CARL DENNIS

CARL DENNIS

Publication of TriQuarterly is made possible in part by the donors of gifts and grants to the magazine. For their recent and continuing support, we are pleased to thank the Illinois Arts Council, the Lannan Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Chicago Community Trust, and individual donors.

TriQuarterly also thanks the following recent donors and life subscribers: Walter Adams Simon). Blattner, ) r, Louise Blosten

Mr. and Mrs. H. Bernard Firestone C. Dwight Foster

Mr. and Mrs. David C. Hilliard

Charles T. Martin

Mr. and Mrs. Andrew McNally

Michal Miller

Fran Podulka

Gilaine Shindelman

Allen R. Smart

Gary Soto

Marc Straus

Lawrence Stewart

Geraldine Szymanski

Scott Turow

NOTE: TriQuarterly welcomes financial support in the form of donations, bequests and planned gifts. Please write to Kim Maselli, publisher. Please see the last page and the inside back cover for names of individual donors.

III nois ARTS � .9_� n_.�.iJ "alll"" _n.nIPIU

This program is partially sponsored by a grant from the Illinois ArIa Council

1997 BOOKS AND BACKLIST

WILLIAM MEREDITH

Effort at Speech: New and Selected Poems

A contemporary of Berryman, Bishop and Lowell, William Meredith is a poet whose unadorned, formal verse marked him from the beginning of his career as a singular voice. This is the definitive collection of Meredith's lifework.

For the past45 years [Meredith] has lookedgenerously and hard at our common human world William Meredith's work suggests that we can recognize the hardest truths about ourselves and still live in the world. -NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

256 pages $39.95, cloth / $17.95, paper

EFFORT AT SPEIt:i;H WI LI EAEDITK

ANGELA JACKSON

And All These Roads Be Luminous: Selected Poems

Drawing from earlier works contained in the chapbooks VooDoo/LaveMagic, The Greenville Club, Solo in the Boxcar Third Floor E and TheMan with the White Liver, this selection of AngelaJackson's poetry is filled with an impressive variety of characters engaged in compelling explorations of identity, creativity, spiritualexperience, and the rites and rituals of race and sexuality. Jackson's ear is keen; her memory of traditions is crystal clear.

---FEM1NlST BOOKSTORE NEWS

152 pages $39.95, cloth / $14.95, paper

The craft and quality ofpoetry has been enhanced byAngelaJackson.

--cmCAGO SUN-TIMES

PAMELA WHITE HADAS

Self-Evidence: New and Selected Poems

154 pages $35, cloth / $14.95, paper

Pamela White Hadas won enthusiastic recognition for her early books ofpoetry, Designing Women and Beside Herself. A decade later, SelfEvidence gatherstogether thebest of that published work and poems never before collected. Brimming with legendary,mythic, historical and imaginary characters-Lilith, Pocahontas, Simone Weil, the wives ofWatergate, a circus performer and others--these poems weave tapestries ofwomen's loves and labors. Perhaps uniquely in our time, Hadas contrasts a spareness of autobiographical detail with an unusual intimacy of tone. Howard Nemerov describes her work as /Iodd, quirky, humorous and exact."

JACQUELINE DOUGAN JACKSON

Storiesfrom the Round Bam

In an inimitable voice,Jacqueline DouganJacksonbraids together stories, anecdotes, history and even veterinary science in a series of dramatic episodes vividlyevoking life on a WlSCOnsin dairy farm. As Jackson recreates the texture and tone of farm life, larger themes emerge: the constant balancingbetween material life and spirit, the quest for humane values within a hard world of business and labor, the difficult lessons ofchildhood. A fascinating mixture ofbiography, oral history and creative nonfiction, Storiesfrom the Round Barn is movingproof that "everything, in all directions, in all dimensions, is bound together."

JOHNNY PAYNE

Kentuckiana: A Novel

Set in a decidedlypostmodem Appalachia, Kentuckiana focuses on the lives of the Miles family. Invented by a real-estate developer who is authoring a report on the neighborhoodshe has created, the imaginary Mileses and their neighborspopulate his subdivision in Lexington,Kentucky. Once presented, the real-estate developer'S creations take on life and speak in their own voices. This is a metafictional romp through one of the most hilarious, fascinating and dysfunctionalneighborhoods in all of recent fiction.

300 pages / $24.95, cloth

240 pages / $24.95, cloth

The Lava ofThis Land: South African Poetry 1960-1996

EDITED BY DENIS HIRSON

296 pages $39.95, cloth / $17.95, paper

The lava of change has spilled over South Africa again as apartheid has ended. What sort of social and artistic surface emerges as it cools? This anthology spans five historical periods in the contemporary development of South Africa, from the worker strikes in Durban in the late sixties to the dismantling of the apartheid apparatus in the nineties. The poems, chosen for their music, their imagery and their sense of language and craft, reveal not only an intense awareness of conditions during the apartheid years, but also reflect the extremes of turbulence and doubt that have followed in the wake of its dissolution.

Displacements: SouthAfrican Works on Paper, 1984-1994

EDITED BY JANE TAYLOR AND DAVID BUNN

This volume offers significant new insights into politics,subjectivity, and aesthetic practice in contemporary South Africa. Over 125 imagesexplore the possibilities ofexpression in a single medium, paper. Essaysby the editors and others shed light on the complicated relationship between figure and ground, and body and landscape, in works produced within a political and historical situation which has legislated space and subjectivity for generations.

In addition to workby South African artists, the volume extends the definition of work on paper to include a selection of new works offiction.

264 pages / $35, paper

BACKLIST

DAVID BARBER

The Spirit Level

Winner of the Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry

Filled with rich detail and striking metaphor, these poems are both technically brilliant and irresistibly inviting. Barber hils tremendous verbal resourcefulness and a musical, evocative language. -Paul Breslin, roEIRY

$29.95, cloth / $12.95, paper

STERLING A. BROWN

The Collected Poems ofSterling A. Brown

EDITED BY MICHAEL S. HARPER

One of the most important of American poets, Brown is known for his handling of folk materials, for his lack of pretension, and for his frank and unflinching portrayal of the Southern African-American experience. This is the definitive collection of his poems.

This is a great book ofpoems, stunning in its artistry andgigantic in its vision. -Phili Levine

$12.95, paper p

ANNE CALCAGNO

Prayfor Yourself

An exhilarating collection of short stories by an author with an abiding understanding of the fragile yet enduring nature of human relationships and of the textures of women's lives.

Calcagno has the clean voice and sharp unblinking eye ofa true storyteller. -Larry Heinemann

Language as maddeninglyfascinating as afifty-car locomotive, perfectly carved, from a single piece ofwood. -Lynda Barry

$26.95, cloth / $12.95, paper

DANCHAON Fitting Ends

Title story included byJohn Edgar Wideman in Best American Short Stories 1996. Each story is a marvel ofcomplexity, dense with meaning and nuance a remarkable collectionfrom a young writer who bears carefulwatching. Veryfewfirst works are as solid, moving and pitch-perfect as Chaon's. -mE CLEVELAND PLAIN DEALER

$35, cloth / $14.95, paper

CYRUS COLTER

The Beach Umbrella and Other Stories

Setmostly on Chicago's South Side, these eighteen stories describe ordinary people whose lives are transformed by small acts of chance or will. From depictions of the black middle class to the dank and dirty tenements of the lonely city, Colter's sharp, spare prose etches perceptiveportraits of people who endure and overcome the most severe threats to their spirits.

Cyrus Colter tackles epic themes as though they were wild horses-and he tames them. -Studs Terkel

$14.95, paper

A Chocolate Soldier

Colter's crowning work, this novel tells the tale of an unlikely friendship which transcends boundaries and circumstances in pre-civil-rights America. This powerful writer should win the attention ofevery serious reader offiction.

--SATURDAY REVIEW

$14.95, paper

The Hippodrome

In the tradition ofhisfictional ancestors, Dostoevskyand Faulkner, [Colter]has produced a work which uses the world ofeverydayreality in a manner beyond the scope ofjournalism or sociology-as an entree to the soul. -James Park Sloan, CHICAGO SUN-TIMES

$13.95, paper

w. S. DI PIERO Shadows Burning

In its intense preoccupation with change and thefrailtyofwhatever continuities ofmemory and imagination we deoise to order the unorderable, [Shadows Burning] makes an important contribution to American poetry. -Alan Shapiro

$29.95, cloth / $12.95, paper

Shooting the Works: On Poetry and Pictures

Elegant tributes to the intersection of art and self, Di Piero's essays are an autobiographical testing of ideas deeply akin to Witold Gombrowicz's diaries. Di Piero's taste and judgments are refreshingly idiosyncratic, hisframe ofreference broad. -PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

$29.95, cloth / $14.95, paper

CAROL FROST

Pure

A fierce, passionate series of meditations on experience and consciousness, morals and customs, and the natural world.

Through her patient dissection ofthe mysteries ofnature, [Frost] comes to conclusions that leave us with a prophetic sense ofdarkness.

-PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

$26.95, cloth / $10.95, paper

Venus and Don Juan

Poems that evoke the complexities of identity, love, and other moral and emotional states.

