a

Scholars and Soldiers:

history of alumni of St Paul’s School and the 1st World War

Volume 2: the Ypres Salient and OPs

Graham E Seel

Graham E Seel has taught History since 1987. He was Head of History and Head of Faculty Humanities at St Paul’s School, 2012 2021. The author may be contacted on spsworldwarone@btinternet.com

Cover image: The Menin Road by Paul Nash (SPS 1903 1906). IWM ART 2242

List of Illustrations

Introduction

Chapter 16. ‘wherever we go, it cannot be to a worse place than the Ypres Salient’

16.1 Ypres and the Salient i) Ypres: the death of a city ii) Ypres: the Salient 16.2 the ‘93’: an overview i) in which they served: armies and regiments / corps ii) in which they served: infantry battalions iii) age at death iv) the deadliest day in the Salient v) where they fell vi) graves / memorials vii) the ‘93’ Roll of Honour

Chapter 17. the ‘93’ and their stories

When Graham Seel speaks directly about his research into the 511 fallen Paulines and others of the 2,500 OPs who volunteered for service in the 1st World War, his passion for understanding and recording accurately the history of both the school and its pupils is evident. His work narrates much fascinating hitherto unknown detail about the generations of OPs who fought and as such it will become a key reference work for those interested in St Paul’s School and the 1st World War. I am proud to be part of an institution that facilitated such work and acknowledge its importance. I also feel privileged to have overlapped with Graham during my time as High Master and to have had the chance to discuss its progress with him and to see this project reach its completion. That it did so during a global pandemic, when another group of young Paulines had their lives impacted by factors beyond their control, only served to emphasise further the need to record our unique experiences for those who will follow us.

Whilst Graham’s work seeks to emphasise the numbers of Paulines who survived the 1st World War and had purposeful lives beyond it, it remains the case that it’s difficult for those of us alive today to imagine what life at the front must have been like for them. However, united as we are by our school, we can feel connected to them and to the past in a special way. Therefore, I am hugely grateful to Graham and to all who supported him in this venture.

Sally-Anne Huang, High Master, St Paul’s School 2020 -

One of the highlights of my time as President of the Old Pauline Club has been the honour of laying a wreath at the St Paul’s School War Memorial on Remembrance Day last year. The sky was the clearest blue and there seemed to be no sound of road, air or river traffic just the silence of over a thousand current Paulines remembering and honouring the 511 Paulines from over a century ago who made the ultimate sacrifice. There was such a sense of unity across generations in the silence.

In these wonderful volumes, Graham Seel chronicles the stories of the 511 OPs who fell and others who survived. It is so important that these tales of gallantry and sacrifice are being told. There is nobody better to do that than Graham given the incredible extent of his research and the quality of his writing. The Old Pauline Club extends its congratulations and enormous thanks to him. Scholars and Soldiers is a hugely important addition to the Pauline Community’s knowledge of OP bravery in the First World War.

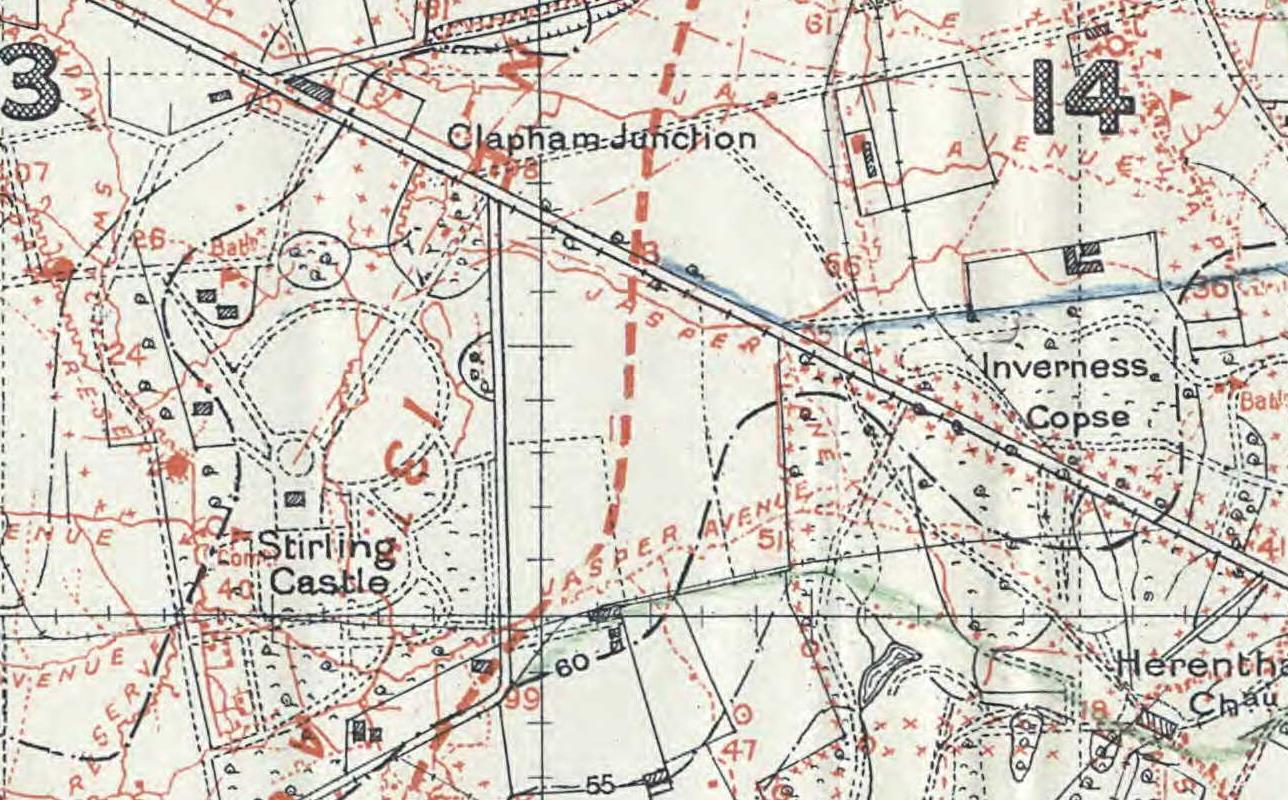

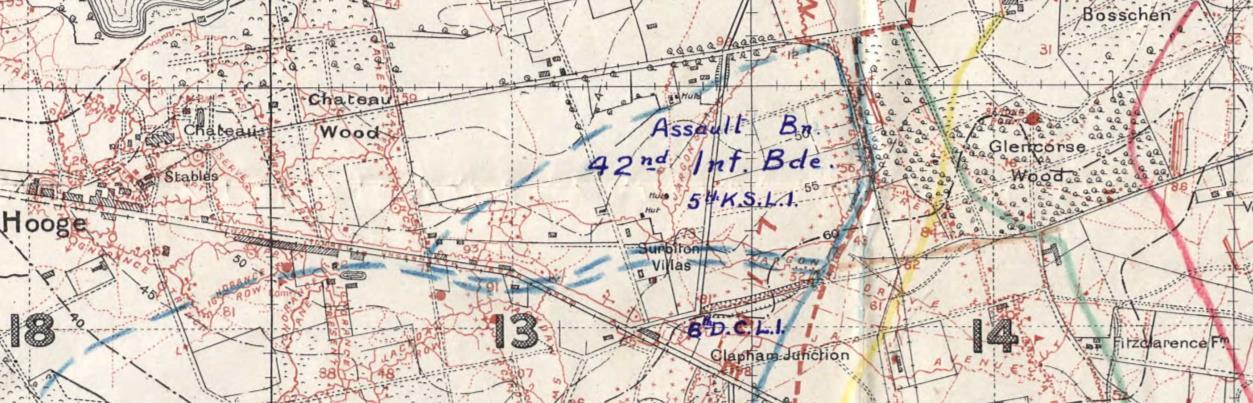

Graham describes Pauline sacrifice in what was “the war to end all wars” at a time when there is war in Europe again. His book is timely and poignant.

Ed, Lord Vaizey of Didcot, OPC President

One of the great privileges of being a Pauline is the sense of being part of a great continuum of learning and endeavour that has continued over many centuries. As governors and Old Paulines our task is to encourage and enable the new generations to share in the great history and the bright future of the school. So while supporting the future development of the school it is vital that we are alive to its past.

Graham Seel has undertaken a massive research project investigating and chronicling the contribution of so many Old Paulines to the First World War and illustrating for us the great diversity of talent that poured into the trenches. In so doing he helps to slay the myth that the soldiers were all fresh from school and heading directly to a muddy grave. Many of them were in their 20s and 30s, the majority of them survived and they participated in a variety of ways and displayed a range of talents. Many continued to have distinguished careers after the war.

It is important, as we look back over the history of the school, to recognise that the First World War dominated the lives of more than a single generation of Paulines and provided a focus for the school life and work that extended beyond the memorials to the fallen. Any study of the history of the first part of the twentieth century must reflect this as well as recognising the contributions of those Paulines who gave their lives willingly and bravely in the service of their country. Graham Seel’s work provides an invaluable record of this period and continues in the great tradition of St Paul’s history by providing a well written and discursive analysis to enlighten the treasure trove of individual stories. This is a great and invaluable resource for historians and for anyone wishing to understand the school of a century ago.

Richard Cassell, Chair of Governors, St Paul’s SchoolWhen I arrived at St Paul’s in 2011 there was no unifying memorial to the Old Pauline fallen and no annual remembrance service. My son had just started at Bishop’s Stortford College, and he rang me on the evening of 11 November to relate how they had heard in their remembrance service of the sacrifice of nearly five hundred Old Paulines in the Great War. Over the next couple of years, a disjuncture between Pauline sacrifice and commemoration was rectified: a small group of staff (notably Richard Girvan, Eugene du Toit and Patrick Allsopp), pupils (notably Joshua Greenberg) and the Old Pauline Association rallied energetically, and soon a whole school service of remembrance was introduced and an inscribed memorial stone unveiled.

But something was still missing. Whenever I looked at those stilted sepia pre war photographs of Paulines, dressed in ceremonial blazers and caps, and whenever I read about their athletic proficiency (and their years in this XI or that XV) in the stiff language of The Pauline magazine, they appeared detached, almost fictional, characters. I related to them as Paulines, but not as human beings.

Not any more. Graham Seel’s painstaking and passionate research rescues 511 Paulines from the anonymity of mass mortality. It replaces sepia with colour. His biographies reveal how various Paulines some irascible, some dubious, some sensitive, some formidable, many courageous wrestled with their conscience and died as a consequence. Graham Seel interweaves their lives with detailed reconstructions of their deaths: in many cases, he can identify where and how they fell, details which were seldom known to their loved ones.

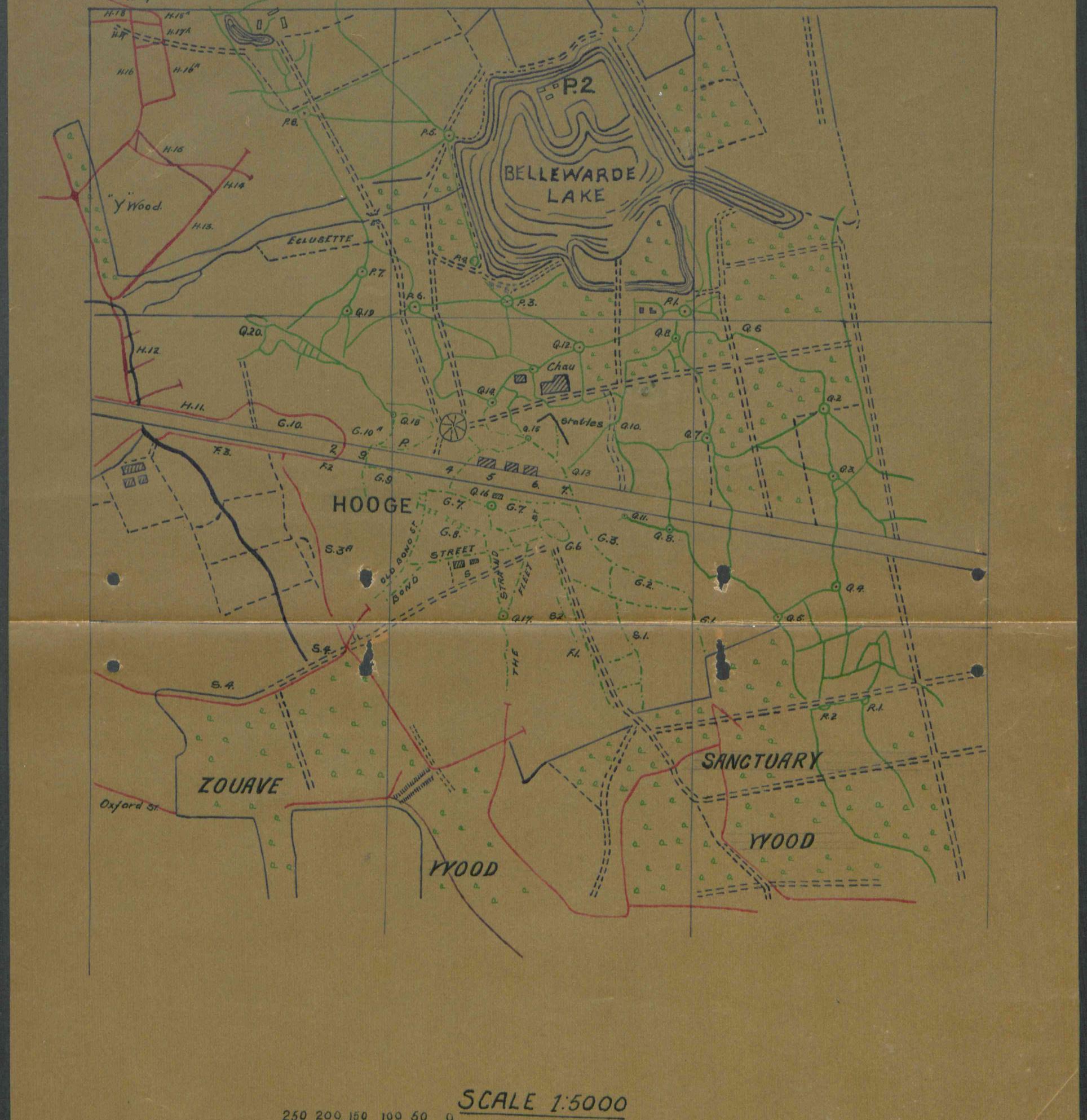

Read in these pages about the Pauline who could throw a cricket ball further than any other, who could hurl grenades clean across no man’s land, who crawled through human detritus in the Hooge crater on a hot August morning, and who died with quiet dignity despite appalling abdominal wounds in a crowded dressing station: in so doing, the fallen are restored as human beings for posterity.

Mark Bailey, Professor of Later Medieval History, University of East Anglia, High Master, St Paul’s School, 2011 - 2020

The origins of these three volumes lie in a project undertaken by a group of pupils working under the auspices of the History Department in 2014, culminating in the production of the commemorative booklet ‘St Paul’s School and the First World War’. It was clear from this exercise that the school magazine The Pauline was simultaneously an astonishingly rich and remarkably underused repository of many of the stories of OPs who fell in the war. Thus, during the years 2014 to 2018, encouraged by the various national centenary commemorations, periodic further use was made of The Pauline, along with other materials in the St Paul’s School Archive, in order to reconstruct the experiences of some of the OPs who lost their lives. Over the same period the school Act of Remembrance evolved to become a whole school occasion, including St Paul’s Junior School, and several commemorative events took place, notably the planting of 490 crosses at the base of the War Memorial in 2018.1 From all of this it became increasingly clear that there was a requirement for a robust, comprehensive history of OPs who served in the war, for more of their stories to be uncovered and for others to be yet more thoroughly researched, and for their graves / memorials to be identified. What follows is an attempt to fulfil these requirements.

Many colleagues have helped in the production of this work, and I hope that I have duly acknowledged their various contributions in a relevant footnote. During the Summer Term of 2020 my colleagues in the History Department, already squaring up to the peculiar challenges posed by the pandemic, gracefully shouldered most of my teaching timetable to allow me to undertake sabbatical leave. I am particularly grateful to Hilary Cummings and her team in the St Paul’s School Library. Ginny Dawe Woodings, the School Archivist, has been unfailingly helpful. Valerie Nolk has been supportive throughout. Owen Toller, Mike Howat and Simon May read either parts or all of the manuscript and drew my attention to infelicities. Michael Grant and Matthew Smith provided indelible good cheer during visits to Ypres. John Knopp has shown endless patience in dealing with my questions military. I am grateful to my family for giving me the space to research and to write and for coining the new verb: ‘to trench’. Finally I wish to thank the Governors, Mark Bailey and Richard Girvan for accommodating my request for sabbatical leave, thereby presenting me with time and resources for the laying of the groundwork for what follows. I appreciate that sabbaticals are increasingly difficult for school authorities to finance and to justify and I hope that the present work goes at least some little way to recompense their faith in me.

1

The figure of 490 is obtained from the number of names of OPs listed as fallen in the first part of the War List. This work revises this number to 511. (See Chapter 6.)

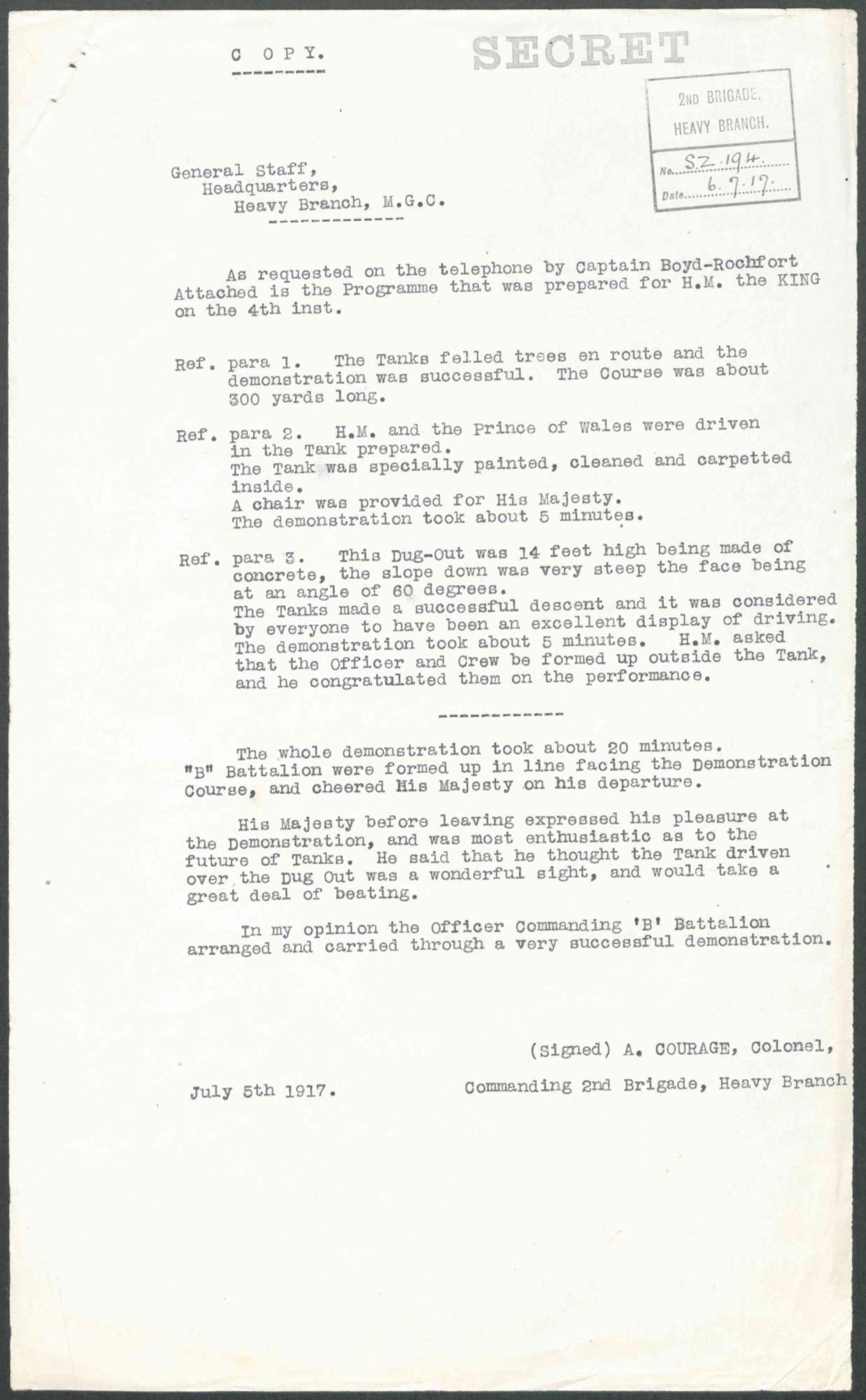

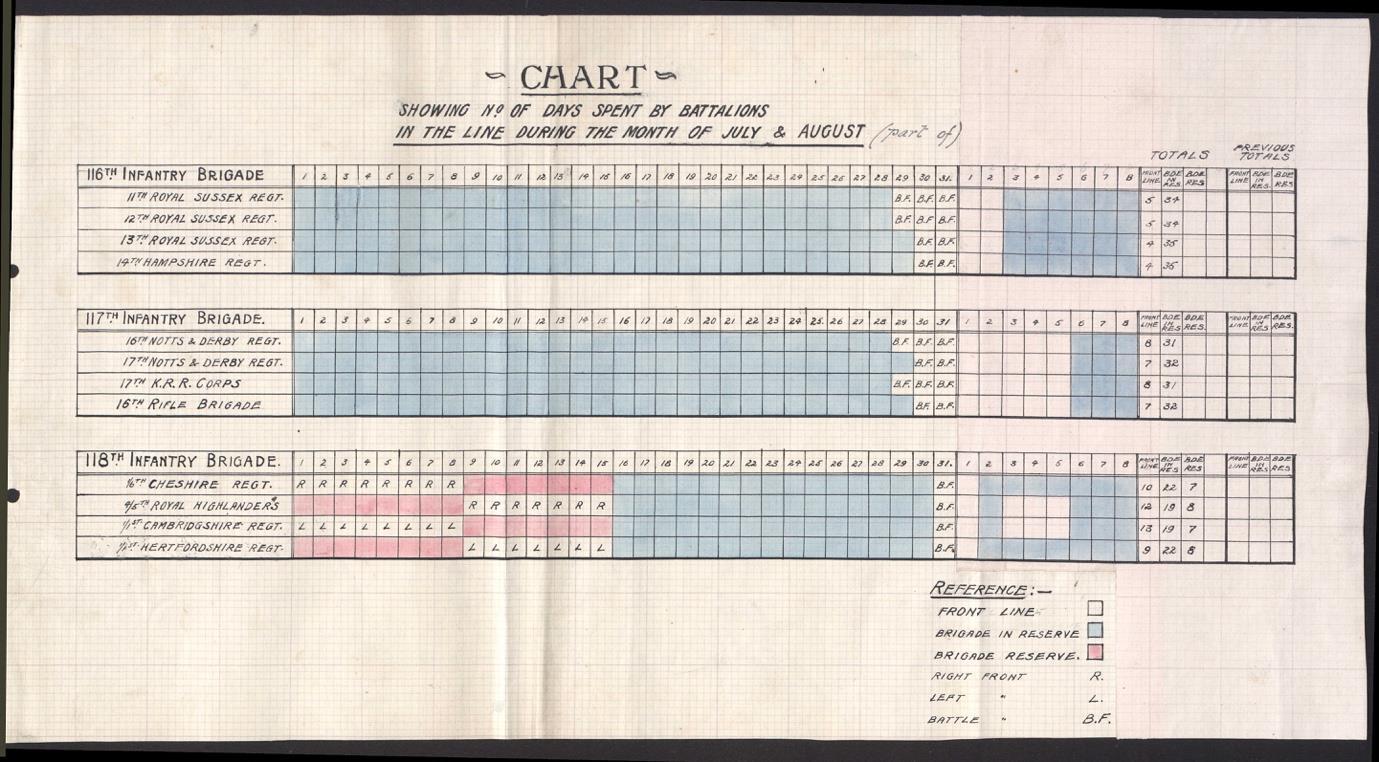

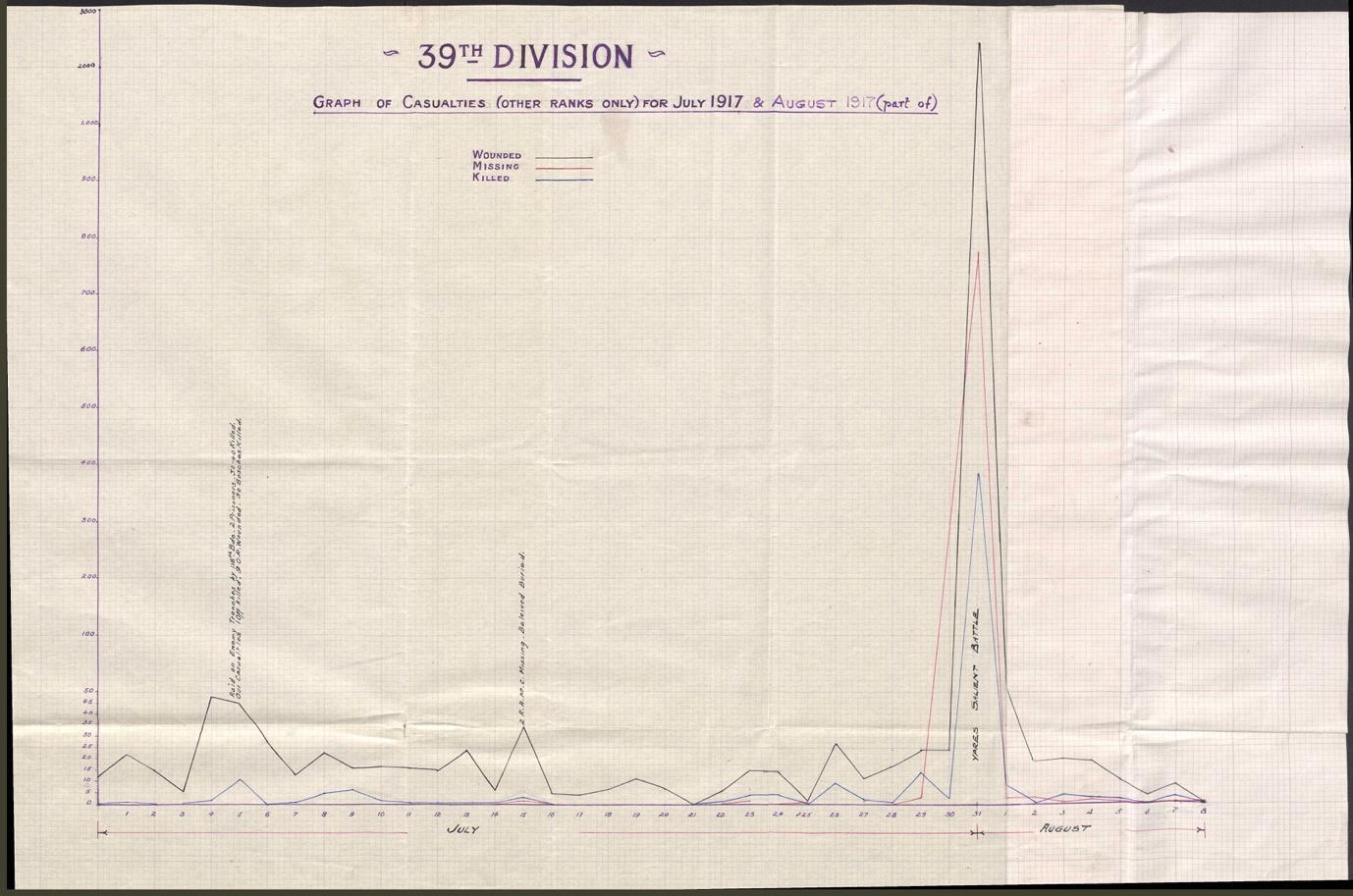

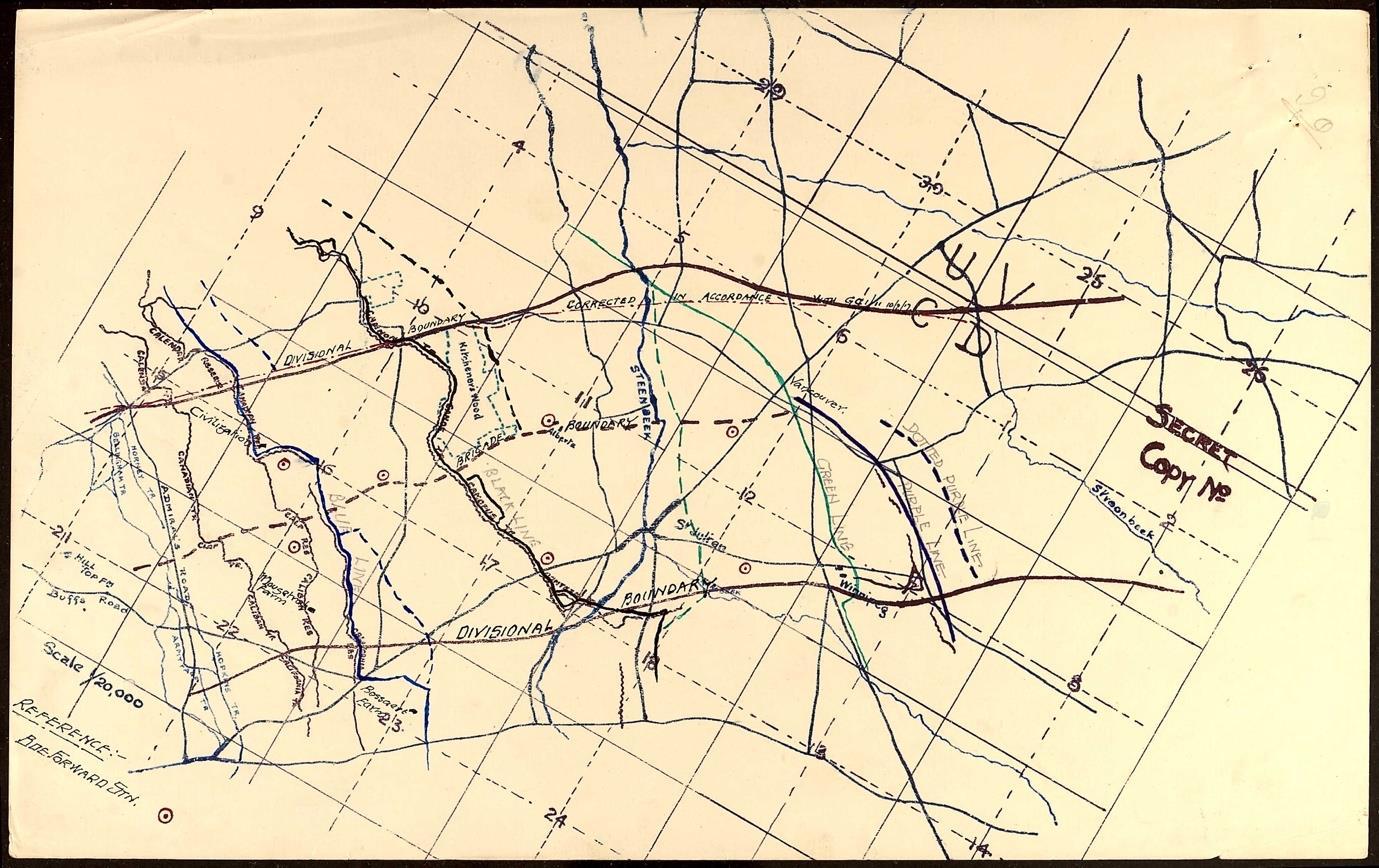

Volume 2: the Ypres Salient and the ‘93’. Images, charts and tables

Part F: Ypres, the Salient and Old Paulines

Chapter 16 ‘wherever we go, it cannot be to a worse place than the Ypres Salient’.

N.1 The Cloth Hall and the main tower of St Martin’s Cathedral

N.2 The Cloth Hall and the main tower of St Martin’s Cathedral in a considerably damaged state, January 1916

N.3 Eglise St Pierre, Ypres. March 1917. Painted by Harold Drummond Hillier (SPS 1906 1910)

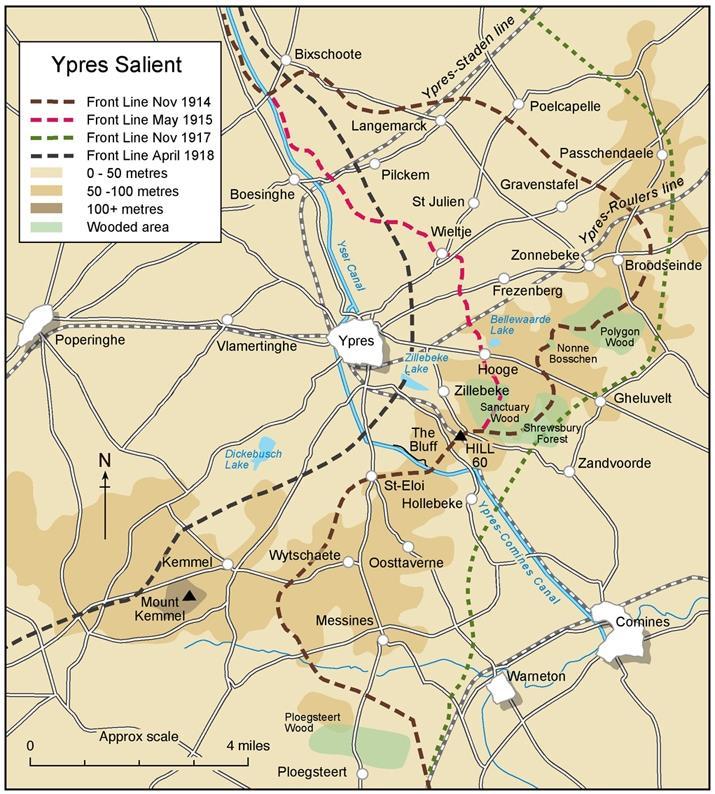

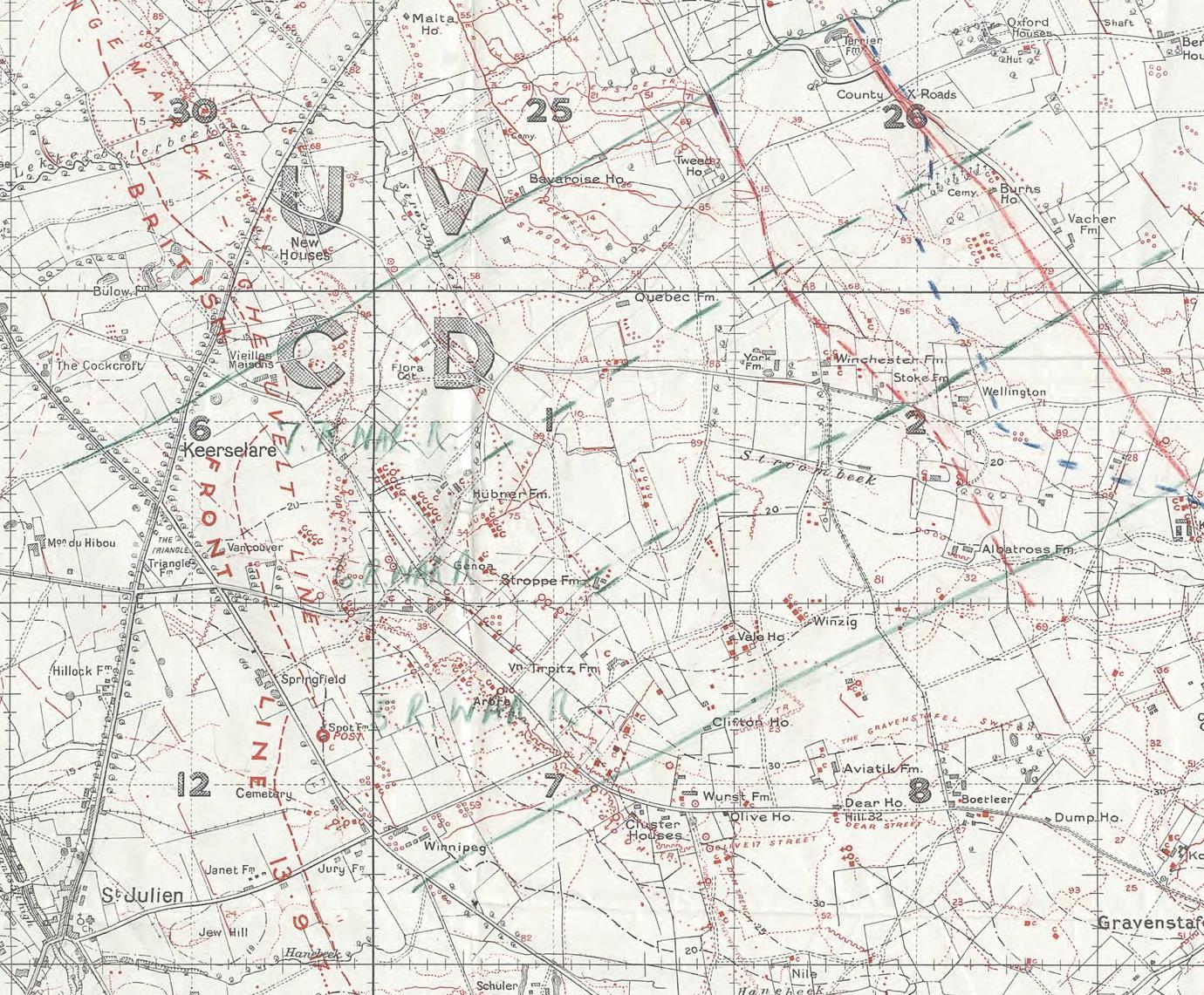

N.4 Map showing the Ypres Salient and the various positions of the front lines, 1914 1918

N.5 Number of OPs who fell and their average age by year 1914 1918

N.6 The proportions of OPs who fell in the Salient with a grave or remembered on a memorial

Chapter 17 The ‘93’ and their stories

L.7 Roll of Honour the Ypres ‘93’

The overall ambition of this work is to provide an accessible record of alumni of St Paul’s School who enlisted during the 1st World War. This material is presented in two volumes, with a supplementary third volume containing maps and photographs of many of the places mentioned. The purpose of Volume 1 (‘Service and Commemoration’) is threefold: 1) to recognise the number of OPs who fought in the 1st World War and to comprehend their reasons for so doing; 2) to identify, quantify and reveal the stories of OPs who served in the war, 511 of whom fell; and 3) to provide a record of the activities and enterprises undertaken by the School to ensure that these OPs are not forgotten. Volume 2 (‘The Ypres Salient and OPs) identifies OPs who fell in the Ypres Salient and uncovers their stories.

The material assumes a broad knowledge of the context of the war the reader who wishes to engage with the historiography of the War will have to look elsewhere.2

Volume 1 is composed of five parts, A E. Part A identifies the total number of OPs who served in the war, the units in which they fought and the ranks and awards they achieved. Of this number 2,914 many were volunteers, encouraged to enlist by the culture of their public school and equipped early with martial prowess by means of a vigorous Officers’ Training Corps (OTC), an institution that became such a feature of many Paulines’ lives that some considered it was ‘Too Much With Us’.3 With the introduction of conscription in January 1916, volunteering ended. Thereafter, everyone who fulfilled certain criteria was obliged to go to war and from this date onwards it becomes impossible to perceive distinctly the extent to which OPs willingly undertook service.4 All that can be said is that the records and the data offer very little indication of recalcitrance and it thus seems likely that most OPs maintained a desire to participate in the war. Harry Waldo Yoxall (SPS 1908 1915, see Chapter 11, Section 11.7) Captain of School in 1915, admitted his discomfort after deciding to stay on to take the Balliol Scholarship before joining up. A keen member of the OTC, he confessed that:

2 Sheffield, G Forgotten Victory The First World War Myths and Realities provides an accessible overview (Headline, 2002)

3 One lunch break a week was given up to an OTC drill parade and part of the margin of the school grounds was grimly decorated with gallows from which hung straw filled sacks into which the novice would be trained to plunge his steel. Wednesday afternoons and sometimes Saturdays were taken up with OTC. See Chapter 2, Section 2.5.

4 See Appendix 1

The Officers’ Training Corps was a partial salve to conscience, and the cadet uniform at least a protection against white feathers. It was difficult to lead a school affected by impermanence, with the elder boys slipping away each week into the HAC [Honourable Artillery Corps] or the Public Schools’ battalion of the Royal Fusiliers.5

Harry’s example is unusual. In numerous cases boys left school earlier than they would normally have done. Most felt that it was their duty to do so; for most, all roads led to France.

Part B revises the generally accepted figure of 490 OPs killed in the war and replaces it with that of 511. This figure represents 17.5 percent of the total number who served, slightly lower than the death rate across all 185 public home and overseas schools.6 After a century of exposure to the ‘pity of war’ poetry of Wilfrid Owen and its associated narrative that the 1st World War begot only death, it comes as something of a shock to learn that for every OP who fell, four survived. The data also encourages a revision of the generally accepted notion that those who fell were by and large very young males composed of a tightly knit cohort who only recently had sat in the school classroom and run on the school playing field. Instances of OPs dying at a very young age exist, but they are few and far between. Their examples evoke a noisy, melancholic sentimentality frequently amplified by the pens of the war poets. In fact, the average age of death of all 511 OPs who fell was 27 years. In 1914 it was as high as 30 years, and never lower than 26 years (in 1917). The data also shows that OPs volunteered from multiple cohorts of leavers stretching back for decades prior to 1914. St Paul’s endured a loss, but it did not suffer a ‘Lost Generation’. Finally, as the stories of the OPs presented here show, there is almost no evidence to support the popular notion that OPs generally fought and fell shoulder to shoulder. Mostly of officer rank and of differing ages, OPs were deployed as leaders across multiple units, a diaspora that thwarted any possibility of a Pauline ‘band of brothers’ stalking the trenches. Indeed, it is of note that OPs often took care to mention in their letters those occasions when they encountered a fellow Pauline at the front, thereby perhaps suggesting the infrequency of such an event.7 The final chapter in Part B identifies the cemeteries / memorials in which the 511 OPs are buried / remembered. The 511 are to be found in all parts of the world, though their greatest concentration is in France and Belgium. It is chilling testimony to the character of the war that 35 percent of OPs who fell have no known grave.

5 Quoted in Mead, A H A Miraculous Draft of Fishes: the history of St Paul’s School (James and James, 1990), p 102

6 See Seldon, A and Walsh, D Public Schools and The Great War The Generation Lost (Pen and Sword, 2013) pp 255 261

Part C narrates the stories of some of the 2,403 OPs who survived the war. Many of these not only had extraordinary wartime experiences but went on to equally extraordinary achievements in their later lives.

