Suffolk Naturalists ’ Society

Suffolk Naturalists ’ Society

Newsletter 111 Spring 2023

If you think this issue is looking a bit thin, or there’s something you would like to write about? Then we want to hear from you. This newsletter is only as good as the contributions put in to it. Next issue deadline: 30th April 2023

Cover

Contents ISSN 0959-8537 Published by the Suffolk Naturalists’ Society c/o The Hold, 131 Fore Street, Ipswich, Suffolk IP4 1LR Registered Charity No. 206084 Editorial Hawk Honey 4 Otters in the River Blyth Catchment Nicky Rowbottom, Ken Derham, Blyth Otter group 5 Insect Migration Raymond Watson 10 Red Pond Water at Alder Carr Farm Joan Hardingham 16 Volunteering and Coppicing Paul Heather 18 Facebook Gallery 22 Double life of Oak Apple Michael Chinery 28 Suffolk’s Wildlife Friendly villages Stewart Belfield & Sophie Flux 17 Motus at Landguard Bird Observatory Nigel Odin 36 Wild cats? No thanks! David Tomlinson 40 Bird feeders Trevor Goodfellow 45 SNS Autumn Members Evening Genevieve Broad 44

photo: Upright Coral Fungus by Justin Gant, taken from our Facebook page.

SNS 2023 Conference Into the Wild

The SNS 2023 conference Into the Wild will look at different aspects of the rewilding debate. We are delighted to announce that we have the following confirmed speakers and look forward to welcoming members and non-members to this exciting, topical event:

Prof. Alistair Driver - (Rewilding Britain) Rewilding keynote busting the myths & making it happen

Dr Tim Gardiner (Environment Agency) Orthoptera in the early stages of postarable rewilding in Suffolk

Dr Keith Kirby (University of Oxford) What might a landscape driven by large herbivore grazing look like & would we want it?

Tony Juniper (Natural England)

Prof James Bullock - (UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology) Restoration & rewilding: complementary approaches for nature recovery.

Prof Bill Sutherland (University of Cambridge) Restoring nature

John Sanderson (Farmer) Rewilding a Suffolk farm

Matt Gooch - (Suffolk Wildlife Trust) A living landscape where rewilding means management

Archie Ruggles-Brise - (Landowner and Environmentalist Essex) Sustainable land stewardship agroecology, tree cropping, beaver wetlands & biodiversity net gain on a traditional lowland estate.

Jake Fiennes - (Holkham Hall Estate (Norfolk)) Making space for nature in the farm landscape

The conference will be held online on two half days, Saturday 4th March and Saturday 11th March 2023, with opportunities to ask questions and a small admission fee.

Cost £5 one day, £8 both days

Please pay in advance online www.sns.org.uk/into-the-wild/ Enquiries: genevieve.broad@outlook.com

White Admiral 111 1

Suffolk Wildlife Trust courses

Suffolk Wildlife Trust has scheduled several courses at its nature reserves over the coming months, such as:

WEBINAR - Reintroducing the Chequered Skipper butterfly to Rockingham Forest

Via Zoom with Susannah O’Riordan, Butterfly Conservation Trust, Tuesday 7th February 7pm

WEBINAR - Woodland Regeneration, Via Zoom with Feodora Morris, Wednesday 22nd February, 7pm

Online Beginners Wildlife Garden Photo course via Zoom with Kevin Sawford, Wednesday 1st March. 7-9pm

Tree ID with Andy Holtham, Redgrave & Lopham Fen, Friday 3rd March 10-4pm

Tree ID with Andy Holtham, Foxburrow reserve, Sunday 5th March 10-4pm

WEBINAR - The Magic of Nests via Zoom with Nicola Coe, Tuesday 7th March, 7pm

WEBINAR - Plants & Native Hedgerows via Zoom with Helen Bynum, Wednesday 22nd March, 7pm.

Meadow Creation Moat House, Hoxne with Marie Lagerber, Thursday 23rd March 10.30-3.30pm

WEBINAR - Martlesham Wilds via Zoom with Michael Strand & Charlie Zakss, Wednesday 5th April 7pm

Wild Writing with Helen Bynum, Carlton Marshes Sunday 16th April, 104pm

WEBINAR - Churchyard wildlife via Zoom with Cathy Smith & Graham Hart, Wednesday 19th April, 7pm

Bird ID (Spring migrants) with Paul Holness, Lackford Lakes, Sunday 23rd April, 10-2pm

White Admiral 111 2

Introduction to Hedgehogs with Paula Baker, Redgrave & Lopham Fen, Saturday 29th April, 10-3pm

To find details of all the Trust’s Wildlife Live Webinars, just follow this link:

https://www.suffolkwildlifetrust.org/wildlife-live-webinars

For any questions or course suggestions, please contact wildlearning@suffolkwildlifetrust.org

We are now on Facebook!

The Suffolk Naturalist's Society Members Group.

If you’re on Facebook and would like to be part of our exciting new group, please email

whiteadmiralnewsletter@gmail.com

Or look out for our new public Facebook page!

White Admiral 111 3

From the editor

Hi,

Hope you all had the Christmas and New Year you hoped for. I spent most of mine laid up with Covid, which put all our Christmas plans out of the window. However, the story could have been very different if it had been a couple of years earlier, so a few cancelled plans is nothing to moan about.

In other news, WOW! Haven’t you all been busy and I’ve been inundated with lots of articles for the newsletter. So much so, I’ve had to put some aside for the next issue, so please do not be offended if you cannot see your article in this issue. Still keep sending in your articles and photos as always to whiteadmiralnewsletter@gmail.com

This issue we’ve some lovely stuff from Otters to wild cats, fish to fungi, birds to bats and lots more. Our Spring members evening and AGM will soon be upon us in April and if you have a talk you’d like to give, please get in touch with Martin Sanford (martin.sanford@suffolk.gov.uk). You can find more details on page 53.

We have our SNS Conference coming up in March with some great speakers and subjects on the theme of rewilding. More details can be found out on page 1.

Keep up the articles and see you soon!