Frost has an uncanny ability to disassociatefrom and observe emotion transforming her observations into shimmering and haunting images.

-LIBRARY JOURNAL

$29.95, cloth / $11.95, paper

EUGENE GARBER

The Historian

Winner of the 1992 William Goyen Prizefor Fiction

Eugene Garber, castinghimselfas both Herodotus and Ned Buntline, has elevated American history in the second halfofthe nineteenth century to thegrandeurofa legend about a mighty civilization ofthousands ofyears ago. -Kurt Vonnegut

$14.95, paper

FICTION OF THE EIGHTIES

EDITED BY REGINALD GffiBONS AND SUSAN HAHN

For contemporaryfiction [Fiction of the Eighties] is a standard-bearer The multiplicity and depth ofthefictional lives here are astonishing wisdom and wildness ofwriters too numerous to thank. -PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

$26.95, cloth /$16.95, paper

TRIQUARTERLY NEW WRITERS

EDITED BY REGINALD GIBBONS AND SUSAN HAHN

With fiction and poetry from ten new writers who have won recognition only in literary magazines, this unique anthology presents the best of new voices discovered through TriQuarterly magazine and TriQuarterly Books.

$39.95, cloth /$14.95, paper

NEW WRITING FROM MEXICO

EDITED BY REGINALD GIBBONS

A carefully chosen sampling of the most vigorous and exciting new short fiction, poetry and essays being written in Mexico today. Gibbons has been guided by a healthy eclecticism and a sense offreshness and authenticity ofconception and execution. -HARVARD REVIEW

$15, paper

DIANE GLANCY

Monkey

Secret

[Glancy's] work brims with American lndian characters who teeter precariously on the border that separates time-honored customsfrom stark new realities [Her] latest collection ofshortfictionfeels like an anthologyofsmall, perfectly realized moments. -NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

$19.95, cloth

WILLIAM GOYEN

Arcadio

One of the most affecting and imaginative novels ever written. Arcadio is the bizarre and fantastic account of a man searching through his dark past for his lost family.

[Arcadio} virtuallypulses with life; it is both audacious and wise; a timelessfable that manages to be boldly contemporary as well. -Joyce Carol Oates

$12.95, paper

Come, the Restorer

A fable of sexuality, Texas country life, religious revivalism and the madness and destruction caused by the oil boom.

A profoundsympathy combined with a great poetic insight constitute Mr. Goyen's wonderful rare gift. -Sir Stephen Spender

$14.95, paper

Half a Look of Cain: A Fantastical Narrative

Never published in its entirety, this rhapsodic and visionary fable of love, lust and loneliness is now available for the first time.

The work ofa gifted, intelligent artist. -NEW YORK TIMFS soox REVIEW

$22.50, cloth

In a Farther Country

A neglectedmasterpiece of desire and loss by a renowned twentieth-century American writer.

Mr. Goyen has the poet's considerationfor the exact word, and he has a great sense oflaughter. -lHENEWYORKER

$13.95, paper

ANGELA JACKSON

Dark Legs and Silk Kisses: The Beatitudes ofthe Spinners

Winner ofthe Carl SandburgAward and the 1993 Chicago Sun-Times Book ofthe YearAward in Poetry

This volume features a variety of characters exploring social identity, the rituals of race relations, the female psyche, creativity and spiritual experience. Angela Jackson has known,for long, what is rightfor her attention and scrupulous investigation. -Gwendolyn Brooks

$25, cloth / $11.95, paper

TRUDY LEWIS

Private Correspondences

Winnerofthe William Goyen Prizefor,Fiction

This visceral unforgettablefirst novel is a brilliantly conceived account ofthe innocence and complicity with which a young woman enters a world ofmasculine fanaticism and abuse. -BOOKLIST

$19.95, cloth / $12.95, paper

THE URGENCY OF IDENTITY: CONTEMPORARY ENGLISH-LANGUAGE POETRYFROM WALES

EDITED BY DAVlD LLOYD

This anthology of poems and interviews presents for the first time in this country the importantEnglish-language Welsh poetry of the 19805 and 19905. Includes workbyJohn Davies, Gillian Clarke and R. S. Thomas, among others.

$39.95, cloth / $14.95, paper

ADRIAN C. LOUIS

Vortex ofIndian Fevers

Wordplay,metaphoricbrilliance, technical virtuosity and a scathingly sardonic critique ofself and society fill this new collection.

Beautifullyaglow with the love oflanguage. -James Tate

Prophetic, terrifyingly intelligent, unconditionallygermane. -Hayden Carruth

First person,jugular: That is the voice ofLouis he refuses to scurry and cry and rides right into our lives with the languageofPound, Williams, and Ginsberg, driven mad by all that he sees. Paterson on the High Plains. -lHE BLOOMSBURY REVIEW

$29.95, cloth / $11.95, paper

LINDA McCARRISTON

Eva-Mary

National Book Award Finalist and Winnerofthe Terrence Des Pres PrizeforPoetry

An immensely moving book,fearless in its passion. Linda McCarriston accomplishes a near miracle, transforming memories oftrauma into poems that are luminous and often sacramental, arriving at a hard-won peace. -Lisel Mueller

$10.95, paper

WILLIAM OLSEN

Vision of a Storm Cloud

Olsen's ability to manipulate language, image and form harkens back to the traditions of Blake and Whitman, while his range of subject and his use of metaphor forge his own unique-and contemporary-artistic signature.

$29.95, cloth / $12.95, paper

JOHN PECK

M and Other Poems

New work exploring the vulnerability and tenacity of human life from a member of a remarkable generation of poets.

Peck has established himself as a majorpoet, opening up territory no one else has attempted. -TIMES LITERARY SUPPLEMENT

$29.95, cloth / $12.95, paper

PETER READING

Ukulele Music • Perduta Gente

The first U.S. publication of the most controversial English poet of the age. Rarely has any poet found a way to address the most appalling and dispiriting aspects of life with such astonishing artistic virtuosity.

$26.95, cloth / $11.95, paper

MURIEL RUKEYSER Out of Silence: Selected Poems

EDITED BY KATE DANIELS

Thefirstofour women poets to enterand engage the Western tradition ofprophetic outrage, she wanned it with the living voices ofthe injured. And in heractivism and gellerosity, rukeyser was as good as her word. -Eleanor Wilner

ThepublicationofOut of Silence is an event worthyofcelebration.

-lHE WOMEN'S REVIEW OF BCX)KS

$28, cloth / $14.95, paper

TIMOTHY RUSSELL Adversaria

Winner ofthe 1993 Terrence Des Pres PrizeforPoetry Poems celebrating the rough beauty of ordinary life and lamenting its inevitable decline.

To read Adversaria is to be in the presence ofa lively and supple and various mind, as tough as it is American. -Li-Young Lee

$25, cloth / $10.95, paper

ALAN SHAPIRO

In Praise of the Impure: Poetry and the Ethical Imagination

A collection of passionate, rigorously argued essays on the situation of poetry in American culture today.

$39.95, cloth / $12.95, paper

MEREDITH STEINBACH

The Birth of the World as We Know It; Or, Teiresias

A brilliant revision of the life of the Greek seer, Teiresias, this novel intertwines time, event and narrative at the intersection of Greek tragedy and contemporary fiction a metaphysical tour deforce Sentence by sentence, Steinbach's writing is as elegant as a neoclassical column. -PUBUSHERS WEEI<LY

$24.95, cloth

Zara

In Steinbach's firstnovel, a strong yet vulnerable woman attempts to reconcile her varying roles as daughter, wife and doctor.

Rich, horrific, beautiful, Zara is about the lifeofa woman extraordinary in every way, and is written in prose as strong andfabulous as Zara herself. I could not admire more this profound and exhilarating novel. -John Hawkes

Steinbach probes vulnerability,futility in a style interlaced with quality and power.

----LC6 ANGELES TIMES BOOK REVIEW

A masterpiece. -BOSTON MAGAZINE

$15.95, paper

MARC J. STRAUS

One Word

Poems by a physician; informed by a keen sense of vulnerability-to pain, to suffering, and to the joy of life.

Offering a new perspective on patient-doctor relations, [Straus] brings humanity into the sterile hospital environment. -BOOKLIST

$29.95, cloth / $11.95, paper

TINO VILLANUEVA

Chronicle ofMy Worst Years I Cronica de mis alios peores

TRANSLATED AND WITH AN AFTERWORD BY JAMES HOGGARD

Abilingual volume ofpoetic meditations on Chicano culture and heritage. Villanueva is a writer to spend time with. -PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

$34.95, cloth I $12.95, paper

BRUCE WEIGL

Sweet Lorain

Weigl returns to both Lorain, Ohio, and Vietnam, to explore the connection between his childhood in a working-class world, and the powerful effects of the American war in Vietnam on all of us.

The Washington Post Book World has described Weigl's poems as "hard-edged, partisan works imbued with the spirits of Philip Levine and James Dickey."

$29.95, cloth I $11.95, paper

What Saves Us

In these wrenching, elegant poems Bruce Weigl writes out of uncompromising memory and vision. Bruce Weigl has become one of the best poets now writing in America.

