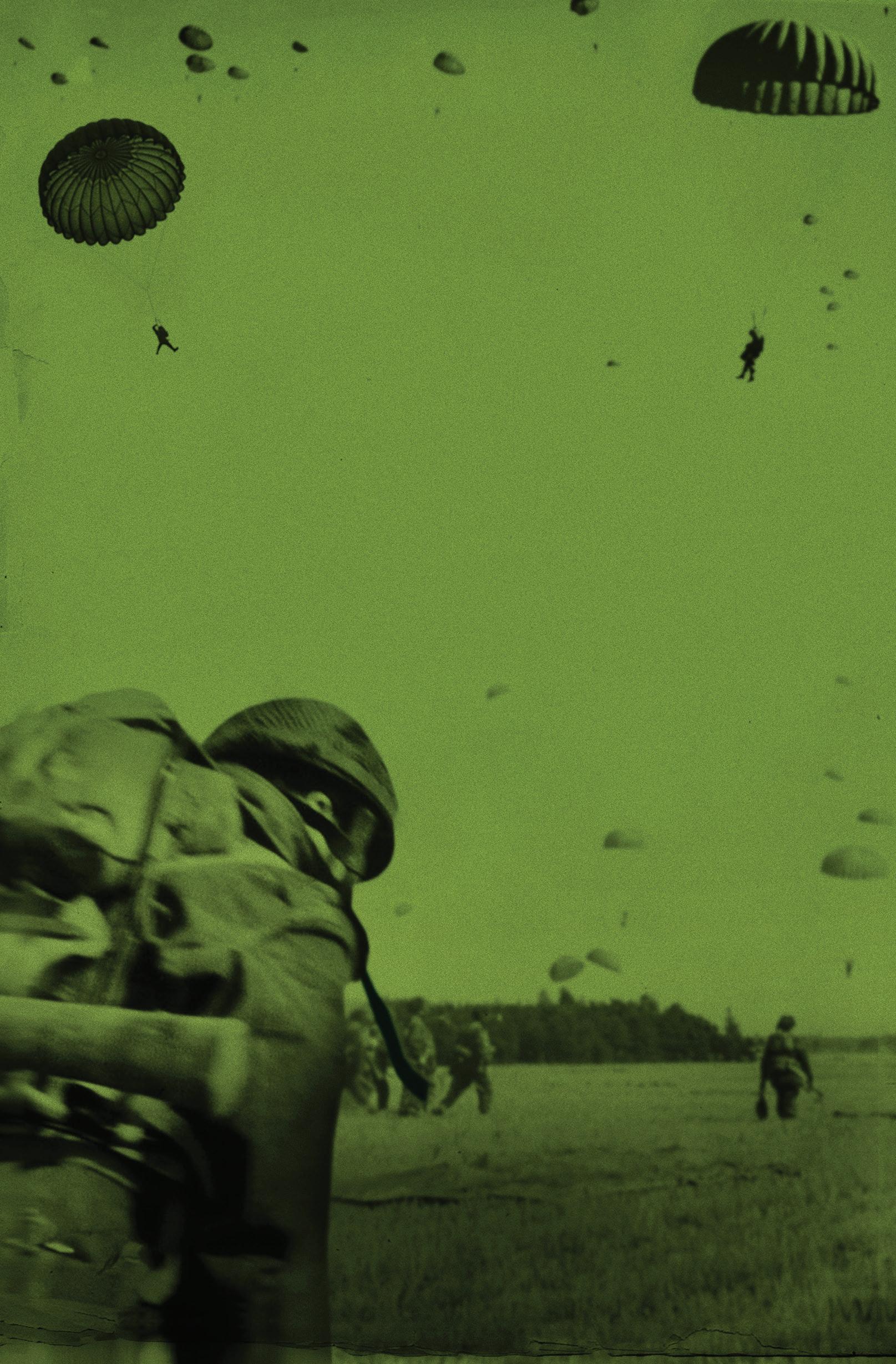

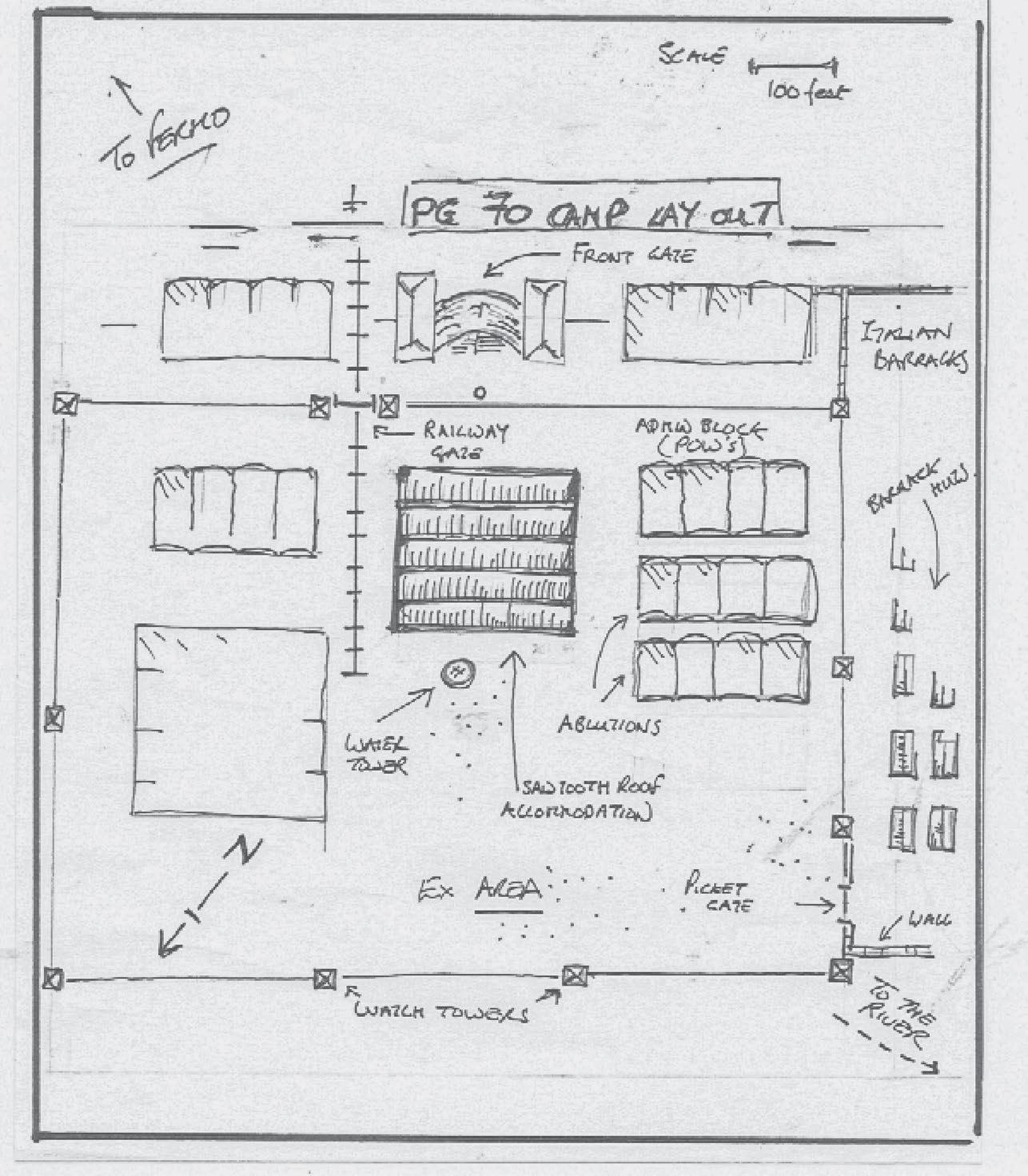

John Humphreys OBE joined the Royal Engineers at the age of fourteen. He was wounded and captured at Tobruk in June 1942, escaped from a POW camp and walked hundreds of miles to reach the British lines in autumn 1943. In 1944, after volunteering for parachute training, he fought alongside John Frost’s 2nd Battalion, The Parachute Regiment (2 PARA ), the only unit to reach the vital bridge over the Rhine at Arnhem. Captured again and although only a corporal, he led a small group of men to escape, and made it back to Allied lines. Twice mentioned in dispatches for gallantry, John remained in the Royal Engineers after the war, serving in the SAS and reaching the rank of lieutenant colonel. As the last living veteran of 2 PARA’s fight for the Arnhem bridge, John Humphreys passed away in 2024 at the age of 102.

Stuart Tootal is an ex-Parachute Regiment colonel, a Sunday Times bestselling author, former corporate global head of security, and currently runs a change management consultancy. He served in Northern Ireland, the Gulf War, Iraq, and led 3 PARA into Afghanistan in 2006.

PENGUIN BOOK S

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London sw 11 7bw penguin.co.uk

First published by Penguin Michael Joseph 2024 Published in Penguin Books 2025 001

Copyright © John Humphreys and Stuart Tootal, 2024

The moral right of the authors has been asserted Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception

Typeset by Jouve ( UK ), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d 02 yh 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn : 978–1–405–96425–8

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For Brenda. Who was in my heart when I flew to Arnhem and for ever after.

Rommel attacks June 1942

North Africa, 1941–1942

Matruh

Scale N

1 mile

toDerna German panzers

Water towers and bakery

Zagazig

Route to the quayside and back Quay

The Fall of Tobruk 21 June 1941

German breakthrough to Alexandria

Fermo Teramo Brindisi Pisa Lucca

Corsica (France)

Sardinia (Italy)

Planned final position of BR XXX Corps

TH SS PZ Div

TH SS PZ Div

Deelen Oosterbeek Nijmegen Apeldoorn Zutphen Beekbergen

British 1 ST ABN Division Polish Para Bde US 82 ND ABN Division

Zuider Zee

Operation Market Garden, 1944

