TriQuarterly is an international journal of writing, art and cultural inquiry published at Northwestern University

TriQuarterly

IriQuarterly

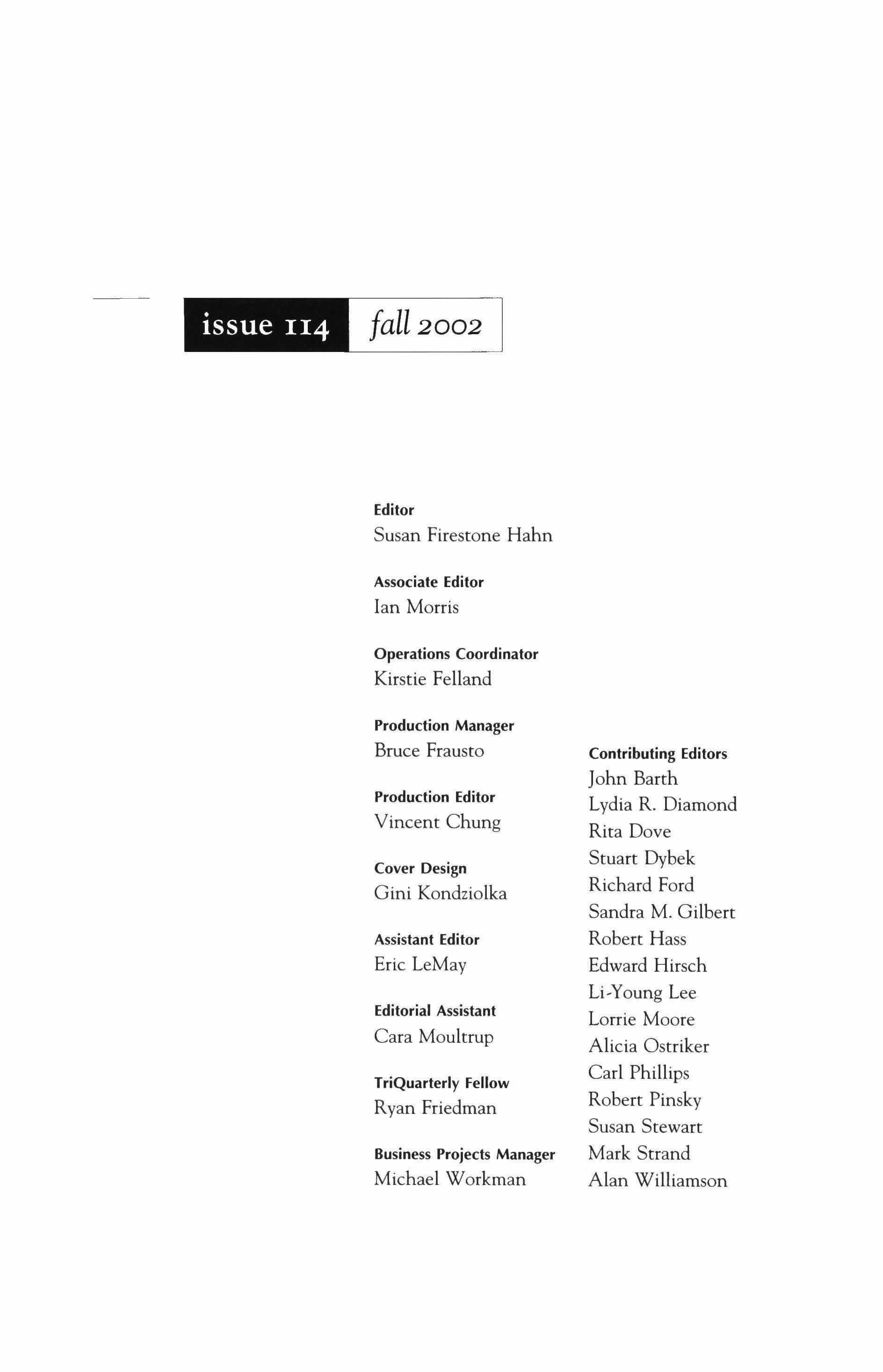

Editor

Susan Firestone Hahn

Associate Editor

Ian Morris

Operations Coordinator

Kirstie Felland

Production Manager

Bruce Frausto

Production Editor

Vincent Chung

Cover Design

Gini Kondziolka

Assistant Editor

Eric LeMay

Editorial Assistant

Cara Moultrup

TriQuarterly Fellow

Ryan Friedman

Business Projects Manager

Michael Workman

Contributing Editors

John Barth

Lydia R. Diamond

Rita Dove

Stuart Dybek

Richard Ford

Sandra M. Gilbert

Robert Hass

Edward Hirsch

Li-Young Lee

Lorrie Moore

Alicia Ostriker

Carl Phillips

Robert Pinsky

Susan Stewart

Mark Strand

Alan Williamson

The editors of TriQuarterly are pleased to announce the addition of a new contributing editor, playwright Lydia R. Diamond, and to congratulate Harriet Melrose, winner of an Illinois Arts Council fellowship for her poem "By Design" (TriQuarterly IIO/II 1), John Dufresne, whose story "Johnny Too Bad" (TriQuarterly II2) will appear in New Stories from the South,2003, and Carolyn Alessio, winner of an Illinois Arts Council fellowship and a 2001 Pushcart Prize for her story "Casualidades" (TriQuarterly 1 to]: 1 1).

FOR THE GIFT OF THE MAN AND HIS WORK

CHAIM rorox

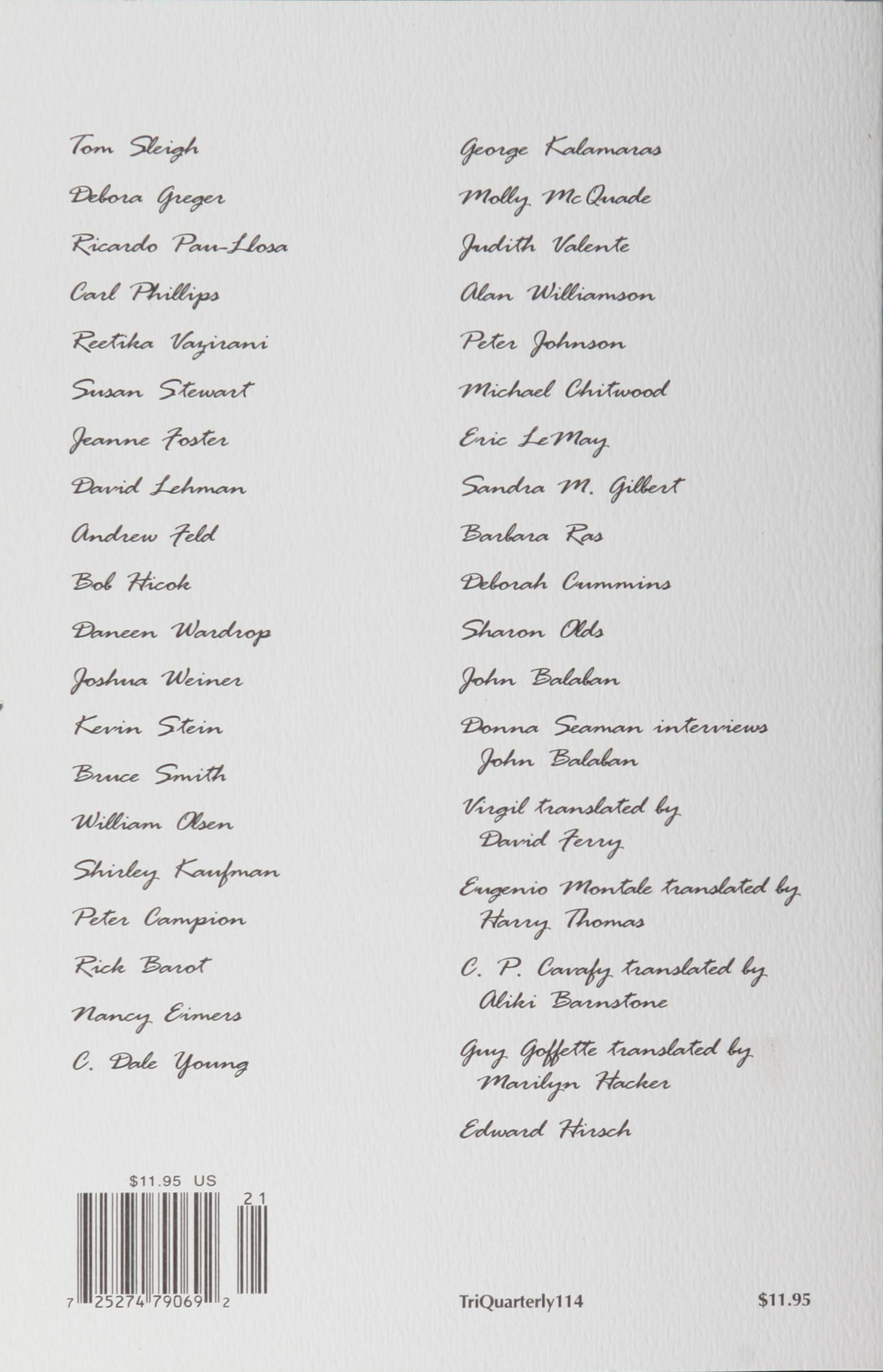

CONTENTS poems 10 New York American Spell, 2001 Tom Sleigh 21 The Later Portraits; The Later Horace Debora Greger 28 Approaching Maiquetia Ricardo Pau-Llosa 30 Tower Window; Trophy; In Stone; Sanctum; The Way As Promised Carl Phillips 40 Nudes; Dedicated to You; It's a Young Country Reetika Vazirani 44 Flown from the generation of WATER Susan Stewart 49 Perfect Tree Jeanne Foster 53 Song David Lehman 54 Dedication Andrew Feld 56 Fallen Bob Hicok 58 Scene That Could Be Used As a Ladle; Late-scape: Scene of Wandering and Scraps Daneen Wardrop

64 Mosaic Joshua Weiner 67 To the Reader Awakened by a Noisy Furnace; Reintroductions Kevin Stein 7 I White Girl, Alabama Bruce Smith 80 All American: First Grade Class Photo; Neither Paradise Nor Below, Nor Up Nor Down; Rag for the Cornish

Tree William Olsen 85 Sanctum Shirley Kaufman 89 Destination Peter Campion 91 Botanicals Rick Barot 93 The Mercator Projection; Shower Nancy Eimers 98 The Dream of Autumn after Rain; Beside the Unnamed Lake; 33rd & Kirkham C. Dale Young 102 Pierre Reverdy, After the Ball George Kalamaras 103 Design for a Necklace Molly McQuade 106 Green; Faces of the Madonna; Winter Journal Judith Valente I I I The Fever of Brother Barnabas; The Christian Year Alan Williamson

