OP Comedy

OP Comedy

It is fifty years since I arrived at St Paul’s as a bursary boy from my prep school. The single event that I recall most often from my school years came in the Autumn of 1977.

Ihad just returned to High House after a week’s suspension – the Blue Anchor had been involved. Peter Thomson (History Department (1961–64 and 1966–84) and Surmaster (1976–84)) ‘invited’ me to his office. “Don’t sit down. This will not take long. Do not waste this opportunity. Go away and think about it.”

So, here is the product of five decades of thought. The School with help from many Old Paulines and across the St Paul’s Community has raised the number of pupils with bursaries to approaching 153 – the number of fish in the miraculous shoal and boys taught at St Paul’s in 1509. These pupils, often without educational advantages earlier in life, have reached the required academic standard to be accepted at St Paul’s and to take up the opportunities available from going to school there. The introduction of VAT on independent school fees and the impact of increased employer National Insurance rates among other rising costs have led the School’s governors to take the decision that bursary costs should no longer be supported by school fee income to avoid further strain on current parents. This leaves a gap. A £3m annual gap. The obvious answer is to reduce the number of bursary places. It seems unlikely that this can have been the intention of the VAT introduction.

The School’s governors have no intention of reducing the number of bursaries and have looked at where they can find savings away from the classroom. The Old Pauline Club, in line with its objects and what is right, is looking for ways it can help. The OPC has increased its annual bursary donation to £60,000 (the equivalent of two full bursaries). This is funded from rental income raised from a highly successful housing

development and investments. Plans for Colets and the Thames Ditton site could in time help to fill part of the funding gap but this is possibly five years or more away. The back cover of this magazine sets out how you can help, please take a look.

Later in the magazine we include our new President Simon Hardy’s (1974–79) AGM statement in full. He concluded, “Looking ahead, the OPC has updated its mission to ‘foster an inspiring, inclusive and enduring fellowship of St Paul’s alumni worldwide,’ underpinned by its values of being supportive, open-minded and courteous. The Club’s actions and activities will be guided by the agreed strategic pillars:

– Support the School’s mission – Cultivate a sense of belonging – Provide a network of mutual support – Recognise Pauline achievements of all kinds – Help others to fulfil their potential”.

Simon has Atrium’s full support.

There are OPs everywhere with branches meeting in Spain, Greece, the USA and Australia in the last year. This magazine has three contributions from Thailand provided by Dominic Faulder (1971–76), Andrew Kemp (1979–84) and Tom Vaizey (1977–82), and one by Alastair Bool (1985–90) from Switzerland. Cambridge, Cornwall, Exeter, London (often) and Oxford are also homes to our contributors.

Our cover shows two new OPs, Alp Karadogan (2020–25) and Patrick Wild (2020–25) winning Gold in the Men’s Pairs at the World Rowing Under 19 Championships. They were coached by honorary Old Pauline, Bobby Thatcher. Atrium

congratulates Alp and Pat and wish them well at Harvard and Cambridge. Later in the magazine, David Herman (1973–75) profiles three Paulines on the centenary of their births. News recently reached Atrium of the death of another OP born in 1925, Ralph Blumenau (1939–43). David interviewed Ralph for Atrium in 2023 asking him about his time at School.

DH – ‘Was it difficult for a JewishGerman refugee to fit in?’

RB – ‘The School was not at all antisemitic,’ he says emphatically. ‘Quite the opposite. There were a large number of Jewish boys then, including quite a few refugees.’

DH – ‘Did they stand out?’

RB – ‘Absolutely not.’

Finally, in the Spring/Summer magazine we described Tel Aviv as the capital of Israel. We apologise for the mistake.

Jeremy Withers Green (1975–80)

The Editorial Board thanks all contributors –particularly Kaylee Meerton, Harry Hopkins, our story spotters and proofreaders and it sends Kate Wallace very best wishes as she heads off on maternity leave.

Atrium’s Editorial Board: Omar Burhanuddin, Jonathan Foreman, James Grant, David Herman, Theo Hobson, Neil Wates and Jeremy Withers Green.

Michael

Alistair

Andrew

David

Charles

Tom

Andrew

Ken

James

Appointments,

Including

The

Nick

Lorie

Alex Paseau: Sine Litteris

Andrew Hillier is an Honorary Research Associate at Bristol University and has written extensively on Britain in China. The Alcock Album: Scenes of China Consular Life, 1843–1853 was published in 2024. His next book, In the Shadow of Empire: Women and the China Consular World will be published next year. His father and grandfather were Old Paulines.

Phil Gaydon teaches Personal Social Health and Economic Education (PSHE), Religious Studies and Philosophy at St Paul’s, and is the School’s Head of Character Education. Prior to this, he created and taught modules for the University of Warwick’s Institute for Advanced Teaching and Learning, and he worked in primary and secondary schools around the country as a Philosophy Specialist for The Philosophy Foundation. He studied for his PhD at the University of Warwick.

John Venning was Head of English at St Paul’s from 1989–2014. He read English Literature at Cambridge and taught undergraduates there for a further three years while failing to complete a PhD. He then taught at Manchester Grammar School, Downside School and Malvern College. Since retirement he has done some part-time teaching, further researching and writing, and cultivates his garden in Cornwall.

Michael Simmons (1946–52) read Classics and Law at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. He qualified as a solicitor and, after serving for two years as an officer in the RAF, practised Law in the City and Central London for fifty years. Since retiring, he has pursued a new career as a writer. Michael is in touch with a sadly diminishing number of members of the Upper VIII of 1952.

Paul Cartledge (1960–64) is a Senior Research Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge and was the inaugural A.G. Leventis Professor of Greek Culture in the University’s Faculty of Classics. He is responsible in various ways for publishing over 30 books,

most recently a biography of Pericles (Reaktion Books). He is an honorary doctor of the universities of Thessalonike, Thessaly and Warwick, and a Commander of the Order of Honour (Greece). He is a Vice President of the OPC.

David Abulafia CBE (1963–67) is Emeritus Professor of Mediterranean History at the University of Cambridge, a Fellow of Gonville and Caius College, and a former Chairman of the Cambridge History Faculty. His books include Frederick II, The Discovery of Mankind, The Great Sea and The Boundless Sea which was the winner of the Wolfson History prize in 2020. He is a Fellow of the British Academy, a Member of the Academia Europaea, a Commendatore of the Italian Republic and Visiting Professor at the College of Europe and the University of Gibraltar. He has been the Apposer at Apposition and is a Vice President of the OPC.

Nick Birbeck (1967–72) graduated from SOAS in 1981 after a prolonged stay in Australia. He worked in Yogyakarta, Indonesia from 1983 to 1995 where he set up an English school, and also taught at Gadjah Mada University, training postgraduate students for overseas study. In 1995, he was employed at the University of Exeter as an Education adviser, supporting academics in all disciplines with their teaching, with an emphasis on the use of IT and, latterly, AI. He retired in 2016 but continues to teach and support academics at Exeter. He was a keen cricket and tennis player until a hip required replacing. He now enjoys gardening.

Tom Hayhoe (1969–73) read History at Cambridge and then served as President of Cambridge Students’ Union before receiving an MBA from Stanford as a Harkness Fellow. He worked for McKinsey and WH Smith before founding retail consultancy The Chambers and chairing the board of video retailer Gamestation. He held non-executive NHS roles for almost forty years, including chairing the Trust responsible for Broadmoor High Secure Hospital.

He now works in regulation as chair of the Taxation Disciplinary Board, the Legal Services Consumer Panel, and the Disciplinary Committee of the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants. He recently began a one-year appointment as Covid Counter Fraud Commissioner, chasing funds lost to fraud and error during the Pandemic.

Luke Hughes (Nasmyth) (1969–74) studied History of Architecture at Peterhouse, Cambridge and has, for the last 45 years, specialised in designing and making furniture for sensitive architectural settings. These include 62 Oxbridge colleges, 32 schools, 24 cathedrals, more than 150 parish churches and 9 synagogues (mostly in the UK but also in China and the USA). He designed the clergy furniture in Westminster Abbey used in the recent Coronation and the interiors of the UK Supreme Court. In 2021, he was voted ‘Craftsman of the Year’ by the Worshipful Company of Carpenters.

Dominic Faulder (1971–76) graduated from the University of Warwick and has been based in Thailand since the early 1980s, working as a journalist, author and editor for numerous organisations. He was a special correspondent for the Hong Kong newsweekly Asiaweek, covering Myanmar (formerly Burma) and Cambodia during the 1980s and 1990s. He has been an associate editor with Nikkei Asia for 11 years and has received numerous international journalism awards. He is a five-time past president of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Thailand and was, for many years, pro bono co-president of the Indochina Media Memorial Foundation.

David Herman (1973–75) studied History and English at Cambridge and English and American Literature at Columbia University. He produced arts, history and talk programmes for BBC2, Radio 4 and Channel 4 (when it was good) for nearly 20 years and since then has written about literature, and Jewish culture and history.

Tom Vaizey (1977–82) after leaving St Paul’s read History at Worcester College, Oxford. He then qualified as a lawyer and has spent most of his career living and working in Hong Kong, India, Vietnam and Thailand, both in private practice and in-house.

