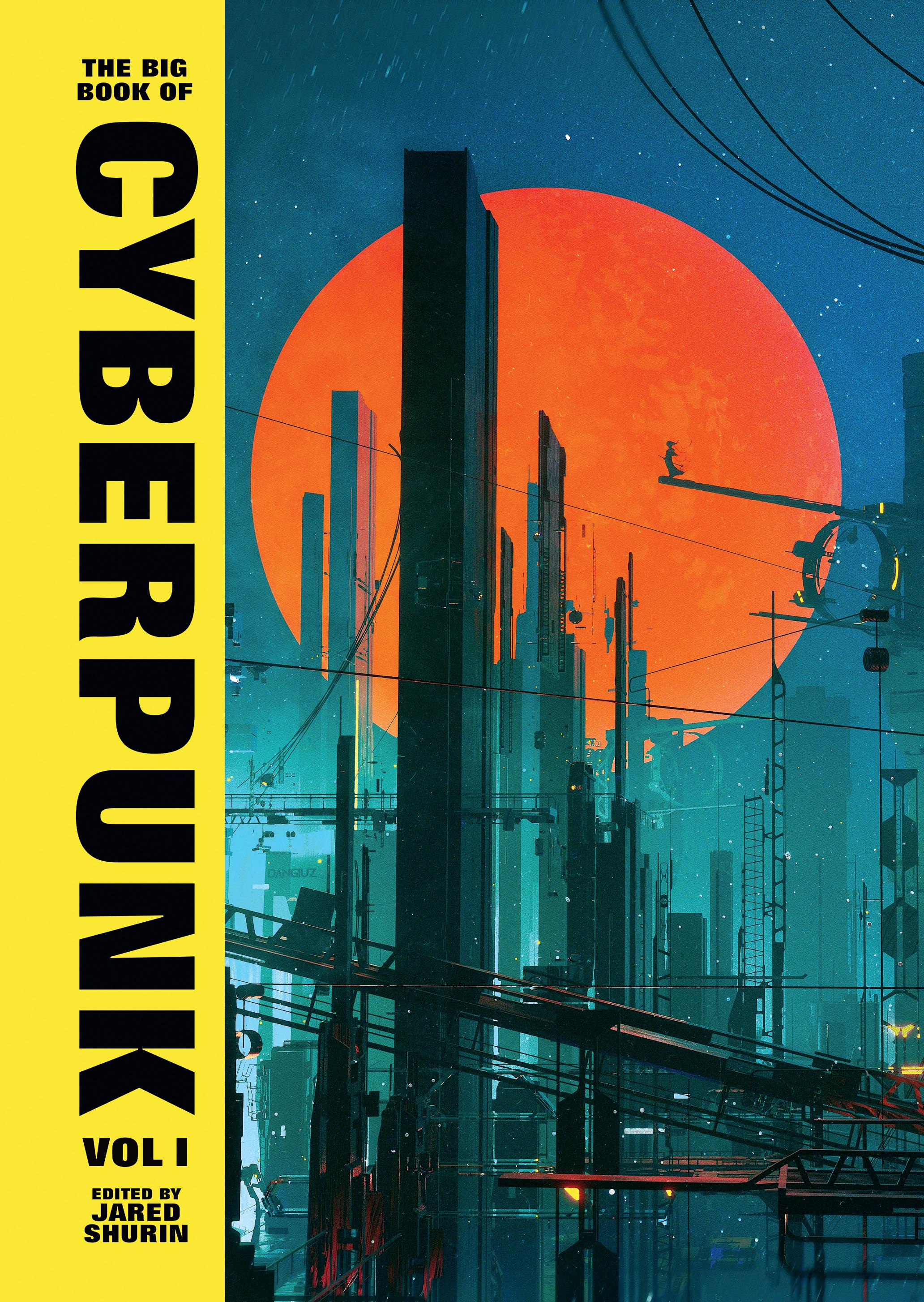

The Big Book of Cyberpunk

Volume One

Vintage Classics is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Introduction and selection copyright © Jared Shurin 2023

The authors have asserted their right to be identified as the authors of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Pages 719–723 should be seen as an extension to this copyright page.

First published in Great Britain by Vintage Classics in 2024

First published in The United States by Vintage Books in 2023

penguin.co.uk/vintage-classics

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781784879297

Typeset in 10/12pt Ehrhardt MT Pro by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D0 2 YH 68

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Editor’s Note xiii Introduction to volume 1 xv The Gernsback Continuum William Gibson 1 SELF 9 The Girl Who Was Plugged In James Tiptree Jr. 13 Pretty Boy Crossover Pat Cadigan 41 Wolves of the Plateau John Shirley 49 An Old-Fashioned Story Phillip Mann 61 The World as We Know It George Alec Effinger 71 Red Sonja and Lessingham in Dreamland Gwyneth Jones 93 Lobsters Charles Stross 105

CONTENTS

viii Con TE n TS Surfing the Khumbu Richard Kadrey 129 Memories of Moments, Bright as Falling Stars Cat Rambo 133 The Girl Hero’s Mirror Says He’s Not the One Justina Robson 145 The Completely Rechargeable Man Karen Heuler 155 File: The Death of Designer D. Christian Kirtchev 163 Better Than Jean Rabe 167 Ghost Codes of Sparkletown (New Mix) Jeff noon 179 Choosing Faces Lavie Tidhar 189 I Tell Thee All, I Can No More Sunny Moraine 203 Four Tons Too Late K. C. Alexander 209 Patterns of a Murmuration, in Billions of Data Points neon Yang 221 RealLife 3.0 Jean-Marc Ligny 231 wysiomg Alvaro Zinos-Amaro 239 The Infinite Eye J. P. Smythe 245 The Real You™ Molly Tanzer 255 A Life of Its Own Aleš Kot 263 Helicopter Story Isabel Fall 273 Lena qntm 291

ix Con TE n TS CULTURE 297 Coming Attraction Fritz Leiber 303 With the Original Cast nancy Kress 315 Dogfight William Gibson and Michael Swanwick 337 Glass Reptile Breakout Russell Blackford 355 [Learning About] Machine Sex Candas Jane Dorsey 367 A Short Course in Art Appreciation Paul Di Filippo 381 D.GO nicholas Royle 389 Consumimur Igni Harry Polkinhorn 401 SQPR Kim newman 411 Gray Noise Pepe Rojo 429 Retoxicity Steve Beard 447 0wnz0red Cory Doctorow 457 Younis in the Belly of the Whale Yasser Abdellatif 483 Synch Me, Kiss Me, Drop Suzanne Church 487 The White Mask Zedeck Siew 497 Degrees of Beauty Cassandra Khaw 507 Alligator Heap E. J. Swift 511

x Con TE n TS Glitterati oliver Langmead 527 Rain, Streaming omar Robert Hamilton 537 Found Earworms M. Lopes da Silva 547 Electric Tea Marie Vibbert 551 Exopunk’s Not Dead Corey J. White 561 Études Lavanya Lakshminarayan 567 Apocalypse Playlist Beth Cato 595 Act of Providence Erica Satifka 599 Feral Arcade Children of the American Northeast Sam J. Miller 611 POST- CYBERPUNK 623 Petra Greg Bear 627 The Scab’s Progress Bruce Sterling and Paul Di Filippo 641 Salvaging Gods Jacques Barcia 673 Los Piratas del Mar de Plastico Paul Graham Raven 683 About the Authors and the Translators 703 About the Editor 716 Acknowledgments 717 Permissions Acknowledgments 719 Further Reading 724

I’m an optimist about humanity in general, I suppose.

Tim Berners-Lee

EDITOR’S NOTE

The Big Book of Cyberpunk is a historical snapshot as much as a literary one, containing stories that span almost seventy-five years.

Cyberpunk, at its inception, was ahead of many other forms of literature in how it embraced (and continues to embrace) progressive themes. Cyberpunk, at its best, has strived for an inclusive vision of the present and future of society. Accordingly, the stories within The Big Book of Cyberpunk discuss all aspects of identity and existence. This includes, but is not limited to, gender, sexuality, race, class, and culture.

Even while attempting to be progressive, however, these stories also use language, tropes, and stereotypes common to the times and the places in which they were originally written. Even as some of the authors challenged the problems of their time, their work still includes problematic elements. To pretend otherwise would be hypocritical; it is the essence of cyberpunk to understand that one can simultaneously challenge and deserve to be challenged.

Cyberpunk is also literature that exists in opposition, and the way it expresses its rebellion is very often shocking, provocative, and offensive. It is transgressive by design, but not without purpose, and I tried to make my selections with that principle in mind.

Jared Shurin

INTRODUCTION TO VOLUME 1

THE DAY OF TWO THOUSAND PIGS

There once lived a man who was naked, raving, and could not be bound. According to the Gospel: “He tore the chains apart and broke the irons on his feet.” It turns out (spoiler) he was possessed. The demons were cast out of the man. Lacking a human host, the demons possessed an entire herd of pigs (two thousand of them, says Mark!). They then ran straight into the ocean.

