OCTOBER

01 02 03 05 04

A dialogue between Iris Van Herpen and Etienne Jules Marey

From Gabriella Boyd to Frank Bowling, new acquisitions of Tia Collection

A BLINK OF AN EYE TIA COLLECTION COLLECTS THE 9-5 WITH CLARE WOODS

An intimate day at the studio

COLLECTION LENDING PROGRAM

InaBlinkofanEye

The pursuit of capturing speed, moments, and time has long preoccupied artists and scientists alike Across centuries, the question of how to visualize movement, to make the invisible visible, has produced innovations that extend beyond their fields, reshaping art, culture, and technology Étienne-Jules Marey, the French physiologist who developed chronophotography in the late nineteenth century, and Iris van Herpen, the Dutch couturier renowned for her experimental garments, stand generations apart yet united by a shared ambition: to translate the fleeting essence of motion into lasting form

Marey (1830–1904) was a pioneer of visual technology. Initially trained as a physiologist, his fascination with locomotion led him to devise an inventive photographic apparatus that could break down the mechanics of movement His multi-exposure photographs of horses, birds, and bulls revealed successive phases of motion layered within a single frame. These ghostly images resembled x-rays of time: fragmented yet continuous, exposing rhythms of motion the naked eye could not perceive Marey’s Cheval Blanc, a study of a white horse in motion, shows the animal as more than a galloping figure; instead, it becomes an amalgam of positions and gestures, a constellation of steps mapped across time and space

By freezing motion into photographic sequences, Marey rendered the ephemeral legible He captured continuity and discontinuity simultaneously: the seamless stride of the horse unravelled into discrete instances, yet recomposed into an image of flow In this way, Marey not only advanced scientific study but also provided a visual language that resonated with artists His images would inspire Futurists and Cubists, whose jagged compositions and multiple viewpoints sought to embody dynamism and time’s passage on canvas What began as science soon became art history

NOUR JAOUDA

Iris Van Herpen, Syntopia Dress, 2018 Silk, organza, stainless steel, and polyester

43.3 by 43.3 by 15.75 inches (110 x 110 x 40 cm)

Over a century later, Iris van Herpen (b 1984) continues this exploration of movement’s intangible qualities, but through an entirely different medium: couture Since founding her eponymous house in 2007, van Herpen has established herself as one of fashion’s most daring innovators, pioneering the use of 3D printing, laser cutting, and biomaterials Her work exists at the intersection of fashion, science, and sculpture, drawing inspiration from marine biology, architecture, dance, and physics. Each collection is less a presentation of clothes than a meditation on transformation, hybridity, and the possibilities of the human body

Syntopia (2018), now part of Tia Collection, epitomises this interdisciplinary approach. Created in collaboration with Studio Drift, whose kinetic installation In 20 Steps mirrored bird flight, van Herpen’s garments materialised the milliseconds of a bird’s wing in motion Constructed from silk organza, mylar, cotton, and acrylic sheets, Syntopia embodies fragility and transformation, themes that underpin her practice. Much like Marey’s photographs, van Herpen’s work seeks to capture what is fleeting and elusive Where Marey dissected motion into visual fragments, van Herpen encodes it into material layers, sculpting time itself into fabric and form

The parallel becomes sharper when one considers how each body of work mediates between stillness and movement Marey immobilised motion to render it legible, producing static images that revealed invisible intervals Van Herpen’s garments, by contrast, are activated through movement. They change as the wearer moves, oscillating between sculpture and performance.

Étienne-Jules Marey, Cheval blanc, 1886

Chronophotograph

Yet, by fixing delicate patterns and translucent structures into crafted materials, she also preserves gestures in tangible form

The result is a paradox: Syntopia is both frozen and alive, at once static architecture and responsive organism

Despite their differences, both Marey and van Herpen share a profound interest in how art can reveal what lies beyond ordinary perception. For Marey, it was the rhythms of animal locomotion, the precise seconds between steps For van Herpen, it is the architecture of flight, the invisible distances between the flapping of wings Both turn motion into structure, time into form

Their work also transcends their disciplines Marey’s chronophotographs, though born of science, became crucial to the avant-garde, influencing artists from Duchamp to Balla Van Herpen’s couture, while rooted in fashion, increasingly inhabits the realms of art and performance Her garments have appeared in museums worldwide, from the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, not simply as clothing but as sculptural objects and cultural artefacts

Placed together, Marey’s Cheval Blanc and van Herpen’s Syntopia represent a continuum across centuries Both confront the same challenge: how to hold on to what is transient, how to preserve what is always slipping away Marey answered through layered photographic exposures, van Herpen through wearable sculptures that morph with every gesture Each makes visible the unseen architecture of time

In the end, what unites them is not only their fascination with motion, but their insistence that the fleeting deserves form Marey’s horses gallop eternally across photographic plates, while van Herpen’s wings unfurl anew with each body that wears them Together, they remind us that art, whether through lens or couture, has the power to translate time itself, to freeze, extend, and reimagine the beauty of movement

