EDITORIAL

EDITOR IN CHIEF

EDITOR | HOW TO BUILD IT

EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTOR

NEWS EDITOR

FEATURES EDITOR

FEATURES WRITER

WRITER

SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER

CONTENT CREATOR

Francesca Webster

Justin Ratcliffe

Charlotte Thomas

Sophie Spicknell

Emma Dailey

Enrico Chhibber

Ellen Ranebo

Marina Vargas

Nick Smits

DESIGN PRODUCTION

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

GRAPHIC DESIGNER

Ivo Nupoort

Beatriz Ramos

INTELLIGENCE

HEAD OF INTELLIGENCE

RESEARCH ANALYST

DATABASE MANAGER

YACHT HISTORIAN

Ralph Dazert

Adil Zaman

Syrine Mellakh

Malcolm Wood

SALES & ADVERTISING

HEAD OF SALES

SALES MANAGER

SALES MANAGER

SALES MANAGER

SALES MANAGER

CLIENT SERVICE MANAGER

SALES ITALY

Marieke de Vries

Justus Papenkordt

Daniel Van Dongen

Charly van den Enden

Nuri Ozkaya

Johanna Borreli

info@admarex.com

CORPORATE

FOUNDER & DIRECTOR

TECHNOLOGY DIRECTOR

FINANCE DIRECTOR

Merijn de Waard

Fabian Tollenaar

Laura Weber

SuperYacht Times B.V.

Silodam 256, 1013 AS, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 31 (0) 20 773 28 64 info@superyachttimes.com www.superyachttimes.com

Cover Images:

Gulf Craft by Gulf Craft

Heinen & Hopman by Justin Ratcliffe Amels 80 by Damen Yachting

How to Build It is published by SuperYacht Times B.V., a company registered at the Chamber of Commerce in Amsterdam, The Netherlands with registration number 52966461. The magazine was printed in February 2025.

With the 2025 Dubai International Boat Show underway as this issue of How to Build It goes to press, it seemed like the perfect moment to take a closer look at UAE-based Gulf Craft. Having presented no fewer than six new models at this year’s show, the SYBass member is expanding its facilities, and diversifying into resort tourism. Part of an ambitious strategy that signals continued growth and innovation, company chairman Mohammed Hussein Alshaali calls it “thinking and designing for the future.”

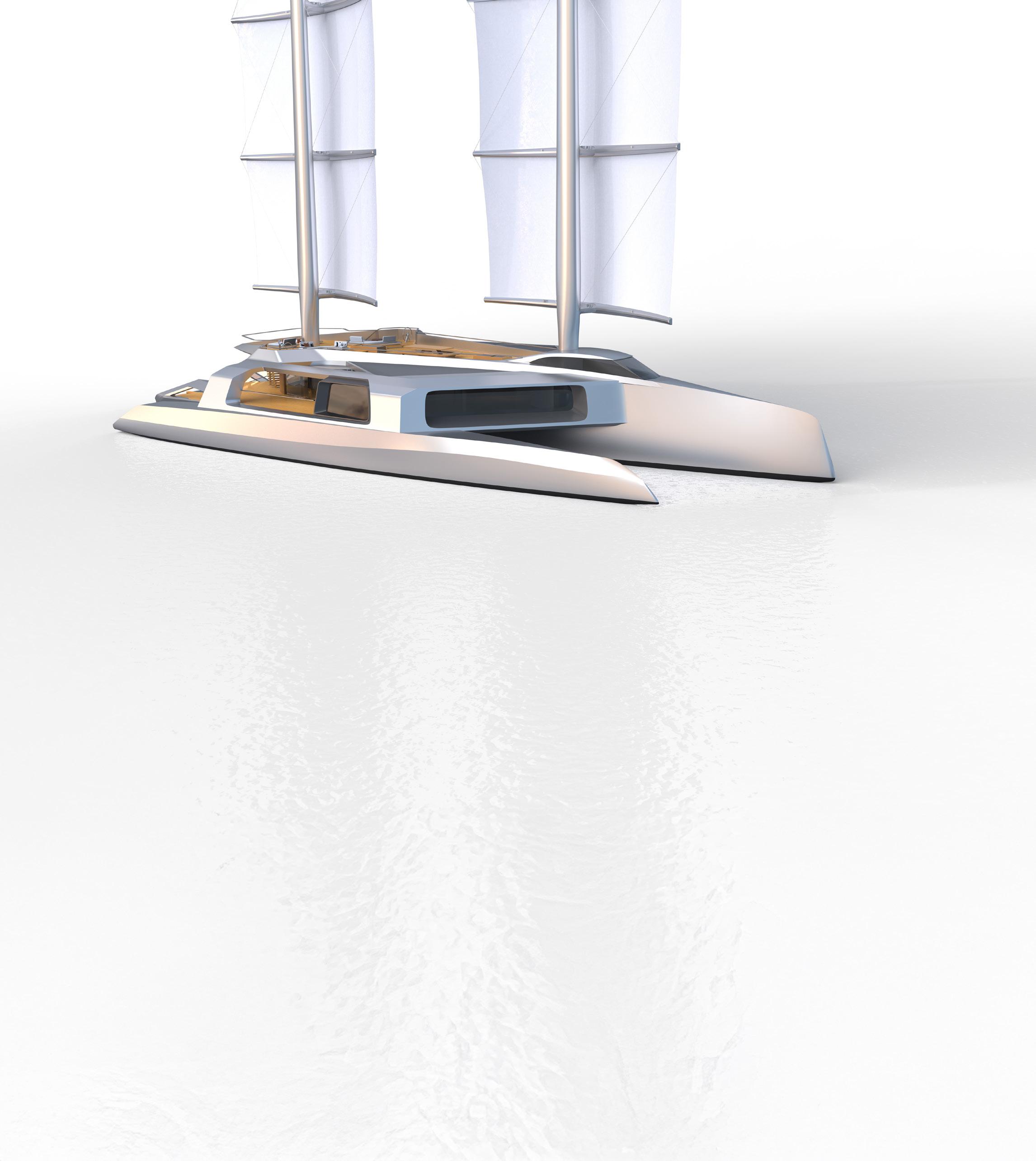

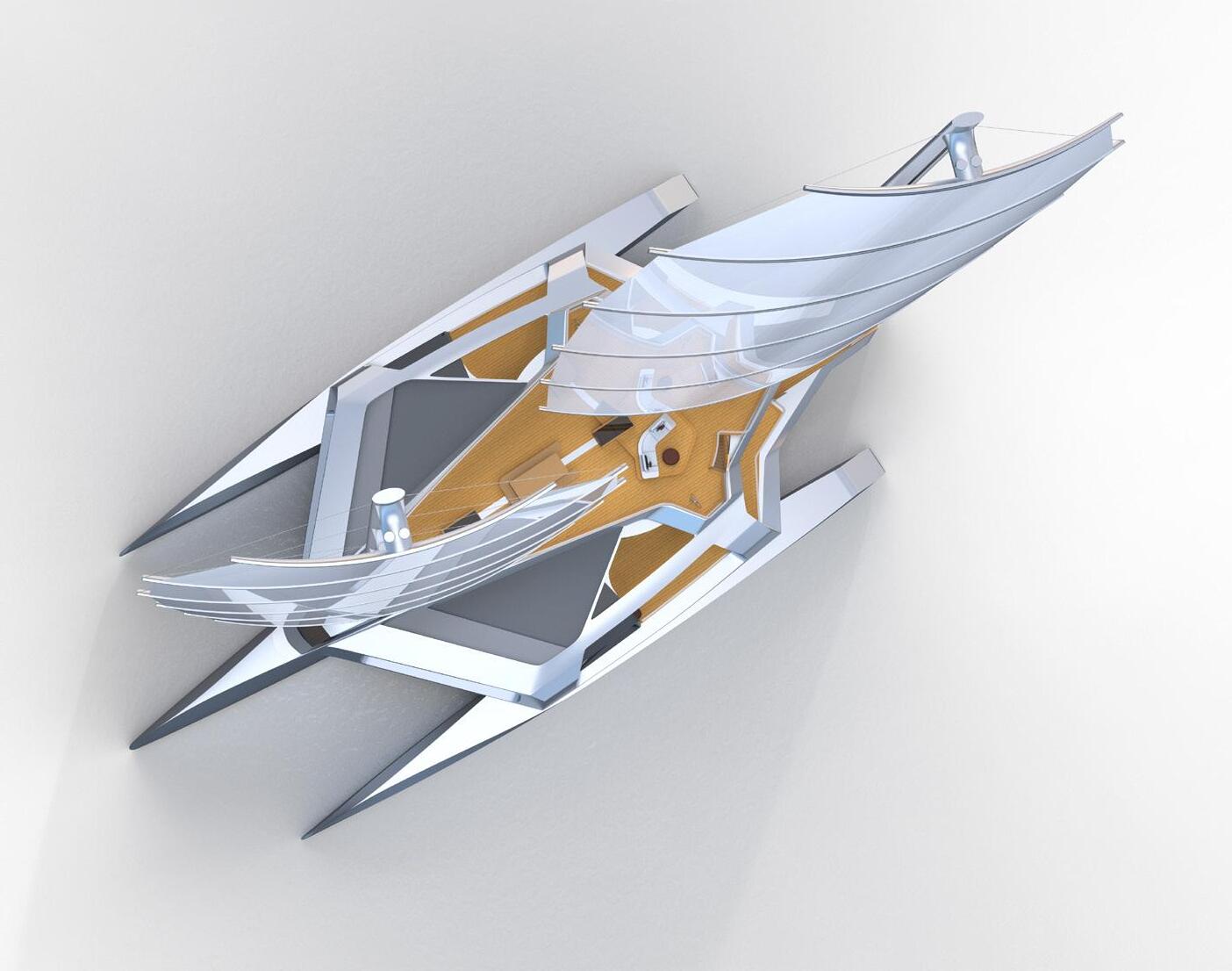

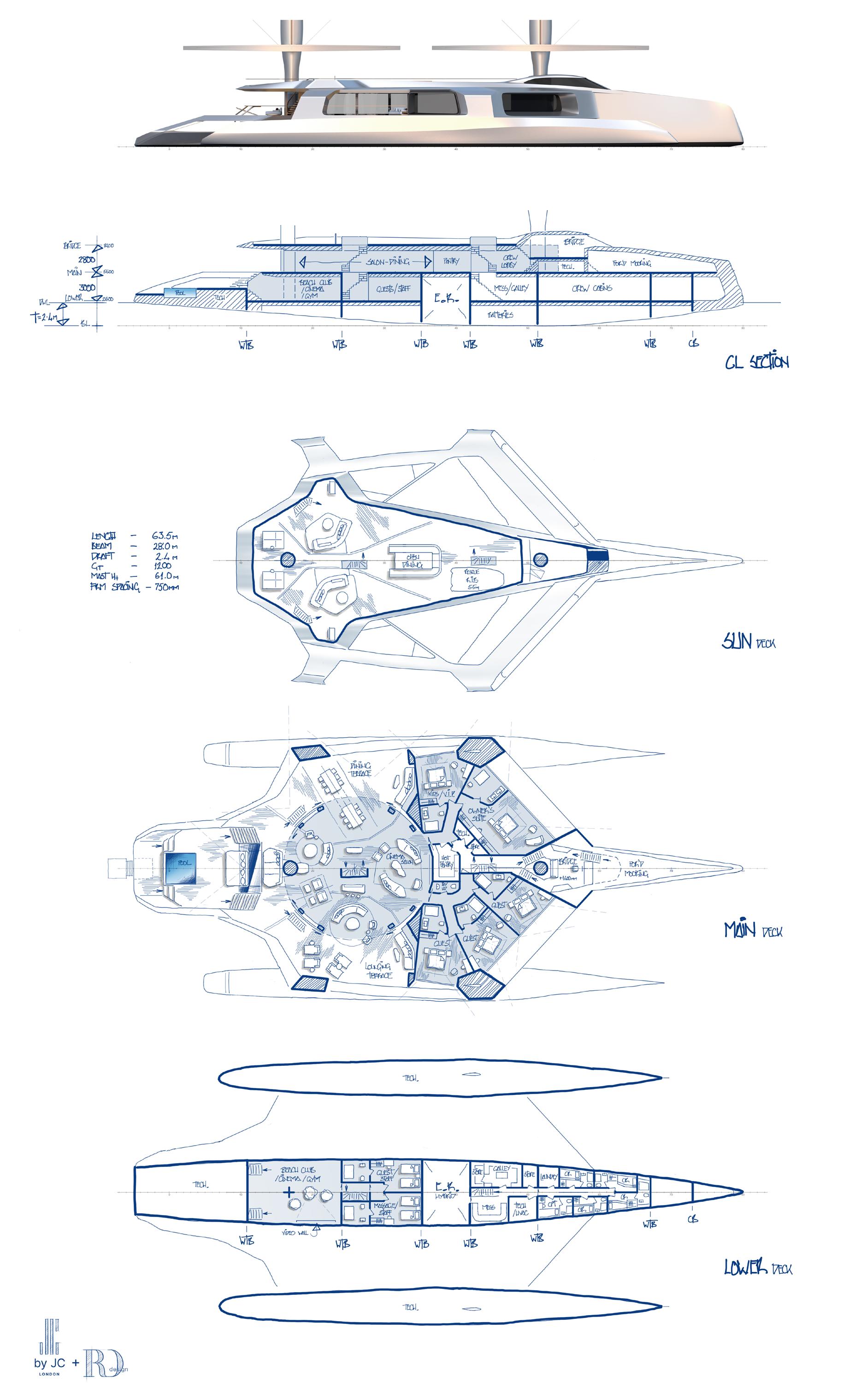

For those still in doubt about the resurgence of multihulls, three innovative projects offer compelling proof. Whether it’s the Oi60 sailing trimaran concept from JC Yacht Architecture and Rob Doyle Design, Rossinavi’s powercat Seawolf X with its cutting-edge AI system for energy monitoring, or the remarkable conversion of a stripped-out carbon maxi catamaran into a 30-metre liveaboard cruiser by Thorne Yacht Design, it would seem two hulls – or even three – are making a decisive comeback.

Our in-build reports feature two very different projects that nonetheless share a similar volume and target clientele. First, the Amels 80, the newest and largest addition to Damen Yachting’s highly successful Limited Editions series, continues its semi-custom legacy of blending fast delivery with tried-and-tested engineering. In contrast, Project Metamorphosis in build at The Italian Sea Group’s facility in Tuscany, highlights the shipyard’s commitment to fully bespoke construction. These two new-builds underscore the unique challenges of semicustom versus full-custom and the complexities behind each approach.

