Go, little boo and wish to a Flowers in the garde meat in the ha A bin of win a spice of wi A hOllS€ with lawn enclosing i A living lIve by the doo A nightingal in the sycamor.

Go, little boo and wish to a Flowers in the garde meat in the ha A bin of win a spice of wi A hOllS€ with lawn enclosing i A living lIve by the doo A nightingal in the sycamor.

EDITOR

MANAGING EDITOR

Charles Newman

Suzanne Kurman

ART DIRECTOR Lawrence Levy

BUSINESS MANAGER

ASSOCIATES

Janet Clevenstine

Janet Bailey

Andrew Cipes

Laurence Gonzales

Mary Kinzie

Allison Platt

Claudia Reynolds

Christine Robinson

Mary Elinore Smith

TriQuarterly is an international journal of arts, letters and opinion, published in the fall, winter and spring at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. Subscription rates: $5.00 yearly within the United States; $5.25 Canada and Mexico; $5.75 Foreign. Single copies will usually be sold for $1.95. Contributions, correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly, University Hall 101, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, 60201. Unsolicited manuscripts are welcome, but will not be returned unless accompanied by a selfaddressed stamped envelope. All work accepted for publication becomes the property of the editors, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1969 by Northwestern University Press. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors.

NATIONAL DISTRIBUTOR TO RETAIL TRADE: B. DEBOER, 188 HIGH STREET, NUTLEY, NEW JERSEY 07110. DISTRIBUTOR FOR GREAT BRITAIN AND EUROPE: B. F. STEVENS & BROWN, LTD., ARDON HOUSE, MILL LANE, GODALMING, SURREY, ENGLAND.

ROBERT CHATAIN

CURTIS HARNACK

CLARK BLAISE

JAMES MCNIECE

ROBERT SWARD

JOHN SEELYE

JORGE LUIS BORGES and

ADOLFO BIOY CASARES

SIMON GRABOWSKI

BERTRAM D. WOLFE

ALBERT R. CIRILLO

KIERKEGAARD'S JOURNALS

Fiction

Notes on the present configuration of the Red-Blue conflict 41

Voice of the town 51

Extractions and contractions 125

Dreamlight 137

Hotel Rivello 149

Critifiction

The true adventures of Huckleberry Finn 5

Three chronicles of Bustos Domecq translated by Norman Thomas di Giovanni 167 Odysseus of the fires 177

Criticism

Leon Felipe: Poet of Spain's exodus and tears 21

The art of Franco Zeffirelli and Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet 69

A rts and Letters

Unpublished selections from The Papirer with an introduction and afterword by Howard V. Hong 100

Translation

GAlUS VALERIUS CATULLUS XLI, XLIII translated by Andrew Wylie 46

FRANCISCO DE QUEVEDO Love constant beyond death 48 Portrait of Lisi which he bore in a circlet 49 translated from the Spanish by W. S. Merwin

JAMES TATE

J. C. OATES

DABNEY STUART

DAVID WAGONER

DICK DAVIS

JOHN E. MATTHIAS

MARK STRAND

JOHN ASHBERY

HUGH FOX

PETER WILD

W. S. MERWIN

J. D. REED

CHRISTOPHER LASCH

TADANORI YOKOO

MARY NOLIN

JENNIFER BRADY

KAREN SAVAGE

BURTON L. RUDMAN

King Claudius 96 Artificial flowers 99 trans

lated by Minas Savvas

Poetry

The eagle exterminating company 40

The struggle to wake from sleep 45

Mop-up patrol 50

To be sung on the water 65 Song off key 94

The diver 65

Homicidal 67

The room 67

The double dream of spring 66

Rural objects 162

Materials for an evocation 94

Fireman 95

Ascent 158 As though I was waiting for that 159 The plumbing 160 Footprints on the glacier 161

Livonia, Michigan 164

Politics and Culture

Toward a new program for the university 197

Art

Illustration front and back cover

Illustration 4

Photos 46, 166

Photo 124

Photos 136, 176

Contributors

208

"If you read it you must stop where the Nigger Jim is stolen from the boys. That is the real end."

Some years ago, it don't matter how many, Mr Mark Twain took down some adventures of mine and put them in a book called Huckleberry Finn-which is my name. When the book came out I read through it and I seen right away that he didn't tell it the way it was. Most of the time he told the truth, but he told a number of stretchers too, and some of them was really whoppers. Well, that ain't nothing. I never seen anybody but lied one time or another. But I was curious why he done it that way, and I asked him. He told me it was a book for children, and some of the things I done and said warn't fit for boys and girls my age to read about. Well, I couldn't argue with that, so I didn't say nothing more about it. He made a pile of money with that book, so I guess he knowed his business, which was children. They liked it fine.

TrlQuarterly 5

But the grownups give him trouble from the start. When the book first corne out the liberians didn't like it because it was trashy, and they hadn't but just got used to it being trash when somebody found out there was considerable "niggers" in it, which was organized by then. Well, the liberians didn't want no trouble, so they took it off the shelves again. And the crickits was bothered by the book too. At first they agreed with the liberians that the book was trash, but about the time the liberians had got used to the trashiness, the crickits decided the book warn't trashy enough, and then when the liberians got in a sweat about the word "nigger," the crickits corne out and said there warn't anything wrong with that word, that it was just the sort of word a stupid, no-account, white-trash lunkhead would use-meaning me, I suppose, not Mr Mark Twain. They said it suited the book's style. Well, the liberians .and the crickits ain't spoke to each other since.

There was a crickit named Mr Van Wyck Brooks who was particular hard on Mark Twain. He said that Mark Twain was the victim of women, mostly his mother and his wife, and his friend, Mr William Dean Howells, who had crossed out all the rough words in his books-including mine. He thought it was too bad that Mark Twain was brung up where he was, in Hannibal, Missouri, which was just a ramshackly river town, and he thought it was even worse that he had got married and went to Hartford, Connecticut, where he got mixed up with the quality, mostly preachers and such. He said if it warn't for Christianity, women, and Hartford, Connecticut, Mr Mark Twain might a corne to something.

Well, Mr Bernard DeVoto put Mr Brooks straight on that score. He showed where Hannibal warn't at fault at all, nor religion, nor women, nor even Hartford. He said that Mark Twain asked to have all them rough words cut out, and that it was his own doing, and nobody else's. He said it was because he wanted to sell his books.

Mr Van Wyck Brooks, now, even though he said some ornery things about Mark Twain, he kinder liked my book. He said it was the only honest thing Mark Twain ever wrote. But Mr DeVoto corne down pretty damn hard on it. It warn't that he didn't enjoy it, because he did-some parts of it, anyway-but he couldn't help pointing out where Mark Twain went wrong. He could see all the little lies and the short cuts and the foolishness that was in it, and he wrote considerable about them in two books of his own. He was

especially hard on the ending Mark Twain had thought up, and said it actually give him a chill.

It warn't that Mr DeVoto didn't like Mark Twain, because he did. He even called him "Mark" most of the time. But he could see where he had his faults, and he didn't hang back none in telling about them. Like sex, which Mark Twain couldn't ever bring himself to write about. Mr DeVoto said it was silly having a fourteen-year-old boy like me not thinking about sex some of the time. He didn't say what kind of sex. He left that up to Mr Leslie Fiedler.

Mr DeVoto was tolerable lengthy, but he didn't settle the matter. The next thing you know Mr T. S. Eliot and Mr Lionel Trilling come right out and said they admired the book. Well, that was foolish enough, but then they went on to say that the ending seemed all right to them, and that was suicide. Mr Eliot let on that Tom Sawyer's pranks and foolishness was on the tiresome side, and Mr Trilling admitted that the ending warn't exactly up to the rest of the story, but they didn't stop here, and that's how the trouble started. Mr Eliot allowed that he didn't know of any ending that was better than Mark Twain's ending, and Mr Trilling said it was fit that I should finish up where I started out, only a thousand miles south. Which was interesting, but a trifle tough.

Well, there was this crickit named Mr Henry Seidel Canby, and he got hopping mad. He said that there warn't no ending worse than that ending, and that Mark Twain ought to be shot for writing it, but he had died anyway, so nobody took him up on it. Then along comes Mr Leo Marx, and give both Mr Eliot and Mr Trilling hell. 'Cording to him, that ending warn't moral, and it was all because Mark Twain couldn't face up to his own story-by which he meant mine. He said that Mark Twain couldn't measure up to the nat'ral ending his book deserved, that he just plain lost his nerve and had to cheat by tacking on a faint-hearted, immoral ending.