Next deadline for copy is April 30th

White Admiral 111 4

Hawk Honey

Felix Cottage Athelington Rd, Horham, IP21 5EG

Editor

1

whiteadmiralnewsletter@gmail.com

Otters in the River Blyth catchment

Nicky Rowbottom, Ken Derham, Blyth Otter Group

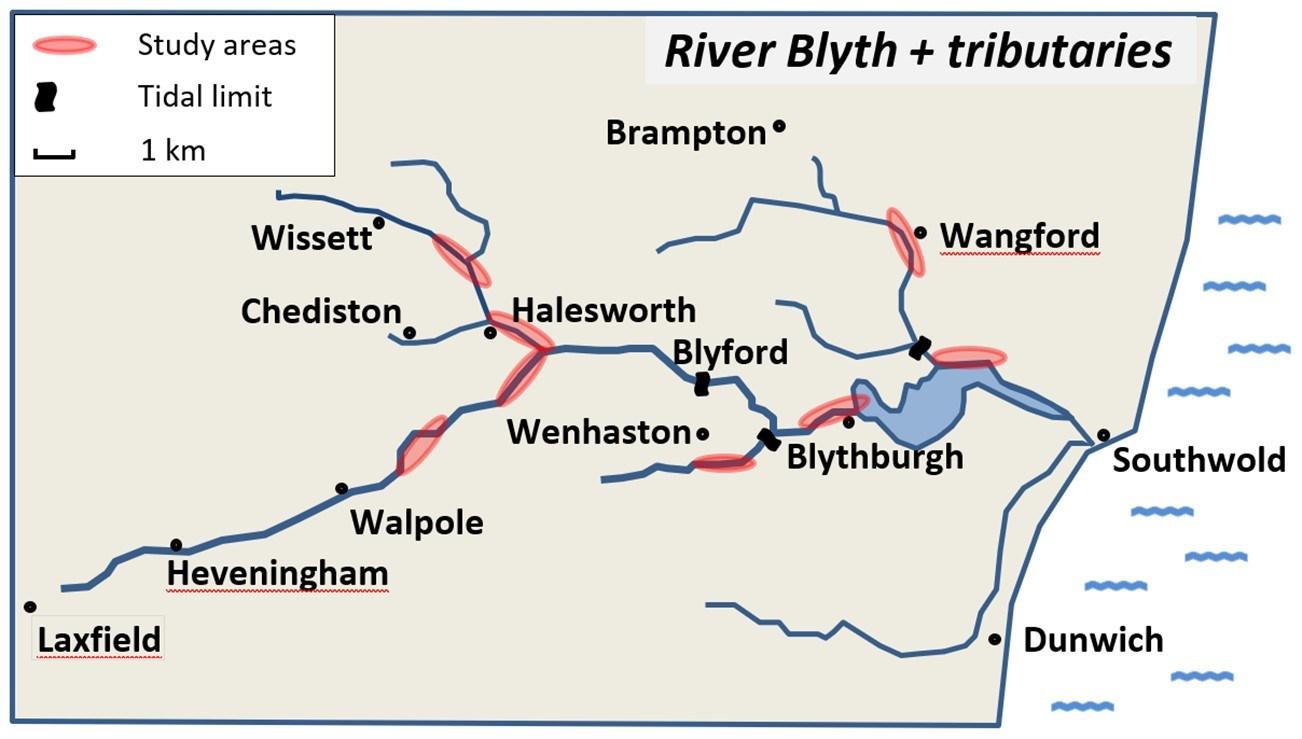

The Blyth catchment

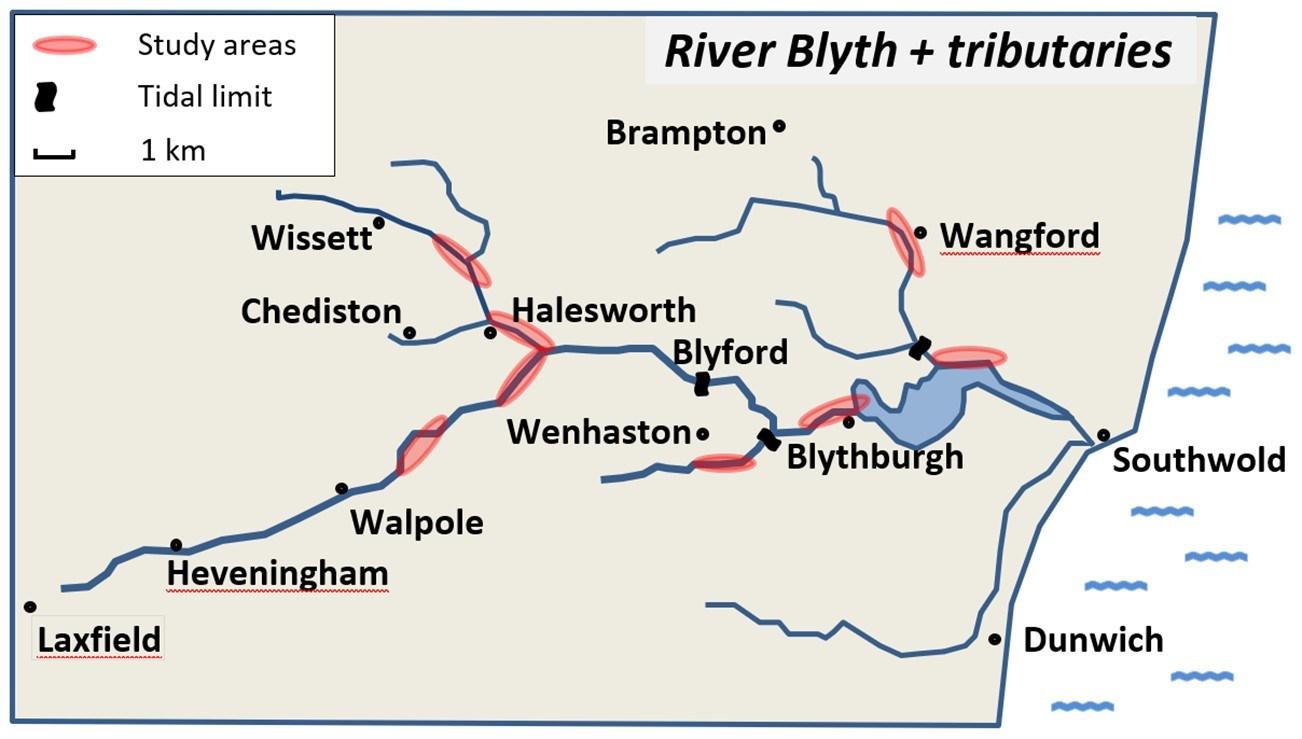

The River Blyth rises near the village of Laxfield and reaches the sea at Southwold, 29 km east. Chediston Brook and Wissett Brook combine just upstream of the market town of Halesworth, and then join the River Blyth itself a kilometre below the town. The freshwater section of the river is approximately 20 km long. After a sluice at Blyford the river is tidal.

Most of the catchment is typical Suffolk arable farmland, with some intensive outdoor pig rearing on the light, sandy soils around Blythburgh, Walberswick and Reydon. Halesworth is the only town it flows through. The flood plain still operates, and floods are seen in most winters. Summer grazing with cattle still survives in the flood plain. The river channel has been heavily modified and the surrounding land drained. The river experiences rapid changes in level after heavy rain, and streams like the Wissett Brook and the Chediston Brook are dry through the summer.

White Admiral 111 5

Along the lower reaches the river has adjoining grazing marshes and reedbeds, some of it designated and managed as nature reserve: Church Farm Thorington, and the Hen Reedbeds (both Suffolk Wildlife Trust) and Walberswick National Nature Reserve (Natural England). The tidal stretch of the river is all within the Suffolk Coast and Heaths AONB.

In the Heveningham estate and in Henham Park (just north of Blythburgh) large lakes now lie alongside tributaries, there are three sets of commercial fishing lakes: at Halesworth, Chediston and Walpole. Throughout the catchment many farm ponds and moats survive, although many others have been neglected or filled in. Garden ponds are popular for otters to feed in, and it can be distressing for people with ponds containing long-lived family pet fish to find the remains of an otter’s nocturnal visit. Adequate protection is essential. The Environment Agency’s 2019 data on ecological status show most stretches of the river as ‘moderate’, but with ‘good’ status on the Huntingfield tributary and the river from Laxfield until joined by the watercourse from Halesworth. The Wissett brook had the unwelcome distinction of being rated ‘poor’.

Study origins and expansion

The Blyth Otter Group volunteers, led originally by the late Richard Woolnough, have been studying otters on the upper reaches since 2016 through spraint analysis at first and, later, by trail cameras, with training and support from the Suffolk Otter Group and Suffolk Mammal Group.

White Admiral 111 6

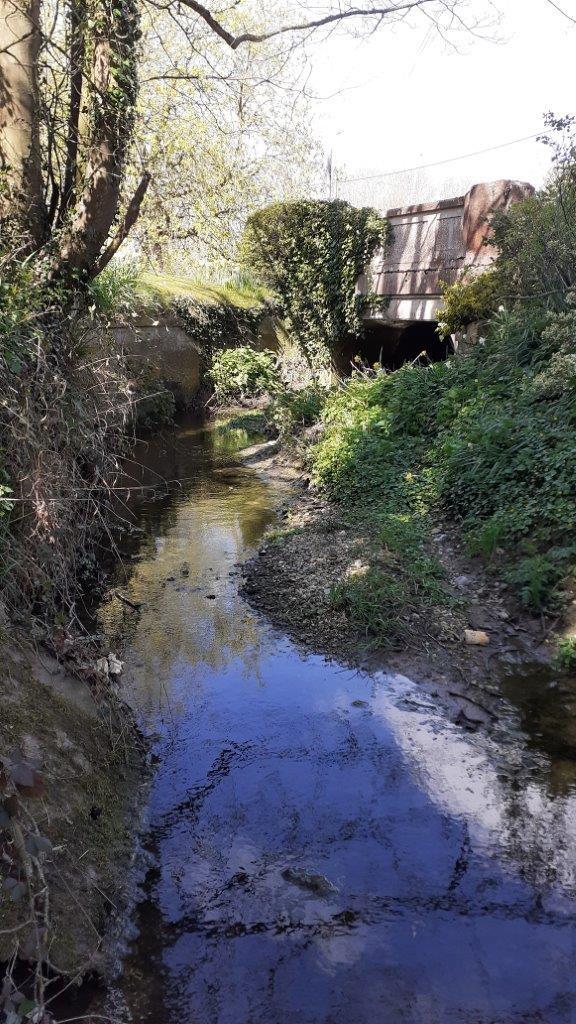

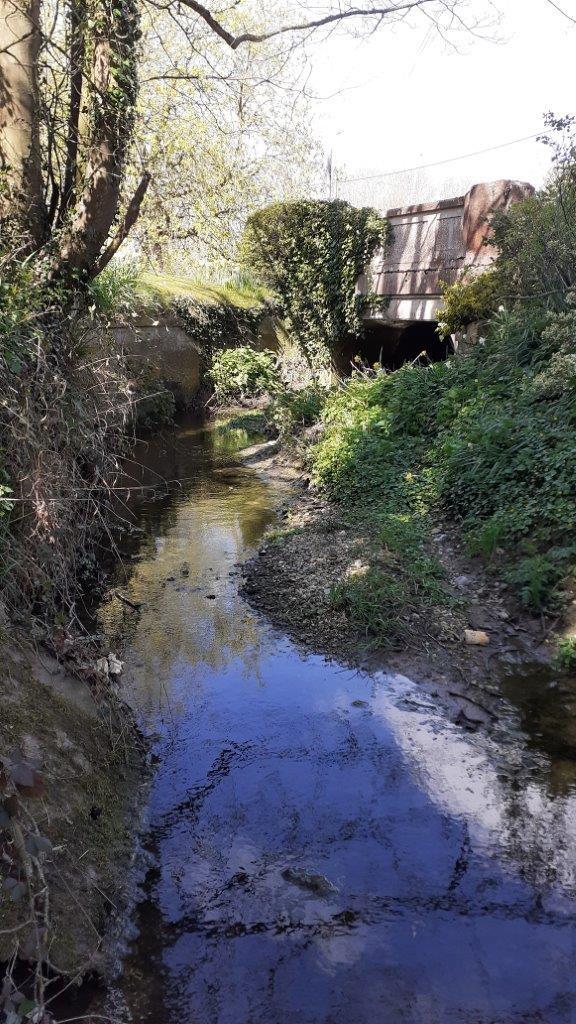

A stretch of the upper river.

Blyth Estuary and Hen Reedbed

Spraint studies (1800 spraints analysed from 7 sites over 4 years) showed the expected dominance of fish, with birds appearing more commonly in summer spraints than in winter. Mammal remains were negligible, but insects (mostly dragonfly larvae and water beetles) were significant. Reassuringly, eels were clearly able to pass the Blyford sluice. Crabs were very frequent in the tidal reaches. Figures from the Environment Agency indicate a steady steep decline in fish in the river over the past 30 years. The Blyth group’s spraint data contributed to Suffolk Otter Group’s online guide to spraint (see references) and were used in 2020 by Claire Roberts of University College London for her MSc dissertation.

The group expanded the use of cameras in 2020, with grant aid from Suffolk Naturalists Society, and made steady progress when the pandemic allowed. Twelve volunteers have been compiling records and meeting monthly ever since (by zoom and then in person) and have created the dataset which is discussed here.

White Admiral 111 7

The group expanded the use of cameras in 2020, with grant aid from Suffolk Naturalists Society, and made steady progress when the pandemic allowed. Twelve volunteers have been compiling records and meeting monthly ever since (by zoom and then in person) and have created the dataset which is discussed here.

The whole-river study

The River Blyth catchment is of a size where the group hopes to get an overview of otter activity in the defined area. Clearly this would not be possible for a large river, nor meaningful for a much smaller one. We are not aware of other studies of this sort. Obviously, otters are not bound by our definitions of an area and can cross from one river to another, but we feel we have a good chance of monitoring behaviour in a fairly well-defined catchment.

The Blyth Otter Group has had a number of automatic trail cameras in operation along the River Blyth and its tributaries in order to monitor otters in the area. Sightings have been recorded at some 25 locations during the period from the start of 2020 to date. Typically, we have about 9 cameras in operation at any one time, although precise details vary as not all cameras are in operation all the time. Sometimes they are brought in if there is risk of flooding. Sometimes they are moved to alternative locations.