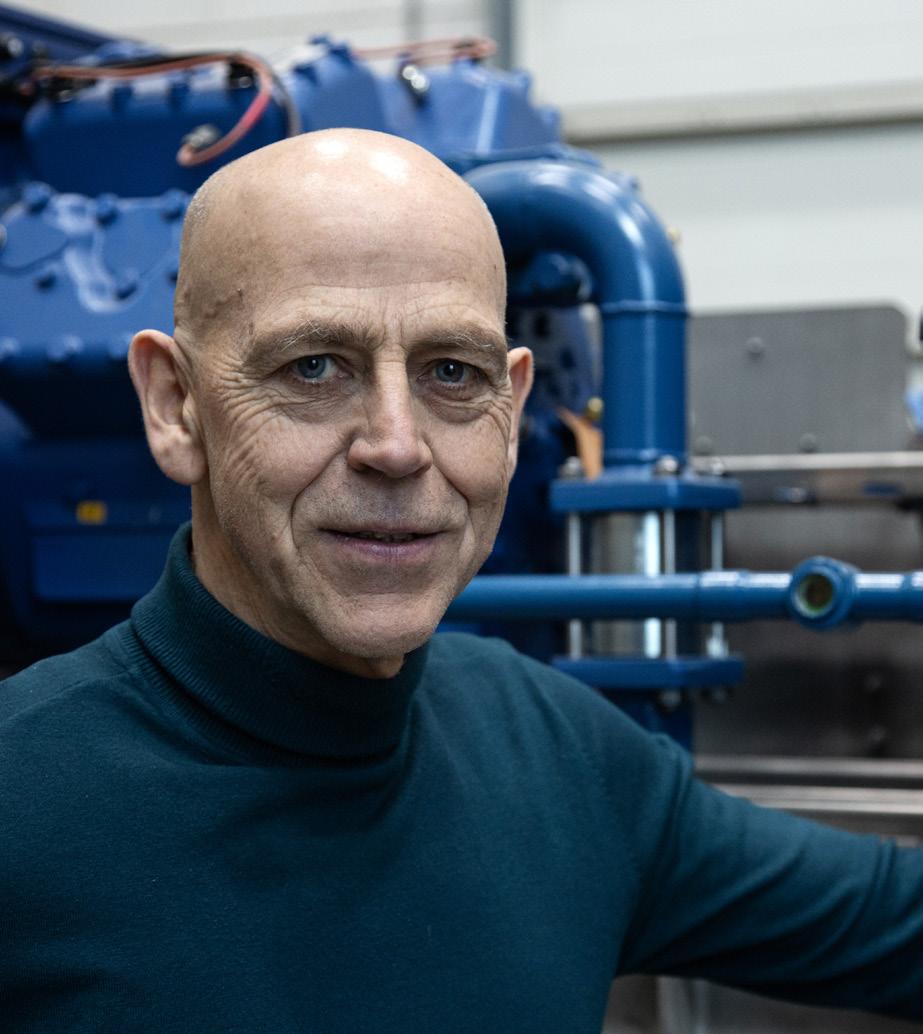

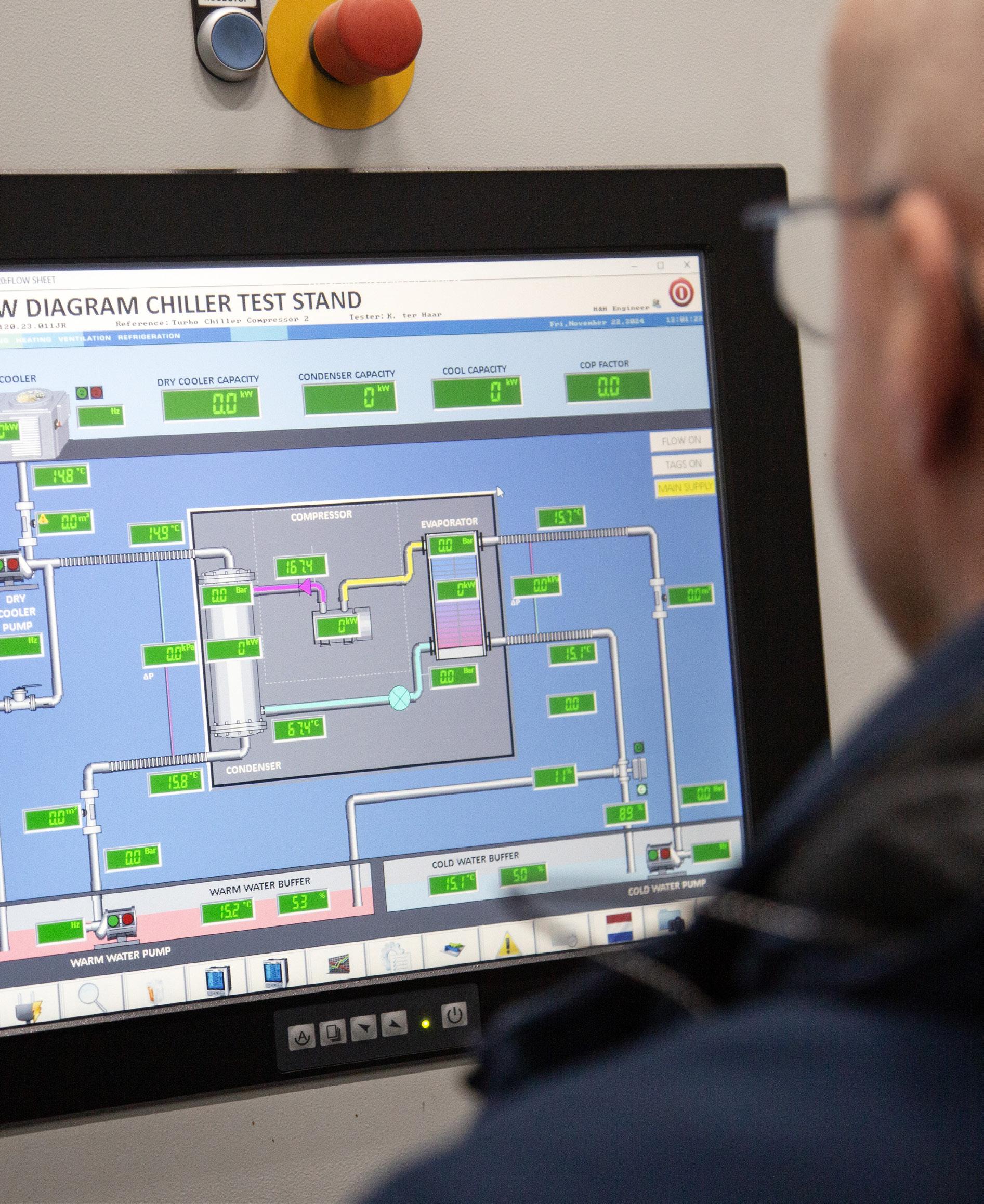

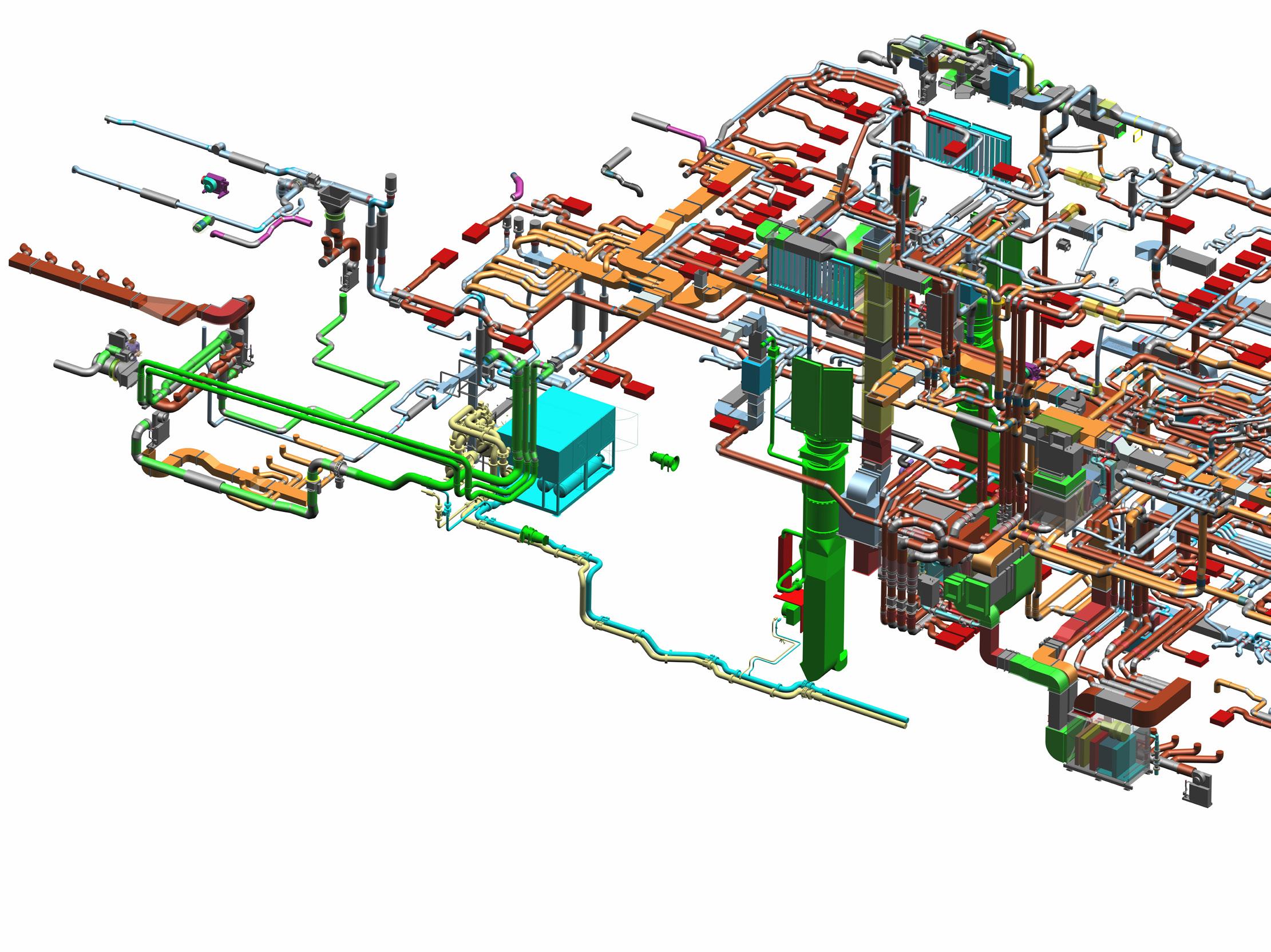

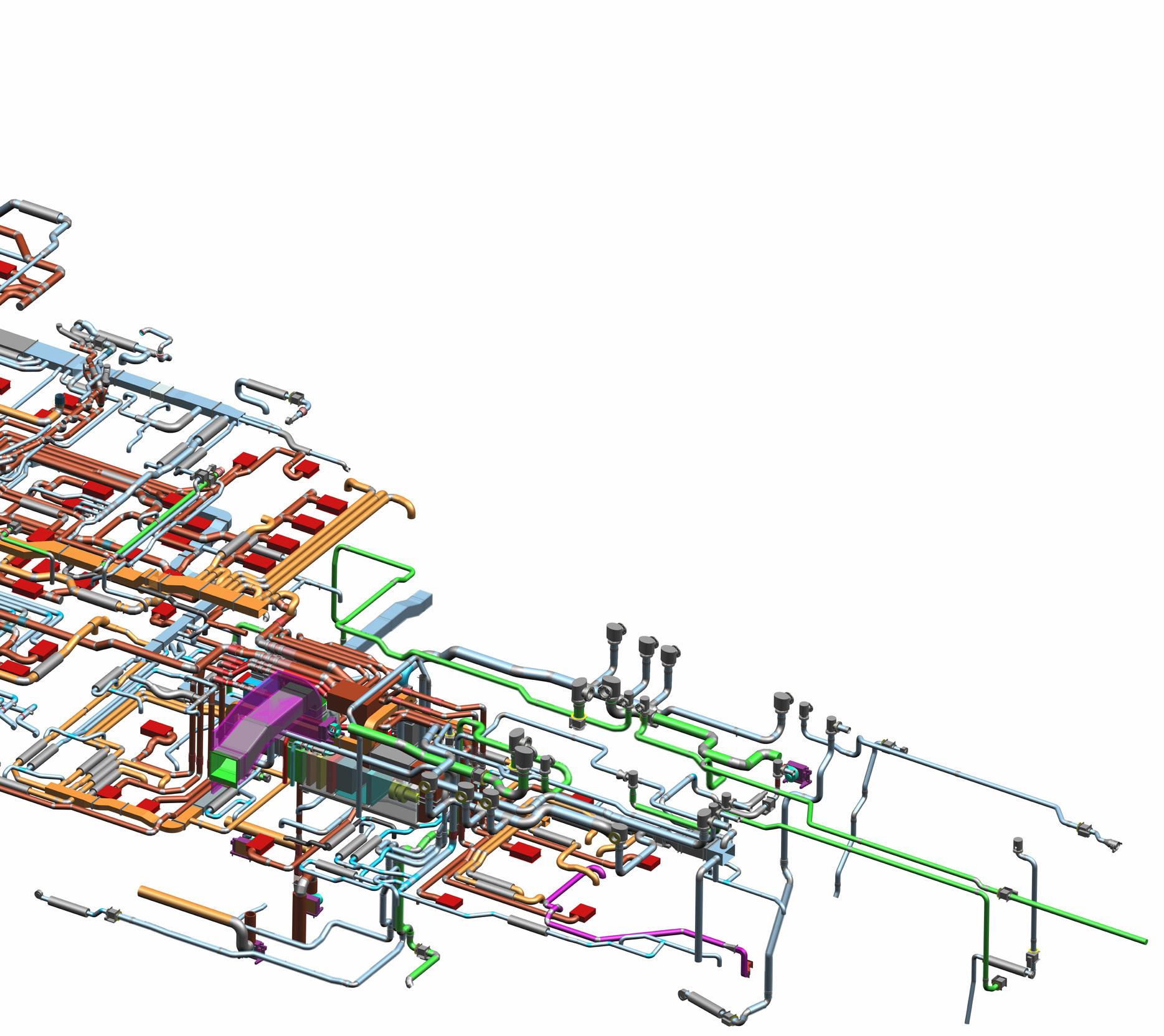

This year also marks a milestone for Heinen & Hopman, celebrating its 60th anniversary as a global leader in HVAC integration. To understand how its climate control technology is evolving to meet today’s demands for energy efficiency, environmental responsibility, and enhanced onboard comfort, we visited its sprawling headquarters in Spakenburg, near Amsterdam.

Innovation remains at the heart of this issue as we delve into groundbreaking ideas and technological developments, from biomimicry and energy recovery from waves to AI-driven design tools that are revolutionising technical design and optimisation processes. And finally, we explore the advantages of composite materials over aluminum for large structures like hardtops and biminis on superyachts. Something for everyone, in other words.

Justin Ratcliffe - Editor

Supplier

24 Business Brief: Moving On Up UAE-based Gulf Craft is expanding its facilities, enhancing client services, and diversifying into resort tourism as part of an ambitious strategy to ensure continued growth.

36 Build Report: Knowing Your Limits

The Amels 80 is the latest and largest model in the successful Limited Editions series from Amels. We report from the Damen Yachting shipyard in Vlissingen where the first units are in build.

49 Concept in Focus: Nokia Moments ‘Oi’ stands for ‘outside-inside’, the driving rationale behind the avantgarde Oi60 sailing trimaran concept by James Carley of JC Yacht Architecture and Rob Doyle Design.

56 Build Report: The Italian Job

One of two 72-metre sister ships in build at The Italian Sea Group’s superyacht facility in Tuscany, Project Metamorphosis is the first superyacht designed inside and out by Giorgio Armani.

69 OEM: Heinen & Hopman

We pay a visit to the Dutch headquarters of Heinen & Hopman as the leading supplier of HVAC solutions to the marine industry celebrates its 60th anniversary.

79 Inside Angle: Richard Bridge

Before setting up Bridge Yachting in 2018, owner’s representative Richard Bridge served as operational captain on some of the most iconic superyachts on the water.

