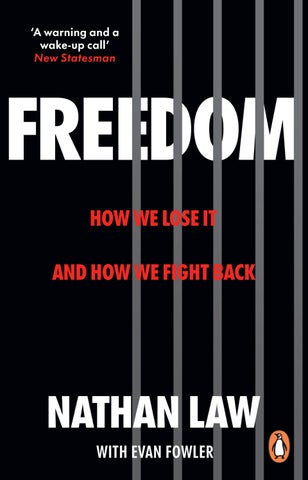

‘A warning and a wake-up call’

‘A warning and a wake-up call’

‘Nathan Law’s agonizing account of China’s ruthless takeover of Hong Kong provides a terrible insight into Beijing’s ambitions – the world needs to read this before other Pacific entities are swallowed up.’

Jon Snow

‘A heartfelt primer . . . the moderate and thoughtful Law is nothing like the radical agitator of Beijing’s imagination.’

Financial Times

‘Freedom is an essential and timely read, warning policymakers, advocates and all people of the erosion to freedom happening before our eyes and equipping us to combat this challenge.’

Speaker Nancy Pelosi

‘A nation’s slide into authoritarianism is a bit like falling asleep – it happens slowly at first, then all at once . . . Law offers a warning and a wake up call.’

New Statesman

‘The fate of Hong Kong concerns all of us, and Freedom is a timely reminder that China’s actions are a challenge to democracies everywhere.’

Kai Strittmatter, author of We Have Been Harmonised

‘Law’s book serves as a record of what his generation stood for – and what has happened to the people of Hong Kong – no matter which substitute version of history Beijing promulgates . . . He reminds readers that every generation must fight for and earn its freedom and democracy.’

Foreign Policy

How we lose it and how we fight back

How we lose it and how we fight back

HOW WE LOSE IT AND HOW WE FIGHT BACK

HOW WE LOSE IT AND HOW WE FIGHT BACK

Nathan Law

Nathan Law with Evan Fowler

with Evan Fowler

Penguin Random House, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW www.penguin.co.uk

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Bantam Press an imprint of Transworld Publishers Penguin paperback edition published 2024

Copyright © Kwun Chung Law 2021

Nathan Law has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

isbn

9781804994863

Typeset in 11.04/15.87 pt Minion Pro by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes. Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d02 yh68.

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

This book is dedicated to all Hongkongers who have marched in the streets to fight for our freedoms. Their sacrifices, especially those of my friends who have been imprisoned in their pursuit of democracy, should not be forgotten.

My phone buzzed in my pocket. Since leaving Hong Kong I try not to check my phone often, to keep my mind calm. China has declared me a dissident and a traitor, and its shadow has grown with its global ambitions and influence. It is a shadow that falls on anyone who challenges the ‘truth’ of the Chinese Communist Party, especially those who are ethnically Chinese – or are deemed so by Beijing, which claims to represent all Chinese people everywhere. It is a shadow that still blocks the light for me, even though I’m now living in the relative freedom of the United Kingdom.

The phone buzzed again. And again. The vibrating had become so constant that I could no longer ignore it. A notification showed that a journalist had tagged me in a post on Twitter (now ‘X’). Concerned, I clicked on the link. I saw my face projected on a large screen at a press conference called by the Hong Kong Police.

On 3 July 2023 the Hong Kong authorities issued a HK$1 million (approximately US$130,000) bounty for information leading to the capture of eight Hong Kong exiles now living in the UK, the USA and Australia. I was one of them.

The others were a mix of activists, lawyers and a former trade union leader. Our crime was that of speaking up for basic freedoms and rights. We had all, according to Steven Li, Chief Superintendent of the National Security Department of the Hong Kong Police, ‘committed very serious offences that endanger national security’. (The intimidation tactics would not end there. In December, five more bounties were issued on exiled activists. How thin-skinned and fragile China must be.)

My phone soon buzzed with messages of support from concerned friends. Perhaps surprisingly, I felt calm, peaceful even. In the past decade, first as the leader of my student union, then as an activist and legislator in Hong Kong, and now in exile in the UK, I had often been made the protagonist of a very particular kind of political drama that repressive regimes stage-manage so well. These events have left me with an excellent poker face when confronted with such daunting personal news.

The government has never stopped trying to hunt me down. I and other exiles receive daily harassment and are targeted by Chinese ‘patriots’. Kidnapping and assault are encouraged and facilitated by the state. We are ‘scum’, according to the Beijing-appointed Chief Executive of Hong Kong, John Lee, who said in an official statement that our ‘destiny’ is to be pursued ‘for life’.

