PRINTING: Mindset over matter?

MARIN: The human factor

PRINTING: Mindset over matter?

MARIN: The human factor

The technical magazine for those involved in the design, construction and refit of superyachts

20 Supplier Spotlight: Oldenburger

A look into the German outfitting company’s plans to increase

and streamline

22 CEO in Conversation: Carol Driessen of Vyva Fabrics

A chat about the business of supplying high-quality fabrics to the yachting industry.

25 Business Talk: Soaring High

Restructuring and reappraisal of its market offering has rewarded Baglietto with a healthy order book and record-breaking revenues.

35 Concept in Focus: Just Wing It

A super-sized sailing yacht with wing masts, is Royal Huisman’s Wing 100 concept the ideal crossover between sail and power?

42 Build Report: One of a Kind

We go behind the scenes of FB283, Benetti’s only full-custom yacht in build and currently approaching completion in Livorno.

54 Build Report: Practically Unprecedented

A closer look at Oceanco’s Project H, the radical rebuild that challenges the industry to reconsider the potential of an existing superyacht to take on a new identity.

67 Operation & Maintenance: Oiling the Works

A visit to Spectro Jet-Care in the UK to find out high-precision fluid analysis can also spot potential problems and failures before they occur.

74 Inside Angle: Building with Burgess

Ed Beckett and Peter Brown have refreshed Burgess’ approach to new-build sales, we found out more.

78 Dockside: Energy Conundrum

Propulsion is only half the story in the battle for energy efficiency when the hotel load is the biggest consumer on superyachts.

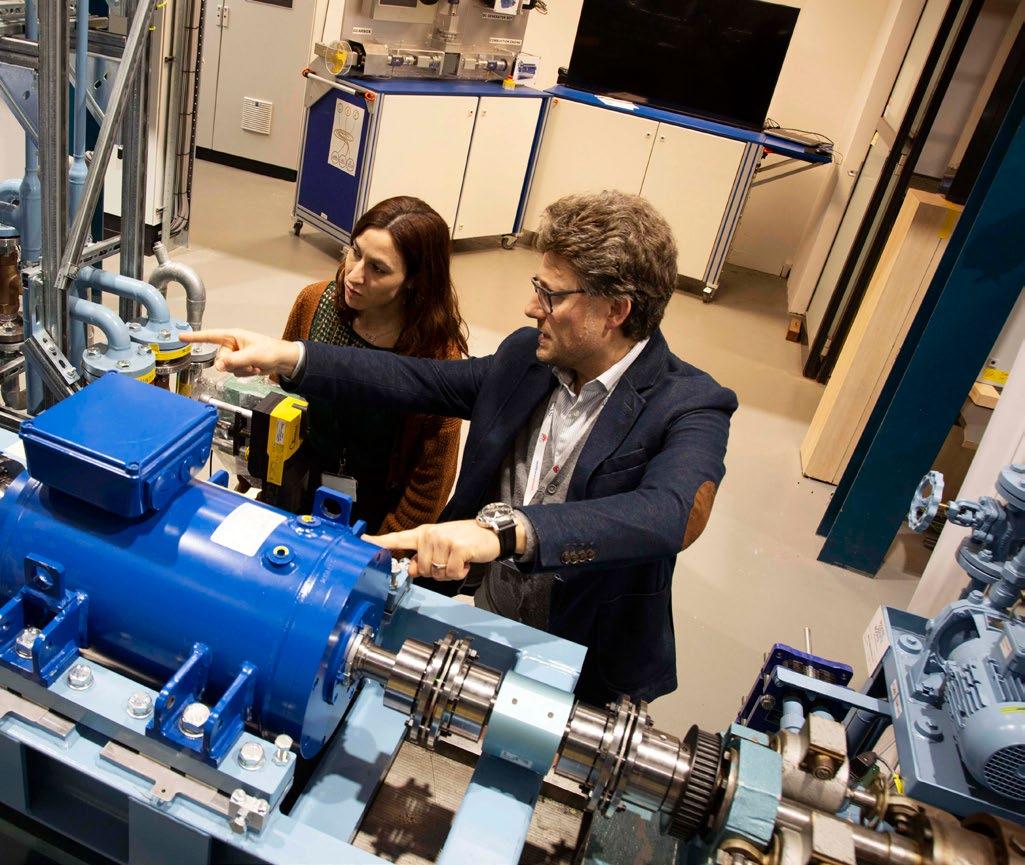

86 Case Study: The Human Factor

Think MARIN, and you think tank tests. But the Maritime Research Institute Netherlands is pursuing a much wider scope of maritime research.

94

Safety & Security: No Smoke without Fire

The industry is reassessing its fire prevention regulations following a spate of onboard fires. But are lithium-ion batteries really the culprits?

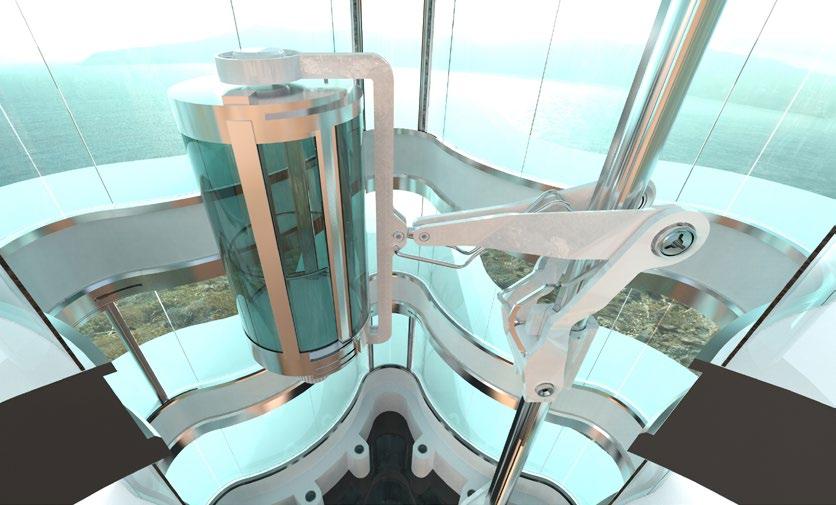

102 Guest Space: Going Up

A visit to Lift Emotion in the Netherlands, a key player in the highly specialised and competitive market for custom elevators on superyachts.

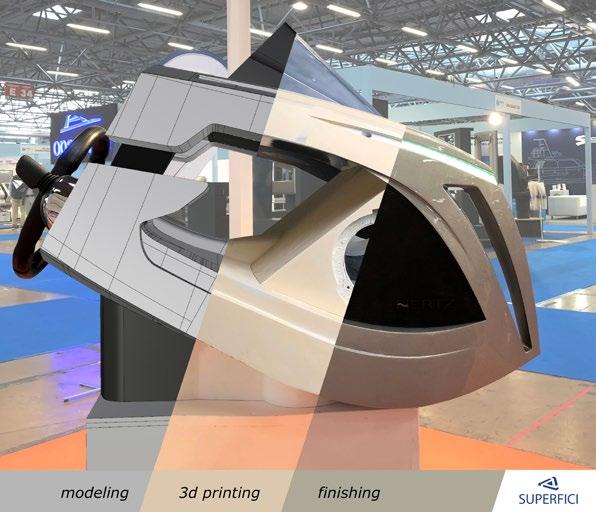

112 New Tech: Print Your Parts

Is 3D printing the miracle solution that will allow us to print entire boats in a matter of days?

118 Refit & Conversion: Grand in Green

A visit aboard a classic Feadship approaching the end of an in-depth refit at the family-run Balk Shipyard near Amsterdam.

129 Ask the Experts: Is a Perfect Paint Job Possible?

We pose this and other coating questions to a panel of industry professionals.

EDITORIAL

EDITOR IN CHIEF

EDITOR | HOW TO BUILD IT

EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTOR

EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTOR

FEATURES WRITER

DIGITAL EDITOR

NEWS WRITER

TRAVEL WRITER

CONTENT CREATOR

VIDEOGRAPHER

Francesca Webster

Justin Ratcliffe

Charlotte Thomas

Phil Draper

Alexander Griffiths

Emma Becque

Sophie Spicknell

Jessamie Rattray

Ruben Griffioen

Muaz Abourched

DESIGN PRODUCTION

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

GRAPHIC DESIGNER

UI/UX DESIGNER

Ivo Nupoort

Beatriz Ramos

Claudia Sabbadin

INTELLIGENCE

HEAD OF INTELLIGENCE

RESEARCH ANALYST

DATABASE MANAGER

DATABASE MANAGER

YACHT HISTORIAN

Ralph Dazert

Adil Zaman

Vicky Linardou

Léandre Loyseau

Malcolm Wood

SALES & ADVERTISING

SENIOR SALES MANAGER

SALES MANAGER

SALES MANAGER

CLIENT SERVICE MANAGER

SALES & MARKETING SUPPORT

Marieke de Vries

Justus Papenkordt

Daniel Van Dongen

Johanna Borreli

Jochem Eenkhoorn

CORPORATE

FOUNDER & DIRECTOR

TECHNOLOGY DIRECTOR

FINANCE DIRECTOR

Merijn de Waard

Fabian Tollenaar

Laura Weber

In my last Editor’s Letter I compared the first issue of this magazine to a custom prototype, adding that we fully intended tweaking the design and optimising the specs in subsequent issues to establish a proven platform for the industry. Six months later, welcome to the ‘new and improved’ second edition of How to Build it.

The sharp-eyed among you will notice that the graphic design has evolved. It is still clean and contemporary, but now a touch crisper and more current. What hasn’t changed is the content, which remains as varied, engaging, relevant and up-to-date as before. The subjects may be technical, but the language and layout is always lucid and concise.

Our cover stories provide an indication of the diversity of subject matter in this issue. Earlier this year I was lucky enough to attend the unveiling of Project H, for example, and have never seen anything quite like it. It certainly piqued my curiosity about the challenges and perceived advantages of rebuilding a superyacht as opposed to refitting or building new.

Likewise, a visit to the famous Maritime Research Institute Netherlands, or MARIN for short, proved an eye-opener. The technicians working there spend a lot of time messing about with yellow models in towing tanks. But they also do much more, such as training crews using kinematic motion machines that can be programmed to simulate virtually any kind of sea conditions and navigation scenarios. Or testing emerging fuels and power systems in a prototype engine room of the future to find the ideal balance between sustainability and efficiency.

And then there’s additive manufacturing. Since becoming more readily available and affordable 3D printing captures fewer headlines, but it’s swiftly being integrated into everyday industrial workflows – including the yachting sector – and it’s safe to say we will see much more of it in the future. Just don’t expect to see a 3D-printed superyacht any time soon. Whatever your sphere of specialisation, I’m certain you’ll find something of interest to read in the pages that follow. Enjoy!

Justin Ratcliffe - Editor

A+T Instruments, UK-based manufacturer of high-end yacht instruments, has appointed Nils Jolliffe as Chief Operating Officer. Responsible for general management and scaling operational processes to support company growth reported to be running at 40 percent year on year, Jolliffe brings with him experience from previous senior positions at Auxitrol Weston, DDC Electronics Ltd, Bowman Power Ltd, Eaton Aerospace and Raymarine.

Last November A+T unveiled its new 520 series of masthead-motion wind sensors, said to be the first production unit sensors that can directly measure wind acceleration/ velocity at the masthead then transmit this to the instrument processor for masthead motion compensation.

“I’ve been amazed by the range of high quality, innovative products A+T have developed in a short space of time and list of customers switching to A+T in the superyacht and race boat market is impressive,” says Jolliffe. “The customercentric, fast paced, can-do attitude of the team is something that really appealed to me and I’m excited to be part of helping the company continue its development and growth. There’s plenty more innovation to come and our customers will love the focus we’re putting on their needs coming first.”

