TAINTED TEAK: The end of an affair?

TAINTED TEAK: The end of an affair?

The technical magazine for those involved in the design, construction and refit of superyachts

ROSSINAVI’S AKULA: Keeping it simple

43

Concept in Focus: The Return of the Nautilus Inspired by a 150-year-old novel, will the Nautilus ever be buildable? U-Boat Worx believes it can.

49 Tech Talk: Staying Connected

Kris Cardona of YOT Ltd offers his take on how new tech is transforming IT and comms on board.

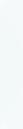

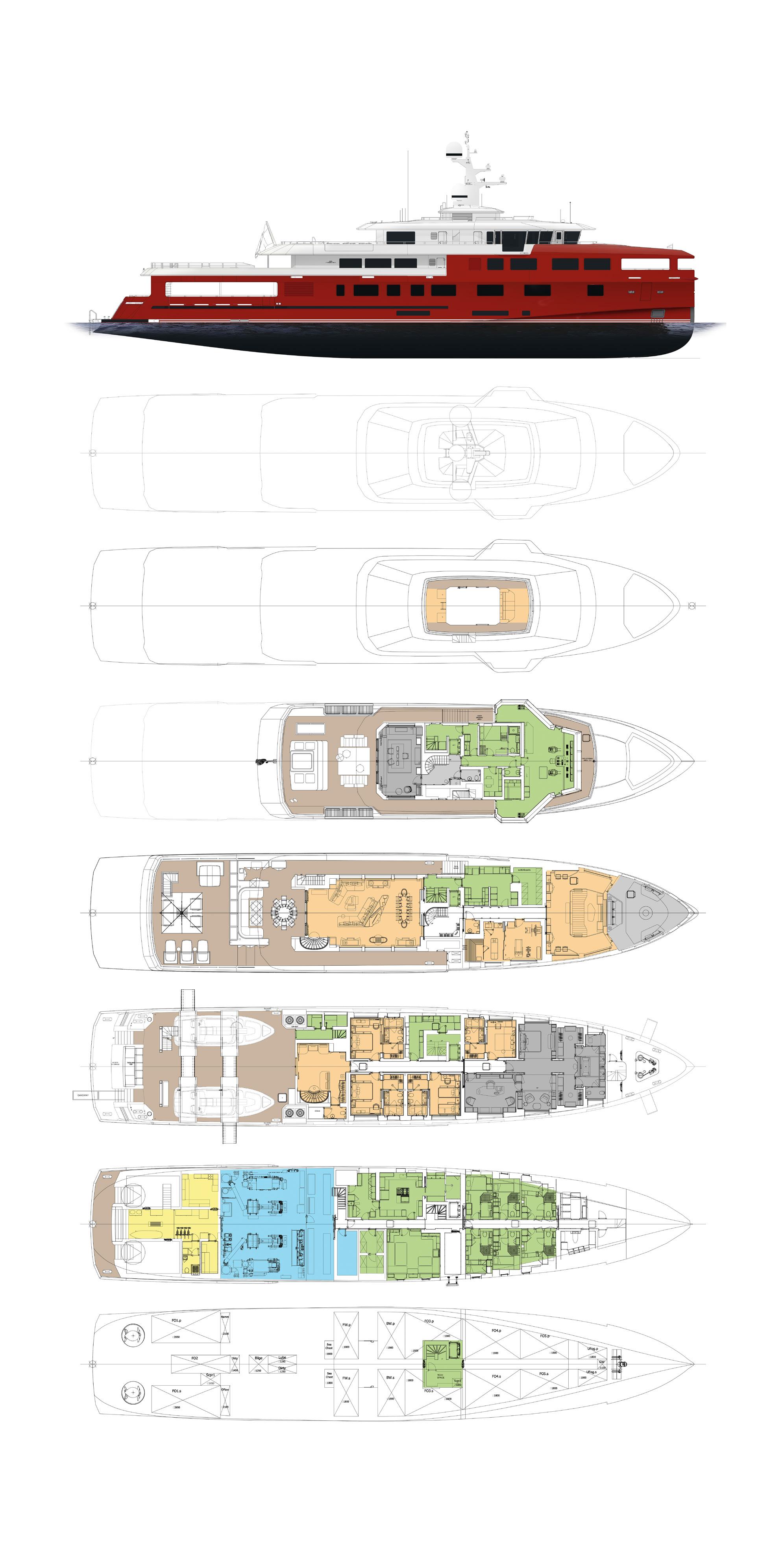

54 Build Report: Keeping it Simple

A sneak peak of 59-metre Akula as Rossinavi’s first explorer yacht approaches completion.

70 Build Report: Pump Down the Volume

Exclusive access to Feadship’s 103-metre Project 1011 in the company of project manager Leo Boonstra and owner’s rep Erik Spek of Azure.

82 Manufacturers: Clear as Crystal

A visit to Tilse GmbH in Germany to find out how the rules and regs are keeping pace with technical developments in glass manufacturing.

94 Sponsored Content: Smarter Anchoring

The team at Swiss Ocean Tech on how high-tech AnchorGuardian can keep your vessel safe.

95 Sponsored Content: Full Custom Craftsmanship

Custom Tenders founder Richard Faulkner on customisation in the tender sector.

96 Inside Angle: Occam’s Razor

Superyacht consultancy Occam Marine is named after a philosophical concept that recommends problem solving by searching for the simplest solutions.

100 Sustainability: Tainted Teak

The search for wood alternatives that can replicate the looks and performance of old-growth teak is fully under way.

110 Sponsored Content: The Perfect Partner

From building viaducts and offshore platforms, Dutch aluminium specialist Bayards has developed into a leading manufacturer of superyacht hulls and superstructures.

112 Case Study: The End of Filler?

Coating experts Wrede Consulting in Hamburg are building a full-size yacht to test new methodologies for fairing hulls and cladding superstructures.

119

New Tech: Rise of the Robots

Is the custom nature of a superyacht a definitive barrier to adopting robotic automation in the build process? Read on.

128

Refit & Conversion: Master of the Seas

A look behind the scenes of 70-metre conversion Project Master at Icon Yachts as the future explorer yacht enters the detailed engineering phase.

140 Refit & Conversion: Flight of the Falcon

When new owners decided to refit 88-metre Maltese Falcon, they assembled as many of the original contractors as possible.

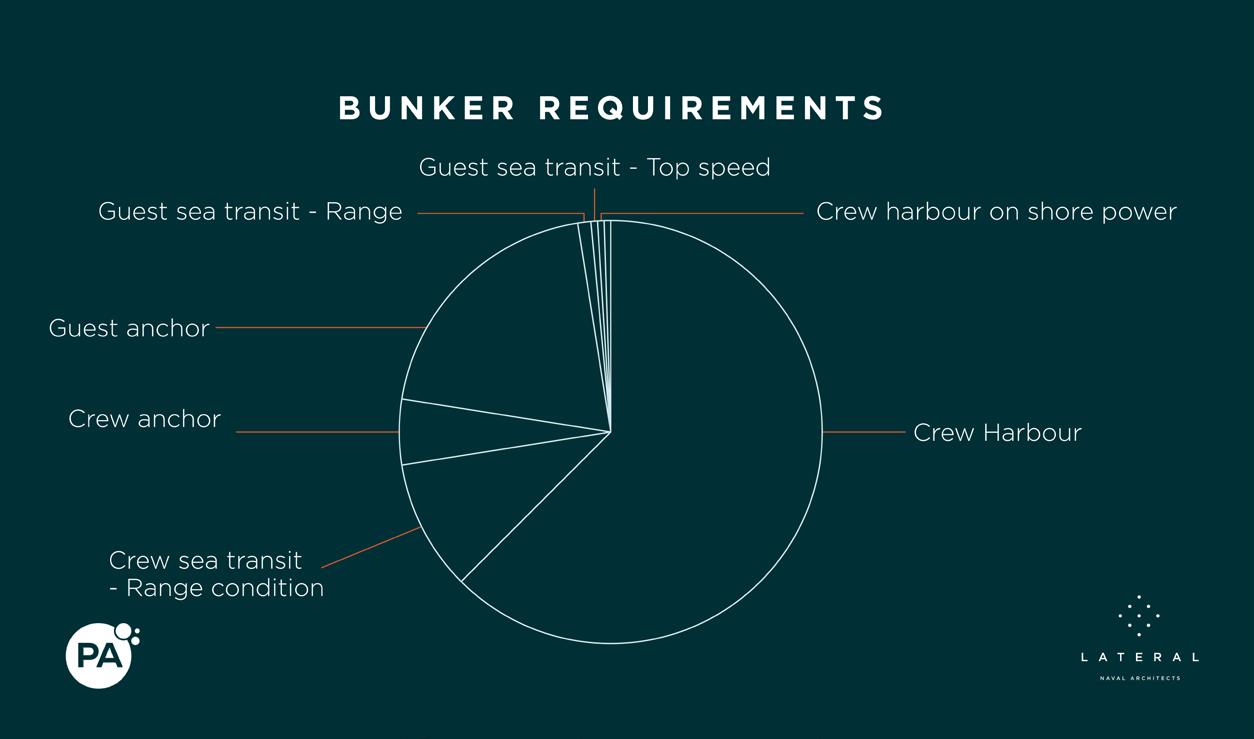

150 Alternative Fuels: We Have the Technology

Lateral Naval Architects and PA Consulting look into the feasibility of developing a hydrogen fuel manufacturing and bunkering infrastructure.

157 Ask the Experts: Light Up Your Life

With more yachts opting for extravagant light portfolios, we speak to a panel of experts in the field to find out how the sector is continuing to evolve.

EDITORIAL

EDITOR IN CHIEF

EDITOR | HOW TO BUILD IT

EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTOR

DIGITAL EDITOR

NEWS WRITER

TRAVEL WRITER

WRITER

WRITER

VIDEOGRAPHER

Francesca Webster

Justin Ratcliffe

Charlotte Thomas

Emma Becque

Sophie Spicknell

Jessamie Rattray

Enrico Chhibber

Amy Larsen

Muaz Abourched

DESIGN PRODUCTION

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

GRAPHIC DESIGNER

UI/UX DESIGNER

Ivo Nupoort

Beatriz Ramos

Claudia Sabbadin

INTELLIGENCE

HEAD OF INTELLIGENCE

RESEARCH ANALYST

DATABASE MANAGER

DATABASE MANAGER

YACHT HISTORIAN

Ralph Dazert

Adil Zaman

Syrine Mellakh

Léandre Loyseau

Malcolm Wood

SALES & ADVERTISING

SENIOR SALES MANAGER

SALES MANAGER

SALES MANAGER

CLIENT SERVICE MANAGER

SALES ITALY

Marieke de Vries

Justus Papenkordt

Daniel Van Dongen

Johanna Borreli

info@admarex.com

CORPORATE

FOUNDER & DIRECTOR

TECHNOLOGY DIRECTOR

FINANCE DIRECTOR

Merijn de Waard

Fabian Tollenaar

Laura Weber

Welcome to this bumper issue of How to Build It to kick-start the boat show season. You’ll notice how this third edition is a good deal fatter compared to when we launched the magazine exactly a year ago, a sign of just how well the publication has been received by marine suppliers, contractors and manufacturers. So well received, in fact, we’ve had to cap the number of ad pages to maintain our editorial focus!

