COMEOWNITY

Mary-Elizabeth Boatey R’27 & the Indy community

Mary-Elizabeth Boatey R’27 & the Indy community

MANAGING

Sabine Jimenez-Williams

Talia Reiss

Nadia Mazonson

WEEK IN REVIEW

Maria Gomberg

Luca Suarez

ARTS

Riley Gramley

Audrey He

Martina Herman

EPHEMERA

Mekala Kumar

Elliot Stravato

FEATURES

Nahye Lee

Ayla Tosun

Isabel Tribe

LITERARY

Elaina Bayard

Lucas Friedman-Spring

Gabriella Miranda

METRO

Layla Ahmed

Mikayla Kennedy

METABOLICS

Evan Li

Kendall Ricks

Peter Zettl

SCIENCE + TECH

Nan Dickerson

Alex Sayette

Tarini Tipnis

SCHEMA

Tanvi Anand

Selim Kutlu

Sara Parulekar

WORLD

Paulina Gąsiorowska

Emilie Guan

Coby Mulliken

DEAR INDY

Angela Lian

BULLETIN BOARD

Jeffrey Pogue

Lila Rosen

MVP

The imagined community of cats whose owners read and write and illustrate and design the Indy

*Our Beloved Staff

DESIGN EDITORS

Mary-Elizabeth Boatey

Kay Kim

Seoyeon Kweon

DESIGNERS

Millie Cheng

Soohyun Iris Lee

Rose Holdbrook

Esoo Kim

Jennifer Kim

Selim Kutlu

Jennie Kwon

Hyunjo Lee

Chelsea Liu

Kayla Randolph

Anaïs Reiss

Caleb Wu

Anna Wang

STAFF WRITERS

Hisham Awartani

Sarya Baran Kılıç

Sebastian Botero

Jackie Dean

Cameron Calonzo

Emma Condon

Lily Ellman

Ben Flaumenhaft

Evan Gray-Williams

Marissa Guadarrama

Oropeza

Maxwell Hawkins

Mohamed Jaouadi

Emily Mansfield

Nathaniel Marko

Daniel Kyte-Zable

Nora Rowe

Andrea Li

Cindy Li

Maira Magwene Muñiz

Kalie Minor

Naomi Nesmith

Alya Nimis-Ibrahim

Emerson Rhodes

Georgia Turman

Ishya Washington

Jodie Yan

Ange Yeung

ALUMNI COORDINATOR

Peter Zettl

SOCIAL CHAIR

Ben Flaumenhaft

DEVELOPMENT

COORDINATOR

Tarini Tipnis

FINANCIAL

COORDINATORS

Constance Wang

Simon Yang

Lila Rosen, Jeffrey Pogue

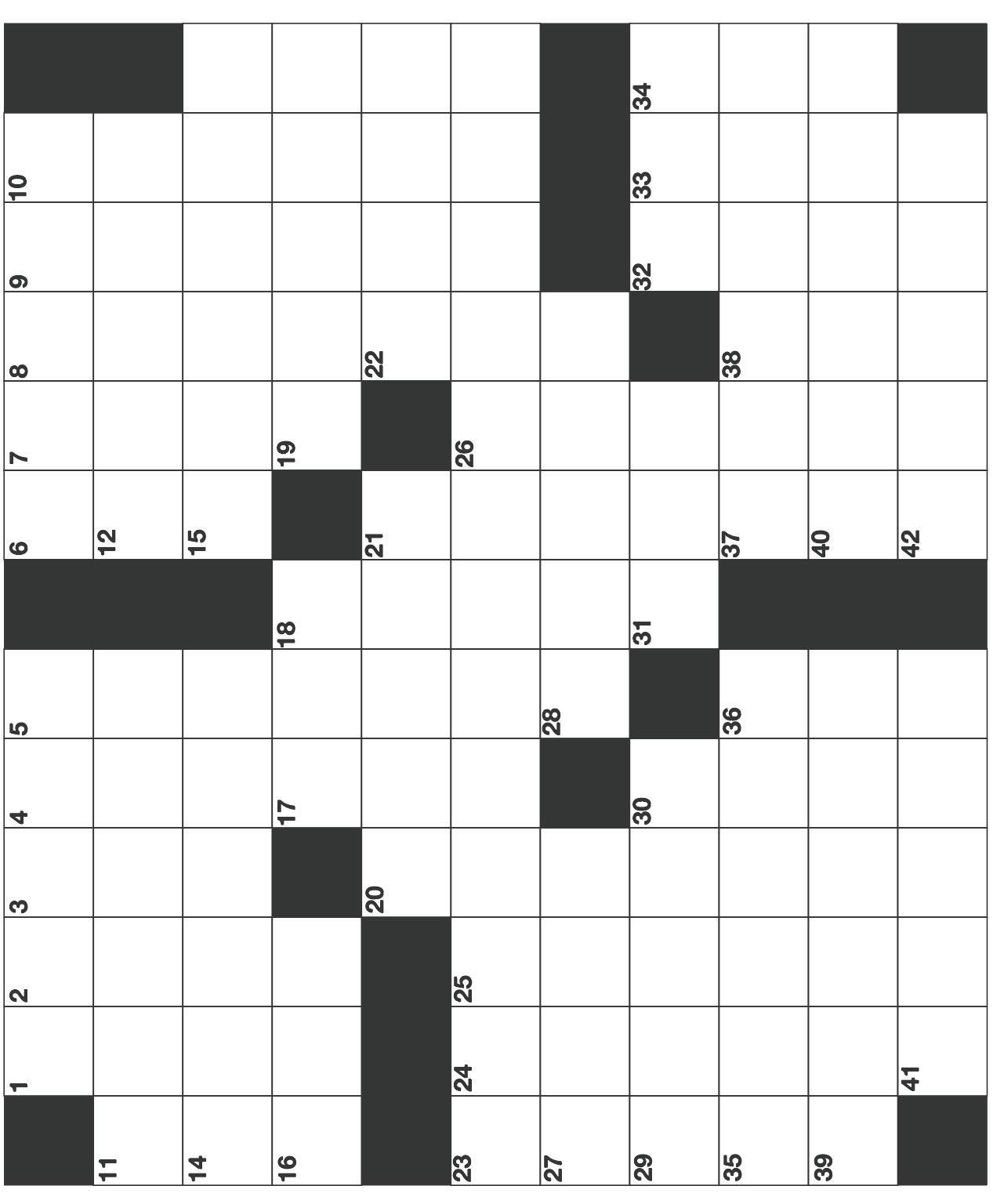

Here’s the nature of our care structure: we are thrown into being (alive; members of the Indy), and, for some reason, we care. We care so much that we had nightmares. We declared, “I MUST GET MY HANDS ON THAT DESIGN FILE. MEB IS MY ONLY HOPE.” We were thrown into Conmag stressed smart stupid happy sweaty hungry full. We said it would be an hour and it was never an hour and actually it was 12 hours of Lepecki and Minecraft End Poem and anything but actually reading Lacan. It was reading a draft and feeling grateful someone put that feeling into words. I’ll remember Conmag as hair salon, Indy as mind, body, and soul so that it's hard not to compulsively text someone or check the Rundown and it's the first thing I think about in the morning. At 2AM we were so single-minded and brainfuzzy that we almost didn’t care that the next day we’d have to stumble into our 9AMs all blearyeyed and pajama-ed. I watched the Rundown like other people watch TV. It was kind of like writing a thesis, but with 100 new friends and with pictures. We cried when adults read the Indy in coffee shops, when married couples bickered over JP’s crossword clues. To select one word we argued over a dozen alternatives. It was ghosts and Albania and desire and diegesis and illuminated manuscripts and I’m cutting SK’s hair and if you want people to understand then you shouldn’t use words or pictures and who cares about legibility anyway. I merged brains with you all and I was happy to do it.

The content of all News & Publications groups recognized

ILLUSTRATION EDITORS

Lily Yanagimoto

Benjamin Natan

ILLUSTRATORS

Rosemary Brantley

Mia Cheng

Natalia Engdahl

Avari Escobar

Koji Hellman

Mekala Kumar

Paul Li

Jiwon Lim

Yuna Ogiwara

Meri Sanders

Sofia Schreiber

Angelina So

Luna Tobar

Ella Xu

Sapientia Yoonseo Lee

Serena Yu

Yiming Zhang

Faith Zhao

COPY CHIEF

Avery Liu

Eric Ma

COPY EDITORS

Tatiana von Bothmer

Milan Capoor

Jordan Coutts

Raamina Chowdhury

Caiden Demundo

Kendra Eastep

Iza Piatkowski

Ella Vermut

WEB EDITOR

Eleanor Park

WEB DESIGNERS

Casey Gao

Sofia Guarisma

Erin Min

Dominic Park

SOCIAL MEDIA EDITORS

Ivy Montoya

Eurie Seo

SOCIAL MEDIA TEAM

Jolie Barnard

Avery Reinhold

Angela Lian

SENIOR EDITORS

Angela Lian

Jolie Barnard

Luca Suarez

Nan Dickerson

Paulina Gąsiorowska

Plum Luard

The College Hill Independent is a Providence-based publication written, illustrated, designed, and edited by students from Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design. Our paper is distributed throughout the East Side, Downtown, and online. The Indy also functions as an open, leftist, consciousness-raising workshop for writers and artists, and from this collaborative space we publish 20 pages of politically-engaged and thoughtful content once a week. We want to create work that is generative for and accountable to the Providence community—a commitment that needs consistent and persistent attention.

