22 minute read

1908–1943 The Steinwalls

1908–1943

The Steinwalls

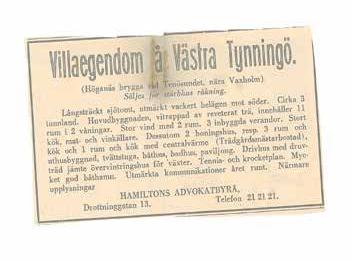

Advertisement

The brothers Georg and Gustaf Steinwall bought Villa Björkudden together in 1908. By then they had each made their names as masters of the restaurant trade, and wanted to crown their achievements by acquiring a summerhouse befitting their status. Their family history does not begin in some German-speaking area as their name might imply, but rather in the far northern Swedish province of Västerbotten. The name Steinwall originates from the profession of their late forefather, who was a surveyor and geographer.

The Steinwalls and Stockholm, A Strange Tale

The road from the far north of Sweden begins with their grandfather, Mathias Wilhelm. Known for being adventurous, choleric and later strikingly handsome, he left his childhood home of Skellefteå in the 1830s to seek his fortunes at sea at the tender age of 15. He ran out of luck instantly, you might say. On his first voyage, his ship was captured by pirates on the Mediterranean and he was taken for ransom to Algeria. Unfortunately for the pirates, led by the local sultan, the Swedish state had a non-negotiation policy for hostages. Instead, it was Mathias’s local parish in poor Skellefteå that had to scramble for the ransom. This would take them three years. Meanwhile, the Pirates rented Mathias out as a slave to Danish and American consulates in Algeria. These years of servitude were something that gave him both a knowledge of language and a hatred for Danes – the former would benefit him enormously.

When the ransoming day finally came, he continued his career at sea, becoming a successful sailor and marrying into money. In 1841, he traveled with the commission of traders who asked the king to grant city rights to his home parish. The request was granted, and Mathias counts as one of the founders of the city of Skellefteå. Around the same time, he decided to go from sea to land and became a prominent trader in wood and leather. This further strengthened his wealth. Though he was gifted in business, his character was not complemented by softness or servility in his social life. No servants stayed in service for longer than the con-

The brothers George and Gustaf kept to their private lives at Villa Björkudden, and in their professional lives operated the restaurant Operakällaren. tracted minimum of one season. When he later died, only one person had stayed with him: his youngest son Mathias Leonard. Left with almost all the inheritance, he moved down to Stockholm to invest his capital in the sawmill industry.

Mathias broadened his property business as one of the go-to agents for foreign companies wanting to get ahead in Stockholm. Meanwhile, he gave equal attention and enthusiasm to an area that his father had never fully understood: his own social life, and later his eight children. All of his children, male and female, got first-rate education. The oldest son Johan was destined to follow in his father’s footsteps and take over the family firm. His two younger sons Georg and Wilhelm underwent thorough, painstaking training for a career in the hotel and restaurant trade.

It was a laborious process for both brothers. The world of service and dining was undergoing a rapid change, and both had the chance to undergo training at first-class restaurants and hotels across Europe. It was then, as it is now, a practical hands-on education where students worked their way up from dishwasher to waiter and upwards. In time, the relationship between the two brothers would develop so that Georg had responsibility for the finances and customer relations while his brother Gustaf was king of kitchen and table settings. It would prove to be the most fortunate of partnerships.

Shortly after the brothers began working in Stockholm, Georg married the adventurous Esther Myrstedt. She came from a family of exceptional heritage, though she caused both her parents and now husband much stress from her ”liveliness.” As a teenager, she competed in diving and was always center-stage at parties. These traits did not cohere with the ideals of a wife in the late 19th century: gracefully modest and quiet, an adornment to the husband. Married women didn’t have any authority until 1918, when equal voting rights for women were passed. Esther had to adapt to her husband’s demands to become less upfront and social. Yet her sense of humor was something he could not control. Throughout her life, she was known in her family for her wit and sarcasm, a stark contrast to her high-society appearance.

The other brother Gustaf found love too; twice. He remained a bachelor longer than his older brothers, and continued to live in the summerhouse with Georg. He married the beautiful Inez Erica Vasseur in 1910, and when the couple’s son Gösta was born, the summerhouse became too crammed. Gustaf bought a villa of his own not far away. In 1922 he re-married, this time to Dagny Feuk, whom he came to live with up to his death in 1936. The spouses of the two brothers would survive their husbands by decades; Dagny passed away in 1956, followed by Esther 1965. They were the ones who carried on legend of these two eccentric brothers, some of which can be found here in the house.