$17 cloth I $11.95 paper -Denise Levertov

THEODORE WEISS

Selected Poems

The definitive selection of poems by one of America's most distinguished and original poets. (Weiss's poetry] is among the most valuable work produced in our time.

$49.95, cloth/$15.95, paper -James Merrill

EVAN ZIMROTH

Dead, Dinner, or Naked

Poems rooted in history, myth and everyday life.

I love the combination ofsmartness, pain, and what one might call conscious postmodern trashiness in this book A profoundly urban book, ofharsh memory andfantasy, set in harsher reality. -Alicia Ostriker

$15, cloth /$8.95, paper

Order from your bookseller or from: \orUn\f'Stem l!niversit)' PI't'8S Chicago Distribution fA'nter 11030 SouUt L.angIey \wnut" Chicago. a, 60628 TEL. 7731568-1550 H.\ 773/660-2235

Name Address City State Zip

*DomesUo-$3.50 first book. $.75 each addltional book *Forelgn-$4.50 first book. $1.00 each additional book

Author/Title Cloth/Paper Quantity Unit Price Total

enclosed

Subtotal Shipping and handling* TOTAL

.J Check or money order

o MastercardNisa number:

Expiration Date Signature:

Editor

Reginald Gibbons

Managing Editor

Kirstie Felland

Executive Editor Bob Perlongo

Special Projects Editor Fred Shafer

Co-Editor Susan Hahn

Assistant Editor Gwenan Wilbur

Design Director Gini Kondziolka

TriQuarterly Fellow

James Lang

Reader

Ian Morris

Advisory Editors

Editorial Assistants

Jacob Harrell, Dylan Rice

Hugo Achugar, Michael Anania, Stanislaw Baranczak, Cyrus Colter, Rita Dove, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Michael S. Harper, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Grace Paley, John Peck, Michael Ryan, Alan Shapiro, Ellen Bryant Voigt

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WRITING, ART AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY.

Subscription rates (three issues a year) - Individuals: one year $24; two years $44; life $600. Institutions: one year $36; two years $68. Foreign subscriptions $5 per year additional. Price of back issues varies. Sample copies $5. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly, NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 60208. Phone: (847) 491-7614. The editors invite submissions of fiction, poetry and literary essays, which must be postmarked between October 1 and March 31; manuscripts postmarked between April 1 and September 30 will not be read. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1997 by TriQuarterly. No part of this volume may be reproduced in any manner without written permission. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America by Thomson-Shore; typeset by TriQuarterly. ISSN: 0041-3097.

National distributors to retail trade: Ingram Periodicals (La Vergne, IN); B. DeBoer (Nutley, NJ); Ubiquirv (Brooklyn, NY); Armadillo (Los Angeles, CA).

Reprints of issues #1-15 of TriQuarterly are available in full format from Kraus Reprint Company, Route 100, Millwood, NY 10546, and all issues in microfilm from Universiry Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. TriQuarterly is indexed in the Humanities Index (H.W.Wilson Co.), the American Humanities Index (Whitson Publishing Co.), Historical Abstracts, MLA, EBSCO Publishing (Peabody, MA) and Information Access Co. (Foster City, CA).

Fall 1997

TriQuarterly is pleased to announce that two works published in 1996 have been selected for inclusion in Pushcart Prize XXII: Best of the Small Presses (1997�98 edition), to be issued in cloth this fall and in trade paperback next summer. The selections are "Courting a Monk," a story by Katherine Min (TQ #95) and "Souls," a poem by Dannie Abse (TQ #96).

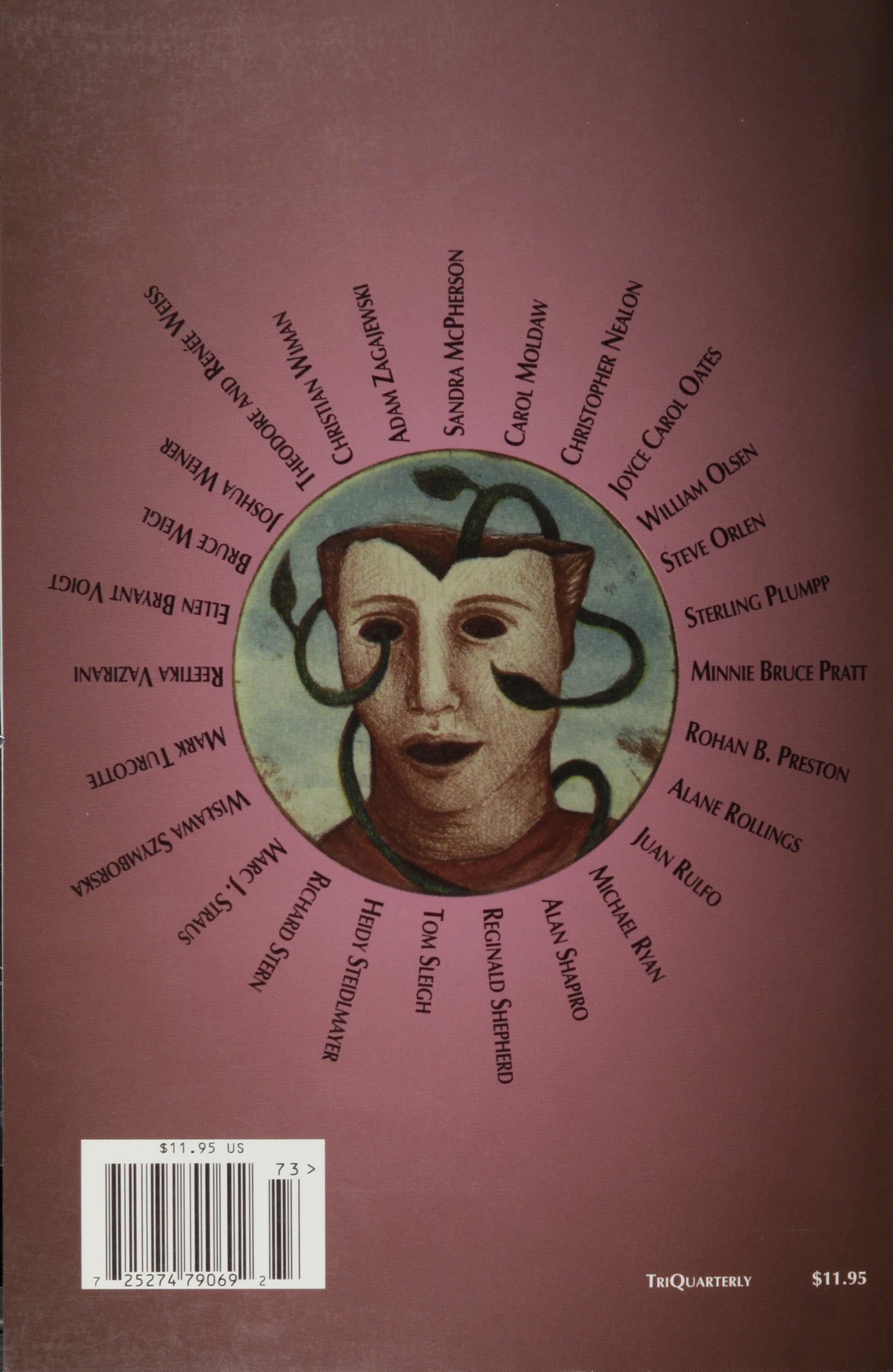

Contents Editor of this issue: Reginald Gibbons Editorial 21 Ghazal I; Ghazal II (poems) .••••...••••....••.............. 24 Agha Shahid Ali Chequamegon; Imaginary (poems) 27 Debra Allbery "And This Is Free" (poem) ........••...................•••. 30 Michael Anania Bells (story) 33 Karen Brennan Atom (poem) .....................••...•..............••............ 36 Teresa Cader Ciudad (poem) 37 Remco Campert Translated from the Dutch by the author and Reginald Gibbons Mai Jen; Crossing the Water (poems) ..•••.•.....•.•.... 38 Carl Dennis A Noh Play in Which the Ghost Does Not Reveal Itself; On the Beach (poems) .....•.......•..... .42 Amy England Testament of Arkey Wilson (poem) ..••............•..• .45 Steve Fay 15

And So Cold (poem) 47 Roland Flint By Dawn's Early Light: The Meteor in the Madhouse (novel excerpt) .48 Leon Forrest With "Nobilis," a preface by James A. McPherson Thaw (poem) •••••••••••••••••...•••••••••.•••••••••••••••••••.•••. 65 Carol Frost Tikuna: Soup (poems) •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••.• 67 Juan Carlos

Translated from the Spanish by Delia Poey and Virgil Suarez The Head is Frightfully Talkative (poem) ..••••••••••• 69 Doreen Gildroy The Love Letters of Helen Pitts; Patrice Lamumba; Matchbook: The Spinnaker (Sausalito) (poems) 71 Michael S. Harper Tweeg (poem) •••••••••••••••••.••••••••••••••••••••••..••••••••••• 77 Brooks Haxton Elegy (poem) •••••••••.•••••••••...•••••••••.•.•••••••••.•.•••••••••. 88 Brigit Pegeen Kelly Mumble Peg; Nude Interrogation; Dream Animal (poems) •••••.••••••••••.••••••••••.••••••.••.•••••••••••.. 90 YusefKomunyakaa Coyote's Circle; Medicine Song; Good Morning America; Black Crow Dreams (poems) 94 Adrian C. Louis 16

