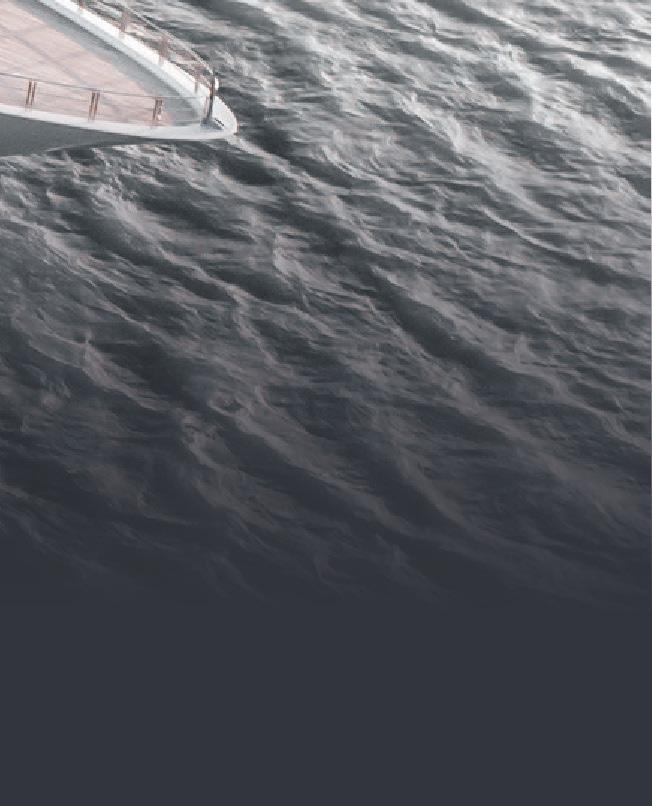

The Domus trimaran concept is certainly impressive. But does it make sense?

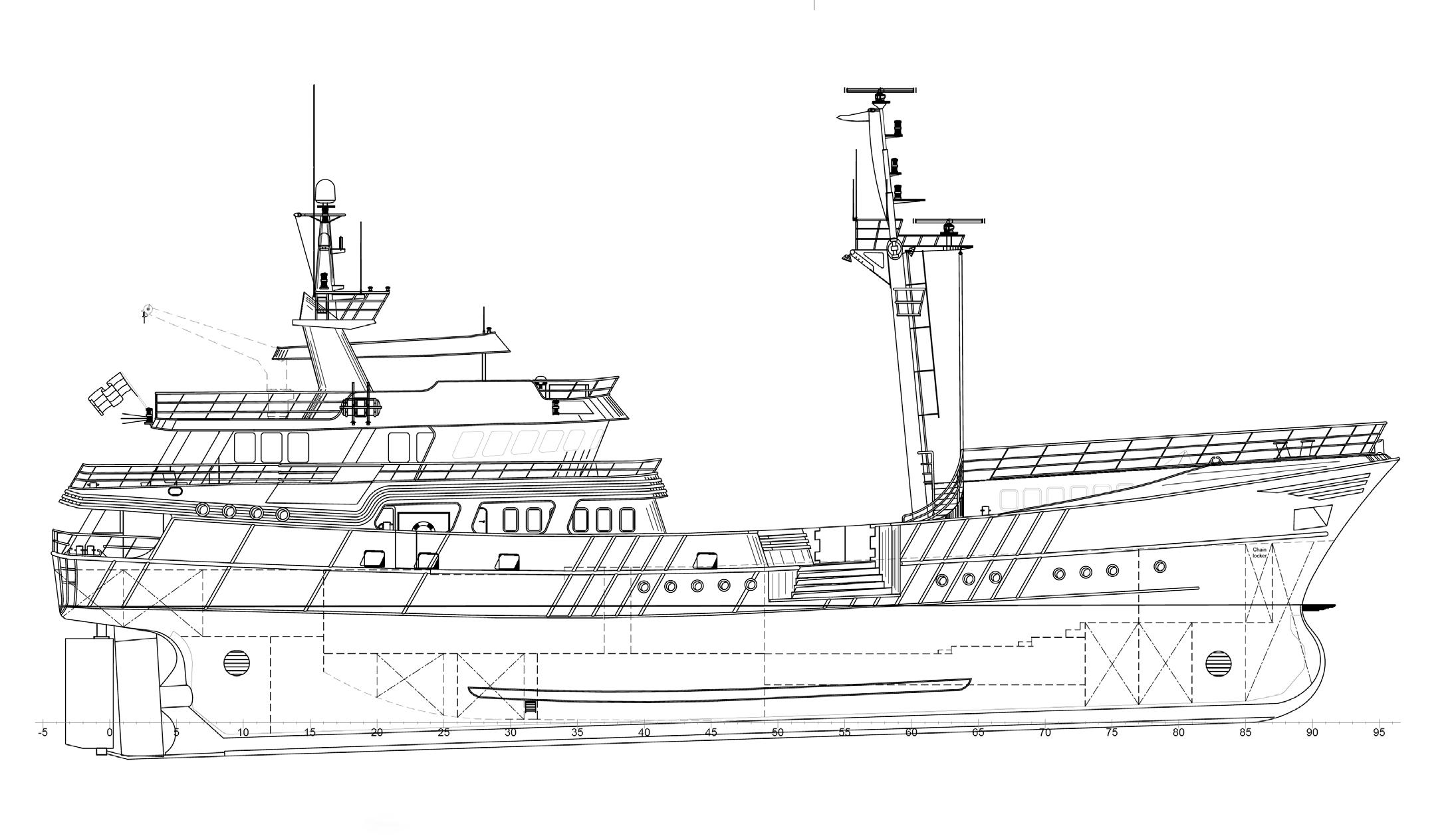

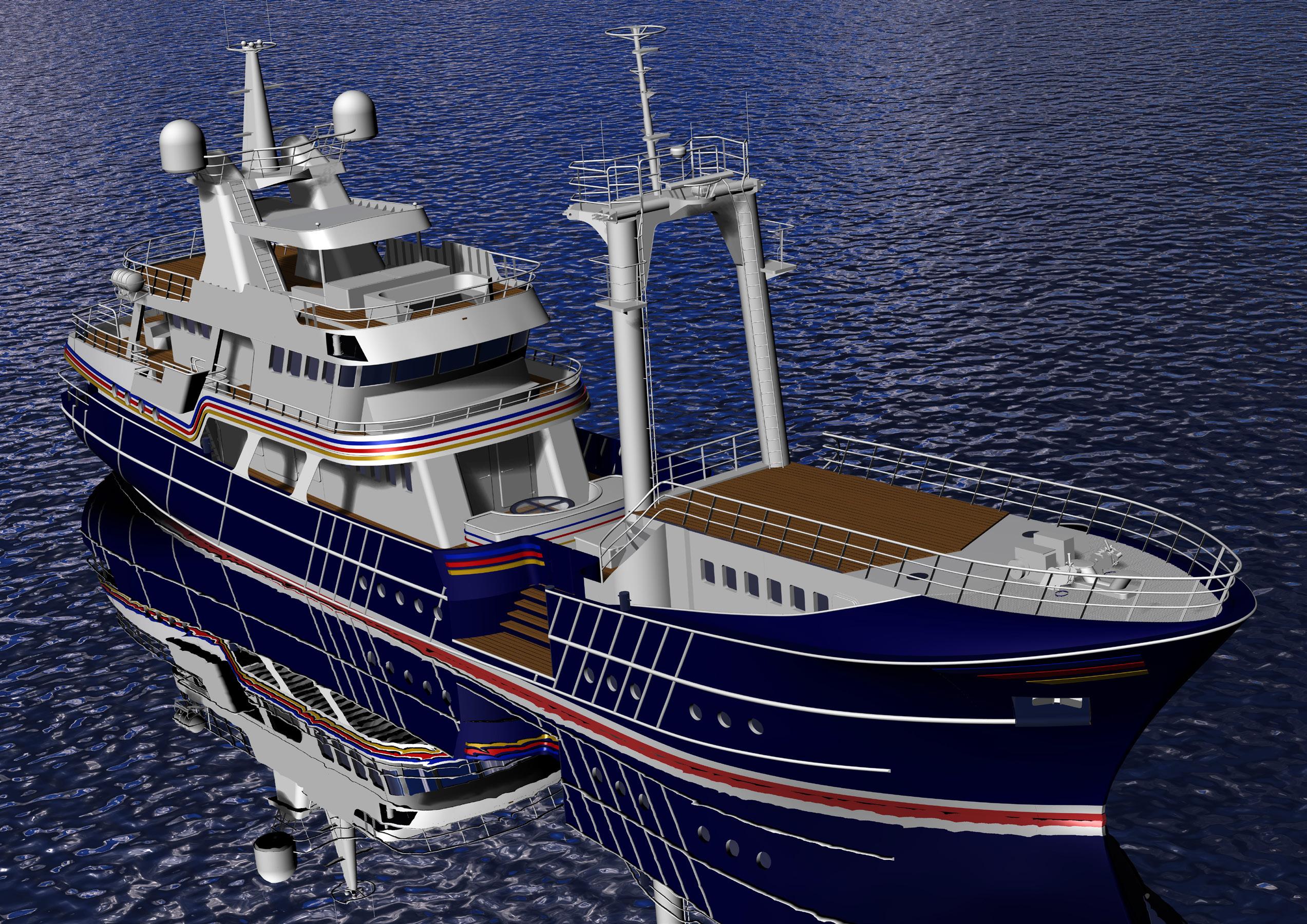

Fourteen years after building started in Chile, 85-metre Project X is completed in Greece.

We

Transforming

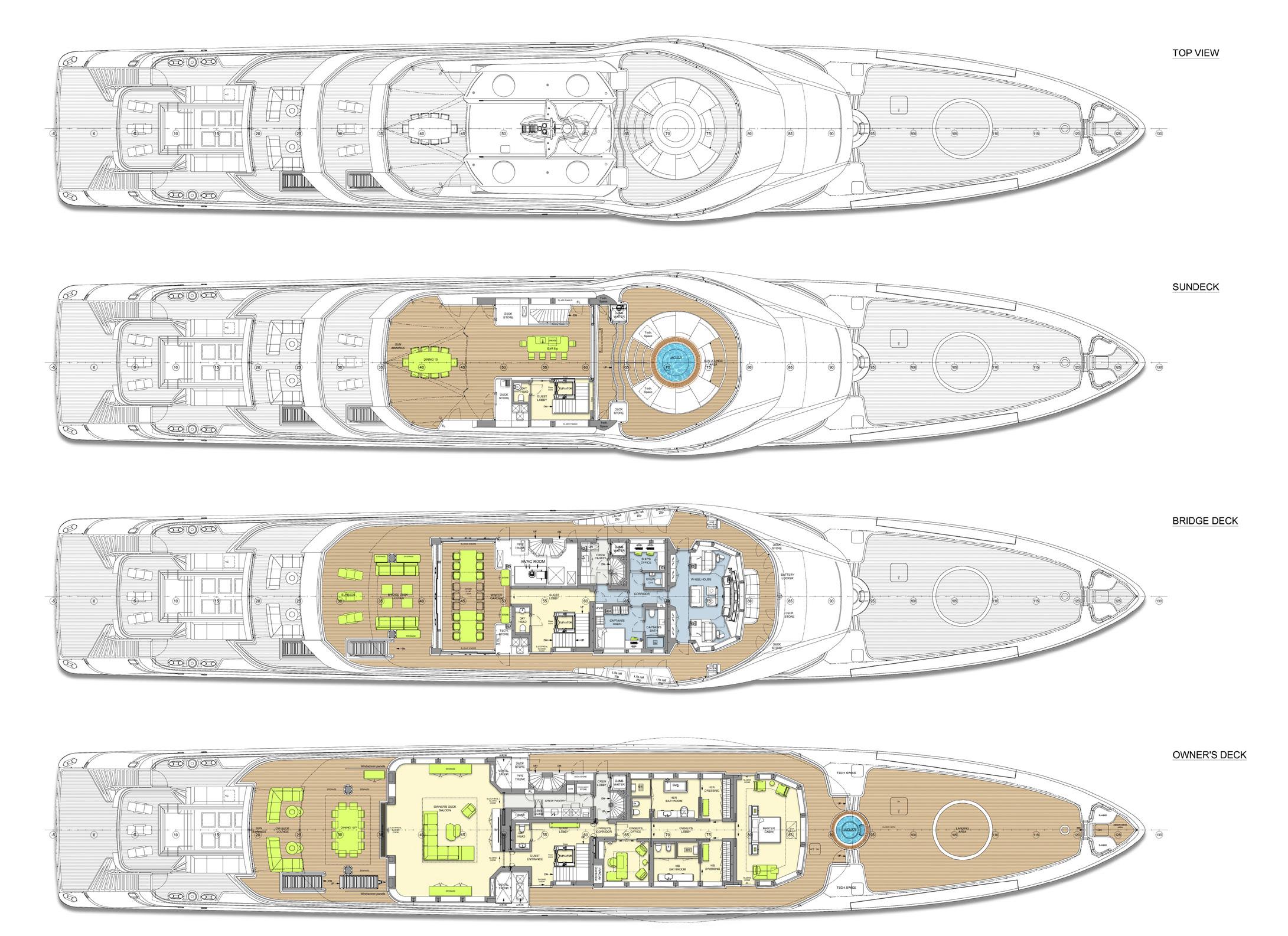

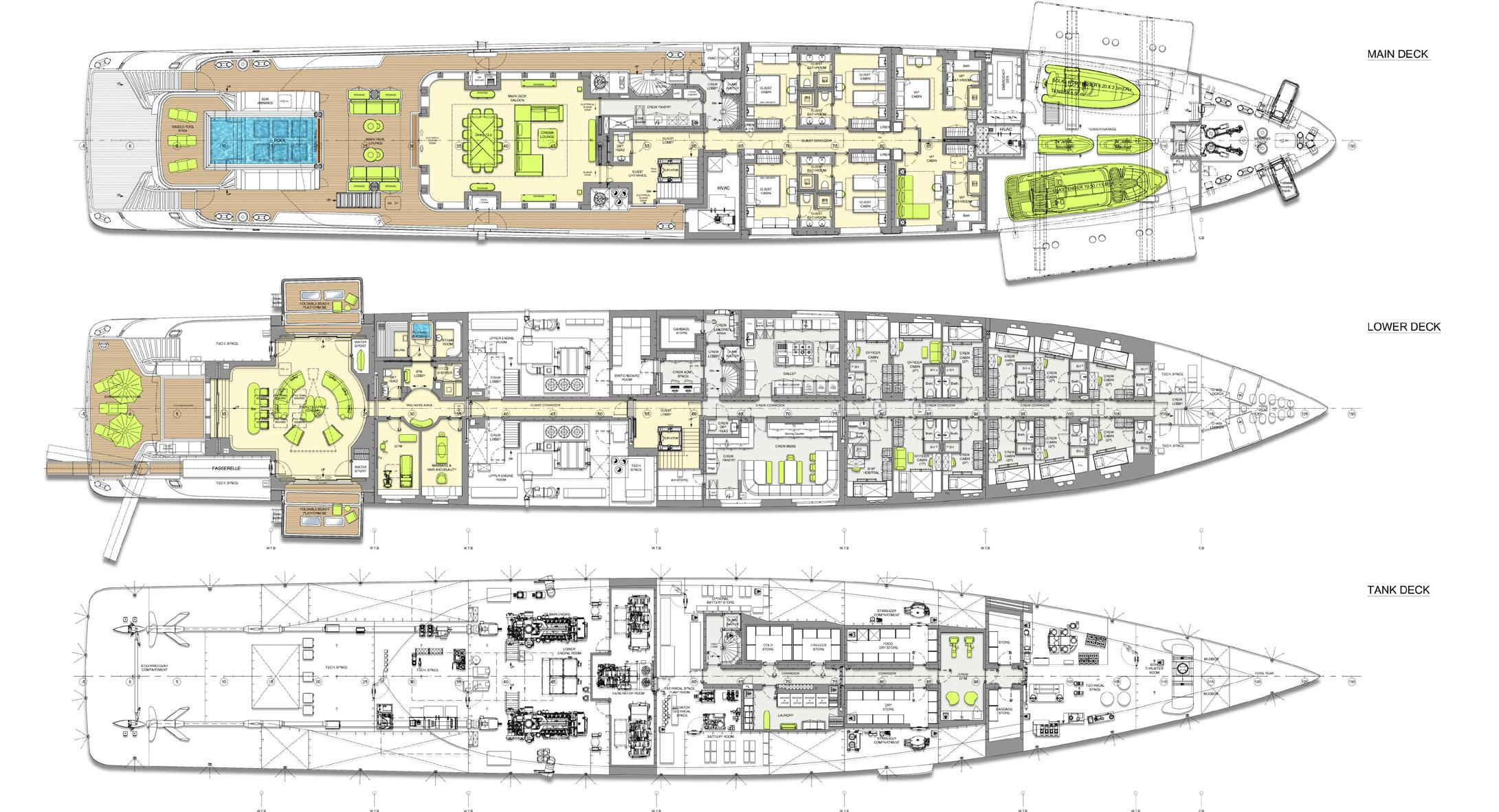

An in-depth study of how the new Amels 80 evolved from initial idea to the final design.

Sustainability: Fuelling Change

Do renewable fuels offer the most immediate sustainability solution for the superyacht fleet reliant on diesel?

Supply Chain: Lean Times

A word with Matthew Francis, supply-chain director at Sunseeker.

A panel of industry experts determine whether a 100-metre sloop is

or even desirable.

For generations, we have been realizing the most extraordinary living spaces with dedication and expertise. On water and on land. As a leading international partner in interior+ outfitting, we turn visions for living into reality – for both indoor and outdoor areas.

We are crafting visions.

