$11.95 US l' 7 25274 79069 2

TriQuarterly

TriQuarterly is an international journal of writing, art and cultural inquiry published at Northwestern University

TriQuarterl�y

Editor

Susan Firestone Hahn Contributing Editors

Associate Editor

Ian Morris

Operations Coordinator

Kirstie Felland

Cover Design

Gini Kondziolka

Editorial Assistants

Samantha Levine

Mairead Case

Assistant Editor

Joanne Diaz

TriQuarterly Fellow

Brent Mix

John Barth

Lydia R. Diamond

Rita Dove

Stuart Dybek

Richard Ford

Sandra M. Gilbert

Robert Hass

Edward Hirsch

Li-Young Lee

Lorrie Moore

Alicia Ostriker

Carl Phillips

Robert Pinsky

Susan Stewart

Mark Strand

Alan Williamson

126

poems

49 Non-canonical

Laurence Goldstein

55 Litany for the Legion of Unrelated People; Written in the Year of the Lake: A Murder; Worker Ants; Anonymous Self Portrait with Dead Animals; Mulberry Tree

Victoria Chang

62 The Missing; Autopoiesis; Briga D. Nurkse

66 Muses for Panic; Bereavement: 1919

Sandra McPherson

70 Fall of Rome; Alaric Intelligence Memo #36

Richard Kenney

I62 On Adoration and Envy; On the Problem of Distinction

Jessica Fisher

I64 Waiting for the Word; Nocturne; On a Drop of Rain

Robert Cording

167 Woman with Plum; Night, White and Gold for Louise Nevelson

Hadara Bar-Nadav

173 The Book of Sleep (IV); The Book of Sleep (XIII); The Book of Sleep (XV); "The World Was Created by Ten Utterances"

Eleanor Stanford

I77 Hospital; Spring, In Five Parts

Marianne Boruch

Contents

Michael

Sande

182

Nothing

Dear Heart,; A Different

McFee 184 Practice

Campana 189

191

fiction 72 Master of

Rodriguez 80 Indie Steven Schwartz 93 Heroes of the Revolution Brendan Mathews 113 Frances the Ghost