In Issue 1 of How to Build It, we published an extensive article (Fuelling Change) on the challenges of switching from fossil fuel to biofuel. We have since learnt that the crew of 44-metre Lammouch, a popular Med charter yacht managed by Burgess, has embraced sustainable change by switching to biofuel.

In November last year the yacht took delivery of 15,000 litres of second-generation biofuel, the culmination of a long preparation process that included included six months of discussions with the engine manufacturer Caterpillar, Class approval and agreement from the owning and management companies.

The new fuel, Cristal Power XTL 100 marketed by Fioul 83, is an HVO (Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil) product derived from the recycling of used cooking oil, treated

with hydrogen and mixed with fresh cooking oil. With no engine modifications required, this biodegradable, renewable fuel reduces CO2 emissions by 50-90 percent and toxic particulates by 80 percent. The fact it is odourless and reduces noise also makes a positive difference in terms of onboard comfort.

Cristal Power XTL 100 is more expensive than conventional diesel for the moment, largely because the used cooking oil collection network has not yet reached an economy of scale.

However, the yacht’s owning company was willing to accept the small additional cost because of the reduction in ecological impact it offers.

“I am very proud to manage a yacht whose owner has taken such a positive, progressive decision,” said Burgess charter manager, Caroline Boisson.

The first version of the Yacht Environmental Transparency Index (YETI), which scores and compares yachts based on their environmental credentials, was launched at METSTRADE 2022 and shared with members of the industry. The tool is designed to “emphasise the operational efficiency of a yacht’s lifecycle to reduce ecological impact by benchmarking vessels against an average operational profile.”

YETI 1.0 works by expressing the calculated emissions in ‘EcoPoints’, which are divided by the yacht’s gross tonnage to determine a relative score that is comparable within its class. The defined classes for YETI 1.0 are <500, 500-3000GT, and >3000GT.

To use YETI 1.0, data about a vessel’s general parameters (speed-power, load determination, generators, battery bank, and heat distribution system) must be submitted on the input sheet. When joining the fleet review, yachts are provided with a feedback report that includes a YETI 1.0 score, an explanation of how this score was determined, comparison to the rest of the assessed fleet within a given class, and suggestions for potential areas of improvement.

“The groundwork has been done, it is now time for the industry and owners to utilise this reliable reference to know where a yacht stands and what opportunities there are to improve its environmental credentials,” says Robert van Tol, executive director of Water Revolution Foundation, the non-profit organisation that is a driving force behind YETI.

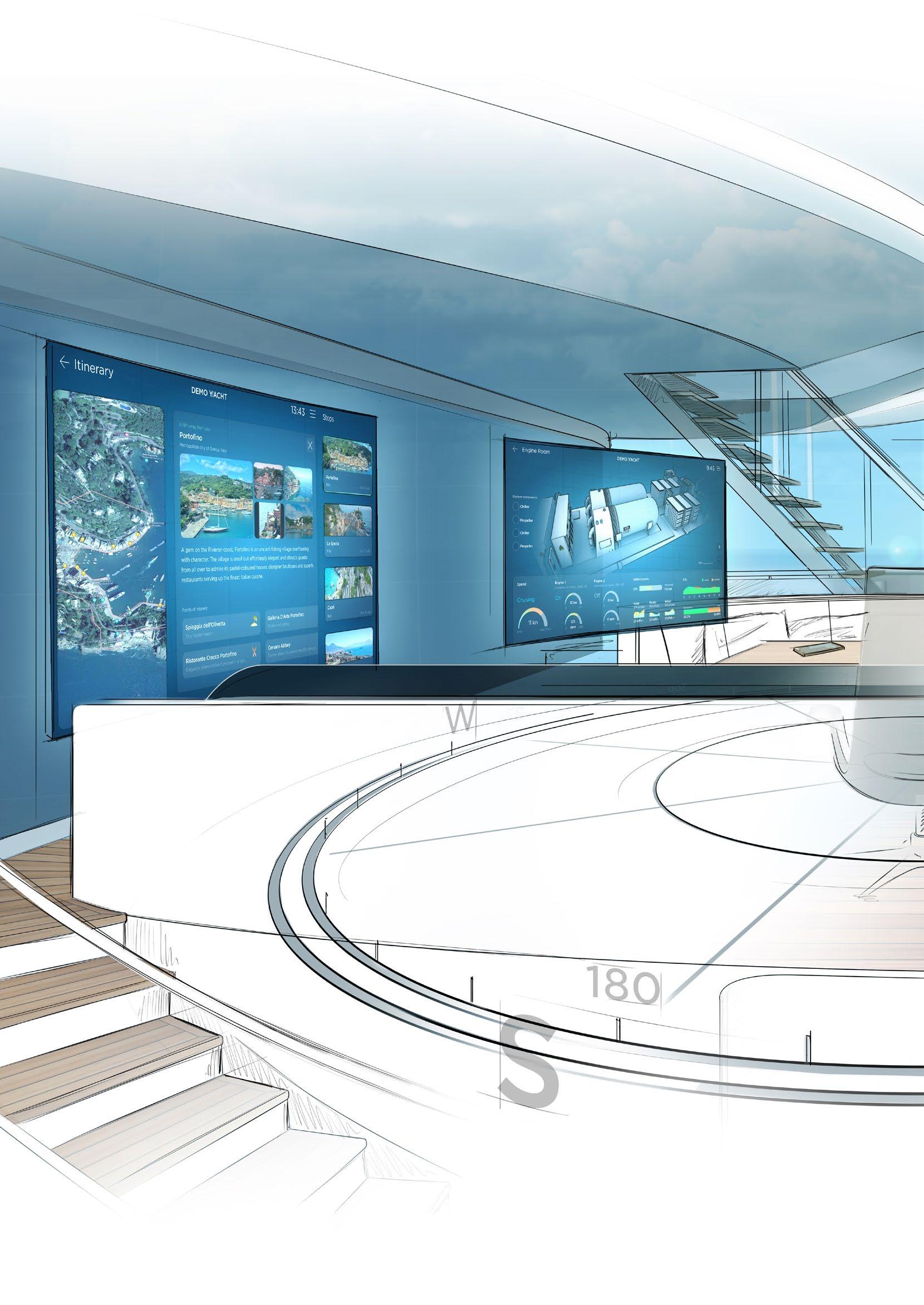

Italy-based Videoworks has responded to requests from shipowners and shipyards by setting up a Connectivity & Communication Solutions Business Unit dedicated to developing cutting-edge solutions in the field of on-board connectivity. It is the latest step in an evolutionary process that was announced last year at the Monaco Yacht Show together with ONE Web, a latest generation Internet experience that provides streaming and IP TV services with a fast connection very similar to 5G, in order to offer on the water what people are used to having on dry land.

“It was important to seize this particular moment because we are witnessing an authentic revolution in the world of connectivity, with systems evolving very rapidly: new technologies, new players with LEO (Low Earth Orbit) satellite systems, such as Starlink and ONE Web, with which we are cooperating closely,” says Paolo Tagliapietra, who is coordinating the new Connectivity & Communication Solutions B. “The stated goal is to have a bandwidth capacity similar to the one we are used to on the mainland. Today’s yacht owners want to be able to access platforms such as Netflix with the same speed and image quality they are used to having in their living room at home. Videoworks guarantees the technology to do so.”

EST-Floattech, Dutch specialists in the development and installation of maritime battery systems, has signed a long-term framework contract with Rolls-Royce Power Systems for its DNV-certified Green Orca 1050 lithium-polymer battery module aboard 10 new-build vessels.

The first order of the new partnership is for nine hybrid fast ferries equipped with MTU hybrid propulsion to be operated by Liberty Lines in Italy between Sicily and Croatia. Each of the modules has a capacity of 10.5 kWh. The sister passenger vessels of identical design will be built at Astilleros Armon in Spain. Of more interest to our readers, however, is a second order for the hybrid propulsion system of Project Arrow, a 76-metre superyacht in build at Turquoise Yachts in Istanbul. Delivery of the 1,512 kWh battery pack is planned for 2023 and the yacht designed by Enrico Gobbi of Team for Design is slated for delivery in 2025. In both cases, the battery systems can be used for cruising speeds of up to 8 knots and in all-electric mode when entering and leaving port, anchoring and manoeuvering for zero emissions and minimal noise.

Australian specialist pump designer and manufacturer Davies Craig has introduced a new range of marine, DC-powered, electric water pumps, the culmination of more than five decades of design and production experience in the field of fluid dynamics. The EWP pumps are unique in that they employ a flat, printed-circuit electric ‘pancake’ motor coupled to an impeller for compact size combined with high-flow circulation capability and low current draw.

Targeting the rapidly growing demand for cooling circulation pumps to maintain thermal stability in lithium-ion battery packs, the pumps can be managed by a patented digital controller which modulates flow rates in response to selected temperatures. The algorithm takes into account not just the actual temperature but the rate of change so that in the case of a rapid increase in coolant temperature, for example, the pump will accelerate to prevent overshooting the selected value.

The EWP is available in 12 and 24 volts and produced in five capacities with the largest delivering a maximum of 9,000 lt/hr. Besides applications in electric and hybrid power systems, they can also serve as circulation pumps in closed-circuit condenser cooling and chiller A/C units.

“Our markets have largely been industrial and automotive, but we know that many of our EWP pumps have found their way into marine applications,” says engineer and company co-founder Daryl Davies. “Now with the rapid evolution of electric and hybrid power plants, we foresee a significant demand for this product and so we established a marine division to develop it further. There are tens of thousands currently in service in automotive applications with a zero-failure rate.”

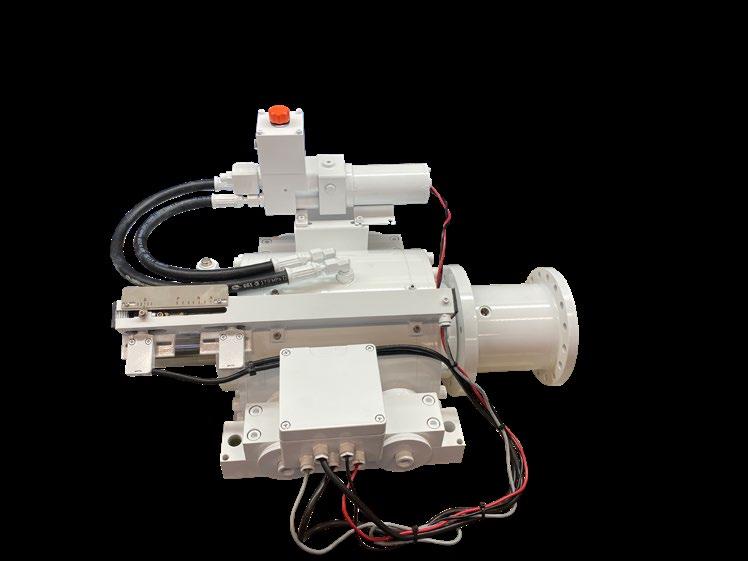

Hundested Propeller, the manufacturer of controllable pitch propellers, controllable pitch gearboxes, thrusters and control units, has announced a new hydro-electric pitch control unit. The compact Hundested FR-ELH is designed for shaft line setups and direct electric drive, or installation aft of a standard reduction gearbox without pitch control. All the pitch control units have high-quality thrust bearing design, long stroke for feathering propellers and can be delivered with semi-flexible foundations. The lightweight FR-ELH weighs around 100kg and incorporates many of the solutions from the hydraulic FR-HP model that has been proven to perform very well, but features new developments for additional benefits. Although specially developed for electric propulsion, it can also be used in conventional drive lines; improved mounting points make it simple to dismount for servicing without losing the alignment of the propulsion line; and easy installation means the only connections are 24V and three wires for feedback signals with no constantly running hydraulic pumps or motors required. Additionally, it can hold propeller pitch without consuming power.