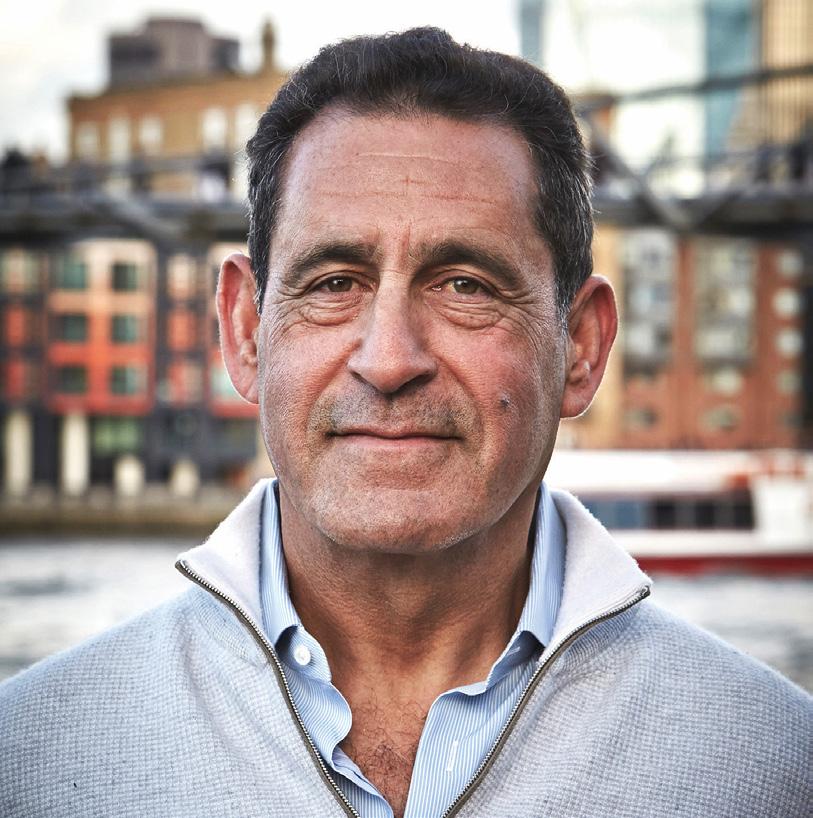

I’ve always been fascinated by the hugely complex business of building a superyacht and how the inkling of an idea in someone’s head is transformed into a finished vessel on the water. In fact, I much prefer investigating that creative and industrial process than writing formulaic descriptions of the completed yachts, and I’m happiest when at the shipyards talking to the naval architects, project managers and production teams.

So you could say the role of Editor of How to Build It is the perfect job for me!

It takes weeks instead of years, but launching a new magazine is not unlike building a yacht on speculation. You have to establish a brief based on your target audience; define the contents and gather a team able to provide that contents (and believe me, there are very few technical journalists writing about superyachts); create a graphic design and layout; and finally put it all into production and deliver the product on schedule. It is an exciting and sometimes exhausting process with plenty of challenges along the way that require patience and compromise to resolve: interviewees are unreachable, hi-res images are unavailable, deadlines have to be stretched, top stories shelved and replacements found at short notice, and so on. But teamwork and a little midnight oil get you there in the end in a scenario that will be familiar to anyone who has working experience of the last 24 hours on a new-build before delivery.

I hope you enjoy reading this first issue of How to Build It and learn something useful from its contents, which is the whole point of the exercise. This is the custom prototype, if you like. Drawing on your comments and feedback, in subsequent issues we fully intend to tweak the design and optimise the specs to establish a proven platform for the industry.

Justin Ratcliffe - Editor

IT IS MORE THAN JUST GLASS.

EDITOR IN CHIEF

EDITOR | HOW TO BUILD IT

EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTOR

EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTOR

EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTOR

FEATURES WRITER

JUNIOR WRITER

TRAVEL WRITER

CONTENT CREATOR

VIDEOGRAPHER

SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER

Francesca Webster

Justin Ratcliffe

Charlotte Thomas

Phil Draper

Georgia Tindale

Alexander Griffiths

Sophie Spicknell

Jessamie Rattray

Ruben Griffioen

Muaz Abourched

Mieke Koen

DESIGN PRODUCTION

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

GRAPHIC DESIGNER

UI/UX DESIGNER

DESIGN INTERN

Ivo Nupoort

Sean Otto

Claudia Sabbadin

Raja Khilnani

HEAD OF INTELLIGENCE

RESEARCH ANALYST

DATABASE MANAGER

DATABASE MANAGER

YACHT HISTORIAN

Ralph Dazert

Adil Zaman

Vicky Linardou

Léandre Loyseau

Malcolm Wood

SALES & ADVERTISING

SENIOR SALES MANAGER

SALES MANAGER

SALES MANAGER

CLIENT SERVICES MANAGER

SALES & MARKETING SUPPORT

Marieke de Vries

Justus Papenkordt

Molly Eve

Johanna Borreli

Jochem Eenkhoorn

FOUNDER & DIRECTOR

TECHNOLOGY DIRECTOR

FINANCE DIRECTOR

Merijn de Waard

Fabian Tollenaar

Laura Webber

SuperYacht Times B.V.

Singel 260, 1016 AB, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

31 (0) 20 773 28 64 info@superyachttimes.com www.superyachttimes.com

Sales Italy: info@admarex.com

Cover Images

Project Illusion photo by Justin Ratcliffe

Project X by Studio Reskos

Technical drawing by MB92

How to Build It is published by SuperYacht Times B.V., a company registered at the Chamber of Commerce in Amsterdam, The Netherlands with registration number 52966461. The magazine was printed in September 2022.

SpaceX, the spacecraft engineering company founded by Elon Musk, has entered the superyacht sector with a satellite internet service.

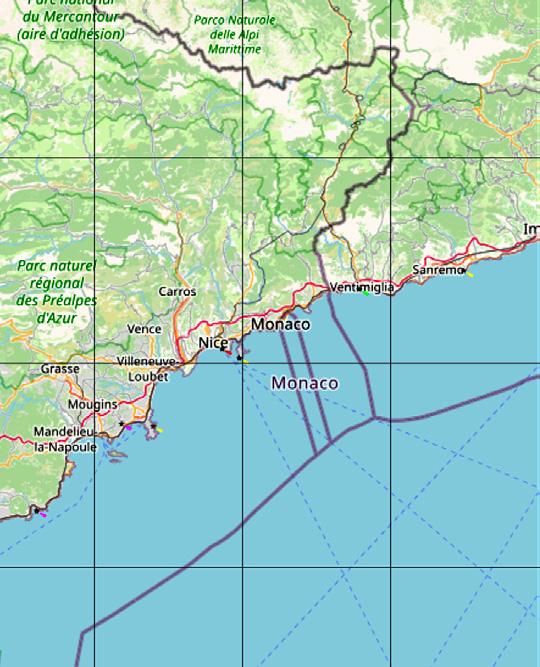

The venture is being spearheaded by the subsidiary Starlink Maritime and the objective is to improve internet speeds onboard yachts around the world. SpaceX claims that the service will allow yachts “to connect from some of the most remote waters in the world, just like you would in the office or at home,” with super-fast download speeds of up to 350 Mbps. Coverage is currently patchy and limited to the Mediterranean and the coast of the Americas and Australia, but this will soon change. Starlink Maritime has a roadmap in place for world-wide coverage, across all bodies of water, by 2023.

Starlink Maritime hardware bears a small footprint, demands minimal above deck space, and comes with an easy-to-install mount,” says SpaceX.

The Esaom Cesa shipyard and marina in the city of Portoferraio on the Mediterranean island of Elba has a new, fully adjustable 880-tonne travel lift for the maintenance, repair and refitting works of visiting yachts. The travel lift was designed to have a slipway width of 14 metres and allows the hauling out of large sailing yachts without dismasting and the transportation of superyachts around seven hardstanding spaces.

The facility currently specialises in the storage, refit and repair of yachts up to 40 metres, but the installation of the new travel lift is the beginning of a phase of major restructuring for the historic Portoferraio shipyard.

“The travel lift represents a great leap in the quality of the services we can offer as we aim to be competitive in a market most requested by yacht owners,” says Umberto Buzzoni, chairman and CEO of Esaom Cesa. “Elba and its related industries will also benefit from our investment with the presence of captains and crews, who will be able to visit and get to know our beautiful island.”

Jennifer Rumsey, president and COO of Cummins has been appointed as CEO of the US-based powertrain manufacturing company. Tom Linebarger ended his term on 1 August as CEO and remains on the leadership board as executive chairman.

Rumsey is the seventh CEO of the 103-year-old powertrain company and the first female to hold the position. According to Bloomberg, “Rumsey’s promotion will bring the number of women leading S&P 500 companies to 34, adding back to the ranks after female leaders at First Republic Bank and Match Group Inc. departed earlier this year.”

Sizing Networks for Bandwidth & Enhanced Performance, Including 5G & Future-Proof LEO Satellite Broadband Solutions

• New Player – New Approach – New Performance

• Fastest Internet Speed – No Throttle – Global Coverage

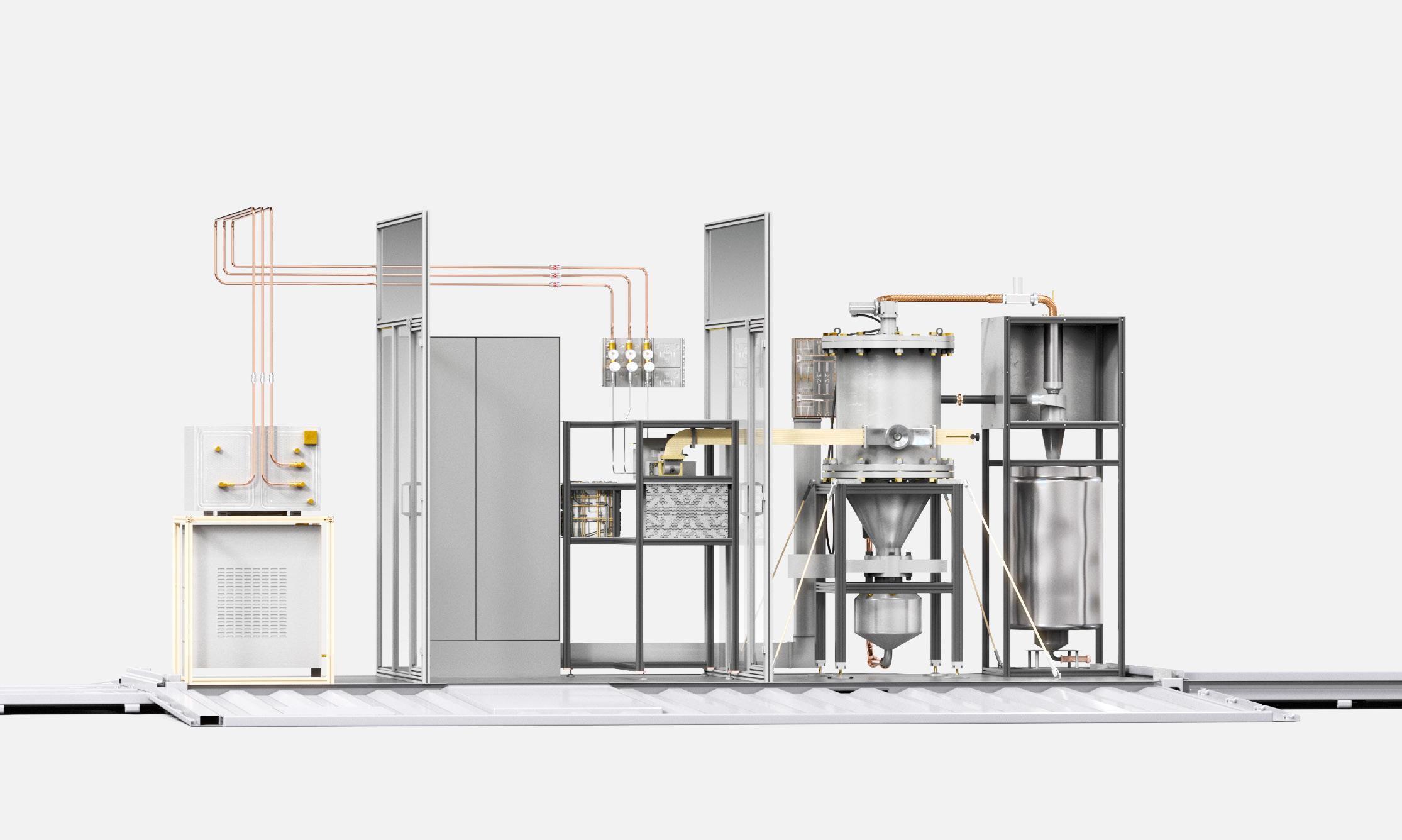

H2Boat has created the first self-producing hydrogen system that can be used aboard sailing and motor yachts. By bringing electrolysers on board, H2Boat has overcome a major issue: how to source hydrogen and opened new possibilities for how hydrogen fuel cells can be used on yachts.

“Yacht owners can find themselves in many different situations, many different countries where refuelling hydrogen is a problem,” says Thomas Lamberti, CEO of H2Boat. “ There currently aren’t any international regulations surrounding refuelling, so it becomes arbitrary with port authorities defining their own systems.

According to H2Boat, the best way to overcome the

issue is by bringing your own electrolysers on board, which can separate the hydrogen from oxygen in water, using a closed system: “The system requires water and electricity, both of which can be sourced everywhere,” he says. “With both of these elements, you can produce and re-charge your hydrogen system in a safe way on board your yacht.”.

H2Boat has overcome the challenges of low pressure through introducing methyl hydrates, which are able to keep hydrogen at a high-volume density under a lower bar storage system. This practical aspect is a core reason why Baglietto has opted for this system with its forthcoming B-Zero project.

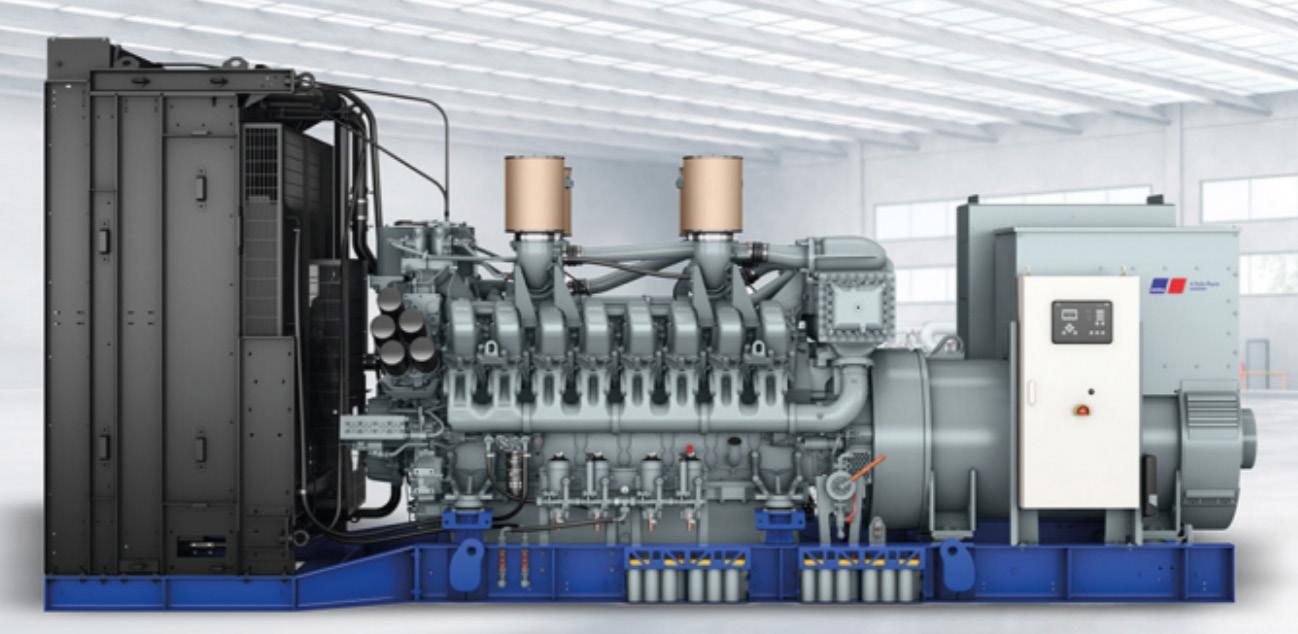

Rolls-Royce business unit Power Systems is entering the hydrogen production market. Innovative technology from German electrolysis stack specialist Hoeller Electrolyzer, in which Rolls-Royce has acquired a 54 percent stake, will form the basis of a new range of MTU-branded electrolysers.

The move is part of the company’s transition from engine manufacturer to provider of integrated sustainable solutions and could play an important role in its efforts to make the shipping industry greener with climate-neutral MTU power generation and propulsion solutions.

“Hydrogen is a key power source for the global green energy transition,” says Armin Fürderer, Director Hydrogen Solutions at RollsRoyce Power Systems. “It can be used in fuel cells, hydrogen engines and in the production of climate-friendly sustainable fuels. With our high-performance MTU electrolysers we’ll contribute to making the necessary hydrogen infrastructure a reality, enabling climate-neutral hydrogen-based operations in all applications.”

Development work on the first MTU electrolyser using a polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) stack from Hoeller is already under way.

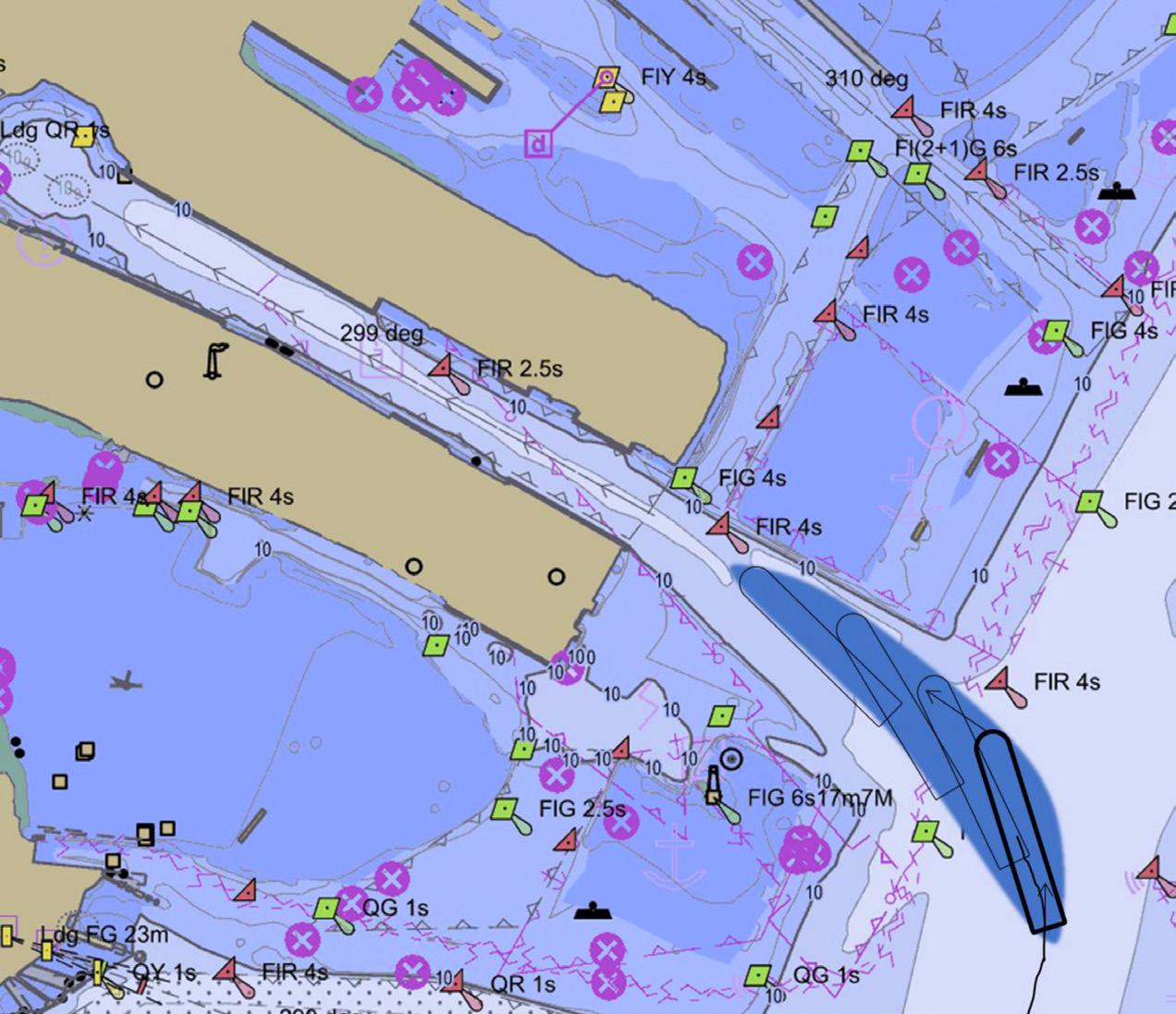

The UK Hydrographic Office (UKHO) has said it will stop its paper chart production by late 2026 to increase focus on digital navigation products and services. Plans to withdraw the UKHO’s portfolio of Admiralty Standard Nautical Charts (SNCs) and thematic charts are in response to more marine, naval and leisure users primarily using digital products and services for navigation. “The decision to commence the process of withdrawing from paper chart production will allow us to increase our focus on advanced digital services that meet the needs of today’s seafarers,” says Peter Sparkes, chief executive of the UKHO.

