EDITOR

Charles Newman

MANAGING EDITOR Suzanne Kurman

ART DIRECTOR Lawrence Levy

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Laurence Gonzales

BUSINESS MANAGER Janet Clevenstine

ASSOCIATES

Janet Bailey

Peter Steele Byers

Mary Kinzie

Christine Robinson

Debra Petranek

Allison Platt

Claudia Reynolds

Mary Elinore Smith

Dianne Wall

TriQuarterly is an international journal of arts, letters and opinion, published in the fall, winter and spring at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. Subscription rates: $5.00 yearly within the United States; $5.25 Canada and Mexico; $5.75 Foreign. Single copies will usually be sold for $1.95. Contributions, correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly, University Hall 10 1, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, 60201. Unsolicited manuscripts are welcome, but will not be returned unless accompanied by a selfaddressed stamped envelope. All-work accepted for publication becomes the property of the editors, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1970 by Northwestern University Press. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors.

NATIONAL DISTRIBUTOR TO RETAIL TRADE: B. DEBOERr 188 HIGH STREET, NUTLEY, NEW JERSEY 07110. DISTRIBUTOR FOR GREAT BRITAIN AND EUROPE: B. F. STEVENS & BROWN, LTD., ARDON HOUSE, MILL LANE, GODALMING, SURREY, ENGLAND.

ROSELLEN BROWN

W. S. MERWIN

JACK ANDERSON

FRANCIS PONGE

ROLAND TOPOR

JONATHAN STRONG

ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER

ROBERT COOVER

JEAN-PAUL ARON

JOHN CAGE

ROGER KEMPF

EUGENE IONESCO

REINER KUNZE

Fiction

What does the falcon owe? 5

Three: Within the wardrobes 13 The basilica of the scales 14 The Dachau shoe 16

Abandoned cities 19

Four: To Bona Tibertelli de Pisis 22

Natural crystals 24 The lilac 25 The plate 27 translated by Lane Dunlop

Four tales: No ordinary fairy 29 Laying the queen 35 My dear friends 37 A great man 45 translated by Margaret Crosland and David Le Vay

Xavier Fereira's unfinished book: Chapter one 143

Altele 208 translated by Mirra Ginsburg

Drama

The kid 59

Pulling punches translated by Ivan Sonier 184

Essays

Diary: how to improve the world (you will only make matters worse) 94

The double desk translated by Ivan Sonier 113

Neither god nor demon translated by Joy N. Humes 204

Translation

The end of art translated by John M. Gogol

56

HAGIWARA SAKUTARO

KONSTANTINOS LARDAS

JOSEPH BRODSKY

OSIP MANDELSTAM

DAVID STEINGASS

DAVE ETTER

DOUGLAS BLAZEK

ARTHUR REIGNBEAU

ANDREW GLAZE

P. S. BYERS

MAXINE KUMIN

GOT LOST

MARK STRAND

RON LOEWINSOHN

GERALD GRAFF

EUGENE WILDMAN

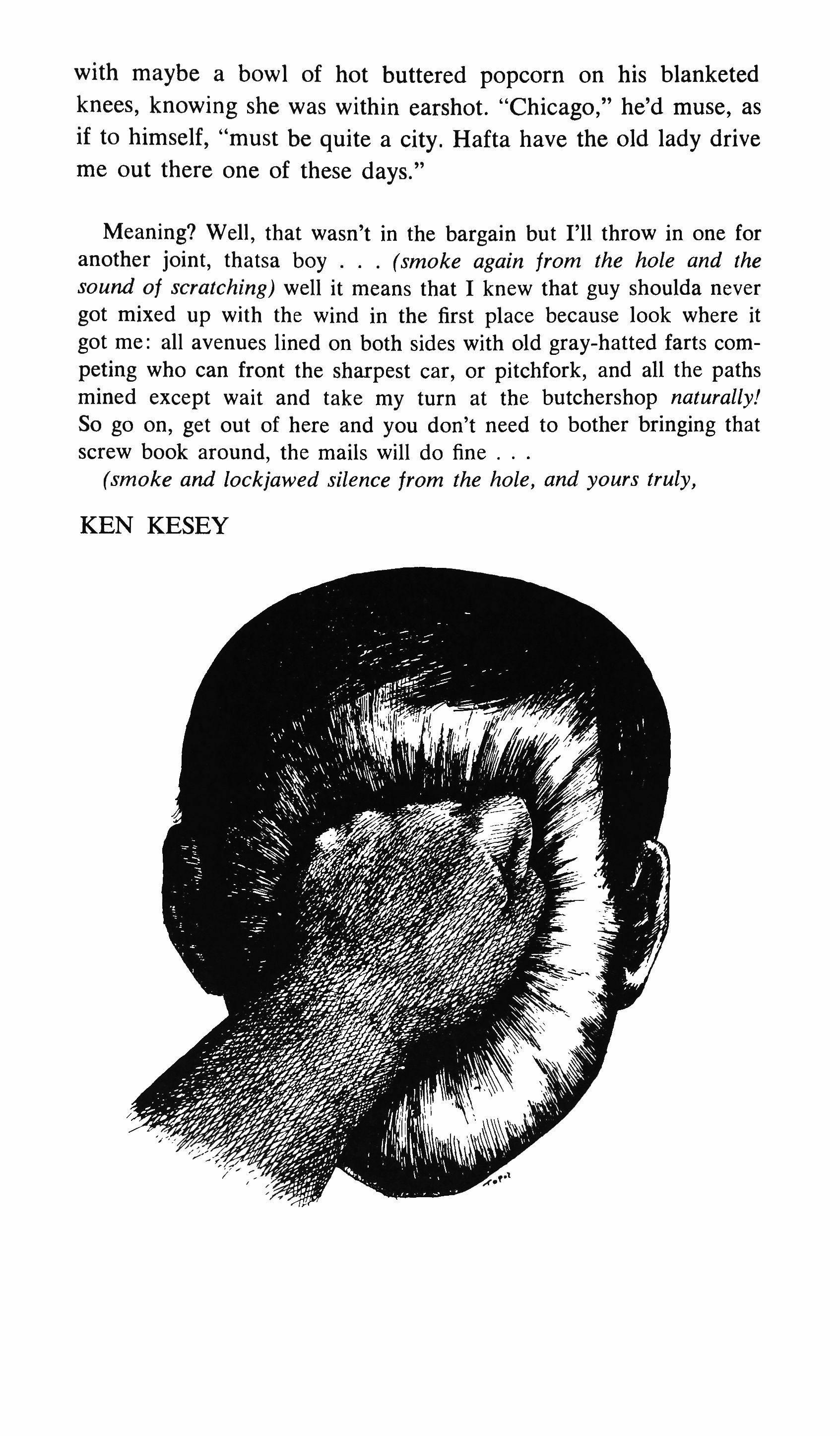

KEN KESEY

Three poems: Terrible mountain 141 Seedling 142 Loneliness 142 translated by Graeme Wilson

