EconomicPersepectivesisthePerseEconomics magazinededicatedtostudentsrunbystudents. Publishedtermly,EconomicPersepectivesseeksto explorethecomplexworldofeconomicsonatheme-by -themebasis.

The fundamental economic problem refers to the issue of scarcity, arising due to infinite wants and needs from a finite number of resources. Thus, economics eventually boils down to a matter of choices from individuals, firms and societies. In the 2025 Michaelmas edition of Economic Persepectives, we are delighted to explore the many dimensions of choice

From behavioural biases that influence an individual's decision making to trade-offs that policymakers face daily to strategic choices made by firms seeking to distinguish themselves in a market, we hope that you will be both enjoy and learn from this issue.

These articles will be accompanied by several current affairs pieces to help keep up with an everevolving economic climate. Learning from the past is just as important, however, so these will be balanced with two pieces on the life and works of some famous economists.

Choice also completes the trinity of themes under our tenure as editors. We began by exploring information, then turned to crisis and finally, now to choice. It has been a hugely rewarding process, and we would like to thank everyone who has contributed to any one of our three editions. Finally, to whoever succeeds us, we are excited to see how you take on the role and make it your own.

Sam R, Ashvik G, Richard Z

Cognitive biases are typically defined as systematic “errors” in judgement. They alter perceptions, distort risk assessments, leading to market inefficiencies, mispricing of assets and irrational trading behaviour. However, this definition refuses to acknowledge the role biases act as a mechanism translating personal values and ethical considerations into financial decisions. In this article, I will explain the various biases shaping financial choice, as well as mentioning preventative measures and the impacts these biases can have.

The efficient market hypothesis, which states that asset prices reflect perfect information in the market, and the rational choice theory, which assumes individuals act rationally and prioritise utility maximisation, fail to consider the impact of cognitive bias. According to Herbert Simon’s theory of bounded rationality, cognitive biases diverge decision making significantly from rational economic assumptions.

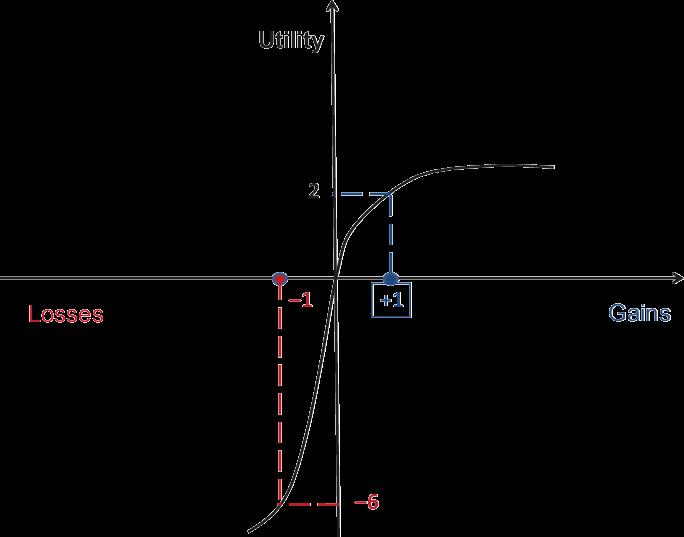

One of the most frequent biases experienced is loss aversion (or sometimes referred to as prospect theory), where the distress caused by losing is felt more intensely than the pleasure derived from gaining equivalent value. As can be seen from the graph below, a steeper gradient in the 3rd and 4th quadrants (loss domain) signify how a loss of a certain amount causes more perceived negative utility than the pleasure derived from an equivalent gain (shallower gradient in gains domain).

A 1979 paper theorised that the pain of losing is psychologically twice as strong than gaining. The stronger emotional reaction experienced can also lead to the disposition effect; whereby one holds onto losing stocks too long in hopes of a rebound, disrupting optimal portfolio rebalancing, and impairing long term returns. This bias can cause individuals to exhibit risk averse behaviour in gain scenarios (avoiding potentially beneficial risk) and exhibit risk seeking behaviour as an act of desperation when facing losses. Examples of this bias manifesting include capital investment avoidance, excessive cash hoarding, and more conservative financing choice. Furthermore, the cost of loss aversion on a firm for example, have the following impacts: a competitive disadvantage, innovation stagnation (R&D investments become underfunded as deemed riskier), market timing failures, stakeholder frustration, and lead to systematic conservative investments. This bias is accompanied by the sunk cost fallacy, in which one continues to invest in something no longer worth it as they have already placed substantial

time, money and effort into it, and reinforces the risk averse behaviour.

Another bias, confirmation bias, can lead to drastically irrational financial decisions. Confirmation bias is where one seeks and interprets data in a way which reinforces preexisting beliefs, discounting contradictory evidence. Confirmation bias is seen in cherry picking data sources, manipulating models, historical pattern recognition, and revenue projection optimism, all altered to confirm the initial belief of the investor. This is highly linked with anchoring bias, in which an investor may fixate on the first piece of information encountered, on an arbitrary reference point, and make all further decisions based on this (interacts with confirmation bias as investors collectively impair objectivity required for sound financial analysis by disregarding contrary data). Anchoring bias is manifested when investors base their expectations on outdated views, resulting in mispricing as too much importance is place on the initial information. It can have serious impacts in acquisition valuations, as the initial price set out by the investor is echoed, inflated leading to a distorted final valuation. Furthermore, in real estate, the initial asking price may act as an anchor, causing a buyer to overpay even if the property is overpriced.

Many biases surround the actual data used to make decisions, and our perceptions of them. The framing effect is a prime example of this – where decisions are made on how the information is presented, rather than on the logic and facts the information provides. This effect can easily manipulate the affect heuristic – one’s tendency to make judgements by consulting our emotions. For instance, the positive feelings associated with concepts like “clean energy”,,” “sustainability” can create a positive effect, leading one to perceive such investments as having lower risk and higher success potential irrespective of underlying financial data. This is linked to the emotional charge or salience of information, which also heavily influences decisions, as more emotive

presentations of a company’s mission may be more likely to attract investors than one presented in another way, linking onto emotional framing of information (which triggers different emotional responses depending on the perception). One's current emotions (mood congruent judgement) can colour financial perceptions – during climate anxiety periods, one may retreat to the perceived safety of traditional investment strategies, whereas in more optimistic moods one may take greater risks.

Recency bias is when excessive emphasis is placed on recent events, assuming those events will occur indefinitely, leading individuals to be swayed by fear of euphoria or recent events. This acts as a survival instinct where the brain processes events from recent memory faster. Recency bias causes extrapolative expectations, as investors may assume that recent market trends will not falter or cease, resulting in overly optimistic/pessimistic forecasts, undermining long term strategy planning, and fostering short-termism in investment behaviour. It can be viewed in the consumerist culture of impulsive spending, making the instant gratification seem more rewarding than distance satisfaction of something potential greater in the future. People often justify these decisions under the belief that they deserve them, known as cognitive dissonance (frequent in “treating” culture). However, this can be prevented by setting financial goals in check with realistic timelines to make future rewards more tangible and present spending more manageable and sustainable.

How can we reduce the impact of bias in our decisions? There are many methods – primarily improving education and awareness surrounding these biases, clarifying financial goals, diversifying info sources, and regulatory frameworks. By taking a systematic, informed approach to make financial choices, seeking diverse information and views, and considering the biases that may sway us while doing so, we can successfully make sound decisions with less of an impact from cognitive bias.

Kiana M, Y12

In a world where every tap on a device reveals a new choice, does it actually increase customer satisfaction, or just add to confusion? In the developing world, choice seems to be an infinitely expanding factor of our lives, where new advancements in technology, in addition to innovation, cause many more choices to blossom into existence. Choices exist because of scarcity.

Resources such as money, time, labour and raw materials are finite, whereas human wants and needs are infinite, making the allocation of resources an important part of global economies. Scarcity forces consumers to prioritise, and choice allows them to select substitutes that best fit their wants and needs. Choice enables prioritisation through the existence of several substitutes for each good or service, offering options to better suit each individual.

While providing more choices seems like a viable solution to fulfilling infinite needs using finite resources, there is an opportunity cost in every decision, making prioritisation a very important part of choice. What about smartphones? How does having too many choices for smartphones impact customer satisfaction? Does it make buyers happier, or just more confused?

Choice is quite simply the act of choosing between

two or more possibilities. In traditional economics, economic agents such as producers and consumers are assumed to be perfectly rational beings, aiming to maximise profit or utility.

Market choice, however, challenges this rational choice theory, making it a fundamental part of behavioural economics, which shows that realworld choices are influenced by emotions, social factors, and an overwhelming number of options available. In smartphone markets, behavioural economics explains why consumers might not be as rational as traditionally assumed; why an individual may choose a more expensive model because of brand prestige (called status bias) or feel paralysed when faced with too many similar options (choice overload).

Buying a smartphone carries an opportunity cost, such as losing out on a holiday. Markets exist to facilitate these choices, providing a platform for buyers and sellers to interact, showing what buyers want which, in turn, indicates the most profitable option to produce for sellers.

