Volume 2, Issue 1:

Volume 2, Issue 1:

UWTSD Wales Institute of Science & Art

Presented by: Residuum Conference

Welcome to Meta Journal:

A collection of articles written and curated by the doctoral and master's students on the Professional Doctorate in Art and Design and MA Art & Design courses at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David (UWTSD). Meta Journal is an integral part of our larger Residuum Conference, providing a scholarly platform where emerging voices in the field of art and design showcase their innovative research and creative explorations. Through thought-provoking articles, and visual essays, both our Journal and Conference seeks to foster critical dialogue and advance the discourse surrounding contemporary art and design topics.

The name Meta reflects our commitment to exploring beyond the conventional boundaries of art and design. It symbolises the meta-level reflections and meta-analyses that underpin our scholarly endeavours, aiming to transcend traditional perspectives and push the frontiers of creative inquiry. Residuum, on the other hand, signifies the residual elements or remnants that persist after an artistic or intellectual process—a nod to the lasting impact and ongoing evolution of ideas explored within our contributors works. Together, Meta and Residuum embody our dedication to continuous exploration, transformation, and the enduring significance of artistic discourse in shaping our cultural landscape, and future world.

Professional Doctorate in Art and Design MA Art &

www.uwtsd.ac.uk

Kaining Zhou

TheDigitalTranslationandCulturalCommunicationof VisualLanguageinChineseOpera:AnAnalysisofGenZ’ s SensoryExperienceandCulturalIdentityBasedonHybrid Ethnography---------------------------------------------------------------------2

Meixin Tian

HowtoimprovetheaestheticacceptanceofChinese landscapepaintingsinmuseums.--------------------------------------------20

Mingmei Xue

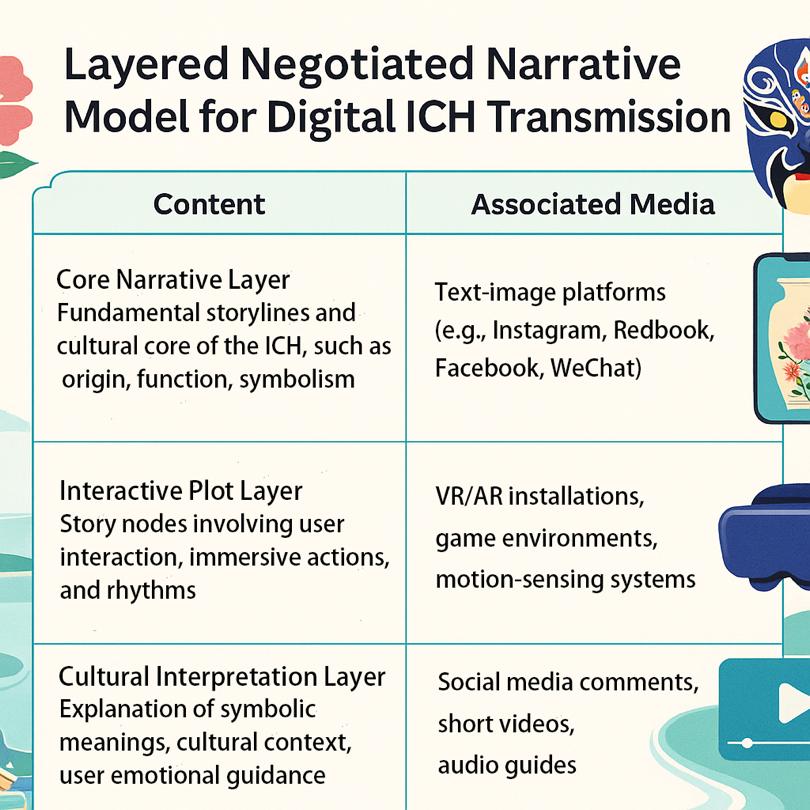

ReinterpretingCizhouKilnMotifsviaSemioticsand TransmediaBranding:AMixedMethodsAnalysisof HeritageSymbolTranslation------------------------------------------------41

Yuanyuan Xiong

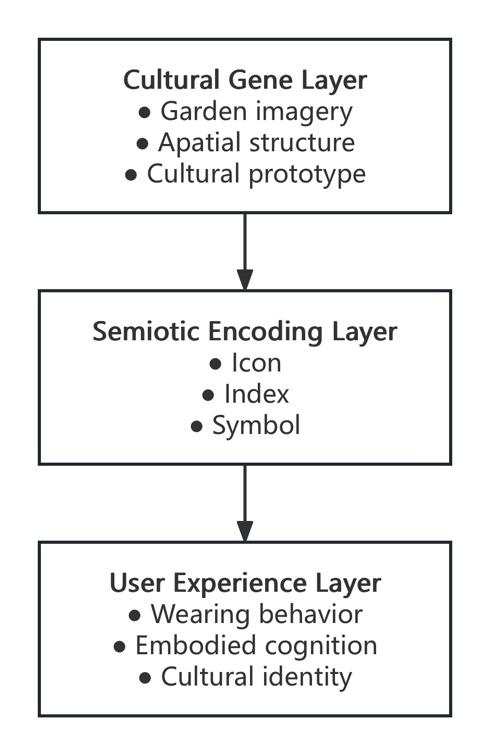

TranslatingJiangnanGardenSymbolsintoWearablejewellery: AQualitativeInvestigationofCulturalEncodingandEmbodied Experience---------------------------------------------------------------------58

Zhiming Yao

VisualCommunicationofCulturalHeritageintheDigital Age:FromHistoricalSymbolstoFutureImagination------------------82

Hanwen Zhang

The Digital Translation and Cultural Communication of Visual Language in Chinese Opera:An Analysis of Gen Z’s

Sensory Experience and Cultural Identity Based on Hybrid

Ethnography

Kaining Zhou

Abstract

This study focuses on how digital media technologies influence the contemporary expression and innovation of the visual language of Chinese opera. It explores the application methods and expressive features of digital media—such as short videos, AI, and VR—in the translation and reconstruction of operatic visual elements. Following a logical framework of "input–processing–output," the research analyzes the media adaptability of opera’s visual genes, the reconstruction pathways of traditional aesthetic styles through digital technologies, and how these changes affect the emotional resonance and cultural identity formation of Generation Z during the viewing experience.

Grounded in a hybrid ethnographic methodology, the study employs four key research methods: case studies, participant observation, in-depth interviews, and rhythmanalysis. It examines platform visual strategies, user interaction behaviors, and perceptual experiences to reveal the interactive mechanisms among visual translation, media logic, and audience experience. By observing both the dissemination paths of digital opera and audience responses, the study addresses the challenges of traditional culture communication in new media environments and explores how visual language can strike a balance between technology and culture.

This research not only contributes to a better understanding of the logic behind the digital dissemination of intangible cultural heritage (ICH) on digital platforms but also provides both theoretical and practical insights into the visual reinvention of traditional arts. It offers valuable implications for the digitization of ICH, youth cultural identity, and visual communication studies.

1 Introduction

1.1 Research Background and Problem Statement

As a comprehensive stage art that integrates performance, music, narrative, and visual design, Chinese opera embodies rich historical memory and aesthetic tradition. Its unique visual expression system—including facial makeup, costumes, stylized gestures, stage choreography, and color schemes—is not only highly formalized and symbolic, but also reflects deep cultural connotations and aesthetic logic.

In today’s rapidly globalizing world, preserving traditional art forms has become an increasingly complex and challenging task. Despite its protection from UNESCO and

all efforts to modernize and commercialize it, the traditional Chinese theater is in steady decline in China. Its viewers have been dwindling over the years (Edström, 2018). With the rapid development of information technology and the pervasive influence of digital media, Chinese opera is increasingly transformed into a consumable and re-creatable cultural resource. As Wang (2022) points out, there exists a structural tension between the slow-paced rhythm of traditional opera and the fast-paced dissemination logic of social media. Platform mechanisms compel adjustments in rhythm, framing, and symbolic representation to compete for attention, thereby altering not only the modes of expression but also the audience’s modes of cultural comprehension. On these platforms, opera is frequently presented through personification, remixing, and AI face-swapping techniques. Gen Z audiences engage through behaviors such as reposting, imitation, and secondary creation. These transformations not only reshape the aesthetic structure of opera but also shift how audiences—especially Gen Z—understand and identify with traditional operatic culture.

