Re-Claiming Space:

Exploring Women’s Presence and Histories in the Gulliesof Chandni Chowk

Suhela Kaur Maini

Master’s Thesis 22/23

MA Architecture and Historic Urban Environments

Bartlett School of Architecture

University College London

Re-Claiming Space:

Abstract

The relationship between women and public spaces has been a long complex and multifaceted issue, deeply intertwined with societal and cultural norms, and historical disparities. These factors have had a lasting impact on the way women navigate their way through an urban landscape. The Indian city, a deeply patriarchal society, bears systemic indifferences and biases that make cities less accessible and welcoming. Reflecting on my upbringing as an Indian woman in the city, the prevailing narrative was that young boys were encouraged to venture out independently, as it was deemed natural for them. I distinctly remember my grandmother’s words that boys needed to step out of the house to release all their energy. The phrase “boys will be boys,” was often used as a justification for this. These narratives might be the beginning of women’s detachment from public spaces, which serves as an inspiration behind this study.

The study focuses on challenging these prevailing narratives and reimagining spaces that are inclusive for all genders. By exploring the gullies of Chandni Chowk, as the case study for the research, it delves into the forgotten history of women who shaped this area. The study incorporates the experiences of six women who visited these gullies and explores their perspectives to better understand their diverse relationships with public spaces, analysing their ideas of comfort and safety. The aim is to encourage women to step out of their homes and cultivate a relationship of pleasure with the streets.

The collective experiences of the participants find their expression on the website, bearing the title, ‘Let’s Go for a Walk’. The website functions as a dynamic tool to showcase the experiences and perspectives of these women, aiming to initiate a discourse around them.

2 3

Image:The Six

Exploring Women’s Presence and Histories in the Gulliesof Chandni Chowk Cover

Walks

Table of Contents

Introduction

1.City for Women?

1.1 Women in the Indian City

1.2 Do Women Loiter?

1.3 Taking the Lead

2. Gullies of Chandni Chowk

2.1 Chandni Chowk: The forgotten history of women

2.2 The significance of Gullies

2.3 The Site

3. Let’s Go for a Walk

3.1.1 Methodology

3.1.2 Limitations

3.2 Main Output: Website

3.3 The Walks: A discussion

3.4 Reflections: An Analysis of the Walks

3.4.1 Feminist Geography

3.4.2 Perceptions of Safety

4 5

A. Places of Faith B. Presence of Streetlights C. Personal Visions Conclusion Glossary List of Figures References Appendix 7 9 9 12 14 17 17 19 21 29 30 31 33 36 39 41 42 42 44 46 49 51 52 54 58

Introduction

The relationship between women and public space has been a subject of ongoing discourse, often revealing concerns that transcend design such as societal biases and historical inequalities. Despite the evolution of the role of women in society, the cities they occupy have failed to accommodate them. Navigating a city for women involves a daily struggle, beyond plotting a route, they must remain cautious of factors such as timing and attire among others. Clara H. Greed, a researcher and planner writing on gendered realities, uses the phrase, ‘Woman in the City of Man’ (Greed 1994, p. 34) As women engage with public space, they are constantly trying to fit into spaces that were not designed to include them. Consequently, it becomes evident that the relationship between women and public spaces is not one of pleasure.

This study embarks on a journey to challenge traditional perspectives and reimagine public spaces as inclusive environments for women. By exploring the gullies of Chandni Chowk, a historically significant area in Old Delhi, India, this research aims to uncover the evolution and hidden narratives of women’s contributions to the city’s development. Through a feminist lens, it seeks to understand how women perceive, engage with, and ultimately reclaim urban spaces. This investigation is not just about streets and structures; it is about redefining the very essence of a city’s accessibility and safety to empower all its citizens, regardless of gender.

The research presented sets out to question, “How does purposeful loitering by women on the streets of Chandni Chowk contribute to reclaiming their presence and challenging historical norms and genderbased inequalities in Indian cities?”

The research seeks to achieve the following objectives:

1. To identify and analyse the genderbased inequalities and biases that women face in urban environments.

2. To highlight the historical and cultural significance of Chandni Chowk, emphasising the role of empowered women in shaping the area.

3. To understand the experiences and perspectives of women in public spaces, specifically in the gullies of Chandni Chowk through the act of purposeful loitering.

4. To contribute to a broader dialogue on gender and public space, aiming for more inclusive and equitable urban environments.

The study is divided into three major parts, navigating through a contemporary setting to a historical and back to present day experiences. The first, titled, ‘City for Women,’ explores the relationship women share with public spaces within an Indian context. Employing theories and viewpoints from different feminist scholars, it sets the scene for the question presented. By highlighting the societal and cultural biases, it explores the framework of loitering in Indian urban environments. The second chapter titled, ‘Gullies of Chandni Chowk’ lays focus on the forgotten histories of the women involved in defining this area. Focusing on two women, Jaha Nara, and Begum Samru, it details their contributions to the stretch identified as the case study for the research. Based on the explorations in the first two chapters, chapter 3 titled, ‘Let’s go For a Walk,’ investigates the main activity of the research. The first section of this chapter focuses on the methodology followed and limitations encountered within the study and goes on to describe the website created as the main output for the study. The second section of this chapter summarises the participants experiences in the gullies of Chandni Chowk, and further analyses them to provide consistent observations through the different perspectives.

7

Imagine an Indian city where women step out when they want to, regardless of the time and what they are wearing. A city where they don’t need to send updates about when they’ve reached home. A city where they sit on corners of the street, taking in the hustle and bustle of their surroundings, stopping at a chai stall, not worried about how many men stand around them. A city where they don’t cover their chests with their bags to avoid stares from the people around them. A city where they have the right to step out for leisure. A city where they have equal right to public space as their male counterparts. Would this be an ideal example of a City for Women? 1

1. City for Women?

The concept of public space and its ownership has been a subject of ongoing debate. Envisioning public spaces as design students, we think of wider streets, easy walking access, better traffic control, green spaces, better housing. Gender often doesn’t stand out immediately as a concern. Only when we start to navigate public space as women first, do we realise there may be a problem. “The problem is that planners have produced policy on the basis of a genderblind perspective, to meet the presumed needs of the public” (Keeble 1969). The presumed needs of the public were seen from a male-centric perspective, owing to the dominance of the deep patriarchy the society was built upon. Leslie Kern, a feminist geographer in her book, Feminist City: Claiming Space in a Man-made World, starts with a sub-chapter called ‘Disorderly Women’: “Women have always been seen as a problem for the modern city” (Kern 2019, p.2).

Cities and therefore by extension public spaces lack the perspective of a decentred male narrative. Looking back, it is challenging to remember if we engaged in conversations regarding gender and what it means for different genders to occupy space in public. Would it have made a difference if we questioned this as young designers or is this a deeply ingrained societal norm that we unintentionally ignore.

1.1 Women in the Indian City

India comes into the picture with a particularly burdened stance on space for women, be it in public or otherwise. Known as a country rich in culture and tradition the country is intertwined with societal norms, substantial expectations, and deeply ingrained gender bias. Additionally, the Indian narrative has been shaped by two significant regimesthe Mughals and the British-which have left a lasting impact on the societal and cultural norms of the country on an already intricate establishment. These layers of authority instilled different ideals for women’s socialisation with their surrounding environments.

Women are given conditional access to public spaces. Though as time progressed, this has changed in certain societies, but having grown up with this narrative tends to make women wary of their surroundings and compels them to self-regulate their actions in public. These ideals have stemmed unconsciously from home and from childhood. Women resort to gender-specific body language to commute in public, be it dressing modestly, taking as little space in public transport, or simply attempting to avoid drawing attention, a behavioural pattern ingrained within generations of teaching. Sara Ahmed states in her book Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others says, “the Patriarchal city is built on the assumption that certain bodies

1. The above lines are a reinterpretation of parts of the prologue in the book, ‘Why loiter? Women and Risk on Mumbai Streets.’

9

have the right to be more present and move freely, while others are excluded or constrained” (Ahmed 2006).

Enter New Delhi, the capital of India, is a city with a population of 32 million. The male to female ratio is 866 to every 1000 men. For the past few years, New Delhi has been named as the most unsafe city in India for women (NCRB 2021). This is the result of a combination of factors, one of them being public infrastructure. Therefore, in the name of safety, women are further confined to their homes. We are aware that traditionally, or according to arbitrary gender norms, men stepped out of the house to work more than women. As our societies progress, both men and women alike step out of their homes to commute to work. “Once women began joining the workforce in larger numbers, they were tasked with the responsibility of having to justify their presence in public spaces as “respectable” by establishing links to their domestic responsibilities” (Joshi 2021). A ‘respectable’ woman is one that has the

correct length of attire, the correct attitude, gets back home at a respectable hour after work, and knows her place in the society. In a society like India, the onus simply falls on women, as it is deemed uncharacteristic for ‘respectable’ women to be out after a certain time.

According to India’s 2011 Census, only about 17% of commuting to work in urban areas are women, of which the number never goes beyond 20% for metropolitan cities like Delhi (Goel 2018). That means for about five men, only one woman steps out to commute to work. And more than a third of women who work do so from home, thereby confining women to their homes. This has certain drawbacks, one of them being restriction from participating in the social or political life of the community, being socially excluded. For women to participate in life outside their homes, be it in neighbourhoods, streets or public transport, the public infrastructure needs to be sensitive to the needs of women. The

inequality between men and women in India is stark, and nowhere more so than on the streets of its cities, which are undeniably the domain of men (Goel 2018).

Another observation that has been made in studies undertaken in the same field, is the different way men and women occupy space in public. In cities in India lounging on a park bench, sitting around a tea stall for their evening tea, or even venturing out onto the streets late at night, is a privilege not enjoyed by women in the same way as men. Shannon Philip, researcher, in his study of urban cities and masculinities calls New Delhi, a City of Men: “They are conditioned to be more ‘public’ than women.This conditioning allows men to gain privileged access to the world outside the home and gives them confidence to be in public without fear” (Philip 2017). This distinction in ownership of public space, or the right to claim space in public is one of the many reasons for gendered violence in New Delhi and largely India.

It is an everyday struggle for women to chart the course of their daily travel. How can

we shape a city to accommodate women without inducing or escalating fear? In our society, women have internalised various fears due to their upbringing. This has significantly influenced their perception and interaction with public spaces. Globally, this phenomenon has been termed ‘female fear’ (Kern 2019), often assumed to be an inherent trait in girls and women. These studies question where, when and with whom women experience fear, with similar results stating women identified cities, nighttime, and strangers as primary sources of threat. Now in a city like New Delhi, deemed the most unsafe for women in the country, if there is ever a crime against a woman, it triggers immediate scrutiny towards her actions—when she left, where she went, with whom, and why. To code the city according to threat level has somehow become natural to a woman’s being in the city. “To truly claim citizenship in the city, we need to redefine our understanding of violence in relation to public space --- to see not sexual assault, but the denial of access to public space as the worst possible outcome for women” (Phadke 2011, p.ii).

