STORIESOF EDUCATIONAL WAYFINDING:

Supporting

the

Educational

Voyages of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Students

Supporting

Educational

Max A. Halvorson, PhD

Santino G. Camacho, PhD Candidate, MPH

Koa Beck, MSW

Tressa Diaz, PhD

Buddy Kalanikumupaʻa Seto-Myers

Jenn Nguyễn, PhD Candidate, MA, M.Ed.

Jane J. Lee, PhD, MSW

Zewei (Victor) Tian, M.Ed.

Alyssa Ledesma, MSW, LSWAIC

Min Sun, PhD

Michael Spencer, PhD

The following core contributors assisted in data collection, cleaning, coding, and copy-editing reports: Dani Canaleta, Marcus Conde, Tasi Jones, Whitney Lane, and Mikyla Sakurai.

Our Community Advisory Board, consisting of Sui-lan Hoʻokano, Kiana McKenna, Inez Olive, Sili Savusa, and Adrianna Suluai, provided critical input to the design, execution, and interpretation of the studies, and reflected and represented the views of their communities in these roles. We also acknowledge the Community Advisory Board for our sister study on Asian and Asian American youth – Jen Chong Jewell, Erin Okuno, Ay Saechao, and Frieda Takamura – for their involvement in the overall conception and design of the study.

It is with a sense of responsibility and a spirit of serving communities that we present our report on educational opportunities among Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NH/PI) students in Washington’s K-12 schools.

These reports will provide the Committee on Asian Pacific American Affairs (CAPAA) and the Educational Opportunity Gap Oversight and Accountability Committee (EOGOAC) with quantitative and qualitative data, along with community-driven recommendations, needed to inform policies and strategies to close educational opportunity gaps for NH/PI students. This work represents a collaborative effort on several levels. A research team consisting of researchers from the NH/PI and As/ AsAm communities was assembled across the University of Washington's School of Social Work and College of Education Our research team combined a wide range of expertise and resources to develop two distinct reports. Although study resources were shared, we have taken care to represent the unique needs and stories of each set of communities.

We appreciate the work of Leah Forester and UW School of Social Work Marketing and Communications on the graphic design and

layout of this report.

We are grateful to CAPAA and EOGOAC in driving this important work forward and prioritizing an update to the initial in-depth study completed by Drs. David Takeuchi & Shirley Hune in 2008. We also hope this report might serve as a resource for communities to use to build on community strengths and address community needs.

We thank the Office of the Superintendent for Public Instruction (OSPI), the Education Research and Data Center (ERDC), and the Healthy Youth Survey (HYS) for sharing important quantitative data on indicators of student performance and wellness, and for their in-depth consultation and research collaboration. These institutions and teams have done extensive and thoughtful work in data disaggregation, allowing for a deeper understanding of the NH/PI community than was previously possible

Finally, we deeply appreciate the students, educators, administrators, and community advisory board members who participated in our research directly. Our communities shared their personal challenges and triumphs, as well as hopes and dreams for the education of NH/PI youth in Washington.

2. Inclusion of NH/PI Data to Drive Equitable Policy

3. K-12 Academic Achievement: Advancing Academic Equity

4. Finding Success beyond High School: Postsecondary Achievement for NH/PI Youth 5. Building Belonging and Wellbeing through Connection and Representation 6. Infusing NH/PI Cultures and Histories into K12 Education 7. Uplifting Educator Representation and Developing Cultural Humility

Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NH/PI) youth and families are full and engaged participants in their learning communities. NH/PI persevere in the face of social and economic challenges, historical underrepresentation in the educator workforce and the school curriculum, and stereotypes about their personalities and academic skills In recent years, strides have been made in NH/PI representation and equity in education data systems, including disaggregation of NH/PI data in federal and state systems from the antiquated “Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI)” category. Though there is an increasing awareness of NH/PI communities as a distinct group from Asians and Asian Americans with specific cultures, educational experiences, and learning, NH/PI continue to experience challenges in their education and wellbeing.

The NH/PI population is the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group in Washington state, with 114,189 total residents as of the 2020 census, compared to 27,654 as reported in the 2008 Education Disparities Report. When considering the welfare of NH/PI students nationally, Washington is one of the most important states to consider, as Washington ranks in the top 5 by population share for Native Hawaiians, Sāmoans, Tongans, Chamorros, Marshallese, and Fijians. Due to differing histories of settler colonialism and Pacific nations’ political relationships with the US government, citizenship within NH/PI communities varies

greatly depending on the island(s) families are from. Citizenship status can impact access to economic benefits and healthcare in the US, which have direct impacts on the educational experiences of youth. Moreover, the challenges of navigating multiple cultures and political statuses are compounded by significant socioeconomic challenges, as over one-third of NH/PI families experience food insecurity.

NH/PI youth are also diverse, with NH/PI in Washington being indigenous to many different nations, states, and territories across Polynesia, Micronesia, and Melanesia In addition, 43% of NH/PI individuals in Washington identify as multiracial and an estimated 14% of NH/PI youth in OSPI schools identify as Queer or Transgender Pacific Islanders (QTPI). Rather than ignoring this diversity, we highlight it as a strength of the NH/PI community and acknowledge the complex ways in which NH/PI youth navigate systemic oppression within the education system.

In the current report, we sought not only to assess the current state of NH/PI educational achievement in Washington state as of 2025, but also to uplift the voices of students, educators, and community members in shaping recommendations to close achievement gaps and advance OSPI’s mission to serve all students

Using

youth and to develop community-informed recommendations. Quantitative data included formal metrics such as grades, graduation rates, and standardized testing scores provided by the Office of the Superintendent for Public Instruction (OSPI), as well as measures of student wellbeing from the Washington Healthy Youth Survey administered to a representative sample of students statewide.

Qualitative data were gathered through focus groups and interviews with students, educators, and administrators who shared their perspectives on the needs and challenges of NH/PI youth.

To ensure that recommendations were grounded in community expertise, we convened a Community Advisory Board (CAB) composed of leaders in the Washington NH/PI community to help interpret findings and shape recommendations.

In our quantitative analysis, we intentionally disaggregated NH/PI data from Asian/Asian American (As/AsAm) data, and when possible, we examined data on specific NH/PI communities (e g , Yapese, Chamorro) For qualitative data, we prioritized representation across diverse Pasifika backgrounds and regions within the state.

and concerning disparities in educational outcomes for NH/PI youth that have not improved since the 2008 report. Whereas data on standardized test scores appear to reflect widening disparities across the intervening years, graduation data may provide some evidence of progress. Disaggregated data reflect variability in academic outcomes, with challenges for non-Chamorro Micronesian youth and relatively fewer challenges for Native Hawaiian and Chamorro youth

These disparities start early – only 1 in 3 NH/PI youth enter kindergarten with the skills needed for a smooth transition. They persist through K-12 education – between 2010 and 2024, approximately 3 in 4 NH/PI students (73%) enrolled in OSPI high schools graduated within 4 years, as compared to 79% of all students. And when considering postsecondary outcomes, NH/PI youth were less likely than most other racial and ethnic groups to complete a 2-year degree (14%) or 4-year degree (21%) in the years following high school graduation. Among those who did complete these programs, however, wages were comparable to members of other racial and ethnic groups during the first few years in the workforce

Notwithstanding rich histories and ways of knowing among NH/PI communities, K-12 academic achievement data reveal persistent

In interviews conducted for this 2025 study update, educators acknowledged (and at times perpetuated) the pervasive stereotypes and lack of representation that students often work against: “I hope that they can see it within themselves and getting out of that categorized mindset that just because you're a Poly boy doesn't mean you have to play football. Just because you're a Poly girl doesn't mean you have to play volleyball. Get into another career path. You don't have to fall under the

categories of what society tells you are…go be a frickin’ scientist.” While educators expressed hope for their students’ long-term success, they noted that there needed to be “more creative, more flexible ways that students can earn a diploma” because academic standards do not always align with to students’ goals or interests.