Planned Allied airborne drop zones Planned main axis of Allied advance Main German disposition s (17 September 1944) 9 TH SS PZ Div

Amsterdam

NETHERLANDS

Turnhout

Borkel

Siegfried Line

Beringen Peer

Leopoldsburg

Route of BR XXX Corps

Geel

I knew that I was going to be late for my last appointment with John Humphreys. My train to London had been cancelled due to industrial action. The one behind it, which had standing room only, was running an hour and a half behind schedule. Packed among my fellow passengers amid an air of collective frustration, I thought of the train journeys John had made crammed in overcrowded cattle trucks that took him into captivity, which were strewn with human faeces, secured with barbed wire and locked tight by armed guards. I wondered what John would have made of the strike action by people paid five times the salary of a modern British private soldier. I suspected he would have forgiven my lateness and made the comment, accompanied by his infectious smile, that at least Mussolini had made the trains run on time. Although I could only guess, as the work to rule on the rail network had made me late for John’s funeral.

John passed away as a gentleman pensioner in the Royal Hospital Chelsea on 17 March 2024, three months after celebrating his 102nd birthday, making him one of the very last of what has been described as the ‘Greatest Generation’. Referring to the 8 million men and women who served in the British and Commonwealth armed forces during the Second World War, the term acknowledges the sacrifice they made to defeat the forces of evil that threatened the freedom of the western world. However, while over 750,000 made the ultimate sacrifice by laying down their lives and hundreds of thousands more were wounded or captured, it was the minority of that

demographic who had volunteered to fight, who saw action on the front line and did so on a near-continuous basis, serving in more than one theatre of operation during six years of conflict. Although only a seventeen-year-old at the outbreak of hostilities, John was a regular soldier. He already had three years’ service under his belt, which marked him out for a cushy role as an NCO instructor where he could stay safe at home training others to go to war. Instead, he deliberately got himself busted back to the rank of private so that he could be sent to a front-line unit.

