Coastal real estate prices rise like the sea

Some counties see doubledigit percent increases

BY DORATHY MARTEL

Compared to the rest of the Northeast, housing in Maine looks like a bargain. According to the Maine Real Estate Information System, the median sales price for a Maine home in 2023 was $353,000. For the Northeast as a whole, the fourth quarter 2023 median was $698,000, as reported online by Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED). Nationwide, the median was $417,000.

But a Maine home with water frontage or an ocean view is another story. Yes, you can find a twobedroom house in Beals listed at $169,000, but that’s a rarity on the Maine coast, where you can also buy a 10-bedroom property on Mount Desert Island for $17 million or an eight-bedroom home for $9,775,000.

Most of the coastal counties have seen a rise in median sales prices from 2022/23 to 2023/24.

The Maine Association of Realtors reported a yearto-year increase of 8.92% statewide; but except for Washington County (down 2.27%), the coastal counties saw significant increases—from a 10.67% rise in

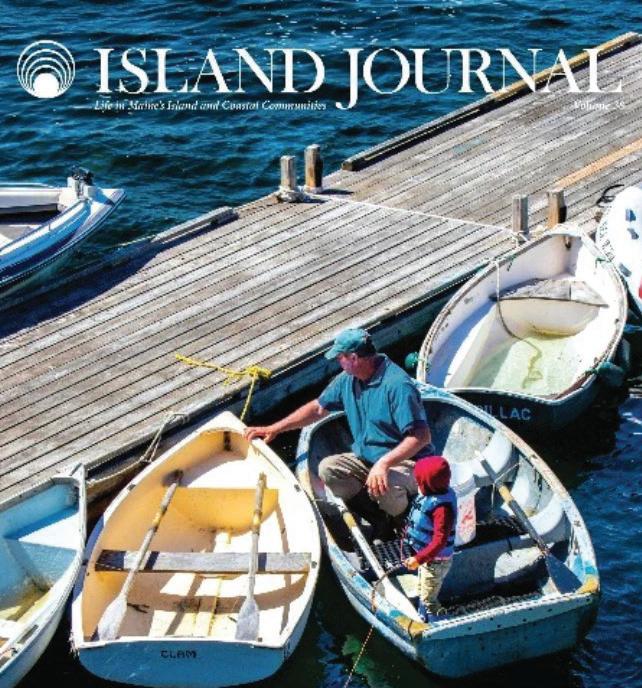

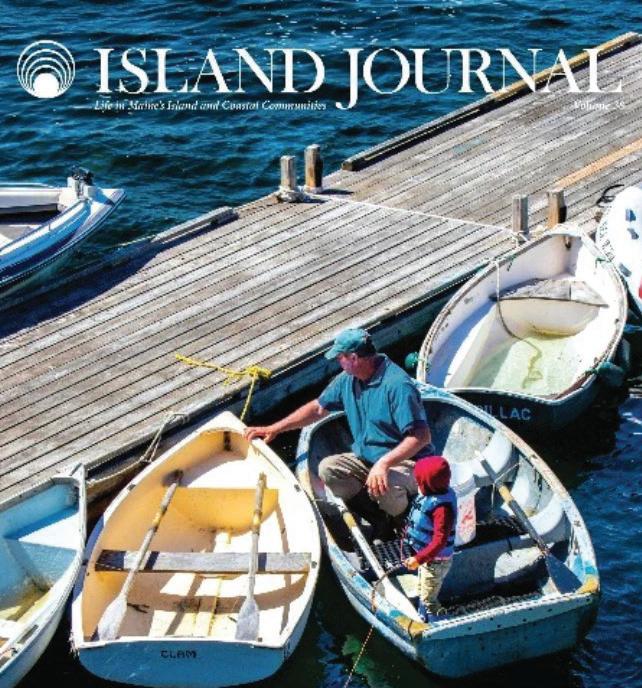

PORT CLYDE RISING—

Knox County to a nearly 32% jump in Waldo County. Cumberland County, with the highest median price in the coastal counties ($525,000), saw a 16.6% increase.

Even with high selling prices, “There’s a shortage; inventory is low right now,” says Tacy Redlon, a broker with Better Homes & Gardens, The Masiello Group, who primarily covers Hancock County and eastern Penobscot Bay.

“That pandemic era could not sustain itself,” she notes, referring to a spurt of activity that occurred

when more people began working remotely and property changed hands in “a feeding frenzy.”

Monet Yarnell, a broker, auctioneer, and waterfront specialist at Sell 207 in Belfast and president of the Midcoast Board of Realtors, agrees that finding saleable properties is a challenge.

“Across the board we have a limited number of properties available,” she says.

continued on page 5

Seafood landing values up $25 million over 2022 Lobster sales to dealers up $72 million, but catch down

The state Department of Marine Resources announced on March 1 that 2023 was another strong year for Maine commercial fishermen who earned $611 million at the dock point of sales, an increase of more than $25 million over 2022.

“The Maine seafood industry continues to be a powerful economic engine for our state,” said Gov. Janet Mills in a press release. “The dedication to sustainability and premium quality by our fishermen, aquaculturists, and dealers is a source of tremendous pride

CAR-RT SORT POSTAL CUSTOMER

for everyone who calls Maine home.”

The jump in overall value is largely attributed to a strong boat price for lobster, Maine’s most valuable species in 2023. The price paid to fishermen increased from $3.97 per pound in 2022 to $4.95 per pound in 2023, netting harvesters an additional $72 million compared to the previous year, for a total value in 2023 of $464 million.

Almost 94 million pounds of lobster was landed in 2023, the lowest in 15 years. Industry advocates have suggested that the catch is a return to average after several years that saw landings of over 100 million pounds.

drop in that population which has triggered a change in the legal minimum and maximum sizes, which goes into effect in January 2025.

Maine oysters were the fourth most valuable harvested product at over $11 million on the strength of a 20-cent per pound increase in value.

“The price Maine lobstermen received last year is a reflection of the continued strong demand for this iconic seafood,” said DMR Commissioner Patrick Keliher. “Consumers and buyers recognize the Maine lobster industry’s longstanding commitment to sustainable, responsible harvesting practices and how it provides a unique, premium culinary experience.”

Maine’s elver fishery once again was the second most valuable in 2023, earning fishermen $19.5 million on the strength of a $2,009 per pound price.

Still, a three-year sampling of juvenile lobster showed an average 40% continued on page 5

NON-PROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE PAID PORTLAND, ME 04101 PERMIT NO. 454 News

published by island institute n workingwaterfront . com published by island institute n workingwaterfront . com volume 38, no. 2 n april 2024 n free circulation: 50,000

from Maine’s Island and Coastal Communities

An aerial view of Port Clyde’s working waterfront shows construction is well underway after fire devastated three businesses in September. See more photos on pages 14-15. PHOTO: JACK SULLIVAN

Take our READER SURVEY Pages 19-20

Newfoundland, Maine share maritime past But Canadian

province’s story diverges from ours

BY PATRICIA ESTABROOK

PHOTOS BY RAY ESTABROOK

Ihad heard that when you went to Newfoundland you felt as though you were in Maine in the 1970s.

Since I remember that period vividly, I thought it might be fun to re-live my youth.But when I got off the ferry in Channel-Port aux Basques, I realized that I had not walked back in history, but I had walked into a dream. The fantastical mountains kneel in the crashing surf and every vista seems to be right out of a Tolkien novel. Newfoundland isn’t, and never was, Maine.

In 1497, the European explorer John Cabot visited Newfoundland on behalf of England. He was looking for gold and spices but what he found was even more important to the hungry people of Europe—cod. The Grand Banks were teeming with cod.

From the early 1500s on, French, English, Portuguese, and Basque fishers came to Newfoundland to change the fishing culture from subsistence fishing of the First People to a major export economy. For more than 400 years cod fishing was the mainstay of the Newfoundland economy.

Well into the 20th century fish flakes (drying racks) lined the waterfront streets of St. John’s, bringing the reek of drying fish and clouds of flies. St. John’s hosted fishing fleets from around the world and the province’s small “outport” towns sent their catches to St. John’s for export.

Cod was king but the fluctuations in price and catch size made

a precarious living for fishers. Gravel-filled glacial till soil and a short growing season discouraged commercial agriculture. Logging never assumed the importance it did in the Maine woods. The fishing industry controlled the economy of Newfoundland and it was a boom or bust existence for thousands of hardy men and women.

