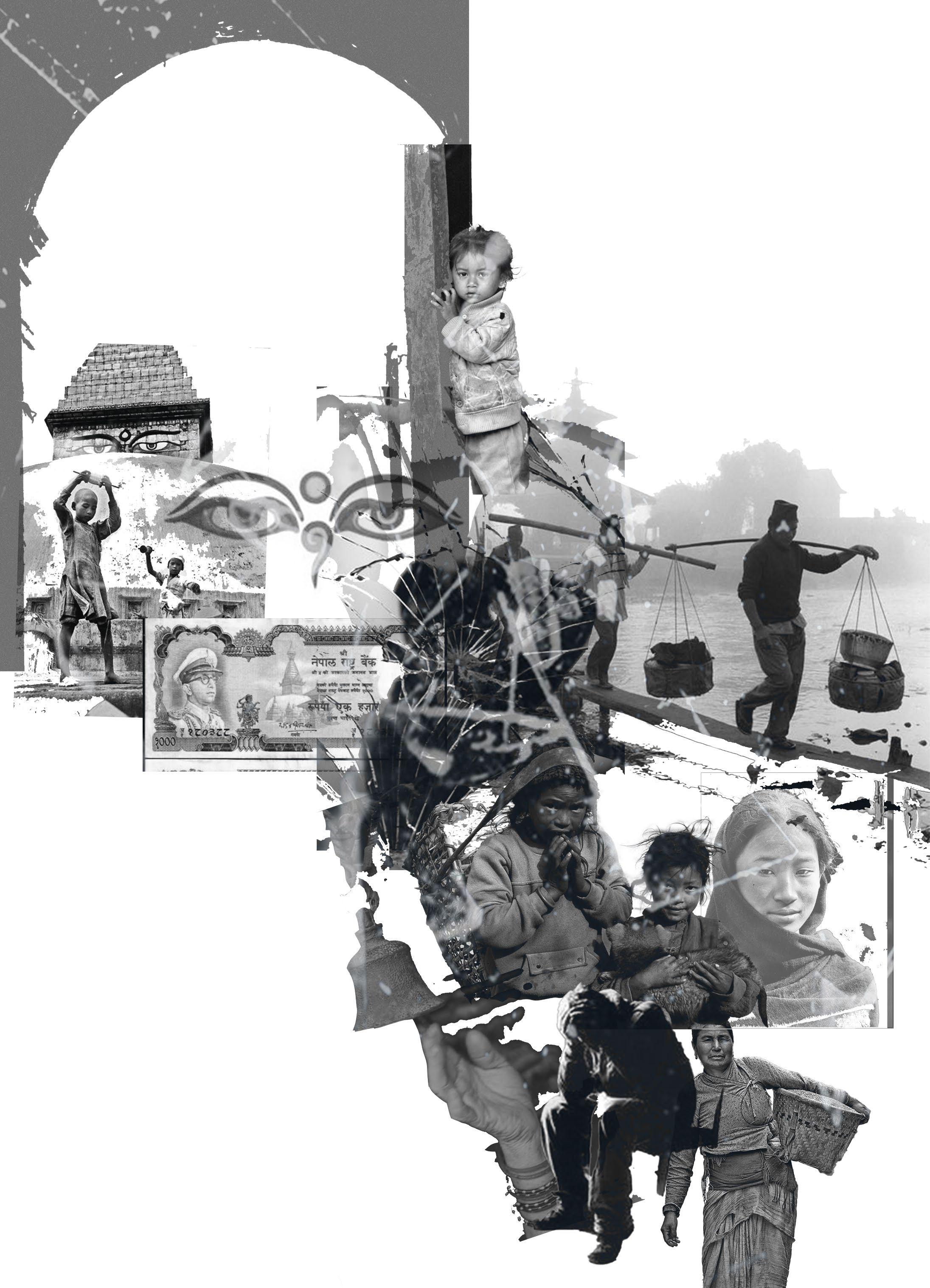

IN THE SEARCH OF FORGOTTEN NARRATIVES, MEMORIES AND A SPACE TO HEAL

SUBECHHYA BOHARA

MASTER’S OF ARCHITECTURE THESIS PROJECT/ 2024 UNIVERSITY OF IDAHO

ADVISOR/ HALA BARAKAT

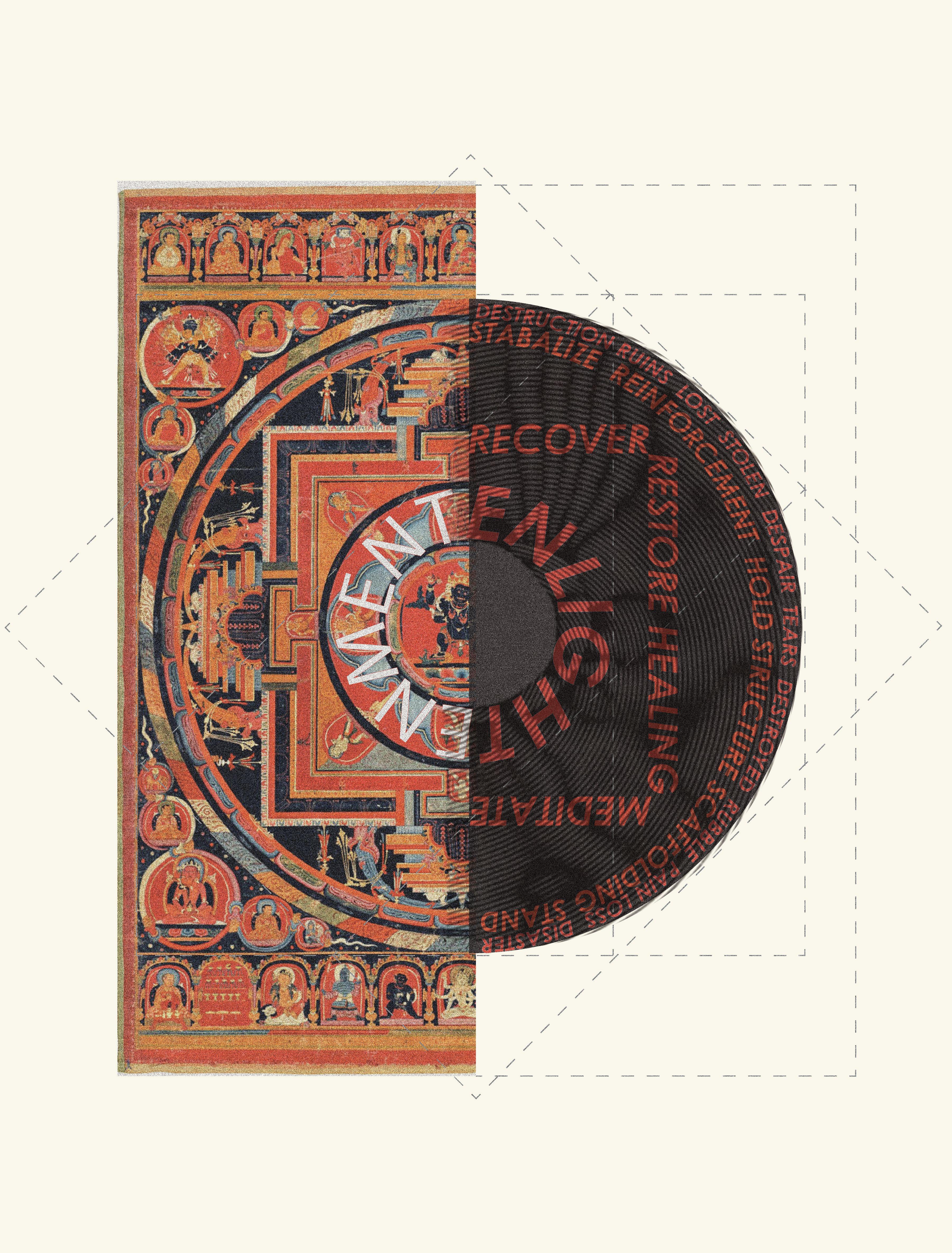

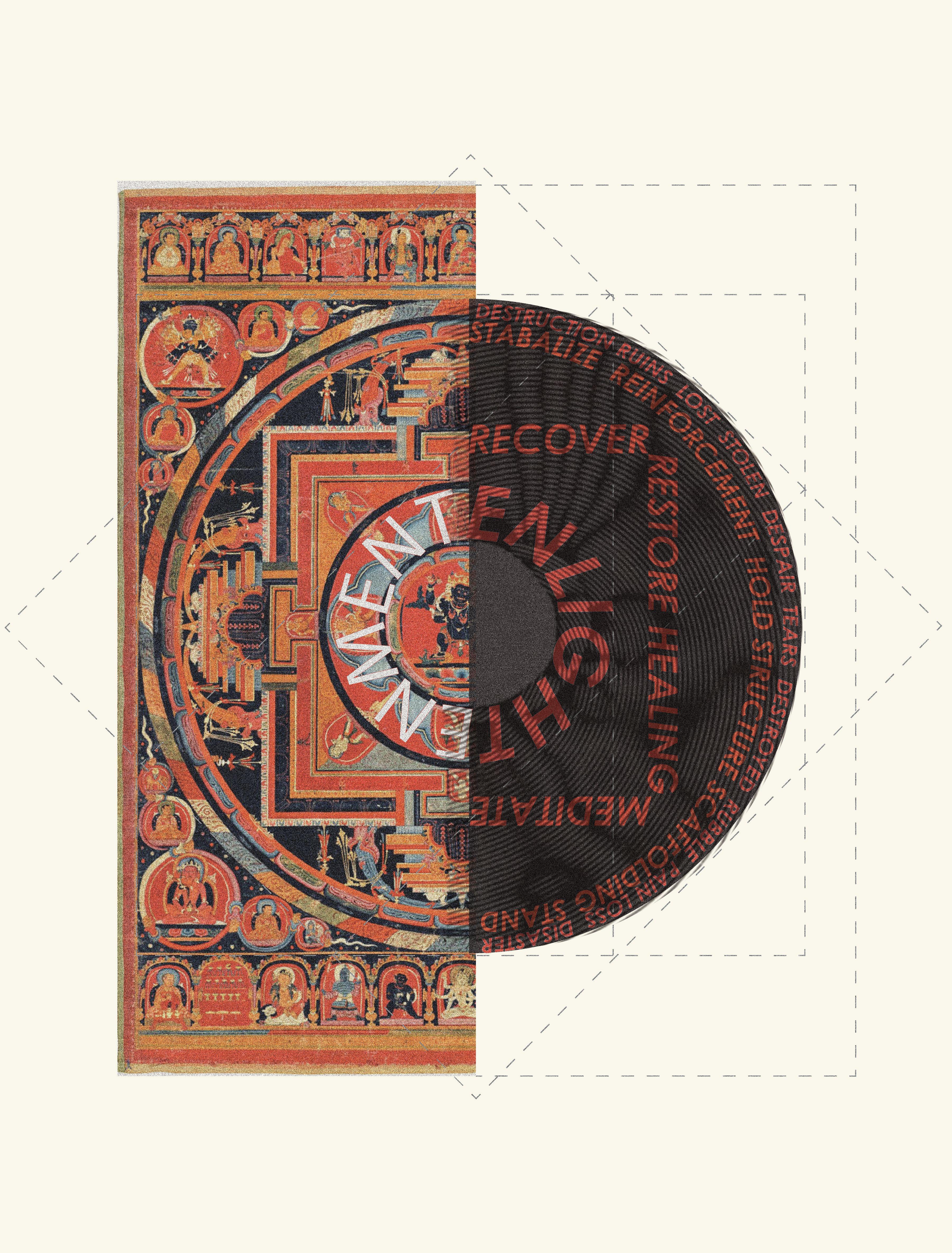

In the MANDALA , we find a sacred space where the mind can rest, heal, and rejuvenate

1/ ABSTRACT ------------------- 5 2/ DRAWING EXERCISE ------------------- 7 3/ CONCEPT ARTIFACT ------------------- 8 4/ PROBLEM STATEMENT ----------------- 10 5/ LITERATURE REVIEW ----------------- 13 6/ CASE STUDIES ------------------16 7/ MAPPING ------------------ 24 6/ CONTEXT & BACKGROUND -------------------26 7/ SITE ----------------- 30 8/ SITE NARRATIVE -------------------34 9/ CONCEPT ------------------ 42 10/ DESIGN & FORM STUDY ------------------ 44 11/ RUIN STUDY ------------------ 48 12/ THE INTERVENTION ------------------ 52 3 / TABLE OF CONTENTS

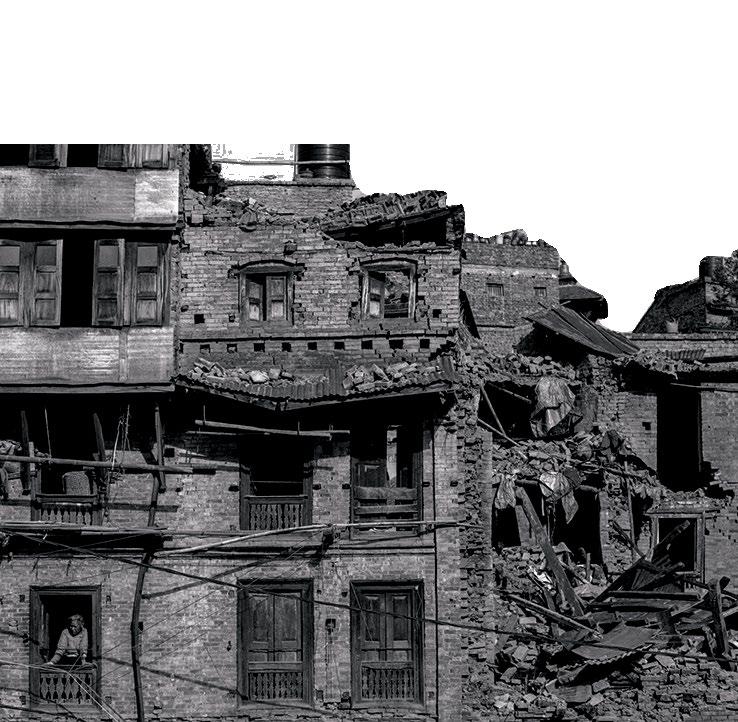

The 2015 earthquake in Nepal threatened Kathmandu’s identity and sense of place beyond physical damage. This thesis aims to explore the intersection of memory of place, healing, and structural stabilization post-earthquake. Inspired by Newari Buddhist Principles, it integrates historic ruin rehabilitation with narrative memorialization, providing a space for healing and revisiting collective scars.

