�CHIVES

EDITOR

Charles Newman

ART DIRECTOR

Lawrence Levy

ASSOCIATES

John Almquist

Colton Johnson

PRODUCTION

Lauretta Akkeron

BUSINESS

Stephen Bornemeier

Suzanne Kurman

ASSISTANTS

Arthur F. Gould

Carol Breyer

William A. Henkin Jr.

STAFF

Adele Wolfberg

Richard Thieme

Joel Pondelik

Mark Malkas

Anne Campbell

Dan Conrad

The Tri-Quarterly is a national journal of arts, letters and opinion, published in the fall, winter and spring quarters at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. Subscription rates: $3.00 yearly within the United States; $3.25 Canada and Mexico; $3.75 Foreign. Single copies will be sold for $1.25. Contributions, correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to Tri-Quarterly University Hall 101, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. Unsolicited manuscripts are welcome, but will not be returned unless accompanied by a self-addressed stamped envelope. The Tri-Quarterly is distributed by the Northwestern University Press. Copyright © 1964 by Northwestern University Press. All rights reserved. The views expressed in the magazine, except for editorials, are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors.

LESLIE A. FIEDLER 7 Poetry, science and the end of man

STE PHE N SPENDE R 15

The literary mood of the 1930's

LIONEL TRILLING 26 A valedictory

ERICH HELLER 35 The artist's journey into the interior: the Hegelian prophecy (part one)