Seven of Sappho's wedding songs 171

Five poems: Almost an elegy 175 Enigma for an angel 176 Stanzas 178 Untitled 181

The candlestick 182 translated by George L. Kline

Four poems 199 translated and with an afterword by Clarence Brown

Poetry

Inside cover, anatomy text, Mankato 50

Chicken 52 Twilight in a railroad town 53

Concerning the epic 54

How to choose your group 57

What's that you say, Cesar? 82

Late news, weather and sports (1968) 112

Lying flat 138 Pain 139

167 168 169 170

From a litany 173

Reviews

After the (mimeograph) revolution 221

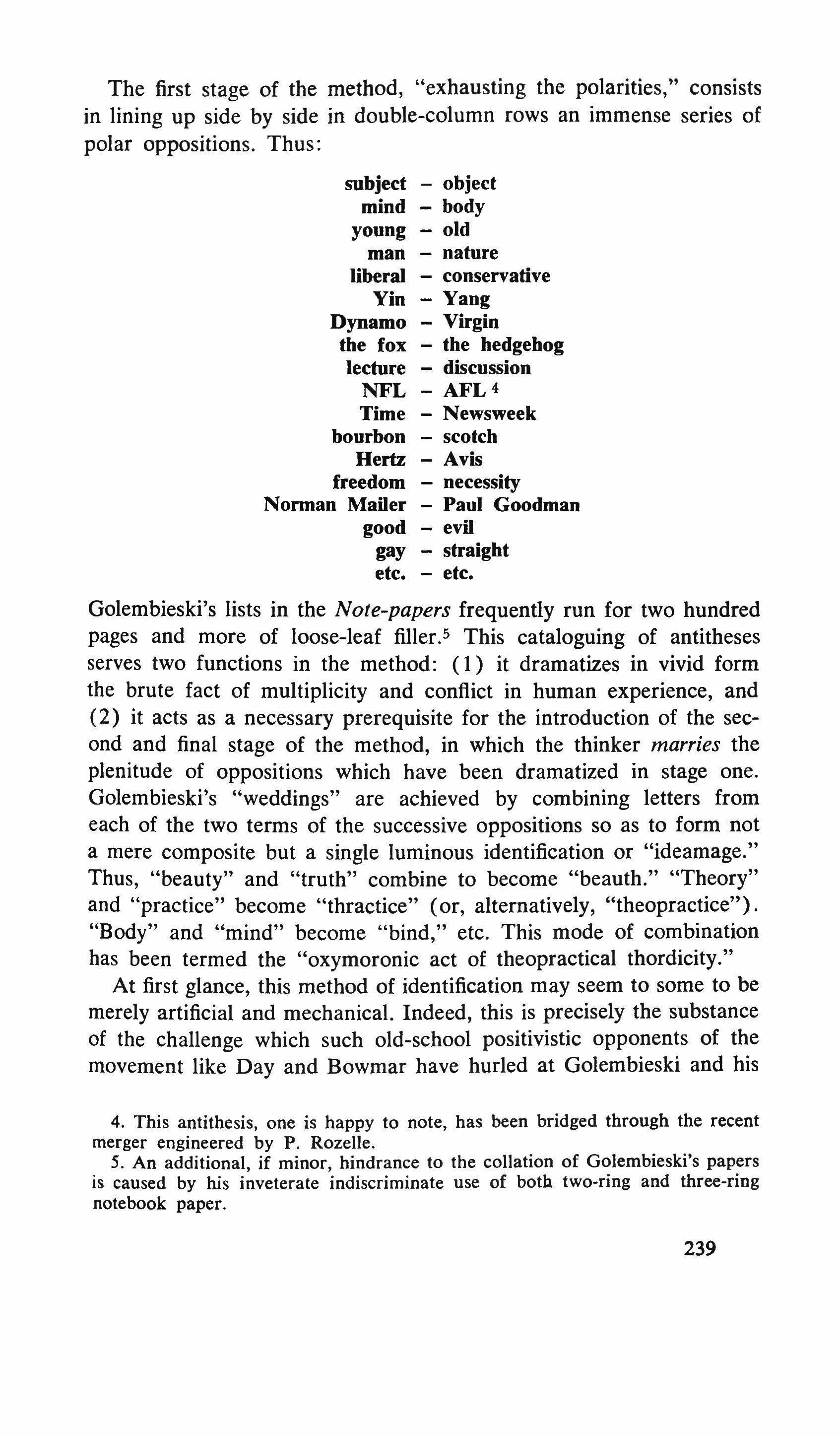

A report on oxymoronism 237

American walkers 244

Correspondence 247

This issue of TriQuarterly is illustrated by Roland Topor

MP 3024-7PN

F., 27, 5'5", 122 lb., hair medium brown worn long (sometimes in gold clip), eyes brown, glasses for reading (tortoise frames). Morning 12/13 had approx. $40 (known), car keys (car left parked outside MP's apt. house). Took few clothes, overnight bag (blue plaid), portable typewriter, small bf w etching ("Clown" by Daumier), 2 small eskimo masks, removed from bedroom wall.

MP and H(usband) had been writing book (study of Kwamiack Indians of Saskatchewan); typed chapters were stacked neatly in basket on desk where husband says they usually were kept. On top of file was found Enclosure (C), with Enc. (A) in typewriter. Enc. (B) was taped on bathroom mirror. Enc. (D), a stapled set of yellowed newspaper clippings, was found by H on MP's pillow, which was neatly covered by bedspread. H claims apt. had been cleaned while he was out that morning. One coffee cup drying in drainer. Approx. 24 hrs. after MP disappeared, H received telegram (nightletter, sent from phone booth, this city),

TriQuarterly 5

Enc. (E) which H identifies as Navajo prayer which he taught MP before marriage. No further communic. from MP; none of couple's friends rec'd communic. H received two bills for dept. store charge account purchases, one for a sweater, the other for a number of novelty items identified as (1) Ventrillo Wonder voicethrower (2) Fur-head, a bar of soap shaped like a face, which grows a beard overnight when placed in water (3) a set of trick mirrors (4) plaster-of-paris mold outfit called "Living DeathMask Set." Purchases totaled $14.53, which H paid.

End file. See attached EncIs. A-E.

ENCL. A:

WORDS = ARTIFACTS

SENTENCES = RITUAL

First prayer of UNBINDING.

t Hohman's Powwows on Arts and Remedies (Eagleton, Penna., 1837) claims following:

a good remedy for hysterics a remedy to be used when anyone is falling away a remedy for calumniation or slander to attach a dog to a person a sure way of catching fish to mend broken glass to prevent the Hessian fly from injuring the wheat to prevent cherries from maturing before Martinmas to prevent the worst kind of paper from blotting to remove a wen during the crescent moon to make a wick which is never consumed to compel a thief to return stolen goods against every evil influence to charm enemies, robbers and murderers a charm against shooting, cutting or thrusting to prevent being cheated, charmed or bewitched a charm to gain advantage of a man of superior strength

Dream of a hunter wearing his hooded falcon Blind on his wrist. Then watch the bird escape. Forgetting hunger, remembering he has wings, He feels his way on the under edge of the sky, Threads through the clouds, Comes down in the safety of distance, And wonders: The falconer is gentle, Has fed him well, has taught him all he knows, And keeps his sight.

Can you say what the falcon owes?

Once in a land that perhaps exists, there lived a king and his little daughter, the Princess. They lived in a regulation castle and were all the things they had to be; in fact (in spite of their perfection) they were even believed to be happy.

One day in spring the King put on the lightest cloak and crown in his closet and took the hand of his lovely little girl. "Let us go for a walk around the palace grounds," he said to her, and she threw down her golden doll and carne to him with a smile of true delight. (She loved her great father perfectly and it was clear to the whole world that he reflected her love just as a still deep pool reflects a star, drinking in its light without a movement, without the hint of a ripple. He never scolded her or made her cry; he was a true king and a forgiving father.)

Hand in hand they strolled the walks in the garden, past the purple berry-bushes and the roses strung up with silver twine, past the shore of the little pond with its pearl cup of a boat tied up on the grassy beach. When they had been once around the grounds and their feet said nothing; not a word of reproach, the king suggested they walk out past the village into the countryside. The little princess had never ventured beyond the gates of the palace and she was thrilled. And she could walk longer with her splendid father, her small hand in his large one!

She was so excited that she chattered, chipped at his ear like a

woodpecker. She laughed at her father's dignified silence and twitted him for talking so little. "Well," she would say, "perhaps kings are not supposed to talk as much as princesses. I'm sure that's it, and my king"-she tugged at his sleeve to reassure him -"my king always does what a king ought to." Though she was a mischievous child, often a trying one (since he never restrained her), she had no standard by which to feel herself judged. He said nothing now but walked steadily beside her. Every now and then, try as she did with her short legs beneath their heavy skirts, she could not keep in step with the king. She would run a few steps, raising the dry dust under her slippers, and match her strides to his, then she would fall behind again. Finally, feeling the pull of her hand, her father slowed his pace to match hers, and they kept on, slowly.

After some time the king stopped. He dropped his daughter's hand and said, "Dear child, I am very weary." He sat himself on a large flat stone at the roadside. "Little queen, if you want to, you can walk on a bit. Why don't you go through those trees-" He pointed to a stand of pines that loomed abruptly like an island in the flat sea of meadow-"and on the other side you will find a lovely brook full of fish with rainbows on their backs."

The princess could hardly restrain her delight. She gave her father a kiss and ran off down the road and across the spongy earth that rose and sagged beneath the trees, mountains and valleys of pine needles. She could see light pricking through the solid darkness in sudden ragged flashes like sunlight glinting off a sword, and the child ran toward it, rolling the hoop of her eagerness before her.

A low growth of bushes stood barricading her way when she approached the light, and she had to skip through it, holding her breath as each thorn scraped through her skirts and through her skin. With an anxious little sigh, she brought her leg high over the last hurdle and down with a decisive thrust, and before she could see it, she had tumbled flat on her chest into a ditch. The ground near the stream was rocky and damp and she had dirtied and torn her velvet dress in a dozen places. Winded, she shook

her skirts out with a fury that was all the more painful in her throat because she was not sure where it came from or where it wanted to go.

There at least was the stream, and it would be coolon her raw ankles. It had been dusk; now the light seemed to dim and go out, and the rainbow fish had gone home, or had turned their promised lights out. If there were rainbow fish. The water darted at her bruises with cold fangs, and she waded back to the bank stung with pain in many places. Something caught at her foot, bit through with a crab's mean grip. In terror she kicked and kicked till it flew off and, wide-eyed, as she saw it arc against the black water and tumble in, she could just make out the rainbow lights winking at her. She pulled her skirts up to her knees and ran, expecting to feel a hand or a claw at her shoulder, in her hair, at her feet, as she felt her way dumbly through the fence of thorns. The forest was blacker and quieter than sleep, and cold-she felt the sudden cold as if someone had slammed a door behind her. Only the unfamiliar sounds of the night harried her home.

When she had flown across the lawn of the castle and rattled the door open, she found her father sitting calmly with a book, wearing his heavy crown again. She could not speak.

"Child, you are home," he said to her simply, as if he were telling her something of value. "Did you see the rainbow fish?" "Father!" The princess stood still as a thorn-tree.

"I couldn't wait for you," he said.

"Father!"

"My precious one, understand. This has always been so. You talked so much. You walked so slowly. You took so long. You could hardly expect-"

She swayed in his words. "But why did you say nothing? You said nothing at all."

