‘A magnificent achievement’ ROBERT MACFARLANE

‘A magnificent achievement’ ROBERT MACFARLANE

Also by Lance Richardson

Lance Richardson

Chatto & Windus, an imprint of Vintage, is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

Vintage, Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London sw11 7bw

penguin.co.uk/vintage global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in Great Britain by Chatto & Windus in 2025

First published in the United States of America by Pantheon Books in 2025

Copyright © Lance Richardson 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

This book is a work of non-fiction. Some names have been changed to protect the privacy of others.

The illustration credits and permissions on pp. 711–15 constitute an extension of this copyright page

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d02 yh68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

hb isbn 9781784743017

tpb isbn 9781784743024

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

To Donna and Murray, who always put us first; and to Theo, who made this possible

A pilgrimage distinguishes itself from an ordinary journey by the fact that it does not follow a laid-out plan or itinerary, that it does not pursue a xed aim or a limited purpose, but that it carries its meaning in itself, by relying on an inner urge which operates on two planes: on the physical as well as on the spiritual plane. It is a movement not only in the outer, but equally in the inner space, a movement whose spontaneity is that of the nature of all life, i.e. of all that grows continually beyond its momentary form, a movement that always starts from an invisible inner core.

—Peter Matthiessen 1

19. New Teachers

20.

21.

22. Ten Thousand Islands

23. Muryo Sensei

24. The Watson Years

25. Homegoing

There was a moment during the writing of this biography when I thought I might be in serious trouble. We had taken our time climbing to Shey Gompa, a Tibetan Buddhist monastery in the shadow of the Crystal Mountain, high in the Himalayas of Nepal, but my body had refused to properly acclimatize. As we ascended to a pass at 17,550 feet above sea level, I’d started finding blood in my nose, and developed a dry cough and chest rattle that suggested, a doctor later told me, the onset of pulmonary edema. Sitting alone at night in my tent near the monastery, I could count the minutes between coughing fits that left me doubled over, aching from the strain. Tomorrow we would need to leave Shey earlier than anticipated (after years of planning, after coming so far) to rapidly descend, retracing a path through the mountains that few foreigners had ever followed, though hundreds of thousands have read about it in a remarkable book.

I first discovered The Snow Leopard, by Peter Matthiessen, in my midtwenties. A friend lent me her beat-up Penguin paperback, and I opened it expecting to learn something about a part of the world, with its vast snowcapped peaks, that I had always found hard to imagine while growing up in hot, flat Australia. The book took the form of an expedition journal, and it began conventionally enough: “In late September of 1973, I set out with GS on a journey to the Crystal Mountain, walking west under Annapurna and north along the Kali Gandaki River, then west and north again, around the Dhaulagiri peaks and across the Kanjiroba, two hundred and fifty miles or more to the Land of Dolpo, on the Tibetan Plateau.”1 But then the book made an unexpected turn. While Matthiessen was accompanying a field biologist, George Schaller, to study the Himalayan blue sheep in its natural habitat, he described this scientific survey as “a true pilgrimage, a journey of the heart.” Matthiessen’s wife had recently died of cancer, and he seemed to be using the expedition as an opportunity to search for something more elusive, a kind of enlightenment. Reading on, I found crystalline descriptions

of landscapes, wildlife, and environmental change—receding glaciers—that now sound like early warning signs we had chosen to ignore. But I also found digressions into Zen Buddhism, mystical experience, and “a primordial memory of Creation.”2

What struck me about The Snow Leopard is the same thing, I think, that has struck so many readers over the past five decades that the book has attained the status of a modern classic. It is steeped in science and spirituality; Matthiessen moves between these seemingly incompatible modes of thought with startling ease. Sentences grounded in empirical observation— “the basio-occipital bone at the base of the skull is goatlike, and so are the large dew claws and the prominent markings on the fore sides of the legs”3— share space with ecstatic declarations like: “I know this mountain because I am this mountain.”4 At one point, he uses geology to explain the formation of Phoksundo Lake, then immediately offers another explanation involving an enraged Bon demoness. In the journal entry for November 4, while performing a sutra chanting service in front of a Buddha statue, he pauses his ritual to identify a bird: “the bill is slim in a pale-gray head, and it has a rufous breast and a white belly. This is the robin accentor (Prunella).”5 He draws on ecology, divinity, ornithology, metaphysics, sometimes in the same paragraph.

There is an interview online where Matthiessen can be seen discussing, with Betsy Gaines Quammen, what he calls the relative and absolute. “The relative would be the scientific,” he explains, and the absolute would be “traditional” forms of knowledge, like religion and myth. Raising his arms above his head and extending his fingers, he describes the two like “arrow points that touch high in the air”: “It’s a wonderful idea, I mean, the delicacy of that—they are together, but they’re also separate.”6 It seems to me that a great deal of The Snow Leopard exists at that delicate touching point. We live in a time of diminishing vocabularies. The English writer and naturalist Helen Macdonald recently lamented the limits of our “secular lexicon,” which comes up short when dealing with the numinous or sublime, “times in which the world stutters, turns and fills with unexpected meaning.”7 Yet Matthiessen attempted to overcome this limitation in The Snow Leopard, a work of voracious open-mindedness. There is something Thoreauvian in the book’s reach; Henry David Thoreau, as Philip Hoare has observed about Walden, sometimes spoke “with the voice of angels, sometimes with earthbound science.”8 Refusing to limit himself to a single register, Matthiessen used a syncretic language to explain what he saw and experienced in the mountains of Nepal. In a lecture given the same year The Snow Leopard was published (1978), he suggested this approach was vital to his life: “As [Archie Fire] Lame Deer says, white man sees only with one eye. What he means,

I think, is that the white man sees only the reality before his eye. Just one description of the universe.”9 A more holistic description was needed, Matthiessen insisted, “if we are going to survive.” He said this as a longtime observer of the violence being inflicted by humanity on the natural world. He understood that our “fragmented and compartmentalized” culture was condemning us all to a grim future.

I found The Snow Leopard thrilling on that first read. I still find it provocative for the possibilities it suggests about thick, layered descriptions that draw just as much from Indigenous knowledge, or spiritual traditions, as they do from the sciences. You could call Matthiessen a poet-scientist; the mystical naturalist. He had blind spots, of course, but his way of seeing tended to be bold, capacious, and hopeful. I initially set out to write this biography because I wanted to understand how he evolved that enviable sensibility. Where did he start, and where did his journey take him? Did he ever find the enlightenment he’d gone looking for in the Himalayas?

thE GEnERAtion oF American writers who came of age during World War II and its atomic aftermath was an extraordinary one: James Baldwin, Truman Capote, William Gass, Norman Mailer, Flannery O’Connor, James Salter, Gore Vidal, Richard Yates. William Styron, another prominent member, once remarked that his cohort was “the most mistrustful of power and the least nationalist of any generation that America had produced.”10 That certainly describes Peter Matthiessen, though in most other respects he stood apart from his literary peers.

He was best known as a nature writer, publishing fifteen books of finetuned prose about shorebirds and great white sharks, Antarctica and East Africa. He was an elegist, penning funereal laments for disappearing species, and a polemicist angry that a species should ever disappear. By the time the modern environmental movement gained momentum in the 1960s, he had already documented a continent’s worth of human abuses in Wildlife in America. Matthiessen’s work, as Bill McKibben has noted, constitutes “key parts of the canon of emergent environmental writing in the twentieth century.”11 Barry Lopez, responsible for significant additions to the canon himself, once wrote Matthiessen a humble fan letter: “I have been reading you since I was in high school, and if one has distant mentors you certainly have been one for me. . . . I don’t wish to make you self-conscious, but these things, these courtesies of spiritual indebtedness are not often enough observed. I wish simply to state my gratitude, and my pleasure that you write.”12

Matthiessen actually resented being labeled a nature writer, even, as Styron put it, “the finest writer on nature since John Burroughs.”13 All those

nonfiction books were, by his own estimation, second-tier achievements. He insisted on identifying as a fiction writer—“I think fiction is the heart of my work”14—responsible for prize-winning novels about missionaries, Caymanian turtle fishermen, frontier outlaws in the Florida Everglades.