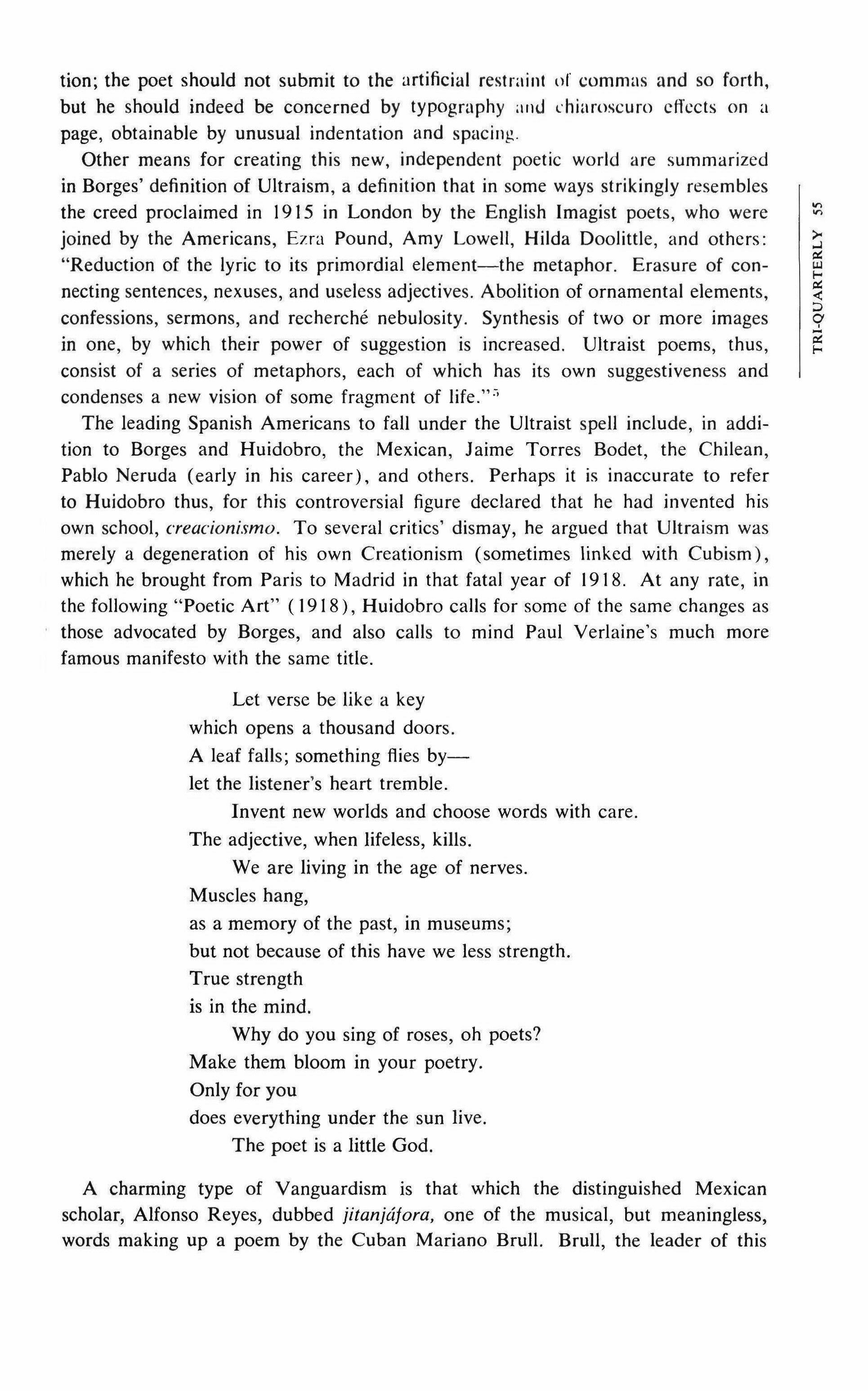

FREDERICK S. STIMSON 50 The birds and the bees: modern Spanish-American poetry

J. B. YEATS 70 On James Joyce: a letter

MARK REINSBERG 77 What republicanism was in the coming election

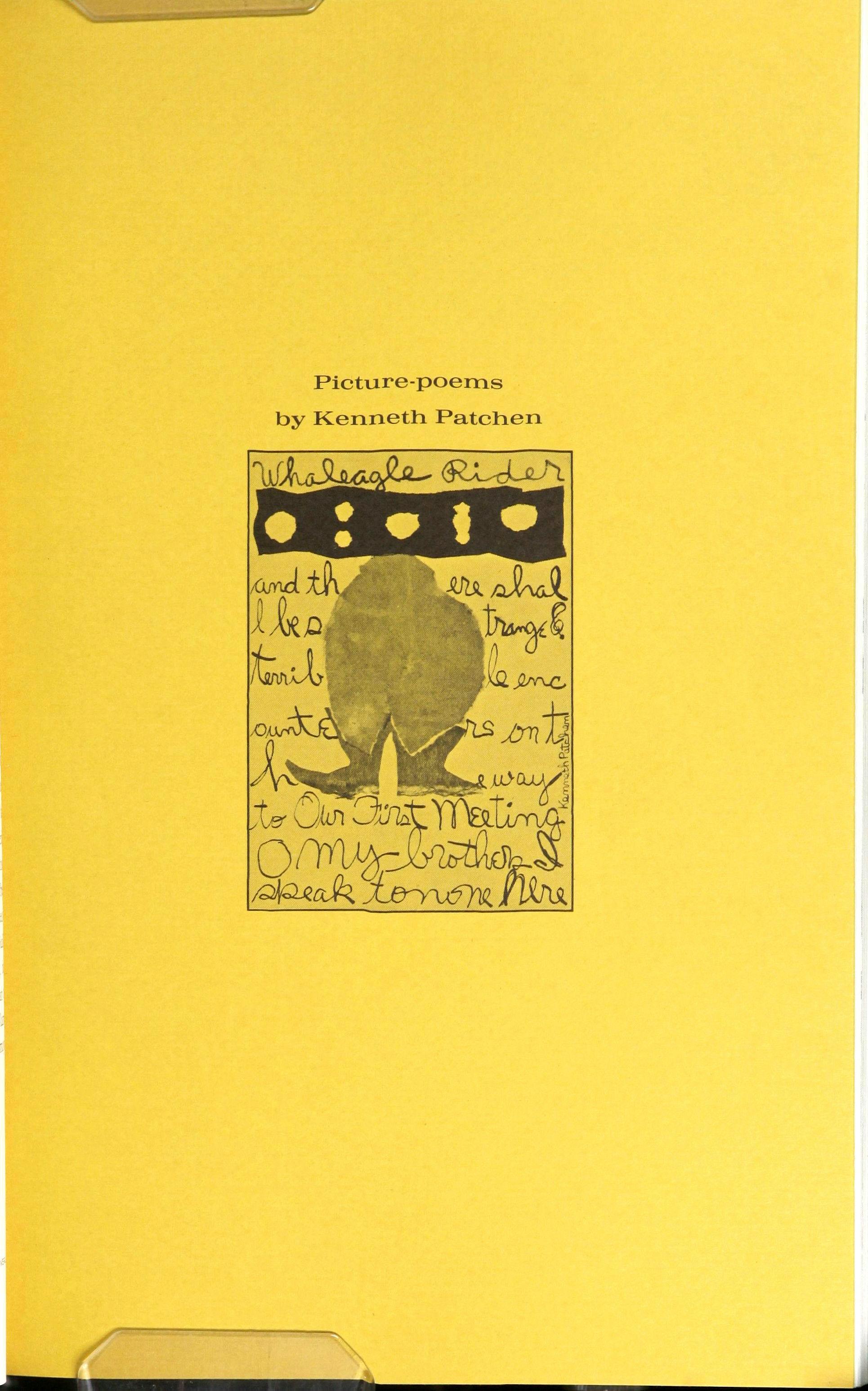

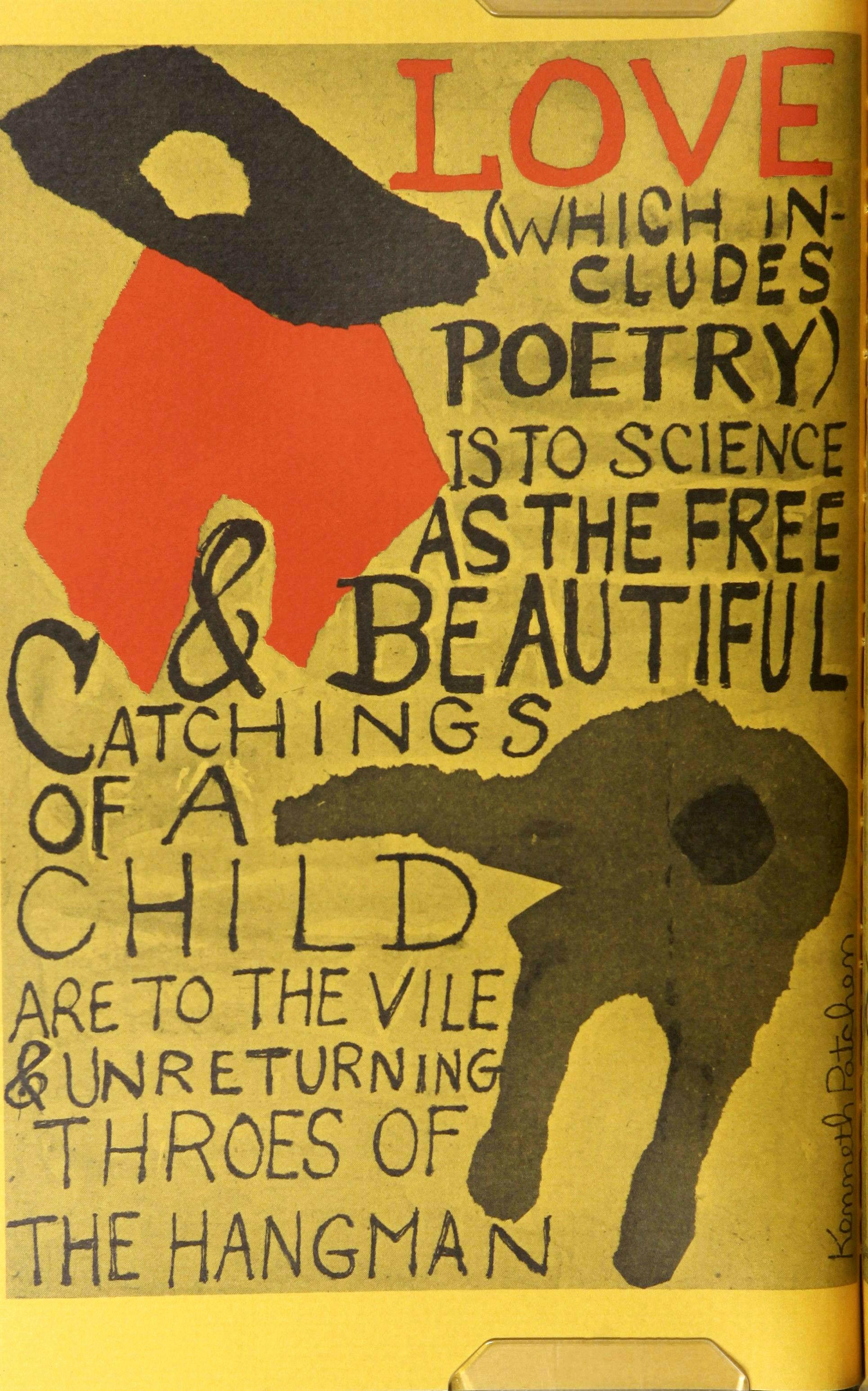

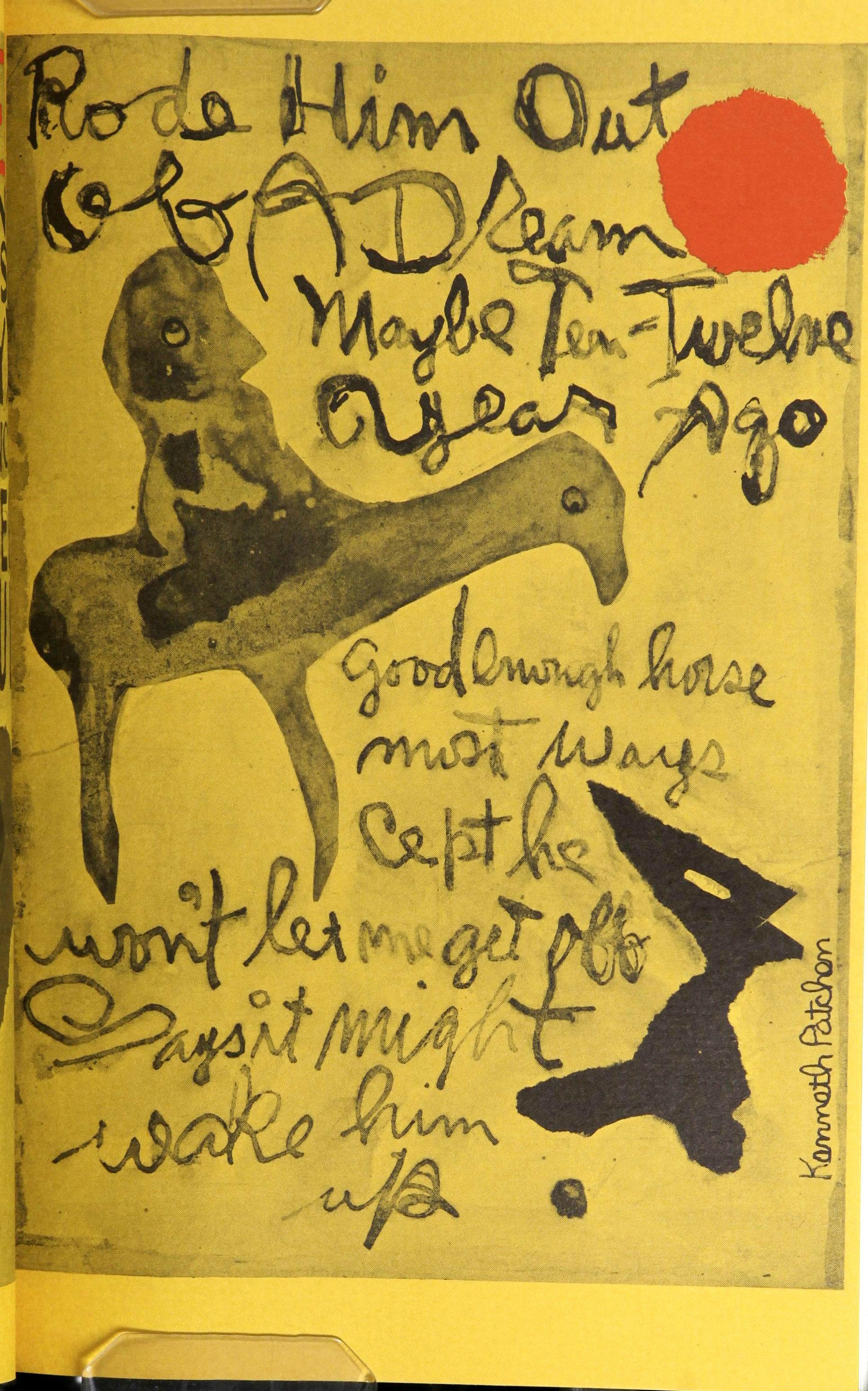

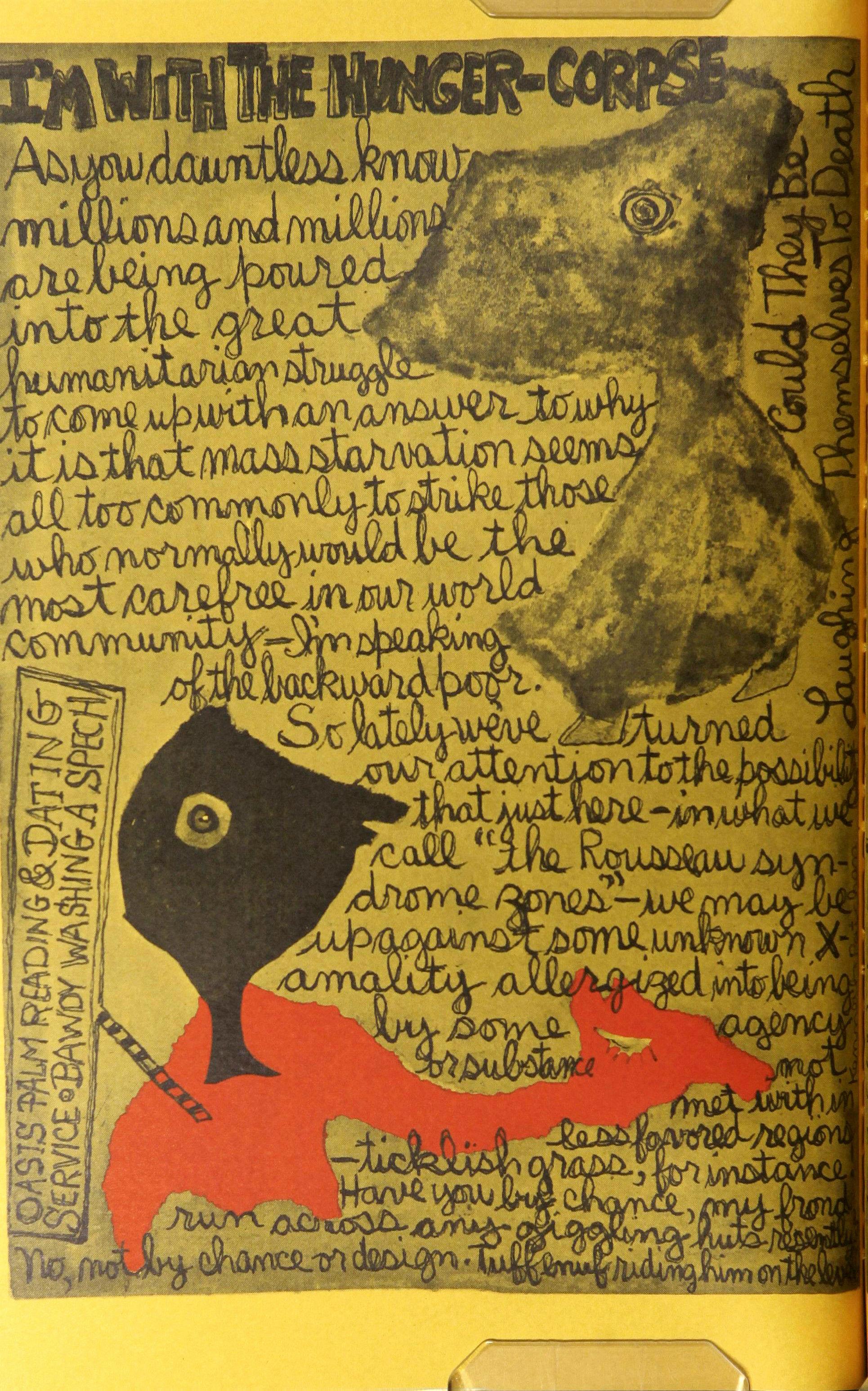

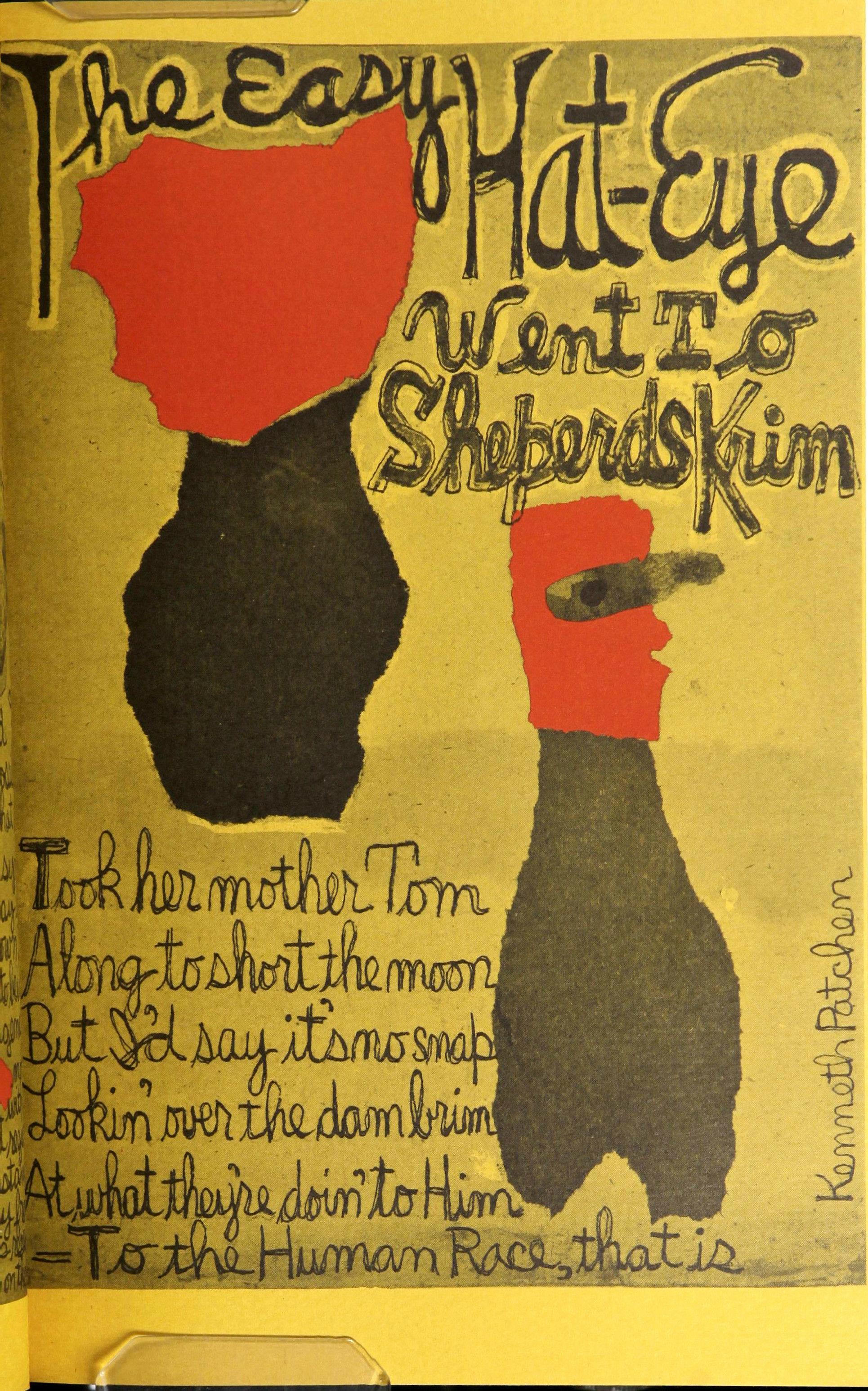

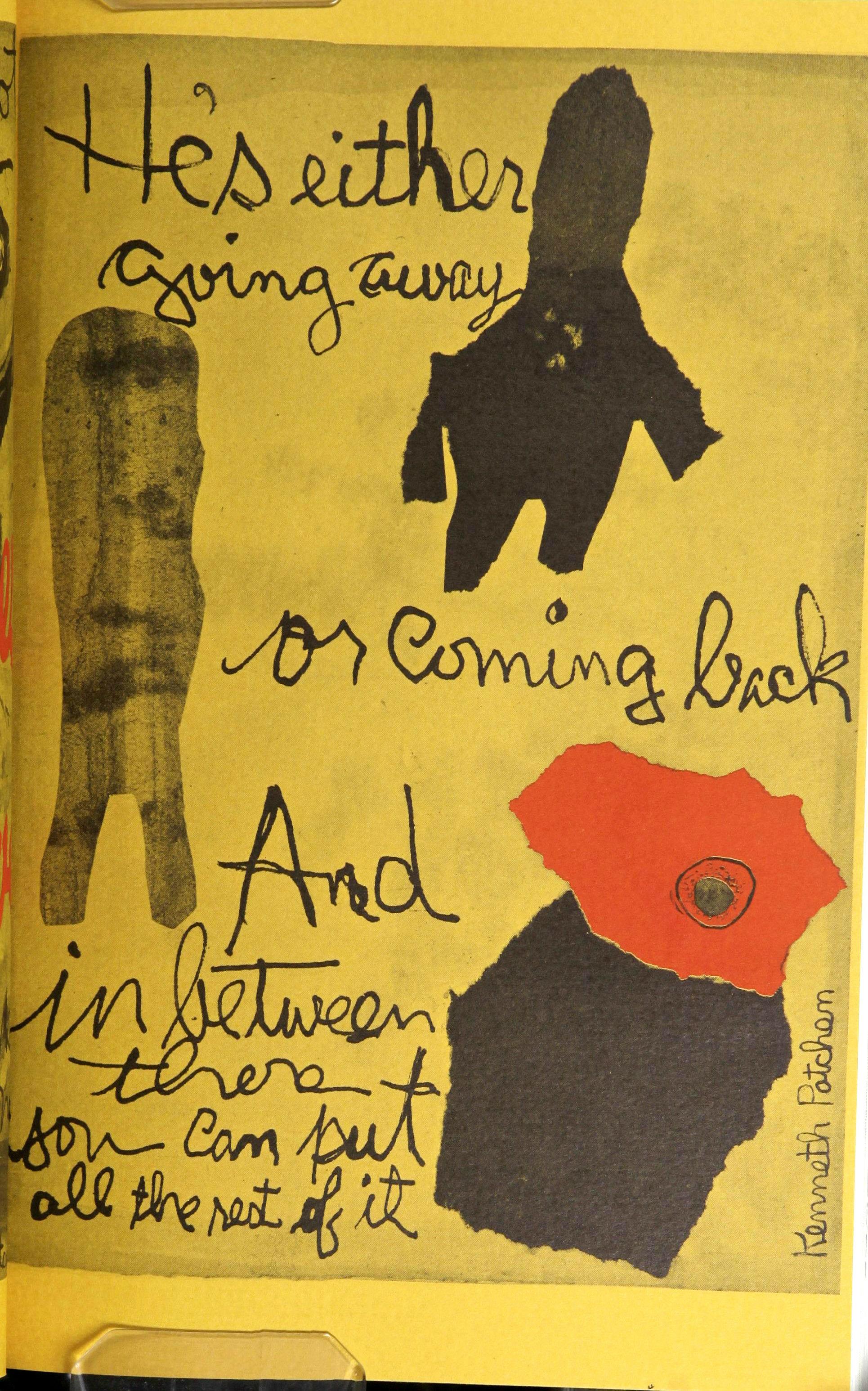

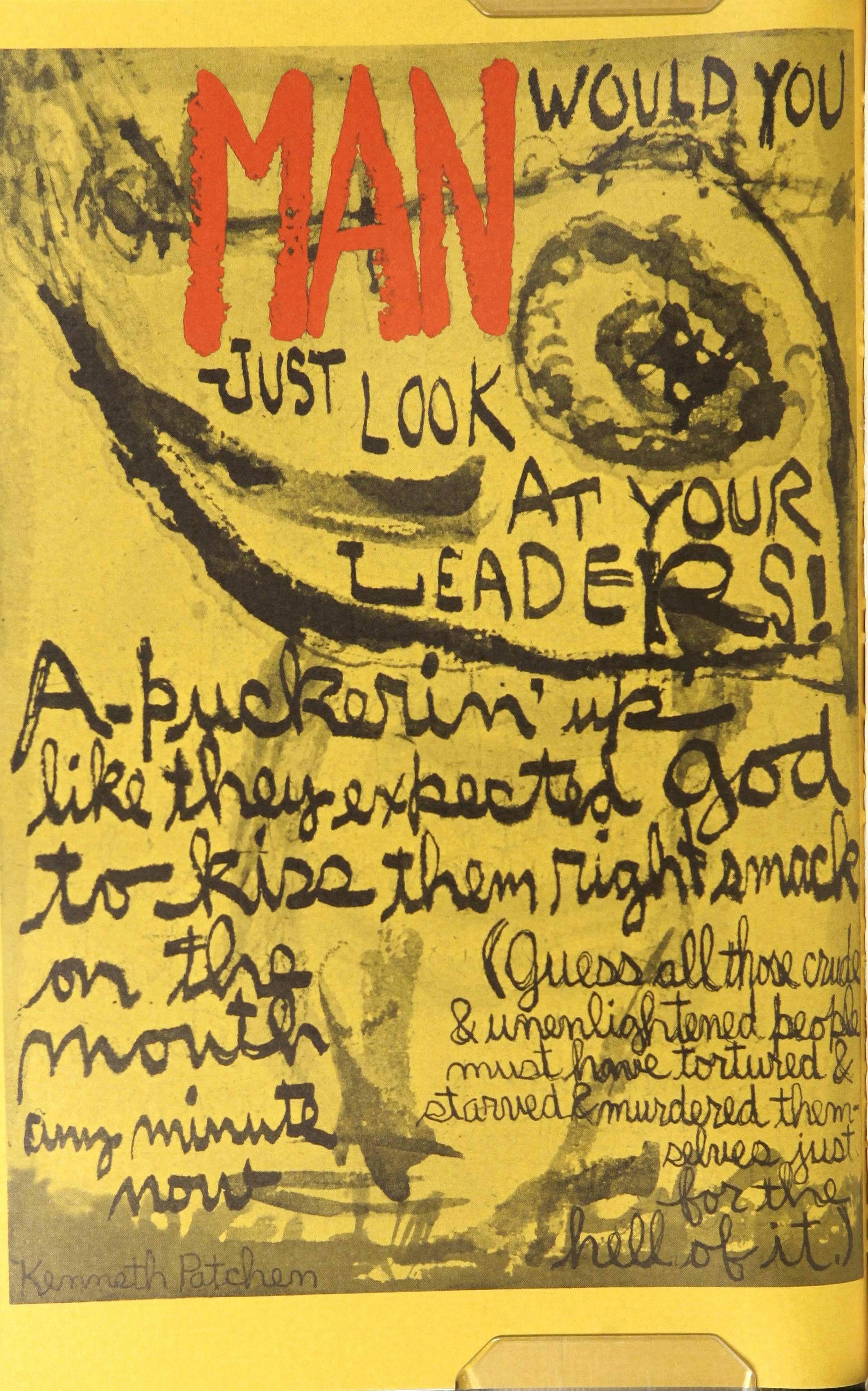

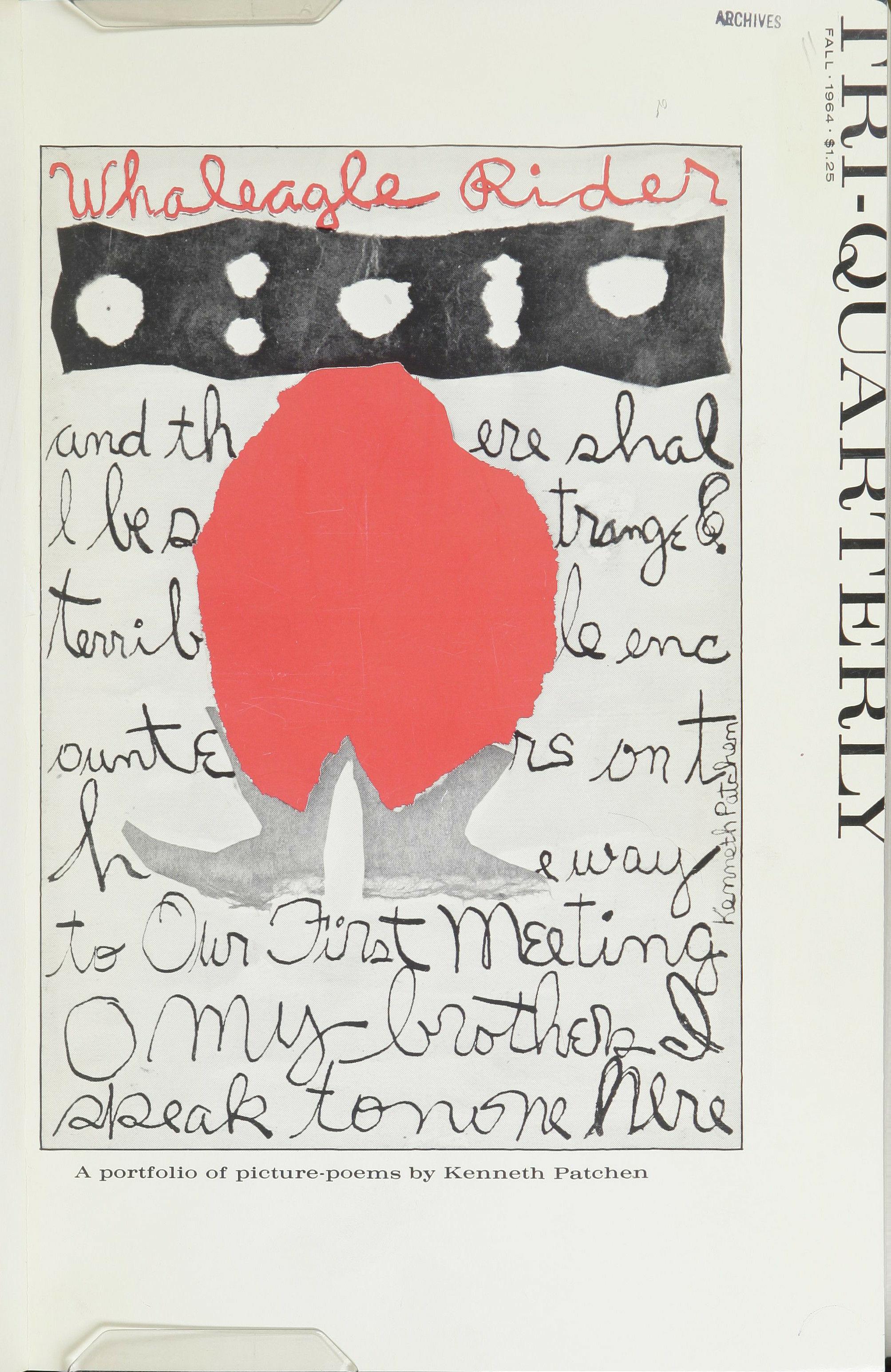

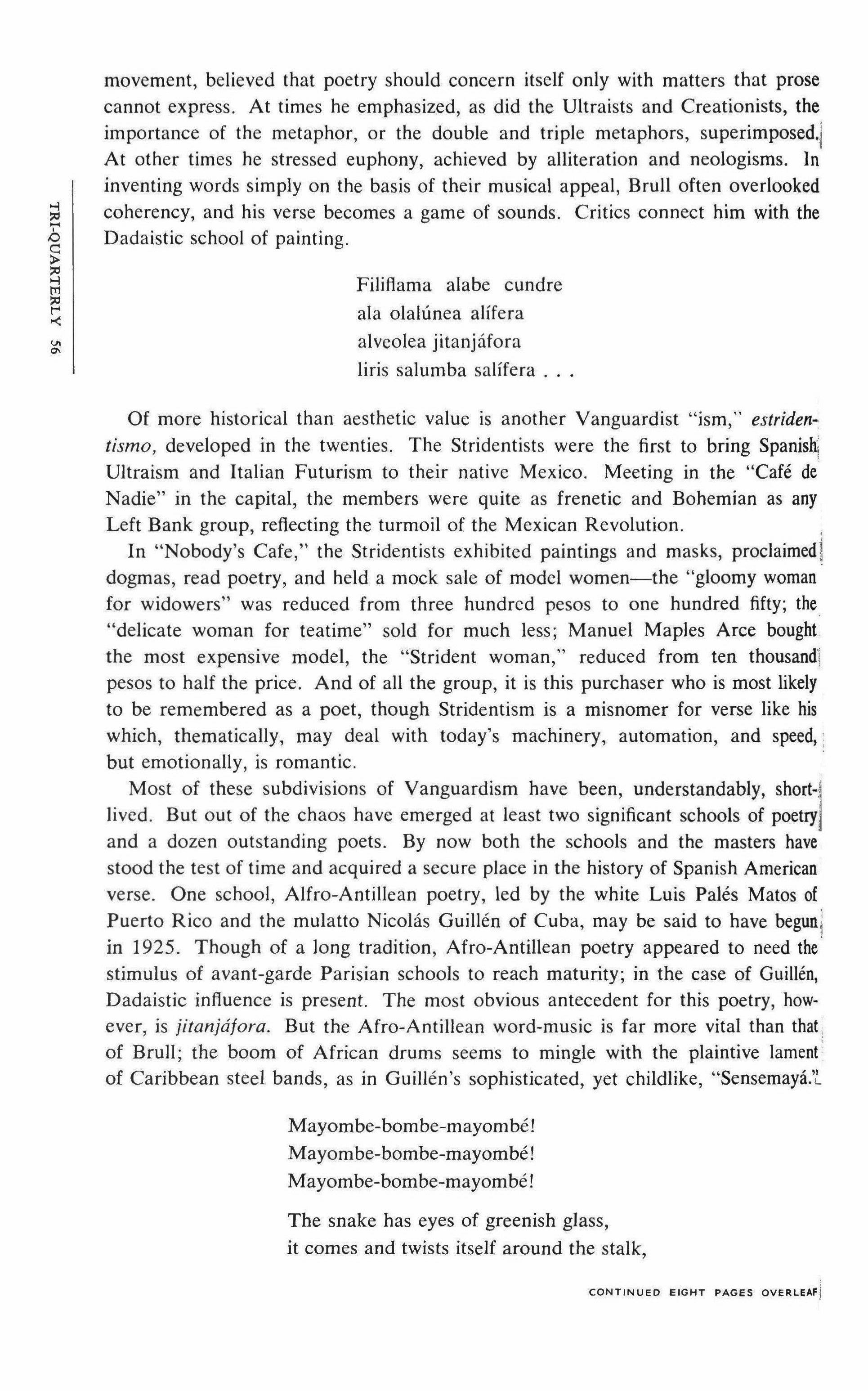

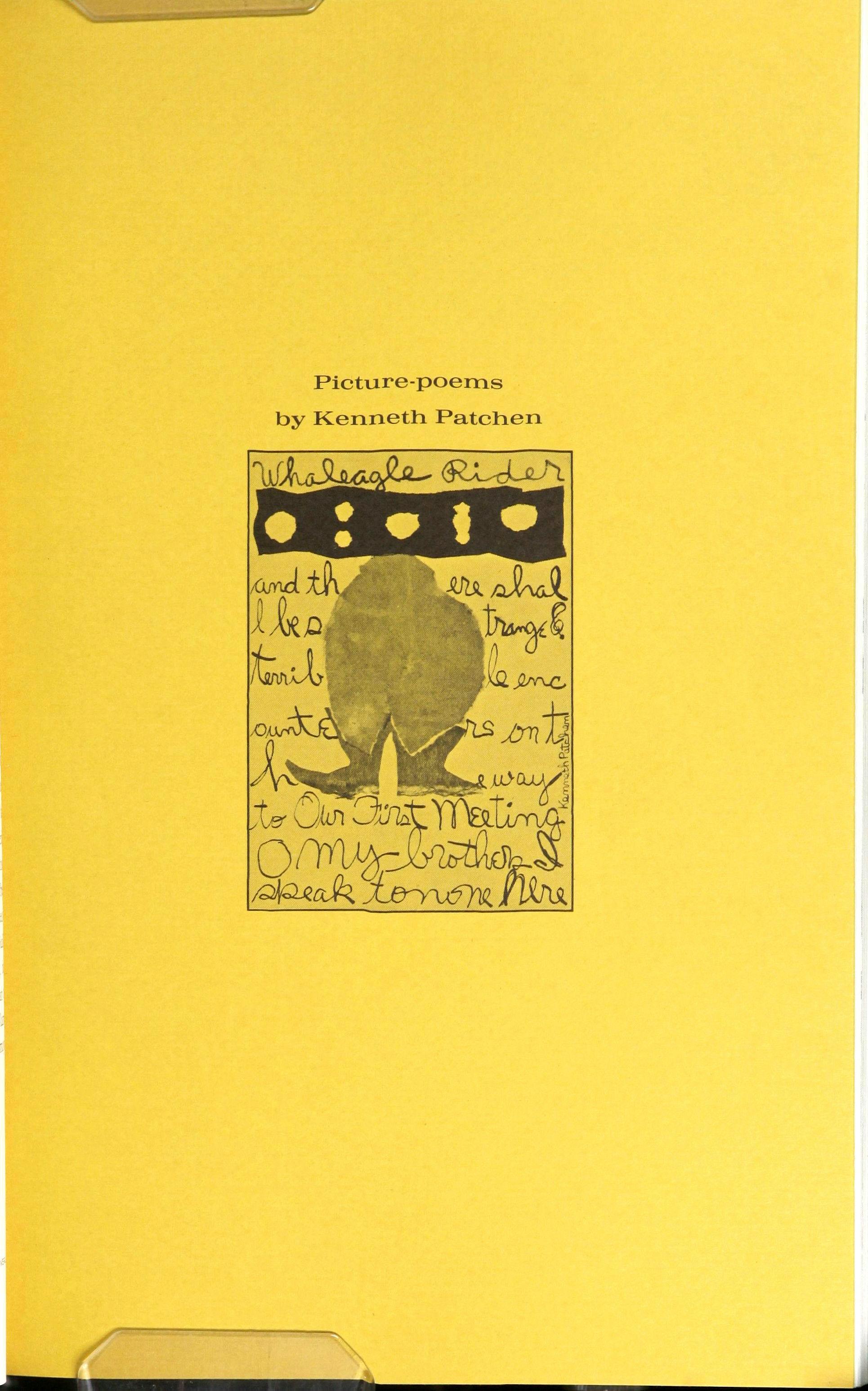

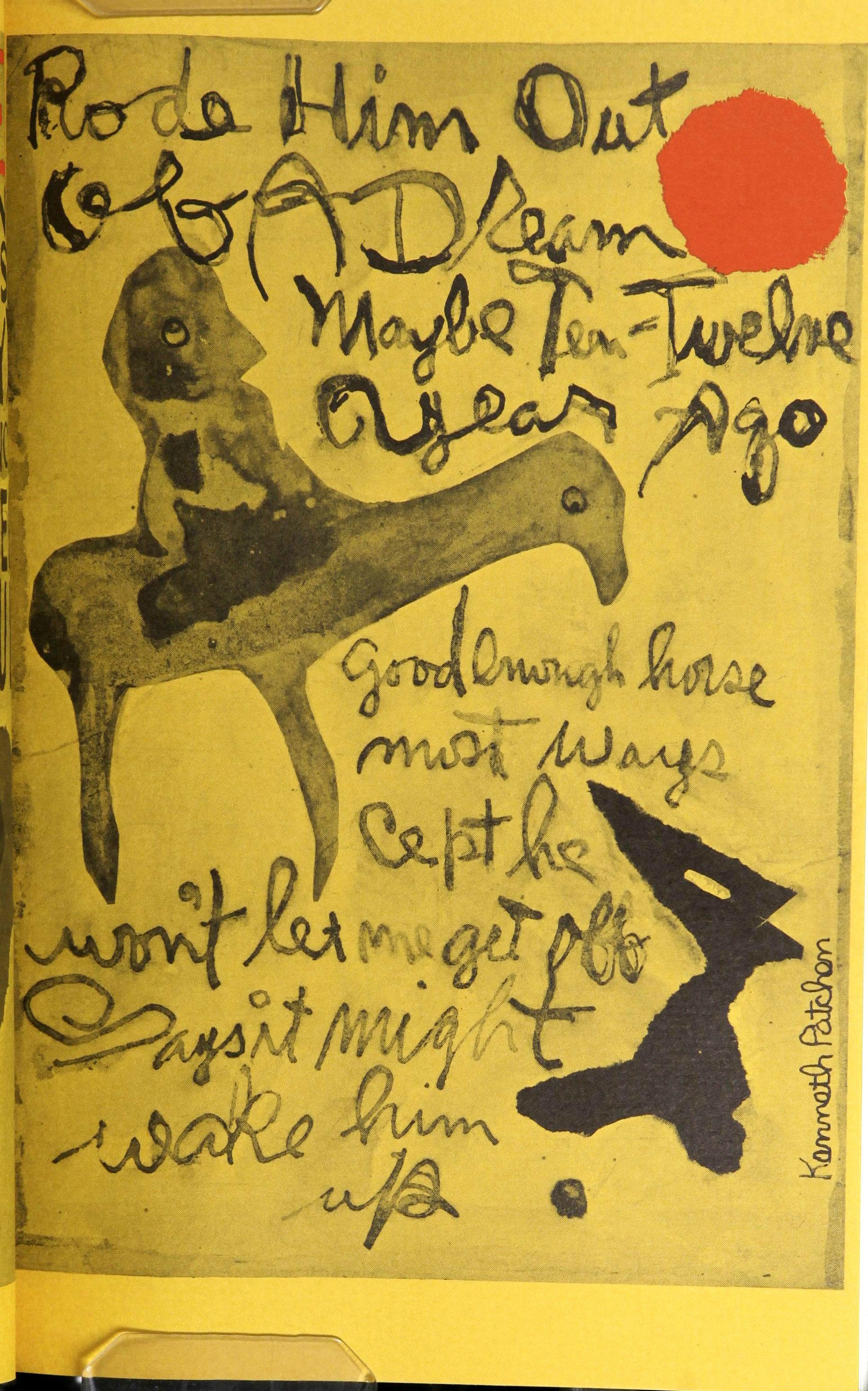

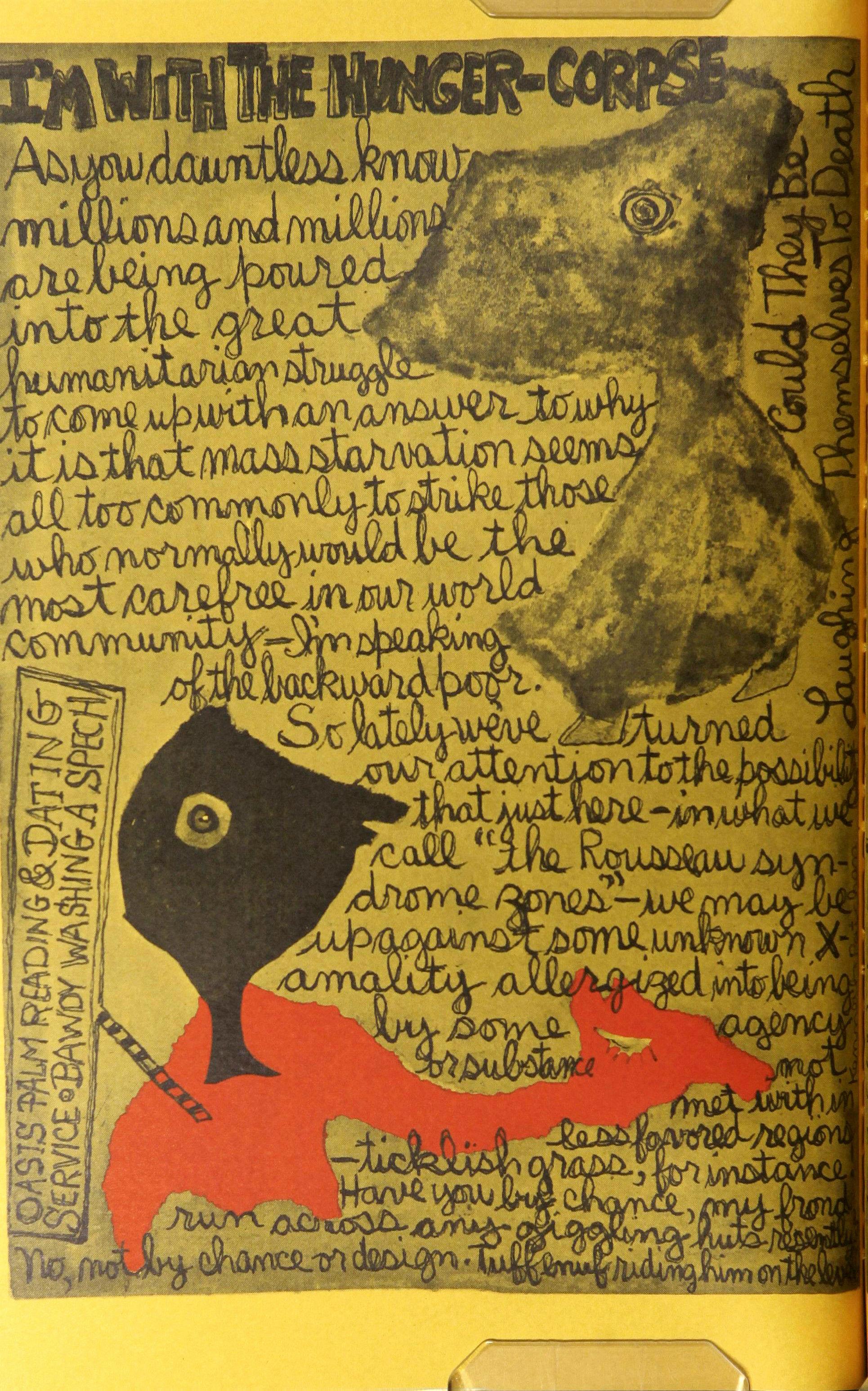

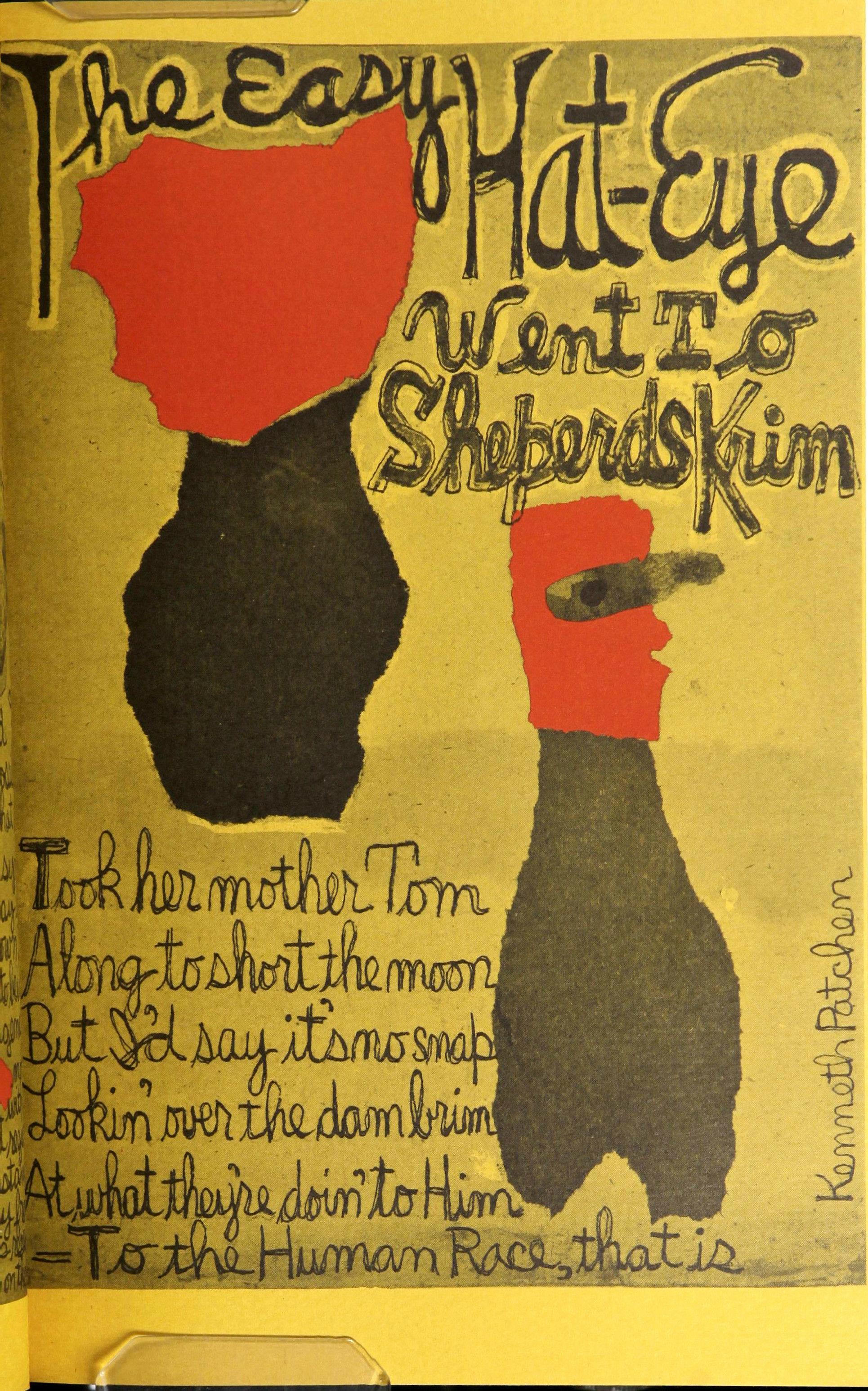

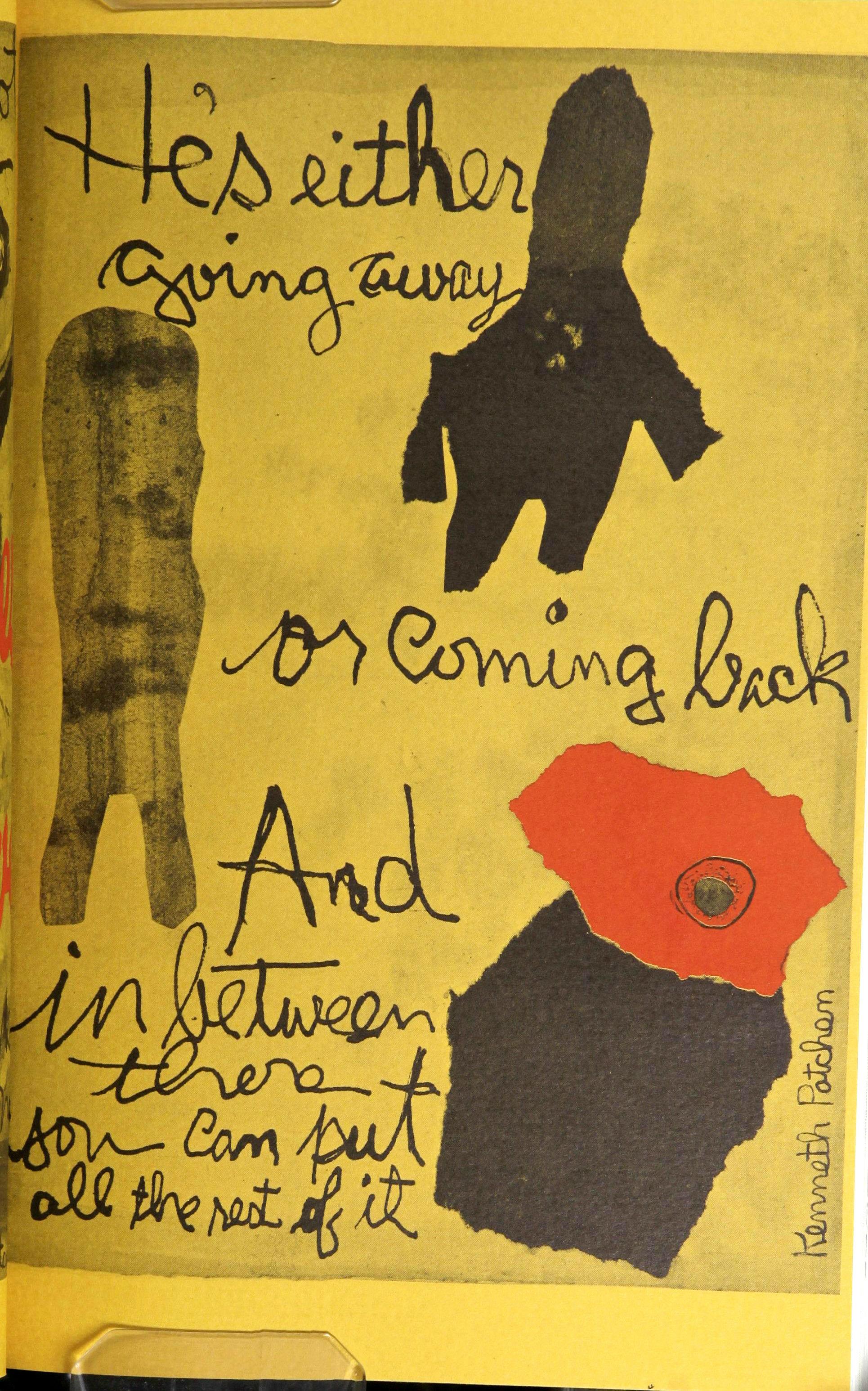

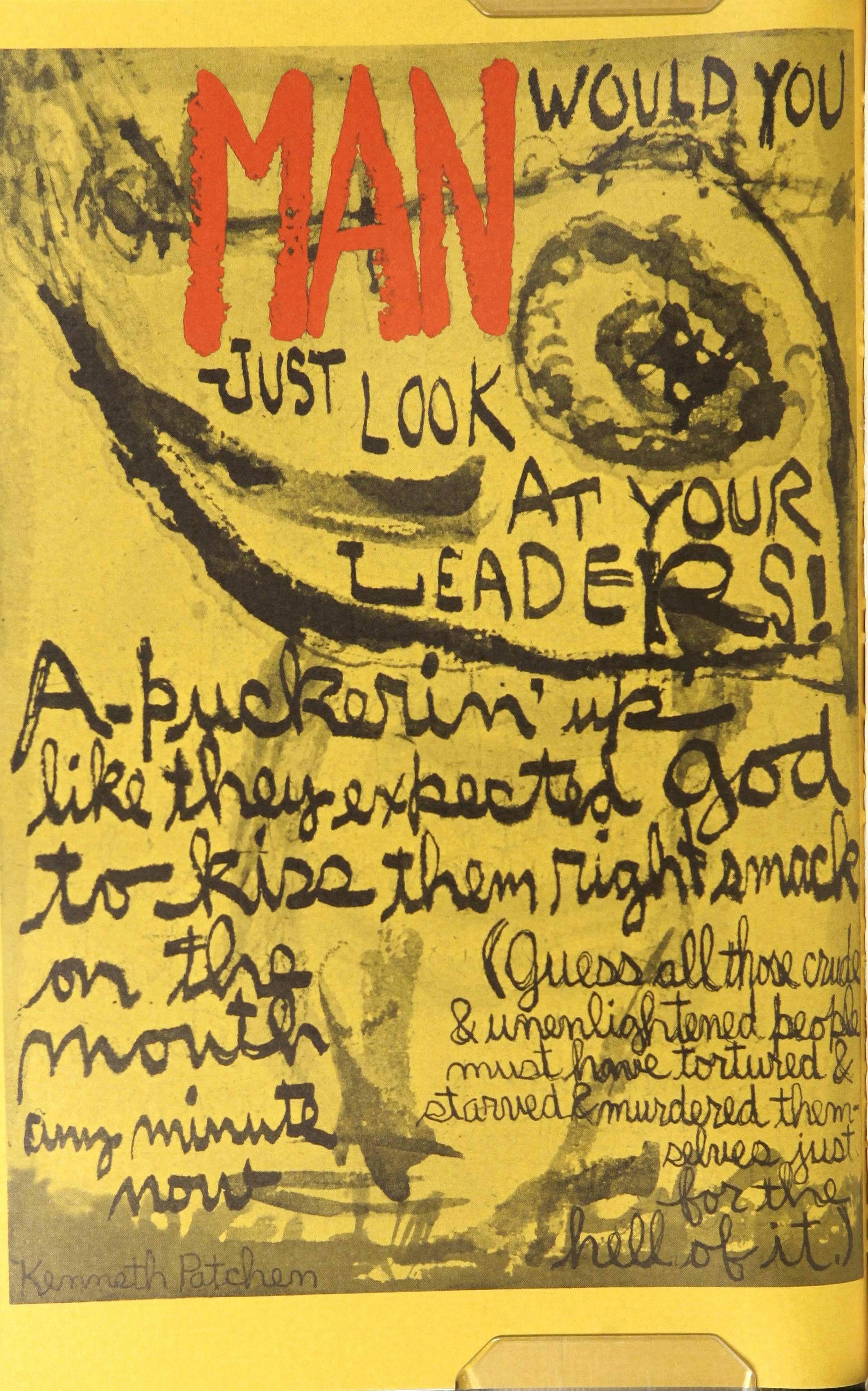

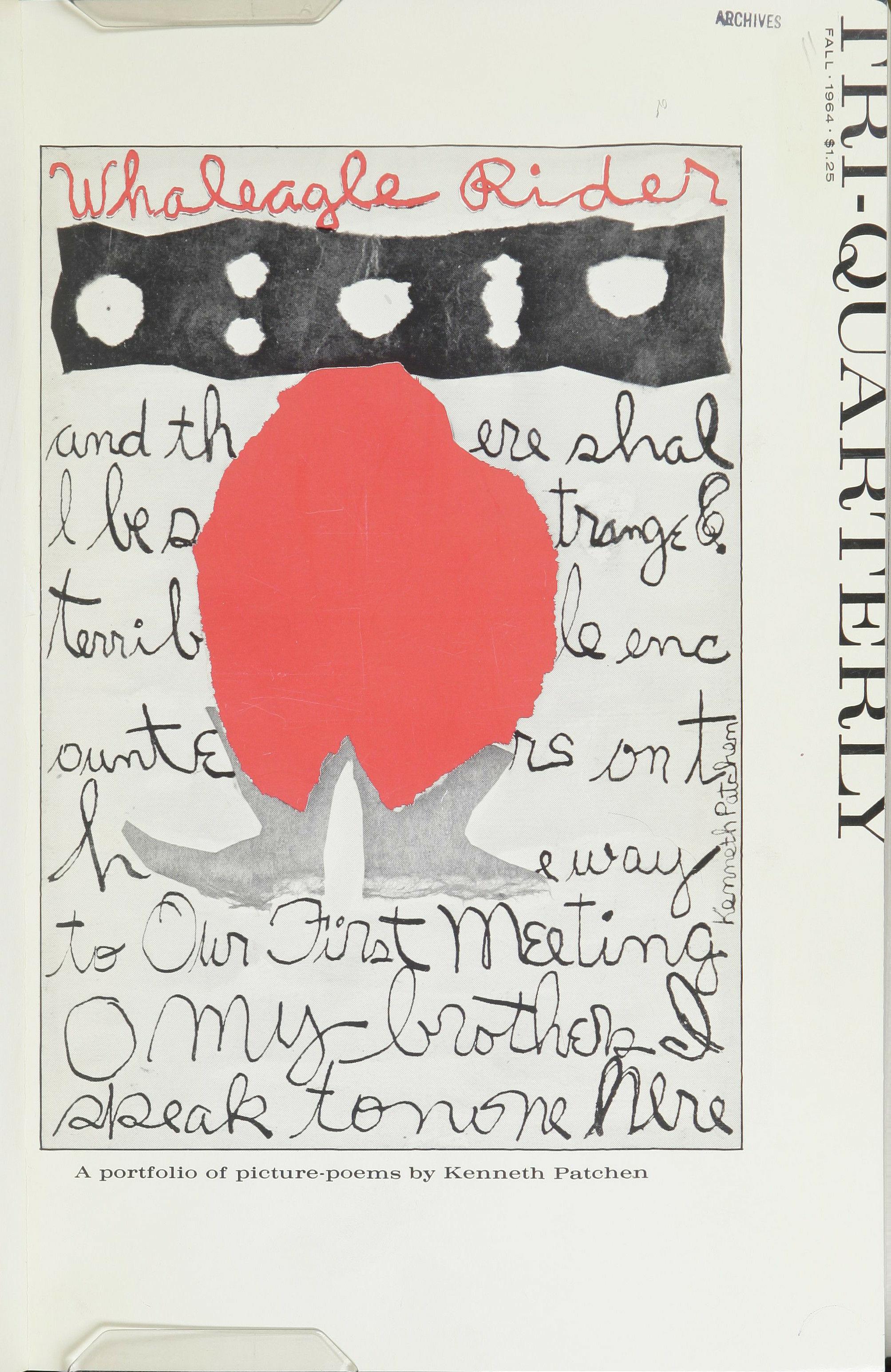

KENNETH PATCHEN A portfolio of picture-poems

Fiction

RICHARD BRAUTIGAN 62 A Confederate general from Big Sur: an excerpt of a novel

Poetry

WILLIAM PILLlN 25 Space music

KOZ'MA PRUTKOV 33 Translated by W. D. Snodgrass and Tanya Tolstoy

WILLIAM STAFFORD 47 From the head archer at Warwick / Chronicler and historian / Isolationists / Extended Haiku / Exorcism

FREDERICK CANDELARIA 61 Firs

DAVID PEARSON ETTER 68 Where I am / On the courthouse steps / Moonflowers / March

WILLIAM A. HENKIN JR. 84 Kafkaball

LUCIEN STRYK 85 Crow / Hearn in Matsue

CONTENTS

