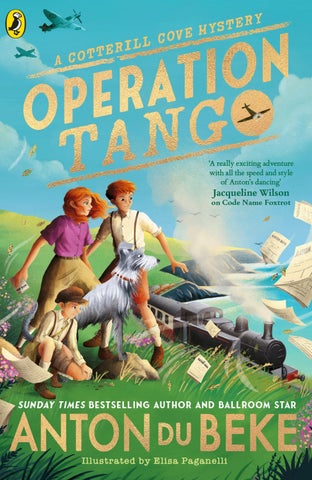

Bestselling author, king of the ballroom, Strictly Come Dancing royalty and household name Anton Du Beke is one of the nation’s all-round entertainers. A consummate storyteller, adept at captivating audiences; his series for adults set in the 1930s have been Sunday Times bestsellers.

Now Anton will whisk young readers and families away on an unforgettable wartime adventure with Operation Tango, his second novel for children.

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Puffin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com www.penguin.co.uk www.puffin.co.uk www.ladybird.co.uk

First published 2025

Text copyright © Anton Du Beke, 2025

Illustrations copyright © Elisa Paganelli, 2025

The moral right of the author and illustrator has been asserted Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Set in 13.3/18pt Bembo Book MT Pro Typeset by Jouve (UK ), Milton Keynes Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn : 978–0–241–69917–1

All correspondence to: Puffin Books

Penguin Random House Children’s One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London s W 11 7b W

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

Thank you to my wonderful twins, George and Henrietta, for inspiring my fictional ones!

Chapter One

A Secret Mission

The moment the school bell rang, Harry Morton ripped off his jersey and bolted for the classroom door. This was it – the moment he’d been waiting for: not just the end of term, but the end of the school year itself. Six weeks of summer stretched ahead of him – six glorious weeks of buttery sunshine, clear open skies and exploring the beautiful hidden beaches of Cotterill Cove.

‘There isn’t anything we can’t do,’ Harry said to his twin sister Rosie – who, having stayed behind to wish their friends goodbye, caught up with him on the cobbled row outside the churchyard. It was almost a year since they’d been evacuated to live with their uncle in sleepy Cotterill Cove, and they’d spent almost all of that time chained to a school desk, reading,

writing and learning about the rule of law. This was their reward. ‘Anything, absolutely anything we want. I bet Uncle Rupert would let us go camping,’ Harry blathered. ‘I’ll bet he won’t mind if we live wild on the cove all summer long, just eating crabs and bathing in the pools at the base of the cliffs and –’

‘There is one thing we have to do first,’ Rosie said. ‘You know, before we start living like cavemen down on the seafront.’

Harry and Rosie reached the edge of the fishing village and looked down on the majestic sweep of the cove, where blue waters glittered under equally blue skies, where seabirds wheeled in grand formation and the colourful sails of fishing boats could be seen out at sea.

‘Oh, yeah? What’s that?’

‘Mum’s birthday, Harry.’

‘Yes,’ said Harry, grinning. ‘There is that.’

Rosie couldn’t blame Harry – the promise of six free weeks filled her with wonder too, and sometimes it was strange to remember that Cotterill Cove wasn’t really their home, that London still existed, all those hundreds of miles away. It had been nearly a year since Harry and Rosie had been sent to Cotterill Cove to escape the bombardment over the city, and in all that time

they’d only seen Mum and Dad once: that wonderful dance at Christmas, when Mum had sashayed in in her fineries, and there was Dad, freshly returned from the war. There’d been some talk of Mum and Dad coming to visit them for an Easter holiday, but in the end Dad had been called back to barracks for training – he was awaiting his orders to return to the war – and the chance kept slipping by. It was funny how quickly one week could turn into a month, the seasons hurtling by. Back at the start of the war, neither Rosie nor Harry had believed they might stay in Cotterill Cove this long. Now, though they still hankered for London – and the Little Mayfair Tearoom, that little dance hall that was Mum and Dad’s pride and joy – Cotterill Cove almost felt like home.