The Brothers, Their Establishment, and the Success

It was through generous donations from their father and elder brother that Georg and Gustaf acquired rights to the most famous establishment in Stockholm, and perhaps all of Sweden: the restaurant of the Royal Opera, Operakällaren. The old 18th-century theater house was torn down in 1892. In its place, a new opera house was erected in the most bombastic style imaginable, drawing vaguely upon the appearance of the royal palace across the water. The old house previously had its restaurant in the cellar beneath the theater hall, giving the restaurant its name.*

The young duo took on the challenge, at 30 and 28 years old respectively, and the public was dumbfounded by the rumors of what the restaurant was becoming. Who were these young outsiders who had been away from town so long? Did they really have a handle on the stewardship of this dear restaurant? The opera house itself was a massive public building project, and unforeseen expenses went through the roof, exceeding every budget. The Steinwall brothers took on ordaining and decorating the restaurant at their own cost; the result looks more like a palace than a restaurant. They showed a spin-doctor mastery that would put any lobbyist today to shame. They commissioned a high-profile artist for the decorative paintings in the grand dining hall. Here Mr. Oscar Björk, famous for his academic paintings, crafted a work based on the ancient Greek-Roman cult of Bacchus, god of wine and ecstasy. Without going into too much detail, the ”titillation” expressed on the walls pushed all boundaries of decency in this era of strict morality. The scandal was imminent. As word got out to the public,

*The colloquial name ”Nobis” comes from a low-class German reference to the steps to hell, used both for the deepness of the entryway and the ruin of a man awaiting down below. The Italian equivalent of this term, ”abissio,” has given the English word abys.

everyone had a view on the matter, including the newspaper columnists. The blunt displays of explicit nudity and moral fragility should never have a place in public society – even less in a temple of the arts, said some. Still others claimed it was a feast for the eyes, drawing upon the tradition of Bacchus as the protector of artists; suitable indeed for an opera. The matter extended to the royal family for intervention. Old King Oscar II personally visited the restaurant during its construction and ”counseled” the artist. This counsel included making the grass in the painting taller and taller. This, as the reader might expect, only furthered the public’s curiosity.

Operakällaren and its accompanying bar’s beautiful décor resembles a castle more than a place for food and drink. By the beginning of the 20th century, the restaurant and bar had become popular places for Stockholm’s elite and artist community alike.

Foto: NOBIS Hotels, Restaurants & Conference

When the restaurant opened on the 4th of April 1897, an onslaught of curious guests packed through its doors. It seemed as though the entire population of Stockholm wanted to taste the main course of the new restaurant and, we can assume, cast a sneaking glance at the walls. Success was evident, and the young men continued to dominate both Stockholm’s and much of Sweden’s culinary scenes until the time they withdrew from public life in 1932. Visiting Operakällaren became a must-do if you wanted to make the most of a visit to Stockholm. In particular, the wine cellar’s wide selection and the illustrated menus were met with praise. The brothers were in some ways ahead of their time; for example, trying to prohibit smoking indoors because it had a negative impract on both the interior and the food. The result wasn’t as intended, and instead of not smoking, guests moved their unwanted habit downstairs to the café. The smoke created such a fog that the restaurant had to close several times, and thus the smoke prohibition was abandoned – until over a century later when it was officially reinstituted. The most significant change effected by the brothers in their years of business occurred just a few years after the restaurant opened. They had both had a proper dining hall and a café, but their main competitor, The Grand Hotel, had something they didn’t: an American bar. First introduced just a few years earlier, the brothers saw their chance when a barber moved out of the corner store in the opera house. They spared no expense creating one of the most accomplished Art Nouveau interiors in the country. The artist community instantaneously adopted the place as their own. Amongst many visitors and was friend and artist Anders Zorn, whom after many years in the United States was so disapproving of the bartenders’ shaking that he got an entire trolley to help himself to drinks that met his high standards. The Opera Bar has remained a popular establishment, such that the interior and atmosphere have been carefully preserved by its owners through the years. Today it remains one of the few complete rooms of its age.

Throughout their entire careers, the brothers were committed to humble and tireless service. They called themselves ‘maître d’hôtel,’ i.e., first waiters, a gesture of great modesty in their time. They also laid the foundation for much of the bustling, opulent restaurants in Stockholm. In response to the strike and looming prohibition, they became two of the coordinators of the Swedish Association of Restaurant Owners. One of the organiza-

A poster from the popular vote on prohibition of alcohol in 1922, created by Albert Engström.