"As for the future, it cannot possibly shock us, since we have already done everything possible to scandalize ourselves. We have so completely debunked the old idea of the Self that we can hardly continue in the same way. Perhaps some power within us will tell us what we are, now that the old misconceptions have been laid low. Undeniably the human being is not what we commonly thought a century ago. The question nevertheless remains. He is something. What is he?" - SAUL BELLOW

There are two kinds of magazines - those which fascinate with nouns, and those which delight in verbs. The former are more proper: dealing modestly with time and life, they assert rather than explain; to sell things, they name things. The latter, more common, more active, tend to make a statement, ask a question, give a command. Their tenses are generally more progressive and less tangible. This is a perfect situation for dialectic, but there isn't one. It is not at all as simple as that. This accounts for the ambiguity of the title - Tri-Quarterly We read it as an adverb - a modified occurrence, in which action and naming are indivisible. It may tell place, sense, manner, frequency, degree, direction. Yes and No are also adverbs.

Pluralism

When Dos Passos said, "All right! Now we are two nations.", he was right save in one particular - the number. Dualism for his generation dramatized a final disgust with the oneness, the phony unities of the modern world. We have since learned that even something elemental as disgust is not easy to come by. In a society where poets use the marketing techniques of advertising, where businessmen hire poets to sensitize their images, where radicals captivate the very audience they are pledged to destroy, where the bourgeois find anarchism fashionable, where the ethics of corporations and universities appear interchangeable, it is difficult to draw that old dialectic taut again. Heaven and Hell are no longer popular concepts in an affluent democracy. The social scientists have given us another, less pejorative vocabulary to explain ourselves. What De Tocqueville noted as the tyranny of equality, what Jefferson envisioned as the chance for each talent to find its own authority, we call now Pluralism - which is both the fear and promise of unlimited possibility. Now we are x nations.

It is possible, of course, that we simply cannot calculate fast enough, that a machine will come up with that number and set us straight again. But that is to assume that mere naming will again suffice. It is who makes use of that pure mathematics, and how, which concerns us. Pluralism means that the number in Dos Passos' retort is an unknown integer. It does not mean that any single reply is inadmissible - but that answers are viable, dangerously so, precisely because they are mutable. Pluralism means that the stuff of each choice is a genuine confusion, and that order may be as various as the unique personalities which lay claim to it.

