is an international journal

published

TriQuarterly TriQuarterly

of writing, art and cultural inquiry

at Northwestern University

TriQuarterly

Editor

Susan Firestone Hahn

Associate Editor

Ian Morris

Operations Coordinator

Kirstie Felland

Production Manager

Siobhan Drummond

Production Editor

Greta Polo

Cover Design

Gini Kondziolka

Editorial Assistant

Lindsay Meck

Assistant Editor

W. Huntting Howell

TriQuarterly Fellow

Sarah Mesle

Contributing Editors

John Barth

Lydia R. Diamond

Rita Dove

Stuart Dybek

Richard Ford

Sandra M. Gilbert

Robert Hass

Edward Hirsch

Li-Young Lee

Lorrie Moore

Alicia Ostriker

Carl Phillips

Robert Pinsky

Susan Stewart

Mark Strand

Alan Williamson

122

The editors wish to congratulate the following three authors who have had their work chosen for reprint in Pushcart Prize XXX: Best of the Small Presses:

Robin Behn (issue 119) for her poem "Pursuit of the Yellow House"

Lucia Perillo (issue 119) for her poem "Sad Coincidence in the Confessional Mode"

Pamela Stewart (issue 119) for her poem "A Haze in the Hills."

Richard Burgin's story "Identity Club" (issue 118) appears in the Best American Mystery Stories 2005 (Houghton Mifflin), edited by Otto Penzler.

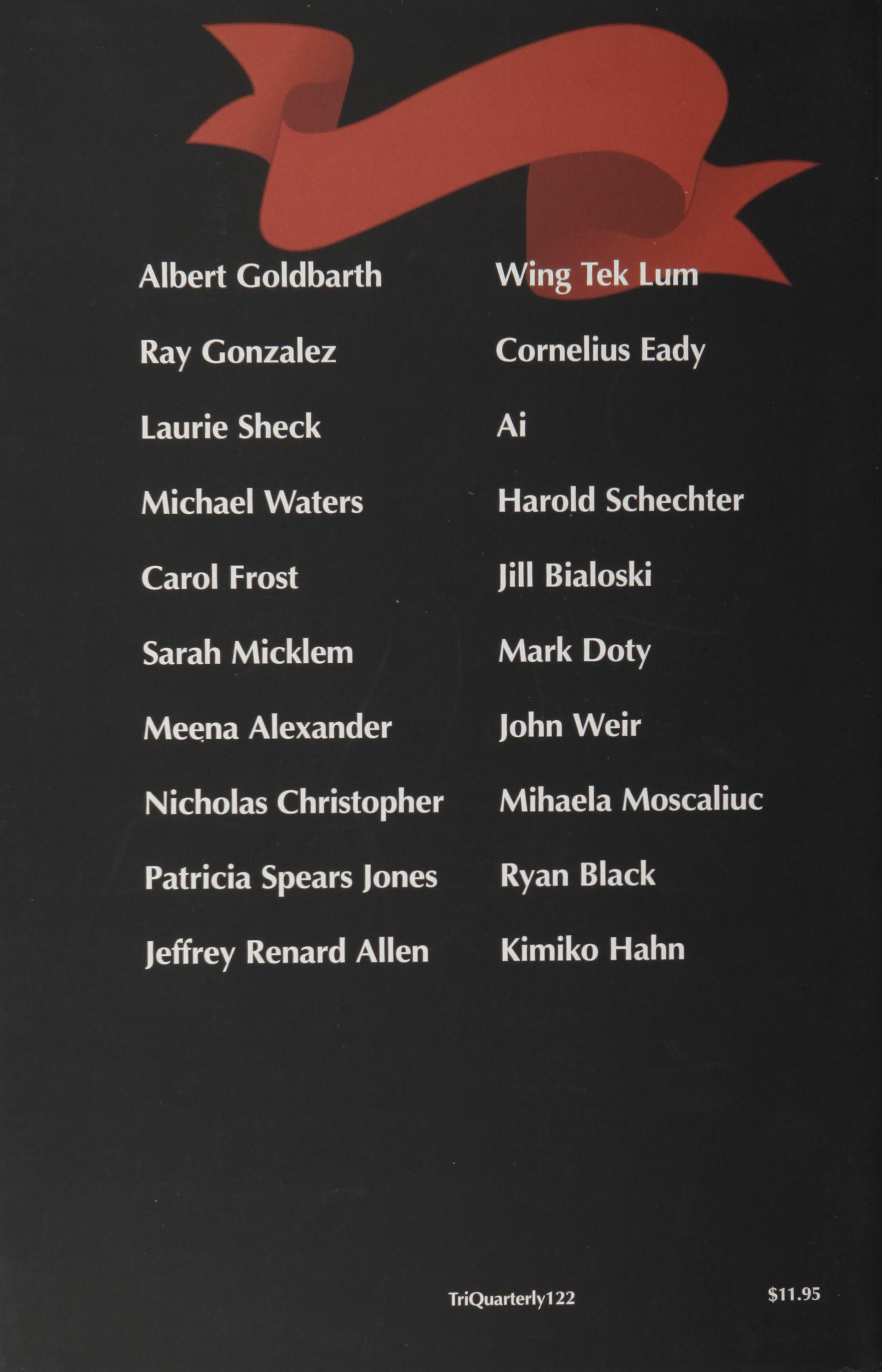

Editor of This Issue: Kimiko Hahn

Kimiko

Walleechu; The Muse of Invention; A History; Crossing

Albert Goldbarth

23 Findings (2); Findings (3); Paintball; El Paso

Ray Gonzalez

30 Poem: The First Remove; Poem: The Second Remove; Poem: The Third Remove; Poem: The Fourth Remove; Poem: The Fifth Remove

Laurie Sheck 35 Processional; Bosporus; 2 Revelation 1:2

Michael Waters 40 Orchid; Clam; Snake Key

Carol Frost

66 14 rue Serpentine

Nicholas Christopher

70 lHay algo mas triete en el mundo, que un tren immovil en la lluvia?; ZTrabajan la sal y el azucar / Construyendo una torre blanca?; zEra verdad aquel aroma / de la doncella sorprendida?

