Sarah Ruyle

Kalie Minor

Layla Ahmed

Ange Yeung

Evan Li

Talia Reiss, Charlie Fitzgerald

Indy Nation

Daniel Kyte-Zable

Emily Mansfield

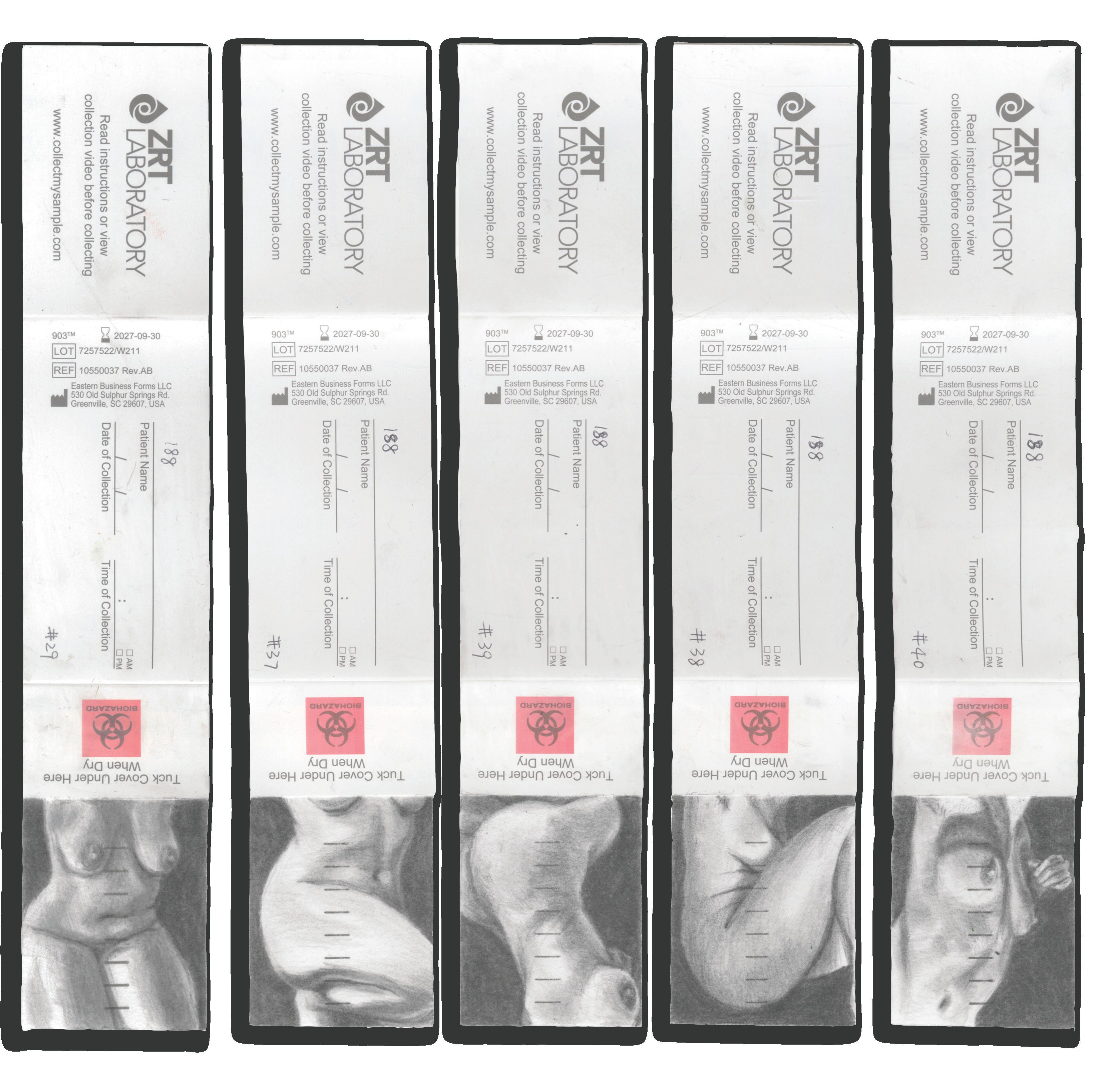

#37–#40

Lucinda Drake

Kalie Minor

Anji Friedbauer, Natalie Svob

Sarah Ruyle

Kalie Minor

Layla Ahmed

Ange Yeung

Evan Li

Talia Reiss, Charlie Fitzgerald

Indy Nation

Daniel Kyte-Zable

Emily Mansfield

#37–#40

Lucinda Drake

Kalie Minor

Anji Friedbauer, Natalie Svob

MANAGING EDITORS

Emily Vesper

Nan Dickerson

WEEK IN REVIEW

Ilan Brusso

Kat Lopez

ARTS

Beto Beveridge

Ben Flaumenhaft Elliot

Stravato

EPHEMERA

Mary-Elizabeth Boatey

Sabine Jimenez-Williams

M. Selim Kutlu

FEATURES

Riley Gramley

Audrey He

Nadia Mazonson

LITERARY

Sarkis Antonyan

Elaina Bayard

Nina Lidar

METRO

Arman Deendar

Talia Reiss

METABOLICS

Brice Dickerson

Nat Mitchell

Tarini Tipnis

SCIENCE + TECH

Emilie Guan

Everest Maya-Tudor Alex

Sayette

SCHEMA

Tanvi Anand

Lucas Galarza

Ash Ma

Izzy Roth-Dishy

WORLD

Martina Herman

Ayla Tosun

Peter Zettl

DEAR INDY

Kalie Minor

BULLETIN BOARD

Anji Friedbauer

Natalie Svob

MVP

Anaïs, April, Kay

*Our Beloved Staff

DESIGNERS

Mary-Elizabeth Boatey

Chen Esoo Kim Minah Kim M. Selim Kutlu

Seoyeon Kweon

Iris Lee

Hyunjo Lee

Anahis Luna

Liz Sepulveda

Justin Xiao

Isabella Xu

Shiyan Zhu

STAFF WRITERS

Layla Ahmed

Aboud Ashhab

Hisham Awartani

Grace Belgrader

Emmanuel Chery

Nura Dhar

Kavita Doobay

Lily Ellman

Evan Gray-Williams

Marissa Guadarrama

Oropeza

Elena Jiang

Daniel Kyte-Zable

Nahye Lee

Cameron Leo

Cindy Li

Evan Li

Angela Lian

Emily Mansfield

Nathaniel Marko

Gabriella Miranda

Coby Mulliken

Naomi Nesmith

Kendall Ricks

Lily Seltz

Caleb Stutman-Shaw

Luca Suarez

Daniel Zheng

COVER COORDINATORS

Johan Beltre

Brandon Magloire

DEVELOPMENT

COORDINATOR

Lucas Galarza

FINANCIAL

COORDINATOR

Noah Collander

Simon Yang

ILLUSTRATION EDITORS

Mingjia Li

Benjamin Natan

ILLUSTRATORS

Rosemary Brantley

Julia Cheng

Mia Cheng

Anna Fischler

Zoe Gilmore

Mekala Kumar

Paul Li

Ellie Lin

Ruby Nemerof

Jessica Ruan

Zoe Rudolph-Larrea

Meri Sanders

Sofia Schreiber

Luna Tobar

Catie Witherwax

Lily Yanagimoto

Nicole Zhu

COPY CHIEF

Jackie Dean

Lila Rosen

COPY EDITORS

Kimaya Balendra

Justin Bolsen

Cameron Calonzo

Jordan Coutts

Kendra Eastep

Leah Freedman

Lucas Friedman-Spring

Christelyn Larkin

Eric Ma

Becca Martin-Welp

Isabela Perez-Sanchez

WEB EDITOR

Lea Seo

WEB DESIGNERS

Sofia Guarisma

Clemence Jeon

Janice Lee

Liz Sepulveda

SOCIAL MEDIA

MANAGER

Eurie Seo

Ivy Montoya

SOCIAL MEDIA TEAM

Martina Herman

Sabine Jimenez-Williams

Emily Mansfield

Kalie Minor

SENIOR EDITORS

Jolie Barnard

Arman Deendar

Angela Lian

Lily Seltz

Luca Suarez

The College Hill Independent is a Providence-based publication written, illustrated, designed, and edited by students from Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design. Our paper is distributed throughout the East Side, Downtown, and online. The Indy also functions as an open, leftist, consciousness-raising workshop for writers and artists, and from this collaborative space we publish 20 pages of politically-engaged and thoughtful content once a week. We want to create work that is generative for and accountable to the Providence community—a commitment that needs consistent and persistent attention.

While the Indy is predominantly financed by Brown, we independently fundraise to support a stipend program to compensate staff who need financial support, which the University refuses to provide. Beyond making both the spaces we occupy and the creation process more accessible, we must also work to make our writing legible and relevant to our readers.