Therefore, the central questions of this study are: How is the visual aesthetics of Chinese opera being re-encoded within a media environment dominated by platform-driven cultural production logic? Do Gen Z viewers form new emotional connections and cultural identities in the viewing process? This is not only a matter of artistic re-expression, but also a critical inquiry into how traditional culture is being reinterpreted and re-accepted in the digital age.

In the face of rapidly evolving media environments, the visual language of traditional Chinese opera is being profoundly shaped and reconstructed by platform-driven logic. This study draws upon the perspectives of two influential theorists—Marshall McLuhan’s theory of “the medium is the message” and Stuart Hall’s “encoding/decoding” model—to construct its theoretical framework. These two theories provide a dual lens for understanding the dissemination mechanism of digital opera: one focusing on how technology shapes content structure, and the other on how audiences reconstruct cultural meaning.

McLuhan posits that the form of a medium determines the way content is expressed and perceived. On short video platforms, the stage rhythm and visual style of opera are compressed and fragmented, transformed into fast-paced visual symbols tailored to algorithmic logic. As noted by (Li, 2025a), integrated media communication emphasizes the “deep involvement of technical platforms in content restructuring and rhythm transformation,” which not only alters the logic of opera dissemination but also reshapes its visual style and the audience’s attention patterns. For instance, TikTok’s recommendation algorithm accelerates the operatic stage language, signaling that the visual aesthetics of opera are undergoing re-coding and redesign under the dominance of platform logic.

At the same time, Stuart Hall emphasizes that the meaning within the communication process is not solely determined by the medium itself, but is constantly negotiated and reconstructed by the audience during the act of viewing. Audience interpretation is often shaped by individual media experiences and cultural backgrounds, resulting in diverse—and at times divergent—readings of the same content. This phenomenon of "decoding difference" highlights visual communication as an ongoing cultural practice marked by negotiation and contestation.

In summary, by integrating McLuhan’s media determinism with Hall’s emphasis on audience agency, this study not only investigates how technology restructures traditional art forms but also examines how Gen Z audiences decode and reinterpret operatic visuals within digital environments. This dual-theoretical approach provides a comprehensive framework for analyzing both the technological transformation of cultural forms and the socio-cultural dynamics of meaning-making in the digital age. The research holds significance for several fields. For media and cultural studies, it deepens the understanding of how traditional arts are transformed in the age of digital media. For visual communication, it offers insights into the evolving grammar of cultural expression on algorithm-driven platforms. And for heritage preservation and youth identity studies, it sheds light on how digital re-creations of intangible cultural heritage contribute to the reconfiguration of cultural identity among younger generations.

As traditional visual culture continues to migrate onto digital platforms, the visual language of Chinese opera is being translated and reconstructed under the influence of platform logic, technological intervention, and user participation. Rather than merely describing media transformations, this study focuses on a deeper inquiry: when opera enters the digital context, how is its visual expression reinterpreted, and can it foster new forms of cultural connection and identity resonance?

The core objectives of this study are as follows:

(1)To explore, from a visual perspective, the modes of expression and translation logic of Chinese opera within the digital media environment.

(2)To analyze how Gen Z audiences perceive, interact with, and interpret digital opera content, and how these processes contribute to their sense of cultural belonging.

(3)To reveal how platform-driven visual mechanisms intervene in the dissemination and identity construction of opera, and how they affect audience reception, interpretive depth, and emotional response.

To address these questions, this study will adopt a hybrid ethnographic methodology, combining platform observation, case analysis, in-depth interviews, and rhythmanalysis to carry out a multidimensional exploration and cultural analysis. The

dissertation is divided into five chapters: research background and theoretical foundations, literature review, methodological design, analysis and discussion, and research conclusion. The final section will propose directions for further research.

The literature review is divided into three thematic sections, focusing respectively on aesthetic genes, media translation, and user experience. Due to space constraints, this chapter will concentrate on the first two research sub-objectives: namely, the media adaptability of operatic visual genes and the mechanisms of translating traditional visual styles in digital media.

The third aspect—audience emotional resonance and the construction of cultural identity through digital opera experiences—will not be addressed in this chapter.

Chinese opera, as a comprehensive art form with rich visual characteristics in traditional Chinese culture, has a visual language system (including costumes, face painting, color schemes, stage movements, etc.) that embodies profound cultural symbolism. However, whether this highly codified visual expression is well-suited for communication in the digital media context is a question worth exploring.

First, effectively identifying the visual cultural genes of opera is a fundamental prerequisite for determining whether it can be effectively translated by digital media. The visual genes of opera include not only costume design, facial makeup, and color systems but also spatial rhythm and visual narrative logic. These elements form a unique aesthetic structure and visual grammar, making opera inherently "visual and transmissible." For example, in Henan Opera, its visual language is reflected in the "high-pitched and bright" musical rhythm, combined with highly saturated colors, large movements, and exaggerated costume expressions (Chen and Chonpairot, 2023). At the same time, existing studies generally agree that the visual expression of opera shows significant potential for digital adaptability.

Zhang (2024) states that Henan Opera, through video websites and online games, has expanded its audience boundaries. Its visual characteristics are easily recognizable and transmissible in social media environments. This "visual equals content" mechanism effectively enhances the visibility and interactivity of opera on digital platforms. The contribution of this study lies in its initial exploration of the plasticity and dissemination efficiency of opera’s visual elements within digital media environments. However, it also has limitations. The research primarily focuses on enhancing visibility and expanding dissemination channels, with limited attention to how visual translation might transform opera’s narrative structure, bodily aesthetics, and cultural meanings. As Fan and Zhou (2021) using the example of "#Who says

Peking Opera is not on Tik Tok," reveals that Peking Opera content on short video platforms is often adapted into plot twists or playful mashups to cater to younger audiences' viewing habits. While this trend increases the activity and participation of opera content, it could also lead to the dilution of its core cultural meaning, causing the "visual genes" to gradually lose their original symbolic depth and cultural significance during dissemination.

Moreover, research shows that the effectiveness of visual communication is significantly influenced by the audience's cultural understanding. As pointed out in Chung (2021), the face painting of Cantonese opera's "Jing Jiao" (clean character) is easily misinterpreted as a comical or caricatured image in cross-cultural communication contexts lacking explanatory mechanisms. Audiences without relevant cultural background are unable to grasp the symbolic meaning of its "righteous" and positive character traits. This demonstrates that, even if the visual form has communication advantages, it must rely on appropriate contextual construction and cultural interpretation mechanisms to achieve effective cultural transmission.

Finally, on a technical level, visual adaptability is also influenced by the media tools themselves. Li (2023) argues that immersive media, such as virtual reality, enhances the experience of intangible cultural heritage. However, if the original rhythm and symbolic system are not respected, it may disrupt the narrative logic and aesthetic coherence of opera. This perspective highlights that, on one hand, technological applications should be consciously designed and adjusted in accordance with the narrative rhythm, visual symbolism, and ritualistic nature of traditional opera. On the other hand, the participatory and interactive characteristics of digital environments compel designers to rethink the encoding of traditional aesthetic elements, ensuring that cultural meanings are fully conveyed within the new media context rather than being excessively consumed or distorted.This discussion points to a crucial value orientation for future practices in digital heritage transmission.

In conclusion, the visual genes of opera have strong potential for digital communication due to their vivid, bold, rhythmic, and regional characteristics, making them well-suited for visually dominant media environments. However, this adaptability is not unconditional and still requires the collaborative functioning of platform mechanisms, audience context, and technological logic. While existing research offers a theoretical foundation for understanding the digital potential of opera’s visual language, systematic explanations of visual symbol translatability, cultural interpretation mechanisms, and boundary conditions remain limited. Further theoretical development and empirical studies are needed to deepen insights into opera’s visual translation in digital contexts.

2.2 How Digital Media Reshapes the Visual Style of Chinese Opera: Translation Mechanisms and Technical Paths

This section will further explore how digital media—especially AI, VR/AR, short videos, and others—serve as technological platforms for visual translation, reshaping the aesthetic logic, expressive styles, and audience perception pathways of Chinese opera. The term “visual translation” here refers not only to the transplantation of formal aspects but also to the reorganization and recreation of perception modes, communication rhythms, and cultural symbol systems in the context of new media.

