from the

Northern New Mexico agriculture & the farm-to-table vision of Juliette

by ELLEN MILLER-GOINS IN NORTHERN NEW MEXICO

, agriculture is less about industrial output and more about heritage — an interplay between land, tradition and community. Nowhere is that more evident than at Juliette, the intimate restaurant at Hotel Willa in Taos. Under the guidance of chef Johnny Ortiz-Concha, Juliette serves food that honors the region’s agrarian past while embracing a modern, nurturing philosophy.

Ortiz-Concha, a Taos native, did not grow up farming, but

he speaks of agriculture with reverence and commitment.

“I grew up in Taos, in my father’s family, and at the Pueblo,” he explains. “That family was a big farming family, so it was in my blood.”

Today, he and his wife, Maida Branch, operate a 50-acre farm where they raise Criollo cattle and Churro sheep and carry on traditional practices, from digging clay for ceramics to foraging wild plants.

We designed Juliette to be kind of a-cultural, The menu consists of local ingredients, raised and harvested with intention and integrity.

The exhibition Timeless Turns: The Legacy of Tío Vivo is on view in the 1830s Luna Family Chapel through October 2025.

TOP: Unidentified girl rides the Tío Vivo carousel at Taos Fiesta 1940; photo by Russell Lee, courtesy Library of Congress.

ABOVE: Jim and Christen Vogel, In Pursuit of Bandits, El Caballito BreaksFreefromFlyingJinny (detail), 2025, oil on panel with vintage boardgame and carrum board, 28.25 x 28.25 in

The 2+ acre campus of Couse-Sharp Historic Site in the heart of Taos features the former homes, studios, and gardens of E. I. Couse and J. H. Sharp, two founders of the Taos Society of Artists. The complex of 19th and early 20th century buildings with original furnishings, ephemera, and art collections entices visitors into the confluence of creativity Taos represents.

We offer exhibition hours, in-depth docent-led site tours by appointment, a unique research center for the study of early Taos art and its cultural context, and special events.

At Juliette, those values trans late into a kitchen where nearly every ingredient is scrutinized — not just for flavor, but for authenticity.

“We designed Juliette to be kind of a-cultural,” Ortiz-Con cha says. “The menu consists of local ingredients, raised and harvested with intention and integrity.”

Though the food isn't overtly New Mexican in style, it's deeply rooted in the soil of the region: spicy pickled car rots from Umami Gardens in Abiquiú, mountain oregano on house-made sheet bread, and herbs from the hotel’s edible garden all speak to the land’s offerings.

The area’s agricultural traditions stretch back more than 2,500 years, with Indigenous communities like the Pueblo peoples cultivating the “Three Sisters” — corn, beans and squash — in sophisticated companion planting systems. In this triad, each crop supports the others: corn provides a trellis for beans; beans fix nitrogen in the soil; and squash shades the ground to retain moisture. These time-tested methods are still relevant in today’s food systems and serve as a blueprint for sustainable agriculture around the globe. Juliette doesn’t replicate these traditions verbatim but draws from their spirit. The restaurant’s edible garden was designed for practical

I grew up in Taos, in my father’s family, and at the Pueblo. That family was a big farming family, so it was in my blood.

continued from 18

use, focusing on perennial herbs like mint and mountain oregano that enrich seasonal dishes.

“We figured we’d be too busy to grow things like radishes or tomatoes,” Ortiz-Concha admits. “So we really went for mostly herbs, and that’s going really well.”

Perhaps the clearest distinction in Ortiz-Concha’s work lies in the contrast between Juliette and /shed, the private, membership-based dinner project he and Branch created. If Juliette is a refined, public-facing extension of their culinary ethos, /shed is its wild, deeply personal counterpart. At /shed, every detail — from the clay plates to the foraged chokecherries — is an homage to New Mexico’s raw terrain.