Newfoundland was a dominion of Great Britain until 1949 when it joined Canada as part of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. In the 19th century Newfoundland considered becoming part of the U.S. and had it done so it might have become more like Maine, but its long history of allegiance to Great Britain shaped the thinking and economy of Newfoundland.

In the mid-20th century two events changed everything: the election of Joseph “Joey” Smallwood

as premier—serving from 1949 to 1972—and the collapse of the cod fisheries.

Smallwood was a visionary leader whose influence on the economy and culture of Newfoundland will be evident for a hundred years. He began the process that took a struggling colony to its present status as a stable Canadian province, but his long tenure as premier was not without challenges.

Smallwood was an innovator who backed numerous attempts to diversify the Newfoundland economy, most of which failed. Cod remained the monocrop of the Newfoundland economy. Then, in 1951, factory fishing changed the cod industry.

In 1968, at the height of the factory fishing period, 810,000 tons of cod were taken in factory fishing by international fishing fleets. By the 1990s the cod fishery had collapsed and a moratorium on cod fishing was established by the federal government in Ottawa. Newfoundlanders are famously proud of their homeland but the changes in the cod industry increased out-migration, particularly to the U.S. The cod processing stations, called fishing premises, that once dotted the coastline were abandoned. The cod drying flakes were removed. Even today the harbors of Eastern Newfoundland are mostly empty.

Fishing boats and pleasure boats are uncommon in the sparsely populated outport communities. This change is often tied to the statement reputed to have been made by Joey Smallwood, “Burn your boats,” when he was trying to

2 The Working Waterfront april 2024

Rough seas, rough-edged cliffs mark the coast.

A St. John’s streetscape shows the bright colors locals favor.

encourage the transition from smallscale fishing to a more consolidated (and he believed) a more profitable factory model. The boats are gone and so are many of the rural outports that were once an important part of Newfoundland’s heritage.

Changes as radical as those of the Smallwood era are unimaginable in Maine. In the period from the 1950s to the 1970s, Smallwood’s administration worked to bring Newfoundland up to the standards of Atlantic Canada and the U.S. One of the most significant attempts to create change was the closing of 200 communities and the resettlement of 28,000 people.

Today, many outports are merely summer colonies. Towns are consolidated. There is no sprawl. Newfoundlanders live within the confines of specific towns with vast empty spaces between settlements.

Almost all commerce is located in major towns and within those towns segregated into shopping districts. In rural towns you don’t step out to the corner store because usually there is no store or even a corner.

The outports are hollowed-out towns. Local schools, those that have not been consolidated, are serving fewer than a dozen children when there used to be hundreds. Parents commute to the major towns and local shopping is unavailable. Still, a love of place keeps residents clinging to the outports even in the face of dramatic changes.

Resettlement has been a challenge for Newfoundlanders but has brought benefits to visitors. In every community there are well maintained walking trails beside

the ocean where you can see icebergs floating by from June through August and the crashing surf all year long. Like Maine, most beaches are rocky and the Newfoundland waves from the North Atlantic are perilously cold.

Today’s Newfoundland seems prosperous in comparison to Maine. There are no mobile homes and every house, every shed, and even every doghouse is clad in vinyl siding. In Newfoundland vinyl siding has gone to heaven. Barns have been replaced by Quonset huts that were introduced during the World War II period and are remarkably common. A generous government and opportunities in the expanding alternative energy fields have brought prosperity

to the average Newfoundland family. Immigration from developing countries will shape the future of Newfoundland.

Downtown St. John’s combines past and present. On Water Street Celtic music from the Clancy Brothers and Irish Rovers billows out of the bars at all hours. Irish folk culture is more vibrant here than in Ireland. Kissing a cod fish in one of these bars allows you to become an honorary Newfoundlander. I skipped the cod but was embraced by a local family from an outport called Renews.

Music and storytelling venues dot the city of St. John’s even in the off season. Newfoundland Celtic music is nostalgic. It celebrates the love of place even more than romantic love. It is also

seductive and makes you fall in love with Newfoundland itself. Everyone in Newfoundland knows the Ron Hynes song, “Sonny’s Dream.” If you don’t learn the words the first time, don’t worry, you will hear it hundreds of times more.

The Rooms is a locus of art and culture for Newfoundland and Labrador. Part museum, part archives, part performance space, it is at the center and heart of St. John’s. The past never dies in Newfoundland and the exhibit at the Rooms about World War I brought me to tears. After two hours of viewing, I mourned for families I had never known.

Memorial University is just a short hop from downtown St. John’s and lends an international air to the city. New Canadians from across the world mingle with students whose heritage in Newfoundland and Labrador goes back for centuries. The new Canadians bring youth and vitality to St. John’s and the hope that they will choose to make Newfoundland their permanent home. The folklore department at Memorial University is considered one of the best in the world. Its influence has renewed interest in mummering, a Christmas tradition that was brought to Newfoundland from Ireland generations ago.

Maine and Newfoundland share a maritime past based on fisheries and the desire for new opportunities. Astute Mainers won’t look to Newfoundland as a nostalgic trip to the 1970s but will see the potential for a joint future of economic and social revitalization.

Patricia Estabrook lives in Belfast.

3 www.workingwaterfront.com april 2024

The Barrenlands in Chidley.

Gros Morne looms over Bonne Bay.

State selects Sears Island for wind port

Islesboro, Friends groups oppose decision

BY TOM GROENING

After years of deliberating on the best site to establish a port to service a planned offshore wind turbine array, Gov. Janet Mills announced Feb. 20 that the facility would be built on Sears Island in Searsport.

Port facilities in Portland and Eastport were under consideration, as was Mack Point on the mainland in Searsport. A hybrid plan that would have included both the existing piers at Mack Point and a new facility on Sears Island also was considered.

State officials asserted that a new “purpose-built port facility” on Sears Island would establish Maine’s place in the growing offshore wind industry and become a hub for job creation and economic development.

The land portion of the facility would allow for floating offshore wind fabrication, staging, assembly, maintenance, and deployment, which would have the turbines towed to their mooring sites. There is deep water access adjacent to Sears Island.

The array is proposed to include 10–12 turbines on semi-submersible floating concrete platforms, designed by the University of Maine’s Advanced Structures and Composite Center.

The site selection process was led by the Department of Transportation and Maine Port Authority, with the state concluding that the Sears Island parcel is “the most feasible port development site in terms of location, logistics, cost,

and environmental impact,” according to its announcement.

Advocacy groups, including the Friends of Sears Island and Islesboro Islands Trust, have expressed their opposition to the proposal, arguing that Mack Point would be a better choice. Mack Point, now owned and operated by Sprague Energy, has hosted port infrastructure for more than 200 years. It is about 500 yards from the site selected on Sears Island.

Environmental groups supporting the project include the Natural Resources Council of Maine, Maine Conservation Voters, and Maine Audubon. Labor groups have also endorsed the Sears Island choice.

Sears Island is a 941-acre state-owned island off the coast of Searsport, joined to the mainland by a causeway built in the late 1980s in anticipation of a container port being built there. Gov. Angus King reluctantly scrapped that proposal in 1996. The container port was one of a half-dozen industrial proposals, which included nuclear power plants, an aluminum smelter, coal gasification plant, and a liquefied natural gas port.

island, was placed in a permanent conservation easement held by the Maine Coast Heritage Trust, while the remaining one-third, or approximately 330 acres, was reserved by DOT for future development.

The site for the wind port is about 100 acres, which is about one-third of the transportation-reserved parcel, and a little more than one-tenth of the entire island. The estimated construction cost is $500 million, with funding likely to be sought from federal sources.

Last year, Mills signed legislation to advance offshore wind in Maine by aiming to develop up to 3,000 megawatts of offshore wind energy in federal waters.

“ The most feasible port development site in terms of location, logistics, cost, and environmental impact…”

After a lengthy stakeholder negotiation process, the island was divided in 2009 into two parcels: approximately 601 acres, or two-thirds of the

Feds make more work visas available

SENS. SUSAN COLLINS and Angus King announced that the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Department of Labor (DOL) are expected to make an additional 64,716 H-2B temporary nonagricultural worker visas available for fiscal year 2024 on top of the congressionally mandated 66,000 H-2B visas that are available each fiscal year.

“These additional H-2B visas are a welcome relief for small businesses throughout Maine that continue to face a shortage of employees,” said Collins and King in a press release. “These visas are a lifeline for our state’s economy, helping businesses meet the increasing demand for their products and services.”

