colony in the Moscow magazine Foreign Literature, Kafka is no longer the secret forbidden prophet of Soviet intellectuals. He can now be openly praised (even though cautiously, as in Voprosy Literatury, no. 5, 1964). The results are electrifying. For example, the Kafka theme of faceless bureaucracy versus individualism in one part of Voznesensky's new poem "Oza"t (November 1964). On the whole Voznesensky opposes only the dehumanizing kind of technology. What he praises is not some flight to a rustic Middle Ages but "a humanized technology." This attitude recalls not only the rediscovery of the humanist Marx of the early 1840's but some of the most influential western theology of today, such as Reinhold Niebuhr's.

By now the western press has repinted examples, like the above, of Communist attacks on Communist alienation. Still bolder statements of the theme, but not for print, have emerged in our personal conversations with the Communist writers of Russia, Poland, Yugoslavia, Hungary, Rumania. These men are not to be dismissed as Red-baiting "lackeys of Wall Street." They are loyal anti-capitalist Party members. Thus "polycentrism" is not only true internationally between Communist Parties, in the sense intended by Togliatti's coinage of that term; it is also beginning (against his intentions) inside each Party. Each Party not only contains the two obvious splits noted in these pages (between cultural thaw and freeze and between political revisionism and dogmatism) but a third and subtler split: between treating people like humans or like cogs, like subjects or like objects. Psychologically the third split is between the rooted and the alienated; it is between what Burkean conservatives as well as humanist socialists would call the mechanic and the organic.

*On April 26, 1965 at the fifth Croation Party Conference in Zagreb such Party leaders as Mika Tripolo denounced the Praxis philosophers of a rehumanized Marxism as "diametrically opposed" to the Party line. The official Yugoslav Party Magazine Komunist called them "uri-Marxist" and "unacceptable."

+See translation in this issue.

For example, the Communist philosopher Lescek Kolakowski, who is trying to re-establish Marxism on a firmer, freer foundation, mentioned to me, during our Warsaw conversation of 1962, the crucial importance-for younger Communist intellectuals and artists today-of facing the dilemma of such technological alienation. The same point has been stressed by the greatest Marxist literary critic of the century, Gyorgy Lukacs." I have heard this point made in so many ways in conversations with poets and artists in eastern Europe; the reality of "the world republic of letters" becomes clearer every time I find the same point in the west. For example, in a leading New York art critic (Harold Rosenberg, 1964): "With everything so convenient and shiny, one hardly knows what's missing. What else can it be but the person himself for whom all this was organized?" Or in an American follower of Simone Weil (Raymond Rosenthal, 1964):

Talk to the teachers in the colleges and you will learn that the best and most intelligent young people are indifferent, benumbed, cynical; talk to any factory manager, and he will tell you the same story about his best young workers This central fact of modern life [is] that the people who create the products of wealth find both the work and the wealth totally empty and unsatisfying. Or in a Parisian from Rumania who has experienced the dilemma both east and west (Virgil Gheorghiu, 1949):

Contemporary society, which numbers one man to every two or three dozen mechanical slaves, must be organized in such a way as to function according to technological laws. Society is now created for technological, rather than for human, requirements We are learning the laws and the jargon of our slaves, so that we can give them orders. And so, gradually and imperceptibly, we are renouncing our human qualities and our own laws. The first symptom of this dehumanization is contempt for the human being. Modem man assesses by technical standards his own value and that of his fellow men; they are replaceable component parts reducing social relationships to something categorical, automatic, and precise, like the relationship between different parts of a machine. The rhythm and the jargon of the mechanical slaves, or robots if you like, finds echoes in our social relationships and our administration, in painting, literature, and dancing to floodlight the hidden ways of life and the soul by means of neon tubes The Russians have bowed down and worshipped the electric light of the West and will suffer the same fate as the West.

Or, finally, in America's leading literary critic (Edmund Wilson, 1964):

There are no great royal leaders today, few great parliamentary leaders. If a Kennedy shows promise of leadership, his eminence may provoke assassination. What we have today, instead of leaders, are the ever-expanding bureaucracies of government, formidable in machinery, mediocre in personnel. The problem we all have to face is the defense of individual identity against the centralized official domination that can so easily become a faceless despotism.

*On April 13, 1965 Lukacs urged a new "Socialist Humanism" to combat the "Socialist Realism", and predicted: "I feel we must have a renaissance of Marxism and that it will come about if we rediscover the humanist essence of Marx." 161 TRI-QUARTERLY

Not royal faces but faceless despotism. And. of course, much earlier in Yeats: "The Muse is mute when public men / Applaud a modern throne." Why mute? Because by now every child knows that a modern equivalent of a throne, whether under free democratic politics or tyrannic Soviet politics, is no longer human or personal or alive. You can no longer have a personal human relationship to it, whether of hate or love, as you could in medieval times toward the bad or good feudal lord of your small concrete locality-and as you could even in modern times until the impersonal industrial revolution replaced local politics as well as personal politics.

Dante could denounce certain rulers or governments and praise others. And feel deeply and humanly involved thereby in a personal relationship. So could William Blake and Nietzsche. So could even Henry Adams. But how can a muse or any human individual today love or hate most* modern rulers, American or Russian, democratic or Communist? The muse senses that most modern rulers don't really exist. They are the bloodless packaging-job (think only of Eisenhower) of some metallic communication technique, the invention of either the Madison Avenue or the Agitprop type of Organization Man.

Though the organization men of both countries are pro-mechanist, they are pro-mechanist for opposite reasons. The opposite reasons reflect opposite national traditions. American capitalism has a cult of technology because America is promechanist at heart. Russian communism has a cult of technology because Russia has been anti-mechanist at heart. The American tech-cult is the rationalization of an inner excess. The Russian tech-cult is overcompensation of an inner lack.