Mr Marx said that Mr Eliot and Mr Trilling warn't no better than Mark Twain. He said they was immoral too, and done nobody any favors by making out that ending was worth more than shucks. He said maybe Mr Eliot couldn't think of a better ending, but he knowed of one, and though he warn't up to messing around with Mark Twain's ending, because that warn't very moral either, he didn't think there would be any harm in suggesting how the story should a come out, which he done. He said the book ought to end so as to make some-

thing out of our escape down the Mississippi. He knowed that Jim couldn't ever a found his freedom down river in no moral way, so that was out, and whatever other ending you chose would just disappoint everybody. But he said that was the point, and the only honest way to end the book was to leave me and Jim no better off than we ever was, but still more or less trying to get clear. He claimed this ending was more moral than Mark Twain's, and it certainly would a been disappointing.

Well, Mr. Eliot and Mr Trilling was squshed fiat, and never did answer up to Mr Marx, but Mr James Cox did. He said that maybe the ending warn't as good as Mr Eliot and Mr Trilling claimed it was, but nuther was it as bad as Mr Marx had let on. He said it warn't perfect, but it was explainable, and that's what was important. He explained all about death and reborning and nitiation, and how it was fit that Jim and I should a come back from the river, because the free and easy life on the raft was a lie. He said what was wrong with the ending was Tom Sawyer, because Tom's style was all wrong. That made Tom biling mad, but before he had a chance to say anything about Mr Cox's explanation, a whole passel of crickits jumped in with theirs, and there was a power of explaining and arguments and reasons the like of which I never heard before unless it was at the coroner's jury where the remainders had been pisoned, stabbed, shot, and hung, and they was trying to figure out what had killed him.

Right in the middle of all this powwow the door opened up, so to speak, and in walked Mr William Van O'Connor. He give all those other crickits a sad kind of smile, like he felt sorry for them poor ingoramuses, and then he let rip with a damn stunner. He didn't mess around with the ending. He said he was only interested in that ending because everybody seemed to think it was the only thing wrong with the book. He said he reckoned they was modest in their estimate, and then he got right to work, down in the innards of the book, and showed how sloppy it was put together. He would tear a part out and show how loose it had been wired in, and then he would reach down and tear out another part. It was bloody, but grand. The floor was simply covered wi-th poor transitors, and c1aptrappy episodes, and melerdramas, and minstrel shows, and sentimentering. Mr Van O'Connor said they warn't nothing, though. He said the worse thing about the book was its innerscents, which was wickeder than the sloppy work by far. He said if you took out the innerscents, you'd

have something, by which he meant the book's skin I reckon, because that's all there was left.

Nobody said a word for quite a spell, and it did seem there warn't nothing left to say, like at the end of a six-hour funeral, where the dear departed has begun to stink a bit and the windows is stuck shut because of the rain. But if there's one thing a crickit can't stand, it's stillness, and after a time they begun to creep around in the wreck, seeing if there warn't anything worth salvage. Mr Henry Nash Smith, f'rinstance, give it a try. He said the important thing was the way Mark Twain told my story, that's what saved it and made it great, never mind how it was hung together. And he said you couldn't take out the innerscents without making the rest go bust, that it was needle and thread for the whole pair of britches. He wouldn't a had it no other way, because it was the innerscents that made the wickedness all the worse. If quality and style counted, he said, it was just about the best damned innerscents on the market. Mr Smith allowed the ending was slack on innerscents, but he seemed to figure the book had stocked up a whole wood-yard of it by then, and could go the rest of the way on credit. Chapter XXXI all by itself had enough innerscents to keep a saint in good supply for a year, with enough left over for a hardshell Baptist or two.

Well, that seemed to keep the other crickits satisfied for a while, but then along came Mr Richard Poirier, and after he got through, what Mr Van O'Connor done seemed like a Sunday-school picnic.

Mr Poirier said the trouble with the book was it warn't innerscent enough, and not just the ending nuther. He said if you chopped off the end you still had too much snake, that you had to keep chopping back and chopping back till you got to Chapter XV or thereabouts, which warn't much farther south than the neck. All that come after it just ain't the true Huck, he said, and some parts above it ain't all that long on innerscents either, having too much society or Tom Sawyer or something else bothersome and contrary in them. He let on that finding the bits worth saving was harder than getting a meal off an owl, and he give it up for a bad job all round. He said it was all because of Miss Jane Austin, a tolerable slim old maid which Mark Twain didn't much cotton to on account of she was always harping on marriage.

After that, it did look like the kindest thing you could do for the book was scrape it up and bury it. People still read Huckleberry 9

Finn, but the ones that see what Mr O'Connor and Mr Poirier done to it say it just ain't the same afterwards. They can't forget the sight of all them parts laying around, and it makes them uneasy.

Well, it was kinder sad, in a way, with everything scattered about and people saying it was a good book they guessed, but it had terrible weaknesses, and nobody really able to enjoy it any more except children. So I thought to myself, if the book which Mr Mark Twain wrote warn't up to what these men wanted from a book, why not pick up the parts-the good ones-and put together one they would like? So I done it, the best I could anyways, only this time I told the story like it really happened, leaving in all the cuss words and the sex and the sadness.

Everything went just dandy till I got to the end. I nailed her down easy enough, but then it hit me that maybe the crickits wouldn't like this one any better than they liked Mr Mark Twain's. Well, after I had sweat over that thought considerable, it come to me that there ain't nothing a body can do except what is in him to do, and since there just warn't no other ending besides that one in me, I said what the hell, and let her ride. All the same, I didn't want no trouble from the crickits if I could help it, so I left in a spare page, where anybody that wants to can write in his own ending if he don't care for mine. I suppose the liberians ain't a-going to like this book much either, but maybe now the crickits will be a little less ornery.

And I want you to understand that this is a different book from the one Mr Mark Twain wrote. It may look like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn at first sight, but that don't mean a thing. Most of the parts was good ones, and I could use them. But Mark Twain's book is for children and such, whilst this one here is for crickits. And now that they've got their book, maybe they'll leave the other one alone.

TriQuarteriy publishes here the introduction and the final chapters of Mr. Seelye's book, which Northwestern University Press will publish in the fall.

Well, I slept like a dead man that night, and woke up after the birds did. The sky was heavy and grayish, and even that early the air was so warm that your skin got prickly with sweat if you budged. The sun was trying hard to break through, but all it could manage was a sickly chalky streak along the east, low down, and the rest of the sky was a washed-out lead color, like old flannel. It pressed on you, and even the damn birds felt it, and seemed to chirp no more than they had to, and then without much heart for it. A day like that meant trouble or tornadoes, pap used to say, and it was best to stay in a hole till it was over. But time was a-wasting, so I crawled out and rummaged up something for breakfast. Then I squatted on the downstream end of the raft to take a dump and figure what to do next.

From where the raft was tied I got a good view of the Louisiana side, for maybe a mile or so down the next bend. There was this little steam-sawmill on the bank there, where they had wood stacked and a landing. That seemed a likely spot to start soundings for the place where they had got Jim locked up. I didn't have no real plan. I reckoned one would come along when I needed it.

So I put on my store clothes, and tied up a few traps in a bundle, and took the canoe and cleared for the mill. There warn't nobody about, but it didn't matter none, because painted right across the front was "Phelps Wood Yard," so as to let the steamboats see it, and I knowed I was somewheres near the farm where they had Jim. About a half mile further down there was a clump of cottonwoods running out into the easy water, and I figured to run in there and hide the canoe whilst I poked around a bit. But I hadn't no more'n cleared the mill before there come a power of whooping and hollering from the shore, gunshots and dogs barking to beat hell. I dug out for the channel, not wanting anybody to see me using around there just then. But that was a mistake.

Because when I was already a hundred yards out somebody come a-crashing through the willow thickets-and I see it was Jim! He was all bloody and his clothes was tore up awful. They had been pushing him hard, and he was all weighted down with chains, too. He took one wild look around and seen me out in the river. He didn't say a word, he didn't even wave, he just charged ahead like he was a-going to run all the way, right off the cut bank. It was more'n fifteen feet

high there, a regular bluff, and he went down like a goddamn stone. I thought he was a goner, sure, but I turned the canoe around anyway and come a-booming back in; I hadn't gone very far when a crowd of men and dogs come busting out of the thicket, everybody yelling and howling at once, making powwow enough for a million. It was just like a bear-hunt, only with Jim for the bear.

"There he goes!" somebody yelled; I thought they meant me, but now I see, sure enough, there was Jim a-coming on as best he could with all them chains on. A couple of men begun to fire and load, only it's hard to hit a mark in the water, and the bullets didn't come nowheres near to Jim, but went a-whizzing past me with a funny little whispery sound that once you hear it you damn well don't ever forget.