We look far and wide to come up with content you won’t find anywhere else and in this issue that includes two exclusive in-build reports. First we visit Rossinavi for an exclusive look at their very first explorer yacht. It’s hard to miss the bright red hull of 59-metre Akula, whose owner was so closely involved in the design process that he taught himself to use CAD software. We also investigate the engineering and technical challenges associated with Feadship’s secretive Project 1011 when her owner asked for a 100-metre-plus yacht with the volume and guest space of a vessel almost twice the size.

I remember writing about the potencial of robots in yacht building years ago. At the time it seemed they were poised to take over messy manual jobs like fairing, sanding and painting, even welding. But that hasn’t happened to any significant extent. We ask if the custom nature of a superyacht is simply not conducive to automation, or whether there are other factors at play?

And talking of filling and fairing, have you ever wondered why we are still adding tons of filler compound to our yachts solely for aesthetic purposes? Coating experts Wrede Consulting in Hamburg believe they have a lighter, faster and more efficient solution – and they’re building a full-size yacht to their theories to the test.

Still in Germany, in addition to doing amazing things with glass on yachts, Tilse GmbH has been instrumental in defining the approval and classification criteria for onboard glazing. We travelled to the company headquarters near Berlin to learn more first-hand.

The industry-wide focus on sustainability and the first prosecutions for the illegal importation of teak from Myanmar mean yacht builders can no longer turn a blind eye to teak of doubtful origin. We look into the most promising wood-based alternatives and investigate which, if any, come close to simulating the prized properties of old-growth teak.

Add in-depth reports on the refit of Maltese Falcon in Italy and the conversion of Project Master in the Netherlands, as well as our regular columns and commentaries from industry experts, and I think you’ll agree this issue of How to Build It is the most stimulating and varied yet. Enjoy!

Justin Ratcliffe - Editor

For generations, we have been realizing the most extraordinary living spaces with dedication and expertise. On water and on land. As a leading international partner in interior+ outfitting, we turn visions for living into reality – for both indoor and outdoor areas.

We are crafting visions.

Following up on our article about 3D printing in issue 2 of How To Build It, the Dutch shipbuilding company Royal Van der Leun has been commissioned with the electrical installation, engineering and automation of a 3D ferry to be used as a passenger vessel during the 2024 Paris Olympics.

In addition to being the largest 3D-printed ferry ever, the vessel will be fully electric, with power for charging the batteries supplied by a hydrogen-powered generator on shore, as well as automatic mooring and contactless charging. Lidar, cameras and RTK-GPS are used for position and course determination, making a captain unnecessary and enabling autonomous operation. The ferry is being constructed by Holland Shipyards Group, with autonomous navigation developed by Roboat for service in France.

Aqua superPower, the British company providing electrically marine superyacht chargers, has continued to expand its portfolio of charging hubs across Europe and the United States. Founded in 2021, the company has now secured £3.2 million in funding from the UK government to deliver a marine charging infrastructure to the UK’s south coast for boats under 24 metres. The company plans to have installed an additional 150 charging stations

globally this year as the demand for charging stations continues to steadily increase. The company is currently ‘partway through building networked charging corridors’, and provides the upfront capital and funds the grid and charging provision to lower the barrier to entry for market players. Aqua superPower is also making headway in continental Europe with chargers installed at the Cala del Forte marina in Ventimiglia owned by Monaco Ports.

A new photovoltaic system has been installed at Amico & Co that will supply renewable energy to cover 53 percent of the refit shipyard’s annual needs and Waterfront Marina production activities.

The on-site system occupies an area of over 4,300 sqm with an array of 1,782 solar panels developing a maximum power of about 1 MegaWatt peak (1MWp). This new investment made by Amico & Co represents another important step towards clean manufacturing and fuller integration of the superyacht

activities with the city of Genoa.

“With some pride we can say that since the very start of our activities, with greater intensity since the early 2000s, we have made investments that have gone in the direction of what we now call sustainability,” says Alberto Amico, President of Amico & Co Spa. “Our strategy was and is the implementation of work process efficiency, particularly through covered and permanent warehouses and other facility technologies, which guarantee 73 percent consumption savings when compared to any temporary facility.”

Azimut-Benetti has signed a deal with Eni Sustainable Mobility to supply renewably sourced HVO biofuel to its fleet. HVOlution, a biofuel made of 100 percent HVO (Hydrogenated Vegetable Oil), is produced in Eni Sustainable Mobility’s Venice and Gela biorefineries from waste raw materials and vegetable residues or from oils generated from crops in a circular economy model. Factoring in the entire logistics and production chain, HVOlution can deliver emissions reductions of up to 90 percent compared to the benchmark fossil blend, depending on the raw materials used for its production. The use of HVO will begin in Summer 2023 for the technical testing of new yachts, sea trials and prototype model handling and owners will be able to take delivery of yachts with HVOlution biofuel already in the tank.

Presented as the next evolution in fully integrated helmto-propeller solutions, Volvo Penta claims its Volvo Penta IPS 40 drive offers outstanding comfort, performance, and sustainability. Building on the efficiency of the Volvo Penta IPS, the new platform is a powerful and flexible solution for superyachts from 25 to 55+ metres with top speeds between 12-40 knots.

“A new star is emerging in our range, where we are looking forward to delivering our trademark helm-topropeller experience to a whole new class of vessels,” says Johan Inden, president of Volvo Penta’s marine business.

Instead of having a bigger engine, the Volvo Penta IPS 40 drive will be powered by two existing D13 engines that are paired with a compact after-treatment system to comply with the latest IMO Tier III standards. But the platform is already prepared for a mix of power sources, from combustion engines running on renewable fuels to fully electric or hybrid solutions. The dual power input design offers flexibility and modularity on the journey towards increased sustainability and can be installed in a twin, triple or quad set-up, meaning each vessel will have from 4 to 8 power sources.

Volvo Penta is carrying out in-house development and in-water testing using its own passenger high-speed ferry test boat, strategically located near its marine test facility in Gothenburg, Sweden. Rigorous testing is in progress to ensure the durability and performance of the propulsion package with field tests in an offshore-energy crew transfer vessel serving as the subsequent phase leading up to the anticipated 2025 delivery.

HamiltonJet has launched a new range of high-efficiency waterjets called the LTX Series. Optimally designed for medium- and low-speed operation, the company has claimed that this is the first waterjet to rival the energy efficiency and bollard pull of the best propeller-based systems between zero and 30 knots.

With its large nozzle, lower input energy, lower jet velocity and lightweight structure the LTX waterjet is lean and low-speed efficient. The absence of hull appendages plus an optimised pump geometry have allowed HamiltonJet customers to save fuel for over a generation, not everyone wants to go fast: “Our customers’ needs are changing and so is our environment,” says HamiltonJet CEO Ben Reed. “We understand that operators not only want to reduce their impact on the environment and lower their energy costs, but also maximise efficiency.”

OneWeb, the global low Earth orbit (LEO) communications network, has launched a Try Before You Buy service and will now take bookings from maritime users who want to benefit from OneWeb’s 100 mbps+ enterprise grade flexible connectivity packages at sea. With 634 OneWeb operational satellites now in orbit, the OneWeb constellation is complete and fully operational down to 35 degrees latitude. OneWeb will have the final ground stations completed and operational requirements in place, ensuring the Company remains on track to deliver full global maritime services by the end of the year.

Now OneWeb will start selling services to the maritime industry, via its specialist maritime distribution partners. OneWeb and its partners have also developed a range of hardware terminal products which are available from trusted maritime communications providers Intellian and Kymeta. Offering hardware terminal products from two established providers with different form factors enables greater choice for customers.

By Georgia Tindale

Beginning a new-build superyacht project is one of the world’s most exciting and challenging undertakings. With a plethora of different factors to take into account – including timescales, costs, competing priorities and so on – it is a remarkable achievement every time a superyacht touches water and the celebratory champagne is poured.

One company which has been diligently working to streamline the build process for all individuals involved is Pinpoint Works. Based in London, Pinpoint Works was founded by superyacht captain, James Stockdale, after he was frustrated with the inefficiency of the workflow and communication found within new build projects.

Fast forward to today, and Pinpoint Works offers a dynamic, affordable and customisable interactive worklist management platform which has already saved countless hours on board vessels across the industry. It has been used to manage ongoing work lists for hundreds of superyacht projects to date, including 200 new builds and over 100 projects which are currently under construction.

Bolstered by the added backing of the financial management experts at Voly Group – whose accounting software has the accolade of being found on board 15% of the industry’s yachts – and who acquired the company in February this year, Pinpoint Works is in the ideal position to help you save time on your superyacht project, whatever your role within the industry. It is a web-based system and is also available for convenient use as a mobile app for iOS and Android.

With its foundations firmly rooted in yachting, Pinpoint Works has been created, tested and approved by a broad range of parties including shipyard project managers, independent contractors, paint surveyors and yacht crew. Just some of the wide ranging pain points addressed by the tool include tracking build progress in real time and managing costs, the reporting of interior and exterior defects, logging unplanned engineering maintenance, improving interdepartmental communication – and the list goes on, with yachts in-build, yachts undergoing refits and survey all able to reap the benefits. Here, we dive into just a few examples of how those working at the heart of yachting have made the most of Pinpoint Works.

Acting as the shipyard’s representative to the client and the day-to-day contact for the owner’s teams, the shipyard project manager or supervisor typically manages one new build project at a time.

For these extremely busy individuals, the pros of using Pinpoint Works include speeding up and streamlining all communications, quick logging and locating of defects on

board, fast and efficient creation of reports to pass on to contractors and other stakeholders, viewing works on a timeline, setting reminders for task follow up, and many more. Indeed, one project supervisor for a 50-metre new build project recently commented on his experience of using the platform. “We use Pinpoint Works frequently. New activities can easily be monitored on all the projects thanks to the daily digest in the mailbox.” Quick tracking of all activities can also be found directly within the system itself through a dashboard for those keen to reduce their email load.