While the Indy is predominantly financed by Brown, we independently fundraise to support a stipend program to compensate staff who need financial support, which the University refuses to provide. Beyond making both the spaces we occupy and the creation process more accessible, we must also work to make our writing legible and relevant to our readers.

The Indy strives to disrupt dominant narratives of power. We reject content that perpetuates homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, misogyny, ableism and/ or classism. We aim to produce work that is abolitionist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist, and we want to generate spaces for radical thought, care, and futures. Though these lists are not exhaustive, we challenge each other to be intentional and self-critical within and beyond the workshop setting, and to find beauty and sustenance in creating and working together.

staff.

c Last summer, WiR’s (fictional/speculative) research and data team put out an open call for erotic confessions. Thousands of (fictional/speculative) respondents came forward to recount stories of intimate secrets, sexy encounters, and calls of the booty variety. While some of the entries are too lewd for print, the following listicle gives readers a glimpse into the lives of select (fictional/speculative) Provosexuals. From the sex-less to the sexed up, there were stories begging to be told, and now we (by we I mean me: if you haven’t caught on it’s just me, and I made up all of these – I am so fucked up!!!!) are begging you to read them. Enjoy!

I had a sex dream where I was having an encounter with the big blue bug. He was big and blue and I was just as small as girls like me tend to be.

I lost my virginity at the Textron mega fauna pavilion at the Roger Williams Park Zoo. I was in 11th grade and I worked at the ticket office. He was an enclosure professional. Don’t worry, he was also in 11th grade.

When I worked downtown, I would perform underground table dances at the barcade after my office job. They were wearing suits. I wore nothing. It was fairly fun, but I can’t say that I would do it again.

There is a neighborhood in North Prov called Wanskuck. When I was in college my friends and I joked that it stood for wanking and sucking. Now I live there in a 600 square foot loft that I share with two roommates, and the geese we raise for slaughter. Life is really a box of chocolates.

I am having an affair. It is very cosmopol itan. We met at Machines with Magnets, where they were playing a mandolin—out of tune. We have taken to meeting at the Cumberland Farms off the interstate. Get it? Cum. We have an icee, a quickie, and that’s that. I’ve never felt like this before.

I often wonder if the people I see on my way to work are cruis ing, or if I am just projecting my own desire onto others. God, I am so fucked up. Sometimes I sit on the bench at Fargnoli Park and Splash Pad, right by Knead Donuts, and I swear the looks these strangers exchange are more than just accidental glances—they are purposeful and charged. One day one of them will proposition me, and although I will respectfully deny (obviously), I will know for sure what their deal is.

Somebody who loves me fucked me at the Providence Place mall. It was quick and easy, and we haven’t spoken since.

I went on a third date at Los Andes. He was cheap and a cheat but I stayed for the Bolivian pockets and flan. He had one too many glasses of upsold wine, and on our way out he fell into the indoor water feature and drowned.

There is a Sex Club in Mount Hope, for respectful adults who like to have a good time. I have tried to attend but none of the nights on the website fit my

( TEXT MARIA GOMBERG DESIGN KAY KIM

LILY YANAGIMOTO )

description. Bashful Babes (Blue!)? Polyamorous Professors? Sober Sextuplets? Elderly Entertainers? Oy Vey Jose, Jewish Latina Night? Where do I go if I am none of the above?

I was given head by my landlord (My landlord gave me head?). It knocked off about 30% from my rent. That’s why I tell all my friends to move to Federal Hill and to put a plastic sheet on their bed.

I have been trying to offer up my body at PVD Things, the cooperative, community-sourced, not-for-profit, democratically run lending library for tools and home repair accessories. So far I have no takers. It appears that most people want garden sheers, not girls with big smiles and kind hearts. Have you been to Chilangos? Apparently it’s got the only good tacos around. I wouldn’t know, I’ve never been, but a guy that I kissed offered to take me

out. I haven’t heard from him in a couple of weeks, but I am sure he is just busy at the Stu…He is a noise performer after all.

I am pretty convinced that I was conceived in Providence, RI. My parents went there for their honeymoon vacation, and nine months later I was born wicked smaht!

Many have heard of the term provhead. It is usually deployed in a derogatory manner towards a friend, acquaintance, or ex-girlfriend who chooses to stay in Providence rather than moving to Bushwick with the rest of us. However, it is rare to find somebody using its dirtier homophone of which I would like to make you all aware in the hopes of bringing it back into circulation. Have you ever gotten it nasty and sloppy? It’s not exactly good, but there is something quirky, charming, and strange about the technique if you let yourself think about it a little too much. Well, my friend, I regret to inform you that you might have received what I like to call ProvHead.

Has anyone gone to Frisky Fries? Are they really as frisky as advertised? As spicy and creamy? As soggy and flaccid? I yearn and I crave.

The other day, Samantha, Charlotte, Miranda and I met at Gift Horse for their Weekly Buck-a-Shuck special. One round of Cold War Martinis turned into two, then three, and then more, and soon we were those unbearable thirty-something year old girls making a twenty-something year old ruckus at the bar. It was the first time since I started my new job as a sex columnist for the Providence Journal (25 cents a syllable!), that I had truly laughed in earnest. That’s the power of female friendship! As Sam and Miranda told us about their most providense encounters, I couldn’t help but wonder, how can one get turned on in a city with such expensive utilities, poor road maintenance, and underdeveloped social services? In other words, how can one be broke but not broken?

I hear that the fish shack near empire street converts into a BDSM dungeon during the off season. I am at least a little titilated..

This fictional research team feels warm and wet! (It is raining outside but there is good heat in our fictional/speculative office).

We also feel figuratively warmed up by all of the potential for good sex in this city. We learned that Rhode Islanders are somehow both horny and lonely, that one can fuck pretty much anywhere, and that for the most part, people are not too concerned about stripping down in the biting Providence cold. We also learned that coffee milk and Del’s lemonade are commonly used for their aphrodisiac effects, and that to fuck is to love where you are from. Providence may not be the city of love in the conventional sense (there is no one to date unless you are willing to sleep with your friends) but it is the city of confusingly sexy people at expensive coffee shops, and there is something very beautiful about that I…I mean we…must say.

MARIA GOMBERG B’26 is big and blue and a bug.

c Early on the morning of September 8, 2023, Jayna Brown, then-chair of the Brown Department of Theatre Arts and Performance Studies (TAPS), sent an email to graduate students and faculty with the subject line “Fwd: Brown/Trinity MFA programs: Admissions Pause.” Brown’s email contained two solitary sentences of commentary: “Please see the forwarded message below from Provost Doyle, regarding the Brown/Trinity MFA program. It is impactful, and I anticipate further discussion.”

Provost Francis J. Doyle III’s message delivered shocking news to the faculty and students of the Master of Fine Arts acting and directing program, which is administered jointly by Brown and Trinity Repertory Company (Trinity Rep), a historic nonprofit theater in Providence. “Following extensive discussion and careful consideration, we have decided to pause admission to the programs for this year’s admissions cycle,” he wrote.

Only three months prior, The Hollywood Reporter had ranked Brown/Trinity Rep (B/T) as the fourthbest drama program in the world. But, after the email, which was sent less than a week into the academic year, a gleaming symbol of professionalized art-making’s potential was on deeply uncertain ground.

The formal partnership between Brown and Trinity Rep began in 2002, with the intent of providing students with holistic training from working actors. B/T continues the model of actor training that Trinity Rep instituted with its conservatory, which was originally founded in 1977. Rachael Warren, a Trinity resident company member and current B/T faculty member, described the program’s current iteration as mirroring the “story-driven, actor-driven” process in the resident company. “We start from the text and we start from a strong point of view. It’s really about bodies and words on stage,” she said. Commitment to practice is also reflected in the curriculum: the cohort of ten actors and two directors share classes in acting, playwriting, and movement, and all have to act and understudy in Trinity Rep main stage productions.

For Nicholas Byers MFA’25, the holistic training emphasized in the partnership was one of B/T’s main appeals: “You’re not only in school to become a great actor, you’re at this school to become a great artist and a great collaborator.” Another appeal for Byers was that B/T had been tuition-free since 2018—made possible by the program’s financial support from Brown University.