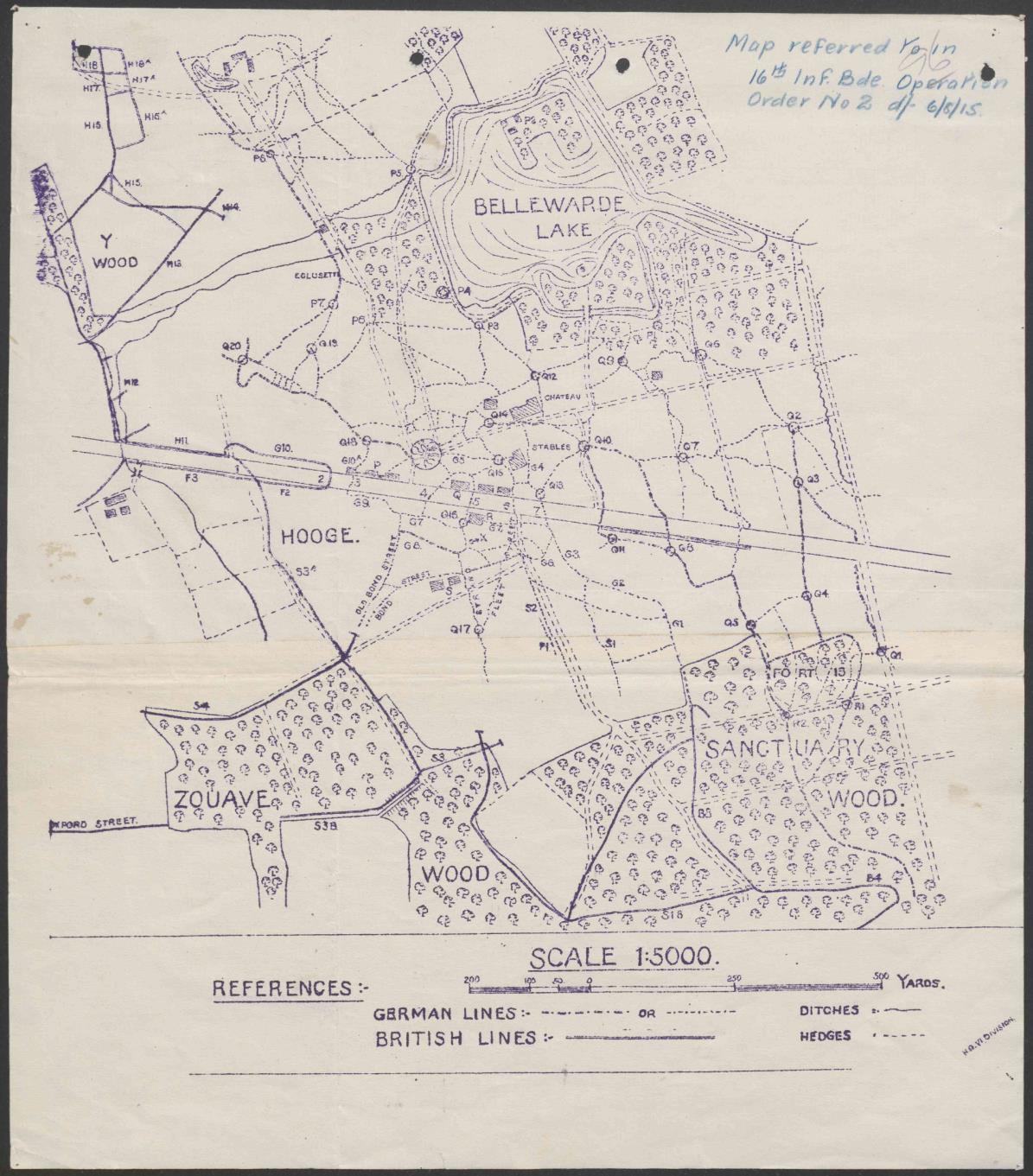

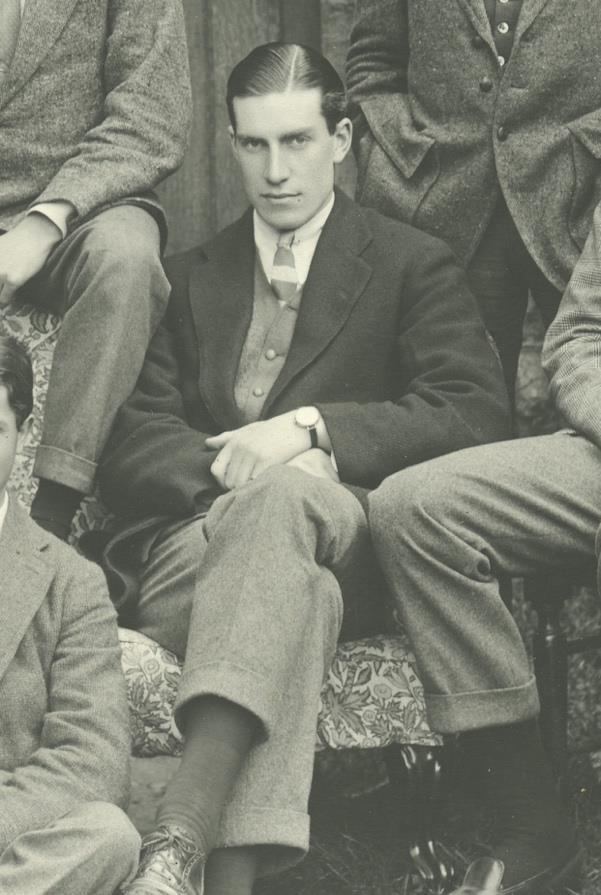

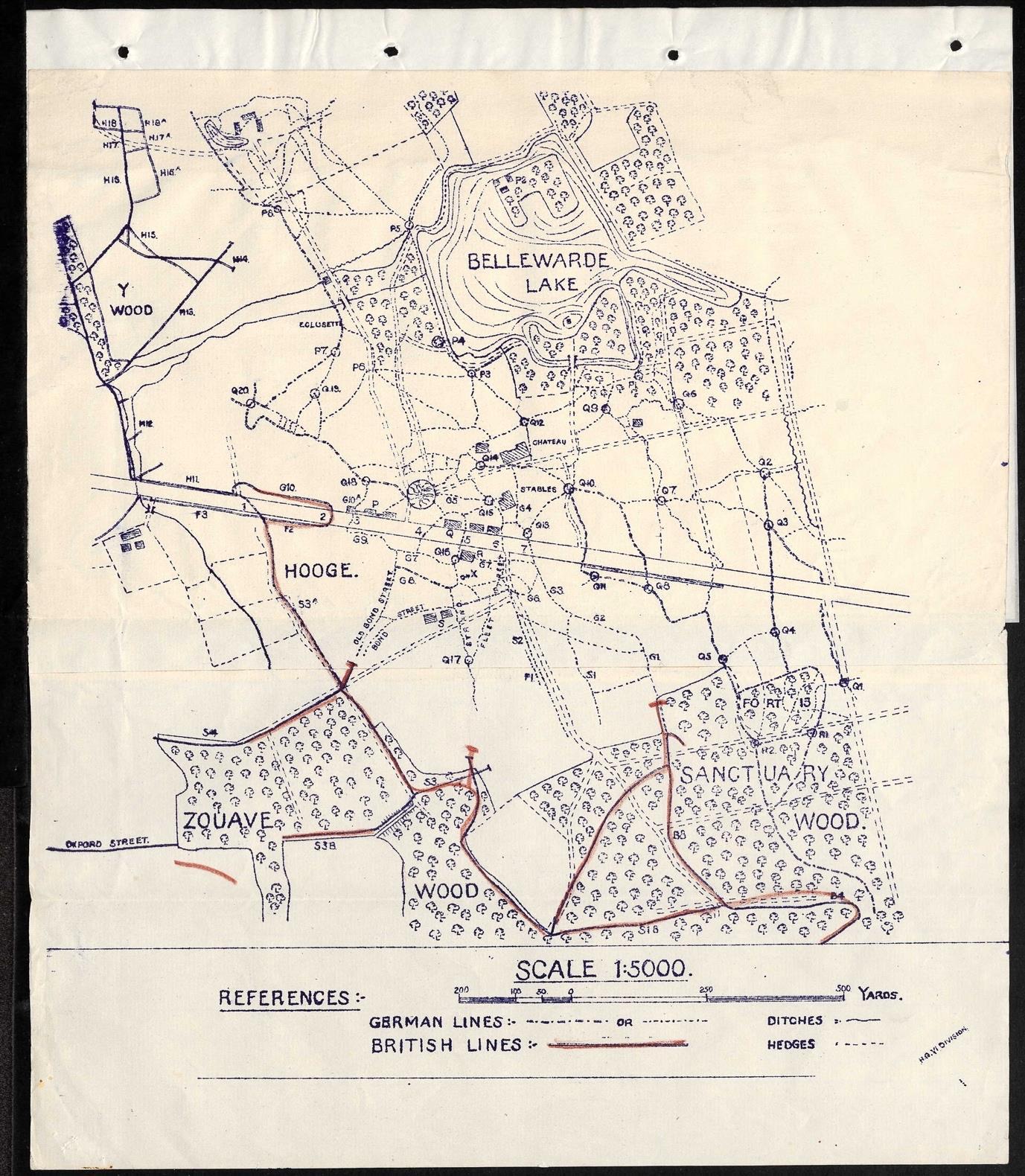

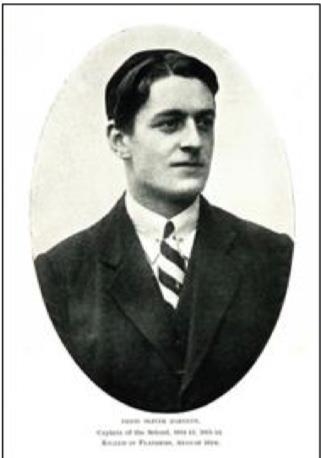

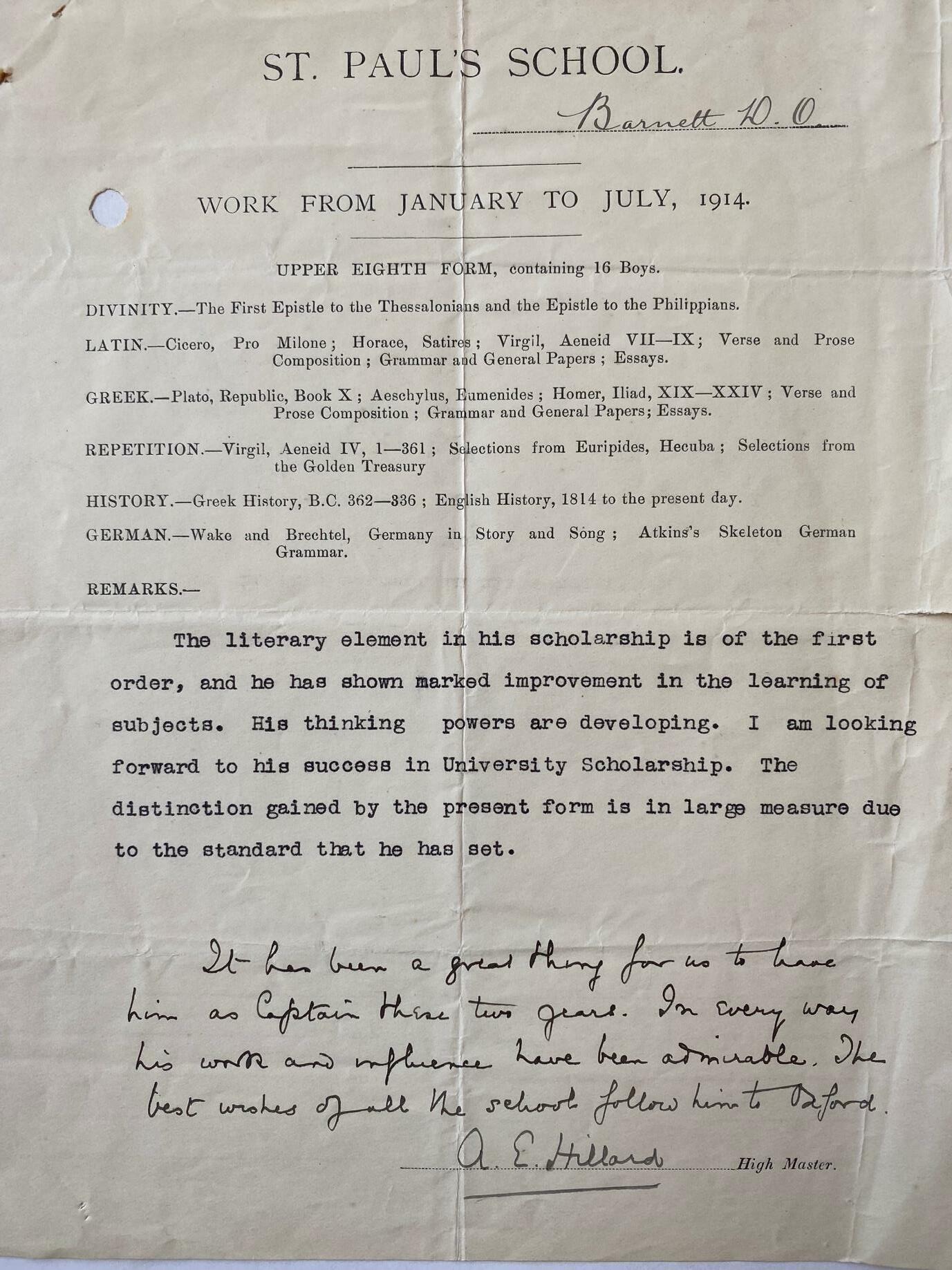

Part D details the various projects and activities undertaken by the School to memorialise and to commemorate the 511, and latterly, others who have fallen in later conflicts, from the end of the war in 1918 to the present day. High Master Hillard (1905 1927) reflected upon the process of memorialisation as early as 1916. In his Apposition address of that year he read from a letter of Denis Oliver Barnett (SPS 1907 1914, see Volume 2), Captain of School in 1913 and 1914, killed by a sniper’s bullet at Hooge (in the Ypres Salient) on 16 August 1915, age 20. Denis had written that ‘It is only the selfish part of us that goes on mourning. The soul in us says Sursum Gorda.’8 (Translated as ‘Lift up your hearts’.) Hillard told his audience that he intended to have these words inscribed on the memorial to Old Paulines after the war, an ambition that for whatever reason remained unfulfilled. The reader may consider that this noble sentiment has been achieved nonetheless by the projects and activities herein described, and no doubt by ones yet to be conceived. Part D concludes with the Roll of Honour.

Part E contains ten appendices. Appendices 2 and 3 consist of letters composed by OPs serving in various theatres of the war and published in The Pauline. Together they provide a compelling, if eclectic, insight into OPs’ experiences of the war.

Volume 2 is composed of two Chapters. Chapter 16 provides a description of the character of the Salient and presents an overview of the 93 OPs who fell in this place. It includes a Roll of Honour of the ‘93’. Chapter 17 narrates in detail the stories of each of these 93 OPs, thereby presenting a compelling case study of the experiences of those of junior officer rank who fought and fell in the Ypres Salient 1914 1918.9 The stories of the 93 OPs are presented in the sequence in which they fell rather than alphabetically by surname. This arrangement means that if the reader chooses to read the material en bloc they will thus gain an outline chronological narrative of the pattern of the war in the Salient.

8 The Pauline, Vol 34 14 Nov 1916 No. 228 p 157. High Master Hillard’s Apposition Address, 26 July 1916.

9 The number of OPs with no known grave in the Salient is appreciably higher (48 percent) than for all who 511 OPs who fell (35 percent), testimony to the particularly grim conditions that prevailed in the Salient.

This volume contains a series of photographs and maps relevant to the stories of the 93 OPs who fell in the Ypres Salient.

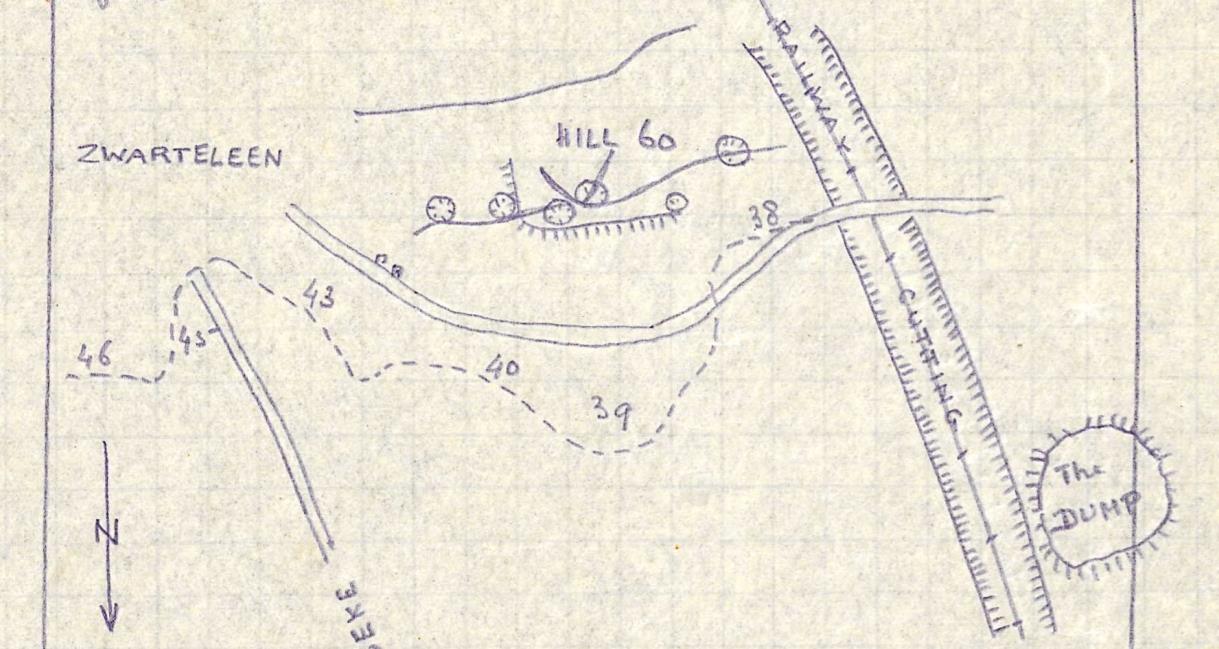

All sources are identified in footnotes. Inter alia, extensive use has been made of the school magazine, The Pauline, and the WO95 war diary material at The National Archives (TNA). I am grateful to the families Hansell and Hillier for allowing me to use material from their respective family archives.

Every effort has been made to identify holders of copyright material. The author would be grateful to hear from any such holder not hitherto contacted.

Chapter 16. Old Paulines and the Ypres Salient: ‘wherever we go, it cannot be to a worse place than the Ypres Salient’.

i)

Shortly before the advent of the 20th century Robert Laurence Binyon (SPS 1881 1888, see Vol 1, Chapter 11, Section 11.5) undertook a sojourn through western Flanders. The result was a book titled ‘Western Flanders: A Medley of Things Seen, Considered and Imagined’, published in 1899. In this work Binyon pronounced the buildings in Ypres, an ancient Belgian city in the province of West Flanders, as ‘the architectural glories of the Middle Ages’. At the city’s centre stood the cathedral and the Cloth Hall, the latter the largest secular building of Gothic Europe, boasting a belfry 230 feet high. For centuries these buildings, protected from the violence of invaders by the great moated walls thrown up by Marshal Vauban in the seventeenth century, had witnessed the ebb and flow of conflict in the landscape they surveyed. Yet, in the hostilities that began in August 1914 they were quickly razed, casualties of an industrial war in which heavy shelling was a defining characteristic. In 1917, when Binyon next wrote about Ypres, he thus described it as broken, a place possessed by the spirits of martial ghosts:

Shattered are the towers into potsherds Jumbled stones.

Underneath the ashes that were rafters Whiten bones.

Blood is in the cellar where the wine was, On the floor.

Rats run on the pavement where the wives met At the door.

But in Ypres there’s an army that is biding, Seen of none.

You’d never hear their tramp nor see their shadow In the sun.

Thousands of the dead men there are waiting Through the night,

16. Old Paulines and the Ypres Salient

Waiting for a bugle in the cold dawn Blown for fight.10

N.1 The Cloth Hall and the main tower of St Martin’s Cathedral (shown on the right half of the photograph) showing some damage as early as October November 1914.11 N.2 The Cloth Hall and the main tower of St Martin’s Cathedral in a considerably damaged state, January 1916.12 10 Binyon, Laurence. Published in Canadian War Records Office, Canada in Khaki:

16. Old Paulines and the Ypres Salient

Emptied of civilians and with its fabric rent asunder, the city had in fact died some time before 1917, attested by photographs such as L.1 and L.2 and in numerous private accounts A particularly rich example of the latter flowed from the pen of George Francis Hansell (known as Francis) (SPS 1908 1909 )

Francis enlisted with the 17th (Service) Bn. Royal Fusiliers on 2nd September 1914, thereby interrupting his studies at Christ’s College, Cambridge.1 Age 22, he crossed to France on 6 October 1915 in the 7th (Service) Bn. East Yorkshire Regiment. After five months at the front, Francis was invalided with shell shock and returned to England in February 1916. In November 1917 he returned to the front fulfilling an administrative role in the Labour Bn. King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, in which unit he rose to the rank of Acting Captain. After the war Francis became an assistant Master at Cheltenham Grammar School, teaching Geography. He died age 29 on 19 September 1922, the result of what his Death Certificate describes as ‘the accidental discharge of an automatic pistol’. He left a wife and two sons.

13

13 Hansell, Francis, Letters Home 1915 1919. 23 October 1915 pp 18 19. Courtesy of the Hansell family.

16. Old Paulines and the Ypres Salient

Francis composed 94 letters home, spanning with few lapses the period from June 1915 to February 1919. On 21 October 1915 Francis’ unit took over a canvas camp near Ouderdom, south east of Poperinghe. It was from here that he set forth on 23 October, instructed to deliver a message to another unit. The journey involved passing though Ypres, the condition of which he described thus:

I shall never forget the appalling sight as long as I live. It seems almost as if we were in another world riding through a city of the dead. In the whole place (and I travelled down many streets) I never saw a single house that was not in ruins. Of course there are no civilians allowed anywhere in the town and the only people we saw in the deserted streets were a few sentries pacing solemnly to and fro and an occasional despatch rider. There were a few other signs of life such as half starved dogs and cats but that was all. The havoc is absolutely indescribable. No description could ever have brought home to me the terrible desolation of the place if I had not seen it with my own eyes. Every article of furniture you can think of lay strewn about the streets, everywhere we came across great craters made in the ground by the heavy shells which the Germans continue to hurl into the town. The railway lines and other metal work were in many cases twisted into the most extraordinary shapes. Once we passed a large cemetery and the smell of dead bodies nearly made me sick for the shells had brought many of them up to the surface. I saw one or two coffins in the gutter. At another place, we passed a little orchard with rows and rows of rude wooden crosses under the apple trees. Here and there an Officer’s cap hung on the top of the cross showed the rank of the “poor inhabitant below”. I think I could fill a book with all the

Old Paulines and the Ypres Salient

wonderful sights I saw in that city of ruins. Yet after all it is only one of many! We passed close by the celebrated Cathedral and Cloth Hall, the ruins of which I dare say you have seen in the illustrated papers. I think if anything had been wanting to rouse my hate for the ‘Bosche’ the sight of these magnificent old buildings in ruins would have done so. What horrible madness this war is!14

Upon leaving the sector on 6 January 1916, Francis wrote to his mother, telling her that: It will be with a light heart that I shall say good bye to the gloomy ruins of Ypres for I hope we shall not be coming back to this part of the line wherever we go it cannot be to a worse place than the YPRES salient.15

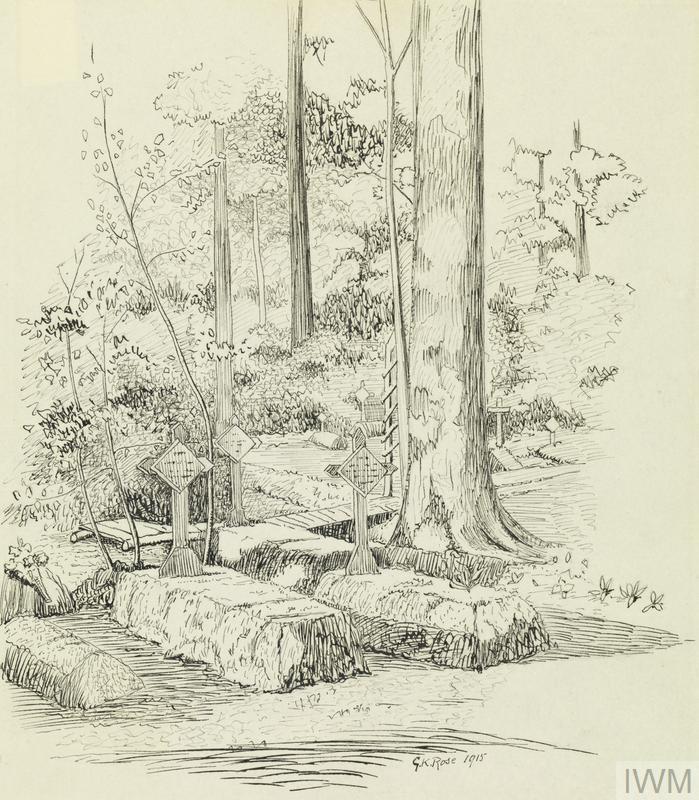

Harold Drummond Hillier (SPS 1906 1910, see Vol 1, Chapter 8, Section 8.10, i), another OP who had experience of Ypres, composed a number of sketches and watercolours of the broken city.

N.3 Eglise St Pierre, Ypres. March 1917. Painted by Harold Drummond Hillier (SPS 1906 1910)16

14 Hansell, Francis, Letters Home 1915 1919. 23 October 1915 pp 18 19. Courtesy of the Hansell family.

15 Hansell, Francis, Letters Home 1915 1919. 6 January 1916 p 43. Courtesy of the Hansell family.

16 Harold Drummond Hillier MC, WW1 Sketches and Watercolours. I am grateful to the family for allowing me to use this material.

16. Old Paulines and the Ypres Salient

Throughout the duration of the 1st World War the city of Ypres was strategically significant, standing in the path of Germany’s planned sweep to the Channel ports. The Germans briefly occupied the city in 1914 before moving back a short distance to the east, thereby effecting a calculated withdrawal in order to occupy the higher ground that existed in that vicinity and to the south. By the end of the same year both sides were digging in and establishing lines of connected trenches.

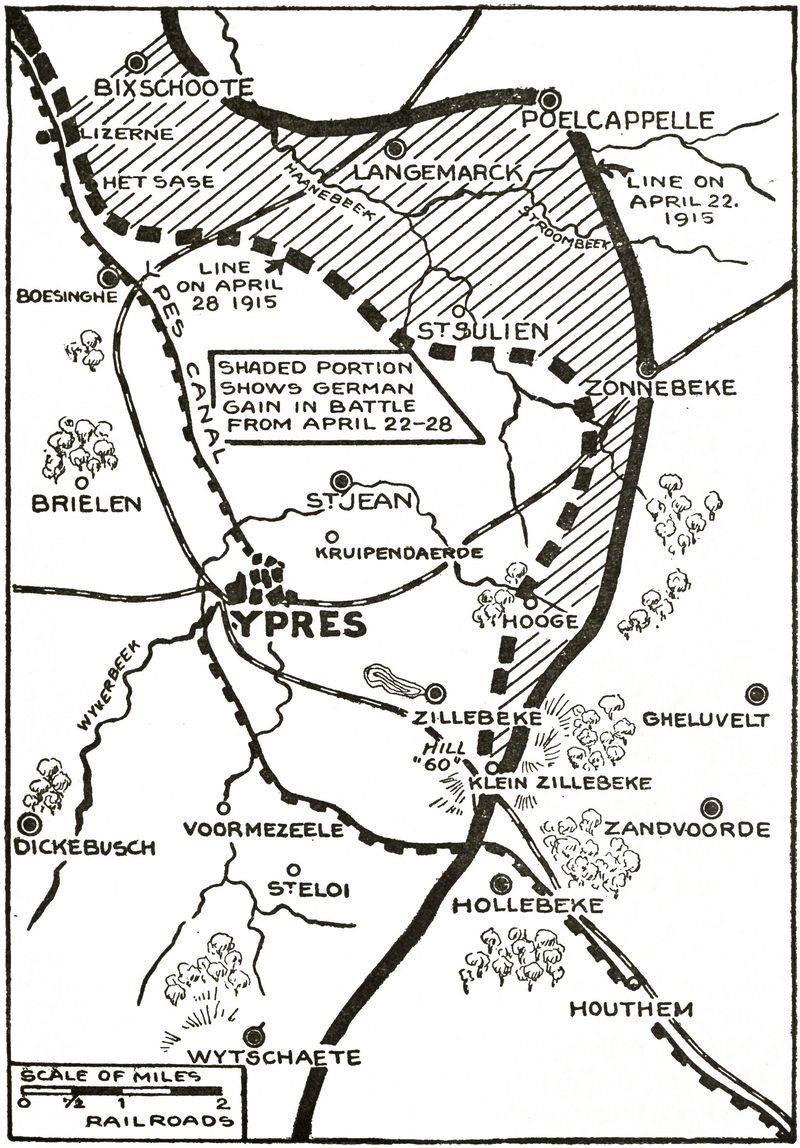

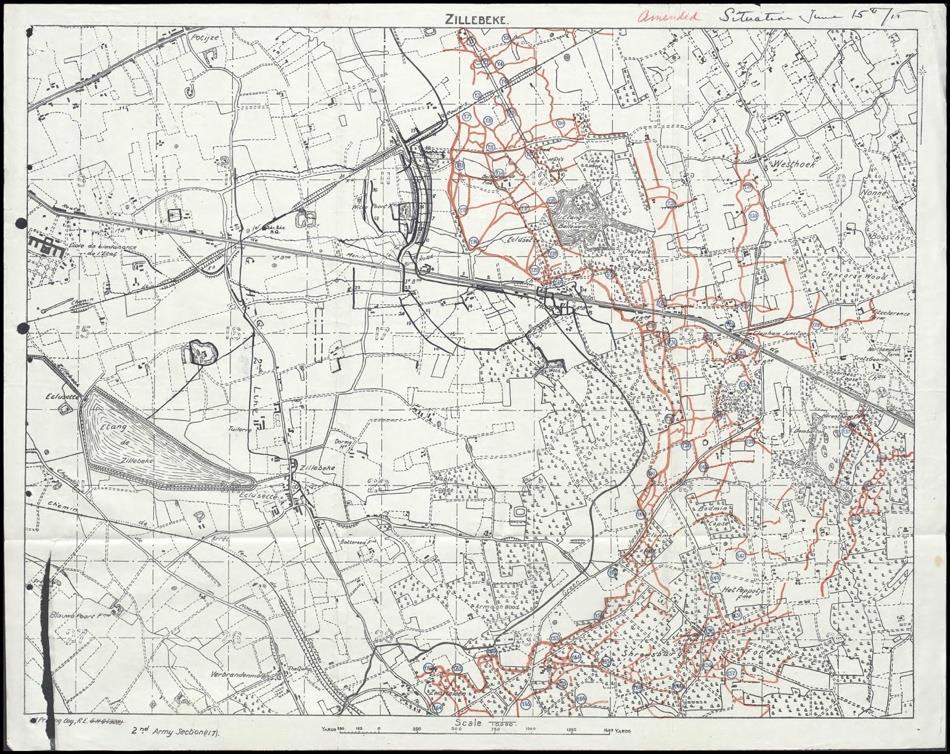

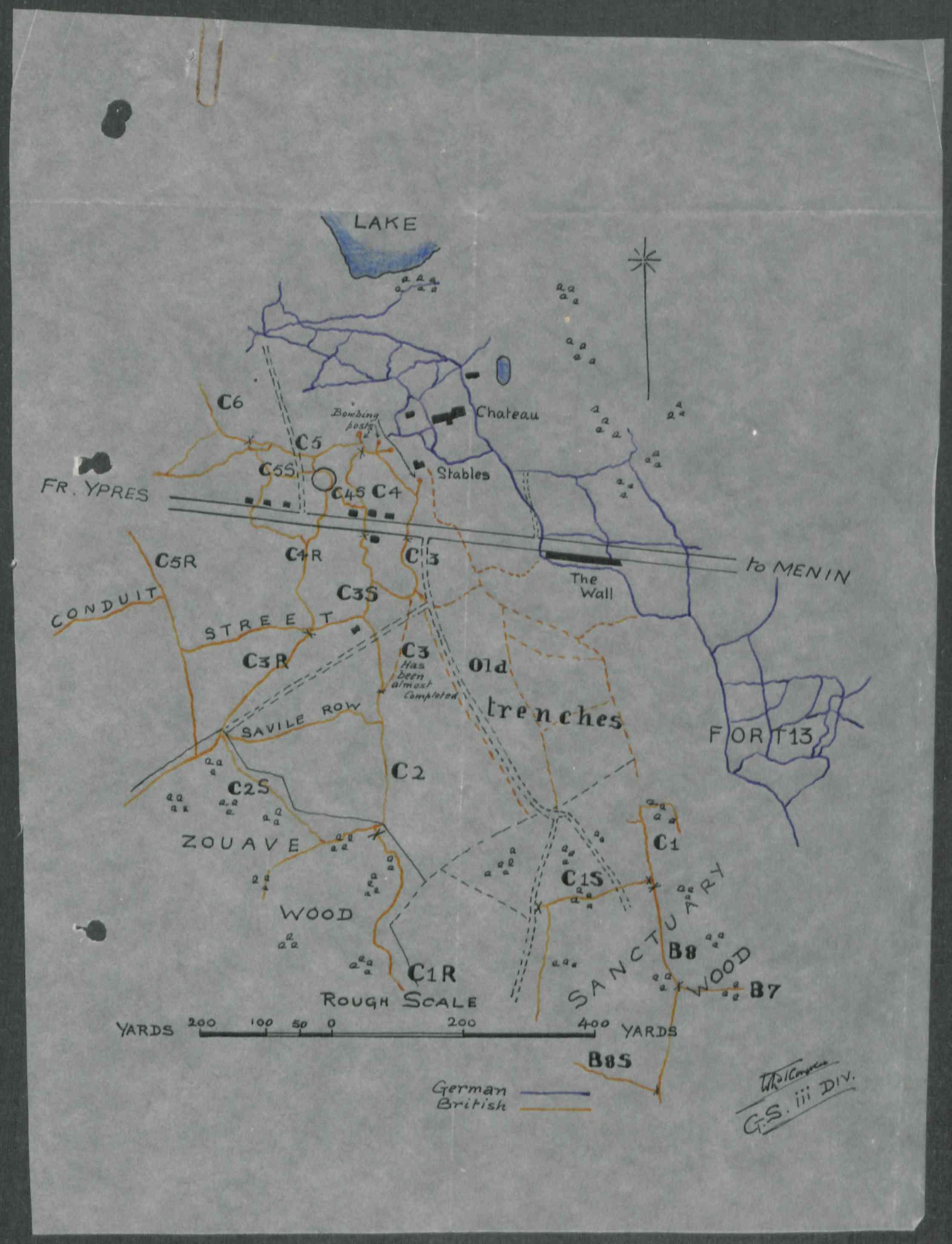

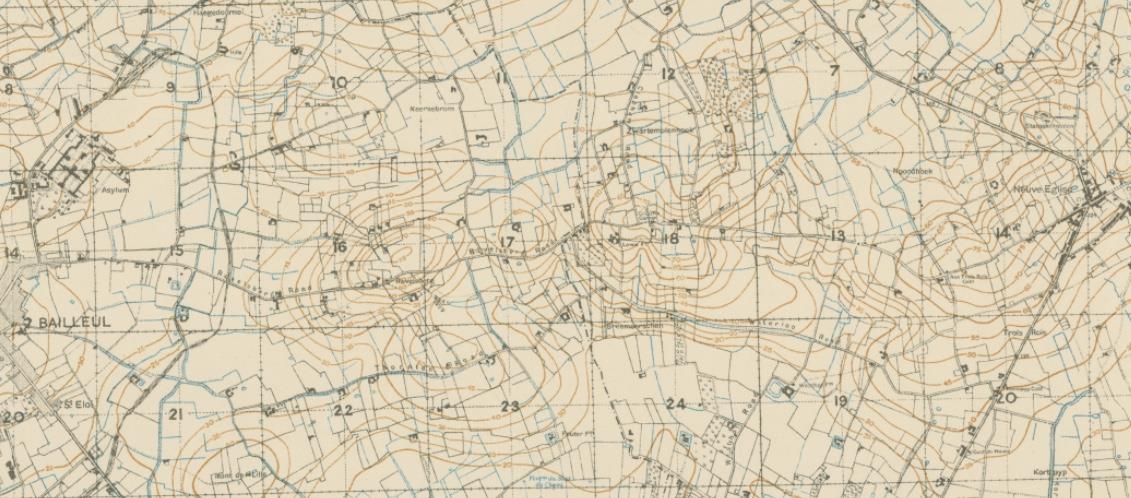

The German withdrawal had the effect of creating a bulge in the line known as a ‘salient’. The resulting salient ran from roughly Boesinghe, four miles to the north of the city, to Ploegsteert, some nine miles to the south. Overlooked by the Germans from three sides, Ypres thus became one of the most dangerous of all sectors along the four hundred mile long Western Front; and in this most perilous sector, there existed the most dangerous place of all: Hellfire Corner a crossroads and a railway crossing on the Menin Road, about one mile to the east of Ypres, that had to be navigated in order to access much of the battlezone. It was thus surely known by many an OP who served in the Salient.

