15 minute read

1949 When the villa became a school

1949

When the villa became a school

Advertisement

Anew time had come for the villa. In the summer of 1950, a summer boarding school was founded on the property. The school had students from all over the country, as well as daytime students from Tynningö and the islands nearby. It was primarily a school for those who needed help improving grades so they could continue to the next level of education, but there were those who went just to advance in one or two subjects.

Our story begins long before this. In 1937, Grethe and Mauritz lived on opposite sides of Öresund, the strait separating Denmark from Sweden. Grethe studied to become a children’s physician in Copenhagen and Mauritz studied humanities in the Swedish university town of Lund. They were both members of student associations at their respective universities. Summer exchange programs were arranged between the universities and both participated. The first time Mauritz saw Grethe, she was wearing the Danish flag’s colors with red trousers and a white blouse. It was love at first sight, confirmed by Mauritz in his own re-telling of the moment: ”And we saw the sun go down, and we saw the sun go up again.”

They were married on Midsummer’s Eve in 1939. Grethe moved to Lund with Mauritz. Two months after they married, the Second World War broke out. Mauritz was drafted and served until the risk of conflict had eased for Sweden. After this, they left southern Sweden for Uppland, north of Stockholm. From the time they met, they had talked about having many children, and from 1941 they would in due time have five. Adding to the growing family, they also adopted a Danish-Jewish boy who had escaped the German occupation on a fishing boat.

Boarding Schools

It was at this time that Grethe had the idea of founding a boarding school. The idea wasn’t strange to the Fagerströms as both had grown up in communal circumstances. Grethe had grown up in a boarding school for future teachers, where her grandfather worked as principal. The institution provided lodging for both teachers and students on the school’s property. Mauritz had grown up on the grounds of a large mental hospital, where his father supervised agricultural work. All employees had their homes on Grethe and Mauritz on a walk in Copenhagen.

the hospital’s grounds. In founding the boarding school, they created an environment for themselves and their children just like the one they had growing up.

Together in 1943 they started ’Rimbo Private Läroverk,’ a private grammar school. They would run the school until 1965. The school became a home for both the students as well as Grethe and Mauritz, who hoped to foster their students into becoming able citizens in addition to passing their exams. The Swedish school system excluded many from the chance of further study. Grethe and Mauritz’s private school offered opportunity for young people who didn’t have the grades to get into the few public schools available. Most of their students graduated with satisfactory results and could go on to university studies or other education.

Grethe had ended her physician studies when she moved to Sweden, but continued reading about children’s and youth psychology among other things. Both she and Mauritz were driven by the desire to improve the lives and opportunities of children. They understood their students as individuals, supporting change and knowledge through positive feedback instead of corporal punishment. The latter was far too present in schools and homes during their time. Mauritz in particular emphasized having fun as a crucial part of learning.

Perhaps he had this insight from his own upbringing. He was one of nine children and was deeply affected by the dull and gloomy circumstances of the mental institution where they lived, as well as his strict and unforgiving father. They were always short on money, and the cost of pursuing secondary education was high. There was still the possibility of being admitted on scholarship for those who excelled, which Mauritz and some of his brothers did. Getting in did not shield him from the degrading experience of being singled out by teachers who regularly reminded him of his low status. He had to hear to comments like, ”you who are here for free should watch yourself!” or ”you who are here as a ‘frielev’ [at the municipality’s expense] can’t...” This went on all throughout school. Mauritz vowed never to treat his or any other children in such a way.

The Reasons for a Summer Boarding School

As was the case with their boarding school, it was also Grethe who came up with the idea for a summer school. The entry requirements for higher educations were rigid, and students had to pass all classes before being admitted to a higher level. If you didn’t pass, your only chance of being admitted to the next level was to study during the summer. These students got a second chance in August before school started for the next term. If they passed they could go on to next level, otherwise they needed to re-do the entire year. The Fagerströms held summer classes at their school for some years before deciding to expand. During these summers, the students had complained that the lake nearby was too small to swim in. It made sense that in the fall of 1949, they bought Villa Björkudden and moved the summer school there. This became a combined school and summer retreat for them and the children.