While the marriage of Brown University and Trinity Rep may have seemed a perfect union, Austyn Williamson MFA’25 compared being in B/T to being “a child of divorced parents.” A fundamental misalignment on what it means to be an art-making institution strained the ideal of a world-class theater combined with a worldclass educational institution. Today, B/T is nearly disassembled, with only the class of 2026 remaining.

In the spring of 2023, B/T underwent an external review: a process typically conducted for graduate acting programs every seven to ten years. Personnel from other reputable MFA programs interview students, administrators, and faculty for their thoughts on the program and any areas for improvement. But the timing of the B/T review was strange: the program had hired a new head of acting less than two years prior, instruction was still not entirely in

person post-pandemic, and the previous external review was only five years earlier.

According to Williamson, students took the opportunity of the external review to give their “thoughts on what the program could do to treat its students better.” In a letter shared by Byers with the College Hill Independent, the B/T ’25 cohort addressed senior leadership of the program and the University, and offered suggestions to improve what they believed to be an “institution that is willing to adapt in service of its students.”

Students wrote that they were “proud and excited to be the most ethnically and racially diverse class that [B/T] has admitted,” yet concerned with the implementation of the Trinity Rep Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion pledge to “create and sustain equitable hiring practices, responsive working environments, and mindful institutional planning.”

The students argued that the program stipends fell “significantly short of being able to afford the average monthly expenses of living as a graduate student in Rhode Island,” according to a separate document they submitted to B/T leadership. The stipend was critical: students were largely unable to earn supplemental income under a demanding and time-intensive schedule. Labor they were expected to perform as part of their education, such as understudying, performing, and ushering, was not being equitably compensated. Many students had to apply for SNAP benefits.

Students also expressed programmatic concerns. Understudy assignments, for example, were communicated to students as professional working opportunities, but they failed to meet professional standards. The document mentioned that students did not feel set up for success in their “professional and creative development” in these assignments, and that many new students operated under a “fear of creating waves” and “didn’t want any form of retaliation” to affect their beginning months at B/T.

Even as the B/T ’25 cohort offered critical insight, they were hopeful that the external review would bring about positive change. In closing their letter addressed to senior leadership, students wrote that they looked forward to a “collaborative process” that would “ensure the financial support of all current and future MFA Acting Candidates.”

But students and many faculty members never got a chance to see the final report on the state of the program delivered to Brown’s administration. Byers said students repeatedly contacted faculty and administrators for a chance to see its contents. “We asked, and we asked, and we asked. We went through every route that we could.”

From the students’ point of view, it remained unclear who had access to the report because, as with “a lot of things with B/T, you go up the chain, the Trinity folks are gonna say it’s Brown, the Brown folks are gonna say it’s Trinity,” Williamson said. Only some leadership at Trinity Rep and Brown would eventually read the report, and fewer still could make administrative decisions based on its contents.

Sophia Skiles, B/T’s current head of acting, described the report as an honest reflection of the views of its participants. “Everyone was very invested in being able to share precisely what was on their mind,” she said. The anonymization of the review, she added, encouraged people to “surface things that are hard to surface because of power dynamics.”

The email from Provost Doyle reasoned that the decision to temporarily pause admissions would allow B/T senior leadership to “carefully examine and identify ways to continue to enhance the artistic landscape and infrastructure on campus.” It noted how the review highlighted the “considerable strengths” of the MFA program, while recommending possible paths toward revising the program as a whole. Although the announcement of the pause was unsettling, Skiles said that communication over the next 16 months “always led me to believe that there was going to be a future.”

But on January 22, 2025, when auditions for next year’s class would typically have taken place, students received another email from Provost Doyle. “Over the past 18 months, based on extensive analysis by and discussion among leaders at Brown and Trinity, and insights from a review of the programs by external experts,” he wrote, “Brown University and Trinity Repertory Company have decided to indefinitely pause admissions for the Brown/Trinity MFA programs.”

“I wish I understood the explanation. I don’t know if I’m even aware of an explanation.”

The decision to completely cease admissions shocked students and faculty alike, even in the context of the initial pause. Aside from surprise, there was “to some degree, anger,” said Skiles, on behalf of students, alumni, and those who had “invested their livelihood and their professional identity in this program.” The decision was also a baffling response to the momentum set forth by the external review. Suddenly, B/T would simply cease to exist altogether by May of 2026. “I wish I understood the explanation,” said Skiles. “I don’t know if I’m even aware of an explanation.”

The language surrounding the closure was muddled. An “indefinite pause” has no timeline, but most people affiliated with the program understood the phrase’s implications. “We haven’t been calling it ‘admission pause,’” said Warren, “we’ve been calling it ‘the program is dead.’” Faculty who only worked with first and second year students are now without a job. The hallways are quieter: “There’s nobody in those rooms except for when there’s class,” she said.

The messy institutional divorce of Brown and Trinity Rep surfaces more questions than answers about the conceit of the partnership. Some viewed B/T as a branding deal, where Brown put their name and funding onto a training program that Trinity Rep grew through its conservatory and previous partnership with Rhode Island College. According to Williamson, “it felt like we were Brown students in name only.” The unceremonious conclusion of Brown’s involvement also marks the cessation of necessary funding for the program—ending the 47-year tradition of theatrical training at Trinity Rep altogether.

While the vacuum left by B/T looms over the future of Trinity Rep, a shift in theatrical training is already underway at Brown.

As B/T comes to a close, students have noted a growing sense of disconnect between their training at Trinity Rep and new structures and resources for theatermaking being developed at Brown, in large part by way of the Brown Arts Institute (BAI). Founded in 2021, the BAI describes itself as a “catalyst and incubator for the arts.” For Daniel Shtivelberg MFA‘26, “BAI is very vague.”

Last spring, for the first time since its opening in the fall of 2023, the B/T’ 26 cohort had a class in the University’s Lindemann Performing Arts Center, which is administered by the BAI. Shtivelberg said that a lot of his peers were eager to have class in the Lindemann’s new state-of-the-art rehearsal studios.

But Shtivelberg was never entirely convinced of the Lindemann’s offerings. What everyone came to realize, he said, is “how the shiny new thing is actually not super, super conducive to the kind of work that we do.” He described the more idiosyncratic rehearsal spaces at Trinity Rep as being much more inviting. Shtivelberg even said that the columns that break up Trinity Rep’s two main rehearsal rooms “spark heat” among students by challenging them to think more imaginatively about space.

Byers, on the other hand, had a different impression of the Lindemann. When he toured the brand new building with his cohort, everyone was thoroughly impressed, marveling at “all of this, and all of that,” before finding out that none of their year’s classes or performances would be held there. Although his class didn’t get much use out of the building, Byers expressed gratitude for other resources offered by the BAI, like grants for solo shows and free cameras on loan. Still, he was frustrated by the fact that the BAI’s resources were left “up to the students to kind of just figure out.”

The closure of the B/T program was announced amid this growing sense that the BAI’s resources were either inaccessible or mismatched with student needs. The program’s closure marked the creation of a new group designed to explore the future of graduate acting education at Brown. In an email to the Indy, Brian Clark, the University spokesperson, wrote that the “working group” is tasked with “examining trends, convening discussions to explore the future of the live arts, and proposing professional development models through which Brown and Trinity Rep can partner.”

Sydney Skybetter, the current director of the BAI and a member of the Trinity Rep Board of Trustees, helms the new working group.

Though he did not use the term “working group,” Skybetter wrote in an email to the Indy that he is working with leadership at Trinity Rep and Brown “arts

departments” in a “distributed, constellated fashion.” In an ambiguous first-person plural, Skybetter wrote later, “we’re not rushing to replicate what existed or to simply fill a gap.” Instead, he’s thinking about “deeper questions,” such as what “rigorous artistic training” looks like “in a research university.”

Skybetter’s particular concern about research-oriented artistic training responds to larger structural and financial trends at Brown. At a faculty meeting last November, a little over a year after the initial B/T admissions pause, President Christina Paxson explained that the University’s ongoing budget deficit results from Brown’s longterm shift from a liberal arts academic model toward a research-oriented model. At the same time that the University began the process to shutter the B/T program, it continued to support large-scale research investments, even in the face of a deficit.

The University’s increasing emphasis on research has been reflected in its funding structures for the arts. Although the BAI’s current mission statement emphasizes “audacious interdisciplinary creative research and practice,” artmaking at Brown has not always been envisioned in such lofty terms. The BAI replaced the Brown Arts Initiative in 2021, which itself replaced the Creative Arts Council in 2016. Whereas the BAI seeks to offer “unparalleled resources” and “cutting-edge spaces,” the Creative Arts Council had a more modest task: supporting “the goals of the individual creative art departments and programs.” The context of the research university has brought about flashier expectations for artistic resourcing on campus, turning attention away from students’ particular needs.

In alignment with the broader mission of the BAI, Skybetter’s constellation of interlocutors is thinking about how the performing arts can fit into the framework of the research university. Meanwhile, the faculty and students of the B/T program remain in the dark as to how their training failed to fit the bill.