Yet the novels were only another fraction of what he got up to in his eighty-six years. He cofounded, while an undercover agent for the fledging CIA, a little magazine called The Paris Review. A few years later, he floated through Peru on a balsawood raft searching for a prehistoric fossil in the Amazon rainforest. He was a member of the 1961 Harvard-Peabody Expedition to Netherlands New Guinea—the one preceding the unsolved disappearance of Michael Rockefeller. He established himself as a strident social activist alongside Cesar Chavez, and then again with the American Indian Movement. His incendiary book defending Leonard Peltier, In the Spirit of Crazy Horse, triggered two long-running libel suits adding up to more than $49 million. There was also his yeti and bigfoot fixation: Matthiessen spent decades hunting for irrefutable proof in forests and swamps, and even convinced The New Yorker to briefly fund his adventures in cryptozoology. The list could go on, though perhaps it should end with his commitment to Zen, so ardent that he ultimately became a roshi in a spiritual lineage said to stretch all the way back to the Buddha.

“People are always asking me to introduce them to Peter Matthiessen,” James Salter once said at a literary conference, “but the thing that is hard to know is which Peter Matthiessen they would like to meet.”15

Many have tried to capture him in a few pithy words. “A traditional earthbound explorer in the space age.”16 “A cross between Solzhenitsyn and Scott of the Antarctic.”17 “A kind of Thoreau-on-the-Road.”18 “The Man of Experience who has Done It All.”19 Maybe “the only writer to have ever won the National Book Award for both fiction and nonfiction” counts as another often used example. The editor Terry McDonell once compiled a list of applicable titles for Matthiessen (boat captain, shark hunter, LSD pioneer . . .), then threw up his hands in exasperation: “It seemed as if what I had written was for a sixth-grade report, trying too hard not to miss anything— a list impossibly naïve in its comprehensiveness. Peter wasn’t there at all.”20

Peter, it should be said, did not make himself easy to find. He was a tangle of contradictions. Though he was rightfully renowned as a vocal champion of Indigenous rights, his attitudes around race and “the Indian” were sometimes complicated. He could be incredibly supportive of other writers, women writers, Native American writers; he could also be brutal if a writer’s work failed to reach his own high standards. He once wrote to the poet and novelist Jim Harrison, after reading a manuscript for Legends of the Fall:

“why do you settle for this prime-time media mock-up tough-sensitive winetasting hard-fucking killer-killing Hemingway cum James Bond spitback who infests all three stories to one degree or another?”21 Matthiessen would never settle. But nor would he tolerate such blunt criticism himself; he had a fragile ego for a Zen priest who liked to preach that ego is just an illusion. Friends often felt they were only ever afforded glimpses of his inner life. His three wives, each subjected to a degree of misogynistic disregard, felt the same way. To his children he was a confusing parent, frequently absent for weeks or months at a stretch. “I love my kids, they’re wonderful and they’re a great blessing to me, but I don’t necessarily think I should have had children,” he confessed to the writer and filmmaker Jeff Sewald in 2006, before cutting himself off with an embarrassed laugh as he realized what he had just said on camera.22

Matthiessen was absent because he was always doing something somewhere far-flung: battling the Tellico Dam in Tennessee; interviewing Cree elders in Manitoba; observing cranes in the Korean Demilitarized Zone. There are few figures in American letters who led such an eventful life during the past hundred years. So why is he less famous than other writers of his generation? A case could be made that his work was too idiosyncratic, too niche—those novels written in Caribbean dialects and backcountry cracker slang—for a mainstream readership. And that is certainly part of it. But a more notable reason might be Matthiessen’s refusal to fit into tidy boxes. He was, and remains, impossible to categorize. He wrote about too many different things, in too many disparate styles. As Pico Iyer put it for Time in 1993: “he juggles so many balls that it’s hard for his audience to follow the high, clear arc of any one.”23 Matthiessen knew this was a handicap. He once complained to Jim Harrison (who thought his friend deserved the Nobel Prize in Literature), “Sometimes I think I make the New York critics very uneasy because they can’t place me, and they kind of wish I would go away, or at least stick to nature writing where I belong.”24

oF All thE pEoplE who have struggled to get a handle on Peter Matthiessen, none have struggled more than Matthiessen himself. This is a major theme in The Snow Leopard:

Upstream, in the inner canyon, dark silences are deepening by the roar of stones. Something is listening, and I listen, too: who is it that intrudes here? Who is breathing? I pick a fern to see its spores, cast it away, and am filled in that instant with misgiving: the great sins, so the Sherpas say, are

to pick wild flowers and to threaten children. My voice murmurs its regret, a strange sound that deepens the intrusion. I look about me—who is it that spoke? And who is listening? Who is this ever-present “I” that is not me?25

Matthiessen hoped to shed his ego in the Himalayas, thus apprehending “what Zen Buddhists call our own ‘true nature.’ ”26 Yet this pilgrimage would take far longer than the two months he spent walking to and from Shey Gompa; it would take his whole life. As a young child growing up in gilded circumstances, he felt a fundamental conflict between the “Peter” he thought he was and the “Peter” his patrician parents expected him to be. As an old man nearly nine decades later, he wondered what would endure once the “I” was finally extinguished by death. In between those points, obsessing over ontological questions about being and existence, he yearned to “simplify,” to regain a “lost paradise,” which often took the form of an imagined “island” where he could dispense with responsibilities and be his original self. This inner journey determined the choices he made throughout his long life; it is the string on which the various beads of his career were strung. It is also the organizing focus of this biography.

I began my research in late 2017, a little more than three years after Matthiessen died of acute myeloid leukemia. He remained a vivid presence for family members, friends, colleagues, neighbors, lovers. I conducted more than two hundred interviews, and some of these people shared correspondence that had not yet entered archival collections. Matthiessen’s first serious girlfriend produced an enormous pile of letters sent by him from Pearl Harbor in 1945 and ’46. Maria, his widow, granted access to two boxes filled with intimate notes spanning four decades, along with a hard drive containing an unfinished memoir and confessional CIA notes. One woman even opened a silver locket and tweezered out a tiny oval photograph: Peter on horseback, aged nineteen. She no longer needed the memento of her distant past.

The Peter Matthiessen Papers are housed at the Harry Ransom Center, which is part of the University of Texas at Austin. Nearly half the material had yet to be catalogued when I started sifting through what now fills 227 document boxes. It took me eleven months just to photograph the moldy typescripts and almost indecipherable journals. Any biography is a mammoth commitment, but few take a biographer to places as disparate as the Hamptons, an Indian reservation, a bird sanctuary, mosquito-infested swamps, and a Zen monastery for days of sutra chanting and zazen on a black cushion.

In May 2022, I set out with Gavin Anderson, a Scotsman who runs an ethical trekking company called Nomadic Skies, and James Appleton, an English photographer, to walk from Juphal to Shey Gompa, the Crystal Monastery

in Nepal, one of those “lost paradises” where Matthiessen found a fleeting sense of contentment. We were joined by two guides, Dawa Gyalpo Baiji and Nurbu Lama, and four local men who organized the kitchen tent and minded our pack animals. As our expedition trudged through dusty gorges and along hair-raising cliffs, I noticed how much had changed since Matthiessen and Schaller had come this way in 1973—everything from the blue tin roofs that now decorated villages to the villagers’ economic dependence on yarsagumba, a caterpillar fungus dug out of alpine meadows and sold to Chinese merchants as a potent aphrodisiac. But I was also amazed at how much had not changed. There were times when Matthiessen’s description of a hermitage, or a shallow cave off the trail, rang with the rightness of a struck bell.

Though I would gradually recover my health as we descended from the mountains, that evening up at Shey Gompa when I was plagued by coughing fits was an alarming experience for everyone, my companions listening to the painful cacophony from their own tents. I slipped into my thermal sleeping bag and tried to steady my breaths. As a distraction, I opened a copy of The Snow Leopard that showed, on its cover, the same monastery bluff where we were presently camped. I had read the book so many times that I knew passages by heart, but now I let Matthiessen read it to me. In 2012, toward the end of his life, he’d recorded an abridged audiobook, which I had also brought on the trek; his deep, gravelly voice was a ghostly echo in this “spare, silent place”27 he had once loved.

