TriQuarterly

an international journal

TriQuarterly is

of writing, art and cultural inquiry published at Northwestern University

TriQuarterLI-ly

Editor

Susan Firestone Hahn

Associate Editor

Ian Morris

Operations Coordinator

Kirstie Felland

Cover Design

Gini Kondziolka

Editorial Assistants

Amy Levine

Elizabeth Cooperman

Assistant Editor

Joanne Diaz

TriQuarterly Fellow

Brent Mix

Contributing Editors

John Barth

Lydia R. Diamond

Rita Dove

Stuart Dybek

Richard Ford

Sandra M. Gilbert

Robert Hass

Edward Hirsch

Li-Young Lee

Lorrie Moore

Alicia Ostriker

Carl Phillips

Robert Pinsky

Susan Stewart

Mark Strand

Alan Williamson

129

poems 20 Doctrine of Signatures; On Overhearing; Ditches for the Poor; Tis a Fayling; On Parlance

David Baker

31 Absence in October; Lying Awake; Frosty Morning; Bach's Requiem

Eamon Grennan

35 Ode on the Letter M; Ode on Laundry, Lester Young, and Your Last Letter; Ode to Anglo-Saxon, Film Noir, and the Hundred Thousand Anxieties That Plague Me Like Demons in a Medieval Christian Allegory

Barbara Hamby

40 The Neighbor Discusses Parkinson's; Clutch D. H. Tracy

43 The Words; On Refusing to Be on the Make

David Woo

95 On Being a Nielsen Family; Parable of the American Stag Party; Colonialism

Kevin Stein

100 Old Recipes

Sandra M. Gilbert

103 The Welcoming: An Ars Poetica

Beth Ann Fennelly

I05 Metaphysician in the Light; Metaphysician in the Dark; A Computerized Jet Fountain in the Detroit Metro Airport

Sidney Wade

Contents

109 Kennedy Center; Florida: Schoolboy on Break; Old Poet

Joshua Weiner

160 To Keep Believing Nimble; Taps

Anne Harding Woodworth

163 Monk; Yucca Mountain

Dabney Stuart

166 Constellations; The Deeper the Dictionary; Don't Come Home

Todd Boss

238 Elegy for My Father, Not Yet Dead; Croton; Ships in Bottles

Robin Ekiss

243 Pale Blouses; Plainsong

Meena Alexander

246 Concrete; Home; Yes; Psalm

Mark Irwin

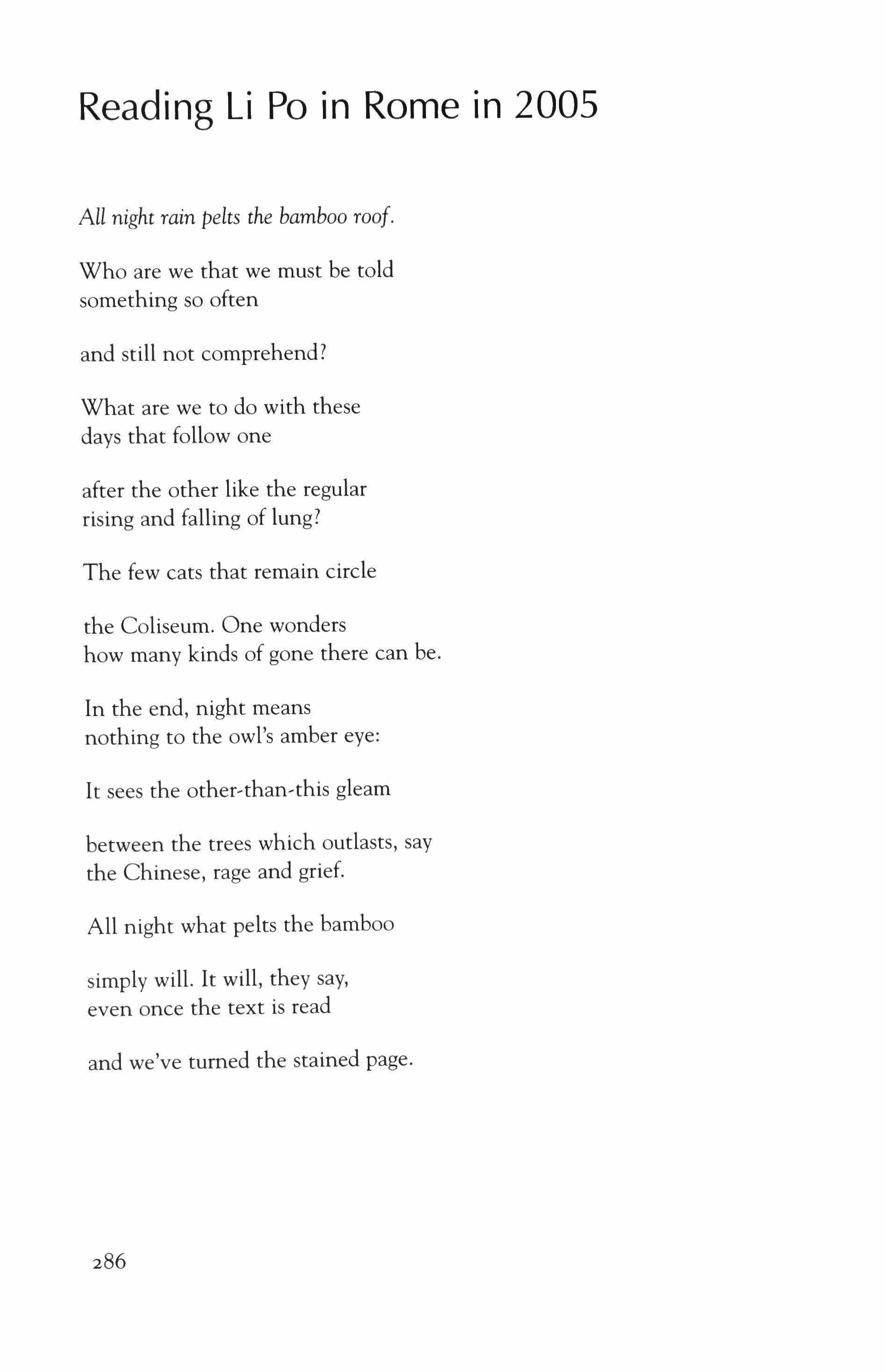

284 Regatta; On Lake Como; Reading Li Po in Rome In 2005

Ann Snodgrass

A Letter in Las Vegas

Richard Burgin

The Hanging Lanterns of Ido

G. K. Wuori 113 Girl There Was a Time

Enid Harlow

125 In What She Has Done, and in What She Has Failed to Do

Patrick Michael Finn

fiction 45

66

PaulYoon 85 Busy

138 This Is What We're Doing

Siobhan Adcock

169 Lisbon

John Tait

178 The Shabbos Goy

David Milofsky

187 His Parents, Naked

Greg

Johnson

198 A Thing of Beauty

A. G. Harmon

223 A Place for Fine Hats

Pamela

Gullard

250 Vigo Park

Alix Ohlin

258 The Daughter of the Bearded Lady

Vincent Precht

essay 9 Ode and Empire linda Gregerson

Cover: Tempestuous by John Galbo

Linda Gregerson

Ode and Empire

In 41 BC, having defeated his enemies in the civil wars that followed upon the assassination ofhis great-uncle and adoptive father Julius Caesar, Octavius declared a general amnesty. Among those who took advantage of this amnesty to return to Rome and pick up the pieces of their lives again was one Quintus Horatius Flaccus, aged 24. He had been a student in Athens when Julius Caesar was killed and had, in the general fervor of republican reform, joined Brutus's army and served as military tribune until the disastrous defeat at Philippi in 42 Be. Horace was penniless when he returned to Rome, his father having died and his father's estates having been confiscated as a result of his own ill-starred career as a patriot in rebellion. What was left of his inheritance he wore on his back, or in his head, for his father-himself a freedman-had made considerable sacrifices to provide Horace with the most fungible and disaster-proof sort of wealth he could imagine, with a superb education. Horace became a scribe, or quaester's clerk, upon his return to Rome, but his real advancement came about through the friendship of poets. It was Virgil and Varius who introduced the young Horace, momentously, to Maecenas, senior advisor to Octavius and patron of the arts. It was Maecenas who bestowed upon Horace the Sabine farm, which became not only a source of stable income for the rest of the poet's life but also a touchstone of spiritual sustenance and renewal.