Pasifika cultures share a holistic sense of wellbeing that values relationships with family members, ancestors, community members, land, oceans, and skies This worldview can conflict with the American education system, leading to disidentification and disconnection Students and educators drew a parallel between a lack of wellbeing and a feeling of disconnection to the school environment. One educator shared “they're not reflected in the curriculum at all. Or celebrated in their buildings for who they are...” A student shared, poignantly: “It just brings me back to my cousin's school. He goes to Utah, and…it's one of the most populated state of Tongans…they had the Tongan mat on the wall decoration 'cause there's that many Tongans and just seeing that…almost made me cry…I wish I had that.”

NH/PI students in Washington experience significant challenges to their wellbeing, contrary to stereotypical beliefs that NH/PI youth are carefree. Statewide, NH/PI youth exhibited the highest rate of depression symptoms of all major racial and ethnic groups, with 2 in 5 (40%) reporting a period of feeling

depressed in the past year. Chamorro (53%), Marshallese (42%), Native Hawaiian (39%), and other combined NH/PI (Chuukese, Kosraean, Palauan, Yapese; 45%) youth were especially prone to depressive symptoms. Anxiety problems were also common among NH/PI youth, with more than 1 in 3 (34%) NH/PI youth reporting at least mild anxiety. Perhaps most alarmingly, nearly 1 in 5 (19%) NH/PI youth report having thoughts of suicide at least once in the past year QTPI students, particularly Transgender QTPI students, had greater disparities in mental health outcomes compared to straight and cisgender NH/PI students where more than 1 in 3 (35%) of QTPI and 2 in 3 Transgender QTPI (67%) reporting having thoughts of suicide at least once in the past year.

A consistent and emphatic theme shared by our NH/PI student and educator interviewees, as well as by our Community Advisory Board, was the importance of bringing Pasifika culture and history into the educational environment to build student belonging, engagement, and investment in their school communities During our interviews, students and educators shared how NH/PI students had challenges connecting with their classes because they did not see much of their Indigenous cultures and histories represented in the standard curriculum. As one student shared, “You want to feel included and represented. We mostly hear about bad events, but I also want to learn how we came together as people – how we survived and thrived.” Despite these challenges, schools can build

connection with NH/PI students and communities by honoring Pasifika identities and allowing these identities to be celebrated in the school setting

Fortunately, NH/PI communities have worked together to create outstanding models for integrating community and culture into schools. Creating institutional support through formal partnerships and acknowledging staff who go above and beyond can advance OSPI’s mission of increasing student belonging and, in turn, educational outcomes.

For example, the United Territories of Pacific Islanders Association of Washington (UTOPIA WA) partners with King County and Pierce County schools to engage youth in programs that cultivate leadership, safety, and cultural identity among QTPI, QTBIPOC, and NH/PI youth

These programs teach Siva Samoa (traditional Sāmoan dance) and other cultural practices through their Nuanua knowledge corner

In Eastern Washington, Marshallese community members implemented a culture and language elective course that allowed students to engage academically with topics around their Marshallese genealogical practices, family, storytelling, language, and culture.

Finally, in the Enumclaw school district, an immersive educational experience based on Pacific Northwest Tribal Canoe Journeys emerged as a key program to increase engagement and graduation rates among Native youth The potential for NH/PI youth to benefit from similar programs, given shared culture as seafaring Indigenous peoples, is high

Having to choose between family, culture, and school is an impossible decision to make for NH/PI students in the Washington K-12 education system. Death, funerals, and grief are sacred moments in the lives of NH/PI peoples. Across Oceania there are distinct practices and ceremonies that are held to commemorate the life of a loved one and grieve their passing. These ceremonies can last anywhere from 1 week to 1 month. To our knowledge, there are currently no formal policies in Washington’s K-12 education system that address student needs for extended bereavement, including accommodations for the length of time needed for cultural bereavement ceremonies. Creating an education system that cares for these cultural needs and celebrates NH/PI students is likely to have profound effects on their academic achievement.

UPLIFTINGEDUCATOR REPRESENTATIONAND DEVELOPINGCULTURALLY RESPONSIVEEDUCATORS

When NH/PI students worked with NH/PI educators, paraeducators, and non-NH/PI teachers who had culturally responsive pedagogical practices, both students and educators noted the support, safety, and trust that these educators provided. NH/PI educators are severely underrepresented in identified as NH/PI (US Bureau of Labor

Statistics) In Washington’s OSPI schools, these numbers are higher, but NH/PI students still struggle to see themselves represented in the educator workforce. Across districts, the percentage of teachers who identify as NH/PI ranges from 0.0% to 2.6%.

As one NH/PI paraeducator shared, “I think having teachers that represent our students is really important…students need to see that there are people who look like them, who understand their culture and are in places… where they can look up to, or people they can look up to...it does make a difference when there are teachers who truly represent their students” Having positive role models can help to counter harmful stereotypes experienced by NH/PI youth that can label them as unintelligent, aggressive, lazy, and/or exotic. Increasing NH/PI representation in schools also help call attention to these damaging beliefs.

During the 2023-24 school year, the number one request from parents to the Washington State Governor’s Office of the Education Ombuds (OEO) was for assistance related to special education, inclusion, and equitable access. NH/PI families were no different, with the highest proportion (60%) of requests to OEO involving special education NH/PI students with disabilities face unique discrimination in special education spaces when these intersections interweave with NH/ PI stereotypes that create perceptions of NH/PI students as aggressive and disruptive. One

teacher even noted that NH/PI boys are sometimes put in special education classes when there isn't evidence to support that change because the threshold for "misbehavior" is lower for NH/PI boys. In addition, stigma remains within NH/PI cultures and other communities of color. Continued recognition, education, and endorsement of a strengthsbased perspective when working with families, can address these challenges. In addition, highquality language navigation services are critical for discussing these complex topics.

NH/PI students dream of futures filled with growth, achievement, and the ability to uplift their families and communities. One student expressed, “For me, it's…my older sister. She just recently graduated college, and she's also going towards the medical field...If I can dream it, then I can do it.” Some students dreams were also tied to wanting greater representation in their education: “I’ve been want teacher…I’ve never seen a Mars It influences me because like I c something." These dreams also certain non-negotiables in carin community, as captured by a st know, the Fa’a Samoa way Take own Take care of your grandm they brought you here, so help them where they are.”

NH/PI educators all shared drea generating an education system Pasifika Indigenous cultural valu harder to make more money is

goal But it's the other things that feel important…how are you in community with each other and with yourself, and what are the things you need to learn in order to do that? And what are the ways in which we need to think about our planet and like non-human parts of like how we interact with the world? I wonder if we were in a place, that with more of the aligned values…how our Pacific Islander students and families would show up differently, and what success would look like.”

These educational dreams challenge us to reflect on whether our systems align with the values that we claim to hold: growth, achievement, family, and community Within many NH/PI worldviews, right relationships with family, community, the natural environment, and ancestors are critical for wellbeing and, in turn, educational success. The following pages offer policy and program recommendations informed by students, educators, data, and community input, to transform Washington’s K12 education system to better support these dreams.

1.BOLSTERLANGUAGESERVICESFORNH/PIFAMILIES.

Effective language navigation services in NH/PI languages (e.g., Marshallese) are essential for family engagement and educational support. Schools and districts should use administrative data and engage communities to identify language needs and share resources across districts, especially for less commonly spoken languages.

2.DISAGGREGATENH/PIFROMAS/ASAMDATAINALLCIRCUMSTANCES ANDDISAGGREGATENH/PIDATATOTHEETHNICGROUPLEVELWHEN POSSIBLE.

Aggregating data can obscure inequities Educational data on NH/PI should be disaggregated by ethnic group (e g , Tongan, Yapese, Kosraean) whenever possible OSPI and ERDC should offer training and guidance on disaggregation practices for educators and administrators If small group data must be suppressed or combined, name the communities represented and consider qualitative approaches or partnerships with community-serving organizations to understand community needs and priorities.

“Double count” multiracial youth in educational data so they remain visible in community-specific data, and continue to develop guidance, with community input, for representing the growing number of multiracial youth in the statewide discourse on achievement and opportunity gaps.