The man, liberated of foul influences, sat there “dressed and in his right mind.” The people around him were comforted. The day of demons was behind them. After a brief period of naked, raving chaos, order had been restored.

Or so they thought.

The biblical story of Legion is an iconic one, perhaps the most well-known exorcism in Western culture.* It is also, perhaps, the perfect metaphor for cyberpunk. It is literature unchained, naked, and raving but only briefly. Depending on which expert source you read, this day of demons lasted a decade or a few short years—or, according to some, it died even before it was born. The pigs went straight into the sea. Order restored.

There’s no question that cyberpunk had a shockingly brief existence as a cohesive entity. Born out of science fiction’s new wave, literary postmodernism, and a perfect storm of external factors (Reaganism, cheap transistors, networked computing, and MTV), the genre cohered as a tangible, fungible thing in the early 1980s, most famously exemplified by the aesthetic of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) and the themes of William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984). The

* It also inspired one of the best X-Men characters.

term cyberpunk itself, as coined by Bruce Bethke, came into being in 1983.* The neologism captured the zeitgeist: the potential of, and simultaneous disillusionment with, techno-capitalism on steroids.

Cyberpunk was born of the punk ethos. It was a genre that, in many ways, existed against a mainstream cultural and literary tradition, rather than for anything definable or substantive in its own right. This is, at least, an argument posited by those who believe the genre peaked—and died—with Bruce Sterling’s superb anthology Mirrorshades (1986). Accepted as the definitive presentation of cyberpunk, Sterling had pressed a Heisenbergian self-destruct button. Once it was a defined quality, cyberpunk could no longer continue in that form.

Although this is a romantic theory (and cyberpunk is a romantic pursuit, despite—or perhaps because of—the leather and chrome), it is not one to which I personally subscribe. While collecting for this volume, I found that the engine of the genre was still spinning away, producing inventive and disruptive interpretations of the core cyberpunk themes through to the start of the next decade. These include novels and collections such as Kathy Acker’s Empire of the Senseless (1988), Misha’s Prayers of Steel (1988), Richard Kadrey’s Metrophage (1988), Lisa Mason’s Arachne (1990), and Richard Paul Russo’s Destroying Angel (1992); as well as movies, television programs, and games such as Paul Verhoeven’s RoboCop (1987), the Max Headroom series (1985), FASA’s Shadowrun (1989), and Bullfrog’s Syndicate (1993). Meaningful social commentary was still being produced as well: Donna Haraway’s “A Cyborg Manifesto,” for instance, as well as the cypherpunks and even the first steampunks.†

By the mid-1990s, however, the hogs had well and truly left for the ocean. The mundanity of the technocratic society had been firmly realized—as expressed, for example, in Douglas Coupland’s Microserfs (1995). And at the other extreme, the visual aesthetic had proved overwhelmingly popular, thriving independently of the ideas (or even the material) that spawned it. Johnny Mnemonic (1995) serves as a painful example of how the visual tropes of cyberpunk no longer bore any connection to its original themes. A bit like Frankenstein’s monster, the cyberpunk style had gone lumbering off on its own, inadvertently appropriating the name of its creator.‡ Cyberpunk slouched along in increasingly glossy and pastiche-ridden forms, but its frenetic glory days were now truly

* Bethke’s story—found in this volume—was written in 1980 and first published in 1983. The term was quickly adopted by the legendary science fiction editor Gardner Dozois, who used it to describe the movement he was seeing in the pages of his Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine.

† This is a larger discussion, but steampunk, even more than cyberpunk, is a genre in which the aesthetic rapidly subsumed its original themes. It has, however, regained its footing as a platform for discussing postcolonialism. Also, airships.

‡ In Storming the Reality Studio (1991), Richard Kadrey and Larry McCaffery make a compelling argument for Frankenstein (1818) as a cyberpunk work, therefore increasing the lifespan of the genre by approximately 170 years.

xvi I n TR o D u CTI on T o V o L u ME 1

behind it. Cyberpunk qua cyberpunk had been pulled apart by the twin poles of banal reality and hyperactive fantasy.

Why would a Big Book be given over to something that lived, thrived, and died in such a short period of time? Because, in this case, the pigs took the long way round.

Cyberpunk’s manifestation in a single and singular form was indeed brief. But it left quite an impression. A lingering dissatisfaction that being well-dressed and well-behaved is a bit, well, dull. The growing realization that chains aren’t the nicest things to wear. A dawning awareness that there are actually a lot of extremely valid reasons to run around and scream (clothing optional). People understood that the world itself was not in its right mind, and maybe the demons had the right idea.

Even as the brief golden era of cyberpunk—the day of Legion—slips further into nostalgia, the legacy of cyberpunk remains not only relevant but ubiquitous. We now live our lives in a perplexing mix of the virtual and the real. At no time in human history have we ever been exposed to more messages, more frequently, and more intrusively. Civilians using bootstrap technology are guiding drones in open warfare against marauding professional mercenaries. Protesters use umbrellas and spray paint to hide their identity from facial recognition technology. Battles between corporations are fought in the streams of professional videogame players. Algorithmically generated videos lead children down the rabbit hole of terrorist recruitment. The top touring musical act is a hologram. Your refrigerator is spying on you.

Perhaps the madman in the cave was not possessed but an oracle. Cyberpunk, however brief its reign, gave us the tools, the themes, and the vocabulary to understand the madness to come. It understood that the world itself was raving and undressed—irrational, unpredictable, and ill behaved. This is how we live, and Legion saw it coming.

WHAT IS CYBERPUNK?

It is impossible to collect The Big Book of Cyberpunk without actually defining cyberpunk. Unless we dare to name Legion, we can’t track the two thousand feral hogs and the spoor they left behind.

Unsurprisingly, given cyberpunk’s robust academic and critical legacy, there are many definitions to draw upon. With a genre so nebulous and sprawling, it is possible for each artist, author, academic, game designer or editor to find in it what they want. Cyberpunk is a land of definitional opportunity, however there are some fundamental principles to uphold.

Cyberpunk has clear origins in both the “genre” and “literary” worlds. The division between these worlds is a false tension that has been remarked on, with their trademark directness, by Ann and Jeff VanderMeer in their introduction to The Big Book of Science Fiction (2016). From its start, cyberpunk stories and cyberpunk authors were bobbing and weaving between

xvii I n TR o D u CTI on T o V o L u ME 1

both literary and genre outlets, as well as commercial and academic presses, traditional and experimental formats, and formal and informal modes of publishing.

Cyberpunk has now been “claimed” by science fiction (or, more controversially, science fiction has been consumed by cyberpunk). But it would be a narrow and inaccurate view of the genre to see it as a wholly science-fictional endeavor.

Cyberpunk is inextricably linked with the real experience of technology. Technology in cyberpunk is not a hypothetical but a fundamental, tangible, and omnipresent inclusion in human life. Cyberpunk’s predecessors largely dealt with technology as an abstract possibility: a controlled progress in the hands of a scientific elite, with visionary, but entirely rational, outcomes. But the reality of the computing explosion is that irrationality reigned, science became decentralised and personalised, and utopian visions were subsumed by capitalism, politics, and individual whim. Technology outpaced not only its expectations but its limitations.

As a genre about technology, and not “science” more broadly, there are limits to cyberpunk’s scope. Technology, in this context, is manufactured. Cyberpunk is not science fiction that explores the ramifications of something inherent (such as the anthropological science fiction of Ursula K. Le Guin), innate (such as fiction that focuses on xenobiology, mutation, psychic powers, or other “flukes of biology” stories), or encountered (such as stories about discovering or exploring alien civilizations, lost worlds, or strange artifacts). By focusing on technology as a product, cyberpunk is about agency: it speaks about change that we are attempting to bring about and upon ourselves.

Cyberpunk exists in opposition to its predecessors. The -punk of cyberpunk is unavoidable: cyberpunk contains a fundamental sense of challenge. The man in the cave wasn’t raving blindly; he was raving against. Cyberpunk pushes boundaries; it is provocative. It tries to find and break conventions. This need to rebel is intrinsic to the genre, leading to experimentation with both theme and form. As noted previously, it also connects to the possible “death” of cyberpunk: once the genre was absorbed by the mainstream, it could no longer exist as a single cohesive rebellion, and fragmented accordingly.

Cyberpunk is neither static nor teleological. Cyberpunk is literature about change. That change can take the form of progress or regress; evolution or revolution; or even degradation. It is not epic in the sense of a grand and ultimate destination. There are no final and decisive conclusions, only, at most, incremental movement. Cyberpunk is often described as dystopian, but dystopia implies a final and established system. Even in its grimmest worlds, cyberpunk presents the possibility of dynamism and of change. (And, similarly, even when set in the most scintillating futures, cyberpunk seeds the potential for regression or disruption.)