10 11

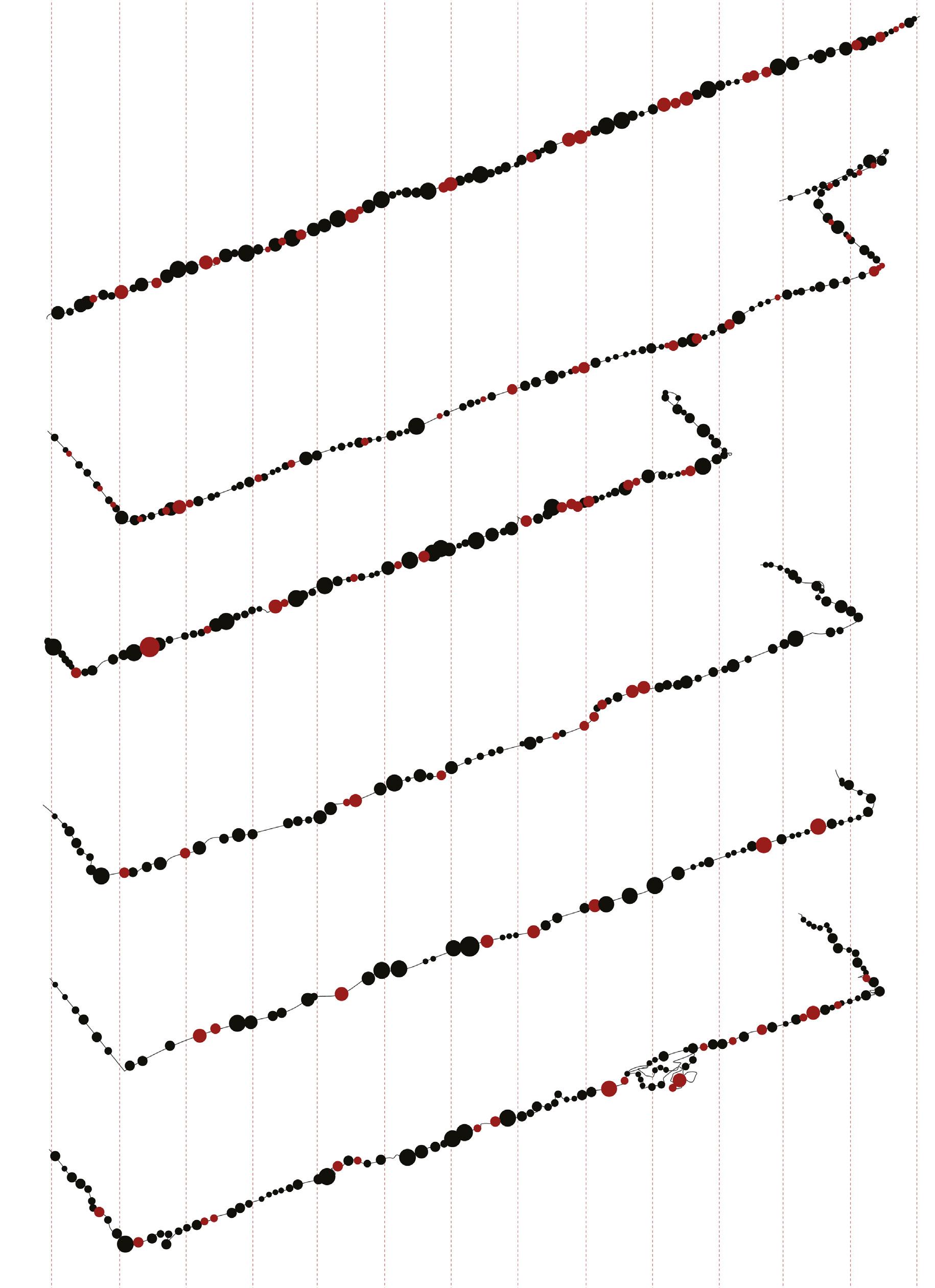

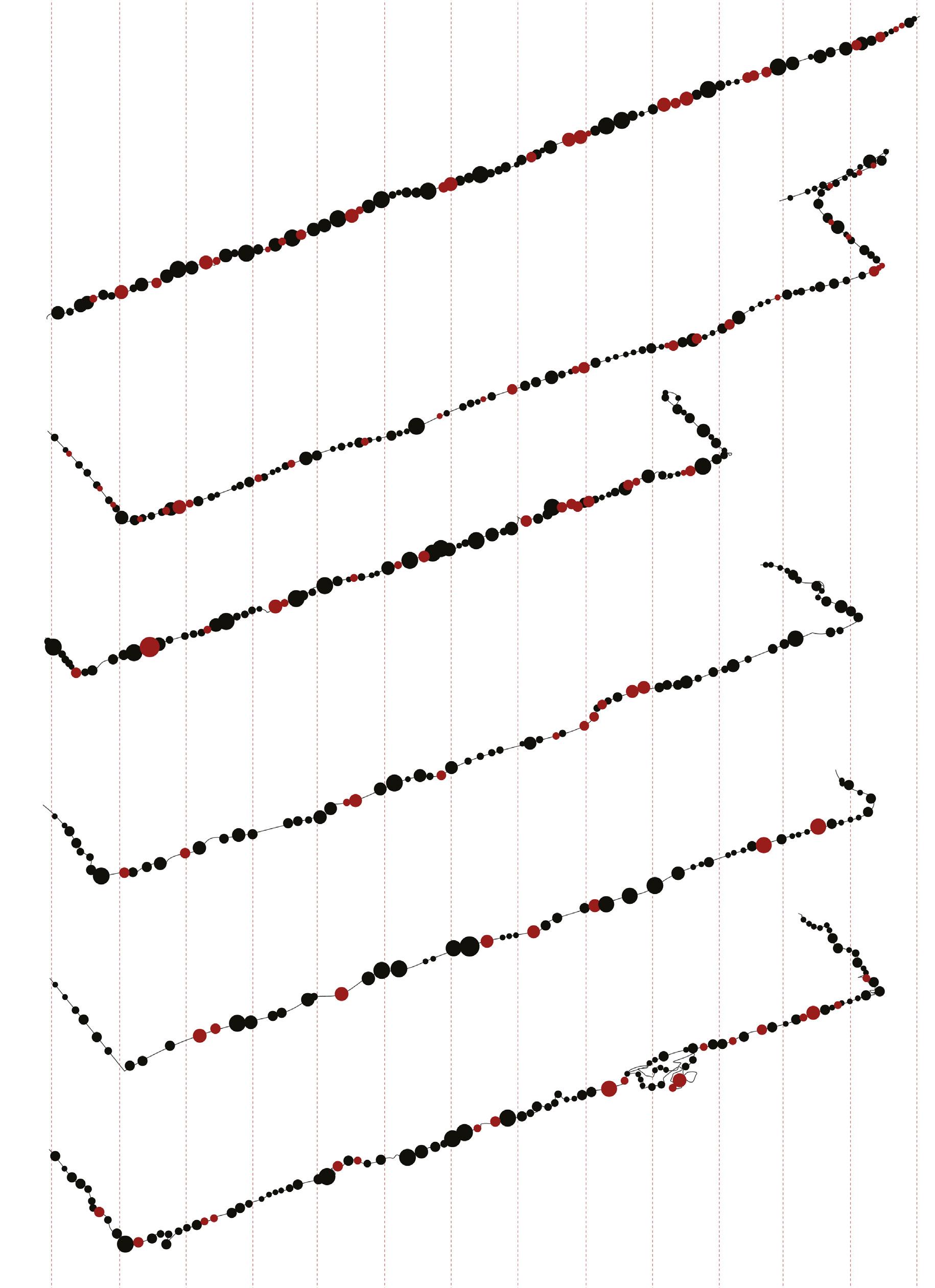

Fig. 1: Women in the Indian City

1.2 Do Women Loiter?

In the previous section, a primary focus was on the intricate and constrained connection that women have with the city, deeply influenced by centuries of entrenched patriarchy and gendered expectations. These prevalent cultural and societal norms have, over time, hindered women from experiencing a more liberated and leisurely relationship with urban spaces. It is crucial to contextualise the concept of loitering within the Indian urban context. When we think of loitering in a city the image that comes to mind is automatically of small smelly corners, narrow alleys, dark lanes, smell of cigarettes and groups of men in loud voices. Consequently, loitering has been negatively perceived and even illegal in certain Indian cities at one point. Shilpa Phadke, Sameera Khan, and Shilpa Ranade explored the process of loitering in their book, Why Loiter? Women and Risk on Mumbai Streets, shedding light on why women often refrain from loitering, a behaviour common for men. “There’s an unspoken assumption that women don’t

loiter or move about freely, if they do, they are up to no good. She is mad or bad or dangerous to society” (Phadke 2011, p.i). Where is the space for women to move freely: to loiter? “Most women that do step out, do so to commute from one place to another or as extension of their duties in the domestic sphere. Women are at best commuters through public space – moving from point A to point B –they cannot lay claim to the city as citizens” (Phadke 2011). Where women are still considered to keep their domestic responsibilities paramount, the relationship with public spaces is not one of pleasure but another way of carrying out their responsibilities.

The question may arise as to why emphasise loitering as an activity. The answer lies in the fact that loitering, by its very nature, serves no purpose other than personal enjoyment. “Since loitering is fundamentally a voluntary act for pure self-gratification, it is not forced and has no visible productivity” (Phadke 2011, p.186). Leisure extends beyond idleness and a mere pastime. It is a time for observation and contemplation without the added constraints of an agenda or purpose. In the urban environment leisure may manifest through different activities. It can mean a stroll through a park, a moment spent people-watching, resting at a tea stop, or a pause to appreciate their surroundings. It is a ‘moment of pause’ to enjoy the mundane or ordinary activities. In essence, leisure signifies a sense of belonging and empowerment. It challenged the notion that public space is for a specific demographic, and asserts that they should be inclusive, equitable and just.

Loitering stands as an act of leisure, with the underlying aim of instilling confidence in women to venture beyond their homes and actively engage with public spaces.

12 13

Fig. 2: A woman seen ‘loitering’ along Marine Drive, Mumbai.

Fig. 3: Cover image for the book ‘Why Loter? Women and Risk on Mumbai Streets’

1.3 Taking the Lead

In this section, the discussion will point to the many women before this study who have made the initiative to contribute to a broader dialogue on gender equity in the public realm. The majority of these dialogues have been initiated by women who have experienced a sense of being marginalised in public spheres, and in their own manner, attempted to challenge this situation.

Kimberly Truong conducted a social experiment in 2017, where she decided not to make way for men and expected them to step aside. She recorded the micro-aggressions, which she called, manslamming; where men ignore the presence of people around them, specifically women (Truong 2017). She has made this a daily activity in her life to assert the need for ‘taking up space’ in public and her right to exist proudly.

Another example points to a female startup ‘Wovoyage’ run by Rashmi Chadha, that seeks to make solo travel through the country a more achievable and pleasurable activity rather than an unachievable task. Established in 2016, her initiative has helped thousands of women from different parts of the world to navigate through the streets of Old Delhi. (D. 2018)

A UK based travel company, ‘Intrepid’ has started recruiting women as guides in parts of Old Delhi to encourage women to step out and roam freely in the city. The aim is to lead tours for women, run by women, in an effort to highlight the culture of India, but also encouraging women to engage in diverse methods of employment (Dunford 2014).

Many online platforms run by women have initiated similar campaigns, that put women’s leisure at the forefront.2 Taking forms of silent protest or acts of performance, they highlight the need for

women to assert their presence and enjoy their time in public spaces. Using strategies from the book ‘Why Loiter,’ an act of silent protest called ‘Performing Loitering’ has begun in major cities through India, as a way to normalise the sight of women out and about in the city taking pleasure in the act of doing nothing. K Frances Leider, a feminist scholar, describes her experience at one such protest, “The women of Why Loiter were not loitering only to make themselves more comfortable doing nothing in the public space of the neoliberal city; they were also loitering for an audience, normalising the idea of women doing nothing in the public space.” (Leider 2018, p.145)

2. Some Instagram accounts that lay focus on women at leisure that have inspired this section are as follows: @women_at_leisure; @girlsatdhabas; @whyloiter.

Additionally, an initiative by the Smart Cities Dive states that, “The number of women that appear in the public realm, during the day and especially at night, is an indicator of the health of a society and the safety and liveability of a city.” (Khatri 2023)

These valuable perspectives offered by various feminist scholars challenge the narrative regarding women's presence in public spaces, striving for a genuine assertion of citizenship and agency within the city.

It is key to remember that not all signs of protest are large and noticeable throughout the world. Small changes in an everyday life signify a similar kind of protest where women silently change the way they operate in the city. These women have taken that step to question the gender biases of several generations and found a way to find pleasure in urban spaces, encouraging several women to do the same. They have made the initiative to take the lead in a dialogue that contributes to gender equity and simply the presence of women in the public realm.

14 15

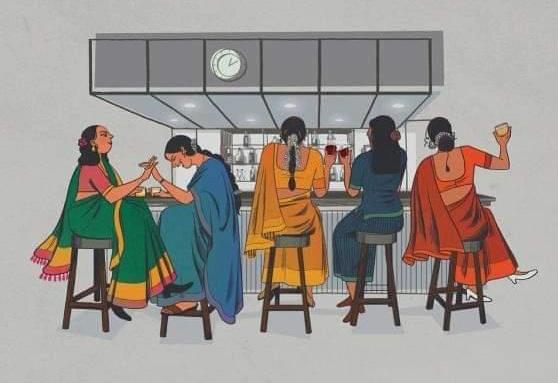

Fig. 5: “Leisure as a way to getting lost in a conversation in public” @women_at_leisure

Fig. 4: “Look around you. How many women do you see in public spaces? Now do you feel afraid or curious?” @girlsatdhabas

“I step out into Chandni Chowk Street: once littered with jasmine-flowers for the Empress and the royal women who bought perfumes from Isfahan, fabrics from Dacca, essence from Kabul, glass-bangles from Agra.”

