The technical magazine for those involved in the design, construction and refit of superyachts

EDITORIAL

EDITOR IN CHIEF

EDITOR | HOW TO BUILD IT

EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTOR

NEWS EDITOR

FEATURES WRITER

WRITER

WRITER

SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER

CONTENT CREATOR

Francesca Webster

Justin Ratcliffe

Charlotte Thomas

Sophie Spicknell

Enrico Chhibber

Ellen Ranebo

Andrea Pefianco

Marina Vargas

Nick Smits

DESIGN PRODUCTION

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

GRAPHIC DESIGNER

Ivo Nupoort

Beatriz Ramos

INTELLIGENCE

HEAD OF INTELLIGENCE

RESEARCH ANALYST

DATABASE MANAGER

YACHT HISTORIAN

Ralph Dazert

Adil Zaman

Syrine Mellakh

Malcolm Wood

SALES & ADVERTISING

HEAD OF SALES

SALES MANAGER

SALES MANAGER

SALES MANAGER

SALES MANAGER

CLIENT SERVICE MANAGER

SALES ITALY

Marieke de Vries

Justus Papenkordt

Daniel Van Dongen

Charly van den Enden

Nuri Ozkaya

Johanna Borreli

info@admarex.com

CORPORATE

FOUNDER & DIRECTOR

TECHNOLOGY DIRECTOR

FINANCE DIRECTOR

Merijn de Waard

Fabian Tollenaar

Laura Weber

SuperYacht Times B.V. Silodam 256, 1013 AS, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 31 (0) 20 773 28 64 info@superyachttimes.com www.superyachttimes.com

Cover Images:

Project Thunderball by CRN Argo 54 by Omikron MTU by Justin Ratcliffe

How to Build It is published by SuperYacht Times B.V., a company registered at the Chamber of Commerce in Amsterdam, The Netherlands with registration number 52966461. The magazine was printed in June 2025.

When the renowned luxury yacht Starfire sought to reimagine its sun deck, only one name could deliver the extraordinary: KMF I Kreative Metallform

The mission? Transform the space into a world-class wellness sanctuary — featuring an infrared sauna, plunge pool, massage zone, and cutting-edge fitness suite — all enveloped within a fully enclosed, 360-degree glass atrium engineered to open and breathe with the sea.

Our German design team brought this vision to life with a bespoke floor-to-ceiling glazing system that appears to float, offering a seamless blend of strength, beauty, and innovation.

The result is an air-conditioned haven of light, views, and unparalleled functionality.

“Guests are in awe. Charter brokers consistently highlight the sundeck gym — it’s a showpiece that gets people talking.”

Paul Duncan - Starfire

At KMF, we take pride in the fact that perfection is our passion

Welcome to the summer edition of How to Build It. In this issue we explore how tradition and transformation are reshaping the superyacht world – from heritage brands adapting to a new era, to bold design concepts pushing the boundaries of what we expect a superyacht to be.

To mark Mangusta’s 40th anniversary, in Business Brief we take a revealing look at the brand’s evolution. Once a byword for power and speed, Overmarine is now embracing engineering innovation and efficiency in a changing market, signaling a shift many legacy players are navigating.

In parallel, the refit of steel-hulled Perini Navi ketch Belle Brise shows how timeless elegance can meet modern expectations. As Lusben strips her back to bare metal, this rebuild project is more than cosmetic – it’s about reconciling the past with the demands of the present.

We also cast a spotlight on radical thinking. Anthos, a concept design from Oceanco and Italian designer Mario Biferali, dares to ask: could a container ship become a luxury vessel, and what are the technical challenges to making it happen? In an industry that prides itself on traditional elegance, Anthos challenges us to see potential where others see limitation.

Meanwhile, the energy transition continues. In New Tech, we examine the promise – and pitfalls – of battery integration. As the sector moves toward hybrid and electric propulsion, builders and owners face a critical question: when is the right time to commit to a battery technology, and how can we futureproof those decisions in an industry with long lead times?

High-speed connectivity is no longer optional. Our AV/IT feature dives into how next-gen marine broadband is finally delivering on its promise, transforming both the guest experience and onboard infrastructure – and presenting new challenges for integrators in the process.

And in our Build Reports, we see these forces converge. Omikron’s Argo 54 and CRN’s Project Thunderball are both ambitious in scale and vision, but what truly unites them is a shared commitment to cross-disciplinary innovation – whether through blending racing DNA with luxury yachting, or merging engineering excellence from northern Europe with Italian flair and flexibility.

Across all these stories, a common thread emerges: this is a sector not just adapting to change, but actively shaping it. I hope they bring you inspiration, insight and a glimpse into the shape of things to come.

Justin Ratcliffe - Editor

27 Business Brief: A Family Affair

Mangusta is 40 years old this year. Long associated with speed, style and power, today the brand is more focused on engineering, efficiency and innovation.

38 Build Report: Cogito Argo Sum

The Argo 54 sailing yacht being being built by Omikron combines raceboat pedigree with superyacht luxury. We visit the project in Greece as it begins the push toward completion

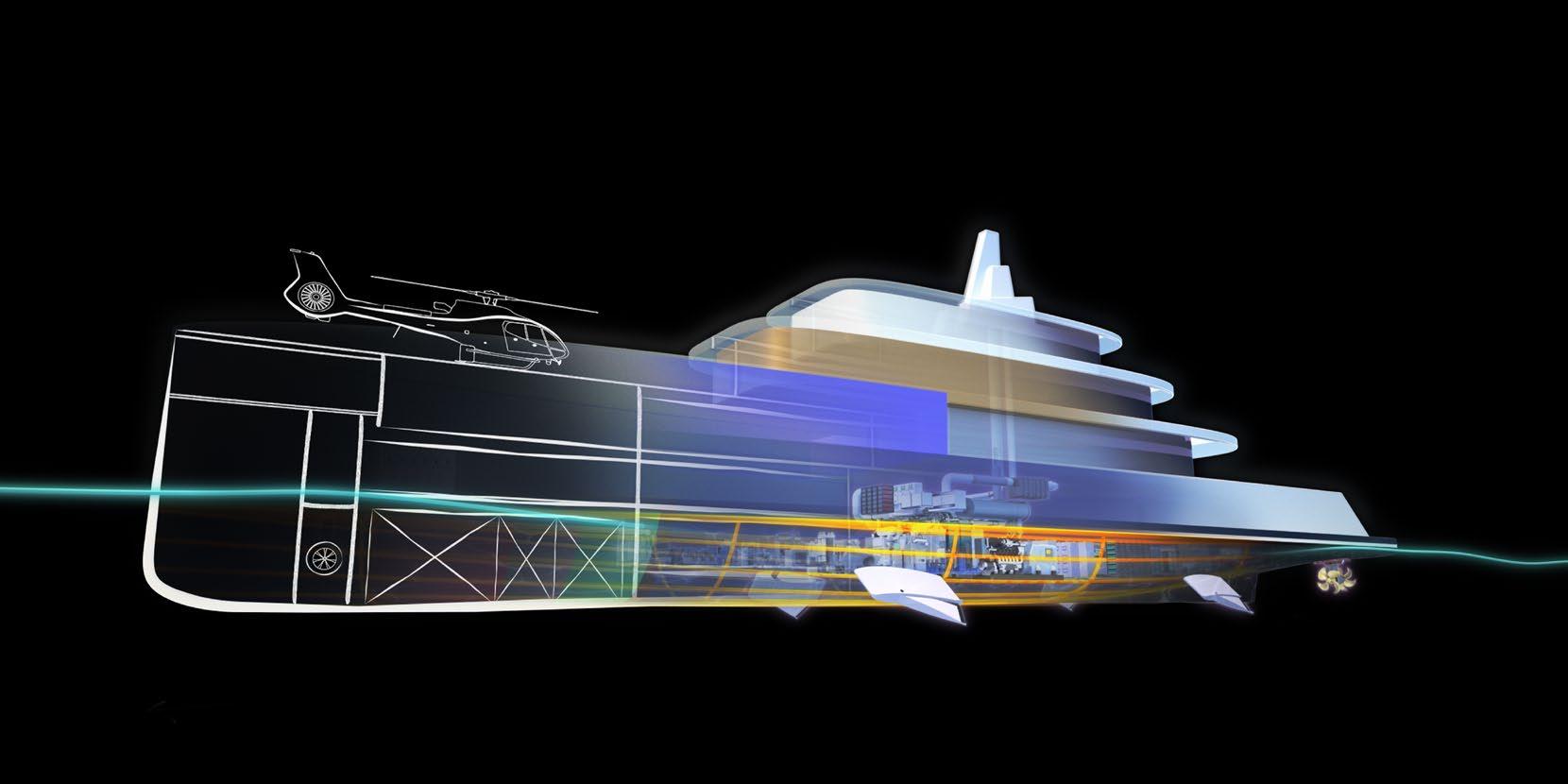

52 Concept in Focus: Contained in a Concept

Can a container ship be converted into a superyacht? Oceanco and Italian yacht designer Mario Biferali certainly think so and developed the Anthos concept to prove it.

60 Build Report: Crossing Borders

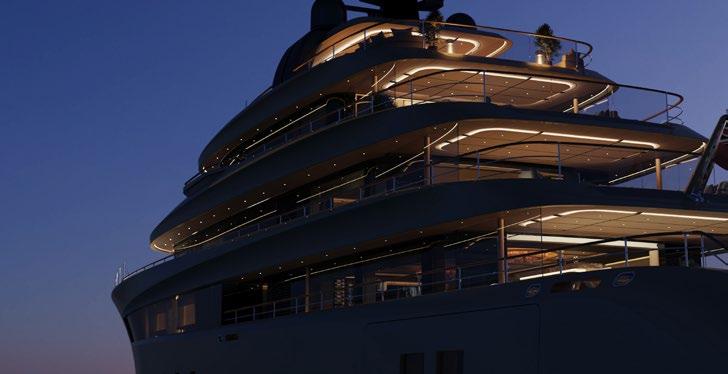

CRN’s Project Thunderball sees the shipyard working extensively with northern European subcontractors in a move that is pushing technical boundaries and blending project management cultures.