This final principle also hints at the limitations of technology. Cyberpunk is not about technological supremacy. In fact, the reverse is true: cyberpunk is about the perseverance of humanity. Cyberpunk accepts that irrationality and personality cannot be subsumed. This recognition is for good and for ill: techno-utopian outcomes are impossible because of our core, intractable

xviii I n TR o D u CTI on T o V o L u ME 1

humanness. But nor should those outcomes even be desirable: our irrepressible need for individuality may keep us from paradise but is, ultimately, the most essential part of our nature. In theme, and often in form, cyberpunk embraces chaos and irrationality, perpetually defiant of sweeping solutions, absolutist worldviews, or fixed patterns.

Marshall McLuhan, one of the great scholars of technology and society, described the same dynamics that led to the development of cyberpunk. McLuhan suggested that, in order to study technology, we step away from admiring the technology itself and instead examine how it shapes or displaces society. This quasi-phenomenological approach finds meaning not in the thing itself, but in our response to it. McLuhan concludes that the “message” of any medium or technology is the scale or pace or pattern that it introduces into human affairs.* Applying this same concept to cyberpunk: it is not the fiction of technology but that of our reaction to it. The technology itself matters only in how it affects “human affairs.”

Cyberpunk fiction is therefore an attempt, through literature, to make sense of the unprecedented scale and pace of contemporary technology, and also of the brutal and realistic acknowledgment that there may be no sense to it at all. As a working definition, therefore, it means cyberpunk is speculative fiction about the influence of technology on the scale, the pace, or the pattern of human affairs. Technology may accelerate, promote, delay, or even oppose these affairs, but humanity remains ultimately, unchangeably, human. It is the fiction of irrationality. Science fiction looks to the stars; cyberpunk stares into a mirror.

It seems tautological, but a definition is only as good as its ability to define. I crawled through almost two thousand works for this book, and, as Big™ as this book is, a mere hundred or so made it in. How did this definition work as a set of practical selection criteria? More importantly, what should you expect to find within these pages?

Cyberpunk is fiction—a self-serving selection requirement, and a controversial one at that. There’s a wealth of cyberpunk-adjacent non-fiction that fully merits a Big Book of its own. From the reviews of Cheap Truth to the ads in the back of Mondo 2000, there are essays, travelogues, manifestos, articles, and memoirs that are immensely important to cyberpunk. But cyberpunk is speculative, not descriptive. The non-fiction inspires the genre, and is inspired by it, but is not the genre itself.

The protagonist needs to be recognisably human. As stated, cyberpunk is about human affairs. Protagonists that are aliens, robots, or artificial intelligence (AI) shift the focus from human social relationships to the relationship between humanity and the other. Human/other relationships can be an insightful way of exploring what makes us human (as seen in great science fiction ranging from Mary Doria Russell to Becky Chambers), but cyberpunk eschews

* Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (New York: McGraw Hill, 1964).

xix I n TR o D u CTI on T o V o L u ME 1

that additional layer of metaphor. To be about human affairs, the story needs to be about humans.

The story is set in the present, the near present, or an easily intuited future. As we project further and further out, deciphering the scale, the pace, or the pattern requires more and more assumptions on the part of the author. Again, this is about the point of focus: the more speculation involved, and the less the manufactured technology is immediately recognisable, the more the story becomes about exploring the wondrous, rather than interrogating the probable. The “present,” of course, is relative. (Objectively speaking, most of cyberpunk is now, disturbingly, alternate history.)

Given the stagnant state of space exploration, this also excludes virtually all stories that take place off-planet or in deep space.* (Again, arguments could be made for films such as Alien, 1979, or Outland, 1981, that take place in deep space, but with oddly minimal evidence of human scientific or social progress.) Similarly, there are very few examples of cyberpunk in secondary worlds or of cyberpunk with magic. As the fantastical becomes more and more necessary to the story, the focus shifts away from human affairs and toward the story’s imaginative underpinnings.

Technology is mediative, not transformative. This is a deeply subjective divide but one critical to what makes cyberpunk a distinct genre or subgenre of science fiction. A story in which technology fundamentally transforms, replaces, or subsumes human relationships is exciting, intriguing, and wildly imaginative but not cyberpunk. A cyberpunk story is one that examines the way technology changes the way humans relate to other humans but still leaves that relationship fundamentally intact. The underlying resilience of human social relationships, for better or for worse, remains the key theme—not the transformative potential of technology.

In the spirit of cyberpunk, it is fair to note that these rules are in no way consistent. There are obvious exceptions to each of the above contained within this book, including AI protagonists, alien encounters, and even the overt use of magic.

The eagle-eyed will also note that I’ve tried to avoid the vocabulary that normally surrounds cyberpunk. As mentioned above, cyberpunk needs not be dystopian, for example. In fact, because of its focus on the resilience of human relationships, cyberpunk is neither optimistic nor pessimistic but brutally realistic. If that realism is often read as dystopian, that is more a commentary on the nature of humanity.

Nor does cyberpunk have to be set in a city, or under neon lights, or wearing

* Is there anything more emblematic of cyberpunk than the corporatization of the space race? When John F. Kennedy announced the ambition of a manned mission to the moon, he declared: “We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people.” Sixty years later, egocentric billionaires are farting radioactive garbage over the south Texas landscape in the rush to get billboards into orbit.

xx I n TR o D u CTI on T o V o L u ME 1

sunglasses, or in the rain, or (god forbid) in a trench coat. These tropes demonstrate the lingering appeal of the aesthetic that stemmed from cyberpunk but have little to do with its underpinning themes. Indeed, some of the most spectacularly non-cyberpunk works can masquerade as cyberpunk. The presence of a parsley garnish does not guarantee a steak beneath.

The last word commonly applied to cyberpunk is noir, and there is much merit to it. Unfortunately, in noir, we find a genre that is somehow even more commonly misinterpreted; confused with an aesthetic than cyberpunk itself. Noir is, like cyberpunk, about human relationships, whether the protagonist’s troubled relationship with their own identity (Dark Passage, 1947) or their conflict with a claustrophobic broader society (Chinatown, 1974). There is even a McLuhan-esque technological change at the center of most noir stories: the modern industrial city and its resultant impact on the pace, the scale, and the pattern of human affairs. Cyberpunk as science fiction noir can be a fairly apt description, but only when used in the thematic sense. It is, however, too often misapplied in the sense of “two genres that both feature rain and trench coats,” which is why I have strenuously avoided “noir” here.

Since cyberpunk is posited in this collection as the speculative examination of technology on human affairs, The Big Book of Cyberpunk is structured to examine the genre along the dimensions upon which those affairs exist: self, culture, system, and challenge. These sections also nod to McLuhan’s concept of the “global village”—a world in which media and technology has made the pace and the scale of human affairs instantaneous and global.* This global village, for better or for worse, is a world that McLuhan envisioned, that cyberpunk speculated upon, and in which we now live.

Each section begins with a (much briefer) introduction, followed by a “precyberpunk” story. As tidy as it would be to divide the world into an orderly, rationalist, technophilic Golden Age and then the raving of cyber-demons, that would be a false dichotomy. Like all cultural trends, cyberpunk has its harbingers, more easily identified with the benefits of hindsight and distance.

For each theme, I’ve included a story that, in its own way, predicts, pioneers, or inspires the cyberpunk that followed. From there, the stories within each section are ordered chronologically, up to—as much as possible—the present day. The sole caveat here is that “publication order” is an arbitrary metric: a story may have been conceived, written, or even submitted long before its publication. But this rough chronological ordering shows how the central themes of cyberpunk stayed consistent, even as the technology or media explored shifted over time. This ordering also demonstrates, in many ways, how cyberpunk has always been self-reflexive, with stories often in gleeful conversation with their forebears both within and outside the “core” genre.

Finally, each volume of The Big Book of Cyberpunk concludes with a section

*

xxi I n TR o D u CTI on T o V o L u ME 1

Marshall McLuhan, The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1962).

on post-cyberpunk. The stories here showcase the “What next?”—a question that has been asked since even before the genre began.

THE SOURCE CODE OF TWO THOUSAND PIGS

For those interested in deciphering the construction of this anthology, there were some functional—if idiosyncratic—editorial rules in place.

Respect antecedents. Notable cyberpunk anthologies include Bruce Sterling’s formative Mirrorshades; Rudy Rucker, Robert Anton Wilson, and Peter Lamborn Wilson’s groundbreaking Semiotext(e) SF (1989); Larry McCaffery’s equally important Storming the Reality Studio (1991); Pat Cadigan’s The Ultimate Cyberpunk (2002); James Patrick Kelly and John Kessel’s Rewired (2007); Victoria Blake’s Cyberpunk (2013); and Jason Heller and Joshua Viola’s Cyber World (2016).

