Maine’s ports poised for growth

Wind turbines, refrigeration capacity point to active future

BY TOM GROENING

The future of Maine’s three state-supported shipping ports is bright, says Matt Burns, director of the Maine Port Authority.

“We have a lot of activities on our plate out to the end of the decade,” Burns said during a Feb. 14 online presentation hosted by the Waterfront Alliance, a Portland working waterfront advocacy group.

Chief among those activities are a growing capacity for refrigerated cargo at the International Marine Terminal in Portland and the role likely to be played in developing offshore wind turbines by Mack Point or Sears Island in Searsport. The third port, Eastport, is a focus for the authority as it works to develop business there.

Burns, whose career included stints on dredge, drill, and cruise ships, has been executive director of the port authority, the quasi-state agency, for less than a year, but he had served as interim director. The authority’s mission is to develop, maintain, and promote port and intermodal facilities “to stimulate commerce and enhance the global competitiveness” of the state.

UNFRIENDLY TEMPERATURES—

Portland has lost some ship traffic as oil deliveries have declined, Burns said, though he acknowledged the carbon-reduction represented by that decline is welcomed. He praised the work Iceland-based operator Eimskip has done in Portland. The company operates in ports around the world.

“They’ve brought the freight,” he said, and have maintained weekly ship service since 2018. The state has invested nearly $100 million in the port since 2009, Burns said.

“Almost everything is brand-new in the last five years,” he said.

Free community college gets good marks Program achieving workforce, educational goals

BY STEPHANIE BOUCHARD

Emma Brezovsky, 18, a senior at Bucksport High School, wants to become a teacher. To achieve that goal, she knows she needs a bachelor’s degree.

“My original plan was just going to be four years at [University of Maine] Farmington,” she said. “But now I’m going to do two at Eastern Maine [Community College in Bangor] and then finish at Farmington. It’s going to be a lot cheaper.”

CAR-RT SORT POSTAL CUSTOMER

What changed Brezovsky’s mind about doing all four years of her undergraduate education at one school is the Free College Scholarship program created through the allocation of $20 million by the state legislature last year. The program has been such a success that there is currently a proposal at the state house to extend funding to support the classes of 2024 and 2025.

While it’s still early, all indicators are that the scholarship program is meeting the first part of its goals, said Daigler.

“We’re getting the students that we’re hoping to get, which is a student who’s at risk of not going on and getting a college degree of any kind.”

Enrollment is up at the seven community colleges, and has especially rebounded at the most rural of the campuses in Washington and Aroostook counties, which as of the fall semester saw enrollment increases of 25% and 31%, respectively.

And Maine is bucking the national trend of young men backing away from higher education. Those enrolled through the

The Free College Scholarship program seeks to address two statewide concerns, says David Daigler, president of the Maine Community Colleges System: that a large number of Maine youth are not going on to get any education beyond high school, and building the state’s workforce. continued on page 8

NON-PROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE PAID PORTLAND, ME 04101 PERMIT NO. 454 News from Maine’s Island and Coastal Communities published by the island institute n workingwaterfront.com volume 37, no. 2 n april 2023 n free circulation: 50,000

What’s known as sea smoke, one of three kinds of fog, was captured on Feb. 4 on Friendship Harbor during that day’s double-digit below zero temperatures. See our story that explains how the different kinds of fog form on page 12.

PHOTO: JACK SULLIVAN continued on page 8

“We’re getting the students that we’re hoping to get, which is a student who’s at risk of not going on and getting a college degree of any kind.”

Fishermen’s Net— Vietnamese street food meets Maine seafood

Signature sandwich recalls French, Vietnamese traditions

STORY AND PHOTOS BY KELLI PARK

At Fishermen’s Net Seafood Restaurant & Market in Brunswick, the new owners are infusing the flavors of Vietnam in their cuisine with Bánh Mì, a traditional Vietnamese sandwich.

Co-owner Hoa (Flower) Truong, 30, purchased Fishermen’s Net on Forest Avenue in Portland in 2018 with her cousin, Quang Nguyen, 33, who wanted to continue his family’s involvement in the seafood industry after 30 years of raising tiger shrimp, fish, and escargot along the shores of Khánh Hòa, Vietnam. After the business was lost to a fire in September 2021, the family reopened on Bath Road in Brunswick within three months and have since made it their own, in more ways than one.

In addition to buying and selling wholesale seafood from local fishermen, including lobsters, crabs, oysters, scallops, and a variety of fish, they ship lobster anywhere in the U.S. within 24 hours. They also sell some specialty items, including caviar, sea urchins, and smoked fish, the most popular of which is salmon smoked with a spicy and sweet maple brown sugar.

Their creativity, however, extends beyond the market and into the restaurant, which has historically served fried seafood and lobster rolls.

“We didn’t have space in Portland because it was just a fish market, not a restaurant. We didn’t even have a chance to think about it,” said Truong, who was a law student in Vietnam and went on to study business administration at Southern Maine Community College.

“When we moved up here, we could think about adding something new.”

Located in between a Chinese restaurant and a seafood restaurant, and with an abundance of Asian-style restaurants in downtown Brunswick, Truong said she wanted to do something a little different by infusing the local culinary scene with a unique combination of Vietnamese street food and Maine seafood.

With that in mind, Nguyen’s mother, Hoa Le, agreed to join the family business after repeated requests to share her culinary talents with a new community. When she wasn’t busy farming fish in Khánh Hòa, Le cooked and sold street food, including the popular Bánh Mì sandwich.

“I make food from experience, not from a recipe. The recipe comes from my mind in that place,” said Le, through a translator. “I love the feeling that people love my cooking! When I cook, and people enjoy it, I feel happiness.”

Truong shares more.

“Her goal is to have people love her food,” she said of her aunt. “She wants everybody here to know about her sandwiches! If the customers support her, she will make 10,000 different kinds of food!”

At Fishermen’s Net, Bánh Mì balances the fresh flavors of Vietnamese cuisine with pickled carrots, cucumber, cilantro, mayonnaise, chili paste, pork pâté, and a choice of lobster, pork, chicken, or shrimp on a French-style baguette, along with Le’s secret sauce, which features zesty hints of lemongrass, ginger, and garlic.

Although the baguette was introduced when Vietnam fell under French colonial rule in the mid-19th century, it wasn’t until the 1950s at the end of French rule that the Vietnamese were able to infuse their own culinary traditions into the baguette to create Bánh Mì. After spreading throughout food carts on the streets of Saigon, it has since become popular worldwide.

“Every morning in Vietnam, I woke up and ate a Vietnamese sandwich. I love Vietnamese sandwiches. It’s a tradition for me,” said Truong. “My husband is American and he wakes up and eats bagels with ham and cheese every day. It’s not surprising that the sandwich is something we eat every morning,” she said.

“We’re proud to be Vietnamese and we’re proud of our cuisine. It’s a small country, but people know about our food,” said Truong. “I was very happy when I posted the Bánh Mì sign and the customers came in and, instead of saying, ‘I want a Vietnamese sandwich,’ they would say, ‘I want Bánh Mì.’” Bánh Mì, however, is

just the beginning. If Le’s culinary zeal is any indication, there’s plenty more where that came from, including Shu Mai, a traditional Vietnamese pork meatball, and lobster pho, a noodle soup, along with the future fusion recipes that will pair together the flavors of Vietnamese street food and Maine seafood.

When asked about her goals for the future, Truong replied simply: “To sell 5,000 Vietnamese sandwiches a day!”

Fishermen’s Net Seafood Restaurant & Market is located at 36 Bath Road in Brunswick. Their websites are www.fishermensnet.me and mualobster.com.

2 The Working Waterfront april 2023

Hoa Le prepares a sandwich.

Hoa (Flower) Truong, left, and Hoa Le.

Hoa (Flower) Truong, left, and Hoa Le prepare food. Hoa Le holds two Bánh Mì sandwiches.

Quang Nguyen.

Lobster landings: catch remains high, price drops

Per-pound value of $3.97 is down from $6.71

FOLLOWING 2021’s historically high values for Maine’s commercially harvested marine resources, harvesters in 2022 earned $574 million, an amount that is consistent with more recent history, according to preliminary data released from the Maine Department of Marine Resources on March 3.

While overall value represents a 37 percent drop compared to 2021, it tracks with the average value of all Maine commercially harvested marine resources between 2011 and 2020, which was $586 million.

Maine lobstermen landed 97.9 million pounds and earned by far the most of all the state’s commercial fisheries at $388.5 million. The perpound value of $3.97 was on par with the average boat price of the decade prior to 2021, but a significant reduction from the all-time high that year of $6.71 per pound.

The result was an overall value decline from 2021 of $353.6 million.

“Maine’s lobstermen were facing tremendous uncertainty about their future last year over pending federal whale regulations, compounded by the high costs for bait and fuel,”

said Gov. Janet Mills. “Yet they still brought to shore nearly 100 million pounds of quality Maine lobster, which reflects this industry’s resilience when confronted with a difficult and dynamic economic environment.”

The lower landings may not speak to a decline in lobster population.

Kristan Porter, president of the Maine Lobstermen’s Association board, told Maine Public that harvesters did not fish as often in 2022, given the lower boat prices. DMR Commissioner Patrick Keliher told WCSH-TV that lobstermen took 50,000 fewer fishing trips in 2022.