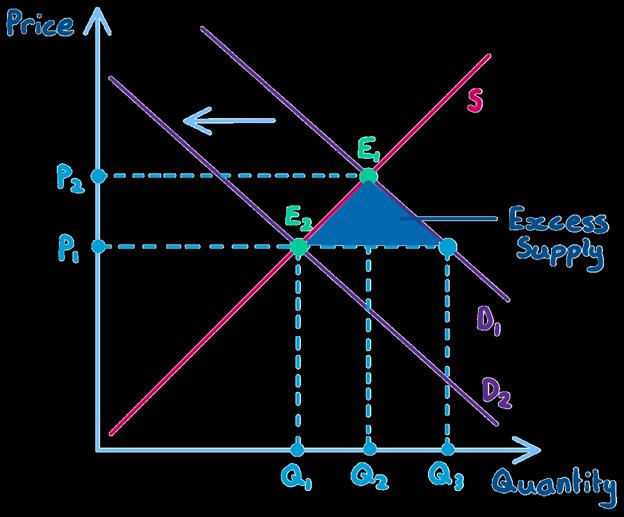

To apply this to a real world example, imagine a leading phone manufacturer has just released a new smartphone model with reduced camera quality but increased battery life. If this is not a desirable change for most consumers, the demand for the product will decrease and so the demand curve (D1) will shift inward, meaning that the

quantity demanded at any given price is lower (at P2, Q1 < Q2). Given a new market equilibrium at a lower price, the production of the new smartphone model would be less profitable since P1 at E1 is higher than P2 at E2 so fewer firms are willing and able to sell smartphones. Producers must ensure features fit consumer preferences as it rewards them with greater sales and profits.

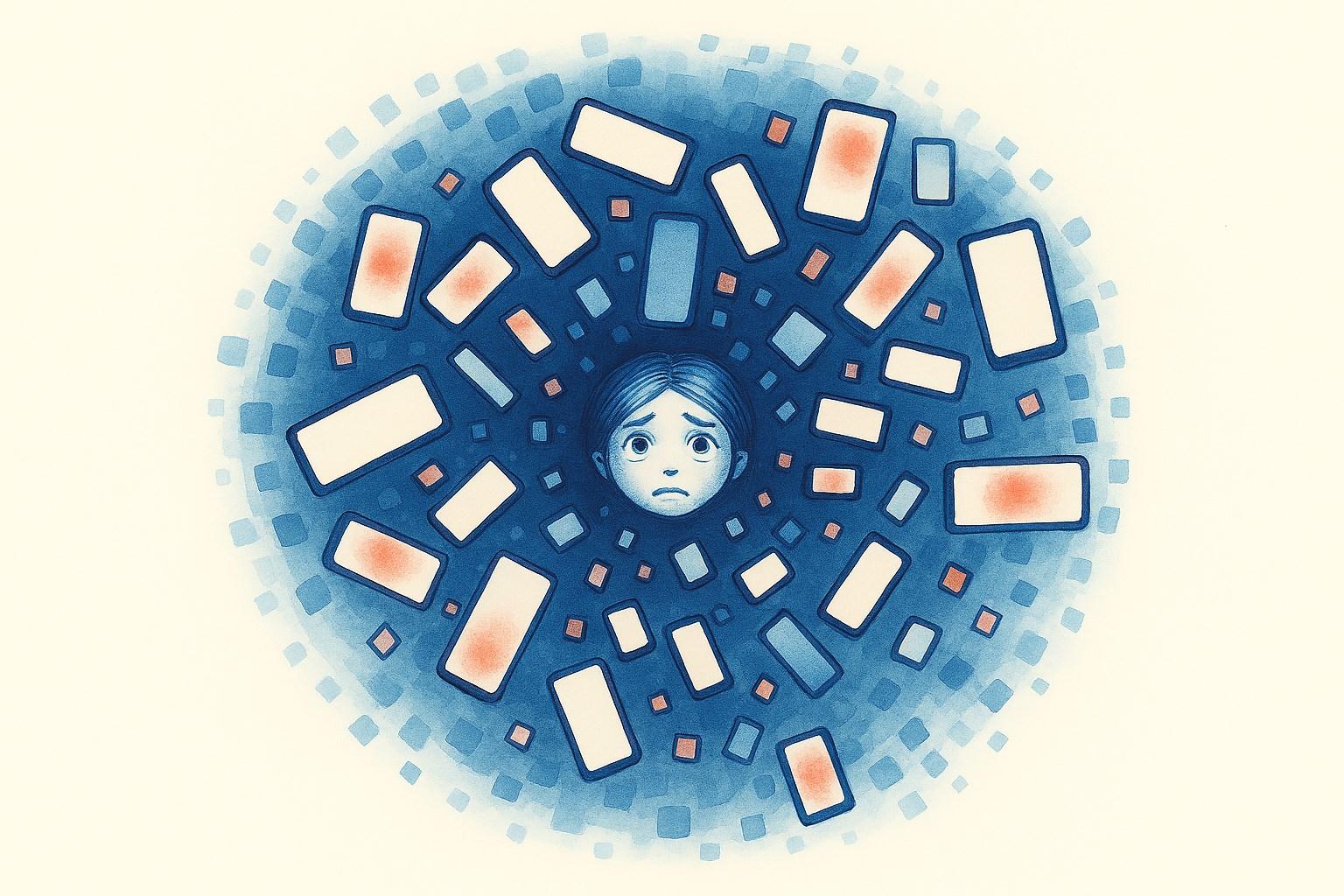

Choice overload in behavioural economics addresses how having too many options can reduce satisfaction. It can also lead to decision fatigue, analysis paralysis and decreased consumer confidence. It is estimated that, on average, an adult makes 35,000 choices a day, which is only an estimate of conscious choices. We often assume that we have the choice of which smartphone to buy once we step into the store but, in reality, subconscious psychological effects influence every consumer's decision.

Decision fatigue is mental exhaustion from comparing too many smartphone features. Each comparison requires thought and energy, which can lead to a subconscious feeling of being overwhelmed by the several options available.

Over time, the overwhelming feeling leads to decision fatigue as consumers give up and focus on the convenience of purchasing over other factors. As a result, customer confidence decreases, causing analysis paralysis as their final choice leaves them uncertain and unsatisfied not knowing if their choice was the best one to make.

Through this subconscious tactic, firms in oligarchical markets, (industries dominated by a few large firms, such as the smartphone industry) are able to influence customer decisions by presenting models that appeal to customers but are not appealing as the best choice for a consumer.

The many choices available to consumers are mostly a cause of increased product variety, which intensifies competition as firms race to capture customer wants and needs within each product. This often leads to price dispersion: premium models demand higher prices while more costeffective options face high competition with products from other brands. In oligopolistic markets (where a small number of large firms dominate the entire industry), such as the smartphone industry, variety holds value in sustaining brand loyalty through categorising consumers into different levels.

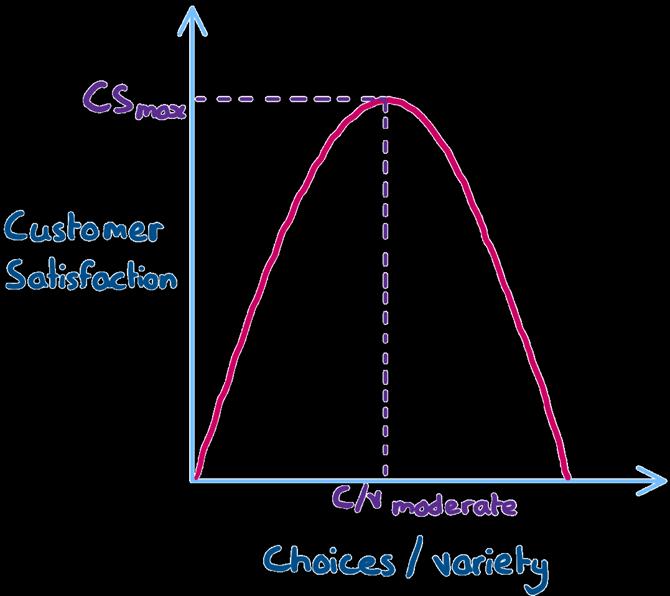

Variety incentivises firms to innovate and appeal to customers due to strong competition in the market. This causes the creation of many models, each with features mildly different from the last. Initially, more choice increases satisfaction (Statista reported that in 2024 Samsung offered over 20 smartphone models worldwide) giving consumers the confidence that they could find one to match their budget and preferences. However, beyond a certain point, choice overload becomes a key part of deteriorating consumer welfare in purchasing products.

Contrary to initial beliefs of many choices being ideal for customer satisfaction, many studies have shown the ideal variety of choice being moderate (as shown in Figure 2).

Moderate choice benefits consumers but excessive variety in the oligopolistic smartphone industry reduces satisfaction. This is a result of too many choices causing decision fatigue and analysis paralysis leading to the regulation of choices being a viable method to maintain customer satisfaction in the smartphone industry.