Each of these editors had their distinct (and occasionally contradictory) vision of the genre, and these anthologies are all, in my opinion, required reading. Rather than imitate their vision, or worse, subsume it, I have kept repetition to a bare minimum. That same respect also applies to all other anthologies, including the Big Book series. Although some authors rightfully appear in this volume and previous Big Books, there are no overlapping stories.

Showcase varying perspectives. Although peak or core cyberpunk was demographically homogeneous (something of which the cyberpunks were, to their credit, fully aware), its legacy is astoundingly and brilliantly diverse. I have attempted to capture how writers from many different backgrounds— demographic, geographic, and artistic—took on the challenge of writing about our relationship with technology and one another.

Cyberpunk is a truly global phenomenon. Storytellers all over the world have used the genre as a means of addressing and discussing their concerns. This is not a recent development; cyberpunk has been a global genre since its earliest days. I’ve sought out stories that show both cyberpunk’s global contemporary presence and its roots. This book includes multiple translations, including five commissioned specifically for this volume—among them the first Englishlanguage appearances of classic cyberpunk stories by Gerardo Horacio Porcayo and Victor Pelevin, two undisputed masters of the genre.

Afrofuturism is an important movement unto itself, with its own unique cultural evolution. It is not “Black cyberpunk,” although the two are often conflated. Treating Afrofuturism as a subset of cyberpunk is to treat it with disrespect. However, there are undeniable parallels, as both genres, for example, present alternative views to a “mainstreamed” culture, and both are robustly transmedia in their creative expression. There has also been some intersection over time, perhaps most popularly in the music, videos, and writing of Janelle Monáe. Their novella, co-written with Alaya Dawn Johnson, features in this volume. “The Memory Librarian” is one of several works within this Big Book that has a foot in both movements, but it would be disingenuous to pretend that Afrofuturism is thoroughly explored herein.

xxii I n TR o D u CTI on T o V o L u ME 1

As a corollary to the principle of diverse perspectives: the de facto Big Book rule is that no author can appear twice in a single volume—and this has been mostly maintained. However, cyberpunk has always been a collaborative genre. Some of its most impressive and defining works were co-written, creating results that neither could achieve independently. Although a very slim loophole, I’ve exploited it, meaning a few names do have the audacity to repeat herein.

Celebrate the experimental. Cyberpunk media included film and television, albums and art, software and games. Many of these formats are impossible to capture on the printed page, certainly not without doing them a massive disservice—although there are some visual stories inside this collection. I attempt to pay tribute to the original cyberpunks by gathering materials from a wide variety of sources: a reflection of the non-traditional publishing journey taken by many of these writers. Inside are stories first published in magazines, anthologies, and websites, but also as zines, liner notes, and fleeting social media posts.

Cyberpunk is not solely the province of science fiction, and herein are stories first published by newspapers, in science journals, in literary magazines, and as role-playing game tie-ins. Due to the combination of provocative content and technologically savvy authors, cyberpunk has always been at the forefront of self-publishing— a trend also reflected here.

Continuing the experimental theme, all the stories in The Big Book of Cyberpunk are self-contained “holistic” works. There are many great stories that require the reader to have preexisting knowledge of the setting or the characters. There are a wealth of fantastic cyberpunk novels that could have provided extracts. Restricting this anthology solely to short fiction was necessary for my own sake.

THE END OF THE BEGINNING

The first story, William Gibson’s “The Gernsback Continuum” (1981) stands outside the five main sections. It is the boot-up sound for the hundred-odd stories that follow.

William Gibson is the figure most closely connected with cyberpunk, not only through Neuromancer and the Sprawl trilogy, but also through his short stories and non-fiction, all of which encapsulated the fledgling genre in its fragile early years. There is no author more appropriate to open this volume.*

“The Gernsback Continuum” defines the problem that cyberpunk would then go on to solve. It shows the fantasies of scientific aspiration, and it repositions visions of progress as the ghosts of value. The story is achingly, poignantly sad. Not because it is set in a dystopian hellscape but because the world is so painfully ordinary. It shows where we are, but through the lens of where we thought we’d be. By setting the recognizable against the aspirational, Gibson

* “The Gernsback Continuum” was also the first story in the now oft-mentioned Mirrorshades. This is a coincidence, but I like it.

xxiii I n TR o D u CTI on T o V o L u ME 1

shows the gap between imagination and reality and sets out the challenge for future writers to fill it—including, as it turns out, Gibson himself. “The Gernsback Continuum” refuted the science-fictional tradition that had prevailed since the 1930s and made space for a new form of storytelling.

Above all else, “The Gernsback Continuum” is simply a beautiful story, perfectly constructed and gloriously atmospheric. Although all stories in this anthology were chosen for their historical and thematic significance, the most important selection criterion was that they are enjoyable to read, and I hope you find as much pleasure in them as I have.

xxiv I n TR o D u CTI on T o V o L u ME 1

WILLIAM GIBSON

THE GERNSBACK CONTINUUM (1981)

mercifully, the whole thing is starting to fade, to become an episode. When I do still catch the odd glimpse, it’s peripheral; mere fragments of mad-doctor chrome, confining themselves to the corner of the eye. There was that flyingwing liner over San Francisco last week, but it was almost translucent. And the shark-fin roadsters have gotten scarcer, and freeways discreetly avoid unfolding themselves into the gleaming eighty-lane monsters I was forced to drive last month in my rented Toyota. And I know that none of it will follow me to New York; my vision is narrowing to a single wavelength of probability. I’ve worked hard for that. Television helped a lot.

I suppose it started in London, in that bogus Greek taverna in Battersea Park Road, with lunch on Cohen’s corporate tab. Dead steam-table food and it took them thirty minutes to find an ice bucket for the retsina. Cohen works for BarrisWatford, who publish big, trendy “trade” paperbacks: illustrated histories of the neon sign, the pinball machine, the windup toys of Occupied Japan. I’d gone over to shoot a series of shoe ads; California girls with tanned legs and frisky Day-Glo jogging shoes had capered for me down the escalators of St. John’s Wood and across the platforms of Tooting Bec. A lean and hungry young agency had decided that the mystery of London Transport would sell waffle-tread nylon runners. They decide; I shoot. And Cohen, whom I knew vaguely from the old days in New York, had invited me to lunch the day before I was due out of Heathrow. He brought along a very fashionably dressed young woman named

Dialta Downes, who was virtually chinless and evidently a noted pop-art historian. In retrospect, I see her walking in beside Cohen under a floating neon sign that flashes this way lies madness in huge sans serif capitals.

Cohen introduced us and explained that Dialta was the prime mover behind the latest Barris-Watford project, an illustrated history of what she called “American Streamlined Moderne.” Cohen called it “raygun Gothic.” Their working title was The Airstream Futuropolis: The Tomorrow That Never Was.

There’s a British obsession with the more baroque elements of American pop culture, something like the weird cowboys-and-Indians fetish of the West Germans or the aberrant French hunger for old Jerry Lewis films. In Dialta Downes this manifested itself in a mania for a uniquely American form of architecture that most Americans are scarcely aware of. At first I wasn’t sure what she was talking about, but gradually it began to dawn on me. I found myself remembering Sunday morning television in the Fifties.

Sometimes they’d run old eroded newsreels as filler on the local station. You’d sit there with a peanut butter sandwich and a glass of milk, and a staticridden Hollywood baritone would tell you that there was A Flying Car in Your Future. And three Detroit engineers would putter around with this big old Nash with wings, and you’d see it rumbling furiously down some deserted Michigan runway. You never actually saw it take off, but it flew away to Dialta Downes’s never-never land, true home of a generation of completely uninhibited technophiles. She was talking about those odds and ends of “futuristic” Thirties and Forties architecture you pass daily in American cities without noticing: the movie marquees ribbed to radiate some mysterious energy, the dime stores faced with fluted aluminum, the chrome-tube chairs gathering dust in the lobbies of transient hotels. She saw these things as segments of a dreamworld, abandoned in the uncaring present; she wanted me to photograph them for her.

The Thirties had seen the first generation of American industrial designers; until the Thirties, all pencil sharpeners had looked like pencil sharpeners—your basic Victorian mechanism, perhaps with a curlicue of decorative trim. After the advent of the designers, some pencil sharpeners looked as though they’d been put together in wind tunnels. For the most part, the change was only skin-deep; under the streamlined chrome shell, you’d find the same Victorian mechanism. Which made a certain kind of sense, because the most successful American designers had been recruited from the ranks of Broadway theater designers. It was all a stage set, a series of elaborate props for playing at living in the future.