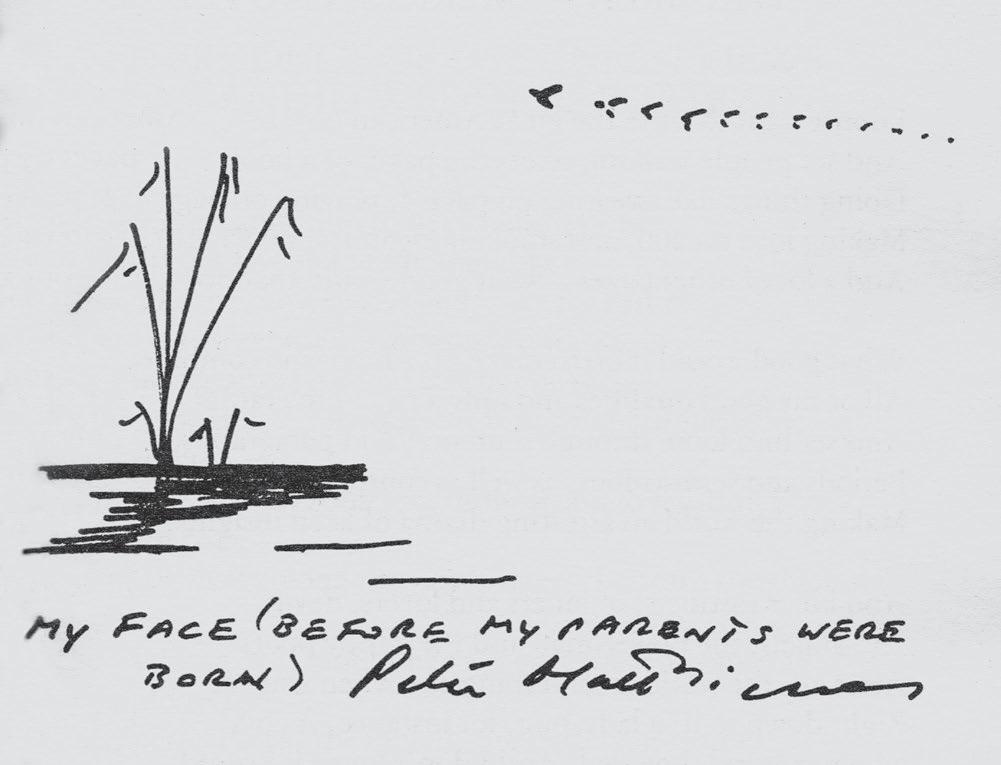

Once asked for a self-portrait to be published in The Paris Review, Matthiessen offered his “original face,” a sly reference to a famous koan (Case 23) from the Mumonkan.

Nothing begins the way we think we see it, there is no real beginning or end to anything, all is memory and change and process. Everything is right here now, remember?

—PM, untitled teisho (September 26, 2000)1

FoR FoUR dECAdEs, whenever he wanted to write, Peter Matthiessen stepped through the back door of his house in Sagaponack, on the East End of Long Island, walked past a grove of apple trees that had never borne edible fruit, and unlocked an ivy-covered shack that was once a child’s playhouse. Inside, a musty smell emanated from rough-hewn woodwork— the long L-shaped desk, which took up most of a small room. Drawers were full of maps, magazine clippings, well-thumbed drafts, and the walls were flaking with pictures of his wife, his friends, the Dalai Lama, the Sasquatch. Somebody had sent him a copy of The Snow Leopard that had been ceremonially burned in the Himalayas; he kept the ashes pinned above the desk in a Ziploc bag. A window ledge nearby functioned as a kind of altar, cluttered with mementos charged with talismanic significance: slate from the Klamath River; a dried snake found on a beach in Baja; a carved praying mantis nose ornament acquired from a tribe in Netherlands New Guinea. Outside, visible through the window, a small stone Buddha meditated on a tree stump. For all those years, Matthiessen had come to his office almost every day he was home and worked for up to twelve hours straight. He’d emerged to eat lunch, prepared by his wife, Maria, and then gone back inside again. He’d come out for dinner, also prepared by Maria, and then, if the words were flowing, returned to his desk. Interruptions and social calls were mostly forbidden. A small sign near the door demanded silEnCE. To be in his office was to be projecting himself somewhere far away: Lake Baikal, or Mongolia, or the Selous Game Reserve in southern Tanzania. His writing studio was a sanctuary and an escape hatch—until the mold began to colonize his files,

and until the cancer, blooming in his bones, made those mental wanderings increasingly difficult, stranding him in a chemo fog.

Twenty days before his death at the age of eighty-six, Matthiessen switched on a computer that had been hastily relocated to a spore-free bedroom in the main house. He stumbled through a maze of poorly organized drafts, searching for the latest iteration of his memoir. “I don’t think I’m going to have time to do it,” he’d told a journalist a few weeks earlier.2 Now he was sure.

The Word document was fifty-eight pages long, nearly 23,000 words. Structureless and rough, much of it was comprised of words to jog various recollections, and questions to himself that still needed answers. But the first half concerned his childhood, and here he’d managed to get down some detailed vignettes. In a roundabout way, tentative as he pulled all the pieces together, these fragments were an attempt to portray a transition he’d been talking about since his embrace of Zen in the early 1970s. A young child is “a part of things,” Matthiessen once wrote, “unaware of endings and beginnings, still in unison with the primordial nature of creation, letting all light and phenomena pour through.” This state of innocence, as most people might call it, in which no boundary is perceived between the leaves, the trees, and the stars in the sky, is inevitably lost as “the ‘I’ begins to form.”3 Children come to understand their “selves” as something separate— apart from, rather than a part of. And when that estrangement happens, they stop perceiving reality directly and instead enter a dream world of ideas and delusions. Much of Matthiessen’s life had been a concerted effort to wake up from the dream. But when had he fallen asleep? His memoir circled this universal mystery.

At the top of the first page, he typed: “ROUGH OUTLINE FOR A BIOGRAPHY (IF ANY).”4 This would be among the last edits he ever made. He left two suggested epigraphs to frame what remained: one from Jorge Luis Borges, about the mystery of writing; and another adapted from something once said to Paul Auster by the poet George Oppen: “Rickety old person peering into the mirror: What a terrible thing to have happened to a little boy!”5

FishERs islAnd is a ridge of low-slung hills, nine miles long and one mile wide, which sits in quiet solitude off the southeast coast of Connecticut. The waters surrounding it are treacherous, clotted with currents that form an unforgiving rip tide, and a lighthouse called Race Rock shines out above a reef to prevent any more shipwrecks. The island’s distance from the mainland—two miles as the shorebird flies, seven by ferry—can make it hard to see clearly across Long Island Sound even on a good day. But if there

is something mirage-like about the place, that is part of the appeal for the island’s residents: Fishers was never meant to be reached by most Americans.

In the spring of 1925, a notice appeared in The New York Times for the “Fisher’s [sic] Island Project.” Spearheaded by Alfred and Henry L. Ferguson, second-generation majority owners of the island, this million-dollar scheme promised “not only new golf links and a 300-room hotel but also a new wharf and harbor facilities for the use of pleasure yachts.”6 Fishers already had history as an elite summer resort: by the turn of the century it could accommodate more than a thousand visitors seasonally.7 That was limited, however, to a small settled section in the west, near the military installation of Fort H. G. Wright; the eastern two-thirds of the island remained virtually undeveloped, some 1,800 acres of rolling moors left to grazing livestock. The cows were now being evicted, and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. was drawing up plans for a real estate subdivision. Construction soon began on a country club in the style of a giant Norman farmhouse. In the words of a later promotional brochure, this club would offer everything from “quiet lounges where one may loaf away tranquil summer days, to gay entertainments with all the friendliness one can only hope to find among one’s own kind of people.”8

Peter Matthiessen was born at Miss Lippincott’s Sanitarium, in New York City, on May 22, 1927—two years after the Fishers Island Project was announced, and just one day (as he liked to point out) after Charles Lindbergh had flown across the Atlantic in the Spirit of St. Louis.9 Miss Lippincott’s combined the attentiveness and security of a hospital with the conveniences of a luxury hotel, which is why it was frequented by Sloanes, Prestons, Benjamins, and Rockefellers.10 Elizabeth Matthiessen—“Betty”— stayed as a guest for two weeks. Then she checked out with her baby to join Erard Adolph Matthiessen, Peter’s father, for a drive up to New London, where the three of them boarded the white SS Fishers Island to ferry back down across the state line. (Though Fishers Island is closer to Connecticut and Rhode Island, it is technically part of Suffolk County, New York.) Once ashore, they glided past a security gate that barred outsiders from the east end. Their driveway, snaking out of sight into a stand of trees, would one day be marked with the wrought iron silhouette of a Native American man, salvaged from an antiques store as an eye-catching signpost.

The Matthiessens had a longstanding family connection to Fishers: Erard’s aunt and uncle had bought a place in the older section sometime before 1913.11 Perhaps this was why “Matty,” as Erard preferred to be called, became a paying member of the new club not long after the roll was opened.12 Fortified with immense wealth, he felt comfortable settling his family in a place where “phone book” was a synonym for the Social Register. On Fishers, adults were served tea and cinnamon toast in a bathing pavilion

on Chocomount Beach; they attended parties at the Big Club, as it came to be known, while the children learned how to swim, play tennis, or sail small boats at “their club,” the Hay Harbor.