Short video platforms have shifted opera dissemination from a stage-centered to an interface-centered logic. Using Tik Tok as an example, Su (2024) notes that Peking Opera short videos have moved beyond traditional "spectatorial" viewing to create emotional resonance and community through interactive ritual chains. For instance, Peking Opera influencer "Guo Xiaojing" posted a backstage makeup video that generated collective excitement, garnering 170 million views and high engagement across likes, comments, and shares. This case shows how short video platforms reframe Peking Opera’s visual style through de-formalization and everyday presentation, making traditional elements like costumes, makeup, and gestures more relatable to younger audiences.

Su (2024) also highlights The Peony Pavilion, a Kunqu Opera educational game developed with the Unity engine, as a model for interactive dissemination. The game transforms Kunqu’s narrative rhythm into virtual scenes, divided into stages such as "Before the Dream" and "Dreaming," where players complete interactive tasks to advance. This reconfigures opera’s lyrical and symbolic style into modular, task-driven experiences suited for user-led, nonlinear exploration.These cases offer valuable insights: human-machine co-creation is emerging as a new norm; integrating opera and gaming through engines like Unity promotes participatory narrative development; and traditional opera’s interplay of reality and illusion naturally lends itself to virtual migration, and the concept of "multimodal interaction" further supports the visual aesthetic analysis within this research.

Second, AI and virtual simulation technologies reconstruct the path of visual symbol generation. Liu, K., Zhou et al., (2022) points out that digital modeling and 3D visualization allow Yue Opera costumes to move away from physical stages and transform into culturally interactive digital assets. This research examines how 3D virtual simulation technology digitizes Yue Opera costumes and applies opera elements to modern fashion design, promoting the digital preservation and dissemination of traditional culture. These technologies enhance both the flexibility of element dissemination and the preservation and display of costume culture. By extracting elements and extending them into modern design, they build a bridge from "opera visual language" to "modern communication imagery." This supports the study's focus on the deconstruction and regeneration of visual language in digital spaces and offers a case for analyzing the link between "opera styling, modern technology, and emotional identity."

Moreover, visual re-encoding is amplified in more interactive media environments. Wang (2024), analyzing the Nuo Opera App interface design, notes that traditional elements like Nuo masks must reconstruct visual guidance logic to adapt to touchscreen operations and user interaction. This shift from "front-stage aesthetics" to "interface control" alters the rhythm and meaning-generation pathways of traditional opera visuals. However, due to a small sample size and lack of development and user testing, further studies are needed on multi-platform synchronization, content co-creation, and dynamic updates.

In terms of platform logic, Jin and Tan (2023) argue that the "visual tag" mechanism in short video dissemination intensifies the selective use of traditional opera symbols. Fast-paced editing, popular filters, and close-up shots encourage creators to prioritize highly recognizable visuals, such as face-changing performances, grand entrances, and vivid costumes, steering opera aesthetics toward consumer pleasure. While "cultural IP development" targeting young audiences enhances transmissibility, it risks promoting superficiality and weakening symbolic depth. Future research should further explore these mechanisms through user data, dissemination experiments, and platform analysis.

Although current research provides valuable insights into understanding the reconstruction mechanisms of opera visuals in digital media, it still has limitations. First, most studies focus on “how technology presents tradition,” with less exploration on how technology triggers the audience’s re-perception of traditional visuals and emotional shifts. Second, there is a lack of horizontal comparisons between platforms’ visual encoding strategies, and there is little theoretical construction on how technological logic reshapes cultural identity pathways.

In conclusion, digital media technologies are reshaping the visual communication structure of Chinese opera through visual re-encoding, platform rhythm, and user interaction logic. This reconstruction reflects not only technical innovation but also the negotiation of traditional aesthetics under media-driven forces. Further exploration of these translation mechanisms will deepen the understanding of the interaction between visual forms, technological logic, and cultural contexts, providing a stronger framework for digital opera research.

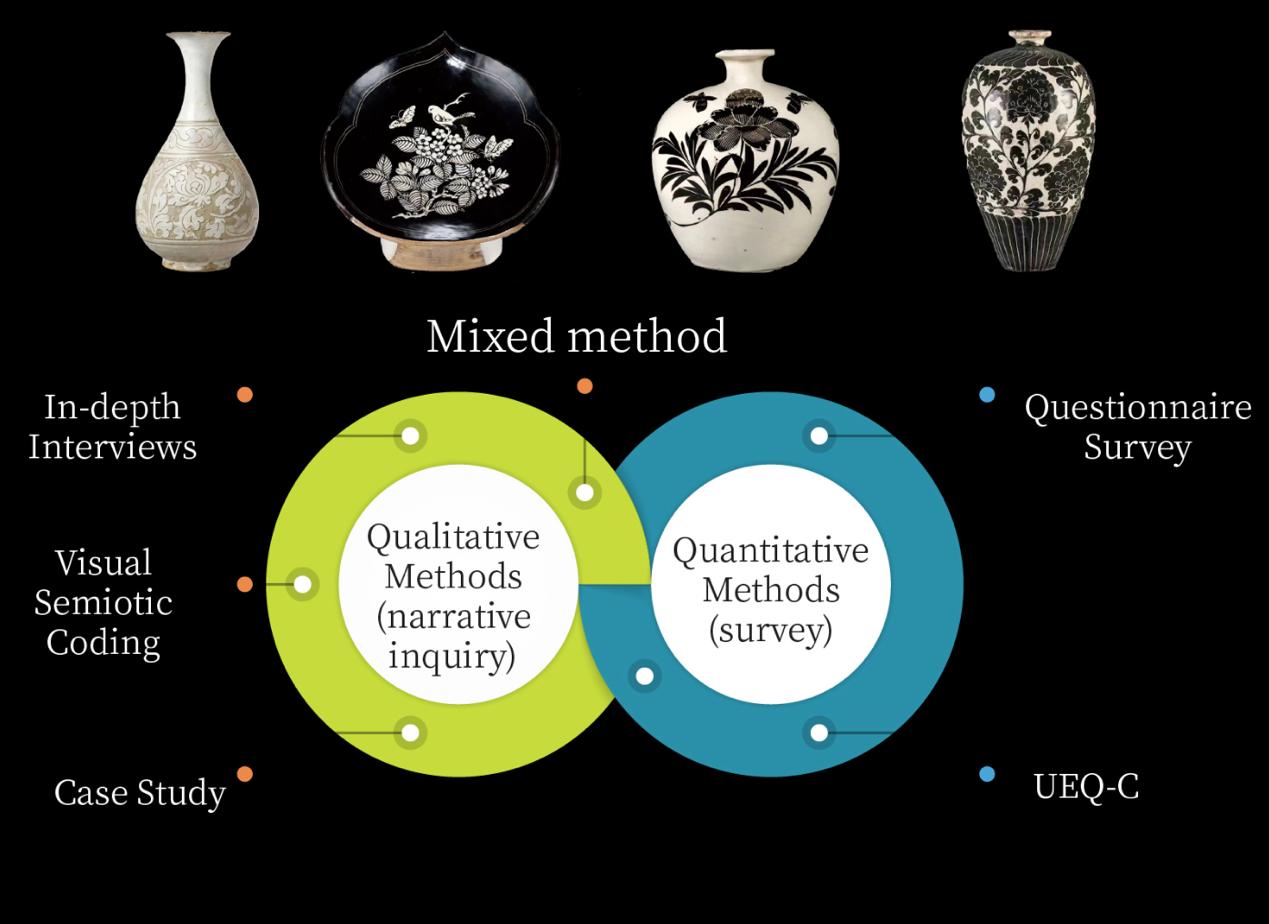

3 Research Methodology: A Mixed Ethnographic Perspective on Digital Opera Visual Research Path

3.1 Research Paradigm and Methodological Framework

Given that the research problem involves the evolution of cultural symbols, the intervention of media technologies, and the complex interplay of audience perception and interaction, this study adopts a qualitative research paradigm to capture the deep dynamics of visual culture in the digital environment.

Qualitative research emphasizes the understanding of “meaning” in social phenomena, focusing on the embedding of context, experience, and cultural environment (Creswell and Poth, 2016). As a highly symbolic art form, Chinese opera’s visual style not only constitutes aesthetic patterns but also carries cultural memory and identity symbols. In the face of the digital media’s reconstruction of visual rhythm and stage logic, a quantitative approach cannot reveal how audiences negotiate the relationship between tradition and modernity, media and culture. Therefore, qualitative research provides a more suitable theoretical and methodological support for understanding how opera visuals are watched, accepted, and reproduced.