Even so, on special occasions, the distance between them felt strange. Rosie still wrote letters to Mum and Dad every week (Harry preferred to scribble a little message at the bottom of Rosie’s, because writing a whole letter felt far too much like schoolwork), but it wasn’t the same as seeing them every day. With Mum’s birthday barely a week away, Rosie was determined to do something special for her. That was why, the very moment they returned to Nautilus House – that brooding manor house up on the headland, where

Uncle Rupert and his faithful hound, Lurch, had been living alone until Harry and Rosie arrived – they settled in the east wing sitting room, surrounded themselves with paints and pencils and ink-pens, and set about making cards. If they made Monday morning’s post, the cards ought to arrive right on time.

Rosie only wished there was some way they might go and visit Mum – and especially Dad, before he was sent back to the war. The bombs had dropped fiercely on London last year, but Rosie kept an eye on the newspapers and knew that the battle in the skies over London wasn’t nearly as ferocious as it had been. She’d asked Mum and Dad, more than once, if she and Harry might make the journey – but Dad said it was still too dangerous, and they would just have to wait for things to calm down. The problem with waiting, though, was that you never really knew how long.

As Harry and Rosie worked on their birthday cards, the wireless radio buzzed away with news from the war. It was unnerving to think that Dad was due to be sent back to the battle. Everything Rosie heard was so discombobulating, she wondered what he might face. Fighting had moved beyond Europe – there was a chance Dad would be sent to North Africa – and, though the Blitz over London wasn’t as fierce as it

used to be, there was still much tension in the air. Right now, the newsreader was announcing that the Australian army had been victorious in the Lebanon – though, where this was and what it might mean, Harry didn’t quite know.

‘Don’t you think the war seems so far away now?’ Rosie asked, as she worked on her card.

Harry shrugged. ‘Not when I want a jam sandwich it doesn’t.’

Rosie looked up. Harry seemed to have forgotten about his card, and was marvelling at an empty jam jar he’d taken from the window ledge and filled with water, running his fingertip round the rim as if he might still discover some strawberry goodness hidden there.

‘That’s a good point,’ Rosie agreed – and, turning back to her card, wrote, ‘We were so grateful for the jam, Mum. How ever did you get a spare jar? Harry and I have been eyeing the elderberries that grow in the churchyard here. When they’re ripe, we’ll make some jam of our own and send it back to you!’

‘Fat chance of that,’ said Harry, reading over her shoulder. ‘Where would we get the sugar?’

‘We’ll just have to start setting some aside.’ Rosie poked at Harry’s shirt. ‘You know, you ought to

take care of this better. They’re rationing clothes as well now.’

This was when the war really felt close: standing in a bread queue, handing over a coupon for bacon or sugar, or counting out cubes of cheese just to make it last. A little while ago it had only been butter and sugar that the Ministry of Food was rationing – but every month it seemed that something new was added to the list. Harry knew it was vital for the war effort, but sometimes it was difficult to understand what a few pork sausages had to do with a worldwide war.

‘No need to tell Mum about that,’ said Harry, trying to hide the hole in his shirt. ‘Just tell her – tell her . . .’ Harry gazed out of the window, over the overgrown, tumbledown garden of Nautilus House and on to the shimmering waters below. ‘Tell her I wish there was something we could do.’

‘You know what she’ll say,’ grinned Rosie, who had heard this from Harry before.

Not that he wasn’t right. Sometimes it felt a little unfair that so many people’s lives were being upended, diminished by the war, and yet Harry and Rosie got to spend it somewhere as lovely as Cotterill Cove. But the war was here too. Mum had always said that every citizen had do their bit, that looking

after the little things was just as important as the big. Find a way to help, however you can, Dad once said – every little thing matters. ‘We’re helping school plant those potatoes, aren’t we?’ she said. ‘And there was the collection of scrap metal, old pots and pans, for the military wagons.’

Harry snorted. ‘Potatoes and old pans are all well and good, I suppose.’