Order is perverse then, when a personality is absent or synthetic. Modern journalism is awesomely adept in avoiding the price of order. In collective editorializing, the personality is subsumed by committee for the sake of consistency. The voice must never catch or waver; that would complicate things. There are the 'Objectivists', on the other

FOREWORD

hand, who would let the "images speak for themselves", Thus, we are treated, in successive exposures, to a president, a quadruple amputee, tomato soup, a debutante, an earthquake - bound together simply because they are all "news". In one case, the perspective is synthetic; in the other it is non-existent. Both lack the unity of personal vision, and the courage implicit. Commercialism is only one kind of cowardice, however. Who knows what to make of that president, that cripple, that girlie, that soup, that disaster?

Art

Modern art is the creative personality's confrontation with pluralism - the sharing of the spectrum. There is an old and engaging ideal that art, literature particularly, might structure reality in such a way as to develop human sensitivity, and if not create values, at least indicate alternatives. A figure as recent as James Joyce is said to have thought that the worst thing about World War II is that it kept people from reading Ulysses. The Sturm und Drang literary reviews at the time of "two nations" believed that after that blasting, what floated back to earth would find new roots, grow new patterns. It is no secret that all the pieces did not fit together. The tradition that Art might affect Life, even uplift it, is now carried on, not so much by artists, but by the profession of criticism, which - whatever its merits as a discipline in itself - must be considered a rear guard action in terms of art.

A most compelling fact of modern life is that much of modern art seems to repudiate it. It is the old debate between Jefferson and De Tocqueville again; whether you choose to celebrate the dynamism or the vulgarity of a pluralistic world. The cultural elite used to allow that people get along pretty well without art. It has taken them the last halfcentury to say that art gets along pretty well without people - since the people confuse their capacity to react with the artist's ability to explore.

It is not for us to gauge the proper relationship between art and society, or even to bring the mind and marketplace together, They are already too close for comfort. The idea that art should serve society is impractical, not because some societies, like ours, have failed at it, or others like Russia, have succeeded all too well- but simply because it is impossible to harness the creative personality to a phenomenon which is more or less than himself. It takes too much out of everybody concerned.

But what if society should serve art? The artist's task, we have often been told, is to question without regard to the consequences. Society's task is less newsworthy, but no less compelling - for they must have the courage to confront questions which not only don't occur to them, but which they could not answer if they did. In that sense, appreciation is a selfless act. It is the audience, themselves, who must reject the synthetic order of those who serve their needs or presume to create them. In the supermarket, the consumer must provide his own synthesis.

The necessity for the artist's personal vision, the value of his partiality is clear. The creative individual has his place, such as it is. Art, and what passes for it, is surely taken seriously enough. Perhaps it is the audience in which we no longer believe.

The University

Proof of pluralism is that we can now talk of the university in the same breath with art and society. Higher education has come in for a good share of attention lately. It has

been criticized both for a willful aloofness from society and its needs, and for a fatally perfect adaptation to society and its impositions. One Ihing is clear - its scope has been immeasurably increased - not only does everyone end up at college, but as institutions, universities have been made responsible for everything from driver training to the preservation of grand opera. Given modern military and technological goals, some have acquired a power, prestige, and concomrnitant awe, once reserved for nation-states. The competition between them is purer than between our oligopolies; the politics within them as proselytizing as in any of our parties. They insist upon tangible credentials from a society whose motive force has always been a pragmatic test of talent. They talk among themselves in specialized languages provocative as any underground, yet justify themselves to society in a common counter-revolutionary rhetoric. They are becoming a sub-culture unto themselves.

Most importantly, perhaps, is the number of artists who are not only educated in universities, but make their subsequent living off them. What this relocation of dissent will cost us is not yet clear. It has gone far enough, however, that the old Bohemian/ Bourgeois debate has been set along new lines; the "academic" and the "beat", or in Robert Lowell's words, between the "cooked" and the "uncooked". We want to elaborate that debate - make the dialectic something more than the rejection of some foul unity. We are not interested in making anybody's career, although we hope our existence may dignify many. We hope to search out new talent, and encourage the established to venture beyond their reputations.

One recalls, however, that universities, like all institutions dependent upon the good will of the community, have not always been receptive to the kind of questions good artists ask. One can then tell artists to avoid such institutions, or demand that the institutions become more accountable. It may be that in the expanding university, we are witnessing an affluent democracy's oblique answer to the patronage system of the old world - although we could not afford to call it that yet. Still, leisure does strange things to people. And the university's function, most magnificently conceived, has after all been roughly akin to the artist's, in that it is pledged to the damnation of spurious order, and devoted to questions that society will not, alone, ask itself. This does not negate synthesis; it simply enhances its value. The university serves art by witnessing the pluralism of society.

All this implies the concept of limited revolution; revolution in the American tradition by chance, in that it makes use of the Establishment. We believe that to be more in accord with both the ideal and the real. This is not the time to profess loyalty to institutions, but to the discipline which keeps institutions alive.

Our task is to assemble. Literary reviews provide no more viable standards than I.Q. tests or annual income. They are simply another alternative; an attempt to bind temperament and action through language. Without resorting to epilogues or manifestoes, we want to embellish those proper nouns and common verbs which have made our culture too often a vehicle for minor aspirations and mock debate. It will be a modern enterprise, perhaps embarrassingly so, in that we are justified by little save our own potential. We're getting dressed up to celebrate the fact we're still looking.

CHN

r

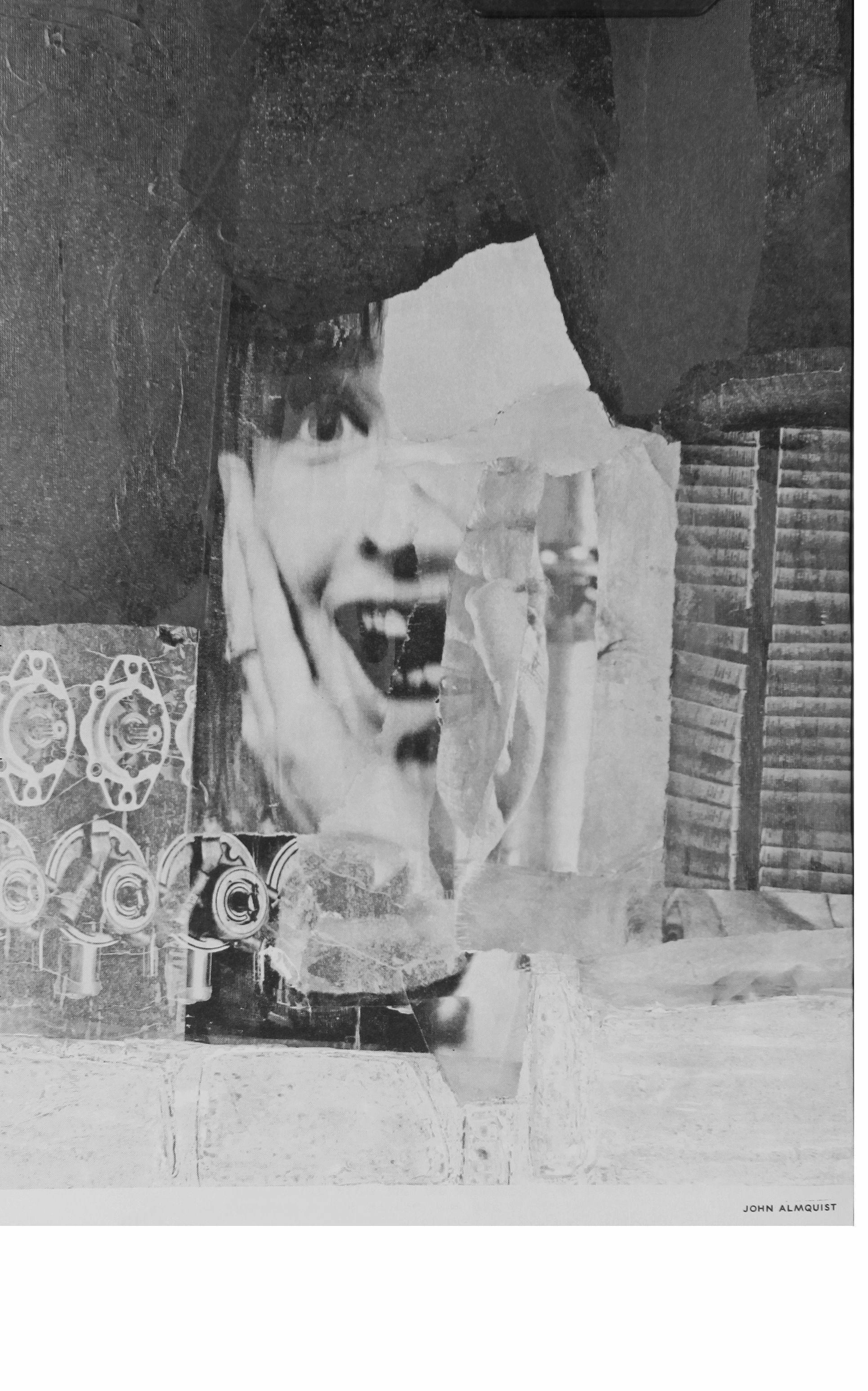

.JOHN ALMQUIST

Poetry, science and the end of man

LESLIE A. FIEDLER

The two languages

That man is an invention, his own invention, I suppose neither poet nor scientist would be inclined to dispute. What was even by Plato's time an "ancient quarrel" between the two concerned only the question of whether he was best defined in terms of "myth" or "reason," "poetry"! or "science." If, however, we begin from the view that man is the creature who invents himself (since he is not, like the star, the flower, the spider, the gonococcus, given) and if we grant further that he invents himself by the process of definition-then we can see that the language in which he chooses to make that definition is of critical importance. But man in our time is born, in theory, to a choice of languages, and offered from the start the theoretical possibility of adopting either the language of science, which aspires to become mathematics, or the language of poetry, which aspires to return to myth. Neither is an ignoble idiom; but, of course, most men are capable in fact of learning neither-only of expressing an allegiance to one or the other in one or another lingua franca of the contemporary world: one of the sub-languages of mass culture. Contemporary man, that is to say, is faced with an actual choice quite different from the theoretical one, a choice between the language spoken by scientists (which has little in common with the language of science) and the language used by poets (which is not quite the same as the language of poetry). In one of these debased tongues or the other, he is driven to explain himself to himself, for without such self-explanation he cannot feel he fully exists.

The confusion of C. P. Snow

If one wants to know what the language of scientists in fact is, he can do no better than to turn to the wicked little philistine (and immensely successful) book by C. P. Snow, The Two Cultures. Mr. Snow's brief essay is an attack on the best, which is to say, the most sensitive, most articulate literature of our century, an attempt to undercut, among others, the reputation of Joyce, Eliot and Orwell, in the guise of a call for the unity of culture. It is also, as one might expect from the

quality of its ideas, an example of the vulgarization of language in our time and a sourcebook for those interested in what has become of the English tongue in the closed world of the contemporary scientist. J n an extended note � Mr. Snow tells us, for instance, blandly and with no hint of dismay that:

Subjective, in the contemporary technological jargon, means 'divided according to subjects.' Objective means 'directed towards an object.' Philosophy means 'general intellectual approach or attitude.' (For example, a scientist's philosophy of guided weapons might lead him to propose certain kinds of 'objective research.') A 'progressive' job means one with possibilities of promotion

In light of which, one is scarcely surprised to discover that Mr. Snow, quite like those of his colleagues who do not write novels, is incapable or unwilling to make such elementary and vital semantic distinctions as those which separate, for instance, "education" and "training," or "science" and "technology."

His failure, needless to say, is not merely linguistic but ideological as well; since such confusion of usage arises from a primary confusion of concepts, and breeds eventually even deeper confusions in the realm of ideas. Simply on the basis of a careful reading of The Two Cultures one might have predicted Mr. Snow's appalling comment that Russian education is superior to the English. What he means, of course, is that the Soviet Union has a vaster program of vocational training, particularly in the technological areas; and this John Wain has pointed out, observing that really Russian education can meaningfully be called neither better nor worse than English education, since the former doesn't exist-not certainly in the ordinary understanding of the word "education" as an organized and systematic attempt to free the mind.

Scientists and the cultural lag

If Mr. Snow's case were an eccentric instance, there would be little point in belaboring his slight study; but he does, alas, speak for the community he claims to represent: the well-trained, scarcely educated, linguistically inadequate New Men in science and technology, whose favorite reading matter is Science Fiction (not even Mr. Snow's books!), and whose ideas about society are the product of a serious cultural lag endemic to inhabitants of laboratories and seminars in physics. Mr. Snow and his New Men, outside of their laboratories, manipulate political and sociological counters as unviable in the contemporary world as simple-minded Newtonian physics. They live, that is to say, among the cliches of nineteenth century liberal humanism, tempered with a few hardy platitudes from pre-Bolshevik, preBomb socialism; and they profer these weary ideas with an air of dedication to the Future, the show of committing themselves to the New.

No end to innocence

They are, of course, in the fullest sense of the word provincials, or, as the language of the times would have it, Squares. But they are not merely comical. Indeed, their enthralment with yesterday'S noble if battered platitudes might be regarded with more sympathy than condescension, certainly without indignation, if it had not been

long established (by George Orwell, for instance) that such willed political naivete at best proves powerless in the defense of freedom, lit worst conceals a yearning for some New Totalitarianism that will inscribe, say, Marxist slogans on its walls and banners. Perhaps it is a dim awareness of this that cues Mr. Snow's special virulence toward Orwell, his insistence on the superiority to 1984 of J. D. Bernal's World Without War-not because the latter is a truer book (the word does not occur to Mr. Snow) but because it expresses a greater "love of the Future," a Future in which Mr. Snow persists in believing that more and more and more science will mitigate the terror which merely more and more science has created.

I do not think it accidental that science as a career, a living, tends these days to attract the kind of mind capable of accepting such a view of man and his world. It is not merely that such a mind lacks the tragic dimension, but that, even more importantly, it contains within itself no subtlety, no talent for self-analysis-and consequently, no awareness of how it is in fact guilty for those evils which it finds easy to attribute to Someone Else. Certainly the mind of the New Scientist contains in itself no devices for halting the drift toward left-colored philistinism which The Two Cultures represents; and that left-philistinism will leave us in tum with no defenses against technological or ideological self-murder, the Bomb or Totalitarianism.

Poetry as self-criticism

In the world of mass culture and the assault on standards, poetry is not immune to vulgarization. It, too, becomes a trade, a means of social-climbing; and the New Literary Men may well be drawn from the status-hungry, imperfectly-literate new middle classes who justify their economic success to their consciences by pledging allegiance to the lost radicalism of their fathers who had hoped better of them. But poetry is, as such, a means of self-criticism, especially in the area of language; it is language which the poet redeems and attempts to make his own. The poet, moreover, unlike the scientist, does not distinguish between a world of work in which precision and respect for truth reign, and a world of "life" where sentimentality and a vague love for the Future are regarded as sufficient. And, finally, the poet is not driven endlessly to find and declare himself (with all the rest of mankind) Innocent, Innocent, Innocent!

I do not mean that poets cannot be misguided or wrong or downright evil in their social ideas. I should like to think that at such moments they are being bad poets as well as bad men, but it is not necessary to believe even this. What is crucial is that fact that in the end the errors of poets can be corrected by the means of poetry-more sensitivity, more subtlety, more respect for the terror of fact, more dedication to the tragic and the true. This is not so of science, which as a Way of Life rather than a discipline has proved notoriously blind, hubristic and sentimental, and which stands now in need of an order of criticism which it seems incapable of giving itself. Indeed, even when individual scientists attempt to practice such criticism, as some have been inclined in the past decade or so, they must become, in order to do so effectively, poets. We stand, perhaps, on the verge of an era when a new definition of the scientist is being evolved, out

of the crisis of conscience born in the morning after the Bomb; but the New New Scientist (beside whom the New Men of Snow will seem Cro-magnon) must, 1 suspect, be imagined by the poets before he can exist in fact.

It is only too easy for poets to make certain criticisms of science which arise from pique and professional jealousy; and, indeed, it is hard for poets to get beyond these at a time when professional rewards and community respect go so consistently to their scientific colleagues. It is not, however, such inter-academic rivalry which interests me, but a profounder order of criticism, the kind mystically expressed by William Blake in the lines:

The Atoms of Dernocritus

And Newton's particles of light

Are sands upon the Red-Sea Shores Where Israel's tents do shine so bright.

and more jestingly, but not less seriously, framed by W. H. Auden in one section of his Modern Decalogue:

Thou shalt not answer questionnaires Or quizzes upon World-Affairs, Nor with compliance

Take any test. Thou shalt not sit With statisticians nor commit A social science.

This kind of criticism poetry must make of science if we are to survive under conditions which will insure that what of us survives is really human, i.e., capable of re-inventing ourselves endlessly. Otherwise we are doomed to the status of the star, the flower, the spider and the gonococcus.

The double function of science

Poetry ideally performs not a single but a double (and apparently contradictory) function in relation to science; it criticizes and collaborates with, attacks and reinforces the other discipline. To make clear the significance and necessity of this double function one has first to clarify the double function of science itself. Theoretically, the "pure" scientist pursues knowledge for its own sake, regardless, and even in contempt of, its uses. And, indeed, certain branches of higher mathematics follow precisely such a course; but they are a little embarrassing to laboratory scientists who are likely to refer to their practitioners as "sort of poets." Most scientific research in fact turns out to have two uses, quite different from each other, even contradictory in their implications.