Ani M, Y12

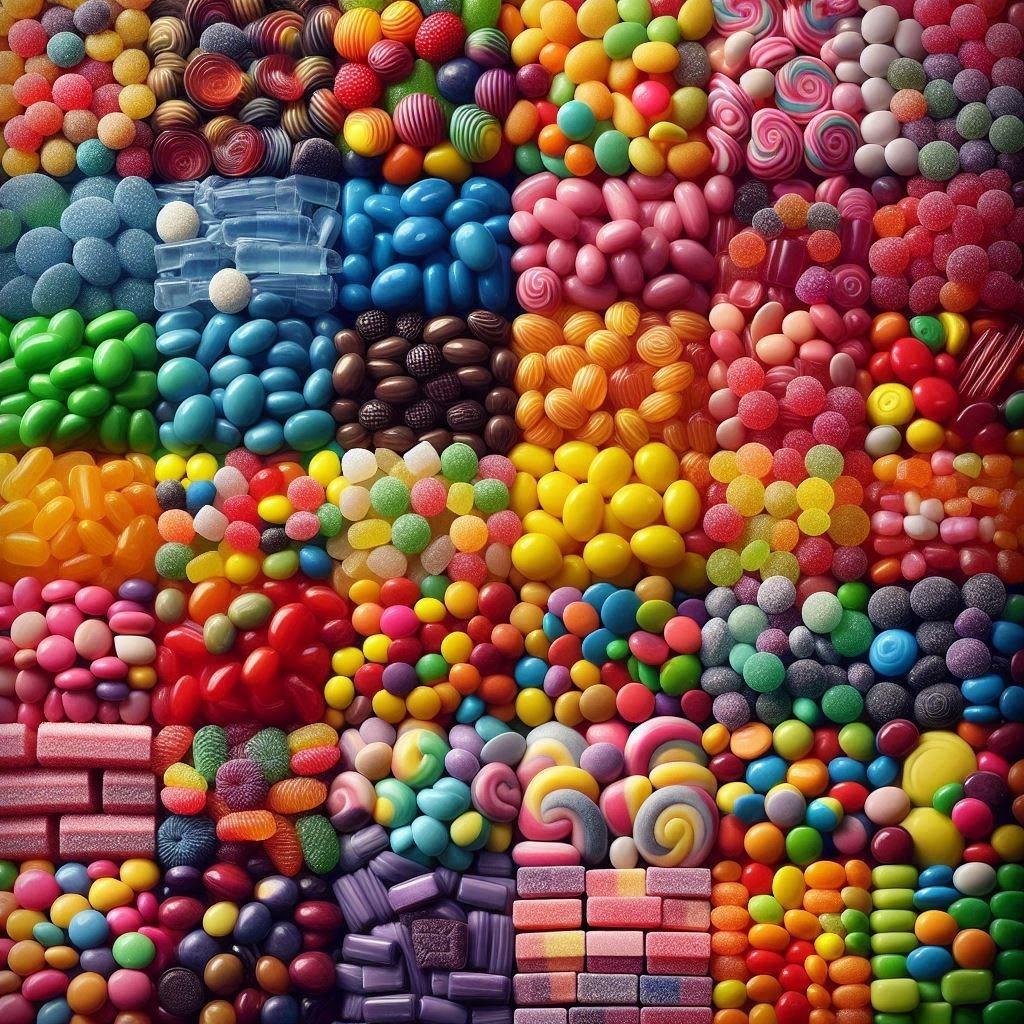

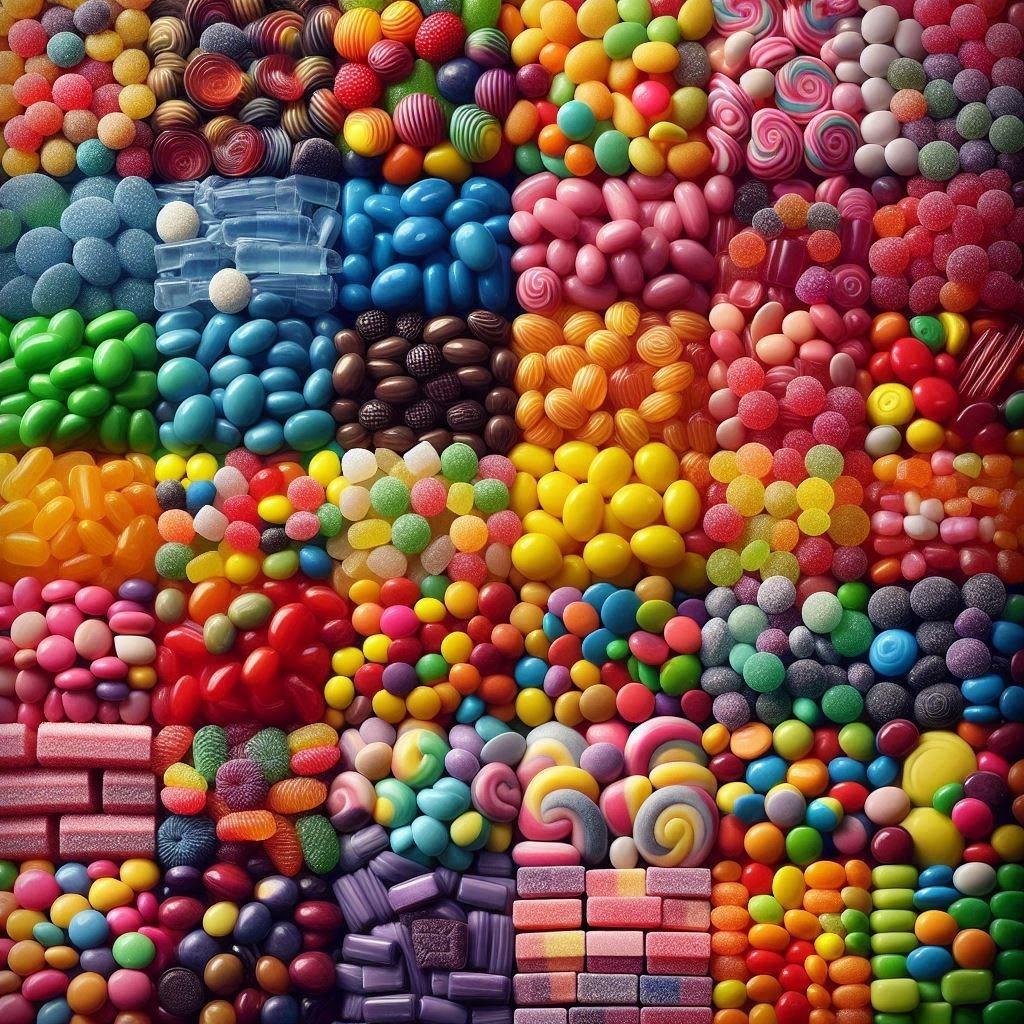

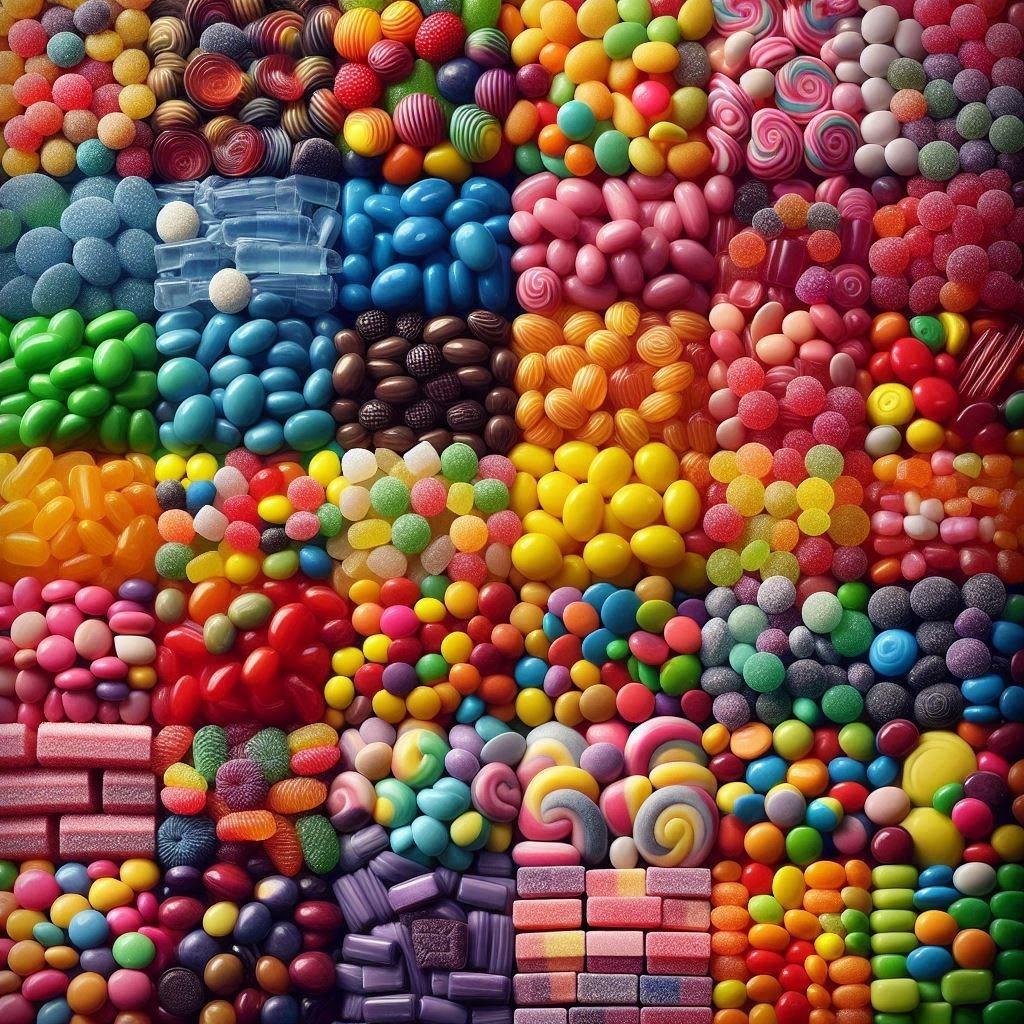

You are standing in the middle of your local shop looking at the array of sweets, snacks and chocolate decorating the familiar sweet aisle. The cheaper store brand options temptingly sit on the lower shelves, yet automatically you reach for the more expensive option that you always buy. Why do we pay extra for something so small and ordinary? It might seem surprising, but this small moment in the middle of the sweet aisle captures how economics works. Beneath the glossy wrappers lies a mix of psychology, decision making and the very essence of consumer behaviour. Economists refer to this as utility; the satisfaction or happiness that we gain from consuming a good or service. Every bite and indulgence is a decision in pursuit of maximum satisfaction.