Peter would dwell in this rarefied milieu for most of his first fifteen summers, and the privilege inevitably leached into his self-understanding, his attitude toward others, his sense of class differences, even his manner of speaking and the words he used. Yet there was another aspect of Fishers that would prove far more influential for a sensitive child just opening his eyes to the world: its extraordinary natural splendor.

The vacation house that Matty designed and built for his growing family was two stories, clad in cedar shingles, with window boxes for geraniums and a screened-in porch full of heavy wicker furniture. The bedrooms were upstairs, and a separate servants’ cottage sat opposite the kitchen door. Behind the house, twin paths meandered down a slope covered with myrtle and blackberry thickets, until they terminated at a private beach, little more than a crescent of kelp-encrusted sand, which faced the distant shore of Connecticut. Here, as Peter wrote in his memoir notes, he would “sit mystified by the water’s unaccountable retreat just as it touched the entrance channel into my sandcastle.”13 Rockpools swirled like miniature galaxies at either end of the beach: he and Carey, his brother, “hunched like night herons,” coaxed out crabs using broken mussel shells as bait. And then there were the birds: osprey, flycatchers, wood-warblers, plovers. Sometimes they used a decoy great horned owl, mounted on a pole on the island’s highest hill, to tempt the hawks migrating south from Canada. It was wildness that animated many of Peter’s earliest memories of “home,” as he liked to call Fishers—untamed creatures, mercurial ocean, the island as a prelapsarian Eden:

The sounds and odors and queer lights at evening are baked in, the sea wrack on white sand . . . body-surfing small waves coming fresh from the Atlantic . . . fishing for tautog and cunner from the old East Harbor dock near the Coast Guard Station; trolling for big bluefish in the Race.14

When Peter was twelve or so, Matty began taking him on boat trips from Fishers down around the promontory of Montauk Point, where the Gulf Stream washes in weakfish, bonito, striped bass, mackerel, and white marlin during the warmer months. Once they counted eighty dorsal fins on a single expedition, a shiver of sharks drifting through “all that emptiness.” Because Peter was a weak adversary against anything of size (“my twiggy arms”), he left the fishing rods to his father’s friends and mounted the cabin roof so he could survey the oily swell through binoculars. One day he spotted his first pelagic whales this way: finbacks, or maybe humpbacks, spouting mist

in the distance. “I was so excited,” he wrote in his notes, “that I never bent my knees to maintain balance in the slow rolling of the boat.” Peter started to pitch overboard, and he would have gone were a seasick guest not alerted to his “cry of doom.” Henry Pelham-Clinton-Hope, the Earl of Lincoln, reached out and grabbed the boy at the last moment.15

“no woRd ConVEys the eeriness of whale song,” Matthiessen wrote in Blue Meridian, “tuned by the ages to a purity behind refining, a sound that man should hear each morning to remind him of the morning of the world.”16 Yet his own Danish forebears were whalers from the Frisian Islands in the North Sea—and not only whalers, but owners of a whaling school that trained others in the art of maritime slaughter. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, their center of industry was Før, or “Föhr,” a stray speck of Denmark, located off the west coast of Schleswig, which had once been colonized by Vikings. Despite a small population, this bucolic island of maize crops and sleepy hamlets was renowned for producing seafarers of exemplary daring; Dutch whaling ships dropped anchor to recruit workers on the way to Arctic fishing grounds.

One of the best was a man named Matthias Petersen, who was just sixteen when he went to work as assistant mate on a ship belonging to a Hamburg merchant. Within a few years, Matthias’s talents had elevated him to commander of his own whaling vessel.17 Uncanny good luck—fourteen whales on a single voyage out of Amsterdam—soon earned him a nickname: Matthias der Glückliche, “Matthias the Fortunate.” While the luck would eventually run out, with Matthias being attacked by French privateers, by the time of his death in 1706 he’d hunted “373 balenas”—an “incredibili successu” that was immortalized in Latin on his gravestone.18

In addition to the wealth based on oil and baleen, Matthias bequeathed two other gifts to his descendants. The first was a coat of arms: Goddess Fortuna, to whom he attributed his “successu,” balancing on one leg above a spouting whale. (Peter would dismiss this as a “truly unfortunate artistic juxtaposition.”)19 The second gift was a surname. Following a custom of patronyms, part of Matthias’s name had been derived from his father: as the son of Peter Johnen, he was a Petersen. Matthias’s own sons were similarly named, and they would have been expected to pass on their own Christian names to the next generation. However, according to the family record, “the respect and reputation enjoyed by Commander Matthias rendered the retention of his name desirable.”20 Hunting all those bowheads had earned him considerable social capital, and his sons decided their own children ought to reap the benefits of association. The custom was therefore suspended. All mem-

bers of the clan, for all future generations, were henceforth anointed sens of Matthias—the Matthiessens.

That an outspoken conservationist should carry such a bloody legacy in his own surname was an irony not lost on Peter. “I’ve been cleaning up after it my whole life,” he once remarked wryly at a public lecture, casting his long environmental record as one of atonement.21 Yet he found the association exciting, too. When the artist Paul Davis presented him with a portrait of himself styled as Captain Ahab, the ultimate whaler who seeks something both tangible and symbolic “over all sides of the earth” (“What say ye, men, will ye splice hands on it, now? I think ye do look brave”),22 Peter hung the drawing in his house, stirred by the likeness.

by thE tiME Peter was born, more than two hundred years had elapsed since the halcyon days of Matthias Petersen. To claim that the Matthiessen fortune “was made in whaling,” as Peter sometimes did, is a romantic edit of history.23 For his immediate family, it was more accurate to say that the Matthiessen fortune was made by three brothers who had emigrated to America in the middle of the nineteenth century. They came from Altona, a small town on the Elbe, just west of Hamburg, which is 120 miles from Föhr.

Ehrhard Adolph Matthiessen (five generations after Matthias) fled the First Schleswig War, which saw Denmark and the German Confederation fighting over control of Schleswig and Holstein. In August 1850, at the age of twenty-five, he arrived on the SS Asia, a sleek Cunard paddle steamer that paced the Atlantic between Liverpool and New York. Though an astronomer by training, Ehrhard turned his hand to a more lucrative profession in Manhattan, joining the banking house of German American financier August Belmont. During the Civil War—having escaped one conflict, he soon became witness to a larger one—Ehrhard was appointed the firm’s managing head, then worked his way up to become a director while he was still the youngest clerk in the company. Meanwhile, his brother, Franz Otto Matthiessen, had arrived sometime around 1857. Franz went into the sugar business. He found employment as a superintendent at refineries in New York and Boston, then built his own, Matthiessen & Wiechers, across the Hudson River in Jersey City. Eventually this would merge into a sprawling national conglomerate, the American Sugar Refining Company, later known as Domino Sugar, and Franz, “considered by those in the business as knowing it as few others ever did,” would amass a personal fortune of up to $20 million—more than half a billion dollars today.24

The third and youngest of the three brothers, Frederick Wilhelm Matthiessen, also arrived in 1857. His métier was zinc. After studying mining in

Freiburg and graduating as an engineer, he traveled to America with a fellow student, Edward C. Hegeler,* and began scouting for opportunities beyond the East Coast. They ended up in La Salle, Illinois, an important trading hub where canal boats from Chicago, ninety-six miles away, met steamboats traveling up from New Orleans, and where the new Illinois Central Railroad chugged through on its route from Cairo to Galena. Here on the bank of the Little Vermilion River, they cofounded the Matthiessen & Hegeler Zinc Company, which smelted Wisconsin ores using Illinois coal. A few years later, in 1862, “demand for zinc in ammunition provided a ready market for the plant output”—a company-handbook way of saying that business boomed by selling bullets to both sides in the war.25 A rolling mill and sulfuric acid plant were added afterward, further enhancing profits. Frederick would try his hand at other pursuits over the years—mayor of La Salle; investor in alarm clocks—but these industrial works stood as his signature achievement.†

Frederick had a daughter, Eda Wilhelmina Sophie Matthiessen. Ehrhard had a son, Conrad Henry Matthiessen. In 1888, she was twenty-two years old, and he was twenty-three. First cousins, they nevertheless married in Cornwall-on-Hudson, New York—a union that was either strongly encouraged or strategically arranged to inaugurate a kind of Matthiessen dynasty in America.26 The newlyweds each funneled part of the financial holdings of their powerful fathers; additionally, through their shared uncle Franz, Conrad would hold various executive roles in the glucose industry. “He received $75,000 a year,” a newspaper later reported about one of these positions, “and at the time was regarded as the highest salaried official of any industrial concern in the country.”27 The marriage kept all this wealth in the family.

