Volume Issue 14 April 2023 the 09 MAKING SPACE TO CREATE 13 SUFFOCATED BY SILENCE 15 BRIGHT PINK MARKER PRESS THE SUBMERGED ISSUE The College Hill Independent * 46 08

From the Editors

My ghost is back with a vengeance. More likely, he never left. My front doorknob still hasn’t reappeared, and at 5 a.m. Tuesday morning I returned home to a mysteriously deadbolted back door.

My brain was cementlike, but the aftershocks from an ill-fated 11 p.m. coffee had made my body bizarrely, momentarily alert, and as I sat down on the stoop to problem-solve, I noticed for the first time that it was balmy out.

Spring feels exactly the same every year, and yet we still can’t stop talking about the weather. Even under the sleepy weight of the sun, I’ve been feeling an old anxiety crop up again—each week passes quicker, things are beginning and many more are beginning to end. Clichés, it turns out, just get truer over time.

Campus is a zoo. They’ve started spray-painting strange multicolored diagrams on the lawns. Soon, the grass will be covered up with new grass, rolled out in sheets like a carpet.

I paused again for a second while I was breaking into my own bedroom window, balanced on an ingeniously overturned trash bin. Gray was starting to creep into the sky. The weak reflection of a streetlight off a neighboring window cast a blurry spotlight onto two bunnies in the driveway. They were sitting facing the road, completely still, like they had never been anywhere else—waiting, or just frozen in time.

Masthead*

MANAGING EDITORS

Zachary Braner

Lucia Kan-Sperling

Ella Spungen

WEEK IN REVIEW

Karlos Bautista

Morgan Varnado

ARTS

Kian Braulik

Corinne Leong

Charlie Medeiros

EPHEMERA

Ayça Ülgen

Livia Weiner

FEATURES

Madeline Canfield

Jane Wang

LITERARY

Ryan Chuang

Evan Donnachie

Anabelle Johnston

METRO

Jack Doughty

Rose Houglet

Sacha Sloan

SCIENCE + TECH

Eric Guo

Angela Qian

Katherine Xiong

WORLD

Everest Maya-Tudor

Lily Seltz

X

Claire Chasse

DEAR INDY

Annie Stein

BULLETIN BOARD

Mark Buckley

Kayla Morrison

SENIOR EDITORS

Sage Jennings

Anabelle Johnston

Corinne Leong

Isaac McKenna

Sacha Sloan

Jane Wang

STAFF WRITERS

Tanvi Anand

Cecilia Barron

Graciela Batista

Mariana Fajnzylber

Saraphina Forman

Keelin Gaughan

Sarah Goldman

Jonathan Green

Sarah Holloway

Anushka Kataruka

Roza Kavak

Nicole Konecke

Cameron Leo

Abani Neferkara

Justin Scheer

Julia Vaz

Kathy/Siqi Wang

Madeleine Young

COPY CHIEF

Addie Allen

COPY EDITORS / FACT-CHECKERS

Qiaoying Chen

Veronica Dickstein

Eleanor Dushin

Aidan Harbison

Doren Hsiao-Wecksler

Jasmine Li

Rebecca Martin-Welp

Kabir Narayanan

Eleanor Peters

Angelina Rios-Galindo

Taleen Sample

Angela Sha

Jean Wanlass

Michelle Yuan

DEVELOPMENT COORDINATOR

Angela Lian

SOCIAL MEDIA TEAM

Jolie Barnard

Kian Braulik

Angela Lian

Natalie Mitchell

WEB MANAGER

Isaac McKenna

WEB EDITORS

Hadley Dalton

Arman Deendar

Ash Ma

GAMEMAKERS

Alyscia Batista

Anna Wang

*Our Beloved Staff

Mission Statement

COVER COORDINATOR

Zora Gamberg

DESIGN EDITORS

Anna Brinkhuis

Sam Stewart

DESIGNERS

Nicole Ban

Brianna Cheng

Ri Choi

Ashley Guo

Kira Held

Xinyu/Sara Hu

Gina Kang

Amy/Youjin Lim

Andrew Liu

Ash Ma

Jaesun Myung

Tanya Qu

Zoe Rudolph-Larrea

Floria Tsui

Anna Wang

ILLUSTRATION EDITORS

Sophie Foulkes

Izzy Roth-Dishy

ILLUSTRATORS

Sylvie Bartusek

Lucy Carpenter

Bethenie Carriaga

Julia/Shuo Yun Cheng

Avanee Dalmia

Michelle Ding

Nicholas Edwards

Jameson Enriquez

Lillyanne Fisher

Haimeng Ge

Jacob Gong

Ned Kennedy

Elisa Kim

Sarosh Nadeem

Hannah Park

Luca Suarez

Yanning Sun

Anna Wang

Camilla Watson

Iris Wright

Nor Wu

Celine Yeh

Jane Zhou

MVP

Annie

The College Hill Independent is printed by TCI in Seekonk, MA

The CollegeHillIndependent is a Providence-based publication written, illustrated, designed, and edited by students from Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design. Our paper is distributed throughout the East Side, Downtown, and online. The Indy also functions as an open, leftist, consciousness-raising workshop for writers and artists, and from this collaborative space we publish 20 pages of politically-engaged and thoughtful content once a week. We want to create work that is generative for and accountable to the Providence community—a commitment that needs consistent and persistent attention.

While the Indy is predominantly financed by Brown, we independently fundraise to support a stipend program to compensate staff who need financial support, which the University refuses to provide. Beyond making both the spaces we occupy and the creation process more accessible, we must also work to make our writing legible and relevant to our readers.

The Indy strives to disrupt dominant narratives of power. We reject content that perpetuates homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, misogyny, ableism and/or classism. We aim to produce work that is abolitionist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist, and we want to generate spaces for radical thought, care, and futures. Though these lists are not exhaustive, we challenge each other to be intentional and selfcritical within and beyond the workshop setting, and to find beauty and sustenance in creating and working together.

01 THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT 00 “GREAT-GRANDMA’S HOUSE (UNCLE WILL)” Amadi Williams 02 WEEK IN WEDDINGS Skye Alex Jackson & Christina Peng 03 THE MYTH OF KING KHAN Anushka Kataruka 06 HELD TOGETHER BY BOOKENDS Mira Goodman 07 MILA’S WORLD Angela Qian 09 MAKING SPACE TO CREATE Graciela Batista 11 ORANGE PEEL, STITCHED Zoe-Anna Rudolph-Larrea 12 THE YOUNG READER’S PRESS FIRST DICTIONARY Livia Weiner 13 SUFFOCATED BY SILENCE Indigo Mudbhary 14 WHITE PICKET BULLDOZER POLITICS Arman Deendar 15 BRIGHT PINK MARKER PRESS Corinne Leong 18 INDIECEPTION Annie Stein 19 BULLETIN Mark Buckley & Kayla Morrison This Issue

46 08 04.14

-LKS

Letters to the editor are welcome; scan the QR code here or email us at theindy@gmail.com!

Week in Weddings

Cake Displays

On the corner of Broadway and Tobey Street, a stark white mansion dubbed The Wedding Cake House gleams among the bustle of traffic. The flamboyance of the house feels out of place in the heart of Providence’s Federal Hill, but, in awe at the rarity of preserved Victorian architecture, I found the craftsmanship refreshing. Built in 1867, the mansion passed from family to family during the 19th and 20th centuries. The house lay uninhabited for years during restoration efforts until the art-feminist community Dirt Palace moved in in 2017 and opened it to artist residencies long and short. The Wedding Cake House even serves as a bed and breakfast, which directly supports their artists. For $100 a night, you can stay in one of their eight rooms. Although I opted not to stay, I did investigate.

Walking up the wooden steps through the narrow entrance, the 19th-century wallpaper and floor-to-ceiling mirrors reflecting off crystal chandeliers struck me. I visited on the last day of an eight day live-in group cohort residency featuring nine artists, including sculptors, photographers, experimental filmmakers, and musicians. Up the psychedelia-carpeted stairs, I was led through four rooms distinct with eccentric decor and mid-career artists’ unique work.

Room 4 was ornamented with deep purple paint complemented by circle-printed wallpaper, an abandoned fireplace and an out-of-place

The Providence Athenæum

I am standing where Edgar Allan Poe once stood.

Enveloped by hardwood shelves teeming with ancient books, the Athenæum alcove is perfect for a romantic getaway. Here, beneath the marble busts of Demosthenes and George Washington, was where Poe last courted the beautiful Sarah Helen Whitman, a widowed poet with long, dark hair cascading down like a waterfall. After relentlessly pursuing Whitman for months with promises of sobriety and a future of literary greatness, Poe finally won her heart and hand in marriage.

While their love story ended (over Poe’s continued drinking problem) two days before their planned Christmas wedding, evidence of their affair remains at the Providence Athenæum today. I squint at the leather-bound book given to me by a receptionist. It’s a picture of Poe’s signature on the American Whig Review, penciled at the bottom of an anonymous poem. (Whitman once asked Poe about the poem; he signed his name to it in an attempt to woo her.) If I look up into the Art Room, encased behind a glass wall on the second floor, I can make out portraits of Poe and Whitman hanging side by side on the far left end.

I’m inside a living belly of history, I think to myself.

The Athenæum (pronounced either ath-uh-NEE-um or ath-uh-NAY-um) is full of Providence lore. This Greek Revival library takes its name from Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom. Located at 251 Benefit Street (a few blocks down from the Van Wickle Gates), the library has collected stories for nearly 200 years. From art and natural history to philosophy and classic literature, the library holds around 175,000 titles, spanning over eight centuries. I am not exaggerating when I say nearly every surface is covered in books. In fact, librarians have thoughtfully placed ladders between alcoves to reach higher shelves.

After snapping a photo of Athena (her statue sits at the entrance), I decide to flip through the card catalog, held in four file cabinets on the

orange mural in the bathroom shower. Zach Ozma, an interdisciplinary artist dressed in peplum shoes, a silver locket and black slacks, had originally spent the week researching trans art in the 20th century. Out of envy toward the other artists’ exhibitions, at the last minute, he molded baby angel sculptures out of clay and paired them with vintage wrestling photos, describing the amalgamation as evoking themes of luck and winnership; bottoming and topping.