The Indy strives to disrupt dominant narratives of power. We reject content that perpetuates homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, misogyny, ableism and/ or classism. We aim to produce work that is abolitionist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist, and we want to generate spaces for radical thought, care, and futures. Though these lists are not exhaustive, we challenge each other to be intentional and self-critical within and beyond the workshop setting, and to find beauty and sustenance in creating and working together.

c Nobody believes me when I tell them Rhode Island is the Cartesian center of the universe. They take one glance at our admittedly underwhelming skyline and lose their ability to Know the Magic. One of the great afflictions of our primate brains is a reverence for that which is large, and that which commands respect. Rhode Island is no raging fire, no towering feat of human innovation. A point on a plane is infinitesimally small, something to be traveled across, something to approach, but never something you can hold between your index finger and thumb. Does that make it any less important? Doesn’t y still equal mx + b?

Indie doesn’t have an origin story. Or maybe it’d be easier to say that Indie’s origins are many as they are none. All she knows is that one day there was no Indie, and the next day there was, and everything was different. The only caveat is that Indie is confined to the bounds of this state, and as a result loves many things about it. She has spent countless hours walking and looking and exploring, and even more just sitting and thinking. Through all these years and all this time she has established what some might call institutional knowledge, and for this week, reviewed, she feels inclined to share what it all means, and where she has found home. Bate your breath no longer. It’s a week in Indie. And this week, we’re learning what to call home.

Indie has often tried to put her finger on what constitutes a home. Many have said it’s where the heart is, and while Indie’s heart feels like this big thing that beats very loudly all the time, it has only ever beat within the confines of Providence. Indie attended PVDFest a little while back—in an effort to connect with her local community, she saw no better opportunity than this day of pure Providence celebration. She made her way down, jovially, to the nexus of this sacred city: Kennedy Plaza.

Here’s something you should know; when Indie first discovered the RIPTA would shuttle her as far as the bus routes could muster, she felt that she had grown wings—or six wheels and a spirit of adventure. It did not matter what time of day, it did not matter the weather, Indie would march her butt down to that grey and under-managed core, and she would wait for the inevitably late 60 bus (or 32, or 40). In the oft overcast days she would admire all the bussers who, like her, could do nothing more but anticipate the arrival of their silver-blue-white chariot. There were high school girls who, when approached by a boy in their class, would roll their eyes and compare hand sizes and take blurry Snaps as evidence of their proximity. There were mothers wrangling small children, whisper-hissing through bared teeth for them to remain close. There were old men with thick filter cigarettes between lips, always spotting someone from years past, always exclaiming with joy when they were close enough to interact. Indie has always felt the truth of Kennedy Plaza acutely, that truth being that it is the center of Rhode Island’s vascular system. The truth being that without the veinature of each bus traversing its noble route, this city would surely perish.

PVDFest, as you may have anticipated, was hosted at Kennedy Plaza. The day of the festivities was not a

cold one, but overcast nonetheless. The lighting was the kind that only has the misfortune of occurring on an especially bad day, the kind that makes one feel two-dimensional. But this was not a bad day, this was PVDFest! There was, on one side of the square, a stage setup which, upon my arrival, was being occupied not by performers but Providencians, singing loudly with one another in an enchanting—if off-key—choir of love. Later on there would be a performance by a guy who wishes he were the child of two gay dads, if those dads were Diplo and Zedd. Lining the streets, where buses usually chug their ways in and out, were food trucks g’lore. Among them was representation from the many enclaves within this shining city. Cape Verdean, Portuguese, Brazilian Irish Catholic. There was Pawtucketian and Cranstonian, and the vague aroma of Dunkin that permeated the air was enough to make one feel exactly where they were. The stars of this Providence-forward fest, however, were the seven-foot tall Lovecraftian creatures. They gyrated and convulsed through the streets, stopping to dance with onlookers and taste ground food with their many proboscises. The light they emitted was a potent, greenish-yellowish hue that smelled faintly of seaweed. I leaned in close to one and it told me a secret. Indie stayed at PVDFest too long, she left humid and embittered, and she wouldn’t have had it any other way.

Now I only bring up PVDFest to frame a very crucial part in this week, as I review it. This week, Indie hated Providence. She hated the stifling city confines. The murky river. The abandoned buildings. Not even a trip to her favorite local co-op could make her any happier. There was no amount of heartwarming people-watching at Kennedy Plaza and no number of hipster stores with colorful homewares priced at a cool $30 that could make Indie any happier. Because it was still freaking cold, she was still freaking busy, and the city was the freaking same as it had always been. Indie was bubbling. Maybe it was in rage, though it

( TEXT KALIE MINOR

DESIGN KAY KIM

ILLUSTRATION RUBY NEMEROFF )

was likely more in discomfort, and she absolutely had to get out. So Indie broke her sacred cosmological rule. Indie left Providence.

When she was little, Indie had a DVD of the 1970 made-for-television, stop-motion special Santa Claus Is Comin’ to Town. She loved how Santa’s big wet eyes glistened with cellophane, and she loved the fake snow that in retrospect was most likely asbestos. But the best part of that DVD, objectively, was the musical number “Put One Foot in Front of the Other.”. In this scene, Kris Kringle teaches the lonely Winter Warlock how to leave his ice cave. “A good way to start is to stand,” Kris advises, since then all you have to do is “put one foot in front of the other.” They dance around in that unnerving, stilted way only stop-motion can capture, and eventually the Winter Warlock leaves his ice cave, the spirit of Christmas at his back, naturally.

When Indie left Providence, she felt like the Winter Warlock. She could hear the jaunty french horn urging her forward, and she marched proudly onwards, leaving her home in the dust. This simile isn’t holding up as well as I had hoped, though, because when Indie left, she immediately missed Providence. In a foreign town with no less than nine barber shops over three blocks, amidst absolutely no co-ops and exactly one boutique Pier 1 Imports run by a woman in debt to a witch, Indie missed her proverbial ice cage. She wanted to go to Prospect Terrace. She wanted to see a rented slingshot whip down the street. So Indie put one foot behind the other. Indie went home.

Here’s the thing about learning what to call home. You can never really know until you’ve left. Then, all of a sudden, you remember everything you miss and you would give anything to be back in the middle of Kennedy Plaza, sweating but somehow also cold, high in a bad way, dancing among the tentacles of Lovecraftian creatures of old.

INDIE P’∞ wants to Save the Bay.

c In August 2017, one hundred people set up an encampment in Bristol, RI, where Brown University’s Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology housed its collections before relocating to Providence this fall. They claimed to be descendants of the Pokanoket Nation, a historic Indigenous tribe from present-day Rhode Island and Massachusetts. Alongside supporters from the FANG Collective (an anti-fossil fuel organization) and the Federation of Aboriginal Nations of America (FANA), a confederation of federally unrecognized tribes, the protesters demanded that the University return their historic Mount Hope land.

The encampment lasted a month before an agreement was signed between Brown and the Pokanoket on September 21, 2017. Per the terms of the agreement, Brown would transfer the Mount Hope land into a “preservation trust, or similar entity,” which would allow the “present-day Pokanoket Tribe” to have ownership over the property. As a part of the deal, the University commissioned the Public Archaeology Lab, Inc. to conduct a tribal sensitivity assessment to determine how much of the 375 acres would be placed into the trust. Per a November 2024 statement from the University, a transfer of 255 acres was finalized, and Brown plans to completely vacate by summer 2026.

The Narragansett have criticized this transfer. Their backlash reflects questions about how both intertribal and institutional measures of identity factor into Indigenous claims to land. Brown’s role in the land transfer, and its acquisition of sacred land in the first place, highlights the impropriety of colonial institutions intervening in indigenous matters.

legal representative, agreed: “Indian-on-Indian conflicts…are a direct result of the effects of colonization and erasure”—conflicts which Brown has exacerbated.

One of the Narragansett’s arguments against the current formation of the Pokanoket focuses on their lack of federal acknowledgement. The early stages of this acknowledgement process emerged in 1934 with the Wheeler-Howard Act, more commonly known as the Indian Reorganization Act. It set aside various grants for tribes, recognized tribal governments by moving them away from federal authority, and ended the U.S. government’s practice of allocating tribal land, which had caused negative economic and cultural consequences for Indigenous nations as their reservations were divided.

Following the 1960s civil rights movement, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) set guidelines for the Federal Acknowledgement Process (FAP) in 1978. The FAP requires tribes to submit a petition for recognition, which must include proof of continuous existence. The acknowledgement process is difficult to pass and subject to criticism as a colonial system. “For some tribal nations and for some indigenous people, [gaining acknowledgement] can be difficult just because of the history of our people,” said Harris. She stresses that federal recognition is complicated by the fact that indigenous people are a “people of oral tradition…who are being persecuted.” She added, “There’s also the fact that the government doesn’t

( TEXT LAYLA AHMED DESIGN ANAÏS REISS ILLUSTRATION LUNA TOBAR )

important things to be interrogating.” Harris explained that “a continued presence in places…is essential to indigeneity because we are about community but also community’s connection with the land.”

Federal acknowledgement additionally provides a pathway for Indigenous nations to affirm their sovereignty and gain access to governmental resources. “There’s programs, funding, grants and all these things that are available to federally recognized communities,” said Dr. Mack Scott, a Narragansett historian and visiting assistant professor at the Ruth J. Simmons Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice. “This federal recognition, even though it’s problematic in many ways, is important for lots of Indigenous communities because it provides [them with]…an opportunity to really assert sovereignty, political, social, and economic power in a significant way.”