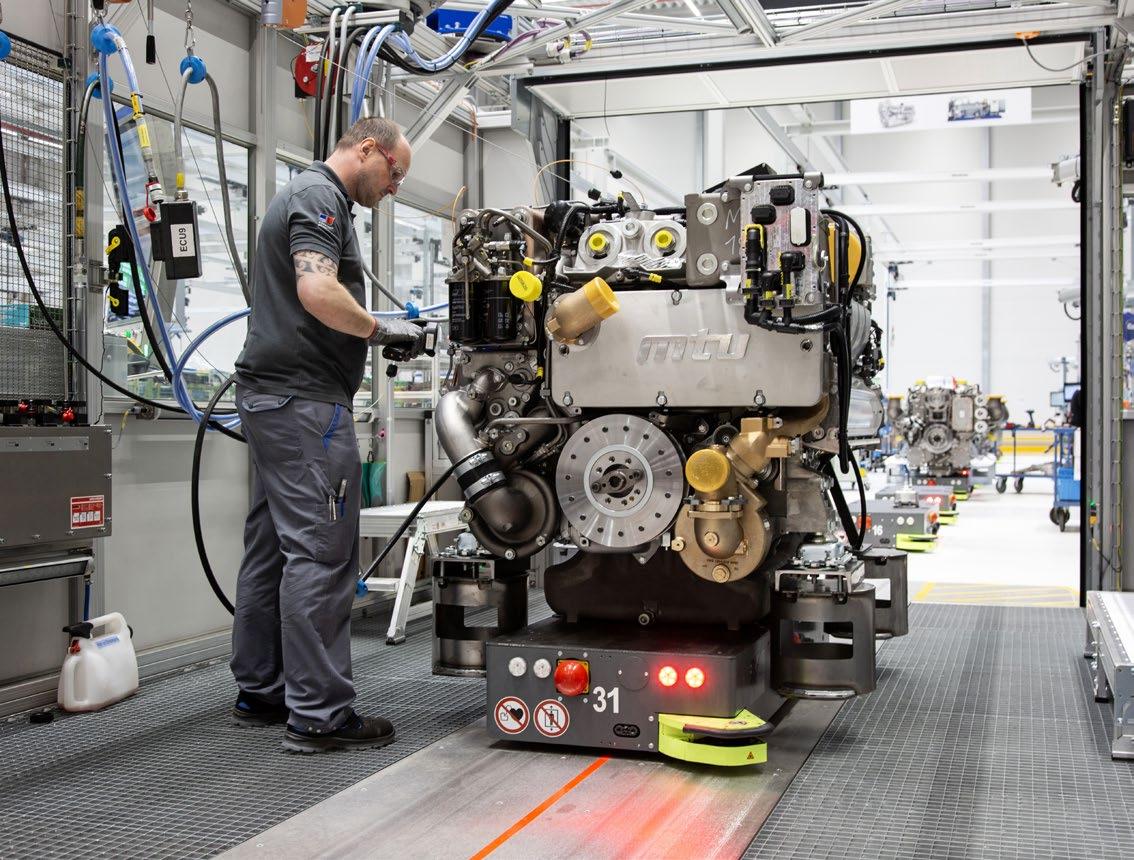

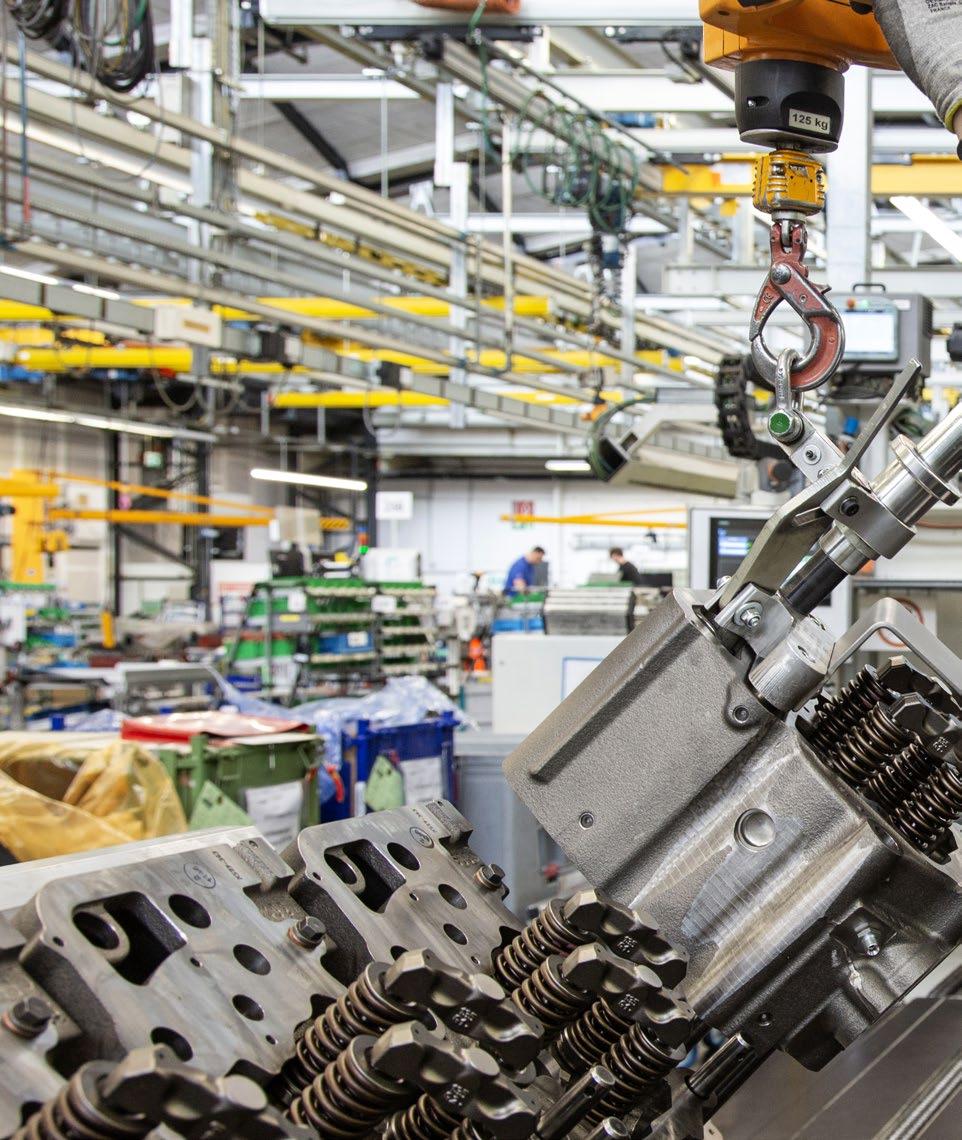

73 OEM: MTU

Mtu Solutions, the Power Systems Business Unit of Rolls-Royce, is transforming its engine production capabilities in southern Germany by investing in cutting-edge manufacturing technology.

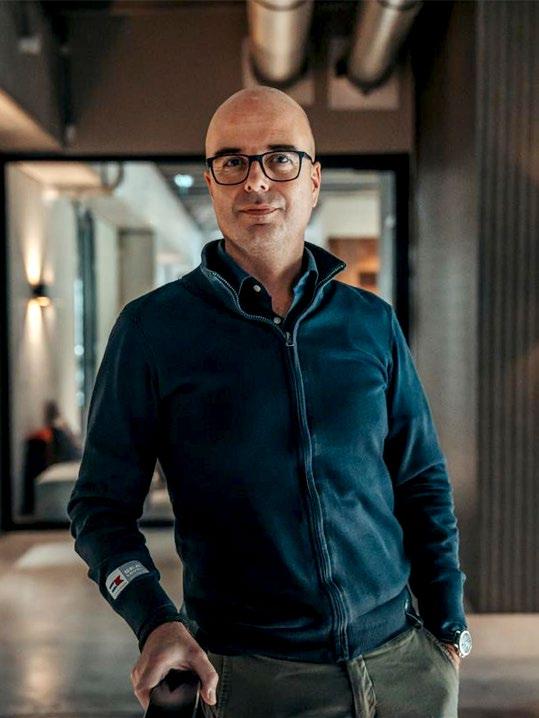

84 Inside Angle: Richard Pearce

The son of a naval captain, Richard Pearce set up his consultancy firm Waterproof in 2013 and has been representing clients in major superyacht projects ever since.

88 AV/IT: Dreaming of Streaming

Fast global marine broadband is finally finding its sea legs. What does this mean for AV architecture on board, and how is it transforming guest control interfaces?

100 New Tech: Batteries Included

When should you commit to a battery technology for a new-build project and will your choice be obsolete by the time the yacht is launched? Read on.

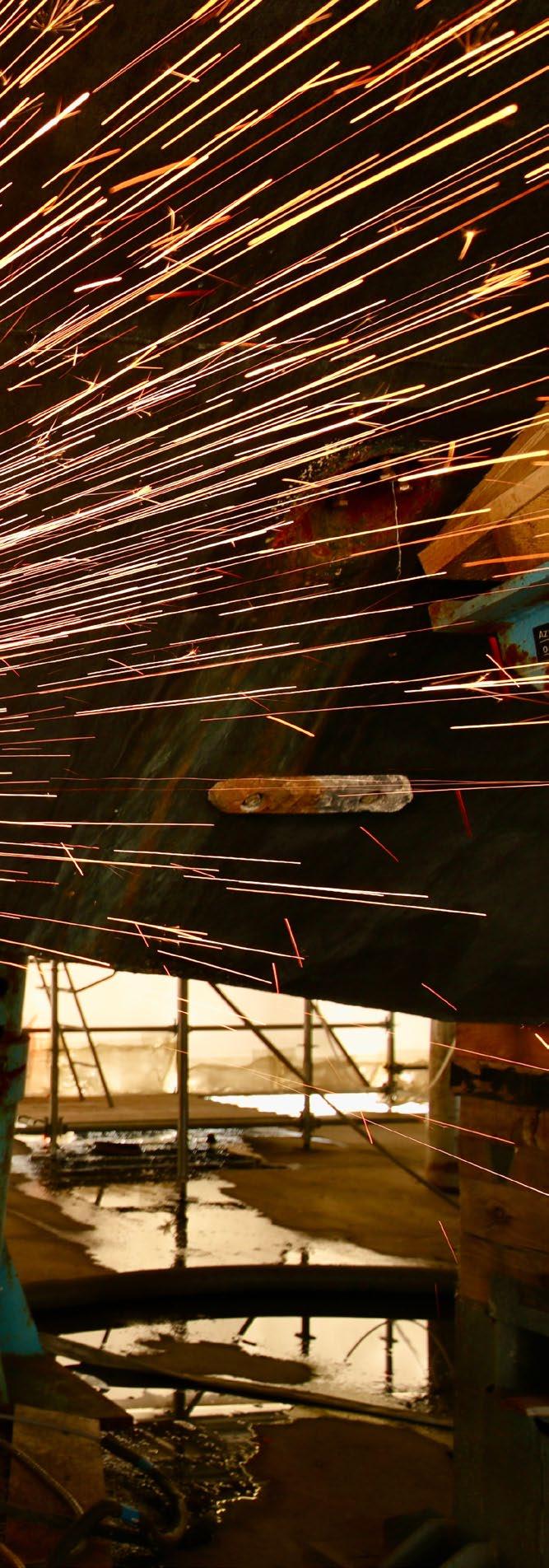

108 Refit & Conversion: Back to Bare Metal

The Perini Navi ketch Belle Brise is approaching the end of a massive refit at Lusben that both honours her classic heritage and ensures she remains relevant in today’s yachting market.

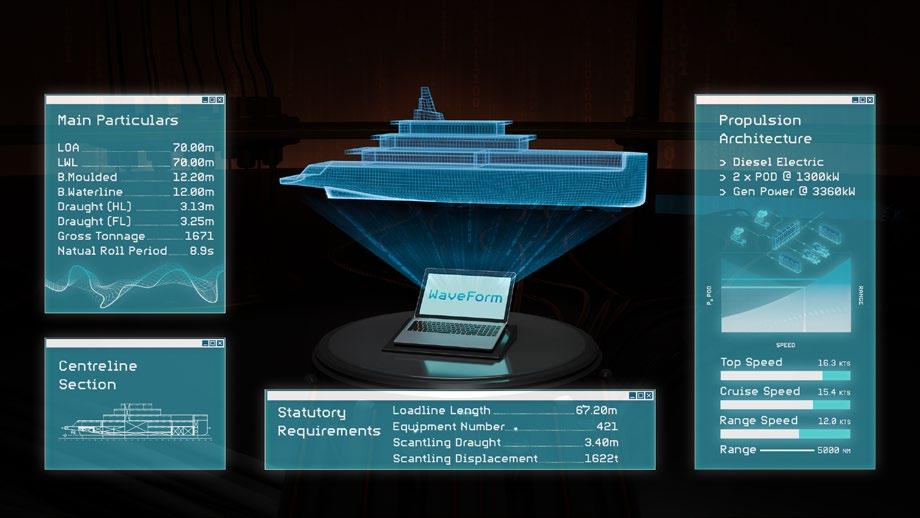

119 Industry Insight: FIT For Purpose

Jeroen van der Knaap of Sea Level naval architects and engineers talks us through the concept of Feature Integration Technology, or FIT for short.

126 Rules & Regs: Tipping Points

Andy King, Director of Stability & Statutory for Houlder design consultancy in the UK, discusses the importance of conducting detailed inclining experiments.