Rosie knew how he felt. The country needed feeding – in a time of war, everybody had to find clever ways to put meals on the table – and there were all sorts of charitable drives to take part in. The pots and pans, and old scrap metal, had actually gone off to help the RAF build new fighter planes (it was amazing to think that the pan you cooked your cabbage in might have ended up battling German planes in the skies over London), but somehow none of it felt enough.

‘Look at it out there, Rosie!’ Harry gasped. ‘Six weeks of summer here! Just think of the adventures we’ll have! But Mum, stuck in London and Dad going off to war again and . . . there ought to be something we can do! There ought to be some way we can help.’

‘There is,’ came a deep, gravelly voice from the sitting-room door.

Harry and Rosie turned.

There, in the doorway, was Uncle Rupert, with his tangles of grey beard, his ruddy cheeks – and his kind, winter-blue eyes. Lurch – whose fur always looked as tangled as Uncle Rupert’s beard – stood loyally at his side, tongue lolling out as if in expectation of a chunk of sausage. It was one of the less-talked-about aspects of war that even pet dogs suffered – Lurch didn’t get a ration book, so he’d been missing out on his traditional sausage supper.

‘What is it, Uncle Rupert?’ Rosie asked, sensing something grave and important.

‘There’s something I need you to do,’ Uncle Rupert began, venturing into the room. ‘A job for you and you alone.’

Those were words sure to make the twins pay attention – for, among the residents of Cotterill Cove, only they knew that Uncle Rupert worked for His Majesty’s intelligence services. The rest of the village thought Uncle Rupert was an eccentric, solitary old man, living in the house on the hill with the two children who’d been sent here to escape the war – but Harry and Rosie knew the truth: Uncle Rupert was the ‘eyes and ears’ of MI 5 along this stretch of the coast, watching out for spies, subversion and enemy invasion.

That was why, as soon as he heard the words, Harry perked up.

That was why he knew something exciting was afoot.

It was the serious look in Uncle Rupert’s eyes.

The sombre way he strode across the sitting room, an envelope in his hands.

Uncle Rupert tried to keep Harry and Rosie out of his Serious Government Business (Harry always insisted on using capital letters when he talked about it; it was just that serious) – but it seemed a task had come up of such critical importance that it couldn’t be accomplished alone. Now, as Harry and Rosie lined up to face him, they couldn’t help sharing a jittery, excited look.

‘I’m afraid things are going to be most taxing this summer,’ said Uncle Rupert.

Rosie braced herself for whatever was to come.

‘And I must ask you to play your part.’

‘Anything,’ Harry exploded. ‘Whatever it is, Uncle Rupert, you know you can count on us.’ For some reason (which Rosie would tease him about later), he even gave Uncle Rupert a grand military salute.

‘We’ve helped you before. We can help you again.’

‘I’m glad to hear it,’ said Uncle Rupert with a deep sigh – as if he’d been expecting some resistance. ‘As you’ll appreciate, this is hardly a job for me. It will take more nimble minds than mine.’

He passed across the envelope.

Rosie watched Harry scrabbling it open. He looked like a boy on Christmas morning.

Then Rosie saw his face drop.

His cheeks turned white.

Harry turned the letter sideways, upside down, back to front, as if he couldn’t work out what it meant. Well, that was no surprise. It had always been Rosie who was good at cyphers and secret codes – which was exactly how Uncle Rupert’s paymasters communicated with him, for Security Reasons (those capital letters were important here too). Cyphers and codes were a game Dad used to play with the twins, teaching them cryptic crosswords and puzzles out of books – but Harry had never had the patience for it. Rosie had been trying to teach him all year.

Now she marched across the room and reoriented the letter in Harry’s hands.

The silly thing was, it wasn’t in code at all.

Suddenly she realized why Harry’s face had blanched:

Dear Rupert, all make sacrifices.

