Editor Susan Firestone Hahn

Associate Editor Ian Morris

Operations Coordinator Kirstie Felland

Production Manager Bruce Frausto

Production Editor

Vincent Chung

Cover Design

Gini Kondziolka

Assistant Editor

Eric LeMay

Editorial Assistant Cara Moultrup

TriQuarterly Fellow W. Huntting Howell

Contributing

Editors

John Barth

Lydia R. Diamond

Rita Dove

Stuart Dybek

Richard Ford

Sandra M. Gilbert

Robert Hass

Edward Hirsch

Li-Young Lee

Lorrie Moore

Alicia Ostriker

Carl Phillips

Robert Pinsky

Susan Stewart

Mark Strand

Alan Williamson

108 The Daughters; On the Line Today; By the Sea

Richard FoxIII Physics & the Secret of Nothing; Cloud Journal

Christopher Buckley

117 A Poem about a Refrigerator

BJ Ward

118 Mrs. Dati; Q and A: Do you write about real stuff or do you just make it up?; The Direct Address: Dear Reader,

Julianna Baggott

121 The Case Against Daedalus

Fred Dings

122 Riddle, Two Years Later; Why We Shouldn't Write Love Poems, or If We Must, Why We Shouldn't Publish Them; Once I Did Kiss Her Wetly on the Mouth

Beth Ann Fennelly 211 "Et Cetera"