The move to digital navigation solutions has been accompanied by a rapid decline in demand for paper charts, driven by the SOLAS-mandated transition to ECDIS and the wider benefits of digital solutions, including the next generation of navigation services. UKHO stated in its release that “Admiralty Maritime Data Solutions digital navigation portfolio can be updated in near real-time, greatly enhancing safety of life at sea (SOLAS).”

Shipyard Supply Co., sister company of Superyacht Tenders and Toys, released its Compressed Air Hover Chocks that allow for full 360-degree movement without the need for heavy lifting.

Space is at a premium on most yachts and when you have a large number of tenders and toys, your storage area can quickly become crowded, making manoeuvring items problematic for crew.

With the air pressure engaged, the chocks hover at 5mm above deck, allowing movement of the tender or jet ski by hand. When you want to stop hovering, an air shut-off valve can be operated, lowering the chocks safely back onto the deck, dispelling the need for complex locking wheels and tie-down points.

The hover chocks make manoeuvering heavy tenders and toys effortless and only two people are required to operate the chock system.

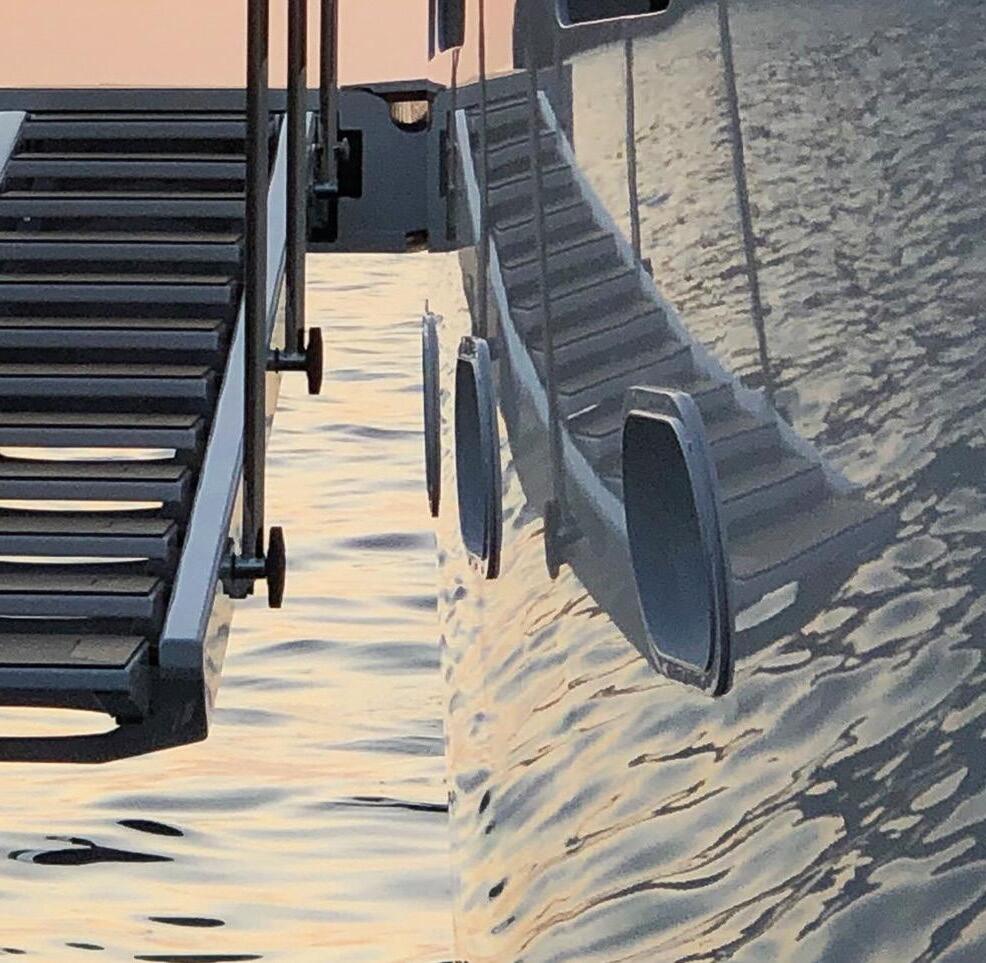

The Italian company Besenzoni is showcasing a wide range products at the Cannes Yachting Festival, including the multifunctional LP 100 plus ladder/boarding platform.

The LP100 PLUS ladder/boarding platform a product designed to help guests make the most of the area. Its principle function is that of a bathing or boarding ladder, but it can also be used as an extension to a sunbathing platform, and a tender lift. Its operation incorporates a hi-lo movement with a retractable hydraulic platform to extend the last step, for easy quayside access. The new product can be seen in action on the new Nerea NY40 Cosmo.

Also on display are LaPasserella and the SalpaAncora in Besenzoni’s BeElectric range, the new series of electrically powered components featuring new styling and more eco-friendly electric technology.

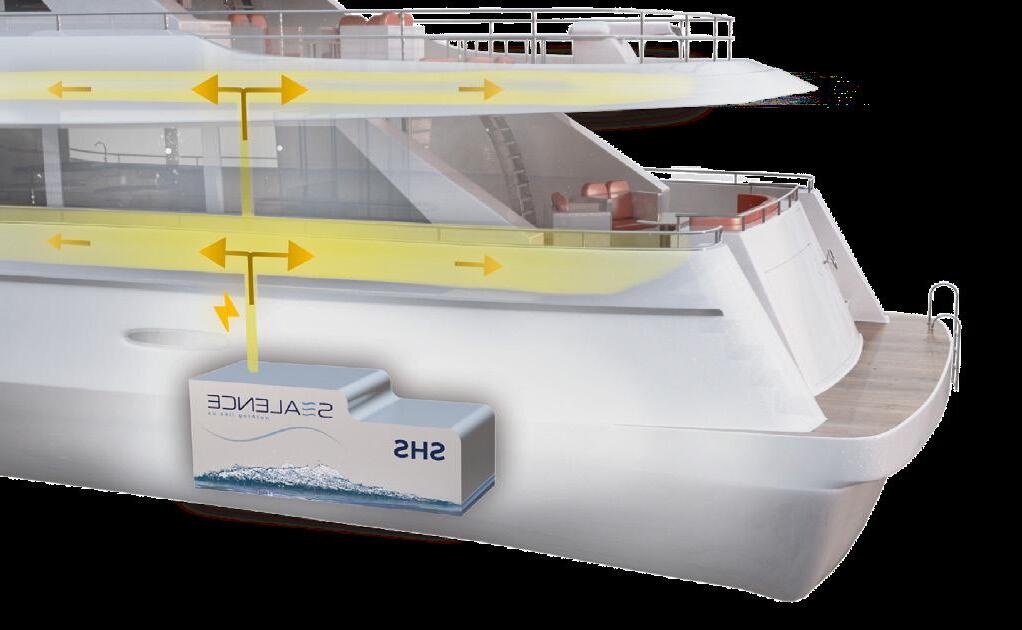

Sealence, that designed and engineered the innovative outboard jet propulsion DeepSpeed, has launched an all-new hotel system, which guarantees at least 12 hours of silent green energy with only 20 minutes recharge to power all hotel services of yachts of 24-30s.

The Sealence Hotel System (SHS) is offered in three size iterations – 80, 160 and 320 kWh – and promises zero vibrations, noise or pollution from its fuel cell system. “Our plug-and-play system replaces onboard generators, which need to run continuously, with a more efficient unit that can deliver the same amount of energy but only requires 20 minutes of charging time,” says Giorgio Caviglia, Engagement Manager and Special Projects at Sealence.

With saftey in mind, its power banks are fireproof, RINA/DNV-GL certified and can be easily retrofitted and integrated.

“Sealence wants to take part in the energy transition process, and to the electric mobility marine scenario, by proposing the first complete turnkey full electric-hybrid powertrain, based on its revolutionary electric jet propulsion technology,” says Caviglia. “Water should be the only footprint you leave behind.”

HP Watermakers

HP Watermakers will present two key products at the Cannes Yachting Festival 2022: Part-NET 2.0 and MWT Basic. Part-NET 2.0, which allows you to comfortably manage the watermaker from the onboard plotter, retains all the innovations of the previous model, but adds more flexibility and functionality thanks to the customisation possibilities and a very intuitive graphic interface.

Milan-based HP Watermakers was the first company on the market to develop its own interface, Part-NET, which is fully compatible with the on-board electronic systems of leading brands such as Raymarine, Garmin, Furuno, Simrad, B&G and Lowrance. Part-NET allows the user to control the entire desalination system, including pressure and all other operating parameters, without any manual intervention required.

“Boats spend up to 85 per cent of their time in a marina taking water from the quay, which often contains a high quantity of calcium and magnesium that can lead to the build-up of limescale,” explains company founder Gianni Zucco. “That’s not just a problem when it comes to cleaning the boats, but also because it can clog pipes and pumps, shower and toilet systems, tanks and the limestone. The added cost and downtime for maintenance can be significant.”

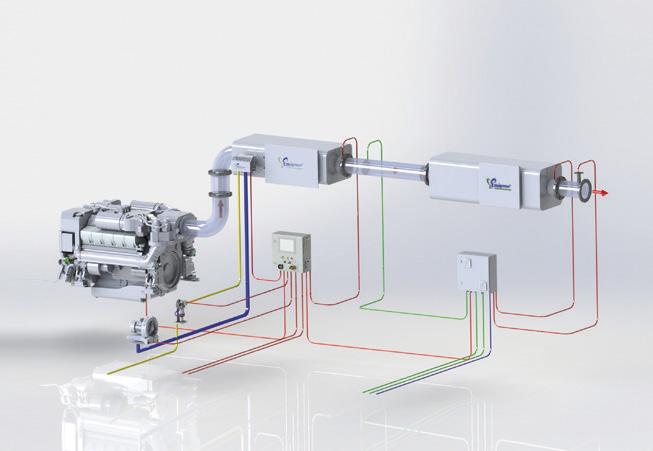

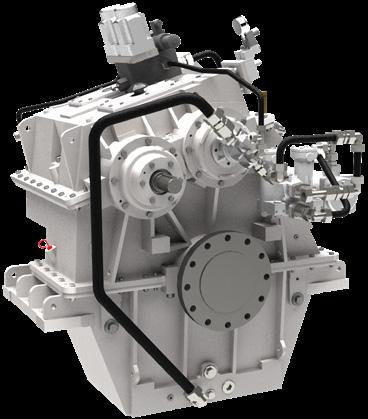

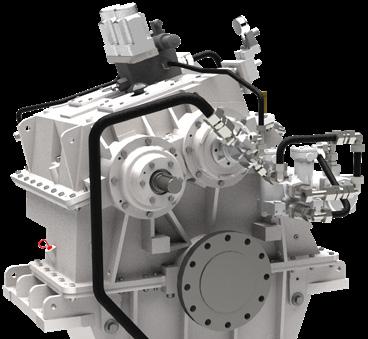

With a prototype under development and a patent pending, Quantum is introducing a new state-of-the-art, hydraulic/ electric power system, the F45 Hybrid, that uses the best attributes of both power sources. It is efficient, quiet and does not generate heat and it offers smooth power and requires 60% less power than a standard system. The F45 Hybrid boasts up to 60% greater efficiencies, only consuming the energy as required, when required. This efficiency is partially due to the elimination of control valves in exchange for a servo motor.

Electric fin stabilizers on larger vessels (60m+), become cost prohibitive due to the prices associated with gear boxes and servo motors. Electric fins with gear boxes must be designed to handle slamming loads which is easier for hydraulic systems to handle with the relief valves. The new F45 Hybrid uses a high dynamic servo motor coupled to a low inertia hydraulic pump, that directly moves the hydraulic fluid in a closed loop to sweep the fin. This greatly simplifies the overall system and removes all the components that make the hydraulics inefficient.

This new technology is a major game charger for the marine industry. The F45 Hybrid - hydraulic/electric solution meets both the long-term energy efficiency requirements and the peak transient energy needs of the closed marine electrical system. The system will be available in June 2023.

The UK-based furniture-maker is renowned for its custom-designed and meticulously built interior pieces. At Monaco Yacht Show the company is showcasing a brand new collection of outdoor furniture created from progressive materials. The collection comprises seven innovative finishes, and the Maze Coral Rise & Fall Table – the first piece from Silverlining’s Sea + Shore range of dedicated outdoor furniture, the result of 18 months of R&D. “Challenging our team to test the limits of contemporary furniture-making, we have developed new concepts for harsh, outdoor environments” says Jim Birch, Silverlining’s head of design. “Throughout we have incorporated sustainability into one-of-a-kind craftsmanship. In developing this collection, we have re-invented techniques, synthesising cutting-edge technology with traditional materials.”

The five tabletop designs, inspired by marine life’s patterns and textures, come in various shape, base and height configurations. The dining and coffee table designs have a telescopic base for easy transitions from daytime dining to evening entertaining. They are available in a total of 210 combinations, including finishes such as hand-shaded wood marquetry and lacquer ombré patterns, intricate two-tone lacquer work, ‘intaglio’ etched stainless steel, and sand-carved polished cast art-glass.

A selection of significant new-build projects at early stages of construction that present opportunities for OEMs, suppliers and subcontractors.

LENGTH: 51.5-metres

BUILDER: Tankoa

COUNTRY OF BUILD: Italy

DELIVERY YEAR: 2025

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Vitruvius

EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Vitruvius

INTERIOR DESIGNER: FM Architettura

Vitruvius Yachts signed the contract for the Vitruvius 10 in April 2022 with Phillipe Briand, head of Vitruvius Yachts, at the helm of the project. The owners requested a large sundeck and plenty of interior space. She will sleep up to 10 guests across six staterooms and be equipped with a hybrid propulsion system. The project will be managed by Albert McIlroy of Optimus Navis.

LENGTH: 47-metres

BUILDER: ProMarine Yachts

COUNTRY OF BUILD: Greece

DELIVERY YEAR: 2026

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Alpha Marine

EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Alpha Marine

INTERIOR DESIGNER: Alpha Marine

In April 2022, Alpha Marine Ltd - Yacht Designers & Naval Architects announced they would be starting construction on a diesel-electric superyacht under the new firm ProMarine Yachts. The semi-custom yacht has the option for different interior layouts with either a five or six stateroom configuration.

LENGTH: 65-metres

BUILDER: RMK

COUNTRY OF BUILD: Turkey

DELIVERY YEAR: 2025

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: RMK Marine and ER Yacht Design

EXTERIOR DESIGNER: ER Yacht Design

INTERIOR DESIGNER: ER Yacht Design

RMK Marine was awarded construction of the go-anywhere explorer in April 2022. The flagship polar explorer has accommodation for up to 12 guests and 20 crew members. She has a library, sauna, gym, beach club, massage room and a medical centre. She will also be one of the few yachts to be classed Polar Code Category B – Ice Class PC 6.

LENGTH: 72-metres

BUILDER: Wider

COUNTRY OF BUILD: Italy

DELIVERY YEAR: 2025

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Nauta Design

EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Nauta Design

INTERIOR DESIGNER: Unknown

Nauta and Wider announced the sale and start of the construction of a steel and aluminium superyacht in May 2022. The yacht will be equipped with the Wider hybrid propulsion system comprising two variable-speed generators of 1,860 kilowatts each and a sodium nickel battery bank of approximately 1MW.

LENGTH: 33-metres

BUILDER: Tactical Custom Boats

COUNTRY OF BUILD: Canada

DELIVERY YEAR: 2025

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Gregory Marshall

EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Gregory Marshall

INTERIOR DESIGNER: Unknown

The NFT of the Tactical 110 was minted on Opensea on March 10, 2022, and is believed to be the first verified NFT yacht sale transaction on the Ethereum Blockchain. The build of the 33-metre yacht is now underway and is expected to take around 36 months and cost around $12 million USD.

LENGTH: 70-metres

BUILDER: Permare

COUNTRY OF BUILD: Italy

DELIVERY YEAR: 2026

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Permare

EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Optima Design

INTERIOR DESIGNER: Luxury Projects

The first Amer 70 Steel superyacht began construction in Tuscany, Italy, in June 2022. The fully-custom design is for a European client and will see Giulio Riva contribute his thirty years of experience in the steel industry to the project as the Director of Works and Quality Control.

LENGTH: 84.9-metres

BUILDER: Royal Huisman

COUNTRY OF BUILD: The Netherlands

DELIVERY YEAR: 2026

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Frers Design

EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Frers Design

INTERIOR DESIGNER: Wetzels Brown

The Dutch shipyard announced the sale of the ‘world’s largest sloop’ in March 2022 at the St Barths Bucket Regatta. Being built for an experienced owner, her massive carbon mast, boom and sail system will be designed and produced by Royal Huisman’s sister company, Rondal.