According to The Providence Journal, the Pokanoket filed a letter of intention to petition for acknowledgement in 1994. However, the Pokanoket are no longer interested in the process. Instead, they formed FANA in 2015 alongside other groups who reject the FAP, arguing that the U.S. government has no right to recognize any tribe.

In contrast, the Narragansett obtained federal acknowledgement in 1983, after compiling thousands of pages of documents that prove their existence over hundreds of years. In the 1800s, the Narragansett were a recognized tribe, but the state of Rhode Island removed that status in 1880. This was illegal under the Non-Intercourse Acts, a series of laws passed between 1790 and 1834 that regulated trade and commerce between settlers and Indigenous peoples.

Indigenous peoples, the law also created a nation-nation relationship with Indigenous tribes.

Regardless of the merits of federal recognition, intertribal recognition serves a more important role in affirming Indigenous presence. The Narragansett do not recognize the present-day Pokanoket. +++

The Pokanoket are widely acknowledged as a historical group, but the Pokanoket Nation as it exists today was formed in 1994 under the nonprofit organization Council of Seven & Royal House of Pokanoket & Pokanoket Tribe & Wampanoag Corporation. “The Pokanoket as a group did not start to appear until the 1990s,” said Harris. “A lot of the people in these roles very well may have Indigenous ancestry, but…a large part of the confusion is they’re taking a historical name.”

The Pokanoket once existed as an independent confederacy, but in the 1610s, the Pilgrims introduced a plague that devastated the Pokanoket population. This forced them to briefly join the Narragansett Confederacy for protection. A 1620 defensive treaty between the Pokanoket leader Osamequin and the Plymouth Pilgrims empowered the Pokanoket to separate from the Narragansett. Osamequin, according to Dr. Scott, “was able to consolidate his authority among the Wamponoag communities and become Massasoit, the Chief Sachem and major leader among the Wamponoag.”

“This distinction matters because there are Pokanoket, and there are Pocassets, and there are all these different Wampanoag groups, but they fall under the leadership of the Pokanoket, who [were led by] Osamequin at the time,” he continued. “But right before that, they fell under the leadership of the Narragansett and their confederacy.”

These relationships and postcolonial distinctions between the Narragansett and Wamponoag Confederacies remained until Metacom’s War (1675-1676). During the war, the colonists killed Sachem Metacom, the son of Osamequin, on the Mount Hope land, which makes it an important site in the Pokanoket’s history. The Pilgrims also devastated Indigenous populations and banned the name Pokanoket in the colonies. “The Pokanoket who survived the war were either enslaved, shipped to the Caribbean as part of the slave trade, or reidentified themselves as Wampanoags as a way to maintain their heritage,” Dr. Palermo told The Public’s Radio. The Narragansett similarly allied with the Niantic tribe and formed the Narragansett nation as it exists today.

This process of ethnogenesis facilitated the blending of traditions, especially because familial relationships existed across different groups. “More so than the name Wamponoag or Narragansett or Pokanoket or whoever it is, who your family was mattered,” said Dr. Scott. “There’s this opportunity for people to be in between communities, so it’s not as hard and fast as colonial distinctions and names suggest.”

While Dr. Palermo argues that a core group of Pokanoket maintained their distinct identity and traditions despite consolidation, Harris and Dr. Scott have not been aware of a modern Pokanoket presence. This contrasts with the relationships between

the Narragansett and neighboring nations, who have hosted and attended intertribal powwows and Thanksgiving celebrations. “How come [the Pokanoket] wouldn’t have been part of those communities that everyone recognizes as being indigenous in this area?” asked Dr. Scott.

This absence has led Narragansett leaders to question the Pokanoket’s identity as an independent tribe. “These splinter groups and social clubs… where have they been and what have they done? Why didn’t they come forward decades ago? Now suddenly they’re here and they’re making life difficult for everyone and they’re discrediting a lot of us because, who are these people?” Narragansett Chief Sachem Anthony Dean “Crawling Wolf” Stanton told The Public’s Radio

Brown’s control over Indigenous land has inflamed tension between tribes. The Mount Hope property was donated to the University in 1955 by the living relatives of Rudolf F. Haffenreffer, a collector who originally bought the land as a summer farm for his family. In addition to its presence on Indigenous land, the Haffenreffer Museum possessed a minimum of 99 Indigenous peoples’ remains, 10 of which belong to the Narragansett, and various cultural artifacts, as the Indy previously reported. This indicates a lack of respect towards Narragansett sovereignty, which extends to how the Narragansett felt about the Mount Hope negotiations.

“It wasn’t until very recently that the University started listening to tribal officials, started working with tribal officials, and just as quickly all of that was abandoned,” said Harris. “I think that is something the university has yet to learn. It’s something many universities have yet to learn—that you can work with a federally recognized individual, but that does not change the fact that you still need to talk with the government…if you want to say you’re working with whatever tribe you want to say you’re working with.”

Harris argues that one of the reasons the Pokanoket encampment was so successful was the publicity it received. “The University, along with state governments, get coerced into recognizing these groups with the threat of publicity, the threat of not being woke, the threat of being seen as close minded. A lot of these people genuinely believe they’re doing the right thing, but they’re doing it for the wrong people,” she said. “I think you can acknowledge the Narragansett people, that you are on Narragansett land. But if you refuse to work with the government of those people that you acknowledge should rightfully be the holders of your land, then you’re not acknowledging us. We’re not acknowledged.”

This refusal to work with the Narragansett government is reflected in Chief Sachem Stanton’s experience in the land transfer negotiations. According to The Boston Globe, Chief Sachem Stanton “said Brown University officials told him the Narragansett Indian Tribe was never considered for the land.”

However, Brian Clark, the University’s spokesperson, stated, “Brown made considerable effort to directly engage interested parties in the future of the

Mount Hope property…[but] the Narragansett Indian Tribe declined to participate in that process.”

Harris theorizes that the Narragansett’s refusal to participate in negotiations was due to “distrust with the University, particularly in regards to [the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act] and stolen belongings and remains of our ancestors.” +++

Despite objections to the land transfer, the University plans to adhere to their agreement with the Pokanoket. As reported in The Boston Globe, the terms of the deed require that the Mount Hope land remain undeveloped, though the Pokanoket are still looking forward to using the space for various gatherings and ceremonies. They are currently working with the Mount Hope Farm, Save the Bay, and state organizations to gain a better understanding of how to maintain the land. The Pokanoket additionally plan to restore Indigenous practices like oyster farming and create opportunities for public engagement like cultural tourism through sacred sites.

For the Narragansett, Brown’s commitment to moving forward with the deal has led to concerns regarding access to land and how this action will impact their governance in Rhode Island.

“This land is sacred. This land is essential to our existence as an Indigenous group of people. Anytime we can have access to this land is beyond value in how important that is to us,” said Harris. “I think the transfer is setting us on a scary slope for state recognition for groups that don’t have any claim, and that will directly affect the sovereignty of the Narragansett people on so many different levels…It’s also telling other organizations that you don’t have to work with the tribal government, and it is affirming a lot of these tactics of manipulation. I don’t know what the biggest impact is because there are so many different ways in which this will impact us.”

LAYLA AHMED B’27 realized how little she was taught.

c Grandma always tells me that Grandpa left the world in 2002, never that he died. Every April 1, Grandma tidies his grave and adorns it with fresh flowers from the grocery store. She even leaves him a couple candies sometimes, which she’s traded in for sugar-free Ricola cough drops in recent years, since they’re ‘healthier.’ The day of his death typically falls a few days before Qingming, the Chinese holiday for tomb-sweeping, so we usually combine the two.

While Qingming may not be as internationally well-known as other Chinese holidays such as Lunar New Year, for many families like my own, it is just as important. Each year, hundreds of millions travel home to honor the dead. The festival originates from a seventh-century BCE legend. While exact details vary, most versions recount the story of Jie Zitui, a nobleman who sacrifices his own flesh to make a soup to save an exiled prince, Wen, from death. Eventually, Wen takes back power, but forgets about Jie, who has moved to a remote mountain with his mother. Wen orders his army to set fire to the forests on the mountain to find Jie, but kills Jie and his mother in the process. Full of remorse, Wen creates Qingming to honor the goodness and life of Jie and to immortalize him. Since the Tang Dynasty, families have gathered every Qingming to pay respects to the dead. Aside from sweeping graves, many families lay out their ancestors’ favorite dishes, light incense, and burn joss paper—money for the afterlife. Others take on more modern approaches to the festival, burning cardboard mock-ups of everything from designer purses to suit jackets. The hope is that ancestors in the afterlife will receive the offerings and bless their families with prosperity.

Spending the morning scrubbing the grave of a grandfather I never knew was not something I enjoyed as a moody middle-schooler. Scraping the dirt from the edges, I’d watch the ants and wood bugs emerge from the mud to traverse across the metal plaque. Why should I care so much about someone I’ve never met? Grandma always made a point of talking to Grandpa’s grave, filling him in on all the major events in all his family’s life: someone’s university graduation, my cousin’s adventures touring as a DJ, and how well his kids had been taking care of her. We barely acknowledged the fact that he was gone. He was as much a part of the conversation as the living around his grave. I never understood why she did this or how Grandpa was hearing her. I thought she was trying to convince herself she could reconnect with the dead.