Boating in Figures, a mid-year statistical analysis by Confindustria Nautica (the Italian Marine Industry Association) has reported that 66 percent of Italian superyacht firms are witnessing a slowdown. As in other countries, the industry experienced more complex economic conditions in 2024 following strong results through 2023, leading to a “normalisation” of growth. The association’s market report reveals that high-end yacht manufacturers continue to see strong demand, while smaller craft producers are faring less well. In the superyacht segment, 34 percent of companies report stable or increasing order books, while 66 percent indicate some level of contraction. Of those, half report reductions of up to 5 percent, while the remaining half cite decreases between 5 and 10 per cent. Within the charter sector, respondents are evenly split between those expecting increased turnover and those anticipating stability, while 7 per cent predict a decline of up to 5 per cent. Exports continue to be a major driver of growth and Italy remains the world’s largest exporter of boats and yachts. Data from Fondazione Edison, a scientific partner of Boating in Figures, recorded an all-time high of €4.5bn in exports of Italian-built yachts in September 2024.

Euro Marine Group Ltd, owner of Lazzara Yachts, has secured a US patent for an integrated sea chest and discharge system that streamlines how seawater is managed aboard modern yachts.

Invented by George Chirakadze, President and CEO of Euro Marine Group, it consolidates seawater intake and discharge into a single structural unit embedded directly into the vessel’s hull, effectively removing the traditional web of leaky through-hull fittings. Already designed into models like the Lazzara UHV 100 and flagship UHV 150, the system provides several advantages, including fewer fittings and failure points, reduced corrosion, cleaner hulls, and better maintenance access within the engine room. Each sea chest has a removable threaded standpipe, for example, allowing engineers to service components while the vessel is afloat, reducing downtime. Moreover, as regulators crack down on biofouling and invasive species transfer, the system’s integrated UV sterilizes incoming seawater on entry, minimising marine growth. “This isn’t about flashy technology,” says Chirakadze. “It’s about solving unglamorous problems in a beautiful way.”

Heinen & Hopman’s HVAC&R solutions seamlessly integrate into your yacht’s design, delivering silent, precise comfort in every space. Our systems ensure optimal air quality, temperature, and humidityallowing you to enjoy every journey in effortless comfort.

GET IN TOUCH WITH OUR TEAM OF SPECIALISTS

Kongsberg Maritime has signed a service representation agreement with G-jet Srl, a leading service provider in the yacht segment and part of the V610 AG group. The company specialises in mechanical and electronic services for Kongsberg Kamewa waterjets, ensuring reliable support for routine maintenance, emergency repairs, and spare parts.

The agreement aims to strengthen this customer support, ensuring yacht clients receive the highest level of service and expertise.

“G-jet has a long-established reputation for delivering exceptional service and support to yacht customers,” says Mateusz Stępkowski, Vice PresidentWaterjets, Global Customer Support at Kongsberg Maritime. “Their proven track record and solid market position make them an ideal partner for us as we seek to enhance our offerings in the yacht segment.”

“This agreement reflects our ongoing commitment to constant improvement, ensuring we meet and exceed the expectations of waterjet clients in the yacht segment,” adds Folena Giulio, CEO of V610 AG. “Together with Kongsberg Maritime, we are ready to raise the bar for customer support and operational excellence in the industry.”

Williams Marine Group, the parent company of Williams Jet Tenders, has expanded its portfolio with the launch of a new standalone brand: Evene Tenders. Its debut Origin 57 is a 5.7-metre superyacht tender equipped with the same Yanmar waterjet drive as a Williams Jet Tender, but with a new rigid hull configuration with no tubes. Clients can customise features and accessories via an online configurator. Production of the Origin Series is underway at Williams’ existing facility in Oxfordshire, with first previews scheduled for the autumn boat shows later this year. An Origin 71 is also planned.

“With our ever-curious nature and pioneering spirit, we are excited to bring an elevated experience to the superyacht sector,” say Group founders Mathew and John Hornsby. “This is a launch that has been decades in the making, but it is just the beginning. The superyacht market has a bright future and with our Evene brand, we’re perfectly placed to fulfill these emerging opportunities.”

Rolls-Royce has named Christian Paolini as Managing Director and Sales Director of Team Italia Marine, its yacht bridge and automation subsidiary. Paolini, formerly Sales Manager at Rolls-Royce Solutions Italia, brings more than two decades of maritime and tech sector expertise to the role.

With Team Italia Marine based in Fano, Italy, the company has delivered over 700 integrated bridge systems since its founding in 2000. Now part of the mtu product portfolio following its 2023 acquisition, the firm supports Rolls-Royce’s “Bridge to Propeller” strategy – integrating navigation, propulsion, and automation technologies.

Paolini’s appointment aims to ensure strategic continuity and expand the brand’s footprint beyond Italy, with a focus on both custom and standardised yacht solutions. “We’re entering a new phase of bridge technology, with AI and predictive maintenance on the horizon,” said Paolini.

Rolls-Royce sees this leadership move as instrumental in consolidating its position in the luxury yacht market. Denise Kurtulus, SVP Global Marine at Rolls-Royce Power Systems, noted: “Christian will guide our Italian specialists into a promising future, leveraging the global strength of the mtu brand.”

The MC² Quick Gyro CARE Agreements offer premium service, ensuring long-term performance, reliability and peace of mind for every journey.

Benefit from priority assistance, fixed maintenance costs, and original spare parts by choosing flexible plans up to five years! More than just a product – a commitment to quality, performance, and customer satisfaction.

MC² Quick Gyro reduces boat roll up to 95%, ensuring comfort onboard at anchor and underway. The range has been designed to meet any requirement, with no installation limits both on new build and refit, from small day cruisers to superyachts.

Easy to install, with no water pumps or additional seawater intakes, Quick Gyro stabilizers are absolutely silent and compact.

For those who believe a white yacht is just not enough, Alexseal has introduced an online Colour Configurator designed to simplify and personalise the yacht painting process. The tool offers users access to over 1.7 million potential colour combinations using 121 solid and metallic finishes. Traditionally, shipbuilders and designers have relied on physical paint samples to visualise finishes. This new digital tool streamlines that process with photorealistic renderings of various vessel types – ranging from sailing yachts and sportfish boats to superyachts. Users can apply colours to different sections such as the hull, superstructure and bootstripe, with real-time updates displayed onscreen.

A 3D viewing lens allows for close-up inspection of colour application on complex shapes and surfaces. Additionally, selected colour schemes are automatically saved and can be transferred between different yacht profiles, helping designers and owners envision coordinated fleets, including tenders and toys. Finally, users can download a PDF summary of their selections for reference or to share with design teams and builders. The configurator provides a practical, flexible alternative to physical swatches, offering greater creative freedom and precision in the yacht finishing process.

Filling your glass with drinkable water from the tap on a yacht – including sparkling water at the temperature you prefer – makes perfect sense instead of stowing hundreds of plastic bottles on board. The GENIUS drinking water dispenser by HP Watermakers is now lighter and easier to install than before. The new edition coupled with the top-of-the-range HP SCA DOUBLE 440 watermaker and directly connected to a tank-linked water distribution system, produces purified chilled and/or sparkling water directly from the tap in the galley, where the device is usually installed. The ultrafiltration system removes all traces of chlorine, trapping bacteria and pollutants with the potential to contaminate water as it travels from the tank to the tap. The bactericidal silver ion treatment system also sterilises the water at the point of exit. Lastly, a re-mineralising filter enriches the water with precious minerals, giving it a pleasant taste.

Awlgrip has unveiled Gloss Finish Primer, a new product designed to save time, reduce emissions, and improve finish quality during the superyacht painting process. The next-generation, low-VOC primer merges two key functions – primer and control coat – into a single application. It delivers a high-gloss finish that enables applicators to instantly spot and correct imperfections before the final coat, eliminating rework and reducing the number of applications required. Developed specifically for the demands of new superyacht projects, the Gloss Finish Primer is part of Awlgrip’s high-performance coatings system. Its advanced formulation features a higher solids content than conventional two-coat systems, helping to cut VOC emissions by up to 50 percent per square metre in line with the brand’s commitment to supporting professional applicators with smarter, more sustainable solutions. “We created Gloss Finish Primer with efficiency, durability, and superior finish in mind,” says Jemma Lampkin, Global Commercial Director for AkzoNobel Yacht Coatings. “It allows professionals to simplify their workflow and achieve flawless results faster. This innovation responds directly to industry demand for faster project turnaround, lower material use, and outstanding quality.”

During Milan Design Week 2025, Officine Gullo, a luxury kitchen producer based in Florence, presented a new collection of galleys and bar units designed specifically for superyachts. The line brings the brand’s signature craftsmanship and attention to detail to the world of luxury yachting, with custom cooking and bar areas that blend design, functionality, and durability.

Traditionally hidden, yacht galleys are re-imagined as welcoming, social spaces. The collection features multifunctional islands, cooking stations and elegant bar units that integrate seamlessly into the yacht’s layout, providing aesthetic value and practical use. Made from high-grade AISI 316 stainless steel, each piece is built to withstand marine environments and can be customised in various finishes. The range includes fitted counters, appliances, and professional-grade BBQs, all tailored to the specific needs of each yacht.

Evac Group, a global leader in sustainability technologies and solutions, has launched Dehydro, an innovative onboard waste management system designed to meet the specific needs of today’s superyachts by using dehydration technology. At a time of stricter regulations on waste disposal to protect marine ecosystems, the new Dehydro system incorporates a high-temperature drying process of up to 180°C to sterilise and dehydrate organic waste, reducing wet waste volume by approximately 80 percent. The system also incorporates features such as, embedded crushing technology and patented de-odorising methods to handle complex odours, generating a sterile, dry by-product.

“The launch of this product marks a key moment for Evac,” says Björn Ullbro, CEO of Evac Group, which already has waste systems installed on over 20,000 vessels worldwide. “Traditionally, innovation in our industry meant developing a great product and then bringing it to market. This time, we reversed that. We started with the customer’s operational reality and identified the best solutions on the market. Complementing in-house innovation with strong partnerships is a clear example of how we’re delivering on our ambition to offer the industry’s most comprehensive water and waste management portfolio.”

BY FRANCESCA WEBSTER

This year marks a milestone for Austrian outfitting specialist List GC, celebrating 75 years of craftsmanship and innovation. With a legacy rooted in precision joinery and a portfolio that spans some of the world’s most iconic superyachts and residences, the company stands at the forefront of bespoke interior outfitting. Christian Bolinger, one of the Managing Directors, speaks with How to Build It about the evolution of the business, the power of long-term partnerships, and what lies ahead.

List GC is celebrating 75 years in business and over 25 years in the superyacht sector. How has the company evolved over that time?

We began as a small local joinery in rural Austria. The first major shift came when Eastern Europe opened up – that gave us access to large-scale hotel projects, which really drove growth. Then came our first cruise ship interior in the late 1990s – the MS Deutschland. It wasn’t an easy introduction to maritime interiors, but it put us on the map. From there, we gradually moved into yachting –beginning with Oceanco around the early 2000s –while still handling hotel and cruise interiors. By 2012, we made a strategic decision to focus exclusively on the superyacht and high-end residential sectors. These markets demand precision, complexity and an uncompromising level of quality – it was clear we needed to align our DNA with that standard.

How would you describe the company’s structure and scale today?

We’re now around 340 people across our Austrian headquarters and our German daughter companies. In the last decade, we invested heavily in our own production facilities – a move that made us more independent and resilient.

We’ve grown from a project management-driven operation into a turnkey outfitter, with around 60 percent of production now in-house. The remainder is handled by long-standing partners, which allows us to maintain flexibility while ensuring quality. That partner network is carefully managed and fully transparent to shipyards and clients alike.

You’ve also made some key acquisitions in recent years. What value have they brought?

We’ve acquired two German companies that were already established suppliers in the yachting industry, Cohrs Werkstätten GmbH and Riederle Werkstätten GmbH –both family-run, with a strong heritage. These integrations have allowed us to increase capacity and gain new knowledge in return. It’s not just about scale – it's about expertise, culture and a shared commitment to quality.

Most recently, we acquired a stake in Interior PROMAN GmbH, a 12-person engineering and project management firm. Many of their team previously worked with List GC, so it was a natural fit. The acquisition has strengthened our internal capabilities and enhanced our ability to deliver on complex projects.