TIA COLLECTION COLLECTS

78 75 by 70 88 by 1 75 inches (150 x 280 x 4 5 cm)

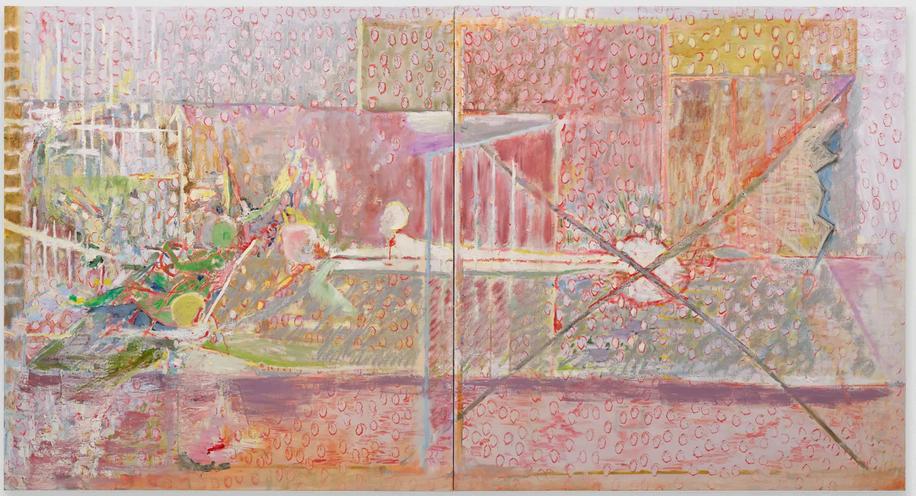

Gabriella Boyd, Floorplan (Green Driver), 2024 Oil on linen

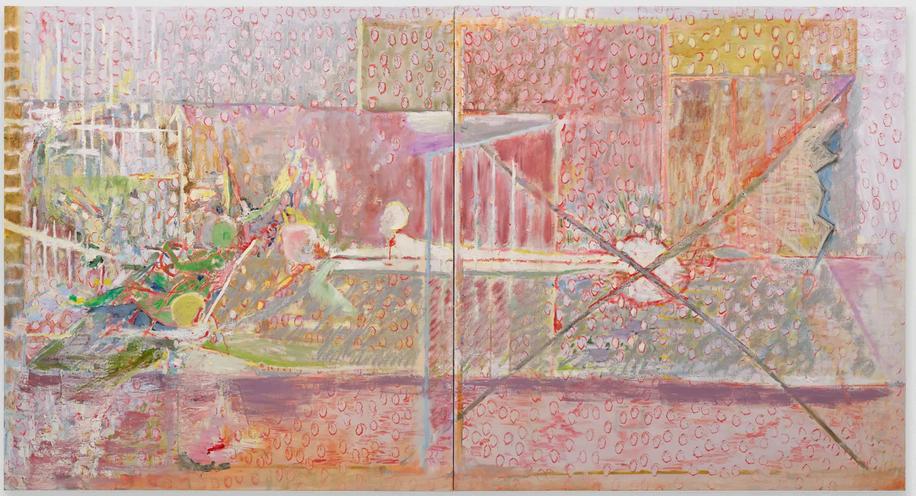

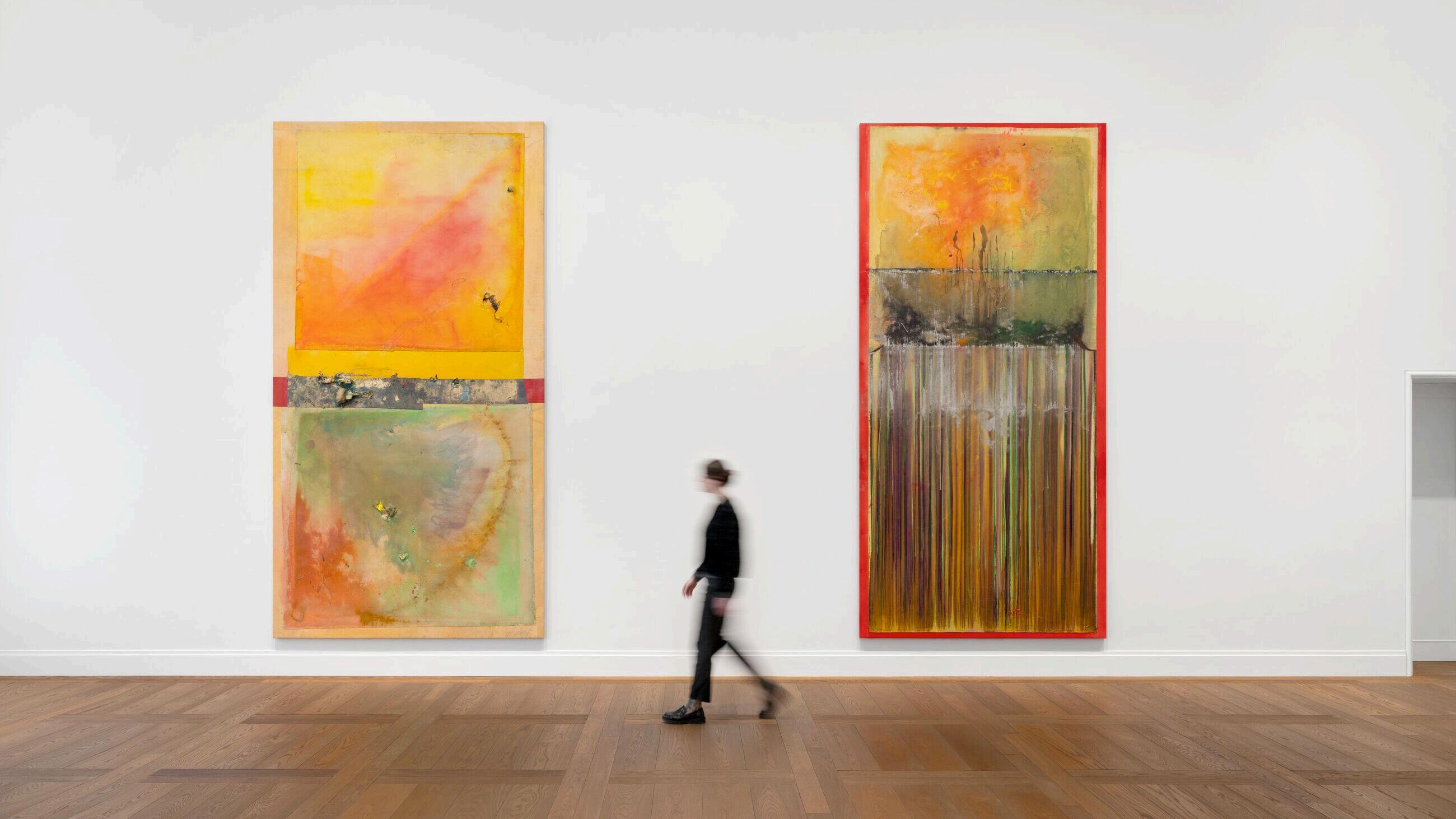

Frank Bowling, Orangecentered, 2023

Acrylic, acrylic gel, and found objects on collaged canvas with marouflage 163 by 85 by 3.125 inches (414 x 216 x 7.9 cm)

The9-5withClareWoods

This week, we turn our gaze to Clare Woods, whose paintings transform fragments of reality into enveloping environments Born in Southampton in 1972, Woods trained as a sculptor before turning to painting, and her work continues to carry that sculptural sensibility, bodies and forms pushed to the surface in sweeping gestures of oil and enamel Rooted in the traditions of still life, portraiture, and landscape, her practice destabilises these genres, shifting them into unsettling spaces that oscillate between beauty and unease.

We’re thrilled to highlight Between Before and After (2018), acquired by Tia Collection, a work that epitomises Woods’ ability to hold the viewer in suspension Here, visceral brushwork and luminous tones blur the line between abstraction and figuration, suggesting a form at once recognisable and elusive

9:00 AM – Through the keyhole, the door unlocks, and the morning ritual begins, a slow sip of Lady Grey tea in a Royal Copenhagen mug, this is the perfect start to the day. Once Wood starts painting, she ends up with a large metal thermal cup covered in paint but filled with jasmine green tea.

What is the first thing you do when you enter the studio?

Woods: I go straight to my desk, put my bag down, and look at the list I left myself the day before. Then I start painting. I have to begin immediately, before any distractions creep in, if it’s a painting day Other days I’ll work with collage, or it might be a mountain of admin, but whatever the task, I always come straight in and get started The list is very important

10:15 AM: Rummaging through piles of photographs, wading through tables layered with paintings.

What’s your first creative decision of the day? Do you always start with a photograph, and how do you choose the photograph, is it visual, intuitive, what kind of photographs intrigue you?