The Brown/Trinity Rep MFA program was an engagement of coinciding interests between two distinguished institutions. But today, Trinity Rep and Brown’s ideals for the future of art-making are diverging. Trinity Rep continues to favor an holistic style of acting education, while the University moves toward increasingly research-oriented notions of theater. Instead of addressing the misaligned goals of training, Brown opted to stop collaborating altogether.

Brown’s abrupt exit also leaves unaddressed the critiques of disjointed administration surfaced in the external review. Tension is inevitable when varying

ideals for art-making meet the reality of operating institutions. Beyond the parameters of B/T, tension between artistic and institutional growth pervades Trinity Rep. Originally established in 1963 by a community of Rhode Islanders, Trinity Rep is now a multimillion dollar organization, and theatermaking is no longer its sole concern. In 2023, the Friends of Adrian Hall skater group accused Trinity Rep of not acting “in good faith as a neighbor” or upholding their “stated community values” when a proposed expansion to their historic downtown theater would have limited access to the only public skate park in Providence. An agreement was reached in 2025 to preserve the park, but the public debates cemented Trinity Rep as a powerful local decision maker that must also reckon with its place in the Providence community.

B/T, at its best, seemed to capture how institutional resources could build community, and its “loss is really crucial to acknowledge,” said Skiles. But the program’s closure “does not mean it’s a failure. Far from it.” Theatermaking, she said, must be built on collaboration between people, and there is no shortage of B/T alumni who will “continue to make extraordinary theater.”

Faculty members like Warren are also hopeful that professional training will continue at Trinity Rep in the future, with or without the financial support from Brown. “It was always about the people. And that’s where the ethos lives, that’s where the artistic priorities and principles live,” she said. “Those aren’t going to evaporate because we’re under different leadership or because the program ends.”

Institutionalizing art-making is its own balancing act—the stability offered by an institutional structure enables artists to engage deeply with their practice and creates boundaries to push against. Skiles noted the luxuries offered by the institutional framework: “Institutions can make promises. Institutions can offer up space and time and tuition-free environments.”

“But I’m not sure,” she said, of “placing one’s faith in institutions as these perfect containers.” Impressive buildings, grandiose titles, and systems of accreditation are superfluous to the foundations of theatermaking. “We are not meant to stay here forever. But we are meant to work in collaboration with each other for as long as we possibly can. There’s no expiration date to that.”

SEBASTIAN BOTERO B’27, BENJAMIN FLAUMENHAFT B’27, and CINDY LI R’26.5 are still playing Zip Zap Zop.

c Frequently, scrolling the main page of the New York Times, I see the following items all in a row: a photo of a bombing abroad, a headline about American classrooms, and a miscellaneous piece of elder millennial guidance: “What is ‘6-7’?” or “No-Chop, So-Good Peanut Butter Noodles.” Perhaps, to some extent, the form of the newspaper grid has always been a confusing conglomerate of competing genres, but has reporting on unspeakable violence and executive overreach ever cohered so seamlessly with listicles and lukewarm analyses of lifestyle? This is a Times of rather aestheticized reporting.

And, but, then again, the paper of record’s lighthearted approach to fascism can also beget such home runs as “Donald Trump’s Big Gay Government,” the late summer dispatch on the out-and-proud gay guy Republicans who work for the Trump administration. The piece was penned by Shawn McCreesh, a White House correspondent for the Times. (Page Six reports he’s dating Vanity Fair editor Mark Guiducci.)

McCreesh knows a thing or two about journalism, so he opens the piece in medias res. Washington’s most powerful men are gathered at the Ned, a private club near the White House. What follows is something like the setup to a joke: Charles Moran, a high-ranking official at the Department of Energy, is seated in a leather armchair, sipping a dirty martini. Officials and underlings visit Moran on rotation throughout the evening. The gag, we learn, is that Moran is gay.

To be more precise, he’s an “A-Gay,” a label McCreesh has ostensibly plucked from the early aughts. A GQ article from 2008 describes the A-Gay as that kind of gay guy who is “smarter, sexier, and far more successful than you’ll ever be.” A-Gays are found on yachts in Capri, in Gstaad, in Sag Harbor, and at Sundance. McCreesh writes the Republican gays in quite the same idiom: glossy-magazine-scene-report.

The Republican gays frequent the Ned and other elevated eateries: for instance, the Occidental, “a retro-chic chophouse on Pennsylvania Avenue.” They also convene at house parties, rooftop parties, and pool parties all across D.C. “The most coveted invitation for a MAGA gay in Washington,” writes McCreesh, “is to one of the parties that Mr. Thiel, the gay Trump megadonor, has been throwing at his mansion near Embassy Row.”

As McCreesh puts it, the A-Gay lifestyle falls somewhere between that of a statesman and the most laddish circuit gay. These Republican gays are fancy, by which I mean that their lifestyle appears rarefied. Their dining habits lean pricey, their fashion preppy, their social circles elite. They don’t necessarily have good taste, but they certainly look like power.

The liberal gays, by contrast, look a good deal more ordinary: one Democrat is caught “looking rakish in a gray Calvin Klein suit,” another “drinking pinot grigio and eating pigs in a blanket.” In fact, McCreesh’s portrait of this burgeoning gay Republican scene is contrasted with the mean, liberal gays who sow division all about town. The Republican gays are building a network; the liberal gays are bringing conflict.

McCreesh attempts to reveal the Republican gays’ hypocrisy by listing the Trump administration’s generally anti-queer policies: the administration has cut funding for HIV vaccine research and for LGBTQ suicide prevention services. McCreesh expects the

Republican gays’ nonchalant responses to read as self-contradiction. It’s difficult, however, to find hypocrisy in the Republican gays’ support for Trump when the administration’s policies to date are not likely to be so materially harmful for these particular gays. As for this fancy sort of gay man, as in the welloff, cisgender, gay man with politically correct taste, let’s say that Trump very well may be the friendliest Republican that ever has been. It probably isn’t true, but it ultimately doesn’t matter because Trump’s acceptance of the A-Gays doesn’t mean much for gay liberation; acceptance, here, looks more like subsumption under a totalizing whole than genuine accommodation of difference.

The Republican gays argue that the “battle for gay rights has basically already been won,” offering up themselves as evidence. In so doing, they are simply noticing the acceptance of a particular kind of gay lifestyle that was intended, from the start, to be acceptable. It’s why McCreesh’s punchline at the start of his article isn’t funny: it isn’t particularly offensive or surprising to find out that the men fraternizing in a private social club are gay.

Acceptability characterizes many fancy aesthetics adopted by gay men these days. I’m thinking, for instance, about @amuxnii, an Instagram account that assembles photos of really-hot-gay-men-in-glamorous-situations. In one video, we see black shoes in an elevator, a Rolex in a black car, suits on the streets of Manhattan: “He’s a gay man who works at J.P. Morgan.” In another, gay men on the hood of a vintage car, walking hand-in-hand through a gallery, in a marbled atrium: “Gay is normal.” The account puts forth sorts of gay lifestyles that are, at once, rather rarefied and completely normal. Normal, that is, insofar as they adhere to normal notions of masculinity; this is a sort of fanciness whose very aim is acceptability.

The account, to be sure, would put things the other way around: the fanciness is a result of acceptance. Take this text overlay: “Gay love is beautiful because it exists despite everything that tried to silence it.” Note the past tense “tried”; as with the Republican gays, @amunxii, with its fancy aesthetics, puts forth beauty as proof of victory over silencing, of acceptance already won. But one has a hard time thinking of the acceptance of men in suits, in offices, in museums as a particularly new social fact.

Perhaps, in reading McCreesh’s piece alongside @amunxii, you can see more clearly what I mean when I say that the Republican gays’ lifestyle looks rarefied. As far as aesthetics are concerned, I’m interested in McCreesh’s evident investment in the styles of living the Republican gays take on, in how their lives appear. @amunxii presents lifestyles collaged together out of images found online; McCreesh’s dishy profile describes the Republican gays in-scene, and thereby makes their lives appear.

Indeed, McCreesh seems intent on making the Republican gays appear as members of a distinct and coherent scene. He offers some light-handed critique of their politics, but he also seems entirely enthused by what they’ve got. Or, how they look, or where they go, or whom they hang out with. And yet, for all of McCreesh’s detailed suggestions of a particular Republican gay lifestyle, I ultimately can’t quite get past the fact that these Republicans mostly just look

( TEXT BENJAMIN FLAUMENHAFT DESIGN MARY-ELIZABETH

BOATEY ILLUSTRATION ANGELINA SO )

like Republicans. As with the gay aesthetics circulated on @amunxii, the Republican gays’ fanciness is heteronormative. Their social scene can’t exactly be distinguished from the surrounding heterosexual world.

But why does McCreesh portray these gays in distinct community? Why does he cohere their ‘scene’ into a New York Times “Style” piece?