After pretending for ten minutes or so that he was still alive, Grandma would finish her rundown as she always did, saying, We’re OK! No need to worry! These trips were typically followed by lunch at a Cantonese diner, and then life went on as normal, as if we had just caught up with a relative we hadn’t seen in a while.

Each time I’ve asked my family or searched for explanations for why death is avoided in conversations amongst Cantonese people, the answer was always the same—speaking about death is bad luck. I never understood why we spoke so cryptically about death: if it happened to everyone eventually, why were we all so scared to acknowledge it? Still, we used the literal word for death—死—quite frequently to describe everything other than death. 死 was to express extreme degrees of sensation, like 熱死 (dying from heat) or 笑死 (dying from laughter).

Most research done on grammars of death

in China attributes the widespread use of euphemisms around death to social taboos related to dying. By using euphemisms, according to comparative linguist Larrag Abdessamad, we maintain an image of ourselves that is both prestigious and polite, promoting social harmony. This only tells part of the story, though. Maybe we avoided talking about death because it was taboo or because it summoned the spirits of ghosts, but more often than not, steering clear of the conversation was simply easier. This avoidance allowed us to move on and adapt to life without our loved ones. To drag out conversations about their deaths was to surrender to the fact that they were gone and weren’t coming back. By not addressing them as dead, their deaths seemed less real, and so did the grief.

Thanks to Grandma’s large role in raising me, I was lucky enough to understand things in Cantonese without trying too hard. Still, because I went to school and spoke to my parents in English, my fluency was merely illusory. I could translate things people said into English, but I had little understanding of the cultural implications of deeper and more complex conversations. I didn’t need to know the crucial nuances of Cantonese to comprehend what a waiter was saying or whether my Grandma wanted me to help her carry groceries to her car. I had gotten away with hearing without listening. I was fluent in vocabulary but not language, let alone culture.

For these reasons, I couldn’t connect with Grandpa on any level. While these visits to his grave allowed me to accumulate a small repository of facts about him—from his obsession with bright-colored Hawaiian shirts to the ballroom dancing clubs he used to frequent with Grandma—they didn’t mean anything tangible to me. In everyone else’s eyes, Grandpa lived on through these little stories, but I couldn’t erase the fact that the only place I learned about him was across from a funeral home at a cemetery.

There was an inescapability to the grammars and narratives of inanimacy that defined how I spoke of and conceptualized death. In Cantonese, my family has always talked about death as a verb: so-andso’s body has left the world (過咗身) or so-and-so has returned to the sky (返咗天). Although I hear conversations about death and funerals often, my family never uses death in its noun form. Death is always something that someone has experienced, centering the subject and the life they’ve lived. In English, death appears in the language in a larger variety of ways. We talk about someone dying, but we often also attach the noun of death to someone: so-and-so’s death. This way of speaking about death as something possessed by the deceased suggests that their death is definitive, the same way we often refer to our dead relatives as my late grandmother or my departed uncle. This absoluteness carried a finality that was somewhat comforting to me.

When 婆婆, my dad’s mom, died my sophomore year of high school, I became uncomfortably familiar with the languages of death and grief. While my teachers and friends consoled me by saying I’m so sorry for your loss or let me know if you need to talk, I was taken aback by how my parents’ and 婆婆’s friends reacted. They’d tell me things like 婆婆 wouldn’t want you to be so sad, or ask my parents how funeral planning was going. In Cantonese, there was little

( TEXT ANGE YEUNG DESIGN SEOYEON KWEON ILLUSTRATION MIA CHENG )

acknowledgement of how we were processing the death, only of how we were moving forward.

In one study, linguists measured the frequencies of different types of condolences English and Cantonese speakers use based on two scenarios, the death of an uncle and a mother. In both languages, interjections along the lines of oh no were frequently used to respond to news of death; however, the similarities ended there. In the case of the uncle’s death, 95 percent of English speakers expressed sympathy to the bereaved through sayings like I’m so sorry to hear about your loss, compared to only three percent of Cantonese speakers. Instead, 65 percent of Cantonese speakers spoke of the future, recommending that the bereaved refrain from grieving too much and accept the change. The linguists observed that although in both English and Cantonese, learning about one’s closeness to the dead was important information to give appropriate condolences, for Cantonese speakers, asking about one’s closeness to the dead was primarily for “the speaker [to] know how strongly to offer future-oriented remarks, rather than for knowing how strongly to express one’s sorrow.”

The way native Cantonese speakers, even in English, expressed their grief to me was jarring, because outside Qingming, I had only interacted with death in the context of sorrow and erasure. In science classes, death was taught to me as was the final stage of the life cycle that followed birth, growth, and reproduction. My teachers explained death to me as when the body ceases to function. This was how I was taught to grieve: mourn until you forget the pain of it all. Each day, the hole left by that person’s death will feel smaller, and eventually you won’t even notice it. To have family friends tell me to stop feeling grief for someone I loved so much felt like asking me to disrespect 婆婆, as if I was pretending not to be sad about her death. To stop grieving was to let her memory slip away.

Because of my disconnect with the way Cantonese culture teaches people to grieve, the language became a residual artifact on my tongue, something I never made an effort to retain but which instead existed as a product of the past. In Braiding Sweetgrass, I read about how Robin Wall Kimmerer learned every word of Potawatomi “with a breath of gratitude for [her] elders who have kept this language alive and passed along its poetry.” This filled me with admiration and a slight tinge of envy. I wondered why my parents didn’t speak to me only in Cantonese and why they didn’t force me to be more appreciative of my culture. They tried, but their efforts were met with my constant resistance. Seeing no practicality in learning Cantonese given its rapidly declining population of speakers, I had measured its worth by its potential utility and allowed for its disappearance. I stood there and watched Cantonese slip from me with little to no remorse.

It took me a long time to understand that these future-oriented remarks weren’t said out of a lack of care for my family and me. My parents’ and grandparents’ friends just had entirely different ways of conceptualizing death and grief. Instead of showing their sympathy through words, they brought homemade soups to our house or taught us new recipes for our Buddhist tradition of eating vegetarian for the first 49 days after the death. All I wanted was for someone to feel sorry for me. I can’t fault myself for

it. I was 15 and didn’t know any better. Everything I had learned in school or through the media told me that death demanded sadness. I’ve come to learn, though, that grief is not individual. It is a collective process that we experience with the people around us. Sometimes, I still cannot let go of grieving 婆婆 or the fact I never met Grandpa and simply move forward with life. But I can laugh about the little things with my cousins—how 婆婆 used to save the wrapping paper from our Christmas presents so she could reuse it or the videos of Grandpa karaoke-ing his heart out after family dinner. My grief didn’t only have to be about sadness.

In her Nobel Peace Prize Lecture, Toni Morrison recounts the story of young people going up to an old, blind woman and asking if the bird they are holding is dead or alive. The old woman answers: “I don’t know whether the bird you are holding is dead or alive, but what I do know is that it is in your hands. It is in your hands.” What Morrison concludes from this interaction is that “if it is dead, you have either found it that way or you have killed it. If it is alive, you can still kill it. Whether it is to stay alive, it is your decision. Whatever the case, it is your responsibility.”

How I remember Grandpa is not up to fate or the timing of when he died. To see his death as incomplete; to continue negotiating with the boundary between living and dead; to learn, memorialize, and

language I can muster to truly represent the life my grandfather led beyond just the food he preferred or the patterns he liked on his collared shirts. Language is, as Morrison states, something that we do. If we let language die, whether “out of carelessness, disuse, indifference and absence of esteem…all users and makers are accountable for its demise.”

For my 婆婆, who I got to live 15 years with, I am determined to make the memories I have of her into something I do. Only many years after her passing did I understand that death was not a permanent loss. The idea that we could still reach death in the afterlife was a revelation to me, but my family, along with thousands of others, had been resisting the finality of death ever since they first stepped onto Canadian soil. Grief was not merely a feeling, but a practice. Grief was her favorite fruits and bakery goods, left at the edge of her grave so she could eat in the afterlife. It was stacks of fake cash that we burned on the cemetery grounds so she and my grandfather could live out the same lives they worked to build for their grandkids. It was every time I forced myself to order in Cantonese at the food court, asked the waiter for a glass of ice water by myself, and cherished the handprints of her homeland she left on the roof of my mouth.

’s grave for the last time before I left for college, I kneeled around the edges to trim the overgrown grass, allowing the ants to poke holes through the newly-exposed earth. Her death was real. It always will be, and I’m still learning to live with that. But she hadn’t really died in the way I understood death. Her friends hadn’t told me to stop being sad because they thought I didn’t love her. In their eyes, she was opening a door into another world, one with less pain, more joy, and maybe even durians, which everyone hated when she ate them at home. She had 過左身; her body had transcended the skies to somewhere further away but not unreachable. I’m OK, I whispered to her. I still miss you. We all do. But we’ll be OK. The breeze hit the leaves with a sound I couldn’t quite decipher, and I smiled because it wasn’t too far off from the incomprehensible jumble of words I heard when 婆婆 accidentally switched to her village dialect. Here, the long stalks of grass held my hand like she always had, and I felt closer to her than ever. This conversation was not done. I would never let it end.