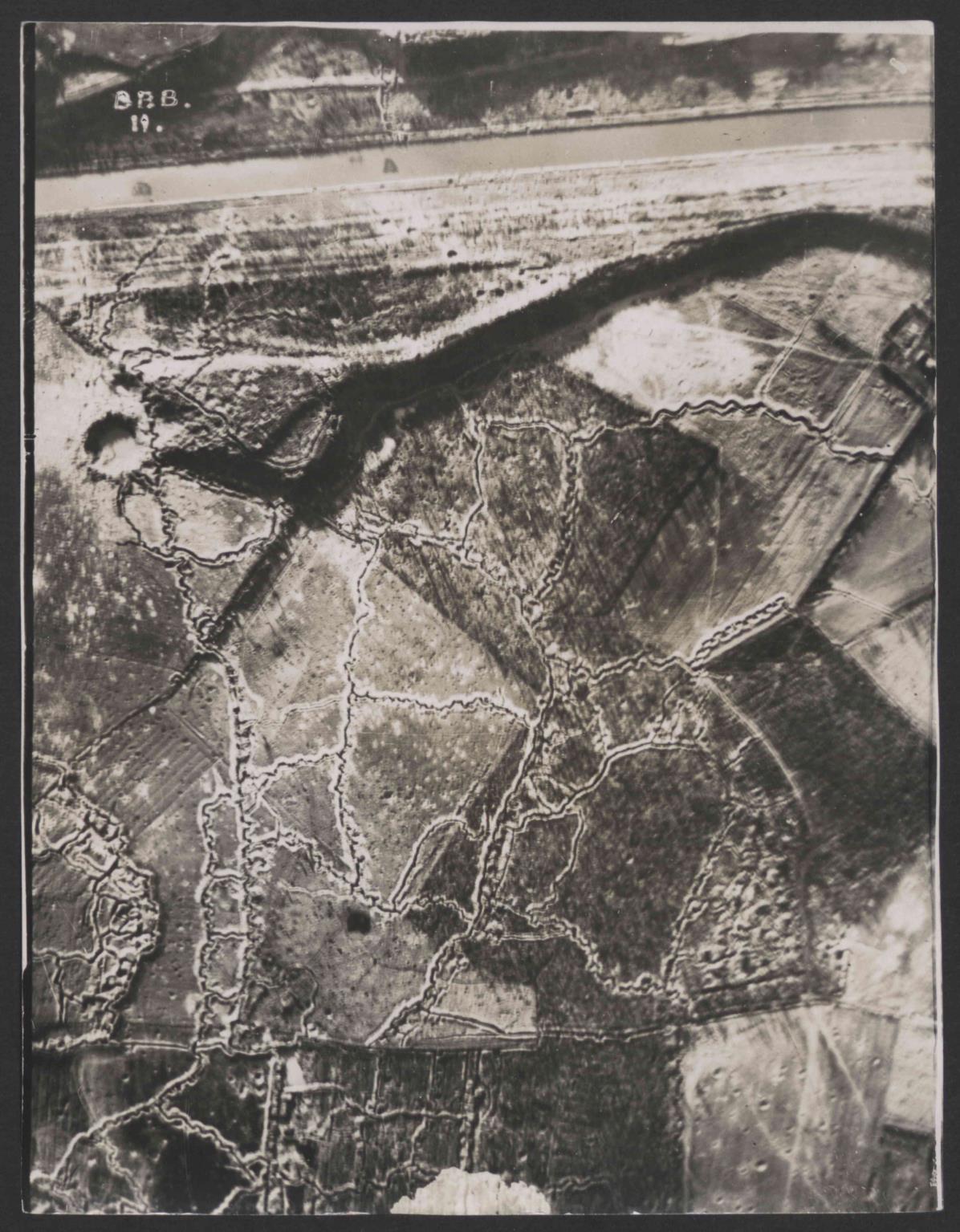

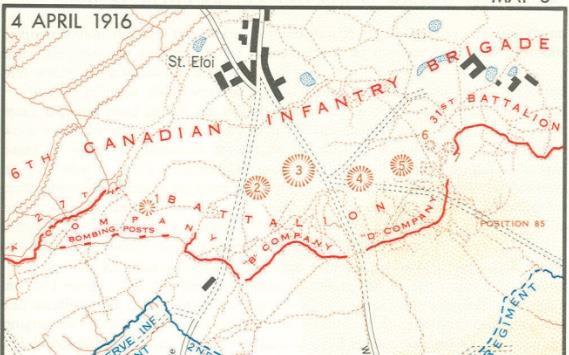

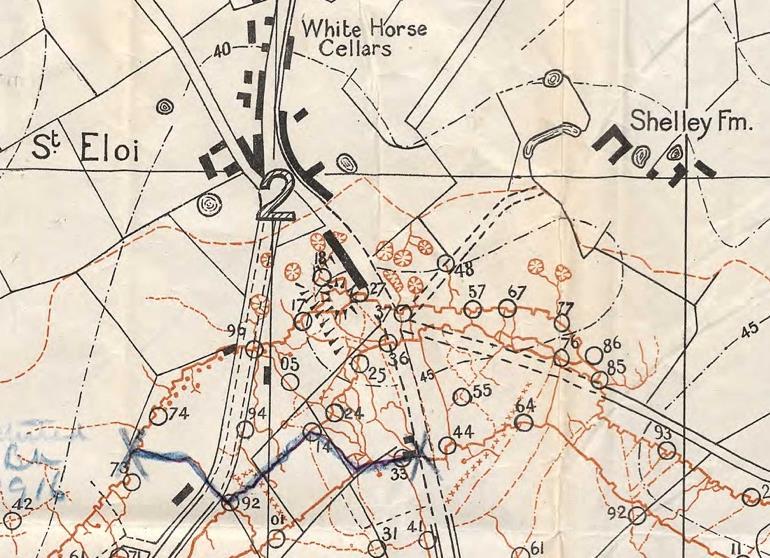

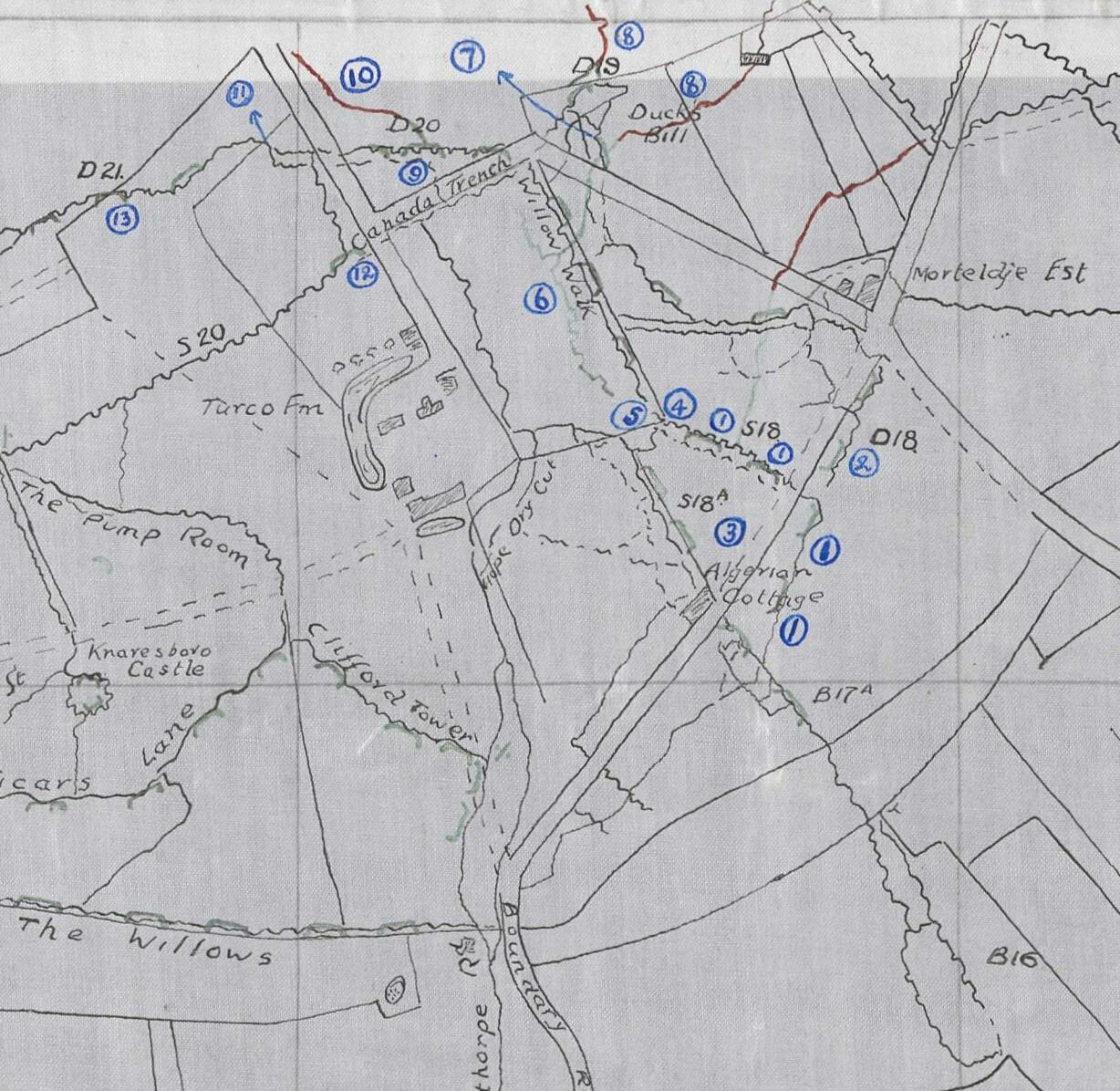

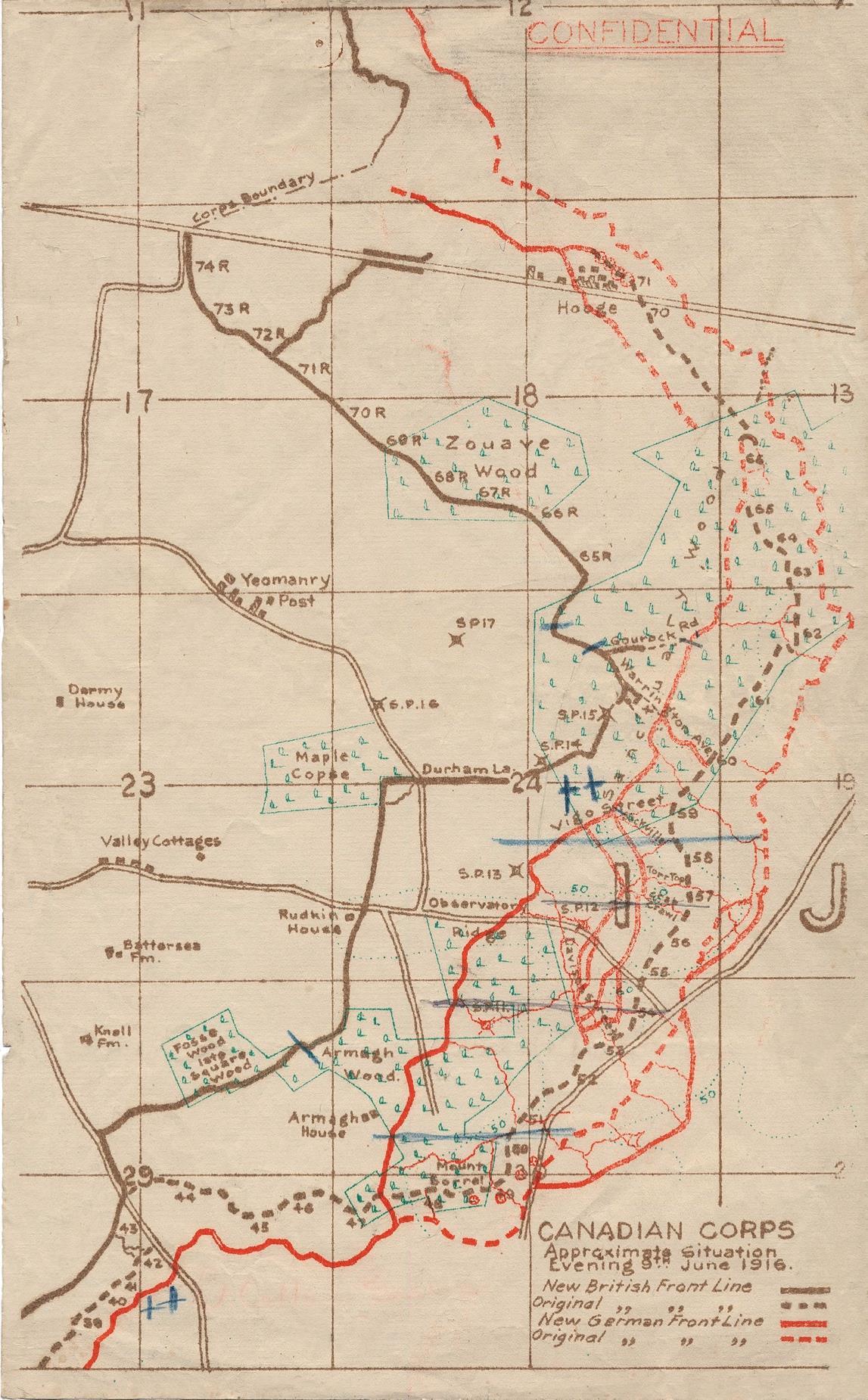

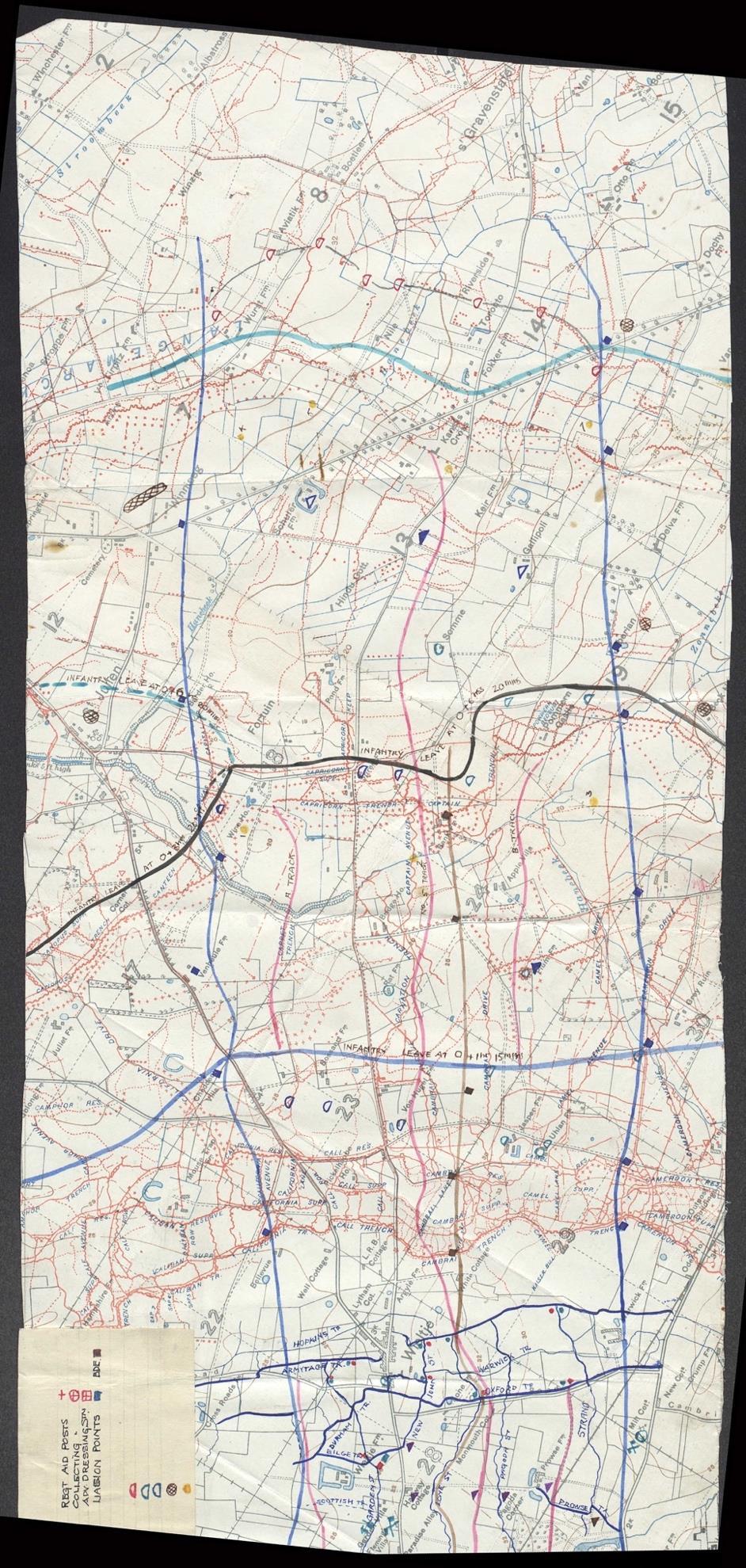

Five large scale battles took place in the Ypres Salient, of which only the Third Battle of Ypres (known as the Battle of Passchendaele, 31 July 10 November 1917) and Fifth Battle of Ypres (28 September 2 October 1918) were fought offensively by the Allies. The in between times were often relatively quiet, the principal activity during these periods being that of trench raiding. Nevertheless, from time to time the Allies undertook operations, notably a series of mining actions at St Eloi (27 March 16 April 1916) and prior to the Battle of Messines Ridge (7 June 14 June 1917), and operations at and around Hooge and Hill 60. For most of the period 1914 1918 the front line around the Ypres Salient remained fairly static, but on occasion it moved several miles, most particularly in the great German offensives of 22 April 15 May 1915 and 9 29 April 1918 (the Second and Fourth Battles of Ypres respectively.)