Maecenas is abundantly present in Horace's written works. He is recurrently addressed, he is praised, he is thanked. His name is the first word in the first poem of the first of Horace's books of Odes: "Maecenas, you,

9

descended from many kings, /0 you who are my stay and my delight " This poem proceeds to inventory the varieties of human calling or estate-athlete, statesman, lord of vast acreage, humble farmer, merchant, idler, soldier, hunter-and to conclude with the poet's own vocation:

What links me to the gods is that I study

To wear the ivy wreath that poets wear.

The cool sequestered grove in which I play For nymphs and satyrs dancing to my music

Is where I am set apart from other men

Unless the muse Euterpe takes back the flute Or Polyhymnia untunes the lyre.

But if you say I am truly among the poets,

Then my exalted head will knock against the stars.

(Horace, Ode I. I, trans. David Ferry)

So the poet's place-not merely his means of sustenance and habitus, his villa in the Sabine Hills, nor even his claim to honor and attention, but his very "link to the gods"-is the abounding gift of patronage. The encomium so central to ode acknowledges tribute paid in varying coin: in acreage, in money, in public virtue, in eloquence and fame. The poet looks to his patron for recognition in material terms and also in judgment; he gives in exchange the ode. I name you Maecenas, and you name me poet.

The history of the ode is governed by two rhetorical poles: large-scale public address and intimate meditation. The thread I wish chiefly to examine here is that which links the ode, throughout its rhetorical spectrum, to the seats ofpublic power. In its origin, the ode is linked to those most public of public events, the civic drama and festivals of ancient Greece. Pindar (522-442 B.C.), who is generally credited with devising the form, wrote his odes to celebrate athletic victories, the three-part structure of the poem corresponding to three movements of the chorus by whom it was sung: a strophe, in which the chorus moved from left to right, an antistrophe, in which the chorus moved from right to left, and an epode, in which the chorus stood still. In subsequent centuries, the Pindaric ode came to be associated with other large-scale public observances: the unveiling of monuments, the formal accession of an emperor, the ceremony of state funerals. The Horatian ode is simpler in structure and often more modest in subject, a single repeated stanza

10

form that may function as a drinking song, an invitation to dinner, or a celebration of fleshly dalliance. In the course of two and a half millennia, the ode has assumed many formal incarnations-tripartite, homostrophic, and, in later periods, much looser and irregular. Its most enduring feature has been not form but occasion. The ode offers praise to a ruler, a patron, an athlete, a friend, to drink or childhood or a Grecian urn. It casts itself as the lyricist speaking-in-public. Coupling with occasion, it marks the boundaries of the self and the social.

And even in its earliest manifestations, the ode has accommodated tonalities and apprehensions that complicate the tautological circuits of patronage and praise. In the third ode of the first book, Horace calls down blessings upon the journey of his friend Virgil to Greece.

May Venus goddess of Cyprus and may the brothers Castor and Pollux, the shining stars, the calmers, Guard you, 0 ship, and be the light of guidance; May the father of the winds restrain all winds Except the gentle one that favors this journey. Bring Virgil, your charge, the other half of my heart, Safely to the place where he is going.

(Horace, Ode 1.3, trans. David Ferry)

But even as he praises the history of human navigation and the courage of men who venture upon the seas, the poet finds himself in darker, more ambivalent territory. He considers those who brave the elements and venture into forbidden realms-the "impious" sailor, "guileful Prometheus," "audacious Daedalus"-as tempting the gods. He modulates from benison to warning: "Is it any wonder, then, that Jupiter rages, / Hurling down lightning, shaking the sky with thunder!" It becomes the business of ode, even as it plays the chords of well-wishing and affiliation, to contemplate the limits of human ambition and to issue implicit counsel.

Moving further in this direction, odes may offer frank instruction to figures conspicuous in the public eye. Ben Jonson's "Ode to Sir William Sidney," written to celebrate the latter's twenty-first birthday in the year I6II, is an example in kind. William was son to Robert Sidney, Lord Lisle, grandson to Henry Sidney, sometime Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, and nephew to Sir Philip Sidney, who was still remembered, in the disillusioned second decade ofJacobean England, as the flower, the consummate poet-courtier-military hero, of the Elizabethan age. Twentyfive years after Philip Sidney's death, his family was still important as a

II

wellspring of literary patronage. But William, having inherited this luminous mantle and having recently attained his own majority, had to date led a conspicuously lackluster career.

Jonson begins by raising a congratulatory toast ("Give me my cup from the Thespian well") but quickly turns to cautionary advice:

This day says, then, the number of glad years Are justly summed, that make you man: Your vow

Must now

Strive all right ways it can

To outstrip your peers: Since he doth lack Of going back

Little, whose will

Doth urge him to run wrong, or to stand still.

'Twill be exacted of your name, whose son, Whose nephew, whose grandchild you are; And men Will then

Say you have followed far, When well begun; Which must be now: They teach you how. And he that stays To live until tomorrow hath lost two days.

(The Forest 14; published as part of the 1616 Folio ofJonson's Works)

Jonson was a master of the ruthless compliment. He had a keen sense of his own worth and of his dependence upon sources of sustenance-the public stage, the private masquing halls, the circuits of aristocratic praise-toward which he felt decidedly mixed emotions. He expected public stricture to be recognized as value,for,money.

American poets have generally been wary of "forcing the Muse" in the service of public occasion. We do not commemorate the Queen's birth, day; the patronage systems to which we subscribe (foundation grants

12

and universities rather than private purses) earn thanks on the acknowledgments page rather than in the body of our poems. However beset or driven by public intersections, the American lyric has largely grounded its authority in inwardness. Ralph Waldo Emerson's "Ode (Inscribed to W. H. Channing)" voices the national (and personal) ambivalence explicitly. First published in 1847, Emerson's "Ode" was dedicated to a clergyman and fellow abolitionist who had urged Emerson to become more active in the anti-slavery movement. The "Ode" begins with an ostensible demurral and apology:

Though loath to grieve

The evil time's sole patriot I cannot leave

My honied thought

For the priest's cant, Or statesman's rant.

If I refuse

My study for their politique, Which at the best is trick, The angry Muse

Puts confusion in my brain.

Emerson felt as keenly as did Channing that the times were evil, that slaveholding was the work of "jackals" and the current war with Mexico a naked act of aggression, that both slavery and the war were stains upon the country, its ideals, and its future:

Virtue palters; Right is hence;

Freedom praised, but hid;

Funeral eloquence

Rattles the coffin-lid.

But he differed with his friend on the deeper diagnosis and thus on the prospects of cure:

What boots thy zeal, o glowing friend, That would indignant rend

The northland from the south? Wherefore? To what good end?

Boston Bay and Bunker Hill

Would serve things still;-

13

Things are in the saddle And ride mankind.

In a world enslaved by "things," Emerson seems to argue, the poet has a more important role to play than that ofpolitical activist, however worthy the cause; his function as exemplar and public conscience exceeds the mere exigencies of topical engagement. "Every one to his chosen work," writes the poet: the "shopman," the "senator," and the servant of the Muse pursue distinct imperatives. But where does this leave the disposition of public affairs? And where does it leave historical perspective? Such transcendence as seems to be at work (the "over-god") "marries Right to Might exterminates / Races by stronger races, / Black by white faces " This does not bode well. And the Muse, who has seemed to scorn the public forum and its noisy methods, finds herself at the climax of Emerson's ode "astonished" by the force of collective uprising in a distant land:

The Cossack eats Poland, Like stolen fruit; Her last noble is ruined, Her last poet mute: Straight, into double band

The victors divide; Half for freedom strike and stand;The astonished Muse finds thousands at her side.

Emerson's sympathies are clear: he bitterly reproaches the nation, his nation, for failing to live up to its promise; he condemns the predations of private greed and expanding empire. But his critique is fraught with ironies and ever in motion: he writes a polemical poem that begins with the renunciation of public polemic; he adapts a public mode (the ode) to reconfigure skeptically the very foundations of public sphere.

Poets love to construe themselves as oppositional, at odds with public decorums and public affairs. But recent decades suggest that American poets are no longer convinced that civic scale and private consciousness, philosophical reach and local idiom, historical imagination and lyric authenticity, are inherently inimical to one another. Nor that public speaking must suppress an active and critical mind. Robert Hass's ode to the English language is keenly aware of the vested heritage in which

it works: the teeth and vocal cords, the goose quills and printers' templates, the consciousness and material embodiments through which each word has passed to be here, in our heads and our hearts, the gorgeous, resilient, capacious, bullying, agent-of-capitalist-expansion global tongue it is our privilege and our burden to inherit. "English: An Ode" appears in Sun under Wood (1996) and is composed in eleven sections. It begins rather slyly: I.

lDe quien son las piedras del rio que ven tus ojos, habitante?

Tiene un espejo la manana.