Galeano

The Corner of Paris and Porter (poem) 103 Thomas Lux Biscayne Boulevard (poem) 105 Campbell McGrath Amazing True Stories (fiction) 109 Elizabeth McKenzie From Crabcakes (fiction) 11 7 James A. McPherson The Walls: An Interview (poem) 131 Sandra McPherson The Peony (poem) 134 Carol Moldaw Self-portrait: First Night (poems) 135 Christopher Nealon Lost Kittens (story) 139 Joyce Carol Oates Ruin Outlasting Sorrow (poem) 144 William Olsen The Shaping Ground (poem) 147 Steve arlen From Ornate with Smoke (poem) 150 Sterling Plumpp The Other Side (poem) 154 Minnie Bruce Pratt 17

Leaf Confetti (poem) ••.••.•••..•••..••••••••••••••••••••••••• 156 Rohan B. Preston Gold Rush: 1848/1996; Positions of Strength (poems) ....•......................................................... 158 Alane Rollings Three Pieces: A Piece of the Night (a fragment); Movie Texts; Life Doesn't Take Itself Very Seriously (prose and poetry) 164 Juan Rulfo Translated from the Spanish by Deborah Owen Moore Authenticity and Authority (essay) 181 Michael Ryan Interstate; New Year's Eve in the Aloha Room (poems) 190 Alan Shapiro Littler Sonnet (poem) 194 Reginald Shepherd The Grid; The Fight (poems) •.••.••••.•••••••••••••••..• 196 Tom Sleigh Heartbreak; Clothesline; Woodsplitting (poems) 200 Heidy Steidlmayer California: An Anthology (novel excerpt) 203 Richard Stem What I Am; Banner Hopes (poems) •....•.•.••••••••• 211 Marc J. Straus Interview with a Child (poem) 215 Wislawa Szymborska Translated from the Polish by Joanna Trzeciak 18

Road Noise (poem) 21 7

Mark Turcotte

Poem for a Holiday at Home; No Complaints (poems) 233

Reetika Vazirani

A Brief Domestic History (poem) •....••.•....•••••••.• 235

Ellen Bryant Voigt

What He Said When They Made Him Tell Them Everything; After the Others; River Journal; The Choosing of Mozart's Fantasie Over Suicide (poems) ••..••••....••...••••..••••.••••.••.••••

Bruce Weigl

The Knife (prose poem)

Joshua Weiner

Thirst; Between the Lines: Three Letters (poems)

Theodore and Renee Weiss

From The Long Home (poem)

Christian Wiman

My Algeriance: In Other Words, To Depart

Helene Cixous

Translated from the French by Eric Prenowitz

Sewing Without Mother: A Zuihitsu

Kimiko Hahn

237

••.•••.•.•.•.•.•.•.•.•.•••.•••••••••• 242

244

•••..••••.••••..••••..............•••.••••..••••.••...•••••••

....•.•..••.•••....••.••••• 251

SPECIAL SECTION;

TO AUTOBIOGRAPHY

APPROACHES

To Arrive from

.......•.•..........••........• 259

Not

Algeria

.........•.....•• 280

19

Dluga Street 288 Adam Zagajewski Translated from the Polish by Bill Johnston Firescapes: A Memoir 294 Evan K. Margetson From Weed 302 Linda McCarriston CONTRIBUTORS 334

size)

Cover etchings (Milagro, front; The Wounded Healer, back) by Teresa Mucha (each four-color, actual

20

Cover design by Gini Kondziolka

Editorial

With this issue of TriQuarterly, 1 conclude my sixteen years as editor, and take my leave of the magazine in order to devote more time to writing and teaching. Editing TriQuarterly has been an exhilarating, difficult, and very rewarding journey through moments of celebration, crisis, and change. It has been an education in itself not only to edit issues but also to steer this small boat through very challenging straits. Funding, circulation and day-to-day operations are consuming problems in themselves, and solving those problems always spiced the selecting of new writing for publication in TriQuarterly. Certain special issues-such as the Chicago, South Africa and Mexico issues-were exceptionally important to me, but looking back at all the issues, I realize that over and over I felt the excitement of setting up for our readers a conversation between and among aesthetic practices and cultural traditions, from all parts of America and from many other countries. I felt this excitement nearly continually, thanks to the superb work that we have received from writers at all stages of their careers and lives.

I am very happy to have made this journey-on me it had an incalculable effect, not only because at the same time I was working at my own writing, but also because I have lived in the crosscurrents of both philosophical and practical questions about contemporary American culture, and about writing in particular. In leaving TriQuarterly, I also leave behind much of my involvement in the tasks and problems of literary publishing. Stepping out of this boat, I realize that my own reflections surprise me a little. While I have no doubts about the value of contemporary writing, I find that I do doubt the adequacy of the institutional and cultural structures without which contemporary writing will be nei-

TRIQUARTERLY

21

ther disseminated nor preserved in the future. Literacy is said to be falling; literary-book sales and literary-magazine subscriptions are economically precarious, especially because the funding for libraries and the success of schools in nurturing an interest in reading and the arts have both declined dramatically, over the last twenty years; trade publishing no longer makes much of a place for serious books; bookstore chains are undermining the very publishers (small and not-for-profit) that provide them with their vaunted variety on their opening days. (They are driving small publishers toward financial crisis by ordering too many books and returning most of them unsold, and by delaying their payments for the books they do sell.) And thus, paradoxically, the economic censorship of ideas and values is probably worse than it has ever been.

Most readers-and I believe there are many more serious readers than we who try to sell our literary books and magazines can reach-never even hear of what we in this small trade publish; they are unaware of much of the important thinking about, and imagining of, experience and consciousness, community and individuality, reality and desire, language and thought, freedom and bondage (political, material and mental). Many readers, if we could only let them know what is being written, would welcome the chance to read more, but the turbines of publicity and mass entertainment whirl with such power, at such high speed, that small publishers cannot match them with our gyroscopes or our whirligigs. The signs are not good that the complex and valuable heritage of imagining, truth-telling, dreaming, literary shaping of human experience, and linguistic mastery and acrobatics, will be available to our inheritors even to the extent that it has been available to us.

Fiction and poetry-mysterious yet ordinary, peculiar yet essential to us, mocked by the American "marketplace," yet, so far at least, surviving at their full depths and heights-remain the most accessible of arts and yet the most unpredictable. They may be, to some, merely "product," and to others, merely "texts," yet they continually and forcefully signify the eloquent dimensions of our experience of the real and the imagined. Without them, how impoverished would our sheer noticing be? By what other signs of life would we recognize other experience, or be moved to the same sort ofpity or anger, love or homage? By what else would we be so deeply entertained? Fiction and poetry also continually reassemble the bewildering and fascinating possibilities of language itself, thus refreshing expression, insight and the way we relate to the world.

We have, as a species, an appetite for each other's consciousness that fiction and poetry reward in extraordinarily rich ways. But if these

TRIQUARTERLY

22

human endeavors and accomplishments are to continue to be important, interesting and available, then the not-for-profit literary-publishing "field"-as we have come to think of it, professionally, for better and worse-needs more hands and more security from the predations of the false gods of profit and loss. In these times, as I withdraw from this field, my great hopes go with this magazine, under its new editor, Susan Hahn-whom I thank for all her help over many years-and with all who work to publish good and great work.

For their help over the years, I offer many thanks to current TriQuarterly staff members Kirstie Felland, Bob Perlongo and Gwenan Wilbur; Gini Kondziolka, our superb cover designer; Fred Shafer, our free-lance intellect of all trades; and the many persons at Northwestern who have given us goodwill, good counsel, and material support. I am especially grateful to President Henry Bienen of North-western for his support of TriQuarterly's new, more financially secure, footing at Northwestern University Press. And I offer heartfelt thanks to Nicholas WeirWilliams and Kim Maselli of the Press, for their enthusiastic willingness to become the stewards of TriQuarterly's future. Many writers, friends and donors, many tireless, inspiring literary-magazine and small-publishing colleagues, many foundation officers have contributed to sustaining TriQuarterly and to renewing my own passion for this magazine and for the good that literary magazines do. May we all-writers and publishers-persevere with our historic sense of purpose and continue to feel great hope and delight in our work.

Reginald Gibbons

TRIQUARTERLY

23

Two Poems

Agha Shahid Ali

Ghazal I

for Edward W. Said

In Jerusalem a dead phone's dialed by exiles. You learn your strange fate: you were exiled by exiles.

You open the heart to list unborn galaxies. Don't shut that folder when Earth is filed by exiles.

Before Night passes over the wheat of Egypt, let stones be leavened, the bread tom wild by exiles.

Crucified Mansoor was alone with the Alone: God's loneliness-just His-compiled by exiles.

By the Hudson lies Kashmir, brought from PalestineIt shawls the piano, Bach beguiled by exiles.

Tell me who's tonight the Physician of Sick Pearls?

Only you as you sit, Desert child, by exiles.