Eda and Conrad had something in common as the children of immigrants: they both lived in the overlap of two cultures. Eda was born in the Midwest, and she learned all the social graces expected of a young American lady; yet she also spoke German with her maids, adored Wagner and Beethoven, and

* In addition to his work with Frederick Matthiessen, Edward Hegeler also founded the Open Court Publishing Company, which sought to reconcile science and religion through open dialogues. In 1893, during the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago, the managing editor of Open Court (and Hegeler’s son-in-law), Dr. Paul Carus, invited a formidable Japanese man named Soyen Shaku to make a side trip to the company’s headquarters in La Salle. Soyen Shaku, who allegedly once said of himself, “My heart burns like fire but my eyes are as cold as dead ashes,” was the very first Zen roshi to travel and teach in America. He would one day be described as the ancestor of American Zen. Peter Matthiessen liked to speculate that an encounter between Soyen Shaku and Frederick, as Hegeler’s business partner, “almost certainly took place” on this landmark visit—an early family brush with a tradition that would one day define the shape of his own life. Nevertheless, such a meeting was at best “unpromising,” Peter had to admit, “since it passed unrecorded in the annals on either side.”

† Matthiessen & Hegeler is now a Superfund site. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency placed it on the National Priorities List in 2003, having found elevated levels of cadmium, lead, and zinc in the soil, along with traces of pesticides and solvents. According to the EPA, a slag pile on the steep west bank of the Little Vermilion River poses “major environmental concerns.”

insisted on elaborate Bavarian Christmases—a five-foot-long centerpiece of Sankt Nikolaus and his reindeer, “hand-wrought of mahogany and bone, and restaged each year with cotton-and-mica snow.”28* Conrad was born in Cornwall, yet his father sent him abroad for school in Wiesbaden, then on to the Collège de Genève, before he was brought back to finish off what Nelson Aldrich Jr. once called the “curriculum” of American blue-bloods, meaning the right college (Yale) and the right affiliations (Sigma Delta Chi).29

An overlap of cultures was where the similarities ended, however. In temperament and personality, Conrad and Eda were a poor match from the start. To illustrate exactly how poor, Peter enjoyed recounting a story about Eda, who was his grandmother:

[A]s a simple precaution, it is said, my grandfather [Conrad] had this good young woman followed by a private detective from the day of their marriage to the day of their inevitable divorce, many years later. (It is related in the family that my grandmother turned around one day on Madison Avenue to confront a little man, saying, “You have been following me, unless I’m very much mistaken.” The embarrassed Pinkerton confessed that he had been following her for eight years and was deeply ashamed of it, whereupon she said, “There, there,” and took him into Longchamps for an ice cream soda.)30

This is probably apocryphal, or at least exaggerated, but the underlying dynamic is accurate enough. Eda was sharp, sympathetic, and unfailingly proper. Her grandchildren—who called her “Muttie,” from Mutti, German for “Mom”—would recall her as bountifully generous: concert seats at Carnegie Hall, “where the fierce baton of Arturo Toscanini would whip the New York Philharmonic to a brilliant froth,” and gifts of rare stamps hailing from “crown colonies in turquoise southern seas.”31 Conrad, on the other hand, was mostly absent from the family narrative, and the few surviving traces of him in public records refer almost exclusively to business exploits, including conspiracy, antitrust, and bilked stockholders.32

After the wedding, Conrad and Eda settled in Chicago, in the affluent neighborhood of Kenwood. Servants outnumbered family members at a red-brick mansion on Ellis Avenue, and this would continue to be the case as the family expanded. Ralph Henry came first, followed by Conrad Henry,

* This ornate construction went up in smoke during the Christmas dinner of 1941, a dramatic event begun by a fallen candle that Matthiessen would fictionalize in his short story “The Centerpiece”: “In the chaos of motion and voices I saw Madrina [i.e., Eda], the only person still seated, observing the destruction as if the ruin of this antiquated treasure was somehow fitting, as if she sensed that, like the tapestries and urns, it was far too venerable and vast to serve the New World Hartlingens [Matthiessens] again.”

followed by Constance Eda, followed by Erard Adolph, named after his paternal grandfather, on May 27, 1902.

The same month that Erard—as in Matty, Peter’s father—was born, Conrad made a substantial purchase back east in Irvington-on-Hudson, a village twenty miles north of New York City. Named in honor of Washington Irving, who died there in 1859, Irvington had started life as four adjoining tenant farms belonging to a Dutch slaveowner who used his land as a provisioning plantation; more recently, the farms had been transformed into sprawling estates for industrial tycoons, plus a small community of servants. Prominent residents had included Cyrus West Field, who installed the cable across the Atlantic seabed; Amzi Lorenzo Barber, “the Asphalt King,” who paved the streets in dozens of American cities; and Franz Otto Matthiessen, who became a recluse there after an unexpected tragedy.33

Franz had bought a slice of Irvington with the intention of leaving it to his only daughter, Helen. But then Helen died of acute appendicitis during a visit to Italy—a shock so enormous that Franz repatriated her body and, according to a news report, kept it locked up in his home for months, “refusing to have it interred.” When Franz had finally died himself in 1901, from diabetes, one of his closest friends told the press that “he was sure Mr. Matthiessen’s death was precipitated by a broken heart.”34 Conrad bought the plot of land adjacent to his late uncle’s estate: Tiffany Park, which had previously belonged to Charles Lewis Tiffany of Tiffany & Co. Two months after the sale, Franz’s widow conveyed the land originally intended for Helen to Conrad and Eda, thereby uniting neighboring addresses into a single sprawling plot. This is how the Matthiessens came to own an enclave of some sixtytwo acres, which they named Matthiessen Park.

in onE oF pEtER’s bEst short stories, “Lumumba Lives,” which he wrote in 1988, a retired CIA operative returns to the old family estate in Westchester County after living in Africa for more than two decades. The town is named Arcadia, and here “[h]is father’s great-uncle, in the nineteenth century, had bought a large tract of valleyside and constructed a great ark of a house with an uplifting view of the magnificent Palisades across the river.”35 Over the years, the great-uncle’s descendants had added “lesser houses”—still stately manors by most estimates—around the valley tract, and it was in one of these houses that the man had grown up. The estate has long since passed out of family hands when the story opens, but now the former agent intends to buy a piece back, to return to his roots and, by implication, to a time before his life became so complicated. He will “reassemble things—well, not ‘things’ so much as continuity.”36

Like many of Matthiessen’s fictions, this will all turn sour before the end of the tale, an explosion of violence denying the man’s longed-for retreat to an idealized boyhood. Yet much of the buildup consists of Proustian flashes, memories resurrecting as he strolls around a landscape he once knew intimately. Here is the gardener’s cottage, where he used to flee when his grandmother made her loathsome cambric tea. There are the train tracks where he’d once placed pennies so the face of “Honest Abe” would be squashed smooth by passing freight cars.

“Lumumba Lives” is a fictional response to an encounter Matthiessen once had with a mercenary pilot who likely helped in the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of the independent Republic of the Congo. (What if the man went home decades later, Matthiessen wondered, and was forced, in a supposedly safe space, to reckon with his role in colonialism?) But the setting and memories are fact: “Arcadia” is Irvington, and many of the man’s recollections belong to Matthiessen, which is why he copied out whole passages from the story into his memoir notes.

At the end of each summer, Betty and Matty closed up the house on Fishers Island and returned with the children to Matthiessen Park. From Broadway, a sinuous downhill drive ended in a carriage circle, where two weathered cannons stood sentinel by the front door. This handsome house of brick and stone—another of Matty’s constructions—had multiple chimneys, a light-filled sunroom (“The world has changed since a private house had a room designed for sun and dancing”),37 and a broad terrace in the rear from which one could watch the Day Line Alexander Hamilton steaming down the Hudson. Nearby were the other “lesser houses” owned by Matty’s brother, Ralph, and assorted friends like the “Littlers, Sweetsers, Robbinses, etc.”38 Thomas McConaughey, the Scottish gardener, lived in the cottage behind a tall privet hedge. One of McConaughey’s sons, also named Thomas, would become Peter’s childhood companion; they founded a boysonly club together in an old chicken coop, its sole purpose being to collect the weekly allowance of other young members as “club dues,” which they then spent at the confectionery on Main Street. The other McConaughey son, Jim, would one day become the family’s chauffeur.