In the temporary pause between destruction and reconstruction, this intervention cradles Kathmandu’s tears, forgotten tales of resilience and loss during the chaos. With locals as the builders and ruins as building blocks, a layer of healing and renewal unfolds. Each passing moment is a testament to the city’s strength, where sorrow births resilience, and shattered fragments pave the path to a brighter future.

By having locals help with construction and using materials from the ruins themselves, this intervention is not just rebuilding; it is reclaiming. This practice not only ensures sustainable rebuilding but also adds a rich tapestry of history to each edifice, safeguarding stories that might otherwise be lost to time.

By providing a space for the people and the entire community to heal, it aims to carve out a new narrative for a place scarred by loss of both people and place, transforming it into a beacon of resilience and renewal.

5 / ABSTRACT

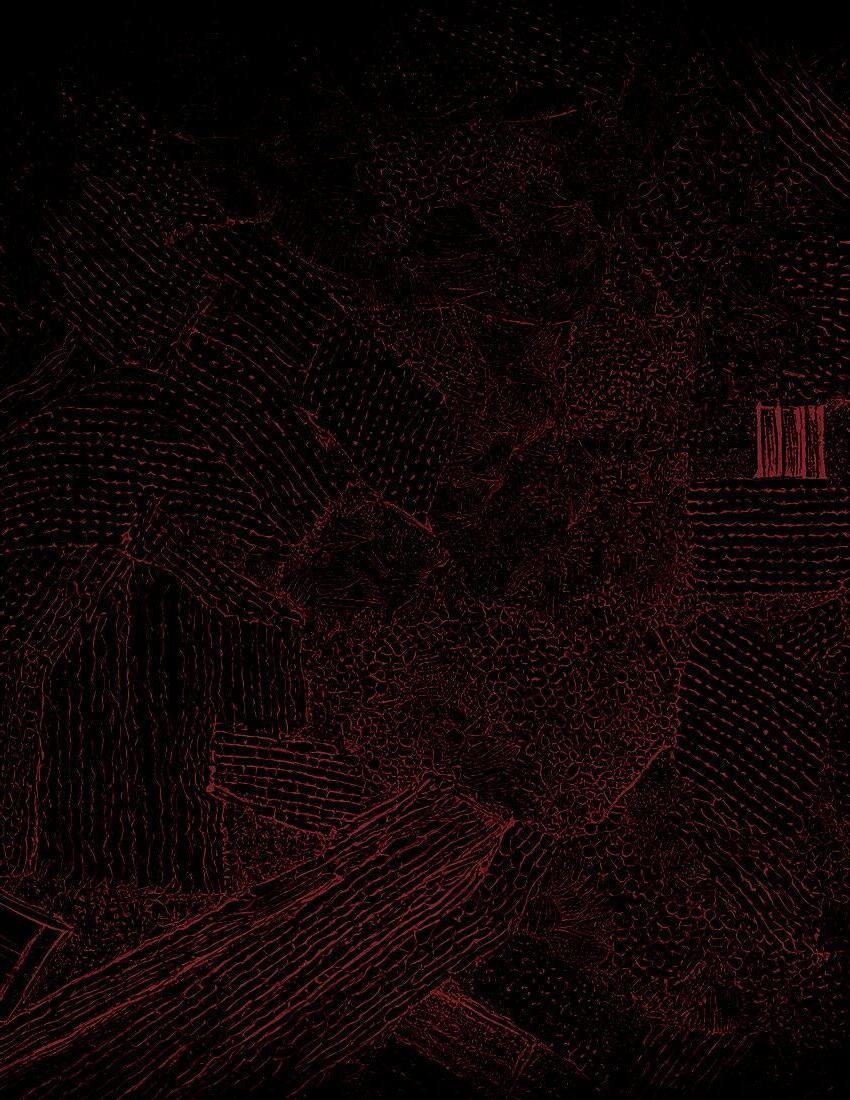

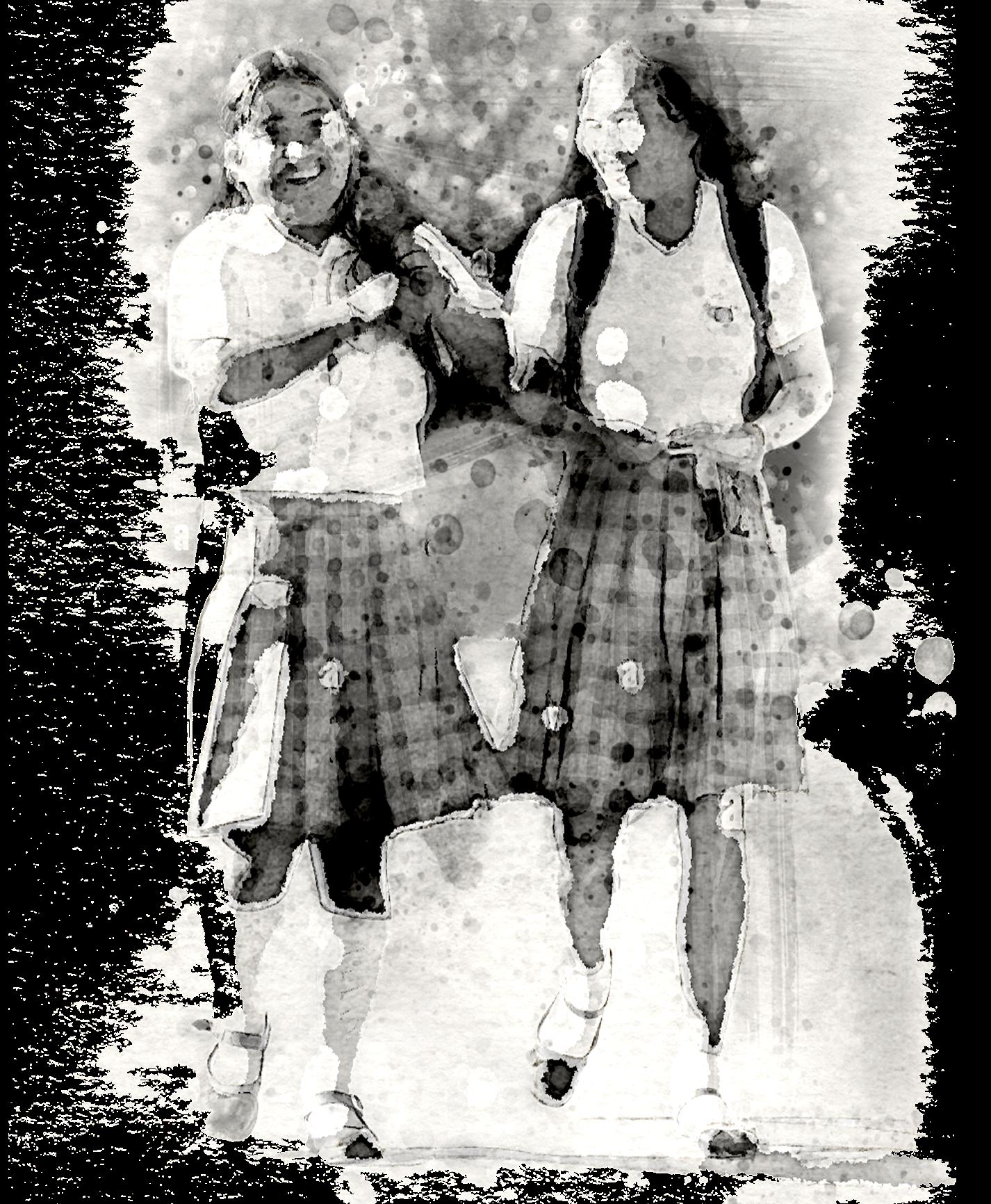

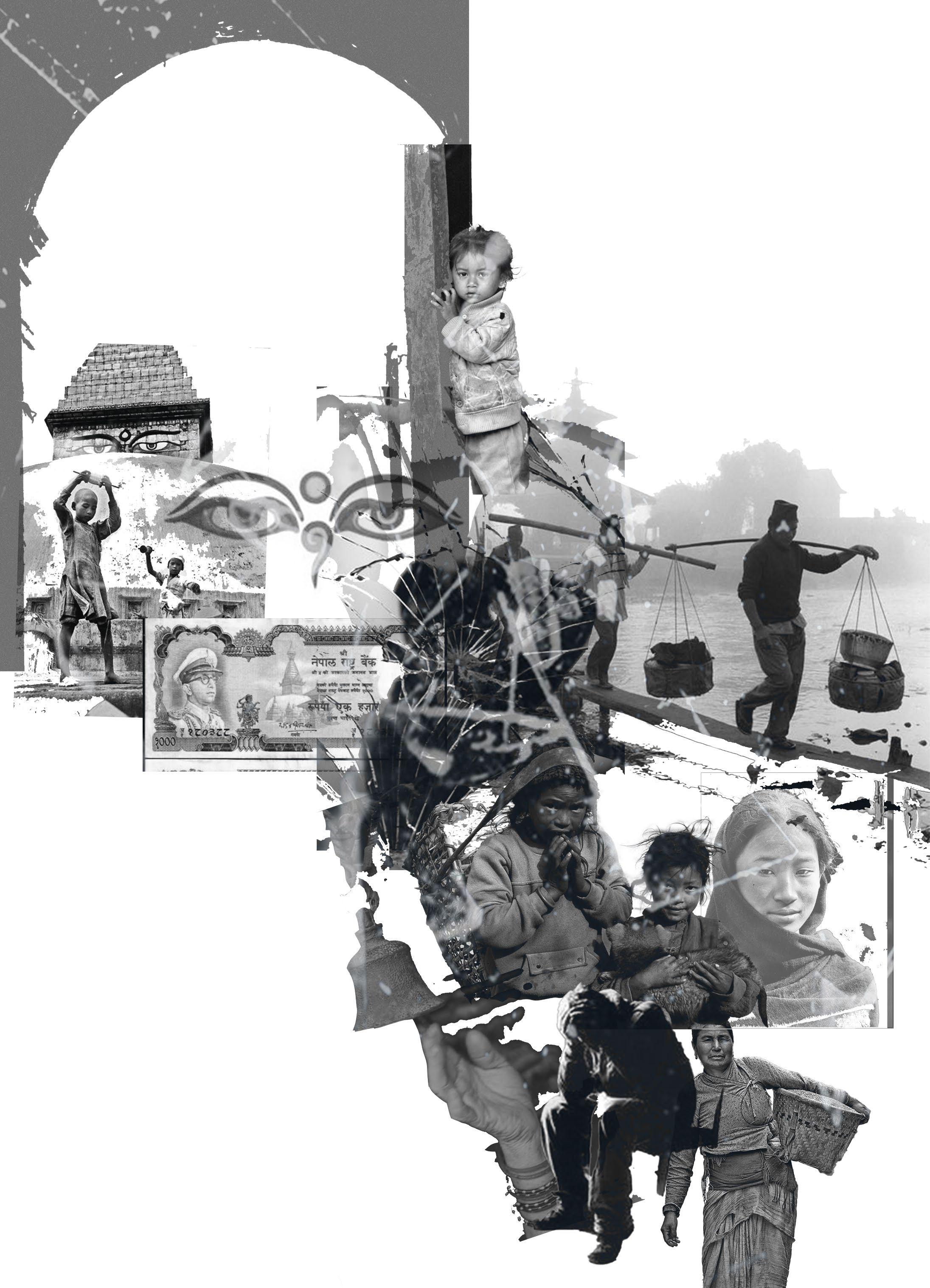

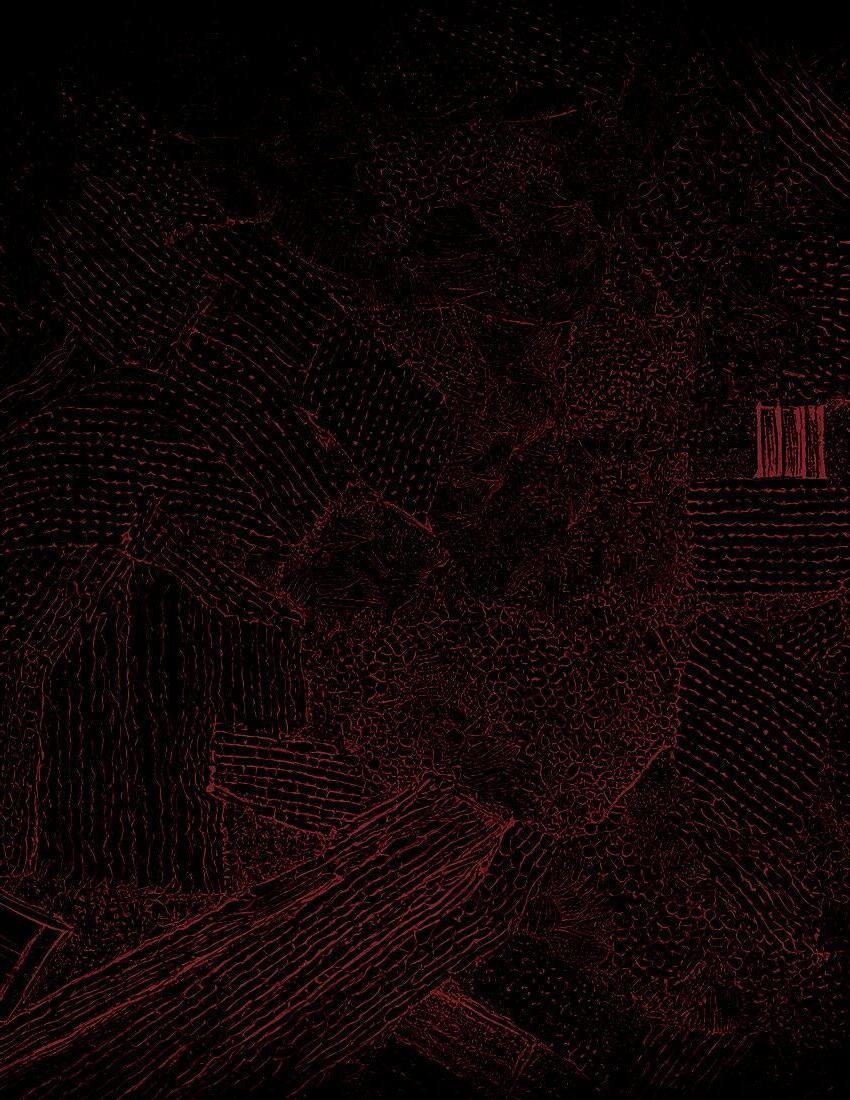

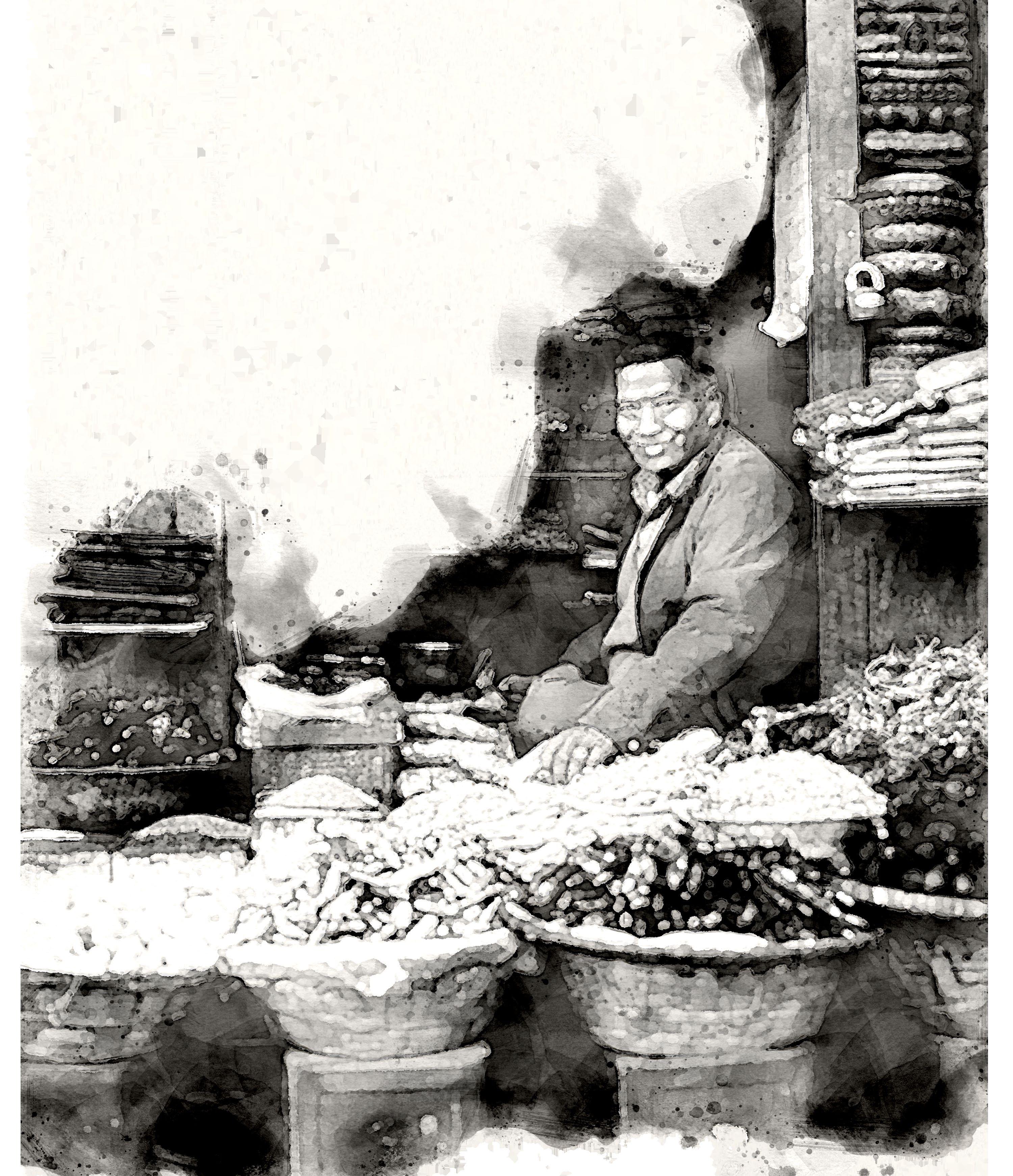

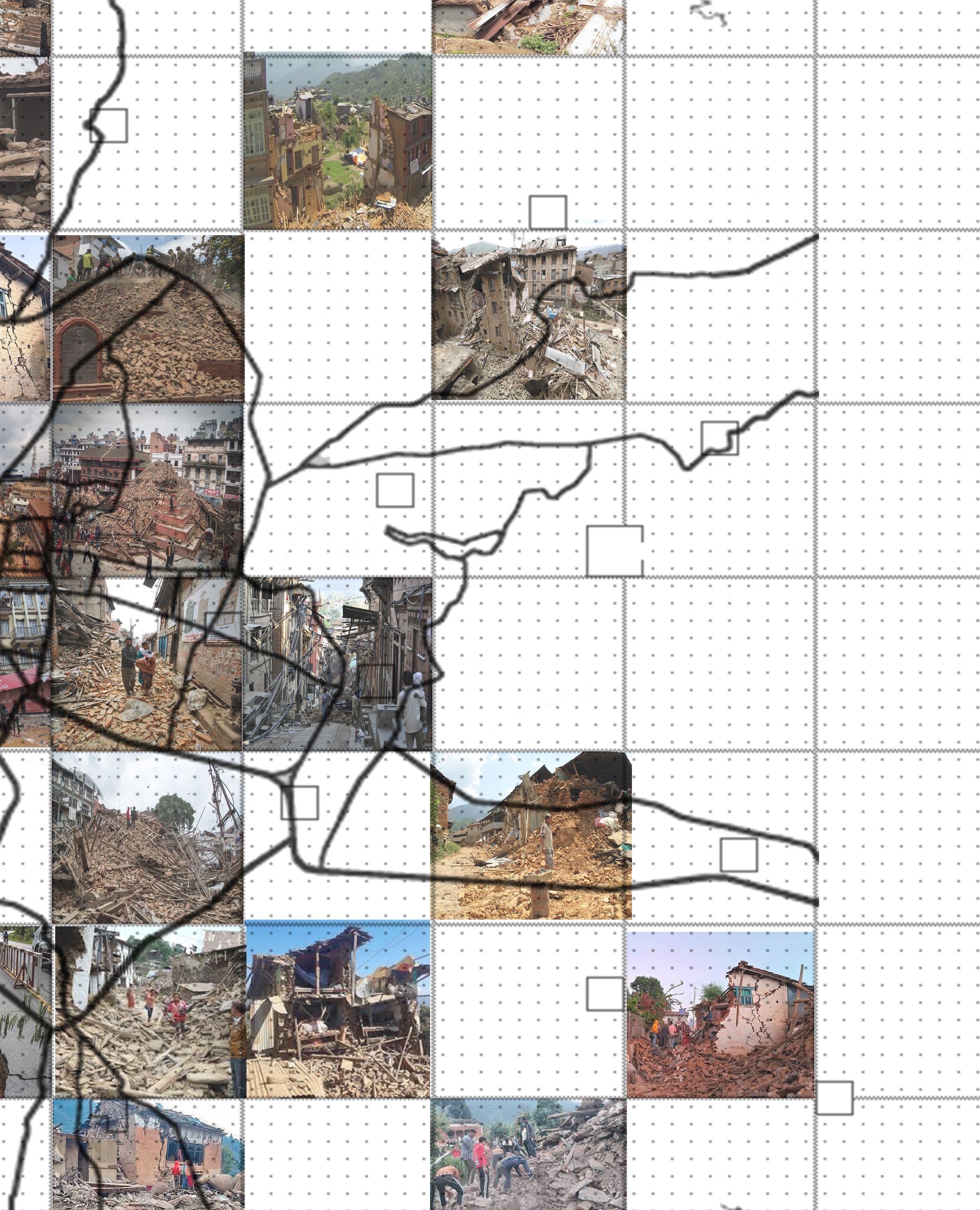

In my drawing, I pour my raw EMOTIONS onto the page, reliving the tremors and tears of the 2015 earthquake in Nepal. Through expressive strokes and poignant imagery, I aim to convey the turmoil, resilience, and eventual hope that emerged amidst the chaos and devastation.

7 / DRAWING EXERCISE

/ CONCEPT ARTIFACT

8

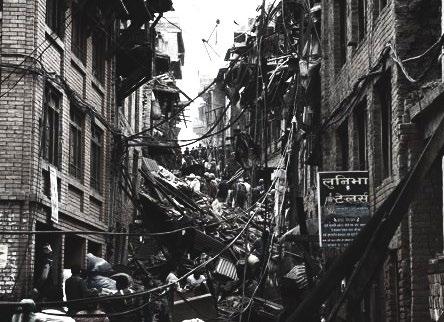

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/shantidva/7008256395/in/photostream/