The first Hundested FR-ELH hydro-electric pitch control unit was delivered in December 2022 for installation aboard a new 88-foot sailing yacht with direct electric drive and power

The Expert Power Control 87 Series is a new type of IP Power Distribution Unit from Gude Systems that offers 30 switchable load outputs, which is the perfect control and monitoring centre for 19-inch racks. The Series offers flexibility, with switchable IP power solutions that make it possible to switch certain devices or areas onboard on and off without interrupting the power to all other devices. This makes it possible to optimise power consumption and save energy.

Smart PDUs provide an extra layer of protection against overvoltage and overheating by being able to cut off power

to specific devices when problems occur. The system also includes Intelligent power strips that are monitoring systems that allow ETOs to monitor and control the power consumption and performance of specific devices. In addition, plug-and-play sensors for the PDUs allow monitoring of ambient temperature and humidity. System-critical conditions on the yacht are thus detected at an early stage.

Switchable IP strips allow you to shut down specific devises for maintenance and repair and Smart PDUs from GUDE can be easily integrated into leading AV control systems.

Italy-based i-Carbon was set up by four friends who combined their experience in project management, engineering and innovation technology with a love of sailing to develop innovative deck gear crafted from metal alloys and carbon fibre. The company’s most recent products include a new range of deck filler caps, stanchions and pop-up cleat.

The i-Carbon fully retractable cleat is mounted recessed into the deck to be perfectly flush with the teak decking. The refined, functional design requires no drainage and they can be fitted without necessarily having to access the deck’s underside.

The new deck fillers are made of marine-grade aluminium or polished AISI316L stainless steel and have an asymmetric handle that gives them a more technical and racier ‘automotive’ look. They can also be custom engraved on request.

Made of pre-preg, autoclaved carbon-fibre tubes with a AISI316L stainless steel base, the i-Carbon stanchion system comprises three types: fixed stanchions that are permanently installed on board; removable stanchions with quick-connect fittings for the base and male plug that carries the carbon tube; and removable stanchions with a deck socket and bayonet coupling device that engages with a 90° rotation. The stanchions are available in three sizes with tube diameters of 33mm, 45mm or 66mm depending on size and Class of vessel.

Having seen how a billiard table on a cruise ship is useless in even moderate waves, a passenger challenged his engineer friends to design a billiard table for use at sea. Cybernetic specialist Svend Heier took up on the challenge and in 2000 a stabilised billiard table was tested on a ferry running between Norway and Germany. During the test trip one of the engineers working on board became seasick. A clever head suggested that he should have a rest on the stable billiard table. It worked, and the idea of a stabilised bed was born along with Stable company in Arendal, Norway.

Billiard and pool tables are not uncommon on superyachts, which led to an unusual partnership between the French company Billards Toulet and Stable to develop a stabilised table aimed at the yacht market. Uniquely, the gyroscopic system is housed inside the table itself to eliminate accelerations due to roll and pitch and neutralise the lateral forces. Sensors pick up the vessel’s movements and the table is automatically adjusted by computercontrolled electrical actuators.

“The reaction time is fast,” says Svend Heier. “We sample the accelerations at 100 Hertz and the system can react to roll periods of down to 1.5 seconds, but on a standard 7-8 second roll period we can eliminate 98 percent of the movements. That is more than enough to play a normal game of pool as the beize cloth provides an element of friction as well.”

Stable is also able to stabilise ping-pong and foosball tables, art and sculptures, wine cellars, gaming zones and workout areas, drone and telescope platforms, antennas and radars, and even bowling alleys.

The Swedish company SKF has developed the first electric, zero-speed fin stabilizer. Under construction for a new-build superyacht in Germany, the electric stabilizer will offer low noise and vibration with the electric motor only turning when the fin is moving. The fin uses only electric parts with no moving parts within the control cabinet. In addition, the stabilizer offers low installation costs due to fewer components and virtually no layout restrictions when compared to traditional counterparts.

Available between 5-9 metres, with larger sizes in development, the first electric fin has been developed as part of SKF’s path to net zero by 2050. The new stabiliser over zero-speed stabilsation and is fully retractable.

devices with soul

plhitalia.com

What for everybody are just command plates, switches or keypads, for us are “devices with soul”, high tech products with an artisanal soul, designed and made in Italy.

The original and elegant Slim collection, with only 4 mm of thickness, confers to the environment a refined, elegant and understated touch. Here, in the brushed brass protected version, with one button.

The second Amels 80 was sold in December 2022, only three months after the first hull. The model was first announced in an online event earlier in the year, and is the first series to have been designed for Amels by Espen Øino. Her owners are keen divers and the yacht will be equipped to accommodate their various passions. She has a 2,175 GT and will have a top speed of 16.5 knots, powered by twin Caterpillar engines.

LENGTH: 79.8-metres BUILDER: Amels COUNTRY OF BUILD: Netherlands DELIVERY YEAR: 2026

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Damen Yachting EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Espen Øino INTERIOR DESIGNER: Jonathan Quinn Barnett

In September 2022, Sanlorenzo signed the contract for its new flagship, the 1,950 GT 73 Steel. A larger sister of the 72 Steel, also currently in-build at the shipyard, the yacht features a diesel-electric propulsion system aimed at minimising emissions and her interior configuration has been designed in close collaboration with her owners. The yacht has a steel hull and aluminium superstructure.

LENGTH: 73-metres BUILDER: Sanlorenzo COUNTRY OF BUILD: Italy DELIVERY YEAR: 2026

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Sanlorenzo EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Zuccon International Project INTERIOR DESIGNER: Unknown

Sold in September 2022 to an American client, the Sportiva 66 has a steel hull and aluminium superstructure. The yacht has a sporty profile with reverse bow design and she is under construction at the Ancona shipyard with Ian Kerr of Kerr Maritime overseeing the technical specifications and construction. The yacht has a top speed of 18.5 knots.

LENGTH: 66.4-metres BUILDER: ISA COUNTRY OF BUILD: Italy DELIVERY YEAR: 2025

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Palumbo Superyachts EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Nuvolari Lenard INTERIOR DESIGNER: Unknown

The new Baglietto flagship was first announced as a speculation construction in October 2022 and the announcement was swiftly followed by her sale in December. The T60 is the largest in the T-Line series and is the big sister of the 52-metre model, of which eight have already been sold. She features a steel hull and aluminium superstructure, has a 1,000 GT and is powered by twin Caterpillar engines to top speeds of 16 knots.

LENGTH: 60-metres BUILDER: Baglietto COUNTRY OF BUILD: Italy DELIVERY YEAR: 2026

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Baglietto EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Francesca Paszkowski INTERIOR DESIGNER: Unknown

Sold in December 2022 to repeat Heesen clients, Setteesettanta, Hull YN 20857, has a lightweight aluminium construction and will be fitted with two compact and fuel-efficient MTU 16V2000M72 (1,440 kW) diesel engines that will offer top speeds of 18 knots. She will accommodate up to 12 guests between a six stateroom configuration.

LENGTH: 57-metres BUILDER: Heesen COUNTRY OF BUILD: Netherlands DELIVERY YEAR: 2026 NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Van Oossanen Naval Architects EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Omega Architects INTERIOR DESIGNER: Cristiano Gatto Design

Enzo was first announced in October by the partner companies SIMAN and Axis Group Yacht Design. She has a six stateroom configuration for up to 12 guests including a full-beam master suite to the fore of the main deck that features large windows offering panoramic views. There is also a VIP stateroom on the upper deck which can be converted when not in use to a gym, home office or playroom. She is powered by twin Caterpillar engines and will have a top speed of 15 knots.

LENGTH: 50-metres BUILDER: SIMAN Srl. COUNTRY OF BUILD: Italy DELIVERY YEAR: 2025

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Axis Group Yacht Design EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Horacio Bozzo Design INTERIOR DESIGNER: Unknown

The Sunreef 43M Eco sailing catamaran has been designed for all-year exploration and incorporated solar panels in her hull, her mast and boom that generates “green energy for unlimited, emission-free cruising”. The customisable yacht will be tailored to her new owners’ tastes and host a plethora of amenities including a spa, bar and fitness area. She is equipped with composite-integrated solar panels, a hydrogeneration propulsion system, electric engines and performance sails. She is also constructed from ethically sourced and sustainable materials, accentuating her eco offering.

LENGTH: 42.7-metres BUILDER: Sunreef COUNTRY OF BUILD: Poland DELIVERY YEAR: 2025

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Sunreef EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Sunreef INTERIOR DESIGNER: Sunreef

This is the first motor yacht under construction from StellarPM, a relatively new name on the yacht construction scene. The company is based in the US, with construction taking place in Asia, and the first ONE 108 has been sold to a North American client. The yacht belongs to the recently launched StellarONE series, and there is also a 40-metre model, the StellarONE 130. She is powered by twin Caterpillar engines to a top speed of 14 knots.

LENGTH: 33-metres BUILDER: StellarPM COUNTRY OF BUILD: Vietnam DELIVERY YEAR: 2024 NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Ginton Naval Architects EXTERIOR DESIGNER: StellarPM INTERIOR DESIGNER: Unzile Acar

Enhance your Superyacht with smart Power Distribution Units

More power safety

Less service deployments

Higher energy efficiency

No more AV downtimes

The German manufacturer Oldenburger has been outfitting yachts for more than 70 years. Today, the company continues to expand with new factory spaces under construction and more than 250 permanent employees working at the facilities in Dinklage, Germany, and an additional 110 situated in Shanghai serving the Australasian and American markets. Despite its broad portfolio of products, including the aeronautical and residential sectors, the yachting industry accounts for 85 percent of the company’s turnover.

BY FRANCESCA WEBSTER

On average Oldenburger works on three new-build and around 30 refit projects per year, of which the major share are full custom. Joining the conversation from the very earliest stages allows the company to implement clauses that protect it and its clients from protracted build schedules. However, offering turnkey solutions means that amendments to design can cause major disruptions to schedules and over the last two years the company has had to navigate through difficult waters, made more complex by supply chain issues.

The current expansion is one of the ways that the company is looking to mitigate increasing costs. Unifying the two Germany-based build facilities on the Dinklage site, the expansion sees the construction of two new build sheds that should improve production flow.

“Four years ago, Oldenburger had three companies, respectively for aircraft, retail and the superyacht market, but we needed to streamline our production processes so that we could focus our efforts on the superyacht industry as main business. While all the markets are still operational, they now operate under one company, situated at the original factory site. Yachting is our primary focus and over the past two years we have been looking to improve our workflow, not only for us but also for our clients, so that we could continue to offer competitive rates and deliver our products on time. However, we were still building between two separate facilities and that cost us in terms of time and money, with a huge amount of travel needed and the team split between two locations. The new facility will unify all of our plus-100 carpenters and joiners under one roof, meaning better teamwork and in the end, better products.”

The expansion will also allow the company to accept more new-build orders over the coming years. Many of its superyacht projects are 80 metres or above and demand for its expertise is increasing every year. While many shipyards have in-house joinery departments, very few are able to keep up with the increased demand for custom projects over recent years.

“When it comes to these very large scale projects, there are very few shipyards that have the expertise, or capacity that we offer,” says Carsten Loge. “This industry demands a high level of skill, you are talking about creating joinery down to the tenths of a millimetre and even small mistakes can cost a large amount of money.”

Oldenburger uses some of the most accurate machinery in the world. Automation is becoming far more prevalent, believing that superyacht quality can only be ensured with all the developed and highly complex machinery. Nesting machines, CNC machines and milling machines are all employed on a daily basis in order to manufacture as efficiently as possible.

Reliance on machinery also helps to reduce energy consumption, something the company has focused on by implementing energy-saving insulation and heat recovery technology. However, while the company is committed to sustainability, it has been very difficult to implement alternatives within the yachting industry, though they do suggest eco-friendly solutions to both designers and shipyards.