3.PROMOTECULTURALHUMILITYFORALLEDUCATORSANDNH/PI HISTORICALAWARENESS

All educators should receive training on NH/PI history, values, and relational wellbeing and reciprocity for Indigenous and NH/PI students. Incorporating frameworks such as Indigenous Connectedness can strengthen student bonds to school. Minimally, educators should meet the Professional Educator Standards Board's (PESB's) Cultural Competency, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (CCDEI) standards. Pre-service and in-service training for educators and administrators should heighten awareness of NH/PI students’ high rates of mental health challenges.

Expand investments in school mental health, with attention to hiring, training, and retaining NH/PI professionals

NH/PI educators and paraprofessionals often serve as informal counselors and should be supported and compensated for this work Offer financial and professional development pathways, especially for paraeducators without 4-year degrees.

5.EMBEDNH/PICULTUREINTOSCHOOLSANDCLASSROOMS.

Support initiatives that bring NH/PI culture into schools, including credit-bearing activities through Mastery-Based Learning Ethnic studies courses should include NH/PI histories, aligning with Washington State’s ethnic studies graduation requirement.

6.INCREASENH/PIREPRESENTATIONINTHEEDUCATORWORKFORCE.

NH/PI teachers are the most underrepresented of all teachers Invest in recruiting, training, and retaining NH/PI educators Opportunities supported by the Professional Educator Standards Board (PESB) and Washington Student Achievement Council (WSAC) should be highlighted in particular: Recruiting Washington Teachers, Bilingual Educators Initiative, Paraeducator Certificate Programs, and Apprenticeship Programs. Cultural competence training should not rely on the “AAPI” umbrella term, but address the distinct experiences of NH/PI communities. Consistent with HB1541 (the Nothing About Us Without Us act), partner with and compensate NH/PI community organizations to develop these educational opportunities.

When assessing disability and crafting individualized education plans, professionals should work against biases that may lead to overdiagnosis of behavioral problems and underdiagnosis of learning challenges. Embrace strengths-based approaches and address stigma within communities of color. School psychologists and service providers should use self-assessment tools to reflect on their practices.

Recognize cultural obligations (e.g., bereavement practices) and provide flexible accommodations so students and families are not forced to choose between school and family.

In line with OSPI’s commitment to LGBTQIA+ students, interweave QTPI narratives into the development of NH/PI studies curriculum, cultural programs, and educator training. Collaborate with QTPI community groups to expand and improve data gender and sexual orientation data categories and ensure culturally specific identities are acknowledged. Provide school districts with communitydriven resources and training.

NH/PI:THEFASTEST-GROWING RACIALORETHNICGROUPIN WASHINGTON

Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NH/PI) students are among the fastest-growing student groups in Washington. From 2010 to 2020, NH/PI were the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group in Washington, rising 62.4% to 114,189 total NH/PI residents in 2020 (see Table 01). This demographic is over 4 times larger than the population count (27,564) in the prior iteration of this report completed in 2008.

When considering the welfare of NH/PI students nationally, Washington is one of the most important states to consider, as Washington ranks in the top 5 by population

share for nearly all the largest NH/PI communities, including Native Hawaiian, Sāmoan, Tongan, Chamorro, Marshallese, and Fijian. Moreover, NH/PI in Washington comprise a share of the population that is three times as high as the NH/PI share of the total US population (1.5% vs. 0.5%) and ranks #3 (after Hawai‘i and California) in the total number of NH/PI residents. Sāmoans are the largest NH/PI group in Washington (31% of total NH/PI population), followed by Chamorros (23%) and Native Hawaiians (13%).

We use the abbreviation NH/PI informed by our partners at the Pacific Islander Community Association of Washington (PICAWashington) in part to distinguish Native Hawaiians, who have a Trust Relationship

DATA SOURCE: AAPIDATA DASHBOARD AND US CENSUS

with the US government, from other Pacific peoples. NH/PI are Indigenous to islands in the Pacific Ocean and descend from people who have cared for their lands, oceans, and skies for centuries before European exploration and continue to do so Within Washington state, the majority (55 1%) of NH/PI residents live in either King or Pierce counties, with roughly equal numbers in each (33,519 in King, 29,358 in Pierce). King, Pierce, and Snohomish counties had the largest number of NH/PI residents in both 2020 and 2003 census data. Clark, Spokane, Thurston, and Kitsap counties also have sizable NH/PI populations as of 2020 data,

with over 5,000 residents in each (see Table 02). NH/PI students of Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction schools are mostly concentrated in southern King County (Federal Way, Auburn, Kent, Highline), Pierce County (Bethel, Tacoma, Clover Park, Puyallup), and Clark County (Evergreen, Vancouver) areas

In the remainder of Section 1, we present the history and context needed to understand how families experience Washington’s K-12 public education system with respect to culture, history, and socioeconomic circumstances of NH/PI families.

DATA SOURCE: 2003 & 2020 US CENSUS DATA

NOTE: MISSING VALUES INDICATE DATA NOT AVAILABLE IN 2008. DATA SOURCE: OSPI.

NH/PI families and youth live, thrive, and pursue their dreams in the context of diverse colonial histories, as they hold ancestry from Pacific Island nations with distinct (but often interrelated) languages, cultures, and political histories. Citizenship status within NH/PI communities varies depending on the islands that families come from and has

unique impacts on access to social safety net provisions and public economic and healthcare benefits in the US – factors that directly shape the educational experiences of youth Our community partners in this work also stressed the importance of factoring NH/PI communities’ Indigeneity in understanding their academic success. Table 04 demonstrates the expansiveness of Oceania and the respective islands, cultures, nations, and communities to which NH/PI communities draw genealogical connections. Within the US, Native Hawaiians, Chamorros and Carolinians

from Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, and American Sāmoans are Indigenous to lands within the national boundaries of the US. The Kingdom of Hawai‘i was annexed by the US in 1893 Due to Hawai‘i’s eventual conversion to a US state in 1959, Native Hawaiians are full US citizens and have full access to social, civil, and constitutional rights such as education, healthcare, voting representation in congress, and voting for the US president. Native Hawaiians also have a formal trust relationship with the U.S. government that is similar to American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/AN) but lacks a federally recognized governing body.

Sāmoans born in American Sāmoa and Chamorros born in Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) are Indigenous to the US but have no formal treaties with the US government American Sāmoans hold US National citizenship status, meaning they cannot obtain certain jobs requiring security clearance, nor have full legal voting rights unless they become naturalized citizens. Residents of Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands are US citizens. However, those living in Guam and the CNMI cannot participate in US presidential elections, do not have voting representatives in congress, nor do they have US Senators. Though not Indigenous to the US, many of

10,13,14 6,15

these Pacific communities were subject to Western imperialism in the Pacific that began with Ferdinand Magellan’s landing on the island of Guåhan (Guam) in 1521 including the Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, French, and Germans, and similarly are impacted by the colonial impacts of these settler colonial entities

Pacific Islanders who are Chuukese, Pohnpeian, Kosraean, Yapese, Marshallese, and Palauan are Indigenous to islands that were once governed by the US as Trust Territories of the Pacific Islands from 1947 to 1994 after World War II. These Pacific Islanders are now citizens of independent Pacific Island nations – the Federated States of Micronesia, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, and the Republic of Palau – and have non-immigrant status under the Compacts of Free Association (COFA) of 1986 and 1989 that their nations hold with the US federal government (see Table 01) Although COFA is meant to provide access to welfare, healthcare, and other benefits their status as non-immigrants is challenged by state structures such as welfare benefit applications. For example, partial citizenship status has historically created challenges for COFA Islanders by limiting access to welfare resources like Medicaid and unemployment insurance because they do not have alien registration numbers often required to apply for welfare. 9,16

TABLE 04: NH/PI COMMUNITY AND COUNTRIES OF ORIGIN

4,9,16 17

CHamoru/Chamorro

Carolinian

Guåhan (Guam), Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas Islands (Luta, Tinian, Sa’ipan, Pågan)

Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas Islands (Luta, Tinian, Sa’ipan, Pågan), Caroline Islands