Currently, most arty-phoney middlebrows are affecting a chic robot-baiting, a flaunted alienation. Their glossy vulgarization does not refute-it merely parodiesthe reality of the dilemma. It is a reality among the more serious articulators of both our countries as well as among the inarticulate millions, especially the younger ones. Whether under so-called socialism or so-called capitalism, youth tends to secede from society. This is especially true of the more interesting young people, the non-squares, the students and artists. In 1965 Russian students will sometimes openly sing songs about Stalin's concentration camps when requested by their elders to sing songs of patriotic ideology. In current Soviet debate the problem is called, in a curiously old-fashioned reference to the world of Turgeniev and nihilism, "the fathers and sons problem." Even while discussing it, the Soviet official propaganda sources are constantly denying that the problem exists (for example, the soeeches of Ilychev or of the Komsomol leaders).

The existence of the problem is shown in the stories with which Soviet youth most identifies: Aksyonov's Ticket to the Stars, 1961, his Halfway to the Moon, 1962 (Navy Mir no. 7), and the 1961 Soviet translation of Salinger's Catcher in the Rye. In Ticket to the Stars, much denounced by dogmatists and later made into a

"Better to say "most," not "all"; because of the moving circumstances of his youthful death, President Kennedy was the exception when tragedy and humanity did break through the inhuman technologies with which Americans try to wall off or rouge up the reality of tragedy. But most rulers and rulings today are what Daniel Boorstin, in his thoughtful new book, calls "an image," a "pseudo-event," and what Gerald Sykes has shown to be the unreality and self-deception inherent in mechanization.

much censored and rewritten movie, a group of rebel teen-agers flees westward from Moscow. Not across the Soviet border-such candor would never see printbut to the west-symbolizing Baltic states of the USSR. Their flight is not for ideology or politics or economics but out of youthful psychological unrest, a boredom with grayness, with bureaucracy, with their fathers. After Nikita Khruschev denounced him in March 1963, Aksyonov had to recant some of his heresies: "I will never forget Nikita Sergeyevich's stern but kind words to me The direction of my future work is to the ideals of Communism Our enemies will not succeed in getting us into a quarrel with our fathers" (Pravda, April 3, 1963). But his mood of revolt-against-grayness continues as the unofficial voice of a whole generation. And artists in other genres-for example, Victor Rozov in drama-have become student favorites for writing in a similar vein.

More important than such works of fiction, the same secession of the young underlies the realities everyone sees with his own eyes, in Russia and America alike. The secession involves separate habits, a way not of thinking but of feeling. It is not a new pattern of values but a vacuum in values, a vacuum yet to be filled by a new post-technocratic order. The causes for this are many, sometimes merely local and temporary. But they include the shared technological erosion of continuity, both in family and in society. It is an erosion of the indispensable social cement, the organic "Burkean" cement that binds the generations vertically in time and binds the individuals horizontally in space-and marks the difference between a living society and a mechanical accumulation of uprooted individuals.

In a pro-Castro poem appearing October 22, 1962 in Pravda, Yevtushenko declares: a free debate between rival schools of culture-he names only socialist realism versus abstract art but implies free cultural self-expression in general-can well be accompanied by the Communist one-party state in politics. According to the poem, the two schools of artists drop their rival paint-brushes to pick up their shared political rifles whenever capitalist imperialism threatens to attack. This example sustains our thesis that western optimists err in expecting political freedom from the thaw movement but that western pessimists err in overlooking the freedom brought by the thaw movement into other areas: cultural freedom and the selfexpression of the human heart. The boulevardier Ehrenburg, the aesthete Voznesensky, the sober Communist war-hero Tvardovsky, the lone Prometheus Nekrasov, and the tribal medicine-man Yevtushenko may differ on many other issues. But these five most active voices of the thaw do share two inarticulate goals: a revolution and a restoration. Let us dare to articulate the inarticulate, by summarizing their two shared goals somewhat like this: (I) a non-Communist revolution of feelings, on behalf of the non-monolithic private life in heart and art; (2) a Communist restoration of "Leninism," on behalf of the monolithic public life in politics and economics. Their second goal contains (as Lenin would say) contradictions. For the real Lenin probably lacked those more human, less ideological and less technocratic qualities they attribute to "Leninism."

TRI-QUARTERLY

Russia's momentum for political liberty is feeble. but here is a possibility that would strengthen it and thereby threaten Communist rule. It is the possibility that one of Khrushchev's successors may try to halt too long, in its repressive phase, the cultural pendulum between thaw and freeze, thereby forcing as a counterreaction the spilling over of cultural momentum into political momentum. This will not necessarily happen; for in Russia the two momentums are separate-they are not a single overlapping freedom as in the West-and only the frustration of Russia's very strong and unhaltable cultural momentum can arouse Russia's very weak momentum for the political kind of freedom. World Communists share with world anti-communists a belief in greater cultural freedom for artists than Russia now permits. Thus the Italian and even the French Communist Parties have refused to accept the Moscow persecution of abstract art even while accepting Moscow's far bloodier political persecutions (like the suppression of Hungary). The strength of the cultural momentum even in Russia, the feebleness of the political momentum especially in Russia-both kinds of freedom desirable but in Russia not equally attainable-are the two most vivid impressions remaining from my many months behind the Iron Curtain. In culture and intelligence Russians are our equals; in pluralist flexibility and easy-going tolerance they are our inferiors; in wisdom, that intuitive human wisdom which only suffering can earn, they are our superiors.

When I asked lIya Ehrenburg what guarantee there was against a return to Stalinism in view of the absence of any Russian movement for political liberty (free constitution, free press, free elections) and in view of the continuance of the one-party dictatorship, he replied: "The guarantee lies not in a constitution or in political institutions nor in the whim of governing individuals but in the new knowledge and strength of the Russian people themselves. For the first time in Russian history the people has become" (we were speaking in French) "mur,"

Hence my cautious optimism about the future changes of Russian cultural and intellectual freedom: not because I trust the intentions of the Party bosses, who are never going to allow free elections or any freedom threatening the Communist framework, but because I trust the new maturity of the younger generation of workingmen as well as intellectuals, who will demand and often get every concession possible within the framework.