One of the biggest challenges facing the outfitting industry is to remain aligned with class regulations, particularly when it comes to fire-proofing interiors. Benjamin Bäker, head of sales and marketing, explains: “The regulations are strongly related to the design of the interior. In a REG-B certified project, everything must be at least flame retardant, while in a REGA project many of these issues can be avoided. So for each project, in terms of classification, we have to make sure that some of the materials can be bent that way. Here we have to certify the materials through a variety of ways.”

Unsurprisingly, R&D is important and Oldenburger has an expansive department dedicated to research. In recent years it has launched patents for a number of products, including ceiling drop guards and teak floor guards, and its R&D team are constantly testing new lacquers and adhesives.

Vyva Fabrics’ brutalist concrete studio, in part designed by company founder and CEO Carol Driessen herself, is quite a landmark in the north Amsterdam boatbuilding enclave near to Damen Shipyard. We paid the studio a visit to talk about the business of supplying fabrics to the yachting industry.

BY ALEXANDER GRIFFITHS

Carol Driessen, founder and CEO of Vyva Fabrics, was supporting her father’s marina business when a job offer from a client led to her working as a European sales rep for an American faux leather manufacturer. She had the knack and found her niche. Vyva Fabrics began from a small harbour warehouse in Amsterdam in 1990 supplying upholstery materials for boats and yachts. Today, it is a successful wholesaler of high-quality fabrics and vinyls.

Vyva Fabrics has grown into a major business. Tell us more about the journey.

It was originally just me and a single line of material, an outdoor material: Sunbrella acrylic. I shipped it from the States in 150-metre rolls – too much for my clients. Rather than waste the material, I created a sample book from the leftovers and went door-to-door to outfitters, designers and shipyards. And that’s how Vyva was founded; I really started from nothing. As my portfolio grew, so did my team. I was initially only interested in the marine industry, but I began taking jobs in hospitality, healthcare and many other sectors. Most of our clients are no longer maritime, but at a conservative estimate, I’d say 70 percent of the yachts built and refitted here in the Netherlands feature our fabrics.

How does Vyva Fabrics fit within the design funnel, and who do you typically liaise with on yacht projects?

It all depends on the project. Many designers that know us and our product portfolio build a complete package for their projects themselves, but others seek advice. There are many things to consider with material choice: durability, quality, sustainability, fire retardancy, costs, and so on. Typically, we liaise with designers and architects that we meet with, but it’s not uncommon for shipbuilders and outfitters to be here in our studio, especially for smaller projects.

How fierce is the fabric segment and is the competition primarily from large well-established firms, or smaller boutique sellers?

There are many suppliers competing with us on price, and quite often they are cheaper than us. Sourcing from regions like China, they can slash costs but they also compromise on quality. This is okay for a lot of buyers, but when you’re in the business of supplying fabrics and materials for superyachts, quality is everything.

Attitudes to sustainability and ethically sourced materials have accelerated dramatically. Do you think non-recyclable materials will be phased out anytime soon?

We do think recyclable or sustainable fabrics will increase a lot and we’re all for it, launching sustainable collections such as Hemp, REVYVA, Dinamica and Econic. We’ve offered sustainable solutions for a decade now, and nobody was interested initially.

Annual turnover: €12.5 million

Number of employees: 20

Number of current yacht projects: 12

Number of materials in portfolio: 30 each in 30 colours

Completed yachts: approx. 70 percent of Dutch fleet

But now if it’s not 70 percent recycled or more, many clients aren’t interested. People are now willing to pay the premium. The challenge nowadays is to produce sustainable fabrics and vinyls without diminishing the quality. We still like working with our PVC vinyls as they’re extremely robust and last for decades, so you could argue that is more sustainable than using a 100 percent pure linen, which needs to be replaced after a couple of years. Due to the high fireretardant specs of vinyls, it’s still work in process and some will never be replaced with sustainable substitutes.

Are there fire retardant materials that are also eco-friendly?

Two years ago we launched our REVYVA collection made from post-consumer PET bottles that is 100 percent recyclable after use with extremely high fire specs. The collection has sold very well and we decided to add a Bouclé or looped yarn version as well.

Besides the fabric collection, in May we’re also launching our first ECONIC vinyl collection. This durable, high-quality artificial leather looks like natural linen and feels pleasant to the touch, but is completely phthalate-free and contains 75 percent recycled, bio-based and renewable ingredients. We also use bio-graded PVC resins from agricultural biomass and forestry, and bio-based plasticisers from soybean oil, which contain no chemical flame-retardant additives but still meet European fire standard EN 1021. The collection has the eco-label OEKO-TEX® Standard 100, which guarantees that the synthetic leather does not contain any substances that could be harmful to people or the environment.

Is the supply chain still problematic? How do you ensure you deliver on time, every time?

Before 2019 it wasn’t uncommon for outfitters to place orders a month ahead of time, but now they’re used to long delivery times so they plan further ahead. When the pandemic broke out we knew we had to change our approach. We have a huge warehouse with plenty of space, so we filled it up and from January to June of 2020 we were just filling our inventory – and it really paid off. Orders from the marine sector slowed down, but demand for outdoor and garden fabrics spiked, bringing sales up by around 30 percent compared with previous years. Many people during the lockdown were investing in their own properties, doing up the interior and exterior spaces. We were crazy busy. And now with the marine business booming, with order books signed until 2025, 2026 even, the supply chain challenges have all but passed. We also have a slightly different mentality and orders are now being placed well ahead of time.

Founded nearly 170 years ago, Baglietto is one of the oldest yacht brands in the world. The company has seen some highs and lows, but recent restructuring and a reappraisal of its market offering has been rewarded with a healthy order book.

BY PHIL DRAPER

Italian semi-custom and full-custom superyacht builder Baglietto had a lot to celebrate as 2022 came to a close. A turnover of around €110 million for the year 2021-22 to the end of August broke all records and, according to CEO Diego Michele Deprati, the year ahead is looking better still with a burgeoning order book as the brand consolidates its position in the competitive sub-500GT sector. The Baglietto management team secured contracts for no fewer than nine new-builds between 40-60 metres last year, an incredible tally by any standard and one that takes the brand with the Soaring Seagull logo to new heights. Overall the brand’s order book now includes 17 projects to a value of almost €370 million. And with four more yachts ‘scheduled but still available’, it has a total of 21 yachts to build over the next three-and-a-half years with an average length of 47 metres – that’s over three kilometres of superyachts.

Roughly 80 percent of Baglietto’s turnover comes from just three semi-custom models: the all-aluminium DOM133, and the steel and aluminium T52 and T60 models. The remaining 20 percent is from fullcustom projects, which in theory at least can be built in any material, including composites. Virtually all the present order book was generated with yacht broker assistance, although it has an office in Fort Lauderdale to support sales and service operations throughout the Americas. It also recently established independent brand representatives in Australia and Brazil, and is actively seeking similar partners elsewhere in the world.

Present client demographics is Americasfocused with some 60 percent of current projects in progress for owners based on that side of the Atlantic. Of the remainder, 30 percent is European and 10 percent ROW. But the intention is to spread the net further afield and spread the risks of any market downturn.

“Our ultimate aim is to grow the business to the point where we can deliver six or seven big boats a year,” says Diego Deprati. “Anything more would start to diminish the levels of service that we pride ourselves on. Our ability to listen and tailor solutions accordingly is what sets us apart and, beyond the attractiveness of our various models, that is really what underpins our recent sales successes.”

Last year, Baglietto delivered one semi-custom model and two full-custom projects. These handovers included Attitude, the second of its DOM133s (although strictly speaking she is the first, as the earlier Run Away delivered in 2020 was slightly shorter, had less volume and was originally billed as a DOM123), the full-custom 38-metre Enterprise (C10235), and the Superfast 42 Rush (C10236).

This year will see five more projects concluded: the third and fourth DOM133s (C10243 and C10244) and the first two Baglietto T52s (C10238 and C10240), plus the full-custom 41-metre Francesca II (C10242).

An increasingly demanding schedule in 2024 should see five handovers: two DOM133s and three T52s. And in 2025 a further three DOM133s and three T52s will be delivered, plus a possible Fast 43 (C10226) that is currently on hold. Further out, there were several 2026 delivery slots at the time of going to press. The only firm delivery that year, however, is the first allnew, 60-metre T60 flagship (C10260), which was sold at the end of last year only three days after the sale of the eighth T52.

“Our ultimate aim is to grow the business to the point where we can deliver six or seven big boats a year.”

Baglietto has two main facilities roughly halfway between Genoa and Pisa. The biggest is in the historic naval port of La Spezia, the second largest city in Liguria after Genoa. The other is in the Tuscan city of Carrara, which lies to the south-east of La Spezia and is famous for its marble quarries. In typical Italian fashion Baglietto employs just 90 people directly, but around 750 people will be working at any one time at its two shipyards.

Since 2015, the Gavio Group has also owned Bertram, the famous North American sportsfisher brand. Now based at a yard in Tampa on Florida’s Gulf Coast, its activities are overseen by Diego Deprati from Italy. Baglietto’s Carrara facility has just started building a Bertram 35 and a Bertram 39 as part of a brand relaunch in Europe planned for this summer. Based on an industrial estate a few minutes’ drive from the sea, the Carrara yard occupies around 10,000 sqm and originally belonged to Cantieri Navali Cerri (CCN), which built fast series yachts in composite until around five years ago. The Gavio Group acquired CCN in 2011 before it saved Baglietto from the wreckage of the Camuzzi Group, which ran the business from 2004 through to its collapse in 2010 following the global financial crisis. CCN had already completed a handful of one-off metal projects up to 50 metres when in 2020 it was merged with Baglietto in a strategic move to optimise synergy between the two shipyards, but also simplify and strengthen Baglietto’s brand identity in a busy market. Today, Carrara focuses its resources on the semi-custom, all-aluminium DOM133s, all of which are then moved to La Spezia for final finishing.

The La Spezia site occupies a 35,000sqm site that was once Cantieri Ferrari. It was acquired in the mid 1990s by the Camuzzi Group when Baglietto was still headquartered in Varazze, the coastal town to the west of Genoa where it all started back in 1854.

There are three main construction sheds in La Spezia with six construction bays – all of them busy – plus the company’s administrative offices, where it builds

the steel/aluminium models and custom projects. Deep-water quays can take yachts up to around 70 metres in length and most disciplines are handled in house, but fabrication work is sometimes outsourced as and when space is needed.

Investment in capacity has been significant in recent years. From the start of its involvement, the Gavio Group has allocated around €60 million to renovating the facilities, with €13 million across the two sites over the past year alone. In La Spezia work will soon start to fill in one dock and extending two others to accommodate what is claimed to be the largest travelhoist in Europe – a gigantic Cimolai machine with a 1,120-tonne capacity capable of moving yachts of around 70 metres. The hoist arrived last summer and clearly demonstrates the management’s ultimate ambitions for the site.

Eight of the all-aluminium sub-400GT Vafiadis-designed DOM133s have been sold to date, all with twin Caterpillar C32 main engines, although two are hybrid versions with twin CAT generators and Siemens control systems. Top speeds are around 17 knots depending on load, but hybrid versions will be about a knot slower and have slightly different GAs. The big selling points are proximity to the sea aft and the high-volume interior. Six of the eight are expected to charter, but all are built to MCA regs. Interior design is open to owner choice.

Baglietto’s steel and aluminium T52 is an evolution of its earlier 46-metre and 48-metre models. Francesco Paszkowski handled the overall design and worked with Margherita Casprini on the interiors of five units. The fourth’s interior will be by Studio Vafiadis, the fifth by Team4Design and the sixth by Alberto Mancini. Of the eight T52s signed to date, most have the standard CAT C32 engines, but the first and sixth are hybrids. The first hybrid is powered by MTU engines with Siemens controls. The sixth will have a CAT/Siemens hybrid installation, and the seventh is a ‘mild hybrid’ comprising auxiliary solar panels and a battery bank for hotel loads during the day, but no electric propulsion.