LENGTH: 52.5-metres

BUILDER: Alia Yachts

COUNTRY OF BUILD: Turkey

DELIVERY YEAR: 2023

NAVAL ARCHITECTURE: Azure

EXTERIOR DESIGNER: Azure

INTERIOR DESIGNER: Unknown

On 12th July 2022, Alia announced that the Alia Sea Club had been sold. The yacht will carry an array of tenders and toys, as well as feature a fully certified helipad on her aft deck. She will also accommodate as many as 10 guests and a crew of 12.

Meet us at Monaco Yacht Show, booth DS | Darse Sud Fort Lauderdale Intl. Boat Show, German Pavilion Metstrade, booth . | SuperYacht Pavilion

The revolutionary, fully electric stabilizers by SKF.

The future is electric – and so are our marine stabilizers. Profit from less installation costs, less noise, less vibration, more space and much more fun! Become % electrified now, no compromises!

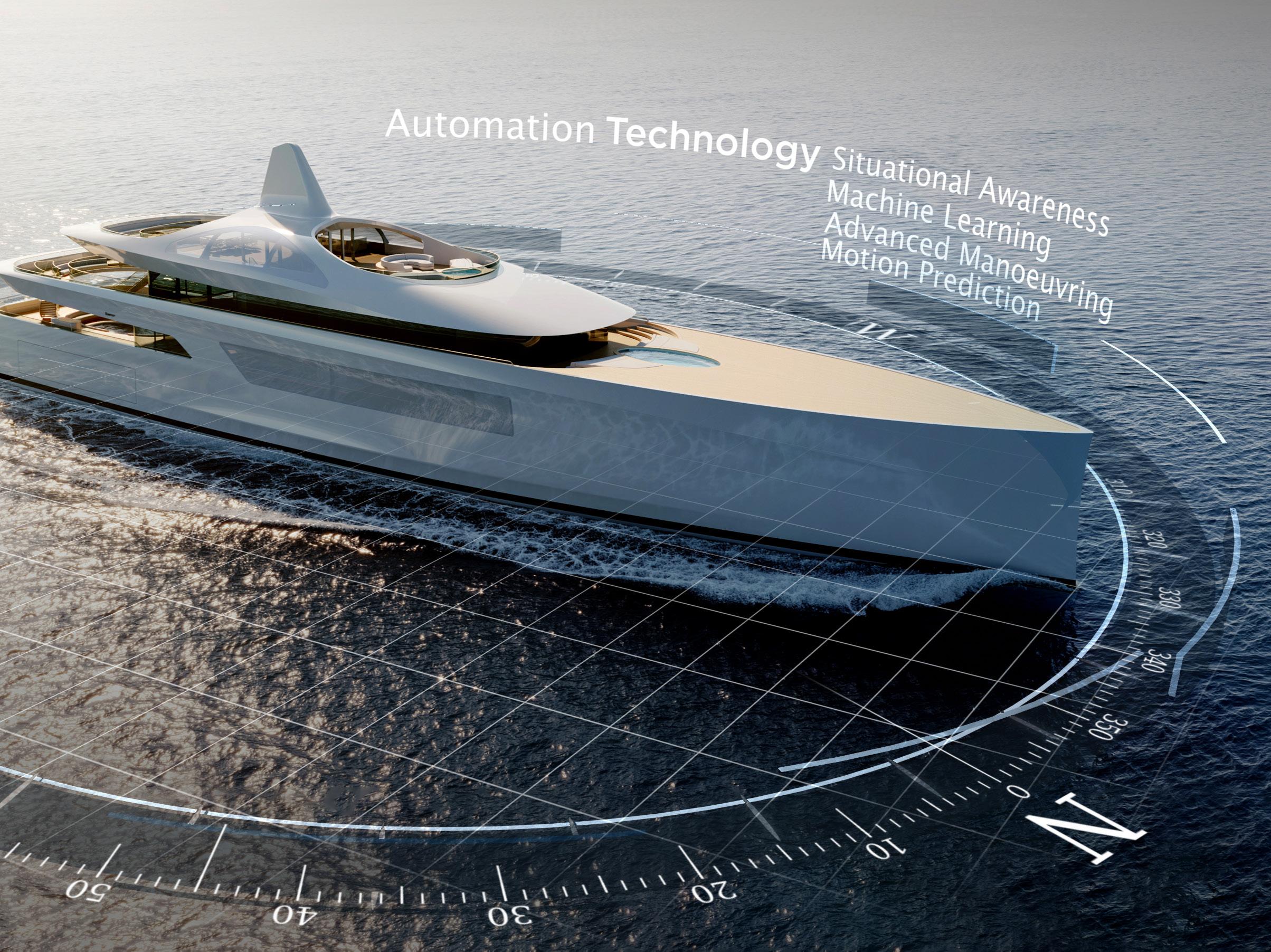

TEAM Italia has been a leader in the integration and optimization of navigation, telecommunications, security and data transmission for over 20 years. The company has delivered over 500 bridge designs, more than half of which are custom integrated I-Bridge® systems. We visit their new showroom in Livorno to take a closer look at the latest integration.

BY FRANCESCA WEBSTER

The conversation of automation is not new, often facing opposition from captains and owners who raise concerns about the safety and security of digitalising navigation. Over the course of the past decade, however, TEAM Italia has been quietly developing software to improve safety and usability. Its fully integrated i-Bridge integrated touch bridge series both looks good and simplifies vessel control by centralising automation within one system.

During the Monaco Yacht Show 2021, the company unveiled its latest I-Bridge® integration, the Dharma Next EVO and 3D, the result of an updated R&D version of its award-winning series that features a brand new Human-Machine Interface (HMI).

This year, 26 yachts with TEAM Italia consoles will be delivered, including the first Custom Line 140, flagship of the Ferretti Group series, equipped with the Onyx Marine (AMS) monitoring system, fully integrated into the I-Bridge®, as well as Navette 33, 37 and 42. In addition, TEAM Italia was entrusted by the Ferretti Group for two full custom projects for CRN, respectively 52 and 65 metres.

The Italian company is also collaborating with the prestigious Sanlorenzo Shipyard, helping to define and develop new and cutting-edge concepts for four yachts with LOAs between 40 and 70 metres.

TEAM Italia is also onboard the innovative “Tecnomar For Lamborghini 63” projects. Which have extremely sophisticated technological solutions specially developed for

this exclusive fleet announced in a limited edition, as well as on board the major TISG projects between 50 and 75 metres.

Like a standard bridge, the i-Bridge system is centralised at the helm station and operates the steering, propulsion and navigation of the vessel. However, TEAM Italia has integrated these functions with almost all other digitally operated systems aboard the yacht. For example, the i-Bridge is able to monitor and run diagnostic reports, offering the captain 3D diagrams of the systems that identify not only the issue, but also make recommendations for the solution.

“Unlike a fixed bridge, the i-Bridge offers unified controls from any desired sector of the vessel, which means that the controls can be accessed from wherever they are needed,” says Massimo Minellla, CEO of TEAM Italia. “Once a system has been integrated onto the control hub, the captain and crew can make a decision about where to view and control that system.”

While many vessels feature a fixed glass or foil bridge configuration, they have a number of limitations. The mechanical integration of the yacht’s control panel is often chosen during the construction of a vessel and therefore is specifically tailored to the original captain, owner or shipyard’s wishes.

Should the vessel’s management be changed, the modification of a mechanical integration requires the complete reconfiguration of the control panels, which can be

We are able to continually update the software remotely, which is more cost effective than having to manually replace systems.

a hugely costly and timely process. TEAM Italia’s automated and touch screen i-Bridge allows for remote reconfiguration and the fully integrated nature of the bridge means that all systems can be operated from each panel, rather than a fixed order of controls, as with a mechanical integration.

The concept of digitally controlled mechanics has raised concerns in the industry over safety in case of faults and software issues that may lead to damages. While the system is digitally controlled, should issues occur with the control of the vessel the i-Bridge can be mechanically overridden. In the case of software related issues, the TEAM Italia engineers are able to run remote diagnostics and, if necessary, access the system and solve the problem without having to board the vessel.

The obvious fears around the possible breach of privacy have also been assuaged. In order for a TI engineer to access the system they must follow a strict protocol and be admitted by the captain of the vessel. The digital system of the vessel is protected by a strong firewall, which prevents accessing any data unless explicitly permitted.

“The advantage is that we’re able to continually update the software remotely, which is more cost effective than having to manually replace systems as with a fixed glass or foil bridge,” says Minella. “Moreover, should there be a specific fault, the onboard engineer can replace the part and we can remotely programme it.”

The i-Bridge system is entirely customisable. During the production process, TEAM Italia works alongside the yacht designers, shipyard and owner’s team to identify and make recommendations for the best solutions for each vessel, offering up-to four separate stations, which can be arranged as per the desires of the owner’s team.

Once the specifications of the bridge have been determined, the system is pre-assembled at the testing facility in Livorno and the captain and owner is invited to test and trial the ergonomics of the setup. This allows for configuration development, both within the software and the stations themselves.

Already turning its mind to the potential of augmented reality, TEAM Italia is currently developing an AR system to aid in the operation of the technical spaces aboard vessels. This will allow its engineers to assist the onboard technical team in the location and repair of faults quickly and cost efficiently.

Superyachts aren’t just about size. They are as much about comfort, convenience and customisation as they are about scale. Even on the very largest vessels, perfection is a marriage of space-saving design with flawless sophistication. Much like moving into a new house, furnishing a yacht for optimal living is an ongoing process. No degree of personalisation in build can ever result in an entirely future-proofed yacht. And at any expense, why would you want it to?

Whether widening, heightening, extending, or optimising, the scope for enhancing a yacht is almost infinite. From transom fenders and custom-fit furniture to innovative storage solutions, tender whips, boarding options, tennis courts, football pitches, and bespoke awnings – if you’ve got the questions, we’ve got the answers.

Since 2018, our specialist team at Shipyard Supply Co. have been designing, manufacturing and fitting made-to-measure solutions for the finest superyachts worldwide. A dedicated design studio with the advantage of in-house manufacturing, Shipyard Supply Co. has built an enviable reputation as the industry’s leading producer of custom deck equipment.

Whether your starting point is an initial concept or a build-ready component, the team will walk you through every stage of consideration. Be it technical drawings, 3D renders, or photorealistic imagery, our designers will ensure your vision is seamlessly portrayed on screen or in print before advancing to manufacture.

Benefiting from a purpose-built facility, our design studio and production team work in complete unison. Employing the finest crafts-

manship in fibreglass, carbon fibre, stainless steel, marine-grade aluminium, hardwoods and more, we have unparalleled control of our processes from start to finish.

Achieving perfection in an environment at the mercy of the ocean presents complex challenges. Far beyond simply mitigating the impact of saltwater or inclement weather, our experienced team are pushing the boundaries of custom deck equipment, pioneering radical solutions to almost implausible scenarios.

Unperturbed by the structural limitations of a yacht, we excel not just in solving problems but in adding honest and tangible value. From effortlessly manoeuvring a 3-tonne tender in a low-ceiling garage to quickly and easily stowing and stacking jet skis, we strive to seamlessly marry usability with practicality.

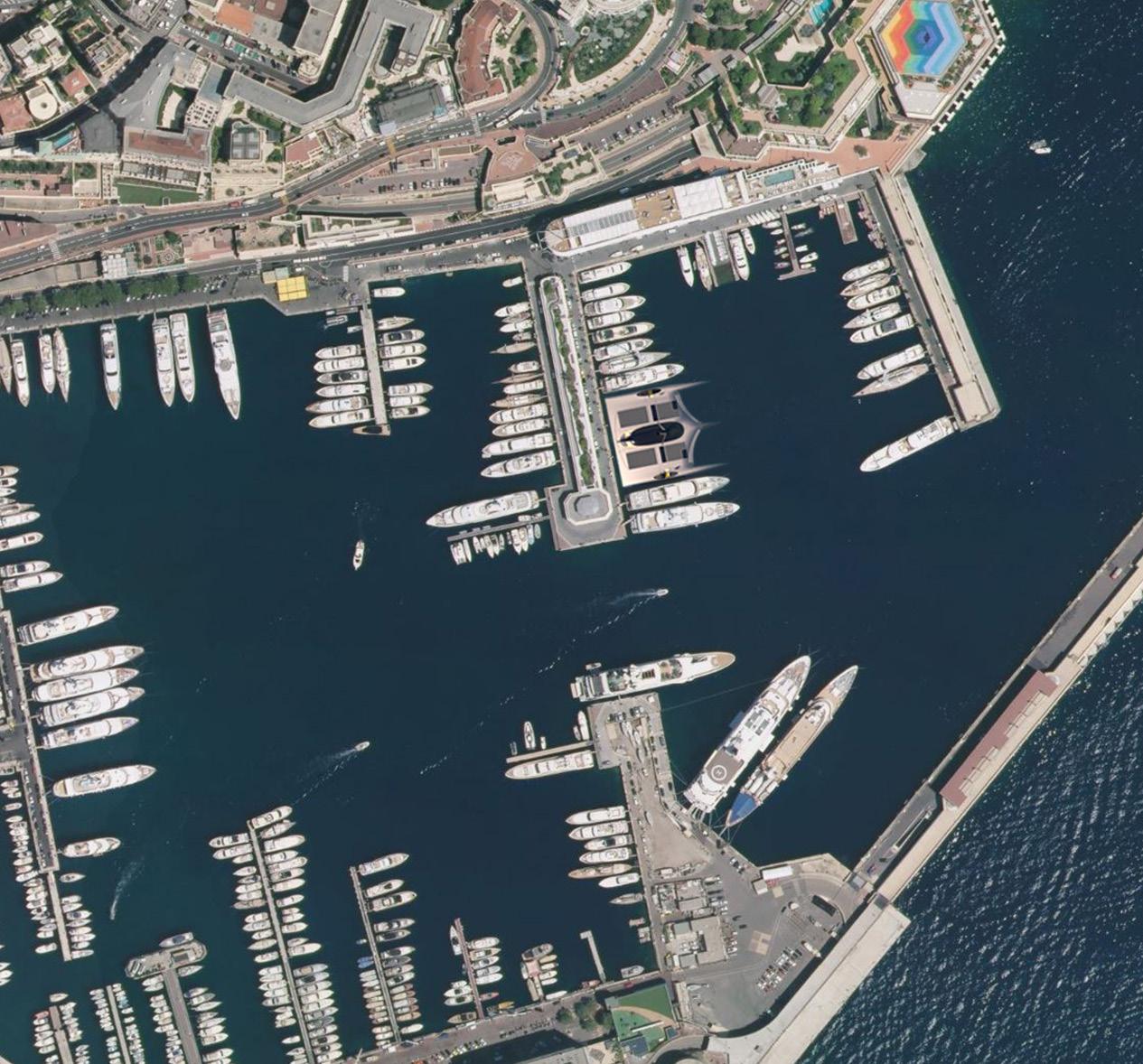

With an office and secure storage in Monaco, we have feet on the ground just a stone’s throw from Port Hercule. Identifying exemplary customer service as the trademark of our offering from day one, both our UK and Monaco teams always go the extra mile (nautical, naturally) in their pursuit of perfection. Shipyard Supply Co. has no affiliations with any materials suppliers and are solely committed to finding the most appropriate solution to any request. Able to cater for every project from individual components to large-scale assembly, the team is ready to bring your ideas to life.

Seable&Co is a new company that gathers together four other businesses with more than 80 years of combined experience in the specialist outfitting of superyachts. We catch up with CEO Willem-Jan Kuipers to discover more.

Willem-Jan Kuipers set up 4SeasonsSpa with business partner Rob Lauwen in 2005 to provide innovative and professional spa solutions for luxury hotels, spa centres and residential spaces. The firm pivoted into the superyacht world when it supplied two Jacuzzi systems aboard Feadship’s 78-metre Venus that launched in 2012. Since then it has worked with all the main Dutch and German shipyards.

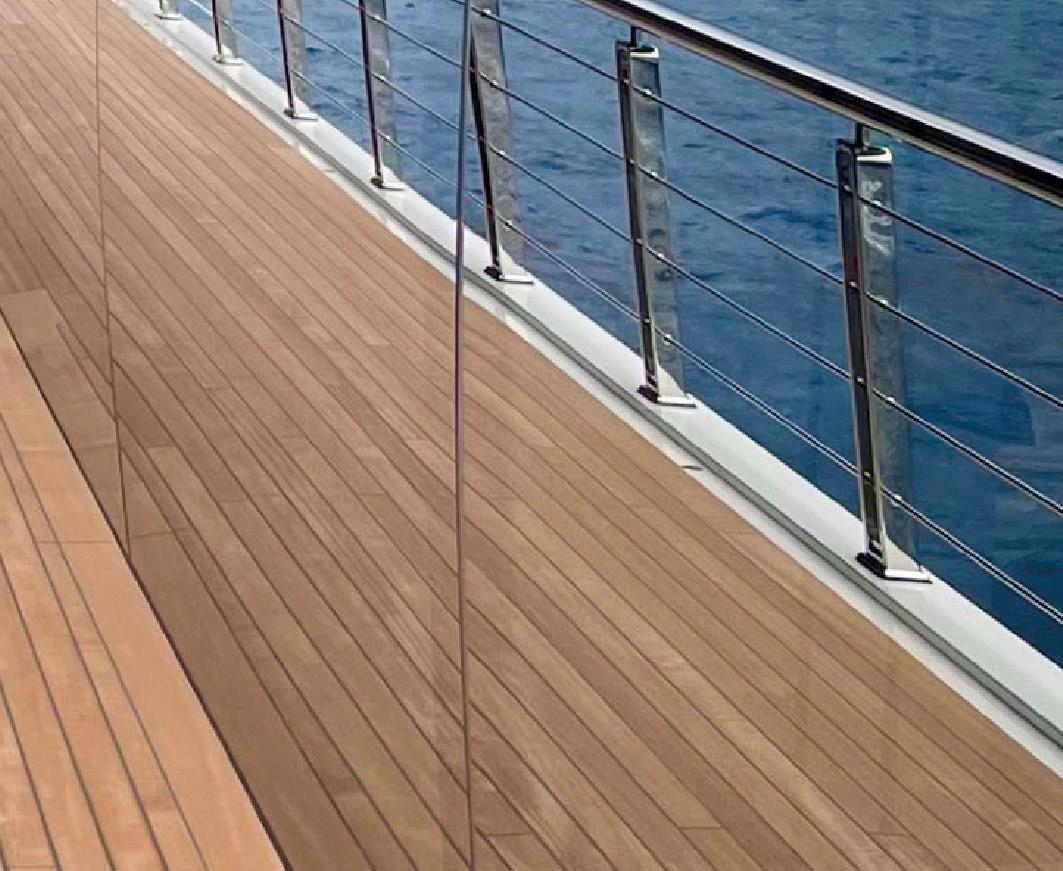

Stone Natural Class, a specialist in the production and installation of luxury stone products, was acquired in 2018. Bloemen de Maas, the supplier of bespoke exterior furniture, caprails and teak decking, joined the group a year later. Last but not, DTG is the group’s in-house innovations team that combines expertise from multiple disciplines with input from the sister companies.