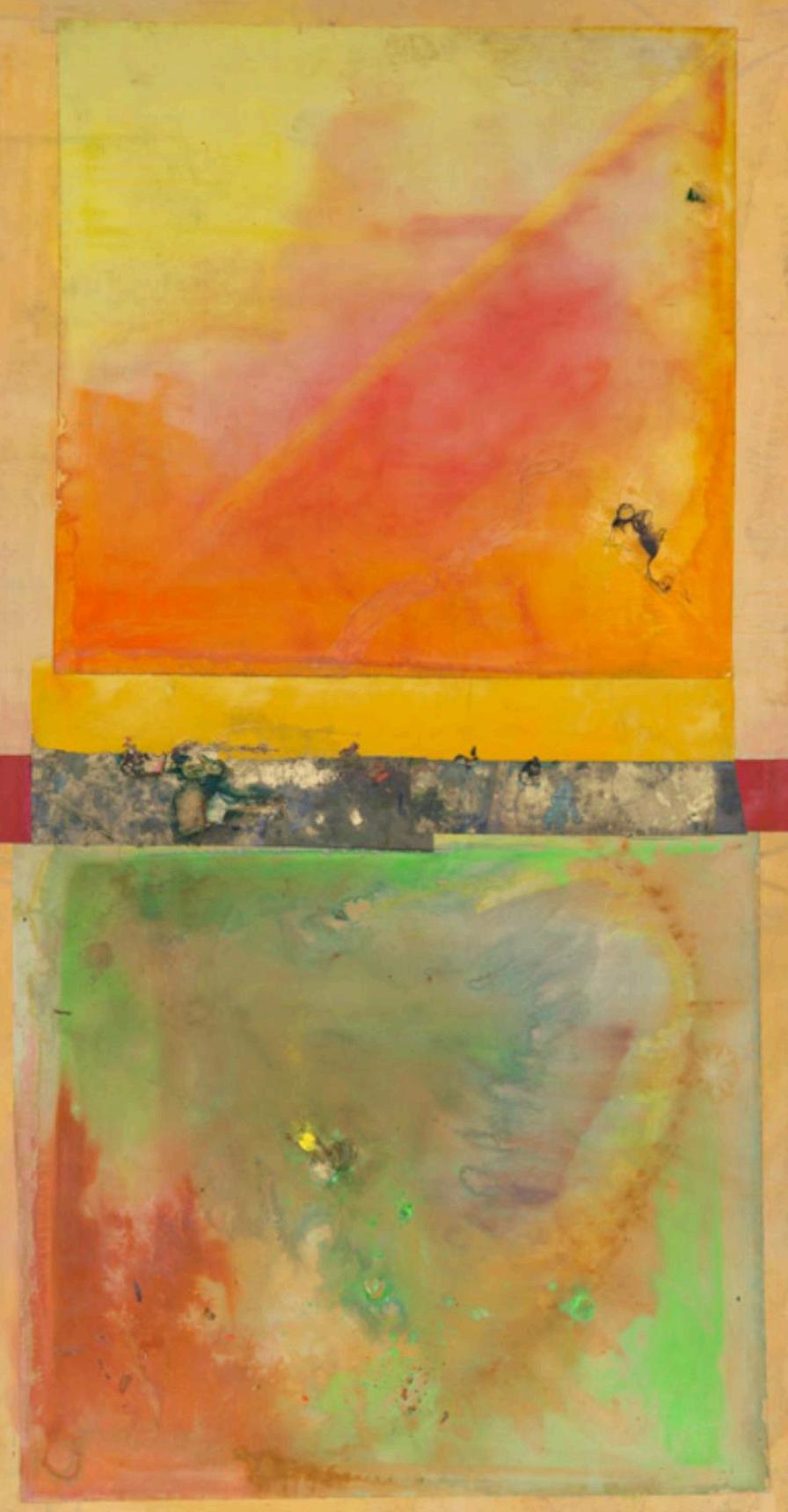

Clare Woods, Between Before And After, 2021

Oil on aluminum

118.11 by 314.96 inches (300 x 800 cm)

Woods: I start working early around 6:30 am and because I work wet on wet I usually work until a painting is complete, this was not possible with the painting in the Tia Collection because of it size, but generally when I am painting I start a new work in the morning The main focus is on mixing the paint and preparing the surface of the panel. The work with the photographs and drawings is the start of the process way before the painting is anywhere near ready to start and can take weeks

11:30 AM – Woods, a maestro of colour and form, begins by applying paint directly onto the aluminium surface, letting the layers of pigment luminesce and interact, each stroke building depth and movement.

What does it feel like when you are immersed in painting? Does it feel performative, almost trance-like?

Woods: It feels very much like a solo performance with no audience Preparation is a huge part of the process, the photography, the drawing, the surface prep, the mixing of paint But when it comes to making the work, I need silence. The noisecancelling headphones go in, and I need an uninterrupted day, no Zoom calls, no visits, no other commitments Then I can begin I move around the horizontal panel, pushing and pulling the paint so it mixes and flows, re-sculpting the source image into the way I see it which isn’t necessarily how it appears in the photograph

You’ve mentioned the light coming through the gesso, how do you think about the interaction of weight, pigment, and translucency in creating a sense of depth or movement?

Woods: The translucency of the paint is directly affected by the pressure I put on the brush, the harder I push, the more the light bounces through the pigment It’s not simply about covering the surface, as in a more traditional approach to painting, but about weight and pressure The act becomes closer to physical sculpting, shaping the image through force and touch rather than simply layering colour.

11:53 AM - A drop of paint lands unpredictably onto the surface.

Are there moments in a painting where accidents or unplanned marks transform the work?

Woods: Yes and these are amazing Also making rejected paintings which is very useful, I learn much more from a bad painting

1:00 PM – A vase of peonies pauses in quiet, petals falling to the cold floor

Flowers appear often in your work. Talk to us about Between Before and After, 2021. Hauntily beautiful, with petals falling and reminding us about the circle of life and the fragility of beauty

Woods: I wanted something to represent a moment of transition between to extreme poles, for example life and death, sickness and health and abstraction and figuration We had just come out of lock down when I made this work and I felt as if I had one foot in the past and one foot in the present with everything looking familiar but feel so odd with no possible planning or knowing what the future could be

2:30 PM – The archive releases another photograph into the light.