Patricia Spears Jones

CONTENTS

introduction 8 Notes Re: Trawl/Troll

Hahn poems 13 Pink

15

Kimiko Hahn

fiction nonfiction review

83 A Young Girl in a Cheongsam; Pragmatic; Capricious

Wing Tek lum

90 The Ghost, The Mountain

Cornelius Eady

94 The Hunt; Fatherhood

Ai

I06 Private Spaces

Jill Bialosky

I I I Notebook / To Joan Mitchell

Mark Doty

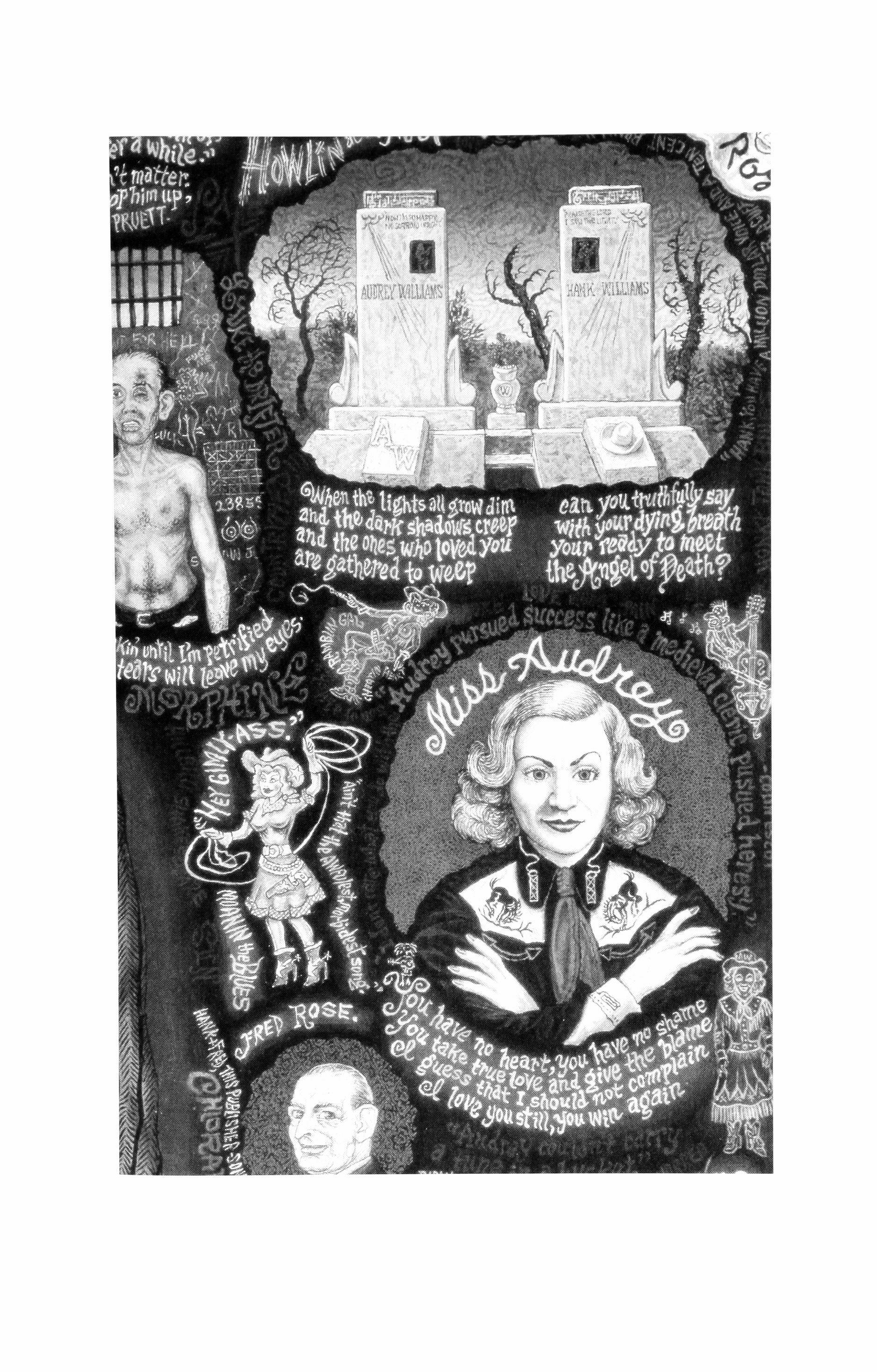

132 Toxic Flora

Kimiko Hahn

44 The Captive Chronologist

Sarah Micklem

74 from Hour of the Seeds

Jeffrey Renard Allen

S3 Encountering Emily Dickinson; from Fragile Places: A Poet's Notebook

Meena Alexander

100 Preface to The General's Son

Harold Schechter

I 17 Everybody Knows, Nobody Cares, Or: Neal Cassady's Penis

John Weir

128 Forfeiting the the Self: Research and Contemporary Poetry

Ryan Black

126 R. Zamora Linmark's Prime Time Apparitions

Mihaela Moscaliuc

134 Contributors' Statements and Biographies

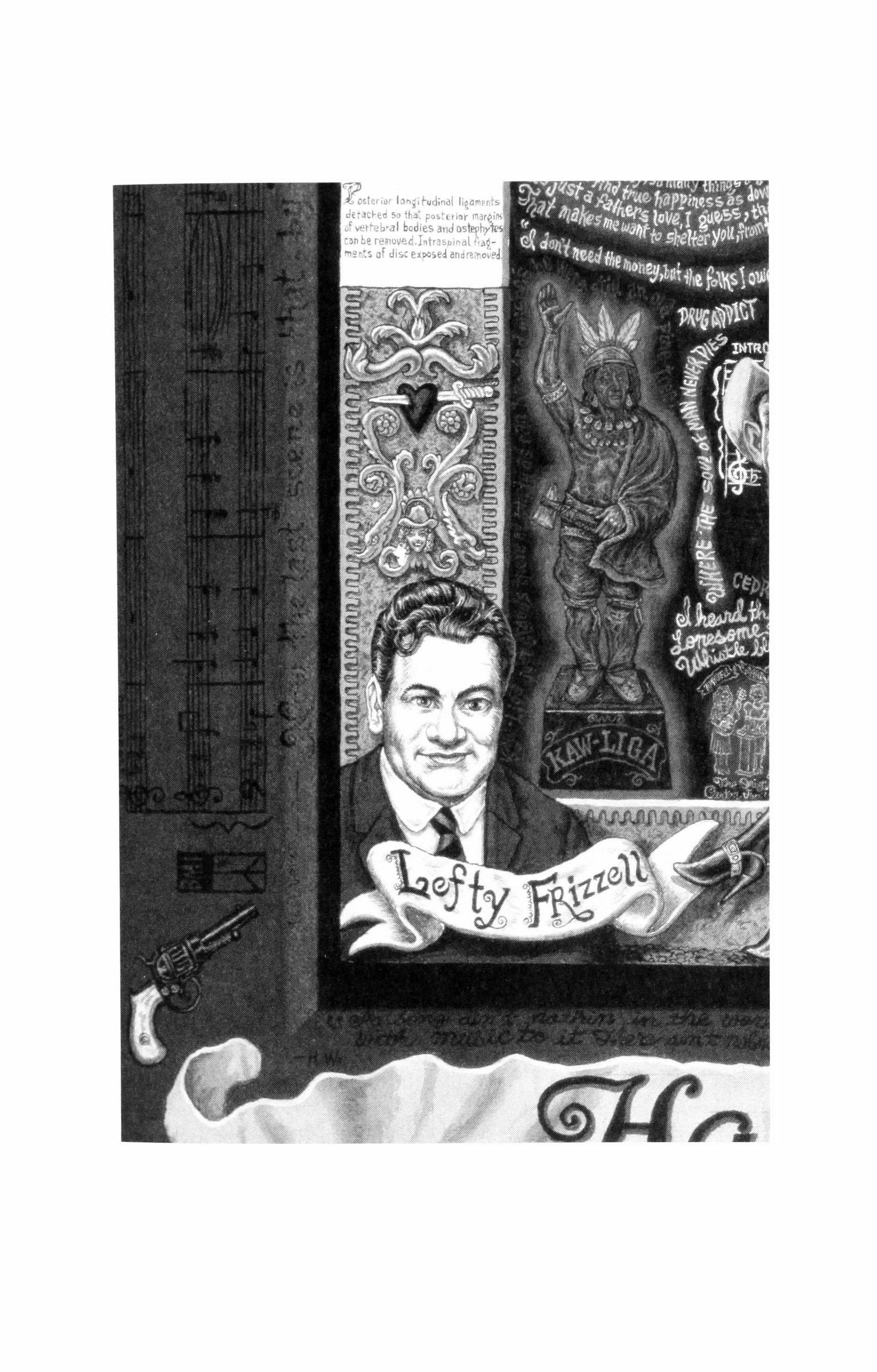

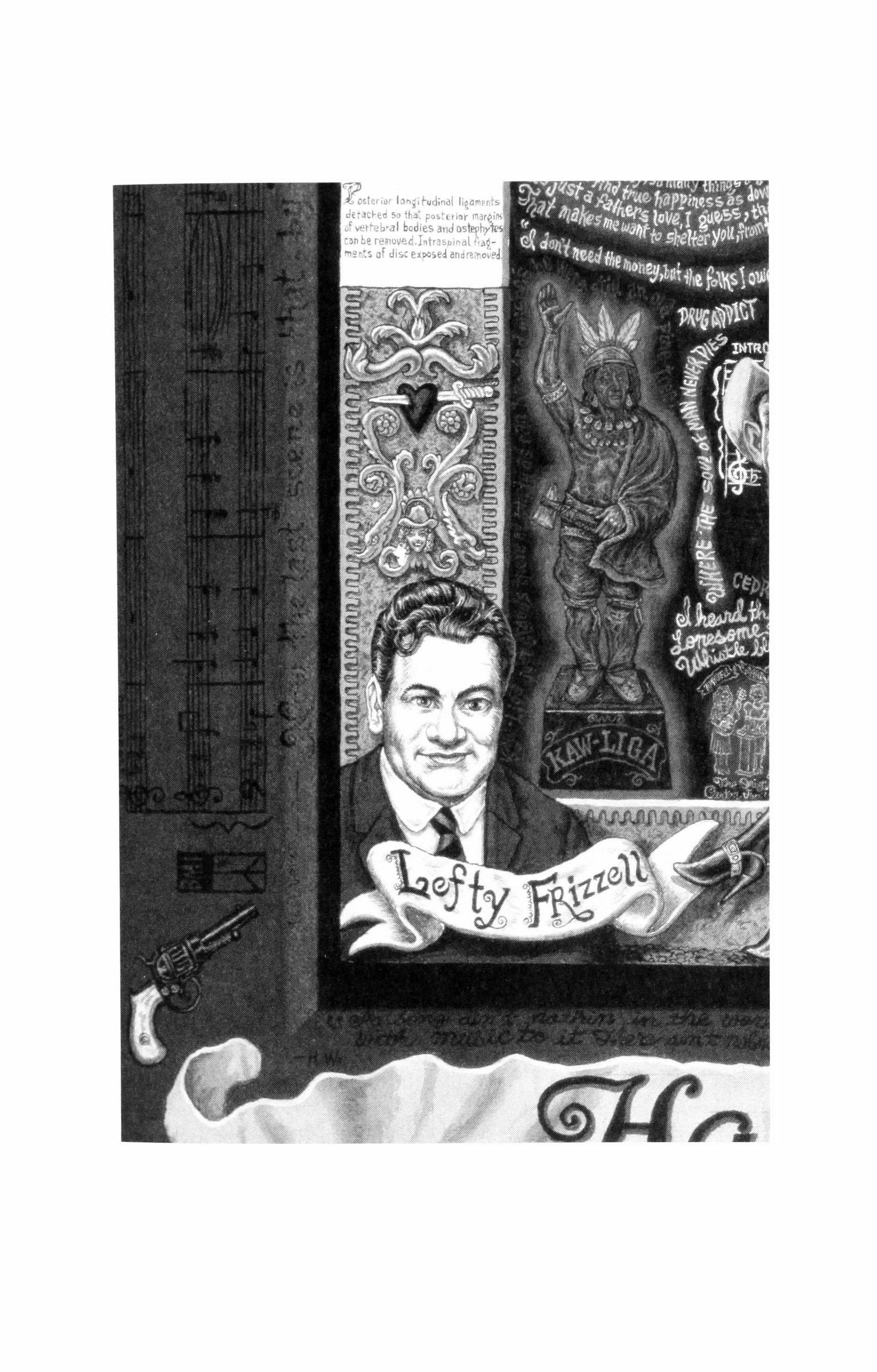

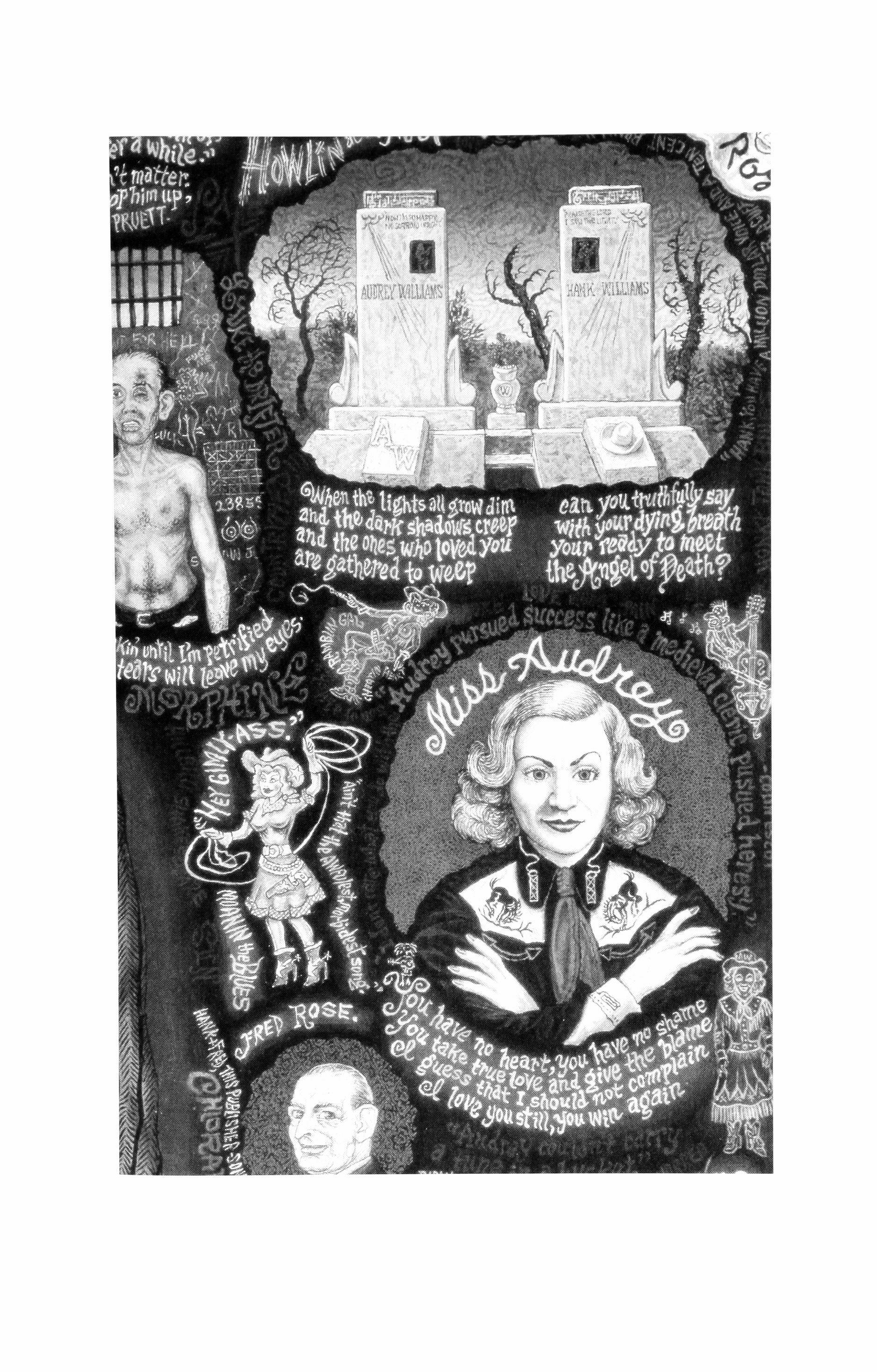

art

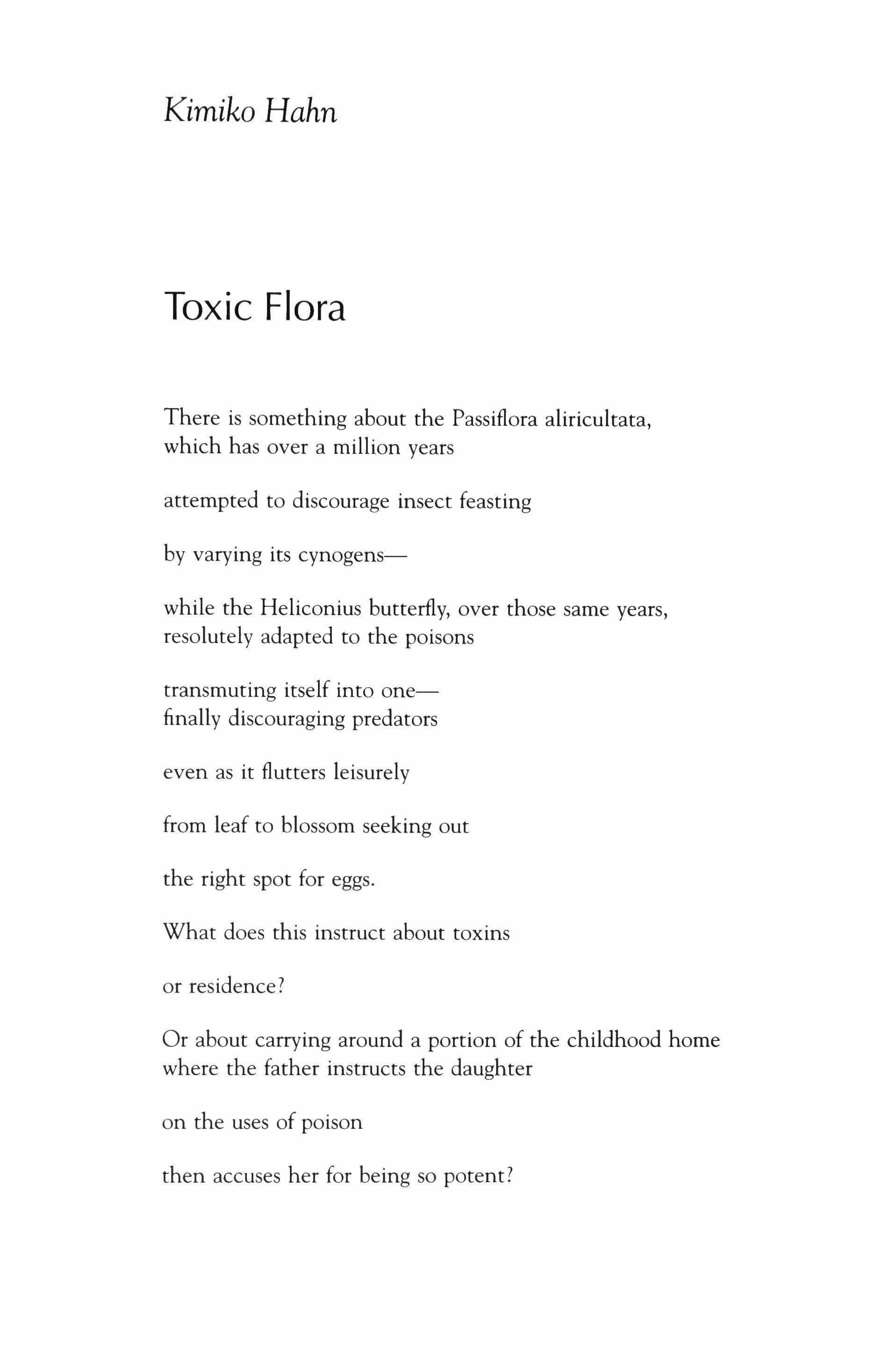

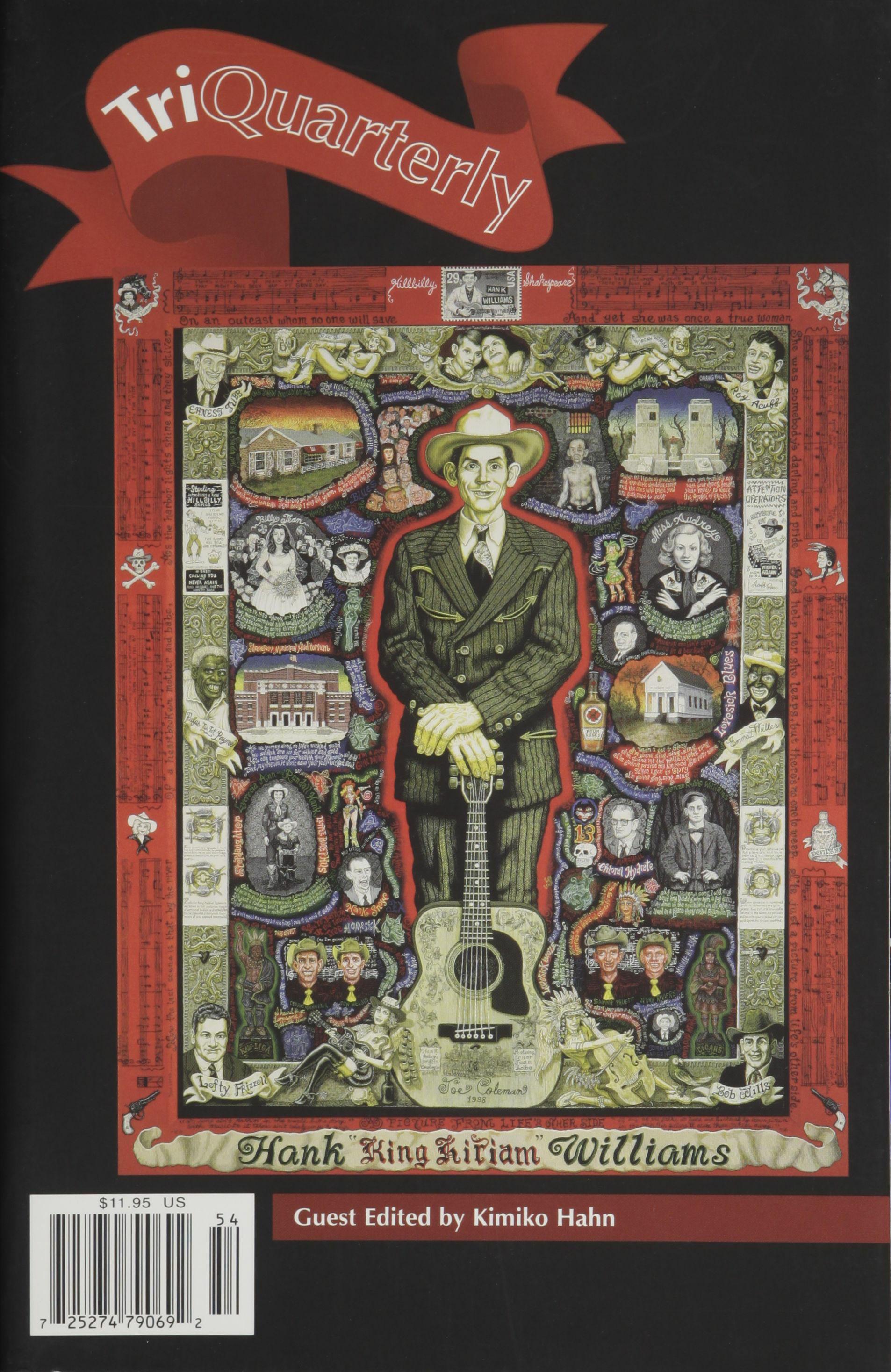

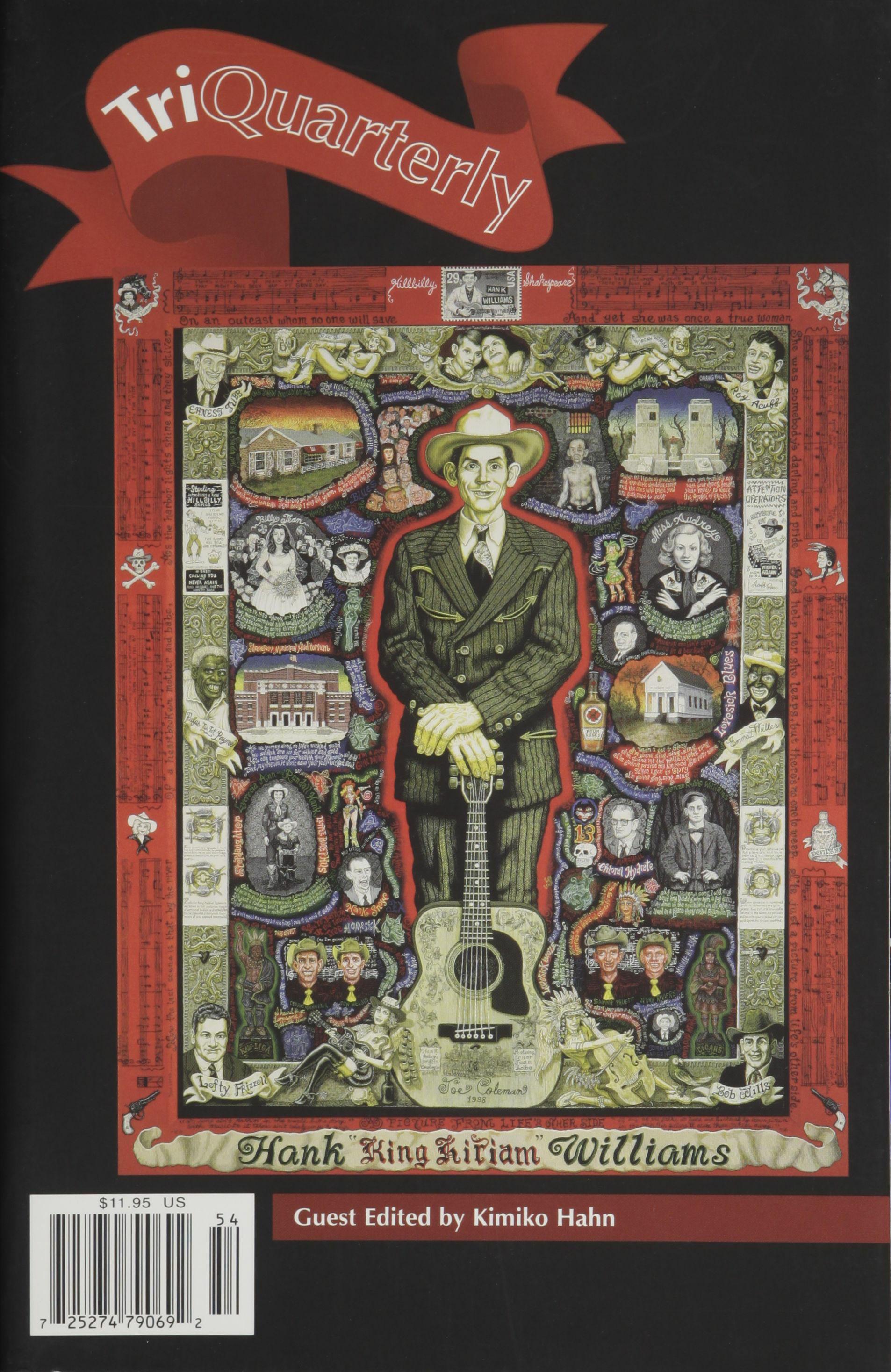

Cover and interior panels: Picture from Life's Other Side [Study of Hank Williams, the songwriter who lived only thirty years, but whose influence on singer and artists of all types remains strong today, fifty years after his death.]

Joe Coleman

Notes Re: Trawl/Troll

Kimiko Hahn

Kimiko Hahn

10/15