"The lines in Spanish," we are told in an endnote, "come from a poem by the Mexican poet Pura Lopez Colome in her book Un Cristal en Otro, Ediciones Toledo, Mexico City, 1989." Which is all very well, but the reader who does not happen to understand Spanish may wish the note had gone a little further. That reader, however, is required to wait: a gentle reminder of the waiting that immigrants everywhere are likely to encounter.

2.

Jodhpurs: from a state in northeast India, for the riding breeches of the polo-playing English.

English at last, as promised by the title. But what sort of English? English based on tributary languages: the English of empire. We begin to sense some sort of lesson. And indeed, the format of the poem has begun to assume the format of a common instructional tool, of a primer or a dictionary.

Dhoti: once the dress of the despised, it is practically a symbol of folk India. One thinks of blood flowering in Gandhi's after the zealot shot him.

The dhoti was not Gandhi's native garb but a garment deliberately recuperated from indigenous India, a garment Gandhi assumed and encouraged others to assume, indeed to produce, by hand and domestically, as part of the resistance to British occupation and British commerce. The dhoti was the centerpiece of economic boycott, national aspiration, and symbolic solidarity across caste lines in mid-twentieth-century India. But the alter-

nately championed and exploited poor are scarcely unique to India. Rather than using the old term, "untouchables," or the official term, "dalits," to identify the traditional wearers of the dhoti, Hass calls them by a name that travels across otherwise-disparate cultures all too well: "despised."

Were one, therefore, to come across a child's primer

Note the use of the subjunctive; note the unspecified subject "one." Note the naming, inside the posited hypothetical, of the object"primer"-whose existence has been implied by the format of the preceding lines.

Were one, therefore, to come across a child's primer a rainy late winter afternoon in a used bookshop in Hyde Park

Note the burnished, English-sounding name, and note, or fail to note until a little later, the slightly cloudy crossed-signal, because Hyde Park in London is not a site for used bookshops. and notice, in fine script, fading, on the title page, "Susanna Mansergh, The Lodge, Little Shelford, Cmbs." and underneath it, a fairly recent ball-point in an adult hand: Anna Sepulveda Garcia-sua libra and flip through pages which asseverate, in captions enhanced by lively illustrations, that Jane wears jodhpurs, while Derek wears a dhoti,

And note how the hypothetical primer in the hypothetical bookshop has begun to assume material weight: it wouldn't be unreasonable to assume a political implication, lost, perhaps, on the children of Salvadoran refugees studying English in a housing project in Chicago. Chicago! That Hyde Park! Some of us will have suspected as much, and will be pleased, in our little way, to have our suspicion confirmed, to have recognized the neighborhood or even the bookstore itself. We find it reassuring (political implications here as well) to find ourselves possessed of local knowledge. One was not wrong, of course, to detect the aura of Englishness: a neighborhood in Chicago named for a park in London bespeaks the complex nostalgias and braveries of colonial emu-

lation. Old imperium: the English in India. Older imperium: the English in North America. Newer imperium: America in EI Salvador, and refugees in America. The movement of populations, and of language, follows the trajectories laid down by money and force.

The poem's next hypothetical is a "high school math teacher" irnagined as a way of filling in the outline of Anna Sepulveda Garcia, second owner of the primer

a former high school math teacher from San Salvador whose sister, a secretary in the diocesan office of the Christian Labor Movement, was found in an alley with her neck broken, and who therefore followed her elder brother to Chicago and, perhaps,

Note the "perhaps," the announced continuation of hypothesis

perhaps

bought a child's alphabet book in a used bookstore near the lake where it had languished for thirty years since the wife, perhaps, of an Irish professor of Commonwealth History at the university had sold it in 1959

Irish: Mansergh. A yet,earlier colonialism, which is why the Irish speak English today, and why an Irishman might find himself earning a living teaching Commonwealth History in a distinguished American university. The reader who does a little searching online may discover traces of the late Nicholas Mansergh, born in Tipperary to a family ofAnglo-Irish (i.e., Cromwellian) origins, honored denizen of Oxford and Cambridge, author of scholarly studies on The Commonwealth Experience, The Irish Question, and Constitutional Relations between Britain and India. (One may also read the political speeches of his son Martin Mansergh, Irish civil servant and diplomat, still very much alive today.) Empire leaves a convoluted aftermath.

-Math, as it turned out, when she looked up the etymology comes from an Anglo-Saxon word for mowing.

How shall the poet imagine an interlocking fate for Susannah Mansergh, first owner of the alphabet book, child of privilege from Little Shelford, Cambridgeshire, and Anna Sepulveda Garcia, who bought it second-hand? Privilege only extends so far: "maybe the child died / of

some childhood cancer-maybe she outgrew the primer" and her mother sold it and was later depressed. "Probably she hated Chicago anyway," the mother, that is, who hailed from Ireland or England or both,

And, browsing, embittered, among the volumes on American history

She somehow felt she should be reading, thought Wisconsin, Chicago: they killed them and took their language and then they used it to name the places that they've taken.

"There are those who think," writes the poet, "it's in fairly bad taste / to make habitual reference to social and political problems / in poems." In such an intellectual climate, the author of an ode must stay several steps ahead of earnestness. He may couch his observations in resourceful hvpotheticals. He may work a witty hybrid of fact and fabrication. He may distribute point-of-view: it is Anna who flees for safety; it is Susannah's mother who notes the ironies ofNew World naming. He may pull a narrative coup: observing "far less objection" when imaginative literature stages an "accidental death" than when it succumbs to "moral nagging," he may unceremoniously kill off a central character: "'Helen Mansergh was thinking about Rilke's pronouns / which may be why she never saw the taxi.' "

Etymology is a river, whose tributaries bind us to farflung daily habits and patterns of observation, all of them local, all of them borne from one locality, of time or place or affection, to another:

In one of Hardy's poems, a man named "Drummer Hodge," born in Lincolnshire where the country word for twilight was dimpsy two centuries ago, was a soldier buried in Afghanistan.

How is it that a boy from Lincolnshire (or Moscow or New Jersey) finds himself transplanted to Afghanistan?

Some war that had nothing to do with him.

Empire requires it. And the fallen were not, in earlier eras, brought home, as witness the roadside epitaphs of ancient Rome. As witness the humbler grave of a British drummer boy:

Face up according to the custom of his people so that Hardy could imagine him gazing forever

into foreign constellations. Cyn was the Danish word for farm. Hence Hodge's cyn.

And country people in Scandinavia tended to take their names from local holdings.

And someone of that stock studied medicine. Hence Hodgkin's lymphoma. Lymph from the Latin meant once "a pure clear spring of water." Hence limpid. But it came to mean the white cells of the blood.

Because the blood is a river too.

In Hardy's poem, the fallen drummer is in fact a native of "Wessex" rather than Lincolnshire, a casualty of the Boer War rather than the Anglo-Afghan War; his body lies in the veldt of South Africa rather than the steppes of Afghanistan. But poets take liberties; "spheres of in' fluence" and the wars that sustain them tend to run together. A poet may be ruthless in his liberties: in the meandering path of etymology (Hodge's cyn), he hears a ghostly confirmation of the childhood cancer he "chose to imagine" as the vehicle for cutting off the childhood he chose to imagine behind the inscription on a title page. "She has (strong beat) / a Hodg (strong beat) kin's lym-phorn (strong beatl-a": in the rhythms of a diagnosis, he hears the rhythms of a popular song "that the woman in Chicago / might have sung to her children as they fell asleep." This is the other woman, the one from San Salvador; the poet has let her children live. "Yo soy un hombre sincero," she sings. The words were written by the Cuban nationalist Jose Marti. The song, Guantanamera, became very popular for a time in the United States. People were protesting another war.

1De quien son las piedras del rio que ven tus ojos, habitante?

So-what are the river stones that come swimming to your eyes, habitante?

A more literal translation of the question with which the ode began would hinge on a possessive: whose (not what) are the stones. But the present poet, troubled by empire, has chosen to forgo the possessive and, in one key term, to forgo translation altogether. The world belongs to those who dwell there: habitante. The language belongs to everyone through whom it has passed.

19

David Baker

Doctrine of Signatures

Willow delights in a moist and wet soil -here being silex babylonica. So notes Edward Stone; then adds (to the Royal Society): where ague chiefly abounds. Consider the genius of the doctrine. When find ye a thing seek there its cure. Or, localize the lore. Across the bramble floodplain, ivy thickens with a talc of poisons, and beside it-root unto root-the pale gem jewelweed, taller, many-round-pronged ovate leaf and sallow bloom, so we've learned to snap the stalk, smear a drop of sap to cool and clear

20

an ivy bite.