Meno 123 The

All This

A. Slomski 131 A Split-Level Life

Joseph

The Severn; The Lawn Like a Forest Calling Ron De Maris

Vincent, at Saint Paul's Sanitarium, Saint Remy de Provence Neil Shepard

Ceremonies Alicita

Joe

Allure of

Heather

Boritz Berger 143 The Sub

David essays 9 Fly Away Home: John Edgar Wideman's Fatheralong

J. Sundquist ISO

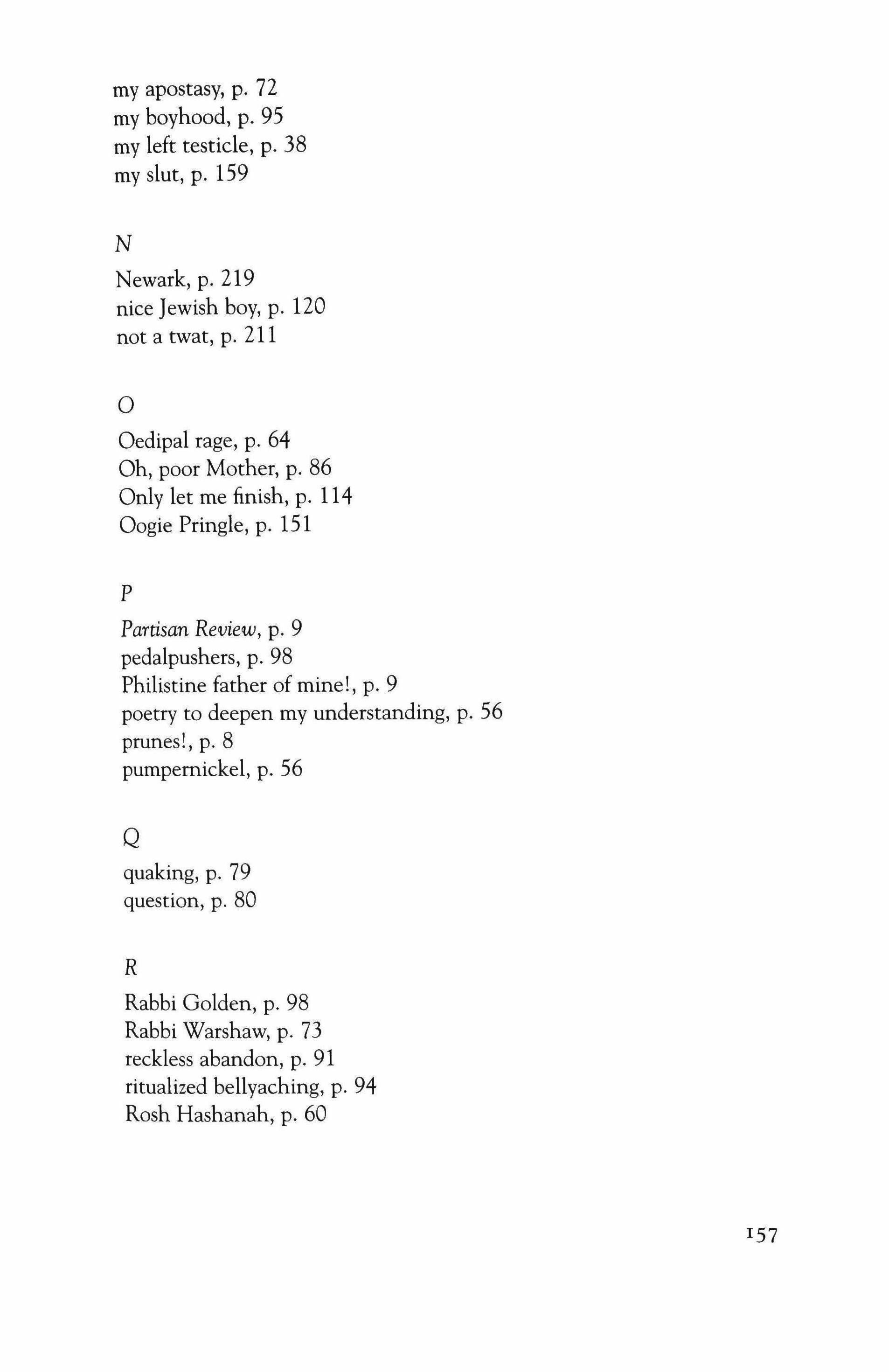

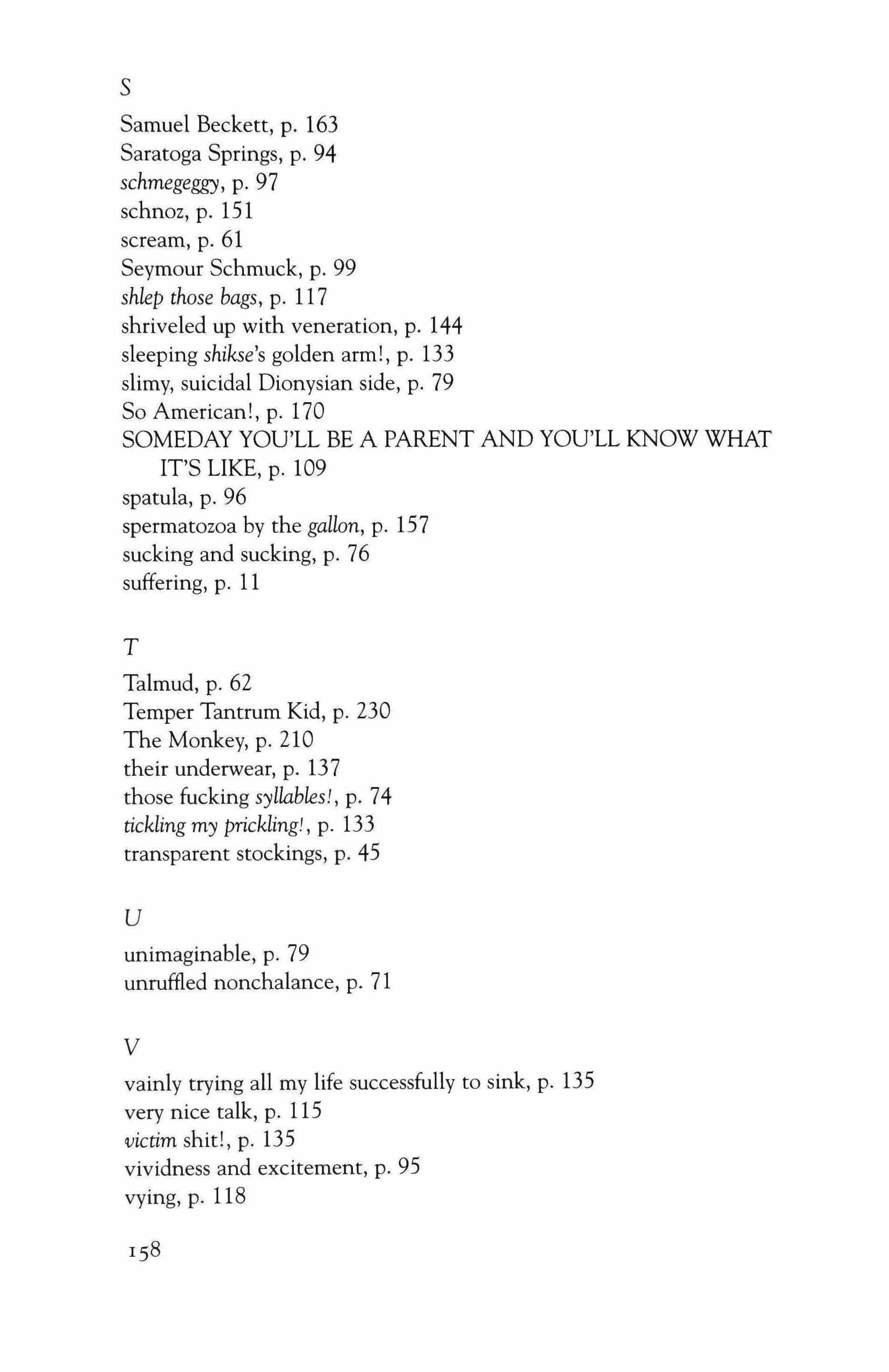

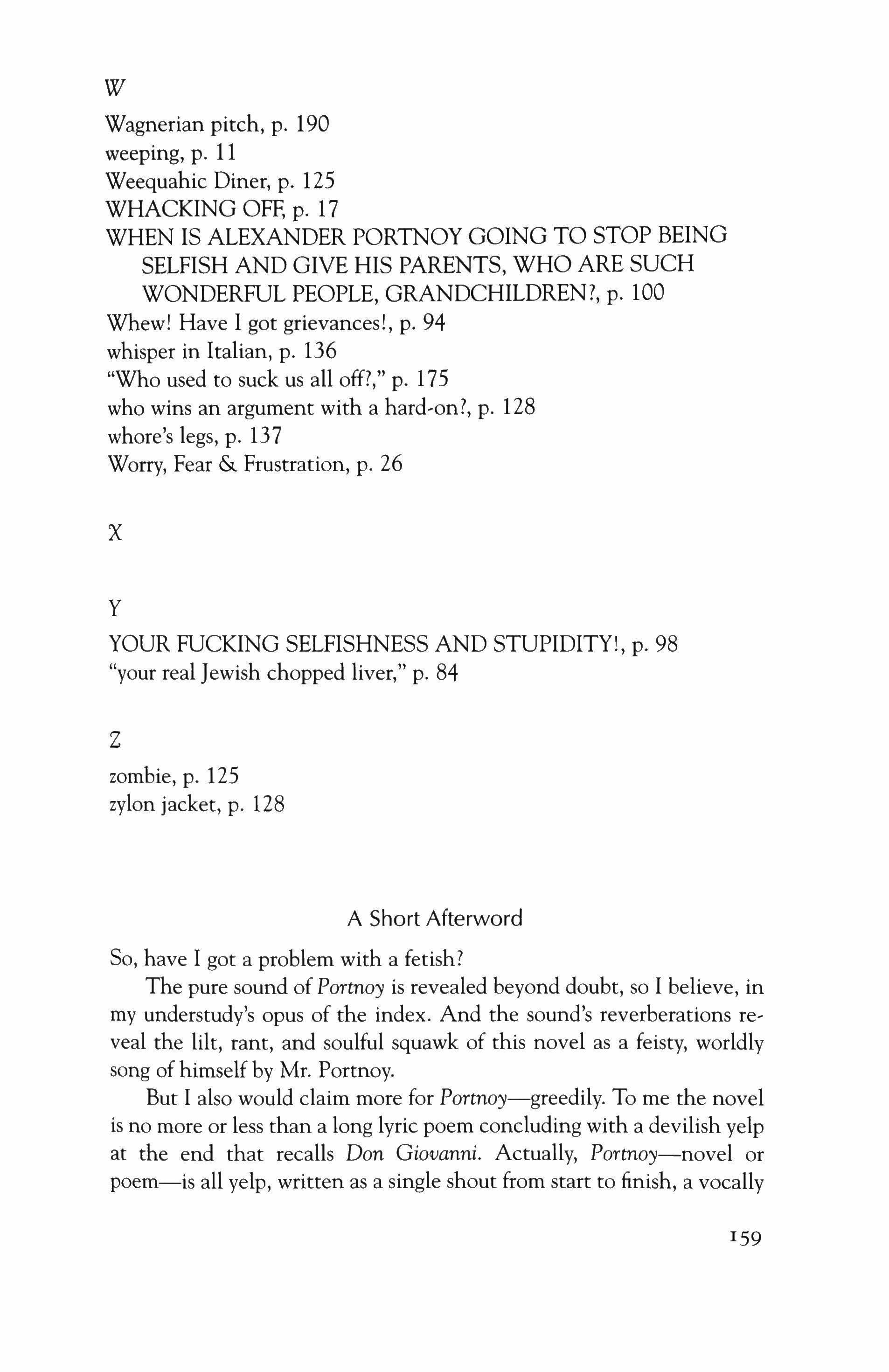

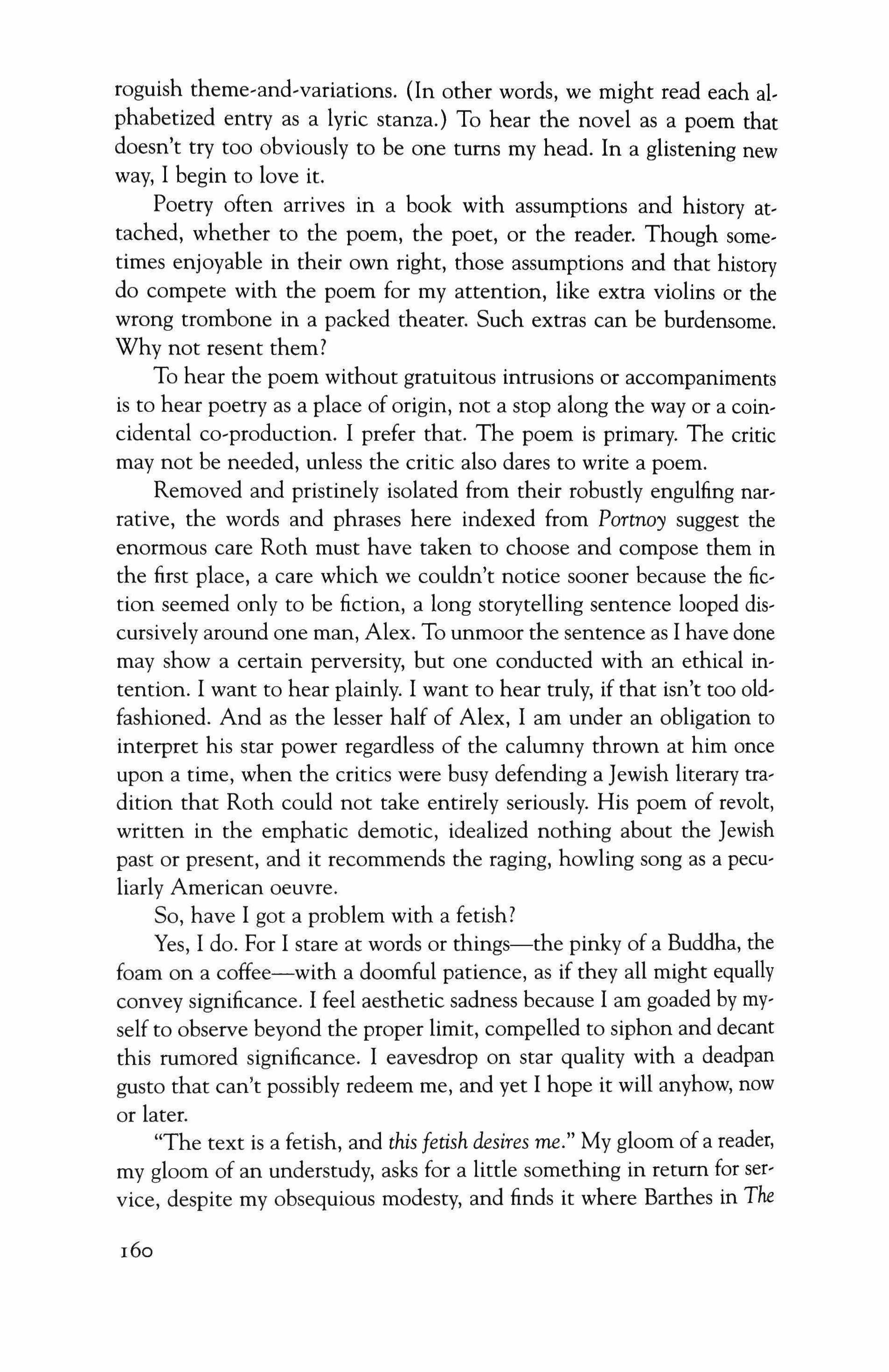

Index to

McQuade 200

Jonathan

Eric

A Fan's

Portnoy's Complaint Molly

Motion, Energy, and Revelation: Tintoretto's Last Suppers

Robert Hahn

translations 29 the professor's knife

Tadeusz Rozewicz

Translated from the Polish byJoanna Trzeciak

193 The Night Songs

Friedrich Hoideriin

Translated from the German by Maxine Chernoff and Paul Hoover

Cover: New Wave No.1, New Wave No.2, New Wave No.3, New Wave No.4, by Virginia Kondziolka: acrylic, chine colle and reflective glass beads that are mixed with the paint on Arches 300 lb. watercolor paper.

TriQuarterly is pleased to announce that Lee Roloff's oral essay, "Kurt Vonnegut on Stage at the Steppenwolf Theater, Chicago" (TriQuarterly 103), will be reprinted in Slaughterhouse� Five (Bloom Guides), edited by Harold Bloom (Chelsea House Publications, 2007).

and that Donna Seaman's essay, "Reflections from a Concrete Shore" (TriQuarterly 118), has been reprinted in Fresh Water: Women Writing on the Great Lakes, edited by Alison Swan (Michigan State University, 2006).

Eric]. SuruUJuist

Fly Away Home:

John Edgar Wideman's Fatheralong

For where does one run to when he's already in the promised land?

Claude Brown, Manchild in the Promised Land

Midway into Fatheralong, his 1994 meditation on black fathers and black sons, John Edgar Wideman casts back beyond the early twentieth, century "vast migration outward" that brought his family from the rural hamlet of Promised Land, South Carolina, to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in order to describe the traumatic beginnings of black America. Weav, ing among evocations of the physical and spiritual resilience that allowed Africans to survive transport and bondage, imagined experiences of himself as a slave, and reflections on modem,day racism, Wideman seeks "a path inward, back to the origins, a territory in my mind I could call home." Here and elsewhere, as one might expect, the fortuitously named Promised Land permits Wideman to play upon the manifold dreams and ironies that have made the Exodus a central metaphor of African American life from the slave spirituals onward. Less predictable is Wideman's wrenching displacement of the Exodus by a metaphor that in recent years has assumed ever greater significance in black life-the Holocaust:

9

The South was a winnowing for African people. The second blow of a double whammy delivered by Europeans. Test of mind after a test ofbody. Think ofmedieval trials by ordeaL Think of the Middle Passage--capture in African wars, forced marches to the coast, confinement in barracoons, crossing the Atlantic packed spoon-fashion in the holds ofships in unimaginably cruel, deadly conditions, sold into perpetual slavery-as a brutal threshing of the physically weak, and then the South as a test just as brutal for the mind.

