25274 79069 2

TriQuarterly

TriQuarterly is an international journal of writing, art and cultural inquiry published at Northwestern University

-,

Tr_iQuarter__,_ly

Editor

Susan Firestone Hahn

Associate Editor

Ian Morris

Operations Coordinator

Kirstie Felland

Cover Design

Gini Kondziolka

Editorial Assistants

Samantha Levine

Elizabeth Cooperman

Assistant Editor

Joanne Diaz

TriQuarterly Fellow

Holly Zindulis

Contributing Editors

John Barth

Lydia R. Diamond

Rita Dove

Stuart Dybek

Richard Ford

Sandra M. Gilbert

Robert Hass

Edward Hirsch

Li-Young Lee

Lorrie Moore

Alicia Ostriker

Carl Phillips

Robert Pinsky

Susan Stewart

Mark Strand

Alan Williamson

130

poems

84 Keats Writes to a Young Poet of the Seventies; My Brief Reign As Emperor; To the Gods of Summer

Debora Greger

88 Approximately Nothing; Natural Selection; To Be Free

Reginald Shepherd

91 Ogling Naomi; Static Electricity

Amit Majmudar

93 Charcoal Suite; Like splayed tulip petals; This is our blind spot

Page Hill Starzinger

98 Titian's Danae; Gardenia Ricardo Pau-Llosa

101 Today-Bored, Puckered, LonesomeI Would Like to Order a Russian Internet Bride; I Am Not in the Wilderness, but at Home, Weak and Thankless; The Practice of Being a Lamb