It is understood that otters tend to occupy a range of river of several kilometres, and that an otter may travel a few kilometres per night in order to find food and patrol their territory. While it is interesting and amusing to see videos of otter behaviour and sometimes to be able to track the movement of an otter from one camera location to another, it is probably more instructive to be able to identify cases where there are distinctly different otters at different locations on the river.

The three years of our study show that otter activity is at least as great in the upper reaches of the Blyth catchment as in the apparently more lush and hospitable area near the estuary. In the period March – September 2020 there were 17 occasions when otters were recorded at very close times at both the Hen Reedbeds (adjacent to the Blyth estuary near Southwold) and upstream near Walpole, some 15 km away. The Walpole sightings were mostly single otters with occasional twos, while the

White Admiral 111 8

sightings at the Hen Reedbeds were in ones, twos and threes.

Occasionally otters have been recorded at three different locations at similar times, suggesting there are at least three distinct ranges of single otters or family groups. For example, on 1 June 2020 there were sightings at Blyford at 01:50, Halesworth Millennium Green at 01:52 and near Walpole at 01:58. On 12 Sept 2020 there were sightings of single otters at Hen Reedbeds at 20:41, Blyford at 20:53 and near Walpole at 21:08, distances that could not be covered by a single otter in those times.

In the period 4 April – 22 May 2022, there were 15 cases of otters at Hen Reedbeds that could not have been the same as otters seen at similar times at or upstream of Halesworth, over 12 km away.

To date we have had 40 cases in 2020, 17 in 2021 and 16 in 2022 to July of different otters seen at different locations at times close enough that a single otter could not have travelled the distance.

Our impression is that the Hen Reedbeds is the main area for breeding and raising cubs, as that is the area where mother and cub groups are most often seen. It appears that there are distinct territories or ranges further upstream with only limited overlap.

Acknowledgement: We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of all members of the Blyth Otter Group who participate in so many ways to this continuing study.

References

The Upper Blyth Report (2019), Otter Activity in the River Blyth, Suffolk Mammal Group & Halesworth Millennium Green

Suffolk Otter Group online guide to spraint: https://suffolkotters.wordpress.com/surveys/diethabitat-and-habits

White Admiral 111 9

A still from one of our cameras

Insect migration

Raymond Watson

What I think of as true migration is, for example, well documented for birds where there is a seasonal movement, there and back, between two parts of the globe. This is rare in insects but there is the case of the Monarch Butterfly in North America. The last generation of the species in a year moves south for winter and then returns part way during the following spring. For most insects migration is simply part of the dispersal mechanism aiming to increase the breeding range of the species. Climate change is playing a part. I am lucky to live near the coast of Suffolk and as a consequence capture many immigrant insects entering this country from abroad. It is not always possible to know if an individual is an immigrant or resident and there are many resident species whose populations are topped up by immigrants.

Eutanyacra picta is an Ichneumonid wasp that can be common on our coast in late summer when its arrival coincides with that of other known immigrant insects. Its larvae are parasitoid in the caterpillars of moths such as the Heart and Dart.

The Ant Lion, Euroleon nostras, arrives from Europe and sets up small breeding populations in suitable locations. It has become well established in the Suffolk Sandlings over the last 30 years or so. Its larvae feed on ants falling down the steep sided pits it builds in sandy soils.

The Harlequin Ladybird, Harmonia axyridis, is an invasive species. It moved west across Europe to arrive in Great Britain around 2004. It is now well established, often abundant and topped up regularly, particularly in the south eastern part of the country. It is very variable in appearance. Its diet is less conservative than most native Ladybirds.

White Admiral 111 10

Above: quin ladybirds colour forms.

Right:

Below:

The Ichneumoid wasp E. picta

Above: A cluster, or ‘Lovliness’ of Harleladybirds (H. axyridis) in their various forms.

The Blue Underwing (C. fraxini)

An adult Ant Lion (E. nostras)

My primary interest is Lepidoptera. I have an Aspen tree in my garden and its leaves are the preferred food for the Blue Underwing or Clifden Nonpareil, Catocala fraxini. The species was resident in Kent around 90 years ago. It has since been considered as extinct apart from rare immigrant arrivals. However a wave of them has arrived, first in 2017. I captured my first one in 2019 and it is now a regular catch for me as it is in many other Suffolk locations.

The Box-tree Moth, Cydalima perspectalis, is an invasive species. Originally from Asia it has spread rapidly reaching Great Britain in 2007. It is now a pest, the larvae defoliating Box. It still arrives as top up immigrant individuals so in unlikely ever to be controlled. A tiny moth at just 5 mm, Cosmopterix pulchrimella was first recorded on the British mainland in 2001. It has since spread and established scattered breeding colonies in the country. First recorded in Suffolk during 2017 it is now seen much more frequently. My catches are mainly during October. It is probably resident in the county but needs to be proven as such by the discovery of the larvae which feed in leaf mines on Pellitory -of-the-wall. Although tiny it is very pretty with the markings in silver and lustrous orange.

White Admiral 111 11

The first British record of Cydia inquinatana was from Minsmere during 2009. My first catch was in 2015. The species has most probably arrived in Suffolk on easterly winds from Europe. It is a regular catch for me now since it is breeding in my garden. The larvae feed on the seeds of the Field Maple. Initially they are inside the immature key but as they develop they feed from outside it so as to avoid falling free of their food supply when the key falls from the tree owing to their feeding.

The Beautiful Marbled Moth, Eublema pupurina, first recorded as an immigrant in the country in 2001 turned up in Suffolk during 2006 has become much commoner in the last 3 years. It remains an immigrant species to the British Isles but may well be establishing breeding populations coastally. The larvae feed on thistles, preferring the common Creeping Thistle. My experience of catching them suggests it is still an immigrant but can arrive in considerable quantities.

Box-tree moth C. perspectalis and C. pulchrimella respectively. Beautiful Marbled Moth, E. pupurina

During the latter part of October this year (2022) there was the arrival of species from North Africa and the Mediterranean area. Species from this part of the world are less likely to be able to establish themselves in the colder British climate

White Admiral 111 12

than other European immigrants. At least 5 species new to the country were added during this period (Steve Nash, Facebook, Migrant Lepidoptera (GB & Ireland)).

The highlight of the invasion was the large number of the beautiful Crimson Speckled Moth. Utetheisa pulchella. Whilst some have made their way inland, particularly over time, they primarily landed on the coast. Many were in fact found on Suffolk beaches as well as in moth light traps. As a first for me mine arrived on the night of 26th October. There must have been hundreds, if not thousands of them, actually made their way over to this country.

C. inquinatana

Top left: Cydia inquinatana

Below: Crimson Speckled Moth. U. pulchella.

Below left: D. ramburialis

White Admiral 111 13

The immigrant invasion gave me two other firsts, the Golden Twinspot, Chrysodeixis chalcites (Below) and the Vagrant China-mark, Diasemiopsis ramburialis. Neither of these species is likely to become resident.

White Admiral 111 14

us on Facebook The SNS has a private members page where you can share your sightings, get ID help and much more.

Hawk at: whiteadmiralnewsletter@gmail.com for your link to join.

Join

Email

SNS 2023 Conference

Sat 4th & 11th March 2023

The SNS 2023 conference Into the Wild will look at different aspects of the rewilding debate.

The conference will be held online on two half days, Saturday 4th March and Saturday 11th March 2023.

See the full advert on page 1 for details of the speakers

There will be a small admission fee. Everyone welcome!

Is your contact information correct?

From time to time, we change email address, or home address and we forget to let others know. If you’ve changed your details recently, please let us know by contacting

enquires@sns.org.uk

AGM and Spring Members’Evening

(in person event)

Wednesday 26th April 2023 7.00 p.m. for 7.30 start.

Bentley Village Hall, Station Road

Ipswich IP9 2BL

White Admiral 111 15

Red Pond Water at Alder Carr Farm

Joan Hardingham

I received an excitable call from my daughter recently “You must go and see the pond – it is red!” “How red?”, “Very red!” came the reply.

As we pump the water to cattle and sheep troughs I took hasty action –and it certainly was alarmingly red. The contrast with the bright green duckweed made it look rather beautiful and other-worldly – but perhaps not good for livestock so I contacted Adrian Chalkley, SNS Aquatic Invertebrate Recorder who knows more than most about pond life.

I have just acquired a microscope through the East Anglian Microscopy Group who hold (free) sessions monthly at Crowfield Village Hall and took a photo with a phone camera of some highly animated protozoans which had round platelets (chloroplasts?) internally of a pinkish hue.

White Admiral 111 16

He replied:

“It's not uncommon to see red water in still waters; lakes, ponds or puddles. The little animals in your photo which are swimming around are clearly (to me at least) some species of either flagellate or ciliate protozoa, I can't be at all sure which from your photos but Cryptomonas. Euglena & Paramecium are common and likely species. Flagellate protozoa have single or double whip like flagella with which they swim, ciliates have short hair like cilia which beat in waves to allow the protozoa to swim.”

So why the red colour?

The red colour does seem to mostly occur in Autumn, at least whenever I've seen it. Now protozoa feed on organic matter, other microorganisms or floating decaying tissues and general debris. Many protozoans have chloroplasts embedded within their cells and may have a slightly green hue for most of the year. However in Autumn when the pond is full of falling leaves the protozoans can absorb such a concentration of tannins, from Oak leaves for example, that the colour changes to various shades of red.

Given the hot summer and the continued above-normal temperatures this autumn & early winter the populations of all microorganisms are going to stay very high until we get a hard frost, this means the water is cloudy with the large population of protozoa and the red colour becomes much more visible to the naked eye. At least the above is my explanation of the phenomenon, though I'd be very interested if you find an alternative theory or to see if contrasting explanations are sent in to White Admiral.

It could be seen as one more example of the effect of climate change, but luckily not detrimental to the livestock drinking the water.

White Admiral 111 17

Volunteering and Coppicing

Paul Heather

My local Suffolk Wildlife Trust Bulls Wood in Cockfield is the location for a fortnightly rendezvous with fellow volunteers between the months of October and March.

The main entrance to Bulls Wood from Parsonage Farm end, Cockfield (Note: No parking at the farm).