TABLE 04 CONT: NH/PI COMMUNITY AND COUNTRIES OF ORIGIN

Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander Group Indigenous Homelands

Sāmoa (Savai‘i, Afi, Manono, Apolima, Upolu)

Sāmoan

Marshallese

Māori

Chuukese

Yapese

Pohnpeian

Kosraean

Tahitian

Tokelauan

Tongan

American Sāmoa (Tutuila, Ofu-Olesega, Ta‘ū, Aunu‘u)

Republic of the Marshall Islands (Ailinglaplap Atoll, Ailuk Atoll, Arno Atoll, Aur Atoll, Ebon Atoll, Enewetak Atoll, Jabat Island, Jaluit Atoll, Kili Island, Kwajalein Atoll, Lae Atoll, Lib Island, Likiep Atoll, Majuro Atoll, Maloelap Atoll, Mejit Island, Mili Atoll, Namdrik Atoll, Namu Atoll, Rongelap Atoll, Ujae Atoll, Utirik Atoll, Wotho Atoll, Wotje Atoll)

Aotearoa (New Zealand)

Federated States of Micronesia (Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei, Kosrae)

Federated States of Micronesia (Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei, Kosrae)

Federated States of Micronesia (Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei, Kosrae)

Federated States of Micronesia (Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei, Kosrae)

Ma'ohi Nui (French Polynesia)

Tokelau (New Zealand)

Kingdom of Tonga

Fijian Republic of Fiji

Papuan (West Papuan)

Papua New Guinea, West Papua

Palauan Republic of Palau

i-Kiribati

Tuvaluan

Ni-Vanuatu

Solomon Islander

Republic of Kiribati

Tuvalu

Vanuatu

Solomon Islands

Furthermore, COFA Islanders’ non-immigrant status allows them to enter and leave the US freely but does not guarantee them permanent residence.

Colonization is a key factor affecting the health and wellbeing of NH/PI students. For example, Marshallese communities have experienced adverse effects to their health and wellbeing due to the Castle Bravo nuclear tests conducted by the US Government. These tests have led to

intergenerational health consequences for Marshallese communities including cancer and disability that have affected long-term economic wellbeing. At least in part due to these colonial histories, NH/PI families living in Washington face significant social and economic barriers, with 58% of NH/PI students reporting receipt of free or reduced-price lunch. Some communities are especially impacted, with Tongan (74%) and Sāmoan (71%) youth accessing free and reduced lunch at especially high rates (see Figure 01).

According to the AAPI Community Data Dashboard, among NH/PI living in Washington state, “Other Pacific Islanders”, which primarily encompasses Pacific Islanders from non-US governed Island nations, and Fijians had the first and second highest percentage of being below the income threshold for Medicaid eligibility. These groups likely include large numbers of NH/PI who do not hold US citizenship nor are COFA Islanders which can limit their access to Medicaid benefits 18 19,20

Furthermore, Poverty and income inequality specifically have well-established impacts on

student academic success, attendance, and absenteeism. Chamorus (7%) and Sāmoans (9%) are also more likely to live below the 138% Medicaid eligibility federal poverty threshold compared to Native Hawaiians (5%) in Washington state. 21

Socioeconomic challenges affect NH/PI students' ability to meet school attendance standards and academic success This socioeconomic context is critical to understanding the ensuing data on academic achievement and well-being as these students may need to prioritize attaining basic needs.

There are between 1,400 and 1,500 Indigenous languages in Oceania that compose nearly 21% of the languages spoken globally. In Washington’s public schools, OSPI data indicate that over 5,000 youth are identified as multilingual learners as of 2023. More than simply a means of communicating, language is a critical component to maintaining Indigenous knowledge systems and original instructions – cultural protocols, ways of being, and practices – that facilitate overall Indigenous wellbeing . 22 23

Historically, the use of Pacific languages in schools across Oceania has been limited, regulated, or banned Limiting and preventing the transference and practice of

these Indigenous languages in schools has commonly been used as a tool of assimilation and a form of anti-Indigenous racism that negatively impacts the health and wellbeing of Indigenous communities and youth. From this perspective, Pacific languages are a form of cultural engagement and expression that can facilitate positive educational outcomes and wellbeing. 24,25

For NH/PI living in diaspora – away from their Indigenous homelands – finding resources for Indigenous language learning can be challenging. Social pressures to learn English and to assimilate to ways of living in the continental US can create challenges for NH/PI students in Washington to learn their Indigenous languages

In our qualitative data, a student describes this dilemma when asked what opportunities they would like to see at their school:

“For me personally, would be the ability to be able to talk, speak and learn and know Tongan Because I'm only second generation American but having first generation American parents means they got to, they had to sacrifice you know Tongan or English and obviously to get a career here you need to learn English

Interview data demonstrated that programs providing language acquisition and integrate curriculum motivated positive educational outcomes for NH/PI youth, including a greater sense of belonging and increased school participation. An educator shared:

“They feel like that's [the cultural program at school] their home. You know, like I said, they don't want to miss. And many families now want to move to the area so they can enroll their student there. Because of course students talk to each other! We have a program with dance, but we still learn about history. We still learn about social studies, they teach us math in our language...they use their techniques to teach our math which make us more understand.”

In addition to cultural engagement for students, language provides a path to parent engagement in their childrens’

education. During interviews, one educator shared, with respect to parents whose native language is not English:

“That's a big disconnection, when it's come to talk about school. Parents cannot even say, hey, how was school today? Do you need me to sign any paper? Or maybe they're signing something that they don't understand because, it's not in their language.”

Language services are essential and have the potential to address the challenges with family engagement that arise for many teachers who serve NH/PI students. One educator shared:

“We have a Marshallese program in the school that teach our language and teach our culture. They see their student more respecting them. You know other people. Rather than, you know in the past.”

Language navigation services in NH/PI languages are essential for facilitating family engagement and assisting educators in meeting the needs of students and their families Schools and districts should assess administrative data to identify language needs, and share resources for languages that are spoken by a smaller number of families.

NH/PI youth are shaped not just by a single Pasifika identity, but by a complex and interconnected set of social and political identities These interwoven identities –socioeconomic status, race, sexual orientation, gender etc. – create unique experiences of oppression by systems and structures of power that impact NH/PI youth educational wellbeing, their sense of belonging, and how they are perceived by others. Our study acknowledges how NH/PI students must navigate multiple systems of oppression within school systems and their everyday lives. 24,26–30

During the 2023-24 school year, the most common request from parents to the Washington State Governor’s Office of the Education Ombuds (OEO) was for assistance related to special education, inclusion, and equitable access. NH/PI families were no different, with the highest proportion (60%) of requests to OEO involving special education In addition to the inherent challenges in navigating these systems and supporting youth with disabilities families often face communication barriers, stigma within the NH/PI community surrounding disability diagnoses, and harmful stereotypes from educators and other school professionals These factors can lead to overdiagnosis of behavioral issues and underdiagnosis of learning problems.

There are limited models for care provision for NH/PI with disabilities that exist in the US. Historically, NH/PI peoples embraced their family members and communities who had disabilities Through the introduction of Western disease and moral disability frameworks, how NH/PI communities value and view their community members with disabilities has shifted. In Aotearoa (New Zealand), community-based frameworks for addressing structural inequity experienced by Pasifika peoples with disabilities have been developed through Whaikaha, the Ministry of Disabled People. The Atoatoali’o framework draws from the Sāmoan word atoatoa and li‘o, meaning to fit/sit perfectly in a circle This framework aims to generate systems of care for Pasifika peoples with disabilities through the values of alofa, fa‘aaloalo, tautua, and va fealoa‘i – values of love and compassion, respect, service, and relationality. Through centering Sāmoan practices, these collective practices are important values and underpin the ways in which many Pasifika cultures provide care for all their community members. 31–33 31–33

34

Within the OSPI system, NH/PI youth receive services for documented disabilities at generally similar, if perhaps slightly lower, rates to the overall student population. For example, 5.5% of all OSPI students receive services for specific learning disability, compared to 5.0% of NH/PI students. Similarly, 2 4% of all students receive services for autism spectrum disorders, compared with 1.5% of NH/PI. In contrast, NH/PI students were less likely to be diagnosed with health impairments (3.6% vs. 1.2%).

