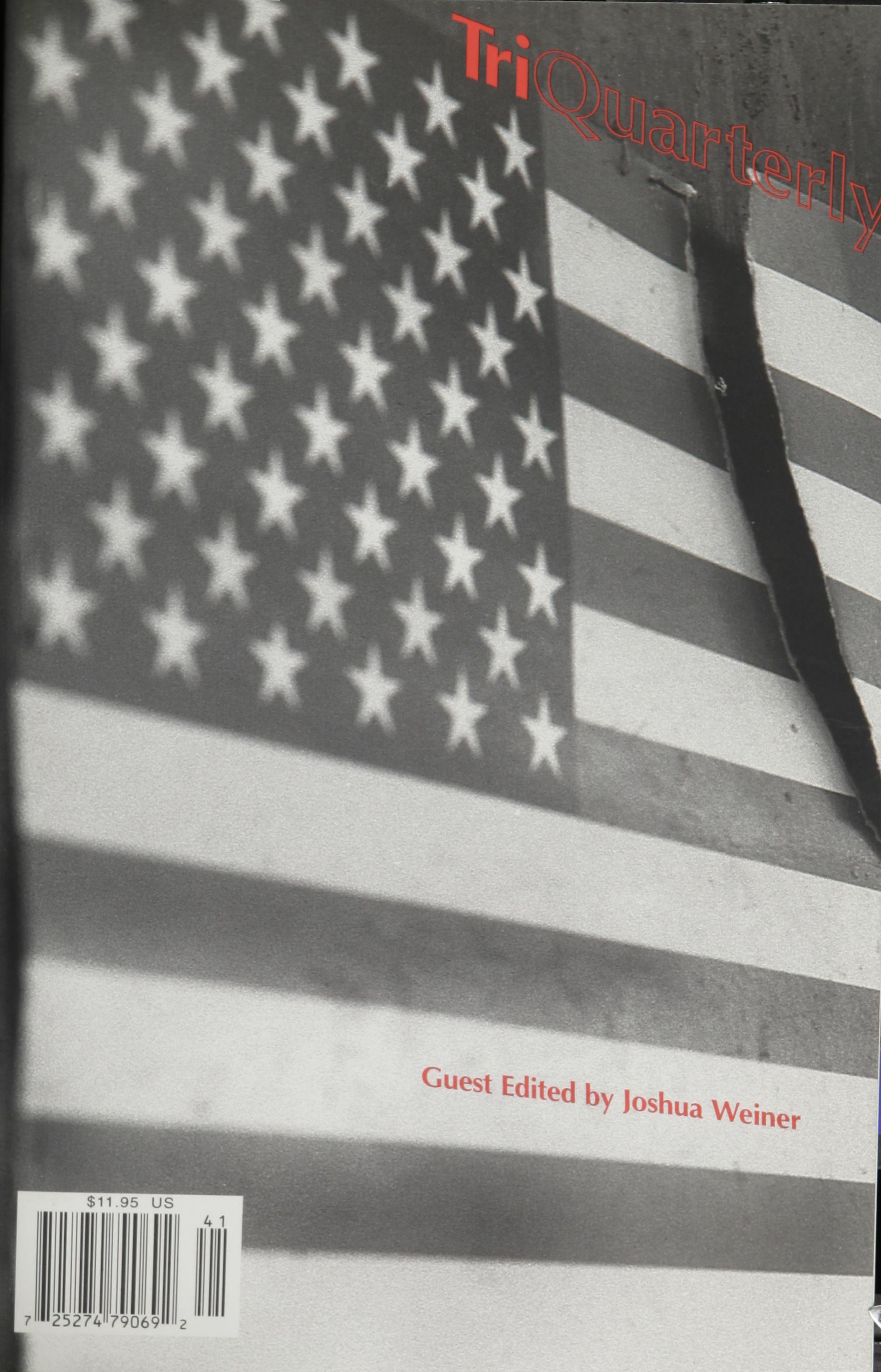

Guest Edited by Joshua Weiner

Guest Edited by Joshua Weiner

riQuarterly is an international journal of writing, art and cultural i�quiry published at Northwestern University

TriQuarterly T

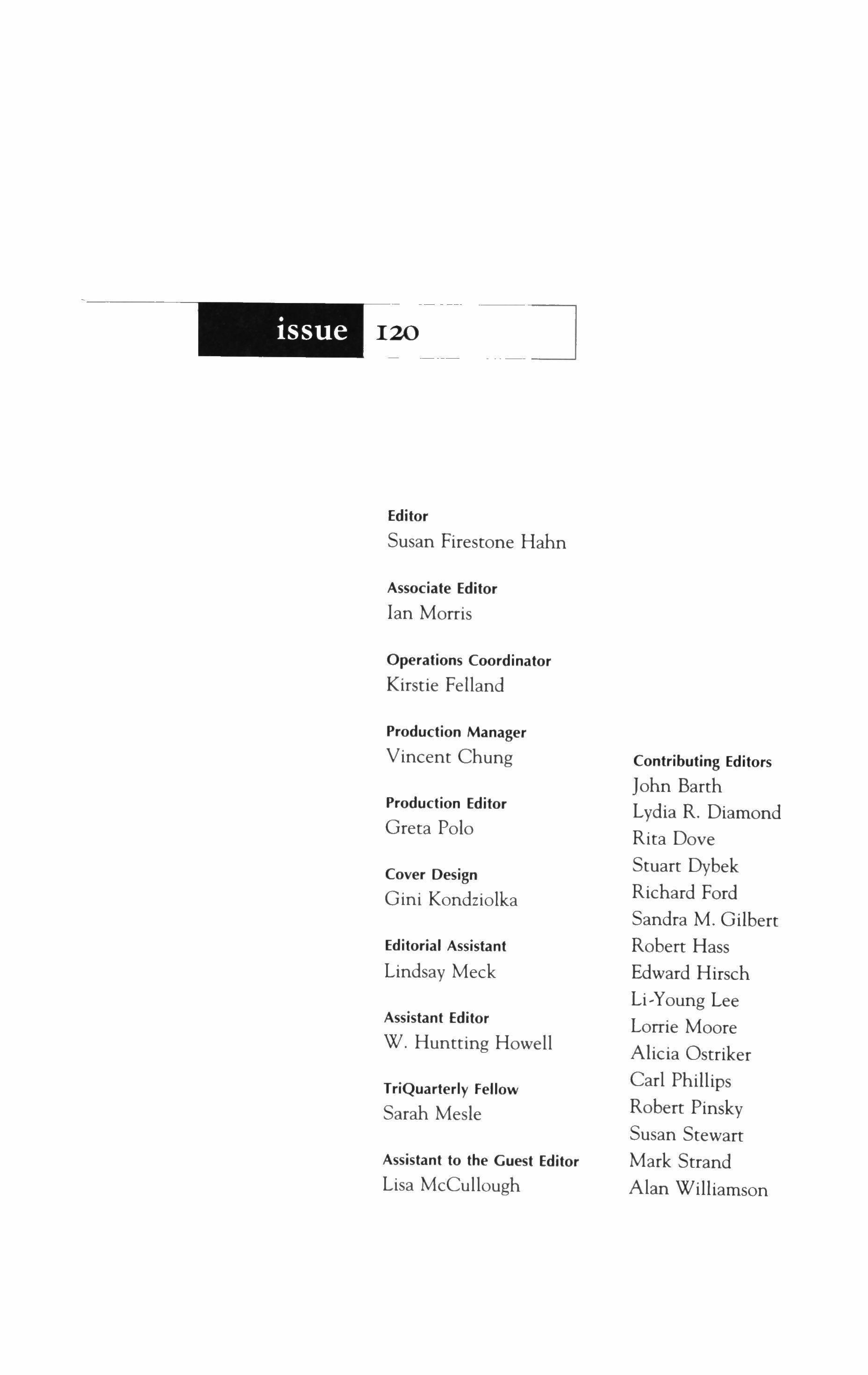

Editor

Susan Firestone Hahn

Associate Editor

Ian Morris

Operations Coordinator

Kirstie Felland

Production Manager

Vincent Chung

Production Editor

Greta Polo

Cover Design

Gini Kondziolka

Editorial Assistant

Lindsay Meck

Assistant Editor

W. Huntting Howell

TriQuarterly Fellow

Sarah Mesle

Assistant to the Guest Editor

Lisa McCullough

Contributing Editors

John Barth

Lydia R. Diamond

Rita Dove

Stuart Dybek

Richard Ford

Sandra M. Gilbert

Robert Hass

Edward Hirsch

Li-Young Lee

Lorrie Moore

Alicia Ostriker

Carl Phillips

Robert Pinsky

Susan Stewart

Mark Strand

Alan Williamson

Editor of This Issue

Joshua Weiner

In Memoriam

Alan Dugan

Thorn Gunn

Hugh Kenner

Leonard Michaels

Czeslaw Milosz

Carl Rakosi

Susan Sontag

Guy Davenport

Translated from the Latin by

Kristina Milnor

ell IV. 2360

graffiti, exterior wall, Pompeii, circa 62-79 AD

Amat qui scribet, pedicatur qui leget, qui opsultat prurit, paticus est qui praeterit. Ursi me comedant; et ego verpa qui lego

He loves, the one who writes; the one who reads is fucked. The critic wants it bad. Who passes by?-he sucks. May bears eat me-I'm the reader and a dickhead too.

6

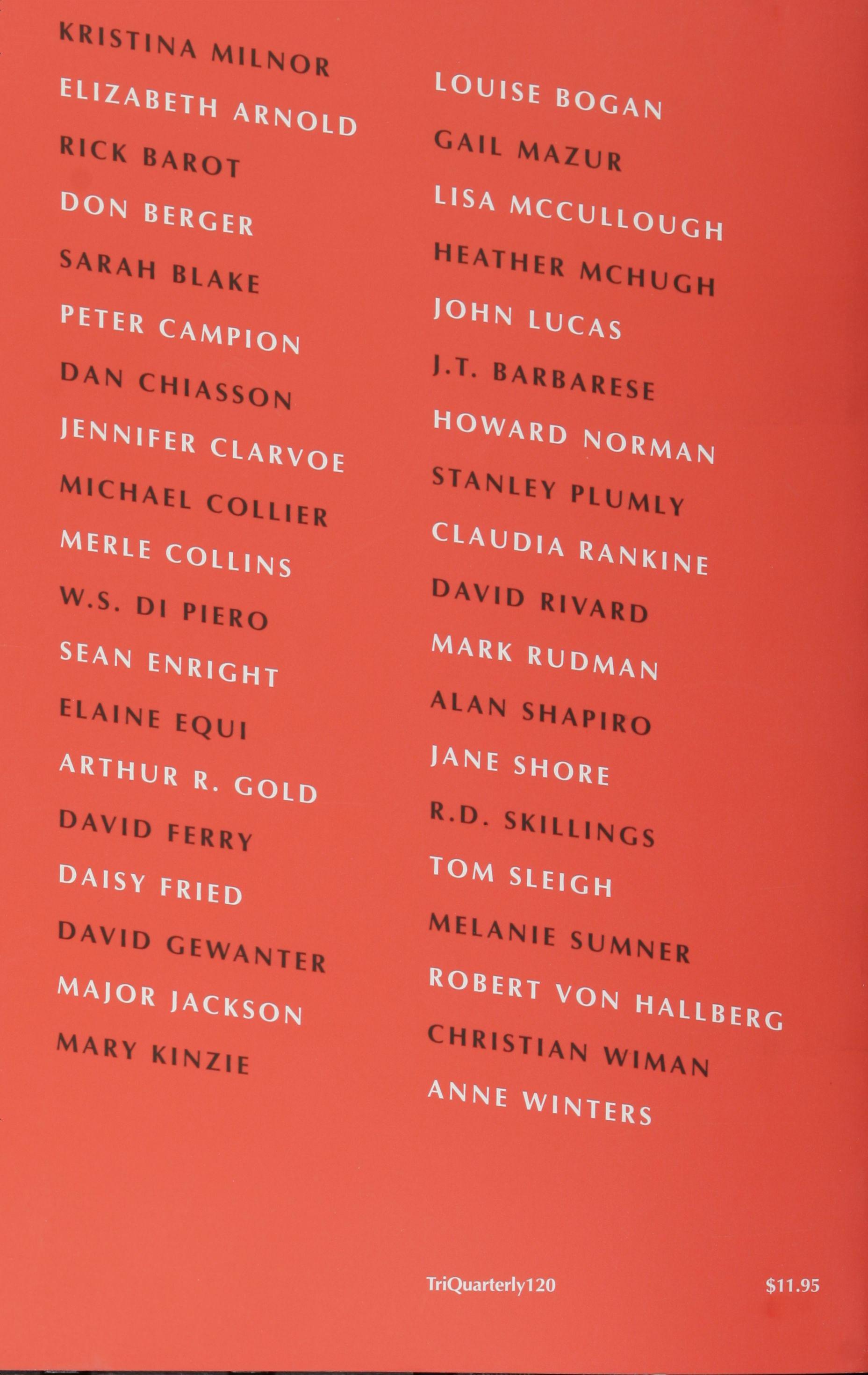

CONTENTS graffiti 6 CIL IV. 2360 Translated from the latin by Kristina Milnor poetry 10 Improvisations: After Archilochos Elizabeth Arnold 17 Pastoral Rick Barot 19 The Sniper; To Likes-to-Have-Fun Don Berger 38 Skin; Stone Peter Campion 40 After Party; Peeled Horse; Georgie, Georgie (II) Dan Chiasson 44 Counter-Arnores 1.3; Counter-Arnores 1.7: That Way Jennifer Clarvoe 47 Turkey Vultures; Common Flicker Michael Collier 57 All in One Day; Increased Security W.S. Oi Piero 60 Allen Ginsberg; Halloween Sean Enright 64 Flaunting My Inertia; Today Is the First Day of the Rest of Your Life Elaine Equi