I think, in a number of ways, gays have always been fancy. Or, at least, some gays, some of the time. I’m thinking about Truman Capote, the Fire Island Pines, Oscar Wilde, drag queens, opera, middle school boys in bowties, Broadway, and so on. Gay men are often caught up in generally rarefied aesthetic tendencies. And for all the many tales of gay guy loneliness, such fancy leanings often cohere around circumscribed gay guy groups. Think: yes, a millennial friend group weekending in the Pines; sorry to say, the perennial sophomore twinks; dandyism in general; and the fey, avante-garde poets of the New York School.

Fanciness might be found in a wide variety of objects from limp wrists to the 11 o’clock number, but most importantly fanciness is an aesthetic about hierarchy. Sometimes, fanciness simply speaks hierarchy (as in: I’m fancier than you). In writing and in art, the fancy object might speak down to its reader, rather ostentatiously. In the case of the A-Gays, fanciness is a lifestyle, a bit like, for instance, being “a bohemian.” Or, maybe, it’s like a digital aesthetic: fancy-core.

It seems to me that McCreesh, the legacy media gay that he is, would have at least an inkling of this particular aesthetic category and the sorts of gay groups by which it has been mobilized. He shows us the group of gay guy Republicans in all of their lavish glory, and in so doing, raises the question, doesn’t this look like gay guy community? The parties and dinners of the Republican gays look, perhaps, like a certain kind of historical gay collectivity. However, I see this portrait as a misapprehension, an incorrect historicization, of these Republicans’ plainly assimilated social circle. McCreesh latches onto the A-Gays’ fanciness as evidence of their apparently developing gay scene, but this fanciness, really, has just as much to do with their positions in Washingtion as with their being gay.

But fanciness, I say, really can work differently; there’s something to McCreesh’s inclination that fanciness might be indicative of gay community. The New York School, for instance, looks a good deal more gay in a specifically gay way. I see the fanciness of this mid-century avant-garde, as being, yes, an expression of its poets’ associations with dominant institutions, and, also, as simultaneously serving particularly gay collective ends. The Republican A-Gays are an elite circle of governmental gay men; this foppish group of poets and painters was an elite circle of art world gays. New York School writing was largely resourced by and organized around dominant art world institutions. Perhaps the most salient example of the group’s proximity to power was Frank O’Hara, who worked as a curator at MoMA.

In 1979, the interplay between the overlapping gay and institutional social worlds of the New York School was read into the language of O’Hara’s poetry by Bruce Boone, a fixture of New Narrative, a later

school of gay avant-garde writing. Boone thinks about O’Hara’s poems as sites of “competing language practices—the dominant language practice of the New York art world of the 50s and the oppositional language practice of gay men.” O’Hara’s work is characterized by a general lack of syntax and a taste for colloquialisms. In line with Abstract Expressionism, the dominant art world ideology of the time, critics would frequently read such elements as evidence of a kind of event of poetic composition, akin to Jackson Pollock throwing paint onto the canvas from above. Boone argues there is also a less overt, more oppositional gay aesthetic at play. He reads O’Hara’s leaping, talky, paratactic style as language that addresses gay men in particular while remaining illegible to the outsider. “With this self-defensive measure,” Boone writes of O’Hara’s parataxis, “the community speaks itself for itself, and not others.”

O’Hara’s poetry, then, is marked by his circle’s association with art world institutions, even as it also works to render his circle distinct from said institutions. In order to read this dynamic of fanciness as distinct from the dynamic I read in McCreesh’s profile of the A-Gays, we might think of the A-Gays’ lifestyle as structurally analogous with O’Hara’s poetics; whereas the A-Gays’ fancy lifestyle is simply an expression of heteronormativity, O’Hara’s language at once reveals his institutional connections and speaks specifically to gay men. O’Hara’s language is hierarchical insofar as its style is aligned with Abstract Expressionism. And, but, the opacity of this very style allows his poetry to narrate his circumscribed gay community. For Boone, it is O’Hara’s capacity to narrate or to call upon a community that makes his aesthetics, specifically, gay. We might, therefore, name as specifically gay what I’ve been calling O’Hara’s hierarchical, fancy aesthetic insofar as this fanciness brings about community.

I will say that I’m wary of the double-edge of gay appearances that queer theorist Lee Edelman describes in the eponymous chapter of his book

Homographesis. Edelman writes that “while the cultural enterprise of reading homosexuality must affirm that the homosexual is distinctly and legibly marked, it must also recognize that those markings have been, can be, or can pass as, unremarked and unremarkable.” He warns us, then, against reading a subject as gay without also staying with the possibility of misreading that very subject. Edelman destabilizes the very logic of identity by which the reading of a gay subject might be possible in the first place. This logic of identity sustains the heterosexual insistence on a strict division between sameness and difference.

On the one hand, my reading of fanciness is attentive to Edelman’s destabilization of gay identity. Even as McCreesh takes the A-Gays’ fanciness as indication of gay community, I question whether their fanciness even has to do with their being gay. Fanciness, as a mark of gayness, is hardly hard and fast.

But, then, what follows from Edelman’s deconstruction of identity is a gay politics that is uninterested in community entirely. Edelman argues that the very insistence upon gay community as a means for gay liberation is itself premised on the logic of identity that a gay politics ought to refuse. For gays to gather together as gays, distinct from heterosexuality, each individual must first affirm the self-sameness of his gay identity. However, Edelman unsettles this very notion of self-sameness by bringing to light the difference internal to any supposedly stable identity.

We might then question Boone’s reading of O’Hara’s community-building language as being necessarily oppositional. Boone finds political utility in O’Hara’s poetics of community; by speaking directly to gay men, O’Hara’s poetry might thereby organize these gay men, distinct in their gayness, against the violence of dominant institutions or the threat of total subsumption to heteronormativity. Edelman rejects a gay politics of this sort, of gay men united in their difference.

And yet, I get the sense that gay community still really does matter: real gay community, distinct in its difference. Trump’s systematic deportations (themselves, removals of difference), stoking of anti-trans panic, and general homogenizing impulse are all very

present threats that require organized opposition. Why can’t we have specifically gay collectivity, undone in its very specificity? Why can’t we have community without stable identity? +++

I think there might be more to O’Hara’s fanciness than the community-building Boone points us toward. I’ll begin with “Poem” (1959). O’Hara attributes to his lover Vincent such a fine opinion as “Ionesco is greater / than Beckett.” Later on, the speaker, the poet: “so I get back up / make coffee, and read François Villon, his life.” O’Hara is really quite the reader, and I’m especially interested in the kind of relationship he brings us into when he writes a scene of reading. O’Hara reads François Villon, and I am instantly brought close to the poem’s “I,” for I am also a reader, am reading at this very moment. And then, I’m at a distance as I remember I’m reading Frank O’Hara, not François Villon. Linking this reading to the biographical fact of O’Hara’s erudition, one can see how O’Hara’s scene of reading is about hierarchy. It’s simple: I behold the poet’s impressively glamorous reading habits. Then, or perhaps in the first place, I am brought to even ground with the poet as I remember we are both, at the same time, reading. And yet, upon being acquainted with the poet, I keep with me the feeling of distance, of being below his fancy reading.

O’Hara as bibliophile, as aesthete, writes a hierarchized scene of reading, and in so doing brings the reader into the kind of relationship that models participation in a circumscribed group. That is, the reader is brought into the group, while keeping close the feeling of being outside of the group; he feels the group’s specificity. Or, perhaps, this fluctuation between proximity and distance is closer to Edelman’s imperative to destabilize identity altogether. Even as the reader reads alongside the poet, the two must necessarily be reading different things; I am reading O’Hara, the poet something else. Any apparent identification must also carry a difference with it. I’d like, I think, to take O’Hara’s fancy aesthetic as doing both things at once: bringing the reader into a specific relation while also destabilizing the very notion of identity by which that relation might be thought to be specific.

In “Saint Paul and All That,” the poet puts his own reading above the reading of “you”:

I read what you read you do not read what I read

As with much of O’Hara’s work, the address is intimate, evidently spoken to somebody in particular. We behold the extent of O’Hara’s social scene. But what if I take the “you” as myself? The “you” becomes split: either O’Hara’s friend or me. I feel, at once, the relation of the poem, this relation’s specificity, and the unsettled identity that makes up this relation, the difference internal to “you.”

Reading together, reading apart, reading together all the same; addressed by the “you,” but then, perhaps, not really. The biographical facts of O’Hara’s fancy lifestyle, his reading habits and his extensive social circle, come to bear on his poetry, hierarchizing the relation between poet and reader. The effect of this hierarchy can be read two ways: the formation of a specific relation and the troubling of the terms by which this relation might be thought specific.

Here is the force of a genuine gay fanciness. I’m talking about something different from the assimilable rarefied lifestyle of the A-Gays, and something more than Boone’s notion of a community-building language practice. I’m talking about a way of making gay lives appear, a gay aesthetic, that balances the defining of distinct community with the undoing of identity. Together fancily, which is to say specifically without specificity.