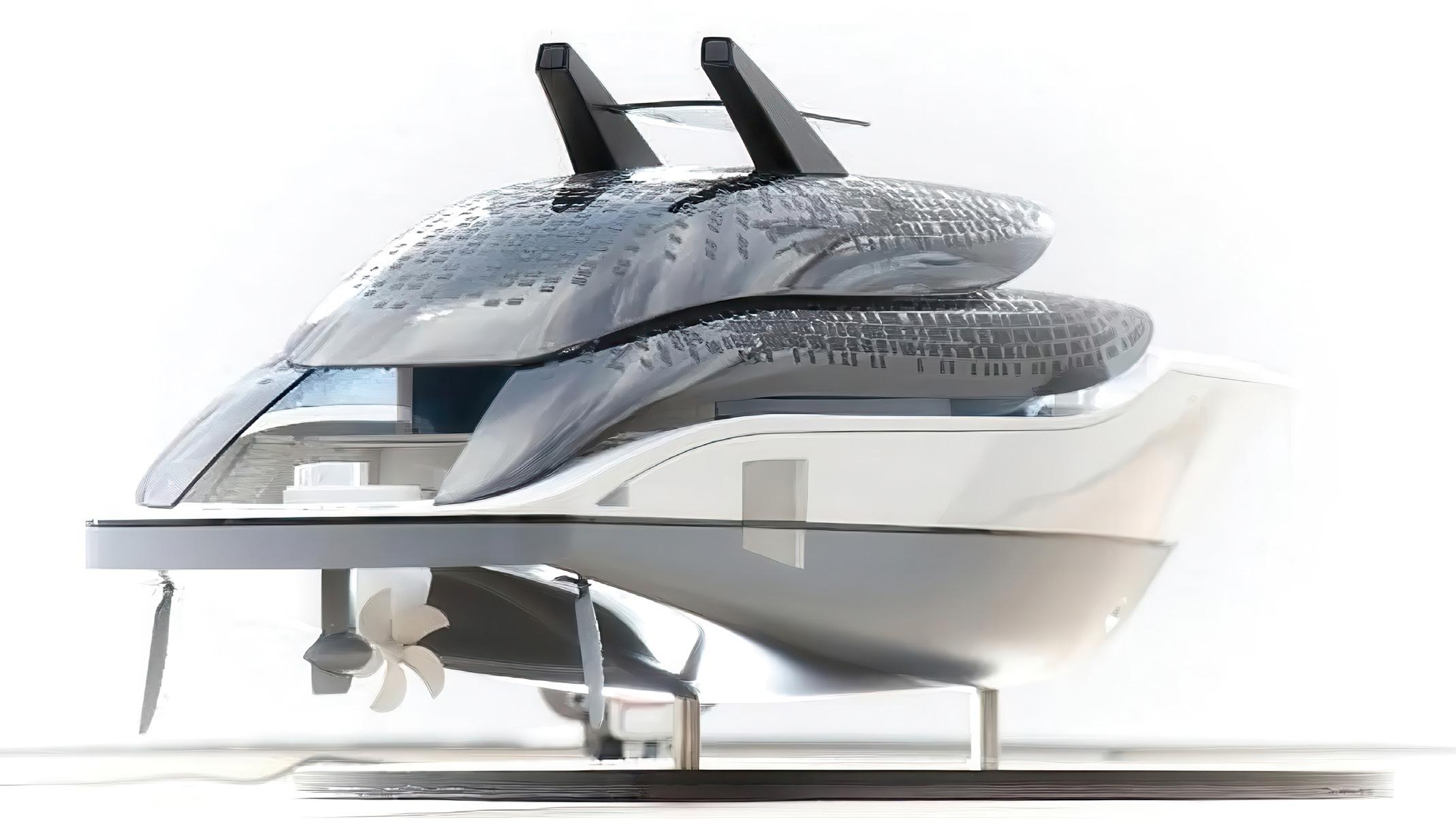

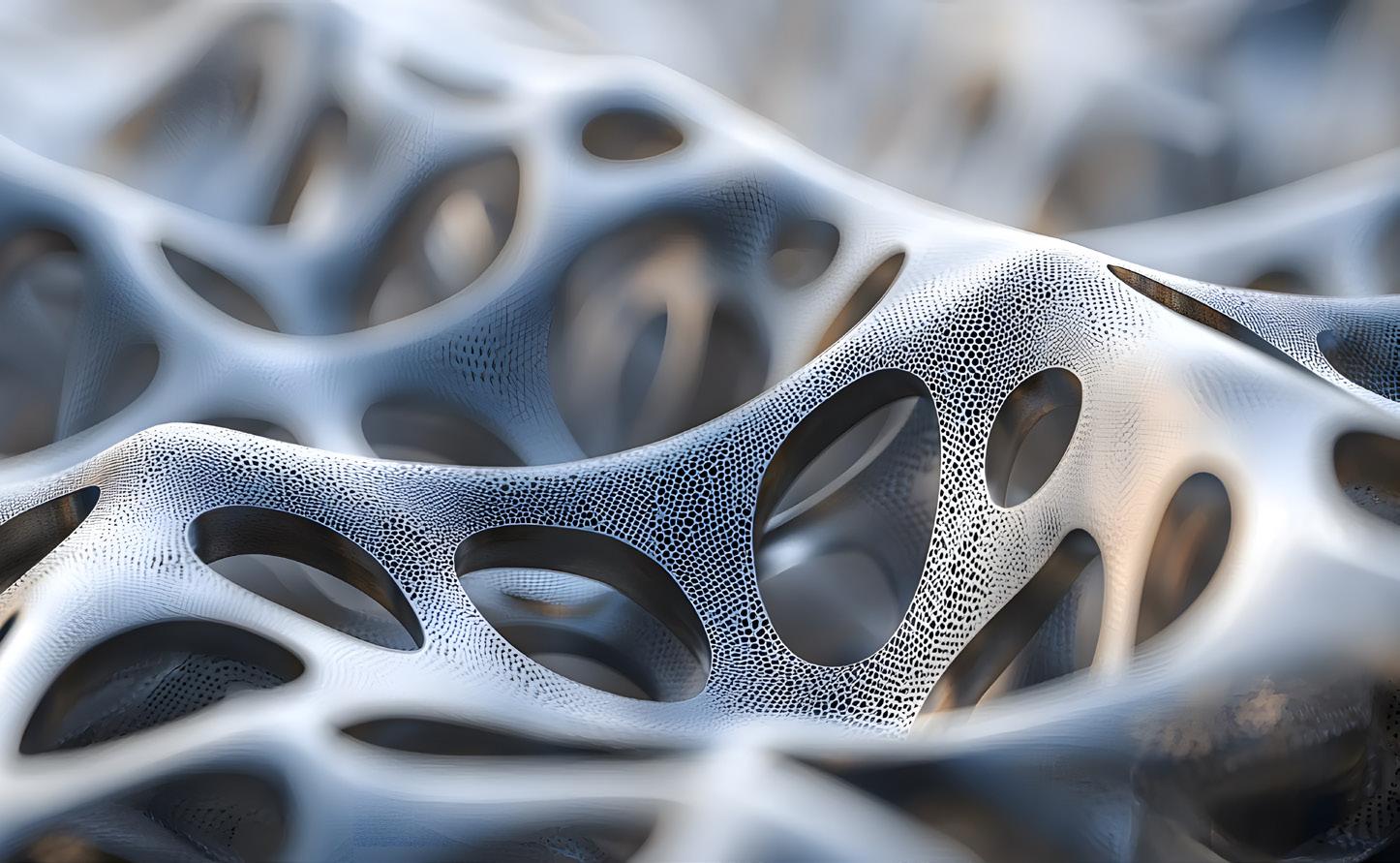

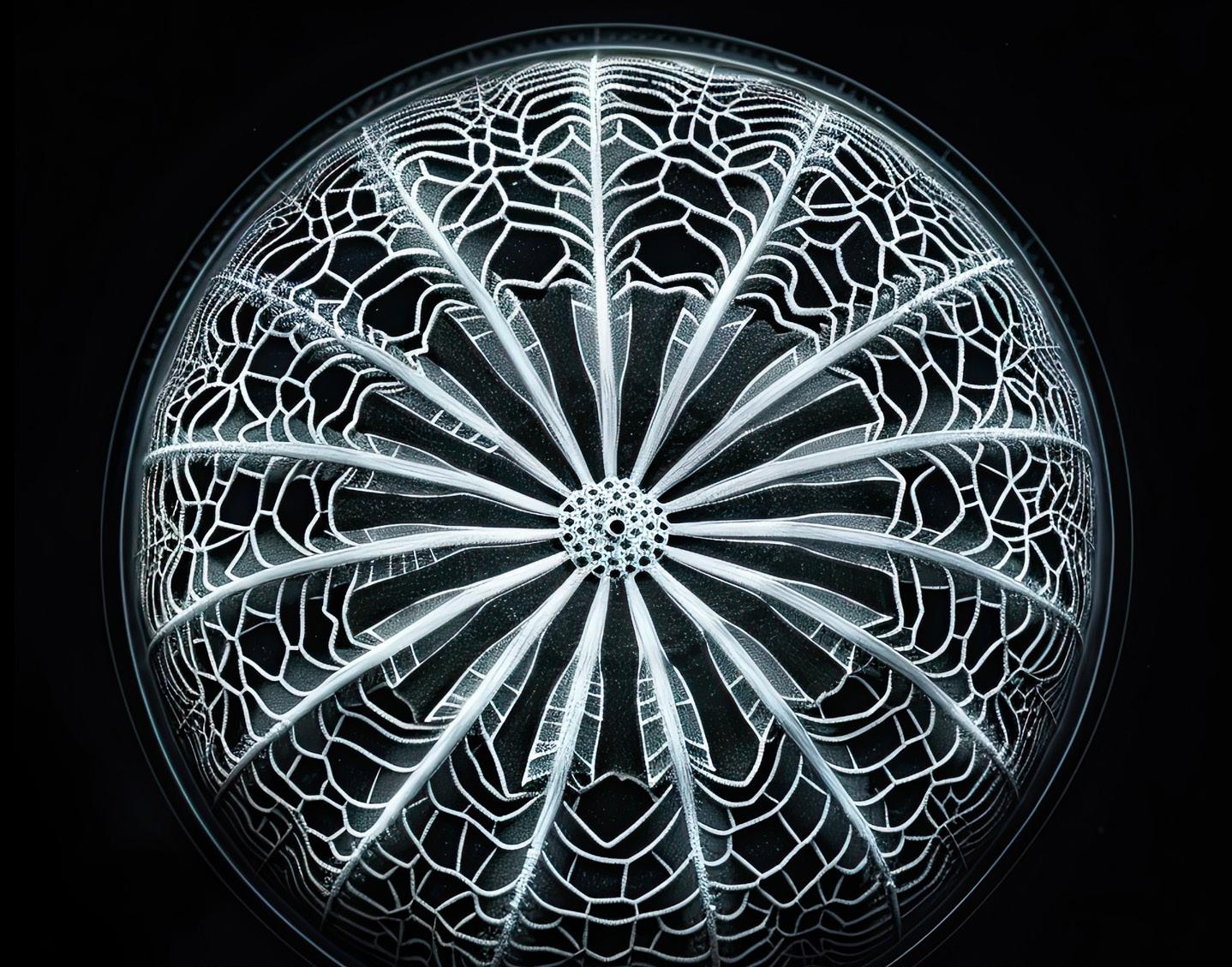

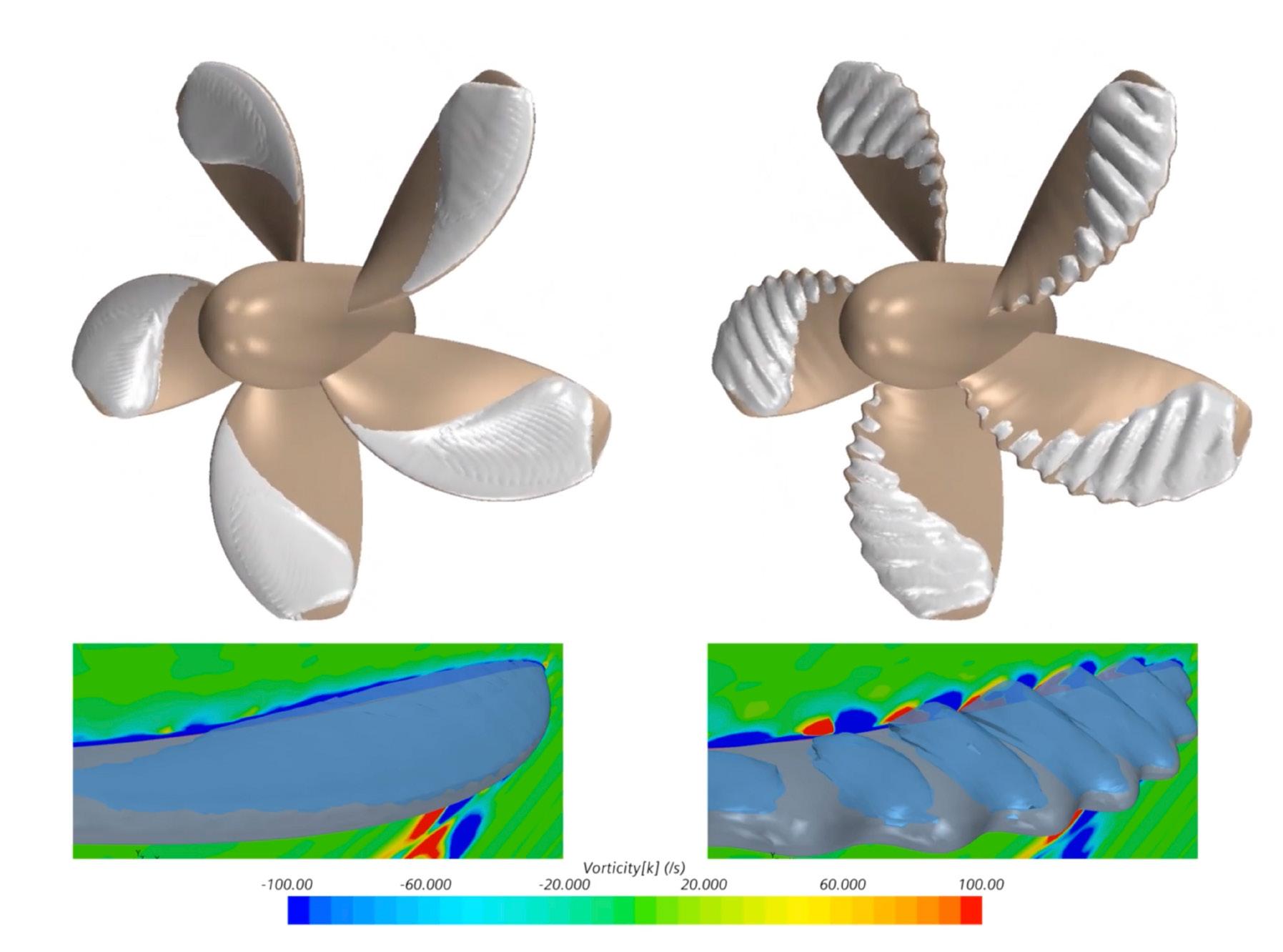

83 Design & Innovation: Natural Ideas

From topological hull design and energy efficiency to propulsors and appendages, is it time for solutions drawn from nature’s example to hit the mainstream?

93 New Tech: The Measure of Intelligence

As AI and machine learning pervade ever more deeply our daily lives, they are being used to assist with technical tasks associated with ship design, construction, operation and maintenance.

101 Refit & Conversion: Expect the Unexpected Upcycling a 15-year-old racing catamaran into a 30-metre liveaboard cruiser comes with a unique set of challenges. We catch up with Thorne Yacht Design in the UK to find out more.

111 Materials: Material Benefits

After more than 15,000 refit and repair projects, BM Composites in Palma de Mallorca has proven the advantages of composites over aluminium for manufacturing large structures such as hardtops and biminis.

119 Rules & Regs: Due Diligence Matters

Rob Papworth, Managing Director of MB92

La Ciotat and Chair of the ICOMIA Superyacht Refit Group, walks us through the many things you need to consider before committing to a refit shipyard.

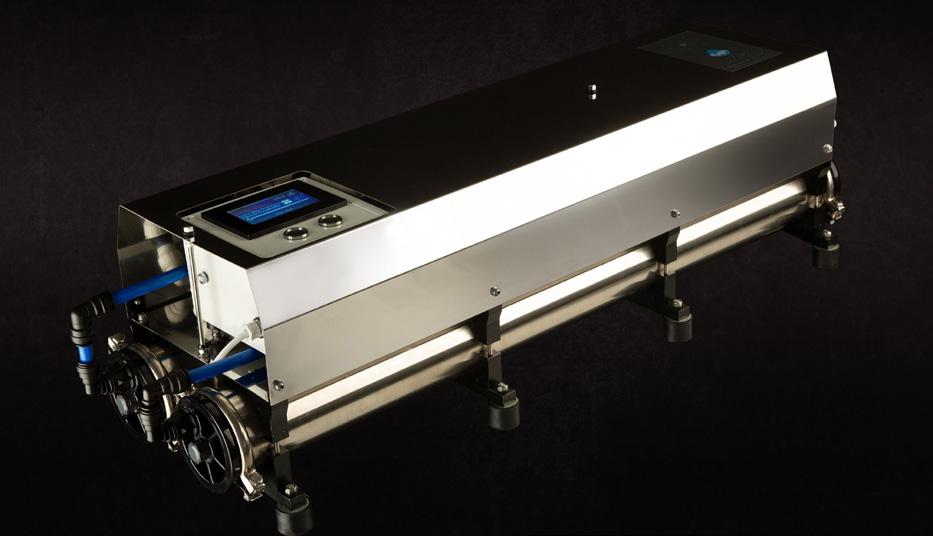

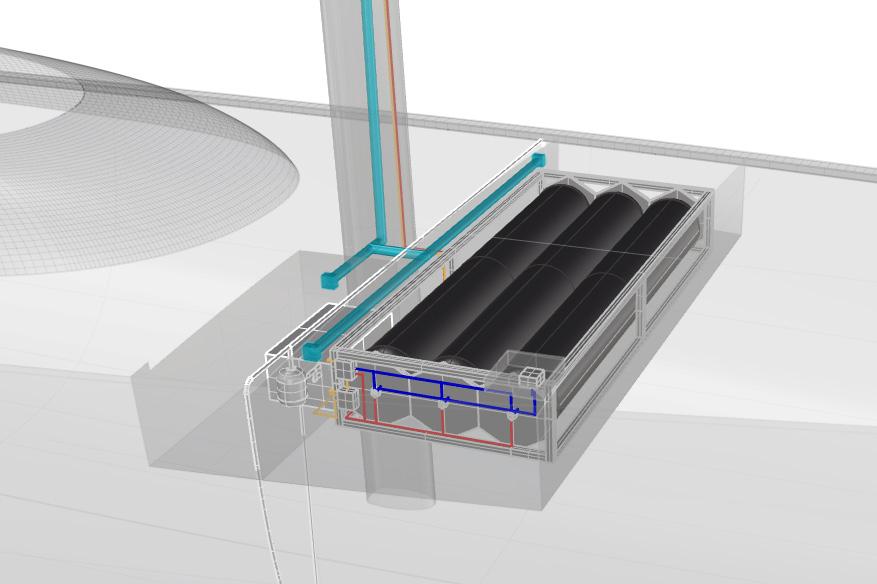

PuRO, a leader in water purification systems, has partnered with Vitters on Project Zero. This fully electric vessel that can operate without fuel tanks prioritises energy efficiency. PuRO adapted its innovative water purification technology –originally designed to purify dock water for yacht maintenance – into a high-efficiency water recovery system for Project Zero. This adaptation enables the yacht to recover and reuse greywater and rainwater, significantly reducing reliance on traditional watermakers and cutting energy consumption.

The collaboration marks PuRO’s first venture into a sustainabilityfocused project of this scale, showcasing the versatility of its systems in reducing environmental impact. While Vitters handles the system’s installation, PuRO has worked closely to ensure seamless integration. Looking ahead, PuRO is eager to further its presence in sustainable maritime projects, leveraging its technology to deliver energy-efficient, multifunctional solutions for yachts of all sizes.

Synergy – the HVAC Consultancy, part of the Bond Group and Bond Technical Management, and Dutch software specialist Delta Digital have entered a business collaboration to bring their combined expertise to the superyacht industry. With a focus on optimising HVAC systems, the agreement signed during METSTRADE 2024 enables the creation of ‘digital twins’ for yacht HVAC systems, allowing for simulated testing of energy-saving enhancements before implementation.

Using Delta Digital’s 3-phase methodology, an efficiency baseline of a yacht’s entire HVAC system can be digitally built over the course of one to two months. The Delta Digital platform then analyses various aspects of the HVAC system, including energy consumption, performance, temperature control and air quality. Any proposed optimised changes can then be made to the HVAC digital twin before being applied by Synergy to a yacht’s actual system.

“We are experts in energy savings, air quality and system improvements, and pride ourselves on being a flexible company on whom you can rely on when making tough decisions during your superyacht project,” says Patrick Voorn, CEO of Synergy–The HVAC Consultant. “This collaboration with Delta Digital will go a long way to supporting that process.”

Royal Huisman has received Approval-in-Principle (AiP) from Lloyd’s Register for its hydrogen-powered fuel cell system designed specifically for sailing superyachts. This system comprises high-pressure hydrogen bottles and a 100kW fuel cell, providing sufficient energy to power the yacht’s hotel load quietly, sustainably and without emissions. The AiP follows a hazard identification study conducted with Lloyd’s Register and external experts to confirm the concept’s safety and offer guidance for subsequent development steps.

This achievement aligns with Royal Huisman’s Project Tidal Shift. By integrating life cycle analysis into each project and proactively offering sustainable options during design and construction, the initiative demonstrates the shipyard’s commitment to environmental stewardship, while the approval of the hydrogen fuel cell concept marks a significant milestone towards eco-friendly and innovative yacht building practices. The shipyard has stressed that the above concept is one of many options available for their sailing yachts.

The Yacht Club de Monaco’s SEA Index has expanded its CO2 certification to assess all fuel cell technologies on superyachts. This update enables owners and stakeholders to evaluate the environmental impact of alternative fuel systems, offering independent, data-driven insights for more sustainable choices. In collaboration with Lloyd’s Register, the SEA Index now rates yachts with advanced fuel cells, including methanol and hydrogen systems, as demonstrated by Sanlorenzo’s 50Steel Almax that achieved a 3-star rating.

Working in collaboration with Lloyd’s Register specialists, SEA Index has undergone a rigorous review to ensure its methodology can now accurately assess superyachts equipped with the latest fuel cell technologies.

Anchoright, the UK-based producer of anchor chain markers, has announced its entry into the superyacht market, driven by demand for its eco-friendly and user-centric chain markers. At METSTRADE 2024, the company exhibited an expanded range tailored for superyachts featuring larger, high-visibility markers designed to enhance anchoring accuracy and safety. Expanding into the superyacht sector is a natural progression for a company aiming to make mooring more intuitive and environmentally responsible.

“Our expansion into the superyacht market is a direct response to the overwhelming demand we’ve received from superyacht owners and captains,” said Quinton Watts, founder of Anchoright. “Superyachts present a unique challenge due to their size and the complexity of their anchoring systems. Our products are specifically designed to provide reliability, accuracy, and ease of use, ensuring the safety of both the vessel and the crew.”

Multiplex offers high end solutions for the biggest yachts afloat. Their carbon boarding systems are second to none.

The multi flap is light, stable, weather-proof, and resistant to deformation. At 4.4 kg per metre and with a quick, simple

fixing system, it can be mounted and dismounted by a single person.

Easy installationand less weight combined with an elegant design have made the sun awning system a product of great popularity. Each sail is individually hand-made, so it will perfectly suit the vessel’s outline. Miscellaneous pole paintings, several types of sailcloth, loudspeakers, and lights can personalize the systems according to taste.

Based on the multifender modular component system, all multifender systems are produced according to individual requirements. This means that we tailor the multifender to all imaginable conditions for vessels up to 12 tons.

Despite its low weight, the multiguard system can withstand a lateral pressure of up to 100 kilograms and has been certified by Lloyds Register. The system is available in a free choice of colours with worldwide service.

The multistair can be used for access directly into the cockpit over the side or stern. It can be swung 90 degrees from a fully horizontal to a fully vertical position, with all steps automatically aligning in parallel with the sea‘s surface.

The lightness of this ladder construction enables easy assembly and dismantling. The use of carbon fibre and stainless steel ensures 100 % corrosion resistance.

Flexiteek International has unveiled its latest innovation in synthetic teak decking, Flexiteek 3. Building on the success of Flexiteek 2G, this third generation combines enhanced aesthetics, improved durability, and a strong commitment to sustainability. Featuring bio-attributed PVC that reduces greenhouse gas emissions by up to 80% and REACHcompliant, phthalate-free plasticisers, Flexiteek 3 is 100% recyclable, making it the company’s most eco-friendly offering yet. Designed to replicate the natural graining and ageing of real teak, Flexiteek 3 is available in a wide range of colours, including the new Ash option.

Bosch Engineering has introduced a new 800-volt electric drive system designed for both recreational and working boats. The SMG 230 electric motor delivers continuous power up to 200 kilowatts, facilitating the electrification of larger vessels weighing between 20 to 30 tonnes. Incorporating silicon carbide semiconductors, the accompanying inverter achieves an efficiency exceeding 99%, enhancing overall system performance. This comprehensive electrification toolkit, adaptable for both 400- and 800-volt applications, offers shipyards and system integrators the flexibility to seamlessly integrate these components into various maritime vessels.

SOL-MATES in the Netherlands produces complete sun awning systems. Set up by five entrepreneurs with proven track records in the yachting industry, ranging from composites and metal construction to 3D engineering and project management, the result of all this combined experience is that they know what works and what doesn’t on superyachts. Their latest manual winch system offers a fast, simple, and costeffective solution for shade systems that are compatible with the smallest diameter uprights, making it a versatile choice for a variety of applications. The system operates using a removable handle to apply tension, which is released with the simple lift of a pin. Pole diameters range from 80mm in carbon fibre to 100mm in a combination of carbon fibre and stainless steel with a maximum height of 2200mm. The poles can be secured to the deck using a bayonet system with a maximum traction of 100 kg. Custom options are available on request.

The introduction of Hydro Generators marks a significant step forward in regenerative sailing for large yachts, offering a sustainable alternative to traditional diesel generators. By operating independently of the main propulsion system, these innovative generators minimise drag and maximise electrical output, allowing yachts to maintain their speed while reducing their environmental footprint. Unlike dualpurpose systems, hydro generators employ a dedicated electric pod with a specially designed fixed-pitch propeller, ensuring higher efficiency without the need for complex modifications. The addition of a low-drag ‘freewheeling’ mode further enhances their practicality, as it allows the system to remain in place with negligible impact when not in use.

Rondal has developed three tailored models; the Hydro Generator 15000, designed for yachts over 50 metres, delivers robust power output for high-demand vessels; the Hydro Generator 9000 Performance, optimised for medium-sized yachts, achieving exceptional efficiency at midrange speeds. And the Hydro Generator 9000 High Speed caters to faster yachts, including multihulls, with a lightweight design suited for highperformance sailing.

Maretron and Raymarine have unveiled a groundbreaking partnership to integrate Maretron’s MConnect® technology with Raymarine’s awardwinning Axiom chartplotter displays. This collaboration combines Maretron’s innovative clientserver technology, which provides real-time access to hundreds of vessel data points, with Raymarine’s intuitive LightHouse interface. The result is a seamless user experience that allows boat owners and OEMs to monitor and control critical vessel systems directly from Raymarine’s high-definition displays, enhancing safety, efficiency, and overall enjoyment on board.

The integration of MConnect brings advanced data visualisation and customisation tools to Raymarine’s multifunction displays, enabling users to create personalised dashboards tailored to their specific needs. Boat builders and dealers can also leverage MConnect’s graphics editor to embed brand-specific aesthetics and designs, offering a cohesive and branded user experience. Available now through Maretron’s dealer network, this partnership reflects both companies’ commitment to delivering cutting-edge innovation and connectivity for the recreational boating industry.

The REVBO range from Bowmaster represents a significant innovation in mooring bollard technology, introducing the world’s first rotating and retracting bollard. This design enables crews to safely adjust mooring lines without detaching them from the bollard, simplifying line handling and enhancing safety, particularly for smaller or less experienced teams. With a compact footprint, REVBO bollards minimise deck clutter while maximising the active line engagement area for optimal performance. Additionally, they meet the latest International Maritime Organization (IMO) safety standards, ensuring reliability and compliance for modern yachting.

The Model 4 REVBO stands out as a rotating and retracting bollard, offering exceptional versatility for docking. Capable of tensioning dock lines during mooring, it retracts to a flush deck level when not in use, delivering a sleek and seamless appearance. Retraction is achieved via a gas strut or powered mechanism, ensuring smooth operation. The bollard lid can be customised to match the deck material, such as teak, for a polished and discreet look.

Constructed from high-strength stainless steel or advanced composite materials like titanium-carbon fibre, the REVBO range provides weight savings of up to 90% compared to traditional designs. This lightweight yet durable construction reduces deck load, making it an ideal choice for high-performance yachts.