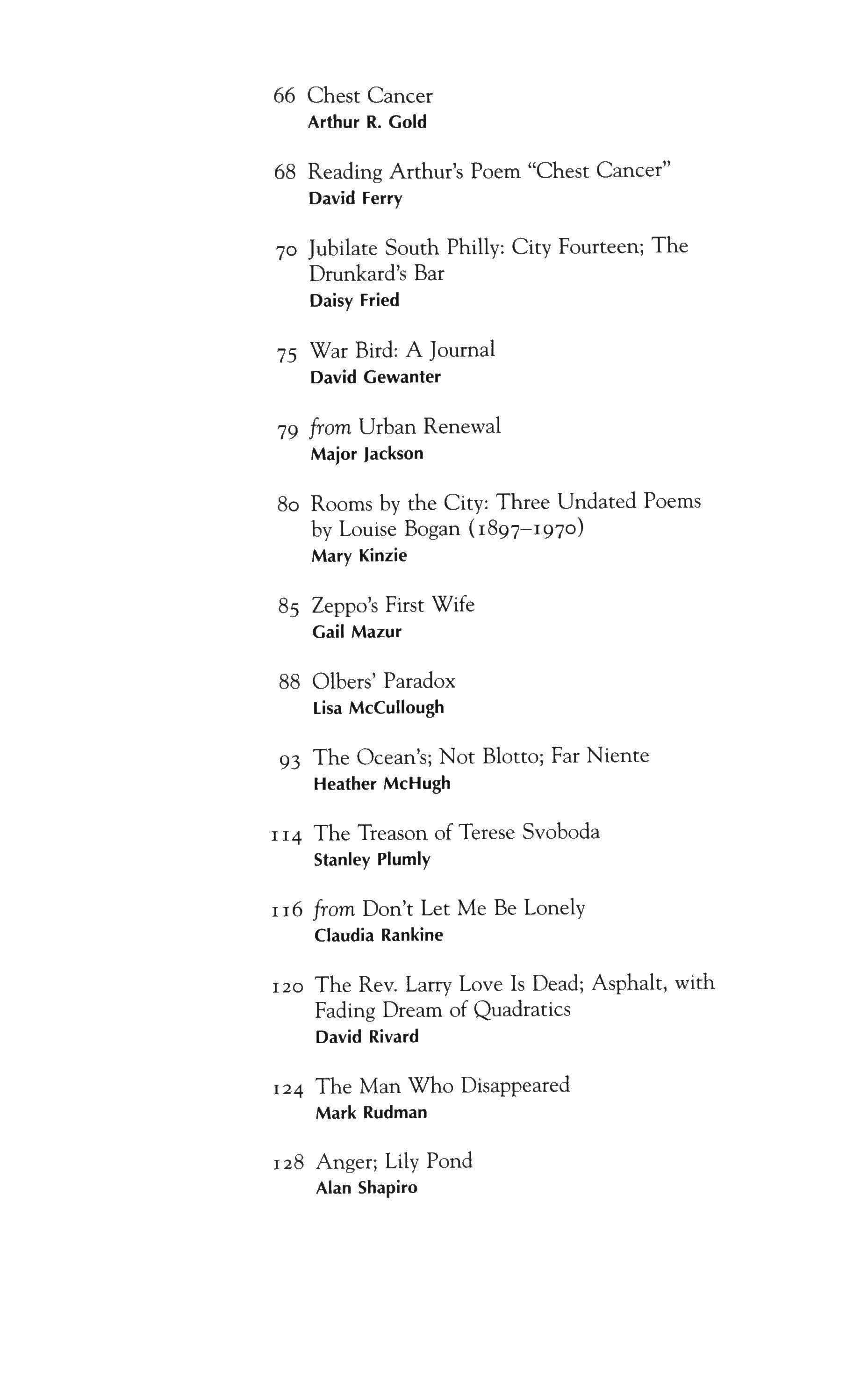

66 Chest Cancer

Arthur R. Gold

68 Reading Arthur's Poem "Chest Cancer"

David Ferry

70 Jubilate South Philly: City Fourteen; The Drunkard's Bar

Daisy Fried

75 War Bird: A Journal

David Gewanter

79 from Urban Renewal

Major Jackson

80 Rooms by the City: Three Undated Poems

by Louise Bogan (1897-1970)