The revolt against nature

The first of these uses consists in providing for mankind an order of knowledge, tested and reliable, which leads to a greater and greater control over the environ-

o

ment. In the end, man not only makes himself but, to a remarkable degree, his ecological context as well; and it is science in its first usc which provides man with dependable means for making a world nearer to his desires than that given him by nature. The admirable aspects of this enterprise are too obvious to need elaboration by poets. Scientists themselves, and their popularizing apologists, are only too aware of them, certainly not bashful about propagandizing in their name. It is in this area that C. P. Snow comes closest to telling unexceptionable truths; but he does not, of course, tell the whole truth.

There devolves on the poet the task of telling the rest of the truth, the thankless job of making a negative case about this aspect of science by commenting on its essential ambiguity and its potentiality at least for evil. Certainly we find everywhere in our society a Fear of Science and the Scientist equal and opposite to the Adulation of Science and the Scientist; and the former scientists themselves seem incapable of explaining. The scientist is, indeed, inhibited from examining the dark sides of his activities by a quality which the poet must begin by describing in his effort to identify the ambiguity and malevolence of the other discipline. This quality is the special hubris of science in the modern world-the scientist's heedless pride in his accomplishment, his simple-minded notion of progress and his view of himself as the Leader of the world's onward march into a Future which he can conceive of only as bringing more and more good to more and more people.

The hubris of science

The poet, who has his own order of pride (less flagrant and suicidal, perhaps), never ceases to remind the chemist that nothing is more outdated, more palpably absurd than the chemistry of the eighteenth century, while the imaginative writers of the eighteenth century, Pope and Fielding, Richardson and Smollet, Voltaire and Rousseau, are still moving and valid. What has become of Humour Psychology, the poet asks; and answers that it remains of interest only for collectors of curiosa or compilers of histories of ideas. But Shakespeare, of course, who flourished in the heyday of that curious theory about the soul, still sits on the shelves of living libraries, still moves the minds of living men. What strikes the poet, however, as a basic weakness, an inherent limitation of scientific truth, evidence that the other discipline deals in opinion and metaphor taken for fact rather than fact itselfseems to the scientist proof that his discipline progresses. Indeed, the scientist is likely always to think his moment of history the greatest moment yet, and to cry out with the naive and tragic hubris of Rutherford not many years ago, "This is the heroic age of Science. This is the Elizabethan Age."

But how soon afterwards the explosion at Hiroshima and the guilts and mutual recriminations which have racked the scientific community ever since! Pride and guilt, pride and nemesis, mad self-infatuation and irreversible doom-it is a tragedy we have all lived, almost Sophoclean in scope and depth; but the Scientist, who is its protagonist, does not really know it, does not know the drama he lives, on which the catharsis of our whole society depends. His kind of mind has invented out of the cataclysm it has created-Science Fiction, the escape literature of the

Atomic Age, books to read before bed, in preference to nailbiting and in hope of exorcising bad dreams. Science Fiction is not, however, sufficient unto our day; our kind of hubris and nemesis, the breakdown of the scientist's optimism into terror must be translated by the poet into poetry, must yield up to us in poetic form the tragic illumination, the transcendent beauty without which we cannot continue to be men in any traditional sense of the word.

Faust and Hiroshima

As a matter of fact, the poet had invented the tragedy proper to our time before our time quite knew what that tragedy meant, had mythicized the scientist before the scientist had quite invented himself in his own prosaic terms. It is the legend of Faust, of course, which anticipated our catastrophe: the crumbling of pride before fear, in the blind seeker who thinks he asks for only power and knowledge, the most immaculate power, the profoundest knowledge-and who discovers in the end that he cannot resist using these means for trivial or catastrophic ends: tailfins or the Intercontinental Ballistic Missile. The artist not only identifies the modern scientist as Faust, not only finds him guilty, in his heedless pursuit of the presumed fact, his mindless faith in progress, of making Armageddon possible. He finds the scientist also guilty, as aider and abettor of the Industrial Revolution, of the neutralization of nature, the demythicization of the universe, and the driving inward (thus compounding madness, inventing new possibilities of insanity) of the spirits who once lived and worked in the outer world.

Asked what makes the stone fall, the fire leap, modern man answers, "Gravity or combustion!" In Dante's time, he might have said, "Love!" Needless to say, he is no more capable now of defining gravity than he was then of defining love; he accepts the one, as he had accepted the other, on faith, a faith which threatens at the limits of ignorance to become superstition. But the level of the ordinary man's faith and definition has been lowered, the complexity and imaginative richness of his counters for explaining the world reduced. What is the neutralization of nature on the level of definition becomes the alienation from nature on the level of experience. Modern man, in a world in which the imperialism of science threatens the last strongholds of poetry, finds himself as much a stranger to his natural environment as to his work or his fellowman. Even the development of modem theories of evolution have not made man feel at home with his animal inheritance, in a time when wild beasts come more and more to be simply what are seen in zoos or sought during set hunting seasons.

The end of free will

Love itself, in a world of mass production and statistics, is translated in a series of events tabulated by Kinsey; and fewer and fewer even among those who do physical labor have any more relation to what they make than what is implicit in the turning of a screw. In an era of the hunting trip, the picnic, the excursion, man becomes a tourist in the only world in which he primitively lived, among animals and gods. For all this the scientist cannot help feeling himself largely,

N

though often indirectly, guilty, just as he is guilty for the general impoverishment of culture, the ugliness of cities, the triviality of the mass arts, and the extension of ennui (once an upper class privilege, a sign of distinction) to everyone. Science becomes technology and technology enables man to broadcast, in color, for twenty-four hours a day the sheerest distillation of boredom. And beyond even this, there are the newest sciences, with their corollary technologies of manipulating minds and engineering consent ("brainwashing," we call it when it is practised by our enemies for purposes other than selling goods), the so-called behavioral sciences, which have reached the point of destroying one of the most perilously constructed and dearly held myths by which men live the life of men: free will.

The other function

There is, however, quite another function of science, a function transcending our need to substitute an artificial environment for our natural one, to subdue the nature out of which we have come. This function involves the chastening of human pride, the giving of offense, the creative disturbance of a culture which inevitably tends to harden into rigid forms. And insofar as science is dedicated to an assault on smugness, well-meaning mediocrity, and insipid "peace of mind"-it is related to art rather than technology, finds poetry an ally rather than an unfriendly critic. The great offensive moments of the history of science have been often enough celebrated, but they cannot be too well known. What is important, and less obvious than the mere fact of their existence, is the sense in which they are closely related to what are sometimes treated as unequivocal triumphs of the first function of science. A single event regarded as an occasion for simple minded rejoicing will stir the poet's scorn, but regarded as an occasion for anguish win his sympathy.

Offense as salvation

It is in Physics that the first great offense was given, in the Copernican Revolution which took man from the imagined center of his universe and placed him on a difficult periphery. And in the Newtonian Synthesis a second offense was added, man forced to regard his cosmos as mechanical rather than living, alien rather than familiar. In the nineteenth century, it was the turn of the biological sciences, with the Darwinian version of the theory of Organic Evolution not only taking from man the illusion of a separate creation, but in its sociological extensions, suggesting that the society he continued to inhabit was less different from the jungle than he had been pleased to imagine. But by Psychology, strange offshoot of physiology, another offense was added, both Freudian and Behaviorist theoreticians suggesting that human action was motivated not by reason but by conditioned reflex or repressed and hence rationally uncontrollable urges. Latest and most terrible of the offenses, however, has been proferred once more by the physical sciences, by the fatal mass-energy equation of Einstein, whose technological implications have been developed to the point where, for the first time, the End of Man is imaginable by the dullest technician. Post-Darwinian Biology had suggested that the human being was a transient rather than a final form in a process without end, but it is an even more terrible thought to contemplate the

possibility that man will not merely be transcended but ended-that man may, indeed, himself end the whole natural process of which he is the hubristic product.

The use of Socrates

In his life-giving function of providing offense, the scientist is one with the artist, a comrade-in-arms in the never-won battle to explode complacency, undercut preconceived ideas, reveal to all men that anguish and disquiet rather than self-satisfaction and repose are the proper human condition. I find it fascinating and hopeful to realize that Socrates, the prototype of all humanists, the manipulator of myths and inventor of the human soul, was when brought to trial before the people of Athens charged with being an evil scientist. In fact, if Plato's notion of facts can be trusted, Socrates despised scientists and spent his entire career seeking for an intellectual discipline more like that of poetry than physics. Nonetheless, in the deepest popular mind (so, at any rate, The A pology tells us) he was identified first of all as "one who searches above the heavens and under the earth," taken, that is, for one of those meteorologists and geo-physicists who began science in the Western World; and in the second place, he was thought of as being "one who makes the worse appear the better cause," that is, was confused with the Sophists, those relativist and sceptical founders of behavioral science as a paid profession.

It was, to be sure, the comic poet Aristophanes who fostered the confusion by which Socrates died, in his thoroughly reactionary and delightful play, The Clouds. And it is the figure invented by Aristophanes (and believed in by the jury which condemned Socrates) that I would like to propose as the model for the New Intellectual, a true hybrid able to function in our two cultures without pleasing any of the wrong people; for it is upon the emergence of such Intellectuals that our survival, in all senses beyond that of mere physical persistence on the face of the planet, depends. The New Intellectual must be not only humanist and mythmaker but also sceptical relativist and scientific amateur; yet he must be neither of these things pompously and stuffily. The Socrates he must emulate is not the tragic figure, the quasi-Christ of Plato; for if the Athenians had been aware of Socrates in this role they would not have condemned him. He must be rather the absurd, pathetic, somewhat ineffectual clown-half schlemiel and half culture hero-imagined by Aristophanes, a type that any society eager to hold on to a pious and enlightened status quo would be delighted to execute.

If we remember finally the comic stigmata of this Socrates: his ugliness, his shrew of a wife, his absent-mindedness, we will be properly aware of his relationship to, say, such absurd figures as Norman Mailer, who believes jousting should be revived, or Don Quixote, who thought so first; perhaps even to Albert Einstein, who, we are told, not only developed the theory of relativity but signed foolish petitions, wore no socks, and when exposed to the novels of Franz Kafka complained that the human mind couldn't possibly be that complicated.

1 I use the word "poetry" to represent one polar use of language, whether in verse or prose, the imaginative use; "science" similarly stands for the other polar use, discursive, objectively descriptive.

2C. P. Snow, The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution, Cambridge University Press, (New York), 1959, p. 56.

The literary mood of the 1930's

STEPHEN SPENDER

FOR ME TO REALIZE how difficult it is for anyone who is 30 years younger than I to 'understand' the nineteen thirties, I have only to remember how people whom I associated with the Edwardians or the pre-1914 era seemed to me, when I was young. What divided me from them-as what divides me from, the young now-was the barrier of a war, which acted like a cage in a zoo, behind which one sees the out-dated animal, surrounded by the stage scenery of his dated native habitat. Whenever the animal is reminded of his generation-as happens with me whenever I am introduced to an audience as a 'poet of the 1930's'-he becomes aware of himself as a monster dragged on from another time and place.

The best way to humanize an earlier period is to be rather insistently personal about it-to insist that is, 'I am here, and I was there.' This is what I am going to do about the Thirties.

The attitude of a younger generation to that of the '30's can be summarized in a phrase: "How can you possibly have been so wrong?" Expanded, this may be interpreted: "How can you ever even have for one moment have thought that the communists could have been right about anything?" The answer to this question is of course, rather simple. It is that rightly or wrongly there appeared to be in the 'Thirties' a choice been Communism and Fascism, between, that is, an authoritarian system of Stalin which although oppressive, far less was known about than is today, a system which had a philosophy and an economy which, even today still remain the alternative to what we call democracy-and another system, of Hitler, openly brutal, obscurantist, wicked, and supported by views which were philosophically absurd, and whose economy was simply war. And that as between these two systems, the democratic powers, hopelessly caught up in a crisis not only of their own economy (which seemed on the verge of total breakdown) but also of their belief in their own freedoms, did not avert the Second World War, for the war was after all, caused by Hitler and not by Stalin, and it could have been prevented. Winston Churchill suggested it should be called the Unnecessary War.

There was a challenge in the 'Thirties' to save civilization and humanity; and the literary mood of the decade was largely coloured by writers meeting, or refusing to meet this challenge. The so-called politics of the period, in the democratic countries, were essentially the politics of the unpolitical. For the first thing that strikes one about this odd and freakish decade is that the voices most stridently raised-the voices which make us think of the 'Thirties' as the 'Thirties'-were those of amateurs, refugees, exiles. The statesmen who might have opposed Hitler and stopped the war were themselves rendered ineffective. It is a striking thought that during the whole of the period from 1933 to 1940, Churchill was reduced to amateur status-by his own political party. The reason why he was put on ice was precisely that he was anti-Nazi. The period which literary people think of today as the anti-Fascist decade was in fact that in which among the democracies there was no effective anti-Fascist opposition. It was this vacuum of democratic will among the democracies themselves, which caused the anti-Fascist movements.'

My concern here, however, is literature, and not politics, though it is difficult to separate the two. It is difficult to look at much of what was written during the period without being diverted to considering the politics which stimulated the writing.

Taking a bird's eye view of the twenty-years, 1919 to 1939, one could make a generalization about them, which explains a great many things that happened in the arts. Quite simply, there was a vacuum, or a whole number of vacuums. Initially, the between wars vacuum was caused by the failure of the victorious powers to lay the foundations of a better world at the Treaty of Versailles. The, withdrawal of America into isolation, and her rejection of Wilson's Charter of the League of Nations, the imposition of punitive reparations on the one hopeful community which emerged from the war-the Weimar Republic-were followed by the complete breakdown of the economy of central Europe in the 1920's: all these voids at first resulted in a corresponding vacuum in literature. There is, surely, the connection of a chain reaction between the Treaty of Versailles, (resulting in that pathetic parody of a new world, The League of Nations) and Spengler's The Decline of the West, and The Waste Land. The literature of the' 1920's expresses the sense of a vacuum. Many of the masterpieces of the '20's1 have what might be called a negative political aspect. The Waste Land expresses despair about the public world-which simply is, the waste land-the perennial lovers endemic in D.H. Lawrence's novels are occupied in evoking instinctual forces and dark gods, as subconscious forces called in against the collapse of the public consciousness of political society. There are even suggestions in Lawrence from time to time that the inner forces can redeem the outer world of politics, after its total collapse. Though expressed in terms of personal relations, E. M. Forster poses ir A Passage to India (oddly enough perhaps the most politically influential novel of this century) the question whether the British should leave India (the answer being that they should, because as long as they are there, personal relations between Indians and English are impossible.)

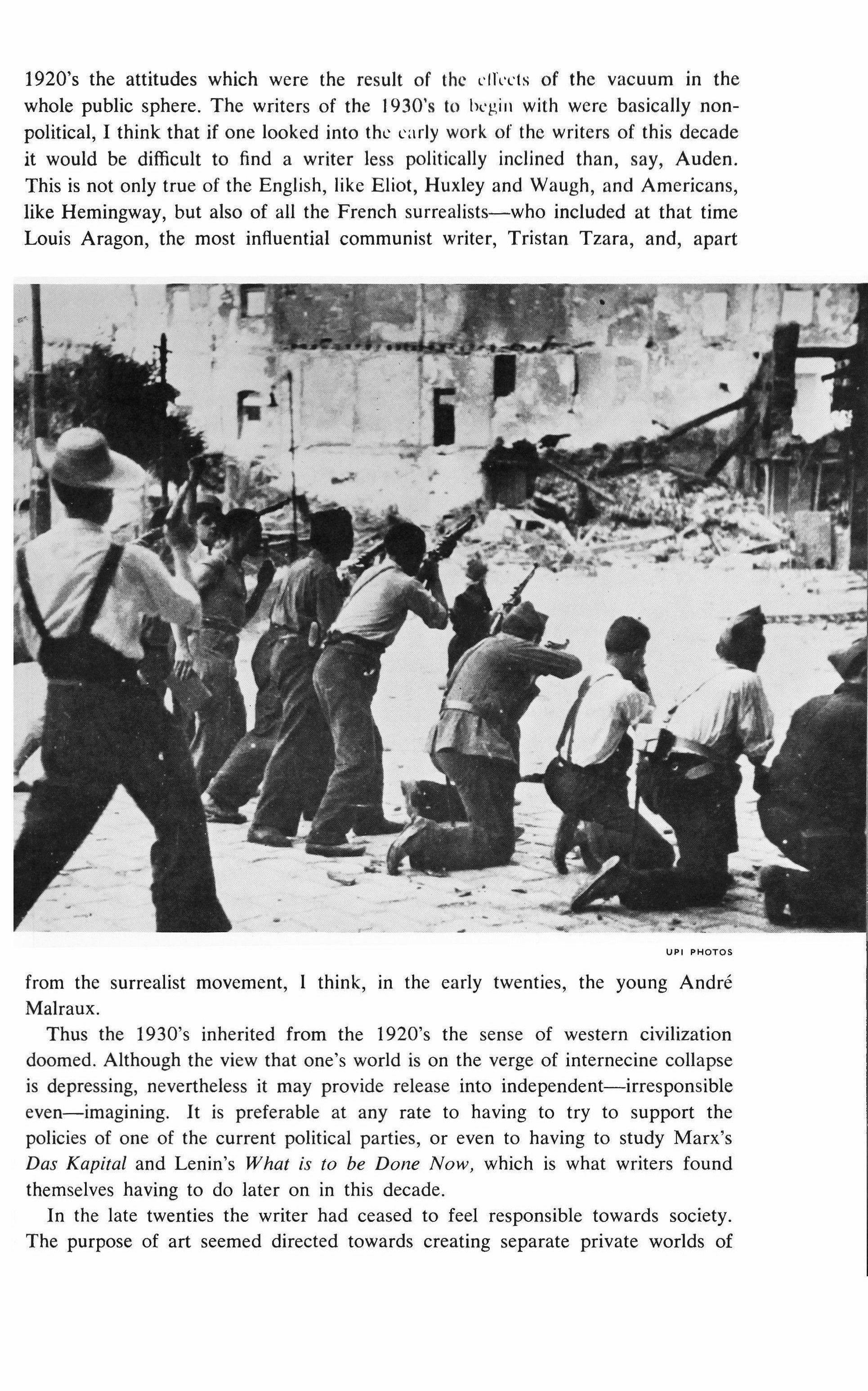

The writers of the 1930's were followers of the writers of the 1920's, whom they not only admired but have continued to admire. They inherited from the