For example, current studies on video games and cross-cultural communication mostly employ qualitative research methods, focusing on the subjects of the study and communication strategies.(Zhang et al. , 2024). Within the qualitative framework, the study further selects "Hybrid Ethnography" as the core methodology. This methodology combines the advantages of traditional ethnography and online ethnography, emphasizing that the researcher must span multiple levels, including offline theater and online platforms, visual communication and user behavior, to construct a dynamic understanding (Postill and Pink, 2012).

The suitability of hybrid ethnography for this study is reflected on three levels:

First, the visual expression of digital opera is highly dependent on platforms. Such dynamic and complex participatory behaviors cannot be fully captured through traditional offline observation; instead, they require immersive, long-term observation within real online environments to uncover the logic of digital opera visual dissemination.

Second, the process by which Generation Z constructs cultural identity increasingly relies on social media’s interactive feedback, emotional resonance, and mechanisms of community belonging. Mere textual analysis is insufficient to fully grasp the cognitive patterns and emotional dimensions at play; rather, a combination of online observation, in-depth interviews, and user content analysis is necessary to deeply understand how Gen Z’s experiences and engages with digital opera.

In conclusion, hybrid ethnography not only integrates media research, visual culture, and audience studies but also addresses the core issue of this study: “how digital opera visuals as cultural symbols are recreated, viewed, and recognized.” It provides a highly operable, theoretically and experientially balanced methodological foundation.

3.2.1

This study selects representative digital opera projects as case studies, such as short video projects that use AI to reconstruct opera scenes or immersive opera performances based on VR technology. By collecting the project's visual design,

platform dissemination strategies, user feedback, and technical usage details, the study aims to deeply analyze the translation path of its visual elements. This method is intended to provide a tangible and traceable basis for specific visual reconstruction practices. For example, the VRChat platform is used to simulate the opera world, including creating characters, watching performances, participating in performances, and online teaching (Jiang, Su and Li, 2025). The extended TAM model proposed in the study introduces variables such as "perceived visual design," "entertainment," "innovation," and "self-efficacy" to empirically explain the user acceptance mechanism of opera culture experience in virtual reality. This modeling strategy provides structured support for understanding the psychological mechanisms of cultural resonance and identity formation in Generation Z audiences during digital opera experiences. In combination with the observations and interviews in hybrid ethnography, this study will also attempt to construct a behavioral path framework of "entertainment—immersive experience—cultural attitude—identity intention."

Through semi-structured interviews, the study gathers the cognitive experiences of both audiences and creators regarding digital opera visuals. The interviewees include: (1) Generation Z audiences aged 18-30 (those who have followed or interacted with digital opera content), (2) digital creators (those engaged in creating opera-related videos or remixing them), and (3) relevant scholars and curators (those engaged in traditional art dissemination research). The sample selection follows a "purposeful sampling + snowball recommendation" approach to ensure the representativeness of different user types. At the same time, involving Generation Z, existing studies have pointed out that when interviewing Gen Z users in the context of digital culture, it is essential to consider their unique identity and aesthetic-related sensitivities. This generation engages with digital visual language, such as emojis and stickers, which they utilize as forms of virtual gifts and expressions of affection. Understanding how these visual elements function in their interpersonal relationships can provide insights into their communication styles and identity formation (Liu, 2023). The interview content will focus on visual preferences, cultural impressions, aesthetic conflicts, and a sense of identity, which will then be analyzed through thematic coding and cross-analysis.

The flexibility inherent in semi-structured interviews facilitates a conversational style that encourages participants to express their thoughts and feelings more freely. This method can lead to the emergence of unexpected themes and insights, as seen in research on the experiences of Korean international students, where music was identified as a companion and a safe space, reflecting deeper cultural and emotional connections (Cho, 2024). The research based on the qualitative interview-based conceptual framework, ten semi-structured interviews were conducted using an interview guide of open-ended questions. This approach demonstrates the value of semi-structured interviews in uncovering nuanced emotional and cultural insights.

3.2.3

This study adopts participant observation,online observations cover activities such as live-streamed opera performances, digital exhibitions, and virtual performance platforms, offline observations include traditional theater performances, festive events, and immersive exhibitions related to opera culture.

The observation focuses on two key aspects: first, user viewing behavior (such as posting comments, sending bullet chats, liking, and sharing), in order to assess participation patterns and levels of engagement in digital opera experiences; second, platform-driven guidance mechanisms, analyzing how pop-up prompts, filter effects, and algorithmic recommendations influence the tempo and pathways of opera’s visual dissemination.

For example, some studies used data obtained from video comment sections on the Genshin Impact official YouTube account. First, veteran Genshin Impact enthusiasts and experts selected high-quality videos that con-tained abundant cultural elements from regions worldwide. This categorization aimed to structure the data collection process more effectively. They divided the videos into ’Cul-tural China’,’ World Stories’, and Real-World Stories based on the video content for comment scraping. In order to capture up-to-date audience reactions, approximately 1,000 of the most recent comments were extracted from the comment sections of the selected videos as of May 2023. (Zhang et al., 2024). This process ensured a structured and multilingual dataset for subsequent sentiment and content analysis.

By comprehensively recording and analyzing these elements, this study aims to reconstruct the dynamic processes of digital opera's visual dissemination across multiple interactive environments, thereby providing detailed empirical support for subsequent data analysis and theoretical development.

Using short opera videos as samples, the study will employ visual rhythm analysis methods to identify the frequency of scene transitions, camera movement styles, and color rhythms. Additionally, by combining the intensity of bullet comments, the timing of comments, and viewing durations, the study will analyze how "viewing rhythms" are influenced by platform mechanisms. This method aims to reveal how "algorithmic logic in visual communication" regulates the aesthetic path at the level of rhythm. As Trubnikova and Tsagareyshvili (2021) notes that rhythm reconstruction is a key media mechanism for adapting traditional art to the logic of social platforms.

In conclusion, these four methods collectively form a multi-path analysis framework from "content production—user reception—cultural negotiation." Case studies provide specific visual samples, in-depth interviews delve into subjective cognition,

observations record platform behavior, and rhythm analysis deconstructs dissemination mechanisms. Together, they serve to understand the core issue of "how digital opera visuals are constructed, disseminated, and recognized."

In terms of ethics, this study will adhere to the ethical norms of humanities and social science research, ensuring that all interviewees give informed consent and that their information is anonymized. All materials used will be authorized by the interviewees, and no sensitive personal information will be involved. In online ethnographic operations, only publicly authorized content, such as bullet comments, reviews, and publicly displayed short videos, will be used. All content will be anonymized during use. Platform screenshots and visual content will be used strictly for academic analysis within the non-commercial research scope.

Furthermore, the research boundaries need to be clarified: the study primarily focuses on the Bilibili and Tik Tok platforms and selects digital opera content from 2022 to 2025. The opera types chosen are primarily Peking opera, Yue opera, and Henan opera. Due to time and resource constraints, the study cannot cover all opera genres and all platform content, nor will it conduct cross-language comparisons.

Regarding methodological reflection, although the hybrid ethnography framework is comprehensive, it may still face challenges such as delayed observations due to the rapid changes in platform cultures and interpretive biases caused by user anonymity. Compared to quantitative research, this study emphasizes subjective experience and cultural identity, but there are limitations in sample breadth and result generalizability. The study did not employ large-scale surveys or content scraping techniques, as these were judged to be less aligned with the research question and resource limitations. If more samples and platform cooperation resources become available in the future, a mixed-methods approach incorporating quantitative components could further enhance the study’s breadth and data support.

This section aims to analyze the suitability of the chosen research methods in addressing the research questions, and, combined with initial observations and analyses, outlines possible directions for the research findings.

As the methodological foundation of this study, mixed ethnography offers the advantage of integrating user behavior, visual communication patterns, and cultural identity construction on digital platforms into an observational system that spans across fields and media. Li, (2025b)pointed out in his analysis of "Dream of the Sanxingdui" that contemporary intangible cultural heritage (ICH) dissemination has formed a nested mechanism of “platform behavior—visual narrative—audience

interaction,” requiring multi-method cross-observation to capture its real dynamics. This study combines case studies, online ethnography, observation methods, and rhythm analysis, mirroring this complex structure of multi-level interaction.