Is it trolling or trawling? We argued-though he wouldn't call it thatand I am still not sure which is the huge open net that drags everything from target to unwanted prizes (dolphins, say) to old high tops. I prefer the aw sound-troll reminding me of those plastic figures, 1963, Roselle Avenue School playground. Barbara and I dug homes for them in the gnarly roots of hickory trees. Anyway.

Trawl. It reminds me of what I want to do.

10/16

Trawl: noun, I. a strong fishing net for dragging along the sea bottom; 2. trawling line, a buoyed line used in sea fishing having numerous short lines with baited hooks attached at intervals 5. To troll

Troll: verb, I. Sing or utter in full, rolling voice; 9. To fish with a moving line, working the line up and down with a rod, as in fishing for pike, or trailing the line behind a slow-moving boat; 14. a lure

10/17

Boland's section "Quarantine" from her love sequence has triggered a series of my own: I've unearthed all sorts of old clippings-mostly from the Science Times-and already have a couple dozen love poems.

Trawl and troll-facets of process.

10/22

Always enamored of exotic diction---especially from outlandish sources. I miss those afternoons as an undergrad-on a break (distraction?) from a research paper, I'd cruise down the stacks, and pull out the rattiest

8

spines--especially from the science section. A facsimile text on cartography. Marine biology. Mycology. The more anecdotal, the more allure.

10122 continued

For "Reckless Sonnets"-reading about the yucca moth in an essay by [ung, it was such a pleasure to scrounge around second-hand book shops until I found a good entomology textbook: straight forward drawings and photos-nothing you'd tear out and frame---on, for example, aphids.