"What should I have told you, little one?" He was well returned to his patience.

"I could have done something! I would have been quiet! I would have run! I would never have left you. Or I would never have come."

9

Her father smiled faintly, quizzically. "Ah," he said and spread his large hands wide.

Jan. 23, 1924

The splendid warmth and style of Alexei Tartakoff were again in evidence last night in a recital which brought him back from his celebrated European tour to an audience that jammed Carnegie Hall. Mr. Tartakoff chose Bach's second partita for unaccompanied violin to open his program and in the Bach and the notoriously wicked Devil's Trill sonata which followed, he showed himself again the unrivaled technical master of the era. His fingers seem to have the strength, speed and certainty of a mechanical instrument which is powered not by a motor but by a great and magnanimous heart. His tone is ripe and brilliant and he has a wealth of nuances in tone and tempo which he uses to ravishing effect. The limpidity he achieved in the slow movement of Beethoven's very familiar Spring Sonata was so lovely and cumulatively so moving that the audience applauded at the end of the movement. This crowd knew where protocol can leave off and passion begin. Mr. Tartakoff's accompanist was Frederick Hopper and his collaboration was exquisite. Mr. Tartakoff has always exercised fine judgment in picking his assistants, but there is apparently more to it: he can elicit great commitment from all who share the stage with him. His personality demands response and gets it. The audience gave it to him last night; there was a ten-minute ovation followed by four encores that left the crowd shouting for more.

The Music Shed at Tanglewood was the scene last night of a rather disheartening concert by the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The program, perhaps, was to blame. It was war-horse night, with a stable of old winners trotted out for the automatic approval of a loyal audience which, itself, is not quite as young as it used to be.

After the Leonore No.3 and the Haydn Clock, about which there was nothing the least bit diverting or unique, Alexei Tartakoff was the soloist. Lexy, the old Russian who used to be billed as the Liszt of the violin, is still a drawing-card, whether for musical or extra-musical reasons one cannot tell if he doesn't feel the hypnotic pull himself.

10

(This reviewer must admit that he doesn't, but perhaps his parents did.) This reluctance to be moved by the charming smile and courtier's bow, and the still ample crown of free-floating hair, leaves one's attention, unfortunately, free to listen to the music Tartakoff produces. It is flamboyant and undisciplined and yet somehow conventional, for all the unconventionalities his sloppiness of phrasing and intonation allow. He sounds temperamental a la Russe, but it is all so familiar, could his heart really be in it? This style would be so easy for a young violinist to learn to ape, with a bit of application, from old records; and one fears that a younger, more limber man could do it better. These days, at least, we must demand more from our orchestras and our soloists than they gave us last night.

April 20, 1958

Last night was a most peculiar one for all who attended the muchpublicized closing concert of this season's Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall. Judging by their response, the audience was as bewildered as it had every right to be. The evening was to mark 'the farewell appearance of the great Alexei Tartakoff, who has appeared in New York only once in the last ten years. Mr. Tartakoff, now a worn-looking 72, has continued to concertize across the country within the last few years; therefore what was at first anounced as a return from retirement for this special concert could perhaps more honestly, if less euphemistically, be called a return from obscurity. In any event, the occurrences of the evening make one wonder what the intention really might have been, and one is at a loss even to conjecture.

A good deal of newspaper attention had been given as well to Mr. Tartakoff's plan to present at this concert his only pupil and protege, so that the occasion was to be one of more than sentimental interest. It was to be both a farewell and a debut, and the latter, judging by Mr. Tartakoff's reluctance to sanction any other student over the. years, made one quite naturally curious and hopeful that a worthy heir would be proclaimed by the abdicating king.

How to say it? To be blunt, the concert was a fiasco, and an extraordinary one. Harlan Temple, who is 23, has the manner of a masterhe swept onstage and bowed from the waist, a more athletic replica of his teacher, dispensed with even the customary gesture of interest in the tuning of his instrument, strode out into the deep waters of the Dvorak A Minor, and promptly drowned. One could not attribute such

fundamentally faulty playing to nervousness, especially when not a hint of discomfort was in evidence. On the contrary, Mr. Temple was more self-possessed than most proven professionals, even suspiciously so. But his technique was wretched, his intonation slapdash, his tone ugly, his general level of sensitivity and musical feeling so low it was virtually absent. This pleasant enough concerto was suddenly ghastly and endless, and when he had done with it, the soloist bowed profusely to a paralyzed audience from which a ragged little sound of applause issued briefly. But Mr. Tartakoff was onstage, clapping proudly, and the orchestra, with Rouben Der Tartesian on the podium, joined with him enthusiastically. No one but the audience looked troubled. One shook oneself to see if it might have been an acoustical fluke or an after-dinner dream. But for confirmation, the master and his pupil were paired in the Bach G Minor double concerto, and the impression persisted. And next to Tartakoff, the untalented boy was an even greater outrage. What a lovely tone and what a cat-squawk juxtaposed! By comparison the aging violinist was the perfect musician again-soaring, agile, strong.

This reviewer, grieved, confused, even angry, cannot help but wonder what will happen to Harlan Temple when he is properly launched (horribile dictu!) and on his own. Considering that he already parades like a child movie-star, he has apparently been brainwashed into believing that he will have, or already has, a career ready-made for him. If so, Mr. Temple is in for a colossal disappointment.

ENCL. E:

Sike saadilil

Sitsat saadilil

Sissis saaditlil

Sini saaditlil

Tadisdzin naalil sahadilil

Naalil sahaneinla

Hozogo tsidisal

Hozogo nadedisdal

Sana nislingo nasado 12

(H's translation) :

My legs for me restore

My body for me restore

My mind for me restore

My voice for me restore

This very day your spell for me you will take out

Your spell for me is removed

Happily I shall go forth

Happily I shall recover

My feelings being lively may I walk

No one who was not born and brought up in them really knows of the life in the clothing drawers, and very few of those who did grow up there are willing to divulge any details of that ancient existence so close to our own, or as we like to say within our own, and yet so unfamiliar. No, they answer, everything has been taken from us from the beginning and you have given us only what you chose to, with no concern for us. What essentials remain to us, the secrets of our life, we will keep to ourselves. If our way of life is doomed as a result of yours, its secrets will die with it, and its meaning. We will not lend those to you for your masquerades.

By now scholars have tried everything to bring those secrets to the light of present-day reality, and with almost no success. Devices for opening the drawers suddenly have revealed nothing but the contents lying like the dead whom the light suddenly surprises. Cameras with flash-bulbs, left in the drawers in houses where no one was staying, and timed to go off during the darkest and most silent hours, have disclosed still more eerie vistas of inert recumbency; always the life has remained cloaked in the motionless forms. Electronic recording devices rigged in the same

TriQuarterIy 13

manner have picked up nothing but the gradual sinking into sleep of consciousness after consciousness in the house, until at last only one alien witness remained awake: the recorder was registering its own unrewarding vigil. It has been claimed that these last results, nevertheless, represent a step forward. If not a record of the life itself, at least they supply a record of the outer world from that life's point of view.

As might have been expected, most of the few sources of information on this life so turned away from our own have come from milieus in which neglect in one form or another has already advanced its work. Loose garments, tossed in unfolded, perhaps uncleaned, long ago, and abandoned to their own shapes, have not always been able to conceal the evidences of a life to which they were born and which they had almost forgotten the need to hide. A darkness from their own world, and an odor of it, clings to them here and there when they are too abruptly hauled into ours. Others that once existed as pairs and have lost their consorts, stray buttons, fragments of ornamentation, demoralized and with a weakened sense of the future, also betray at times the existence of other mores, other values, other hopes, if not those things themselves. These are not ideal witnesses, perhaps, but is there any such thing?

At any rate it is hard to sort out probability from sectarian wishful thinking, in the scant testimony thus gathered. The witnesses suggest that their own order of things, its darkness, its anticipation in which time plays no part, its community without sound, its dances, its dances, whatever they may be, are part of an order that is older than the cupboards and will survive them. They also infer quite calmly that the world of uses, for which they were fashioned and in which they are worn, knows almost nothing of reality.

There is disagreement about the dates of each phase of the present edifice. No one can establish incontrovertibly when the first primitive chapel was constructed on this site. Parts of the

crypt survive from that earliest place of worship. Massive squat squared pillars of gray stone. Medals and military decorations of a later day have been affixed to them on all sides like cloaks, and glitter in the light of the votive candles. The church has been rebuilt at least three times, incorporating the designs and proportions of successive ages. Each time it has been considerably enlarged. The facade has moved west. It is from there that we enter. From farther away. The transept has broadened like the canyon of a gray river flowing between us and the chancel. Most important of all, each time the ceiling, the ceiling has risen.

It cannot be seen. Not from anywhere in the basilica. All that meets the eye when one looks up, wherever one is, are the scales. Like leaves they hang everywhere above the worshippers and the curious. They are suspended at all heights, from those that can barely be descried through the pans and chains of others lower down, to a few which seem to be almost within reach-an illusion caused by some trick of perspective, as one discovers if one finds oneself near them. They are of all sizes, from delicate brass instruments such as apothecaries still use, to vast measures with pans that a heavy man could stand in, beams thicker than an arm and longer, and chains in proportion. And they too are of all ages. Some of them, it is said, are older, much older, than the first building itself. They were brought from far away and their origins are legendary like that of the grail. But none of them belong to our accounts any longer. No one climbs to examine them.