“It allows us to do things restaurants can’t do legally,” Ortiz-Concha notes. “We serve milk from our cow or nettles from the mountains.

Juliette is the domestic version; /shed is the wild one.”

Still, the two projects share a core belief: that food should be nurturing, honest and grounded in place. At Juliette, this philosophy translates into thoughtful decisions like using grass-fed beef tallow for French fries, or sourcing green chile from Don Bustos, whose family has cultivated the same seeds in Santa Cruz for generations.

continued on 24

ing expansion on sacred land, and resisting threats to sacred sites like Chaco Canyon itself.

“We started that [DNA project] … be cause of our water situation,” Picuris Pueblo Lt. Gov. Craig Quanchello says. “Our water has been stolen for about 201 years now, and we're trying to get it back."

‘‘

It was during that struggle for wa ter rights that the Pueblo turned to science as a new tool in an old fight. Quanchello, then serving as governor, initiated a partnership with renowned geneticist Dr. Eske Willerslev of the University of Copen hagen, who had gained international acclaim for analyzing the DNA of Sitting Bull.

Published in Nature in April 2025, the study sequenced the genomes of 16 ancient Picuris individuals and compared them with 13 living members of the tribe. The findings showed strong genetic continuity — and a clear link to individuals buried at Chaco Canyon’s Pueblo Bonito, the largest of the great houses that once anchored a vast political and spiritu al network

Crucially, the study was led by Picur is and conducted under their terms.

“This time, the tribe was involved in every step,” Quanchello emphasiz es. “That was important. Too many times before, we’ve been excluded."

Located in the Hidden Valley of the Picuris Mountains, Picuris Pueblo has been continuously inhabited for over 700 years. Archaeological evi dence dates occupation as far back as 1250 C.E., with micaceous pot tery, elaborate kivas and ceremonial

We started that [DNA project] … because of our water situation. Our water has been stolen for about 201 years now, and we're trying to get it back.

... Our traditions speak to this link. This DNA, it just gives voice to what we’ve always known.

Picuris Pueblo Lt. Gov. Craig Quanchello

murals affirming its cultural rich ness. Scholars have often debated what became of the Chacoan peo ples after the canyon’s depopulation in about 1150. But Picuris' oral history has long pointed to a migratory con nection — a belief now strengthened by both science and archaeology.

“Our traditions speak to this link,” Quanchello says. “This DNA, it just gives voice to what we’ve always known.”

Even as Picuris gains recognition for its historical and cultural signif icance, the community continues to fight for something more elemental: water.