Dennis Boerman, CFO; Jeremy Elschot, MD SeableStone and group commercial director; Pieter Piers, MD SeableWood and group operations director.

Under Seable&Co, these four original companies have been rebranded as SeableSpa, SeableStone, SeableWood and SeableStudio.

Why is now the right time to rebrand as Seable&Co?

It’s the last stage in a process that we’ve been building since the acquisition of Stone Natural Class and Bloemen de Maas. Together these companies share the same vision of craftmanship, innovation and collaboration, and we’re working on projects together more and more. It is now time to also evoke this shared vision and approach to our clients and the market and see our craftsmen operate as a true team.

Your first superyacht project was little more than a decade ago, but you now have around 50 projects under way. How do you account for this rapid expansion?

After we started with Jacuzzis onboard yachts, shipyards started asking if we were willing to take on a wider scope of responsibilities, including the stone, marble and mosaic work for both the exterior pools and interior spa areas. That led us to acquiring Stone Natural Class, which has worked with Heesen Yachts, Royal Huisman and Moonen

€20 MIL approx. Annual turnover

120 Group employees

50+ Current projects

200+ Completed yachts

for many years. Our conversations with shipyards continued on a strategic level and as the exterior areas became more important and more complex, they asked us if we would take on a full exterior outfit. And that led to the acquisition of Bloemen de Maas, which has been working with top Dutch shipyards for the past 40 years.

Where does DTG – now SeableStudio – fit into the equation?

It was formed as an internal start-up to further boost our in-house innovation. We saw there were quite a few innovations within our companies that were not really taking off, so the idea was to nurture those innovations to the point where they would be able to enter the market successfully and then bring them back to the operating company. A good example is a product we’re developing as an alternative for natural teak. It’s based on 60 percent teak dust from the production of furniture made from plantation teak, which is then mixed with recycled resins and other additives. We also decided to add a UV stabiliser so the product keeps its colour rather than fading like natural teak, because that’s the main reason crews sand the decks. The end result is a material that is 90 percent natural or recycled, requires less maintenance, lasts longer and is applied with the same skill as teak planking. The whole development and testing process was much more manageable in a separate business unit.

What proportion of your work comes through the shipyards or owners’ teams?

I would say 90 percent of our work is directly with the shipyards. But our exterior scope is

high on the agenda for owners, to the extent that for some it might even the main reason they buy a yacht in the first place. In this context, we usually talk to the owner’s team at a very early stage together with the shipyard. Some owners’ teams even contact us before selecting the yard, but nine times out of ten the shipyard is our client. I spoke of collaboration earlier and I see a lot of potential for improvements in these relationships in terms of creating efficiencies. Seable&Co was initiated by listening to clients and bringing together our different areas of expertise, whether it’s exterior or spa spaces. Each of the group companies takes about 50 percent of their work from projects that require two or more of our core disciplines. The other 50 per cent is still on an individual basis. I believe this is a healthy way of approaching the market that keeps every business unit very client focused.

How do you see the outfitting sector evolving, and Seable&Co. along with it?

We are experiencing quite rapid developments with bigger and more complex projects, but if you look at the industry a lot of the subcontractors in the industry have remained the same. You could argue that is a good thing and a sign they are competitive and in good health, but I’m not sure whether all of them can keep up with that complexity. Some companies are perhaps ahead of the curve, but there are far more smaller companies that are likely to have difficulty dealing with more complex projects in terms of contracts, project management, HR, the legal and financial side, and so on, which are all part of the industry growing and becoming more professional. This is the logic behind Seable&Co. By dealing with finance, HR and commercial strategy on a group level, we are basically providing a platform that helps deal with the complexity of projects on an operational level.

As for the development of the market, we see designers, owners and shipyards continue to ask for new features and finishes on board. Recent examples include outdoor firepits, a custom DJ-booth, an outdoor cinema and an artwall waterfall feature. The job of Seable&Co is to work across mediums to translate imagination into reality.

When it comes to helping an owner feel at home and comfortable on board his or her yacht, there are few that wouldn’t argue that the choice of interior and exterior furnishings is a key part of creating the desired onboard ambience. We speak to the experts at the German outfitting company Vedder to answer our burning questions about superyacht outfitting in 2022.

What are the main things you need to consider when designing, creating and installing furniture for yachts?

Moritz Schmidinger (head of project development): At Vedder, as we only focus on custom yachts, this means that every yacht is its own prototype. It is always an exciting challenge to realise and bring the design to life because you start from scratch with every project you do – we harness technology such as 3D engineering to help us assess how best to realise a project.

Another factor is the need to integrate so many different systems – audio, AC, sprinkler, electric and so on – and make them invisible. This is a complex process which needs to simultaneously fulfil all design requirements, safety aspects and also be functional for crew handling.

How much of your work is carried out in-house?

Nicolas Held (managing director): We offer a complete turn-key, in-house process, from the provision of samples, mock-ups and 3D engineering through to production, delivery and installation. We have our own assembly team and internal site managers, as well as experienced external fitters with whom we have worked for a long time. Excitingly, since 2022, we also now have our own metal branch, so we will be increasing manufacturing in-house here as well! At Vedder, we are characterised by a very high degree of prefabrication. This helps us reduce assembly efforts and, most importantly, enables us to carry out projects smoothly, execute them to the deadline and to the highest possible quality.

How do you decide which materials to use?

Christian Menz (head of exterior): As a company which is proud to have outfitted more than 5 percent of the 100 largest 60-metre-plus superyachts since we completed our first project in 1970. We profit from this long-term experience to help us select suitable materials that meet all design and customer expectations but also guarantee longevity. We achieve this by carrying out rigorous tests. Importantly too, since we cover both interiors and exteriors at Vedder, we are able to transfer our indoor flair to the outdoors – only the materials differ, for example, you might need to use waterproof materials like GRP or carbon fibre for the exterior.

How do you keep on top of changing client requirements?

Nicolas Held (managing director): We have a dedicated R&D department and we know how materials work, thanks to the wide experience which we have acquired over the years. Paired with leading innovations, this knowledge enables us to create unparalleled latitudes for designs that resist sun, wind and salt water. As just one example, we use environmental simulation tests in a time-lapse sequence to rapidly determine the effects of UV radiation and salt water, allowing us to optimise the materials we use and continually improve our end product.

Business has never been better for Omer Malaz, founder of Numarine. The Turkish brand celebrates its 20th anniversary this year having repositioned itself as a builder of highquality, value-for-money trawler-explorers.

BY PHIL DRAPER

“Ten years or so ago the average size boat we were building was less than 20 metres and all our models were mainstream – composite planing designs, a mix of hardtops and flys,” says Omer Malaz, owner and CEO of Numarine near Istanbul.

“Although we were a relatively small boutique brand, our principal competitors back then were always the big players like Azimut, Princess and Sunseeker.”

Today, the shipyard’s average delivery is more like 27 metres and it is series building nothing but trawler-explorers in composite and steel. Its competitors now include the likes of Horizon and OA in Taiwan, Sirena in Turkey and Cantiere delle Marche in Italy.

“It’s a strong, growing corner of the market and we’ve been very lucky to be in the right place at the right time,” says Malaz rather modestly.

Malaz is clearly enjoying himself, which is important. He started Numarine because he loved boats and grew up boating with his family. The passion drives the man and the business and for the past two decades his own yachts have been literally of his own making. Few yard owners spend as much time afloat as Malaz and fewer know their products as well.

The way Malaz’s own boating tastes have changed over the past decade serves as an appropriate metaphor for his business. Malaz says he used to speed along at 35 knots screaming at the family to sit down. The horizon was the destination. Time aboard was fun, but the passages could be fraught. These days it’s just as much about the journey.

Today, Malaz is Numarine’s sole shareholder. Over a decade ago he decided to step back, reduce his original 100 percent stake to just 30 percent, and virtually live aboard his own boats with his young family. He timed that

exit well. Just a few days before the global financial crisis kicked off in 2008, he sold the controlling interest to the Dubai-based private-equity firm Abraaj Capital, part of the then €8 billion Abraaj Group.

By 2012, things were less rosy for Numarine and for its majority shareholder, which ended up dissolving under a cloud. In May of that year, Malaz stepped up and reacquired 100 percent control of Numarine. For the next five years he ran the business on its original track. He knew something fun-

Capacity 500,000 man-hours

With an overall length of 32.84 metres, the 32XP was Numarine’s first model to sport a steel hull, although the superstructure is mouldedin-house like the smaller models. Displacing 270 tonnes fully loaded, the first 32XP launched back in 2017 and three more of

this 299 GT model were delivered between 2018 and 2020.

During 2019, a client pushing for more space prompted what has since become the 350 GT 37XP, which has the same beam and hull shape, but an extra 4.51 metres in length overall, an extra half knot of top-end speed

with the same engines, another 40 tonnes of fully loaded displacment, and an extra 51 GT.

The first four 32XPs and the two 37XPs have already delivered and six more are on order. With the run rate heading for little more than two per year, deliveries now stretch into late 2024. The success of the 37XP, which displaces 310 tonnes fully loaded, has rather pushed the 32XP into the shadows. No others have been ordered since the first 37XP splashed, principally because potential 32XP clients have deemed the 37XP premium worth paying. The basic price of a 32XP is €10.5m with a typical delivery ending up around just over the €11.5m mark. The 37XP’s basic price is presently €12.5m.

damental needed to change, but without straying from Numarine’s core strengths: financial solidity and industrial expertise.

That solution eventually became a trawler-explorer focus. Indeed, Numarine hasn’t delivered one of its old planing hardtop or flybridge models for five years and all the old tooling has been destroyed.

That change of focus proved a winner and Numarine was recently the first yacht builder in the country to be accepted into Turquality, the Turkish government’s brand accreditation and grant support initiative. Only the most efficiently managed businesses are accepted into this programme, which requires rigorous vetting by independent auditors.

Currently, Numarine employs 250 people directly, but it would normally have nearer 330 people employed locally, and its model portfolio includes four chunky XP trawler-explorer models. The design credits are the same as they have always been since the very beginning with exterior and interior design by Can Yalman and naval architecture by Umberto Tagliavini. There are at least 25 Numarine trawler-explorers out there already and another 18 or so swelling an order book that extends well into 2024.

The 22XP and 26XP, the smaller two models in the series, are both composite, respectively CE Cat B and Cat A designs. The larger two, the 32XP and 37XP, are steel/composite designs built to Class with RINA. The next new model will be a bigger composite design, but as we go to press the precise designation is being kept under wraps. Numarine’s proposed new flagship is the 45XP, a steel and aluminium trideck with a 9.25-metre beam. With a ball-park base price of €19.5m, this 498 GT

The first composite model was the four-year-old 26XP, which weighs in at 78 tonnes dry. Still a best-seller, the first hull was delivered in 2018 and was conceived from the outset to be flexible for either displacement or planing roles. Its hulls are moulded in halves and are finished with or without an extra moulded-keel insert used to create the necessary profile. A planing version uses a flatter central keel section and separately moulded spray rails bonded to the exterior of the hull after demoulding.

Of the 17 26XPs delivered to date, five are semi-displacement/planing versions, powered either by a pair of 1,550hp MANs for a top speed of around 27 knots or twin 1,200hp MANs that top out just below 20 knots. The owner of 26XP#21 has opted for twin MAN V12-1800s, which should mean a 30 knot top speed.

Five of the remaining dozen were fast-displacement versions, driven by twin 800-hp MANs at 14.5 knots, or 13.5 knots by twin 560hp MANs. Prices begin at €4.54m for a slow displacement version and nearer

€5m for a planing version, but a finished yacht will usually include up to 10 percent more in terms of extras.

The 22XP, the smallest model that weighs in dry from 53 tonnes, is also the newest and is similarly versatile as regards displacement and planing performances. Both versions are priced competitively. In displacement guise, which represent most sales to date, the 22XP has a basic price of €3.58m, but again the usual set of extras account for around 10 per cent more.

At €3.93m, the basic price of a 22XP, reflects the fact that it will have a 25 knot planing specification and triple the horsepower with twin MAN 1200s instead of a pair of 425hp Cummins diesels that top the model out at just under 13 knots.

The first 22XP launched in early 2022 and two more have since splashed. The fourth will be another planing version and should be delivered before the end of the year. The present production schedule has three more completing during 2023 and probably six more in 2024.

yacht is still a long way away from reality. Despite a couple of existing 32XP and 37XP clients being close to taking their next step up with the builder, the stars are not quite aligned.

Building a boat of that size would be a step too far at Numarine’s present facility in Gebze, which is perched on a hill in an industrial estate some 20 minutes inland. The biggest current models already prove a logistical challenge every time one needs to be transported down the hill to either Tuzla Marina or the nearby RMK Marine, where Numarine does its pre-delivery commissioning.

“The current 35,000sqm site has served us well,” says Malaz, “but the next step up will need to be taken from new waterside premises.”

To that end Malaz has already acquired 30,000 sqm of land for a new factory, and has an option on another 30,000 sqm next door. The location is Yalova to the southwest and the other side of Osman Gazi Bridge, roughly half an hour’s drive from the present site in Gebze, but just 20 minutes further out from the centre of Istanbul.

The first phase involves an investment of €20m over the next 2.5 years. Malaz expects to break ground there by the end of year and that the first boats will start on that site within 18 months. Given the build time for a first new 45-metre yacht is likely to be around 24 months, don’t expect to see a new flagship splash for perhaps at least another four years. Eventually, Malaz suspects the whole Numarine operation may well relocate to the coast.

“There are no plans for us to build smaller than the 22XP,” he says. “Our facilities are no longer geared for the sort of volumes that are required to build smaller models cost-effectively.”

Having a large, loyal customer base out there is a big help and repeat business is an important component for the brand. One Turkish client is presently on his fifth Numarine and is negotiating for his sixth.

Overall exports account for around 70 percent of Numarine sales. Since it started Numarine has built and delivered 160 boats, of which just 40 were sold new to Turkish buyers. Sales to the US have been strongest by far in recent years. Happily, the present crisis in Ukraine has not impacted Numarine in terms of owners. Since the beginning it has only had four Russian new-build clients.

Up until three years ago Numarine had a dealer network. Various distributors around the world included the brand in their portfolios

and the network approach was largely responsible for the success of the brand during its first decade when the product range spanned 52-105 feet. However, three years ago it was decided to change the distribution strategy and end all exclusive agreements as well as the dealer margins that went with those agreements, which had been as high as 25 percent for some models.

What that means in theory is that Numarine now sells direct, but in practice many of its deals are concluded with the help of yacht brokers and one broker has engaged with the brand more than any other to earn ‘preferred broker’ status.

“Alex G Clarke at Denison is a great example of what we can achieve,” says Ali Tanir, Numarine’s international sales manager. “He has been responsible for no fewer than six sales over the past year alone. And we hope a recent deal with Patrick Coote at Northrop & Johnson in Monaco will yield similar results for us in Europe.”

Last year, Numarine delivered five boats in total: four 26XPs and one 37XP. However, owing to the continued success of the 26XP and given the ramping up of the new 22XP range, it is now back firmly in growth mode and has 12 deliveries scheduled for this year: four 22XPs, six 26XPs and two 37XPs, which should see turnover exceed €50m, a new record. 2023 is looking similarly solid. The order book presently includes four 22XPs, three 22XPs and three 37XPs.

Numarine is always prepared to start hulls on speculation to shorten delivery times and to maintain an efficient flow of production through its facilities. Given the reputation for self-sufficiency they trade on, explorer specifications tend to be higher than more mainstream yachts, which means add-on costs are relatively low, rarely adding more than around 10% (excluding engine choices) to the final price.

Although the metal hull fabrication is carried out by a nearby subcontractor in Tuzla, the company is virtually self-sufficient in terms of construction disciplines and usually produces all its own composite tooling. It is still the only builder in Turkey with its own five-axis CNC machining centre, one of the biggest of its kind in Europe. Moulding techniques vary, but all are closed process. Hulls and superstructures are vacuum-infused and bulkheads are vacuum bagged and cut using templates. Smaller parts make use of RTM (resin transfer moulding) techniques.

Gurit is its composites engineering partner and Scott Bader is the principal supplier of polyester and vinylester resins and gelcoats, while composite reinforcements mostly come from Turkish local manufacturer Metyx. The composite boats are available with a choice of three gelcoats – white, off-white and light grey – whereas the metal yachts are painted with Awlgrip systems.

Other key partners include ZF for gearboxes; Teignbridge for shafts and props; Kohler or Cummins-Onan for generators (although supply chain issues make these items particularly difficult to source at the moment); Raymarine for bridge displays (although Garmin or Furuno instrumentation are options for US-bound boats); Sleipner for thrusters and CMC for electric fin-stabilisers; Dometic for HVAC systems; Besenzoni in Italy or Data and Bofa in Turkey for mechanical deck systems; and Van Cappellen for the sound and vibration mitigation.

Productivity is essential for any series builder and from the start Numarine has had an industrial approach to boatbuilding, always trying to improve quality and margins. For the past dozen years production has been overseen by technical director Malcolm Hutchison, who previously spent seven years, with Pearl Yachts as COO (Numarine was once a contract builder for the UK-based brand, which is how he got to know the company).

The cost of labour is, of course, one of Turkish industry’s biggest advantages. Wages are probably a quarter or even a fifth of what western Europe is paying. The first 26XP used to take 50,000 man-hours to build, whereas they are currently talking fewer than 40,000. The first 32XP took over 120,000 man-hours, but now a 32XP requires under 90,000 man-hours and the bigger 37XP sister takes 100,000 man-hours (the latter omitting the labour required to fabricate the steel hulls).

Numarine has delivered more than 160 boats over the past 20 years, an average of eight boats a year. Today, it’s delivering a dozen yachts per annum and soon that annual tally will be nearer 15 once its new waterside facility is up and running properly, but it will still be small enough for Numarine to have a personal relationship with each customer.

“And I want to know them all,” concludes Malaz.