He went on to fight in North Africa for eighteen months and had attained acting rank as a sergeant before he was wounded and captured at Tobruk. For many who fought with the Desert Rats of the 8th Army that would have been enough. However, John made repeated attempts to escape from captivity in order to get back into the war but had to spend twelve months as a POW in Italy before he was eventually successful. After learning to speak fluent Italian he escaped by masquerading as an Italian guard and then walked half the length of enemy-occupied Italy to reach the safety of his own lines. On returning to the UK , despite losing his rank as a sergeant and having his pay cut in half, he turned down the opportunity to become an officer. Fearing the months of officer training would mean that he would miss out on the opportunity to take part in the impending Allied invasion of north-west Europe, he defied the instructions of his chain of command and volunteered for parachute training to join the Airborne Forces.

Having experienced the brutality of combat once, few soldiers willingly rush back to the sound of the guns. However, John’s burning desire to get back into action resulted in his becoming the last surviving veteran of a battalion group of paratroopers who jumped into Arnhem in September 1944

xiv

and managed to fight their way to the infamous bridge spanning the Lower Rhine, which they held for four days before they were overwhelmed by superior enemy forces. What makes John all the more remarkable is that when they ran out of ammunition and his officers told him to surrender he chose to escape as the building they were defending burnt and collapsed around them. Although eventually hunted down and captured, he then went on to break out of a POW camp in Germany and made it back to Allied lines to continue to serve with another front-line para unit until the end of the war.

John told me something of his extraordinary story when I met him in the Royal Hospital Chelsea in April 2023. I then spent the next seven months visiting him weekly to capture his wartime exploits in detail. Eight decades on, his memory was exceptional. However, regardless of age, recall of battlefield events is seldom precise or complete. It is the natural order of things. Ask a section of soldiers about their recollections of the same combat event they took part in and their respective accounts will vary even hours after the action. There were also patches of amnesia, and certain aspects were obscured by the passage of time. On occasion he was openly vague about the strategic circumstances, time and dates surrounding an event, which is hardly surprising. As a relatively junior NCO, the span of his strategic horizons was often confined to the narrow field of fire from a trench, the 600yard range of a Bren gun or what he could see from the barricaded window of a shell-torn house as he dodged the bullets being fired at him from the other side of a street. Certain details re-emerged gradually from the mists of time as we spent hours talking, poring over maps and looking at photographs together.

As the weeks of constantly visiting John went by, we debated and analysed the findings of my investigation into

xv

official war diaries, the outcomes of my research trips to Italy and the Netherlands, and the accounts of other veterans and subject-matter experts. If there was an element of doubt about the precise sequence of things, we corroborated findings as best we could from my research against John’s own version of events, agreeing on a balance of the most probable. Regardless, I was struck by the number of incidents, personalities, sights and sounds that John could record. Often with a level of visceral technical colour detail, which went into the very heart of an action with all its noise, fear, smells and chaos.

John related such accounts in matter-of-fact manner, while betraying a humility and a level of humour that belied the dramatic nature of his experiences. The look of surprise on a German panzer commander’s face as John hurtled past his tank in a 3-ton truck in search of an errant company commander or how he shot down SS grenadiers like fish in a barrel when they tried to escape from their armoured halftrack. When he talked of such occurrences I could still see the light of battle in his eyes. John also talked about the dread moments and the minutiae of the privations of soldiering. Being sick with fatigue having held a position without sleep or food for a week. The arse-popping fear he experienced as two SS troopers dug their pistols into his belly and the small of his back and he thought that his time had come. Or the infestations of lice and starvation rations that ravaged his body as a prisoner.

All the events described in the following pages took place, and they have been represented as they appeared to John with the aid of my research. All the people mentioned are real. However, the names of certain characters who appear in the text have been changed out of respect for them and to

spare their relatives, where the details of a particular incident may cause distress.

In writing this book, John had only one concern, and that was to do justice to the character and courage of the men he fought with. In the risk-averse and self-obsessed nature of today’s expectation-oriented society, they stand out as a remarkable fraternity, which was fashioned by danger, death and a willingness to sacrifice their lives so others might live. John always said that it was an honour and a privilege to have served with them. For me it has been an honour and a privilege to have known John, to be able to describe him as my friend, and to help him tell his important story, which we were able to complete before he died. As a former paratrooper myself, John and his generation set the standard for the airborne fraternity that endures today. Given what his generation went through, his place in that remarkable wartime brotherhood, the longevity of his exceptional life, and that his story was captured right at the edge of living history, John truly deserves the title ‘Arnhem’s Last Para’.

It was raining again and the air was pervaded with an atmosphere of dank desperation. Through the gloom of the morning, I caught the briefest of glimpses of the muzzle flash at the window in the street opposite the schoolhouse, before instinctively dropping for cover. Almost instantaneously, I felt the impact of the machine-gun rounds as a small blizzard of bullets smacked into the brickwork of our building and splintered the lintel above my head. ‘Bastards,’ said Joe. ‘Did you see him, John?’

‘Yes. He’s at the second window from the right on the third storey across the street. Ready?’

Joe feigned movement at our own window and dived out of sight again. Simultaneously I pushed the Bren up on to the sill, beaded the gun’s sights on to the offending target and exhaled as I fired a long killing burst. The enemy Spandau flashed momentarily, a couple of rounds thudded into the side of our building, and then the firing stopped abruptly.

‘Bloody hell. You got him, John. Saw the bugger fall backwards!’ Joe exclaimed.

‘And now I know what he was doing, Joe. Shit! There is an assault squad of Jerries immediately outside.’ The troublesome German machine-gunner had succeeded in drawing our attention to cover the approach of a squad of SS troopers who had managed to crawl close up to our walls and were preparing to launch an attack with grenades, flamethrowers and machine pistols. ‘Stand to! Stand to!’ I shouted. Joe repeated the alarm and it reverberated throughout the house

as other men took it up and rushed to man the barricaded windows to begin firing their Brens, rifles and Stens down on to our attackers.