Prayer Rag

interview

translations

122 Trinity in P

Eric LeMay

126 Readings from The Book of Eduardo

Peter Johnson

133 Men Throwing Bricks; The One Day

Michael Chitwood

135 Chocolate; Remnant

Sandra M. Gilbert

138 No One Argued about What to Call the Birds

Barbara Ras

139 Why Insist

Deborah Cummins

141 Attempted Banquet; To Our Miscarried One, Age Thirty Now; Western Wind

Sharon Olds

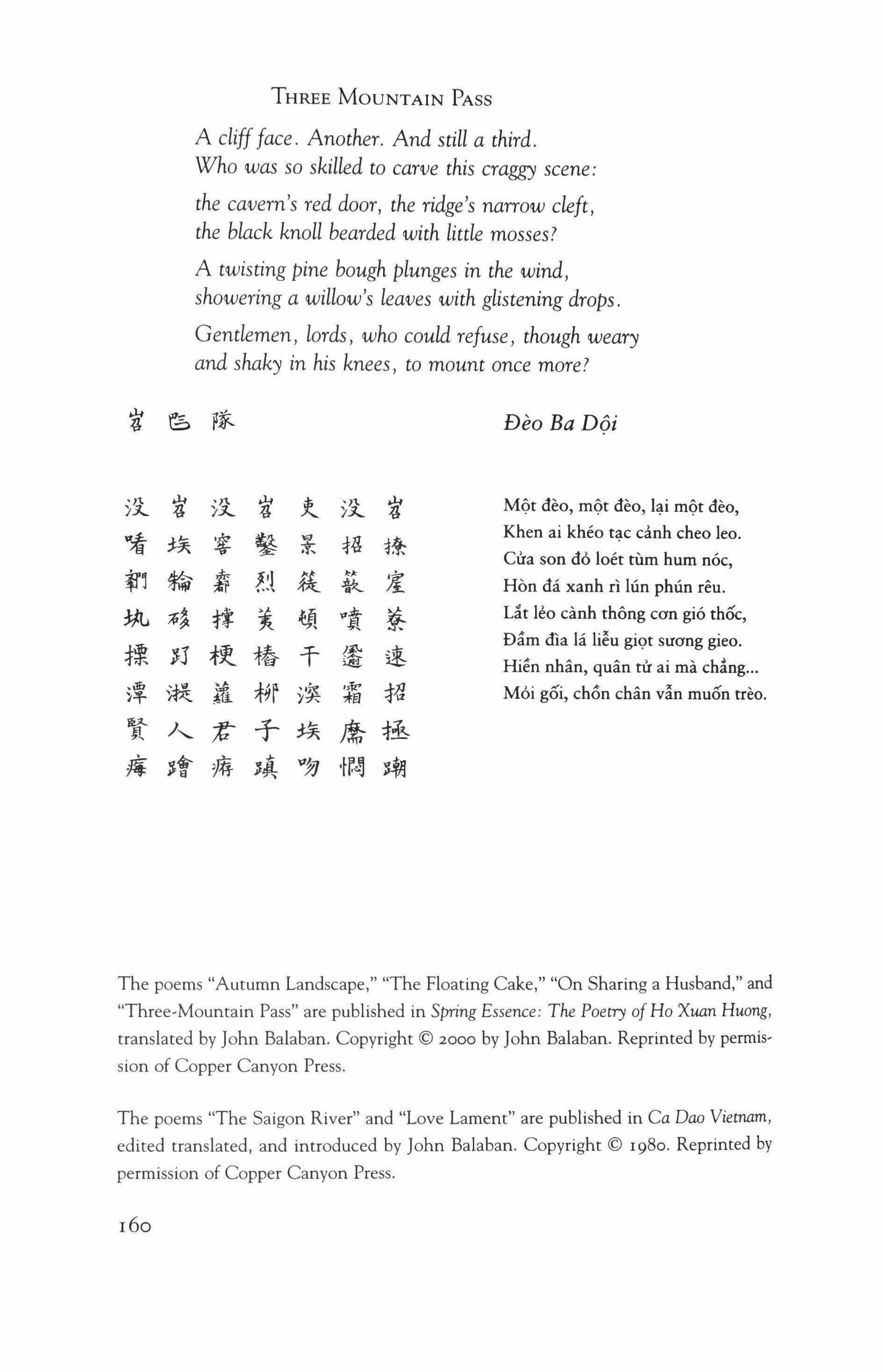

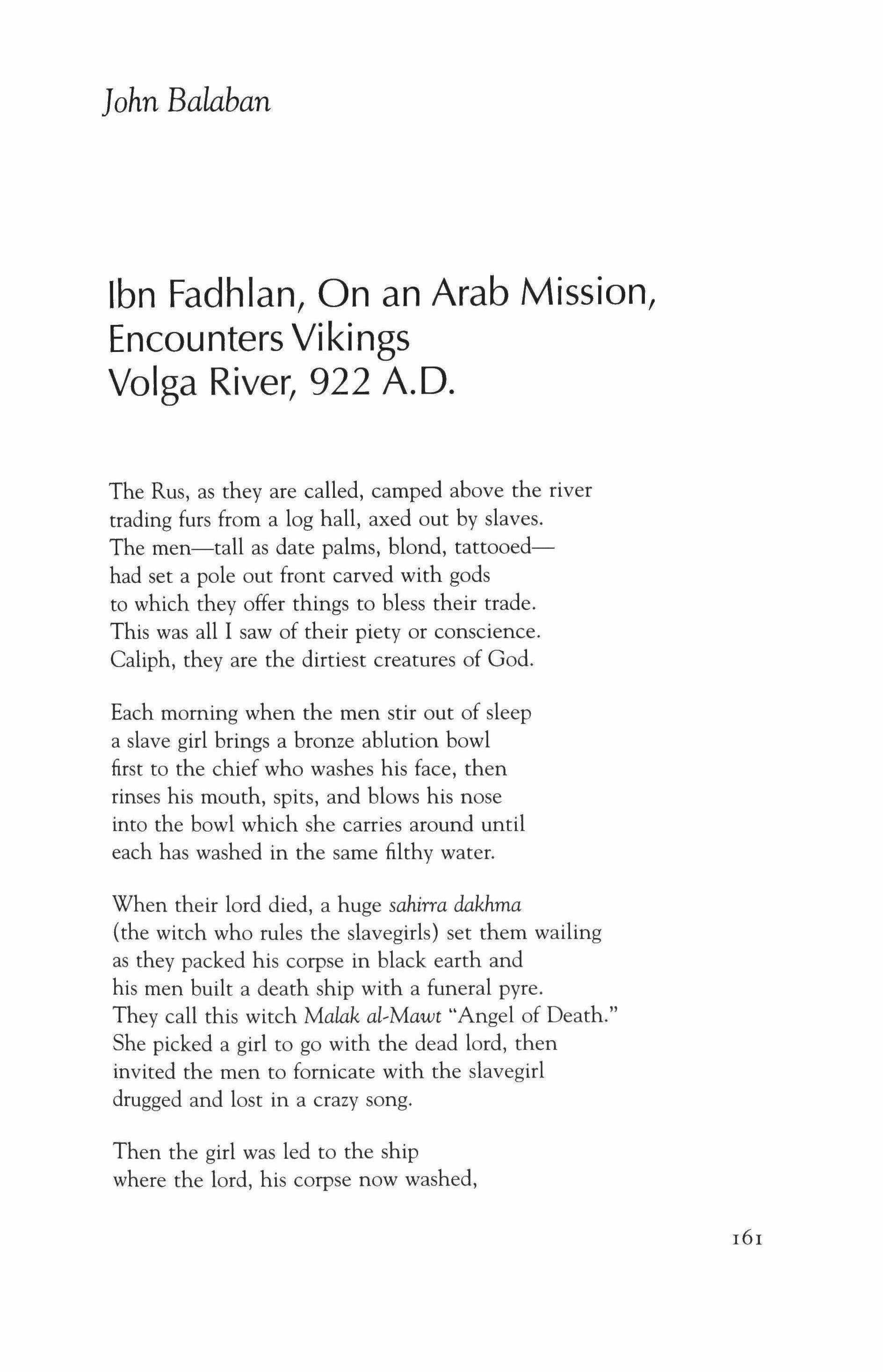

161 Ibu Fadhlan, On an Arab Mission, Encounters Vikings Volga River, 922 A.D.

John Balaban

185 Whitman Leaves the Boardwalk

Edward Hirsch

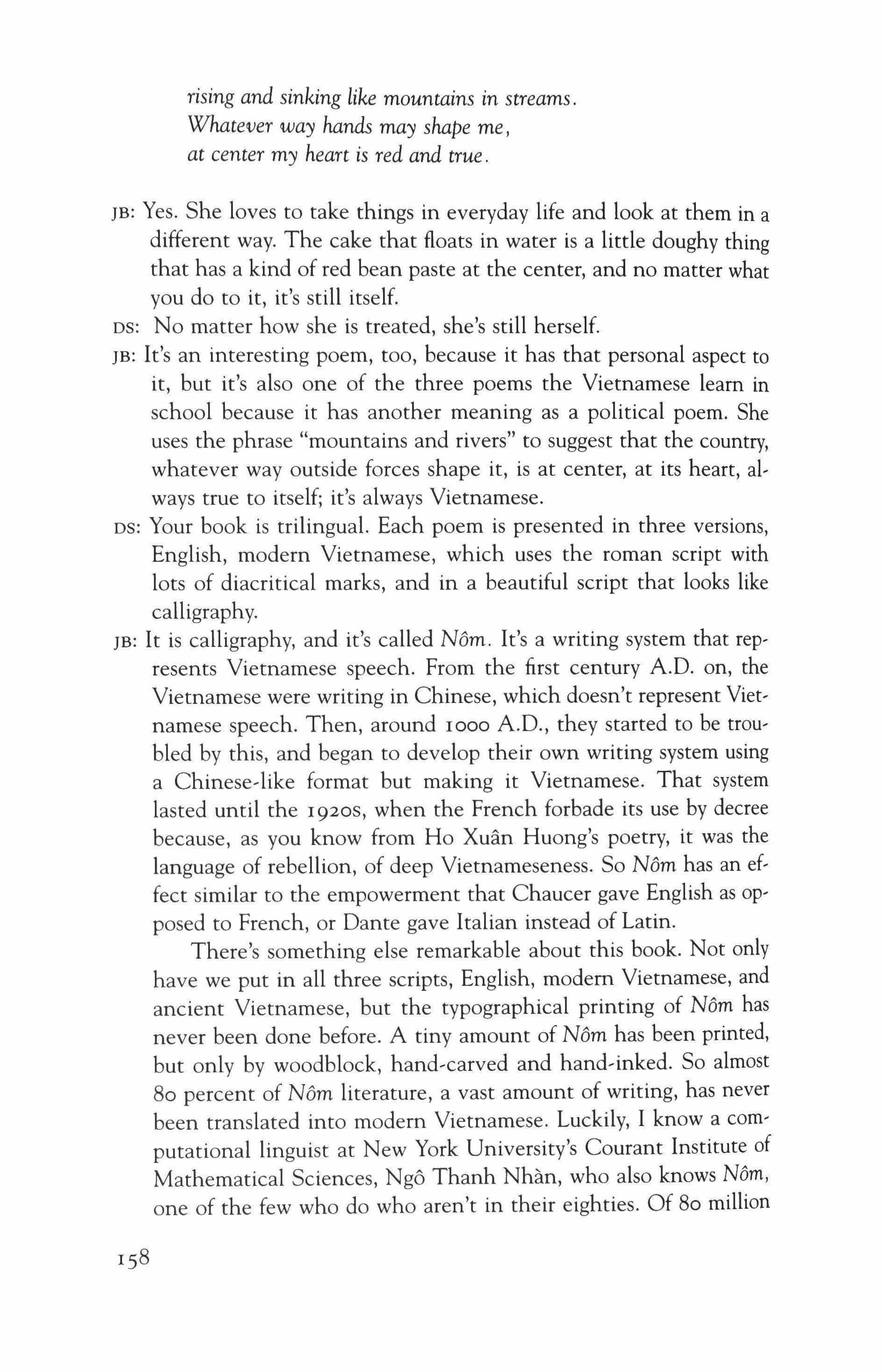

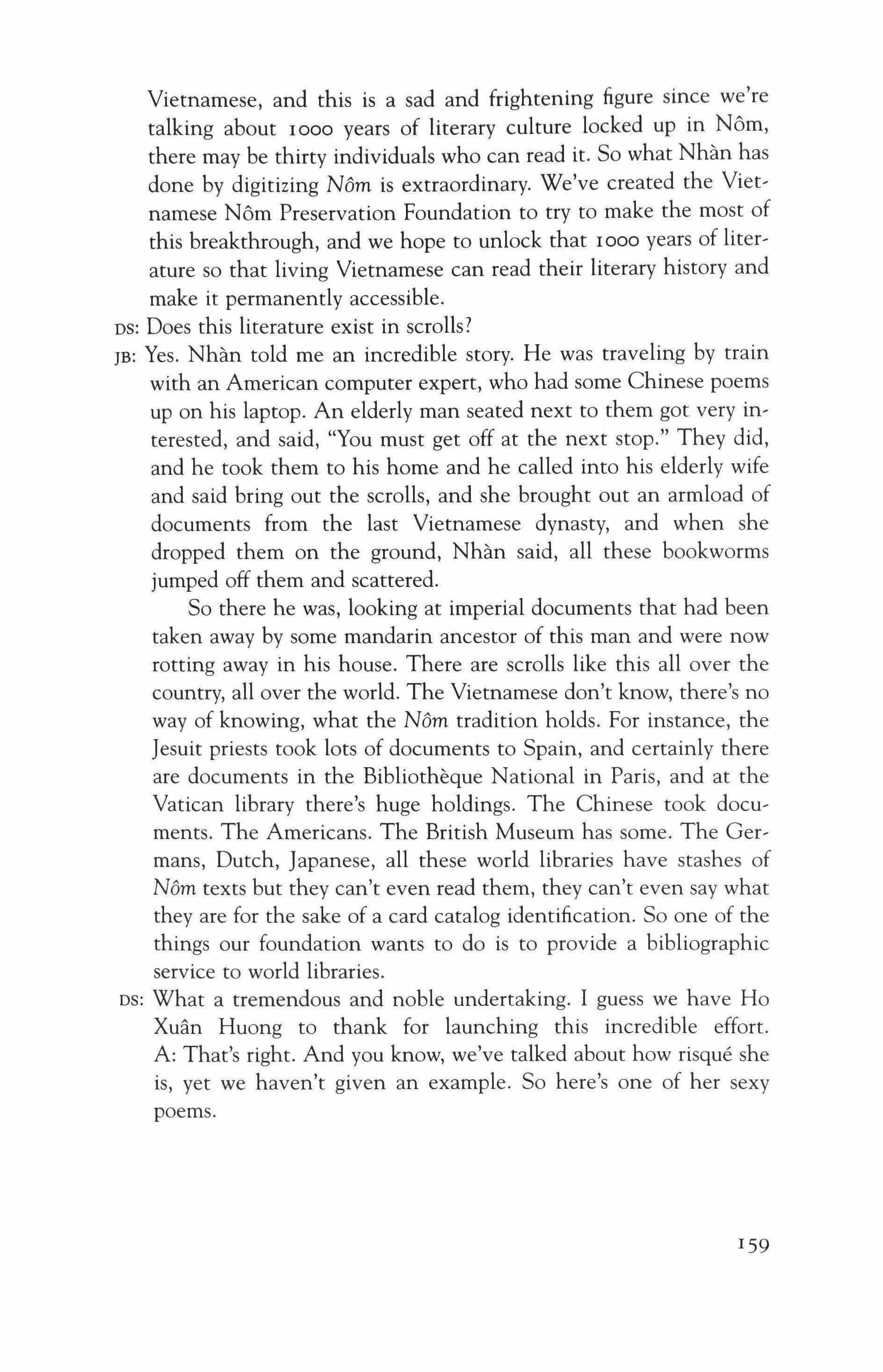

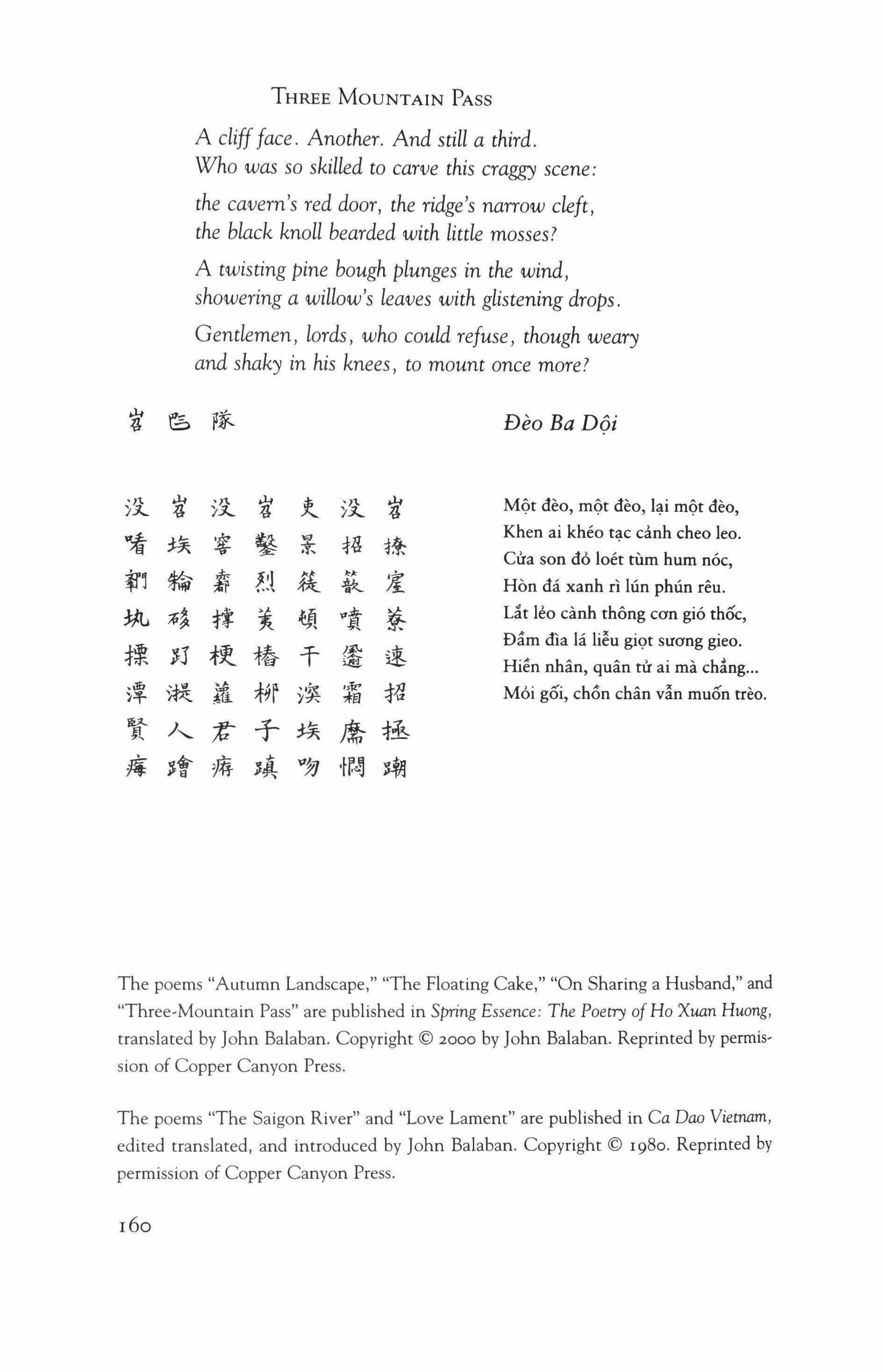

147 A Conversation with John Balaban

Donna Seaman

163 from Second Georgie

Virgil

Translated from the Latin by David Ferry

165 Xenia I; Xenia II

Eugenio Montale

Translated from the Italian by Harry Thomas

176 To Stay; Candles; King Dimitrios; The Horses of Achilles

c. P. Cavafy

Translated from the Greek by Aliki Barnstone

180 In Memory of W. H. Auden; Poet in Groningen

Guy GeoffeHe

Translated from the French by Marilyn Hacker

186 Contributors

