Park ICM in Partnership with NAVO Presents

Park ICM in Partnership with NAVO Presents

Wednesday, May 7, 2025 • 7:30 p.m.

1900 Building • Mission Woods, KS

Dear Esteemed Patrons and Lovers of Music,

As we wrap up our 22nd season at the International Center for Music at Park University, I find myself reflecting on the profound impact that music has on our lives. It’s not just the sound that resonates, but the emotion and dedication behind every performance that truly moves us. As Artistic Director and founder of this institution, I am continuously inspired by the exceptional talents of our students, faculty, and guest artists who pour their hearts into their craft. Kansas City is a remarkable place, home to a community that cherishes and supports the arts with unparalleled enthusiasm. Our concert series is designed to bring you closer to the magic of live music, offering an intimate and accessible way to experience the brilliance of our performers.

Our mission remains steadfast: to create an environment where musical excellence thrives, free from the distractions and financial burdens that often hinder artistic growth. At Park ICM, we are committed to nurturing the next generation of musicians with the same intensity and focus that shaped my own musical journey.

This season, we are proud to present a lineup that includes not only our extraordinary students and faculty but also internationally acclaimed guest artists whose contributions to the world of music are nothing short of legendary. In keeping with our mission, we will also introduce you to the newborn stars, the bright talents who represent the future of classical music. Each concert is an opportunity to witness the convergence of passion, discipline, and talent, creating moments that linger in the heart and mind.

I invite you to join us in celebrating the transformative power of music. Your presence and support are invaluable to us, fueling our drive to reach new heights of artistic achievement. Together, let’s create a symphony of shared experiences that transcends time and space.

With deep gratitude,

Stanislav Ioudenitch Founder and Artistic Director International Center for Music at Park University

P.S. Each performance is a manifestation of our shared love for music. Your presence and applause amplify our drive to elevate the art form further.

VIOLIN SONATA NO. 10 IN G MAJOR, OP. 96 ..................................................................

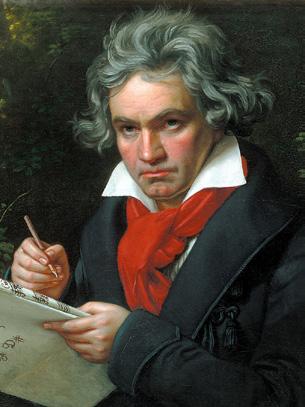

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Allegro moderato

Adagio espressivo

Scherzo: Allegro - Trio Poco allegretto

VIOLIN AND PIANO SONATA NO. 2 ..................................................................................

Allegretto

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

Blues. Moderato Perpetuum mobile. Allegro

SOLEILS COUCHANTS

2 PIECES

VIOLIN SONATA NO. 1

Nadia Boulanger (1887-1979)

Nocturne

Cortège

Lili Boulanger (1893-1918)

Béla Bartók (1881-1945)

I. Allegro appassionato

II. Adagio

III. Allegro

Photo: Kenny Johnson

Stanislav Ioudenitch

Known for a ravishing technique and his compelling musical conviction, pianist Stanislav Ioudenitch is part of the elite group of Cliburn Gold Medal winners, having taken home the Gold Medal at the 11th Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. His profoundly warm and intelligent performances have won him prizes at the Feruccio Busoni, William Kapell, Maria Callas, and New Orleans competitions, among others.

Ioudenitch has performed at major international cultural centers including Carnegie Hall (New York), Kennedy Center (Washington, D.C.), Gasteig (Munich, Germany), Conservatorio Verdi (Milan, Italy), Mariinsky Theater (St. Petersburg, Russia), International Performing Arts Center (Moscow, Russia), The Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory (Moscow, Russia), Forbidden City Concert Hall (Beijing, China), International Piano Festival of La Roque d’Anthéron (France), Théâtre du Châtelet (Paris, France), Bass Hall (Fort Worth, Texas), Jordan Hall (Boston, Massachusetts), Orange County Performing Arts Center (Costa Mesa, California), and the Aspen Music Festival (Aspen, Colorado).

Ioudenitch has had the privilege to perform with the conductors James Conlon, Valery Gergiev, Mikhail Pletnev, James DePreist, Günther Herbig, Asher Fisch, Stefan Sanderling, Michael Stern, Carl St. Clair, and Justus Franz, and with orchestras including the Munich Philharmonic, the Mariinsky Orchestra, National Symphony (Washington, D.C.), Rochester Philharmonic, Honolulu Symphony

and the National Philharmonic of Russia. Chamber music partners have included the Takács, Prazák, Borromeo, and Accorda quartets.