Source: https://cdn.downtoearth.org.in/dte/userfiles/im

10 / PROBLEM STATEMENT

ages/01-nepal.jpg BEFORE AFTER

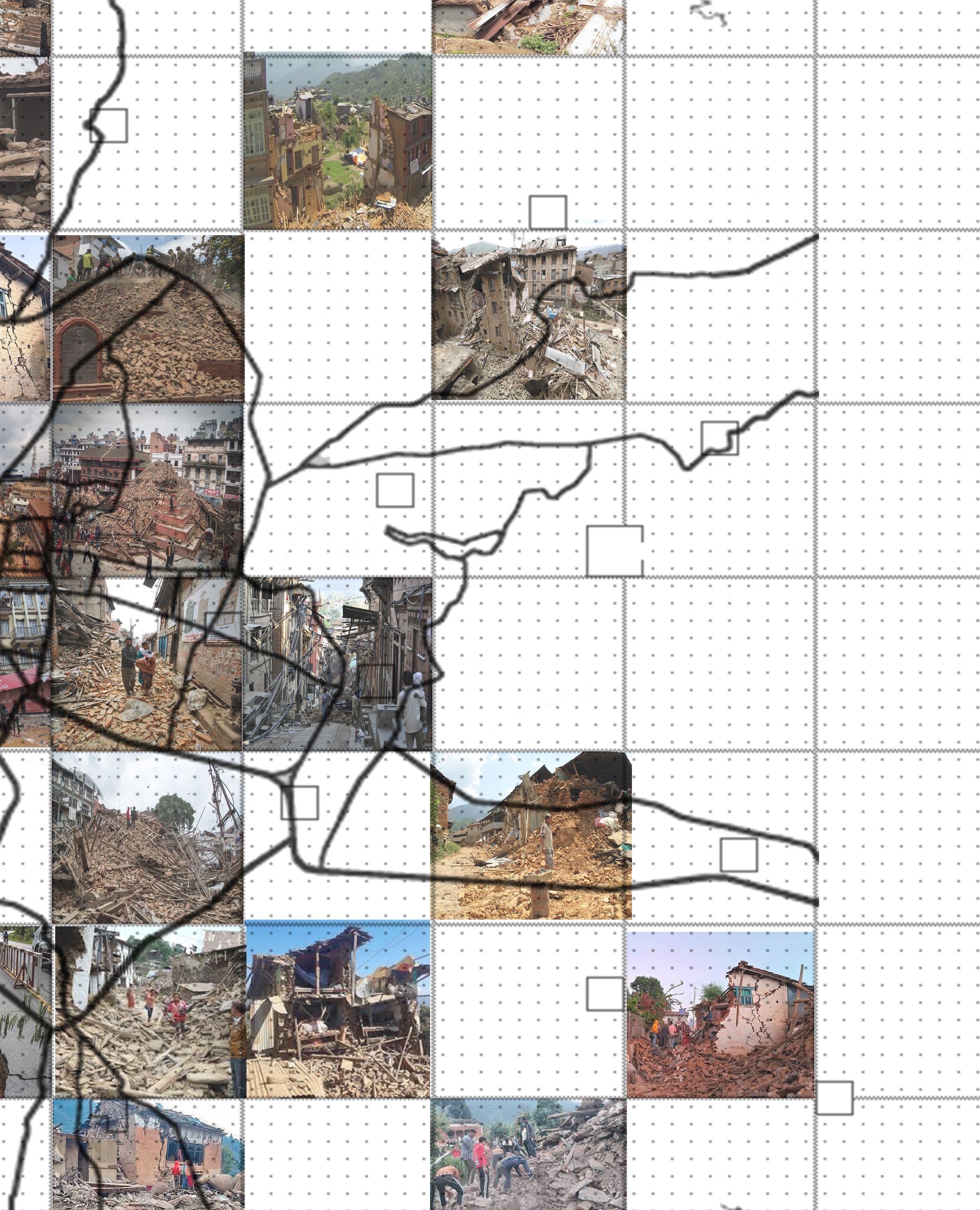

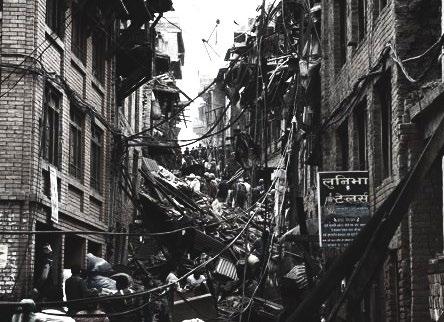

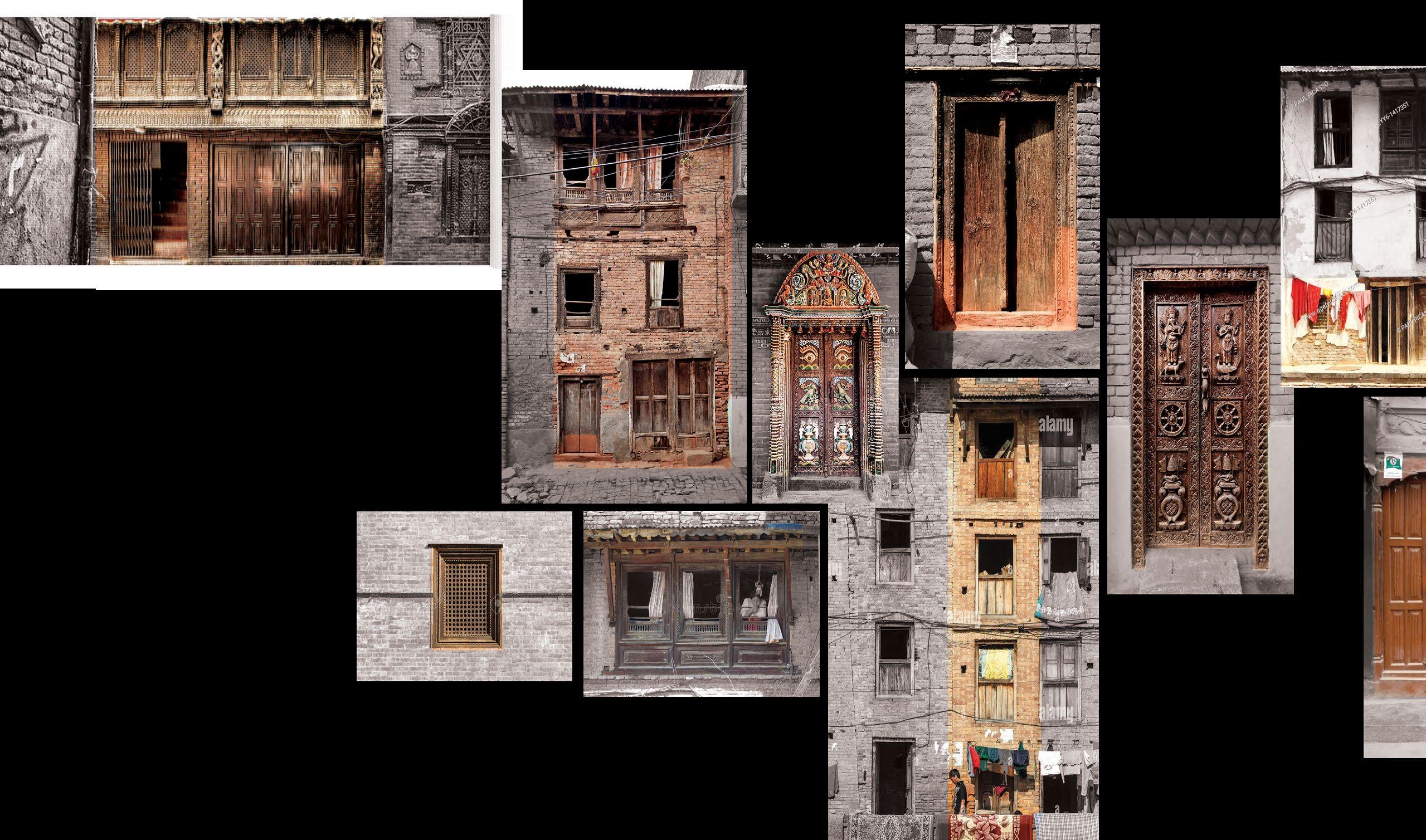

Nepal, located in a seismic risk zone, witnesses several natural disasters related to seismic activities like earthquake, landslide and avalanches every year. But the 2015 earthquake was one of the worse disasters in Nepal’s history, severely impacting 11 central districts. These seismic events resulted in significant loss of life, injuries, and the destruction of countless homes and cultural heritage sites.

After the 2015 earthquake, even I found myself living in one of those tarpcovered structure you see in the previous page. After escaping an earthquake that killed thousands of people in my community, me and my family had to fight for space in a muddy field just so we could have a roof over our heads. There were hundreds of people who were stranded with no family or shelter. This is just for a few days; we will head back home in no time; This was the thought going through everyone’s head that day. But nature had different plans for us. The earth did not stop shaking for the next couple of months. What is thought to be a temporary shelter soon became our homes. But there was no one that came and helped us at the lowest point of our lives. Nearly 700,000 people were estimated to have either lost their houses or lost their source of income pushing them below the poverty line after these earthquakes.