-Agha Shahid Ali 3

2. Gullies of Chandni Chowk

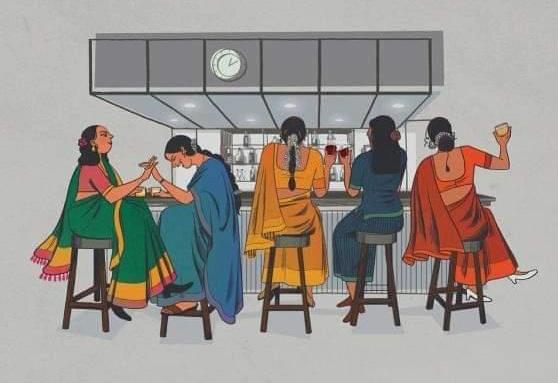

The case study for this research project is Chandni Chowk, a marketplace in Old Delhi, lined with several historic monuments making it rich in the culture and heritage. Through its old-world charm, one is transported to the times of the Mughal rule which was known for the many architectural marvels they built in India. Most landmarks that are remembered today tell the story of the brave men or Emperors that built them. But in this area, there are many landmarks that were connected to the women of the Mughal Empire. Their names remain absent or forgotten. Historian, Anita Anand notes, “Women’s histories fall through the cracks many times” (Anand 2023).

With this sentiment in mind, selecting this particular stretch for the project thrusts the forgotten narratives of these remarkable women into the limelight.

2.1 Chandni Chowk: The forgotten history of women

The Mughal Empire allowed women with a certain social class to own land and other property. Most of them, highly educated, used their resources to build different landmarks that still command a place in the landscape of the city of Delhi. They built several mosques for worship, one of them being Fatehpuri Masjid, the mosque at the other end of Chandni Chowk, tombs for their husbands or sons, and several Mughal Gardens. “They were an integral part of the politics, made administrative decisions, maintained their own armies, and even planned murders, so why are they just mentioned as wives and agents of pleasure” (Suresh 2016)? Over time, these stories have been overwritten and their contributions to the city have been minimised. These histories, important to show the agency women had in the past, have been largely forgotten.

3. A verse from Agha Shahid Ali’s 1980 poem titled, “After seeing Kozintsev’s ‘King Lear’ in Delhi” describing the streets of Chandni Chowk.

17

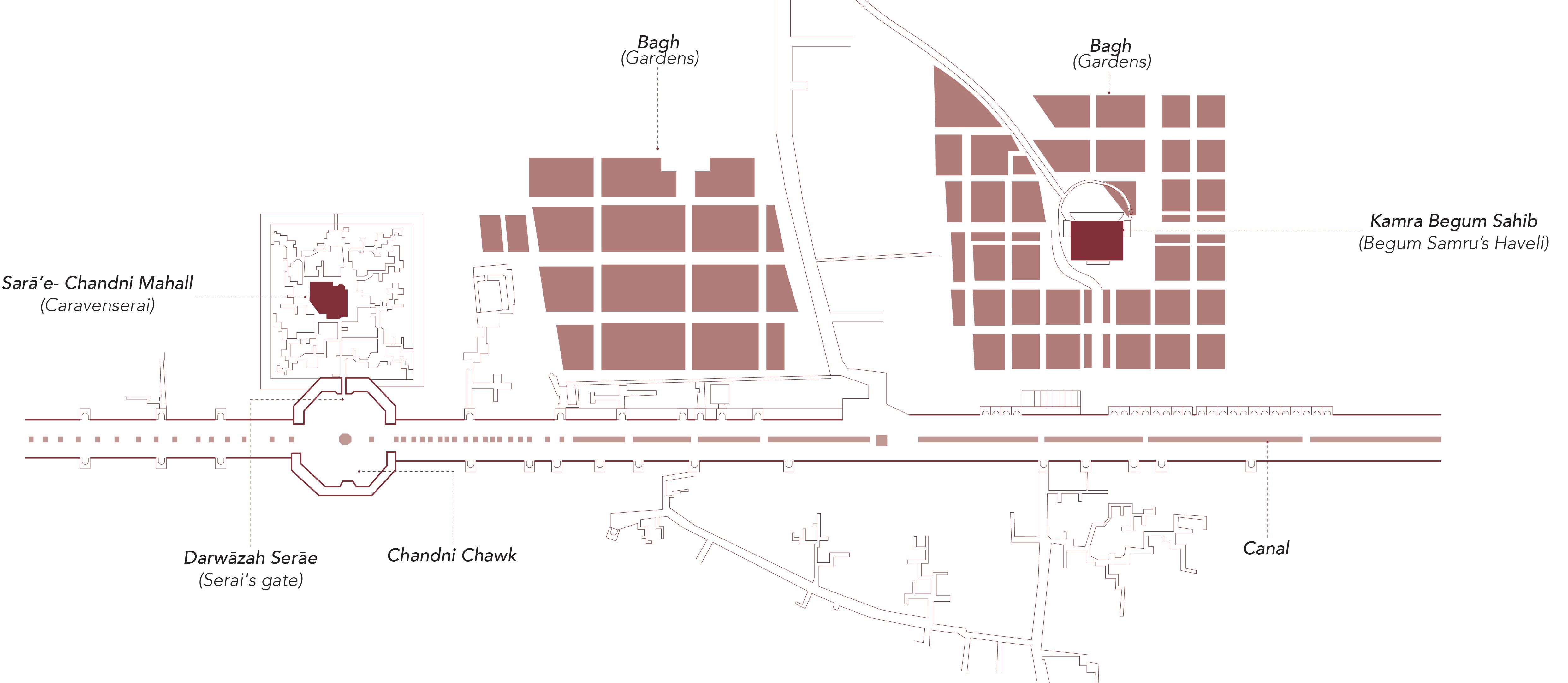

In this study the women under discussion are Jaha Nara and Begum Samru, two women from different time periods in the Mughal empire:

Jaha Nara, born in the year 1614, was remembered as one of Shah Jahan’s favourite daughters. Upon her mother’s deathin the year 1631 she inherited a sum of 50 Lakh (5 million) rupees. She was known as a patron of the arts, crafts, and architecture with great influence and resources, and used her elaborate wealth to spread these through the empire. She was also responsible for commissioning the designs for Chandni Chowk.

2.2 The significance of gullies

Both women held a position of stature in the empire and left an indelible mark on the history of the city and largely the history of our country.

Begum Samru on the other hand was not born into royalty. Born as Farzana in the year 1753, she was a Kashmiri dancing girl. She married a European military officer, Walter Reinhardt ‘Sombre’. His nickname ‘Sombre’ was corrupted to ‘Samru’ therefore, she came to be known as Begum Samru. Upon his death, she inherited his estate, and spent much of her time in her haveli in Chandni Chowk (built in 1806), socialising with the Mughal Royal family and British Officials.

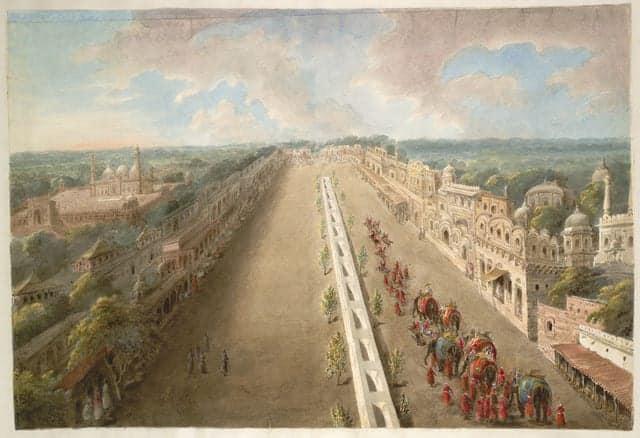

Chandni Chowk, one of the liveliest markets in Old Delhi was established in 1650 by Jaha Nara, the daughter of the reigning emperor of Mughal India. In the Mughal Empire’s capital, Shahjahanabad, Chandni Chowk stood in the middle and was a main artery joining the Lal Quila, the residence of the emperor, and Fatehpuri Masjid. The name ‘Chandni’ translates to ‘silver’ or ‘moonlight’ which reflected the design of the marketplace. It had a canal running along the main street and the water was used to reflect the moonlight. On the other hand, ‘Chowk’ translates to public square. The main artery bifurcated into narrower streets called gullies, with the market running alongside these gullies. Chandni Chowk was a centre for art, architecture, and crafts. Through the progression of time, it has seen many changes from Mughal India to British India and presently, independent India. Within the loud, crowded, and chaotic market of Chandni Chowk, one can find anything and everything that they require. The aroma of the food market mingled with the loud vendors and shopkeepers calling out to customers is just one of the many charms of Chandni Chowk. As one strolls through this vibrant marketplace, echoes

of its rich history echo from every corner, rendering it a captivating tapestry of the past and present.

The gullies of Chandni Chowk have many untold tales of history. “These were the streets where emperors paraded, and commoners led their ordinary lives” (Karman 2020). The focus of this research project lies in the gullies of Chandni Chowk. Gullies are the central lifelines of the city of Delhi. They are a reflection of the public realm and are inherent to a city sphere in India. They serve the city in a similar manner as public squares or piazzas do in countries in the West or in Europe, though they differ in the general geometry. Gullies are narrow lanes or informal streets that are occupied by predominantly by pedestrians with an added layer or two or three wheeled vehicles. In Chandni Chowk, these gullies also have vendors sitting by the side as well as shops that encroach onto some areas. They were designed for the use of walking but have with time accommodated different kinds of traffic. Though it adds to the charm of the market, at the same time it also adds a layer of chaos.