I recall the archetypical scene of German officers in their greatcoats and shining boots processing long lines of Jews stumbling from trains that have transported them from every comer of Europe to the death camps. Some refugees would be directed by their captors to the right, some to the left. One direction meant immediate gassing and cremation, the other a living death of near starvation, unremitting hard labor in concentration-camp factories. A strong body was openers, served as your ticket to helL It qualified you to undergo the next trial, the mind's struggle to survive in spite of the body's imprisonment, suffering, degradation. Its theft, appropriation. Minute by minute, day by day, each prisoner chose to live or die. The burden of choice, the final selection occurs in the mind. They could decide to own you, house you, feed you enough to keep you alive. Yours to determine what choices their choice'S leave you.

The underground history of the camps must be remembered, written, and celebrated. The story of how strength of mind, individual and collective, altered the genocidal master plan, how the horror that destroyed so many could be transformed into a rite of passage for some, then for a people, a nation.

Yes, I want to consult the record. Learn facts, the official documentary evidence, witnesses, proof. Simultaneously I must not neglect the many other ways the past speaks. Through my father's voice, for instance. His hands. His eyes. Me. Sooner or later I get to myself. Another way my father speaks. To me. Through me.

It's not simply a matter of things happening again and again. That's not the burden of our personal and collective history. It's that these things never stop. Certain unexamined assumptions about "race" and color continue. The idea of"again" or "oh no, not again" is deceptive because it mixes good news with the bad. "Again" dilutes the horror, the truth of the workings of the paradigm of race.

10

As the two historical experiences are joined together in the "underground history of the camps," the Holocaust at once clarifies slavery, by providing a more immediate frame of reference, and obscures slavery, by confusing inhuman practices dedicated to racial extermination with inhuman practices dedicated to enhancing wealth. Suddenly introducing the Nazi genocide into his narrative but then gradually altering his description of the concentration camps into "a rite ofpassage" that applies as well to African Americans, Wideman posits that the ancestral story he seeks to recover is one about genocide and its survival. But his cunning use of the second person, which recurs in different forms throughout Fatheralong, adds a dimension of intense autobiographical significance. Sometimes a synonym for "one" or "one's self," sometimes a way to address his reader, the "you" evoked here in reference to the concentration camp prisoner modulates over the course of Fatheralong into Wideman's son Jacob (Jake), serving a life sentence for murder in a Tucson prison, a fate startlingly like that of Wideman's brother Robert (Robby), sentenced to life in prison for armed robbery and murder, a story that Wideman told to great critical acclaim a decade earlier in Brothers and Keepers.

"I am a descendent of a special class of immigrants-Africans-for whom arrival in America was a life sentence in the prison of slavery," Wideman writes in "Doing Time, Marking Race," a 1999 essay on American prisons. Doing time is just one of the many forms of imprisonment "legitimized by the concept of race" in America, which looks to "white-coated technocrats and bottom-line bureaucrats for efficient final solutions." As in Fatheralong, he argues that the "holocaust" ofslavery has not ended but is now carried out by the criminal justice system, an analogy with particular force for Wideman, who belongs to a family in which at least one male of every recent generation has been imprisoned. "Oh no, not again" thus has a triple meaning: the mystery and heartbreak of the son's tragedy repeating the brother's, both part of the fatal "paradigm of race" working itself out over and over again in the incarceration of black men, about which Wideman's phrase is a variation on "never again," the injunction against repeating the Holocaust.

On August 13, 1986, barely a decade after Robby Wideman went to prison and two years after John's widely praised account of his brother's life in relation to his own, sixteen-year-old Jake Wideman, seemingly without motive, stabbed to death Eric Kane, a companion rooming with him on a summer camp trip to Arizona. Jake avoided the death penalty by pleading guilty to first-degree murder and was given a life sentence in

II

September 1988. {At the time Jake also confessed to an unsolved 1985 murder, but he later recanted.) In articles that appeared almost simultaneously the following year, Leslie Bennetts {writing in Vanity Fair} and Chip Brown {writing in Esquire} suggested that the favoritism shown by Wideman and his wife toward their older son, Daniel-who like his fa' ther before him was a top student and basketball star, though a less skilled player than his younger brother-and their decision to move back east because Daniel had been admitted to Brown University, was a precipitating factor in Jake's seemingly irrational crime. Both Bennetts and Brown portray the Widemans as self,absorbed and strangely cold in the relatively close community surrounding the University ofWyoming, where Wideman had taught since 1973. Their picture of the Widemans as preoccupied with their son's treatment and their own pain following the murder, but oblivious to the grief of the Kane family, is not countered by anything in Fatheralong or in Wideman's 1990 novel Philadel, phia Fire, likewise an investigation ofthe historically freighted, too often tragic relationships between black sons and black fathers in which Jake's crime and punishment also playa central role.

"You may believe I'm being presumptuous," Wideman wrote in a let, ter to the Kanes, who thought Jake should get the death penalty, "that I'm offending you by proffering my forgiveness," when instead "I should be begging for yours." Yet he asked for no forgiveness and offered no apology, choosing to express his communion in suffering through an elegant, esoteric prose in which questions of blame are attenuated {"per' haps in your view, Jake is the cause of Eric's death and, therefore, deserves to be punished"} and causality is mystified {"what possible pur, pose is served when people become victims or perpetrators of senseless violence?"}. Wideman's letter would remain the private message of shared anguish it was surely intended to be did it not adumbrate so clearly the peculiarly irresponsible autobiographical voice featured in Fatheralong, as in Philadelphia Fire before it. In both books, black life, from the Middle Passage through the contemporary penal system, is portrayed as never-ending subjection to a "final solution"; in both, questions of responsibility, guilt, and remorse form an ineluctable riddle centuries in the making.

"I am the father of my son," Wideman writes in Philadelphia Fire. "Son's father. Father's son. An interchangeability that is also depend, ence: the loss of one is the loss of both." The chiasmus of "Son's father. Father's son," a figure that reappears in Fatheralong, defines a pathological repetition in which Wideman the "good" seed is thrust harshly into

12

the role of father of the "bad" seed, the one chosen in this generation to fulfill the terrible anti-promise of family and nation. As in Philadelphia Fire, the search for a lost self in Fatheralong comprises a search for lost sons, brothers, and fathers at once personal and representative. From E. Franklin Frazier to Kenneth Clark to Daniel Patrick Moynihan to Orlando Patterson, critiques of the black family have portrayed it as wracked by inherited patterns of psychological damage and paternal irresponsibility relegating fathers to a fated, futile cycle-"fathers in exile, in hiding, on the run, anonymous, undetermined, dead"-and turning the nation into a "vast orphanage" in which the official policy is "to keep [the] inmates confused by concealing from them their biological origins." The archetype of the African America filial relationship today is "the child visiting prison, speaking to his incarcerated father through a baffle in a filthy Plexiglas screen." But surely the reverse-a father visiting his son in prison-is the more awful, soul-wrenching event.

Pearls That Were His Eyes

As a boy, Wideman resisted his grandfather's proposal to make a trip to Promised Land-"No thanks, Grandpa. I don't think I want to travel back to slavery days this summer"-but Wideman the adult has a different attitude toward the "roots thing." Having already spent a brief time researching his family's origins while on a lecture tour in the South, he persuades his estranged father, Edgar Wideman, to make a family pilgrimage, repeating the journey that Edgar had made as a child with his own father. The journey thus embeds an essential feature of Brothers and Keepers and Philadelphia Fire-the black community's precarious patrilineal order, from the Middle Passage to the modem black ghetto-in an equally precarious epistemological journey back to the region that Wideman now describes in Fatheralong as "a parent, an engenderer, part of the mind I think with, the mind thinking me."

His pilgrimage reverses the 1906 journey ofhis paternal grandfather, Harry, to Pittsburgh, part of the massive migration of African Americans from the agricultural South to what Frazier called the "cities of destruction" in the industrial North over the early decades of the twentieth century (the black population of Pittsburgh increased by nearly fifty thousand between 1910 and 1930). Fatheralong thus takes its place in the genre that Robert Stepto has designated the narrative of immersion, wherein a ritualized return to the South, actual or symbolic,

I3

leads the protagonist in search of lost modes of "tribal literacy." From W. E. B. Du Bois's Souls of Black Folk and Jean Toomer's Cane to more recent works such as Albert Murray's South to a Very Old Place, Toni Morrison's Song of Solomon, and Anthony Walton's MississiPPi, African American literature features numerous reversals of the northern migration. In the classic texts of descent, the ancestral world of slavery, the "Egypt of the Confederacy," as Du Bois called it, is often a terrain of anxiety and terror, even as it is charged, at the same time, with the bittersweet sentimentality expressed by James Baldwin when he argued that the Negro born in the North is not unlike the son of a European immigrant traveling to his father's homeland: "both are in countries they have never seen, but which they cannot fail to recognize." Tenderness for the "Old Country" of the South, as Baldwin wrote in "Nobody Knows My Name: A Letter from the South," is not absent from Fatheralong, but it is everywhere darkened by ruptures in the ancestral legacy that Wideman's homecoming to Promised Land might hope to discover and preserve.

In the course of their journey and conversations, John and Edgar Wideman put together a fairly sound genealogy of the Wideman men running back to the time of bondage: John, Edgar, Hannibal (Harry), Tatum W., and Jordan, all of them descended, it seems, from the fortuitously named Moses Wideman, "one of the first to buy land on the old Marshall Plantation just after the Civil War." Settled in 1870 by eleven freedmen and their families, the all-black community of Promised Land grew to some three hundred families over the course of a century. Some twentieth-century residents, reports Elizabeth Rauh Bethel in Promiseland, her 1981 study of the community from its beginnings through the 1970s, recalled being told by their grandparents that the name was given by the governor of South Carolina, while others joked that the name had a different origin: "They only promised to pay for it, but they never did!" In point of fact, Promised Land was not a misnomer. As Bethel shows, the settlers' decision to build their way of life upon diverse subsistence agriculture, with only a modest investment in unreliable cotton crops, gave the families of Promised Land a degree of independence and self-reliance unusual for the region. Despite the sometimes exorbitant interest rates charged by white lenders and periodic racist vigilantism, the citizens of Promised Land generally found that the promise of emancipation was not an empty one.