New projects in early stages of construction that present opportunities for OEMs, suppliers and subcontractors.

Barnes Yachting has announced the construction of two 52-metre projects at the Turkish commercial shipyard Orion Yachts. Project Tide is the first of the two in-build, with metal cut this December and the second hull due to begin in February. She is a self-funded project, with the goal of creating an in-house charter fleet. Top features of the 52-metre yacht include her six stateroom layout for the accommodations of as many as 12 guests, a 4,000 nautical mile range and her steel and aluminium construction.

LENGTH: 52-metres BUILDER: Orion Yachts GT: 499 GT COUNTRY OF BUILD: Turkey DELIVERY YEAR: 2027

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Axis Group Yacht Design EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Horacio Bozzo Design INTERIOR DESIGNER: N/A

The first hull of the new 51.1-metre Mangusta Oceano 52 model is under construction at the Overmarine Group’s shipyard in Pisa. This model is being developed jointly by Overmarine’s Engineering Department. This steel and aluminium displacement yacht falls under the 500 GT category. During the press conference, Mangusta highlighted that their extensive research into glazed surfaces and strategic technical modifications have eliminated barriers across all decks.

LENGTH: 51.1-metres BUILDER: Overmarine GT: 499 GT COUNTRY OF BUILD: Italy DELIVERY YEAR: 2027

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Overmarine EXTERIOR DESIGNER & INTERIOR DESIGNER: Alberto Mancini Yacht Design

In-build at the Turkish shipyard and due for delivery in 2026, the yacht, currently for sale, is a monohull with a ketch sail arrangement. She has a steel hull and aluminium superstructure and will be powered by twin Baudouin engines.

LENGTH: 40-metres BUILDER: Bodrum Oguz Marin GT: 258 GT

COUNTRY OF BUILD: Turkey DELIVERY YEAR: 2026

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Bodrum Oguz Marin EXTERIOR DESIGNER & INTERIOR DESIGNER: Bodrum Oguz Marin

The B.Yond 57M marks a new chapter for Benetti as part of its Voyager series, integrating advanced hybrid propulsion and eco-friendly technologies. This 57-metre superyacht seamlessly combines versatility and functionality, positioning it as the ultimate vessel for extended cruising. She is characterised by extensive glazing, providing guests with light and bright interiors, which benefit from extended views of the horizon and a gentle flow of sunlight.

LENGTH: 57-metres BUILDER: Benetti Yachts GT: 1,000 GT COUNTRY OF BUILD: Italy DELIVERY YEAR: 2027

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Benetti EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Lobanov design INTERIOR DESIGNER: Bonetti / Kozerski architecture DPC

Announced in October 2024, this latest project is a full-custom design, due for delivery in 2027, she has a four deck arrangement with a large aft deck including a swimming pool. Regarding her performance, the 56-metre yacht is set to be powered by twin Caterpillar engines that propel her to a top speed of 16.5 knots, with a range of 4,500 nautical miles.

LENGTH: 56-metres BUILDER: Baglietto

COUNTRY OF BUILD: Italy

YEAR: 2027

EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Team for Design - Enrico Gobbi INTERIOR DESIGNER: Enrico Gobbi & Carlo Lionetti

ARCHITECTURE: N/A

The keel of Heesen’s speculation project Grace was laid in December. As with all other Heesen steel yachts, her hull will be welded off-site at Talsma to avoid cross-contamination with any aluminium production. Also known as Project 21350, the 499 GT Fast Displacement yacht will feature a hybrid propulsion system for optimal comfort and silent cruising capabilities in all sea conditions.

LENGTH: 49.9-metres BUILDER: Heesen GT: 499 GT

COUNTRY OF BUILD: The Netherlands DELIVERY YEAR: 2027

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Van Oossanen Naval Architects EXTERIOR & INTERIOR DESIGNER: Harrison Eidsgaard

Sold to a European client, the first hill of the new series is due for delivery in 2025, having been started on speculation. Constructed with a composite hull and superstructure reinforced with carbon, the yacht measures thirty metres in length with a maximum beam of 8.1-metres. This provides interior volumes typical of vessels exceeding forty metres, with a gross tonnage of approximately 260 GT.

LENGTH: 30-metres BUILDER: Extra Yachts

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Extra Yachts

Italy

DESIGNER: Studio Agon

German shipyard Abeking & Rasmussen has announced that the keel of their new 79.95-metre superyacht Abeking 6516 has been laid in a ceremony held at the G&K SteelCon premises in Poland. Abeking 6516 will feature design from the drawing boards of a well known UK-based studio, which will adorn her with a “modern but cosy interior,” according to the shipyard.

LENGTH: 79.95-metres BUILDER: Abeking & Rasmussen

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: N/A EXTERIOR DESIGNER: N/A

YEAR: 2025

DESIGNER: Laura Brocchini Design

COUNTRY OF BUILD: Germany DELIVERY YEAR: 2026

DESIGNER: N/A

Founded in 1997 by Peter Joachimmeyer and catering predominantly to the superyacht industry, Kreative Metallform (KMF) in Germany has established itself as a pioneer in the fabrication of high-quality stainless steel components.

BY FRANCESCA WEBSTER

KMF designs and manufactures a broad range of products, but is best known for its foldable doors and moveable windbreakers, particularly its patented electric stacking door. The company initially focused on shopfitting, commercial interiors, and trade fair construction before pivoting into the superyacht sector, completing its first yacht exterior project in 2010. The following year it installed its first wind protection system. Since then, the company has installed approximately 120 wind protection systems on both new-build and refit projects.

The KMF production facility in northwest Germany spans 2,000 square metres and is equipped with advanced machinery, including CNC technology for high-precision machining and laser welding capabilities. On average, KMF delivers currently approx. 20 custom wind protection systems per year, equipping around seven superyachts.

While foldable doors remain the company’s best-selling product, over the years it has developed its line in response to evolving market demands, especially with the increasing preference for flush decks and uninterrupted design. During the development of the 141-metre Lürssen Nord, for example, KMF were tasked with designing a transparent windbreak system without impacting the deck aesthetics. The result was the development of the electric staking gate, which stores glass elements up to a length of 12 metres within the ceiling, eliminating the need for floor bushings or deck rails and offering unobstructed views for guests.

In order to achieve this KMF developed a new guiding system arranged vertically within columns or a niche in the deckhouse wall. The glass is then secured using a patented clamping system designed to compensate for thermal expansion in dynamic marine environments where temperatures can fluctuate between hot climates such as the Middle East and the low temperatures of the polar regions. KMF’s innovations extend to foldable doors that offer exceptional reliability and maintenance-free performance, requiring no adjustments after installation.

Each project undertaken by KMF is a testament to the company’s focus on Each project undertaken by KMF is a testament to the company’s focus on precision and personalisation. The lead times for projects vary depending on their complexity, with smaller assignments, such as single windscreen doors, requiring two to four months, while larger projects such as installing 20 windscreen systems on a newbuild yacht can take up to eighteen months. The company’s capacity to handle complex projects is evident in recent advancements, such as an electric gym enclosure system. This innovative design utilises air cushions and electric motors to move an 8-tonne platform across the deck of a yacht, doubling as a pool cover.

Research and development has been instrumental in KMF’s growth. The company actively collaborates with shipyards, designers, and yacht owners to address unique challenges, resulting in cutting-edge solutions that set new industry benchmarks. Partnerships with top shipyards such as Lürssen and Abeking & Rasmussen highlight its reputation as a trusted industry leader. From height-adjustable tables to sliding hatches and wind protection systems, KMF’s products are about the fusion of innovation, craftsmanship and luxury. With a proven track record and commitment to quality, Kreative Metallform continues to shape the future of the superyacht sector.

SUNBRELLA ® TIMELESS & ON THE ROAD DESIGNED WITH LASTING STRENGTH AND CLEANABILITY BUILT IN. EXPERTLY CRAFTED, THIS BROAD PALETTE OF COLOURS IS SUITABLE FOR ALL PROJECTS AND ARE PERFECT FOR PATTERNED OR TEXTURED COMBINATIONS. INDISPENSABLE ESSENTIALS THAT STAND THE TEST OF TIME.

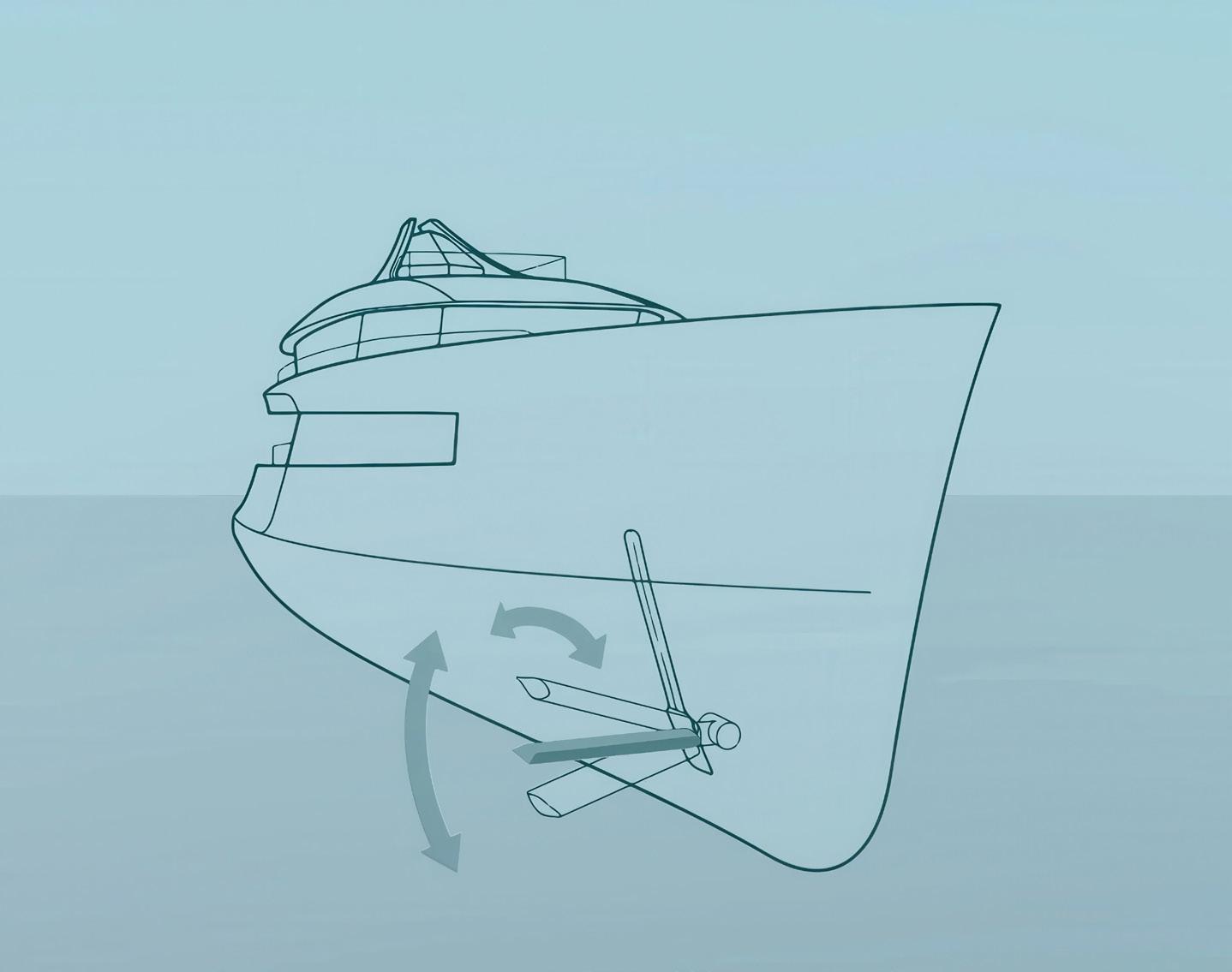

From pioneering Zero Speed stabilisers that transformed onboard comfort at anchor to advanced solutions like the F45 electric-hydraulic hybrid power system and new electric e-Fin stabiliser, Quantum Marine Stabilizers has been at the forefront of stabiliser developments. Company founder and CEO John Allen (above) shares insights into Quantum’s journey, the challenges of shifting from hydraulic to hybrid and electric, and offers a glimpse into what the future holds for stabilisation technology.

BY FRANCESCA WEBSTER

What has been Quantum’s most impactful innovation in stabilisation?

Without a doubt it has been the Zero Speed stabilisers. Their innovation really changed the game. The concept of stabilisers that worked while at anchor simply didn’t exist before we spearheaded the development and introduced the product around the year 2000. The effect was immediate – owners could now anchor without experiencing disruptive rolling. But of course the major challenge was finding that initial owner willing to take risk. Considering most yacht owners spend the majority of their time on board while anchored, this breakthrough was transformative.

And how long did it take for the industry to recognise this technology and for competitors to follow suit?

Initially, recognition was gradual. We focused on retrofits first because they’re faster and more straightforward to implement, allowing us to build credibility quickly. In the first two years, we retrofitted about ten yachts. These early adopters became advocates, prompting shipyards to take note when their clients requested this technology for newbuilds. The real turning point came when charter guests began asking brokers specifically for yachts equipped with Zero Speed Stabilisers. Within about two and a half years, the technology gained real traction. Our first major competitor was Naiad, followed later by larger players like Rolls-Royce and more recently CMC. But we had a solid three-year lead before it became an industry standard.

How many stabiliser systems do you produce and install annually on superyachts?

The numbers have evolved over time. In our peak years, we produced up to 100 systems annually – an impressive figure, especially for smaller yachts of 50 to 60 metres. Nowadays, we handle fewer projects, averaging around 30 to 40 systems per year, but these are much larger, more complex, and therefore significantly more costly. Despite the reduced volume per year, our revenue remains decent due to the scale and sophistication of these systems.

What drove this shift towards hybrid technology, with the F45 and now the fully electric e-Fin?

The shift was driven by a desire for efficiency and reduced power consumption. We had toyed with the idea of electric stabilisers years ago but didn’t have the technology or the right expertise at the time. The F45 system, which uses proven hydraulic technology enhanced for better energy management, emerged as a frontrunner for larger yachts. It’s versatile and adaptable, leveraging energy storage capabilities that make it highly efficient. The e-Fin, suited for yachts between

40 and 65 metres, was designed with simplicity and quieter operation in mind. It lacks hydraulic components, making it a more streamlined solution for mid-sized vessels. The main challenge when it comes to introducing entirely electric systems for the larger yacht segment is ensuring the longevity and reliability of electric systems, particularly the gears and motors.

Tell us more about the energy storage solutions you’ve integrated with the F45 and E-Fin?

For the e-Fin, we use capacitors akin to batteries, allowing us to store surplus electricity from the yacht’s systems for peak demand. The F45 goes a step further with a flywheel-based system that stores and releases energy more efficiently with a power density nearly ten times that of capacitors. These innovations help stabilisers consume less power at zero speed and recover energy when the yacht is underway, especially in rougher conditions.

What do you produce in-house or out-source??

We don’t manufacture every component in-house, so choosing suppliers with proven track records is critical. We consider factors like longevity, availability, and support. For instance, the PLCs we use come from multiple brands to avoid dependency on a single source. This strategic diversity ensures that if a supplier discontinues a product, we can pivot to alternatives without compromising system integrity, or having to potentially redesign an entire product around that missing component.

How much of Quantum’s resources go into R&D?

Approximately 20 percent of our technical efforts focus on new development. This includes everything from attending industry trade shows to sourcing new technologies. The goal is to blend research with practical solutions insights, ensuring we remain at the forefront of innovation while maintaining reliability. It has been our unwavering commitment to R&D over the last 40 years that has helped us to elevate the brand and maximise stabiliser performance. For example, the testing and continuous re-development of our hydraulic systems over the past several decades, gave us insights that led to the development of both F45 Power System and the e-FIN electric stabiliser.

Finally, what is Quantum’s next frontier in stabilisation and motion control?

We’re refining the XT-Fin design, and looking into independent fin movement with real-time lift and drag measurement – an evolution we expect to unfold over the next couple of years.

Heinen & Hopman’s HVAC&R solutions seamlessly integrate into your yacht’s design, delivering silent, precise comfort in every space. Our systems ensure optimal air quality, temperature, and humidityallowing you to enjoy every journey in effortless comfort.

GET IN TOUCH WITH OUR TEAM OF SPECIALISTS

Gulf Craft started out over 40 years ago building composite fishing boats and runabouts. In 2003 it launched its superyacht division and by the end of the decade had delivered 18 vessels over 30 metres across four continents. Now the UAE-based shipyard and SYBAss member is expanding its facilities, enhancing client services, and diversifying into resort tourism.

BY JUSTIN RATCLIFFE

At last year’s Dubai International Boat Show, Gulf Craft announced it was restructuring as a holding company. The news was a footnote at the time, but its significance is not to be underestimated as what is now Gulf Craft Group pursues an ongoing strategy of consolidation and diversification. That process is already starting to bear fruit.

“Having different factories in different sites and different product ranges brings pressure to control the way you work and how best to be competitive in local and international markets,” says Abeer AlShaali, Deputy Managing Director at Gulf Craft Group. “We stepped back a bit to see where we are and who is our competition so we can streamline our activities under a unified vision while providing each brand with sufficient space to develop independently.”

Gulf Craft currently operates out of three facilities – a shipyard Umm Al Quwain and separate service centre in Ajman, UAE, and another yard in the Maldives that builds small passenger vessels. Its product range spans from the leisure lines – Oryx cruisers and SilverCAT multihulls – to the Nomad adventure yachts and Majesty superyacht series, which includes the 56-metre Majesty 175, the world’s largest all-composite production yacht. As part of its corporate restructuring, these facilities are being augmented and the product portfolio remodelled.

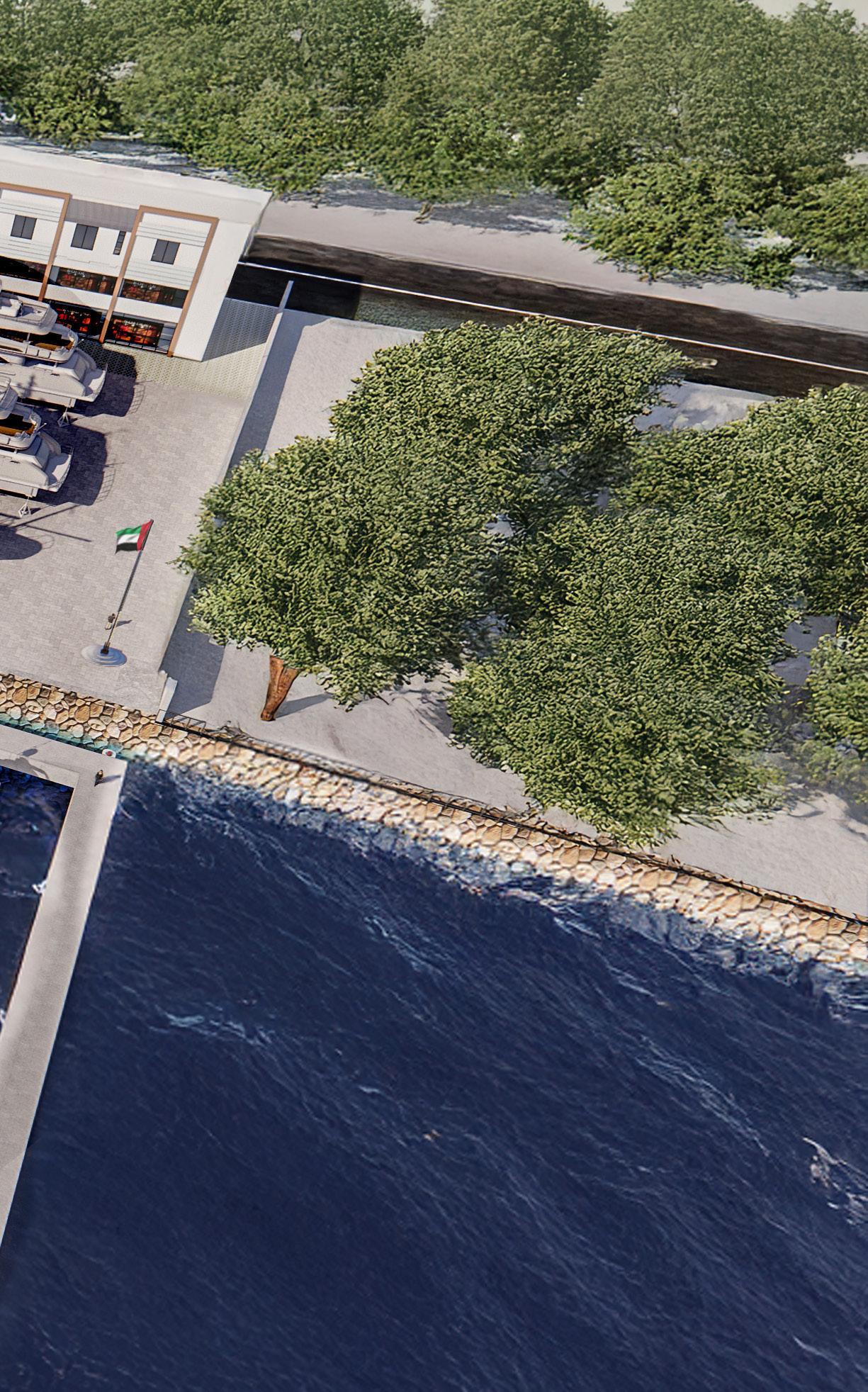

The service centre in Ajman is being upgraded and moving into new premises with a 600-tonne travel lift and berthing for vessels of up to 80 metres to better serve the growing number of superyachts visiting the Gulf region. With the new service facility expected to be operation by the summer, the existing yard will be repurposed as a manufacturing facility for the smaller leisure lines, which will free up space at the main facility in Umm Al Quwain to focus on the Nomad and Majesty series. At the same time, a marketing effort is under way to rationalise brand perception of the group’s four brands that cater to different demographics and different users.