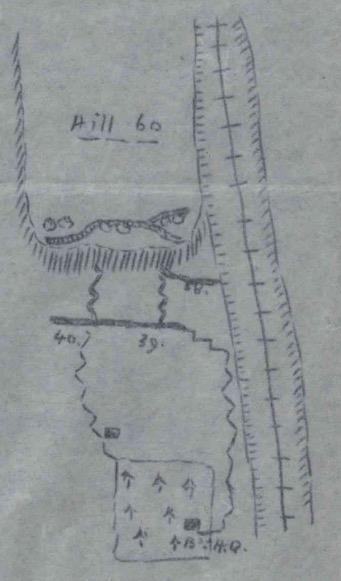

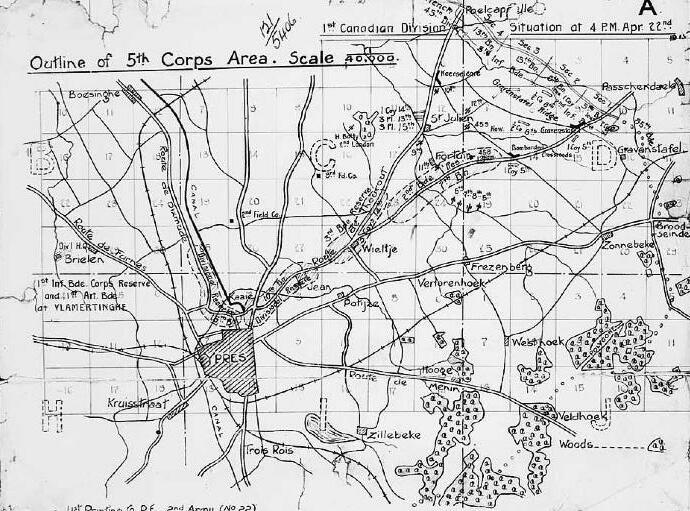

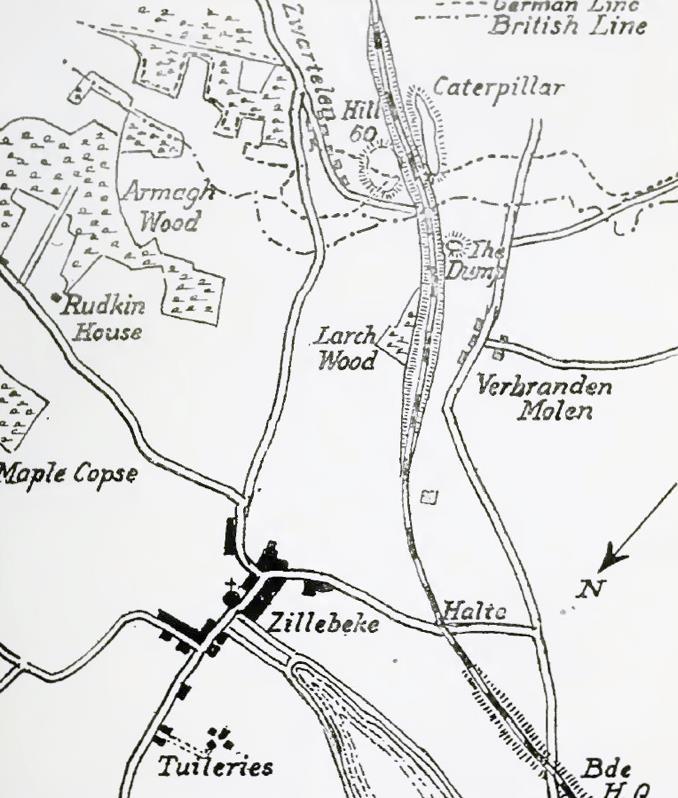

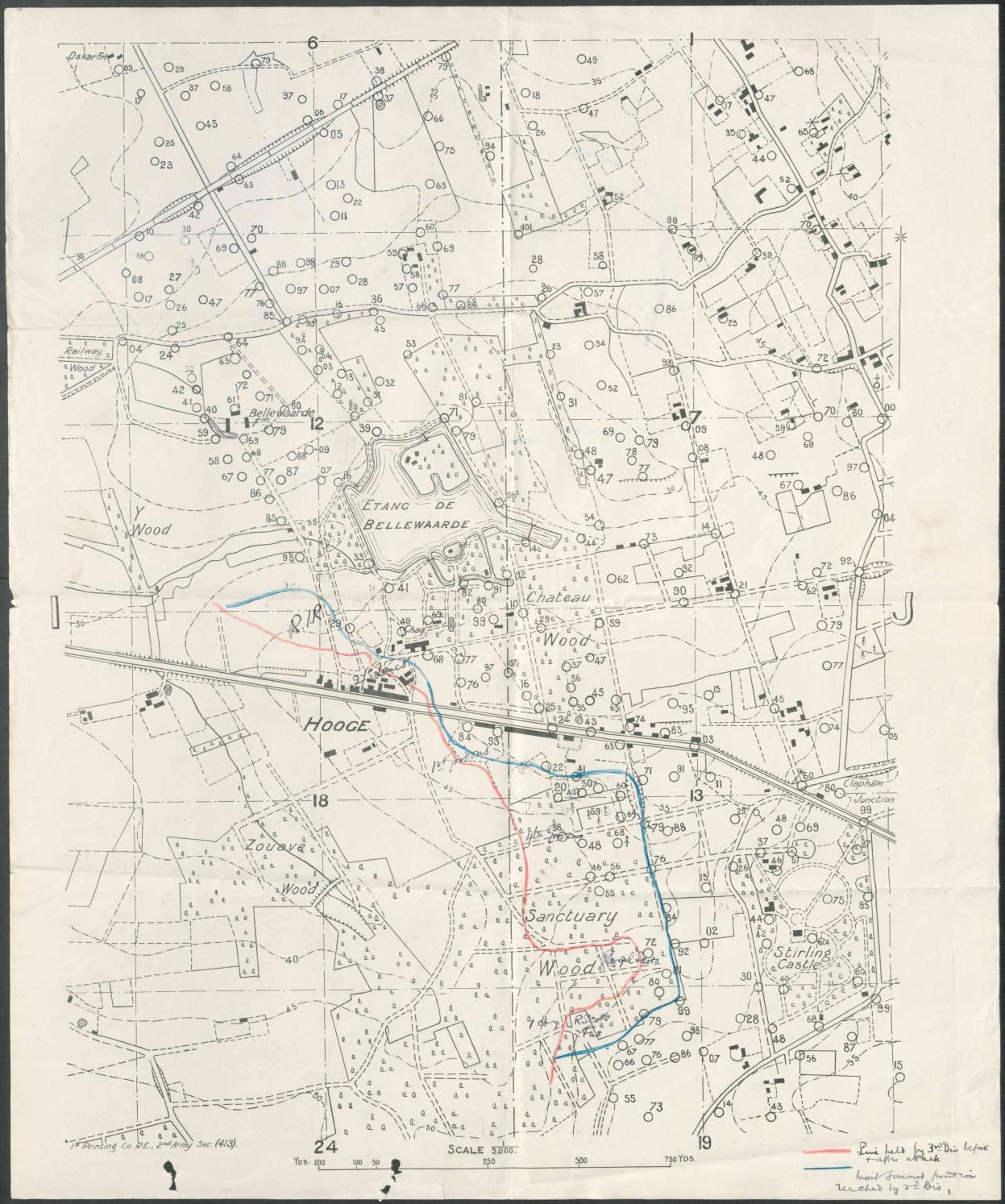

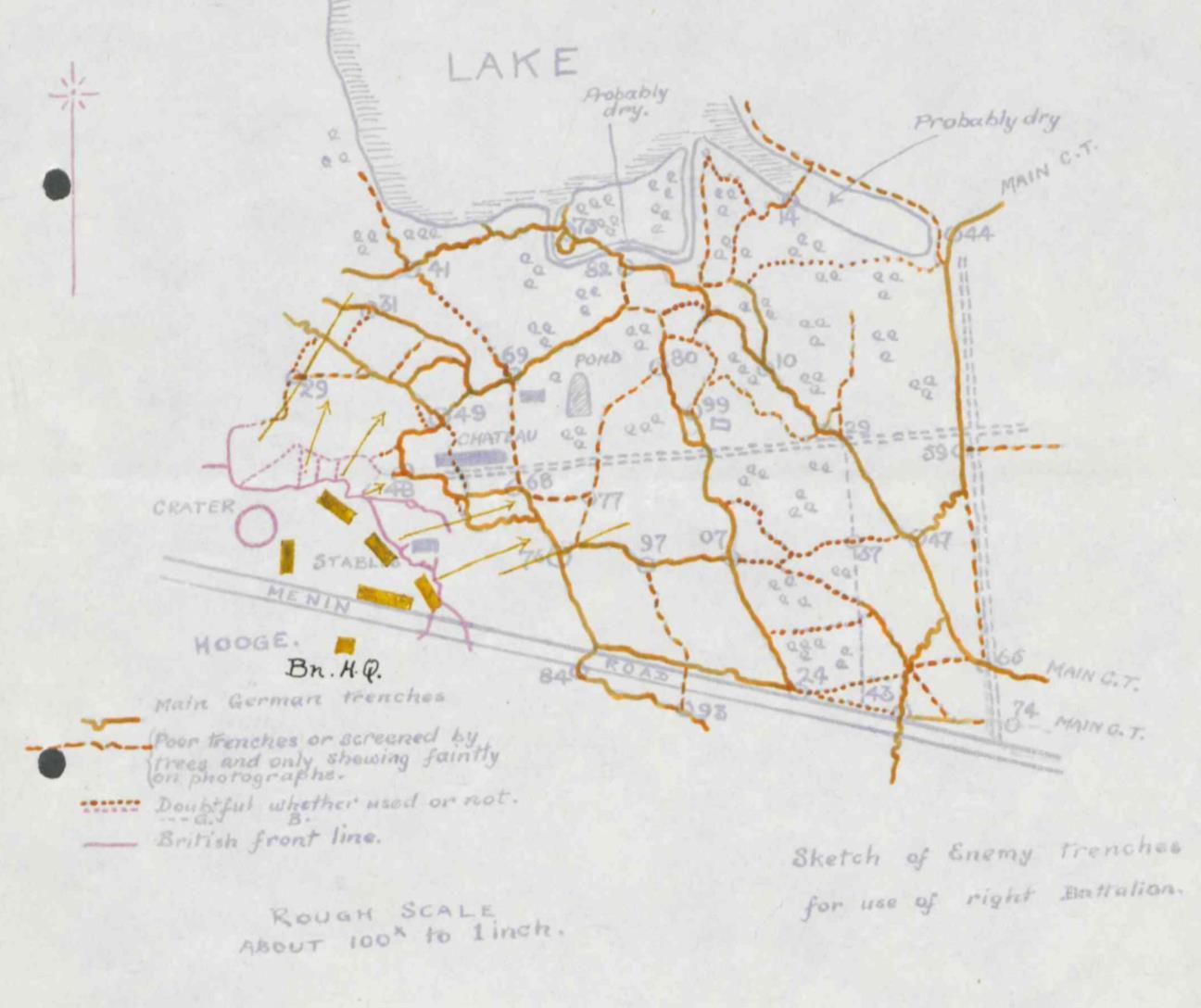

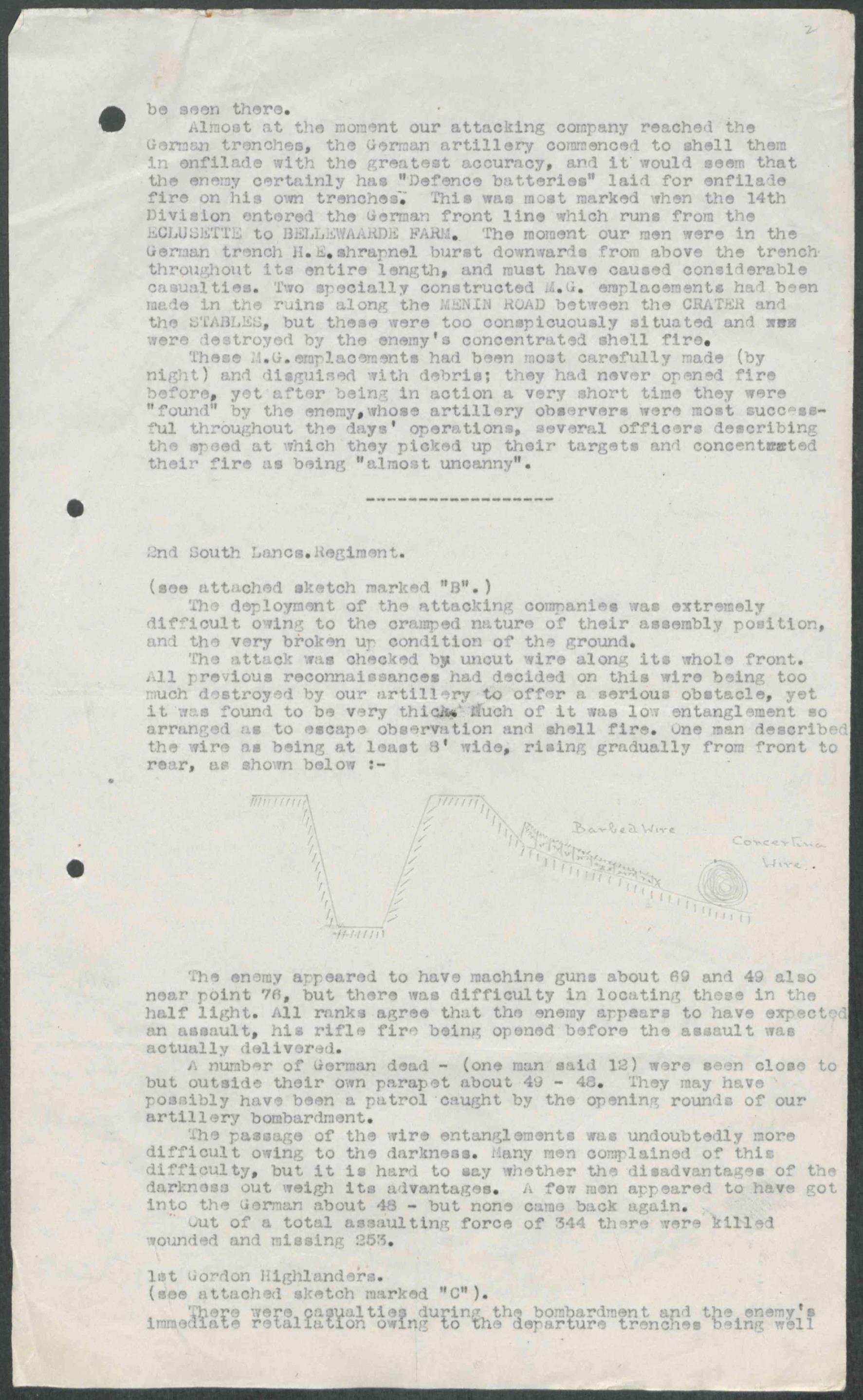

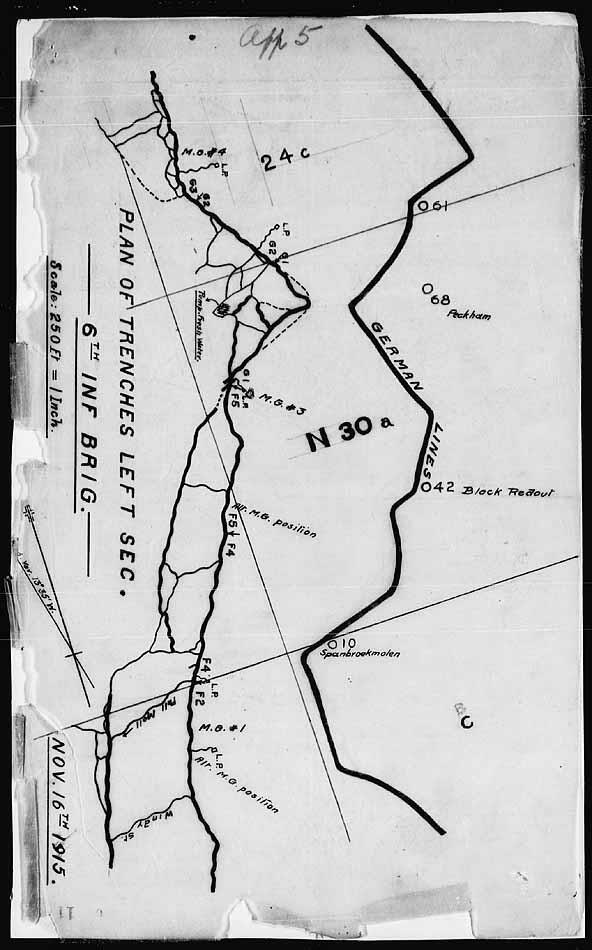

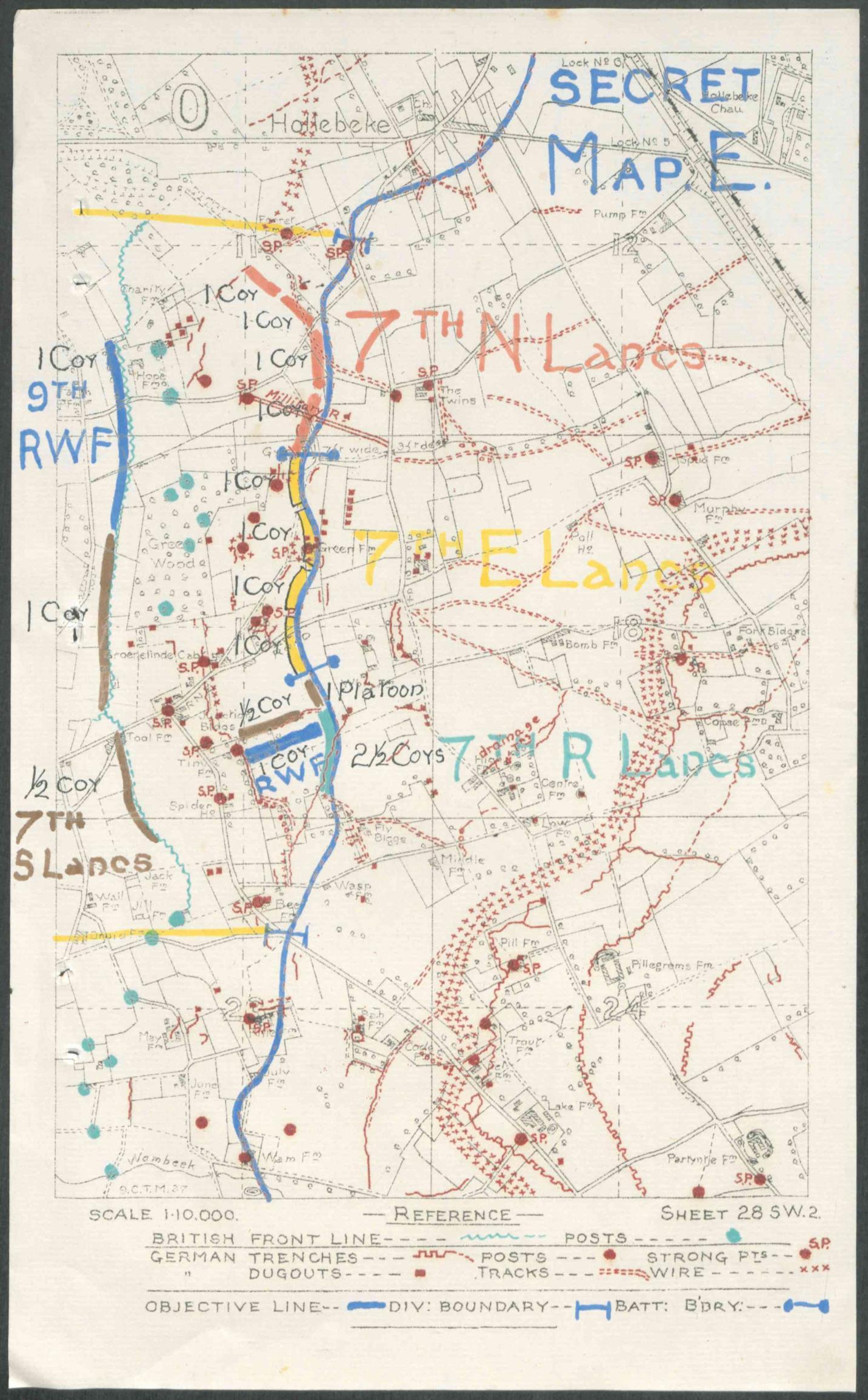

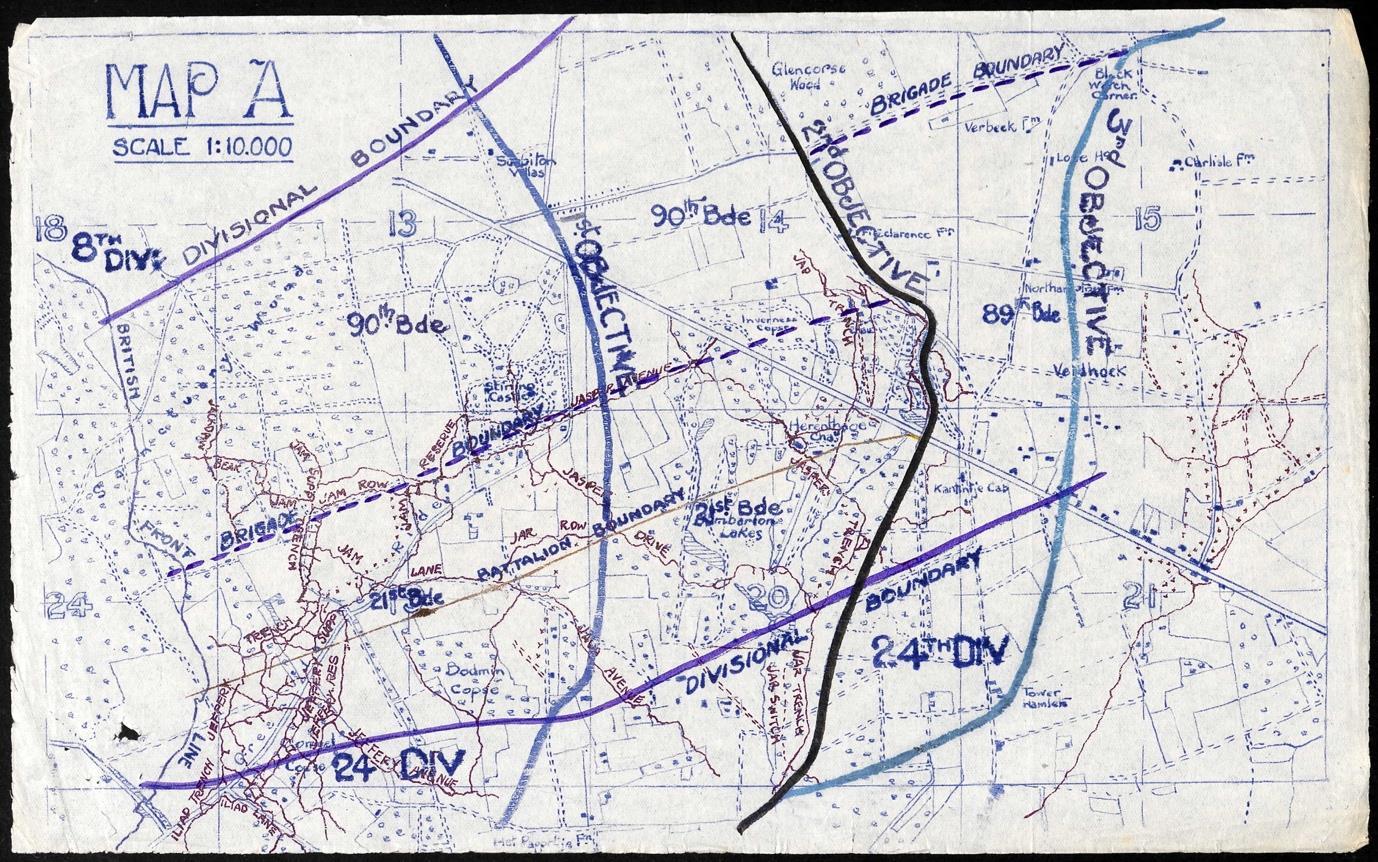

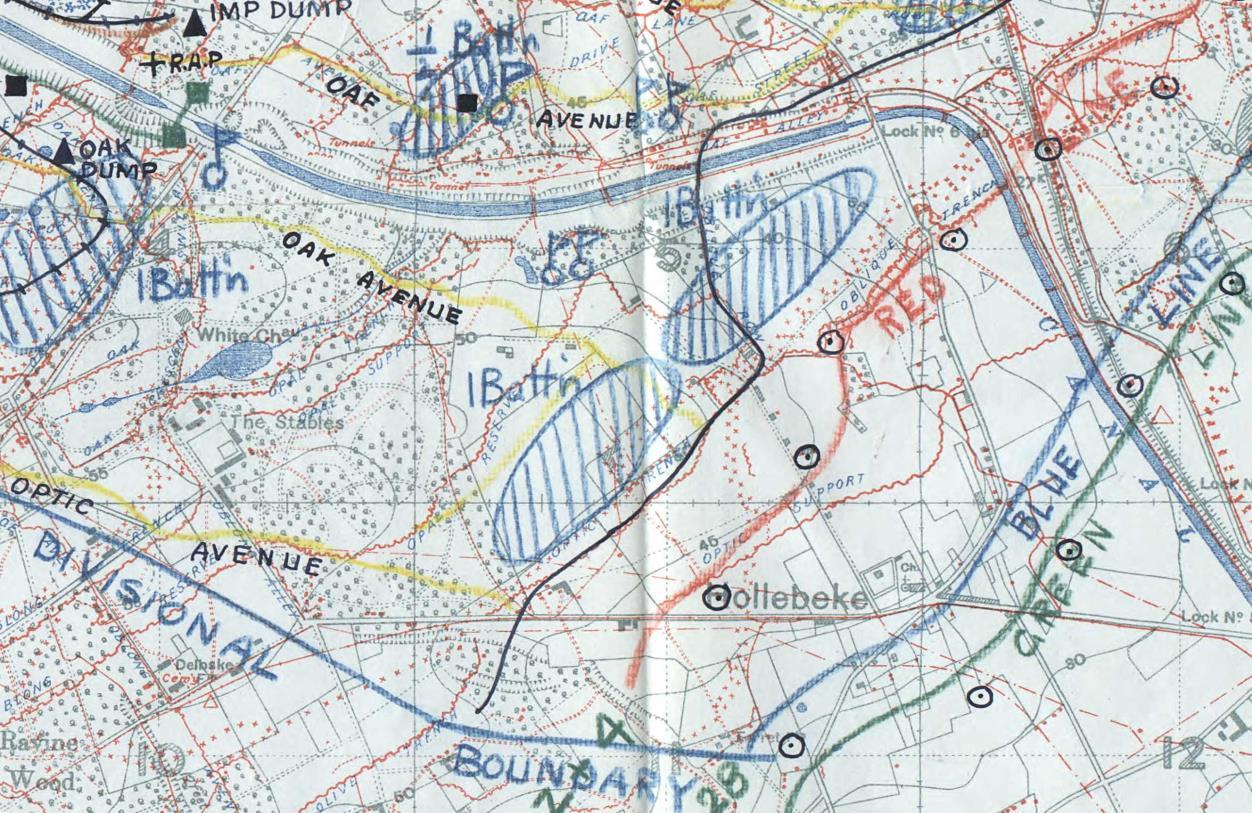

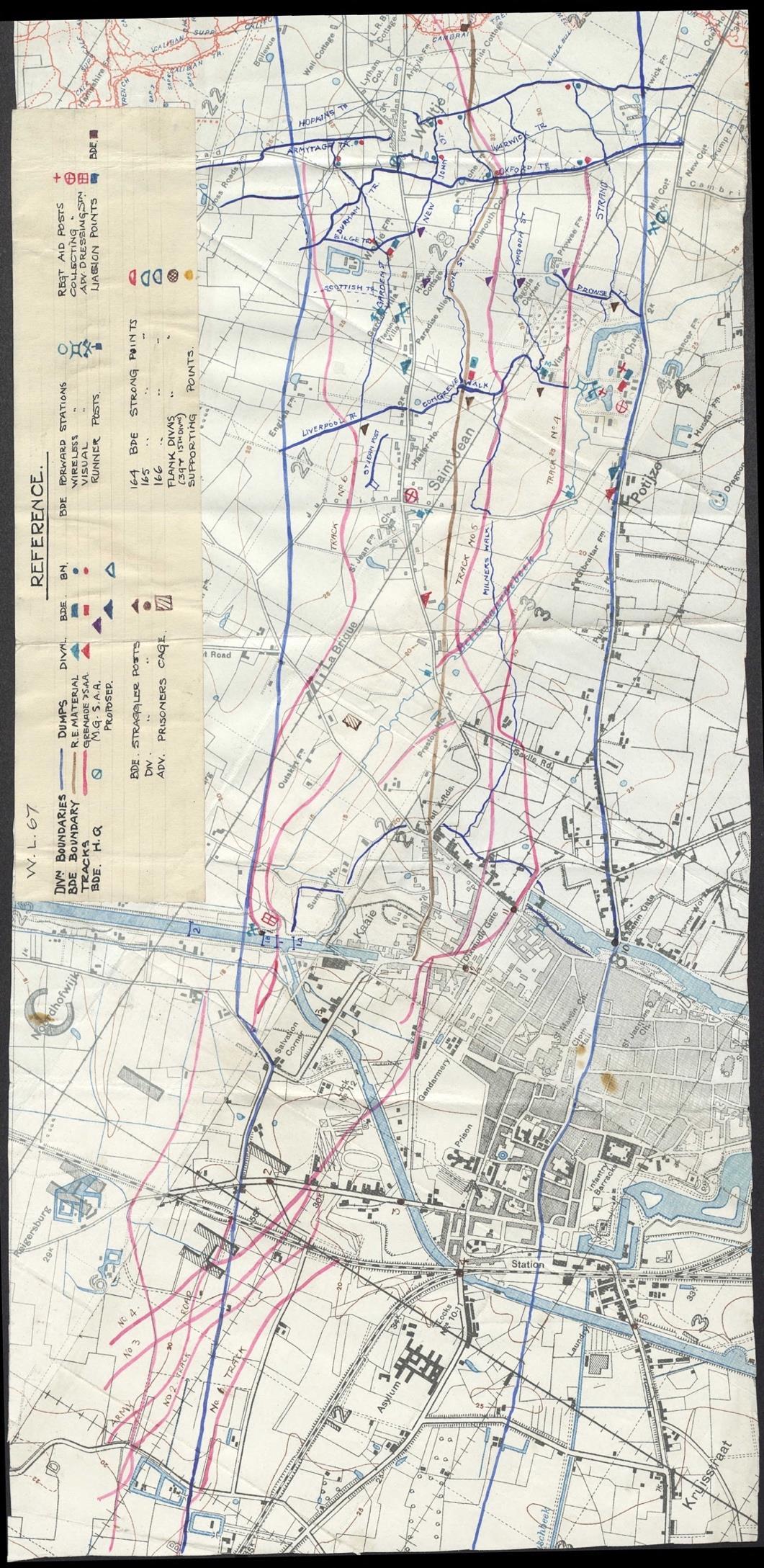

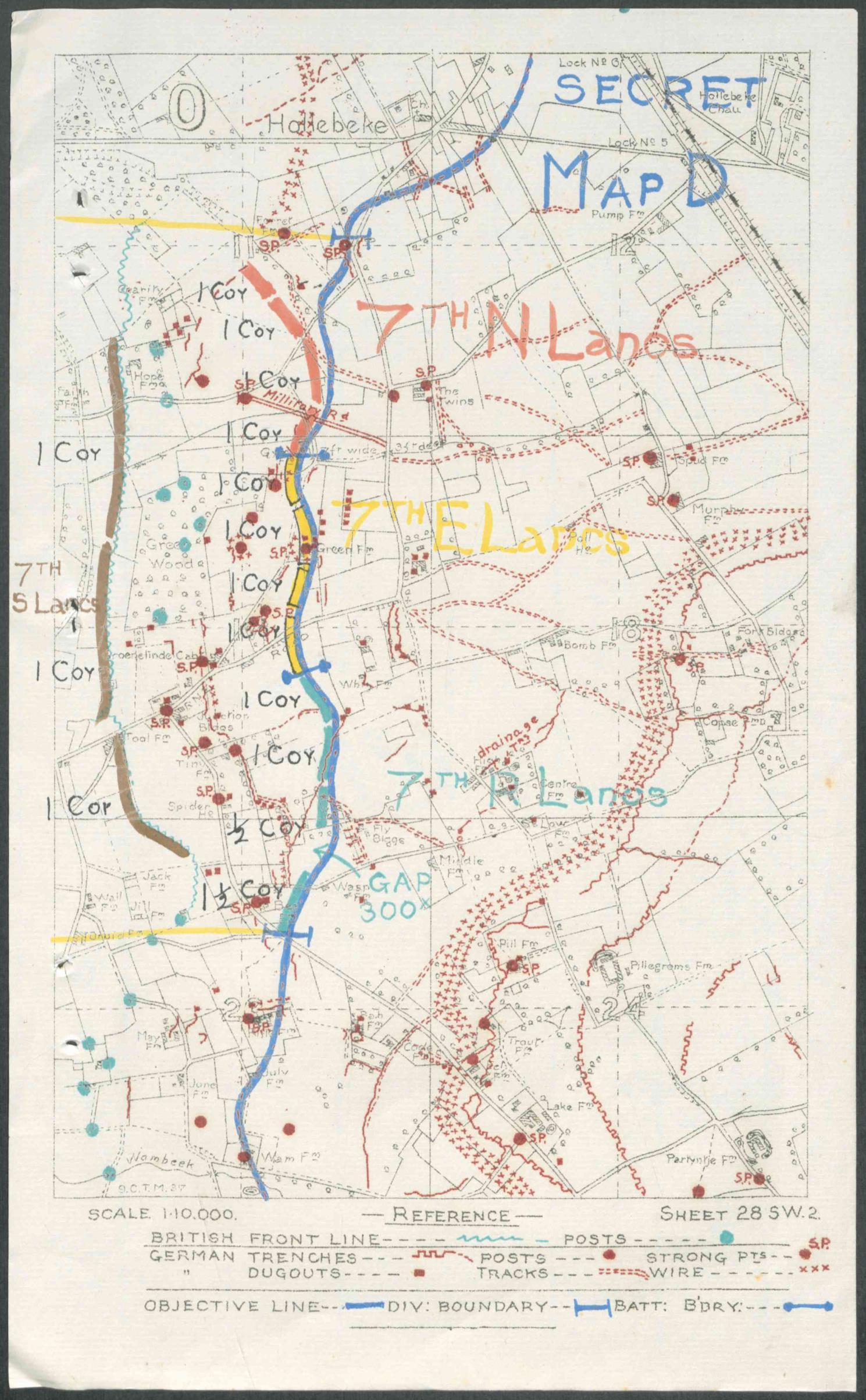

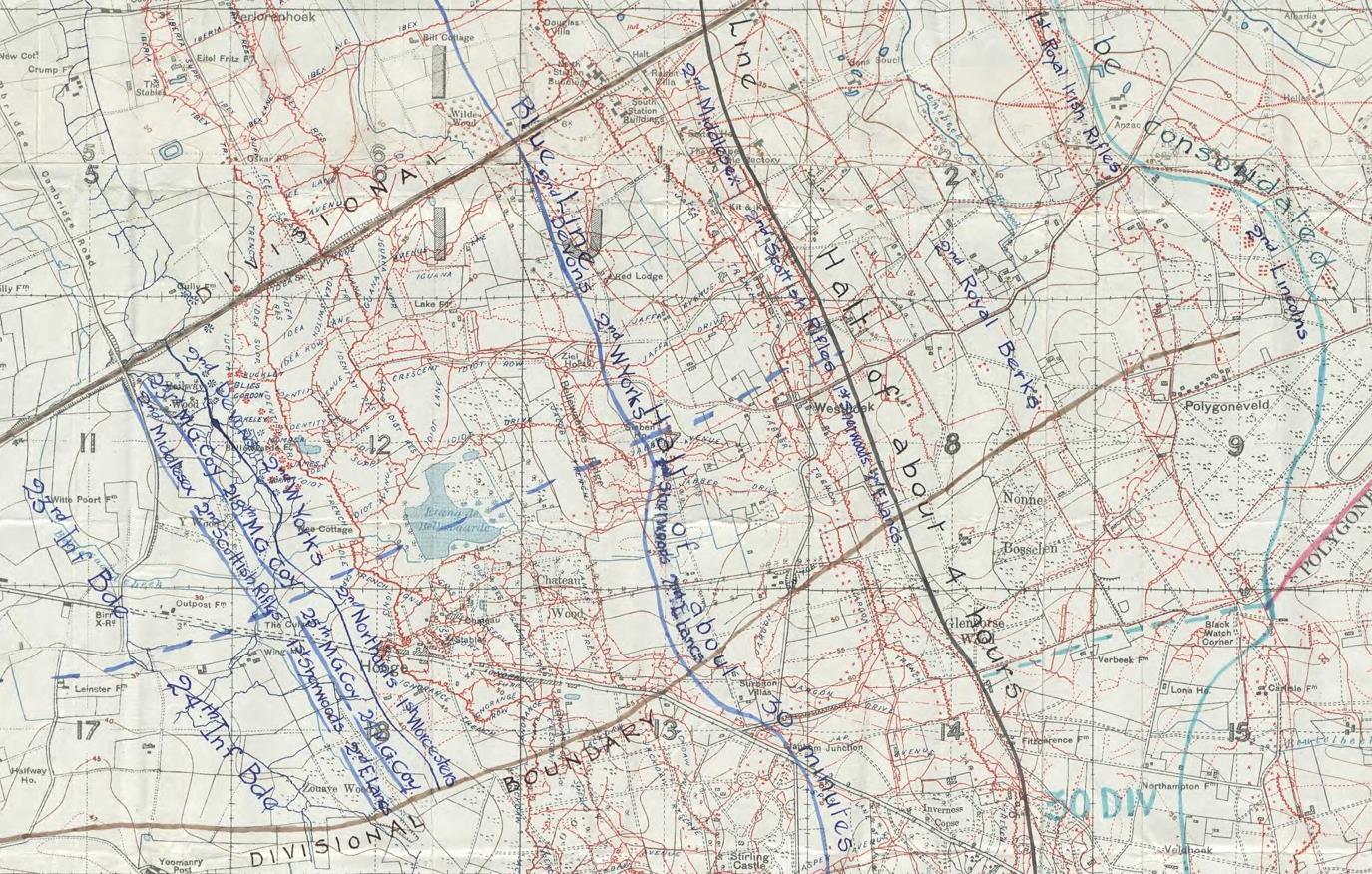

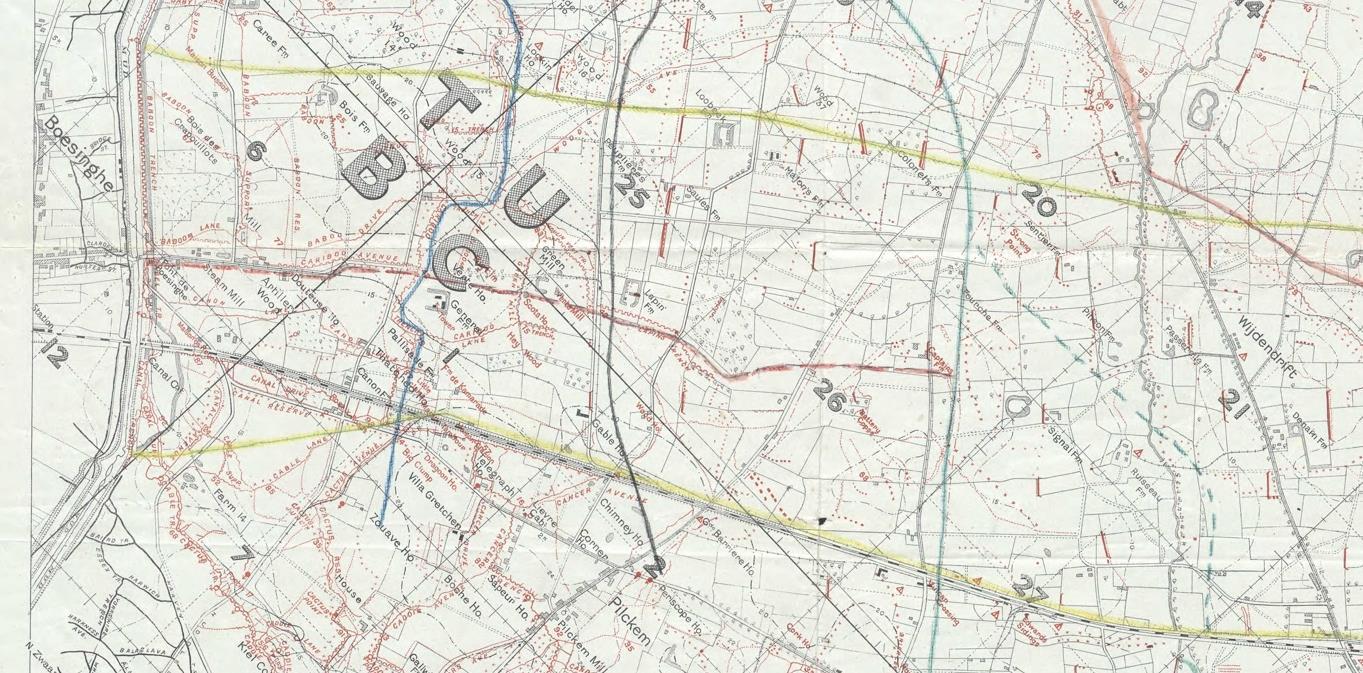

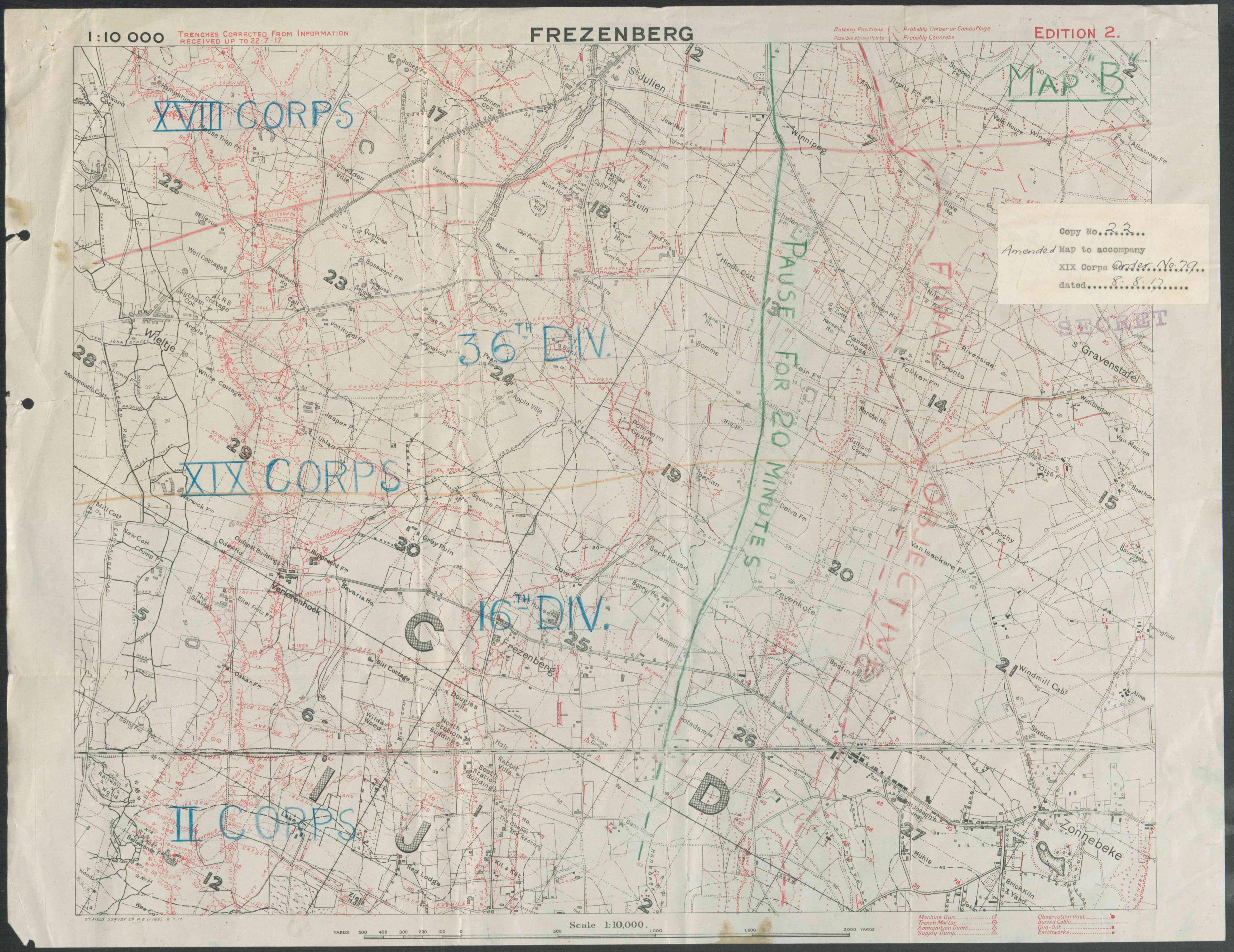

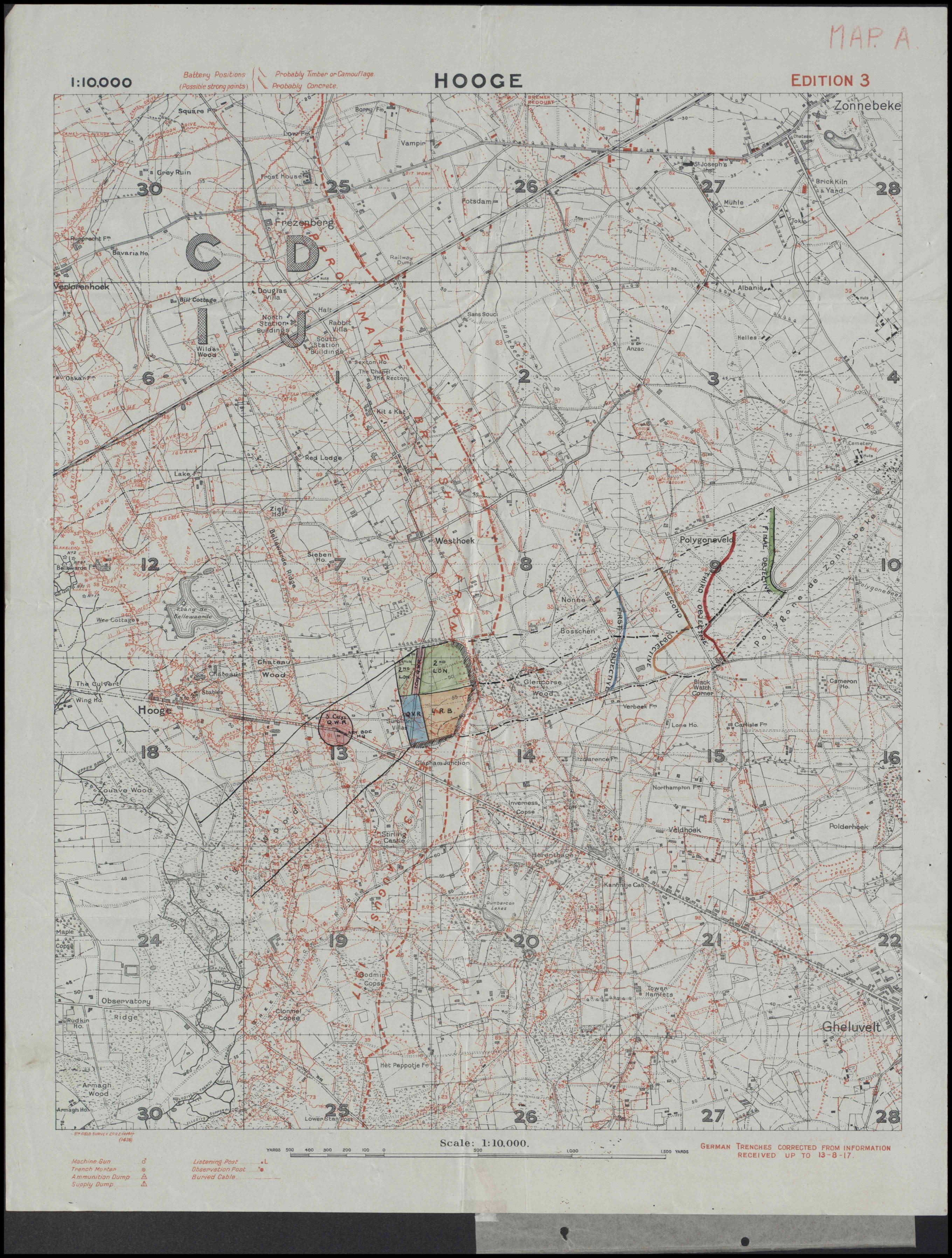

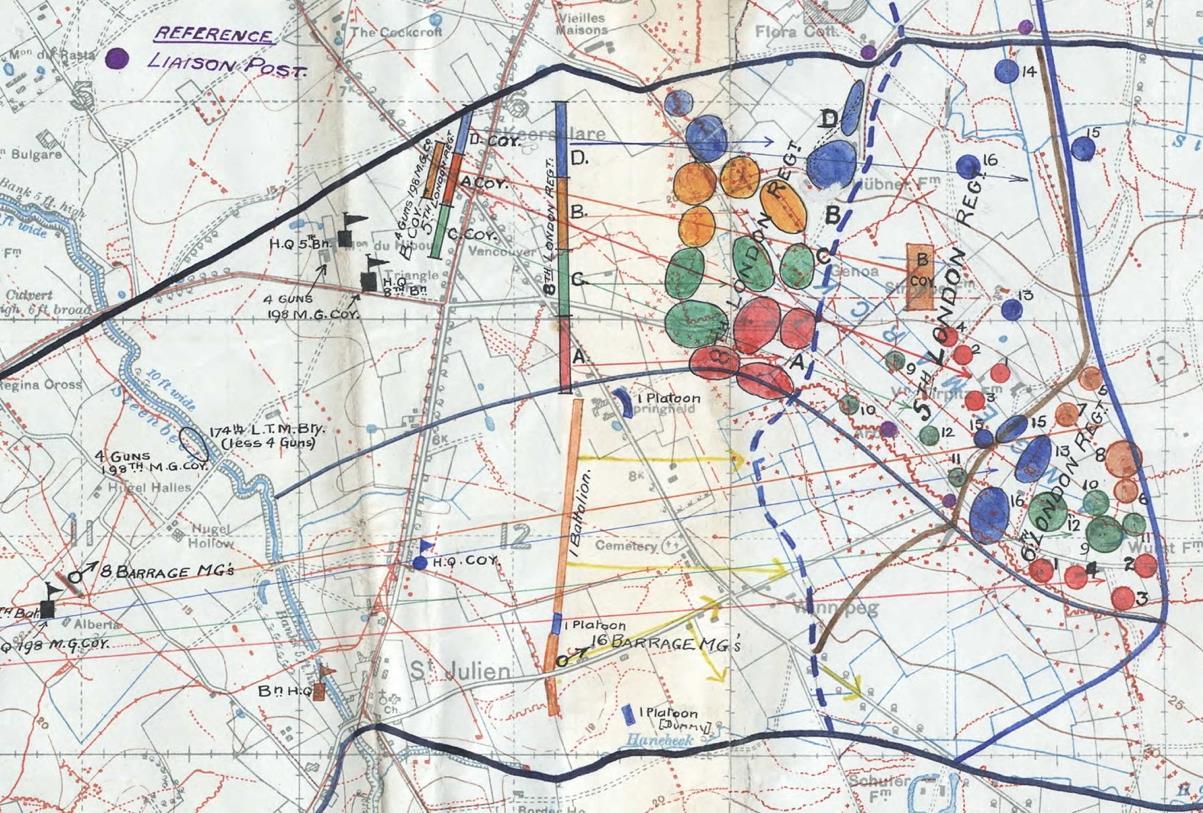

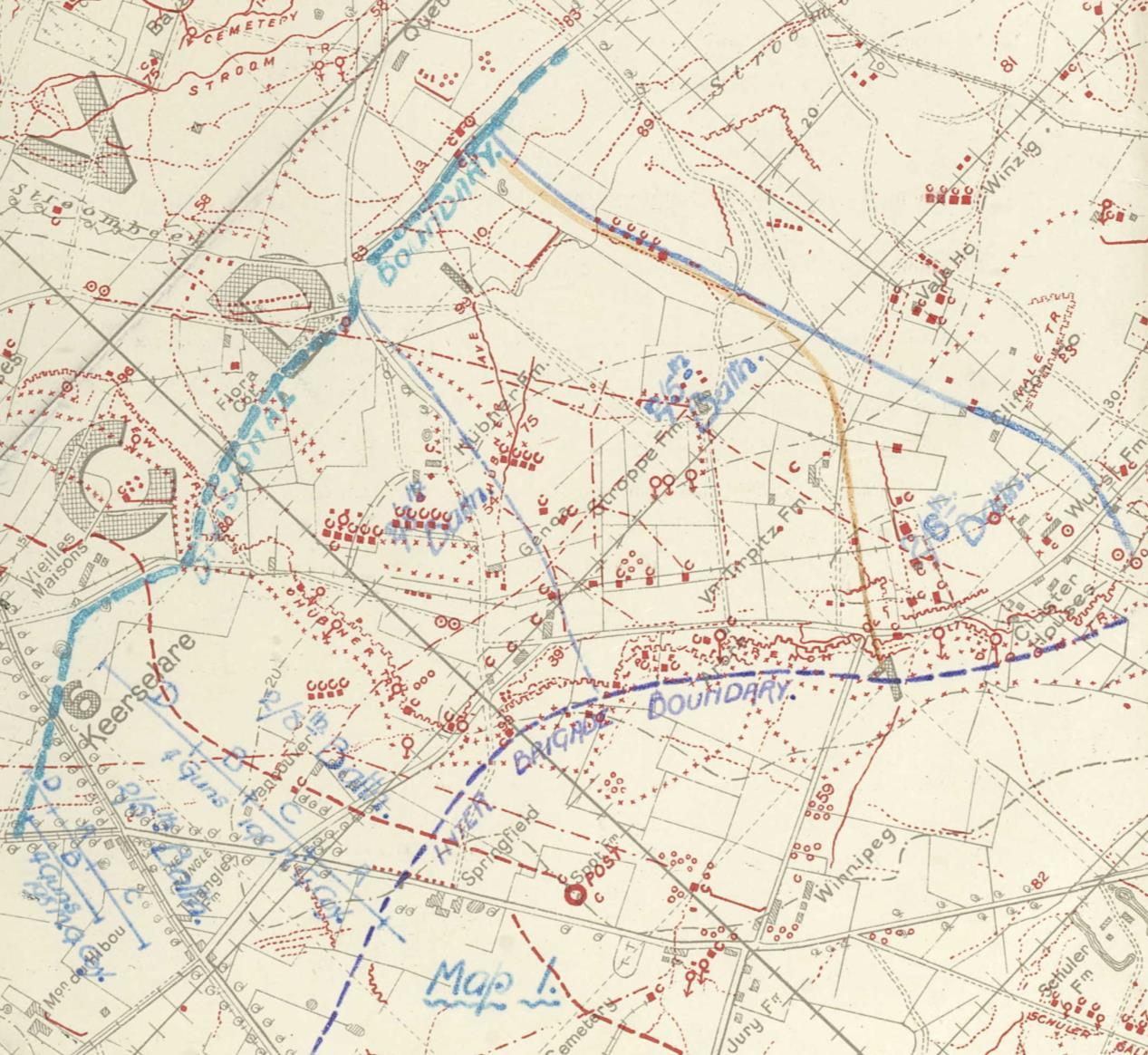

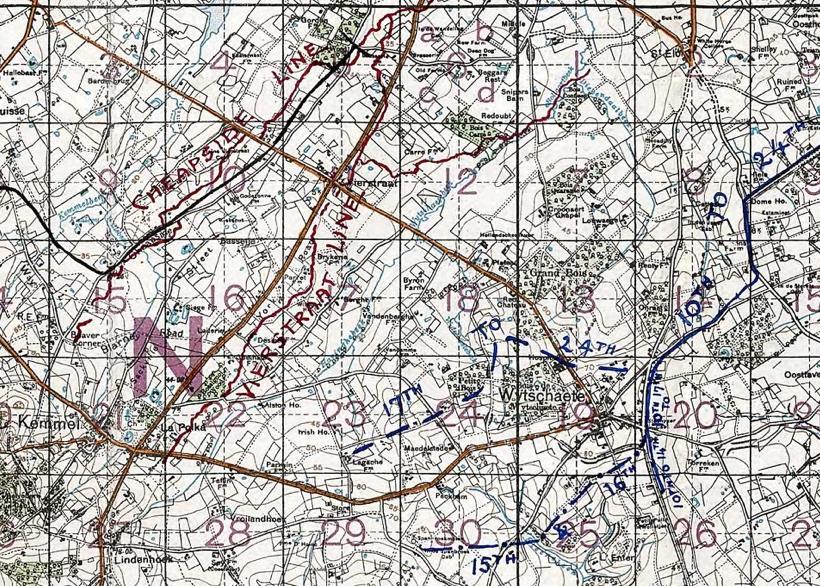

N.4 Map showing the Ypres Salient and the various positions of the front lines, 1914 1918.17

17 Map courtesy of CWGC

16. Old Paulines and the Ypres Salient

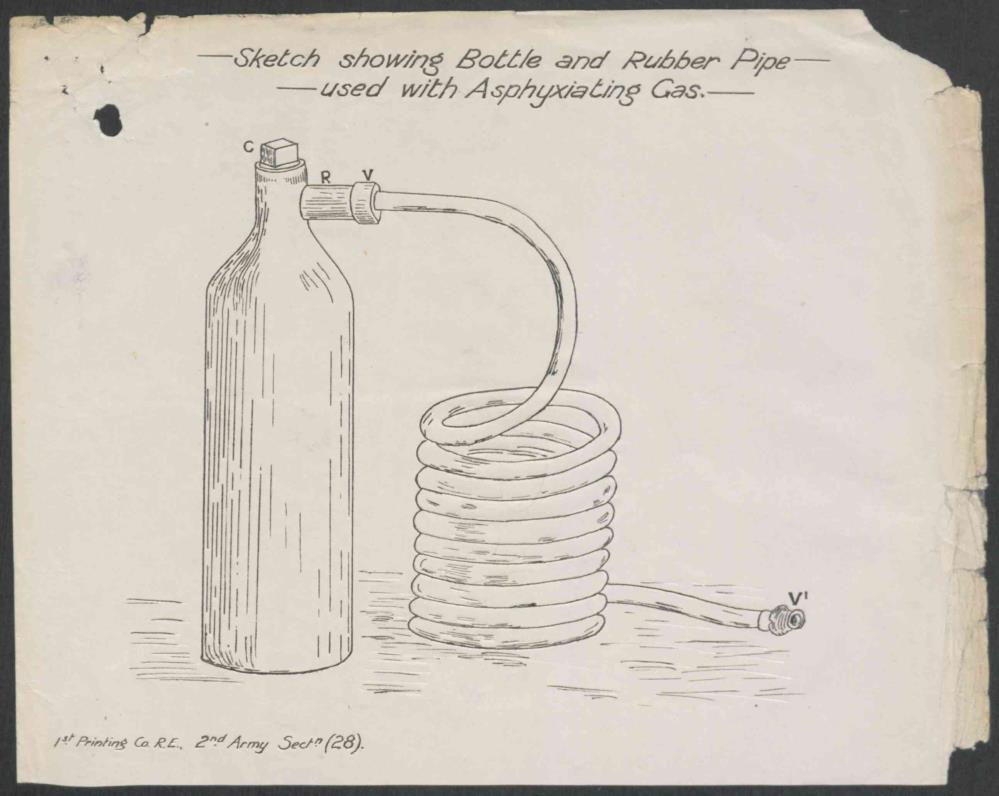

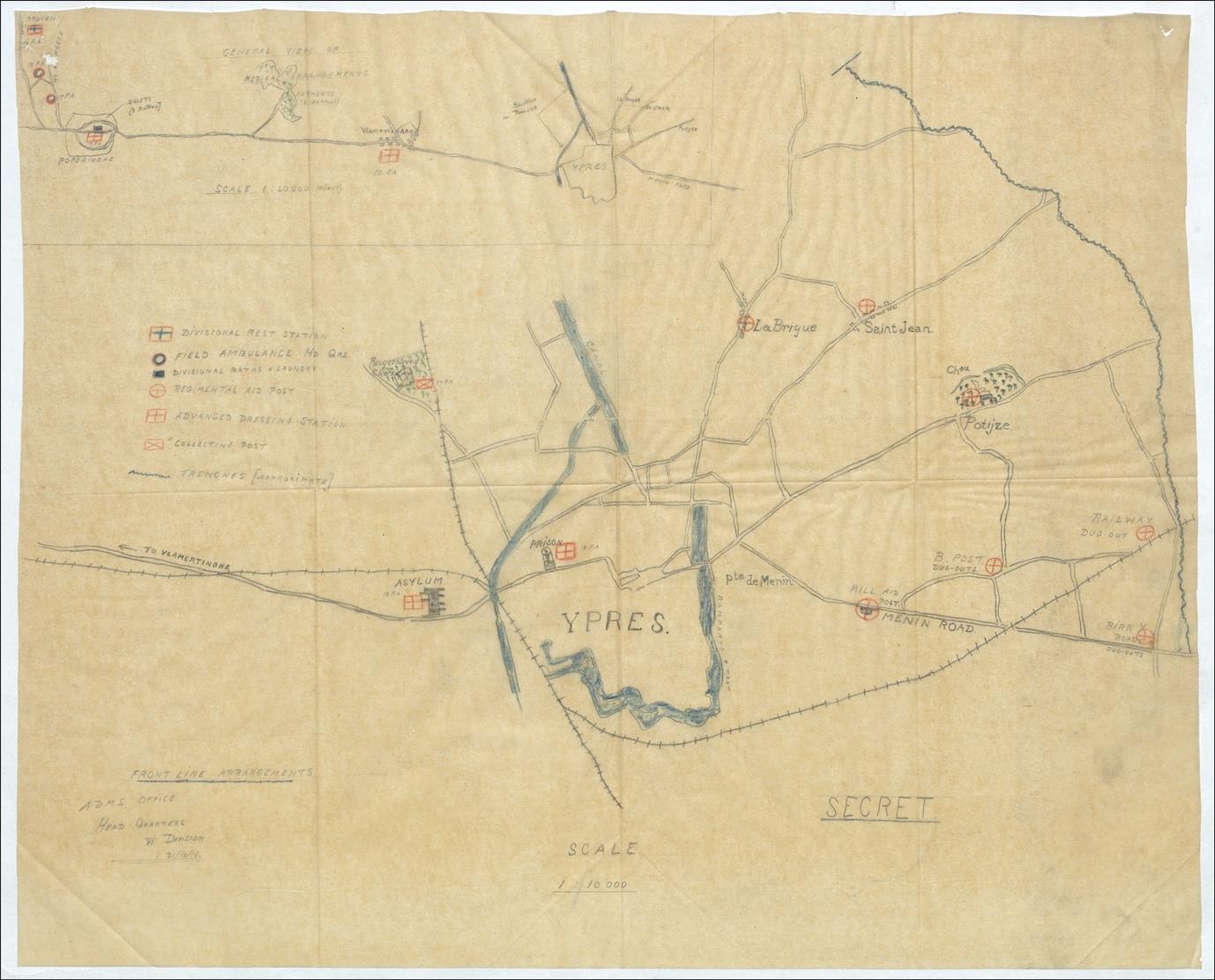

By the time the guns fell silent, the Salient had claimed 185,000 Commonwealth lives, of whom 93 are OPs. Among this number, evident in the stories that follow (see Chapter 17) are those who fell victim to one (or more) of machine gun fire, shelling, a sniper’s well aimed bullet and the notorious Flanders mud; others succumbed when their aircraft fell from the sky, when their lungs filled with asphyxiating gas or in the terrifying hand to hand combat that took place underground. Their stories collectively show the multifarious ways in which men sought to kill each other during the years 1914 1914

The biographies of the 93 OPs are presented here in chronological form according to the date they were killed. In this way they narrate the history of the Ypres Salient, substantially from the viewpoint of a subaltern.

16.2 the ‘93’: an overview

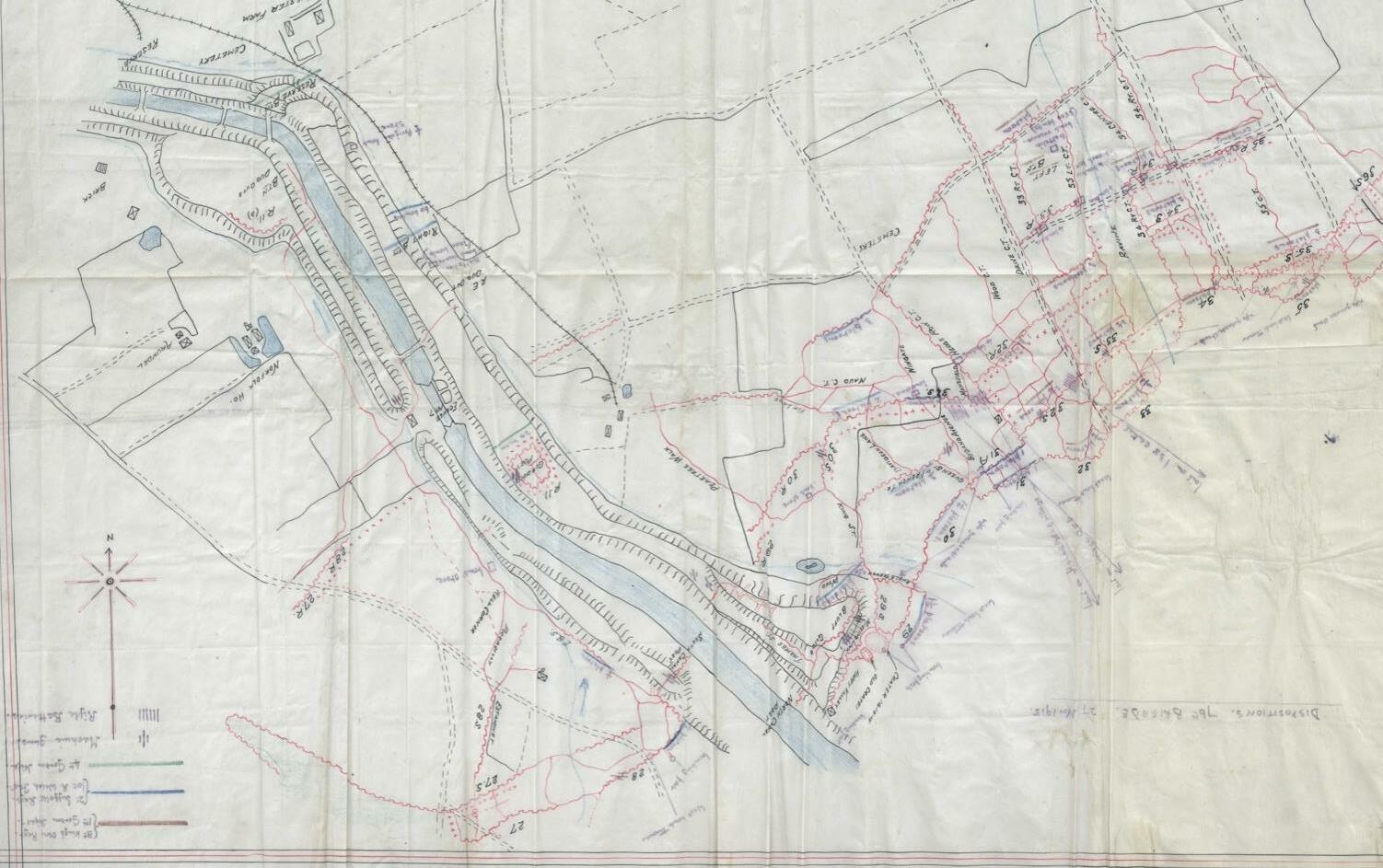

i) in which they served: armies and regiments / corps

Of the 93 Old Paulines who fell in the Ypres Salient 1914 1918 a majority 81 were soldiers in the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), the overseas force furnished by Britain. Of

16. Old Paulines and the Ypres Salient

the remaining 12, nine were soldiers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, two fought in the Australian Imperial Force and one in the Indian Army 18

The 81 who served in the BEF did so across a variety of regiments / corps: 59 served in infantry Regiments 9 served the Royal Artillery 5 served in the Royal Engineers 4 served in the Royal Army Medical Corps 2 served in the Royal Flying Corps 1 served in the Royal Army Chaplain’s Department 1 served in the Tank Corps