For Wideman, however, what counts is not Promised Land the historic black community but Promised Land the metaphor of black

modernity. Even if it did realize the "Reconstruction ideal of land dis, tribution and black autonomy" for its first residents and some of their descendents, Wideman's Promised Land is principally an emblem of freedom's betrayal in the long aftermath of Jim Crow. Were our grand, fathers "running from something or running to something?" he asks in Brothers and Keepers. "Was escape the reason or was there a destination, a promised land exerting its pull?" Because Wideman's return to the land of the fathers must be measured against the adversity of present-day sons, the Exodus from Promised Land, South Carolina, to the Promised Land of the North, like the originating exile from Africa to a land of en, slavement, the American Babylon, redoubles the cycle of illusion. In contrast to Murray's South to a Very Old Place, a kaleidoscopic, jazz, cadenced narrative of cultural recollection written in the language of tribute, one result of the flourishing black life migration created, Father, along is steeped in the language of alienation, as though to confirm that the lives of his descendents have betrayed rather than redeemed Moses Wideman's original bequest.

Just as Wideman finds no road sign pointing the way to Promised Land and no indication of it on maps, so he finds no Africans, no slaves, mentioned in the "Chronological History ofSouth Carolina (1662-1825)" that serves as the standard research guide at the public library in nearby Greenwood. He does, however, find a willing mentor in Bowie Lomax. An epitome of the southern gentleman and scholar, Lomax conveys a wealth of knowledge about the region and its families, and he teaches Wideman how to utilize the town's archive of wills, bills of sale, appraisals of real estate, and other documents necessary to reconstruct the Wideman geneology. Both his kindness and his tutelage remind Wide, man that their lives are as "intimately intertwined" as were their fathers' and grandfathers' lives before them.

Yet as a repository of the South's past, Bowie Lomax also reminds Wideman of the disparate meanings of literacy and property for white and black southerners-specifically, the difference between Lomax and Edgar Wideman, just as smart, just as curious, but denied the prospects that "had enriched the career and life of the white man." Abruptly, Wideman envisions shattering Lomax's skull, "spilling all its learning, its intimate knowledge of these deeds that transferred in the same 'live, stock' column as cows, horses, and mules, the bodies of my ancestors from one white owner to another." A "grave full of chained skeletons," he writes, would not have been more disturbing than Bowie Lomax's illustration of the "solid, banal everyday business,as,usual role slavery

15

played in America's past. Meticulously, unashamedly, the perpetrators had preserved evidence of their crimes."

The reference here, of course, is to Hannah Arendt's notorious portrait of Adolf Eichmann as the personification of the "banality of evil," while the archival evidence of slavery's mundane transactions remind Wideman that the Nazis scrupulously archived the procedures of the Holocaust-to the point of collecting materials for a museum of[udaica so as to document their triumph over an people who, when annihilated, would be remembered only in a Nazi version of their historical significance. Standing for the white suppression of black history, Lomax pro, vides a way for Wideman to delineate the kinship of master and slave, at once symbiotic and subordinating, and with it the analogous relation to the master's language in which the black writer is inevitably caught. Insofar as it is dependent upon the slavery practiced by his ancestors, Lomax's career as professor and local historian, says Wideman, makes him no less the slave master: "Hadn't the historian's career been one more mode of appropriation and exploitation of my father's bones, the pearls that were his eyes. Didn't the power and privilege to tell my father's story follow from the original sin of slavery that stole, then silenced, my father's voice?"

In his allusion to T. S. Eliot's line from The Waste Land-"Those are pearls that were his eyes"-Wideman summons up, through Eliot's own allusion to The Tempest, one of his favorite texts. Like Philadelphia Fire before it, Fatheralong includes numerous references to Euro-American literature, the canonical tradition whose "collective psyche," as Wide, man remarked in a 1995 interview with Michael Silverblatt, he absorbed as a student and then reworked under the influence of black father figures such as Richard Wright, James Baldwin, and Ralph Ellison in order to find his own voice. Because their fathers' stories, like their songs and their bodies, can be "stolen, silenced, alienated from them, sold, corrupted," African Americans must recognize that white masters such as Shakespeare, Eliot, and Joyce, like the white masters of the plan, tation South, cannot be disregarded but only imaginatively, antagonisticallyengaged.

Recent interpretations of Shakespeare's fable have focused on its prefiguring of colonialism and slavery in the Americas, with particular attention to the rebellious energy, as well as the peculiar eloquence, of Caliban-a prototype of the slave, the colonial subject, and, at length, the postcolonial firebrand. In Philadelphia Fire, a guerilla children's the, ater thus performs the playas social critique, with fractured families and

their surrogates telling a story of exile and imprisonment that forecasts a modem panorama of empire, slavery, and genocide. "Exiled, dispossessed, [a] stranger in his own land," Wideman's "Godfather Caliban" is a reincarnation of black storytellers from the African griots down to Malcolm X. In Caliban's anguish over Prospero's theft of the island from his mother Sycorax-"Him broke my island all to pieces. White folk weeping and wailing cause all lost. Ship lost. Fader lost. Storm take ebryting away"-lies a tale that has never ceased to illuminate the situ, ation of the world's people of color. No revisions can, or need, change the play's core: "The saddest thing about this story is that Caliban must always love his island and Prospero must always come and steal it So it ends and never ends." In reciting Miranda's famous speech on speech ("Abhorred slave I pitied thee, / Took pains to make thee speak"), it is apt that Wideman includes the remainder of her condemnation of Caliban-"But thy vile race, / Though thou didst learn, had that in't which good natures / Could not abide to be with; therefore wast thou / Deservedly confined into this rock, who hadst / Deserved more than a prison"-for in professing his own need to acknowledge Caliban, "this thing of darkness," Wideman speaks not only of his incarcerated brother but now, too, his incarcerated son.

One may say that Wideman, in his adaptation of The Tempest, joins Derek Walcott, who, in "The Muse of History," chided those postcolonial writers who speak only in "the groan of suffering, the curse of revenge," and therefore reject the language of the masters because they cannot separate "the rage of Caliban from the beauty of his speech," which is nothing less than the "language of the torturer mastered by the victim." Yet neither the rage of this Caliban-Rhodes Scholar, Ivy League professor, acclaimed writer-nor the beauty of his speech offers solace. Rather than repair the breach between black fathers and black sons, moreover, Wideman's strategy renders it more pronounced. De, picting the crimes of his brother and son in terms of Shakespearian allegory makes them abstract-mitigating Wideman's pain, no doubt, but also mitigating culpability. Like the "not again" of Fatheralong, "never ends" transforms colonialism into fascism, entangling the tragedies of brother and son in a long history of racial depredations, rising at last to full,scale genocide, for which no single man or family among the count, less victims can be held accountable.

Just as brother and son cannot be saved, so the generation-bygeneration fractures in the ancestral narrative, Fatheralong seems to say, cannot be healed by the language of the master, the language of the

torturer. But perhaps a coherent story of fathers and sons, one which escapes the never-ending cultural, as well as literal, imprisonment of the "vile race," can be recovered if only Wideman is able to read the fragmentary signs hidden beneath the master's version of history-the "stories layered within other stories graveyards buried behind, within other graveyards. All the missing African names of things."

Things Fall Apart

In a 1986 speech at the University of Pennsylvania upon receiving an honorary degree, three months before Jake committed murder, Wideman expressed doubt that "progress" is a valid notion. Rather, he said, "the notion of a circle is a much warmer and richer idea for a culture, for me, than simple linear progression." ("To be who you are you must draw your own circle," he writes, addressing Jake, in Philadelphia Fire.) At times in Fatheralong, the circle is such a figure, as in its association with his mother's encircling arms, which make a shape "concentric, overlapping, intertwined, generations long gone and yet to be born connected indivisibly," a shape of harmonious and unbroken circles "expanding, contracting, rainbow circles you can visualize an instant if you don the mask of Damballah, hold all time, Great Time in your unflinching gaze." Ifhe could find his fathers in Promised Land, Wideman has said of Fatheralong, inevitably "the arc had to lead to sons," creating a circular flow such that there would be "no difference between the stories of the fathers and the sons," the two seamlessly joined in a repeating loop. But after Jake commits murder, repeating the crime and the fate of his uncle in just such a loop, albeit negatively, the millennial Great Time of the African ancestors seems a bitter commentary on the unraveling lives of the descendents of the patriarch Moses Wideman and the "arc" of genealogy as illusory as the arc of the rainbow. The conundrum of the circle is nowhere more evident than in the master trope of Fatheralong, which reveals not linear progress but mocking, cyclical meanings at every juncture. "A motherfucker, ain't it. This daddy search," Wideman fears, may be only "a ropa-dope trope containing enough rope to hang you up terminally, you black bastard." Most immediately, "father" refers to Edgar Wideman, a distant figure who abandoned his family during Wideman's childhood, maintaining a relationship with his son that was supportive but far from intimate. Resonant within every reference to Edgar Wideman, however, is Wideman's

portrayal of himself as a father, the two of them inscribed in a historic lineage in which connections can be made, the crude genealogy filled in, but in which it is not possible to discern sequential or causal mean' ing, and from which no sustaining spiritual typology can be derived. "The Daddy I blessed, the Father in the Lord's Prayer," Wideman recalls, referring both to the heavenly Father and the real father, "were words said aloud, about someone absent."

An early childhood episode, in which Wideman innocently calls his father a "spoor," only to be smacked in the face for his unknowing insolence, is illustrative. Although Wideman the boy meant to convey only something "vaporous" by the word he picked up from Tarzan books, Wideman the writer means something else in the words he puts in his young mouth: "It's the trail they follow when they hunt some elephant or something." His father's anger, as he remembers, revealed to him not only the tricky instability of words but also their power to reveal signifying truths. The opposite of its homonym "spore," which might stand for the vitality of insemination-even the enlivening, transcendent nationhood of the black "diaspora," its etymological cognate-"spoor" is, instead, redolent with connotations linking animal feces to degraded origins in Africa, mercilessly deriding the actual father even as Wide, man holds forth the abstraction of "father" as the key to his own and his people's elusive identity.