PERCENTAGES CALCULATED BASED ON N=16,821 NH/PI STUDENTS AND N=1,156,481 TOTAL STUDENTS.

In the 2023 Healthy Youth Survey, approximately 2 in 5 (40%) NH/PI students reported having a disability or chronic health condition – higher than some groups in the 2023 Healthy Youth Survey Rates for other major racial or ethnic groups ranged from 30% among Asian or Asian American (As/AsAm) to 53% among AI/AN. This includes 19% of NH/PI students with a developmental or intellectual disability, and 10% with a learning disability.

NH/PI educators and paraeducators are often the individuals who take on the responsibility of supporting families and

encouraging them to access these services. As one NH/PI educator noted during interviews:

“I think of the families and I think of the parents wanting the supports for their students and how they advocate for that and what they need for that, and oftentimes – I am the one as a teacher – I'm their point person. I provide that information and walk them through the system, in getting the supports for their students.”

Educators who have strong bonds and trust with NH/PI families, particularly those who are also NH/PI or who are close allies to their

communities, help students to gain access to disability resources. As one NH/PI paraeducator noted, “it's often not broadcasted about what you can do to be a part of those programs and how to get the resources for people to come to your homes and help with self-care at home.”

Disability accommodation services aren't usually well-advertised, and families may find it challenging to access and participate in them if they do not have people within their communities supporting them in navigating these systems. NH/PI educators are also critical for helping students get enrolled in special education or ensuring that students aren't incorrectly put in special education. Our Community Advisory Board members who work closely with families of youth with disabilities shared the importance of reducing stigma by adopting a strengths-based approach in schools. Addressing this stigma is likely to lead to more engagement in needed services.

Racial identity is layered and complex. Identifying as multiracial extends beyond family lineage and is further complicated by aspects such as lived family experience, culture, ethnicity, physical appearance, selfregard, and public perception For example, a student may identify privately as Hawaiian and Chinese, but introduce themselves as a Hawaiian student. These chosen and stated identities may differ from how students are perceived, and change across contexts. Multiracial NH/PI students are also impacted by intersectional systems of systemic racism and settler colonialism, where the politics of blood quantum have historically been used to disidentify or discount NH/PI claims to belonging to their Indigenous communities and cultures.36,37

Approach disability from a strengthsbased perspective and explicitly consider the role of stigma among communities of color

RECOMMENDATION1.3:

When assessing disability and crafting individualized education plans, professionals should work against biases that may lead to overdiagnosis of behavioral problems and underdiagnosis of learning challenges

School psychologists and other service providers who work with communities f color should examine their practices r bias using self-assessment tools

Nearly half (43%) of NH/PI living in Washington identify as multiracial (see Figure 1) This is the second-largest multiracial group by proportion after AI/AN. Notably, both groups share a history of settler colonialism on their Indigenous homelands, often resulting in displacement and migration –factors that likely contribute to their multiracial heritage.

FIGURE 02: PERCENTAGE OF RACIAL GROUPS IDENTIFYING AS MULTIRACIAL IN WASHINGTON, US CENSUS DATA

38

While there are threads of commonality across multiracial experiences, multiracial identity is multi-layered and fluid, with multiracial individuals identifying differently across the lifespan Experiences are often varied and encompass alienation, impostor syndrome, a connection to multiple communities, and in some situations, privilege relative to monoracial peers. NH/PI student experiences of social exclusion –alienation and impostor syndrome – are rooted in settler colonial ideologies that have historically undergirded policies and social practices used to restrict NH/PI people’s ability to make claims to their Indigenous homelands, resources, and peoples.

36

The consequences of multiracial identity for NH/PI youth may depend on where youth live relative to their native lands. In Washington, these youth grow up, at least in part, away from their native lands, and this disconnection can have a strong impact on their sense of self and belonging. During our interviews, NH/PI youth share a range of responses from strengths to hardships that reflect the complexities of identity in the context of colonization, assimilation, racism, and acculturation. Students reflected on both the strengths and challenges associated with identifying as multiracial NH/PI.

I have my fair share of both because I get a lot from just one person, like my grandma, because she's full Filipina and she likes talking about the Philippines and she's talking about her culture and what they do. And when it comes to my Chamoru side. Every time there's a party it’s all Chamoru people...they have bonds between them that I see more culturally than other people at my school.

39

Navigating multiracial identity entails not only how NH/PI youth identify and feel internally about their racial and ethnic identities, but also the external social experience of how others perceive and treat them Navigating multiple racial stereotypes can be a challenge for multiracial youth:

For me, I feel like I've experienced, like kind of both stereotypes like. I don't, I guess, like my teachers kind of thinking that I’m good at math. I don't know. Like, the Asian stereotype that, like Asians are better at math. And, for like my Sāmoan side, a lot of like my teachers, they just kind of joke that ‘cause Sāmoans are like big and like strong, and scary, I guess. I don’t know.

Pasifika peoples have always had genders and intimacies that existed outside of cisheternormativity – the normalizing structures that privilege cis-binary gender and heterosexuality. Before colonization by Western nations, NH/PI peoples across Oceania had societies, cultures, and communities that embraced genders that embodied peoples’ journey beyond masculinity and femininity, including Fa‘afafine, Gela’, Mamflorita, Māhū, Kakol, Vakasalewalewa, Fakaleiti, and many more. These third gender roles encompass broader conceptions of third-gender or gender-fluid identities that do not map clearly onto Western conceptions of gender Western terms such as LGBTQIA+, Queer, and Transgender do not fully represent the roles and identities described by the aforementioned traditional Pasifika language terms. In Washington state and increasingly

across the US, these communities have adopted the term Queer and Transgender Pacific Islanders (QTPI, pronounced cutiepie). Like the term MVPFAFF+ (Māhū, Vakasalewalewa, Palopa, Fa‘afafine, Akava'ine, Fakafifine, Fakaleiti) used by Pasifika communities in New Zealand and Oceania, the QTPI label seeks to embody the complexity of identity and culture that exists within the Pasifika context of gender identity.

Having cultural spaces, communities, and families all contribute to the wellbeing of QTPI across their life course. This connectedness helps QTPI to address disruptions to their cultural belonging and histories that occurred through the introduction of settler colonialism Providing care for QTPI within schools, their communities, and families that holistically supports and affirms them in the totality of their NH/PI, Queer/Transgender identities is essential to their academic success and overall wellbeing. 40,41

In the current study, QTPI, NH/PI, and nonNH/PI educators all shared how they continue to resist systemic oppression and settler colonialism by providing culturally specific spaces for QTPI youth that perpetuate care and love. In one interview, a QTPI educator reflected on the impact their cultural group has had on their QTPI students and noted they have “seen multiple students who come to us very shy and timid, and it only takes them a few weeks to a month and they are fully blossoming in their identities at school and comfortable with who they are.”

QTPI students expressed great pride in being Pacific Islander and understood their role within our communities as storytellers, healers, and often the ones who preserve our cultures in the face of colonialism. One student reflected “to be honest, the main thing about me being queer and Pacific Islander together. You know, QTPI, is that knowing that I had this long line of ancestors who are also part of the same experience.”

They spoke to the strength and resilience of our people, with the hope of pursuing lives that mirror these attributes passed down from our ancestors. Joy and laughter characterized conversations with these students; a direct reflection of the kinship they shared with one another. These sentiments were supported by an interview with an educator that described one of their QTPI students as a light that everyone gravitated towards and was beloved by their peers They explain that throughout the student’s transition “the school and the community were able to really support and embrace the student, and like the student spoke at graduation and was like the President of our PI club for like multiple years, so felt, I think really seen.”