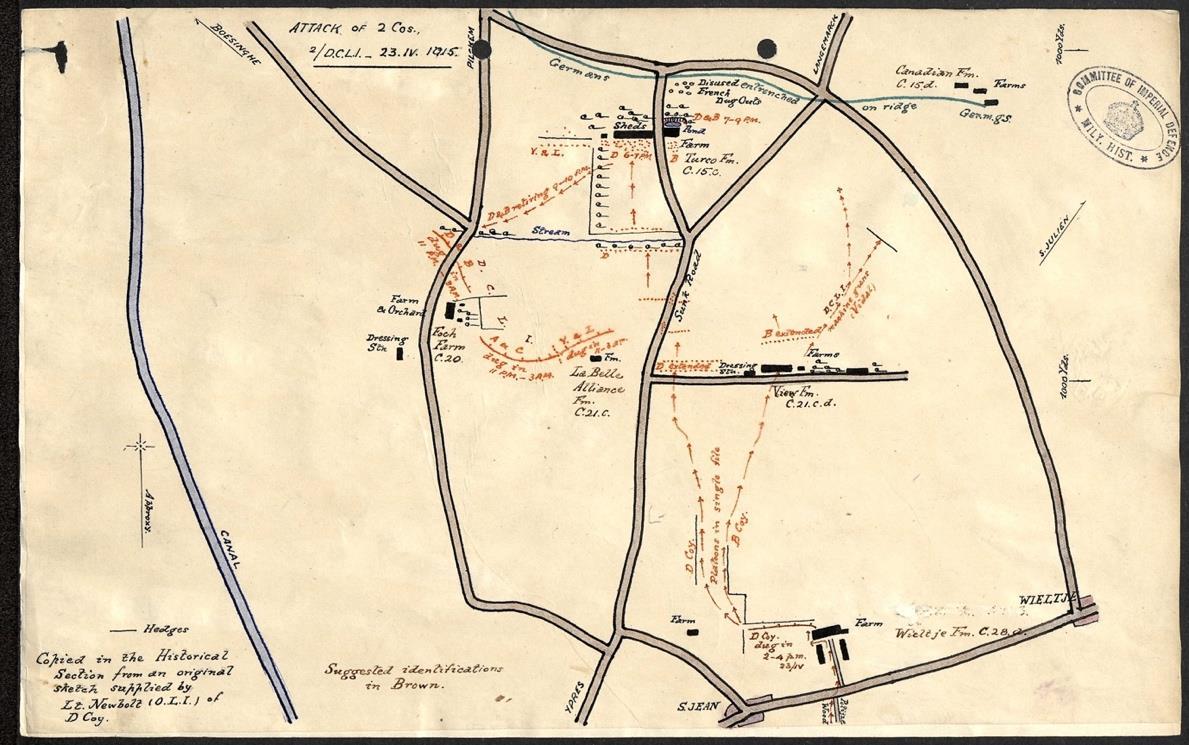

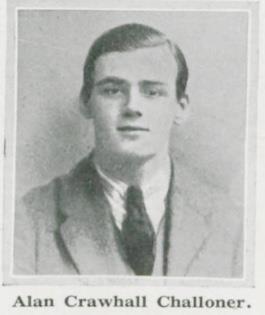

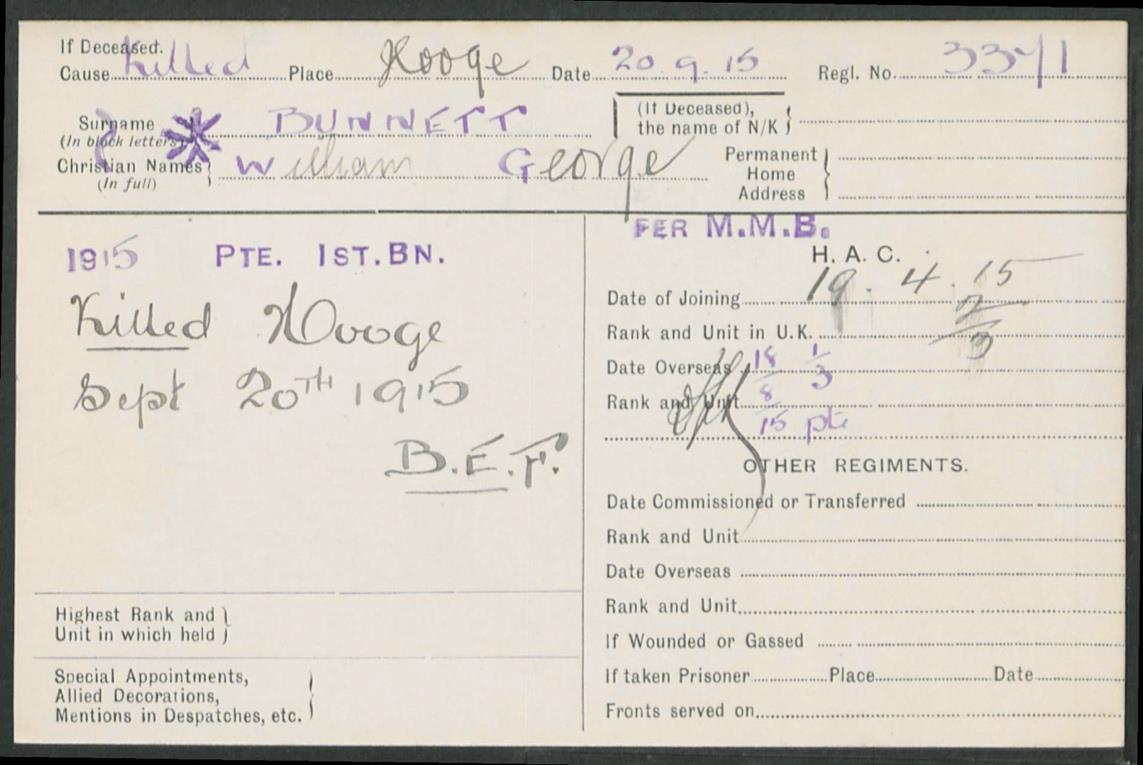

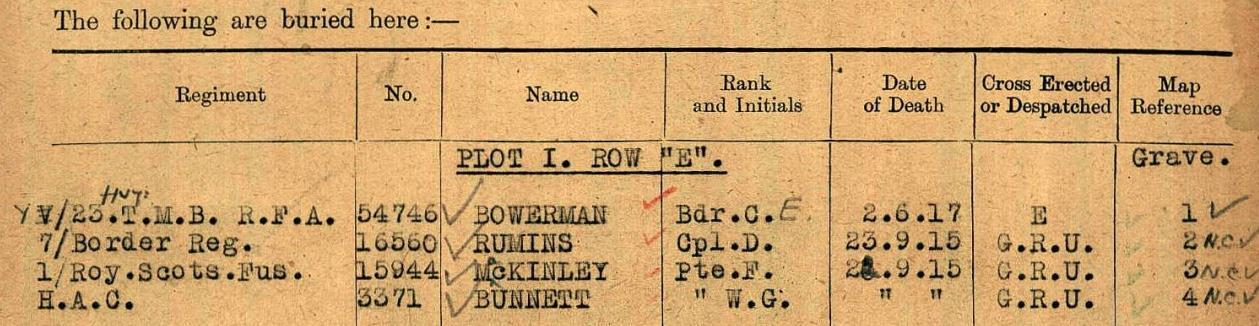

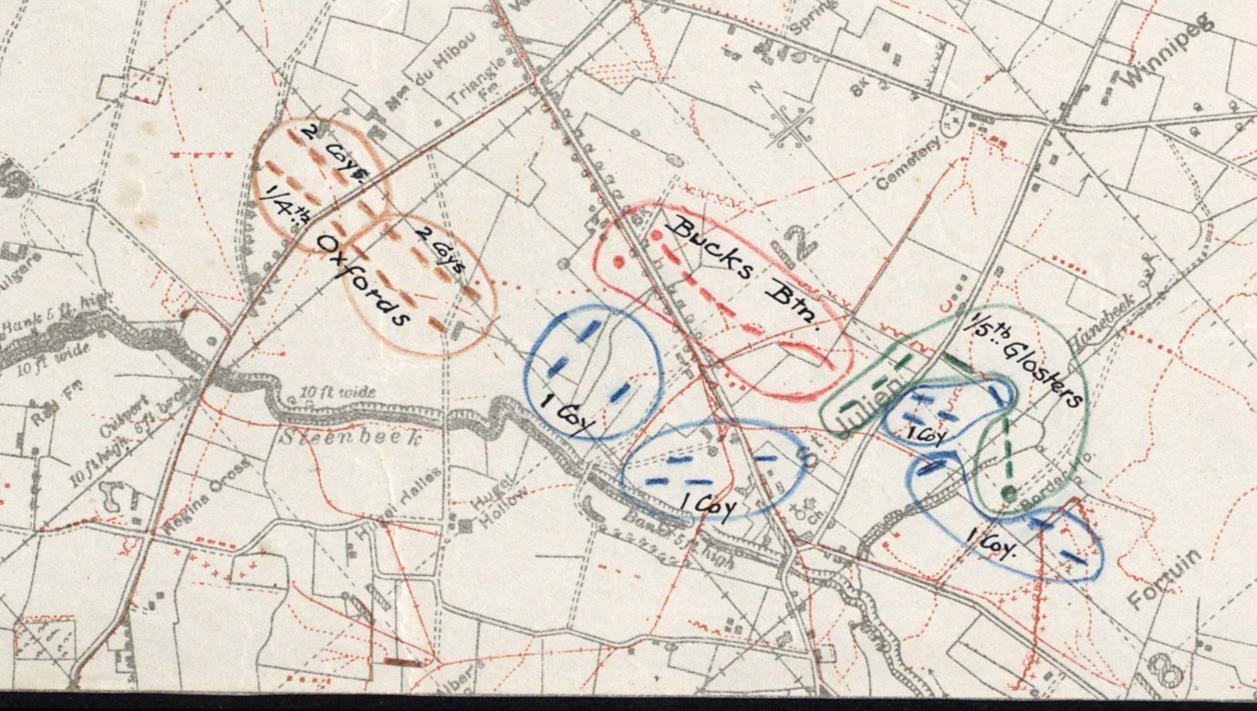

Most OPs (76 of the 93) who fell were of officer rank and as such were deployed in units that met the requirements of the army rather than any personal choice. Thus, the 59 OPs who served in infantry regiments were distributed across 54 different battalions in 34 different regiments. (The most popular regiments were the London and Middlesex, in which eight and seven of the 93 OPs served respectively.) In only five instances did OPs serve in the same battalion of the same regiment: Challoner and Hyman (6th (Service) Bn. Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry); Paull and Bunnett (No. 1 Coy. HAC); Goodale and Johnston (1st Bn. King’s Shropshire Light Infantry); Knight and White (1/5th Bn. London Regiment) and Shoobert and Gulbenkian (23rd (Service) Bn. Middlesex Regiment). In none of these five instances did OPs fall on the same date. Frequently of substantially different ages and rank, there is every likelihood that even these OPs may not have been aware of their common alma mater. The logistics of war thus militated against any capacity for the existence of a Pauline ‘band of brothers’, and where any such existed it was ephemeral and necessarily small in scale.

The average age of all OPs who fell in the Salient was 27 years, the same average that exists for the remaining 418 OPs who fell elsewhere. Variations from this average in 1916 and 1918 are most probably a manifestation of the small number of OPs who fell in the Salient in each of these years. Meanwhile, the higher than average age of death in 1914 is best

18 Those who fought in the C.E.F were: Merrit, C M; Jennings F S W; Fraser, A P; Fince, H A I; Mack Jost N R; Dobson W J. Marshall, K E D fought in the A.I.F. Scott, T H fought in the Indian Corps.

16. Old Paulines and the Ypres Salient

explained by this cohort of OPs consisting mostly of established, regular soldiers. (See Chart N.5.)

N.5 Number of OPs who fell in the Salient and their average age by year 1914 1918

No. Who Fell and Average Age Vs Year 1914 1918

No. Fall Av. Age

iv)

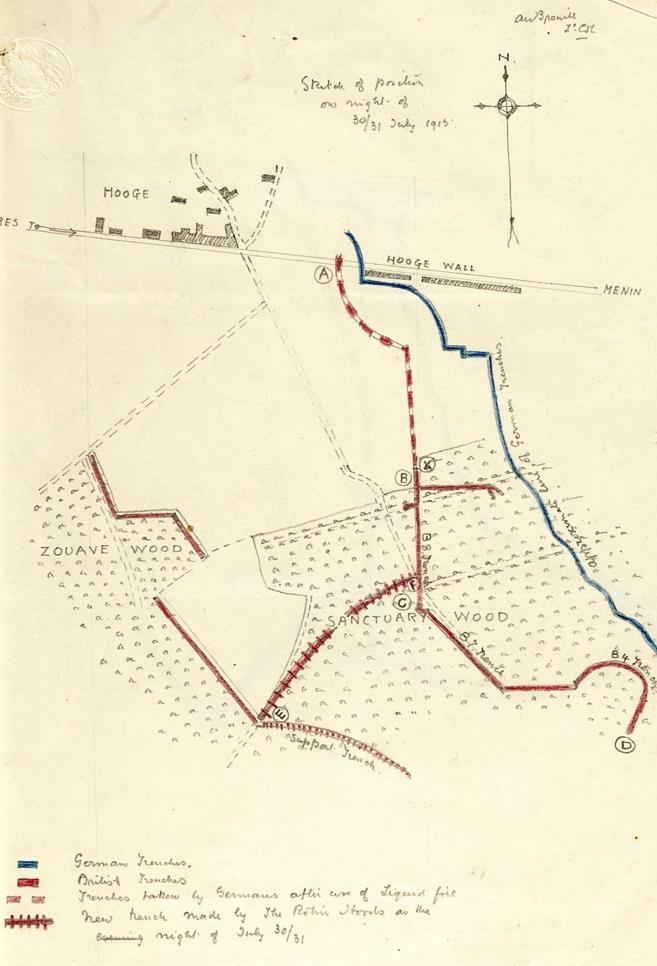

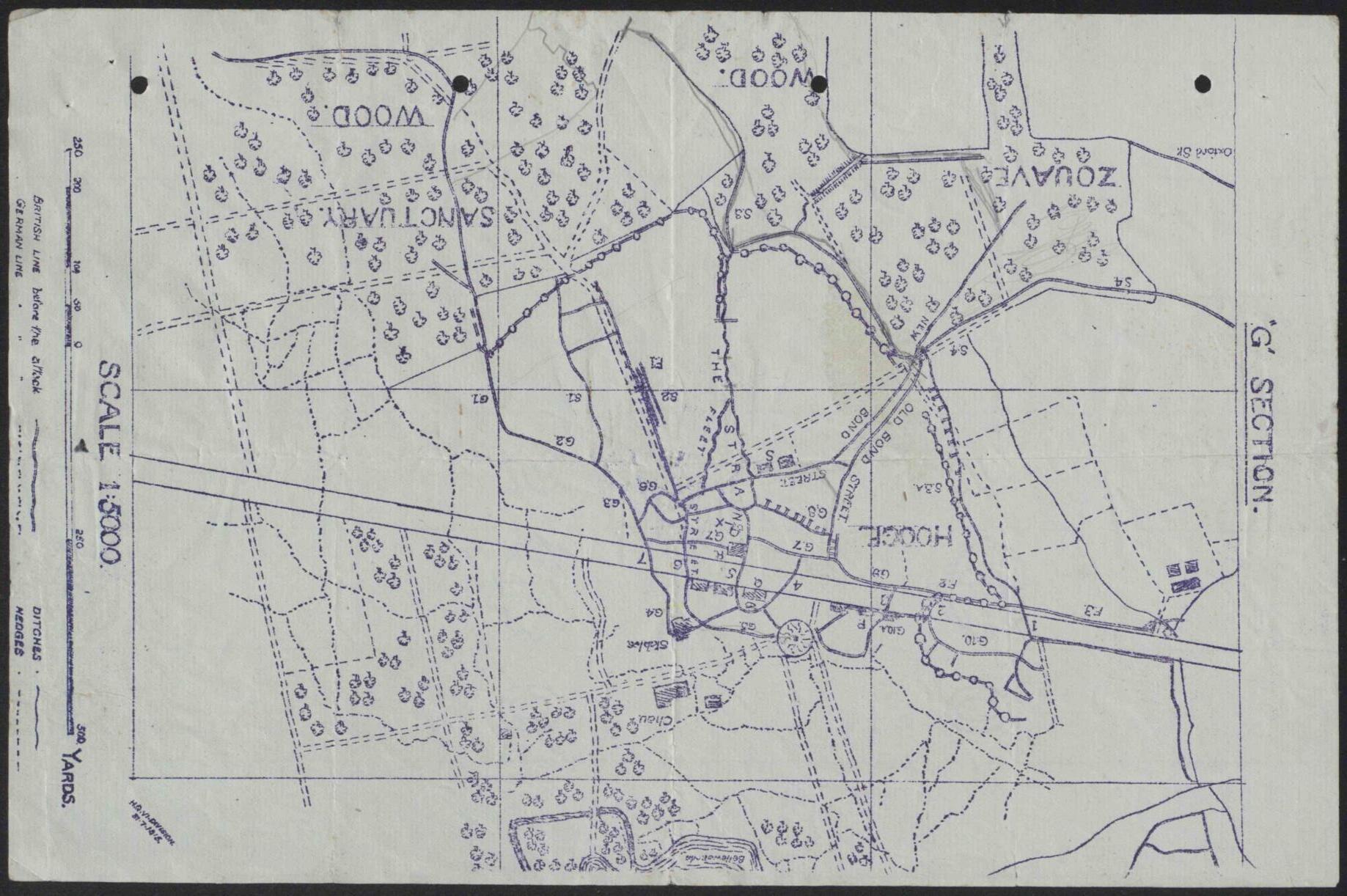

The most perilous day to be an OP in the Salient was 31 July 1917 the opening day of the Battle of Passchendaele on which occasion seven OPs fell.

v)

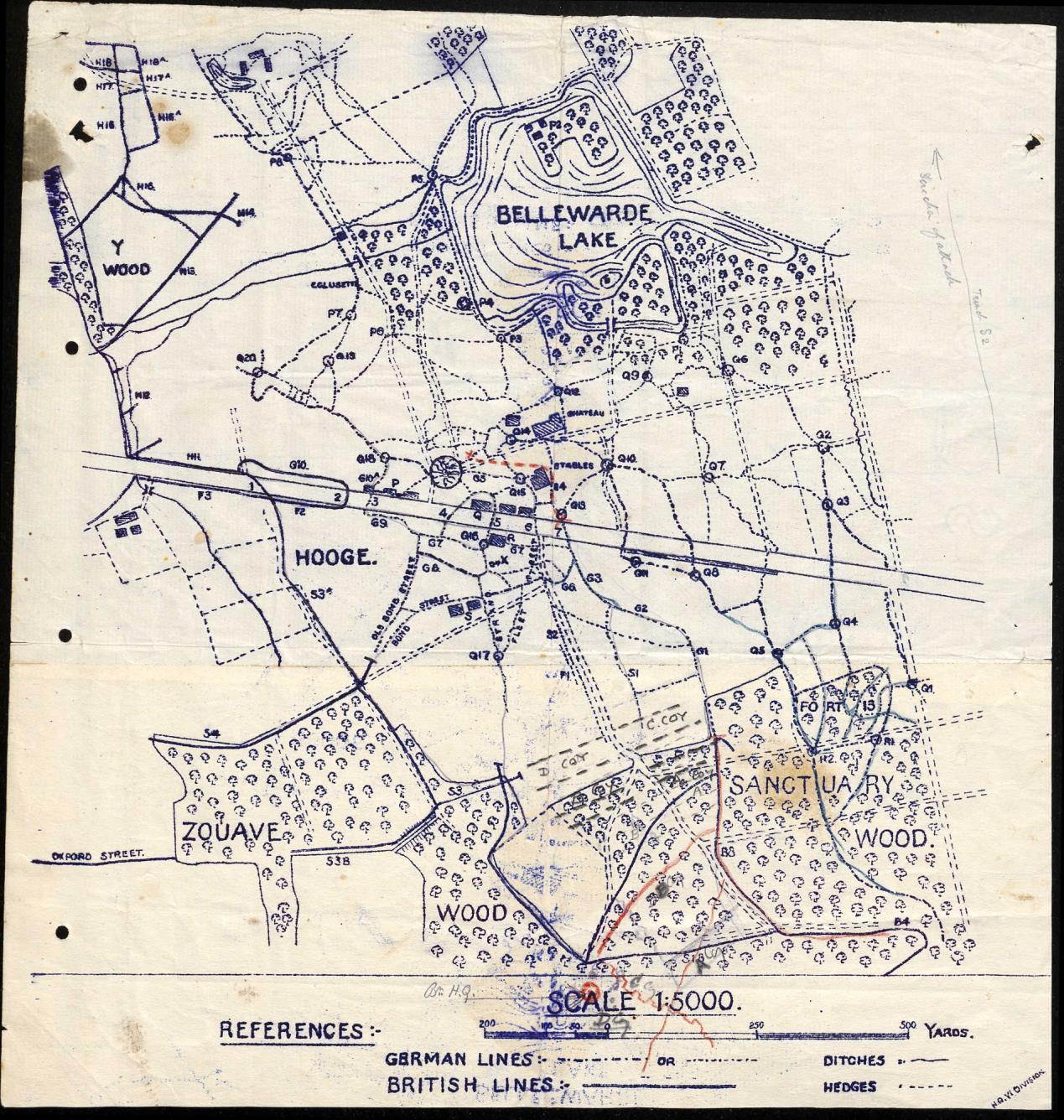

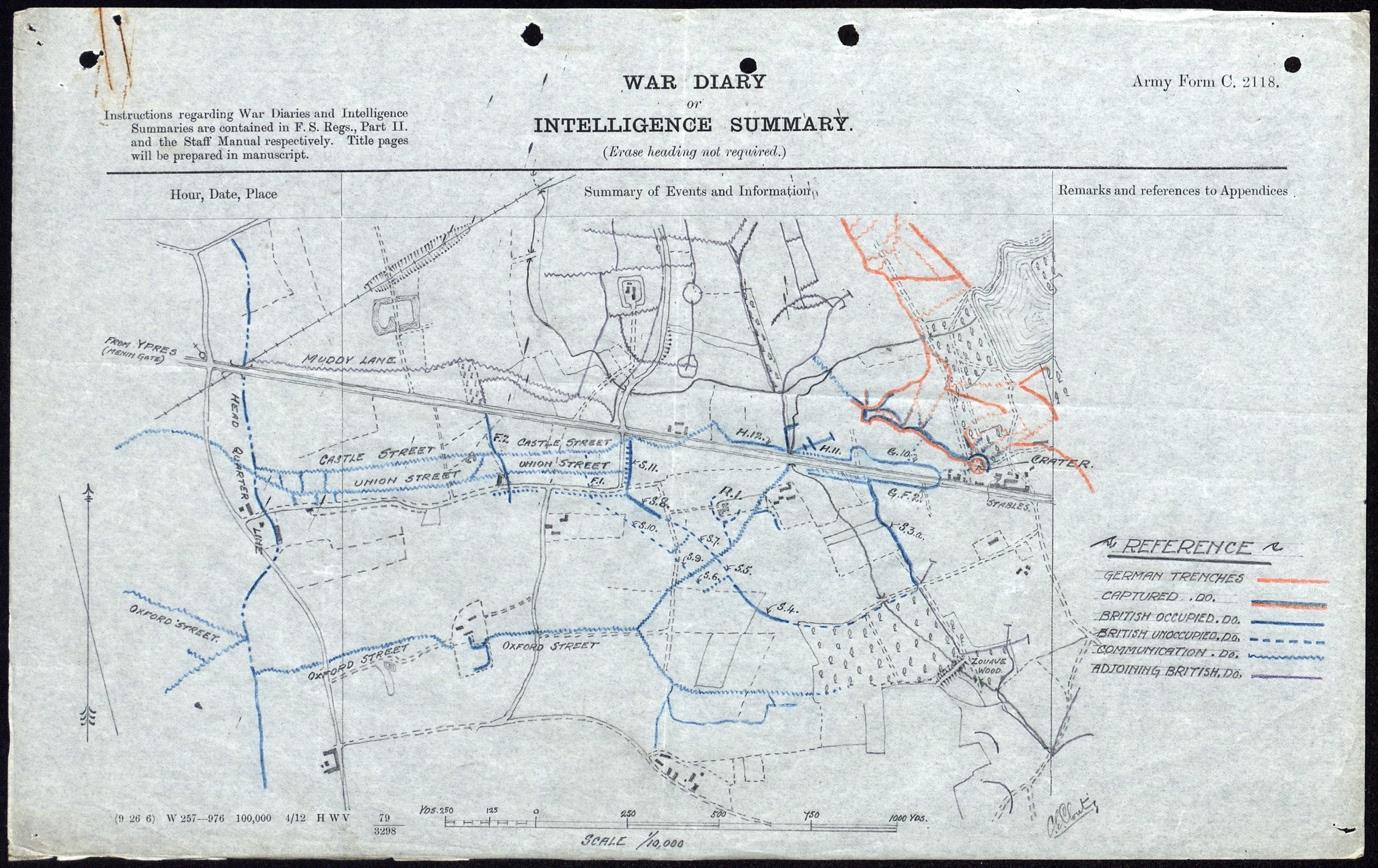

OPs fell in all sectors of the Salient. The greatest number nine fell at or near Hooge, three of whom fell on the same day (9 August 1915); eight fell in Ypres itself and seven fell at or near Passchendaele.

vi)

It is testimony to the industrial nature of the war fought in the Salient that almost half of OPs who fell in the Salient (45) have no known grave, their bodies lost in the Flanders mud. The majority of these (32) are remembered on the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial.

Forty eight OPs are buried in 30 different cemeteries established throughout the Salient and behind the lines. The largest concentration of OP graves in any one cemetery is seven These lie in Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery, a burial site used by a significant Casualty Clearing Station dealing for wounded extracted from the front.

16. Old Paulines and the Ypres Salient 9

N.6 The proportions of OPs who fell in the Salient with a grave or remembered on a memorial

vii) the ‘93’ Roll of Honour

Proportion: Graves Vs Memorial Grave Memorial

48%52%

The Roll of Honour of the 93 OPs who fell in the Ypres Salient is presented in N.7. The names of the fallen are listed in chronological order, consistent with the order in which their stories are told in Chapter 17.

N.7 Roll of Honour the Ypres ‘93’

Surname Initials At SPS Regiment

Died Age

Fairlie F 1892 93 Royal Scots Fusiliers 22 Oct 14 36

Miller F W J M 1907 08 Grenadier Guards 23 Oct 14 22

Watson G 1894 96 London Regiment 01 Nov 14 34

Farmer J D H 1906 11 RFA 04 Nov 14 21

Barton A T L 1907 10 Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers 07 Nov 14 20

Crowe W M C 1885 89 Royal Warwickshire 11 Nov 14 42

Paull A D 1908 12 HAC 12 Dec 14 20

Knight H M 1908 09 London Regiment 11 Jan 15 21

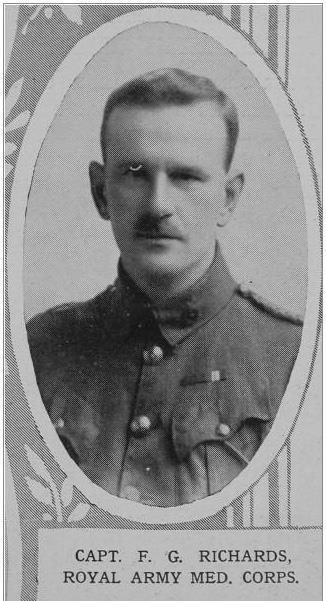

Richards F G 1885 90 Royal Army Medical Corps 05 Mar 15 40

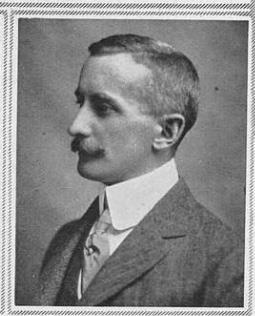

Johnson P J Viner 1889 90 Wiltshire Regiment 12 Mar 15 39

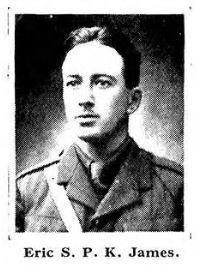

James E S P K 1901 06 King's Royal Rifle Corps 17 Mar 15 27

Child G J 1906 10 Yorkshire Light Infantry 18 Apr 15 23

16. Old Paulines and the Ypres Salient 10

Southgate L M 1906 07 Canadian Expeditionary Force 22 Apr 15 22

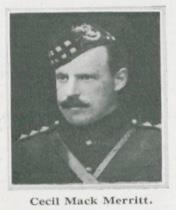

Merritt C M 1890 95 Canadian Expeditionary Force 23 Apr 15 37

Scott T H 1897 1900 Indian Army 26 Apr 15 31

Nash F O C 1891 96 Northumberland Fusiliers 27 Apr 15 37

Butcher C G 1907 09 Dorsetshire Regiment 02 May 15 23

Maurice S 1902 05 Royal Engineers 11 May 15 28

Jennings F S W 1895 1900 Canadian Expeditionary Force 06 Jul 15 33

Challoner A C 1904 11 Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry 30 Jul 15 23

Long Innes S 1891 94 Royal Lancaster 04 Aug 15 37

Goodale A W 1908 13 King’s Shropshire Light Infantry 09 Aug 15 20

Hall V 1903 07 London Regiment 09 Aug 15 26

Walsh G P 1907 11 Sherwood Foresters 09 Aug 15 22

Barnett D O 1907 14 Leinster Regiment 16 Aug 15 20

Bunnett W G 1913 14 HAC 20 Sep 15 16

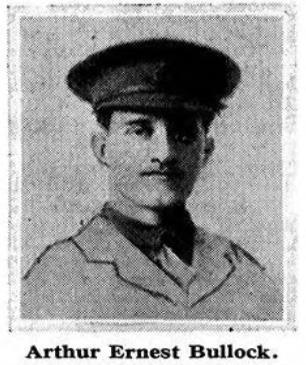

Bullock A E 1901 08 Royal Army Medical Corps 26 Sep 15 26

Goldsworth D W 1907 11 South Lancashire Regiment 26 Sep 15 21

Fraser A P 1906 07 Canadian Expeditionary Force 15 Oct 15 24

Graham A F 1908 10 RGA 11 Nov 15 22

Calthrop E F 1889 93 RFA 19 Dec 15 39

Sifton W A 1908 12 South Staffordshire Regiment 25 Dec 15 20

Haigh A G 1899 1900 Royal Engineers 15 Feb 16 30

Boddy G G D 1904 07 Royal Fusiliers 27 Mar 16 26

Johnston A L 1901 08

King’s Shropshire Light Infantry 22 Apr 16 26

Finch H A I 1891 97 Canadian Expeditionary Force 28 Apr 16 37

Mack Jost N R 1909 11 Canadian Expeditionary Force 03 Jun 16 20

Mitton R H 1892 95 Canadian Expeditionary Force 03 Jun 16 36

Dobson W J 1890 97 Canadian Expeditionary Force 09 Jul 16 38

Haldane J O 1891 92 Rifle Brigade 09 Aug 16 37

16. Old Paulines and the Ypres Salient 11

Brown I M 1902 04 Royal Army Medical Corps 15 Nov 16 28

Frankland J C 1914 15 Loyal North Lancashire Regiment 10 Jan 17 19

Misquith J C 1905 09 RFA 04 Feb 17 26

Moses V S 1911 16 RFA 04 Jun 17 19

Allard P H 1908 11 RFA 23 Jun 17 23

Foulsham A P 1911 16 RGA 20 Jul 17 19

Beit R O 1902 07 London Divisional Engineers 28 Jul 17 27

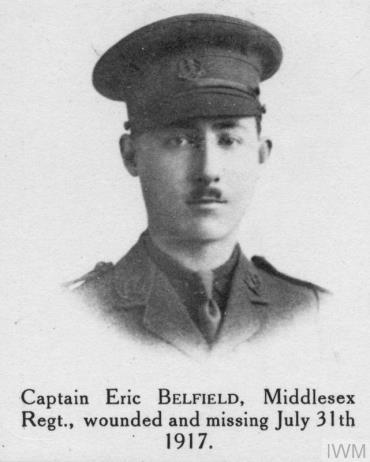

Belfield E 1905 06 Middlesex Regiment 31 Jul 17 26

Chibnall R S 1909 13 Suffolk Regiment 31 Jul 17 20

Coburn C I 1896 03 King's Royal Rifle Corps 31 Jul 17 32

Johnstone J D 1913 15 Royal Lancaster 31 Jul 17 19

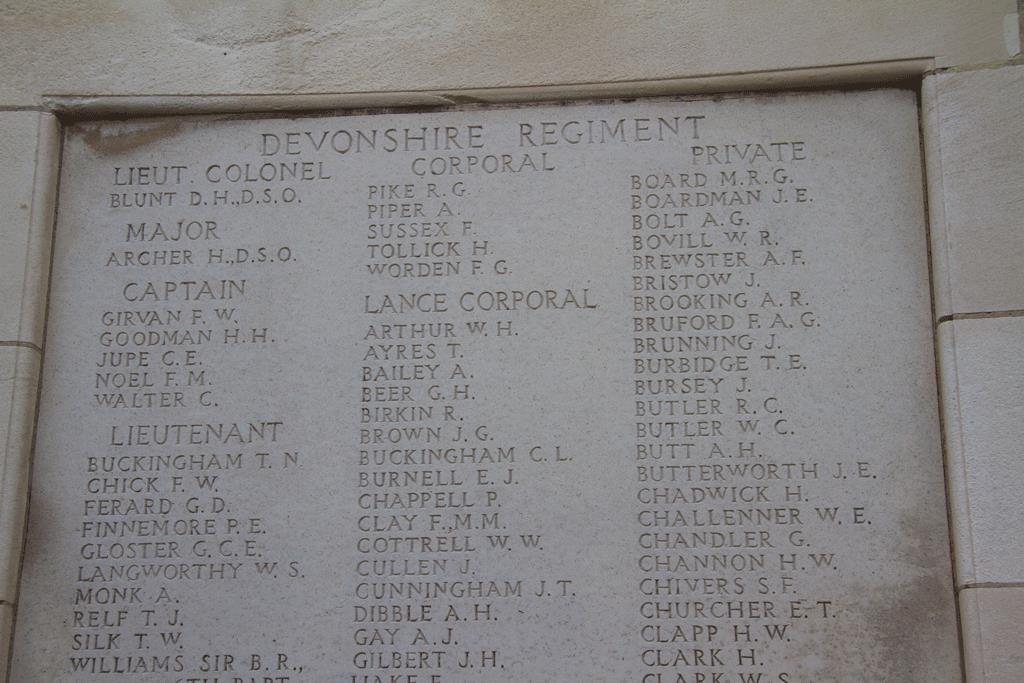

Ley G A H 1905 08 Devonshire Regiment 31 Jul 17 26

Shoobert N 1903 06 Middlesex Regiment 31 Jul 17 27

Wickham J N(S) D 1907 10 King's Own Royal Lancaster Regiment 31 Jul 17 25

Scratton G E H 1908 11 Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, attd Black Watch

01 Aug 17 24

Winckler von M W 1907 12 Middlesex Regiment 01 Aug 17 23

Solomon E J 1906 12 South Lancashire Regiment 02 Aug 17 23

Johnson H G 1912 15 Grenadier Guards 07 Aug 17 20

Martin S S 1907 12 Middlesex Regiment 11 Aug 17 24

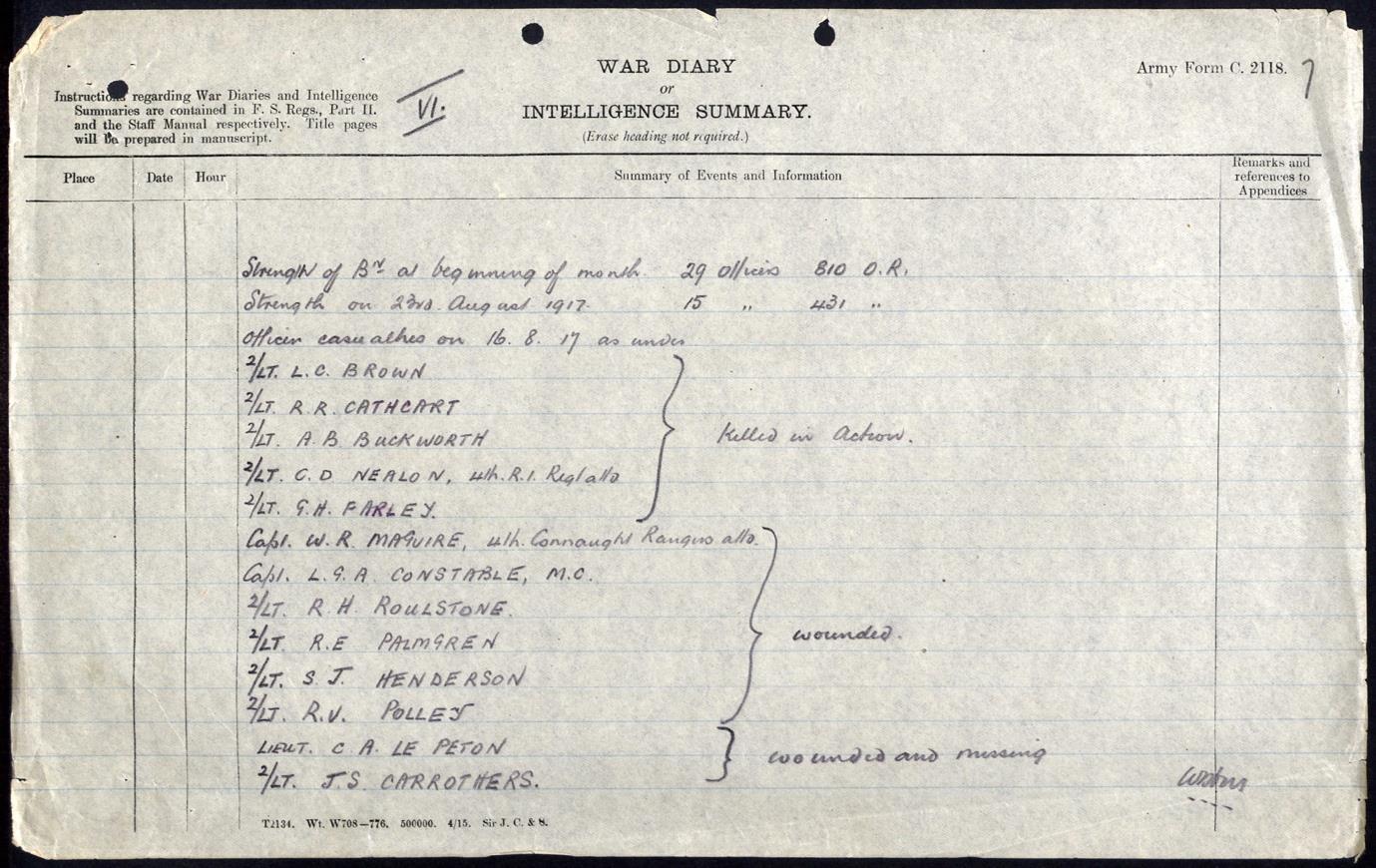

Bowman C H 1910 16 Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry 16 Aug 17 20

Buckworth A B 1913 15 Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers 16 Aug 17 19

Rinder C H B 1911 13 London Regiment 16 Aug 17 20

White A B 1901 04 London Regiment 17 Aug 17 29

Hyman R L 1905 06 Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry 22 Aug 17 25

Manson G P 1912 13 Somerset Light Infantry 24 Aug 17 20

Royal Dawson O S 1896 1903 Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry 25 Aug 17 32

Sandys W E 1908 09 Royal Flying Corps 05 Sep 17 24

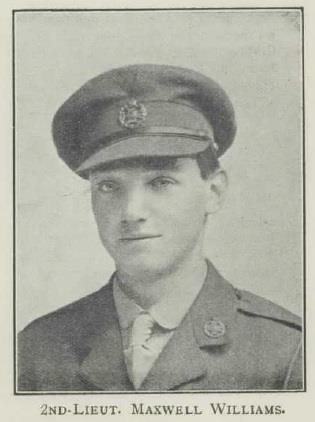

Williams M H 1914 15 London Regiment 19 Sep 17 33

Chown F J 1912 16 Royal Flying Corps 20 Sep 17 19

Gulbenkian K 1905 08 Middlesex Regiment 20 Sep 17 22

16. Old Paulines and the Ypres Salient 12

Reynolds G G 1910 13 London Regiment 20 Sep 17 21

Manning G A 1904 09 Royal Engineers 26 Sep 17 26

Chester G F G 1887 93 London Regiment 29 Sep 17 40

Chetham Strode E R 1906 09 Border Regiment 01 Oct 17 26

Langworthy W S 1910 12 Devonshire Regiment 04 Oct 17 22

Samuel C V 1903 05 Royal Warwickshire 04 Oct 17 28

Fink L A L 1905 06 Bedfordshire Regiment 05 Oct 17 26

Beamish E D 1902 03 Australian Expeditionary Force 11 Oct 17 30

Marshall K E D 1905 07 Australian Expeditionary Force 12 Oct 17 26

Davies F C 1898 1903 Royal Army Medical Corps 17 Oct 17 33

Aldridge D J 1899 1901 Royal Marine Light Infantry 26 Oct 17 33

Harding W J 1899 1900 Army Chaplain's Department 31 Oct 17 31

Riddle G J 1907 10 Canadian Expeditionary Force 06 Nov 17 25

Bennett W Sterndale 1907 08 Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve 07 Nov 17 24

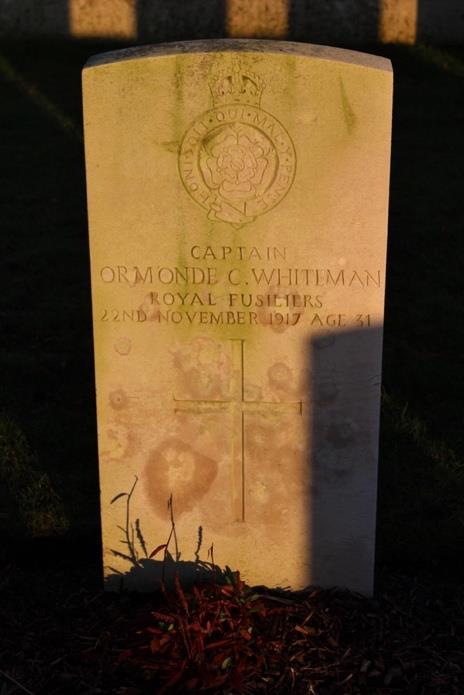

Whiteman O C 1899 1903 Royal Fusiliers 22 Nov 17 31

Sowinski J L 1905 06 RFA 28 Nov 17 27

Troup S H 1906 11 Royal Berkshire Regiment 02 Dec 17 25

Chambers R S B 1898 02 King's Royal Rifle Corps 24 Dec 17 31

Smalley R F 1890 95 South Staffordshire Regiment 14 Apr 18 41

Tovey Harry T 1892 96 RFA 22 Apr 18 37

Symons C L 1912 17 Royal Engineers 23 Apr 18 19

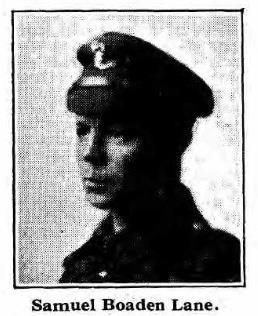

Lane S B 1896 97 Royal Dublin Fusiliers 20 Sep 18 35

Beaty Pownall G E 1890 95 Border Regiment 10 Oct 18 41

16. Old Paulines and the Ypres Salient 13

1914: OPs who fell in the Ypres Salient

Fairlie, Captain Frank 22 October 1914, Poezelhoek SPS 1892 1893

2nd Bn. Royal Scots Fusiliers, D Company Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial Panel 19 and 33 Age 36

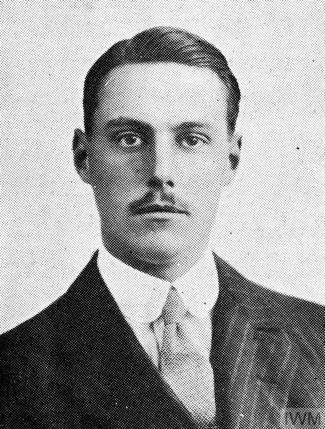

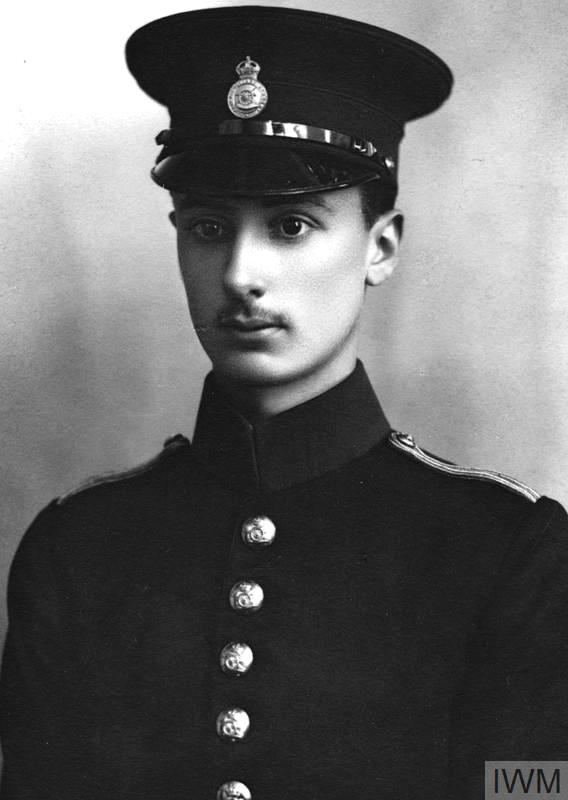

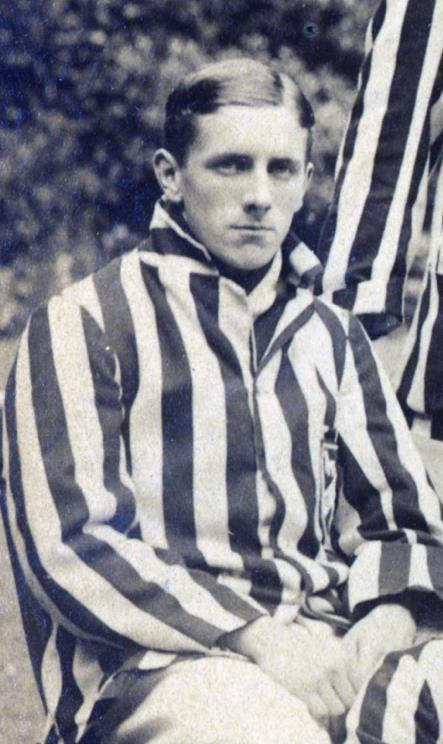

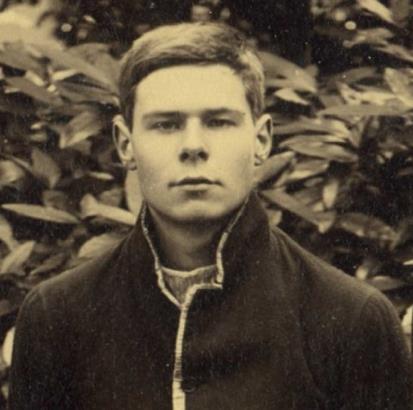

Frank Fairlie19

Frank Fairlie (SPS 1892 1893) was a regular with considerable experience by the time war broke out in 1914. He obtained his commission in the Royal Scots Fusiliers in 1901 and served in the South African War, 1899 1901, being present at operation in the Orange Free State; in the Transvaal, west of Pretoria, including actions at Frederickstad; and in Cape Colony, south of the Orange River, receiving the Queen’s medal with four clasps. Frank was promoted Lieutenant in June 1905 and from 1911 to 1913 was employed with the West African Frontier Force. He was promoted to the rank of Captain in 1912. In 1914 The Pauline reported that he was restored to the Royal Scots Fusiliers as a Supernumerary Captain.20 He fell at Poezelhoek.