Wideman's reestablishment of a bond with his northern father through the journey south, back through his familial diaspora and in quest of his beginnings in the African diaspora, is partial at best. The stories told in Fatheralong are less a proof of that bond than a substitute for it, standing weakly in place of the filial relation he has not hadand that he has now lost with his younger son. The book's evocative but perplexing title is the central instance of this ambivalence. Drawn from Wideman's childhood misunderstanding of the gospel song titled "Farther Along" as "Fatheralong," the mistake fuses the distant, mysterious God who dwelled in the Homewood African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church with the distant, unfamiliar father, Edgar Wideman. By the time he comes to deploy it in his memoir, however, the gospel song has taken on a more complex and darker meaning. In its message that earthly suffering will be understood only in the afterlife, "Farther Along" speaks of the mystery of affliction when "death has come and taken all our loved ones," while at the same time the Lord permits the prosperity of those "living wicked year after year." The song's chorus counsels patience and redemptive hope: "Farther along, we'll know

19

more about it. / Farther along, we'll understand why. / Cheer up, don't worry, live in the sunshine. / We'll understand it all, by and by." But in the 1956 version by Sam Cooke and the Soul Stirrers cited by Wide, man, the variation of "Cheer up, my brother, live in the sunshine," had to seem all the more painfully hollow in view of the incarceration ofhis brother and his son.

In his journey south and his journey within, the duplicity of "Fa, theralong" makes Wideman's narrative of immersion simultaneously personal and eschatological. The ever,receding horizon of the march to Canaan-the "dream deferred" generation after generation, as Langston Hughes styled it-is bound up in the ever-receding promise of nurturing fatherhood, which points forward and backward at the same time. Sam Cooke's recording of "Farther Along" reminds Wideman of an arcing rainbow, and this figure of the covenant, which had already appeared with special destructive potency in Philadelphia Fire, at length evaporates into the dreamtime of an African past. "By and by" is when deliverance will arrive, says Wideman, "the unbound Great Time of our African an, cestors," or what he heard in Bob Marley's adaptation of "I'll Fly Away" (in "Rasta Man Chant"): "One bright morning when my work is over / I will flyaway home."

In its traditional lyrics, "I'll Fly Away" points first of all to the after, life: "Some glad morning when this life is over, / I'll flyaway / To a home on God's celestial shore." In Wideman's use, however, the parallel "home" of Africa, more or less implicit in any number of spirituals and gospel songs, comes quickly to the fore. Even more powerfully than the South, it may be hoped, Africa will prove to be the redemptive home, land, the unsullied, unencumbered place of black origins. In Paule Mar, shall's Praisesong for the Widow and Morrison's Song of Solomon, to cite two contemporary examples, the mythic flight to Africa is an ernboldening legend of recovery-lost ancestral arts reborn in modem story' telling with a spiritual force that reconciles the biblical Exodus with African exile. In Fatheralong, however, the Great Time of African an' cestry, what English captures in the elusive and mysterious phrase "the fullness of time," is projected in so deracinated a form that its value comes to seem purely conceptual.

Wideman refers to Chinua Achebe's anti-colonial novel Things Fall Apart in order to suggest that "father stories" such as the one he is writing are about establishing origins and thus "legitimizing claims of ownership, occupancy and identity." At the outset of Achebe's novel, the wrestling match between the hero, Okonkwo, and Amalinze the

20

Cat is likened to the ancient match between the clan's founder and the spirit of the wild that established the right to settle the land. Okonkwo's victory, in Wideman's characterization, reiterates that of the founder-it is "an intersection like the one drawn with chalk on an earthen floor to summon Loa, like the crossroads sacred to Damballah where the living and the dead pass one another, like the X Malcolm chose to signify being lost and found." Identified in Haiti, according to Zora Neale Hurston, as "Moses, the serpent god," Damballah, god of rainbows, lightning, and fertility, is a benevolent deity who holds past and present in harmony. His preserving power was clearly in evidence when Wideman chose Damballah as the title of a 1981 short story collection dedicated to Robby. In a preface that takes the form of a letter to his imprisoned brother, Wideman quotes from Divine Horseman, Maya Deren's study of Haitian voodoo: "Damballah Wedo is the ancient, the venerable father; so ancient, so venerable, as of a world before the troubles began; and his children would keep him so; image of the benevolent, paternal innocence, the great father of whom one asks nothing save his blessing To invoke [Damballah and his pantheon] today is to stretch one's hand back to that time and to gather up all history into a solid, contemporary ground beneath one's feet."

"Who are the truly dead?" Wideman asks in Fatheralong. He would be the American voice of the dead as Achebe is the African voice; he would stretch his hand back in time, gather up all history, and become the "conduit of traditional wisdom that teaches the dead are those who don't speak and are not spoken of, those not connected by vital words, those whom the stories have forgotten, who have forgotten the stories." His stories, that is to say, would remember his own dead-those who do not speak and are not spoken of, like the lost brother, the lost son. Through his stories "ancestral spirits" alive in the rhythms of African music and oratory would reassert themselves, as they do in black American jazz dance or the "choreography of a fast-break slam dunk on a playground basketball court"-what "happened once in a certain righteous fashion striving to happen righteously again. Father son. Son father." Even as it suggests again that the loss of one is the loss of the other, the chiasmus of "Father son. Son father" here holds forth the possibility that at the crossroads with an African past-Malcolm's transitional X between the discarded history of slavery and the future invented by righteous black folk-will be found the secret of black salvation.

2I

Lest basketball seem an inadequate metaphor to carry such meaning, Wideman returned to it with a vengeance in a later book on the game's place in African American culture and his own life, Hoop Roots. Contracting both genealogical and cyclical time into a powerful alliterative phrase, the title is a succinct figure of ancestral longing that aims to repair the rupture of paternity through connection to the Great Time of mythical forefathers: "We went to the playground court to find our missing fathers. We didn't find them but we found a game and the game served us as a daddy of sorts." Like the ring shout of slave culture or the self-sustaining, historically renewing circularity of jazz improvisation, Wideman argues, the pursuit of "playground hoop" is a survival tactic transformed into a way of being. "Hoop" is a "response to the mainstream's long, determined habit of stipulating blackness as inferiority, as a category for discarding people, letting people crash and burn, keeping them outsiders," but, like jazz, it is also a folk art knitting together past and present, an absorption in "one-time and one-more-time play in a saturated present tense, live performances immaterial and transient, enduring over time only if faithfully repeated. Time the thread stringing the beads. Great Time separating yet also connecting the individual and the communal experience."

"Hoop," however, is far from unequivocal. In Philadelphia Fire, the neighborhood basketball court, enclosed in cyclone fence, is said to be "part of the final solution," and the narrator suffers a nightmare in which an anonymous black boy, another figuring of Jake, is lynched from the rim: "A kid hanging there with his neck broken and drawers droopy and caked with shit and piss. It's me and every black boy I've ever seen running up and down playing ball." It is not insignificant that Wideman's daughter, Jamila, after a standout career at Stanford University, went on to success in women's professional basketball. Insofar as the sport may have been a precipitating factor in his son's tragedy, however, and insofar as it remains emblematic of educational opportunities squandered in pursuit of fame and fortune that will be achieved by only a miniscule percentage of black men-not in the Great Time of Damballah but in the "Miller Time" of the NBA-"hoop," like the dangerous crossroads of "Father son. Son father," is less the site of recovered African time, an intersection with the dreamtime of the ancestors, than the site of one more relationship that has been "brutally usurped, mediated by murder, mayhem, misinformation."

African retentions-African "survivals," to use an older term but one more pertinent to Wideman's narrative-are among the most

22

evanescent ancestral legacies in Fatheralong, as though the trail into an African past were no more than elephant dung remembered from a Tarzan story, the most bankrupt, cliched vision of ancestry imaginable. Here Wideman refers to, without naming, Richard Wright's Black Power, an account of his journey through Africa and Ghana's progress toward independence. "The inadequacy, the failure of his black fathers, the proof of racial inferiority seemed evident everywhere in the ramshackle cities of the Third World," laments Wideman. "Wright's deepest insecurities and fears, the legacy of his illiterate, brutalized sharecropper father had pursued him, caught up with him, taunted him with nightmarish intensity, ironically, at the very moment Europeans appeared to be ceding control of Africa to Africans." Wideman means to set himself apart from Wright, but he must have found Wright's conclusion about the Africanisms present in the rhythms of black American dance congenial. Neither biological nor mystical, argued Wright, such survivals were fragile remnants of traditional "African attitudes" preserved by the African American who could find no other "system of value or belief that could interpret the world and make it meaningful enough for him to act and rely upon it." But for how long can a people be sustained by such inchoate signs of descent from some lost place and time, how long find in them "a daddy of sorts ?"

In the end, evidence of patrilineal collapse can be found even in the geographic shape of South Carolina, which reminds Wideman of Africa-"only stumpier, foreshortened, the graceful, gradually tapering tail of the continent is missing," as if topographical truncation is accompanied by cultural deformity. Likewise, although the interstate highways intersecting at Columbia appear on Wideman's map to mark symbolic "Xs carved across the face of the state," here is no crossroads leading to the Great Time of the ancestors but only the signature of identity obliterated. The "Valentine heart shape" of South Carolina, the "heart of the Confederacy," is "a heart violently mutilated."

Wideman's account of Things Fall Apart leaves silent, but implied, the fact that Okonkwo's tale concludes with his suicide and the clan's disintegration under the law of empire. At the novel's end, the colonial District Commissioner has consigned Okonkwo, now untouchable among his clan, to the book he is planning-"perhaps not a whole chapter, but a reasonable paragraph, at any rate"-to be entitled The Pacifi� cation of the Primitive Tribes of the Lower Niger. Wideman is no more able

23

to flyaway home to his fathers in Africa than he is to recover proof of his paternal covenant in Promised Land, South Carolina.