Along with multiracial youth and youth with disabilities, QTPI are sacred members of NH/PI communities, and their resilience is in direct connection with the preservation of NH/PI cultures and peoples. It is important to acknowledge these aspects of our interviews that depict joy and strength, especially considering the challenges that are presented within our data for youth with intersecting marginalized identities

Through the Pasifika (a term often used in the NH/PI diaspora) Indigenous lens, wellness cannot exist without balance between spirit, body, and mind NH/PI students can thrive when their holistic wellness is supported and in balance The Indigenous Connectedness framework offers a culturally grounded way of understanding health in Indigenous communities. It emphasizes that strong connections to family, community, land, ancestors, and spirit are central to wellbeing. When these connections are disrupted, health challenges can arise. This perspective highlights the importance of supporting relationships across generations and with the environment as key to promoting wellness, especially among Indigenous youth. This model also presents pathways through which systemic racism, colonial oppression, and climate change

adversely impact the health and wellbeing of Indigenous communities and children.24,42

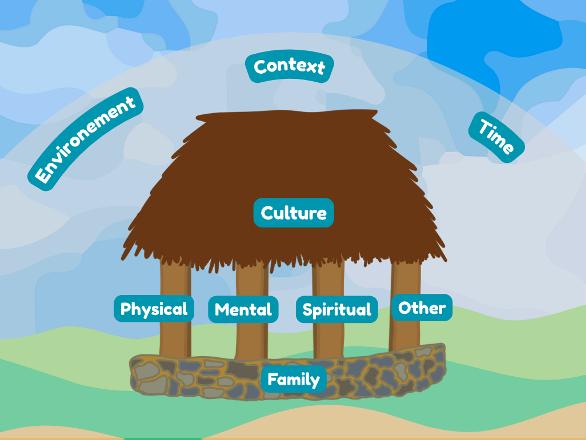

The Fonofale model for health also highlights the importance of connectedness in the health and wellbeing of NH/PI communities. The Fonofale uses a fale (traditional Sāmoan house) as a metaphor for NH/PI health where family is at the foundation (fa‘avae), the most important component for NH/PI health. There are four posts (pou) that rise from that family foundation. These represent the spiritual, physical, mental, and other components of Pasifika health. At the top is the roof (falealuga) that represents culture, values, and beliefs with the understanding that these are evolving with our people and comprised of both traditional perspectives and modern or alternate cultural adaptations. Around the entire fale is the cocoon in which time, environment, and context are all recognized as important components of health.43

Both the value of family and the tensions between school responsibilities and family responsibilities are demonstrated by the following quote from a student:

“For example, I'm culturally bound…to take care of my elders and my own family members…I used to live with my grandmother recently to take care of her mostly. But living with her, just me and her that really took away a lot of opportunities for me, and you know I don't want it to sound like a bad thing, because at the end of the day I will forever be grateful to have been able to live with her and take care of her because she's taught me many things about my culture, and I'm grateful for that...It was my own grandmother, and it was also part of the culture. You know, the Fa‘a Sāmoa way. Take care of your own. Take care of your grandmother, you know they brought you here, so help them, you know. Help them where they are.”

In our study we’ve found that for students, family is at the center of their educational wellbeing and success. For example, when asked about systems of support within education and wellbeing one student reflected how their parents were important to achieving their roles and dreams: “they've always instilled that mindset in me. Like if I can dream it, then I can do it. That's just what kept me going.”

These two frameworks highlight the role of relationality – the idea that individuals exist within a network of reciprocal connections to one another, to the land, and to their ancestors – in the school setting Healthy relationships between students and their teachers, their peers, the classroom, the curriculum and the overall education setting all have notable impacts on student wellbeing and academic engagement. In Aotearoa (New Zealand), educational scholars have noted the importance of these relationships for NH/PI students' wellbeing, particularly how they see their worldviews reflected in their relationships with these individuals, systems, and environments.

One educator shared:

24

44

“I…often wonder if we lived in a culture that was maybe more aligned to…the collectivistic culture of…Pacific Islanders…in which like making more money or working harder to make more money is not the end goal, but it's the other things…like how are you in community with each other and with yourself…and what are the ways in which we need to think about our planet and like non-human parts of like how we interact with the world? I wonder if we were in a place like that with more of the aligned values…how our Pacific Islander students and families would show up differently, and what success would look like that would be different.“

Educators who serve Indigenous and NH/PI youth should receive cultural competencytraining on the importance of relational wellbeing Utilizing models such as the Indigenous Connectedness framework in an educational setting can help students create and maintain bonds to school, self, and culture

In this report, we emphasize the unique strengths and challenges that NH/PI youth experience, and we present recommendations on addressing these challenges informed by the data and crafted in collaboration with our Community Advisory Board. Whereas the

individual-oriented measures of success collected by the education system, data from our interviews and qualitative focus groups place a complementary spotlight on the relational and interconnected approach our communities bring to supporting thriving, happy, and successful youth.

REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION FROM PACIFIC ISLANDER COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION (PICA) OF WASHINGTON COMMUNITY DATA REPORT

The aggregation of NH/PI into the umbrella category “Asian American and Pacific Islander” (AAPI) has historically perpetuated educational and wellbeing disparities for NH/ PI students by masking the unique experiences of by NH/PI youth. In some cases, coalitions formed around “AAPI” identity can lead to greater numbers, power, and representation when advocating for a common cause However, when these interests diverge, the erasure of NH/PI

community needs can have dire consequences for NH/PI communities. To take a concrete example, characterizing the language needs of “AAPI” families might seem like a straightforward task. However, according to 2023 Healthy Youth Survey data, [SGC1] the language needs of As/AsAm students and NH/PI students differ with 36% of As/AsAm students speaking a language other than English at home, compared to 21% of NH/PI

Data aggregation can conflate NH/PI individual experiences of educational stereotypes with numerically dominant groups like East Asians. For example, the “model minority myth” often used to describe “AAPI” populations overlooks the distinct stereotypes that NH/PI face that characterize them as academically underachieving or disruptive.5,45,46

Thus, data aggregation can mask these experiences of prejudice and racism that strongly impact a student’s belonging, selfworth, and identity. Conflating NH/PI and As/ AsAm experiences under “AAPI” can impede NH/PI students’ access to safety, resources, wellbeing, and achievement within the Washington K-12 educational system.

Disaggregate NH/PI from As/AsAm data whenever possible

FIGURE 06: PERCENTAGE OF HYS PARTICIPANTS SPEAKING LANGUAGES OTHER THAN ENGLISH AT HOME, DISAGGREGATED TO PARTICULAR NH/PI COMMUNITIES Chamorro Marshallese NativeHawaiian Sāmoan Tongan

Furthermore, aggregation of NH/PI communities into a singular racial category also fails to capture the heterogeneity of experiences among specific NH/PI communities, contributing to their erasure and disparities. Further disaggregation of data can help identify and address the distinct needs of specific communities. For example, as many as 82% of Marshallese students speak a language other than English at home, compared to 30% of Sāmoan students and 36% of Tongan students In this example, these data point

toward prioritization of language services for Marshallese students and families.

Educational data on NH/PI should be presented in a maximallydisaggregated formatdowntothe level ofparticularethnic communities (eg,Tongan,Yapese, Kosraean) wheneverpossible

Prior to the Office of Management and Budget’s Directive 15 to disaggregate As/AsAm and NH/PI groups in 1997, data on NH/PI across the US was obscured by a combined “AAPI” category Directive 15 led to NH/PI data disaggregation at the federal level (e.g., in the Census) and by state-managed data systems in many states including Washington. More recently, Directive 15 has been updated in 2024 to push further disaggregation of NH&PI data, as the directive requires the collection of detailed race and ethnicity data (e.g., Sāmoan, Tahitian) when feasible.

49(p15)

At the state level, the Washington education system has been at the forefront of data disaggregation movements, and continued advocacy by communities has led to the adoption of additional data collection beyond the federally required minimum. In 2009-10, the Washington Office of the Superintendent for Public Instruction (OSPI) implemented a two-question format to first present the six federal categories, and, based on those responses, subsequently report the detailed categories. These response options were further expanded in 2016.

A lack of representation in data and in the discourse around race and ethnicity can lead to NH/PI students feeling “erased” and disconnected from their school communities. During the day-to-day life of youth in Washington schools, it can feel alienating and disconcerting to be prototyped as similar to As/AsAm students. When asked about

As/AsAm and NH/PI wellbeing, one administrator shared:

“I think one thing right off the top of my head is that battle of the model minority myth. I think that there's still a perception that our AA and NHPI students are seen in that lens.”