Clad in their distinctive mottled-green camouflage smocks and black leather belt kit, the Germans were also screaming out orders as they broke cover and attempted to push home their assault. A Jerry with a flamethrower was shot down first in a fusillade of automatic fire. No one was going to let that bugger get anywhere near us. Others began to drop as they rushed forward to get close enough to lob stick grenades. Firing their sub-machine guns from the hip as they came on, they were cut down and fell, adding to the piles of their comrades that we had already killed during previous attacks. ‘When the hell will these fanatical bastards give up!’ Joe shouted as he changed the magazine of his Sten. ‘So much for no more than a few old men and boys defending the bridge. No one said anything about the bloody SS !’

‘So much for our intelligence stating this would be a walkover,’ I retorted, as I clipped home a fresh magazine on the Bren and started firing again. The enemy platoon attacking our corner of the building was not alone. Numerous assaults were being launched on all sides of the schoolhouse, and some made it through. I heard the shout of ‘Grenade!’ from the confines of an adjacent classroom and the muffled boom as a German potato masher went off. There were more frantic shouts from somewhere on the floor below us of ‘They are in the building!’ and feet pounded down the staircase, which was slick from the blood of the wounded, as a counterattack was launched to push the Germans back out of the building using grenades and close-quarter Sten gunfire.

Then it was over almost as suddenly as it had started and the cry went up of ‘Cease fire! Conserve your ammunition and only fire if you have a definite target in your sights.’ It

was one of our officers getting a grip on the chaos of repelling the assault and readying us for the next one. ‘Here they come!’ he shouted. ‘Take cover!’ The audible plop of mortars being fired meant that we needed no encouragement. It was the Germans’ standard response to stonk us with a heavy dose of high explosive in the immediate wake of the failure of one of their attacks.

I didn’t bother to count the time of flight. I knew the indirect-fire weapons were close and their bombs were only seconds away. We were sprawled on the floor and pressed tight against the walls when they landed. Each projectile that hit the roof and sides of the building sent a shock wave of concussion through its structure, showering us with plaster dust and falling debris. The schoolhouse was a stout building and could withstand the shock of high explosive, but shrapnel and blast still manage to find their mark. When it ended, there was just enough time to carry the wounded down to the cellar, where our one overwhelmed medic worked in what had come to resemble a slaughterhouse. His supplies of morphine and surgical field dressings had long since run out and he plugged wounds and bandaged scores of mangled men with whatever rags or strips of cloth came to hand. The brief respite also gave us time to count our ammunition, which without resupply or the relief that we had been promised was running low. ‘How much have you got left?’ I asked Joe.

‘A couple of mags for the Sten and a grenade. How about you?’

‘About the same for the Bren, a few loose clips of .303 rounds, then I’m out. If XXX Corps don’t get here soon, we are going to be buggered.’ Then we heard the clank and squeal of grinding metal tracks. But the armour approaching our position along the main road that ran from Arnhem’s town centre was not the advance tanks of the British Second Army.

‘Jerry Tigers!’ someone shouted. Two of the great armoured beasts lumbered into view and then one of them stopped less than a hundred yards from the schoolhouse, while its counterpart continued on to engage the other 2nd Parachute Battalion positions closer to the bridge. We could hear the menacing mechanical whir of its turret and its main armament being depressed as it brought its 88mm gun to bear. Then we heard the whipcrack as it fired. The huge panzer rocked backwards as it sent a high-velocity round screaming through the upper storey of the building like an express train from hell. As a lightly equipped airborne force without our anti-tank weapons, the beginning of the end had begun.

War was declared on 3 September 1939. There was no formal announcement from our chain of command, not even a proclamation posted on the company noticeboard, just the unearthly wailing of the air-raid sirens that sent us scuttling to the shelters. In the weeks that followed, the clear blue sky of an Indian summer above the barracks at Shorncliffe became dotted with silver barrage balloons, which had been hoisted to protect the nearby docks at Folkestone against German bombers that were yet to come. However, the declaration of hostilities had not stopped the military’s obsession with bullshit, and four months later we were still mounting the daily guard with all the pomp and ceremony of a peacetime army.

I noticed the look on Bert Hall’s face when he saw me getting ready to present myself at the guard mounting parade one cold January morning in 1940. ‘You must be mad?’ he hissed, so as not to attract the attention of the more junior sappers in the barrack room.

‘If you go out like that, the RSM will have your guts for garters and you’ll lose your tape.’

‘I know what I’m doing, Bert,’ I replied. But in truth, I was not so sure. I instinctively felt the single corporal’s stripe stitched just below my right shoulder and knew it was unlikely to remain there for very long.

Lance Corporal Bert Hall was the same age as me and was my mate. Our fathers had both served in the Royal Engineers and we had first met as boys in the garrison town of

Chatham, the regimental home of our fathers’ corps. Educated in local army schools, we had played war together and fought the civilian kids, who went to different schools and lived in the houses down by the old naval yard. They were always the Hun, and we and the other army brats in our gang were known as barrack rats. At fourteen, we both went to the army’s technical apprenticeship college in Chepstow as boy soldiers, and spent the following three years furthering our education and learning to become military tradesmen. Bert and I both passed out as top-rate tradesman fitters, gaining high enough marks in our exams to be selected to begin our adult army careers with the Training Battalion Royal Engineers at the School of Military Engineering, located at Brompton Barracks in Chatham.

I left Chepstow as an apprentice technician corporal, a boy soldier’s rank, held the title for the college’s 100- and 200-yard sprint and had broken the school record for the long jump. At Chatham there were few sporting accolades to be won and I reverted to the rank of a lowly private soldier, referred to as a ‘sapper’ in the Engineers. The dark clouds of war were already gathering before we arrived there in February 1939, and we promptly started training to fight the type of war that our fathers had fought. The first six weeks were spent in rudimentary military instruction and square bashing on the asphalt parade ground in the centre of the barracks. Conditions were spartan and we slept between army blankets without sheets. The average day started at 0500 hours, and we washed and shaved in cold water. When we were not being drilled, doing PT, being taught how to handle our bolt-action .303 Lee–Enfield rifles or carrying out marching exercises with picks and shovels, we were preparing for inspections and frantically cleaning our kit. If an item was white or metallic and could be worn, it was either subjected

to frenetic polishing or layered with Blanco. If someone moved and spoke in a different accent to our squad instructors, we stood to attention and saluted them. However, engagement with our officers was rare and it was the NCO s who held sway over us, with the drill sergeant and Regimental Sergeant Major the gods among them.