The ancient tradition of coppicing is thriving as it has for many years and wildlife has adapted to the conditions over centuries. It is a process of woodland management that encourages certain trees to produce new shoots despite being cut down to an inch of their lives. It helps to strengthen the trees, provides a constant supply of wood for burning, hedge layering, thatching, pea sticks along with many other uses. It also aids the creation of different habitats for animals, flora and fauna.

Bulls Wood is at least 800 years old and is an ancient broad leaf wood that comprises of hazel, ash, maple, oak, holly and willow; it also has a varied selection of wild plants such as Herb Paris, Early Purple Orchid,

White Admiral 111 18

Common Orchid, Oxlips, Ransomes (Wild Garlic), Wood Anemone, Wood Sorrel and Celandine. Our very small, rare and highly secretive dormouse is a resident and the overhanging canopies are designed to encourage them to travel with relative ease.

What do the volunteers do on a cold, sometimes wet Sunday morning every fortnight from October to March. Sometimes it is hard not only to wrench yourself out of bed to be on duty for 8.30am but also then to undergo physically exertion. This includes cutting up logs with a bow saw, carrying logs to a designate wood pile, sorting out different lengths and widths of wood (some for thatching, fence staves/supports), clearing space between hazel stools that then have to be covered with brash (the left overs from the felling and sorting). This covering process helps to protect new growth from the local roe and muntjac deer, the latter being the worst offender due to their small size that enables them

White Admiral 111 19

A recently constructed dead hedge, layered to keep out deer.

to squeeze through small gaps in the cover/undergrowth. Dead hedge layering is another form of creating a barrier to prevent incursion from the deer.

The ‘team’ of volunteers is allocated to a designated area in October within the wood that is determined by the age of the growing wood; ideally work will commence on a section that has had between 20 - 25 years of growth.

Whilst the work is physically demanding, the rewards are most beneficial. It keeps you fit (and not fit to drop!), you experience nature at first hand with potential sightings of woodcock, hares, pheasants, the sound of buzzards overhead, woodpeckers, nuthatch, blue tit, great tit, and long-tailed tit. The odd robin will

White Admiral 111 20

From left to right: Oxlip. Wood Anemone and dead hedge layering.

The coppiced area cleared during winter 2021/22 showing excellent growth on the hazel stools as a result of our fencing keep the deer out.

come close by, seeking a free meal from the ground that has been freshly disturbed. It is a chance to watch the season change with the oncoming spring presenting new life and your mental health has also benefited by being in tune with nature.

Finally, it is not just physical exertion, we do enjoy a mid-session break, sitting around our fire, eating food, consuming a hot drink, sharing stories and putting the world to rights.

A grand morning out!

AGM and Spring Members’Evening (in person event)

Wednesday 26th April 2023 7.00 p.m. for 7.30 start.

There is plenty of parking and refreshments will be available.

Bentley Village Hall, Station Road

Ipswich IP9 2BL

Please join us!

White Admiral 111 21

out.

Facebook Gallery

A selection of photos from our new Facebook page

Fromtop left clockwise: Candlesnuff (Xylaria hypoxylon) by Alan Thornhill

Green Elf Cup (Chlorociboria aeruginascens) Hawk Honey

Coral Slime (Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa) Hawk Honey

Upright Coral Fungus (Ramaria stricta) Gary Lowe

White Admiral 111 22

White Admiral 111 23

White Admiral 111 24

Top: Stewart Belfield found this Slow worm (Anguis fragilis) at Minsmere.

Left: This Lovliness of 16 spot Ladybirds (Tytthaspis sedecimpunctata) on a gatepost at West Stow along with this lovely Orange Ladybird (Halyzia sedecimguttata) Below

White Admiral 111 25

Top: Isochnomera cyanea, a Nationally rare Oedemerid beetle found by Jerry Bowdrey at Kelsale.

Below: Kidney spot Ladybird (Chilocorus renipustulatus) found at Lackford by Joe Myers.

White Admiral 111 26

Top: Silver-washed Fritillary(Argynnis paphia)by James Corton

Below: Male Blackcap (Sylvia atricapilla) by Chris Cotton

Below

White Admiral 111 27

Left: Another Upright Coral fungus fromJustin Gant.

Below right: Crimson Spotted Footman moth by James Corton.

left: Some frozen spider web from Chris Cotton

The Double Life of OakApple

Michael Chinery

Most people with an interest in natural history will be familiar with the oak apple gall – that pale, fleshy growth that sprouts from oak twigs in the spring – but not so many will be aware of its complex life story. The gall is caused or induced by the gall wasp Biorhiza pallida, a small brown, ant-like insect, and the story begins when a female lays her eggs in an oak bud in early spring. The larvae hatching from these eggs start to feed on the bud tissues and something in their saliva causes the tissues to change, forming the gall instead of the normal bud tissues.

Numerous gall wasp larvae live in the gall, each in its own little chamber, and feed on its nutritious tissue. When fully grown, they pupate in the gall and winged adults emerge during the summer. Each gall yields either males or females and then the fun begins. After mating the females crawl down into the soil and seek out the oak’s fine rootlets in which they lay their eggs. This leads to the development of a very different kind of gall – a small bead-like structure up to 8mm in diameter and containing a single larva, although the galls usually develop in small clusters.

The young gall wasps remain in these subterranean galls for about 18 months and the new adults do not emerge until the end of the second winter. These are all wingless females and they are able to lay fertile eggs without mating. They climb up the oak trees, often in very cold weather, and lay their eggs in the buds to start the cycle all over again.

White Admiral 111 28

Mature Oak apples in the spring

Left: Vacated asexual galls of Biorhiza pallida on an oak rootlet.

Above: A wingless asexual female B. pallida just emerged from its rootlet gall.

This alternation of sexual and non-sexual or asexual generations is typical of the many gall wasps that live on our oak trees, but while most species are happy to stick to one species of oak, several species require two different hosts in order to complete their life cycles. Andricus kollari is a good example. The asexual generation of this insect grows up in the familiar marble gall on our native common and sessile oaks, but then transfers its attention to the introduced Turkey oak, where the sexual generation develops in tiny egg-shaped galls in the buds.

Left: Mature marble galls of Andricus kollari

Right: Sexual galls of A. kollari nestling in a Turkey oak bud.

White Admiral 111 29

Although galls on oak trees are probably the most familiar, you can find galls on a wide variety of woody and herbaceous plants. You will probably be surprised to learn that we have about 2,000 different galls in this country, induced by a wide range of insects as well as by mites, fungi, and bacteria. The galls can occur on flowers and roots as well as on the stems and leaves. Some are quite colourful and attractive and it is worth looking out for them on your walks.

The Suffolk Naturalist's Society Members Group is now on Facebook.

Email: whiteadmiralnewsletter@gmail.com for your link to join.

White Admiral 111 30

Above: A Knopper gall, induced by the asexual generation of Andricus quercuscalicis on an acorn. This is another 2-host species, with the sexual generation inducing tiny galls on the catkins of the Turkey oak.

Suffolk’s Wildlife Friendly Villages

Stewart Belfield & Sophie Flux

Something is stirring in the villages of Suffolk and beyond. Residents are coming together and starting projects to protect and enhance wildlife in their local communities. Sometimes, like the villages of Risby and Bredfield, they go by the name of a ‘wildlife-friendly village’; sometimes by another name, such as the wonderfully named ‘Wild About Campsea’. Whatever the name, these communities are intent on making their gardens, churchyards, verges, green spaces, woodlands and fields as wildlife-friendly as possible. With the compounding effects of climate change, environmental loss and pollution, nature needs all the help it can get; and it’s finding that help in communities across Suffolk. In this article, we are going to talk about Suffolk villages, but much of what we say can apply to towns and city districts up-and-down the country.

The first place to designate itself as a ‘wildlife friendly village’ was Risby. It happened in 2019. A group of local resident set about distributing wildflower seeds, building mini wetlands, and engaging in a host of other activities. Soon they found themselves featured in a Countryfile program. Bredfield Wildlife Friendly Village followed on their heels. Other villages and communities have included local environmental action within their broader Climate Emergency strategies. ‘Green Snape’, ‘A Greener Waldringfield’ and ‘Martlesham Climate Action’ are good examples, and there are many more. Wildlife-friendly communities are spreading and growing in capacity. This is happening because of the determined activities of community members, and the sharing of ideas that happens when communities come together.

If the notion of wildlife-friendly villages sounds rather parochial, it’s worth considering the factors of scale and proximity. An individual garden is small-scale, but a collection of gardens ups the scale considerably: plenty of room fora hedgehog to roam! Private gardens in Britain cover an area bigger than all of the country’s nature reserves

White Admiral 111 31

combined estimated at over 10 million acres. If we add to that community green spaces, the size of the contribution to environmental care by village communities increases even more. Next, in terms of proximity, consider that most Suffolk villages are surrounded by arable land, and most of that land is now an ecological desert. The existing and the potential biodiversity in village gardens will be vastly greater than the biodiversity in the surrounding fields. When most wildlife finds the surrounding fields to be lacking in the kind of food and shelter they require, village gardens provide a haven.

Song Thrushes – a much loved but declining species - have moved from areas of intensive farming to breed in, or close to, gardens. Song Thrushes in gardens fare better that those living on farmland.

What sort of community places, events, meetings and communication forums might provide opportunities for wildlife-friendly practices? Clearly, appropriate means will vary from community to community, and it wouldn’t pay to be too prescriptive. Let’s look at some possible means:

White Admiral 111 32

Risby WFV members sowing seeds

• Hold events ‘in the field’ that provide direct experiences of nature: wildflower walks, moth mornings, bat evenings, bio-blitzing, and so on.

• Organise work parties, where small groups of people come together to do such things as plant trees, maintain ponds, or create spaces for wildflowers to grow.

• Hold indoor events. These might be meetings in the local village or community hall, with subjects like wildlife-friendly gardening.

• Hold events for children and encourage nature connectedness at an early age. Get them outdoors, bug-hunting or pond-dipping (if you’ve got a pond). Devise nature-related indoor activities, such as drawing, solving puzzles or poetry writing.

• Create a community Facebook group. With correct management, this can be a good means of community communications, and can be helpful in building nature awareness.