Over coffee, Cohen produced a fat manila envelope full of glossies. I saw the winged statues that guard the Hoover Dam, forty-foot concrete hood ornaments leaning steadfastly into an imaginary hurricane. I saw a dozen shots of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Johnson Wax Building, juxtaposed with the covers of old Amazing Stories pulps, by an artist named Frank R. Paul; the employees of Johnson Wax must have felt as though they were walking into one of Paul’s spray-paint pulp Utopias. Wright’s building looked as though it had been designed for people who wore white togas and Lucite sandals. I hesitated over one sketch of a particularly grandiose prop-driven airliner, all wing, like a fat, symmetrical

THE BIG BOOK OF CYBERPUNK 2

boomerang with windows in unlikely places. Labeled arrows indicated the locations of the grand ballroom and two squash courts. It was dated 1936.

“This thing couldn’t have flown . . . ?” I looked at Dialta Downes.

“Oh, no, quite impossible, even with those twelve giant props; but they loved the look, don’t you see? New York to London in less than two days, first-class dining rooms, private cabins, sun decks, dancing to jazz in the evening . . . The designers were populists, you see; they were trying to give the public what it wanted. What the public wanted was the future.”

I’d been in Burbank for three days, trying to suffuse a really dull-looking rocker with charisma, when I got the package from Cohen. It is possible to photograph what isn’t there; it’s damned hard to do, and consequently a very marketable talent. While I’m not bad at it, I’m not exactly the best, either, and this poor guy strained my Nikon’s credibility. I got out depressed because I do like to do a good job, but not totally depressed, because I did make sure I’d gotten the check for the job, and I decided to restore myself with the sublime artiness of the Barris-Watford assignment. Cohen had sent me some books on Thirties design, more photos of streamlined buildings, and a list of Dialta Downes’s fifty favorite examples of the style in California.

Architectural photography can involve a lot of waiting; the building becomes a kind of sundial, while you wait for a shadow to crawl away from a detail you want, or for the mass and balance of the structure to reveal itself in a certain way. While I was waiting, I thought of myself in Dialta Downes’s America. When I isolated a few of the factory buildings on the ground glass of the Hasselblad, they came across with a kind of sinister totalitarian dignity, like the stadiums Albert Speer built for Hitler. But the rest of it was relentlessly tacky; ephemeral stuff extruded by the collective American subconscious of the Thirties, tending mostly to survive along depressing strips lined with dusty motels, mattress wholesalers, and small used-car lots. I went for the gas stations in a big way.

During the high point of the Downes Age, they put Ming the Merciless in charge of designing California gas stations. Favoring the architecture of his native Mongo, he cruised up and down the coast erecting raygun emplacements in white stucco. Lots of them featured superfluous central towers ringed with those strange radiator flanges that were a signature motif of the style and which made them look as though they might generate potent bursts of raw technological enthusiasm if you could only find the switch that turned them on. I shot one in San Jose an hour before the bulldozers arrived and drove right through the structural truth of plaster and lathing and cheap concrete.

“Think of it,” Dialta Downes had said, “as a kind of alternate America: a 1980 that never happened. An architecture of broken dreams.”

And that was my frame of mind as I made the stations of her convoluted socioarchitectural cross in my red Toyota—as I gradually tuned in to her image of a shadowy America-that-wasn’t, of Coca-Cola plants like beached submarines, and fifth-run movie houses like the temples of some lost sect that had worshiped blue mirrors and geometry. And as I moved among these secret ruins, I found myself wondering what the inhabitants of that lost future would think of

T HE G ER n SBACK Con TI nuu M 3

the world I lived in. The Thirties dreamed white marble and slipstream chrome, immortal crystal and burnished bronze, but the rockets on the covers of the Gernsback pulps had fallen on London in the dead of night, screaming. After the war, everyone had a car—no wings for it—and the promised superhighway to drive it down, so that the sky itself darkened, and the fumes ate the marble and pitted the miracle crystal . . .

And one day, on the outskirts of Bolinas, when I was setting up to shoot a particularly lavish example of Ming’s martial architecture, I penetrated a fine membrane, a membrane of probability

Ever so gently, I went over the Edge—

And looked up to see a twelve-engined thing like a bloated boomerang, all wing, thrumming its way east with an elephantine grace, so low that I could count the rivets in its dull silver skin, and hear—maybe—the echo of jazz.

I took it to Kihn. Merv Kihn, freelance journalist with an extensive line in Texas pterodactyls, redneck UFO contactées, bush-league Loch Ness monsters, and the Top Ten conspiracy theories in the loonier reaches of the American mass mind.

“It’s good,” said Kihn, polishing his yellow Polaroid shooting glasses on the hem of his Hawaiian shirt, “but it’s not mental ; lacks the true quill.”

“But I saw it, Mervyn.” We were seated poolside in brilliant Arizona sunlight. He was in Tucson waiting for a group of retired Las Vegas civil servants whose leader received messages from Them on her microwave oven. I’d driven all night and was feeling it.

“Of course you did. Of course you saw it. You’ve read my stuff; haven’t you grasped my blanket solution to the UFO problem? It’s simple, plain and country simple: people”—he settled the glasses carefully on his long hawk nose and fixed me with his best basilisk glare—“see . . . things. People see these things. Nothing’s there, but people see them anyway. Because they need to, probably. You’ve read Jung, you should know the score . . . In your case, it’s so obvious: You admit you were thinking about this crackpot architecture, having fantasies . . . Look, I’m sure you’ve taken your share of drugs, right? How many people survived the Sixties in California without having the odd hallucination? All those nights when you discovered that whole armies of Disney technicians had been employed to weave animated holograms of Egyptian hieroglyphs into the fabric of your jeans, say, or the times when—”

“But it wasn’t like that.”

“Of course not. It wasn’t like that at all; it was ‘in a setting of clear reality,’ right? Everything normal, and then there’s the monster, the mandala, the neon cigar. In your case, a giant Tom Swift airplane. It happens all the time. You aren’t even crazy. You know that, don’t you?” He fished a beer out of the battered foam cooler beside his deck chair.

“Last week I was in Virginia. Grayson County. I interviewed a sixteen-yearold girl who’d been assaulted by a bar hade.”

“A what?”

“A bear head. The severed head of a bear. This bar hade, see, was floating

THE BIG BOOK OF CYBERPUNK 4

around on its own little flying saucer, looked kind of like the hubcaps on cousin Wayne’s vintage Caddy. Had red, glowing eyes like two cigar stubs and telescoping chrome antennas poking up behind its ears.” He burped.

“It assaulted her? How?”

“You don’t want to know; you’re obviously impressionable. ‘It was cold’ ”— he lapsed into his bad Southern accent—“ ‘and metallic.’ It made electronic noises. Now that is the real thing, the straight goods from the mass unconscious, friend; that little girl is a witch. There’s no place for her to function in this society. She’d have seen the devil if she hadn’t been brought up on The Bionic Woman and all those Star Trek reruns. She is clued into the main vein. And she knows that it happened to her. I got out ten minutes before the heavy UFO boys showed up with the polygraph.”

I must have looked pained, because he set his beer down carefully beside the cooler and sat up.

“If you want a classier explanation, I’d say you saw a semiotic ghost. All these contactee stories, for instance, are framed in a kind of sci-fi imagery that permeates our culture. I could buy aliens, but not aliens that look like Fifties’ comic art. They’re semiotic phantoms, bits of deep cultural imagery that have split off and taken on a life of their own, like the Jules Verne airships that those old Kansas farmers were always seeing. But you saw a different kind of ghost, that’s all. That plane was part of the mass unconscious, once. You picked up on that, somehow. The important thing is not to worry about it.”

I did worry about it, though.

Kihn combed his thinning blond hair and went off to hear what They had had to say over the radar range lately, and I drew the curtains in my room and lay down in air-conditioned darkness to worry about it. I was still worrying about it when I woke up. Kihn had left a note on my door; he was flying up north in a chartered plane to check out a cattle-mutilation rumor (“muties,” he called them; another of his journalistic specialties).

I had a meal, showered, took a crumbling diet pill that had been kicking around in the bottom of my shaving kit for three years, and headed back to Los Angeles.

The speed limited my vision to the tunnel of the Toyota’s headlights. The body could drive, I told myself, while the mind maintained. Maintained and stayed away from the weird peripheral window dressing of amphetamine and exhaustion, the spectral, luminous vegetation that grows out of the corners of the mind’s eye along late-night highways. But the mind had its own ideas, and Kihn’s opinion of what I was already thinking of as my “sighting” rattled endlessly through my head in a tight, lopsided orbit. Semiotic ghosts. Fragments of the Mass Dream, whirling past in the wind of my passage. Somehow this feedback-loop aggravated the diet pill, and the speed-vegetation along the road began to assume the colors of infrared satellite images, glowing shreds blown apart in the Toyota’s slipstream.

I pulled over, then, and a half-dozen aluminum beer cans winked goodnight as I killed the headlights. I wondered what time it was in London, and tried to

T HE G ER n SBACK Con TI nuu M 5

imagine Dialta Downes having breakfast in her Hampstead flat, surrounded by streamlined chrome figurines and books on American culture.