So what does this bounty mean? It means I live in fear of being betrayed. Simply knowing my address or my routine carries a substantial financial value. This information could so easily lead to my abduction and forced ‘repatriation’. This is not paranoia: under Operation Fox Hunt, these practices

have become state policy. For me, it means I need to look over my shoulder more often than before. I am denied the kind of casual relationships which people in a free society take for granted.

It remains a distinct possibility that China could issue a socalled ‘red notice’ to Interpol, meaning I would automatically be detained during transit should I travel internationally and deported via a third country with which Hong Kong or China has an active extradition treaty. These include Spain and Portugal, who have a history of acting on Chinese requests, but also, more surprisingly, France, Italy and Belgium.

I’d already been put on wanted lists multiple times, and my peaceful advocacy work consistently framed as extreme, violent and unreasonable. These bounties represent a new level of intimidation and repression aimed at the Hongkonger community in exile. But it is our job to remember. Within Hong Kong, the peaceful protests of 2019 have been replaced with something altogether more violent. There are now thought to be over 1,700 political prisoners in the city, and the number continues to grow. A student who shared social media posts in support of the protests whilst studying in Japan was arrested on her return to Hong Kong and charged with sedition. People have been accused by the authorities of supporting me financially, as indeed you may be doing by buying this book. And yet, we are told, Hong Kong is open for business as usual.

When the news of the bounties broke, I was in Taiwan. The Taiwanese government reached out immediately to ask whether I needed police protection. They of all people could

understand the risks. This country, which the Chinese Communist Party also dreams of bringing to heel, is the closest I can get to reconnecting with my cultural roots. Despite all that Beijing does to isolate the country, to coerce and influence its people and threaten its democracy, Taiwan’s story has been one of success. Its dynamic and flourishing civil society is a beacon of tolerance, innovation and progress. Taiwan has faced up to its history, including the fifty years the country spent under a repressive dictatorship, and can today engage honestly with its past, its culture and with the world. It is a model of what China could be if it weren’t for the Communist regime, and for that reason the People’s Republic of China is determined not to recognize Taiwan’s existence.

Under President Xi, Beijing has steadily escalated military action across the Taiwan Strait, ending past practice and the status quo that had informally recognized a median line that neither side would cross. Diplomatic pressure, including the routine use of economic threats as dependency on China has grown, has been increased to isolate Taiwan from both recognition and international fora. Beijing refuses to allow Taiwan observer status at the WHO despite its success handling the pandemic, and perhaps partly because of the role it played in alerting the world to Chinese obfuscation.

China continues to conduct what many experts consider to be the most sustained and sophisticated application of cognitive warfare in history. The techniques it pioneers and tests in Taiwan, and Hong Kong, are increasingly being adapted and used globally to divide us, undermine trust in

democratic institutions and frame an understanding of world history that is defined by Beijing.

Yet for all that Beijing does, it has not stopped the people of Taiwan from embracing their distinct Taiwanese identity. Despite Chinese threats, they reject Beijing’s narrative of ‘reunification’ and hold firm in their stance that Taiwan is a de facto independent political entity – a position supported by all three of the main Taiwanese political parties today.

On 11 July 2023, a few days after the bounties were issued, I received a call from a close friend. He told me that my family were on the Hong Kong news and that their home had been raided that morning. The knock on the door came at 6 a.m., and my mother and brother were taken to the police station, where they endured hours of interrogation. The police wanted to know whether they still had any relationship with me and if they had in any way assisted me in my advocacy work.

Being an activist standing up against an authoritarian regime is a lonely experience, and one of suffering. No one chooses this path. Rather, circumstances and the experience of gross injustice lead one here. It means severing ties with family and loved ones, as it is through those we love that such regimes seek to control us. It is said that in China guilt is carried for five generations, and five generations may be targeted for punishment and retribution.

The Hong Kong authorities knew I had cut all ties with my family. The interrogation they endured was not about information, but a form of collective punishment. Unable to get

me, they knew that this would hurt me. It was a demonstration of their power and of my vulnerability.

It has been three and a half years since I last saw my family. On the day I left Hong Kong, I remember having dinner with them at home. I couldn’t even tell them that I was about to leave. It was a simple meal – steamed fish, stir-fried greens and a bowl of white rice. But as simple as they may have been, how each dish tasted is imprinted on my mind.