Steinwall Created Sweden’s First Wine Label

Astory that reflects the brothers’ influence on Swedish culture is also a story about port wine. Their father Mathias Leonard Steinwall was one of Stockholm’s largest importers of high-quality alcoholic beverages. Everything from cognac, sherry, single malt whiskey and in particular, Very Old Superior Red Port Wine. This mid-range port wine was introduced in the middle of the 19th century by Grönstedt’s Wine Shop, and quickly became a top-seller. The name was long and complicated, and the wine soon became more well-known by its nickname ‘Grådask’ (Eng. ‘Dirty Grey), after the color of its label. It would take until 1905 for the name change to be officially registered, which then marked the creation of Sweden’s first domestic wine label. In the Steinwall family tradition, the story goes that Georg was behind this stroke of genius. But they and others in Sweden’s spirits manufacturing and importing business were forced to become government-run in an effort to decrease drinking in the country.

The level of care given to creating beautiful, yet simultaneously personal, menus was unmatched.

tion’s more publicly-known efforts was the mobilization against prohibition in 1922. They engaged the artist Albert Engström, a frequent visitor to Operakällaren, to create the main poster for the anti-prohibitionists. The result was one of the most famous posters ever created in Sweden: picture the artist himself staring angrily at you, pointing towards a crayfish and stating, ”NO! Crayfish demand these [alcoholic] beverages! You have to denounce crayfish if you don’t vote No on the 27th of August/Albert Engström.” The vote – the first with female participation – was won by anti-prohibitionists with the smallest possible margin, and many blamed/ thanked Mr. Engström as responsible for tipping the scales. Instead of prohibition, the outcome of the vote gave Sweden an alcohol rationing system that would be in place until 1955.

The Archipelago - Palace of the Steinwalls

Georg and Gustaf Steinwall bought Villa Björkudden in 1908. By then they had already made their place in the crème de la crème of Stockholm’s restaurant business, and now wanted a summer home to mirror their family’s status. For them, the site was just as much a stage to host large parties as it was a space for family leisure time. On the Höganäs peninsula where the house is situated, the family was already surrounded by many members of high society, who also happened to be their core customers. The short commute enabled them to continue working during the summers, an intensive time for the restaurant, though Georg often complained that it put a strain on family life. Another critical component of the choice and location of their summer retreat was sailing. Some years before they bought Villa Björkudden, they had joined the Royal Sailing Society and acquired an 18-foot yacht by the name of Hermione.

The Steinwalls maintained and added to the complex of buildings and greenery now commonly known as the Archipelago-Palace. It was during this time that the smoking lodge was added to the glass-walled gazebo, giving the opportunity to enjoy the views even on rainy days. The greenhouse and flowerbeds were both extended, and a combined tennis and cricket field was built. The big house remained the heart of summer life, and a rare glimpse into it is offered by one of Georg’s grandchildren who recorded his memories:

The motor yacht of the Steinwall brothers, which they used to fare to and from Stockholm and their holiday retreat.

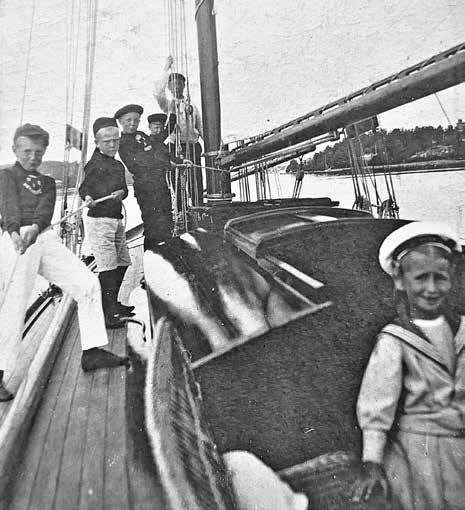

Children outside the gazeebo on Björkudden. Children had a central place out on Björkudden. Children and the grandchildren spent most of their long summer leaves out here. ”The large house had 22 rooms, crenellations on the balconies and a tall tower which we grandchildren believed to be haunted.