All such gains, limited but far from phoney, succeed precisely because they never smash the Communist framework itself. (In contrast with Poland, no Russian writer I talked to wants to go outside that framework or restore what they rather vaguely and anachronistically call "capitalism".) The present dictatorship, harassed by Party dissensions at home and abroad and facing the two fronts of literary revisionists and Chinese dogmatists, simply lacks that monolithic strength which enabled Stalin to ignore popular pressures and to send 15,000,000 inconvenient citizens into slave labor camps. Most observers J met, many of them Party members, agreed that the Zhdanov days cannot be repeated and that the Party itself will ultimately have to put up with a lot more cultural independence.

On March 16, 1963 the Stalinist Kochetov published a threatening article in Literaturnaya Gazeta. The article demanded "deeds" rather than "words" against the rebel poets. It proposed a giant grab-bag union to replace the present separate

Writers' Union, Painters' Union, etc. This giant union would gather all the arts under a single centralized Party control, organized by the Party from above and crushing the local semi-independence of separate unions. Example of semi-independence: on the issue of expanding Russia's cultural freedom, the Kochetov dogmatists were being steadily defeated by the Tvardovsky Iiberalizers inside the present Writers' Union (both factions being led by Party members). Therefore, the then powerful I1ychev likewise urged such a grab-all union to discipline the individualists. But nothing came of the notion. The press has simply stopped discussing it.

Even at the height of the freeze, the leader of Leningrad's dogmatists, the poet Alexander Prokofiev, complained that the public would rather buy the rebel poets than the loyal ones (Pravda, March 27,1963). Once again, as with our similar earlier quotation from Sergei Pavlov of the Komsomol, the dogmatist winners were striking a plaintive note inconsistent with the decisive victory they claimed that spring. Nor were they victors long. Resented by most fellow writers, they were too dependent on Kozlov, Ilychev, and Suslov, of whom Kozlov died January 30, 1965 and I1ychev was demoted March 23, 1965. Early that year the Leningrad Writers' Union was free at last to revolt against Prokofiev. The Leningraders elected a neutral figure, not thaw but neutral, to replace "this hated Party toady and boot-licker," to quote an off-the-record Soviet rebel.

A second consequence of the removal of Kozlov and Ilychev (coming only five days after the latter's transfer to a high Foreign Office post) was the attack on Kochetov and his magazine Oktyabr for clinging to the Stalinist past and using "an extremely strong tone" against all new talents (Pravda, March 28). Does this mean Party commitment to liberalization? Probably it merely means another minor pendulum swing. Moreover, the same Pravda piece went out of its way to stress that it saw nothing unusual in Oktyabr's recent campaign against Solzhenitsyn, who no longer has Khrushchev to protect his indictments of neo-Stalinist bureaucrats.

During 1963-64 critics in Red China praised Kochetov as one of the few Russian writers they found ideologically sound. This fact, more likely than a new liberalization prematurely hailed by wishful thinkers, helps explain the 1965 Pravda attack on Kochetov; the N.Y. Times account (March 29) failed to mention this motivating fact. Conversely the Red Chinese attack of August 1964 on Voznesensky and Yevtushenko led to greater public kindliness toward them by Russia's rulers. Not what you write but who praises or attacks it abroad, may determine your status back home. What has undermined Kochetov is not his intolerant authoritarianism, which he shares with Russia's rulers, but the kiss of death he received from Red China. Moreover, his freeze magazine sells less and has less influence than Tvardovsky's thaw magazine; and the Party despises failure, even among its own champions.

A word of background about Kochetov. His rather courageous stubbornness is worthy of a better cause. A lean sinewy war veteran, Kochetov showed more guts than many thaw advocates when he defied Khrushchev by openly speaking out for the "MTS" (Stalin's Machine Tractor Stations, which Khrushchev denounced and abolished). Whereas Khrushchev favored Tvardovsky, inviting him to family 20 TRI-QVARTERL Y

festivities on the Black Sea, Kochetov has been publicly praised (but not really protected from severe press criticism) by Suslov, the top ideological dogmatist of post-Stalin Russia and a prime mover in overthrowing Khrushchev in October 1964. Kochetov's novels include The Yershov Brothers, 1958 (a pro-bureaucrat, antiintellectual rebuttal to Vladimir Dudintsev's pro-intellectual, anti-bureaucrat novel, Not By Bread Alone, 1956) and Secretary of the Oblast Committee, 1961, attacking among many other things the young rebel poets of the thaw. While paying the usual vigorous lip-service to anti-Stalinism, the latter novel contains an insinuatingly anti-Khrushchev, pro-Stalin scene, in which the hero (a Party official) and his wife look up adoringly at a picture of the Stalin they claim to repudiate. Already the Literaturnaya Gazeta of December 16, 1962, while still under its thaw editorship, accused Kochetov of crypto-Stalinism, putting his career in jeopardy under Khrushchev and after. In late 1963 Khrushchev attended a private preview of the movie based on the novel. At the Stalin-picture scene, Khrushchev reportedly started screaming with rage that he would never tolerate such officials in the Party and that the scene must be censored.

It was sometimes difficult to make Russian thaw zealots understand how instinctively we detest the very principle of censorship, whether by a Soviet Bircher like Kochetov, who tries to suppress Tvardovsky's magazine as "nihilistic poison kowtowing to the west," or by liberalizers against Kochetov. We here mention Khrushchev's wrathful censorship of Kochetov. (never published so far as we know) in order to stress that Khrushchev's famous rages were not solely against the thaw camp, even though the world better knows-because more public-his rages against modern paintings in December 1962 and against Ehrenburg, Nekrasov, and Yevtushenko in March 1962. As of 1965 Kochetov has retained his Party posts, and Khrushchev has been fired.