And it would be unthinkable to take one down. In the course of the many centuries since the last building was finished, two or three have fallen. One can imagine the terror that swept through the devout who were present when one of the silent measures suspended above them suddenly detached itself, with a sound of metal snapping and groaning, from what had seemed its everlasting equilibrium, and had crashed down through the lower choirs of chains and hammered pans, setting up a clangor of cymbals, a rocking and lamentation that left the farthest scales in the remote ceiling swinging and vibrating with dying songs.

The fallen measures lay like dead supplicants on the granite floor. No one touched them. No one was sure what they meant. No one knelt to pray near them on the bare stone unless the crowd of worshippers pressed them closer than they would have chosen to be. In time iron railings were erected around the collapsed measures where they ·lay. Black cloth was draped from the rail and removed only between the evening of Good Friday and Easter morning. Candles-not votive lights but thick columns of wax the color of the faces of the dead-flickered perpetually at the corners of the enclosures.

As for the scales suspended above, it would be hard to say at a glance whether they are still or moving. A distant quiet hangs in the pans like dust. And yet the eye that remains fixed upon them for some time detects, or seems to detect, a scarcely perceptible motion, such as we think we see if we stare for long at the faces of the dead. And in fact the scales are at all times in motion. Often it is so slight that the unaided eye could not discern it at all if it were not that the thousands of minute swayings all cast shadows into the thickets of chains, beams, pans, and the shadows magnify the movements, giving that impression of a breathing lost in itself. Occasionally a single balance will forsake its equilibrium, without apparent warning, and one of its pans will slowly sink farther and farther as the other rises, then even more slowly right itself. The phenomenon has fostered various explanations. Some say it is due to a death. Some ascribe it to a peculiar fervor of prayer. Others declare that it is the dove descending. Or a wind. Past, present, or to come.

My cousin Gene (he's really only a second cousin) has a shoe he picked up at Dachau. It's a pretty worn-out shoe. It wasn't top quality in the first place, he explained. The sole is cracked clear across and has pulled loose from the upper on both sides, and the upper is split at the ball of the foot. There's no lace and there's no heel.

He explained he didn't steal it because it must have belonged

to a Jew who was dead. He explained that he wanted some little thing. He explained that the Russians looted everything. They just took anything. He explained that it wasn't top quality to begin with. He explained that the guards or the kapos would have taken it if it had been any good. He explained that he was lucky to have got anything. He explained that it wasn't wrong because the Germans were defeated. He explained that everybody was picking up something. A lot of guys wanted flags or daggers or medals or things like that, but that kind of thing didn't appeal to him so much. He kept it on the mantelpiece for a while but he explained that it wasn't a trophy.

He explained that it's no use being vindictive. He explained that he wasn't. Nobody's perfect. Actually we share a German grandfather. But he explained that this was the reason why we had to fight that war. What happened at Dachau was a crime that could not be allowed to pass. But he explained that we could not really do anything to stop it while the war was going on because we had to win the war first. He explained that we couldn't always do just what we would have liked to do. He explained that the Russians killed a lot of Jews too. After a couple of years he put the shoe away in a drawer. He explained that the dust collected in it.

Now he has it down in the cellar in a box. He explains that the central heating makes it crack worse. He'll show it to you, though, any time you ask. He explains how it looks. He explains how it's hard to take it in, even for him. He explains how it was raining, and there weren't many things left when he got there. He explains how there wasn't anything of value and you didn't want to get caught taking anything of that kind, even if there had been. He explains how everything inside smelled. He explains how it was just lying out in the mud, probably right where it had come off. He explains that he ought to keep it. A thing like that. You really ought to go and see it. He'll show it to you. All you have to do is ask. It's not that it's really a very interesting shoe when you come right down to it but you learn a lot from his explanations.

Back of the adobe haciendas are reed huts set amongst the overseers' rotting privies. There, Indians wearing dirty loincloths are set to work with mortar and pestle to grind down strange metals: tungsten, bismuth, antimony, manganese. Although they are given a ration of a cup of brackish water every morning, the heat is so intense that their thirst remains unslaked. They are never allowed to leave their benches, not even to go to the toilet. As a result, streams of urine trickle constantly along the dirt floor, turning it to mud. The overseers are always drunk. Sometimes they waste whole afternoons by taking turns raping the Indian girls right there on the benches. But Indians and overseers alike are plagued by syphilitic fevers which rot the body with fits of shaking and green foam at the mouth. In front of the haciendas is Assumption Square, over which towers the Cathedral containing the remarkable Madonna of the Gourds, Bishop Laszlo's most precious treasure. At the opposite end of the square stands the Capitol. From time to time, the Secretary of the Interior stops counting his silver coins, looks out the window, grins, and spits

TriQuarterly 19

tobacco juice onto the statue of Jesus Valdevinos-Feo at the Battle of Moltavis Rock which stands in the square below.

There are no suburbs. The streets stop at the wheatfields, where the iron helmets are set on black sticks to frighten off eagles. Beyond this point, the wind begins, as hard to ignore as stomachache. The townspeople fear two things always: drought and frost. Aldermen appear on television to blame infiltrators from the East. Revivalists set up tents in Courthouse Square, opposite the Granada Theatre where a movie is playing about the defeated tribes at the Battle of Moltavis Rock. No one goes to the movies much these days. The balcony has been roped off since 1956. Some nights a strange wind hisses in from the prairies, covering the sidewalks with a thin layer of dust. Then everyone is frightened. A curfew is imposed. The sheriff searches the Yellow Pages for Negroes. But inside the houses Sunday dinners continue with gravy boats on the tables and fathers standing to say grace. Milking machines glitter in shop windows. Nevertheless, children flee daily to the wheatfields. Kids in baggy overalls crouch between the stalks and try to imitate the wind's hiss. Laszlo, the immigrant's son, is there, fingering the dress of a patient girl as they watch the state trooper's headlights vanish down Highway 27.

The walls and windowpanes are so clean people forget they are there. People forget things regularly, despite thick sweet cream in their coffee. On almost ev_ery parlor wall is a reproduction of Laszlo's famous painting, now in the National Gallery, of General Svedlin at the Battle of Moltavis Rock. It is the sky in that painting which is remarkable-one can even feel the breeze off the Baltic-so remarkable it becomes more real than the real sky above the real sea. The traffic comes and goes in great waves. Sometimes the streets-the widest boulevards as well as the lanes of the Old Town-are clogged with cars, bicycles, buses, and lorries barely able to inch forward. Then, suddenly, as though

someone had forgotten about traffic, the streets are deserted. Even cripples and the most timid visiting goatherds from the farms can cross in mid-block without being run down. But where is there to go? The stores are empty now, as are the cafes, cups of coffee still steaming on the round white tables where minor bureaucrats sat only minutes before nibbling buns and discussing the news. As evidence of how much may be forgotten, one evening by the light of the signs in Market Square, I asked the prostitutes who gather there what city they thought they were in. Many said Christiana, Danzig, Kovno, or Port Arthur. It was only after several hours of questioning that I found one who named a city I recognized, and I went home with her and paid her handsomely.

There are two cities here, neither of which exists. By day, the site is a flat expanse of desert sand. But when a storm approaches, the wind makes the sand fly up into the air and momentarily assume the shapes of minarets, bazaars with squabbling merchants, the countinghouses of the Shah, camels on the highroad, and a great jeweled gate swinging open upon a sequestered private square with date palms and amaranths and veiled ladies eating sherbet beside a fountain whose clear water falls from the mouth of a stone lion into a mosaic basin with a sigh of tiny bells. At night, it is another city, a city built of shadows, whose sinister shapes loom imposingly, then melt as one draws near. Yet one may catch glimpses of leprous beggars in rags, of English schoolmasters buggering little boys, and of the explorer Laszlo near the end of his life trying to find solace in a haze of kief. Then the voice of the Prophet thunders across the desert: "Abandon the desolate places and the places of deceit. Set yourself upon the path of wisdom and take heed that, unlike the mighty chieftain Ahmid Faz, you are not felled by an assassin's arrow watching wild horses race in the moonlight across the plain toward the Sea of Marmara while on your way home victorious from the Battle of Moltavis Rock."

May she be thanked by a few words issuing from the same Roman source, the still-infantine marvel who has come to live among us, bringing the toys of an oneiric imagination, that show the working of the most precious of undersea apparatuses, organs of origin: this Mediterranean, the ear and mouth of the world, our mother-country with pure eyes.

At a time when arrogant, although good-natured, contempt is the usual attitude, you give us-despite the modesty of a small picture format-with the confiding generosity of a heart overflowing and lively, from a nature opulent and laughing as a spring, the dark half of your life which redeems the other, that half most hidden through an absurd shame of what it reveals, which you display under the clear Adriatic or Tyrrhenian glass, the richly colored viscera of the depths, of the clefts of rocks, like those of a frog's opened belly, this animal being the symbol of metamorphoses because t he undergoes them from the first moments of his life.

t Tr. note: Ponge's spelling is pource que, a reinforcement of meaning such as in "for because."