Bone-Haunted Dust

Perhaps it was Wideman's middle-class, mainstream success as much as his marriage to a white Jewish woman that led him to think of the con' versos of early modern Spain, those Jews who accepted conversion to Catholicism rather than be expelled by the edict of 1492. Conversion did not forestall their persecution-both conversos and marranos, secret Jews, continued to face the wrath of the Inquisition-but Wideman's point has to do with twentieth,century America, where Jews were pro' gressively absorbed into the ethnically differentiated but raceless category "white." America has evolved no official term such as conversos to describe blacks who embrace the mores of the dominant group because such a word would acknowledge that "racial categories are permeable," whereas Wideman's conviction, borrowed from the century-old Ianguage of biological racism, is that in America "an Ethiop cannot be washed white. Leopards can't change their spots." Here, at last, is the most persistent Africanism, the one ineradicable gift of the ancestors.

The last section of Fatheralong, excepting a final coda devoted once again to probing, futilely, the origins and meaning of Jake's act of rnurder, describes events surrounding the wedding of Wideman's older son, Daniel, and his African bride, Maimuna. The blend of American and African customs, including the good wishes delivered by the bride's African parents and the groom's grandmothers, one black, one Jewish, provides a moment of harmony and hope in a book of discord and de, spair. As Maimuna's father describes what the ceremony would be like among the Islamic elders of Sierra Leone, Wideman mourns his own fa, ther, inadvertently left behind at a motel and stuck in Labor Day traffic--once again an absence in his son's life, once again the Wideman patrimony betrayed, disrupted. Danny's maternal grandfather, Morton Goldman, does not speak. It was the camp he owned in Maine, where the Wideman boys spent summers while growing up in Laramie, that sponsored the trip to Arizona during which Jake murdered Eric Kane.

"Maybe Promised Land lies where it does to teach us the inadequacy of maps we don't make ourselves," Wideman speculates, and the necessity of reimagining "connections others have forgotten or hidden." Or perhaps Promised Land is "a sign of denial, of terrible misgivings, of a

past and present unhinged." This uncertainty in characterization haunts Fatheralong, where past and present jut into one another without resolution. No teleology governs Wideman's inquiry. The dissolution of the progressive family narrative is signaled in the dissolution of narrative order in the text: "I'm remembering things in no order, with no plan. These father stories. Because that's all they are."

This heartbreaking comment appears late in the book, in the midst of Wideman's recollections of Jake as boy, as he is searching for clues that might explain so archetypal a black male story of crime and incarceration. But the comment, by its self-referential nature, could appear anywhere in the book, and it could apply throughout to the simultaneous breakdown of genealogical and narrative form. Like the episodes assembled into the story called Fatheralong, memories flare up with the brilliance of explanatory value only to give way quickly to another thought, another analogy, another attempt to discern a logic in black life. Within the annihilating cataclysm detailed in Fatheralong, the erasure of inherited, redemptive lineage carries with it the erasure of paternal responsibility and narrative authority alike. Wideman's search for origins succumbs, at every tum, to the judgment of the masters: People are easier to kill if they are "nobodies who began nowhere, go nowhere, except back where they belong. Nowhere."

In the final chapter of Fatheralong, Wideman returns to an archeological rendering of Promised Land, South Carolina. But the obscured road to the old Wideman place, where Wideman and his father fail to discover any signs of the family dwelling, now merges with the dusty rural road outside the Arizona State Prison Complex in Tucson, where Jake Wideman serves his life sentence. Finding himself on "the same road always, going nowhere," drifting "like [his] African ancestors, through a strange land," Wideman broods on another of his father's gospel songs, "Way in the Middle of the Air," not because he believes in his mother's and father's God but because of the music's marginal sustenance. This exilic memory leads into two other linked meditations.

The first concerns a photographic exhibition staged by the South Carolina Humanities Council based on a discovered cache of undeveloped nineteenth-century photographic plates of African Americans, whose public showing had the disturbing effect of creating a largely fruitless search for vanished ancestors, as though the guests were "wandering through a gallery of ghosts." The second meditation concerns Wideman's reading of Winthrop Jordan's Tumult and Silence at Second Creek, which reconstructs an abortive 1861 slave uprising near Natchez,

Mississippi, an extensive but only partially decipherable event that resulted in the execution of at least twenty,seven and possibly as many as forty slaves who apparently calculated to join forces with the Union army.

As Jordan's study illustrates, writing the history of such an event is no easy task. His opening chapter, "Evidentiary Sounds and Voices," dwells on the ambiguity of documents; the fragmentary, unreliable nature of memory; and the impossibility of reproducing the physical, not to mention the emotional, texture of human life more than a century gone by-most of all, perhaps, the inflections of "human sounds generated under conditions of great psychic and physical intensity." It is "be' yond the scope of our standard vocabulary," writes Jordan, fully to convey "the sounds a man or woman may make under the lash." History must be read, in such circumstances, out of the most enigmatic evidence-for example, the message found in a bottle following the hang, ings that ended the 1800 conspiracy led by Gabriel Prosser: "dear frind, brother X will come and prech a sermont to you soon, and then you may no more about the bissiness." In quoting this passage-"brother X" is thought to have been Gabriel-Wideman suggests that one must learn a kind of "night vision," develop an appreciation for the "an, cient linkage between blindness and prophecy," in order to read such signs for their hidden historical meaning, much as he has attempted in Fatheralong.

It is not the slave conspiracy alone that Wideman recalls from [ordan's book, however, but his fleeting mention of a post-Civil War slave refugee camp. Once Natchez had been occupied by Union troops in 1863, refugee blacks began arriving at the camp by the thousands, according to one account, with untold numbers dying of disease and malnutrition. The devastation of war and the collapse of the plantation economy, exacerbated by the Emancipation Proclamation, ereated hoards of displaced people living in "doomed encampments, exiled far enough away from the cities so the racket and stench of slow death by starvation did not worry the townsfolk's sleep." In later years, picnickers would continue to find the bones of those who had perished in the camps-while a century and a half later and thousands of miles away, Wideman's feet now "[scuff] up the bone'haunted dust of their remains on the desolate road outside the prison," as though the refugees of slavery were reincarnated in the black prison populations of the late twentieth century.

In his journey of descent to the South, Wideman comes away with

26

only fragments of identity. Like the bones of unknown ancestors, knowledge lies buried and unrecoverable in Promised Land, "where the origins of the family name begin to dissolve into the loam of plantations." The powers that denied freedom-first slavery, then the Black Codes, then Jim Crow, now a self-replicating cycle of black male incarceration"still rise like a shadow, a wall between my grandfathers and myself, my father and me, between the two of us, father and son, son and father," poisoning their "primal exchange." In the precarious struggle of a people "to negotiate a Middle Passage with something valuable of them, selves intact," Wideman charges, the nation itself, "as it presently functions, stands between black fathers and sons." In counterpoint to the "steel bars, electrified fences, concertina wire, concrete bunkers, and gun towers" of the Tucson prison, the precise, objective meaning of the word "camps" in his contemplation of Natchez elongates across space and time to include not just the despair ofJohn Edgar Wideman, middle, class black man mourning the imprisonment of his middle-class black son, but also the winnowing of early African people in the "death camps" of slavery and its aftermath.

Wideman remarked in his interview with Michael Silverblatt that his intention in Fatheralong was to fashion a sense of filial legitimacy, to "speak to my sons, to preserve for them, and to create for them, a sense of belongingness, a sense of authority, and to demonstrate to them how much a claim they had to this land and to their identity." Measured against the evidence of the memoir itself, however, one would have to conclude that Wideman finds no such identity and discounts any sense of belonging, except to a class of people destined, generation after generation, for lives of disenchantment and brutalization. The title of the preface to Fatheralong, "Common Ground," thus refers not to some ide, alized national consensus on matters of racial justice, for by Wideman's estimate racism is so pervasive in American life that there can be no shared assumptions or goals. But common ground does exist among African Americans to the point that any two black people meeting in the street are instantly joined by an unspoken "shared sense of identity, the bloody secrets linking us and setting us apart." The legacy of slavery and segregation creates a compact at once negative and positive. "To our everlasting shame and glory what we may recognize first is something we are not"-namely, not white, or perhaps Wideman means, in fact, not "American"-"and then because of, in spite of that, something we are: ." survivors, carrymg on.

To cite again the passage with which we began: "The underground

history of the camps must be remembered, written, and celebrated. The story of how strength of mind, individual and collective, altered the genocidal master plan, how the horror that destroyed so many could be transformed into a rite of passage for some, then for a people, a nation."

If Fatheralong may be trusted, it is not clear that Wideman believes in such a transformation or, if he does, that he has the psychic fortitude or artistic intention to record anything but its failure. Rather than a rite of passage that ennobles and liberates, his own return to Promised Land shows the endpoint to be an illusion, the journey a circle. Fatheralong concludes by revealing itself to be an extended letter to his imprisoned son, with the closing word, "Love," hanging alone, followed by no signature, in the emptiness of the page.

Tadeuz R6zewicz

Translated from the Polish by Joanna

Trzeciak

the professor's knife

1. Trains

a freight train cattle cars in a very long line it goes through fields and forests through green meadows over grasses and wild herbs so quietly the buzzing of bees can be heard it goes through clouds through golden buttercups marsh-marigolds bluebells forget-me-nets

Vergissmeinnicht this train will not leave my memory

a pen rusts

flies away on its quill turning beautiful in the light of awakened spring Robigus nearly unknown the demon of rust-from the second tier of gods devours tracks and rails steam engines

29

the pen rusts ascends glides soars over the earth like a nightingale a rusty stain on a blue sky crumbles falls to earth flies south

Robigus who in ancient times digested metals -though he did not touch golddevours keys and locks swords plowshares knives the blades of guillotines and axes the rails that run parallel without getting any closer

a young woman flag in hand issues signals and disappears from memory towards the end of the war a gold train departed Hungary departed for parts unknown "gold"? or so it was called by American officers mixed up in that they knew nothing they heard nothing they are dying off anyway

gold trains amber rooms sunken continents

30

Noah's ark

maybe my Hungarian friends heard something about this train maybe the Kursbuch survived the last train schedule

from besieged Budapest

I'm standing in the last car Inter Regnum-of the train to Berlin and I hear a child beside me cry "the oak tree is running away! into the forest " a cart carries children away I pull the bookmark out of the book a Norwid poem 1 I build a bridge between past and future

The past is only today, lagging behind The wheels-a village and not A something somewhere, a spot

No one has ever seen, can ever find. 2

freight trains cattle cars the color of liver and blood in a long line loaded with banal Evil banal fear despair

1. This scene mirrors one depicted in "The Past" by Polish poet Cyprian Norwid (1821-1883).

2. Here R6zewicz quotes in full the last stanza of "The Past." The translation of these lines is taken from Cyprian Norwid, Poems, Letters, Drawings, edited and translated from the Polish by Jerzy Peterkiewicz, poems in collaboration with Christine Brooke-Rose and Bums Singer. (Manchester, UK: Carcanet, 2000), p. 48.