The Party has tried to build up anti-western, anti-experimentalist poets such as Vladimir Firsov, who boasts of being too wholesome to look at modern art. Firsov is a thought-provoking example of the extraverted Soviet "square": his not untypical existence proves that a very young Komsomol secretary (Moscow chapter of Writers' Union) can today still talk like a very old Stalinist. Here is a summary of his remarks of 1963 in a private conversation with a foreigner I know in Moscow: "There are tendencies that alarm us in modern Russian poetry. Influenced by jazz, the twist, and Picasso, instead of our Russian folk art, they lack Soviet national pride and grovel before western bourgeois culture." Firsov was especially angry at Yevtushenko for his allegedly sympathizing more with Jewish than Slavic victims of Hitler in his poem "Babi Yar." (That same year Khrushchev forced Yevtushenko to add lines about the Slavic victims; Yevtushenko told friends he only yielded because of a loss of nerve on the part of Shostakovich, who set the poem to music.) Firsov fell into a fury against "Babi Yar," calling it a sinister anti-Soviet poem. He tried to explain its popularity in the west by a secret conspiracy of "Jewish influences over the American press." These remarks reveal how easily anti-thaw and anti-cosmopolitanism can pass into anti-Semitism even today, recalling-though admittedly less bloodily-the Stalin-Zhdanov purge of leading Jewish writers after 1948. The philistine Firsov mentality about art and letters, a

bourgeois kind of bourgeois-baiting, is in a small, despised minority among Communist writers. Among Communist bureaucrats-hence the dramatic tensions of the thaw-it is far from a minority.

The above mentality of Firsov and the bureaucrats may best be called National Bolshevism, a cousin to German National Socialism, and all this in the name of that international "cosmopolitan", Karl Marx. Compare Firsov's reaction to "Babi Yar", and his warning against "Jewish influences over the American press," with the earlier remarks of the literary critic Nikolai Gribachev (Krokodil, February 20, 1953). Gribachev is commenting on Stalin's plan to torture and shoot the "plotting" Jewish doctors as agents of the "Joint," the Jewish charity organization:

There is weeping at the rivers of Babylon, the most important of which is the Hudson. The "Joint" has been plucked, that vulture dressed in the pigeonfeathers of charity From Jerusalem to London creeps the perplexed muttering of the Zionist leaders Let them weep; this will not move us to pity Even the grave will not reform them.

In 1965 Gribachev is still a leading critic, much praised and quoted by the Party. He is the chief rival of Kochetov for leadership of the anti-thaw National Bolshevik camp. Like Kochetov, Gribachev also has savagely satirized Yevtushenko (Pravda, January 27, 1963).

The hounding of Yevtushenko by Kozlov, Ilychev, Firsov, Kochetov, and Gribachev is only understood in the west when you realize the importance of antiSemitism (disguised as anti-cosmopolitanism) in National Bolshevik propaganda. In Kiev I vainly tried to get permission to visit nearby Babi Yar, where a Soviet apartment house and not a memorial is to cover th� graves of the biggest Nazi pogrom of the war. The issue came to a head in September 1961 with Yevtushenko's best-known poem, which begins by lamenting the lack of a Soviet memorial. The National Bolsheviks attacked the poem ferociously the same month. One of their organs (Literature and Life, September 27) called him un-Russian and accused him of defiling Russia with "pygmy's spittle" because he wrote about Jewish rather than Russian sufferings under Hitler. A publicized counter-poem yearned to see "the last cosmopolitan," a pogrom-inciting parody of the original poem's yearning to see "the last anti-Semite." Khrushchev, the balancer, condemned both poems by later firing both editors. In early I 963 Khrushchev forced Yevtushenko to rewrite "Babi Yar" by inserting a reference to the non-Jewish Russian victims of German invasion.

By accident the same issue of the pro-thaw Literaturnaya Gazeta which published "Babi Yar" (September 19, 1961) published Russian translations of poems by Richard Wilbur and me, on the occasion of our cultural-exchange visit. Thereby I was able to obtain this otherwise unobtainable issue, which speedily sold out to Yevtushenko's followers. Naturally I studied carefully this published version; neither it, nor its translations in countless American books and newspapers, are the full version which I heard him read in Moscow in mid-September (and which Michel Tatu of Le Monde assures me he witnessed on a later occasion). A significant omission states that anti-Semitic feelings in Soviet Russia today (officially denied) "still are rising on the fumes of alcohol and in conversation after drinking." 221 TRI-QUARTERLY