22 TriQuarterIy

Aside from our enchantment in the deep confiding of such a feminine treasure, offered almost as soon as we leave the children's corner of the Claudians and the doges of Venice, with the blood's prodigious, inherited science, freed by vivacity in the dream of a daringly aristocratic nature, we see in it with feeling the unofficial preoccupation of all humanity, amid the heartbreaking degradation of our meridional Europe, under the endless tread of savage fogs to its shores, to the lips of the sacred mouth that utters our values.

Yet we also know, we always find on the beaches of the warm sea interior to our romanity, to fling them at the forehead of the ossianic Goliath-and the skill with a sling of our sororella makes us passionate in this hope-these indestructible concretions, hard as toadstone, polished and incessantly seized in the bosom of the glaucous, calm viscosity.

For us, certainly, young Italian sister wearing the Cavourian tricolor so like our own, for all of us who have given the world several rebirths after so many centuries, it no longer can be a question of old values admired until now: we find on our desolate coasts realities infinitely more ancient, beyond all mythology-yet the pure-eyed bath retains its virtue, and the objects, long fondled, which it casts up: roots, stones, stumps, shells, antique amphorae decorated by sea worms, which once again make a setting authentically primitive where, cuffed by the wind, we walk-are offered to us bright and washed by the same liquid reasoning, actively dreaming. It is the same in us, dissolved yet present in our blood.

Yet, as on the beaches I saw these animal remains, of shellfish that were alive not long ago, in such numbers that I ask myself whether life did not, after all, precede inertia, and far from being born of a setting anterior to it, will have formed it with its rubbish and relics-so in my mind, at its shores, throat and lips, have I found to honor you formulations and words.

Oh! the hidden precious stones-flowers that already saw. Rimbaud, After the Deluge

We discover in Littre, that marvelous casket of old expressions, that Fontanelle, in giving the eulogy of Tournefort (the botanist), described nature as hiding in profound, inaccessible places (the caves of Antiparos) "to work there," he says, "at the vegetation of stones." As Rene-Just Hauy, the crystallographer of about the same period, spoke of "flowers," so our mineralogists sometimes fall into this platitude without knowing it, no doubt through their taste for an academicism which it is our evident raison d'etre, if there is one, to disgust them with, as well as the whole public, Controlling, then, this exact opposite 0/ uneasiness yet quite violent, which grips us at the sight of natural crystals, and profiting from a sang/raid very useful here, we will ask the idea of the flower to kindly sit down again. And even other images, such as, for example, the bird-that-perches, a dove or seagull I suppose, which, no longer corresponding to present knowledge and which I can do nothing with, will not enter at all into our authentic surmise.

Why then, at the sight of natural crystals, do we find ourselves so suddenly gripped? Perhaps it is because it concerns something like the best concrete approximations of pure reality, that is to say, of pure idea: may one order it as one wants! So! We have to hide too and go back down at least several steps in succession! But let's look again THERE ! Yes, there, at last, the coordinated qualities of fluid and stone!

The solidity proper to mineral matter is enough to explain its lack of interest in the process of reproduction, or even (generally) in that of extension. It knows itself eternal, or nearly so, and comes to neglect almost entirely its appearance or form. But, as it undergoes all the same the most intense and renewed physical attacks (without disappearing, which is all that it cares about), so for a long time it has been nothing but an amorphous chaos,

if indeed it was ever ordered. It is known besides that the solid state of matter is that in which energy is lowest. Thus the mineral kingdom reigns only as one says that sluggishness or indifference reigns. There is, in stones, a passive, sullen non-resistance towards the rest of the world, on which they seem to turn their backs.

Yet in the midst of this dull chaos-by virtue of its faults or cavities-grow rare exceptions to this rule. That is why, when we see them, we are sure to be gripped! Instead of the eternal clouds the sky at last, momentarily pure, with stars! At last, stones turned towards us, that have opened their eyes, stones that say YES! And such knowing looks, such winks!

Here it concerns homogeneous kinds, whose elements are perfectly defined, growing by juxtaposition of identical atoms bound by identical ties, which give their geometric shape to the stone. So much so that, in the so-called liberty of the faults which their surrounding society offers them, what do they develop, if not their special tendency in its strictest purity? Whence their elan, their limits, their marvelous limits! At once, perfection. No arguments here, but concrete EVIDENCES and, by these evidences (LIMITED), what powers! Clear of any cloud, of any shadow, the least light is immediately trapped in them, and cannot leave: and then, it clenches its fists, fidgets, scintillates, tries to flee, appears almost simultaneously at all the windows, like the mad host of a house set on fire (by himself)

By the inflorescences, judge a little the shrub's emotion at the time of its yearly branching.

It is chemistry, pink turning blue, effervescence and violet profusion in the paper-filter test tubes of the lilac.

A drop of the cluster fusion sometimes falls, but what fantasy in the descent! It is the bee, with stinging consequences for the experimenter. 25

THE LILAC to Eugene de KermadecYoung people will have to excuse me, who doubtless see it with another eye: spring, for me, over forty, is a congestive phenomenon, of a rather repellent appearance, like the face of an apoplectic, in this sense (at least) purplish, groaning, musician though it is.

The vegetal and floral manifestations and the nightingale's trills that at night replace them: I am glad, rather, to be less expansive! This unveiling of nipples, varicose veins, hemorrhoids disgusts me slightly.

Let us observe it now in the doubled and trebled lilac:

By the obstinacy of a natural cohesion in the swarms of inflorescence, judge a little, see, feel, and read there a little of the agitation, the rich emotion which the shrub feels and provides, and not only to its executioner, at the time of its yearly branching.

It is chemistry, pink turning blue, effiorvescence and violet proconfusion in the paper-filter test tubes, the bouquets formed by a mass of soft nails of cloves, mauve or blue, of the lilac.

Filter, I said So much so that a drop of the cluster fusion sometimes falls, like the point of the exclamation-point: but what fantasy in the descent! It is the bee, with stinging consequences for the experimenter.

May one really hope, henceforth, for something more from it than superficial flowering? t

After which, it may be used only as an adjective, thus: "Lilac: after the flowers the sky's profusion between the leaves of the shrub of this name."

This may be the best way, I imagine, to go from everything before to blue.

t Tr. note: Untranslatable pun on ej-fieurement (flowering, superficial).

To consecrate it here, let's not overly nacre this everyday object. No prosodic ellipsis, however brilliant, for stating rather flatly the humble interposition of porcelain between pure mind and appetite.

Not without some humor, alas (the animal inside stays there better! ), the name of its beautiful matter was taken from a shell. We, a footloose species, should not stay there. It has been named porcelain, from the Latin-by analogy-porcelana, the vulva of a sow Is this enough for appetite?

Yet all beauty which, urgently born of the waves' instability, rides on a shell Isn't this too much for pure mind?

Be that as it may, the plate was born in this way of the sea: multiplied at once, besides, by the benevolent juggler who sometimes replaces the gloomy old man in the wings who gives us barely one sun a day.

That is why you see it here in several different kinds, still ringing like ricochets immobilized on the sacred linen of the tablecloth.

This is all that one can say of an object that gives more food the more it doesn't food for thought.

translated by Lane Dunlop

t Tr. note: There is a play throughout on plate (assiette): Asseoir, prend assiette, etc.

Everyone knows the story of the three wishes. A fairy suddenly turns up and invites you to make three wishes, which she will grant. Who hasn't heard this sinister tale over and over again? Even I, whose martyred childhood was spent in a home where my parents took it in turn to beat me over the head with an iron bar, even I have heard it a thousand times. 'What stupid rubbish!' you say. 'How can anyone go on repeating such absurdities?' Well, I came across a fairy once, so perhaps you'll believe me.

But I'd better tell you this adventure from the beginning.

One day, when my father, drunker than usual, had just driven a great nail into my forehead so as to hang a picture there that I hadn't appreciated sufficiently, I said to myself: Wouldn't it be comforting if a fairy arrived just now and granted me three wishes.

I'd hardly had this thought when there was a knock on the door.

TrlQuarterly 29

My father was sleeping off his cider on the floor. My mother was bleeding so much from a wound in the back that she could barely move. (I'd never seen her without a knife planted between her shoulder-blades.) So 1 went to open up.

On the threshold of our wretched hovel stood an aged and very shabby-looking woman. She said to me: 'Well, my fine young man, have you got a thousand francs for me?'

1 was already thinking of the three wishes. So 1 squatted down beside my father and gently took his wallet from an inside pocket and gave the old woman a banknote.

1 saw her eyeing the rest of the wad.

'You couldn't manage another?'

'Sure, but that'll have to be the last.'

Still peering longingly at the wallet, she agreed. The notes disappeared up her skirt. 1 thought: I've been a fool. She's no more a fairy than 1 am.

At that moment she uttered a sigh and grumbled: 'Well, go ahead, son. Make your two wishes and they'll be granted.'

'What d'you mean, two wishes? Why not three?'

'You only gave me two banknotes that 1 know of.'

'Oh, if that's all .'

1 went back to my father and relieved him of another note. The old woman pocketed it, grumbling.

'It's a bit late. Still, never mind. Get on with your wishes.'

1 took a deep breath to reflect. But it was no good. 1 already heard myself saying, 'I want to be rich. The richest person in the world.'