julianna Baggott

106 Roaming Interiors of Charles Burchfield Paintings; Song of a Plowman

G. E. Murray

157 My Parents Contemplate Moving a Last Time; Fifth of July; Crawl Key Wind; Morning, after a Sleeping Pill

Nancy Eimers

164 This Ecstasy; Postdiluvian Chard deNiord

Contents

166 Riddle; The sweet by-and-by

Laura Kasischke

168 Mia

Derek Mong

ql In Ka'anapali: Central Illinois, Late October; The Bridal Party

Judith Valente

176 Outer Banks; He Tells You About the Dress

You Wore; Pearl

Debra Nystrom

206 The Red Hat; The Other Flower; The Solution to Yesterday's Puzzle

David Wagoner

210 Chalk Pictures; Kingdom

Charlie Smith

213 Birth Event; The Rumor of Evolution

Pimone Triplett

220 Farsickness; Multiverse

Megan Harlan

223 The Promise of the Body Is Its Dream

Jonathan Fink

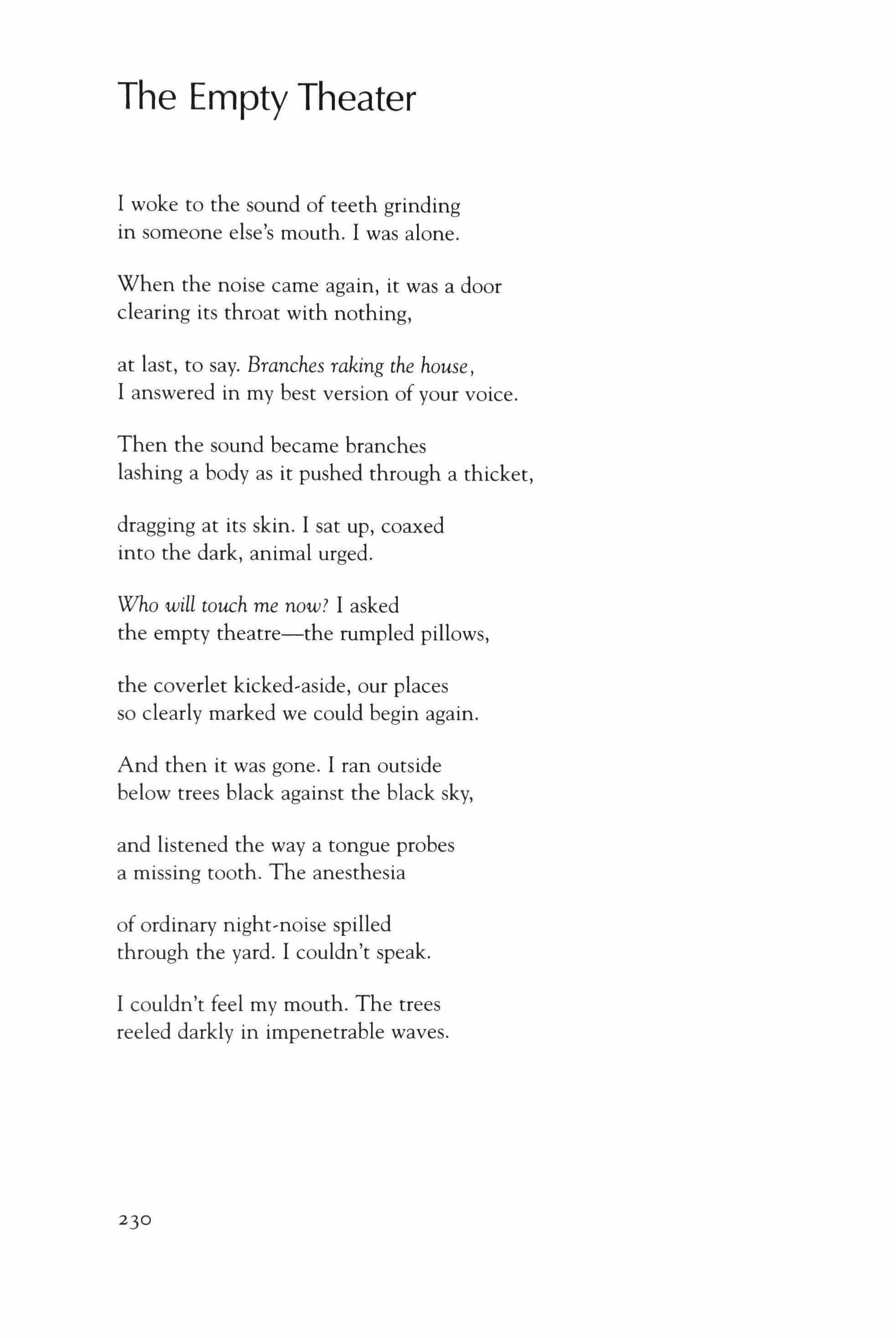

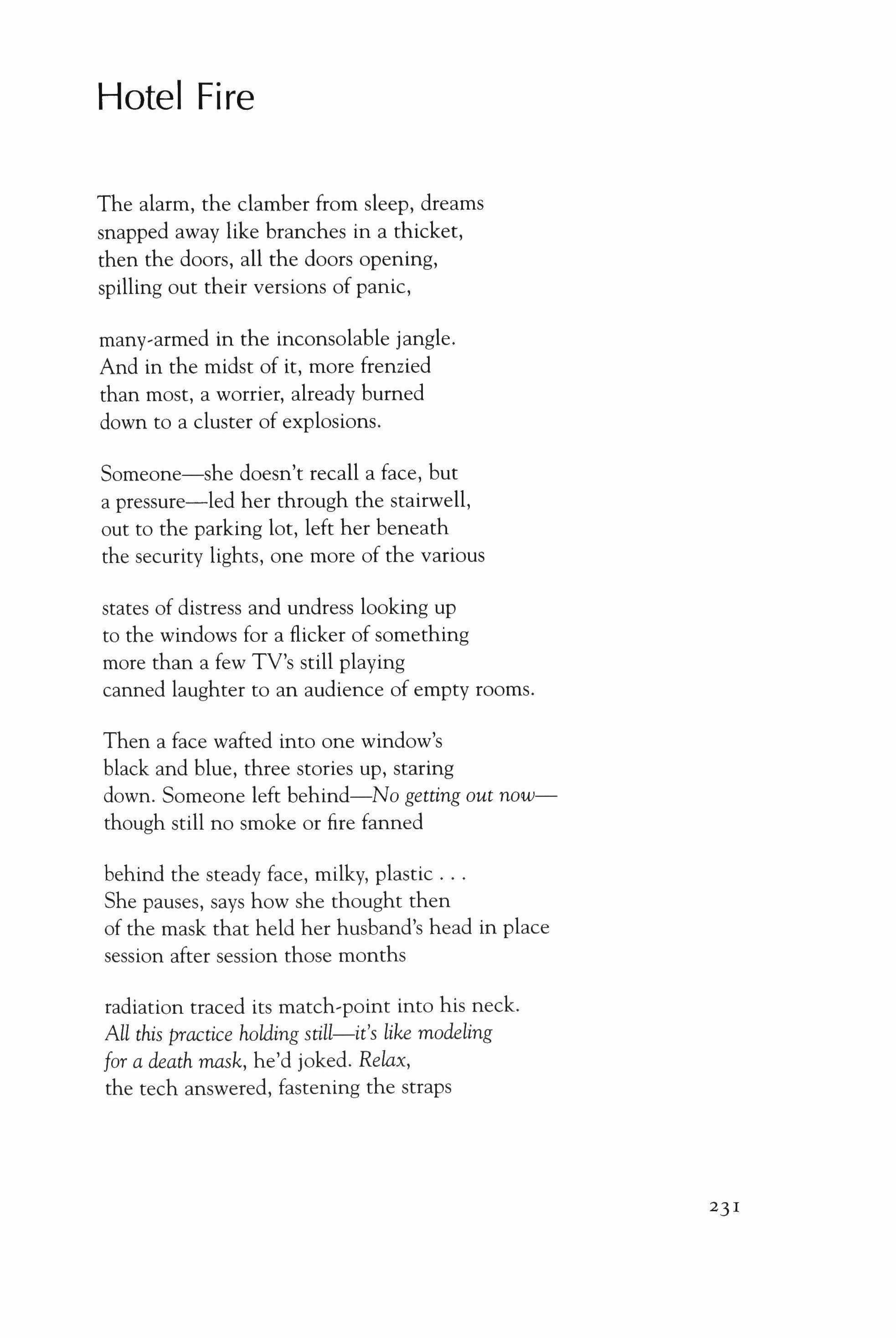

227 The Lake; The Empty Theater; Hotel Fire

Corey Marks fiction

18 The Clothes of the Master

Charles Baxter

27 Emergency Run

David H. Lynn

41 The Strip Mall and the Shaolin Temple

Marie Myung-Ok Lee

60 Lester Higata's String Theory Paradise

Barbara Hamby

69 The Dead Woman

Mary Morris

112 Luna

R. T. Smith

IIB The Bird Sisters

Rebecca Rasmussen

140 Howls

Steven A. Dabrowski

ISO Lying

Celeste Ng

180 A Bedtime Story

John J. Clayton

193 Matrilineal Descent

Erika Dreifus

essays 9 The Meistersinger of Macon

David Kirby

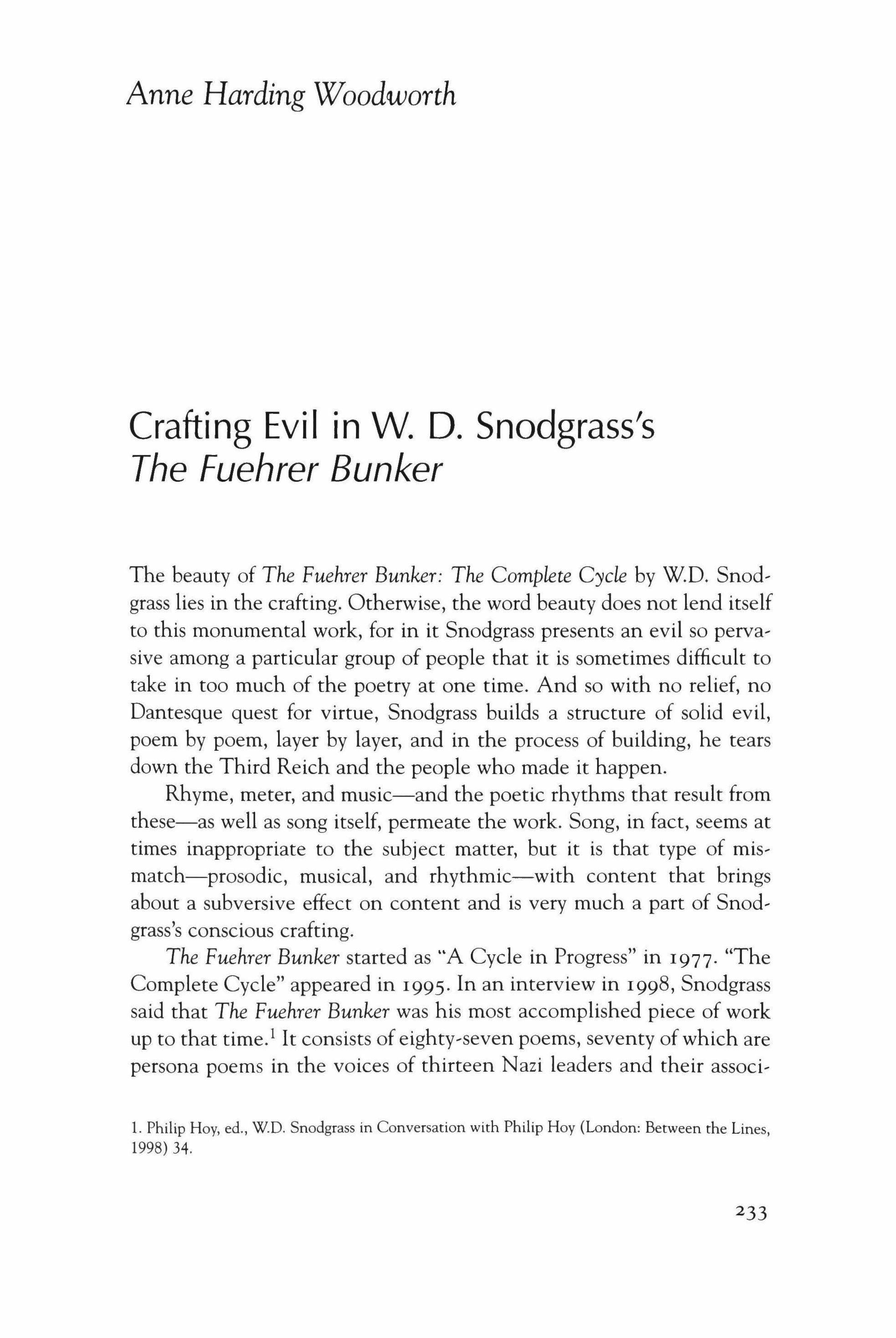

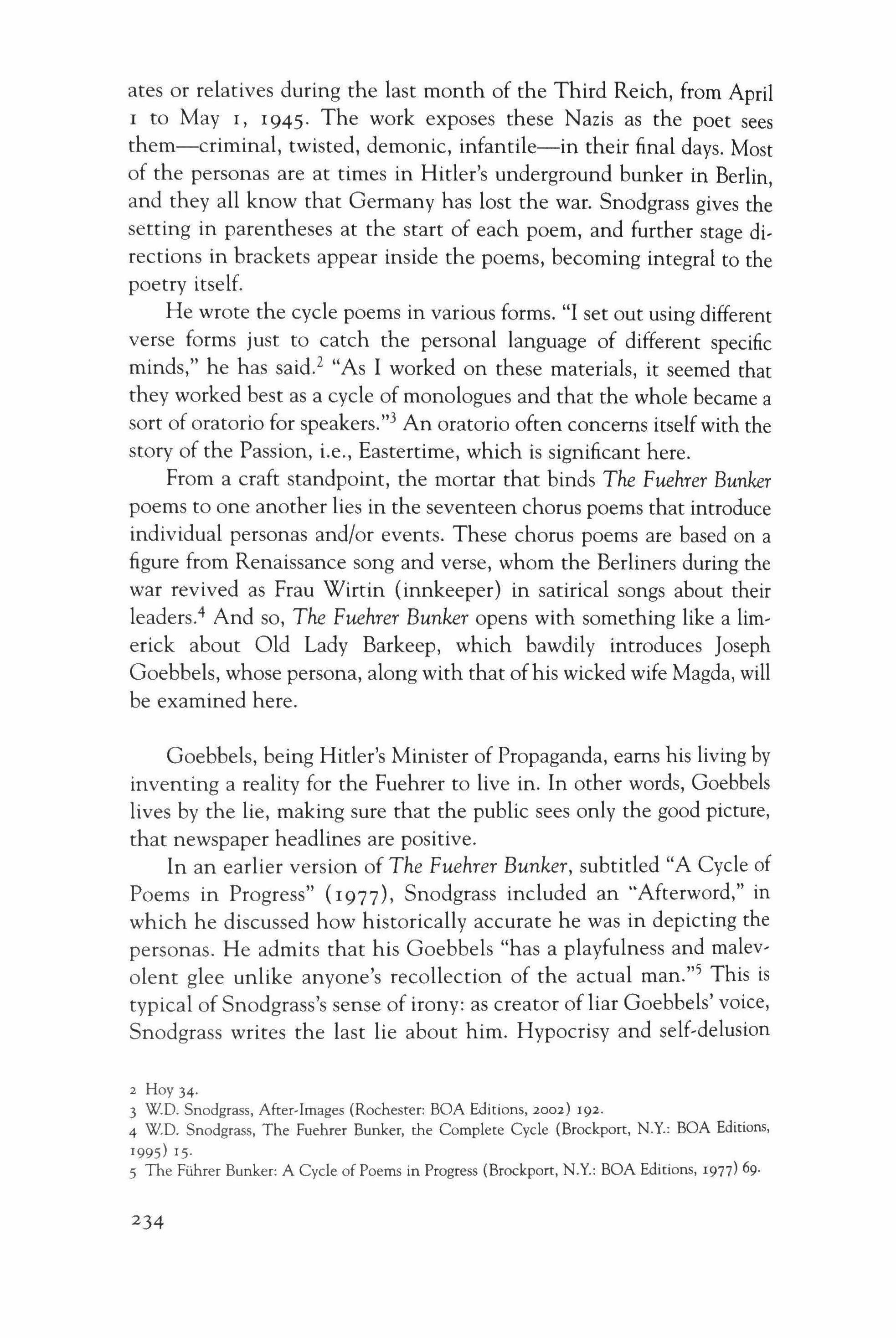

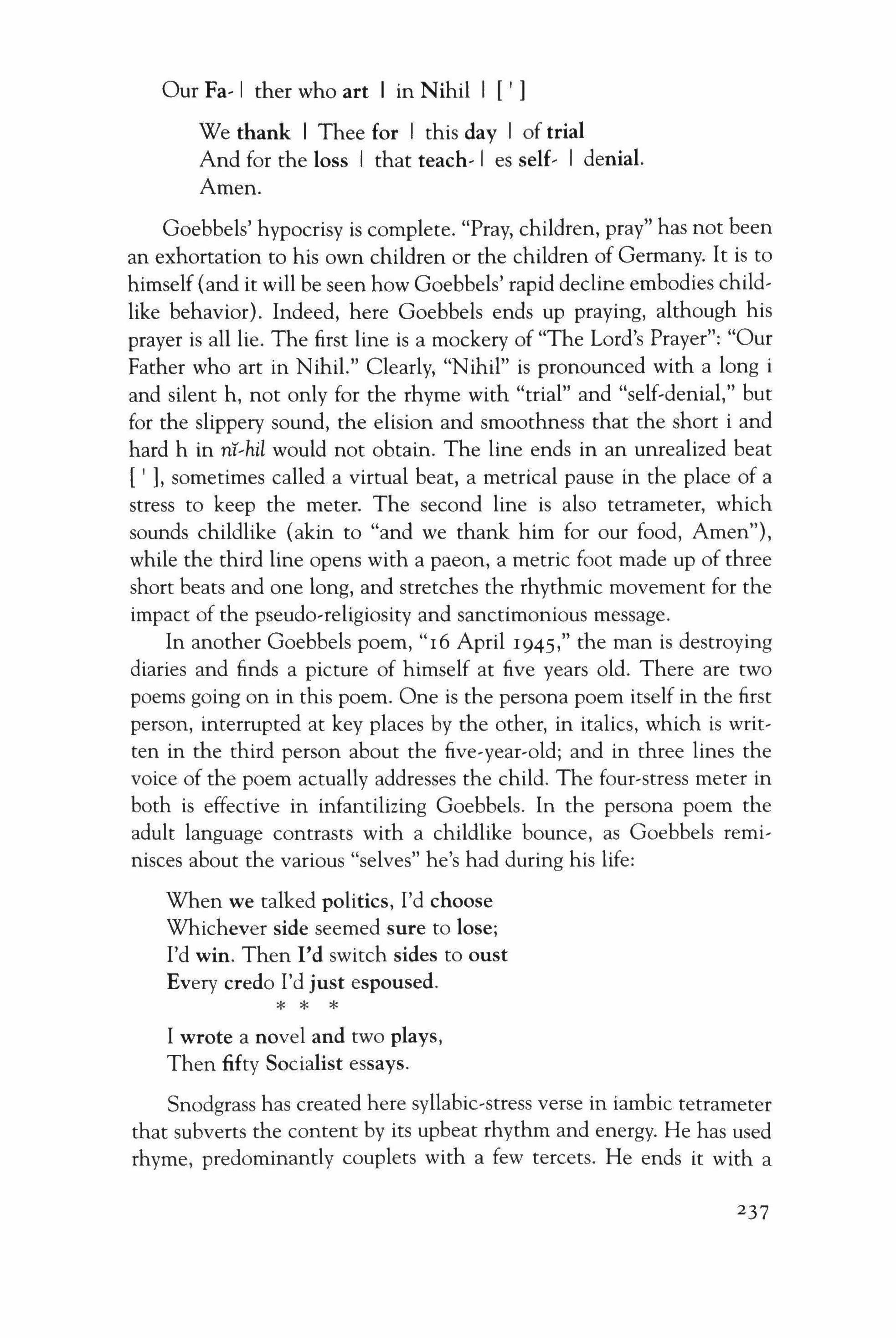

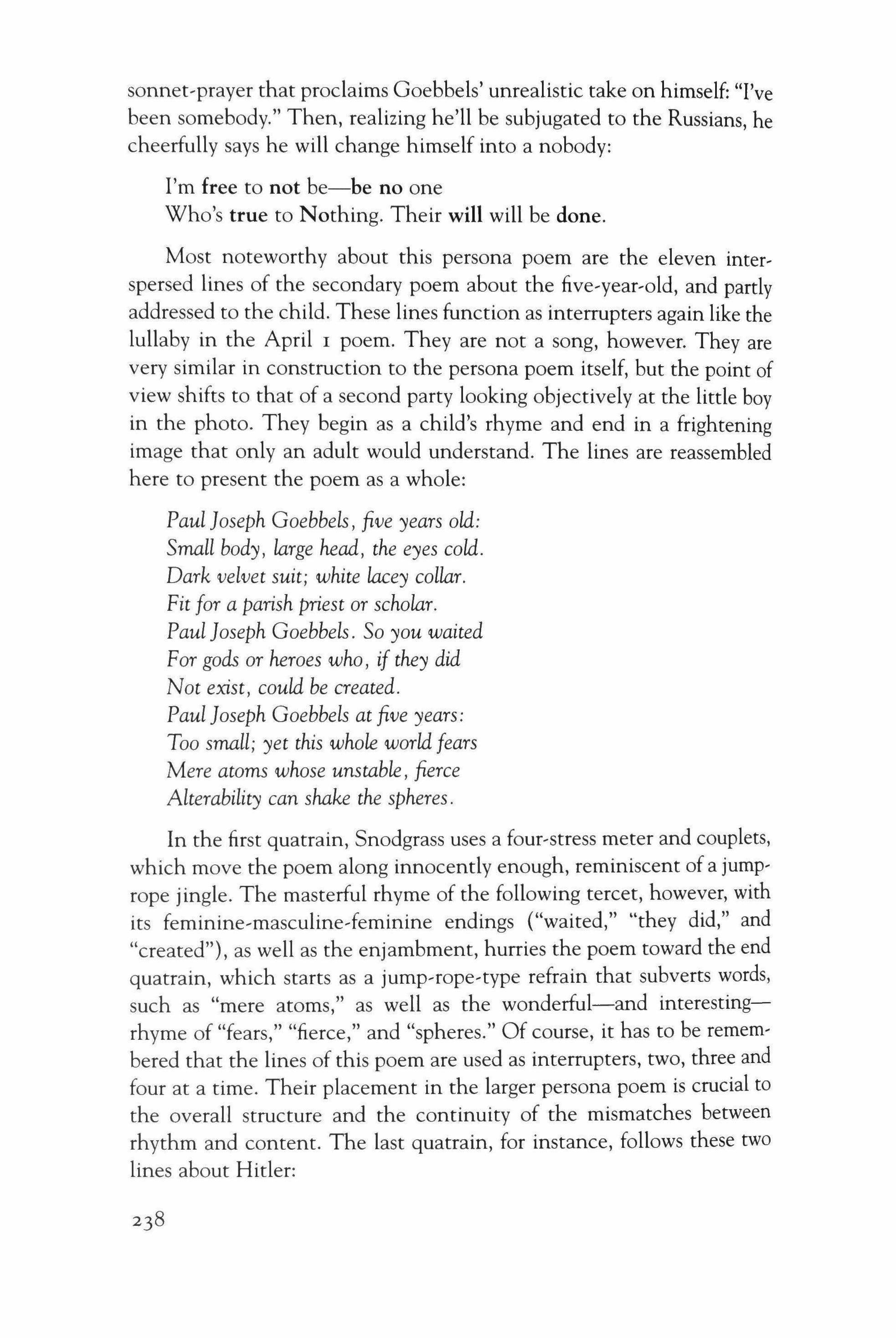

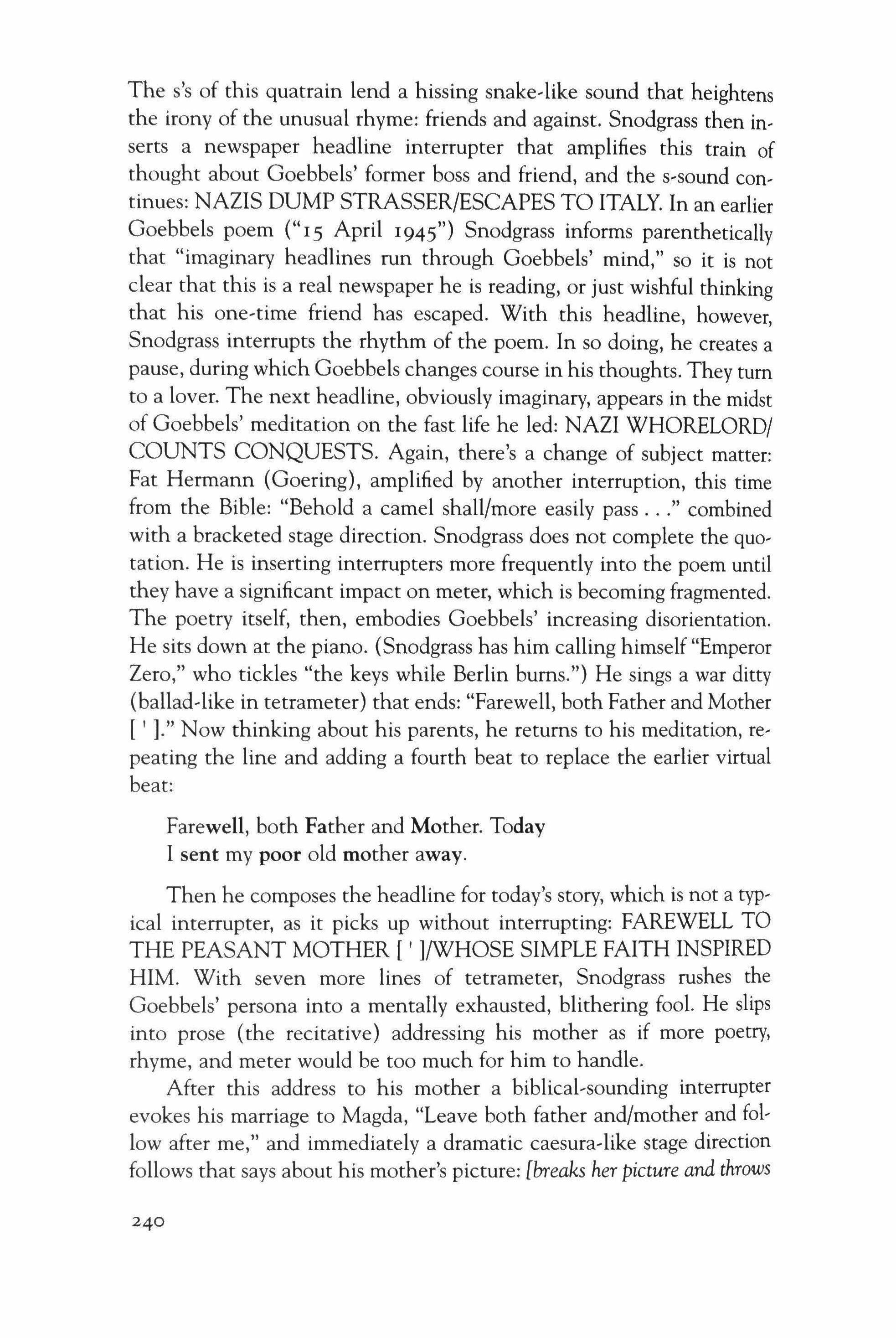

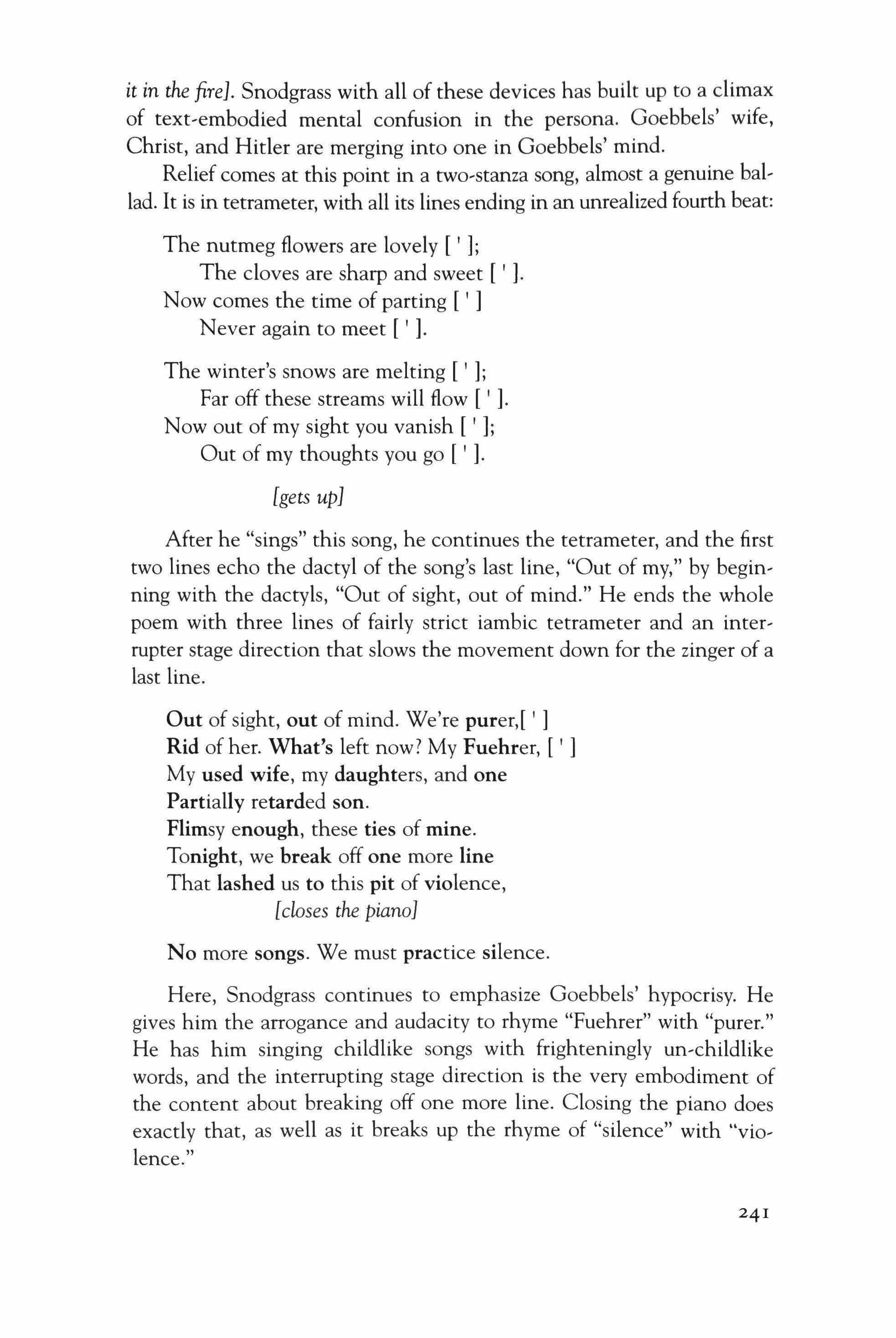

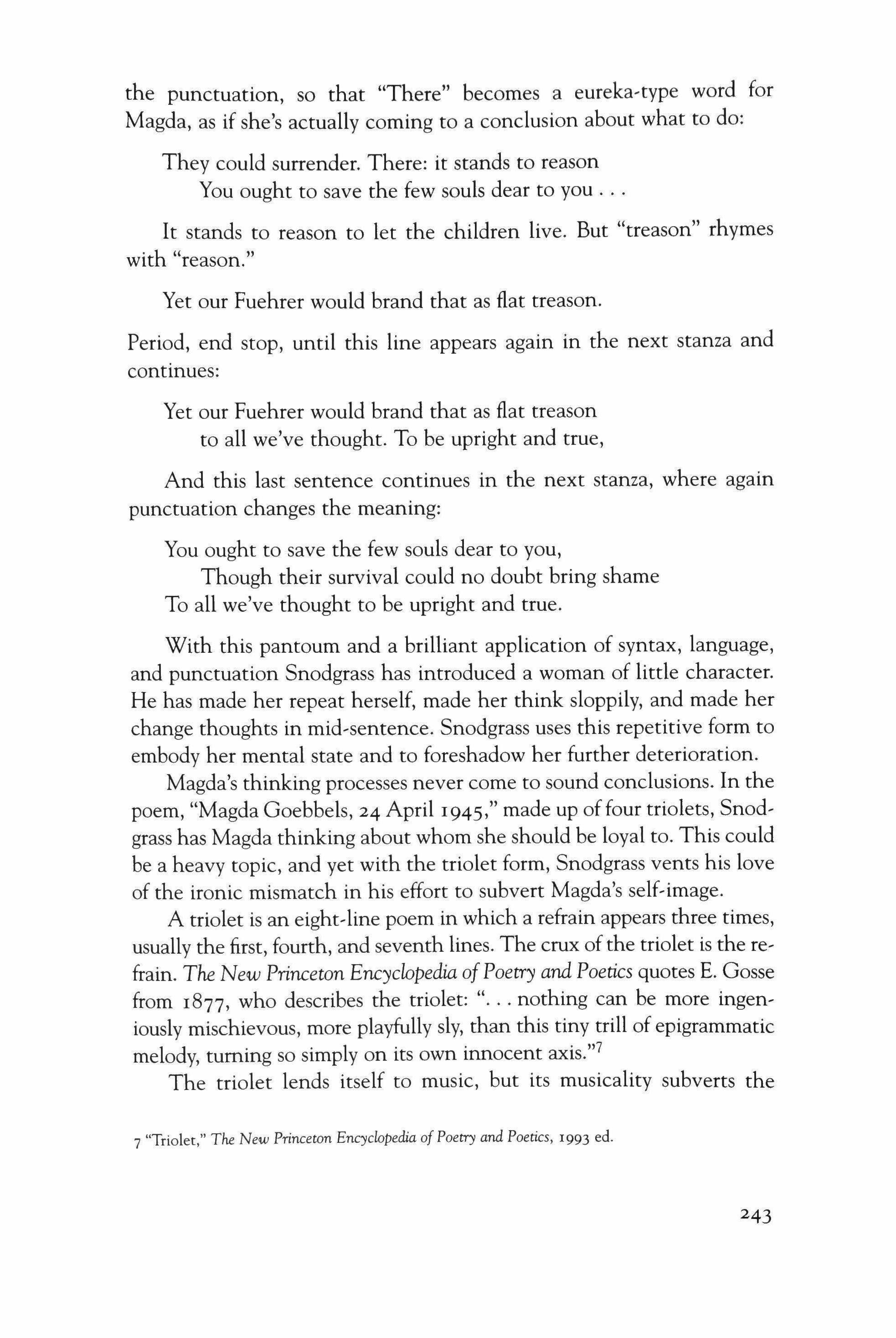

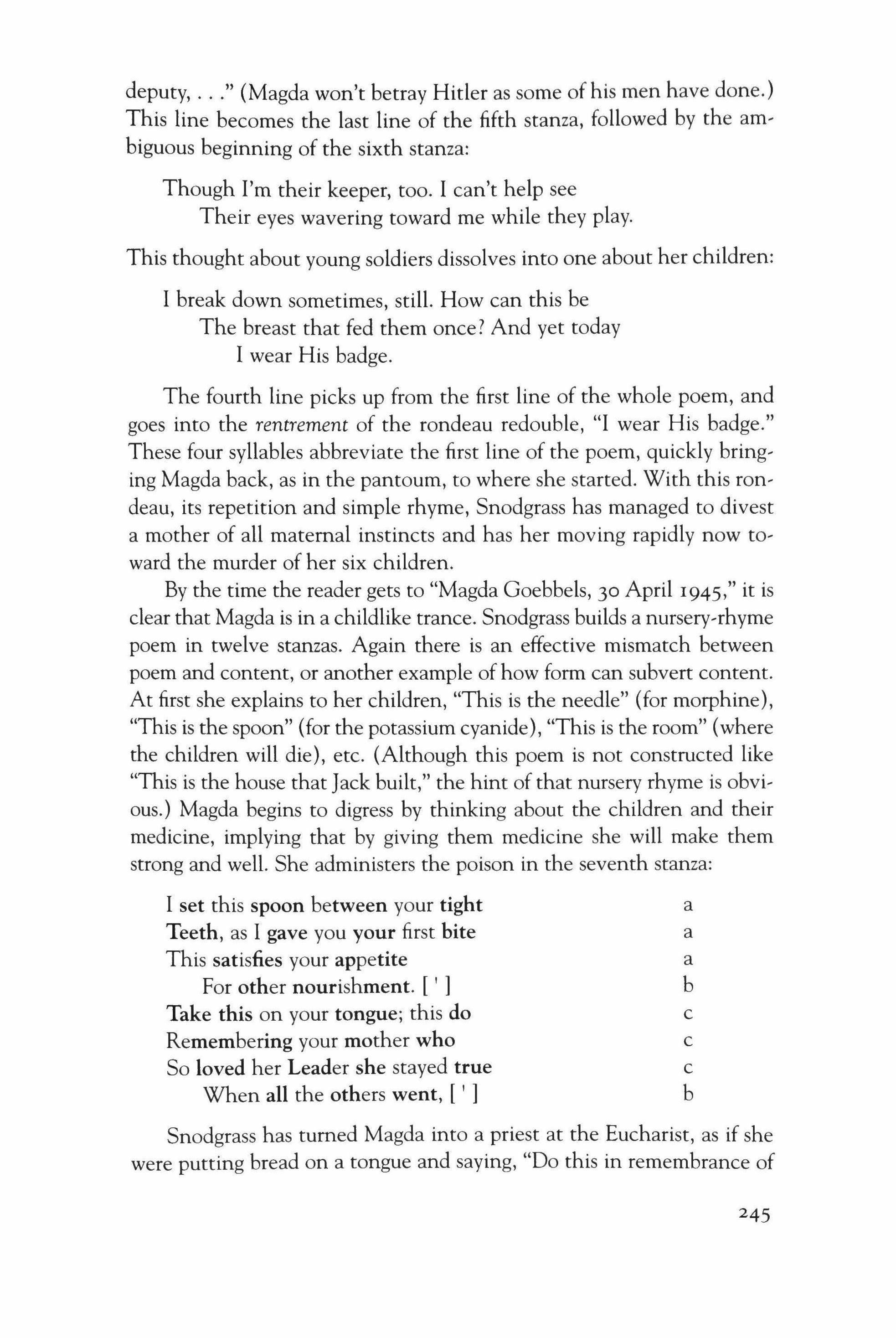

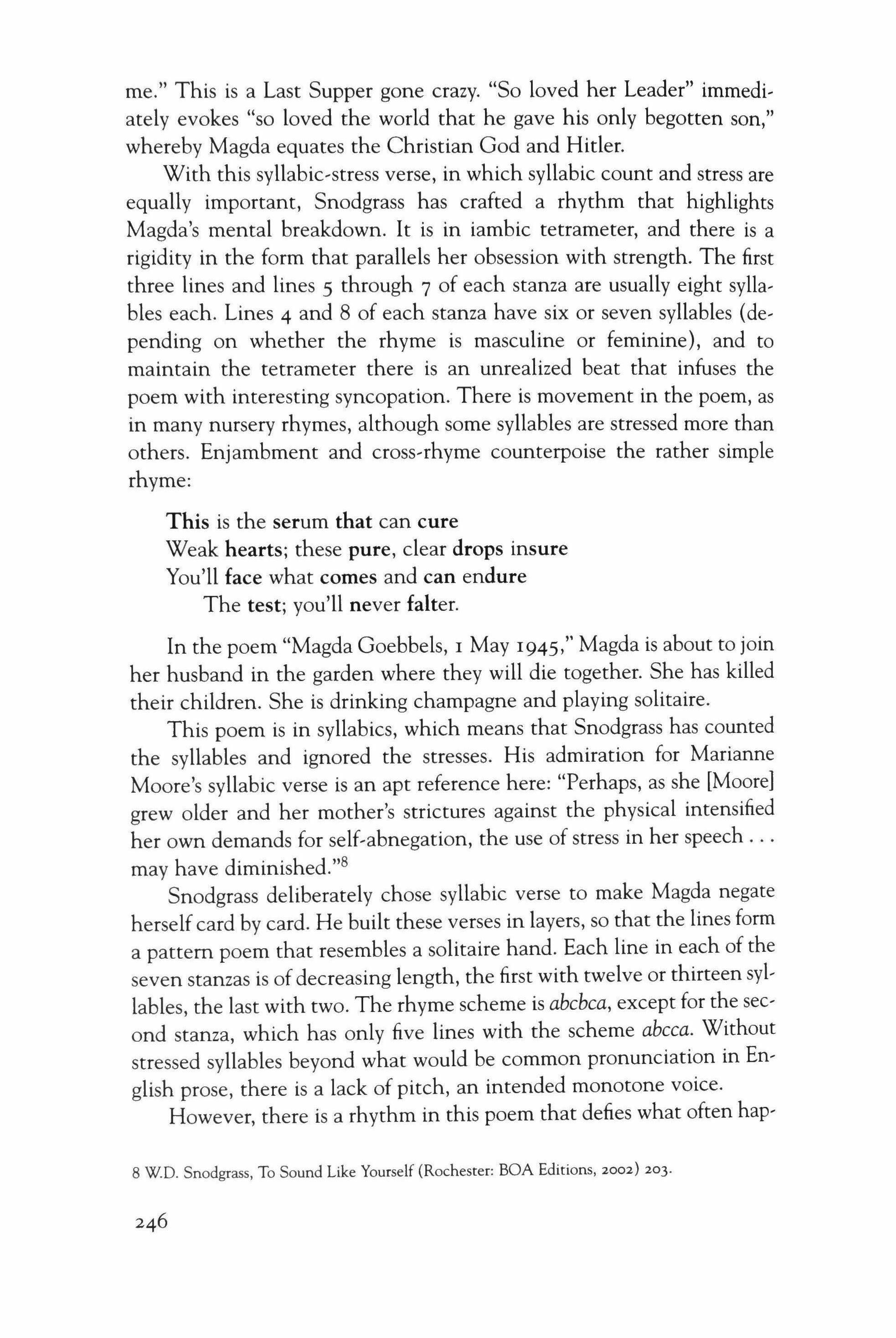

233 Crafting Evil in W.O. Snodgrass's

The Fuehrer Banker

Anne Harding Woodworth

translation

109 September's Children

Patrice de La Tour du Pin

Translated from the French by Jennifer Grotz

Cover: Pomegranates by John Matt Dorn

David Kirby

The Meistersinger of Macon

Ooh! My Soul

"What are you doing in my cousin's apartment?" asks Little Richard, and the answer is that I've come to Macon to write a travel piece for the Washington Post and also do research for a book on the Georgia Peach himself. Willie Ruth Howard is two years older than her celebrated relative, which makes her seventy-seven, and even though it's a hot day, I've put on a sports coat and brought flowers, too, because I want her to think I'm a gentleman and not just a fan trying to hop aboard the singer's coattails.

When the phone rings, she talks for a minute and says, "It's him," and "He wants to talk to you," but before I can start telling Little Richard how the world changed for me when I turned on my little green plastic Westinghouse radio in 1955 and heard a voice say, "A, wop,bop,a,loo,mop,a,lop,bam,boom!" he says, "What are you doing in my cousin's apartment?" and then "Uh-huh. Well, look around you. You can see that my cousin is very poor, can't you?" and I'm thinking, well, she looks as though she's doing okay to me, but who am I to dis, agree with Little Richard, so I say, "Sure-yeah!" and he says, "Well, then, what I want you to do is get out your checkbook and write her a check for five hundred dollahs!" and I'm thinking, [eez, I brought her these flowers

9

Heeby leebies

When you call the Macon-Bibb County Convention and Visitors Bureau, the first thing you hear is a familiar voice shouting, "Hi, this is Little Richard, the architect of rock 'n' roll, talking to you from my hometown of Macon, Georgia!"

And you think, architect? The word conjures up a larger world, that of Leonardo and Michelangelo, say, who were to Renaissance Florence what Little Richard, Otis Redding, and the Allman Brothers were to twentieth-century Macon, the one group making paintings and statues and cathedral domes just as the other made soul music, rock, and blues, each in a little, out-of-the-way town and at the same time.