But then a big-assed man with a broadbrim straw and a red goatee held up his hand and hollered: "Hold your fire, goddamn it! That nigger hain't wuth a Continental, dead!"

I figured the man was Mr Phelps, because that's the way it always is. The people most anxious to shoot a nigger that ain't done just right is/always the ones which ain't got any money tied up in him, whilst the man who's got an interest in that nigger, why he's more careful about the nigger's health than his own.

All this time poor Jim kept on a-humping through the water towards me, with only his head showing on account of the chains. He had that worried look a dog gets in the water, and I knew he was having trouble with all that iron on him. But I had to let up paddling because them rips on the bank seemed particularly anxious to shoot somebody, it didn't much matter who.

"You, boy!" Phelps shouted. "Stop that nigger!" He begun to jog along the top of the bank so as to keep up with me and Jim, but warn't having an easy time of it because of the brush growing there. Him and most of the others was fairly awash with sweat, and their clothes was black and limp. Some had throwed themselves down on the bank and was passing a jug around, watching another man who was running around trying to get the dogs together. But they was having such a good time scampering back and forth barking at the place where Jim had jumped off that they paid him no heed. You could see it made him mad, and when the men with the jug begun to poke fun at him and laugh, he got so riled up he hauled back and kicked one of his own hounds right off the bank into the water.

It was an ornery thing to do. There ain't no harm in a hound, only sometimes they get so excited they can't hear nothing but their own barking and howling.

I says to Phelps, polite as pie:

"I'd like to help you sir, but I'm only a boy, and that nigger IS a full-grown man."

"Well, bring that goddamn canoe in here and I'll stop him!"

"There ain't no place," I says, and that was the plain truth. The bank was so high along there that you couldn't a beached a danged scow, let alone a canoe. Just then Phelps run whack into a clump of willows and knocked off his hat. I seen then he was bald as an egg, except where there was a little turf around his ears and the back of his head. It was black, like his eyebrows, which was thick and bushy and run in a straight line across. He didn't look nothing but mean.

All above that line was a bone white, and below was red as a turkey where he had been sun-burnt. He was glistening so with sweat it looked as though somebody had varnished him.

He says:

"Listen, boy. You see that cave-in about fifty yards down?"

A body would a had to been blind not to, so I said I did.

"Well, you head right for it, and I'll cut around and meet you there.

There warn't anything else I could do that I could see, so I said I would, and he and his men cut back from the bank, where there was less brush. Jim was getting close now, and I could hear him groan whenever he could get his head up to take in air. The rest of the time all you could see was his wool and his eyes, which was all bloody whites, bobbing back and forth. He was having to use most his strength just staying afloat. It was awful to see, but I give him as good a smile as I could work up, the sort of weakly thing you put on when somebody is in their last sickness, and you knowed it and they knowed it, but nobody will let on anybody knowed it.

I looked ahead to the cave-in place, which was getting closer all the time, and I see that the cottonwoods on that little point of land was just a bit further down, and that if Jim and me could get past that point, we'd be clear, because nobody on the bank would be able to see us through them trees.

So now I had a plan, or leastwise half a plan, and the other half come to me in a flash. It was for all the world like one of those

puzzles, where all you got to do is figure out where one piece goes and all the rest simply finds their own way.

Phelps and his crew come out of the thickets just then, and I swung the bow round as if to make a run in. The old man he begun to clamber down towards the water, half-sliding in the greasy muck. He had his gun with him, and was holding it out with one hand, so there was only the other free to help himself with, and being so fat and all when he was about half-way down he fell right on his ass and slid to the water's edge, a-cussing to beat hell as he went.

I got up and moved towards the stern end of the canoe, like I was about to get the forrard end high so's to beach it. But then I made as if to stumble, letting go the paddle so it would fall in the river downstream and out of reach. Phelps seen it all.

"Jesus H. Christ! What did you do that fer?"

I begun to rip and carryon, and told him I couldn't swim and would drown for sure and it was all his fault.

"Hain't you got but one friggin' paddle?"

I shook my head, but that was a lie. The other paddle was snuggled down under the front seat, and all the time we was getting closer to the cottonwoods.

The drift was keeping Jim in line with the canoe, but I see he was pretty much played out. He warn't pulling ahead any more, just struggling to keep his head out of the water. But if he could only keep afloat a while longer, everything would be all right. Even if I couldn't pull him in, he could grab a-holt of the stern, and I could clear for the Mississippi side. It was wide down there, more'n a mile across, and there was considerable hiding places-creeks and backwaters and such. They wouldn't ever find us. Once it come on dark we would strike out for the island where the raft was hid, cut her loose, and be fifty miles downstream before daylight. Then I could hunt up a hammer and cold chisel somewheres, and we'd get Jim out of them damn chains for good and all.

Old Phelps was still down in the cave-in, having one hell of a time trying to get back up on the bank, like a red ant caught in a doodlebug hole. One of his men crept down to give him a hand, but when Phelps took holt of it, he give such a tug that the man come a-tumbling down with him. Somebody had fetched along a rope, like they always do when they go nigger hunting, and next they got it around Phelps and begun to haul him out. He warn't no lightweight, and it

took considerable hauling. About the time he was reaching out for the top of the bank, some of the men noticed a steamboat coming up the channel and let out a holler, which the rest joined in with, firing off their guns and jumping up and down, making a power of noise so as to get the pilot's attention. That left only one man on the rope, so down Phelps went to the bottom, leaving the man cussing and spitting on his burned hands.

Well, the pilot seen them, and even give a couple blasts with his whistle, but he kept on a-chunking upstream, most likely figuring they was a bunch of drunks and rowdies, wanting to get on board at the sawmill landing.

By now I was nearly to the cottonwoods, but I had been spending so much time looking back that I only then see what I should a seen before, that them trees was on a sandspit built up by the water from a big creek that emptied in right there, and if I didn't buckle to my spare paddle right away, the current would take me where I didn't want to go. I fairly bent that paddle, and got through the wash and in towards the easy water by the bank, but when I turned around and looked for Jim, he was already fifty yards out. Well, I'd druther not have old Phelps see me pull Jim into the canoe whilst we still had less than a gunshot betwixt us, but I didn't have any choice. Besides, the way the current come a-booming out of that creek mouth, there was a good chance we'd be pretty far out before I caught up with Jim.

Well, I laid into the paddle again, and went shooting out into the river. It warn't a minute before a ball went whizzing past and then I heard a pop from the shore, and then two or three more whistled by, and there came a popping like it was Fourth of July. The creek was still carrying me, so I just lay down in the bottom of the canoe, knowing my only chance was to stay low. A couple of bullets thunked into the wood, but it was two-inch thick cypress and I couldn't a been safer if I'd been behind a stone wall.

I could tell by looking at the streaky gray clouds that the canoe was swinging this way and that, and then after she worked out of the current she swung south and held a steady course. By then the shooting had stopped, so I poked my head up and looked around. The sawmill was out of sight now, behind the spit with the cottonwoods, so I sat up and looked for Jim. I couldn't see him nowhere, and next I stood up, bracing myself with the paddle, but it warn't no use. There was nothing on that whole broad river but me, and I

knowed then that there warn't no sense looking for Jim, because he was somewhere deep down under, drug down by them goddamn chains.

Well, I knowed it wouldn't do no good to cry, because all the crying in the world won't bring a dead man alive, but I couldn't help blubbering a little anyhow. For Jim was the best cretur, and he was the only true friend I had, even though he was a nigger, and a runaway, too. I guess I didn't rightly know how much he meant to me till he was gone, and I remembered all the good times we'd had on the river, and how fine everything had been up to when them two thieving sons-a-bitches come along and ruined it all.

And even if that old river took us right down to Orleans, Jim and me could a rigged some kind of sail and headed for South America and had some fine howling adventures there, the kind Tom Sawyer only read about. We might a found the Treasure of the Inkers Tom was always jawing about and come back in fine style, dressed like nabobs and smoking seegars, with enough dt.mn yaIler boys to buy Jim's children and his wife and any other relations he had a mind to set free.

But now he was gone, just as if he hadn't ever been alive, not even leaving something behind to bury or mourn over, which is a nigger's worst fear, because then he's sure to come back and ha'nt the places where he was happiest, and groan and carry on so because he can't come back, never, only as a ghost, and then only at midnight when everybody is gone or asleep. If I only knew where he had sunk, I would a gone fetched one of them nigger preachers and paddled him out to pray over Jim, but it warn't no use, because the current would a carried him somewheres else, downstream, till he caught on a snag, maybe. There warn't no use in doing anything, because cannon wouldn't bring him up, nor quicksilver in bread, nor prayer, nor cussing, nor crying. Jim was gone forever, down deep in that old muddy river.