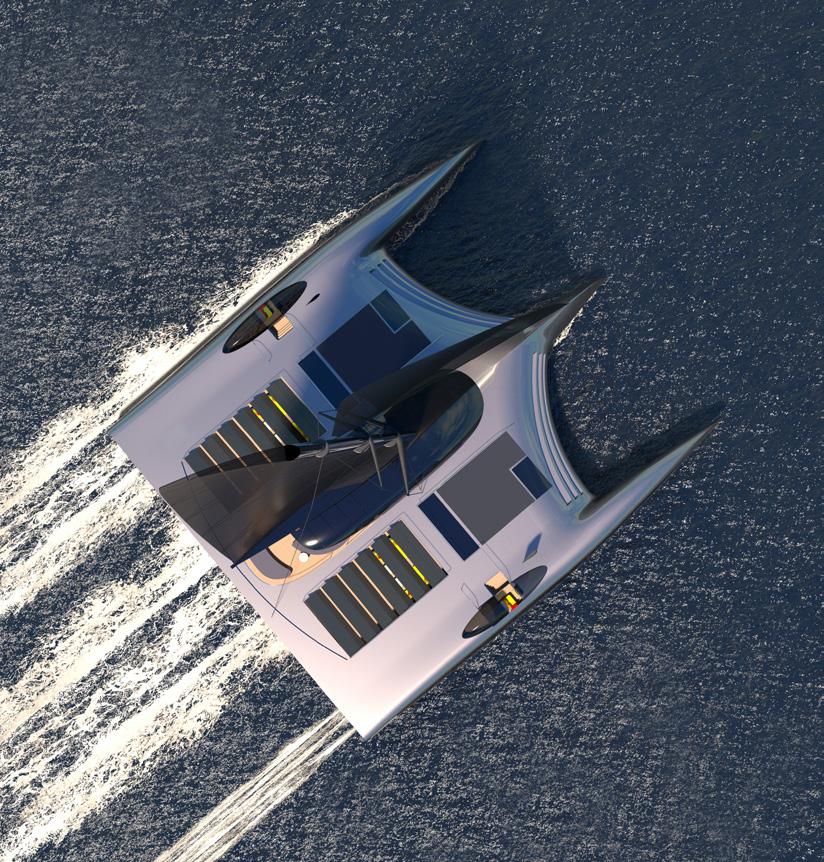

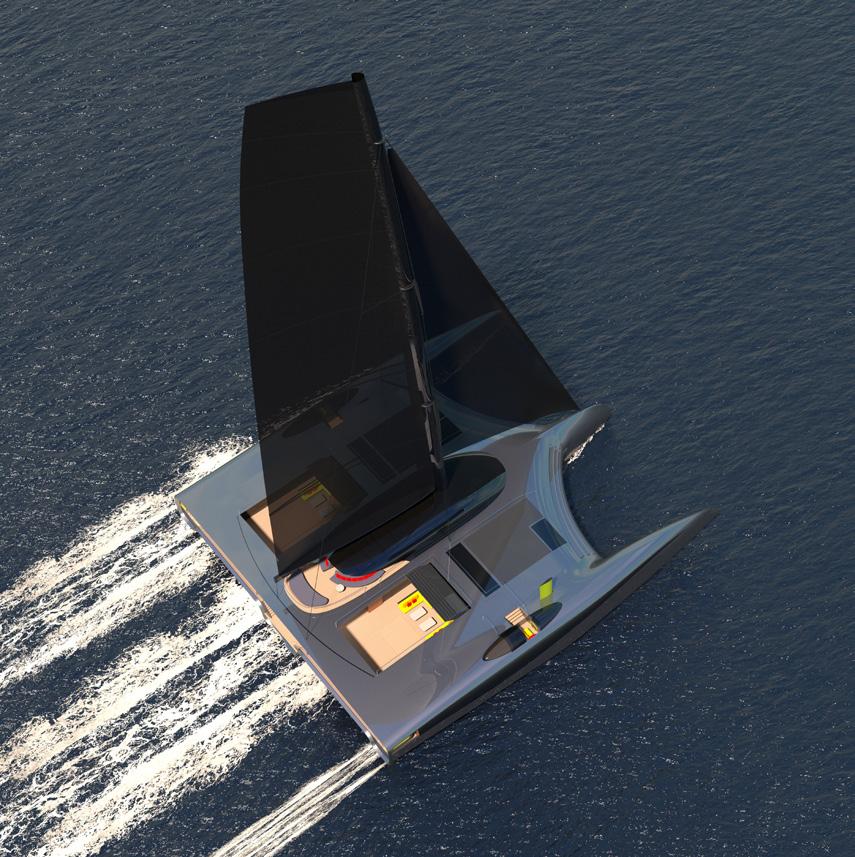

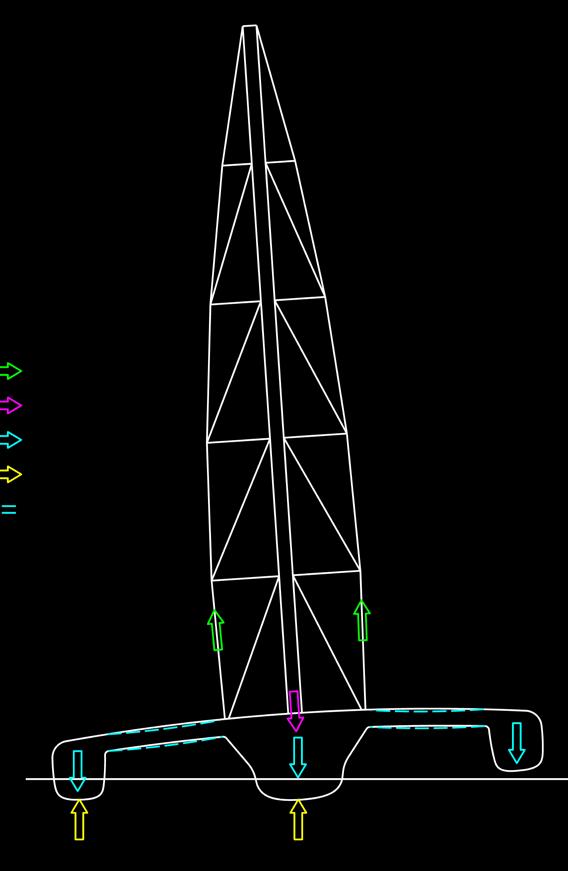

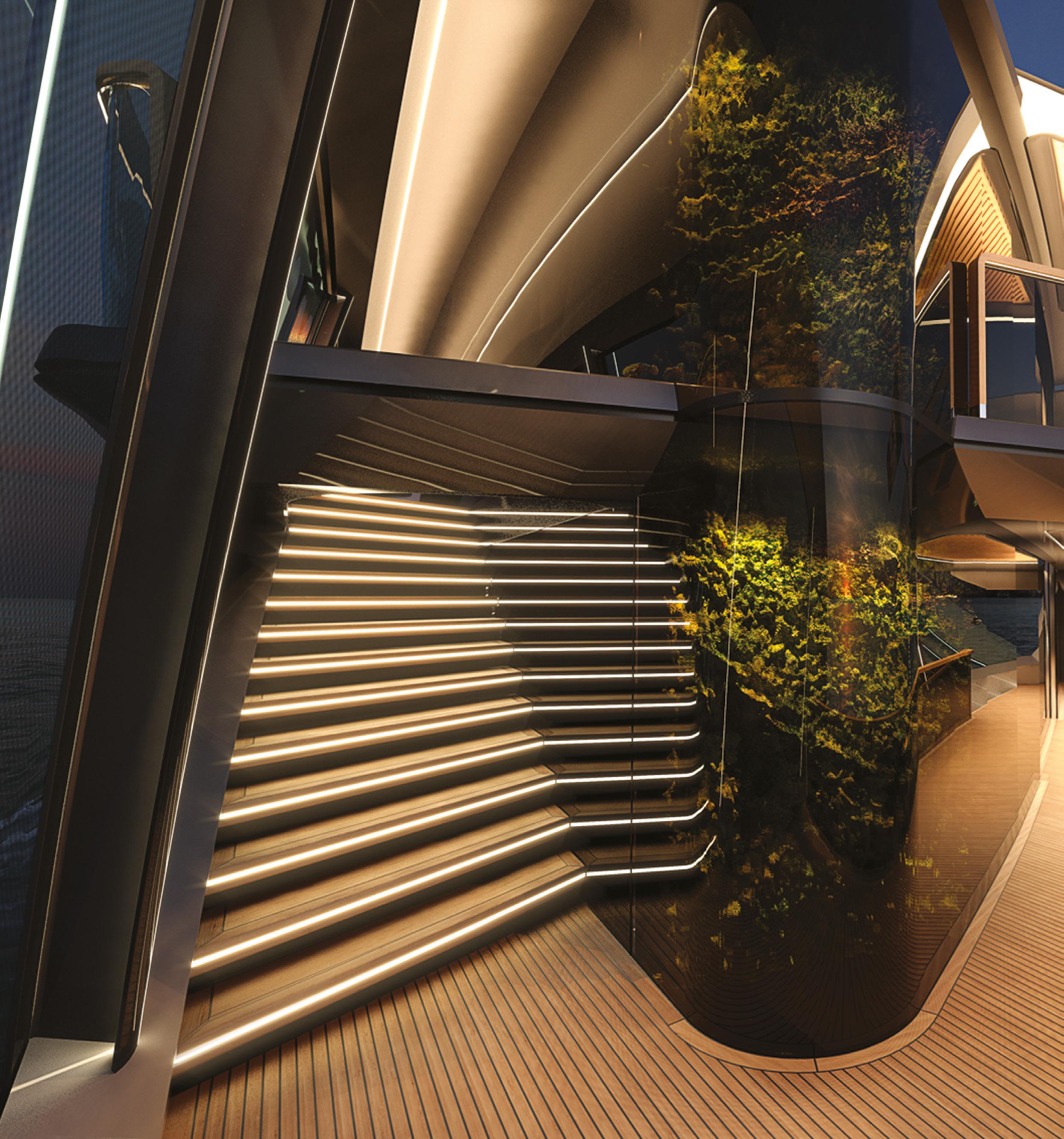

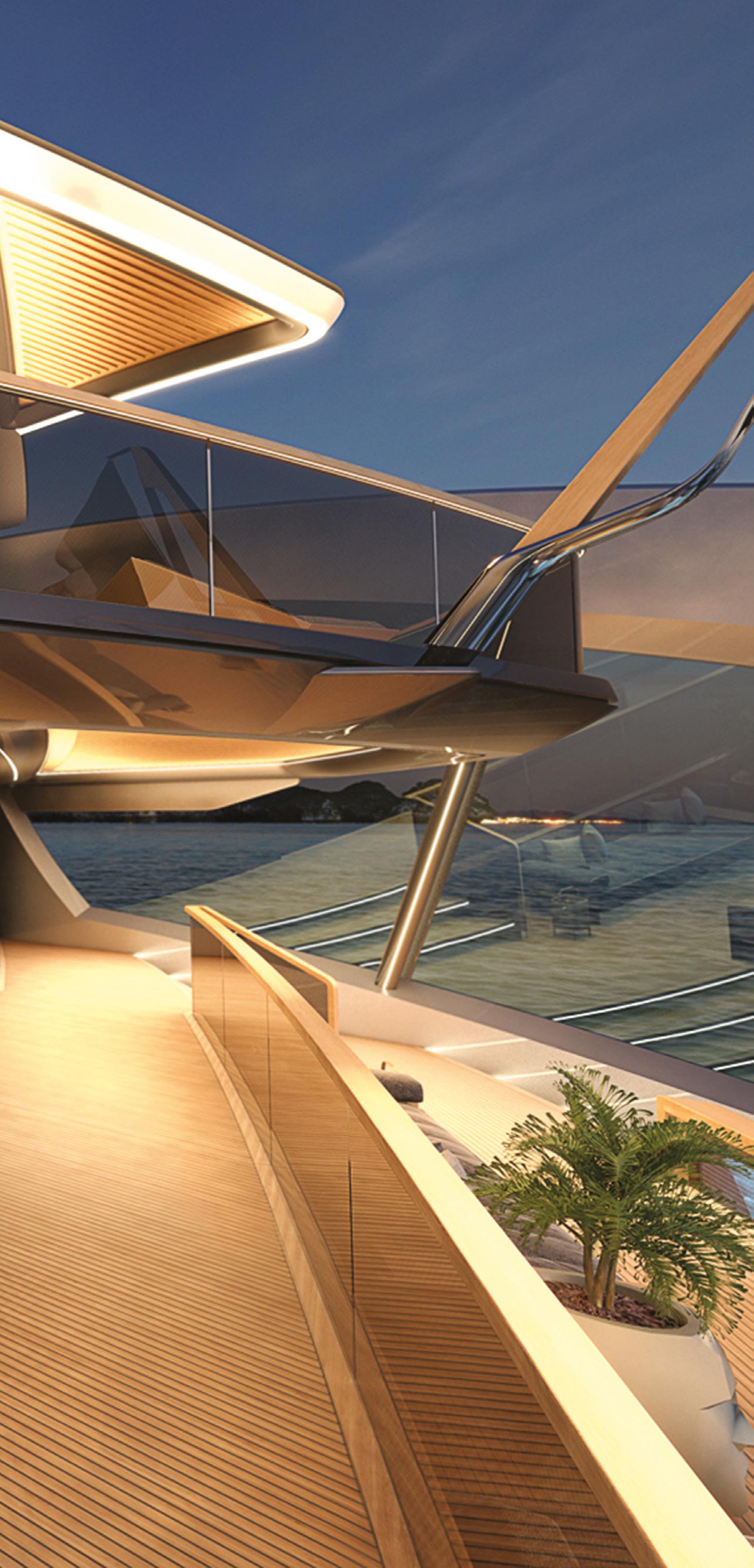

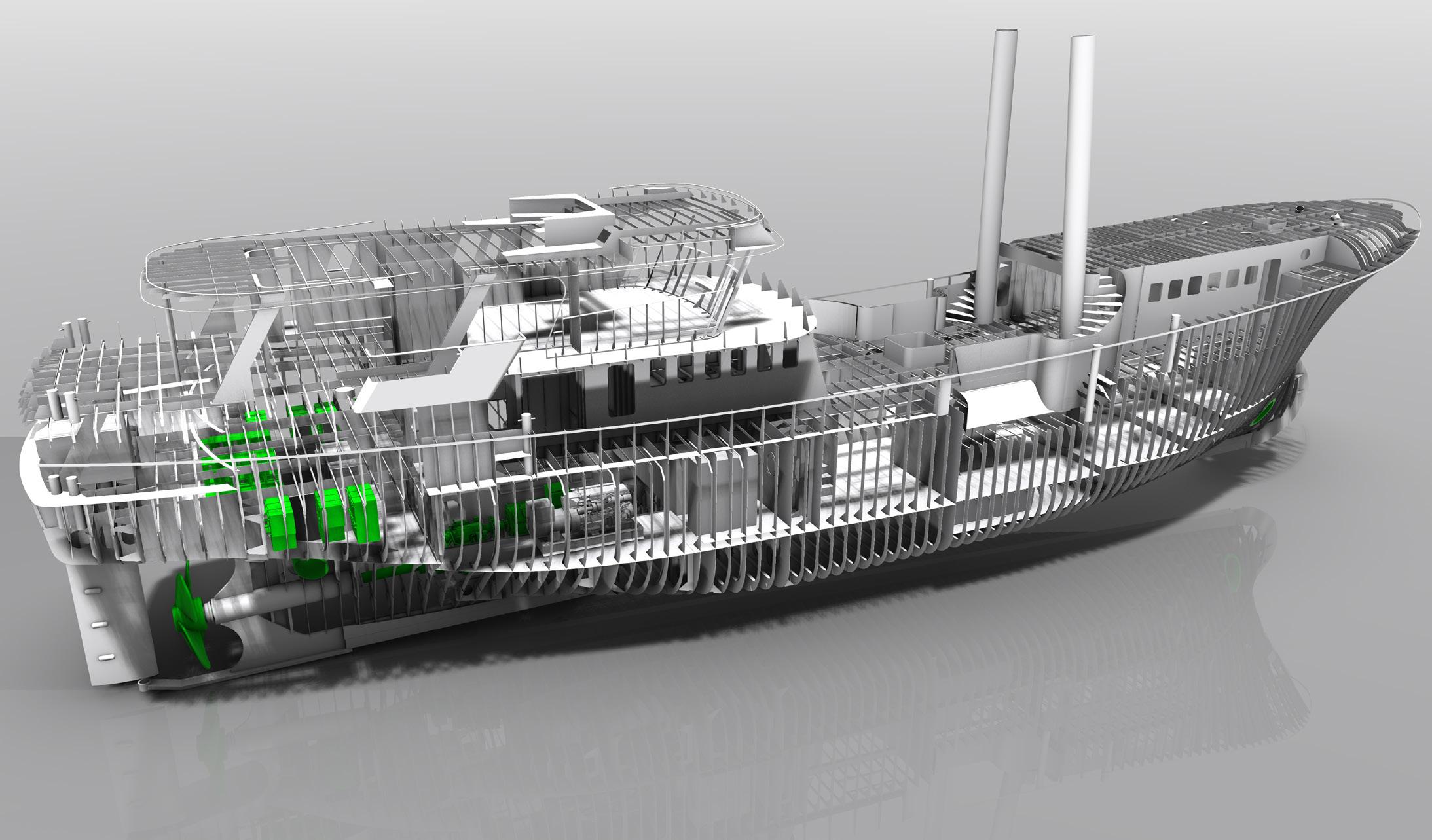

The 40-metre Domus concept by Rob Doyle Design and Van Geest Design grabs our attention because we are unaccustomed to seeing multihull yachts on this scale. But is it buildable and are the zero-emission technologies it proposes realistic?

BY JUSTIN RATCLIFFE

“Project Domus grew out of a request from a client for a 40 metre catamaran, and we dived right into it,” says naval architect Rob Doyle, founder of the eponymous studio. “But the more we looked at it, the more we realised the catamaran configuration was too limiting. I’m a keen cat sailor and they work great within quite a specific set of criteria, but when you take them out of a certain size zone you start to see problems arising. After battling with these issues we decided to take a different approach and go a little crazy.”

More space, better performance, less draft and significantly lower heel angles under

way than comparable monhulls. These are just some of the reasons why over the last few years there has been increased interest in large catamarans. However, once you get over 40 metres these advantages may be outweighed by higher build costs, the complexity of distributing systems across two hulls, and the structural challenges resulting from the immense racking forces as they move through the water.

When Rob Doyle Design decided to reassess the catamaran brief from a different angle they took as a reference point 63-metre

Project Fury, a monohull sailing yacht concept created with Van Geest Design in 2021. Fury revised the relationship between gross tonnage or interior volume and its relation to overall length and displacement. A conventional 63 metre sailing yacht would ordinarily have a volume of around 500GT; Project Fury pushed this to over 700GT, a remarkable increase of 40 percent. What would happen if they expanded that concept and applied it to a trimaran?