Of the mastersingers who came out of Macon, Little Richard is the undisputed champ. In June, 2007, his 1955 single "Tutti Frutti" topped Mojo's list of "100 Records That Changed the World"; the magazine calls it "the biggest bang in the history of pop music." That song also appeared on Here's Little Richard (1957), the artist's debut album and one which was ranked number 50 in 2003 on Rolling Stone's top 500 greatest albums of all time.

Little Richard has been credited by James Brown, who called him his idol, with "first putting the funk in the rock and roll beat." Smokey Robinson said that Little Richard is responsible for "the start of that driving, funky, never-let-up rock 'n' roll." Capricorn Records founder Phil Walden said the "greatest rock and roll singer of all time, and the one who still possesses the truest, purest rock and roll voice, is Little Richard." And Dick Clark proclaimed him "the model for almost every rock and roll performer of the'50S and years thereafter."

Truly global, Little Richard's music electrified such figures as Friedrich Nietzsche, who said, "Little Richard sums up modernity. There is no way out, one must first become a Richardian." And Thomas Mann wrote in a letter that "I am defenseless when it comes to Little Richard's music," adding that if he saw a performance of "Tutti Frutti," he "wouldn't be able to write a line for at least two weeks."

Actually, Nietzsche and Mann were talking about another Richard, and if you substitute "Richard Wagner" for the name of the pop artist (and "Wagnerian" for "Richardian" as well as Parsifal for "Tutti Frutti"), you have their actual statements. The core idea is the same, though: unheralded, an artist appears who embodies the culture you thought you knew and expresses it better than anyone else, and, by doing so, he advances that culture to a new level. Not only that, he does so in a man-

10

ner that transforms all cultures everywhere. It was Little Richard who gave Mann the phrase "world-conquering artistry" and led him to say, "Fifty years after the death of the master, the globe is ensconced in this music every evening"-whoops! I mean Richard Wagner gave Mann that phrase, not Little Richard! Still, fifty years after "Tutti Frutti" hit the airwaves, the music of Macon's meistersinger rules the world.

Before he became the architect of rock 'n' roll, Little Richard was readying himself to play that role. In Macon, it seems everybody has a story about Little Richard. For example, Tommy, a young health care administrator, told me his parents had gone to school with Little Richard and knew he was going to be an entertainer even then because, when the teacher left the room, the precociously outrageous Mr. Penniman would put the trash can on her desk, sit on it, and sing "Sitting on the slop pot, waiting for my bowels to move." (Which, as Tommy sang it, sounded uncannily like Little Richard's 1956 hit "Slippin' and Slidin'.")

And Willie Ruth Howard, Little Richard's cousin, told me how the tot who would be the meistersinger beat out rhythms on every surface he could find, crooned Louis Jordan songs, and followed a musical vegetable vendor around the neighborhood as he sang about his wares; later, he would write "I Got It" about the little old man in a billy goat cart. Before he knew it, the Wagner of rock 'n' roll was preparing for stardom, scripting a role for himself and then, as the German composer never did, stepping into it.