You often say that your work stems from a sense of anxiety or fear. What is your greatest anxiety as an artist? And what is something you want viewers to take from your work or from how you paint through fear?

Woods: I think my biggest fear as an artist is to be ill and not be able to work.

You’ve spoken about anxiety and fear being present in your workhow does that tension inform the physicality of your brushstrokes?

Woods: I think the representation of the mundane or banal in contemporary practise is obviously not just a picture of a vase of flowers, the painting goes beyond the subject matter

How do you want people to feel when they stand in front of your large-scale canvases?

Woods: I never prescribe what I want people to see or feel but the large scale works do allow people to be up close and in the work and this is when the image will breakdown and become much more abstract , then when they move away to will make more physical figurative sense

What draws you to flatten the images in your paintings?

Woods: I take photos of real life, I then draw them and make a drawing that is very simple I then re paint using this drawing as a guide, sculpting in paint to recreate the image as a new form of its original self The flattening comes as part of the process

3:10 PM - A thought of what might go wrong, a chance encounter, hovers in the air.

Q: Do you leave anything up to chance in your painting process?

Woods: Pretty much the whole painting process has elements of chance in it, the mixing of the colours on the painting surface is chance and the way the paint settles is chance, I have an idea, a drawing and a photograph to look at but the act of painting is all about chance and surprises.

Do you feel the ‘fear of something’ as an energising force or a quiet companion while you paint?

Woods: Totally and energising force, I think it has been my main driver for my whole life

4:45 PM – A brush hits the surface, dragging pigment across white gesso.

How does working from above, using your shoulder rather than your wrist, change your relationship to the surface and the way the colours respond?

Woods: I could not paint like I do if the painting was upright but it does come with the drawback that I can’t see the work until it is finished and dry and I stand it up The movement comes from my shoulder to create much more gestural and larger marks, but this also gives way more strength and the ability to use pressure in the process

4:58 PM - A pause as light filters across the studio floor

When you’re painting close to the surface, and only later stand back to see the whole, how does that distance shift your understanding of the work?

Woods: For me this is just the next part of the process, I do have surprises when things are very good and I do also have rejects that have to be destroyed, it’s all part of the process and the learning.

5:00 - The day stretches toward evening light, the scalpel rests.

What is the last thing you do at the studio each and every evening?

Woods: I clean away all the mess, cover the paint, hang up my apron, take off my painting boots and go upstairs to the office and make a list

When a painting is finished, or reaches a point of resolution, what do you feel has been captured: a physical experience, an emotional state, or something entirely abstract?

Woods: When a painting works for me it captures what it is to be alive and human and to try and make some sense of now

Q: You mentioned once that being an artist is an addiction, a hard habit to break. Are there any things or addictions you have in your day to day life, do you listen to a track repeatedly, do you binge a bag of crisps every day at quarter past 5?

Woods: Diet Coke

Clare Woods (b 1972, Southampton) is a British painter whose background in sculpture informs her distinctive approach to painting Working in oil on aluminium, she uses sweeping, gestural brushstrokes to both build and dismantle form, transforming still life and the human figure into psychologically charged, abstracted visions.

Tia Collection is proud to spotlight Between Before and After (2018), a work that epitomises Woods’ exploration of fragility and transformation Suggesting the body through distortion and luminous colour, the painting suspends the viewer between recognition and obscurity, presence and absence, a meditation on the delicate thresholds of human existence

COLLECTION LENDING PROGRAM

Otobong Nkanga, We Come from Fire and Return to Fire, 2024

Hand tufted carpet, glazed and smoked raku ceramic, obsidian, shungite, tourmaline, labradorite, handmade rope, metal connectors, Murano glass with black palm kernel oil and palm oil

283.5 by 106.3 by 133.9 inches (720 x 270 x 340 cm)

Otobong Nkanga

Musée d’Art moderne de Paris, Paris

10/10/2025 - 2/22/2026

The Museum of Modern Art in Paris presents the first monographic exhibition of Otobong Nkanga. Born in 1974 in Kano, Nigeria, and based in Antwerp, Nkanga has, since the late 1990s, explored themes of ecology, resource extraction, and the deep ties between body and landscape Drawing from personal history and research, she creates networks between people and environments, reflecting on both the damage and the healing potential within natural and social systems

Educated at Obafemi Awolowo University in Nigeria, the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam, Nkanga works across media painting, installation, tapestry, performance, and poetry Central to her practice is the idea of strata: layers of material, memory, and meaning that reveal the interdependence of bodies and land Through this lens, she examines the movement and exploitation of materials, goods, and people, confronting environmental and colonial histories while envisioning paths toward repair and renewal

Janet Lippincott, Untitled (Church with Green Landscape), 1963

Oil on canvas with collage 40 by 48 inches (101.6 x 121.9 cm)

Pursuit of Happiness: GI Bill in Taos

Harwood Museum of Art, Taos, NM

9/27/2025 - 5/31/2026

This exhibition, Pursuit of Happiness: GI Bill in Taos, reframes the narrative of post-World War II artistic movements by focusing on artists who lived, worked, and connected in Taos from 1945 onward. These artists established the next significant wave of abstraction in the region, enriching the community with their extensive creativity and international connections Through works from the Harwood Museum of Art’s permanent collection and important loans from regional and national sources, the exhibition will illustrate Taos's contribution to national art discussions and explorations during the post-World War II era.