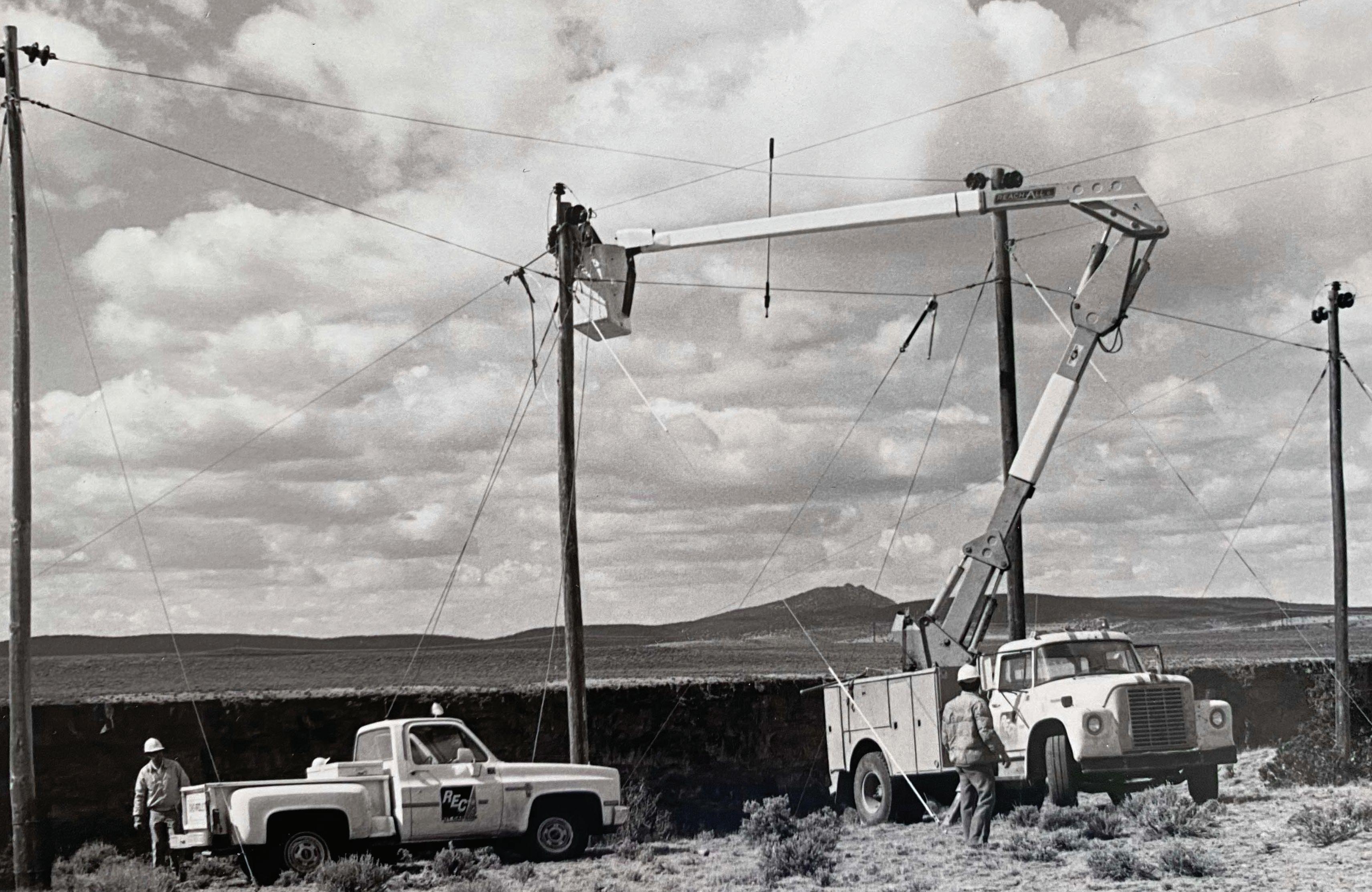

For over two centuries, water that once flowed through the Pueblo’s Rio Pueblo watershed has been diverted over the Sangre de Cristo Mountains to irrigate farms in the Mora Valley. Three diversions — con structed between 1820 and 1882 — carry the waters of Alamitos Creek, Rito la Presa and Rito Angostura to Mora Valley acequias in Cleveland, Chacon and Holman.

continued on 36

IN 2021 , Pueblo leaders visited Alamitos Creek and were stunned to see a newly cemented diversion berm — one without even a headgate to allow flow toward Picuris.

Outraged, Quanchello declared, “It’s time to take it into our own hands … It’s going to get dirty. Someone’s going to get hurt.”

Soon after, the berm was mysteriously breached. No one claimed responsibility. The Office of the State Engineer declined to speculate. But for the Pueblo, it was a symbolic act of resistance.

“We’ve never relinquished our rights,” Quanchello says. “Not to land, not to water. We’re still here.”

Another battle plays out on Copper Hill, a windswept summit stained blue and green by mica and copper remnants. Once the site of traditional clay gathering — called “Mowlownan-a” or “pot dirt place” — the land was later buried under tons of waste rock from open-pit mica mining.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, the Picuris fought to reclaim the land from Oglebay Norton Specialty Minerals. The Pueblo argued the land was never rightfully ceded and filed an aboriginal title claim. Though their initial legal challenge was dismissed, they ultimately succeeded in halting further mining and negotiated the return of the land.