“Majesty Yachts has always been about five-star luxury superyachts and everyone knows what it stands for,” says Gulf Craft Marketing Manager Alexander Souabni.

“The Nomad adventure range has not been shown in Europe or the US, but it resonates with a very strong niche and I’m looking forward to relaunching the brand, because part of the new company structure is about consolidating the way we perceive and present each brand. Not just externally but also internally, because once you’ve internalised perceptions, it's much easier to communicate them to our markets in the US, Europe, Australia, and here in the Gulf.”

In the same vein, Gulf Craft recently set up a new process department with the aim of enhancing closer relationships with its superyacht clients and continuously improving the in-build experience. To reduce paperwork, for example, it will soon be possible to sign off new work orders online and a new dashboard is in development that will allow owners to follow the build of their yachts remotely.

“In the past it was the sales team that looked after these things, but we felt we needed a dedicated department,” says Costas Eliopoulis, Chief Process Officer. “Our job is to really get to know the client inside and out, which helps us in a variety of different ways to build stronger relationships and increase client confidence.”

“At our core we are boat builders and anything else that we do is going to be connected with being out on the water.”

Gulf Craft Maldives was set up in 2002 to build small service vessels for transporting people and goods between the coral atolls that make up the marine republic. Because the products and client profile are very different from Gulf Craft’s yachting production, the shipyard was allowed to operate semi-independently and became by far the largest supplier of such craft in the region. In 2022, Eliopoulis was dispatched to optimise the management, engineering and production processes at the Maldives factory. As former quality control manager and then general manager of production at Gulf Craft, he was able to boost both efficiency and profitability. He was also tasked with reviewing the local markets and especially water transport for the region’s high-end resorts.

“What we found was that our luxury transport craft were not in sync with market expectations,” recalls Eliopoulis. “Wealthy holidaymakers are spending up to $25,000 per night at these resorts; they arrive First Class or by private plane, and we needed to offer vessels that provided a similar transport experience on the water. By listening to the needs of 5-star resorts in the Maldives, we developed an entirely new line of multihull limousine tenders that combine exceptional style, elegance, and comfort to meet the premium standards of luxury transport.”

It is not just the boats that are being upgraded. The existing shipyard in Thilafushi will become a one-stop refit and service centre as the finishing touches are put to a brand-new facility of more than 74,000 square metres in North Male Atoll that can build up to 72 feet (approximately 22 metres). This new shipyard, which will double production with an eye also on export, is just the first phase of an ambitious development project for a five-island atoll owned by Gulf Craft that includes luxury residencies, a 5-star resort complex, and even a submerged restaurant. With the shipyard already operational, the first of these real estate projects is due to open in spring 2025.

“At our core we are boat builders and anything else that we do is going to be connected with being out on the water,” says Abeer AlShaali. “Our investment and diversification in the Maldives is all part of that, but it also gives us the agility to be able to generate other revenue streams in an industry that is far from recession-proof.”

Another increasingly relevant function of the Maldives facility is as a stepping stone to the growing Asian markets and beyond. The UAE has bilateral trade agreements with India and Australia that reduce or remove import tariffs – often a stumbling block when exporting luxury goods overseas. Last year, Gulf Craft was a key sponsor of the inaugural Qatar Boat Show in Doha, historically a strong market, and this year it will debut eight brand new models at the Dubai Boat Show. However, the USA is by far its principal market for the larger yachts and remains the focus of efforts to increase sales in that sector.

“Americans understand the advantages of composite in hot and humid climates like Florida, combined with light weight and low draft for cruising the Bahamas,” says Souabni. “That’s not always the case in Europe where opinion is more traditional and once you get over a certain size, the preference is often for steel and aluminium.“

When Mohammed Hussein AlShaali –Chairman of Gulf Craft – co-founded the company in 1982, he was building on a successful career as a diplomat that overlapped with the new business enterprise (his last government position was as UAE Minister of State for Foreign Affairs from 2006-2008). Last year he received a 'Lifetime Achievement Award' at the annual Boat Builder Awards during METSTRADE. The following is an extract of his keynote interview at the Gulf Superyacht Summit in Dubai shortly afterwards.

To what extent has your experience as a diplomat and skill set as a negotiator helped you in the commercial world of luxury yacht building?

To put it very simply, it’s all about public relations and being able to communicate with people. Whether in diplomacy or in business, it’s about communication and I think that is the common dominator with building boats for people. Now it's probably more complicated than that when it comes to politics and here I would like to differentiate between diplomats and politicians: politicians work for themselves or their party; diplomats work for their countries.

After the Majesty 175, you’re due to launch the Majesty 160 next year. What are the advantages of building in GRP at that size compared to steel and/or aluminium?

In 2016 when I announced we were building the 175, people thought it was a crazy idea and that it couldn’t be done. But we built the yacht – which is 56 metres overall but also 780 gross tons –and it was successful in every aspect regarding performance, stability, noise and vibration, and so on. I believe GRP has many advantages, especially for places like here in the Gulf where the weather is hot and humid and the water is very saline and unkind to metal. GRP requires less maintenance but it’s also lighter, which means less draft, which is ideal for the shallow cruising grounds here and in the Caribbean, for example. In fact, before announcing the 175, we did a study with the designer Frank Mulder and the results of that study showed that we could realistically build up to 200 feet in GRP. Beyond that size, steel or aluminium is the logical choice.

Would you ever consider building in steel or aluminum?

Actually, a few years ago we thought about it. But after a lot of study and research we decided against it because we preferred to build on our 40 years’ experience of working with composites. We intend to stay in the same market and size range for composite yachts, so it makes no sense for us to increase our competition with other brands by building metal boats. When you look at the Majesty 160, for example, the competition starts to thin out because at that size our clients come to us because they prefer to have a composite boat. Having said that, we do provide refit and maintenance services for steel and aluminium superyachts and that capacity will increase when our new service facility comes online this year.

Yachting in the Gulf is on the increase and Gulf Craft is part of that. What has to be done to ensure continued growth for your brands?

Well, I don't think anything is guaranteed in the future. If we look at what's happening in the automotive industry, for example, we see things can change very quickly and that raises alarm bells. We survived the 2008 financial crisis and the Covid pandemic because we adapted; we channelled our efforts into thinking and designing for the future. We could do that because we have stayed small and adaptable. If we can diversify and stay nimble, I hope we will not only survive but also thrive.

Just prior to the Gulf Superyacht Summit last December, Gulf Craft had five yachts over 30 metres in various stages of construction packed into its main shed in Umm Al Quwain (as the restructuring of facilities progresses the aim is to have to 6-8 superyachts in build at any one time), including two Majesty 120s, the all-new Majesty 112 and Majesty 100 Terrace (both launched at DIBS 2025), and the first 49-metre Majesty 160, which is sold and due to launch in early 2026. When the 160 leaves the shed, minus her radar mast, she will have just 150mm of air room below the gantry crane.

Interestingly, the Majesty 160’s naval architecture was originally conceived by Van Oossanen Naval Architects for a steel hull and adapted for building in composite. Gulf Craft was an early adopter of composites for large yacht construction and pushed the boundaries with its 56-metre (780GT) Majesty 175. Depending on structural and safety requirements, it can combine GRP, Aramid, Kevlar and carbon fibre with PET foam cores using a variety of techniques from laying up by hand and resin infusion to vacuum bagging and resin infusion transfer (RTM). Convincing the class societies that it could build in composite to steel equivalence was a long and arduous process requiring 128 different lab tests, but Gulf Craft’s methodology is now class-certified for structural and fire integrity.

I had not visited Gulf Craft for several years and was impressed by the increase in digital automation with 3- and 5-axis CNC machines and other state-of-the-art technology installed throughout the facility. Six more cutting and milling machines were due to arrive for the interior joinery department alone, as well as a robotic painting and sanding unit with a UV curing booth that will drastically reduce downtime during the painting process.

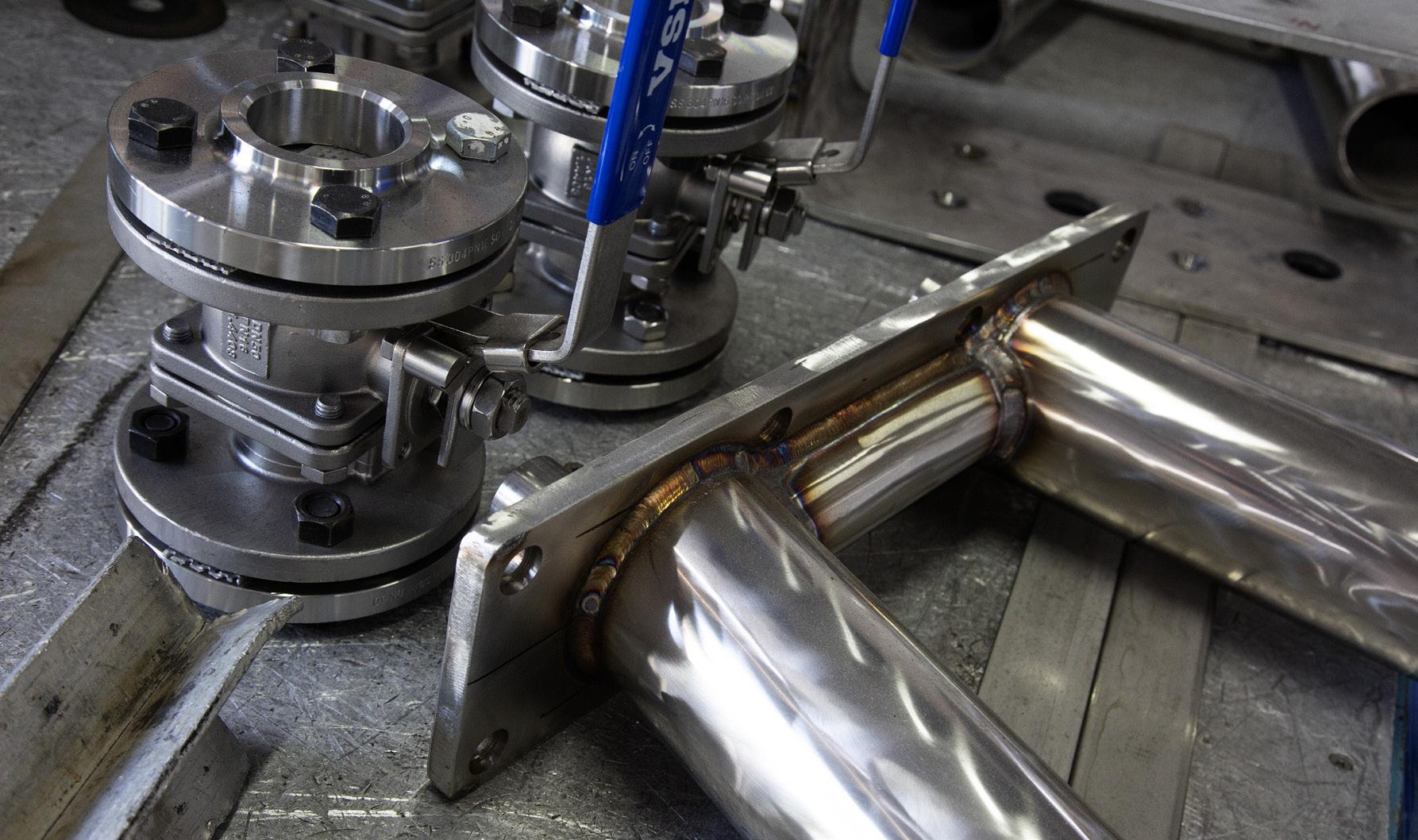

Clockwise from top left: Gulf Craft has taken delivery of several new CNC machines; a render of the new Majesty 160 in build; flanges and bollards produced in-house; the Majesty 175, the world’s largest composite production yacht.

“It makes no sense for us to increase our competition with other brands by building metal boats.”

JUSTIN RATCLIFFE

More remarkable is just how much Gulf Craft manufacturers in-house. This amounts to just about everything apart from the main machinery and systems, including switchboards, steering wheels, escape hatches, pipe flanges, ventilation ducting and the laserwelded, stainless-steel cabinets for the galley. A review is even under way to determine the viability of setting up its own glass factory. Gulf Craft cannot rely on the same network of local suppliers and subcontractors that have grown up around shipyards in Europe. The only way they can ensure high quality and a reliable supply chain is to do a lot of the work themselves in-house. That takes a large and skilled workforce, some of whom have been with the company for over 30 years and have worked their way up to management positions.

“For 42 years we’ve been building up the industry locally; there was no one else to do it for us,” says Abeer AlShaali. “We now have a strong combination of people from our C-suite to the shopfloor workers that know our products and understand boatbuilding. But we’re always looking at ways we can get better, and I think that is reflected in how we’ve been able to take our yacht construction to the next level.”