Match Majnoon (he kneels to pray on a wine-stained rug) or prayer will be nothing, distempered mild by exiles.

"Even things that are true can be proved." Even they?

Swear not by Art but, 0 Oscar Wilde, by exiles.

Don't weep, we'll drown out the Calls to Prayer, 0 SaqiI'll raise my glass before wine is defiled by exiles.

TRIQUARTERLY

24

Was-after the last sky-this the fashion of fire: Autumn's mist pressed to ashes styled by exiles?

If my enemy's alone and his arms are empty, give him my heart silk-wrapped like a child by exiles.

Will you, Beloved Stranger, ever witness Shahidtwo destinies at last reconciled by exiles?

TRIQUARTERLY 25

Ghazal II

for Anthony Lacavaro

I say This, after all, is the trick of it all when suddenly you say "Arabic of it all."

After Algebra there was Geometry-and then CalculusBut I'd already failed the arithmetic of it all.

White men across the U.S. love their wives' curriesI say 0 No! to the turmeric of it all.

"Suicide represents a privileged moment Then what keeps you-and me-from being sick of it all?

The telephones work, but I'm still cut off from you. We star in America, fast epic of it all.

What shapes galaxies and keeps them from flying apart? There's that missing mass, the black magic of it all.

I'm smashed, 0 Enemy, in your isolate mirrorWhy the diamond display then-in public-of it all?

Before the palaver ends, hear the sparrows' songs, the quick quick quick, 0 the quick of it all.

For the suicidally beautiful, autumn now starts. Their fathers' heroes, boys gallop, kick off it all.

The sudden storm swept its ice across the great plains. How did you find me, then, in the thick of it all?

For Shahid too the night went "quickly as it came"After that, 0 Friendl, came the music of it all.

TRIQUARTERLY

26

Two Poems

Debra Allbery

Chequamegon

I know how not to tell this. A dented can held freezing water from the lake. It was like washing our hands and faces with fire. Think of Sterno scent, of coffee grounds. In the van, upholstery peeling off the seats.

We stopped somewhere for tools and groceries. Walked into a reservation bar to ask directions. The darkling rusted swivel of that place. Its heavy door.

It was April, ice still edging everything. Each breath a drink of well water laced with tin.

We climbed a fire tower, wind splintering through its metal grids. Later we stood on a pier as narrow as a gangplank, the blue-black wince of the lake glinting all around us.

TRIQUARTERLY 27

In the woods I let him say his words. They sounded like leaves, years and years of leaves.

But this is where I get lost every time. The bare trees. What I didn't do. His ghost laugh loose above me, red strip of cellophane snagged in the grass. When we walked back half of the trees we passed were marked for cutting, yellow bull's-eyes, a slapped splash of suns. I followed him, you understand. I disappeared.

Y

TRIQUARTERL

28

Imaginary

Kalispell last night, a highway payphone, he dialed her number. Recognition slanting her voice like the trace of an accent she had tried to lose. Who is this? she had repeated into the static, then colder, quieter, Who is this. And him not answering, just trying her name, the small shape of it, saying Would you please talk to me, ice-rough rain slicing through, until, after a few long minutes, she hung up. He's sure she'll think but never believe it was him, not after all these years, and the black cloth of distance, the weather's erasures.

TRIQUARTERLY

29

"And This Is Free"

Michael Anania

for Sterling Plumpp

for Sterling Plumpp

In this film, now thirty years old, a blues band is playing on Maxwell Street, a woman with narrow legs and white shoes dances beneath her own raised hands; at the curb a man extends three fingers toward the music, feeling its edge spill toward him as though it were a subtle property of the air, a Braille he reads there, sentence by sentence, his smile tilting away, his balance uncertain; ecstatic, he nods, yes, that's right, sorrow's joy now trembling in his grasp.

Two girls lean against a stained wall in unison; arms, legs, shopping bags pass; fingers bend into fret-lines, fingernails along the shoaling strings flash like wavetips, and the song says, "You spent all my money on whiskey and wine," Meister Brau boxes filled with broken-faced dolls, the stitched creases where their arms fold forward darkening,

TRIQUARTERLY

30

and the song says, "Love ain't half as good as you said it would be," a tu-tone jacket flapping at his sides, another dancer spins once and talks back to the guitar;

brown paper twisted up tight, bottle cap turned down against it; pass it around, it is a breath that catches in your breath something going from hand to hand, its words

thick and burning in your throat, and the song says, "Left me" and "alone" and "like a river" and "jelly roll" and the street has a wet sheen, "flyaway, flyaway" and the song says,

sunstreaked window and security grate, doorway, doorway, a forearm of gold watches, shadows draped like damp cloth, rooflines and hubcaps, and the song says, "like a sweet girl should,"

city curling its long arms inward, "string of pearls, string of pearls," lost in the beat of it, hands (always), lined palms offering diamonds sideways like secret insinuations;

a boy on his knees in the street hand-jiving a cardboard box, a woman selling housewares reaches toward him-she wants her box back; pennies skip over paving bricks, and the song says, "out in the kitchen with a butcher knife," an edge to whatever moves through shadow and out into the street's mid-Sunday light, fingering the chord into place, voice leaning,

amps set up among cinders and broken glass, hat pushed forward, meaning free�and�easy, and the song says, "raise my hand feel better" and "if only you just understand."

TRIQUARTERLY 31

The market goes on, bundles of socks, Tshirts, coats, jackets, boxes of records in tattered paper sleeves, pencils, crayons, roll-ends of linoleum, window shades, cards of bobby pins and bluebird barrettes, rubber'banded place,settings, paper cups, dollar bills fanned from raised fists, snap counts, fingers popping, change chanted thumb to palm.

And the song says "you," meaning he or she, and "me," meaning you and I, and "my," meaning ours, and "so good," meaning so good, then "I guess I got a touch of the blues."

TRIQUARTERLY

32

Bells

Karen Brennan

At irregular intervals the bell tolls. It tolls eight times and then it may toll seventeen times a while later, at no particular hour. Occasionally it tolls twenty-one times, waits a beat or two, and just when you feel you are drifting off to sleep, it tolls once more, a single hard resonance of iron on iron clanging into the dead of night, into the motionless air and the stultifying heat and the whine of mosquitoes. There may be a man ringing the bell, we imagine, standing in the belfry at all hours, night and day, his life devoted to ringing the bells of the cathedral as some are devoted to shopping or travel. I ring the bell when I want to, he tells his wife who brings him his meals in a brown sack. Lately, she has been conveying the complaints of the tourists as well, who are irritated by the irregularity imposed upon their lives by the caprice of the bell ringer. What's with the bell? There seems to be no purpose except to annoy us.

The man, Jose, looks thoughtful. He talks to his wife with his mouth full of bread. The bell has no purpose, eh? he says to his wife; call her Renaldia. He is wearing Levis and a vintage Beatles T-shirt with missing sleeves. His biceps and pectorals are overly developed in proportion to the rest of his body, since it takes tremendous strength to ring the bells. First he must swing his body over a parapet; then, holding the long rope to which the heaviest bell is attached (400 pounds), he positions himself on the stone ledge overlooking the city. Generally he pulls four ropes at once, each attached to bells of differing weights, and what this produces is not, as one would expect, the sound of multiple bells ringing, but an impression of unadulterated clarity on the listener, a brief conviction that time indeed will never pass but is doomed to the moment and its endless reiteration of itself.

TRIQUARTERLY

33

At first, as a teenager, Jose had neither the strength nor the will to ring the four bells at once. In those days, he was happy to be punctual, to mark the angeles, matins, compline, and so forth. But something hap' pened to make him have contempt for punctuality; it was as if the bells themselves had overtaken him, as if their rhythms were purer and more accurate than time itself because, he reasons, if time is ignored perhaps it follows logically that we will live forever. But he keeps this idea to himself and does not share it even with Renaldia, who would not under, stand.

Lately she has been growing a little mustache and its appearance, like two faint smudges of ash above her lip, fill her with foreboding. She worries that is she changing into another person, that bad fortune has suddenly flapped in her direction, wafting away the old Renaldia and dragging forth this new one with a mustache.

There had been a time, actually, when she had been more patient with Jose who was, everyone knew, impractical and antisocial, who pre, ferred his hours spent in the belfry, surrounded by stone and echoes and staggering perspectives, to an evening in his casita with Renaldia and her mother and their three or four children-he couldn't keep trackmilling around his knees. He prefers loneliness to society, a long view to a myopic one, and the ringing of bells which seem to him to mark, instead of time, that which is more unsettled-a cloud's passing, for example, or the death of a dog, or a boy's sneeze. And Renaldia had understood this as a wife will always understand the quirks and short, comings of her dear husband compared to, say, Martin Gonzalez who plays baseball with his kids on weekends and cooks enchilada sauce from scratch.