It warn't only that I felt low-down and miserable because Jim was dead, that warn't the half of it. Because my conscience begun to work on me, and told me it was all my fault that Jim was dead, and if I had only listened to it before, and done what it said to do, he'd still be alive. It warn't no good blaming the King and the Duke, because they was sent by Providence to trouble us so we'd do right, along with the snakeskin, and the fog, and the rest. For that's always

His way, to toss evil in a man's path so he'll do good, and if a body don't pay heed to a little nudge, why Providence'll kick him ass over teakettle next trip around.

First He sets your conscience a-picking at you, and if that don't do it, He'll send you a little misery, like a blister, maybe, or a hole in your pocket so you lose something you're particular fond of, or snarl your trot-lines, and if you still don't mend your ways, he'll knock you all kersmash. A body can put up with a talky conscience, but once Providence has it in for him, goodbye! After that, you ain't got no show at all, and only a mullet-head like me will try his luck and stay in the game for another hand. Providence was. in it from the very start, and there warn't a damned thing we could a done about it. I suppose I should a been grateful to Him for drownding poor Jim instead of me, but I warn't. It was ornery and wicked, and I knowed it, but I didn't even try. That's how bad I felt.

I had left off crying for a spell, and was just lying in the bottom of the canoe thinking these thoughts when, blump! she runs into some willows hanging down from a bank, and a little shower of tiny leaves came tickling down over me. I sat up then and pulled the canoe in under the willows where there was a kind of cave, cool and dark, and I laid back down and tried to think of what I should do next, but it warn't no good. Nothing would come.

All around it was still and Sunday-like, with everything hot and gray. Gray sky, gray water, everything seemed to have had the color squoze right out of it. The air was full of them kind of faint dronings of bugs and flies that make it seem so lonesome and like everybody's dead and gone, like the sound a spinning-wheel makes, wailing along up and sinking along down again; and that is the lonesomest sound in the whole world. When a breeze would come along and quiver the willow leaves it made me feel mournful, because it was like spirits whispering-spirits that's been dead ever so' many years, or them that's just died. It made me wish I was dead too, and done with it all, and pretty soon I started in blubbering again, and I kept it up off and on until I fell asleep.

Next thing I knowed I woke up with a start, and there was a boombooming outside on the river like they had got cannon out to raise Jim, but it warn't, it was the storm coming on. The wind swished through the willows something fierce, and I pulled back in as far as I could go. The river was all whitecaps in a flash, foam a-blowing in

a line straight as a ruler could make, and then there come a monstrous clap of thunder overhead and another, and the lighting split everything wide open. The rain come then. It beat down like hailstones, and steam rose up from the river so you couldn't see a thing, just a solid sheet of white. The water come trickling through the willows, so I unrolled my blanket and covered up, lying there and listening to the thunder and the swoosh of the rain until I went asleep again. I dreamt then, bad dreams, but I won't tell you what they was about. I already told you.

When I waked up again it was dark night, and the rain had stopped. Leastwise it had stopped outside, but it kept a-dripping down around me through the willows. My blanket was soaked, and my clothes, and the skeeters had sat down on me for dinner, so I figured I might as well get moving once again, and pushed out from under the willows. It took me an hour or two, but I found the little island where I had the raft hid, and clumb aboard. I didn't stay long. I tossed what I wanted into a sack and put it and the gun into the canoe, and the rest I left for anybody that wanted it. Just before I shoved off, I took a last look around to make sure I hadn't forgot anything, and the sight of that lonely raft, all shadows and emptiness, sent a dern lump into my throat like somebody's hit me there. I got into the canoe and never once looked back.

I scrummaged a meal out of some scraps and then I lay down in the canoe with my pipe and thought over what I was to do next. Money warn't no problem, because I still had a silver dollar left in my pocket, and the canoe was worth ten dollars any day. I thought maybe I would go on down to Orleans and ship as a cabin boy on one of the big riverboats. Or maybe head out for the Territory all by myself. I didn't give much of a damn either way. When there's nothing you want to do, or got to do, why you can do anything, but there ain't much joy in it.

Tom Sawyer, now, I knew he'd give his right arm to be me, and to be able to come back to St. Petersburg from the dead, and have

Aunt Polly and Becky Thatcher a-weeping over him and maybe have a big parade up to the jail and then a showy trial before they took him out with a brass band to hang him for helping a nigger escape instead of being killed by that nigger and properly dead. Oh, Tom could do it up bully, but somehow I didn't much cotton to the idea. Besides, most likely pap would get a-holt of me again, or even worse the widow, who'd start in sivilizing me all over again, and I couldn't a stood it. I been there before.

It was monstrous quiet out on the river that time of night, and somewheres far off there was a church bell ringing, but you couldn't hear all the strikes, only a slow bung bung and then the next one would drift away before it was finished and there would be nothing for what should a been a couple of strikes, and then you could hear bung bung, again, and then nothing. At that time of night all the sounds are late sounds, and the air has a late feel, and a late smell, too. All around you can hear the river, sighing and gurgling and groaning like a hundred drownding men, and laying there in that awful dark, I could hear the river terrible clear, and it seemed to me like I was floating in a goddamn graveyard. Being out there all alone at that time of night is the lonesomest a body can be. The stars seem miles and miles away, like the lights of houses in a valley when somebody stops on a hill to look back before going on down the road, leaving them all behind forever; and my soul sucked up whatever spark of brashness and gayness I had managed to strike up since that afternoon, and then all the miserableness come back, worse than ever before. But dark as it was and lonesome as it was, I didn't have no wish for daylight to come. In fact, I didn't much care if the goddamn sun never come up again.