The supplemental allocation is expected to include 20,000 visas for workers from Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, and Honduras. In addition to the 20,000 country-specific allocation, 44,716 supplemental visas would be available to returning workers who received an H-2B visa, or were otherwise granted H-2B status, during one of the last three fiscal years.

Collins and King have consistently pushed DHS and DOL to increase the availability of H-2B visas, and they have worked to ensure that the H-2B visa program is efficient and effective. Last

year, they successfully urged the agencies to release the maximum number of H-2B visas, marking the first time the departments issued a single rule making available H-2B supplemental visas for several allocations throughout the entire fiscal year.

In June 2023, Collins and King sent a letter sent to DOL Acting Secretary Julie Su requesting an explanation for the extreme delays affecting the processing of labor certifications for H-2B visa applications.

The DHS appropriations bill passed by the Senate Appropriations Committee on July 27 includes report language drafted by Collins directing DHS, in consultation with DOL, to produce a report on “the economic impact of the H-2B visa program on a state-by-state and national level; the estimated number of H-2B visas that would have been required to meet demand in FY 2023 on a state-by-state and national level; and any adverse economic impact that resulted from the inability to meet such demand.”

As required by law, employers must first make a concerted effort to hire American workers to fill open positions. H-2B visas fill needs for American small businesses when there are not enough able and willing American workers to fill the temporary, seasonal positions.

disappointed in the governor’s breach of the state’s commitment” to prioritize Mack Point over Sears Island.

Islesboro Islands Trust said it would intervene “using every legal means available.” The group supports offshore wind “but affirms that the offshore wind manufacturing facility should be built at Mack Point,” according to a statement it issued after the site was selected.

Mack Point consolidates industry in one location, economizes on existing infrastructure, and replaces and remediates Mack Point’s brownfield history, the Islesboro group noted. It also said that construction costs at both sites were close to equal and that a rail line is available at Mack Point.

“This was not an easy decision, nor is it one that I made lightly,” Mills said of the site choice.

“For more than two years, my administration has evaluated Sears Island and Mack Point thoroughly and with an open mind, recognizing that each site has its own set of benefits and its own set of drawbacks.”

The governor acknowledged that the island, which has recreational trails developed by the Friends group, “is enjoyed by many people.”

Former Islesboro Select Board chair Arch Gillies said he was “profoundly

Dan Burgess, director of the Governor’s Energy Office, said a port “is a critical step … supporting the generation of clean, affordable, reliable energy for Maine and the region.”

Matthew Burns, executive director of the Maine Port Authority, said “Our heritage as a seafaring state makes perfect sense for utilizing one of Maine’s best assets, its deep-water ports.”

David Gelinas, president of the Penobscot Bay & River Pilots Association, noted that Sears Island “will minimize impacts from southerly winds and seas, while providing safe shelter for smaller vessels that will be necessary to service the port,” and offers the most direct approach in and out of the Searsport navigation channel and allows the existing docks at Mack Point to continue accommodating vessels.

NEW ON THE PATROL—

4 The Working Waterfront april 2024

The newest Maine Marine Patrol officer Amos Abbott, shown here with Col. Matthew Talbot (left) and Department of Marine Resources Commissioner Patrick Keliher (right), will serve in the FriendshipWaldoboro-Cushing patrol region.

Mills seeks disaster declaration

Gov. Janet Mills has formally requested that President Joe Biden issue a major disaster declaration to help Maine’s eight coastal counties recover from the back-to-back severe storms on Jan. 10 and Jan. 13 which brought significant flooding and damage.

In a letter to Biden, Mills noted the cost of damage from the two weather events—estimated at $70.3 million for public infrastructure damage alone—is beyond the ability of the state to address.

If the president approves the governor’s request, Maine would gain access to federal funds it could use to repair damaged roads, bridges, public buildings, utilities, and other public infrastructure in Washington, Hancock, Waldo, Knox, Lincoln, Sagadahoc, Cumberland, and York counties.

In addition to requesting public assistance, the governor asked Biden to authorize individual assistance to eligible families impacted by property damage in Washington, Hancock, Waldo, Knox, Lincoln, Sagadahoc, Cumberland, and York counties.

“Given that affected homeowners are also having to recover from demolition of the waterfront infrastructure that inherently supports their livelihood, the Individual Assistance program is just one

REAL ESTATE continued from page 1

Also, what buyers want tends to be very specific, and, says Yarnell, “Homes are so unique... It’s like a fruit basket.”

Proximity to amenities and airports are among the factors buyers consider. Elizabeth Banwell, senior vice president and broker at Legacy Properties Sotheby’s International Realty in Portland, notes: “A lot of times people have in their minds that they want to be a certain distance from Portland or Boston.” Yet she also sees activity in places such as St. George, which has had “a little boomlet,” and Eastport, where a house listed for $375,000 received an offer of $699,000.

Redlon sees buyers looking farther Downeast than they intended, seeking more affordable properties than they can find in Camden or Belfast.

The buyers are a mix of in- and out-of-staters. Redlon says many of her buyers are “early retirees”

SEAFOOD VALUE

continued from page 1

“Maine’s elver quota of 9,688 pounds expires after this year,” Keliher said. “Fortunately, because of the strong management measures we’ve instituted here in Maine, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission American Eel Board has decided that the existing quota will remain in place, preventing what could have been a loss of millions of dollars in income for Maine’s elver industry.”

Through an addendum to the fishery management plan for elvers, ASMFC will establish the number of years the current quota will remain in effect.

Softshell clam diggers earned $13.8 million in 2023, which made the fishery the state’s third most valuable.

“DMR’s Nearshore Marine Resources Program, launched in 2022, has been working hard to support this vital fishery through outreach, funding, and collaboration with towns to develop effective shellfish management strategies,” said Keliher.

More information about the program and funding opportunities can be found on DMR’s website.

necessary component to the comprehensive recovery needs of disaster survivors spanning all eight coastal counties,” wrote Mills in her request. “With much of the marine and aquaculture field operating out of primary homes with private docks, hundreds of disaster survivors are now fighting to sustain generational family businesses with limited support.”

Maine produces 90% of the nation’s lobster, she noted, “and is home to a thriving marine economy now at risk of decline. The recovery of Maine’s coastline will require the support of every federal resource available, and due to the compounded affects sustained by the coastal primary homeowners that help to sustain Maine’s economy, recovery is uncertain without the Individual Assistance program.”

The governor has also separately proposed $50 million to help communities rebuild infrastructure and enhance climate resiliency by introducing it as standalone legislation rather than as part of the forthcoming supplemental budget. It’s complemented by $5 million in her supplemental budget to help another 100 cities, towns, and tribal governments create local plans to address vulnerabilities to extreme weather through the Community Resilience Partnership.

who have “some energy and some ideas,” and that the more expensive properties are generally going to incomers. Yarnell’s clientele skews younger and is a split of people from Maine and from other states. Banwell, too, sees both buyers from out of state and those who were already living in Maine.

Fears about climate change don’t seem to be dissuading buyers, despite widespread reporting on flooding in Maine in late December and early January and concern about the ability to insure property. All three brokers interviewed said they are frank with potential buyers about the reality of living near the water.

“I do think that people will be more aware,” says Redlon. “They’re going to get some wind and they’re going to get some tide rises.”

Yarnell adds that, “Someone might choose to be a little higher as long as they have access to the beach.” People who are attracted to the coast because they have boats tend to do their research, she says.

Maine oysters were the fourth most valuable harvested product at over $11 million on the strength of a 20-cent per pound increase in value.

Menhaden, used as bait for the lobster fishery, was the state’s fifth most lucrative fishery in 2023, with a landed value of more than $10 million.

Maine’s groundfish industry also saw an increase in landings and a more stable price due in part to investments DMR made in the Portland Fish Exchange, Vessel Services, and the Maine Coast Fishermen’s Association with COVID relief funds from NOAA.

“DMR is proud to have supported fuel, ice, and landing fee rebate programs at the Portland Fish Exchange and Vessel Services,” said Keliher. “These programs, which helped to reduce costs, along with market stability enabled by MCFA’s Fishermen Feeding Mainers program, were critical to maintaining and increasing landings of groundfish in Maine. It’s important work and a positive story; fishermen were able to keep working, critical infrastructure has been maintained, and fresh, healthy Maine seafood went to schools and families in need.”