Charles Rafferty

Quezaltenango

Jeff Tietz 213 Contributors

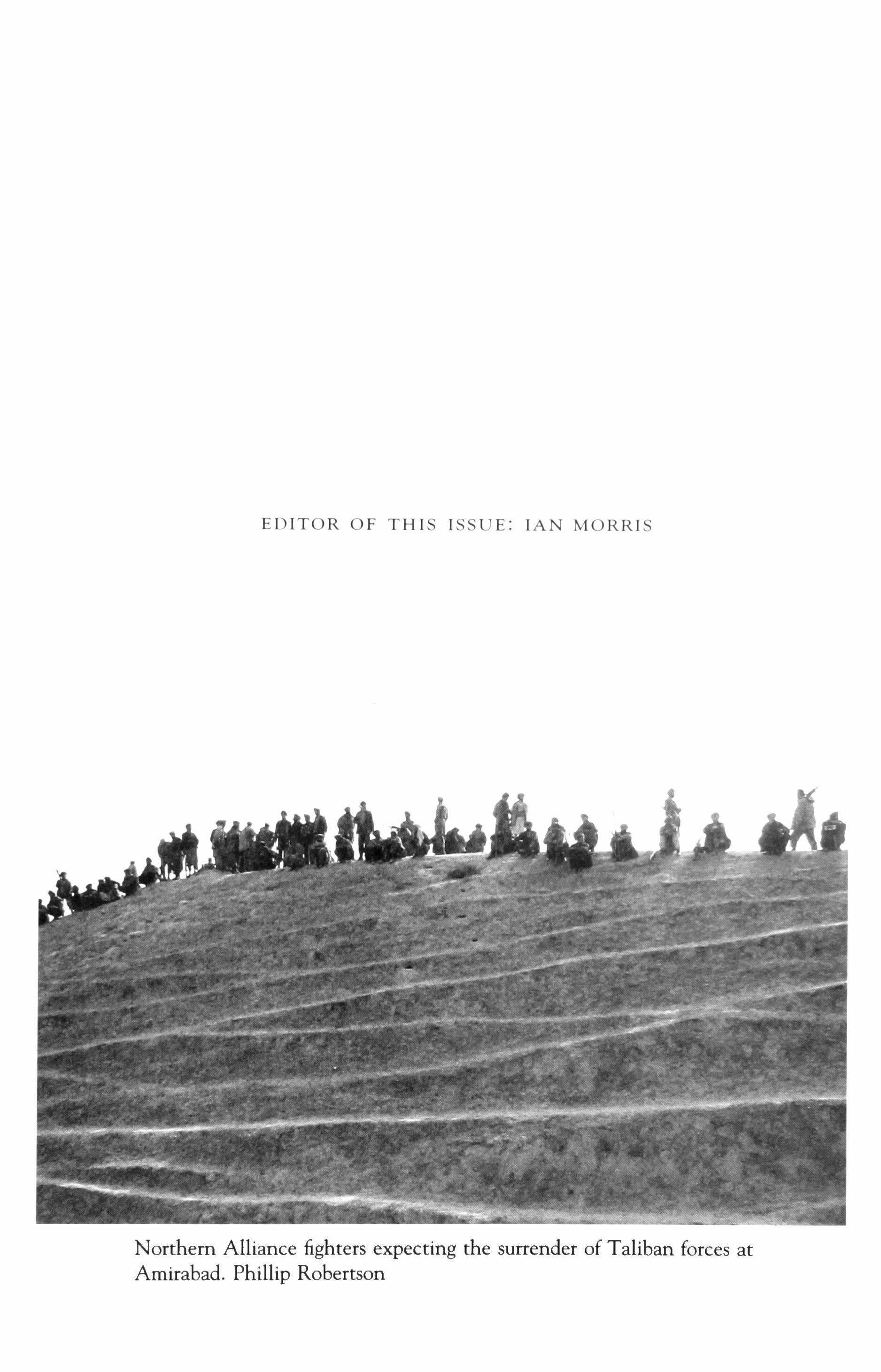

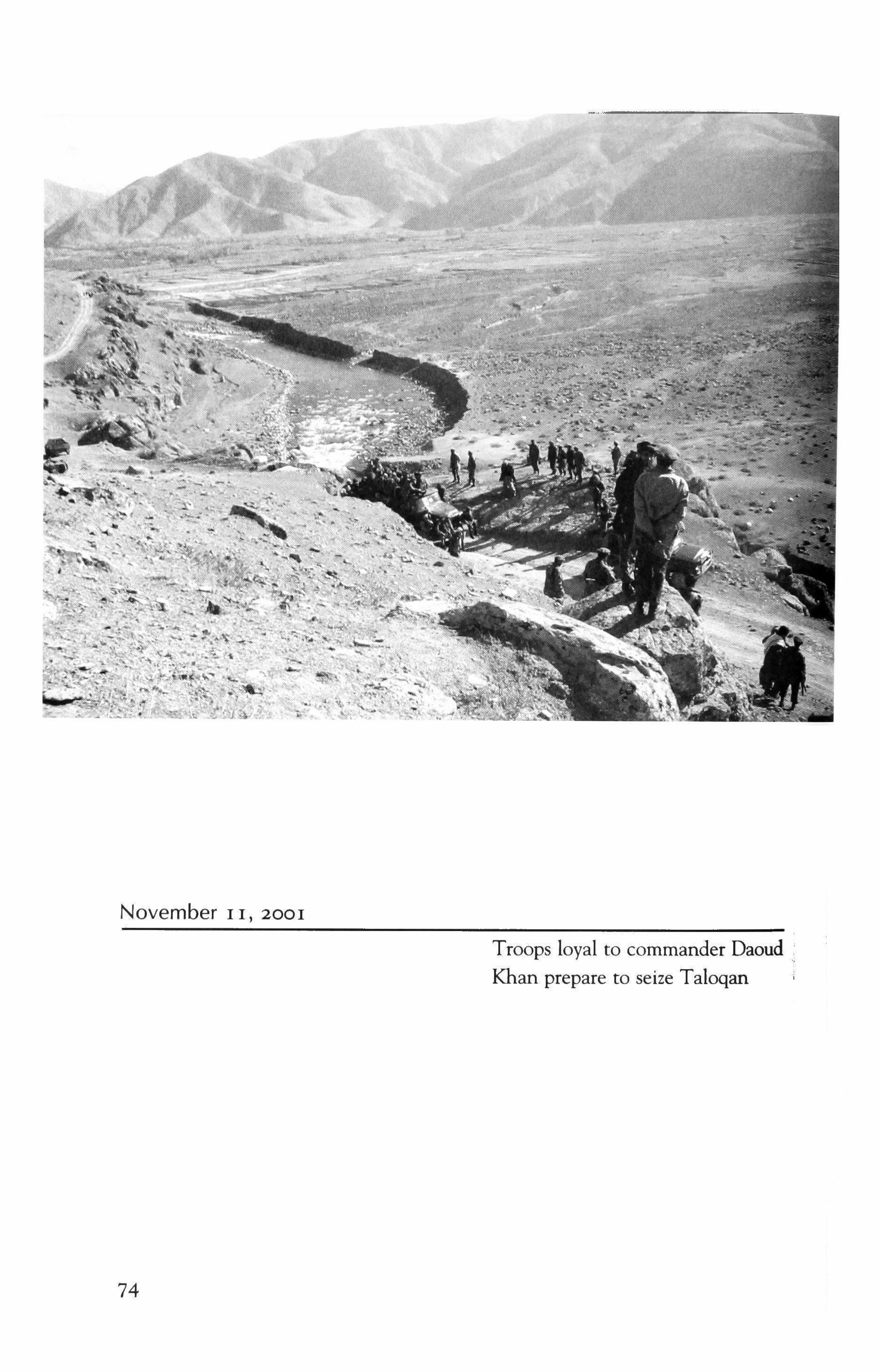

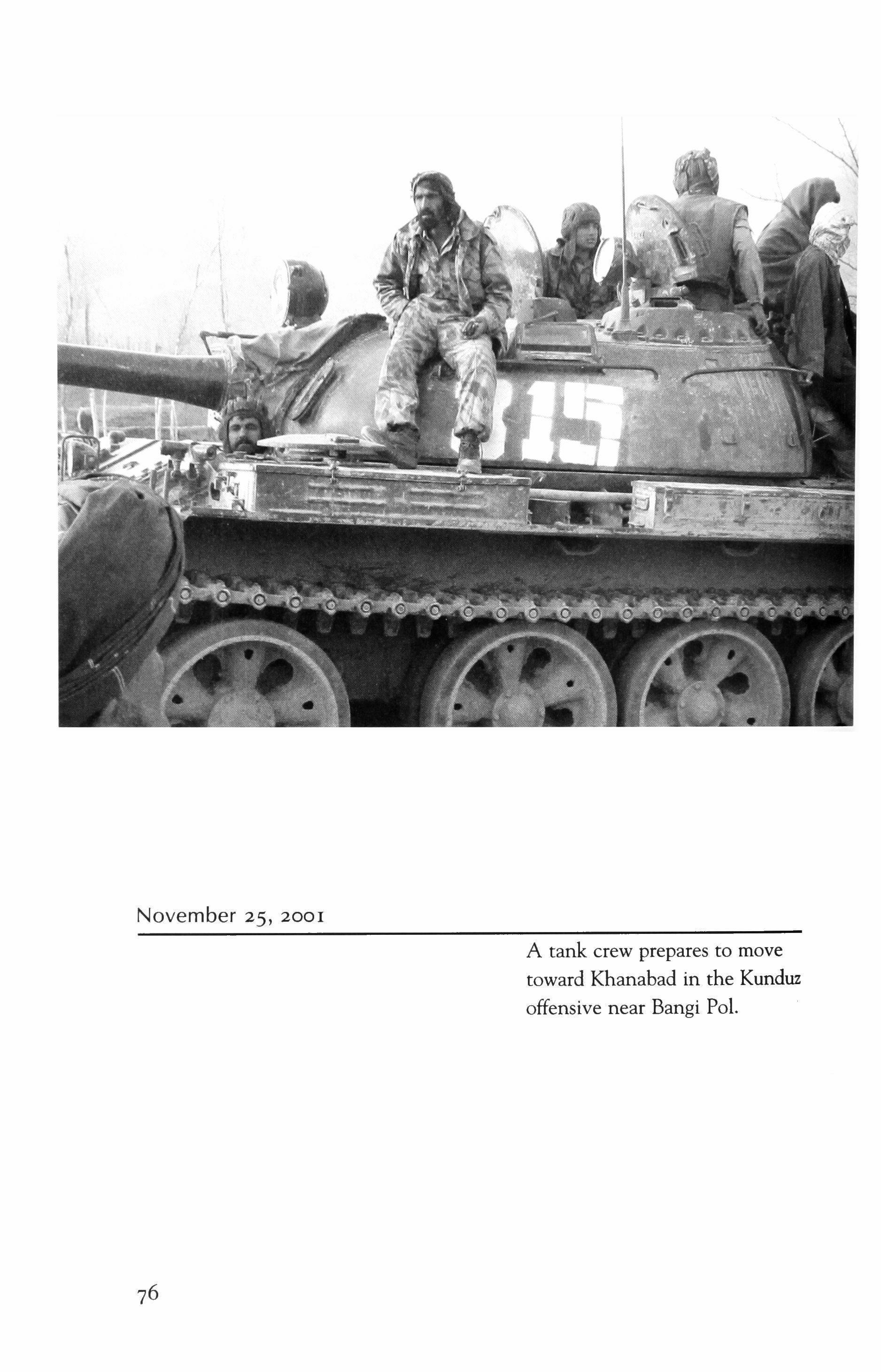

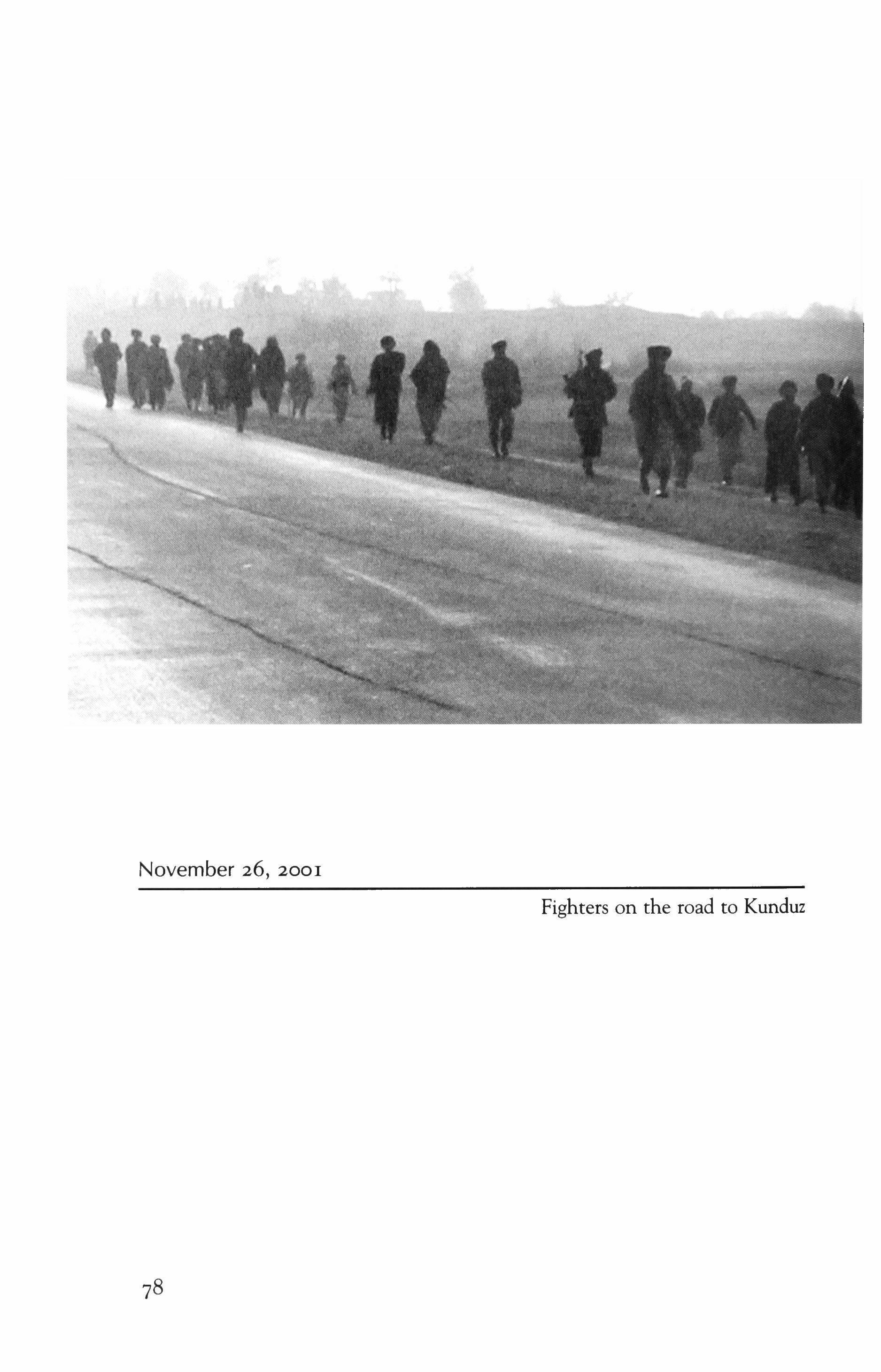

Front Cover: Fighters on the road to Kunduz in the moments before the battle for the town, November 26, 2001

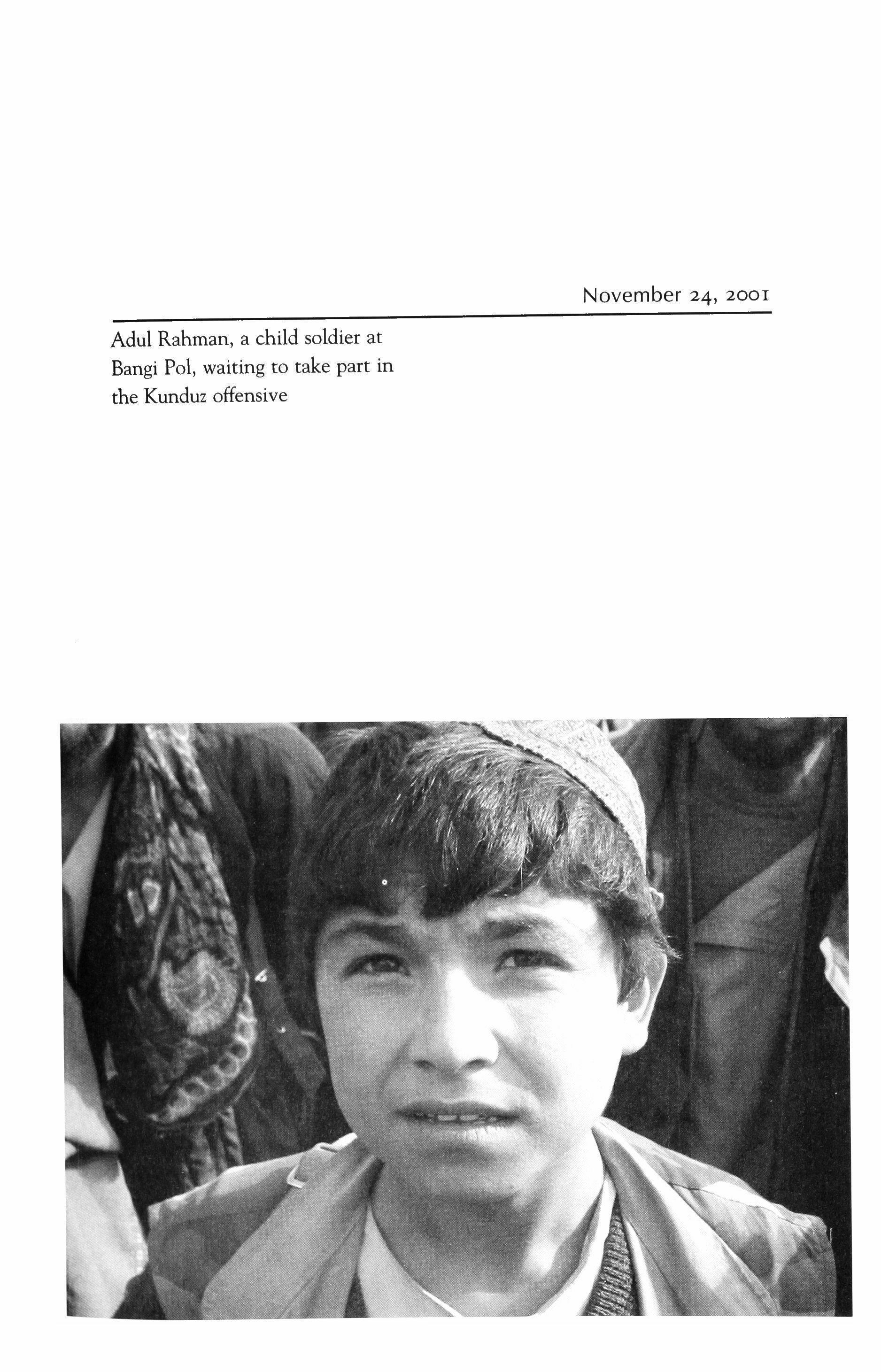

Back Cover: Uzbek shepherds drive their flock through the front near Bangi Pol, November 24, 2001

Photos by Phillip Robertson

Already catastrophe!

In the small peasant village people arise

To Sophie's betrayal of Juan, Her loving intended, in the night. Juan is loose like a jaguar, and Someone is going to die.