Taos was a hub for the first era of abstraction following World War I, influenced by figures like Mabel Dodge Luhan and modern artists such as Andrew Dasburg, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Emil Bisttram. During the Great Depression, Taos artists found support through the U S government's backing of Regionalism and Social Realism. However, it was at the close of World War II that the next major phase of abstraction swept through Taos, driven by a generation of veterans who arrived to study under the GI Bill (the Serviceman’s Readjustment Act) Despite its small size, Taos hosted several art schools during this period, including the Mandelman-Ribak Taos Valley Arts School (1947-1953), the Bisttram School of Fine Art, and UNM’s Summer Field School of Art (1929-1956).

This exhibition will precede the publication of Tia Collection and MaLin Wilson-Powell’s book, The Pursuit of Happiness: World War II, American Artists and the GI Bill, which highlights thirty international, national, and regional GI Bill artists who profoundly impacted the art world

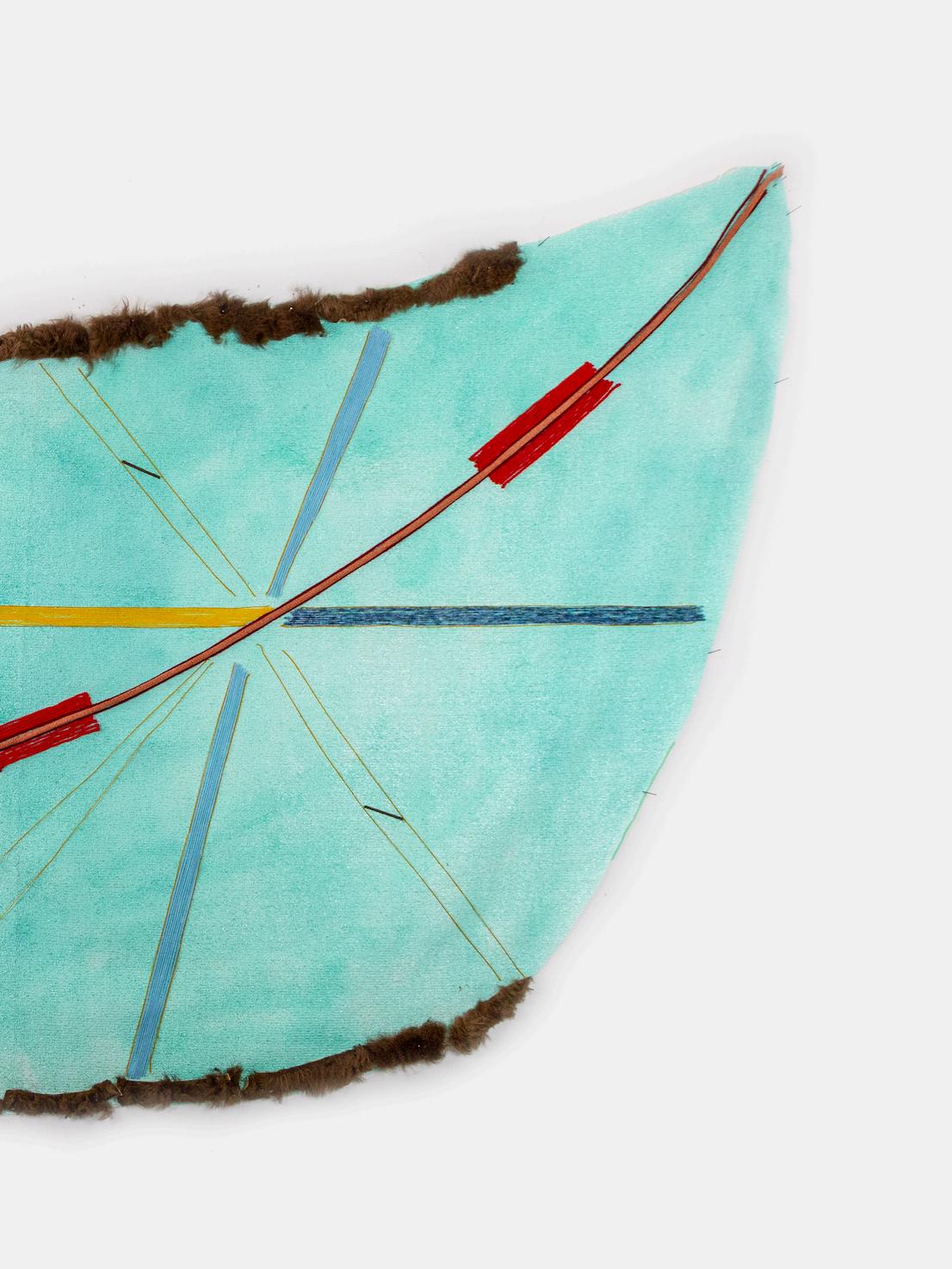

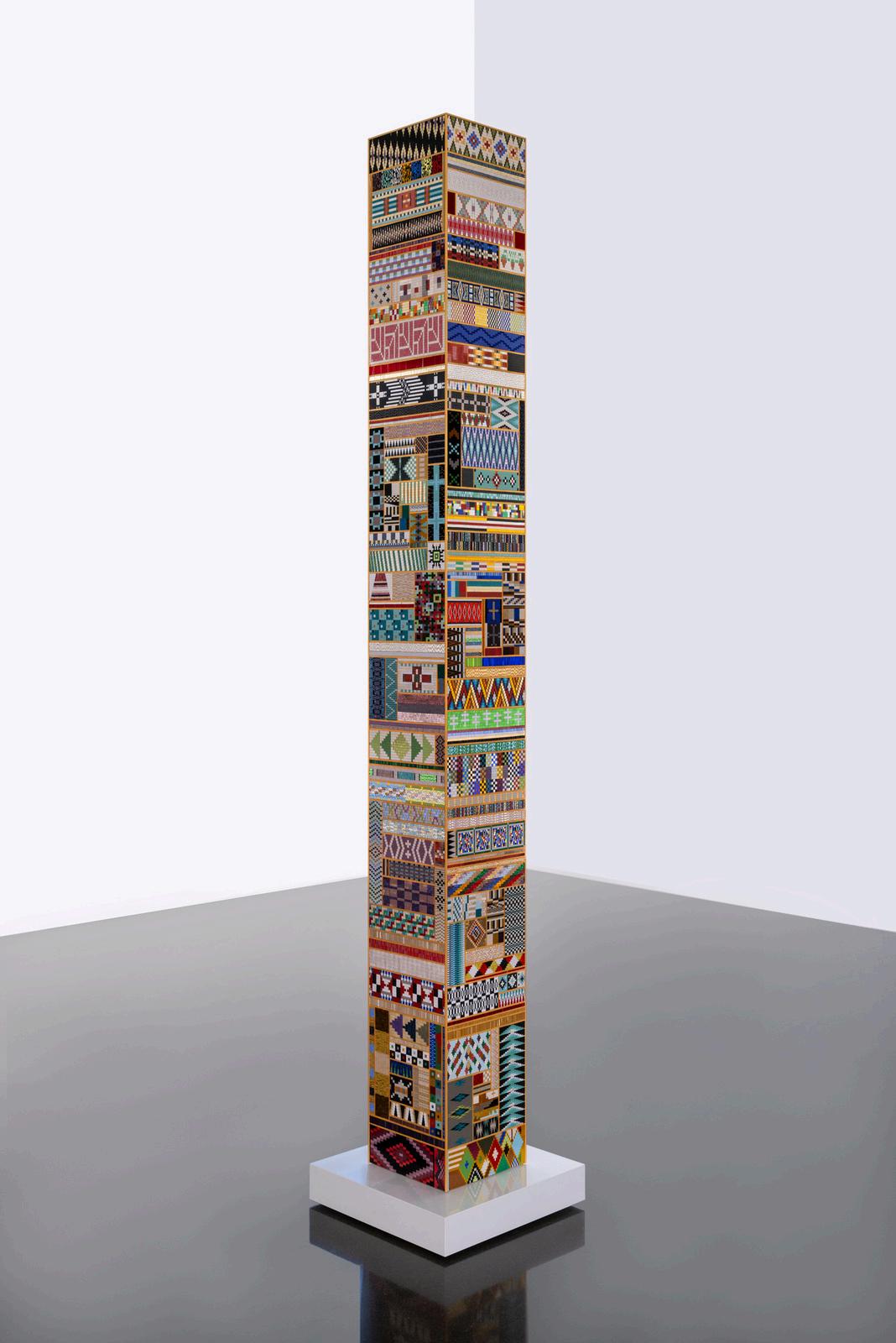

Dyani White Hawk, Visiting II, 2024-2025

Acrylic, glass bugle beads, thread, and snythetic sinew on aluminum panel, quartz base 144 by 15.5 by 15.5 inches (304.8 x 39.4 x 39.4 cm)

Dyani White Hawk: Love Language

Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN

10/18/2025 - 2/15/2026

Rooted in intergenerational knowledge, Dyani White Hawk’s (Sičáŋǧu Lakota, b. 1976) art centers on connection between one another, past and present, earth and sky By foregrounding Lakota forms and motifs, she challenges prevailing histories and practices surrounding abstract art Featuring multimedia paintings, sculpture, video, and more, Love Language gathers 15 years of the artist’s work in this major survey.