BENJAMIN FLAUMENHAFT B’27 recently realized that y’all does not in fact mean all…it means you all...or does it?

c The opening lines of “Naked Patients,” a song I love by the alt-rock band Happyness, go: “There’s something so funny about a sick body / and the things that it does that it shouldn’t do.” The title itself conveys a sense of absurdity, conjuring images of raving, stircrazy disease victims sprinting disrobed through hospital hallways.

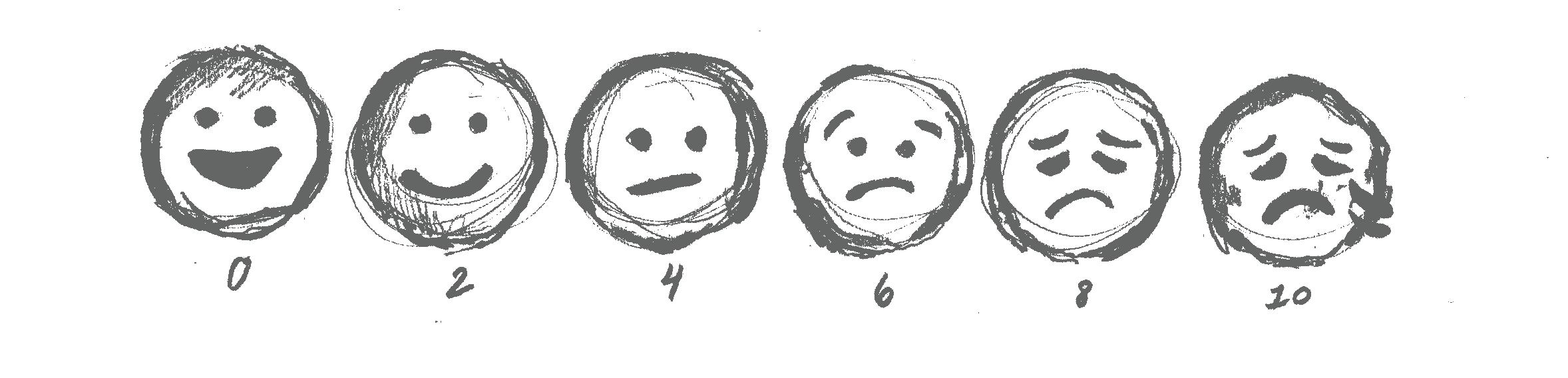

( TEXT CAMERON CALONZO DESIGN ROSE HOLDBROOK ILLUSTRATION MERI SANDERS )

In May of this year, I spent every day, from sunrise to sunset, at Anaheim Regional Hospital in California, accompanying my mom in her various states of unconsciousness, pain, and fear. A meningitis infection was ravaging her, as she had already been immunocompromised from seven years of dialysis treatment for end-stage renal disease. The doctors told us after she had mostly recovered that they didn’t think she would ever make it out of the hospital. But even when she was firmly in the grip of psychosis, she never ran around naked or shouted at the nurses. Her next-door neighbor in the critical care unit did, though. Some days we’d hear him screaming “FUCK GOD” and I’d try to stifle a laugh. Other days I was more somber and empathetic. Even when I did laugh, I never felt any scorn for him, or amusement at his mania. I think that after so many hellish days spent on a stiff chair next to my mother’s limp, machine-breathing body, I was searching for something, anything, to lift my spirits.

+++

Maybe something is lost within you when you’re sick. After about a week on life support, the doctors were finally able to wean my mom off the ventilator. They removed her chest tube, which meant that as soon as her throat readjusted to being empty, she would be able to speak normally again. It took longer than expected for this adjustment to happen—for the first few days, she sounded like a ghost, or a smoker. It wasn’t just her voice that was different either: my mom, a child of the most high God, kept saying things like “I’m in hell!” Or, when I would stand at her bedside and cry, telling her how much I loved her and how strong she was, she would simply roll her eyes and look away. She would thrash about, to the point where the nurses restrained her limbs to stop her from hurting herself or others. Now, she tells me that she thought she was being abducted by aliens, and that’s why she put up such a fight.

+++

In the film Gummo, two scrawny ‘white trash’ rascals break into another boy’s house, planning to get revenge on him for killing some of the cats they were supposed to kill (for money) (it’s a weird movie). Once inside, they realize that the boy isn’t home: all they find are some photos that he’s taken of himself crossdressing and his comatose grandmother hooked up to life support in her bedroom. She’s catatonic, lying with her hands clasped over her chest like a corpse on display at a wake. She has barely any hair on her head, and the loudest sound in the room is her mechanical, uncannily rhythmic breathing. The elder of the two trespassers, Tummler, says this is “no way to live” and pulls the plug: “She’s always been dead.” He has a point. There’s not really any such thing as “brain dead”—without presence of mind, a body is nothing; the heart doesn’t know it needs to pump, the lungs don’t know they need to expand and contract. What about a present mind with a malfunctioning body, then? What do we call that?

+++

In her essay “Illness as Metaphor,” Susan Sontag argues against illness as metaphor. She says, “The

most truthful way of regarding illness—and the healthiest way of being ill—is one most purified of, most resistant to, metaphoric thinking.” Artistic figurations of sickness as other things—as a journey, as a weight on one’s shoulders, as a supernatural force—can be affecting, but they are perhaps the furthest thing from representative. To me, at least, pain does not feel like anything other than pain. While it often lends itself to abstraction in hindsight, in the moment, there is nothing interesting or fantastical about it. It just hurts, until it doesn’t. Metaphor is transmutation—one thing becomes another, more exciting thing. As much as we long to, we cannot transmute our bodies into something different or better. Modern medicine works wonders: it can transport a body from the “kingdom of the sick” to the “kingdom of the well” in a matter of days, hours, even minutes. But what it cannot do is instantaneously turn sickness into something it fundamentally is not. The sickness subsides, and is often eventually eradicated, yet for the moment, it remains.

Political prisoners subjected to physical and psychological torture often recount their experiences as contrary to general conceptions of a linear pain response. Instead, political prisoners report that as more violence is inflicted on their bodies, their ability to feel pain diminishes. One man whose tormentors burnt his flesh with a torch attested, “It did not hurt too much because I was so feeble that I did not care.” Another torture victim called beatings ineffective because “after the first few blows, you don’t feel anything.” Many also report that the different variants of pain—burning, freezing, aching, cutting, and so on—often combine to create not a greater sum of suffering, but a reduction in discomfort. After a finger was severed from his left hand, a victim claimed that subsequently losing a finger from his right hand did not double the pain, but instead replaced and relieved the initial pain. Torture as a method of extracting information is predicated on the assumption that the further you push the body, the easier it is to break the brain. However, contrary to what diagrams like the Wong–Baker Faces Pain Rating Scale might lead one to believe, pain does not correspond to some abstract unit of measurement (zero = smiley face = no hurt), and there isn’t necessarily a direct correlation between the amount of discomfort one experiences and the severity of bodily injury.

In his book Feeling Pain and Being in Pain, Serbian philosopher Nikola Grahek articulates two inverse distortions of human pain responses: “pain without painfulness” and “painfulness without pain.” In both cases, pain is not a proportional biological reaction to physical harm, but rather separate and contradictory. This complicates the idea of a “breaking point,” the concrete threshold of injury which the body can endure. Even the ultimate threshold, that of life and death, is malleable. Once she had recovered, my mother described her experience of going into cardiac arrest—her disembodied self approached a river of robed apparitions, one of them my late grandfather, before suddenly being pulled back by Jesus. All this is to say (as is usually the case): maybe things aren’t so binary.

+++

For the past seven years of my life, I’ve gotten these enigmatic fainting episodes every few months. It starts out with some relatively mild abdominal pain, similar to indigestion, which then intensifies over the next 30 minutes until I pass out. I’ve felt that these

episodes send me into an altered state of consciousness. Sometimes I’m snappy, even aggressive towards the people trying to help or comfort me. Other times I’m reduced to sobs, a Jesus-on-the-cross, why hast thou forsaken me kind of desolation. My mind goes to strange places when I’m in this much pain: once, as I was drifting along the shore of consciousness, all I could think about was a memory of eating lunch next to the playground in elementary school, trying to finish as fast as I could so I would have more time to play handball. There was nothing especially distinctive about that day, nor was I reminded of it by anything in particular in my immediate surroundings. It’s important to note that all but one of these episodes happened in the comfort of my home. It was as though the pain, coupled with the familiar environment of my childhood bathroom, had unlocked this one hyper-specific, arbitrary moment in my life. It’s strange, a bit like déjà vu, lacking an identifiable trigger. In the only episode I’ve had in public, I collapsed on the floor of a Vietnamese restaurant while waiting for my takeout pho order, and the EMTs wheeled me out on a gurney.