In practice, case studies help identify the mechanisms behind the visual style of digital opera, especially in short videos and virtual performances. These include how elements like color, composition, and dynamic rhythm translate traditional stage visuals. How high-frequency visual elements (e.g., "appearance," "face-changing," and "virtual costume redesign") gain more visibility through platform algorithm recommendations, or how platform technologies affect traditional visual communication, can also be explored.

At the same time, the collaborative use of online ethnography and observation methods reveals the participation paths of Generation Z viewers in digital opera. From bullet screen interactions and comments to secondary creative videos' visual choices, users are no longer mere "receivers" but important participants in reconstructing the cultural meaning of opera at a visual level. While studies on digital media and traditional culture have explored various technical paths of visual re-creation, most still lack attention to how users engage with these visual transformations. For instance, existing research on Genshin Impact and cultural communication tends to emphasize the dissemination of traditional Chinese culture within China and on the global stage.. Studies focusing on the case of Genshin Impact offer valuable perspectives on advancing international collaboration in the gaming sector, innovating China's cultural tourism models, and fostering sustainable development. However few studies have investigated cultural interaction in the cross-cultural communication of video games through direct access to authentic and objective audience data (Zhang et al. , 2024).

This gap similarly applies to the study of digital opera, where user engagement with reimagined visual elements remains underexplored.As Li, (2025b) noted, in digital contexts, "likes, shares, and the imitation of visual symbols" themselves have become a new rhythm of cultural consumption . This behavior model provides a basis for studying the generation mechanisms of digital visual identity.

The combination of in-depth interviews and rhythm analysis also strengthens the logical connection between "watching—perception—identity." For example, Liu, Z., Yan, et al., (2022) found in their research on the VR dissemination of "Hua’er" that visually intense rhythmic performances are more likely to evoke users' cultural connections . In the pre-observation phase of this study, users in the comments section mentioned that short video opera clips with fast rhythms and vibrant colors were "impressive" and "felt more like a visual game." These feedbacks will help further understand the relationship between visual translation and aesthetic reception.

In summary, the methodological approach adopted in this study provides an effective observational channel for exploring the visual evolution and audience identity paths

of digital opera under platform mechanisms. This section also lays the foundation for more systematic theoretical analysis in the following chapters.

4.2 Preliminary

First, from the perspective of media ecology theory (McLuhan, 1964), media itself is not merely a tool for transmitting information; it profoundly shapes the structure of content and how it is received. In the dissemination of digital opera, the platform's content logic, interface structure, and interactive rhythm determine how opera visuals are translated and reproduced. For example, the content algorithms of platforms like TikTok and Bilibili tend to reinforce rhythm and high-visibility symbols (e.g., masks, climactic singing sections), fundamentally reshaping the traditional "slow rhythm, delayed development" of opera's visual aesthetics.

Secondly, from the perspective of "embodiment" and "embodied cognition" theory, Generation Z viewers' behavior in watching opera is no longer a passive act of "viewing," but an active engagement through sensory perception, emotional participation, and interactive rhythms embedded in digital experiences(Song, 2023). In their study of the intangible cultural heritage project "Hua’er," Liu, Z., Yan, et al., (2022) noted that when digital visual narratives connect with users' bodily experiences, they transform viewers from "observers" to "immersed participants," thus stimulating a higher level of cultural identity. Research shows that immersive experiences, interactive rhythms, and interface designs can trigger users' "cultural bodily memories," and this experiential structure is one of the potential paths for digital opera to achieve recognition.

Additionally, Midyanti and Sukmayadi (2021) pointed out in their discussion on the fusion of local wisdom and digital art that digital platforms are not "alternative spaces" to traditional culture but rather a "crossroads" that fosters cultural regeneration. They noted that in digital performing arts, "local knowledge is re-encoded and participatively re-presented through media, becoming a shared space for viewers to co-create and imagine". This closely aligns with what this study has observed in terms of secondary creations, comment interactions, and rhythmic resonance.

In conclusion, the theoretical framework used in this study emphasizes that media not only reconstructs the visual structure of opera but also intervenes in the process of users' perception and identity formation.

4.3

The study faces several limitations. First, the sample size is constrained by the platform's data transparency and resource limitations, and the representativeness of online ethnography and observation methods is limited. Second, the interview sample did not fully cover the internal differences within Generation Z, which may affect the overall judgment of the mechanisms of cultural identity formation.

Moreover, the theoretical support remains somewhat weak. Although this study focuses on media ecology and cultural participation, it does not delve deeply into macro-critical perspectives such as platform governance and algorithm structures. Subsequent research could expand to include more platforms, comparing their differences in visual representation and user participation mechanisms. It could also explore emerging trends such as AI-generated and virtual opera idols, examining how they align with youth cultural consumption habits.

In conclusion, the methods used in this study show practical value in understanding visual translation and audience interaction, but there is still room for improvement in sample coverage and theoretical depth. Through further platform expansion and theoretical enhancement, the breadth and depth of digital opera research can be enriched.

Conclusion

This study focuses on how digital media technologies reconstruct the visual language of traditional Chinese opera and further explores the emotional resonance and cultural identity paths of Generation Z viewers in digital viewing contexts. Through the mixed ethnography framework, the study integrates platform visual samples, user behavior observations, in-depth interviews, and rhythm analysis, unveiling the mechanism of traditional visual aesthetics' reinvention in the digital environment from the logic of "media technology—visual translation—identity generation."

The study indicates that the visual expression of opera shows significant adaptability when facing short videos, AI, VR, and other media. Traditional opera is shifting from stage space to platform space, from continuous narratives to fragmented, fast-paced, and symbolic visual reorganization. However, it also faces challenges such as the weakening of cultural context. Meanwhile, the study preliminarily finds that this visual translation not only changes the way opera is expressed but also stimulates Generation Z’s new understanding and resonance of traditional culture through interactive behaviors, rhythmic perception, and viewing participation.

This study not only addresses the practical issues of ICH dissemination in the context of media transformation but also provides an interdisciplinary paradigm for research on digital visual culture, platform mechanisms, and youth identity, expanding the possibilities for the dissemination and regeneration of traditional art in the digital age.

References

Chen, L. and Chonpairot, J., 2023. ‘The impact of Henan opera aesthetics characteristics upon the Henan people’. Journal of Roi Kaensarn Academi, 8(2), pp.450–460.

Chung, F.M.Y., 2021. ‘Translating culture-bound elements: A case study of traditional Chinese theatre in the socio-cultural context of Hong Kong’. Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 14(3), pp.393–415.

Creswell, J.W. and Poth, C.N., 2016. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage Publications.

Cho, H., 2024. ‘"I feel safe when I listen to Korean music!": Musical engagement and subjective well-being amongst Korean international students in the UK’. Journal of International Students, 14(4), pp.760–780.

Edström, E. (2018) ‘Moving forward: An essay on how to contemporize the traditional Chinese theater without severing the tradition’, Critical Stages, [online]. Available at: https://www.critical-stages.org/18/moving-forward/ [Accessed 4 May 2025].

Fan, H. and Zhou, X., 2021. ‘Content innovation and optimization strategies for short video communication of traditional Chinese culture: A case study of “#Who says Peking Opera isn’t on Tik Tok”’. Publishing Horizon, 11, pp.67–71. (in Chinese)

He, Y., 2023. Research on the integration of Chinese traditional cultural elements in the video game industry [Master’s thesis]. Central South University. (in Chinese)

Jiang, Y.P., Su, C. and Li, X.C., 2025. ‘Virtual reality technology for the digital dissemination of traditional Chinese opera culture’. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 41(4), pp.2600–2614.