THE END

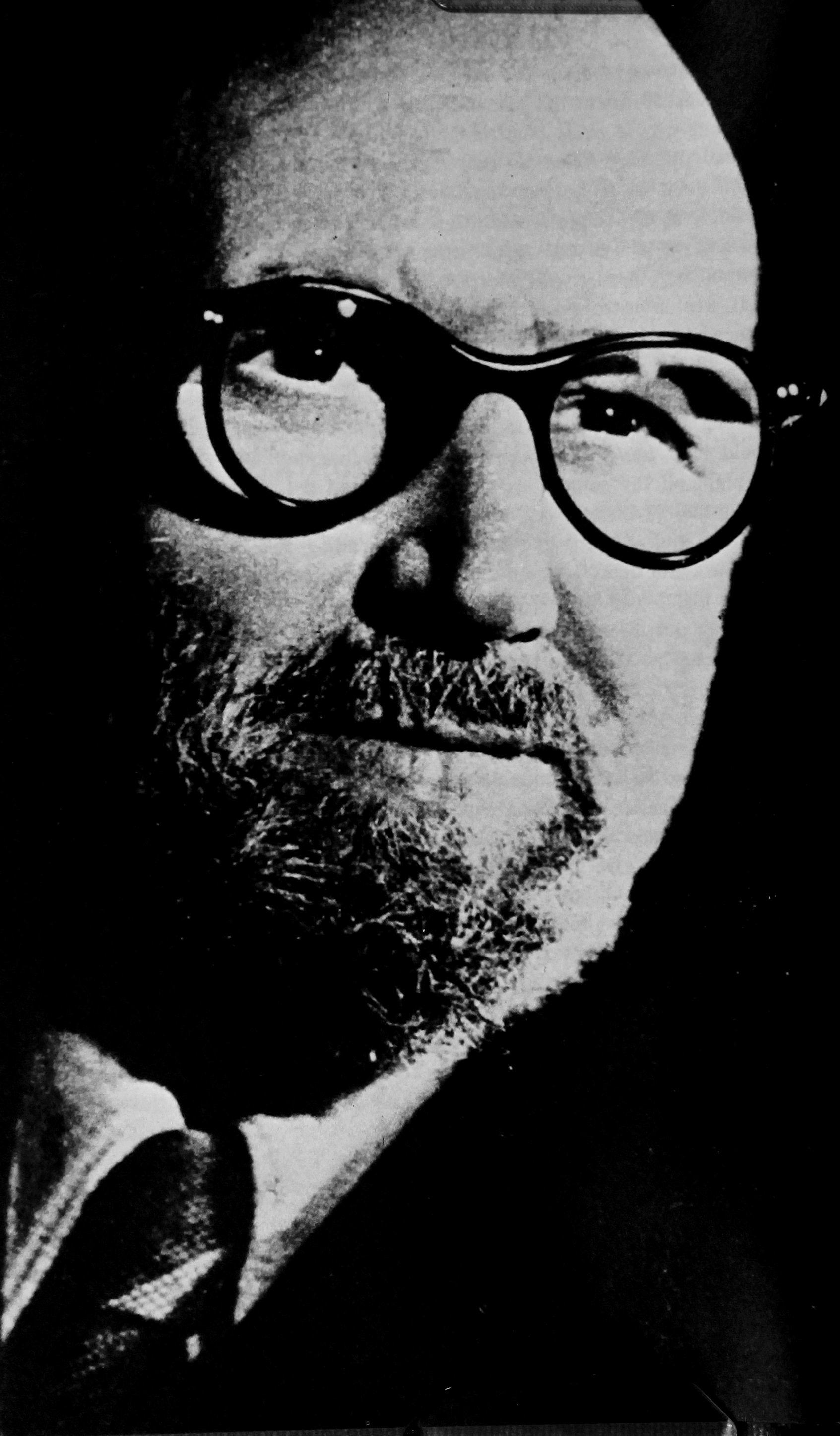

On the eighteenth of September 1968, one of Spain's greatest poets, Leon Felipe, died in self-imposed exile in Mexico. Because he was the humblest and simplest of poets, a solitary who neither followed the fashion, nor served the directives of a party, he has not been written about in English nor translated.' At his death twenty Spanishspeaking lands mourned, but the New York Times published neither a news note nor an obituary, nor, so far as I have been able to ascertain, did any other journal of our country record his passing.

Since the day in 1919 when he read his first sheaf of still unprinted poems in El Ateneo de Madrid to a startled audience of Spain's intellectual and literary elite, he has published a steady stream of separate poems, volumes of verse, poetic dramas, essays, and translations of Walt Whitman, T. S. Eliot, and other poets of our tongue.

1. In a bibliography of over 100 items concerning him in Leon Felipe, Obras Completas, Buenos Aires, 1963, one article with translations by me, and one by H. K. Jones, and one doctoral thesis, were the only entries in English.

TriQuarterly 21

He leaves behind him twenty-two slender and not so slender volumes of verses. At eighty, old and exhausted, he bade good-bye to his muse in a book entitled jOh, este viejo y rota violin! For a year or two the broken violin was still, but then he began to write again. When I visited him in Mexico in 1965, I found him old and spent and overwarmly dressed on a hot summer's day. Yet he spoke with animation and gave me a little handful of recent poems in manuscript which he asked me to translate. One of these, Auschwitz, the only poem he ever devoted to the fate of the Jews, won him Israel's top poetry honor, the Sourasky Prize, the equivalent of 50,000 Mexican pesos, along with twenty hectares of land in Israel planted with 1,000 pines. The 50,000 pesos he gave to his faithful housekeeper, Trini (Trinidad Corona Zurita), the pine grove bearing' his name he claimed as his burial place. But the President of Mexico and the country's literary notables, as well as his loving sister, Salud, who had shared his exile in Mexico, willed otherwise, so he lies buried in the Spanish Cemetery in Mexico City, the city in which he spent most of his adult life and published most of his work. The book that he had thought would be his last (jOh, este viejo y rota violin!) was published by the Mexican Fonda de Cultura Economica, and a posthumous volume is now on the press of the Universidad Nacional Autonoma. Thus Mexico claims him as its adopted son, but President Diaz Ordaz, speaking at his funeral, recognized that he belonged first of all to Spain and then to all Spanish-speaking lands, pronouncing him "the greatest poet of the Spanish tongue of his epoch."

Though he left Castile in his young manhood, and returned only twice to the Iberian peninsula, once during the Spanish civil war to take his stand and read his poems to the soldiers defending the Republic, and a second time to do penance for some regretted act by sitting for six months among the shepherds on the hills of Portugal; and though he wandered for over forty years from land to land in Latin America publishing his books and reading his poems in most of its culture capitals, wherever he went he carried with him the mountains and plateaus and visions of Castile. He entered into poetic quarrels with its Archbishops and Bishops after they blessed Franco's sword, he grieved over its tragedies, carried on familiar dialogues with Don Quixote and Sancho, and with Juan Ruiz, Archpriest of Hita (author of El Libra de Buen Amor, dead in the flesh since the fourteenth century). In whatever land he lived, he continued to write and recite the most castizo of Sp�9ish verse in a simple poetic vein

that had its origins in Juan Ruiz and Cervantes and Jorge Manrique. The spirit of Spain enveloped him completely. The songs he sang, the moods he expressed, his thoughts and feelings, his landscapes and horizons, his images and gestures, the public and passionate loudness of his voice even in the intimacy of a tertulia, his dramatization of each moment along with the dramatization of self and emotions (in his youth he was for a while a traveling comicoy, his tragic sense of life and his familiarity with God, the Devil, and Death, all proclaim him the voice of the Spanish land. Even when he denies his country, he does it as only a Spaniard could. Consider for instance this succession of negatives in the self-portrait with which he opened his first book.

What a pity that I cannot sing according to the usage of the times as the poets of today sing! What a pity that I cannot sing with throaty voice those brilliant romances to the glories of the fatherland! What a pity that I have no fatherland!

I know that history is the same, the same always, passing from one land to another land, from one race to another race as pass those storms of summer from this region to that region. What a pity that I have no region, a little fatherland, a provincial country! I was fated to be born in the entrails of the Castilian steppe to be born in a town of which I remember nothing; I passed the blue days of my childhood in Salamanca, and my youth, a dark youth, in the Mountain country. Since then I have never once dropped anchor, and none of these lands raises nor exalts me to be able to sing always in the same tone

to the same river that passes rolling the same waters, to the same sky, the same field, and in the same house.

What a pity that I have no house!

A house sunny and emblazoned, a house in which to guard along with other rare things an old armchair of leather, a worm-eaten table (which would tell me old domestic stories .) and the portrait of a grandfather .of mine who won a battle.

What a pity that I have no grandfather who won a battle, painted with one hand crossed on his chest, and the other on the hilt of his sword! And, what a pity that I haven't even a sword!

For what am I going to sing if I have no fatherland, nor a provincial land, nor a house

sunny and emblazoned, nor the portrait of a grandfather of mine who may have won a battle, nor an old chair of leather, nor a table, nor a sword? What am I going to sing if I am a pariah who hardly has a cloak! who is compelled to sing only of matters of little importance!

In this self-portrait every stroke is a negation, but a negation of traits so profoundly Spanish that what emerges is a poet who is the natural voice of Spain. The "things of little importance" of which he sings are the inward events of his spirit. As we read him we feel that we know him as well as he knows himself, yet the physical happenings of his private life remain as unknown as his name to the multitudes who have read or heard him recite his verses. The name they know him by is but his given name, or two given names,

Leon Philip. But in the church register of the pueblo of Tabara in the Castilian province of Zamora, where he was born on April 11, 1884, his name is set down as Leon Felipe Camino Galicia. His patronymic or family name is thus Camino (Road), a prophetic name, for all his life he was a wanderer. His poetry is the record of a pilgrimage: the titles of his first two books, Versos y oraciones de caminante (Part I, Madrid, 1920; Part II, New York, 1930) contain the road itself in 'he form of el caminante (the wayfarer or pilgrim). Perforce he had to drop his family name lest people see in their title an inept word-play upon his patronymic. Thus, from the outset he entered without family or name into the world of poetry. Volume I of the Oraciones was published in Madrid in 1920. With the freshly printed volume under his arm he set out that same year for the New World, to continue a lifelong pilgrimage already begun in Spain itself. He had begun his journeying as an apothecary, setting up a shop first in one town, then in another, and ending this portion of his journey as apothecary on the penal island of Fernando Po. His next trade was that of comico: despite the term used, he played tragic rather than comic parts in theaters allover Spain and Portugal. In the New World he was to continue his career as a wandering comico by reading his own tragic verse in the theaters of every capital of Latin America.

How he got to the penal island of Fernando Po off the coast of Africa is a matter of conjecture. According to published accounts he went as a civil servant, but a member of his family told me that he had knocked down a man in a cafe for insulting his woman companion, the fall resulting in death from a skull fracture. Thus, the year spent as an apothecary on Fernando Po might well have been a gentle sentence for justifiable and unpremeditated homicide. In any case, he was reluctant to talk of his life on the island. One day he recited to me a poem beginning "Gobernador de la Isla, Gobernador General ," excoriating the Governor of Fernando Po. When I expressed enthusiasm and asked him to dictate the lines so that I could translate them, he would not repeat them. "It is nothing," he insisted, and would never recite the lines again nor commit them to paper. It was after he completed his year on Fernando Po that he left for the New World.