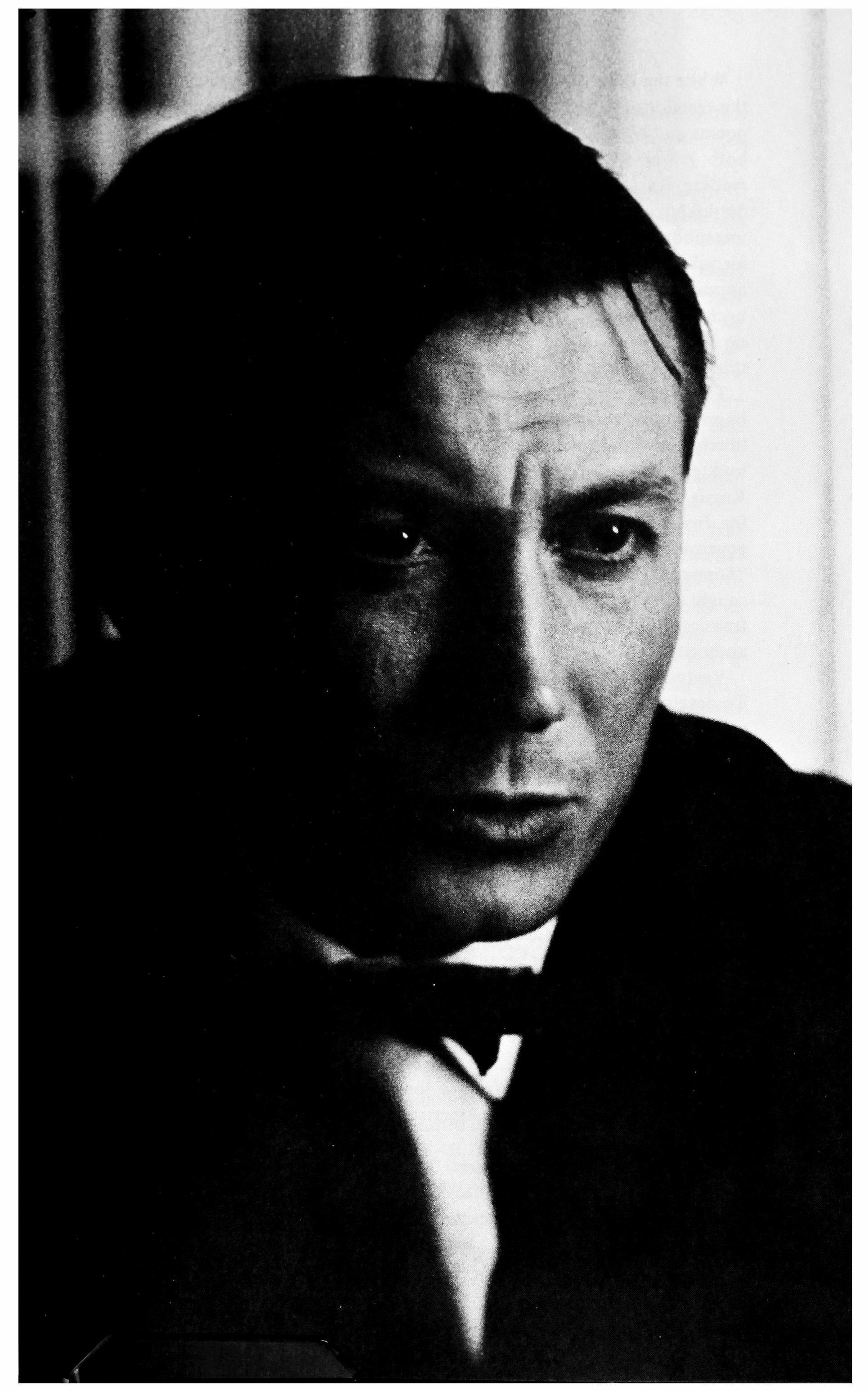

While the then 28-year-old author was reading this and other poems, I watched the reactions of the Moscow student audience. They were moved by all the lyrical poems and by a few of the social-conscience poems, but "Babi Yar"-combining both genres-was the one poem they made him read twice. During the second reading Russian men burst into tears (and not just the "hysterical schoolgirls" Sholokhov accuses him of bewitching). They burst into tears at the evocative metaphors about Anne Frank ("frail as a twig in April"), at the compassionate identifications ("Today I am as old in years as the Jewish people"), and at the appeal to the honor of his fellow Slavs: "0 my Russian people those with unclean hands have often loudly taken in vain your most pure name There is no Jewish blood in mine, but I am hated by every anti-Semite as if a Jew, and for this reason I am a-true Russian."

The whole evening of poetry-reading provided my most memorable personal impression of contemporary Soviet youth: its passion for the arts, its passion for liberty and racial tolerance. There, all around me, was the Russia I have learned to love, the Russia of generous aesthetic and ethical commitments. It was a young Russia that cheered, cried, and laughed out of a natural, unaffected enthusiasm for free poetic self-expression, bursting forth far beyond the intentions of the government's halfhearted half-thaw. These are the sort of people who shouted "Sonnet 66!" spontaneously at a poetry meeting during the Stalin era when they caught sight of Pasternak. The not-so-cryptic reference was to a line Pasternak had translated from one of Shakespeare's sonnets: "And art made tongue-tied by authority.'

Yevtushenko's most authentic aesthetic endowment is his long, wavelike rhythm. To develop this gift to the full, and thereby to enrich Soviet literature permanently, will take time, work, inwardness. I hope he will not lose too much energy and time on the short-run kind of politics, whether as martyr-rebel or as indulged semiofficial rebel-in-residence. I hope he has enough free hours from the national and international spotlight to do the less dramatic, more essential homework of disciplining his craftsmanship and resisting his addiction to fireworks. Be that as it may, his decisive influence on the new generation, especially in leading it back from tractor obsessions and abstractions to concrete warmth and human dignity, makes his role one of the most rehumanizing forces in Russia today.

My longest conversation with Yevtushenko took place on October 8, 1961. The date sticks in my memory because it was being celebrated as Poetry Day in Moscow. On that day people of Moscow form groups of as large as five thousand, standing for hours in cold weather on Mayakovsky Square, to hear their favorite poets reading aloud. Before his evening reading on Poetry Day, I spent three or four hours with Yevtushenko and his wife at bookshops and in the Prague Restaurant. There he read me excerpts from a long unpublished poem and jotted down its theme for me to take back to America; he called it "my message of friendship to American youth."

This unprinted poem is an appeal for good will between Americans and Russians. It describes men of both nationalities traveling together in a future rocket ship to the planet Venus. What do they talk about during the long trip? Is it about rival

economic statistics of their respective steel industries? Is it about government or political slogans? No, not for one minute; in the end they spend their time swapping anecdotes about love affairs.

The ending may seem frivolous, but we must not judge it in our western context. We must judge it in the Soviet context of a hitherto total crushing of private life. There it comes as a welcome portent of a return from robots to humanity.

After his enforced silence of spring and summer 1963, preceded by his publicity stunts of 1962, many Russian and American critics spoke of Yevtushenko as a fiash-in-the-pan, now passe. They spoke too soon. On December 14, 1963 he reemerged on the public platform with one of the most effective and most enthusiastically received readings of his career. It suggests, being accompanied by a new writing streak, that his more serious literary career has only begun. His future literary stature will depend not on his politics but on his learning to tighten into disciplined beauty his sprawling rhetoric.

Westerners do Yevtushenko a disservice by exclusively praising his political contribution. The old Irish freedom-fighter O'Leary once remarked to Yeats that you may be permitted almost any crime for the sake of your country except bad verse. Most of Yevtushenko's political poems are bad verse in a good cause. Meanwhile, what gets lost in the shuffle is Yevtushenko's excellent non-political love poetry. At heart he is not so much the tribune of "revisionism" as the troubadour of the "conspiracy of feelings." When I asked his ally, Ilya Ehrenburg, why the Young Communist League temporarily expelled Yevtushenko in the 1950's, Ehrenburg replied: "Puritanism is the curse of the Soviet arts. Yevtushenko's love poetry was guilty of revealing the State secret that men are physically different from women." Here, for example, is a poem from his second volume, that of 1955; in contrast with his unsensuous rhetorical abstractions in politics, note the felt concreteness of "bang the door" and "slide to the floor":

My love will come

In from the pouring dark, from the pitch night without stopping to bang the taxi door she'll run upstairs through the decaying porch burning with love and love's happiness, she'll run dripping upstairs, she won't knock, will take my head in her hands, and when she drops her overcoat on a chair, it will slide to the floor in a blue heap.