On the strength of a per-pound increase of nearly $300, Maine’s elver harvesters earned $20 million in 2022, placing it as the state’s second most valuable commercial fishery. The value of Maine-caught elvers reached $2,131 per pound, which has only been exceeded twice in the history of the fishery.

Soft shell clams netted Maine harvesters $16.6 million, ranking the fishery as the state’s third most valuable in 2022.

“By funding new positions at DMR to address climate change impact on clams and other nearshore species, the state has taken the vital step in supporting the resilience of this and other important fisheries in the nearshore, like mussels, seaweed, and worms,” said DMR Commissioner Patrick Keliher.

At $12 million, the value of Maine’s menhaden landings in 2022 increased by more than $1.6 million over 2021 and ranked the popular lobster bait as Maine’s fourth most valuable fishery.

“Maine achieved a major win in 2022 for both lobster and menhaden harvesters, with an increase in state quota from two million pounds to more than 24 million pounds,” said Keliher. “That ten-fold increase in state quota will provide both menhaden and lobster

harvesters much-needed certainty in their ability to harvest and source bait.”

The value of Maine scallops in 2022 reached $8.7 million, one of the highest in the history of the fishery and making it the fifth most valuable overall for the state last year.

An additional bright spot for Maine harvesters was the jump in landings and value for alewives, another important lobster bait. Alewife harvesters caught 3.3 million pounds, an increase of 1.4 million pounds over 2021, and earned $1.5 million, an increase from the previous year of over $800,000.

“The work of our harvesters, dealers, and processors to sustain our resources and deliver the world’s best seafood is something for all Mainers to take pride in,” said Keliher. “I urge all Maine people to support our fishermen and coastal communities by enjoying Maine seafood.”

To locate a dealer selling seafood from Maine, visit www.seafoodfrommaine.com.

Reports for all species can be found at www.maine.gov/dmr/fisheries/ commercial/landings-program/historical-data.

3 www.workingwaterfront.com april 2023 G.F. Johnston & Associates Concept Through Construction 12 Apple Lane, Unit #3, PO Box 197, Southwest Harbor, ME 04679 Phone 207-244-1200— ww w gfjcivilconsult.com — Consulting Civil Engineers • Regulatory permitting • Land evaluation • Project management • Site Planning • Sewer and water supply systems • Pier and wharf permitting and design

Bud Staples 13 www.workingwaterfront.com . April 2020 Sea Farm Loan FINANCING FOR MAINE’S MARINE AQUACULTURISTS For more information contact: Nick Branchina | nick.branchina@ceimaine.org |(207) 295-4912 Hugh Cowperthwaite | hugh.cowperthwaite@ceimaine.org | (207) 295-4914 Funds can be utilized for boats, gear, equipment, infrastructure, land and/or operational capital. Lower Interest Rates Available Now!

John Martin, Bud Staples, and Elsie Gillespie chat around the woodstove at the annual town meeting.

Gerald “Punkin” Lemoine

Linkel

Locally owned and operated; in business for over twenty-five years. • Specializing in slope stabilization and seawalls. • Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) certified. • Experienced, insured and bondable. Free site evaluation and estimate. • One of the most important investments you will make to your shorefront property. • We have the skills and equipment to handle your largest, most challenging project. For more information: www.linkelconstruction.com 207.725.1438

Construction, Inc.

Like our stories, columns, and photos? Check us out and “like” The Working Waterfront on Facebook!

2022

of the fishery…

The value of Maine scallops in

reached $8.7 million, one of the highest in the history

The shameful history of a ‘notorious’ slave ship captain

Maine’s Frederick Drinkwater flouted ban on slave trade

BY TOM GROENING

Maine has a proud history of seafaring captains who braved the open ocean in pursuit of trade and fish. Capt. Frederick Drinkwater is not one of them.

Drinkwater, according to research completed and presented by Kate McMahon of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, participated in the slave trade. McMahon shared her research in a Feb. 3 online presentation hosted by the Maine Conservation Voters group.

Drinkwater, born in Yarmouth, “was one of the most notorious slave ship captains of the 1850s and 1860s,” said MCV’s Kathleen Meil in introducing McMahon. What is especially shameful about Drinkwater’s story is that he—and many other Maine- and New England-based ship masters— engaged in the slave trade decades after the 1808 U.S. law making it illegal.

“Slavery touched nearly every continent on the planet,” McMahon said, “and it really was driven by waterways.”

The slave trade began in earnest in the late 1500s, she said, and by the time it ceased in the 1860s, there had been about 40,000 trans-Atlantic voyages dedicated to transporting enslaved people, mostly from West Africa. The voyage itself was the first threat—some 12.5 million left Africa as captives, but only 10 million landed on U.S. shores, a mortality rate of about 15%, McMahon said.

“By 1750, enslaved people were being brought to Maine,” she said.

Among the known ships built in Maine for the slave trade before it was banned include the Knutsford (1761) of Berwick, the Hereford (1770) of Sheepscot, and the Rising Sun (1772) of Biddeford. The last of these sank with all 241 captives perishing at sea.

Opposition to the horrors of slavery emerged as early as the late 1700s, with Rhode Island passing a law banning slave traders in 1787. Massachusetts did the same in 1788.

Some were prosecuted for violating the law, but the merchants continued “with ease,” McMahon said.