Reverend Stone, faith being a genus of need, put his mouth to the thing-

Crack willow, its name, the ice on it broke the top branches down, until it was stripped, a glassine mass of shards shining fire in morning's hard light. Whip willow, a thing being its name. Or torch, to light the way to bury the dead by the path. One willow, our willow, grew by the pond. Grew shaggy; grew down. With leaves in "finely toothed margins," the book said, "and furnished with the two small leaf-like appendages, known as 'stipules,' at their bases." Its bracts fringed with hair. Its leaves "convolutei.e. rolled together in the bud, like a scroll of paper." These leaves technically "lanceolate," tapered to a point, fine� serrated, gray bloom at the underside -and tasted there of quinine, bitter remedy for malaria. Dried for three months in a baking oven a pound of willow bark. Applied this to fifty more-faith being antidote to suffering, in this case

rheumatism-to which each responded with excellent result. Thus salicylates, for a century following, yield an acid analgesic for healing (headache, heartache, shredded muscle, sore or tom tendon );

21

and yield for Bayer Pharmaceutical, in 1899, a formula for "the most popular drug in the world."

Find ye what ye need among its other.

Other being, by the doctrine of signatures set forth by Philippus Aureolus

Theophrastus Bornbastus von Hohenheim-a.k.a.

Paracelsus-c. 1530, nature's way of making meaning, counterpoint, and

remedy to each poison, each disease, each bodily discomfiture. Nature being God's provident gift of usage. Thus lungwort, to cure pulmonary stains; thus gravelwort (urinary stones) and bloodroot for vomiting; maidenhair fern to mend baldness. Thus shaking palsy is overcome by poplar (as quaking aspen) leaves; and lily of the valley, writes William Cole, cureth apoplexy by Signature; for as that disease is caused by the dropping of humours into the principal ventricles of the brain: so the flowers of this Lily hanging on the plants as if they were drops, are of wonderful use herein. -Switch willow, our tree, or broom, for the wealth of downfall after wind, the implements we might make.

But this time: sleet, great snow, then gale, from which our willow shattered downward, ice-

22

toppled, explosive over deep drifts, and shone for days in the sun to follow. One willow.

For our gathering, as leaves to bum, limbs to sweep; as holding hands with our child, to sing there to a cat buried with his ball, a little food, and a willow-switch to dig his way out; as in to amass, understand, stand beneath, fold, as hands, as in harvest, as a storm will gather, or army will, or something wholly unforeseen but, now, in-

evitably broken on the white ground around us, and nothing to do but grieve. Thus weeping, for the shape of its branches, the shed leaf, a shudder of things in wind.

Weeping, as the story of our willow, and something else that grew, root unto root, beside us, beneath, within, instead. Suffering being antidote-. Thus petal of iris, a bruise polstice; and St. John's wort, writes John Gerard, with oile the color of blood, remedy for deep wounds. Once a willow grew beside a fine pond. Two shadows lived in its shadow. And raised a child. And watched a ruining storm, which -we hardly believed our eyes-was a sign of the life one comes to know as one's own.

23

On Overhearing

I can't tell what disaster is can you? Let's consider the question untethered from the usual anchors. Fifteen, afire (are you still here?), first out of the car, and still she doesn't run into the house but whirls, blue wild wind in a tank top. Her mother is redder by the time she slams her door, shaking the Sentra, and those two have at it, girl astraddle the curb, mom one wing grabbing for something, gnat in the air now can you?

As the big Canada geese bleat over, end of August, end of days. One after another wide tectonic sheet of them planing the slate sky. So the earth below slips by, no gasp. I can't tell what is shifting now the geese sky the earth keeping my feet can you yet? They flap, honk-that high automotive-and a feather in the leaves in the trees (something's happening somewhere bad I just know it), the leaves still on the trees but the color gone, tone of long-washed cloth, and the little sister is there listening at the picnic table, brushing their brandnew rescue dog Molly the drooler Molly mop. The infinite is at hand only (I read this somewhere, can't recall) with respect (can you?) to the finite. Meaning look out. As your heart wings toward its own calling disaster. Then they're done slam slam going in. It's the little one who does not go in no not for a long long while.

Ditches for the Poor

from the French, the middle ages-roughlyas fosses aux pauvres, denoting common graves, by which we take to mean the practice of the period by which are sewn into their shrouds the dead, the bodies then stacked.

Language is, in itself, already skepticism, writes Levinas. A fissure opens. An opportunity for, what, clarity? Closure, perhaps, through which these instances of proximity maybe-.

When the graves became crowded-there,

imagine the ninety lumps, the layers of dirt dividing strata of bodies, the several-yards-byseveral-yards hole having been filled-the churchkeeps redug the ditch, disinterred the nameless in decay to install the newer

dead. Old bones, to the charnel hall. There is no narrative to such anguish-as from the corpse no odor. As from a gathering loss mere ennui. Think so of the others -the grieving livingwaiting with their needles, to stitch anew.

Tis a Fayling

Thus, my guilt; of my shame, corresponding; and anguish, like blood on an egg, I have nothing more to say, for I am stretched up bare in a clover field under many mad stars; I am unfit wholly in the just eyes of the lord of stars, I am not (listen, you can hear this fayling sunder the smeared trees) with my breath, nor of it; or I am in a white bed not my own; or my own; liquid not dew bruising my face; I can lick it in my lip comer. (Tis a fayling of his expectation). As, who can endure to have their love despised? Among men who shall know? But of my part I shall no more speak, unless make worse this deficiency. From his fearful poetry, all tending to depress the Creator-for sure his Power shines forth in our Infirmity-thus his warning (which I do not heed) to prepare them for Necessity, End, and Usefulness of Afflictions. 1669. How prepare? Even Reverend Wigglesworth, "enduring the most dreary, unproductive, lonely period of his life becomes living proof of the necessity of afflictions." Thus Bunker his associate expires; his daughter Mercy so departs; and Esther dies "though the exact date is unknown"; and his voice lifts up as never stronger in fierce alarm. What means this Paradox? Afflictions are like Ballast i'th' Bottom of a Ship, yet every puff would quickly set us over, and sink us in the Ocean Sea no more for to Recover. I have nothing more to say,

yet am my body's own, of evidence. Of my shame (see the towers how they once again evaporate), I carry (see men flying, as if swallows wing-shot) (a boy in Baghdad coddling his mother's eye in his palm) blood on the egg (now of black-cps in a narrow valley, beneath the swept mountains of Caracas), I carry my lover's breath as a precious stone. And are these (yes they are) my fayling? Of my part I have no more words, for my breath is not with me, she is with me, constellation of winged things beneath the bamlight breathes over our skin here like a savored thing. It is a savored thing. And yet I find a heart, he moans, so dead, and I have found prevailing this week such a Spirit of whoardoms and departure, I am afraid of my owne Vile Heart that I shall one day fall. Thus fall. "After twenty years of 'widoehood' and almost constant distress, Wigglesworth scandalizes-," and Mather must renounce them both, Wigglesworth his former tutor, and she "your servant mayd of obscure parentage, & of no church I question whether the like hath bin known in the Christ, ian world." (Thus my mouth her tongue the waters ripe and rippling through our body of the world.) Everywhere; this breathing skin resounds. So I may not speak? Then Lord I must sing.

On Parlance

He was packed with gear, and in the parlance of the ever ready, he was good to go, thumbs up. He was halfway out the squad before it stopped. His partner, equally can-do and equipped, having left the truck at idle, dogged his heels across the neighbors' porch and slammed the screen. There we were at windows, worrying who'd died or taken ill, fallen through the night. Red lights raced the yard, the yard next door, to ours, to trace the artery of road and rural heart -this one's box farmhouse, this one's smoke-tree manorthe countryside less neighborhood than scattered arclights, cankered barns, and gutless cars.

What could it mean our neighbors' yard was junk, heady weeds and broken muddy glass, three dogs tethered by day like charms against civility-yet their garden a perfection: peas on strings, raised beds

of com, cutting flowers strictly rowed by color, height. You could see their working as a kind of play. I haven't mentioned the crisis that kept us up at night. When the driver came out, slow steps, and stowed their gear, the animal growl of the diesel idling, we couldn't tell what happened. Then the first one in, the last one out, who turned and slowly waved into the neighborhood, the night. What did it mean? It could mean all was well. It could mean goodbye.