He continued: “The ease and flexibility of the platform for inserting comments make it a powerful and versatile tool which third parties of the project can also use. Reports can be used for official purposes as an attachment to the PODA [Preliminary Operation and Delivery Acceptance] during a new build process or to officially close a report of a warranty period after two years.”

Managing all elements of the project on behalf of the owner, this team functions as the day-to-day link between the shipyard and owner. The benefits of using Pinpoint Works for this team are numerous and include super-fast and efficient communication, the ability to quickly generate reports for daily/weekly meetings, defects and non-conformity, paint inspections, room acceptance, FAT/HAT/SATs and much more.

Finally, it is worth noting that Pinpoint Works has also made waves further afield, with a project manager for the technology integration specialists HMC – responsible for installing AV systems on yachts and cruise ships – commenting on his recent experience of using Pinpoint Works. “We have successfully used Pinpoint Works during installation, commissioning, and handover for new build and refit projects on yachts and cruise liners at the largest scale. Pinpoint Works adds value to our company by providing a truly collaborative and coordinated software solution.”

With service locations in West Palm Beach, Fort Lauderdale, Istanbul, La Spezia, Antibes, La Ciotat, Barcelona and Mallorca, Heinen & Hopman will be at your disposal around the clock. From installation to 24/7 service, Heinen & Hopman’s skilled engineers are aware of the divergent problems that can be encountered onboard.

Meet us at the

Winner of the Queen’s Award for Enterprise: Innovation 2022, Compass is a cloud-based programme accessible by multiple users across various platforms and devices. It runs efficiently on iOS or Windows and can be used on laptops, tablets, and desktop computers. Clients have access to a range of services to support regulations & compliance and, most importantly, navigation of the seas. The platform offers digital chart corrections, passage planning, map overlays with weather, warnings and MARPOL, weather reports, integrated Imray cruising guides and licence and regulation compliance management. The platform can also be supported by a digital yacht manager to support the yacht in all of its activities.

Viareggio-based Inoxstyle has launched its latest product, the hand-crafted Nautical Shower. Made from either Marine Grade AISI316L stainless steel or carbon fibre with an array of finish options, the Nautical Shower has been designed to align with any yacht design and is protected from even the most severe weather conditions. Assembled without the use of tools, the shower is quick to assemble and the water connections are invisible. The Nautical Shower is lightweight and is custom made to measure for each superyacht project and the new carbon fibre option can be combined with stainless steel appliances for a unique and stylish finish.

Besenzoni has developed a new range of ladders/platforms called Oceano: currently including 3 models (LP100 Plus, LP200 e LP300), which differ in size and finish, but it is always evolving and expanding. The installation of these multifunctional ladders/platforms, totally tailor-made according to the yacht’s characteristics, allows to benefit from an additional space at the stern that can be exploited in many ways, offering a pleasant bathing experience, allowing the guests on board to fully enjoy the sea and the contact with the water.

Their main function is as a bathing ladder or from boarding/ disembarking but they are not limited to this since they can be used both as an extension of the beach area and as a convenient tender lift platform.Among the features of this multifunctional ladder is the ability to lift loads of up to 400 kg safely with the simple use of the hand control that manages its handling in a very smooth and intuitive manner.

Multiplex integrates “Tulip” lights into its awning system which means that the top seller from the Bremenbased carbon specialist can also be used in the dark. Multiplex developed the so-called “Tulip”, a very elegantly designed, non-dazzling lamp that shines in red, green, blue and white and which can also be dimmed. The highlight of the “Tulip”, is that it serves as an uplight that can be used to illuminate the awning or - turned by 180° with a flick of the wrist - to shine downwards and illuminate the floor. The milled aluminium body in which the LEDs are cast is waterproof to protection class IP 67. The “Tulip” draws energy from a rechargeable battery that only needs to be recharged after 16 hours.

Mounting or dismounting the lamps is done in seconds. In addition to easy handling, the innovative multiplex product is characterised above all by a very long service life - the LEDs are designed for an operating time of 50,000 hours.

Luxury Carpet has just launched its new Ocean Collection, inspired by waves, atolls, shells, mother of pearl and jellyfish. Taking cues from marine life, the new collection has been designed for use as both flooring and as decorative items suitable for any area of a yacht’s interior. Elisabetta Santoro, who has worked with Luxury Carpet on a number of previous collections, has designed this new sartorial collection specifically for the luxury yachting industry. After a preliminary search of images and a selection of the best for shapes and colors, the marine subjects have been adapted and the shells’ streaks, nacres’ shades and jellyfishes’ tentacles become textures of rugs and carpets produced by Luxury Carpet Studio. This aspect has been developed using an embossing technique, a particular hand work that requires a lot of careful craftsmanship.

The 55 inch HD series X multi vision display from Hatteland technology. This cutting edge 4K widescreen chart table uses ultra-high definition back lit LED technology, is optically bonded and comes with several mounting options. Having recently completed a project on the 89m Amels Here Comes The Sun’, the feedback from Captain Colin Boyle has been extremely positive - “The new touch screen chart table has been a welcome addition to the bridge. We’ve already incorporated the screen into a number of daily tasks, while passage planning, we can for example, simply place a weather overlay over charts, lay waypoints at the push of a finger or simply zoom in or out on points of interest.

On top of that we can view radar, CCTV, GA drawings, share itinerary with the owner and a whole host of other tasks and with it being fully adjustable at the touch of a button, it’s proving user friendly and very adaptable.

FMD (Fundamental Marine Developments) was founded on operational experience in the naval, superyacht and cruise ship sectors. The FMD Glass Crusher has a 20-litre bin that can contain around 60 wine bottles or 160 small beer bottles. Built in stainless steel it can crush a Champagne magnum into sand in less than 10 seconds, reducing its volume by 90 percent. The German company takes an environmentally responsible and creative approach to solving enduring problems encountered when treating waste streams on board vessels while conforming to the requirements of

MARPOL Annex IV &

V.

Italian manufacturer Bonomi won a DAME award for its electric Joy cleats. Available with a 12V or 24V motor with working loads from 80-500kg, the range made from polished 316 stainless steel offers a safe and effortless way to secure the correct tension on mooring lines without the need of additional locking device. The self-tailing Joy system integrates a freely rotating roller to take up the mooring tension with a motorised, toothed sheave like a winch. By bringing together in a single piece of hardware all the functions needed during docking procedures, the Joy range does away with winch-assisted cleats often found on large yachts.

MarQuip maintains its Exhaust Heat Exchanger is the most compact in the world. Most heat recovery systems are bulky and installed in parallel with the exhaust to ensure liquids don’t boil and damage the system when heat from the exchanger is not being used. These exchangers have their own hot valves to re-route exhaust gases through the bypass. Developed with partners Kelvion GmbH and Seable&Co, MarQuip’s Exhaust Heat Exchanger has no bypass or hot valves. The design guarantees cooling over the exchanger without the need for warm water thanks to the combination of a cooling back-up system and wet exhaust.

Named after the Japanese cherry blossom, the 71.75-metre motor yacht represents a noble new generation of Feadship yachts that combines uncompromised luxury, technology, engineering and propulsion. Sakura was started on speculation, Sakura’s interior draws on the ‘Japandi’ style with its combination of Scandinavian warmth and Japanese minimalism. She features clean exterior lines with light colours and bright spaces inside. Sakura will be equipped with twin MTU engines, providing her with a top speed of 14.5 knots, a cruising speed of 12 knots and a range of 4,500 nautical miles.

LENGTH: 71.76-metres BUILDER: Feadship COUNTRY OF BUILD: Netherlands DELIVERY YEAR: 2025

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Azure Yacht Design EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Studio De Voogt INTERIOR DESIGNER: FM Architettura

Project Spyder will span five decks with a beam of 13.8-metres. Some of her core features include a 100 square-metre beach club, complete with four opening balconies for terrace use, a beauty massage room, a bar and a spa. She’ll also have a 10.3-metre swimming pool, a helipad and a wellness suite on the sundeck. The Italian Sea Group collaborated with brokerage Kitson Yachts for the contract of the yacht, which is due for delivery in 2027.

LENGTH: 88-metres BUILDER: Admiral COUNTRY OF BUILD: Italy DELIVERY YEAR: 2027

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Admiral EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Espen Øino International INTERIOR DESIGNER: FM Architettura

Unveiled at the Monaco Yacht Show 2022, the Swan 128 is the latest addition to the Swan Maxi range. As the second largest model to be released by Nautor Swan since the Swan 131 (launched back in 2006), the full-carbon Swan 128 superyacht is a brand new model which completes the upper segment of the builder’s Maxi range and will be fully RINA classed upon completion.

LENGTH: 38.9-metres BUILDER: Nautor Swan COUNTRY OF BUILD: Finland DELIVERY YEAR: 2025 NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: German Frers EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Micheletti + Partners INTERIOR DESIGNER: Loro Piana Interiors (Misa Poggi)

Sold to a Mexican owner, the Panorama 53 builds on the Panorama 50 platform unveiled in 2022. The Panorama 53M is designed with an innovative hybrid e-MOTION propulsion system composed of twin MAN diesel engines, four variable speed generators, two permanent magnet electric engines, and a generous pack of lithium polymer batteries. She can accommodate up to 12 guests in her five spacious staterooms at the bow on the lower deck. Her owner’s suite is situated on the main deck and includes a small private external terrace.

LENGTH: 53-metres BUILDER: Admiral COUNTRY OF BUILD: Italy DELIVERY YEAR: 2025

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: The Italian Sea Group EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Piredda & Partners INTERIOR DESIGNER: Unknown

The yacht was sold in March 2023 to a European customer and features a steel hull and aluminium superstructure. Her design will be characterised by a dynamic profile with the typical ISA hallmark of the three arches connecting the decks. Additionally, the beach club will have the ability to be an open platform to transform the aft deck lower-level space into an expansive living area equipped with a gym, lounge, and spa meeting all the needs of those onboard.

LENGTH: 66-metres BUILDER: ISA COUNTRY OF BUILD: Italy DELIVERY YEAR: 2025

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Palumbo Superyachts EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Studio Vallicelli Design INTERIOR DESIGNER: Alberto Pinto

The model was first announced in December of 2022 and the first renderings of her interior spaces revealed a chic contemporary design, with bold, organic shapes and patterns throughout. The yacht provides accommodation for up to ten guests across five sumptuous staterooms. The sale was facilitated by David Legrand and Alain Auvare of Fraser Yachts representing the seller at Palm Beach international Boat Show 2023.