Technology clearly plays a role in your evolution. How does it shape your work today?

Technology touches everything – from process engineering to final fit-out. On one side, we’ve invested in digital tools like 3D engineering, CAD/CAM integration, and additive manufacturing. We currently run six 3D printers full-time, which support both prototyping and process development.

On the other side, we focus on integrating innovation in a way that supports design intent. Much of our R&D isn't about visible change – it's about what sits behind the finish, ensuring technical feasibility and longevity without compromising aesthetics.

We also collaborate closely with designers to help realise their vision. That balance – between creativity and practicality – is where our technical strength becomes invaluable.

You’ve spoken about managing complex stakeholder relationships. Can you expand on that?

Yacht interiors are always multi-stakeholder environments. The designer, the shipyard, the owner’s team – we’re often contracted by one party while delivering on the vision of another. That makes stakeholder management critical.

We train our teams in communication, cultural sensitivity and transparency. Long-term partnerships with shipyards help too – they enable us to maintain consistent teams who understand each other’s expectations and workflows. In this business, trust is earned over years, not months.

How does your heritage as a family business shape your culture today?

List GC remains family-owned, and that ethos runs deep. While day-to-day management is in the hands of Josef Payerhofer and myself, we work very closely with the List family, who remain actively engaged.

It’s not just about governance – it’s about values. The family presence creates continuity, trust and accountability. Many of our employees have been with us for decades, and that stability translates into consistency for our clients.

And finally, which projects are you particularly proud of?

It’s always difficult to name names, given confidentiality, but we’re proud of the diversity of work we’ve delivered – from 30-metre high-performance sailing yachts such as Ribelle to full-scale 100-metre-plus new-builds like MY Ahpo, where we were commissioned with the project management of the interior design on four decks and a total of 745 m².

What I find especially rewarding is when we can support repeat platforms with shared teams – it streamlines delivery and deepens collaboration.

What’s next for List GC?

We’re committed to controlled, sustainable growth. That includes continued international expansion and greater diversification in the high-end residential space, particularly through cross-selling to yacht owners. We’re also seeing growing demand for our services beyond Northern Europe – in regions where clients want Northern European quality but choose to build elsewhere. We’ve already delivered projects under that model, and it’s a space we’ll continue to explore. Above all, we want to stay true to who we are: a trusted, technically skilled partner who helps bring the most ambitious interior visions to life.

Find out more and reach out to the team now at www.listgc.at | mail@listgc.at

New projects in early stages of construction that present opportunities for OEMs, suppliers and subcontractors.

Project Omega will feature both exterior and interior design by RWD and naval architecture by Lürssen. She will be able to accommodate up to 20 guests across 10 staterooms. The superyacht will be equipped with a beach club, a dive centre, and ample outdoor spaces designed for entertainment and relaxation.

LENGTH: 122.5-metres BUILDER: Lürssen Yachts

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Lürssen Yachts

EXTERIOR & INTERIOR DESIGNER: RWD

Lazzara Yachts’ new model marks the shipyard’s entry into the expedition segment, with construction due to begin in early 2026. Constructed with a steel hull and aluminium superstructure, the Lazzara EX 165 will come in at just under 500 GT and is designed for long-range cruising.

LENGTH: 50-metres BUILDER: Lazzara Yachts

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Lazzara Yachts

EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Lazzara Yachts INTERIOR DESIGNER: N/A

Composed with a steel hull and aluminium superstructure, the displacement yacht has been designed for ocean crossings and is the result of a collaboration between renowned designer Enrico Gobbi of TEAM for Design and the technical department of Palumbo Superyachts.

LENGTH: 45-metres BUILDER: ISA GT: 440 GT COUNTRY OF BUILD: Italy DELIVERY YEAR: 2027

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Palumbo Superyachts

EXTERIOR & INTERIOR DESIGNER: Team for Design

Cantiere delle Marche (CdM) has announced the sale of the first 32.01-metre RAW 105 yacht. The CdM yacht features a bold, yet strong exterior design and derives from the RAW series, which was first announced in September 2024.

LENGTH: 32.01-metres BUILDER: Cantiere delle Marche

GT: 250 GT

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: N/A EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Giorgio Cassetta

Comprising a steel hull and aluminium superstructure, once complete ALY651 will be the flagship for the Turkish yard. ALY651 showcases a five stateroom configuration, with her owner’s suite boasting a private lounge area and floor-toceiling windows.

COUNTRY OF BUILD: Italy DELIVERY YEAR: 2026

INTERIOR DESIGNER: N/A

LENGTH: 65-metres BUILDER: Alia Yachts

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Diana Yacht Design

GT: 1,400 GT

COUNTRY OF BUILD: Turkey DELIVERY YEAR: 2028

EXTERIOR & INTERIOR DESIGNER: Sinot Yacht Architecture & Design

With an expected delivery date of 2027, the Columbus Crossover 47 yacht combines contemporary aesthetics with functionality and stems from the same platform as the Columbus Crossover 42 model, which is also in-build.

LENGTH: 47-metres BUILDER: Columbus Yachts GT: 499 GT

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Palumbo Superyachts

COUNTRY OF BUILD: Italy DELIVERY YEAR: 2027

EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Hydro Tec

INTERIOR DESIGNER: Hot Lab

Advertisement

For 75 years, Wards Marine Electric has been the unseen force powering your dining, sailing, and onboard connectivity for the ultimate yachting experience.

Marine Part Sales

Engineering

Surveys

Custom Panels

Refits

Painting

Dockside Services

Engraving

Suppliers

Dockside Rentals

@wardsmarine

wardsmarineelectric

@wardsway75

Dutch production and engineering firm Beekmans began life building steel hulls for Trinitella yachts in 1960. Since then it has delivered stainless steel and glass installations – encompassing railings, balustrades, telescopic awnings, staircases and pool glass – to approximately 200 superyachts. Specialising in vessels between 60-120 metres, projects include Nobiskrug’s Artefact, Delta Marine’s Moonstone, Lürssen’s Octopus, and Oceanco’s Kaos.

BY GEORGIA TINDALE

The blueprint for Beekman’s approach today was formed in the 1970s: instead of positioning and welding bollards on yachts, the process was standardized and the bollards were bolted onto a yard-supplied double plate. This was the starting point for preproducing components and improving efficiency. Finding modern, technical solutions to the issues that occur on board is where Beekmans finds its raison d’être “Machine-building employs methods which are far ahead of yacht building, which is still very traditional,” says Sales Manager Mike Gilsing. “We integrate these into our products and processes to boost quality and efficiency. Yacht building is sometimes old-fashioned, so we use this to our competitive advantage.”

Twenty-five years ago, when the industry was still measuring by hand – using pencils and cardboard templates placed on top of bulwarks – Beekmans introduced digital measuring with laser scanners placed on tripods: a far more precise technique which is now widespread. These highly accurate measurements can be taken on any global location and then be inputted into 3D programs, ready for production modelling. This technique was put into practice when the captain of the 62-metre Oceanco Queen Mavia asked Beekmans for a new sundeck windshield that was the same as its sistership, 63-metre Lucky Lady, by removing the toprail that obscured the horizon. Measurements for the windshield were taken in Asia, and it was installed just three months later on the other side of the world during the Cannes Film Festival.

Beekmans brought glass production in-house in 2017 in response to the decreasing quality of glass provided by its external suppliers. Consistently falling below durability and strength standards, this had been causing project delays – a frustrating obstacle, particularly for the shorter timelines required by its numerous refit projects. A portion of Beekmans’ 9,000-square-metre Den Bosch facility is dedicated to a CNC glass center, glass cutters, laminating area and chemical toughening bath, to produce glass that complies with Lloyds Register and other class society standards.

“Producing both the glass and stainless steel ourselves is unique,” says Gilsing. “Even when working with shipyards such as Heesen, which is only a 30-minute drive away, this is a major driver of efficiency and enables us to control delivery times. If we produce a railing for them, we can measure the yacht wherever it is located and then build the whole product in our workshop, knowing that everything fits and meets our standards. We only weld and polish on board when it is impossible to avoid, as working on board always takes triple the time.”

Beginning with glass windshields as early as 1999, Beekmans has also been tasked with creating all-glass railings in response to changing design preferences. “The trend is for owners seeking greater contact with the sea and their surroundings by having more glass in the general structure of their yachts, and the same principle applies to railings,” says Gilsing. The extensive refit of the Amels Here Comes the Sun in 2021, in which Beekmans’ team installed an all-glass railing on the aft deck, is one such example.

Notably, there is a balance to be struck between pleasing aesthetics and feelings of safety for those on board. The 90-metre Oceanco motor yacht Dar features fully glass bulwarks with a profile on top.

“I would always advise to put something on top of your glass balustrade, whether it be stainless steel or teak”, comments Gilsing. “It can be very subtle, but if guests can only see glass, they might be scared that the railings won’t work, so this provides a sense of psychological security.”

Looking to the future, Beekmans has plans to develop a new product: high-tech portlights that bypass the requirement for deadlights or storm covers, thanks to the strength of the glass, which is set to be significantly higher than standard values for Class approval.

“Security deadlights have to be put somewhere, and although yachts are big, there is never enough space,” explains Gilsing. “Moreover, with this product, no provisions will have to be made in the interior design for bolting in the deadlights.”

INTRODUCING BELLUS & LINEOS: A REFINED INDOOR AND OUTDOOR FABRIC MADE FROM SOLUTION-DYED ACRYLIC

AVAILABLE IN WARM SOPHISTICATED & INTENSE COLOURS BLENDS DURABILITY WITH A SOFT LUXURIOUS TOUCH THAT ELEVATES BOTH COMFORT AND

Beginning with 126-metre Octopus in the 1990s, GL Yachtverglasung near Hamburg has developed, designed, delivered and installed glass on board some of the world’s most recognisable superyachts, including Sailing Yacht A, Artefact, REV Ocean, Solaris, Excellence, and more. CEO Lars Engel discusses the challenges posed by sanctions, and how a passion for complex and spectacular projects has driven business success to date.

BY GEORGIA TINDALE

What drives you to succeed in business?

Passion. You need passion to work in such a niche industry, and also to have an understanding of what happens every day behind the doors of a construction hangar. The outcome at the end is something exceptional. Passion is necessary because without it you won’t be driven to follow through in such a complex business. When we first worked on Octopus, it was so enjoyable that I decided that we needed to start a whole new company specialising in glass for spectacular yachts. The element of fun is very important to me and the team as a whole. We’re not interested in delivering a set number of projects per year, but in rising to the extraordinary challenges posed by individual projects.

Are there any specific strategies you’re planning to tackle future challenges and ensure continued growth?

We specialise in larger superyachts – the minimum is 70 metres, occasionally a little less, but only when it involves very complex glazing. The current major obstacle is overcoming the sanctions, which are a showstopper for our niche market. The relevant question isn’t one of growth, but the justification for the future of an entire industry. To combat this and in response to requests, we have been motivated to identify and create a new niche, which is a work in progress. Because yachting is a project-based business, we know and accept that our results will go up and down. We can mitigate this because our main business, GL Spezialverglasung, provides special glazing for public and private transport companies as a supplier, repair and spare parts service provider.

What proportion of your work is in-house?

There is a very limited number of companies – not more than about five – we partner with to source the glass we need for our projects. The market simply doesn’t offer the quality of people and knowledge we require, so we basically only work with our own employees. When taking on projects, we are very careful about the resources we use and managing our capacities sensibly. To this end, we offer support for designers and engineers from various industries, the execution of installation works on new build projects, and overall after-sales and services, so our clients get 360-degree project management. This provides both them and us with a greater degree of security.

How important is staff training?

Training is very important to us: all our technicians are extremely well qualified. Once they start with us, they receive training to become bonding specialists. It takes around 18-30 months to get them to the point where they can deliver the workmanship we expect. Between both our companies, we employ nearly 200 people and around 150 technicians who need to be retrained every year, so it is a huge investment for us. Thanks to the experience and expertise of GL Spezialverglasung and close collaboration with renowned research institutes, we are the first company worldwide with DIN 2304 certification, the quality assurance for adhesive bonding processes.