But these days Renaldia's understanding is wearing thin. There is the fact of the mustache, for one thing, which seems to announce a change in her relationship with Jose, indeed a change in life itself, because what is an omen if not profound, its power extending beyond itself? So Renaldia, instead of proffering silently and without judgment the lunch, es and dinners that Jose requires, instead of mounting peacefully the 223 steps that lead to the little room where more often than not Jose can be seen squatting and peering at slivers of the city between the chinks of stone, this Renaldia is liable to stomp gracelessly up the long flight of stairs with fury in her heart. Then she sets the meal in front of Jose with a noisy clatter and proceeds to contribute to the disturbance herself, complaining to Jose about his absence, the lack of money for children's clothes, her mother's annoying habits, the filthy air, how the TV has

TRIQUARTERLY

34

terrible static, et cetera. When she exhausts these personal topics, she moves to a litany of the complaints of others-the maestro at the children's school who needs a new truck, his Uncle Tonio whose filling fell out of his tooth, and winding up with our complaints, the complaints of the tourists to whom time is nothing if not everything and so are particularly vulnerable to any fluctuation in the day's activities.

Lastly, when Jose's impassive face has darkened and his eyes have drifted away-because for only so long is he able to listen before his own thoughts, so familiar and comforting, in their large vague shapes, intervene-at this point Renaldia points to her mustache which, she claims, has been sent to punish her for losing control of her husband. Clearly, I am turning into the man of the family because the man of the family has flown the coop! And what if it grows darker and longer, then what? What will your brother, Mr. Macho, say? And how about my mother, do you ever in your selfish life think of her, Jose, her own daughter with a mustache curling up at the ends and who knows maybe a beard next?

Understand, it isn't that Jose isn't moved by the appeals of Renaldia or even that he isn't compassionate about the mustache which, he would have to agree, is a bit off-putting. Rather, it is that, like a priest or an artist, like anyone with a vocation, Jose cannot stop doing what he has been doing. No more than he can stop the ideas about time and eternity from rolling into his mind like a lustrous fog. We imagine him thinking: At this minute in this city everything may have changed and the day that was yesterday might be today and who knows where today is? And this is how it goes night after night, through the sticky heat of May and the torrential downpours of June, when the rainfall sounds more like bodies and furniture plummeting to earth and when the bells peal intermittently, invading our dreams like life.

TRIQUARTERLY

35

Teresa Cader

We leave here barefoot, carrying maps we cannot use.

Come to the valley where stars illuminate the night: our atoms are forged in that fire. We see ourselves transformed.

The day is here when we see galaxies with our naked eye. That long descent into the body is our first death. Why fear any other? Numinous accidents comprise our lives.

Let the gods embellish their stories with grails and bones. We can indulge them anything we choose.

The universe is our fingernail, our obsessive thought.

TRIQUARTERLY Atom

36

Ciudad

Remco Campert

Translatedfrom the Dutch by the author and Reginald Gibbons

We were in the hottest part of Spain I went to scout the walled city that had been completed centuries before by order of the king outside the walls there was nothing but hard sun on the hard ground eternity for as long as eternity may last undisturbed by anything built

I lingered in the shade of a portal I imagined a shed for a donkey a cave for a vagrant but the only thing I saw was trembling stillness all day you lay sick in the room not a good beginning for our trip that you didn't want to go on with me I realized only later

TRIQUARTERLY

37

Two Poems

Carl Dennis

MaiJen

This is the evening I was hoping for, The one when my bad times are transposed to stories Offered as a small return for the story you've just told me Here at this window table in the Mai [en restaurant On rain-washed Elmwood. How once, When drink had driven your dad from the family, Meeting you on the street, he gave you his promise, In a voice cold sober, to send you the dress You needed for confirmation, and how you felt When it never arrived. A sad story That makes me happy I've carried for years Memories that till this evening I've never valued.

This is the rainy April evening toward which our lives, Despite the odds, have been moving for decades Along different paths, without our knowing, So we might notice through this rain-streaked window How glinting streetlamps and street reflections, Stoplights and traffic, set off by contrast Our easy calm, our stillness.

This is the conversation that can have no midpoint, However clear its beginning, if it has no end. And why would we turn to ask for the bill, Why don our raincoats and walk to our cars And join the pitiful traffic that has to make do

TRIQUARTERLY

38

With the dream of a life behind it or a life ahead?

The past we need is only a kind of currency Stamped in red with the date of this day. And the fabulous future is beginning to understand If it wants to meet us it will have to swallow its pride And come to our table, not wait for us to come looking, For we have no plans to go anywhere.

TRIQUARTERLY 39

Crossing the Water

How disappointing for you, the hero in the fairy tale, Having proven yourself too pure for the spells of witches And too slippery for the chains of giants, to come at last To the bank of the river you glimpsed in a visionWith hills on the other side as green as you dreamed them And the hill town just as inviting, there where true companions Destined for you are waiting with the princessOnly to find the current too fast for swimming.

It can't be easy for someone who's always prided himself On never asking for help to hurry along the bank In hopes of finding a boat for hire. Not easy to settle, For want of another choice, on a ferry like mine, Dirty as a coal barge, smelly as a fish smack. And then to find that I'm the boatman, a raggedy hunchback With an eye that seems both crafty and servile. What could be worse for making the good impression You were hoping to make on regal spirits Who even now are planning a feast of welcome.

Worse than all this is what you'll feel in a minute, Halfway across, when I mention the poling fee You forgot to ask: how when you step ashore You have to present me to the welcoming party

As your trusty companion, the person you owe the most, The one they'll have to honor if they want your friendship. Sit down and get a grip on yourself. This fit of anger And pride will pass. Think of all I've had to swallow To admit I haven't the winning manners you have, That I have to borrow your name to be accepted.

Even with a partner like me you'll still be admired Though now less for your lonely virtues Than for your loyalty, impressive in its commitment To a man with no graces to recommend him. And because you're obliged to keep up appearances And don't want to be a poser who smiles and hates,

TRIQUARTERLY

40

You'll try to find something about me worth liking And maybe succeed. But for now pretending's enough. Look. We've arrived. Step ashore. Here come the greeters I'll love more than you will, feeling as I will more keenly The distance between the good they'll do me And the little I'll do for them in return.

TRIQUARTERLY

41

Two Poems

Amy England

A Noh Play in Which the Ghost Does Not Reveal Itself

1

-What are you doing?

-Digging; that is, in the ground.

-What are you digging for?

-Things that are broken. See-(holds up part of a lamp made of marble).

2

-(Humoring him) I have a whole flashlight. I'll give it to you.

-What would I do with that? I know everything about it-it wouldn't let me in.

-Into what?

-The past. This is archaeology.

3

-The past led to us. So, we're in the past.

-Not this past-(His wave indicates temples like abstract sculpture, conversation as philosophy and violence as reverence.) The past behind me has led to-indescribable things.

TRIQUARTERLY

42

-You're on your hands and knees digging.

-I'm not desperate, merely careful. The material is fragile (uncovering a three-breasted Aphrodite).

4

-You're the picture of abjection. -That may be so. We wanted to be Greece, or Greece and Rome at once. Perhaps it was the wrong thing to want, but I think we only didn't understand it; we left out except I can't say "we" anymore

5

-Get up. Scraps of pottery! Your soul's a rag. Look how your glasses are mended with safety pins. Stop blinking at me. Get up.

6

-A rag. Maybe. But I'm not leaving off just yet.

TRIQUARTERLY

43

On the Beach

You might have encountered it this way: A knight and his squire have reached the eaves of the Dark Wood. The squire sits on his heels and watches the knight's face. The knight's face is set toward the trees, but he does not see them, or how the road van, ishes into them so quickly. He sees his object, how golden it is. He seems, in fact, to have bent his thoughts on this end so completely that it dwells in him, and radiates from him, his luminous face, the eaves of forest.

Or this: A group of children saying "I dare you" to a girl at the side door of a house. Her friend would like to go in with her, is too frightened. Everyone knows about the ghosts there. The winter evening already dark. A car turns and passes; its headlights flash on the one unboarded window.

The man and woman have reached the border. From a hill on the other side, a mirror signal-"Safe now," "Come ahead." In the snow he will leave tracks, but the pines will give him cover. She doesn't love him enough to go with him. Also, a woman dreamed that she and her lover stood at the doors of an elevator, the green arrow lit and the bell sounded; when the doors opened she got on. He didn't. But sometimes the attendant embarks on the journey also.

He or she, with the maid she loves as a sister, the devoted but slightly shorter friend. About to leave for or just returned from the woods/ocean/underworld/sky, they stand in the electric shadow of battle, and the lightning is a sword, or the sword flashes like lightning, or the setting or rising sun makes a brief red lamp below the day's clouds. However, I saw in a picture book how the moon was rising at the edge of the swamp; her hood fell back, and she was by her own light reflected in the foul water. She was herself hero, light, attendant, and edge of time, and static, for the branches caught her and she couldn't get free.

He stood at the mouth of the cave, felt its tomb-breath on his face. His companion was a horse too broken to protest. Nothing shone, but then, he wouldn't be coming back.

TRIQUARTERLY

44

Testament of Arkey Wilson

Steve Fay

I wake at sunup with my feet pointed toward Arkansas. I wonder if it was providence that the trailer was already turned that way when me and Patsy bought it and moved our little daughters, Dolly and June, up from the flood plain, our son, Cantrell Jr., already dead in prison, never learning to read even as good as me, getting fired from jobs Hank helped me help him get. A bruised reed, he ain't going to break, Jesus preached, but Canny shot a cop who caught him smoking near drained Lima Lake.