LENGTH: 52.6-metres BUILDER: Mengi Yay COUNTRY OF BUILD: Turkey DELIVERY YEAR: 2025

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Mengi Yay Yachts EXTERIOR DESIGNER: VYD Studio INTERIOR DESIGNER: VYD Studio

Project Tempest features a sprawling saloon with expansive windows, and the main deck features a full-beam owner’s suite complete with a private desk/vanity area and his and her bathrooms. On the lower deck, two twin staterooms and two double suites offer flexible arrangements. Riza Tansu has meticulously crafted the interior design, reflecting his signature laid back beach house style. Combining wooden flooring, light surfaces, minimalist lines, and contemporary aesthetics exudes tranquillity. Performancewise, she is powered by twin MAN engines giving her a cruising speed of 13 knots and a top speed of 16 knots.

LENGTH: 37.3-metres BUILDER: Aegean Yachts COUNTRY OF BUILD: Greece DELIVERY YEAR: 2025

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Endaze Marine Engineering EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Riza Tansu INTERIOR DESIGNER: Riza Tansu

Developed around the Tankoa T450 concept by Giorgio Cassetta, the TX450 is a new version based on the same 45-metre design, but developed into a full-custom project. The TX450 features a four deck arrangement with all guests staterooms situated on the main deck – an unusual feature for a yacht in her size category. There is a generous master stateroom and the yacht’s social areas are focused around the upper and bridge decks. The interior also offers a gym, spa area and a convertible room, which brings the number of the guest cabins up to six if required.

LENGTH: 45-metres BUILDER: Tankoa COUNTRY OF BUILD: Italy DELIVERY YEAR: 2025

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Tankoa EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Cassetta Yacht Designers INTERIOR DESIGNER: Cassetta Yacht Designers

Announced in the Summer of 2022, Project Bullseye will feature a five deck configuration designed exclusively by London studio Winch. Liz Cox who heads the Cecil Wright build team will be working with Winch Design who have previously worked on builds such as Slipstream. Nobiskrug’s in-house will work to ensure the hull is perfectly optimised in terms of seakeeping and propulsion efficiency.

LENGTH: 77.2-metres BUILDER: Nobiskrug COUNTRY OF BUILD: Germany DELIVERY YEAR: 2025

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Nobiskrug EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Winch Design INTERIOR DESIGNER: Winch Design

Originally signed with Brodosplit shipyard for a Swiss client, the build yard for Vela has recently changed, with the owner opting for the Brodotrogir shipyard as an alternative. Croatian press reported that the contract for Vela was signed for nearly €17 million for the construction of the steel hull and aluminium superstructure. According to sources within the yard, the entire project is expected to exceed €100 million.

LENGTH: 128-metres BUILDER: Brodotrogir COUNTRY OF BUILD: Croatia DELIVERY YEAR: 2026

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Unknown EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Unknown INTERIOR DESIGNER: Unknown

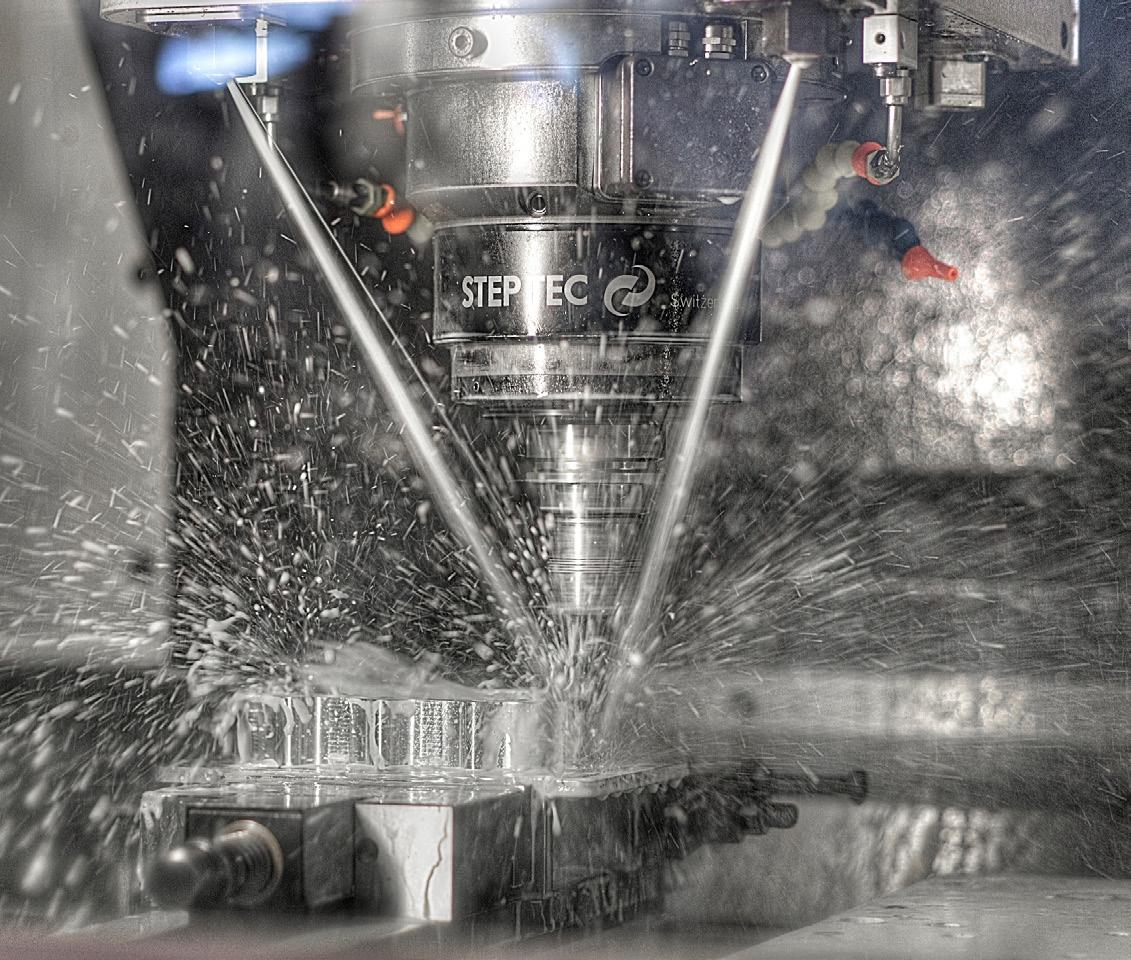

HP Watermakers emerged in 1995 as a branch of the Zucco family’s manufacturing company specialising in the production of high-pressure parts for watermakers. With a production facility on the outskirts of Milan, everything from the design to the final factory testing takes place in-house.

BY FRANCESCA WEBSTER

One of HP Watermakers’ most recent innovations, the HP Part-Net interface, has transformed the way desalination plants are utilised on board yachts. Even before the introduction of Part-NET, its RP TRONIC pressure regulation system had propelled HP Watermakers ahead in terms of user-friendliness. But watermakers were still hidden away inside technical spaces or engine rooms. Part-NET shattered this norm by bringing the watermaker onto the multifunction display (MFD), allowing captains to access all functionalities directly on any chartplotter or domotic system.

HP Watermakers carries out its own research and development to stay at the cutting-edge of technological developments. As a small, nimble family company, it has the agility to swiftly respond to new challenges and ideas. With a technical team with decades of experience in the field, it can turn an idea into a final product within days by employing advanced machinery such as CNC laser-cutting machines, 5-axis turning and milling machines. By producing 85 percent of the components in-house, HP Watermakers maintains a steady control over the manufacturing process to guarantee high quality.

“While the industry faces numerous challenges today, we’ve proactively tackled supply chain distribution by maintaining a substantial stock of materials for the production of hundreds of units,” says Gianna Zucco, co-founder of HP Watermakers.

“The small-scale manufacturing setup requires a high level of stock to facilitate fast deliveries and prevent material shortages that could disrupt production and cash flow. To build a solid foundation for the company, our management has consistently reinvested its profits into securing a stable and sustainable supply chain.”

Approximately 95 percent of production is destined for the yacht and superyacht industry, amounting to around 400 units per year and the company is among the few watermaker companies worldwide that manufacture a significant portion of their own components. Moreover, since 2019 it has helped pioneer the production of the only MFD-interfaced watermaker available on the market, garnering acclaim from end-users in the process. Recently, a new addition to its product lineup was revealed: the most compact 500 lt/h unit on the market. Built on the frame of a 120 lt/h unit, it consumes just 3KW/h.

Looking ahead, the company anticipates significant developments in the sector as people spend longer stretches of time aboard their yachts, necessitating the autonomous generation of energy and water as basic necessities. “In this scenario, our strategic positioning as a supplier becomes crucial as we

Producing more than 300 units per year, HP Watermakers had a turnover in 2022 of €3 million, with a prediction for 2023 to exceed this turnover. The company supplies 80 percent of its products to businesses outside of the Italian industry and 95 percent of the turnover comes from the luxury yacht market.

Principal yachting customers are; Dutch yards Wajer, Steeler and Vanquish, Italian yards Azimut, Sanlorenzo and Absolute and the Spanish yacht builder Sasga and the company’s top model is the SCA Model launched to the market in 2021.

strive to guarantee the always-on production of fresh water on board,” says Zucco.

Digitalisation has emerged as a vital component of the company’s operations. In 2017, it introduced its BiBi® system, enabling remote control of the unit via the internet. Over 200 yachts currently utilise this service, allowing HP service technicians to identify and prevent issues by remotely accessing the units. By diagnosing problems and dispatching the appropriate parts before the issue escalates, BiBi® has proven to be a powerful asset in ensuring problem-free cruising. Moreover, installing BiBi® comes with a four-year warranty.

To ensure comprehensive service and support for the global fleet of yachts, the company operates four offices and stores worldwide, located in Fort Lauderdale, Dubai, Cape Town and Male. It has also established a sales and service network spanning 53 countries, which allows the team to swiftly address the needs of clientele across the globe.

“As HP Watermakers continues to pioneer advancements in the water desalination sector, we are focused on pushing the boundaries of innovation,” concludes Zucco. “By leveraging cutting-edge technology, expanding our global presence and prioritising customer satisfaction, we are poised to shape the future of watermakers for the yachting industry.”

In 2020, the family-run engineering firm Iacomelli changed hands for the first time in its 60-year history when American businessman Chris Bizzio took over the helm. Based in Pistoia, Tuscany, Iacomelli is a key supplier of steel carpentry and engineering to the yachting industry. We caught up with Chris to find out how he has navigated taking over a wellrespected Italian firm, tripled the company’s turnover and reinvigorated production workflow

BY FRANCESCA WEBSTER

What motivated you to take over Iacomelli in 2020 in your first experience of the superyacht sector?