He was in the right place to do just that. The history of America is that of scam artists, swindlers, posers, and other marginal figures. The country is even named after such a mountebank: a recent issue of the New York Times Book Review features a piece on Amerigo Vespucci, who bluffed his way into prominence; the pull quote reads "As it turns out, America-this nation of hucksters, dreamers and spin doctors-was named for the right guy." There's a direct lineage between Amerigo and the ventriloquists and con artists who are immortalized in the work of Charles Brockden Brown, Hawthorne, and Melville and who take the form, in the twentieth century, of Doctor Nobilio, the Macon "town prophet" and spiritualist Little Richard remembers from his boyhood, and the Doc Hudson whose medicine show the singer joined as a youth. With teachers like these, it isn't long before Little Richard is bedecking himself in pancake makeup, mascara, pomade, capes, and jewelry. With a tradition like this, it's no surprise that the most important force in twentieth-century pop music is a gay black cripple (one of Richard's legs is shorter than the other) from the wrong side of the

II

tracks. The song "Heeby [eebies" contains the line, "Bad luck baby put a jinx on me," but in Little Richard's world, a jinx just might be a good thing.

Keep A Knockin'

Little Richard first steps into a recording studio in 1951, when he is eighteen. He tries to imitate his idol, Billy Wright, but he lacks Wright's dynamics, possibly because this is the first time he has sung without a live audience to give him the yells, whistles, and waves that drive his show forward. He produces one hit that sells well in Atlanta and Macon, a song called "Every Hour," but in an occurrence that became commonplace in his early career, the song is re-recorded by Billy Wright himself as "Ev'ry Evening" and eclipses Little Richard's version.

In 1952, Little Richard cuts four new tracks, but these, too, go nowhere. In 1953, again he cuts four tracks; not only do these tank as well, but in a clash over the singer's swagger and attitude, Little Richard is beaten by Peacock Records owner Don Robey and suffers a hernia that won't be repaired for years. In a later session, he cuts four new tracks for Peacock, but these are never even released.

Little Richard keeps a-knockin' on the door of show biz success, however, and in 1955 sends Specialty Records a tape in a wrapper that producer Bumps Blackwell describes as "looking as though someone had eaten off of it." The songs on the tape show promise, but probably Little Richard would never have recorded again had he not hounded the staffers at Specialty till they agreed to bring him into the studio for a final try.

This time, the persistence pays off.

I Got It

As James Brown and Smoky Robinson point out, Little Richard began with piano-driven rock; his boogte-woogie piano recalls the use to which that instrument was put in the big-band music of the roaos. To this melodic structure he adds the infectious beat of funk, defined by music historian Anne Danielsen as "bass-driven, percussive, polyrhythmic black dance music, with minimal melody and maximum syncopation." Thus the vast musical potential of the piano is added to the funk

12

that, as Danielsen says, is "a difficult thing to play properly, because it should in fact be played everything but properly."

Indeed, the song that changed the music forever is a most improper song. The 1955 recording session with Bumps Blackwell at the helm has been productive but lackluster, though during a break, Little Richard begins to pound the piano and sing a paean to the joys of anal intercourse: "Tutti frutti / Good booty / If it don't fit / Don't force it / If you grease it / Make it easy," and so on. The music is electric and the lyrics totally unacceptable, so Blackwell calls in songwriter Dorothy La Bostrie to write new ones. Little Richard is too embarrassed to sing the song to La Bostrie's face, so he sings to the wall while she makes notes for the new lyrics. The musicians take a break, come back, and with Little Richard pounding the piano again, nail the song in three takes.