18 19

Fig. 6: Princess Jaha Nara aged 18

Fig. 7: Portrait of Begum Samru

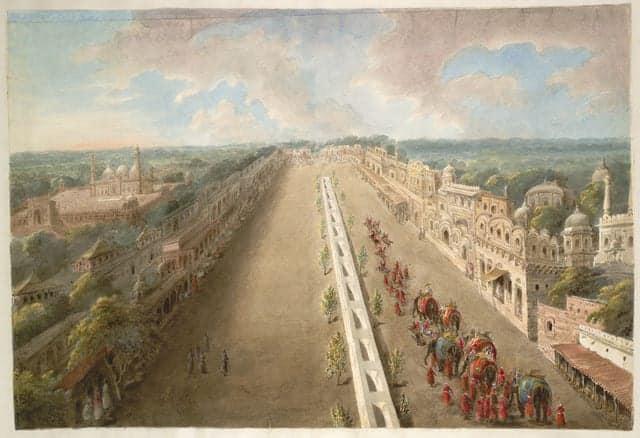

Fig. 8: Chandni Chowk bazar in the year 1815

2.3 The Site:

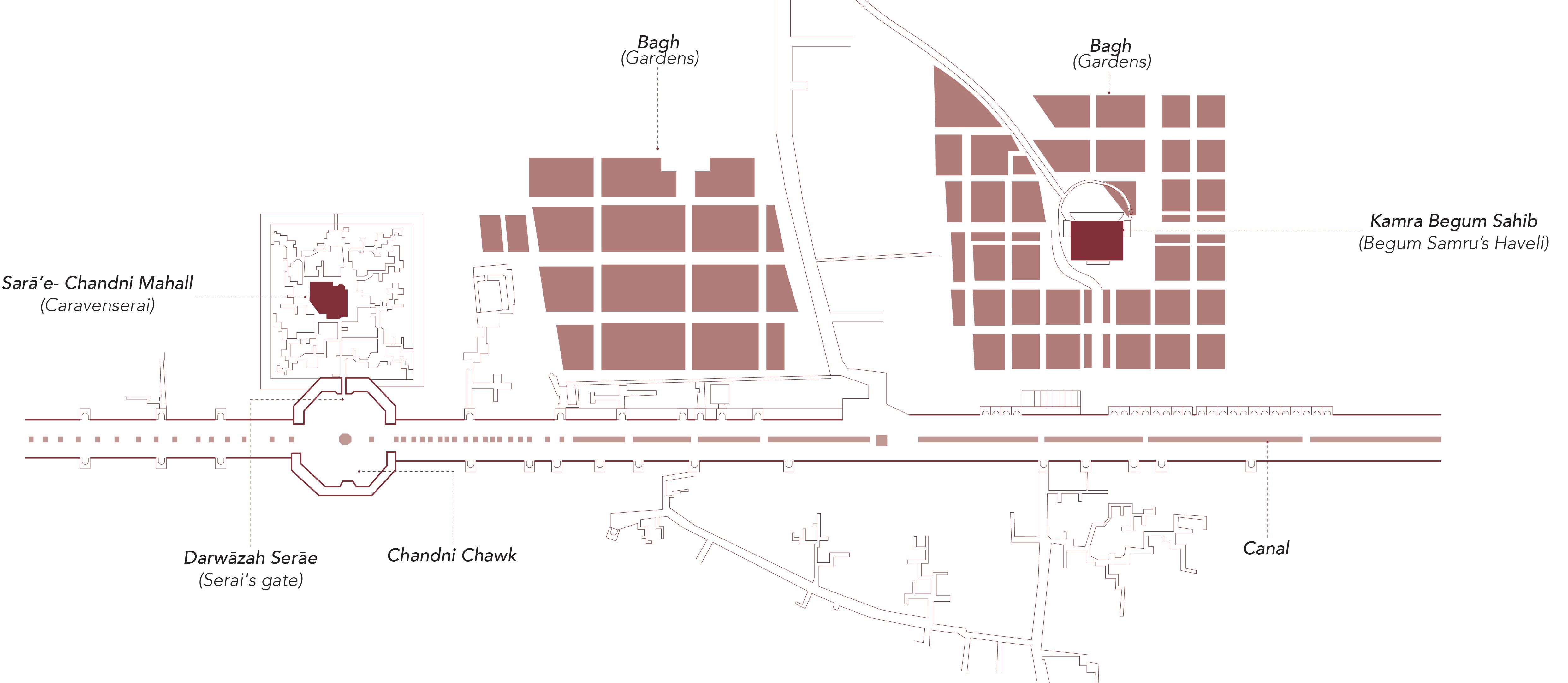

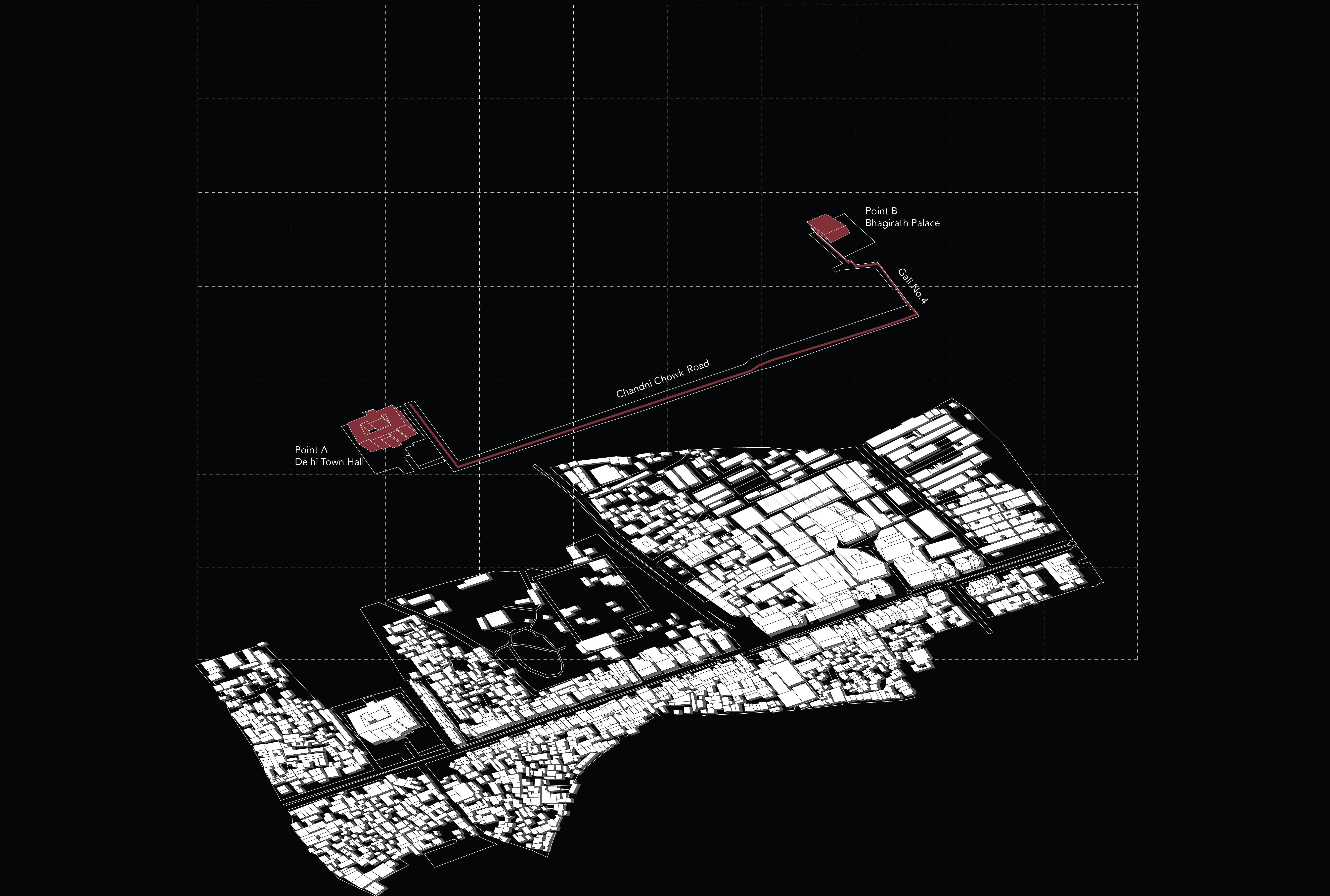

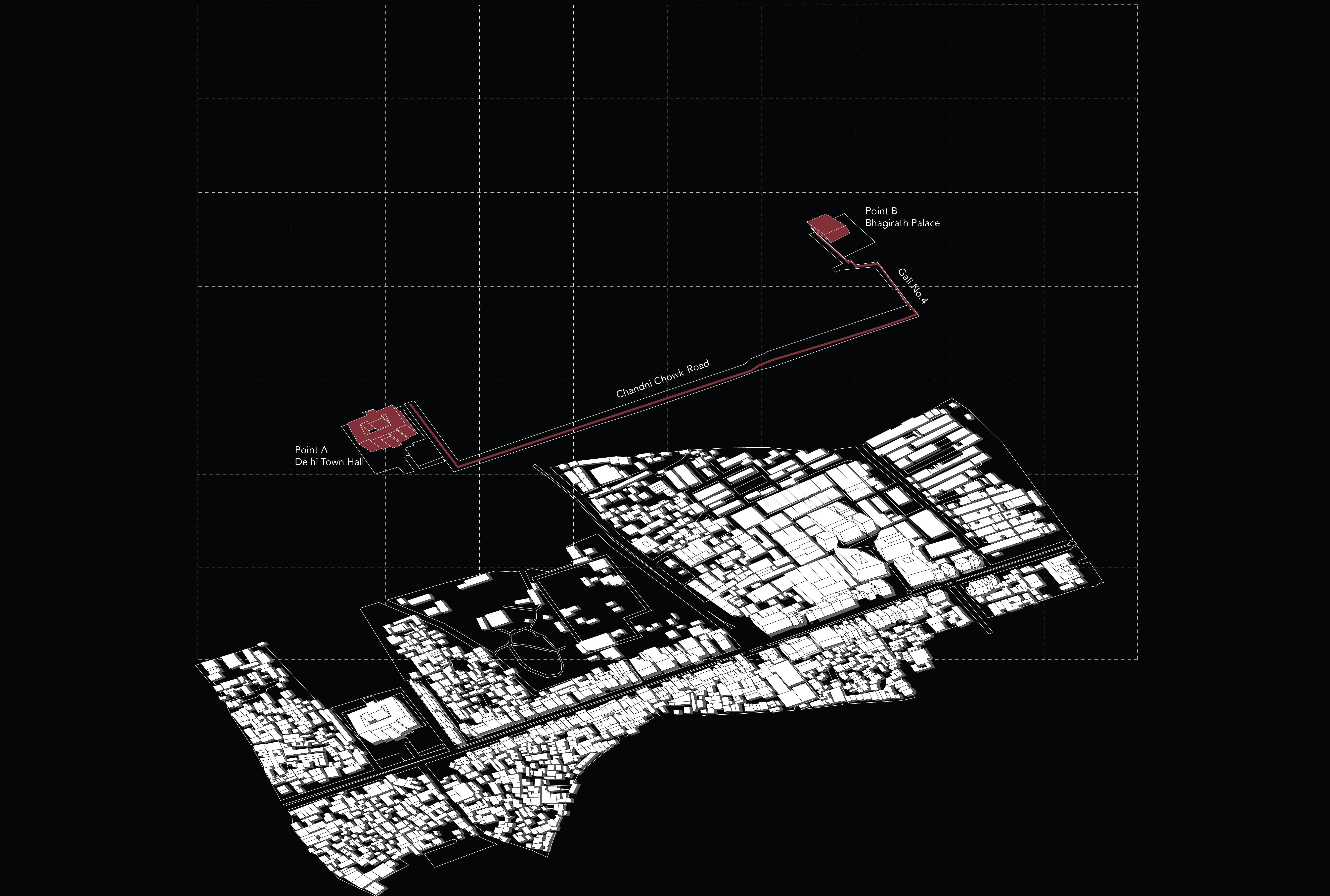

In Section 1.2, it was emphasised that women predominantly function as commuters within public spaces, often constrained by specific objectives, symbolised by the straightforward journey from “Point A to Point B”(Phadke 2011). They navigate through urban landscapes with a purpose or a defined set of duties. Keeping within this framework of Point A to Point B, the subject of this discussion is a one-kilometre stretch within Chandni Chowk. This particular journey commences from the present-day Delhi Town Hall, denoted as Point A, and culminates at Bhagirath Palace, designated as Point B. This section delves into the rationale behind selecting these specific points for the research investigation illumaninating their historical significance and evolution over various time periods.

Jaha Nara: Point A: The site where the current building of the Delhi Town Hall stands was originally a Caravanserai, a roadside inn for the travellers within the Mughal Empire. Located within the Begum ka Bagh (Queen’s Gardens), Stephen Blake recounts that Jaha Nara once said: ‘I will build a serai, large and fine like no other in Hindustan. The wanderer who enters its courts will be restored in body and soul and my name will never be forgotten’ (Blake 1991). After the Revolt of 1857— an integral moment in the history of India that marked the formal end of the Mughal Rule and transferred power of the country directly to the Queen of England— the caravanserai was demolished. A new colonial style building was built between 1860-63 in its stead and stood as the seat of the Municipal Corporation of Delhi from 1866-2009. Today it stands in the heart of Chandni Chowk, restored and a reflection of the past authorities of the country.

21

Fig. 9: Painting from the 1820s of Begum Samru’s Haveli located in ‘Begum ka Bagh, presently at Aga Khan Museum, Toronto

Fig. 10: Jaha Nara Begum’s caravanserai that formed the original Chandni Chowk

Fig. 11: An excerpt of a 12-page panorama from Sir Thomas Metcalfe’s collection

Begum Samru: Point B: Bhagirath Palace, for marketgoers in Chandni Chowk is an important building today as is also called the ‘Light Bazaar’, as it houses multiple electrical stores. Between the 18th and 19th Century, Begum Samru owned this building. Begum Samru had rose the ranks by lending her army to the Mughals as well as the British East India Company. She was gifted some land in Chandni Chowk by a Mughal emperor, and in 1806 she built a haveli within a large garden in that area. It was built in a purely European classical style, the first of its kind in Chandni Chowk. Historian, Mrinalini Rajagopalan notes that, “the architectural style of Begum’s home dismantles and reimagines the traditional

distinctions made between masculine and feminine spaces, domestic and political realms, and European and Indian decor, reflecting a cosmopolitan identity” (Rajgopalan 2018, p. 175).In this haveli she held her own court as well as numerous parties frequented by the British as well as courtiers from the Mughal Empire, an anomaly at the time. After her death, the haveli went on to become the Delhi bank, operated for the British officials. Destroyed heavily once again in the Revolt of 1857, the haveli went on to become first the Imperial Bank and then the Lloyd’s Bank. It is now known as Bhagirath Palace and does not hold the same beauty as it once did.

Gully: The ‘Chandni Chowk Road’ and ‘Gali (gully) No.4’ are the streets that connect point A to point B. The main Chandni Chowk Road in the past was the street with the canal in it. It was used by Mughal emperors for processions, one of them heavily documented by Sir Thomas Metcalfe in his series ‘Reminiscences of Imperial Delhi’, titled, A panorama in 12 folds showing the procession of the Emperor Bahadur Shah to celebrate the feast of the ‘Id, in 1843. After the Revolt of 1857, the canal was bricked up, and the same street served as a procession for the British over time.