I worked for over 25 years in both the consulting and fashion business, but always as a director or CEO. Other than having been on a yacht, I knew very little about the superyacht sector. At around 50 years old I told myself I should try the entrepreneurial side of working as both my grandparents were entrepreneurs and my father had his own business. A lawyer friend of mine told me that Iacomell was looking to sell. Iacomelli had a generational issue as the children already had their own career paths and none of them wanted to work in the company, so it was destined to be shut down. Fortunately, I was able to step in. I found a company rich in craftsmanship, knowhow, and much goodwill in the industry. I was able to use my experience acquired in areas such as supply chain and business development. Since I joined the company our sales have grown three-fold.

How have you navigated the changing landscape in the sector, particularly with Italian shipyards buying up key suppliers?

Our strategy is to focus more towards handmade custom products. The expertise we have in matching metal carpentry with electronics or hydraulics and giving the customer a turnkey solution is almost unmatched in the industry. We strive to develop unique solutions that best answer our customers’ needs. I see that shipyards are taking over key suppliers, but after a while these suppliers stop innovating because they are absorbed by the “system”. We are free to explore different aspects of our business and to find out-of-the-box solutions. Some may think the share of the pie is getting smaller, but when you’re able to find bespoke solutions for your customers, you have a new market open to you.

How have you adapted to the cultural and business differences as an American owner taking over an Italian company?

Well, let’s say it’s like “rigour meets creativity”. Obviously, my background brings to the table rigour, processes, budgets, P&L, cost controls etc. but then I must match this with Italian design, creativity, craftsmanship, unstoppable searching for solutions, and the ability to develop different paths to the same result. As an American I view things as the glass being “half full”, while some Italians often take the “glass half empty” perspective. I try to navigate between these two assessments. It’s not always easy and certainly challenging. To change a company culture like that of Iacomelli, which has been around for over 60 years, is not something you do overnight, in fact my approach is to demonstrate with facts that sometimes there are better ways of doing things. Italians are not afraid to express their emotions, even at work. And meetings

can sometimes appear to turn into heated debates. It’s important to consider this as constructive conflict that will help everyone work more effectively and build stronger relationships of trust.

Are there any specific strategies you want to implement to ensure the company’s survival and growth?

I think for us the path is to give the customer custom turnkey solutions. Our products are made by hand unlike our competitors, most of whom use machines. This way of working adds to production times, but the result is a higher quality and higher functioning products. Today’s shipyards are pushing the development and innovation to their suppliers, and we need to meet that challenge. In Iacomelli since I took over, we have invested over €900,000 in innovation, but we also have to offer shipyards new or pioneering products that can involve a mix of materials to solve, for instance, an issue of weight. My plan is to grow – in sales, in efficiency and in the goodwill our customers have towards us.

Are there any steps you have taken to strengthen and secure the supply chain for Iacomeli’s operations?

One area we are working on is to give our suppliers access to immediate payments, so by working with us we can address immediately the issue of giving the supplier the necessary working capital to fulfill our orders. In essence we work as a bank for our suppliers. Another area is visibility. We try to give our suppliers visibility in the mid-term, the so-called “demand forecasting”, so that they see and understand what is ahead for them in the future. The third area is lifetime value. If you are a supplier and work with us, over time your lifetime value will grow as our relationship continues as we like to build on our relationships over a long period.

Are there any plans to diversify Iacomeli’s client base or expand into new markets?

I would love to grow internationally, especially in northern Europe, but unfortunately Italian companies don’t have a great reputation in an international field. Sure, there are some great Italian companies, and our design and creativity are outstanding, but if you dig a little deeper, issues such as reliability, deliveries, willingness to serve the customer, language, all come into play, so I get a lot of push-back from international customers as they are reluctant to partner with us. It’s difficult to change this mindset but I won’t give up trying. Regarding our expansion strategy I would love to branch out in the superyacht sector. Today we develop doors, pantograph doors, sliding doors, mooring doors, tender garage doors, stern platform doors, etc. I need to see where I can diversify, but always within our sphere of legitimacy.

devices with sound

That spread by Belcanto, our audio system, perfectly integrated with our controls and sockets collections: emotion to listen and beauty to admire. In the picture, the Il Contralto speaker, integrated in a control plate from the PLH Mono series.

Showroom - Via Voghera, 4a - Milano | info@plhitalia.com | plhitalia.com

Heesen Yachts has gone from strength to strength since Frans Heesen acquired Striker Boats in 1978. According to our own market intelligence, over the last 10 years the shipyard has delivered an average of three to four yachts per year with an annual turnover of around €200 million.

BY RALPH DAZERT & JUSTIN RATCLIFFE

Asmall industrial town in the southern Netherlands about 90 minutes by car from Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport and far from the sea, is not the most likely place to find one of the world’s top superyacht shipyards. Nevertheless, the municipality of Oss is home to Heesen Yachts, one of the area’s biggest employers with approximately 500 staff on its payroll and up to 500 more engaged as external contractors.

Following the war in Ukraine and the sanctioning of one of its UBOs, last year Heesen announced that the company ownership “is once again 100 percent Dutch” and controlled by a Dutch foundation presided over by Heesen CEO Arthur Brouwer and Chairman of the Supervisory Board, Anjo Joldersma. Coming in the wake of the Covid crisis, the shipyard handled a tricky situation speedily and transparently with no effect on production or sales.

“The transition to a Dutch foundation has not impacted Heesen’s day-to-day operations,” says Mark Cavendish, Heesen’s CCO, who returned as a board member after Friso Visser stepped down from the role earlier this year. “The change in ownership structure was primarily aimed at ensuring long-term stability. And yes, we do expect this structure to remain in place in the foreseeable future.”

While the yard’s original shed is still in operation and currently houses the 50-metre full-aluminium, semi-displacement Project Jade, there are no fewer than seven other construction halls, of which six contain covered drydocks. During our visit, there were nine new-build projects in various stages of construction at the shipyard. Another four projects were in earlier stages of construction elsewhere in the Netherlands and two further yachts were undergoing sea trials.

While Heesen outsources the construction of its steel hulls in the north of the country, it builds its aluminium hulls in-house in Oss (the aluminium superstructures are made close to the yard by a local subcontractor). In 2000 the shipyard established its own furniture factory, Heesen Yachts Interiors, when it acquired the Oortgiese company close to the Dutch-German border, but it also works with external contractors for the interiors.

“The change in ownership structure was primarily aimed at ensuring long-term stability. And yes, we do expect this structure to remain in place in the foreseeable future.”

Heesen Yachts is a leading exponent of building superyachts on speculation, but the practice requires deep pockets and brings inherent risks. Heesen CCO Mark Cavendish explains:

“The decision-making process for starting a new spec build involves many factors, such as – but not limited to – the level of inquiries for certain yacht models or sizes, the availability of capacity in our sheds, financial considerations, the capacity of our workforce – you name it. Our management team will make the final decision, but all departments give their input in order to have full buyin when we make the choice for a new speculation yacht to start. However, in the end, the choice always remains somewhat of a calculated risk. At Heesen, we’re well prepared to take this risk, as we have shown over and over across several decades that we are very good at selling yachts.”

The fact that even its series yachts have custom interiors by established international designers would seem to add an extra dimension to speculation projects in terms of costing. Series yachts are sold at fixed prices, but presumably some designers cost more than others?

“The choice of a certain designer over another for a new speculation project does not really have a significant impact on the price of a yacht,” continues Cavendish. “We set a budget for the designer and some parameters for them to work with. However, if the designer has a particularly good idea, but it would stretch the budget, then we can be flexible if we think it will make for a more attractive yacht commercially.”

“The current business model is centred on three distinct product lines: Series, Smart Custom, and Full Custom, which offer varying degrees of personalisation and speed of delivery.”

Over the years, Heesen’s product strategy has evolved to suit market needs but has generally aimed at combining series, semicustom and full custom production. The current business model is centred on three distinct product lines: Series, Smart Custom, and Full Custom, which offer varying degrees of personalisation and speed of delivery. At first glance, this is confirmation of the way the company was already operating, but the difference lies in the messaging: “The aim was to bring more clarity to our product offering by refining our terminology,” explains Cavendish. “In a competitive market, a clear proposition is vital for success.”

There is a lot of fudging when it comes to defining what terms like ‘series’, ‘semi-‘ and ‘full-custom’ actually mean in the superyacht world and the lack of clarity can sometimes be misleading. Heesen likes to keep the record straight, not least as an aid to managing its own clients’ expectations.

“For instance, if a client arrives late in the build cycle and wants all kinds of changes, we have to gently explain what we can and cannot do,” says CEO Arthur Brouwer. “We have to be very careful that these instances don’t start a snowball effect in our production that takes up too many resources. If there is a significant delay in the build cycle of one project, it can affect others and that can be very risky for the shipyard. We have managed significant changes without issues,

but there have been others where we felt we couldn’t accommodate all the changes requested and had to let the customer go.”

Series production has traditionally been Heesen’s bread and butter, accounting for up to half of its production. It is important to note, however, that the interiors are always customised and only six to 12 units in each series are built. Moreover, as in the automotive world, a life-cycle change is introduced after every fourth to sixth hull (the latest in these periodic changes is the new 50-metre Steel series designed by Harrison Eidsgaard announced at FLIBS last year). This allows products to be adapted to the market and technological developments, while avoiding over-supply of the same yachts down the line when they enter the pre-owned market.

Heesen has the in-house engineering capacity for one or two full-custom project like Project Skyfall and Project Sparta per year. Any more and it has to start in-sourcing some expertise as the lead times for the engineering are that much longer. Alongside that it can handle a Smart Custom project and two or three series yachts.

“We can adapt our workflow, but the stretch starts when we have two Smart Custom projects that begin close together, for example, because we have to scramble all our resources at the pre-production stage,” says Brouwer.

Ever since Frans Heesen agreed to build Octopussy that broke the 50-knot barrier and was the fastest yacht in the world when delivered in 1988, technical innovation has figured strongly in Heesen’s makeup. Nowadays that innovation is focused less on raw speed and more on combining performance with fuel economy. In 2013 it launched 65-metre Galactica Star, the first yacht with a Fast Displacment Hull Form (FDHF) devised by Van Oossanen Naval Architects, which offers resistance values that are typically 20 percent lower than a well-designed hard chine hull form at semidisplacement speeds. In 2014 it was the turn of 42-metre Alive, the first yacht with a Hull Vane, a patented foil also by Van Oossanen that is fitted below the transom to reduce water resistance and pitching motions. Model tests at the towing tank of Wolfson Unit in Southampton showed fuel savings of 20 percent at 12 knots and up to 23 percent at 14.5 knots. In 2017 the yard delivered 50-metre Home, the first hybrid-powered Fast Displacement yacht (the entire Heesen range is now offered with hybrid propulsion). Last but not least, 80-metre all-aluminium Galactica, its largest yacht to date, features a patented ‘Backbone’ structure for additional rigidity with zero weight penalty.