It's not always easy to see the seams in history, the rifts between what came before and what after. But this is such a seam. This is when, to paraphrase Keith Richards, a once monochrome world is filled with colors we're still trying to find names for. And it takes a song as dangerous as "Tutti Frutti" to be that powerful: in Die Meistersinger von Niimberg, the young knight Walther is eventually successful in his quest to become a master singer but fails at first because his song is "too radical."

All Around the World

Little Richard's genius lies in his invention of an "improper" style that no other musician could counterfeit.

Not that they didn't try. Little Richard's raucous style, genderbending persona, and sexually suggestive lyrics were anathema to the authorities, which is why a number of his hits were tamed and reissued by white artists, notably {and laughably} Pat Boone, whose cover of "Tutti Frutti" actually outperformed the original, rising to #12 on the Bilboard charts as opposed to the source record's #17. But when Boone released a bowdlerized version of "Long Tall Sally," the Little Richard original outperformed it on the Billboard charts, #6 to #8. Bill Haley took on Little Richard's third major hit, "Rip It Up," but once again, the original version prevailed. All successful artists go through a period of educating their audiences and persuading them to accept a new art form, and Little Richard was no exception; with his succeeding releases, the master didn't face the same chart competition from his pale imitators.

13

Of course, Little Richard's best imitators learned everything they could from him and then developed their own music. Consider Otis Redding's deliberate and repeated attempts to model himself after Little Richard or this description of the first appearance at Liverpool's Cavern Club by four gangly and barely known young men: Beatles biographer Bob Spitz writes that "the audience stirred and half turned while [master of ceremonies] Bob Wooler crooned into an open mike: 'And now, everybody, the band you've been waiting for. Direct from Hamburg-.' But before he got their name out, Paul McCartney jumped the gun and, in a raw, shrill burst as the curtain swung open, hollered: I'm gonna tell Aunt Mary / 'bout Uncle John / he said he had the mis'ry / buthegottalotoffun

The rest isn't just Beatles history but the history of pop music the world over. To the south, in the London suburb of Bromley, David Bowie took note. Back in New Jersey, so did Bruce Springsteen. Up in Minnesota, Robert Zimmerman declared in his high school yearbook that his one ambition was to join Little Richard's band. Rick James, Prince, Justin Timberlake: the line goes back to one man. To one song, really, to a bawdy shoutfest that was cleaned up in a New Orleans recording studio in 1955 and became the most influential song in the world. "Tutti Frutti" was a pebble in a pond; it shaped artists and albums, who then shaped artists and albums on their own. The influence hasn't stopped, and it won't.

Maybe I'm Right

The photographer Robert Doisneau, who chronicled life in Paris for a period of sixty years and whose best-known photo, "Kiss by the Hotel de Ville," has hung on thousands of dorm-room walls (and now web sites), once said, "The world I tried to show was a world I would feel good in, where people would be kind, where I would find the affection that I wanted for myself. My photos were a sort of proof that such a world could exist."

And what is the equivalent world that Little Richard made? Wolfgang Schneider writes that Wagner's music provided Thomas Mann's characters with a "delighting adrenalin surge, holding the promise of flight and freedom" and quotes Mann's secretary at Princeton as saying that, when the German novelist listened to Tristan and the Gotterdammerung, "his face, normally so controlled, gradually lets go and becomes

14

soft, mild, full of pain and joy." A surge of pain and joy, the promise of flight and freedom: what better description is possible of the world of Little Richard?

But as it has been revealing to put the American master in the context ofGerman culture, let us take that repositioning a little further, and here I tum to Mark Edmundson's remarkable recreation of Anna Freud's explanation of her father's work to the Nazis when they questioned her in Vienna on March 22, 1938. "My father knows you better than you know yourself," Edmundson imagines her saying. "For years he has been writing about the hunger for the leader-your Hitler, your halfmonster, half-clown-s-and all the others who've come before and all who will come later in his image." The father of psychoanalysis "understands how the leader brings oneness to a psyche-and a state-at odds with itself. He knows how the inner life is divided-ego battling id, prohibition battling desire, in incessant civil war-and how painful that division can be." And then, as though she somehow knew about the six-year-old boy who was dancing and singing for pennies in Macon even as Nazi tanks rolled through Vienna, Edmundson's Anna says that "the great man shows the people how to indulge their worst and most forbidden desires-and then to congratulate themselves for doing so Under the leader, inner conflict relaxes, people become unified. All of their energies flow in the same direction: They become intoxicated; get high, and stay that way."

Half-monster, half-clown, a leader can bring people together in benign ways as well. The meistersinger of Macon, the Wagner of rock 'n' roll, Little Richard is an anti-Hitler who melts racial divisions and gets people of all kinds out onto the dance floor, jiving together.

A foxy warrior, Little Richard fought against what cultural theorist Joseph Roach calls "the staggering erasures required by the invention of whiteness." Every song he sang and every show he performed was played out against the larger backdrop of American racism, in a world where Ed Sullivan presented Fats Domino at his piano but hid his band behind a curtain (presumably the trombone player stood well back) so white TV viewers wouldn't have to deal with too many black faces at once, an act of "erasure" exceeded only by the 1954 CBS production of the Adventures ofHuckleberry Finn that showed Huck alone on his raft, having excised the slave Jim, whose quest for freedom is the book's driving force. You can gauge the relationship between the rise of civil rights and the success of "race music" simply by juxtaposing two newspaper headlines from the era: the one reads "SUPREME COURT

15

OUTLAWS SEGREGATION" and the other "TEENAGERS DEMAND MUSIC WITH A BEAT, SPUR RHYTHM & BLUES."

But it would be wrong to sanitize rock and make it a force for social good, to say, as Mavis Staples has, that "It's all God's music-the Devil ain't got any music." Rock does unlock the id. Writing ofthe effect of"Long Tall Sally" on the audience in the Cavern Club, Bob Spitz says "it was convulsive, ugly, frightening, and visceral in the way it touched off frenzy in the crowd." The whole point of the song contest at the heart of Die Meistersinger von Nurnberg is for the young knight Walther to win the hand of the beautiful Eva, and how can a song work miracles if it isn't magic?

By the time I got off the phone with Little Richard in Willie Ruth Howard's apartment in Macon, I had agreed to give her, not the five hundred dollars he requested, but the ready cash I had in my wallet, which came to eighty-eight dollars: fittingly, the same number of dollars as there are keys on a boogie-woogie piano. She and I talked a while longer, and the next thing I knew, I was standing outside and wondering whether what I had experienced was a dream or something that had really happened.

That's the way the music works, though.

Notes

Print sources for this essay include Rick Coleman's Fats Domino and the Lost Dawn of Rock 'n' Roll, Anne Danielsen's Presence and Pleasure: The Funk Grooves ofJames Brown and Parliament, Peter Guralnick's Dream Boogie: The Triumph ofSam Cooke, Joseph Roach's Cities ofthe Dead, Bob Spitz's The Beatles, and, of course, Charles White's The Life and Times of Little Richard. Greil Marcus' The Shape of Things to Come: Prophecy and the American Voice helped shape my thinking throughout, and The Mojo story entitled "100 Records That Changed the World" was of vital importance. Other important short works include Wolfgang Schneider's "Mann and His Musical Demons" in Sign and Sight, Mark Edmundson's "Freud and Anna" in the Chronicle of Higher Education, and Nathaniel Philbrick's review of Felipe Femandez-Arrnesto's Amerigo: The Man Who Gave His Name to America in the New York Times; these are all readily available on line, as are the appropriate web pages I used from both Wikipedia and Wilson & Alroy's Record Reviews. The Mavis Staples quote is from "Respect Yourself: The Stax Records Story," which aired on PBS stations in 2007.

And while it wasn't a source of facts per se, throughout the writing of this essay I listened to the three-disc set called the Specialty Sessions, the many false starts and variations on which schooled me in the raw sounds that underlie Little Richard's shrewd, tricksy arrangements. The section heads in this essay are titles of songs on the three-disc Specialty Records set that constitutes the greatest source of information about Little Richard's early music, especially the 2:24 song that turned the world from one color to many.

Charles Baxter

The Clothes of the Master

In a rarely read and acutely disturbing late story by Henry James, "The Clothes of the Master," an odor of corruption has been subtly mixed with the rarefied air of privilege. Underneath its surface, the tale concerns the ruination of a soul.

I first read this story because it had been recommended to me by an older writer, a wise and kind man whom I had admired and loved. By coincidence, a few months after this man died, his daughters mailed a cardboard box to me. The carton had my address printed on it with thick lettering from a laundry marker, and a return address was there too, with B.'s surname and a street number I did not recognize. When I opened the box, I found some clothes, but no enclosed letter or explanation.

"What is it?" my wife asked.

"I don't know," I said. "I think these are some of B.'s things," I said. Then I looked them over. "Yes," I said. "That's what they are. They're his clothes."

I went through the box. All the fabrics smelled of him. His was a clean soapy odor, quite pleasant, and I remembered it from my visits to the apartment that he and his wife shared in New York. In the carton mailed to me, his woolen sport coat had been folded and placed at the top, and inside one of its pockets was a soiled handkerchief. In addition to the hanky, I found two dollars, a paperclip, a rubber band, and some loose change. I tried to put on the coat, but B. had been quite thin, and several sizes smaller than I was. I could hardly get my arms through the sleeves.

But I could remember visiting him on the Upper East Side when he would greet me at the door wearing that sport coat. A compulsively neat man, he would ask me to wipe my shoes before I stepped on the white carpet (the apartment often looked so clean that only such a compulsion would account for its spotlessness), and then, after I was comfortable, he would disappear into the kitchen to make tea. On one occasion I arrived on a very hot day in mid-June, and his wife, seeing my bedraggled condition, made me a root-beer float. They were always attending to your needs in that apartment and would give you food and drink almost before you yourself had noticed that you were hungry or thirsty.

I would sit in their living room and listen to him if he happened to be in the mood for talking, but more often, especially when he grew tired, he would ask me questions about myself, and, in order to please him and his wife, I would answer his inquiries at length, trying to be charming and witty.

But at other times I would inquire about his own writings and about literature.

"What's hard about getting old," he once said, "is that you don't have the time to re-read all the books you love. You have to say goodbye to some of them." In one of these conversations, I asked him whether he felt that way about any of the novels of Henry James, especially the late ones-whether he loved them and felt that he had to let them go, too.

"Oh, no," he said. "All those qualifications and shadings don't seem dictated by necessity. In late James, they've just become habitual. I find the prose somewhat tiresome."

I once said to him that I wondered whether a contemporary writer could ever employ that style.

He shrugged and said with a smile, "Well, you could try it."

Then, for some reason, he recommended James' story "The Clothes of the Master," from 1905. He said, "Almost no one has read it, but it's quite interesting." With some trouble, I found a copy of this story in a university library; after studying it, I was rather befuddled. I searched for some commentaries. There are very few. Critics seem to have avoided engaging the story's plot or themes, finding the tale both convoluted and naive. Why had B. recommended it? I searched through the story for clues.

In "The Clothes of the Master," the "Master" referred to in the title is Newell Schillingsworth, a painter. The other central character, the narrator (who, in a characteristic Jamesian move, never gives himself a

name}, characterizes his initial role in the story as the older painter's youthful acolyte.

This apprentice, the anonymous narrator, after having been given a note of introduction by a fellow painter, arrives at the master's studio in Tuscany where Schillingsworth appears to be putting the finishing touches on an "indescribable" painting, unshowable in any gallery at, tended by cultured ladies or gentlemen. A lengthy passage intervenespages of torturous throat,clearing-before the horrors of this painting are suggested. As the story puts it, "It was certainly not, in all other respects, a deficit of proportion or of proper ordering, but rather that my keen survey of its [the painting's] contents came up baffled by his wish, as it were, to set forth the morbidly inaccrochable to a public blissfully unaware of his more subtle triumphs."

Whether the painting depicts a sexual encounter or a violent one {or, indeed, some other subject entirely}, the story does not say. Nor does the narrator's roundabout description establish whether the painter has employed a model, or models; all this is left to the reader's troubled conjecture. From the sentences on the page we learn, simply, that the subject of the painting is "appalling,"-i.e., what it depicts is so terrible that one simply cannot discuss it without turning into a goblin oneself. This judgment does not seem to be a result of the narrator's prudery; it is, in an odd sense, objective.

Schillingsworth, however, appears to be unapologetic about his artistic procedures or his handiwork. Indeed, he presents himself to the world as cheerful and benign. This outlook of his makes matters worse. The "Master" appears to be at peace with himself and his visionsshame is not one of his available emotions. He has adjusted to the doubleness of his art and psychic conditionings and as a result has developed a system of private and public "showings," separating the greater part ofhis work, those daytime paintings that can be "displayed," from that of the minority, those nightmarish ones that must be kept hid, den away in de facto storage, or else exhibited surreptitiously, in the most intimately discreet galleries

The paintings of Schillingsworth's "unshowable" subjects, it is also made clear, are not simply obscene, obscenity constituting a certain variety of innocence. Instead, obscenity serves as a kind of monotonous background to what might be termed "the metaphysically abhorrent." By itself, obscenity cannot for long occupy an adult mind, and nothing in the presentation of nudity or even sexual congress is particularly shocking to those for whom travel and the world's variety are a known

20

quantity. No: what disfigures the paintings is "something beyond dark, ness that reeked of foul avarice," a mixture of greedy ghastliness, sexual malfeasance, and blasphemy, a "darkness beyond the dark," the story in' forms us in a characteristic repetition. "I turned away from his representations, in a condition all confused," the narrator continues, "by the existence of a not insignificant, and appropriately proximate, pit into which I felt myself, almost smilingly, by the artist, lightly dropped."