Presently, Chandni Chowk has lost much of the historical prominence it once held. Many individuals have characterized this bustling marketplace as an unsafe environment, particularly for women. Navigating through the throngs and chaos can be an uneasy experience for some women. This street in Chandni Chowk is used as an example to represent different streets in the city and by extension how women interact with public space, which is discussed further in the next section. The decision to select this site for the study is underpinned by its role as a reflection of a pivotal public space, enriched by its historical significance.

22 23

Fig. 12: Map of Chandni Chowk from the 1850s

Fig. 13: The Site:Point A to Point B identified in present-day Chandni Chowk

Fig. 13: The Site:Point A to Point B identified in present-day Chandni Chowk

Fig. 14: Timeline showing the evolution of Point A, Point B and the gully over a period of time

Fig. 14: Timeline showing the evolution of Point A, Point B and the gully over a period of time

“Not all protests are marches, some are strolls.”

- #whyloiter4

3. Let’s Go for a Walk

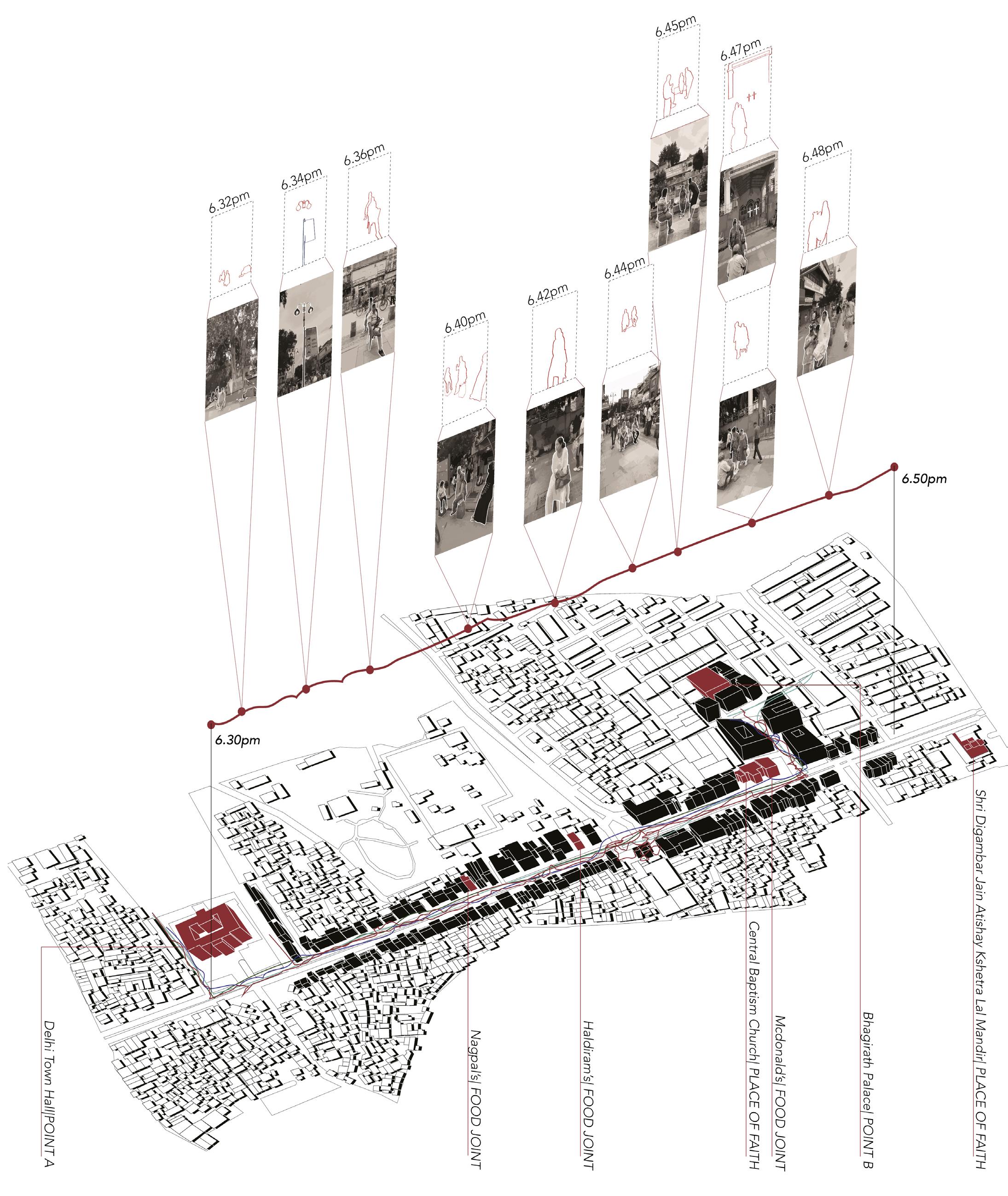

Chapter One, titled ‘City for Women?’, explores women’s relationship with public spaces, burdened with societal and cultural norms, ingrained within a patriarchal system. It also sets the framework for ‘loitering’ in the Indian context. With the exploration of Chandni chowk as a site for the study in the last chapter, this section seeks to integrate the two to form the main activity for the project. The framework of loitering as discussed in section 1.2, is set within the context of the Point A and Point B identified within Chandni Chowk. This section follows the journey of six women who walk the gullies of Chandni Chowk, exploring their narrative and experiences of their relationship with the streetscapes in question.

As the final stage of the research project, this chapter strives to integrate the elements from the preceding research to form an intricately woven narrative that shapes the primary outcome of the project.

In the book "Why Loiter," the authors suggest, "Not all protests are marches; some are strolls" (Phadke 2011). The primary activity that shapes the outcome of this research is constructed within the framework laid out by numerous feminist scholars discussed in Chapter 1. It also endeavours to put their theories to the test in real-world settings. This activity aims to investigate whether women in New Delhi

4. A hashtag widely used on the instagram page @whyloiter

would be inclined to take a leisurely stroll as an assertion of their right to public space, providing valuable insights into the actual experiences of these women on the ground. It serves as a form of performance, a silent form of protest that isn't an attempt to overhaul the entire system in one go, but rather a gradual process aimed at empowering women to gradually reclaim their rightful agency in public spaces. The chosen title for this primary output, 'Let's Go for a Walk,' conveys the simplicity of the act of walking, which, for many, may actually be a point of contention and carry deeper societal implications.

This chapter is structured into two distinct sections. The initial section addresses the methodology for the core activity, incorporating an explanation of the guidelines provided to the participants and an acknowledgment of the study's inherent limitations. Subsequently, it delves into an examination of the website, which serves as the primary medium for presenting the research study's findings. The latter portion of the chapter centres on the experiences of the women, providing a concise overview of their respective walks. This section proceeds to conduct a thorough analysis categorised into two main sub-categories: Feminist Geography and Perceptions of Safety.

28 29

3.1.1 METHODOLOGY

The activity guidelines asked the women to walk individually, preferably during the evening, along a designated route in Chandni Chowk, New Delhi. This journey is an attempt to reclaim the same predefined route, but with an element of spontaneity. Through the act of purposeful loitering and subsequent analysis, the study aims to comprehend the significance of the simple act of solitary evening walking along the streets, with an aim to reclaim space in the urban environment, through leisure. This exploration seeks to delve into the everyday-ness in the urban environment, asserting that women possess an equal right to engage with the city as their male counterparts do.

It is important to acknowledge that the predefined Point A to Point B were a suggestion for them, allowing for flexibility rather than being compulsory. This consistent route was also selected to facilitate comparisons between the walks, aiming to identify shared perceptions of safety amongst different women.

All the information obtained was gathered indirectly, establishing this project as a collaborative effort between the six women and the researcher, with the emphasis placed on the data they individually collected. Each participant was wellinformed about the purpose of the activity. They were introduced to the project through a set of general guidelines (see Appendix), which were open to interpretation based on each participant's perspective.

Throughout their journey, they documented their experiences by capturing photographs or video clips. Additionally, they submitted

written accounts detailing their observations, aiming to capture their reflections (see Appendix). Finally, the participants conveyed their reflections and aspirations regarding this specific gully through rough sketches, offering a visual representation of their experiences during the walks. While the participants did not face any immediate threat, their names have been anonymised in the study, to avoid any potential risks or threats that may arise in the future.

3.1.2. LIMITATIONS

Given my time constraints, I was unable to personally visit the site. Therefore, the majority of the women who participated were either part of my immediate social circle or an extension of it. These women are all young professionals who commute for work five days a week. Most of them either hail from New Delhi or have relocated there for career prospects, making them familiar with and frequent travellers within the city.

Initially, efforts were made to ensure diversity in terms of age groups for the project's participants. However, due to various factors such as prior commitments and limitations in personal transportation, coupled with varying degrees of willingness, the age group representation had to be adjusted. As a result, the final group of six women selected for the project are all in their late twenties. They utilised a combination of private and public transportation methods, similar to their daily routines, to travel to Chandni Chowk.

Another challenge the research encountered was the weather conditions in New Delhi. Throughout the month of July, Chandni Chowk and its surrounding areas experienced severe flooding due to heavy rainfall in the capital city. This unfortunate weather event led to a reduced number of participants compared to the project's initial expectations. However, in hindsight, this limitation allowed for a more in-depth exploration of the experiences of these specific women. The study would have benefitted from the data of women who lived in the area. Unfortunately, since I was unable to visit the city, it was difficult to find residents of Chandni Chowk to partake in the activity.

30 31

3.2 MAIN OUTPUT: WEBSITE

The collective experiences of the participants find their expression on the website, bearing the same title, 'Let’s Go for a Walk: Women’s experiences from the gullies of Chandni Chowk.’ The website functions as a dynamic tool to showcase the experiences and perspectives of these women, aiming to initiate a discourse around them. It serves as a platform for sharing their journeys and narratives, providing insights into their relationship with the alleyways and the broader public space.

By featuring only six participants, the website offers an intimate view of their individual interactions with public spaces, providing a micro-level vantage point. Incorporating a blend of visual elements and their shared observations, the analysed data is presented through a combination of graphics and visuals. These visuals spotlight the 'moments of pause' experienced by each participant during their walks, employing silhouettes and highlighted objects to illustrate what captured their attention. Additionally, through the showcased videos, the website’s viewers are invited to virtually accompany the women on their walks, providing an opportunity to witness and immerse themselves in the streets from the women’s unique perspective.

a wider discourse on these crucial matters.

Please note that the subsequent sections offer a summary of the observations made through the participants’ walks, and the full analysis of this study can be explored on the website

The website as a digital tool serves two main objectives. The first is to foster awareness and comprehension of the perspectives of women within public spaces, specifically, the gullies. Secondly, it seeks to inspire women to venture out for leisure, cultivating a sense of enjoyment and comfort in their urban surroundings. Additionally, it hopes to join conversations surrounding gender dynamics and safety considerations, inviting Fig. 16:

5. For more information please visit: https://letsgoforawalk.cargo.site/

32 33

Let’s Go for a Walk: The website

Fig. 15: Let’s Go for a Walk: Landing Page

34 35

Fig. 17: Videos from the participants. Available on website

The subsequent section provides a concise summary of the participants’ individual experiences, offering insights into their perspectives on the walks.

Upon closer examination of the collected data, it becomes evident that the participants interpreted the guidelines in their own unique ways. Some recorded themselves walking through the entire stretch, whereas some only documented parts they thought were integral to the research. This may have also had an impact on their experience as participant 3 states in her document,

“One can also note that due to the constant presence of a camera which was used for vlogging/documenting the entire walk, perhaps people were unwilling to engage negatively. They become more aware of the fact that they are being recorded in case they behave negatively towards women.”

Another important observation is that one of the participants was unwilling to travel to Chandni Chowk all by herself, especially in the evening. She took a friend along therefore on a Sunday afternoon making them participants 4 & 5. This further emphasises the perception of some gullies being unsafe, keeping women from truly enjoying their urban experiences.

“I had a negative preconceived notion of the streets of Chandani Chowk. When I signed up for this activity the first thing I did was, called a friend who could tail me during the walk.”

Though these participants walked through the gullies separately, they were never a few hundred metres apart so they could spot each other at all times. Her friend talks about it not being as uncomfortable as she imagined,

“The CCTV cameras do reassure one in such crowded space; however, I would still not venture to Chandni Chowk alone. You can get lost in the throng of people and it feels like there are 20 eyes following you everywhere with eager shopkeepers chasing you every few minutes.”