The mouth of a gun, the mouth of a boy who can't let on he can't read, the mouth that gets you into trouble behind bars, the mouth of his mother, my wife, hardly talking for a year after that.

And there was Hank, my friend, who hired me sometimes to help repair grain elevators with his crew, or drive to Keokuk or Davenport for a part, or even fix them sandwiches so he could slip me five bucks when I was let go from bartendingHank trying to raise those two kids without a wife, relying on half-crazy relatives scattered in a half-dozen little towns: Pontusuc, Keithsburg, Buffalo Prairie, and places like Shanghai that ain't even on a map.

TRIQUARTERLY

45

And that day finding Hank collapsed one more time, an attack of the hernia he wouldn't get help for, lying there on the hardened, spilled tar behind his toolshed,

him reaching up to me, saying, Arkey, someday tell my kids just before he passed out.

Just what to tell them, he didn't have to explain. I knew he meant more than to straighten them out about some gossip on his family he guessed had got around to them, he meant something about a father's guilt that he couldn't do better-what I wish I could ask somebody else to say to mine, for me, but with Hank gone I got nobody to ask.

Oh, he didn't die then, he finally had to get the operation, lived the long life of the ornery, I used to say, for years after that. But what I said to him then, sitting with him to wait for the ambulance, noticing how even with his rough, work-dirty hands he looked like a worn-out kid finally taking his nap, what I said was how Jesus said to give the little children a cool drink of well-water.

Not the water of the Mississippi, I thought, remembering my own home along the delta, and what I'd seen of the fevered generations of this whole land.

TRIQUARTERLY

46

And So Cold

Roland Flint

This morning I see icebox in WCW's plum poem, written the year I was born, and realize I've been changing it in my head to refrigerator, not a box someone carried ice to, with tongs (once or twice a week), from a truck or wagon, a swatch of old carpet padding his shoulders to bear it on, backache contorting his bed all night, chilled to the bone by what would save the plums' unchangeable poem.

TRIQUARTERLY

47

By Dawn's Early Light: The Meteor in the Madhouse

(Part III)

Leon Forrest

"Nobilis": A Preface

I first met Leon Forrest in about 1973. I was commuting between Berkeley, California, and Chicago trying to research a story on an organization on the West Side of Chicago called The Contract Buyers' League. Whenever I went to Chicago in those days, I stayed with a friend in Hyde Park, a lawyer named Marshall Patner. I think that it was in 1973 that Leon's first novel, There Is a Tree More Ancient Than Eden, was published. I had read this novel at the same time that I had read Al Murray's Train Whistle Guitar. I thought both these books were as bad as a motherfucker, and I was trying to get the Atlantic Monthly to allow me to review both of them. During that bleak time, during the down-time of the 1960s, I was fighting to maintain my sense of black people as teachers to the larger society. Leon's book, in this respect, was a godsend.

Leon came to Hyde Park, during one of my trips from Berkeley into Chicago, met me at Marshall Patner's home, and we drove off to get some barbecue. I know now that Leon likes to celebrate Chicago as a haven for hustlers, and I know now that he was probably studying me to see what new con might be appearing. But I also know now that there was no con. I simply liked him. I liked him exactly in the way that Peggy Price, his future stepdaughter, liked him. She told me once that if she were ever on a deserted island, the one person in the world she would want to be there with her is Leon Forrest. Many years later, another woman, Barbara Fields, told me this same thing in different words. Now, after knowing Leon, and his wife Anne, for well over twenty-five years, I feel obliged to add my own voice to their assessments.

The sources of character are mysterious. In the past they were located

TRIQUARTERLY

48

in family or in geography. These days they are located in one's assessment of one's self as a victim of sociology. But I think now that there is still another source, one still steeped in mystery. Leon Forrest is a linkage with this mystery. He has character in abundance.

Leon never talks about his own problems. But he has a profound wisdom about your own. Between 1980 and the present, I have talked by telephone, sometimes several times each week, about my own problems. He has listened. He has been a human island of wisdom and advice and personal warmth for me, and probably for a great number of other people as well. When I was broke he invited me to read at Northwestern. When I doubted myselfhe dismissed those doubts by saying, "Ah, man." His gentle voice has been a lifeline for me during the maturing parts of my life.

I love this Negro.

In recent months, I have been studying the history of the Roman Republic and its transition into an Empire. I know now that what the Romans called "The New Men" were people who had risen from obscurity into positions of public responsibility. They were suspect because of their origins, but still they brought infusions of emotional and intellectual and moral energy into the interstices of the fading Republic. Marius, Gaius, Julius Caesar-they confronted the challenges, coming from all sides, in their efforts to maintain the meaning of codes that had begun to erode. Many of these New Men fell. But their legacies lived on. They were not aristocrats, but the intensity of their internal fires made them noble, simply because they had purpose.

Leon Forrest is such a man. While his sense of Empire is limited to Chicago, and while he still celebrates Chicago as a hustler's city, he has sought out the noble impulses in his city-in blues clubs, in jazz sessions, in Mahalia Jackson's voice, in the masqueradings ofConfidence People, as well as in devotion to the crooked but essential honesty of his hometown.

I love this Negro. And I wish him recovered health and a certain steadiness on the case.

-James A. McPherson

TRIQUARTERLY

49

Why Was I Born? It had been a simple enough task: return to Williemain's Barbershop; retrieve the eyeglass case with my reading spectacles inside. I would go the absent-minded playwright's nut-role route. The barbers would love it!

Discovered I had misplaced the reading glasses when I had gone to Memphis Raven-Snow's Funeral Home to give the secretary the cashier's check, so that we might commence the process of bringing the dead body of my kinsman, Leonard Foster, back from New York {where he had died of crack cocaine}.

No doubt, I had dropped the case at Williemain's. The secretary had found a pair of glasses off a dead man's body, that I used as a substitute for reading and signing the prescribed document of release.

Now just as I was leaving, three long-legged lads-draped in bright colors-entered, almost knocked me down, and immediately took seats in the rear of the shop.

My right hand was on the doorknob of Williemain's Barbershop {feeling in self-possession now that I had secured my own gold-rimmed glasses and no longer dependent on the glasses of a dead man}.

Just as I was turning the doorknob, Galloway Wheeler revisited his rage and trembling over "those belligerent black punks" in the shop earlier that morning. Then he said in Latin {as if to throw the youthful newcomers off}: "Can such anger dwell in heavenly minds?" My tutor over forty years ago, when the very best high schools still offered four years of Latin if I commenced a series of recollections over the honored, now lost, past, I'd never get out of here.

"What is this world of ours coming to!" Wheeler now bewailed. "The promised end," he warned, by making the scissors sound off as mock sabers clashing, just above the head of the choirboy, in his chair, from Pilgrim United.

I felt my hand start to tum the doorknob, for I knew Mister Wheeler sought an extended run of amen arpeggios {in Latin, or in English} in order to affirm his dour state of mind.

One of the ministers who once upon a time had derived a monthly stipend from the mayor's slush fund for certain politically supportive Negro preachers, was clearing out his throat. Then Rev. Alfred Belton declared: "Mister Wheeler, let's not forget how before the ranting, licentious mob of homosexuals, Lot was ready to compromise the flesh and blood of his females: 'I have two daughters, both virgins; let me bring them out to you, and you can do what you like with them but do not touch these men.' I say this to say that Almighty Gawd has a divine

TRIQUARTERLY

50

plan, beyond the scan of man!"

Outside a white Bronco drew up to a sudden pause, in the early dusk of the November day.

Someone in a ski mask hanging out of the window. Sudden hail storm of rifle fire. Bursts of charged lightning crashed the shop's windows. I was hit twice: high right shoulder and left leg. Fell to my knees, with the doorknob in my right hand. Plaster, shards and fragments of shattered glass everywhere. Framed pictures of famous black legends, athletes and entertainers came tumbling down: wall to floor.

I saw Galloway Wheeler collapse in a pool of blood.

Craig Cratwell was hit in the left thigh; I saw him hobble over to his colleague's side to aid Mister Wheeler.

Seemingly unharmed, Rev. Belton was screaming for help. (The frame from DuBois's portrait over his shoulders.)

Before my bleary-eyed vision the three newcomers, in their silver slippers, somersaulted into talented hurdlers: they vaulted over me as lodestars. I felt staggered in violent pain from head to toe. Then my body fell forward

Too long, so soon, the medics were placing us upon white slabs and we were rolled away and elevated up, up, UP. A fire alarm hailed our way; we zoomed and snaked through the late-afternoon streets; the ambulance truck swirled, twisted its way in and around bound-home traffic. Was I going into a state of shock?

A young blond female medic asked: "Where were you hit?" Then a black medic was loosening my sports jacket, and shirt. He sent his stethoscope to my chest. She was doing my pulse. "What is your name?" I felt damp and dislocated. Black and blue, with the blood of my body everywhere. All I could think was: the wicked wounds were over there and back down here and the absurdity of being of being in the wrong place at the wrong time So I said: "Lucifer Wrongstreet, lady." Then the imminence of death. "Where are my eyeglasses!"