On 11 October the 2nd battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers (21 Brigade, 7th Division) had been in Bruges awaiting final orders for the relief of Antwerp. However, when news was received that Antwerp had fallen and that enemy forces were of significant scale, the unit had marched in a south westerly direction via Roulers to Ypres, arriving on 14 October and on that night had billeted close to the railway station. The next day 21st Brigade occupied 19

20

© IWM HU 121877

The Pauline 1914, Vol 32, no. 208 p 42

17. the ‘93’ and their stories

outposts in the line Zillebeke Wieltje. Then, very early in the morning of 17th October, the Fusiliers marched eastward and occupied a line north of the Menin Road, roughly Poezelhoek Reutal. From here they advanced as far as Terhand, the 2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers entrenching on a spur running south west from that place. In this location the battalion came under heavy fire and was thus ordered to withdrew on 19 October and establish a line a line between Reutal and Poezelhoek, about a mile in length. After the enemy had broken through this line, A Coy led a counter attack at 5 pm on 22 October down the line of houses at Poezelhoek, ‘clearing the houses of snipers who had caused some loss and considerable annoyance, as they went’.21 This counter attack progressed as far as the Poezelhoek Reutal road, before having to turn back in the face of enemy attack. This was the action in which Frank was killed.

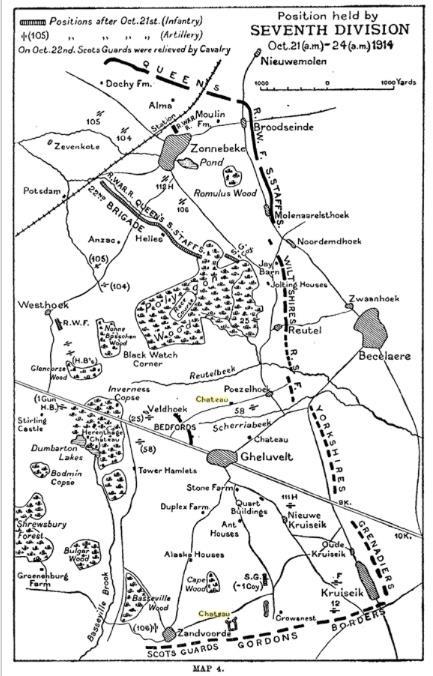

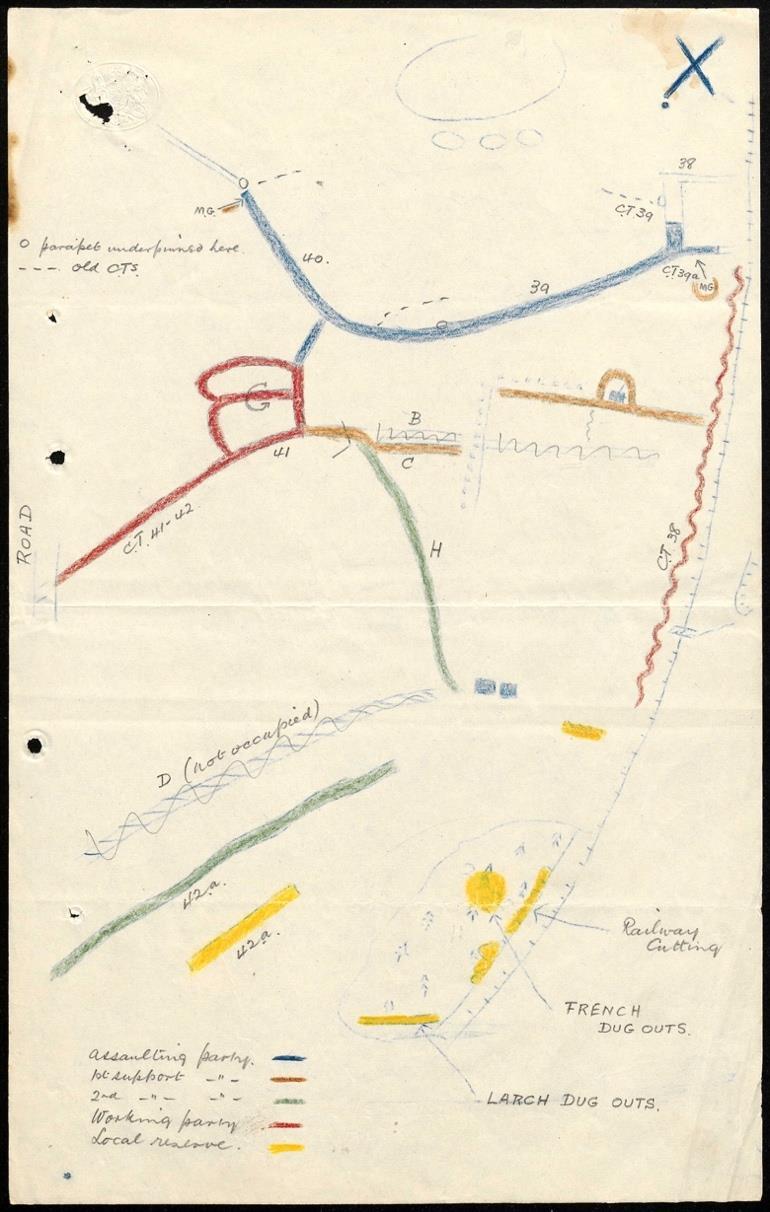

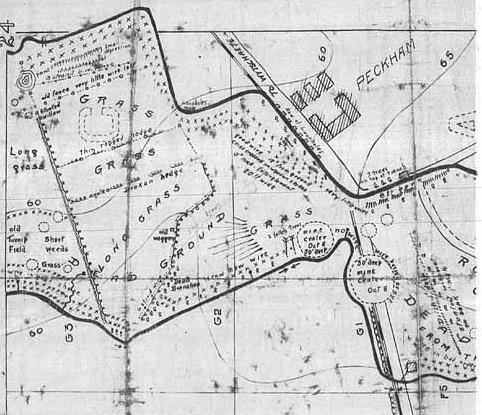

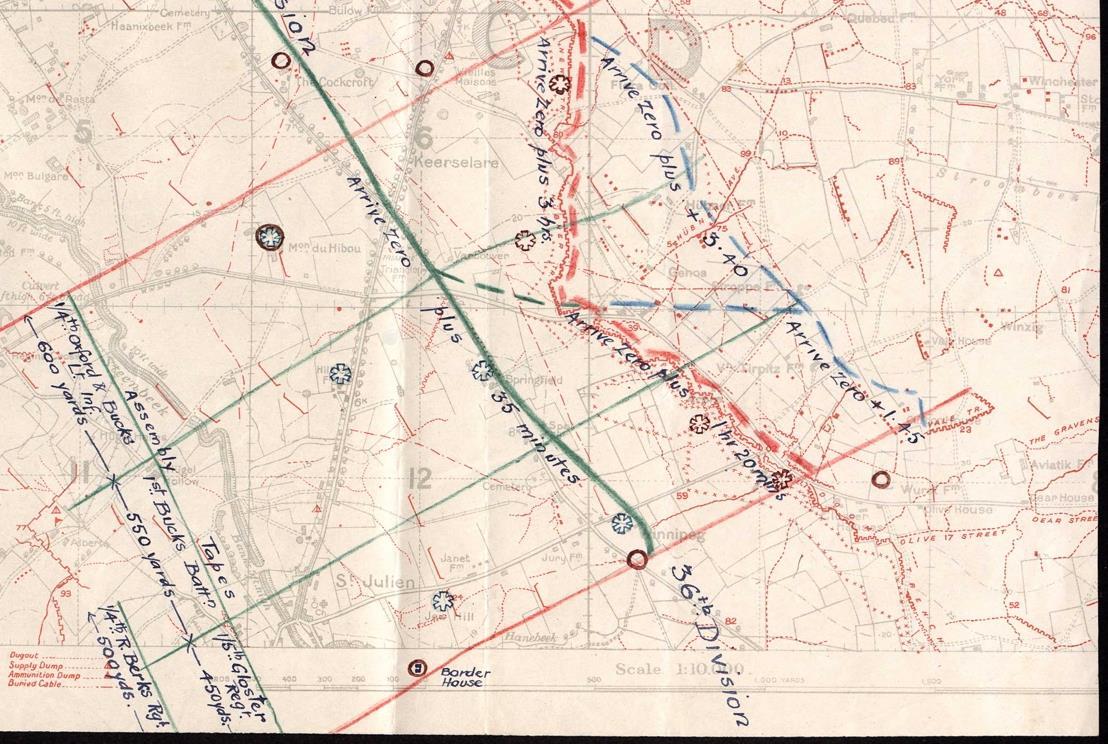

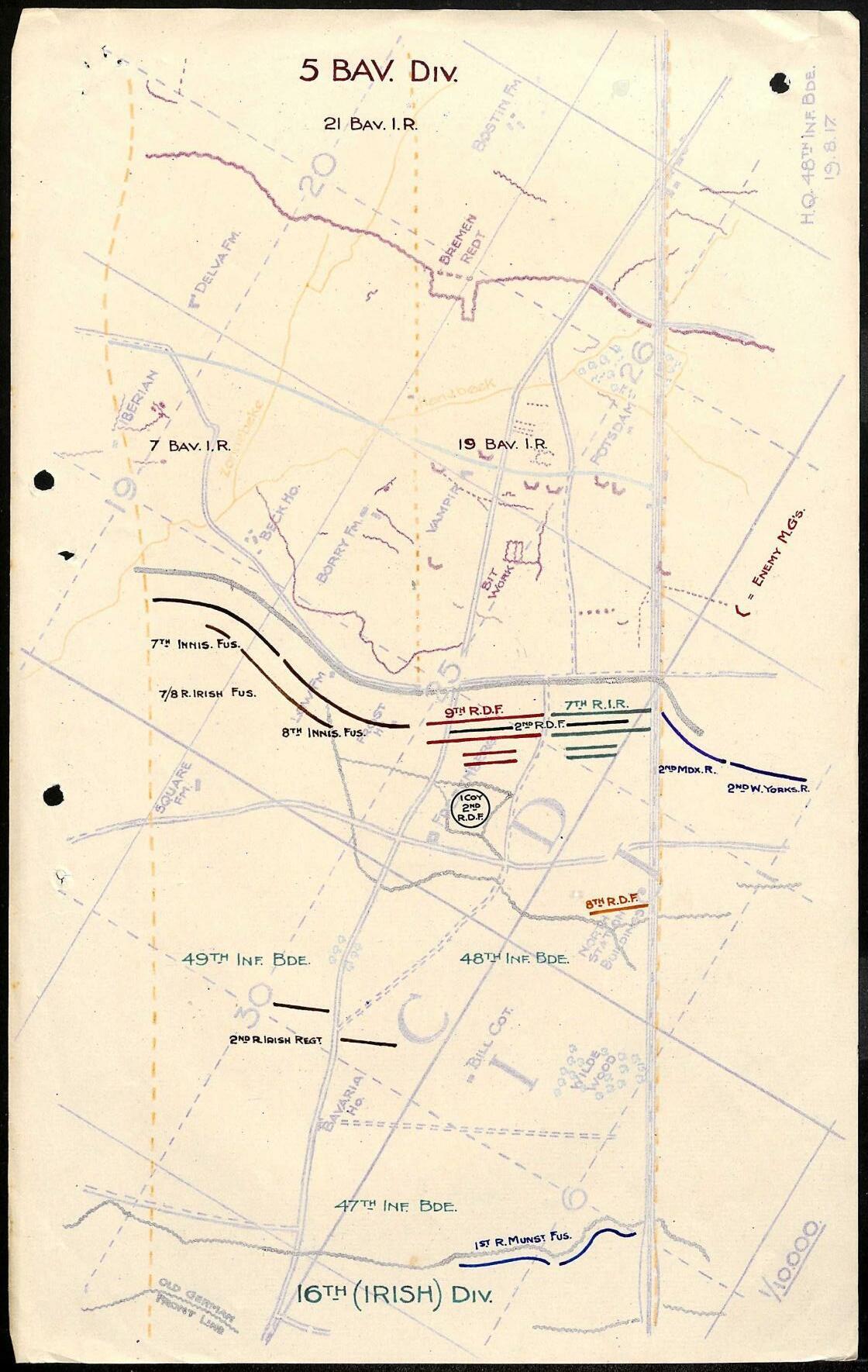

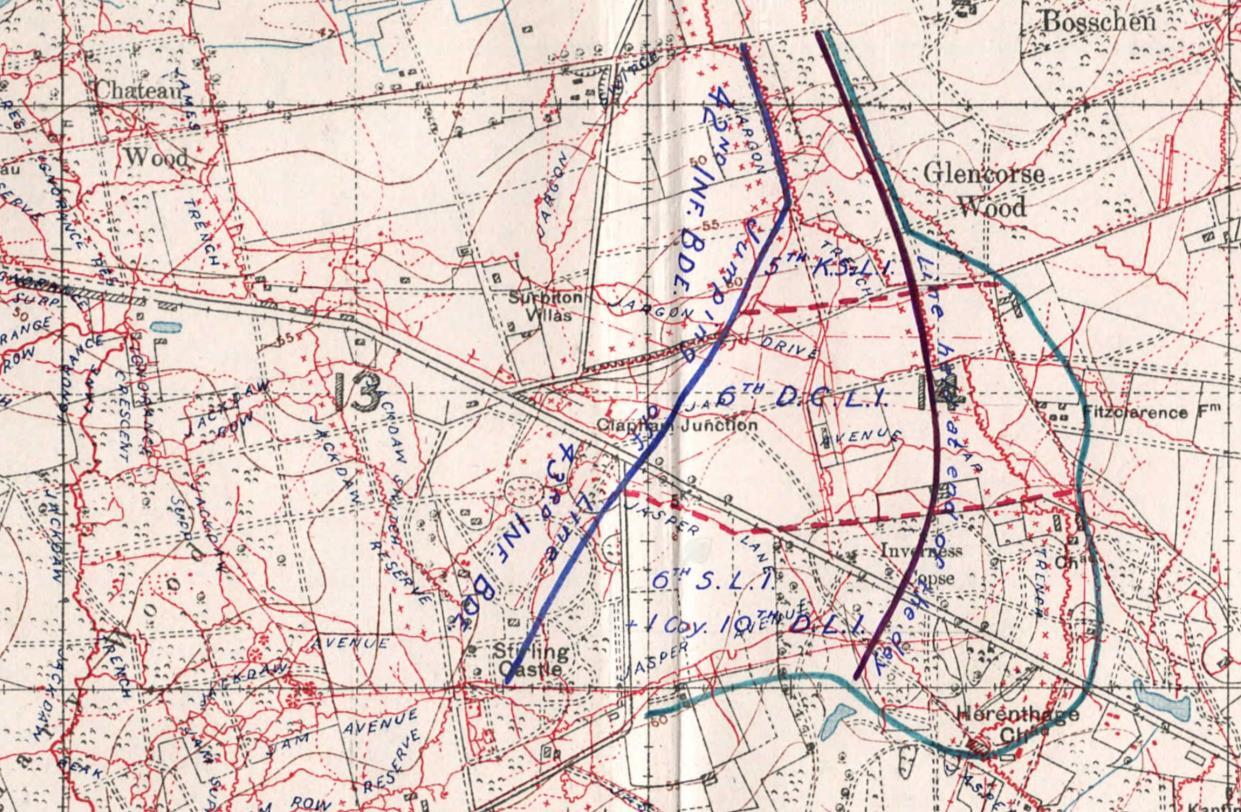

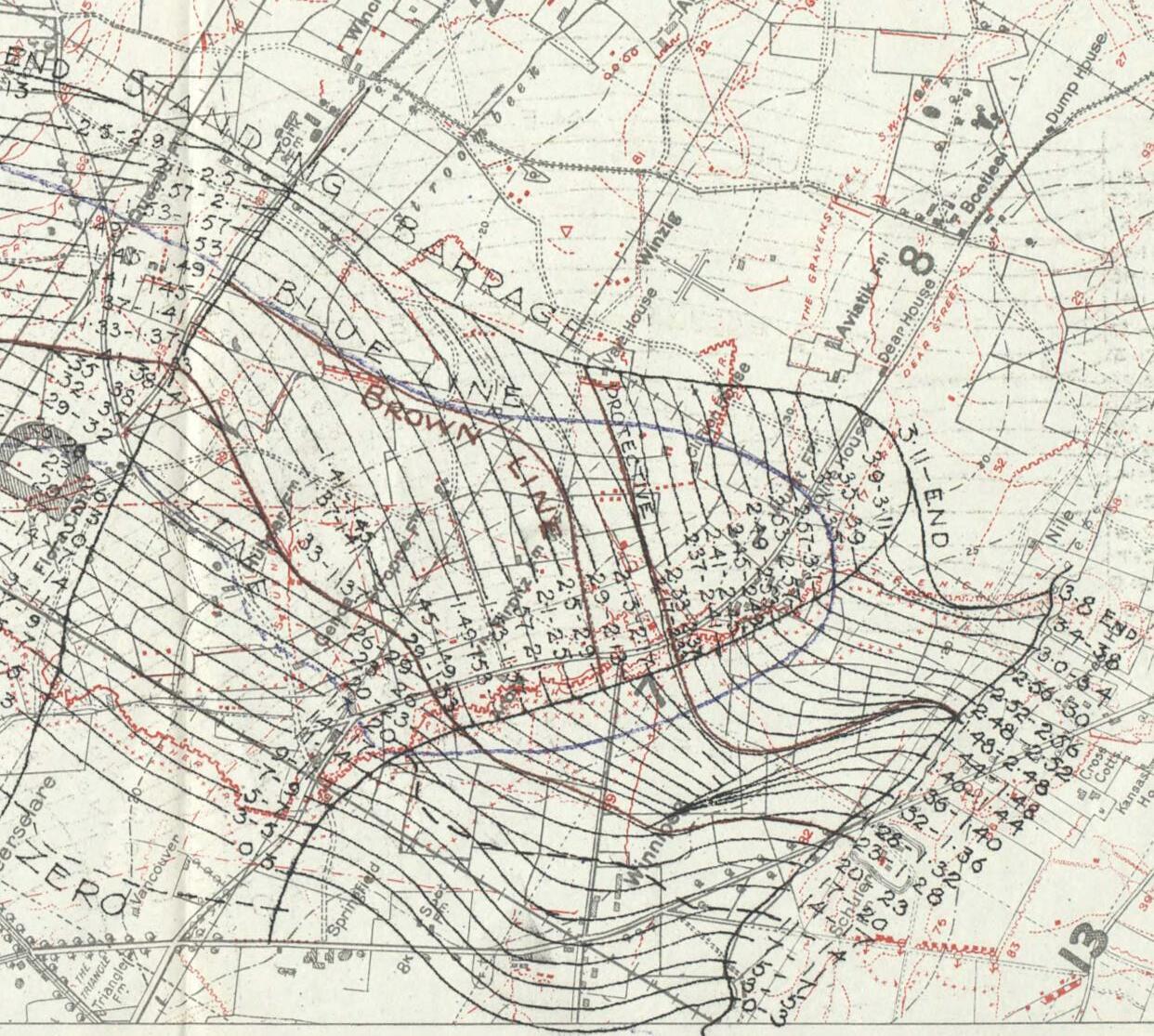

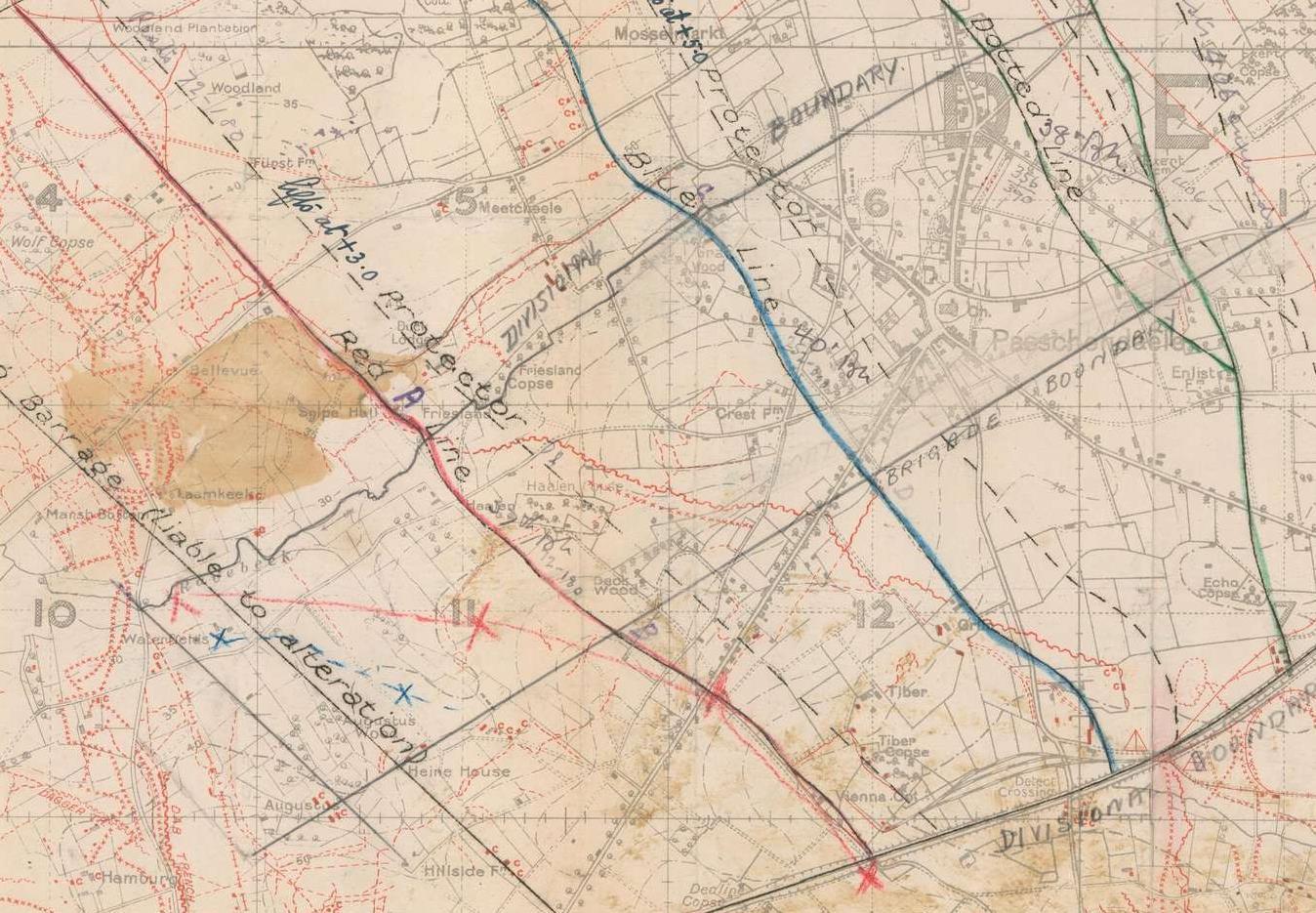

Map showing the line held by 7th Division 21 24 October 1914.22

21 TNA WO 95 1659 2

22 Atkinson, C T The Seventh Division (Eastbourne, 1926) p 5

17. the ‘93’ and their stories 2

The Seventh Division official history asserts that:

Towards the evening [of 22 October] the Fusiliers attempted to recover the trenches evacuated on the previous day, and A company and part of D [Company] counter attacked down the Poezelhoek road, clearing the houses of snipers. One big house in the centre of the village was stubbornly defended and Captain Fairlie of D Company was killed heading an attack on it, but the house was quickly surrounded, whereupon its occupants surrendered.23

A slightly different version of events is given by John Buchan. He states that:

In the evening of 22 October Major Ian Forbes of A Company, with parties from C and D [Companies], attacked in order to retake D’s position, and cleared the houses in Poezelhoek, but the enemy proved too strong to permit the task to be completed. Captain Frank Fairlie fell while receiving the surrender of some thirty Germans he was shot by one of them.24

The Glasgow Daily Record and Mail provides a yet different narrative:

Several brilliant charges had taken place against the enemy, who attempted to occupy some buildings [at Poezelhoek] which would give them a big advantage. At dusk about twenty Germans managed to get into one house, from the shadows of which they opened a galling fire into “A” Company’s trenches. Major Forbes undertook to surround the house and capture them. On being called on to surrender they offered to do so, and Major Forbes walked up to one man who held out his rifle to take it, when the hound suddenly drew his rifle back and fired at the Major in the stomach. Fortunately the bullet went low between his legs, causing no damage. It was in the skirmishes which took place among these buildings that Captain F. Fairlie was killed.25

Major Ian R.I.F. Forbes recalled the death of Frank and noted that for days he could see the bodies of his men lying in front of the trenches, one of whom was Frank. At 1 pm on 25 October a party went out into No Man’s Land to collect and bury the dead. Carrying only shovels, it managed to lay a number of men in a trench for burial but, when the enemy opened fire, Frank’s body had to be left where it lay.

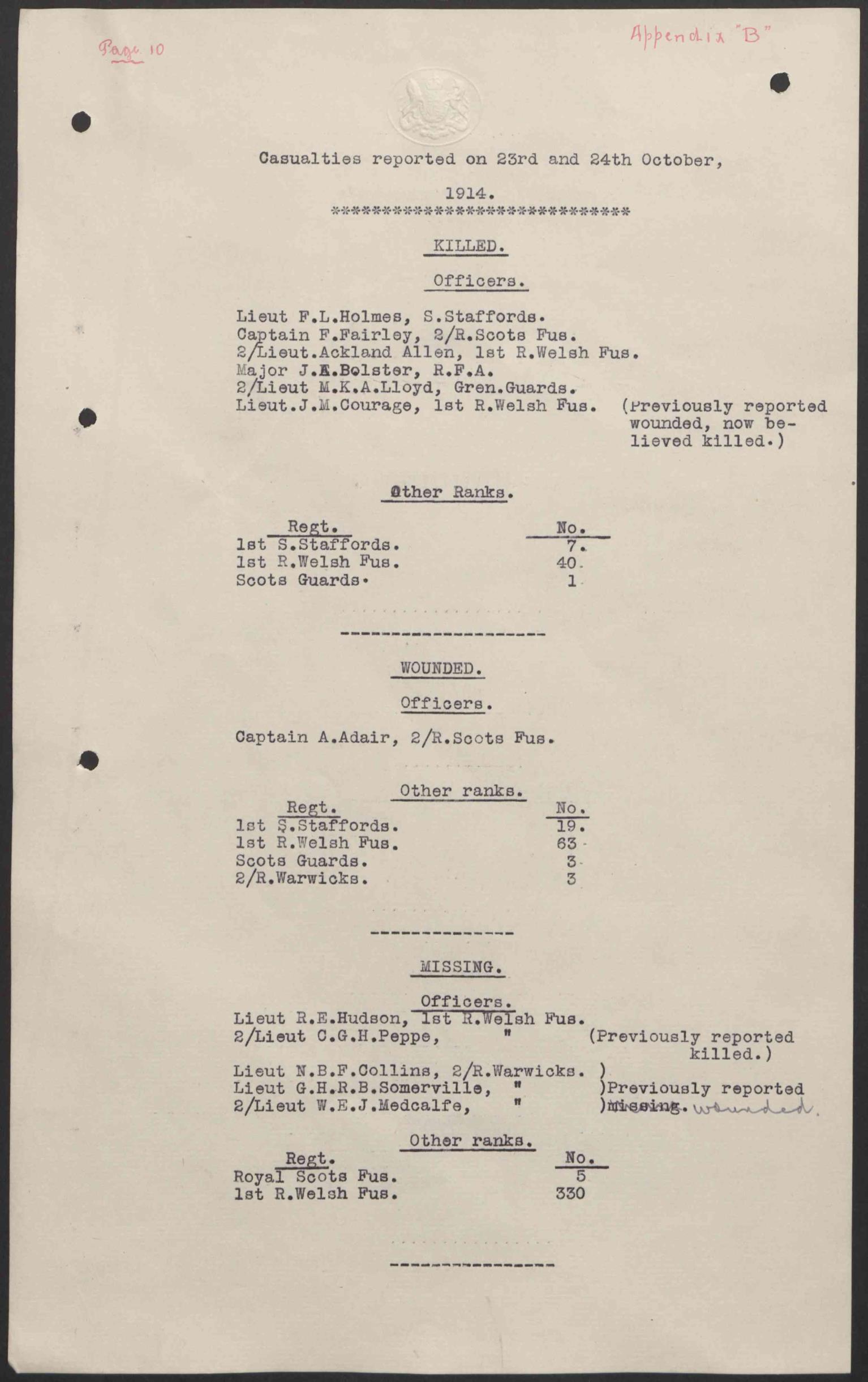

List of 7th Division casualties on 23 October, showing ‘Captain F. Fairley’ [sic].26

23 Atkinson, C T The Seventh Division (Eastbourne, 1926) p 44 24 Buchan, J The History of the Royal Scots Fusiliers (Edinburgh, 1925) p 301 25 From an article in the Glasgow Daily Record & Mail, Nov 1914 26 TNA WO 95 720 1

17. the ‘93’ and their stories

Miller, Lt Frederick William Joseph Macdonald 23 October 1914, Zonnebeke SPS 1907 - 1908

2nd Bn. Grenadier Guards, No. 2 Company Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial Panel 9 and 11 Age 22

Frederick William Joseph Macdonald Miller28

After leaving SPS, Frederick appears to have attended Royal Military College, Sandhurst. He was gazetted to the Grenadier Guards in February 1912 and was given his lieutenancy in August, to date from 30th June 1914. He fell a short distance to the north of Zonnebeke.

On the afternoon of 19 October General Monro, commanding 2nd Division, was duly ordered to move north east of Ypres on the following day. Accordingly, on 20 October the 2nd Grenadier Guards (4th Guards Brigade, 2nd Division) marched at 5 am in the bitter cold from Boeschepe to St Jean, a distance of some 18 km, arriving at around 3.30 pm. From St Jean they were instructed to march via Wieltje towards St Julian where they were held in readiness to support the left of the 7th Division around Zonnebeke. By the evening of 20th October, 2nd Division had thus established a line running from Zonnebeke to just east of Langemarck in anticipation of an advance planned for 7.30 am on 21 October at which time they were ‘to cross the Zonnebeke Langemarck road … and attack in the direction of Passchendaele.’29

28 IWM HU 125656

29

TNA 2nd Division Operation Order No. 26, 21 October 1914

17. the ‘93’ and their stories

In the early morning of 21 October the 4th (Guards) Brigade moved into position immediately to the west of Zonnebeke where it was concealed behind Point / Hill 37. The 2nd battalion Grenadier Guards diary states that the unit:

Marched at 6 am to a position of assembly near Hannebeck Brook [sic] about 2 miles west of Zonnebeke. Then advanced about 1&1/2 miles towards Paschenbael [sic], meeting with some opposition. Eventually entrenched a line … Counter attack at dusk beaten off. Germans came on saying “We are the Coldstream”.30

The historian of the Regiment records the incident thus:

Before long the sky was lit up in all directions by the farms which the enemy was burning. By this illumination the Germans attempted a counter attack, and came on shouting, "Don't fire, we are the Coldstream." It was characteristic of the German thoroughness of method to master this regimental idiosyncrasy, and say Coldstream and not Coldstreams. But the [2nd] Battalion had not fought for two months without learning the enemy's tricks, and as spiked helmets could be distinctly seen against the glow of the burning farms, they fired right into the middle of the Germans, who hastily retired.31

Over the course of 22 23 October the 2nd battalion entrenched its position as best it could: The trenches, composed of isolated holes which held two or three men apiece, were exposed from the left to enfilade fire, but there the battalion had to remain for two days, shelled intermittently.32

The Divisional History describes how:

The night of the 22nd had for the 4th Brigade been one of comparative quietude, but the 23rd opened with a terrific hostile shell fire along the whole line, which continued with great vigour throughout the day.33

The 2nd battalion diary records that Frederick was killed on 23 October, the author adding a little detail:

30 TNA WO 95 1342 1

31 Ponsonby F, The Grenadier Guards in the Great War, Vol 1 (Macmillan, 1920) p 145

32 Ponsonby F, The Grenadier Guards in the Great War, Vol 1 (Macmillan, 1920) p 146

33 Wyrall E, History of 2nd Division (Thomas Nelson, 1916) p 119

17. the ‘93’ and their stories 6

In the evening, Lieutenant Donald [i.e.Macdonald] Miller, who had come out originally with the battalion, and had fought all through the retreat, was killed by a high explosive shell.’34 Frederick’s body was lost in the ground on which he fell.

34 Ponsonby, The Grenadier Guards in the Great War, Vol 1 (Macmillan, 1920) p 146

17. the ‘93’ and their stories

Watson, Private George Watson, 1112 1 November 1914, Messines SPS 1894 - 1896

1/14th Bn. London Regiment (London Scottish), B Company 35 Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial Panel 54 Age 34

After leaving SPS, George joined the staff of the Secretary’s Office at the Great Western Railway and was employed in that capacity when war broke out. He joined the 1/14th battalion London Regiment (London Scottish) in 1908, soon to become famous as the first Territorial unit to be bloodied in the War. George fell in the vicinity of the windmill, just to the north of Messines.

Having failed to retain and develop their success at Gheluvelt on 31 October the Germans re focussed their attack onto the southern part of the Salient, between Messines and Wytschaete. After some confusion, the 1/14th battalion London Regiment (1st Guards Brigade, 1st Division) was moved to this part of the line.

Even before George engaged with the enemy in the period 31 October 1 November he must have been exhausted, for on each of the previous few days the unit had been on the move. Having arrived at St Omer at midnight on 27 October the battalion of 750 strong was moved by motorbuses overnight 29 30 October to Ypres, arriving in that place at 3 am. This was a nine hour journey, undertaken in a fleet of about thirty four London buses. The experience was a wretched one, especially for those riding on the open top deck. One member of the battalion later recalled:

The road was abominable. Our particular bus was ditched four times which meant that we all got out and pushed the other buses did not fare much better.36

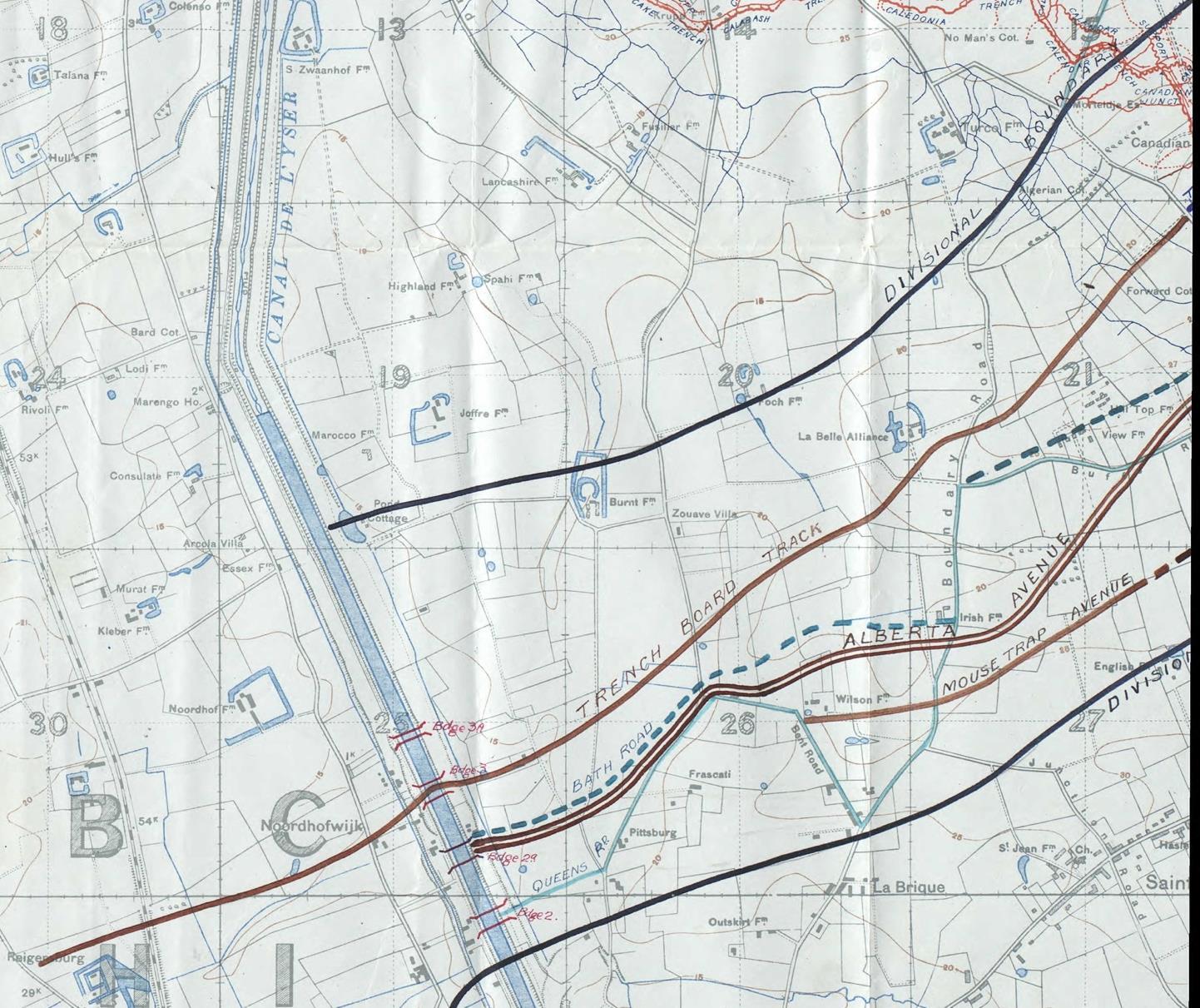

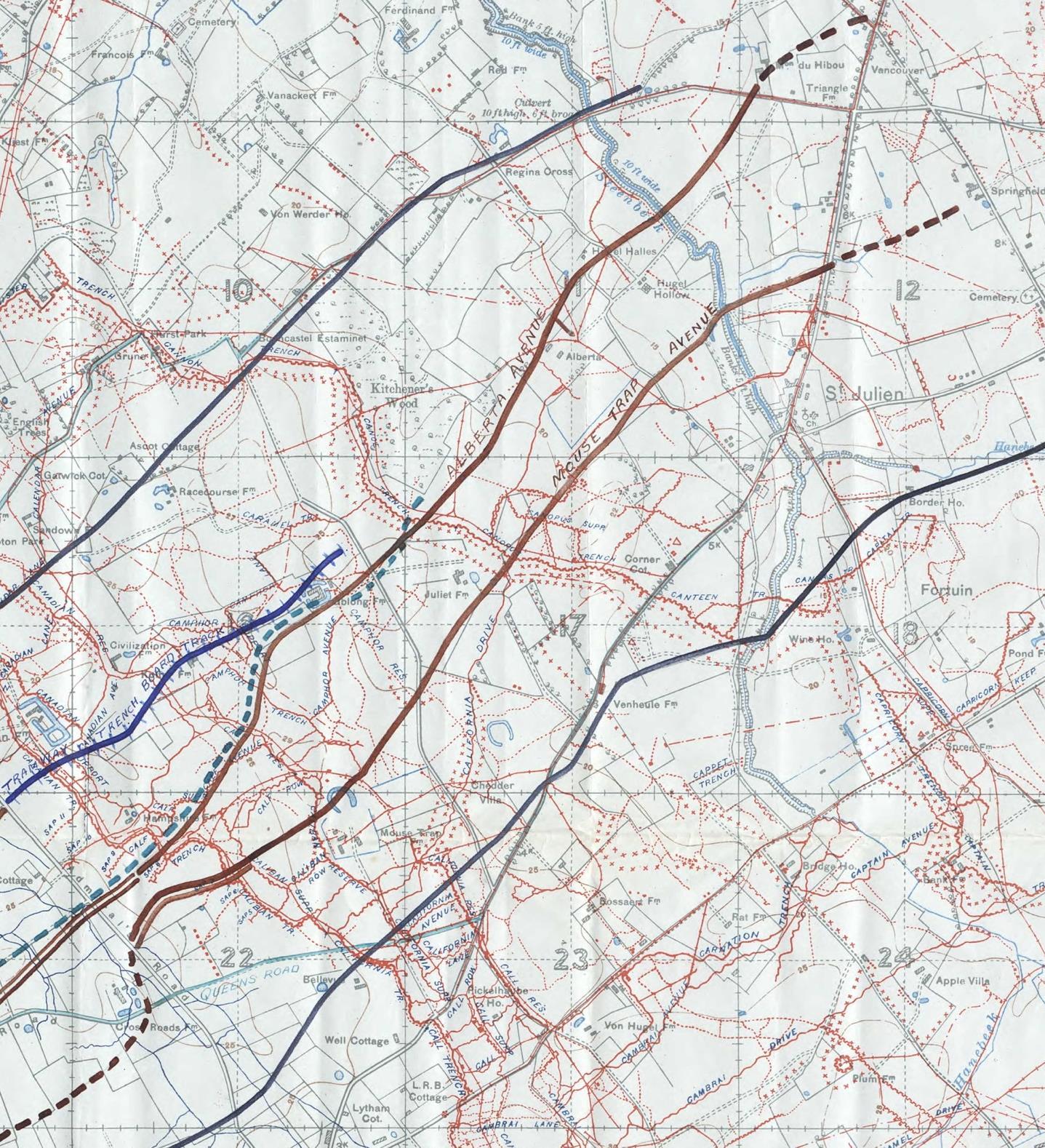

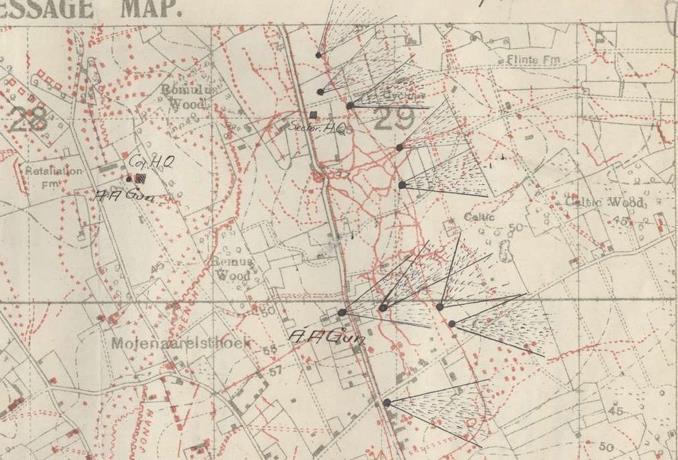

This image shows the 2nd Royal Warwickshire Regiment being transported through Dickebusch on their way to Ypres on 6 November, but this is the same as the transport experienced by Watson.37

35 This battalion was the first Territorial Force to experience action. 36 Baxter Milne. Quoted in Lloyd, M, The London Scottish in the Great War (Barnsley, 2001) p 34

37 © IWM Q 57328

17. the ‘93’ and their stories 8

At Ypres, some men slept in the Cloth Hall, though any meaningful rest was thwarted by the Germans releasing at first light a cannonade of intense and rapid fire upon the town. In the morning of 30 October, having breakfasted at 6 am and then paraded two hours later, the battalion marched up the Menin Road to a reserve position near Hooge later known as Sanctuary Wood passing a continuous stream of wounded men making their way back to Ypres. However, at 4 pm it was ordered to march back to Ypres, from where it travelled by motorbus to St Eloi, south of Ypres, arriving at 7.50 pm. Here the unit was provided with a hot meal and those lucky enough to find shelter grabbed some sleep. At this moment it seems that the original intention was to send the battalion into action shortly after midnight, the men having been roused to parade at about that time. However, representations were made as to their collective exhaustion and this plan was altered. Sandy Innes, a signaller with the battalion described the experience thus:

Spent ten hours of last night on bus in rain and finally at Ypres and slept in the Town Hall. At 10 am we parade and march out to north east to within 400 yards of firing line. Lie there for four hours and after seeing lots of wounded return, we march back to Ypres and mount our buses again. Ride to St Eloi and finally bunk down in a house only to be called out at 11 pm and sent back to bed.38

At 6 am on 31 October the unit marched south east from St Eloi for about a mile, at which point it began to prepare a reserve trench. However, at 8 am further orders were received 38 Baxter Milne.