Tuesday 15 July

I cannot thank you enough for your kind o er. When we heard what a splendid job you had been doing looking after the Morton twins, I dared hope you might o er us the same help – but one does not like to presume. Nevertheless, Manchester is no longer safe for dear little Jasper. At only eight years old he is distraught at the idea of leaving his dearest mama, but in these dark times we must

I have reserved him a ticket on the three p.m. train from Manchester London Road station on Saturday 19 July. Please can you come to Manchester to escort him back to your house? I will pack him extra sandwiches to share with you on your return journey. He is, I promise, a most delightful boy and I’m sure he will settle in well

I have reserved him a ticket on the three p.m. on your return journey. He is, I promise, a most to Cotterill Cove.

My love and best wishes, Aggie Shute

He doesn’t like any potatoes except baked, He doesn’t like pork chops but is in love

PPS with sausages.

PPPS

At bedtimes he likes a story and a poem, but he’s promised he can live with just one or the other. Make sure you do all the silly voices!

PPPPS devil for vegetables.

Make sure he eats his vegetables – he’s a

PPPPPS satchel.

I’ll send his ration book in his little

Rosie and Harry looked up at Uncle Rupert’s solemn face. ‘I suppose you know who Jasper is?’ he said. There was much stuttering, mostly from Harry, before Rosie said, ‘He’s Mum’s cousin’s little boy, but we haven’t seen him in –’

‘However long it’s been, it’s not as long as me,’ cut in Uncle Rupert. ‘I’ve never met the little tyke.’ He clapped his hands together. ‘So here’s your mission. I can’t leave the Cove, not tomorrow – so I need you to take the midday train into Manchester. Jasper and his mother will be waiting for you on the platform, with butter.

beneath the railway clock. You’re to bring him directly home, and try not to cause mischief on the way. Is that understood?’

At last Harry managed to form a sentence. ‘We were going to go exploring tomorrow afternoon – with Caro and Griff, if he’s finished on the boats in time. We were going to take our bicycles and follow the coast road.’

‘That particular adventure will have to wait.’

But Uncle Rupert was not an unkind man, and when he saw how disheartened Harry seemed, he added, ‘It isn’t forever. I’ve promised Aggie that Jasper can stay until the end of the summer. Just six weeks, while things settle down in the city. And you two must know how that feels? To be sent away from home?’

Harry tried not to let his disappointment show. The frisson of excitement he’d felt when Uncle Rupert asked for their help had been snuffed out in an instant, and now he was left wondering at what the summer had in store. In his mind’s eye, it had been full of exploration and adventure – and, who knew, perhaps even stumbling across some way of really helping the war effort. Something that was a little more exciting, anyway, than potatoes or pots and pans. Cotterill Cove was a quiet town, but sometimes

the most dramatic things happened where you weren’t expecting – why else would Uncle Rupert be stationed here, working in intelligence? The summer might have been about helping Uncle Rupert in whatever shadowy mission he was on – but now it was going to be about . . .

‘Babysitting,’ grumbled Harry.

But Rosie shot him a warning look. She felt the disappointment too, but Dad’s words kept coming back to her: every little thing matters. By helping Uncle Rupert, she decided, they were helping the war effort. Uncle Rupert had his duties in Cotterill Cove; if she and Harry went to pick up Jasper, they were helping him fulfil them.

Folding the letter, she smiled brightly and declared, ‘We’ll bring him back safely, Uncle Rupert.’

‘That’s the spirit,’ Uncle Rupert declared. Rosie might have been mistaken – but it seemed, now that this particular task had been taken off his hands, he was suddenly more sprightly. ‘And when you get home, there’ll be a reward waiting: one of Mrs Buxton’s wild strawberry cakes. Well, there’s no rationing wild strawberries and honey. Twins, tomorrow evening, you’ll eat like kings!’

‘Cake,’ said Harry the next day, as they boarded the little train at Cotterill Cove station and watched the rugged coastline flickering by. Out there, sunshine was glittering on the perfect water. The fishing boats, with their patchwork sails and proud figureheads, danced on the horizon. The twins’ friend Griff would be out with his father, bringing in the day’s catch. They were meant to be meeting him this afternoon, along with Caro – whose family ran the Crown and Anchor pub in the village – to go exploring the rock pools along the jagged Devil’s Finger, but instead they were slumped in this carriage, with only a bag of humbugs between them, on quite possibly the worst ‘secret mission’ anyone had ever undertaken in the History of Forever.