In the long first scene, however, we also learn that some of Schillingsworth's patrons know perfectly well about the "products of darkness" and have, furthermore, purchased them. These collectors may have triumphed over sanctimoniousness, but they know better than to display their acquisitions in their own houses or to talk openly about them. The news of the existence of Schillingworth's grim visual horrors has spread among the knowing and has produced a higher valuation of their counterparts, the bright studies of household decor, the seascapes, the still lifes, and the portraits of beautifully earnest young ladies for which Schillingsworth had gained a respectable worldwide reputation. Indeed, the existence of what the story calls the "shadow,stricken visual sonnets" if anything gives greater value to the "odes to joy and the luminous." The existence of unspeakable visions appears to be the gold in, side the coin that gives the coin its value.

All this takes many pages to set out; the story's exposition is labored. The narrator begins his artistic apprenticeship to the Master. Many servants attend to the older man's needs, and to those of his wife, their almost,grown children, and the narrator. Three years pass. Schillings, worth (some irony is certainly intended by the name's clear reference to money) sickens from an obscure disease and goes into a fateful decline.

During this period, he bequeaths to his now-mature apprentice his working clothes, the smocks he has always worn while applying paint to his canvases. But there is a catch: one set of clothes, it seems, should be worn for painting the studies of light and joy, another set for creating the evidence of the dark. Here the story's debts to Robert Louis Stevenson, on the one hand, and Nathaniel Hawthorne, on the other, become apparent. In any case, the master on his deathbed also, and obliquely, offers the hand ofhis daughter to the younger man, the narrator, who has, all along, been attracted to her, for her great beauty and for her purity of heart.

Schillingsworth's daughter is called Lily. As the name suggests, she presents to the world an unstudied charm and grace, an inward

21

spontaneous loveliness. Despite her great beauty, she lacks vanity or any apparent wish to exploit her beauty for worldly advancement. Though she has lived long in Europe, she is, or at least appears to be, at heart, "an American girl in spirit," though she shows "no evidence of the vulgar, groundling, taste." Instead, she combines forthrightness and "an unsullied, if educated, innocence." We begin to understand that Lily has admired her father's apprentice, who, we now learn, is "not unacquainted with the formulas of soothing grace, those seductive murmurings of seemingly effortless charm." They marry on the first anniversary of her father's death.

At about the time of the marriage, Schillingsworth's apprentice begins to wear, while painting, the eponymous clothes of the master, and the alert reader will be unsurprised to learn that the narrator's initial project consist of two wedding portraits ofhis wife, the first in the bright style, but then, inevitably, the second, in the dark style acquired from Schillingsworth through practice, observation, and trial-and-error, and duly executed while attired in the garments appropriate for the shadowstricken sonnets. In other words, the second portrait of Lily will constitute a tainted representation ofher beauty, as if the narrator, in marrying her, had learned-as she herself had learned-something of the depths of erotic longing and degradation in which true love may still discover itself also to be an ingredient.

Somewhat to his surprise, the narrator finds that Lily does not shirk from modeling for him, nor is she taken aback, or at all shocked, to see herself rendered in his canvas, "among the spectral array of the higher and more luminous angels and demons at no great distance from herself." (The sentence seems somewhat deliberately unclear.) Indeed, she appears to be ready for this assignment, and, what is worse, practiced in it.

Our narrator, in what is one of the story's more dramatic turns, discovers that Lily, whom he had thought to be innocent, may in fact be the carrier of a knowingness concerning the subterranean realms of which he has had very little inkling. He cannot tell whether the corruption he detects is located in his wife or in himself. Nor is it scrupulously clear, in the closing pages of the story, where Lily may have learned what she knows, or where she may have acquired her apparent ability to bring about a change in her husband; when the dark portrait of her is completed, she contacts her father's friends and admirers, whereupon the morbidly disturbed painting is sold in this artistic black market for an immense sum, equal to the greatest fees once paid to the Master.

22

In completing this dark portrait, the narrator has achieved, we are to understand, the status of a master himself. And it is also at this juncture of the story that the narrator, still a young man, discovers that he has (perhaps) contracted a disease, not immediately fatal, but one that, by slow degrees, produces physical decline and psychic destabilization, a malady resembling the one that Lily's father succumbed to. If Lily has the disease herself, she shows no sign of it. She remains pure and uncontaminated, while he is riven with a "subtle consternation."

In the concluding paragraphs of the story the narrator struggles to return to the world of still lifes, seascapes, and the portraiture of innocence, but a "thick dismal weight," and "a shifting, as if by degrees, toward the darkening of the eclipse" make him incapable of a vision in which the metaphorical full morning sun illuminates everyday things. Lily, who has never stopped "appearing to be the summoned ambassador of permanent glory" but whom we know to be, instead, somehow a missionary on behalf of darkness, begins to take on the role of caretaker to stricken artistic conscience. She brings shadows and darkness, as it were, into her husband's studios for him to paint. And yet, in this last movement of the story, he finds himself in rebellion against her cultivation.

There was not, in my last estimation, a sight so mean that true artistry could not find a manner, a sole flick ofthe brush, to bring it back to light, that is to say, to heaven; and if the donne were to locate its origin in such a world as this one, clotted as it was by desires all doomed by the degraded, the sullied, and the sordid, still, I surmised, the art that I was yet to discover, while mortally diseased, might, through enduring the disease itself, and resisting it, prove to be my redemption, and not yet my undoing.

When critics have quoted from "The Clothes of the Master," it is these brave words that they have usually cited, as one of Henry }ames's-the author's-late professions of faith. Lily has been compared to Kate Croy, in The Wings of the Dove, and may in fact be a belatedly revised version of that figure of control and duplicity. That said, the story leaves a particularly sour taste. In this story, degradation is certain, and redemption, if imagined, nearly unreachable. The story presents us with a curious view of marriage, artistic endeavor, and moral and spiritual degradation in relation to success. One closes the elderly book of stories containing "The Clothes of the Master" with a peculiarly uneasy feeling, close to vertigo. The book itself is likely to be from the library (the story has rarely been reprinted), and time will have had its

23

way with it: most copies have broken spines and carry with them the musty smell of oxvdized paper.

My own story, however, does not quite end there. Following my friend's death, I wasn't especially puzzled by the arrival of the carton containing cast-offs from his clothes closet. Almost everyone who has lived through the death of a relative or a loved one knows that the process of grieving is intensified and complicated by the leavings, the remnants, the house, hold objects. What do you do with all the garments belonging to the de' ceased, drenched in memory? The red dress worn to the summer party, the scarf wrapped around the neck all winter long? The swim suits, the beautiful junk jewelry, the tarnished trophies for athletic achievement, the perfumes? What do you do with the framed certificates, the proud diplomas, the photo albums, the personal correspondence ofhandwritten notes? What do you do with the little brass trinkets, the glass paper, weights? The person who is mourned somehow lives on in these things. You are not suffering a haunting, but the existence of the surviving effects is not quite benign. You can't just put the collected household objects in the dumpster. If you do, you'll pay for your thoughtlessness in memory and in dreams.

So it is understandable that my friend's daughters would have ernptied his closet-his wife died at almost the same time that he did-into these cartons and mailed them off to the people who knew him and loved him.

Some of the clothes they sent me I threw away, but because Ire, membered the woolen sport coat from those occasions when I used to visit him, I hung it up on my clothes rack next to my own shirts and jackets, a few of which acquired trace odors ofhim. Every morning when I dressed for work, I would see that coat, and every evening, when I dumped my dirty socks into the hamper, I would see it again, swaying in the closet in the breeze from the heat grates.

I grew exasperated by my inability to deal with this reminder of B.'s existence. It didn't seem right to keep the coat around, but it seemed equally mistaken to dispose of it. Finally I had a dream one night in which B. came to me and said, "You have to let me go." He made some other statements, but that one-"You have to let me go"-is the one I remember.

The next evening I put his coat on a different hanger, went through its pockets one more time, and took it downstairs. As if I were sneaking some criminal substance into the next county, I put his sport coat into

the trunk of my car. I lifted the garage door, peered up and down our residential block (no one else was out at that time of night), and after getting in behind the wheel, I started the engine. While I drove to the box for Goodwill donations, I thought of the strange and disturbing Henry James story, "The Clothes of the Master," he had asked me to read and which, to tell the truth, I had disliked, and I thought of the two slightly gimmicky props in the narrative, the contrasting smocks, one for light paintings, one for dark, handed down from the master to his apprentice. I wondered, once again, why B. had recommended the story to me and why (or if) he had liked it himself, or if he had read any of the criticism of the story, much of it written in dreadful half-dead academic prose.

I reached the strip mall on the west side of town where the Goodwill box was located. After parking the car and turning off the ignition, I sat for a long time behind the wheel. In front of me, two teenagers were standing outside a jewelry store, looking in through the window display at a set of rings, necklaces, and earrings. Very soon these two, a blond boy smoking a cigarette and his dark-haired girlfriend with her hand in the back pocket of the boy's jeans, would probably be married; very soon they would start their own collection of odds-and-ends that someone, someday, would have to dispose of.

I turned on the car radio. An announcer read a weather forecast. There would be colder temperatures, rising winds, and possible snow. Having popped the trunk, I got out of the car, leaving the radio on, and reached in for the sport coat. The teenagers, hearing the radio, turned around to watch me as I took B.'s sport coat to the Goodwill box and dropped it in through the chute, although first I buried my nose in the fabric one last time to remember him. For some reason I cannot explain, I felt both guilty and sorrowful.

In any case, when, upon returning to our house, I entered the bright heat of our kitchen, my wife looked at me quizzically, and I meant to say, "Well, I finally got rid of it," but what I actually said was, "Well, I finally got rid of him," and when I heard myself misspeaking, self-condemned with a slip of the tongue, I sat down on the floor and broke into sobs.

B. never acted like a master, and I was never his apprentice. By the time I first met him, I was too old for that. The only times I had ever been an apprentice to anyone were those occasions when my older brother had tried to wise me up about life. Many decades after my childhood apprenticeship to him, at a time when he lay dying in the hospital, I asked him whether he had made any special funeral arrangements. "Dress me up as a Viking," he said, and for a moment I wondered

whether he meant the football-playing variety, or the actual kind, with spears and horns and bearskin. "Put me onto a huge boat," he said, "one of those barges, and push it out into the lake, and set fire to it." He smiled at the thought of a blazing Viking funeral. I smiled too.

But he had been a manufacturer's rep, not a Viking, so after he died, I was delegated to go into his apartment to find a sport coat and slacks to bury him in. I picked out a blue blazer and a pair of plain gray cotton trousers. I also picked out a pair of tasseled loafers that I knew he had liked. I found a bright red necktie for him. No one ever tells you that someday you may have to dress someone you love for eternity. The closet gave off my brother's familiar odor, which I had known my entire life. He had saved me from drowning, and he and his girlfriend had once taken me along on a date, so I could know what it was to be happy.

On the day I chose his burial clothes, I sank to the floor underneath his jackets and sat there next to his collection of shoes, and later I told my friend B. about how I had had to pick out the coat, shirt, tie, and trousers and casket in which my brother was buried, and B. nodded, as I knew he would, and still later, out of the stoic resources of art, its lifegiving duplicities, I concocted a nonexistent Henry James story, "The Clothes of the Master," a melancholy gothic tale, and I imagined B. as its reader, to contain my grief.

David H. Lynn

Emergency Run

So, okay, Caroline has done this a thousand times. Or if not, then it seems like it and it's been plenty enough. Sometimes they'll be gone already by the time the emergency squad arrives, and there's nothing she or the team can do. CPR. Defibrillators. The body will jerk and jump and flop back. Nothing.

Others, they look like nothing's wrong at all, them a bit vexed at the fuss or puzzled maybe. Maybe they'll be cradling their left arm like it hurts or is suddenly heavy. What made them decide it was a heart attack and call 9 I I? She wonders that sometimes. Of course, many's the time they're wrong-no attack, just indigestion or the flu.

But this run is tense. Out of sync from the get-go.

Randy Jenkins, their squad leader, has paged her twice in four minutes, even though at the first buzz from the dispatcher she rushed straight away from the old woman whose blood sample she was collecting. (The insurance company won't reimburse for a second visit, but that goes with doing this job.) The damn pager trills again on her belt as she's pulling in next to the squad's ambulance-she can see Randy at the wheel. Then she's up shotgun and no joke from him, no flirt, nothing, (a relief for sure, but also goes to show things are out of whack), and he's already got the vehicle rolling.

Not that there's far to go, just up the road to the Student Health Center. Even on a short run the squad is supposed to use the siren. Randy doesn't bother. But as they wheel into the drive, Caroline thinks it's as if some kind of silent siren has been blowing its head off anyway,

a special whistle that has the college students milling around outside, watching, glum and scared. They've only come here so Doc Hazzard could check them out for STD's or asthma or strep.