Desert nights in that country are enormous; the moon is closer. I watched the moon for a long time and decided that Kihn was right. The main thing was not to worry. All across the continent, daily, people who were more normal than I’d ever aspired to be saw giant birds, Bigfeet, flying oil refineries; they kept Kihn busy and solvent. Why should I be upset by a glimpse of the 1930s pop imagination loose over Bolinas? I decided to go to sleep, with nothing worse to worry about than rattlesnakes and cannibal hippies, safe amid the friendly roadside garbage of my own familiar continuum. In the morning I’d drive down to Nogales and photograph the old brothels, something I’d intended to do for years. The diet pill had given up.

The light woke me, and then the voices. The light came from somewhere behind me and threw shifting shadows inside the car. The voices were calm, indistinct, male and female, engaged in conversation.

My neck was stiff and my eyeballs felt gritty in their sockets. My leg had gone to sleep, pressed against the steering wheel. I fumbled for my glasses in the pocket of my work shirt and finally got them on.

Then I looked behind me and saw the city.

The books on Thirties design were in the trunk; one of them contained sketches of an idealized city that drew on Metropolis and Things to Come, but squared everything, soaring up through an architect’s perfect clouds to zeppelin docks and mad neon spires. That city was a scale model of the one that rose behind me. Spire stood on spire in gleaming ziggurat steps that climbed to a central golden temple tower ringed with the crazy radiator flanges of the Mongo gas stations. You could hide the Empire State Building in the smallest of those towers. Roads of crystal soared between the spires, crossed and recrossed by smooth silver shapes like beads of running mercury. The air was thick with ships: giant wing-liners, little darting silver things (sometimes one of the quicksilver shapes from the sky bridges rose gracefully into the air and flew up to join the dance), mile-long blimps, hovering dragonfly things that were gyrocopters

I closed my eyes tight and swung around in the seat. When I opened them, I willed myself to see the mileage meter, the pale road dust on the black plastic dashboard, the overflowing ashtray.

“Amphetamine psychosis,” I said. I opened my eyes. The dash was still there, the dust, the crushed filter tips. Very carefully, without moving my head, I turned the headlights on.

And saw them.

They were blond. They were standing beside their car, an aluminum avocado with a central shark-fin rudder jutting up from its spine and smooth black tires like a child’s toy. He had his arm around her waist and was gesturing toward the city. They were both in white: loose clothing, bare legs, spotless white sun shoes. Neither of them seemed aware of the beams of my headlights. He was saying something wise and strong, and she was nodding, and suddenly I was frightened, frightened in an entirely different way. Sanity had ceased to be an issue; I knew,

THE BIG BOOK OF CYBERPUNK 6

somehow, that the city behind me was Tucson—a dream Tucson thrown up out of the collective yearning of an era. That it was real, entirely real. But the couple in front of me lived in it, and they frightened me.

They were the children of Dialta Downes’s ’80-that-wasn’t; they were Heirs to the Dream. They were white, blond, and they probably had blue eyes. They were American. Dialta had said that the Future had come to America first, but had finally passed it by. But not here, in the heart of the Dream. Here, we’d gone on and on, in a dream logic that knew nothing of pollution, the finite bounds of fossil fuel, or foreign wars it was possible to lose. They were smug, happy, and utterly content with themselves and their world. And in the Dream, it was their world.

Behind me, the illuminated city: Searchlights swept the sky for the sheer joy of it. I imagined them thronging the plazas of white marble, orderly and alert, their bright eyes shining with enthusiasm for their floodlit avenues and silver cars.

It had all the sinister fruitiness of Hitler Youth propaganda.

I put the car in gear and drove forward slowly, until the bumper was within three feet of them. They still hadn’t seen me. I rolled the window down and listened to what the man was saying. His words were bright and hollow as the pitch in some chamber of commerce brochure, and I knew that he believed in them absolutely.

“John,” I heard the woman say, “we’ve forgotten to take our food pills.” She clicked two bright wafers from a thing on her belt and passed one to him. I backed onto the highway and headed for Los Angeles, wincing and shaking my head.

I phoned Kihn from a gas station. A new one, in bad Spanish Modern. He was back from his expedition and didn’t seem to mind the call.

“Yeah, that is a weird one. Did you try to get any pictures? Not that they ever come out, but it adds an interesting frisson to your story, not having the pictures turn out. . . .”

But what should I do?

“Watch lots of television, particularly game shows and soaps. Go to porn movies. Ever see Nazi Love Motel ? They’ve got it on cable, here. Really awful. Just what you need.”

What was he talking about?

“Quit yelling and listen to me. I’m letting you in on a trade secret: Really bad media can exorcize your semiotic ghosts. If it keeps the saucer people off my back, it can keep these Art Deco futuroids off yours. Try it. What have you got to lose?”

Then he begged off, pleading an early-morning date with the Elect.

“The who?”

“These oldsters from Vegas; the ones with the microwaves.”

I considered putting a collect call through to London, getting Cohen at Barris-Watford and telling him his photographer was checked out for a protracted season in the Twilight Zone. In the end, I let a machine mix me a really

T HE G ER n SBACK Con TI nuu M 7

impossible cup of black coffee and climbed back into the Toyota for the haul to Los Angeles.

Los Angeles was a bad idea, and I spent two weeks there. It was prime Downes country; too much of the Dream there, and too many fragments of the Dream waiting to snare me. I nearly wrecked the car on a stretch of overpass near Disneyland when the road fanned out like an origami trick and left me swerving through a dozen minilanes of whizzing chrome teardrops with shark fins. Even worse, Hollywood was full of people who looked too much like the couple I’d seen in Arizona. I hired an Italian director who was making ends meet doing darkroom work and installing patio decks around swimming pools until his ship came in; he made prints of all the negatives I’d accumulated on the Downes job. I didn’t want to look at the stuff myself. It didn’t seem to bother Leonardo, though, and when he was finished I checked the prints, riffling through them like a deck of cards, sealed them up, and sent them air freight to London. Then I took a taxi to a theater that was showing Nazi Love Motel and kept my eyes shut all the way.

Cohen’s congratulatory wire was forwarded to me in San Francisco a week later. Dialta had loved the pictures. He admired the way I’d “really gotten into it,” and looked forward to working with me again. That afternoon I spotted a flying wing over Castro Street, but there was something tenuous about it, as if it were only half there. I rushed to the nearest newsstand and gathered up as much as I could find on the petroleum crisis and the nuclear energy hazard. I’d just decided to buy a plane ticket for New York.

“Hell of a world we live in, huh?” The proprietor was a thin black man with bad teeth and an obvious wig. I nodded, fishing in my jeans for change, anxious to find a park bench where I could submerge myself in hard evidence of the human near-dystopia we live in. “But it could be worse, huh?”

“That’s right,” I said, “or even worse, it could be perfect.”

He watched me as I headed down the street with my little bundle of condensed catastrophe.

THE BIG BOOK OF CYBERPUNK 8

SELF

The notion of identity—and the many and heated discussions around it—has long been explored through fiction. Cyberpunk is no exception. Of the many different relationships that constitute human affairs, the self—how we see, perceive, and define ourselves—is perhaps the most complex. Until we know who we are, how can we understand our place in the world?

Cyberpunk has always understood that technology has the power to affect even this most intimate and individual relationship. Who we are—who we think we are—is, like every other social construct, mediated by technology.

In the early days of the genre, cyberpunk fiction was rightfully fascinated by the idea of our virtual selves. The existence of cyberspace presupposes our cyber-selves. Is our online presence a projection? A twin? A shadow? What is the tenuous connection between these planes—are there physical or moral repercussions for how our digital self acts in their world? Decades later, we are no closer to answering the questions that cyberpunk was the first to ask.

Cyberpunk also looked at technology’s broader potential for personal transformation: how much it can change us; what we can become; what we can and can’t leave behind. Modern understanding of identity is that it is a layered and dynamic concept. Humans are not one thing. Who we are can shift depending on the context we’re in, the company we keep, the choices we make, or that are made for us. Cyberpunk fiction is a way of exploring the tension between the fluidity of identity (lubricated by technology) and the immutable essence of what makes us human.

This section opens with James Tiptree Jr.’s excellent “The Girl Who Was Plugged In” (1973). In terms of vocabulary and technology, it sets the tone for much of the cyberpunk fiction that would follow. It also raises questions about the impact of virtuality on identity: Will it be liberating to “depart” ourselves for another body, or is there something damaging about severing that connection? What harm is caused by a society that makes that possible or, in fact, encourages it?