You installed the longest curved glass panel ever made onto Nobiskrug’s Sailing Yacht A. What are the complexities of working at that scale?

As with many of our projects, this required us to think beyond the existing limitations of what is perceived to be possible. On Sailing Yacht A, it wasn’t just building and installing the world’s longest curved glass panel of 15 metres, but also creating and installing the underwater windows, which presented unprecedented complexity. This is why we’re continuously identifying new methods, equipment and engineering to make ‘mission impossible’ possible.

There’s also the question of logistics. On Solaris, for example, the largest glass pane was 12 metres by three metres and weighed 5.2 tonnes. Everything was over the limits for the transport of the glass, so we had to develop and find new solutions. When we first sign our projects, we don’t always know what will be possible, but we always make it happen, thanks also to our strong R&D department.

As a company, we love intricate and challenging builds. Our latest 114-metre project has a special arrangement on one of the decks that has never been realised in glass until now. It’s a yacht that doesn’t look like a yacht, so you will either love it or hate it!

www.multiplexgmbh.com

Mangusta celebrates its 40th anniversary this year. Long associated with the speed, style and power of its Maxi Open yachts, a quieter revolution has been unfolding and today the brand is more focused on engineering, efficiency and innovation.

BY JUSTIN RATCLIFFE

The origins of Mangusta read like a case study in bold entrepreneurial thinking. In the early 1980s, Giuseppe Balducci – a young marine electronics engineer from Tuscany – walked away from Tecnomarine, which dominated the fast yacht market at the time with its Cobra range of open yachts capable of speeds in excess of 35 knots. He set up Overmarine in Viareggio with the aim of building his own boats in a move that was both strategic and symbolic.

Balducci’s choice of brand name – Mangusta is Italian for mongoose, the small but fearless predator that devours cobras – made his intention crystal clear. Overmarine went on to build 85 units of the Mangusta 80, while steadily gaining ground as a pioneer of Maxi Open yachts, overtaking its rival and establishing a reputation for performance combined with stylish Italian design.

Giuseppe Balducci continued to work right up until his death last year aged 87, but the company he founded is still headed up by his children, Maurizio and Katia Balducci.

Until a decade or so ago, Mangusta’s legacy was rooted in composite construction and high-speed performance with a shifting lineup that ranged from the Mangusta 72, the entry model equipped with Arneson surface drives and a top speed of 40 knots, up to the mighty Mangusta 165 powered by triple mtu 4000 series engines coupled with RollsRoyce KaMeWa waterjets. Then the 2008 financial crisis came along and the economic downturn that followed led to a decisive change of strategy.

“The drastic market slowdown from 2010, especially for luxury sports boats, led to an influx of used vessels returning to the market due to leasing complications, which made it difficult for us to sell new units at competitive prices,” recalls Maurizio Balducci, CEO of Overmarine Group. “Ironically, these used Mangustas, still in excellent condition, became our biggest competitors, so we decided to enter a different segment with different products.”

In an entirely new direction for the brand, Overmarine turned its attention to displacement yachts in steel and aluminum.

With this in mind, the group joined the bidding for the bankrupt Baglietto and Cantieri di Pisa brands, but setbacks led to it abandoning the attempt. In 2012 it announced its own 22,000-square-metre facility purpose-built in Pisa for metal construction up to 70 metres.

The same year marked the debut of its first full-displacement yacht, the Mangusta Oceano 148. The composite design by Stefano Righini recalled the styling of its open range, but it was the precursor to the Mangusta Oceano 42 Namasté, Overmarine’s first steel and aluminium tridecker designed by Alberto Mancini that introduced a completely fresh aesthetic to the brand in 2016. The current Oceano line-up of six models from 39 to 60 metres is now Mangusta’s largest range.

Mangusta’s shift from composite-only to metal construction brought with it a major learning curve. Initially supported by external consultants, the team quickly developed in-house expertise and today the technical office in Pisa employs around 15 engineers and designers who can handle all the key design phases from naval architecture through to interior outfitting.

Building in metal requires more preengineering than composite construction and this meticulous mindset has been carried back into the technical design of the yachts at the heart of its heritage – the high-performance Maxi Opens. Far from the popular perception of these as simply very fast day boats for blasting along the French Riviera, evolving client needs means they also have to offer comfort for extended cruising. Family-friendly layouts, larger crew quarters, and a practical balance between interior and exterior spaces are other key selling points. While performance is still an essential ingredient, there was also growing concern about fuel efficiency.

“Initially, our goal was to build the fastest luxury boats on the water,” says Nicola Onori, Overmarine’s technical director. “But over time, we realised there was much more value in optimising for fuel efficiency, onboard

comfort and sea-keeping across a range of speeds – not just at the top end.”

A case in point is the evolution of the Mangusta 165. Originally outfitted with three mtu 4000 series engines delivering 3,440kW each, it could reach a blistering 42 knots. But the trade-off was high fuel consumption. Since 2016, the Mangusta 165 has been fitted with four smaller mtu 2000 units of 1,930kW each, delivering a slightly lower top speed, but offering up to 30 percent better fuel efficiency in cruising conditions. This shift wasn’t just about the number and power of the engines – it also allowed for smarter weight distribution, ultimately improving balance and responsiveness without sacrificing the brand’s performance DNA.

“It all boils down to power-weight ratio”, says Onori. “To build high-speed yachts, you want light but powerful engines. Lighter yachts also mean more speed for less fuel, which in turn means lower emissions. The three mtu

“Everything we’ve learned from building fast boats has been carried over to this new generation of semi-displacement metal yachts.”

4000 series engines weren’t specifically designed for marine use, and at around 13 tonnes with their gearboxes they were big and heavy. The latest generation 2000 series weigh less than half as much, so we’re already saving a lot of weight.”

Overmarine’s Maxi Open range today includes the entry model Mangusta 104 REV – a far cry from the Mangusta 72, the entry model ten years ago – and the Mangusta 165 REV, both designed by Igor Lobonov (a third model, the Mangusta 132E, is not due to be continued beyond the two units in-build).

The composite hulls and superstructures are manufactured in Massa and then transported to the facility in Viareggio for outfitting. In a significant example of precision tooling, the mould for the Mangusta 165 REV is now CNC-milled in sections then assembled into a single piece to ensure a perfect match with the digital design, eliminating inconsistencies and streamlining later stages of production.

Moreover, Overmarine is one of very few shipyards that produces its own fibreglass and other composites through its subsidiary company Effebi Spa, which allows for extensive testing and optimisation of both materials and lamination techniques (the company is also experimenting with natural fibres such as basalt in combination with bio-resins, but not for major structural components).

“While many yards use sandwich construction for the hull, we prefer singleskin construction,” says Onori. “Although a sandwich structure reduces weight, we believe a single-skin hull offers better vibration resistance and mechanical strength in the event of impact. So our hulls are single-skin and laid up by hand, but we do use vacuum infusion for the upper decks and superstructure. We also use carbon fibre where necessary – primarily to reduce weight and improve rigidity, especially in the superstructure.”

Top: The Mangusta GranSport 54 El Leon was the first Mangusta to cross the Atlantic and cruise around the world. Facing page: Outfitting the engine room aboard a Mangusta 165 REV in Viareggio.

Overmarine’s strength lies in its ability to manage controlled complexity across build materials, propulsion architectures and model lifecycles at its facilities in Massa, Viareggio and Pisa. Nearly all the major construction and outfitting proceses are carried out in-house, thanks also to specialist subsidiaries Effebi and Elettromare being part of the group.

Current production is based on three lines: Mangusta Oceano, Mangusta GranSport, and Mangusta Maxi Open REV, each tailored to a distinct style of yachting.

The Oceano line designed by Alberto Mancini is the tri-deck displacement series built for ocean-going capability in steel and aluminium with a focus on comfort, volume and extended cruising range. The six models in the range from 39 to 60 metres prioritise onboard comfort and range over speed.

The GranSport line, also designed by Mancini, combines high performance with long range. The GranSport 33, 45 and 54 are designed for cruising at fast displacement speeds without sacrificing efficiency, comfort or style. Blending sporty lines with generous living spaces, the series offers a more dynamic yachting experience. All but the entry GranSport 33 are built of aluminium.

Lastly, the open-style models in the composite Maxi Open line define the brand’s design DNA. Focused on speed, elegance and on-the-water lifestyle, the planing Mangusta 104 REV and Mangusta 165 REV capable of 35-plus knots are designed by Igor Lobanov (the outgoing Mangusta 132E is an in-house design).

Mangusta debuted the first Mangusta GranSport 33 at the 2020 Fort Lauderdale Boat show in the midst of the Covid pandemic. The entry-level composite model in its fast displacement series (since extended to 34 metres to accommodate SCR units and the only one with Volvo Penta IPS propulsion) with exterior design by Mancini was joined by the all-aluminium GranSport 45 and GranSport 54. Together they represent a happy median between the Maxi Open line and the more cruise-oriented Oceano range, and lessons from both have been integrated into their technical design.

“We maintain focus on advanced hull design, efficient appendages, optimised weight distribution, and weight savings wherever possible,” says Onori. “Everything we’ve learned from building fast boats has been carried over to this new generation of semidisplacement metal yachts.”

In collaboration with Pierluigi Ausonio Naval Architects, Overmarine came up with what they call the Fast Surface Piercing Hull or FSPH, basically a round-bilge hull form with bulbous bow hull that cuts through the sea surface without planing. Together with the four-engine configuration perfected for the Mangusta 165, the hull design allows for high speeds with relatively low installed power. In the case of the GranSport 54, it also provides an oceanic range of 4,800 nautical miles at 12 knots and 3,500nm at 14 knots. In fact, in 2018 the GranSport 54 El Leon (her owner’s fourth Mangusta) became the first Mangusta to cross the Atlantic Ocean and went on to complete a world tour of 52,000 nautical miles.

Although Mangusta has made meaningful strides in propulsion efficiency and all its yachts are HVO-ready, it has not yet built a yacht with hybrid propulsion. Rather than lagging behind competitors in the energy transition, this is the result of a strategy focused on meeting client expectations and optimising efficiency within practical limits.

“We’re in a transitional phase and multiple solutions are being explored across the industry, but no definitive single path has so far emerged,” says Balducci. “We’re evaluating emerging propulsion systems such as methanol and dual-fuel engines, but technical limitations remain – especially the space required for alternative fuel storage, which is often incompatible with yachts under 500GT. Instead, we’re doing everything possible to achieve the best performance within the dimensional and regulatory constraints.”

Mangusta’s operational geography reflects the brand’s response to an evolving market. Ten years ago it was all about Europe, especially France, where there is still a legacy office in Golfe-Juan. Today, the US is its biggest market and served by an office in Miami Beach headed up by Stefano Alunno, whose local knowledge of customer needs helps preempt requests and provide turnkey solutions.

The brand’s presence is growing in the Middle East, where notably at this year’s Dubai International Boat Show a Kuwaitiowned GranSport 33 generated strong interest and high-quality leads. Dubai’s strategic appeal lies in its cultural diversity, but Turkey has a ready-made yachting culture with strong potential for growth. Overmarine now has a direct representative in Bodrum, a former Mangusta captain deeply familiar with the product who has already sold a Mangusta 165 into the country, for instance.

“Markets shift a lot over time and what was true ten years ago has already changed,” adds Arianna Toscano, head of image and communication. “The idea is to expand beyond our traditional markets, but in a sustainable way that doesn’t over-extend our production resources.”

Perhaps the most old-fashioned – and quietly powerful – part of Overmarine’s approach is its relationship with its clients. Mangusta yachts often remain with their original owners for a decade or more – a rarity in a world of quick trades and fleeting fashion. As Balducci points out: “We don’t advertise much. Our best marketing is a satisfied client.”