‘Mrs Buxton makes a good wild strawberry cake,’ said Rosie – who was better than Harry at seeing the bright side of things.

‘Yes,’ said Harry, ‘but now we’ll have to share it three ways.’

Rosie stifled a laugh. ‘Uncle Rupert’s right, you know. Last summer, it was us being sent away from home. Jasper’s probably nervous. Quite likely he’s scared.’

Out of all the things Harry disliked in the world, knowing that Rosie was right might have been the

worst. He pulled himself up and pressed against the window to watch the sparkling waves rushing by.

‘What do you remember about Jasper?’ he asked. ‘We have met him, right?’

Rosie nodded, but she said not a word.

‘Well?’ asked Harry.

‘Well – what?’

‘I can tell you’ve got something more to say. It’s the way you make that face. Go on. Whatever it is, it can’t be worse than what I’m thinking.’

‘They came to visit the tearoom once. But it must have been . . . four years ago? Five? We were so young, I can hardly remember.’

‘Hardly remember what ?’ demanded Harry. Rosie was dodging the question.

‘Well, I think it was Christmas, and Jasper and his mother were visiting London. Mum and Dad wanted to show them the tearoom, so we invited them one afternoon when there were dances and . . .’

It was when Harry and Rosie reminisced about the Little Mayfair Tearoom that they missed London the most. Mum, Dad, and the music of the Little Mayfair Tearoom – there was no better combination in the world. It was difficult to believe that it had been almost a year since they last laid eyes on the place. Almost a

year since they had listened to the music in the tearoom, seen the customers flocking out to dance, crept down from bed to watch the ladies and gentlemen in their elegant suits and gowns, waltzing and foxtrotting and tangoing to the sounds of the band. There was sometimes music in Cotterill Cove – in the Crown and Anchor, on a Saturday night, there was even dancing – but it was nothing like back home.

‘Well, do you remember when all those dancers started crashing into each other? When that lady in her ivory dress spun into the stage? And the gentleman in the dinner jacket fell flat on his face? And all because . . .’

Harry gasped. ‘Somebody had poured milk all over the dance floor!’

‘Not just somebody,’ said Rosie. ‘Jasper.’

‘And then he cried that there wasn’t any milk left,’ Harry remembered. ‘So much crying the band had to stop playing – and said they wouldn’t play until he was quiet. It was putting them off their rhythm!’

‘Jasper’s mum just said he had –’

‘Very musical crying!’ Harry snorted. ‘And we were sent upstairs to look after him – but, every time we turned away, he was making for the stairs, or screaming from the window, or . . . or breaking my model boat.’

‘Pulling out my doll’s hair.’

‘Yanking out all the feathers from the pillows on our beds.’

Rosie gave a crumpled smile. ‘Then he told his mum it had all been us, and she believed him. She gave a him a biscuit and said he’d been a darling.’

Harry slumped in his seat.

‘That was five years ago,’ said Rosie, with a shrug. ‘I’m sure things are different now. And Harry, it isn’t nice to be sent away. Jasper’s younger than we were when we were first sent to Cotterill Cove – and we had each other. Six weeks is a long time. A whole summer holidays.’

‘I know,’ said Harry. ‘Just think of the fun we could be having.’

‘He’s bound to be homesick. Don’t you get homesick, Harry? And don’t lie to me – because I know you do.’

Harry was about to say, ‘I’m sick of this train – that’s what I’m sick of,’ but Rosie was right. It wasn’t that he pined for home every night, and it wasn’t as if he hadn’t found things to love in Cotterill Cove – there were new friends, the grand sweep of the bay, and who wouldn’t love the wild freedom of living at Nautilus House? But sometimes it still stabbed at him, that he couldn’t hear the music of the Little Mayfair Tearoom each night – and, now that Dad was being summoned

back to the war, it had been weighing on him more and more. It would have been nice to have spent the last few months at the tearoom with Mum and Dad, just like in the old days. Sometimes, he wondered if they’d ever get to go back home – and what home might be like, if they ever did get there.