10/24

A pull to language itself-the sounds, the play-a love I trace as far back as my mother reading "How the Rhinoceros Got His Skin." Kipling's words to my five-year-old ear-comestible, oriental, splendor, the Upland Meadows of Sonaput-were all magic. Kipling knew that. He knew what a colony could yield. Spicy, hot, shadowy. Other-ness. Even to a child's ear the words throbbed.

(Even to an "Oriental"?)

10/25

Research never seemed strange. Then mixing diction: high/low, childlike / adult, technical/colloquial. Precedents like Bishoppink swim bladder peonies lice-infested

The language in "The Fish" is as delicate as lace. Made intricate with a variety of sounds (-which are Latin-I'll have to ask S), informalities, preoccupations, etc. Tonal variation follows.

From Adrienne Rich's essay, "Woman and bird" (What Is Found There): "But I found myself pulled by names: Dire Whelk, Dusky Tegula, Fingered Limpet, Hooded Puncturella, Veiled Chiton, Bat Star, By-the-Wind Sailor, Crumb-of-Bread Sponge, These names-by whom given and agreed on?-these names work as poetry works, enlivening a sensuous reality through recognition or through the play of sounds (the short i's of Fingered Limpet, the open vowels of Bull Kelp, Hooded Punturella, Bat Star); the poising of heterogeneous images (volcano and barnacle, leather and star, sugar and wrack) to evoke other worlds of meaning."

9

10/26

Vehicle. Tenor.

10/27

Invited to guest edit TriQuarterly, I've decided to focus on writers who typically base their work on research or outside sources. Some of my early influences-Patterson, The Waste Land, Donne, Dickinson, Suna no anna. Marvin Gaye's "We don't need no escalation."

10/28

The beheadings are madness. These guys are not a part of any kind of dialog because any answer for them is, "God says so." Unbelievable. Here: a U.S. leader, a liberal, has commented that Americans, too, have allowed religion to veto science. I feel more angry than frightened.

10/29

From the Science Times article by Anahad S. O'Connor, "Piglets Buried in Bogs a Clue to Mystery": "By studying the remains of piglets buried in bogs, Ms. Gill-Robinson also determined that limited exposure to air and shorter burial times were also significant in assuring preservation Each of the three peat bogs in the experiment contained different environments, resulting in various levels of preservation. One piglet, buried for 17 months, exploded upon gentle touch Other piglets were reduced to fragments of muscular and skeletal remains."

11/2

Waiting election results. All year, all season nothing but competitive advertising. Repub-lexicon.

11/2 continued

The Republicans won the great spin contest.

11/4

Theo van Gogh murdered on the 2nd-stabbed by a Dutch Muslim youth, offended by the short TV documentary, "Submission." The piece, made with Ayaan Hirsi Ali, denounces violence against Muslim

10

women "by filming words from the Koran written on the lacerated flesh of women."

11/5

poetsagainstwar.com

11/13

For so long I didn't appreciate Marianne Moore-didn't like her mannered aesthetic. But in searching for a way to use a varied diction (especially scientific), I returned to her Complete and found entrance. I've gotten past the "armor" which Charles points out in his book is not to shut herself up in metal, but to enable her self to set out.

Spruce�cone regularity armored/zmr-ezner uninjurable/artichoke

Her odd, clotted use of quotations: or as she put it, "Statements that took my fancy which I tried to arrange plausibly."

11/14

Is it true that [ung worked to revive the forgotten language of images -images that Freud tried to translate into logic? The poet joins [ung in matching image to impulse. Dickinson's lexicon.

11/15

Trolling. Tossing a line out of moving boat and seeing what bites. I haven't let the line stray deep enough. Too many of my new pieces feel like all craft, no bite. I'll put them aside for a while.

11/16

Work coming in. I need to ask each writer to comment on how they arrived at their sources-how or why. I am disappointed that several do not have work they can give me at the moment-Jaime is completing his book from the points of view of historical figures, two women; Jessica's last book, Dreamlungle, would have been perfect; Arthur just turned in his new manuscript, some poems having to do with knots I thinkII

11/20

Vendler observations on Moore are helpful. About the animal stuff: "In part, Moore was herself to blame for this absurdity: her distrust of emotions made her increasingly submissive to fact; her isolation made her more dependant on books Animals became an end in themselves, as human beings became more remote or more repellent."

I can imagine doing just that. I am getting crankier by the day. I can't stand being around people who are only interested in themselves or act in a superior manner (never ask what H or I am doing; say stuff like "oh I need your advice" as a way of suckering me into talking about them; lecturing about Iraq or talking endlessly about children).

"But the shield of the animal metaphor eventually became almost impenetrable."

"It was true of Moore that she was too reclusive for some things to touch her, not because she had no feeling but because she had so much."

Thankfully I have my daughters.

12/20

Trawling for the metaphor's tenor whether one line or many. At this point, it's tough because I cannot afford to return to the easy tenorsthose from the past. There is something deeper than the Giant Squid. How to fathom that?

12/20

Inundated with end of semester work. On the news: war and tsunami disasters.

1125

Hoax on the internet-the terrifying Blob fish that fascinated was NOT tossed up by the tsunami-although it IS real.

Barfield's chapter on "Strangeness": "No genuine lover of poetry and words can pick up a book on say Botany or Metallurgy, and read spores and capsules and lanceolate leaves, of pearly and adamantine lustres, without feeling poetically enriched by that section of the new vocabulary which actually impinges on his own present consciousness of Nature."

12

Kimiko Hahn

Pink

From a report on fourteen dead piglets buried six months in a Scottish bog then exhumed to note stages of preservationone exploded upon touch, a second was reduced to fragmentsthere's a lesson on limited exposure.

That is, the boy who ruled against intimacy two nights in a row or another who couldn't take slinky fabric.

I, too, preserve varying degrees of loss at high cost. Pink linoleum. Pink fishnets. Pink piglet at the country fair that decomposing summer. Fear of the Ferris wheel. That pink light meant for those who seek rapture in casual rupture.

13

Albert Goldbarth

Walleechu

What would we have offered then, in those days, as she wasted (it seemed hourly) like a movie of death at triple,speed-a year of our own?-an arm of our own? What lacquered box of happiness would we have gladly given, to reclaim our mother from what she'd become on a sheet that, after a night of pain and leaking, was a butcher's tarp? A legI-a leg of us for a day of her? Although the heart is not a bivalve, it can be spaded out of the chest and given away-would we have done that, say a month of it in exchange for a month for her? Would we have hung it on the kind of tree that Darwin saw,

"the altar of Walleechu," on the high and empty plain approaching Bahia Blanca? Here, on the leafless branches of that solitary presence, the local Indians had attached, "by numberless threads," their various tokens of beseechment, "meat, bread, pieces of cloth, cigars, &c."-and "poor people not having anything better, only pulled a thread out of their ponchos, and fastened it to the tree." But a luxury ocean liner, with all of its orchestras and silver champagne buckets, is only a trinket to the gods-how could they want some little knot of a child's hair? And yet they do, it seems. What wouldn't we abandon for their favor? In the days

15

of my love-troubles, I might have offered my tongue on a salver for what it had said. Or my eye-would that do? On a fishhook and a swaying length of nerve? Another bit of human glitter for the jackdaw sensibility behind this tree. Here, take it, let it dangle and gleam in the blanched sky of this country.

The Muse of Invention

Noon: they were happy. One o'clock: they had hurt each other again. As if they couldn't tell which atmosphere they breathed in best, so needed alternation. In this, the clock complied: seemingly, the machinery of the day can grind a new emotion hourly. The bedroom sun, compacted in the gel in the jar, to the look of a shrunken head The bedroom sun, a patient, golden hand at rest on the top of the conga drum. They know that some year later on, in retrospect, the proper combination of these everyday components will be obvious-this here, and this: resentment; minus the ottoman, and with the heavy X of two crossed wrenches like the design on a crest: forgiveness-but the muse of invention is wary of committing herself too readily. Darwin, encamped on one of the southern islands of his five-year voyage -enbosomed, he wrote, for he loved this place-observed a sudden amplitude of color as the flap of flight again, and then again, and then again, in what his eyes saw as a sequence of these units as they almost, almost, blended unbroken into a ribbon of indigo shine. And even so, he didn't foresee cinema. Nor did Leonardo give the world the printing press. Amid the twigs and stickers of the forest floor, amid the city's colonnades, and especially amid the itch of the flesh, and the warring oaths that rive a human heart, they did what they needed to do, and the future took care of itself.

A History

She curled up, to a fetal lump; she didn't want me touching her, a friend confides. And I remember I'd secede, a pint-size irate eight-year-old refusenik, from the nation-state of empty endless chitter that my family (extended: down to cousins and their current dates) became, on herd occasions like Thanksgiving or erev* Passover. Maybe an hour or so would go by, then my mother or father show up at my bedroom door in rage mode and aghast at the incomprehensible sight of a child so elvishly weird, he'd rather read in solitude than join the familial gabble. There were times they looked at me with love conflicted by the kind of dread suspicion

that we see in thirteenth-century accounts of clerics shocked to come across a brother reading alone (= secrecy, hereticism) and in a perfect silence: sure the Wicked One had granted him unnatural powers, in payment for his Soul." What Wordsworth calls "that inward eye" became, as well, an inner mouth, with which we drank straight from the page, without the need for a community approval and a public mediation.** And although I've shared the common hoi polloiish dream of celebrityhood-the limo, the adoring crowds, the headlines-equally common for us is the image of the starry face in shades, the starry hand held up against the paparazzi. So when Nathan (that's my friend above) and Dee (my friend, the "she" above) attended Anya's Sixties Retro party I remember Dee got vodka-sotred=-thanks to Nathan's stony-cold sobriety: they always counter one another-revved up with the juicy roar of an old crop duster, jumped in (fully clothed) the hot tub, and rose up crowing

18

into the vodka bottle like a megaphone "Leave me alone!" (= pay me attention). We're confused, we human beings. Of course. We corne from a world of 100% attachment and osmosis; we remember it subconsciously as a world of isolation. In those movies of the fetus developing there it is, lips and larynx learning their first text; reading in private.

The initiating "first night" of a Jewish holiday.

Originally in monasteries, reading was a group activity-reading was always and only a group activity. The ear required "corroboration of what the eye was seeing," says Leonard Shlain. "In order to know what he was reading, a monk had to actually hear himself." But then during the Middle Ages, Roger Chartier tells us, "one stratum of readers after another mastered the technique of silent reading. The first were the copyists working in the monastic scriptoria. Then, scholars in the universities. Two centuries later, the lay aristocracy."

Suddenly, the reader was freed from anyone else's scrutiny. This radical ability made possible the immediate internalization of script or print. The book and its oneperson audience could form a bonded unit that was separate from the outside world. Intellectual work became an intimate act. In devotional reading, silence allowed a direct relationship between the individual and God. The Bible, a love letter, these were portable now, to a sanctum: woods, bed, crawlspace. Emerging ideas of what the "self" is, and what a given person's capacity for "reflection" is, grow evident: "to be alone with my thoughts."

In many ways this makes the novel possible; and what we call "author-ity" came to reside not in the overculture ethos, but in the author-with whom the reader established an insular back-and-forth. And of course in religious, political and erotic matters, the way was paved for previously unthinkable audacities. Pepys's diary says: "Up, and at my chamber all the morning and the office, doing business and also reading a little of L'escholle des Filles, which is a mighty lewd book." And then, that silly encoding of his: "It did hazer my prick para stand all the while, and una vez to decharger."

Crossing

The Catuaro mission is situated in a very wild place. At night jaguars hunt the Indians' chickens and pigs. We lodged in the priest's house. He wanted to know what I thought of free will, of how to raise the soul from the prison of the body, and, above all, about animal souls. When you have crossed a jungle in the rainy season you do not feel like these kinds of speculations.