“We decided to simplify matters and basically build a monohull with outriggers or armas, which meant all the systems and engineering could be centralised in the main hull,” says Doyle. “Everything just fell into place from there.”

Trimarans are usually beamier than catamarans, which equates to more interior volume and deck space. With three hulls in the water there is also better damping effect on a trimaran at anchor than a catamaran, and vastly reduced motions compared to a monohull. Domus is designed to heel at angles of around two degrees to allow the weather hull to come out of the water for less drag and higher performance, but also more comfort under way. These factors make a trimaran an attractive proposition for motor yacht owners interested in making the transition to sail.

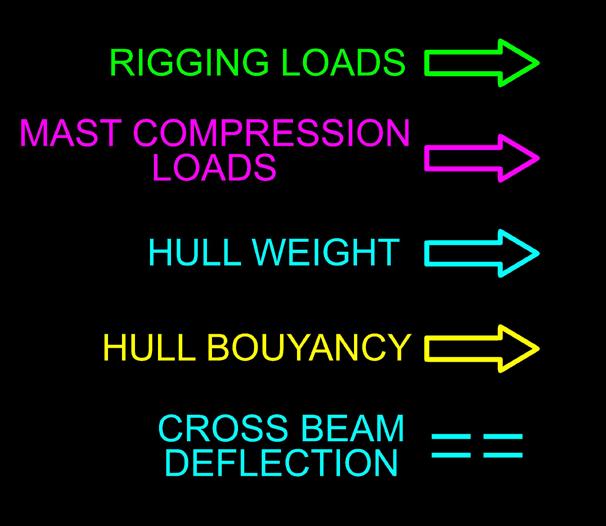

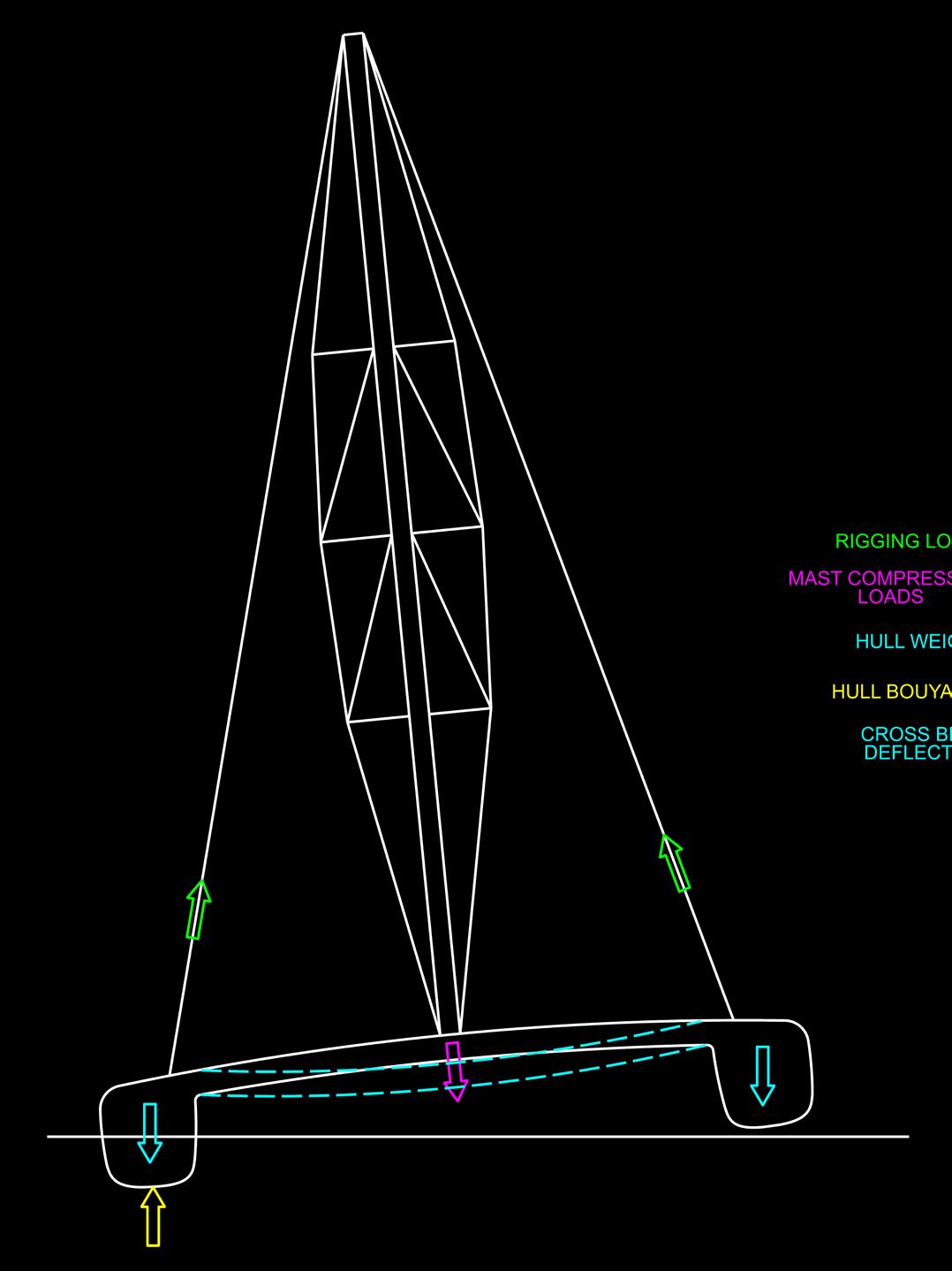

The moment of inertia is an important parameter in civil engineering and naval architecture when sizing or selecting a beam structure. It is basically a calculation of the stress caused by a moment on the beam and can be defined as the resistance offered by a cross-sectional area to deflection primarily by bending.

A beam is a structural element that primarily resists loads applied laterally to the beam’s axis (an element designed to carry primarily axial load would be a strut or column). The loads applied to the beam result in reaction forces at the beam’s support points. The total effect of all the forces acting on the beam is to produce shear forces and bending moments within the beams, which in turn induce internal stresses, strains and deflections.

Another plus is that the rigging forces are taken by the main hull, so the crossbeam structures can be simpler and lighter than a catamaran.

“The structural challenges are not as bad as you might first think,” says Mark Small of Rob Doyle Design. “In a standard multihull you have a single beam taking all the loads and into the armas. But because of the nature of Pieter van Geest’s single deck design we actually have an upper and lower beam that together create an incredibly strong closed loop. We’re dealing with the same moments of inertia, but they’re now separated by nearly three metres from top to bottom.”

The result is effectively a huge floating bungalow supported on three hulls with an interior area-versus-length ratio that is off the charts in comparison with monohull sailing and motor yachts, but also sailing catamarans. Domus has almost 800 square-metres of usable interior area, which is not far short of 88-metre Maltese Falcon. The largest private sailing catamaran

afloat, 44.2-metre Hemisphere, has around 350 square-metres of internal space.

“At the beginning it was strange to work with three hulls, but as soon as we decided to have everything on one level it became much more straightforward,” says Pieter van Geest. “It meant we could come up with a villa-like layout with no stairs and airy, semiopen areas. Family life in a way is about protection, so we wanted to build around that idea with secure access to the sea but no need for complicated opening systems.”

It was important that the mast was Panamax for transiting the Panama Canal. To keep the mast height in check a double luffed mainsail was chosen to achieve some of the efficiency of a wing but using a hoistable soft sail. Rob Doyle calculates that it provides between 15-20 percent more drive than a conventional sail plan of the same size.

Like those used by the America’s Cup foiling monohulls, the double skinned sail comes off both sides of the mast instead of the centreline and both skins are joined

at the leech to give a true wing shape, but the soft material means it can be reefed and dropped and stored on the boom. The wing shape is adjusted by rotating the mast, which shortens one side of the wing and lengthens the other. This allows for more lift, less drag, and to increase the angle of attack without losing the air flow.

“Oddly, the rig is probably the most challenging aspect of the whole design,” says Doyle. “That’s because the trimaran configuration has a massive righting moment and just stops heeling at two degrees, unlike a monohull that goes on absorbing forces by continuing to heel. That means the rig has to be designed and built like it’s set in concrete and you need reliable systems that can ease the sheets automatically at peak loads.”

The outer hulls are also fitted with forward daggerboards set at a slight inward angle, not for foiling purposes but to provide some positive lift and prevent the tendency of all multihulls to bury their bows.

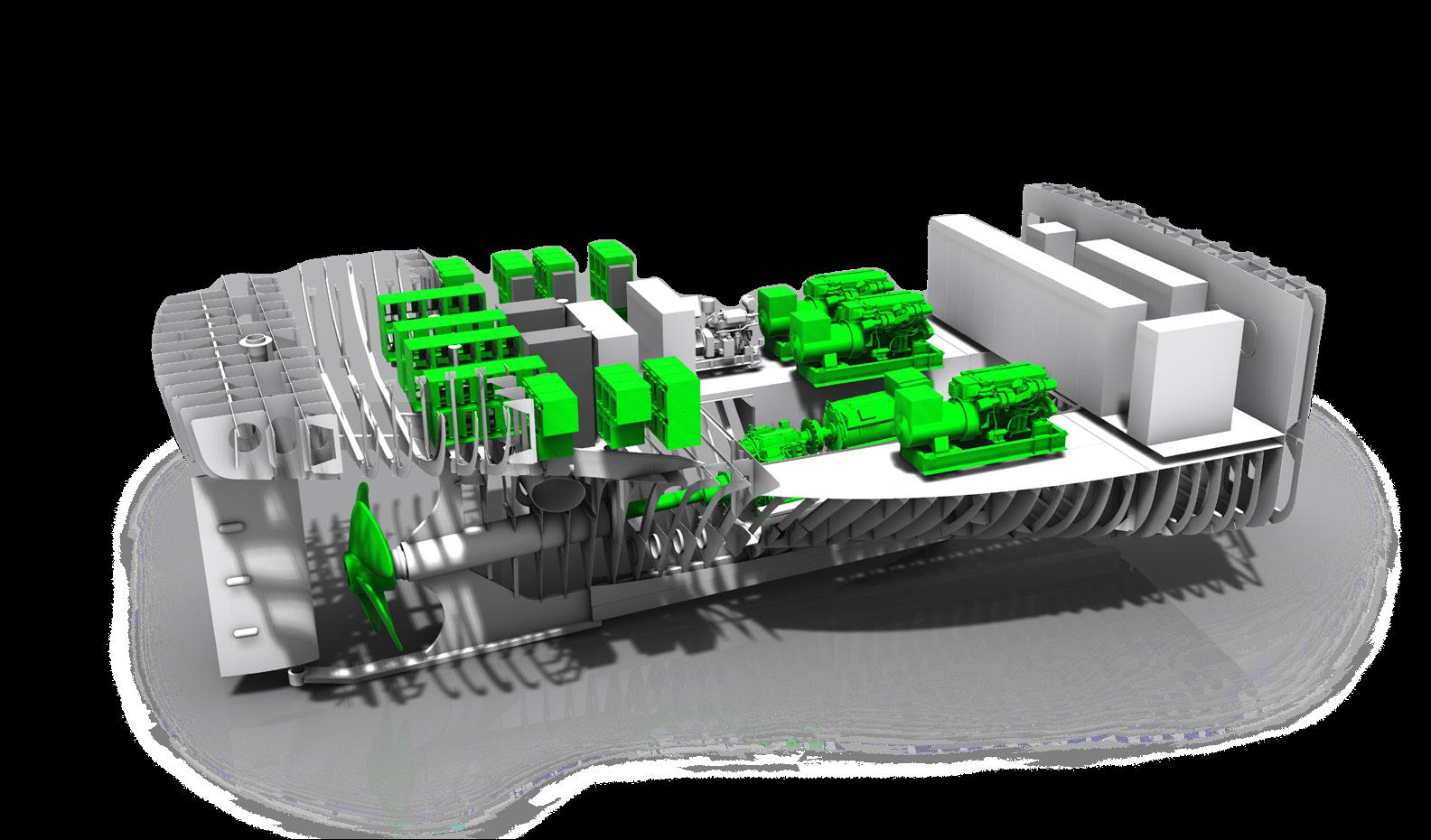

Another advantage of the 35 metre beam is that it offers more surface area for the solar cells that are a key part of the power generation systems aboard Domus, which also draw on hydro regeneration, hydrogen fuel cells and battery storage for fully silent operation with zero emissions while at anchor. Again, a lot of the power generation solutions came off the back of creating the Fury concept, a high-performance sailing yacht that provided an opportunity to explore energy recovery from the propulsion system, which in turn influenced the energy storage and generator system capacity.

“We added hydrogen fuel cells into the mix as a direct replacement of the generators,” says Small. “There is still work to be done in that area, but the technology is commercially available and in use. Then we thought ‘Wouldn’t it be great if we could make our own hydrogen through electrolysis’. That technology is also commercially available and we can do that if the boat keeps on sailing, but as we all know superyachts spend 80 percent of their time at the dock.”

Despite the enormous surface area the trimaran offers, solar energy for when the yacht is stationary is also limited because the deck space is also used for other purposes. The key is balancing the various power generation technologies. Based on normal operations in the Mediterranean and Caribbean the designers expect to be able to run all the hotel loads from the solar panels over any 24-hour period with excess energy stored in the batteries for peak shaving.

In fact, when sailing, the yacht can generate about 170 percent of the total energy required on board and that excess energy can be used to create hydrogen. The other advantage is that electrolysis splits water to produce hydrogen and pure water, which is used to produce more hydrogen but also means less reliance on watermakers, a significant power drain on large yachts.

“It’s important to stress that we’re using standardised technology here, nothing especially new or fancy,” adds Small. “The only questionable thing we have at the moment is getting approval from Class for the electrolyser system, which is not there yet.”

Yacht concepts explore new solutions and untried possibilities, but that is not to say they shouldn’t also be feasible. Beyond encouraging potential clients to question conventional solutions, the designers of Domus went out of the way to research all avenues and the result is eminently buildable. The concept can easily be stretched to 80 metres and remain emission free (beyond that size and the amount of renewable energy required to run the onboard loads becomes prohibitive) and could conceivably be shrunk below 500GT.

“We see concepts coming out with every permutation of not thinking stuff properly in the early stages,” says Doyle. “Some of them get a lot of attention and you know there’s going to be a very disappointed owner when he gets into reality of the design. After extensive design research and analysis, we strongly believe if you want all the benefits of multihulls at 40 metres or more in size the only practical solution is a trimaran.”

What are the considerations that owners should bear in mind when looking to refresh the look of their vessel with a new paint job? We caught up with Mark Bournas, Sales and Project Manager at superyacht paint consultancy company CCS, and Dean Smith, director of superyacht consultancy company, Hampshire Marine.

First off, you might be asking yourself the question: “Why would I need a paint consultant for my yacht anyway? Surely it can’t be that complicated.” As with many aspects of yachting, however, the past decade has seen a shift toward professionalisation that renders the services of a specialist consultancy company like CCS invaluable.

“In the past, when someone was interested in building a yacht, they would visit the shipyard, often with their families, and be heavily involved during the build and development process – this created a basis of trust between the yard, contractors and clients,” says Bournas. “As a result, any disputes would often be sorted out between all of these parties and risks were lower

In recent years, the industry has professionalised, meaning that a potential owner will look around for the best commercial contract instead of going to the yard where he feels most comfortable. This increases competition between yards/contractors and means that contracts are leading instead of a relation between the yard and owner.

“This increased professionalisation is a positive thing but it means that you need to have specialists involved in every stage of a build/ refit, alongside strong and dedicated project management from a company like Hampshire Marine,” continues Bournas. “This ensures that the contract is lived up to, and vitally, that owners’ expectations are managed throughout the project.”

Indeed, informed by his 25-plus years of experience representing the owner’s side, Smith highlights the importance of harnessing the technical know-how of a company like CCS.

“The question from the owner is always going to be about appearance: how to achieve an extremely high-quality finish, even in bright sunlight, and how to ensure the performance

and durability of the paint job over time. This is such a key area for any yacht project, and so you need a specialist to oversee this. It’s not just about the paint going on: it’s also the process of how you prepare the surfaces. For example, with a refit project, it could take between 6-8 months and the preparation time can take as much time as the actual painting.”

Once you’ve decided to take the plunge and paint your superyacht it would be natural to ask: “how do I ensure that the paint contract covers my interests, as well as simultaneously including all of the relevant technical and aesthetic criteria and meeting warranty conditions?”

“Having a proper paint contract in place is obviously vital, but it must not be forgotten that painting a superyacht, just like building one, will also involve real craftsmanship,” responds Bournas. “The goal should be that all of the specialists involved will contribute to the finished product and should not just be there just to make their own involvement look better by setting unrealistic criteria. At CCS, we help you navigate the small print to ensure that you don’t run into any issues down the line, and keep your superyacht looking beautiful for as long as possible.”