17. the ‘93’ and their stories

to march to the ridge area just north of Messines to participate in a counter attack from the trenches established by the 2nd Cavalry Division. Private J O Robson of B Company recalled:

We marched up the road into Wytschaete. Gendarmes were turning inhabitants out of the town, and we met a pitiful procession of refugees mothers with babies in their arms, little boys carrying huge loads, old grannies pushing dilapidated perambulators full of clothes, sheets and all sorts of odds and ends. At the door of a convent on the right stood a group of nuns all, I believe, killed by a shell shortly afterwards.39

Moving under heavy shell fire, the troops first traversed the Wytschaete Wulverghem road and then, by following the course of the Steenebeek, arrived at about 10 am at L’Enfer Wood. From this position the battalion was deployed to consolidate a gap in the line marked by two farms adjacent to the Messines Wytschaete road, later known as Hun’s Farm and Middle Farm. To the north of the latter stood a windmill, already severely damaged.

From L’Enfer Wood elements of the 1/14th London Regiment (London Scottish) were ordered up the slope to the line of trenches a little to the east of the Messines Wytschaete road. The unit diary records that the:

The cavalry trenches were reached under heavy shrapnel and big gun fire about 10.30 am, but as there was no room in the cavalry trenches the best cover obtainable had to be searched for, it being impossible to advance further unsupported. The battalion lay under heavy fire until dusk when the firing ceased.40

The Report on Operations by GOC 2nd Cavalry Division tells a rather different story. It states that the London Scottish:

Although exposed to a very heavy shell fire, and an enfilade fire on their left from a maxim [gun], attacked most successfully and re took all the trenches, and stopped any further German advance on Messines, although some of the enemy remained in the village. The battalion retained its position for the rest of the day although exposed to heavy shell fire.41

Any reprieve, however, was only temporary. Beginning from about 10 pm on 31 October, there was desperate fighting for the next eight hours. Sir Hubert Gough, GOC 2nd Cavalry Division, reported that: 39 Ibid pp 37 38 40 TNA WO 95 1266 2 41 TNA WO 95 1117 1 Report on Operations of 2nd Cavalry Division 30th, 31st Oct and 1 Nov

17. the ‘93’ and their stories 10

Our men firing steadily inflicted enormous losses but our line was too feebly held to be continuous and gradually between the gaps the enemy got through and began surrounding our various detachments. Constant counter attacks with the bayonet were made by our cavalry and the London Scottish and the trenches constantly re taken. …. About 2 pm [sic: this must be 2 am] most of our troops had fallen back from the trenches …. The London Scottish were still in their trenches at 5.45 am, which they held by repeated bayonet charges … ‘A’ Company of London Scottish in reserve took up a position in rear of the trenches … which protected the rear of the companies in the trenches and prevented them being surrounded for some time and they then maintained their position until daylight, when they retired fighting through the Germans, although practically surrounded…. There was great confusion owing to the darkness, the noise, the extent of the front, and it was impossible for officers and men to know where to go and what the situation was.42

The Messines Wytschaete Ridge had thus been lost.43 Of their total number of 750 before the encounter, 1/14th London Regiment (London Scottish) endured casualties of 9 officers and 312 Other Ranks.44 George’s body was not retrieved and was lost. During 1 November the remainder went into billets at La Clytte. The scale of loss was in part because some 50% of the Mark I rifles proved useless for rapid firing owing to faulty magazines, as well as being outdated and rounds having to be inserted singly by hand. Treating some of the wounded, Captain Henry Owens of the RAMC was told by one combatant that ‘it was quite alright but [they] were surprised that volunteer troops were sent actually into the fighting line they hadn’t expected it.’45

The Official Regimental History concludes thus its chapter on the events of 31 October 1 Nov:

So ended the Battle of Messines. The London Scottish, hastily assembled from detached duties a few days before, with no preparatory training, with defective rifles and without their machine guns, had been flung into one of the most desperate fights of the War. At a most critical moment they had held back the rush of overwhelming numbers long enough to prevent a break through that would have imperilled the whole position about Ypres.46

42

TNA WO 95 1117 1 7. Report on Operations of 2nd Cavalry Division 30th, 31st Oct and 1 Nov

43 In fact Wytschaete was re gained by the French, though lost again to the Germans on 13 November. The Germans dug in on the higher ground and were not dislodged until June 1917.

44 The 2nd Cav Division suffered a total loss of 1,455 men in 48 hours. TNA WO 95 1117 1 Report on Operations of 2nd Cavalry Division 30th, 31st Oct and 1 Nov

45 IWM, Owens Mss, 80/23/1, memoir.

46 Lindsay, J H (ed) The London Scottish in the Great War (1926) p 42

17. the ‘93’ and their stories 11

Farmer, 2nd Lt James Douglas Herbert 4th November 1914, Westhoek SPS 1906-1911

9th Battery, XLI Bde, Royal Field Artillery Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial Panel 5 and 9 Age 21

After leaving St Paul’s James attended the Army College, Farnham and the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. He was gazetted as second lieutenant to the Royal Field Artillery in 1913 and went to the front with the BEF in August 1914, initially with the 17th battery of the XLI Brigade before being transferred a few days before his death to the 9th battery. He fell at Westhoek.

In the opening days of November 1914 the three batteries of XLI Brigade (2nd Division) were to give cover to infantry units of 2nd Division north of the Menin Road. All three batteries were located in close proximity to each other on top of the ridge at Westhoek.