In 2005, Picuris purchased the U.S. Hill Mine outright. By 2009, the Pueblo completed full reclamation of the site — planting seeds on the scarred earth and reestablishing access to the sacred clay source.

But it wasn’t just about restoring land.

“There’s a deep connection between the loss of our clay and the erosion of our language and culture,” Quanchello says. “Bringing that place back was like bringing part of our identity back.”

With their DNA now linking them directly to Chaco Canyon, the Picuris have joined a broader coalition of Pueblo nations opposing oil and gas drilling near the sacred site. The Biden administration’s 20-year ban on new leases within 10 miles of the Chaco Culture National Historical Park, issued in 2023, was a hard-won

‘‘ We’ve never relinquished our rights; not to land, not to water. We’re still here.

Picuris Pueblo Lt. Gov. Craig Quanchello

victory. But it now faces threats from H.R. 4374 — the “Energy Op portunities for All Act”— sponsored by Arizona Republicans and backed by energy interests.

Tribal leaders argue Chaco’s fragile structures cannot withstand the vibrations of nearby drilling.

“We were seeing signs of deteriora tion,” Quanchello says, noting that the Bureau of Land Management continued to issue leases despite the moratorium.

To bolster their advocacy, Picuris cited the DNA study as proof of ancestral ties to the site.

“We lobbied hard to stop the drill ing. The DNA just gave us another tool, another way to be heard,” Quanchello explains.

TOWARD

Today, the Picuris number fewer than 400, but their vision is expan sive.

Their field school collaborations with institutions like Barnard College and the Archaeological Institute of America are training a new generation in ethical, commu nity-led research. Their legal and scientific strategies are creating new models for tribal sovereignty and historic preservation.

BUT FOR QUANCHELLO , it always comes back to the land — and the people.

“Our DNA might tell the story in one way,” he says. “But it’s our stories, our songs, our fields, our fight — that’s what really ties us to this place.”

As science finally catches up with Indigenous truth, Picuris Pueblo continues to assert its presence — not just as descendants of Chaco, but as protectors of a legacy still unfolding in the canyons, rivers and sacred soil of Northern New Mexico.

Abel, Heather. “On the Trail of Mining.” High Country News (June 23, 1997).

Benanav, Michael. 2021. “Picuris Pueblo in New Mexico Fights Centuries-Old Water Battle.” Searchlight New Mexico (Dec. 16, 2021).

Kuipers, James R. 2010. “Reclamation of the US Hill Mica Mine.” Kuipers & Associates, LLC.

Lohmann, Patrick. “House Spending Bill Would Ban Chaco Area Drilling.” Source New Mexico (Sept. 15, 2021).

Pinotti, T., Adler, M.A., Mermejo, R. et al. 2025. “Picuris Pueblo oral history and genomics reveal continuity in US Southwest.” Nature, ed. 642 (April 30, 2025).

Radley, Dario. 2025. “Ancient DNA confirms Picuris Pueblo’s ancestral link to Chaco Canyon.” Archaeology News (May 1, 2025).

She is survived by her daughters Linda Diaz and Kathy Fierro, and granddaughter Jenelle Roybal, whom she raised, and is also survived by a large and numerous family.

Her brothers Jacob and James "Jimmy" Viarrial served as governors of the Pueblo of Pojoaque, and now her granddaughter, Jenelle Roybal, is serving as the governor of Pojoaque Pueblo, as well.

Maria Phoebe Petty Viarrial is recognized and honored here as a beloved and strong matriarch of the Pueblo of Pojoaque, El Norte and regions beyond.

