UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

BBC Children’s Books are published by Puffin Books, part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

www.penguin.co.uk www.puffin.co.uk www.ladybird.co.uk

First published 2024 001

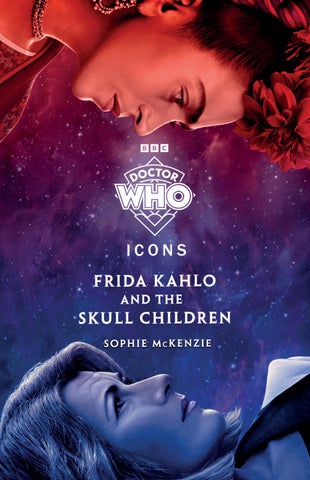

Written by Sophie McKenzie

Copyright © Sophie McKenzie and BBC Distribution Studios Limited, 2024

BBC and DOCTOR WHO (word marks and devices) are trade marks of the British Broadcasting Corporation and are used under licence. BBC logo © BBC 1996. DOCTOR WHO logo © BBC 1973. Licensed by BBC Studios.

The moral right of the author and copyright holders has been asserted

Set in 11.5/15.5pt Bembo Book MT Pro Typeset by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–1–405–96992–5

All correspondence to:

BBC Children’s Books

Penguin Random House Children’s UK One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens London SW 11 7BW

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

Teresa

‘Feet, what do I need you for when I have wings to fly.’

– Frida Kahlo

The more she hurried, the more everything hurt. Frida gritted her teeth as she made her way after her sister.

‘Cristina!’ she shouted, her annoyance building along with the pain in her back and hip. ‘¡Más despacito! Slow down!’

But Cristina didn’t seem to hear. She didn’t stop until she reached the park gates. Then she turned and waved at Frida, still at the far end of the road.

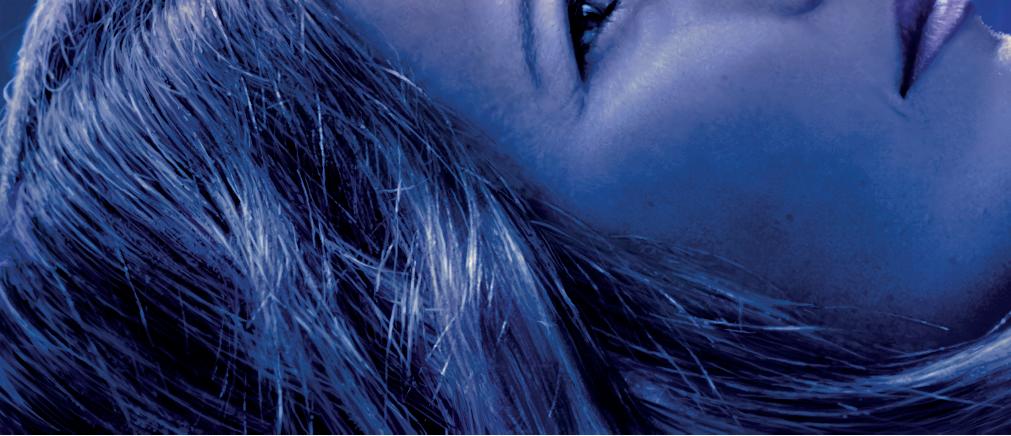

Frida glared at her. Cristina was just a year younger than she was, but the two sisters couldn’t look less alike. The difference wasn’t in their colouring – both had thick dark hair and brown eyes – but whereas Cristina wore an expression of openness, Frida was angry and intense, her

heavy brows knitted, and her face closed and resentful, reflecting the pain that was her constant companion.

Their clothes marked them out as very distinct personalities too. Cristina, just blossoming into womanhood at seventeen, wore a figure-hugging silk coat: scarlet, with a pink lace trim around the collar. Frida’s style was entirely her own. She liked to dress to express her identity which, on some days, meant a long skirt and loose blouse and on others, like today, a mannish suit teamed with slicked-back hair and dark eyeliner.

Her mother hated her looking like that. ‘¡Qué traje feo!’ she would say, shaking her head. ‘Such an ugly outfit! You look like a boy!’

But Frida didn’t care. Clothes should show who you were and how you felt. They weren’t just for keeping warm or cool in, or, as her mother would have it, to impress people. Clothes were part of your identity. And that was nobody’s business but your own.