White Admiral 111 33

• Make links with local schools. Your community might have resources (such as a wildflower meadow or woodland) that could be used by local school children and help stimulate their connection with nature.

• Try getting your local Parish Council, local landowners and local businesses on board. You might meet some frustrations, but you might be surprised at the degree of willingness to help.

Many of the activities of Wildlife-friendly villages may not appear to directly help nature. During an organised wildflower walk through a local meadow, a group people share a delight in the flowers they see and, together, try to remember what they are all called. A woman posts a picture on the local Facebook group of a woodpecker on her bird feeder and exclaims that it was a wonderful surprise. Neither of these activities does anything directly to help nature recover from its current perilous plight, but these people are connecting with nature and they might just want to do something to help conserve the nature they love. Put more formally, nature connectedness might prove to be a stimulus and form the basis for pro-nature behaviours.

Several Wildlife-friendly Villages have website that provide lots of information on local actions that can be taken, and have been taken, to help nature and enhance the local natural environment. Two websites that you might like to visit are: Bredfield Wildlife-friendly

White Admiral 111 34

A wild patch in the church grounds in Bredfield

Village ( https://bredfieldWFV.org.uk ) and Risby Wildlife-friendly Village ( https://wildlifefriendlyvilllage.co.uk ). On these websites you’ll find: hints on wildlife-friendly gardening; examples of wilding local green spaces, guides to local nature; feature articles; learning resources; and links to other like-minded organisations

Whatever is done, it is most important to make links and join with other villages and organisations to share knowledge and learn about wildlife preservation. Help create a network of wildlife-friendly havens. Nature

White Admiral 111

A wildflower walk in Bredfield

Motus at Landguard Bird Observatory

Nigel Odin

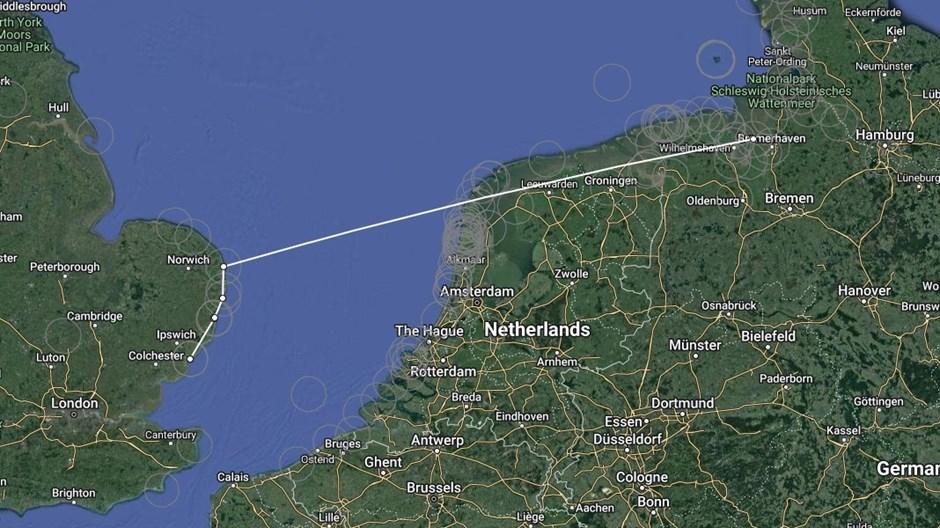

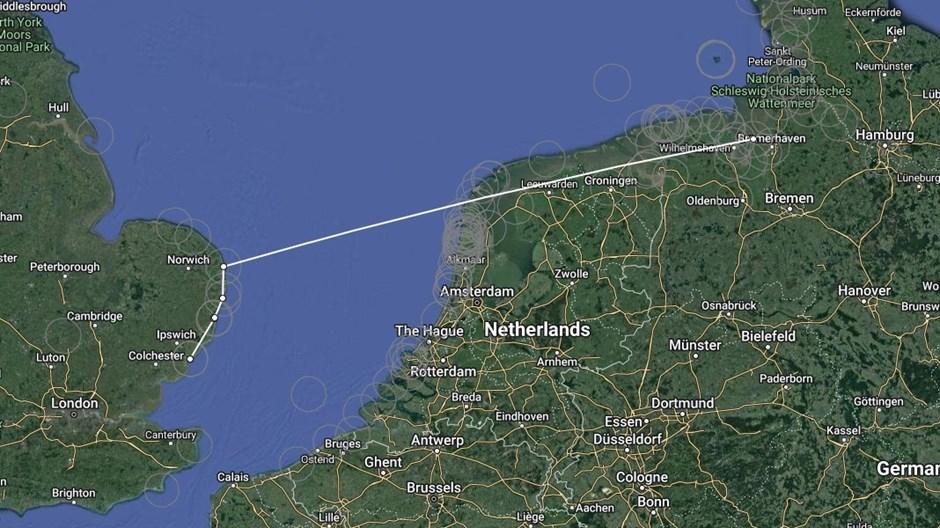

Motus is an international collaborative system that uses automated radio telemetry to track tagged individual birds, bats, and larger insects. In April 2019 a Motus receiver aerial was kindly supplied and fitted at Landguard Bird Observatory by Wageningen Marine Research based at Wageningen University, Holland. The Cranbrook bursary, administered by Suffolk Naturalists Society, provided £450 funding to cover the running costs for the three years 2020 to 2022 for internet connectivity and electricity costs.

The aims of the study are research into the migration of Nathusius’s bat from the continent through Suffolk using nanotags and research into the changing migration pattern of birds across Europe and Africa through Suffolk.

The outcome of the study is an opportunity to collaborate with European and North African colleagues in the detection of bats and birds migrating through Suffolk using automated telemetry. Suffolk is at the forefront of this new technology, reporting early pioneering results in The Times, on social media and on the internet across Europe and the USA.

Research is ongoing and largely dependent on researchers fitting tags on their study species. The network of receivers is growing in the UK following the first towers fitted in East Anglia. The way the system works is that data is owned by the individual who fits the tag but a lot of it is publicly available to all on www.motus .org

This Blackcap was fitted with a tiny nanotag at Landguard in the spring of 2021 weighing 0.26g to track its departure direction &

White Admiral 111 36

potentially its subsequent movements. This was the first bird in the UK to be fitted with a Motus automated VHF tag, which naturally falls off after three to four weeks. potentially its subsequent movements. This was the first bird in the UK to be fitted with a Motus automated VHF tag, which naturally falls off after three to four weeks.

Motus tracked Blackcap

This Motus tagged Blackcap ringed Landguard September 28th 2021, left Landguard 0300 hrs on October 2nd. It then disappeared off the radar for a couple of days before being recorded at 2320 hrs 154 km away at Dak Zwin Natuur Park, Belgium on October 9th. It was then logged at 2200 hrs a further 396 km away at Carolinsiel, Germany on October 10th 22 hr 41 minutes later having covered the distance at an estimated minimum speed of 17 km/hr suggesting that it pitched in somewhere between the two sites during daylight hours. Later the same evening it was detected at Jade Weisel Port & Wilhelmslaven, Germany covering the 28 km in 25 minutes at an estimated speed of 66 km/hr. After that it was noted at Frieburg, Germany on October 12th still heading north-east in the autumn! Another Blackcap tagged at the same time was detected by the tower at Sandwich Bay Bird Observatory, Kent as it headed south which is in a direction that one would expect it to take. But times they are a changing?

White Admiral 111 37

Since the tower was installed at Landguard, apart from nine Blackcap tagged here it has detected a German tagged Robin, Blackcap from Kent and the following originating in The Netherlands – 2 Bar-tailed Godwit, Knot, Blackbird & Starling.

Nanotags on larger birds last longer. Two different Bar-tailed Godwits originally tagged heading north in the spring in the Netherlands by Wageningen University & Research have been tracked in August 2022 by the tower at Landguard on their autumn migration south. The second of these is shown above. It was tracked leaving the Dutch coast near Texel on Wednesday 17th August and travelled the 275 km to Landguard in 3hrs 35 mins at 76 km/hr.

The information being learned about Nathusius’s Pipistrelle bats, coordinated by UKBats over the last couple of years is basically mind blowing (to me at least!). The bulk of this work has, so far, been largely in Norfolk & Suffolk with an expansion in this project in the pipeline for 2023. The tower at Landguard has detected five of these bats as they go up & down the East Anglian coast, often being detected by different towers on the same night.

Additionally, four bats were fitted with tags at Landguard on the evening of May 5th 2022. Three of these bats were later on logged at

White Admiral 111 38

Bar-tailed Godwit track

multiple towers in The Netherlands & Germany as they migrated across to the continent with the fourth one logged up the coast. An example of one of the movements up the East Anglian coast and across to Germany is shown above.

One of the issues with all this pioneering work on migration is that it is resulting in more questions being asked than answered! Lord Cranbrook was a great supporter of research into bats & birds and would have been fascinated by the results being discovered so far by this international research.

White Admiral 111 39

Watch this space...

Nathusius pipistrelle track

AGrand Day Out!

Wild cats? No thanks!

David Tomlinson

When I wrote in the autumn issue of The White Admiral about re-introductions (Big Zoo or Restoring the Wild) I suspect that I gave an impression of being all in favour of releasing lost beasts and birds into the British countryside. If so, I apologise, for that’s not really true. I do, for example, have reservations about the establishment of the white-stork colony at Knepp in Sussex. It has been widely claimed as a successful reintroduction, but I have my doubts whether it really is, as the evidence suggests that it’s really an introduction, and there’s nothing re about it.

I did some research into the history of white storks nesting in the British Isles. The authoritative Birds in England (Brown & Grice, 2005) makes no mention of this species ever having nested in England. Instead we have to look to Scotland, when “in the year of our Lord fourteen hundred and sixteen….a pair of storks came to Scotland and nested on top of the church of S Giles of Edinburgh, and dwelt there throughout a season of the year”. This is the English translation from the original Latin text in the Scotichronicon. Whether you believe it or not depends on whether you believe in fairy tales. David Bannerman, writing in Volume VI of his 12volume work The Birds of the British Isles, notes tersely “Comment on an occurrence reputed to have taken place over five hundred years ago is superfluous.” Curiously, though, many modern ornithologists seem to take this extraordinary record as fact.