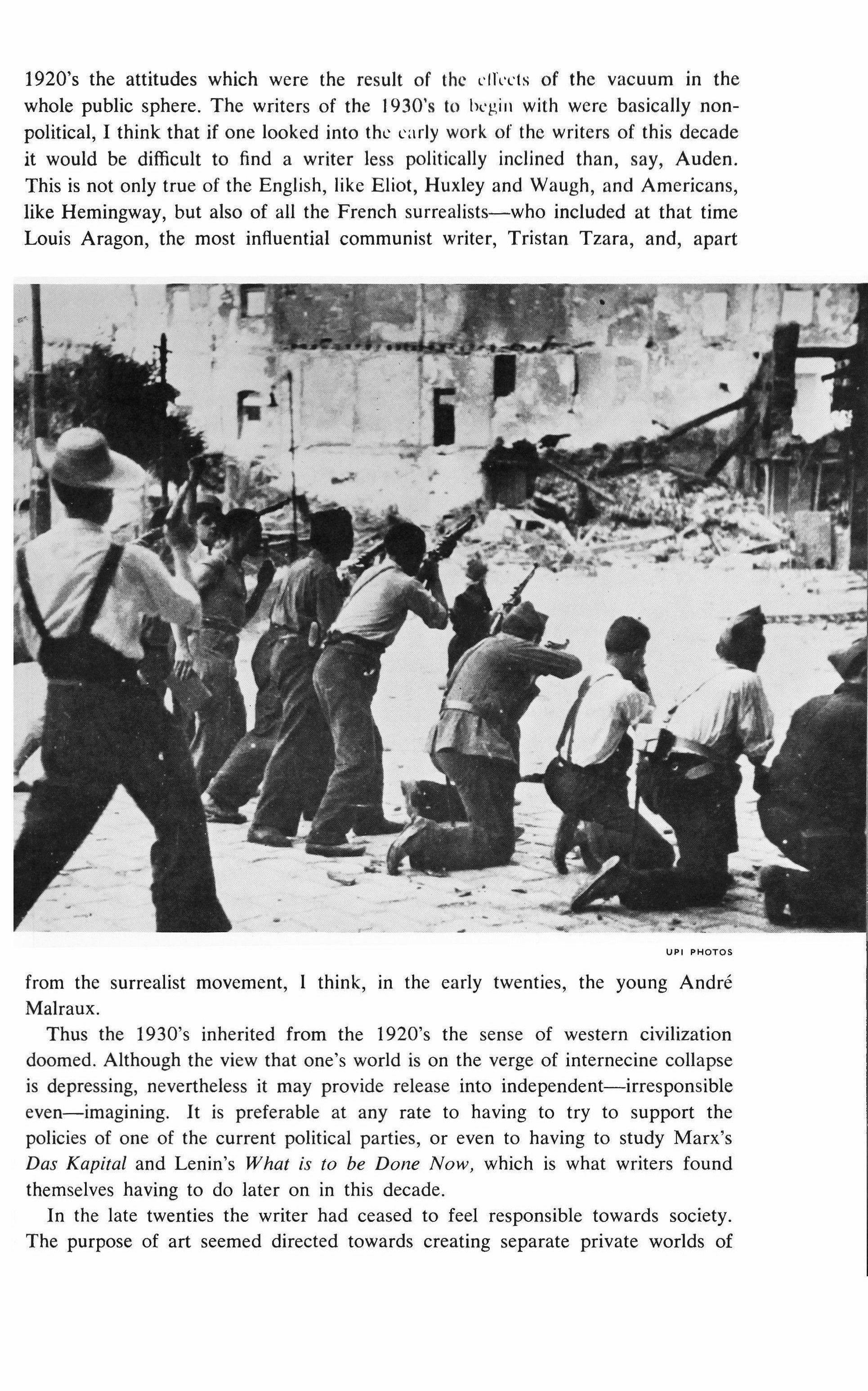

1920's the attitudes which were the result of the l'Ikl'ls of the vacuum in the whole public sphere. The writers of the 1930's to begin with were basically nonpolitical, I think that if one looked into the early work of the writers of this decade it would be difficult to find a writer less politically inclined than, say, Auden. This is not only true of the English, like Eliot, Huxley and Waugh, and Americans, like Hemingway, but also of all the French surrealists-who included at that time Louis Aragon, the most influential communist writer, Tristan Tzara, and, apart

from the surrealist movement, I think, in the early twenties, the young Andre Malraux.

Thus the 1930's inherited from the 1920's the sense of western civilization doomed. Although the view that one's world is on the verge of internecine collapse is depressing, nevertheless it may provide release into independent-irresponsible even-imagining. It is preferable at any rate to having to try to support the policies of one of the current political parties, or even to having to study Marx's Das Kapital and Lenin's What is to be Done Now, which is what writers found themselves having to do later on in this decade.

In the late twenties the writer had ceased to feel responsible towards society. The purpose of art seemed directed towards creating separate private worlds of

UPI PHOTOS

the imagination, incorporating values derived from the past but with no hope that they would influence the life of existing contemporary institutions. Poetry could simply be regarded as a ritual for releasing forces of the unconscious. The surrealists regarded it as this and so did a good many writers who were not actually surrealists.

Being young, the writers of the early 'Thirties' did not feel quite as discouraged by the spectacle of The Waste Land as their predecessors had been. Somewhere on its grounds even, they discerned a Fun Fair. They showed a certain appetite for disaster, a feeling for the destruction of the West not dissimilar to the 18th century taste for Roman and Gothic ruins. They discovered-as poets have done before them-that catastrophe is exciting. They were stimulated by the fantastic imagery of revolution which began not with surrealism but with the Russian films of the early 20's, Ten Days that Shook the World, Earth, and so on. A link between this admiration for civic violence and destruction and for Revolution is to be found in the near-surrealist poem which Aragon wrote in praise of the USSR soon after he joined the communist party. He praised the revolution for producing such surrealist effects as the destruction of towns by sheJlfire. We were to see plenty of such do-it-yourself surrealism in the next thirty years.

Auden's early poetry is full of images of public disaster transformed into a kind of gloating poetry (the Germans have a term for this-Schadenfreude);-

You cannot be away, then, no

Not though you pack to leave within an hour, Escaping humming down arterial roads:

The date was yours; the prey to fugues, Irregular breathing and alternate ascendancies

After some haunted migratory years

To disintegrate on an instant in the explosion of mania Or lapse forever into a classic fatigue.

What sets this before the 1930's is its detachment. The poet is the mere spectator of a civilization falling into decay. It is still the attitude of the 20's.

What happened to the 1930's writers was that a combination of events at first challenged their sense of detachment, and then put them through sympathy and intelligence, imaginatively and sometimes actively, at the centre of those events. It seems to me that the first of these events was the slump, beginning with the Wall Street collapse of 1929, and resulting in the mass unemployment which affected European countries as well as America, from 1929 to 1933. The unemployed were not like victims of the German inflation of the 1920's-which happened far away and was the result of seemingly uncontrollable circumstancesvictims who could be regarded with the same hopelessness and lack of involvement as those of a natural disaster, a flood or volcano. The unemployed were palpable there, the workers, the poor, not only poor but also workless. They represented the breakdown of the middle class system of investments, over-production, competition, free market, rents, private incomes and so on. They gave

00

palpable expression to the bad conscience of money, which though often suppressed does nag at the more sensitive members of all exploiting class. It is of course a historical fact that ever since the mid-nineteenth century the European intelligentsia has been anti-bourgeois. Whenever a situation arises in which antibourgeois feeling assumes political expression, European intellectuals have found themselves-often to their own amazement-supporting the proletariat against the bourgeoisie. Witness Baudelaire's support of the Paris Commune. In the 1930's there was a strong revival of anti-bourgeois feeling.

Unemployment demonstrated that the system which put invested money into the pockets of one class could no longer provide jobs for the working class which it exploited. This meant that middle class intellectuals who were themselves beneficiaries of this middle class system, felt that it was no longer justified. They had an uneasy feeling that they themselves were not justified, unless they could support policies and parties which could remedy the situation.

Remedies for unemployment which today could be accepted as non-partisan, were all regarded in the 1930's-even when they came from a Roosevelt-as socialistic. Hence to be sympathetic towards millions of people who were unemployed and to support the measures which would cure unemployment wasas supporters of the New Deal were later to find-to be a socialist, halfway to being a communist, as it seemed then.

The second event which produced the situation of the 1930's was the victory of the National Socialist party in Germany in February 1933. The third was the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in the spring of 1936.

The triumph of Hitler had the effect of strengthening the bond between those whom Jules Romains in his novel called "The Men of Good Will"-the nonpolitical intellectuals forced into politics-and the victims. Just when the crisis of unemployment was beginning to be overcome, Hitler produced a new set of victims-his political opponents, liberal, socialist and communist, and independentthinking intellectuals. There was the burning of books, the exiling of writers, the persecution of Jews, a revival of mediaeval horrors in the centre of Europe. Among other things Nazism was a political movement directed against the life of the intellectuals. It converted intellectual activity into a political interest, a kind of "lobby" of the intellectuals. Nor was this just a domestic German affair. By a series of political coups, Hitler having removed all the German grievances arising from the Treaty of Versailles, went on to occupy Austria, to threaten freedom in other countries, and to make massive preparations for war. The master race had ambitions not only to control Germany but Europe and ultimately the whole world.

I have suggested that essentially the attitudes of the 1930's are to be seen as the result of the existence of moral and political vacuums, which became filled by the intellectuals in the absence of statesmen who were prepared to state and defend freedom. Confronted by Hitler and Mussolini, the governments of England offered nothing but that absence of moral response which really characterized European politics of the democracies ever since 1918. No protests were made against acts in Europe which victimized innocent individuals and outraged traditions of freedom of expression which had been won as the result of centuries of

struggle. More than this, Hitler's and Mussolini's aggressions were scarcely protested against, sometimes they wen: condoned. As a writer like the Catholic Georges Bcrnuncs discovered, to be a traditionalist in the sense of supporting the living qualities of Christ, was to be a revolutionary.

Essentially then, anti-Fascism was a moral and cultural protest made by individuals in the absence of any cll'cctivc protest by governments supposed to represent democratic and liberal principles. Politically, the anti-Fascists were themselves inexperienced. They had only a moral position, a moral indignation, without a political organization or programme. They were, as I have suggested, amateurs; a conscript army of refugees, professors, writers, etc.

This is where the communists come in. I n the absence of any effective antiFascists among professional politicians of the democracies, they provided the anti-Fascist movement or movements with analytic attitudes, with organization, with a programme. They did not do so by openly taking the lead, but by organizing the great anti-Fascist movement of the Popular Front, and, at a later stage, the International Brigade.

Having provided the organization, the communists of course gained control of it. That they did so was sinister, and in the long run it was also self-defeating, because when it was realized firstly that the communists had the effective power of organizations which professed only a militant liberalism, and still further. when the nature of Stalinism became apparent, the popular front disintegrated.

However, the influence of communism in the '30's was not entirely due to their being Machiavellian. It was fundamentally due to the fact that for a number of years before the war they were able to provide an analysis of the situation of the democracies confronted by the Nazis and Fascists which broadly speaking seemed correct. In addition to this they were in a situation in which they were critics, critics, that is of moral and even literary attitudes. They were outside Russia, even literary critics of a high order, in the tradition of literary criticism combined with social criticism, of Matthew Arnold and Ruskin. The early writings of Edmund Wilson, much influenced by Marxism, are of this kind, as are the writings in which the emphasis is more on society and politics than on literature of Dwight MacDonald. But the 1930's added a great impetus to criticism altogether. Their great influence on the literary mind was precisely this: that communism provided a challenge of conscience in a situation in which the intolerable evil of Fascism was not met by the democracies. This was a challenge which extended far beyond politics and deeply influenced the arts.

When one looks back at the '30's now, it seems that the anti-Fascists should have looked at Stalin and seen that he was just as bad as Hitler. At the time it was not so clear that he was as bad. And even if he was bad he made sense \\ here Hitler made wanton nonsense. More importantly than this, however, the antiFascists did not look to Stalin as much as today may appear. They needed only look at their own situation, and see that again and again a Marxist analysis seemed to apply to it. Firstly, what they saw was that there was a breakdown of the capitalist economy. As a result of this, in certain countries reactionaries had set up singularly brutal dictatorships, suppressing not only their direct political op-

ponents, but all those freedoms on which intellectual life depended. The democracies did nothing to stop Hitler and Mussolini. Why? Because they themselves had leaders who suspected that the nature of the choice before them was fundamentally either to ignore the Nazis or resist them, perhaps aiding Communism. This general impression that there was an either/or choice between Communism and Fascism one also applied to oneself if one was an anti-Fascist writer with liberal views. Given the fact that there was an absolutely intolerable oppression in the world, that a war threatened which might destroy all remaining freedoms of civilization why-much as one might be moved-did one do so little about it? If one was a poet why did one write poetry which expounded noble ideals, when what was required was a literature resulting in action? Why did one go on defending the freedom of oneself and others as artists to express themselves in whatever way they chose, when the very bases of all artistic freedom were threatened? If one examined one's own conscience didn't one suspect that one sympathized with the other side, or at least condoned its actions, because in one's heart of hearts, (in common with a whole succession of British and French premiers) one wanted nothing to happen or one even preferred Fascism to revolution. Isn't it true that what was really required of one was that one should belong to another class-with interests opposed to those of one's own, but still more opposed to those of Hitler-and this was what one could not face? And then-since Stalin was there-wasn't one glad to believe the worst of Russia because this provided one with an excellent excuse for inaction in a conflict in which ultimately it was necessary to choose between Communism and Fascism?

Today these self-questionings may seem absurd, because there is no single alternative between Right wing or Left wing dictatorships confronting us. In fact, we do live within a kind of third force of liberal democracy. But they did not seem absurd in the Thirties. Moreover they were not just questions which one asked oneself, in the silence of one's own room. The 'Thirties was a period of magazines called by names like Left Review or New Masses, theatres called the Group Theatre, committees of writers, meetings, and these organizations were always printing what were in effect inquisitions conducted usually by lesser writers on superior talents because the more gifted did not transparently assert the political views which the lesser writers believed it to be the first aim of literature to express. One had in all this a terrible glimpse of what meetings of the Unions of Writers in communist countries must be like. In the '30's, one of the worst things one could be called was an essayist.

Not that some of the criticism was not acute and revealing. The best book of literary criticism appearing in England in the '30's is Illusion and Reality, by a young Marxist called Christopher Caudwell, who was afterwards killed in the International Brigade. In this there is a chapter about Auden, MacNeice, Day Lewis and myself demonstrating that we were sympathizers who had not really made the revolutionary choice. We were amused by being still bourgeois at heart, if not having 'gone over' to the proletariat.

As a result of the attacks by the communist intellectuals on the liberal fellow travellers, the 1930's gradually took the form of an uneasy alliance between the

N

ideological communists and the liberals who kit forced to choose communism as against Fascism, but who were divided in their consciences. On the one hand they saw that this was an occasion on which the price to be paid for preserving certain freedoms might be the sacrifice of other freedoms in order to defeat the evil of Fascism. E. M. Forster expressed a view which was characteristic of a ;l liberal living in this dilemma when he wrote that the future lay with communism,

but it was not a future in which he wished to participate. On the other hand

liberals were almost pathologically incapable of accepting communist ideology

and discipline. A liberal may be forced into the position of thinking that in a

choice such as that of the 1930's between communism and Nazism he has to accept

communism. But in his heart he is less capable of accepting the idea that freedom and truth have to be sacrificed to the cxigcnccs of political action, than a conservative might be.

So the literary 1930's do not present the clear picture of a communist-dominated united front anti-Fascist movement which we tend to see them as. In fact there was within the anti-Fascist camp a bitter debate about ends and means. The most quoted of all sayings was Acton's famous dictum that all power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. The International Brigade which was communist-dominated contained many members who had joined it in the belief that it was a democratic army, and who were disillusioned when they found this was not so.