Mangusta’s evolution is a story of quiet leadership where long-standing values meet forward-thinking design, and where each yacht is still, at its heart, a family affair. This philosophy is rooted in making purposeful products that speak for themselves, relying on word-of-mouth and high build quality to grow the brand – a refreshingly deliberate approach in an industry often driven by glitz and spectacle.

From the glistening hulls of Mediterranean icons to the precision-applied coatings on explorer yachts far afield, the name Nautipaints Group has long been synonymous with excellence in superyacht paint refinishing. With operations spanning nearly fifteen locations worldwide – from Palma and Barcelona to Genoa and La Ciotat – the company has built a reputation for delivering refined, resilient finishes that mirror the expectations of the most discerning clients.

At its core, Nautipaints remains dedicated to the meticulous craft of paint refinishing and refit services –a discipline the group has elevated through obsessive attention to quality, a commitment to artisan-level techniques, and an ever-expanding suite of specialised underwater and surface treatments.

Quality control as a cornerstone

“A paint project is like a journey,” says Nautipaints CEO Toni Salom, “with well-defined waypoints guiding us towards a flawless finish.” It’s a philosophy grounded in decades of expertise. As Head of Quality Marc Sáez explains, the company achieves consistent excellence by combining premium materials with strict procedures and ongoing evaluation.

“Each project begins with a tailored assessment of the yacht’s condition,” Sáez notes. “We choose the most suitable materials from trusted suppliers, then apply a controlled process using monitoring technology to track everything from adhesion and layer thickness to ambient temperature and humidity.” Every stage undergoes rigorous inspection to meet exacting aesthetic and technical standards.

This precision is adapted to the intricacies of modern yacht construction. Whether working on aluminium, wood, steel or composite hulls, Nautipaints begins with thorough surface preparation, followed by the application of bespoke primers under optimal conditions. Intermediate coatings and final topcoats are applied with meticulous care, subject to layered inspections, adhesion testing, and final client approval.

Nautipaints’ central hubs in Palma and Barcelona serve as the operational core for its mobile teams, enabling swift deployment across Europe and beyond. From Finland to Port Tarraco to Marseille, delivery is consistently precise – the same standards, the same signature finish.

Over the past twenty years, the company has executed more than 250 full or partial paint projects, treated nearly 600 hulls with premium antifouling over the last decade, and worked on yachts up to 123 metres. These achievements reflect a core strength: Nautipaints’ systems and expertise scale seamlessly, regardless of location or vessel size. Notable recent work includes the paint project on the iconic 88-metre Maltese Falcon

This reach is underpinned by a robust internal framework. “Our approach rests on three pillars,” says Joan Salom, Deputy General Manager and third-generation member of the Salom family. “Quality control, project management, and planning.” Clients and shipyards benefit from clear specifications, detailed tender documentation, and a welldefined plan led by a dedicated Project Manager.

Execution is only part of the equation. “Refit is a collaborative effort,” Salom adds. “Reducing uncertainty builds trust. From quotation to completion, every stage is managed with clarity and control.”

While top coat refinishing remains central to Nautipaints’ operations, the company has expanded into specialised underwater services, including advanced antifouling, protective tank treatments, and precision water jetting for highperformance surface preparation. Tank protection – from bilges to ballast systems – is delivered with the same technical rigour and environmental care as any topside project.

This is underpinned by a forward-thinking training ecosystem. Staff are regularly upskilled through manufacturer-led sessions and in-house development, ensuring alignment with evolving products and application methods.

As the industry embraces new materials, sustainability goals and increasingly complex designs, Nautipaints continues its confident growth – guided by a simple mantra: Do it right, do it once.

Find out more at www.nautipaints.com

The Argo 54 has been teasing sailing superyacht fans since the project started back in 2020. As the 54-metre sloop begins the push toward completion at Omikron Yachts in Greece, we take a closer look at how the powerful yet lightweight aluminium project with sustainable sailing technology is coming together.

BY CHARLOTTE THOMAS

With its distinctive reverse bow and aggressive wedge-shaped hull, the Argo 54 sailing yacht presents a striking picture. A combination of Juan Kouyoumdjian’s raceboat sensibilities, the aesthetics and engineering nous of superyacht-savvy Rob Doyle Design, and the interior design skills of Mark Whiteley, the project pushes boundaries in terms of styling, naval architecture, structural design, and systems technology.

The idea sprang from the owner’s desire to create a modern, lightweight sailing superyacht that would be capable of fast cruising with guests and core crew, as well as racing with expanded crew and a bigger wardrobe of sails. The yacht would also feature a diesel-electric drivetrain that included a battery bank fed by renewables – hydro-generation in particular. The owner (who owns the shipping company that comprises Olympic Marine, the parent company of Omikron Yachts, and who was also behind the conversion of the 106.5-metre motor yacht Dream) tapped Kouyoumdjian to tackle the naval architecture and sailing elements in what is the designer’s largest project to date.

“The main brief was to design and engineer a superyacht that would be very well-balanced in breezes from five to 50 knots, and which would deliver a very pleasant experience from the helm,” begins Philippe Oulhen, design coordinator for Omikron Yachts. “The yacht was to have an owner suite and four guest suites, plus accommodation for seven to eight crew. She would run in both cruising mode – with a cruising sail set and reduced heel angles – and racing mode, with more crew, a bigger sail wardrobe, and a lighter displacement thanks to removing cruising gear, tender and deck furniture.”

With the Juan Yacht Design team creating the hull lines, the Rob Doyle Design team was brought in to style the yacht and look at the structural engineering to create as light a displacement yacht as possible. Their studies showed that they could build the hull in aluminium for less than a carbon structure and with more flexibility and volume for internal arrangements. In addition, stripping out unnecessary weight and systems became a focus of the project.

“We didn’t want to re-invent the wheel – it was important to use systems and equipment that are available on the market with a track record.”

The yacht’s lines include a reverse bow and lengthy forefoot overhang, a wide, low stern with a wine-glass shaped aft canoe body, and a centreboard-style swing keel. The hull also has a degree of tumblehome to take advantage of wider beam without increasing deck windage.

“The hull shape was optimised with our inhouse CFD cluster and know-how, with our method of feeding our velocity prediction program with 6DoF (six degrees of freedom) simulations covering wide true wind speeds and angles,” says Oulhen. “The stern bustle adds volume aft while the keel is up – when the longitudinal centre of gravity moves back – and the yacht’s stability and fore-aft trim at anchor will be controlled by this aft bustle and forward water ballast.”

The yacht features several design innovations, including the centreboard keel design (see sidebar) and a force-feedback system for the helms. “The novel steering system is an important part of the build,” says Nikolas Dendrinos, chairman of Omikron Yachts. “A standard hydraulic system doesn’t deliver ‘feel’, but it’s hard to sail fast if you don't understand the loads and what is happening with the rudder.”

Omikron opted for a system comprising two mechatronic actuators on the rudders that monitor loading, with the data sent via electrical signal to the helm to be translated into real-time force feedback. “It's similar to the fly-by-wire system on modern cars,” Dendrinos says. “For us this was very important to create the feel of a smaller boat – it will be very fast, very responsive, with twin balanced rudders.”

While the project features some technological leaps and involved in-depth FEA (see sidebar), most aspects of the design have been kept to tried and tested solutions.

“We didn't want to re-invent the wheel – it was important to use systems and equipment that are available on the market with a track record,” confirms Oulhen.

“The project is a nice coordination of good solutions working well together, with a prime example being the keel – the concept existed, but we refined it with all the partners. The same is true for the steering system, which tackles a major feature of the brief for the sailing. It’s proven fly-bywire technology that is well-implemented.”

Rather than opting for a big main engine with a PTO and a couple of generators, the design relies on a diesel-electric drivetrain with two full variable-speed generators that feed into a DC bus system and then into a 540 kilowatt-hour battery bank.

“It means you can run the entire system off the grid, and get a quiet ship,” says Rob Doyle, principal of the Rob Doyle Design studio. “The generators can be smaller and can be run at optimum load.”

At its core is an 800-volt DC bus with the batteries able to deliver between seven and 24 hours silent sailing and anchoring depending on loads, and with the gensets charging the batteries in one and a half hours. The yacht uses a special water-cooling system for the motors and drives in order to keep the system small and light.

“The chillers are also designed for energy recovery and efficiency,” adds Omikron Yachts head of design, Filippos Stratakis.

“There are five chiller units that ramp up in sequence according to demand, rather than having one big chiller unit that’s on all the time. The heat from the air-con system and generators is recycled, and the whole system delivers efficiency improvements of 25 to 40 per cent, and up to 75 per cent under some conditions. We did this to reduce the batteries needed for the hotel load and therefore reduce the weight, and we can also operate the hydraulic sailing systems and winches without running a generator.”

In addition to the generators, power will come from hydro-generation while sailing via a retractable aluminium shaft drive, which the design team worked on with Ship Motion.

“We basically wanted maximum blade area for hydro-generation with the prop running in reverse,” says Doyle. “Their prop guys did some research and designed an optimised propeller for maximum generation while sailing. It was the first step on the ladder of the technology that we’re already integrating into other boats, which is allowing them to do a full transatlantic without running a generator.”

With the Argo designed to start sailing in as little as four knots of breeze, and with hydrogeneration really kicking in above eight knots of boat speed, projections are the system will produce up to 55 kilowatts. However, the yacht is designed to sail in heavier airs too.

“In Greece we have very strong winds compared to the Med as a whole,” says Vassilis Kouvaris, Omikron Yachts’ project manager for the Argo 54. “We can go from zero to 50 knots, and 30 knots is very normal – these are no-go conditions for sailing superyachts, but this boat has been designed to sail in them easily.”

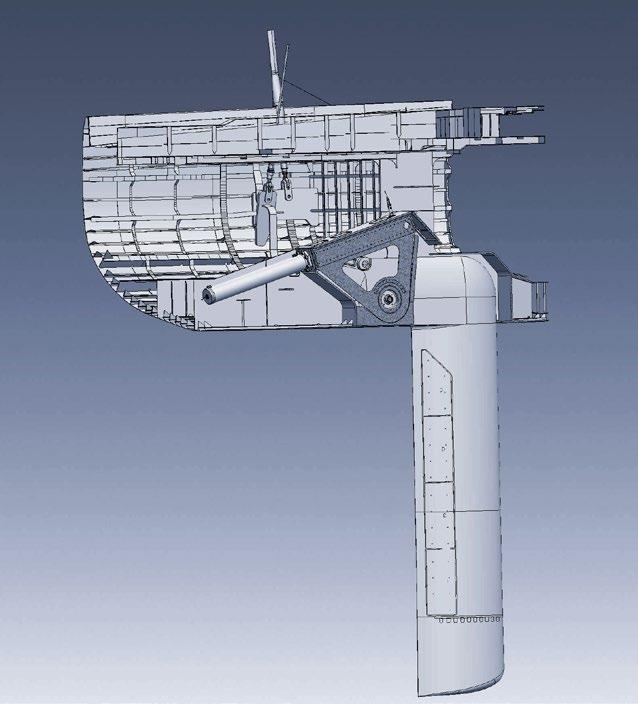

The Argo 54 uses a centreboard swing keel design built by Italian specialist keel-builder APM Keels. It has a ram mounted on the front side of the mechanism to pull the keel down and push it back up. An additional lock-step design in the keel box ensures that the keel is self-supporting when in the raised position, meaning the ram can be disengaged and removed if necessary.

“With all the big boats we’ve done the biggest problem we have is always dealing with the fuse and the grounding load, followed by the difficulty in undertaking standard maintenance on the mechanism,” says Doyle. The team designed a new type of fuse, so if the yacht grounds with the keel down, the will fuse break and the keel will pull away from the hydraulic ram, meaning the shock loads don’t get transferred to the rig, chainplates or keel box.

“It also means you don’t get ram compression, you don’t damage the seals, and you don’t get atomised hydraulic oil in the technical space,” adds Doyle. “It also allows you to re-engage the ram and push the keel up over the lock so it’s locked in the raised position, then you can back off the ram, change the fuse, re-engage the ram, bolt it all back together and you’re good to go – there’s no need to get to a dry dock.”