ANGE YEUNG B’28 has definitely never stolen the pineapple buns from the Qingming offerings.

c To find the male G-spot, you simply have to probe two inches into the rectum. Push down. It’ll feel like a rubbery golf ball, packed tight with thousands of nerve endings ready to ferry waves of pleasure to the brain. Finding Brown’s G-spot is even easier. Just open Sidechat. Actually, it’s more like a reverse prostate: thousands of digital nerves anonymously transmitting the school’s most shameless desires to one purple, smiling app. Think the serial DMer, the sporadic, halfhearted attempts at planning hookups in the BrownU Gay group chat, the confessions to Nelson crushes. It’s a little locus of desire in Brown’s body politic. Let’s stimulate it. Let’s see what comes out.

“Why is Brown University considered a top university when all of the students are bottoms?” It’s a dumb joke, posted anonymously on Sidechat, and worse, it’s unoriginal. While my most karmic shitpost—“As a straight man, deleting Grindr has drastically improved my quality of life”—required hours of ingenuity and workshopping, this trending post is a trite rehash of a meme that’s been making rounds in the gay community for years: the top shortage. The fact it’s statistically false—according to a 2011 study, gay men identify as tops or bottoms in equal proportions—matters little. The idea that tops are becoming an endangered species is intractable in the general queer male consciousness, making its appearance in banal jokes, uttered only half-jokingly. At Brown, the question is reformulated. It is no longer about the shortage of tops, but the surplus of bottoms. What demand undergirds this apparent oversupply of bottoms? What desires make Brown students pursue this historically degraded position?

What does it even mean to be a bottom? For 71% of you, Indy* readers, bottomhood is a lived experience (data is gathered from an online “Are You a Top or Bottom” quiz administered to my friend group), but for the ignorant few: bottoming, at its fundamental, sexological level, means playing the receptive role in penetrative sex. But when it’s mobilized within discourse (think of the endless memes, tweets, and replies calling certain celebrities bottoms), it becomes less about someone’s preferred sexual position and instead about their very body and being. “You’re such a bottom” is issued when your masculinity comes up short, when someone gets a whiff of femme, of abjection.

In his seminal work “Is The Rectum a Grave?,” Leo Bersani traces the perception of bottomhood from ancient Greece to AIDS-crisis America, articulating how even in societies in which homoerotic relations weren’t stigmatized, bottoming was. In ancient Rome, for example, men could enjoy gay sex freely without fear of losing their masculinity or social

status as long as they played the penetrative role, the top, the master. Bottoming, on the other hand, was thought to be an “indecorous role for citizen males,” a position meant to be occupied by those lower on the social hierarchy. The physical act of bottoming, then, is inextricably tied to its political and social perceptions, rendered feminine, diseased, and passive.

Bersani’s key intervention was his refusal to rescue bottomhood from its abjection. His contemporaries attempted to theorize queer culture and its associated practices positively, understanding cruising, for example, to be a cosmopolitan site where people could freely explore the “erotic possibilities of the body.” Bersani, however, refused such optimistic conceptions, arguing that they only sanitized sex, which at its core was fundamentally violent, hierarchical, and self-shattering. To him, bottomhood’s suicidal positionality was not caused by homophobic or misogynistic discourse but rather inherent, an inner truth that reflects the true face of all sexuality.

Bersani insisted that sex was not a matter of pleasure, but rather jouissance. In Freudian psychoanalysis, while pleasure plays a regulatory role in an organism (I gain pleasure from eating until I am full), jouissance is pleasure that repeats itself indefinitely until it is indiscernible from pain (I keep eating even though my stomach is agonizingly full). Sex can operate in the same way, acting as “ecstatic suffering” which pushes the human past their sense of self, identity, and subjectivity. Bottomhood is a specific mobilization of this jouissance, one that destroys not identity writ large but gay men’s specific identification with the “masculine ideal.” For Bersani, identification with and desire for a socially constructed understanding of manliness is partially constitutive of queer male desire. Simultaneously, it is queer men’s failure to measure up to such masculine ideals that results in their marginalization. The rectum is a grave precisely because it is where this ambivalent relationship to masculinity goes to die. The bussy is just that good. But is it? For as much as Bersani critiques others for celebrating sex as radical resistance, he seems uncomfortably close to doing the same. His last lines declare that bottoming represents “jouissance as a mode of ascesis,” a comparison laden with moral implications. Ascesis is the practice of severe self-discipline often for spiritual or religious enlightenment. Importantly, it is a practice that ignores the world and its realities and politics, focusing solely on the body, the self, the singular. Indeed, in “Is the Rectum a Grave?,” Bersani hand-waves systematic marginalization away as a derivation “of the indissociable nature of sexual pleasure and the exercise or loss of power.” Social battles become matters of the body. Politics

becomes self-help, and Bersani has only one tip: be a bottom. It’s the only virtuous sexuality.

Of course, desire is far too messy to be streamlined into a single end or announced unqualified as moral. When Anonymous screams into the BrownU Gay Community chat, “WHERE ARE THE BUFF MEN HELLO???” on a Thursday evening, he’s probably not thinking about how getting his back blown out can shatter his internalization of the masculine ideal. However, under Bersani’s theorization, bottoming inherently becomes an act of resistance.

At Brown, it is precisely this tense dynamic between messy desire and virtuous positioning that undergirds the mass identification with bottomhood. In “Top or Bottom: How do we desire?” Kay Gabriel argues that it is the conflation of passivity and virtuosity that allows a “dissimulation of complicity with dominant structures [in] certain urban upwardly-mobile queer social scenes.”

Thanks to the work of the Brown University Gay Liberation group in the early 1970s and broader social movements, queer Brown students now enjoy, generally, more institutional and administrative support from the University. Given that 40% of our student population identifies as queer, in many spaces at Brown queerness no longer marks social marginalization. Many queer students at Brown are aware that they should engage in a type of radical politics, understand themselves to be a part of a larger community and history dedicated to activism, but don’t know how to extricate themselves from their positions of privilege. After all, Brown is an exploitative institution, and many students, however unwantedly or unconsciously, don’t want to let go of the comfort associated with that. Given that Brown has the highest median income of the Ivy League, some of these students also have personal complicity in the same capitalist structures that queer radicalism was once positioned against. Class privilege is of course not universal. They must conciliate two competing desires, must internalize and cohere this split identity.

In Poor Queer Studies, Matt Brim explicates the cognitive dissonance that arises when queer activists, scholars, and pedagogy begin to “[court] institutional status within the academy.” When confronted with the possibility that the disruptive and radical potential of queer studies may be incorporated and tamed by the neoliberal regime of the academy, queer scholars leverage an academic critique of administrative systems, allowing themselves to “continue to imagine that a defining feature of the field of Queer studies is its impulse to fuck up the academy.” Even as the University happily allows Queer studies courses to be included in its curricula, queer scholars

“dramatically position [them]selves as subversives, thieves, vandals.”

Brim’s point is not that queer resistance cannot exist within the confines of the university, but rather that as long as resistance takes the form of intellectual critique instead of pushes for material change, like admitting more low-in come students, it will be no more than a performance. Resistance becomes an act of naughtiness, still safely within the bounds of what the University has deemed acceptable.

Bottomhood operates in a similar way, switching out intellectual critique for sexual politics. By claiming the virtuous position of bottoming, students are able to lay claim to a progressive sexual politics to occlude their lack of a material one. Guy Hocquenghem, in his book Screwball Asses, documents how rich white French gay men would specifically pursue marginal ized Arab workers. Within this exploitative dynamic, “bodies with a phallus but no penis are drawn towards bodies which have a penis without a phallus.”

Hocquenghem’s distinction between penis and phallus—penis as a specific sexual power while phallus, in Freudian tradition, as a more general social power— reveals the limits of Bersani’s theorization. While bottoms may face sexual abjection, their identity is not wholly constituted by it. It is no longer the age of the Roman empire—sexual and social marginalization do not map so cleanly onto each other. They are disjointed, two separate axes. The powerful bottom (not to be confused with power bottoms) is no longer an oxymoron.

For Hocquenghem, it is the incongruence between sexual and social power that the privileged bottom finds so erotic. However, their sexual encounters with marginalized bodies are played off as a selfless sacrifice on the part of the bottom, in which getting “fucked in the ass by the people my father and grand father have fucked in the colonial wars” serves as a sort of social reparation. Telegraphing their bottomhood allows Brown students to participate in a repeti tive, masturbatory form of disavowing priv ilege—a disavowal which assuages their guilt and dissonance. However, since this disavowal is limited to the personal poli tics of the body, it is usually in name only, lip service.