Room 6 was distinguished by an exposed bathtub, red floral wallpaper with identical bedding, and firewood sitting dormant. Julia C Liu, a filmmaker and graduate of Brown University, had set up a Seagull medium format camera in the middle of the room, a shiny black box that appeared too complicated to touch. She demonstrated loading the film with ease, opening the focus ring viewfinder, while describing how the little camera had shaped her love of taking moody portraits.

Decorated in pink, pink, and more pink, Room 3 must have been made for Alex Pizzuti’s presentation of an experimental film featuring American Girl Dolls who “kiss a lot.” They mixed new footage with archival film from their childhood to create a vignette-style narrative. I asked about the inspiration behind the manipulated assortments of Dolls laying dormant on the wooden floor. Alex explained that it came from “the wannabe supermodel antics that

main level. Organized in alphabetical order, the card catalog is a register of all the items in the library’s collection. While most cards are printed in 21st-century ink, some are etched in pencil. They were written in library hand, a type of special handwriting taught in library schools before typewriters were popularized. According to the leather guidebook I was handed, Head Librarian Grace Leonard spent 13 years cataloging the thousands of cards I see.

I carefully flip to a card from 1884. This one is yellowed and slightly thinner than the others. This card is more than a century older than me!

we imposed on our dolls in the early 2000s.” I couldn’t agree more.

In Room 2, Rya Drake-Hueston lay sprawled out on a twin bed in delicate white clothing, while Sara K Dunn perched on a wobbly wooden table, pointing to their elaborate reconstruction of a “decrepit Victorian dollhouse.” Decorated with grand tree branches and colorful paper flowers, the house represents the “soulfulness of New England homes” and the natural cycles of life. “The lace flowers represent a form of flocking, of bringing past queer identities and narratives, which had been kept from being recorded, to the surface.” I stayed staring at this piece, in silence, for the longest.

Spiraling down the staircase, I wondered when I would come back to sink further into the history, inspiration, and possibilities contained inside these rooms. Exiting, I met another artist, musician Dailen Williams (“Caloric”), who described her showcase to me as the grabbing and snagging of synthesizers, electronic sounds, and tapes mashed up with external noises in the hopes of making this unlikely sonic patchwork into something beautiful. She says that she wishes more of the piece was pleasing to the ears, but something in her candied personality tells me that the piece, just as the Wedding Cake House, is its own delectable anomaly.

- SAJ

until further notice.

I stare into the glass case, captured by the vibrant green hue. Most of the books on display are gold and blind stamped, which produces a shimmering effect under the shelf light. I continue to stare until, before long, the library is preparing to close. As I’m forced to tear my eyes away from the emerald green books, I make a mental note not to touch them in the future.

“So cool,” I write in the guest book before exiting. Cold night air drums to the beating of my tell-tale heart.

- CP

02 VOLUME 46 ISSUE 08 WEEK IN REVIEW

TEXT SKYE ALEX

ILLUSTRATION

JACKSON & CHRISTINA PENG DESIGN TANYA QU

AVANEE DALMIA

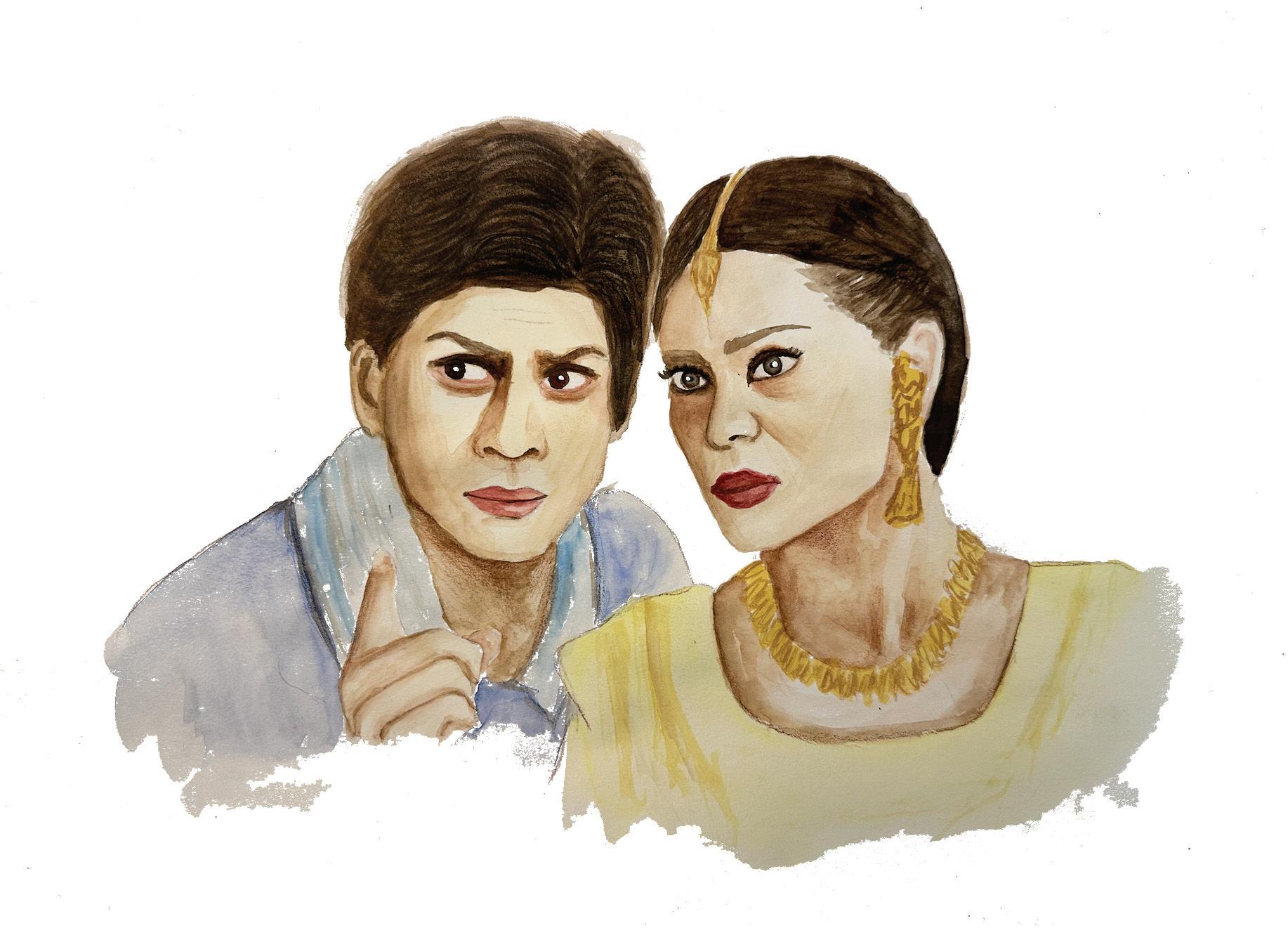

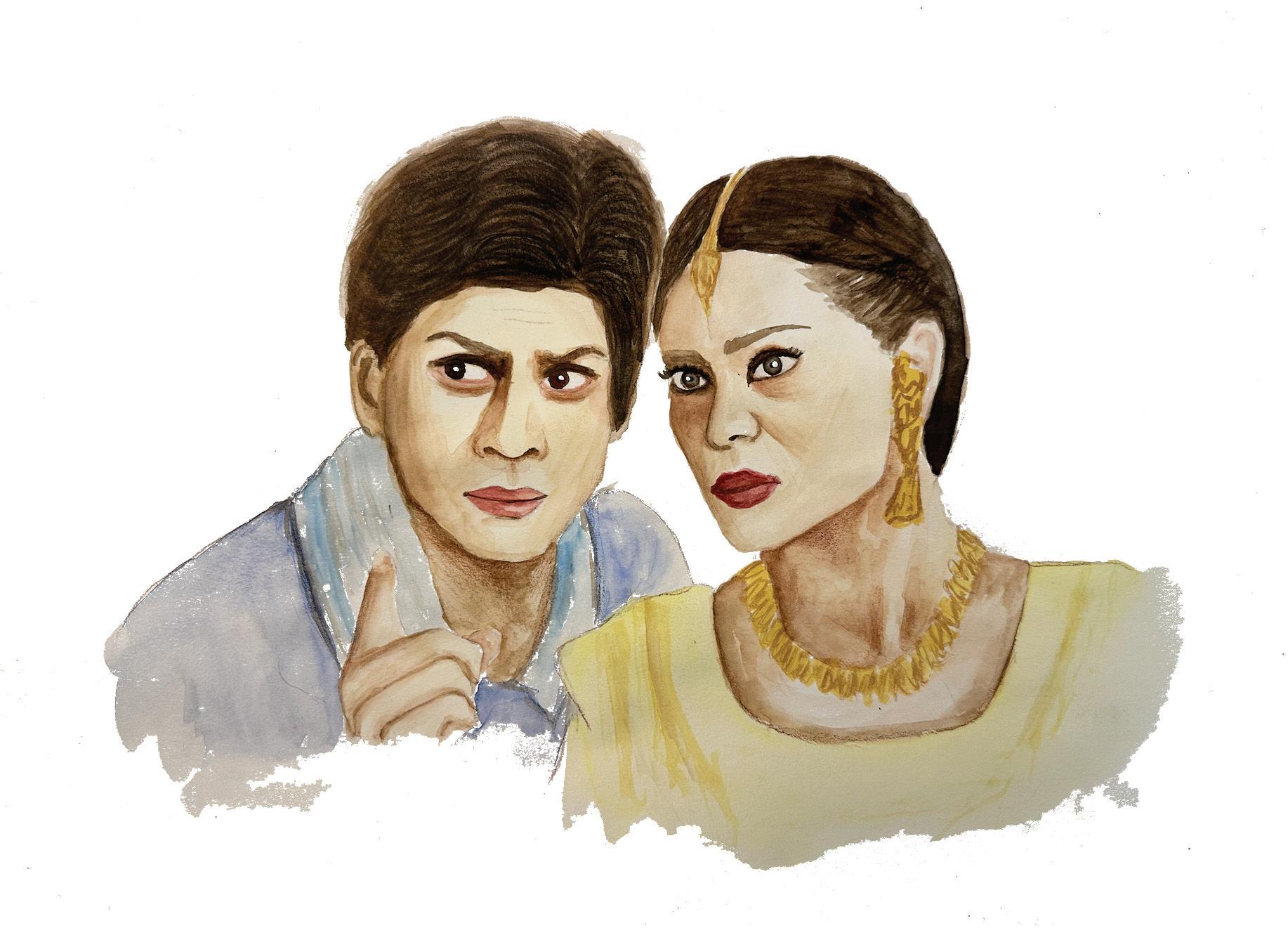

THE MYTH OF

KING

Love, secularism, and Bollywood superstar Shah Rukh Khan

I’m three years old, being rushed to the hospital as my mother goes into labor, about to meet my baby brother for the first time. All I can talk about is how his birthday will be the same as that of the only man, other than my dad, who I’d loved in my entire tiny life.