His teachers have included Natalia Vasinkina, Dmitri Bashkirov, Galina Eguiazarova, and Karl Ulrich Schnabel, Leon Fleisher, Rosalyn Tureck, William Grant Nabore at the International Piano Foundation in Como, Italy (the current International Piano Academy Lake Como). He subsequently became the youngest teacher ever invited to give master classes at the Academy. He also studied at the UMKC Conservatory of Music under the direction of Robert Weirich.

As the founder of the International Center for Music at Park University in Kansas City, he currently serves as both Artistic Director and professor of piano, while also holding a position as a piano professor at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music. Recently, his contributions to the field of music education were recognized with the prestigious appointment to The Fundación Banco Santander Piano Chair at the Reina Sofía School Of Music in Madrid, Spain

Stanislav Ioudenitch is the founder of the International Center for Music at Park University (Kansas City) where he is an Artistic Director and professor of piano.

Photo: Andrej Grilc/Helge Krückeberg

Maria Ioudenitch

American-Russian violinist Maria Ioudenitch captured the attention of music lovers worldwide in 2021 when she received first prizes in three international violin competitions – the Ysaÿe, Tibor Varga and Joseph Joachim – as well as numerous special prizes at these competitions, including Joachim’s Chamber Music Award, the prize for Best Interpretation of a Commissioned Work and the Henle Urtext Prize. In 2023, she won the Opus Klassik Award in the category “Chamber Music Recording of the Year” for her debut album, Songbird, on Warner Classics.

Recognized for her innovative programmes, her first album on Warner with pianist Kenny Broberg, spans from Franz Schubert and Fanny Mendelssohn to Nikolai Medtner and Nadia Boulanger. In upcoming concerts, she performs concertos by Mendelssohn, Sibelius, Mozart, Tchaikovsky, and Barber, as well as Vivaldi’s “Il Grosso Mogul”, while this season’s recital programmes include works by Lera Auerbach and Germaine Tailleferre, alongside standard violin repertoire.

Highlights of the 24/25 season include debuts with Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich as part of the Orpheum Foundation’s concert series, with Trondheim Symfoniorkester, with Sofia Philharmonic and with Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, with whom she also goes on tour. She is also invited by Heidelberger Frühling, Deutsche Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz, Philharmonisches Orchester Heidelberg and Philharmonia Frankfurt. Maria will return to Dresden Philharmonic for the New Year’s concert, after a very successful tour together in the UK in 2024. Upcoming debut appearances in the USA are with the Cincinnati and Detroit Symphony Orchestras.

Named “Great Talent“ by the Konzerthaus Wien, a programme that supports young artists on their way to the top of the world, she gives various recitals at the Wiener Konzerthaus. As an active chamber musician, she participates in chamber music tours with Ravinia Steans Music Institute and Marlboro Music Festival.

Maria Ioudenitch has made her debuts with hr-Sinfonieorchester Frankfurt, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin (at Berlin’s Philharmonie), MDR-Sinfonieorchester Leipzig, Düsseldorfer Symphoniker and Münchner Symphoniker as well as with NDR Radiophilharmonie Hannover, Lithuanian Chamber Orchestra, Utah Symphony und Kansas City Symphony. She works with conductors such as Andrey Boreyko, Donald Runnicles, Alpesh Chauhan, Marta Gardolińska, Holly Hyun Choe, Jonathan Bloxham, Yi-Chen Lin, Ryan Bancroft, Kevin John Edusei, Stanislav Kochanovsky, Andrew Manze, Jan Willem de Vriend, Robin Ticciati and Ruth Reinhardt.

Maria grew up in Kansas City and began playing violin with Gregory Sandomirsky at the age of three. She continued her studies with Ben Sayevich at the International Center for Music in Kansas City and Pamela Frank and Shmuel Ashkenasi at the Curtis Institute of Music and completed her master’s degree and Artist Diploma at the New England Conservatory, where she studied with Miriam Fried. In 20212023, she was mentored by Sonia Simmenauer as part of her new initiative, zukunfts.music. From 2021-2023, Maria also completed her Professional Studies program at the Kronberg Academy, working with Christian Tetzlaff.