The exhibition unfolds across four sections named by the artist to speak to Indigenous value systems: See, Honor, Nurture, and Celebrate. See introduces visitors to White Hawk’s worldview. Opening with early pieces that combine quillwork, beadwork, and painting, the artist examines, dissects, and reassembles elements of her own Sičáŋǧu Lakota and European American ancestries Visitors will encounter Lakota forms and teachings that inform her practice, alongside works addressing urgent issues of settler colonialism and oppression.

In Honor and Nurture, White Hawk uplifts family, ancestors, and community Her acclaimed Quiet Strength series honors the labor of Indigenous women by referencing Lakota quillwork in the form of large abstract paintings. The exhibition’s final section, Celebrate, marries traditional techniques with outsize scale, paying homage to small gestures that hold great meaning. Featured here are a new series of glass mosaics, beaded sculptures, and White Hawk’s monumental Wopila | Lineage paintings. Made in collaboration with a skilled team of studio beadworkers, these shimmering expanses of pattern and color invite close inspection of both their material construction and their historical underpinnings

About Tia Collection

Founded in 2007, Tia Collection is a global art collection with a mission to support artists and institutions by acquiring and loaning works of art Tia fosters dialogue, stewardship and scholarship of art through its lending program, partner exhibitions and publications.

For more information, contact us at info@tiacollection.com

IMAGE CREDITS:

Cover: Clare Woods, Between Before and After, 2021 © Clare Woods Tia Collection. Courtesy of the Artist and Martin Asbaek Gallery, Copenhagen Photo by Liselotte H Birkmose

Page 3: Detail of Clare Woods, Between Before and After, 2021. © Clare Woods. Tia Collection. Courtesy of the Artist and Martin Asbaek Gallery, Copenhagen Photo by Liselotte H Birkmose

Page 4: Iris van Herpen, Syntopia Dress, 2024. © Iris van Herpen. Tia Collection Images courtesy of Iris van Herpen Studio, Amsterdam, NL Photography by Yannis Vlamos. Model: Sabah Koi.

Page 6: Detail of Iris van Herpen, Syntopia Dress, 2024. © Iris van Herpen Tia Collection Images courtesy of Iris van Herpen Studio, Amsterdam, NL. Photography by Yannis Vlamos. Model: Sabah Koi.

Page 8: Étienne-Jules Marey, Cheval blanc, 1886 Chronophotograph

Page 10 & 11: Mona Hatoum, Hot Spot (stand), 2018, 6/8. © Mona Hatoum Tia Collection Photography courtesy of the artist and White Cube. Photo by Ollie Hammick.

Page 12 & 13: Gabriella Boyd, Floorplan (Green Driver), 2024. ©

Gabriella Boyd Tia Collection Image courtesy of the artist and GRIMM Gallery, London, UK. Photography by Greg Carideo.

Page 14 & 15: Frank Bowling, Orangecentered, 2023 © Frank Bowling Tia Collection. Image courtesy of Hauser & Wirth, Photographer: Anna Arca.

IMAGE CREDITS CONTINUED:

Page 16 & 17: Clare Woods in front of her painting Between Before and After, with her dogs in her studio Image courtesy of the artist

Page 19: Clare Woods, Between Before and After, 2021. © Clare Woods. Tia Collection. Courtesy of the Artist and Martin Asbaek Gallery, Copenhagen Photo by Liselotte H Birkmose

Page 21, 23 & 25: Clare Woods’ studio. Image courtesy of the artist.

Page 27: Clare Woods in her studio Image courtesy of the artist

Page 28 & 29: Teresa Baker, Converging, 2023. © Teresa Baker. Tia Collection. Image courtesy of the artist and de boer, Los Angeles, California; Photo. Jacob Phillip.

Page 30: Otobong Nkanga, We Come from Fire and Return to Fire, 2024 © Otobong Nkanga Tia Collection, Santa Fe, NM Image courtesy of the artist and Lisson Gallery.

Page 32: Janet Lippincott, Untitled (Church with Green Landscape), 1963. Tia Collection. James Hart Photography.

Page 34: Dyani White Hawk, Visiting II, 2024-2025. © Dyani White Hawk Tia Collection Courtesy the artist and Bockley Gallery Photo by Rik Sferra.

Page 38: Press image of New legacies: How a new generation is reshaping art collecting and patronage, featured on Art Basel.

New legacies: How a new generation is reshaping art collecting and patronage

Art Basel

9/25/2025

The Art Basel article explores how a new generation of collectors is redefining legacy and patronage, with a spotlight on Tia Tanna and Tia Collection Tia, who grew up experiencing art through travels with her father, has developed a thoughtful, research-driven approach that complements his instinctive eye, allowing the collection to honor its roots while expanding into new territories like couture and emerging contemporary artists. Under her guidance, Tia Collection has taken on a philanthropic role, from funding a £20,000 institutional grant with the Henry Moore Foundation to supporting exhibitions at the Barbican and National Galleries of Scotland. As the sole heir to the collection, Tanna reflects on responsibility and the importance of establishing her own voice, offering a fresh, forward-looking vision of what collecting can mean today