I’m five years old, sitting cross-legged on a brown cushioned wooden chair, eyes trained on the boxy TV set across the glass dining table, oblivious to my mother nudging morsels of beans and carrots and coconut into my mouth. I can’t tear my eyes away from the screen, I can’t miss a single piece of dialogue, despite already being able to recite the entire movie with my eyes closed—I can’t even afford to respect my anti-vegetable principles while he’s on screen.

I’m 12 years old, my neck craning up at the fancy stadium box a few meters away in the Eden Gardens cricket stadium in Kolkata. I’m trying to catch a glimpse of him coming out to wave to his team and his fans at the Indian Premier League. I see him very briefly and wave frantically in vain—but he disappears back into his fancy stadium box. My heart sinks a little. Maybe next time.

I’m 18 years old, stuck at home thanks to the pandemic, comforting myself with his movies and his interviews, grinning widely like a child, impervious to the fact that in those moments I was just another fangirl who could be cast aside as silly, frivolous, idealistic, irrational by the world outside.

I’m 21 years old, cheering in an American cinema, holding onto an overpriced ticket and an overpriced bucket of popcorn as I stare up at the screen, alongside my college friends, most of us barely containing ourselves as we see him finally appear on screen after his four-year hiatus. The

KHAN

movie is objectively bad, nothing more than a commercial entertainment enterprise, but who cares—Shah Rukh Khan’s presence on the big screen is all we need. +++

Shah Rukh Khan (born Shahrukh Khan) was born into a middle-class Muslim family in a refugee colony in New Delhi. He was the son of a freedom fighter, Mir Taj Mohammad Khan, a participant of the Khudai Khidmatgar movement, a nonviolent resistance against the British Raj. His father passed away when Shahrukh was a teenager. As his family grieved and recovered, Shahrukh started acting, mostly on stage and then in various television shows. After his mother’s death, he moved to Mumbai in the 1980s to pursue movies and his relationship with Gauri Chhibber, who came from a wealthy conservative Hindu family from Delhi. They married in a traditional Hindu wedding in 1991. The same year, India opened up its borders to globalization and loosened market and finance restrictions, suddenly propelled on the world stage while growing at inconceivable rates. Shortly after, Shahrukh too was catapulted into Bollywood superstardom with his film Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (DDLJ) in 1995. The film centered on the motif of embracing Western modernity while preserving tradition, the primary conflict faced by the film’s main characters representing the Indian diaspora in the U.K. It broke records both in South Asia and amongst the South Asian diaspora worldwide, netting $62 million in total earnings as of 2017 (adjusted for inflation). Twenty-seven years after its release, the film is still running in the cinema at Maratha Mandir,

Mumbai. An ‘outsider’ of humble beginnings became the face of an industry heavily steeped in nepotism almost overnight, going on to become the shining symbol of romance and Bollywood for nearly three decades.

Shah Rukh Khan, or King Khan, King of Bollywood, King of Romance, and so on, as he is now affectionately known, has been the most prolific actor in the Indian film industry, specifically Bollywood, for nearly 30 years. His films (more than 90 in total) explore themes of love and romance; Indian national identity; connections with diaspora communities; and gender, racial, social and religious differences and grievances. Every year on his birthday for the past 20 years, tens of thousands of fans have steadfastly crowded outside his mansion in Mumbai, creating a traffic blockade on the boardwalk, as he greets them from his balcony (for a few years, crowds gathered there every Sunday). He is considered to be the most popular actor in the world, estimated by a popularity survey to be recognizable to more than 3.2 billion people around the world. Only a week ago, he won the 2023 Time100 reader poll by TIME magazine. In his own words articulated during his TED Talk in Canada, “I sell dreams, and I peddle love to millions of people back home.”

Through his characters and public persona, the idea of Shah Rukh Khan takes on different meanings for different people. While for some, he is the ideal romantic in a hypermasculine and patriarchal world, for others he is the manifestation of secularism in India, where rights of religious minorities are increasingly being encroached upon.

03 THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT

+++ ARTS TEXT ANUSHKA KATARUKA DESIGN ANNA BRINKHUIS ILLUSTRATION SAROSH NADEEM

In his filmography, Shah Rukh is most celebrated for his role in romance movies, which have formed the core of the genre within Bollywood. From the mid-1990s to the early 2010s, these films have defined aspirations and dreams of love for the millions of consumers of Bollywood, especially South Asians born in the ’80s and ’90s. His repeated portrayal of the ‘romantic hero’ for two decades, his ‘woman-friendly’ designated filmography, and his loyal female fan following have caused him to be dubbed a ‘women’s hero.’ This is impressive in an industry which has, for most of its existence, explicitly catered only to the primary consumers of cinema in India: men. In 2017, six out of 10 moviegoers in India were men. According to India’s National Family Health Survey, between 2019 and 2021, only 10 percent of women visited a cinema hall at least once a month, compared to 24 percent of men.

For most of Shah Rukh’s career, his male contemporaries have all been hypermasculine, goal-oriented men starring in action or comedy movies. Meanwhile, female leads in those years were just supposed to be pretty objects without personality, like all the female characters in Dil Chahta Hai (2001), each of whom were just helpless and beautiful. For several decades, masculinity in South Asia has been portrayed in terms of physical strength and/or wealth and career success. A man provides for his family and protects the ‘honor’ of the women in his household, who themselves have no agency whatsoever, like Veeru in Sholay (1975) rescuing his helpless lover Basanti from a dacoit. Despite the man being emotionally immature and lacking baseline communication skills and self-expression, the women in these films simply fall for him just because he is strong and successful. For the men who primarily fill India’s cinema halls, this was the ideal man.

Shah Rukh’s popularity amongst South Asian women is less surprising, then, given the nature of his movies (romantic or otherwise) and the respect, time, and personality often accorded to female leads in them. Economist Sharayana Bhattacharya extensively explores the factors behind his appeal to South Asian women in her book Desperately Seeking Shahrukh: India’s Lonely Young Women and the Search for Intimacy and Independence. After extensive interviews with fans, film critics, and journalists, she finds that female fans interviewed often perceived Shah Rukh’s characters as treating love interests and other female characters with significant love, care, and respect. His characters made them feel ‘seen’ and special with his humor and charm, which is unfortunately uncharacteristic of most male leads in Bollywood movies. His breakthrough film, DDLJ, showed his character Raj trying to win over the women in his love interest Simran’s family by helping them out in shopping and domestic chores. At the risk of glorifying basic standards of decent behavior, this was a revolutionary moment for the women interviewed by Bhattacharya, who watched a man peel a carrot on screen and interact with different women in the same household for the first time.

Shah Rukh’s characters are also often softer men, vulnerable men, anxious men, or men at the edges of society who have been rejected, taunted, outcast. In every one of his romance films, his character has at least once dramatically looked into the camera with tears in his eyes, asking for love, approval, consolation. The popular machismo Hindi saying, “mard ko dard nahi hota” (man does not feel pain) is laughable when one thinks of Shah Rukh’s characters, who feel a lot of pain, over and over. He anxiously pines for his father’s love as an adopted son in Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham (2001); he struggles with marital infidelity in Kabhi Alvida Naa Kehna (2006); he dreads his imminent death in Kal Ho Naa Ho (2003); his eyes well up with empathy for villagers in poverty in Swades (2004); he is

taunted and cast out for his Muslim identity in Chak De! India (2007) and My Name Is Khan (2010); and he recovers from his divorce and separation from his son, even as a side character, in Dear Zindagi (2016). He and his characters are a breath of fresh air in an industry that refuses to move beyond hypermasculine hetero action heroes.

Bhattacharya highlights how movies starring Shah Rukh also happen to be correlated with a greater amount of dialogue by female characters as compared to other contemporary Indian movies. She deems this a result of the genre Shah Rukh typically features in, as romance movies provide a need for more conversation between love interests. This disparity is further emphasized when we consider mainstream Indian cinema today, where movies with an equal proportion of dialogue between leads of different genders rarely dominate the box office, with the exceptions often being films starring Shah Rukh. His opposing female leads also seem to have more personality and exert more agency in relationships: They have their own conflicts, like Naina in Kal Ho Naa Ho carrying around her family’s emotional burden, hoping to move on; their own priorities and eccentricities, like Anjali in Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham, a funny, cheerful woman who runs a sweetshop in Delhi (one of my personal favorites); or just grow through different joys and struggles, like Kaira in Dear Zindagi, a cinematographer (not a love interest) seeking out therapy to process family conflicts and breakups. These women aren’t just the helpless, dependent arm candy—pretty prizes for men to win by defeating some other man—but are often multidimensional personalities who are admirable and relatable.

Aside from the actor himself, multiple directors, scriptwriters, producers, media professionals, film reviewers, even fans are responsible for the creation of Shah Rukh’s mythos. He has mentioned how he initially just wanted to do action movies; it was the director of DDLJ, Aditya Chopra, who pushed him into his romantic persona after his father, Yash Chopra, discovered and cast Shah Rukh as an anti-hero in the film Darr (1993). According to Aditya Chopra, Shah Rukh’s “eyes have something that cannot be just wasted on action.” Additionally, Shah Rukh’s lack of sex scandals off-screen and his charming public persona strengthen the dreams that his characters build. His real-life love story with Gauri Chhibber could easily be a romance movie he’d act in. An often-quoted story, recounted in an interview with David Letterman, involves him flying to Mumbai after Gauri breaks up with him before roaming the 50 or more beaches in Mumbai to successfully find Gauri and propose to her. In all his interviews, people seek his opinions on love, romance, and relationships. His replies are witty, respectful, and often informed by his own love story, to which he seems consistently dedicated, again an anomaly among male Bollywood celebrities. He appears to be disarmingly charming and endearingly self-aware of his own flaws. The Shah Rukh Khan myth is thus an amalgamation of the charming and respectful man he shows during interviews, and of all the positive attributes of popular characters, especially the romantic ones, he’s played. This mythos, regardless of the real man under it, is of a soft, vulnerable, intelligent man who loves, respects, and cares for women; sees us for who we are and who we want to be, while being effortlessly romantic and charismatic. To some extent, Shah Rukh has now infused the ideal man he shows on screen with his own real-life public persona, according to his own admission: “I’m an employee of the myth of Shah Rukh Khan.”