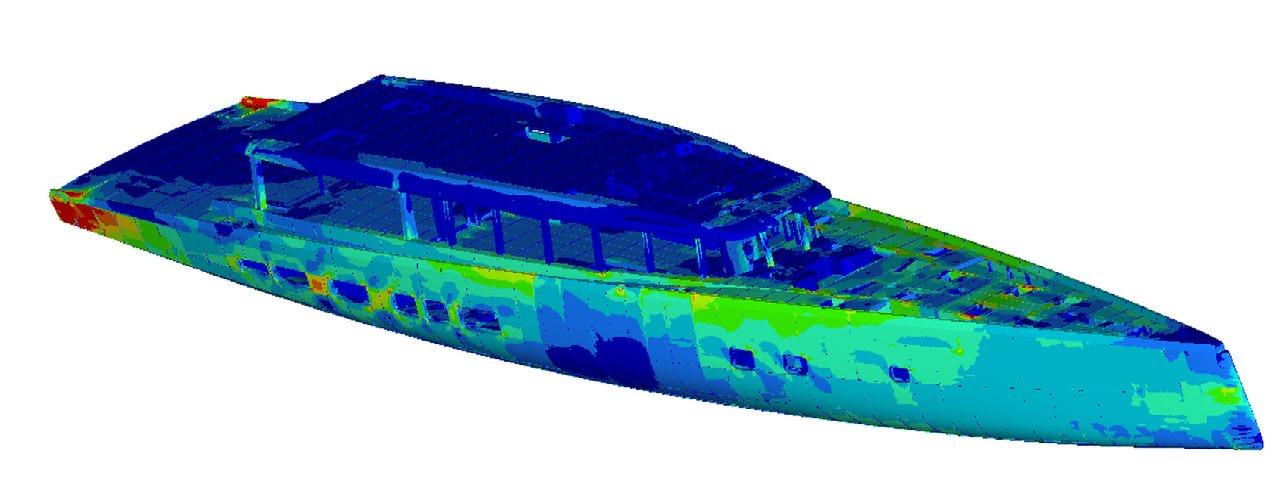

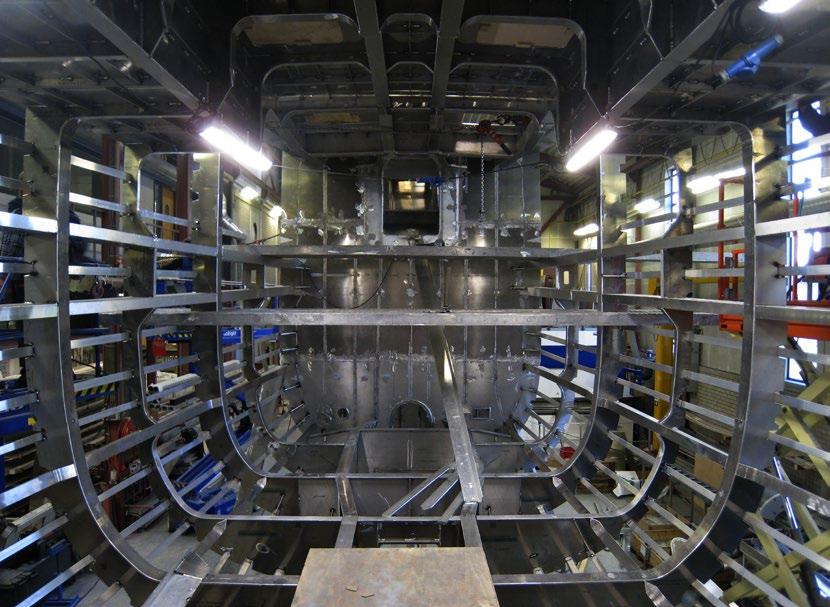

Hull fabrication was done at the Gouwerok Shipyard in the Netherlands and was completed in November 2022. “They are one of the best aluminium builders in the world,” enthuses Doyle. “In their contract they guaranteed a maximum deflection of three millimetres concave over six metres, with zero convex. It was like an aircraft fuselage – you could have polished it and sent it out the door.” A notable feature is that the hull doesn’t have a standard frame size, each one being designed for the load case. FEA was used to optimise the scantlings by playing with different frame spacing and longitudinal structure to see which models yielded the lightest weight. This has had other interesting impacts: by concentrating the major forces from rigging and keel through three key reinforced frames, the team was able to reduce the amount of structure required for the deck. Indeed, the turnbuckles for the shrouds are in the engine room, a result of the chainplates being located in the turn of the bilge. The mast itself comes from Southern Spars and is deck-stepped, supported by Aerosix rigging.

“Gouwerok in the Netherlands is one of the best aluminium builders in the world. It was like an aircraft fuselage – you could have polished it and sent it out the door.”

At the project’s core is a carefully engineered and beautifully constructed aluminium hull and deck weighing just 62 tonnes, which according to Dendrinos makes the Argo 54 the lightest aluminium hull ever built for its length, saving around 35 tonnes of aluminium compared to a standard build. The engineering required the Doyle team to delve deep into the rules in order to keep the structure as light as possible while still meeting class requirements.

“We approached the structure from first principles, while also considering the differences in class rules – a Lloyd’s boat wouldn’t fit under DNV, for example, and a DNV boat wouldn’t fit under an ABS programme,” says Doyle. “But it was a fantastic bit of research, because it showed that if you push the meaning of each rule to its limits they all come out about the same, with weight within a couple of percentage points of each other.”

With the shipyard choosing to build

to Bureau Veritas came an interesting conundrum when the surveyor said that the size of the frames needed to be doubled. In order to keep their lightweight design, the team did full finite element analysis (FEA) to prove every part of the hull’s structure was sound. This had an additional benefit: “We discovered that a historic phenomenon with plating distortion around the chainplates wasn’t due to the aspect ratio of plates, as had previously been thought, but was from the stresses running around the turn of the bilge and creasing the boat – something that only detailed FEA could show,” explains Doyle. “We ended up beefing up the plating around the structure of the hull where the chainplates are located way more than what the rule specified, and we were then able to go back to class and point out the problem, and recommend they upgrade their rules.”

A notable feature is that the hull doesn’t have a standard frame size, each one being designed for the load case.

Previous spread:

Below: At the time of our visit major

Sitting in a vast shed at the Skaramangas shipyard near Athens, much of the hotwork has been completed and the hull has been faired. The project has been making slow but steady progress since the hull arrived in Greece at the end of 2022, but the team has also been waiting for technology to catch up – in particular in relation to the DC grid system, which is being engineered by Baumüller, a German company specialising in systems for commercial shipping.

Work will soon start engineering the interiors and building mock-ups at Olympic Marine to confirm cabin layouts, crew areas and other details before ordering in the materials for the production of the interiors proper. The interiors, which will feature lightweight Nomex core construction, will be built at Olympic Marine in parallel with progress on the technical fit-out at the Skaramangas yard. Dendrinos estimates a further 18 months of build time before the yacht is launched.

The owner and crew will be making good use of that time. Because of the performance nature of the hull and the sail plan, the yard has bought a Volvo 70 (also designed by the Juan Yacht Design studio) from the 2012 edition of the Volvo Ocean Race for the crew and owner to train on.

“Sailing at these kinds of speeds is a different mentality, and we will also step to a hydraulic system on the 70 similar to what the Argo will have,” says Dendrinos. “If you have infinite power to control your sails, it becomes more complicated because you can’t feel the loads. The training is also key to ensuring the owner won’t need a large crew of professional racers to enjoy the yacht – he wants to sail with his friends.” For all the convention-defying aspects of the Argo 54, that aspect at least, it seems, is convention to its core.

All sorts of working vessels, from ocean-going tugs and fishing boats to ice breakers and naval vessels, have been converted into superyachts. But not a container ship – at least not yet. Doing so requires rethinking every aspect of a ship designed exclusively for carrying cargo. That didn’t dissuade Oceanco from teaming up with Italian yacht designer Mario Biferali to develop Anthos.

BY JUSTIN RATCLIFFE

Conversion means razing the entire internal structure down to the double bottom and rebuilding it.

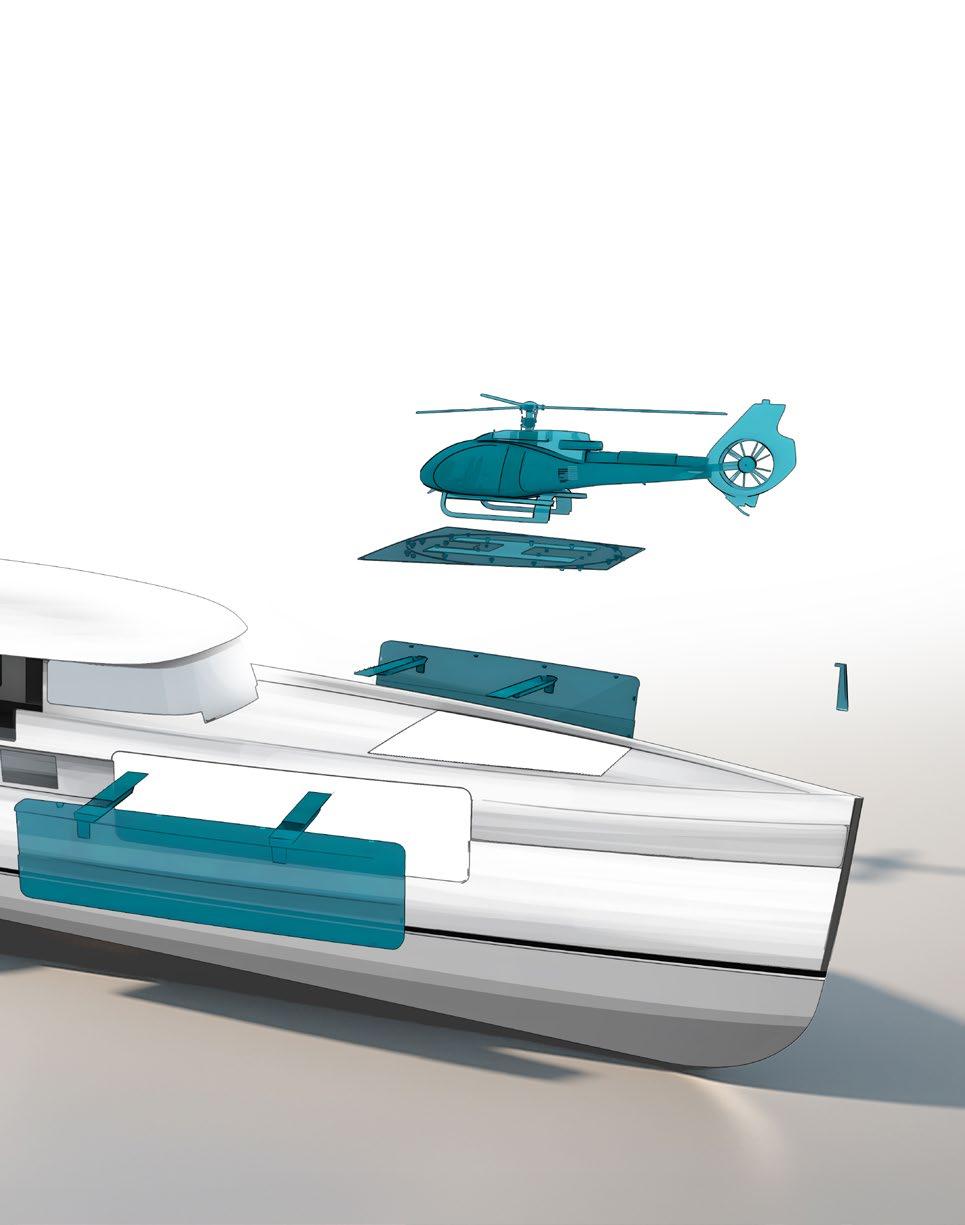

Mario Biferali was first drawn to the idea of naval regeneration while researching his PhD thesis that analysed the evolution and increasing size of yachts over the decades. Blending the words ‘naval’ and ‘yacht’, he coined the term Nacht to describe the process of breathing new life into a container vessel by transforming it into a luxury yacht. Having previously worked with Oceanco as an engineer on several new-build projects, including the 109-metre Bravo Eugenia, Biferali approached the Dutch builder to explore the idea further. The result was Anthos, a 150-metre concept first presented at last year’s Monaco Yacht Show and based on the complete rebuild of a container ship.