Utility captures something invisible - happiness. This makes it one of the most human concepts in economics which allows us to explain choices and decisions. The more satisfaction a product gives us the higher its utility. For example, when you eat the first biscuit out of your favourite biscuit pack the rush of happiness and satisfaction is undeniable. However, by the 4th or 5th biscuit the satisfaction fades or can even be replaced with unhappiness or discomfort. Economists refer to this as diminishing marginal utility which is the idea that each additional unit of consumption provides less satisfaction and happiness than the one before. We can use this to explain why people do not just buy the cheapest chocolate or sweets in bulk as the aim of their purchase is not to get the most chocolate

or sweets but instead to get enough satisfaction and happiness through them. This means that even if it costs more, the choice can still be economically rational as you are maximising happiness, not quantity.

Not everyone values chocolates and sweets in the same way. One person may be happy to pay £2 for a Lindt truffle, while another person would prefer a £1 Dairy Milk over the Lindt truffle. This difference in preference illustrates subjective value which is the idea that the worth of something depends heavily on individual preferences and beliefs. Economists use willingness to pay (WTP) to measure this. It refers to the maximum amount an individual is willing to pay for a level of satisfaction they will achieve from a product. For instance, if your favourite snack or sweet gives you more satisfaction from its cheaper alternative, you are assigning more value to the experience of your favourite snack or sweet which leads to your WTP being higher. In this case, price is not just a number but a reflection of value of a product to an individual.

However, personal preferences are not the only factor. Modern economics increasingly recognises how easily influenced; impulsive and emotional consumers are, which influence our decisions making them irrational. Economists refer to these concepts as behavioural economics. Brands use this in many ways. Small characteristics like a

distinctive wrapper, familiar logo or nostalgic slogans can change the amount of satisfaction consumers will think they will gain resulting in a boost in perceived utility. In fact, in many blind taste tests participants are unable to tell the difference between branded and unbranded sweets. Despite this they still believe the ones (often the branded sweet) taste "better". This belief has economical value. Furthermore, behavioural economic effects such as anchoring and framing also have large impacts. For example, when you see a £3 “luxury” chocolate next to a £1.50 bar, the cheaper one suddenly seems like a bargain even though you might never have paid that much otherwise. Brands use these strategies not only to sell products but to sell narratives which shape our WTP.

The rational and irrational consumer

Nonetheless, there is still a limit to how much we as consumers should and are able to indulge. For every choice and purchase we make we give up the value to buy something else. This means that every purchase has an opportunity cost which limits the choices that consumers make to be within a budget constraint so that they have to constantly balance between costs and satisfaction. In theory, this should be the domain of the rational consumer who seeks to balance utility and income. However, in practice this is often impossible because of emotions. Sometimes, the comfort of the familiar chocolate bar outweighs the logic of saving money. This blend of emotions and logic reminds us that economics is not just about numbers but instead about people and the choices they make every day.

When consumers behave this way, firms strive the respond strategically. Specifically, snack companies spend millions in studying and understanding what drives consumer utility and how to capture it for their benefit. For example, PepsiCo who own UK snack brands such as

Walkers and Doritos, spent £5.7 billion in marketing and advertising expenses globally in 2023. They use price discrimination to offer different version of the same product each targeting a different WTP. For example, many snack brands offer fun size, standard and deluxe versions of the same product. Additionally, brands use product differentiation to justify price gaps despite production costs being similar. They use characteristics such as new flavours, improves wrappers or seasonal editions to make consumers feel like they are buying something special. Lastly, Market segmentation divides consumers into distinct groups. For example, children are often drawn to bright packaging while adults are drawn to darker, "sophisticated" chocolate. These strategies all stem from the concept that consumers attach meaning and satisfaction to a product more than just the taste. In the sweet aisle this creates a miniature marketplace of preferences.

Next time you debate over which chocolate or sweet to grab, remember that you are participating in a quiet experiment in economics. Your decision over something as simple as a snack or sweet reveals your preferences and your budget properties. Economists refer to this as revealed preference which is the idea that people's choices reveal what they value more than what they say they value. For example, the moment you pay more for your favourite snack, you are revealing that the added satisfaction is worth the extra cost. So next time you unwrap that familiar chocolate bar, think of it as more than a treat. In that moment, you are demonstrating how personal preferences shape economic behaviour which acts as a reminder that even the simplest choices reflect deeper principles of decisionmaking.

Eshika S,

Y12

Why vote strategically? A game-theoretic teaser

Strategic voting, also known as tactical or insincere voting, occurs when voters cast ballots that do not reflect their sincere preferences. In the UK’s First Past the Post system (FPTP), strategic voting is inevitable. This is due to the system enabling only one candidate to become the MP in each constituency, so the votes for all other candidates go to waste. Consequently, the all-ornothing system results in many voters choosing to work around the system to achieve the best available outcome, instead of voting for who they believe is the best candidate and risking wasting their vote. Recent polling by Electoral Reform UK has shown that ‘almost a quarter of voters' plan on voting ‘tactically’ in the next election’. In the UK, strategic voting is seen most prominently to prevent a Reform UK or Conservative candidate from winning the seat

This is clearly shown in the diagram above from the Guardian which illustrates the opposition party in each constituency that is best placed to beat the Tories and/or prevent a Reform UK candidate from winning the seat.

Duverger’s Law as an equilibrium claim

Coined by French jurist and politician Maurice Duverger, Duverger’s Law states that electoral systems that vote for a single winner in each district tend to result in a twoparty system emerging. This is mainly due to the psychological effect (the wasted-vote logic) and the mechanical effect (the ‘winnertakes-all’ system making third parties irrelevant). Concerning the psychological effect, a classic example of strategic voting surrounds a supporter of a party placed third or lower in the constituency voting for one of the front runners as they are preventing the possibility of wasting their vote - this is known as the wasted -vote logic.

However, it is necessary to note that Duverger’s law is not always valid. The formal rational choice theory displays that deserting third or lower placed parties is not always utilitymaximising, thus highlighting a key flaw to

Duverger’s Law.

Additionally, the law is criticized for ignoring social context, and its institutional determinism that suggests a FPTP electoral system will inevitably lead to a two-party system, regardless of a country’s unique social structure. Hence, Duverger’s Law can be viewed as a theoretical equilibrium, as it is an equilibrium prediction conditional on beliefs and instructions.

Game theoretic predictions vital to strategic voting can fail for two main reasons:

1. Behavioural frictions – partisan identity (where an individual’s political party affiliation is a core component of their personal identity), loss aversion (the behavioural tendency for the fear of losses to outweigh their desire for equivalent gains), and expressive utility (the intrinsic satisfaction of voting itself) can dominate voters’ behavioural choices and lead to an unpredicted outcome at the polls.

2. Incomplete information – elections have hidden turnout costs including the weather, queues, and ID rules on the election day. As election prediction models with incomplete information do not take these into account, strategic voting cannot work effectively and predicted pivotality can be incorrect.

Conclusion: don’t hate the player, fix the game

Undoubtably, tactical voting is a significant problem, especially in the UK’s FPTP electoral system. This is because it creates entrenched duopolies, wastes votes, distorts preferences, and dampens turnout - often due to many voters rationally abstaining if they believe they are in a safe seat constituency. Importantly, over time tactical voting can result in preference distortion which locks in misread preferences so manifestos and candidates can drift away from true voter tastes.

Crucially, strategic voting weakens democratic legitimacy. Democracy is defined as a form of government in which the people hold political power. One of the core principles of a democracy

is the ability to hold an election. Thus, since tactical voting undermines the legitimacy and accuracy of elections, the result is a weakened democracy.

Henceforth, it is pivotal that the UK undergoes electoral reform to gain an electoral system that works for voters, not one that voters must work around. The UK is the only democracy in Europe to still use the outdated FPTP system for general elections. Under a proportional system the need for strategic voting is diminished. Ergo, the question remaining is which electoral system would be the best for the UK.

Notably, the Single Transferable Vote (STV) system involves voters numbering the candidates out of a group of representatives for a larger area. Voters can put numbers next to as many candidates as they like, therefore they can include back up choices, in case their first choice does not get enough votes. As a result, STV enables people to vote for their preferred candidate without the fear that their vote will be wasted. STV is used in Ireland, Scotland, Australia, and Malta. Crucially, the system puts the power in the hands of the public and ensures democracy is present.

In conclusion, tactical voting highlights the flaws of the UK’s FPTP system and calls for electoral reform. However, the question of which voting system should be used is an essential detail, where STV serves as a powerful viable solution. For now, it is vital to criticise the necessity of using tactical voting in the FPTP system and explore new options for the future.

Modern life seems defined by choice. From the cereal aisle to our streaming watchlists, we’re surrounded by options of varying flavours, colours, and genres. Yet beneath this illusion of freedom lies a quiet form of control. The way these choices are presented through their order, framing, or default settings, can shape what we decide more powerfully than we realise. This phenomenon is the manipulation of choice, a subtle architecture of influence that increasingly governs how we shop, spend, and even think.

Dating back to key figure Adam Smith, economists once assumed humans were rational beings. Given options, we’d calculate costs and benefits and pick the optimal outcome. However, behavioural economics shattered that illusions. According to this new theory, our choices are, in reality, deeply sensitive to social context and design.