Designed by Francesco Paszkowski, the steel and aluminium 1,000GT T60 will have double the volume of the T52, despite still being a trideck. The hull design is presently being tank-tested. Key features include a 60-sqm beach lounge with pool and a walkaround upper deck that can be configured as a private owner’s deck, which leaves room for four guest cabins forward on the main deck and the option of a fifth on the lower deck. The standard powertrain includes twin 3512 Caterpillars, which should deliver a maximum 16 knots and transatlantic range at a 12-knot cruise speed.

Baglietto admits to having the same supply-chain issues as everyone else in a post-Covid world. For instance, whereas orders for engines pre-pandemic where placed six months in advance, now that lead time is between 12-14 months.

“Plus, of course, prices have shot up by anything from 10-40 percent,” says technical manager Andrea Lavagnino.

“That means on average bought-in materials and equipment are now around 15-20 percent more expensive.”

Despite supply-chain pressures, Baglietto is still quoting 30-month build windows for the DOM133 and T52 models from cutting metal to final delivery, and a T60 should only take a couple of months more. The tenth DOM133 and ninth T52, for example, which are the next available as of January 2023, come with early 2026 delivery slots and fabrication will start this summer with or without clients. Baglietto is lucky to have the Gavio Group’s financial muscle behind it should it need to fund speculatively, but given the current health of the order book that eventuality seems unlikely for the foreseeable future.

One of five Bagliettos launching this year, the 41-metre, all-aluminium, 300GT Francesca II is a custom project for American owners. Their previous yacht was a Cerri Flying Sport 102 built at the old CCN operation and their new sports fly two-decker, based on a Bacigalupo planing hull, has a reduced draft for the Bahamas. Francesco Paszkowski oversaw the design and again worked with interior specialist Margherita Casprini on the interior. The first unit is referred to as a ‘Superfast 42’ with triple 1,920hp (1,432kW) MTUs coupled to KaMeWa waterjets for a top speed of 33 knots. Handover is in spring 2023.

Beyond having two DOM133s and two T52s on its schedules with hybrid propulsion, plus a mild hybrid project, like other yacht builders these days Baglietto is keen to be seen to be doing as much as possible on the sustainability front.

One initiative is billed as Bzero, an unusual hydrogen fuel cell solution that harnesses solar energy to extract hydrogen from seawater – essentially taking the H out of salty H2O using AEM-type electrolysers. The solar energy required will come from photovoltaic panels located on hardtops and spare areas of superstructure. The hydrogen produced will be stored in solid form at room temperature and at relatively low pressure of just 10 bar. As this process is virtually continuous there is no need to store large quantities of the fuel and smaller tanks mean more space on board for guest amenities. The solution is deemed more sustainable than more mainstream solar power solutions because it reduces the reliance on lithium-ion batteries. Using a small generator overnight could see hydrogen harvested 24/7, which is much better for the environment than

running big generators inefficiently.

This spring should see a test rig installed in shipping containers in La Spezia, but as with other fuel cell solutions, the concept is only suitable for hotel loads (RINA looking at certification for a 55kW system) and cannot realistically be scaled to include powertrain requirements.

“The main downside to this technology today is cost,” says CCO Fabio Ermetto, the joined the Baglietto management team in 2021 bringing with him invaluable experience from his time with Camper & Nicholson, Fraser Yachts, Heesen and Benetti. “At the moment it looks like being more than double the hybrid premium. Plus finding the space needed for the associated hardware inside and out is problematic. For instance, it would be much harder to find the necessary room aboard our DOM133, which would probably need to forfeit a guest cabin or possibly even two for it, but it would be much easier to accommodate aboard a T52 or T60 without obviously compromising guest real estate. Despite these drawbacks, I’m confident Baglietto will be building boats with such systems on board very soon.”

Th ree years ago Baglietto hadn’t launched a yacht not designed by Francesco Paszkowski for over a decade. The Florentine designer has done more than any other to define the brand’s signature aesthetic and continues to do so, but other designers are being welcomed with a view to expanding its market offering. Argentinian designer Horacio Bozzo, for example, penned the exteriors of 40-metre Club M (C10232) and 54-metre C (10231), full-custom projects with interior design by Achille Salvagni and Hot Lab respectively. The DOM 133 is designed by Stefano Vafiadis, who is being primed to take over the family studio from his father Giorgio, while Alberto Mancini and Enrico Gobbi are also busy on projects. It’s safe to assume that there

will be collaborations with other designers in the future.

Such has been the success of the DOM133 that Baglietto is already working on what comes next. Look out for a smaller 35-metre or 300GT-ish DOM model from early spring this year with the first scheduled to launch in 2025, and there are also plans for a slightly bigger version. Although both these will be DOMs in terms of philosophy and designation (the name comes from the Latin word ‘domus’ meaning home) they will be quite different in terms of specification, although expect both to still be available with either conventional or hybrid propulsion.

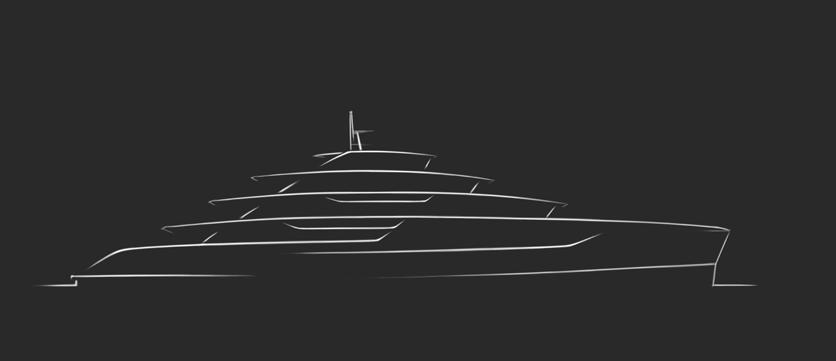

The 100-metre Wing 100 sailing yacht concept was first unveiled by Royal Huisman in September 2022 and claims to redefine the performance, handling and energy efficiency of large sailing yachts by harnessing wing mast technology. But does such a rig make sense for a super-sized yacht?

SOPHIE SPICKNELL

Wing masts have been gaining momentum as an efficient and sustainable solution for both the commercial and superyacht sectors in recent years.

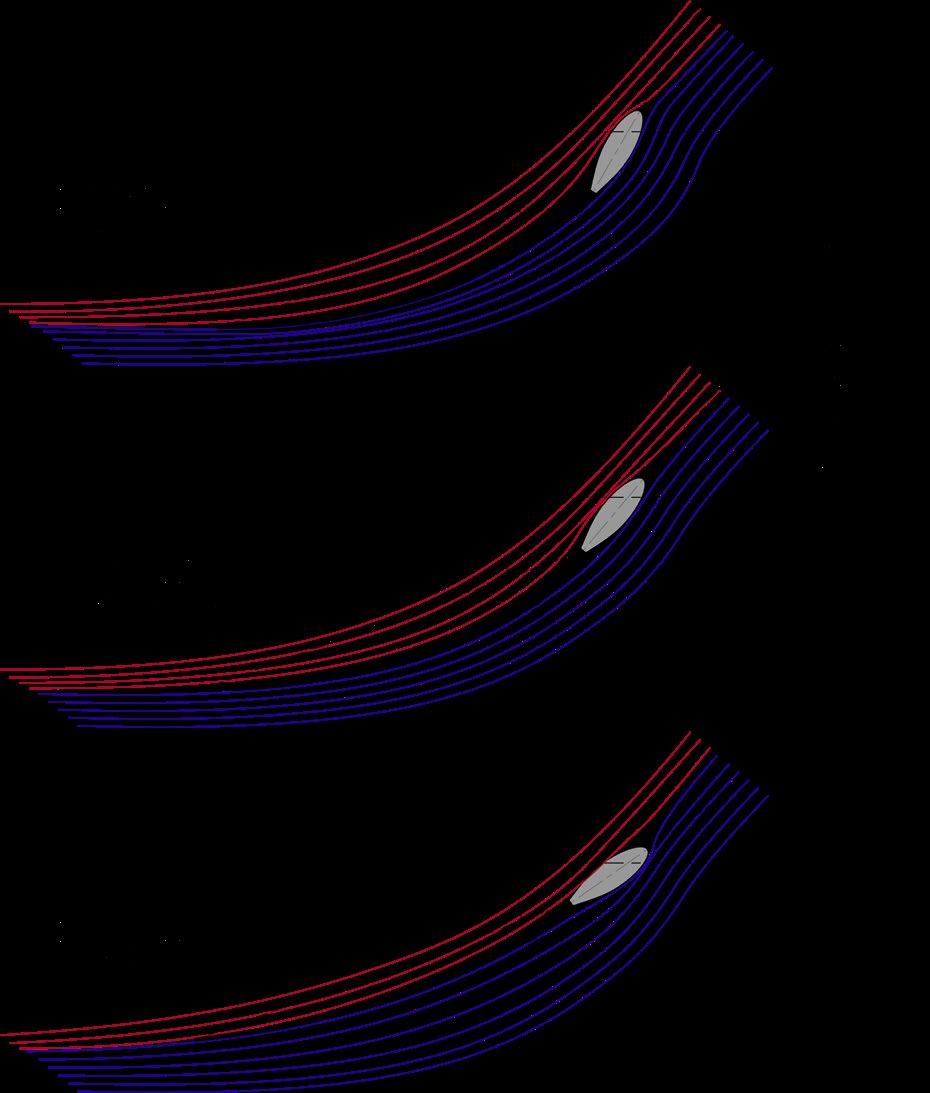

The rotating airfoil-shaped wing mast makes a smooth transition from mast to sail on the leeward side. This provides cleaner airflow around the mast, thus less drag and more power driving the vessel (the shipyard calculates the yacht will be capable of 24 knots under sail). The wing mast dimensions and structure can also take greater compressive loads without buckling, so can be self-supporting.

Moreover, conventional sailing rigs require time and crew effort to set, manage and take down, meaning that shorter passages are often made under power. The rig system of the Wing 100 is based on a proven concept and the mainsails and staysails of the combination wing mast/soft sail rig can be set in a matter of minutes.

“The Wing 100 is designed as a sailing yacht with a very efficient sail plan aimed at minimising crew requirements whilst maximising sailing capability,” says Erik Wassen, senior designer at Dykstra Naval Architects in Amsterdam, which worked with Royal Huisman on the concept (the interior design is by Mark Whiteley). “The Wing 100 has the ability to feather the main sails for unfurling, furling or reefing, even when sailing deep courses. The rig ensures a fast and efficient performance, but can be comfortably managed by remote control, and if the wind strength increases, the sails can be rapidly de-powered to ensure a modest angle of heel.”

“The Wing 100 is designed as a sailing yacht with a very efficient sail plan aimed at minimising crew requirements whilst maximising sailing capability.”

Can a wing mast rig be built on such a scale? Not a problem for Royal Huisman, which can draw on the expertise of its sister company Rondal, a leader in the manufacture of very large composite masts and integrated sail management systems. In fact, the Wing 100 concept has two 73-metre, free-standing wing masts with airfoil profiles, and each mast is complemented with a single in-boom furling mainsail and furling jib.

“The masts are able to rotate 250 degrees, or 125 degrees each side, to allow changes to the sail set without changing course,” says Wassen. “The free-standing wing masts have no standing rigging or associated deck clutter and the masts are rotated relative to the boom by hydraulic rams. By changing the mast rotation angle the shape of the airfoil can be adjusted to maximise or reduce the power generated by the rigs.”