Heesen has sold 37 yachts in total since 1 January 2013 for an average of 3.7 sales per year. These comprise 10 projects started for the client (Full Custom or Smart Custom) and 27 on speculation. 20 of the total number of sales were for yachts between 40 and 50 metres, 12 between 50 and 60 metres, and five over 60 metres LOA. At the time of writing, the company had 14 projects in-build.

2023:

` 80m Full Custom, full-aluminium GENESIS (sold)

` 67m Full Custom, steel SPARTA (sold and for resale by owner)

` 60m Full Custom, full-aluminium ULTRA G (sold)

` 55m Series on spec, steel fast displacement RELIANCE (sold and for resale by owner)

` 55m Series on spec, steel fast displacement APOLLO (sold)

2024:

` 56.7m Series on spec, full-aluminium fast displacement AKIRA (sold)

` 55m Series on spec, steel fast displacement SERENA (sold)

` 50m Series on spec, aluminium semidisplacement JADE (available)

` 50m Smart Custom, based on the 50m steel displacement OSLO 24 (sold)

2025:

` 55m Series on spec, steel fast displacement VENUS + 20950 + 21050 (all available)

` 50m Series on spec, full-aluminium fast displacement ORION (available)

Within its three product lines, Heesen builds fast displacement and semi-displacement motor yachts in steel or aluminium between 49 metres (up from 37 metres not so long ago) and 80 metres, with a sweet spot somewhere in the middle. But the business strategy that Heesen excels at is building yachts on speculation, a potentially risky practice that it has honed to perfection (see sidebar). These are the projects that the shipyard finances and starts building itself with the aim of selling them at a later point during construction (half of the projects currently in-build were started on spec). The advantage is that owners don’t have to wait for so long for delivery and means the yard can guarantee availability to the market in the future. This proved especially true in the immediate aftermath of the Covid pandemic when demand exceeded supply. “Yacht building has changed insofar as you used to be able to plan a year or two in advance,” Brouwer notes. “Now you have to look four or five years ahead.”

Key to the success of Heesen’s on-spec build program is the close relationship it enjoys with the brokerage community. The annual Heesen Ski Cup in the Italian Dolomites, for example, is a coveted trip among brokers. The event is all about having fun, but has a serious side too as a ‘thank you’ to their hard work during the course of the year. Heesen has good reason to be thankful as the vast majority of sales, whether new-builds or pre-owned yachts, are concluded through brokerage houses.

The current facilities in Oss, as well as the surrounding bridges and waterways, mean the shipyard cannot build much over 80 metres, but this is not seen as a drawback. The market for 90-metre plus superyachts is smaller and driven by a handful of yards like Lürssen, Feadship and Oceanco. Attempting to break into a new category would also risk impacting the yard’s margins: “We are content with our current facilities in Oss and have no plans for a second facility,” says Cavendish. “We are committed to optimising our operations and delivering exceptional yachts from our existing premises.”

Although no longer a family company, Heesen retains a familiar design DNA and a strong brand identity. This may be one reason why it has avoided joining the trend for building catamaran and explorer yachts. Its XV67 concept, for example, began life as the Xventure, a 57-metre expedition yacht, but has been restyled as a bluewater voyager that will inspire owners to venture into new terrain in 7-star comfort.

“The XV67 designed by Winch Design is not a rugged explorer with a utilitarian look as we’ve come to expect from explorer yachts,” says Cavendish. “On the contrary, it’s a concept design that belongs to our Full Custom yacht proposition, and is a refined luxury yacht with exploring capabilities.”

It is well known that superyacht sales are hard-wired into the global economy. With an ongoing war in Europe, shifting inflation and widespread recession on the cards, the economic outlook is far from rosy and SYT iQ registered a drop in new motor yacht sales over 40 metres of about 40 percent during the first quarter of 2023 compared to the same period in 2022. Heesen’s CCO, however, is confident that the company is better prepared than most to weather these market fluctuations and is not unduly perturbed by the uncertainty.

“While it is too early to draw definitive conclusions, it is worth noting that the first quarter is typically the slowest in terms of sales,” offers Cavendish. “Let’s see what the rest of the year brings.”

Everything you love about Awlcraft 2000, including tried and trusted application characteristics and repairability, but now enhanced with our next generation color platform.

Awlcraft 3000 gives you deeper, more vibrant colors and a long lasting, high gloss finish to turn heads.

Our 26-berth marina facility and 4,000 ton ShipLift, operational since 2019, represent the latest components in our extensive and technically advanced refit facility. But it is the skill of our workforce, our operational partnership and our rapport with our clients that makes a refit complete. It’s why Amico & Co and Genoa are together redefining what a refit and superyacht hub can be.

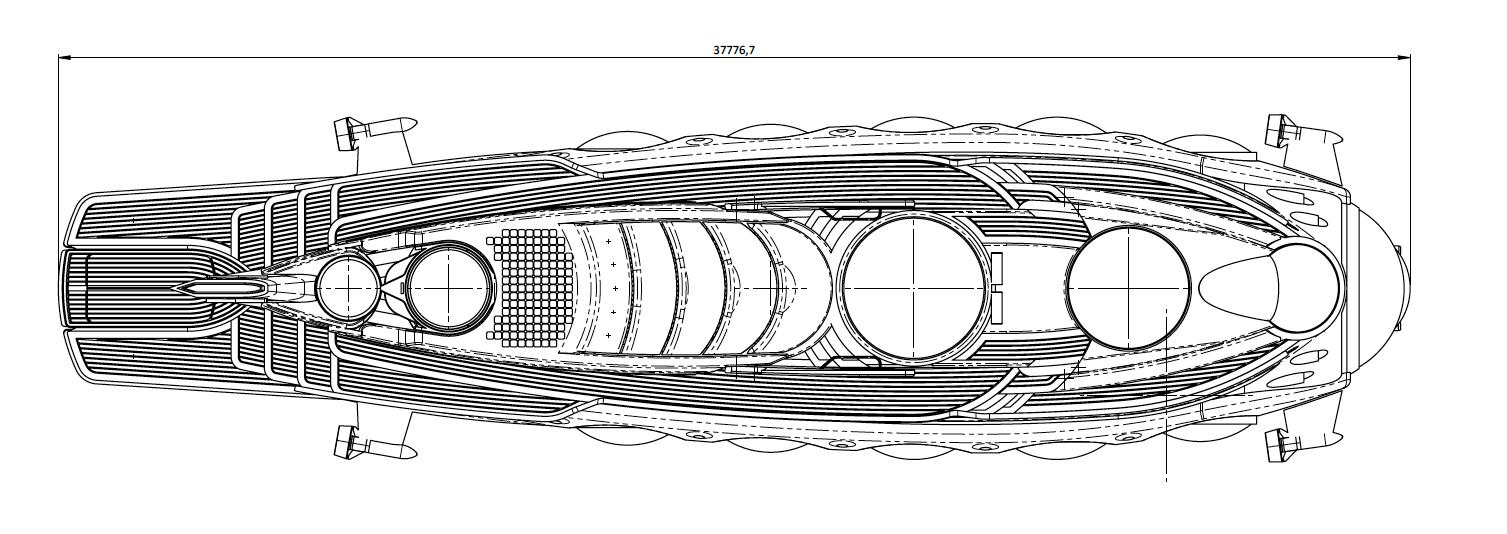

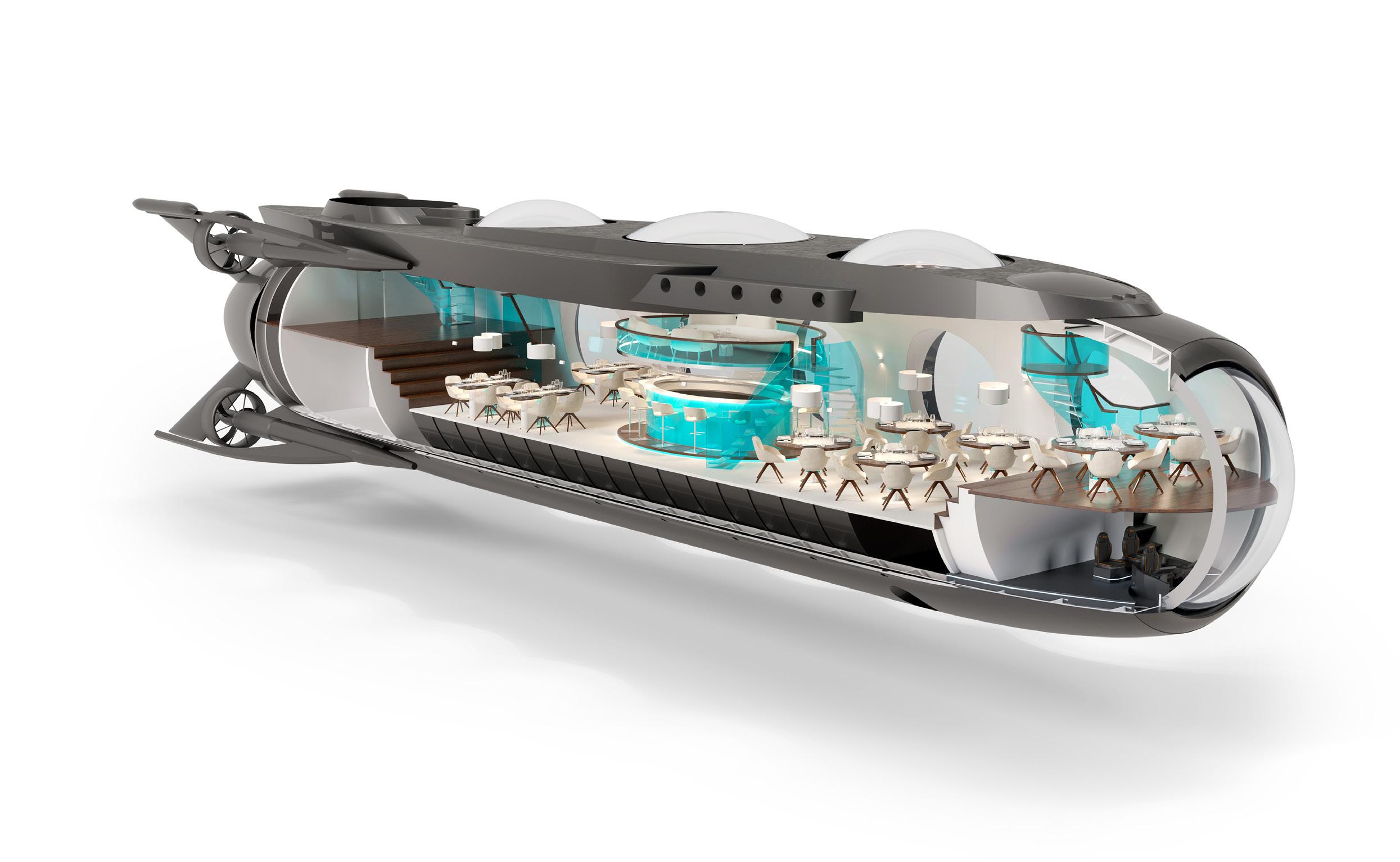

U-Boat Worx unveiled its Nautilus yacht-submarine concept at last year’s Monaco Yacht Show. The Netherlands-based company followed up earlier this year with new interior renders in partnership with Officina Armare and the project has since grown from 37.5 to 42 metres in length. But can a vessel inspired by Jules Verne’s fictional novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea ever be a feasible proposition?