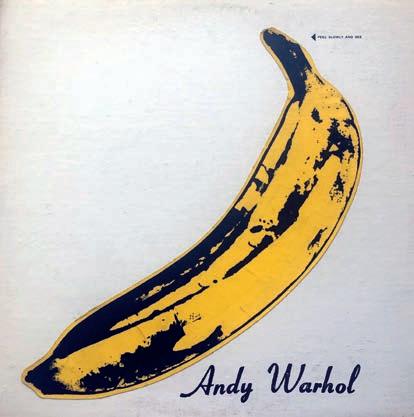

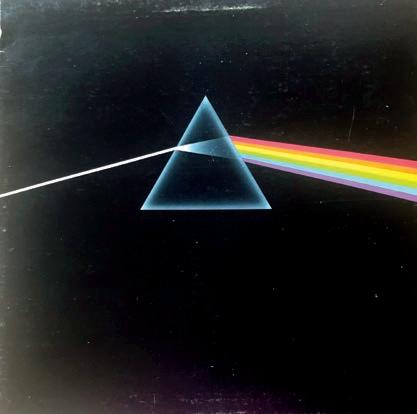

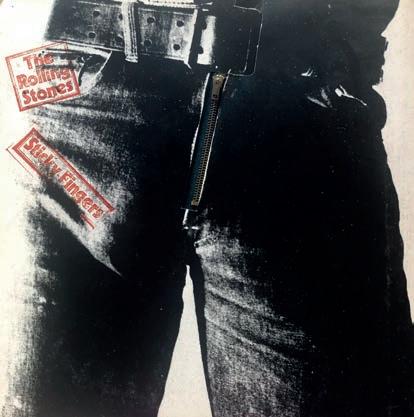

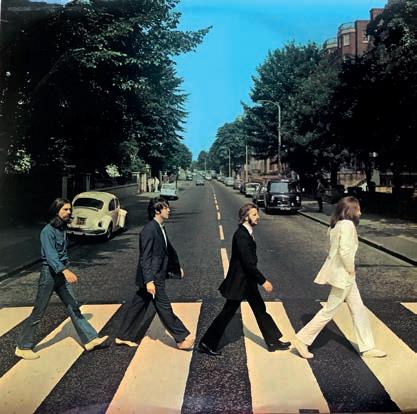

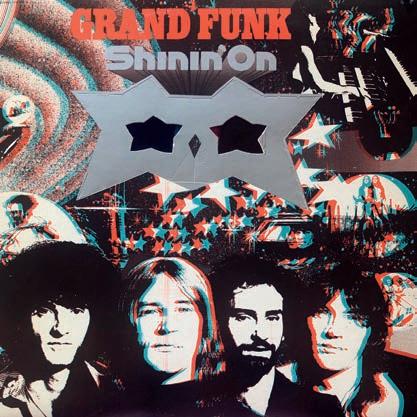

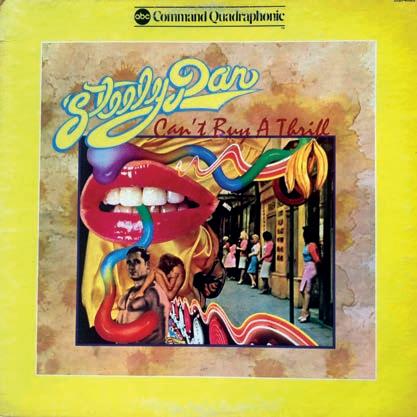

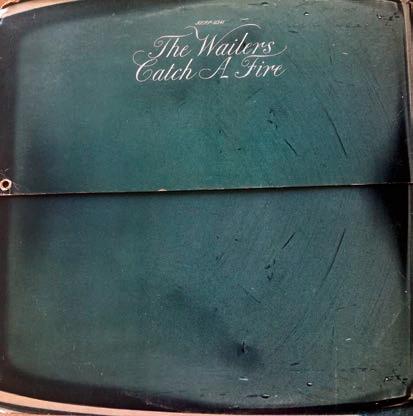

Ken Clark (1978–79) attended St Paul’s for A Levels. His Headmaster in Canada knew the High Master, Warwick Hele, and thought it would be a good experience. After St Paul’s, Ken graduated with a BA from the University of Western Ontario and qualified as a Chartered Accountant. From 1989 to 2024, Ken held Senior Positions in Internal Audit in various multinationals. He retired in 2024. He has contributed articles and reviews to the unofficial John Cale site Fear is Man’s Best Friend and assists a local charity shop to value vinyl that has been donated.

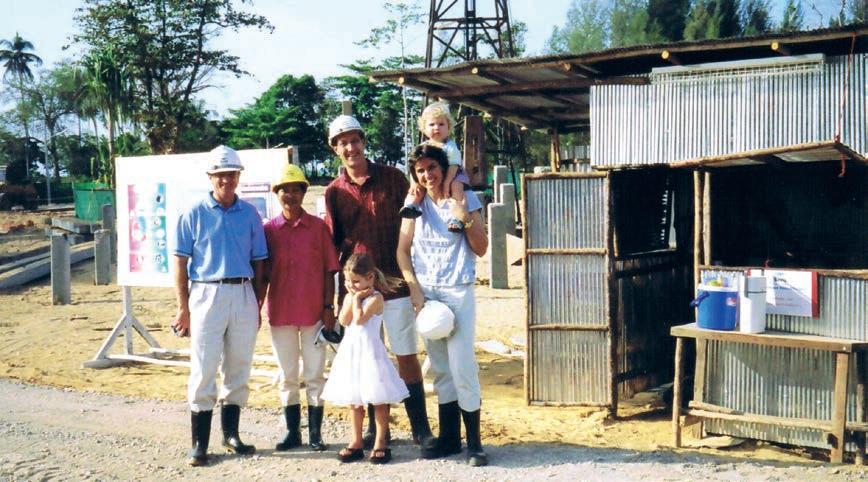

Andrew Kemp (1979–84) graduated from Loughborough University, before spending over 35 years in global hospitality, working across the UK (including at Colets), Hong Kong, Thailand, and now Singapore. He is the co-founder, with his wife Kate, of The Sarojin – a multi-award-winning luxury resort in Thailand renowned for its sustainable tourism. Based in Singapore, Andrew is a passionate golfer, sailor, and active volunteer. With two grown-up children living in the USA and UK, he remains committed to community engagement, environmental conservation, and fostering crosscultural connections through travel, hospitality, and regional collaboration.

Richard Bool (1980–85) has been Headmaster of Lingfield College, an HMC school of 900 pupils, since 2011. Before that, he was a Housemaster at Sherborne School, and then Deputy Head of Ardingly College.

Alistair Bool (1985–90) escaped the life of a City lawyer and has been living in Zurich for 25 years, working for a charitable investment foundation. He loses at tennis most weeks to Jamie Nettleton (1985–89).

Alex Paseau (1988–93) is Professor of Mathematical Philosophy at the University of Oxford and Stuart Hampshire Fellow at Wadham College. He has written several books and numerous research articles on logic and the philosophy of mathematics. At Oxford, he teaches these fields as well as metaphysics, epistemology, the philosophy of science, the philosophy of language and the philosophy of religion. He is the editor-in-chief of the Journal for the Philosophy of Mathematics and was previously an associate editor of the journal Mind

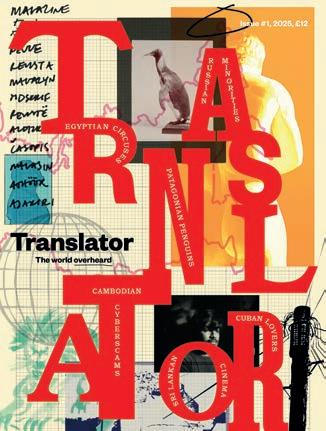

Charles Emmerson (1990–95) is a writer, historian and editor. He studied at Freiburg, Oxford and Paris and has worked in think tanks in Brussels, Geneva and London. He has written three books: The Future History of the Arctic, 1913 and Crucible, an account of Europe and America in the tumultuous years 1917–1924, with strong parallels to today. He is the editor of Translator, a new magazine of translated reportage from around the world.

James Grant (1990–95) sits on the Old Pauline Club’s Executive Committee as Sports Director, as well as holding the posts of Chairman of the Old Pauline Cricket Club and Honorary Secretary of the Old Pauline Golfing Society. After a career in event organising and charity fundraising, he now works at St Paul’s School as Associate Director, Alumni Relations. He is a Vice President of the OPC.

Lorie Church (1992–97), when he is away from the workplace, Lorie encourages people to put letters in little squares. He has had puzzles published in various titles internationally. As well as contributing to the Listener series, Mind Sports Olympiad and Times daily, he sets Atrium’s crossword.

Neil Wates (1999–2004) worked in the property sector for 15 years before training as a Psychodynamic Therapist and Counsellor. He is a trustee of a UK based charitable trust and an NGO committed to the alleviation of social

violence in East Africa. He also founded Friendship Adventure, a craft brewery based in Brixton. Neil is on the OPC Executive Committee.

Jimmy Kent (2000–05) read Philosophy at Warwick University followed by a summer at Berklee College of Music. He then studied Songwriting at Belmont University, Nashville. He now performs in nursing homes mainly to Alzheimer and dementia patients.

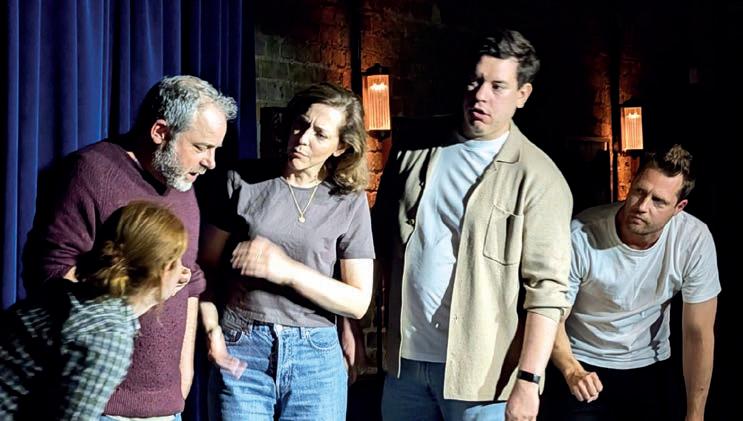

Oliver Gilford (2006–11) is a writer, TV producer and comedian. He has performed at Fringe festivals around the UK, worked on programmes like Big Fat Quiz of the Year and A League of Their Own, and written for international stage tours in the West End and Australia.

Yas Rana (2009–14) is the head of content at Wisden, host of the Wisden Cricket Weekly podcast, and is one of the lead commentators on the Surrey CCC livestream. He was also recently the captain of the Old Pauline Cricket Club 2nd XI.

Dear Sirs,

If a magazine were a person yours would have no ego

What a wonderful publication Atrium has become under your stewardship. I am afraid I do not agree with Messrs Porter and Willis (Letters, Spring issue). For them, membership of ‘the St Paul’s Community’ is defined by participation in alumni activities. Not so for me. I have never felt more connected to the School, nor more grateful for, and aware of, what (thanks to my parents’ sacrifices) it gave me than when reading the latest issue of Atrium. That grateful recognition of something I was given came not from reading news of reunions in Buenos Aires or Bangkok, but from the voices that spoke to me in your superb selection of articles. I do not think it is fanciful to suggest that your authors will themselves have connected with their inner Pauline when writing for what they knew to be a Pauline audience.