How to Run a Summer School

Grethe, Mauritz and Mauritz´s brother Kjell made up the summer school’s staff. Grethe taught classes in mathematics, physics, and chemistry. Mauritz taught Swedish and German, and Kjell was responsible for courses in Latin and French. The summer school was run like a family business. When their children were old enough, they too helped with running the school. The gardeners Oscar and Ester Carlsson followed from the grammar school in Uppland and worked with the summer school until 1965. More than just a gardener, Oscar was a jack of all trades. He tended to practical matters on the property, from repairs to emptying the latrines, as well as managing the flowerbeds and landscaping. Ester also worked in the kitchen in addition to gardening. The first year, all food was bought from Johansson’s General store, the small red house near the main road to Björkudden. After a few years, they began to get fresh milk delivery by boat. When the general store later closed, the groceries had to be retrieved by boat from Vaxholm.

Before the students arrived, the bedrooms were prepared and everything was made tidy with tablecloths and flowers. Flags were raised on the flagpole atop the house so that all students arriving by boat from Stockholm

could see it from afar. The Swedish flag on top, with the Danish flag just below. The student rooms were furnished with military bunk beds, writing desks, drawers and bookshelves. All of the upstairs bedrooms were occupied by students except the small room to the right of the great staircase. This was the isolation room, only used if someone got sick – this gave the sickly some privacy and prevented the illness from spreading. The first evening upon arrival, when some students may have felt a bit lost, Mauritz eased the tensions by playing his harmonica.

Time for Recreation

Classes went until noon, and the time after lunch was kept free for leisure. Most students used this time to go down to the bridge and swim. Some went to the old bathhouse to sunbathe there, now reserved as girls-only for those who wanted to soak up rays with discretion. Others played ping-pong in the gazebo. All meals were eaten together in the dining room at a long table. A short piece of railroad track hung from an oak branch near the dock, and was used as a makeshift gong to announce dinnertime.

Grethe and children during their first summer on Tynningö, 1950.

When the signal rang out across the yard, everyone came sauntering from all directions toward the dining room. After dinner, there were two hours assigned for homework. Almost every night there was dancing in the common room and sometimes on the porch. In the common room, students could smoke if they had permission from a guardian. Many students did smoke, and as the wooden structure of the house was extremely flammable, safety measures were taken.

A New School System Marked the End

In 1962 the Swedish Parliament passed a bill that changed the system of primary education. Now, primary school was required for all children for nine years. This reform was intended to remove class differences in society, and wouldn’t hold students back if they failed one subject at the end of the term. It ended the split-education system in Sweden and introduced a base-education with primary education open to everyone. This new system was successively implemented region by region until fully implemented in 1972. With this reform, the summer school was no longer necessary. The last classes at Björkudden were held in the summer of 1967.