Some vocal ruminations first though.

Sophie: How strange, how voiceless the larks today.

Juan: How hot the fired steel of my rage

Those times my dearest fell to slights of devotion.

Soon all the villagers gorge on this infidelity.

More songs and crescendos. Three mocking crones

Loose howls on stage, as Sophie's new man Croons, falsetto, in transit to the country's borders.

A waft of hope: pleas made, souls scraped raw While honor wrestles forgiveness.

Thunderclouds boiling, over the housetops. Trumpets! Shouts!

All of the villagers gather for blood flow, In chorused horror.

Let it happen, The gushing from chests and bellies.

LARGE GLISTENING DROPS DESCENDED SLOWLY AGAINST A BLUE MOUNtain cliff in the background. Delighting in the shushing sound of the downpour, Haris remembered one of the early Buddhist Suttas: "I am free from anger, free from stubbornness; I am living for a night on the banks of the Mahi; my house is roofless, the fire is extinguished. Rain on now, 0 cloud, if you will!" Maybe that meant, Don't worry and rejoice in the rain; or, attack me now that I am exposed and see whether I care.

And only when the downpour came to his ridge and hit him, did he realize that it was a hailstorm-white ice, the size of sparrow eggs. For a moment he imagined the hail was sparrow eggs which could feed the whole Bosnian nation (except the nation was no longer whole, and never was). You'd collect the eggs and boil them, and eat them in the flimsy shells. To avoid the falling assembly of water stones, he walked under a canopy of pine trees.

He sat in the lotus position, inhaling the aroma of rosin, while his pants grew soaked from the prickly ground. He buzzed "Om" to end his meditation, but instead of emptying his mind and attuning it to the harmony of the universe, he thought how coincidental it was that the electricity resistance unit was designated by the same sound, Ohm. He thought whimsically that his mind was an Ohm-meter, and perhaps the harmony of the universe consisted not of going with the flow of the forces but in resisting it. He walked out bowing to avoid the low

tree limbs-the needle rows on the branches resembled spacious garments on the arms of Jesus or some other loosely clad prophet who stretched out many hands as though he had become Shiva-and nearly bumped into Hasan, who said, "You're talking to yourself or something?"

Their sergeant passed by in a personal cloud of tobacco smoke.

"Shit, this business of being Muslim sucks," Hasan said. "We should get wasted on slivovitz, and we aren't allowed a drop!" He trumpeted his nose, whose tip, once released from the grip of the thumb and forefinger, changed from pink-white to glowing red. "A shot of brew would cure me, I swear. A few jokes would help, too. Can you tell me a good one?"

"Hum. Can't think funny right now."

"If you can't, I'll tell you one. Coming home from Germany, Mujo drives into Tuzla in a new Mercedes, and he rolls down the window and waves to the people in the streets. Hey, what are you waving for? his friend Jamal says. Almost everybody now has a Mercedes. Yes, Mujo agrees, you are right about that, but not everybody has hands." Hasan laughed and repeated the punch line but Haris did not laugh.

Hasan cleared his phlegmy throat and spat. "Whoever invented war should be killed-it's so damned boring."

Haris took another deep breath, savoring the pines, and exhaled, feeling the hairs in his nostrils tickle. Perhaps he should have pulled out the nose hairs, but then, why would he? They probably filtered out the dust and now enhanced the smells. Snakes smell with their tongues, and who's to say we don't with our hairs?

Hasan stared at him, with his bulging blue eyes, and said, "Oh, I understand. I am not exactly an enthusiast myself. I'll let you in on a secret. I'd rather be sailing, but I was drafted."

The hailstorm was over and the last echoes of it exhaled a lush silence, and with his eyes closed Haris luxuriated in the aftermath beauty of the vanished sound.

But the quiet was short-lived since Hasan continued talking. "How about you? Did they hound you down?"

"I was a pacifist, still am, and I dodged the Yugoslav People's Army draft. But in Sarajevo, the park I used to gaze at from my favorite cafe disappeared. People cut down the trees and burned them at home in pots and makeshift stoves, smoking up their apartments. The park became a bald meadow, with little tree stumps sticking out, like severed arms, with chopped hands gone, as though the trees had stolen-what,

air?-and were then mutilated according to the Koran laws. I thought, you can't take trees from us, and I volunteered."

The sergeant limped back out of his cloud and said, "What are you two jabbering about? Come, join the group."

They followed him. "Our scouts are back," said the commander, a husky man with a black and white beard (white on the cheeks and black on the chin). He pointed out two thin men, who looked smoked out on cigarettes, with sunken cheeks and sparse yellow teeth.

"Tell them what you told me," said the commander.

"Holy Smoke," said one of the scouts in an amazingly low voice, "we made it to their position. You can go around the mountain, and there are no obstacles. They have no idea that we are here."

"They don't even have guards posted outside their camp," said the other scout, blinking, while one side of his face twitched. "You can see them down there." He invited the soldiers to the ridge and lent them his binoculars to see the men who roasted a pair of oxen on spits and placed lambs to cook in the chest cavities of the beasts.

It was dusk and a mist arose from the valley and covered up the distant scene.

The commander laid out his plan. One half of the troops would go around the mountain, and the other would attack directly from this side, in two hours.

Haris and his companions walked gingerly for fear of stepping on mines even if the scouts had no trouble beforehand. Not only would the mine hurt whoever stepped on it but it would also reveal the Muslim position.

They approached the upper edge of the camp. Haris tried to control his breath, to enjoy the aroma of plum trees and roasted lamb-flesh, which wafted on the mists, but there was no enjoyment in his breath and no self-control. His heart pounded into his lungs and interrupted his breath, and it skipped beats, and accelerated in a rush, syncopating a strange rhythm he hadn't experienced in a long while, of pure fear. The mist probably made it safer to advance than clear air would, but it added the invisibility and unknowability, No meditation and no mantra could slow his heart now.

All of a sudden, bullets splashed the mud around him, startling him. Guns right next to him fired back into the mist, to where the shots resounded.

"Forward, for Bosnia and Allah!" the commander shouted.

Haris fired into the sounds, and crouched on the ground, and then crawled forward, with mud freezing his elbows and knees, which he didn't mind, nor did he mind sharp stones scraping him since his fear acted as an anesthetic.

They kept shooting and getting closer and closer to the fire, and suddenly, there were men upon them, and they hit one another with rifle butts, bayonets, knives, and fired from close range, and even wrestled to strangle one another.

Shrieks, and swear words, and prayers, and mother's and father's names mingled with bullets and blood and urine. The two companies of soldiers fell upon each other as though a medieval battle were fought, or even an ancient one. The crusaders, however, had used shields and armor as had the ancient Greeks and Persians, and here, bayonets and knives and steel fell directly on skulls, flesh, and bones, which cracked, opened, and poured out marrow.

Haris jabbed a rushing silhouette with his bayonet, straining to spear him. The man fell back and shouted at him, "Fuck your sun, shine!" Haris couldn't tell the man's features in the dark-but he couldn't relent; the large silhouette wiggling on the ground-and kick, ing and nearly breaking Haris's shin---could rise and throw him down unless he kept pressing. And so, not even quite sure that he had his point at the right spot on the man's body, or even whether it was on the man's body.

Haris leaned into the dark. He pushed but the bayonet wouldn't pierce the man, and so he threw his body on the rifle butt and felt the resistance of the abdomen finally give, and the bayonet sank into the fallen man's rib cage. That sinking of the knife, for a brief moment a triumphant slide, suffused him with revulsion. He left the bayonet in the body of strange groans amidst which emerged one more oath, "Your Serbian Mother!" And then the man gurgled blood in his throat, and so these were the last words, with which he didn't exhale but as, phyxiated.

The throat of the already dead man still gurgled. Did Haris get one of his own? Would a Serb swear like that? Yes, he could. But wouldn't a Muslim, thinking that Haris was a Serb, be more likely to swear like that? And would it be less horrible if the man indeed was a Serb rather than a Muslim?

At that moment he was hit over the head with a stone, and the dank mist of the battle-slope lifted to be replaced by warmth spreading

through his head. When he came to, white clouds swiftly drifted a dozen yards above him. Haris stood up; he could barely keep his balance. Each step he took hurt his head, wobbling his brain.

He tripped over a corpse with a cracked skull and the brain hang, ing out of it and quivering and collecting pine needles from the ground. He felt his brain quivering the same needle-pricked way; he touched his right temple, and his fingertips slid through a tepid gluey wetness.

He crawled to the edge of a rock and looked on-down below him lay scattered cattle bones and one rusty tank. He crawled into the camp, and found more corpses of his comrades, from both contingents. He concluded that the two sections hadn't attacked the Serbs, but each other. Where were his live comrades? What if he were the only survivor?

The thought horrified him, but it also appealed to him. If the mountain belonged to hawks, wolves, boar, and foxes, and he were the only human being around, he'd be free to roam, to drink from clean brooks, never to speak again, never to exchange lies and friendly fire of one kind or another; then he could indeed be spiritual. He remembered one of his favorite Suttas, which he had learned near the felled park, to pass the time, in Sarajevo, years before:

"Having abandoned the practicing of violence toward all objects, not doing violence to anyone of them, let one wish not for children. Why wish for a friend? Let one walk alone like a rhinoceros."

He had always loved solitude, and so even amidst the busy city, he hadn't formed strong attachments-at least not to people, but to cafes, yes. The few girlfriends he'd had eventually abandoned him upon realizing that he wasn't the marrying kind, and so for years he hadn't been with any women although he occasionally lusted. But up here on the mountain, he wouldn't be bothered by lust either. If he were absolutely alone, he could be a good Buddhist; he could meditate well.

But he wouldn't be alone on the mountain. He'd be in the company of a hundred corpses whose ghosts would scrutinize him and molest him in his dreams. He had gruesomely killed a man, and his karma couldn't bring him freedom from pain, let alone Nirvana. One side of his face went numb, and an ear buzzed. He had a concussion, no doubt, but were some of his arteries severed if the dura mater cracked? If so, he might even want a hospital, but who would trust one in these con, ditions? A concussion while people were dying of wounds would receive

the lowest priority, and the hospitals were so shoddy No, better to die like a wild cat, in hiding, alone. Even outdoor domestic cats usually managed to die out of sight, to bother nobody and not to be bothered by anybody, as though they had attained enlightenment, so why couldn't he?

He limped into the camp into the debris of CD players, TV sets, cases of empty beer bottles, boots. He found a walkie-talkie. When he flipped it on, it crackled; the batteries were good. He slid the walkietalkie into his pants pocket.