This statement clearly reflects the conflation that can happen when educators have mental models that automatically group As/AsAm and NH/PI students together As a result, NH/PI students’ needs and desires to learn about their histories, cultures, and experiences and to see themselves reflected in curriculum can go unmet (See Section 6).

Adding to the complexity of understanding NH/PI youth experiences, the islands, territories, and countries encompassed by the NH/PI label also exhibit highly distinct cultures, histories, and citizenship statuses with respect to the US.

NH/PI data aggregation can erase the heterogeneous experiences of students who are represented by the NH/PI racial category. NH/PI students differ across different dimensions such as history or context of entry to the US, citizenship status and Indigeneity which are not adequately captured by a single aggregated category of NH/PI. This report seeks to address this gap by disaggregating as much as possible. Each NH/PI community faces unique facilitators, barriers, and issues in their youth’s education , and high-quality disaggregated data can aid efforts to support these underserved communities.

NH/PI youth benefit when all parts of their multiracial identity are nurtured and valued. This necessitates a deeper understanding of multiracial NH/PI youth narratives and interwoven identities that transcend the racial binary of Black/White, contradict the conflation of NH/PI and As/ AsAm communities, and that are rooted in Indigenous understanding of identity where all parts of an individual’s genealogy are important to honoring their responsibilities and roles to their communities and cultures. Promoting pluralistic views of society among parents and educators can foster an environment conducive to identity development and sense of belonging Moreover, institutionalizing a culturally responsive school environment that incorporates a wide range of diverse perspectives from multiple ethnicities and cultures, inclusive of NH/PI cultures and worldviews, can create space for multiracial NH/PI youth to navigate complex experiences related to belonging, self-esteem, and assimilation 50 51,52

From a policy perspective, it is critical to develop guidance on multiracial youth when it comes to understanding educational strengths, barriers, and disparities. Current guidance from the US Office of Management and Budget includes a category for those endorsing two or more races from the set of seven federal categories (AI/AN, Asian, Black or

African American, Hispanic or Latino, Middle Eastern or North African, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and White). This “two or more” category is often analyzed as its own coequal category However, analyzing multiracial individuals’ data separately from their constituent identities leads to exclusion from their own communities’ data. For small groups like NH/PI, many of whom identify as multiracial, this can exclude a major portion of communities from priority-setting and decision-making. We propose that “doublecounting” (e g , a student who identifies as NH/PI and Black could be included in both groups’ data) can allow multiracial individuals to contribute to the multiple communities they are a part of, and their Indigenous understanding of how these identities impact their experiences.

“Double count”multiracialyouth in educational data sotheyare notex fromtheircommunities’data Deve guidance,with communityinput, on growing numberofmultiracialyouth should be represented inthe statewide discourse on academic achievementand opportunitygaps

There is a notable movement by Pasifika communities to collect their own data and to be closely involved in the ownership,

of data on their own communities. This movement has been referred to as “data sovereignty” and allows communities to share their own rigorously collected data to advocate for their own needs PICA’s 2024 Community Data Report is a transformative, thorough, and carefully crafted example of these efforts, and highlights the needs of the Washington Pasifika community. In our own experience working with our Community Advisory Board to craft the current report, we found input from our Community Advisory Board to be critical in directing our resources toward asking the most relevant questions. In addition, working with communities is necessary to interpret quantitative and qualitative data with the necessary state, local, and

Findwaysto include small groups in published data, even ifitmeans combining with othergroups Ifdata needto be suppressed orcombined, communities whose datafall intothese categories should be namedwheneverdata are reported When data are hardtofind dueto small numbers orchallenges in data collection, workdirectlywith communities (including providingfunding, ifpossible)to understand communityneeds and priorities

community context to ensure accuracy and rigor We encourage readers to explore the report further, and state, county, and local data agencies and decision makers to work with NH/PI communities to develop data systems that reflect the experiences of NH/PI communities.

K-12 academic achievement data show substantial and alarming disparities in educational outcomes for NH/PI youth that have not closed since the 2008 report. Whereas data

on standardized test scores appear to reflect widening disparities across the intervening years, data on graduation rates may provide some evidence of progress. Disaggregated data reflect variability in outcomes, with particular challenges for COFA youth

We intentionally refrain from offering

FIGURE 07: PERCENT MEETING STATEWIDE STANDARDS IN HIGH SCHOOL (10 OR 11 GRADE, DEPENDING ON SUBJECT) TH TH

recommendations in this section, as the figures presented provide a snapshot of student achievement, but do not directly

indicate specific solutions. Although shifts over time in statewide standardized testing make it difficult to compare examination

DATA PROVIDED BY OSPI. BLANK BARS INDICATE TOO FEW DATA POINTS WERE AVAILABLE TO REPORT DATA IN ACCORDANCE WITH DATA SHARING AGREEMENTS

passing rates across years, NH/PI students demonstrated poorer performance across English and Language Arts (ELA), Math, and Science – proficiency rates of 29 6% in ELA, 7 3% in Math, and 19 3% in Science – than in 2008 data. In 2008, 73.6% of NH/PI students

met proficiency in Reading and 80.1% in Writing; 30.3% in Math; and 20.1% in Science. Notably, disaggregated data were difficult to obtain for smaller NH/PI groups, including Chuukese, Fijian, Tongan, and other COFA Islanders. Grade point average (GPA)

data were also alarmingly low, with medians ranging from 1.0 to 2.7 (out of 4.0), depending on the NH/PI community.

Between 2010 and 2024, approximately 3 in 4 NH/PI students (73%) enrolled in OSPI

FIGURE 09: ON-TIME HIGH SCHOOL GRADUATION

high schools graduated within 4 years.

When disaggregating data to specific NH/PI communities, the graduation rate was highest for Melanesian, Native Hawaiian, Chamorro, and Sāmoan students, and lowest for Micronesian (Chuukese, Kosraean, Marshallese, Palauan, and Yapese) groups, who also were included in the Other NH/PI (combined) group for data privacy reasons.

DATA PROVIDED BY OSPI.

The 2008 Achievement Gap report demonstrated that NH/PI students’ trajectories after high school often do not meet the goals and dreams that they and their families hold. Data from the 2008 Beyond High School study cited by the report revealed that NH/PI youth were less likely to plan to attend college and less likely to attend college (both 2-year and 4-year) than their peers. Academic goals and dreams beyond high school remain an important and complex theme for NH/PI students.

In interviews, educators acknowledged (and at times perpetuated) the stereotypes and lack of representation that students often work against:

“…Having agency to direct the opportunity and the pathways for their lives. We don't have that…‘These people, they don't value education.’…Shoot, there are even scientists claiming that we don't have the propensity for education…ethnic studies is about revealing the realities to the students and giving them the agency to deal with them … leveraging their identity in the classroom.”

Although they hoped their students would find success in high school and beyond, they acknowledged that there need to be “more creative, more flexible ways that students can earn a diploma” because current academic standards were not always tied to students’ goals and interests.

For their part, students shared varied perspectives on their own hopes and dreams that were broader than completing high school or attending college. A student shared “I wanna pursue my dream Cause like, lately I’ve been wanting to be a teacher, so I was like, I’ve never seen a Marshallese teacher…It influences me because like I could start something.” Another student shared the importance of continuing cultural traditions and serving others: “I always hear stories like, ‘Oh, you know, fa‘afafines back then, we really took on like roles of caretakers, teachers, people who, you know, healers ’ Hearing that it really makes me feel like I should lead a life of the same path, or at least similar.”

Rather than sharing hopes for college degrees, grades, or salaries, NH/PI youth and educators focused on familial and community responsibility, impact, and representation Even so, postsecondary degree attainment can facilitate these dreams and be a step along the path toward their achievement. Some students shared this sentiment, for example:

"I'm surprised only one person that I know has went to college IfeellikeI needtodothisformyfamilyand makemoneyformyfamilyby education.”