A 14-year-young person can be recognized as a great and inspiring soul. Such was Violet Michele Xolpaxwii Shields, who succumbed to the ravages of cancer on Sept. 17, 2024 at the age of 14. The words of her mother follow here:

"Violet was born in Santa Fe, NM on August 21, 2010, on a beautiful summer day, while sunflowers bloomed. Her mother, Feliza is from Santa Fe. Her father, Dewey is from Picuris Pueblo and Mescale ro. Violet was a gift from the Divine and the greatest blessing in her parents' lives. She cared greatly to not hurt anyone. Her intellect was very sharp and it poured out from her old, deep soul. She was described as a role

school sports, loved music and played various instruments, and loved to dance, especially Flamenco.

"One of her favorite times was dancing Matachines at Picuris for Christmas, as the Malinche dancer when she was age seven, as well as the other traditional dances, and took part in pueblo life.

"At age 12 she was diagnosed with bone cancer in her upper right arm. The cancer

tained Honor Roll and played French Horn in band though it was hard to breathe [with] radiation and chemotherapy.

"Violet is a massive soul made of brilliant light, and lived as a radiant love on this Earth. This is why her mother nicknamed her, 'UltraViolet.' Her absence is a super massive black hole in our hearts and we yearn to be with her again when our time here is done."

Violet remains a great inspiration in El Norte and beyond. Help fight childhood

Ambrose J. Mascarenas of Llano, a strong and inspiring leader and fine "caballero" for many decades in Taos County and El Norte, died on Feb. 7, 2024 at age 85.

He was a man of many accomplishments. He was born June 21, 1938; he attended middle school in Vadito and high school in Tooele, Utah, and he returned to graduate from Peñasco High School. He and his wife, Mary Trujillo Mascarenas, were married on Sept. 22, 1958 at San Antonio Padua Church in Peñasco.

He served in the U.S. Army Reserves and also worked in law enforcement and in mining, including in Grants-area uranium mines. In 1963 he and Mary returned to their ranch lands in Llano; he was never idle and was known as a hard worker.

He had a tremendous sense of humor, and was a talented guitarist, playing the guitarron and singing at family, church and community events.

continued on 52

Let the river guide you — into the heart of Northern New Mexico

by ELLEN MILLER-GOINS

THE EMBUDO VALLEY

along the Rio Grande on NM 68 between Española and Taos is a patchwork of acequias, orchards, farms, vineyards and mountain views — a place where history, geology, agriculture and art intersect to create one of Northern New Mexico’s most unique areas. A destination for wine lovers, curiosity seekers and art collectors, Embudo and Dixon are villages

that pulse with tradition.

“Embudo,” meaning “funnel” in Spanish, is named for the conical hills through which the Rio Embudo empties into the Rio Grande. The valley itself is part of the Rio Grande Rift, a vast geologic fracture that stretches from Colorado to Texas. This rift, created by tectonic forces some 29 million years ago, forms the Rio Grande Gorge. According to geologist Thomas Charlton, “the valley appeared first, and the river followed,” flowing

through a corridor formed by volcanic upheaval and subsidence. The Taos Plateau and Española Basin are part of this complex, layered geology that includes lava flows, fault lines and sediment-filled grabens.

Modern settlement in Embudo began with the 1725 Embudo Land Grant, but the valley’s 20th century character was forged by two driving forces: the railroad and the Presbyterian mission movement.

Embudo Station, opened in

1881 by the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad on its narrow-gauge “Chili Line,” was vital for transporting local chile, wool and goods to markets in Colorado. Locals called it the "lifeline of the valley." According to local memoirist Antonio Durán, the train was so beloved that even its mispronunciations — “Emburro” for Embudo — became part of local lore. Durán’s recollections highlight the train’s impact on village life before the rails ceased operation in the 1940s. continued on 58

Since 1965, Florence Jaramillo (Mrs. J ) and Rancho de Chimayó have honored the legacy of New Mexico through the recipes, stories, and traditions passed down through generations. Join Mrs. J throughout the year for monthly specials that celebrate Rancho’s rich history — and this October, join us for anniversary specials to commemorate 60 unforgettable years!