In the crates of empty beer bottles he found a full one. He pinched the tip between two rocks trying to pry the cap open. The glass cracked. He poured the beer into his aluminum container. Maybe he'd drink some glass.

At the upper rocky edge of the camp, a dozen brown ravens greedily pecked at a man's entrails. Behind them appeared several people from his unit, backlit by the morning orange sun, and walked around the corpse, and the ravens ignored them, and kept feasting.

"What a relief to see you," said Haris.

"I thought you were dead," said Hasan, who had a black eye.

"What are you doing here?" Mirzo, another soldier, whose neck was bandaged, said. "Why are you alone?"

"I wonder about that, too."

He stood up and as he straightened his body, he felt a sharp pain around his lower ribs. Did I break them when I jumped on the butt of the rifle?

"It's peculiar there are no Serbs," Haris said.

"Yes, peculiar," the commander enunciated.

Hasan tilted each empty bottle for a few old drops and made sucking noises.

"Stop it, disgusting slob," the sergeant said. "Aren't you scared of their germs? Just imagine all those Serbian mouths slobbering over the bottles; it's like kissing them."

"I'll kiss bottles any time," Hasan answered. "And germs, I am sure I already have them; they have nothing new to offer to me. And if your spittle is made of beer, I'll kiss you, what the hell."

"Watch your tongue!" the sergeant said, and then addressed Haris, "What's your theory, Haris?"

"Look at them, they are still eating," Haris pointed toward two ravens who played a tug of war with a stretch of the long intestines. The intestines glowed crimson with the sun shining through them.

But he was the only one noticing. His comrades surrounded him and stared at him. Why didn't they answer the questions or address them to each other but just to him?

"You aren't answering my question, soldier," the commander said. "Somebody must have told them what we were up to."

"Maybe the scouts?" Hasan said. "They were there ahead of us all and they could have told them."

"The scouts are dead," the commander objected.

"That doesn't mean they didn't inform the Serbs."

"If they had, they would have known better than to go along with us and die.

"Who could have predicted we'd kill our own?" Haris said.

Haris didn't know what to do with his hands, and he scratched a stone cut on his forearm. He put his hands into his pockets.

The commander looked Haris up and down. "How come your pockets bulge so much? Empty your pockets!"

Do I have to take this? Haris thought. I guess that's how the military system works, on obedience, not resistance, almost like Tao. He emptied his pockets. The walkie-talkie fell into the grass.

"Who do you need to talk to?" the commander asked.

"I don't need to."

The sergeant ejected green spittle through his yellow teeth. "I heard him talking to himself; he was ratting on us. He hid in a thicket!"

"That's a jump to conclusions. I found the walkie-talkie here at their campground, and naturally, I picked it up. Wouldn't you?"

"And who were you talking with under the trees?" the sergeant asked.

"Oh, those were just yoga mantras."

"Mattress?" the commander combed his beard with his long fingers. "You mean you slept under the trees?"

"No, mantras, you know, Hindu and Buddhist incantations, short prayers."

They were deafened because a Phantom jet flew low over them.

"Rich bastards, drop your bombs or go home!" Hasan shouted.

"Let's see who he's hooked up with." The commander flipped on the walkie-talkie, and said, "Hey, man, where are you? Over."

"You sound strange. You got drunk? Over."

"I wish. What about you? You got any beer?"

"No, just a lot of whores, plum brandy and white wine."

"OK, let's exchange some, I got lots of whiskey from those UN bozos. Bozo booze. Where are you now?"

"What do you think? Over."

"Oh, of course. I'll stop by tomorrow."

The commander flipped off the walkie-talkie.

"So, that's your partner? You warned them, and now they are down, all the way in the valley, probably getting a reinforcement to hunt us. I think it's time to move out of this place."

"But how could we? This is such a good strategic location," said the sergeant.

They didn't walk far-two hundred yards away from the campsite, where most of their dead lay.

Two soldiers tied Haris to a tree and the commander said: "Convince me you didn't do us in. Think up something, make a good story. You have an hour. If your story's no good, we'll bury you alive with those whose deaths you have caused."

At least half of the company had survived. Gradually they appeared from the woods, and from behind the rocks, and they joined in the digging efforts, and some of them bandaged each other, and a couple tended to a man who was dying from many knife wounds, while several stood on guard.

They used shovels from the Serb trenches and fought through the stony land, digging next to the pines and cedars. Haris smelled smoke from so much metal hitting rock and sparking up. They collected wristwatches, and wallets, which they combed for German marks; they gathered tobacco and cigarettes. They placed four bodies in each hole. Several men kept glancing at Haris darkly, and later, they threw soiled stones at him. One stone struck Haris in the ribs. Mirzo, when passing by Haris, spat into his face. The sergeant slapped Haris, hitting him above the ear, where he'd been struck down with a rock. Flashes of green light appeared before Haris's eyes, like northern lights filtered through leaves, and his vision oscillated. He couldn't keep his head up and he let it slump, and rested his chin on his sternum. The rope cut into his wrists.

In the meanwhile, men prayed and read from the Koran. Several men wailed, some wept silently, others frowned and paced, and one man, apparently out of his mind, would now and then bellow with laughter, until Hasan bloodied his nose. From then on the man whimpered and sniffled.

The burials went on with somber dignity.

The fact that nearly half the company was being buried was a tragedy, but at the same time, the occasion was a triumph of sorts. The company now controlled the mountain ridge and the river valley roads. It was to be expected to have some losses, and that the losses came from friendly fire could not annul the fact that they did control the mountain from which they could strafe the land and several roads.

Haris's hands, tied to the branches above him, tingled from the lack of circulation. His woolen pants itched him, and the sweating around his groins irritated him, and the more helpless he was to do anything about it, the greater the itching, and he thought that he'd give a finger or two if he could just properly scratch the damned irritation. How far from meditation this is, he thought; if he had meditated better, he would have been able to control his state better-he may have strolled in the battlefield, invisible, intangible, and even if struck down, he would have had the good sense to die rather than to come back to life with a concussion to go through the strange resurrection cum crucifixion. He found support for his sensation of guilt in this recalled verse, "All that we are is the result of what we have thought: it is founded on our thoughts, it is made up of our thoughts. If a man speaks or acts with an evil thought, pain follows him, as the wheel follows the foot of the ox that draws the carriage." He could not recall what evil thought he'd had but was sure he'd had one. He thought about the verse again, and the wheel that follows the foot of the ox kept turning and returning-to the ox. Now, what did the oxen think that was evil, to be burned on a spit? He licked his cracked lips and his throat hurt from dryness.

The grisly commander walked up to him. "Hey, are you Orthodox, Catholic or Muslim?"

"I am a Buddhist."

"That's a good one." The commander smiled the way many do upon hearing a joke that's cute but not quite funny. "What were you raised as?"

"An Atheist, of course. Weren't you?"

"What was your parents' religion?"

"They were Muslims. But they never went to the mosque."

"Well, then, you are a Muslim."

"No, Buddhist, as I said."

"You swallow fire, walk on nails, put your feet behind your neck, or do whatever they do?"

"I don't mean it as a religion, but as a nation."

"Come on."

"Could I have a glass of water? I'm dying of thirst."

"Buddhist nation, you say, here?"

"You can be Muslim or Christian anywhere, why not Buddhist?"

"You are making fun of Muslims being a nation in our country? I see, there's a Serb lurking in you. That's what they like to do."

"Don't I have freedom of choice of religion and nation?"

"Nobody does. That's fate. And how the hell could you become something so freakish?"

"Not that I like being a Buddhist, but in my formative years, I read that crap and so that's how I think and who I am."

"Well, if you don't like it, change it, be a good Muslim."

"Can't. You said one cannot change."

"But you did-just drop your act. I don't find it a good story."

"I wouldn't mind changing, but I became Buddhist in my formative years, late teens, early twenties, the most philosophical years of our lives. Remember in the sixties there were books all over Sarajevo about herb healing, meditation, Buddhism, Hinduism, astral projection, and so on. All that stuff came from Belgrade. They already planned to distract us, get us to fantasize and talk in cafes every night till dawn, while they went to military academies and studied engineering or started smuggling goods from Italy or joined the Mafia. You think they read that stuff in Belgrade? No way."

"You are crazy!"

"You call me crazy. You have a better explanation for what's going on?"

"Well, you got a point, but that doesn't mean that any nonsense should make sense. Plus, your giving me this theory about Serb conspiracies won't convince me that you aren't working for Serbs."

The sergeant lit a cigarette and began recreating his personal cloud, but the commander said, "No smoking."

"What's wrong with smoking now? The Koran says nothing against it."

"The tree might catch on fire."

"In this weather? If it did, it might be a good way to deal with this devil."

"In any weather-look at the rosin oozing from the bark. That bums like petrol. By the way, don't talk back to your superiors."

The sergeant huffed out a blue streak and trampled his cigarette under his boot.

"Well, that was nice, but you used up your time." The commander petted the white sides of his beard. "You could have convinced us that you didn't betray us. All right, try it in five, six sentences."

"Why would I convince you of anything? If that's what you believe, go ahead, believe."

"It's a shame. Now that you have talked about your weird religion, I can see that you could easily do all sorts of unpredictable things; therefore I believe that you turned us in. Sergeant, what do you think?"

"I agree with you."

The commander then addressed Hasan, who stood with his arms crossed. His black eye was even more swollen than before, and it shut.

"Soldier, how about you?"

"I have no idea."

"But you heard him talking stealthily under the trees?" said the sergeant.

"Yes, I heard him, but I don't know if he was saying anything."

"So, see my friend, the jury is unanimous," the commander said. "The trial is over."

"It's no trial, but unfounded opinions," said Haris.

"Don't contradict your superiors!" Sergeant interceded.

"Not even when my

"When your life is in question, you guessed that right," the cornmander said. "I don't think it's in question any more. Mirzo, Hasan, go ahead, shoot him."

"How, to execute one of our own?" Hasan objected. "I think it's enough that we have killed off half of our company. You want to go on?"

"You got a point," said the commander, "but that's precisely why we should shoot him-he caused too much grief."

"I think it would be better, according to our laws, to cut his tongue out," the sergeant suggested. "That's the offending organ-let's just cut it out and move on."

"I kind of like the idea, but no. If you cut his tongue, he'll bleed to death. You'd have to have a way of stopping the bleeding for the sentence to make sense. Plus, I do believe he would be resentful afterward if he survived, and I wouldn't trust him with arms around us. Shoot him."

"I can't, if you'll excuse me," Hasan said. "I am no longer sure he did it. And he's a friend of mine. I admit he's weird, but who isn't. It would be weird not to be weird."