Sonata in G major, Op. 96

All but one of Beethoven’s violin sonatas were written during a concentrated period between 1798 and 1803, when the composer was experiencing his first Viennese fame and crystalizing what might be called his first maturity. After the dramatic “Kreutzer” Sonata of 1803, the composer let nearly a decade pass before he approached the genre again. This was indeed a decade of great artistic and emotional upheaval for Beethoven, as he began to realize that, at the height of his new fame, he was going deaf. Works unleashed by this spiritual crisis include epoch-defining masterpieces such as the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Symphonies, the Fourth and Fifth Piano Concertos, the Violin Concerto, the Triple Concerto, the “Appassionata” Sonata, the three “Razumovsky” quartets, the Quartetto Serioso, and the opera Fidelio.

Around 1811-1812, Beethoven emerged from this stormy decade with music that was more experimental, reflective, confident and, to an extent, deeply personal. He began his final sonata for violin and piano probably in early 1812, during a period in which he had experienced frequent illness and had been sent to Bohemian spas, notably that at Teplice, to “take the cure.” Other works were uppermost in his mind, though, in particular the Eighth Symphony, which occupied much of the rest of 1812. He resumed the Violin Sonata in Vienna later that year. Its first performance was on December 29, 1812 at the home of one of the composer’s primary benefactors, Prince Lobkowitz, featuring the French violin virtuoso and composer Pierre Rode. The pianist for the occasion was not Beethoven himself, as would have been usual, but another of the composer’s financial backers, the Archduke Rudolph — who had been his piano student since 1803.

“I have not been in a great rush to compose the last movement merely for the sake of being punctual,” Beethoven wrote, clandestinely, to the Archduke, “but more because, in view of Rode’s playing, I have had to give more thought to the composition of this movement. In our Finales, we like to have fairly noisy passages, but Rode does not care for them.”

Evidently Rode’s playing had begun to drop off during these years, and although it might be simplistic to say that Beethoven altered his music, the violinist was indeed known for being ill-prepared for public performances. It is of some note that when the sonata was published in 1816, it bore a dedication not to Rode but to Rudolph. The Archduke had of course been a major source of income for the composer for many years; he also was possibly the closest thing that Beethoven ever had to

a best friend. He became the dedicatee to a large number of Beethoven’s major works: the Piano Trio Op. 97 (now known as the “Archduke” Trio), the Fourth and Fifth Piano Concertos, the Grosse Fuge, three piano sonatas including “Les Adieux,” and most notably the Missa Solemnis, composed for the Archduke’s consecration as Archbishop of Olomouc (though not completed in time for his ceremony).

The opening movement (Allegro moderato) is unlike anything in Beethoven’s chamber music up to this point. Beginning with gentle, bird-like trills and declamatory phrases, it embarks on a serene and emotionally uncomplicated journey of exploration — including surprising, yet naturally flowing, adventures into remote keys. Here as elsewhere in the sonata, we seem to be looking ahead, to elements of the composer’s heavenly late style. The Adagio espressivo explores the tranquil landscapes of Beethoven’s best slow movements; in rather unprecedented fashion, it leads directly into a disruptive Scherzo: Allegro in G minor, whose Trio (set in the Adagio’s key of E-flat major) attempts, perhaps, to join slow movement and scherzo into a single unit. The finale (Poco allegretto) is a set of variations on a deceptively innocuous theme, which nevertheless invites, again, a passage of E-flat major toward the end.

Ravel is known to concertgoers chiefly for his extroverted orchestral works, yet no full understanding of his music is complete without an exploration of the smaller-scale works. In addition to the large number of solo piano works are seven major chamber works that present a variety of styles and approaches.

Beginning with the Debussy-influenced String Quartet from 1903, Ravel explored combinations with harp, winds, and strings (Introduction and Allegro), then wrote a Basque-influenced Piano Trio, a sweetly impressionistic Cello Sonata, and the fiery, Roma-inspired Tzigane (“in the style of a Hungarian rhapsody,” the composer wrote), which began as a virtuoso concert-piece for violin and piano before it was orchestrated in 1924. Some say Ravel saved the best for last. The quirky Violin Sonata in G major is called No. 2 today only because of a posthumously published student piece from 1897 that came to be called “No. 1.” The Sonata No. 2 was composed in 1923, not long after Ravel had moved to a country house in Montfort-l’Amaury in the north of France. He befriended the violinist Hélène Jourdan-Morhange, with whom he shared a love of jazz, and dedicated the sonata to her. It was Georges Enescu, however, who presented the world premiere, in 1927 in Paris, with the composer at the keyboard.