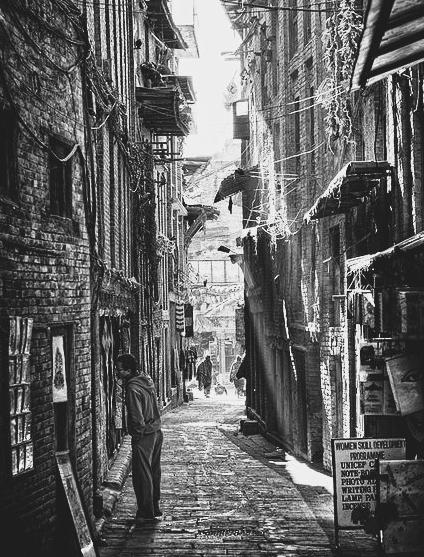

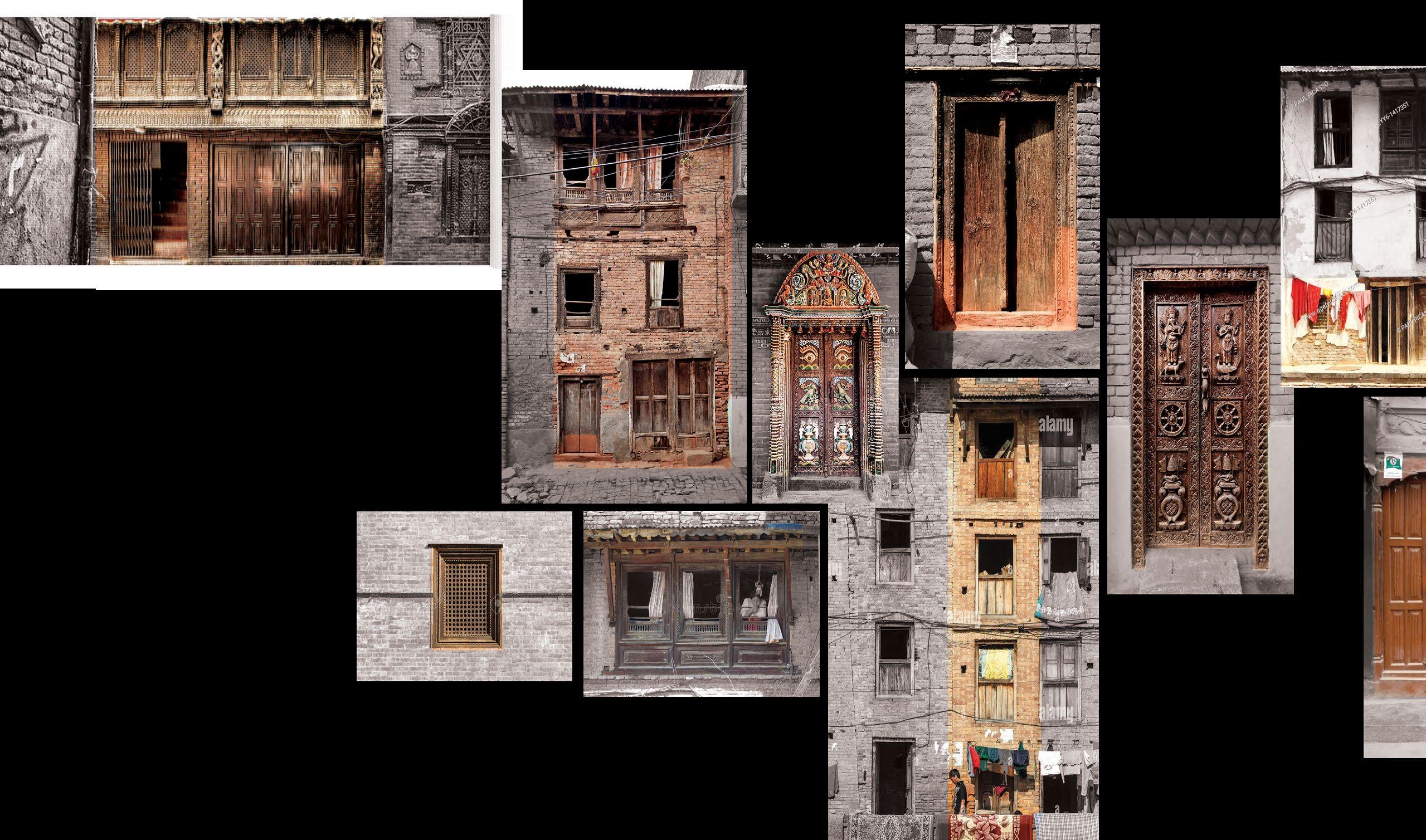

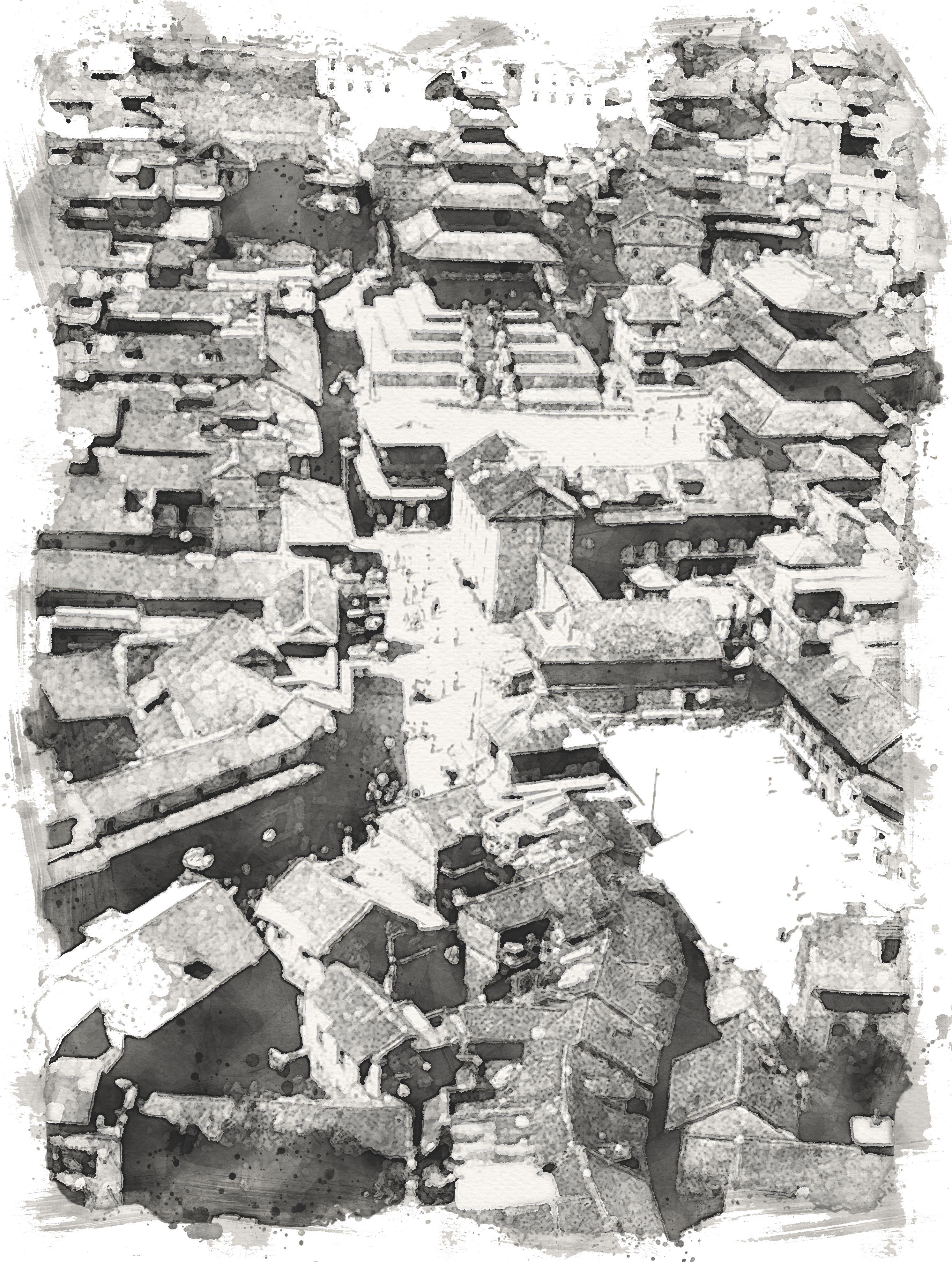

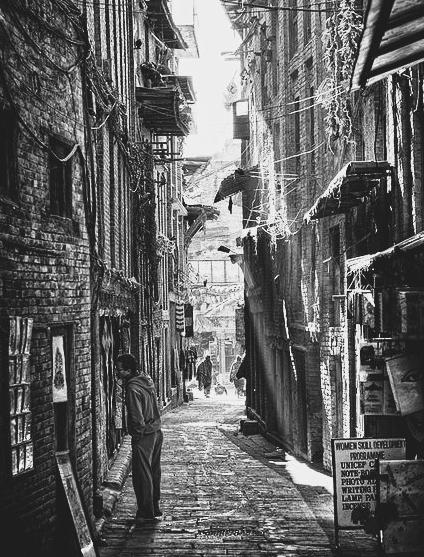

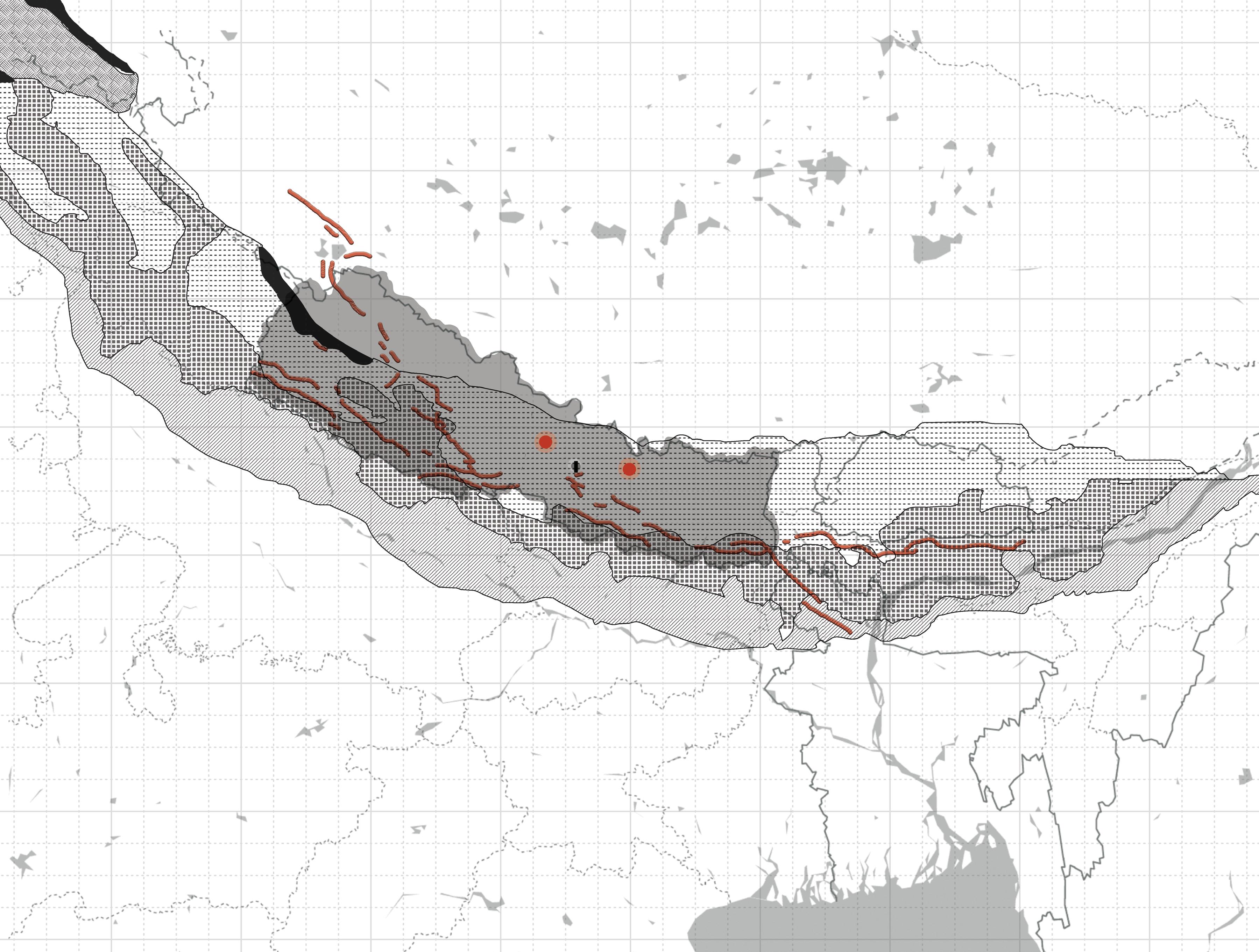

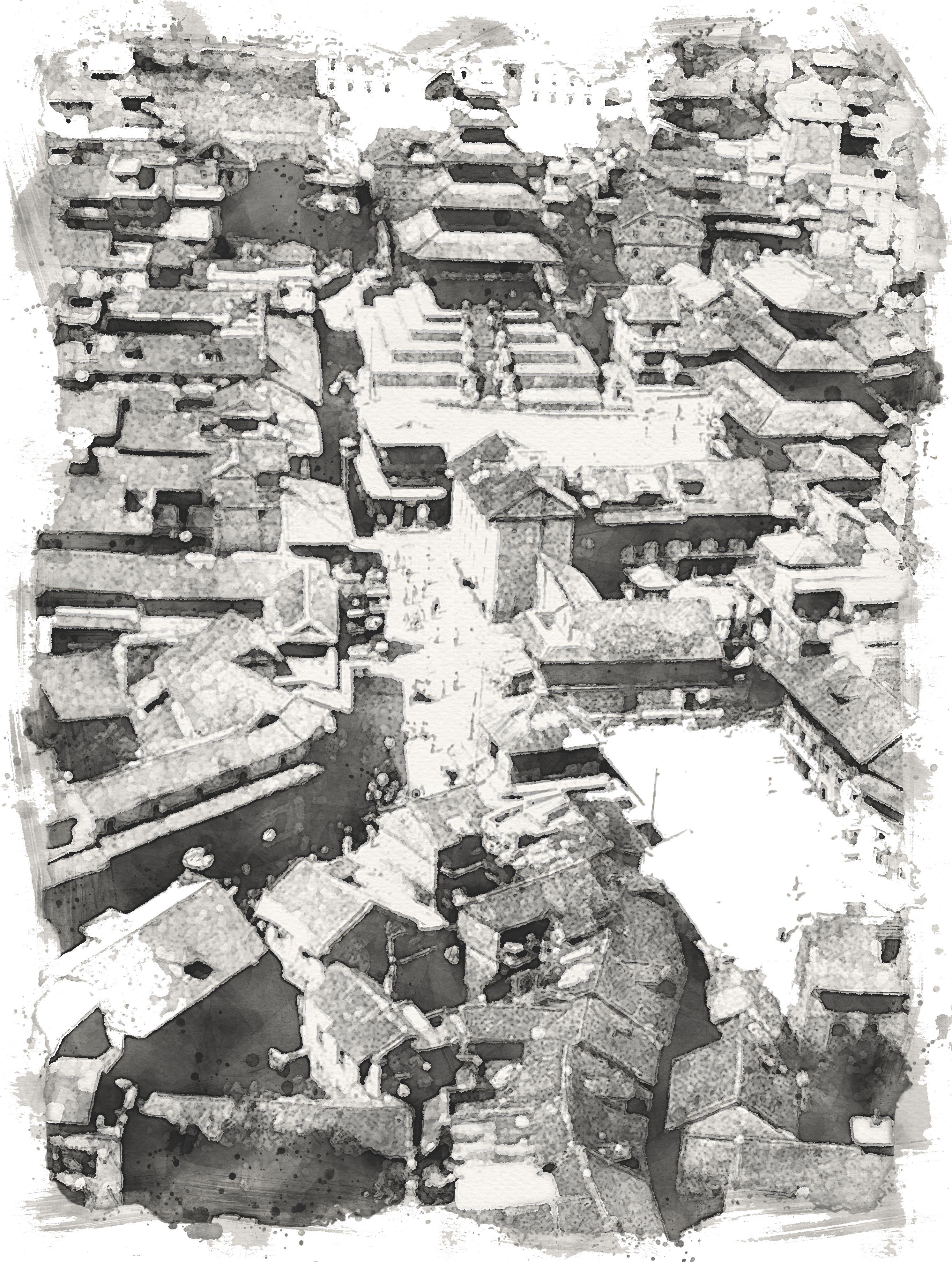

Kathmandu’s architectural identity lies in its traditional townhouse-style mud brick buildings, intricately carved wooden facades and narrow alleyways, each standing the test of time through generations. Among the ruins of the 2015 earthquake, most of them are these historic buildings. But the reconstruction methods has shifted in construction methods, with the majority of traditional mud brick buildings being replaced by reinforced concrete structures. Approximately 60-80% of the rebuilt buildings now stand as modern interpretations of their historic predecessors, constructed using materials and techniques that prioritize strength and durability.While some attempts have been made to preserve the aesthetic charm of the past by incorporating traditional facades into these new constructions, they represent only a small fraction, around 7-15%, of the total rebuilt structures. The remaining buildings, once integral to Kathmandu’s architectural fabric, have been lost forever, leaving behind a void in the city’s collective memory.

Beyond the physical destruction, these losses represent the erasure of culture, sense of place, and, tragically, loved ones. As this thesis concludes, it underscores the importance of reimagining these ruins not just as remnants of the past, but as opportunities for renewal and healing. By repurposing these ruins, we can create spaces that serve as both physical and emotional anchors for the community. Whether transformed into memorial sites or community centers, these reclaimed ruins have the power to reconnect individuals with their cultural heritage, provide solace in times of grief, and foster a sense of belonging and resilience in the face of adversity.

“Sometimes different cities follow one another on the same site and under the same name, born and dying without knowing one another, without communication among themselves. At times even the names of the inhabitants remain the same, and their voices’ accent, and also the features of the faces; but the gods who live beneath the names and above the places have gone off without a word and outsiders have settled in their place. It is pointless to ask whether the new ones are better or worse than the old… (Calvino, 30)” - Invisible Cities, Italo Calvino