Rosie was still looking at him. He didn’t need to tell her what he was thinking, because twins always knew.

‘I’ll help him settle in,’ he said, as the train chugged on, ‘but I’m still hiding our pillows.’

Soon the train had left the coast behind and was travelling inland, crawling into every local station and sitting in sidings while freight trains rumbled by. By now not even the humbugs were enough to keep Harry’s impatience at bay. Rosie had brought along a collection of old newspaper puzzles – Dad had been collecting them, and Mum had sent them up with the last jar of jam – but Harry had almost no interest in puzzles. Instead, he kept bringing out Dad’s silver pocket watch, which he always kept in his short-trouser pocket, and counting the seconds. ‘We’ve been sitting here too long,’ he said as they waited at a village station for passengers to embark. ‘We’re going too slowly. We must be half an hour late by now!’

The train ground into another station and lingered on the platform, while yet more precious minutes of summer flew past.

‘This is the last stop, isn’t it?’ Harry groaned. ‘Promise it’s the last stop.’

Rosie abandoned her puzzle book and looked out of the window, where she could see the spire of the famous Manchester Cathedral not too far in the distance. ‘What station is this please?’ she asked a fellow passenger.

‘Manchester Oxford Road,’ the man replied.

Next Rosie looked at the little paper timetable she’d picked up in Cotterill Cove, and checked the time on the station’s clock. ‘Yes, Harry, I think it’s the last stop before Manchester London Road station.’ Then her own face crumpled and she said, ‘But the train had better get going quickly. We’re twenty-eight minutes behind schedule. There’ll hardly be a spare second to grab Jasper and get back on a train to Cotterill Cove.’

‘We’d have been better off down at the cove,’ Harry groaned. ‘We could have been building a campfire by now. We could have caught a big fat crab or lobster.’

Harry pressed his face longingly to the window. The station at Manchester Oxford Road was grey and dreary, with grey shadows moving behind the windows

of its ticket office and barely a passenger to be seen. Not at all like the wide, open seascape of Cotterill Cove, he thought dreamily.