The individualistic approach to violin-piano texture in the opening movement (Allegretto) calls to mind Ravel’s own reservations about the compatibility of the sound of the piano with string instruments. He is known to have stated that, in his view, the violin and the piano were “essentially incompatible instruments, which not only do not sink their differences, but accentuate incompatibility to an even greater degree.” The result, however, does not betray any sense of conflict in the inception of this dazzlingly subtle movement, which gives proper due to each instrument even if they do each seem at times to ignore the presence of the other player. (Some have suggested that violin and piano begin in different keys, ostensibly at least, not joining up until nearly 20 bars into the movement.)

Ravel’s fascination with jazz had begun in the early 1920s, some of which he had heard in Paris after World War I. (There are even bits of ragtime in the 1919 chamber opera L’enfant et les sortilèges.) In 1928 Ravel would travel to America, finally, where he saw Funny Face on Broadway, visited the Cotton Club and Savoy Ballroom in Harlem, and arranged for a meeting with George Gershwin, who performed his Rhapsody in Blue for the awed Frenchman.

Ravel would later incorporate elements of jazz into his music, most famously in his Piano Concerto in G and the Concerto for the Left Hand. But the earliest appearance of true jazz idiom is found in this sonata’s slow movement (Moderato). Opening with banjo-like “strumming” in the piano, the violin “sings” what Ravel calls blues here, complete with flatted thirds and sevenths and torchy portamento slides; the musicians then switch roles momentarily in the middle of the movement. In contrast to this lugubrious interlude is the wildly motoric finale (Perpetuum mobile: Allegro), whose charisma provides almost no relief for the violinist.

The composer would later advocate for more attention to jazz styles, criticizing his “serious” American counterparts for not taking the music more to heart. “I greatly admire and value — more, I think, than many American composers — American jazz,” he said to The New York Times’ critic Olin Downes. “I am waiting to see more Americans appear with the honesty and vision to realize the significance of their popular product, and the technique and imagination to base an original and creative art upon it.”

Nadia Boulanger entered the Paris Conservatory at the remarkable age of nine, where among her teachers was Gabriel Fauré. She also took private lessons with organistcomposer Louis Vierne and others. Nadia tried repeatedly to earn the Conservatory’s prestigious Prix de Rome, but in the end it was her gifted younger sister, Lili, who became the first woman ever to win the fellowship. The year was 1913, and 19-year-old Lili wowed the judges with her grand cantata Faust et Hélène. Lili, who completed her prize year in Rome despite illness, was one of the most brilliant composers the Conservatory had ever seen, but her career was cut short when she succumbed to bronchial pneumonia and probably tuberculosis at the age of 24.

The Boulanger sisters grew up in an aristocratic and profoundly musical family. Their mother was a Russian princess, Raissa Myshet skaya, their father was the prominent composer Ernest Boulanger. Paternal grandparents were Frédéric Boulanger, a renowned Paris Conservatory professor, and the mezzo-soprano Marie-Julie Halligner, a distinguished Parisian opera star. Both sisters left their mark. Nadia grew into a gifted pianist, a disarming composer, and one of the most influential teachers of the 20th century. Among her students of harmony, counterpoint, and composition — mostly at the American Conservatory at Fontainebleau — were Aaron Copland, Elliott Carter, Astor Piazzolla, Philip Glass, David Diamond, Quincy Jones, David Conte, and even conductors such as Daniel Barenboim, Igor Markevitch, and John Eliot Gardiner. Nadia’s music, which often suggests the influence of Debussy, is marked by transparent textures, chromatic harmonies, and meticulous counterpoint. She wrote Soleils Couchants in 1909 on the opaque, achingly beautiful text of Paul Verlaine, the influential Symbolist poet of the 19th century. The vocal setting, arranged here for violin and piano, moves toward an emotional “ping” at each mention of setting suns and reaches a climax at “strange dreams, like suns setting on the shores, vermilion ghosts, drifting endlessly.” The song is an extraordinarily profound and perceptive reflection of the text.

Setting suns (Paul Verlaine)

A faint dawn pours onto the fields the melancholy of setting suns.