This book was first written in 2021. Since then, the situation in Hong Kong has only got worse. Criticism, however constructive, is seen as dissent. The families of activists and even lawyers are harassed. With a muzzled press and disbanded civil society, Hong Kong citizens today scream in silence. In 2019, a quarter of the population demonstrated peacefully on the streets for democracy, sheltering each other with a sea of umbrellas. Now, on social media, only ‘patriotic’ voices dare speak. Turnouts for sham elections are at record lows; the stock market has fallen back to a level last seen when it was handed over by Britain in 1997. And politicians celebrate the city’s newfound ‘harmony’.

I am only one of many who have sacrificed their personal liberties and future in hope of a democratic and free Hong Kong. We know all too well what it feels like to lose our home, our freedoms and with it our dignity. We also know how much Hong Kong’s loss means to the world.

The fight for democracy is long and hard. An idea can take years, and often generations, before it is realized. Through trials and tribulations we nonetheless march forward in pursuit of a dream so much of the world shares.

I hope this book will show you why Hong Kong matters, why our hopes are universal and why our fight is so important in a world increasingly challenged by a rising China. This is a book that tells my story and those of many Hong Kong citizens. It has taught us the value of freedom, and how it is always worth fighting for.

Free Hong Kong. Democracy Now.

What is freedom? And what does it mean to live in a free society? These are two of the most profound questions we can ask. They have inspired passionate debate across the globe, and across civilizations, for a very long time. In the West, the philosophical tradition of freedom is often traced to the Greeks, and to its personification in the idea of liberty or eleutheria. In China, questions of freedom were also central to the writings of Laozi, Zhuangzi, Confucius and Mencius, and manifest themselves in the ideal of the Great Unity (大同). While the ways in which we understand freedom may differ, at its core are universal questions about how we understand ourselves, and how we relate to each other. For some, it comes down to the relationship between authority and obedience. For others, freedom begins with an individual’s ability to live with dignity. But, as with all of our most profound questions, there is no simple answer.

What it means to be free and to live in freedom changes with time and circumstance. In times of distress, when we feel threatened, we may forfeit more of our freedom in the hope of finding stability and strength within a collective. But

remove that threat and our demand to live in freedom always reasserts itself. What matters is that we keep asking these questions. It is only with discussion and deliberation that we move closer to the truth as it is for our times.

Hong Kong, my home and the city that defined the person that I am today, is on the verge of becoming an authoritarian state. How did Asia’s most liberal, open and cosmopolitan city, with a thriving civic society and institutions that were once seemingly so robust, change so fundamentally? How was a flourishing and free society undermined from within? What does it mean to be free in a world increasingly shaped by the rising authoritarian power of the People’s Republic of China (PRC)?

This is not an academic book – it’s not about abstract concepts, but about how freedom is felt and lived. For that reason, it is deeply personal. It is a reflection on the ‘freedom’ that is chanted on the streets and which inspires both hope and sacrifice. The word may mean different things to each of us, and it may pull on our hearts to different degrees, but we all wish to be free. We all need to be free.

In 2017, when I was twenty-four years old, I was convicted by a Hong Kong court for having incited and participated in an unlawful assembly. Three years earlier, I had called for a protest against the Hong Kong authorities that did not have their prior approval. Though the protest was peaceful, tensions were high. The court submission states that security guards were injured during scuffles, though no one was seriously hurt. No one was hospitalized, for which I am thankful. Certainly, it was never anyone’s intention for anyone to be hurt.

It was 26 September 2014. I was on a hastily erected stage

at Civic Square, which was filling up with protestors. We had not applied for a permit for assembly because the protest had unfolded spontaneously. We also believed in our inherent right to protest. After all, we were only calling for the democratic reform we were promised under our own constitution. I called out, encouraging more people to enter the square and join us. Students, white-collar workers, activists and many others heeded the call, and as they climbed over the barriers that ringed the square, there was soon a large crowd. Spirits were high, and the scene, though chaotic, was also peaceful – we were energized, not angry.

Suddenly the lights were turned off and we were pitched into darkness. From among the assembled protestors a group of undercover police officers rushed up on to the stage. They surrounded me, grabbed my hands and declared that I was being arrested. I was pressed against the stage backdrop and could hardly move. As the police led me away through the crowds, shock soon turned to anger. Protestors sought to record what was happening with their phones. In response the police attempted to confiscate them. While police and protestors struggled, no one was intentionally assaulted by either side. Hong Kong had yet to lose its innocence.