5 www.workingwaterfront.com april 2024 156 SOUTH MAIN STREET ROCKLAND, MAINE 04841 TELEPHONE: 207-596-7476 FAX: 207-594-7244 www.primroseframing.com G eneral & M arine C ontraC tor D re DG in G & D o C ks 67 Front s treet, ro C klan D, M aine 04841 www. pro C k M arine C o M pany. C o M tel: (207) 594-9565 National Bank A Division of The First Bancorp • 800.564.3195 • TheFirst.com Member FDIC • Equal Housing Lender DREAM FIRST Advertise in The Working Waterfront, which circulates 45,000 copies from Kittery to Eastport ten times a year. Contact Dave Jackson: djackson@islandinstitute.org 43 N. Main St., Stonington (207) 367 6555 owlfurniture.com A patented and affordable solution for ergonomic comfort Made in Maine from recycled plastic and wood composite Available for direct, wholesale and volume sales The ErgoPro 43 N. Main St., Stonington (207) 367 6555 owlfurniture.com A patented and affordable solution for ergonomic comfort Made in Maine from recycled plastic and wood composite Available for direct, wholesale and volume sales The ErgoPro

Reliable transportation for all of your island needs 207-466-2636 www.midcoastbargeworks.com

from the sea up

The storm damage we cannot see

Community response must include compassion

BY KIM HAMILTON

ALMOST TWO MONTHS after the January storms pummeled the Maine coast, we are still piecing together a full picture of the destruction.

In the direct aftermath, of course, communities could document buildings now angled slightly off their foundations or entirely set adrift, pilings separated from their pins, and beaches and coastal frontage now missing yards of sand and soil.

We know hundreds of commercial boats are at risk of a curtailed fishing season because they can no longer land their catch on their usual piers and wharves. Delays are costly. They mean fresh catch won’t make it to market, not only depriving consumers of exceptional Maine seafood but also reducing the livelihoods of harvesters and their families.

The observable and documented damage to our coastal infrastructure was so widespread and costly that Gov. Mills requested that President Biden issue a Major Disaster Declaration. Approval of that request unlocks essential federal funds to repair an estimated $70.3 million in damages to public infrastructure.

Many of Maine’s fishermen and aquaculturalists, however, operate out

of their homes and from private docks. Because of the exceptional impact to these private facilities, the governor’s request also included special consideration for individual households through the federal Individual Assistance Program. The request is in addition to new proposed state funding to strengthen community climate resilience and infrastructure.

While some may chafe at the timeline, the bureaucracy, the politics, and the paperwork, these funds will be a lifeline for this state and our coastal and island economies.

Anyone in the disaster preparedness and recovery fields knows, however, that the cost of a disaster is more than material. There are profound, important, and long-term mental health costs that often go unseen or unrecognized. Studies after hurricanes Sandy and Katrina have shown an increase in PTSD in the immediate aftermath and the persistence of depression long after a damaging storm. A growing body of research on the changing climate and recurrent, severe storms also points directly to the public and mental health costs.

While getting back to a new normal is important, people differ in their ability to reset and adjust. Repeated extreme events are especially challenging for older people, people with

rock bound

Maine—our next big moves

Time to confront harsh realities

BY TOM GROENING

I HAVE A SHARP memory of Angus King’s inauguration as governor in January of 1995. I was editor of the Republican Journal weekly newspaper in Belfast then, and we had endorsed him for the office.

As an independent candidate, I found his thinking on the issues of the day refreshing, and since he was bound to neither major party, he could be candid about where he stood, instead of parroting party lines.

Our kids were ten and seven at the time, old enough to understand some of the governor’s speech and I had them watch it. King included a specially made film by Bar Harbor’s Jeff Dobbs, he of High On Maine fame, featuring footage shot by helicopter (today it would be a drone) of the coast and inland parts of our state, with narration extolling Maine’s rich and proud history.

It was a master stroke by King, coming as it did as Maine was crawling out of the recession of 1991, which was especially severe in the Northeast.

I’ve long felt our state has an inferiority complex, probably formed by

what was essentially an economic slump from 1930 to 1980. We were poor. Many jobs relied on hard, seasonal resource extraction—fishing, logging—textile and shoe manufacturing, and processing agricultural products like chicken and potatoes.

Along comes King in 1994 with his “Maine is on the Move” gubernatorial campaign, and suddenly we begin to believe it and start noticing and reporting back how fast the ship of state is cruising.

I was reminded of this during Gov. Janet Mills’ State of the State address in late January. She took the unusual step of providing many of her policy proposals to the legislature in writing, while focusing her in-person remarks on what might be described as a moral call to the state.

Specifically, she highlighted two hits the state has taken in recent months— destructive storms and mass shootings. Both demand our action.

The shootings—18 massacred in Lewiston in October and four in Bowdoinham in April—demand a rethinking of our policy on guns, despite being a state with a long tradition of responsible use.

disabilities, people with a history of trauma, and first responders.

It’s not difficult to understand why. The flooding of the causeway between Deer Isle and Stonington, for example, made access to emergency care especially precarious. Flooded communities all along the coast faced the same kind of heightened uncertainty.

The disappearance of the historic South Portland fish shacks produced yet a different kind of loss. They simply slipped into the ocean, erasing family histories and cultural touchstones overnight. There isn’t a price tag for that kind of grief.

Fortunately, we have tools to address these hardest-to-quantify damages, the psychological ones. Healing begins with community support. In this sense, Maine coastal and island communities have a lot to teach the world. Our coastal and island communities are models of connectedness, and staying connected is a salve for mental anguish.

The January storms are good reminders to exercise our community muscles, to check in on our neighbors, and to frequent local businesses, even weeks after the initial damage. Our colleagues at Maine Seacoast Mission and the Maine Coast Fisherman’s Association have resources that can help, too.

A solutions mindset can also have healing powers. This is why efforts like the state’s Community Resilience Partnership are so important. As one of the service providers, Island Institute, along with many others, is fostering community-wide conversations in island communities to help build resilience in the face of climate change. There are models of community resilience taking root in towns across the state from which we can learn and draw strength.

Maine coastal communities will emerge from the January storms stronger, more informed about the pernicious impact of sea level rise, flooding, and extreme weather, and they will resolve to act. I hope we’ll all emerge stronger, too, in our appreciation for the curative powers inherent in closely-knit communities and the ongoing need to attend to the storm damage that we cannot see.

Kim Hamilton is president of Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront. She may be contacted at khamilton@islandinstitute.org.

Mills persuasively argued that some commonsense steps—strengthening the law that allows a judge to order the seizure of weapons and closing the loophole that allows people banned from owning guns to purchase them privately—would go a long way toward making Maine safer.

And being seen as a “safe” state is critical to our economic future. Tourism surveys show this status is a big part of our allure. Citing King again, who often says that Maine is a big, small town, the safe vibe also is key to how we function, from our local government and community institutions to our neighborly concern and charitable generosity.

The storms Maine got walloped by— heavy rains in December that wiped out roads and bridges inland, and two big wind and rain events in January that coincided with high tides which devastated working waterfronts and more—must be understood as related to a warming climate.

Yes, we’ve seen devastating storms before; remember the 1978 blizzard? But 2023 was the warmest year ever recorded globally. And the years trailing it on the top ten list are all from

this century. Warmer air holds more moisture, increases wind speeds, and expands the ocean. So, of course our storms will be worse.

Addressing our carbon pollution is overdue, but perhaps now it will no longer be seen as a hyperbolic warning. It’s happened, and its impacts will cost us millions. If we want to conserve what we have, both natural and built, and hang onto more of our money, we must act.

Mills’ creation of the Maine Climate Council sure looks wise at this point. Setting goals, on both climate and guns, is an important first step, but now we need state government—including those on both sides of the aisle—to implement changes. They won’t all be painless. But they surely will help us avoid the all-too-fresh pain of mass shootings and catastrophic storms.

Tom Groening is editor of The Working Waterfront. He may be contacted at tgroening@islandinstitute.org.

6 The Working Waterfront april 2024

INFLATION BUSTER—

Even in 1900, people made the short trek across the harbor from Portland to Peaks Island to enjoy that offshore experience. Information on the Library of Congress website notes this is the Forest City Landing in 1900. The sign on the building reads “The Peaks Island Ferry Reduced and Keeps the Fare at 5 (cents) between Portland and Peaks Island the Year Around.”