White Admiral 111 40

Greece

Like most people, and I’m sure almost all birdwatchers, I do have a soft spot for white storks.

I remember once walking at dawn through the town of Zafira in Extremadura on New Year’s Day. There was an almost eerie silence, suddenly broken by the beak-clattering of a pair of white storks, a wonderfully evocative sound. Storks are doing well in this part of Spain, and many pairs are already back on their nests by late December.

I have another memory of storks in Spain. I was watching birds at Lagunas de Villafáfila in Castilla y Leon (much the best place in Spain to see great bustards). In front of me was the Salina Grande, a large shallow lake with a colony of nesting avocets. A white stork landed on one of the islands where the avocets were nesting, and proceeded to snaffle up avocet chicks as it stalked along the shore, ignoring the hysterical protests of their parents. It was reminder that these storks aren’t vegetarians.

Mention of great bustards prompts mention of the apparently successful reintroduction of these impressive birds onto Salisbury Plain. The last great bustards on the Plain struggled on to about 1820, but remarkably they lasted longer in Suffolk, where the last nest was noted in a rye field

Had a sighting or a close encounter that you’d like to share?

Then let us know.

whiteadmiralnewsletter@gmail.com

White Admiral 111 41

delighted to think that they are back in Wiltshire, where I’m tempted to go and see them.

The Brecks must have been a fascinating area until the Forestry Commission blanketed them in conifers. The area may no longer be suitable for bustards, but is it for lynx? There have been suggestions that these cats could be released into the forest, and there’s no doubt that there would be sufficient food, in the shape of deer, to provide for scores of them. However, they are anti-social animals that like big territories, so the Forest would only provide room for two or three pairs, so not sufficient for a healthy population.

Lynx have been extinct in Britain for a very long time, with the last evidence of their occurrence here ranging from around 180AD in Sutherland to 450AD in North Yorkshire. However, evidence suggests that their extinction was caused by humans rather than habitat change, which is why this species is regarded as a possible subject for reintroducing. Kielder Forest is one suggested location, though the local sheep farmers are, generally speaking, not enthusiastic about the idea. The Kennel Club owns a large piece of land adjoining Kielder, the Emblehope and Burngrange Estate, and it has also objected to the possible release of lynx, but you can hardly imagine a club whose sole focus is dogs being keen on anything to do with cats. I think that the proposal is quite feasible, and much better than the proposal to release captive-bred wildcats in Devon.

As you may have read, there is a project being proposed by the Devon Wildlife Trust to reintroduce wildcats to Devon, and at the time of writing is has announced that “it wants to appoint what is believed to be England’s first ‘Wildcat Project Officer’. The successful candidate will lead a feasibility study which will judge whether wildcats could be reintroduced successfully to the region.” Apparently “conservationists are now keen to explore the animal’s reintroduction, stressing that they once played an important ecological role in our countryside and could do so again”.

Interesting idea, but I’m not convinced. We all know that domestic cats

White Admiral 111 42

and their feral cousins are not exactly wildlife friendly - the most recent study suggest that they kill around 270 million animals in the UK every year. In comparison to domestic cats, wild cats are professional killers, and quite what their impact might be on our surviving native wildlife has yet to be measured.

Last year I had the rare treat of watching, and photographing, a wildcat hunting in northern Greece, where these animals are relatively common. (I have had previous sightings in the area, and once found an individual tom cat killed on the road). These animals show all the characteristics of pure wildcats, with big, bushy tails with black cylindrical rings, stripes rather than spots on their fur, plus rather short legs. Visually, they show no signs of hybridising with domestic cats which is a very real concern if wildcats were to be released anywhere in England. The impossibility of stopping wildcats hybridising with feral or domestic cats is one of the most compelling reasons for not going ahead with the proposed introduction, but do we really want another serious predator to contend with anyway? I think not.

Editor’s tale

Hawk Honey

Back in 2020, just before we went into lockdown, whilst working at Lackford Lakes, my colleague had several visitors come into the centre saying that they thought they had seen a lynx towards the western end of the reserve near the village. The grass was long and sightings were sketchy and we had put it down to a local resident who was known for

White Admiral 111 43

….

their several breeds of cat that used to visit the reserve and thought no more of it.

Arthur Rivett from the Suffolk Mammal Group was doing camera trap surveys of otters on the reserve and would come in on a Monday morning to change over the cards and review the footage. This particular Monday, Arthur was checking the footage when he suddenly called me in to show me video footage and a beautiful Bobcat (Lynx rufus) walking up to the camera and sitting down right in the middle.

The Trust reserve team set into action to try and capture the Lynx, affectionately called Lionel the Lackford Lynx, working with Banham Zoo to arrange the setting up of traps. Sadly, Lionel was shot by a farmer who caught it attacking its chickens. Lionel was treated and returned to its owner who

Top: Lionel sits in front of the trail cam and contemplates his decisions to escape.

Left: Only days later, as reported in The Sun, Lionel is shot and captured.

Acknowledgements:

Many thanks to Arthur Rivett for allowing the use of his trail camera images.

Will Cranstoun and Ben McFarland from Suffolk Wildlife Trust.

White Admiral 111 44

Bird feeders

Trevor Goodfellow

I love watching the bird feeders through the window throughout the year, but they are much busier in the harsh winter months. The selection of birds is quite varied over the year, and it is easy to be misled in to thinking there is not much about. A quick totting up of species numbers can be surprising: Robin, Blackbird, Great tit, Blue tit, Wood pigeon, Collard dove, Stock dove, Great spotted woodpecker, and occasional Coal tit equals 9 species right there.

Long tailed tits arrive in numbers usually about 9 together, Goldfinches up to 20, Greenfinches are stable at around a dozen, a few Chaffinches, song thrush and Dunnocks too.

In the winter there are occasionally Brambling, a few more Chaffinches that arrive with Siskin and Redpoll, Fieldfare and Redwing nearby, but seldom near the feeders. Magpie and other corvids are feeder raiders in early spring and will steel 5 fat balls before I get up in the morning.

I find it fascinating to watch there different feeding habits. The Goldfinch and Greenfinch are usually tolerant of their own species, but both get feisty when the feeder is fully occupied. The Greenfinches are bullies and will knock a Goldfinch off the perch.

All the tits are ‘smash and grab’ merchants, quickly landing and seizing a sunflower heart, immediately fly off with to eat under shelter in nearby hedging. The finches however cascade down from overhanging trees to present a conveyor belt of hungry beaks queueing to land in vacant

White Admiral 111 45

Male and female Greenfinch Chloris chloris

feeder spaces.

The arrival or departure of a Greater spotted woodpecker always causes panic, whether it is their long beak, or their flight resembles a predator, I don’t know.

Of course, where there is a steady appearance of small birds., it is not long before Mr or Mrs Sparrowhawk arrive at speed to pluck an unsuspecting bird from the feeder, or after a very short mid-flight chase, capture and eat it.

A woodpecker wastes a lot of seed by knocking it out on to the ground and finches leave mostly the pointed end of the sunflower hearts which also fall to the ground. This may be ideal for Pigeon, Chaffinch and doves to feed on, but one must be mindful of attracting rats. This is unavoidable but can be managed.

I provide sunflower hearts and peanuts all year round and niger seed on occasions although the Goldfinch will always take sunflower hearts as their first choice.

As you can imagine, I buy a lot of seed and in winter will easily use a 20kg sack of sunflower hearts per month to fill up to 6 feeders. I may have 2 peanut feeders and 2 or 3 fat ball feeders too.

As I write this it is minus 2 degrees centigrade so keeping an ice-free water supply for the birds is a constant concern.

I have also recently erected a bird table about 100m from the house, for the specific purpose of feeding Buzzards and Kites. Since the recent avian flu .

White Admiral 111 46

Male Great-spotted woodpecker Dendrocopos major

A charm of Goldfinches Carduelis carduelis

problem, I have stopped collecting roadkill for this purpose, so I now scrounge scraps from my local butcher. These morsels consist of bone with tiny amounts of meat and pigs’ ears etc. The Buzzards – probably the same pair that fed on otter kills previous winters, now feed daily safe from the risk of disease. The table is positioned such that CCTV can zoom in plus it is visible from my house. I have only once recorded a Red Kite feeding on the table but they have often been seen close by. It is not my intention to stock the ‘road-kill bird table’ outside the winter period.

I would advise everyone to have a bird table or at least a feeder or two but be patient, I had so few birds at first that the seed used to rot in the feeders, now I have to refill them at least daily. It is important to keep some food available for the birds through the winter, but best to have some food all year round so they know where to come for food. I have noticed that if I move a feeder even just a few feet away, they appear to be confused and take a while to change their flight plan.

Always clean the feeders regularly. Killer viruses are spread easily

The SNS has a private members page where you can share your sightings, get ID help and much more.

Email Hawk at: whiteadmiralnewsletter@gmail.com for your link to join.

White Admiral 111 47

us on Facebook

Join

SNS autumn members evening 2022

Genevieve Broad

We were delighted to be able to meet in person as a Society after two years of Covid and Zoom meetings! Despite atrocious weather on the night of 24th November, with end of the world thunderstorms and flooding, we welcomed about 50 people to the members’ Evening at Bentley village hall. The programme was hugely varied with talks ranging from arable field margins and moths to the new SNS Facebook account and East Anglian fish. A huge Thank You to all our intrepid, knowledgeable and enthusiastic speakers for contributing to a lively evening!

Farming with Wildlife

Patrick Barker described the conservation work on his 525 ha clayland arable farm in MidSuffolk where he and his cousin, Brian, manage the farm using natural methods where possible. This includes, for example, letting the earthworms do the work instead of ploughing; leaving marginal land for wildlife under a stewardship scheme; trialling a low input method; and a project to assess the benefits of flowering margins around arable fields for beneficial insects. This project was supported by an SNS grant and run in collaboration with the University of Suffolk.

These natural methods have produced records for species never before recorded on the farm including Chinese Water Deer, nesting Meadow Pipit and Reed Bunting (previously recorded in winter), over 20 species of Aculeata including Melitta Tricincta and Melitta leporina and 27

White Admiral 111 48

species of Diptera. Total records to date are: 127 species of moth, 23 species of butterfly, 15 species of dragonfly, 46 species of bird, 6 species of mammal and a grass snake.