Eamon Grennan

Absence in October

The trees are gilded ramparts: rising, they come between earth and the blue dome over it, receiving phalanx after phalanx of purposeful birds that steady themselves on the forced flight south, their blood

humming a tune from when trees were only feathery green uprights of ferns nibbled by ancient relations. The shipwrecked air like shards of stained glass sent home from Vallombrosa: the

multitudinous leaves, drowning, burning, turning to particles of the painted world, broken mirrors glimmering like candle-glow, going out in flashes, snatches from the spellbound speech of the world

that's closet-thronged with secrets. At the edge of every path traveled this morning I found a margin of shadow, caught the scratchy sound of spectral voices giving a bit of their all to this autumnal tunnel of a day

lit with absence, winey leaves, hot breath, needles.

31

Lying Awake

Night thoughts keep him pinned to glittershapes on the curtainsfallen leaves caught in their last incarnate colors. The fabric ghost white. At the slightest breath a slow, spectral motion. His dream a man' umental skeleton of metal: raw light crucifies a few spars of leftover scaffolding. Scattered at its foot are toys, kettle, bed, the kitchen dishes; chenille scarf, silver breast-brooch, amber necklace; the gold and lapis lazuli bracelet, its freckled deep blue hoarding light. He will hear the small birds on the feeder, or the hawk's high-up screaming. A broadwing blazon, ginger-tailed, on a cloud that winter has turned the color of weather-yellowed canvas.

32

Frosty Morning

The plume of steam from the tall chimney casts its own wavering black shadow on red brick, suddenly transparent and radiant with the sun streaming through it, molecular lift-off of light becoming a live lick of shade, a climbing vine of blackness, a design that won't stay still, then vanishes. My own shadow covers a goose feather fallen in the clabbered grass near water, the feather silver-trimmed and stiffened by the thinnest skin of frost. The soccer field's transfigured to a patch of Elysian dazzle, and the avenue is bright-lined with maples-leaves still green but falling in showers now frost has bitten twigs and sent this strict convulsion of chill into every limb, filling the air with quickness, spinning a hymn to descent, declension, each curling leaf a brief dialogue between light and shade, the body caught up in its own reversals. And out in the fiery glare against my window the bronze sheen of the finch's thick beak, rose glow of its head and chest, the shadow, the sunflower seed it's cracking, prints on the sill, its tiny sign and bottom-line signature final.

33

Bach's Requiem

When I sawall those voices-heard them hold together against death, pay no attention to traffic clamor in the city outside-when I saw so many differences could be brought to a single understanding like thatas a flock of starlings at no known signal will rise, hover for an instant so you can see each individual and the glint of each wing, then in a swoop will become one thing, tilted into a single tight formation and slowly spreading the net they've woven in air that shimmers between their solid, darkly iridescent bodies, and you see how the bodies and parceled air make one happen�fact you have no name for, although it has composed itself out of the accidental shape things take, the way the music is resolved, is resolute in its one winged body, part after part pushing it out of the jaws of the dragon, soaring (a net of birds) into lightthen I knew, though my own thoughts would not be light, that the dark had its own limits and would, in spite of bonechill, lift, be lifted.

34

Barbara Hamby

Ode on the Letter M

Midway through the alphabet, you are the tailored seam that ties Adam to zephyr, atom to uranium, sword that takes up a new God, little lamb, turns him into a flame spewing Visigoth, and Byzantium becomes Constantinople, the new Jerusalem, hallelujah, bombs away. Or are you the flim-flam man working small towns in Mississippi-Troy, Denham, Tishamingo, Yazoo City-hawking a serum that will cure everything-warts, impetigo, ringwormfade wrinkles, spark a wilting libido. Oh, yes, ma'am, dose your husband, and that rooster will crow again, thrum like a well-tuned violin. A masterful scam it was until the day that pretty little school marm purred like a pussy cat, locked you in her maximum security prison with gold rings, aluminum siding your new game, the highway nothing but a dream of freedom, because one letter can change a grin to grim, plug to plum, slut to slum, a few blankets and wampum can get you Manhattan, itself once New Amsterdam, because sometimes we seem to be a quorum of idiots on a plague ship in a sea of phlegm and fog, rumors of disease flying like crows in the scum of clouds heavy with hurricanes. Or the bride and groom in black and white, God bless their Viet Nam, here's hoping for years of pound cake and hymns. There's a charm in myopia, witness Monet's chrysanthemum, a blob of pink and blue, his lilies smears of thick cream on green. I take off my glasses when I can, though I'm as lost as anyone, searching for the perfect dim sum

35

restaurant, locked in my high gothic scriptorium, scratching for words as rats scratch for cheese-Muenster, Edam, Livarot-for there are worlds in worlds-Mozart's requiem the dark river Figaro sails on or The TIn Drum spawned by the SS. Who can guess the mysteries that cram our brains? Not I, said the little black cat. Fie, fie, foe, fum, I smell the blood of everyone. Like Robert Mitchum in Cape Fear, the ghouls are out, ripping the flesh off prom queens and popcorn girls, and as the storm clouds swarm like killer bees, I'll be searching for my Tiny Tim, om mani padme om, God bless us, every worm.

Ode on Laundry, Lester Young, and You r Last Letter

I'm folding laundry in an apartment in Paris, listening to Lester Young's whispering sax embarrass the afternoon with its lax hold on each note, letting one go, then pulling it back into its bell, strutting a bit, Mr. Cock-a-doodle-doc, and then soaring over sooty buildings like a raven, all mad roaring far below. You've been dead twelve years, my darling, and still I look for you in passing faces-eyes, hands, the trill of your laughter, but you're gone much as the arpeggio that disappears into Oscar's piano solo or the black 'Tshirts under the stacks of boxer shorts and lime green cotton panties, the piling on of hurts, warts, dirt and the scraping away. There's my stardust erupting on the other side of the solo. I must have read your last letter a thousand times, the paper almost transparent. I look at the curve and taper of your handwriting for a message beyond the words, and between the up slanted lines of a's and z's I've heard you promise everything that time has taken back like Billie's wounded voice, arched and pulling now on the CD player. I am left here with three mementos-the letter, a photo booth black and white with four frames, a stutter of time, both of us with long hair, mine blond, yours as dark as a starless night, laughing at nothing. And there's the scarf you knitted full of holes, that I take out every winter and wrap around my neck, touching it as if I were touching you one last time. So many things have changed. I've cut my hair, and it has darkened, as the day has. What if you were sitting with me now, Billie and Lester sliding between each other's voices, the register soaring and dipping like a hunter's bird. What could I say I didn't say? There is only this-the every day of laundry, this music, the honking trucks on the street below, and women with bags rushing home on winged feet.

37

Ode to Anglo Saxon, Film Noir, and the Hundred Thousand Anxieties

That Plague Me Like Demons in a Medieval Christian Allegory

Yo, Viking dudes, who knew your big-dog cock-of-the-walk raping and pillaging would put us all here, right smack dab in the middle of a decade filled with the stink of war. Yes, sir, boys and girls, we're eating an old sock sandwich, but we're speaking English, kind of a weird fluke (a piece of luck, not the parasite), because the kick, ass Angles were illiterate hicks while the sublime Greeks had been writing poetry for a thousand years, heck, history and philosophy, too, though they shellacked the Trojans and a lot of other guys as well, stuck them with their bronze age swords, testosterone run amok, or so I'm thinking here from my present perch-a swank appartement in Paris, swilling champagne, clothes black, as if my past were un chef d'oeuvre by Jan van Eyck, the soundtrack written by Johann Sebastian Bach or his son, rather than the Three Stooges,Lawrence Welk debacle that really occurred. My mind's a train wreck of two lingoes, twenty,six letters, and thousands of quick images from movies, French-yes, but mostly aw-shucksma'am Hollywood westerns or policiers in stark black and white, and I'm the twist, tomato, skirt, the weak sister who rats out her grifter boyfriend, palms a deck of Luckies she puffs while scheming with the private dick to pocket twenty large, or I'm the classy dame, sick of her stinking rich life and her George Bellamy schmuck of a boyfriend. That's when Bogart's three-pack-a-day croak (dialogue by Raymond Chandler) sounds like music, maybe Miles Davis, and you're up the five-and-dime creek, rna chere, because love can tum you into a mark, punk, jingle-brained two-bit patsy who'd take a fast sawbuck for snitching out her squeeze to the cops. Or you're the crack

whore with an MBA standing on the corner in chic Versace rags, falling for the D.A., till the Czech drug lord plugs him. So who are you? Not the hippie chick of your early twenties or the Sears-and-Roebuck Christian drudge your mother became, though Satan still stalks

you on a regular basis. Is that guy a slick operator or what with his Brylcreemed hair and pock, marked face? There's still smallpox in Hell, so you push him back whenever you can, grow orchids and for dinner cook risotto alia Milanese, because knick, knack paddy whack, you're counting on something, not luck or rock and roll, though you've been there-at the HIC with Mick Jagger prancing around like a hopped-up jumping jack on speed. Non, rna petite Marcella Proust, this is the joke, when your mother prays for you, your miserable heart ticks a little more like a Swiss,made watch, and when you speak, does French come out? Nah, it's the echo of those shock-jock Vikings, hacking their way across Europe, red-haired, drunk on blood and blondes, and though your husband looks like the Duke of Cambridge, that's not what you love so much, ya dumb cluck, but his Henry [ames-Groucho Marx-Cajun shtick. Knock, knock. Who's there? It's Moe, Larry, and Curly, nyuk nyuk, nyuk.