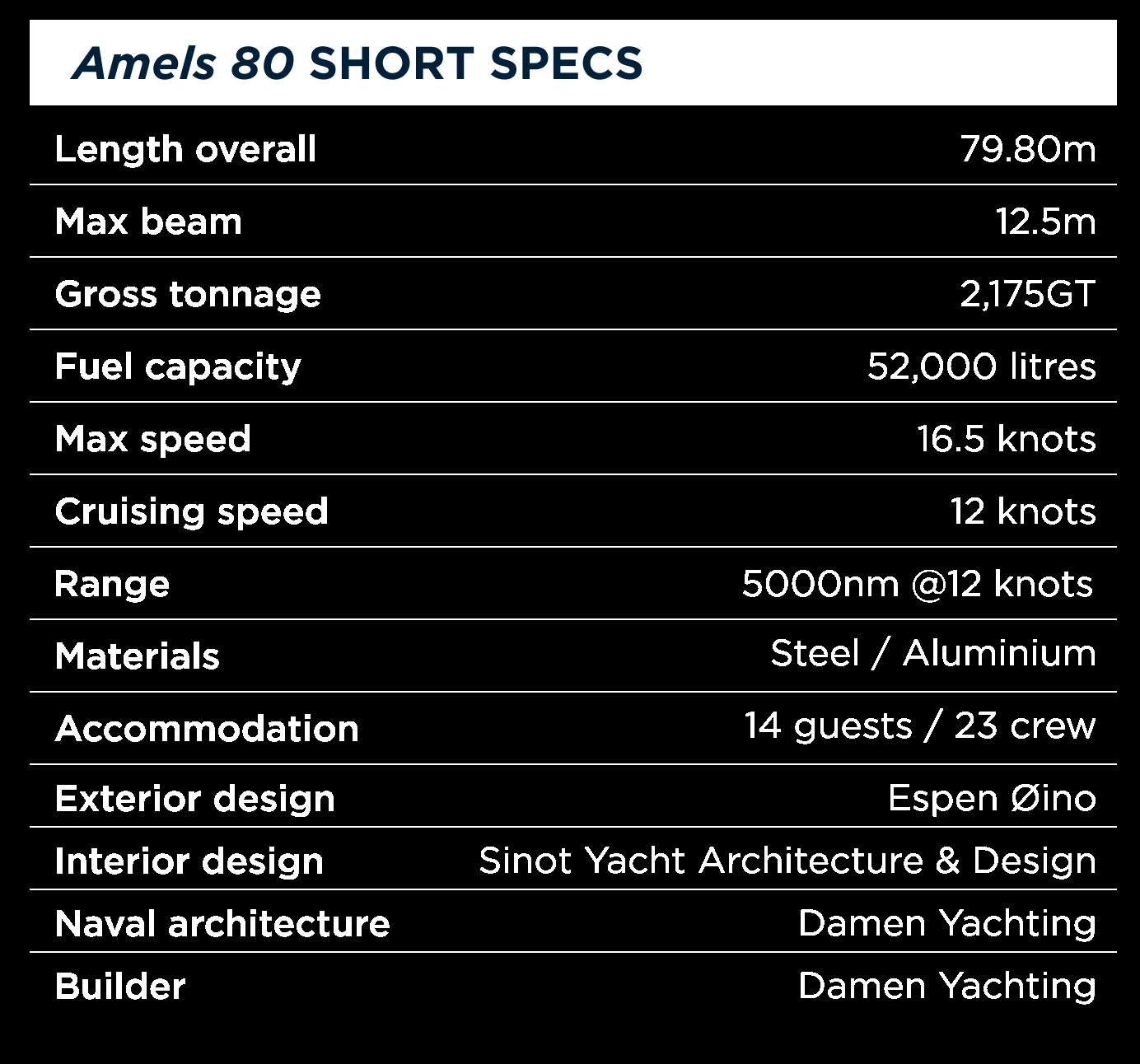

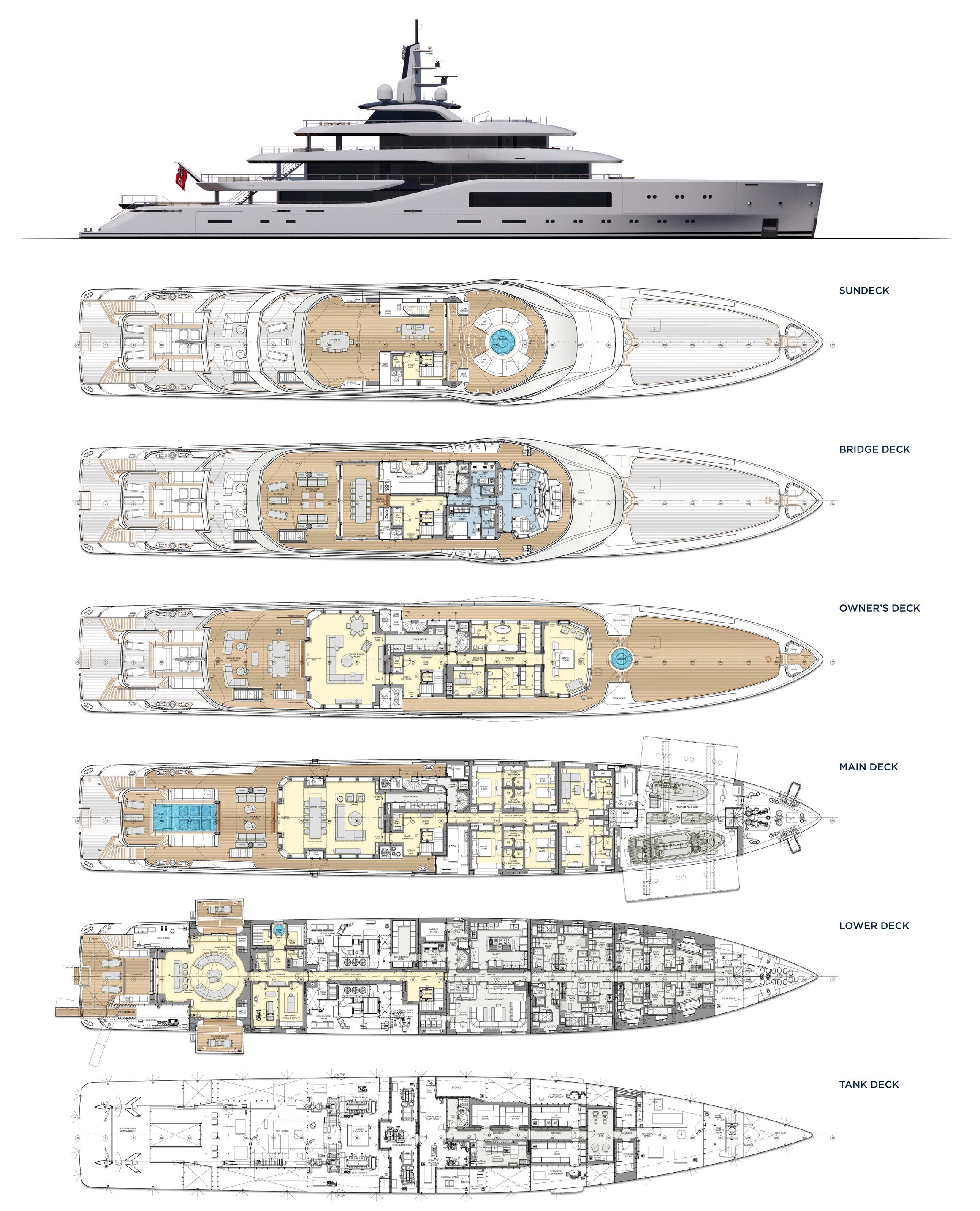

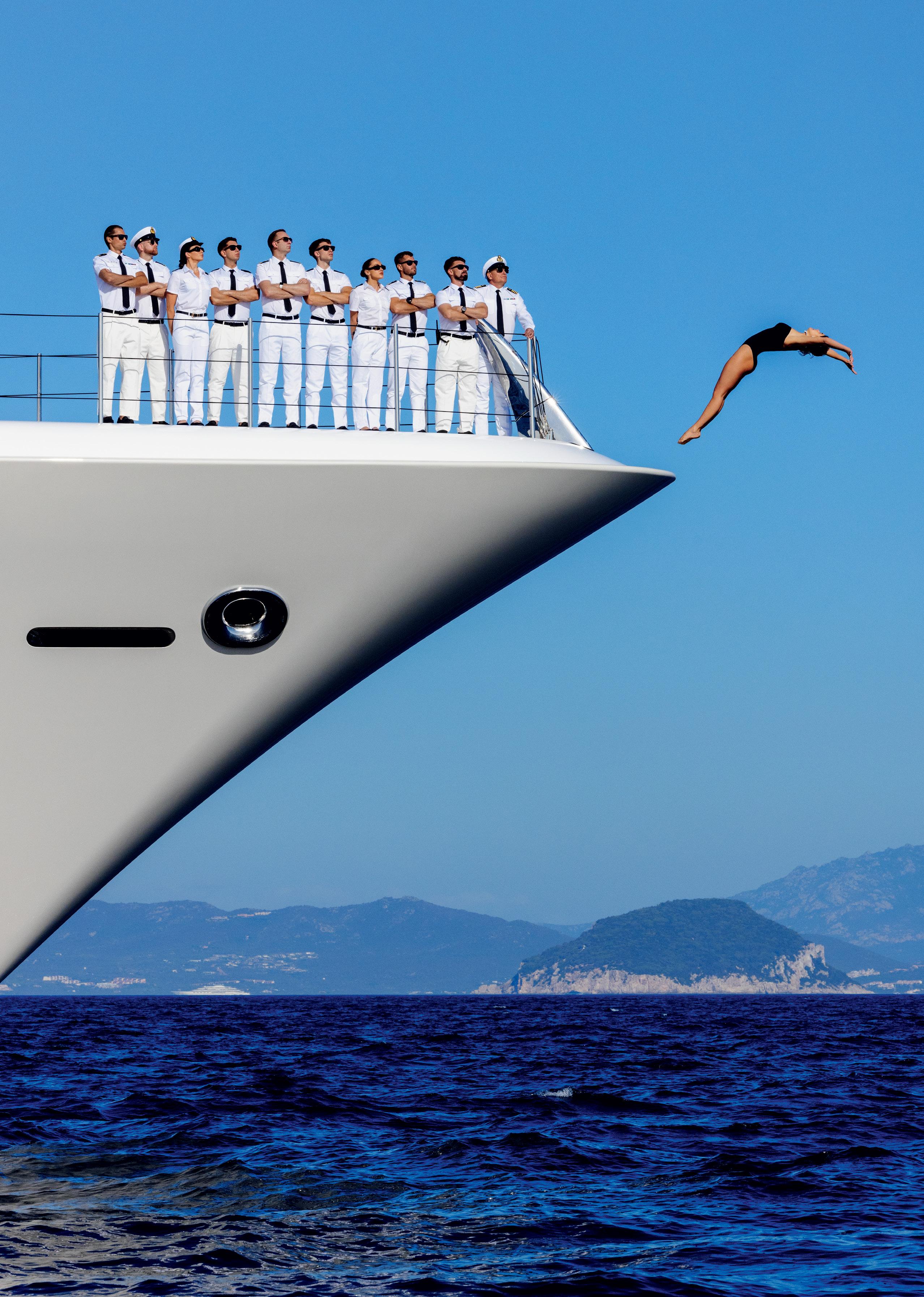

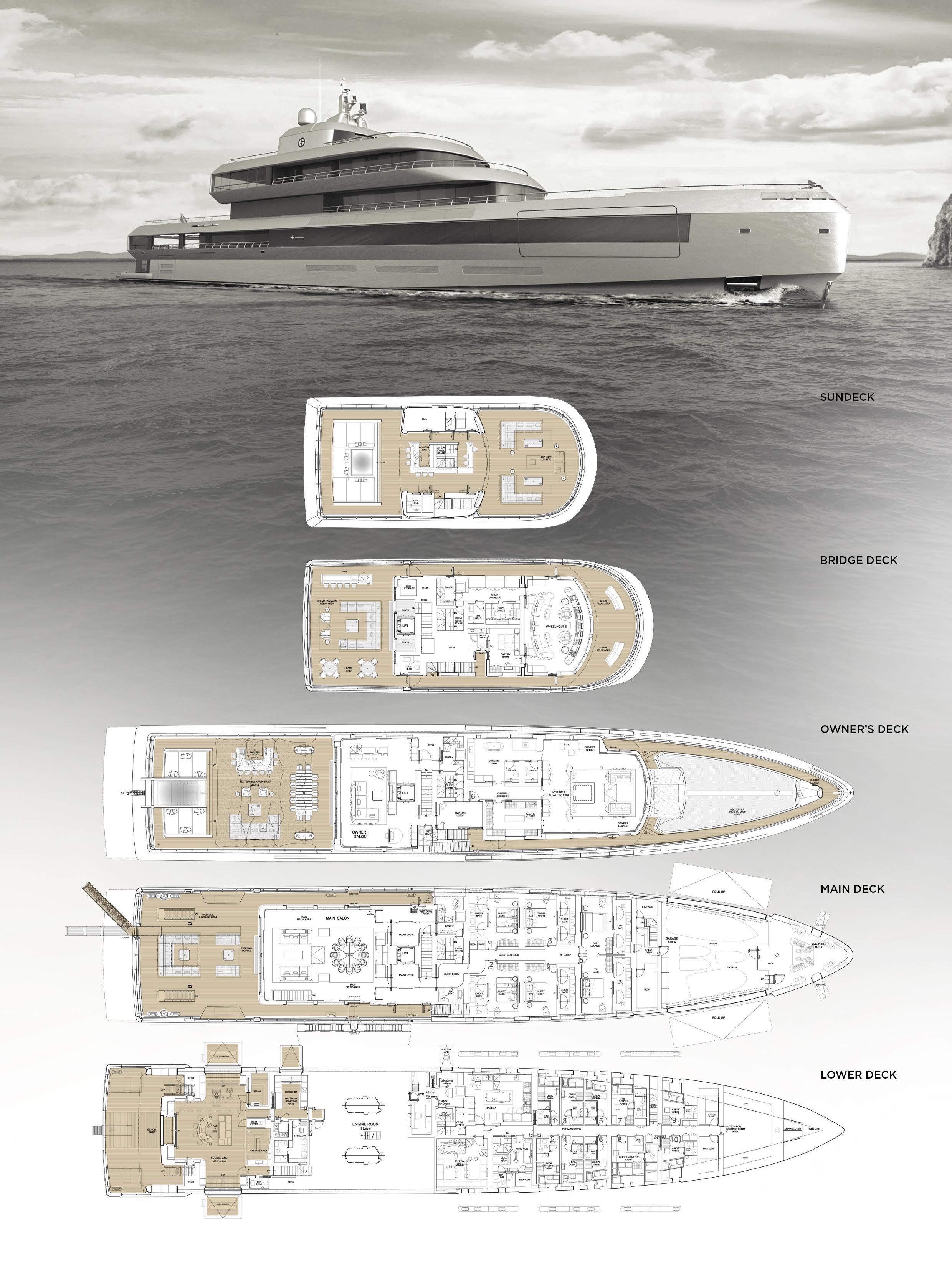

The Amels Limited Editions fleet, one of the most successful semi-custom stories in superyacht history, shows no sign of slowing down with four units of the Amels 80 – the latest and largest iteration – sold and another two in production before the first has even left the shed. We talk to the Amels team and visit the first units in build at the Damen Yachting shipyard in Vlissingen.

BY JUSTIN RATCLIFFE

When Deniki, the first Amels 171, was launched back in 2007 she was the forerunner of a new generation of superyachts based unashamedly on semicustom principles from a builder bestknown for its full-custom projects. The idea was to streamline construction and reduce delivery times by combining a common hull, superstructure and engineering platform, but still allow for a high degree of customisation to the highest Dutch standards of finish. The original plan was to sell six in six years.

Twenty years after Amels first presented its semi-custom strategy at the 2005 Monaco Yacht Show and 50 deliveries later – including 25 of the Amels 180 alone – the Limited Editions concept is still going strong. That kind of longevity doesn’t happen by chance. The Amels 80 flagship and the new-generation Amels 60, both designed by Espen Øino, have evolved from previous models, but have also benefitted from careful planning and astute marketing.

“Marketing an existing semi-custom line is harder than a new, attention-grabbing custom project,” admits Sarah Flavell, Marketing Manager at Damen Yachting. “The option to customise has always been part and parcel of the Limited Editions concept, but that gets harder as the yacht gets bigger; once you

get to 80 metres and 2,175GT there is much more client expectation. The challenge is to make sure we don’t drift away from our build philosophy and end up turning a Limited Editions into a full-custom yacht.”

This challenge works both ways and on occasion a client interested in a full-custom project may be tempted by the lower cost, proven platform and shorter waiting time of a Limited Editions that has been started on speculation. Flavell points out that it depends on the client and how much they want to be involved in the whole design and build process:

“The Limited Editions allow certain clients to take away the parts of the build process they don’t like, but still enjoy the parts they do like,” is how she sums it up.

Client requests are sometimes integrated into later versions of the same model and become standard features. This happened with Entourage, the second hull in the Amels 60 series, when the owner wanted a different window design and an extended sundeck that were carried through into subsequent builds. The same is true of the open-plan layout of the owner’s bathroom on the second Amels 80, which has been adopted for hulls three and four.

As the Limited Editions series have grown in size, the lessons learned from previous iterations have been carried forward into their successors. The Amels 60, for example, is the descendent of the 55-metre Amels 180, and the 80-metre flagship is the follow-up to the 74-metre Amels 242. This evolutionary progression involves not just the technical platforms, but also the onboard features desired by owners (and required by captains and their crews). In the case of the new flagship, this meant Amels already knew what prospective owners were looking for in an 80-metre yacht. The harder task was to create a design that had both broad appeal and its own identity in a pre-defined package.

“Market trends tell you that building an 80-metre yacht on spec is not the thing to do, because there are not many in build and owners want more customisation,” says Flavell. “Yet we’ve sold four within a very short space of time, which suggests there is a demand for that size of yacht with a set of build parameters that provide certain features at a certain price and guarantee the build time.”

“The Amels 80 ticks so many boxes from a client perspective because we learned from the 74-metre,” adds Jan van Hogerwou, Commercial Executive North America.

“Everything we know now about what owner’s want on a yacht of this size comes from that previous successful series. Throw in very competitive pricing and a short delivery time, and I believe it’s the best offer in its class on the market.”

The interior design, the first collaboration between Sinot Yacht Architecture & Design and Amels, is a good example of this philosophy in action. Although tailored to the owners’ requests, the shipyard has looked to standardise features and dimensions as much as possible. In the guest cabins, for example, the wardrobes and drawers are of the same size and occupy the same footprint. The same is true in the crew cabins, which also have bunks sized to take standard mattresses and make procurement easier. Standardisation means fixed furniture items can be batch produced in advance for subsequent builds, reducing downtime for faster and more efficient installation.

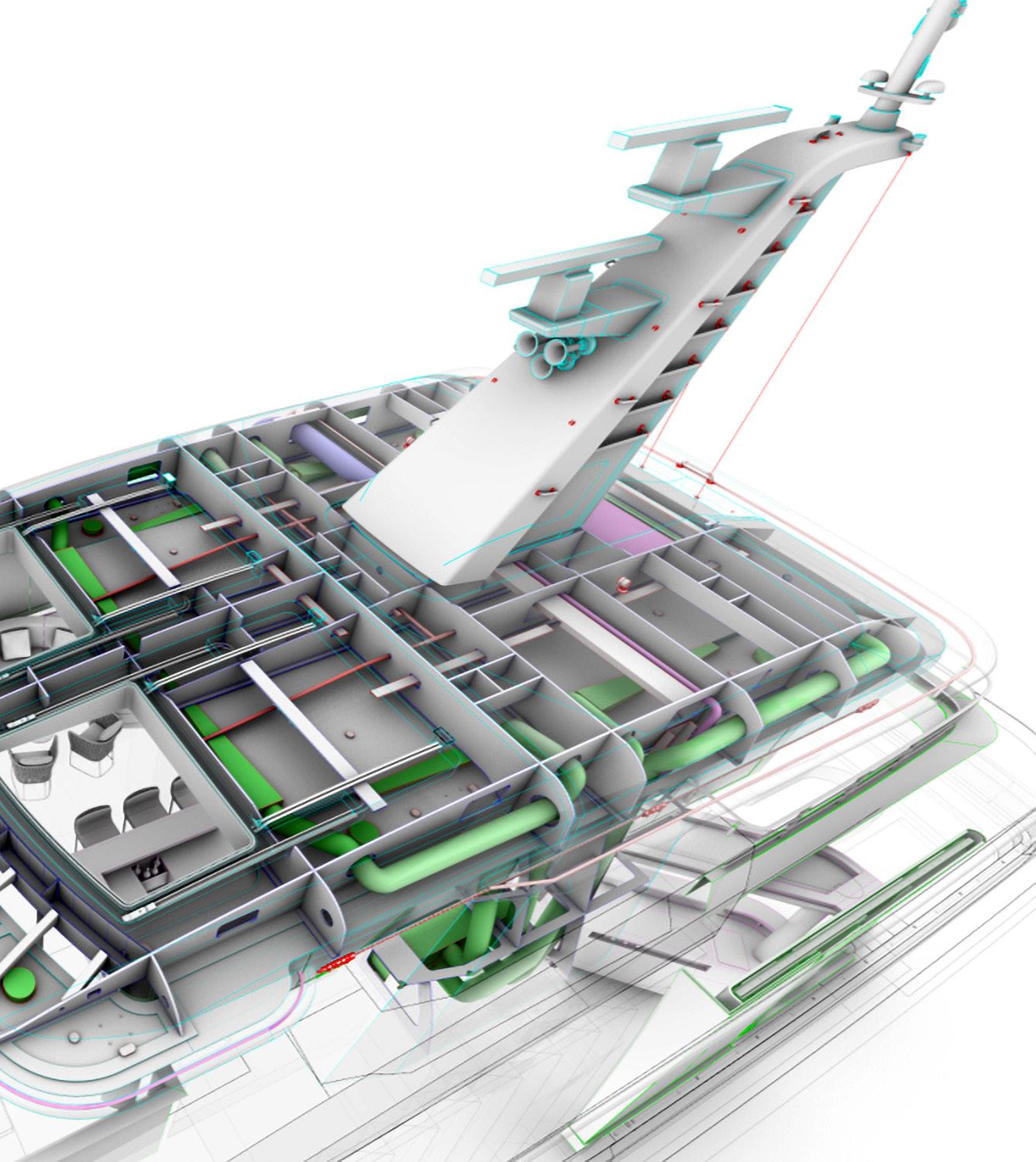

Amels does not build its hulls and superstructures on site in Vlissingen. This is done in at Damen Shipyards Galati in Romania for the Amels 80 and at Damen Shipyards Gdynia in Poland for the Amels 60. They are then transported or towed to Vlissingen for fitting out. At the time of our visit, hull 8003 was traversing the Bay of Biscay on her way to The Netherlands and by the time you read this article, hull 8001 will likely have left the 200-metre covered dry dock. Behind her, 8002 will also exit the dry dock to make space for the new arrival and then take the place formerly occupied by 8001. It takes roughly 15 months for the construction work in Romania, a month for the transfer, and a further 18 months for the outfitting, fairing and painting. With the major hotworks complete and main machinery and piping already installed, the Amels shipyard is basically a well-oiled assembly facility.

“Keeping the heavy welding work and systems installation separate means that when the yachts arrive in Vlissingen we can really focus on achieving a perfect interior and exterior finish,” says Adriaan Roose, Amels Design Manager. “It wasn’t always this way, but we learned that we can work more efficiently and provide much higher quality by separating the build processes.”

Romke van der Linde, Amels project manager for 8001 and 8002, worked on the first Amels

171 when he joined the company 18 years ago. As an indication of how far information technology has progressed since then he taps a Wireless Access Port (WAP) on the Amels 80. “We have 152 of these throughout the yacht,” he says. “Deniki had just eight.”

He also points out an array of steel storm shutters and hatches used to seal the unfinished vessels during transportation. Because the exterior design is standardised, these are shipped back to Romania to be re-used. Waiting nearby to be hoisted on board 8001 was the transom door for the beach club. The glass-fronted shell door folds down into a recess in the swim platform while another folding hatch closes on top of it for a flush, teak-decked finish. Suspended from the scaffolding cocooning the yacht was also the hull door for the forward tender garage. The 11.5-metre door had been rigged up in front of the garage opening so it could be painted using the same batch of metallic topcoat. All the hatches and shell doors are manufactured at the facility in Romania.

“The decision to produce our own shell doors was taken over ten years ago when we had projects in build that were dependent on the delivery of those doors,” says Roose. “There are very few suppliers for these big doors and if one goes belly up, which has happened, it can add several months to the build schedule. We simply cannot take that risk.”

Future additions to the Limited Editions fleet is the topic of ongoing discussion. In the current market, the likelihood is that a new model would fall between the Amels 60 and the 80-metre flagship. The difference between the two in terms of internal volume is more than 1300GT, so plenty of room for an intermediate option. Building bigger brings more pressure to customise and additional risks for the shipyard, a lesson learned from Here Comes the Sun: the full-custom project, the largest Amels to date at 83 metres (later extended to 89 metres), could have been built as a Limited Editions, but was considered too risky to build on speculation. Moreover, Amels has seen a trend among owners to invest in a Damen Yachting support vessel, another proven platform with 19 sold to date, that offers extra capacity for tenders and toys without building a bigger mothership. The same thinking applies to the Damen Xplorer series, whereby the 60-metre model is being built on spec (two units are currently under construction), but not the 80-metre version.