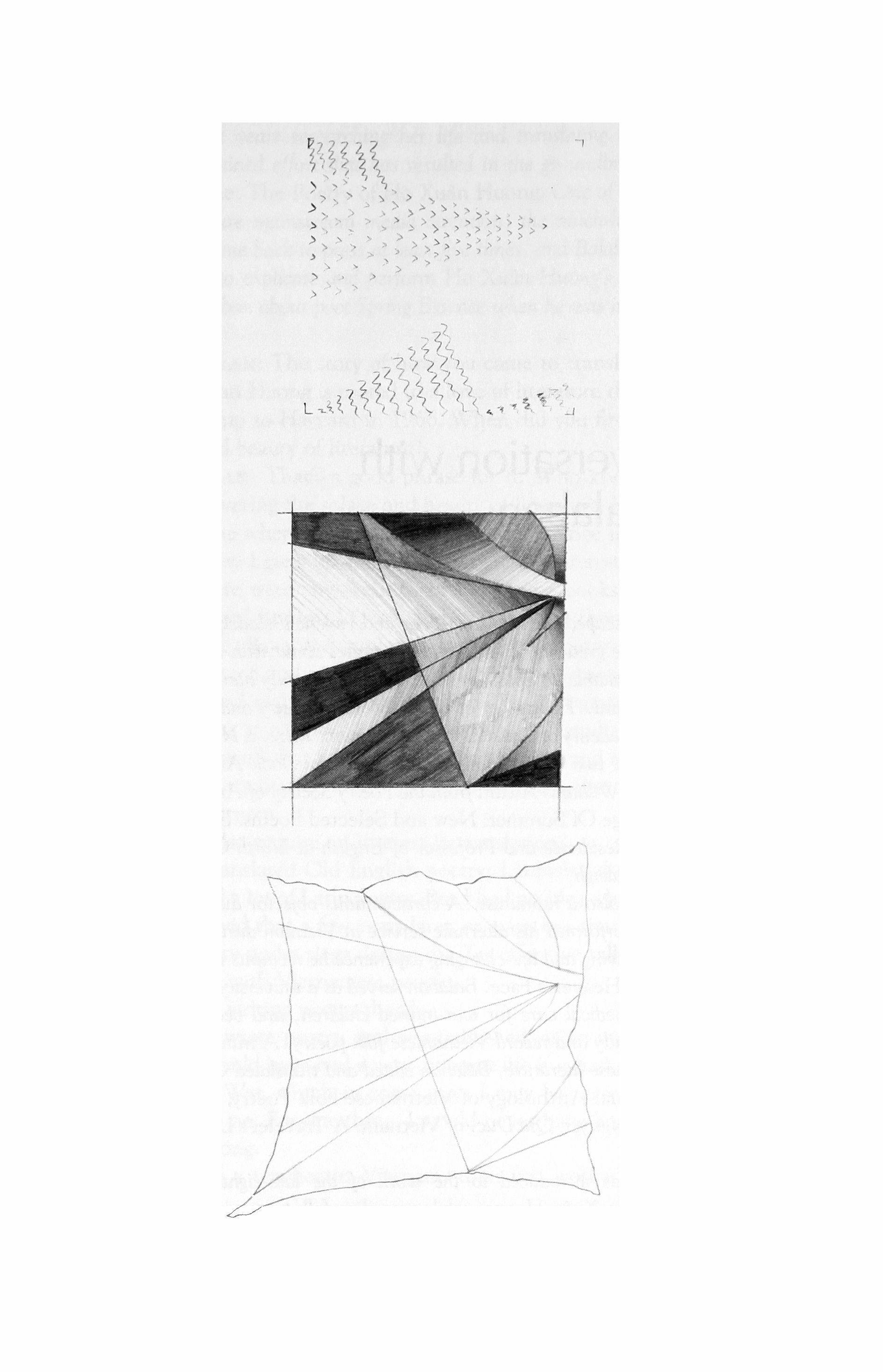

Cover and preparatory sketches: Virginia Kondziolka, Exposed View: Scaled Reflections, 1997, 17.5" by 16", watercolor on tom, cut, and shaped paper with reflective glass beads

Note: TriQuarterly 113 cover photograph by Doug Macomber

Tom Sleigh

New York American Spell, 2001

I/Omen

What was going on in the New York American Black/red/green helmeted neon night?

The elevator door was closing behind us, we were the ones

Plunging floor after floor after floor after floor

To the abyss-but it was someone else's face Staring from the screen out at us, someone else's face

Saying something flashing from the teleprompter: Though what the face said was meant to reassure, Down in the abyss the footage kept playing,

All of it looping back like children chanting The answers to nonsensical riddles, taunting A classmate who doesn't know the question:

"Because it's too far to walk" "Time to get a new fence" "A big red rock eater." And as the images rewound And the face kept talking, the clear night sky

Filled up with smoke and the smoke kept pouring Itself out into the air like a voice saying something It can't stop saying, some murky omen

Like schoolkids asking: "Why do birds fly south?"