This discussion of freedom (and the “curse” of being anchored to a physical presence) is found through many of the stories in this section. Pat Cadigan’s “Pretty Boy Crossover” (1986) describes a world where physical beauty is upheld to the point that the body is itself made the ultimate sacrifice. The criminals of John Shirley’s “Wolves of the Plateau” (1988) use the power of the virtual plane to free themselves and become something more. In “The World as We Know It” (1992), George Effinger’s sleuth, Marîd Audran, encounters communities that prefer virtual worlds to physical ones, despite the high cost of maintaining the suspension of disbelief. Gwyneth Jones’s “Red Sonja and Lessingham in Dreamland” (1996) uses the virtual world as a form of psychotherapy: online identities allowing repressed appetites to run free.

Once plugged in to the augmented world of Jean-Marc Ligny’s “RealLife 3.0” (2014) (appearing here for the first time in English), our protagonist experiences reality and the virtual fantasy side-by-side, with predictable dispiriting results.

In Aleš Kot’s “A Life of Its Own” (2019), the virtual becomes a cage, with those same dreams used to keep you entombed (thanks, in no small part, to the fine print). Kot’s story is notable because at no point is the physical world preferable: the grievance is the concept of being trapped, not the prison itself.

Charles Stross’s madcap satire, “Lobsters” (2001) features a MacGuffin (or is it?) based on the profit potential of digital crustaceans. Surrounding that central conceit is a whirlwind of influences: our protagonist attempting to maintain his own self-identity while being buffeted by political, financial, technological, and romantic winds.

In Sparkletown, the setting of Jeff Noon’s “Ghost Codes of Sparkletown” (2011), the self can be endangered by cultural ghosts: fragments of music that float through a haunted graveyard of burned-out CPUs.*

J. P. Smythe’s “The Infinite Eye” (2017) is a story that descends in a direct line from Tiptree’s, again describing a corporate world where the desperate sell themselves to stay afloat. In “The Girl Who Was Plugged In,” our protagonist receives an ecstatic reward, and a chance to live the fantasy. In “The Infinite Eye,” they merely receive a paycheck (and, presumably, no health care). In the final story in this section, qntm’s “Lena” (2021), a man is blessed/cursed with virtual immortality, give or take some messy version control.

* Jeff Noon’s story was first composed on Twitter, and has since been reincarnated in various forms, including as the inspiration for the album Ghost Codes by The Forgetting Room. This is the story’s first appearance in this “holistic” form.

THE BIG BOOK OF CYBERPUNK 10

The fluidity of the self is not solely contained in the virtual realm.

Anna, in Richard Kadrey’s “Surfing the Khumbu” (2002), is “living in machines and flesh at the same time,” a scenario that will leave the reader quivering in both fear and jealousy. In Cat Rambo’s “Memories of Moments, Bright as Falling Stars” (2006), technology—in this case “memory,” both biological and computational—is embedded in the body, both a resource and a drug.

Karen Heuler’s “The Completely Rechargeable Man” (2008) reads more like a fairy tale than your average cyberpunk short. It describes a lonely individual whose life is so technological that he has become a form of entertainment. The titular character in Christian Kirtchev’s “File: The Death of Designer D.” (2009) is the source of mystery on several levels. Why did she die? What was she fighting against? And who was she in the first place? The singular letters of “D.” and her investigator, “K.” are reminiscent of Kafka, as D. battles to have an identity in a world of “gray lemmings.”

Transhuman aspiration runs amok in many of these stories. Jean Rabe’s “Better Than” (2010) is the tale of a lost soul, addicted to self-transformation, with an identity so degraded as to be totally lost.* In Alvaro Zinos-Amaro’s “wysiomg” (2016), we also have transient, fragmented identities, with biology and identity both subsumed into an anarchistic internet culture.

“The Real You™” (2018) by Molly Tanzer takes the control of the self to its ultimate conclusion with “Refractin,” a treatment in which your face is completely removed. Tanzer’s story is focused less on the perplexing how, but on the why—what could compel someone to remove their identity entirely, and what would be the repercussions of living faceless in society?

Several of the stories in this section are devoted to the intersection of the self and destruction. Not self-destruction, per se (although that is often the case), but stories that explore our slavish, one-sided devotion to technology that only exists to harm us. Sunny Moraine’s “I Tell Thee All, I Can No More” (2013) is a tale of truly forbidden love, centered around a romance that crosses all possible boundaries. It is, in the best cyberpunk tradition, a story that simply should not work, but Moraine somehow spins beauty out of nightmare, while never letting us forget the true horror beneath.

“Four Tons Too Late” (2014) and “Helicopter Story” (2020) are also about a savage blend of human and machine, as well as the subservience of the self to the military-industrial complex. In the former, K. C. Alexander describes the psychological toll on a new type of veteran. They have been, in every sense, a “good soldier”. But what is the reward for loyalty to an inherently callous system? In “Helicopter Story,” Isabel Fall reclaims a transphobic meme and uses it as the vehicle to describe a society that suppresses gender identity while simultaneously

* Cyberpunk fiction exists as much in movies, television, music, and games as in literature. Jean Rabe’s story is one of two in this book that originated in the setting of FASA’s Shadowrun, a long-established role-playing game that mixes fantasy tropes and cyberpunk, and has done much to introduce new audiences to the latter.

SELF 11

worshiping at the altar of hyper-militarized machismo.* The story asks “Have you ever been exultant?” and then brutally condemns a world where the only way to answer this question positively is by transforming yourself into a weapon of war.

The capacity of technology to make new selves is a fascination of cyberpunk: the ability to create an identity, or even a living being, out of whole cloth. Cyberpunk’s fixation on androids could be argued away as another aesthetic trope (thanks, Blade Runner), but it is a natural extension of the genre’s discussion of the virtual self and transhumanism. At what point does technology allow us to imitate the self so precisely that it becomes a new self of its own? And does that new being have a soul, or even the right to exist?

Phillip Mann’s “An Old-Fashioned Story” (1989) is a slice-of-life tale (apologies for the pun), in which a couple set about fixing their household android and, in the process, reveal a great deal about themselves.

In “The Girl Hero’s Mirror Says He’s Not the One” (2007), Justina Robson’s Girl Hero inhabits a completely fabricated identity that has been imposed upon her. But despite being forced into a specific role (or Role), she owns it, and takes agency over the illusion.

Lavie Tidhar’s “Choosing Faces” (2012) is one of the author’s trademark satires, featuring a particularly famous martial artist in his greatest battle(s) yet. It is hilarious, and reminiscent of Warhol with the way it addresses the tragic erosion of the self that stems from celebrity culture.

Neon Yang’s “Patterns of a Murmuration, in Billions of Data Points” (2014) is one of the few stories in this book with a nonhuman protagonist—in this case, an AI swarm that collectively takes action to solve the death of their “mother.” As compelling as our hive-mind protagonist is, this story uses them as the lens through which we can watch the fumblings of human behavior, as the humans attempt to wield this technology to their own advantage.

Every other dimension of human affairs is external—the author has the advantage of distance. Writing about the self, even a fictional self, is necessarily personal. Even blurred through the lens of fiction, there’s an emotional connection that’s unavoidable. Writing about space voyages or football is undeniably complex, but lacks the same closeness. The interest is in what’s happening out there: in the void, on the pitch. These cyberpunk stories, however, are intimate. They are not about the out there, but the right here. Whatever is happening with technology is inescapable; in our face. It is uncomfortable. We lack the distance to have perspective, or to make objective decisions. That is a reflection of cyberpunk’s central theme: despite our best (or worst) efforts to suppress it, we are inevitably, irreversibly, irrationally human.

* The meme—“I sexually identify as an attack helicopter”— emerged on Reddit and 4chan a few years before this story was first published, and was used to dismiss the notion of nonbinary gender identity and the principle of self-identification. This story not only makes sense without the original context but, rather gratifyingly, will long outlive it.

THE BIG BOOK OF CYBERPUNK 12

JAMES TIPTREE JR.

THE GIRL WHO WAS PLUGGED IN (1973)

listen, zombie. Believe me. What I could tell you—you with your silly hands leaking sweat on your growth-stocks portfolio. One-ten lousy hacks of AT &T on twenty-point margin and you think you’re Evel Knievel. AT &T? You doubleknit dummy, how I’d love to show you something.

Look, dead daddy, I’d say. See for instance that rotten girl?

In the crowd over there, that one gaping at her gods. One rotten girl in the city of the future. (That’s what I said.) Watch.

She’s jammed among bodies, craning and peering with her soul yearning out of her eyeballs. Love! Oo-ooh, love them! Her gods are coming out of a store called Body East. Three youngbloods, larking along loverly. Dressed like simple street-people but smashing. See their great eyes swivel above their nose-filters, their hands lift shyly, their inhumanly tender lips melt? The crowd moans. Love! This whole boiling megacity, this whole fun future world loves its gods.

You don’t believe gods, dad? Wait. Whatever turns you on, there’s a god in the future for you, custom-made. Listen to this mob. “I touched His foot! Ow-oow, I touched Him!”

Even the people in the GTX tower up there love the gods—in their own way and for their own reasons.