He admired the United States from a distance, but when he went to live there from 1925 to 1929, first in New York and then in Ithaca, he did not feel at home. In New York he taught Spanish at

a Berlitz school, a thankless task, prepared for a professor's post under Maestro Federico de Onis at Columbia University, then went to Cornell to teach Spanish literature. In New York City he found life tolerable enough, for he lived in a Spanish enclave of the intellectuals who taught the literature of Spain in the various colleges and universities of the city. They talked their nights away in conversation so animated, passionate, and loud that one after another of New York's none too quiet restaurants bade them to take their talk and patronage-more talk than patronage-elsewhere. Their quest for a meeting place ended on Second Avenue in the Cafe Royale, frequented by Jewish intellectuals who were no less noisy, so that there they could talk the night away unmolested. When Leon Felipe got to Ithaca, however, he found the silence deafening. One day, in the middle of a semester, he walked out of the university with the exclamation, "En este desgraciado pais, no hay conversacion." He abandoned his academic career and headed once more for the noisy talkfilled cafes of Latin America.

Though his home now was Mexico City, his spirit continued to haunt his native Spain while he continued his restless pilgrimage from land to land-in quest of what? The places of publication of his many volumes mark the stages in an unending journey: Mexico City, Vera Cruz and Merida in Yucatan; Havana and Panama City; Quito, La Paz, Santiago, and Buenos Aires; New York, Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, and Palma de Mallorca.

What was this caminante looking for? For peace, which to the end eluded him? For answers to the questions, Who am I?, What is man and what is his destiny?-questions that ask themselves endlessly in all his poems. To Who am I? he finds many answers, all fragmentary, all humble and self-deprecating, except when he lays claim to the mad and sacred office of poet and prophet. On this claim he harbors no doubts; he identifies himself unhesitatingly with all the mad poets and angry prophets of other lands and times, bidding presidents and bishops be silent when he speaks with the ancient voice that is his heritage. At other times he is prone to identify himself with the outraged and injured, with the lowliest and most disfigured of creatures, as in his verses to be set under the painting by Velazquez of the grotesque and misshapen dwarf known as El Niiio de Vallecas ("While this battered visage exists no one departs from here!")

More often he identifies himself with Don Quixote and Sancho, as readily with one as with the other, for to him both are one. He talks familiarly with them; pleads "put me in your band, knight of

honor!", interposes himself in their debate on whether the shining object on their road is a barber's basin or the helmet of Mambrino. From the compromise of the basin and helmet fused in one, as basiyelmo (basin-helmet), he moves to an ascending hierachy, "Basin, helmet, halo, that is the order Sancho," voicing the hope that all may follow the ascension from basin to helmet to halo. With that we are at the heart of his creed, a creed not unworthy of the vision of the mad knight of La Mancha.

Again he offers himself as a candidate for other bands, the Nazarene's as well as the Manchegan's:

I too am hungry and thirsty for justice, Nazarene, take me into your band. In order to follow you, I have no need to abandon goods or kin for I am poor and alone and without a great love to redeem me.

The poet does not draw much distinction between the knight of La Mancha and the carpenter of Nazareth-are not both mad and both in search of justice in a world where men have forgotten it?

When news of Franco's uprising surprised Leon Felipe in Panama, and the Archbishop of Panama endorsed the rebellion, the poet began an angry debate with the Catholic hierarchy that was to characterize his creed thenceforward. Witness for instance the poem:

I KNOW WHERE HE IS

God who knows everything is a simpleton and now he is kidnapped by some bandit archbishops who make him say over the radio "Hallo! Hallo! Here I am with them." But that doesn't mean he is on their side but that he is there a prisoner. All he tells is where he IS so that we may know and may save him.

There is another aspect of the poet's God, infinitely remote, not to be talked to intimately or called a simpleton. In this aspect God is a Creator who started things going, then abandoned man to his own resources. It is in this spirit that Leon Felipe glosses the lines of the mystic poet, Fray Luis de Leon:

HE CAME HERE THEN WENT AWAY

And Thou leavest, saintly pastor, Thy flock in this dark vale -Fray Luis de Leon

He came here then went away. Came, set our task and went away.

Maybe behind that cloud there is one who works even as we and maybe the stars are only the lighted windows of a factory where God has to distribute a task just as here.

He came here then went away. Came, filled our strong-box with millions of centuries and centuries left some tools and went away

Behind you there is no one. No one, neither teacher, nor overseer, nor boss. But time is yours. Time and this chisel with which God began creation.

There are no theological complexities in this faith: a God who is now a captive simpleton, now a remote creator; a Christ scarcely distinguishable from Don Quixote; a hierarchy that can be challenged to strip itself of its vestments and submit itself to judgment naked

in the public plaza; an egalitarianism that concerns itself with the elevation to full human dignity of the lowly and the misbegotten, urging on all human beings the path to salvation of basin, yelmo, halo.

The second volume of his Verses and Prayers of a Pilgrim begins with the simple avowal:

I ride with rein tight restraining my flight for the point is not to be first and alone but to get there with all and on time.

The same book contains the apostrophe to the Nino de Vallecas already referred to, and a conception of the social order expressed in:

Always there will be superior snow robing in ermine the highest hill and humble water toiling below to turn the wheel of the mill. And always a sun -both slayer and friendchanging to tears the snow forever and to clouds the water of the river.

When I visited Leon Felipe for the last time, in 1965, one of the poems he gave me in manuscript to translate showed that the feud he began with the Archbishop of Panama in 1936 had not been altogether patched up even three decades later:

WHAT HAS HAPPENED TO THE DOVES?

The doves on the Piazza de San Marco

Which the municipality of Venice was breeding for the tourists have all died suddenly-

The dove of Picasso that I kept as a relic in the covers of an old notebook has disappeared-

In the Ecumenical Council, no one knows what has happened to the Dove of the Anunciation->-

And the Vatican is in consternation because the Dove of the Holy Spirit is ill.

They say that all over the world now there is a deadly epidemic among the doves-

And the Council of Peace-cannot find anywhere at all a single dove.

Leon Felipe's poetry and his prose are scarcely distinguishable from each other. Here are some lines from the introduction in prose to The Clown Who Gets Slapped and the Man with the Fishing Rod, written in 1938 at the end of the war:

For today and for me, poetry is nothing more than a luminous system of signs. Fires that we light here below, among the shadows we have found, so that someone may see us, so that they do not forget us. Here we are, Lord!

And everything there is in the world is mine and worth entering into a poem, to feed a bonfire

That is my esthetics, old now and enduring still. Old because it was written before the present tragedy of Spain-how many centuries in the consciousness of a true and grieving Spaniard! -and enduring because among the shadows of this tragedy it continues to seem to me the only one: the esthetics of a ship lost in the mist. Today more than ever poetry is for me organized fire, signal, call, and flame of shipwreck. And every good combustible is excellent poetic material. Everything, even prose. The prose here, now, in this poem, is neither extrapolated nor only exegesis. It is a poetic element which gains quality not with rhythm but with temperature. The line of the flame is today the organizing and architectonic line of the poem. The image is worth as much as the law, yes, but the image on fire. And the poetry of this hour, to get a place in the vanguard of knowledge, does not have to be music or measure, but fire

Here is a comparable passage from his introduction to The Spaniard oi the Exodus and Tears, read aloud in the Palacio de Bellas Artes of Mexico City to an audience of Spanish exiles and Mexican literary men on September 12, 1939:

We live in a world which is falling apart and where all effort to build is vain. In other times, in epochs of ascension or fullness, the dust tends to agglomerate and to cooperate, obedient in structure and form. Now form and structure crumble and the dust reclaims its liberty and autonomy. Nobody can organize anything. Neither the philosopher nor the poet. When the hurricane blows and throws down the great fortress of the King, man seeks protection in the ruins. These are not days for calculating how to set the main rooftree free, but to see how we can escape from being crushed by the old dome that is crashing about us. No one today has in his hands anything but dust. Dust and tears. Our great treasure. And treasure they would be if man could command them. We are poor because nothing obeys us. Our wealth was never measured in what we have, but in our way of organizing what we have. Ah, if I could organize my tears and the scattered dust of my dreams! The poets of all times have worked with no other ingredients. And perhaps the grace of the poet is no other than that of making docile the dust and fecund the tears.