39

D. H. Tracy

The Neighbor Discusses Parkinson's

The average age of onset: fifty-eight. The actuarial tables propose a date

but I've already beaten odds. I age by losing the odd individual page

at a time, at intervals, all while you fear a tragic accident. Smile, will you. Fatal and degenerative differ in that one will let you live and one you leave your will. Whatever culls the cells of the substantia nigra pulls

no other fast ones. I think I hear it feast, sometimes, a pig on truffle, picky beast

passing up the scrumptious gray cerebral glands of mope, resent, and funereal

gloom I could have done without. Ignored. If only Parkinson had been as bored

with motor skills, I would not have noticed, before consulting my neurologist,

my half-mile at the pool creep up from thirty to thirty-five and forty minutes, and birdie

tum to bogey. A stiffness in the back. She has me in her office read the plaque

and counts my two'beat blinks. To test my balance she jabs my shoulder. Parkinson's talents

are improving monthly. Swallowing takes concentration; my bowels, owing weeks of arrears, stage noisy filibusters. My larynx slackens, sulls, and hardly musters

a wheeze to justify the Think loud signs plastered everywhere like valentines.

Anne put one on the mirror. Nothing to lose. In about four years I will have to choose

a single victory over the medication: the paralytic fetus, number one,

or, two, the flailing, spastic dyskinesia. There you have it. Figures, facts, no drama,

my overt wish that you should sympathize, sit in my den and listen, subsidize

my hobby. In your heads live my travails. If and when, for me, the carrot fails,

I have a serviceable stick to lever my bony balking donkey forward. Whether far or not, farther. Longer in the saddle. You might exercise your choice of battle.

41

Clutch

Something like a clutch, the two of us communicate the will to one another to move, and as one spins the other must, in contact with his mate, spin with her unless the pedal disengages them and leaves them both to whine alone in air without a way to know the other's aim or use their specious freedom from the pair.

If you protest my model of us makes one the driving, one the driven, giving one pride of place, recall life engine-brakes as often as it climbs, and has us revving loudest in our worst deceleration, when on the half that had been blithe about us is borne a little care with each gyration to moderate our tumbling apparatus.

So they function best who come to grips, and travel farthest fastest who beware the mismatch of intention in the slips that leave their coupling that much worse for wear; let us therefore use our hard,won touch to ride but not to ride it, me and you pressing close together inasmuch as is in us to be coming through.

David Woo

The Words

In the novel a story unspools in lines, Tangled vines crumple from the chill, And words clear the view to the mountains

With an absence of words: no houses, no roads.

There a newly released wolf is sniffing

The ground for first prey, among snow drifts

Punctuated with burnt pinecones.

The word "restraint" disrobes above a hot spring.

Far from the secret airstrip where white dust

Bums the nostrils with the folly of dollars, Down to the alcove under a meadow

Where the dispossessed hide with field mice,

The words lace up their aglets along lines

Knotted and knotted to no end except The End, like the shoes of a dead man

Tied in the casket by a delicate stranger.

I close the book and reach for a letter unopened For days, not forgotten, not untouched, As if it were something growing within me, Something I can palpate with rising terror.

The basket of cloudberries and dill still sits

On my desk, made of someone else's words.

The letter opener gleams in my hand.

If I read the words, my life will happen.

43

On Refusing to Be on the Make

If I had turned around at the right time and seen what was behind me, I would know what my actions meant: that everything served the same cause, and was known to serve the same cause, as if I were transparent and could see motives flowing through me, like a picture frame held over a trout-filled stream. Now I must go on walking and walking along these blind paths where dreams no longer exist because the self itself has gone clear. On the bridge in autumn, leaves are falling from trees I can no longer see. Lovers are holding hands that carry invisible photo albums of the families they will never have.

But I am walking on, for once, without questioning what lies behind. As for the future, how can I help but judge you by how gracefully you brush aside the falling leaves?

Or how selflessly you tum to me and remove one clinging to the small of my back.

44

Richard Burgin

A Letter in Las Vegas

Because their words had forked no lightning.

Dylan Thomas

The letter he emailed to your hotel a few hours after your conversation lay on the bed beside you and just looking at the exclamation points that recurred fugue-like throughout it made you resist reading it again. But what other choice did you have? For nearly forty-eight hours the same hideous "horror movie" of two nights ago had been playing repeatedly in your mind, the "movie" that had made you call your brother and him write you in the first place. The only other option to escape it was the TV in your room but it had just three unwatchable channels working so it wasn't really an option at all. You knew that Sid, at the front desk, who you'd paid to misinform your brother, wouldn't fix it. He'd already promised to send someone up twice but no one had come.

You picked up the letter. It was odd-you avoided someone and then you found yourself scrutinizing their letter.

"Darren, I'm going to write you very candidly," it began. "There's no question of pride anymore as there often was between us-I'm far too scared for that! You need to come home now, you know that. If you don't, it would be the worst, most self-destructive thing you could do!

"You told me once that you sometimes think of me as the police you keep trying to outrun or outwit as if my goal is to arrest you rather than

45

just being with you. I say this now, and everything else only because I want you to fight the mess you're in instead of running away from it. Remember, I've known you your whole life and right now I may be the only person, besides you, who can help you!"

You looked away from the letter, staring straight ahead at the Venetian blinds. You were aware there was a fundamental conflict in the way you and David were thinking about your situation. To him it all boiled down to your getting out of Las Vegas immediately to have your operation and deal with your other medical problems at horne in Philadelphia. But to you the primary issue was how to get to the next moment without seeing the "horror movie" again, how to escape from it, if only for a few minutes. So far, the letter wasn't working very well but you still returned to it, this time skipping ahead a little.

'''Sins are like snowflakes, no two are alike.' You once wrote that in a letter to me, your proud and slightly envious older brother, while you were still getting your MFA and I agreed and obviously remembered it. Are you sure your not returning my phone calls or emails I've been sending all day isn't your own special kind of sin, the sin of making me worry so much I'm on the verge of flying out to Vegas myself to try to find you? I wonder if you realize what I'm going through, especially when I remember all your dark, hysterical talk on the phone like 'Death is tucked into life like an invisible napkin' and 'I have a lifetime of regret without the lifetime to regret it,' (you see how I can quote you) among other cheerful thoughts. I think you were born spouting aphorisms. You should have lived in ancient Greece!"

You laughed. That was what you thought you needed to "feel" him again-that sarcastic humor of David's and the kind of passionate innocence that lay behind it. In feeling all that, you finally got relieffrom the horror movie so you went back to the letter once more.

"Before Las Vegas, I thought your life (and our relationship) was at least functional. More specifically you were already somewhat avoiding me but you were under a lot of pressure after the results of your biopsy and, of course, I was shocked too! Still my feeling, based on what you told me on the phone, was that you were in reasonable spirits about going to Vegas, even a bit excited since you'd never been there before. And why not? The university there was paying you well, you'd already been interviewed and had your book praised by the ciry's best known alternative paper and you were even going to have your reading televised by a local cable TV show! And your reading was, you admitted yourself, from any objective point of view a success and was received with warm,

spontaneous applause. It was a kind of grand slam-like winning all the literary slots. Also, you said, your host from the English department there couldn't have been nicer and more solicitous. You said you two had met at a convention the year before and immediately taken a liking to each other. You see how I remember everything you tell me! I even remember you said he looked like you with his mustache and hair still dark {one way or another}. Already, he'd gotten you a ticket to one of the Cirque de Soleil shows playing at the Strip for the night after your reading. At the airport, filled with slot machines and showgirls, he gave you a warm hug."

You could see and even feel that hug from Bennet again but with it the image of David suddenly faded to extinction and the horror movie came rushing back. You let the letter flutter to the floor then like a giant, indoor, Vegas snowflake. You felt betrayed because you'd hoped the letter would give you an escape by making you think of your brother. Instead, it only restimulated and intensified your Last Vegas memories. Moreover, you were too tired and overwhelmed to struggle against that now and had already surrendered to the idea of going over everything in the movie one more time in the hopes of finally exhausting it. You were still seeing and feeling the hug-whether you closed your eyes or notand hearing Bennet say once more during your drive into town, "I'm sorry we couldn't get you a better hotel, but at least it's within walking distance of the Strip."