31

banal children women girls in the blush of youth

do you hear the cry for one sip for one sip of water all of humanity cries for one sip of banal water

I build a bridge between past and future the rails run parallel trains fly by like black birds ending their flight in a fiery oven from which no singing rises to the empty heavens the train reaches its destination becomes a monument through fields meadows and forests through hills and valleys it speeds quietly and even more quietly train of stone stands over the abyss if it's brought to life by cries of hatred of racists nationalists fundamentalists

32

it will fall like an avalanche on humanity not on "humanity"!

on a human being

II

The Egg of Columbus after all these years I'm sitting with Mieczvslaw! having breakfast the twentieth century is ending

I slice the bread on a cutting board spread butter on it add a pinch of salt

"Tadeusz, you eat too much bread

I smile I like bread

"you know"-I say"a loaf of fresh bread a loaf, a heel buttered or with bacon bits in lard with a dash of ground pepper"

Mieczyslaw rolls his eyes

I take a bite of crust I know! salt isn't healthy bread isn't healthy (white bread!) and sugar! that's death

3. Mieczylaw Porebski (b. 1921), Professor Emeritus of Art History at Jagiellonian University in Krakow; major theoretician of avant-garde art.

33

do you remember "sugar makes you strong"?! that was probably a Wankowicz4 slogan Wankowicz Wankowicz we were "a superpower" then but sugar doesn't make you strong anymore

would you like a soft-boiled egg?

Mieczyslaw asks eating an egg for breakfast gets you off to a good start

Mieczyslaw is standing by the stove

Tadeusz! when I'm boiling an egg don't talk to me because well because once again I forgot how long it's been boiling

don't you have a watch or a clock or a timepiece after all we are entering the twenty-first century supermarkets intemets all kinds of hourglasses hour glasses (?) I'm never sure which in modem households in Germany they have all kinds of gadgets clocks they all ring beep or sound alarms! they have these clever contraptions where you can boil a whole egg without heating the shell in the microwave or perhaps the shortwave I know nothing about it Mieczyslaw, soon we will be eating virtual eggs without the yolk

4. Melchior Wankowicz (1892-1974), Polish writer, author of the trilogy Following in Columbus' Footsteps [W slady Kolumba}, 1967-69. His slogan, "Sugar Makes You Strong," contributed to the success of the Polish beet sugar industry during the inter-War period.

34

because the yolk isn't healthy maybe not us but our grandchildren

Tadeusz! try to understand that boiling an egg requires attention concentration even it'll probably come out hardboiled

Germans Germans they're so technological high tech eggs techno and metal music are not for us and so?! so? how's the egg we'll see in a minute You taught me how to crack a hard,boiled egg I tap the shell but you in one decisive move cut off the top of course the egg is in its holder you don't muck up the spoon or your nails

how's yours?

mine's good not too hard not too soft but what were you doing I saw that you poked a hole in the egg before you plopped it in the water what did you poke it with a needle? I never saw that trick before today it figures mine is hardboiled aren't you using too much salt

well you know a soft boiled egg without salt and pepper

35

there are certain principles and when it comes to the boiling time my aunt had a solution: say three hail marys for a soft-boiled egg

but that is no solution for atheists and this is an atheist speaking?

what kind of atheist am I have you ever seen a real atheist or nihilist in Poland?

there have been freethinkers atheists materialists communists activists marxists and even trotskyites and so?!

and so they were in such a hurry to join the pilgrimage of the cultural and artistic elite from Warsaw to Czestochowa'' it's always been that way every family had a Jew or priest inside everyone there is a heroic monk Robak'' [ankiel or Konrad Wallenrod7

how does Konrad Wallenrod fit in?

I'm not trying to scare you but you were a bit too liberal with the salt you know there are gaps in memory I know listen if you were to cut off my head I would not be able to recall

5. Czestochowa, Poland is the destination of an annual Catholic pilgrimage paying homage to the Black Madonna.

6. Robak and Jankiel are protagonists of the Polish epic novel in verse, Pan Tadeusz, by Adam Mickiewicz. Robak, a mysterious monk, serves the patriotic cause as he repents for the misdeeds of his youth. [ankiel, a musically gifted Jew, is an exemplary Polish patriot.

7. Konrad Wallenrod, title hero of Adam Mickiewicz's historical novel in verse, is a classic example of a subversive patriot: Lithuanian by birth, Wallenrod rises through the order of the Teutonic knights and becomes their Grand Master only to lead them on a disastrous expedition.

what happened with Columbus' egg Columbus balanced an egg? how was he able to balance it on a table on its end I need to consult the encyclopedia

you have your way and I have mine

scrambled eggs with sausage or bacon is out of the question at this point

I recall what Norwid said about the Matejko'' exhibit in Paris in 1876 (I think) you know I've been heavy into Norwid for two years now and I want to write a little book a lesson about Norwid or a lesson learned from Norwid about the Matejko painting Norwid said - this had escaped me even though I know practically everything about MatejkoNorwid called it "national scrambled eggs" he was talking about "Sigismundus' Bell" I don't know where the painting is now in Palais de l'lndustrie (in 1873)

National scrambled eggs! between you and me neither Europe nor America knows what true scrambled eggs are like that's right how is the Norwid coming along not too well to tell you the truth it's moving at a snail's pace Art is like a banner on the tower of human work?

he's unbelievable

8. Jan Matejko (1838-1893), Polish painter known for his paintings ofhistorical subjects, often patriotic in content.

9. A nearly exact quotation from Norwid's Promethidion (Paris 1851), a book-length poem on the topic of art, written in the form of a dialogue.

37

Shadows in the afternoon we visited Hania in the cemetery Hania passed away five years ago Mieczyslaw was left alone

Robigus the demon of rust coats the past in rust covers the words eyes and smiles of the dead covers the pen we continue on to the tombstone of Przybos's'" wife Bronia daughters grandchildren came to the funeral from Paris New York

Julian wanted the elder one to become a gardener an orchardist perhaps he dreamt that in his old age he would have his very own apple tree that he would write avant-garde poems in the shade of the apple tree in the shade of a tree that he would continue to do his thingKochanowski's thing!' but the metropolis the masses the machine brought a painful surprise to the avant-garde poets became a trap

10. Julian Przybos (1901-1970), Polish avant-garde poet.

11. Jan Kochanowski (1530-1584), a giant of Polish Renaissance poetry, credited with transforming the Polish language. He often wrote beneath a linden tree, the subject of one of his best-known poems.

III

the transport began

freight cars and cattle cars loaded with banal evil started to move from east west south and north

freight cars loaded with banal fear banal despair

to this very day banal tears run down the faces of old women

after the war miraculous paintings wept and living women wept sculptures wept people wept

IV

The Discovery of the Knife

Mieczyslaw sent me a letter in 1998 in answer to my question where the knife came from if he made it himself if he found it if he stole it if he dug it out of the ground (the age of iron) if it fell out of the blue sky (miracles happen after all)

Mieczyslaw:

"I've thought more about my knife, the one made from the hoop of a barrel.

39

It would be carried in the hem of my death camp clothes since they might confiscate it and one could pay dearly So it served its purposes, not just utilitarian but far more intricate ones {it would be worth talking about sometime} Robigus covers the iron knife in rust and slowly devours it

I saw it for the first time on the Professor's desk sometime around the middle of the twentieth century strange knife I thought a knife neither for cutting paper nor for peeling potatoes nor for fish or meat

it lay amidst Matejko and Rodakowski amidst Kantor Jaremianka and Stern'? amidst sheets of paper amidst Alina Szapocznikow Brzozowski (also Tadeusz) and Nowosielski 13 amidst conference papers and index cards

12. Henryk Rodakowski (1823-1894), painter known for his portraits and allegorical scenes. Tadeusz Kantor (1915-1990), best known as an outstanding and highly original figure in 20th century European theatre; played a crucial role in unifying the Krakow artistic communiry. Maria Jarema [a.k.a. [aremianka] (1908-1958) major avant-garde painter, sculptor, and set designer; studied under Xawery Dunikowski. Jonasz Stem (1904-1988), painter known for his abstract paintings, collages and mixed media. In 1943, during the liquidation of the Lwow ghetto, he faced execution by firing squad, feigned his own death, and escaped.

13. Alina Szapocznikow (1926-1973), sculptor particularly noted for her small scale sculptures where her delicate style and sensitivity to materials expressed itself; created her own vocabulary of form for reflecting the changes that happen in the human body. During World War II. she was a prisoner in concentration camps at Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen, and Theresienstadt. Tadeusz Brzozowski (1918-1987), painter known for a deepening surrealism approaching an abstract formalism. Jerzy Nowosielski (b. 1923), painter and theologian whose style is strongly influenced by the Orthodox iconic tradition.

"strange knife" I thought I picked it up and put it back where it was

Mieczyslaw went into the kitchen to make some tea (and he makes really strong tea black as extract I always dilute it)

another twenty years passed

"strange knife" I thought it lay between a book on cubism and the last page of a review article he must use it as a letter opener in the concentration camp he peeled potatoes with it or used it for shaving

why yes-the Professor saidvegetable peels could save you from death by starvation

the order of his desktop reflected the state of his mind

you know Mieczyslaw I will write a poem about this knife years passed our children went to school grew graduated

it was 1968 1969 man walked on the moon I don't remember the exact date it was the infamous March the March of "writers go writel'I'"

14. First part of an anti-Semitic slogan, completed by "Zionists go to Zion." The "anti-Zionist" aspect of a much wider 1968 Communist assault {under Premier Wladyslaw Gomulka} on dissident intellectuals and students drove close to 20,000 Jews to leave Poland.