+++

After my mom’s big health scare last May, I began the long, convoluted process of screening to become a kidney donor. Before all the physiological testing— which included a 48-hour urine collection, 35 tubes of blood, a CT scan, and a 24-hour blood pressure cuff— they gave me an initial psychological evaluation. This seemed to be aimed at identifying any obvious issues which might complicate my viability as a living organ donor and, of course, ensuring I was aware of the numerous risks associated with the procedure and its aftermath. Some real questions they asked me: “How would you feel if your mother’s body rejected your kidney?” “How would you feel if you developed kidney disease after donating?” “How would you feel if your mother died on the operating table?” (to which I deftly responded “Probably really sad”). In the end I was disqualified—apparently the way my arteries are positioned makes it unsafe for them to surgically remove my smaller kidney. Upon learning this, I felt a great deal of grief. I’d been holding out hope for years that when my mother’s end-stage renal disease worsened, I would eventually be able to sacrifice a part of myself to heal her, and it would be a great, selfless decision which made us both better off. Her healthy again, me righteous and heroic. That can’t happen now, but I can’t say a part of me wasn’t relieved. I don’t think I’d be strong enough to handle it all.

CAMERON CALONZO B’28 has an ambulatory electroencephalogram coming up.

( TEXT ELLIE WU

ILLUSTRATION LILY YANAGIMOTO )

c On a sunset walk by the lake, I asked my mother what she appreciated most about moving to the U.S. when she’d left so much behind in China. She told me, staring out at the rippling water, that she loved the nature of our Pacific Northwest—the mountains we’d hike every summer, the tiny wildflowers that sprouted in the spring, the skiing to chase away the wintertime blues.

Although my mom loves being active outdoors, her knees have been crackly since I was a kid, which she attributes to the damage done in her 20s by a blustery Qingdao winter. Lately, the stiffness had been getting worse, coinciding with trouble sleeping and mood swings. My mom was 50-something and going through perimenopause. She decided to go to physical therapy, asking me to come along in case she didn’t understand some of the staff’s English instructions.

The white-haired woman helping my mom with her exercises told me that menopause could cause a 20% loss of bone density, and might be contributing to my mom’s weaker knees. I was shocked, and worried—one/fifth was no small number. The physical therapist recommended Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT), which could reduce menopausal symptoms including bone loss, sleep disturbances, and irritability. It was a common treatment, she advised us, which many women choose to take in order to combat the effects of aging.

The term menopause was coined in 1821 by the French physician Charles-Pierre-Louis de Gardanne, combining the Greek words men (month) and pausis (cessation). Before Gardanne’s standardization, menopause was commonly referred to as a “critical age” or “women’s hell” by male physicians in France and Britain, reflecting an understanding of menopause as a sort of “crippling disease.” Theories on the possible causes of this ‘affliction’ date back as far as ancient times: In his dialogue Timaeus, Plato proposes the notion of the “wandering womb,” which he describes as an “animal […] desirous of procreating children.” When “remaining unfruitful,” the womb would get “angry” and wander throughout the body, obstructing breathing and “causing all varieties of disease.”

Over 2000 years later, Western thinkers continue to conflate menopause and disease. In 1966, the American gynecologist Robert A. Wilson published his bestselling book Feminine Forever, writing that “[m]any physicians simply refuse to recognize menopause for what it is—a serious, painful and often crippling disease.” However, this “disease” was treatable: Wilson argued that through estrogen therapy (a form of HRT), “every woman alive today has the option of remaining feminine forever.”

In 1942, 25 years before Wilson’s book, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had approved the synthetic estrogen Premarin to treat the hot flashes, joint pain, mood swings, and other symptoms that can accompany menopause. However, Premarin, whose name refers to the drug’s extraction from the urine of pregnant mares, did not become popular until shortly after the publication of Feminine Forever. In the decade that followed, Premarin became the fifthmost prescribed drug in the U.S., rising to number one by 1992

These included preventing heart disease and even blindness, which had not been endorsed by the FDA. Wilson’s son even revealed that his father had been paid by Wyeth to promote the drug.

Public opinion on menopausal hormone therapy and other estrogen therapies continues to be contested. Recent data compiled by the FDA suggests that HRT can be administered safely in the shortterm: According to the FDA, starting HRT within 10 years of the onset of menopause can have numerous benefits, which for most women outweigh potential risks. The WHI, on the other hand, cites its previous 2002 study and points out the lack of sufficient research and drug trials to inform decision-making about taking HRT. Currently, Premarin’s website lists the drug’s harmful side effects, noting that they depend on the duration of treatment and their combination with other medications.

In his promotion of Premarin in Feminine Forever, Wilson described aging women as “flabby,” “shrunken,” “dull-minded,” and “desexed.” To Wilson, being “feminine” was equivalent to being young and sexually appealing to men. If a woman refused HRT, the consequences would be “unthinkable,” since, according to Wilson, “[a]ll post-menopausal women are castrates.” Through this disparaging language, Wilson portrayed the natural process of menopause as a deficiency disease which had to be treated.

Viewing post-menopausal women as diseased stigmatizes the natural process of aging, implying that women are only valuable to society for their youth and attractiveness. Furthermore, this understanding of menopause as a deficiency implies that a woman is not a woman without her reproductive ability. Reducing women to wombs, this view of menopause as a deficiency disease signals that women’s reproductive function is their only value within society.

stress reduction techniques for emotional well-being. Menopause is viewed as the “second spring,” when the female body enters a new stage, shifting from fertility and reproduction to conserving and nourishing the self.

This view of menopause reflects TCM’s holistic approach to healing. The ancient text The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine, dating to around the second century BCE, posits that diagnosis and treatment for any condition must be predicated on a recognition of environmental and personal factors. TCM continues to practice this philosophy in which health is not only grounded in a healthy body, but also dependent on maintaining balance with nature and one’s surroundings.

In her influential 1991 book “Whose Science? Whose Knowledge?,” the American philosopher Sandra Harding argues that science is not valuefree, but one of the most ideological practices in modern society. Although we may view science as concrete truth, the history of women’s health shows how science is deeply influenced by prevailing patriarchal norms. Terminology, too, is an ideological practice: The term hormone “replacement” therapy itself is revealing, implying that the natural loss of hormones post-menopause must be corrected. It also misleadingly suggests that HRT restores the body to a pre-menopausal state, while HRT simply regulates levels of estrogen and progesterone through a fixed dose in 24-hour intervals. This is to ensure that these hormones activate the relevant receptors to minimize specific menopausal symptoms, rather than mimicking the monthly cycle of estrogen and progesterone fluctuation. But this idealization of the pre-menopausal state necessarily encodes the view of menopause as a disease with ‘symptoms,’ contributing to Western medicine’s pathologization of the female body’s natural changes.

Although TCM was also developed within patriarchal structures, it provides an alternative to the Western biomedical model which separates body from mind and defaults to male anatomy. Aiming to balance energies within an individual, TCM recognizes that each person is different. This emphasis on personalization as key to good health allows TCM to identify menopause as a natural stage in women’s lives, rather than a pathological aberration deviating from the male standard.

Its popularity suddenly plummeted after a 2002 federal study from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) revealed that Premarin was associated with increased risk of stroke and breast cancer. Lawsuits against Wyeth, the developer of Premarin (now acquired by Pfizer), identified how the company had advertised Premarin’s supposed greater benefits.

An alternative to this rather antifeminist view exists in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), which views menopause not as a disease, but as a natural part of a woman’s life cycle. In TCM, menopause stems from shifts in qi, a medical and philosophical concept. Qi is thought of as the invisible, fundamental substance of the universe, which manifests in two complementary and opposing attributes, yin and yang The human body is also believed to be a microcosm of the universe with qi as the lifeforce that circulates throughout, providing energy to organs and protecting them from pathogens, ensuring the smooth function of bodily processes.

TCM theorizes that our lives follow cycles of qi, from early childhood to old age. A woman’s life is divided into seven-year cycles; the beginning of the seventh cycle at the age of 49 marks the onset of menopause. During this process, the qi of the tian gui—a vessel governing reproduction—begins to decline, resulting in an imbalance of yin and yang energies in the body. To restore balance, TCM prescribes herbal medicine to alleviate dryness, foods with cooling qi to counteract excess yang in the body, and

Although I had initially been worried for my mom, I realize now that menopause is simply a natural part of aging, appearing differently for everyone. Over the phone, I found that my mom was actually never afraid of menopause. She told me that she wasn’t even sure if her knees or sleep disturbances were effects of her perimenopause, since she’d always had a bit of trouble sleeping after coming to the U.S.

+++

When my mom and I got home from physical therapy, I told my mom to ask about HRT at her annual medical examination. But her female Chinese American doctor told her that she didn’t need HRT. In fact, she told us that my mom was looking especially good for her age, likely because of all her biking and skiing and pickleball-playing. For her perimenopause, the doctor said it would be okay to just keep doing her knee exercises and following her health regimen—a mix of American pills and Chinese remedies like swallow’s nest soup.