Jin, J. and Tan, L., n.d. ‘Research on the dissemination strategies of Sichuan-Chongqing folk culture from the perspective of new media’. Unpublished manuscript / publication info unavailable

Li, H., 2025a. ‘Research on the dissemination of traditional opera art in the era of integrated media. Jingu Cultural and Creative’. Jin Gu Wen Chuang, (04), pp.90–92. (in Chinese)

Li, H., 2025b. ‘Characteristics, problems, and development paths of opera art transmission empowered by digital technology’. New Chu Culture, (04), pp.48–51. (in Chinese)

Li, Q., 2023. ‘Research on virtual reality design in the inheritance of intangible cultural heritage’. Art Edition of Packaging Engineering, 44(18), pp.337–340. (in Chinese)

Liu, K., Zhou, S., Zhu, C. and Lü, Z., 2022. ‘Virtual simulation of Yue Opera costumes and fashion design based on Yue Opera elements’. Fashion and Textiles, 9(1), p.31.

Liu, R., 2023. ‘WeChat online visual language among Chinese Gen Z: virtual gift, aesthetic identity, and affection language’. Frontiers in Communication, 8, p.1172115.

Liu, Z., Yan, S., Lu, Y. and Zhao, Y. (2022, April) ‘Generating embodied storytelling and interactive experience of China Intangible Cultural Heritage “Hua’er” in virtual reality’. In: CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems Extended Abstracts, pp. 1–7.

Midyanti, H.I. and Sukmayadi, Y., 2021. ‘The intersection of local wisdom and digital innovation in performing arts’. Interlude: Indonesian Journal of Music Research, Development, and Technology, 1(1), pp.43–60.

Postill, J. and Pink, S., 2012. ‘Social media ethnography: The digital researcher in a messy web’. Media International Australia, 145(1), pp.123–134.

Song, N., 2023. Embodied presence in creation: A study of digital interactive performance art [PhD thesis]. Nanjing University of the Arts. (in Chinese)

Su, M., 2024.’ Interactive rituals and digital empowerment of Peking Opera videos on social media’. Film Review, (21), pp.41–45. (in Chinese)

Trubnikova, N. and Tsagareyshvili, S., 2021. ‘Digital challenges for creative industries: Case of opera’. In SHS Web of Conferences (Vol. 114, p. 01008). EDP Sciences.

Wang, X., 2024. ‘Interface interaction design of Nuo Opera mobile apps under the background of new media’. Research on Printing and Digital Media Technology, (S1), pp.1–6+17. (in Chinese)

Wang, Y., 2022. ‘A study of strategies for high-quality communication of opera culture in the context of media integration: On the networked survival of opera culture’. Development, 4(2), pp.35–41.

Zhang, D., 2024. ‘Exploration of digital dissemination paths of Yu Opera in the context of new media’. Jiaying Literature, (24), pp.112–114. (in Chinese)

Zheng, C., 2010. ‘Regionality, locality and folkness: On the characteristics and future trends of regional opera’. Journal of Hubei University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), 37(06), pp.1–6. (in Chinese)

Zhang, B., Zhou, M. and Pu, C., 2024. ‘The ninth art, tells the story of cultural China and the world: Cultural interaction in cross-cultural video game communication—based on ‘Genshin Impact’ YouTube comments’. PloS one, 19(10), p.e0311317.

Meixin Tian

Research Questions

1. How are Chinese landscape paintings displayed and viewed in museums?

2. How does the aesthetic reception of Chinese landscape paintings differ across cultural contexts?

3. How are the artistic conceptions of Chinese landscape paintings displayed and interpreted?

Research Objectives

This study first analyses and compares the display methods and audience reception of Chinese landscape paintings in museums in China and the UK. It explores how the artistic conception of Chinese landscape painting is conveyed and presented within

public museum spaces. By collecting audience feedback on their viewing motivations and aesthetic experiences, combined with an analysis of display methods, this study identifies the cultural meanings, limitations, and challenges in the cross-cultural presentation and reception of Chinese landscape painting. Further, it highlights the potential and value of multimedia-based display approaches. Finally, it integrates personal creative practice to explore the feasibility of using digital technologies to enhance the dissemination and understanding of Chinese landscape painting.

Abstract

This research focuses on the aesthetic reception of Chinese landscape painting within museum contexts, particularly examining the differences in exhibition practices and audience interpretation between Chinese and British cultural settings. Since the 19th century, when Chinese landscape painting first entered Western museums, its display has long been dominated by Western visual logic, neglecting the native aesthetic mechanisms and spiritual essence inherent to its art form. Today, the exhibition of Chinese landscape painting remains influenced by Western display practices, drifting away from traditional aesthetic experiences. To investigate this, the study adopts an interdisciplinary approach combining archive analysis, case studies, and audience research. The archive analysis provides historical and theoretical foundations, case studies reveal how exhibition methods affect the transmission of artistic conception, and audience research supplies empirical feedback on reception. Drawing on a phenomenological perspective, the research emphasizes the importance of subjective audience experience. Personal artistic practice introduces digital technology into landscape painting exhibitions, exploring immersive and interactive formats. This study enriches cross-cultural discussions within the museum and art dissemination fields and proposes innovative strategies for the contemporary expression of Chinese traditional art.

This research focuses on the phenomenon of the aesthetic reception of Chinese

landscape paintings in museums. It is divided into four parts. First, it traces the collection history of Chinese landscape paintings in British museums and examines how they have been displayed in both Chinese and Western museums, along with the underlying aesthetic logics. The literature review then summarises key studies on Chinese painting viewing practices in China and the West, identifying research questions. Following this, the methodology section describes the case study approach and analyses the researcher's connection to the study from an ontological perspective. Finally, the discussion explores how the findings inform both academic practice and personal artistic creation. This research defines Chinese landscape paintings

Like Yang (2023, 348) defines, Chinese artists refer to traditional landscape paintings as ‘mountain and water’ paintings. Mountains and water are conceived as partners rather than objects, with the two components representing the two immanent polarities of Tao. The Chinese landscape paintings in this research refer to the landscape painting drawing by the traditional Chinese ink materials and the Chinese philosophical mindset.

The collection of Chinese paintings, especially Chinese landscape paintings, by public institutions such as British folk and museums can be traced back to the Victorian period in the 19th century. Today, British public institutions such as the British Museum and the V&A Museum still retain a large number of precious collections of Chinese landscape paintings, but the extent of their research and display is far from truly reflecting their value. The British Museum holds 1,138 Chinese landscape paintings from the Ming and Qing Dynasties, but currently, less than 10 of them are on display (British Museum, 2025). On the other hand, according to the doctoral research of Huang (2010, p11), a scholar from the University of St Andrews, on the collection history of Chinese paintings in the UK, the lack of professional training in collection institutions and individuals, as well as the motivation to collect as postcard souvenirs, have led to the failure to truly understand and recognize the collection history of Chinese paintings in the UK.

Huang (2010) points out that since the 19th century, Chinese painting gradually entered museums in the UK, but it was not truly understood or fairly appreciated at first. In the early days, a large number of Chinese paintings entered Britain as "export paintings". Most of these works were created to cater to Western tastes, depicting customs, clothing,

etc., and were regarded as ethnographic materials rather than artistic treasures. They lack the presentation of the inherent aesthetic traditions of Chinese painting, resulting in the British public's one-sided and superficial understanding of Chinese art. It was not until the early 20th century that Laurence Binyon's efforts promoted a deeper understanding of traditional Chinese painting in Britain. During his career at the British Museum, he actively purchased Chinese paintings, such as those from the Stein collection (1909) and the Wegener Collection (1910), and popularised knowledge of Eastern paintings through numerous publications and lectures. However, Bin Yang and his colleagues were also deeply influenced by Japanese art and Western aesthetics, which often led them to be biased in their judgments of Chinese painting. Overall, Huang (2010) 's research concludes that Chinese painting has long been viewed from the perspective of the "Eastern Other" in the UK. The ethnographic function in the 19th century, the Oriental fantasy in the early 20th century, and the "alternative modernity" in modern art exhibitions all demonstrate their externalities and one-sidedness in aesthetic evaluation and historical positioning. This reveals the historical background in which Chinese paintings were misunderstood in the Western context.

In the contemporary exhibition context, the differences in the viewing of Chinese paintings between China and the West still exist. The viewing differences of Chinese painting from the perspectives of China and the West stem from the different understandings of visual and spiritual experiences by the two cultures. Cao and Yu (2005, p.91) pointed out that Chinese painting emphasises the viewing methods of "wandering the eyes", "careful appreciation" and "privacy", and its scattered perspective and spiritual composition pursue an immersive experience of the viewer's soul. In contrast, Western painting focuses on focal perspective and spatial restoration, emphasising the objectivity of vision and physical presentation. Therefore, its way of viewing is more inclined towards collectivisation and externalisation.