Dykstra Naval Architects was instrumental in the development of the Dynarig and sail-assisted cargo ships, although Royal Huisman is at pains to point out that the Wing 100 is a true sailing yacht and not a heavy sail-assisted motoryacht. Like the Dynarig, however, the concept is designed to appeal not only to die-hard sailors, but also motoryacht owners looking to reduce their environmental footprint.

“Sustainability is crucially important for all of us and for future generations,” says Royal Huisman CEO, Jan Timmerman.

“The emergence of sailing yachts on this scale, with the level of energy efficiency and eco-responsibility offered by the Wing 100, would have been unthinkable just a decade ago”

“Yacht owners and the yachting industry obviously want to contribute by reducing environmental impact and by limiting the use of valuable natural resources.”

The Wing 100 will have an electric propulsion system that can be adapted to alternative power sources as new fuels or hydrogen fuel cells become available. A hydro generator powers the onboard systems and charges the battery bank. While under sail up to 200 kilowatts of energy can be harvested in this fashion, which Royal Huisman claims is equivalent to a fuel saving of over 40,000

litres during the course of a year. The renewable energy systems further include 480 square metres of solar panels integrated into both her masts, which can generate 250 kilowatts of energy or another 20,000 litres of fuel saved in a year.

“The addition of the vertical solar panels on the masts allows the Wing 100 to generate more energy without the need for a motor,” says Timmerman. “In total, the Wing 100 is calculated to save over 225,000 litres of fuel per year compared with similar sized, conventional engine-powered superyachts.“

Although alternative energy technologies are evolving all the time, they are not always new. Royal Huisman built the world’s first truly hybrid sailing yacht in 2009, the ketch-rigged sailing yacht Ethereal , noted for her pioneering hybrid propulsion system and 500kWh of stored energy in a Li-ion battery bank. From that moment on, energy efficiency and hybrid propulsion have been at the forefront of the shipyard’s R&D.

Moreover, solar cells have already been integrated into wing masts, although on a smaller scale. The 24-metre polar expedition sailing yacht NanuQ launched in 2019 by KM Yachtbuilders to a design by Dykstra Naval Architects, has two freestanding, rotating wings masts by Hall Spars with a soft sail combination. Each wing mast is covered with 20 solar panels per side for a total of 40 square metres of panels. The main sails are handled by closed-front OceanFurl booms with hydraulic furling motors and can be reefed at virtually any angle of sail.

Like NanuQ , the Wing 100 concept is designed to be built in full aluminium rather than steel to benefit from the lighter weight with no significant loss in structural stiffness. Less weight combined with the hull’s shallow-draft canoe body means less hydrodynamic resistance.

“Typically for a 100-metre yacht to go upwind you would want a deep, high-aspect ratio keel, but the draft may be limited to five or six metres for practical reasons,” says Wassen. But because the Wing 100 is so big, a deep keel is not needed for stability, but is required for the side-force production. So a centreboard is one possible option to increase sailing performance”.

The raised foredeck allows the structural beam to be full-height and increase the structural stiffness, while the free-standing rig reduces both local and global loads on the structure.

“If you have a ketch or a sloop, for example, a rig of this size induces massive rigging loads and mast compression, increasing the longitudinal bending moments on the vessel,” explains Wassen. “But with a freestanding mast you don’t have this issue. The absence of shrouds and spreaders also emphasise her minimalist aesthetic.”

“The team at Royal Huisman is incredibly excited to be at the forefront of this conceptual revolution,” concludes Timmerman. “The emergence of sailing yachts on this scale, with the level of energy efficiency and eco-responsibility offered by the Wing 100, would have been unthinkable just a decade ago.”

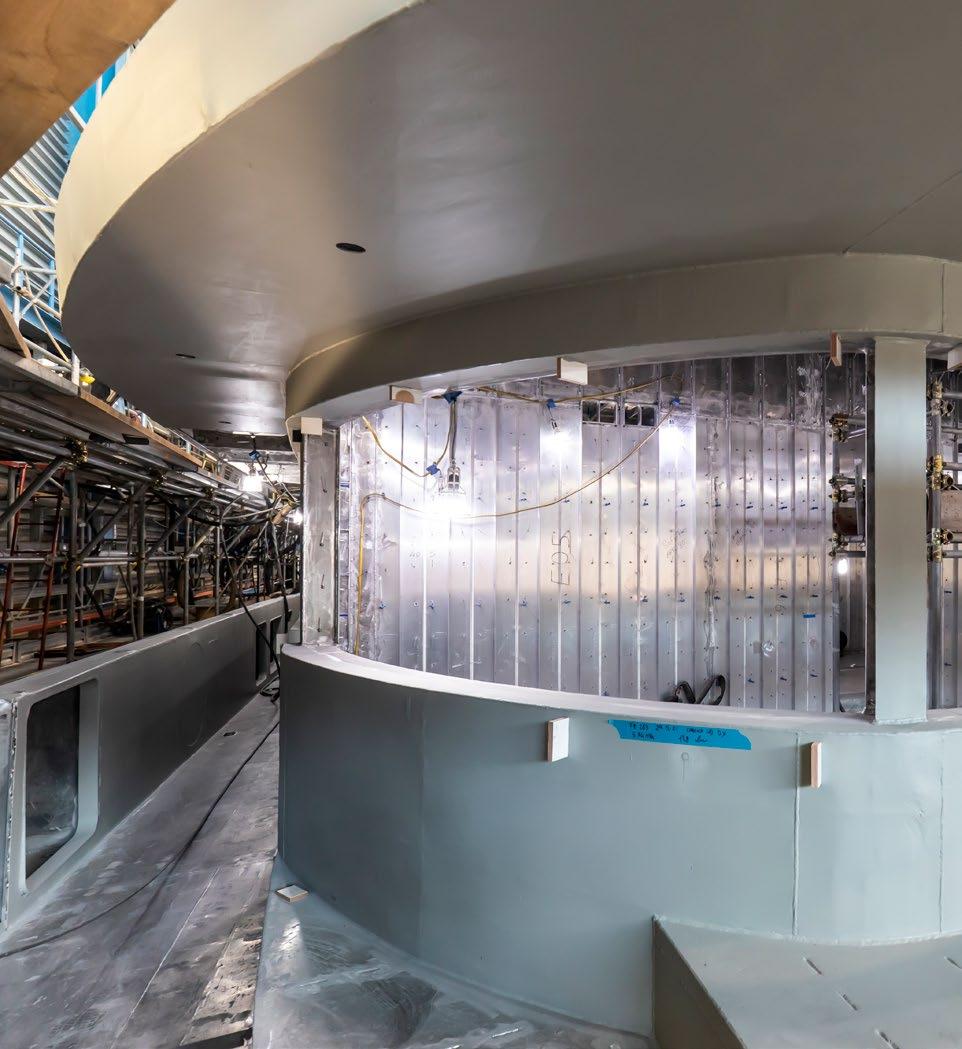

As Benetti focuses resources on its series superyachts, the only full-custom project currently in build is FB283. Launched in January and approaching completion, we visited the 62-metre steel and aluminium yacht in the company of designer Giorgio Cassetta, owner’s representative Nicola Nicolai and the Benetti production team, to find out what makes her one of a kind.

BY JUSTIN RATCLIFFE

The story of FB283 began with a meeting during the 2019 Monaco Yacht Show when a client approached Benetti for a fullcustom yacht in the 60-metre size bracket. Matters moved quickly and Giorgio Cassetta was taken on by the client to define exterior and interior design and layout. By the end of the year Nicolai Yacht Consulting & Project Management had been engaged to represent the owner and finalise both the contract and technical specs. A build contract was signed in February, 2020. Less than three weeks later Italy was the first European country to impose a lockdown in response to the worsening Covid-19 pandemic.

“There was a period of intense discussion and planning before the contract,” says Benetti project manager Elisabetta Maria Di Noto. “The owner wanted to be able to cruise comfortably at 20 knots – fast for a steel-hulled displacement yacht – with very low noise and vibration levels. This already presented a technical challenge, but he was also adamant that he didn’t want any surprises during construction in terms of added costs. So we went into a lot of detail to be absolutely certain that everything was spot on before cutting metal.”

“The final owner’s meeting took place at the beginning of February when we coordinated all the involved parties to finalise the contract details,” adds owner’s rep Nicola Nicolai. “Agreeing on all the revisions and finalising the design and specifications of a 60-metre, full-custom yacht typically takes many months – we did it in two,”

The total external glazed area aboard FB283 covers 223 sqm and weighs approximately 8,500kg. The very large single panes of curved glass were supplied by Viraver, which has manufactured glass for multiple Benetti projects, including 107-metre Luminosity, as well as other Italian shipyards. The Padua-based company has invested in some of the most advanced technologies for glass processing. These include gravity glass bending systems able to produce large curved surfaces of up to 6.5m x 3.10m without flaws or undulations, a state-of-the-art chemical toughening plant, a gigantic autoclave (9m x 3.5m) and various ‘clean’ rooms for assembly in a controlled environment.

Gravity bending is a process by which the glass sheets are loaded onto a bending die that supports only the edges of the sheets to avoid distortion, then subjected to heat treatment in a gravity bending furnace. When heated to the viscoelastic phase at 580–640°C, the glass literally sags into the desired shape by the action of gravity under its own weight. The process combines digital accuracy with human expertise as the furnace operator determines how much heat is applied and where to facilitate bending. Domenico Miceli, Viraver Sales Director, calls it “industrialised craftsmanship.” The technology to bend glass on such a large scale was relatively new when FB283 was being designed and Cassetta was quick to take advantage.

The biggest single panes on the yacht are those in the upper salon. Measuring 5.9mx1.8m they comprise three layers of laminated glass plus two interlayers to produce a stronger yet thinner installation. Given the sheer size of the windows, IR filters inserted between the layers significantly reduce the transmission of solar heat and thus power demands on the air-conditioning system.

“Combined with chemical toughening, the ‘structural‘ interlayers means less material can be used to achieve better mechanical performance,” says Miceli. “In fact, the panes on FB283 are just 33mm thick, which is over 40 percent less compared to ISO 3254:1989 requirements using thermal hardening techniques and normal PVB interlayers. That means less weight, higher strength and better optical quality.”

The arrival of Covid piled on more pressure. Nicolai worked for Benetti as director of project management for over ten years before setting up his own consultancy firm, and Cassetta has long experience of collaborating with the shipyard on production models and full-custom projects. Both know the company inside out and hand-picked the project team headed up by Di Noto.

“Because the groundwork had already been done before signing the contract we didn’t have a lot of wriggle room, but Covid meant we had to completely change our way of working,” says the Benetti project manager. “We set up weekly online meetings with Giorgio and Nicola to flag up and settle problems. We also enabled the client to make a decision or state his preference in a timely manner and, in some cases, even ahead of schedule. During the pandemic he even learned Italian!”