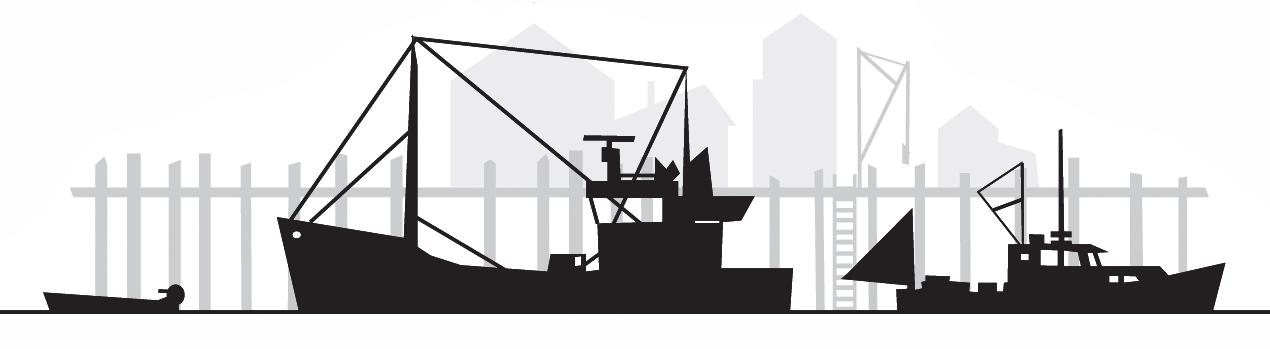

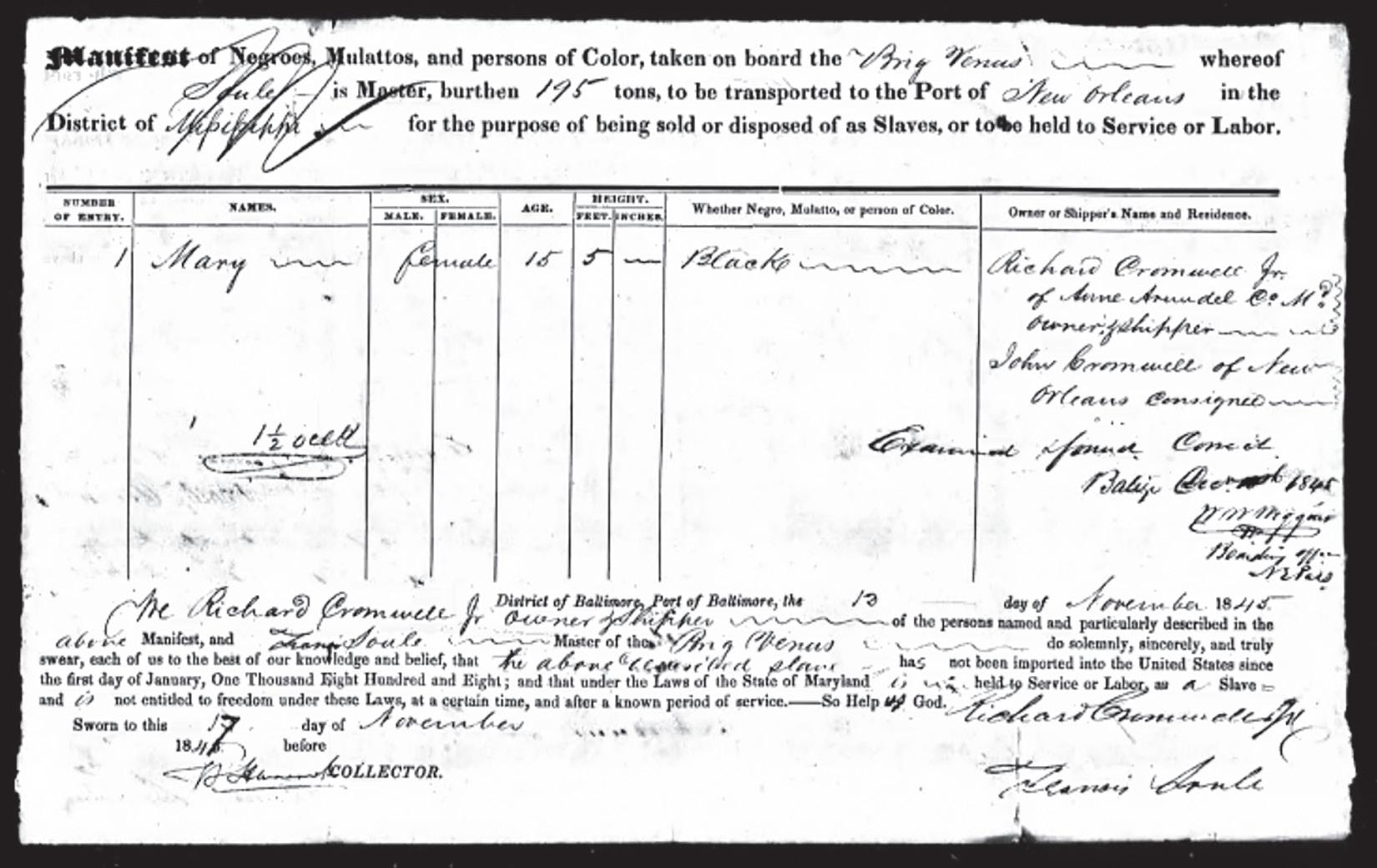

And yes, “Mainers were quite involved in this trade,” particularly in the 1840 to 1850s era, transporting enslaved people from the upper South to the lower South. Manifests for the Susan Soule and Venus, built and/or owned by Rufus Soule of Freeport, show a 15-year-old girl and one-year-old and six-year-old children among the “cargo.”

McMahon said while Great Britain banned the slave trade in 1807 and the U.S. followed in 1808, the law lacked teeth. The Act of 1820 asserted that participation in

the African slave trade was now to be “considered the most heinous crime on the high seas,” equal to piracy, a crime carrying punishment by death.

“But it really didn’t suppress the American slave trade in any substantial way,” she said, and in fact, officials seemed to look the other way on this illicit activity.

Only one Mainer, Nathaniel Gordon of Portland, was convicted under the law in 1861 and executed in 1862.

Frederick Drinkwater, who served as a kind of case study in McMahon’s presentation, began his seafaring career captaining ships in the coastal trade between Portland and Boston. But by 1850, he was deeply involved in the slave trade.

Among his exploits, flouting the law, were trips to Liberia with a cargo of freed AfricanAmericans, taking as many as 500 back to that continent “whether they wanted to go or not,” she said.

Drinkwater seems to have transported slaves to Havana, Cuba, and in 1857, he lived for part of the year there. One of the ways captains like Drinkwater escaped legal action was by disposing of ships used in the illegal trade or by renaming them, McMahon said.

“Frederick Drinkwater never suffered a single legal consequence,” she said.

The illegal slave trade fleet employed as many as 1,000 men. In the period from 1850 until 1865, some 20,866 enslaved people were transported in Maine vessels from Africa to Cuba, with an average of 647 per voyage.

A report in 1854 by the New York Times estimated the industry’s value at

$11 million, or about $330 million today.

“Maine’s slave ship fleet was nearly four times more valuable than the timber industry” in the 1850s, she said.

McMahon is an advisor to the Atlantic Black Box Project, which works to unearth the region’s ties to slavery.

“I think it’s important for us to unpack this history,” she said.

4 The Working Waterfront april 2023

Kate McMahon

Only one Mainer, Nathaniel Gordon of Portland, was convicted under the law in 1861 and executed in 1862.

A slave manifest for the brig Venus, owned and/or built by Rufus Soule of Freeport. The top line lists “Mary,” a 15-year-old.

A newspaper report on a slave ship arriving in Kittery.

From here to there—

Adventures of a yacht delivery skipper

Castine’s Cam Brien finds maritime niche

BY STEPHEN RAPPAPORT

It’s early October, still hurricane season, and Cam Brien, a professional yacht delivery captain, among other nautical gigs, is sailing a brand new 39-foot sailboat across Frying Pan Shoals, 15 miles off Cape Fear on the North Carolina coast, headed for the Annapolis Boat Show.

Brien had flown from his home in Castine to St. Augustine, Fla. where he planned to pick up the boat and head north, sailing “outside” along the coast from Florida to Beaufort, N.C. before following the sheltered Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) to Norfolk, Virg. then up Chesapeake Bay to Annapolis. As so often happens with boats, the plan changed.

Brien had already lost a couple of days before leaving St. Augustine because the boat wasn’t ready for sea. Besides normal provisions, he had to buy some basic navigation equipment required for a safe passage—a not uncommon situation for a delivery. Such purchases are always billed to the boat owner.

At the boat show, the broker offered Brien a chance to join his office and Brien seized the opportunity, though three days later, Brien said, “all of a sudden, the world is locked down,” thanks to the onset of COVID.

Despite the pandemic, or perhaps because of it, Brien has stayed busy delivering yachts—larger or smaller, primarily sail—locally in Maine and along the Atlantic coast. Not all those deliveries have been exactly low stress.

With bad weather forecast and the boat pounding, going head on into the wind-driven seas, Brien headed for shelter and ducked into the little port…

“You always think you’re going to fly in one day and take off the next, and it never works out that way,” Brien said. “I think there’s a certain sentiment out there that the boat is just what it is, and a lot of times the clients don’t want to pay for extra stuff. But I’m not going out there half-cocked.”

With bad weather forecast and the boat pounding, going head on into the wind-driven seas, Brien headed for shelter and ducked into the little port at Wrightsville Beach where he could join the ICW. After a few days on the ICW, with a couple of nights spent in marinas and a couple more anchored out— in the remote Alligator River and behind a stuck bridge just outside of Norfolk—Brien and the boat reached Annapolis.

Along the waterway, Brien and his crew enjoyed the hospitality at the marinas where they waited and avoided the worst of the weather, as well as anchoring in remote rivers miles from any signs of human activity.

“You always have a good time when you stop when you weren’t really supposed to be there, but circumstances worked out,” he said.

A 2014 alumnus of Maine Maritime Academy’s small vessel operation’s program, Brien worked on tugs in Alaska and spent several years working for Moran Towing on the Gulf Coast, moving barges loaded with grain from New Orleans to Puerto Rico and, more stressful, barges loaded with petroleum products.

“That was really interesting, but it really wore on me because I really worried about either spilling it or blowing it up,” Brien said. Eventually, he returned to Castine, teaching at MMA for a year while also doing occasional stints on tall ships in the Caribbean and starting Fairwater Marine Services.

About four years, ago, a phone call to a yacht broker friend in Florida got him into the yacht delivery business—his first trip as skipper, delivering a new 41-foot sloop from Palmetto, near the mouth of Tampa Bay, to the Miami Boat Show and back again afterwards. On the way to the show, Brien made an unplanned stop in Key West for a night to avoid heavy weather.

One trip involved delivery of a 66-foot, $2.5 million sailboat— the first of its type delivered to the U.S.—from Baltimore, where it came off a ship from France— to Newport, R.I., where the new owners would take formal delivery. The summer trip—down the Chesapeake then offshore from Cape May, N.J. to Narragansett Bay, but no more than 12 miles offshore thanks to the boat’s insurance— was complicated by the failure of the yacht’s high-tech mainsail furling system, non-functioning air conditioning, and the presence of the owners.

They turned out to be good shipmates who let Brien do his job as captain, and one of them was a professional chef, so meals were better than usual on deliveries.

Not all of Brien’s memorable deliveries involve big boats doing offshore passages. Recently, he delivered

Cercerelle, one of three classic Rozinante yawls designed and commissioned personally by L. Francis Herreshoff in 1972, from Rockport to East Blue Hill. The elegant little sailer easily made the 40-plus mile trip through exquisite Maine scenery in one day, despite light breezes along the way.

5 www.workingwaterfront.com april 2023

Cam Brien

The Sedna, a J/46 underway near Gloucester, Mass. Rappaport delivered the boat from Darien, Conn., to South Freeport in 2020.

book reviews

Defying authority in a Maine mill town

Memoir recalls battles against poison, abuse

represented success in America. The two things towering over the towns were smokestacks and steeples. That visual cue symbolized power and authority—the mill and the church could demand unquestioning respect.

newly-divorced with six children, and with a pronounced “cockiness.”