MAtty MAtthiEssEn nEVER spoKE about his own early memories of Irvington. Conrad and Eda had relocated there from Chicago by 1903. That year, before Matty could walk or talk, his six-year-old sister Constance died for reasons that nobody recorded. In 1904, Eda then gave birth to another son, Matthies, who died after six days.

In the grim atmosphere of a double-bereavement, Matty was raised by

nannies. He would see his mother at dinnertime, his father more rarely. As an adolescent, he was sent away to Hotchkiss for four years of boarding school; meanwhile, his two surviving brothers, both considerably older, went off to fight in the Great War. By graduation, his parents’ marriage was approaching its inevitable denouement. It seems unlikely that they ever legally divorced, as Peter claimed, but Eda began spending much of her time down in Manhattan, in a luxurious eleventh-floor apartment on East 60th Street that looked over the horse broughams in Central Park South. Conrad stayed in Cornwall, or spent time in Kerhonkson near the Shawangunk Mountains. Eventually Eda would list herself as head of the household.

Peter once asked his father about the family background. Matty’s reaction was “somewhat bemused.”39 He was uninterested in dwelling on the past, perhaps because thinking about it was painful. Matty’s daughter, Mary (Peter’s sister), would come to suspect he’d suffered from bouts of depression in his childhood, though specifics with Matty were always impossible to excavate. He was one of those men who carefully avoid anything that might summon up strong, unwieldy emotions like anxiety or loneliness. “I had always thought that I possessed a certain armor to protect me from things such as this,” he wrote in a letter in 1977, stunned to find himself experiencing grief after the death of his wife.40 This “armor” was as much cultural as personal, and it manifested as a demeanor of insouciant ease: “Matty,” fitting over Erard like a sport coat.

Matty was described by Thomas Guinzburg, longtime president of the Viking Press and one of Peter’s closest childhood friends, as looking like “a Marine Corps master sergeant,” or like Burt Lancaster if the actor lost most of his hair.41 He had a “massive head that reminded you of the ancients,” another friend observed, and there was something “vaguely brutish” about his presence.42 Tall and imposing, he could intimidate when he wanted, but Matty was also a consummate host who liked nothing more than to socialize at parties or on one of his motorboats, rubbing shoulders with people who were susceptible to being charmed. Charm, that ambiguous power which allows one to attract others while also maintaining a protective distance, was something both of Peter’s parents wielded with expertise. “I didn’t say they were lovely,” Maria Matthiessen once clarified about her in-laws for a documentary filmmaker: “I said they were charming.”43

Matty met Betty at a Yale dance. He was studying for a Bachelor of Science at the Sheffield Scientific School, a middling student (Cs and Ds) who seemed to expend most of his energy on extracurricular distractions like St. Anthony Hall, a fraternity and literary society.44 Betty was working as a clerk in a New York department store, possibly Bonwit Teller; she had come up to New Haven on a visit with a friend. “She was a fabulous dancer,”

recalled Mary, “but god knows what she wore on her back because she didn’t have a penny.”45

Elizabeth Bleecker Carey was born on August 28, 1903. She lived with her family in Short Hills, New Jersey, in circumstances that her strict and rather dour mother might have described as genteel poverty, though they still had enough resources to employ a Black housekeeper named Addie McLeod. Betty traced her paternal ancestry to Reverend William Norvell Ward, who had once been the friend and confidant of Robert E. Lee. In 1842, Reverend Ward had acquired a Federal-style farmhouse between the Potomac and the Rappahannock Rivers, in Richmond County, Virginia, named Bladensfield, which would remain the family seat for generations (“our old place,” Peter once called it).46 From Bladensfield during the Civil War, Reverend Ward had offered support to another friend, Jefferson Davis, while two of his sons died fighting what a family history book called the “Yankee raiders.”47 After hostilities ended with the Wards on the losing side, they were left with “one silver quarter and a heap of Confederate money, now not worth a dime.”48 The eldest of the Reverend’s seven daughters, Martha Ward, soon moved to Baltimore, where she was widowed young and forced to make ends meet by taking in student boarders from Johns Hopkins. Martha’s son, George Carey—Peter’s grandfather—dreamed of returning to Bladensfield and transforming it into a prosperous farm, but his young wife vetoed that idea (too remote and dilapidated), so he settled for ill-suited odd jobs in her native New Jersey instead. This persuasive wife, Mary Seymour Jewett—Peter’s grandmother—traced her own roots back to white Anglo-Saxon Protestants such as Horatio Seymour, the eighteenth governor of New York, and a man Peter would come to admire for having championed the rights of Native Americans in the nineteenth century.* Mary Seymour Jewett had no money either, just unimpeachable Victorian values, which she used to rule the Short Hills home like a tyrant.

Betty attended the Ethel Walker School on scholarship. After that early leg up, however, the rest was left to her. Photographs capture her glamorous profile, long and lithe like a Modigliani painting. Her beauty was paired with a fluty laugh, an idiosyncratic sense of propriety—a name like “Emma” was, in her estimation, only fit for a servant—and a belief, also probably

* Governor Horatio Seymour was quoted by Helen Hunt Jackson on the title page of her book A Century of Dishonor (1881): “Every human being born upon our continent, or who comes here from any quarter of the world, whether savage or civilized, can go to our courts for protection— except those who belong to the tribes who once owned this country. The cannibal from the islands of the Pacific, the worst criminals from Europe, Asia, or Africa, can appeal to the law and courts for their rights of person and property—all, save our native Indians, who, above all, should be protected from wrong.” Matthiessen found this “unpopular opinion” deeply moving, and he would discuss Seymour at length in his own incendiary work, In the Spirit of Crazy Horse.

derived from her mother, that she was destined for a higher station in life. Betty made her debut in 1922. She did not go to college, though she would one day regret that decision as she strolled through Rome with a daughter who could tell her all the things she’d never learned. While she waited for what came next, she worked in the city and socialized at parties where people played games like the “peanut jab”: “With hat pins each player in turn jabs for a peanut until he misses, when the next one tries.”49

What ignited the spark between Betty and Matty? Here was another subject never discussed with the children. Matty was well-heeled; Betty had breeding and refinement; yet it was more than merely transactional. “She thought he was kind of a hoot,” said Jeff Wheelwright, their grandson. “He wasn’t a stuffed shirt. She liked that about him. I can see them in a room full of people on Fishers Island at a cocktail party, and he was the most relaxed, comfortable-in-his-skin fellow there. He was kind of a complete guy. Maybe too complete, because once the party was over, he was still being cool.”50

More than five hundred people attended the wedding. Performed by Reverend Malcolm Douglas at Christ Episcopal Church in Short Hills, the ceremony was held on October 11, 1924. Betty had seven bridesmaids; Matty’s best man was his brother, Conrad Henry Jr.51

The honeymoon, a two-month grand tour of Europe, began with a voyage to Southampton on the RMS Majestic, the largest ocean liner in the world, with a marble swimming pool and library containing some four thousand volumes. After excursions through England, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and Italy, the newlyweds concluded with skating and skiing in Switzerland. “Although it’s just been too perfect and we’ve had the most wonderful time,” Betty wrote to a cousin, both she and Matty were looking forward to seeing “the good old U. S. A. again,” where one didn’t need to unpack and repack “every five minutes.”52

As soon as they returned, Matty was admitted to Columbia University— an Avery Hall program that aimed to train architects who “fearlessly accept the modern problem; solve it in the modern way, but always conform to those elemental truths which have ever expressed that beauty and good taste which distinguishes all true art and has come down to us as our precious inheritance.”53 Betty had no desire to work now it was no longer necessary, so she joined committees and played bridge to raise money for the nearby hospital at Dobbs Ferry. She also began having the children: Mary Seymour was born eighteen months before Peter, on October 9, 1925; and George Carey (called “Carey” by all) was born fifteen months after, on August 15, 1928.

Lacking any example from his own upbringing, Matty struggled, by his own admission, to be “demonstrative” with his offspring.54 And while Betty kept an eye on them, she followed the example of her friends by delegating

the laborious child-rearing to nannies, preferring to prioritize the needs of her fickle husband instead. Leaving Mary, Peter, and Carey at home, they attended Sunday teas, tenpin bowling tournaments, suppers in the Crystal Room of the Ritz-Carlton. They watched the Harvard-Yale Regatta on the Thames River, and performed in revues at the Tarrytown Music Hall, where the Chorus Men (including Matty) competed against the Chorus Girls (including Betty) in elaborate comic routines.