This myth, however, looks over pertinent flaws of the characters it constitutes, along with those of the man himself. In his older movies in particular, he usually ‘wins over’ his love interests through persistent persuasion, often verging on literal stalking and toxic, possessive

behavior. For example, in Dil Se.. (1998), he follows his love interest around the country like an obsessive creepy stalker, at one point almost forcing her into a kiss. In his older work, while the female lead might have personality, the female side characters are reduced to the background: like the sacrificial, unconditionally loving, homemaking mother in Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham. These flaws were often overlooked on first viewings by people like Bhattacharya’s interviewees and myself—we traded them for the dream of emotionally vulnerable, caring, and respectful men, despite wincing at every instance of encroachment upon women’s boundaries in his movies. Additionally, between 2011 and 2015, Shah Rukh started choosing to play the blockbuster ‘action hero’ brand of man in films like Chennai Express (2013) and Happy New Year (2014), much to the disappointment of his fan base. Despite usually seeming to have progressive, feminist views, through his respect for women and their agency evident in his media interactions, Shah Rukh himself has distanced himself from the word “feminism,” notably stating in a 2016 interview, “I don’t want to sound pro-feminist…” simply to seem apolitical and avoid media outrage. He thus follows the example of many other Bollywood celebrities, who made similar statements around the same time, effectively betraying his most ardent fans while causing cracks to appear in the myth of Shah Rukh Khan. According to Bhattacharya, Shah Rukh “isn’t a feminist icon, but certainly a female one.”

The ideal romantic man is not the only myth that Shah Rukh carries around him. As a Muslim superstar in India, he is also often encased in the idea his success and filmography creates. India, a Hindu majority country with multiple religious communities, and its Constitution have historically strived toward ideals of secularism since its independence. However, the country’s modern history is replete with communal clashes, especially between the Hindu and Muslim communities. Additionally, there exist systemic socioeconomic disparities between upper-caste Hindus and all other religious groups, with Muslims continuing to occupy the bottom rung of the country’s socioeconomic ladder.

While Shah Rukh has intentionally been “peddl[ing] love” to his admirers for decades, he is also often inflated by multiple social commentators and journalists—frankly, idealists—to embody India’s secular ideals as a self-made Muslim actor. His statistically impossible, dizzying ascent from a common, Muslim middleclass outsider family into the highest rungs of superstardom; his history of engagement with both Christianity, in his Catholic-school upbringing, and Hinduism, through participation in a traveling theater group depicting Hindu mythology; his inter-religious marriage (a phenomenon which continues to be inconceivable in India’s current political climate); and his own secular, progressive views on religion and faith make him the perfect poster boy onto whom Indian liberal intellectuals can project their secular ideals. In the past decade, at nearly every media event, alongside questions on love and life, he is asked for his thoughts on secularism or religion or simply asked “what is a good Muslim?” unfairly pushing him to be the spokesperson and representative of the Indian Muslim community—the second largest Muslim population on the planet—while consistently forcing him to prove his patriotism as an Indian Muslim.

In the mid-2010s, he played Muslim leads in a series of movies, two of which tackle Islamophobia at the national and global level. My Name is Khan depicts an autistic Muslim man living in San Francisco in the aftermath of 9/11 whose stepson was murdered due to his last name. In it, the lead travels across the country

04 VOLUME 46 ISSUE 08 ARTS

+++

spreading the message: “My name is Khan, and I’m not a terrorist.” In Chak de! India, he plays an ex-hockey player disgraced by India’s national team due to losing a tournament to Pakistan as a Muslim captain (a fate several Indian Muslim sports players face after losing matches to Pakistan), seeking to win back his country’s approval by training India’s women’s hockey team for the world tournament. These roles prompted far-fetched articles on Shah Rukh’s “silent rebellion” against Hindutva hegemony, and interpretations by people like journalist Rana Ayyub of a “big, brave message” from a prominent Indian Muslim. The actor was swift to deny any deeper meaning behind his choices in roles, and continues to present himself as apolitical.

I personally find this aspect of Shah Rukh’s myth to be far-fetched, finding this to be a reaction to the religious intolerance of the current administration. After all, he is a wealthy, privileged actor, who has never actually commented on politics in the media or otherwise. To say that he is secretly fighting against Hindu hegemony in India is presumptuous, and seems like an idealistic projection of political hopes. What holds true, however, is the fact that he does come under more scrutiny and attack as a prominent Muslim actor. Shah Rukh does not sweep his religious identity under the rug, which makes him stand out more even amongst other Muslim Bollywood superstars, who either downplay their identity, avoid playing Muslim roles, or are not prominent or influential enough to draw polit ical attention. In recent years, religious conflicts and disparities have risen with the ascent of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and the spread of his ideology of Hindutva which seeks to establish political and cultural hege mony in India. Shah Rukh and his identity too have faced consis tent verbal and even attempted physical assaults, such as Hindutva activists throwing stones at his car in 2016, recently culminating in calls for a boycott of his most recent movie Pathaan (2023).

Shah Rukh’s filmography often subtly, and sometimes explicitly, nods to love for the country and its traditions. This is evident in the balancing of Indian tradition and Western modernity in movies like separated from his country and family in Khushi Kabhi Gham, the desire for progress and upliftment for his fellow Indians in dying for his country against civil disruption caused by the woman he loves in loyalty to the Indian army in (2004). Journalists Vishnu Sharma and Eram Agha of The Caravan, a liberal long-form jour nalism magazine, deconstruct this omnipresent patriotism by hypothesizing Shah Rukh’s need to consistently prove his love for the country and its traditions as a prominent Indian Muslim to retain his superstar status, which may hold a grain of truth. In the early years of the Modi administration, he expressed his own frustra tions at rare moments of public political open ness about the need to prove his Indianness, being forced to represent all Muslims, and India’s religious intolerance, after which he was immediately condemned by BJP politicians and Hindu extremists on the news and in real life. As the strong backlash posed a danger to his and his family’s physical and mental peace and safety, he has since completely withdrawn from making any comments on religion or politics in the country.

In 2021, Shah Rukh’s son Aryan Khan was accused of possessing hard drugs at a party, unlawfully held in prison, and denied bail for six days, even when no drugs were found. Journalists and activists attributed this unjus tified attack on Shah Rukh’s family to both the Modi government’s pattern of targeting

Bollywood celebrities in drug cases and Shah Rukh’s high-profile Muslim identity. Most recently, his action movie Pathaan faced backlash and loud cries for boycott by politicians, media personalities, and extremists on account of the lead actress, Deepika Padukone—who has supported anti-BJP protesters in the past— wearing an orange bikini. Orange, specifically the shade of saffron, is the color of the BJP, and wearing ‘revealing’ clothing of that color was apparently “offensive” to Hindu sentiments. This, compounded by Shah Rukh’s lead role in the movie, was enough for BJP’s extremist supporters to threaten cinema halls and regular moviegoers’ safety. Despite this, Pathaan overwhelmingly broke box office records all over the world, quickly becoming the top-selling film of January 2023, even beating Avatar: The Way of Water on release day. Videos of Hindu extremists accusing fellow BJP supporters of betraying their religion by betraying the boycott circulated the internet, with most responding by shrugging their shoulders and stating they had to go, because of Shah Rukh Khan. This was the actor’s first movie in four years, and even the prominent calls for boycott and anti- Pathaan media discourse were not strong enough to oppose the fan fervor backing Shah Rukh. I myself joked at the time that maybe Shah Rukh was the uniting force India needed.

across the thousands of interviews and accounts of interactions with him available online by journalists, media personalities, fans, and coworkers. His distancing from politics and from the word “feminism,” his controversies, and even outbursts of anger in the media have no impact on the myth itself. He’ll continue to be envisaged as the symbol standing against state-sponsored religious extremism or (in my case) as a romantic “women’s hero” waiting for his love, standing in his signature pose, arms outstretched.

In a country where love and public displays of love and affection are constantly ostracized and condemned across lines of religion, caste, and sexuality; where interreligious, inter-caste, inter-community, and queer couples are in consistent physical and social danger; where women’s bodies and sexualities are tightly controlled through legal and social systems; where 93 percent of marriages are arranged, the idea of Shah Rukh has been the symbol of hope for the possibility of love and intimacy for millions of South Asians.

In his own words at his TED Talk, “...India decided somehow that I, the Muslim son of a broke freedom fighter who accidentally ventured into the business of selling dreams, should become its king of romance, the ‘Badshah of Bollywood,’ the greatest lover the country has ever seen... with this face.”

05 THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT

+++ ARTS

TEXT ANUSHKA KATARUKA DESIGN ANNA BRINKHUIS ILLUSTRATION SAROSH NADEEM

Held Together by Bookends

Oil on canvas, wire, polymer baked clay, acrylic paint, newsprint, paper, cardboard, mini clothespins, beads, fabric scraps, a repurposed doll shirt

When experiences end, objects are the only things that are stuck in time, holding together memories. By recreating these objects, I was able to bring value and life into otherwise ordinary things that usually get thrown out. The detailed lettering of a Marlboro cigarette box, the grooves on a tiny replica record, and the color pattern of an old sweater; these details filled the objects with life, and the labor I put into recreating them allowed them to bear the weight of the experiences that I’m honoring, grieving, and missing.