"Don't go all soft and wobbly on me, soldier," said the commander. "But if you don't want to, all right, there are enough angry men who will. Sergeant, go get three or four."

The commander asked, "Do you have any last wishes?"

"Yes, untie my hand please so I could scratch my balls."

"Serious?"

"Yes, serious. Are you? This is absurd. Just because I prayed by my' self, I am accused of treason!"

"You didn't pray to our gods, but to foreign gods, which is treason enough. And it's clear what you were doing with the walkie-talkie. Let's not go through that again. You've wasted enough of our time."

"Could you please untie one of my arms? I am dying from the itching."

"All right," said the commander but did nothing.

The sergeant came with three men. The commander ordered them to shoot, one in the head, one in the neck, one in the chest. The men stood some twenty paces away and lifted their rifles.

Haris did not grow terrified. The terrors had spent themselves, and the injustice of the accusations, the absurdity of it all, calmed him. He wanted to lift his head, to stare at the men who could do this, but everybody could do everything, and there was nothing marvelous in that. He drew a deep breath, and it hurt his rib cage, and his head pulsed, and his ears buzzed. Why didn't they shoot? It would be good if they already had, but this waiting broke his tranquility. The pain in his head grew loud as though a waterfall had burst from a mountain next to his ear.

He heard thunder or gunfire and didn't know whether it came from afar, or whether he was being shot. He closed his eyes, and saw himself slide out of the rope, with the skin of his hands tom off. He saw his body on the ground, and had the impression that his eyes were hovering separate from it somewhere in the tree, like owl's eyes, and observing as blood gushed out of his right temple. He heard shouting of men and laughter. So that's what happens in death, your eyes float and look, and nobody can see them, and they can see everybody and everything, and at the moment, he thought he could see even into the valley, from where a smoke came smelling of coal. Or perhaps that smell whiffed over the chasm of years, from his childhood, when his village in the valley outside of Sarajevo filled up with steam and smoke, deliciously smelling of coal and heavy oils, promising arduous journeys to the shores that bear exotic fruits, such as kiwi, which he'd

never tasted but dreamed of, and which, if the war ever ended, perhaps the country would import, and he would melt the seeds on his tongue. Or perhaps the smoke came from the guns and spilled oil on the rusty Serb tank below. He was sure that he was well nigh dead, and that concept comforted him, but amidst it all, he gathered a surprising impression that he was drawing another breath, empty, full of purified being and nothingness, perhaps the emptiness of the universe, peace beyond the sorrow of existences and deaths.

He enjoyed the grand vision of departing from life, but something very basic interfered. There was a shout in Hasan's voice, "Stop! Men, stop, stop for God's sake. Don't shoot. Look what 1 found!"

The men lowered their rifles and turned around.

"What is it now?" the commander said.

Hasan held up a black book with red-colored edges. "A New Testament in Cyrillic was on a scout's body. And look, his ID card says he was no Esad but [ovan. A Serb with a false identity. He betrayed us!"

"So? Being a Serb means nothing," said the commander. "Marko is a Serb, and he's one of our best fighters."

"The soldier has a point," the sergeant said. "Who do you think would be more likely to betray us, this freak or the guy who reassured us that Serbs hadn't bothered to post any guards?"

"Somebody has to be punished. The other guy is already dead; he can't be punished. Men, line up and shoot! What are you

Presently shots resounded from all the sides of the camp. Before it became clear what the shots meant, and before anybody had the time to hide, several sniper shots struck the three would-be executioners in the head, and they fell.

Several of the remaining men jumped to the ground and tried to hide behind rocks, and others ran in disarray to the former Serb camp and into the heathers, but grenades and machine gun fire forced back many of them to the initial position.

Haris observed from his suspended station, with his wrists bleeding. The commotion didn't scare him; he did not care whether he would be struck. He thought it strange that what meditation hadn't managed to accomplish, the concussion combined with torture and threat of shooting did: perfect equanimity, atharaxia of the mind. But then, didn't Dalai Lama undergo persecution of all sorts? How would Dalai Lama like to be in his position? Would he attain Nirvana like that?

Serb soldiers had some thirty Muslim men under gunpoint. There were at least three hundred Serbian soldiers in the camp. They picked

up the Muslim guns and tossed them into a pile, which looked like twigs lined up in circle for a bonfire.

"Where are your Mujahadeen?" asked the Serb commander, a freshly shaven man, whose cheeks were rosy and flushed with triumph. "What? No Afghanis?"

He looked around, and rested his eyes on Haris.

"And who do you torture here? We saw you were about to execute him."

"Traitor. He was giving information on our positions to you," Mirzo said.

"Oh, was he?" The Serb captain walked up to Haris. "Did you do noble deeds for which they give you credit here?"

"No," Haris said.

"You aren't under their control, brother! Speak freely."

He kissed Haris on the forehead. "You look awful. Have a sip!" He held up a jug of red label Johnny Walker and poured, and Haris, who hadn't had any water in almost a day, gulped.

"There! You can always tell a good man by a good gulp!" The com, mander cut the ropes to free Haris's hand, with his sparkling knife, which resembled a dagger. Once released from the suspension, Haris fell. His arms wouldn't move to protect his face, and it struck the wet ground. He felt like passing out, never to awaken again, and to relax infinitely, but he didn't pass out. He drew breath through his nose, for' getting that it was lodged in the ground, and he inhaled dirt; some of it stayed in his throat, some went down his windpipe. He rolled over and coughed, and each cough shook his brain.

"Oh, my brother," the Serb captain said. "We'll make them pay for this!"

He lifted Haris and gave him water from his aluminum flask. Haris washed out his mouth, spat, and then drank. His nose and his vision cleared. He was struck by how miserable the remainder of his company looked. He felt a tinge of the old triumph, such as he'd felt when he was riding the butt of the rifle and sliding the bayonet into a man's rib cage-the triumph of survival at the expense of the enemy's life. All the enlightenment which he'd experienced tied to the tree seemed to be lifting away as a morning cloud, and what remained were the petty details, gaps among the men's brown teeth and plastic Coca-Cola bot, ties on the ground, and with these details, old passions pressed his mind.

The Serb captain said, "I can see the flicker in your eyes. Wouldn't you love to shoot them? I won't take that away from you. I'll give you

a machine gun and you can strafe them all down. We'll rope them together, and after you finish several rounds, you will have killed every single one of them! How does that sound?"

Haris didn't answer. It sounded, of course, terrible. If he said he wouldn't do it, would he be executed himself? If he declined to do it, wouldn't someone else do it? Weren't the men goners, no matter what? And what is the difference between death and life? The more he thought about it, the more tempted he was to accept the offer to shoot, but a Dhamapada verse came to him and distracted him. "As a fish taken from his watery home and thrown on the dry ground, our thought trembles all over in order to escape the dominion of Mara, the tempter." All right, my thoughts, tremble on. Trembling may be good, it will save men.

"Oh," the captain shouted, "they were about to make Swiss cheese out of you, and you hesitate!"

"To tell you the truth, I don't want to shoot anybody."

"But you will enjoy it, I can tell."

"He's not one of yours!" shouted the sergeant from the Muslim company. "I am the one who gave you the call! Don't shoot me!"

"Nenad," the Serb captain addressed a red-cheeked soldier, "is that your radio connection?"

"So that's what you look like!" the red cheeks boomed. "Stevo, I thought you were dead. The connection went out, and then some strange guy talked to me. I was sure they killed you! Great to see you, man!"

"So you are our hero," the Serb captain said. "Come out, brother, join the party!"

Haris wondered what that meant for him; would the Serbs now shoot him? His breath accelerated. After all, he did like being spared, he did like survival, no matter what he thought and how he philosophized. If he hadn't philosophized, he would have already killed the sergeant, and would be free to live.

The captain offered the sergeant to drink from the jug, which was nearly empty. Pretty soon, the sergeant mingled with the Serb soldiers, hugging them, and laughing all too loudly while Haris stood, gazing vacantly, next to the captain.

"Now then, what do they torture you for? What good did you do after all?" the captain asked Haris.

"Buddhism."

"That's a good one! But you do look gaunt like some kind of monk.

Have another sip."

Haris took a gulp of the Scottish invasion. His vision turned a shade darker, as though the shot had toned down the lights in his brain, and the pain in his temple gave him a sudden stab, and he winced.

"Buddhism, ah? You know, I used to be a Buddhist. For a whole week."

"Treason, too."

"I see, you didn't communicate with us, you didn't do anything. Religious fanatics. Damned fundamentalists. You got to wipe them all out, I'm telling you. How else are we going to get along? I mean, I'd understand if they had got the right man to torture, but you? All right, machine-gun them! I'll help you."

I should resist, thought Haris, and tiredly, he lay prostrate on the ground, and the ground felt good and inviting, and he could barely open his eyes.

"You know," the captain said. "That is one thing I liked about Buddhism. It seemed calm."

Hasan shouted, "Don't do it, my brother, I tried to save you!"

A soldier kneeled down next to Haris, and adjusted the train of heavy bullets.

And many voices came, both beseeching and cursing Haris. He looked over the aim, framing his former companions. The aim and the companions trembled and shook and oscillated darkly into silhouettes. He blinked, and when he opened his eyes again, he saw nothing. He closed his eyes, opened them, but around him was a brown darkness. The voices grew louder and shriller from all the sides. Somewhere far away there was a thundering, and for a second he wondered whether the crackling explosions came from his machine gun, and he leaned over and felt the barrel. It was cold, comfortingly cold, and it balmed his bloodied wrists.

YESTERDAY, A WOMAN ASKED ME, what was it like?

Some people know a vague biography, that I've seen war. She asked me this question at one of those visiting writer's affairs, the obligatory dinner after the reading. We were at a Middle Eastern restaurant, the table spread abundantly with flat bread, hummus, stuffed grape leaves, falafels, tabbouleh and Israeli salads, the main course skewered lamb.

A television over the bar filled with eerie images from the newest war-quick edits of camera angles from jet cockpits, square targeting grids locking onto tanks, trucks, an airport runway, buildings, then the bombs were lasered in, each a streaking black pellet, followed by impassive spectacles like primitive video games, white flashes, roiling black-and-white explosions.

All of us at the table-intellectuals all-must have understood the idea that people were dying with each replay. But we didn't see them. We weren't meant to see them. We passed bread, served ourselves wine.

The woman sitting next to me asked again, what was it like? Not meaning to treat war casually, but still, wasn't there something else we could talk about at this meal?