This foundation gave rise to the idea of choice architecture – the framework in which decisions are made. For instance, a supermarket isn’t just a collection of goods, it’s a behavioural experiment: eye-level shelves are stocked with premium brands, impulse snacks are placed near the checkout, soft lighting is used in the bakery to make shoppers linger. While the architecture doesn’t remove choice, it certainly tilts it.

Fundamentally, there is a distinction in this system between nudging and manipulation. On the one hand, a nudge is a gentle push toward a behaviour that benefits us, such as placing healthy food at the front of a cafeteria line. Manipulation, on the other hand, hides its intent, exploiting cognitive shortcuts for profit rather than welfare.

The effectiveness of the manipulation of choice depends on human psychology. Human minds rely on mental shortcuts (heuristics) to simplify decisions, which can be easily exploited.

An example of this is the anchoring effect. When a product is “marked down” from £199 to £99, the original price becomes a mental anchor, thus making the discount feel irresistible even if the item was never worth £199. Another example is the framing effect. This occurs when people react differently if told a product is “95% fat-free” versus “contains 5% fat”. The facts are identical; the framing changes the feeling.

Equally, loss aversion (the tendency to fear losing something more than we value gaining it) is important. Therefore, brands often use “limited time offers” and “only 2 left in stock!” to trigger urgency. Similarly, the default effect explains why most people stick with pre-selected options, whether that’s an auto-renewing subscription or a data-sharing preference.

Psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky

exposed these quirks in human reasoning. What began as academic insight into irrationality has evolved into a powerful toolkit for persuasion and manipulation.

In the marketplace, manipulation is heavily integrated into business models. Designers and marketers carefully craft experiences to steer users toward profitable actions including clicking, buying, or subscribing.

Retailers use decoy pricing, involving adding an overpriced option to make a slightly cheaper one look like a bargain. Streaming services auto-play the next episode to keep viewers hooked. Ecommerce platforms highlight “best-sellers” to harness social proof. And countless websites employ dark patterns which are deceptive design tricks like hidden unsubscribe buttons that exploit the human tendency to rush and trust.

Even small tweaks can have large effects. In 2012, British tax authorities increase payment compliance by simply adding a line to reminder letters: “Nine out of ten people in your town pay their taxes on time”. A small appeal to social norms boosted honesty. While behavioural insights for efficiency began as a research project, it can now become a blueprint for subtle coercion.

It’s not only businesses shaping choices. Governments, too, use behavioural science to guide citizens toward better outcomes like saving more, eating healthier, or reducing waste. For example, the UK’s “Nudge Unit” designed opt-out organ donation systems that dramatically increased donor rates. Similar initiatives encourage pension savings or prompt consumers to reduce energy use. These decisions are categorised as what economist Richard Thaler calls “libertarian paternalism” (the idea that people should remain free to choose, but the structure of those choices should steer them toward what’s good for them). However, it could be argued that even benevolent nudges can be manipulative. After all, who decides what’s “good”? And how transparent should these interventions be?

In the increasingly digitalised society of the 21st century, the manipulation of choice has become algorithmic, personalised, and invisible. Social media platforms use engagement algorithms that learn what keeps users scrolling, from outrage to affirmation, and feed them more of it. The architecture of the feed itself is a choice design: infinite scroll, red notification badges, variable rewards. Each element is carefully engineered to hijack attention and ensure that users return.

E-commerce sites personalise pricing and recommendations, subtly guiding spending patterns. Political campaigns micro-target voters with tailored messages. AI-driven systems can now predict preferences, narrowing the space for spontaneous or independent choice. In this digital ecosystem, manipulation may not feel manipulation. It feels like convenience.

As online systems become more integrated into daily life, the manipulation of choice has become a market force. Firms no longer compete only on price or quality, but on their ability to shape consumer behaviour through data and design. Predicting and steering choices is now a valuable economic asset.

This may raise new kinds of market failures. When businesses profit by exploiting cognitive biases, competition can reward manipulation rather than innovation. As a result, attention becomes a scarce resource while consumer welfare becomes the casualty.

Consequently, regulators are beginning to respond. The EU’s Digital Services Act and AI Act target deceptive “dark patterns” and demand transparency in algorithmic decision-making. Additionally, economists argue for behavioural transparency to retore fair competition.

Ultimately, the challenge ahead is balancing efficiency with ethics. Behavioural economics has revealed how easily choice can be shaped; the next step is ensuring that this mechanism serves both consumer and corporate interests.

Rachel L, Y12

In illegal markets, the strict hierarchy reflects economic logic. Gangs tend to operate like businesses, following strict order which incentivises each of the worker based on their level within the gang. Since the higher ups face worse punishment for their participation, they tend to be far removed from the lower ranked foot soldiers to reduce their risk. This is amplified even further by the presence of informants within the gangs. Thus, keeping their identity hidden is critical to minimising this risk However, the question is why the lower rank soldiers remain there even though they earn little more than a McDonalds worker and face a 7% chance of death per year in Chicago. Is it the respect? Could be... Is it an inherited line of work? In most instances no! Most people attribute participation to the fact that the lower-level workers hope to climb the hierarchy. This is supported by the Lazear-Rosen tournament model, where the highest rewards are so large that they justify the personal risk, creating an optimism bias that traps the gang members within the hierarchy as they overestimate the

likelihood of the positive effects and underestimate the negative effects. So why is working in a gang so appealing despite average gang wages being only slightly higher than the legal alternatives? It’s the potential and unlikely reward of the future that drives the foot soldiers into this industry.

Competition within gangs is driven by economic and behavioural factors and the result can often appear to be irrational from a profit perspective. Gangs compete especially at their borders to gain territory, reputation and a stronghold on the market sometimes at the cost of their profits and lives. During gang wars there is a sharp drop in the price and quantity of drugs sold by the gangs (about a 20-30% drop off). This is where the behavioural economics comes into play as this behaviour from a traditional economic perspective is irrational and inefficient. Concepts such as loss aversion (where people try to avoid losses as much as possible as they feel those effects more than that of the benefit of their earnings) and relative status bias (where gangs only really care about their status compared to other gangs) these

concepts tell us why gangs spend so much time defending or expanding their territory. Furthermore, the foot soldiers may even start conflict as it can lead to a boost in their standing in the gang as they gain a “tough” persona which can lead to better wages in the future and promotion opportunities. These social incentives are damaging to the gang as despite the initiator gaining social credit, the gang collectively is worse off. So why do gang leaders decide to go through with these gang wars despite knowing the potential danger? Due to their overconfidence as they believe that they can eliminate the threat without much loss. This would lead to a monopoly in the area which could allow the gang in future to charge exorbitant prices as there is less competition from their rivals This motivation can lead to not only gang conflict but also predatory pricing schemes where the gangs take on a loss on each of their sales to drive out the competition as the lower prices results attracting more demand in the short-term, hoping to undercut and drive competing sellers out of business. If the

competition persists then it is hard for the gangs to stop due to the sunk cost fallacy as they have already invested far too much therefore, they do not back out even if it appears to be the more rational decision. This is even more important in an illegal setting as if a gang stops this behaviour, they will lose status and thus face a humiliation.

In conclusion, gangs base their tactics on economic and behavioural factors. These factors influence their long-term control over their territory and over other territories. We also come to learn to that gangs act like corporations in their hierarchy and in some of the ways they deal with competition from rivals, employing predatory and pricing and oligopolistic behaviour.

In a world of mostly free trade, one of the oldest tools of economic policy remains arguably the most controversial: the tariff. Its job is to make goods of foreign countries more expensive than those made domestically. Many countries around the world use tariffs to protect local industries, safeguard jobs, or raise revenue. But while these sound like reasonable goals, the real repercussions of tariffs are far more complex. Lying beneath the surface is a question that every economist should ask: who really pays the price?

While tariffs may favour national interests at face value, this is not always the case deep down. If a country makes imported steel more expensive, domestic steelmakers can sell more of their own product and hence boost local jobs and output. Governments can also collect extra tax revenue in the process. However, the costs rarely stop with the foreign producers. Often, they find their way to the domestic consumers in the form of higher prices.

effectively pushed toward domestic alternativeseven when they are lower in quality, less efficient to produce, or simply more expensive than normal. It's an invisible cost of market distortion: resources get pulled away from where they can be most productively used, and consumers end up with fewer options.

A clear example is the tariffs the US imposed on imported steel and aluminium in 2018, to stop cheap imports and make domestic production more competitive, thus helping American labour. With higher import costs, car manufacturers and construction firms that relied on steel and aluminium had to pay more for foreign materials. These costs didn’t just disappear; they were built into the final prices of goods. Several studies showed that the financial burden was passed on to American consumers and businesses. In trying to "protect" certain industries, this policy had quietly taxed millions of ordinary households. This all points to one of the most important costs of tariffs: a reduction of choice. When imported goods become more expensive, consumers are

However, this effect goes further. Choice is one of the core freedoms in a free-market economy: the ability for individuals to choose what they buy, from whom, and at what price. When tariffs intervene in that process, they reduce what economists' term as consumer sovereignty. A policy designed to bolster national self-reliance can ironically narrow the availability of personal freedom in the market. The consumer, accustomed to choice and reasonable prices, suddenly finds some products have vanished from store shelves or become unaffordable.

But it is misleading to say that tariffs are always hurtful. Throughout history, there have been instances where they have been helpful, or at least they claimed to be. Perhaps the most famous claim is that of the infant industry argument, argued by economist Friedrich List, in which young industries in developing nations may need

temporary protection from established foreign competitors. They might never survive long enough to grow, innovate, and achieve the efficiency necessary to compete on a global scale.

Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan all used tariffs in strategic ways during the mid-20th century to nurture young industries such as steel, shipbuilding, and automobiles. Crucially, the measures were temporary and were often combined with tough government oversight and clear targets for eventual competition. Once those industries matured, many tariffs were reduced or taken away completely, enabling firms to prosper internationally. However, in practice, this is a difficult balance to strike.

Politically, tariffs are a tempting option because they play to a sense of economic nationalism. Promising to "protect" domestic jobs and industries is far more popular than having to explain the abstract benefits of free trade. But protectionism can quickly spiral into retaliation. When one country imposes tariffs, others often respond in kind. The result is a trade war, in which both sides lose. Anyone might guess that the 2018–2020 U.S.–China trade conflict is a good example:

businesses suffered from uncertainty, supply chains were disrupted, and consumers in both countries ended up having to pay more. Protectionism that starts off as a form of defence can quickly turn self-defeating.

This problem was illustrated more than two centuries ago by classical economist David Ricardo through his theory of comparative advantage. He argued that nations should specialise in producing the goods they can make most efficiently, and trade for everything else. Specialisation benefits all trading partners because global resources can then be used more productively. Tariffs interfere with his process: they encourage countries to produce goods that others could make more efficiently, wasting resources and reducing overall welfare.

What that all suggests is that tariffs are not simply about economics; they are about priorities. Should a government protect some jobs and industries, even if it means higher prices and fewer choices for its citizens? Or should it embrace open trade, accepting temporary disturbances for long-term efficiency and variety? The answer is not so simple, because each policy reflects a specific view of what economic success entails.

Economies that trade freely tend to innovate faster, to produce more efficiently, and to give consumers more choice. Tariffs, though sometimes justified as a developmental tool, must therefore be used with great caution. When applied broadly or indefinitely, they risk doing the opposite of what they intend-that is, making an economy less competitive, less dynamic, and less free. Ultimately, the cost of a tariff is not measured quantitatively, but is measured in lost opportunity, reduced efficiency, and choice forgone.

To the question of who really pays, there is one clear answer: the consumer whose freedom to choose is quietly lost in the name of national strength. With economic policies, there is always a trade-off. As much as tariffs will strengthen certain industries, they will do so at the expense of an important principle underlying all market economies: the freedom to choose.

Aryan N, Y12

One day. 24 hours. Hundreds of decisions. What should I have for breakfast? What clothes should I wear? Which slice of toast should I eat first? Every day, we are faced with hundreds of conscious and subconscious decisions that, in some way, contribute to shaping our lives. When framed in that way, you would expect every decision to be optimal and perfectly rational, like an economist; however, how irrational are humans in their daily choices?

Economics assumes that we make rational decisions; economic agents act to maximise utility. To do this, consumers weigh the costs and benefits, fully utilise all available information, and then make a decision.

However, it is clear to see that consumers do not act rationally. Consumers can't perform a costbenefit analysis on every decision they make, partly because it is impossible to quantify utility. Take, for example, eating a fruit; there are health benefits to doing this, but say you didn't like the fruit. Of course, eating too many fruits can also be bad. Thus, a consumer has to eat the optimal number, say 4.5, but then they must consider the negatives: pollution, packaging, and the opportunity cost.

Overall, it would be impossible, and nothing would get done, so consumers use heuristics, mental shortcuts that simplify decisions but can lead to errors. An example is five a day; while this heuristic is likely not the optimal amount to consume, it is an easy and quick way to help consumers get close to optimal levels. Through the use of heuristics, consumers attempt to act rationally but are still imperfect.

Another example of consumers being rational is the loss aversion theory. This ties quite closely to recency bias, which essentially means that things that have happened recently you think have a higher chance of happening again. With that in mind, the loss aversion theory states that people are more upset by a loss than by the equivalent

gain. For example, if you won £100, you would likely feel quite happy; however, you'd likely feel more sad if you lost £100 than the happiness you felt for winning £100. This isn't rational; nominally, these are the exact amounts, but consumers have irrationality in their decisionmaking. For example, the saying 'quit while you're ahead' exemplifies the phenomenon of loss aversion

in practice. Another example is that people might be unwilling to sell an asset at a loss, even though the price could decrease further, because they do not want to incur a loss. They would rather hold on in anticipation of a bounce-back.

Firms are also irrational in decision-making. In economics, we assume that firms act to maximise profit. In reality, we know this is not the case; for example, some firms may act to maximise sales, revenue, or profit, satisfying. Or achieve other objectives such as environmental responsibility and corporate social responsibility. Some firms may choose to revenue-maximise to

gain market share or to be seen as more stable borrowers by banks. This would occur at a point where the marginal revenue equals zero. This will be seen as irrational because why would a firm produce beyond an output where its profit isn't maximised? However, they might do this to gain brand loyalty or to achieve a massive market share. Firms may also choose to 'profit satisfy', which is not profit maximisation, but instead producing at a level where profit is reasonably high, but not the absolute maximum. This could be because they choose to increase wages, which increases costs to a higher than optimal level and decreases profits. This would be seen as irrational, as firms should want to produce at the lowest possible price. However, in reality, you can see why this might be done to keep workers and make them happy, ultimately increasing long-term productivity at the firm. Finally, firms that commit to social responsibilities, such as protecting the environment, can incur very high costs and be irrational to do so, especially if the costs are unnecessary. However, due to growing social pressure, you might see firms doing this, which again seems irrational, but actually happens often in reality.

Therefore, it is clear to see that firms, and every single economic agent, act irrationally every single day. Consumers and human error are involved. Also, unlike any other, it is practically impossible for consumers to make decisions as a result of perfectly rational thinking, when emotion is very rare to see a firm acting purely to maximise profit. Some firms, like monopolies, do, and thus it is seen, but it is unlikely, partly because it is very hard to do, as it can be challenging to retain workers if you pay them a lower wage than competitors. They are more likely to profit satisfy where they attempt to make a fair profit but realise it is impossible to have costs exactly at a minimum.

Judging by public consensus and their revealed preferences, people love cities. Metropolises such as London, New York or Tokyo burst with large population numbers, which is catered to by global firms that tend to cluster towards the central business districts in such cities. Across the world, it is estimated that almost a quarter of people live in cities that boast populations of over a million, which is a near 100% increase from what it was just 40 years ago. London houses 15% of the UK population, and yet is responsible for 25% of its GDP.

Economists generally consider this to be a good thing. Big cities and large-scale business hubs benefit from “agglomeration”, the wide-spread impacts that come from people living in close proximities. Recruitment for workers becomes easier, due to the increased supply of readily available labour. Firms and people alike benefit from shared infrastructure and reduced costs of transaction. Density allows ideas to flow through physical networks, which has potential to fuel both productivity and innovation.

Swedish economist Gunner Myrdal founded the theory of cumulative causation, which provides links to how these central hubs can form, such as in London. Once an area gains a small advantage, like

early advantages in trade, access to the Thames or political power, it attracts firms, which then creates jobs, which then attracts more people, then leading to a positive feedback loop of growth. Once the hubs are established, they become difficult to replicate elsewhere, which can be attributed to factors such as sunken infrastructure.

Central hubs hold inherent potential for profitability as they make most out of these agglomeration economies.

Past the positive externalities of profitability, market stimulation and job opportunities that follow urban density, equally pressing drawbacks exist. High congestion rates that come with greater scales of commuting puts strains on the environment and ramps up air pollution. The demand for housing, for example, in densely populated areas can greatly drive up property prices, which creates a regressive barrier between individuals affording housing. London holds an average housing price of £485,000 for first time buyers. This then has the ability of catalysing social issues such as homelessness or exacerbation of poverty rates.

Architecture therefore, becomes a vital mechanism to design cities around their density. With the UK’s

2050 Net Zero pledge for carbon control, urban design has taken a shift towards prioritising sustainable and environmental lenses. Rooftop gardens, green spaces or even living installation walls are all methods of greening that act as environmental relief. The softening of harsher urban edges with nature builds calmer, and more harmonious atmospheres which has shown to improve productivity. With widespread integration, greening can also aid the mitigation of air pollution in major cities. Similarly, the rise of purpose-built homeless shelters and low-income

targeting social housing indicates awareness of the rise in unhoused individuals.

With economical and architectural thinking in hand, agglomeration can become something greater than growth... a model for successful, sustainable, and socially aware cities.

Will J, Y13

Originally viewed as the defining principle of the modern state system, sovereignty, the ability and authority of a state to govern itself as well as its people without the interference from external parties, has become increasingly contested within the 21st century, an era of ever growing interdependence. As global challenges such as climate change, pandemics such as COVID-19, and trade disputes which all transcend their national borders has meant that states have turned global governance frameworks, once from the United Nations (UN), the World Health Organisation (WHO) to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in order to coordinate cooperative and collective action to solving problems on a global scale. However, the components which encourage and promote this cooperation, often limit the autonomy of the nation states, thus effectively eroding traditional notions of sovereignty. May this be through binding security resolutions,

international law, negotiated agreements, shared decision making, enforceable commitments and many more, national as well as international decision making is now shaped by organisational forces that are far beyond domestic control. As a result, this raises questions about the choices states must make in order to balance their interdependence with the need for collective action, thus becoming a choice between autonomy and the benefits of cooperation. This article will explore how such frameworks can contribute to the erosion of sovereignty in international policies.