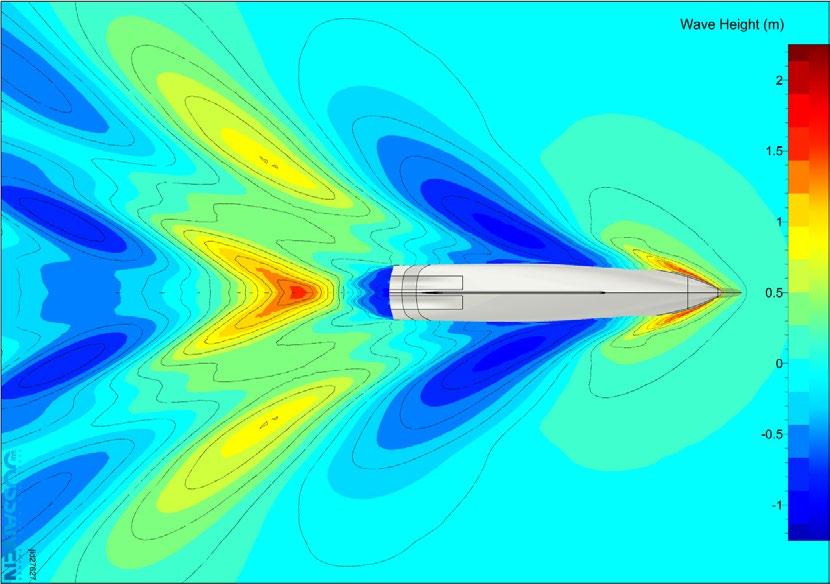

Although no sister ship was available, the owner had chartered various Benetti yachts and referenced Spectre , the 69-metre full-custom yacht with exterior design and layout by Cassetta and project management by Nicolai that has a top speed of 21 knots. Van Oossanen Naval Architects were tasked with designing a Fast Displacement Hull Form that was then tank tested at MARIN in the Netherlands (see sidebar p.51). The build team was unable to attend these tests because of travel restrictions, but they were patched in by live video feed together with the owner.

Beyond the need for speed, the owner also specified ceiling heights of 2.3 metres throughout and an oversized tender. In fact, the forward garage houses a customised 10-metre Novamarine BS100 – enormous for a 62-metre yacht – and to get her in and out the portside shell door is 11 metres in length. The big garage and high ceilings presented challenges for both designer and shipyard.

“Contractually, ceilings heights usually refer to the interiors, but in this case the exterior decks and the staircases were included,” says Nicolai. “Even the technical spaces on the tank deck have full-height ceilings. That took a lot of fine-tuning and we were working to tolerances measured in millimetres.”

To aid precision and streamline the production process, it was decided from the start that the entire yacht, from net

space drawings to fitted furniture, would be designed in 3D for optimal accuracy between departments. Combined with the coordination done at the planning and design stages, 3D design meant the shipyard could fast-track construction despite the complications caused by Covid. Because they were unable to meet in person, Cassetta provided the owner with 3D googles and a web-based stereo VR tour for viewing ‘walkthrough’ renders of the exterior and interior that were constantly updated as the project evolved. When the hull and superstructure arrived in Livorno in November 2021, outfitting started immediately and double painting shifts were set up to keep the project on track. Within 15 months the yacht was ready for launch.

Facing page:

Following spread:

Although the general arrangement is broadly conventional, closer inspection reveals elements created to serve an informal family lifestyle aboard an exclusively private yacht. Cassetta reappraised the conventional main salon and dining room, for example, by eschewing the formality of a space that occupies prime real estate but is rarely used. Instead he designed a widebody, open-plan living and dining area, and a six-metre-wide flush connection with the open aft deck through sliding glass doors that open completely. Combined with very large, one-piece windows supplied by glass specialists Viraver (see sidebar), the whole area – inside and out – is designed to be a bright, airy and relaxing hub for all the family at any time day or night.

“Life on superyachts mostly take place on the upper decks and the main deck is often dead space,” says Nicolai. “In Giorgio’s layout the main saloon and aft deck are designed to create a social area over 20 metres long and bring life back to this overlooked part of the boat.”

The classic beach club set-up in the transom, which does not always make the smartest use of available space, was also reassessed to create a combined entertainment and storage area. So in addition to a hammam and massage room, there are racks for bikes and paddle boards, stowage for fishing gear, a dive room with compressor, hanging space for drying wetsuits and extra washing machines.

“The basic idea is that although this not a huge yacht, the onboard spaces and layout have been

designed to suit a very specific purpose and usage,” says Cassetta. “We challenged most of the commonly accepted ergonomic criteria, such as the risers of the exterior staircases that we made less steep and hence much more comfortable than usual.”

The passarelle in the stern is designed to rotate 45 degrees so it can be used when the yacht is moored alongside in the marina, avoiding the need for a side-boarding ladder. In fact, the widebody design prompted discussions with Cayman Registry about fire boundaries and escape routes from the lower deck accommodation. The solution was to use the main staircase as a secure conduit to the upper deck pantry that exits onto the side deck – arguably a safer muster point than the main deck in a badly listing vessel.

The exterior profile is crisp and uncluttered with a subtle reverse sheer in the bow that adds a muscular touch to the graceful lines. Hidden from view in the forepeak is a cosy nook that Cassetta calls the ‘love seat” (the mooring station is on a technical deck below) and the glazed structure on the sundeck houses gym equipment. Exterior detailing is minimal and wherever possible integrated into the functional design, as in the case of the louvred bulwarks on the upper deck that serve as freeing ports for green water to drain overboard.

The interior design, also by Cassetta, reflects the purity of the exterior styling. Based on oak, leather and brushed travertino, the effect is sober and classic yet clean and contemporary.

The acoustic design of FB283 was entrusted to Cergol Engineering in Trieste, specialists in noise and vibration numerical analysis with over 30 years of experience.

“This project was particularly challenging because of the yacht’s high displacement speeds,” says company founder Valter Cergol. “Generally speaking the faster the boat, the higher the frequencies and the louder the noise, but to meet the contractual parameters you can’t just throw more weight at the damping treatments and insulation materials because that may affect the yacht’s performance.”

Besides floating floors throughout that nowadays are standard on large luxury

yachts, this meant prescribing a range of materials of varying thicknesses depending on the location on board, from rock wool and ceramic fibre to sandwich panels in rubber, cork and calcium silicate.

Cergol Engineering was also responsible for the vibration analysis to mimimise resonance between the hull structure and the main potential sources of vibration like engines, generators and propellers, even at high cruising speeds. One of the most effective solutions for damping torsional vibration excitations in this respect is the drive train with Smart-Link flexible couplings by Rubber Design between the propeller shaft with a separate thrust bearing, and the gearbox.

As the name suggests, the patented Fast Displacement Hull Form (FDHF) by Van Oossanen Naval Architects combines the efficiency of a full-displacement hull at low speed with the top-speed performance of a semi-displacement yacht. As a comparison, the FDHF’s resistance values are typically 20 percent lower than a well-designed hard chine hull form at semi-displacement speeds. More commonly associated with aluminium hulls, the challenge was that FB283 was a steel-hulled yacht with a high speed requirement.

“The owner was very well informed and was aware of the compromise required when choosing between speed and comfort in terms of motions,” says Managing Director Perry van Oossanen. “He was concerned about sacrificing too much comfort to reach the desired speed? So we really had to push to keep the comfort levels as high as possible despite the speed requirement.”

Typically, when a hull is optimised for high speed you get a ‘stiff’ boat with a high GM (metacentric height) and an uncomfortable, jerky rolling motion. Thanks in part to relatively flat surfaces on the after part of the hull that generate some lift as the yacht moves through the water (FB283 is also fitted with an interceptor to further reduce drag), the FDHF can exceed theoretical hull speed but still provide the kind of soft and stable ride in waves that a displacement hull is famous for. “You have to be very attentive to how to balance both factors,” says van Oossanen. “It’s more a question of finding the sweet spot than doing something radically different.”

MARIN was able to assist the project team in this respect. At the time of the tank testing, Enrico Della Valentina of MARIN’s yacht division was leading an ISO working group to establish a comparative scale of motion-related comfort aboard large

yachts. Now in effect as ISO 22834:2022, it compares designs and layouts, identifies the most comfortable positions on board and evaluates the impact of stabilisation systems.

It works by selecting a minimum of five zones (typically a crew cabin, the wheelhouse, the master suite, the main saloon/dining room and the beach club) and appoints each area a maximum of five points whereby the higher the number the higher the onboard comfort. Of course, you need to make it all visible and understandable so MARIN has an app that allows clients to select multiple onboard areas and compare motions in various sea states, headings and speeds.

“The owner was very intrigued by this discussion,” says Della Valentina. “Clients can choose as many onboard areas as they like, but they need to be distributed along the length of the yacht to fully appreciate the difference in motions. I also say they shouldn’t to be scared about simulating the most demanding conditions, because it’s a kind of a crash test. This is not a case of showing how bad a vessel is, but how good it is.”

Benetti’s last full-custom launch was 107-metre in 2020 at the end of its so-called ‘Giga Season’. Of the 55 yachts currently in build averaging over 44 metres in length, there are no other one-off designs. This makes FB283 all the more unique, especially as despite a demanding brief and global pandemic the project progressed in record time for a Benetti custom build.

“That wouldn’t have been possible without all the advance planning and close collaboration between the owner’s and builder’s teams,” says Nicolai. “Shipyards don’t like changing their standard work practices, but in this case everyone was driven by the desire to find what was best for the project.”