06 EPHEMERA

Mira Goodman B’24

VOLUME 46 ISSUE 08

She admitted to me with a roll of her eyes that maybe she liked him. I looked away and smiled. I had known Mila for long enough to understand that she was like a cat: elegant, prideful, and repelled by romantic declarations. Rather than discouraging boys from pursuing her, this galvanized them. A challenge, they thought, and set themselves harder to the task. Soon they were doing everything to impress her, each attempt eliciting a cool amusement, their efforts transformed into anecdotes offered up at our weekday dinners. Jordan said he’d never met anyone like me. Can you believe that? with a smirk. She had lots of casual sex, but for all the time I had known her I was never able to picture her so vulnerable as now. It was disturbing to think of her sprawled on a bed, panting and out of control. She exhaled a lungful of smoke into the summer night.

Our time in college was melting by. Sophomore year ended and some of us less glamorous ones stayed in town for the summer. When Mila asked to stay with me, I agreed immediately, without stopping to wonder why. Our friendship rested upon both my separateness from her other life and my unconditional acceptance of it.

“My friends had a bet,” she said, “That Aaron and I would end up dating. But I never date.”

“I know,” I replied. We sat on the cement steps in the courtyard of my apartment complex, sharing a joint. The courtyard was small but well-kept. Sidewalk bordered a generous plot of grass, which, by some miracle, had persevered against a relentless New England heatwave. Mila and I were dressed in barely anything, flip-flops and cotton shorts. I flicked the lighter every so often. Our faces were rhythmically illuminated.

Sometimes it was hard for me to look at Mila. Her eyes were so big and brown. She had full, plush lips like an old Hollywood star. I was still unsure why she chose me. She only ever played at loneliness, had an unshakable place in the campus constellation, whereas I had known the real thing and therefore felt like there was always some distance between us, no matter how many times we laughed with one another.

Maybe it was because I was a ready audience. I listened carefully; her increasing mentions of Aaron hadn’t escaped my notice. She slid them into our conversations with studied carelessness, as if she wanted me to think they didn’t matter to her one bit. “He did call me gorgeous today,” she would say in her low voice, drawing her words out so they lingered in the air. “So, yeah.”

I swallowed my impulse to laugh, like I did with everything else she divulged. Too proud to admit her feelings, or truly unmoved? At first, I wasn’t sure.

When I first started hearing about Aaron, I never thought he would have a chance. He was a close friend, Mila informed me, months ago. It was just starting to become spring. He was emerging from a fling with Harmony and I heard from everyone that he had called her “babycakes.” Mila tolerated that behavior in friends, but she was not one to take interest in laughingstocks.

But, “I learned how to drive today,” Mila had said on that momentous day, late afternoon in my apartment’s kitchen. She said it in the falsely

casual tone I would come to know well. “In Aaron’s mom’s BMW.”

“He let you drive his BMW?” I had asked. I was facing away from her— washing dishes, or chopping vegetables, half listening. “But you’ve never driven in your life.” She was smiling, watching me, waiting for me to tease the story out.

“Well, he was doing all the work.”

I looked at her, still confused.

“I was on his lap.”

But Mila had said it so carelessly that I had forgotten soon after. Mila and I had met only recently. But I had long known that beautiful girls had different platonic boundaries with men. I just assumed, by the way she said it, that this was another example of how we differed that should go unmentioned—to provide evidence, maybe, that I, too, was one of the beautiful girls and could grasp the inner secrets. Aaron was Aaron, earnest and a bit oafish, an occasional character in her retellings. This was how I understood our world until one ordinary Monday, when he approached me at the gym, and shared a secret.

It now rested on the tip of my tongue as we sat on the stairs, sweet and satisfying. I rolled it around my mouth like a sucker. It was nearly killing me not to tell her, and I was fairly sure she already knew, but I didn’t want to be the transgressor. Here it was: Aaron’s family had a place on Martha’s Vineyard. He was throwing Mila a trip this weekend, a characteristically ham-fisted surprise, because you can’t really surprise someone with a beach trip, what with the packing and planning and million people through which the secret could get out. When he was inviting me, he even forgot to include it was supposed to be a secret. “I would love it if you came. Mila talks about you all the time,” he said. I had almost asked her about it, confused by his sudden warmth—I didn’t even think he knew who I was—before her roommate sent me an emergency text.

It had been strange to finally talk to Aaron after hearing so much about him. Everything about him was big—his handshake, his laugh. I instantly understood why he was so well-liked. There would be many of us, driving in three separate cars and then taking the ferry. Mostly they were Mila’s housemates, but some, like me, were recruited from disparate corners of her life.

We would leave tomorrow at midday. The gesture was so extravagant that I bit my tongue in an effort not to spoil it. Was this normal? I felt giddy. Aaron is throwing you a birthday party in Martha’s Vineyard, Mila We both went to public high school. And he thought to include your friends, even the ones he doesn’t really know

“So, someone’s gonna lose that bet,” I said, and I turned to look up at her. The air was cool after a scorching day, the sidewalks fresh and new, and Mila looked totally at ease, draped across the stairs like they were the most comfortable cushions in the world. “And, you know. It’s funny to see you like this.”

“It’s embarrassing,” she groaned, but she smiled, too. In the darkness, she seemed more like a girl than I had ever seen her. I saw a rare flash of softness on her face. She had tried extinguishing it but I now saw that such an act would be impossible. “There will definitely be money changing hands,” she said. And threw the filter into the grass.

The car had been mysteriously procured. We crammed into the backseat with our luggage. We each had some awareness of one another on campus but had never spoken. Mila’s pull had drawn us together. We were the miscellanea, her collected girls, and we shared a similar quality that leapt out now that we were squished together: a certain meekness, an eagerness to please. We sat thigh to thigh.

Cleo had a face that reminded me of a doll, her skin freckled and clear. Thick-lashed, plumpcheeked. She was biracial and had grown up in an affluent New Jersey suburb. “Stephen Colbert’s house gives out the best Halloween candy.” Her family went to the Vineyard every summer. We spent the car ride exchanging pleasantries. We talked about her computer science class and our shared disdain for dining hall food. I could’ve fallen asleep. But Cleo’s eyes on me were like a foal’s.

We parked and dismounted in a vast lot and piled into a bus. It lumbered to the harbor, too slow, threatening to arrive after the ferry departed. We sat facing each other, backs to the windows, tapping our feet and adjusting the backpacks that sat between our knees. Catching up with the others was the goal; they were already on the ferry, having left in a different car an hour earlier. I kept checking my watch. No one else seemed to be worried about the time.

But Cleo had noticed, too. “We might still make it,” she said. “If we run.” For some reason I believed her. There was some force hidden behind her voice. It confused me, just like the revelation that she was close with Benny Huxley—known philanderer with a senatorial smile, who had spoken Mandarin to me once at a party. How doesn’t she know that he wants to sleep with her? I wondered, but it was only a momentary confusion. Unlike Mila, it was Cleo’s nature to see pure intentions.

When we stepped off the shuttle, the ferry was still docked. We began to run—and then to sprint. I glanced back at Cleo. Her mouth was slightly open, a beatific smile on her face. We savored the pumping of our legs, our hair lifting from the backs of our necks so the breeze could

+++

LIT 07 THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT TEXT ANGELA QIAN DESIGN ANDREW LIU ILLUSTRATION SYLVIE BARTUSEK

touch them. Her backpack thumped against her shoulders, straps flapping.

“Come on!” she cried, and we pounded onto the ferry. We sent the metal gangplank clattering. We slung down our bags after we had gone as high as we could go. In the distance, the island looked like another world, cloudless and green. I loved being by the ocean. We looked at each other, breathless, giddy with relief. Of course, we had made it. Cleo in her wisdom had said we would.

The outdoor deck was populated by rows of chairs. The rest of our car filtered onto the ferry and joined the others, who had welcomed us onboard with relieved laughs and open arms. Mila saw us standing together admiring the view of the sea, and came to join us.

She squeezed my side. She looked as pristine as ever, even dressed in a hoodie and sweats. Her hands were neatly manicured and adorned with several rings. “How was the ride?”

Side by side, I was startled to see how similar Mila and Cleo looked. Cleo’s skin was darker, and her hair was in braids. Mila had a few more curves, while Cleo was built like a sapling. But Cleo stood at Mila’s height, and shared her brown eyes and full lips. Moreover, people bent to them in the same way. Mila knew this, and exploited it; Cleo most certainly did not.

I asked, “Was the trip a surprise for you, in the end? Did Aaron pull it off?”

We looked at each other and began to laugh. “Aaron, pull off plans? They were talking about going into my room and packing me a bag, then throwing me into a car,” Mila said. “Then, they realized that they were describing a kidnapping.”

“I wonder what they would’ve packed for you,” Cleo said. She was looking between Mila and me, smiling along. She fidgeted with the string of her hoodie.

“I’d be borrowing shirts all weekend.”

“I wonder whose,” I said, and we widened our eyes at each other, and laughed.

Talking gave way to enjoying the passing scenery. To our left we could see the open sea. To our right was a partially wooded island full of houses, and behind it, the sun was setting. Even the sunset here was more brilliant than at home. The air smelled sweet and open. The ferry had brought us to Narnia. “Almost there,” I said, and I could almost feel the relief of stepping inside.

+++

The boys had raided Aaron’s fridge for punch ingredients. I saw an empty bottle of limoncello laying next to the bowl. “I need to show you something,” Mila shouted over the music. We were both drunk. The kitchen led into the main room, where Mila’s friends were loosely packed and dancing. She may have seen the look on my face and gestured to the fridge, which was crowded with magnets from American cities. The faces of rosycheeked families peered up at us from Christmas cards. I touched one of them with a fingertip, afraid to move it even by an inch.

She opened the door and brought out a bottle of prosecco, unopened. Her favorite. “Aaron got it for me,” she said. “Let’s share it on the beach tomorrow.”

Steven arrived at the house in a blindingly bright white Audi. He was someone’s friend who was on the Vineyard for the summer. Solid and pale, with a heavy-footed swagger. I watched his eyes go straight to Mila. She was leaning against the counter, nursing a drink.

I could see her amusement as they began to talk. He took up a lot of space, pacing in a wide circle and gesturing with his arms. From my

vantage point, he seemed to become increasingly agitated, circling wider, volume rising, while Mila remained even and relaxed, a picture of control. He was trying to provoke her; she was making her sly responses. They were toying with each other. Mila at her sharpest. People began to gather and watch. “She’s not the one,” someone told him, “she’s not the one.”