Offshore wind threatens centuries of fishing Proposal creates more problems than it solves

BY GLEN LIBBY

THE NEW ENGLAND electric grid— ISO New England—has a website that includes a display featuring two pie charts that show where our electricity is coming from, updated in real time.

Right now, “renewables” are at 7% of our total energy mix.

Wind is 28% of that 7%, solar is 10% of that 7%, and the rest of the renewables come from burning wood, trash, and methane from dumps.

Hydro isn’t listed as renewable, natural gas and nuclear usually make up the lion’s share, with hydro averaging around 9%.

Then there are imports, which vary during the time of day and what the weather is like—wind and solar are very weather- and time-of-day- dependent.

Many people today think that offshore wind power will be able to give us abundant (long-lived?) clean energy.

The water in the Gulf of Maine is very deep, any turbines sited there will be on floating platforms anchored to the seabed with giant chains. It is important to remember that the Gulf of Maine is the life blood of all our coastal fishing communities.

I participated in an interesting project some years ago when the Maine Coast

Island Institute Board of Trustees

Kristin Howard, Chair

Douglas Henderson, Vice Chair

Kate Vogt, Treasurer, Finance Chair

Carol White, Programs Chair

Bryan Lewis, Philanthropy Chair

Shey Conover Secretary, Governance Chair

Megan McGinnis Dayton, Ad Hoc Marketing & Communications Chair

Michael P. Boyd, Clerk

Sebastian Belle

David Cousens

Michael Felton

Nathan Johnson

Emily Lane

Michael Sant

Michael Steinharter

Donna Wiegle

Tom Glenn (honorary)

Joe Higdon (honorary)

Bobbie Sweet (honorary)

John Bird (honorary)

Kimberly A. Hamilton, PhD (ex officio)

Fishermen’s Association was formed. We worked with Island Institute to document how each fishing community extended far out to sea. Each community has traditional grounds that have been worked for centuries by fishermen from those communities. Fishing sustains coastal New England.

If offshore wind industrialization is allowed in these fishing grounds the communities connected to these areas will suffer. Are you willing to take a map of the state of Maine and eliminate the fishing grounds for these fishermen?

concrete, carbon fiber, and whatever else goes into the industrial power stations off the edge of the continental shelf after they break down.

Offshore substations that convert AC power to DC power will be continuously pumping 90-degree water into the ocean when the turbines are spinning.

If offshore wind industrialization is allowed in these fishing grounds the communities connected to these

Just going somewhere else seems reasonable to some, usually people with no fishing experience, but it is much more complicated than that.

areas will suffer.

Pieces of the equipment like turbine blades will break off, the bottom will be jet-plowed to lay cables, and you will not be able to set your fishing gear in these areas ever again, or until the next glacial period pushes the steel,

And yet the premise for offshore wind is that it is clean energy, good for the environment, and it will help control the climate, so we don’t die from global warming.

Now go back to the ISO New England data and ask yourself: “How many offshore wind turbines will it take to raise the percentage of power for the New England grid to have a meaningful impact on emissions?”

Data gets presented about how many megawatts of power each turbine produces, so-called nameplate power. That number assumes that they function at 100% capacity all the time. Nameplate is used to predict how many homes will be powered by turbines. The truth is that they only produce on

THE WORKING WATERFRONT

Published by Island Institute, a non-profit organization that works to sustain Maine's island and coastal communities, and exchanges ideas and experiences to further the sustainability of communities here and elsewhere.

All members of Island Institute and residents of Maine island communities receive monthly mail delivery of The Working Waterfront.

For home delivery: Join Island Institute by calling our office at (207)

average just below 40% of the time, so any data about homes must take this into consideration.

The Gulf of Maine is a unique ecosystem, almost an inland sea, and incredibly productive. It is this productivity that sustains our coastal fishing communities. This productivity is driven by currents that originate in the Bay of Fundy and circulate throughout the Gulf of Maine unobstructed.

These currents have evolved over centuries, since the ice sheets retreated, and marine species depend on an unobstructed flow to live and reproduce as they have for centuries. Industrialization of our fishing grounds puts this at risk.

Maine should wait to develop other sources of power that won’t harm our fisheries and are robust enough to eliminate a substantial portion of our carbon emissions.

Offshore wind power is the wrong choice.

Glen Libby is a 45-year veteran of the commercial fishing industry and now runs Port Clyde Fresh Catch. He lives in Port Clyde.

Editor: Tom Groening tgroening@islandinstitute.org

Our advertisers reach 50,000+ readers who care about the coast of Maine. Free distribution from Kittery to Lubec and mailed directly to islanders and members of Island Institute, and distributed monthly to Portland Press Herald and Bangor Daily News subscribers.

To Advertise Contact:

Dave Jackson djackson@islandinstitute.org

(207) 542-5801

www.WorkingWaterfront.com

7 www.workingwaterfront.com april 2024 op-ed

594-9209 E-mail us: membership@islandinstitute.org • Visit us online: giving.islandinstitute.org 386 Main Street / P.O. Box 648 • Rockland, ME 04841 The Working Waterfront is printed on recycled paper by Masthead Media. Customer Service: (207) 594-9209

Maine’s lighthouses face troubling recovery

Damage from storms not easily repaired

BY SARAH CRAIGHEAD DEDMON

Back-to-back storms slammed into the coast of Maine on Jan. 10 and Jan. 13, breaking state records for the highest tides since 1978 and delivering extensive damage along the entire coastline. Though final tallies are not in, statewide damages to public infrastructure—things like piers, roads, and bridges—are estimated at more than $70 million.

The storms also delivered extraordinary damage to more than a third of Maine’s lighthouses.

“What really hurt us was that the storms were so close together,” says Bob Trapani, executive director of the American Lighthouse Foundation (ALF). “Whatever the 10th compromised, the 13th just took it out. These old foundations didn’t stand a chance in the back-to-back battery.”

Many of the damaged lighthouses are structures that have already seen their fair share of violent weather.

“The Hurricane of 1938 wiped out Rhode Island’s Whale Rock Light and the keeper was never found. It did a lot of damage to other lighthouses, too, and killed seven lighthouse service members,” says Jeremy D’Entremont, historian for the U.S. Lighthouse Society and host of the society’s longrunning podcast, Light Hearted.

“There have been a few other storms in history that did a lot of damage to lighthouse properties,” says D’Entremont. “But other than the 1938 hurricane, they don’t compare to these storms.”

Costs to repair Maine lighthouses might be measured in the millions. At least 24 of Maine’s 67 lighthouses were damaged in the January storms, according to a survey conducted by ALF, and more damage reports are expected this spring, for offshore lights still difficult to reach in winter waters.

“Routine maintenance on a lighthouse is something you can schedule, you can budget for it. Offshore, that might be $20,000 every five years,” says Ford Reiche, who restored and owns Halfway Rock Light in Casco Bay. “But then you throw a storm at it and it’s $250,000, and that can’t be phased. That’s the thing that’s going to throw a lot of chaos at these lighthouse owners.”

trip to survey 23 Maine lighthouses, including Mt. Desert Rock Light and Matinicus Rock Light, both more than 25 miles offshore.

“It pulls at your heart to see the damage,” says Trapani. “I don’t think people understand. The sea does unimaginable things at these places.”

How—and in some cases, if—the most damaged lighthouse properties will be restored is an open, and urgent, question, says Trapani.

“What’s sad is, if we’re not able to strengthen these lighthouses today it only becomes more expensive tomorrow, and will we even have all of them?” asks Trapani. “Time is not on our side with these lighthouses.”

In February, Gov. Janet Mills requested a Major Disaster Declaration from President Biden. If approved, it could make available some Federal Emergency Management Agency grants for qualifying nonprofits.

At least 24 of Maine’s 67 lighthouses were damaged in the January storms.

On the high end, some Maine lighthouses might need $2 million in storm repairs, says Reiche.

“Some of the biggest costs will be the access points. Ram Island in Boothbay lost the walkway from the island to the lighthouse,” Trapani says. “As of right now, the Coast Guard can’t even access that light. Whitehead Island was another one where the boathouse collapsed and was pretty much destroyed. They lost their entire walkway to the pier.”