BY JUSTIN RATCLIFFE

U-Boat Worx knows what it’s talking about when it comes to manned personal submarines. Its model range – all designed and engineered entirely in-house using leading-edge 3D and FEM software tools – can accommodate from one to 11 people and operate at depths from 100 metres up to 3,000 metres. The company has a perfect safety record after many thousands of dive hours all over the world and its Cruise Sub 7 model carried on expedition-style cruise ships recently completed more than 1,000 Antarctic dives in a single season.

“Our expertise for the past 15 years has been underwater vessels; now we have to start thinking like yacht designers as well,” says Lex van Rijswijk, who heads up the Nautilus design team at U-Boat Worx. “Naturally, we started with a feasibility study to determine whether it was buildable at all, but we’re well past that stage and it’s definitely feasible.”

The 1,610-tonne vessel will have a depth rating of 150 metres, but it has to also work as a yacht on top of the water, which is why U-Boat Worx has partnered with leading Dutch shipyards and marine research centres to assist with some of the technical parameters such as strength, weight, propulsion, speed and range when operating on the water’s surface. The pressurised hull will be built of stainless steel, whereas the deck structures will be a mix of stainless steel and GRP. The four circular viewing ports on each side of the hull, which are close to four metres in diameter, will be of acrylic as on all U-Boat Worx submersibles (the windows bear an uncanny resemblance to an engraving in the first 1871 edition of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea that shows Captain Nemo at the helm of of the Nautilus behind the “bi-convex” window of the pilothouse).

Top: What the seascape might look like through the yacht-submarine’s viewing ports.

Facing page: The hardtop folds away and the tender is launched for underwater operations.

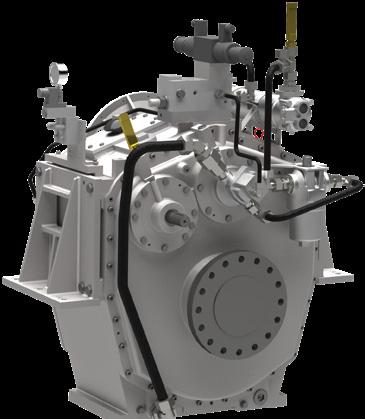

A specific area of research for the project partners has been the propulsion package. Diesel-electric systems on yachts are not designed to operate at a depth of 150 metres, while U-Boat Worx is more accustomed to working with much smaller propulsion systems. The most likely solution is a hybrid diesel-electric drive with batteries and the design team is in contact with propulsion suppliers to see who can the deliver the optimal outcome.

“Nautilus is an evolution of our Under Water Entertainment Platform [UWEP] that we presented in 2021,” says Roy Heijdra, head of marketing at U-Boat Worx. “It’s about the same length but the main difference is that the UWEP platform is fully electric, because we envisioned it to be a shorebased operation where people go out in the morning, have lunch on the water, maybe do another dive in the afternoon, and then return to base. Nautilus, on the other hand, is conceived as both a submarine and a fully functioning yacht that needs more range, hence the hybrid diesel-electric propulsion.”

The idea is that Nautilus will engage dieselelectric drive on the surface and full electric battery power below the water. U-Boat Worx predicts it will be able to remain submerged for six hours at four knots, while in DE mode on the surface it will have a range of around 3,200 nautical miles at 8-9 knots.

“One of the first practical considerations that came to my mind is the sundeck equipment,” says Heijdra. “Do you have to stow everything below deck when you submerge? We asked our design partners to look into this and they came up with a pretty unique deck set-up whereby most items can remain on deck. The bar fridge, for example, is housed in a watertight housing. Another thing we had to take into account were the hydrodynamics in submerged mode, so features like the hottub and louvred hardtop can be retracted for less resistance and better speed and range underwater.”

Clearly, a 42-metre yacht requires a tender of some sort and there is dedicated docking slot in the stern platform. But what happens to the tender in submarine mode? In fact, the tender always remains on the surface because an important safety precaution for all manned submarine operations is that communications with the surface must be maintained at all times, which effectively means having an officer on standby in a waiting tender. Clearly there are safety factors that affect submersibles much more than yachts, not least the immense pressure at 150 metres underwater (pressure increases in relation to the surface by 1 bar for every 10-metre increase in depth, not accounting for atmospheric pressure), and U-Boat Worx is liaising closely with the classification society DNV. The principal design philosophy underlying DNV rules for submersibles is that redundancy is provided for all the essential systems, so that in the unlikely event of a failure they all remain functional and safe surfacing is guaranteed.

“The pressure hull and all pressurised components are required to undergo tests that significantly exceed the design diving pressure,” says DNV submersible expert Jonathan Struwe. “All the systems are tested during the various manufacturing stages, then again under controlled diving conditions, and finally at design diving depth. The role of the class society in all this is to ensure an independent critical review of the design by considering any foreseeable failure modes and load cases, reconfirmed and proven by load and functional tests.”

“The pressure hull and all pressurised components are required to undergo tests that significantly exceed the design diving pressure.”

Surface stabilisation systems, either fins or gyros, are the subject of ongoing research, but the low-rise, hydrodynamic superstructure brings with it the advantage of in-built stability: “We have much more hull structure below the water than ‘superstructure’ above centre of gravity means the vessel has a very low centre of and a higher centre of buoyancy [the centre of the volume of water displaced by the hull],” explains van Rijswijk. “This is the opposite of what you find on a conventional yacht, and so Nautilus is already much more stable and may not require further stabilisation. And if the conditions get too rough, you can just submerge!”

The General Arrangement has also to be finalised. Currently the proposed layout includes a master stateroom and four guest cabins, an observation lounge and gym, as well as accommodation for up to six crew. Because of the need for redundancy,

the technical spaces will likely occupy a higher portion of the hull volume than a yacht of comparable size. What has been fixed are the positions of the deck hatch and the elevator in the back of the vessel (provisioning a yacht or submarine of this size by the stairs alone was not deemed feasible). The rest is still open for discussion and layouts can be customised according to client preference.

Despite the engineering and classification challenges that lie ahead, Roy Heijdra is optimistic they are all surmountable and that a modern version of the Nautilus will see the light of day more than 150 years after Jules Verne first floated the idea.

“We’re talking with actual clients and we’re going to build this thing,” he concludes. “If I had to put money on it, I would say that in the next two to three years we will build a Nautilus.”

A reliable and constantly available internet service on board depends on a well-designed and managed IT infrastructure. In this occasional series of dispatches from industry contributors, YOT Ltd technical director Kris Cardona offers his views on how new tech is transforming the maritime industry.

BY KRIS CARDONA

“As yachting has evolved, so has the need for shoreside IT support with remote service providers and remote monitoring solutions.”

The recent technology shift has been facilitated by the emergence of new Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite-based technologies, such as Starlink and OneWeb, each offering their own advantages. The vast increase in bandwidth capabilities in the maritime industry parallels the shift in the early 2000s in the traditional home/ office setting, where slower ADSL lines and server rooms were eventually replaced by faster fibre broadband connections and cloud-based services, maximising continuous server power. This transformation is paving the way for a new era of connectivity in the maritime industry, allowing for more efficient operations and improved communication between vessels and the shore.

In recent times, IT and comms have undergone rapid evolution, transforming the maritime industry by offering more than just basic email and fax services onboard. Thanks to the introduction of LEO technologies, vessels now feature advanced systems that provide always-on, high-speed internet similar to that of a well-equipped office. As a result, this has unlocked a world of opportunities, such as the emergence of automated navigational functions and even unmanned autonomous vessels that were once deemed impossible.

The increasing demand for high-speed internet at sea has brought added pressure to improve onboard bandwidth, manage the QoS and improve SD-WAN capabilities. However, rather than simply flooding the network with bandwidth, we’re exploring using SD-WAN technologies to enhance the efficiency of these connectivity sources, particularly by leveraging cloud solutions in a secure manner. Better to focus on embracing the future of IT and developing a hybrid onboard/cloud-based service that integrates seamlessly and securely to enjoy the benefits of the cloud without entirely relying upon it.

Almost every intelligent system onboard now needs to talk to the IT network. These smart systems are increasingly complex and designed for office/home-based environments that simply connect to the cloud services. Work areas on modern yachts now resemble floating offices, with systems and servers integrated into a network that allows for the broadcast of AV streams and the interaction of various devices. In the past, network engineers had to ensure that all systems would continue functioning even if the internet connection was down. However, the current onboard IT systems are much more advanced and require cloud-based services and even more bandwidth to function efficiently.

As the maritime industry continues to embrace cloud-based services like Microsoft 365, onboard email servers are becoming less common, with users opting to access their messages from anywhere in the world with an internet connection. This shift to cloud-based services is not limited to email. Other onboard services, such as the AV systems, are also transitioning now that they have stable WAN infrastructures, which before LEO technologies were considered unreliable. Nowadays, multiple high-speed internet connections are available and it doesn’t have to come at a high cost, especially compared to traditional systems.

The evolution of technology in the maritime industry has led to the development of more intelligent onboard solutions, including high-quality 4K video streaming and cloudbased services. However, this new landscape brings with it the heightened threat of cyber-crime. As IT networks become more complex, it is vital to ensure these solutions are implemented securely, with backups in the cloud and the appropriate technology to encompass all cloud bubbles into a single, secure environment.