In “Invisible Cities,” Italo Calvino paints a vivid picture of Maurilia, a city characterized by its layers of history and cultural influences, echoing the complex narrative of urban life. Similarly, Kathmandu, with its rich tapestry of stories woven through time, memory, and collective imagination, embodies a narrative of resilience amidst change. This paper sets out to unravel the intricacies of Kathmandu’s story, tracing its evolution and contemplating its future within the cyclical framework of the mandala. As Kathmandu navigates the delicate balance between preservation and progress, it faces a daily dilemma: to cling to the remnants of decay or to embrace the promise of renewal.

The architectural forms of Kathmandu play a crucial role in reflecting its layers of history. The narrow alleys, adorned with mud-brick houses and intricately carved wooden facades, create a sense of permanence and stability for its residents. However, despite their stillness, these structures are constantly at risk due to the frequent earthquakes in Nepal. These natural disasters challenge the perceived stability, highlighting the fragile nature of the city’s architectural heritage.

Buildings and shared spaces serve as focal points where diverse groups converge, fostering shared experiences and the formation of collective identities. The immutability of architecture makes it a potent tool for shaping historical narratives; through selective retention or destruction, the meaning of structures can be reconfigured, altering perceptions of the past. Rebuilding after destruction holds symbolic significance, serving as a means to either reinforce the fractures caused by upheaval or to mend the fabric of community life. In this process, new landmarks emerge, becoming touchstones for collective memory and shaping the trajectory of future narratives.

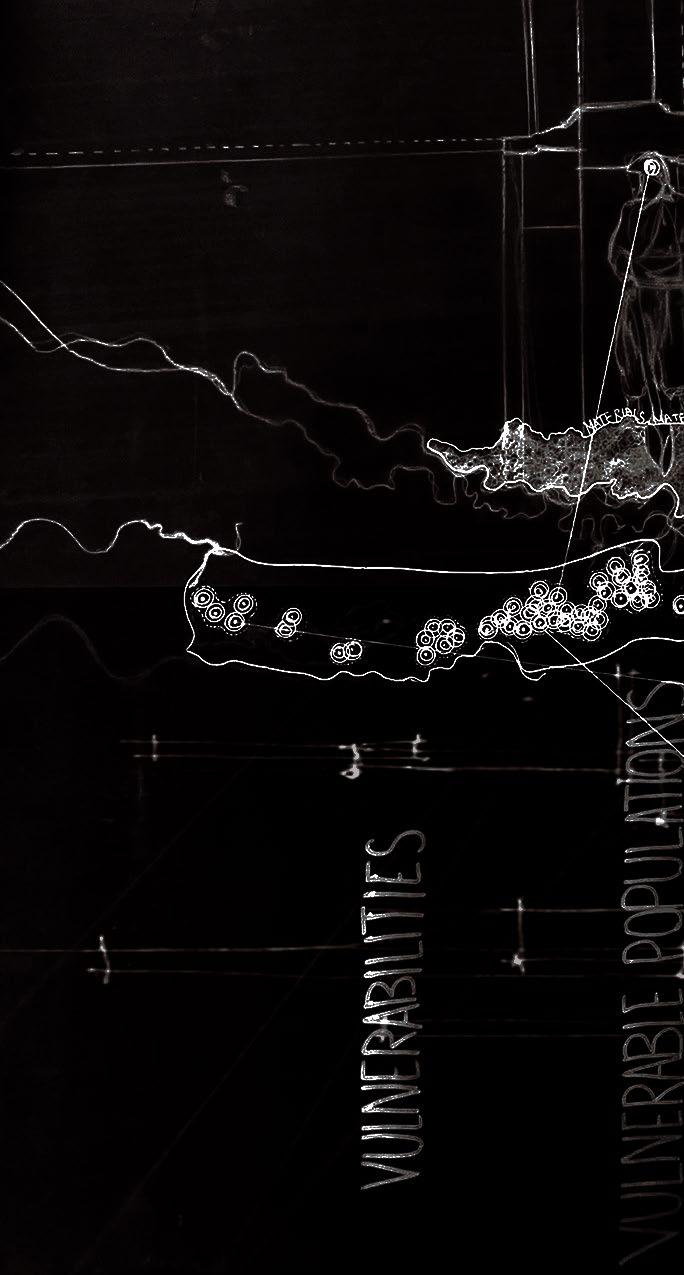

Nepal is geographically set in a region which is highly prone to multiple natural hazards, and it falls under a high-risk seismic zone of the Himalayas. In April and May of 2015, two huge earthquakes of 6.8 and 7.2 Richter scale originating from the Gorkha district shook the entirety of the country along with all surrounding countries. 11 districts (Ramechhap, Gorkha, Sindhupalchowk, Nuwakot, Dhading, Kathmandu, Bhaktapur, Okhaldhunga, Solukhumbu, Lamjung and Syangja) that are centrally located on the Map of Nepal were declared to be the most severely hit. These 2 disastrous quakes claimed the lives of almost 9,000 people, injured 22,000 and took down over 500,000 houses and cultural heritage sites (Sapkota). Multiple different landslides and avalanches that were triggered by these earthquakes and aftershocks also added to the death tolls and property damages in the following years.