Cleo was in the middle of it all. There was something about how she moved—like she hadn’t quite learned how to use her limbs—that was entirely captivating, and I could tell she was unnerved by the attention. People were helpless to admire her. She smiled with relief when Mila approached her. They began to mouth the words of a familiar song. Mila tossed her magnificent head, sending a wave of hair over her back.

Then, Mila turned and met my eye. For just a moment, before she could hide it, I saw a strange expression on her face. Almost as quickly, it receded, schooled into blankness, gone.

The party had moved upstairs, but Cleo and I were sitting at the darkened kitchen table. We were sharing a bag of Cheetos and listening to the thunder of feet on the ceiling. Next to us, a window looked into the backyard, which in the night seemed grassy and lush with its half-shapes and shadows. Cleo looked lost. She had excellent posture, and unlike the rest of us, was fully covered up in a hoodie and jeans. She looked like somebody all parents and teachers adored.

“Have there been any boys this semester?” I asked, partly out of idleness, partly because she was beautiful with her hands resting on the kitchen counter.

“Not right now,” she said. Her voice was wistful. “At the beginning of the year, Aaron and I talked, but then it kind of ended. I was thinking about rekindling something. But I think he might be into Mila.”

I could’ve burst out laughing. I shoved a Cheeto into my mouth. There was an unreal

The next morning, Aaron drove the three of us to a beach in a maroon Jeep. We were wearing our bikinis and the sun was out. “Before we leave,” he said over the wind of the open top, “everyone has to jump off the bridge at least once. It’s what people do here.” There was no trace of awkwardness between any of them. It was as if I had fallen asleep and dreamed the whole night.

The bridge was higher than it looked from the beach. Mila had to be cajoled into it, but now the three of us peered down into the water with trepidation. “We’ll do it,” Mila said. I felt a rush of affection toward her. She sounded scared.

We watched a pair of young girls, ten or eleven, clamber onto the railing and launch themselves into the water without a hint of fear. Their skinny bodies fell away into the ocean and landed with a loud splash; I watched the way their heads reemerged from the water, plastered with hair, and how they shook the water ecstatically from their eyes.

I climbed onto the railing. My knees shook. The water looked so far away. Every one of my instincts was telling me to go back to the safety of the beach. I looked over—the others, stunning in their wholesomeness, were sitting on the rocks to cheer us on.

“We do it,” I agreed, my throat tight, and took Mila’s hand. Cleo mounted the bridge next to me. Her face was serene, like she jumped off high bridges every day. She took my other hand.

“Don’t be afraid,” she said.

Three, two, one: We flung ourselves off of the bridge. I shrieked. The water flew towards us, growing larger in a matter of seconds, and I tore my hands away from them, my stomach soaring.

I hit the water with a smack and sank in, felt my bikini top slip from my chest. The water was perfectly cold. I stayed there for a moment. I felt perfectly aware of my body, every pull of my muscles and kick of foot. As I adjusted my suit and swam toward the shore, limbs pumping, blood pounding, I knew what it felt like to be Mila and Cleo and all the girls who got to experience the best of life. I emerged. I shook water off my body. I climbed up onto the rocks and into the sun.

quality to the night, to all of it. It seemed foreign now to imagine Aaron in love with anybody but Mila—even his entanglement with Harmony felt more like a practice round, a rehearsal, a diversion in the face of Mila’s sheer unattainability. I suspected that even if Harmony knew this she wouldn’t care. Cleo felt different, though. I couldn’t imagine her being a diversion.

I only nodded, making a small noise of sympathy. I wouldn’t be the one to tell her that her suspicions were true. How much more obvious could it get? But I wanted to reach out and touch her hand. Upstairs, the party pounded on. The moonlight came through the window. I wanted peace for us. I wanted enchantment. It turned out that I wanted a lot of things.

08 VOLUME 46 ISSUE 08

+++

LIT

ANGELA QIAN B’24 likes coffee ice cream.

Making Space to Create

N landscape than RIPTA bus commutes, and no one has endeared me more to this quaint city than all the people I met beyond College Hill—most younger than 16. It was on Broad Street as a freshman that I first realized the vastness of Providence past Wickenden Street and Downtown. Locals on the bus would run into each other and catch up about husbands, kids, and the chaos of the pandemic all in between two stops until they were forced to part ways. Spanish was used in most interactions, and I saw Puerto Rican and Dominican flags at every corner. The want and need to return to that scene and sense of community was what led me to work for Providence CityArts for Youth.

At the end of Fall 2022, I learned that the organization planned to shift their operations into Providence mid dle schools and, due to budget cuts, run fewer classes at the Broad Street location. The news brought me back to that image of the yard, the children waving at cars with family members or school teachers that would pass by and the giggles of kids chasing after each other in a game of tag. The classes would continue, but it wouldn’t be the same. With the loss of the space would come the loss of the community, the team, and the place of comfort that anchored so many. * * *

From July 2021 to June 2022, I was an artist-mentor and intern for the non-profit organization, which is located near the Ontario stop on the RIPTA R-Line and conveniently next to America’s Food Basket. CityArts provides free after-school arts education and care, primarily serving elementary and middle schoolers studying near the Broad Street facilities. Their workshops span the visual arts, design, music, dance, digital media, theater, and creative writing.

When I walked in every Tuesday and Thursday at 3:30 p.m., I would be greeted by joyful screams and an attack of clinging hugs from the kids—it was homework help time and they were eager for alternative forms of entertainment. After the kids completed a measly couple of multiplication exercises and chowed down a few snacks, the then-programs director, Camille, would announce it was time to play. The news would immediately incite a swarm of kids rushing toward the yard to soccer balls, hula hoops, and at times low hanging tree branches.

In my search for a community beyond College Hill, I found that place informs the community just as much as people do—endlessly informing one another. Now, I find myself working at Project Open Door (POD), a RISD-affiliated organization. POD provides free, quality art-and-design programming to high school students in Providence, Pawtucket, Central Falls, and Woonsocket through its Saturday Portfolio Program, after-school programming, and summer studios. Led by skilled teaching artists, Saturday classes and workshops are held on RISD’s campus, and students are given college IDs which provide free RIPTA fare and library access. I have been a teaching assistant at POD for almost a year and have encountered a similar sentiment of community, in addition to a supportive and cooperative dynamic ordinarily exclusive to older students.

I kept asking myself the same questions of its space, students, and the impact of the organization: I wondered what they liked about POD, the space, the people, the classes, the community? What had them coming back?

Avari, a high school junior who has been a POD student for about a year, shared with me that it was the feeling of growth he had found there, as well as the

METRO 09 THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT TEXT GRACIELA BATISTA DESIGN GRACIELA BATISTA & SAM STEWART ILLUSTRATION GRACIELA

BATISTA

Leo and Natasha, a student and teaching artist, at Project Open Door

Caitlin, the assistant director, adding songs to a class playlist at Project Open Door

community of artists that made him feel welcomed and inspired.

“I’ve grown a lot as a person; I’m more confident in myself. If I wasn’t able to join this program, I’d be totally a different person,” he said. “[POD] is a very accepting atmosphere, a lot more than school and family for many people.”

Leah, a high school sophomore and student at POD for almost three years, shared that “POD has been a big part of me.” She described the program as a support circle: “POD has helped me come out of my shell, and feel more self-sufficient.” Initially joining due to her interest in art, which she discovered early in elementary school, she ended up finding the people that have now become her closest friends.

Nicole has been part of the program for a year and a half now and is a junior in high school. When asked about what brought her to POD and what kept her coming back, she talked about how her school focused on STEM classes and didn’t have any art programs, so she explored her passion at POD. “[At POD] I was able to create a film with my best friend,” she said. “[POD] has helped me discover myself more by exposing myself to different per-

spectives, since everyone here is an artist.”

The strong friendships and artistic growth V—a sophomore in high school—has experienced at POD has kept them coming back in the past year and a half. They talked about how POD has supported them during hard times through friendships and mentors. “Overall this program has helped me in so many ways,” they said. “I can’t even begin to comprehend how different my life would be if I wasn’t in POD.”

The organization’s interim assistant director, Caitlin Gomes, shared a few of the patterns she has noticed about today’s youth: “They have a lot to say, given time and the space to do so, and aren’t afraid to show themselves.” Providence art education spaces, in my view, are that time and space. During adolescence, a space and community to congregate, share ideas, and grow and learn with is endlessly important—and vital for those that don’t have the same security elsewhere. Finding myself part of that community for the kids and teens, and being a face they could rely on every week, has been the single best part of my experience in Providence, Rhode Island.

10 VOLUME 46 ISSUE 08 METRO

CityArts, view from Broad St.

GRACIELA BATISTA R’24 loves to play tag in the yard.

This piece is a collaboration between myself and my grandmother’s house. It features an orange peel, which she peeled and I sewed back together with a bent tapestry needle. I then superimposed it onto a piece of logarithmic graph paper I found in my late step-grandfather’s office. In making the piece, I was playing with the idea of color, the bridge between the physical and the digital, and the mixing of familiar and unfamiliar forms. The piece is meant to be slightly uncomfortable, evoking fleshy skin stitched together with sutures, yet also colorful and commonplace.