Despite the fiercely pulsating pain in my shoulder and my blazing lower left thigh, my right hand retained its strength. Both medics kept trying to get the doorknob out of my right hand; I kept pumping it like the trigger of a gun.

I heard the words come and upon my unclean lips I started to mumble: "Hail Holy Queen, Mother of Mercy, our life, our sweetness and our hope-to thee we cry poor, banished children of Eve Was I going to lose my life or a limb? And then I faded into a brilliant spider's web of oblivion and light.

TRIQUARTERLY

51

Sometimes, as a high-flying child, I would bear witness to a swift, ghastly yet gloriously lucid Light. Then a sheath, or cone, would skyrocket out of itself upon this road of darkest night. A Light so real, royal and raw, keeningly dreadful, majestically turbulent and perilous to behold, that I thought my world-even The World was about to consummate the Promised End. The first expression out of my mouth was: My Lord and My God, why hast thou forsaken me? And before I would have time to reach my long white bed: Almighty God was about to strike me down, dead

Suddenly from the tips of my toes to the temple of my being I came to feel: why my path is astonishingly blessed (out of captivity, this profoundly accusatory moment, even as I still felt the shock in my kneecaps). And across the way, the light in the tower of the darkened church, where runaway slaves-out of the alabaster South-had hidden 150 years before.

Crossing my way-just now as I moved on tiptoe out of Terror and flung my way home-my satchel full of books, rocks, slingshots, marbles, comic books, a tambourine, a homemade crucifix, and a string of crystal rosary beads, the color of bruised blood. What if I had gone the other Way? Not the long way home.

Illuminated initially down this long road homeward ever so high flying in the distance: an anointing moon, in solo-song ascendancy. So that I would almost proclaim aloud, in the beautiful tranquility of spiritual symmetry cast out by a moon's soprano sax sliver of a silvery lucidity on a bending note: "Here God, Himself, must live, and this lyrical spectacle of beauty is His reflecting Eye."

Light of His Body is spangled out of the Eye. A stellar Beauty of moon and a furnace of stars of such supreme magnificence I thought I heard strains of Bach's "[esu, Joy of Man's Desiring," come alive from my Aunt Eloise's large, wonderful, old stucco blond Philco, down in the basement, where we had clustered about in an unbroken, unbowed circle to hear the rung-by-rung exploits of our secular savior Joe Louis, the Brown Bomber, in fifteen rounds of boxing or less We didn't need to be told this soldier was "a credit to his race."

This illumination of God's visage cast out of the moon's roaming, rambling eye and then the clusters of stars Ahahah yes, but if all of this is true, then understanding God Almighty, His nature and His mysterious purposes will always plunge me back before myself to the question: What isn't a manifestation of His creation, if Blake was right? "Whatever it is that Lives is Holy." Too much to bear witness to the ter-

TRIQUARTERLY

52

rible Light of this "truth." I was shocked just now down to the sockets of my knee caps. Not in submission, nor surrender, for I would always be condemned to the Hellish Quest Search down some solitary road-I seemed to have known that from Jump-and without Diogenes' lamp. But where did this mysterious road lead? I was furious as a harp-threaded, Coltrane soprano sax, blistering the flickering, last dying wick of candlelight tongue of Being out of a church of ashes. Unless and untilworld without end-the arch Ancestral experience took me over, and "God Struck me Dead!"

Yet the beauty of this expanse of night-at first Light-was in its way as Van Gogh's Starry Night Aunt Eloise and I had witnessed at the Art Institute. Had the painter seen beyond blinding sight and then His fingertips, touched by the Thunder-Head of this God-head unfolding the power of the Holy Ghost to the Daft genius's temple, topped by a crown of candlelights?

Time and again, until I came to tearfully expect it, I stood there in the fabulous shock this suddenly enraptured moment meant, leading me into, conducting me out of, this apron of Holy Light onto a stage of sudden naked blackness, and then thirty paces into pitched night: this bolt of a terror bathing of Light-streaked labyrinths. Made me try to dance my way out of the reaches of its mad Beauty, yet essay to recognize the power it had over me (as nine cone-piercing points of ultimate conviction, judgment and accusatory searchlights), through me, beneath, as one moved to a Holy Roller dance of dervish, defiance and deliverance

Yet not unlike a sizzling and brilliant razor nearing your body, if you didn't strip your pockets and unfold all of your belongings to the heady figure, in ski mask, before you: that robber on the wrong-way-road home, years before. Called simply: The Mother Goose.

Searchlights-as ray guns-stripped out the last lights of pristine bright sparkling in our eyes. Seized. "Niggers don't blow a breath," the cop cried; two squad cars jammed us. Slammed-up against the graffitisplashed wall. Spread-eagled to the nines and raked up, over and out like weeds, with their nightsticks. Nape, backbone, tailbone, thighs, balls, nuts, shinbone, anklebone. Pickpocketed by the Po-lice state. Revolvers at the ready. Spittle for eyes, their haggard jowls were the color of purple pigs' feet. As we young reckless, partying lions came leaping and crashing out of Hyde Park, by dawn's early light. We were high. Thought we were excruciatingly cool. Sober now. "You apes, take your heads out of your asses You deader than doornails." Blazer was

TRIQUARTERLY

53

on his nameplate. After someone handed the Watch Commander his tinted glasses, we were released on his word. "Wrong niggers," he whispered, in a hoarse whiskey,tranquilized voice, as we flung over each other to see who could get out of that door feet-free-first.

But now I was being rolled in upon a long white table, in the waiting room to death? I knew not operation salvation. At the apron of the swept-about partition I could see scores of shoes coming and going in a frenzy; a babble of tongues. Remove the bullets and pluck out the eyes of my assailants. Then I thought: no. Not an eye for an eye. Punks weren't aiming for me. Kids in the orange-and-red jackets. Vengeance is mine, sayeth.

Rolled away again and again, world without end. Hypodermic to the arm: an explosion of Light occurred. Soon I was gone, in tune to a last sudden visage of Light over Jordan in my drifting-away eyes: I was truly long'gone into the twilight.

You see it was all something akin to when as a twelve-year-old, you are warned time out of mind not to go over into the area where the bad folks live: The Sizzling Skillet. And so as soon as possible, you bound breathlessly over there, out of your familiar darkness, with a rabbit's foot-hopping speed, into the brimstone blackness. Not only because in putting The Sizzling Skillet down with such scorching and imaginative (also lying) intensity, coupled with the Light illumination of mythical experience, the admonishing adults have unwittingly transmuted the area-in perfect pitch-into a beguiling aria called Lucifer's Haunts. Meanwhile, five minutes and twenty-seven seconds later-hurdling down another road-they are celebrating their folk wisdom, spun up from brutalizing experience, with the retainer: "You see you got to go there to know there."

Lucifer's Haunts, indeed. For this was not my first time in this hospital bed, under uncanny circumstances, but that other time, at the razor's edge of floodlights On my way "home" to the Gypsy-faced woman of havoc and heaven. Armed with A Love Supreme for me, triple-extrastrength Tylenol for Gertie, and picture puzzles for the girls

At the razor's edge of a flaming Lucifer. And when I almost got hung up in the nude to tell the naked-butt-truth (up up up and out of Gertie's bounteous bed).

I could catch a glimpse of her ex. His well-strapped razor held aloft and glinting in his huge hambone of a right hand (his left pitched to choke out a flame). A new kind of sweat burst across my temple. Past the john, twenty-one steps from the bedroom door cracked open the

TRIQUARTERLY

54

length of a boot. Screaming on each other in the hallway. Murdermouthing beyond a series of bitter venomous arias. The fireman's voice: a belching exhaust pipe of carbon monoxide. Her voice full of vipers, fangs, acid and ashes. Would I be consumed body and soul in the bitch of their asphyxiating gas? Thought Gertie had changed those damnable locks. Firefighter had not changed his mind. The devil's in the tumblers. Whipping the only two things I saw in reach, her red negligee about my loins {we'd burned up the bedsheets in tumbles and twists}. Donned a puffy white, beltless robe. Heard Gertie hit the floor. Down for the long count? I was up at the window's ledge, ripped up the shabby green window shade in a gulp. Thank God we had opened the window, all the way, before things got steamy. Heard pounding steps of the fireman's wrath trampling forth to carry me? So, with a Hail Mary and a Geronimo I went Flying! like Batman, in the midsummer morning, or was it as a bat out of hell?

Crash-landed into the alley below. Did I break my kneecaps? Found there an hour later by scavengers, who turned me over {red negligee, white robe and all} to the ambulance drivers. Probably thought I was a dropout from a haunt of hermaphrodites. Yours truly ended up at this Forest County Hospital, where I was born. Coming in and out of consciousness. Then I was asking Cuz LuCasta: "Is my leg broken? My kneecaps? My arm? Oh my aching head! And it hurts down here and especially back down there. Am I going to lose a limb?"

"Wonder you didn't lose your natural short-arm, boy," Cuz Lu said. Her next strapping? "How many times you think you got to die? Don't need to puzzle that out, chile! How many times I warn you, time out of mind, 'bout stirring up still-glowing coals in other men's hot beds?"