With these caveats in mind, we report data in this section on college enrollment, completion, and postgraduate wages in the following section. We acknowledge these outcomes likely reflect only a small part of a broader definition of achievement, and present recommendations in other sections of this report to address existing disparities.

Fourteen percent of NH/PI graduates between 2013 and 2019 from Washington’s K12 public schools went on to complete a 2year degree and 21% went on to complete a 4-year degree on time. Melanesian and Native Hawaiian graduates were most

likely to complete postsecondary degrees

Though a direct comparison with data from previous reports was not possible, these estimates compare favorably to the previously reported overall population rates of achieving a 4-year degree in WA state in 2006-08 for NH/PI adults. Only 8% of Chamorro adults in WA had a 4-year degree in 2006-08; however, 20% of Chamorro OSPI graduates completed a 4-year degree The same is true for Native Hawaiians (27% of OSPI graduates vs. 14% of adults) and Sāmoans (15% of OSPI graduates vs. 3% of adults). Disaggregated data were not available for other NH/PI ethnic groups in 2008. Overall, these 4-year degree completion rates potentially indicate progress toward higher education among NH/PI Washingtonians.

DATA PROVIDED BY OSPI. FOR 2-YEAR DEGREE COMPLETION, 2013 TO 2019 DATA WERE USED TO ALLOW STUDENTS 18 MONTHS TO ENROLL AND 3 YEARS (1 5 TIMES THE PLANNED PROGRAM LENGTH) TO GRADUATE FOR 4-YEAR DEGREE COMPLETION, 2013 TO 2016 DATA WERE USED TO ALLOW STUDENTS 18 MONTHS TO ENROLL AND 6 YEARS TO GRADUATE

AND

MarianaIslander Micronesian NativeHawaiian Sāmoan Tongan Melanesian OtherNH/PI(notlisted)OtherNH/PI(combined))

Students graduating from OSPI schools may enroll in degree programs, but move into the workforce before completing a degree As a consequence, enrollment data can help to flesh out the picture of postsecondary achievement among NH/PI students. Approximately 4 in 10 (39%) of NH/PI graduates from Washington’s K-12 public

schools went on to enroll in a 2-year degree program immediately after high school, and more than a quarter (28%) enrolled in a 4-year degree program The rate of 2-year degree enrollment was the lowest among the broad racial and ethnic groups, and the rate of 4-year degree enrollment for NH/PI graduates was comparable to that of AI/AN and Hispanic youth. Some variability exists in degree enrollment across NH/PI communities, with Melanesian and Native Hawaiian graduates most likely to enroll in either program.

FIGURE 13: PERCENTAGE OF OSPI GRADUATES ENROLLING IN 2-YEAR AND 4-YEAR DEGREE PROGRAMS, PRESENTED BY NH/PI COMMUNITY

A 2018 estimate from Washington State Institute for Public Policy estimated that a college degree provides, on average, $192,047 in benefits to a graduating student across their lifetime, and a total benefit of $406,473 when also accounting for benefits to taxpayers, higher education providers, and legal and healthcare systems We investigated whether the added wages of a college degree might differ by race and ethnicity with respect to salaries earned in the years immediately following degree attainment.

The value of a high school, 2-year, or 4-year degree for NH/PI graduates was comparable to the value of the same degree for youth from other racial and ethnic groups.

Whereas recent NH/PI graduates with a high school education made about $35,000 per year, those with a 2-year degree made around $39,000 per year and those with a 4year degree made around $45,000 per year. These figures varied across communities, with Chamorro 4-year graduates notably making around $52,000 per year. Tongan and Micronesian graduates had lower salaries across the range of educational attainment.

FIGURE 14: MEDIAN HIGHEST EARNING YEAR FOR OSPI GRADUATES.

$60K

POST-GRADUATION WAGES WERE ASSESSED FOR THE 2013 TO 2016 COHORTS TO ALLOW STUDENTS TO COMPLETE A DEGREE PROGRAM AND HAVE 2 OR MORE SUBSEQUENT WAGE-EARNING YEARS DATA PROVIDED BY OSPI

FIGURE 15: MEDIAN HIGHEST EARNING YEAR FOR OSPI GRADUATES, PRESENTED BY NH/PI COMMUNITY

DATA PROVIDED BY OSPI

For many NH/PI youth, wellbeing is multifaceted and relational, defined by relationships with people, land, ancestors, spirituality, and cultural identity. This worldview, expanded upon in Section 1.2, asserts that wellbeing resides as much in relationships as it does in the individual’s psychological health Western frameworks of wellness and health, in contrast, are typically focused on individuals’ struggles and ways of coping. Even so, they provide an important snapshot of wellbeing for NH/PI youth. Socio-emotional health and academic success are intimately reliant upon one another; when students feel a sense of belonging and healthy identity development, they are more likely to be successful in educational environments. The following section presents quantitative and qualitative data on NH/PI student wellbeing, along with recommendations to support and strengthen it

56 57

A common theme in our interviews was that NH/PI youth often feel as though they are not as valued and visible in the school setting as their peers. One Tongan student shared, “It just brings me back to my cousin's school. He goes to Utah, and…it's one of the most populated state of Tongans there and I know one of their schools, they had the Tongan mat on the wall decoration 'cause there's that many Tongans and just seeing that low-key almost made me cry. I'm like, ‘Wow, I wish I had that.’”

This disconnection can be viscerally felt and can negatively impact students’ investment in school. Moreover, students may desire to learn about the history or relevant social issues of their people When this curiosity isn’t rewarded, this can further widen experiences of disconnection. Another student shared how they learn are not afforded opportunities to learn about their histories, cultures, or issues at school, “For me, it'll be through my grandpa because he draws a lot… So, like I always be asking like, oh, Papa, what does this tattoo mean?...he has all these Sāmoan artifacts around his house also. So I'll also be asking on that. But my school, they don't provide like the Oceania side of history.”

“It just brings me backto my cousin's school He goes to Utah, and it's one ofthe most populated state of Tongans there and I know one of their schools, theyhadtheTongan matonthewalldecoration'cause there'sthatmanyTongansand justseeingthatlow-keyalmost mademecry.I'mlike-

‘Wow,Iwish hadthat.’”

Educators also observe how this lack of representation affects their NH/PI youth, with one educator sharing “they're not reflected in the curriculum. At all. Or celebrated in their buildings for who they are as people.”

Another educator shared:

“Our district has this goal of increasing sense of belonging But I

don'tthinksense

of belonging

cantrulyhappen whenwe don'tstartto bevery intentional aboutthe spaces thatwe are in and creating those spaces inwhich are familiarand helpfulto our students…”

alienated, one educator shared:

“Now as far as the bullying, we've still seen and witnessed a lot of cultural change that needs to happen within the staff part of things, making sure that they're educated with some of the trainings we do have at [organization] that are available to them.”

One important way to engage NH/PI students is to teach their histories and allow students to engage with their own cultures in an academic setting (See Section 6).

58–61

This educator also spoke about creating a Pacific Islander club at their school to connect students in the celebration of NH/PI cultures. These challenges to belonging are only heightened for QTPI youth who navigate an additional and complex layer of identity and belonging. Referring to QTPI being bullied and

Research has shown that affirming spaces, supportive parents, and community are protective factors for LGBTQIA+ youth mental health. Camacho et al. found colonization creates disruptions to QTPI connectedness to their cultures, communities, families, and ancestors that proliferating the exclusion and policing of QTPI belonging within their Pasifika communities Fostering connectedness through cultural values like Inágofli’e’ (care and affirmation) and alofa (love and respect) through extended kinship networks like chosen families and community care can also improve the wellbeing of QTPI youth, by nding the connectedness and cultural onging of QTPI youth within their school d local communities

ough we do not have specific data on rming spaces or parental relationshipsand pport for QTPI’s gender and sexual entation from the Healthy Youth Survey, the vor project found that nationally 56% of PI youth in their study had access to BTQIA+ affirming spaces at school, yet only % of QTPI youth had access to affirming

60

homes. Affirming community spaces were also available to 15% of QTPI.