“As much as people love the explorer concept, that is not currently reflected in the time it takes an owner to commit compared with a more conventional superyacht,” says Flavell. “So Anawa, Pink Shadow and La Datcha were all built for owners with very specific uses in mind. Added to that, there’s nothing to stop our Limited Editions yachts going off the beaten track, and they have been.”

Like the Amels 60, the 80 comes with a standard hybrid power package with twin Caterpillar diesel engines and PTO (Power Take Out) and PTI (Power Take In) electric drives with systems integration by RH Marine. Top speed is 16.5 knots with a cruising range of 5,000 nautical miles at 12 knots. You can sail under diesel power with the main engines on, but also at low speed or while manoeuvring with the main engines off using just the generators to drive the e-motors for less noise and vibration. There is also the option of electric stern and bow thrusters for station-keeping capability.

There is a battery bank, but this is designed for peak shaving (although technical space has been put aside to install up to 1MW of batteries), and a fully automated energymanagement system provides constant monitoring of consumption to allow the hybrid solution to engage as workload demands. The system basically means that engines can run at their optimal load with the batteries absorbing peaks in demand, avoiding starts and stops for higher efficiency and less wear and tear. Full diesel-electric propulsion with pods was considered, but after analysing the pros and cons Amels opted for the efficiency, flexibility and redundancy of a hybrid system.

“Marketing an existing semi-custom line is harder than a new, attention-grabbing custom project.”

Perhaps the biggest challenge for the project team, however, came before metal cutting even started. The Amels 80 started out as a 75-metre design and the decision to lengthen the hull by five metres (the exact LOA is 79.80-metres) was taken on the suggestion of a prospective client who wanted a bigger beach club. Three months before the finalised design package was due to be handed over to the production department, the Amels team went back to the drawing board to re-crunch the numbers based on the longer and slightly wider specifications. The 150-square-metre beach club with its side terraces and transom door that opens flush with the stern platform is now a central feature of the Amels 80. Some builders are moving away from the enclosed beach club on the lower deck in favour of a terraced main deck aft. This is because beach clubs on smaller yachts can easily turn into dark, unappealing spaces in the bowels of the boat. Removing them also makes construction simpler. The beach club on the Amels 80 works because it has the space it needs to make it work.

“The redesign was a lot of extra work late in the day, but I’m glad we did it,” says Roose. “It meant both the beach club and the pool above are bigger and the yacht looks sleeker on the water. I also think that 2,175GT is something of a sweet spot in the market right now and offers a platform that make owners feel they have a much bigger boat.”

Let’s preserve what inspired our passion

Discover our solutions to drive sustainability and improve value REFIT FOR THE FUTURE!

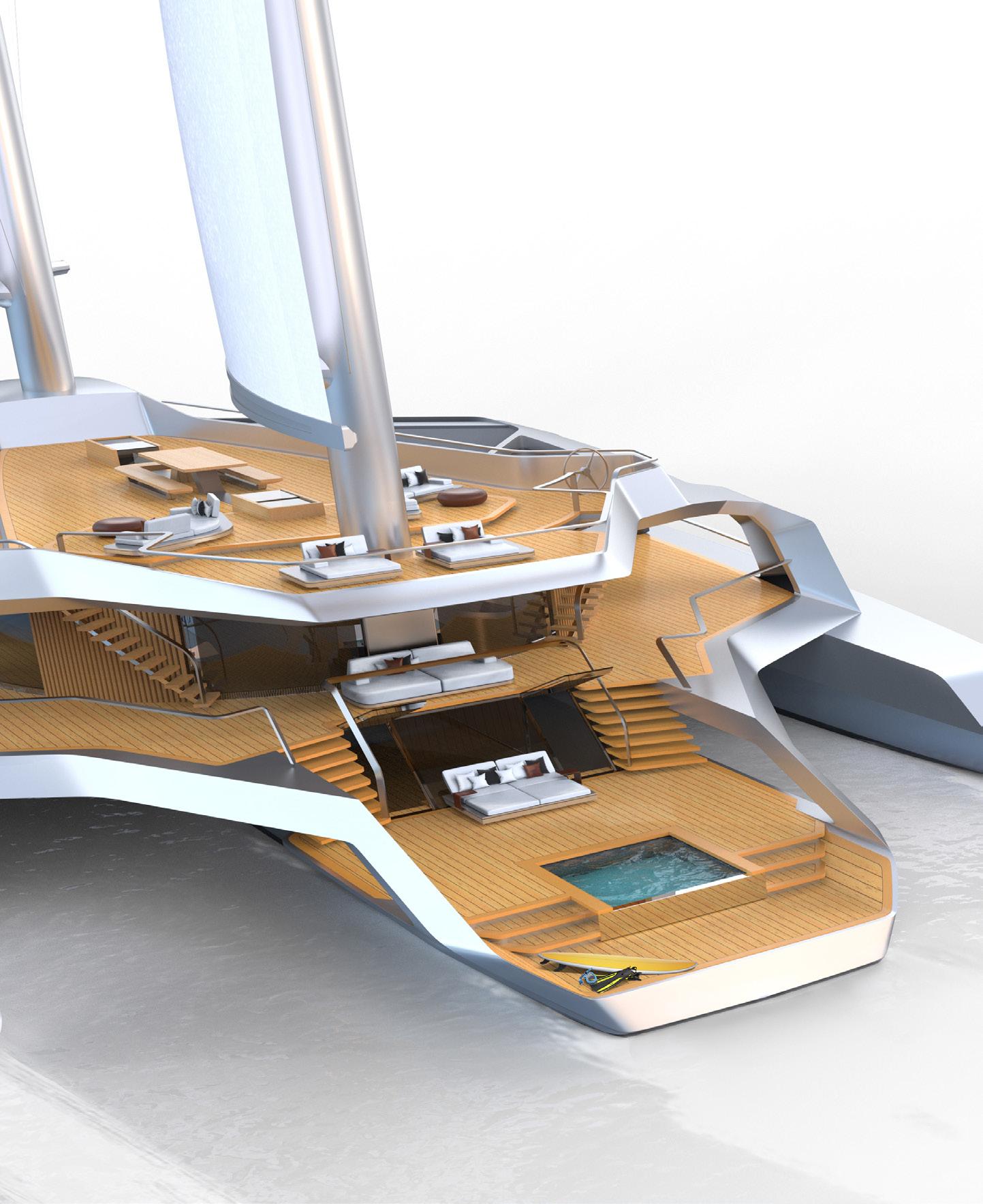

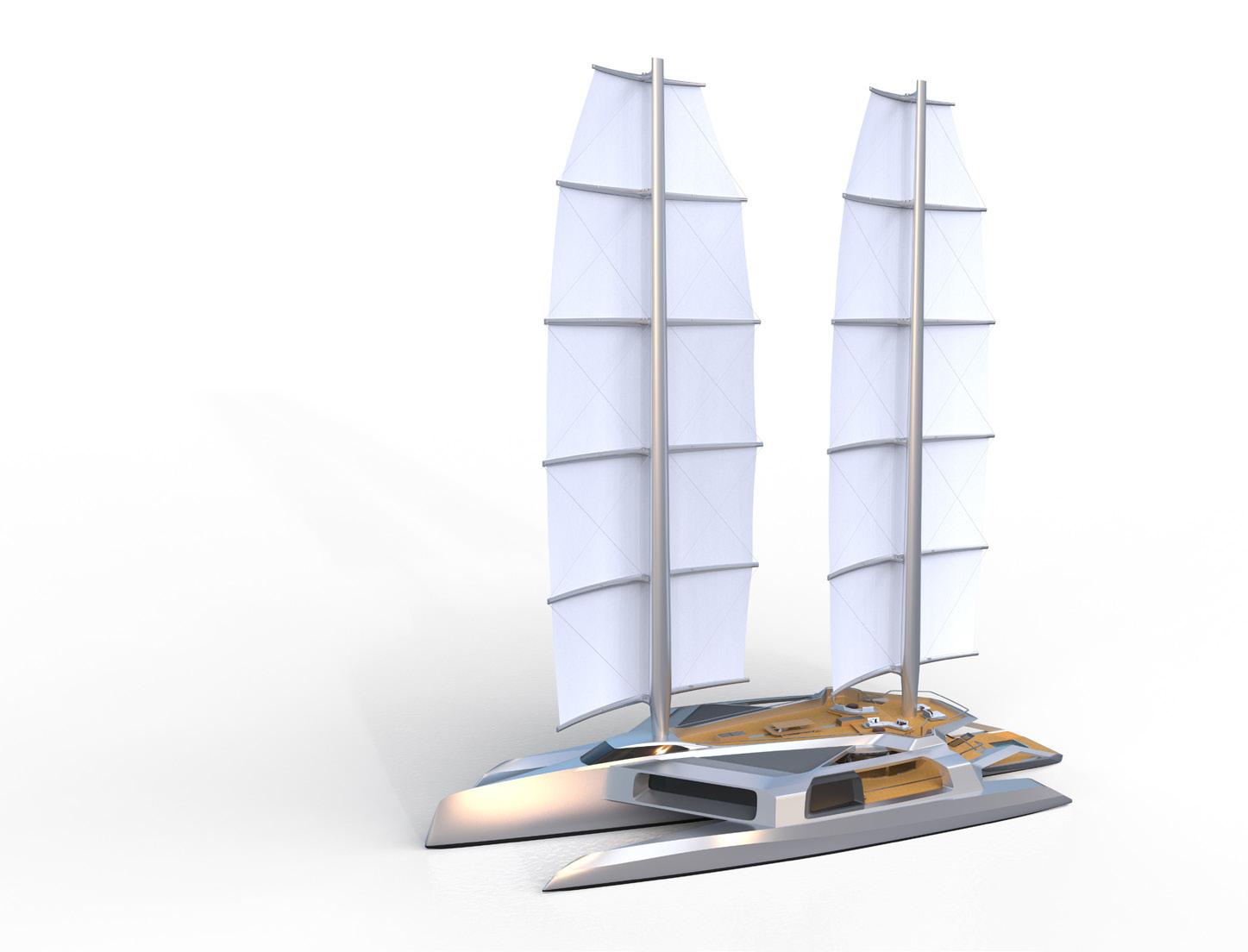

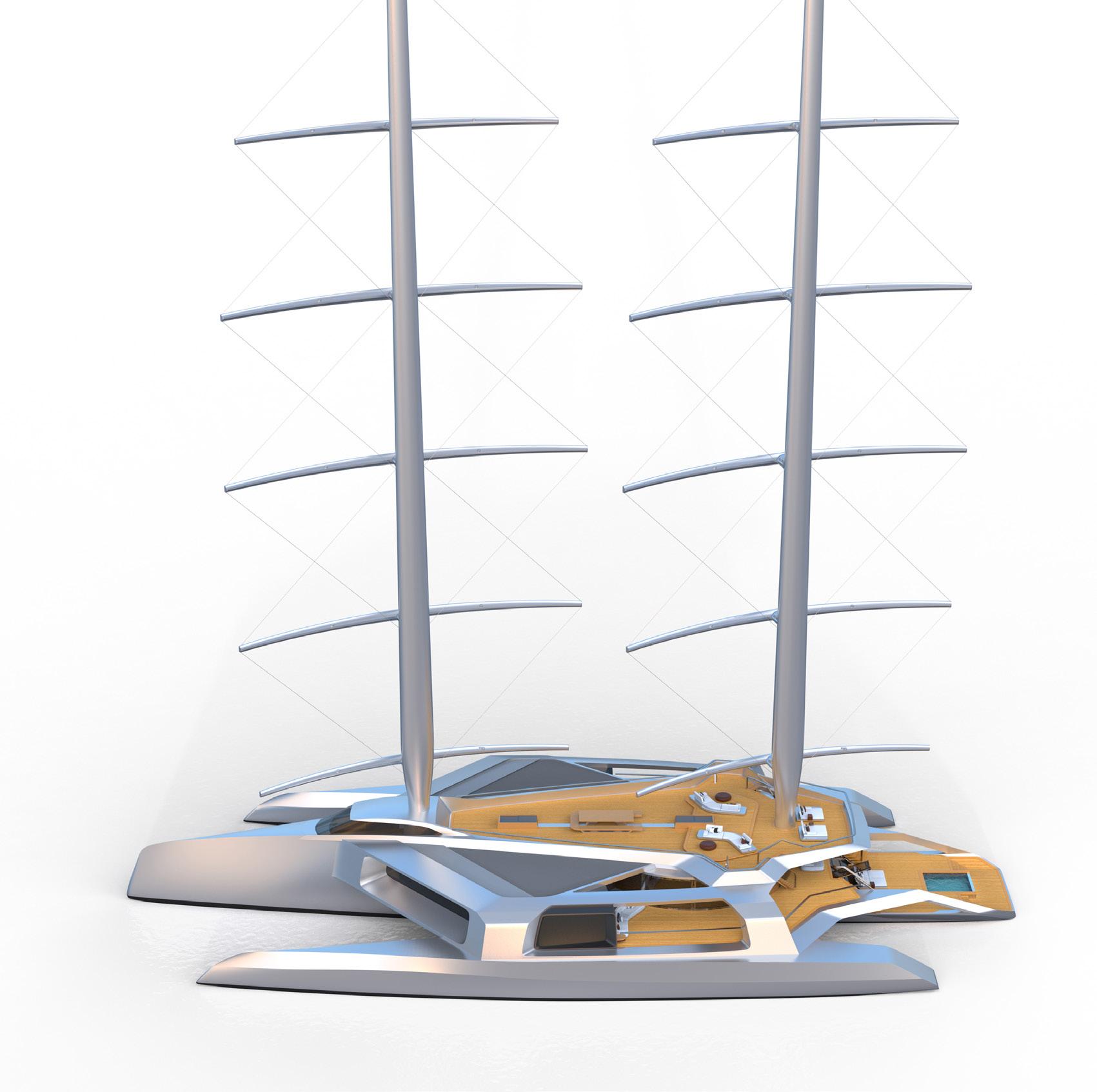

The Oi60 is a design study for a 63.5-metre sailing trimaran by James Carley of JC Yacht Architecture and Rob Doyle Design. The avantgarde concept builds on the positive reception of another multihull project, the smaller Domus concept with Van Geest Design that we reviewed in the very first issue of How to Build It.

BY CHARLOTTE THOMAS

“I‘ve been sailing much of my life and was intrigued by the whole idea of a world explorer trimaran and being able to cover a lot of ground quickly in a luxurious but sustainable way,” begins James Carley, a naval architect and chartered engineer who honed his design skills at the studios of Martin Francis and Bannenberg & Rowell. Carley’s bold exterior design and interior layout for the Oi60 are strikingly different, but the basic principles behind the trimaran configuration remain the same. Trimarans are usually wider than catamarans, which means more interior volume and deck space; maximum heel angles of two degrees allow the windward hull to come out of the water for less drag, higher performance and more comfort under way; three hulls in the water are also more stable at anchor with vastly reduced motions compared to a monohull; and unlike a catamaran, all the systems and engineering can be centralised in the main hull, which means fewer structural stresses and deflections – all factors that might persuade owners to switch from power to sail.

The armas or outriggers are effectively for buoyancy purposes only and while they can be used for tankage and storage, all the guest accommodation and interior living spaces are concentrated on one level on main deck with the crew quarters and services on the lower deck in the central hull. This makes for a more inclusive onboard experience and vastly improves circulation flow for both guests and crew by avoiding the inconvenience of multiple decks –evident in Carley’s innovative ‘radial’ layout. It also brings cost savings by simplifying the systems design and construction.

“Sailing yachts can cost twice as much to build per gross ton as motoryachts,” Rob Doyle points out. “We approached this project by pricing it as if it were a conventional motoryacht with two rigs, but designing outwards instead of upwards. We’ve calculated the volume at over 1,200GT, which is equivalent to a 65- or 70-metre monohull, but you get the huge open and semi-open deck spaces that only a trimaran can offer for free, so to speak.”

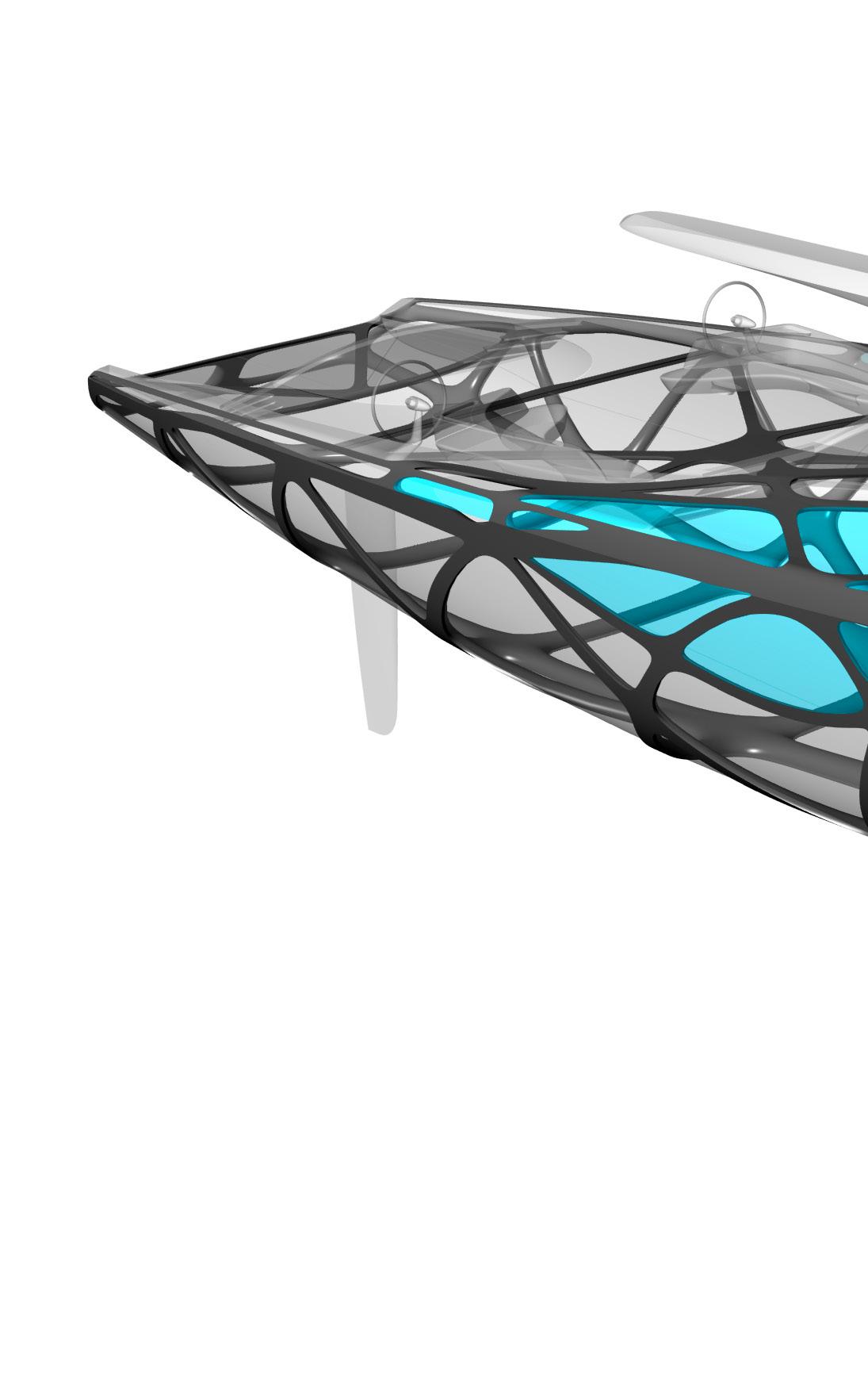

It is no coincidence that the ‘Oi’ in the concept name stands for ‘Outside-inside’. Like Domus, the crossbeam connecting the three aluminium hulls is, in effect, a huge perforated box that offers excellent strength and rigidity. The perforations or cut-outs have been designed around the choice of build material, load paths, boundary conditions and other constraints to offer enormous semi-open areas as well as giant windows, especially in the forward-facing suites. The result is something that could easily double as the villain’s futuristic lair in a James Bond movie.