Mary Kinzie

85 Zeppo's First Wife

Gail Mazur

88 Olbers' Paradox

lisa McCullough

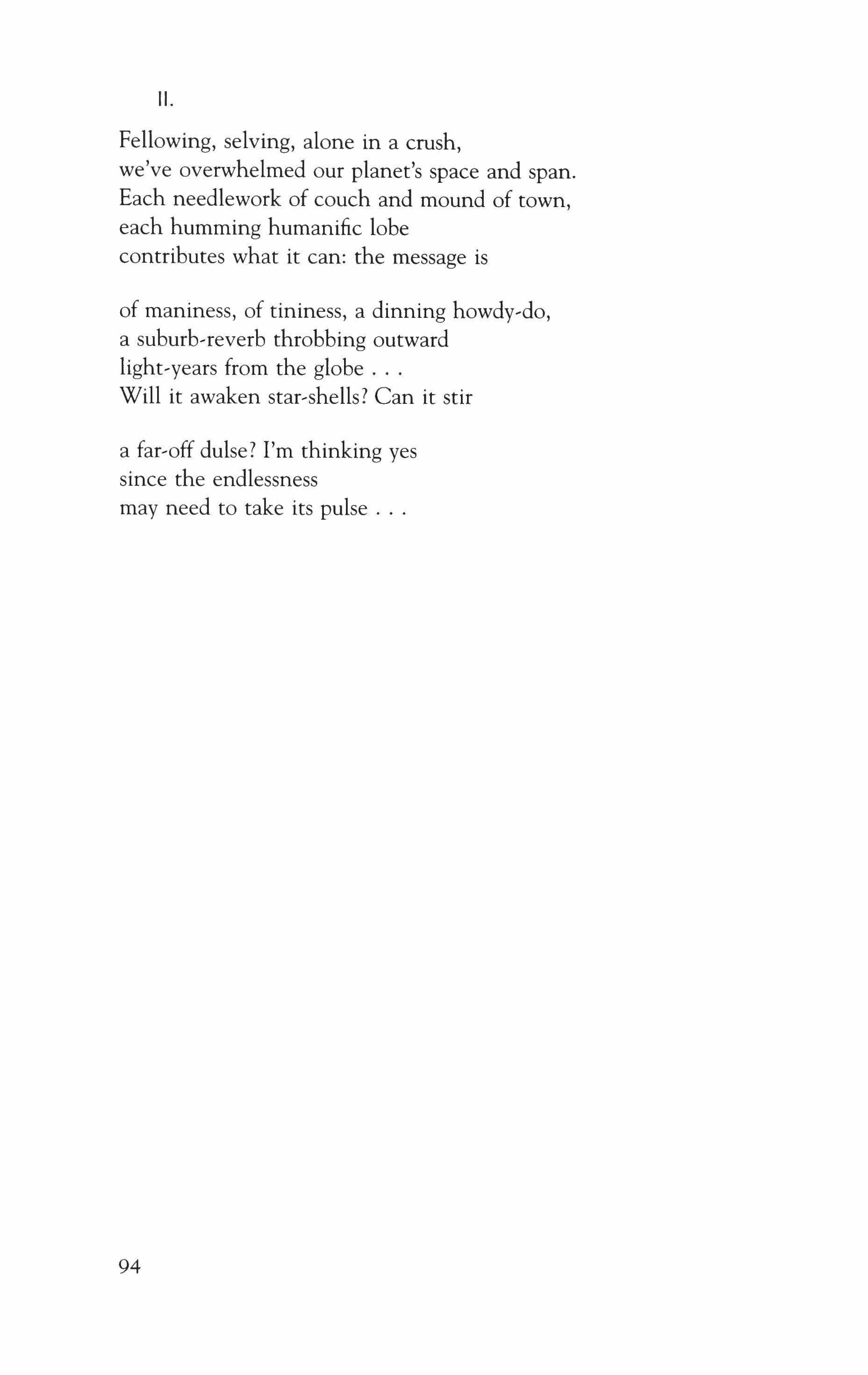

93 The Ocean's; Not Blotto; Far Niente

Heather McHugh

114 The Treason of Terese Svoboda

Stanley Plumly

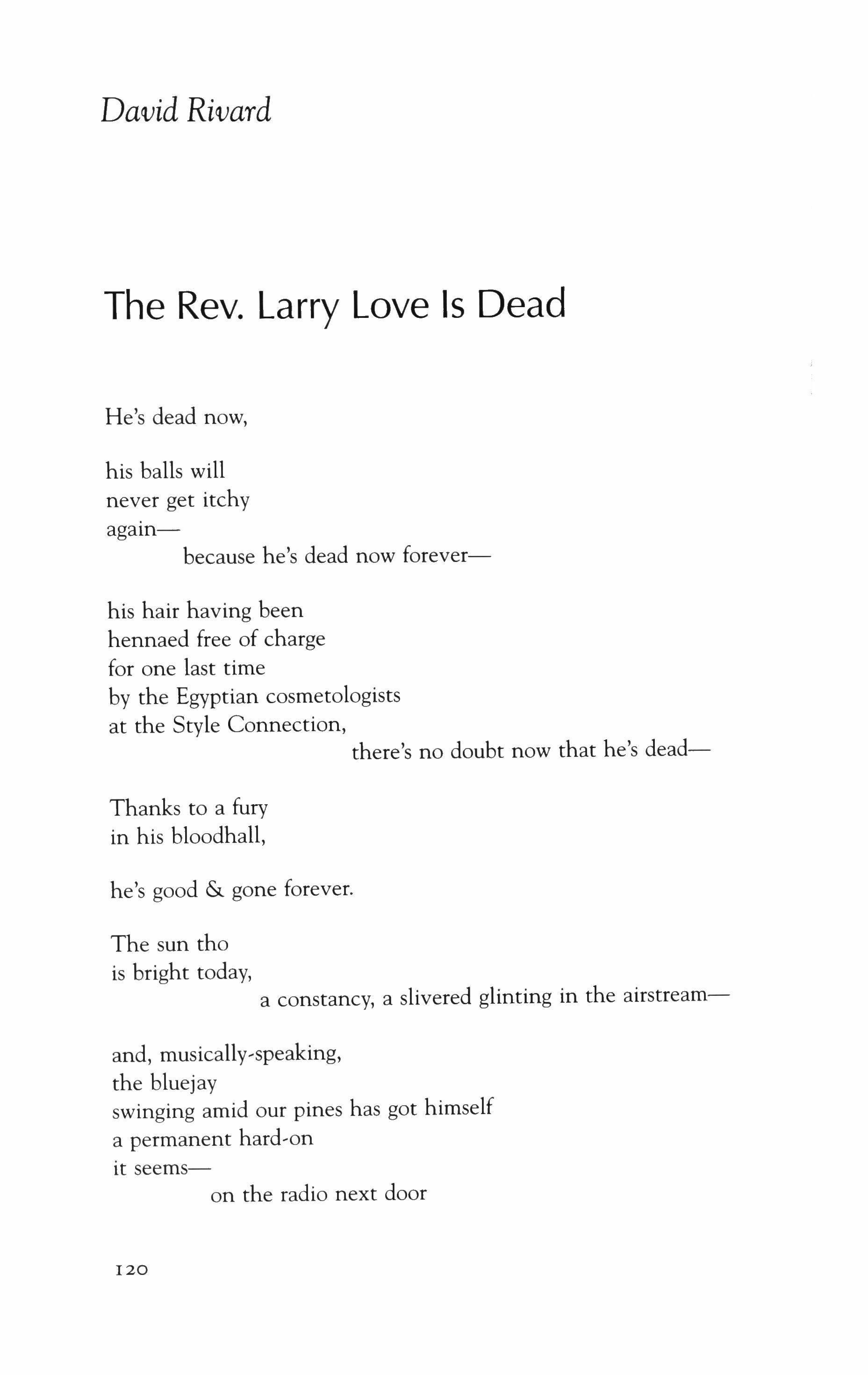

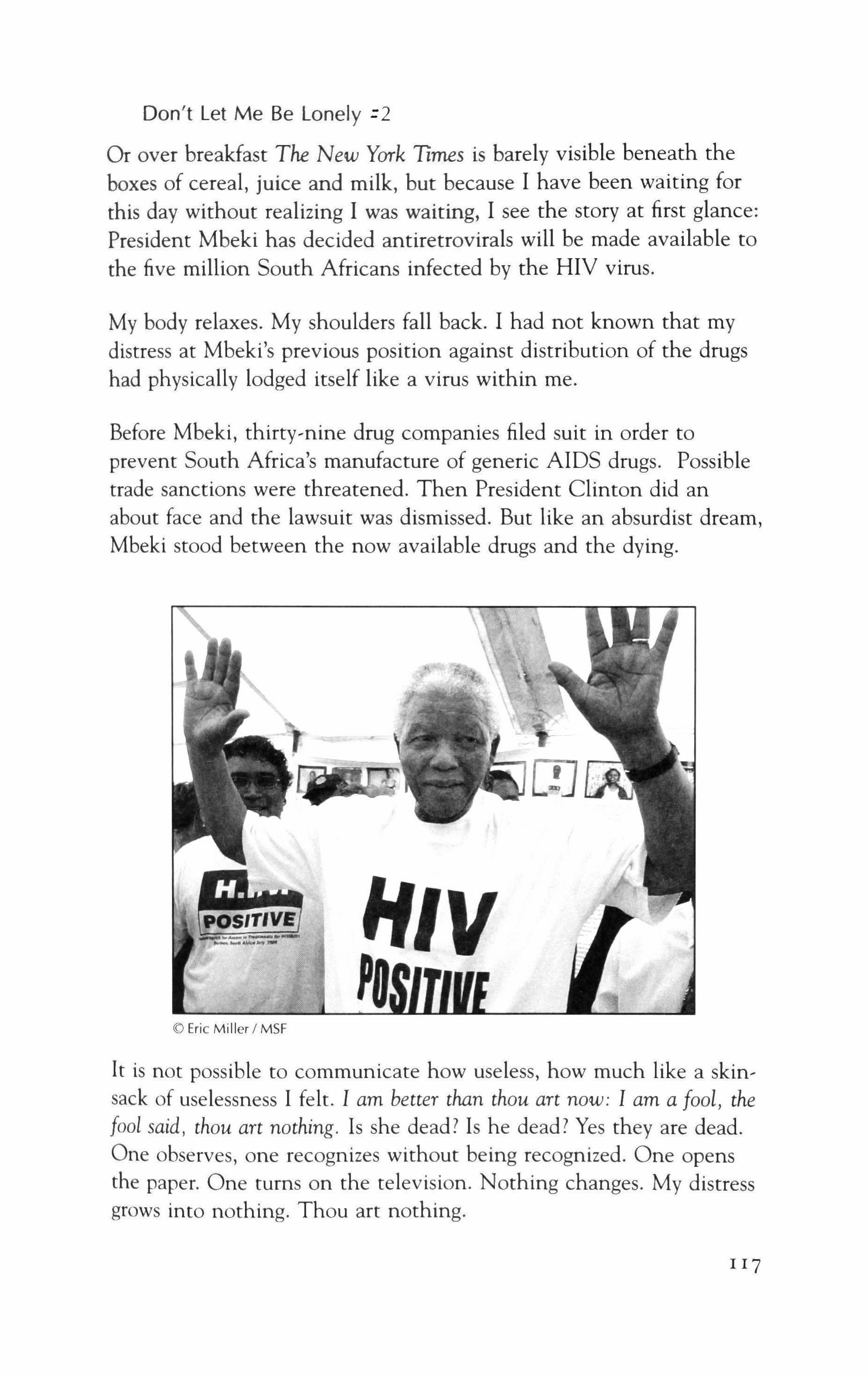

II6 from Don't Let Me Be Lonely

Claudia Rankine

120 The Rev. Larry Love Is Dead; Asphalt, with Fading Dream of Quadratics

David Rivard

124 The Man Who Disappeared

Mark Rudman

128 Anger; Lily Pond

Alan Shapiro

Jane Shore

The Mouth; Graffiti Tom Sleigh

Sweet Nothing Christian Wiman 202 The Grass Grower

Anne Winters

Public Law 94-344

John lucas

from The Year

Sarah Blake

The Wealth of the Dreams

Merle Collins

from Each in His Own Way

R. D. Skillings

Killing the Cat

Melanie Sumner

from Don't Forget Me

Howard Norman

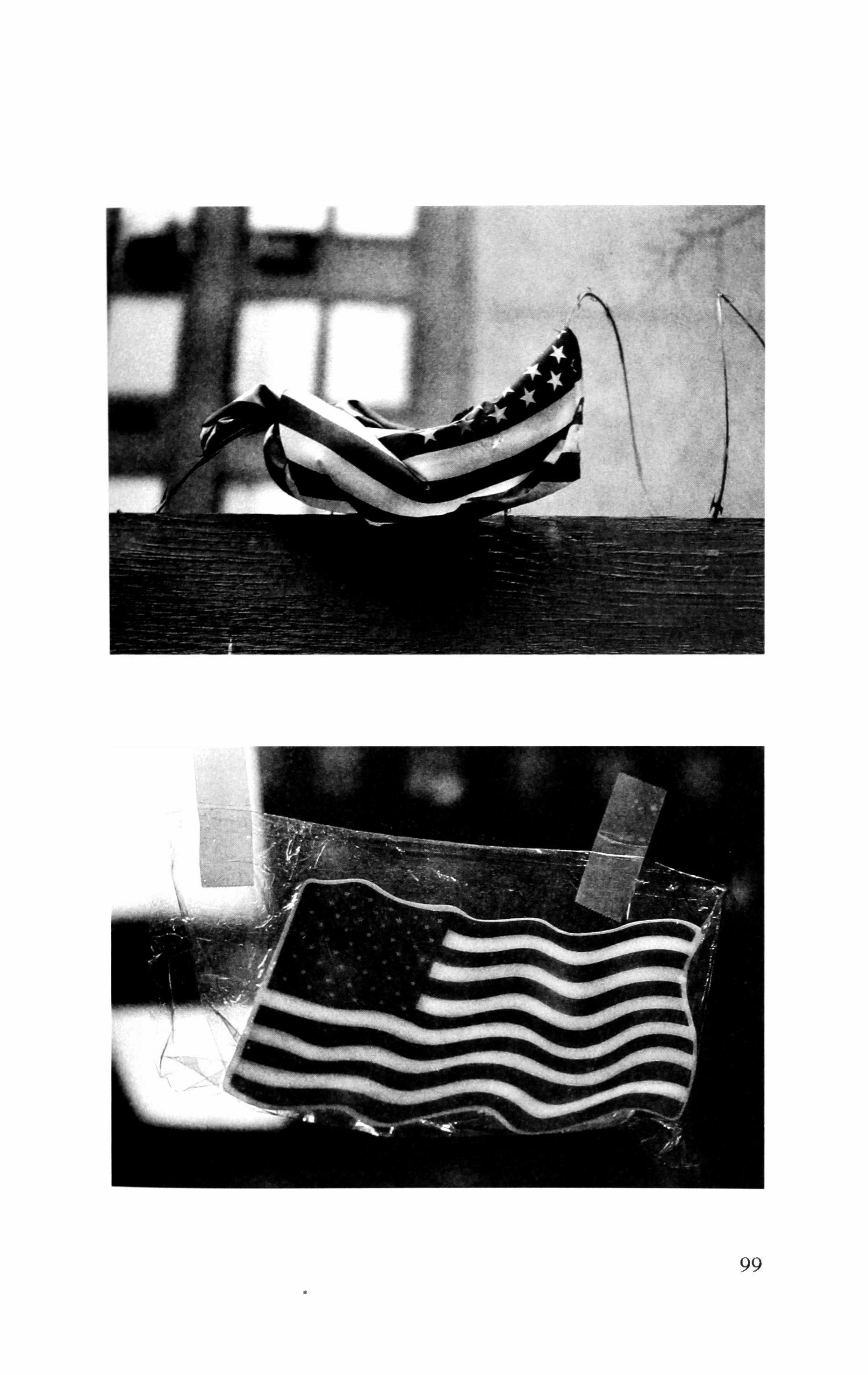

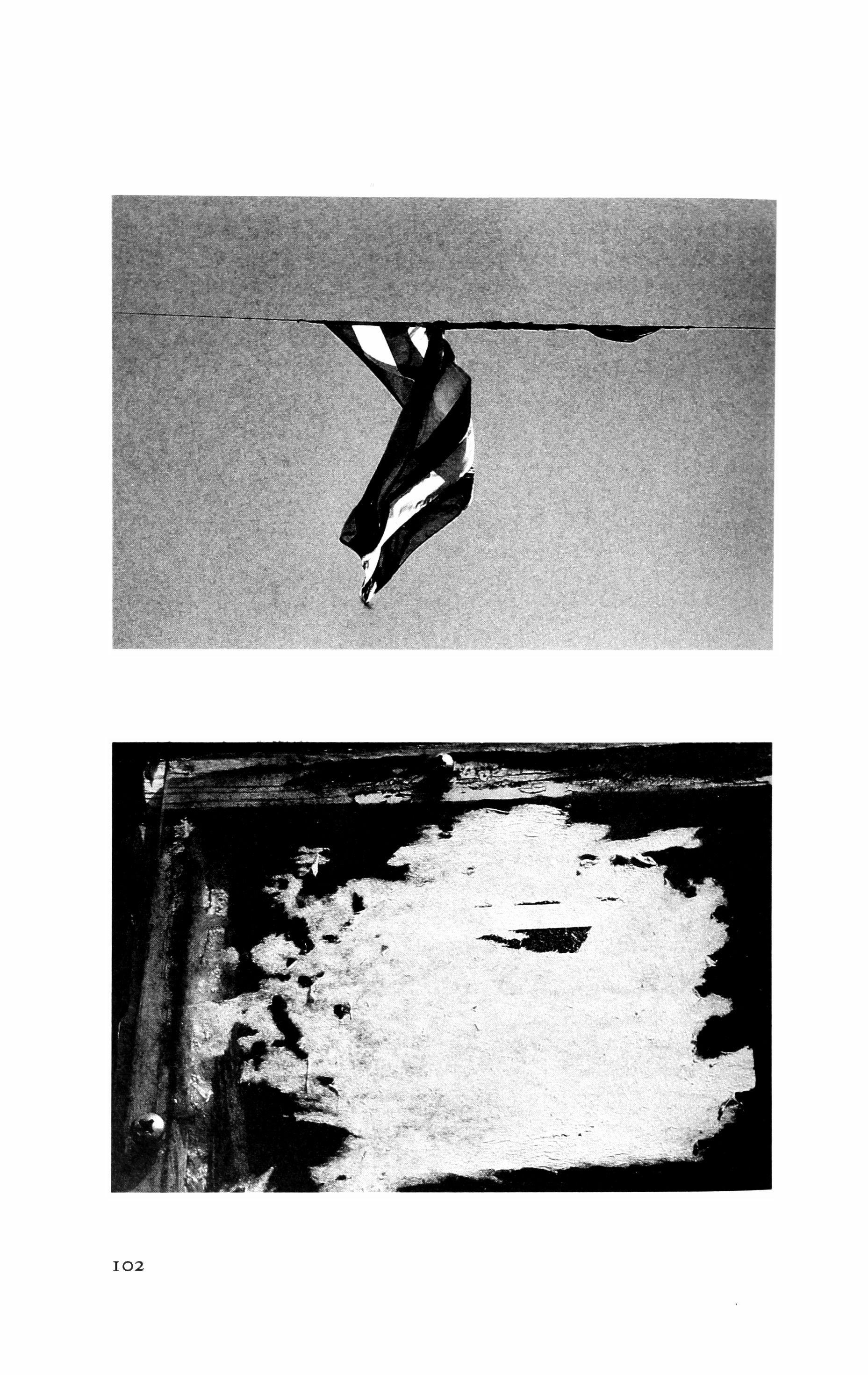

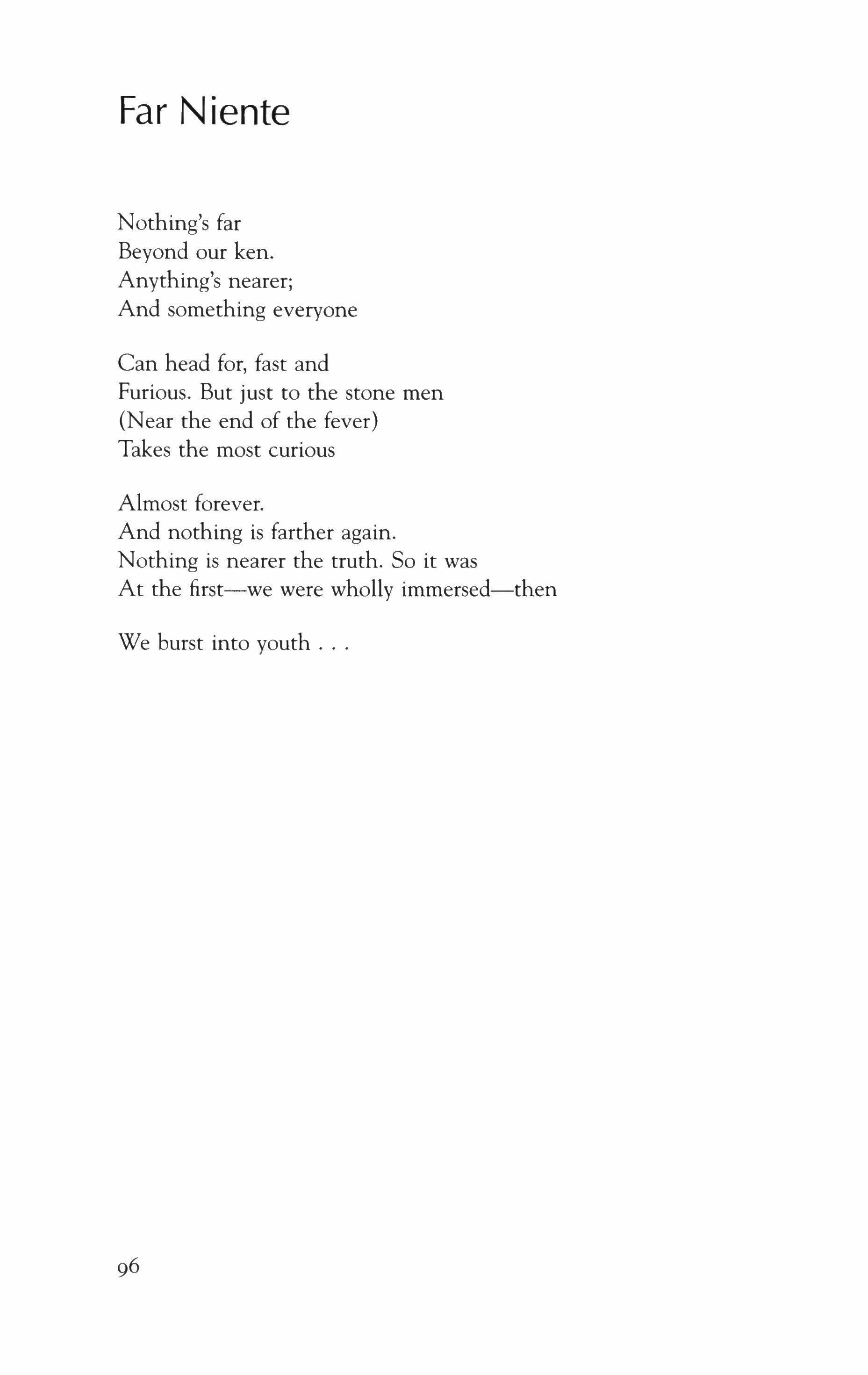

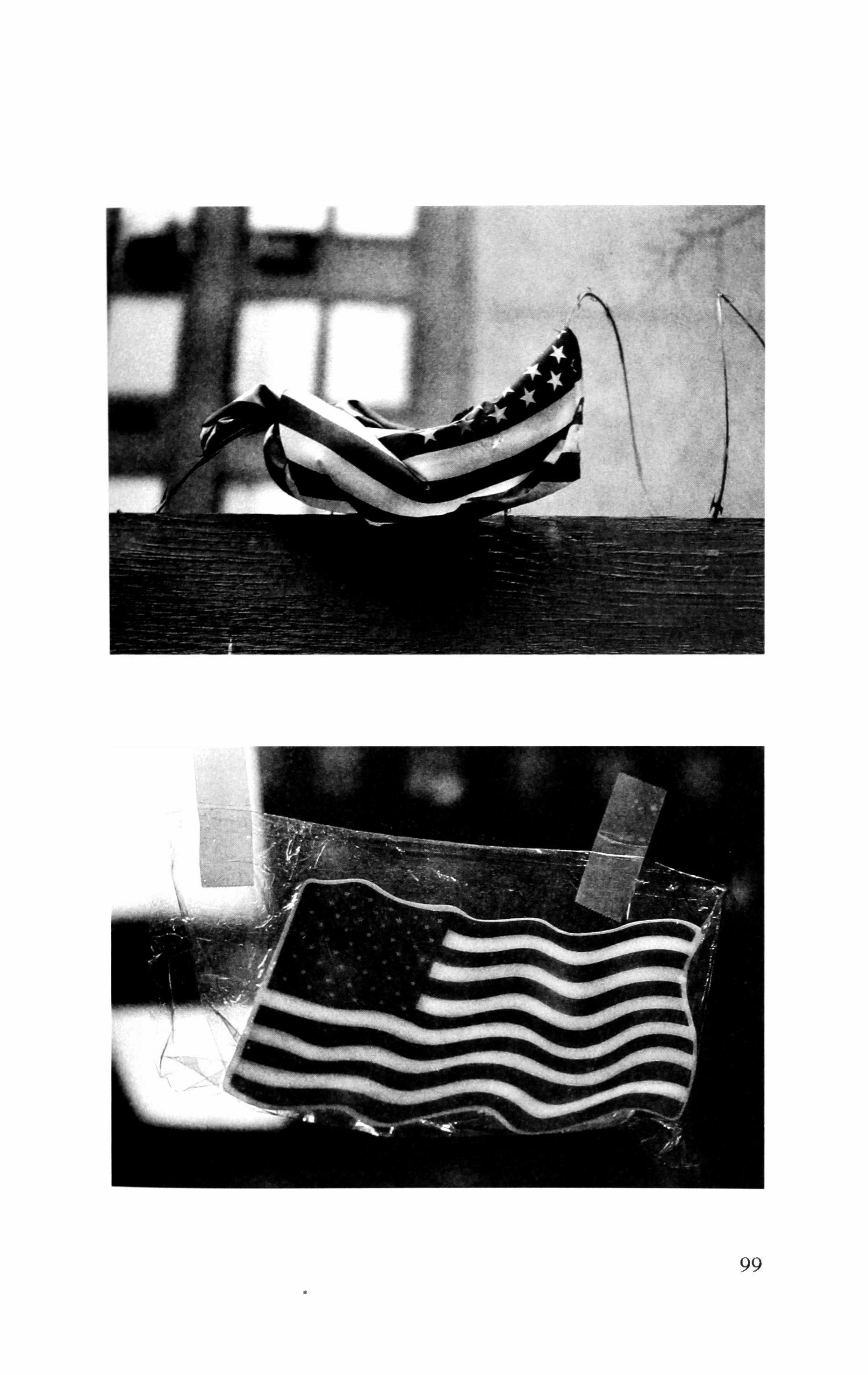

Flag Code

J.T. Barbarese

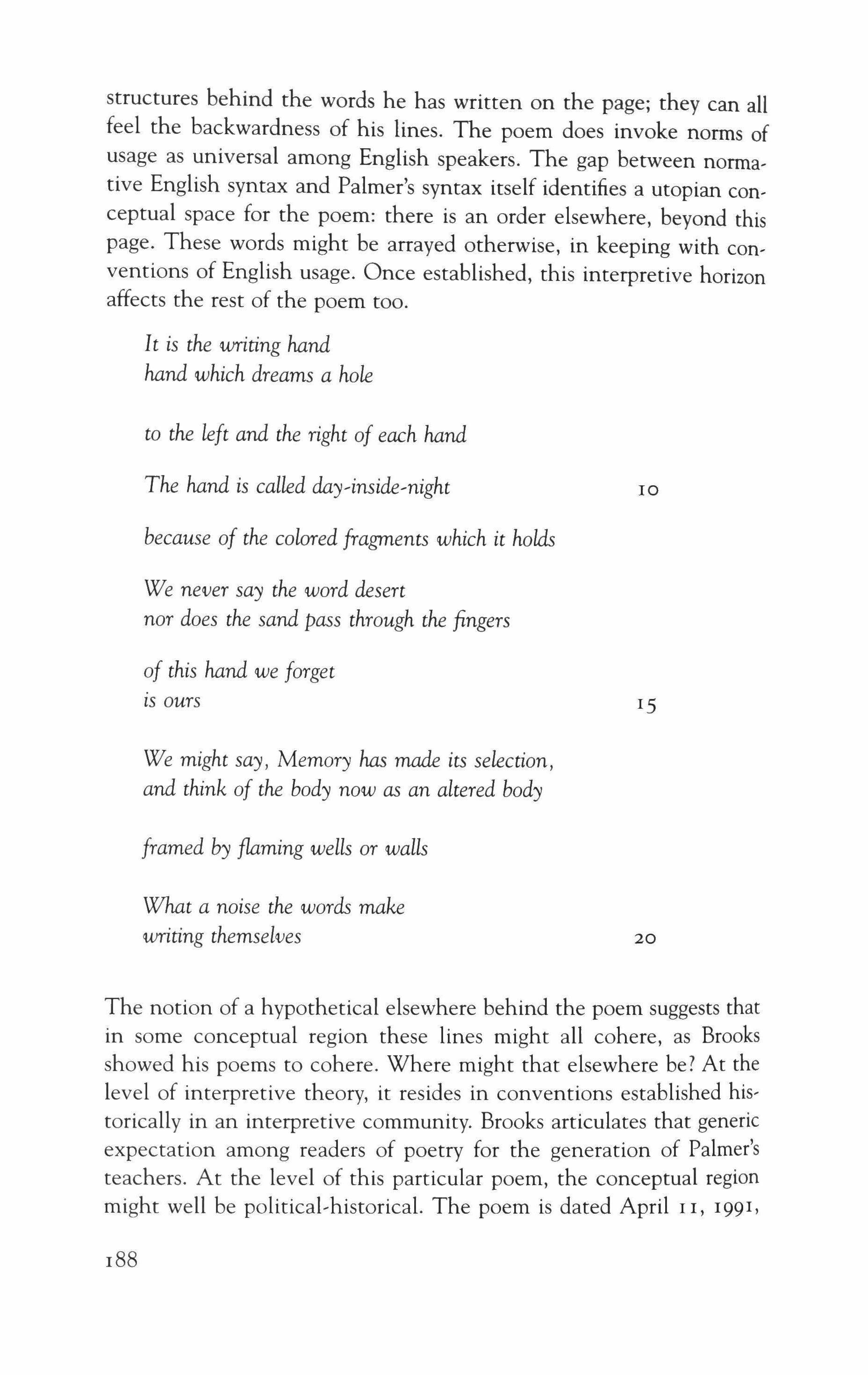

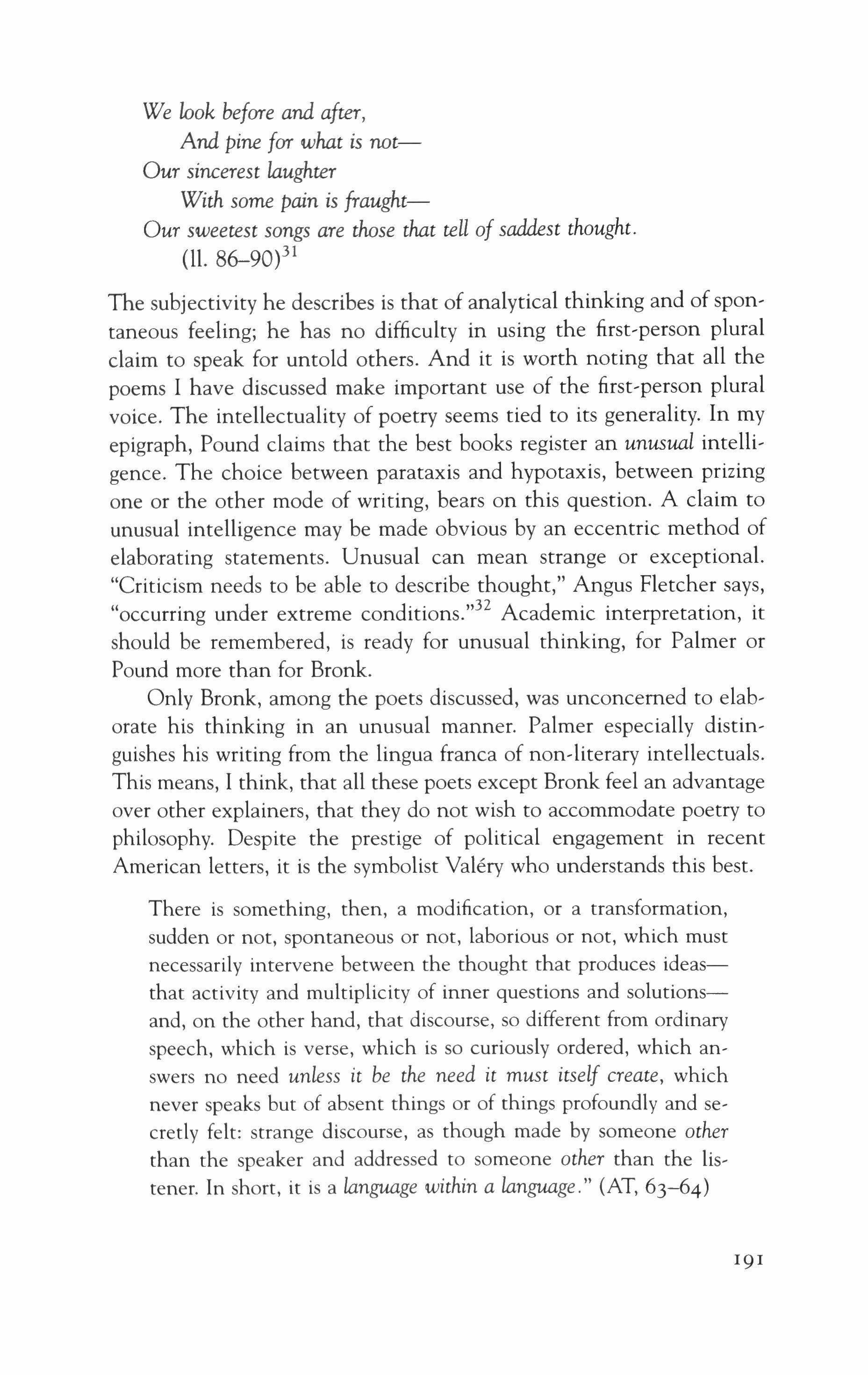

I Lyric Thinking

Robert von Hallberg

Contributors Cover Photo: John lucas

photo

fiction memoir criticism

essay

135 The Mausoleum

149

194

97

23

49

137

152

108

105

7

I

207

Elizabeth Arnold

Improvisations: After Archilochos

OXYRHYNCHUS PAPYRUS xxi.2313 fr. 5

A word, what's spoken, a single burst of passion. Rivers break their bounds, fish leap,

split the mirrory border entering air. Ribbon of blood out of a wrist.

Line up your shields, accept no gifts, fixed sign of Zeus, or of Poseidon: one nod and the ash-poled javelin

arcs, zeroing in, or a ship sinks as if through a fissure. And you, then, you?

No words for knowing nothing any longer.

10

OXYRHYNCHUS PAPYRUS (3rd C. A.D.)

I'm not much in for a general who is tall, loves the image of his own wreathed curls, his meticulously shaven face, and swaggers. I'll take a craggy-legged short unhallowed man, feet right on the ground

-as if secured by talons. I want him planted, full of heart.

I I

OUT OF ATTICUS fr. 2 (p. 41 des Places)

See the prow of that high ridge? -sheer, punished

through and through as pumice stone like hardened foam?

There the sharp-eyed eagle sits ignoring your assault.

12