I have never felt more thoroughly a Pauline, or more at ease with being one – or, yes, more proud – than when reading what I have started to think of as Atrium journalism: clever, funny, self-deprecating, critically acute and intellectually curious pieces that speak to me of what I learned in those Barnes classrooms, and of what I have carried with me from there into adult life, far more powerfully than news of ‘alumni activities’ ever would.

I think the School owes you all a huge debt of gratitude. If a magazine were a person yours would have no ego but would be thoroughly at ease with its own excellence, considering itself the equal of any of its peers – including celebrated national publications. And it would be right to do so. A final shout out, too, for the excellence of the graphic design: it is a pleasure to look through as well as to read.

Yours,

Geoffrey Matthews (1972–77)

Dear Atrium,

I have just had the pleasure of watching again Antony Jay’s film Four High Masters. Messrs Oakeshott, James, Gilkes and Howarth sound like a respectable firm of country solicitors. In fact, they led the school from 1938 to 1973 covering no less than three periods of drastic upheaval. Oakeshott had the hardest task in converting a London day school into a country boarding school with all the distractions and uncertainties of a world war around him. There was then the return to the Hammersmith site to manage in time for the re-opening there in 1946. James and Gilkes, both former junior masters at the school, were the continuity candidates before Howarth masterminded the move to Barnes. At least he did not have to cope with the horrors of war. For two academics to learn new skills so successfully is truly a remarkable achievement.

Tony Jay did a great job with his interviewing technique in coaxing the story out of guarded academics. It is a long way from Yes Minister. Nowadays, no High Master can exist without a well honed and well taught interviewing technique. The time has come for Tony’s successor to bring the story up to date. Any volunteers?

Best wishes, Michael Simmons (1946–1952)

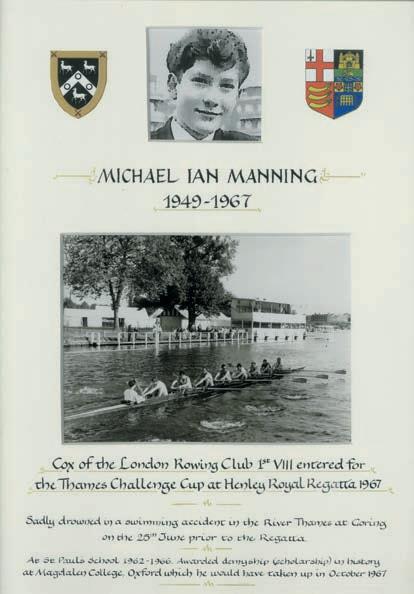

Michael Manning Dear Atrium,

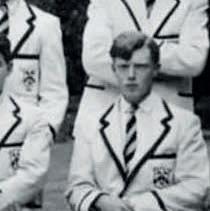

I am writing concerning a contemporary of mine at the school, Michael Manning (1962–66) who tragically drowned in 1967 whilst taking part in the Henley Regatta as cox for the London Rowing Club.

He was a close personal friend both at school and with my family. His tragic loss and achievements at school both academic and sporting were remarkable and other Pauline memories of him featured in letters in Atrium in successive editions in 2021. As Rupert Birtles (1963–66) so justifiably says Michael deserves to be remembered and this letter is by way of telling the School and Old Paulines that there is now a memorial to Michael.

Shortly after the mentions of Michael in the Atriums, I had occasion to meet the then archivist of The London Rowing Club, Julian Ebsworth (not an Old Pauline), and following conversations about Michael, Julian very kindly set about preparing a memorial.

It takes the form of a framed illustration of Michael, his coxing the LRC 1st VIII, referencing the St Paul’s crest and his Oxford award. It hangs in the Ashton Room at the Boat-house of The London Rowing Club on Putney Embankment. With very best wishes, Ashley Badcock (1961–1966)

Set out below are extracts of a letter from Philippa Alden to Robin Dodd (1961–65)

Dear Robin,

I wanted to write to say thank you so much for putting together the piece about my father, Robin Alden (English and History department 1962–65), which appeared in Atrium in October 2024.

Your description of my dad brought him to life again before my eyes. It was touching, moving and amusing. As a child, the evidence of his passion for rowing was all around me, from the pink paddle with gold italic lettering recording the bumps his crew achieved at Worcester College, hanging in the hallway, to the endless crew pictures lining the walls, to the frequent visits to Henley, and the ever present Leander scarf that unfortunately got shredded by my hamster one winter night when mum covered its cage with it to keep it warm. Not a popular family pet after that!

Famously, my dad was not present at the birth of my brother James in Barnes as he was uncontactable on the river coaching a St Paul’s crew.

I am very grateful to you for caring enough to write the article and so recognise the importance of my father’s contribution to rowing during his time at St Paul’s.

All best wishes, Philippa Alden

Enough is enough

Dear Atrium,

Whilst I am sure Simon May’s was an excellent lecture; I think the time has passed for continuing to honour Cotter (Classics Department 1928–65) and Cruickshank (Classics Department 1947–73) with a biennial lecture in their memory.

My memory of them both, and that of my peers in the History 8th, is very negative. I do not doubt their academic excellence (and in Cotter’s case his excellence as a bridge and croquet player, which seemed to occupy a lot of his time and attention), but they were hopeless teachers of boys whose instincts and ambitions did not lie with the Classics but who nevertheless required some Latin and Greek in combination with their principal A Level subjects. Regarding Cotter, we had to complain actively that he was not teaching us adequately and as a result he was replaced by a teacher who had perhaps achieved less renown but who prepared us well for the examinations and subsequent Oxbridge entry. My ire rises whenever I see their names mentioned and I do not think that they should be celebrated quite so fulsomely. Cotter retired 60 years ago; enough is enough.

Best regards, Rupert Birtles (1963–66)

Dear Atrium,

Next year, it will be 120 since our father TL “Tom” Martin first entered St Paul’s School; the following year it will be 70 since his bicycle accident outside the School a few weeks before his retirement, after 37 years service. Without further delay we can expand on his various Pauline connections through 70+ years of his life (including 28 years as Old Pauline Club Secretary).

He came to St Paul’s in 1906, with his twin brother Steve (1907–12) joining later having been quarantined for mumps. He recorded his school experiences between 1906–12 in detail, followed by higher level coverage of his first years at Cambridge (1912–14) and his war years up to 1919. He describes how in the latter period he became interested in Old Pauline affairs, while continuing to watch School rugger and cricket matches when possible. He wrote a diary covering his last two Cambridge terms in 1920, with many Pauline incidents. With these connections in mind, it is perhaps not surprising that on 22 June he “went up to St Paul’s School, interviewed the High Master and accepted post as master”.

His time as a master is well-celebrated in Staff Notes of the November 1957 Pauline. Here are a few extra vignettes: His role in charge of music (before the School appointed a full-time Music Director) brought him in contact with Gustav Holst at the Girls’ School. He took on a minor role in an informal run-through at SPGS of Holst’s opera “The Wandering Scholar”. Ralph Vaughan Williams was present, and in a letter to Holst he wrote that “the most obvious amateur of your lot (the schoolmaster) was far the most successful because he was thinking of his words and his part all the time and not worrying about his damned tone”.

The Great Hall organ used to be water-powered, and Father noted that on a quiet weekend the organ’s pressure gauge would pulse gently in time to the London Hydraulic Company’s pumping station at Walton-onThames 14 miles away.

During the horn virtuoso Dennis Brain’s (1934–36) time at St Paul’s, Father gave him organ lessons as well as in Latin. Dennis’s tragic car accident in 1957 occurred while Father was hospitalised, and he subsequently assisted Ivor Davies (Director of Music 1950–65) in persuading the great and good to give a series of Memorial Concerts in the Great Hall.

After Father's death, we found in his capacious wallet many photographs, just one of which related to his time as a master. It is a small photograph of him sitting at his desk in Room 5 during a lesson, and was taken by Oliver Sacks (1946–51), who signed the photo before giving it to him. Father had kept it for at least 35 years, for much of which time Oliver was not in the public eye.

At a Mercers’ Company Dinner for Prefects and OPs, we learned that Father had on one occasion taught without his trousers on. When challenged on this, his reasoning was simple: riding his bicycle the four miles from Ealing

to School in wet weather one day, his estimate of just the cycle cape without over-trousers turned out to be poor. Rather than sitting in soaking clothing, “all having seen much worse in the showers”, he hung the offending trousers over a radiator and taught discreetly from behind his desk. While this tale may raise a modern eyebrow, it also encapsulates the man: constructive and rational rather than conventional.

Mother and Father both continued to attend School matches and Chapel throughout our time in the ’60s, continuing to attend School Chapel in Barnes until 1980, when they moved to Shalford, near Guildford. After his death in 1982, a Memorial Service was held in the Chapel and his ashes laid under a magnolia in the School grounds. It seems that these were unwittingly moved during subsequent renovations, but we may kindly assume that as such he continues to be a part of the School, just as he was in life.

Yours sincerely, Charles Martin (1960–65) and Robert Martin (1962–67)

PS: On a personal note, his father-in-law was EHH Lee, OP (1879–84) – thereby just missing West Kensington, whom Father met with his future wife as part of his OPC duties. In line with current fashion, we can thus show ancestral connections between the last days of both West Kensington and the City Schools.

The Old Pauline Trust was set up at the time of the Old Pauline Club’s centenary in 1972. Its aim was to establish a substantial capital fund, the income from which would be used to benefit members of the Club and the School.

The Trust makes awards of up to £500 to Old Paulines undertaking charitable projects around the world. These have included volunteering for a leading human rights agency in Delhi, a gap environmental project in Borneo, and volunteer work with Mercy Ships on the coast of Africa.

Last year, Henry Ferrabee (2016–21) was granted £500 which went towards his estimated flight and accommodation costs of around £1,000 for his trip to Egypt where he worked for the Centre for Arab-West Understanding.

This is the letter he sent to the Trust’s directors on his return from Egypt.

Dear Old Pauline Trust Directors,

I am writing to express my gratitude for the grant to travel to Cairo for the final part of 2024. The grant enabled me to join the Centre for Arab-West Understanding and aid their ongoing work in creating a dialogue between Western and Arab audiences.

Within the first two days of being in Cairo I was invited to a Christian archaeology conference in Heliopolis to contribute expertise in Egyptian Archaeology to the conference. I was able to meet many leading figures within the Roman Catholic and Coptic Church as a consequence of being there, opening my eyes to the workings of both churches in Cairo and beyond. Without the grant, I would not have been able to make it to Cairo until much later (if at all) and I wanted to start by noting this experience as a direct result of the grant. Despite not being a practising Christian myself, being thrust directly into a coveted meeting between some of the most important institutions in the region is an experience I will carry with me for the rest of my life.