13 / LITERATURE REVIEW

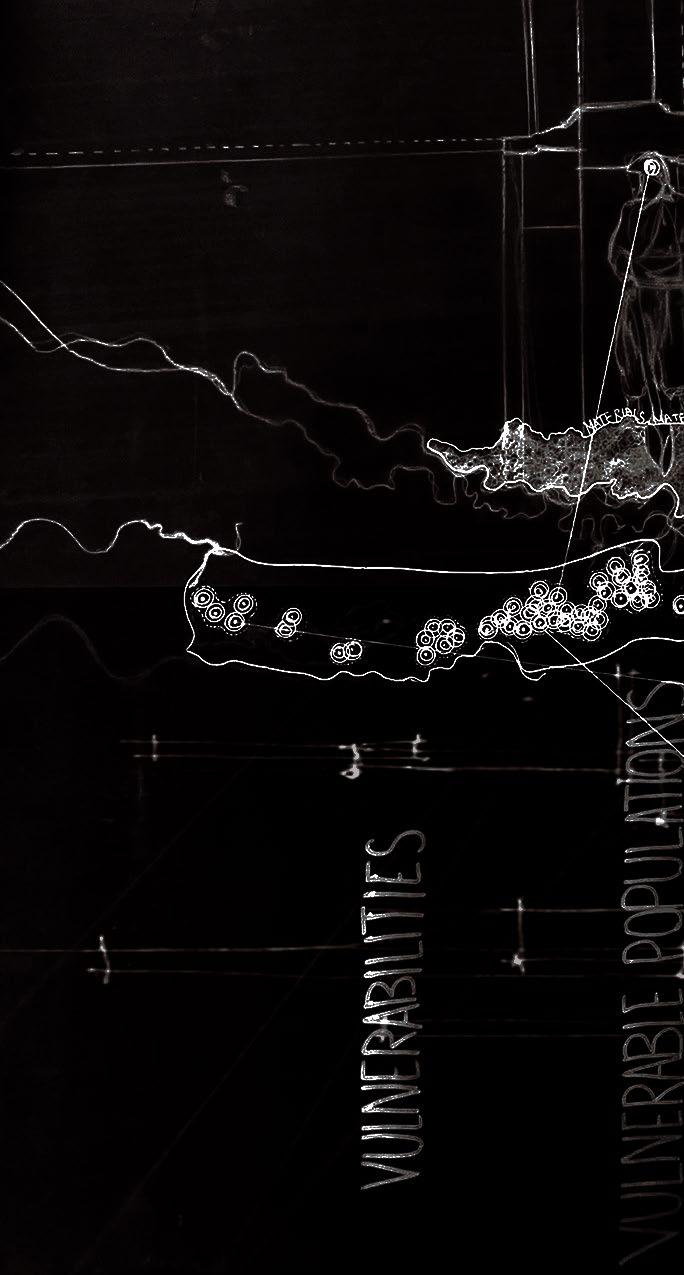

These earthquakes both lasted about a minute and did unrepairable damage to the infrastructures and to the people’s livelihoods. But these effects seem pretty insignificant when compared to the long-lasting effects it had on people’s lives, economy, and mentality. Nearly 700,000 people were estimated to have lost housing or lost sources of income ultimately pushing them below the poverty line. Among these 700,000 people, most of them were in the marginalized population.

The article, “Progress after the 2015 Nepal Earthquake,” explores how we can learn how to target those vulnerable populations. By looking into challenges faced by residents of Ramche village, Sindhupalchok District, post-disaster. Language barriers hinder their communication with the government. It underscores the need for an inclusive emergency response, considering race, gender, and economic class. Analyzing variations in housing, economic security, and health among different groups is crucial for effective planning. Social vulnerability analysis aids in anticipating needs and allocating resources. Asking pertinent questions is the first step in understanding community needs and power structures.

Following the identification of issues in prior articles, our attention now turns to exploring potential solutions. “Safer Homes, Stronger Communities: A Handbook for Reconstructing after Natural Disasters” offers guidance on empowering communities to rebuild post-disaster, mitigating future risks. It stresses the importance of community empowerment, emphasizing real representation in policy-making and recovery efforts. Recognizing the diversity within affected communities, it advocates for tailored approaches that address varied needs and capacities, highlighting the significance of social and economic factors in shaping outcomes (Jha).

Looking ahead, Kathmandu stands at a crossroads, grappling with questions of identity and resilience. As the city embarks on the journey of renewal, it must draw strength from its rich cultural heritage and collective memory. Architecture, in this context, emerges as both a reflection of the past and a catalyst for change, offering opportunities to reimagine the city’s social and economic fabric. By empowering communities to shape their own destinies, Kathmandu can chart a path towards a more resilient and equitable future for all its inhabitants.

In conclusion, Kathmandu’s journey of resilience offers valuable insights into the complexities of urban life and the challenges of post-disaster reconstruction. By peeling back the layers of its history and cultural heritage, we gain a deeper understanding of the forces that shape its identity and trajectory. Moving forward, inclusive, community-driven approaches to reconstruction offer a path towards a more resilient and equitable future for Kathmandu and its inhabitants. As the city navigates the complexities of preservation and progress, it must draw upon its rich tapestry of narratives and collective imagination, forging a path towards a brighter tomorrow.

WORKS CITED

1. Aid and Recovery in Post-Earthquake Nepal: Independent Impacts and Recovery Monitoring Phase Five. The Asia Foundation, 2019.

2. Bangdel, Dina. Manifesting the Mandala: A Study of the Core Iconographic Program of Newar Buddhist Monasteries in Nepal. 1999.

3. Bajracharya, Srizu. “Breaking down the Concept of the Mandala.” The Kathmandu Post, The Kathmandu Post, 2 July 2019, kathmandupost.com/ art-culture/2019/07/02/breaking-down-the-concept-of-the-mandala.

4. Bevan, Robert. The Destruction of Memory : Architecture at War - Second Expanded Edition, Reaktion Books, Limited, 2016. ProQuest Ebook Central http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uidaho/detail action?docID=4615247.

5. Halbwachs, Maurice. “Space and the Collective Memory : The Group in Its Spatial Framework.” On Collective Memory , 1950.

6. Jha, Abhas K., and Jennifer D. Barenstein. Safer Homes, Stronger Communities: A Handbook for Reconstructing After Natural Disaster. World Bank Publications, 2010.

7. Loos, Sabine. “A Data-driven Approach to Rapidly Estimate Recovery Potential to Go beyond Building Damage After Disasters.” Communications: Earth and Environment, vol. 4, no. 40, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1038/ s43247-023-00699-4. Accessed 10 Oct. 2023.

18. Sapkota, Jeet B. “Progress After the 2015 Nepal Earthquake: Evidence from Two Household Surveys in One of the Hardest-Hit Mountain Villages.” Sustainability, 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111677. Accessed 15 Oct. 2023.

16 / CASE STUDIES

The case studies selected for this project each offer unique insights into the themes of memory, remembrance, disaster, rebuilding, and the passage of time within the realm of architecture. These case studies comprised thesis projects completed by other architecture students, encompassing a diverse range of approaches and perspectives. Through the examination of these projects, we gained valuable knowledge and inspiration, discovering innovative strategies and design solutions for addressing the complexities of post-disaster reconstruction and memorialization.

ARCHITECTURES OF HIDING

The concept behind this project is to redrawing ones old family home through memories as that is all they have. The work demonstrates how orthographic points of view—which rely on separation, hovering, disassembly, and cuts through objects—can speak to and about emotional life. Home holds a familiy’s stories and memories. I plan to try to recreate these memories of the people who have lost their houses and their memories.

IF THESE WALLS: AN ORTHOGRAHIC MEMOIR JAN PADIOS

THE SECULAR HOUSE: A MANUAL FOR PRESERVATION AND

IMPROVEMENT OF VERNACULAR STONE DWELLINGS IN BHUTAN MANUELA REITSMA

POLYTECHNIC UNIVERSITY OF TURIN, ITALY

ARCHITECTURES OF RECOVERY

Bhutan is in very close proximity to Nepal. The gography, population, poverty and other conditions of Bhutan are in line with Nepal’s. In this project, a solution to re-building houses after earthquakes in Bhutan have been explored. They have proposed a very technical and data based solution. But, the solution is true to the old local cultures and traditions . It uses materials that have been used in the community of years. I would also like to see how I could apply the connection of culture and traditions .

SEISMIC

ARCHITECTURES OF NARRATIVES

This project explores squatting in the city of Berlin through film and interviews. It introduces Berlin and the effects of squatting upon the city. To explore this problem, they start with interviewing the squatters to understand their stories from their perspective. I plan to use this process of collecting stories. Writing the stories of the vulnerable population is very important to pin point the problems that need to be prioritized. Exploring documenteries and news interviews also might be another way of doing this.

RECIPROCATION OF THE RECLAIMED CLAIRE BURRELL LEEDS

UNIVERSITY, UK

BECKETT

PLAN

DE ZHEJIANG, CHINA

PAULA SALAS SANCHEZ

ARCHITECTURES OF ABANDONED

This project starts with a series of collages that tell the stories of the past; convey the problem and then goes into the new proposal. The representation of the data collected and mappings are very detailed but clear. The graphics help convey the concept and ideas behind this project very well. I think that this way of communicating will be very effective in my project too. I plan of using their graphical representation to inspire my representation for my project.

EN LA PROVINCIA

DE REACTIVATION DE ENTOMOS RURALES

UNIVERSITY

HENRY ALDRIDGE

OF CAMBRIDGE, UK

ARCHITECTURES OF UNPREDICTABLE

Time is not always linear. In this project, they have explored the effects of time to their project. What are the different directions that the future holds and how can we predict the appropriate solutions for those? I asked AI, how it imagines the future of Nepal if there is a earthquake and how it would be if not. The constant building and destroying erases a lot of the complexity of cultures and architecture . How can we be prepared to face these problems and what can be done to eleviate this problem?

LONGEVITY

REUSE IN

UNKNOWABLE FUTURES:

AND UNPREDICTABLE

SOUTHWARK

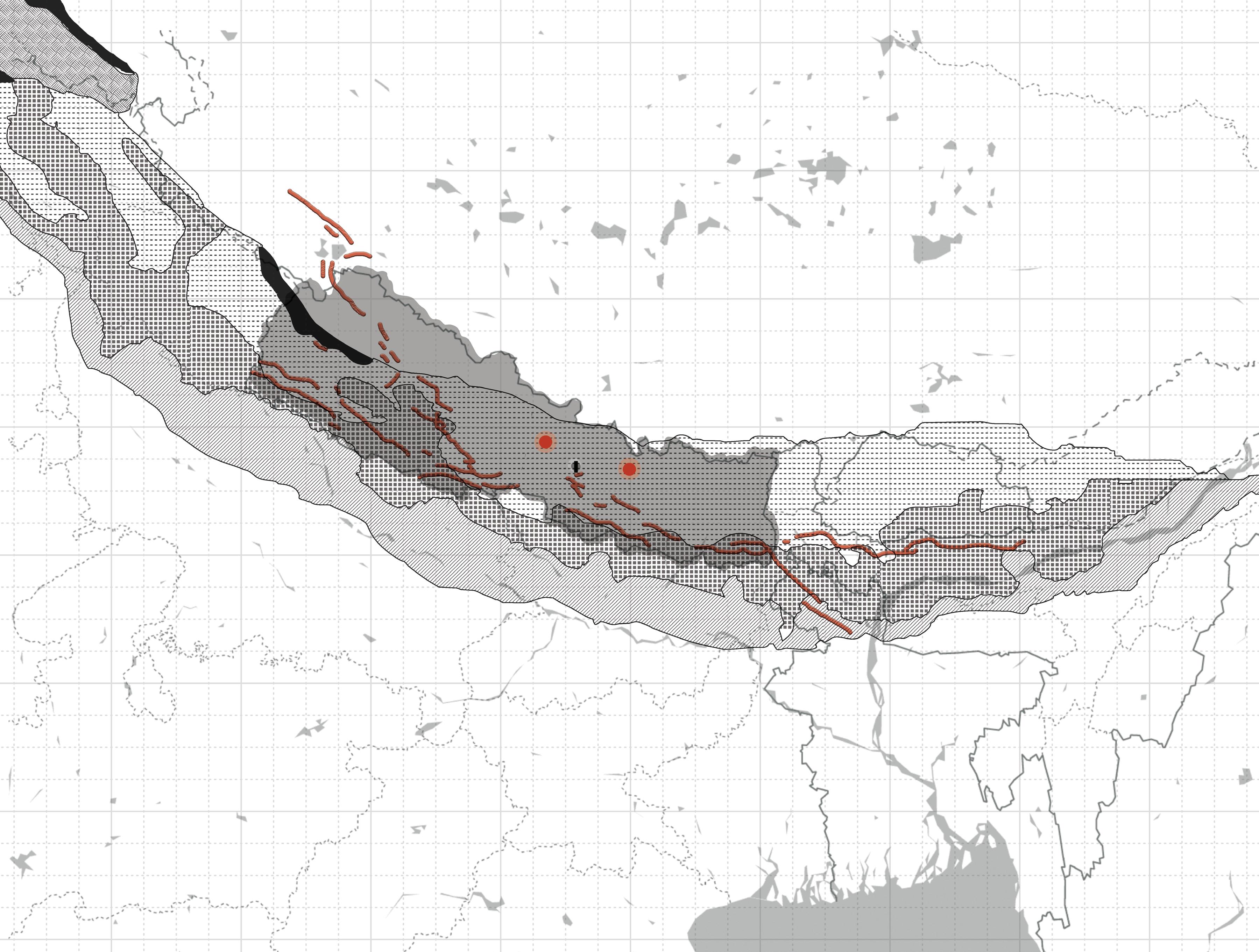

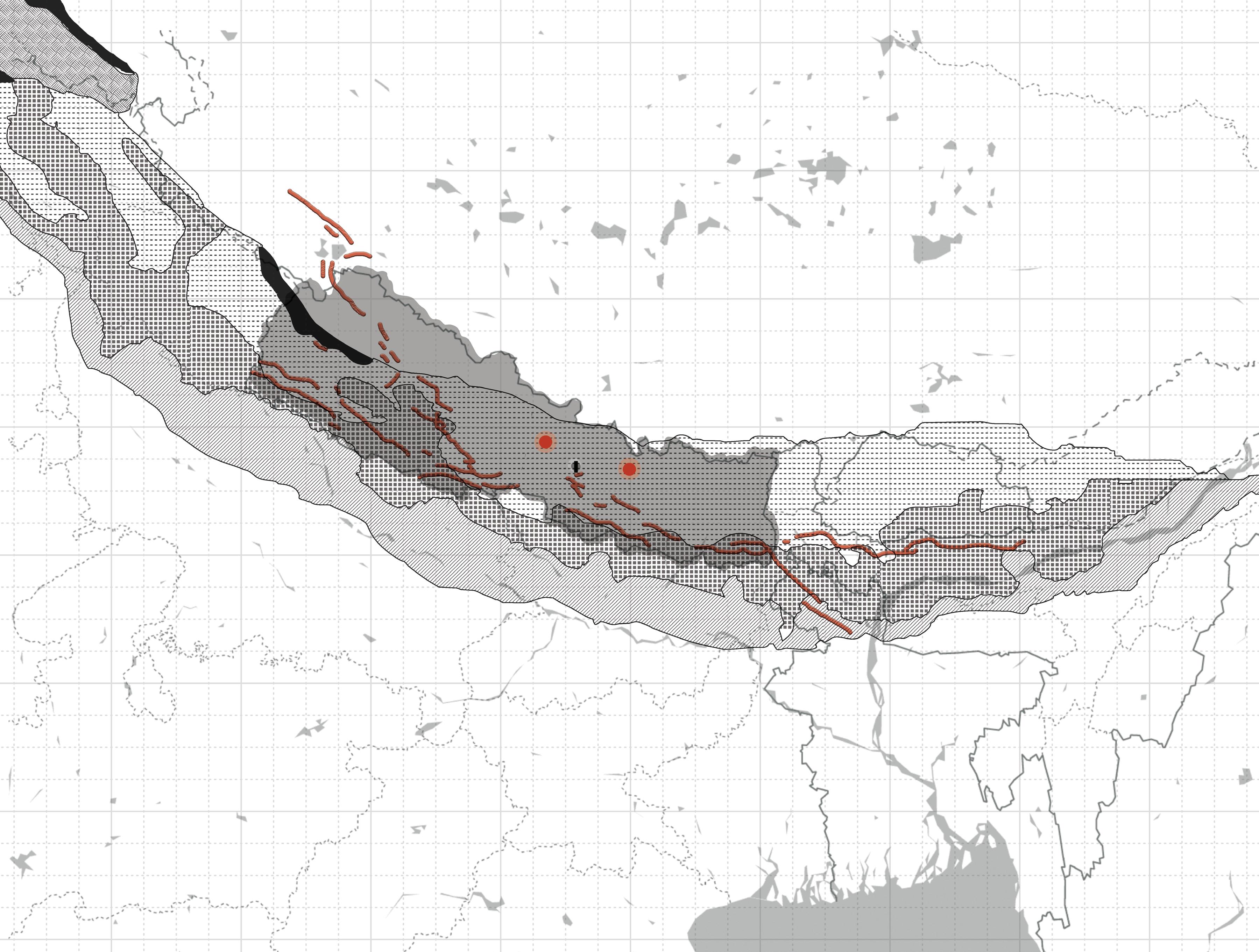

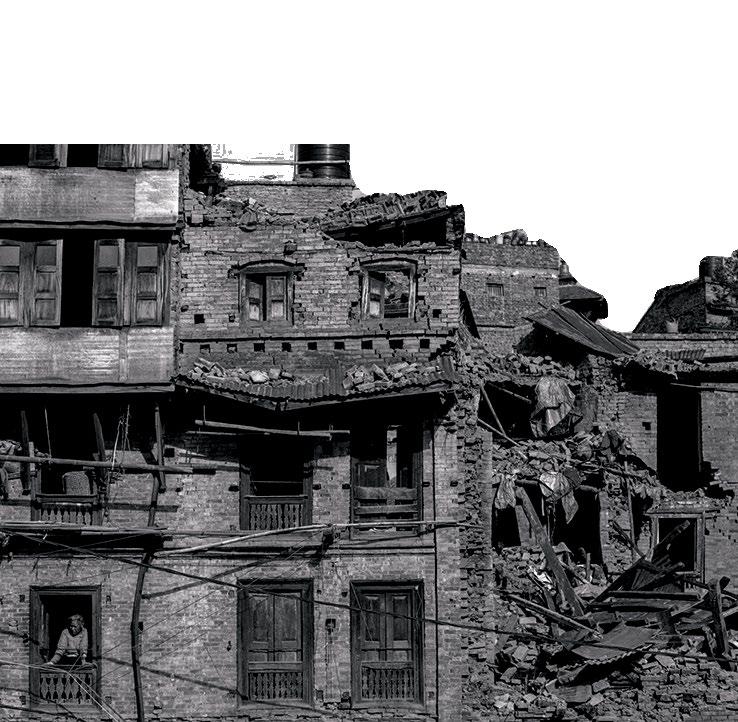

L OGISTICS BEHIND AN EARTHQUAKE

TECTONIC PLATES AND NEPAL

2015 EARTHQUAKE LOCATION

INDIAN CONTINENTAL LEGEND

24 / MAPPING 80 30 82 78 76 26 28 32 34 36 38 40 80 82 78 76 NEPAL NEIGHBOURING CONTEXT

NEPAL AREA TRANS HIMALAYAN PLUTON OPHIOLITE BELT KATHMANDU VALLEY 7.8 MAGNITUDE APRIL 25, 2015 7.2 MAGNITUDE MAY 12, 2015 HIGHEST DAMAGE AREA

KATHMANDU

EURO-ASIAN CONTINENTAL PLATE

84 86 88 90 92 94 84 86 88 90 92 94 30 26 28 32 34 36 38 40

CONTINENTAL PLATE

TETHYAN HIMALAYA GREATER HIMALAYA LESSER HIMALAYA ACTIVE FAULT LINES THRUST FAULT

7 / CONTEXT & BACKGROUND

CITY CENTER HISTORIC BUILDING TIMELINE

CITY CENTER HISTORIC VERNACULAR VS. MODERN

ARCHITECTURAL

ARCHITECTURAL TRENDS TIMELINE BUILDING TIMELINE

7 / CONTEXT & BACKGROUND

7 / SITE / THECHO

MAJOR CITIES PROJECT SITE OTHER POSSIBLE SITES 4 O M I SN RD I EV SUIDAR MORF ERTNECUDNAMHTAKSELIM01 15 MINSDRIVERADIUSFROM PATAN C E N T R E4 MSELI

LEGEND

Historically, Thecho has been an integral part of the Kathmandu Valley’s narrative, tracing its roots back to ancient times. The valley itself is renowned for its significance as a hub of civilization, with evidence of human settlements dating back thousands of years. Thecho, like many other towns in the valley, carries remnants of this rich history, reflected in its architecture, temples, and cultural practices.