This difference has caused misinterpretation in the contemporary exhibition system. Tang (2012, p. 13) criticises the display method of simply hanging Chinese paintings in Western art galleries, which undermines their original privacy and spiritual viewing mechanism. Chen (2012, p. 8, p. 21) points out from the perspective of architectural design that the spatial logic of modern art galleries is incompatible with the "view" of

Chinese painting, and the traditional artistic experience has been weakened. The "Westernisation" of this display method not only obscures the original aesthetic connotation of Chinese painting but also weakens its dissemination power and cultural value in the contemporary context.

Therefore, it is important to study the display and viewing of Chinese paintings. As Li Geye (2021, p. 105) points out, the interaction between the exhibition space and the works determines the way the audience accepts and the aesthetic effect. This research not only contributes to the contemporary expression of Chinese painting, but also responds to the development issues of the discipline of Chinese painting itself, reminding the audience to think about the contemporary significance and identity of Chinese painting, as well as what it means for different audience groups.

Figure 1: Chinese landscape paintings in the British Museum. Picture from the author,14,03 2025.

In this study, the literature is mainly divided into three categories: the collection history of Chinese landscape paintings in the UK, the display and viewing of Chinese landscape paintings in the UK, and the display and viewing of Chinese landscape paintings in China. I particularly paid attention to the research gap between Chinese and English literature. For this research, the above-mentioned literature is the channel through

which I understand and approach the phenomenon of the display and cognition of Chinese paintings. They provide the research background and historical experience. However, as Hall (2001, p. 89) said, archives are not created out of thin air. Each archive has a pre-history, which originated from the context at that time. Therefore, in my research, I will critically compare how the research subject (Chinese landscape painting) is recognised in Chinese studies and Western studies, and what the differences are in their presentation methods, as well as what historical background and context these differences stem from.

In the first part about the collection history of Chinese landscape paintings in the UK, I mainly referred to Huang’s research. His doctoral dissertation focused on the formation period of the British Museum's collection of Chinese paintings from 1880 to 1920, which was the peak of collecting Chinese artworks. It involves extensive and complex relationships between China and the UK, public museums and private collectors, as well as the collection, display and interpretation of Chinese paintings. Huang (2010) 's research reveals the historical processes, such as the reasons, motivations and changes in collecting interests of Chinese paintings by British public institutions and private collectors, especially the mutual influence with the contemporary Japanese art trend. He pointed out that the collection and research of Chinese paintings in the UK have not been analysed in depth (Huang, 2010, p9). These contents provide a historical background for my research, enabling me to compare the role changes and cultural identities of Chinese paintings in the Western public sphere. Not only in the 19th century, but his research also extended to the attention and collection of modern Chinese paintings in British museums from the mid-20th century to the present. Taking the British Museum and the Ashmolean Museum as examples, he explored the vision and strategies of British museums in forming modern Chinese painting collections in the second half of the 20th century. It focuses on the history of the institutions, acquisition policies, and the collections of Chinese painting art in these two museums (Huang, 2020). Although his research did not directly discuss the relationship between the works and the exhibition space, it provided a new perspective for my research, offering references in terms of the sources of the collections and acquisition strategies. This also reflects the aesthetic changes in the West towards Chinese paintings.

Next, I will analyse the differences in the viewing and understanding of Chinese paintings from the perspectives of China and the West based on the theories of scholars Wu Hong and Clunas on the viewing of Chinese paintings. Wu Hong and Clunas are respectively representative scholars in the fields of Chinese and English for the study of traditional Chinese art. Their theories both start from their own cultural and educational systems to understand Chinese art. Wu Hong (1996) accurately summarised the viewing mechanism of Chinese painting, especially landscape painting, including the changes in viewing perspectives and contemporary viewing contexts. This perspective embodies the aesthetic requirements of traditional Chinese painting. In contrast, Clunas (2017) focused on the relationship between Chinese painting and audiences of different identities. He analysed the differences in the perception of Chinese paintings between Chinese and Western audiences, as well as how the concept of Chinese paintings was formed and evolved during the viewing process. Therefore, the traditional perspective of Chinese painting adopted by Wu Hong and the perspective of Western art historians represented by Clunas can infer the reasons for the cognitive differences of Chinese painting in the local and cross-cultural contexts from the levels of aesthetics and art history.

Finally, I will focus on the display research of Chinese paintings in the academic circles of both Chinese and English. As the birthplace of Chinese painting, the Chinese academic circle has rich experience in the research of Chinese painting. However, compared with the research on Chinese paintings themselves, the research on the display and viewing of Chinese paintings in the contemporary context started relatively late, but it has shown an upward trend in recent years. As Li (2021, p.104) pointed out, the display of Chinese paintings in the public domain is related to the development of Chinese museums since the 1990s. The research on the display and viewing of Chinese paintings in the Chinese academic circle began with Professor Li (1989) of Tsinghua University's reflection on the insufficient representativeness of Chinese paintings in contemporary exhibitions at the 7th National Art Exhibition. Taking this exhibition as an opportunity, he keenly perceived the development crisis of Chinese painting in the exhibition under the influence of Western modernism and other trends, as well as the

problem of insufficient representation in the exhibition. He pointed out that as a cultural representative with a history of several thousand years, the discipline of Chinese painting itself and its development limitations in exhibitions also echoed the thoughts of the Chinese art circle on the transformation of Chinese painting at that time (Li, 1989, p. 4). Although the author did not directly analyse the specific display methods of Chinese painting, he directly pointed out the challenges that Chinese painting faces in contemporary public space exhibitions compared with other art media, inspiring the audience to think about the disciplinary significance of Chinese painting and the role it plays in contemporary public Spaces.

In the past two decades, this topic has been highly focused by scholars from multiple fields such as aesthetics, architectural design, and computer science. Cao and Yu (2005), scholars from the field of aesthetics, paid attention to the viewing differences between Chinese paintings and Western paintings relatively early. They summarised three typical ways of viewing Chinese paintings by combining ancient Chinese painting theories, including moving viewing, experiencing the details of the picture and the requirement for private viewing. During the same period, the interactive works designed by scholars Shen, Yang and Xiao (2009) from the field of computer science at Shanghai Jiao Tong University provided a precedent for the multimedia display of Chinese paintings and played a pioneering role. They combine Chinese landscape paintings with Musical Instruments. Viewers can interact with the Chinese landscape paintings on the screen and create content by manipulating the guqin. This way of combining music and paintings ingeniously integrates two representative Chinese cultures. It not only enhances the visiting experience of the audience, creating an immersive visiting experience that encompasses both vision and hearing, but also expands the cultural connotation and exhibition methods of Chinese paintings, strengthening their cultural appeal. In the past decade, the research on the display of Chinese paintings has expanded to fields such as architectural design and literature. For instance, Chen (2012), a scholar from the Department of Architecture of Tsinghua University, took the design project of Yongchuan Art Museum in Chongqing as a case to analyse the limitations of the exhibition of Chinese paintings in contemporary architectural Spaces. He first pointed out that Chinese painting, as a type of painting with a unique appreciation paradigm, has obvious differences from the modern art museum display system originated in the West (2012, p. 8). From the perspective of

architecture, he summarised the entertainment-oriented and complex tendencies of exhibition Spaces such as contemporary art galleries, which also led to the conceptualisation and flattening of the exhibits there, and the stripping of their own aesthetic characteristics. Meanwhile, he also analysed the unique aesthetic characteristics of different forms of Chinese paintings and sorted out the ideal display space for Chinese paintings. In the project of Yongchuan Art Museum, he specially designed the external form, internal space and open space of the art museum building based on this aesthetic ideal of Chinese painting. The research project of Chen (2012) provides a relatively comprehensive case of the display space of Chinese paintings, expands the viewing perspective of Chinese paintings from the limited indoor space to the museum architectural space itself, puts forward more precise design requirements, and also provides a reference for the display form of Chinese paintings in contemporary public Spaces. Furthermore, Liu from Shanghai University (2020) noticed the differences in the philosophical logic of the viewing methods of Chinese paintings by Chinese and Western theorists, providing a theoretical reference for understanding the aesthetic acceptance of Chinese paintings by Chinese and Western audiences. These documents are based on the local display context of Chinese paintings and have a relatively accurate observation of their display status.