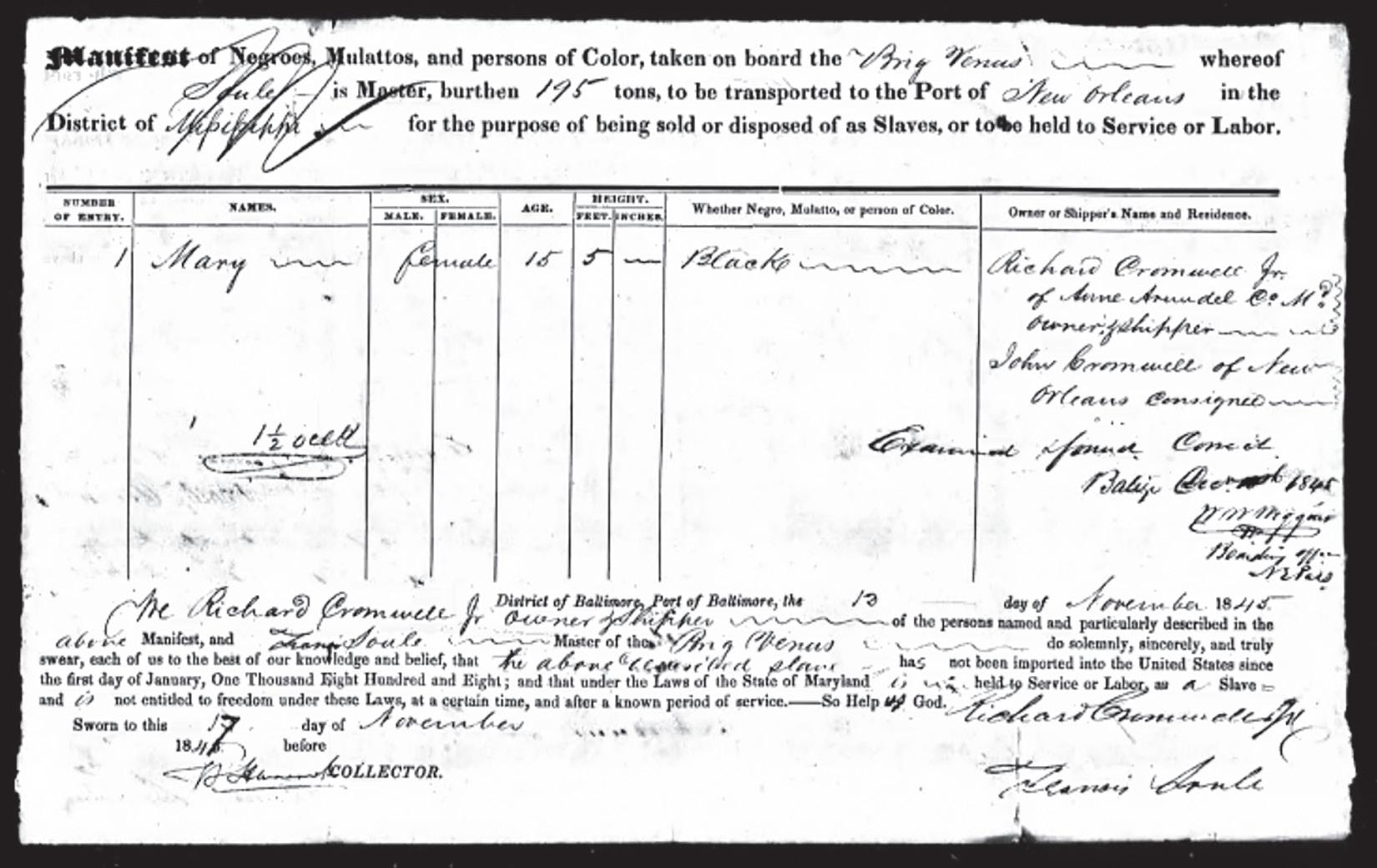

And Poison Fell From the Sky: A Memoir of Life, Death, and Survival in Maine’s Cancer Valley

By Marie Therese Martin (Islandport Press, 2022)

REVIEW BY TINA COHEN

THE POISON IN Marie Therese

Martin’s And Poison Fell From the Sky: A Memoir of Life, Death, and Survival in Maine’s Cancer Valley is the toxins emitted by the paper mill she grew up near in Rumford. Few people called it poison; denying the health threats was a way residents of Rumford and Mexico, flanking the mill on the Androscoggin River, tried to avoid that reality, instead seeing the mill as a source of steady paychecks and the industry as inevitable, with generations of ties to it.

Many in the community had Acadian roots, coming from Canada originally. With new opportunities, this life

Martin’s childhood was typical, she writes, one of three children of Catholics, with French-Canadian ancestors. But the family was decimated by the father’s philandering and her mother demanded he move out. Shock and shame followed the divorce.

The community blamed her. Martin’s conflicted feelings about Catholicism grew when her mother sent her off to boarding school where she was expected to become a nun. After two years of misery and loneliness, she returned home, gratefully, to Rumford.

But again being exposed to sickening smells and visible pollution in the river, Martin began to recognize the mill’s lethal potential. She writes, “I had always been interested in environmental issues. I loved my hometown but hated the familiar smell of caustic chemicals that invaded everything... On bad days my eyes burned and taking a deep breath made my lungs ache.”

A nursing degree, supported by a scholarship, meant she returned again to Rumford to work at its hospital. Disregarding warnings from co-workers, she dated a doctor she found appealing, despite his being twice her age,

Generational conflict follows star-crossed sailboat

while superficially an account of her year on a star-crossed sailing vessel, is at its core an account of a family grappling with its own version of those troubles.

Her surprise pregnancy served as entrapment. “Doc” said he’d marry her, and expected her to take on parenting his own children (plus the three they’d have together), be his full time office assistant, and sublimate her own needs, always, to his.

While that might seem a traditional arrangement to some, Martin saw the dark side and how he controlled her. But she would not consider divorce. She began to see similarities between what she was expected to overlook as dangers—the mill spewing poison, the church teaching unquestioning obedience—and ignoring her husband’s verbal and emotional abuse.

Yet the toxic relationship served as a catalyst—they began working together to document the illnesses and cancers occurring locally. With so many reported cases, their area had become known as Maine’s “Cancer Valley,” and more people were asking questions.

On a national level, Maine Sen. Ed Muskie was crafting environmental protection laws, leading to the Clean Air Act of 1970 and the Clean Water Act of 1972.

Martin writes: “Despite these changes, our local and state governments were not doing anything to protect the people impacted by a polluted environment… Without

good-paying jobs, there would be no economy here or anywhere else in our rural state. The mill provided a living wage for the whole town, and in exchange, the paper industry as a whole was given carte blanche.”

The couple began to speak out about the cancer, linking it to chemicals released by the paper mill. They paid a high price for their advocacy, receiving tax audits, record reviews, a lawsuit, and social ostracism. When Doc died of cancer, his heroism in confronting the polluters was noted. One editorial said, “He spoke truth to power.”

Martin kept up the fight. Readers of Kerri Arsenault’s award-winning memoir, Mill Town, will be familiar with Martin’s work because Arsenault, who grew up a generation later in nearby Mexico, also recognized the toxic environment. Her investigation utilized the careful records Doc and Martin had kept.

Poison Fell From the Sky deserves your attention as Maine’s coastal waters continue to be impacted by the mills still discharging waste into the rivers that flow into our bays. Humans and wildlife are still exposed to toxins. Questions continue to need to be asked.

Tina Cohen is a Massachusetts-based therapist who spends six months of the year in Vinalhaven.

Elizabeth forms a close friendship with another teenager escaping her family, Kim. Amid recollections of shipboard misadventures, Elizabeth returns persistently to her poisoned family life.

They then sail from Veracruz to the Panama Canal, with plans to sail on to the Galapagos Islands. A storm at sea makes up one of the story’s most vivid episodes.

Sailing at the Edge of Disaster: A Memoir of a Young Woman’s Daring Year

By Elizabeth W. Garber, Toad Hall Editions (2022)

REVIEW BY DANA WILDE

By Elizabeth W. Garber, Toad Hall Editions (2022)

REVIEW BY DANA WILDE

AMONG THE MANY weird things that were happening during the social upheavals of the 1960s and ’70s, one of the weirdest was the wholesale revolt of children against their parents. Of course parent-child enmities have never not existed. But in those decades an unusual resentment developed between the generations.

Every family stricken by those rifts dealt with them in their own ways, and Belfast resident Elizabeth Garber’s book Sailing at the Edge of Disaster,

Garber tells us in mainly chronological order about her father’s decision in 1971 to send her, age 17, and her brother Woodie, 15, to an alternative school aboard the square-rigged sailing ship Antarna. We get a very uncomfortable picture of the emotional abyss between the kids and their overbearing father at home in Ohio. The father arranges for Elizabeth to be a summer assistant to the organizer, Stephanie, of the Oceanics School. By September the students and teachers are gathering at the ship docked in Miami.

The ship is not ready to sail. The students are put to work on the extensive repair and maintenance projects needed to make the vessel seaworthy.

Elizabeth, being something of a bookworm and an obsessive journal writer, is charged with creating the onboard school library. It soon becomes apparent that not only is the ship not ready, but there isn’t much of a crew either, including no captain.

The narrative follows a kind of picaresque of events re-created from journals, letters, and other sources.

Late in the Miami part of the story, her father turns up unexpectedly to “help out” on the ship. When he announces at the end of his weeklong stay that he’s decided to remain and sail with them, Elizabeth and Woodie close ranks to stop him. This is a turning point for both the kids and the story.

Shortly afterward, more than halfway through the book, the Antarna is finally seaworthy, has secured a captain and crew, and sets sail. Even the departure, however, is complicated by legal obstacles stemming from frictions between organizer Stephanie and the ship’s owners who, for reasons unknown to the kids, seem to be undermining the project.

They sail to Key West, then Veracruz, Mexico, where murky maintenance and legal problems have to be addressed. The students are sent off to explore by themselves in Mexico, providing to the narrative a welter of episodes of wild rides, drunken fiascos, and close scrapes typical of what you’d likely expect of American youth turned loose with a backpack, a few dollars, and a bus ticket.

In Panama, the trip comes to a bizarre end when the ship owners conspire with the Panamanian military to block the Antarna in the canal. Shots are fired. Amid a zoo of wayward adults— including the apparent con artist and probable procuress Stephanie—the kids have come to admire the old captain.