Peter was two years old when Wall Street crashed in the fall of 1929, foreshadowing a decade in which nearly five out of ten white families and nine out of ten Black families would slip below the poverty line.55 But not the Matthiessens. “The Depression had no serious effect on our well-insulated family,” he later acknowledged in an essay for Architectural Digest.56 The only notable adjustment seems to have been an increased sense of noblesse oblige. As dozens of Irvington townsfolk from “virtually every conceivable trade” began registering at town hall with a Mayor’s Committee on Unemployment Relief, Matty doled out private jobs around Matthiessen Park.57 Betty cochaired a Ways and Means Committee “to bring about a SOLUTION of the present EMERGENCY,” and she was singled out for praise in an Irvington Gazette editorial for combating a “WRONG ATTITUDE” among certain members of the community—“that there was no real need for any action.”58 Betty also worked to distribute several hundred milk bottles, which residents were encouraged to fill with silver coins for the relief funds.59

But Peter was gesturing toward something important when he chose the phrase “well-insulated,” because for all their generosity, Matty and Betty maintained a buffer between themselves and the misery sweeping the nation. This would be a common theme for his parents, who treated money, like charm, as both a means of reaching out and as a defensive bulwark. If anything broke through the barricade to create an uncomfortable situation, they recoiled in disgust.

One Saturday afternoon in 1930, a deliveryman came to the house with new upholstered chairs from Carl von Schenk, a local furniture dealer. Matty and Betty were out, so a maid answered the door and then retreated to take a telephone call. As the deliveryman went about his business of unloading goods, a middle-aged woman followed him inside the house. By her “manner,” a newspaper later reported, the woman conveyed to the man that she was “a member of the family.”60 Calmly, she headed upstairs to the second floor, then returned, a few minutes later, and told the deliveryman in a “cultured voice” that she was going to inspect the stock in his truck. She promptly disappeared. That evening, Betty came home to discover a ransacked dresser in the master bedroom: gone were assorted jewels—a rope of seed pearls, a diamond necklace—worth $13,260, or more than $240,000 today.61

Claire Ritchey was forty-four years old, a door-to-door saleswoman for Harford Frocks of Cincinnati. She was apprehended two days later in Leonia, New Jersey, having pawned some of Betty’s larger pieces to a skeptical broker for just $300. In its coverage of this “unusual crime,” the Gazette was quick to poke fun at the idea of a female burglar, labeling Ritchey’s actions “a real broad daylight robbery.” But little attention was paid to her motive. What drove a woman who was able to successfully sell dresses to Irvington housewives— meaning she presented as middle-class—and whose husband was a printer for the New York Herald Tribune, to commit a heist and then trade the loot for a pittance? “Mrs. Ritchey claims that this was her first offense and that she lost every sense of reason in committing such a crime.”62 She was desperate enough to have tried other houses first, though, including Ralph Matthiessen’s. It is reasonable to suppose she was a casualty of the times.

At the district attorney’s office in White Plains, Ritchey pleaded with Betty for forgiveness. Betty was “sympathetically inclined” after hearing all the details, The New York Times reported. But the violation was too upsetting. “Mrs. Matthiessen said she would press the charge of first degree grand larceny.”63 Matty signed the paperwork.

At siX yEARs oF AGE, dressed in gray flannel, red tie, and scuffed black shoes, Peter matriculated at the tony St. Bernard’s School, which offered, in his words, “a British faculty, first-grade Latin, and strong Old World ideas about corporal punishment and other enlightenments not municipally approved in New York City.”64

After graduating from Columbia, Matty had gone to work for Henry Otis Chapman & Son, an architecture firm responsible for bank buildings and upmarket private residences. Chapman & Son had an office in Midtown Manhattan, and he traveled back and forth from Irvington, which is less than an hour away by train. Once the children reached school age, however, the family moved for fall and spring terms to a leased apartment at 1165 Fifth Avenue. Central Park was directly across the street (the reservoir and meadows were visible from the living room windows); Brearley, where Mary enrolled, was a short drive or bus ride away; and St. Bernard’s was right around the corner, four stories of brick and limestone on East 98th Street. Here “pink-kneed St. Bernard’s boys,” escorted by their nannies, would brush past “sullen youth of the more sallow neighborhoods” just a few blocks further north.65 It was the closest Peter had yet come to the hard truths of poverty.

St. Bernard’s was one of the best private schools in the city, and its purpose was to prepare boys for the best boarding schools in the country.66 Founded

in 1904 by an Englishman named John Card Jenkins, it was rigorous, Christian, and inherently conservative—the motto, Perge Sed Caute, means “Push on, but cautiously.” Days were long (8 a.m. to 5 p.m.), and sportsmanship was prized almost as highly as scholarship. Many decades later, Peter, carousing with another “Old Boy” from St. Bernard’s at a party, would still be able to sing the school’s Football Song, which had been drummed into his head like the Hail Mary: “We do not mind the winter wind / Or weep o’er summer’s bier, / Nor care a jot if cold or hot, / So long as football’s here. . . .” The competitive spirit was encouraged each year at Sports Day, where students went up against one another in races, then watched from the sidelines as their chauffeurs took a turn.

In the classroom, Francis Ritchie’s First Steps in Latin was a compulsory text, and students were expected to memorize poetry by the likes of John Masefield and Robert Browning. One master, Vere Manders, used Greek mythology to illustrate the fundamentals of storytelling. Peter excelled in history and reading comprehension, learning how to diagram complex sentences to tease out the grammatical function of every word, which was “invaluable for a career in writing,” he later commented, appalled that his own college students (when he eventually became a teacher himself) were incapable of saying “what part of speech ‘however’ is.”67

But all this learning paled, in his memory, when compared to the discipline. As veterans of the Great War, some faculty members seemed to treat the classrooms as extensions of the front line. Erasers were lobbed over desks at the inattentive; ears were grabbed and twisted; outstretched palms were slapped raw; and an aptly named Mr. Strange punctuated his points by applying a ruler to the base of Peter’s skull.68

One morning, the young Matthiessen was escorted, with James W. Symington, a future chief of protocol of the United States and four-term member of the U.S. House of Representatives, to the school auditorium, where they were handed pairs of boxing gloves. A master then commanded them, as Peter recalled, to beat up “two sullen little boys, similarly dressed and gloved but scarcely half our size, just to give them a taste of what it felt like to be bullied.” Peter and James protested, to no avail; then they “dabbed” at the little boys “unhappily,” everyone teetering on the verge of tears.69 That night, Peter confessed to Matty what had happened in the auditorium. Matty exploded in anger, growling that the British schoolmasters had broken every rule in the book. He threatened to report the teacher to the municipal authorities and withdraw both his sons from school. This response so unsettled Peter, being wildly out of character for his father, that he refrained, lest Matty carry through on the threat, from mentioning “bombardment,” another supervised game in which students pummeled the

weakest members of the class with soccer balls until they were pinned against the wall and pleading for mercy.

Like James Symington, several of Peter’s classmates would grow up to become prominent public figures, including Arthur Ochs “Punch” Sulzberger, publisher of The New York Times. Some would remain lifelong friends with Peter, including the landscape painter Sheridan “Sherry” Lord, but none would loom as large in his future as the boy named George Ames Plimpton. Even at the age of eight, “George was gangly limbed and plummy voiced, an extroverted participant in school Pierrot shows and Shakespeare plays,” and already possessed, Matthiessen wrote, of “that bright-eyed pointy-nosed expression found in woodland creatures on the point of mischief.”70 It would be years before their friendship bore its legendary fruit, The Paris Review, but the seed was planted at St. Bernard’s. Peter coedited a newsletter, The Weekly Blues—“ORDER YOUR COPY OF THE BLUE AHEAD TO AVOID DISA POINTMENT”—and George was a colorful presence in its irregularly typewritten pages: “Plimpton forced home many runs with his wildness. . . . Third base Matthiessen played poorly. . . . All the outfielders were perfect in their role of day dreamers.”71

Matthiessen later said that George Plimpton, like many children raised in strict but fortunate circumstances—his father was the prominent lawyer Francis T. P. Plimpton, a close friend of Adlai Stevenson—“had a naughty streak, which was one reason I liked him, being perpetually in trouble myself.”72 No doubt it helped that they lived in the same building.* This proximity meant that George quite possibly (Peter hedged on this point, his memory fuzzy) joined the Matthiessen brothers in committing acts of terrorism against pedestrians in the street below. The stratagem was simple: paper bags pilfered from the kitchen, which Peter and Carey, and maybe George, filled with water and then lobbed out the living room window, aiming for “a good splashy near-miss.”