After the storms, Trapani and Reiche embarked on a 243-mile helicopter

Access to FEMA grants to pay for lighthouse storm repairs will depend in part on who owns the damaged lighthouses, whether they’re public or private property. Of Maine’s 67 lighthouses, part or all of 33 lighthouse properties are owned and operated by a branch of government—some state, some federal, and some municipal, with clear sources of funding. In some cases, nonprofits care for all or part of the property while the government runs the lighthouse works. Sixteen are owned by private individuals, and 18 are mostly the responsibility of nonprofits.

The American Lighthouse Foundation is ramping up to assist in the competitive and complex FEMA grant application process. Federal grants might also be made available

for prevention measures, or disaster mitigation, too, to prevent more damage in the future.

“We need some professional folks who can help us navigate hazard mitigation as well as disaster relief,” says Reiche. “What I’m going to do at Halfway Rock is secure the dock and the ramp and the boathouse more securely to ledge. If measures like those had been taken before the January storms, the statewide lighthouse damage would have been much less.”

Many of the hazards that damage lighthouses, like high winds and flooding, aren’t covered by insurance policies. And even in a year without punishing storms, access to historic preservation funding is nearly nonexistent.

“The grants are very, very hard to come by. I have never gotten grants for Halfway Rock,” says Reiche. Halfway Rock’s light is currently not functioning because, during the storms, water crashed through the building housing the light’s electronics.

“Most of the lighthouses in Maine are in the hands of local organizations that just have no resources. It’s astonishing because these lighthouses are built to last, but now we’re up against a new level of intensity and there are no established pipelines of money,” Reiche says.

working on something,” says Mohney. “The challenge and the responsibility that these stewards have taken on is to their great credit. Because for Maine, these are symbols of the state, and these organizations that have assumed ownership have taken on the responsibility to preserve those for everyone.”

There’s one way any Mainer can help lighthouses, says Trapani, and that’s by choosing the Maine Lighthouse License Plate. In 2021, Maine lighthouse supporters came together and founded the Maine Lighthouse Trust, which then purchased the license plates now sold by the state. Ten dollars of every plate goes directly to the Trust.

“This organization is going to take that money and grant it out to those organizations most in need,” says Trapani.

“ Time is not on our side with these lighthouses.”

—Bob Trapani

Though Maine isn’t home to the most lighthouses—that distinction belongs to Michigan with 129—it is home to some of the most iconic lighthouses, like Pemaquid Point Light, which is featured on the Maine state quarter. It lost part of its 19th-century bellhouse in the storms.

There isn’t a lot of historic preservation money in the state’s grant program, says Kirk Mohney, Maine’s state historic preservation officer. The agency provides technical assistance to anyone undertaking historic projects and currently holds preservation covenants on the 25 lighthouses that were transferred to nonprofits through the Maine Lights program.

“We’re in a fairly regular conversation with the groups that may be

“Maine lighthouses are some of America’s oldest as a group and they have a great place in the history of our nation,” says Trapani, who has penned six books about lighthouses, including his most recent release, Beacons of Wonderment: A Fascination with Maine’s Lighthouses.

“Maine lighthouses are especially beautiful,” Reiche says, “and there’s also something unique about the nature of the Maine coast. Our lighthouses aren’t on long, flat beaches like many states are. Maine lighthouses are on heights of land, and some are way offshore, in the most grisly locations. These are badass lighthouses, for sure.”

8 The Working Waterfront april 2024

The January storms flooded the foundation of Islesboro’s Grindle Point Lighthouse.

Down the drain, and then what?

Casco Bay’s runoff problems exacerbated by storms

BY STEPHEN RAPPAPORT

After the weather Maine experienced in December and January, even the staunchest climate change skeptic had to admit that something is up.

Three powerful storms—a rainstorm in December and two coastal windstorms in January—roared through the state.

Several factors, other than their arrival in rapid succession, made those winter storms unusual. They brought lots of rain, especially in December, but very little snow. The two January storms brought the highest tides seen along much of the Maine coast since at least the blizzard of 1978.

They wrought uncountable hardship and, in aggregate, millions of dollars in damage to public and private infrastructure primarily as a result of flooding, both inland and in Maine’s many harbors.

The washed-out roads and bridges around the state were obvious—guests and workers at the Sunday River were reportedly trapped at the ski resort for more than two days before the road was reopened—and photos of flooded businesses, destroyed wharfs, and other damaged coastal infrastructure made national news.

But there was another consequence of the storms that received, perhaps, less immediate attention: the impact

of runoff from the torrential rain and receding tide—stormwater—on the state’s coastal ecosystems.

That was the topic of an online “Coffee with the Casco Baykeeper,” Ivy Frignoca, hosted via Zoom by the Friends of Casco Bay in early February. Stormwater runoff and pollution have been long-term concerns of the organization and its Baykeeper, and the network of citizen “water reporters” have been monitoring their effects on the Casco Bay watershed for years. Those effects, positive and negative, are both significant and growing.

Frignoca explained that stormwater is “any form of moisture that falls from the sky” in quantities significant enough to “run off from the land into our waterways.” Stormwater can become polluted both by what’s in the atmosphere—dust, chemicals—and by what it comes into contact with on the ground.

“And that could be, say, cow manure or fertilizers from farm fields. It could be fertilizers and pesticides from lawns. And it is increasingly any kind of pollution that is on our urbanized landscapes, like heavy metals, car exhaust, cigarette butts, pet waste, anything on our built surfaces that collects there and then runs off in the water.”

In winter, additional pollutants come from the salt used to keep roadways, steps and sidewalks free of ice, which ultimately washes into streams and

Bridge work planned in Acadia

IN PARTNERSHIP with the National Park Service, the Federal Highways Administration will begin the rehabilitation of Jordan Pond Road bridge in March. The historic bridge is in the village of Seal Harbor (town of Mount Desert) and carries Jordan Pond Road over Acadia National Park’s carriage road between Day Mountain and Stanley Brook Bridge.

During construction, traffic will be detoured through the park via Stanley Brook Road until Memorial Day weekend when alternating one-way traffic on Jordan Pond Road will be possible. Vehicles exceeding 10 feet, 4 inches in height will be detoured along other routes.

In addition to the Jordan Pond Road bridge, the next bridge to be rehabilitated will be the Wildwood Entrance bridge, which is pending funding. This bridge carries the Park Loop Road over an abandoned carriage road in the park near Wildwood Stables.

The bridges have a concrete substructure with granite facing. Over

time, cracks develop in the joints of the bridge, which allow water to seep inside the structure. This causes the interior concrete structure and drainage system to deteriorate over time. The work will involve removing the granite facing to expose the substructure and coating it with waterproof sealant. The rehabilitation will help maintain the structural integrity of the bridges for decades to come.

Funding for the project is through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law), an investment in infrastructure aimed at helping grow the economy, enhance U.S. competitiveness, create good jobs, and build a safe, resilient, and equitable transportation future.

For information about Acadia National Park, visit www.nps.gov/ acad or call 207-288-3338. Join online conversations on Facebook (facebook. com/AcadiaNPS), Twitter (twitter. com/AcadiaNPS), and Instagram (instagram.com/acadianps).

brooks and makes the water too salty and “toxic to aquatic life,” she said.

The greatest problems with runoff into the Casco Bay watershed, though, come from excessive levels of nitrogen pollution. Nitrogen provides critical nourishment for the phytoplankton at the base of the bay’s marine food web. Too much nitrogen, though, can lead to excessive blooms of algae that “can cause serious health problems in the bay,” Frignoca said.

In urban areas, the problem is compounded when runoff is so heavy that it overwhelms the capacity of the combined stormwater and sanitary sewer collection and treatment system so that raw sewage floods into the bay. Near Back Cove in Portland’s Bayside neighborhood, the city is installing four underground tanks that will hold millions of gallons of combined stormwater and sewage—which would otherwise have flowed straight into Back Cove—until it can be treated.

According to Frignoca, the problem is growing. In the past year, she said, Portland alone dumped 373.6 million gallons of combined sewer overflow into Casco Bay, nearly twice the amount that flowed into the bay just five years ago. That increase can be attributed both to heavier and more frequent rain events and increased development resulting in more impervious surfaces—roads, driveways,

buildings—that reduce the capacity of the ground to absorb stormwater.

The Department of Environmental Protection has studied five distinct watersheds over a period and looked at the impacts of growing urbanization on stormwater pollution. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the two most threatened were the Fore River watershed and coastal Casco Bay—areas with significant growth over the past few years.