You remember that you actually thought the hotel charming. With its low to the ground design, earth tone colors, palm trees, and outdoor swimming pool it reminded you of a California hotel. Your brother was right in a way-all things considered, you were in pretty good spirits when you arrived. David was a lawyer and was careful and often accurate, though in a limited sense, with his observations. For instance, from an "objective" point of view your reading was a success. There was a good-sized crowd {considering your books aren't commercial and you were reading from a short story collection}, "spontaneously warm applause" and then the added glamorous touch of those cable TV cameras focusing on you. All of this was heady stuff for you who were used to twenty or thirty people at most of your readings and naturally this gratified you. You even remembered wishing David were at this reading, as he had often been before in lieu of your professionally preoccupied parents. But it was also equally true, and this David would never understand, that on another level the "warm applause" tortured you, that what you wanted instead was a shocked explosion from the audience

47

because you wanted to change their lives, not just make them appreciate another "good" writer. Though you never felt this when you went to other writers' readings, that was no consolation at all. Because you didn't transform your audience in any way, you felt a kind of depression gnawing at you. Given your age and your cancer you probably never would, so you looked to women, once again, to give you an injection of the kind of excitement your work had once more failed to provide. You didn't have to wait too long.

After the reading, Bennet took you to dinner at a Thai restaurant with a group of university professor/writers and a couple of graduate students. One of the students was a part Thai, part American named Maya. She was quite pretty and energetic with a secretive side that appealed to you. You were attracted to her but she was young enough to be your daughter so you were careful not to let yourself get too encouraged. But soon she mentioned a quasi-famous poet/professor old enough to be your father, who had once taught both of you, albeit at different times and at different universities, and she said twice that the whole term she'd had a mad crush on him. From that moment on (as the song goes) you virtually ignored the other people at the table and focused on her.

Because of the fear you had after learning your biopsy results and the torturous decision you had to make about what kind of treatment to pursue for your prostate cancer, you were on a new medication for anxiety that gave you a kind of instant social courage. You also had two or three drinks. She was drinking, too, though less ardently than you, but seemed eager enough to answer all your questions. She said she was lonely and felt completely disconnected from Las Vegas. She didn't even know how to drive. She'd been living near Boston before, where driving a car wasn't that important. She went to the university at Las Vegas a year and a half ago because she'd won a fellowship there, which was now essentially what she was living off.

"That's why I didn't buy your book," she said, a little ruefully.

You told her that, of course, you would give her a copy of your book. You said, don't you have lots of friends, perhaps you also said "admirers" in an obvious allusion to how attractive she was (though she was definitely more attractive in a New England than a Vegas kind of way). She said she stayed home almost every night, and had never even seen much of the Strip. She'd had a hard enough time adjusting to Boston once she came to the States but the Vegas sensibility was still alien to her. Interesting to observe, she said, but impossible to feel at home in.

"But what will you do? You have to get out of here." (Come with

me, you wanted to say because, though you are over fifty your romantic fantasies are as frequent and extreme as a sixteen-vear-old's.)

What you did say was that you wanted to see the Bellagio and the other great hotels and why didn't she go with you after dinner so you could see them together and, who knows, maybe even gamble a little.

"As long as you're living in a place you may as well see what it's famous for," you said.

"Sure, why not?" she said, smiling. She seemed charmed by you, maybe also impressed by your writing, maybe not, but definitely charmed, which was more important to you these days when your sexual future was so uncertain because of your cancer and the present seemed to be all one had.

"Just don't let me lose too much of my money," she said.

"We'll only gamble with mine," you assured her.

At this point, you remembered that the aging poet to your left interrupted you and started asking you some questions. It was all you could do not to snap at him. You assumed, at first, that he was making nice because he wanted you to arrange a similar type of reading for him at your university-something you figured you only owed Bennet, your host. But a few minutes later he began directing his conversation at Maya. It was soon obvious that he was trying to hit on her as well despite the fact that his dowdy wife was seated immediately to his left. Those were difficult moments-as was the whole rest of the dinner, followed by the obligatory, absurdly prolonged goodbyes in the parking lot. But, you reminded yourself, it was really like one of those televised storm warnings where the storm never materializes and when you and Maya rode in Bennet's car while he drove you up the Strip amidst much good cheer and joking and deposited you at one of the entrances of the Bellagio, you were feeling giddy again.

The big hotels of Las Vegas are not so much hotels as worlds (each with its own theme), which they were not shy about announcing either with giant fountains and sculptures of faux rockets or with golden pharaohs and sphinxes. In one world, you saw a giant replica of the most famous landmarks of New York that went on for a block, including a "Coney Island" amusement park replete with roaring rollercoaster and screaming children.

The Bellagio was supposed to be the classiest of the hotels but, like so much of Vegas, its beauty was inseparable from its vulgarity. In its casino, as in all Las Vegas casinos, you entered an underground world without time, where clocks were as absent as the sky, just in case a

49

knowledge or even dim awareness of time might distract the gamblers from the steady stream of money they were pumping into the slots or black jack tables.

The two of you walked around this maze, alternately appalled and delighted. You walked almost a mile before settling at a little bar at a far end of the casino. It was clear by now that neither of you had an interest in gambling but you wanted to drink, and even more to have her drink.

"Well," you said, indicating the giant space around you, "bright lights, big city."

She laughed and, naturally, you liked that.

You finally persuaded her to drink a Manhattan. You joined her with another vodka tonic. Since there was so little alcohol in the drinks you knew it would take a while to loosen her up. You began to ask her questions, specifically about her childhood, then, later, after her second drink, about her past love life. Like most lonely people she was eager to talk and was soon describing life in a rural Thai village. You told yourself to listen closely, to really try to understand this person but it was difficult, like listening to someone explain how to do a puzzle without being able to quite understand where to put a few key pieces. It was not that her story was boring or without revelations. You could sense, for example, when she described her intensely ambivalent relationship with her American father who'd died of a heart attack a few years ago why she gravitated towards older men. You tried harder to concentrate as she described her few lovers, including the main one with whom she'd broken up and reconciled a number of times and who still called her. He was a foreigner-part Oriental, part Hispanic. She told you more than once where he was from, as well as his name, but you couldn't remember either no matter how angry it made you not to know. You thought ofhow Maya lived in a separate continent from you because ofher background and age. Then you started thinking about the invisible life of your cells and the way they'd turned against you in your prostate and tried to remember something David had written you about courage. That made you take another drink. You put your hand on her shoulder, briefly touched her hair. She didn't respond although she didn't say or do anything to stop you.

Finally, you paid for the drinks and said, "Let's take a walk." The bartender was starting to talk too much to Maya-as if he were the son of the professor/poet in the restaurant-and you were relieved when she said she wanted to walk too.

50

Meanwhile you popped another pill and a few minutes later finally felt the high you'd been hoping for. Almost immediately you realized you were lost, but you didn't care.

"It's like Halloween in here."

"That's what Vegas is," she said, "Halloween 2417."

The next thing you knew you were walking through an elaborately rendered faux Parisian village replete with its bistros and patisseries. It vaguely occurred to you that you might now be in a different hotel, but it hardly mattered.

Then you began to offer some unsolicited insights about her ex, boyfriend's on again, off again behavior. You felt that as the older, pre' sumably wiser person you were expected to use your presumptive power of mature advice as a way to demonstrate how she could benefit by hanging out with you. Maya listened to you closely as you enunciated, as well as the vodkas and Xanax in your body would permit, your relationship advice.

The truth is your own advice soon bored you and during the last half of your speech you were already thinking again about the different can, cer treatments available to you; radioactive seed versus radical prostatectomy versus laparoscopic surgery. David naturally advised you to take the most conservative approach, which was open surgery and you had in fact ultimately listened to him and made an appointment with a sur, geon. But you continued to think about alternative treatments anyway. Remembering all this you realized that talking alone wasn't going to help you get through this night. Moreover, with your girlfriend Margo estranged from you, this was possibly your last real chance to make love in your life.

"Oh, this is lovely," you said about an outdoor "French cafe" you two just discovered under a cleverly constructed "chestnut tree."

"Let's have one more drink."

"I think I'm pretty high," Maya said.

"Nowhere near enough."

"I don't know."

"You're being far too rational, especially for a poet."

"But I write fiction," she said, correcting you as she sat down at the table.