Like the father young Elizabeth seems always to have wanted, he comes through to get them all out safely.

The Antarna adventure is over. But the story continues on to detail the aftermath, involving partly an aborted project to find a second sailing gig, and particularly Elizabeth’s desire to deal with her family life. Back home in Ohio, she makes a detailed plan to kill her father.

The book is framed and infused by this fraught relationship. In the shadows of Sailing at the Edge of Disaster’s tale of teenagers’ life in a floating experimental school, is a picture of the troubling family issues that drove parts of the culture-wide youth rebellion in the tumultuous 1960s and ’70s.

Dana Wilde lives in Troy. He is a member of the National Book Critics Circle.

6 The Working Waterfront april 2023

Fraying family is unwanted ballast

When admitting you’re wrong is the right move

A captain’s candid confessions reveal the vagaries of ocean

relationships aboard ship, what it’s like to make difficult decisions under lifethreatening circumstances—in short, all the important things one can only learn from time at the helm in the dead of night, on the bridge, or in the privacy of the captain’s cabin.

It’s this point of view that makes Reading the Glass so fascinating, even to a sometime sailor like myself.

Reading the Glass: A Captain’s View of Weather, Water, and Life on Ships

By Elliot Rappaport, Dutton/Penguin Random House (2023)

REVIEW BY DAVID D. PLATT

By Elliot Rappaport, Dutton/Penguin Random House (2023)

REVIEW BY DAVID D. PLATT

A FEW OF us get to know everything: doctors, editors, various experts, philosophers, TV pundits, religious gurus—and, now after reading Elliot Rappaport’s Reading the Glass: A Captain’s View of Weather, Water, and Life on Ships, I must add sea captains. Rappaport has served worldwide aboard a variety of vessels, including Maine Maritime Academy’s schooner Bowdoin and two sail training ships of the SEA Education Association that have taken him across the Atlantic, into the Arctic, and to the far reaches of the Pacific.

In the process he’s learned just about everything there is to know about the world’s weather, sea conditions, and maritime history—plus lots more about customs on faraway islands,

Lest he leave the impression he’s always right, this author/captain isn’t afraid to admit he’s wrong, especially when it’s time to turn the ship around as conditions deteriorate. Predictions are only as good as the information that goes into them, Rappaport makes clear, and new or better information can change everything.

His is a voice with real authority, made more so by the admission that from his shipmates’ perspective, a captain with the guts to listen to others is the best kind of captain to have.

Some of this book’s best passages are Rappaport’s descriptions of weather and the forces that drive it from below, on the sea surface, or aloft. Natural forces merge with history at times.

“The Pitcairns,” he writes of the islands made famous by the Bounty mutineers, are “the newest rocky extrusions of a continuous land factory” where undersea volcanoes beget mountaintops surrounded by barrier reefs, all exacting their price on water temperatures, ocean currents,

Art, the early years

Dickerson’s novel speculates on origins of art

The Santanda people divide the year between two caves, Greenhearths in the greenseason and Snowhearths in winter. They are hunters and gatherers, living mostly on deer and fish. We follow their lives, with Okyo providing asides—short italicized passages—that reflect on the day-to-day goings-on, be it the power of the art he makes or tension with Kocho, his rival.

Telling Stone

Maine Authors Publishing

REVIEW BY CARL LITTLE

WHO WERE THE first artists and why did they make art? Those are the central questions that prompted Scott Dickerson to write Telling Stone. Set in paleolithic times, the novel tells the story of 20-year-old Okyo, a “man apart” in his band of people, the Santanda, and how he searches for meaning through carving and painting—and seeks love—a hearthmate—from cave to cave.

Okyo uses his art to pay tribute to the creatures that sustain his band. A carver at the beginning, he learns how to paint from Pitto who joined the Santanda from another tribe. Their mediums include red ocher and charcoal. They paint “seeking power.”

Dickerson creates a poetic vocabulary for his fictional clan. His compound nouns include words for various animals—tallanterlered (red deer), silversides (salmon)—as well as various plants, tools, ceremonies, and body parts. There is a glossary at the end, but turning to it will take some of the fun out of figuring out the meaning of a particular word. What’s a lifedrumcave? Fireseed? Orangebelliedflash? Tuskedgrunt? Succulents? Snowpissrock? Talkswithtail?

and the atmosphere moving overhead. Traditional mariners in canoes learned the ways of such places, traversing vast stretches of the Pacific long before modern navigation.

“When I’m sailing other coasts,” Rappaport writes from an isolated harbor in the western Pacific, “the chart edges tend for me to fill with the familiar, even when I’m far from home… here is the opposite: We are surrounded at close hand by amoebas and in the distance are locations even more mysterious… clouds boil into the sky around us, atmospheric volcanoes that I suspect are driven by massive evaporation and instability over the warm puddles of lagoon water, underlit by a fantasy palette of green and blue, they hover above the shallows and then drift offshore, bringing us hourlong lashings of rain, sudden calms followed by lurching gusts that render sailing almost impossible, the timing between torrents too short to set sail productively,” he writes.

“‘This is like trying to pitch a tent at the end of an airport runway,’ I tell the mate.”

He takes in sail, starts the ship’s engine, and imagines an early French navigator “floating helpless in his wooden ship, hung with creaking spars and frayed hemp canvas. He asked for it, the islanders might say, standing by their canoes hauled safely up on the beach.”

From melting Greenland ice to the flooded subways of New York following a stronger-than-usual hurricane,

Rappaport explores the unfolding catastrophe of climate change.

“Do sailors now see the effects of climate change at sea?” he wonders. “Are the storms worse? For working mariners the one-storm-at-a-time imperative of seafaring can make longer patterns more difficult to visualize,” he writes. “But here we are, I think, in mid-September, with two months left of hurricane season and already out of names. This once-in-alifetime occurrence has happened twice since I bought the car I am driving. It will happen again in 2021.

“On the radio I hear that America’s dry western forests are ablaze from Los Angeles to Seattle. The jet stream carries their microscopic particles to us here in New England, a high plume of dust that’s drawn a pink-gray scrim across the early morning sky.”

Then the early sun bursts into the center of his windshield, “seemingly near enough to visit—there is a star out there, I remember—a thermonuclear forge. It is 93 million miles away but, like an overfilled woodstove, suddenly too close for comfort.”

For a sea captain who knows everything and understands the meaning of the barometric glass, the message is disturbingly clear—clear enough, he hopes, to change course before it’s too late.

Telling Stone is no Clan of the Cave Bear or One Million B.C. Where that book and that movie heightened the drama of early ancestors to the nth degree, Dickerson takes a quieter route, the narrative nearly violence-free. That said, there’s a close encounter with a bear—an alleater— several hunting scenes, and a couple of fairly steamy sexual encounters.

Some elements of the story seem out of place, too modern in concept. Would women of that ancient time discuss masturbation? Maybe. Would a cave artist muse, “If you have to talk about your painting, what you have painted does not tell its story”? Perhaps. On the other hand, the story of how “sharpness came to be” or Okyo’s wondering at how fish eat their young and how this relates to his consuming his childhood are memorable.

The novel is timely: recent research on cave drawings has uncovered new theories about how the early artists worked. One article is titled “For Over 20,000 Years, Neanderthals Spat Paint On This Stalagmite” while another declares “Cave Paintings Show Neanderthals Were Artists.”

Werner Herzog’s film Cave of Forgotten Dreams has spurred additional interest as has commentary from the likes of critic Jerry Saltz who urges pilgrimages to see cave art.

Dickerson earned a master of philosophy in human ecology degree from College of the Atlantic in 1995 before becoming director of the Coastal Mountains Land Trust. You sense his COA ties through his sensitivity to the ecology of this long-ago world (and the tribal gatherings recall his alma mater’s All College Meetings).

In Telling Stone’s afterword Dickerson notes how none of us can know “how these people lived, loved, revered, feared, celebrated, honored, or in any other way engaged with other people, animals, or the entities of their imagination.” As he stated during a book talk in COA’s Davis Center for Human Ecology in January, Telling Stone is speculative fiction. As such, it engages you in wondering about the motives of the first artist—to record, to venerate, to find joy? These questions keep you reading.

7 www.workingwaterfront.com april 2023 book

reviews

David D. Platt is former editor of The Working Waterfront.

Carl Little lives on Mount Desert Island.

PORTS continued from page 1

Construction of a long-planned 107,000-squarefoot, $55 million cold storage facility was set to begin in late winter. The project, which will include photovoltaics offsetting 20% of its energy use, is expected to be fully operational February 2024.

Burns said the port now uses 150 plug-in refrigerator containers, but that number will grow to 450. Radiation scanning equipment to screen incoming containers also will be added to the facility.

The port is aiming to handle 3,000 20-foot-equivalent—or TEU—containers annually, up from the current 900 TEU capacity, with the infrastructure expected to be in place by the end of the decade.

“Eimskip is considering larger vessels,” he reported. “They’re trying to find ways to bring additional volume into the port,” either with more ships or bigger ships.

Adding larger cranes, yard trucks, dredging the berth from 32 feet at mean low tide to 35 feet, and creating more pier surface are all goals.

A plan by the state of Maine to locate a dozen floating wind turbines to demonstrate and study wind power potential in the Gulf of Maine is approaching implementation. The Pine Tree Offshore Wind project would be sited south of Monhegan Island, pending approvals, but proponents hope the turbines will be in the water this year.