Alexander von Humboldt, 1799

It was difficult for anyone to travel in the Year of Our Lord 960, and unthinkable for a woman. So novitiate Theophna doesn't think, she lets her savvy honor guard of noble-household louts do that, while she attends to the unfamiliar requirements of every immediate step she takes on this dangerous journey -"to go instruct the daughters of the Count in matters Spirityl." The honor guards' conversation is little but swineherd-style cursing, as well it might be: the way is undrained bogs, and forest so thick it's like straining through the interstices of a solid. When a wolf attacks one night, and is with great pains overcome and slit, "there were found in its belly, parts of human limbs." Another night, a straggler is disemboweled by a rampaging boar. The threat of human marauders is ever present: they rape, they pluck a victim's eyes out as if lazily swiping eggs from a nest. The rivers have no bridges and the mountain demands that they crawl on all fours.

It's recorded that when Theophna arrives a week later, at midnight, chilled and starved and blistered, dreaming fish soup and a heated bath, and the governess suggests that she fly straight to meet her wards and begin their lessons in the holy mortification of the flesh, the pious Theophna is heard to utter a string of words not found in the Bible.

1.

20

2.

She'd arranged a date for 7:00 at the west side Budget Inn, a "reg," a once-a-month on business here from Omaha, with tastes that leaned toward infant nursing fantasies (both tit and bottle), normally an easy three-bill hour, but her brother is heavily dying in the paralytic increments of Lou Gehrig's disease, and outposts of her breaking heart befuddle her usually quick-click mind (and dim the responses lower down of her little purrer, her moneymaker) and jezus at the comer of 4th and Dumplestead she runs a red and smashes a parked VW van, which shatters eleven nippled bottles of Similac in the back seat, then the cops show and her goddam proof of insurance card is in her "real" purse at home and not of course in her bag with the peekaboo nightie, talcum, and pacifier (although she feels the need to fake a guarded rummaging-through), which means it's 9: I 5 when she knocks at his door with a combination of eat-me-lover sexual flair and sheer frustration breaking over her smeared face, and she's suddenly on the bed-edge damnit weeping, she's the infant, and when he asks in worried kindliness if she'd care to join him in prayer, she cracks the one good bottle of babygoo over his bald head

3

all reminding her, as recollected the next day in tranquility, of that quote from Alexander von Humboldt I've used here as an epigraph.

Because she's read his journals (she was a naturalist in her earlier life), she knows (and might take hope from this-as might we all who fancy how no one part of our fractured psyches ever wholly disappears) he only half-believes his words. He's traveling to the foothills (for his astronomical observations) over land its natives say "will crush a man's life like a maggot's." Their pirogue tips into the chocolately river waters, and saving not only himself but his specimens-book is a panicky matter of risking attack by piranhas. Crocodiles await the unwary. A jaguar snatches their mascot dog from camp, they hear

21

its cries of dismemberment. The heat. The waist-high pit of mud. There are so many gnats and mosquitoes that to breathe in is "to drown in gnats and mosquitoes, they so replace the air." They reach their destination, a run-down monastery, exhausted and tom. But that night, doesn't he leave his bed? -not to set up his extensive equipment, but none the less to sprawl on a hilltop, closer than on the plains to the sky and its mysteries, the sky and its burning incorporeal presence.

22

Ray Gonzalez

Findings (2)

When millions of cicadas emerge across the eastern United States for a rare mating season, they will appear as tasty morsels to pets that could get sick from eating the insects, officials warned. The insects are protein-rich but their hard outer shells can cause vomiting and constipation in cats and dogs. Scientists also report that the oil from fingerprints on electric guitars will eventually change the sound of the instruments, even causing them to go out of tune over a period of time and creating short-circuits in the electrical system inside the body of the guitars. Researchers discovered that a tiny grooming instrument, used to trim nose hairs, leaves metallic shavings in the nostrils each time the user turns the tiny teeth in the device. Heart surgeons in Chicago found eight undissolved cholesterol pills blocking a man's heart valves when they opened him up. If you take four cups of green tea and mix them with one quart of car engine oil, the resulting liquid can power a lawn mower for six months. Scientists at the University of Ohio crossed geranium plants with bluebells. The plant that grew as a result had deep black petals on circular blossoms and a sticky red-colored resin seeped out of the plant. Scientists in both California and Russia claim to have achieved miniature nuclear explosions inside condoms made from the stomach linings of sharks. When a U.S. Wildlife team reached the top of a peak in Alaska, they found a frozen lake with several dozen old horseshoes embedded in the ice. South Korean scientists formed thirty new strains of DNA when they cloned panda bear embryos from the stem cells of condors and boa constrictors. The British Medical Association recently reported that smoking cigarettes stops fingernails from growing, while smoking marijuana makes ingrown toenails go deeper into the skin. Marital beds facing east windows make married couples have sex more often. Marital beds facing west make them have infrequent sex.

23

Eight volunteers in a lab study ate a blended combination of chicken hearts, oatmeal, catsup, crushed Twinkies, raw squid, and horseradish for one week. No one threw up, only two disliked the taste, and all eight reported a higher rate of recalling their dreams in the morning. Engineers discovered microscopic cracks in solar panels that powered a fish hatchery in Oregon caused extra sunlight to filter into the growing tanks. The results were that several hundred trout with three eyes hatched for several days. Psychologists in a special study in Manhattan found that people who crossed against red lights had more confidence in their working environments and made higher salaries than those who waited for green lights before crossing. They also found higher mortality rights among those crossing against the red lights. Skunks urinate more often than porcupines. Electric guitars for left-handed players blow fuses more often than common right-handed guitars. An average of four hummingbird eggs fit inside the normal human belly-button.

Findings (3)

New research suggests that pointing enhances understanding. In some cultures, pointing is a faux pas, sometimes even insulting. New research is turning this social don't on its head, showing that hand gestures, such as pointing, can enhance the understanding of messages. An Alaskan scientist found that grizzly bears, during the spring season, spin in a tight circle right before charging their prey. He found the bears charge head on during winter. A woman who swallowed three penny coins swears they came out as nickels at the other end. A psychiatrist who examined her found a quarter under her tongue. Scientists in Austin, Texas took a skunk and fed it nothing but cornmeal for three weeks. After that time, they found the sac of offensive musk had completely dried and the skunk was unable to spray. A robot, exploring a narrow cave in New Mexico, lost all power and contact with the technicians on the surface as soon as it stopped next to an ancient clay jar lying in the cave. They were unable to recover the machine, which was stalled forty feet below the desert. It was discovered that circumcised men are six to eight times less likely to have intercourse in the missionary position. Mexican surgeons removed three dead baby alligators from the stomach cavity of a bull that escaped from a ranch in northern Mexico, then was found dead a few miles away. The surgeons were perplexed because alligators are not native to that part of Mexico. NASA scientists have concluded that the total number of satellites of unknown origin they are now tracking stands at 2,314. A new study concluded that eating raw onions raises the heart rate in men, but lowers it in women. Internet investigators have been able to keep track of a larger number of individuals downloading illegal music with new software that interprets the warmth given off by their hands on the keyboard, which sets off magnetic sensors under the keyboard letters that are directly tied to the program that analyzes the warmth and identifies it in the same way fingerprints are identified. A Pennsylvania biologist uncovered the code that makes saliva in the mouth tum to cooking oil. American scientists announced that they will no longer accept research samples of dinosaur egg fossils from countries outside the U.S. They refused to

state a reason for banning them. Researchers found that repeated exposure to low-level magnetic fields, such as those emitted by vibrators and VCRs lead to a higher rate of prostrate cancer in men.

Paintball

April 8, 2004 El Paso Times: Paintballs Fired into juarez Community from U.S.

In Anapra, one of the poorest neighborhoods in Juarez, Mexico, across the border from El Paso, residents claim that they are being shot at with paintballs from the U.S. On the night of Monday April 5, the attackers hit two children and three pregnant women. One child was hit in the face, near his eye. The shootings take place at night and Anapra residents say their attackers use laser scopes and night vision gear. They dress in black so as not be easily spotted. El Diario reports that they use a tan colored truck to get into position on a nearby hill. Anapra residents say that the Border Patrol has seen the paintball shooters and has done nothing to stop them. One Anapra resident told EI Diario that neighbors "will respond" if the harassment does not stop soon.

The paintball explodes on the stray dog in yellow blood, its howls mistaken for the observant coyote in the hills.

The paintball flattens against the pregnant woman in blue streaks, the shade of blue impacting on how her baby will be born, live, and die.

The paintball kisses the adobe walls and spills letters in an alphabet more villagers understand than the black and white graffiti of their long lost gang.

The paintball flies in the heat before opening in a geometric shape that changes the face of the child into an image any border justice organization would fight to place on their website.

The paintball stings the brown back of the shirtless boy with a green star that will form a scar he can never wash off.

The paintball buzzes through the swarm of flies circling the outdoor latrines, its impact against the stall sending the insects into an orange frenzy.

The paintball electrifies the Mexican flag in the plaza with a purple haze that gathers a crowd around the flagpole in the morning.

The paintball miraculously bounces off the baby in the arms of the woman before disintegrating in a pink cloud that gives the clay jars on the well a Wal-Mart competitive design.

The paintball zooms into the eye of the innocent old man, the last thing he sees turning red as if red was the only color he remembered from those days in San Luis Potosi when his mother took him to the wall of roses and showed him where his father died.

The paintball blends with the olive green Border Patrol van, whose driver mistakes the impact for a bullet and is shocked the illegals crossing the river are finally armed.

The paintball destroys the statue of La Virgen de Guadalupe, its power cracking the figure's right arm as the film of unknown color wraps the statue in a light many worshippers had been praying for.

The paintball decorates the door of La Bruja, the town witch emerging into the night with a crooked stick tied in multi-colored ribbons that send the shooters scrambling into their van.

The paintball illuminates the border in a storm of bees, the shooters running out of balls as dawn arrives to give birth to the sparkling, broken windshield on their van, the last two boys they targeted holding the warm pistol between them, their three bullets escaping into the air without giving a clue as to what color could describe them best.

The empty paintball cases add color to the desert, the rainbow dirt washed by the next sandstorm into the Rio Grande, whose radioactive waters offer more colors than the latest version of the game.

EI Paso

Every morning, barefoot children dive into the radioactive waters of the Rio Grande, their parents holding the international bridge hostage in protest over the right to live. When the bridge is opened again, some will die and some will cross without fear. Each time the sun comes up, streets in El Paso lead to the top of the mountain where a tall, concrete Christ dies on the cross. Pilgrims trek up there and sometimes disappear.

When the day is the day, the river changes course and moves through the valley of labor and rows of black trees. When chile is picked, the fields tum blood red. What is gathered is lost.

What disappears is found under the arches of the oldest church in town. Headless men are seen in doorways, their headless women lighting fires in the ovens of the blackest rooms.

Every afternoon, people arrive to inhabit old houses boarded up for years, their cars hot to the touch, the roads across the desert leading them here. Some will stay, some will keep going before it is too late to cross the frontier.

Each evening, pictographs on the rocks leave new messages by changing shape before fading with the wind. What the symbols mean is known only to those born here and have never left. Each night, bats fly out of the horizon to escape wherever they have been, their flight into the canyons weaving a darkness toward the new morning that brings a sky that passes beyond the border and takes history away.

Laurie Sheck

Poem: The First Remove

Was taken by. And the rest scattered. Extremity

Planting itself in me until I gTOW most Northerly and lost-all tundra,cold whiteness and mistrust.

Winter,taught, ignorant, unsolved.

Daylight in its first and narrowest pulses. Reddish sky. This noiselessness in mind-space. What does astray look like, and what is the sound of capture, The sound of breaking free? Her footsteps moving off into snow,deeps and never-to-come.

The never-returned of her, smoke from a way-station burned down. And thus she continued. And thus in mind's secret, and in so bitter a cold.

30

Poem: The Second Remove

The others hiding away when they took her. Eventually I learned other words. Assere for knives. Toras: North, Satewa: alone.

Always a breakdown of systems that will not be restored. Something cuts itself in me. It is not a question of refusal. Esteronde: to rain. Tesenochte: I do not know.