Through the imagery shared by the participants, there were also some observations in the way participants walked through the gullies according to their convenience and perception of safety. While the longer stretch of the walk was along a wider gully, Chandni Chowk Road, well-lit and pedestrianised, the last two to three hundred metres of the stretch were in a comparatively narrower gully, Gali No.4, not as well-lit as the previous one and more chaotic and crowded. Hence, participant 1. made a conscious choice of not entering the second stretch noting,

“There were moments when I still felt a tinge of concern to enter the narrower lanes where the crowds could become overwhelming.”

The participants’ detailed experiences is beyond the scope of what has been presented in this section. The full documentation, therefore, is shared on the website.

36 37

3.3 THE WALKS: A DISCUSSION

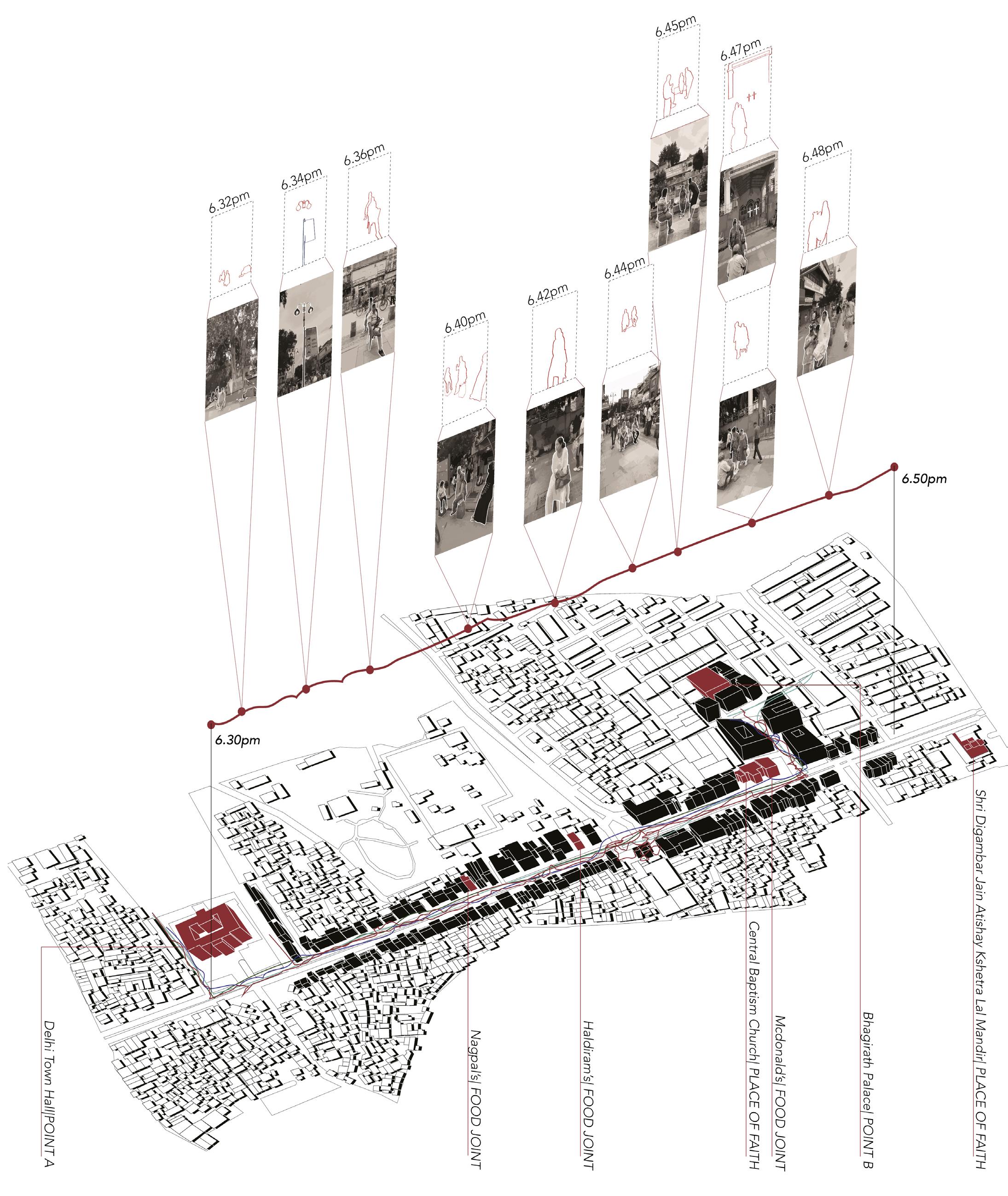

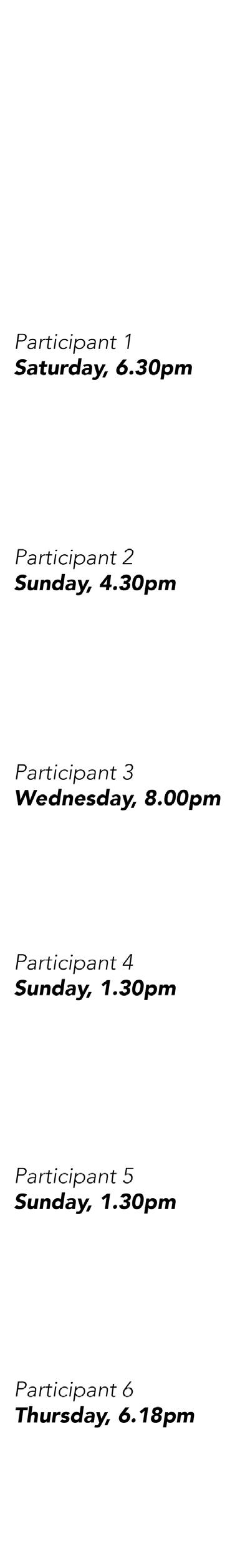

Fig. 18: ‘Moments of Pause’ diagram for Participant 1

3.4 REFLECTIONS: AN ANALYSIS OF THE WALKS

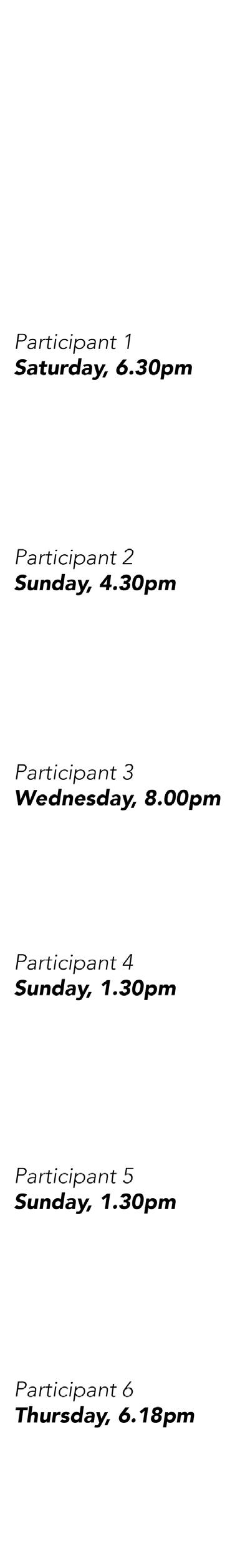

Participant 1

Saturday, 6.30pm

Participant 2

Sunday, 4.30pm

Participant 3

Wednesday, 8.00pm

Participant 4

Sunday, 1.30pm

Participant 5

Sunday, 1.30pm

Participant 6

Thursday, 6.18pm

The walks undertaken by the participants of this project might not appear to make a substantial impact, but it is these same routine tasks that the research study aims to scrutinise. Reflecting on consistent observations from the walks of the different participants to piece together the experiences of these women in the gullies of Chandni Chowk, the study seeks to understand the impact it had on their relationship with the public space.

Section 1.1 titled ‘Women in the Indian City’ discusses ‘female fear’ in relation to the gendered violence the city of New Delhi faces. In Chandni Chowk, the levels of fear may not be of an alarming nature. Additionally, out of consideration for the project’s purpose and the well-being of the participants there was no intention to ask them to visit unsafe parts of the

city. Although Chandni Chowk is a widely frequented part of the city, there may be spaces that women may want to avoid.

Simultaneously, there could be segments of the street that they are comfortable visiting or would willingly consider in the future. These segments might contribute to their collective experience, potentially reflecting nuances of the urban environment that might be inconspicuous at first glance. However, when we aggregate the results of the walks, these nuances become apparent. As we navigate this section, we go through the analysis of the participants’ walk in the two primary subsections. The first titled, ‘Feminist geography’ questions the presence of women on the street. The next, ‘Perceptions of Safety’ helps us understand the different ways in which safety is perceived in public spaces by different women.

39

Fig. 19: Analysis of walks for all participants.

3.4. Feminist Geography

The term ‘Feminist Geography’ was apparently discovered by Margaret Wente, a columnist for Globe & Mail, to prove that humanities and social sciences were worthless enterprises. Leslie Kern uses the same term to reconcile the meaning of feminism to its function in actual public space. She says, “A geographic perspective on gender offers a way of understanding how sexism functions on the ground” (Kern 2019, p.13).

During the analysis of the different walks of women who undertook the activity in Chandni Chowk, there was a noticeable difference in the way men and women populated the streets. In the context of the project, ‘Feminist Geography’, simply translated to the quantity of women compared to men present on the street. One could potentially argue that there might be more men than women in the city overall. However, given that this market area is recognized for accommodating a larger number of shops for women than for men, the analysis seeks to raise the question: where are the women? This outcome doesn't necessarily imply that women have limited access to this area; they still visit, but it remains an interesting observation. Participant 4 notes,

“The men to women ratio was not at par, but being a woman on the main road I did not feel scared.”

The diagram illustrating this section, shows the different paths taken by the participants and employing coloured circles shows the difference in numbers between men and women on their walks. The inclusion of a diagram to illustrate the paths taken and the gender distribution adds a visual element that enhances understanding. This visual representation can be an effective tool in conveying the findings of the study.

40 41

Fig. 20: Feminist Geography: Exploring the presence of women in Chandni Chowk

Male

Female

3.4.2 Perceptions of Safety

Reviewing the data received by the participants, there were certain elements that were consistent across all their observations, contributing to their comfort in the gullies of Chandni Chowk. The project analyses two of these consistent factors, the first being ‘Places of Faith’ and the second being the ‘Presence of Streetlights.’

A. Places of Faith

The gully chosen in Chandni Chowk stands out for its uniqueness, it holds a Mandir, a Masjid (Mosque), a Gurudwara (Sikh Temple), a Jain Temple and a Church. Collectively, these landmarks display the rich cultural diversity of India. The participants on their walks found the areas around these places of faith specifically comforting, and it added to their perceptions of safety during their walk.

In a research project published on an online platform called ‘Behan Box,’ focusing on gender dynamics, a study of leisure spaces in Raghubir Nagar, another neighbourhood in Delhi, brought forward similar results. Interestingly, there is a park near Point A (Town Hall) on Chandni Chowk Road, where I anticipated the participants might spend some time; however, all of them actually walked past it. The co-authors of the Behan Box article state, “The women of Raghubir Nagar count on faith-based places or places of worship. Through faith, they also develop bonds with other women in the community… Activities related to faith allow women to take a break from the tedium of work and domestic chores” (Sapra 2023). This observation resonates with what is discussed in the book "Why Loiter?" by its co-authors. They note, “Women also use religion, and more specifically, religious activities and functions for which it is relatively easy to get familial and societal sanction, as opportunities to enhance their access to the public” (Phadke 2011).

The participants for this project made similar observations on their walks, as participant 2 notes,

“The Gurudwara, Mosque, Jain temple, and Hindu temples on the way also add to this safety factor, obviously. One could stop for longer periods of time at any of these places of worship to calm down, catch your breath, and experience some peace or to simply pray.”

During their walks, two participants dedicated some time to visit the gurudwara. These elements potentially play a role in why women perceive these spaces as being comfortable to visit at all times of the day.

42 43

Fig. 21: Places of Faith: Exploring the ‘Perception of Safety’

B. Presence of Streetlights

The presence of adequate lighting in a public space doesn't exclusively contribute to the safety of women. Individuals, regardless of gender, who visit public spaces value well-lit environments. Hence, it often stands out as one of the primary aspects considered during the redevelopment of such places. However, its role in enhancing the perception of safety should not be underestimated.