The core of my research in Cairo centred around Egypt’s ambitious 2030 Electric Vehicle targets. With the support of the grant and the institution, I have been able to highlight Egypt’s EV charging infrastructure which may hinder the government’s ability to hit their 2030 targets. I am looking to publish my report in the coming weeks which will look at foreign investment in Egypt and potential European export markets. This research has already attracted interest from several companies which have headhunted me since I have been back in London. Without the grant this would not have been possible and I am very grateful for the OPC’s generous scheme to encourage research projects like this.

The second part of my work at the Centre for Arab-West Understanding focused on transliterating Arabic articles into English for Western academics, to access our database and understand what the Arab press were saying. We were notably able to communicate a story about the rise of Hayat Tahri al-Sham in Syria just a week before they eventually mounted their attack that would take over the Assad regime. Being in the epicentre of a highly conflicted region with Sudan to the south, Gaza to the east and Syria to the northeast, I came away from Egypt with a revitalised passion for development management.

Now that I am back in London, I am applying to Development Management courses at King’s, LSE and Cambridge in the hope that I can pursue a career within an international institution.

I would say I left Cairo with a different perspective on the Arab world and Arab unity. Regardless of whether I am successful in my next steps, I will take my experiences in Cairo with me throughout my life and I made friends that I will keep for the rest of my life. Creating a network in Egypt will be invaluable as the country continues to attract sizable development aid in its bid to modernise. With a large workforce, a big energy capacity, investment in its energy transition and investment in modern infrastructure, I believe the country will become an even bigger geopolitical power over the next decade. Outside of the country’s abundance of natural resources, it also has an important geostrategic position and I hope that now I have a proper network foothold in the country it will benefit me throughout my life as it becomes a more powerful global player.

Sincerely,

Henry Ferrabee

I was once invited to address a lunchtime gathering of international headhunters and quipped that I had one of the worst planned careers imaginable. It stirred a brief flicker as the blood drained from their brains to their guts and postprandial somnolence descended.

I arrived in Bangkok in March 1981 and disliked it. Good food and wonderful temples, but not really East nor West with sticky pavements and endless rows of hot, inhuman concrete shophouses. I checked out on 1 April and paid the cashier, who asked where I was heading. “The southern bus terminal”, I replied. She shook her head.

“It’s closed for three days – we’ve had a revolution,” she said. “Well, why didn’t you say?”

“You didn’t ask.”

A Monty Python moment that changed my life and set me off as an observer of coups and more in Southeast Asia’s Buddhist nations – particularly Burma, Cambodia and Thailand. I already had some amateur experience of juntas from my gap year in South America in 1977, long before smartphones, ATMs and email.

Thailand has had some 22 putsch attempts since its first revolutionary coup in 1932 overturned then Siam’s version of absolute monarchy. My April Fool’s Day Coup actually failed, but there have been 13 “successes” – the most recent in 2014.

I then encountered a New Zealand journalist who wanted to visit Burma – as Myanmar was then known – for a soft feature on Thingyan, the Buddhist lunar new year and water festival. He needed a photographer, and I could take pictures. We made the cover of The Asia Magazine, a Hong Kong colour supplement with a decent regional circulation.

Burma was utterly enthralling – a story waiting to be told. This former British colony – home to George Orwell as an imperial policeman and Spike Milligan as an army brat –had refused to join the Commonwealth, dropped out of the Non-aligned movement it helped found, and effectively fallen off the map. It had fewer than 30,000 visitors annually and journalists were banned; they had to sneak in on seven-day tourist visas.

The country was still in the grip of General Ne Win, a xenophobic dictator who socialised with Lord Mountbatten and Barbara Cartland on his visits to a house in Kingston for Ascot and was soft on Princess Alexandra. The general seized power in 1962 and crashed the economy of one of Southeast Asia’s most naturally rich nations with a madcap variant of socialism. The United Nations designated it a Least Developed Country. Fascinated, I decided to base myself in Bangkok as a freelance photojournalist. I eked out a living with stories on Burma for the Bangkok Post and others, but always without a byline to ensure access.

An old lady turned tarot cards for me one afternoon in Bangkok's Lumpini Park and predicted a life in Thailand with a family and companies of my own. I scoffed since nothing of the kind was on my agenda. I returned to London armed with clippings and features, hoping to burst upon Fleet Street and a dazzling media career, but it was not so simple. Argentina had invaded the Falklands and interest in Southeast Asia waned even more than it had after the fall of Indochina in 1975.

I was offered a job editing a magazine back in Bangkok and took it. The tarot lady turned out dead right. Come August of 1988, when Burma erupted into a massive nationwide rebellion in numbers seldom seen anywhere, I was ensconced as a freelance correspondent, and one of only a handful of journalists with any background on the country.

One of the great privileges of being a journalist is occasionally having a ringside seat at momentous times when history in the making is almost palpable. On August 3, 1988, I was stuck at a junction beneath Rangoon’s soaring, gold-encrusted Shwedagon Pagoda when thousands of students suddenly swept through out of nowhere. Their teenage leaders paused only to unfurl a fighting peacock banner, the Burmese symbol of student rebellion, then raced down into the heart of the city, roaring past the American and Indian embassies – the world’s most powerful and largest democracies respectively.

I arrived in Bangkok in March 1981 and disliked it. Good food and wonderful temples, but not really East or West with sticky pavements and endless rows of hot, inhuman concrete shophouses.

Military spies were still everywhere, but the police had taken the afternoon off. Completely alone, it was a heartstopping incident. The product of a privileged London environment, I had never seen a comparable display of raw, desperate courage in the face of such a fearsome security apparatus. What I saw was a trial run for nationwide demonstrations that kicked off five days later on the supposedly auspicious “8/8/88”. The military killed some 3,000 unarmed civilians over the next six weeks. Another 500 alleged looters were picked off after a coup on September 18. Many were youngsters scavenging.

The following year, I interviewed Senior General Saw Maung, the first interview with a Burmese head of state in some three decades. I also had the last interview with

democracy icon Aung San Suu Kyi before her first bout of house arrest for what would be total of 15 years. Saw Maung went mad. Suu Kyi today languishes in a rat-infested prison in Naypyitaw, the military-built capital that literally fell apart in a recent earthquake.

Myanmar is once more a violent black hole in Southeast Asia – a region that is otherwise largely a significant success story. Modern Bangkok gleams and is one of the world’s most visited cities. The vital watchtower from which mainland Southeast Asia is still observed, it has given me a career and family, introduced me to incredible people, good and bad, and taught me that the most important part of journalism is to bear witness.

Desiderius Erasmus

My guest co-author for this issue is a Dutch visitor to my home town of Cambridge named Desiderius Erasmus. You may know his witty work In Praise of Folly, though what he really loves is to immerse himself in the Greek text of the New Testament. He is an old friend of John Colet, Dean of St Paul’s, and he has generously allowed this letter that he sent to Dean Colet to be included in my article:

To his friend Colet, greetings!

Cambridge, 29 October 1511

Something came into my mind which I know will make you laugh. In the presence of several Masters of Arts I was putting forward a view on the Assistant Teacher, when one of them, a man of some repute, smiled and said, “Who could bear to spend his life in that school among boys, when he could live anywhere in any way he liked?” I answered mildly that it seemed to me a very honourable task to train young people in manners and literature, that Christ himself did not despise the young, that no age had a better right to help, and that from no quarter was a richer return to be expected, seeing that young people were the harvest-field and raw material of the nation. I added that all truly religious people felt that they could not better serve God in any other duty than the bringing of children to Christ.

He wrinkled his nose and said with a scornful gesture: “If any man wishes to serve Christ altogether, let him go into a monastery and enter a religious order.” I answered that St Paul said that true religion consisted in the offices of charity – charity consisting in doing our best to help our neighbours. This he rejected as an ignorant remark, “Look,” said he, “we have forsaken everything: in this is perfection.” “That man has not forsaken everything,”, said I, “who, when he could help very many by his labours, refuses to undertake a duty because it is regarded as humble.” And with that, to prevent a quarrel arising, I let the man go. There you have the dialogue. You see the Scotist philosophy!

Once again, farewell! Erasmus

Most of us, it is true, have no command of ‘Scotist philosophy’, though I do know how dense the works of the medieval philosopher Duns Scotus are. But Erasmus’s defence of the teaching of children resonates today, even in an increasingly secular society. Indeed, there was something rather secular about the school to which Erasmus was evidently referring – St Paul’s, which our founder carefully placed under the supervision not of the

Cathedral Chapter but of the prime Livery Company of London. Actually, Colet’s great wish was for the students to study Greek in order to understand the Greek text of the New Testament. But it seems that William Lily, the first High Master, was keen on pagan authors, and opened up the curriculum in Greek and Latin to ancient writers he had read while studying in Renaissance Italy.

Erasmus declined Colet’s invitation to serve as the first High Master, despite the impressive salary – double that offered at Eton. However, Erasmus dedicated a school textbook entitled ‘On the abundance of things and words’ (De Copia Rerum et Verborum) to Colet, which eventually turned into a Europe-wide bestseller. It is a rather impenetrable forest of Latin phrases, intended to improve Latin style. Yet, along with the Latin grammar compiled by Lily (with help from Erasmus), it laid the foundation for how Latin was taught, so much so that Eton stole the text of Lily’s book and it became known as The Eton Latin Grammar; but, Hugh Mead tells us in his lively history of St Paul’s, it remained in use at our school beyond 1840.