The old woman raised her arms with a groan. 'And how d'you think 1 can manage that? Why d'you think I'm reduced to begging alms from down-and-outs like you? If I'd enough money to make your fortune I'd begin by dressing decently. 1 haven't a rag to wear. 1 haven't even got enough to pay for a rejuvenation cure.'

'You can't give me a fortune?' 1 said incredulously.

'Didn't 1 just say so! 1 might have done once. I've given fortunes to lots of people in the past. But my funds have gradually become exhausted. Misguided speculations, Russian loans, the 1929 crash

now 1 haven't a sou. I'm ruined. It wasn't easy to get used to; one has one's pride. But 1 take care of myself, even if 1 am poor.'

'I see

1 thought for a bit. 'All right,' 1 said after an embarrassed silence, 'I want love.'

Her face lit up. 'That! That's easy enough.' She gave a wicked grin and began to undress.

'Hey! You must be mad. 1 asked you for love!'

'I understood you all right. That'll cost you another three thousand francs.'

'What!'

'Look here,' she said irritably, 'you don't think I'm going to give myself to a shit like you for nothing? 1 should've thought three thousand was reasonable.'

'O.K., forget it. No love.'

By now she was hopping mad. 'You said it, you said it, you can't go back on it now. You'll have to get on with it, little one, whether you like it or not.'

1 relieved my father of three more notes.

When it was all over she asked: 'Well, what's your third wish?'

'My third wish? But I've only had one!'

'What about the money? Didn't you ask for money?'

'But 1 didn't get any!'

'What's that got to do with it? It was a wish all the same. Never mind, I've a soft spot for you. Your second wish, then, if you must haggle.'

'1 want power and strength. 1 want to become master of the world.'

'You're all the same! You won't die of originality! Come here. Oh, how stupid you are. Come here, don't be afraid.'

1 wasn't very reassured but there was nothing to lose. She grasped one of my arms and began to massage it.

'1 didn't ask you to teach me judo, it's power 1 want.'

'It's all the same,' she replied peremptorily. 'Depends how you look at it. Hold your arm like this, put your foot there, and woops! No, wait, not like that. You put your foot here, not there. Just a tick, 1 can't remember any more. Wait while 1 look at the handbook.'

She brought out from beneath her skirt a book without any covers and spotted with grease. 'You don't happen to have any glasses, do you? I've forgotten mine. No? Too bad. I'll teach you another grip. Come here.'

'No, don't bother. 1 know enough already, thank you.'

'All right, all right, it's all the same to me. And your third wish?'

'Health.'

She gave me a disturbed look. 'What's wrong with you?'

'I'm not ill. 1 simply want to be in permanent good health.'

She burst out laughing. 'You are a one. Just permanent? Look, I'm going to give you a sovereign remedy.' She fumbled in her skirts and brought out a tube of tablets. 'These are aspirins. They're marvelous for headaches.'

'But 1 never have a headache. My parents have hit me with that iron bar so often that my head's become quite insensitive.'

'Then what are you complaining about? Still, 1 can give you

some advice about looking after your health. Now, take me. How old d'you think I am?'

She looked so old that the question seemed meaningless. Does one guess the age of mountains?

'Thirty-two!' she announced triumphantly. 'And I've lived, I can tell you! What d'you think of that?'

'How is it possible?' I asked, my hands clasped in awe.

'It's simple.' She glanced nervously at my parents groaning on the floor, as if nervous of being overheard. 'You've got to keep straight, never cast a clout in April, and drink grog, plenty of grog. It's good, grog. By the way, you don't happen to have any stew left, do you?'

'I'm sorry, no.'

She looked disappointed. 'Right, then I'm going.'

An idea suddenly struck me. 'If I give you another thousand, could I make a last wish?'

Her eyes shone with greed. 'You certainly can!'

I removed another note from my father's pocket. 'Well then, I want to be rid of the sight of my parents. If it's not my head they're hammering at, it's my nerves. I don't care how you manage it, I just don't want to see them any more.'

'O.K., little one, that's easy enough. I must admit, they're not a very attractive sight. You're more of a pet yourself.'

'Cut the cackle. Get those monsters out of my sight and have done with it.'

'Don't worry. You'll be surprised. Close your eyes.'

I closed my eyes. The atrocious pain made me shriek.

'Open your eyes.'

I opened them, but everything was still dark. I heard the old woman say, 'Cheerio, cock, think of me if you ever have any grog left. And don't forget to put some 90% spirit on your eyes. I'm not sure if the needle was clean.'

I've never seen my parents since. 33

Once upon a time there was a little boy. When people asked him what he would like to do when he grew up, he always answered, 'When I'm big, I'll have the Queen.'

It is easy to imagine people's consternation when faced with this idee fixe which was rendered even more absurd by the shortage of queens. For hours on end father and mother would attempt to reason with their child, but he was as obstinate as a mule and remained deaf both to advice and threats.

And Gaspard, as the obsessed boy was called, grew up unaware of his parents' anxiety, lulled by his folly. He went to primary school, then on to secondary school. He was an average pupil who found learning easy and made the least possible effort. One day the psychologist attached to the school asked the parents to come and see him.

After coughing several times and uttering painful 'Er's' he began. 'You are aware of course that it is my job to put young people through professional aptitude tests. Now, and this is the point of our discussion, Gaspard happens to be a most unusual case. The fact is that the boy has no aptitude for anything. .'

'But he's a good scholar,' the mother protested. 'He .'

The psychologist motioned her to be silent. 'Let me finish. He has no aptitude for anything except .'

'Except for laying the Queen. I know this may sound silly but it's a fact. I think the best thing is not to oppose his vocation. Maybe he'll give it up of his own accord?'

The father shook his head skeptically. 'Oh no, sir, he won't give it up. Even when he was very little he wouldn't talk of anything else.'

'In that case .'

Gaspard's parents went sadly back home.

Gaspard became a strong young man, not too handsome and not too tall, but pleasant and energetic. He passed his exams moderately well and then announced his intention of traveling round the world.

35

His mother wept: 'You're going to look for a queen, my poor son, you'll face endless dangers!'

His father was more realistic. 'Very well,' he sighed, 'if that's what you want. But don't cherish too many illusions. You can't have the Queen just because you want to.'

Gaspard walked for miles. Many miles. The soles of his feet were practically raw when he finally reached the last surviving royal kingdom. He immediately went to see the Queen.

'What do you require of me?' she asked.

'I want to fuck you.'

The Queen made no reply, but Gaspard could see that the idea did not displease her. He then went up to her and placed a hand on her left breast. The Queen smiled nicely and ordered her women to leave.

When they were alone she stood up and went over to a more spacious throne. She invited Gaspard to sit down beside her. Naturally he did not need any persuasion.

He tried to put his arms round her waist but she stopped him. 'Not just yet,' she murmured.

'Why not?'

'If you succeed too easily you'll be disappointed,' she replied, blushing.

'You little fool, you don't have to worry on my account.'

He drew her head towards him and kissed her on the lips. He stroked the roof of her mouth with his tongue

When they separated the Queen was breathing deeply. 'Let me get my strength back,' she begged.

'There's no point, really there isn't.'

He lifted the heavy brocade dress. The Queen had lovely, wellcurved legs, enhanced by pale blue silk stockings. He unfastened her garters and caressed the inside of her thighs with the palm of his hand. She tried hard to keep her knees together but Gaspard's hand was moving gently between her thighs. As it moved higher resistance weakened. Soon there was plenty of room for two hands in the space just below the crotch of her knickers. Gaspard duly put them there.

Then the Queen became impatient. She was panting like a spaniel. To make it easier for him to remove her knickers she reared up on the throne, supporting herself against the back.

'Sit on my knee,' suggested Gaspard. He had unfastened his trousers.

The Queen obeyed. Gaspard took hold of her by the waist, lifted her easily and placed her slightly higher. The Queen trembled and showed the whites of her eyes. She shuddered violently when after several unsuccessful attempts she managed to get into the right place.

She said hoarsely, 'Caress my breasts, hard, my scepter .' Then: 'What's your name?'

'Gaspard.'

'And mine is your Majesty. Oh!'

The Queen leant back and began drooling. Gaspard was afraid of dropping her but he succeeded in taking hold of her again.

Later, when she was fastening up her clothes, the Queen asked him hopefully, 'What are we going to do now?'

'Nothing. I'm going back home. I'll come again soon. 1 love you.'

The Queen shook her head bitterly. 'You're all the same. As soon as you've got what you want it's impossible to keep you.'

She sighed. 'Yes, everyone wants to fuck the Queen, but nobody wants to marry her.'

'Rufus, old chap! Delighted to see you!'

Rufus Thorp loosened his shirt-collar, undid his tie and took a deep breath. That clap on the back had winded him. He studied the man's unfamiliar face without emotion. It meant nothing to him.

'Y' our e er

'What? Don't you recognize me? But 1 do understand, it's such a long time Guillaume! Guillaume Silliver!'

'Guillaume Silliver .' repeated Rufus. 'I really don't remember.'

The unknown man smiled. 'Oh, yes, you do! You're just putting me on. You always used to do this. You used to enjoy pulling people's legs even when you were at school.'

'I don't think so,' protested Rufus. 'Were you at school with me?'