The concept of sovereignty which has traditionally been perceived through the Westphalian model, which was developed in Europe after the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, and based on the state theory of Jean Bodin and the teachings of Hugo Grotius, with The Peace of Westphalia being considered the origin of this model, which established the principles of territorial sovereignty, legal equality

and non-intervention in the affairs of other states. Under this framework, states are considered independent, and are therefore fee to determine their own laws, policies, and governance without interference from external powers. However, due to both increasing interdependence and globalisation, this has been limited, which has meant that states now have to work within the complex economic, political and legal obligations set by intergovernmental organisations and multilateral treaties and agreements.

Conversely, global governance refers to the coordination and cooperation of both systems and institutions that manage issues that go beyond national boundaries. These include formal organisation such as that of the UN, WHO and the WTO, as well as informal organisations such as Non -governmental Organisation (NGOs) through networks and treaties that aim to coordinate international action. Thus the core purpose of global governance is to address challenges that cross national borders that cannot be effectively solved by a single state, such as climate change, trade and pandemics. However, while such systems and networks are designed to encourage and promote cooperation and stability, it also redistributes both power and authority away from nation-states. As a result, sovereignty today compared to the past is being continuously shaped by the demands and constraints of global governance.

An obvious example of how international coordination can simultaneously advance global goals while limiting national sovereignty is through climate governance. The Paris Agreement (2015), adopted under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which commits signatory states to limit global temperature rise and to submit Nationally Determine Contributions (NDC's) which must outline their emission reduction targets. While participation is voluntary, the agreement creates binding expectations through various means such as reporting, peer review and international pressure, and if states fail to meet their pledges they risk financial penalties, criticism and reputational damage within the global community. Furthermore,

domestic policies, such as carbon pricing, renewable energy targets and emission targets, are increasingly be shaped by international standards and norms. This advancement therefore illustrates what scholars describe as a form of "soft coercion", where sovereignty is constrained by global expectations. While the Paris Agreement embodies the collective commitment of nation states to address and aim to repair a shared crisis, climate change, it also demonstrates how the pursuit of environmental governance can ultimately erode the autonomy of individual states. Ultimately, the Paris Agreement illustrates how global governance requires nations to make difficult choices between upholding their own policy preferences and committing to shared global goals.

In addition to this, the COVID-19 global pandemic highlighted the emerging influence of global health governance in which it shapes national policy and its response as well as the tension brought with it concerning state sovereignty. The WHO, through their Internation Health Regulations (IHR, revised 2005), requires all member states to report outbreaks, share data and to adhere to international health guidelines which aim to prevent and minimise cross-border disease spread. While these regulations are not legally enforceable in the same way that domestic law is, they do however exert a significant political pressure on the member states to conform to these regulations. During the pandemic, many governments faces criticism for deviating from WHO recommendations such as the United States under the Trump administration (which downplayed the severity of the pandemic, promoted unproven treatments, diverged from WHO's guidance on mask use, testing and social distancing), Bazil under President Jair Bolsonaro (which discouraged the mask use, promoting drugs such as hydroxychloroquine which was directly advised against by WHO), Tanzania under President John Magufuli (who discouraged testing, and claimed that the country was COVID-free through prayer which prompted direct criticism from WHO officials) as well many more governments, while others depended heavily on its technical and logistical assistance. Moreover, the proposed WHO Pandemic Accord, which is currently under negotiation, has further reignited debate over the

balance between collective security and national autonomy. With critics arguing that such agreements could enable international organisations undue influence over domestic health measures, supporters view them as necessary in order to maintain a coordinated global response to such a widescale issue. Therefore, the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates how global health governance, though crucial for dealing with transnational crises, can actually limit a states' freedom to act independently, which in turn can erode the traditional views of sovereign authority in the interests of global cooperation and coordination. Moreover, international trade provides another example of how global governance frameworks constrain national sovereignty. The WTO, which was established in 1995, regulates trade relations between its 164 member states through a system of binding agreements and dispute settlements. Member states must world to align their domestic trade laws with WTO principles, those of which include non-discrimination and market access, and if fail to do so, they risk facing sanctions and/ or retaliatory measures. As a result, this framework effectively limits the governments' ability to seek independent trade or industrial polices which may conflict with global trade rules. Furthermore, current trade agreements are increasingly extending beyond traffics in order to include standards on intellectual property, environmental regulation as well as labour rights, all of which further embed the global norms into domestic law and governance. While some argue that these provisions aim to prioritise the global market efficiency over social objectives (particularly in developing economies which have less bargaining power compared to other developed economies). Once again, while participation in WTO is voluntary, the interdependence makes withdrawals from the organisation with politically and financially costly. Consequently, trade governance demonstrates another way in which sovereignty is being eroded, evident where economic stability as well as access to global markets come at the expense of national policy autonomy.

Across climate, health and trade, global governance frameworks illustrate a shift in how sovereignty

works in the international system, with states now sharing authority through intergovernmental institutions and treaty agreements. This sharing of power can be seen as both a constraint and as a sense of freedom and adaption, while national autonomy is limited, participation in global governance allows states to organise collective agreements and outcomes that would also include mutual benefits which are secure, which would otherwise be unattainable in isolation. David Held (2002) and Anne-Marie Slaughter (2004) both describe this as a form of "post-sovereign governance" where sovereignty as a result becomes "relational" rather than "absolute". Yet, this raises questions about accountability and legitimacy, particularly when global institutions make and enforce decisions that affect populations without direct democratic input. Therefore, the erosion of sovereignty under global governance frameworks presents not only a loss of control but also a transformation of political authority in response to an increasingly interconnected globe.

In conclusion, global governance frameworks have reshaped the traditional understanding of sovereignty. States are no longer isolated, instead they are all participants in an interconnected system that seeks cooperation and agreement. While such frameworks (mentioned above with the example of climate policy, health governance and international trade) have partially eroded independent decision-making, it has also enabled states to address challenges that go beyond national borders. Thus, sovereignty as we know it today, is not "abolished" but rather has been redefined through negotiation, shared authority and dependence on other states, where the aim and challenge of the 21st century lie in maintaining accountability within these global systems. However, looking into the future, as uncertain as anything, it is clear that states will continue to face the challenge of balancing sovereignty with the demands for interdependence. Furthermore, the emergence of new technologies, global migration and cyber threats, will likely mean that states will require an even greater cooperation, which in turn will require more shared decision-making.

Arya L, Y12

The ‘AI Bubble’ is rapidly reshaping markets and policy debates, and is emerging as central to how investors, tech firms, and policymakers address both the promise and risks of this new technology. A way to gauge public sentiment toward new technologies is to examine the stock market, and a quick glance now reveals unparalleled optimism.

Over the past year, AI-related equities, particularly amongst the ‘Magnificent Seven’ tech firms and a surge of startups have soared in value. More than 1,300 AI startups now have valuations of over $100 million, and nearly 500 boast valuations of at least $1 billion. However, this has occurred often without parallel increases in revenues or profits. Investment in data centres, specialised chips, and AI infrastructure has reached historic highs, with global spending on generative AI forecast to reach $644bn in 2025, representing a 76.4% jump from 2024. These investments and valuations echo classic bubble patterns, such as intense index concentration, circular transactions, and vendor financing.

Unprecedented choices confront investors: whether to join the AI ‘gold rush’ or exercise caution in an overheated market. Retail investors, in particular, have had an outsized influence in recent rebounds and surges, amplifying volatility through their collective decisions. Meanwhile, institutional investors debate when (and how) to pivot as warning signs, such as profitless growth and overvalued startups, proliferate.

Like bubbles of the past, AI is about optimism

versus realism. A tug of war shaped by conscious choices about what future value AI can actually achieve against the current hype. Even seasoned analysts draw comparisons to previous boom-andbust cycles: exuberant investment in internet, telecoms, or housing sectors eventually gave way to painful corrections when reality diverged from expectation.

Beyond the market, government and firm choices will play a decisive role in shaping the direction of the AI economy. Policy makers are considering tighter regulations on data privacy, security, and fair competition - choices that could slow or channel growth. Firms face choices around capital allocation: whether to double down on expensive infrastructure and talent or pursue more cautious, incremental strategies. Some leaders urge restraint, noting that only a fraction of current AI deployments deliver measurable returns, and that the risk of catastrophic fallout increases if hype outpaces performance.

The fact that the AI boom is anything but monolithic is

one important realisation. Although attention is drawn to headline valuations and spending - more than $400 billion by tech companies in 2025 alone - they conceal significant differences in who gains and how value is created. Only around 5% of AI projects currently produce real, quantifiable commercial effects, and the majority yield little to no return on investment, according to MIT research. This indicates a "innovation chasm" where a large portion of cash is invested in hype and experimentation, but only a small portion results in increased productivity, efficiency, or new sources of income. Adoption also varies greatly: businesses and industries that successfully incorporate AI tools into their workflows and decision-making processes experience success, while others remain stagnant or remain doubtful.

The scale of AI infrastructure investment - the submarine cables, sprawling data centres, custom silicon chips - is unprecedented. This physical layer, unlike some bubbles based purely on financial speculation, forms durable backbone assets that can underpin future growth. Yet, this asset-heavy profile also means excess capacity, rapidly rising costs, and complex supply chains susceptible to shocks. The choice companies face is whether to continue ‘doubling down’ amid uncertainty or to pivot to more sustainable,

incremental strategies that emphasise ROI and operational integration.