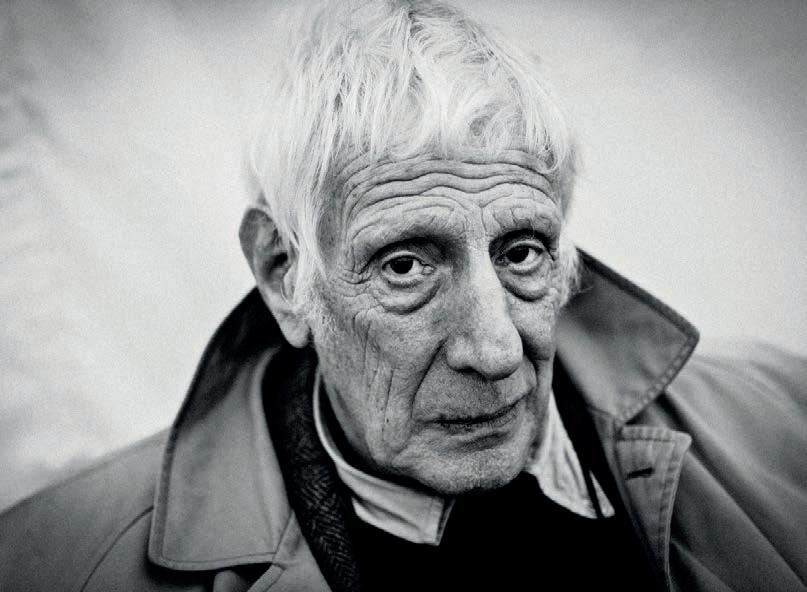

My own contact with Erasmus has taken several forms. My Ph.D. viva took place in his set of rooms at Queens’ College, Cambridge, of which one of my examiners was a Fellow. And then there was Dr P N Brooks, who taught me my O Level History and part of my A Level as well; for him, everything revolved around the age of the Reformation. His learned monograph on Thomas Cranmer’s Doctrine of the Eucharist is not exactly bed-time reading, but Erasmus, Luther and Cranmer were his constant points of reference. Dr Brooks died in March of this year at the age of 94. After St Paul’s he moved to the new University of Kent for a few years as a Lecturer in History, and then to Cambridge as a History Lecturer in the Divinity Faculty; and he became a Fellow first of Downing College and then of the recently founded Robinson College, as well as taking holy orders in 1967. He could often be seen wending his way up Trinity Street on his way to lecture at the Divinity School, deep in thought, with his head down and his gown flung over his shoulder, echoing the donnish ways that, for better or worse, have largely vanished from Oxford and Cambridge in the last few decades.

Colet’s era is long ago, and Greek is little – too little –studied at St Paul’s nowadays, but it is exhilarating to think that we, as Old Paulines, are connected to the great scholars of Renaissance Europe: not just Colet himself, but Erasmus of Rotterdam. St Paul’s may not have been founded by kings or queens but – better still – it was founded by people with adventurous minds.

Paul Cartledge (1960–64) remembers Mike Weaver (English Department 1961–63)

MLHL ‘Mike’ Weaver, who died last year aged 87, taught me for ‘AO’ (Alternative O Level) English in 1961–2. He had come to St Paul’s by happenstance –rather than as part of a planned school teaching career – not long after obtaining a Double First in the Cambridge English Tripos at Magdalene (the college of one S Pepys (1640s)). When he was teaching us Lower Eighth Classicists, Mike was in his mid-twenties, and a radical, belying the conservative reputation and indeed esprit of his alma mater. (The huge kerfuffle over the Cambridge English Tripos, involving at its centre Colin MacCabe, was yet to come – in the 1980s.)

Mike left St Paul’s in July 1963, to return to Cambridge, where he helped pioneer and promote a movement known as ‘concrete’ poetry then practised by the uncanny likes of Ian Hamilton Finlay (the creator in 1966 of the avant-garde ‘Little Sparta’ sculpture garden near Edinburgh). Over thirty years, besides visiting positions in the States, Mike held two permanent UK academic jobs, first at Exeter University (he was by origin a West Countryman, from Penzance), then at Oxford, where he became a Reader in American Literature and a Fellow of Linacre College, retiring early in 1997.

At both his universities he was also able to develop and teach the second of his two main specialisms. As a pathbreaking photography historian, he wrote books on early practitioners Julia Margaret Cameron, Alvin Langdon Coburn, and Henry Fox Talbot, as well as curating The Photographic Art: Pictorial Traditions in Britain and America (The Scottish Arts Council and The Herbert Press Ltd, 1986). That side of his career is very well covered in Geoffrey Batchen’s expert obituary notice in History of Photography 48.1 (2024/25), Pages 163–66.

What of Mike’s primary field of expertise and teaching us? In 1961, it was rightly

deemed that we Classicists aged 14 to 15 who had moved up from Remove bearing our meagre haul of O Levels (six in my case) were desperately in need of some breadth of instruction and study away from our super-rich diet of Greek and Latin texts (served up genially by AG ‘Tony’ Richards, School Librarian and sonorous bass). Hence our being required to take a couple of AO Levels, one on either side of the ‘two cultures’ divide identified by C P Snow in 1959. In the History of Science paper, we all failed (top mark 32 per cent.); I achieved a grand total of 20. In mitigation, we were not actually taught the stipulated curriculum but instead dabbled in such chemical mysteries as saponification, how to make soap!

We did rather better in our other required AO Level, in English literature –or was it English language literature? – taught to us by Mike. What exactly the prescribed curriculum comprised we never learned, though we did know that it included as our set text Shakespeare’s Coriolanus – in which Richard Burton starred as the eponymous traitor in a recording made in 1962 (still available on YouTube). But Mike was anyway not one to be constrained by the limits of any curriculum. He did teach us Milton, ‘the greatest’ of John Colet’s ‘children’ (David Bussey), who entered Christ’s College, Cambridge exactly 400 years ago. But in addition to the revolutionary, heretical Paradise Lost (which we read rather glamorously in a US paperback edition handily published in December 1961) Mike introduced us to Samson Agonistes: a dramatic poem set in… Gaza, inspired by the ancient Greek tragedians and adorned with an epigraph from Aristotle’s Poetics (Milton was a supreme classical scholar).

And then there was Mike’s real passion, near-contemporary American Literature. In 1971 he would publish a monograph on poet William Carlos Williams (famed, not least on the

London underground, for his 1934 effort, ‘This is just to say’). As I recall, though, he did not teach us any Williams but rather a curious trio of prose works by another member of the same New York literary circle, the experimental novelist and screenwriter Nathanael West (né Nathan Weinstein, 1903–1940). Who could ever forget The Dream Life of Balso Snell (1931), Miss Lonelyhearts (1933), or The Day of the Locust (1939) – all collected in Novels & Other Writings (Library of America, 1997) – if only for their titles?

I am not now quite sure why, but ten years ago, in June 2015, Mike and I were happily reunited – together with his second wife and fellow photography historian, Annie Hammond – in Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum (where I had done the bulk of my research for a 1975 DPhil in the archaeohistory of Sparta). Thereupon he kindly gave me a signed copy of his The Photographic Art, together with a letter written in longhand on a scrappy piece of white paper (not proper ‘writing’ paper). I quote its somewhat cryptic conclusion in full:

Some keywords to tempt you, in no particular order: John Simpson, David Cohen as Dr Faustus , Parker & Whitting, Headmaster of Harrow (James), and Jack Hylton’s Band, Juke Box Jury. Your memory will be ten years better than mine, of course!

I think I can parse all or most of those references, but what exactly lay behind the last two I never did fathom.

RIP, Mike, one of the most extraordinary persons I have had the privilege and pleasure to be taught by, or indeed, to have known.

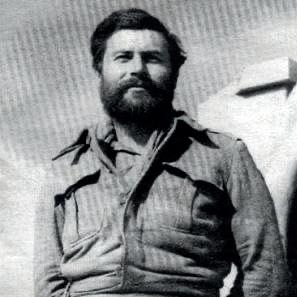

The School’s Librarian, Hilary Cummings, when discussing the rare books donated by the OPC to the School at Feast Services, highlighted George Murray Levick’s (1891–95) Natural History of the Adélie Penguin.

It had included a section about the animal’s sexual proclivities that was deemed to be so shocking it was removed to preserve decency. Levick, who had written the passage in Ancient Greek so only educated gentlemen would understand the depravities he had witnessed, then used this material as the basis for a separate short paper, Sexual Habits of the Adélie Penguin, which was privately circulated among a handful of experts. He had written it while acting as surgeon and zoologist on the British Antarctic Expedition 1910–1913 when he and 5 companions had to survive for seven months in complete darkness, living off the land, in an ice cave and through an appalling Antarctic winter. Mount Levick is named after him in the Tourmaline Plateau in Antarctica.

Levick, who had written the passage in Ancient Greek so only educated gentlemen would understand the depravities he had witnessed.

On his return he served in the Navy’s Grand Fleet in the North Sea and Gallipoli and during WW2 he acted as an instructor in survival techniques at the Commando training school in Scotland. He also found time to found and act as the first Secretary of the Royal Navy Rugby Union, to undertake pioneering work in training the blind for physiotherapy, to establish the Hermitage Craft School for disabled children and to act as Medical Director from 1922 to 1950 of the Public Schools Exploration Society.

Levick died in 1956 at the age of 79. At the time of his death, Major D Glyn Owen, chairman of the British Exploring Society wrote: “A truly great Englishman has passed from our midst, but the memory of his nobleness of character and our pride in his achievements

British Antarctic Expedition 1910–13

cannot pass from us. Having been on Scott’s last Antarctic expedition, Murray Levick was later to resolve that exploring facilities for youth should be created under as rigorous conditions as could be made available.”

Apposition is something of a mystery to the majority of Paulines. Once a year for over five centuries the cleverest boys attend School for a 16th Century ceremony to collect the Kynaston Prize for Greek, the Isaiah Berlin Prizes for Philosophy or some such.

Atrium blagged an invitation this year. St Paul’s often feels like a 500-year-old institution that pays little or no attention to its history. Admittedly, we have a High Master and a Surmaster. Our head boy is called Captain of School. Half term is sometimes still called Remedy. But our chapel would be full if 5% of the pupils turned up and there is nowhere that all the pupils from senior and junior schools can assemble at the same time other than ‘Big Side’. It feels very 21st Century.

Apposition takes you back to Henry VIII’s reign, just after the printing press had been invented. It starts with Matins with an anthem sung in Latin. The Chairman of Governors in his Mercer robes introduces the ceremony. Four Paulines then declaim. The subjects are diverse and fascinating: China’s Belt and Road initiative, Laurence Binyon, A Sky Survey and Alzheimer’s. The Apposer, Professor Imre Leader (1976–80) reviews their work and recommends to the Master Mercer that the High Master should keep her job for another year. The Master Mercer duly obliges. Pauline violinist Richard Eichhorst plays Solo Sonata No. 4, Movement 1 by Ysaye quite exquisitely. The ceremony then reaches its boring part as the book prizes are handed out and the audience of proud parents claps. The High Master concludes Apposition by acting relieved that she and her husband will not be out on the streets that evening despite 21st Century employment law. The School’s internal inspection is all over for another year and St Paul’s can return once again to the 21st Century and weeks of external examinations.