41

but someone broke my pen

I spent the night at Mieczyslaw's he lived in the building of the academy of fine arts

on Warsaw's Fauburg de Cracovie

rainy evening police and special units unmarked cars police cars nightsticks long nightsticks in the fog helmets riot shields

the next day I ran into Przybos in Zacheta Gallery'" what do these students want he asked he acted a bit shocked surprised then he started to explain to me

Strzeminski's theory of the after-image "stud " stu ents he said as if to himself

I returned home Mieczyslaw's daughter

Joanna asked me over dinner "what do we do now? but I got the impression she knew better than her father or Przybos better than I what to do I answered "keep calm"

Joanna smiled and left the room

Mieczyslaw was in the hospital on Szaserow St. he awoke from the anaesthetic

I sat alone in his study familiar paintings on the wall

Strumillo'f Nowosielski Brzozowski

Mieczyslaw's self portrait from the time of the German occupation the knife lay on the newspaper

15. Zacheta: a society set up in 1860 in Warsaw to promote Polish art after Poland lost its independence. Since 1900 it has had its own building, still used for prominent exhibits and other cultural events.

16. Andrzej Strumillo (b. 1928), painter, graphic artist, photographer, and curator for the Ethnographic Museum in Krakow.

in the airport I read the signs writers go write Zionists go home {or was it the other way around?} after returning to my home soil these signs had a certain feel to them {a feel? of what?}

Aleksander Malachowski asked me to grant a TV interview I said that one small step a human footprint on the moon will change the world and mankind How naive.

VTrains Still Depart only now from memory

for Oswiecim Auschwitz

Theresienstadt Gross-Rosen Dachau for Majdanek Treblinka Sobibor for history

Blind tracks trains depart from small stops from giant railway stations turned into art museums Hamburg Paris Berlin here the artists assemble their installations trains steam engines rust on decommissioned rail lines Robigus covers in rust signal boxes switches soccer fans and army conscripts demolish train cars celebrating the happiest day of their livesleaving the army'?

17. Army service is mandatory in Poland.

43

others take the oath kiss the flag parents wives girlfriends cry the band plays a march but the other train which I see (before my mind's eye) rebelled left the tracks the rails the lights the switches it rides over the green meadows over dirt roads and wild herbs moss water sky clouds the rainbow's arch is this Treblinka asks a young girl in the blush of her youth I recall her lips and eyes like a handful of violets it is Rose from Radomsk "I called her Rose because you had to call her something so she would have a name" I don't remember her real name the train rides over pillows of silver and green

moss

across forest roads and clearings through woods of the just and unjust

44

But this is Alina18, I think to myself

Alina the sculptor Xawery Dunikowski's student'? in a cattle train opens the window leans over kisses the wind closes a window maimed by barbed wire

I sit so close that our shoulders are touching "something fell into my eye" I lean over

I have a clean handkerchief I say please lift your eyelid we will do a little surgery without anaesthetic she smiles through the tears don't be afraid

I say it's only a speck of dust

it's not the first time that I've done this procedure you're my lab rabbit (she doesn't yet know that she will be experimented upon)

that's all-I saythe tears will wash it all out

I wipe her eyes here's the culprit

I show her a sharp black sliver of coal

allow me to introduce myself my name is Tadeusz

I'm Rose Mom and I are going

18. A reference to Alina Szapocznikow.

19. Xawery Dunikowski (1875-1964), sculptor who severed ties with academic conventions. His works gave voice to the subjective expressions and existential anxiety of the artist. He was imprisoned at Auschwitz from 1940 until the end of World War II.

45

from Theresienstadt to Treblinka

Mom is in the restaurant car they split us up her car is at the end of the train

we will be getting off at Treblinka you know I'm dying of hunger seriously

1 am so hungry

1 could eat a horse or a carrot beets a head of cabbage and where are you going Sir? if 1 may ask me? wherever! off to the woods to gather mushrooms to pick berries to get some fresh air

1 am a Satyr the girl laughs

now 1 can tell you a secret I get off at the next station the place where the unit stops is called "tall trees"Zo

VI

The Last Century

1 look at the knife it could have served to cut bread a knife from the iron age -I thought - from an extermination camp

The iron age shame truth honesty fled treason deceit fraud violence came

20. The code name for the place where the partisan unit in which R6zewicz served during World War II was stationed.

in their place and the criminal desire to own things cunning man carved up the earth with borders the earth which was until then common to all just like the light the sun the air cruel iron came into the world and something even more cruel than iron- gold 21 Knife made from the hoop of a barrel a barrel of beer or some other barrel with a handle so ingeniously bent

Hania the Professor's wife passed on

when the Professor sits with his eyes closed in silence thinks writes prepares a lecture departs from his scholarship towards math and philosophy or maybe logic and mysticism recalls what he did with that knife in the camp sliced and apportioned the bread protected every crumb didn't peel potatoes (nor throw out peels because they could save someone from death by starvation)

years passedwe count between the two of us we are 160 years old

21. This is a translation of an excerpt from Anna Kaminska's liberal translation of Ovid's Metamorphoses, Book 1.

47

the twentieth century has come to an end

the Professor lives alone works doesn't sleep listens to music

I came to Ustron-' from Radomsk from memory from out of the past

I came to Ustron in July of 2000 from Wroclaw Krakow by way of Wadowice

I wanted to see the hometown of the poet [awierr-' I was moved I saw his mountains his clouds the house he grew up in the school the simple church

22. Mieczyslaw Porebski splits his residence between Warsaw and Ustron on the Baltic Sea. 23. Jawien was one of the pen names of Karol Wojtyla, who became John Paul II.

Laurence Goldstein

Non-canonical

Padraic Colum (1881-1972)

Shortly before the Cold War antagonists trumpeted their twin ICBMs, I read, in a chill, somber library vault, your saga Nordic Gods and Heroes, retelling the sorcery and "wonder-weapons" of Thor, Loki, and the rest, and ending in Fimbul Winter's "burnt and wasted earth." My thirteenth year. Now I was a man.

A poet's jobbery, this child's bible of doom, written just after the Armistice, waiting, in red re-binding, for a new period of troubles, tendered the matter-of-fact friction of headlines. Irish bard of ruin, of world's wolfishness, nothing of your book rang false, that year, when armies clashed in Sinai, and bombs fell on Suez.

Selma Lagerlof (1858-1940)

"0 Larry, it is the truth about the two sexes!"

And if she, my ninth-grade instructress, Norwegian-born, blue-eyed, so testified, I had no choice but open The Story of Gosta Berling and read of woman's obsession with unworthy man.

But was it true? Not on my steady pulse did any unremitting, forlorn pursuit make claim. I was not enough of a Gosta, not feckless, not heartless, nor even charming.

49

Yet females of this kind wept, and still do, in the self-destroying ecstasy of love. I yearned to be unworthy of their pure clinging devotion. I failed. Was that what you intended, Miss Osterfjord, when you steered virtuous, Jewish me toward this dangerous book?

Fran{:oise Sagan (1935-2004)

That sex could be an embarrassment of the body, a kin to sunburn, bugbites, stomach distress, at the same time one craved it unremittingly, seemed in 1957 the message, or revelation, of Bonjour Tristesse, supreme piece of Chick Lit I devoured, one long Sunday afternoon, to feel, viscerally, how the other half felt, whose hangups made me more neurotic than them.

It was all about the father, I learned. That old Mediterranean cult, that Freudian bilge that put teen suitors in competition with the alpha male. So now I could strategize, now I deployed the physical tricks and tropes that made jeunes filles less sad, less filial.

Jan Valtin (1905-1951)

"Communism" was so much the verbal sign for subversion, transgression, world-shaking resistance to the blithe, bourgeois life I led, of course I read Out of the Night at fifteen as a primer and guide for my rebellious twenties. Semi-fictional, semi-factual, this memoir of double-agency by the masked assassin Richard Julius Herman Krebs taught me that Nazi thuggery mirrored the Soviet model, that free love (with the enchanting Firelei) broke the heart in seven places.

The Kremlin's bulldog, his reprinted confessions now grace the Forbes Book Club, along with First, Break All the Rules and Flat Tax Revolution.

50

Friedrich Durrenmatt

Friedrich Durrenmatt

(1921-1990)

At sixteen I saw Lunt and Fontanne impersonate his estranged lovers, Claire the prodigal zillionairess and her prey Anton Schill. She bribes the villagers to murder him, her erstwhile, virile seducer, and they do.

In the nuclear age, he said, only comedy makes perfect sense-or absurd sense.

How droll and middle-European The Visit was, how impossible to forget. "The world is for me something monstrous." And for me, too, as I measured later news against this parablelust, money, revenge: the Lords of Life.

It takes no atom bomb to lay us low. Doing what comes naturally does the trick.

Herbert Read (1893-1968)

At the dawning of the Age of Aquarius, verdant with my generation's seminal cultures, I was turned, wrenched, from one glory to another. The Green Child was the efficient cause, for Siddartha-like it cycled me past utopia, back before pastoral infancy, and I sank with Olivero into the crystal cave of non-strivers, "laid out in troughs filled with petrous water."

This was not death; the Romantic child ("her face was transfigured, radiant as an angel") de-sublimated me, and as I descended her siren call scattered murmurs of resistance. On the high ramparts, "We Shall Overcome" bullied the aged century like the fascist pledge.

51

Michael Gold (1893-1967)

"You are fated to live in the workers' world," he wrote, as if admonishing me, not the new masses, who consumed his columns collected in Change the World! After high school I took a summer job handling titanium. I wanted / didn't want to be of the masses, my bitter co-toilers on the factory floor.

"If the Nazis won the war, I'd still be hauling these boxes of metal around," one spat at me, "So what was the war about?" Only the working class could be an instrument for social progress, Gold claimed. "Save yourself," they urged me.

I enrolled at UCLA, "Jew U," where the classics turned out not to be proletarian.

Mary McCarthy (1912-1989)

How ivory was my tower! Burnished atop the hills of Westwood, elite enough to keep all high school renegades la,bas. Were there higher-ed serpents to beware? The Groves of Academe advised: Look around. Henry Mulcahy, who poses as a Red to keep his tenure on a liberal campus is the poster turncoat of your milieu. Get used to it.