You felt a tinge of pain or something like it. You hated it when people caught you not listening to them, especially since you couldn't stand it when they didn't listen to you.

"But all fiction writers want to be thought of as poets or at least as

51

being poetic," you said, trying to recover. "Wasn't it Faulkner who said 'every novelist is a failed poet'?"

She laughed. "That's a good saying. Did you used to write poetry too?"

"Oh sure. Wrote it, failed at it, abysmally, then gave it up permanently for fiction at which I also failed, though less spectacularly."

She laughed. She was on your side again and soon agreed to have a drink. You realized now that you not only were attracted to her but liked her too and you reached across the table and touched her hair. She let you, at least for a few seconds, then the waitress appeared, with half her tits showing, took your order for drinks, and everything seemed right for a moment.

But nothing ever stayed the same in Vegas for very long, as if each roll of the dice revealed how time changed every moment. It was like cancer that way, too, although cancer changed much more slowly, at least in the beginning.

You waited till you were both through with your next drinksensing that at last she was high-before you touched her hair again and part of her face. She didn't respond as you hoped but she let you do it. You pictured your hotel room with its pathetic television and you knew you needed her there with you-could already picture what you'd do in bed together.

"I really like you," you said. "Do you think you like me?"

She hesitated-and you decided not to let her answer.

"As soon as we started talking in the restaurant I sensed a connection between us, didn't you?" you said, appalled by how trite you sounded.

She half nodded and finished her drink.

"It's so rare that that happens so I think you have to act upon it when it does. It's just crazy and tragic really when people don't. I mean we're all gonna die in such a short time-yet people hold back out of fear and pride-that's the insanity of it."

You were aware that you were rambling and still sounded like an old hippie but in a way you thought that might help win her over-to show her that inside, once she got past your aging face and body you were young and in certain ways even younger than her.

"Don't you feel that way about me too? Tell me the truth."

"I feel a connection

"Good, me too," you said, touching her just above her knee.

"Can I ask you something?" she said.

"Sure."

"How old are you?"

It was, of course, the worst question she could have asked. You wanted to yell at her, There's no time here so why are you asking me that?

"Oh God, let's see, I think I'm 2006," you said, making her laugh. "Hey, it's getting really hot in here, have you noticed? Let's take a walk, okay? Let's take a walk together."

So after you both finished your drinks and you paid up you two started walking again through the remains of the French village. But walking wasn't really what you wanted to do and soon you began putting your hands on her and telling her how much you liked her again.

"I think that's your drink talking," she said, slipping away from you. "I think you're just very high."

"No," you protested. "Just very attracted to you."

She was walking ahead of you and you struggled to catch up.

"I have to get home now," she said, avoiding your eyes. "It's getting late."

You saw then that it was hopeless and told her you'd get her a cab. Then you asked a couple of people how to get out of the hotel and set about trying to follow their directions.

It's amazing how quickly people disappear-first from your sight, then from your mind (which takes a little"longer) and then from the earth itself.

You were outside the Bellagio waiting for a cab. The strange beauty of the Strip flared up at you-the lights and trees and fountains.

You both commented on it before you got in the taxi.

You wouldn't touch her again, you wouldn't put either of you through that. Instead you sat a polite distance apart and asked a few more questions about her school and thought about your cancer and when it was time for her to get out you actually shook hands with her before getting back in the cab and telling the driver to take you to your hotel, which was a relatively short distance away.

But once you were back inside your room you immediately began to panic. It was so small and forlorn like your own personal section of hell and it only had those three idiotic channels. With nothing to distract you, you began thinking about your different prostate options. If you chose brachytherapy and had the radioactive seeds implanted you might have minimal side effects and if you were one of

53

the lucky ones, which the brachytherapists placed at 70 percent, you might never miss a beat in your sex life, and even if you were one of the unlucky 30 percent, there'd usually be a grace period of a year or so before you'd become impotent. The brachytherapists had just published a study saying their twelve-year survival rates were comparable to open surgery but the surgeons weren't buying it, at least not publicly. While conceding that the five-year rates were comparable they said the long term data wasn't sufficient to compare it to the "gold standard" of radical retropubic prostatectomy. What "Gold Standard" you asked yourself, as you paced around your room-the gold standard of castration?

It was too excruciating to think about. You took yet another Xanax, then not much later another, turned on the TV, lay down and thought about Maya. When that soon proved too painful you thought about David instead. That was easier, especially when you concentrated on your relatively happy childhood, and you soon closed your eyes.

You could remember again the kingdom that you shared with him. You were two little kings in a white palace with a yard lined by trees and flowers which magically expanded, it seemed, to accommodate your endless games of baseball and badminton, hide and seek, and snowballs and sledding downhill on your Christmas sleds or sometimes just on garbage can covers-the wind in your face the whole way.

Inside the house you two played your games of chance; Parcheesi and Monopoly, Gin Rummy and Fish or just rolling dice-the eternal game, it turns out, in Las Vegas (just as in your life which would be nothing now but a game of chance forever). Cards were fascinating then, as were raisins, hearts of celery and lettuce, the roots of carrots, long banisters and enormous chairs and closets that stored toys and hid witches. As your older brother by two years, David protected you from the witches, as he continued to try to do throughout your life.

You thought a little more about him but you had a restless spirit and body-it's what often made you identify with ghosts. This time you suddenly rose from your bed of death, as you thought of it, and the next thing you knew you were on the streets heading towards Maya's apartment, moving as fast as you'd ever moved in your life. "I have cancer but I'm flying," you thought. Nothing, not your humiliation, your age, your brother, or your cancer would stop you now. Then you thought of the lines from Dylan Thomas: "Because their words had forked no lightning they / do not go gentle into that good night." If your words at the reading had forked lightning, Maya wouldn't have resisted you, instead you

54

would have forked her. But now your action would fork lightning because nothing would stop you.

You wondered briefly if you could get inside her building-yet in a moment that problem disappeared when an elderly man leaving the building at the same moment you were trying to enter held the door open to let you in. You thanked him and went directly to her apartment where you knocked but got no answer, then found yourself listening at the door for signs of her. "It's Darren," you finally said. "Can I talk to you?"

You anticipated more resistance but she opened the door, wearing a bathrobe.

"What are you doing?" she said.

But you didn't feel you had to answer that question as you began to unfasten her robe, and felt her slender, squirming body beneath it. "So this is what rape is," you thought just before the door opened again and a man entered the room. Was it her longtime Hispanic/Oriental lover, was it, inexplicably, David?

You opened your eyes, the TV was on and you were still in your hotel bed but no one was with you. It took you quite a while to understand your dream and even that what had happened was in a dream contained, as it was, like a subset within the larger dream of your life, yet different from it. Perhaps it was caused by overmedicating yourself, perhaps you were even half awake and guiding the events as you never can do in a real dream. All you knew was it was 3:45 A.M. and you were wide awake with nothing watchable on TV and no possibility of sleeping. There was no one you could phone either, because you were in a different time zone from anyone you knew. Of course, you could have called your brother but you didn't believe that or think of him as someone you could benefit from calling. It's the weirdest thing. At first, you never think you can confide in him but later when your troubles thicken and some permanent damage has already been done you end up telling him everything. But this didn't occur to you then. He wasn't even a blip on your radar screen. There was nothing on your radar screen (not even Maya despite your recent "dream"). Nothing but the desire to get high so you could fall back asleep. You weren't even scheduled for any human contact until three o'clock tomorrow afternoon when you and Bennet were supposed to drive to the mountains. (You would end up canceling that event as well as the Cirque du Soleil with the excuse of "mild food poisoning").

Originally, Maya was going to go with you and Bennet to the moun-

55

tains but there was little chance of that now. Sizing everything up, you put your clothes on, including your new brown leather jacket because it made you feel tough and confident, rinsed your mouth, swallowed a Viagra and hit the streets.

When you were first dropped off at your hotel and had a few hours to kill before your reading you'd walked around your neighborhood and noticed three things: all the free sex flyers in the newspaper stands with photos of various girls who would "dance" for you in your room (you collected quite a number of those), a couple of hookers walking the street who looked like crack whores, and a twenty-four-hour convenience store where they sold alcohol. You cursed yourself for not thinking ahead and buying something to drink earlier-although the refrigerator in your room wasn't working so whatever you drank would be warm.

You bought a couple of large cans of beer and started walking back to your room when you saw a hooker. She was black and a little chunky and the two of you walked up to each other simultaneously. She said her name was Pandora. Her blouse was low cut and her belly button was sticking out but otherwise there was nothing whorish about her. She was overweight and not much more than average looking, though of course she was young enough to be your daughter and therefore attractive for that reason alone.