'Of course I was. You know that as well as I do. By the way, I've moved. Here's my new address.' The unknown man handed Rufus a card. 'Come and see us one day, we'll talk about old times. Angela would be delighted.'

'Yes, Angela! Don't tell me you've forgotten her as well?'

'No, I don't think so,' stammered Rufus. 'Angela, yes of course.'

'I must dash, I'm in a hurry. See you, Rufus!'

'S ' ee you

Rufus was left alone on the muddy pavement. Around him, people were running backwards and forwards in the sort of hysteria that's brought on by the approach of Christmas. It was very cold, but nobody seemed to notice it.

Finally Rufus shrugged his shoulders and continued on his way. 'I mustn't attach any importance to this ridiculous incident. I've ten days' holiday in front of me, ten quiet days when I won't have to supervise the brats at school. I'll make the most of it. I'll get on with my novel tomorrow.'

The next day he got up just before noon. He put on a pair of corduroy trousers and a thick pullover, savoring the opportunity of being able to dispense with a tie. He went to a little restaurant where the service was slow but the cooking good.

After finishing the hors d'oeuvre he was quietly waiting for his meat and vegetables when he noticed a man seated near the radiator. There was nothing remarkable about the man apart from the exaggerated attention he was paying to Rufus. His gaze was glued on him as firmly as a fly to flypaper. Embarrassed, Rufus forced himself not to stare back, but he couldn't help casting furtive glances at the man. He saw the same thing each time. The man seemed fascinated.

Rufus received the meat course with relief. He concentrated on his plate and lost interest in everything else.

Suddenly a hand stopped his arm just as his mouth was opening to remove a piece of meat from his fork. He sat there stupidly with his mouth open, his eyes fixed on the inaccessible food. He swallowed his now useless saliva and put down his fork. The man was standing in front of him. 'Excuse me, sir, aren't you Rufus Thorp?'

Rufus nodded.

'I'm Saul Grimbach!'

Rufus didn't actually say 'So what?' but the expression on his face showed what he felt.

'Saul Grimbach,' repeated the other in a vibrant voice, 'Saul Grimbach!'

'Do 1 know you?'

'Do you know me? Embrace me, Rufus, 1 never thought I'd see you again. When you risked your life to save mine, when 1 saw you leaving in a lorry

'I? 1 saved your life? 1 left in a lorry? When?'

'During the war. Oh!'

Still staring, the man who claimed to be Saul Grimbach collapsed onto a chair beside Rufus. 'I know! You've lost your memory! You must have been through hell! It's horrible! But you didn't talk, did you? You didn't tell them anything?'

The other guests in the restaurant had stopped eating. They realized that they were witnessing a most unusual scene. They were carefully registering all the details so that they could regale their friends with them later.

Rufus didn't reply. He left the rest of his meal, paid the waitress at the counter and fled. Just as he was going through the door, Saul Grimbach hurled a telephone number at him.

'Forget it!' Rufus shouted at him nastily. 'I don't know how much you're being paid for this play-acting, but you've certainly earned your money!' He banged the door and vowed he would never set foot in that place again. 39

It must have been a joke. It couldn't have been an accident. This was the second time someone had been making fun of him. A man standing on the pavement opposite nodded to him, although he was a total stranger. Rufus didn't respond. Then an arm waved from the door of a car and a young woman flashed a radiant smile at him. Rufus replied with an insult. He was quivering with rage. His day was ruined. He couldn't write a single line of his novel, that much was obvious.

'I'll go and have a Calvados round the corner-to pull myself together-then I'll try to work.'

Aldo was the first person he saw at the bar. 'Hello, Aldo, how are things?'

Aldo looked at him coldly. '1 beg your pardon?'

'What's the matter? I was only saying hallo!'

Aldo looked at him blankly. 'You said hallo to me, but 1 don't know you.'

After his initial astonishment Rufus burst out laughing. 'So it was you who organized all these goings-on? I must admit they were perfect!'

Aldo's feigned surprise was perfect too. 'I don't understand what you're talking about. How do you know my name?'

'Oh, that's enough. Don't overdo it, the joke's not funny any more. If you don't want to say hallo to me, O.K. But I'd like to know what's eating you!'

'Nothing's eating me, sir. You're the one who should watch it!'

Rufus went back to his apartment. Just as he opened the door the telephone began to ring. He picked up the receiver.

'Hallo,' said a woman's voice. 'Is that you, Rufus?'

'Who's speaking?'

'It's Denise.'

'I don't know anyone called Denise.'

There was a silence. Then the voice went on: 'Have you forgotten me?'

'That wouldn't be difficult.'

'Rufus, are you joking?'

40

'No. Frankly, I've got other things to do.' He banged down the receiver.

What was going on? He had always hated practical jokes. Why had Aldo picked on him? He wouldn't have thought him capable of such nastiness or such persistence. He suddenly wanted to tell someone about it. He decided on David.

After the telephone had rung five times, David picked up the receiver. 'Hallo.'

'Hallo, David. This is Rufus.'

'Who?'

'Rufus Thorp.'

'Who's he?'

Rufus hung up. He was beginning to panic. He took a bottle of Creme de Cacao out of the refrigerator and poured himself a small glass. He hated Creme de Cacao but it had been a present from Georgia Georgia! He'd forgotten her!

He rushed to the telephone and called the gallery where she worked. As usual he had to wait a few moments before he was

put through to her. As soon as he heard her cold voice he realized that there was no hope. 'Georgia, it's Rufus. Something incredible's happening to me, Georgia. .'

He talked quickly, hoping he could get in first and melt her heart before hearing the fatal words 'Rufus? Don't know him.' Unfortunately she interrupted him at once. 'Who's speaking?' 'Rufus Thorp. And don't say you've never heard of me. .'

A click told him that she had hung up. So it was all over. He had lost Georgia. He drained his glass of Creme de Cacao, seized his address book and systematically called all his friends. Not one of them recognized him or appeared to remember him.

He felt terribly alone. The whole thing was getting so out of hand he could no longer think of it as a joke. What could have happened? He hadn't quarreled with anyone, taken part in any extortion or signed any defamatory statement. What had people got against him? Did he have to prove his innocence? And who was to be the judge?

The sight of his dreary apartment was suddenly too much for him. He slipped on a coat and went downstairs. He bought a newspaper which he read from end to end. He didn't find in it, as he had half expected to for a moment, mention of a man with the same name as himself who had recently acquired a bad reputation.

A little man snatched the paper out of Rufus' hand. 'Hi, I was coming to see you.'

Rufus seized him by the lapels of his raincoat. 'Beat it,' he hissed, 'before I smash your face in!'

The little man sniggered. 'Have it your own way. If you don't want me to pay back the thousand francs you lent me. .'

'You don't owe me anything!'

'Come on, now! Cast your mind back. Didn't you lend anyone a thousand francs last week?'

'Yes, in fact I did. But not to you. I lent it to David.'

'There, you see! Here. .' The little man slipped a note into Rufus' pocket. 'You'll have a lonely old age ahead of you if you're going to take that sort of attitude!'

'1 was in a bad mood, I'm sorry,' said Rufus, joining in the game. 'Come and have a drink at my place.' 'O.K.'

As soon as they had crossed the threshold Rufus caught the little man by the throat: 'Who are you? Did David send you? What are you after?'

'What's the matter with you? You're crazy,' groaned the wretched man. 'Surely you remember Justin Picon .'

The little man succeeded in wriggling free. Rufus punched him on the nose and blood began to flow. 'Come on, you bastard, tell me what your dirty game is, talk or else. .'

Justin Picon rushed toward the door. Rufus kicked him in the stomach and knocked him flat.

'Rufus,' begged the midget as he lay on the floor, 'don't hit me! I've given you back your thousand francs, what else do you want?'

This clumsy piece of self-defense sobered Rufus up at once. His hatred vanished, leaving him terribly depressed. He opened the door. 'Go on, beat it, but tell the others to stop bothering me. I don't want to play any more. Call it a day.'

Justin Picon fled. He was going down the stairs four at a time until a loud thud told Rufus that he had slipped and was sliding down the others on his back. He didn't laugh. He shut the door. He lay down and closed his eyes. What do they want? What crime are they trying to punish me for? The little man didn't drop his act for one minute. Who was behind it? One of my friends? What's the reason for this hatred? Did Georgia lay it all on? Hasn't anyone stood up for me? Suppose I'm going mad?

He thought it over but rejected this last explanation. He possessed letters and photographs which proved the contrary. It would have been easy for him to confound his tormentors. Should he go to the police? He shook his head. The police couldn't do anything for him. Lying was not forbidden by law. The best thing is to go on living as usual. 1 won't see my old friends any more. I'll turn my back on those hypocrites. I'll work.

During the next few days he carefully followed this line of con-

duct. He made considerable progress with his novel and finished several short stories. He went out as little as possible, for strangers kept coming up to him in the street, greeting him like an old friend and even going so far as to invite him to their homes. They gave him cards and soon Rufus acquired the habit of tucking them into his wallet.

On New Year's Eve loneliness drove him out of his apartment. He had always spent that evening with his friends. Now they were far away. Not one of them had shown up. He went into several bars but naturally he met nobody. He came home and slipped into bed with all his clothes on. Tears trickled down his cheeks like streams of burning lava.