Rancho de Chimayó ... a timeless tradition.

aboard the

Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad which operates in the scenic landscapes of

aboard the historic Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad which operates in the scenic landscapes of

Colorado and northern New Mexico. Journey back in time experiencing the Old West as it was in 1880, as you venture over the highest mountain pass reached by rail, cross gorges and trestles, blast through tunnels, and chug across alpine meadows and high deserts. Depart from Antonito, Colorado or Chama, New Mexico for a ride of a lifetime!

Climb aboard the historic Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad which operates in the scenic landscapes of southern Colorado and northern New Mexico. Journey back in time experiencing the Old West as it was in 1880, as you venture over the highest mountain pass reached by rail, cross gorges and trestles, blast through tunnels, and chug across alpine meadows and high deserts. Depart from Antonito, Colorado or Chama, New Mexico for a ride of a lifetime!

Climb aboard the historic Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad which operates in the scenic landscapes of southern Colorado and northern New Mexico. Journey back in time experiencing the Old West as it was in 1880, as you venture over the highest mountain pass reached by rail, cross gorges and trestles, blast through tunnels, and chug across alpine meadows and high deserts. Depart from Antonito, Colorado or Chama, New Mexico for a ride of a lifetime!

Colorado and northern New Mexico. Journey back in time experiencing the Old West as it was in 1880, as you venture over the highest mountain pass reached by rail, cross gorges and trestles, blast through tunnels, and chug across alpine meadows and high deserts. Depart from Antonito, Colorado or Chama, New Mexico for a ride of a lifetime!

by ELLEN MILLER-GOINS

UST ABOVE ESPAÑOLA’S HISTORIC PLAZ A , the Bond House Museum invites visitors to explore the community’s Native, Hispanic and Anglo roots. Once the residence of businessman and civic leader Frank Bond, the home today offers an immersive journey into the layered history of the Española Valley.

Built in 1887, the original structure was a modest tworoom adobe built by Frank Bond after his arrival from Quebec, Canada. He and his brother, George, had moved to Española during its early railroad boom to establish GW Bond & Bro., a mercantile venture that would grow into the largest wool and mercantile empire in New Mexico. Frank Bond was also an instrumental leader, serving as Española’s first ex officio mayor. By 1911, Bond expanded the home with a two-story territorial-style addition, blending adobe with Victorian elegance — red-tile gabled roof, dormer windows, brass fixtures and a columned front porch.

“The house itself tells the story of how Española transitioned from a tent town into a commercial center,” says Norman Doggett, a docent with the San Gabriel Historical Society, which operates the museum.

Permanent exhibits introduce visitors to the region’s early Pueblo inhabitants, the impact of the railroad and the "Chile Line," and the rise of early merchants — including the Bonds themselves. The museum’s rotating exhibits have ranged from lowrider art and petroglyph projects to local quilt collections and a “Valley Heroes” tribute featuring over 100 community-nominated residents.

“We try to make the exhibits

engaging for all ages,” Doggett says, noting that school groups are encouraged to create craft projects tied to each exhibit’s theme. “It’s about building a connection between our history and the younger generation.”

Artifacts housed in the museum include military memorabilia honoring Española’s veterans, antique farm tools from local donors, yearbooks from area high schools, and a 15-minute slideshow of archival photographs that chart the town’s transformation through the decades.

The Bond House itself has survived adversity. A fire in the 1930s destroyed the kitchen ceiling but spared the rest of the structure. After being sold to the city in 1957 for $10,000, the home was used for municipal offices until 1978. Thanks to community advocacy and the San Gabriel Historical Society, the home was saved from demo-

lition, placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980, and restored in 2000.

Dedicated as the Bond House Museum and Cultural Center in 1982 it now stands as one of the few historic anchors in a town struggling to preserve its past amid modern development.