ELLIE WU B’28’s mom’s knees are feeling stronger.

c There is something strange in how we speak of Israel’s destruction of Gaza. I recall the furor unleashed by genocide scholar and Brown historian Omer Bartov’s opinion piece in the New York Times this July, which concluded that Israel’s actions in Gaza constituted a genocide. The Times has, in the past two years, published at least 40 pieces addressing this question, including one from November of 2023 in which Professor Bartov argued the opposite. We—by ‘we’ I mean ‘well-meaning liberals’—ascribe an almost priestly quality to these determinations: If Bartov/the International Court of Justice/[insert your favorite well-respected institution/scholar here] declares that Israel is perpetrating a genocide, then surely someone will do something about it. It is as if we are awaiting an encyclical from the Vatican that will render the atrocities we consume from afar understandable and, consequently, soluble.

I have been thinking, amid this frenzy, about the concept of genocide—about the work that it does, and about the ends that it serves. Polish-Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin coined the term genocide in his 1944 book Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, which found wide readership in the United States as World War II drew to a close. “New conceptions,” wrote Lemkin, “require new terms. By ‘genocide’ we mean the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group.” Novelty mattered to Lemkin; he did not want yet another word for the horrors of war, which had already been treated extensively since World War I. He wanted, rather, a way to describe the essential difference inherent to Nazi Germany’s campaign against Jews, Slavs, and Roma—that difference being its destructive intent, that the mass death of these peoples was not incidental to, but instead the motive for, the plans of Hitler and his cadres.

Lemkin knew of earlier mass killings; his plans for a monograph on the history of genocide contained such chapters as “Genocide against the Aztecs” and “Genocide by the Germans against the Native Africans.” The novelty of genocide, then, was conceptual more than empirical. What Lemkin really introduced was a new kind of naming: a term that could lift certain types of violence out of the ordinary and

place them in an exceptional category, one characterized by civilizational rupture and the total unmaking of a people. Genocide was to describe the forced “disintegration [...] of national groups,” and thus depended on imagining its subject as a kind of ‘world’ whose destruction could be figured as ontological break, rather than mere accumulation of death. By naming this disintegration and therefore exceptionalizing it, he gave the designation the force of judgement: a speechact that would bind reality rather than just recording it.

But to make such a judgement demanded a vantage from beyond the ‘world’ being destroyed—a judge at a remove from the event to be classified. Only a year after Axis Rule’s publication, Soviet soldiers were raising their flag over the Reichstag, and Hitler’s body was being doused with petrol. The Allied victory gave mid-century internationalists exactly this vantage: The 1945–46 Nuremberg trials of Nazi officials were to allow the victors to stand outside history long enough to identify and condemn the alreadyended event, and thus prevent its recurrence. It was to be, in essence, a secular Judgement per above.

That posture was an illusion. The judges’ power to name derived not from their metaphysical removal but rather from the application of sovereign power— the court could speak as final authority only because it spoke for the victors. The pretense of universality (embodied in the charge of “crimes against humanity”) concealed the tribunal’s contingent nature: had Germany won, there would have been no tribunal at all, no humanity to speak in its own name, no ‘event’ to categorize. The extrahistorical stance was possible only because history had already been decided; the pomp and circumstance surrounding the naming of the crime was but decoration atop the total victory that had already been achieved.

+++

My great-grandmother was born in Saaz (now Žatec), a small city in the German-speaking Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia. She was thirteen in 1938, when Adolf Hitler annexed the region; she and her family left on the last train out of the country. The

( TEXT COBY MULLIKEN DESIGN BENJI NATAN ILLUSTRATION SEOYEON KWEON )

choice was prescient. By May of 1939, more than 20,000 of the roughly 25,000 Sudeten Jews had been deported; few Jews remained by the time Allied forces liberated the Sudetenland from Nazi rule in May of 1945. With the end of the war came reprisals: In 1943, the Czechoslovak government-in-exile had adopted a resolution to deport Germans from recaptured territory, and, as soon as its monopoly on legitimate violence had been restored, took to implementing it. In June of 1945, the reconstituted Czechoslovak military arrived in Saaz and rounded up some 5,000 of its male German residents. Czech forces marched the Germans to the nearby town of Postelberg (now Postoloprty), where 2,000 of them were shot.

The “final solution of the German question,” as put by Czechoslovak president Edvard Beneš in November of the same year, was far from secret. Leaders like Churchill, Beneš, and Stalin openly discussed the expulsions, couched for liberal audiences in the language of security and administrative reality, and, for the war-wearied masses of Eastern Europe, in the language of revenge and collective punishment. Some 12 million Germans would ultimately be displaced—the largest movement of an ethnic group in European history. The explanatory framework for so massive an application of sovereign power was that of the “population transfer,” a term enshrined in the 1945 Potsdam Agreement, which encouraged occupying powers to undertake the “orderly and humane transfer of German populations” into Germany proper.

Population transfer was not a description, but a redescription. In framing the forced transfer—and, in many cases, massacre—of Germans as administrative necessity rather than the unmaking of a world, the victors carved an exception out of the exceptional category (genocide) they were in the process of inaugurating. The deprivation of the ‘human rights’ of Germans and the prosecution of the deprivation of the rights of Germany’s victims were not mutually exclusive but rather mutually reinforcing. Just months after President Truman’s delegation signed off on the mass deportation of Germans at Potsdam, his chief prosecutor Robert Jackson was preparing

destructions—that is that of World War II’s agressors— were being concurrently named out of universality.

Potsdam and Nuremberg revealed the tenuousness of ‘genocide’ as a clarifying speech-act; the power to name the absolute crime lay with the same sovereign whose ‘power to except’ (and thus justify) violence could produce the very crime it prosecuted. Universal categories (like “crimes against humanity”) appeared, in this light, to be mere fig-leaves for realpolitik; the power to name, rather than enabling absolute clarity, might enable only obfuscation. Such was the prediction of German legal theorist—and Nazi jurist—

Carl Schmitt, who in 1932 warned that a war waged in service of lofty universal ideals like “pacifism” would, ironically, be “unusually intense and inhuman,” since the enemy of such ideals would necessarily be an enemy of humanity, and thus would have to be “not only [...] defeated, but also utterly destroyed.” Indeed, just as Nazis were being deemed enemies of humanity at Nuremberg, analogous violence was being enacted across Central and Eastern Europe.

Key, for Schmitt, was that every political community (even those like ‘humanity’ that claimed universality) concealed a decision: who was friend, and who was foe. Whoever made such a decision was necessarily the sovereign of that community—“Sovereign is he who decides on the exception,” as put in his 1922 treatise Political Theology. The legal order, Schmitt was saying, appeared universal only because it could be suspended; the decision to name one instance of destruction ‘genocide’ and another ‘population trans fer’ would always rest with the sovereign. Genocide, that is, could only be produced alongside that which was not genocide, and vice versa. The sovereign was not so much discovering the distinction between two types of violence as drawing the sovereign had to sit beyond the norms they suspended, and indeed beyond the acts and subjects they judged.

Schmitt saw this position as fundamentally theologi cal. Whereas God had once occupied this ‘place beyond’ (the norm) from which abso lute judgement could be pronounced, the sovereign atop the modern state now filled an analogous role: they would stand outside the legal order, suspending it where necessary, and in turn determining which lives were protected and which lives were marked for destruction. The sovereign, that is, was a sort of secularized God-figure. (Schmitt was not an atheist; he merely observed that Western Europe had ceased to think in terms of theology; that, in a sociological sense, God was dead.) The universal categories at the disposal of this sovereign—humanity and crimes against it— inherited too a theological structure. They presumed an external vantage point from which they could be applied, a subject so authoritative that its use of the

categories (via naming, designation, discernment) would itself constitute a fulfillment of the categories’ prophetic power—one whose indictment of a crime would be equivalent to its prosecution of it.

This is naming at its most powerful: God’s words have force, a transcendental force that remakes rather than describes. And it is this force to which we moderns have aspired in our genocide conventions and international tribunals and haughty opinion pieces.

If we take for granted that naming and action have been divorced from one another—that their apparent alignment at Nuremberg was momentary and inci dental—it would be appealing, amid the impotence of the Western left in the face of Gaza’s destruction, to harken back to a time in which the two were more closely bound. We find such a world in the Hebrew Bible. “Now go and smite Amalek,” Samuel commands King Saul in 1 Samuel 15, “and utterly destroy all that they have.” God has named Amalek, a nation at war with Israel, herem—subject to total destruction. This naming is not a description but an imperative: designating a people for destruction is coterminous with executing that destruc tion. The dutiful Saul immediately carries out God’s will, killing all of the Amalekites save for their king, Agag, and sparing his best livestock—that is, “all that was good.” For this he is reprimanded by Samuel, God’s messenger, who proceeds to “[hew] Agag in pieces.”

face of a state that says, ‘I will do this because I can,’ is an unsettling reality. Genocide is supposed to be a crime so total that it commands the world; Gaza exposes a world beyond this command.