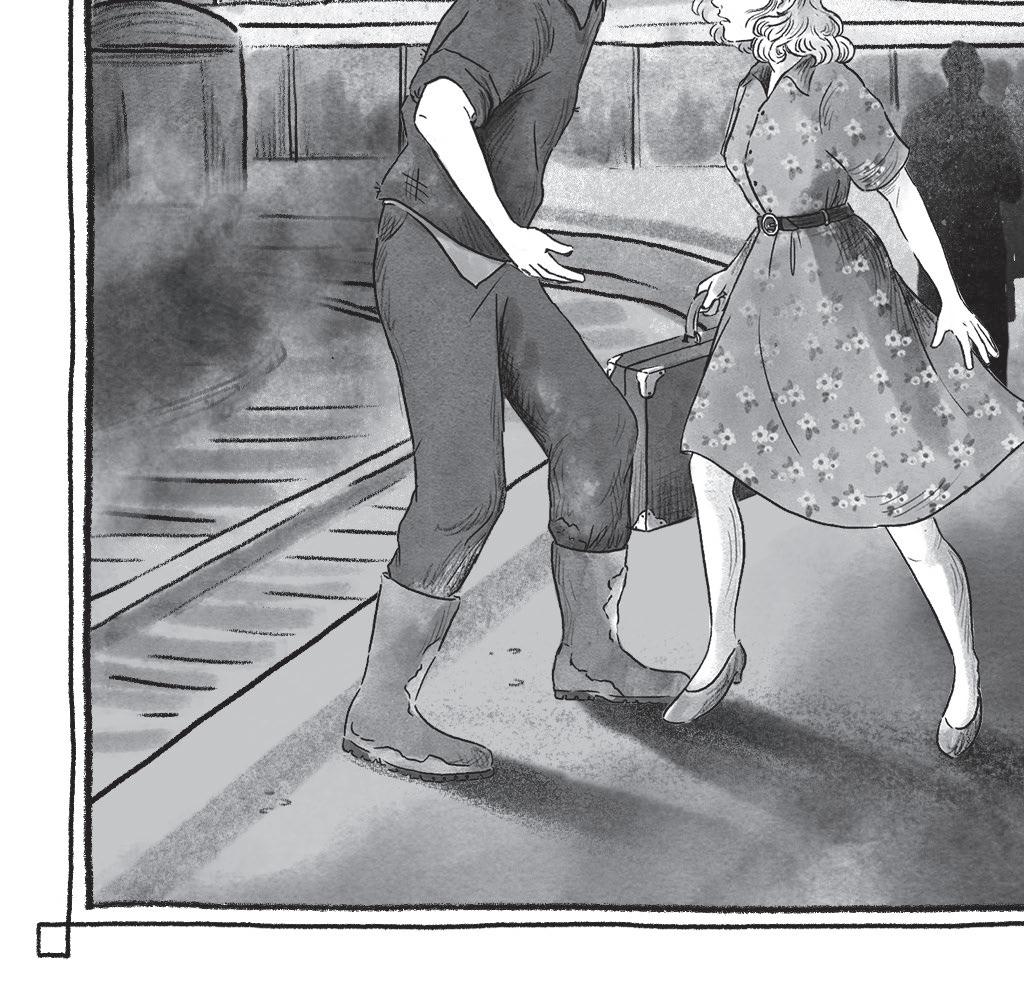

On the other side of the station, across the railway tracks separating their train from the ticket office, a lady in a summery sun dress and striking red beret was standing on the platform. Harry could tell she was anxious, because her fingers were quite as restless as his own. Beneath the striking red beret she had locks of long yellow hair. At her side sat a small tortoiseshell suitcase. Idly, Harry wondered where she was going. Ticket in hand, suitcase waiting – she had the whole summer in front of her, to do with exactly as she wished, while Harry was a virtual prisoner inside this carriage, his summer ruined before it had even begun.

‘Harry, stop staring!’ Rosie laughed.

But Harry couldn’t, because at that moment another figure appeared.

A lanky young man, with raggedy black hair, raggedy black clothes, and wellington boots caked in earth, had emerged from the ticket office and marched directly towards the lady in the red beret. Harry could not have imagined two people any more different than these, but apparently they knew each other,

because – though he couldn’t hear a word – they were very quickly in the midst of a heated conversation. As he watched, the lady turned dramatically away, only for the raggedy young man to follow. The lady might have been angry, but she certainly wasn’t telling him to go away – not even when he took a step altogether too close, then seized her by the wrist.

‘Rosie, look. What do you think’s going on out there?’

Rosie was minded to tell Harry that it was none of his business – but the moment she joined him at the carriage window, she faltered. The lady in the red beret had ripped her hand away from the raggedy man, and seemed to be giving him a fierce rebuke.