On the other hand, the research on the display of Chinese paintings in the English academic circle is insufficient. The research on the display and viewing of Chinese paintings in the English academic circle started relatively late. It has only received certain attention in the past five years, mainly focusing on digital display. The current research is still led by Chinese scholars and developed based on domestic research cases in China. Compared with the research of Chinese scholars, the research on the display of Chinese paintings in the Western academic circle is incomplete, insufficient, and even periodized. On the one hand, it is because the aesthetic characteristics of Chinese painting are quite different from those of Western painting. On the other hand, it is also because of the unreasonable and monotonous display that this ancient art medium has not been fully understood by Western audiences and scholars, which has led to its underestimation. It is worth studying how Western audiences perceive this Eastern art medium and whether this perception is different from that of the 19th century. It can reflect the status and cognitive changes of the Chinese cultural image in the West.

The research in English focuses on the exploration of virtual reality (VR) technology

in the display, education and dissemination of traditional Chinese paintings. Ma et al. (2012) were the first to propose combining audio, 3D modelling and high-resolution images to achieve an immersive exhibition experience of long scrolls such as "Along the River During the Qingming Festival", laying a multimodal interaction foundation for subsequent research. Jin et al. (2020, 2022) further digitised and reconstructed Chinese paintings such as "Spring Dawn in the Han Palace" in a VR environment. Through empirical research, they demonstrated that immersive learning can significantly enhance learning motivation and cultural understanding, especially outperforming traditional touchscreen systems in terms of detailed memory and spatial cognition. Mu et al. (2024) emphasised the crucial role of episodic narrative in cultural accessibility and emotional resonance through the VR reconstruction of the murals in Cave 61 of Dunhuang. In terms of artistic expression, Cheng et al. (2023) focused on the three-dimensional translation of Chinese painting lines in VR, exploring the contemporary expression of traditional line drawing through the composition of spatial layers and 3D models. Li (2020) and Liu et al. (2024) approached from the perspectives of thematic creation and colour perception to discuss the possibility of combining VR painting with Serious games, emphasising that the unity of technical beauty and cultural spirit should be taken into account in artistic creation.

Overall, scholars unanimously agree that VR can effectively enhance the display and learning experience of Chinese paintings, but they also point out that there is still room for in-depth optimisation in aspects such as narrative structure, style restoration, and interactive design at present. Future research should further promote the development of personalisation, collaboration and multimodal interaction to achieve the true reconstruction and cultural inheritance of traditional art in the virtual space. Through the comparison of research in the Chinese and English academic circles, it can be seen that there are limitations in the display of Chinese paintings in different contexts, as well as the huge potential of digital technology in enhancing the viewing and aesthetic acceptance experience of Chinese paintings. My research will delve into this field and offer my own artistic creations to provide new references for the display of Chinese paintings.

Methodology

In this section, I will explain the relationship between my background and this research from the perspectives of ontology and autobiographical ethnography, as well as how this research question was discovered. As Mao et al (2024) summarised, the help of autobiographical ethnography to art studies lies in providing a creative or research method that combines subjective experience with critical analysis, which is particularly suitable for exploring identity, power relations and social issues in art practice. My artistic creations, personal diaries and previous research results on Chinese landscape paintings, etc., constitute the sources of literature for my autobiographical ethnography. Reference materials of such personal experiences will also be collected from the interviewees as a source of information reflecting the visiting experience of the audience.

First of all, my artistic creation experience is closely related to Chinese landscape painting. Since I started learning Chinese painting in Hangzhou in 2018, I have accumulated seven years of creative experience. When I was sketching in Zhejiang Province, which is the birthplace of the renowned Wu School of Painting, I was deeply attracted by the profound heritage of Chinese landscape painting. Through the study of Chinese painting theory, I have realised that Chinese landscape painting pursues spiritual freedom, bringing a sense of inner belonging and aesthetic experience at the spiritual level to both the audience and the author. As Cao and Yu summarised (2005, p. 91), the purpose of Chinese painting is by no means the art form itself, but rather to achieve the artist's exploration of the deep meaning and the pursuit of the infinite symbolic meaning in spirit through it. Therefore, Chinese landscape painting has become a way for me to express my spiritual pursuit, and this spiritually oriented medium is in line with traditional Chinese philosophical thought.

On the other hand, as an art teacher, I have deepened my understanding of Chinese landscape painting in my teaching and creative practice and gained new insights into its display methods. As Li and Bhattarai (2025, p. 91) pointed out in their research on autobiographical ethnographies and art education, art education encourages scholars to know themselves in different ways. During the teaching process in the museum, I found that the display context of Chinese paintings is vastly different from the traditional way of viewing. Chinese painting, as a genre of painting with extremely strong privacy and individuality, has always been displayed in private Spaces such as study rooms in China,

requiring individuals to touch and manipulate the artworks. This also contradicts the public nature of modern art museums (Chen, 2012, p. 14). In most contemporary exhibition Spaces, Chinese paintings are not specially placed according to their materials and framing forms, which gives the audience, especially students who are not familiar with Chinese paintings, an illusion that this medium is equated with other Western paintings on display. Especially after coming to the UK, I found that this kind of exhibition practice deepened the stereotypical impression of Chinese art and hindered the audience's objective understanding and recognition of Chinese paintings in a cross-cultural context. Therefore, my experiences in artistic creation, teaching and museum visits have generated a sense of responsibility for promoting Chinese art, inspiring me to study how Chinese painting can be presented and understood more effectively in the contemporary cross-cultural context.

My research will adopt interdisciplinary research methods. While addressing the issue of insufficient display and acceptance of Chinese landscape paintings, guided by the

research conclusions, I will apply multimedia digital technology to my doctoral creation, opening up new paths and experiences for the digital display of Chinese landscape paintings. My research design refers to the phenomenological method to analyse the aesthetic acceptance phenomenon of Chinese landscape paintings in specific public Spaces from the perspectives of museums, the works themselves, and the audience.

First of all, I will adopt the archive analysis method to sort out the display and viewing situation of Chinese landscape paintings in museums. As Hall (2001, p. 92) said, archives are not inert historical collections; they are in an active and continuous conversational relationship when questioning the past. This highlights the research value of the exhibition records in the contemporary context, providing a critical perspective for reflecting on the past and the present. By analysing the exhibition records, exhibition reviews and related records of the British Museum, the National Museum of China and the Shanghai Museum, it helps me position the research cases and understand the display characteristics of Chinese landscape paintings in different public Spaces as a whole. Thus, I can compare and restore the exhibition practices of the past and the present and find out the differences in their display and aesthetic acceptance. This method is widely used in the fields of Chinese painting and museum research. For example, Huang (2010) adopted the method combining historical documents and cross-cultural research, and reconstructed the acceptance process of Chinese paintings in the UK from the 19th to the 20th century through museum archives, letters and exhibition records. Li (2020) sorted out the entry points of Chinese painting creation and VR painting technology, the development process of VR painting technology, as well as the possibility and necessity of its development through literature analysis.

After identifying representative exhibition cases through literature analysis, I will adopt the method of case analysis to explain how the artistic conception of Chinese landscape paintings is displayed and interpreted by museums from both the aspects of Chinese landscape paintings themselves and the curatorial practice of museums and evaluate the effectiveness of this practice in combination with the following audience interviews. In addition to the exhibition cases in the literature, I will also analyse the exhibition practices of Chinese landscape paintings in the contemporary British Museum and museums in China. Case studies are widely applied in museum research and are typically used to conduct critical evaluations of specific cultural phenomena. For

instance, Huang (2010) transformed the aesthetic conception of Chinese landscape paintings into visual and cultural narratives through the interpretation of British museum exhibitions and curators. Cao and Yu (2005) combined traditional works such as "Along the River During the Qingming Festival" to analyse the conflicts between ancient viewing methods and modern exhibition models, thereby constructing three representative viewing paradigms of Chinese paintings. These case analyses highlight their value in revealing real problems and exploring solutions.

Finally, I will collect the visiting experiences of Chinese landscape paintings from the audience through questionnaires and interviews in the museum, and compare them with the above research results to verify the effectiveness of the display of these works. For instance, whether its explanation is clear, whether the meaning of the work is definite, and whether the display of the work is reasonable, etc.