The shattered of, and then the narrowness opening where the vanished touches itThen how the mind recombines and overthrows-

31

Poem: The Third Remove

Sometimes a bare peace, a restoration. Too much veil in me, she thinks, if otherness is to sift further in, And must sift further in. Reason is a fragile wing. But I must cross and cross over even so. Far into otherwise and shatter, The irreconcilable estrange of me breaking. Why must the mind cover itself why hide itself why bind itself in quiet and in dark-

32

Poem: The Fourth Remove

But stripped of certain, how the mind hacks and starves itself

As if there were no settlement to return to anymore, Jealous of the sweeping rain and in night-season cold under it.

I went on foot and careless. She, who once was traded for a gun. She, led away into Removes. The cut thread of her, the and with bitterness I carried. And then nothing but wilderness, And being taken by, and a sorrow that cannot.

33

Poem: The Fifth Remove

Suspense carries so many edges of broken in it, So much curve. Still, I think there is no comfort of mind but in this unmended and selfCanceling passage. My self-stung eyes

Lead me awkward and away. I can feel no before or after anymore, only how time slips

Back and forth on my skin, stretching out or circling in, cryptic And unticking. The only sin is limitation. Unbound by human severity or knowing, these woods

Unlock themselves plainly. Chance roughens what I am. Ransom is a hollow act.

34

Michael Waters

Processional

One stacks her cells in the spiral staircase of an empty snail�shell writes J. Henri Fabre regarding bees in one rhapsodic essay praising my dear insects for such resourcefulness, but on January 30, 1896, in his famous but cruel textbook experiment, he rearranged the scent that marked the trail assumed by a single, unwavering line of the common caterpillar who spins his great purses in pine branches, their path now circular, so these stubborn leaf-foragers traveled for hours, then days, spooling miles till exhausting themselves, finally starvingall to the wonder of their rational recorder who possessed even less

35

sympathy for humans, sketching in his journal the virgin's bower (Clematis vitalba), the famous beggar's herb which reddens the skin and produces the sores in request among our sham cripples.

Bosporus

for Mihaela

Zigzagging eighteen miles north from the Sea of Marmara to the Black Sea, we lean toward Europe on our left, toward Asia failing now, at dusk, on our right, two souls tugged toward each point of the compass toward the past with its previous lives, toward the future with its final, unswerving destination: death. Or not: hadn't we visited the House of the Virgin where Mary had thrummed patience after the resurrection, Christ's tomb exhaling only foreign fragrance, her son's cerements twisting in dust? Swathed in blue, she coaxed savory & dill in her garden, wheedled fierce daylilies while awaiting airy summons.

Outside the house, tourists thronged the cobblestones, knotted invocations to fence wire: Our Lady grant world peace; heal me; whisper the winning numbers into my deaf ear. They scribbled pleas on scarves, soiled bandages, underwear, streamers of toilet tissue, their thwarted desires blue-blacked in the common language of desperation, in linked sequences of DNA that conspire to keep us ordinary. Hail, Mary

Here on the Bosporus, where two continents begin their inexorable drift, their seismic fragmentation toward solitude & ruin, I consecrate my offering: that scrap tom from a battered Lonely Planet guidebook, inscribed, then crumpled & tucked into some postulant's limp panty hose, its one word faded now by sunlight, its

37

single looped prayer commencing its formal dispersal: my howl, my thirst, my tether: your name grown pale on paper, becoming breeze that salts our lips, becoming weather.

2 Revelation 1 :2

-six human subjects dying

each on a bed on a platform beam scale each monitored for loss of urine loss of air from lungs, evaporation of moisture due to death-sweat, due to feardeath of r" patient: the beam drops and does not bounce back recording the loss of three-fourths of an ounce

2nd patient: a sudden drop at the exact moment of death: one and one-half ounces rd. th 3 patient: 4 patient: et cetera

Dr. Duncan MacDougall of Haverhill, MA after observing all six deaths concluded that a loss of substance not accounted for by "known channels" occurs at death, hence

"Hypothesis Concerning Soul Substance Together with Experimental Evidence of the Existence of Such Substance": American Medicine II (4): 240-43 (April 1907)

39

Carol Frost

Orchid

In light's white rum in the light of the mind bees come to the fertile stigmas where with moderate degrees of force Darwin tested

Orchideae: the "wildest caprice"meaning cross-pollination: meaning their sensitivity to pencil needles camel-hair brushes and his fingers:: Some wild orchids sicken by self-pollination:: others take on shapes so insects may alight thrashing calyx: or resemble a pollinator's mate: smell luscious rotten:: so life spreads borne on a zephyr's back:: spreads outside my window under the gold surface of water: poured ointment of fishparts: dazing: whirling through chambers of Byzantium:: mind's handiwork.

Clam

What the sea does and what the sea does for Molluska: living in the gills of fish:: secreted a stony coat:: formed siphons anus stomach gills aorta foot:: the red tides come and go: bacterias salinities boats storms:: compelling the imagination-Tarzan in an Coyuca Lagoon: giant lips around an ankle: slitting the muscles and kicking free after breath's gone:: named cherrystone littleneck quahog Moby's Queequeg.

Now the water's sixty degrees and a fisherman with Giacometti forehead seeds mesh bags fish gone deep into channels and rivers shine cold:: not for its brilliant anatomy nor just for the money does he work so in this America:-malls where thousands of sweet meat pounds are bought-: not for the generations drowning by drowning:: being alone sun and wind

41

Snake Key

Our sense of origin ourselves bedeviled:

Apollo Saturn: in the rose black garden Eve:: loving: killing:: labyrinthine the journey:: can't myth be left behind:: how it would be to start mid-kingdom:: standing by river water in marshes never colored by another's eyes: saurian ripple: flashing lances and silver spray of sunshine through eat's claw palmetto: flung paths to the coast:: Muir describes two Negroes in firelight as devils: they give him johnny cake: dire music of the ibis he recalls: there are malarias:: wind

still fevers the tide: a small skiff lifts over the bar to the outermost key: you can draw lime trees: you can collect sea-worn shells: you can count the snakes: you can: but there's no way only back where you were::

TodCriU, IOI'l�jhidjnal h�a�l'nts den'thd 50 1.h�: pOitUU't' fI1ar�iM d"",'eb-al bodies and osb>vhfli' c'n be reRloved.Intr".indl t.•�mE:r:ts of disc e,:(pO>ed andre;f!oveJ

Sarah Micklem

The Captive Chronologist

From Anticlimactic Folk Tales of Abigomas, collected and edited by Dr. Marcel Auerle

The captive horologists built a new tower and succeeded in making the clock run, after they had adjusted its astronomical parts for the change of latitude.

The Ancient Engineers, by L. Sprague de Camp, who is in no way responsible for the confabulations and fabrications in the following story.

The foremost chronologist of the Isle of Abigomas was bored. His every hour seemed to pass more slowly than the longest hour of the longest summer day, when one has plenty to do and no desire to do any of it. Thyodo had already made the finest clock in the world for his hometown of Lynka, and now he scorned such commissions as came his way, even as he executed them: middling clocks for middling places, with payment in flea-ridden fleeces or all the salt pork and fava beans he could eat for a twelvemonth. On such a diet he had been pared very thin indeed.

The clock was renowned throughout the Isle of Abigomas, but the island's inhabitants never gave a thought as to how its marvels were accomplished. Thyodo would gladly have boasted of the great water

44

wheel that motivated the clockworks, hidden deep in a shaft con, nected to a cave in the sea cliffs; he would certainly have mentioned the ingenious escapement of his own invention that parceled out the force of the inconstant waves and tides in order to advance the gears by precisely calibrated amounts-had anyone asked him. In those days the hours of a summer day were long and the hours of a summer night short, and vice versa in winter, and his clock, by means of intricate mechanisms, dutifully reported this shrinkage and expansion. He would have been eager to explain all that, had anyone expressed the slightest interest.

But Thyodo was a great many years old, and the clock had been made when he was young, and most people, if they thought of the clock at all, thought it had always been there.

The chronologist was bored and supposed he would be bored up to and including his last hour. But it was his misfortune to live while the Grand Khan and his four sons and other relations were engaged in sub, duing the civilized nations of the world. They subdued eastward to the Sea of Japan and westward to the Danube (a river they crossed and quickly crossed back again, since there was nothing worth the trouble of keeping on the other side), and in passing they subdued Abigomas as well.

The island had been conquered frequently in the course of history, with the usual horrid results that do not need to be enumerated here. But sooner or later the conquerors always turned their attention else' where, for the Isle of Abigomas was rocky and out-of-the-way, and its only potable water fell from the sky.

The islanders knew what they must do: submit and wait. Everyone had heard that the Grand Khan built pyramids from the severed heads of those who dared to defy hirn-s-v.ooo here, 80,000 there-and every, one believed it. So when the son of the Grand Khan's second cousin twice removed set foot on the island with some forty or so soldiers, the denizens of Abigomas surrendered immediately and the pillaging and raping went on without further ado. The troops were thorough, win, kling out the few valuables to be found: necklaces of lapis and car, nelian buried in pigsties, golden coins in hollow roof tiles, and virgins, sworn to silence, adrift on rafts in dank underground cisterns.

The Grand Khan's kinsman, Tan Gent, searched high and low on the island for something worthy to send to the Conqueror of the Civilized Worlds, and in the town of Lynka he found it: a marvelous clock in a high stone tower. To mark the hours, life-sized mechanical people

45

emerged from the tower and twirled about on a platform high above the town square. Some struck tambourines, others played whistles, and one sang, every hour a different song. Tan Gent climbed round and round the spiral stairs to the very top of the tower, and there he beheld stars of pearl set into a dome of midnight-blue enamel; this firmament turned slowly upon the axis of the polar star, its motion nearly imperceptible save for the creaking of the gears. The sun, a golden lamp, made its way east to west on a revolving wheel, rising and setting at the horizon of the floor, and the wheel moved south or north according to the seasons. Another wheel carried a silver moon. Ruby planets wandered through the constellations of the zodiac. The floor, a mosaic map of the sea and its islands, with Abigomas quite naturally in the center, was cunningly suspended amidst the clockworks. Doves and bats had sprinkled it with droppings. Lovers had scattered chicken bones and greasy wrappings from their picnics, and smoky lamps had dimmed the sky's blue enamel, but this did not obscure the splendor of the clock in the eyes of Tan Gent.

Of course this clock was Thyodo's invention, and when he saw the soldiers scrambling up the tower and taking the clockworks to pieces, he screamed at them. It was fortunate that the soldiers took him for a madman, for they believed madmen were sacred and let them live, no matter how much of a nuisance they were.

Soon Thyodo understood that they were not stealing the jewels or the gold, silver, and bronze of his mechanism, but rather the whole device, and he set to chiding and scolding and bidding them to "Have a care, you dolt! You'll break it!" He felt obliged to begin dismantling the clock himself, lest it be damaged, and before another hour had paraded and sung, the chronologist came to the attention of Tan Gent. Thyodo made it known to him, with the help of an interpreter, that he had invented this marvelous clock {no better ever had been or ever could be made}, and it would never work again for there was not a man anywhere else on earth clever enough to reassemble it.

In no time Tan Gent took the chronologist captive, and sent the man and his clock, including every stone of the tower, to the Grand Khan as tribute. Thyodo's journey to the Grand Khan's summer encampment was tedious and dangerous. There is no need to dwell upon the seasickness and stenches, the bony camels, rude companions, and thieving beggars, the maggoty food, arid winds, and other torments he encountered before he came to the camp of the Grand Khan and was left there with the pieces of his clock in a heap, and not a word in

common with the ambassadors, astrologers, priests, prophets, saints, and soothsayers, not to mention the mountebanks and madmen, con, cubines, quacks, and chroniclers, who attended the Scourge of the Known Kingdoms-in short, the cream and flotsam of eight con' quered civilizations, for the Grand Khan collected people as well as plunder.

Soon Thyodo found himself, like his companions, subsisting on mice, marmots, and sheep's entrails, getting drunk by midday on the fermented mare's milk known as cosmos, and squatting by campfires of smoking horse dung in dust storms, his hands too idle, his tongue too industrious, having learned six or seven languages in which to quarrel about the nature of divinity or to wager on how long it would take the Khan's army to undermine the walls of such-and-such a city and behead its male inhabitants. Waiting for the Grand Khan to take notice.