All participants who ventured out later in the evening made the observation that the main street, Chandni Chowk Road, was well-lit creating a sense of comfort during their walks. Chandni Chowk underwent redevelopment in 2021, and part of its manifesto read “lighting and illumination of shops and buildings” (Sisodia 2022). This aspect was particularly appreciated by participants who experienced the street after its redevelopment. Though it adds to a positive experience for all people visiting this street, it is unlikely that women would go into a street that is not well-lit, whereas men may still do so.

For instance, in the previous chapter the observation was made that one of the participants chose not to enter the second segment of the walk in Gali No. 4, owing to inadequate lighting and chaotic streets. She notes,

“The need for continued efforts to improve lighting and infrastructure in such areas became evident to ensure the safety and comfort of women traversing these paths.”

The perception of safety is a highly complex and subjective matter that can be shaped by each individual’s experiences. What one considers safe, may not be of the same value to another. These may be based on physical environment, societal and cultural norms, personal experiences. But to make public space more equitable for all, it becomes imperative to examine outcomes like those presented in this study. Through such analyses, the aim is to cultivate an environment that is comfortable, safe, and inclusive for everyone.

44 45

Fig. 22: Presence of Streetlights :Exploring the ‘Perception of Safety’

C. Personal Visions

As a concluding activity for their walks, the participants conveyed their reflections and aspirations regarding this specific gully through rough sketches, offering a visual representation of their experiences during the walks. These have been included in the website to show their individualistic approach towards the issue. The full documentation for all participants is availbale on the website.

Participant 2:

Participant 1:

“The need for continued efforts to improve lighting and infrastructure in such areas became evident to ensure the safety and comfort of women traversing these paths.”

“Only possible danger zones are once you go beyond a certain point in Gali No. 4., and if you are walking to Town Hall from the Metro.”

Participant 5:

“While a lot has been done to make the street pedestrian friendly, however there is little shade to escape the heat. In the sparse areas you have some shade you will find people sleeping on the pathways.”

46 47

Fig. 23: Personal Visions: Participants’ reflections and aspiraions from their walks

Conclusion

The relationship between women and public spaces in India and around the world has been studied to a large extent. By incorporating perspectives beyond urban design, I have made an attempt to understand the deeper concerns that surround these. The objective of highlighting different histories around women and incorporating those into the stretch for the case study was to show the agency women had through the past. The aim is to use that as an inspiration for women to foster empowered relationships with public spaces.

The activity titled, ‘Let’s Go for a Walk’, highlights the importance of redefining women’s relationship with public spaces. By inviting women to reclaim the streets by purposeful and leisurely walking, the project makes an attempt to shed light on the multifaceted nature of safety, comfort, unrestricted and unconditional access to public spaces.

However, the project acknowledges that achieving equitable and inclusive spaces for all demands more than just acknowledging safety concerns. There is a need to address deeper concerns such as societal and cultural norms, systemic indifferences, gender biases among others. “But once

we begin to see how the city is set up to sustain a particular way of society — across gender, race sexuality and more — we can start to look for new possibilities” (Kern 2019, p. 176). Over the decades, numerous feminist movements have advocated for the fundamental right to equitable and unconditioned access to urban spaces. The concept of an inclusive city only comes to light when it accommodates the diverse spectrum of its citizens, ensuring that women are equally accounted for. Envisioning an equitable city is one that caters to every citizen of that city, not specifically to any one facet of society. “It is only when the city belongs to everyone can it ever belong to all women” (Phadke 2011, p. 188)

Ultimately it is not only about reclaiming space, but also reclaiming narratives and experiences for women to create cities that belong to all. This project’s attempt to initiate a dialogue and encourage women to take ownership of public spaces is a critical step towards sustaining a more inclusive environment for all. By embracing a holistic approach that considers diverse perspectives and narratives, we can work towards reshaping our cities where all individuals, regardless of gender, can enjoy unrestricted access, leisure, and true belonging.

48 49

Glossary

Bagh: A type of garden built during the Mughal reign, influenced by the Persian Gardens. Its intent was to be a representation of utopia, using all elements of nature.

Begum: Derived from the Persian language, it was an honorific used during the Mughal reign to address women of a higher social status.

Fatehpuri Masjid: a mosque built by one of Shah Jahan’s wives, Fatehpuri Begum.

Gurudwara: Sikh Temple

Haveli: A Hindi term for a traditional townhouse or mansion in the Indian Subcontinent.

Hindustan: It is the Persian term for the Indian subcontinent, used during the reign of the Mughal Empire. After the partition of India, it continues to be used as the term for the Republic of India.

Masjid: Mosque

Mandir: Hindu Temple

Partition of India: The Partition of India in 1947 served as the dissolution of the British Raj, and resulted in the form of two independent dominions, India, and Pakistan. The Indian Independence is celebrated on the 15th of August.

Red Fort: Known as ‘Lal quila’ in the Hindi or Urdu language, the Red Fort served as the royal residence of the Mughal Emperors. Commissioned by Shah Jahan, the fifth emperor of the Mughal empire, it was built in 1638. It remains as a unique piece of architectural history in Old Delhi today.

Revolt of 1857: A major rebellion against the British East India Company, that served under the sovereign of the British Crown. Resulting in a large death toll, it was known as the formal end of the Mughal Dynasty and shifted power of the Indian Subcontinent to the British Crown.

Shahjahanabad: The walled city designed in 1648, when Shah Jahan, the then Mughal Emperor decided to shift the capital of the Empire from Agra. It remained the capital till the fall of the empire in 1857.

50 51

List of Figures

Cover Image:The Six Walks. (2023). Image by Author

Fig 1: Chowdhury, A.R. (2010), Untitled [Digital Print] The Hindu. Available at: https://www. thehindu.com/news/cities/Delhi/Guards-to-escort-women-in-office-cabs-at-night/article15721957. ece (Accessed:September 2023)

Fig 2: Lecercle. (2007). Haji Ali Dargah. [Photography] Available at: https://www.flickr.com/ photos/lecercle/485952528/in/photostream/ (Accessed: June 2023)

Fig 3: Phadke S. & et.al. (2011). Why Loiter? Women and Risk on Mumbai Streets. (New Delhi: Penguin Books), Cover Image.

Fig 4: Ahmed, S. (2018). “Look around you. How many women do you see in public spaces? Now do you feel afraid or curious?” [Photography] Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/ BieOOgnnYm0/?hl=en-gb (Accessed: June 2023.)

Fig 5. Dhingra, P. (2023). Bar Menu for India International Centre, New Delhi. [Design Print] Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/CrDOFCCSq2X/?hl=en-gb (Accessed: September 2023)

Fig 6. Lalchand. (1632). Princess Jahanara aged 18, Agra or Burhanpur .The British Library, Add Or 3129, f.13v. [Drawing] Available at: https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2017/06/portraits-ofdara-shikoh-in-the-treasures-gallery.html (Accessed: June 2023)

Fig 7. (1780-1815). Begum Sambre, Ruler of the Indian Principality of Sardhana; India; Oil on Ivory; [Drawing] Public Domain. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Lens_-_Inauguration_du_Louvre-Lens_le_4_d%C3%A9cembre_2012,_la_Galerie_du_ Temps,_n%C2%B0_195.JPG (Accessed: June 2023)

Fig 8. Ram, S. (1815). Watercolour of The Chandni Chowk from the top of the Lahore Gate of the Fort, the canal depicted running down the middle. The British Library. Shelfmark: Add.Or.4827; Item number: 4827. [Drawing] Available at: https://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/ addorimss/t/019addor0004827u00000000.html (Accessed: June 2023)

Fig 9. (1820-1830). The palace of Begum Samru at Delhi. India, Delhi. Aga Khan Museum. Toronto, Canada/Twitter. [Drawing] Available at: https://twitter.com/DalrympleWill/ status/1178738063494799361 (Accessed: June 2023)

Fig 10. Metcalfe, T.T. (1795-1853). Reminisces of Imperial Delhi. Jahanara Begum’s caravanserai that formed the original Chandni Chowk. The British Library. [Drawing]. Available at: https://www. bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/addorimss/t/019addor0005475u00058vrb.html (Accessed: June 2023)

Fig 11. Metcalfe, T.T. (1795-1853). Reminisces of Imperial Delhi. A panorama in 12 folds showing the procession of the Emperor Bahadur Shah to celebrate the feast of the ‘Id. f. 59v-F. The British Library. [Drawing] Available at: https://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/addorimss/ a/019addor0005475u00059vf0.html (Accessed: June 2023)

Fig 12. Map of Chandni Chowk from the 1850s. (2023). Diagram by Author.

Fig 13. The Site. (2023). Diagram by Author.

Fig 14: Timeline. (2023). Designed by Author. Images in Timeline from (L-R)

14.1: Lalchand. (1632). Princess Jahanara aged 18, Agra or Burhanpur .The British Library, Add Or 3129, f.13v. [Drawing] Available at: https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2017/06/portraits-ofdara-shikoh-in-the-treasures-gallery.html (Accessed: June 2023)

14.2: 1780-1815). Begum Sambre, Ruler of the Indian Principality of Sardhana; India; Oil on Ivory; [Drawing] Public Domain. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Lens_-_Inauguration_du_Louvre-Lens_le_4_d%C3%A9cembre_2012,_la_Galerie_du_ Temps,_n%C2%B0_195.JPG (Accessed: June 2023)

14.3: Metcalfe, T.T. (1795-1853). Reminisces of Imperial Delhi. Jahanara Begum’s caravanserai that formed the original Chandni Chowk. The British Library. [Drawing]. Available at: https://www. bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/addorimss/t/019addor0005475u00058vrb.html (Accessed: June 2023)

14.4: Bourne, S. (1877). Clock Tower At Chandni Chowk Delhi, Old Photo 1877. [Photograph] Available at: https://www.past-india.com/photos-items/clock-tower-at-chandni-chowk-delhi-old1877-photo/ (Accessed: June 2023)

14.5: Banerjee, J. (n.d). Yellow-painted brick and stone carved white stone trim. [Photograph]. Available at: https://victorianweb.org/history/empire/india/13.html (Accessed: August 2023)

14.6: Ram, S. (1815). Watercolour of The Chandni Chowk from the top of the Lahore Gate of the Fort, the canal depicted running down the middle. The British Library. Shelfmark: Add.Or.4827; Item number: 4827. [Drawing] Available at: https://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/ addorimss/t/019addor0004827u00000000.html (Accessed: June 2023)

14.7: Metcalfe, T.T. (1795-1853). Reminisces of Imperial Delhi. A panorama in 12 folds showing the procession of the Emperor Bahadur Shah to celebrate the feast of the ‘Id. f. 59v-F The British Library. [Drawing] Available at: https://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/addorimss/ a/019addor0005475u00059vf0.html (Accessed: June 2023)

14.8: (1877) “The Imperial Assembly of India at Delhi: the Viceregal Procession passing the Clock Tower and Delhi Institute in the Chandnee Chowk,” Illustrated London News. [Digital Print] Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Procession1877.jpg (Accessed: June 2023)

14.9: Gosavi, S. (2020) Cook, S. Chandni Chowk in Delhi: The Complete Guide. 2020. [Digital Print]. Available at: https://www.tripsavvy.com/chandni-chowk-delhi-the-complete-guide-4177530 (Accessed: September 2023)

52 53

14.10: Yadav, A. (2021) Akhtar, S. Heritage Chandni Chowk opens in new avatar. (Hindustan Times, New Delhi) 2021. [Digital Print]Available at: https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/ delhi-news/delhis-heritage-chandni-chowk-market-gets-new-lease-of-life-kejriwal-inauguratesrevamped-stretch-101631471246151.html (Accessed: September 2023)

14.11: Metcalfe, T.T. (1795-1853). Reminisces of Imperial Delhi. South view of Begum Samru’s House. The British Library: Shelfmark: Add.Or.5475; Item number: ff. 47v-48. [Drawing] Available at: https://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/addorimss/s/019addor0005475u00047vrb.html (Accessed: June 2023)

14.12: Harriet & et.al. (1858). The Bank of Delhi. The British Library. Shelfmark: Photo 193(12); Item number: 19312. [Photograph] Available at: https://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/ photocoll/t/019pho000000193u00012000.html (Accessed: June, 2023)

14.13: Gosain, V.S. (2016). Begum Samru’s erstwhile home now houses a bank. Biswas, S. Discovering Old Delhi through a woman’s lens (Hindustan Times, New Delhi) 2016. [Digital Print] Available at: https://www.hindustantimes.com/art-and-culture/discovering-old-delhi-through-awoman-s-lens/story-SJhpxlnypCGYgqtAKdjatJ.html (Accessed: June 2023)

Fig. 15: Let’s Go for a Walk: Landing Page. (2023). Designed by Author.