"What time is it when an elephant sits on the fence?"

"What's big, red, and eats rocks?"

10

2/1 n Front of St. Vincent's

A woman hugging another woman Who was weeping blocked the sidewalk. Nobody moved for a moment.

They were an island caught at the tide turning: Such misery in two human bodies.

Then the wearing away of the crowd Moving flowed over them and they Were pulled swiftly along down the sidewalk.

I I

3/Joke

Faces powdered with dust and ash, there they were In the fast food place, raucous and wild, splitting The seams of their workclothes, weary to hysteria

As they hunched in their booth next to the buffet Under heat lamps reflecting incarnadine Off pastas and vegetable slag. Then the joke

Ignited, they quivered on the launchpad, Laughter closed around them, they couldn't Breathe, it was as if they were staring out

From a space capsule porthole and were asking The void an imponderable riddle While orbiting so high up in space

That the earth was less than the least hint Of light piercing the smoke-filled, cloudless night. (What was the joke about? Nobody knew.)

And then they stopped laughing and stared into their plates, Ash smearing down their faces as they chewed.

12

4/Spell Spokenby Suppliant

to Helios for Knowledge

from the Greek Magical Papyri

Under my tongue is the mud of the Nile, I wear the baboon hide of sacred Keph.

Dressed in the god's power, I am the god, I am Thouth, discoverer of healing drugs, Founder of letters. As god calls on god

I summon you to come to me, you

Under the earth; arouse yourself for me, Great daimon, you the subterranean, You of the primordial abyss.

Unless you tell me what I want to know, What is in the minds of everyone, Egyptians, Greeks, Syrians, Ethiopians, of every race

And people, unless I know what has been And what shall be, unless I know their skills

And practices and works and lives and names

Of them and their fathers and mothers

And brothers and friends, even of those now dead, I will pour the blood of the black-faced jackal

As an offering in a new-made jar and put it

In the fire and bum beneath it what's left

Of the bones of all-praised Osiris,

And I will shout in the port of Busiris

The secrets of his mysteries, that his body, Drowned, remained in the river three days

And three nights, that he, the praised one, Was carried by the river into the sea

And surrounded by wave on wave on wave

And by mist rising off water through the air.

To keep your belly from being eaten by fish, To keep the fish from chewing your flesh with their mouths,

To make the fish close their hungry jaws, to keep The fatherless child from being taken

13

From his mother, to keep the pole of the sky

From being brought down and the twin towering Mountains from toppling into one, to keep Anoixis

From running amok and doing just what she wants, Not god or goddess will give oracles

Until I know through and through just what is in The minds of all human beings, Egyptians, Syrians, Greeks, Ethiopians, of every race

And people, so that those who come to me, Their eyes and mine can meet in a level gaze, Neither one or the other higher or lower, And whether they speak or keep silent, I can tell them whatever has happened And is happening and is going to happen

To them, and I can tell them their skills

And their works and their names and those of their dead, And of every human being who comes to me

I will read them as I read a sealed letter And tell them everything truthfully.

14

5/From Brooklyn Bridge

Sun shines on the third bridge tower: A garbage scow ploughs the water,

Maternal hull pushing it all out beyond The city, pushing it all out so patiently-

All you could hear out there this flawless afternoon Is the sound of sand pulverizing newsprint

To tatters, paper-pulp ripping crosswise Or lengthwise, sheering off some photo

Of maybe a head or maybe an arm.

Ridiculous flimsy noble newspaper,

Leaping in wind, fluttering, collapsing, Its columns sway and topple into babble:

All you'd see if you were out there Is air vanishing into clearer air.

IS

Pressed against our seats, then released to air, From the little plane windows we peered four thousand feet

Down to the ground desert-gray and still, Nothing seeming to be moving on that perfect afternoon, No reminder of why it was we were all looking, Remembering maybe the oh so flimsy

Wooden sawhorse police barricades as the woman

In front of me twisted her head back to see

It all again, but up there there was nothing to see, Only the reef water feel of transparency

Deepening down to a depth where everything Goes dark and nothing moves unless it belongs

To that dark, darting in and out or undulating

Slowly or cruising unblinking, jaws open or closed.

6/From the Plane

7/Spell Spoken by Suppliant

to Helios for Protection

from the Greek Magical Papyri

This is the charm that will protect you, the charm That you must wear: Onto lime wood write With vermilion the secret name, name of The fifty magic letters. Then say the words: "Guard me from every daimon of the air, On the earth and under the earth, guard me

From every angel and phantom, every Ghostly visitation and enchantment, Me, your suppliant." Enclose it in a skin

Dyed purple, hang it round your neck and wear it.

8/Roll of Film: Photographer Missing

Vines of smoke through the latticework of steel Weave the air into a garden of smoke.

And in the garden people came and went, People of smoke and people of flesh, the air dressed

In ash. What the pictures couldn't say Was spoken by the smoke: A common language

In a tongue of smoke that murmured in every ear Something about what it was they'd been forced

To endure: Words spoken in duress, Inconsolable words, words spoken under the earth

That rooted in smoke and breathed in the smoke And put forth shoots that twined through the steel,

Words plunged through the roof of the garages' Voids, l-beams twisted; the eye that sawall this

Tells and tells again one part of the story Of that day of wandering through the fatal garden,

The camera's eye open and acutely Recording in the foul-smelling air.

from a Sumerian spell, 2000 B.C.

Like molten bronze and iron shed blood pools. Our country's dead melt into the earth as grease melts in the sun, men whose helmets now lie scattered, men annihilated by the double-bladed axe. Heavy, beyond help, they lie still as a gazelle exhausted in a trap, muzzle in the dust. In home after home, empty doorways frame the absence of mothers and fathers who vanished in the flames remorselessly spreading claiming even frightened children who lay quiet in their mother's arms, now borne into

oblivion, like swimmers swept out to sea by the surging current. May the great barred gate blackest night again swing shut on silent hinges. Destroyed in its tum, may this disaster too be tom out of mind.

9/Lamentation on U r

Joy on a Sunday

Pulsing there like a wound in the air

Turning to a mouth that sings what

My parents in their thirty-fourth year

So loved to hear in her throat

There are so many reasons they could offer: The delayed pain of war In the bedroom,

The sorrow that "many boys didn't come home

Joy on a Sunday

Morning to hear her voice, palpable, throaty, Enjoying the immense

Obstacles overcome the way love, Abrasive and intense

Even when it hungers in shadows

Dissatisfied, breasts bulwarks of Lips and eyes.

Mother, Father, they're downstairs listening

To Judy Garland sing, Zing went the strings of my heart

Clang clang clang went the trolley

The man who got away

How unendurably sweet and perfect Is her tone!-

Though the undertones are raw, raw to the bone

The lacerating flair

Of her make-shift mastery, her voice

Shredding into rags she wore

Like finery, Casting off the old Judy

And no reason Or cliches about wars

Suffice.

Mother, Father, and Judy together, United in

Their momentary rapture,

Seated on a couch in orbit through the stars, Look down on all that happens And will happen

And keeps on

Happening while the record turns.

20

Debora Greger

The Later Portraits

I. Red Light

Like angels in old paintings, half there, half not, women in their underwear

drifted into view. Like tropical fish nosing up to the glass of an aquarium

lit with red light, at nine in the morning they look bored: the footsteps on the cobbles

round the dirty ribs of the Oude Kerk were worthless, being mine. Bored as the winged blondes

who crowd old altarpieces, none of the women was as white, not even the transvestite.

Two centuries after it had died, the Dutch East India Company lived on, behind the great whitewashed shell of a church from which every angel had been stripped.

Remains of the old stained glass had been rehung, a few bright islands in a Pacific of blank panes.

2I

II. Stained Glass

Inside the old church, I stood in a puddle of light that had fallen, sanguine, from the scraps of a gown of glass. I stood at the blushing door to the sacristy.

Locked. Could Saskia Uylenburgh, promised to a painter beneath her station, have read the words in soot and gold leaf on the lintel? The thorns of old Dutch scratched out Marry in haste, repent at leisure. I stood on a stone in a vast North sea of church floor, beside a slab with her first name and a date. Her husband would live on till even his portraits had fallen out of fashion. Apprentices long gone, he would pay to be rowed to the field where a young murderess had been hanged, her skirts tied shut to prevent further spectacle.

With a tenderness brutal from long practice, he would draw her twice, on the best Japan paper.

III. Light Rain

Not far from his old house in Amsterdam, that Sunday morning, Rembrandt stood in the doorway of Madame Tussaud's. He was shorter than I expected. Did we see eye to eye? Not quite. He stood at an easel, his brush lifted as if to catch a tear, a drop of rainanything to make a mark, however faint.

22

Who could afford to sit for him in death? And where were the famous furs, the gold chains?

His robe, his paint rag, stirred in the wind. Where was the Venetian mirror that had looked

so long and hard at him? He looked through me, just a wet tourist on the Nieuwe Zijde.

He looked toward the Jordaan. Where was the girl named Anne, who'd hidden in an attic during the war?

She would have been seventy,two this year. Let the dead paint the dead.

23

The Later Horace

I. To the Eighties

Enough! So the gods sent snow to Rome? Invited to dine with enemy or friend, good Romans brought a sack of the stuff to chill the wine.

So what did we bring to the Eternal City? Your pocket picked, we watched the yellow Tiber, its broad back empty, the present lying in ruins

about us. We walked the way tourists walk through history, nose in a guide book to the dust.

If some Roman bought a Vespa with your credit card,

we didn't know that yet. The old river god bent a little and drifted off. Who prayed to him to change the course of events, and poured wine down the bank?

In a church that seemed to grow out of a temple, we stood, barbarians too late to do anything but note a Roman column sliced in wheels like a carrot

to decorate the floor. I've lost the word for that. I've seen a ceiling bossed with New World gold, and did not pray under it.

At the Protestant Cemetery

outside the old city, I saw a bus pull up. From it poured French teenagers who stood in a ragged, giggly line so each one could peek

through a chink in the wall-at what? They seemed unchanged by whatever they saw. I took my place behind them and, through an eyehole

the size of a picture postcard, saw the grave of the young Keats. What was it to them, that stone carved in English for one whose name was writ in water?

II. To the Nineties

o my subtropical students, you'd want wings of your own! To be borne on the fluent air that lifted of a morning from the swamps paved over.

o parking lots of Florida, let a poem begin. Poet turned bird, wings barely flapping, I'd drift out of the classroom, and lift like a vulture toward the Interstate,

looking for lunch. Late afternoon would find me in the next county, roosting in a cypress up to its knees in the Styx. The skin on my ankle would roughen.

It reddened. I was feathered at the elbow. What poetic voice was mine? The raptorous moan of a schoolgirl dragging a line of yours into her own language,

blushing furiously, cursing you under her breath. Dear Horace, I would pick your bones so clean, cleaner than your critics. What more could you ask?

VI. To the Double Oughts

Was Spain rattling its spears? And what of Scythia? Don't ask me, dead Roman. Forget foreign affairs. In the New World, I thought we were guarded by an ocean.

Up the east coast, a smooth-cheeked tide receded, the sand left ashen. A sea-rose shook. The blade of a moon sharpened while we slept in early September.

Our cost of living rose in taller and taller towers, but don't worry. I had simple needs. I liked things big. Love no longer wore us out at night. There's nothing to see-

go back to your own stony bed, old Quinctius, under the umbrella pine. Let the wine god shoo away the wolves who worry your grave.

There's no longer a slave to mix spring water with wine gone vinegar. Lie down next to the bones of that woman Horace called easy. He used her name to shame her, and made her immortal instead. Where is her hair, once done like a long-dead Spartan girl's, in the very latest style? Tell me her lyre survived.