EMOTIONS BEHIND AN EARTHQUAKE

7 / SITE NARRATIVE

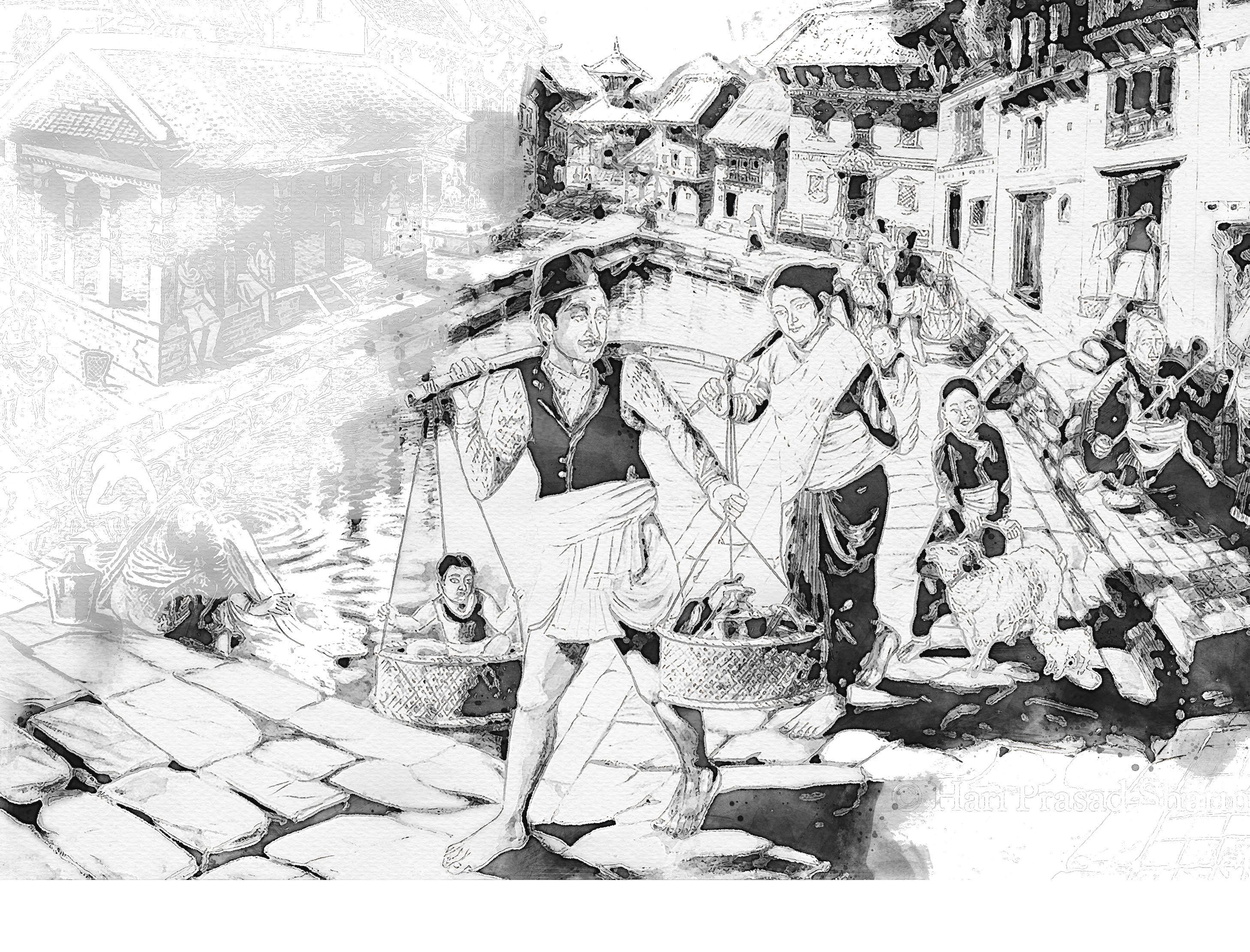

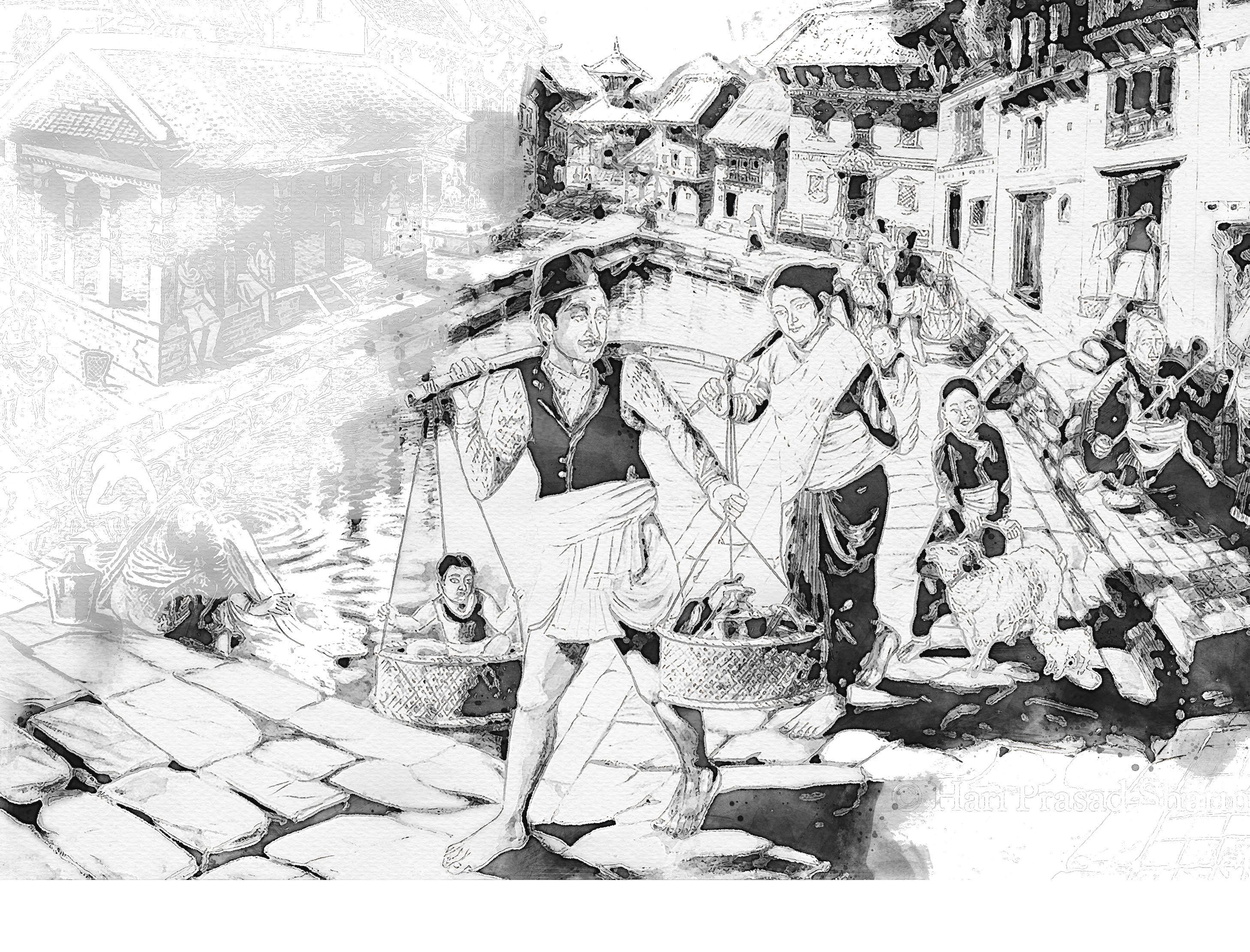

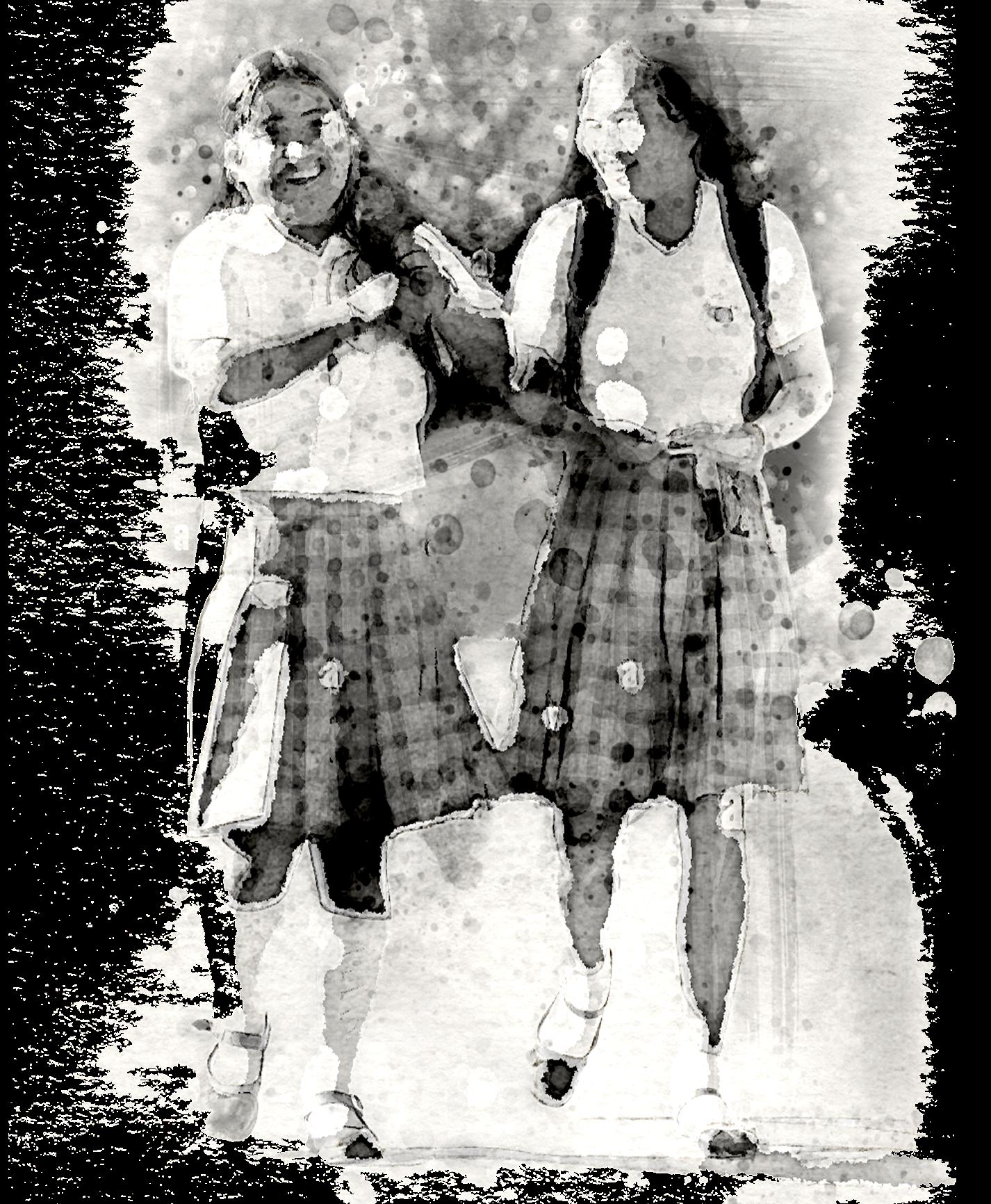

My name is Sahana Chitrakar. Tour guide by day, survivor by night. This valley has been home to the vibranT Newari comMunity for cenTuries, shaping every aspecT of our culTure – from the inTricate arChitecTure to the delicious cuisine. We are the natives of this land, guardianS of itS traditionS and legacies.

WelCome to The Kathmandu valley, a city sTeeped in hisTory and culTure!

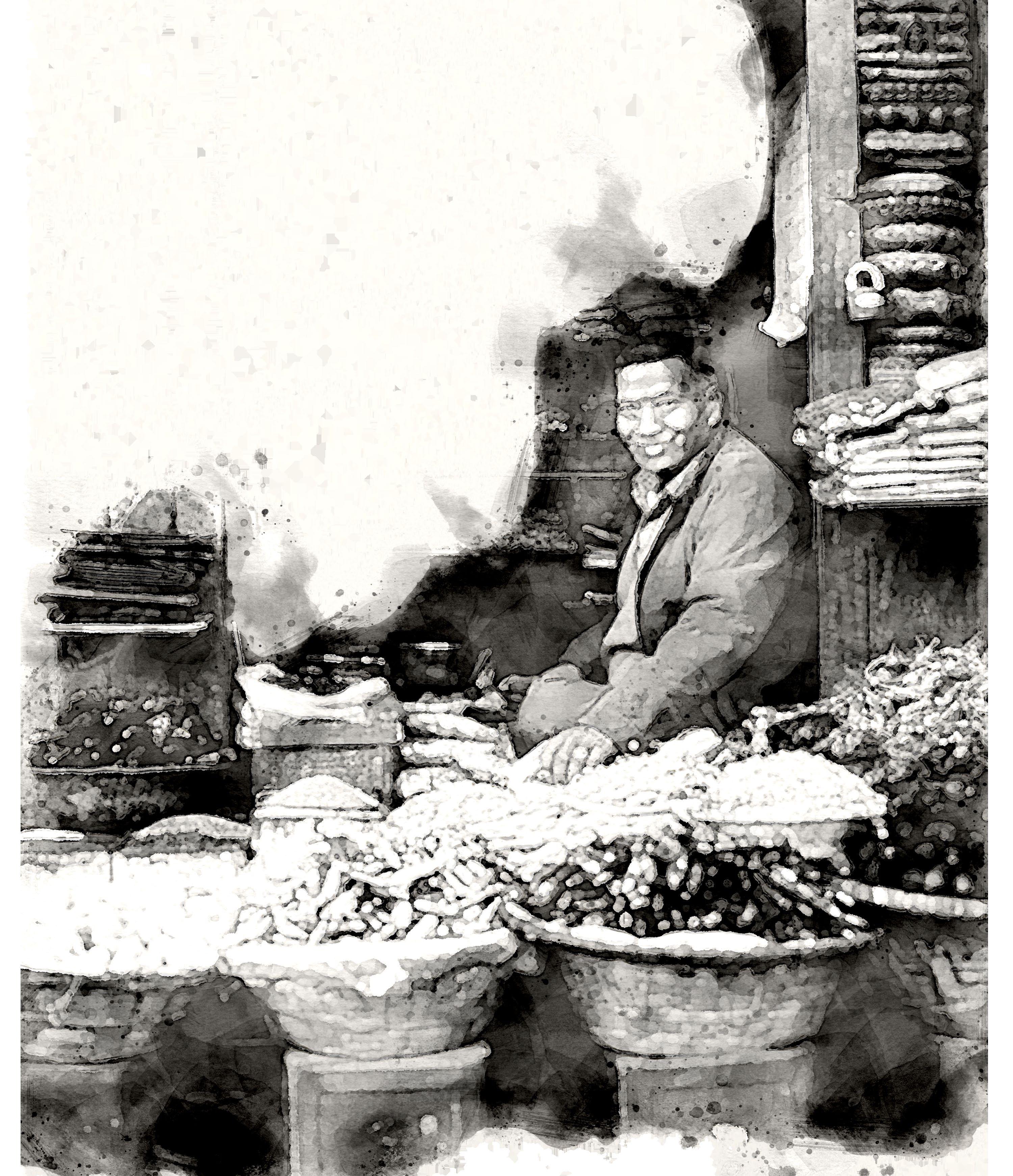

For generationS, my anCesTorS thrived ofF the land. But as Kathmandu evolved, so did we. ShifTing from agriculTure to comMerCe, our family also Started iNto BuSiNeSs.

The traditional houses in the valley are a reflecTion of our collecTive heritage. BuilT in a towNhouse-sTyle, each dWelling is not jusT a home but a piece of a larger puzzle, inTricately conNecTed to itS neighborS. all The houSeS are also depeNdeNt To eaChoTher StruCturally.

I ThiNk iT WaS iNflueNced By The Silk road ThaT paSsed righT Through iT.

Within ThaT puzzle, my family home also sTands as a corNerStone—a repository of memories that span generationS. iT is more than jusT bricKs and morTar—it is a vesSel for our hisTory aNd our heritage. every crevice and corNer holds a sTory conNecTing us to our pasT—a reminder of our values and traditionS.

ThiS houSe iS also The oNly Source oF our FaMily’S iNcoMe. My parenTs conTinued this legacy, pouring their hearT and soul inTo our family businesS.This businesS has been the bacKbone of our family, providing for our every need—from my education to my grandparenTs’ retiremenT.

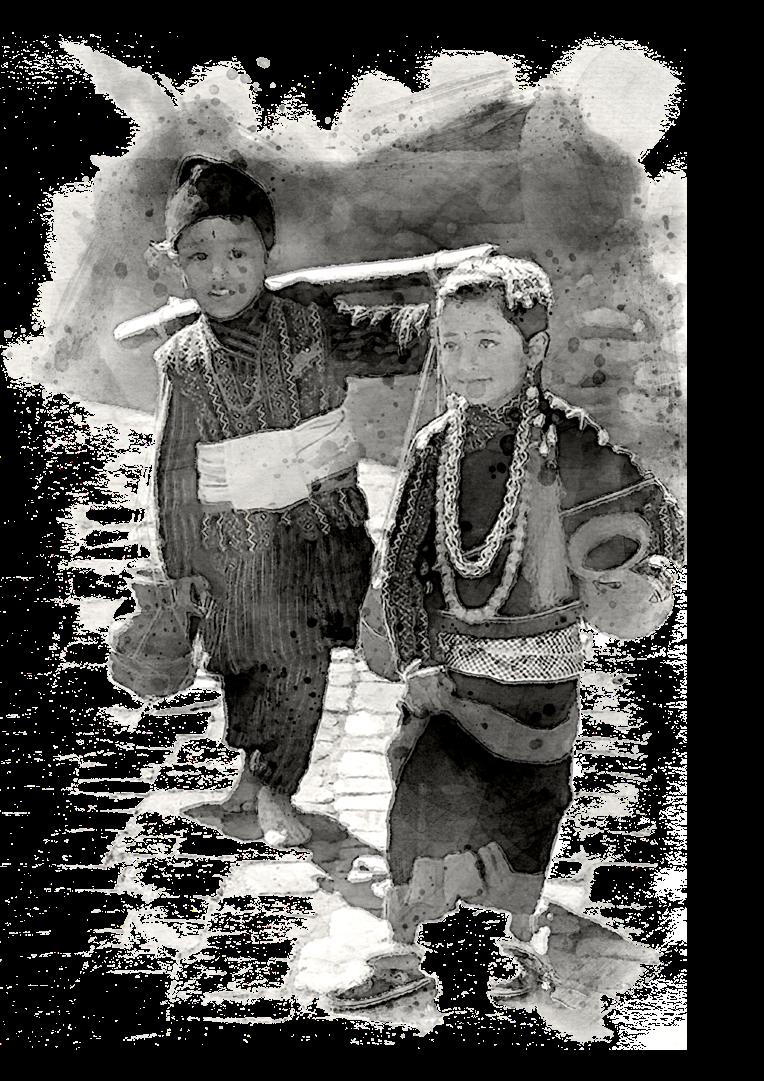

you Two BeTter ruN To geT To School oN TiMe!

WhaT Should We Study aFter high School?

do you ThiNk I CaN BeCoMe a piloT? or Should I JuSt TaKe over My FaMily’S BuSiNeSs? iS ThaT Too SaFe? haha!

ruN! ruN! ruN!

ruuuuuuuuuuuu!

But when disasTer sTrucK, our peaCeFul world crumBled iNto ruBbleS. overNight, we wenT to fighting for survival on the sTreetS. everything changed; We losT, our home, our family aNd our livelihood. We were lefT with nothing but rubBle and memories.

Definitely NOT ENOUGH FUNDS FOR RECOVERY NOT ENOUGH FUNDS

hoW do We geT over ThiS?

iS There a Way ouT?

while the Whole world mourNed the losS of heritage, for us, it was a luxury we couldn’t afFord. liviNg iN The TeMporary Shelters WiTh No Source oF iNcoMe aNyMore The FuTure oF our FaMily looKed hopeleSs. The reCovery FuNdS We goT FroM The goverNmenT WaS also all SpeNt oN BaSiC Needs.

Today, I find myselF navigating through The alleys of Kathmandu, guiding otherS through the city I love. But my owN path feelS iS unCerTain. guiding tourisTs may be a necesSity, but my oNly dreaM iS the resToration of our home—a dream I canNot bear to abandon.

Rooted in the rich cultural heritage of the Newari community native to the Kathmandu Valley, this semi-pernament architectural installation draws inspiration from the profound symbolism of the MANDALA . More than just a geometric design, the mandala embodies the cyclical nature of life, representing both birth and death. Its creation at the outset of festivals and rituals, only to be erased upon their conclusion, reflects the transient yet eternal essence of existence.

Embracing these principles, this project becomes a tangible manifestation of the mandala’s transformative journey. Like the process of constructing and dismantling a mandala, THIS ARCHITECTURAL INSTALLATION SYMBOLIZES THE PATH TO HEALING – A JOURNEY OF RECOGNIZING DESTRUCTION, PROCESSING LOSS, ACKNOWLEDGING PAIN, AND ULTIMATELY, FINDING SOLACE AND RENEWAL.

7 / CONCEPT

DESIGN & FORM STUDY

7 /

By examining the origins of the mandala and envisioning the artist’s initial strokes, I gained insight into its organic evolution. Drawing from this exploration, I used the deconstructed mandala as a foundational blueprint, shaping a model that could seamlessly integrate with its intricate geometry. This model, conceived to rest atop the deconstructed mandala, serves as the basis for the intervention. Supported by bamboo scaffolding, it gracefully rises above the ruins, harmonizing with the surrounding landscape while embodying the essence of both tradition and innovation.

RUINS AS MINES

48 / RUINS

STUDY

In sustainable construction, local materials like clay, wood, and bricks are REPURPOSED to reduce environmental impact, forming the foundation of the intervention. Bamboo, lightweight and locally sourced, is the sole new material introduced, emphasizing ecofriendly practices. This approach not only minimizes waste but also highlights resourcefulness and sustainability. Additionally, repurposing these materials adds new stories and memories to them, creating a sense of continuity and connection. This cyclical process extends their lifespan and ensures their legacy endures, embodying a sustainable ethos that honors both the past and the future.

50 / RUINS STUDY

USED TIMBER

CLAY

USED BRICKS

WIRES

DOOR FRAMES

DESTRUCTION

LOSS

GRIEF

SENSE OF PLACE

53 / THE INTERVENTION / JOURNEY OF HEALING

DREAM RESTORE

54 / THE INTERVENTION

TRANSVERSAL SECTION

Re-used Stairs

Personal Belongings hung by Vistors

3’ 9’ 3’

7’ - 0” 15’ - 6” 20’ - 6” 31’- 0”

0’- 0”

Bamboo Scaffolding

Shallow Foundation

Re-used Timber Beams

Clay & Mud Wall

Ruin

EXPLODED AXONOMETRIC

CENTRAL SPACE- END OF JOURNEY

STAIRS AND PATHS

SCAFFOLDING

THE RUIN

BAMBOO

OF JOURNEY 56 / THE INTERVENTION

SPACE