There was a time when Frida had worried a lot about how people saw her. She’d even been embarrassed by the limp that was the legacy of the polio she had contracted when she was a small child. But then, six months ago, came the terrible crash on her way home from school. The bus collided with a trolley car, leaving Frida with a shattered pelvis and much else broken in her body.

Now it didn’t bother her what people thought.

Mostly she just felt angry at the world.

Breathing heavily from her exertions, she reached Cristina at the park gate.

‘Why didn’t you wait for me?’ she demanded.

Cristina smiled. ‘Sorry, manita.’

Frida shook her head. Sometimes, she felt more like Cristina’s mother than her sister. The year between them had never seemed so vast. Had she ever been like Cristina, all pretty dresses and flirty glances? No, even before her accident

Frida had been serious and determined. The smartest of his children, Papa said, destined to be a scientist or a doctor.

‘Don’t be cross.’ Cristina waved her delicate hand towards the clear blue sky. ‘The sun is shining and there are boys we know in the park!’ She giggled.

Frida rolled her eyes. No wonder Cristina had got so dressed up to come out today. ‘So, this so-called “walk” we’re having is basically to give you a chance to hang out with boys ?’

‘No, it’s to give you a chance to get out of the house and talk to people.’ Cristina sighed. ‘It’s just Pablo from church and some of his friends. I thought you’d be pleased to see them.’

Frida made a face. She hadn’t been to their local church, San Juan Bautista, since before her accident, and sometimes reflected that this was the one positive thing to have come out of the whole terrible business. Not that her mother saw her lack of attendance in that light.

‘¡No seas pendeja! Don’t be such a jerk!’ Cristina went on. ‘Alejandro and Agustina haven’t been round in ages, and you have hardly been out since your . . . since you . . .’ she trailed off.

Fury swelled in Frida’s heart. This was so typical of her sister, to try and engineer a social gathering for her. Kind, yet clumsy. Frida hated the fact that neither her supposed boyfriend nor her best friend had come to visit her in the

longest time. Why couldn’t Cristina see that the last thing she wanted was to be reminded of their absence from her life? Why couldn’t she understand that Frida felt too raw, too focused on managing her pain to think about joining other teenagers to chat about parties and school and who-liked-whom?

‘I don’t want to talk to Pablo right now,’ Frida snapped. ‘Or his friends. I’m going to sit in the shade for a bit.’ She strode through the park gates, heading towards the large copse of trees on the right.

‘Suit yourself!’ Cristina called after her. ‘We’ll come and find you in a bit.’

Frida didn’t reply. She was still fuming. But, as she stomped across the grass, she felt guilty for being so cross. Cristina had only been trying to help. It wasn’t her fault that Frida was so far away from wanting to socialise. How could she expect her little sister to understand her when literally nobody else in the world did?

Despite the bullying and loneliness that her limp had caused Frida as a little girl, it was only since her terrible accident last September and the months of agony and isolation that followed that she really understood life’s great truth: suffering was what it meant to be human. For months after the accident, she had been bed-bound, unable to walk at all. Now she could move, but it hurt when she did.

Her pain was all she had now. It was her life. Her future.

Frida reached the wooden bench opposite the copse of trees and sat down, rubbing at the ache in her hip. She gazed across the vast expanse of grass to where Cristina,

now a tiny speck of red in the distance, was strolling towards a group of other teenagers, all dressed in blues and greens. Frida watched as her sister got swallowed up by those she had come to meet – a drop of blood dissolving in a sea of water.

The ease with which they moved mesmerised Frida. There was a lightness about them. How she envied the freedom of their pain-free bodies, the lack of fear that any action might make the agony worse. Shaking off her self-pity, Frida focused on the trees ahead. The light caught in their branches and revealed the skeleton spines inside their pale green leaves. April was a beautiful month in Mexico City and Viveros de Coyoacán Frida’s favourite outside space.

She took a deep breath of sweet, warm air, trying to ignore the pain that crawled through her body. Across the grass, the leaves on the trees seemed to shimmer then blur into each other. For a moment, Frida thought her eyes were playing tricks. She blinked. But the blurring got stronger. It was like she was seeing a whole section of the park through water. Her jaw dropped. She glanced around – nobody was there, nobody else was even looking.

She focused back on the strange, fuzzy mass. What was happening?

She stood up, barely registering the sharp ache in her lower back. Hurrying as fast as she could, she made her way across the grass. She kept her eyes fixed on the blurry section of trees. It was like that intense shimmering you sometimes get on the hottest days of summer, when the heat is so thick you can almost touch it.