“Mario’s technical background means that he’s not given to fluffy thinking,” says Wim Verhoeff, sales director at Oceanco. “When he sent the initial general arrangement it was already pretty much spot on with regard to watertight integrity, fire zones, allocated space for HVAC systems, and so on. Our job was to make sure it could be built.”

The core idea behind Anthos – to leverage the high volume of a commercial hull while introducing an entirely new internal architecture and a forward-thinking approach to propulsion and comfort – aligns with Oceanco’s Life Cycle Support initiative, which aims to give existing vessels a new lease of life. Unlike conventional conversions of decommissioned or aging support ships, Anthos begins with a structurally sound, operational container vessel. This reduces material waste and conversion costs, while still offering a faster timeline compared to new builds.

Still, the donor vessel’s condition is obviously critical and the team has shortlisted a dozen or 1990s-era container ships with a gross tonnage around 12,000 GT – a volume expected to increase post-redesign. For example, 150-metre Meratus Mamiri (IMO 9106649) was built in 1995 and has a volume of 11,964GT, and MSC Belle (IMO 9203904) is a 148-metre vessel of 12,004GT launched in 1998. Both have a beam of 23 metres. Though service life varies, vessels such as these are often retired due to market forces rather than physical wear and tear.

“Maritime transport is cyclical and tied to global trade,” Biferali explains. “During downturns, shipowners face oversized fleets. When that happens, some vessels are sold off, others are scrapped, but many remain in good operational condition despite being commercially obsolete.”

From a technical design perspective, the concept poses both opportunities and challenges. The hull of a container ship compared with that of a bulk carrier or an oil tanker has a finer, more hydrodynamic form designed for low-resistance cruising, which is not dissimilar to large yachts. This is reflected in their block coefficient – the ratio of a vessel’s displacement to that of an equivalent cuboid, which essentially defines the ‘fullness’ or ‘fineness’ of the hull shape. Expressed as a value from 0 to 1, a container hull has a block coefficient between 0.6-0.7, compared to 0.80.9 for fuller-form cargo vessels, and 0.5-0.6 for fast naval corvettes or frigates.

The beam of a 150-metre container ship aligns with that of a conventional superyacht of similar length, but fully laden the draft can draw 8-9 metres. This is why container ships rely on various ballast systems to maintain stability when unladen or in port. For yachts up to 90 metres in length, Oceanco avoids ballast tanks in order to prioritise the luxury areas and minimise the complexity of onboard systems, but over 100 metres some form of ballast is desirable to maintain trim and compensate for fuel or water consumption during longer voyages. As Anthos would already have a built-in ballast system, Oceanco would balance weight distribution and optimal draft with system upcycling and sustainability considerations. “Partial or full reuse of ballast systems is ideal to lower the carbon footprint associated with new construction or system overhauls – if compatible with the new yacht’s operational needs,” says Verhoeff. “ To enhance onboard comfort further we would also include an active underway stabilisation system.”

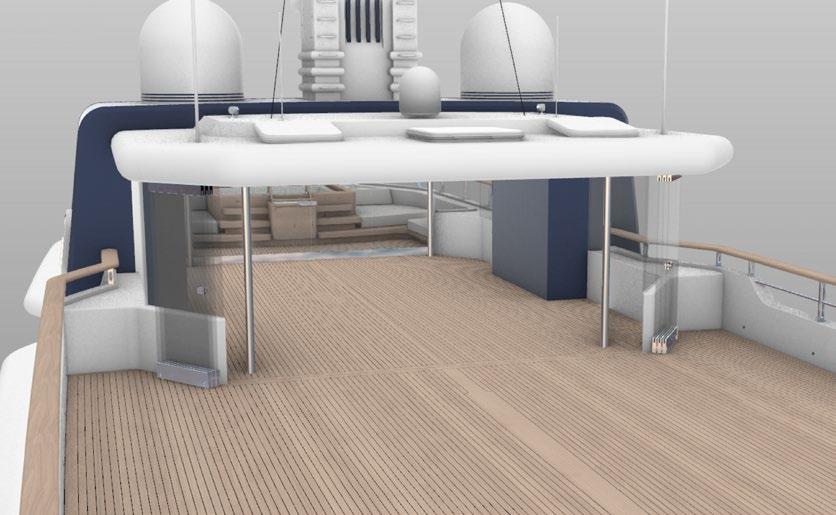

Structurally speaking, the conversion would be substantial. Container ships are designed and built very differently to yachts. They have no continuous main deck running the full breadth of the ship, for example, and fewer transverse bulkheads. Instead, they are made up of several holds with deck hatches and each hold is equipped with “cell guides” that allow the containers to slot into place. Conversion means razing the entire internal structure down to the double bottom and rebuilding it, removing the deck hatches and adding an extra tier to the hull topsides, as seen in the renders of Anthos Moreover, in conventional yachts the superstructure bulkheads are usually aligned with the watertight subdivisions in the hull. Here again Anthos departs from the norm as the superstructure is comprised entirely of the owner’s ‘tower’ spanning 284 squaremetres over three decks with lounges, offices, a media room, and 298 square-metres of terraces, including a private sundeck above the wheelhouse. Anthos’ hull accommodates two full decks and an under-lower deck for technical equipment, tankage and crew support functions. Installing new decks in former cargo holds would require extensive steelwork, along with floating floors, noise isolation, and flexible machinery mounts. The guest accommodation – including two double-height super VIPs – is housed on the guest lower deck. The leisure lower deck contains expansive social spaces such as port and starboard side ‘Sea Gardens’ with vertical green wall, a full-beam terrace overlooking the stern, full-beam gym, wellness zone, double-height sports court, and a cinema room. Many areas are modular, allowing repurposing for scientific research or philanthropic activities. In the fore section are 27 cabins for 54 crew members.

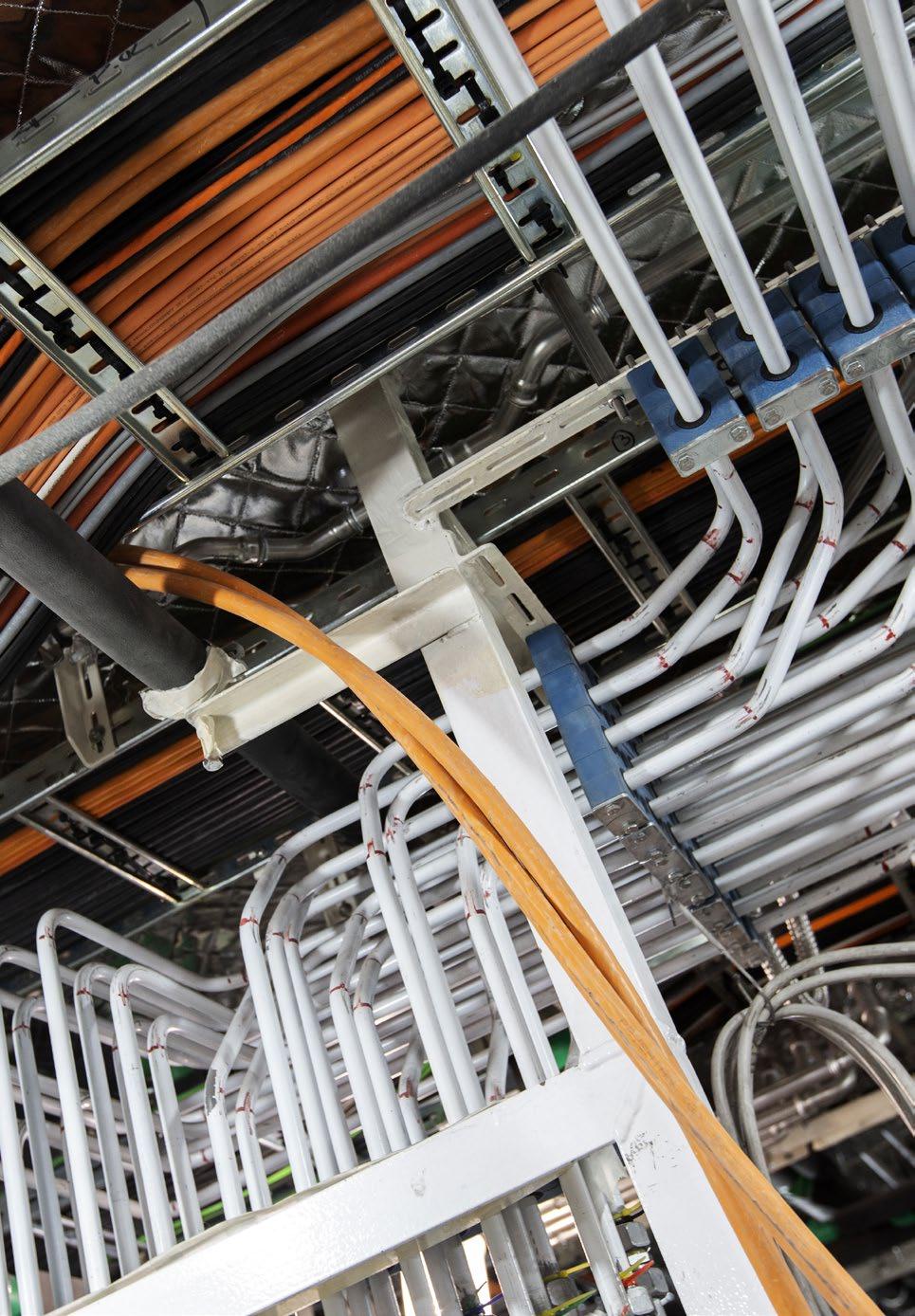

Biferali began planning for HVAC, cable routing, technical spaces and insulation early in the design process, but circulation flow was a particular challenge in the long, narrow hull. The solution is multiple points of vertical access along the length of the hull to minimise travel distance for guests. The crew have dedicated routes to maintain operational efficiency without infringing on the guest zones.

A central question emerged: just how much structural modification can a hull of this scale tolerate?

Considering the many hull perforations envisaged for panoramic windows and folding platforms or balconies, including a 14-metre long aperture for the tender bay and a 19-metre swimming pool amidships on the top deck, a central question emerged: just how much structural modification can a hull of this scale tolerate? The original double bottom and box-like arrangement of wing tanks, also used for ballast, provide longitudinal strength, as would the extra steel plating for the redesigned hull topsides, while new bulkheads would add transverse strength. Full FEM analysis would be required to verify the resilience of the final structure. The scale of Anthos means it can accommodate Oceanco’s Energy Transition Platform (ETP) – a modular energy architecture developed in collaboration with Lateral Naval Architects that enables a future-proofed path to zero emissions. Designed for staged retrofitting, the ETP can accommodate new configurations and specifications to integrate future technologies

and alternative fuels as they come online.

“We know that in the coming years we will see a lot of changes when it comes to alternative fuels, so we want to be prepared for that energy transition,” says Verhoeff.

The donor ship’s medium- or slow-speed engines could be upgraded or replaced with a dual-fuel methanol system, for example, which seems to be the most plausible interim solution for yachting. However, because methanol is less energy dense than diesel, it requires roughly 2.5 times more storage volume. A container hull has the space for more tankage, which a regular superyacht does not.

“Time saved – rather than cost – is usually the main advantage of conversion over building new,” Verhoeff concludes. “While a new 150-metre build might take up to five years, a conversion can cut 12 to 24 months from the schedule. For many owners, this time advantage is more valuable than cost efficiency, particularly in a market where demand for larger, bespoke vessels is high and availability is low.”