OUT OF STOBAEUS, A,\'THOLOGY 4.46.1 0 & OXYRHYNCHUS PAPYRUS xxii.2313 fro 1 a

Nothing can throw me off my footing the way god's blotting-out of the sun has,

as if he'd pasted wet clay over it, darkening the noontide.

No way now to hide the fact that though we're standing in one place

we're travelers to whom anything can happen: fish grazing in the slant-hilled meadows,

cows on the kelp-beds-c-such are ours now, pastures wavering under water.

13

Backbone of an ass, this island, scrub-wooded spiky waste land brimming.

OUT OF PLUTARCH DE

12.604c

EX/La

14

OUT OF STOBAEUS, ANTHOLOGY

4.20.45

I lie miserable with longing, broken by such pain it outdoes war wounds, pierced to the very bone thanks to the gods.

15

OUT OF PLUTARCH

Some Saian stammerer has my shield, frail board between me and the void

I threw behind a bush and ran. So I saved myself, so what?

I'll find another just as fine.

Rick Barot

Pastoral

Here is the dusk with its pink plastic bag in the tines of a branch, the wheeze in the wind's throat before the wind lies down on water. Here is the brink revealing the icy spring's pulmonary green, the grasses softly becoming.

The water is like the dark part of an x-ray sheet, possessing into itself the shadows building between trees, shrubs roundly black like pots. Traced onto nothing, here is my grandfather pushing breath out of his locking lungs, and memory dividing like his cells: the papery, hollowed-out face; the brown mash of herbs he sipped, trying to outwit what had lodged there, the crone of another self, the enraged sibyl shrinking, taking the world of him with it. It is stupid to keep seeing the body in the world, its parts

illuminated in the easy salary of images: hospital tubes in the coiled garden

hose, the plastic bag in the tree waiting like a lyre. And yet by these errors

what's beneath is sometimes fathomable: you running on the Potomac's banks, your lungs pumped with the medicine that cures you as it didn't my grandfather, the rain drumming mist out of the ground, the mud a gradually clinging weight.

Heading back, you decide to scale a country club's wall, diving naked into the unguarded pool to wash off the mud. You tell me this as I try to unfurl your hands, and you finally open them, showing damage that a door or hammer has brought on each knuckle, the outlasting scars coarse as the nodes on a branch.