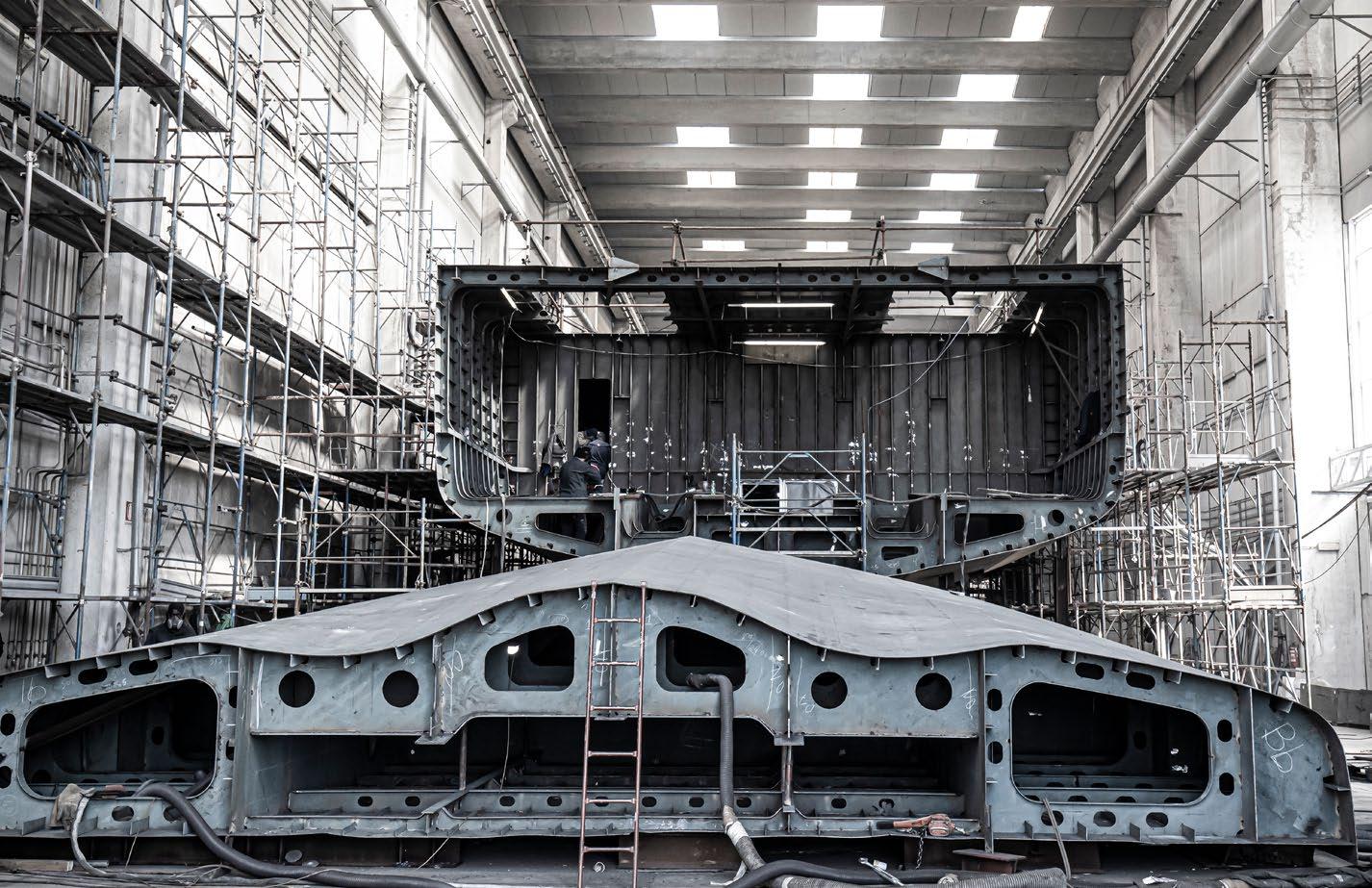

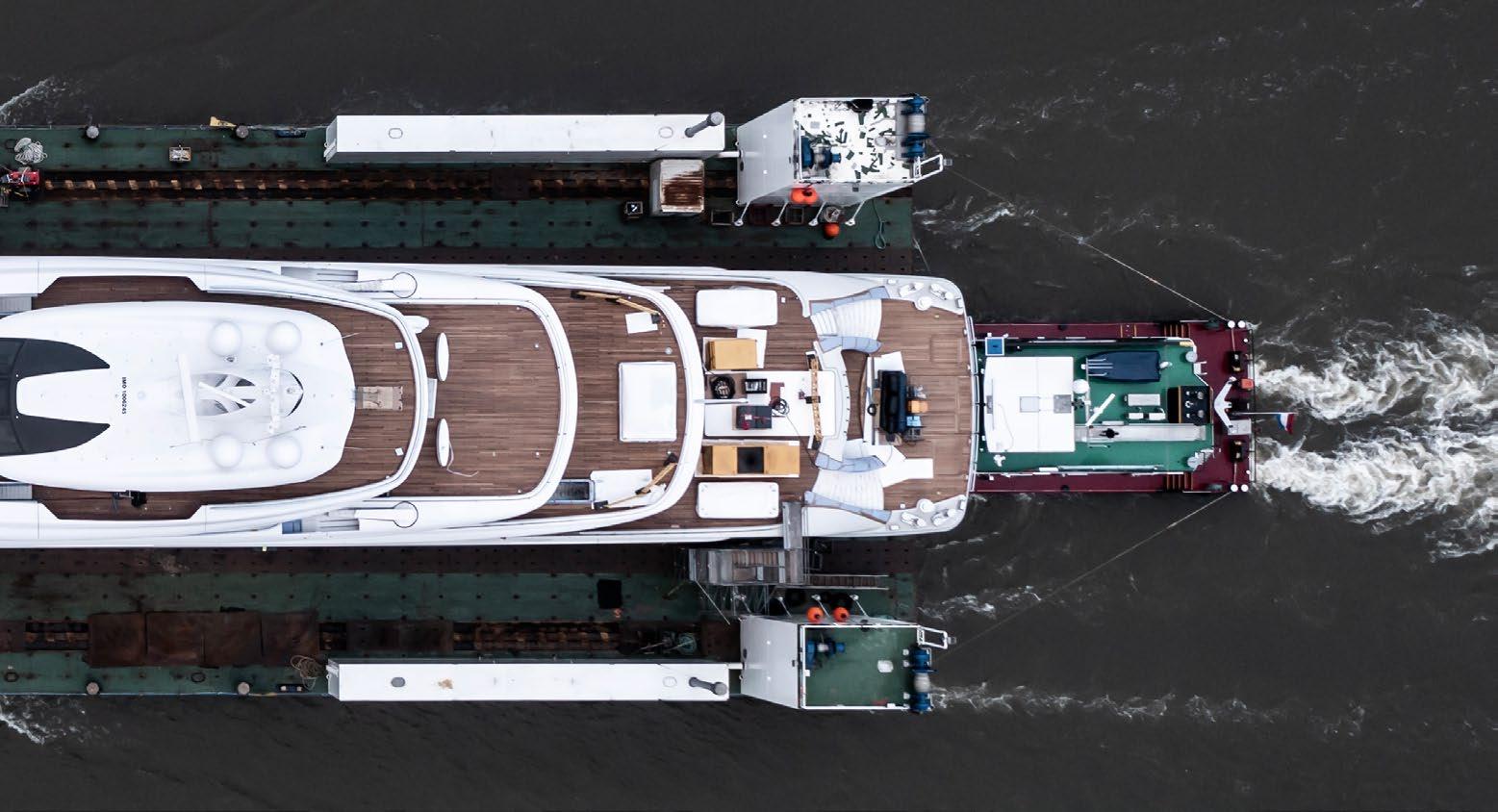

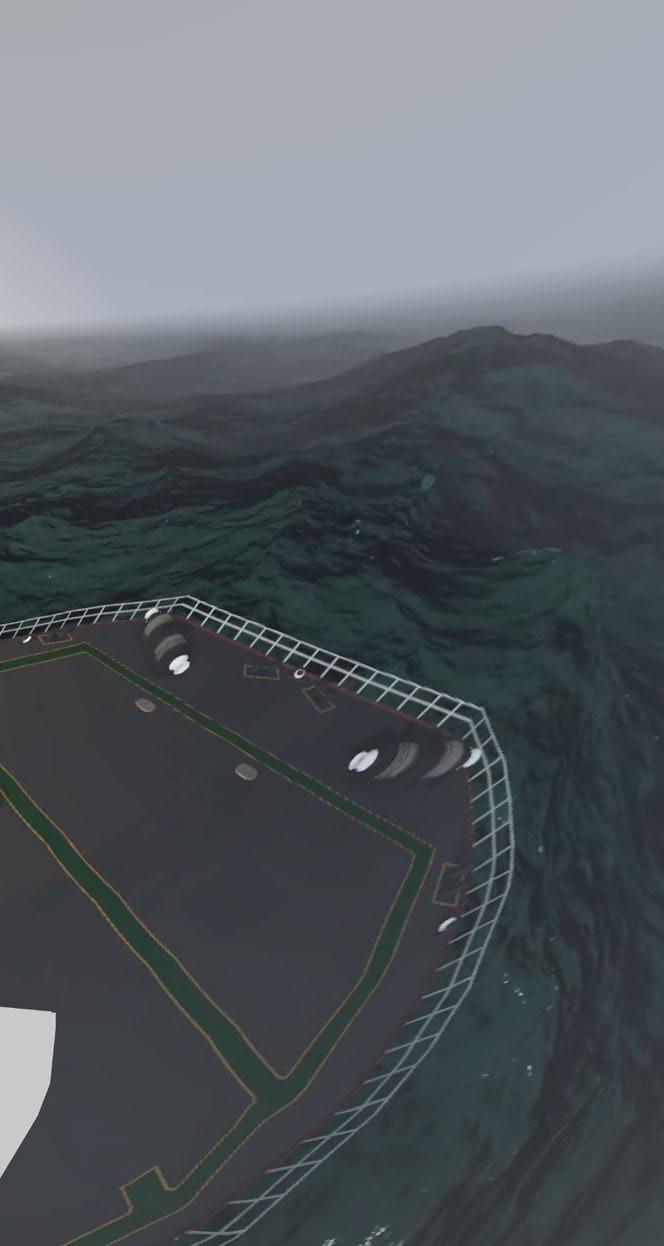

“A revolutionary yacht that has undergone a complete transformation which is practically unprecedented in its scale and nature” is how Oceanco describes Project H . We talk to her owner’s representative and the shipyard’s project engineering manager about one of the most ambitious rebuilds ever undertaken.

BY JUSTIN RATCLIFFE

At what point does a refit become a rebuild? There is no hard and fast rule, but a safe bet is that when you start removing superstructure and replacing major systems, you’re talking rebuild. In the case of Project H , there is virtually nothing left of the original yacht except her hull, and even that has been extended and modified. This is a rebuild that challenges the entire industry to reconsider the potential of an existing superyacht to evolve and take on new shapes. The original yacht was launched by Oceanco as Al Mirqab in 2000. Designed by Richard Hein, one of the shipyard’s original investors, at 95 metres she was the largest Oceanco until 110-metre Jubilee (now Kaos ) came along 17 years later. Powered by triple, military-spec MTU 20V 1163 TB93 diesel engines for a massive 30,000 combined horsepower, she hit 30 knots during sea trails. When the yacht became available in 2018 and was acquired by her current owners, the stage was set for Hein, founder and CEO of The A Group in Monaco, to be reunited with both the yacht and the shipyard that built her.

“We wanted to do something different and so we sat down to show that you could take a very high-tech yacht from 20 years ago and make her IMO Tier III compliant under today’s regulations.”

Rebuilding was not originally envisaged. However, an initial survey revealed that the engines and generators were showing their age, the result of many hours on the clock, and would need to be replaced. That led to a discussion about bringing the yacht into IMO Tier III compliance – the first hint that something more than a major refit was being considered. The second was when UK-based studio Reymond Langton Design was engaged to create new concepts for the exterior as well as the interior design.

“When it comes to refits, people in the beginning have a certain intent and that is modified as the project develops,” says Hein, as the outfitting of Project H continues at Oceanco following her floodlit presentation last January. “We wanted to do something different and so we sat down to show that you could take a very high-tech yacht from 20 years ago and make her IMO Tier III compliant under today’s regulations. We also wanted to give her a completely new look; not just a cosmetic facelift and a new lick of paint. Once that decision had been taken, things started moving very quickly. The yacht was completely re-engineered and redesigned to Oceanco standards, as with any new construction, and she now carries a full 2023 certificate.”

Various new-build shipyards in northern Europe were approached, but were dissuaded as the scale of the redesign became apparent and the extent of the likely disruption to their production schedules emerged. Their reaction was unsurprising. Attempts are made to keep so-called ‘emergent work’ to a minimum during refits. But like the proverbial onion, the extent of work only becomes apparent as the layers are peeled away and the danger is that the expanding work list will eat away at the icing on the yard’s cake in terms of profit.

Rebuilding removes a lot of that uncertainty, but not the risk. Processes such as cutting away old superstructure and stripping out machinery are not part and parcel of building new yachts. Even starting with an existing hull requires a lot of reverse engineering to fit new machinery into existing spaces.

“I’ve worked at Oceanco since 2007 and only ever done new-builds,” says Marco Kal, Oceanco’s project engineering manager.

“Starting with something already, even if it’s just a hull, requires a very different approach in terms of engineering and construction, organisation and project management. All your drawings are 20 years old and they did things a lot differently back then. That was the biggest challenge for me in the beginning and, to be honest, it follows you all the way through the rebuild programme. We had to start from scratch.”

“About the only piece of heavy equipment that remained in place is the 300kW ZF electric bowthruster, but that was completely overhauled, so is effectively new.”

“The turning point came when I was flying back to Monaco and one of the Oceanco directors was travelling on the same plane,” recalls Hein. “We got talking and fixed an appointment at the shipyard the following week to talk. During that meeting, it became clear that Oceanco had the capacity and, just as important, the will to do this. There was common interest between all parties concerned to see what we could do with it. So nearly 17 years after I’d sold my shares in Oceanco, I found myself back there and felt at home very quickly.”

By mid-September 2019 the yacht was in the newly acquired Zwijndrecht construction facility and metal cutting began in early October. Eight metres were added to the steel hull in stern and two metres to the forward deck line. Several new transom shapes were tank tested in the water basin at MARIN. Despite the increase in displacement and changes in weight distribution, the hull is now more efficient with a cruising range of 6,000 nautical miles at 14 knots, which jumps up to 7,500nm at 12 knots.

“The naval architecture and engineering were intense,” says Kal. “Life was made easier by the fact that she was already a high-volume

vessel for her length and we had room to play with. We can also build a bit lighter these days but, even so, we removed 110 tonnes of steel and added 198 tonnes during the hull extension. In the process, the gross tonnage increased from 3,045GT to 3,521GT.”