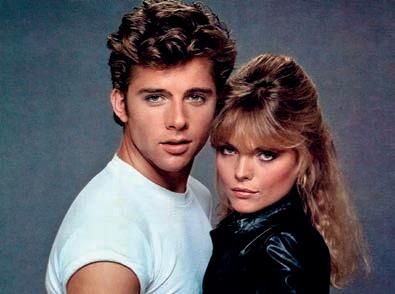

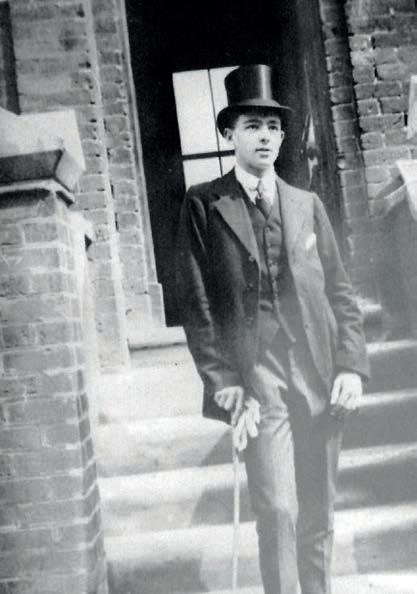

John Venning (Head of English 1989–2014) writes. Official biographies do not seem to mention Maxwell Caulfield’s (1972–75) schooling. Surprisingly frank in many other details, they do not feature St Paul’s.

Maxwell Peter John Newby was born in Derbyshire in 1959. By 1965 his parents had parted, though Maxwell seems to have retained some fondness for his Derbyshire origins, referring to himself as a Darby (sic) lad in one email address. His mother reverted to her maiden name, Findlater, and it was as Maxwell Findlater that he first acted, appearing as a child, Ted, in the 1967 film Accident (Joseph Losey) written by Harold Pinter and starring Dirk Bogarde, Michael York, Stanley Baker and Vivien Merchant.

His entry in the St Paul’s Register from Colet Court in Autumn 1972 calls him Maxwell Connell with a stepfather, R Connell, a Motion Picture Executive of Kensington. A member of F Club, he played in a Junior Colts XV and acted in at least two plays, The Boyfriend and Romeo and Juliet. He was popular with friends and had no apparent reason to be unhappy at School.

Most online lives describe him as having been kicked out of his home aged 15, by an American stepfather, a former US Marine called Maclaine. He certainly has a half-brother called Marcus Maclaine, a musician.

The register describes him as leaving St Paul’s from 6Y in July 1975. One of his friends, a fellow wing-forward, met him shortly after his leaving school at the dental hospital in Leicester Square. He was dressed in a skin-tight, lime-green hotel page’s uniform. The explanation for this costume was that he was earning his living, and an Equity card, by dancing at The Windmill Theatre. Dancing, naked, in various revues seems to have enabled him to survive.

By 1979 he was in the USA, ironically able to get a green card because of his stepfather’s nationality. The stage name Caulfield is attributed to his admiration for Holden Caulfield in J D Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye

His revue experience seems to have stood him in good stead in the plays in which he took off some or all of his clothes, but his range was much wider than that for in 1989, he was playing John Merrick in The Elephant Man when he met Juliet Mills, the British actor eighteen years his senior, whom he married with little delay. Their soulmates’ relationship survives happily to this day.

The roles for which he is most popularly remembered were as Michael Carrington in Grease II opposite Michelle Pfeiffer (the film did not have the blockbuster success of its predecessor) and Miles Colby in Dynasty and the spin-off The Colbys. His stage, television and film credits list a remarkable range of roles, occupying every year of a long career. He even appeared for a year in Emmerdale

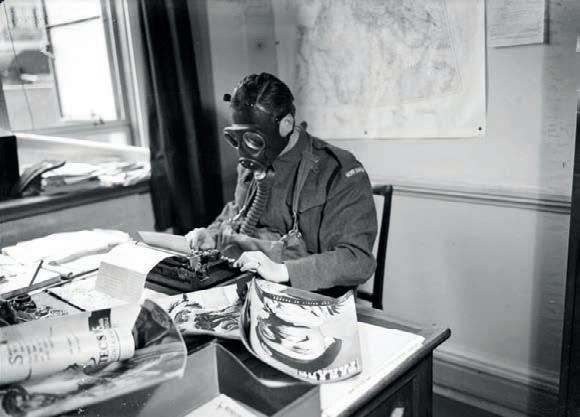

Luke Hughes (Naysmith) (1969–74) who served in the regiment in the 1980s, during the last decade of the Cold War reveals the Artists Rifles’ Pauline connections.

Foreign terrorists seeking shelter on British soil under the pretence of asylum? Expansion of military forces in Europe? Unforeseen threats the next generation must face? Re-introduction of Conscription or National Service? It is all in recent news so not that hard to imagine.

What is harder to imagine is David Hockney, Damien Hirst, Anthony Gormley, Francis Bacon, Lucien Freud signing up for weekly drill sessions or shooting practice on Hampstead Heath. The idea of the avant-garde artists as part of a woolly Bohemian demi-monde, contemptuous of any whiff of patriotism or support for The Establishment is still deeply ingrained.

It was not always so.

After the Crimean War (1853–56), with half the British Army on garrison duty around the Empire, there were insufficient forces available to be deployed for home defence of the British Isles. This was brought into focus after the Orsini affair, an assassination attempt by Italian nationalists on the life of Emperor Napoleon III in Paris on 14 Jan 1858, when eight people died and 150 were injured in the blast, but not the Emperor. It transpired that Felice Orsini and his co-conspirators, backed by English radicals, had travelled to England and made the bombs in Birmingham. In today’s parlance, that equates to foreign terrorists sheltered on British soil. When in April 1859 France joined forces with the Austrian Empire for the Second Italian War of Independence, there were fears that Britain might get caught up in the maelstrom, not least because the French army was so much larger than what remained in England – a tempting target.

The perceived danger of invasion led to the creation of the Volunteer Force, which over the next century and a half has evolved into what is now known as the Army Reserve.

One of the components was the creation of The Artists Rifles, the brainchild of a young art student, Edward Sterling, which gathered painters, architects, poets, sculptors, musicians and actors into a volunteer military unit based at the Royal Academy. The list of founding members, many Old Paulines, included G F Watts, Dante Gabriel Rosetti, John Everett Millais, Edward Burne-Jones, William Morris (who could not march), John Ruskin, Ford Madox Brown (who mistakenly shot his own dog on exercise), Frederick Leighton, William Blake Richmond, and John William Waterhouse. It also included Gerald Horsley, architect of St Paul’s Girls’ School.

The regiment was popular and grew quickly, first serving with distinction in the Second Boer War and most notably in 1914. So great was the number of volunteers that three battalions were able to mobilise within weeks, setting off for Boulogne on 26 October 1914. They included lawyers, doctors, engineers, sculptors, painters, architects, musicians, opera-singers, stockbrokers, clergymen (one of whom went on to be a Sergeant Instructor in the Machine Gun Corps), three Chinese speakers and a deep-sea diver.

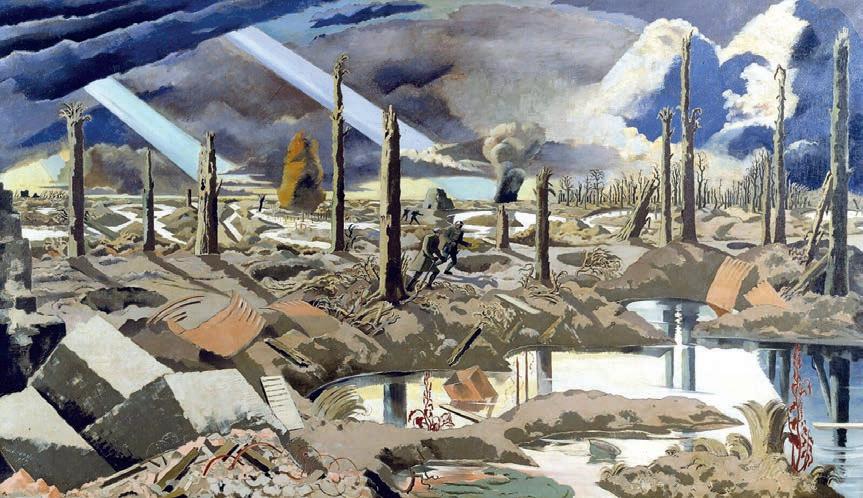

Old Paulines, with their own Officer Training Corps already well-established, were a natural source of recruits; middle-class, well-educated, creative, egalitarian and London-based. Artists like the sculptor Eric Kennington (1900–04), the artists John and Paul

Nash (1903–06), the poet Edward Thomas (1894–95) joined such luminaries of the Artists Rifles as Charles Jagger (sculptor of the Artillery Memorial at Hyde Park), the graphic artist Alfred Leete (creator of the famous Kitchener recruiting poster, ‘Your Country Needs You’) and the poet Wilfred Owen. A larger number were commissioned as officers as soon as they arrived in France, being distributed to the Guards, every infantry regiment and to many of the Corps, including the Royal Navy and Royal Flying Corps. The remainder formed a fighting battalion and saw battles at Passchendaele in October 1917 and at Welsh Ridge near Marcoing on 30 December 1917, captured in oil so vividly by John Nash in his painting, now in the Imperial War Museum, ‘Over The Top’

No other single unit suffered such casualties during the WW1. Out of more than 15,000 mobilised, 2003 were killed and over 3,000 wounded. Eight Victoria Crosses, 52 Distinguished Service Orders and 822 Military Crosses were awarded to those who served.

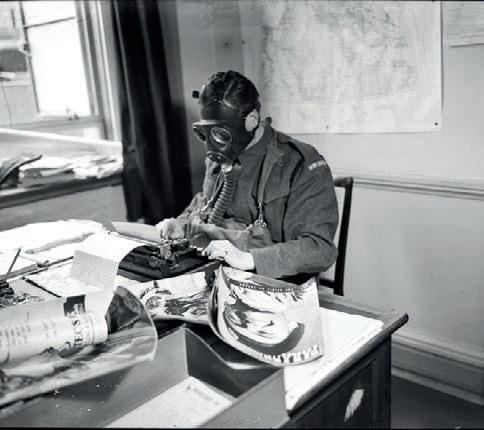

By 1937 the Artists Rifles were designated purely as an officer producing unit. Personnel were trained as officers, with their creative talents much appreciated. Barnes Wallis (inventor of the bouncing bomb) Desmond Llewelyn (‘Q’ in early James Bond movies), the cartoonist Cyril Bird (known as ‘Fougasse’ viz. ‘Careless Talk Cost Lives’) the dance-master Victor Sylvester and the playwright Noël Coward – all wore the uniform of the Artists Rifles.