The nurses and receptionist aren't doing much better. They're flapping themselves about in little circles as the squad skids up on the loose gravel, its lights flashing silent and wild.

As team paramedic, Caroline is swinging out her door before the vehicle has fully stopped, jogging quick but under control onto the porch. Randy and Steve Coady, a student trainee who's been riding in back, will hump the equipment behind her.

Like most every afternoon, Doc has been on duty in the two-and-ahalf story clapboard house. He's waiting for them in his office. Subdivided over decades and added onto by happenstance, the health center is a complete hodge-podge of elbowed hallways and improvised partitions.

Caroline realizes-the kind of thing you realize in a rush-she's never actually been in Doc Hazzard's office before. She plunges through the door, and the dark little room is crammed with books and random bits of medical equipment, and maybe a dozen old clocks, some of them with their pendulums happily wagging away. Oh yeah-somewhere she's heard that he collects them. But she's never been in this office before, which strikes her as kind of strange now that she doesn't really have time to think about it.

He's sitting in an old wooden desk chair, gazing towards her and very still, which is also something she can't remember ever seeing, him sitting down. Except maybe when he's crammed hunkering on his haunches next to her in the back of the medic, tending whoever is lying on the gurney, the two of them rolling with the sway of the vehicle on its rush toward the county hospital.

"Hey, Doc," Caroline says, all sweetness and light as she wraps the pressure cuff around his arm. "When did this all start?"

"It's nothing," he says. Just as she expects him to say.

"Okay, I hear you." She's working quick, already pumping the cuff tight and reading her watch. "But when did you first notice this nothing?"

He won't look her in the eye, and with his pale blue eyes and his pout and his shock of wild hair, even if it's thin and graying, he might be impersonating an obstinate schoolboy. "Yesterday. It was just stress. It's probably just stress." But the doctor is also gray, his skin clammy, blood pressure low and pulse not what it should be.

"I'll bet you never even called it in, did you? Did Nurse Radcliffe figure it out and make the call?" Caroline's shaking her head and not giving him time to reply. "You ought to know better," she mutters.

"Can you get that thing in here?" she yells. But the gurney won't make it into the cluttered office, so Randy and Steve set the brake and tear the straps loose on the other side of the door.

"You come on now," she orders.

"I don't need this. I can ride with you," he says, not quite whining and not even convincing himself.

She helps him up from the chair, a hand under his elbow, lifting, urging him forward at his own pace. He makes it to the gurney, and he's panting now, and sweat beads are popping on his neck and brow. First he sinks onto the padded seat, then sort of rolls full out. While the boys are strapping him down, chest and legs, Caroline notices him close his eyes, letting go just a little bit, just for a moment.

She fumbles with the buttons on his starched and ironed shirt-she knows there'll be hell to pay if one pops off-so she can put the stethoscope against his chest. The long scar startles her, though at some level she knew it would have to be there, a blue-white rip that's probably more pronounced right now anyway, slicing from the top of his sternum down at an angle across his ribs and into the softer flesh below his belt. Seeing it, she's surprised the wound didn't kill him after all, all those years ago.

And that's when a sudden surge of warmth catches her by surprise, almost a thumping blow to her chest. As if an attack sympathetic to his own has flushed through her. Except it's different. She recognizes it right away and falls back a step, startled, needing to consider or get a better look, while Randy and Steve roll the gurney toward the medic.

She's worked with Jeremy Hazzard better than nine years now. At first she lived in mortal terror-him brusque and impatient, demanding a perfection that always seemed just beyond the furthest finger-tip-reach of achievable when it came to equipment properly sanitized and stowed, procedures precisely choreographed, and patients triaged, bandaged and, most precious of all, stabilized.

Down time could be just as awkward. Doc Hazzard never made small talk easily, never went out with the crew for a simple beer. Or if he did try and hang out, say in the ready room on a Sunday, maybe football on the big TV and pizza slices passing hand to hand, he'd be restless and stiff, twitching almost.

The E.M.T. training he supervised was tough too, every detail, every drill. But she didn't mind the toughness. It honed her, challenged her.

But early on she was scared, no-wary-of him because he seemed, well, so out of place. Almost like he came from a different planet. Look at the way he was about his shirts-the only personal possession he'd fuss over. She knew some of the girls at the laundry, and they'd just roll their eyes. His collars had to be ironed just right. Not too much starch -but they better be crisp. And those precious cuffs. French cuffs, for heaven's sake. Who in Ohio did that? Except Caroline knew he didn't actually wear them full out with cufflinks most of the time. Routine and ritual: first thing every work morning, standing in the window of the health center, he pops the little studs out of the cuffs, slips them in his pocket, and folds the sleeves back, once, twice, exactly so.

Once, she'd thought about buying him a set as a thank you, given all he'd done for her. His birthday was coming up-a fact she discovered only by chance from one of his ex-wives, Sandy, who maybe was still married to him at that point. But the only kind they had at Wise Jeweler's on Mulberry Street, cufflinks with little train engines or gold hearts soldered on, they didn't look like the ones he wore, somehow so simple and elegant, and she felt stupid even caught studying them in the glass case like it was for some exam. She bought a nice card instead. Which she suspects he never got around to opening.

But what intimidated her, early on at least, was more than his education (which you'd have to spy in his voice anyway because, unlike every other doctor in the county, diplomas weren't hanging overhead to prove him some kind of blue-ribbon stud) or where he came from or even the damn cufflinks. It was in the bits and pieces she'd pick up through the grapevine, from ex-wife Sandy and others too-stuff anyone else would parade around in stories for the rest of their lives. How he'd been wounded as a medic in Vietnam, for starters. Apparently the healing of that scar across his breast and belly was slow, difficult, never really complete, though he was already in med school by then. Afterwards, he builds a practice up in Cleveland. Only to abandon it, no warning, no explanation-Caroline figured that must have been the beginning of the end with Audrey, ex-wife number one.

So why pick Coshocton County? Talk about rhyme, reason, and none of the above. No one has an answer to that one. First, sort of out of the blue, he volunteers to take over the emergency room at County, duty none of the local G.P.'s want to touch. It's always been a low-mantotem-pole rotation. Then, maybe five years later, the college dean begs

30

him to fill in for Dr. Shepard, who's been ministering to students almost since horse-and-buggy days. In his seventies, he'd become a little too eager offering breast exams to the coeds. Dr. Hazzard's responsibilities will last only a few months while they hire someone permanent. Promise.

And then comes the years she knows almost first hand. Did they ever really search for a replacement? Doc Hazzard steps in to the little student health center-almost starting from scratch to where it is today-and unlike the emergency room or his own practice, the duties of college physician give him off-duty time for training the emergency squad. And there's the women's shelter too. And the homeless services, and the county jail. Any local organization with sense enough to ask his help, because he can't, won't, ever say no.

This all is what's puzzled her. Doc Hazzard a mystery, like a foreigner or a strange pet you don't ever understand but get used to. It was who he was, and after a while it just didn't bother her anymore.

She never expected to be doing this anyway. She volunteered to join the squad because that's what Randy was doing after he dropped out of the Nazarene College on the other side of town. It was a way to spend more time with him, because they were together then. Then after a couple of years they weren't together, because Randy had been doing something more than flirt with Rhonda Jean Owens. At least that was the excuse she told both him and herself when she broke it off. But by then she'd already passed the first two levels of E.M.T. certification, and Doc Hazzard was encouraging her, baiting her, daring her through the final rigorous stages of paramedic training. She wasn't about to leave and go back to what her life had been.

When the moment finally arrived, he was the one carrying the long cardboard tube like a baton out into the fire station's parking lot. He motioned for her to climb into their ambulance. "Look at that," he said admiringly. "Do you realize? You just worked some magic, Caroline." He gestured from front to back with a wave of the baton then handed it up to her. Inside was her paramedic certificate. "All you had to do was set foot up there and this squad wagon became a medic. I think that must mean it's for real." He shook her hand. "I'm proud of you."

She'd felt a rush then too, for sure. Gratitude, pride, not a little disbelief.

She jogs out to that same medic just as the boys finish hoisting the gurney up into the back. They tum, waiting for her to scramble in as well.

3I

They'll ride up front, this time with both siren and lights at full blast for sure.

But Caroline hesitates. Not so much a hesitation as a hiccup, a double bounce on her toes before she's up and through and the door is swinging shut behind. And she's watching herself tend to him. His eyes are closed again, his breathing shallow, a light pant. She should touch him to check his pulse again and she hesitates, again. His eyes flicker open and he looks up at her.

"Hey," he murmurs. "Last time I was on my back this way, they'd brewed up a whole war around me. I hope there's no fuss like that this time."

The wan little smile he gives her is like a knife, slicing through the muscle of her chest, releasing the warmth and pressure that flooded there only moments ago. Caroline never cries-she's one tough broad, as Randy often boasted, sometimes not a happy boast, but she's come to like the notion-so naturally the tears are already running down her cheeks and dripping off the tip of her nose. When she wipes at them with the back of her hand she makes an almighty mess.

Fortunately, Doc Hazzard's eyes are closed again. And his vitals are stable, so she takes two seconds to wrestle a tissue out of her jeans pocket. Here she is, breaking one rule after another of the hygiene he's been so insistent on while teaching her.

Shit, she's thinking. Shit, shit, shit.

No goddamn warning or hint or nothing, just the overwhelming fact and certainty smacking her between the eyes.

Why now? she wonders.

It's horrible.

Not to mention absolutely nuts.

What it's not is anything like that platonic stuff that Randy is always gassing about while trying to get back in her pants. But it's not really hot either-about sex. She doesn't want to sleep with him.

Well, maybe she does, but that's not the point.

It sure as hell isn't maternal.

She just wants him. Every little bit and scrap of him.

Caroline never cries and she's thirty-five years old and never been in love, not like this, and she's been so proud of it. Now what the hell is she supposed to do?

Normally, she'd make a clean hand-off at the emergency bay, but this time she's walked the gurney all the way through to the curtained cubi-

32

de and helped transfer him up into the hospital bed. No one seemed to notice her, not even him. Well, why the hell should he?

Back out at the medic she cooks up a ragged excuse about checking on some one else who's already been admitted. So Randy and Steve make the five-mile run horne without her. It's not like she's essential. There are two other paramedics they can call and seven E.M.T.'s.

She just needs some space to calm down. To think.

This isn't life or death, not in any immediate sense. If he's actually suffered a heart attack, it hasn't been catastrophic. They can almost certainly deal with it. She's sure of that. Once they'd got him off the gurney, the doctor on duty had them pushing an l.V. into his arm with the usual cocktail of blood thinner, muscle relaxant, anti-coagulant.

Ahead there may be surgery, of course. Angioplasty or even a bypass. But she knows he's not about to die on her.

Maybe life would be easier if he would.

She shakes her head at that thought and then discovers that the thought has set off a trembling from her legs right up to her throat.

He must be fifty. She figures for a moment. Probably more-closer to sixty.

That doesn't matter either.

Wandering into the waiting room was a bad idea. It's sure as hell no refuge. She'd hoped to slip into a seat in the far comer and let the rush and swirl sweep around her while she calmed down and thought it through and recovered herself. But it's a quiet Tuesday afternoon. She knows too damn many people. Seems like half the folks she's ever rushed here in the wagon are back for some kind of procedure or test. They're all so grateful, and have just got to express it.

Not to mention the nurses, the techs, even some of the doctors, ones not convinced they're the second coming.

Everyone figures it's real nice to say hi.

Sometimes, she thinks and not for the first time, living in a small town is a pain in the ass.

Steve Coady is still working on the squad wagon when Caroline returns to the station late in the afternoon. He's already emptied the cabinets and storage bins in the back for a thorough washing out. Now he's restocking as she comes in the door. Ifhe's had any classes today-and she

33

knows he's been developing a bad habit of skipping-they'd be over anyway. It's not like he's involved in athletics or a frat. Training as an E.M.T., being part of the emergency squad, has become the center ofhis social life.

No one else is hanging around. The weekly training session will be tomorrow night, Wednesday, as usual. So once the cleaning is done, all he can do is wait for the next emergency call while playing video games in the rec room.

For the first time in better than six months Caroline wishes she had a smoke. She drops her backpack in a comer and hangs her coat on a peg.

"Hey," she says to him.

"What's up?" Steve glances round at her.

His jeans are riding so Iowan his hips-and he hardly has hips to begin with-she's not sure what keeps them up. Which proves to her, as if she needs the proof, that there's a decade difference between them. But she likes the look of those plaid jockeys peeking out and the non-hip hips.

"Pretty quiet," she says. How lame can you get? "For sure." He shrugs.

"Listen," she rushes into it and won't hesitate any more and here it comes because otherwise it's never going to happen and she doesn't know how she'll get through the evening on her own and she'd thought about Randy for maybe one-millionth of a second and how he's been angling for it and how Rhonda Jean sure would deserve it, and how she knew she'd enjoy it too, except that he'd be just so damn pleased with himself and she couldn't live with that, and spending the night as per most every other night with one of her girlfriends sure as hell won't do, what with little Stevie unexpectedly waiting right here. "I was on my way, you know, just going to throw some dinner together," she says. "It's just as easy to cook for two. And I think somewhere there's this bottle of wine someone left behind. Anyway. Or are you supposed to do the cafeteria?"