Don Berger

The Sniper

When I reached him, he looked already bored with what I'd say to him, so he opened his mouth and closed his eyes, and I wrote our name across his cheek in pen. "What's yesterday?" it seemed he thought, his hand hanging barely over the puddle.

I sat, I coughed, and couldn't wait to get back to my poem, the one he'd been living without. The dirt from his nails I placed under his nose, and it moved. The apple, heart-sized, I rested where his voice would have been, a choice between cutting something open and dropping a big board over it, to gawk at. His spell, if that's what it was called, had ruined the phones. Up with the policeman, I pushed it, him, on top of the wide, wet, sticky line.

A spider tried to kneel, a pine cone adjusted itself on the needles,

19

the air in his lungs hid from us, the lights tried to talk, the car looked up, and the blue squirrel yanked on the sock as though related to it.

Many think it was just another god trying to crash the party, the earth scraping against the universethose were the words they used exactly. On my soul, it wasn't that.

20

To Likes-to-Have-Fun

Horace taught me who not to sound like, How not to be great, infections on both heels And stupid, stupid to decry. It feels Weird, nothing for soft eggs, where the wing Used to be attached in the habitable region Around a star. We opened up the dictionary And it was the first word we saw. We read The definition and we liked it, A purple mylar balloon, a giant yellow Butterfly, rigged with sadness, and radical, Corporate, the fertile ground. It wasn't A question I had no answer for. There isn't A need for the lights on the dimmer. Give yourself

Three months, she said, the world isn't ready For you yet. I told myself, tell myself, I wouldn't use I, and she believed it, sitting on ads With our fingers crossed: "How to Enjoy Poetry So You Can't Forget Who I Am." Someday All those leaves might come back and don't Go skipping dinner just because you're not Here anymore. I saw Joan Allen, And last month, in "The Contender" She blew me away. A girl said to me, "I Did not finish my reading," and I answered "Slava, what are you doing, reading War And Peace?" And she was. And she was Russian, Too. To look up internalize and my role Slips through me I think: prose poetry from Now on, letters, websites that specialize in Sorting out truth from fiction. You are so Great that I can breathe through my ears When thinking of the night I saw with more Than my eyes this person who said in a minute She walked a lot, and the feeling when everything Shows its teeth's secret joy that's how hills

21

First arrived, you know, and your outfit that Included a scarf under the face to describe Different things all of them synonyms for Pulling off the tablecloth but leaving Nine tenths of the dishes, and all of the glasses, Long-stemmed and tumblers both. I knew So much less not to bounce it off the front door

And see who comes out, could not, thank god, Get a signature on the dirt there.

Now it's today, the mother of all days. Use it

When you want the earth to shake when you want To have a real effect, beautiful one.

22

Sarah Blake from The Year

August, 1941

War was coming. Everyone said it. But no one truly believed what they said. The heat which had been building all spring, the heat and the worry of waiting for Hitler's next move had burst into flame at last. Now that we could see it, it was, curiously, a relief. He was taking Russia. We half-listened to the unpronounceable names of cities and towns falling the way people listen to the names of medicine before they are taken ill themselves.

Outside the windows here, it was gulls and swallows dividing an undivided sky, the clear blue draped over a flat green sea, day after hot summer day. The trap boats were returning to the pier with fish so big caught in their weirs, the tail ends had to be sawed off and tucked inside the gutted bodies to fit the four foot boxes stacked and stapled and bound up Cape for the city markets. Summer people and sailors clogged the streets, and by seven o'clock signs were up in the cafe windows, saying NO MORE LOBSTER. NO MORE PIES. Joe Di Maggio had hit fifty-six straight, and England still stood. We drank, we smoked, we cheered the Yankees and the Brits.

And our boys were not going. Roosevelt had promised, twice. He spoke bluntly, as if he were one of us, but he wasn't, thank God, and

23

nobody thought so. Never mind the Navy destroyers that had begun to maneuver in the waters a mile or so off the East coast, he had said the boys were not to fight in foreign wars. Nobody knew the ending. All the movies and the songs, the terrible pictures, none of it had happened or been made. It was the end of summer. And the lights were still on.

In the bar at Grand Central Station, the whoosh of the revolving doors let couple after couple into the busy crowded room full of smoke and chatter. The old man watched them in the long mirror stretching above the length of the bar. The men in suits raised their fingers to the maitre d' signaling how many, the women turned aside and studied the room. Some men, like himself, were alone and made directly for the bar, where they shrugged off their jackets and folded them across their laps. Every time the doors moved, the distant hammer of trains in the station outside chung-chugged and moaned, the mechanical beams of industry crossing and recrossing the luncheon hour. It was hot as hell and the fan overhead moved the damp shirts of the men from right to left, cooling against their skin as it moved.

"Hello, Boss," she said and dropped onto the stool beside him.

It was characteristic of Miss Frances Bard that she always seemed to appear without warning-though he had been sitting here waiting for her-as though she'd merely stepped through the veils dividing one moment from the next. She was not a female's female. Short and square and old as the century, she was the one your eye flicked over on the street. Once, he laughingly accused her of having an advantage over other reporters. Because I am nothing to look at? she had asked him. Because they forget you're a woman, he'd answered. That's what you think, she had smiled at him then.

"Yes," she nodded up at the bartender. "Whatever he's having."

She turned to the old man, conspiratorially. "What are you having?"

"Bourbon and water."

"One never should drink bourbon before six o'clock," she observed. "Scotch?"

"Scotch," she tipped her glass gently against his, "is for the servants."

He shot her a look. Though her tone was light, she seemed exhausted and wary, like a cat who has narrowly escaped a bath. She'd been over there since '38, chasing the war as it raced through country after country, the whole goddamned continent going up in flames. She had gotten in everywhere and pulled out story after story. Then a month ago, Joe Link of Reuters had called from London and said Max ought to pull Frankie out and bring her home. She'd done something.

24

There'd been some incident on a train Max couldn't get. But he could, n't get ahold of her either, not anywhere. Jimmy, Roger, even Ednone of them had seen her or heard from her and London was full of eyes and ears. Hell, they were the press corps. But Frankie seemed to have disappeared. Until this morning, when she'd called him at his desk and told him she was back and she was through.

They drank in silence. Their long association had taught him to be quiet until there was something to say. And often there was nothing at all to say other than the four or five sentences that had brought them together. Most people he knew, his wife included, wouldn't make it through an hour on the promise of four sentences. But Frankie Bard was like a camel. She could hold her words for days-as long as she could watch the goings on.

"I had forgotten what all this looks like."

He glanced into the mirror and saw she was staring at the people in the restaurant behind them.

"All what?"

"This-" she pointed. "No one here thinks they're in any danger."

"They've left it outside," he suggested.

"No, they haven't," she tipped her chin at the scene behind them played out in the glass. "They don't believe it's there."

He watched one of the men behind him lean over to his companion and say something in her ear. The woman turned her cheek toward his whispering mouth, though her attention remained on the menu in front of her. Then she smiled. The clatter above and around them was protective as a bower. "Human nature," he ventured.

"No, Max." Frankie crossed her arms in front of the drink. "Arnerican nature."

He chuckled, uneasily. "Sounds like you want them to pay."

"That's right," she nodded.

"For what?"

She shrugged. "For this," she nodded again at the ordinary lunch behind them. One of the waiters crossed through the smoke with a tray held high on his way to the kitchen, and the people leaned away from him as he passed. The talk in the room was a low insistent murmur against which glasses clinked and silver clattered upon the china.

"People can't imagine what they haven't seen," he answered. "That's why they need you."

"Beg your pardon, Max, but that's horseshit."

"You signed up to see what they haven't," he observed. "You can't

blame people for it."

"Why in hell you think I'm quitting?" she asked, coolly.

"Hell of a year to quit," he fired back.

She finished her drink. The bartender sidled down the length of the bar, his approach the question. The old man nodded without looking at him. Frankie was one of the best of the women war correspondents, mentioned in the same breath as Margaret Bourke-White and Martha Gellhorn. Privately, he'd have argued she was one of the best, period.

"Take a break," he said.

She shook her head. "I want to get off the bus."

"It's the only story there is, Frankie."

"Hell it is," she answered.

"I don't get it."

She shrugged and kept her eyes on the mirror. "Maybe I'm not up to telling it."

"That's bull, and you know it." The old man thrust out his chin. Frankie didn't answer.

"I used to think you wrote a story like a hunter threw a spear," she said after a while. "You aimed. You drew back your arm and then you hurled and it landed."

She seemed to him, just then, like someone pointing out the view from the edge of a cliff. She was almost gay. He watched her, helpless.

"You know why it landed-why it mattered?"

He shook his head.

"Because of God."

"God?"

"It mattered because I thought someone was up there watching, holding the whole thing together." She shook her head. "Can you beat that? It turns out I believed in God."

He sat quite still, not wanting to frighten her, as if not only she, but he too, stood at the edge of some grave drop.

"But if it's only luck up there-if there is no God-then nothing matters. Words flutter up into the ether and float back down. The end and the beginning, the middle, no matter."

She had jumped, she had jumped, and he couldn't reach an arm to grab her. She turned her head away from the mirror and back to him, and he felt her eyes on him before he turned to look at her. "I've seen enough, Max. It is only luck up there. That's all I have to write. Nobody should read that."

He sighed. She stared aside at the perfect patrician line of his pro-

file, the line that caused the girls in the secretary pool to call him the Yankee Clipper behind his back, and then turned away. He looked at her. "OK," he said, seeing she had begun to cry.

"OK?' She pushed away the handkerchief he offered her, and wiped her eyes with her fingertips. "OK?" she repeated almost laugh, ing, and then she gave up and covered'her face with her hands.

Someone's joke rose in the background and hit its mark, and the sudden tremendous burst of laughter fell down around the room like rain. Frankie turned around on her stool wiping her eyes and caught sight of a woman entering the bar on the crest of that laughter with the grace and self-consciousness of a creature just released from its cage. She was lithe and bare-armed and her skirt skimmed just above her tanned legs as she moved. Max turned around also, and the two of them watched the woman sit down and lean her elbows upon the table-languorous, hot-and rest her chin on her hands, her long bare arms folding into two soft hooks.

"Do me a favor," he said, "go out to the Island, or the Jersey Shore, somewhere closer. "

That brought a little smile. "It's only Massachusetts, Max."

"But that town's full of fairies."

She tipped her empty glass against his. "I like fairies."

He grunted.

She leaned over and kissed him on the cheek, old man who had taught her everything she knew. He raised his hand but didn't look at her-he was finished. He was tired. Then as soon as she was gone, he wanted her back and swiveled to call after her. But she had taken off swift as a bird and was making her way, here and there through the tables, tiny, crooked and electric. He let her go. She had seen everything. She had been the one under him who had seen it all-Poland, the Blitz, the fall of Paris. And she had sent it back to them at their desks and she had made them look it directly in the eye. Whatever the hell that meant. He signaled the bar man for the tab. Nothing could be looked at directly in the eye, and he knew it. He looked up at the mirror over the bar and the dress whites scattered among the tables had the effect of a field of cotton lit up by the weird wild light that always precedes a storm.

-c-

Inside the station there were soldiers and women, fixed in attitudes of hurrying and waiting, the waiting room full of boys being sent all over the country on buses and trains, their olive drab backs leaning over books and maps, sprawled in the too tight seats moving from New York to Omaha. Tennessee. Georgia. The Carolinas. As this was the earlyafternoon train out of the city, there was little to be loaded, and Frankie turned back around to watch the crowd. The steady human conversation thrumming around her, punctuated by shouts, arched up into the marbled domes of the station's ceiling where the gathered sound bowled before dropping back down. She leaned against the wrought-iron gate separating the tracks from the station and closed her eyes. It was the purest kind of song to her, this anonymous unintelligible murmur, this chaos of voices set loose and sent high. She opened her eyes and gazed up at the clock where the hand stitched second to second toward the top. What she saw before her in the station was merely what she saw. Boxes and slants. The green shunts of summer lilies stuck in a pot by the ticket booth. And she a woman of middleage, only. Nothing to look at, nothing to see. And nothing to report. It was a nearly unbearable pleasure.

At Nauset, Frankie descended the New York train and walked the four blocks through the central town on the Cape, sullen in the late afternoon heat, to the bus for Franklin. Mr. Flores sat in the shade cast by the bus and pushed himself up onto his feet, ambling forward to take her bag.

"Hello, Miss Bard. Good trip down?"

"Yes, thanks."

He nodded and pointed her toward the bus's open door. Frankie pulled herself up the three short stairs and into the bus. The others looked up at her as she appeared in the aisle, looking without looking, in the manner of travelers. She noted a foreign couple, several women sitting alone, and an assortment of men all clustered round Flores at the front of the bus. Frankie nodded and made her way towards the back. One young woman had her head in a thick book, the curve of her neck laid bare as her hair swept forward. She had not looked up at Frankie, and didn't stir as Frankie passed her by. Mr. Flores swung himself into his seat, and the engine roared into life, shaking the floor under Frankie's feet.

They left Nauset, and swept through the villages without post offices along the dunes under the eyes of the men sitting in the porches, breaking off conversation to stare as the bus slid past. Self-styled

watchmen at the ready. For what? Frankie stared down at them. War? But no one was ready-the hammer had been back so long, people had grown accustomed to it and did not really believe it must strike. And no one knew, she thought as the bus slid past, anything. Grown men and women went about these days as earnestly and deeply absorbed in pretend as children-no, not like children-like the mothers of children, whose eyes she had long ago concluded were stitched up and turned inwards, away from the sky and the streets, toward the coolshuttered hours of the monotonous comforting routines they shepherded. Protected by the sing-song coo, the puss and fuss. How long before naptime? How much to get done in an hour? The soft calibrations, the ceaseless rhyme of plotting and planning.