To be clear, this is not to say that being a bottom immediately means complicity or participation within these dynamics. Rather, it is to interrogate the ambivalence and desire that underpins the identification with bottomhood at Brown. Where do we go from here? Is it possible to renegotiate bottomhood in a way that does not simply abdicate social responsibility? Or perhaps it is the very category of bottomhood that allows such dynamics to exist? The simple truth is that for all the theorization, many people bottom simply because it is pleasurable. Of course, pleasure is always already caught up in politics, but we don’t need to wait for a world where sex is finally clean, finally ethical, finally good. We will be waiting forever. Think, but don’t think too hard, about your body and its pleasures. That’s the delicate balancing act of finding the male G-spot. When you’re looking, don’t probe too hard or too deep. It’s only two inches into the rectum. You’ll know when you’ve found it. Your body will tell you. Push down.

EVAN LI B’28 is definitely not a bottom...

You break open the shell with your fingernails and suck down the insides. You continue along the path as you slurp the other three. A trickle of water grows louder as you move forward. You come to a clearing where a new path veers up to a cave.

Do you venture to the cave or follow the

Darkness and cold. Rattling energy of particles, zooming everywhere. From above, a point of light shatters, fragments spill into everything, collide and chime like tiny bells. Light

You lean back against the trunk and listen to the rustling leaves. You notice, on the lowest branch, a nest woven from sticks and moss. In it: three eggs pale as a porcelain doll.

A deep voice reverberates: “Find the button.”

“Find the button.” Your ears ring.

“Am I going to be okay?”

Silence.

You stumble to your feet and steady yourself against two smooth walls. Through burn ing eyes, you see you are enclosed in a perfect cube of bright white.

You run your hands along each wall, searching for anything that may quiet the scream ing light. Finding nothing, you lay on your back and clench your eyelids shut. Still the light burns haloes into your vision.

You stand. Rising onto your toes, you stretch your hand far into the light. You jump, pointing your fingers, and something gives: click.

The walls rip at the seams, leaving you floating in a cold, open void. You plummet through the darkness. Air roars past you, tears in your eyes, blurred arcs of blues and greens. You smash into a bed of moss, and the breath gusts from your chest.

You lie flat, watching your stomach rise and fall. The cool air fills your mouth and floods your body. You breathe as if swallowing the stars. The night is so beautiful that you weep, and the tears burn an icy path past your temples.

You lift your neck and a world lies before you. You want to see more. You want to see everything. You stand up and run, the moss squishing beneath your heels. In the starlight, you see the silhouette of a forest drawing near. You claw through brush at the head of a trail, and a thorn lodges itself in the soft arch of your foot. You continue as the sun begins to rise, and with it, a gnawing hunger. Eventually, you come to a large, knotty oak.

Do you pluck the eggs from the nest for your breakfast or climb the tree hoping to spot a larger meal?

You follow a brook until you arrive at the base of a waterfall, which crashes at your feet and sprays your skin with cool mist. Seeing your reflection in the water, you realize how dirty you are. Your face is smeared with yolk and mud, and there are

Do you swim in the basin or climb the rocks to

You enter the basin of the waterfall and swim towards its collision point. The spray coats your face and gets in your eyes. You don’t care; you want to feel what it’s like at the source. Eventually, you reach the wall of water. At this point, you can’t open your eyes. You put your hands into the crushing pressure. Then your head, your whole body. The force of the mighty waterfall pulls you under.

Go to the river at the bottom.

Do you stop at the tree or continue along the path?

A steep rock face stands in front of you. You begin to climb, slipping your fingers and toes into the crevices. Your left hand grabs for a rock hold and slips. You hang on by your right hand, your feet swinging back and forth. Before you can catch your breath, the piece of wall you were holding suddenly crum bles from the mountain. You fall and smash into the basin below.

Go to the river at the bottom.

( TEXT TALIA REISS & CHARLIE FITZGERALD

A dirt track directs hopping to and from is warmed by the bounds for something to a fork in the path. and greener; a vine

You snap off a head as you creep him in a clearing, no time. In one the branch into turns to look give. You reach and tear a fistful bring it to your take a bite.

Do you

You climb to the lowest branch and hug the fat trunk for balance. As you hoist yourself up, branch by branch, your leg catches on a shard of bark, and blood dribbles down to your ankle. Your stomach growls. You look out at the landscape, the tops of some trees, the bodies of others. In the distance, you see a small deer, nibbling at the grass.

Do you chase the deer or climb higher in search of something more?

You scurry up until you see the world stretch far into the horizon. You spot a bear fishing in a stream. You make up your mind to hunt it, but the branch snaps. You tumble down, scraping yourself on twigs and gnarls. You hit the ground hard. Your ankle snaps.

You limp to the edge of the stream and slump down on a crooked rock. Gently, you gather water in your cupped palms and let it stream down your legs, stinging in your wounds. The edges of your vision darken and the sounds of the forest—the chirping and rustling, the humming of insects—circle your head like an orbiting moon. You slip into the river.

Go to the river at the bottom.

even as your back foot scrapes the dirt and leaves a trail of crimson. You hit a rock and lose your balance, collapsing. Darkness and rain. The sensation of sliding, the ground carrying you along.

Go to the river at the bottom.

You continue along, passing daffodils, each with a becomes denser. Hanging is something golden, honey. As you reach your for a dollop of sweetness, bees surround your stumble into a gushing and stinging, and struggling

Go to the river

directs you deeper into the forest. You enjoy from the light patches where the ground sun. You begin to search the trail’s something to satiate your hunger. You come path. To the left, the forest gets thicker vine swings across its entrance. The right beautiful hill.

The slope of the mountain is tiring, but patches of wild strawberries are a welcome snack. The grass is thick; the trees are few and far between. In the distance, you see the moss fields you came from—to think you’ve made it this far in a day. A breeze deliv ers the scent of damp earth. You continue upward. A

Do you explore the crevice or continue to the peak?

You move along. You see a pair of golden-winged warblers stacked on top of each other, flapping wildly. Just as you spot a thicket of golden berries, a deer scampers in the distance.

Inside the cave, the air is cool on your skin, and damp. You shiver and step into the beam of light that cuts the darkness. Your stomach grumbles. Something growls back at you. You look over your shoulder, expecting a beast, but all you see is a small, green bug on the cave’s wall. You pick it off and squash it between your teeth. Its legs tickle your

a branch and wield it above your creep towards the deer. You find clearing, calmly grazing. There is one motion, you leap and plunge into his soft underbelly. The deer look you in the eye. His muscles reach your hand into the open flesh fistful of muscle from bone. You your lips. It smells like iron. You

you walk on or lay down?

yolky middle. The forest Hanging from one branch a buzzing mass, oozing your finger inside, hoping sweetness, hundreds of honey hand. You run until you gushing stream. You are swollen struggling to breathe. river at the bottom.

Do you chase down the deer or check out the fruit?

Do you stay or go?

You kneel and pluck a berry from the vine, squishing it between your fingers. Its guts leave a sticky residue on your skin and you sniff your fingers: so sweet. The others, plump, invite you to indulge.

Do you eat them? Yes or no.

You place one berry on the center of your tongue and mash it against the roof of your mouth. You realize how hungry you’ve been, and you crave more. You scrape them off vines and swallow them in piles. As you bring the last berry to your lips, your fingers slacken, and your vision spins. You fall to your hands and knees, spitting yellow, crawling until you arrive at a stream. You submerge your face in the water and swal-

You wander until you come to a precipice. You drop a rock and it falls for a while before you hear a splash below. Your heart pulls you forward and without thinking, you have stepped over the edge.

Go to the river at the bottom.

You exit the cave, emerging into daylight. Mountains intersect the horizon ahead of you. The beauty invites you toward them. You run down the slope, the momentum making you lose control of your legs. They slip out from under you, and you’re sent tumbling down, gathering cuts and bruises. A river stops your fall, leaving you limp in the water.

You lay down under the bush and let yourself drift off. You hear a quiet rattle beside your face. You turn to it, and a snake sinks its fangs into your plump cheek. You shriek, sprinting towards the sound of water, hoping to rinse the venom from your blood. As you move, the world sways, streaks of emerald and blinding sun. You arrive at the river and throw water at your face, but you are dizzy, so dizzy. You fall.

Go to the river at the bottom.

A profound sadness washes over you. You curl beside the creature, your back against his belly, and fall asleep, weeping. You dream that you are held in a giant hand. She rocks you gently back and forth, a baby in the softest cradle. You jerk awake. A massive, moving shadow looms. You scramble backwards and land in a stream. Distorted through water, the last thing you see is the fanged, open mouth of a grizzly bear.

Go to the river at the bottom.

As you continue to the top, the air thins and your fingers tingle in the cold. The jagged rocks prick your heels, but you don’t care. You need to summit the mountain—to finish what you started. Soon, though, the adrenaline wears off, and you struggle to fill your lungs.

Do you continue up or sit down to watch the sunset?

You nestle into thick grass. As the sky burns coral and yellow, you close your eyes to rest, but the ground beneath you begins to grumble, and you jolt awake. Above you, mud bubbles down the mountain, engulfing the rocks, pulling you along with it. You try to rise, but the tide is strong. It glues your eyelids shut and fills your mouth. Wet and quiet.

Go to the river at the bottom.