X 11 THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT

Zoe-Anna Rudolph-Larrea B’25 Orange Peel, Stitched Orange peel, graph paper, thread, digital collage

Livia Weiner B’24

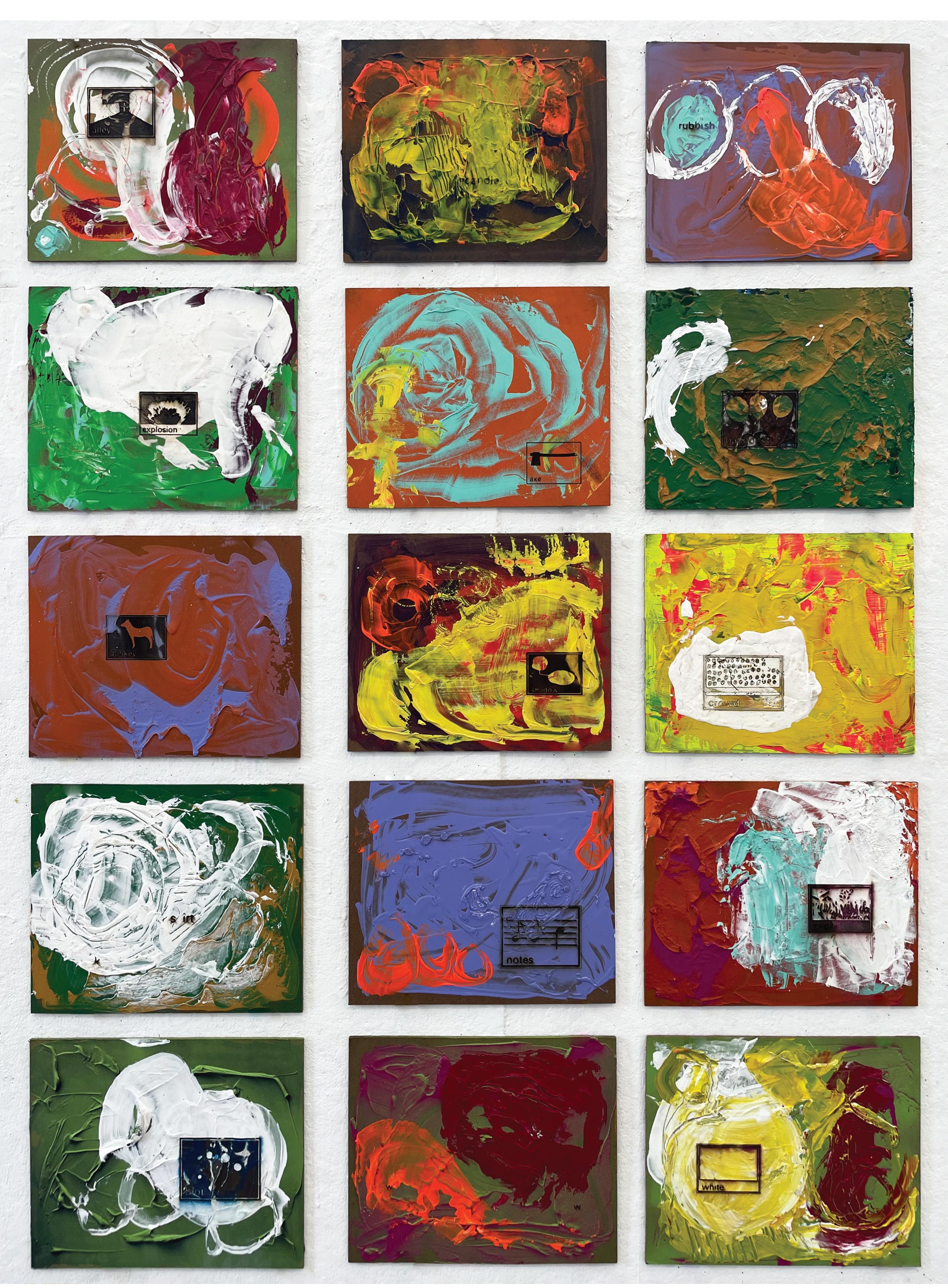

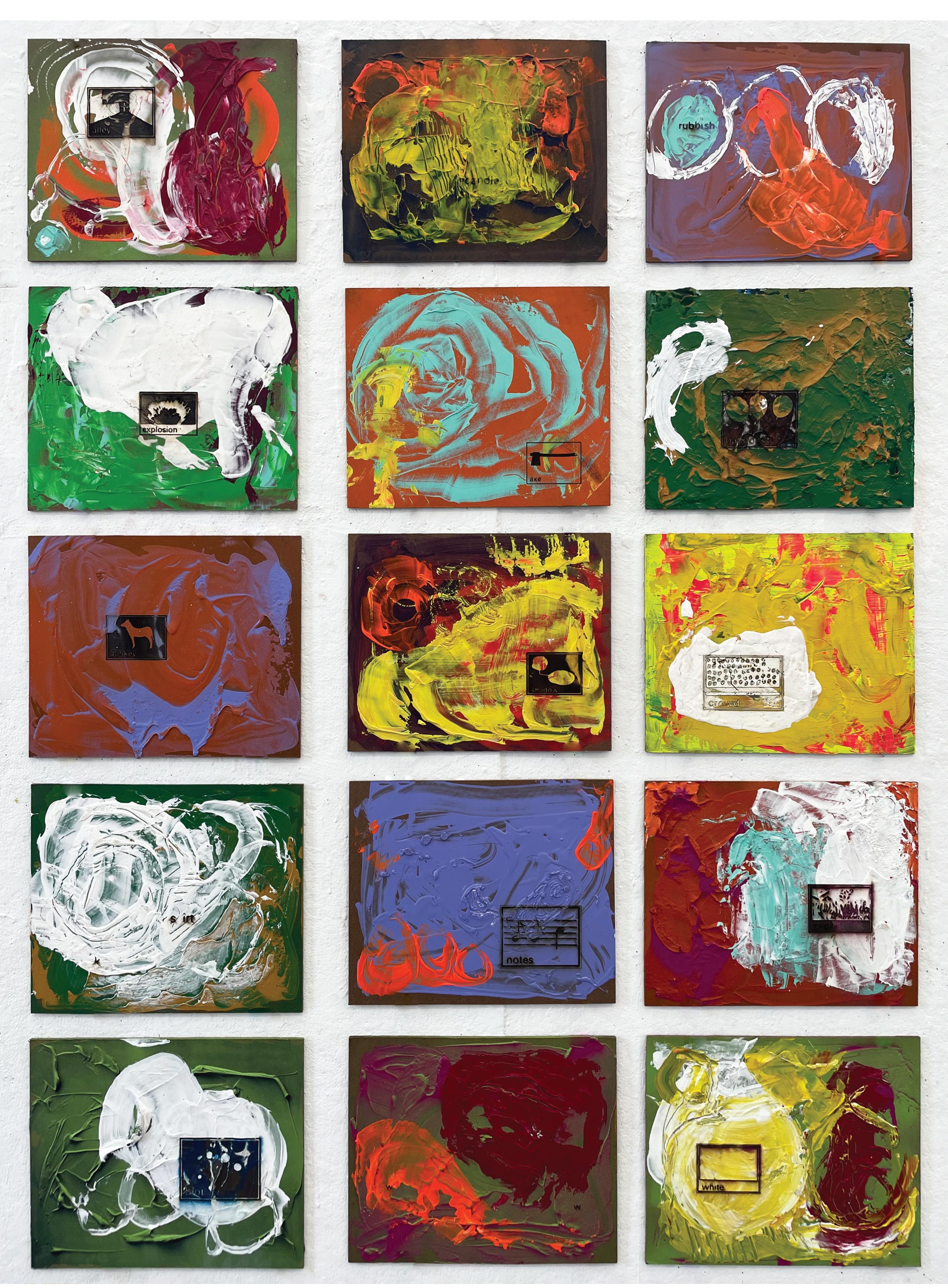

The Young Reader’s Press First Dictionary

Acrylic, spray paint, laser cutter

In this series of fifteen paintings, I’ve piled dozens of layers of colorful paint and used a variety of materials—fingers, hands, hair—to push it around. I then used a laser cutter to burn images inspired by a 1970s children’s dictionary on top of my paint mounds, exposing lost layers of paint underneath. Here, I’ve combined the hands-on with the mechanical, the random with the deliberate.

12 EPHEMERA VOLUME 46 ISSUE 08

Suffocated by Silence

An Exploration of an Untold Migration Story

Many families have a piece of history that is the perpetual elephant in the room; the gap in the record, the moment of pause between conversations. For my family, this is my cousin, B., and the story of his time in the United States.

When I was seven or eight, my aunt and uncle visited my house in San Francisco. This was unusual, since we always visited them at their house in Kathmandu, Nepal—never the other way around. I used the opportunity to show them my pink dollhouse and brag about my very difficult spelling homework.

Almost a decade later, my dad finally told me the reason behind their only trip to the U.S. It was a typical summer afternoon in Kathmandu. We were in the car, driving from one relative’s house to another, stuck in one of the clogged traffic circles scattered throughout the city center. My legs stuck to the leather seats as I held a cold water bottle to my neck and a medley of top 40 songs played softly on the radio. It had been silent in the car, each of us lost in thought as we stared out our respective windows, until my dad suddenly launched into speech.

My cousin B. came to the United States on a student visa to attend a small university in Texas. My dad described the university as a poor choice for B.—it was in a small town he was completely unfamiliar with and had very few people of color. “I think he wanted to be a rock star and had this dream to make it big in the United States,” my dad told me, trying to rationalize why B., with a stable and promising future waiting for him in Nepal, would suddenly jet off to a country he was completely unfamiliar with. My aunt and uncle visited us in the U.S. about four years after B. enrolled at this university.

B. eventually dropped out. On a road trip to visit distant family in Oklahoma (to be specific, the cousin of a second great uncle; in Nepalese terms, a close relative), he was pulled over by a Texas state trooper for a broken tail light, who found him in possession of hard drugs and no documents legally allowing him to be in the country since his student visa had become invalid once he left school. He was then sent to jail in Texas. There, he called my father, who, until that phone call, had thought that his nephew was happily working away at an undergraduate degree, not struggling with a drug problem and making spontaneous cross-country road trips.

I don’t remember what excuse my dad told me when he flew off to Texas, but whatever it was must have worked because I had no idea this trip happened until that afternoon in the car. Beyond my fairytale-like stereotypes of cowboys

and sheriffs with shiny gold badges, I don’t recall hearing any mention of Texas during my childhood.

When my dad tried to describe the jail where B. was being held to me that afternoon in the car, his ability to speak failed him. He turned toward the window, looking in the direction of Swayambhunath, the big Buddhist shrine that towers above the Kathmandu skyline. My dad— the star of nationalist plays at his elementary school in Godavari, extrovert extraordinaire who could talk a stranger’s ear off for hours about anything—faltered when trying to put into words the feeling of seeing B. behind the glass as they spoke on the jail’s visitation phone.

During my dad’s visit, my cousin refused to elaborate on his drug problem or why he had dropped out of college. But, my dad cared about B.; this was his brother’s child after all, and wanted to get him out of jail. So my dad went to a pawn shop to buy a bail bond from a man with a swastika tattoo—a strange connection to home, where the swastika isn’t a hate symbol but one of religious compassion and worship.