I don’t think George was there the day when, peering out the window, dripping bags at the ready, we saw a woman killed outright as she tried to cross Fifth Avenue to Central Park: the poor thing stepped out from

* For a while, anyway. Sometime around 1936, Matty relocated the family to another apartment in the fortress-like edifice of 1185 Park Avenue. Peter’s memories of this building focused on the trains outside, which exited a subway tunnel “like dragons from beneath one’s feet.” The writer Anne Roiphe, who lived there at the same time, offers a more nuanced portrait in her book, 1185 Park Avenue: “Doormen with white gloves and gold braid on their hats opened the taxi doors. Elevator men with Irish names and shining shoes pushed levers forward or backward. . . . In the large windowless basements with gray stone walls Negro laundresses washed clothes by hand in white enamel tubs. . . . From eight in the morning till six at night the steam rose from the heavy pressing irons, ten, twenty laundresses at a time bending, standing, the smell of human sweat mingling with soap powders hanging in the wet and heavy air.”

between two parked cars. It was early in the morning and the taxis were going lickety-split—wham! 73

Their nanny, Maisie O’Brien, yanked the brothers away from the carnage, but too late to stop them from absorbing the details. Flesh slamming against metal (“as if the woman had attacked the taxi”)74 was a sound that would echo through Peter’s head for years, the first incursion of the real into a sheltered childhood.

A warmhearted Irish woman, Maisie was a doting surrogate parent. During the four school years the family resided in New York, she chaperoned Peter around the city to the Madison Avenue Armory, where he practiced his equestrian skills in the drill ring; to the American Museum of Natural History, where he liked to inspect the imposing skeleton of Tyrannosaurus rex; and to the Bronx Zoo, where lions and elephants kept “solitary counsel” in cages. (“I don’t doubt that a lifelong interest in wild creatures, shared with my brother, Carey, had its inception in those lordly Victorian halls.”)75

One afternoon, Maisie took her charge to the Ringling Bros. Circus at Madison Square Garden. Sitting amongst five thousand spectators, eating pink cotton candy from a paper cone, Peter watched, spellbound, as something went terribly wrong: “a missed ‘catch’ on the high trapeze, a small arching body, a split second of suspense, and once again that scary thump, much louder than sawdust striking a young woman’s soft body could ever be thought to produce.”76 Here was another shock he would never forget: Miss America Olvera, who had declined to use a net, was rushed to hospital with facial lacerations and badly broken arms.77

two Months shy of Peter’s tenth birthday, Matty made the surprise purchase of an old colonial house and forty-seven acres of land in rural Connecticut.78 Stamford was a growing hub of American manufacturing—the company headquarters of Pitney Bowes, Clairol, and Schick Dry Shaver, Inc.—and it was home to some 45,000 residents. Matty’s acquisition was near enough to reach the conveniences of Stamford, yet far enough away, five miles northwest, that it also felt secluded. Long Ridge, with its fallow hills and farmland, was so sparsely populated that number addresses were rarely used there. You could write a letter to “the Matthiessens on Riverbank Road” and it would inevitably find its target.

The house was shaded from the street by a line of prosperous conifers. A separate garage featured an upstairs apartment for staff. A dirt track climbed to a large barn, and a stream meandered its way across the property: a tributary of the Mianus River, shaded by a multitude of maples and oaks. A

previous occupant had installed stonewall horse jumps on an open grassy course, maintained for foxhunting. The only conspicuous sign of modern times anywhere close by was the Merritt Parkway, then under construction just down the road.

There were several reasons why Matty and Betty might have felt compelled to make such a drastic change of scene. Even if the Depression had, as Peter said, no material impact on the Matthiessens, it transformed Irvington, which had already seen the Ardsley Club sold off and converted into the Hudson House Apartments. Vast private estates were fracturing into smaller lots, and even Matthiessen Park had undergone at least one significant subdivision. Matty would sell his last few acres in 1941, thereby abandoning the town at what was clearly an inflection point, cloistered privilege giving way to the commuter suburb that Irvington is today.79

But perhaps a more compelling reason was fatigue. “They were getting a little sick of their social life,” Mary recalled—“or my mother was getting sick of Dad’s social life.” The excitement of being in Irvington or New York “wore off a bit, and maybe they thought it would be better for us to be in the country.”80 This aligns with a letter Betty had written to The Irvington Gazette in which she argued that play was “the most important means for the education of a child. If we do not allow children to have a normal childhood now, they can not come back and have it later.”81 A “normal childhood,” at least as Betty understood it based on her own in Short Hills, was simple and unfettered—an easier proposition in rural Connecticut than it was on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in the 1930s.

Mary quickly adjusted to her new circumstances. She sunbathed, played tennis at the Field Club, and made a large group of friends around Bedford Hills, New Canaan, and Greenwich, including George H. W. “Poppy” Bush, who would go on to summarize her in a presidential biography as “very pretty, very flirty. Fine body. Cute sense of humor.”82 But for Peter and Carey, the move was nothing short of a revelation. They were enrolled in the Greenwich Country Day School but left alone on weekends to run wild. If Fishers Island was an Eden inhabited for a few months each summer, Long Ridge, with its frogs, turtles, and salamanders, offered the same blissful communion with nature year-round.

One day the brothers discovered a copperhead den on a rocky slope that Matty had cleared near the house. Thrilled, they pinned snakes behind the head using a forked tree branch, captured seven, carried them into the house, and christened them with fanciful names like Morgan le Fay. “You know the kind of desk that has cubbyholes?” said Ormsby “Cis” Hanes, a friend who would eventually marry Carey. “The snakes were in the cubbyholes.”83 The brothers acquired other species via mail order, or through their parents’

social connections: Raymond Lee Ditmars, the esteemed herpetologist at the Bronx Zoo, presented Carey with the gift of an eastern indigo snake, which Peter later declared “a glorious addition to our rather drab local collection.”84 The boys let the serpents slither over their shoes, or hid them in heart-stopping pranks during Mary’s sleepovers. (“They thought it was a riot,” said Shirley Howard, a friend of Mary’s who discovered a garter snake in her bed.)85 The brothers also invited the neighborhood kids over to watch, for twenty-five cents a viewing, frogs and mice get swallowed whole. “Peter hoped you would appreciate his collection,” said Tom Guinzburg. “He was almost like a little child showing his special dolls. He was very particular about what he had and what they seemed to mean to him.” Other boys his age hoarded baseball paraphernalia: “His room was a repository of living things.”86 Eventually Betty, having decided the menagerie was too dangerous, ordered the boys to destroy all the snakes, but Peter just released them outside when she wasn’t paying attention. He likely avoided drawing her attention to the venomous snakes he caught during family vacations on Captiva Island in Florida: Eastern diamondback rattlesnakes, coral snakes, pygmy rattlers, and water moccasins.*

Betty installed a large bird feeder in the yard, and this, too, became an object of fixation for her young sons. “I must have worn out a half dozen dog-eared copies of that small blue book,” Peter once commented, referring to Roger Tory Peterson’s A Field Guide to the Birds.87 He convinced his father to install an elaborate coop up a narrow ladder in the barn. “In adolescence I needed a lot of solitude (and got somewhat more than I bargained for) and would perch up there under the eaves with the barn swallows and spiders, exulting in my dovecote for hours at a time, watching my pretty fliers come and go through the small entrance.”88 The question of where the doves went, liberated by flight, was fuel for a young boy’s imagination.

Matty turned out to be as handy with tools as he was with his golf clubs, and the old social engagements were soon replaced with outdoor projects: cutting down trees, filling in ponds, digging new ponds. Having left Henry Otis Chapman & Son when the senior partner died, he now opened his own

* One spring when Matthiessen was in his twenties, he went birdwatching with a friend in a Gulf Coast bayou. The friend, a pilot, stepped on a water moccasin. “He jumped back, ashen-faced,” Matthiessen recalled. “I was scared, too, but I wanted that snake for an undamaged specimen to take home. I found a strong stick, pressed it down right behind the snake’s head—hard but not too hard—and while he was pinned, grabbed him at the neck, forefinger and thumb tip under the lower jaw as he writhed, mouth open to show the cotton-white interior. Back at the airstrip, I took a two-gallon jug, filled it with water, and slipped the snake in, still very much alive, making the pilot very nervous because the Piper was a two-seater and I held the jug on my lap; the landing at New Orleans was light as a flower petal to avoid breaking that jug. We left instructions to clean and refuel the plane, but next morning, we found four of the airport crew surrounding the untouched plane in horror, even though that snake [left inside] had died overnight.”