Even in a poem of laudable political symbolism ("Nefertiti", Moskva, No.2, 1964), where the Pharaoh is the Party and Nefertiti is art, the sole aesthetic meritif only one could get Yevtushenko to admit it-is in the sensuous concreteness of the incidental images:

He had armies, chariots, But she has eyes, eyelashes

And her throat curves astoundingly Pharaoh was sullen in his caresses, Crude in his actions

Because he felt the fragility of power

Beside the power of this fragility.

Fundamentally Yevtushenko is not a political animal at all, though like his hero Mayakovsky he tries to be one. Yevtushenko is in the tradition of the magnetic, self-dramatizing Byronism of Lermontov, with just enough narcissistic hamminess to annoy his more serious friends when he exploits his personality for the crowds but with enough real poetic genius to make them gladly forgive him and deeply believe in him. What makes it so painful to predict his future candidly is the fact that this Russian Byronizing tradition has an undercurrent of unconscious selfdestructiveness, constantly oscillating between would-be folk hero and would-be martyr, b�tween matinee idol and Grand Pariah.

Tragedy in different ways brought early death to Pushkin, Lermontov, Gumilev, Mayakovsky, Yesenin, Mandelstam, Tsvetaeva. Their examples doubtless reinforce the innate martyr penchant I observed in Yevtushenko. Once when he playfully asked me to predict his future, I said I feared he had a compulsion someday to meet his Zhdanov-indeed to provoke his Zhdanov, as Pushkin and Lermontov partly provoked the duels that killed them and as Gumilev practically taunted the Party into shooting him. Later Yevtushenko asked me with strange excitement if I really thought my prediction would come true. Obviously, I hope it won't. But in March 1963 it almost did. This was when Khrushchev and Ilychev denounced him for publishing his autobiography without Soviet permission in L'Express of Paris (five installments, February 21-March 21). I don't mean to condone the detestable Soviet censorship, including the so-called "Pasternak law" of 1958, by which Soviet authors may not publish books abroad without prior permission. Yet Yevtushenko's 1963 martyrdom was not forced upon him by the censorship but by himself; he provoked it deliberately by his Paris publication. Nor can it be argued that he was ignorant of the "Pasternak law". He himself had mentioned this law, and his respect for it, to a friend of mine in Moscow as the reason why he did not let his manuscripts go abroad. And it is known he was aware of being shadowed by the Soviet secret police during his actual Express interview.

The dogmatist faction, from Kochetov in literature to Kozlov in politics, were against Yevtushenko anyhow; because of his thaw position in general and his opposition to their anti-Semitism in particular. But his illegal Paris publication, so easily avoidable, swung the Party neutrals against him and made him the Saint Sebastian of their slings and arrows. Even Tvardovsky had to differentiate himself from Yevtushenko on this issue. Russia's poete maudit could no longer be protected even by Khrushchev, who in 1962 had personally authorized the October 21 appearance in Pravda of Yevtushenko's long-banned poem "The Heirs of Stalin," which for years had been circulated in secret.

Moreover, Yevtushenko more than once hints in his poems at self-destruction. This fact, plus his temporary depression during the Ilychev witch-hunt against him

TRI-QUARTERLY

may have caused the suicide rumors about him-false ones fortunately-which swept Russia in 1963. It is with superstitious certainty that I feel he will eventually contrive his Zhdanov, his Lermontov duel, his Mayakovsky or Yesenin darkness. It would equally suit his personality under tsars or commissars, east or west; nobody can stop him. The analogy of doom is with Dylan Thomas, except that the intoxication is even more with romantic self-sacrifice than with alcohol. The Siberian Ukrainian in Moscow and the BBC Welshman in New York, two country boys too quickly jaded by early fame, are avatars of the artist as sacrificial * animal.

Public meetings are the best chance for uncensored expression. Even when a speech has been blue-pencilled by the censor beforehand, the emotional excitement of a meeting evokes spontaneous outbursts from both floor and rostrum. These outbursts show what the Russian people are really thinking: for example, the wild and safely anonymous applause that I heard after Yevtushenko's first reading of "Babi Yar." The same kind of applause on the same evening greeted his remark that Lenin had approved free literary self-expression and that Castro currently approved abstract art. This is how daring points are handled in public; attributing them to Communist sacred cows is the needed reinsurance against the eavesdropping Soviet Birchers. But what counted was not Yevtushenko's shallow praise of the Russian and Cuban dictators but the spontaneous glee of the audience at the mention of free art.

Another significant burst of enthusiastic applause, at a meeting I attended, greeted a tendentious pun. Yevtushenko was quoting a verbal slip by Alexei Surkov, a high official of the Writers Union, also a member of the Central Committee. The Party zealot Surkov had intended to repeat a standard Soviet admonition: "Never forget you are writing for an audience of 200 million people." In Russian the plurals of "people" and "rubles" sound somewhat alike, and the house went wild with hooting laughter when Yevtushenko alleged that the admonition slipped out as: "Never forget you are writing for an audience of 200 million rubles."

Lunching with Surkov as fellow guests of the novelist Konstantin Simonov (Surkov's former pupil at the Gorki Writers School), I found Surkov possessing more candor, humor, and independence than his enemies, the thaw writers, had led me to expect. For example, I was struck by his candor about his recent Stalin worship and his emotional shock at the 1956 suicide of his friend and favorite novelist, Fadeyev, long Stalin's watchdog in the Writers Union. Surkov seemed unnecessarily insistent, in a very personal way, in warning me not to conclude that thesuicides ofFadeyev and Mayakovsky were caused by the wound ofdisillusionment with communism. It eased him to blame the suicides on alcoholism. The alcoholism

"For a later and better-documented substantiation of this 1961 intuitive reaction to Yevtushenko, see Priscilla Johnson's superb Khrushchev and The Arts, Cambridge, Mass., 1965, page 41, where she quotes him as calling Voznesensky and himself, albeit in a different context, "a generation of the sacrificed".