The melancholy lulls, with sweet songs, my heart, which forgets itself to the setting suns. And strange dreams, like suns setting on the shores, vermilion ghosts, drifting endlessly, are still drifting, like great suns setting on the shores.

Lili’s compositional output, produced largely between 1909 and her death in 1918, consists primarily of choral works, chamber music, and songs. Deux Morceaux were composed for violin (or flute) and piano in 1911 and 1914. Like her sister, Lili felt the profound impact of the music of Debussy, and much of her music walks a line between the late-Romantic world of Fauré and the impressionistic styles of the early-20th century. The Nocturne, dedicated to a family friend, Marie-Danielle Parenteau, is a serene evocation of night, with lush pedal tones and rocking rhythms in the piano that are like water lapping against a shore. Lili evidently created an orchestral version of this lovely piece that included harp, clarinet, and strings, but it was never published and is currently lost. The lively Cortège was composed in June 1914, when Lili was staying at the cold and damp Villa Medici during her Prix de Rome residency (which had been delayed because of illness). The piece conveys an energetic, rather than a funereal, cortège. It bears a dedication to Yvonne Astruc, a violinist friend of the Boulangers, who recorded the piece in 1930 with Nadia at the piano.

Of the three most revolutionary composers of the first half of the 20th century — Schoenberg, Stravinsky, and Bartók — it is the last-named whose imprint on subsequent music is the most difficult to assess. Arnold Schoenberg, who devised a potent and widely imitated system for atonal composition, remains the most influential intellectual musical figure of the past century. Even though his music is seldom played, his example came to be viewed as the inevitable end-game of the “breakdown of tonality” that began in the late-19th century and continued into the early-20th. Stravinsky, ostensibly the most accessible composer of the

three, has become a household name. Less cosmopolitan than Stravinsky and less relentlessly systematic than Schoenberg, Bartók forged a peculiar style that was more personal and more specifically “national” (though not “nationalistic”). While Stravinsky was the darling of the Parisian avant-garde, Bartók made arduous travels through villages in Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and even northern Africa, transcribing thousands of folk tunes and recording many with primitive wax cylinder technology — the melodic substance of which would, eventually, seep into his own music. Knowing Bartók’s relationship to folk music is essential in understanding his music beginning around 1920 — when the composer began to seek ways to fuse the folk tunes he had gathered with densely sophisticated tonal and rhythmic styles. This was also a period in which Bartók’s fame began to spread. In the spring of 1922, his theater works Duke Bluebeard’s Castle and The Wooden Prince were mounted in Frankfurt. In August of that year, the First Violin Sonata appeared on the program of the First International Salzburg Festival. The following year, his Second Sonata was performed at the first meeting of the International Society of Contemporary Music. Also during this period, works such as the Piano Sonata, the First Piano Concerto, and the Out of Doors suite were warmly received.

One of the most interesting families of the Bartók circle during the 1920s were the d’Aranyis, two of whose three daughters — Adila and Jelly — were gifted violinists. (They were also great-nieces of Joseph Joachim, Brahms’ favorite violinist.) Bartók grew fond of the girls, and especially of Jelly, who in 1921 asked him to write a violin sonata for her. It was a joyous task for the composer, partly because he was in the midst of his complex and controversial Miraculous Mandarin score at the time. (Jelly d’Aranyi was also the dedicatee of Ravel’s Tzigane and of works by Vaughan Williams and Holst.) Bartók completed the score in November 1921, and during his London tour as concert pianist the following year he and Jelly performed it at a private recital. The sonata would later receive its public premiere in Vienna by violinist Mary Dickenson-Auner and pianist Eduard Steuermann. Bartók would also dedicate his Second Sonata (1922) to Jelly, which the two performed in London in May 1923. These sonatas remain two of the composer’s most fascinatingly complicated, yet ineffably engaging, instrumental works. “The tonal language can often seem unfamiliar, exotic to the point of austerity,” writes the violinist James Ehnes, “or even downright confusing upon first hearing, but the infectious rhythms and the intensely personal narrative of the solo lines are elements with which one can immediately connect.” The opening Allegro appassionato is rhapsodic, severe, dissonant, and ultimately lyrical. Constant shifts of texture, tempo, and mood create a cataclysm of emotions, which builds to a climax that then descends into a restatement of the initial themes. The plaintive Adagio opens with a cadenza-like solo from the violin; ultimately the piano joins with markedly tonal harmonic material. The Allegro finale is a series of increasingly violent episodes, folk-like in character and culminating in a stamping, percussive climax and bracing coda. Here both musicians are pushed perhaps a bit beyond the normal virtuosic requirements of a sonata.