Ricardo Pau Llosa

Approaching Maiquetfa

At last the sea details in our descent from Himalayan heights to the tropic earth, so that a handful thousand feet or so provide wave and crest, the white tear of surf and the rattle of lines that is the sea's liquid skeleton. The ellipse of my plane window becomes arena for the infinite jostle, blue and gray and those unnamable shades the crucible of afternoon and latitude conspire to paint. But it is the surf and not the horizon of palette that draws my eye. How spaced this chess of foams on waters that buried galleon and whale, quenched cannibal and volcano, invented the globe. It is not the sea that remembers them; its toll calls no one. Memory is the land. Surf merely counts the beats of space and pressure, the mathematics of that matter upon which tonnage glides or plummets according to angles and speeds. Abacus to the cardinals, the sea counts. In that it resembles the winged air, but there are no rifts of tide here, no signatures of reef forcing the jangle of liquid into white bursts, flowery wounds. The sea alone negotiates memory and time, is tangible but resists the palmed forms of land, yet pooled in hand has time's mirror invisibility.

In mounts and blank scrapes the sea is scored by the eye though it is printless as air. What then to make of the sudden line of white trajectory that opens an arrowhead on the unpatterned page beneath me? The wake of the ship is no different in hue or physics from the break of wave, but line speaks intention. The gasp of whale, the Sisyphean roll of trash from crest to crest, even the soft widest arc of wave can be discerned from man's voyage through nature. However small and briefly, it is man that makes the sea tell a story other than itself. When finally the plane lands I ponder the tarmac as I did the sea, just feet away. Gray as wet sand, packed with bony rubble like a flood of broken shells, the tarmac is scrolled with tar squiggles, calligraphies where heat broke the poured hardness, sealed wounds. Worms or strands of algae might compose a similar parchment of farsi canticles or merely man's response to his linear spoor on the sea. For when we repair our handiwork we are most natural, random rhythmed, and speak through work the world's clean tongue.

29

Carl Phillips Tower

Window

The glass is old: through it, the worldits partscoming up: is it spring then?

To look through it, I could be looking through river-water, the river slowing but never down, quite, to stillness-

I had thought so, I had wanted to think so. Was that wrong, then?

Last night, the storm was hours approaching. Too far, still, to be heard. Only the sky, when litless flashing than quivering brokenly (a wing, not any wing, a sparrow's)-for a sign.

It seemed exactly the way

30

I've loved you.

And you a stone, marked Gone Alreadyyou a leaf, marked Spattered Milk in that light, then out of.

I closed my eyes. I dreamed again the dream called Yes: the worst is true. In it, I wake.

I lean my head against the glass. How cool the glass is.

31

Trophy

When was the burning that offire?

When was it fear?

When sorrow?

That any gesture can be understood as the necessary, mostly incidental price the body pays for whatever response comes past gesture, past the body that made it:

to what extent can this be said, and it be true? and it be false?

Under what conditions?

Under whose conditions?

Thus the waves. Thus the light of the sun across them.

Above me, what before had seemed entirely that to which my own passage-swift, coracled, resplendent, over the water-might stand compared

II

32

are clouds now, now interruption, the way that water is interruption, the land only ending apparently,

there, where not so long ago I pushed off from it, it does not end It seems I am rowing, it seems to the rhythm of a song there's nothing left of except the rhythm, no notes, a broken line, the words, to -guessing-sing to, No, sing No, I'll have no other-

Say what you will.

Say all you have to.

I have looked to the water: there it was, of course, doing the water's version of pucker, then bloom, then sprawL

33

I look to the shore as if toward everything that, once, I stood for, andhow soon, already-

almost, I cannot see it, I look to the water, I am rowing, it seems

34

In Stone

Their clothes; their rings as well, until at last they wore nothing. All was visible: flourish; humiliation; some things, more than others, looking almost the same. As if Not only tom but lavish let be the angle all tearing starts at, as if this were the rule, each splitting open around, unfolding from-so as, incidentally, to exposeits wet center. The kind of sweetness that carries a room, but there was no room. Howat first a sweetness; how, by turns, a gift, a darkness. Very dark, especially, about the trees, where trees were. Like being a child and told, all over again, Think of Christ as of a pilot�boat, a launch delayed slightly, but reliable, it will come- There, beside the shifting fact of all that water. What's done is done.

35

Sanctum

Then broke off reading.

Then closed his book.

Systematic, erotic, not unreluctant, half-shedding earlier versions of itself undone, undoing-was that the body, no different finally from the light as he'd grown tired of seeing it over, over again, depicted?

Hovering.

Nakedness, it had always been translatable: "what lacks assistance" -how had he not noticed?

Deceit, trespass, whether risked or actual: as boring at last as the kind of gesture that looks each time like, for its flourish, Here it ends, it must, when --does it?

A coffered ceiling-s-

A single window, round, leaded and,

viewable from it, the usual horses, black, caparisoned, across their backs the stiff marriage of brocade and a velvet crimped, crumpled, to heraldic effect-

Why not? he said.

Why can't l? he said.

Twin bells, those questions, seeming, ringing as from a bracelet at the wrist that had worn no bracelet.

He moved at first, as if deliberately, in concert with what he believed

might least offend. And only then as if for flight.

37

The Way As Promised

(Santiago de Compostela)

He shot the ass in the head. Simple. He filled the hole between its eyes, open, with a spray of indigofor blue, he said, for yellow, sweetleaf-and all was green: the bush clover soon to be translated into hay, the blades of the willow beneath which he told us

Technically, the weight of pain is the weight of shadow and it was true. It was as he'd said: we passed protected. Here's where our mounts, thirsting, took of the water, fell swiftly dead, and thereby saved us. Here's where we stopped to bathe, and for the first time saw him nakedone tattoo: a deer, gutted, pinned in what he called your standard

Chrisr-on-rhe-cross position, by which, it seems now, he meant in no way a thing unholy. Here he is, taking my handfirst to his chest, then his mouth, saying, as if toward someone who has not read as much already, This road goes far. And herepast that-saying Listen, what makes the truth so difficult is also what draws us to it: how clear it is.

A single road. As far as Santiago.

39

Reetika Vazirani

Nudes

Manet Degas in a book

Pissarro Seurat speck upon speck waterlilies nude bathers a breast gloves at the opera couples abandoning ship wooing Child don't cry we'll be back at sunup

Next day the sun a dot to map my bearings

My cabin's near the dark Stevedores hauling my trunk Abroad the door says Whites Only Who am I in the middle of?

Puffs of steam quickly the train took me from a black umbrella on the street

My pages turning become Berthe Morisot's slender fingers on a sofa taking one lover to X out a gentleman

Who will paint the blood between us?

In their time peonies and zinnias became cinema

I see my mother point to pleasure like an unplucked root Father your money was a cold smile and the British I started to talk like them

My camera forgave no one my album my atlas Bombay London New York father mother three of us nude room I'm in the middle of

Dedicated to You

It is the thing you do open a book by someone you like who never knew you you leaf through to see which words are dedicated to you

What gives you this posthumous feeling

Well you like his work and want your name in it like on his dance card when there were evening dances at your grandfather's supper club You see Miguel Hernandez and Mirabai Dickinson Ghalib and Hayden "Don't Kill Yourself" Carlos Drummond de Andrade but not you you wonder when you will appear This is more than the desire to see you engraved in stone as an original donor to the Morgan Library or listed in your alumnae magazine Charter Member of the President's Circle

This is the affair you had dedication is only part of the proof the rest is in hand-cancelled stashed in a box made of sandalwood lined with department-store tissue The rain presses you to find you are there in the pantheon You knew it this poet born in England died in 1950 after India's Independence when murder was breakfast cereal and people hoarded fists your grandfather divorced your grandmother

who went for a Muslim in Bombay no more dances at that house of cards

Therefore your mother an only-child gave birth to orphans DC the fifty states and Puerto Rico

You fly across the world like mail in 1968 in the bright days of war and department store parades

This poet loves her readers and you loved him who died before you were born

42

It's a Young Country

and we cannot bear to grow old James Baldwin Marilyn Monroe Marvin Gaye sing the anthem at the next Superbowl

We say America You are magnificent and we mean we are heartbroken What fun we chase after it Can't hurry go the Supremes Next that diva soprano for whom stagehands at the Met wore the Tshirt I survived the Battle

We leave for a better job across the frontier wish you were here in this hotel two of us one we are with John Keats on his cot in the lone dictionary I'm falling on dilemma's two horns

If you are seducing another teach me to share you with humor Water in my bones and the sound of a midnight phone Hello love I am coming I do not know where you sleep are you alone

We grow old look at this country its worn dungarees picking cotton dredging ditches stealing timber bullets prairies America's hard work have mercy leaders in order to earn a perfect ten some step forward some step back neighbor here's a seat through orange portals lit tunnels over Brooklyn Bridge Golden Gate weather be bright wheels tum yes pack lightly we move so fast

43

Susan Stewart

Flown from the generation of WATER

a breath flew across the water, a breath, a thread, of living fire that stretched across the surface of the water

and the water moved in time, oblivious, cold as a mirror, cold as time itself that mirrors only water, mirroring water just as water coldly mirrors skywhat I know about the water is written in the water, what the water is is written in the water, the weft of water is woven in the water but the thread of living fire cannot be woven; everything falls, everything dropping down from where it came, a drop oozing from a leaf,

a pear-shaped bead, a pendant then pulled up into a sphere,

an egg, a sphere, then pear again, elastic, pulled, then a pause before the pause, the comic plop splashed on the stone-

44

look and listen and you will lose the other, the next drop beginning

that will wear this one away, as the drops wear, invisibly, the stone back into water-

jug and cup in pieces in the rain, kettle in the rain, leaking rain; take the bucket to the springhouse, go inside the mossy silence, dip your arm to the elbow and push against the thickness, going deeper into water, black into the darkness, the source of water waiting there, far beneath the water and the water black as coal, black as any earth-mined thing; then bring it to the daylight and it will clear again, clear in the clear glass, invisible

over hands, a blessing falling, a dangling happiness, blessed nothingness that nothing does not need, and you will learn to find the source of the water, how thirst comes before the search for the source and searching is a thirst that can't be slakedyou were made from water and you are made of water and drawn to it as surely as the forked stick of the dowser to dissolve like pain or memory, to dissolve stirred and drifting, to disappear into the form of what was always waiting, forget what stood as dread or care there in the distance; rest your head, unthinking on the water's lifted palm,

45

rest your head and all your limbs will float like risen weeds-

most beautiful of all things, of all things on the earth, is light cast up in motion from the surface of the water, most beautiful of dancing things, the light cast on the bridges, the light cast on the bow, and on the sleeping faces, dancing light from water glancing, wavering, like a voice where voice is lifted all at once out of the heft of wordswhat I can write of water melts in the light of light on water, the water given, giving, cannot be held in time; rain driving down against the bridge, driving all night without intention,

erasing the hearts and letters scrawled across the blocks of stone---declarations of love and strife, gone in the morning light; a white page floats on the surface of the river, caught in a clutter of branches that flooded down from summer stormswater that carries the memory of mountains into the sea's forgetting, water that begins under shad-blow and redwood and swirls under willows in the swollen meadows, washing up a seed or carp, bloated on treeless sands, a message in a bottle stays in the bottle and the bottle stays lodged between branches of coral; distich stitching of oars, catch and slap and ripple, S, letter of rivers, sound goes surer the deeper it descends,

far beneath the surface, the invisible wreck, while the great logs bob through the skin;

snow on the sea melts into the sea and snow on the river melts into the river until the river gathers into ice below snow, its freezing equation of loss and gain and motion hidden from view, element buoying and resistant, element most flattering to error, element deadly to fools and self-deceivers: lift your head and you will drownthe water drags you down by the knees, drags you with its invisible net, and pulls you under into the minute where your life unreels its sequence of dreams: you were born in the month of water and born from the water's arms and carried across the ford to the fountain made of nails and baptized there in tears where the blue washed over the windowscountry of salt and bitterness, tide of wasted wrack and goads, the clothes strewn on the beach like shells, empty as any emptiness;

cause is as distant as snow in the mountains where snow is the cause of all things-

one night in particular, night drenched and steaming, a moonless night on the street of the militia, the book of hell lay in the gutter, the pages oozing, the black print blurred back into pulpy weight;

I wrapped it in my coat and carried it to my room laid it, spine up, on the vent

47

where it steamed like the soggy diaper of a long-neglected child,

the pages stiffened apart from each other and could not be turned again:

angels and thieves and warriors and liars lovers and readers silent in their chambers

stream from the circus of the dead parade of blackboards and gowns

silence in the wood and fiercest sun glinting from the steel face of the sea

long nights beneath the drumming roof afternoons pressed by the weight of the water

the clothesline collapsed, the sheets in the mud and at morning the dew spread like stardust on the grass-

where is the water of the sopping weight, the water shed at the moment of the cry?

where is the water that died into water so the water, eddying, would clear away its stain?

breath buried like a treasure beneath the water, breath breathing its secret under water,

depth of love and force of strife swept by the roiling water, swept

where the warp is woven in the water,

thread of living fire that leaves no scar on water,

thread of living fire that never ends

Jeanne Foster

Perfect Tree

March 6, 2000

All your smallest branches were laced with frost, in the moonlight, spun, an intricate net, strong enough to catch even gods if they should fall.