Once we had passed our basic training, which served to strip any last remaining shreds of civilian humanity from us, we started our sapper training. Engineers provide the rest of the army with the ability to live in the field, fight from a defensive position and move across a battlefield, while seeking to deny the enemy’s ability to do so. Consequently, we learned about bridge building and were taught watermanship skills to operate 22-man assault boats and other collapsible craft. We were instructed in conducting demolitions and taught how to make charges using highly explosive ammonal compound, primed with guncotton, and set off with Cordtex fuse. We spent an inordinate amount of time constructing long dog-leg trenches and fire steps and learning how to revet them with planks, as well as being taught how to shore up tunnels and construct fortifications that would not have looked out of place on the Somme. There was plenty of bayonet drill too, which involved charging while screaming at the top of your voice and stabbing straw dummies with a 17-inch steel 1907 pattern bayonet, a weapon and practice that my father would have been familiar with. Other weapons handling included learning how to strip down and fire the Lewis gun, which had become the standard light automatic squad weapon by the end of 1918. The ones we had were knackered, prone to stoppages and were well past their sell-by date. However, while the coming of another war in Europe did little to change our syllabus or methods of instruction, it did force a change in the duration of the course.

In August, the Training Battalion was split in two. Half of those on the course were sent to Elgin in Scotland and the other half to Shorncliffe. No one discussed the reason with us, but the move was to increase the training capacity of a rapidly expanding army. Spurred on by the Munich Crisis of 1938, Britain had begun its rearmament programme the year before. When Bert and I joined the regulars as adults at the start of 1939, the army stood at 224,000 troops, with another 325,000 Territorials. By that September, it had expanded to just over a million men under arms as all adult males registered for military training were called up. Living up to its regimental motto of ‘Ubique’ (‘Everywhere’), the engineers accompanied the army on all its operations. Fearing it would be short of the engineering support needed to fight another war with Germany, plans were being laid to train up to 100,000 sappers to swell the ranks of the corps. The expansion of the training programme also provided opportunities for the likes of Bert and me.

Having been boy soldiers and technically schooled as apprentices, training as sappers came easily to us and that gave us an advantage over recruits who had no previous military experience. Drill, pressing tunics, polishing buttons and shining our heavy ammo boots until they shone like glass were already second nature to us. We were also fit, robust and used to the strictures of army discipline and assimilating military training, qualities that marked us out as potential instructors. If he was lucky, before the onset of the war a peacetime sapper might take three years to be promoted to the rank of lance corporal. However, training a rapidly expanding corps of engineers would require more instructors, and they were in short supply. The Royal Engineers’ more experienced soldiers and junior NCO s were being posted to units sent to France with the British Expeditionary

Force (BEF), whose first divisions began to cross the Channel the month war was declared. As a result, the shortfall in instructors had to be made good from newly qualified sappers. Additionally, instructors had to have rank.

Having passed out in the top percentage of our intake, Bert and I along with a dozen others were selected to join a three-month cadre to be trained as junior NCO s. Although that did not mean there was any let-up in the emphasis on bullshit. Initially, the primary qualifying criterion for becoming an NCO seemed to rest with one’s ability to drill a squad of marching men. That in turn rested with the competence to give the right words of command on the correct foot. So, we shouted ourselves hoarse and drilled until we would have made a King’s guardsman proud of our foot drill. We also learned how to mount and present guards, prepare a charge sheet and manage the administration of a section of ten men. In the evenings we swotted up for written tests on the more practical tasks of combat engineering, and we began to receive instruction in how to give instruction and train others to become sappers.

As well as accelerating one’s career, promotion to lance corporal also carried the incentive of additional pay. When I sewed on my lance corporal’s single chevron stripe at the end of the cadre, I was officially still only a boy soldier as I would not be eighteen until the following January in 1940, and was paid as such. However, the elevation to rank increased my pay from two to six shillings a day. It amounted to a significant hike in my salary, not least as the entry fee to the local dance hall was five shillings.

It was Bert’s idea. ‘How are we ever going to get to know any birds, John, if we don’t know how to dance?’ he said after we attended our first pay parade as newly promoted NCO s. He had a point, and in our off-duty moments we

started a different type of cadre, involving dancing classes run at a local club. Having become experts in explosives and bridging, learning how to waltz, foxtrot and tango became an additional part of our repertoire. After several lessons we were competent enough to put on our dress uniforms and go to the Leas Cliff Hall down on Folkestone seafront and dance to Victor Sylvester’s ballroom band. The added bonus was that beer was fourpence a pint. And Bert was right – we did get to know some girls.

The rank and the pay, along with the status of being an instructor and the new opportunities it brought to get to learn about the opposite sex, made for a heady combination. Especially for a seventeen-year-old who had lived the sheltered life of a barrack rat, growing up in an environment made up entirely of the army’s schools, apprentice college and adult training. I had fallen in love with combat engineering and particularly enjoyed blowing things up. I also had the liberty to enjoy my new-found position. When not instructing or pulling a 24-hour duty as the barrack’s deputy guard commander, which came round every few weeks, I could go dancing with Bert, head to the pub or take a girl to the local cinema.

However, by the start of 1940 the novelty of training civvies to become basic sappers in a third of the time it had taken to train us began to wear off. Seeing them sent to activeduty units in France also began to rankle. Folkestone was a staging point for units being sent across the Channel, just as it had been in the 1914–18 war, and from our vantage point in the camp I often watched squads of soldiers being marched down to the docks. As long columns of khaki threaded their way along the seafront, I found myself wondering if my father had marched along the same route on his way to the Western Front. It bothered me that I was safe at home, while thousands of men headed to the front line in France.