Fig. 16: Let’s Go for a Walk: The Website. (2023). Designed by Author.

Fig. 17: Videos from the participants. Available on website (2023). Image by Author.

Fig. 18: ‘Moments of Pause’ diagram for Participant 1. (2023). Diagram by Author.

Fig. 19: Analysis of walks for all participants. (2023). Diagram by Author.

Fig. 20: Feminist Geography: Exploring the presence of women in Chandni Chowk. (2023) Diagram by Author.

Fig. 21 :Places of Faith: Exploring the ‘Perception of Safety’. (2023). Diagram by Author.

Fig. 22: Presence of Streetlights: Exploring the ‘Perception of Safety’. (2023). Diagram by Author.

Fig. 23: Personal Visions: Participants’ reflections and aspiraions from their walks. (2023). Diagram by Author.

References

Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006.

Anand, Anand, and Dalrymple, William. Empire: The Search for Truth, 12 June 2023.

Baffoe, Gideon, and Shilpi Roy. ‘Colonial Legacies and Contemporary Urban Planning Practices in Dhaka, Bangladesh’. Planning Perspectives 38, no. 1 (2 January 2023): 173–96. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/02665433.2022.2041468

‘Basanti: Women at Leisure (@women_at_leisure) • Instagram Photos and Videos’. Accessed 11 September 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/Cw--Cxjyb1R/?hl=en-gb.

Bhagwati, Sonali, Samir Mathur, Sonali Rastogi, Durga Shanker Mishra, and Vinod Kumar. ‘Delhi Urban Art Commission’, n.d.

Bhakuni, Tanuja. ‘A Journey from Begum Samru’s Haveli to Bhagirath Palace’. Zikr-e-Dilli. Accessed 13 September 2023. https://zikredilli.com/delhi-depository/f/a-journey-from-begumsamru%E2%80%99s-haveli-to-bhagirath-palace

Blake, Stephen P. Shahjahanabad: The Sovereign City in Mughal India, 1639–1739. New Delhi: Cambridge University Press, 1991. ‘Chandnichauk’. Accessed 26 June 2023. http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/ pritchett/00routesdata/1600_1699/shahjahanabad/chandnichauk/chandnichauk.html

Chaudhuri, Zinnia Ray, and Suresh. ‘A Walk through History: The Forgotten Women Who Helped Shape Delhi’. Text. Scroll.in. https://scroll.in, 30 September 2016. http://scroll.in/ magazine/817669/a-walk-through-history-the-forgotten-women-who-helped-shape-delhi D, Dipti. ‘This Delhi Travel Startup Is Making Women Solo Travel in India a Piece of Cake’. YourStory.com, 29 January 2018. https://yourstory.com/2018/01/travel-startup-wovoyage-rashmichadha

Dunford, Jane. ‘Women Lead the Way on a Tour of Northern India’. The Guardian, 4 March 2017, sec. Travel. https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2017/mar/04/india-female-women-guides-delhiagra

Ehlers, Eckart. Shahjahanabad/Old Delhi: Tradition and Colonial Change. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden GmbH., 1993.

Firstpost. ‘Scars of a Rebellious Delhi: Kashmere Gate, Khooni Darwaza and Other Reminders of the Great Rebellion of 1857-Living News , Firstpost’, 30 March 2019. https://www.firstpost.com/ living/scars-of-a-rebellious-delhi-kashmere-gate-khooni-darwaza-and-other-reminders-of-thegreat-rebellion-of-1857-6337601.html

‘@girlsatdhabas • Instagram Photos and Videos’. Accessed 12 September 2023. https://www. instagram.com/p/BieOOgnnYm0/?hl=en-gb

Goel, Rahul. ‘From Walking to Cycling, How We Get around a City Is a Gender Equality Issue’. PTRC Training. Accessed 14 June 2023. https://www.ptrc-training.co.uk/News/ArtMID/6886/ ArticleID/36563/From-walking-to-cycling-how-we-get-around-a-city-is-a-gender-equality-issue. Goel, Rahul. ‘How the Design of India’s Cities Is Feeding Gender Inequality’. The Swaddle, The Conversation (blog), 5 September 2018. https://theswaddle.com/how-the-design-of-cities-isfeeding-gender-inequality-in-india/

Goel, Rahul ‘Indian Women Confined to the Home, in Cities Designed for Men’. The Conversation, 30 August 2018. http://theconversation.com/indian-women-confined-to-the-home-in-citiesdesigned-for-men-101750

Goel, Vijay. The Emperor’s City: Rediscovering Chandni Chowk and Its Environs. New Delhi: Roli Books, 2003.

Greed, Clara H. Women and Planning: Creating Gendered Realities. London: Routeledge, 1994. Greenpeace India. ‘Power The Pedal’. Accessed 14 June 2023. https://www.greenpeace.org/

54 55

india/en/power-the-pedal/

Gupta, Narayani. Delhi Between Two Empires, 1803-1931. New Delhi: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Hussain, Eisha. ‘Why Delhi’s Sex Ratio Ranks Among The Worst In India’. BehanBox (blog), 7 September 2022. https://behanbox.com/2022/09/07/why-delhis-sex-ratio-ranks-among-the-worstin-india/

Jain, Mayank. ‘Indian Women Are Loitering to Make Their Cities Safer’. Text. Scroll.in. https:// scroll.in, 18 December 2014. http://scroll.in/article/695586/indian-women-are-loitering-to-maketheir-cities-safer.

Kapoor, Manan. ‘Chandni Chowk: Jahanara’s Glorious Moonlight Square That Turned to Dust’. Sahapedia. Accessed 15 June 2023. https://www.sahapedia.org/chandni-chowk-jahanarasglorious-moonlight-square-turned-dust

Karnam, Nikitha. ‘Watch History Unfold At Havelis In Chandni Chowk’. Travel.Earth (blog), 15 November 2020. https://travel.earth/havelis-in-chandni-chowk/ Keeble, Lewis. Principles and Practice of Town and Country Planning. London: Estates Gazette, 1969.

Khanna, Navya, Prarthana Puthran, and Navya Khanna and Prarthana Puthran. ‘Women In Public Spaces: When Gender Is Ignored While Shaping Cities’. Feminism in India, 11 November 2020. https://feminisminindia.com/2020/11/12/women-in-public-spaces-street-safety/.

Khatri, Taz. ‘Designing Safe Cities for Women | Smart Cities Dive’. Accessed 14 June 2023. https://www.smartcitiesdive.com/ex/sustainablecitiescollective/designing-safe-citieswomen/1052876/

Kern, Leslie. Feminist City: Claiming Space in a Man-Made World. Toronto: Between the Lines, 2019.

Liddle, Swapna. Chandni Chowk: The Mughal City of Old Delhi. New Delhi: Speaking Tiger Books, 2017.

Liddle, Swapna. ‘Women Patrons and the Making of Shahjahanabad’. Sahapedia. Accessed 13 September 2023. https://www.sahapedia.org/women-patrons-and-the-making-of-shahjahanabad.

Lieder, K. Frances. ‘Performing Loitering: Feminist Protest in the Indian City’. TDR/The Drama Review 62, no. 3 (September 2018): 145–61. https://doi.org/10.1162/dram_a_00776

Making History at Home: Begum Samru and Her Nineteenth-Century Residences, Dr. Mrinalini Rajagopalan, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IdnzE8AE9b4

MAP Academy. ‘The Courtesan Who Commanded an Army: Begum Samru’, 7 April 2023. https:// mapacademy.io/the-courtesan-who-commanded-an-army-begum-samrus-extraordinary-journey/ Modgil, Chandrima. ‘The Way I See It’, 2022. https://thewayiseeit.cargo.site/.

NCRB. New Delhi: National Crime Records Bureau: New Delhi, 2021.

NCRM. ‘NCRM Resource | Walking as a Participatory, Performative and Mobile Method by Maggie O’Neill and Tracey Reynolds’. Accessed 17 June 2023. https://www.ncrm.ac.uk.

Oberoi, Shamolie. ‘Why Loiter? Book Review: Imagining Our Streets Full Of Women’. Feminism in India, 1 June 2015. https://feminisminindia.com/2015/06/01/why-loiter-book-review-imaging-ourstreets-full-of-women/

Pani, Samprati. ‘Walk Economy’. Chiragh Dilli (blog), 17 October 2022. https://chiraghdilli. com/2022/10/17/walk-economy/

Phadke, Shilpa, Shilpa Ranade, and Sameera Khan. Why Loiter? Women and Risk on Mumbai Streets. New Delhi: Penguin Books, 2011.

Philip, Shannon. ‘New Delhi: A City of Men?’ Views & Voices, 3 August 2017. https://views-voices. oxfam.org.uk/2017/08/new-delhi-city-men/.

‘Portraits of Dara Shikoh in the Treasures Gallery’. Accessed 14 June 2023. https://blogs.bl.uk/ asian-and-african/2017/06/portraits-of-dara-shikoh-in-the-treasures-gallery.html

Priyanka. ‘How Women’s Dissent Is Impeded by Lack of Access to Public Spaces’. Smashboard, 23 November 2021. https://smashboard.org/how-womens-dissenting-abilities-are-impeded-bylack-of-access-to-public-spaces/

Rajagopalan, Mrinalini. ‘Cosmopolitan Crossings’: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 77, no. 2 (1 June 2018): 168–85. https://doi.org/10.1525/jsah.2018.77.2.168

Sapra, Saleha, and Anupriya Aggarwal. ‘Aaram Ki Jagah: Tracing Leisure Spaces For Raghubir Nagar’s Women Vendors’. BehanBox (blog), 22 June 2023. https://behanbox.com/2023/06/22/ aaram-ki-jagah-tracing-leisure-spaces-for-raghubir-nagars-women-vendors/

Sen, Harini Nagendra & Amrita. ‘Our Cities Are Designed For Men, By Men’. The Third Eye (blog), 5 January 2022. https://thethirdeyeportal.in/structure/our-cities-are-designed-for-men-by-men/ Singh, Nalini, and Shaheen Islamuddin. ‘The Making Of New Delhi a Study of Destruction of PreColonial Settlements and Memories (1860s-1920s)’, 2023.

Sisodia, Manish, and The Hindu. Chandni Chowk heritage structures to get facelift in Phase II revamp plan, 2022.

Smashboard. ‘How Women’s Dissent Is Impeded by Lack of Access to Public Spaces’, 23 November 2021. https://smashboard.org/how-womens-dissenting-abilities-are-impeded-by-lackof-access-to-public-spaces/.

Tahir, Romaisa. ‘Women Reclaiming the Urban Spaces’. RTF | Rethinking The Future (blog), 24 March 2022. https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/architectural-community/a6508-womenreclaiming-the-urban-spaces/

Thakur, Dwijendra Nath. ‘Feminism and Women Movement in India’, n.d.

THE FUNAMBULIST MAGAZINE. ‘# TOPIE IMPITOYABLE /// The Space a Body Occupies: Marianne Wex’s Striking Gendered Photos’, 30 January 2014. https://thefunambulist.net/editorials/ topie-impitoyable-the-space-a-body-occupies-marianne-wexs-striking-gendered-photos Truong, Kimberly. ‘I’m A 5’1 Asian Woman & I Spent A Week NOT Moving Out Of Men’s Way’. Accessed 21 August 2023. https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/2017/08/167417/manslammingexperiment-personal-story.

Valentine, Gill. The Geography of Women’s Fear. London: Royal Geographical Society, 1989. VP, Sashikala. ‘#ChandniChowk: Old Delhi’s Women Are Now Charting Their Own Course’. Newslaundry, 19 July 2019. https://www.newslaundry.com/2019/07/19/chandni-chowk-old-delhiwomen-patriarchy

Wrede, Theda. ‘Introduction to Special Issue “Theorizing Space and Gender in the 21st Century”’. Rocky Mountain Review 69, no. 1 (2015): 10–17.

56 57

Suhela Kaur Maini

Master’s Thesis 22/23

MA Architecture and Historic Urban Environments

Bartlett School of Architecture

University College London

Fig. 13: The Site:Point A to Point B identified in present-day Chandni Chowk

Fig. 13: The Site:Point A to Point B identified in present-day Chandni Chowk

Fig. 14: Timeline showing the evolution of Point A, Point B and the gully over a period of time

Fig. 14: Timeline showing the evolution of Point A, Point B and the gully over a period of time