DEP has begun to develop new stormwater management rules for the state that Frignoca hopes will address, and perhaps require the use of “low impact development” methods that can reduce that size of impervious surfaces. The new rules won’t come anytime soon, though.

According to Frignoca, a stakeholders committee and a DEP technical advisory group working on a new rule hope to finish their work by June and the department can then begin the formal rulemaking process. Its proposed rule would go to the Board of Environmental Protection for public hearings and eventual adoption.

The rule would then go to the legislature for further hearings, possible amendment, and approval. The end product of that process would then go back to the Board for adoption. In the meantime, increased stormwater runoff seems likely to have a growing impact on Maine’s waterways.

9 www.workingwaterfront.com april 2024

Independent. Local. Focused on you. Boothbay New Harbor Vinalhaven Rockland Bath Wiscasset Auto Home Business Marine (800) 898-4423 jedwardknight.com

stories, columns, and photos?

Like our

Check us out and “like” The Working Waterfront on Facebook!

Photo correction

To the Editor:

The photos of the storm damage in the February/March issue of the newspaper were great, but the ruined lobster shack in Bernard on Mount Desert Island is not the town wharf, as the caption read, but a private wharf and shack down the road a few hundred yards.

The town wharf made out just fine.

Bill Weir

Bass Harbor

Information helped victim

To the Editor:

Thank you for the beautiful coverage by Tom Groening of our Damariscotta “Break the Silence of Domestic Abuse” event on Nov. 7 at the Skidompha Public Library (“Domestic abuse—voices and vocabulary found,” December/January issue).

The article has already helped at least one island dweller.

A woman living on a Maine island got in touch with me wanting information to provide to her friend who is trapped in domestic abuse so her friend could see the patterns of abuse and know she was not alone. I was able to suggest the caller get a hold of the current issue of The Working Waterfront and hand that to her friend, since all the information she was seeking was in that story.

This coverage of us in The Working Waterfront spreads the word to Maine’s island and coastal communities about Finding Our Voices as a statewide, grassroots, and survivor-powered resource for women and children trapped in domestic abuse and the friends and family who are worried about them. The timing, as winter set in, was important.

Thank you, Island Institute, for this important newspaper.

Patrisha McLean Founder/CEO Finding Our Voices

letters to the editor

Dissenting review

To the Editor:

First of all, thank you for the work you do—The Working Waterfront is an excellent publication.

I read Tina Cohen’s review of Martha Tod Dudman’s Sunrise and the Real World in the February/March issue of The Working Waterfront, and I must admit to being somewhat puzzled. As a work of fiction, it was a fast and engaging read with descriptions of the Sunrise facility that were authentic.

Facilities such as this were, and maybe still are, largely staffed with the undertrained, underpaid, underappreciated, and unprepared. However, this was not the point of the book, which was not so much a piece of historical fiction as a great story with an amazing twist, that kept me enthralled until the bitter end!

John B. Macauley

Otter Creek

Chasing submarines

To the Editor:

I enjoyed the December/January issue’s “In Plain Sight” column by Kelly Page of Maine Maritime Museum on the wooden vessels built in small boatyards in Maine during World War II.

My dad served as a captain of SC 698, a subchaser, in the Pacific during the war. The subchasers, at 110 feet—about the size of the smaller Vinalhaven ferries—with three officers and 24 crew members, sailed from the East Coast to the Pacific, often without radar or electronics relying only on celestial navigation.

My dad had grown up sailing and was part of the “90 Day Wonders” who were rushed through training to fulfill the need for officers with prior experience on the water. At the end of the war he was a lieutenant commander of a destroyer escort.

Ted Treadwell wrote two books on his experience during the war as a junior officer and captain of a wooden subchaser. His books, Splinter Fleet and

Taste of Salt, gave me insight into those experiences not talked about by those who had served on those small boats as part of the under-appreciated “Donald Duck Navy.” They are very good books and makes one much admire those who serve and work today on relatively small boats.

Ruth Cutler

Vinalhaven and Ashford, Conn.

JFK connection

To the Editor

I was reading The Working Waterfront February/March issue and noticed the photo of Boothbay Harbor before 1951. I live in Portland but grew up in Boothbay Harbor. I am 77 years old and still have relatives in Boothbay Harbor.

The church in the photo is Our Lady Queen of Peace Catholic Church. President Kennedy went to that church in the same year that he died. It is located on Atlantic Avenue on the East Side of Boothbay Harbor. The main part of Boothbay Harbor is located on the West Side of Boothbay Harbor. Boothbay Harbor has changed significantly over the years. The white house in the photo is where a good friend of mine grew up. He is still a fisherman and still lives in that house!!

Atlantic Avenue has grown a lot— hotels, motels, restaurants, and condo developments. The movie Carousel was filmed in Boothbay Harbor in 1956 at Brown’s Wharf on Atlantic Avenue.

Ken Pinkham

Portland

More on the church

To the Editor:

The church building in Boothbay Harbor shown in the February/March issue is now part of a multi-church grouping from Brunswick to Newcastle, and most photos are of the white version that anchors postcard photos so well. As for the history: The foundation was laid

in 1916, the steeple finished in 1924, and the church consecrated in 1926. Originally, the exterior was covered in cedar shakes, then painted white in the early 1950s (at any rate, before my husband moved here ca. 1955).

Mary O’Keefe Kellogg East Boothbay

Point, counter-point

To the Editor:

As a long-time reader, I have followed closely the articles and letters in The Working Waterfront concerning the issues surrounding lobstering, trap lines, and right whales. The paper will print a story with very well-reasoned arguments from the lobstering community and industry representatives and excellent points are made.

However, some of the points made leave questions that beg to be responded to directly from the other side. Unfortunately, many of those points are not taken up until perhaps another issue of the paper, maybe months later, and again specific points may not be directly addressed.

There never seems to be a article where the sides are talking directly to one another and about very specific points raised by each. The whole exercise is fragmented and I as a reader am left not knowing what to think.

With your most recent issue I fear the same thing may happen with concerns about seaweed farming and the science regarding health and sustainability of these practices. My hope would be that the Island Institute through The Working Waterfront could sponsor a forum where both sides are present, discuss this back and forth, and take questions. Or it could just be a joint interview and printed in the paper. One way or the other, I for one am needing a bit more help sorting through these very important issues.

Michael Hussin Pelham, Mass.

The Working Waterfront welcomes letters to the editor, which should be sent to Tom Groening at tgroening@islandinstitute.org with “LTE” in the subject line. Longer opinion pieces are also considered but should first be cleared with the editor.

10 The Working Waterfront april 2024

guest column

Fishing for trash

Lobster gear retrieval remains challenging

BY BEN FULLER

A RECENT RADIO program on Maine’s lobster industry reminded me of island cleanups, the efforts to clean the stacks and tangles of lobster fishing debris.

In the radio program, answering a question about fishing trash, Patricia McCarron of the Maine Lobstermen’s Association noted that most cleanup effort was “under the radar” and done by volunteer and not-for-profit organizations.

McCarron is right. For 30 years or so I’ve been one of those volunteers who works shoreside cleanups, on islands and on the mainland. I’ve worked big ones, resulting in construction dumpsters full of crushed traps, ones that brought in several hundred traps that came off islands by ramp barge, ones that took trailer loads to the recycling center. Indeed, we now have a metal trap recycler in Maine.

I’ve filled boats with trash bags full of rope, buoys, and miscellaneous gear. I’ve put donation dollars towards the gas to move this trash to dumps and to dump fees.

It wasn’t like this when I was young. The traps were wood and rotted. The line, while petrochemical based, deteriorated in a few years from sun and water. As I recall, trap buoys were transitioning from wood to foam. So, as a marine and fisheries historian, I got curious.

Buoy rope and other fishing gear like nets started transitioning from natural fiber shortly after rope makers took advantage of what had been learned making parachute cord of nylon during World War II. Now it is rare to find any natural fiber cordage at all, and makers

have worked to make it more resistant to solar and use degradation.

Metal traps are far more recent. Aquamesh, the provider of the majority of trap metal, was developed by Gloucester, Mass. fisherman James Knott Sr. in the late 1970s. He patented it and put it into production in 1980.

The wire is welded, then galvanized, then coated in polyvinyl chloride. Tough stuff indeed. These traps rely on a few bricks to provide ballast to keep them anchored to the bottom. The old buoyant wooden ones needed concrete or metal ballast.