Patrick also described the results of turning over Fairoaks Farm Westhorpe entirely to a stewardship scheme in 2020 using regenerative farming. Watch out for future articles by Patrick in White Admiral/ Suffolk Natural History about his work to combine successful farming with supporting wildlife.

A brief update on moths in Suffolk

Neil Sherman, County Recorder for moths, explained how climate change is really beginning to have an effect on moths in Suffolk. SBIS hold 1.4 million moth records, thanks to our dedicated and knowledgeable County Recorders, present and past, and the enthusiasts who regularly submit their moth records.

The False Mocha, living amongst scrub oak trees in the Brecks, has declined nationally and was last seen in Suffolk in 2009, although the habitat has not changed. The Lappet moth, a hedgerow species, was last seen in 1995. It is also declining nationally, probably due to the impact of milder, wetter winters on overwintering larvae.

On the other hand, records for the Jersey Tiger have shot up from a single record in Westleton in 2004 to a cluster of recent records in the coastal areas of Felixstowe, Ipswich, Stutton and Holbrook with just a few records in the west of the county. The Hoary Footman, which feeds on lichens, was first recorded in 2003 in Orford Ness, but by 2020, had colonised the centre of Suffolk and the coast.

White Admiral 111 49

The huge Clifden Nonpareil or Blue Underwing is the size of the palm of a human hand. Once rare, it is now common and widespread with records submitted every year, often from river valleys and the coast. The Oak Rustic, which feeds on Holm Oak, was first recorded in Suffolk in 2018, after spreading rapidly from its arrival in the UK in 1999.

The Channel Island Pug, which feeds on tamarisk, first arrived from Europe in 1984. There have now been three records, all in 2022, from Felixstowe, Landguard and Neil’s garden at Purdis Farm, Ipswich! The Alchymist, another large moth, has distinctive white hindwings with a black outer band and feeds on deciduous oak trees. Out of only 30 or 40 British records, four are from Suffolk with 2 seen in 2022.

The warm spell in late October brought an invasion of the unmistakable very rare migrant Crimson Speckled moth to Suffolk. A good number of records were made, including 13 at Shingle Street in a single day.

SNS Facebook Group

Hawk Honey, editor of White Admiral newsletter, has set up a new SNS Facebook Group designed to enable members to ‘Communicate, Share and Enjoy’. Please email Hawk for a link (whiteadmiralnewsletter@gmail.com) – this is valid for two days to enable members to sign up. The benefits of this free service include sharing sightings, advertising events and help with identification.

White Admiral 111 50

Hawk asked everyone to send their species records to the County Recorders as this is the only way to ensure the records reach the SBIS database. Don’t rely on social media!

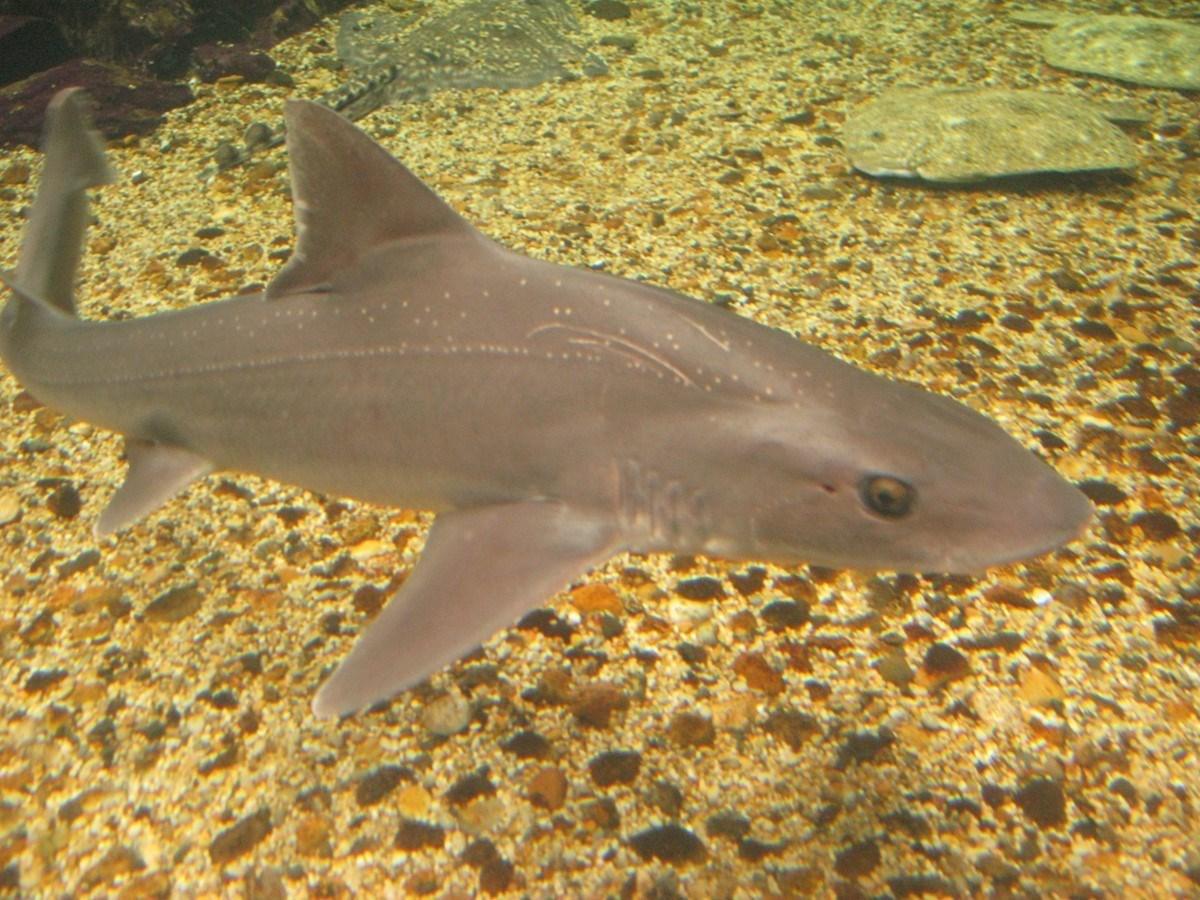

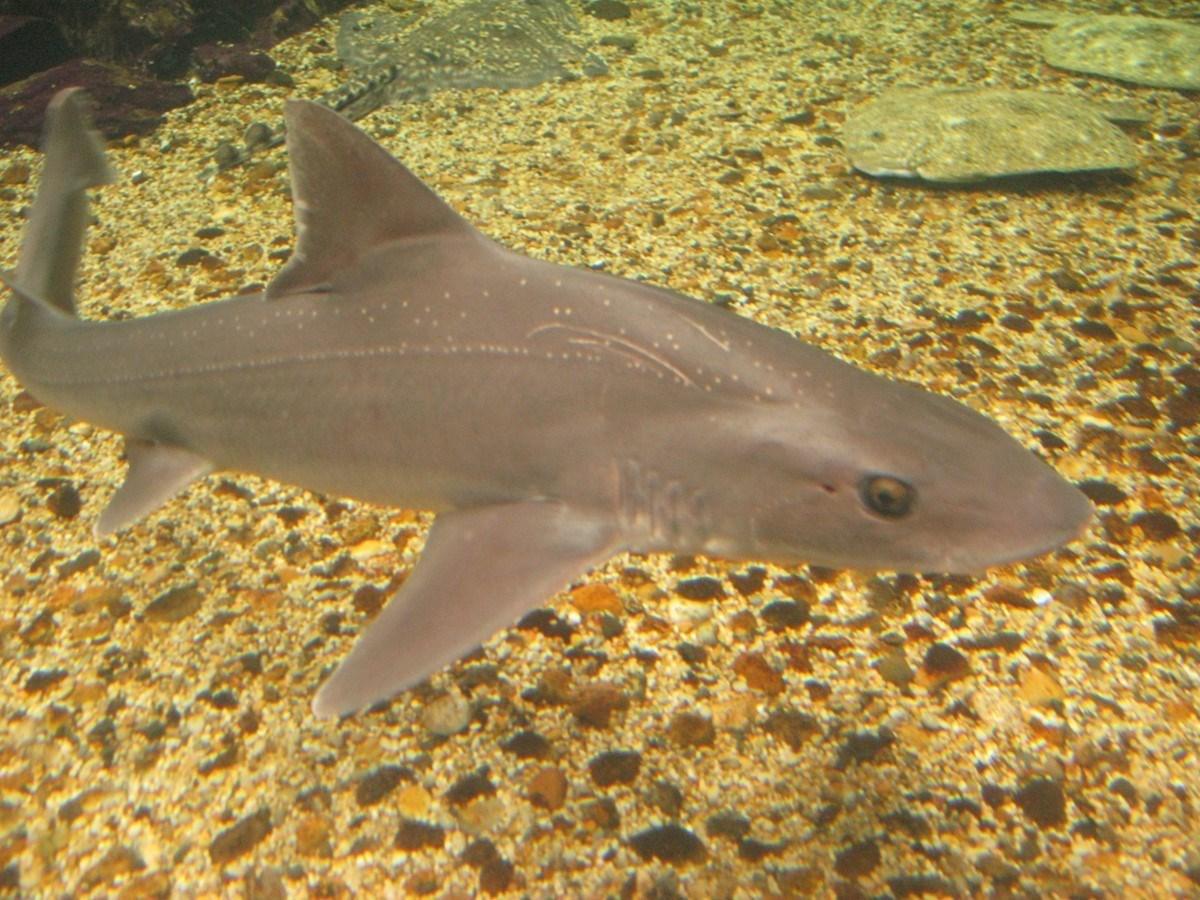

Fish and Fisheries off East Anglia

Jim Ellis, senior scientist and advisor for elasmobranch fish and ichthyology at the Centre for Environment, Fisheries, and Aquaculture Science (CEFAS) explained that the fishing fleet operating from the East Anglian coast is composed primarily of smaller vessels, and that many of the gears used are similar to those used 100 years ago, although with more modern materials for construction. These include pots for Crab, Lobster and Whelk; various gillnets and driftnets for Sole, Thornback Ray and Herring; longline for Cod, Bass and Thornback Ray; and otter trawl. More than 100 fish species have been recorded from the waters of East Anglia.