You shake from the biting cold and howling winds of snow. The sun glows—an arc at the horizon. You can see everything; the whole world surrounds you. By now, you can’t stand the freezing wind, and you start to get dizzy. You lose your balance and tumble down the icy cap, falling into the glacial river that cuts the mountain.

Go to the river at the bottom.

You are floating, pulled by the current of a deep river. The water feels warm and gentle. It’s hard to tell where you end and where the water begins. You have no desire to move at all, and you couldn’t if you tried. That’s okay. The river embraces you and absorbs your hunger, your fear. The stars glitter above you: the brightest one becomes a flower with spiraling petals. You feel nothing but warmth in your belly and a smooth rock, which has somehow found its way into your palm. You circle your thumb over its surface and press. You feel something give: click. The stars multiply and merge, turning the sky a shimmering white.

A gnarled hand wraps around your forearm, and you are lifted from the river. A man holds you, his face fusing worry and hope: “You’re okay.”

TALIA REISS B’27 and CHARLIE FITZGERALD B’28 wished they could stay on the moss (they’re not the best decision-makers).

Queerbaiting

RGB

CMYK

Act of faith

fool’s errand piece of shit

point of sale

PEN

penis

byzantine

benzedrine

stack exchange

coffee exchange

Lucas

Luca

panopticon

hardon

Depop vape

gutter cig

STS

STD

List

University

NYSE: GRND George Lucas

NYC Grindr Georg Lukács invagination

atmospheric lack indy nation ambient despondency length

Temu scooter girth walk of shame ShePVD the desert of the present TheyBoston the present of dessert Drake Orientalism The Amish goal-oriented mindset. Post-coital using everything

Pre-marital using everything

GCB Wednesday Twin Peaks girl, the boycott Twink Geeks

( TEXT DANIEL KYTE-ZABLE DESIGN MARY-ELIZABETH BOATEY ILLUSTRATION MEKALA KUMAR )

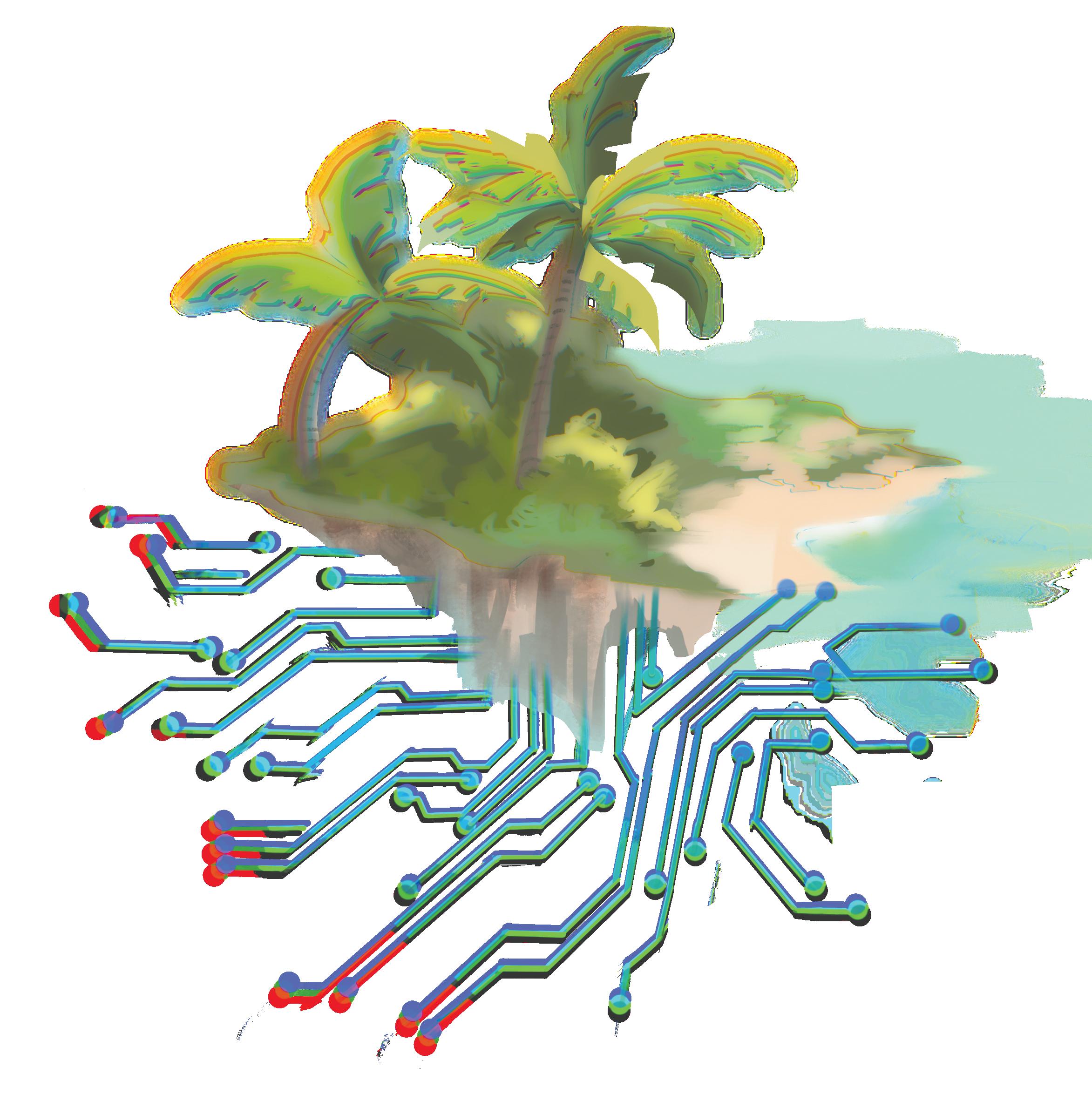

c “God,” according to Ellis Webster, is “smiling down on us.” Webster is the premier of Anguilla, a British overseas territory the size of 0.038 Rhode Islands and with a population of 15,000 people. Over the past half-decade, the tiny Caribbean island has come into 230 million USD, amounting to more than a tenth of its GDP. This was enough money to renovate its airport, build a vocational school (supplementing its sole public high school), and give seniors free healthcare. Yet where did the money come from? Anguilla didn’t discover offshore oil. Nor did it cull its wealthy in bloody revolution. Rather, the island is making use of one of its oldest national resources: its name.

In the mid-90s, as the boundaries of the Internet slouched beyond American borders and over the International Date Line, the IANA (Internet Assigned Numbers Authority) procedurally doled out domain extensions to foreign nations: .fr to France, .ru to Russia and, crucially, .ai to Anguilla. As the so-called “AI Boom” has taken off among the entrepreneurial elite, a myriad of new start-ups and private-sector research firms have tried to register .ai domains—rather than the mundane .com—and have shelled out thousands of dollars in fees to the Anguillian government. As of late 2024, over 533,000 .ai domains have been registered, which includes Twitter and Stability, the company behind Stable Diffusion.

The link connecting these Caribbean islanders and Silicon Valley technocrats feels tenuously strung. At first glance, their shared history is one of names colliding senselessly at high speeds. The island was named “Malliouhana” by the Arawaks, a broad term for its first inhabitants; its subsequent renaming was purportedly the work of Christopher Columbus— anguilla meaning “eel” in Italian—who sailed by the island in 1493. The ISO 3166-1, the globally recognized database of country codes used by IANA, has no .an. Why did .ai win out?

AI’s eventual supremacy as an all-purpose moniker for SaaS-creating, slop-producing systems was more unexpected. In the late 1950s, professors using CLPS-y tools to study “thinking machines” were

informally dubbed cyberneticians. Partly to avoid boosting the ego of their more-popular colleague Norbert Wiener—the ‘inventor’ of cybernetics—they agreed to call their research by a different name. Of the candidates, “artificial intelligence” stuck. Though their original methods fell out of fashion in the 1990s, and the logicians and cognitive scientists who belonged to the initial cohort were steadily replaced by statisticians and computer scientists, the term remained.

I can’t help but ponder how arbitrary this narrative feels on a symbolic level. That “AI” won out as a fad term. That the domain extension is this universally-agreed upon website index. That it’s supposed to reflect the technological zeitgeist. That Anguilla is eel-shaped and not blob-shaped. That too many islands are already named after Columbus. Webster seems to agree: “It’s just lucky for us.”

The chain of causality seems to start with a man that only wears sandals. It’s 1966: Jon Postel, a self-described “mediocre student,” transfers to UCLA from community college. At UCLA, he cultivates an obsession with computer networking—then an emerging science disentangling itself from its predecessor, the study of radar and

missile detection. As a graduate student, Jon is invited by his peer, Vint Cerf, to attend the weekly meetings of a small research group interested in connecting computers across different West Coast universities. UCLA’s CS department doesn’t exist yet; much of the project’s funding comes from a different, undisclosed group.