March 7

An owl appeared, shadow, on your lowest branch and turned his head around to the right and then the left. He left to deal death, towards the ground, talons first. They who were turned prey, not in my range of sight.

March 8

A more frequent visitor, and by day, the blue tit, who swipes his little beak along a branch, side to side, as a knife sharpener slides the flint along a blade one side then the other. Sometimes they are two in your limbs, nodding their blue-black caps, extending their lemony yellow breasts to the sun.

49

March 9

In rain, too, you glisten, but are not spun by light; and in wind you are so closely knit that all your branches tremble as a whole down to the smallest twig.

March 10

You were grown straight by the wheel of nature; though still in your youth, with a fine knowing of how to present yourself to the world. Not an inch of pride. Hiding out from nothing. Simply beautiful.

March 11

When the pruners came to shape the olive trees, they also took their shears to the other trees standing around as young trees do, but they left you alone.

March 12

I have a feeling you were grown for a special reason, planted outside the window by a person I do not know, maybe in memory of a sister, or a favorite pet, but I can guess that she who planted you was at a loss, and did not want to be alone, and needed a friend, as I am and do not and need you. How graciously you take the role.

March 13

Spinoza wrote: only those who are very free are very grateful to one another You have freely given your presence to me;

50

and I have given to you my gaze all winter long. Even in the night you glow into the room.

March 14

Goodby, silver sister of my young mother, before I knew her.

(Greve in Chianti)

52

David Lehman

Song

Slap that bass and I'll play the trumpet.

Beat the drum and I'll moan on the sax.

Luck be a lady, fate be my strumpet, And I shall write sonnets about sex

On your body, with sauce, have a martini (Bombay, straight up) and try to teach you

To spread the word about our destiny

In letters that may not reach you.

That's the way of the word, like it or lump it.

You can protest, refuse to pay your tax.

You can rub the lamp and command the genie

To elect you president and then impeach you.

You can weep watching "Oedipus Rex"

Or let beggars beseech you.

In the end you depend on a fickle text And letters that may not reach you.

53

Andrew Feld

Dedication

We argued about the difficulty of degree, the exhibitionist on stage, flaunting his fluent ease, his keyboard mastery. Poor puppet, beating at his box of strings.

We wanted more, didn't we?-a deeper adeptness, the border between performance and performer blurred, erased. It was for this we put our best demeanors on and took our student seats under the three jutting concrete tiers, beneath the full-priced tickets. We sat in a concentrate of time, as in the way the house lights dimmed, the great candelabra reduced to three bronze dots ellipsing on the Steinway's burnished wood, a trill announcing the Divertissement, Etude, Nocturne, the concert hall reduced to a small room where a young man sits trying a few notes out, each tentative thought hanging in his head like a pocketful of change scattered on a white plate, the bright possible in a dark room, gleaming, unchosen, unspent, while in the bar below a woman waits for him, the only woman in the bar. She lets the men there buy her drinks, a glass of vin ordinaire, maybe a Johnnie Walker Red, and flirts, knowing what all these workmen think of her, and her boyfriend. They think he has the easy life, and that she is the easy life.

54

She likes their envy and their scorn; it fits her like a soft, clinging woolen skirt and makes her feel as if her life was composed by choice, not accident. The piano player renders all this a little too stiffly, with too much distance, insufficiently rubato, the notes hanging in tight clusters, a sheaf still waiting for the whetted scythe as two headlights sweep across another mile of Illinois wheatfield. The vehicle is now the smaller room of a compact heading home, content in the ordinary. So when the wished-for place arrived, as if a car radio suddenly started to play the memory of a music heard in a dream, it was our brilliance, alone, to recognize the moment that fulfills a lifetime's work, the long sequacious notes stretching like lines across a field of shifting, bowed heads, bringing the unthought-of, unknown to us, music and musician dissolving in union, and then, consummated, the harvest in, milled down and shipped away; and in a room with the lamp dimmed, the lid of the keyboard clamped shut, the couple lie in bed together, eating torn-off pieces from the loaf of good bread two coins taken from the white plate bought them, while the music starts moving through a succession of rooms, each one larger and more expensive, until the piece is finished. Then the musician stops, waits, and bows: once to the applauding crowd and once to the now-silent instrument.

55

Bob Hicok Fallen

As sometimes fish appear in unexpected places, on my table say under glaze, or my breath when I put it in a car and carry it to the ocean, I looked down

leaving the park with its new diamond and old sellers of heroin, the park which is a sudden bowl in the city, a scoop out of the earth where rain collects as a larger animal of water, where rain becomes puddle becomes lake,

down at my feet which were far away and lonely, past my feet to what the architect of summer intended to be grass under the stairs, long and reaching for light, for the meal of sun, when a man. When a man

looked up from under the stairs. When he moved I thought land had twitched, a wind-flicked scrap of grass or that a mirage had blown my way. It was a hand reaching out, to wave or shoo

56

who's to say, then two white moons under the stairs and I stopped, looked between wide boards into the eyes of a man. Not dead,

not yet but soon to judge by shape and feeble moves, absence of teeth, of shoes. Nat dead like others over whom I've stood, ancestors in manicured rows, our beloved gathered as crops or strewn wherever a wagon stopped or shovel found ease for its tooth. Hi

my mumble to the man not living, not dead, who drew a finger to his lips, puckered and leaking air, shushing me not to tell, when like a whale he dove back into his flesh and closed his eyes to erase me and the blue seance of sky. I walked

out of the park, out of his home and have since walked out of my life many times when he conjures his way back into my eyes, a man under stairs who whispered to me with his skin how easy it is to startle breath, how quickly my shadow might pack its bags and leave.

57

Daneen Wardrop

Scene That Could Be Used As a Ladle

A train's harmonica-not so far away.

Bird cheeps like children

manic from not wanting to go to bed.

From their capacious leaves catalpas pull evening.

Regular on the rail, wheel-clack clack.

If I could wish for everyone I would wish shade of catalpas, whisk of birds, relectiveness of trains.

Touxu from Qiaozhou takes a moon out of his pocket, unfolds, and posts it on the sky.

Now we may pour wine.

But I would not like the responsibility of wishing for everyone.

Perhaps the young man from Qiaozhou could do it. Or you.

Wish for change to continue though it breaks your heart.

Touxu wishes for a wife that can cross from dream to night.

58

Falling blossoms filling his robes.

A sparrow flies low scallops across the street.

The spout of wine runs with a thousand moons balanced in its pouring.

The young man walks up the back steps lit with change.

59

Late-scape

Bats, cinders, rising to ash but not stars.

A booming car lows its beat for blocks around from behind car windows sealed by bass.

Touxu won his wife by responding, before the courtiers could, to "A beautiful spirit seeks out the court of Qiaozhou," to make a lu-shih couplet, "A noble mind loves the calyx of the lotus."

River sweeps, holds moon in place.

Touxu tried to pull the arm of his wife through the sac between dream and night.

Bats' anonymity, outsidebut if they get inside, very famous to the cats, the soffets, my savage brain.

He ladles more crysanthemum wine, about to forget the thought he just landed on.

Was it something about crinkling rivers, broadening faces?

A car's muffler hangs, jangling the length of asphaltthen two red eyes flare, fold.

60

In the streams between trees bats fish with mouths open.

He can't remember, the river satined? the face winked-shut?

Fear is a wish to leap to the white plain before change.

On the other side of dream, stuck in night, fear's leap and flap.

Instead of his wife's hand, bees cling to his clothes. He's awake.

Three bees on his pillow. Still wine in frill bowl.

Scene of Wandering and Scraps

Devotion of the rock humbled on its hard borders takes sun in to itself

Poet wandering the hazed mountain to write a line on a scrap as it came to him, throw it in the bag with other scraps?

At night, no matter what gleanings, he'd piece together a poem of lu-shih couplets.

(One day's walk, one poem.)

Though the rock stays put we don't forget intercalations of rely-poly underneath.

(The poet's shoes fit like bridles.)

At night he'd eat rice and clay and cry.

Spider in the webwith one flex of its many knees, tightens the universe to it.

(The poet's shoes fit like foxgloves.)

At night he'd eat rice plump and shiny, and exhale.

The groundhog's hole in the shank of hill. She leaves the hill, walrus trot, slow, no neck and all-over glossy. It would be tip-toe in some languages. Hides under the Dodge in the driveway. Raises her bulk to stand on two legs,

lift to a tiger lily with love.

Love without a neck that can bull its gravity so the length of a kiss.

And chomps the tawny head off, tiger lily crumpled in her mouth.

(The poet's shoes fit like skin.) At night he eats rice and cloud and wipes his chin with moon.

Joshua Weiner

Mosaic

Will we remember you, baby we never knew, never saw, never touched, child we never touched though flesh of our flesh, whose skin we never smelled with a cutting inarticulate animal love made of our one love formed from dream shards and diverging strands, the splits we sequenced to envision you, now without a name (the name we would have called out to the living, or the dead; but if the dead never lived, outside another body in this world?)

So I seek my shelves, my selves, the same to find there in some ancient work fate and character inscribed as one mending to action, in time and blind, assured of striding the right path to experience; thus pathos, to learn to know through pain.

Do we need then to entertain, perhaps, that character can be remade, and so fate made plastic by true intentions' heat?

(And if one is hardly one, a cipher, unbegun?)

Such is pride, scratching figments of pliability, false characters.

Proud parents, we say

Yet when I say "you" the peak of energy in utterance climbs to question elements of whowho died by this mosaic of a gene, (mosaicism, pathogen's crooked path to crippling deviation) who did we bum to ash, whose ashes did we carry to the coast, whose ashes did we set down on that rock high above a sea caressing like a lullaby, it was that quiet, barely a breeze to carry further the remains

So I had to lean into the small heap of ash to make from my breath a single strong current and send the ashes over-; yet when I breathed in, my nose inches from them, (I could make out, I thought, the larger chips of bone) particles of ash lifted to my throat and stuck there. I coughed, swallowed some ashes, my face close enough to the ground, I recognized like a word an ant-with effort, with continually renewed determination and its famous instinct for logisticscarrying as if along a legendary route

65

another ant, dead, its own ant, across the cliff pathetic chimera of grief, earth-dweller gathering beyond reason in an awkward script of movement this improbable coincidence, chance strand in the ninth position, the body's winter deformation.

A mosaic now of unborn possibility: the future had breathed like a muslin veil we peered through to see ourselves with you in another life (in the nucleus), nucella

of the new, nut meat hungered for as we prepared to pass through curtains puffed with beckoning (chance currents, lapsing to fainter cadence)

-yet when I breathed in-

We see ourselves there still, where we cannot pass through to, disappearing avenue, mosaic of promise, musaicum, music, museum

Broken code, unwritten book we cannot open. You were our girl we never held that memory so wishes it might read.