She was pretty, a classic face with high cheekbones, perfect skin, and she projected a girlish adoration toward me, flirting in that way some girls have of reaching out a hand to touch my arm. This woman

was a professional dancer as well as a poet, and she looked it-she car' ried herself with that athletic self,consciousness of her body in space. I have to admit that I was starting to fall for her a little until she asked that question. She wanted to know, needed to feel it, if only from some' one who had seen. She tossed a neatly braided rope of red hair off her bare shoulder in an arrogantly flirtatious way. She leaned her dancer's body in closer and asked me again, someone not used to being denied, demanding this time, so what was it like?

What I didn't say-that my brother, Harry, lived with me now. He was a real veteran of war. War would always be with us in our house. She should by all rights be asking him not me. Harry had been living with me permanently since my divorce but on and off for years before that, since I had returned from a war in South America and got him out of the v.A. hospital, just signed him out, as simple as that, what they called an A.M.A.-against medical advice.

I'll never forget the happy feeling that winter morning, settling into seats on the train, that special heightened consciousness, that elation, we were still alive. It didn't matter so much to me that Harry was giggling to himself like the gentle madman he had become, his face pressed against a window, a finger drawing shapes of numbers in the fog his breath made on the glass then watching them disappear. We were two brothers braced against forward motion, me somehow expecting we could recapture our lives and live them differently. The air brakes of the train let loose, the car lurched ahead. The way our seats were facing, we were riding backwards into the city, and we've carried on like this, for years, looking behind us to the rest of our lives.

Year after year, in cycles, Harry started out living with me, at first in student apartments, later on in homes with my wife and daughter. We would make it OK together for a few months at least, until we got on each other's nerves. Then he would move out, try to make it on his own. We would set him up in apartments, in cheap rented rooms, on his disability checks. My wife or daughter would get him a cat so he might not be so alone. Always, after a few months of this, he would end up off his medication. He had different explanations-he was tired of feeling so downed out all the time, or the medication made him impotent and fuck it, man, he'd say, I just wanted to get laid.

None of this told the real story. The sadness he carries is like hands reaching into his insides, squeezing, the grief of war never far away. It recedes for a while, can almost be forgotten, but it always returns, sud, denly, like a seasonal flood. He turned his cats loose into the neigh,

borhood. And I would find him weeks later, homeless, out on the streets not so differently than the way we had lived sometimes when we were kids. Or a call came in from a social worker in some hospital psych ward in a distant city explaining that he had been brought in by the police, was being held for observation, a danger to himself and oth� ers. I would travel to wherever it was, sign him out. He would move back in with me again. This has been our cycle, years and years. We're brothers. We've always been each other's keepers. He was doing much better recently, as if leveling out, staying on his meds, his anti-psychotic pills, keeping to a daily routine like a religion. Mostly, he watches TV, old movies in black-and-white, endless reruns on cable, "Hawaii Five�O," "The Rockford Files," "The Dick Van Dyke Show," "Cheers," never tiring of seeing the same movies and episodes over again as if comforted by their repetition, lying half-sleeping on his couch. He does keep up with the news, which we watch together most evenings. In between, he walks two times a day to the stores, cooks his meals, vacuums the carpets, feeds the dog, keeps the lawn green. Sometimes, he picks up a harmonica and tinkers around. Nights, he retires to his room and scribbles in notebooks. He has two tall bookcases full of these spiral notebooks stacked one on top of the other. There must be at least five hundred of them, each an inch thick. Most of what he writes is scattered thinking, schizophrenic diaries, outlet for his psychosis, as the psychiatrist he pays for privatelyhe wants as little as possible to do with Y.A. doctors-calls them, incomprehensible scribbling but filled with phrases that jump up off the page with clear rationality when they can be deciphered from his enraged handwriting. He doesn't want me to read them. Examples from today, noted quickly by sneaking into his room: what they did to me these people they won't leave me alone this is all because of them the voices are real real is what they send me to see there must be more to civilization than mammals, insects wiU take over the earth the ones who really kiUed Kennedy these blue dots we'U have them kiUed we'U kiU them all no mercy bomb the shit out of them kiU them

And so on. My brother is reacting badly to the new war on TV. Even as he's trying to live in his own way a more or less regular life, he's suddenly drenched like by a thunderstorm. He's started leaping off his couch in jerky, compulsive energy bursts, throwing himself to the floor and doing pushups on the carpet-fingertip pushups-a thousand a day, I've counted, in sets of fifty. In between sets of pushups, he slams out the side door of our house, jogs down the block and around the

park at least four times a day, which must add up to ten miles. We both know what he's doing. He's preparing himself, getting ready just in case. On the other hand, I've taken up cigarettes again after being so proud of myself for quitting. We haven't talked about this. He does his pushups. I walk around the house lighting one after the other as if I'd rather commit slow suicide than have to think about any war again. We keep putting on a face, pretending we're perfectly dry. We don't talk about it. We don't need to say anything.

Recently, I came downstairs in the middle of the night for another pack of cigarettes. I had been fighting with my girlfriend, one of those stupid arguments born of too much stress and tension that can rise up out of nowhere, mostly my fault for being so on edge. We had said ugly things no one should ever say. Our voices must have been loud enough to wake the neighbors. We were able to recover only by just stopping. StoP! she shouted. She was right. We held each other, saying we were sorry. But I was upset, smoked out, came downstairs. I found my brother in his underwear, sitting on his couch, his TV dark. He wasn't usually up this late. The way he looked at me gave me an instant jolt of panic that he had quit taking his pills. He was an old man suddenly, gray hair hanging at his shoulders, his gaunt, starved expression hollowed out with exhausted sadness, his old soldier's defeat. He said flatly, without bitterness, as if sharing a mere fact, "Not once in my life has a woman said she loves me."

Yesterday, the pretty woman at the table flipped her rope of long hair, demanding, so what was it like? "It's hard to remember," I answered, finally. "Whatever happened, it was over like that," I said, snapping my fingers right in her face to make her jump.

There was a time in my life when I went looking for war. Part of this was for classic reasons common to many men-as a way to prove myself, establish my fame. If I were to die in war then so be it; if I were to stay alive, it would be on certain terms, as in the funeral speech of Pericles: Choosing to die resisting, rather than to live submitting, they fled only from dishonor, met danger face to face, and after one brief moment, while at the summit of their fortune, escaped, not from their fear but from their glory.

I had never seen a war except on TV-video reports from correspondents doing stand-ups in safari jackets set against chaotic green backgrounds, sounds of distant gunfire, B-52S dropping bombs from

their bellies like great shirting birds, orange explosions, black smoke, drum-beating helicopter blades, newscaster voices narrating shaky footage of soldiers hunkering low or slogging through rice paddies or humping sandbags, muddy roads teeming with the fleeing dispossessed, shell-shocked peasant faces in close-ups, pure human misery bleeding through the screen.

Watching, I knew I was missing something. I couldn't even sit and watch but had to leap up and pace around the room, frustrated and en� raged. Damnit, I should be there instead of where I was. Not that I hadn't been in battles-peace marches and sit-ins, with nightsticks, tear gas, handcuffs, police vans. As a journalist for the free presses, I had been there for all of this, the grief-stricken shouting after students were shot down by government soldiers at Kent State, the roiling tens of thousands marching on Washington, chanting, cat-calling, those days of rage.

More than this, I had lived through a military regime in Argentina when I had been an exchange student, was even shot at in a car while racing away with student companeros from painting walls with the deliriously oxymoronic symbol and slogan:

P J V P jMuerte ala dictadura!Which signified: Peron returns. Peronist Youth. Ironically juxtaposed to: Death to the dictatorship!

We believed with deluded madness in our imaginary desire, that the return of strongman Juan Peron from exile to power could mean a promised social democracy.

I had been arrested three times in Argentina at street demonstrations, the third time had my head split open like a grapefruit. My adopted family bribed my way, still bleeding, out of the detention center. And I finally followed their advice, with some good luck, in applying to college back in the U.S.A.. I said quick hasta prontos to my militant buddies to take up an offer for loans and cafeteria jobs to work my way through the vaunted University of Chicago, notorious at that time for accepting neurotic, politically minded students, even one with an unorthodox, patched together school record like my own that showed big unexplainable gaps between eighth grade in the U.S. and a diploma in Buenos Aires, half a world away, awarded by an obscure private academy run by militant French priests. I returned to the United States with leftist dreams, idealistic visions of revolution, all power to the people. After two years at Chicago, I had compiled a police file for civil

disruption two-inches thick, along with a clippings portfolio from the free presses about half that thickness filled with articles carrying my by-line or written under a pseudonym. This was the Nixon era of harassment of the press and quasi-fascist dirty tricks. Some of my journalist colleagues claimed to have had their phones tapped, their mail stolen, their apartments broken into, their research and notes mysteriously vanishing. Many of us agreed to use the same pseudonym as a protest, "Frank Malbranche," for our most anti-government stories. Under my own name, I had placed several free-lance photos with UPI, United Press International, that now-ruined, once-major wire service. My best photos were of anti-war demonstrations, battles in the streets. A few had been published in newspapers all over the globe.

So I thought I was going places in journalism, my college grades were high, but this wasn't enough. My slow conclusion was that I had to fight back from the inside, make the ultimate sacrifice, get my head shaved. I became obsessed with the idea of enlisting, fantasized about secretly slipping my fellow grunts in basic copies of "The Daily Worker" and preaching to buck privates the Marxist ideology direct from the streets of the Movement that all private property is theft, explaining that, though I was a committed Socialist against the war, I could no longer buy into the bourgeois elitism of college deferments while the working class and repressed minorities did most of the fighting and dying. From the bunkers, I would write articles for the free presses that subverted the system from within. Then suddenly, that war was all but over. The United States had lost. What would sacrificing myself for that ever prove?

And there was my brother Harry. He had been sent over there, drafted in a sense but not really, since a judge gave him the choice to volunteer or go directly to prison after a bust for marijuana possession, so he enlisted. He came back from Vietnam after seven months of his combat tour to spend the next two years in hospitals-first good Army facilities, in Japan, in Denver, then he was discharged and dumped off like a sack of trash into the callow neglect of the V.A. institutions. They shipped him out straight into the Psycho Corps-our troops in gray pajamas, tens of thousands of them like a jittering, babbling voodoo army wandering hallways and grounds, rubber slippers and filthy smocks like uniforms, this new branch of the disarmed services composed of post-Vietnam crazies it was dawning on me Harry might be serving in to the end of his days.