During the general demobilisation of the Territorial Army at the end

of the war in 1945, the Artists Rifles was disbanded.

But the story continued.

The Special Air Service had a much shorter history but no less impressive. Created from the vision of David Stirling in the North African desert in 1941, where they destroyed more German aircraft on the ground than were destroyed in the air, in Europe, they disrupted German lines of communication, coordinating the activities of Resistance Groups and restricting the free movement of German reinforcements. The travel writer, Eric Newby (1933–36), was awarded the MC for his raiding role on the Sicilian coast in 1942. The British government saw no further need for such an insubordinate irregular force after the war and the SAS Brigade was disbanded on 8 October 1945.

Members of the Artists Rifles had, meanwhile, continued to meet since the end of the war, convinced of the need that even in the atomic age their skills of initiative, endurance and intelligence would be required, entertaining the hope that the Regiment would be re-constituted as part of any post-war Territorial Army. Similarly, some like-minded members of the SAS were still operating in small units supporting SIS activities in Greece. By 1946 it had dawned on the War Office that a Territorial Army should indeed be re-established and that there was an urgent requirement for unconventional troops for ‘special operations’.

On 8 July 1947, 21st Battalion, Special Air Service Regiment, (Artists Rifles) (Territorial Army) was created. Over 100 men who had served in the

wartime SAS joined the new regiment. Often when two highly individualistic units are merged, one becomes a casualty of its history, its traditions regarded as a curiosity, not particularly interesting and more than likely obsolete. The blend of these two units into 21 SAS was however a very happy one going from strength to strength with highly creative men of action, combining tough fighting with novelty in tactics, everyone a master of their craft, able to operate alone and without orders.

For the last 78 years, now titled 21 SAS (Artists) (Reserve), the Regiment has been at the forefront of special operations serving with distinction during the Cold War, in Bosnia, Iraq and Afghanistan. The last Academy Guard was held at Burlington House, inspected by the then Prince of Wales, as late as 1984 and on the East wall of the entrance is displayed the impressive memorial to those who died in the two World Wars.

It is the 150th Anniversary of the birth of Edward C Bentley (1887–94) inventor of the clerihew. Below is the entry from Ward’s Book Of Days for March 30th.

“On this day in history in 1956, died Edward Clerihew Bentley.

Bentley was a journalist and novelist, remembered as the inventor of the clerihew, an irregular form of comic biographical verse.

Edward Clerihew Bentley was born on 10th July 1875, at London. He attended St Paul’s School, London, where he became friends with GK Chesterton, and in 1893 went to Merton College, Oxford. After Oxford, he worked as a journalist on several newspapers, particularly the Daily Telegraph, and practised journalism, for his entire professional life.

Bentley invented the Clerihew, aged 16, as a diversion from his schoolwork. Both he and Chesterton became adept at their construction. The clerihew was originally called a baseless biography, but Bentley personalised it by calling it by his unusual middle name.

Here is one of the originals:

Sir Humphrey Davy Abominated gravy. He lived in the odium Of having discovered sodium.

In 1905, Bentley published Biography for Beginners, a collection of clerihews, under the name E. Clerihew. This was followed in 1929 by More Biography, and in 1939, he brought out Baseless Biography. In Clerihews Complete, published in 1951, all of Bentley’s clerihews are collected.

Here are a few examples:

The people of Spain think Cervantes Equal to half-a-dozen Dantes; An opinion resented most bitterly By the people of Italy.

The meaning of the poet Gay Was always as clear as day, While that of the poet Blake Was often practically opaque.

I doubt if King John Was a sine qua non. I could rather imagine it Of any other Plantagenet.

Bentley died at his home in London. One wit included in his obituary the lines:

Incidentally, Mr. Bentley Will someone write a Clerihew When they bury you?

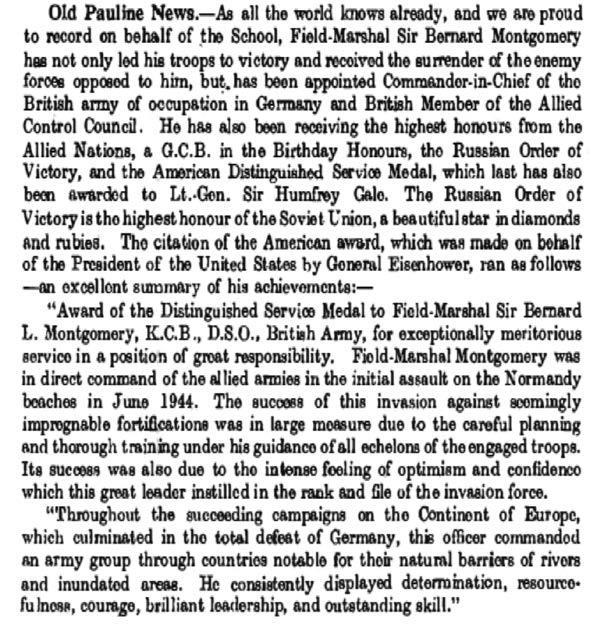

Generations of Paulines will remember the ‘Monty Map’ in the Montgomery Room.

While the room may now be on the ground floor of the School’s new building, the map, used for planning Operation Overlord with Winston Churchill and Supreme Allied Commander US General Eisenhower, still takes pride of place as an incredibly important national historical document. The Old Pauline Club has agreed to support the School by funding the refurbishment of the map and its frame.

Hayhoe (1969–73) remembers his sailing days at St Paul’s.

I was already a dinghy sailor when I arrived at St Paul’s in January 1969 but spent my Saturdays that summer as the scorer for the cricket 2nd XI. On the way to matches, I heard master Alastair Mackenzie (English and Latin departments 1957–93) quizzing the captain about another sport where he spent his Sundays, already performing at national level. This was Philip Crebbin (1965–69) who, with John Tindale (1964–69), played an important role in the establishment of sailing at St Paul’s by winning a Firefly class dinghy (named Tin Bin in their honour) for the school at the Public Schools’ Championship. He went on to represent Great Britain in the 470 dinghy class in the 1976 Olympics where he came sixth, was selected in the Soling keelboat class for the 1980 Games before the British team boycott and was later technical director and skipper in America’s Cup and Admiral’s Cup campaigns.

St Paul’s had a keen sailor on the staff in Dr Mike Hudson (Master in Charge 1966–71), who had raced with the University of London sailing team and at national level in the Firefly class. Building on the Public Schools’ Championship success, he secured funding for the purchase of four Enterprise dinghies which, along with Tin Bin, were kept at London Corinthian Sailing Club (across the river from St Paul’s) from 1970 and named after Old Paulines with maritime connections. This allowed sailing to be established as a school sport and also meant that, without a boat of my own, I could race one of the Enterprises and later the Firefly at London Corinthian and on the “open meeting circuit”.

Although we never matched the Crebbin/Tindall achievement, the St Paul’s team (racing either with 4 or 6 sailors in two or three boat team racing – a high tactical branch of the sport, where you try to secure collectively better finishing places than the competition by slowing them down) was second only to Sevenoaks School (perennial seedbed for numerous sailing stars) among schools in the south-east of England in the early 1970s. Among the School’s sailors in my generation, Will Henderson (1968–73) went on to captain a British Universities championship winning team and win the national team racing championship, narrowly missed selection for the 1988 Olympics, and became the only person to win three time both the prestigious Prince of Wales Cup for International 14 dinghies and Sir William Burton Cup for National 12 dinghies. Others made their mark in the administration of the sport: Michael Camps (1969–73) was UK chair of the International Finn class (for many years one of the Olympic boats) and I served as Vice Commodore of the Royal Ocean Racing Club, organiser of the Fastnet Race.

Sailing remains one of the top sports in the UK, with an unmatched Olympic medal tally and the schools’ team racing scene is thriving, but without St Paul’s. Sadly, despite the odd individual performance by Old Pauline sailors of later generations, I understand that sailing disappeared as a School sport in the 1980s and no longer provides the training ground for sailing talent that it did in my time.

Extract from Alex Harbord’s (Modern Languages department 1928–67) obituary in The Pauline in 1983 for Frank Commings (1931–36, Master 1954–64, Surmaster 1964–74).

“My first encounter with him was at Sports Day in 1932, when we used to have the now outmoded event of ‘Throwing the Cricket Ball’. This event was ‘open’, that is to say, without age limit. Most of the 1st XI competed, naturally. To our surprise, a boy in his first year out of Colet Court had the nerve to enter for it, and win it, to the chagrin of the 1st XI.”

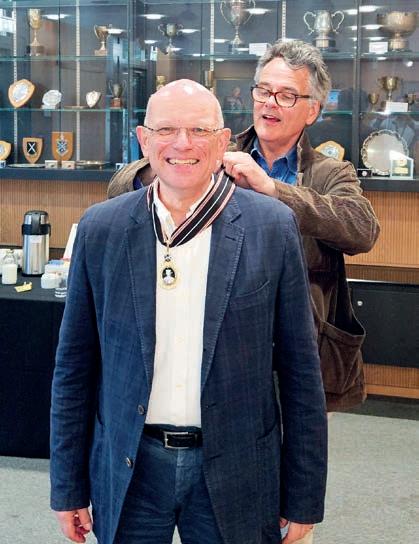

Fifty years on from a recordbreaking feat, Mark Mishon (1969–74) has again been feted.

On the 50th anniversary of his World Pancake Eating Competition victory in London, Major League Eating has awarded Mark the title of MLE Commendatore. Mark’s feat of eating 61 pancakes in 7 minutes in 1975 helped lay the groundwork for the modern era of competitive eating.

“By bestowing this honour on Mark, we hope to commemorate his historic achievement, while reaffirming the special relationship between the UK and America,” said MLE Chair George Shea. “Competitive eating acts as a United Nations of sport – there are no borders in eating, and we celebrate this with our global commendatore award.”

MLE has contacted UK Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer, offering to hold a joint award presentation for Mishon in Parliament.

In 1975, having only recently left St Paul’s, there was some amusement and amazement among former school mates and masters and he donated a copy of the Guinness Book of Records to the then Walker Library.