“On the bigger motoryachts with four or five decks, everyone tends to congregate on one particular deck anyway, so why not have it all on one multi-purpose level?” asks Carley. “We can still carve more intimate spaces out of that much bigger space to suit different needs throughout the day. And a lovely change is that we’ve been careful not to be greedy by trying to fill up every square of interior, hence the semi-open areas.”

makes for a more inclusive onboard experience, and improves circulation flow for both guests and crew.

Critical to the whole concept is a feature that is still under wraps. Like Domus, the masts will be Panamax but unlike the earlier concept that had a hoistable, double-luffed mainsail to achieve some of the efficiency of a wing sail, Rob Doyle Design has devised a new self-supporting, joystick-controlled square rig called the Moonraker (named not after the Bond novel, but the topmost sail on the fastest square riggers of old). Rob Doyle Design claims the Moonraker offers superior performance at less cost and refer to as the Dynarig’s ‘Nokia moment’.

“We’ve signed an NDA wih Southern Spars who are undertaking a research program to verify performance and the Moonraker will be officially presented later this year,” says Mark Small. “We’ve been sitting on the Dynarig concept for years, but never got to version two-point-oh and without giving away too much, the critical point about the Moonraker is what the Dynarig can’t do. We hope to achieve downwind performance similar to a spinnakered ketch, which will make passagemaking much quicker. And critically, it will be cheaper to build than an equivalent Dynarig, so basically win-win.“

88-metre Maltese Falcon and 106.7-metre Black Pearl, currently the only yachts launched with Dynarigs, have full-carbon masts and spars. This would not necessarily be the case on the Oi60 and the masts could be of aluminium, since the trimaran has so much righting moment anyway, there is less need for a superlight but super expensive high-modulus rig.

Critical to the whole concept is a feature that is still under wraps: a new self-supporting, joystick-controlled square rig called the Moonraker.

James studied naval architecture at the same time as Rob and Mark at Southampton University and the opportunity to collaborate came when he left Bannenberg & Rowell to set up his own design studio. The immediate inspiration for the Oi60 was a YouTube video he saw of a group of freewheeling friends sailing a performance catamaran from Tahiti to Hawaii. James got to thinking how to make long-distance sailing even faster and was initially keen to add foils to boost speed and comfort still further, but was dissuaded by Rob and Mark.

“At this size the structures involved would be enormous and if you have a problem with them, you have a very big problem,” says Rob. “We figured it was also unnecessary, because we have loads of performance already at hand and the idea is to make the iO60 as cost-effective to build as possible. Why would you open the door for that kind of added complexity and cost?”

Given the huge surfaces area the trimaran configuration offers, it makes sense to cover it with solar panels to generate renewable energy. Rob Doyle Design reckons that 300 kW/h per day could be produced from some 300m2 of photovoltaic cells to reduce generator loads for hotel use. Moreover, when sailing the freewheeling propellers can regenerate energy to store in batteries for future use. At hull speed the extra drag makes little difference, but the prop blades can also be folded when performance under sail is a priority.

“We’ve calculated that when sailing, the solar cells and regenerative propellers can produce all the energy that's required on board, including HVAC, which will be way in excess of what's actually needed to run the vessel,” says Mark. “It’s a pragmatic combination of renewable and regenerative for what will be a diesel-electric or hybrid diesel-electric boat.”

Although prospective clients have expressed interest in the concept, its designers purposely avoided undue influence from owners while developing the concept.

“Most owners have preconceived ideas of other boats in their heads,” says Rob. “We wanted to nip that in the bud so we could come up with something new and fresh. James came to us over a year ago with a blank piece of paper and we took our time developing his ideas into something very unique. Sometimes you have to give these creative projects time to develop, so we didn’t rush it or try to mash three or four other boat designs together.”

As naval architects as well as designers, all three are well aware of the technical

and financial constraints associated with designing superyachts. After all, if the aim is to provide owners and shipyards with solutions that are both new and viable, there is little point in coming up with ideas that are ultimately unbuildable.

“We see a lot of concept projects that can't be built, or they can be built but would cost half a billion to manufacture,” Mark points out. “We always balance the creative with the technical, which also means taking into account factors that may affect the price. We would never have started with the concept unless we thought it made sense.”

“I would really love to see it get built,” ends James. “Done right, I think it could be very special.”

The masts and spars could be of aluminium, since the trimaran has so much righting moment there is less need for a lightweight carbon rig.

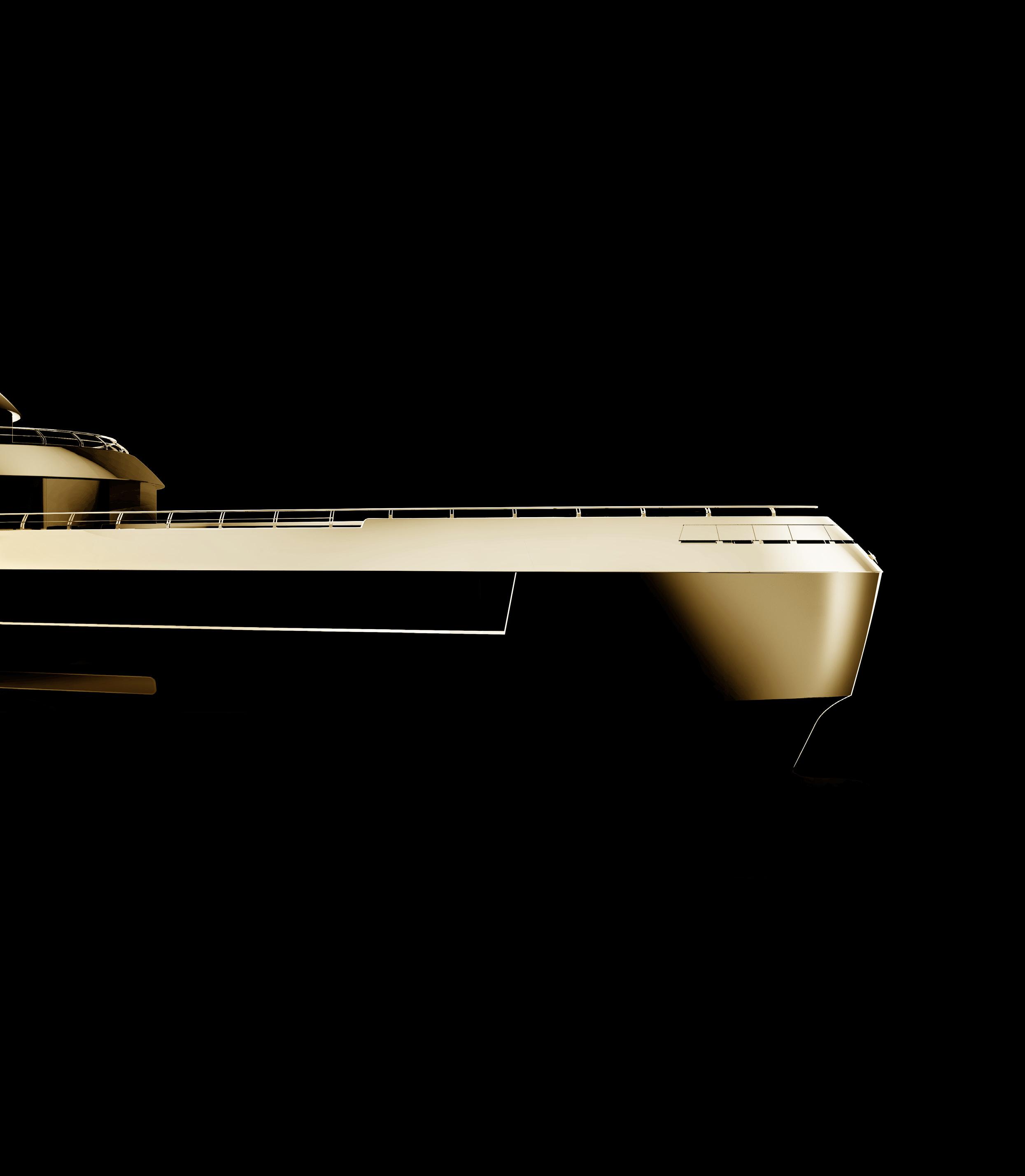

Project Metamorphosis, one of two 72-metre sister ships in build at The Italian Sea Group’s superyacht facility in Tuscany, is the first superyacht designed inside and out by Giorgio Armani. We visited the yard to catch up with the project leaders as the yacht prepares for her technical launch in April.

BY JUSTIN RATCLIFFE

The idea of inviting Giorgio Armani to create a custom design for the Admiral brand came to Giovanni Costantino, CEO of The Italian Sea Group (TISG), when he was walking past the Emporio Armani store, a vast building that occupies a whole block in Milan’s city centre. Armani was no stranger to TISG having twice refitted his own yacht, 65-metre Main, at the group’s NCA Refit facility. It took another six months for the two men to meet in person, but it didn’t take long for the famous fashion designer to take up the challenge.

Working to a heavily revised concept platform, the collaboration required constant back-and-forth between Armani’s creative team and the shipyard’s engineers. Armani would sketch ideas, which were then transformed into detailed blueprints by the shipyard’s engineering team, who made adjustments for practicality while staying true to the original design intent. The dynamic ensured that the 2,070GT superyacht would embody the designer’s signature style that blends discreet aesthetics with functional luxury, but also meet the required performance and technical parameters. IYC's global managing partner Michel Chryssicopoulos quickly found a buyer for what became Project Metamorphosis and her sister ship, Project Visionary, sold a few months later.

“The challenge was to craft a bold visual statement without relying on unnecessary ornamentation,” says Costantino. “The yacht had to be practical to operate, but also a piece of modern design that conveys timeless beauty."

Armani’s minimalistic aesthetic makes ample use of glass, both externally and internally, with full-height panoramic windows on multiple decks. In fact, there are 310 square metres of external glass windows supplied by Sedak GmbH, amounting to 15.5 tonnes in weight (in addition to 230 square metres and 4.5 tonnes of decorative interior glass). The windows on the main deck and bridge deck are also cantilevered outboard Skat-style – these glass panes are not only massive, they also had to be able to withstand extreme weather conditions at sea without compromising the overall aesthetic.

“One of the first things we did was a feasibility study and FEM analysis to make sure the structure could take the stresses the yacht would be subjected to during her life,“ says project manager Davide Santagostino. “This analysis had to take into account not only the weight of the glass, but also the stresses caused by water movement and the external forces in high wind-load conditions. Further engineering was required with regard to weight distribution and stability, and we had to find creative ways to place internal structural pillars without disrupting the open-plan layout.”

The cantilevered glass further provides for an angled skylight above the main window pane in the guest cabins and bathrooms on main deck, which noticeably increases the amount of natural light entering the interiors. The sky lounge on the bridge deck, designed as an versatile cinema area for year-round use in summer and winter, has electrically operated floor-to-ceiling glass panes on three sides. The panes measuring up to 1.8 metres in diameter can be stacked in the open position to provide a plein air space in warmer weather or a more enclosed, sheltered environment when cruising colder climes. Forward of the very spacious wheelhouse is a deep Portuguese bridge that can be used as a relaxation area for the crew.

In the spring of 2024 Project Metamorphosis found a new owner in a sale brokered by Darrell Hall of Yachtzoo. The change of ownership, just three months before the projected launch, presented further challenges for both the shipyard and the new owner’s team.

“When I came on board, we were already at a stage where we realised there would be several adjustments necessary to meet the new owner’s requirements for personal use and with a view to charter," says Captain David Pott, who joined the project shortly after the resale. "Sustainability was not a prime motivator for the owner, but he was keen to integrate eco-friendly measures into the design as much as possible. He wanted a yacht that was able to go the distance – both literally and figuratively – and do so responsibly in full compliance with environmental regulations.”

The owner's desire to explore high latitudes – the Northwest Passage is just one item on a planned multi-year circumnavigation – meant uprating the yacht to Polar Class 1C certification, the lowest ice classification based on first-year ice in the Baltic Sea and Arctic Ocean. Although the hull was built with an ice belt of 12mm steel plating to withstand some ice conditions, the former owner had not opted to pursue formal certification. The shipyard team got to work to make the modifications required to meet the requirements. Amongst other measures, this involved upgrading the rudderpost, pintles, steering gear and propellers, installing freeze-protection valves, making new stability calculations that take into account ice accretion, and addressing environmental protection requirements.

“In the end we were able to add more urea tankage without compromising the yacht’s cruising range of 6,000 nautical miles.”

Facing page:

The latter led to an owner’s request for enhancements to the yacht’s SCR (Selective Catalytic Reduction) system by increasing the urea storage capacity. Injected as a water-based solution, the urea undergoes hydrolysis to produce ammonia, which reacts with NOx in the catalytic elements, effectively converting the harmful pollutants into harmless water vapor and nitrogen gas. Under Tier III diesel emissions regulations, in theory a vessel is required to carry only enough urea to run the SCR within a NOx Emission Control Area (ECA), but the owner wanted to use the system regardless of where his yacht is in the world – a prescient decision given that the list of ECAs will expand to include the Mediterranean as of May of this year. Besides neutralising NOx emissions, the SCR system also reduces exhaust noise and helps trap soot particles so they don’t find their way onto the deck, into the swimming pool and into the water around the yacht.

“This was a major modification as we had to rework the tankage to include more urea storage, which impacted the yacht’s fuel capacity,” says Andrea Bigagli, TISG Corporate Strategic Director. “In the end we were able to add more urea tankage without compromising the yacht’s cruising range of 6,000 nautical miles.”

“We took the view that emissions regulations are getting stricter all the time, so why not try to reduce as much as possible our environmental impact from the outset?” adds chief engineer Sam Needham. “We asked the shipyard to investigate the possibility of having the SCR units running all the time and they were happy to do that, which is a big improvement from our side. Basically, the yacht will run out of fuel before it runs out of urea.”

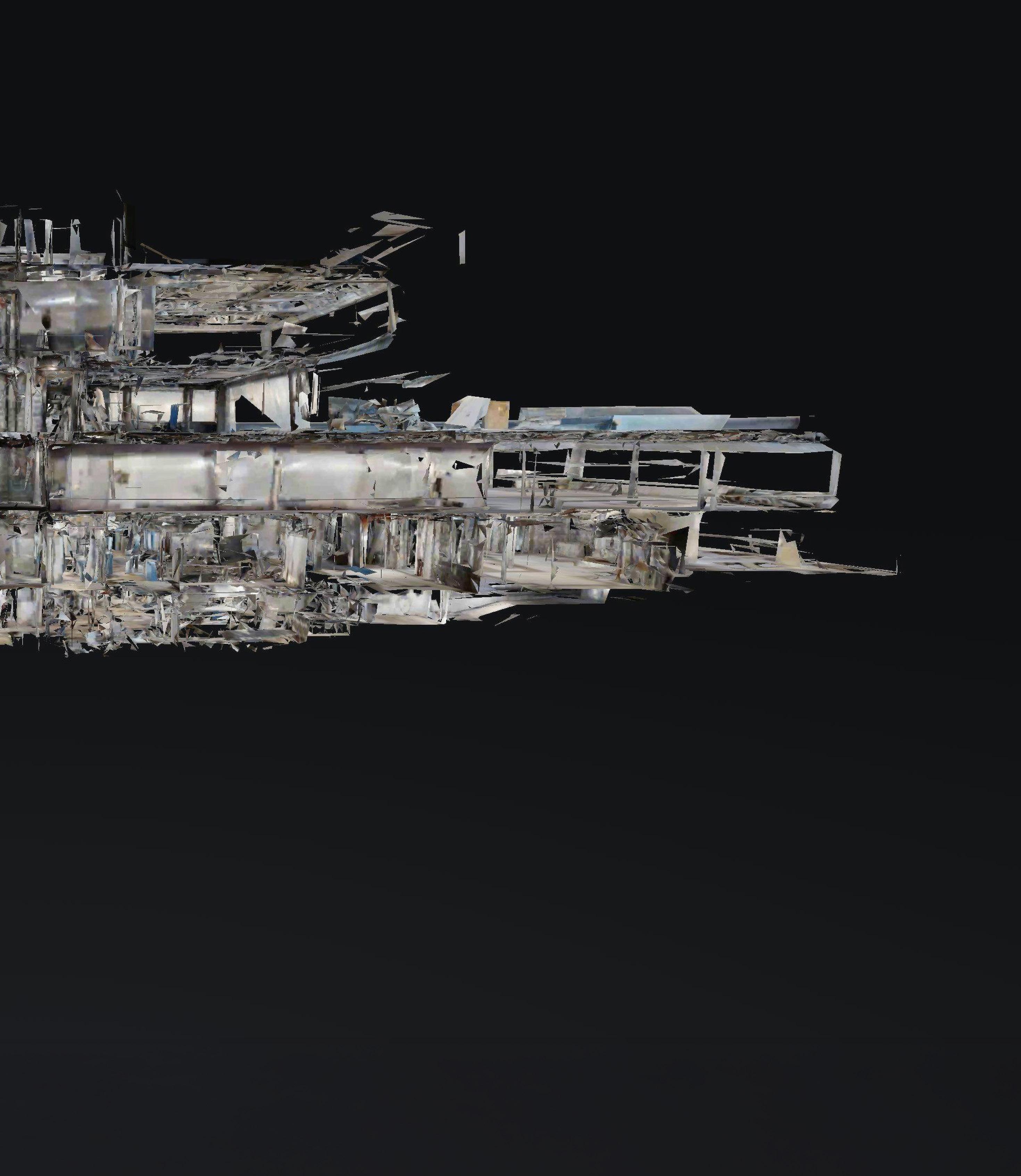

Individual images can be stitched together to

Shortly after the yacht changed hands, the owner’s team brought in Paul Shersby of Film360 Ltd to create a complete ‘digital twin’ of the project during construction using a Matterport LiDAR camera to capture spaces in high-resolution 3D. Working at night when the yacht was empty and progressing from tank deck to top deck, at the time of going to print Shersby had scanned the entire yacht four times (a complete 3D picture takes 500 scans or more) at intervals of six to eight weeks. While the system has been used to provide navigable interiors of finished yachts and residences for commercial purposes, the

technology also allows the owner’s team to remotely track the construction as it progresses.

“It’s been a really useful tool that I think will be picked up by others,” says Captain Todd. “For example, we can see all the cable and piping runs, where wi-fi routers are located, the black and grey water routes –basically everything below the deckheads or behind the walls before they’re covered up. It means if there’s a leak or other issues later on, we have a better idea of where the problem might be without having to take the interior to pieces.”

In line with the owner's desire for a techsavvy and future-proofed yacht, the AV/IT systems underwent substantial upgrades.

Working alongside AV/IT integrator Pibiesse, four Starlink antennas were added to the spec and cabling was augmented to ensure high throughput, redundancy, and future scalability for data-heavy applications like live video feeds, conferencing, and multimedia entertainment.

“Given the rapid advance of high-bandwidth systems, this upgrade was designed to futureproof the yacht’s AV/IT capacity in years to come,” says Bigagli. “The idea is that as new tech emerges, it can be seamlessly integrated into the existing infrastructure without requiring a complete system overhaul.”

Another important upgrade came in the form of an integrated bridge system from Furuno. This high-end addition improves the yacht’s navigation and operational capabilities, but also extends the vessel's usability in far-flung and possibly uncharted locations. The new bridge equipment includes FLIR thermal cameras and a

“He wanted a yacht that was able to go the distance – both literally and figuratively.”

WASSP multibeam sonar for mapping the seabed in high-resolution 3D. Using a tender in advance of the mothership, the system’s wide-angle sonar transducer maps the seafloor to find the safest passage and anchorage. The yacht also features telescopic wing stations with floors that pop up flush with the deck when extended, and a pantographic mechanism for the console controls inside the bulwarks.