The turbines, Burns noted, would be the largest structures in Maine.

“We’d be building skyscrapers, essentially,” he said. The state is considering Searsport as a port location, weighing using the existing Mack Point facility on the mainland, or Sears Island about 500 yards away, or a combination of both. Eastport’s Estes Head facility is also in the running.

Deep water access, no overhead restrictions, a cargo staging area, heavy loading capacity (up to 6,000 pounds per square foot), and 1,500 feet of dedicated wharf frontage are needed to store, assemble, and launch the floating turbines, Burns said. The turbines would be towed to the chosen site.

“We want to do all of that at one of our ports,” he said. “It’s exciting stuff.”

Though Searsport is a likely location for the work, Eastport is still under consideration, he added. Groups based in Searsport and Islesboro have argued that Sears Island is not appropriate for the activity. The stateowned island has been divided, with 650 acres put in conservation, and the remaining 300 acres reserved by

COMMUNITY COLLEGE

continued from page 1

the Department of Transportation for possible port uses.

“We’re collecting data from all sites,” Burns said, and working with stakeholders.

The state has invested nearly $100 million in the port since 2009, Burns said.

The existing port at Searsport needs dredging, he added, though the railroad link to that port is more viable with recent ownership changes. Maine now has two class 1 lines, CSX and Canadian Pacific, he said, with CSX purchasing Pan Am Railways and Canadian Pacific acquiring Central Maine & Quebec Railway in the last year. Eastport remains a challenge.

“We’re trying to fund new opportunities for Eastport,” Burns said, and it now has a mobile harbor crane, joining Portland and Searsport in having that equipment.

The port authority has its own goals, Burns said, which include developing a comprehensive plan for the ports that looks ten to 20 years ahead, completing several grant-funded projects, hiring additional staff, and developing a more visible presence in the state.

Free College Scholarship program are 49% men and 50% women, Daigler said.

The scholarship program supports students who received or will receive a high school diploma or its equivalency from an in-state or out-of-state school in 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023 by covering the cost of tuition and mandatory fees (but not room and board). The average cost of tuition and mandatory fees at Maine’s community colleges is $3,700 a year. Students must reside in Maine to be eligible for the scholarship.

The expectation is that many of the students who get the training through the scholarship program will likely return to their communities to live and work. While that remains to be seen, it’s vitally important that the pathway for such an outcome exists, said Kristy Hastings, student services coordinator at Mid-Coast School of Technology in Rockland.

“Without the trades programs and the programs that the community colleges offer,” she said, “our community doesn’t survive.”

A spokesperson for the state’s Department of Economic and Community Development said in an email:

“Free community college is an opportunity to tackle multiple challenges in Maine’s economy at one time. It is clear that we need a workforce that can meet the needs of in-demand jobs. This will not only help to start to address our state’s workforce challenge but will also give those students the opportunity to have a meaningful career so they can stay in Maine long term. It creates paths and opportunity for students who say tuition is a barrier to furthering their education.

“While we recognize that this investment alone won’t solve the state’s workforce challenges, we believe it is a good step forward for both the students enrolled, the communities they will live in, and the organizations they will either start or work for.”

The Free College Scholarship program is a “huge” opportunity for students and Maine communities, said Heather Davis, a guidance counselor at Bucksport High School.

“It probably opens more avenues for students to have this opportunity that might not be able to afford it otherwise.”

It also creates additional options for students, like her son who attends Mount Desert Island High School, who are worried about the future of traditional mainstays of Maine’s economy.

“My son is a fifth-generation lobsterman,” she said. “His heart and passion are in the family history of the generations of lobstermen, but right now he’s thinking, ‘I need to go to school for business or have a backup plan in case this is a crossroads for the industry.’”

The community college system offers more than 300 programs to present students with a broad array of options, the system’s president said. There are more traditional classroom-heavy courses, but there are quite a number of experiential pathways, too, which are popular with students.

Seventy-seven percent of the students in the Free College Scholarship program are enrolled in career and technical education programs, he said. Those include trades, such as welding, heating, and electrical, and healthcare, the field with the highest enrollment.

“The vast majority of our students are actually using this to get trade-based skills,” Daigler said. “In order to get a job with a career opportunity, you have to have a skillset.”

Applications for the current funding of the Free College Scholarship program are still being accepted. To learn more about the program, go to www.mccs. me.edu/freecollege/.

8 The Working Waterfront april 2023

An aerial view of Mack Point in Searsport.

PHOTO: COURTESY MAINE DOT

Maine Department of Transportation officials watch an Irving ship near the Mack Point terminal in Searsport in 2013. FILE PHOTO: TOM GROENING

Fear of aquaculture not reasonable

Large or small, industry would be well regulated

BY ORLANDO E. DELOGU

BY ORLANDO E. DELOGU

AN ARTICLE IN the February/March issue of The Working Waterfront outlined the fact that an increasing number of coastal towns in Maine fear, and are interposing regulatory measures that bar or limit, new and/or expanded aquaculture activities in their respective towns (“Towns fear, fight aquaculture expansion”).

Similar (and somewhat stronger) views were expressed in a recent Portland Press Herald article that on one hand supported traditional, small-scale, locally owned aquaculture activities, but on the other was wary (seemingly to the point of exclusion) of larger-scale corporate aquaculture undertakings that may or may not be rooted in Maine.

In my view, we need to get over these fears. Expanded aquaculture activities, including farming, harvesting, and processing of seaweed, salmon (and other finfish), clams and related shellfish are an extension of, and the logical future of Maine’s historic fishing, clamming, and lobstering activities.

Global warming, the warming of Maine’s nearshore waters, coupled with overfishing by small, historically unregulated boat owners, are irrefutable factors in the decline of traditional fishing activities.

clammers and wormers over-harvested; and firstgeneration aquaculture activities (with no security to operate in a fixed offshore water area) struggled to survive.

In the early 1970s the regulatory powers of Maine’s Department of Marine Resources were strengthened. This was seen as essential to stop overfishing by small independent boat owners, to stop overharvesting by small independent harvesters of clams and worms, and to breathe life and order into small first-generation aquaculture activities. DMR could now grant secure leases to defined water and seabed areas.

Third, bigger is not inherently bad—L.L. Bean and BIW are examples staring us in the face. Larger aquaculture entities can realize economies of scale. They are more likely to not only grow and harvest a product, but also to engage in the more lucrative “value add” of processing and shipping a growing range of marine products into national and global markets. This translates into more jobs in Maine.

Aquaculture builds on a historic base of marine-related activities…

Groundfishing will never be what it once was, and traditional lobstering is under increasing pressure to limit the location, gear used, and annual take of this marine resource. Annual take is also threatened by the inexorable movement of spawning lobsters to colder northern and eastern waters. The geographic center for lobstering on the East Coast is (or soon will be) Hancock and Washington counties in Maine and eastern Canada.

Expanded aquaculture activities in Maine (some by large corporations) can/will replace jobs being lost by declining employment in traditional fishing/ lobstering activities. By utilizing offshore waters and land-based facilities to grow (in controlled settings) and process a variety of marine organisms, aquaculture will produce new employment opportunities. Further impetus for aquaculture growth is the growing global need/demand for marine (proteinladen) food products, and for an expanding array of non-food products (fertilizers, cosmetics) that derive from harvested seaweed. Some seaweed extracts are today being used as thickening agents in pharmaceutical and biotechnological applications.

Our fears must be tempered by several realities.

First, global warming is not going away. Marine scientists and oceanographers tell us this warming will continue for years and decades to come. This will further reduce Maine’s traditional fishing and lobstering activities.

Second, romanticizing the virtues of small-scale, locally owned fishing and aquaculture activities serves no one’s interest—left to their own devices, local small-scale fishermen over-fished; independent

Moreover, we should bear in mind that DMR’s statewide powers to regulate extend to corporate entities of every size. This agency is in a far better position than individual towns to monitor, regulate, and license the larger-scale aquaculture activities that seek a place along Maine’s coast.

It has the technical staff, the jurisdictional reach, the legal power, and an enforcement apparatus in the Marine Patrol to regulate as fully as necessary individual or corporate entities that seek to utilize Maine’s shoreland, intertidal land, and submerged land for fishing, harvesting, or aquaculture activities.

Fourth, we need to realize that we have a lot of shoreland. We control a lot of ocean.

There is ample room to protect small-scale marine organism growers and harvesters and at the same time make room for larger-scale operations with the capital resources needed to build today’s modern aquaculture facilities in a responsible manner and then to market their products nationally and globally.

In short, we need to get over our fears and our tendencies toward parochialism. Aquaculture builds on a historic base of marine-related activities and is good economics looking to the future. In Iowa, they know corn; in West Virginia, they know coal; in Texas, they know cattle. In Maine, we know the sea and marine organisms.

We can control and will benefit from a healthy and growing range of aquaculture activities. We can do this.

Orlando Delogu is a 57-year resident of Portland who taught law at the University of Southern Maine for 40 years. His law expertise includes environmental and land use, and he has served on Maine’s Board of Environmental Protection, the Portland City Council, and the Portland Planning Board.