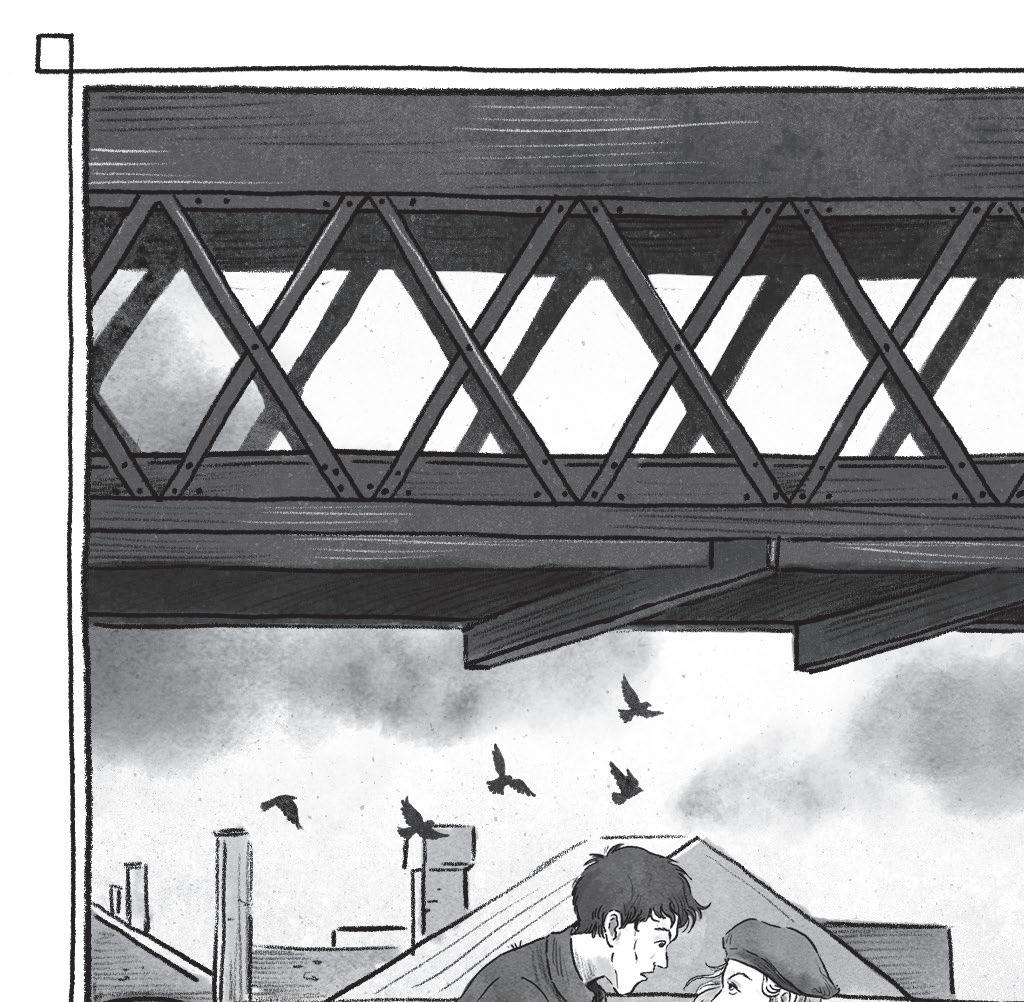

A train whistle blew. Harry muttered, ‘Finally!’, fully expecting the train to start moving again – but, in fact, it hadn’t been their train that whistled. Another was sailing into the station, filling the opposite track. One moment the lady in the red beret and the raggedy man were confronting each other; the next they had vanished behind a black locomotive pumping out reefs of grey steam and dragging a dozen carriages behind it.

Rosie took the pocket watch out of Harry’s hand and said, ‘Even I’m getting impatient now. We’ve really got to get going.’

‘But didn’t you see ?’ gasped Harry, whose mind was still racing.

‘All I see is that we’re running out of time.’

‘He took hold of her,’ Harry protested.

Harry was still trying to explain the feeling he had in the bottom of his stomach – that something out there was very wrong indeed – when another shrill whistle blew. Their own train had started moving at last.

In pure frustration, Harry hammered his fist on the glass. Now he’d never see what the raggedy man and the lady in the red beret were up to on the other side of the station.

Slowly at first, the train slid forward, picking up speed as it came along the platform.

‘I’m telling you, Rosie – something was odd about that. Have you ever seen two more unlikely travellers than –’

In the corner of his eye, he saw a flicker of movement. A figure had appeared in one of the carriages of the opposite train.

Harry saw him only briefly as their own train slid past, bound at last for their final stop, Jasper, and the fulfilment of their secret mission for Uncle Rupert – but there was no doubt about it.

The raggedy man had got on to the train.