It was just after returning from Christmas leave at the start of 1940 that I finally got an interview with the officer commanding our company. ‘I would like to go to France, sir,’ I said, standing to attention. I have long since forgotten his name and he clearly did not know mine.

‘Err, ah yes, Lance Corporal . . . er’ – he looked down at his notes – ‘Humphreys. I’ve seen your numerous requests to be posted away from the battalion. Out of the question, I’m afraid. You are of far more value to the war effort staying here to train men needed at the front.’

‘But sir . . .’ I started, before the sergeant major standing to one side of the desk cut me short with a dry cough that dared me to say another word. The major kept his attention on his papers. The interview was clearly over.

I paused for a moment. The major looked up at me, raised an eyebrow and quietly said the word ‘Dismissed.’

I just managed a ‘Thank you, sir’ before I threw up a salute, turned to my right and automatically fell in with the sergeant major’s rhythmic chant of ‘Left, right, left, right . . .’ as he marched me out of the OC ’s office.

A week later, with the chain of command clearly closed to any appeal, I hit on the idea that the army’s obsession with bullshit was my ticket to France.

‘You really are fucking mad,’ Bert reiterated, looking with dismay at my regimental buttons and the brassings on my belt, which remained deliberately unpolished. He threw another shovel of coal into the stove that was doing its best to take the chill off the large 30-man barrack room.

‘Strewth,’ he said when he saw that I had also removed two buttons from my greatcoat as I prepared to head out of the barracks to form up for the parade in front of the guardroom.

He was right about the RSM having a fit. In fact, he went

apoplectic. I glimpsed disbelief turn to rage in his eyes as he looked me up and down as I stood in line with the other members of the eight-man guard. As a junior NCO, I was the deputy guard commander of the small body of men charged with guarding the camp. I should have been setting an example to the six recruit sappers. I felt the RSM ’s spittle on my cheek as he raged at me, his voice full of outraged invective and spite. I caught the words ‘bloody horrible man . . . disgrace to the corps . . .’ and that he would ‘make an example’ of me. Finally, he shouted, ‘Place that man under arrest!’ Within seconds my forage cap and belt had been removed, and my rifle was taken off me by the full corporal commanding the guard. I was then marched into the guardroom at the double and locked into a cell to await my fate.

Two hours later I was back in front of my company commander. This time the conversation was even more one-sided, but at least he remembered my name. Two minutes later, I was in the corridor outside his office, no longer a lance corporal, and being handed a movement order and a rail warrant by the company sergeant major. I was ordered to return to my barrack room, pack my kit and hand in my bedding before making my way to the railway station in Folkestone. Bert and some of the lads were gathered round my bedspace when I got there to collect my kit. ‘What on earth were you thinking?’ Bert said as he helped me stuff my belongings into my kit bag.

‘Sappers can’t instruct sappers,’ I replied. ‘You need to be at least a lancejack to do that. Once he’d busted me, I knew the major would have no choice but to post me to a unit that would be going out to join the BEF.’ I waved my rail warrant at him as if I had just won the lottery.

‘I told you you were mad. You had it cushy here, mate.’

‘But I don’t want cushy, Bert,’ I replied. ‘I want to get to France and do my bit.’

Packed and with my blankets folded and handed into the bedding store, I said farewell to the lance corporal instructors I had trained with. Bert saw me off at the barracks gates. He wished me luck and reminded me of his concern for my state of mind before we shook hands. I hitched up my webbing equipment with its pouches and pack, shouldered my kit bag and slung my rifle. I walked through the gate and touched my rail warrant to check it was still in my pocket. As far as I was concerned, it was my ticket to active duty in France.

If I had been allowed to have my own way, I might have become a sailor rather than a soldier. The conversation about my future came up once when I made my way back from school in Singapore in the autumn of 1935. I was thirteen years old and along with the rest of the family had accompanied my father on his last posting in the army to the imperial possession located on the tip of the Malay Peninsula

The clouds above the bay were full of the threat of the seasonal monsoon downpour as the ferry from Blakang Mati crossed the southern straits of Keppel Harbour and edged the last few yards towards the jetty on the smaller island of Pulau Brani where we lived. Both islands lay off the shore of the main island of Singapore and I could make out my father waiting to greet me on the quayside. It was unusual to see him there, standing upright among the throng of local fishermen, coolies with their rickshaws, and the mothers of colonial families in their white dresses and straw hats waiting to pick up younger children. In his tropical pith helmet and khaki uniform – heavily starched short-sleeved shirt, kneelength shorts, long thick socks, puttees and ammo boots – and with a cane locked under his armpit, he stood out from the rest of the crowd.

My father came from Sussex tenant-farming stock. He was an eighteen-year-old agricultural labourer when world war broke out for the first time in 1914. Responding to Kitchener’s call for volunteers, he signed up almost

immediately, joined the Royal Engineers as a sapper and was posted to France. After the war, jobs on the land were scarce so he stayed in the army, reaching the rank of staff sergeant. He was a reserved man of few words, and he never spoke of his wartime experiences, although his medals told their own story. When he dressed in his parade uniform or the family gathered for the Remembrance service on Armistice Day, among the awards fixed to his chest were the 1914 Star, the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. They marked him out as one of the ‘Old Contemptibles’ of the British Expeditionary Forces that had stopped the Kaiser’s army at Mons and gone on to fight in other bloody battles in the trenches on the Western Front over four years of attritional stalemate and slaughter. Together, he referred to his medals as ‘Pip, Squeak and Wilfred’, the names of the characters in a popular cartoon strip run by the Daily Mirror that coincided with the issue of the medals after the war. Along with their bronze stars, silver medallions and the bright, rainbowcoloured ribbons, the quaint nickname stuck. It was an odd contrast to what they represented. Deep down I suspect that my father had seen too much of the horrors of war, that it had shaped him and had a bearing on his disposition as a parent.