Advertise in The Working Waterfront, which circulates 45,000 copies from Kittery to Eastport ten times a year. Contact Dave Jackson: djackson@islandinstitute.org

9 www.workingwaterfront.com april 2023 156 SOUTH MAIN STREET ROCKLAND, MAINE 04841 TELEPHONE: 207-596-7476 FAX: 207-594-7244 www.primroseframing.com DEP • Corps of Engineers Submerged Lands • Local Permits Commercial Fishermen, Residential, Municipal ...we do the work...you get the results! reasonable, fixed prices money back guarantee LEBLANC ASSOCIATES, Orr’s Island, Maine Call: Joe LeBlanc 207-833-6462 or leblancjd@comcast.net Permits for coastal structures... NEW OR EXISTING DOCK, PIER, RAMP, FLOAT, RIP RAP leblancjd@outlook.com G eneral & M arine C ontraC tor D re DG in G & D o C ks 67 Front s treet, ro C klan D, M aine 04841 www pro C k M arine C o M pany C o M tel: (207) 594-9565 National Bank A Division of The First Bancorp • 800.564.3195 • TheFirst.com Member FDIC • Equal Housing Lender DREAM FIRST 43 N. Main St., Stonington (207) 367 6555 owlfurniture.com A patented and affordable solution for ergonomic comfort Made in Maine from recycled plastic and wood composite Available for direct, wholesale and volume sales The ErgoPro 43 N. Main St., Stonington (207) 367 6555 owlfurniture.com A patented and affordable solution for ergonomic comfort Made in Maine from recycled plastic and wood composite Available for direct, wholesale and volume sales The ErgoPro

guest

column

The radical idea of public parks

How we define and understand them is important

BY TOM GROENING

I WAS WALKING recently along Belfast’s Harbor Walk, a paved trail that follows the shore along a large lawn area where a shuttered poultry plant once stood, past a boat dealer and marina, across Main Street and, amazingly, through the Front Street Shipyard, offering views of yachts, ocean-going fishing vessels, and whale watch boats.

And those views are so intimate and close that I often touch my hand to a propellor or tap a hull with my knuckle. The plastic wrap around the 440-metric ton lift rustles in the wind, and I have to guide the dog away from the edge, because given half the chance, she’d consider a leap into the water.

The final stretch, as I walk it from the southwest to the northeast, takes me across the former Route 1 bridge. Or, a walker or biker can continue northwesterly for a couple of miles along the Rail Trail, as it’s known, following a former railroad bed.

It’s a silly question, but I pondered it nonetheless—is this a park? The term “greenbelt” is often used to describe this sort of public infrastructure. You’ve heard of the repurposing of elevated train systems in New York, for

example, turning them into walkways with benches and planters.

A friend in Belfast who has served as mayor and city councilor launched what I thought was a radically subversive endeavor decades ago, creating a small volunteer group called GreenStreets! While more conservative city government officials probably thought it was an innocuous effort, like the garden club hanging flower baskets from light poles, in reality, trees that will grow tall and live for 40 years were being established along the main thoroughfares.

In once sense, it wasn’t radical—elms once lined many Maine downtown streets, it’s just that disease killed them. Yes, the city is on the hook for maintenance, but trees make a downtown cooler in summer and more inviting to visitors.

An aside—another volunteer group once cleared a little-used parking lot of trash, abandoned shopping carts, and branches, and a then-city councilor chastised them, saying it meant the city would now have to care for the lot.

We had a friend who came to Maine to attend college and her boyfriend at the time refused to take her to Acadia, saying it wasn’t real Maine wilderness, and instead preferred the wilds

reflections

of—ironically enough—paper company land up north. Acadia does have a genteel quality, with its carriage trails, arched bridges, paved roads, and heavily walked trails. But wander off those trails and the rocks, streams, and trees are real.

When the Land for Maine’s Future fund was first established, purchases tended to lean toward tens of thousands of inaccessible acres in the north, and yes, stopping clearcutting and spraying insecticides on that land is a win. But soon, LMF’s conservation focused on places people could actually visit.

In the early 2000s, I reported on Camden’s efforts to spruce up the park adjacent to the town’s library and the amphitheater that was its back yard.

I learned that both were a gift in 1931 by Mary Louise Curtis Bok, from a wealthy magazine publishing family, and that the amphitheater was designed by Fletcher Steele and is considered the first public Modernist landscape. The adjacent Harbor Park was designed by the renowned Olmsted firm under the direction of Frederick Law Olmsted Jr.

In any season, those landscapes, though relatively small, are visited by locals and tourists. So parks can approach being art, right? Visit and see if you agree.

Holding history: Archiving Islesboro past

Island’s stories come to life in cataloging work

Reflections is written by Island Fellows, recent college grads who do community service work on Maine islands and in coastal communities through the Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront.

BY OLIVIA LENFESTEY

MOSTLY, MY DAYS on Islesboro are filled with the kind of intangible busyness distinctive to life on an island. In addition to working on a sea level rise adaptation project, my work on Islesboro is to restore the exhibits at the Grindle Point Lighthouse and Sailor’s Memorial Museum and create an online catalog of the artifact collections.

Throughout the fall and into the winter, I have been working at the historical society where the museum’s artifacts are being stored while the interior of the lighthouse is repainted. The historical society building is in the old town hall, a tall cape style built in 1894 and echoey with the sounds of the past. The artifacts take up most of the space, framed black and white photographs line the walls while 18th century baby

cradles and rusted lighthouse lanterns lay on tables in the center.

The archiving process is slow and strange. Each object must be handled carefully as I photograph, measure, identify, number, and enter that data into the cataloging software. This is a process of familiarization, allowing time to sift through the objects, large and small, to hear the story that our collection is telling.

Among the museum artifacts, I find many odd things—antique barometers, wreaths made of human hair, shell lattice designs crafted by sailors off at sea, and far too many boat models to keep track of. Each artifact is different and peculiar, curious and inviting.

I find myself contemplating how all these things have come to end up here, on Islesboro, three miles offshore in the middle of Penobscot Bay.

I have come to understand this process as a hands-on method to learn the idiosyncratic history of the island. Before beginning my fellowship, I could not distinguish between different types of navigation lights on a schooner, nor the purpose of a Taffrail log. Now, I

have held them in my hands and felt their unique history. Everything I find is coated in dust, but with each tedious entry, the many layers of the island’s past begin to unravel.

Recently, I have been receiving help from other community members to complete the catalog. People who work at the Historical Society, or who otherwise know Islesboro’s history because it is also their family’s history, have generously offered me help. Through these collaborations, the artifacts we identify move through time and come alive.

I hold up a sepia photograph of a man with a large mustache, kind eyes, and stern expression, held in a rusting metal ovular frame. Recognition sweeps across the faces of the women I am working with. “Oh, I think that’s Amasa Hatch. He built the house across from where I live now.” No one is unknown on an island.

Linda, the former librarian, takes photos of the portrait and the measurements of the frame, calling them out to me so that I can enter the information into the computer. Meanwhile, Carrie, an islander who has been visiting Islesboro since she was a child and an employee

I recently received a press release about the Outdoors for All Act, co-sponsored by Sen. Susan Collins, which would “expand outdoor recreational opportunities in urban and low-income communities” and “allow for equitable access to the benefits of local parks, from job creation, to shade and tree cover, to clean air…”

The Europeans who built our towns brought with them another progressive idea—establishing a village green. In some towns, the green was a place farmers could graze their livestock. Talk about collectivism.

In Belfast, the green is actually a public square on which the First Church was built along with the city’s public high school. The city’s founders knew these public institutions were critical to growing a successful community. How we understand the variety of public spaces is important, but more important is to invest in and protect them.

Tom Groening is editor of The Working Waterfront. He may be reached at tgroening@islandinstitute.org.

at the Historical Society, looks up the identified man in the latest edition of Islesboro Island History, covering the years of 1893-1993. She finds that Capt. Hatch had nine children, one of whom was named Wealthy.

My work in the museum has taught me to see history and places as continuing stories. At the end of my day, as I drive home down the island’s only main road, I stop at the small grocery store. Before I check out, I chat with a man in between the aisles and ask him what his name is. Last name Hatch. I smile, grab my last items off the shelf and think that perhaps he has his great, great, great, great grandfather’s eyes.

Olivia Lenfestey works with the Grindle Point Lighthouse Museum and Islesboro’s Sea Level Rise Committee. She grew up in Santa Fe, N.M. and graduated from Pitzer College in Claremont, California, where she studied English, creative writing, and environmental analysis.

10 The Working Waterfront april 2023

rock bound

BY THE SEA SIDE—

This image from the Library of Congress shows a view of Old Orchard Beach. The sign, seen here from the opposite side of its intended audience, reads “Sea Side Park.” Do readers have any information about the buildings shown here? Is the turreted structure still standing? Email editor Tom Groening at tgroening@islandinstitute.org.

BY LARISSA HOLLAND

BY LARISSA HOLLAND

LIKE MOST OF Generation Z, many of my early life milestones were bookmarked by incredible sociopolitical events. I graduated high school in 2016, the same year as a shocking U.S. presidential election and the second deadliest mass shooting in the country.

When I graduated from college in 2020, the first in my family to do so, it was via Zoom, sitting in the family room of a friend’s childhood home while the coronavirus pandemic was in its earliest phase, wreaking havoc across the world.