Atrium’s congratulations go to Patrick Spence (1981–85) on a stunning evening at the recent British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) awards.

Accepting the prize for limited drama series on behalf of ITV’s Mr Bates vs the Post Office, Spence, who is the show’s Executive Producer, said the response to the show proved that the public “cannot abide liars and bullies”.

Mike Sacks, who taught at St Paul’s in 2004–05 as a Colet Fellow, is running for congress in New York’s 17th District.

A lawyer and former TV journalist, Mike said he has become so disillusioned with the state of politics in the USA that he has decided to do something about it. While Atrium would never wish to be seen to take sides politically, we wish Mike every success with his future in politics.

Giant, written by Mark Rosenblatt (1990–95), won ‘Best New Play’ at the Olivier Awards, as did John Lithgow for Best Actor and Elliot Levey for Best Supporting Actor.

This was hot on the heels of wins in the categories of ‘Best New Play of 2024’ and ‘Most Promising Playwright’ at the Critics’ Circle Awards.

Sam Grabiner (2007–12) has won his first Olivier Award, picking up ‘Best New Production in an Affiliate Theatre’ for his play, Boys on the Verge of Tears.

The award, which is the highest in British theatre, comes after his 2024 win for best debut at the Stage Awards. “I’m going to take this incredible award as a challenge to keep trying to make work that feels intimate and true,” Sam said in his acceptance speech.

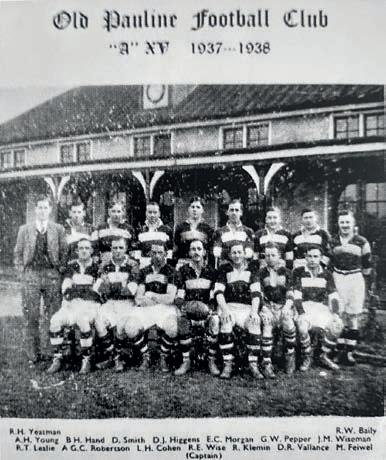

Bernard Law Montgomery (1902–06) is the one we all know about but, as John Dunkin (1964–69) highlights, St Paul’s has others who shared his nickname.

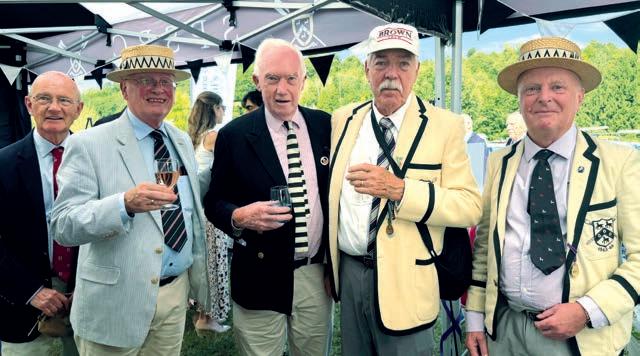

Reymond Hervey de Montmorency (1888–90) was a triple Blue at golf, cricket and racquets. After leaving Oxford he taught briefly at Malvern College before becoming a modern language master at Eton from 1900 to 1927. He became the best golfer produced by the School and was a co-founder of the Old Pauline Golfing Society in 1909. He played for England v Scotland, Amateurs v Professionals and for Britain in the first international GB v USA held at Hoylake (he teed off against Bobby Jones) in 1921; a competition that later became the Walker Cup. De Montmorency’s commitments at Eton restricted his playing opportunities and he did not play in The Open until 1927, when he was 55 years old.

Herbert Montandon Garland-Wells (1921–26) was a triple Blue at cricket, football and fives at Oxford and a successful amateur games’ player who captained Surrey County Cricket Club. In 1929 he won an international cap playing as goalkeeper for England against Ireland at football. His Wisden obituary is complimentary about his leadership. He is described as displaying “a touch of unorthodoxy in the tradition of Percy Fender”. He was liked by the professional players as he showed no sign of any amateur aloofness. After the Second World War his career as a solicitor prevented him from resuming his cricket career. Thereafter his main sports were golf and bowls at which one can only assume he excelled. His nickname was part of the war effort in the Second World War with ‘GarlandWells’ used when sending messages ‘en clair’ in reference to General Montgomery. The Germans never cracked it.

Sir Edward Montague Compton Mackenzie’s (1894–90) time at School is thinly disguised in his third novel Sinister Street (1913). St Paul’s is St James’. High Master Walker is Dr Brownjohn. Mr Elam is the eccentric Mr Neech. During the First World War Mackenzie served with British Intelligence in the Mediterranean. He loved it ‘as a boy enjoys playing pirates’ and his greatest adventure and triumph as ‘Director, Aegean Intelligence Service’ was the recapture of the Cyclades Islands. After the publication of his Greek Memories in 1932, he was prosecuted under the Official Secrets Act for quoting from supposedly secret documents. Both Monarch of the Glen, published in 1941, and the TV series it inspired were enormously successful. His most famous book is probably Whisky Galore, published in 1947 and turned into a classic film. Away from writing and being a spy, he was President of the Croquet Association and the Siamese Cat Club. He co-founded Gramophone, the still-influential classical music magazine. He was also a founding member of the SNP. He is even believed to have presented the Snooker World Championship Trophy to Joe Davis.

In May, the Director of the Parker Library, Professor Philippa Hoskin, held an event to celebrate the publication of a Festschrift in honour of Life Fellow Dr Patrick Zutshi (1969–72)

Dr Zutshi, a medieval historian, has been a member of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, for 50 years and was until 2015 Keeper of Manuscripts and University Archives in Cambridge University Library. He is a member of the Commission Internationale de Diplomatique, and his principal research interests are the papacy in the later Middle Ages.

The Festschrift, Popes, bishops, religious, and scholars: studies in medieval history brings together essays by over 20 of Patrick’s colleagues and friends, all distinguished scholars in medieval history. The volume reflects both Patrick’s wide scholarly interests, ranging from the administration of the papal curia to intellectual and legal history and the mendicant orders, and his extensive network of colleagues and collaborators.

Professor Hoskin, who contributed an essay to the book, said, “Patrick and I have known each other and worked together for nearly 20 years on various projects. We held the event in the Parker because Patrick is a long-standing Corpus member and partly because of the manuscripts and early printed books arrayed around us. Not only is Patrick a wonderful scholar, he was keeper of the Muniments at the University Library for many years.”

Atrium warmly congratulates Dr Zutshi on his distinguished career and the publication of this book in his honour.

Chris Rampling (1986–91) has been appointed the UK’s Ambassador to the Netherlands. Chris said it was “An enormous honour to be appointed His Majesty’s Ambassador to the Netherlands from this summer. A wonderful country and a crucial partner for the United Kingdom.” Chris has been working as Director of Security at the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, and was previously the UK Ambassador to Lebanon. He was awarded the Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George “for services to British Foreign Policy and National Security” in the King’s Birthday Honours List. He is an OPC Vice President.

Professor Stuart Russell (1974–78) has been appointed a Fellow of the Royal Society. Stuart studied Physics at Oxford and Computer Science at Stanford before joining the faculty of the University of California, Berkeley, in 1986. He is also a Professor of Computational Precision Health at the University of California, San Francisco, an Honorary Fellow of Wadham College, Oxford and a Vice President of the Old Pauline Club.

James Harding (1982–87), Editor and Founder of Tortoise Media, has been appointed as Editor-inChief of The Observer after Tortoise Media acquired the newspaper. Previously, James served as Director of News and Current Affairs at the BBC (2012–18). He was also Editor of The Times (2007–12), winning Newspaper of the Year in two of the five years he edited the paper. On taking over recently, James said that The Observer will be independent, liberal and internationalist under Tortoise.

Tom Adeyoola (1990–95) has been appointed as Executive Chair at Innovate UK, the UK’s Innovation Agency which helps businesses develop the new products, services and processes they need to grow through innovation. Tom said: “I’m thrilled, excited, honoured and rightly anxious to do justice to the opportunity and responsibility. I may be a start-up guy and this an arm’s length government bureaucracy, but it’s a role I couldn’t possibly turn down, as it represents the biggest lever opportunity there is to turbocharge the UK innovation ecosystem.” Tom is an OPC Vice President and a School Governor.

Stuart Shilson (1979–83) was awarded a CBE in the King’s Birthday Honours List “for services to the Order of St John and to Change Management”.

Andrew Makower (1974–79) was awarded an OBE in the King’s Birthday Honours List “for services to Parliament”.

Atrium (unless otherwise described) uses reviews provided by authors or their publishers.

Phenomenal Properties and the Intuition of Distinctness: The View from the Inside

Andrew is Professor of Philosophy, University of Missouri.

We experience the intuition of distinctness when, for example, we attend introspectively to the phenomenal redness of a current visual sensation and it seems to us that very property could not literally be a physical property of neural activity in a certain tiny region of our brain. The book begins by arguing that the intuition of distinctness underlies certain otherwise puzzling attitudes manifested in debates both inside and outside philosophy about whether physicalism (or materialism) can accommodate phenomenal properties (or qualia). It then argues systematically against the dualist suggestion that the intuition of distinctness gives us reason to reject the physicalist view that phenomenal properties are physical, and to adopt property dualism instead. In the course of the argument, it defends an unorthodox version of representationalism and offers positive accounts of what makes our introspective knowledge of phenomenal properties special, how introspection could tell us that an introspected property is physical, and what the subjectivity of phenomenal properties could be. Finally, after critically surveying previous attempts to account for the intuition of distinctness consistently with physicalism, it elaborates a novel explanation of the intuition of distinctness. The intuition arises because introspection is, in a certain way, conceptually encapsulated, as a result of which we are unable to do something that we can do in the case of every other kind of identity claim that we believe or entertain, and therefore unable to believe, or even to imagine believing, that an introspected phenomenal property is physical.

Translated by Edward Williams (Modern Languages and Creative Arts Departments 1983–2020).

Consultant Dr Ryan Buckingham, Head of Physics.

What are we made up of? What holds material bodies together? Is there a difference between terrestrial matter and celestial matter – the matter that makes up the Earth and the matter that makes up the Sun and other stars? When Democritus stated, between the fifth and fourth centuries BCE, that we are made up of atoms, few people believed him. Not until Galileo and Newton in the seventeenth century did people take the idea seriously, and it was another four hundred years before we could reconstruct the elementary components of matter.