On October 29, 1969, Postel’s team sends one word—“login”—across their new system. Said system crashes. Their counterparts at Stanford see one halfword—“lo”—pop up on-screen. Thus, ARPANET, the first predecessor to the internet, is born. Over the 1970s, ARPANET spreads to universities on the East Coast and across the Atlantic; the number of host computers balloons from nine to 213. By 1990, Postel and his colleagues are regularly convening with government and military officials—at some point, Postel boards a helicopter to troubleshoot the Air Force’s computer system and, following military orders, puts on real shoes.

Though by most accounts a soft-spoken, unassuming man, Postel presents as a buccaneering figure in the days of the pre-internet—a “hippie-patriarch,” per Cerf, capable of beating “the Sphinx in a staring contest.” Purportedly driven by a distaste for bureaucracy, he appoints himself “numbering czar” of ARPANET, an effort which quickly births an organization to name the entire Internet: the IANA. After the absorption of ARPANET into the Internet, it is Postel who, amidst a power struggle with the federal government, moves two-thirds of the Internet’s servers to his laptop. It is Postel who invents the Internet address as it exists today. And it is Postel who leads the assignment of domain names to other nations, including Anguilla.

+++

One year before the assignment of .ai, American cryptographer Vince Cate rented a 2-bedroom house in Old Ta, Anguilla, not far from then-Queen Elizabeth’s official Anguillian residence and the Arawak Beach Club (perhaps a rare public-facing sign of the island’s original inhabitants). He moved from San Jose for “tax purposes,” per his own admittance. After attempts to start a digital currency business ended in failure, he founded Anguilla’s first internet service provider. Most of Vince’s tenure in Anguilla is best summarized by an erratic yet predictable checklist: ☑ renounced US citizenship, ☑ paid 5,000 USD to become a citizen of Mozambique (picking up Anguillian citizenship along the way), ☑ invited Internet users to “become international arms dealers” by breaking American restrictions on the sale of information tech.

Cate’s personal website features his crypto blog, an explanation of how wind turbines cause global warming, and a link to ‘islandboys.ai’. In it, Cate proudly declares his philosophical motives for moving—to never be “in one place long enough to be captured by the government.” He does not mention his primary source of work since the late 90s: singularly administrating .ai for the Anguillian government.

In 1994, Postel allegedly received a call from Cate inquiring whether .ai could be assigned to Anguilla. Postel, noting that the extension was unused, acquiesced. This supposed initial correspondence might explain how Cate became de facto manager of the domain extension. His internet service provider, Offshore Information Services (OIS) is responsible

for managing the .ai auctions. “Cate” and “Webster” are the sole Anguillian names mentioned in most coverage of the .ai boom. A la Postel, Cate’s distaste for bureaucracy has ironically landed him in one of the more central positions in the island’s government. The narrative that we might admit to following is this masculine, Crusoe-esque one. We can ascribe the successes of nation-states to the lucky, ever-assertive Individual, to the perpetual entrepreneur! The chain of causality is discrete, random, unknowable. History must be ruled entirely by individual pursuit and by coincidence; it is merely a set of permutations of objects, places, things and names.

+++

As though it were that simple. We need only prod a little deeper to uncover, concealed amid the arbitrary, the very contours this narrative obscures. Among the recipients of ARPANET’s first “lo” were scientists employed by DARPA and Raytheon. ARPANET, as later revealed, was originally a DoD project, funded by dollars redirected from the construction of ballistic missiles. Initial communiqué’s bounced from national labs to the Pentagon and NSA headquarters. The IANA was a federally contracted organization until 2016, prior to and following the rise of the first commercial internet service providers. It was this organization—guided by some mixture of American military, government, and capitalist interests—that acted on behalf of the rest of the world. Anguilla, far removed from the IANA’s private meetings, had little direct say in the matter.

A fair share of the Caribbean’s tech workers hail from the United States and Europe. Many of them— think Cate, John McAfee, and the founders of charter cities like Guatemala’s Prosperá—fit a certain techno-libertarian archetype. You know the one! The platonic tech emigré knows what Web3 is; the platonic tech emigré has mixed feelings about Peter Thiel; the platonic tech emigré, driven into “digital nomadism” by spiritual conflicts with Government, conveniently finds a gig managing the tech infrastructure of some tax-free Caribbean island. The Anguillian fortune is interwoven with our domestic politics— partially precipitated by foreign brain drain and then managed by a certain emigré’s experience with the US government.

American media has presented coverage of the .ai boom as a spectacle. How curious it is that our corporations are beholden to that tiny island…how small did you say it was again? In Rhode Islands, please. The default view holds these islands as perpetual victims of the shrewd, ever-domineering Western businessmen; that Anguilla maintains the rights to its fortune comes as a surprise to the editors at the New York Times, who billed the island as an “Unlikely Industry Player.” In this there is some truth: Anguilla is preceded by a long list of less-fortunate islands who, in some attempt to capitalize on their national resources, suffered many an unexpected misfortune. Though these misfortunes are sometimes perceived as comic in Western media coverage, their effects are nonetheless grave. In the West, Nauru is best remembered for the misappropriation of the funds from ecologically-destructive phosphate mining (run in part by the Australian government) to finance a dead-end West-end musical about Leonardo da Vinci. Niue lost millions after selling the rights to its domain

extension, .nu, to an American businessman. Citizens of Tuvalu, which self-administrated its domain extension .tv, found themselves awoken in the middle of the night by Japanese businessmen looking for phone sex operators. +++

The struggle for Anguillian self-determination was by no means trivial. Saint Kitts, another Caribbean nation, administered Anguilla on behalf of the British Crown for much of the 20th century. The Saint Kitts government became famous for its mismanagement of the Anguillian treasury—in a famous incident in the early 1960s, funds set aside for an Anguillian pier were used to build a pier in Saint Kitts. Anguilla successfully seceded only after forcibly ejecting the Saint Kitts’ police force and standing off against the Royal Navy.

Curiously absent from the Postel-Cate narrative are the voices of the island’s civilians, who played an instrumental role in realizing their own fortune. In a letter to the editor of the Anguillian Newspaper, Anguillian citizen Avenella (last name not found) notes that it took several years of “wrangling, begging, and arguing with the British,” for Anguilla to be officially recognized as a country and thereby earn .ai as a separate country code. Avenella decries that the “.ai domain” is their “oil,” a popular (not national!) resource to “cherish, preserve and advance.” This depiction is far from the one given in Western media; far from a flimsy consequence of etymological bumper cars, it is the direct—if surprising—product of decades of geopolitical striving.

There is little mention of the Anguillian revolution in Western media. Paradoxically, the telling of this history as ‘arbitrary’ is fundamentally governed by a Western public imagination. In this framework, these islands are experienced along certain axes: as tourist destinations, as military bases, as supporters of unpopular American interests in the UN General Assembly. Under these conditions, they figure into the American psyche as objects with singular purposes and no agency. The equal weighting of names, symbols, individuals, and governments that makes this history feel ‘arbitrary’ only occurs when we perceive these nations as powerless to begin with, when we correlate whole cultures with sands and sunburns. Only then do their ‘surprising’ attempts to stake out wider influence strike us as ‘comical.’

Over the course of her letter, Avenalla does not clearly differentiate whether Anguilla agency can be attributed to the island’s people or to God—but she firmly rejects any notion that the island’s success is somehow causeless. She concludes with an indirect rebuttal to Webster: “It is an insult to God’s presence, providence, protection and provision,” Avenella writes, “to relegate the .ai domain to ‘luck’.”

DANIEL KYTE-ZABLE B’27 is not wearing sandals.

c “D-d-d-d-d-d-dit.”

My classmate, a man in his mid-forties, sounded an alveolar trill—a vocal percussion meant to resemble an automatic weapon. This was his response to my question, “您为生做什么工作?” (What do you do for a living?). He had originally responded with a word I did not understand. Sensing my confusion, but unable to explain in English, he then pantomimed shooting a machine gun.

Middlebury College’s Language School is world-renowned for its success in supporting “rapid language acquisition.” With the enthusiastic encouragement of my Chinese professors at Brown, I decided to take my language learning more seriously by immersing myself in a Mandarin program for eight weeks. Within three days of arriving in Middlebury, Vermont, I signed the dotted line of the Language Pledge, agreeing to use Mandarin as my only language of communication while attending the program. Failure to comply would result in expulsion.

The Business of Language

“Everything is language” - Octavio Paz

My world had shrunk to the 350 acres of Middlebury’s campus. As the sun rose over the bedewed Vermont grass, I marched to my early morning lecture, then my small group drill section, and finally the dining hall for a scheduled lunch block. My vocabulary was reduced to the pored-over pages of my textbooks, and the lessons I attended daily organized my social interactions. I grew accustomed to awkwardly answering the curated questions of my teachers at the lunch table, mastering the small talk I had rehearsed from my flash cards: I was good, thank you for asking. I was busy, and planned to do homework later in the Davis Library. The food is not bad. My favorite is pizza.

All my answers seemed to satisfy my peers and professors, but for one:

“Why did you decide to come to Middlebury?”

“Because the government forced me,” joked the military men. “Money,” teased many of my older classmates, though with a tinge of seriousness. “Job opportunities,” said my younger peers, earnestly. When I expressed that I was there because I am interested in Chinese culture and the ways we make meaning across languages, my peers tilted their heads skeptically.