TRI-QUARTERLY 127

was there, all right; but to make it the cause of suicide is a very revealing evasion of a deeper question: what wound caused the cause? Then the conversation turned to the rival novels of the revisionist Dudintsev and the dogmatist Kochetov. When I asked, "Whom do you consider the better novelist of the two?" Surkov replied, "Both are worse." The reply indicates a gift for epigrammatic brevity and malicious independence that makes him better than the robot dogmatist he is accused of being.

To be sure, the rebel poets have the best of reasons for hating Surkov. He was a leading persecutor of Boris Pasternak. He even made a special trip to Italy (about which Feltrinelli told me in Milan) in a futile attempt to stop the Feltrinelli publication of Zhivago. Privately some of the rebels say, perhaps unjustly, that Surkov's real motive was his being superseded by Pasternak not only in the affections of the Muse but in the affections of Olga Ivinskaya, Surkov's secretary before becoming the Lara of Pasternak's Zhivago, (In 1964 she was released from a Soviet prison camp, where Party vindictiveness had sent her, on the pretext of currency charges, after the great poet's death.) In the 1960's Surkov, once head of the whole Writers Union, has been replaced by the more extreme Kochetov and Gribachev in the leadership of the literary dogmatists. Surkov even temporarily added his signatureand then withdrew it-to a petition of December 1962 for cultural liberty. His deriders would better understand his militancy if they took into account the physical torture he suffered from Whites during the Civil War. The militancy, which one must reject but not without compassionate understanding, is explained by his poem "Portrait" (translated by the able British journalist Alan Moray Williams):

Having survived the iron storms, he found His home destroyed, his wife and children dead; And from the tears that stubborn pride kept bound He's become blackened both in heart and head.

Under the pine-tree's shade he sits alone, A forest streamlet running at his feet.

If this man's eyes should chance to meet your own, You'll understand, friend, how Revenge is sweet.

It will be recalled that the March freeze of 1963 halted the publications and foreign travels of the rebel writers. The travel ban has continued for most of them through 1965. Evidently the Party will not soon again give passports to deviationists, who might speak indiscreetly abroad. However, the publication ban ended in autumn 1963 when Ehrenburg and Voznesenskyappeared in Pravda and Yevtushenko in Yunost. Coming just after the ban,this autumn material must have been scrutinized particularly closely by the censors. Let us see whether our own scrutiny can find any common denominator in it. The existence of a common denominator for these three pieces would throw light on what the Party of the 60's expects of its freer spirits.

Ehrenburg's autumn piece was an article attacking the foreign policy of Mao and praising the Russo-American test ban (Pravda, September 6, 1963). Yevtushenko's piece was an anti-war poem of similar outlook (Yunost, September). Voznesensky's

was a poem praismg Lenin and attacking war-mongers (Pravda, October 13, excerpted from a longer, less political poem published elsewhere). It seems more than coincidence that all three re-appearances emphasized the current anti-Mao peace-line. The Party must have reached a decision that, instead of the crude Kozlov tactic of silencing its rebels, it is now subtler to let them again attack neo-Stalinists but those of China, not Russia. One can well see why the censorship would be pleased, for reasons not intended by Voznesensky, with his excerpt in Pravda,'

The school of Lenin is a school of peace

Don't pin Lenin's name to him

Who plots his progress on a pile of bones, Turning half a planet to scorched earth.

This unnamed bone-piler and earth-scorcher, who wrongly claims Lenin's name, can only be a reference to Mao. Probably it is an amalgam of Stalin and Mao as joint Communist Genghis Khan. The Party press of that very time was accusing belligerent Red China of resurrecting the Mongol world-conqueror, who indeed had boasted ofhis piles ofbones. Admittedly the Party youth organ (Komsomolskaya Pravda, December 7) had good reasons-namely "socialist realism"-for attacking the poem's "formalist" style as "artificial". But the Party censors had even better reasons-namely anti-Chinese politics-for reprinting the excerpt in Russia's leading newspaper.

By thus aiding Party propaganda, are the three rebels betraying their independent ideals? Not in terms of their own special audience. To write against Red China has two different meanings, depending on the audience level. For the rebel in-group, anti-China is Aesopian language for pro-west, pro-thaw, and anti-dogmatist in general. At the same time anti-China has merely a literal meaning for the larger out-group of Pravda readers. So both sides gain by the thaw-freeze compromise which Kozlov's incapacitation make possible. The question then arises: which side is exploiting the other and which side is being outwitted? In the short run the Party gains more, or it would not allow such publications in the first place. But as with Khrushchev's anti-Stalin speeches of the Congresses of 1956 and 1962, the long-run effects can neither be foreseen nor controlled; they are likely to reverse the short-run Party gains.

So rm-ch for the 1963 pieces of political rehabilitation. In contrast, Tvardovsky's Navy M\ r of February 1965 features more openly rebellious pieces of prose or verse by Ehrenburg, Yevtushenko, Nekrasov, and (posthumously) Pasternak. Yevtushenko's new poem was written during his enforced 1963 exile amid the fisher folk of northern Russia. It asks the rulers to allow "a wider mesh" for Russian fish. Of course, this plea is merely repeating his usual double-level symbolism for more personal liberty. His year of suffering and exile has deepened but not changed his usual themes and techniques. The same cannot be said of Voznesensky. He is developing new themes and techniques after his ironic 1963 recantation (when he promised the Party "to work harder"), With him everything is more fluid and muted than with his more flamboyant friend.