We fell into an uneasy conversation as we walked along the mile-long coastal road that led to his army married quarters, which were situated on the slopes leading up to the barracks at Fort Canning on the eastern end of the island. Around us the harbour was busy with sampans plying their trade, shuttling between the large cargo vessels and mighty grey warships that lay at anchor. The humid air was full of the sound of construction, as work commenced on building the naval dockyard facilities and 15-inch gun emplacements that formed part of the imperial Far East strategy, designed

to make Singapore impregnable in the face of any future threat of Japanese aggression.

Clearly my own future was on my father’s mind.

‘How was school today, son?’ he asked.

‘Good, thank you, Father,’ I replied, and gave an outline of what we had studied in our classes that day. However, I sensed that my father wasn’t really listening.

‘What do you want to do when you finish school?’

My elementary school education was due to end in January of the following year, when I reached my fourteenth birthday. Given my father’s army pay, continuing my education at a fee- paying grammar school wasn’t going to be an option.

‘I want to join the Navy as a boy artificer,’ I replied.

Although the school on Blakang Mati was run by the army, some of the pupils had fathers serving in the Navy. One of them had told me that if I passed the necessary entrance examination I could get into Naval Artificer’s College in England. It would provide me with five years of technical training, and at the end of it I would leave as a qualified artificer engineer with the rank of petty officer. I looked out to the harbour. A destroyer was making steam and preparing to lift its anchor, the crew busy on her decks and the White Ensign fluttering stiffly in the breeze. The idea of a career at sea, with all its prospects for adventure and travel, appealed to me.

My father made no comment, and we were soon at the gate to our married quarters, which stood in a uniform row of similar whitewashed bungalows set among a thin glade of tall palm trees. My father glanced up at the sky as the first heavy raindrops splashed on to the path up to the house. ‘You had best get in and help your mother with the other children,’ he said, and ushered me inside. There was a rumble of thunder above the bungalow as the heavens unleashed a

torrent of rain on to the roof tiles and I went to lend a hand with my younger brothers and sisters.

The monsoon was still upon us in early November when my father told me to make my way up to Fort Canning to sit the exam for what I thought was for the Naval Artificer’s College. It was as I expected. Lots of questions on maths, with an emphasis on algebra, as well as some basic science, and physics exercises, all to be completed in an allotted time. Over the weeks since the conversation with my father, I had worked hard to prepare for the entrance paper and felt confident I had passed when the invigilator told me to stop and put down my pencil. The shock came when I looked at the back of the last page, which told me when to expect the results after the army’s examiners had marked the paper. It was only then that I realized I had just sat the entrance examination for the army technical apprentices’ college in Chepstow. I was soaked to the skin by the time I made it down the hill to the bungalow. It made no difference to my father when I tried to remonstrate with him. ‘Don’t think for a moment that you are going to the Navy, boy,’ he said. ‘You are going to the army technical college, and you better make sure that you work hard and pass out high enough to get into the Royal Engineers.’

The subject was never discussed again, and my fourteenth birthday came and went at the start of 1936. In April I went back up to Fort Canning, this time with my father, and found myself standing in front of his commanding officer and being sworn into the ranks of the army. The colonel seemed ancient. He mumbled his way through the oath of allegiance, and I struggled to make out the words I was required to repeat after him. It didn’t seem to matter, as before I knew it I had placed my hand on a Bible and sworn to serve my sovereign and my country. In taking the king’s shilling I was

committing to join the army, although I never received the silver coin with George VI ’s head on it.

A few days later I was saying goodbye to my mother and father at the quayside of Singapore’s main harbour terminal. I hugged my mother awkwardly, said cheerio to my siblings and shook my father’s hand. I was then handed over to the charge of a grizzled senior NCO. With that, wearing my first pair of long trousers and hauling an oversized suitcase, I followed the sergeant up the gangplank of the troopship Neuralia, which would be taking me back to England and the start of my career in the British army. I was four feet ten inches tall and weighed just over 100 pounds. My father used to tell me that I had been ‘born in a kit bag’. It just so happened that it was an army one, and not a Navy one.

Based in the north London borough of High Barnet, 296th Field Company Royal Engineers was not the battle-ready unit I expected it to be. Located in a drill hall just off the high street in St Albans Road, the 296th was a Territorial Army outfit in the process of being mobilized for active service in France. In January 1940, an army field company of engineers was meant to have a war establishment of six officers and 250 other ranks, split into a headquarters section and three field sections. However, when I arrived it could muster about fifty soldiers. There were no officers, and the major due to command the company had yet to be posted in.

On arrival I presented myself to the company sergeant major, a man in his later middle years who sat behind an untidy desk strewn with nominal rolls, reports and returns, no doubt listing all the things the unit needed but still did not have. He looked slightly harassed and seemed to be running the show. I noted the ribbons on his new battle-dress jacket denoting service in the last war. Having knocked on his open door, I entered the office, marched in and halted with a crash of my ammo boots a foot from the front of his deck. The CSM looked up in mock alarm. ‘Steady on, lad,’ he said. ‘Stand at ease. Who are you?’

‘1877368, Sapper Humphreys. Reporting for duty from Shorncliffe. Sir!’

The sergeant major looked down and searched for a sheet of paper among the mass of those scattered across his desk. He found what he was looking for. ‘Sapper?’ he enquired. ‘I

was expecting a lancejack.’ Sparing him the details, I told him I had been reduced to the ranks for a poor turn-out on parade. ‘Bloody hell,’ he said, eyeing my neatly pressed service dress jacket, badges now properly polished and my highly bulled boots. ‘You look smart enough to me, lad. There must have been a mix-up with the paperwork, and God knows I need experienced NCO s to sort this lot out if we are going to have a hope in hell of being ready to go out to the BEF. We are under-strength, don’t have any officers or the right kit or any vehicles, and the blokes we do have are a bunch of under-trained part-time soldiers or militia men being posted in without any training.’ He paused.