To think I was always surrounded with a crowd of friends, and now I'm alone. I wasn't a bore. People laughed when I made jokes. I had good table manners, I took an interest in other people, I comforted them when they were unsure of themselves, I was never tactless. What happened? Did I suddenly exasperate them?

All at once he understood. That's it, of course! As a friend I was too perfect, too good to be true. I typified friendship, really. In fact I had a certain market value. And my friends sold me! When they pretended to ignore me they were simply trying to respect market conditions. The unfortunate buyers are running after me in order to take advantage of their recalcitrant acquisition! As for me, if I refuse, I shall have neither the old friends nor the new ones! I'll always be as alone as I am now. Why should I let them think I am vulgar and brutal? I'm sure one lot is just as good as the other. Have I any right to turn my nose up? I'm not at all demanding. Anyone could be my friend. They don't have to be gifted in any way!

He leapt up, rummaged in his wallet and took out a card at random. There was a telephone number on it. 'Am I speaking to Monsieur Urs?'

'Yes, you are.'

'This is Rufus Thorp.'

He waited, his heart pounding. The silence was short-lived.

'Oh, Rufus! I didn't recognize your voice! We were expecting you. Don't tell me you're not coming?'

'Oh no,' replied Rufus, at once very much at ease. 'I was telephoning because I'm a bit late.'

'That's all right! Hurry up! We're having a marvelous time here!'

'O.K., I'm on my way.'

He combed his hair in front of the mirror, and then picked up the bottle of Creme de Cacao.

I mustn't be too well-behaved with this lot if I am to keep them, he thought as he banged the door behind him.

All I can see from my window is a wall. From time to time I can hear strange noises, soft, guttural, clucking sounds which seem to come from the side that's out of sight. But I can't see anything. 'When the people know those who govern them they cease to respect them.'

My room is white and completely bare. I'm young. I don't know my age, but I don't think I've been alive very long. I go to lessons along a deserted corridor. There too there are walls all round, but I'm no longer alone. There are people, not all young, and officers who instruct us. We have to say 'sir' when we speak to them and we may only speak to them if they ask us a question; otherwise we're punished.

The punishment is painful. I was punished once. I don't remember why, which is just as well or I would deserve another punishment. I was fastened to a stake against the wall with my hands tied behind my back, and I was beaten.

They're punishing someone at this very moment. I know this because he left by the corridor immediately to the left of mine. As usual, they put a bandage over his blinkers and tied his wrists together. I'm watching because the scene happens to be taking place within my range of vision. They're hitting his fingers. The officer is supervising the punishment, so it must be a senous

matter. He carefully selects the spot before raining sharp blows with a black metal rod. I look on. So that's what it is! For the first time I understand what caused my pain. I imagined it was something worse. Fingers are, after all, only extremities. And I thought my inmost self was being beaten! I watch and smile. After the class the officer told me to follow him. He was kind and sympathetic. 'You don't realize the fact,' he told me, 'but you've got good marks.'

I didn't know. Of course I did my best. I've always done what I was told without arguing or grumbling; it never occurred to me to rebel. But I didn't think my goodwill would be apparent, or that I had yet been pardoned for the crime that had led to my punishment.

I followed the officer into a small brick building where there was someone without blinkers sitting behind a desk. I couldn't see very well. He picked up a sheet of paper and read it. I recognized my number which occurred frequently. My heart was beating so fast that I was afraid I might faint-and then I noticed him smile. We went out. Someone took my arm and led me back to my room.

I was pleased. All these people had been nice to me. I was pleased too that I didn't understand. I didn't want to be punished any more. I began to sing and dance all by myself. I was sure I would soon be promoted.

The next day someone came to take me to another room which was exactly like my own. This one was all white too, and had a window looking onto a wall. I was told that in future I would be living there. In the evening an officer I didn't know came to see me. He talked to me seriously. 'You have gone up two classes, missing one out. It's most unusual. You must try to be worthy of the confidence we have shown in you. You are now responsible for a sector. But take care: one mistake and you will be demoted.'

I was moved. I wanted to speak but I couldn't. When he had gone I went through a crisis. I began to tremble.

I tried to stop myself but without success. Was it a crime? They would demote me! I was afraid I wouldn't be able to go to sleep before the warders made their rounds, but I did.

The following morning after classes a woman came to my room. She wore a bandage over her eyes. She explained to me what I had to do to her. I hope I did it well. Afterwards she said good-bye to me and stumbled out. I suppose she was being punished.

I did some sums. All on my own I found the square root of 659. I knew the result was correct because I tried all the methods of checking it and it came out right each time. I also looked after my sector. 1 had a pile of papers to sign. I signed three thousand of them and tomorrow I'll have just as many again. But I'm proud. When the officer came he told me I have beautiful handwriting. He asked me what I thought of the woman.

'Very nice, sir, I'm glad she was wearing black.'

He raised his eyebrows. 'Oh? Do you like black, then?'

'I think it goes well with the whiteness of the room, sir.'

He smiled at me. 'You'll have another one tomorrow. Go on, you're on the right track.'

In the middle of the night I was awakened by shouts and piercing howls. 1 put my ear to the wall to find out where they were coming from, but they stopped almost at once.

The telephone rang.

'What is the result of your latest calculations?'

'187 489 568 690.'

'Put 187 489 568 689.'

I made the correction. After that I couldn't go to sleep. 1 counted sheep, which is said to be helpful, but at two thousand 1 was still awake. When the light came again 1 was tired, but everything went off well in class.

The woman who came to the cell was dressed in white. She too had bandaged eyes. At first she called me 'sir.' I went very red. 1 explained why. She went very red too. 'I didn't know. 1 didn't do it on purpose. You mustn't tell anyone.'

When she left I telephoned and described everything that had happened.

'You've acquitted yourself very well,' said the officer who came to see me. 'It was a test. You'll probably move up.'

He was right. I even received a decoration. I was led to the brick building and the man without blinkers drove a nail into my chest. It hurt badly but I didn't complain. Just think, the man told me I was the youngest person to be decorated and as a result I acquired certain rights.

'Thank you, Mr President,' I said.

This was because over the desk there was a notice which said that the man must be called Mr President.

He smiled. 'From now on the town is in your power. Continue as you have begun and you will have nothing to complain about.'

'I don't complain, Mr President.'

When I got back to my room I saw some black flowers in a vase and that pleased me. 'You see,' I said to myself, 'everyone's nice to you. If you behave well you won't be beaten.' I applied myself to my work. All my results were correct first time.

Later three men came. They fixed up some equipment with wires and springs all over the place. When they had finished they left. I went up to the equipment to take a look. Immediately a screen lit up. There were flowers on it, like the ones in my vase. And then they began to fade and feathers appeared in their place. Music came from behind the apparatus. It was nice music, very sweet and very sad. It made me want to cry.

'As long as I don't have a crisis like the other one!'

And then a thought struck me: Suppose it's a test!

But afterwards they explained that it wasn't. They had confidence in me.

A different woman came to see me. Her eyes were not bandaged; she wore blinkers like me. She was dressed in black but I didn't like her. Her eyes were cruel. Suddenly she whispered something into my ear: 'Give me a flower.'

Why should I give her a flower? For what reason? I shook my head vigorously. She was angry. She called me 'dictator' and

said that I had had her brother killed and that she wanted me to die. As I expected, I suffered an attack of nerves. She saw me trembling and laughed cruelly. 'Ah, you're trembling! I hope you die of it,' she cried.

Sobs choked my throat and I could hardly breathe. I was suffocating. Perhaps I was going to die.

Fortunately two officers came in just in time. They seized the woman and took her away. The President called me to him. He told me that it was an attempt on my life; that the more powerful one is, the more enemies one has. Finally he gave me permission to punish the woman myself.

The officer-instructor gave me the metal rod and told me what to do. But I already knew. I hit hard. The officer told me that I could become an executioner if I wanted, but I refused. I prefer to concern myself with the town. It means more work, but afterwards there are black flowers and the sad music. Apparently people will remember me after my death.

translated from the French by Margaret Crosland and David Le Vay

1

Consider the belly, loose

In the midwest. Consider the midwest

Belly: the two joined. This Cannot be done forever.

2

Though there is evidence. Sunbeam's Rise to fame. Grain Belt. Fruit of the Loom exists

For the basket trade.

Resting in this bay, generations

First view the world.

3

Misty hills back over river towns

Just behind pool hall doors, in

Top lofts hay elevators endBellies glow blond and sleek as puppies, Their cheeks pullet egg smooth, Each potato dimpled.

4

The belly may bare hair

Pinwheeling to tickle the button like a sneeze. This becomes a mystery of hysteria; The belly unfolds to giggle all day.

s

A fleshy billboard, big

As the side of a barn, the blue Veins falling into order.

CHEW MAIL POUCH

It says, slouching in the weeds.

Bradley Mitchel rippled his belly

Like Florida bridges during hurricane. "Corduroy road or stockade fence," he'd ask, Pointing to his belly muscles. Then, Hands framing the button in a slit: "I'm looking under the last of the girls' Sixty yard high hurdles."

7 Let us approach the belly.

8 The odor. Fright as scale intensifies.

Recall the hulk of prairie buffalo which swam Blue Earth River in Mankato, How it would feel to ride them.

9