My dad was able to bail B. out of jail; the next step was to find a lawyer. To his surprise, he found a Desi lawyer in Texas who was willing to work with him and recommended getting my cousin deported in order to avoid jail time in the U.S. In the midst of all this, without my dad or the lawyer’s knowledge or involvement, my cousin was transferred to an ICE holding facility, and for a period of time, my dad and the lawyer had no idea where he was.

When he reached this point in the story, my dad and I had just stopped outside my uncle’s workplace to pick him up. As my uncle, B.’s father, approached the car, my dad started to speak more quickly. We were talking about the elephant in the room and couldn’t be caught in the act.

With my dad rushing through the final details, I learned that he and the Desi lawyer were eventually able to get B. out of the holding facility and my cousin was ordered for deportation.

As my father told me this story, I was struck by our privilege—the privilege of being familiar with the American legal system, the privilege of being able to afford a lawyer, the privilege of having a family support system. In the U.S., millions live in fear of deportation every day, and most undocumented immigrants in the U.S. fear the locations they would be deported to.

During the time this was all happening, B. refused to acknowledge the advantages he’d been given and didn’t leave the U.S. despite

his deportation order. Instead, he stayed in San Francisco but refused to speak to my father. In a moment of desperation, my father forwarded him a plane ticket back to Nepal, but soon after he received a message that the booking had been canceled. After all the effort he had gone through to get B. out of the prison system, this was the final straw. B. was dead to my father after that.

It is unclear what B. was chasing and what future he thought was here for him in the U.S. My dad said that he wanted to pursue music, and that he thought he’d make it big on American Idol, a platform through which the American Dream spreads internationally.

My uncle and aunt’s trip to the U.S., it turns out, had been a last-ditch effort to convince B. to come back. I know B. returned to Nepal but when and how he was able to stay so long in San Francisco despite having been ordered for deportation are details I never found out. That random summer afternoon is the only time I’ve ever heard my father talk about it, and my uncle opened the car door before I had the chance to reply.

+++

My family prides itself on our education. We migrate for the sake of learning: my dad to the United States for an electrical engineering degree, my uncle to Russia for a civil engineering degree, and my grandfather to Germany for a master’s degree. We’re not a family that gets caught in foreign countries in possession of drugs. To be caught in the act of talking about this would be contradicting the narrative of my family— educated and law-abiding, and thus deserving of the privilege we have.

Our family isn’t representative of the average Nepali migrant—every year, hundreds of thousands of mostly young Nepali men leave home to work in countries like Qatar, Malaysia, the UAE, and other countries to send money home to their families. This is such a common occurrence that at the Tribhuvan International Airport in Kathmandu, there’s a line just for this class of Nepali migrants, separate from the lines for Nepali citizens and foreigners. But my family doesn’t step foot in that line. The reason B.’s story is so taboo is because it disrupts the narrative that due to our education and work ethic, we deserve the privilege we have, to not have to be in that line. B.’s tale shows that when our family migrates, we’re not always the “model minority” that we so pride ourselves on being.

My father never brought the story up again. It’s a difficult experience for him to speak about— why would he want to relive that day in the

13 THE COLLEGE HILL INDEPENDENT

WORLD TEXT INDIGO MUDBHARY DESIGN GINA KANG ILLUSTRATION JULIA CHENG

Texas jail? Additionally, if I had to speculate, he probably wants me to be proud of my family, to view myself as part of a legacy of learners. I have so many questions for him about B., but who am I to make him relive one of the worst days of his life? Thus, the silence and my complicity in it continues.

A few months later, in a seminar about Indian religions at Brown, the topic of Desi parents comes up in a discussion about The Namesake. We’re laughing about their insane expectations and cut fruit when someone brings up how difficult it can be to communicate across generations in Desi families. I rarely contribute in this class, but that day, I decide to say, “We never tell them anything because they never tell us anything.” And I remember my dad in the car and the swirling, vertigo-inducing feeling I get when I think about all the things I don’t know and will never know about my family. For example, for many years now, I’ve wanted to ask

them, point-blank, if they’d accept me marrying a woman one day. I know many of my cousins hate queer people—transphobic comments about the sex workers in Thamel abound after a few glasses of whiskey—but when it comes to my father’s generation, all that exists is silence.

My cousin is now a quiet 38-year-old with a steady office job in Nepal—to think of him behind a glass window in an American jail is to think of a different B., one that I’ll never know. My conversations with him never go deeper than if my studies are going well and if they have any good Nepalese food in Rhode Island. Sometimes I want to ask him: why? Why did you stay in the U.S. after what you went through in Texas? Why would you stay in a country that actively didn’t want you there? Why did you believe in this warped American Dream so strongly? Most of all: do you realize how lucky you are? But I know I’ll never ask him these questions, because I know we’ll never talk about what happened.

Hypothetically, I could approach B. any time and ask him all of these questions. But I already feel like an outsider in so many ways, from my bad Nepalese to the fact I’m rarely in Nepal, only for a few weeks each year at best. To ask him these questions would be to lose the already small amount of belonging I have. Perhaps this is how generational silence is created, through the fear of losing your place in the family.

Are these words an attempt at breaking that silence, even if they’re in a language that a lot of my family doesn’t speak, printed in a publication thousands of miles from where they live? It depends on if I send this article to them or not. Odds are, I probably won’t.

White Picket Bulldozer Politics

Hindu nationalism in the Indian diaspora

Last year in August, on the 75th anniversary of India’s independence from the British Raj, a bulldozer was among the many floats present at a parade celebrating the event in a New Jersey town.

A banner that accompanied the float was decorated with pictures of Yogi Adiyanath— the chief minister of India and member of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Adiyanath has been accused of using bulldozers to destroy mosques and Muslim-owned businesses and homes in Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state with a Muslim population of nearly 20 percent. Since the election of the BJP’s figurehead, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in 2014, India’s Muslim population (numbering nearly 200 million) has been the subject of increasing violence and hate-speech. From genocidal pogroms, to legislation revoking citizenship rights, to the destruction of Muslim religious spaces and institutions, the bulldozer has come to symbolize the brutal creation of a Hindu rashtra (literally “nation”).

The BJP’s perversion of India’s secular foundations has led many educated and economically-privileged Indian Muslims to look abroad to escape anti-Muslim hostility. Since the widespread rise of Hindu nationalist rhetoric in the 1990s, my father’s side of the family, Indian Muslims from the southern state of Karnataka, have emigrated to escape social exclusion, economic oppression, and the threat of violence. But, paradoxically, my diasporic identity is still shaped by these forces.

Growing up in suburban Texas, I have been conditioned to expect Islamophobia from white conservatives. From comments questioning my citizenship status, insinuations of being a “terrorist,” and other microaggressions, it was always evident to me that my religious and cultural identity was the subject of conservative, white supremacist hate. However, I slowly began to realize that even within my own diasporic community, my Muslim-ness placed me on the margins. From my identity being the punchline of jokes by my Hindu friends to one of them telling me their parents wouldn’t let me

enter their homes, it became clear that the same social exclusion my family had tried to escape had bulldozed its way into my own community.

My experiences with imported and domestic Islamophobia expose the interrelated and historical relationships between white nationalism and Hindu nationalism, also known as Hindutva. In the 1930s, Nazi leaders looked to ancient Indian civilization as the basis for an Aryan theory to substantiate their claims of a ‘pure superior race.’ This theory proclaims that an ancient Indo-European culture provided the basis for all civilizations and manifested in the iconography of the Third Reich through the adoption of the swastika, a religious symbol in Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain faiths. Under the Aryan theory, religious minorities, particularly Jews in the Nazi context and Muslims in the Hindu context, are cast as threats to racial purity and constructed as ‘inauthentic’ national subjects.

Contemporary celebrations of Nazi-alligned Indian historical figures and even Hitler himself illuminate the increasingly genocidal rhetoric the BJP is adopting against its Muslim population. When I visited India last summer, I distinctly remember a family friend who is a professor at a local university venerating Hitler as a ‘model leader,’ going so far as to quote his manifesto, Mein Kampf. Between 2003 and 2010, Hitler’s autobiography sold over 100,000 copies in India and has been translated into numerous regional languages. More recent political manifestations of white Christian nationalism have garnered support from both U.S.- and India-based Hindu nationalist organizations. The Republican Hindu Coalition and the Hindu Sena (a far-right paramilitary group in India) have venerated Trump and his anti-Muslim policies, such as the proposed Muslim registry and his 2017 travel ban.

Given the rise of racialized Islamophobia in the West post-9/11—the Orientalist construction of non-Muslims such as Sikhs and other South Asians as Muslim via phenotypic markers—Hindu nationalists in the diaspora have worked to formulate their identities against white nationalism’s resurgent

“Other” (Muslims). This project requires them to position themselves as the perfectly assimilable, white-adjacent, model minority. Bulldozer politics in the diaspora are reflected in the proliferation of Hindutva-aligned actors in political institutions, the privileging of high-paying careers, and resistance to legislation addressing caste-discrimination, which all affirm notions of Hindu ‘superiority.’

In spite of this encroaching Hindu fascist ideology, I have to believe in the subversive, radical potential of the diaspora. As a child of interfaith (Hindu/Muslim) marriage, being in diaspora has allowed my family to escape the effects of a BJP-concocted conspiracy theory known as ‘love jihad.’ This Islamophobic propaganda campaign paints interfaith relationships and families as demographic warfare wherein Muslim men supposedly ‘steal’ Hindu women and force them to convert to Islam. ‘Love jihad’ and legislation requiring interfaith marriages to be reported in advance are attempts by Hindu nationalists to deny solidarity across religious lines, to vilify the transformative power of love.

My inter-religious identity reveals the true power of the diaspora in undoing the divides that characterize contemporary Indian politics. My family’s story gives me hope in the possibility of living together again. In order to recognize the worth of pluralism and repair the ruptures in the subcontinent, we in the Indian diaspora must acknowledge the role that white and Hindu supremacy plays in continuing to divide us. This is a complicated process that requires a political awareness not only of what is going on back home, but also what is happening in our own backyards. Only then might we stop the bulldozer in its path.

ARMAN DEENDAR B’25 is anxious yet cautiously hopeful.

14 WORLD