The Bubble’s Broader Economic Role

AI investment today serves as a major prop in the US economy, supporting GDP growth, corporate earnings, and stock market valuations, even as broader wage growth has stagnated and vulnerabilities manifest in loan defaults and supply chain disruptions. This raises challenging questions about sustainability: Is the AI bubble masking deeper systemic weaknesses? Can productivity gains from AI “catch up” before the reckoning arrives? Or will the bubble burst, triggering a painful, yet perhaps necessary, reset in tech valuations and economic expectations?

Avoiding a dramatic crash and realising AI’s transformative potential will require tempered expectations and strategic discipline. Investors need to align valuation with foundational business metrics. Firms must emphasise integration and incremental innovation over chasing hype cycles. Policymakers must strike a balance between innovation freedom and thoughtful regulation. Society at large must grapple with the social and economic impacts that accompany this seismic technological shift.

In this light, the ‘AI bubble’ can also be seen as a crucible of choice - a crucible where decisions made now will determine whether AI propels a new era of productivity and prosperity or becomes a cautionary tale of misallocated capital and lost opportunity. How markets, firms, and governments navigate this uncertain terrain will determine whether it leads to a boom, a bust, or a lasting transformation.

The conflict between Israel and Palestine has shaped the region’s politics for decades, but it has also had a quieter, long-term impact on how economies across the Middle East function. Patterns of instability, restrictions on movement and trade, and repeated political breakdowns have created economic structures that are hard to separate from the conflict itself. Israel has been able to develop a strong, modern economy, while the Palestinian economy has grown under far more restrictive conditions. These dynamics don’t stay contained within the two territories; they spill into neighbouring countries, shaping investment decisions and long-term development paths across the region.

A big part of the current economic setup dates back to the 1994 Paris Protocols. The agreement essentially tied the Palestinian economy to Israel’s. Israel controls borders, customs and the flow of imports and exports, while the Palestinian Authority adopted much of Israel’s tax and trade framework. This created a situation where Palestine doesn’t have access to independent trade routes or full control over which goods enter and leave its territory. As a result, most Palestinian exports still go to Israel, and trade costs remain well above regional averages because of delays and restrictions at crossings.

The fiscal side is tied in as well. The PA’s budget depends heavily on “clearance revenues” taxes collected by Israel and then transferred. These transfers make up the bulk of the PA’s income, which means that any interruption has an immediate effect on public salaries, social services and government operations. Over the past several years, there have been multiple periods when these funds were partially withheld, creating financial stress that ripples through the entire economy. It is difficult for any economy to grow when

its main source of revenue is vulnerable to political tension.

Labour mobility reflects a similar pattern of dependence. For decades, many Palestinian workers have sought employment inside Israel because wages are higher and opportunities more consistent. The domestic economy, limited by restrictions on movement, investment and infrastructure, has struggled to create enough jobs. Although the number of permits for Palestinian workers has changed over time, the overall structure hasn’t shifted much: many households rely on income from jobs in Israel. Over the long term, this has made it harder for the Palestinian private sector to develop, because skilled and semi -skilled workers are pulled toward short-term, external employment rather than domestic industry.

These economic dynamics don’t just affect Israel and Palestine. Investors tend to view the Middle East as an interconnected region, so instability in one place increases perceived risk in others. Jordan is often the clearest example. Its economy is tied to both Israel and the Palestinian territories through tourism, trade and energy cooperation. When violence escalates, tourism declines and investment decisions get put on hold not only in the immediate conflict zone but across neighbouring countries. These shifts aren’t always temporary; once investors redirect capital toward more stable regions, it can take years to rebuild confidence.

Regional integration has been another casualty. Over the past few decades, there have been multiple proposals for cross-border industrial zones, energy grids and infrastructure projects meant to connect the region

economically. Most never moved forward because political instability made long-term planning too risky. In other parts of the world, similar projects have helped reduce costs and expand markets. Without them, Middle Eastern economies remain more fragmented, with inconsistent access to resources and markets. This limits the kind of supply-chain development that has driven rapid growth elsewhere.

Neighbouring countries also bear fiscal pressures related to the conflict. Jordan and Lebanon, in particular, have hosted large refugee populations for many years. While this reflects humanitarian commitments, it also strains national budgets, especially in countries already dealing with high debt levels or limited revenue. When governments must allocate large portions of their budgets to short-term needs, they have less capacity for longterm investments in infrastructure, education or healthcare. This affects development paths for decades, even after immediate crises fade.

Israel’s economy, though comparatively strong, is not insulated from the effects of prolonged conflict. Defence spending takes up a significant share of the national budget. While this investment has supported technological innovation in some sectors, it also limits how much can be spent on social services and other civilian priorities. Inequality within Israel has grown over recent decades, and some analysts argue that the country has developed into a two-track economy: one highly advanced and globally competitive, the other shaped by high security costs and uneven access to opportunities.

In the Palestinian territories, especially in Gaza, the constraints are far more severe. Economists often describe the situation as a “low-level equilibrium trap,” where uncertainty, limited access to capital and repeated cycles of destruction prevent the economy from breaking out of stagnation. Gaza’s economy has contracted multiple times since the blockade began, and its unemployment rate

remains extremely high. Restrictions on construction materials and industrial inputs make rebuilding difficult, and even basic infrastructure including electricity and water systems has been repeatedly disrupted. These conditions make longterm planning almost impossible for both businesses and public institutions.

These economic challenges have direct human consequences. High unemployment and restricted mobility limit opportunities for young people, who make up a large share of the population. When job prospects are uncertain, students may feel less motivated to pursue higher education, and many skilled individuals look for ways to leave when possible. Over time, this reduces the stock of human capital something every developing economy depends on for future growth. Once a significant portion of young, educated people start seeking opportunities abroad, it becomes much harder for local institutions and industries to rebuild.

Taken together, the economic effects of the conflict reach far beyond what appears in GDP figures or short-term market indicators. The Palestinian economy operates under conditions of limited autonomy; Israel’s economy carries long-term costs tied to a heavy security burden; and neighbouring states absorb pressures through reduced investment, strained budgets and disrupted trade. Understanding these dynamics doesn’t diminish the political or humanitarian dimensions of the conflict. It simply shows that the economic consequences shape the region’s trajectory in ways that are easy to overlook but hard to reverse.

Any long-term improvement would require not just political progress but also more stable economic structures that allow people throughout the region to participate fully in trade, investment and production. Without that, the economic costs of the conflict will continue to accumulate across generations, shaping development in ways that are felt long after individual crises end.

Harry L Y13

There has been a meteoric rise in nuclear energy stocks such as Oklo (OKLO), Cameco (CCJ), Centrus Energy (LEU), and Constellation Energy Group (CEG). These companies have experienced a rapid increase in share price (roughly 60% YTD across the sector) as their demand has grown. The increased demand for nuclear energy can be explained in three major ways, and this article will also consider other factors relating to the growth of nuclear energy in relation to AI.

Firstly, energy is very necessary to power AI models, and apart from their water consumption, energy is the most important factor. As of April 2025, around 1.5% of global electricity is spent on powering data centres. Moreover, the International Energy Agency (IEA), estimates that global datacentre power demand could increase by between 128% and 203% by 2030, mostly because of AIrelated energy consumption. In 2022, AI models used 460 terawatt hours of electricity, and IEA expects this to double by 2026. “This demand is roughly equivalent to the electricity consumption of Japan,” says the IEA.

Furthermore, nuclear energy is reliable as it can be produced continuously and does not rely on external factors such as wind or solar.

Secondly, nuclear energy in particular is seen as a positive alternative to other energy sources as it is low-carbon, needing a very small amount of fuel, and whilst still being non-renewable, it has a much longer time scale than other non-renewables. Nuclear energy can be contracted for much more effectively than oil or gas, as the price is not as volatile. To offer a comparison, large-cap oil companies are struggling as demand tapers off for ‘dirty’ energy, and supply far exceeds demand, creating a surplus of 1.9 million barrels/ day.

As a result of its clean and reliable reputation, nuclear energy investment has increased globally. France and Japan are restarting nuclear expansion, while China is building dozens of new plants, with some specifically powering AI-related industrial zones. In the UK, the government announced a £14.2 billion investment to build Sizewell C nuclear plant in June 2025. Across the Atlantic, the Trump administration is committing more than $80 billion to buy reactors from Westinghouse Electric Co. CCJ owns a major stake in Westinghouse, meaning its share price surged by around 25% in late October 2025 as this deal positively impacted Westinghouse, and therefore CCJ. This is a demonstration of positive sentiment towards nuclear energy by Trump, as he pledged to increase capacity from 100GW to 400GW by 2050. This injection by government improves the credibility of the nuclear sector, encouraging AI tech giants to make contracts of their own.

Microsoft signed a contract to receive energy from Three Mile Island nuclear plant for the next 20 years, owned by CEG, and paid $1.6 billion.

Finally, plentiful innovation within the sector has caused fast growth as many companies find ways to differentiate themselves. For example, OKLO –chaired by Sam Altman (founder of OpenAI) from 2015 to April 2025 – produces microreactors which can cost as little as $50M for the most compact model. These small modular reactors (SMRs) offer an alternative for nuclear energy, as they provide scalability, with potential for deployment near data centres. This adaptability would allow nuclear energy to improve existing infrastructure without needing new development, as SMRs can be used instead of large power plants. Clinching this innovation is the production of HighAssay Low-Enriched Uranium which is the only form of uranium that can be used in SMRs as it is a more efficient, advanced fuel. LEU is the only US-based producer of this fuel, and as the Trump administration ramps up protectionist/isolationist economic policies using tariffs, the location of LEU has guaranteed demand.