The subject of the great debate of this time is suggested by the Title of Aldous Huxley's book Ends and Means. Huxley argued that war was never justified because the means cannot justify the ends, indeed if the means used are war then the ends become converted into the dictatorships and lies which are the process of war. It is basic of course to the communist thinking that the ends do justify the means. In the first edition of his poem Spain published after he had been to the Spanish Civil War, one sees Auden trying to convince himself that the ends do justify the means, that today we must accept the ephemeral pamphlet and the boring meeting, the lie and the necessary murder. In fact, I know that he never convinced himself of this, but the dilemma of the Spanish Republic Civil War was that it seemed necessary at one time to accept it.

In 1937, Andre Gide went for a famous visit to Russia, as a communist sympathizer. This was for many people a turning point for on his return he published the journal of his visit called Retour de l' URSS. In this he criticized various things in the Soviet Union, such as the occasion on which he had been asked to send a very adulatory telegram to Stalin; and he mentioned that individual Russians had approached him and reported grievances.

I happened to be attending the Congress of Intellectuals held in Madrid at the time of the publication of Gide's journal. This Congress was attended by now famous peo.ple: Andre Malraux, Julien Benda, Andre Chamson, Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos, Pablo Neruda, Nicholas Guillen, Jose Bergamin, La Pasionara, among them. The whole meeting was divided on the question of Gide's Retour de I'URSS. I remember one famous speaker saying that he was against it because it would give comfort to those Fascists who were, during his speech, firing shells (at any rate, one shell) on Madrid. I remember my total lack of sympathy

�

--i �

�

�

�

for this argument (I remember incidentally, asking Malraux what he thought of the Gide journal and his saying: "Russia and Gide is u love affair, and I never have views about people's love affairs.")

I remember also that as soon as I returned from the meeting in Madrid I left in Paris a note to Gide to say that I supported him in the publication of his journal, and that I then saw Auden, who agreed that political exigence could never justify the suppression of the truth.

All this is rather simple-minded, and perhaps sounds as if it were meant to appear noble. One has to set against all the arguments the fact that some of the best young English writers of their generation-Julian Bell, John Cornford, Ralph Fox, Christopher Caudwell, died in Spain, fighting in the International Brigade.

Perhaps one should also bear their deaths in mind when one thinks about George Orwell, who was a solitary dissenter; an anti-Fascist, but still more anti-anti-Fascist during the 1930's. Although a man of the left, Orwell conceived at the time of the Spanish Civil War a bitter hatred of the Left, particularly of the left wing intellectuals. Long before many others he saw the evil of Stalinism. He held that the sin of the left wing intelligentsia was that they supported one kind of totalitarianism-accepting its lies and propaganda and injustices-against another totalitarianism. Fundamentally his criticism was that they adopted theoretical attitudes about matters involving murders, injustices, and a terrible propaganda of lies, without ever having experienced the realities of the public events about which they theorized. He was justified in attacking people like myself who hovered on the fringe of events, less justified if his criticism was meant to apply to people who fought in the International Brigade. His position really was that you had to practice what you preach. He himself joined not the communist dominated International Brigade, but a Catalan anarchist division. He fought on the Catalan front, where he was wounded.

Orwell's position is important, because it implies that one should not separate opinion about issues like the Spanish Civil War from action. It also leads one to reflect on the even more remarkable case of Simone Weill, who throughout the 'Thirties and 'Forties adjusted her own standard of living to that of the victims of the period-almost starving herself, in order that she might share the life of those in concentration camps. We have lots of people who have progressive views about the evils of our times, we have some who are prepared to agitate, even a few who are prepared to fight: but what is very rare is people who are prepared to live the lives of the victims and the oppressed. That Orwell joined not the International Brigade, but a battalion of Spanish anarchists on the Catalan Front, that he lived not just as a soldier, but as a worker, gives him a great authority. He may often have been wrong, he added, but he was right in a way which makes his wrongness more significant than that of the theoretical correctness of the intellectuals of the left. It was the rightness of those who practiced what they preached.

Today a good many young writers, in England especially, feel a kind of envy for the poets of that decade because 'they had something to believe in.' For several reasons, the envy seems to me not unjustified. Very few really did believe in the ideologies of the decade, rather they felt conscripted into having to support them, as a result of the inertia of the democracies challenged by Fascism. Those who

did believe most strongly were writers like John Cornford, Christopher Caudwell, Ralph Fox, Julian Bell, and many others, who were killed in Spain. One cannot really feci envy for talents prematurely cut off. The overwhelming feeling of the most talented artists in the '30's was that they did not really wish to do propaganda, however good the cause might me. Meetings of writers and artists often took the form of the politically minded trying to bully those who felt that their art could not in any overt way be linked with politics. There is nothing to envy in all this.

However in one or two respects, the 'Thirties' writers are to be envied. The most important of these is that if one lived through this decade one learned to realize that we all of us in modern society function inside a machinery of interests which control and persuade us to serve them. One learned to ask oneself "Whose side are the people who run the government really on?" And often the answer was that the government and the ruling class were secretly opposing the values which they were pretending to defend. Even more important than this one learned to suspect one's own motives, to see oneself as being much more a product of the society to which one belonged than the independent-minded individual one liked to think oneself being. One also learned to feel extremely suspicious of false rebels, people who indulge in gestures, and who act as though they were responsible to no one except themselves. One realized that those who indulge in futile gestures are probably being useful to their opponents: the Beatniks are the justification of the Squares.

Lastly a good deal that was interesting was written in the 'Thirties': most of the political poetry lacks partisan conviction-it rarely wholeheartedly supports the political cause, yet it does nevertheless communicate anguish: the anguish of the concentration camps, the anguish of the writer struggling with his own conscience, divided between extremes. Anti-Fascism was not a monolithic political movement. It was a tormented debate, a struggle of private conscience against public wrongs. Echoes of this reverberate in Arthur Miller's After the Fall. They will probably go on echoing through better works as yet unwritten.

Nor is the situation of the 'Thirties' altogether dead. It is perhaps this which leads to the curious paradox that although the 'Thirties' seem so dated and difficult to understand, yet most of the artists of the 'Thirties' are still in the ascendancy. The reason may be that in large areas of the world Thirtiesh struggles still go on. For example, France has never-c-or if so only very recently-altogether got out of the mood of the 'Thirties.' Jean Paul Sartre with his tortured political conscience, his feeling that although he cannot be a communist, the communists are always 'correct' and the bourgeoisie always wrong, his deep concern about the grimmest realities of situations-for example, police torture-is with all his virtues and defects, the epitome of the 'Thirties.' It seems likely that with the deaths of a few old men-General de Gaulle, General Franco and Salazar-situations resembling the Spanish Civil War may recur. Even in America the same forces of feeling and bad conscience are called into evidence by the struggle over Civil Rights, as were evoked in the 'Thirties:

So the 'Thirties' evinced a model, a pattern, of consciousness of the struggle of underlying social forces in our society. For this reason the social conscience which they represent may not be dead but only sleeping.

Space Music

I have not felt God's presence in my house or on my street for some time; and frankly, I have small need for a God in the sky; the vastness of glittering space is not my notion of a human or acceptable temple. I want a deity dwelling in the kitchen or bedroom, not far from the Eye Light which with the dreaming antennae of the senses is the only Testament.

I lift my eyes skyward at 3 A.M. when sleep fails me to see if the Old One is hiding up there, where the stratospheric gas recedes to an absolute zero. I'd hate to be engulfed by it, to be seized by its fantastic blue, to be dwindled to a mote. On the radar can be heard the interstellar particles which some say is God humming a cosmic tune. This singing dust is neither sad nor joyous. It just sounds off! Molecules darting through airless distances, whirring, colliding.

I think of some Messaien fluting in the stillness or some Webern tinkling on the piano, Das Augenlicht, like icicles falling; except, of course, these were men, making a human music. Alone in the night I want to hear familiar passagaglias of wind in the doorways and windows or along the telephone wires, instead of this absurd cosmic ting-a-ling. It is evident to me that where the rooftops end with their sprinkling of sparrows, begins an ambiguous realm useful for its changing hues and as a setting for nests of lights. Not for a Temple. I see the rooftops calmly breathing their vapors and candelabras of chimneys intruding into the moonlightand I turn away from the nearest galaxy to about 100 feet above the telephone wireand this is the limit of my faith. Welcome back, God!

WILLIAM PILLIN

A valedictory

LIONEL TRILLING

WEN

PRESIDENT MILLER invited me to speak here today-stipulating, it will reassure you to know, that I speak briefly and not too seriously-he used a convenient shorthand in explaining to me what my role was to be: he said that he wanted me to serve as the valedictorian of this year's class of honorary doctors. It is a happy kind of task and I am glad to attempt it. And yet I must be conscious that in my undertaking I confront a substantial difficulty. The valedictory address, as it has developed in American colleges and universities over the years, has become a very strict form, a literary genre which permits very little deviation. We all know what its procedure is. The chosen graduate begins with a conspectus of the world into which he and his classmates are now about to enter. His view of the world is not calculated to inspire cheer, it is usually pretty grim. He speaks of the disorder and violence that prevail in the world, perhaps even close to home. He speaks of the moral and intellectual inadequacy of society, of the dominance of personal self-interest, of indifference to the welfare of others and to all ideal considerations.

This constitutes the first movement of the valedictory form.

In the second movement the speaker turns his attention to the graduating class. in whose name he is saying farewell to their college. He remarks on the shelterer life which the members of the class have been privileged to enjoy for four years He speaks of the intellectual and spiritual ideals which have been instilled intc them and goes on to observe how these will be denied and assailed by that harsh world which is now to be the scene of their new endeavors.

And then, in a concluding movement, the speaker urges his fellow graduate! to hold fast to the virtues of the educated man and to try to exercise them in the hostile world which, in the degree that it opposes them, has need of them.

In short, the defining characteristic of the valedictory address is its statement of the opposition between the university on the one hand and the world on the other.

How well we know this opposition! For the academic person it may constitute a chief element of his sense of himself and of his position in society. It is

charged with a most moving pathos from which the academic man may derive justification and courage. Surely no academic has ever failed to take heart from Matthew Arnold's famous apostrophe to his own university, of which the opposition is of the essence.

"Adorable dreamer," says Arnold to Oxford-"adorable dreamer, whose heart has been so romantic! who hast given thyself so prodigally, given thyself to sides and to heroes not mine, only never to the Philistine! home of lost causes, and forsaken beliefs, and unpopular names, and impossible loyalties! what example could ever so inspire us to keep down the Philistine in ourselves, what teacher could ever so save us from that bondage to which we are all prone the bondage of"-and here Arnold quotes Goethe-s-" 'was uns alle biindigt, DAS GEMEINE''': what binds us all, the narrow, the mundane, the merely practical.

This was, in point of fact, Arnold's actual valedictory to Oxford when he had concluded his term as Professor of Poetry at the university, and you plainly see that it contains the whole mystique of the valedictory, that it gives ultimate expression to the idea of the opposition between the purity and gentle nobility of the university set over against the crassness of the world.

And what is a designated valedictorian to do if he finds that he cannot accept this established valedictory mystique? I am in just that situation. For some years now, it has seemed to me that the opposition between the university and the world, or at least half the world, is diminishing at a very rapid rate. Gone are the days when H. L. Mencken could laugh a book out of court by referring to its author as Professor, or Dr., or, worst of all, Herr Professor Dr. Gone are the days when middle class fathers groaned and middle class mothers wept when their sons announced their intention of making a career in the university-scholarship and teaching now appear to the parental mind as amounting to a profession like another, and throughout the land we hear the low purr of satisfaction that accompanies reference to "my son, the one who's abroad on a Fulbright," "my son, the one who's working on genes."

Perhaps there is no more striking fact in American social life today than the rapid upward social mobility of our academic personnel, the upward movement of the university itself in national esteem. If ever the university was the object of condescension as the place where abstraction consorted most happily with incompetence, it is now, perhaps more than any other American institution, an object of admiring interest and even of desire, as suggesting the possibility of a life of reason and order. I have the sense that the authority the university has over people's minds grows constantly. No less constant is the increase of the university's scope-it seems to be a chief characteristic of our American culture that virtually any aspect of human life can be thought of as an object of study, and that eventually the intellectual discipline that develops around it seeks to I find shelter in the university. Nothing is too mundane, nothing is too instinctual, i nothing is too spiritual for the university to deal with.

What is a valedictorian to do? How is he to evoke the appropriate valedictory pathos of the opposition that the world shows to the university when so much of the world is trying to crowd itself into the university? And he is the more debarred

from the valedictory mystique and pathos if his own impression of the state of affairs is supplemented by a reading of Clark Kerr's recent book, The Uses of the University. Dr. Kerr is president of the University of California and thus speaks with no small authority about university affairs. He tells us that we are witnessing a rapprochement of ever-increasing intimacy between the university and the world.

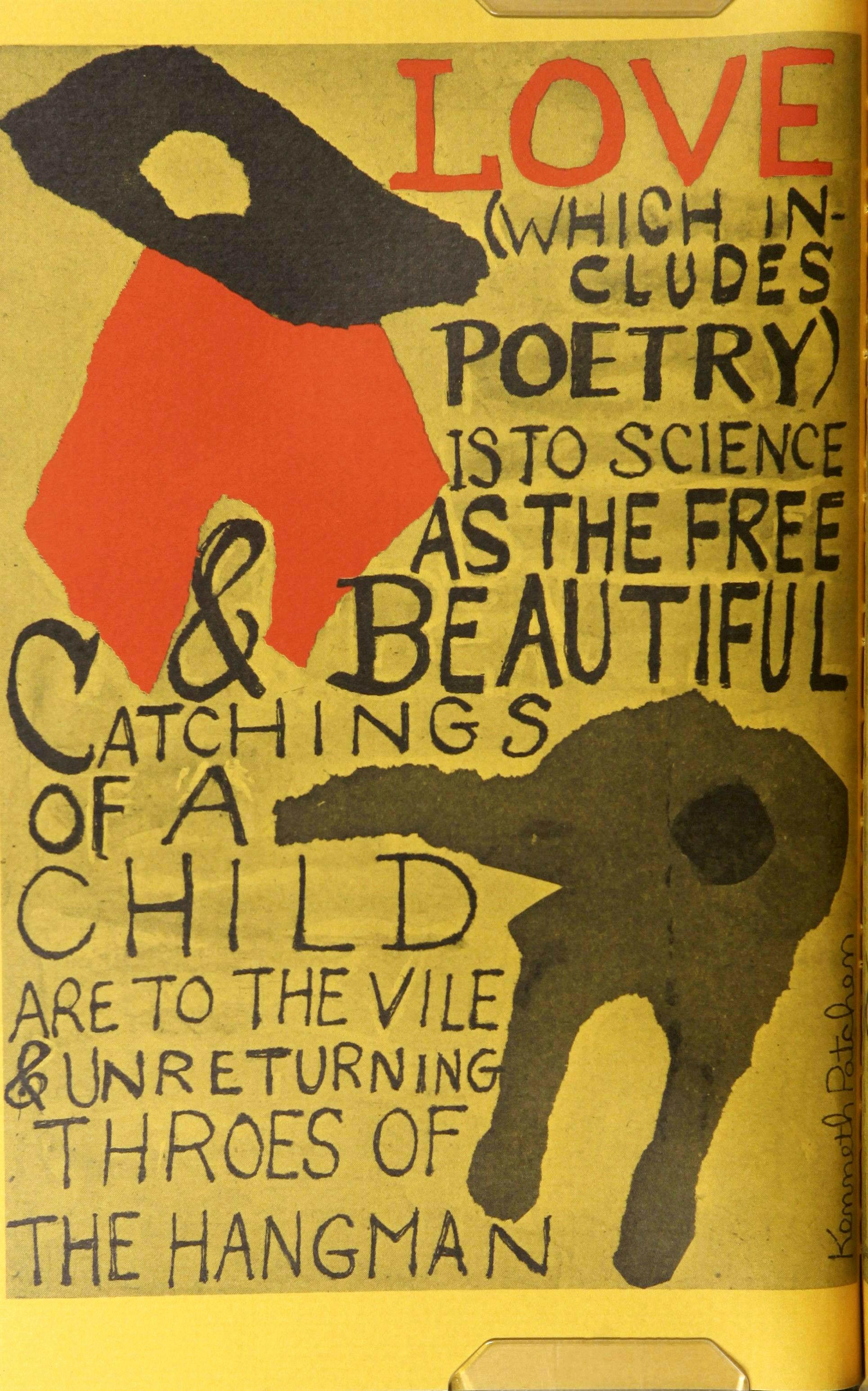

But this puts it all too mildly. How far things have gone in this new direction is strikingly suggested by Dr. Kerr's statement-it is the statement not only of a university president but of a distinguished economist-that the university has become one of the decisive economic facts of our society. Dr. Kerr speaks of the university as being at the center of what he calls "the knowledge industry," and he is not using a mere figure of speech when he makes that phrase. He does not mean that the university's activity and organization may be thought of as in some ways analagous to the activity and organization of a manufacturing or a processing industry. Nor does he mean that the knowledge that universities develop is a commodity which business men are eager to possess. He means that the existence of our universities bears a relation to the national economy that is materially comparable to those enterprises whose achievements are noted in the Dow-Jones averages. He tells us that "the production, distribution, and consumption of 'knowledge' in all forms is said to account for 29 percent of gross national product ; and knowledge production is growing at about twice the rate of the rest of the economy." And he goes on: "What the railroads did for the second half of the last century and the automobile for the first half of this century may be done for the second half of this century by the knowledge industry: that is, to serve as the focal point of national growth. And the university is at the center of the knowledge process."