“The Bond House is a reminder of what Española once was — and what it can still become,” Doggett says.

The Bond House Museum is open through the efforts of volunteers and donors. For more information or to support the museum, visit the San Gabriel Historical Society or contact bondhouse@espanolanm.gov.

Bond House Museum

105 W Palace Ave, Santa Fe 505-476-5200

Open Wednesday, Friday and Saturday, noon–4 p.m. bit.ly/bondhousemuseum

THIS 200-YEAR-OLD ADOBE holds a complex piece of American history. The Carson House & Museum, once a Masonic tribute to the legendary frontiersman, is undergoing a transformation — one that seeks to engage with the full breadth of Carson’s legacy and the contested history of U.S. expansionism in the Southwest.

Built in 1825 and purchased by Carson in 1843 as a wedding gift for his bride, Maria Josefa Jaramillo, the house became a family home for more than two decades. Carson and Josefa raised their children here, including adopted Native American orphans. But Martin Jagers, board president of Kit Carson House Inc., which operates the museum, emphasizes that the story is no longer about glorifying a single man — it’s about embracing a more inclusive narrative.

“The house is a lens into a much broader story,” Jagers says. “We’re adopting a framework promoted by the American Association for State and Local History that encourages museums to move beyond static storytelling and in-

corporate multiple perspectives — especially those that have been historically marginalized.”

That shift is critical when addressing Carson’s most controversial role: his leadership in the 1863–64 Navajo Campaign that culminated in the Long Walk. Though Carson initially refused orders to forcibly relocate the Diné, he ultimately led a brutal campaign that devastated Navajo communities.

“It's not about erasing Carson,” Jagers says. “It’s about telling the truth — even when that truth is hard.”

Current exhibits still reflect the museum’s earlier focus. Rooms are sparsely furnished, with panels highlighting Carson's career as

by grants from the Town of Taos and the State Historic Preservation Office, the museum recently completed drainage work to protect the adobe. A preservation plan identifies the adjacent Romero House as a future phase, with hopes to open it as exhibit space.

“We envision using the Romero House to explore the broader impacts of Westward expansion,” Jagers says. “That includes the Governor Bent assassination, the Taos Revolt, the Navajo campaign, and how all of this affected Native, Hispanic, and settler communities in Northern New Mexico.”

Carson’s wife, Josefa Jaramillo, a prominent Taoseña and sisterin-law to Governor Charles Bent, plays a key role in this reimagined story.

“Our new signage is The Carson House & Museum,” Jagers says. “It reflects Kit, Josefa and family. We want to expand on Josefa’s

preserving the household while Kit was away.” Josefa and Kit are buried together just down the street in Kit Carson Park, now the focus of a renaming effort that reflects changing community values.

Meanwhile, the museum is developing new ways to engage visitors. An upcoming outdoor exhibit — funded by Taos County lodgers' tax — will feature QRcode audio stations about adobe construction, recent restoration, and Carson’s legacy.

“We’re not trying to tell people what to think about Kit Carson,” Jagers says. “But we are committed to presenting history honestly and inclusively — because that’s what this community deserves.”

Carson House & Museum

113 Kit Carson Road, Taos. 575- 758-4945

Open Monday through Saturday, 11 a.m.–4 p.m.; and Sunday, noon–4 p.m. kitcarsonhouse.org

At CHRISTUS St. Vincent Regional Cancer Center, our team of experts provide patients with the most comprehensive cancer treatment. And, because of our membership in the Mayo Clinic Care Network, our providers can access the clinical trials and second opinions on your behalf—at no additional cost to you.

Only

•Radiation

•Infusion center

•Advanced technology

CHRISTUS St. Vincent

Regional Cancer Center

445 St. Michael’s Drive

Santa Fe, NM 87505

(505) 913-8900

•Imaging

•Nutritional guidance

•Acupuncture

•Clinical trials

•Supportive care

•Massage therapy