Dreading that the Grand Khan might take notice.

The Grand Khan did not sleep above three hours a night, and accomplished more conquests in a month than most people dream of in a lifetime. He was a busy man, and yet he did not forget. Two years, three months and twenty days after arriving at his court, Thyodo received a summons to appear before him. Need I say that the chronologist's knees were knocking together, and his face was pale in spots and red in others, and sweat stained his filthy robe? The Grand Khan was used to all that, and he commanded Thyodo to rebuild his clock promptly, and gave him men and coins, as many as he could possibly need, to that end.

It would not do for the clock to reside in a fixed stone tower, for the Grand Khan had not given up his nomadic ways. Though he had by then founded his capital, with its mud brick and tall gates and endless palaces, he did not feel perfectly at ease inside any structure which was not circular, felt-covered, and capable of being picked up and moved from place to place-which was not, in other words, a yurt. He preferred his summer and winter camps, and besides was often out and about vanquishing people. Therefore Thyodo raised a clock tower of wood rather than stone, founding it not on solid earth, but rather on a wide cart such as the ones the Grand Khan's army used to carry the largest yurts from place to place. The cart had axles as thick as the masts of ships; twenty oxen strained their mightiest to draw it. The cartwheels turned the clockworks by means of Thyodo's escapement, and when the cart was parked, slaves provided the impetus instead, running inside a suspended wheel. Thyodo was a slave himself, though

47

it had escaped his notice, and he also failed to notice the slaves' sore feet and their despair at running so far without getting anywhere at all.

After all, Thyodo was preoccupied. He had his calculations to do again (for the hours of a summer day or a winter night were ever so much longer that far north), and over and over again whenever they moved an appreciable distance, and the works altered accordingly. To assist him he called on arithmeticians, astronomers, astrologers, and artisans.

And of course it would not do for the floor of the Grand Khan's clock to show a mere sea when he was the Emperor of the Worthwhile World, so a mosaic map of precious stones and golden tiles was laid to show his huge realm (what was known of it), and, in the center, his splendid yurt and the 360 yurts of his wives and concubines and their seamstresses.

The Grand Khan was pleased when the clock was done and the mechanical people issued forth to play their songs. He had been wont to consult his diviners each morning to find out whether the day was lucky or unlucky, which they determined by means of burning sheep's shoulder blades, ascending into trances, communing with demons, and the like. How much better to know, not only the auspicious day, but also the auspicious hour for any undertaking! He chose soothsayers from among the captive hierophants of many religions to consult the clock to determine when he should massacre, hunt, sacrifice, or fornicate. For in those days any clock worthy of the name did not just tell time, but what the time signified.

Thyodo had proven himself wrong. The clock was more splendid now than it had been in Lynka, more than ever a Mirror of the Glorious Heavens. The Grand Khan rewarded his chronologist with a yurt of his own, twelve alluring concubines, one for each hour of a long winter's night (should he be so inclined), and sixty stubborn camels. The concubines were not as alluring as all that; being captives themselves, they were given to weeping at night and moping all day. But there was one who seemed to find Thyodo more amusing than alarming, and between the two of them they invented a comfort he had never known before in his solitary life. If she had a flaw, it was her decidedly large nose, as noses the size of a button were then in vogue, though to be sure buttons hadn't yet been invented.

For a time Thyodo lolled on his bed of laurels, but idle hands and an industrious tongue brought him trouble. Though he was by then an elderly man of fifty-nine, well past the age of indiscretion, he quarreled with a navigator, a geomancer, an alchemist, and a philosopher over

the nature of Time. The navigator held that Time moved in a circle, and in another 5,667 years everything would begin again, and in 1,533 more years they would all be sitting around the fire and making exactly the same arguments; the geomancer claimed Time proceeded in a helix, offering as proof the seasons, which always returned but were never exactly the same; the alchemist postulated that Time would go on in a straight line until it reached its end when man was perfected, which he calculated would occur in 777 years; the philosopher argued that Time did not exist, for nothing ever changed, and all notions to the contrary were illusions. Thyodo set out to prove that Time was complete and unmoving; it held every moment that ever had been and ever would be, and we merely crept along it like ants on a long blade of grass, unable to see the beginning or the end. In the ensuing brawl, the philosopher died, pierced by Thyodo's blade, which was not at all illusory. The chronologist was sorely wounded by the geomancer, and he languished on a bed of lamb's wool while his injuries healed and his concubines nourished him on cosmos from the Grand Khan's own mares. It was summer and the hours were long. Flies buzzed about Thyodo's yurt and settled in the corners of his eyes, and his favorite concubine occasionally waved her hand to send them buzzing away again. He had time and more time and more and more time to mull over the splendor and cruelty of the Grand Khan. He was not angry with his master. What use? One might as well be angry at an earthquake or a gale. Still, he hoped his dearest great-niece had escaped ravishment, and that his amiable sister still sat at her loom, weaving the softest woolens on the island. He thought of the town of Lynka fondly, more fondly than when he lived there, and wondered if anyone had fed his cats. He waited upon the song of the clock to tell him another hour had passed, and the song didn't come. Time, which sometimes had seemed to rush by (as a road rushes by under the wheels of a jiffy drawn by fast horses), and sometimes to dawdle, now stood still. Or he stood still in it. How many breaths to an hour, how many heartbeats to a breath? It occurred to Thyodo that an hour could be divided into intervals, and each of those intervals subdivided, and those subdivisions divided and so on and on. Was there a smallest instant, the tiniest possible iota of duration? Or was Time infinitely divisible? If he were slow enough, or maybe fast enough, he might pass the time, not from one moment to the next, but from one moment to the next smallest, and thereby experience eternity in an hour. The concubine dozed; the flies dozed. Thyodo's breathing slowed and still the clock did not sound.

49

Fortunately Thyodo had never heard of Zeno, and his mind was of a practical bent, not disposed to become mired in the quicksand of infinity. Instead, he bethought him of a clock to portion out an hour by drop after drop of water, or grain after grain of sand, or tooth after tooth of a gear, a clock to measure out time with such scrupulousness that a man might know, not only the hour, but when he was in the hour by halves or thirds, quarters, fifths, tenths, what have you. He gave one particle of the hour to each of his sixty camels, mentally herding them about into groups (which could be accomplished more easily in theory than in fact), and so determined that sixty was an ideal number for his purpose, being divisible in many convenient ways. Thus Thyodo invented the minute, though he pronounced it minute (mI-noot'), on account of its tiny size. He hypothesized much smaller intervals, but he thought there could be no practical use for such puny moments, and he stopped short of creating seconds or milliseconds, choosing instead to concentrate his thoughts on a clock that would announce the sixtieths of an hour to passersby.

The flies began to buzz again and the concubine waved her hand, and he constructed this marvelous new clock in his mind until it was complete. He gave it a round face of blue enamel, with sixty white pearls all around, and an arrow that pointed always upright as the dial turned on its axis and the minutes marched by, and sixty miniature musicians to pop out of doors, one for each minute, to blow one note on a whistle or bang one beat on a drum. The sounds, if played at a quicker pace, would have made a martial tune, but doled out slowly the effect was funereal. At the quarter hour four musicians would play at once, and on the hour they would all come out to make a racket.

The hour did pass eventually, and a good many days too, before Thyodo rose from his sickbed and begged an audience with the Grand Khan, who was pleased to see his captive chronologist up and about and aflame with enthusiasm for his new clock. Need I say that the Subjugator of Civilizations gave Thyodo men and coins without stinting to build this device, which, when it was done, astonished even the most jaded sycophant who dined on the scraps of mutton from the Grand Khan's table? As for the Grand Khan himself, he was enraptured.

It is known the world round that the Grand Khan died after falling from a horse, though there's some dispute amongst scholars as to whether he was riding to the hunt or to war (apparently none of them have noticed that it was unlikely a man raised in the saddle would do

50

such an awkward thing as falling out of it}. But on the Isle of Abigomas, they tell a different story.

By the time Thyodo made his way back to Lynka, he was a very old man indeed. He had remaining to him eleven camels and a wife, and he wore a long but scanty white beard and spoke in a strange accent. The soldiers had left years before; nevertheless Thyodo found the Isle of Abigomas much changed, and not for the better. His cats had run wild, and the young women, even his great-niece, were not as lovely as they had been, for the weight of sullen sorrow they carried at their defilement. The young men devoted themselves to thieving and giving and taking offense. The old women, such as his sister, had become beggars, and the old men sots, and the only folk who prospered in Lynka were the locksmiths and the barkeeps.

Thyodo was a man of great but narrow imagination. He supposed the lack of his clock had led to this unregulated civic life, and he set about building a new one, which was a wonder in its day. It can still be seen in Lynka's town square. The time it tells is almost always wrong, now that hours are monotonously the same length no matter the season. It does not keep track of minutes. Thyodo had sworn he'd never again have anything to do with them, for they were too dangerous.

Perhaps he can be forgiven for hubris about his invention, for it was Thyodo who brought about the downfall of the Grand Khan, albeit unintentionally.

As the story goes, the Lord of the Far Horizons kept his two splendid clocks with him at all times, and captured more soothsayers to determine propitious uses for the bounty of minutes Thyodo had given him. Being a god himself, and not a particularly jealous one, the Grand Khan made little distinction between religions, so long as the various priests and practitioners paid him tribute and prayed to or for him (it didn't much matter which). But his diviners, from his own people as well as many conquered ones, not to mention those who came as proselytizers and never went home again, were not so tolerant. Every evening he sent them a list of the undertakings he planned for the next day, and every morning the soothsayers were to present him with a chart showing how he should dispose of his minutes. They could not agree; it often came to accusations of heresy, witchcraft, clock-tampering, and plain wrong-headedness, not to mention fisticuffs, so that the Grand Khan did not get his chart before dinnertime, and then was forced to scurry about, as fifteen minutes of his day might be allotted to riding horseback, and the next twenty, being ill-omened, to sitting

51

safe in his yurt, and then twelve to meeting ambassadors from backward reaches of the world, such as Paris, and so forth. His night too was broken into smallish pieces: five minutes in the third hour after midnight deemed beneficial for impregnating his twentieth wife, followed by forty minutes in which he would surely dream a prophetic dream, and yet he must stay awake for the next ten, lest a nightmare come calling.

The Grand Khan was the hardiest of a hardy people. He could ride day and night, through four changes of mount, and then bind a cloth tight about his ribs to keep him upright and ride another day and night. He could live on the blood and milk of his horses, and his horses could live on the scantiest of grasses, and so he and his herds and his army never gave much thought to provisions. Some chronicles maintained that they lived on air.

But the Grand Khan, who had never yet been defeated for long, was defeated for good by his new regimen. He went from fatigue to weariness to a peevish and listless exhaustion. The chase lost its savor when he must hunt three quarters of an hour but no longer, lest he come upon an unfortunate minute while on horseback. His wives and concubines complained, and bribed the diviners in order to receive more {or less} of his attention. The Ruler of Far-Flung Lands discovered that the smaller his time was minced, the less he seemed to have of it. Moment by moment he was diminished from a great man to a petty one, until, in an unlucky hour that the soothsayers failed to predict, he succumbed to a surfeit of minutiae. He was the first person on earth to have done so, but by no means the last.

His sons and grandsons went on conquering without him. Then they fell out, and the empire divided and subdivided again until what was left of it no longer recognized itself. But that's neither here nor there.

If an Abigoman tells you this tale, you will see him shrug when he reaches the end, as if to say, "I know you won't believe it, but there it is." And if you then wonder aloud what became of Thyodo, the storyteller will take you to see his grave, which lies under weeds and an everlasting bronze sundial. The sundial can no longer do its work, being overshadowed by a spreading yew and twelve tall cypresses. If you ask, politely, why the grave is untended, your guide will shrug again. Presumably Thyodo does not mind, for he no longer creeps along the weary road of Time, but rests in eternity. And presumably Time takes no notice of whether we measure it or not-any argument to the contrary is the province of theoreticians, not collectors of tales.