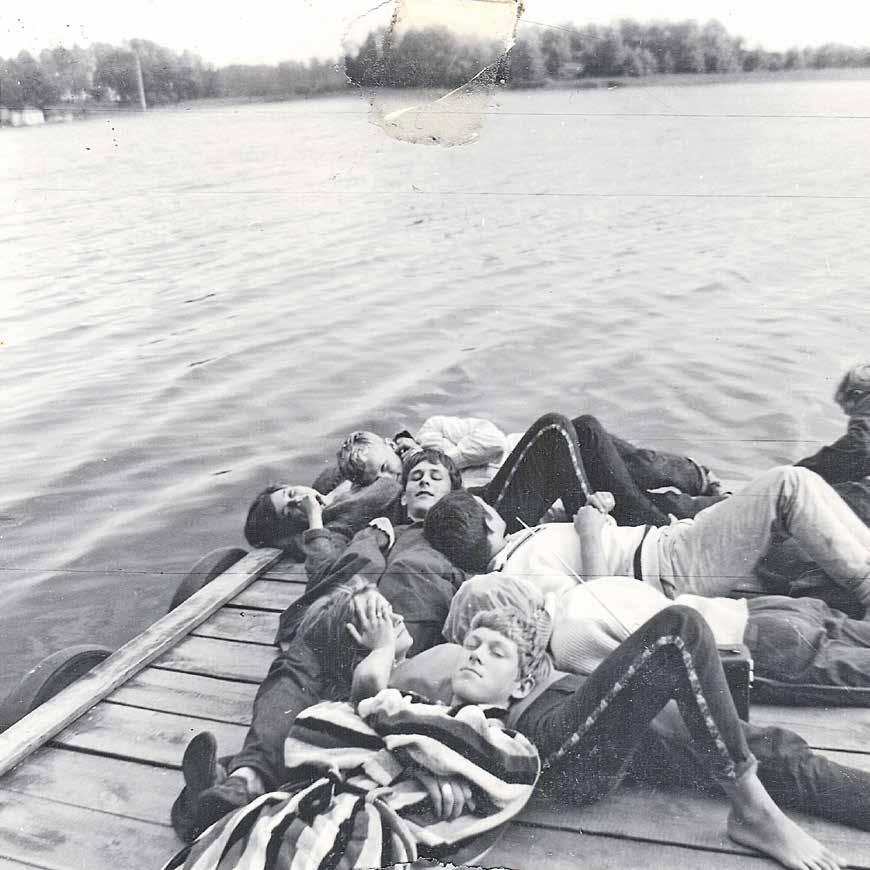

Bathing students, 1964.

A Memory of Torbjörn Fagerström

We arranged dances almost every night, and danced to Sinatra and Elvis. I got to help with miscellaneous chores: each Saturday the gravel paths were to be tended and the latrines emptied for example. As we had no refrigerator, I had took the boat into the city of Vaxholm each day to get groceries. We were wholly self-sufficient when it came to vegetables and berries. The Carlssons who lived in the gardeners cottage were like a couple of house gnomes tending to the greenery. One time, one of the students switched the contents of the sugar jar before breakfast. Mauritz noticed immediately and forced the boy to eat a bowl of salty cereal.

Students listening to Top 10 on the jetty, 1962. Torbjörn lays in front. Annika lays on her stomach with curlers in her hair.

Memories of Bibbi Fagerström

When we approached Vaxholm, we were all filled with anticipation. The moment the wheels touched the bridge leading into town, we all burst into a song we had made up ourselves: ”We have arrived in Vaxholm, We have arrived in Vaxholm, We have arrived in Vaxholm...” There were no car ferries back then. When we arrived at the dock, we loaded everything onto the beautiful mahogany boat and headed out toward the island.

As we approached the house, everyone who had already arrived would come out on the bridge to greet us. We were all eager to jump onto dry land. One time our dog jumped out too early, landing in the water, and had to swim the last few meters. My memories from the summer school are primarily how we children lived and coped with the students. I used to go with my uncle by boat into town, where my mom had ordered fresh bread from Zander´s bakeshop. We went during the morning when the students had classes and returned in time for lunch. In the common room we played cards, and it was there I learned to dance along with my elder brother and the older students. When we children got older, we were gradually assigned more chores at the school. I had a summer job as a cleaner, a washer, and managed the kiosk. The latter was something I enjoyed very much. The kiosk was in the cellar. I had business hours after lunch and dinner, using a small window as a service counter. It was mainly popular amongst the students for purchasing sweets before homework hours. When summer ended and the boat came to pick us up, we always thought it was so sad.

Grethe with a Danish student cap. A student lifts Bibbi and Peter, 1963.

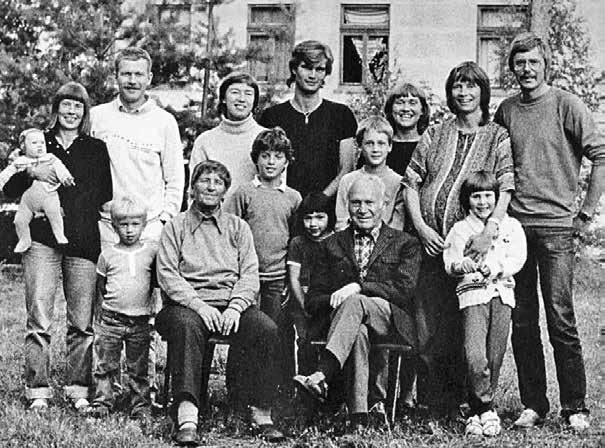

The students enjoyed being on the bathhouse roof. Peter, 1965. Grethe and Mauritz with family, July 1983. Taken on the old tennis court with the house in the background. Photo: Per Janse.