As dramatic as it sounds, this is the world we are all navigating, albeit with different proximities to the crisis. Youth, in particular, hold a unique amount of the world’s weight as they work to find their place in the fight for an equitable, healthy, resilient future, all while often being too young to vote.

This endeavor is made increasingly complicated for rural youth, as the bridge between our lawmakers and the concerns of rural communities has not been masterfully constructed.

Island Institute Board of Trustees

Kr istin Howard, Chair

Douglas Henderson, Vice Chair

Charles Owen Verrill, Jr. Secretary

Kate Vogt, Treasurer, Finance Chair

Carol White, Programs Chair

Megan McGi nnis Dayton, Philanthropy & Communications Chair

Shey Conover, Governance Chair

Michael P. Boyd, Clerk

Sebastian Belle

David Cousens

Michael Felton

Nathan Johnson

Emily Lane

Bryan Lewis

Michael Sant

Barbara Kinney Sweet

Donna Wiegle

John Bird (honorary)

Following the 2016 presidential election, the Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) at Tufts University conducted a study that found a majority of youth residing in rural areas live in what is called a “civic desert.”

A civic desert is an area characterized by a severe lack of access, opportunities, and resources designed to encourage civic engagement. The lack of reliable public transportation, the limited financial and public infrastructure to invest in youth-focused groups and organizations, the geographical distance between rural youth and the space where a majority of civic resources take place, and inadequate political engagement on rural issues all are contributing factors to civic deserts being prominent in rural communities.

“There is not a large population of young people in rural areas to begin with,” said Edge Venuti, a Washington County-based rural youth organizer with JustME for JustUS, a youth-led organization advancing climate justice and civic engagement in Washington, Hancock, Penobscot, Franklin, and Kennebec counties. “This makes traditional

coalition building very difficult,” she says. “Additionally, due to our distance from the state house and any major city, rural youth may not know who their local representatives or law makers are.”

The study conducted by CIRCLE indicates that youth living in a civic desert are generally less experienced in civic and political life and largely disengaged from politics. This was true of my lived experience, in which the first time I learned of Maine’s legislative accomplishments and set-backs was during my junior year of high school when I attended Dirigo Girls State at Husson University. The opportunity came at a time I could drive myself, since my family was often too busy working to provide transportation to extracurriculars.

Perhaps the only good thing to come from the COVID pandemic was the increase in remote and digital-based organizing. Despite broadband limitations across rural America, the internet and social media have allowed new opportunities for civic participation in various organizations, coalitions, and social movements that are increasingly used by young folks.

THE WORKING WATERFRONT

All members of the Island Institute and residents of Maine island communities receive

In fact, social media has been used effectively as a tool for social justice activism in the wake of a global pandemic, the Black Lives Matter movement, and the very real fear around a changing climate.

Young folks possess many characteristics that make them powerful civic actors, not the least of which are their unique perspectives on local issues and being an inexhaustible source of energy and passion for social change.

“Listening to young people offers an important perspective from someone who will be living in this world for the next 50 years,” Venuti says. “Everything changes all the time and it’s important to listen to the younger generation because they understand the change while it is happening, and they do so very differently than the majority of our lawmakers.”

Putting the fears, questions, passions, and demands of our younger citizens at the heart of policy is when our representatives and lawmakers will have the most impact, because it is today’s youth who will define the next generation of politics.

Larissa Holland is development advisor for the nonprofit JustME for JustUS.

Editor: Tom Groening tgroening@islandinstitute.org

Our advertisers reach 50,000+ readers who care about the coast of Maine. Free distribution from Kittery to Lubec and mailed directly to islanders and members of the Island Institute, and distributed monthly to Portland Press Herald and Bangor Daily News subscribers.

To Advertise Contact: Dave Jackson djackson@islandinstitute.org 542-5801

www.WorkingWaterfront.com

11 www.workingwaterfront.com april 2023 op-ed

by the Island Institute, a non-profit organization that works to sustain Maine's island and coastal communities, and exchanges ideas and experiences to further the sustainability of communities here and elsewhere.

Published

monthly

Working Waterfront.

home delivery:

the Island Institute by calling our office at (207) 594-9209 E-mail us: membership@islandinstitute.org • Visit us online: giving.islandinstitute.org 386 Main Street / P.O. Box 648 • Rockland, ME 04841 The Working Waterfront is printed on recycled paper by Masthead Media. Customer Service: (207) 594-9209

mail delivery of The

For

Join

Making our ‘civic deserts’ more fertile Nonprofit JustME for JustUS engaging rural youth

Fog happens—here’s how Maine is among foggiest places in the world

BY TOM GROENING

BY TOM GROENING

In the late 1700s, the people who established what today is Belfast at the top of Penobscot Bay first built their homes on what locals call the East Side of town. A small cemetery, with crude slate gravestones, is all the evidence that remains of that foothold, since those early European arrivals soon moved to the shore west of the Passagassawakeag River.

The story that local historians tell is that the cool fog that perennially swept up the bay on the East Side nudged those residents to seek homes on the warmer, drier side of the harbor. To this day, on otherwise fine spring days, that fog flows up across the early settlement site and Route 1.

There are three highincidence fog regions in the U.S.—the Pacific Northwest, the Southern Appalachians, and the Maine coast.

Fog is no stranger to much of the New England coast, but according to meteorologist Mike Clair of the National Weather Service in Gray, we in Maine have some bragging rights on the weather phenomenon—we’re one of three “hot spots” in the U.S., and one of three regions in the world that see daytime fog in the summer.

“Fog is saturated air,” Clair said. “When the dew point and the air temperature are the same, you often have fog.”

The Midcoast and Penobscot Bay regions are prime environments for fog, he said.

Clair was invited by the Penobscot Marine Museum to speak to a virtual gathering on “Fog Along the Maine Coast,” part of its “Fog & Ice” lecture series. Meteorologists identify three kinds of fog, based on how it forms: radiation, steam, and advection.

12 The Working Waterfront april 2023 A close working relationship with your insurance agent is worth a lot, too. We’re talking about the long-term value that comes from a personalized approach to insurance coverage offering strategic risk reduction and potential premium savings. Generations of Maine families have looked to Allen Insurance and Financial for a personal approach that brings peace of mind and the very best fit for their unique needs. We do our best to take care of everything, including staying in touch and being there for you, no matter what. That’s the Allen Advantage. Call today. (800) 439-4311 | AllenIF.com

or

the coast of

rewards. We are an independent, employee-owned company with offices in Rockland, Camden, Belfast, Southwest Harbor and Waterville.

Owning a home

business on

Maine has many

Sea smoke over Friendship Harbor on Feb. 4 during that day’s double-digit below zero temperatures.

PHOTO: JACK SULLIVAN

Radiation fog occurs when “heat is lost into space on clear nights, cooling at the surface until moisture condenses.” This is common in summer and fall.

Steam fog, also known as Arctic sea smoke, occurs when very cold air moves from the land to over the ocean.

“Typically, when you would see it, it would be a cold wind blowing offshore,” Clair said. The cold, dry air picks up the moisture from the surface of the water. It can also occur over lakes.

But the bulk of our fog is the advection kind. This occurs when moist air from over warmer waters south of Maine moves over the cooler Gulf of Maine and condenses. The moist air also can originate over land southwest of the state in summer.

“This is one of the more common ones we see in the summertime,” Clair said. “These are the kinds of events where you’ll have it be foggy at the coast, then clear just a few miles inland.”

There are three high-incidence fog regions in the U.S., he said—the Pacific Northwest, the Southern Appalachians, and the Maine coast. Showing a world map, Clair noted that “Most of the world does not see fog in the daytime in the summer,” but those that do include the North Pacific (near Japan and Korea), the Arctic, and the Northwest Atlantic (Maine to Greenland).

Maine’s particular experiences with fog are influenced by its topography, Clair said.

“The Midcoast, PenBay regions have higher elevations along the coastline compared to the rest of the state,” he said, with some hills and mountains rising “as much as 1,500 feet. This allows air coming off the ocean to quickly cool and condense as it rises,” turning into fog.

Dynamic ocean currents in the Gulf of Maine also juice up fog here. The Nova Scotia, Eastern Maine Coastal, and Western Maine Coastal currents mix warmer and cooler waters. In the summer, water temperatures can range from the 60s and 70s in the

middle of the Gulf of Maine, yet “In the Midcoast and Downeast, we hang onto those 40s and 50s,” again causing condensation of moist air.

Tides in Maine, ranging from 10- to 22-feet, also bring colder water to the surface, hastening that condensation.

“No matter how warm the Gulf of Maine gets in the summertime, you’re still going to get the tides changing water temperatures,” Clair said.

Showing a video of satellite imagery along New England, he explained how the Massachusetts and Nova Scotia coasts could be clear while Maine’s coast was socked in with fog, pushed up by prevailing winds and intensified by the warm, moist air meeting cool water. And yet even in an era when satellites can capture this movement, fog is often a surprise.

“Models for marine fog are not very good at forecasting,” Clair said.

While walking along the bay last week, the sky was slate gray meeting water just as gray except for bright, white caps topping the swells in an easterly wind. Scattered through the monotones, the dark green of the spruces on the off-shore islands broke the gray and white which was enough color for me until a cardinal and his mate dropped down to the snow six feet in front of me on the path.

Let me help you make your move to a Maine property where you will notice marked contrasts, whether winter, spring, summer or fall, from other places you’ve lived knowing you are making the right decision.