Meena Alexander

Encountering Emily Dickinson

Encountering Emily. How did it happen for me? Her lines leap and I duck, tum skittish. Her voice does not leave my head. I am scared and it has taken me decades to return that radiant vision. I came upon her poems when I was twelve or thirteen, and living for part of each year in a hot country, just south of the Sahara desert. It was Khartoum, in summer time, 114 degrees in the shade. In the school library I came upon a battered book, an anthology, the covers were peeling.

What was it, that book, I ask myself in an attempt to be precise. I cannot tell, though I can still recall the size and shape and the covers, worn beyond legibility. It was there I found a few of her poems. "Wild nights" was there, how can I forget it? I took the book home, logging in my name in my best handwriting in the library ledger.

I sat on the gravel at the edge of the verandah, in the shade of a neem tree. I could see the dark dates on the palm at the edge of the manicured lawn, the blinding blue of a sky without rain. Her words cut straight to the heart of what I felt to be my secret life, all that my mother and the centuries of a strict patriarchal tradition had crossed out, desire with nowhere to inscribe itself, fled to the dark waters of secrecy:

#269

Wild nights-Wild nights! Were I with thee

53

Wild nights should be Our luxury!

Futile-the winds

To a Heart in port

Done with compass

Done with the chart!

Rowing in Eden

Ah-the Sea!

Might I but moor-tonight

In thee! 1

"Futile-the Winds." I loved the pause there, after the word "futile," and I murmured the words to myself, they entered my inner ear. I learned that poem by heart. I was used to learning poems by heart, Wordsworth, Verlaine, Shelley, Rimbaud, all manner of lyrics that my strict colonial education led me to, in the girl's school that housed my early years. And Emily Dickinson's poems seemed so well suited for "by hearting," as it was called in that other life I had led in India, where a portion of a good upbringing was learning to memorize the classic, bits of Tagore, Vallathol, Mirabai, Psalms from the Bible.

Though Dickinson as an American poet had played no part in the classical world that was laid out for me as an inheritance, and perhaps even in part because of this lack, I clung to her. She was my secret. I glimpsed the life of a grown girl forced to tum inwards, in a poise so fierce that it fled what commonly passed for decorum. And through her I touched a lyricism that imploded the bounding lines of grammar.

I say this for in those early years when I wanted so very much to be a poet, and nothing but, the peculiar fixity of a given language seemed to be designed quite precisely to keep me from myself.

In my dreams, much as a swimmer might, I dove under the dividing lines of languages, Malayalam my mother tongue, Hindi, English, French, Arabic and then I swam very fast. And Emily was my secret swimming companion.

Now there was no way I could possibly have formulated what passed through my head in the way I have put it down here. Far from it, but these were truths dimly sensed. So true, though I had no words for them. In those days, my great concerns were how to escape my mother's designs to lead me into life through the portals of an arranged marriage, and my father's designs to teach me the truths of Newtonian

54

physics. Poetry seemed to me to be the way to cull the blossoms of an interior life, one which was answerable to no one. So I turned to Emily, whose lines once encountered are hard to evade. It seemed to me that she had understood something that no one else had.

#710

Doom is the House without the Door

'Tis entered from the Sun-

And then the LuU1er's thrown away, Because Escape-is done-

The first line of this poem kept returning to me in dreams, with the dull thud thud of the d sound, ontology of an impossible life, end to everything.

No wonder then, and I realize it now, though earlier I had clean forgotten that after the line "Because Escape-is done"-comes a stanza that leads us away from the house without a door, to a dream of what happens outside. This is a realm as exterior as things can get in Dick, inson-"Where Squirrels play-and Berries dye-" a space where phenomena paint themselves over a realm of fatal necessity. Essential ephemera. Maya.

And I use the word maya, familiar to me from childhood, from the strict Advaitic philosophy my maternal grandfather schooled me in, Sankara's word for the realm of all passing phenomena, field of the sen, sorium.

Perhaps this is why I could not remember that stanza at all, writ, ten by a poet perpetually haunted by elsewhere, though Puritan necessity fed her, nourished her febrile lines. I will spell out the second stanza so that the whole of this poem appears:

'Tis varied by the Dream

Of what they do outside-

Where squirrels play-and Berries dye

And Hemlocks-bow to God-

And now as I read them again, those lines put me in mind of an, other great woman poet, Akkamahadevi also know as Mahadevyakka, from the classical bhakti tradition of India, writing in Kannada, the sharp aphoristic words she composed in the twelfth century C.E., ani, mated by desire so impossible that it burnt up flesh, illicit love of Lord

55

Siva to whom she proclaimed herself betrothed as she wandered about, her sari torn off, clad only in her long flowing black hair.

Here is one of Akkamahadevi's poems, a Kannada vacana in A.K.Ramanujan's inimitable translation:

Like a silkworm weaving her house with love from her marrow, and dying in her body's threads winding, tight, round and round, I bum desiring what the heart desires.

Cut through, 0 lord, my heart's greed, and show me your way out, o lord white as jasmine. Z

To return to Emily, clearly she did not wander around naked. Her white gowns, her bonnets, her life within the compound and streets of Amherst are justly celebrated. Yet in her poetry she did roam, far, wide, stripping herself free, at times with great difficulty, of all that might trammel her. And so it is in Emily Dickinson, rather than in Akkamahadevi, the latter surely closer to home in terms of the traditions I was born to, that I have found an iconic instance of what I think of as a poetics of dislocation.

I am speaking of the way in which for Emily Dickinson, the joints of what one commonly takes for granted, the everyday, have come apart and into the multiple gashes rendered so cryptically in her lines, a species of eternity enters in.

If for Akkamahadevi desire spins out the cocoon of death, for Dickinson death is the silk of impossible desire, a fabric that sears, terrible predicate of love. How else to make sense of the quivering identity at the heart of her enterprise, that blinding lyric flash possessed by no other poet I can think of.

#647

To fill a Gap

Insert the thing that caused itBlock it up

With other-and twill yawn the more

You cannot solder an Abyss with Air.

All that is solid peels away and the soul is left haunted by an unerring sense of what she calls elsewhere "the bright Absentee" first cousin surely to Mallarme's "Absente de tous bouquets."

To round off, I tum to a few lines composed by Emily Dickinson in 1862, just a year after "Wild Nights," a poem in which the present ex, ists as a figment, a slash of light without which we could not live, and underpinning it, a spiritual longing touched by despair, rendering an art of extremity as sharp and clear as anything the mortal mind is capable of conceiving. As I read the poem again I think of how these lines have an eerie connection to our lives at the edge of the twenty, first century. They seem to me, utterly contemporary.

There is a journey, she calls it "our journey" and almost at a fork in the road where eternity starts, the speaker halts. Before the cities which one imagines filled with people, comes the "Forest of the Dead." No explanation is given, for this strange and yet seemingly natural tum of topology in a time of war.

#453

Retreat--was out of Hope

Behind-a Sealed Route

Eternity's White Flag-BeforeAnd God-at every Gate

In a mystical transformation, wounds have turned into gates, sites of perpetual surrender, portals to divinity.

Notes

I The numbers and texts of all the Emily Dickinson poems cited in this essay are taken from The Poems of Emily Dickinson, edited by R.W. Franklin (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003).

2 A.K. Ramanujan, Speaking of Siva, Speaking of Siva (Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1973), page 116.

57

from Fragile Places: A Poet's Notebook

Triptych in a Time of War

I searched on the Internet for lines by Enheduanna, the great poet of Mesopotamia, the first poet in recorded history. Afterwards, I could not bear the windowless office I had been given at the Graduate Center and so I walked up to the eighth floor atrium and opened my eyes and on a high wall saw the Dove of Tanna, Frank Stella's piece filled with light. I had first seen the image, in that way, at that angle, lit by the sun, a week or so earlier when David Harvey had addressed a few of us and listening to his words I had turned my eyes to the bright talisman of peace on the wall.

Back in my office I wrote lines in which I felt the beginnings of a poem. But because the printer in the English Department was out of order I emailed the lines to myself so that I could retrieve them in the safety of my home. Later as I sat and wrote I thought of bombs that burst roofs and walls, a woman poet who did not have the luxury of sitting at her desk and writing, a poet flung out of her home, forced to cross the shattered street. This is some part of the email I sent myself. There is in it, I think, some impatience with myself and also some real awareness of the limits of the poem.

Friday March 07,2003,4:26 pm

Dear Meena

you are not so far today. why must you email these messages ,as ifpen and paper were hard to find, or a printer. On the Dove of Tanna the artist cut up bits of aluminum and painted them over into the dove's tail, the arrow's flight, the green bough that signifies the lifting of the waters While you're at it why not think of the door you have opened, perhaps portal would be a better word, onto the layering offragile places whose petals spurt scents from Paris and Istanbul and Rome. Or blood spurting from the cut aorta. Wrapping it in raw silk will do no good The rest of the email contains lines that incorporate what was to come, lines I had to sculpt into shape to make the bare bones of the poem I began in the building 365 Fifth Avenue.'

58

May 18, 2003. I went to the Met to see the First Cities exhibit. The darkness of the silk that draped the walls sent out a pervasive gloom, but the ancient artifacts, bird and spouted vessel and golden ram prancing in a flowering thicket snared the heart.

I found myself in a comer of an inner room and there in front of me was an alabaster disc. Its thickness amazed me, at least six inches in depth, that creamy stone onto which was cut the figure and face of Enheduanna, leading the array of priests, an image I had only seen on the Internet. Without knowing what I was doing I made the sign of the cross, an instinctive thing I have carried with me from early childhood, a sign I make in the presence of something sacred. As if in a dream I gazed at her face, the cheekbones scooped away, damage hurting her throat but the profile incised there, the hands held out, the precious poem.

I took my friend Gauri to face the alabaster disc and I said to her, I will stand here to take darshan. And I stood there for a long time.

59

Poet at the Piano

My mind moves to another country, to which we are bound in the terrible intimacy of war. But it is not just of war I wish to speak, nor of streets filled with all the desperation that comes in the aftermath of the burning of buildings, the burning of children instead of paper. I want to speak of the task of poetry, what place the poem might have in the wreckage we humans can make of our shared world.

There is a poem that plays in my head, as much for its musicality as anything. Yet its matter is close. A poem called "Mozart 1935." In it Wallace Stevens addresses the poet: "be seated at the piano." Even if stones are thrown in the streets, even if there is a body in rags being carried out, the poet must sit at his piano. And the lines rise to a magnificence Stevens could muster at need:

Be thou the voice,

Not you. Be thou, be thou

The voice of angry fear,

The voice of this besieging pain. 2

I think this poem has been in my head in a hidden buried way all these days. I read it first in Khartoum where I first read so many poems that are still important to me. I was in the library by the Nile. There was gunfire in the streets, civil unrest. I was a teenager then and anxious to make sense of the world and only the near mystical twists and turns of the poem could afford me that "starry placating" Stevens evokes.

In March 2003 I bought two black notebooks. In one I pasted out the pages I was printing of the cycle of Gujarat poems, written after a visit to the relief camps there, camps that housed the survivors of ethnic carnage. All the poems including "Letters to Gandhi" had come in an overflow of emotion that kept me from sleep. I needed the security of bound covers, within which I could turn pages and take flight from poem to poem.

I had to move back and forth between the poems to make a deeply personal sense out of that chaos. A week or two later I started another notebook, which I labeled "Raw Silk" and in that book I set drafts of three poems which also came to me at great speed, a wind smashed bouquet, pain and grief at the destruction of war, joy in the face of beauty that can sustain us. Some of the images that came to me echoed those that had blossomed in my head in the days and nights of a Delhi winter when I sat in quiet in a patch of sunlight brooding on what I had

60

seen and heard in the relief camps in Gujarat. So into my notebook I pressed the images that came to me, through layer after layer of sense.

Running my fingers through the notebook I see lines I have writ, ten in my squiggly hand. They are lines that tell of how I had tried to make a pure lyric out of the title poem of my new book "Raw Silk" but without my knowing it, a border was crossed.

March 20, 2003