The funky girl on the street, she just loves. Grooving on their beautiful lives, their mysterioso problems. No one ever told her about mortals who love a god

and end up as a tree or a sighing sound. In a million years it’d never occur to her that her gods might love her back.

She’s squashed against the wall now as the godlings come by. They move in a clear space. A holocam bobs above, but its shadow never falls on them. The store display-screens are magically clear of bodies as the gods glance in and a beggar underfoot is suddenly alone. They give him a token. “Aaaaah!” goes the crowd.

Now one of them flashes some wild new kind of timer and they all trot to catch a shuttle, just like people. The shuttle stops for them—more magic. The crowd sighs, closing back. The gods are gone.

(In a room far from—but not unconnected to—the GTX tower a molecular flipflop closes too, and three account tapes spin.)

Our girl is still stuck by the wall while guards and holocam equipment pull away. The adoration’s fading from her face. That’s good, because now you can see she’s the ugly of the world. A tall monument to pituitary dystrophy. No surgeon would touch her. When she smiles, her jaw—it’s half purple—almost bites her left eye out. She’s also quite young, but who could care?

The crowd is pushing her along now, treating you to glimpses of her jumbled torso, her mismatched legs. At the corner she strains to send one last fond spasm after the godlings’ shuttle. Then her face reverts to its usual expression of dim pain and she lurches onto the moving walkway, stumbling into people. The walkway junctions with another. She crosses, trips, and collides with the casualty rail. Finally she comes out into a little bare place called a park. The sportshow is working, a basketball game in three-di is going on right overhead. But all she does is squeeze onto a bench and huddle there while a ghostly free-throw goes by her ear.

After that nothing at all happens except a few furtive hand-mouth gestures which don’t even interest her bench mates. But you’re curious about the city? So ordinary after all, in the future ?

Ah, there’s plenty to swing with here—and it’s not all that far in the future, dad. But pass up the sci-fi stuff for now, like for instance the holovision technology that’s put TV and radio in museums. Or the worldwide carrier field bouncing down from satellites, controlling communication and transport systems all over the globe. That was a spin-off from asteroid mining, pass it by. We’re watching that girl.

I’ll give you just one goodie. Maybe you noticed on the sportshow or the streets? No commercials. No ads.

That’s right. No ads. An eyeballer for you.

Look around. Not a billboard, sign, slogan, jingle, sky-write, blurb, sublimflash, in this whole fun world. Brand names? Only in those ticky little peep-screens on the stores, and you could hardly call that advertising. How does that finger you?

Think about it. That girl is still sitting there.

She’s parked right under the base of the GTX tower, as a matter of fact. Look way up and you can see the sparkles from the bubble on top, up there among the domes of godland. Inside that bubble is a boardroom. Neat bronze shield on the door: Global Transmissions Corporation—not that that means anything.

THE BIG BOOK OF CYBERPUNK 14

I happen to know there are six people in that room. Five of them technically male, and the sixth isn’t easily thought of as a mother. They are absolutely unremarkable. Those faces were seen once at their nuptials and will show again in their obituaries and impress nobody either time. If you’re looking for the secret Big Blue Meanies of the world, forget it. I know. Zen, do I know! Flesh? Power? Glory? You’d horrify them.

What they do like up there is to have things orderly, especially their communications. You could say they’ve dedicated their lives to that, to freeing the world from garble. Their nightmares are about hemorrhages of information; channels screwed up, plans misimplemented, garble creeping in. Their gigantic wealth only worries them, it keeps opening new vistas of disorder. Luxury? They wear what their tailors put on them, eat what their cooks serve them. See that old boy there—his name is Isham—he’s sipping water and frowning as he listens to a databall. The water was prescribed by his medistaff. It tastes awful. The databall also contains a disquieting message about his son, Paul.

But it’s time to go back down, far below to our girl. Look!

She’s toppled over sprawling on the ground.

A tepid commotion ensues among the bystanders. The consensus is she’s dead, which she disproves by bubbling a little. And presently she’s taken away by one of the superb ambulances of the future, which are a real improvement over ours when one happens to be around.

At the local bellevue the usual things are done by the usual team of clowns aided by a saintly mop-pusher. Our girl revives enough to answer the questionnaire without which you can’t die, even in the future. Finally she’s cast up, a pumped-out hulk on a cot in the long, dim ward.

Again nothing happens for a while except that her eyes leak a little from the understandable disappointment of finding herself still alive.

But somewhere one GTX computer has been tickling another, and toward midnight something does happen. First comes an attendant who pulls screens around her. Then a man in a business doublet comes daintily down the ward. He motions the attendant to strip off the sheet and go.

The groggy girl-brute heaves up, big hands clutching at body parts you’d pay not to see.

“Burke? P. Burke, is that your name?”

“Y-yes.” Croak. “Are you policeman?”

“No. They’ll be along shortly, I expect. Public suicide’s a felony.”

“. . . I’m sorry.”

He has a ’corder in his hand. “No family, right?”

“No.”

“You’re seventeen. One year city college. What did you study?”

“La—languages.”

“H’mm. Say something.”

Unintelligible rasp.

He studies her. Seen close, he’s not so elegant. Errand-boy type.

“Why did you try to kill yourself?”

T HE G IRL W H o W AS P L u GGED In 15

She stares at him with dead-rat dignity, hauling up the gray sheet. Give him a point, he doesn’t ask twice.

“Tell me, did you see Breath this afternoon?”

Dead as she nearly is, that ghastly love-look wells up. Breath is the three young gods, a loser’s cult. Give the man another point, he interprets her expression.

“How would you like to meet them?”

The girl’s eyes bug out grotesquely.

“I have a job for someone like you. It’s hard work. If you did well you’d be meeting Breath and stars like that all the time.”

Is he insane? She’s deciding she really did die.

“But it means you never see anybody you know again. Never, ever. You will be legally dead. Even the police won’t know. Do you want to try?”

It all has to be repeated while her great jaw slowly sets. Show me the fire I walk through. Finally P. Burke’s prints are in his ’corder, the man holding up the big rancid girl-body without a sign of distaste. It makes you wonder what else he does.

And then—the magic. Sudden silent trot of litterbearers tucking P. Burke into something quite different from a bellevue stretcher, the oiled slide into the daddy of all luxury ambulances—real flowers in that holder!—and the long jarless rush to nowhere. Nowhere is warm and gleaming and kind with nurses. (Where did you hear that money can’t buy genuine kindness?) And clean clouds folding P. Burke into bewildered sleep.

Sleep which merges into feedings and washings and more sleeps, into drowsy moments of afternoon where midnight should be, and gentle businesslike voices and friendly (but very few) faces, and endless painless hyposprays and peculiar numbnesses. And later comes the steadying rhythm of days and nights, and a quickening which P. Burke doesn’t identify as health, but only knows that the fungus place in her armpit is gone. And then she’s up and following those few new faces with growing trust, first tottering, then walking strongly, all better now, clumping down the short hall to the tests, tests, tests, and the other things.

And here is our girl, looking—

If possible, worse than before. (You thought this was Cinderella transistorized?)

The disimprovement in her looks comes from the electrode jacks peeping out of her sparse hair, and there are other meldings of flesh and metal. On the other hand, that collar and spinal plate are really an asset; you won’t miss seeing that neck.

P. Burke is ready for training in her new job.

The training takes place in her suite and is exactly what you’d call a charm course. How to walk, sit, eat, speak, blow her nose, how to stumble, to urinate, to hiccup—deliciously. How to make each nose-blow or shrug delightfully, subtly, different from any ever spooled before. As the man said, it’s hard work.

But P. Burke proves apt. Somewhere in that horrible body is a gazelle, a houri, who would have been buried forever without this crazy chance. See the ugly duckling go!

Only it isn’t precisely P. Burke who’s stepping, laughing, shaking out her shining hair. How could it be? P. Burke is doing it all right, but she’s doing it

THE BIG BOOK OF CYBERPUNK 16

through something. The something is to all appearances a live girl. (You were warned, this is the future.)

When they first open the big cryocase and show her her new body, she says just one word. Staring, gulping, “How?”

Simple, really. Watch P. Burke in her sack and scuffs stump down the hall beside Joe, the man who supervises the technical part of her training. Joe doesn’t mind P. Burke’s looks, he hasn’t noticed them. To Joe, system matrices are beautiful.

They go into a dim room containing a huge cabinet like a one-man sauna and a console for Joe. The room has a glass wall that’s all dark now. And just for your information, the whole shebang is five hundred feet underground near what used to be Carbondale, PA

Joe opens the sauna cabinet like a big clamshell standing on end with a lot of funny business inside. Our girl shucks her shift and walks into it bare, totally unembarrassed. Eager. She settles in face-forward, butting jacks into sockets. Joe closes it carefully onto her humpback. Clunk. She can’t see in there or hear or move. She hates this minute. But how she loves what comes next!