We sat together on splintery benches on the campus of the crumbling v.A. hospital in Northport, Long Island. I would take the train out there then walk. It was two miles from the railroad station through the quaint town like something out of a Norman Rockwell painting then up a hill on a road lined with sugar maple trees to that collection of run-down, red brick buildings with roofs of busted shingles, ragged grounds messy with rotting leaves. I would sign in at the desk of my brother's ward. All the nurses came from somewhere else, Asian countries, mostly, the Philippines or Korea or Indonesia. They spoke mainly broken English. A lot of the inmates suffered from the delusion they had been captured by gooks and were prisoners of war. I never spoke to Harry's doctor-not even sure he had a doctor-but the ward nurse always said his condition was unchanged. His diagnosis: schizophrenic reaction to wartime stress.

I would get a pass to take Harry out for some air. We weren't supposed to leave the grounds. He would be waiting for me in the day room, slumping in a battered folding chair in front of a TV where the picture was always snowy or rolling. Nobody cared. My brother was a starved-looking version of his former self, broomstick arms hanging out his gray tie-back hospital smock with trails of food and juice stains down the front. His feet barely shuffled along, his Thorazine stagger. \ Drug side-effects kept his hands cramped up, fingers curled like blunted talons. They had left his fingernails to grow out, long and filthy. His hair was unwashed, uncombed, sticking out every which way in a wild growth. His blue rubber slippers were peppered with cigarette burns. No amount of my complaint forms or angry confrontations with V. A. staff made any difference to change this negligent treatment, this lack of any care. This was America, after all. This was a wounded warrior's reward. We sat together mostly in silence under the unkempt trees. We passed a joint. In those days, staffers at the v.A.s quietly recommended marijuana for the post-traumatic effects of war. It kept the patients more subdued. The inmates from Vietnam stayed as stoned as possible most of the time, not that an uninformed observer would have noticed much difference.

What Harry had been through, I mostly didn't know. He had served as a door gunner on a helicopter in the Asha Valley. He had volunteered for combat duty, something that made me envious, disgusted, and proud all at once. There had been a severe shortage of door gunners during that brutal campaign. All I had managed to put together

about his combat experience was that, because of this door gunner shortage, they had given my brother too many doses of amphetamines during the battle to keep him going, a sustained action, it was called. He didn't sleep for two weeks. He burned his hands raw changing out red-hot M-6o barrels. In combat, he just forgot. He showed me the scars, like the lines on his palms had melted into shiny white smears. They had sent him up again with hands wrapped in gauze. One evening, he got back to base around dinner time, jumped out of his Huey, marched straight into the officer's mess tent. He popped off two smoke grenades, one yellow and one red, bowling them out between the tables. He could laugh at his memory of all those officers hitting the deck, diving under tables, coughing and choking, crawling in panic for air. Everything else was a mystery, what exactly he had seen, what he had experienced of war, and if he had actually killed another human being.

War was something he almost never spoke about. Whenever I prodded him, he would tell bits and pieces of his story of panicked officers taking cover in red and yellow smoke. He laughed, more a crazed high giggling than real laughter. This had nothing to do with the pot. Pot smoked under such circumstances had no effect to get us high, it was just harsh, deadening smoke. I told him I was thinking about enlisting. His laugh shut off like with a switch. His starved face went slack, jaw dropping open, a line of drug-induced drool trailed from his lower lip. But his green eyes were sharp, jumped to either side as if he were seeing dark outer things or invisible people-he had said more than once what he saw were blue dots. Without turning to me, as if speaking for the sake of whatever he was wary of in the air, he said, "Don't go. Don't even think about it. Not over there."

He retreated back into his usual silence. I don't know why that bothered me so much, how he wouldn't say more, except that I was obsessed to know, needed the experience even if only through him of what it was like-the fear, the danger, smells of gunpowder and cordite, the hot pressure of an exploding mortar round like a hurricane force desert wind. I had to be there. I had to know what it was.

One cold autumn afternoon we sat like this, worse than this because we said so little to each other that I was beginning to wonder why I was making the effort to hump it out here at least once a month, hitchhiking maybe twenty hours from Chicago to Manhattan then catching an expensive train to see him, like what difference did it make, anyway? They had turned him into a zombie. Or maybe he was

holding out on me intentionally, after all we had been through to' gether. We had spent three years, on and off, taking care of each other as homeless kids, had slept in hippie crash pads, cheap hotels, even in a cardboard box, had rebounded home, such as it was, then suffered and run away again, in cycles, from the torment and physical abuse of our parents. There was a time when we had kept each other alive. And it was like a violation of brotherhood to think he was holding out on me now, consumed by my self-pitying feelings of loneliness and betrayal, that sense of broken trust hitting like quick cold stomach cramps so I actually sat leaning over, arms wrapped around my middle. Or I would have to stand up off the bench and pace around in aimless circles, kicking at the wet rotting leaves, holding back shouts of rage.

I decided then and there I would go find my own war. There were plenty of wars out there, damnit, I was going to find one. No matter that I was only a year away from a college degree-one of those Great Books general studies programs heavy with literature, foreign languages, the Greeks-doing more than OK by any outward standards, especially considering what we had come from. Still, my life felt point, less, filled with days one knows are forgettable, books and lectures blur' ring into meaningless phrases, empty words one would never recall. I just couldn't let it all pass me by.

On my return to Chicago, I readied myself, working out in the gym, running laps, processing paperwork for a leave of absence for next quarter while at the same time defrauding banks by taking out new col, lege loans. I was going off to war. It would have to be a war no one knew much about. That way, I could write free press stories and take photographs. Maybe I could pull off a good enough article to sell to a major magazine. Why not? In the right kind of war, hell, I might even make my reputation.

So it came to pass that I found myself trudging through undergrowth in a dense artificial forest, on my way to a war-artificial because we were moving through some kind of immense Argentine tree farm recently purchased by the multinational wood products subsidiary of Shell Oil Renewables South America, that oil company as ubiquitous as any ancient god. The trees had been planted there two decades ago, a test forest seeking to discover some balance of commercial and native species that might also sustain wildlife. The test forest had been declared a failure, sold out to Shell, scheduled for clear cutting and re-

placement planting with a monoculture consisting of genetically rna' nipulated pines.

My guide, a Guarani Indian companero in the militancy named Sikfn, was explaining this to me in melodious, breathy commentary as I followed his sweated,through, coarse peasant shirt back through showering twigs, leaves, bits of branches flying up from his whacking machete blade, steel scraping and ringing with each rhythmic stroke, clearing bamboo-like undergrowth from an old log skidder trail in a jungle he spoke of with apologetic sadness, as though he blamed him' self, as if it were his own failed garden. He slashed along ahead of me, lamenting the disappearance of the trebol tree with its medicinal bark, the scarcity of white quebrachos and incense trees. Rolling off his tongue and up through his nose in sing-song tones were Guarani names for other trees-kurupa'yra, tagyhu, peterevey, yvyaraneti, urunde'ymi-trees which used to grow abundantly in the region, meaning, less to me except for the musical sound of their names. Animal species were vanishing, the oso hormiguero grande-the anteater bear-the gray fox, two kinds of exotic peccaries, and the tatu carreta, which I understood to be a kind of armadillo as big as a wheelbarrow. The beloved jungle of his childhood used to be filled with colorful birds, rare green parrots, gorgeous blue and gold macaws. Patrolling helicopters of the armed forces of Paraguay and Argentina-Bell Helicopter Hueys part of zmn-Communisr aid from the United States-the thump, ing noise and turbulent winds of their blades beating low just over the treetops caused parrots and macaws to drop dead out of their nests from fright. The ones that didn't drop dead abandoned their nests and flew off, never to be seen again. The forest we were slashing through seemed empty of birds. Sikfn was a walking encyclopedia of jungle fauna and flora on the way to extinction. I was getting the idea that his war wasn't as much with enemy troops across the border, on the other side of the rivers, as with the forces of economic development despoiling the whole immense Parana and Amazonian riparian zones, seeking to turn his patria GuaranI-his tribal Fatherland, as he called it with a nostalgia that already predicted its defeat-into one incalculably huge and profitable agribusiness plantation. What I didn't tell him was that I believed, as Borges, that nadie es la patria-no one is a patria. By extension nor could be any tribe of men. But I disagreed with Borges that men should nevertheless aspire to be worthy of such patriotic oaths. How could anyone claim to be fighting for a Socialist vision of the International and still speak that

hateful word, no less than a proverbial curse on all mankind, patria? Fatherland, with its flag-waving, fascist connotations. I didn't say anything. Sikin was the contact given to me through friends of friends, as is the way of so much journalism, to guide me to a revolution.

The revolution now had a human face, fine featured like most Guarani, disarmingly not very traditionally American Indian looking but more similar, say, to faces of southern Italian peoples, without the Roman nose, his skin a coffee-with-cream brown. He had a tall muscular body he carried erect with held-in dignity, as if powered by his awareness of centuries of struggle by his people, his persistent resignation to carryon the fight, as he kept saying, like he had been born with it as a duty, the fight for my people.

Listening to Sikin, I could be filled with the power of his belief, that this was a war for liberation. The way he spoke such inspiring platitudes, one bum-scarred white lid, naked of eyelashes lowering halfway over a wandering milky eye-an injury from his youth, trying to make a pipe bomb that had exploded on him-he took on a harsh but seductive look, especially when he had a few drinks in him. That eye suddenly fastened on something, on some enemy he could see in memory or in the air, the scarred lid lowering over it, giving him the hard, cold look of an experienced killer, a warrior's capacity to size up any man as if already drawing a machete with murderous intimacy across his throat. I had seen this look before, in street thieves, in gang kids who carried guns in New York, mostly when they were paranoid and crazy on meth highs. There were a lot of men with that look along this riverfront, in bars filled with scarred, ragged characters, smugglers, the rnensu, the contract laborers at the edge of homicidal drunks, fresh from logging camps or plantations up the rivers. The Parana region where three countries meet is legendary for its frontier roughness.

The only name I knew him by was that one name, Sikin. He had a Spanish name, Juan or Jose Marfa or Fernando, but he refused to use it, insisting on his name in Guarani. Like most children of indio exiles, Sikin had learned from his parents the sing-song language of Guarani, their patriotic vision of Paraguay as expressed in a lyric tradition called ocara poty-jungle flowers-the sentimental nationalism in songs and mythic incantations that many of the leaders of the resistance movements could recite from memory and which, from what I could comprehend, envisioned Paraguay, despite its bloody history, as some perpetual Eden blessed with an abundance of innocence and bananas.

The day before, we rode hour after hour in his pickup, out through

the scrubby brown grass plains of the chaco, where the cows looked like racks of bones covered by sun,burnt hides. We bucked our way off on a system of rutted dirt roads through mud hut and tin,roofed cinderblock villages filled with scattering chickens and barefoot, big eyed indio children who chased after us with shouts of glee, dark mothers staring out darker doorways, then we were off again on the rough roads. Here and there, as we passed, small flocks of Nanduces-Rhea ostriches-would leap up out of tall grass, fleeing in gangly comic dances on stick,like legs into groves of thorny trees.