The Park University International Center for Music Foundation exists to secure philanthropic resources that will provide direct and substantial support to the educational and promotional initiatives of the International Center for Music at Park University. With unwavering commitment, the Foundation endeavors to enhance awareness and broaden audiences across local, national, and international spheres.

Vince Clark, Chair

Steve Karbank, Secretary

Marilyn Brewster

Lisa Browar

Stanley Fisher

Brad Freilich

Ron Nolan

Benny Lee, Treasurer

Shane Smeed

John Starr

Steve Swartzman

Angela Walker

Karen Yungmeyer

Stanislav Ioudenitch, Founder & Artistic Director, Piano Studio

Behzod Abduraimov, Artist-in-Residence

Gustavo Fernandez Agreda, ICM Coordinator

Peter Chun, Viola Studio

Lolita Lisovskaya-Sayevich, Director of Collaborative Piano

Steven McDonald, Director of Orchestra

Ben Sayevich, Violin Studio

Daniel Veis, Cello Studio

The Park University International Center for Music’s Patrons Society was founded to help students achieve their dreams of having distinguished professional careers on the concert stage.

Just as our faculty’s coaching is so fundamental to our students’ success, our Patrons’ backing provides direct support for our exceptionally talented students, concert season, outreach programs and our ability to impact the communities we serve through extraordinary musical performances.

We are continually grateful for each and every one of our Patrons Society members. For additional information, please visit ICM.PARK.EDU under “Support Us.”

We gratefully acknowledge these donors as of April 15, 2025.

SUPERLATIVE

Brad and Marilyn Brewster *

Steven Karbank

Benny and Edith Lee

Ronald and Phyllis Nolan

John and Debbie Starr

Steven and Evelina Swartzman

Jerry White and Cyprienne Simchowitz *

SUPREME

Jeffrey Anthony

Brad and Theresa Freilich

Shirley and Barnett C. Helzberg Jr. *

Holly Nielsen

Steinway Piano Gallery of Kansas City

Gary and Lynette Wages

EXTRAORDINAIRE

Vince and Julie Clark

Stanley Fisher and Rita Zhorov *

Susan Morgenthaler *

Rob and Joelle Smith *

Kay Barnes and Thomas Van Dyke

Lisa Browar

Mark and Gaye Cohen

Suzanne Crandall

Charles and Patty Garney *

Doris Hamilton and Myron Sildon

Colleen and Ihab Hassan

Lisa Hickok and Brian McCallister *

William and Regina Kort

Jackie and John Middelkamp *

Kathleen Oldham

Kevin and Jeanette Prenger, ’09 / ECCO Select

James and Laurie Rote *

Stanley and Kathleen Shaffer

Guy Townsend

John and Angela Walker *

Nicole and Myron Wang*

Phil and Barbara Wassmer *

* 2024-2025 Member

Maria and Stanislav Ioudenitch in recital (presented in partnership with Park ICM)

Wednesday May 7, 2025 7:30pm 1900 Building

An evening of chamber music with Beethoven, Alberga and Brahms.

Friday May 9, 2025 7:30pm. 1900 Building

NAVO Chamber Orchestra led by Shah Sadikov performs Montgomery, Mozart, and Lena Frank.

Sunday May 11, 2025 2pm. Southminster Presbyterian Church

Imagine hearing — and seeing — every keystroke of a world-class piano performance in your own home. With spirio , you can enjoy music captured by renowned pianists, played with such nuance, power, and passion that it is utterly indistinguishable from a live performance.

Thousands of recordings by steinway artists are available at the touch of a button on the included iPad.

The library of music, videos, and playlists expands monthly and spans all genres. In addition to today’s greatest musicians, spirio delivers historic performances by steinway immortals , including Duke Ellington, Glenn Gould, Art Tatum, and many more.

- Becky N. Lowry, MD Physician Internal Medicine

For me, there’s nothing more rewarding than the meaningful connections I make with my patients. Maybe it’s growing up in a small town where those personal values remain strong. Or maybe it’s the belief, shared with all of my co-workers, that people come first. Whatever it is, the opportunity to provide care is a privilege I never forget. To schedule an appointment, call 913-588-1227 or visit KansasHealthSystem.com/Appointments.