She grimaced. The passengers joggled along inside, their luggage comfortably strapped to the roof of the bus, their small things clasped on their laps or beside them. There was room on the bus. Though the fan whirred above the driver's head, Frankie had preferred to sit at the back, watching the scrappy trees spin by. Above and around, the leaves on the trees burst like hands and the single white houses splashed out of them like dashes. The ride down to Franklin was familiar; she'd written up the town for the Federal Writer's Project in '37. Franklin was the bait at the end of the sandy hook sticking fifty odd miles into the Atlantic and waving slyly back at the shore. The first thing she remembered losing there was her sense of direction. Ringed by the yellow-white sand dunes and water on all sides, North and South seemed to switch points on the compass, and the sky was no help. It was a place swollen by fish and the smell of fish, of cod oil, of the broken spars of whale bones and masts spat back from the sea onto the broad swath of beaches behind the town. Pilgrims of one sort or another had always come: first the Puritans, then the whalers, and then at the tum of the last century artists arrived, wrapping their gay scarves on the tops of old dories and painting them; and policeman's daughters who had come down from Boston mixed with the patti-colored crowds, saying wasn't it fun, wasn't it something how the Mediterranean sons of fishermen walked arm and arm with the Yankee gold and the bright lights of the summer theaters glowed out into the dark.

Frankie opened her eyes, her heart pounding. The bus had stopped. The door swung open and she smelled the sea in the air. Everyone had descended but the little child-woman she had noticed reading a book early on in the trip. Through the window, Frankie watched until they disappeared inside the Ogwee bus station, the brown door closing upon

them with a bang. The two women remaining behind sat in absolute quiet, as though a curtain had fallen, dividing act from act. The younger woman had put her book away and now sat bolt upright and forward, as if she feared missing something. A runaway, thought Frankie, though she was quite well-dressed in a skirt and silk blouse, her fair hair cut short and feathering along the straight edge of her col, lar. In any case she was the sort that needed tending, the very pale, small,breasted women who tip their faces up to men, smiling delight, edly as babies. Idly, Frankie began to count the beats of silence be, tween them, until at last the little creature turned slightly, as if to meet Frankie's gaze, aware of her attention, and gave a noncommittal smile-a mechanical gesture like a hand put out to ward off the sun. Frankie nodded, companionably.

It's all right, she addressed the woman's back, who had turned away and picked up her book again, I have no interest in you. The bus bounced a little as Mr. Flores climbed up behind the wheel followed by new passengers.

Vronsky was making love to Anna.

Emma read the sentence again, distracted by the ugly little woman behind her. Did Tolstoy really mean making love? She couldn't think so. Having sex? It would be so bald written on the page like that. Surely they can't have been making love here and there like this in the nineteenth century. It must refer to something else, something more benign. She flushed, a little guiltily. Not that having sex wasn't be, nign-of course it was, it led to babies, after all. Though the things that she and Will had begun to do in the dark had nothing whatsoever to do with babies. But Anna and Vronsky? They had been constrained, wasn't that the idea? Perhaps it was the translation. She flipped to the cover of the book and read the name beneath Tolstoy's-Constance Garnett. Emma thought she understood. Vronsky had whispered some' thing loving to Anna, or soothed Anna lovingly, or something like that, and Miss Garnett had translated it this way instead, painting what ought to be a pink scene-scarlet. Probably a spinster: the pathetic type who reads passion into the crooked twist of a shut urn' brella. Like that woman in the back of the bus.

She pushed her bottom back a bit against the seat so that she sat up the straighter. Anyone looking, anyone who knew who she was, that is, must approve the slim upright neck upon its narrow shoulders, the chin tipped forward beneath a pair of frank blue eyes. There's the

30

Doctor's fiancee in a very attractive skirt with a matching scarf thrown round her shoulders. She stared out the window. Since she had said to Will Fitch-hurriedly, afraid to look up at him, all right, yes. Yes, I will-something firm and satisfying and entirely new had entered into the frequent chaos of her mind. As though Ed Murrow's voice, that brave, impassioned masculine voice, full of its own urgency and volume had laid down the track upon which she now hummed. Clarity ran over that track, and purpose. And she meant to do something good. Pamet. Then Dillworth. Finally Drake. Closing her eyes, Emma recited the names of the towns known to her only by Will's letters in which the geography ofher new land was mapped by the various ailments of the people he treated. Heart disease. Bursitis. A pair of twins delivered in Drake which was a miracle, wrote Will, given that the mother had neither the time nor the transport to get off Cape quick enough"Bobby high or low?" The man's voice in front of her broke in. "Too damn high for comfort."

"They won't extend it."

The second man didn't answer and looked out the window. He had a broad nose hung over a chin which fell away sharply. Emma found herself watching this ledge, as if for some sign. He stared out the window for a moment. "Sure they will," he said, turning back to his companion.

Emma sat back, annoyed at herself for listening in. It served her right. She had heard it this morning and tried to forget it, had forgotten it in fact, but now here was this talk again. Would they extend the draft? Certainly, said some. Why? The others said. One year is enough. But it didn't matter to her, she protested to the slight reflection of her hands on her lap in the window. Will wouldn't go. He had said as much. (Though not definitively, she said to herself, scrupulously honest even in her dismay. He hadn't yet applied for the deferral.) But he shouldn't go. He was the only son of a fatherless family. He was the sole doctor for miles. The scrub trees outside the window whirled round and she stared. Nothing, she said to them. Nothing is going to happen. There came a slight breeze. Will must defer. That was all.

Mr. Flores hunched low over the wheel, peering into the slanting light, and Emma felt the line spinning her closer and closer in. The stark white houses of Woodling passed one after another. Through the Tralpee forest they went, the squat beechwood flinging away on either side, until at last the bus reached the crest of the hill before Franklin. And as the bus stuttered at the top in the beat before descending, she sat up straight wishing-suddenly, unaccountably-that the line be-

31

tween her and the town would snap. Mr. Flores's fist paused above the gearshift. The dunes spread wide around them.

For a brief instant Emma felt they might fly. The sky through the broad front window called. And she nearly stood up in her seat imagining herself able to continue straight, the road falling away as the bus rode forward into the illimitable air. But the gears caught, and the bus shuddered down into the high hills of sand. Down they rode until the tarmac pulled free of the dunes and curved toward the sea, jogging alongside the gray harbor into Franklin.

Franklin, Massachusetts was not a town of whimsy. She saw that right away. The two roads, one leading toward, one leading away, followed the bend of the coastline and most of the houses were strictly set down along those roads. There were others that followed neither the pattern of necessity or practicality, but seemed built for a view. The wide picture windows of these houses framed a gauntlet of open stares. Unruffled, the bus churtled past, the stark lines of the tar roofs triangling into the early summer evening. The flag snapped in the wind above the steep pitch of the post office, and the bus slowed to a crawl as Mr. Flores negotiated the narrow street shared now with people walking, hallooing to the bus, on bicycles spinning alongside.

Emma put her hand out upon the back of the driver's seat to steady herself, a flush rising in the hollow of her throat. She had prided herself on how quickly she would get the names of all the townspeople, showing off her knowledge to Will, whom she imagined would return every night as if to a theater of her making, delighting to find himself in his familiar town, revealed and illumined now by Emma's perceptions. Emma meant to be an asset to him in this way. He would be the best doctor, because his probes need not be blind.

But the flesh was a different matter. Arriving, as she had, straight into the center of the town, the slightness of her imagination struck her full force. For here they all were already. Two women in conversation on the comer broke off to stare as the bus pulled to its stop. The town was not waiting to start up with her arrival. The town was clearly already itself-without her. There was a tall man standing with his back to the bright white doors of what looked to be Town Hall, not staring so much as appraising the bus. Her heart tripped faintly, feeling all the secrets around her, all the plots. She sat still in her seat for a moment, collecting her gloves, marshaling the courage to find Will in the crowd, certain he was just there on the other side of the bus waiting with that impatient exacting smile of his. The aggressive little

32

woman from the back of the bus brushed past her, causing Emma to look up and then she did make out Will's head above the line of some others coming toward the bus, his long body tipped forward. One felt that he had much on his mind, and much to do. He had caught sight of her through the glass and he waved. She waved back and the scarf slipped off her shoulders as she rose up, bolted up now, she was that happy, and through the empty bus towards the door.

"Hiva." His head came around the open door and he was up the stairs just as she arrived at them and he reached for her and pulled her directly into his arms. She raised her mouth to his and the warm familiar lips pressed hers, softly at first and then more deeply as he gathered her even closer so she could feel the whole hard length of him against her skirt. Though they were right out in public, she closed her eyes and moved into the grotto of their kiss where it was dark and cool, her lips opening under his, and then with a happy moan she pulled herself away from his lips, back out into the light.

"Hiya," she smiled up at him breathless, a little prick of pride rising up at the sight of him right there before her. How had she managed it? She had sat beside him in restaurants, on buses, walked next to him on the streets of Cambridge, the familiar length of his stride a comfort, almost like knowledge. They knew each other this way. He had shepherded her round, his arm under hers, his hand at the small of her back propelling her into smoky rooms, and back out again. They had talked and laughed. They had even quarreled. And then, suddenly one afternoon in the spring, he had been hers. It was crazy, mad-but that was part of the story, wasn't it?-his number for the draft was called and he had stuffed the telegram in his pocket and gone down on his knees right there in the Back Bay post office. And she looked down at him and began nodding before he had opened his mouth. They had arrived at the pact like children. It was the next step, the only step, the serious one. As if, joining hands, they had each closed their eyes and jumped, jumped without holding their breath.

He leaned down to read the title of the book in her hand, still holding tight to her as he did. Her scarf had slipped off her shoulder and the long triangle of her bare skin gave off a bright heat like summer grass. "Like it?" he asked.

"Could they have been making love in the nineteenth century?" she pulled her gaze away, offering up the last thing, least important, that had rested on the shelf of her mind.

"I don't see how we'd all have gotten here if they hadn't," he teased.

33

"No, no. Look." She opened the book right there on the top step of the bus and rippled through the pages, sharply aware of his eyes on her shoulders and arms. They had kissed. They had touched each other through layers of silk and wool. Through jackets and trousers and blouses and skirts. There had been nothing more, but his eyes might as well have been hands, her skin prickling and flushing as he put his foot on the stair next to hers and the hem of his jacket slid open. "There," she pointed.

He looked down and read, "Vronsky was making love-" "It's so naked," she said and then blushed, "to say it like that."

He pressed against her. "Like what?"

"On the page. Wouldn't the readers have been shocked? I am."

"You are not," he whispered.

"I am," she giggled, leaning her shoulder into his. "I really am. A modern reader."

"Everyone understood it to mean something else." "Sex?"

"Courting," he answered, his smile lighting up the impossible inches between them.

"Oh," she sighed happily. "Well, you would know."

"Come on," he put his hand under her elbow to draw her down the stairs. "Let's go home."

Through the open door, they saw a suitcase had sailed off the busman's hook, flying for a moment in the air until it crashed down and split upon the ground, cracking open upon the sidewalk neat as a tapped egg.

"Oh!" cried Emma.

There was a full moment of quiet. Will stopped where he was at the door of the bus, staring down at the voluptuous explosion of what must be Em's underthings cascading over the popped sides of the case upon the pavement before him. They were numerous, silky, and a twilit blue, tossed and flung in a delirious striptease, showing themselves like sirens. He'd never seen the color of her things in the daylight. He squeezed Emma's hand tucked in his behind his back.

With a garbled stab at an apology, the bus driver disappeared around the back of the bus.

"No one else saw," Will said to her, "I'll step around and help Flores. That'll give you a minute." Emma nodded, letting go of his hand and slipped off the last of the bus stairs onto the pavement. She had to fight the urge to fling herself onto the smashed case and cover the strewn clothing with her body, but that woman from the bus was leaning against the railing on the pavement, watching. Emma looked up at her.

34

"Shall I help you pick up!" asked the woman.

To her own surprise, Emma found herself nodding. The two of them kneeled down without another word to gather the stockings, the soft bras and the slight blue panties from the ground. The woman was so quiet and so careful with Emma's things that the bride's throat closed over with tears.

"It's only clothing," said the woman quietly. "It doesn't mean anything."

"I know," Emma whispered back.

"Then don't let him see you cry," advised the woman. "He'll think you are ashamed."

Emma's hand hovered over a nightie and she flushed up. What did this woman know about Will, or about what he would think? She tossed the thing into her case.

"I'm not ashamed in the slightest."

Frankie heard the warning in the girl's voice and glanced across the suitcase at her, pleasantly surprised. "Fine," she answered. And then, as an afterthought, she added, "I'm Frankie Bard."

Emma looked into the woman's square but not unpleasant face framed by a dull blonde frizz of hair. "Hello," she answered.

"And who might you be?"

Emma threw the last of the things in the suitcase and closed the lid. "Emma Trask," she answered, snapping the locks. "Soon to be Fitch."

"Nuts," said Frankie with a disarming smile. "A bride. And here I had pegged you as a runaway."

It was the first time Emma had laughed in days. And she would always remember that bubble of her laughter overtaking her there on the sidewalk at the reporter's feet, her things disarranged, the green slant of the trees behind Miss Bard's head and the evening sun warm on her own back. Will came round from the side of the bus and reached out his hands to pull her up to him. It would all be all right, she decided there and then. And she had laughed out loud again, falling into the circle of Will's arm.

"Thank you," he smiled down at Frankie. "You've been a great help."

He had the good looks and easy manner of someone who is used to having the smile of the world turned upon him. "You're very welcome," Frankie answered.

"Let's go home," he said to Emma, putting his hand down to help her up.

"All right," she smiled and scrambled to her feet. And he grabbed

35

her suitcase with his free hand, never letting her loose from his side. Then off they started down the front street away from the green. Several paces away, Emma turned her head in the crook of Will's arm to find Frankie still standing on the pavement where they'd left her, taking a good look round.

She had ambled every grass alley, walked up and down each and every lane that stretched the three blocks between the two long streets in town, sketching into her notebook the slant of roofs, the exuberant ridiculous gardens writhing out of the tiny plots and the fishermen, stinking at the end of the day, walking their barrows home through the summer people, emerging in their linens and poplins, bathed and glistening from the day on the beach out in the late afternoon light, feathering over the lanes with their laughter and their bright unbelievable immunity, everyone out jigging for fun. Here in the land of vacation, Frankie had written then, nothing touched them, nothing dropped. They strolled and chattered, looking in shop windows, like water lilies nudging slowly down an easy stream.