Lobstering is one of the few fisheries where the gear sits and waits without attendance of a boat, unlike floating and towed net fisheries and baited line fisheries. Unattended gear is subject to wave motion and currents and has the risk of losing surface connections. Indeed that is one of the risks of the newly proposed ropeless gear fishery, which could result in more derelict traps, ghost traps.

around. There is one effort underway, Buzz Scott’s OceansWide, which uses divers and sonar and plans to use remote underwater vehicles to locate ghost traps. In a test in Boothbay Harbor in 2021-22, some 2,000 traps were retrieved using two boats. Scott has established a not-forprofit to continue this project.

Second is providing some clean-up resources. Currently the fishing industry may be the only one in the state that isn’t responsible for cleaning up its trash. Maine citizens and industries pay dump fees and some pay haulers to take their trash to the dump. The ocean is not a dump, neither are the ocean shores.

Metal traps are far more recent, developed by Gloucester, Mass. fisherman James Knott Sr. in the late 1970s.

Clean-up efforts are indeed under the radar. Ghost traps are the ones which have lost their buoy ropes from the buoys being cut off or a knot coming undone. And there are a lot, maybe a million or more; about 10% of the traps used each season are lost.

Today’s traps have doors that deteriorate to keep them from fishing. But they move around and get tangled in huge balls of fishing gear as the sea pushes them

Shoreside cleanups are principally led by land trusts cleaning the land for which they are responsible. Landowners also clean up their shores. These need volunteer gangs to cut ballast bricks from traps and pile them to be crushed, if the equipment is available, or removed whole. They need trucks and trap trailers to take them miles to the only recycling center in Maine. Lots of organization is needed to gather the volunteers and the transportation. Funds for the out-of-pocket costs need to be raised. And permission needs to be obtained from the Department of Marine Resources. Maine regulations prohibit anyone except the owner from touching fishing gear, so all those buoys hanging up as decoration are illegal.

Two things can be done to make cleaning up derelict gear easier.

First is a regulation change that allows people to clean up derelict gear without penalty. If someone is out in a skiff along the shore and spots a pile of lobster rope, some beat up buoys in a tree, or a trap that has come ashore, there should be no penalty for loading that gear in their boat and taking it to the dump.

Herring Gut Science Center names new director

SARAH D. OKTAY, PhD has joined the Herring Gut Coastal Science Center as executive director. She had served as the executive director for the Center for Coastal Studies located in Provincetown Mass. Oktay has spent the past 30 years conducting oceanographic research, teaching, fundraising, and communicating with the public.

Herring Gut president and co-chair Philip Conkling said Oktay “brings to Herring Gut a distinguished scientific background and deep leadership experience with key New England marine organizations. I have every confidence that Sarah will broaden and deepen Herring Gut’s education and community programs going forward.”

From 2018-2021 she was director of strategic engagement for the Natural Reserves System at the University of California Davis, representing six field stations and marine labs in Northern California. Prior to that, Okay was director of institutional advancement

at the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory in Gothic, Colorado.

She received her B.S. in marine science and a Ph.D. in chemical oceanography from Texas A&M University Galveston. From 2003-2016 she was executive director of the University of Massachusetts-Boston Nantucket Field Station, a marine lab and field station on Nantucket Island. Her research focused on coastal processes, watershed health, pollution transport, and harbor water quality.

After 9-11, she mapped the chemical signature of the World Trade Center ash and tracked its fingerprints in the Hudson River, coincidentally discovering hospital waste residues from sewage in New York and New Jersey.

Oktay is an invited member, national board member, and 2020 president of the Society of Women Geographers, and has been on the boards of many civic and nonprofit groups. She served as president of the Organization of Biological Field Stations, a professional

organization representing several hundred field stations and marine labs across the globe, from 2014-2016 and has been on that board for 13 years. She currently serves on the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary Advisory Council.

Oktay’s nine years of service on the Nantucket Conservation Commission has been featured in Vanity Fair, Yankee Magazine, Cape Cod Times, ABC. com, CNN, the movie Rising Tides and many other news outlets. She was also a science adviser for actor Mark Ruffalo, advising on topics such as climate change, fracking, and water quality monitoring for the non-profits he founded. In 2020 she released a book of science-based poetry, Sifting Light from the Darkness and recently released the first of four books of Nantucket-focused natural history essays.

She also is part of the founding team for The Virtual Field, a project designed to bring place-based experiential science to classrooms around the

How could this happen? McCarron figures there are 4,700 lobstermen, of whom 3,000 are active. Currently, the law allows each fisherman to have 800 traps; these need to be tagged annually at the cost of 75 cents per trap. Those fees go to the Lobster Management Fund of the DMR which supports lobster fishery research, licensing management, and regulation enforcement.

If you added a nickel to the tag fee or take one from the current fee, you’d get $40 for 800, or half the cost of a tank of truck gas. If there are 3,000 who have 500 tags each, that’s $75,000.

If those funds were targeted toward cleaning up shoreside debris, finding and removing ghost traps, or going after giant rolling balls of derelict gear, it would sure help. It would help buy gas for boats and trucks, rent construction dumpsters, and pay dump fees. More importantly it would be a start on helping the industry clean up its waste. Other businesses and individuals pay to dispose of their waste. Why not fishing? Perhaps it is time to make this a bit more visible.

Ben Fuller is curator emeritus at the Penobscot Marine Museum, a registered Maine Guide, a regular contributor to WoodenBoat and other publications, and long-time volunteer for shoreside and roadside cleanups.

world. She strongly feels that scientists should communicate with the public and provide educational services to all ages, and that place-based learning is the best route to achieve that.

11 www.workingwaterfront.com april 2024

Sarah D. Oktay, PhD

Beavers helping create wetlands in Acadia

Park staff identify where they have worked

BY CATHERINE SCHMITT

Mount Desert Island is a watery place, thanks in part to the presence of beavers.

Park staff and researchers have identified more than 250 beaver-influenced wetlands in the park. Beavers have limited space in Acadia’s steep topography to create “new” wetlands; instead, through their dam-building on streams and ponds, they expand, connect, and diversify existing aquatic ecosystems.

Beavers adjust water levels to support their plant-based foods, and to maintain access to their shelters of sticks and mud. In the process, they create habitat for all kinds of other plants and animals.

Beaver wetlands are also important spaces for humans.

When the canoe was a primary means of travel, beaver-created networks of surface water enabled people to move through the landscape and access important food, medicine, and materials. A few Wabanaki people had been hunting beaver and catching fish in 1604, when they encountered European navigator Samuel de Champlain along the shore of the place he later would name “Isle de Monts Desert.”

They traded some of their beaver furs, according to Champlain, in return for bread, tobaccco, and other items, which suggests that pelts were still common enough to be traded for “trifles.”

At that time, beaver fur was one of the most highly valued items of exchange between North America and Europe. The demand for fur contributed to the demise of beaver across the continent. Locally, beaver had been trapped to extinction by the 1800s, but animals from interior locations continued to supply a ready market.

In 1882, local newspapers reported that “large poke bonnets, with high tapering crowns” made of beaver fur in shades of bronze, green, red, brown, black, and white were in fashion and

10,267 beaver furs (of unidentified origin) had sold in London.

Without beavers to maintain them, many wetlands dried up and began to fill in with grasses, shrubs, and trees. Geologist Ellen Wohl calls the period between 1600 and 1900 when beavers were hunted and trapped out of the landscape the “Great Drying.” Trees spread into the desiccated soil of the meadows, and water drained more quickly into stream channels.

At the same time, a growing population of humans was filling in and altering wetlands and building roads across streams and valleys. Most people forgot how to live alongside beavers, although the memory of beavers persisted in Wabanaki oral history, and in place names on the MDI landscape: Beaver Meadow Pool (below Bubble Pond), Beaver Dam Pool (Bear Brook Pond), Beaver Brook Valley (Otter Creek-Cromwell Brook), and the Beaver Pool behind Sand Beach.

between the mountains, rewatering the land, reclaiming meadows from the cedar forests that had expanded in their absence. By 1932, beavers were living in Little Harbor Brook, and Marshall Brook on the west side of Mount Desert Island.

Their presence was newsworthy, as the Bar Harbor Times reported in 1934 that “A large beaver has made his appearance in the brook above the cemetery bridge, felling trees and evidently making preparations to spend the winter there.”

To a beaver, the flow emanating from a culvert is a “leak” in the water-retaining complex of dams and channels that must be repaired.