This requires carefully managing the expansion of the IT perimeter from a single onboard ‘shell’ or network to multiple online services in the cloud to prevent cybercrimes. If skilled hackers are determined to damage your IT infrastructure, they can. For every service you sign up for, from Microsoft 365 to Netflix, a piece of information is shared with the service provider, whether large or small. Every service is a way in or out – a doorway that a hacker or virus can penetrate. And a yacht can have hundreds of user accounts with brands like Cisco, HP, DELL, Kerio, Sophos, Acronis, Veeam, Zinwave, Peplink, Poynting, QNAP, Axis, and many more. By adding security layers to your IT infrastructure, you put in place more obstacles that need to be overcome, but also give yourself more time to react and mitigate any damage as much as possible.

There are many IT problems to juggle on board, and now in the cloud, in order to keep the vessel, crew, guests and owner safe from any threat. As yachting has evolved, so has the need for shoreside IT support with remote service providers and remote monitoring solutions. These providers have the resources to help owners, captains, crew and guests resolve any hardware or software problems that may arise quickly and with minimal interruption. What might have taken ETOs and AV/IT officers weeks to sort out a few years ago, can now be resolved in just a few hours by an experienced shoreside integrator and service company.

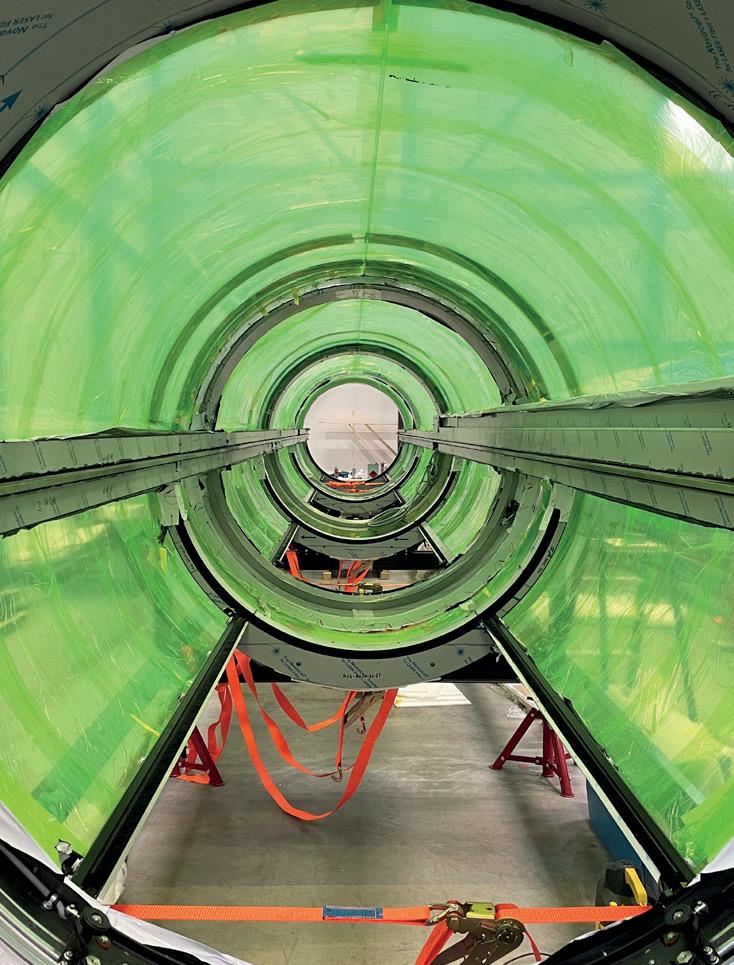

Akula , Rossinavi’s first explorer yacht, is what it says on the tin: a robust, unfussy, steel-hulled passagemaker custom designed and built for adventurous round-the-world cruising.

BY JUSTIN RATCLIFFE

Akula is Ukrainian for ‘shark’ and at almost 60 metres in length and 1,240GT 240GT represents a huge step up for her Swiss owner. His previous motor yacht after switching from sailing boats was the first 24.5-metre Naumachos 82, the pocket explorer of just 180GT launched by Cantiere Navale di Pesaro in 2007. Despite the massive difference in scale, however, the two yachts have more in common than the bright red paintwork of their hulls.

“We’re either cruising or at anchor and covered 6,000 nautical miles or more each year with the Naumachos” says the owner during lunch in Pisa close to where the yacht was undergoing final preparations prior to her launch.“I started thinking of a larger boat because we spend several months on board at a time and needed more space, and because we also planned to do a world cruise I wanted to be able to remain at sea for up to 30 days without reprovisioning or refueling.”

“I started thinking of a larger boat because we spend several months on board at a time and needed more space, and because we also planned to do a world cruise I wanted to be able to remain at sea for up to 30 days without reprovisioning or refueling.”

The owner turned to Andrea Carlevaris, founder and senior surveyor of ACP Surveyors in Viareggio, with whom he had struck up a friendship when buying the pre-owned Naumachos. The original idea of finding a suitable donor vessel for refitting was dropped when nothing was available that suited his specific wish list. So attention turned to building a custom yacht, originally under 50 metres and 500GT, although to paraphrase a line from a famous film about another shark, it quickly became clear he was going to need a bigger boat.

With bold exterior lines by Gian Paolo Nari and interior design by FM Architettura, the owner was deeply involved in defining the yacht’s layout and technical details. He even learned to use CAD software and

knew in advance what domestic appliances he wanted for the galley (Electrolux).

With an initial spec list in hand, the pair approached several leading European shipyards, but the focus kept revolving back to Rossinavi as the most capable and accommodating. A build contract was signed off at the end of 2020.

“Building new is always challenging, but if you then go full-custom the choice of yards is drastically reduced,” says Carlevaris. “Rossinavi were willing to build within the tight timeframe and during the Covid lockdown, which was quite a risk for them. We had an able shipyard and an owner who knew what he wanted; my job has been to help both parties build the best possible product – oiling the wheels, if you like.”

The owner’s wish list explains many of Akula’s aesthetic and technical attributes. He was adamant from the start that the hull should be unfaired with a commercial finish. Carlevaris wasn’t convinced because of the impact it might have resale value, but the owner was wholly unconcerned, arguing that adding tons of filler for purely aesthetic reasons makes no sense on an explorer yacht (he refers to Akula as a ship) designed to carry a container on deck if necessary.

“If you look at building a custom boat from an economic point of view, you wouldn’t build it all,” says the owner. “Besides, I wanted a yacht for my own use, not for some potential owner in the future.”

Another unusual choice was synthetic decking instead of teak throughout the yacht. This was driven by a determination to use sustainable materials where possible, a desire that informs the whole project, but also because it requires virtually zero maintenance. The eventual choice was heavy-duty Bolidt more commonly found on cruise ships, instead of its sister company Esthec whose products target the yachting industry.

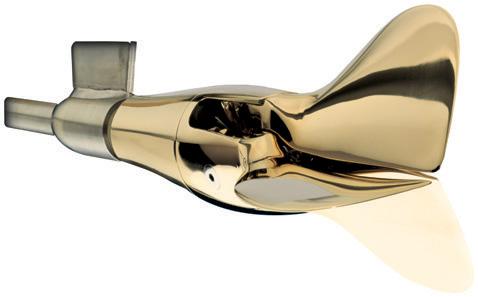

The owner further wanted diesel-electric propulsion with azimuthing pods. Akula’s electrical energy comes from four variable frequency Caterpillar (C32 and C9.3) generators driving twin Veth L-drive thrusters with counter-rotating propellers. Offering quiet and efficient propulsion with DP capability, the full integrated 2,600kW package will provide a predicted top speed of 14 knots and a range of 5,500-plus nautical miles at a cruising speed of 12 knots.

“We developed our experience of dieselelectric propulsion with projects like Endeavour II, Polestar [ex-Polaris] and Alchemy,” says Federico Rossi, chief operating officer at the family-owned shipyard. “With full-custom yachts, especially when the build time is quite restricted, it makes sense to use systems and solutions that you’ve already worked with and can guarantee will provide the required performance.”

Like Polestar, Akula also meets the requirements of Class II of the FinnishSwedish Ice Class Rules (FSICR). For steelhulled vessels with no ice strengthening, Ice Class II means the yacht is able to operate independently in very light ice conditions. Akula has some local hull reinforcements and heated sea chests, but will still require a pilot and accompanying vessel when summer cruising in high Arctic waters.

Essential for spending long periods on board was the complete separation of the crew and guest circulation flows, as well as a private study area for both the owner (on the bridge deck overlooking the open aft deck) and his wife (adjacent to the master stateroom on the main deck forward) where they could work uninterrupted. The yacht is Starlinkready, but in addition to VSAT the owner specified a Poynting Wavehunter 5G antenna dome with the highest throughput cellular internet connection available on the market for fast and seamless connectivity.

The real estate dedicated to these work spaces, which on other yachts might serve as a media room, sky lounge or more guest accommodation, is a clear indication of the owner’s priorities. In fact, Akula has just three guest cabins, all on main deck, plus a convertible lounge next to the master stateroom, for a maximum of 10 guests including the owners, although most of the time she will carry less than half that number. Despite her diminutive size, the Naumachos 82 was able to carry more passengers.

The lower deck is devoted to the crew accommodation and hotel services with an enormous pro-spec galley, walk-in fridge and freezer, dry store, large laundry, and a goodsized crew mess. A service hatch in the side of the hull allows crew in a tender to load/ offload provisions when at anchor. Further, galley has an adjacent scullery, an additional working area used for cleaning dishes and storing utensils that houses a glass crusher and refrigerated waste storage unit: “I bet you won’t find another superyacht in-build today with a scullery,” says Carlevaris proudly.

Aft of the switchboard and engine rooms is a garage for storing bikes, paddle board and other toys, as well as the pod compartments and two workshops – one for the engineer and one for the owner. “I like to tinker,” says the owner by way of explanation.

In addition to the separate guest and crew staircases, a service lift runs from the technical space on the under-lower deck

“Building new is always challenging, but if you then go full-custom the choice of yards is drastically reduced.”

up the bridge deck. Used by both guests and crew, the landing doors open on both sides into their respective areas to respect guest privacy (the entire yacht is designed to be disability-friendly so the lift, passarelle and passageways are wide enough for a wheelchair to pass). The pantries on each deck are more like small galleys.

Rossinavi is accustomed to resolving the daily technical challenges of building custom superyachts, but Akula is unlike anything they’ve done before – and not just because she is the shipyard’s first explorer yacht.