TRI-QUARTERLY 129

Western books on Soviet literature classify Yevtushenko as a political poet and Voznesensky as a pure aesthete. This contrast holds true only of their more publicized poems. It ignores Yevtushenko's unpolitical love lyrics. And it ignores the essential political parts of Voznesensky's book of 1962, The Triangular Pear. His Pear rapidly sold out its printing of 50,000 copies. And over 10,000 listeners attended Voznesensky's readings from it in one meeting of autumn 1962. Both his aesthetic and political merits would be just as great had he sold only ten copies and read to an audience of ten. We cite the figures merely in order to contrast Soviet and American attitudes toward serious poetry. Why the mass following of poets in Russia? First, because the poets, from Pushkin on, have always been regarded as the conscience of the country. Second, because now the poets offer a smuggled, underground religiosity to the religion-starved Russian people. This is why so many Soviet poets now chant their lines in precisely the manner of the Greek Orthodox liturgy. Probably they are not conscious of doing so. Without falling into the Soviet error or putting politics above aesthetics in poetry, let us not go to the opposite extreme; let us not pretend there are no political intentions. The present writer happens to believe that narrow political aspects are irrelevant to aesthetic merit but that broad ethical aspects (for example, the racism in Pound's Pisan Cantos) are not irrelevant to aesthetic merit. Most American critics disagreed with the writer* in regard to his ethical questioning of the Poundian aesthetic; on such issues honest minds in free debate can fruitfully disagree. But no matter how we assess them, ethical intentions and even narrowly political intentions-from Dante through Voznesensky-are emphatically there. Politically the Soviet in-group audience substitutes "Russia" for "America" in many cases where the out-group (with which, being larger, the censor is more concerned) takes its "America" straight. The endless examples include "Song About An American Soldier" by the guitar-playing Bulat Okudzhava. This favorite Soviet student song makes no sense except as a rebellious Russian soldier song. In this light consider the four following American references in Voznesensky's Pear,'

J. When Voznesensky says, "You are looking for India and will find America." the in-group reader substitutes America for India and substitutes Russia for America.

2. One of the poems tells of being trailed by a comically exaggerated mob of FBI men in America. Here the poet satirizes the penchant of the Soviet secret police to go gumshoeing after intellectuals. This penchant was satirized by Nekrasov's American travelogue (Novy Mir, November 1962, the same issue as Solzhenitsyn's One Day; November still remains the high-point of the thaw). Nekrasov's insult to the cherished Soviet secret police was savagely attacked by the Government (Izvestia, January 20, 1963, an opening gun-after Khrushchev's anti-art outburst of December-of the '63 freeze).

3. An ode to Lenin is set among sequoias in California. Here Voznesensky somehow manages, without disrespect for his hero Lenin, to satirize the Soviet genre of pious official propaganda.

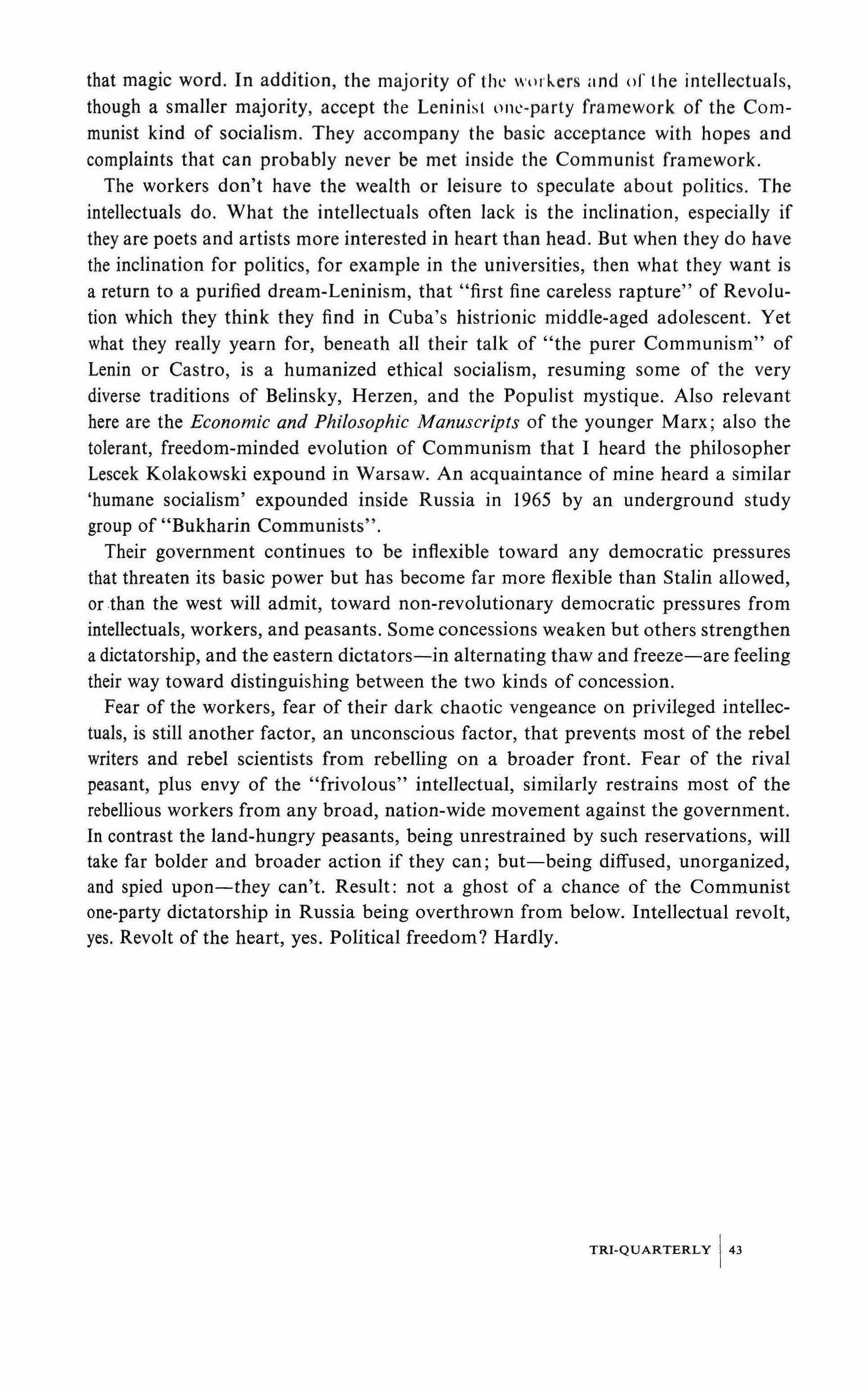

*P. Viereck, "Pure Poetry, Impure Politics, and Ezra Pound," essay in Commentary magazine, N.Y., April 1951; reprinted in The Unadjusted Man, Boston, Beacon Press, 1956.