66

Kevin Stein

To the Reader Awakened by a Noisy Furnace

You've heard the one about the two-bit crook who, when fingered for the cops, spills all. He sings, they say, like a canary, and thus avoids jail. As does his boss, who whispers "In God We Trust" in a few open palms.

In time the guy finds decent work in another city. He settles into domesticity, until one winter poof, he's gone. Come spring, fisherman haul up their catcha corpse without head or hands, face or fingerprints.

Well, what of the dictator, little matter which, plush among the palms and many-fingered dates, who so hates to hear a complaint, even the silent language of the deaf, he will not have it. No, no, no.

So when the dissident, a plump word for so thin a man, asks for sleeping mats, a generous gruel, some pencils for the boys to scrawl on banana leaf, the big man, the fat man, the sovereign

can't fathom the insult. Abashed, he whispers in a curled attentive ear, and the deed is as he wished. Still, the thin man, the man who speaks with his hands won't shut up-even with each finger lopped off by bolt cutting shears. Sure, silence blankets each marble step while the stitches heal and the new moon raises its scimitar. Then the thin man, the deaf man whumps the stumps of his palms

like a drum, and the beat speaks a word, grunt and anthem even his ears can hear. And you, reading this snug in your downy bed, the furnace thumping its thump, you hear it too, or something very like it.

And now when it thumps again, you'll think not of that but of this-the petty crook and the innocent dissident-how language like a song cost one his life, and song like language gave the other his back.

Or sort of. You'll fester there beneath the sheets, thinking my story's all wrong, aghast at its skewed mix of guilt and innocence, word and silence. Perhaps then you'll think this the stitch

to thread these both, and money's hand in each, and think the story teller, yes, me, is some moon-eyed Marxist on relief. Simmer down. Be patient. The furnace ought soon click off.

When it doesn't, you'll stumble up in slippers and trip on your sleeping yellow dog in route to notch it gentle down, gas prices on the rise. Back in bed, all three of us, yes-you'll feel

but not see the deaf man and me-the three of us will curse and blow in what hands we have: a cold hand that says or does any human thing, the rueful hand that writes it down.

68

Reintroductions

Actually black in color, indigo buntings have no blue pigment. The diffraction of light through the structure of their wings makes them appear blue.

The Audubon Book ofNorth American Birds

"Sweet Mother of God," the curse wings fire from a man whose hand's been slammed in the truck door, his language blue and woundedas was the Virgin herself, blue not only in sadness but also in dress, her robes a color not unlike these indigo buntings we're returning to the flood plain farmed thirty years by a salt magnate now gone, his dirt levee, too. Nothing much grew. The silt's gift sifted only an inch or two, then sand, river rock, and tax write-offs. The almighty buck. I'm lucky enough to be here because I know a guy who knows the Ranger whose smashed hand lit blue flame, so I say "sir" a lot, nodding to the park's khaki Lancelot of the plastic fold-up table. Our chivalry's redundant at 5 A.M., as all acts of love come pursed in darkness or shadow, penumbra of the soul. Did I say all?

Around us, spring peepers give forth their chorus of hours, each day an eon in heavenly sway, each coupling stirring the froth of back and forth, this world and not. I want to believe, and believing's mostly want. And though it's not extinction were making extinct hereonly a rift in earth's silk stitching-I'm sappy daft enough to trundle a boom box that loops the birds' digitized warble to calm and comfort them, each phrase and note repeated to calm and comfort.

In cages draped with oven-warmed towels, these birds must think we're gods or fools. Ah, yes. Maybe it's the nothing we're filling with wings, or these wings that rise on nothing. Maybe the blue that's really black, the blue that isn't. Whatever lifts this occasion begs the reintroduction of me to me, eye to eye,

though who am I to me? The question lingers a lifetime, which is to say, till death-the moment of knowing also our last. Or not-knowing, also our last. I am waiting still, meaning calm, and still meaning yet. I am both and nothing, both nothing and the press of air against flesh.

I am despot and savior, I am cynic and dreamer. I am the boy at the door and the door locked on him. I am the one who dutifully records the day's time, temperature, and wind speed. I am the one who forgets his NO.2 pencil.

I am the buntings black in low scrub.

I am the sunlight that flames them sudden iridescent blue. I am the one who makes the introductions: Birds, this is your world. World, these are your kin. Amen. I am the one who's turned away when the cage door's flung open.

Bruce Smith

White Girl, Alabama

I came home to Alabama from a spot where a singing, dancing mouse ran an amusement park and in my state there was a bus boycotta seamstress fingered with the "segregator" and the "little niggers" walked and the "big niggers" talked in the paper of Gandhi and Reinhold Niebuhr whoever they were, besides, we didn't take the bus. My secrets were skin and what inside was for a boy, imagining that, and God the Negro preacher said would fill his belly with Jim Crow.

It was an open, red,mouthed summer that smelled of brine, or I did, I was not clever,

I was merely alive in a peach dress and dry unlike the wet-with-knowledge one the seamstress wore. I had a heart and it was angry and it was uppity and it was a townie heart compared to my sister's who boo-hooed hers through the phone from the University in Tuscaloosa.

My lips swelled. My heart swelled in my chest (I couldn't call them breasts) and in my legs and arms. I pinwheeled through the noisy brightness of the blue voodooed

71

with pins of rain. My sister had problems that were men

I wanted too, a movie sort of thing or a song, unwritten, unrehearsed, thrilling that turned a mica-flecked mud if I gave it thought like mixing brown and white and buckshot and the light.

Where was the place I could go that wasn't all summer, our way of life, or animal?

I waited inside, then inside the inside. Close like a closet in the thunder, there to dis�close (I sometimes thought in words instead of pressures on the skin) what would be the cure or ransom of the country which meant my plain faced "fokes," that kind of country, and the dark citizens of Tuskeegee and the conspiracy of places ruled by Kennedythe country. I wouldn't let him in my pants. That summer we added in your pants to everything until it wasn't a joke but the picket fence and gate of the unspoken. Or between the sheets we tacked on between the sheets to the names of songs, "Come Softly to Me between the sheets. I wanted lovers or enemies and I got fleas and dreams between the sheets where the music mingled with klavem and heat lightning and self-kisses and the sprinklers hiss

White Girl, II

My cat died. My brother put new axles in his truck. I learned about the Mohammedan angels of the beats. In the same week. There was a thing: conformity or not. To be otherwise born in a city

and smell like no one else was like shutting your eyes walking in the dusk and hearing the cries of the crickets and seeing just how far you can go with all the looks and God and saxophone

music coiled in your guts (and gold like that) and no one knows it, and you snap out of it and you're a regular tragedy in a ditch, maybe an orphan like my mother now at forty.

That I must live that life is like an engine started up inside a truck without an engine.

How does it run and with what high test and fumes from what fossil and at what cost?

I'm feeling the one life minus the nine of the furred thing that was mine

who curled at night on my middle with her motor and black invisible.

(She stuck her wedge head between my knees and wanted relief from being )

It's how I knew, First, I had a soul and, Second, I had nothing, holy the supernatural

extra brilliant intelligent kindness of the soul It wasn't a pet. It wasn't bible school.

My mother saw how difficult I had and would become. The cat lashed its tail like a dragon.

73

White Girl, III

The plates were heavy. Two hands could barely tilt them from their rings of gravity. White with gilt edges. I hung over the plates like a prime rib and mimed the ad,lib prayer to bribe the butcher, the intuition, the miscellaneous curses where the god of Alabama drove the hearse after a tornado or a riot or a fire. We burnt something and perspired. The silver and the service had a heft that meant we wasn't trash. Weren't. My mother spent

considerable of father's on glazed and fired clay that mirrored the interior that was Friday in my head (and on the radio in my head) but was Tuesday otherwise scraping a tine across the hollandaise and across the red, fat-flecked pool of blood. I held the dull scalpel of our worth as in the operating room where they stitched my girl wounds.

(Ten years from now a lover will kneel and lick me, my blood, and say he wants to taste the mystery and I say from this distance, men, listen the mystery is obviously always and is hidden.)

You would think the light reflected in the room would lift things and make a vacuum out of shining nothing to counterbalance the springs of a scale which has in one pan killing

74

and in the other pan that brilliant singing. Red, red, Kruschev and the Chinese, they hated things

we loved. Was I wrong, but was red bad? Just eat your meat and zip it kid, they said in the nice way they have of choking you like the dogs with their looped nooses who go after the flesh around the ribs of Negro boys as they go after, under the table here, their toys.

75

White Girl, IV

My body was a strange, familiar place like a mock up of a town that had my face, a place I went to as a child, transported by my parents in the way back of the Ford, a crosshatched landscaped of red dust and drama like mother's house in Andalusia, Alabama.

I watched the town/body in the dark like a film of rain. My body filled like an ark with two of every character: the white sportscaster and Jackie Robinson, the ballerina and the dance master, the Negro and the cop, the banker and the robber, the butcher and the meat, the mother and the sob her daughter made, the mosquito and the slap, the bream and the fisherman, orders of devils and seraphim.

In my body they swayed and slammed into one another while bombs went off in Birmingham.

I visited this town until my hips unfurled their wings and I was a girl in shorts like a bucket and a big space between the button and the embrace of myself above and below. Then the quiet town was in the throes of integration, intervention, injunctions and all the other shuns that made the body no longer an illusion and when I found out about the other Andalusias-

One was a chicken. One was in Spain, with its moors, guitars, and gypsies. It made me feel under siege and real in a way I didn't know I could be or wanted to be, peopled and ghostly.

77

White Girl, V

How can my blood mean nothing when to the Freedom Riders it means everything?

My body makes a throne for the little thingget ready, get ready, then the fanfare, then just kidding like God to Job after the afflictions, just kidding then nothing: the red ribbons and bows come down in melancholy that feels like the flower overflowering, part mercy and whatever's left is manslaughter they can't arrest me for, the men. What's the difference between

a German Shepherd with rabies and a girl before her monthly?

Lipstick, sister says. And so you go without a kiss, my prince. Without my lips in their pout.

Oh, I have a fire hose trained inside me to flush me out,

although when the fire hose is trained on the racial children my same age who won't let go of integration it's different. The blood is different. When I think train I think The Southern Crescent to New Orleans or father's shave and drive to the office where he's a slave

he says. But trained is Uncle Tom and step and fetch and brotherhood. I know this much.

I know when my blood is done I'm a woman and not and everything goes on

being the same (for me and them) and I wanted to be another name shouted or whispered to someone. What was the question?

79

William Olsen

All-American: First Grade Class Photo

Don't bring up your sad and buried childhood

Carlos Drummonde de Andrade

How shiny his tow-hair, like carlights his shiny buttons, how clean the teeth, how white the cardigan, blue the eyes that might not recognize me enough to pity what childhood has sired and deserted,

the large hand his slipped on like living gloves, the hull his little ribs forgot their littleness for, the mists of belief systems that enveloped him, the heart that learned to race, or skip a beat-

a little red white and blue All-American emblem sewed to his sweater as if to shield him or make him take the shield-how loved he was, this shiny grade-school photo, all the kids

(like the wisecracking stars of Hollywood Squares) lined up one moment, sat in the same chair, for backdrop the map turned round, (like missing children on milk carts, or like windows in Rear Window)

flashed in the light (there is no other light) we're all well on the other side of now: there where all our longing was to be older whatever outlasts that flash, was just a puff,

80

the school windows we looked out for the view, the view we were of ourselves in the photos embarrassed before our singular natures, our faces all agreeability,

blank as buttons, or boutonnieres still boxedfaces quiet with such quiet as outlasts the popping, spontaneous, repetitious bulbs, our crossing over ruled and squared enough:

it was the sort of submission that asks for more.