Finally in the matter of style, we must give the poet a chance to explain the exaltation and passion in his voice, its way of resounding in a restaurant so that the music ceases and all eyes turn astonished toward our table, no matter how intimate and friendly the talk. In his Ganards la Luz=-Biograiia, Poesia, y Destino (Mexico, 1953), the poet takes account of this hubbub in a remarkable apologia pro voce sua:

This exalted tone of the Spaniard is a defect, very ancient now, of our race. Ancient and incurable We talk in a wounded shout dissonant forever, for ever because three times, three times, three times we had to scream ourselves hoarse in history until we tore our throats to pieces.

The first time when we discovered this Continent and had to shout beyond measure. Land! Land! Land! We had to shout the word so that it could resound above the roar of the sea

and reach the ears of men who had remained on the other shore. We had discovered a new world, a world of new dimensions that, five centuries later during the great shipwreck of Europe, man's hope would have to cling to. There were good reasons for talking loud, good reasons for shouting!

The second time was when there went out into the world, grotesquely arrayed with broken lance and paper visor, that extravagant phantasm of La Mancha, launching outrageously into the wind the word forgotten by men: Justice! Justice! Justice! Then too there was good reason for shouting!

The third cry is recent. I formed part of the chorus. Even now my voice is still strained from hoarseness. It was the shout we gave from the hilltop of Madrid in 1936 to warn the sheepfold, to rouse the goatherds, to wake up the world: Hey! Look out! The wolf is coming! The wolf is coming! The wolf is coming! No one heard. No one They closed all the shutters. They made themselves deaf, they plugged their ears with -eement, and to this day they do no more than ask like pedants: but why does the Spaniard talk so loud?

Yet the Spaniard doesn't talk loud. The Spaniard talks on the exact level proper to man, and those who think that he talks too loud think so because they listen from the bottom of a well

Above all, Leon Felipe is the poet of Spain's tragedy. If it is frustrating to try to introduce to my countrymen a poet unknown to them by selecting a handful of examples of his work from twentyodd volumes of poems, it is no less difficult to know what to select from the grief that possessed him, filling four successive volumes and coloring all the poetry of the last thirty years of his life. What shall we select to introduce this grief of the poet to those who have never heard his name? Shall one take a few lines out of the fivehundred-line poem of an angry prophet who already foresees the Republic is defeated because of the factions ("Syndicalists, Communists, Anarchists, Socialists, Trotskyists, Republican Leftists") who are tearing it apart with their quarrels, who have "used up in a thousand egoistic combinations all the letters of the alphabet for their partisan initials, and affixed in a thousand different ways on cap and jacket the red and the black, the sickle, the hammer and the

star," each band seizing its private booty without so much as a decree of expropriation, and already planning to flee the shipwrecked land "stealing the seat of a child in an autobus of evacuation"? This prophetic vision is dated Valencia, June 29, 1937, though the Republic dragged out its existence for almost two years more, until March 28, 1939.

Or shall one take a few lines from the long lament for the dead land in the forty-eight-page threnody published in Mexico in 1938 called The Clown Who Gets Slapped and the Man with the Fishing Rod, subtitled Poema Trdgico Espaiiol, where the lament for Spain alternates with bitter scorn for England that, under the shelter of the one-sided "non-intervention" of the "Non-Intervention Committee," went fishing during the crisis while the Italian and German members of the Committee intervened with munitions, troops, and bombardments from the air?

Having apprised the reader of the difficulties of selection, I shall take a few lines from the third and greatest of the four book-length poems of the grieving poet on the civil war. It is entitled The Axe, subtitled Spanish Elegy, and dated Mexico, 1939.2 The poet dedicates it without prejudice:

To the Knights of the Axe

To the Crusaders of Rancor and Dust

To all the Spaniards of the world.

Thus the poem embraces Francisco Franco and his cohorts no less than the warring factions on the Republican side. The all-embracing lament for all Spaniards is one of the sources of its greatness. Space forbids my quoting more than a tiny fragment of this long and simple monody of pain with its intolerable iteration of anguish expressed in the simplest words of common speech. Yet a fragment may serve to give the reader some notion of what these thirty-eight pages of sustained and cumulative pain must be like. These lines are from the invocation:

Ah the sorrow this sorrow of no longer having tears this sorrow

2. The fourth book is entitled Spaniard of the Exodus and Tears, also published in Mexico in 1939. The four books are 23 pages, 48 pages, 38 pages, and 176 pages long in their original editions.

of having no more tears to water the dust!

Ah the sorrow of Spain which is now no more than wrinkle and dryness screwed up face dry grief of earth under a sky with no rains gasp of a well sweep over an empty well. Oh this screwed up Spanish face this face dramatic and grotesque dry dusty weeping for the dust, for the dust of all things ended in Spain for the dust of all the dead and all the ruins of Spain for the dust of a race now lost in History forever!

Dry weeping of dust and for dust. For dust of a house without walls of a tribe without blood of ducts without tears of furrows without water

Dry weeping of dust for dust that will no longer agglomerate neither to make a mud-brick nor to raise a hope. Oh yellow accursed dust given us by the rancor and pride of centuries and centuries and centuries For this dust is not of today nor came to us from abroad we are all desert and African

Nobody here has any tears and for what are we to live

if we have no tears?

For what have we any longer to weep if our weeping does not bind?

In this land tears do not bind neither tears nor blood Sandy earth without water wrung flesh without tears rebellious dust of rancorous rock and hostile lavas yellow atoms and sterile of unfruitfulness vengeful motes sand quarry of envy wait dry and forgotten till the sea overflows

Why have you all said that in Spain there are two bands if there is only dust?

In Spain there are no bands in this land there are no bands in this accursed land there are no bands there is only a yellow axe which rancor has edged sharp an axe which falls always always always implacable and tireless on any humble union: on two prayers that fuse on two tools that interlace on two hands that grasp each other. The order is to chop to chop to chop to chop till dust is reached down to the atom. Here there are no bands

there are no bands neither reds nor whites nor patricians nor plebeians

Here there are only atoms atoms that bite one another

From here no one escapes for tell me, friend ropemaker, is there anyone who can braid a ladder of sand and dust?

Spain your envy was mightier than your honor and better you have guarded the axe than the sword Under its edge has been made dust the Ark the race and the sacred rock of the dead; the chorus the dialogue and the hymn; the poem the sword and the craft; the tear the drop of blood and the drop of joy And all will be made dust all all all Dust with which nobody nobody will ever make either a brick or an illusion.

Leon Felipe wrote The Axe when he had first returned to Mexico at the moment of Spain's last agony. It seemed to him that Spain was lost forever, that the Spaniard in exile, unlike the Jew in the Diaspora, had no faith in his own election to sustain him, no mission and no possession left to him, unless he could squeeze from dry, pain-seared eyes a tear in which there might be hope not of Spain's but of man's redemption. In a public address on the occasion of the poem's publication, there is a moving suggestion of this as Spain's continued mission in exile. And in the midst of the overwhelming sorrow there is, if not a note of hope, yet of defiance of the forces of destruction which have triumphed in Spain. Embedded in the discourse are several more personal fragments of verse, one dealing with his own poetry, one addressed to all Spaniards, one addressed to Franco:

Yours is the treasury the house the horse the pistol. Mine is the ancient voice of the land. You remain with everything and I naked wandering through the world but I leave you mute MUTE! And how are you going to gather the wheat and feed the fire if I carry off the song?

To close this inadequate presentation of a poet unknown in our country, I must remind myself that this is not so much an introduction as an obituary notice. Hence, I shall close with a few examples of his work culled at random from the poet's lifelong dialogue with Death. When one touches the body of his work, one feels that one has touched not a shelf of books but a man. Unique. Completely incorporated in his poetry that is at one and the same time this single man's unique life and the expression of the destiny of all Spaniards, and-so the poet thinks-of all men. Sometimes he insists on his uniqueness, as when he writes:

Wayfarer, no one went yesterday, nor goes today, nor will go tomorrow towards God by this same way on which I go

For each man a new ray of light is kept by the sun

But when he gazes on the distorted face of EI Nino de Vallecas, he describes a trajectory that all men must follow:

From here no one escapes!

As long as this distorted head of the Nino de Vallecas exists no one departs from here. Noone. Neither the mystic nor the suicide.

First this wrong must be set right, first this enigma must be resolved. And resolved by all of us together

And useless, useless is flight (neither up nor down is there any escape)

Until one day (one fine day!) the helmet of Mambrino turned halo adjusts itself to the temples of Sancho and to your temples and mine as if made to order.

Then we'll exit together All of Us off the stage into the wings: You and I and Sancho and the Nino de Vallecas and the mystic and the suicide.