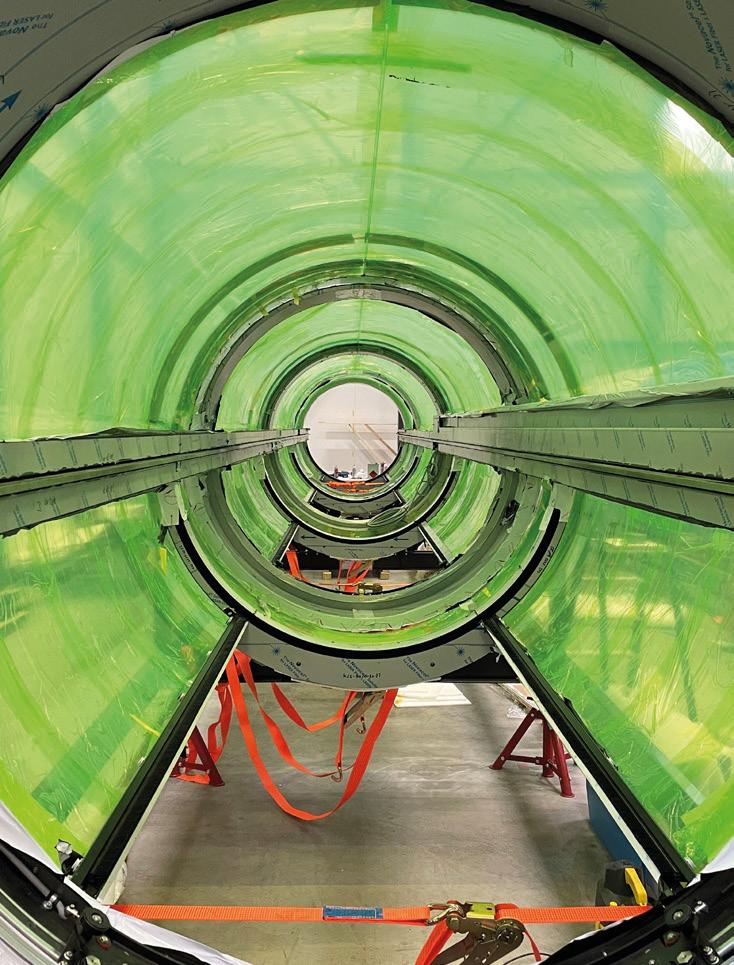

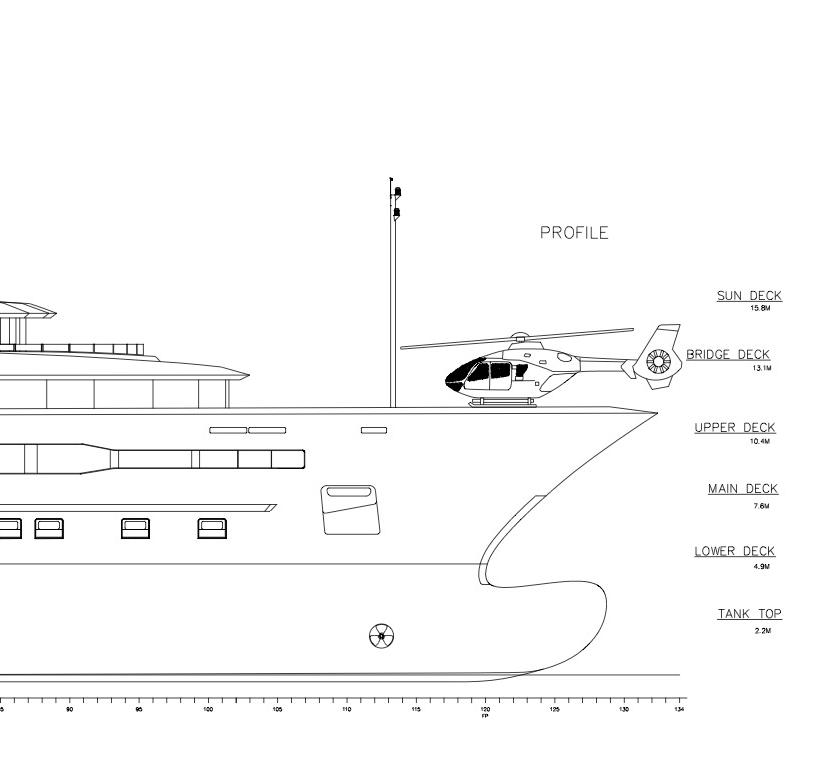

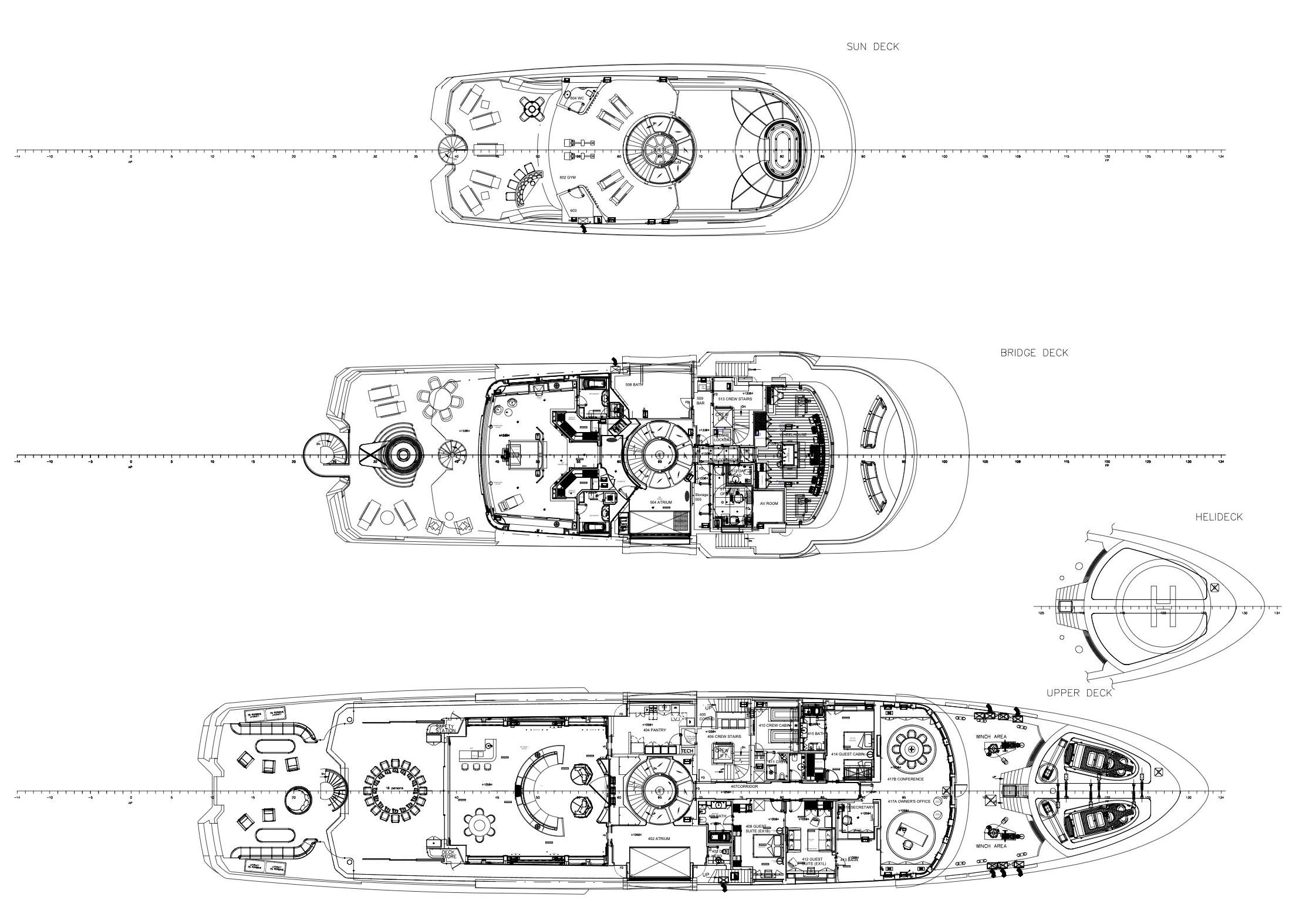

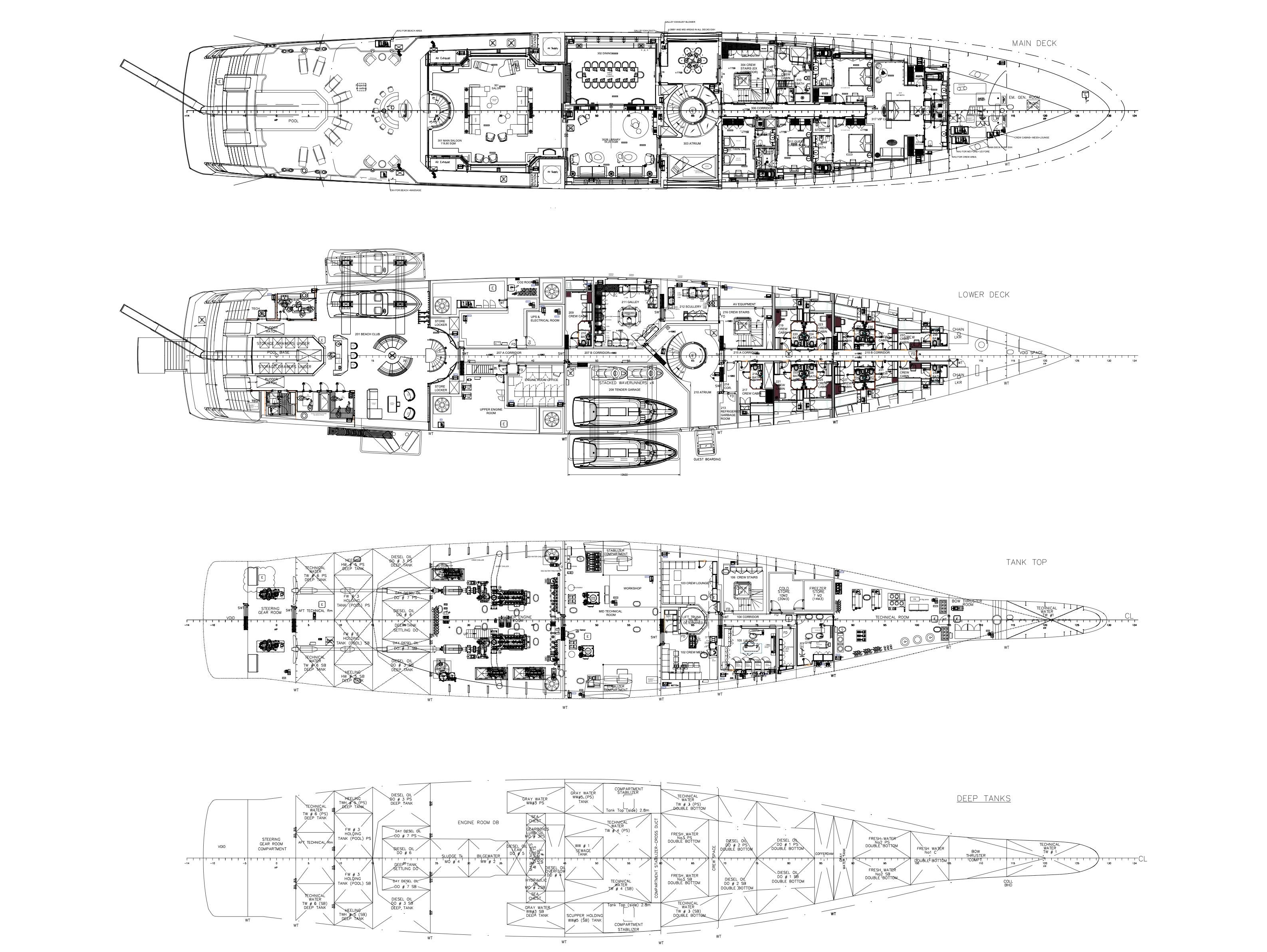

The 14-year odyssey of Project X began at the Marco Yachts yard in South America in 2008. Relocated for finishing to the Golden Yachts shipyard in Athens, we visited the yacht as she was finally nearing completion.

BY CHARLOTTE THOMAS

Building or refitting an 85-metre yacht is a serious undertaking for any yard, but when an owner approached Golden Yachts in Greece to discuss the completion of a previously stalled project, the team took it all in their stride. After all, they had recently launched their largest new-build yacht to date, 95-metre O’Pari, and already built a fleet of charter superyachts that the yard also owns and manages. Add company founder Captain Paris Dragnis’ experience of owning multiple yachts and commercial ships and it seemed the project was well within the team’s capabilities.

By the time we visited the project in Pireaus, Athens, it had been three years of hard graft, but Project X was on schedule for completion despite the many changes required both through necessity and to meet her owner’s new requirements.

Project X began life as a Ken Freivokh-designed 85-metre yacht with a distinctive glass tower amidships. Her keel was laid in October 2008 at the Marco Yachts yard in Chile, but the project was put on hold. In 2011 the hull was moved to the Delta Yachts yard in Seattle where she lay dormant in a car park. Fast forward eight years, and she was

spotted leaving Seattle in 2019 on a transporter bound for Greece. What followed has not been straightforward.

“I spent almost a week in Seattle three-anda-half years ago surveying the vessel,” begins George Chairakakis, Projects Director at Golden Yachts. “My first impression was that it was a very demanding project, full of hidden problems to be resolved. When something has been ‘abandoned’ for so long it is a big challenge for the shipyard to undertake the completion and to deliver it.”

It wasn’t just the project itself that was demanding there were the requests of designer

When something has been ‘abandoned’ for so long it is a big challenge for the shipyard to undertake the completion and to deliver it.

Ken Freivokh, who retained an active role in the project, and the interior architects Massari Design in Italy. The team also had to modify the hull to accommodate a 3 metre extension; make sure that the system schematics were brought up to date; and bring the yacht into modern commercial compliance.

“We had to uprate a boat that was initially designed as a private vessel, and to consider how to modify the general arrangement to comply both with commercial coding and with new regulations,” says Chairakakis. “The boat is now fully compliant with Malta Commercial Yacht Code 2020, which was one of the most difficult parts of the project.”

The changes from the original design have been significant. First and most obviously there is the stern extension, which allows for a beach club with glass-sided pool, and which takes the overall length to 88 metres. Then a touch-and-go helideck was added to the bow area. Two garage doors and a 9-metre balcony were added aft, along with redesigned garage space to accommodate an owner-supplied Pedrazzini tender, as well as a hammam and sauna in the beach club.

For the interior a major tweak was the area around the central atrium, where two decks have been cut away on the starboard side to create an imposing entrance hall rising 9 metres high and dominated by the three large ‘X-windows’. Trademark Freivokh glass ‘spokes’ surround the elevator column, which

runs from the lower deck, five stops up to the sundeck. The elevator itself, built and supplied by Lift Emotion in the Netherlands, has the largest diameter of any glass lift installed on a yacht of this size. In addition to the changes to the GA, naval architecture and general engineering, there was the challenge of breathing new life into a vessel that had been lying dormant for close to a decade.

“It was a steel hull with a partially completed aluminium superstructure,” says Chairakakis. “It had a partial piping network which we largely disassembled, scrapped and rebuilt from scratch, and there was no cabling, no cable trays even, no machinery, nor even the bases for the engines. There was nothing on board.”

It fell to the Golden Yachts engineering and projects teams to hone the modified design and bring it up to the latest standards. This inclued re-specifying all the machinery and systems and bringing the yacht within modern expectations for emissions and environmental performance.

A central feature of the original design was a large glass lift rising five decks through the yacht, surrounded by glass floor spokes and deckhead panels which are something of a Ken Freivokh trademark. Engineering and building the elevator fell to Dutch specialists Lift Emotion.

“The project started in 2009 and we were involved in the pre-design stages with Ken Freivokh,” says Mike

Brandt, CEO of Lift Emotion. “Then during 2020 we received the order from Golden Yachts to materialise the design for this special elevator.”

The five-stop lift measures 2.5 metres in diameter – the largest trunk installed on an 80 metre yacht to date – and the internal diameter is 1.8 metres. This allows for a lift cabin with a 1,125-kg payload and 15-person capacity. The drive system is hydraulic with an inverter drive and is set in a tandem 11 suspension, meaning two telescopic jacks that pick up the cabin.

“Installing glass lifts is a time-consuming and difficult task, and also means a lot of people in the central staircase – not only elevator people but also other companies working in that area of the boat,” says Brandt. “This is not nice for the yard, nor for all the people involved.”

For this reason, Lift Emotion likes to pre-assemble as much of the shaft and cabin as possible. In the case of Project X, the pre-glazed lift trunk

was delivered to the yard and the whole five-stop, six-deck elevator and cabin installed in a few days.

Project X had the machinery space under the lowest lift stop to integrate the machine room into the lift structure, so the pre-wired pump unit with controls was already installed when the system arrived at the Golden Yachts yard. “In the second week of our installation visit the lift was already running up and down,” says Brandt.

The inside of the trunk also has to look nice, and Lift Emotion created two pillars with integrated guiding and cylinders for the jacks, and these are covered in decorative materials to match the staircase and general design theme. The cabin essentially floats between the two pillars. The final touch is a cabin roof to match the sundeck glass roof and distinctive spoked round ceiling of the yacht.

“We started with the modifications the owner requested, such as the bow helideck area, and the naval architecture for the stern extension,” says project manager Panagiota Mandragou. “We also had to alter the main engines, generators, systems and piping as rules and regulations change over the years, and the trends now are different to when the project was started.”

The team overhauled the engines and generators, then upgraded the technical package by adding diesel particulate filters and other

elements to reduce emissions. Elements of the structure were re-engineered to allow for the cutaways when creating the guest atrium, for example, and major modifications made to steel structures and partitions inside the yacht to comply with regulations.

Moreover, while Golden Yachts was completing the superstructure in the first year of the project, Freivokh and the owner made a lot of alterations, including more crew cabins, the bow modification and helideck, adding or changing storage areas, the garage, the SO-

LAS crane and pantries, and fully modifying the tank-top deck. The project team resubmitted all the drawings to Bureau Veritas for review, including the original drawings from 12 years ago.

“There were the drawings of Freivokh from the start of the project, but the completion of these structures, the installation of the glass elevator, and the whole reinforcing of the boat and the modifications were all Golden Yachts design and construction,” says Chairakakis.

“It was challenging for our plan approval engineers to get approval a second time for the jobs done by another shipyard.”

Coordinating such a complex build and doing it inside a strict delivery schedule comes down to considerable project planning and manpower resources. During the last year of construction as many as 350 people were working on board at any one time. Many of

Project X’s interior design draws on a huge palette of materials and fixtures and fittings from a long list of suppliers and subcontractors. Those materials range from exotic leathers, snake and fish skins – all perfectly matched to a repeating pattern – to varieties of marble with stainless steel inserts and decorative panels made using resin and molten metal.

“A contemporary aesthetic remains throughout the guest areas with natural colours, white tones, soft tactile finishes and leather and fabrics all over, even in the deckheads,” says Dimitra Agapitou.

All the guest and VIP cabins, which are located on the main and upper decks, have personalised colour themes and in total around 150 different materials were used in the interior.

“I think this project has the most materials we’ve used so far, which has definitely made it one of the most challenging,” says Agapitou. “It’s also different working with an external client, but we have previous experience fulfilling special requests and we’re a team of young, hard workers and experienced people who are all ready to collaborate to complete such a project.”

those were carpenters working on the interior, for which the guest areas were mostly handled by teams from northern Italy and Greece. The exquisite stainless steel work such as the curved exterior staircases is by a Greek supplier who works solely for Golden Yachts. Indeed, most of the contractors are long-standing collaborators and it is the yard’s investment in relationships that paid dividends during recent issues with the supply chain.

“It would have been really difficult in the past two or three years without our longstanding contractor relationships,” says Dimitra Agapitou, Interior Design manager at Golden Yachts. “Having established these collaborations over many years has meant that problems can be resolved via email and with photos, as well as affording the opportunity to get ahead of the supply chain issues.”

In spite of these difficulties and the wider challenges, Project X falls seamlessly into