I wasn't paying much attention to landscape. From time to time, I lifted my camera and took a few miserly shots, conserving film. I was thinking about what lay ahead, that if I could just pass their tests, get on the good side of the guerrilleros) they might take me with them deep into the jungles to see, close-up, exactly what I was looking for.

Not that there wasn't some good talk to pass the hours, and going over with Sikfn my rudimentary Guarani, a language whose high nasal vowels and frequent gutturals I could barely get my mouth around. Guarani has a syntactic structure similar to Japanese and some Polynesian languages. The subject comes first, the verb at the end. Tone alters everything. There are nasal vowels, like high humming notes through a tenor kazoo, and guttural sounds, like a whispered gargling. Intoned either way, these sounds completely change the meaning of words. I kept referring to a book I carried in my bag-it was later de, stroyed-the hardcover edition of EI Idioma Guarani; gramdtica y an, tologia de prosa y verso, by a Jesuit priest whose name I can't recall. In the bucking pickup truck, I flipped to a list of phrases in Guarani with Spanish translations which were comprehensible only by knowing certain juxtapositions. The specific often acts as the generic in Guarani, one idea stands for similar ideas. Saying a thing often also signifies something else as well as itself-the wing of the bird standing for half of the distance to somewhere, or the justice of God was a phrase widely used for medicinal fruits-which I understood to be like Shakespeare or Homer using a thousand sail for a thousand ships) only it was far more complex than that, more deeply encoded than any European language ever imagined being. I had been listening to the language for days in the riverfront bars, and when Sikin spoke it with contacts. It seemed to me not so much a spoken language as a kind of singing filled with high reverberating hums and low airy tones, a music like indigenous wooden flutes. Guarani phrases kept slipping and sliding over each other fluidly, like mixing river currents, in an endless substitution, an

infinitely recycling metonymy. As we rode along, Sikin listened patiently to me butchering phrases from the book. "It's really easy to learn Guarani," he teased. "All you have to do is be born here, speak it about thirty years and you know it perfectly."

Guarani is more complicated than its difficulty with nasals, gut, turals and juxtapositions. Though most verbs are made up of two syllables, many can be almost infinitely agglutinated to make contextually precise conjugations. The verb to clean-I was taught this when we stopped for a supper of rice and boiled beef in a spicy sauce, served on a plank table, in lantern,light, by a lonely country store owner's wife, who kept giving Sikfn flirtatious sneers like a challenge, demanding a response as she cleared our plates---could be made into a nine syllable conjugation, a single word intoned through the nose, meaning, did you clean it all up yet? Guarani is a language with a limited vocabulary but with almost infinite precise ways to conjugate verbs for any specific sit, uation. Sikfn's good eye was directed at the wife as she bent over a red plastic tub, giving her hip a little haughty kick each time she wiped a plate pulled out of the soapy water. She was plump as a guayaba fruit, especially in her hips, shaped like a pear, but she had a pretty face, puffing her cheeks like a blowfish then letting short haughty laughs out between her fleshy lips. Blue flies buzzed our plates. She stood over us, waving them off, her pure heat a warm homey perfume like rising bread. She was alone, as were so many Guarani women, her husband off for months on contract labor, or across the river to the war. Sikfn got us all going on the verb to love, like a game-jahohayhu, the specific verb in Guarani for love between human beings.

Sikin hoisted the woman's runny'nosed children up onto his lap, showing them off as if they were his own. In his Guayaki-Guaranf dialect, he said there was a way to add syllables to the verb which con' veyed love for a daughter before she reached puberty, a different sound when she becomes a woman, another when she marries. He set the lit, tle girl down and lifted up the little boy, making the conjugation of the verb for the love of a father for his young son, another for when the son reaches manhood. The kid looked at me with owl eyes, holding out his shredded chewed stub of raw sugar cane, inviting me to share. For man and woman, there were ways to say I love you for both before and after making love. Sikfn repeated these verb phrases heavy with implications, directed at the store owner's wife, and I thought I could see her fleshy legs tum red from her skirt down to the walked over heels of her rope soled shoes. Verbs in Guarani are present tense-as if

now is what really matters--when something happens indicated by a simple framing word if needed, as in yesterday, we love, last week, we love, a year ago, we love, tomorrow, we love. Sikfn went down the list, making me repeat after him, as the woman served us glasses of aguardi� ente-cane liquor. What I thought I was sure of out of this game was that, as it would have been said in good Guarani, tonight Sik{n and the woman love. But he made it clear after our drink, no, we had another hour of driving before sleeping. He left money on the table. Calling her compafiera, accepting her regretful clinging embraces, her wet kisses on our cheeks, we said goodnight. We escaped into the darkness.

We spent the night in an empty Shell company storage shed at the edge of the tree farm. Sikin hung two hammocks that smelled of motor oil by low hooks in the mud walls of the hut. We swung into them, our bodies just barely clearing the dirt floor. Sikfn took off his boots, rolled to his side. He instantly fell asleep with an easy breathing. I lay awake. This was the first time I had ever tried sleeping in a hammock, and, closing my eyes, it was a strange feeling, like being hung out over some immense space. With every swing, my body started up as if trying to catch itself from falling. Cockroaches the size of sparrows buzzed through the air. A spider as big as the spread fingers of my hand hung in a web in one comer of the tin roof, darkly visible in a crack of moonlight. None of this bothered me. I was all impatience and anticipation for what might happen in the morning. And, after all, I had spent nights in far worse places. I found the bottle of scotch in my bag, drank some, then finally fell asleep.

Before dawn, Sikfn was ready by the truck, sipping mate tea through a nickel straw from a gourd. I joined him, the warm bitter tea soothing, as stimulating as coffee.

We readied our bags. I checked to make sure my camera was on top, loaded, lenses within easy reach. Sikfn opened the glove compartment of the truck and I saw him slip a big black pistol with extra clips into his bag. I hadn't known it was there. I swallowed, dry in the mouth, reminded of where we were going, what I was looking for.

Sikin said we should get moving before the sun got too hot, we would be on foot now until we reached the river. I tried to joke with him, saying how it wouldn't be as hot as what he'd missed last night. Last night, he seemed to enjoy my allusions to what could have happened. Not this morning. "Too many men end up face down in the river," he said. "In any case, I'm married."

This surprised me, his first reference that he had a wife. I had as' sumed he had no family. I'd have asked more, but something in the way that milky eye fixed on me made it clear he regretted letting me know even this much about his family, as if letting people know too much could get them killed.

We started off through the jungle, that failed tree farm, that artificial forest. He pulled out his machete. He started slashing the way ahead of us, through bamboo,like undergrowth. We set off down the old log skidder trail. He began to list the musical indio names of trees, telling me about his jungle as if he were ashamed, as if it were his own failed garden. He lamented the loss of the animals, the birds, the scarcity of certain trees, white quebrachos and incense trees, especially the trebol, gone nearly extinct. He turned to me with a bitter laugh. He began singing a string of syllables in a verb phrase in his GuayakiGuarani dialect. All I could make out were the root sounds of the verb to love. As best as I could comprehend, it signified, I love you, my mid, dle,aged wife, medicine gathering at the trebol tree.

Sikfn repeated this long gurgling brook of a verb phrase several times as we worked our way through the bush. Slowly, his point sank in. For his people, the extinction of a tree meant wiping out forever one way to express love.

Not that I paid so much attention to this at the time. I didn't say that I didn't care much for Sikfn's jungle, its trees, its animals. Every, thing in it seemed poisonous, a hassle, full of thorns. Just being out in nature like this caused in me a terrible and irresistible compulsion to start chain,smoking. My head felt like it was packed with hot, dirty wash cloths. My stomach fluttered with bouts of nausea from anti, malaria pills. It was tough to breathe in the wet tropical atmosphere less oxygen than superheated steam. It was hard to see with sweat drip, ping into my eyes in the green half-darkness of the overhanging trees. In about ten minutes, I was hardly able to focus on anything more than taking just one more step, one more breath, one more step. And so we moved on through the jungle.

My right boot slipped in something gooey. A sickening stench billowed up like a sweet spray of rotten fish. A little involuntary shout of disgust escaped me. I stopped, kicking, trying to shake a clinging, drip, ping glob of stuff off my boot.

Sikin turned, pushed back his straw hat. Ay,ha-he let loose this strange sound, half laughter, half an expression of surprise. His wan'

dering milky eye rolled independently of the other with a wary glance at my boot. In his slow, lilting indio Spanish, he said, "Old nest of zacaruyu snakes."

I froze. I understood I'd stepped into a small sink-hole of eggs with numerous decayed, half-born hatchlings. I didn't have the chance or breath to ask follow-ups like what kind of snakes? Were the snakes venomous? Sikfn gestured with his machete and said, "Many snakes in the trees," then he signaled urgently we should press on ahead. That was right on with me. We started to do this, with me looking only at my boots, ready for snakes.

Something hard cracked me dead center on the forehead.

Owww-my eyes shut in a reactive squint. More things began raining down, rock-like, green, spiny hard fruits like horse chestnuts, a bombardment of them pelting us from all directions. We both ducked instinctively and covered our heads. Sikfn's good eye looked up with a surprised fear and I was also afraid. Leaves jumped around in chaos. The red jungle earth was hopping with these rock-like things-like green apricots with tough ridges-but most of them bouncing around only after they hit our bodies. They felt like a flurry of small left hooks punching into my back and ribs.

We heard them then, barking, ooking, one or two deep-throated, male-dominant screams. I pulled a forearm from in front of my eyes and saw quick movements, black-brown leaping creatures the size of cats high in the trees. Far up, in twos and threes, they swung down, hanging by their prehensile tails, fuzzy brown arms winging the green missiles with perfect aim, whizzz�bap! Right on the nose if I hadn't lifted my arms to block them. Monkeys?

The few breaks of sky between high branches were black with their movements, diving and swooping like some horrifying flock of huge wingless bats. Common Tufted or Brown Capuchin monkeys-the kind often domesticated and turned into cute little organ-grinder monkeys in crackerjack hats begging for tips-Cebus apella have rarely been known to gather in troops of more than ten to fifteen. But I swear there were hundreds of them up there that day, everywhere flying around in fantastic acrobatic shows from branch to branch through the trees. They were nasty, white fangs flashing, like rabid dogs, barking, snarling, crying out in gleeful screams, giving it everything they had in an outraged, coordinated attack to drive two puny human invaders off their turf.

All of a sudden, this incredible number of green rock seeds came