Proper Order

Grethe and Mauritz shared equal responsibility for the school and students. They reasoned and made decisions together. Both had contact with the students and their parents. Their personalities complemented one another. Grethe wanted to have a system and order to everything: papers, books, and money. She was detailed and organized. Mauritz was more spontaneous and an optimist. He has said himself that he has always taken life as it comes and that there will always be a way. And it usually works out for the best in the end. He was a warm and joyful person with a boisterous laugh. It was, for example, Mauritz’s idea to name all of the buildings on the property after their own children: Åsebo – the elongated house where there were once pigs and a shoemaker during the refugee camp’s time; Tobbe-torp – the henhouse that was later torn down; Anne-häll – the gardener’s quarters; Bibbi-bad – the bathhouse; and Peter-ping – the gazebo where students played ping-pong. There was one house remaining, and he named that one ‘Smålandsstugan’ as a reference to his own roots in Småland.

The Memories of Annika Fagerström

It was never easy being the principal’s daughter. I was a teenager and here were all these fantastic, sweet, funny students, and among them some really good-looking guys. In my early teens I stayed with the students and wanted to seem loyal to them, otherwise risking becoming an outcast in the group. Mom and Dad got more and more tired as the summer went by but I simply could not tell on my friends – the guys using the fire escape ladder to sneak into the girls rooms, or the ones who ventured into Vaxholm late at night. Whenever I participated, just like the rest of the students who got caught, they gave me a scolding like I never got at home. My parents were outraged, understandably since they responsible for all those youngsters and feared anything could happen to them.

When I was 17-19 years old, I got my own room in ”the closet” – a small maids room above the washing room that had a secret staircase. It was wonderful to have a place of my own. From there I could lay and listen to the radio all through the night or smuggle visitors up through the secret staircase. And best of all, from there I could eavesdrop on engaging conversations taking place in the washroom below me.

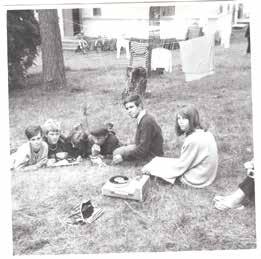

Down in the cellar, 1962. Students playing records in front of the house, 1962. Torbjörn second from the left. Annika furthest to the right.

Students playing in front of the cellar door, 1965. The large water and milk jugs can be seen along the wall. The building where the latrines were housed.

The Collective at Villa Björkudden

In the middle of the 1970s, the Fagerström family rented out parts of Villa Björkudden during the summers. Tippi and Stig Unge and eight of their friends found the house via an advertisement from Mauritz and Grethe, and they fell head over heels. They shared the house with the Fagerström family and had the upper floor as well as the small kitchen. If they wanted to bake bread, they could sneak into the large kitchen with Grethe’s permission and use the oven there.

Most of the people in the collective had jobs in the city and commuted from Tynningö. They took bicycles on the boat in the morning, and when the boats docked at Strömkajen they biked to their jobs. They were city people and appreciated Björkudden’s unique environment, which allowed them to grow their own vegetables in the garden, go down to the jetty on foggy mornings and drink a cup of tea with the sound of the Vaxholm boats in the distance.

Throughout history, Villa Björkudden has been a gathering place for many parties, and the collective was no exception. They often had parties, which often ended up with many empty bottles. Afterward they had to take the little rowboat, with its unreliable engine, and fill it to the brim with empty bottles. Then they would steer carefully toward Vaxholm, and about halfway there the motor often died, and they would have to row the rest of the way. When it was time for the Midsummer party, they cleared out the verandas and flung the doors wide open. They scrubbed the floor and hung string-lights across the ceiling. Often, people came who no one seemed to know. One man who was mistaken for being Tippi’s colleague came one Midsummer’s Eve. He put on his bathing suit and laid out on the jetty. No one had invited him, but no one disturbed him either. He knew that on Midsummer, there was always a party at Villa Björkudden. The rain often leaked into the great hall on the upper floor, and it became a whole orchestra when the raindrops reverberated differently in each of the glass bottles and buckets placed on the floor. In the summer of 1978, it was so rainy that Stig passed time waiting for better weather by building a small house of glass bottles in the likeness of the Tynningö house. It is a clear memory that still stands on the couple’s fireplace mantle.