‘Get yourself along to the tailor’s shop, lad, and get that tape sewn back on. And while you’re at it, get it sewn on to a set of battle dress. We don’t wear service dress around here any more and the army expects us to wear this stuff.’ He indicated his own loose-fitting uniform.

Despite having to hand in my smart, well-tailored service dress and hat for the shapeless side cap, rough woollen shortjacket blouse and thick serge trousers that passed for battledress, I had fallen on my feet. I had my rank back, and the semi-organized chaos and inexperience that pervaded 296th Field Company in those first few months worked to my advantage. I could be valued for putting my own experience to good use and play a real part in helping to get the unit ready to go to France. There was also a distinct lack of bullshit, as things were too dire and too important for that.

Over the next four months our numbers began to build and more equipment came in. In February, a TA major was posted in as the OC , although I had little to do with him, and the young officers who started to join the company proved themselves to be just as inexperienced and remote as he was. However, by April we had our full complement of officers,

as well as 228 men, although their quality and military experience varied, and specialized engineering kit and 15-cwt and 8-cwt trucks were arriving. Moving out of London, we were sent to Pangbourne and lived in tented camps in order to be close to the River Thames, where we practised building pontoon bridges and watermanship skills.

As the army began to grow in size, accommodating it and finding land for it to train on became a major challenge. Before leaving London, the gradually swelling ranks of 296th Company were lodged with civilian families. However, this was hardly conducive to building a cohesive military unit, which needs to live as well as train together. Consequently, the south of England became one mighty armed camp as reinforced Territorial units moved out of their urban drill halls and gathered under canvas in more rural areas, often in the grounds of large country estates.

We moved into the manicured deer park of Basildon Park. Situated on the higher ground on the west side of the Thames, the grounds of the estate sloped down to the river, less than half a mile away. As well as ample space for pitching our tents and its close proximity to a water-training area, the Palladian mansion provided accommodation in grand style for company headquarters and the officers. It went some way to explaining why we rarely saw them, as we froze in our tents that winter or toiled with assault river boats and bridging equipment to build pontoons extending from one bank of the river to the other. Most of the officers came from the comfortable, professional, office-based middle classes. So, in truth, there was little they could offer in the way of practical expertise when it came to combat engineering and I was glad that they stayed out of the way and we could be left to get on with teaching the sappers the skills they needed.

At the beginning of April 1940, Hitler invaded Denmark

and Norway. Although the small Anglo-French force sent to help the Norwegians was quickly defeated and withdrawn, it was anticipated that the major showdown with the Wehrmacht would take place in France. The UK ’s priority was to build up the BEF, which remained inactive in defensive positions facing the German army along the French frontier. We anticipated joining them once we had reached our full manning levels and completed our training. While the Allies and the Germans faced off against each other across the French Maginot and German Siegfried Lines, the sense of a phoney war prevailed. Back in England, our training continued, although there was little sense of urgency.

At the end of the month we moved to another tented camp set up in the Rushmoor Arena near Aldershot, which had been built in the 1920s to host military tattoos. Before the war, the military shows and displays of marching troops, horse-drawn artillery and mock battles in armoured vehicles had drawn large crowds. Now the troops that gathered there were training for the real thing, when it came. The Blitz had not yet started, and the Battle of Britain was still to be fought when we marched down Queen’s Avenue, which runs through the centre of the Aldershot garrison.

I was now a full corporal, bearing two stripes on my arm, and was in charge of a squad of sappers. I did not tell them to seek shelter when the air-raid siren began to wail. We had become used to hearing them and the bombing attacks they were intended to announce had always turned out to be false alarms. So we kept step and the whistle of a stick of falling bombs took us by surprise. The first detonated with a mighty crack to our front, with four more spreading away from us in a column of exploding destruction. The noise was earsplitting but amid the smoke and confusion we managed to remain on our feet untouched by the blast or the scything

shrapnel. A group of five civilians who had been approaching us seconds before the bombs hit had not been so lucky. As the smoke cleared, we saw them. Badly wounded, they lay on both sides of the road among blackened craters and debris. A cyclist had been decapitated and his severed head lay a few feet away from me. While still suffering from shock, we did what we could for the injured and waited for the ambulances to arrive.

It was our first taste of death and destruction and a salient lesson of what might be awaiting us when we got to France. A few days later, on 10 May, the German army launched its invasion of the Netherlands and the BEF and the French army advanced into Belgium to meet them. The phoney war was over and the prospect of going into action was on my mind when I was told to report to the CSM .

‘You wanted to see me, Sergeant Major?’

‘Yes, Corporal Humphreys. Orders have come through that we are to move to France in the next two weeks and we are going to be sent up the line to join the BEF. However, I am afraid that you won’t be coming with us.’

My mouth dropped open. ‘Why not, sir?’

‘Because you are what the army calls an “immature”, so you’re not old enough to go. You need to be nineteen, Corporal, to serve overseas. It’s the law, I’m afraid.’ I would not be nineteen until January 1941, and that was still eight months away. I was gobsmacked, and the CSM saw it. ‘Hold on, son,’ he said. ‘Let me put a call through to the garrison headquarters to see what can be done.’ I waited while he made the call. The sergeant major explained the predicament to the voice on the other end of the line. I heard him say ‘Right, sir, I didn’t know that,’ and ‘OK , sir, we’ll see if it works,’ then he said, ‘Thank you, sir,’ and put the phone down.

‘That was a staff officer in the HQ ’s admin branch. He

says that if you can get your father or mother to sign a certificate of consent, that will allow you to go to France.’ I thanked the CSM and dashed off to get the necessary form from the company orderly room to send to my father. Fortunately, he had recently returned to England from Singapore, having retired from the army. I knew he was staying with relatives until he had decided where to work and settle, so I sent the form to them, asking for a speedy reply. My father duly signed the consent certificate and posted it back to me. However, he need not have bothered.