Not much had changed. If anything, Frankie thought standing there, the town seemed slightly more mad for fun. The summer people were honking and singing and taking up their places on the porches and in the cafes, their voices lighting along the lanes like birds come back again to feather over the bone choir of this seacoast town. Sailors on shore leave walked in packs down Front Street, and the local girls linked arm in arm, pretended to look somewhere else. As she stood there, she heard a shout and then a crash, a clang of metal on metal, and then right away the swooning warble of a trumpet as the guesthouses along the rim of the harbor swung into sound, and a tea dance orchestra started to play.

Perhaps she had made a mistake coming here, she thought uneasily, leaning over to grab the handle on her bag. Perhaps there was no quiet to be had. Though Europe was falling apart, splintering and exploding, at least she understood the direction. But all this-she gazed down the street-motion without purpose, where was it going? There was a movie house now, and a dance hall, but the whoops and hollers seemed to come from all over town. The whole damn place was a cup and a saucer and everyone danced on the rim. She picked up her bag, her portable Royal, swung her satchel over her shoulder and walked to the end of the sidewalk, waiting for the line of Chevys and Plymouths to thin. She glanced over at Alden's Market and as quickly

looked away. Alden had said the door to her cottage would be open and she had packed some nuts and a bottle in her bag. There was time enough to reintroduce herself, this golden gleam of invisibility was too good to break. She stepped off the curb and crossed over, passing the broad steps of the post office and heading back in the direction she'd come until Front Street veered away from the water to meet up with Commercial, heading single-rnindedlv out of town.

37

Peter Campion Skin

Your other guests all tanked, all trickled out to traffic now that mole and marble sheen was the center of the whole apartment.

Your skin my fountain. Terraced avenues and fenced-off reservoirs where the searchlights swivel and dribble back, the water, dirt paths all ramified, all spinning around us. Five years and the night returned to faint traces of trellised jasmine and cat scent.

This phantom still locked outside the peeling porch clawing the cellophane and misted clover.

Stone

Impervious sphere that a glacier left for me to palm you shimmer then shut yourself with such finality you seem an emblem of the friend who "shut himself"

His ebullient dope on lover after lover opened the room and held us there so many times and he rose from his clinical blear so many times thumb and pinky miming some buffoon on the phone he made it easy to ignore his slow erasure turning us to the people jabbering to stone

as the two hundred dollars a week of powder left only his dresser drawer floating with photographs the moon of his forehead flecked by psoriasis

39

Dan Chiasson

After Party

After Horace

Helena, when you froth with the names of stars I wonder whether it's a star's kiss, a star's trace from last night's after-party that perplexes me.

You can't buy the tears that adorn my eyes on eBay or in the diamond district. Those bruises on you aren't temporary henna tattoos.

Some star put them there after the after-party, before he made you taste the back of his throat. I know what happens at those after-parties, where

Absolut sponsors everything. Everyone puts a drop of honey somewhere up inside their body and the game is, where is it, who can find my honey drop?

Meanwhile where is your Horace? Home, as always, translating some poet's thousands-of-years-from-now agonies into his frantic, ancient Latin.

Peeled Horse

After Horace

Helena, now that you have moved away to a patrician county in New Jersey, there's a horse under your ass, where I once was.

I would like to make that horse into an anatomical drawing of himself, all bone and tissue and staring eye sockets.

I've studied the masters: Battista Franco's cabinets of femurs and knees, and the banana-peel exposed skulls of Lucas Kilian-

how would you like to ride that peeled horse, its bone saddle rattling all day, turning your ass to bone in the New Jersey afternoon?

41

Georgie

Whether to twine the flowers around the maples, whether the chipped antler found in the sod

portend a hot summer, whether a hot summer portend interiors fogged by breath, reeking of sweat and shit, and can the hoe save us, and can the spade, and if we pot the peach pit in a terracotta pot

will we have peaches next year, will we have peaches ever, if the clouds overhead spell Angie and Ed

have we seen something spectacular? Is there a pilot somewhere with an agile plane who'll write what we say in the sky? I wish I were a tree, wrote Herbert for sure then I should come to fruit or shadewhat use, what use the pulse that makes the poem race weakens me, what use, I found a shriveled cherry and a shrimp tail in my suit pocket, I never wear it, you see, it hangs in the closet. The shrimp tail was mica and the cherry was a hardened brain. Until the sparrow nest upon me, 0, what use am I?

Georgie (II)

The flowers that fade, the flowers that don't, the wax begonias made to look like real ones

by an artisan in Quebec, the wax insects that buzz nearby and the wax fragrance that attracts them,

the wax lovers walking idly, their wax promises, the entire scene done in a shoebox with a peephole

to grant the wax lovers privacy, which is to say to make your looking, your mere looking, forbidden and therefore wonderful-what was that again, listenthis wax man and woman, what disappointment is it now bows him down, as she half-comforts him while her other half makes a call on a cell phone?

The flowers beam anyway, clueless. They ignore usif what I mean by "us" is the wax lovers, you and I,

making a fetish of our privacy again, putting joy in someone's eye. And that's what I mean by us.

43

Jennifer Clarvoe

Counter-Amores 1.3

All's fair; I think I'll let you go-too small to keep. And I don't care whether you call me back or not. Perhaps I've aimed too low (below the belt); I think I'll let you go.

You wouldn't last a minute as my slave, would you? (Oh, you don't know what you have to lose. Besides, I know your middle name, computer passwords, your recurring dream or nightmare that these secrets you record, that seem secure behind the darkened screen, open to other keyboards, every word winks like the girl you hoped would wait unseen.)

Love has nothing to do with it. I take what I want and lie about it later and blame you, sweetheart. Oh, I take the cake and let them eat it, too-and that's the matter, isn't it? Eat and be eaten. Who survives I might at last consent to keep as slave. Might. My sister Fates-one spins, one weaves, one cuts the thread. I do not grieve ever. What's dead is dead. Leave me alone and I'll get back to writing something else. You'll be forgotten when they read this poem: it's only better-than-average sex that sells.

44

The Lady of the Tapestries can touch the hom of the animal she loves so much, touch anchoring the world that she holds dear and lets go, praying, a man seul disir.

Tapestries unravel. Beasts are dumb. I think I'll let you go. (Or let you come.)

45

Counter-Amores 1.7

That Way

It is wrong for him to hit her in that way, across the face-completely wrong. That way madness lies. When Malkovich hits Kidman in Campion's Portrait of a Lady, man turns beast. But Gilbert Osmond is a beast to Isabel when he is least a beast, when he refuses to display his rage at her; he is most cruel when his rage is coldest, softest, quietest-and she cannot fight back, can hardly even speak or move. His tone, when he at last does speak is grave, sincere, with all the subtlety of the subtlest threads that tether her, subtlety so much more cruel than outright violencethat's why it's wrong, that outright violence. If he had hit her, that would let her goit would explode in her and let her go. When he hauls off and hits her, he is changed just as surely as Lycaon is changed into a wolf by the force of his emotion, and Actaeon to a deer by his emotionchoked with rage the tyrant cannot speakthe breathless, panicked victim cannot speakthe body registers rage and fear past words, and Isabel and Osmond are past words, where words can't reach, about to burst the story at the bursting point: this is the story that tells us, now that violence exists, it exists the way the real body existsto free us, from the things we do not say. The body exists to free us in that way.

Michael Collier Turkey Vultures

The red drill of their faces, pink tipped, grubbed in gore, cyclopean in their hunger for the dead but not the dying, lugubrious on their perches from towers, in trees, where they convene like ushers on church steps.

Heads sculpted to fit cane handles, claws to dibble seed, to sort out the warp of sinew from the woof, unwind the gray bobbins of brain. Assiduous as cats as they clean, wing scouring wing, until the head polished like a gem gleams,

and the ears no more than lacey holes are sieves for passing air or molecules of gas. These birds, who wear the very face of what will lastcongregating but not crowding, incurious and almost patient with their dead.

47

Common Flicker

Old nail pounding your way into bark or creosote, intermittent tripod of legs and beak, derrick, larvae driller, when I look up from my mind I see what you are: feather-hooded, mustached, gripped to the steady perch; an idea of the lower altitudes sparged with color, a tuber of claws and wings and an eye unmarred.

Wing�handled hammer packing the framer's blow face stropping the hardness, drumming and drumming, your song is your name.

This will cure me, you declare. This will heal the fractured jaw J soothe the vibrating helve so I can eat J so I can sing.

Merle Collins

The Wealth of the Dreams

When those who were still alive gave Normandy his allotted six feet, they piled the usual amount of dust behind the door. Their industry heightened by the mournful hymns honoring his departure, the diggers shoveled in more and more dirt to make the door secure. But once songs were done and people gone, the part of Normandy that was not body would not be held back by the body's confinement to dust. There were people he wanted to see, and eventually, also, messages he wanted to convey.

When he visited the daughter, she woke without any memory of what he looked like during the visit, woke knowing only what his instructions were, where she should go, what she should do. She thought of it as a voice speaking to her, but perhaps it was more like a hand indicating the things to be done. She wished she could say, like the mother said, that she had seen him standing on the other side of a clear stream, large as life. But when she recalled the meeting there was no stream, no body, not even a voice, just the memory of a feeling, the knowledge that there was something to look for and a particular place to look for it, the certainty that this knowledge had been transmitted to her by the father.

The mother talked about it all-the visits, the stream-as if she weren't really interested. The sons seemed amused when she told them. But the daughter remembered finding, once, a letter that talked about longing. The mother had looked at it, folded it, and put it in the

49

pocket of her dress. She'd said, "Is a wonder the way mother's things belong to everybody and everybody else's things belong to them alone." And the mother had turned to the kitchen window, humming a tune with no name, no apparent lyrics. The daughter remained troubled by the thought that between the parents there must have been some spark, somewhere, not too long before, for the father to have this thought about longing and write about it. She couldn't imagine it, a longing between those two people. The mother had always acted like no spark ever existed, at least not a huge one, and even though you might imagine she had once been affected by a dis-ease called youth, it was definitely not, thought the daughter, a condition that would explain her being associated with longing into her fifties, which was about the time the note was written. The mother had always warned about the dangers of sparks ignited by the opposite sex and now here she was, receiving a letter that suggested she might be, or might have been, susceptible to just such igniting. The daughter didn't like thinking of the mother as someone susceptible to sparks ignited by the opposite sex, and certainly not by a father known for the careless igniting of sparks among various people. And with these unsettling thoughts still at the back of her mind, she was not impressed by the mother's offhand attitude to the father's visits.

It was true, though, that on principle the mother didn't think people should show too much interest in the dead when they visited. Besides, she did have some unpleasant memories from those forty-five years of life with Normandy, and those memories were the ones that occupied her head in the days immediately following his departure. Sometimes, when the boys phoned from America, or when her sister came by to visit, the mother would say, "you know he was around again last night," or "he came by night before, you know." Once, she said, she got up knowing she had talked to him but couldn't quite remember what about. She explained to the daughter, "It was just as natural as ever, like me and you talking here."

One night, he came with a truck to pick her up. "I was in the truck already," she said to the daughter and to Mr. Jonas, who had stopped by to find out how things were. "I was going with him, but then he stopped to give somebody a lift. You know what he was like, always stopping to pick up somebody." The mother made a wide sweep with her right hand to indicate the number of stops Normandy had made along the way. "That was him," she said. "Tout moun-everybody. One thing you could say about him, he wasn't selfish with his vehicle. And

50

if you sitting inside of it and you busy, you still had to wait while he picked up people. Now he's over there, and still wasting time stopping for everybody on the road."

Mr. Jonas said, "I could vouch for that; a very nice man with his vehicle."

The mother turned her head toward Mr. Jonas, but said nothing. And then a breeze picked itself up and pushed the banana trees until they were bending low to one side. Up on the hill, a branch from the mango tree gave a crack that made everybody tum to look. Mango always made sure it never looked too unbending in the wind. Its branches would try to acknowledge Wind's presence with a bow. Even when Wind didn't push hard enough for Mango to bow, mango leaves would rustle in acknowledgement of Wind's presence. That way, there was no need for Wind to push hard, because Mango made sure the world knew that, tall and imposing as it was, it was not too proud to bow. But this time, Wind seemed to want to make a special point, so it pushed hard at the mango branches. And a branch crashed down on to the gliricida tree stretching up below Mango, stayed hanging there for a few heartbeats, then sank noisily to the ground, dragging part of the gliricida with it. And everything went silent; quiet, quiet, like the world was holding its breath while some body or some thing went by.

Afterwards, when you could feel the world take a breath again and continue, Mr. Jonas said, "Miss La Porte, you realize somebody was passing?" And the mother, the daughter, Mr. Jonas, all of them nodded in understanding.

So most people knew that Normandy La Porte was a continuing presence in and around Bwa epi Dlo. People were always making comments and giving advice about this.

One man said, "I not surprised; I know he couldn't leave just so." Another said, "You must put a candle on the verandah, Miss La Porte, to help light his way."

And another suggested, "He just want to see how things going. He don't mean any harm; is not a bad spirit."

And just to prove that Normandy was around in truth, a green cricket made its appearance on his clothes brush one morning. Auntie Eva, who stayed with her sister at Bwa epi Dlo most times now, said, "Well yes, that settle it. We don't need more proof than that."

Some days, the dog---called Tres by the daughter because it had barked three times when it first came to the house and Auntie Eva thought that symbolic-Tres kept whimpering and wagging its tail and

51

looking up the hill under the grapefruit tree. A clear sign that somebody was around, Auntie Eva said. I could tell from the beginning that dog had something special about it.

And although Nana didn't want to tempt Fate by being too welcoming to the dead when they came by, she accepted her husband's visits as a matter of course. So when the mango crashed down on to the gliricida without warning, she knew there were more people listening to her than she could see, and that was all right with her. Everything she was saying in her story was true. "So, anyway," she said, "he stopped for this man. And then I decided that I couldn't go yet. I had to go back because I forgot to close the door. And he said to me, 'Okay, go on. I'll wait for you.' So I got out of the truck and walked back."

The daughter asked, "He told you to go back? He reversed to wait for you?"

"I don't know. I just know I went back."

"But let's get this thing straight. You had left, remember?"