Just a puff, the oak leaves from the school's one oak hanging in noisy clumps for their lives by their lives, just a puff our first grade, Class of Not So Quick,

Class of Noisemakers spastic most of the time, turning, topsy turvy with gesticulation, never blowing away (although we did), watching that oak strip all year, never seeing enough,

Oak of Deciduous Distinctions, each leaf hanging to its life without the slightest knowledge sunlight was on it that spectacular way that sunlight has of being little weight,

our families out of the picture, we spectacularly lit by some half-seen, half-felt embarrassment before our very own accepting natures, we memories that fidgeted without moving much,

disciplined by light that doesn't think or read, light that sits down anywhere it pleases without a chair or school desk, or permission slip, our each smile holding up a WELCOME mat,

yet another one-time all-told chosen generation, each portrait the size of an uncanceled stampunused, untraveled-pupils, flash-lit pupilsremaining seated for all that any light was worth,

81

for all that any light reveals-the view we werewe singularities lined up for our turn, even the precocious troublemakers fallen in linefaces white as petals, white as surrender flags,

white as sharks, as teeth, white slowed to glacial, white as surprise in the eyes of someone just shot that remembers to breathe and live, and lives, or doesn't Americans, we were family members first

inside the family car or the family restaurant, home in the family room, watching family TV: inside the family we were the only "we"; at school we were a slightly different "we."

Our baby booming smiles must have shot forth too unexceptionally to have marred our future staring like possibility from the ruled windows of America baring its inner lives-

even if there is no singular consciousnessI can bring back maybe every other name, I can believe this much of our shared past, I can believe this much of our past can't touch us to hurt us,

I can see that little All-American emblem my mother sewed to my fleece-white cardigan, I can affirm a "we," a generation without a purpose yet except to beam.

Neither Paradise Nor Below,

Nor Up Nor Down

The one'legged beggars in Rome are like the Signorelli figures on the west wall in this cathedral in Arezzo. The figures pulling themselves, and each other, limb by limb, out of and up from flesh-colored ground.

This cathedral, striped horizontally with different colored granite, the dull pink and dull gray of well-washed prisoner clothes, later will be the color of translucence, then, long after human history, a color all hollow, then the color of space as far as the night can see.

Just last night I dreamed there were escalators in the cathedral, and madonna-like figures like unearthed terra cotta warriors posted in corners of sensory neglect, and all the subways and the architraves and station islands and all holy location vacated by everything I ever was and am but perspective. A dream wasn't a cathedral, and it wasn't the Rome Terminal, and it wasn't day or night.

Now the cathedral houses a piece of cloth that someone is said to have said he saw bleed, making imaginable Sight itself.

The newly resurrected are still there, struggling to free themselves in a cathedral light that looks palpably like the light in the Rome subways as it drapes the one-legged beggars. Only these stay put for as long as they beg. One woman, at the end of her work day, covers up her stump and its imploring pucker. She rocks by her crutches to the escalators, rising, like all the others, in single-file, there being no room to rise to daylight's last cries but one by one.

Rag for the Cornish Prayer Rag Tree

The rags of missing peoples mock us in a little wind: rags, and shoes, and potpourri have inherited the tree, this blue mitten, that stained green lace strip, this yellow curtain strip of crescent moons and other curtain strips hanging practically on air, blue shoe string, red-black threaded boot string, two baby shoes turning just like row boats.

This tree of perpetual arrival, a shoe-tree, is one more life to pray for. On this tree of things that No One Wants, on this pompon of prayers some rags flutter in the gray sea wind and blow sometimes all the way to the Irish Sea, other rags hang on and can't fall, and these make us the sorriest. Here's one finger of a wedding glove what love will do to leave even a trace.

This tree bandaged by moss, onto which prayers are lashed, has rags for winter leaves.

Its winter shade a trash-shade cast by trash, this tree going nowhere has a luggage tag with no return address for no luggage and a Magic Tree Deodorizer and a thumbnail sized Buddha at the bottom of a dope baggie filled with water, eyes wide obeying its nature like a child, gulls blowing around like the litter they eat as to never entirely blow away.

These things no one particularly loves, things once we had, and held, hang on the drab wish of all prayer, for prayer to cease to berags tied tight on this tree for pagans and Christians and Wiccans, this multitudinous tree where we rid ourselves of our shoestring prayers.

Here's the lowliest, a raindrop-scourged violet thread, ghost of a string, a shoestring wraith tied to the lowest twig to trouble the holy watershow does sunlight, how do our shadows not get blown away when it's this windy?

What is the prayer for such a tree, what new trash can we tie to this tree of trash?

It can't require much strength for me to rent this rag and tie it tight and leave with one less prayer.

Shirley Kaufman

Sanctum

On top of a hill near the Lebanese border, Micha Ullman dug a grave, then cut through the rocky outcrop and sculpted a throne. As if he'd uncovered its archetypal shape out of pure limestone. He raised the throne and tilted it backwards, wedged between rocks on both sides of the grave. A throne to lean back on (if you dared) facing the overwhelming sky, trusting the stone to bear your weight, suspended over your own death.

Once he dug holes in Israeli and Arab villages, and filled each with earth from the other. It was '73. Right after the war. We lived on a cul-de-sac called Neve Sha'anan. Place of Tranquillity. That too was conceptual art.

I looked out of remembered windows: my daughters hopscotched to our front door, the towers of the bridge like heavenly beacons through the San Francisco fog. Frames of an old life that never hung straight. I drifted from dreams or Satie or the white whale as the fog drifts, staring out and back again. And back still farther. Small lakes. Small forests of spruce and Douglas fir around Seattle where I hid as a child. Benevolent branches. The shield and scent of them.

85

Houses across the road where I live now are set back from the street, stone from ancient quarries hewn and fitted together like giant bricks: yellow rind and flesh of casaba in the first slice of morning, color of milk tea with a spoonful of honey at noon when the light is strong, rose quartz at dusk.

To live in Jerusalem is to feel the weight of stones. Stone walls around the City. Solemn stones in the digs. Hard-hitting stones. Names chiselled on stone lids over the dead.

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair! That bleakness when I walk through ruins below the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif, below the sun and moon of the Dome and Al Aqsa, when I touch the colossal stones hurled down by the Romans who smashed the Temple and sacked the city, when I lay the palm of my hand on pitted history. 3

Sometimes, writing, I watch the words grow heavy when I place them in rows on the page. Deliver me from a city built on the site of a more ancient city whose materials are ruins, whose gardens are cemeteries. Whose people are desperate in their claims.

Sometimes I need to be nowhere. A place without history.

A life of wandering like the desert generation of Moses

The wandering Jew. But that brings me back into history.

Sealed rooms. Windows criss-crossed with tape so the glass won't shatter. A dark noose of memory around my neck.

2

Coffins covered with flags and flags burning. I need to be nowhere.

4

The first time I climbed the road to the sculpture garden to find Turrell's stone sanctum, Space That Sees, I went alone. Entered the narrow passage, fingers sliding across the cool stones. Arrived in a bare room radiant with light.

Isn't that how they always begin, the delicious stories? Through a secret passage, up a beanstalk, down a hole.

Cut into the ceiling was one square opening. When I looked up the sky looked down entirely empty, more blue than any blue dazzle outside. All the unblemished blueness of a Mediterranean summer in one clear window. No glass. No screen. Nothing between.

I sat on the ledge tucked into the stone surrounding me, stared till the light became pulse and substance, and I could taste its language in my mouth. There was no end to it.

During the Vietnam war James Turrell was jailed and placed in solitary confinement. His cell so cramped that he could neither lie down nor stand. Dark as the bottom of a well. He could see nothing. But strangely he discovered there never is no light even when light is gone you can still sense light.

5

I walk from my home in changing seasons, down through the Valley of the Cross, up the path through the olive trees to the gardens surrounding

that room. Often thin wisps of clouds leave a smoke trail across the blue square over my head, or clusters of vapor form and dissolve the way thoughts quicken with words before I lose them.

I have seen two ravens cross in an instant and disappear beyond the frame. I have seen the sky-space in silence. And with a child who shouted to break the silence. Once, lying down on the ledge, stretching my body on the stone, I saw it like newly dyed cloth in India, still wet and silky, spread out on the air to dry.

It has become the eye in the center of my head, the eye of the vastness around it.

I have seen the movement of the unseen sun. How shadows change on the interior wall. As I have changed.

What is there out there watching over me? Watching me watching it?

6

You and I on the stone ledge

The immensity of space watching through one small window the immensity of our failures.

Let's sit here together on the throne as if suspended over our own deaths. Let's lean back-easy-against the supporting stone, and trust it to bear our weight a little longer.

88

Peter Campion

Destination

Part glamorous, part penitential, tunnel follows tunnel, then halls through the concourse, the fuselage. It's like long tubes that funnel out through the dark, this exhilarated force so constant, even now, in the dim light by my bed, to lull myself, I plot a course of my own imagined networks through the night. Though they keep leading to that hellish hotel

two weeks ago. Some couple's screaming fight, then the low moans, more screaming: who could tell what room it came from? It came from the blaring stack of rooms. And listening to those voices swell through the walls, I felt as if those halls in back of me gave way: as if the people's souls

themselves were swarming there in a ragged pack, through a brambly, whacked-out maze of knolls and gullies So tonight: of every place I can call back, how weird that this one consoles my restlessness the best. When I tum to face the window, it's just my view of Berkshire Street,

the flood,lit baseball park. There's not a trace of any nightmare wood. Though in this sweet

chill from the air conditioner, now I sense what it is that comforts me: that more complete

calm, that I unwillingly dreamed, as my tense body finally gave to sleep that night.

There was a field. Behind us, a chain,link fence, just a thin line now, wavered on the height

we must have descended from. All around, those others' faces waxed and waned from sight,

their shadows stretched across the littered ground, stretching as far as the glistering sign

of a city miles away. The only sound was the wind, but pushing on, over the shine

off power stations and junkyards, you could see that city rise from the long horizon line.

Rick Barot Botanicals

1. Cosmos Sulphurus

You can carry me there only so far: to the boy's lips blowing on the leaf, pink and cool and dry,

to the roadside trash, spit, and soot you lord over, a few of you half living beside the fence, one manner

of speaking that the day has: king-purple, skinny stems, the blossoms hollow as ventricles when you

close for the night: seeing carries me there only so far, my incomplete half coveting in spite of you the hopscotch-chalked pavement, the boiling eggs knocking on each other, the couple in a doorway's black maw, the neighbors woken and brought this disquiet: threat of storm becoming actual rain

nailing down on the sulk of you, heads inclined, made amenable, your petals already piecing into the chalk.

2. Bouquet, Hawthorn

Who will get taken. Who will put the shimmering thing in its vase, white buds on the antlers. Who will give it up, unforced, unmarauded. What strongbox notion of self: clear, clean as the water. Drop the aspirin. Trim the too-long branch. Persuade.

Who will get to decide the translation: is it the severed head in the stream, or the candy of getting touched.

You can be sheepish for now. Be negotiable. It's the fish that occasions the fishline and the hook, the arm throwing out its pelagic lines.

Who has the heart. Who will have the first and the last word. After you. No, after you. Who will be ahead this time around.

Drop the crushed aspirin, trim the long branch. The thing will keep for days.

92

Nancy Eimers

The Mercator Projection

The italic hand commended itself to map-makers of the 16th century because they found it to possess fluency, legibility, and elegance.

R. A. Skelton, foreword to Mercator: A monograph on the lettering ofmaps, etc. in the I6th century Netherlands

As if Kalamazoo were a point on an old Dutch map, I feel the letters superimposed in italics across the houses tonight, oblonged and elegant, tilted right, long ascenders-the K and the land one long swooping, a descender-the z-flying over and under us, this place we live all joins and ligatures for once, like a split-rail fence or the tree branches. No pen-lifts or stops in the hand of this map-maker. He has us down. And if we are whatever we've come to tonight, let them, the letters, hold us in place for another sixteen centuries. All over town the trees are coming down, for power lines, for traffic lanes, for new apartment buildings and little upstart malls, trees sawn down to the stumps, so the ganglia of the roots remain submerged, and you feel the sway of a charmed amnesia underground, forgetting one charmed thing at a time, a tree, a line of trees let go and go and go as a hand opened suddenly lets go its hold on a tugging rope-lets go its place and the rope is long gone. Tree, lot, clapboard house.

93