I had broken the law. But I was also exercising freedoms of assembly and protest which are guaranteed under Hong Kong’s constitution, known as the Basic Law. The protest itself was called because we wanted a fully elected legislature returned by universal suffrage, and to be able to vote for our Chief Executive, as the head of Hong Kong’s government is called. This was the promise Beijing had made when Hong Kong was returned to Chinese sovereignty in 1997, and it is a

promise that matters to Hong Kong people. So, to put it simply, I was jailed for asking Beijing to honour its word, to respect the constitution it had agreed for Hong Kong, and to treat Hong Kong people not as subjects but as citizens.

In July 2017, one month before my imprisonment, I was disqualified from my seat in Hong Kong’s Legislative Council on orders from Beijing. That I had been elected to one of the Council’s popularly contested seats and could therefore claim, unlike the majority of pro-Beijing legislators, to have a democratic mandate, only made me more of a target. Unable to persuade people not to give me their vote, the Chinese government chose instead to change the rules.

Within a year, and despite having sworn my oath of office to the word, my oath had been declared void and I was one of six pro-democracy legislators to be removed from the Council. A strong showing in the ballot had given us the numbers to block legislation requiring a two-thirds majority – the most power possible in a system rigged to favour Beijing’s candidates. The six disqualifications happened to be exactly the number needed to swing the numbers back in Beijing’s favour.

In the context of this political turmoil, and knowing that I was being targeted, I was anxious about my sentencing. Unlike in Mainland China, where the one-party dictatorship has a long and continuing history of political persecution, Hong Kong was meant to be different. In former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s famous phrase, we were supposed to be ‘One Country, Two Systems’ – two systems not only in our economy and in our structures of government, but in the way power is exercised. This model of governance was meant to preserve not only business confidence in the city, but also the values and

way of life of a distinct and free Hong Kong community. Being sent to prison for a peaceful protest was new. It represented a worrying sign of how Hong Kong was changing.

My case, which was one of several that year, was the byproduct of a deteriorating political climate marked by Beijing’s increasing intervention in Hong Kong affairs, which had been steadily building over the past decade. Investment in Hong Kong had become leverage for economic control; and economic interest, coupled with political oversight, had increasingly corrupted Hong Kong’s political and business elite. Most insidious was an attempt to reshape Hong Kong society to the values and narratives promoted by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). That there was pushback from the people was not a surprise. That the Hong Kong authorities had now resorted to repressing their critics was shocking. A new chapter for Hong Kong had begun, and for activists like me jail became inevitable.

Sitting in the dock and listening to my verdict being read, I remember taking a deep breath to steady myself. It was surreal to be in this position – no matter how much you try to mentally prepare yourself, it’s always hard to accept that you are going to be separated from your loved ones. I looked at my mother, who was in attendance at court alongside my friends. I saw her weeping.

My parents had divorced several years ago. While I regret that it had to be this way, I carry no resentment. I am particularly close to my mother. It was she who sheltered me, cared for me and raised me. To see that I, her youngest son, had become a cause of worry for her deeply affected me. I had only ever wanted her to be happy. Now I was the troublemaker

sitting in the dock. As I faced jail that day, my mother, who in her heart knew that what I was doing was right, nevertheless faced her own form of penance. She continued to weep as the judge announced my eight-month sentence.

I told myself that such trials and tribulations were to be expected and vowed not to let it faze me. If I could get through these tests with a calm and open mind, and hold by my conscience, then I might have the right to call myself a true political activist. I did my best to remain positive about having to go to jail. However, prepared as I was for the verdict, I was nevertheless deeply affected when I heard the judgment read out in court.

Looking back, what shocked me most was the realization that laws which were supposed to enshrine our rights could, in the wrong hands, so easily turn into a tool of oppression. It made me question my faith that the legal system was there to protect the powerless. I had expected our right of assembly, my good character and the fact that I had no previous record to be weighed against what seemed to me a minor crime – one which essentially amounted to shouting encouragement to strangers. To jail me seemed disproportionate. But the government, it was now clear, was sending a signal.

The use of the law to serve the political agenda of autocracy, to suppress a peaceful protest that simply asked for government to be accountable to the people, left me horrified. This was not how it was supposed to be in Hong Kong, and the public took to the streets to make their feelings known. On 16 June 2019, 2 million people marched in protest in Hong Kong in support of freedom and the democratic movement. That’s a quarter of the population. Many waited