It annoyed Nana, this way the daughter had of pointing things out. In fact, she didn't like the way generally that the younger generations wanted to cut and measure everything. They liked to say, "let's get this thing straight," as if things in life were ever straight, as if the straight way you could see things with your eye was the only way that existed, as if it was any kind of straight way at all. It was as if young people, or at least younger people, because some of these impatient ones not even that young, it was as if they didn't feel good if they couldn't put each thing in its proper comer. Good luck to them. They would have a lot of not feeling good to deal with, because most times things just don't have a proper comer. But young people were like that. Sometimes they asked questions as if their lives depended on it, very careful about the questions and not even waiting to listen for answers.

And Nana told the daughter, "I don't know how you dream, but the way my dreams go, things don't happen one after the other. What I tell you is what I remember. I came back." And she was irritated enough to add, "You're a dream doctor or something? I tell you the story as I remember it. He let me get out of the truck, I went back, and for some reason it took me a long time to close the door. And I looked down at my clothes and said to myself, I can't go like this, my dress too dirty. I not ready. I have to go and change. And he probably sent the man to see if I still wasn't ready, because I could see him-the manpeeping from the other side over there, looking for me." And Nana lowered her head and positioned her hands on the chair, looking to-

52

ward the garden outside, so that the daughter turned to look at the bougainvillea, purple and prickly, half-expecting to see a wall and a man straining to look, feeling a little bit foolish and a big bit relieved when she saw only the purple bougainvillea, thick, sturdy, unmoving in the breeze. Mr. Jonas looked over to the big tree behind the boucan where they used to store cocoa and nutmegs and produce from the fields. He could remember Mr. LaPorte pointing his gun up into that tree by the boucan and shooting a manicou clean dead. Mr Jonas cleared his throat and looked at the mother, waiting for the rest of her story.

"I don't know what else happened," Nana continued, "but I know I didn't get back into that truck. Or you would be looking for me this morning and I would be clean gone."

And Nana laughed the laugh of the calm at heart, the ones who could say something like that because being clean gone was not an idea that troubled them in the slightest. The daughter watched the mother but didn't laugh with her. Mr. Jonas, carrying a face that didn't open itself easily, slapped his water boots with the flat part of his cutlass. The mother and daughter looked down at the cutlass and the water boots, recognizing the print of the sound. The father used to do that slapping sometimes, making that same sound.

"Praise God," Nana said, moving her eyes from Mr. Jonas' boots to look first at the land and then at the two people listening to her. "Praise God and hope for the best, is my philosophy. I like to think I'm reasonably sure about something good the other side, because God not evil, and he could see if you're trying your best. And it makes no sense killing yourself worrying about what will happen whether you like it or not. But let him go his way," she said of the husband who kept insisting she follow him. "Let him go his way," she repeated, looking at the mango tree and at the gliricida branch askew below it. "He had his time, and although I'm ready to go any time, I want to live out all of mine. Let him go his way," she told the mango tree, "go, and leave me alone."

But although Nana was putting up a fight because she had a mind of her own and the strength to go with it, she knew, of course, that people who had gone before did not always leave the living to their own devices. They helped in various ways, but were generally good about not interfering too much, and would make their presence felt mainly when a situation was out of control, when, as the saying goes, water more than flour. Those who had gone long before were usually the ones who were more restless, and although most times they kept quiet, they could get noisy when things were too obviously not going right.

53

And that had happened one time that nobody would ever forget, a time that came to be known on the island as the time of the dreams. One person after another had a night visit from an old head during the time of the dreams-from a grandmother, or a great,grandmother, or an old lady they didn't recognize, or an old man who looked familiar but whose face they couldn't quite place. People couldn't generally remember what these visitors said, but those they visited came back to the world of the waking with a profound sense of desolation, a sense of instructions unspoken, of something horrible that must be rernembered, a distress so debilitating that it kept people looking woefully all about them. People dreamt of visitors standing, weeping and moaning, of streams of dirty water, of strange figures-very short, waddling men, women with long white dresses-figures sharpening cutlasses at a grinding stone that kept turning and turning with nobody there to tum it, nobody even pouring water to wet the cutlass while it was being sharpened at the stone.

Everybody had a memory that lingered from that time of the dreams. In those days, Normandy was alive-in fact, he wasn't to take his leave until a full thirteen years later-he was alive and he said then that the noise of streams in Bwa epi Dlo was louder than ever, and it was becoming more frustrating that he couldn't see them. And night visitors had come streaming through Bwa epi Dlo, walking in long lines, rushing from mountain shelters in panic, moving towards the sea, looking over their shoulders with faces full of fear, hurrying to make a getaway in small fishing boats. Normandy saw them. Norma, who was living with Nolan at the time but visited every so often, saw them, and even Colin, who was just out of school and still living at Bwa epi Dlo in those days, saw them as well, because those were the days before he stopped knowing how to dream. Carl was living some' where else with his wife and his mind was probably too full of confusion to dream, so he saw nothing. And for some reason the dreams did, n't come to Nana. You can't say for certain why these visitors do the things they do. You have to judge from what you know about those they come to visit, or those they choose not to visit. Perhaps they knew Nana well enough to feel she would ignore the message. They knew she would be inclined to shrug her shoulders and say, well, if a thing is to happen, it will happen. So you could guess from that they were leaving their message where there was at least a chance somebody would want to do something about their feelings, even if they didn't know what to do.

54

In that time of the dreams, one woman had her visitor not when she was asleep, but in broad daylight; so you have to believe these messengers were desperate. The woman was walking home one evening, not too late, really, about half past five, and she was alone on the dark stretch of road near to the old sugar mill, the part where all the trees touch each other and link leaves across the road. She realized that a man was walking toward her. An old man, barefooted, khaki looking clothes, she said she believed afterwards, though she couldn't be sure. He weaved a bit in the road, stumbling from one side to the other and back again, and the woman thought he looked drunk. In fact, she thought at first it was Mr. Juice, a man people had christened with this name in honor of the sugar cane juice, because he boiled the rum him' self and he drank it like water, so that his walk was always wandering and wavy. But then she realized this man was shorter than Mr. Juice. And for some reason she didn't look too closely at his face. They say things happen like that, you know. These visitors could keep you from focusing. So when you asked the woman afterwards what he looked like, she would say: He was barefoot. He was old. His hair was gray, I suppose. Hardly any hair at all, I think. Or she would say: He was old, I think his hair was gray; he was barefooted. What she remembered, though, was that when she said Good Afternoon, words so natural that the man would know he just had to say the usual, Good afternoon, dear, and go on his way, or if he was too drunk to answer, just go on his way, but instead of a very natural and very human response like that, he said something totally unexpected. He was moving in his wandering zigzag and mumbling, so that the woman kept moving slowly and she watched him out of the comer of her eyes as he mumbled. And what you think he was mumbling?

"You find the ax? A gold ax? You see how they cut me down and now I have no place to stay? They used a gold ax. You have to find the ax."

The woman said she heard the words but they didn't really register until later. She said she wanted to stop and tum back to look at the man but she couldn't. She said it was as if something tie her. You know how sometimes you're in bed but you're not really sure you're asleep, and you know you're trying to move but you can't because it's almost like something tie you to the bed? That's what the woman said she felt like when she walked past the man and heard him muttering. Still, be, cause she was a woman with a very determined spirit, she forced her head round so that she was looking back over her shoulder. And she could see him, hand lifted slightly as he stood, back to her, weaving

55

and mumbling: "Not any ordinary iron ax," she heard him say; "not a silver ax. A gold ax. You must find the ax."

And by the time the woman was back to herself, by the time she could tum fully around and give the man her attention, he was leaving the road to go down into the track, near to where somebody had bought the piece of land below the road and had just cut several trees, making the ground ready for building. The woman was curious enough, and brave enough, her friends said when she told them, to walk back and try to get a better look at the man as he made his way down into the clearing. But although she looked down, she could no longer see him, not in the cleared land below the road, not up or down the road on which she was still standing. She wanted to dive down into the clearing to look, she said, but she didn't have the courage. Something was telling me not to do that, she said, and everybody could understand. In fact, people only wondered why the thing hadn't told her not to walk back and try to see anything.

Since then, the woman looks with care into the face of each person she meets. She wants to be sure to recognize messengers when they come. But now as far as she can tell she meets only the living, who also communicate strangely at times, but by and large she is able to find help unraveling what they say. The good thing is, now that she is keeping an eye out for the dead, she never misses an important message from the living.

56

w. S. Di Piero

All in One Day

Fat ravens chop from leafless elms and sail like shadows across my window, nervous souls backlit by a reddish sky full of snow that hasn't fallen yet. Waxwings passed last month to stuff their crops with holly berries. Starlings cry from wires

Today's news says a dark, unworldly matter makes up the universe we call ours, passing through everything, leaving no trace, we're drenched with energy that blows stars apart and farther from us speeds explosions I see in dreams, like last night, when each time I named a constellation it became another.

On a day like this, crows budding on the crabby oaks, the blood ghosts I see in human forms could be a necessary fantasy of nerve cells, dopamine, or appetite, bodies modeled from phantom fluids, passing through a world that doesn't exist, or exists in the mind of God.

I thought the child hooting at a ruff of fallen leaves would shovel them at me like a war or bridal game, but the armfuls scooped above her head rattled down,

57

wrinkled flames on her shoulders, and she tested its atomized perfume, clapping her orange mittens, fall's first child, hollering

Come down here, you!

That's when I felt most alive inside matter's reechy stuff, unseen, intensely real. Later, riding into town, held and rocked by the L's steelworks, from my seat I saw the season crouch behind the platform, and a college girl, pigeon-toed and pale, standing there in bawling November, rails and gravel moonlit like snow, the world's freaked bark scraped to pith, an express blowing through whipped leaves around her feet

Our mud-flake life, and rain sheets, contracting to a brown, glassy drop that clung to her reddening hair.

58

Increased Security

Venus, demure tonight, as always, sharp in my western sky, which flops each time the Fourth of July's sheet-lightning fireworks blow from the eastern side of town, hooping embarcadero lights, black bay and bridge, star light, star bright, seer, solid and chaste in her infinitude, calmly waiting to watch the oceans buckle, cities bum, while Catherine wheels and maypole pom-poms mock her constancy, far off sugared surprises flaring orderly reds and purpled blues above the silent pod of black-and-whites and fireboats, fighter jets cruising, chopper beams fingering the crowd

I can't see here, don't need to see to know that while kids sing a jingling brass band march, be kind to your web-footed friends for a duck may be somebody's mother, the sky shrieks at Venus, mother of all, who watches from her distance, hears the booms and alarmed whistles over the heads of mothers who squeeze their children's hands, fathers boosting sons and daughters up onto their shoulders, the better for them to catch the air, for balance, still grabbing at the artificial fires we all look up to, while we wait for more.

59

Sean Enright

Allen Ginsberg

In the ultimate tribute to a great poet, I am going to make it with Allen Ginsberg, he will be the first man I have ever diddled, so don't be surprised if nobody comes.

This bang ensures my passage not only into the venue of Allen's cosmic love, but also into leftist journals and gay porn mags. Margins across America bend and I hop across, Hellman's in hand, since a large straight white male normally gets it on with the following ingredients only: soybean oil, whole eggs, vinegar, water, egg yolks, salt, sugar, lemon juice, natural flavors, and calcium disodium to protect flavors that tend to merge if left alone to simmer together in the pot, the spices getting it on with juices and the oils helping everybody flop, even the eggs.

Allen is probably humping Jerry Garcia right now in the vast Buddhist nil, worlds colliding and not just metaphorically, Jerry wanting to dick and boink, to scrog and strap and ball, and Allen mounting, riding, humping, creaming, getting off and making the scene, but I'm not jealous, I have grown large-hearted in your death, Allen, like the simpering nephew.

60

Allen, my Allen, welcome to my authentic ritual of universal confluence, my merging of all disjointed parts of a universe touched by your love. Sober as sand, I meditate toward the whole of things

I can't seem to see, beyond my piece of the puzzle. Talk about a plot, my father worked for the CIA, so you can imagine how paranoid I am, who practiced steaming open envelopes with him, above a shrieking kettle. He was looking for answers, too, but other people's answers. I won't condemn him. He died unable to catch his breath, not even cool enough to take the joint I held out to him.

Allen, I pray wherever you are you're getting it on with the best of them, giving Dante what-for, jumping Marvell's bones, lollygagging and getting some, because

This ain't the song This ain't the song that would do you wrong

Halloween

It is the night of the dead of the night. I fumble for the triggers of my household ghosts, Gone to gods, my father who sometimes called me Lad, And my grandfather who until I was thirty called me Boy. Soon my father is fiddling, fiddling with his Jugular bolts in the foyer. Grandfather muses about where he Left his cape and noisily files his teeth with a rasp.

Remember Yeats? He longed to sleep on a wooden board

To discipline himself. Tonight I love him, layout wine for my dead, Who drink when I set my glass down, sipping my breath With their avid senses, playing impossible pre-physics tricks, Enamored with the ways I scratch and waste time I later recall as being charged with meaning. My ghosts of value! Oh wavering accountants!

Outside, the miked pumpkin moans the open vowels Of Rachmaninoff's Vocalese, that totemic, pulmonary, grim song. Toys scattered across the grass roughly Symmetrize our son's failed mission to the moon: A no-terrain vehicle upended on a tree-root, a spade, A strainer and a sunflower pennant stuck in sand, His one small leap across the front yard.

He is outside, waving the steel Army-issue whistle

My father never got to give him. My wife wears her hair down like a willow. Other houses on the street sit back, gasping. It is Enough for them to have sent their envoys to our rite: The slow girl dressed as a tango dancer, a fiddler crab, A cat and a red-headed Ninja. Another father is dressed

As Alice Cooper, with scrawled-on eyeliner tear tracks And a tiny laughing bag hidden beneath his coat. We pass among trees made silver. A word made unanswered. The cowboy who is also my son shows his candy to Death

Who comes as the boy in black from across the street, With a black mesh face, and an unwhisrling paper scythe.

Elaine Equi

Flaunting My Inertia

like a droopy coat of arms. Always languidly on edge, the less I do, the more exhausted I become, and the more I envy those who do even less. Call me an energy conservationistgrown giddy with the thought of wasted time. Even in nightmares, my own fears take after me with slow relish, knowing there isn't any need to hurry. Here is a girl who never ran for anythingnot office, or a man, not even a bus.

Today is the First Day of the Rest of You r Life