Commercial fish

Five species account for about 85% of the annual fish landings into Suffolk: Thornback Ray, Sole, Cod, Herring and Bass. Other species landed include Lesser-spotted Dogfish, Flounder, Starry Smooth-hound and Blonde Ray. Thornback Ray, which is locally abundant, is often marketed as ‘skate’, which can lead to confusion with Common Skate, a species that has declined in the southern North Sea. Sole (a medium sized flatfish) is an important species for the local fleet, particularly from spring to autumn. Other commercially important flatfish include Plaice and Turbot. Cod is a northerly fish species and has been less

White Admiral 111 51

common in the waters of East Anglia in recent years. Whilst Herring isn’t as important for the local fleets compared to the early 20th century, this small pelagic fish is still seasonally important. Bass is a large species (occasionally up to about 100 cm in length) of high value, and the coastal waters of East Anglia can have important nursery grounds for the juveniles.

Sharks, Rays and Skates (elasmobranchs)

In addition to Thornback Ray, a range of other elasmobranchs occur around East Anglia, including Spurdog (a species that was overfished but now the population is increasing again), Starry Smooth-hound, Lesser-spotted Dogfish (or Catshark) and Blonde Ray. Other species, such as Common Stingray and Thresher Shark are also reported occasionally.

Less Common Fish in East Anglian Waters

A range of other fish species may also be encountered around East Anglia. The Wolfish is a northerly species and had been reported from Norfolk in the past. Species such as the Common Dragonet, Sea Scorpion, Pogge (or Hooknose), Grey Gurnard and John Dory are

White Admiral 111 52

interesting bycatch species, and all have fascinating adaptations related to their diverse life histories. For example, the bottom dwelling Pogge have sensory barbels and Grey Gurnard have specially adapted fin rays to detect invertebrate prey living in the sand and mud. Lesser Weever is found on sandy shores at low water, and the Greater Weever is also reported very occasionally. Both species have venomous dorsal spines that can give a nasty shock to the unwary fisher (or paddler!). Old accounts of Suffolk fish include species such as Atlantic Sturgeon, a species now very rare in European Seas, and Hagfish which is normally found further north and might not have been recorded reliably.

Jim’s message: ‘Please don’t ignore the beauty and diversity of fish!

AGM and Spring Members’Evening (in

person event)

Wednesday 26th April 2023 7.00 p.m. for 7.30 start.

There is plenty of parking and refreshments will be available.

Bentley Village Hall, Station Road

Ipswich IP9 2BL

Members are invited to give short talks to share experiences of Suffolk natural history. If you would like to give a talk, please contact Martin Sanford (martin.sanford@suffolk.gov.uk).

You may also like to bring along specimens, books (or anything else of interest to naturalists) for display.

Please join us!

White Admiral 111 53

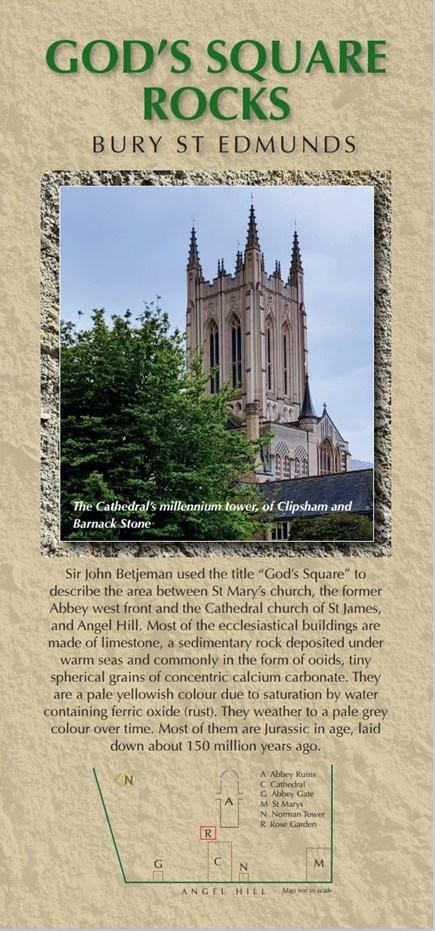

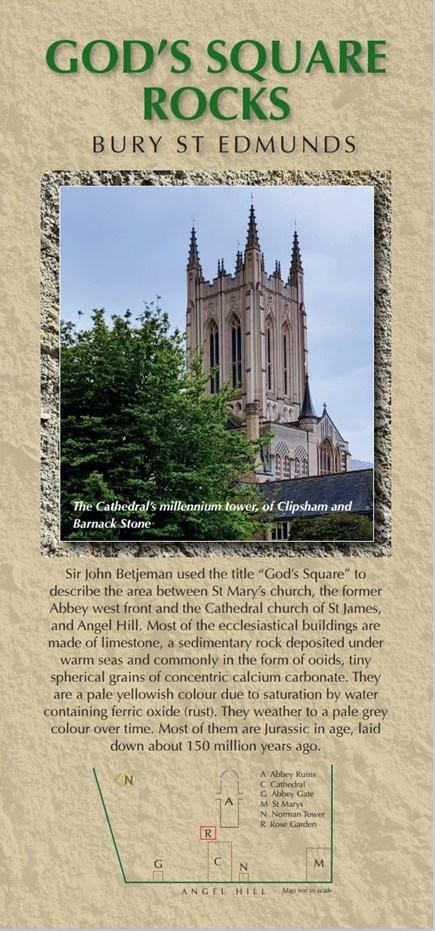

God’s Square Rocks

Caroline Markham

GeoSuffolk has written a new leaflet about the building stones of the Cathedral Gardens in Bury St Edmunds - John Betjeman’s ‘God’s Square’. The text is by Tony Redman (who was Surveyor of the Fabric to St Edmundsbury Cathedral), with photos and captions by Caroline and Bob Markham respectively. It was published as part of the celebrations for the 1000th Anniversary of the Abbey of St Edmund, in time for the celebratory ‘Picnic in the Park’ in July 2022. GeoSuffolk’s stand at this event in the Cathedral Gardens featured the new leaflet with a variety of building stones for visitors to handle. One unusual (and popular) specimen was part of a borehole (for electric cables) core through the wall of Blythburgh Church showing the rubble interior. Flints cut through by the diamond drill show impressive, curved cut surfaces. The leaflet is available free from the Cathedral information centre in Bury St Edmunds – or download it from our website archive at www.geosuffolk.co.uk

White Admiral 111 54

Flint God’s Square Rocks leaflet.

White Admiral 111 55

Clipsham Stone, a limestone, with fragments of fossil shells, in the southwest exterior of the Cathedral.

Oolitic limestone forms the top of the sundial in the Cathedral Rose Garden.

Swedish granite in the American Airforce memorial in the Cathedral Rose Garden.

Flint rubble core from Blythburgh Church

White Admiral 111 56

Suffolk Naturalists’ Society Bursaries

The Suffolk Naturalists’ Society offers six bursaries, of up to £500 each, annually. Larger projects may be eligible for grants of over £500 – please contact SNS for further information.

Activities eligible for funding include: travel and subsistence for field work, visits to scientific institutions, scientific equipment, identification guide books or other items relevant to the study.

Morley Bursary - Studies involving insects (or other invertebrates) other than butterflies and moths.

Chipperfield Bursary - Studies involving butterflies or moths.

Cranbrook Bursary - Studies involving mammals or birds.

Rivis Bursary - Studies of the county's flora.

Simpson Bursary - In memory of Francis Simpson. The bursary will be awarded for a botanical study where possible.

Nash Bursary - Studies involving beetles.

Applications should be set in the context of a research question i.e. a clear statement of what the problem is and how the applicant plans to tackle it.

Criteria:

1. Projects should include a large element of original work and further knowledge of Suffolk’s flora, fauna or geology.

2. A written account of the project is required within 12 months of receipt of a bursary. This should be in a form suitable for publication in one of the Society's journals: Suffolk Natural History, Suffolk Birds or White Admiral.

3. Suffolk Naturalists' Society should be acknowledged in all publicity associated with the project and in any publications emanating from the project.

Applications may be made at any time. Please apply to SNS for an application form or visit our website for more details www.sns.org.uk/pages/bursary.shtml.

The opinions expressed in White Admiral are not necessarily those of the Editor or of the Suffolk Naturalists’ Society.

The

Suffolk www.sns.org.uk

Naturalists’ Society

The Suffolk Naturalists’ Society, founded in 1929 by Claude Morley (1874 -1951), pioneered the study and recording of the County’s flora, fauna and geology. It is the seed bed from which have grown other important wildlife organisations in Suffolk, such as Suffolk Wildlife Trust (SWT) and Suffolk Bird Group (SBG).

Recording the natural history of Suffolk is still the Society’s primary objective. Members’ observations go to specialist recorders and then on to the Suffolk Biodiversity Service at The Hold to provide a basis for detailed distribution maps and subsequent analysis with benefits to environmental protection.

Funds held by the Society allow it to offer substantial grants for wildlife studies.

Annually, SNS publishes its transactions Suffolk Natural History, containing studies on the County’s wildlife, plus the County bird report, Suffolk Birds (compiled by SBG). The newsletter White Admiral, with comment and observations, appears three times a year. SNS organises two members’ evenings a year and a conference every two years.

Subscriptions to SNS: Individual membership £15; Family/Household membership £17; Student membership £10; Corporate membership £17. Members receive the three publications above.

Joint subscriptions to SNS and SBG: Individual membership £30; Family/Household membership £35; Student membership £18. Joint members receive, in addition to the above, the SBG newsletter TheHarrier.

As defined by the Constitution of this Society its objectives shall be:

2.1 To study and record the fauna, flora and geology of the County

2.2 To publish a Transactions and Proceedings and a Bird Report. These shall be free to members except those whose annual subscriptions are in arrears.

2.3 To liaise with other natural history societies and conservation bodies in the County

2.4 To promote interest in natural history and the activities of the Society.

For more details about the Suffolk Naturalists’ Society contact:

Hon. Secretary, Suffolk Naturalists’ Society, The Hold, 131 Fore St, Ipswich IP4 1LR. enquiry@sns.org.uk

Suffolk Naturalists ’ Society

Suffolk Naturalists ’ Society