Steve looks at her, trying not to show how astonished and eager, both, he is. "Whatever," he says, a beat too quick to be as cool as he wants it to be. "Sure."

Back in her apartment above the laundromat, she pan-fries a flank steak. Which is a mistake because in about five seconds smoke is billowing up to the ceiling. Naturally the smoke detector sets off in the doorway. Steve climbs on a wobbly chair to yank the battery while she's

34

shoving windows open on both sides of the room. A blast of steam from the dryers below blows through. And they're laughing, howling at the idea of their own crew rushing over here to the rescue. Which is good, the laughing.

By the time they're sitting at the table most ofthe smoke has cleared and the steaks are damn good. And before the bottle of rioja is quite empty she's leading him back to the small bedroom, letting him think he's the one doing the leading.

The wine has worked its way into her head and she's a smidge high and into this. Nothing delicate or romantic about it-they're both peeling off clothes and clambering towards the unmade bed. The boy has a silver ring in one ear. And a small tattoo, maybe a flower or a dolphin, he's squiggling too much to get a good look it, above his right nipple.

He's trying to be a bad boy, she thinks, and he's so not.

He's just cute.

And with that thought it starts to go wrong.

He's already on top of her, in too much of a hurry, just like boys his age always used to be, she remembers too well. And she'd like him to go down on her or maybe have a little fun with this. But that's academic anyway because she's thinking now, so already it's too late.

Naturally, it means she's going dry.

"Ow," she gasps, biting her lip, as he pushes into her.

"Huh?" he mumbles, thrusting.

"Nothing. You go ahead."

She's lying back and trying not to let it hurt too much. She's gone from thinking about what a nice boy he is, even if he's a baby, to not even thinking about him at all. It's Doc Hazzard now and only him, and she feels guilty, as if she's being unfaithful.

No, it's worse than guilty-she feels bad, this is what hurts, because she's being unfaithful to herself.

It's him she wants, more than ever, as this nice boy finishes more quickly than he wanted. He's the one feeling guilty, she can tell, as he lies panting on top of her breasts, because he thinks he's disappointed her.

"There, there," she murmurs, running her fingers through his hair to comfort him.

After Steve has retreated to his dorm room-no way she was going to let him stay the night, not that he seemed inclined-Caroline gets dressed again and storms around the apartment, cleaning and

35

rearranging, doing the dishes, stacking her videos and compact discs. Panting and flustered and thoroughly wretched, she undresses again and starts to climb into the shower but thinks better of it and runs the bath, hot as she can stand. Luxury for a midweek evening.

What now? she at last permits herself to wonder as bubbles billow over her breasts and belly. Hijacking the boy wasn't a mistake, at least as far as she's concerned. But it hadn't distracted her the way she hoped. Might as well never have happened. Point is, it sure didn't help with the real problem. Even if Stevie does what boys do and it gets back to Randy, so what?

That thought stops her for an instant. How many years, decades, has it been since she's felt anything like that? Felt nothing. Not caring what Randy thinks or says or does-it ought to be liberating, something to toast. If the fact it took her this long weren't so sad.

But none of that matters either. Only Doc Hazzard. He's a dull ache just under her breastbone. Each breath aggravates the bruise.

Oh God, she sighs and inhales a stinging wad of bubbles.

The real problem -he's twenty years older than her. More.

No, it's not that either. It's that he's never noticed her as anything other than a trainee or an apprentice, maybe finally a colleague, even if she's not a doctor. But never a hint that she might mean more than that to him. She doesn't take it personally-she's known him long enough. Through two wives for certain.

Caroline didn't really know Audrey from up in Cleveland. She still visited occasionally when Caroline was first volunteering with the squad. And later, with a gap of three or four years between, there was Sandy. Who Caroline did know and liked a lot, and through Sandy she got to see what the man was like to live with.

He was a saint.

He is a saint.

Saints are hell to live with.

Would he notice her now, if she thrust herself upon him?

Could she live with such a man if he did take notice?

Something else long on her mind: it would seal that deal once and for all. She'd never have kids. She knows from what Sandy once confessed-it was during the divorce, Sandy gabbing blearily after too much chardonnay at a solidarity lunch-that he decided on a vasectomy while he was in med school, before either Audrey or she came along. He didn't want the worry or responsibility of his own children. He was too busy worrying about other peoples'.

* * *

Caroline is still creating the list of reasons why it would drive her crazy, living with this man, as a second tub of water cools.

She'd wind up killing him or, more likely, herself.

This little game she's playing helps. It really does.

It's convinced her, totally, that she is beyond help or reason altogether.

In the days that follow she has the feeling she's wading through a kind of dream or dare-that she's testing herself or the limits of a fantasy that can't possibly be real or work out any way she might imagine.

Tracking his physical status is easy. Given his importance to their operations, the emergency squad receives regular updates. And the early news is modestly reassuring. The initial attack was relieved quicklyonce Doc relented, once Nurse Radcliffe called 911, and once the squad finally got him to emergency. But now the question is how much damage the heart muscle suffered. A CAT scan has been ordered, and of course they're monitoring his vitals.

For the time being Caroline quietly cancels the rest of her life, anything beyond her regular shifts for the squad. She isn't available to run medical checks for insurance companies. Or to administer flu shots at the health department. Or to stand by with her kit in the dark comer of the high school gym during a big basketball game (though that alone costs her seventy-five bucks).

Not that she can muster the courage to visit his bedside. That would be too weird.

From time to time she finds it hard to breathe.

On the fourth day after arriving at Coshocton County Hospital, an impatient Doc Hazzard is scheduled to be shipped up to the Cleveland Clinic for further tests and, most likely, an angioplasty procedure. By rule and insurance regulation he's supposed to travel by ambulance. Like any other private citizen he'll have to go private. (The college township rescue vehicle can't be out of commission for most of a day to ferry him.) Which is exactly what he expects, though over the course of a day and a halfhe also declares loudly and often to his colleague, Harry Nemitz, who is also now his cardiologist, that none of this is really necessary. Why not let him drive himself the two hours and no one be the wiser? Naturally, reports of this dialogue spread across the small community within a very little while, provoking knowing nods and not a little laughter.

37

What takes some doing is Caroline calling Vince Clippinger, who owns a private ambulance and also serves as local pest control consultant, and convincing him she might be interested in working some overtime after all. She has a sudden need for the extra pay, and no, she isn't going to explain. He hesitates. Vince has been after to her to come over to the private sector longer than his own patience. As a good faith gesture, she adds before he can draw that next breath, she'd be willing to ride shotgun up to Cleveland no fee, just to get the lay of the land in his operation.

Doc Hazzard is more annoyed than surprised when she climbs out of the strange vehicle at the hospital entrance and swings the back open for him. He's supposed to be strapped onto the gurney again for safety's sake, but that far he won't go and she's not going to press him. With a hand from her he steps up into the ambulance, almost as if they're heading off on a regular run. Abandoning her shotgun post in front, Caroline perches on the bench opposite him.

"Ready to roll," she calls to Vince, who's catching a quick smoke by the electric doors with one of the ER nurses.

"How long have you been moonlighting?" Doc asks, once they're on the highway.

She's finding it hard to look at him, partly because the full, deep sweep of her feelings has flooded from her belly into her chest and up into her throat, partly because he doesn't look well, not at all. "Just started," she mumbles, eyes on the gurney between them.

"I'm sure Vince Clippinger pays better than the township can do."

"For sure." She nods vigorously, miserable.

He's wearing his street clothes, khakis, a perfectly ironed, perfectly blue shirt, its cuffs invisible within a windbreaker. But the clothes seem to belong to someone else, his belt cinched tight an extra notch to hold his pants up. His skin is pale, almost bluish, with the papery fineness she's seen in plenty of older people, her own father first among them. And a crease has appeared between his eyes-she's sure it's new. Who knows what caused it? Pain or worry, or something else entirely.

How does she take all this in without looking at him? She wonders at that.

She reaches for a stethoscope and surprises herself with her own impulsiveness. "I want to check you," she says. Not waiting for a response, she comes closer to him and opens the top button of the shirt. She listens to the valves controlling ebb and flow, the pulsing whoosh of a

heart. From the comer ofher eye glimpses again and recognizes the pale purple-blue scar. Now, an intimate after tending him those few days ago, she knows its secret route across his breast and heart and belly. Oh, that scar. She draws the stethoscope away and averts her eyes as he buttons his shirt.

When Caroline was a young girl, ten, eleven and twelve, she had an occasional dream of discovering that one or the other of her parents had died or gone away for good. Worst was that in all the dream's variations, she never had the chance to say goodbye-no last hug or kiss or acknowledgement of love. It filled her with an aching and desperate sadness that lingered even after she woke. Their actual deaths, within a few months of each other and years later, hadn't been nearly so painful, or painful in a different, stretched out, final kind of way.

The memory of the dream, which blossoms now unbidden for the first time in many years, takes her breath away but gives her courage to glance up and confirm that new crease in Doc's dear and drawn face, the pale blue of his eyes, which have never been so pale before.

And it comes to Caroline, a caustic benediction of the old dream, that Doc Hazzard is going to die. Oh, not now and not in Cleveland, and maybe not for years to come.

Death has never scared Caroline. The idea has never plagued her, though she knows that others endure a horror of extinction all their lives. The practical reality, on the other hand, hand in hand with the profession she has chosen, has been inevitable and sad too almost always, and natural in its own way. Why worry or fear it?

Her mother passed away first-there was surprise in that, certainly. A woman never sick, not even sick the day they found her. Time came to wake up and she didn't. It was no surprise, however, when Caroline's father followed his wife those few weeks later. What place on earth did he have without this woman who'd been with him from the small school in the small town and on through his life?

Others have died along the way, inevitably. More than a few while Caroline was tending them. She'd be trying to coax a little flicker of breath, a heartbeat, nursing them hard. Only for what had been life to flutter into coldness, into nothing. Sometimes the paramedic felt frustration at her own impotence. Sometimes, perhaps after a long struggle, where she felt she wasn't wrestling just the body before her but something darker, almost willful-she sensed that, yes she did, and never spoke of it -after a spasm from the heart suggested she might win after

39

all, only for the beat, one-two, one-two, one, to miss the next stroke and subside, then a sudden raw outrage might surge through her. It made her want to wail and pound her fists against the cooling body. To all ap� pearances, however, she was always controlled, always professional.

But now it all feels like a cruel trick, a conspiracy of the universe. Not that she fears her own mortality-that's no more an issue than ever. But why should Doc Hazzard have to die? Not the sound ofhis heart but the glimpse of the ancient scar has brought the truth home. Only now at this advanced age does the puzzlement arrive for her, when she ought to be too old to think of marriage or children or death. It is a gift of her dreams and of the scar and of the crease between his dear eyes. Ever and forever without end. That's what death is, and he is going to die.

She looks that fact full in the face. And suddenly, gently, something lifts from her and passes away.

She's surprised, feels a little guilty. Why should this be?

She's able to gaze now at Doc as if he can be the one to answer.

"How you feeling?" she asks.

He answers with a shrug. "Never better." Wry, impatient, distant, he sits opposite her, hands between his legs.

She loves this man, that's as true as ever, and admires him, teacher and friend. A protective, possessive kind of love to be sure. She nods slightly to herself, confirming it.

But she's come to a new place. She has been released from a spell as if a fever has broken suddenly and entirely. It's a relief, but a weary, sad relief.

She feels a bit chilly, and lonely too, as if, in some manner, she's been left behind.

Doc Hazzard smiles and notices nothing, knows nothing. How like him, dear man.

Marie Myung Ok Lee

The Strip Mall and the Shaolin Temple

He'd been at this so long now, he recognized each prospective student as an easily categorized type as soon as they walked through the splintering door. There was the lady who did aerobics who wouldn't last two weeks amidst the fetid barefoot smell of the do-jang. There was the slightly crazed macho-man who wore dragon-embroidered satin jackets and carried his gear in a gym-issued workout bag he would have customized by adding in fabric paint or Wite-Out,-NEVER SURRENDER!!!!

There would also be, always, multiple bratty kids whose mothers had lost control of them and were now turning them over to him as if he were some kind of Life Skills Drill Sergeant instead of a martial arts instructor. At the opposite end of the spectrum would be the Korean child whose parents held the age-old belief that regular exercise would provide extra stamina for the long nights at the SAT cram schools; these kids were always instructed to stay away from the non-Korean kids, lest they become corrupted. Lastly, there would be the hobbyists, usually bored soccer moms or dads who took the classes to have something to do while waiting for their kids.

Mr. Kim=-, one of the bored soccer-moms was saying to him right now. Or should I call you Master Kim?

You can call me Sebastian, he said, to his great surprise. Part of the allure of taking Tae Kwon Do was being forced to learn all the Korean titles of respect: Sahbumnim, Sunsengnim, Kyosunim, KwangjangnimMaster, Teacher, Professor, Senior Student, President. It was quite a

41

novelty for the kids, who routinely called their parents by their first names-or by expletives-and so they happily used these titles and even delighted in the bowing that accompanied such exalted appellations of respect. To reinforce it, he insisted that everyone, including parents, refer to him as Master, and he was President to the students who could memorize a long string of vowels: Kwang-jang-nim. This was the first time he'd suggested someone call him something else. And where did Sebastian come from? His name was Chang-jae.

Sebastian. She smiled. Should I take my shoes off?