As befits a poet of the Spanish people, Leon Felipe is on intimate terms with Death. After the Spanish civil war, his dialogue with Death moves to the foreground of his poetry. As he reaches his biblically allotted three score and ten, he devotes an entire book to Death, under the title Ganards la Luz=-Blograiia, Poesia, y Destino. Thenceforth this theme remains central to his writing. Here are a few fragments of a poet permitted to write his own obituary.

I. EH DEATH, LISTEN HERE!

And now I ask: Who speaks last the gravedigger or the Poet?

Have I learned to say: Beauty, Light, Love, God

only to have them stuff my mouth when I die with a shovelful of earth? No.

I have come and am here, I shall go and return a thousand times in the Wind to create my glory with my tears.

Eh Death listen here! I am the one to speak last: for your scythe is no scepter only a simple, necessary working tool.

The days pass, and the years, life runs and one does not know why he lives The days pass and the years, death comes and one does not know why he dies. And one day a man sets to weeping just so, without knowing why he is weeping, for whom he is weeping or what the meaning of a tear is. Then, on another day one goes away forever, without anyone's knowing it either and without knowing who he is nor why he came here thinks that perhaps he came only to weep and howl like a dog howl for yesterday's dog who has gone, for tomorrow's dog who will come and will likewise depart without knowing whither and for all the poor dead dogs of the world. For is not man a poor dog lost and alone without a master and without a known habitation? And cannot Man weep and howl in the Wind just so because he wants to as the sea howls For why does the sea howl? Senor Arzipreste why does the sea howl?

There are birds larger than us, I know that. There is a bird in the bedroom much larger than the bed. There is a photograph of a dead bird somewhere, I can't remember. There is a wingspan that would put us all in the shadows.

There is the birdcall I must anticipate each night. There are feathers everywhere. Everywhere you walk there are feathers, you can try to hop over and between them but then you look like a bird. You are too small to be one.

You look like a tiny one-winged bird. If you are your mother will come and kill you. If you are not you will probably beat yourself to death.

But what matters is that every room in the house is filled, is filled with the cry of the eagle. Exterminating the eagles is now all but impossible for the house would fall down without them.

There is a photograph of a dead bird somewhere. Everywhere you walk there are feathers. You look like a tiny one-winged bird. There is the birdcall. There is the wingspan.

JAMES TATE

the city, once carefully divided into zones designated for specific modes of operation, has now become an environment of undifferentiated hostility. This may be in part attributed to the rediscovery and exploitation of abandoned tunnel systems. Territorial boundaries have lost their former importance, and elaborate perimeter defenses have become wholly obsolete. Mobile squads, lightly armed and equipped only for short journeys, can strike effectively at any area throughout the city by utilizing the labyrinthine systems of tubes and ducts. Previous distinctions between day and night combat techniques are now no longer respected. In one series of synchronized raids which Blue forces mounted against Red medical facilities during late February (limiting our specific analyses to the current year now under study), locations attacked reported 40% destruction of buildings and

TriQuarterly 41

equipment, and 80% disruption of activities for a period in excess of twenty days; Blue controllers, however, listed only three casualties among their units, all of them men who lost their way in the ventilation shafts and could not crawl clear before the detonation of the explosives.

would not, perhaps, have made any difference to the progress of the conflict but for the personal magnetism of one of his subordinate commanders, Lieutenant Maurice Eugene Rademacher, of whom we will have occasion to speak at greater length below

". only three of them. I watched while they helped each other unsling their radios and packs and sit down on the sidewalk with their backs together, facing outward, their legs in a three-pointed star. Although they maintained a watchful posture, they seemed unconcerned over their exposure to the possibility of sudden attack. Leaning together as they were, they could not have risen separately. I was about to sneak off to get help when they began an activity, and I grew curious. All of them were dressed in the coveralls of Blue semiskilled semi-combatants; from the pockets of their uniforms they had taken sandwiches wrapped in waxed paper, dill pickles or perhaps sweet pickles likewise individually wrapped, hard-boiled eggs and raw carrots. One of the three pried open the top of his battery case and took out a plastic bowl covered with a plastic lid; when they opened the lid I saw that the bowl contained potato salad. Each of the men covered his lap with a white handkerchief. The handkerchiefs were stained brown in several places, as if they had been burned in ironing. The men fell to eating, chewing silently. Again I was about to slip away, but one of them turned to the man on his left and said something, apparently something funny, because all of them laughed

entrepreneurs. For example, during the summer months, June, July, and August, movement of supplies through authorized channels fell off to the degree expected with the onset of warmer weather; yet in this same period, nonessential items such as personal electronic equipment, photographic supplies, liquor, cigarettes, etc., were discovered at a rate more than four times greater than that predicted by Civil Defense officials. Apartments where such commodities were discovered lay scattered in all areas of the city, and the reticence of the guilty to discuss the source of their contraband indicates both con-

fidence in and reliance upon the clandestine network by elements of the population.

following the case of Lance Corporal Whittaker, we note that the transition from semi-skilled noncombatant to semi-skilled combatant was not made without difficulty. The nature of the new authority structure to which he found himself subordinated did not readily enlist his sympathy, and, on more than one occasion, he was disciplined for negligence and insubordination. In March, a few weeks before his capture by a Red scouting party, he was reclassified from semi-skilled to unskilled combatant. In the unskilled ranks he seemed to find what he had been searching for; letters from this period reveal his satisfaction. "Dear Eleanor," he writes on March 16th, "I'm finally in it at last "

elements of the third, fourth, and seventeenth artilleries were positioned around the monument, their sights trained (figuratively speaking) on the objective; the remainder of the three units was dispatched to key intersections along the avenue and on the outskirts of the park. At dawn on the second day of the siege, under the cover of a chilling rain, ground troops made the initial assault upon the stadium. The accuracy of fire from the artillery positions was remarkable, taking into account the high trajectories made necessary by the intervening buildings. made largely of canvas, and painted flat black, all metal fittings and braces similarly blackened. Powered by nearly noiseless propellers, the crafts were invisible in the night sky unless directly overhead

everywhere the same general listlessness and apathy. CD men on the scene were confounded. Women wandered the streets seminude before men who took no notice of them; children lounged in gutters allowing filthy water to trickle over their limbs; dogs and cats lay down suddenly at random in the paths of military vehicles, and were crushed without a sound. Of course, the lethargy of the animals made it apparent to investigators that the disorder was not of natural origin, and word was quickly dispatched to Blue section headquarters that the area was under chemical or biological attack by incapacitating but apparently non-toxic agents and refuted vigorously the charge of depersonalization made

by Dr. Forbes. Commander McDonald introduced lengthy citations for heroism earned by men of his regiment in the first half of the year. Testimony was produced to the effect that morale and esprit de corps were higher than ever before. Several Red chaplains were called upon to submit tape recordings of interviews with men who complained of depression or despair, but, counteracting the effect of those melancholy exhibits, psychiatrists from Red hospitals were able to cite "returned to duty" statistics which corroborated Commander McDonald's position. A Blue surgeon, invited to participate in the hearings because of his reputation as a brilliant amateur Psychological Statistician, objected to everything which had been said concerning the morale of men in McDonald's unit. The surgeon claimed it to be highly probable that the men, although enthusiastic over the personal qualifications of their commanding officer and the history of their organization, had lost the goal-orientation which the hearings were convened to discuss. "Thus," he concluded, "the relative enthusiasm of such an individual combat group has no real bearing on the matter. Better to deal with men unattached to any of the more glamorous units. If I were to begin to study this problem, I would deal first with the semi-skilled and skilled semi-combatants who are shuffled from one support detachment to another. It is among these men that the sense of purpose and achievement disappears first. ."

repairs made at twice the usual rate yet only one-half the previous cost. Skilled noncombatants for the first time seemed to "catch fire" over the issue of victory or defeat.

frame house. In the kitchen, Captain Hawes' wife was preparing dinner. His two children lay on their stomachs on the floor of their bedroom, playing with a set of wooden blocks. A black dog dozed on the porch. It was approximately 4: 15.

casualties, however, do not tell the whole story. Psychologically, the Autumn Offensive was nothing less than a triumph. Following the destruction of communications in adjacent precincts, noncombatants and semi-combatants swarmed into the street, assuming their assigned defense positions without specific instructions. Blue elements mingled with the crowd, distributing propaganda literature, talking to the Red men and women who perhaps had never seen a Blue before. No shots were fired. The reaction of Red headquarters came swiftly, as had been anticipated by Blue strategists. Massive artillery barrages

every morning I wake permanently and then

I blow myself up like a balloon

I sense a zipper untracked I sense the closets bulging with clothes and piles of shoes to be sorted two by two