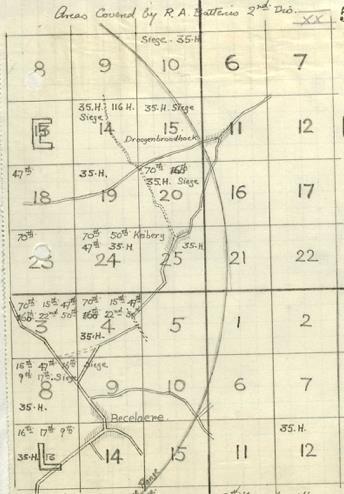

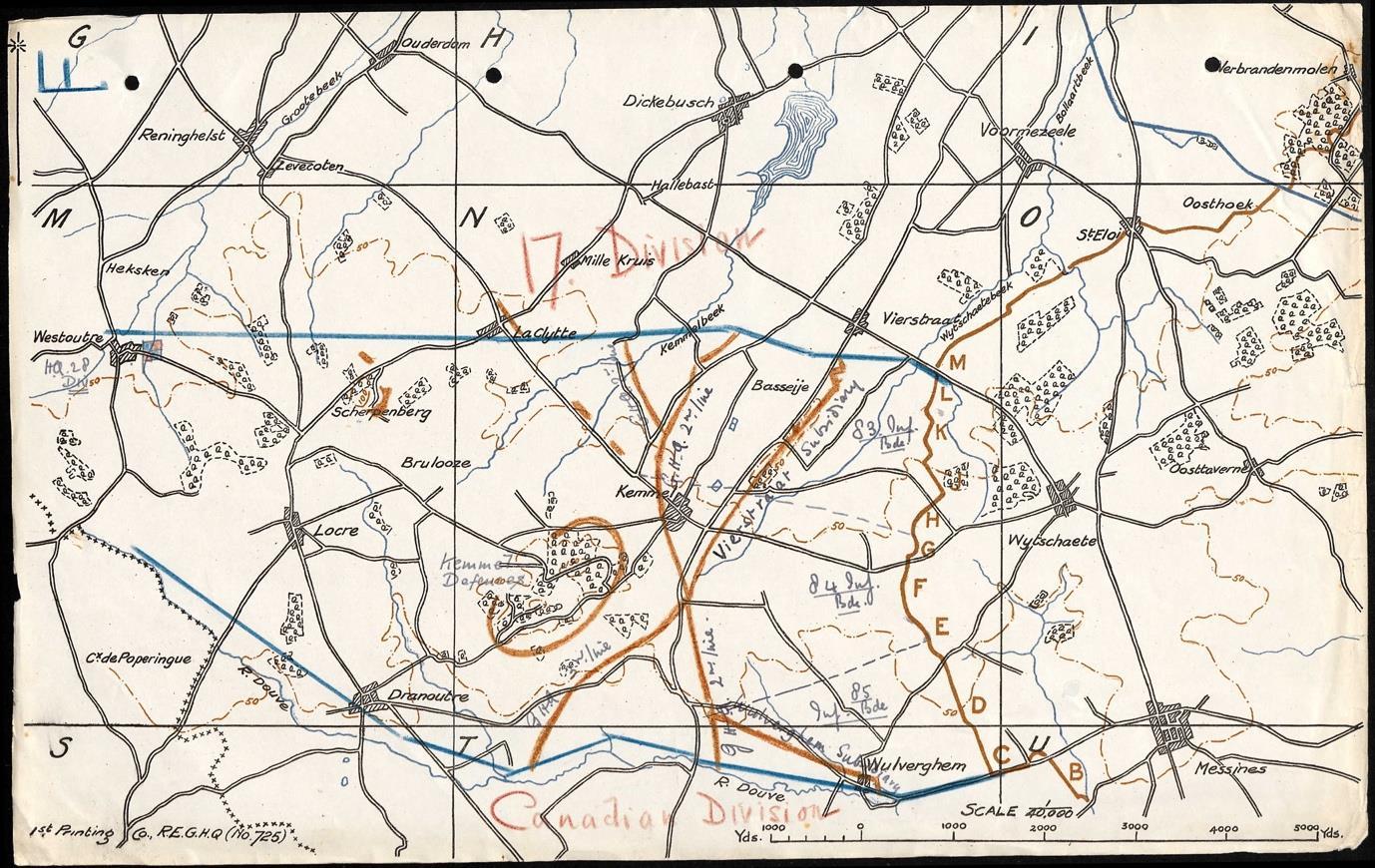

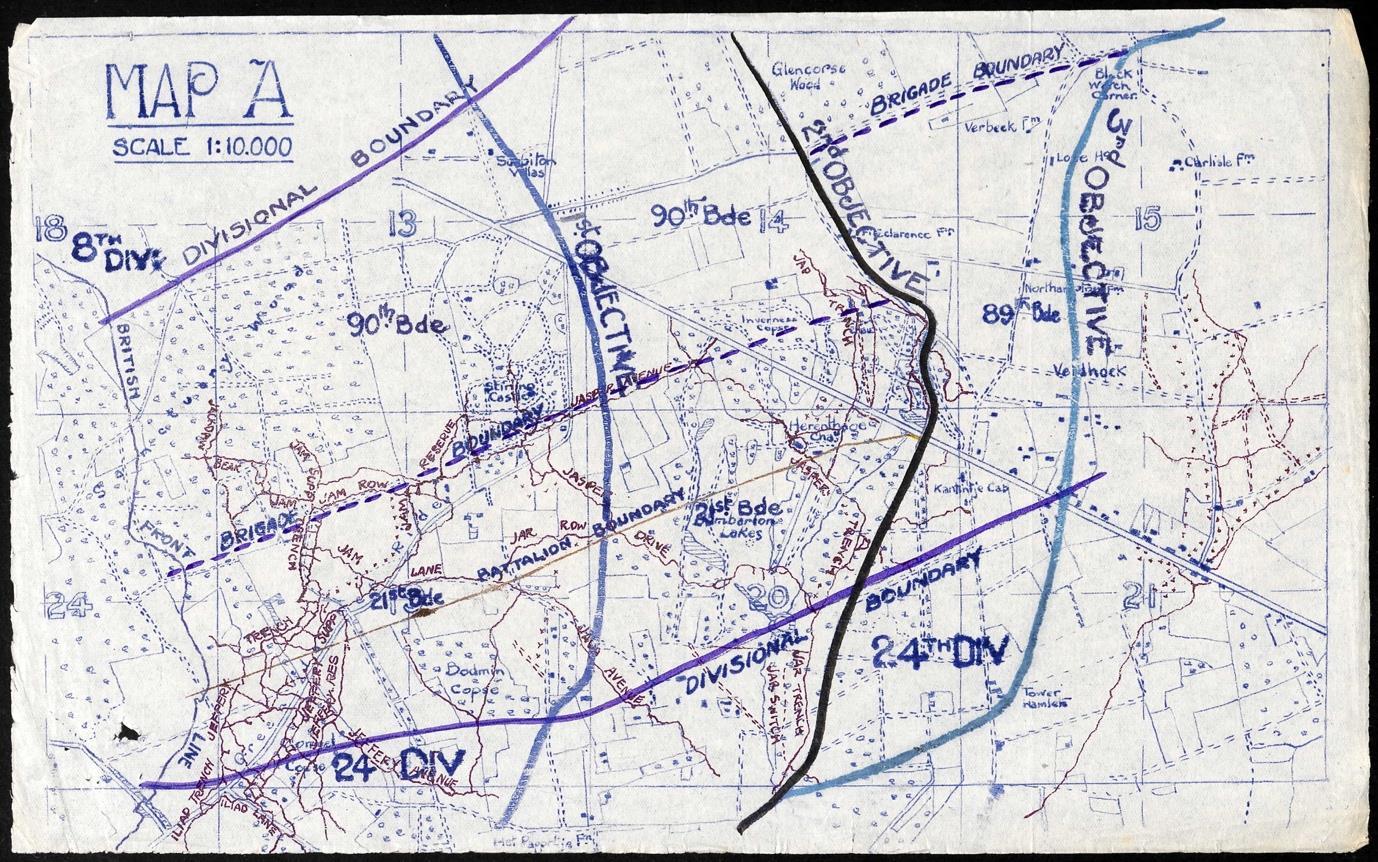

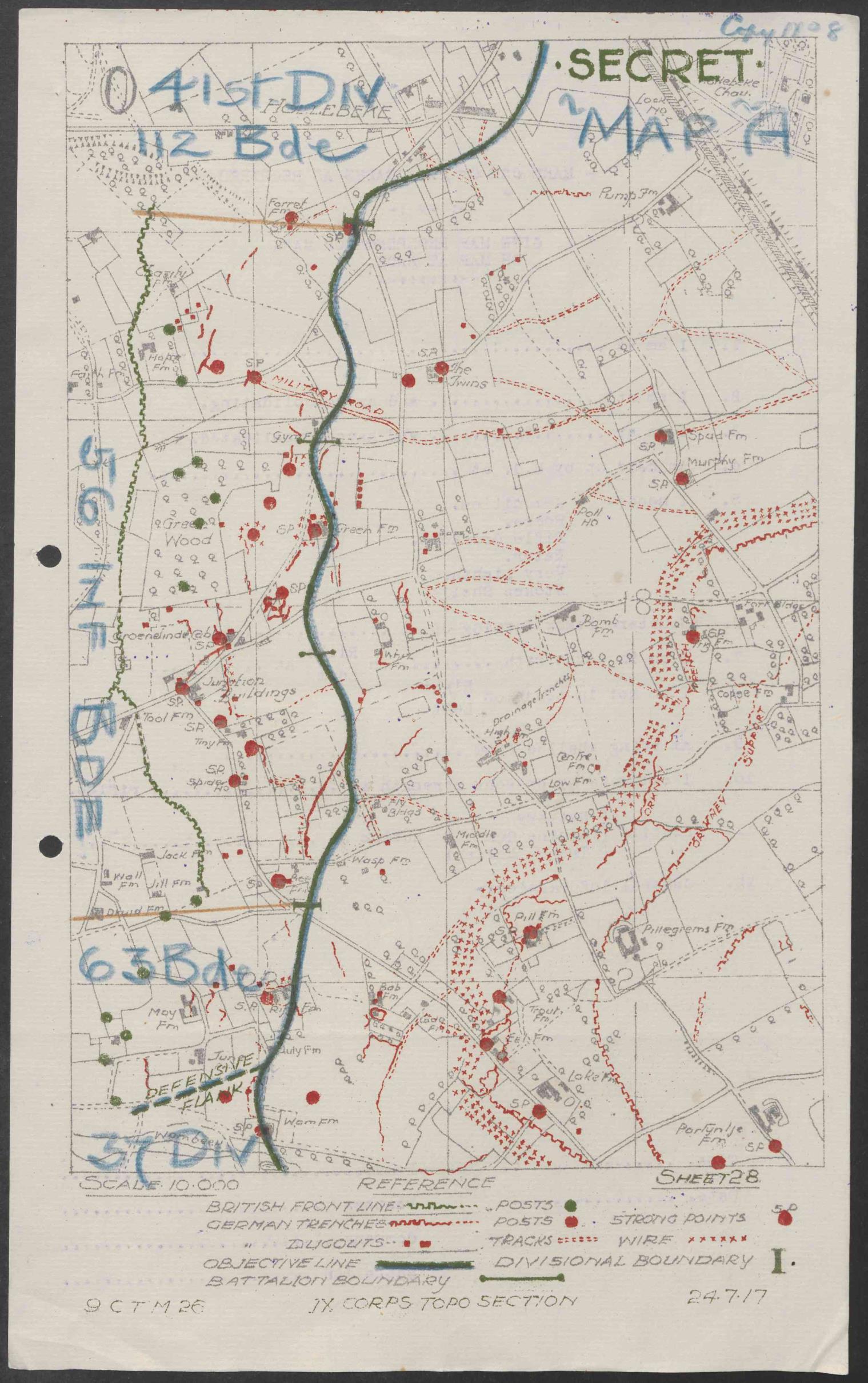

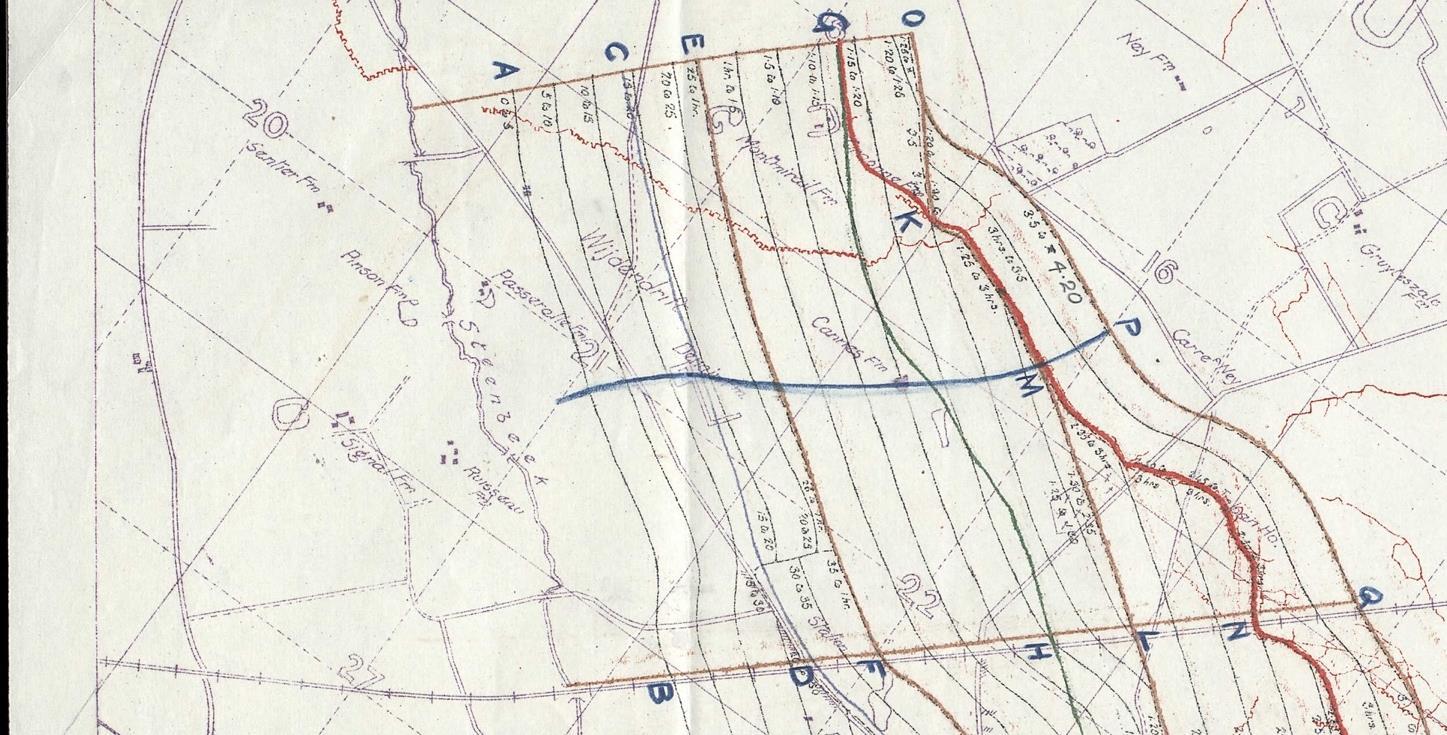

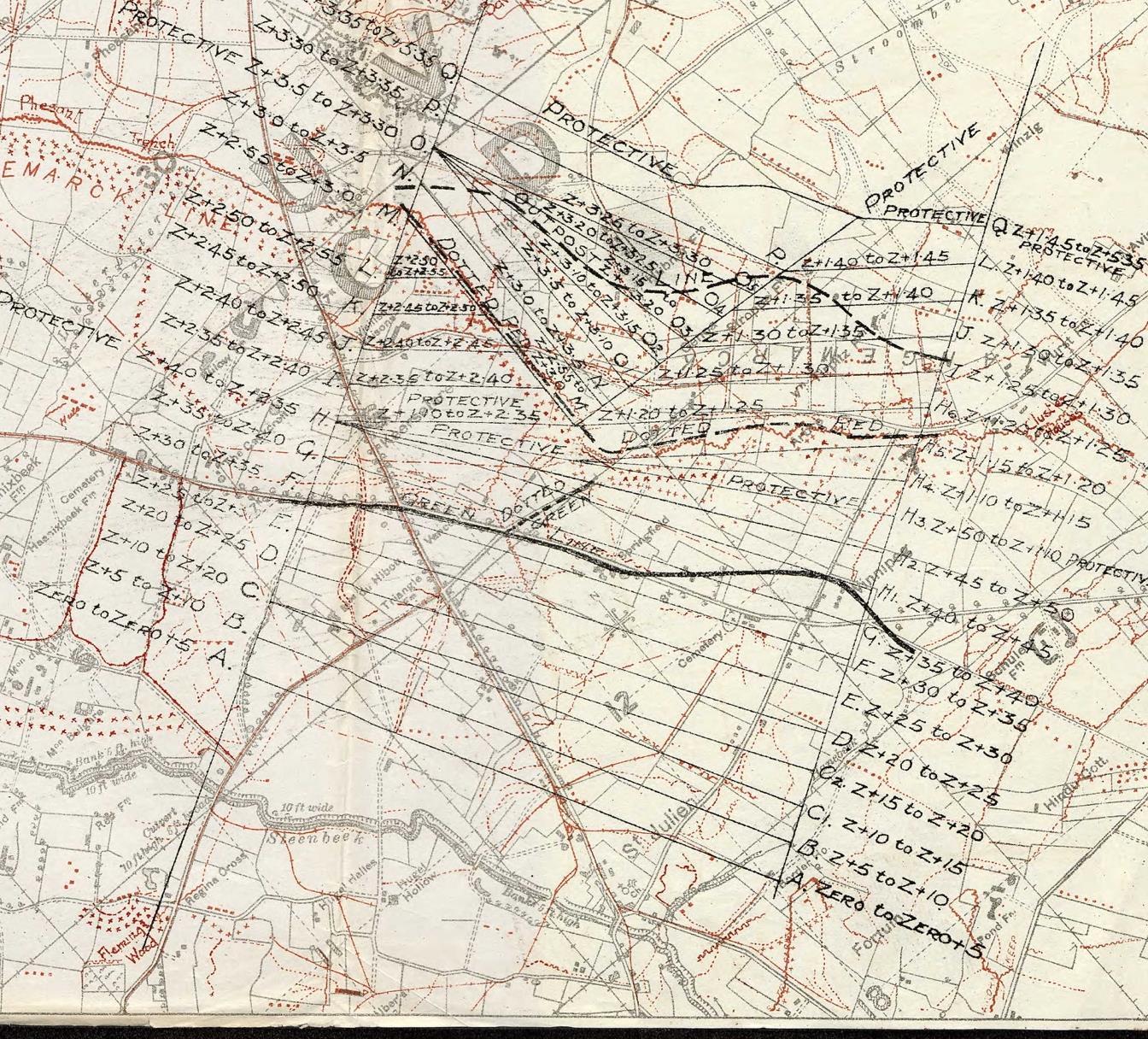

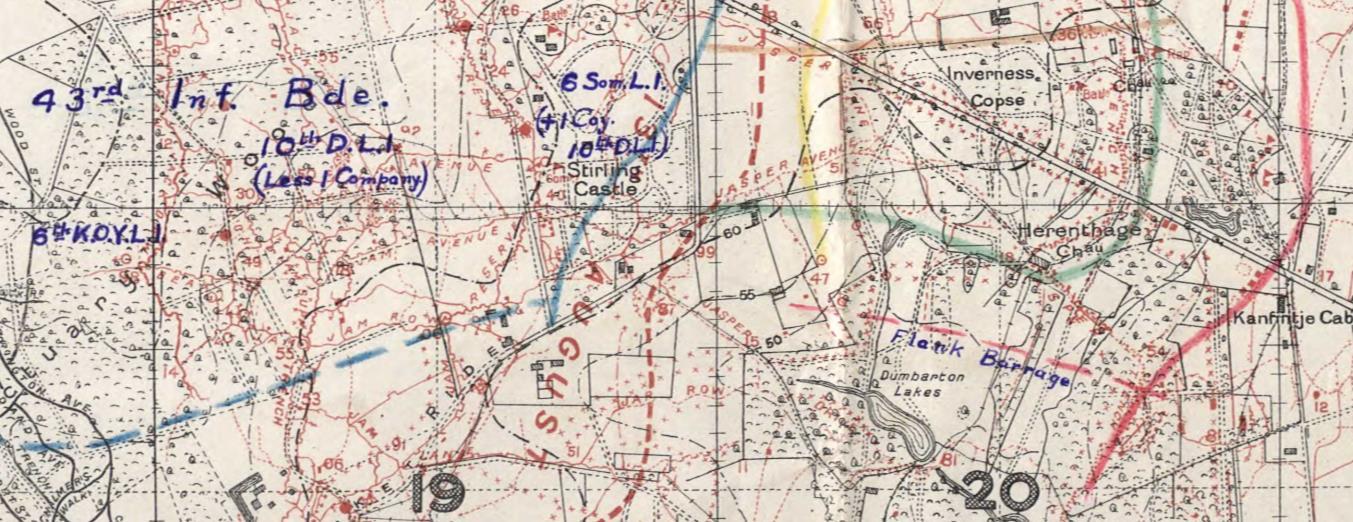

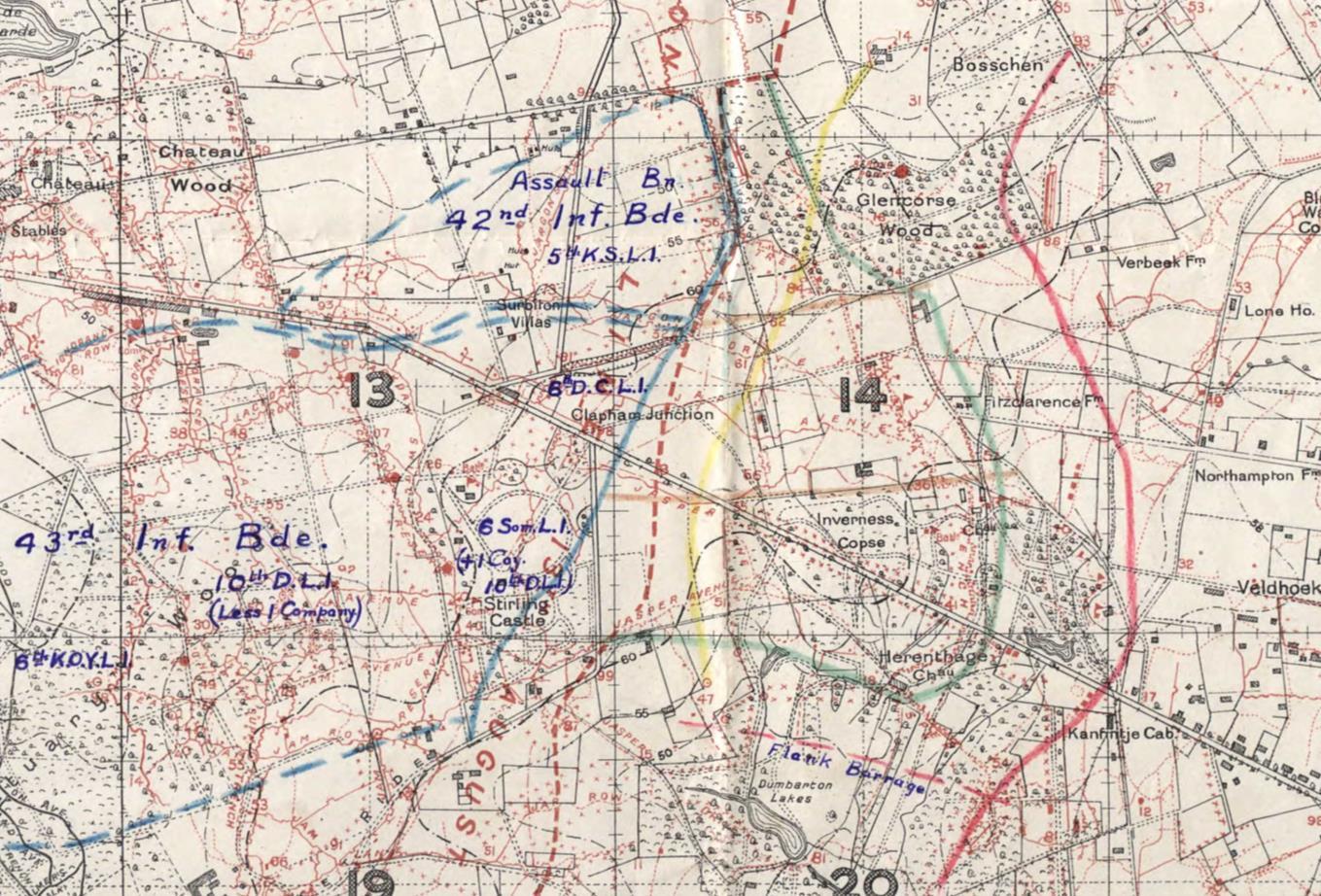

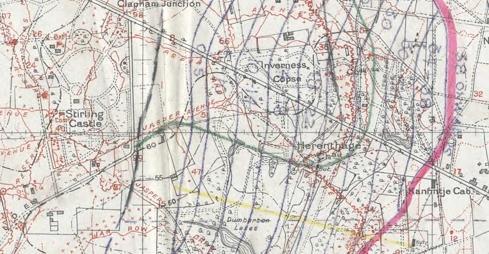

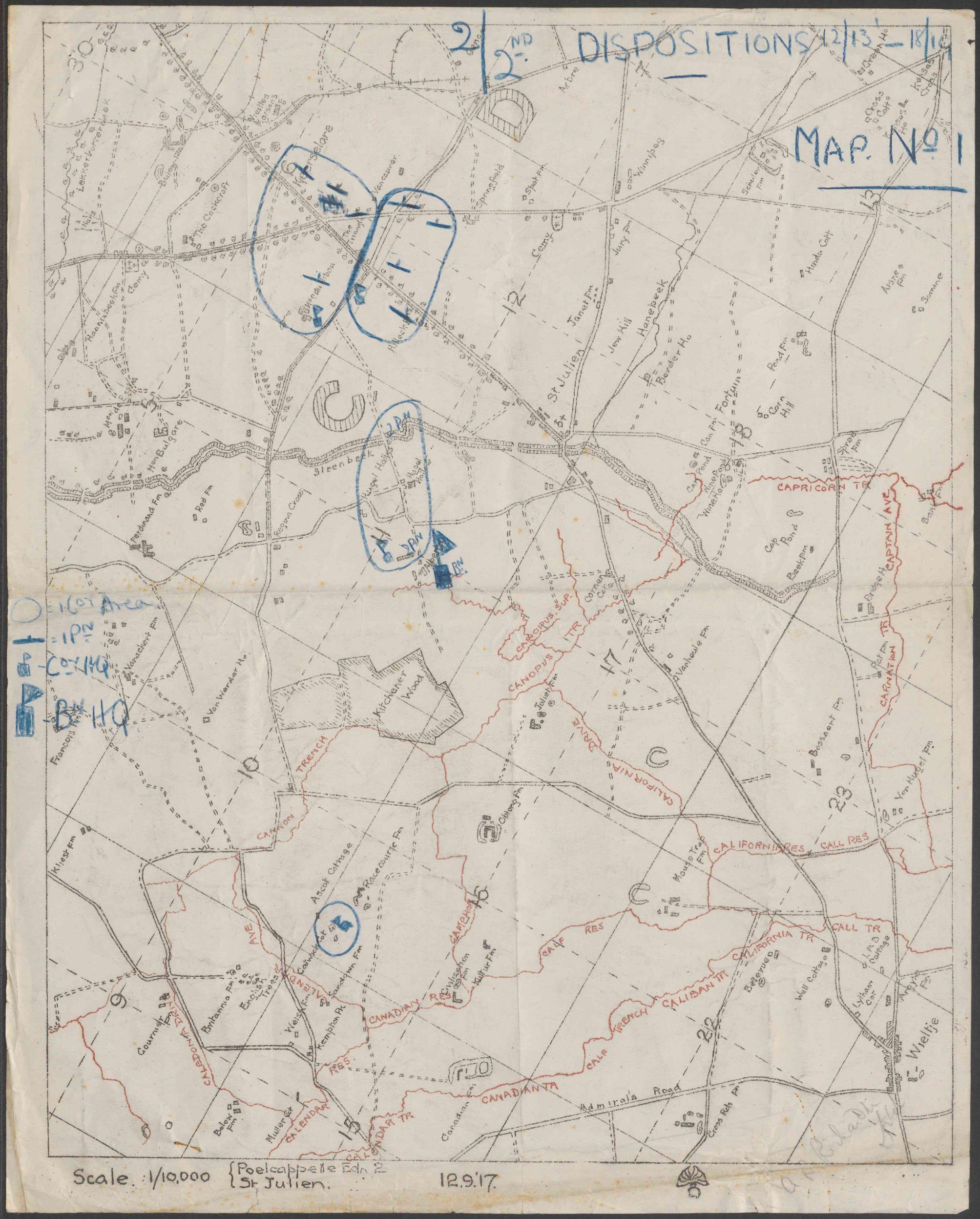

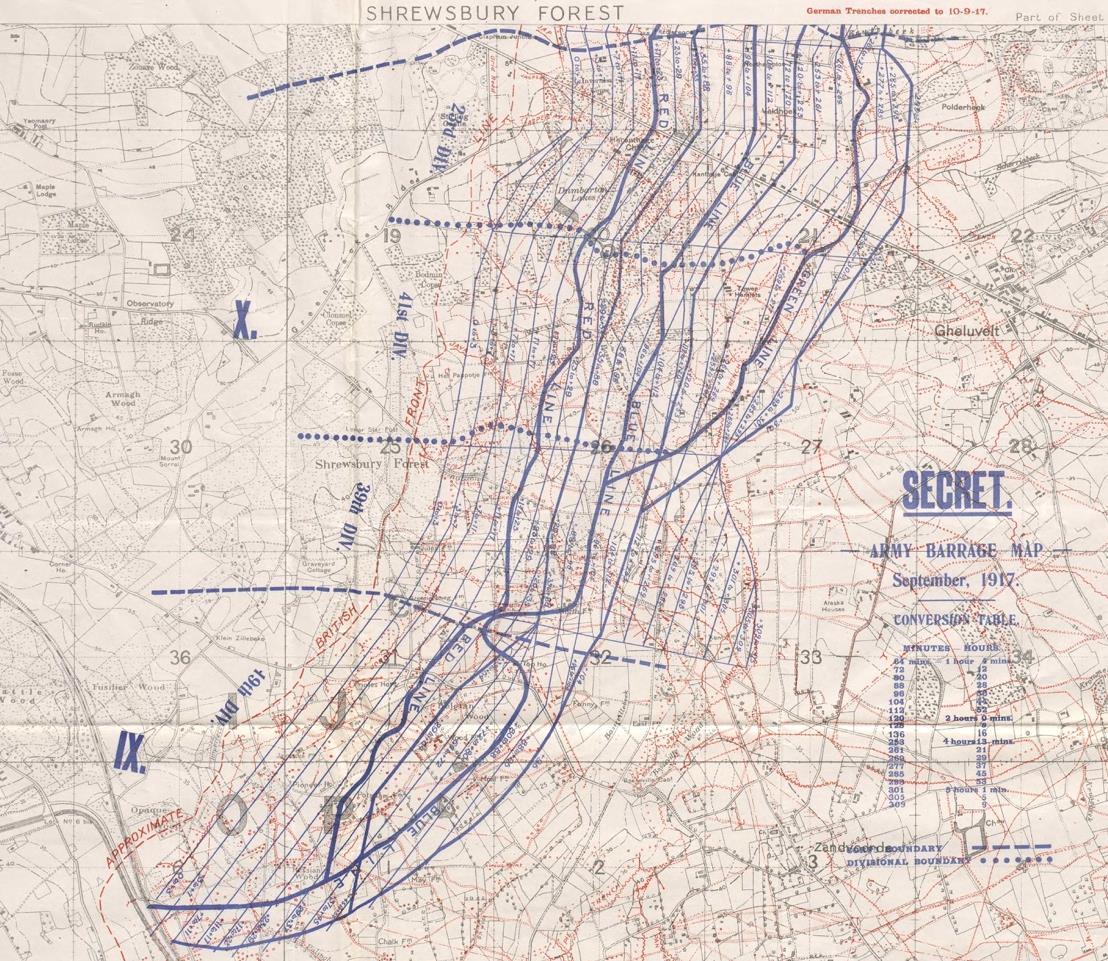

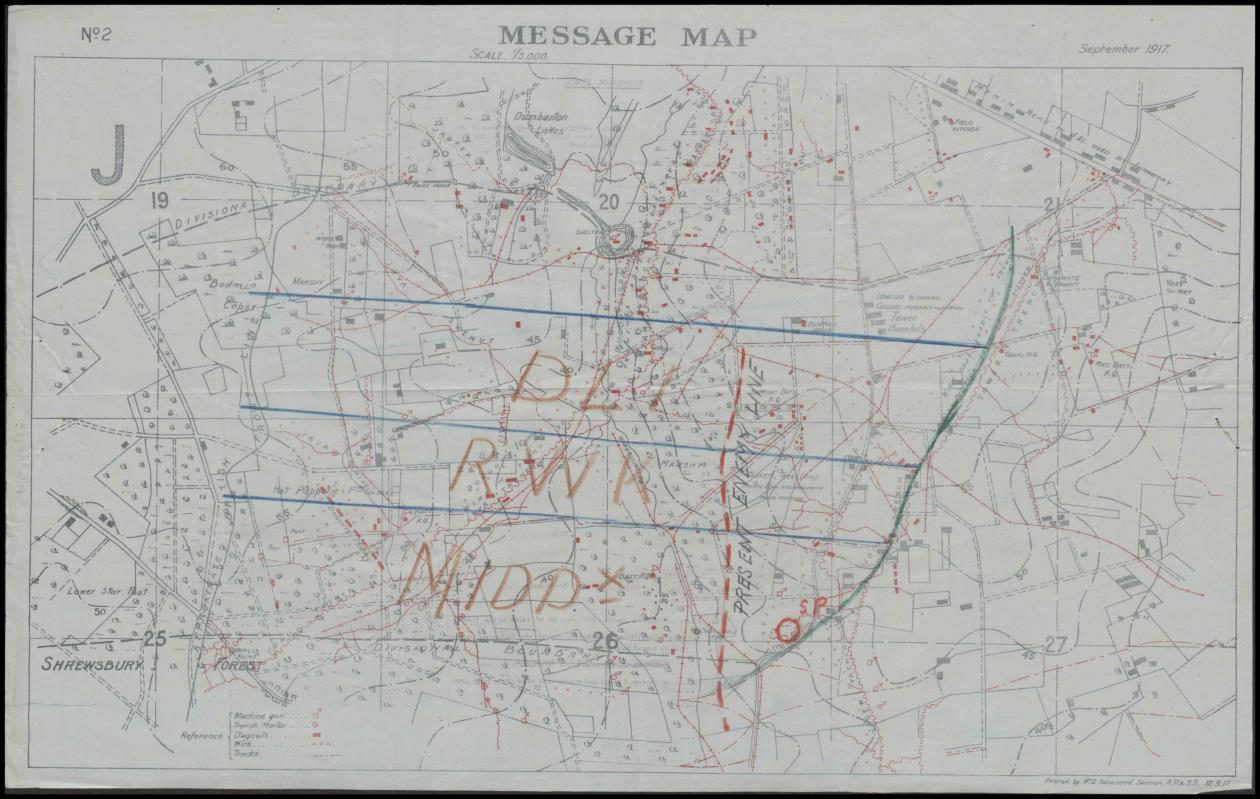

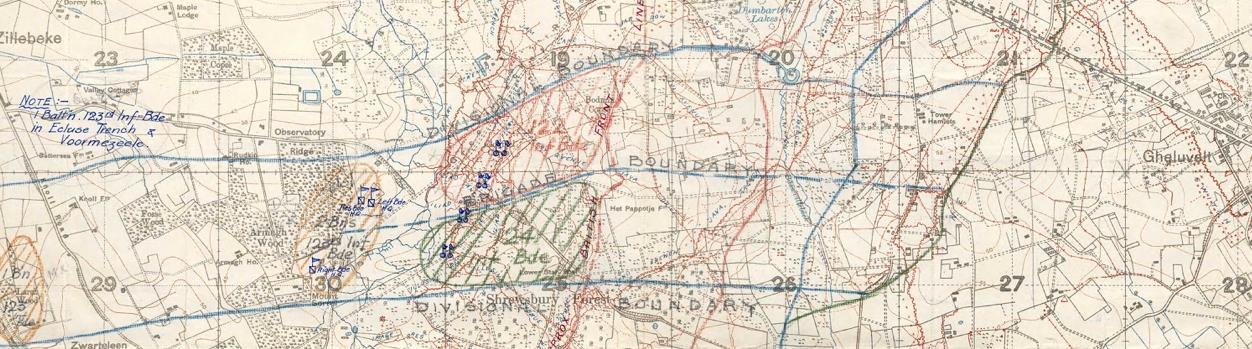

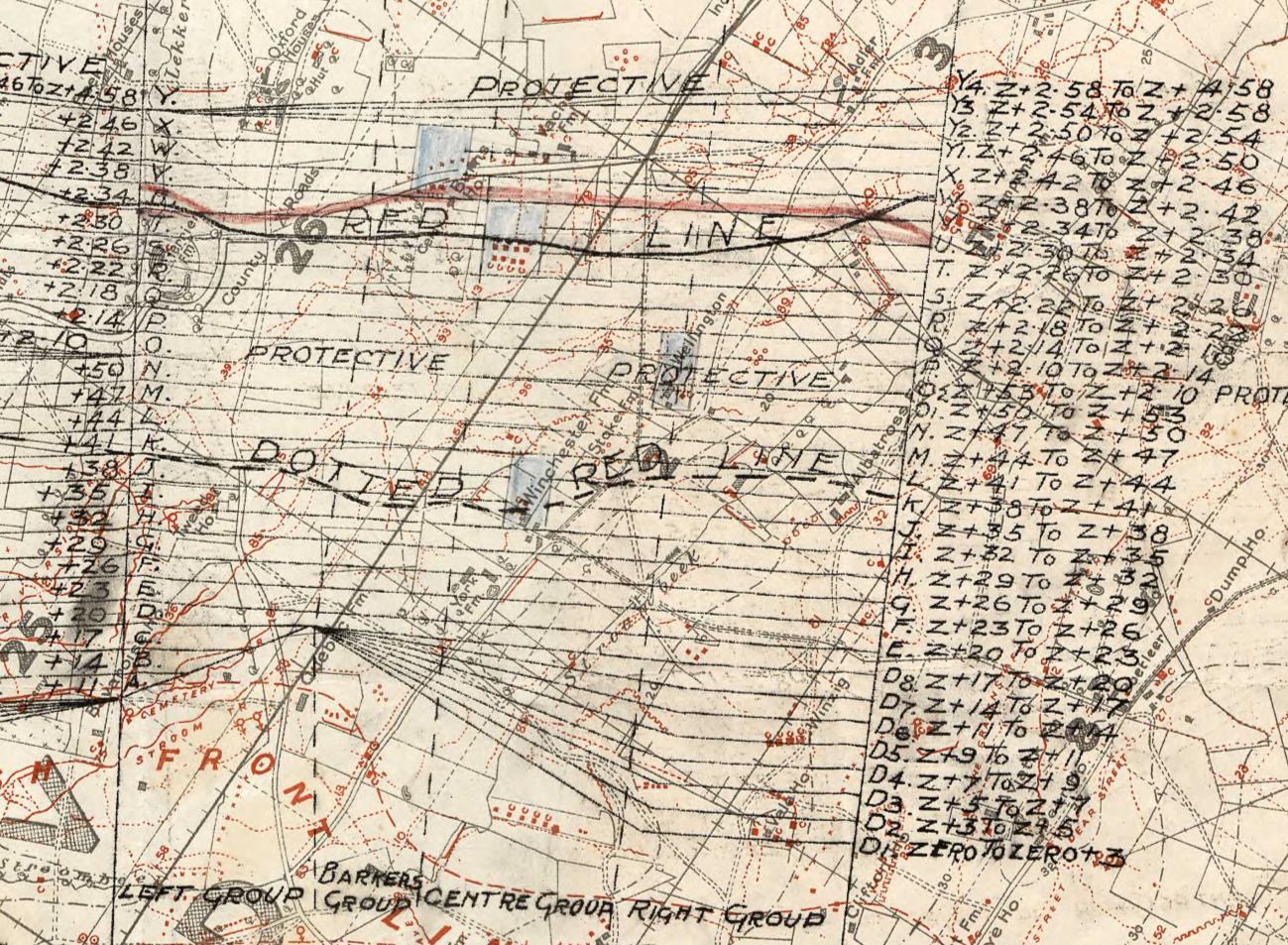

Map showing the location of, and areas covered by, the Royal Artillery Batteries of 2nd Division in November 1914. The three batteries of XLI Brigade (9th, 16th and 17th) are located in the bottom left hand square.48

47 © IWM (HU 121895) 48 TNA WO 95 1313 1 4

17. the ‘93’ and their stories 12

Map showing the disposition at Westhoek in November 1914 of the three batteries 9th, 16th and 17th of XLI Brigade.49

A F Becke provides a detailed description of the arrangement of the batteries of XLI Brigade at Westhoek: [The] HQ [of XLI Brigade] and all 3 btys [i.e. batteries, 9th, 16th and 17th] were all situated in the vicinity of Westhoek. The Brigade headquarters itself was in a splinter proof dug out at the side of the Chapel to the south of the cross roads. …. The Brigade dressing station was situated at the corner of the cross roads in Westhoek … The 9th battery’s position was along a fence that formed the southern boundary of the garden of a small two roomed cottage. To screen the guns, big branches of trees had been cut down and planted vertically along the fence, thus giving to it the appearance of a small belt of saplings. From the front only the

49 TNA WO 95 1326. This map is dated 11 November, but the batteries had not moved their location since the death of Farmer on 4 November.

17. the ‘93’ and their stories 14

gun muzzles were visible, and even they could only be seen with difficulty. To permit, however, of extreme traverse it sometimes became necessary to uproot one or two of the branches. In order to give protection to the detachments, narrow slits had been dug behind the wagons, and an extra slit served as a command post. 50

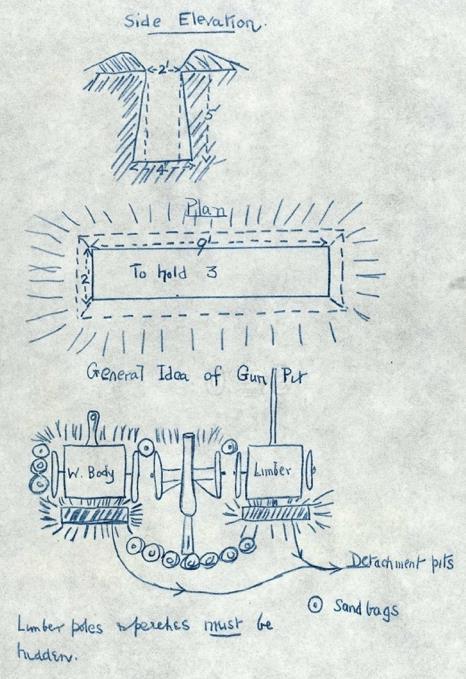

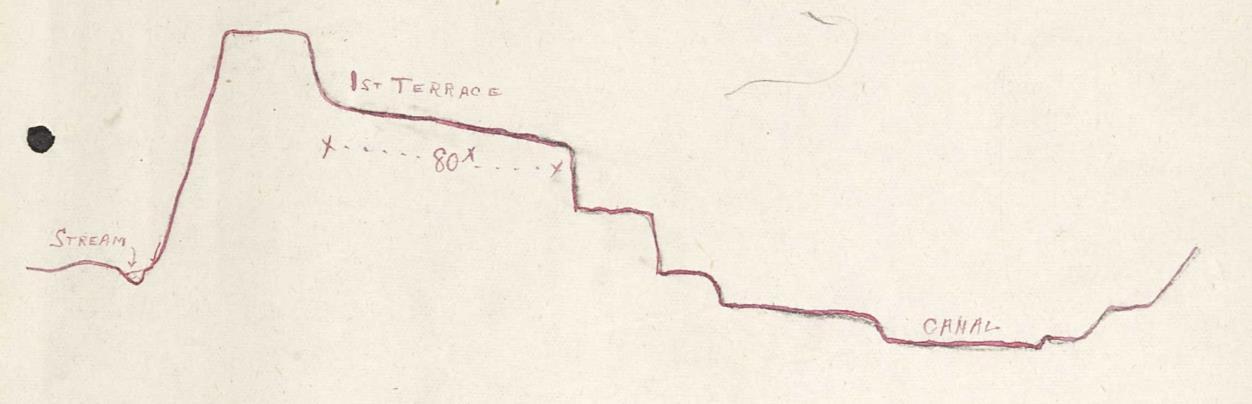

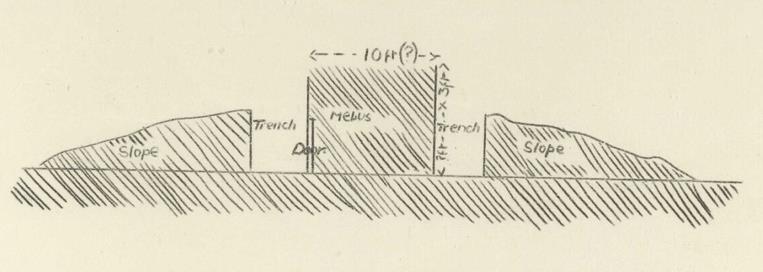

A diagram showing the arrangement of a gun pit with which James will have been familiar.51

50 Becke, A F XLI R.F.A p. 153. This article is hosted in XLI unit diary December 1914 TNA WO 95 1326 1. This final sentence actually applies to 16th battery, but is equally applicable to all three of the 41st Brigade batteries. 51 TNA WO 95 1313 1 4

17. the ‘93’ and their stories 15

The unit diary of 9th battery reports that on 4 November ‘2nd Lieut J. D. H. Farmer was killed by a heavy howitzer shell which burst in the battery’, suggesting that he was the unfortunate victim of a local accident rather than any enemy action.52 The diary does not indicate the fate of James’ body, but in documentation presented to the Imperial War Museum by his father, it is stated that James was ‘buried at Westhoek’. 53 When 17th battery incurred two casualties on 3 November the diary of this unit states that ‘gunners [George] Cottrell and [Joseph] Blackshaw were buried in the rear of the officers’ billet in the evening’ the billet most probably being equivalent with XLI Brigade HQ, shown on the map above.54 It seems likely, therefore, that this too is the final resting place of James, his remains thereafter lost like those of Cottrell and Blackshaw no doubt pulverised to oblivion in the heavy enemy shelling that occurred during the battle of Nonne Boschen on 11 November.55 52 TNA WO 95 1326 1 53 © IWM HU 121895. This detail was submitted for the Bond of Sacrifice publication. 54

Battery https://www.ancestry.co.uk/interactive/60779/43112_1326_0 00000?backurl=&ssrc=&backlabel=Return#?imageId=43112_1326_0 00041 55 In the text accompanying an image of Farmer presented by his father and in the possession of the IWM, it is stated that Farmer was buried at Westhoek. There is a memorial panel to him in Mundesley Church, Norfolk. https://www.flickr.com/photos/43688219@N00/9531373106/in/photolist fDetLb fwfMa5

17. the ‘93’ and their stories 16

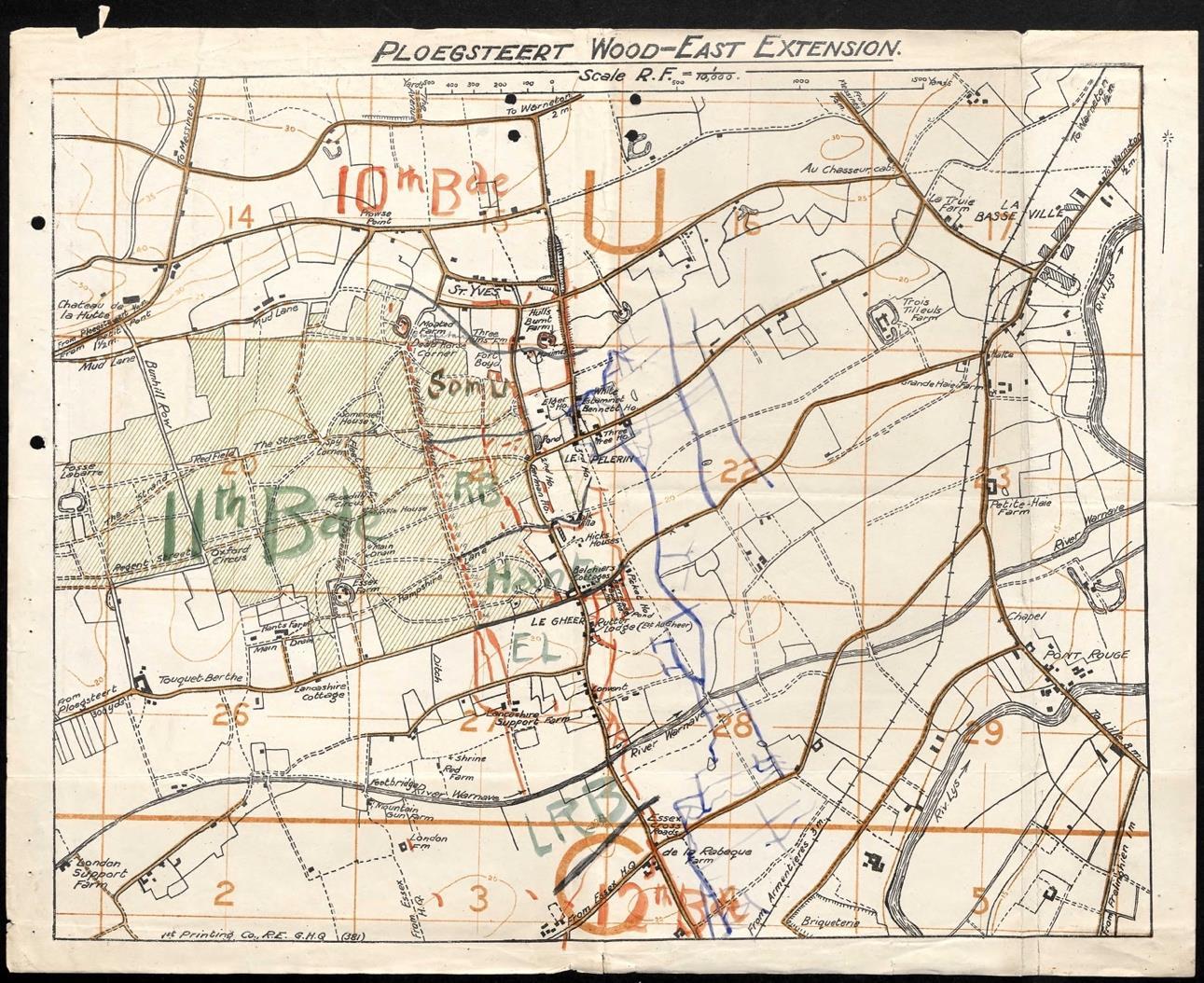

Barton, 2nd Lt Albert Thomas Lionel 7 November 1914, Ploegsteert Wood SPS 1907-10

2nd Bn. Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers Ploegsteert Memorial Panel 5 Age 20

The Pauline is silent about the schoolboy career of Albert. His one and only mention is on the list of those noted as ‘Missing’ in the December 1914 edition.56 The record is similarly silent about his activities after having left SPS in 1910, though clearly at some point he signed up to fight with the 2nd battalion Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers (12th Brigade, 4th Division).

On 7 November the line in the southern part of the Salient between Le Touquet and St Yves was held by 4th Division. On this day, from 2.30 am onwards, the Germans focussed their attack against Ploegsteert Wood, described by a soldier in the Seaforth Regiment as being ‘very similar to an English pheasant covert with dense undergrowth which made it very difficult to get through and impossible to see any distance.’57 By all accounts the assault was unusually severe, the Germans employing six infantry and two Jager battalions. Towards 7.30 am, under the cover of a thick mist, a large group of Germans had breached the front line trenches and penetrated the wood, at which point the 2nd Inniskilling Fusiliers were employed in counter attacks.

The unit diarist recorded that the battalion:

Went out in the morning to recover trenches on the edge of Ploegsteert Wood. Two desperate assaults were made, led by Captain G R V Steward, on the trenches which the Germans had taken from the Worcester Regiment. We were unfortunately repulsed with many casualties … 2nd Lieutenant A T L Barton, wounded and missing.58

Albert’s obituary, published in The Pauline, provides a little more detail:

On 7th November [Albert] volunteered off the sick list to lead the attack on a Saxon trench, but fell wounded on the parapet [towards the eastern edge of Ploegsteert Wood] and has not been heard of since.59

56

57

58

59

The Pauline, 32 214, December 1914, p 218

TNA WO 95 14831 7

TNA WO 95 1505 2

The Pauline, 34 224 April 1916 p 41

17. the ‘93’ and their stories 17

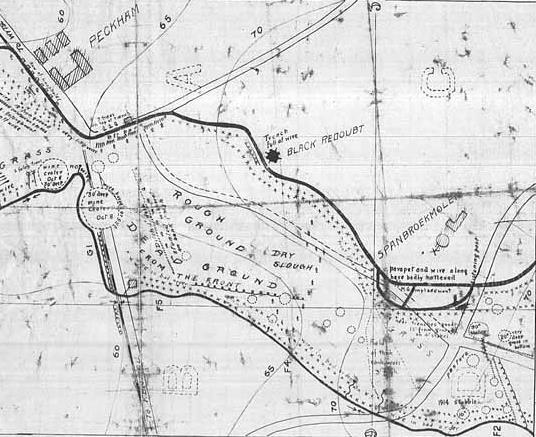

At 5.30 pm on 8th November the 2nd battalion Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders moved into Ploegsteert Wood to relieve the 2nd Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, a process described as ‘a very muddy walk’ and not completed until 11 pm.60 Their unit diary includes a particularly clear map, showing the piecemeal nature of the trenches that the 2nd Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers had established in rather desperate circumstances.61 60 TNA WO 95 1365 1 61 TNA WO 95 1365 1

17. the ‘93’ and their stories 18

Crowe, Captain William Maynard Carlisle 11 November 1914, Glencourse Wood / Nonne Bosschen

SPS 1885 - 1889

Royal Warwickshire Regiment; attached 1st Bn. Northamptonshire Regiment Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial Panel 8 Age 42

Aged 17 years and 10 months in July 1888, William was described by his schoolmaster at St Paul’s as ‘painstaking and industrious but has not great strength in any subject’.63 Upon leaving SPS William attended the Royal Army Medical Corps at Sandhurst, obtaining his commission as 2nd Lieutenant in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment in July 1891. He was promoted Lieutenant in 1893, became Captain in September 1898, and retired in August 1907, joining the Reserve of Officers. William was a member of the United Service Club and of the Swiss Alpine and Swiss Ski Clubs. He married Elizabeth Hannah Stanley, a widow ten years his senior, at Trinity Church, Upper Chelsea on 5 November 1904. William was attached to the 1st battalion Northamptonshire Regiment (2nd Brigade, 1st Division) at the time he was killed. He fell in the vicinity of Glencourse Wood / Nonne Bosschen.

An early winter’s mist hung in the air in the morning of 11 November, the day on which the Germans launched an attack all along the front from Messines in the south to Polygon Wood in the north. Along this nine mile front fewer than 7,800 men faced twenty five German battalions totalling some 17,500 infantry. The massive German infantry attack began at around 9 am, preceded by a three hour long bombardment which, all accounts agree, was unprecedented in its intensity. Just north of the Menin road, the 900 yards of front between Veldhoek and Polygon Road was held by 1st Guards Brigade (1st Division) and was composed of some 800 officers and men. Trying to determine a route around the 62 IWM HU 120648 63 School Reports, with the permission of St Paul’s School Archive

17. the ‘93’ and their stories 19

resistance with which they met, the Germans found their way into Nonne Bosschen (Nun’s Copse) by 10.15 am on 11 November. The situation was indeed grave for the British, for not only was the line thin but on the western side of Nonne Bosschen the Germans would not have met with any organised resistance they would have penetrated and broken the British line. In these desperate circumstances, 1st Guards Brigade (1st Division):

Asked for the 1st battalion Northamptonshire Regiment to restore the situation as the Germans had broken the line. The Northants arrived at 1st Bde HQ and were ordered to clear Nonne Bosschen Wood [and the south east corner of Glencourse Wood].64

Unfortunately, the unit diary for 1st Northamptonshire for November 1914 is mostly missing, and what has survived offers little illumination.65 For the period 26 October to 15 November it simply states that ‘the regiment was heavily engaged most of the time. In fact, on 14 November there were only two officers left and about 300 men’.66 The narrative for this period for 1st Northamptonshire can only be reconstructed by a complex process of cross referencing with multiple other unit diaries, personal accounts, a close study of maps and visits to the locations as they exist today.

The 1st battalion Northamptonshire Regiment had been in and out of the front line in the woods surrounding Veldhoek chateau just north of the Menin Road for several days prior to 11 November. At 2.30 am on that day they had once again arrived in reserve in the north eastern corner of Sanctuary Wood and were looking forward to being sent out of the fighting area for a rest. However, from 6.30 am the line they had only recently vacated was subject to the ‘the most terrific [shell] fire that the British had yet experienced.’67 Infantry at the front crouched for cover in the bottom of ill formed trenches and holes in the ground, the survivors then enduring an onslaught by Prussian Guards brought up especially for the purpose. As the Official British History puts it:

When at 9 am after two and a half hours’ bombardment, the German artillery lifted its fire, twenty five battalions of the most famous regiments of the Prussian Army at least 17,500 infantry moved forward on either side of the Menin road, from the shelter of the woods

64

TNA WO 95 1267 1 4 and TNA WO 95 1227 1

65 Quite possibly it suffered the same fate as that of the unit diary of 1st Guards Bde. An inserted note dated March 1922 in TNA WO 95 1261 1 reads: The diary of the 1st Guards Brigade for November 1914 is not available as it was lost when the Headquarters of that Brigade was destroyed by shell fire during the first battle of Ypres.

66 TNA WO 95 1271 1

67 Edmonds, J E Official History 1914 Vol 2 (Macmillan, 1925) p 421 and TNA WO 95 1376 1

17. the ‘93’ and their stories 20

facing the British centre. Opposed to them, counting all the reserve, were nineteen battalions and three cavalry regiments, totalling no more than 7,850.68

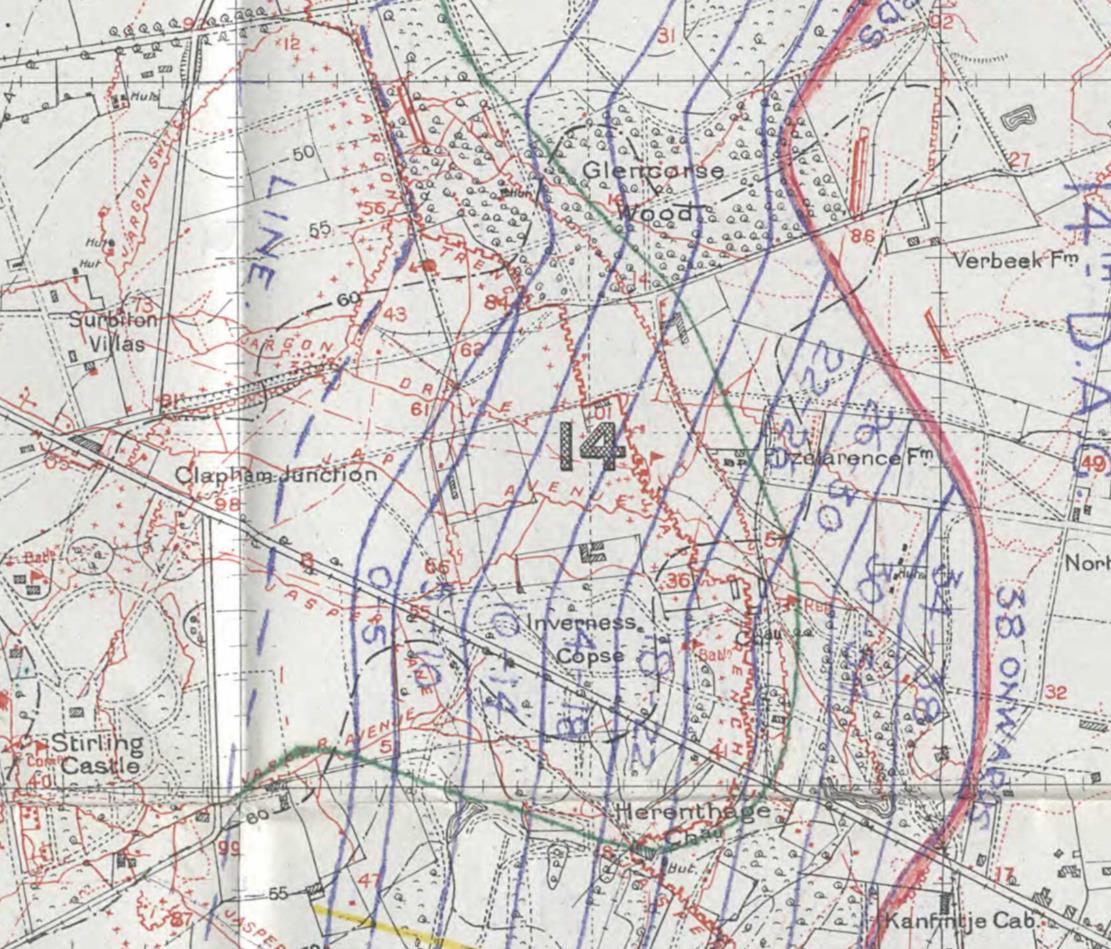

Upon their arrival at 1st Brigade HQ at 11.20 am on the southern edge of Glencourse Wood, one Company of 1st Northamptonshires was ordered to clear the southern edge of Nonne Bosschen; another to do the same at the south east corner of Glencourse Wood, whilst the other remained in reserve. By 3.30 pm the Germans were pushed back, the extent of their retreat checked by the unfortunate eventuality of the French guns some four thousand yards to the northwest, near Frezenberg, shelling the line occupied by the Northamptons.69

There is a dramatic eye witness account of the progress of the 1st battalion Northamptonshire by Lt Col H R Davies, 2nd Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry, who, located at Westhoek, was well placed to observe events. He recalled that:

About 10 am [on 11 November] we were turned out as there had been a German attack on the 1st Brigade who held the ground a little north of the Ypres Menin road. I was ordered to take the regiment up to Westhoek …. [From here] I could see the Northamptonshire Regt (1st Division) advancing on our right into the southern part of the wood Glencourse Wood, in later maps lying south of Westhoek. I also found Col Lushington commanding a brigade of artillery here in a dugout near a shrine just beyond the village. He told me that the Germans were in the Nonne Bosschen Wood and that he had some of his gunners, cooks etc and anyone he could collect under his adjutant with rifles facing the Germans in front of us. …. It was obvious that the Germans must be cleared out of Nonne Bosschen as they were here in dangerous proximity to some of our guns and to some French guns … I [therefore] sent A and B Companies to clear the Nonne Bosschen, advancing from north west to south east. … When A and B came out on the south eastern edge of the wood they were joined by the [1st battalion] Northamptonshire on the right and by some Connaught Rangers (sappers) on the left. Led by Dillon they charged the Germans out of the trenches, some of the enemy turning and running when the attack was 30 or 40 yards off, and others surrendering. Most of those who ran were shot. There was still another trench held by the Germans in front and there is no doubt that this would have been taken too, but unfortunately the French artillery, not realising that our attack had progressed so quickly, began firing shrapnel into our front line so that the attack could not get on. It took some time to get the French artillery stopped and by that time it was dark.70

68

Edmonds, J E Official History 1914 Vol 2 (Macmillan, 1925) p 427 69 See TNA WO 95 1227 1 70 TNA WO 95 1348 1

17. the ‘93’ and their stories 21

Without further evidence it is impossible to determine precisely the final moments of Captain Crowe but it seems that he was killed either during his unit’s participation in the clearing of Glencourse and Nonne Bosschen Woods or, having survived the close combat fighting, that he was a victim of the misplaced French shell fire. Even if in the first instance he had suffered injury rather than instant death, continuous enemy rifle fire made the collection of wounded impossible. In addition, a storm had turned the ground into a water logged, muddy quagmire so much so that the Official British History asserts that:

The general condition, including the bitter cold, made the night of 11 12 November 1914 one of the most miserable ever experienced by the troops in Flanders.71

71 Edmonds J E, Official History 1914, Vol 2 (Macmillan, 1925) p 444

17. the ‘93’ and their stories 22

Paull, Private Alan Drysdale, 721 11 December 1914, Spanbroekmolen SPS 1908 - 1912

1/1st Bn. Honourable Artillery Company, Number 1 Company72 Wulverghem Lindenhoek Road Military Cemetery III. C. 9. Grave epitaph: He Being Dead Yet Speaketh Age 20

Alan Drysdale Paull73

Alan was the eldest son of Alan Paull and his wife Catherine. During his time at SPS between 1908 and 1911 Alan was a Corporal in the OTC. Upon leaving SPS, he joined his father’s business as a quantity surveyor. He joined the Honourable Artillery Company on 14 October 1912. Something of an athlete, Alan played rugby football for the HAC and represented them in boxing against Cambridge University in 1913. He went to France with the HAC (7th Brigade, 3rd Division) from 18 September 1914. Alan fell just to the south of Spanbroekmolen on the Wytschaete Messines Ridge.

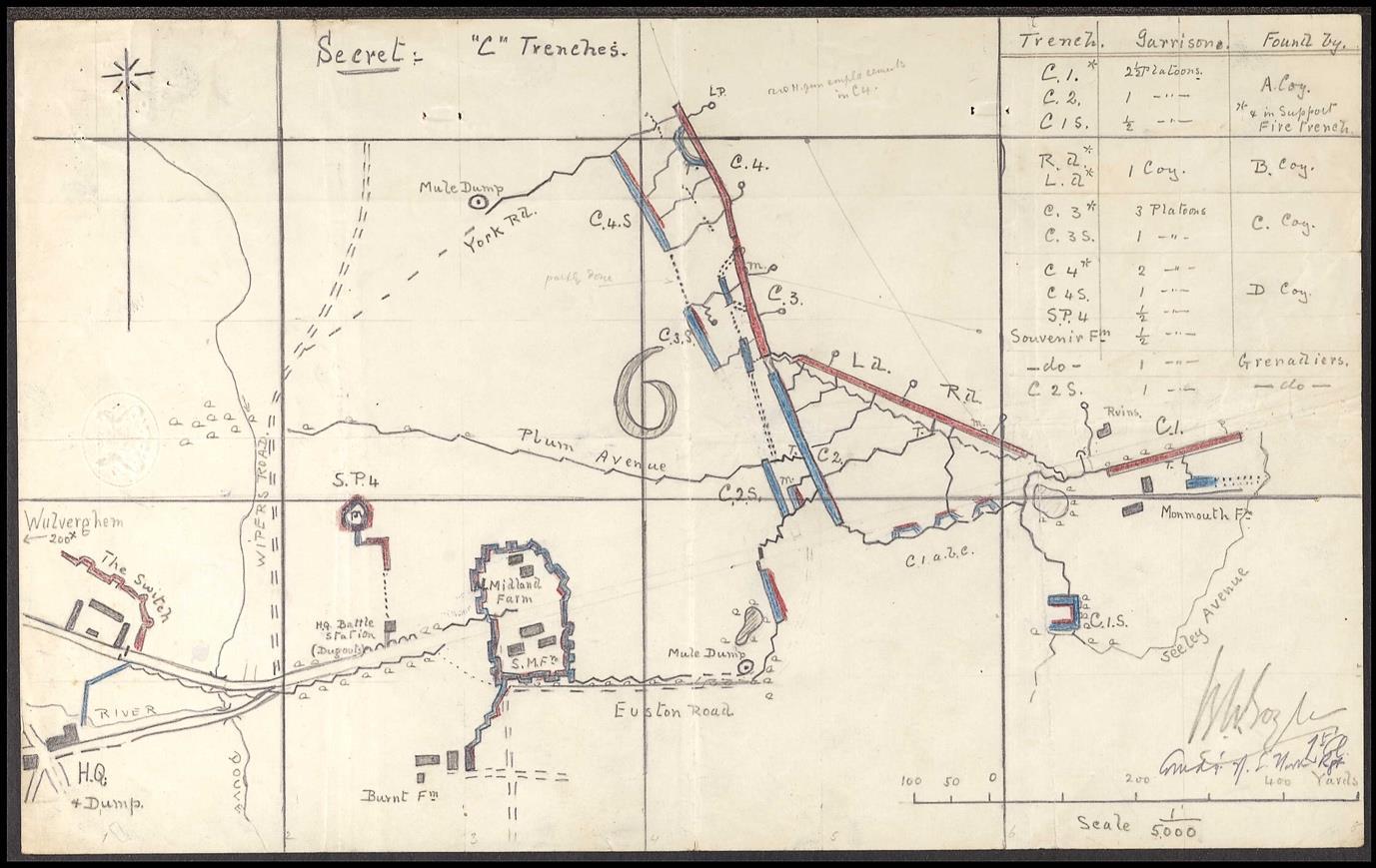

By December 1914 the increasingly wet and cold weather had led to a stalemate, each side rotating their units in and out of the trenches as best they could. The 3rd Division held the line at the southern end of Messines Ridge, overlooked by the Germans who now possessed the higher ground having taken both Messines and Wytschaete. At 1.30 pm on 9 December the 1st HAC left their billets at Westoutre and marched to Kemmel via La Clytte; at 10.30 pm they took up position in ‘F’ trenches immediately south of Spanbroeckmolen.

72 The Honourable Artillery Company was a unique regiment in that it included both infantry and artillery units. Alan was in the former

73 De Ruvigny’s Roll of Honour

17. the ‘93’ and their stories 23

By all accounts the weather was awful, frost and snow at intervals, but chiefly heavy rain rendering the trenches more or less unserviceable. During the night of 9 10 December the unit diary describes how:

The men were chiefly employed in baling out mud and water from the trenches which in places was 3 or 4 feet deep. Most of the communication trenches had become impassable and some men who had got stuck in the mud had to be dug out, this taking some hours to do.

The following night, 10 11 December:

Endeavours were made to improve the trenches and to minimise if possible the discomforts of the men in them by putting in fascines, planks, barrels etc for the men to stand on. These however soon sank in the mud and were of little use. 74

The commander of 9th Brigade noted that:

The sanitary condition of the trenches is bad. It is reported that insufficiently interred corpses are to be found in some trenches and no latrines appear to exist in any of them … The trenches on the right of the line [i.e. those occupied by the HAC] appear to be flooded in wet weather. 75

The official regimental history of the HAC provides a particularly vivid description:

Our trenches had been made by the French, and were nothing but ditches full of liquid mud; there was no wire in front, and no material of any kind, nor were there any communication trenches. The only way the front line could be approached was over the open through a sea of mud, and across a bullet swept area. Bullets came through the parapets as though they had been butter. In some of the trenches the parapet was only breast high, and in order to get cover during the daytime the men had to sit in the mud on the floor of the trench, and very often a man would find himself sitting on the chest of a mutely protesting Frenchman who had been lying there for a month or six weeks.76

The German trenches were on considerably higher ground, and their position at Spanbroekmolen was one of the strongest centres of resistance of the German line on the entire Wytschaete Messines Ridge. Thus placed, and at an average distance of 100 yards

74

75

TNA WO 95 1413 1 4

TNA WO 95 1425 1 2 Notes by A P Wavell, Bde Major, 9th Bde dated 29th Nov 1914

76 Goold Walker, G (ed) The Honourable Artillery Company in the Great War 1914 1919 (London, 1930) pp 24 25

17. the ‘93’ and their stories 24

from the line occupied 1st battalion HAC, sniping was constant and deadly; and it counted Private Paull as one of its victims. The unit diary records that Alan was shot on 11 December and the following day notes that ‘Pte Paul [sic] was buried by a party under Sgt Major Atkins and that he [had been] hit while taking up rations.’77 Alan’s entry in De Rugvigny’s Roll of Honour states that he was buried ‘at Kemmel by a cottage known as “Paull’s Cottage”.78 In fact, Alan was initially buried at location SW 28. N.35.a.5.4, about 1 and ½ miles south west from where he fell and some distance from Kemmel.79 His body was removed from here to Lindenhoek Road Military Cemetery as part of the grave concentration process in 1919. (The maps show no evidence of there having been a cottage at the original site of his burial. 77 TNA WO 95 1415 1 78 De Ruvigny Roll of Honour 79 See CWGC B.R 57

17. the ‘93’ and their stories 25

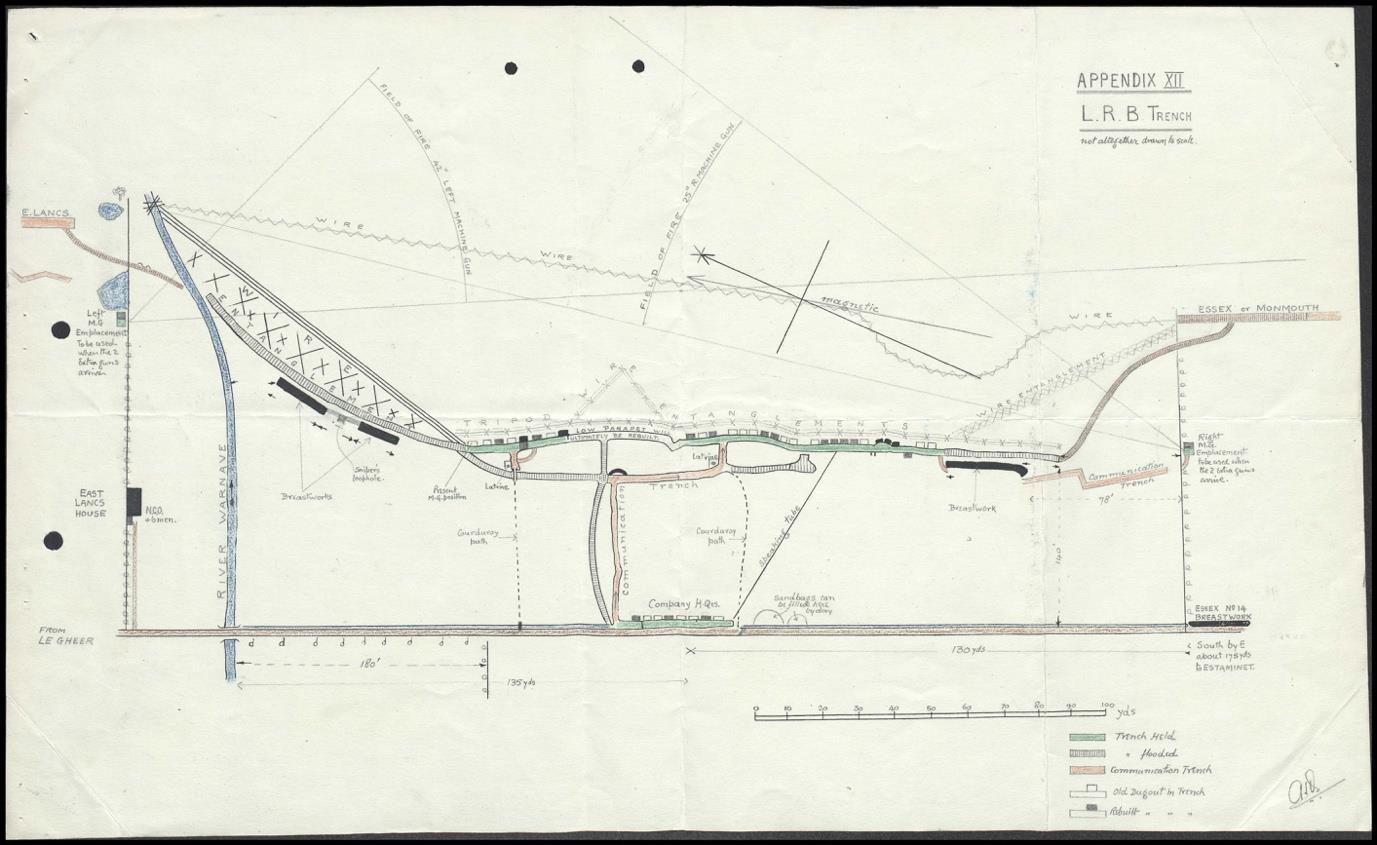

Knight, Rifleman Henry Manning 9860 11 January 1915, Ploegsteert SPS 1909 1909

1/5th (City of London) Bn. (London Rifle Brigade) London Rifle Brigade Cemetery III.A.6 Age 21