I remember that big house so well; you entered after passing the combined tennis and cricket court where ‘grandpa’s swing’ hung, as we called it. Then you came to the half enclosure glass veranda where you have drinks after dinner. There you entered a large hall with double-doors in lounge furnishing, a fireplace, the staircase to the upper floor and the colossal window with many colors in it. On the left, in the hall, were Georg´s drawing room and library, and to the left of that was Ellen’s salon full of beautiful furniture, and straight ahead was the dining room. This was only used when the weather was terrible. Passing this [the dining room], you came out to outdoor dining room. It was walled-in on three sides and opened towards ”the smaller waterway toward Stockholm.” If you sat with your back against the waterway, you could still have a nice view thanks to the colossal mirror on the opposite wall that gave full visibility of what was taking place on the water.

If you went through the great hall on the upper floor, there also was a smaller staircase for the servants, and there was large number of bedrooms. On the righthand side of the great staircase, there were guest bedrooms. After that came Ellen’s husband’s bedroom for her husband as well as one for her sister Margareta, married to Hamilton, with three children and a nanny. Further, there were more rooms that have escaped my memory. The attic was huge but unfurnished. It wasn’t haunted, but we children thought it was! From there, you could climb all the way up the wooden steps to the peak of the tower. If you removed hatch there, you had a fantastic view of large parts of the archipelago.”

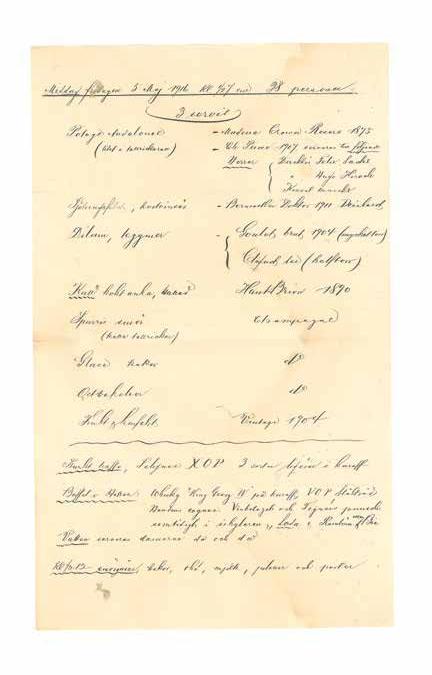

Children and grandchildren always had a place at Björkudden, but apart from this also served the brothers and their two main passions: sailing and parties. These two hobbies defined life at Björkudden; regular dinner parties often had over 20 guests present. With Sweden’s best chefs and by far the most well-equipped wine cellar available, the results couldn’t be anything less than glorious. This is evident in studying the two preserved menus from 1916, when the war was raging in Europe and rationing was harsh: Madeira wine from 1848 with dessert, asparagus, fresh dairy, meat and exotic fruits. This was wealth beyond what money could buy in this time of food shortages. The dishes were complemented with precise in-

structions to the staff: that whisky should be poured into a cooled carafe before serving, and make sure the ladies present are offered water ‘from time to time.’

To be invited to Villa Björkudden was an honor that few earned, and could be compared more to a fine dining establishment than an archipelago retreat. It functioned as an unofficial extension of their restaurant, open only to their core customers; a place you could never ask for access to but required an invitation. The journey out to the house began in the family’s stylish motorboat; to have been invited to the villa at all was a sign of high status, a stamp of approval for the rich and famous. This symbol of international luxury and hint of a grand lifestyle is still present in the collective memory of the islanders on Tynningö. If you talk to them about the villa, it isn’t long before the Steinwalls’ time is mentioned, which they hold to be a golden age. It was a time that lasted into the mid-1930s. Georg passed away in 1938 after a life marked by hectic activity and a taste for better things. By then his brother had already passed two years prior. Georg’s estate sold the house which again changed in ownership, ending up in the hands of Gustaf Åkerström in December 1944. He had altogether different plans for the house than for it to be a grand mansion. A new chapter in the diverse story of Villa Björkudden.

Esther Steinwill in summer clothing on Villa Björkudden’s jetty. In the background, one of the guests rows out toward the large sailing yacht Herminoine.

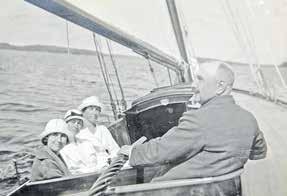

Top left: Georg Steinwall with daughters, 1920s.

Bottom left: The Steinwall Brothers with friends and guests on the way to Sandhamn, clearly happy to be having a beer. Photos on the right, from the top: Georg, Esther and child out sailing, late 1920s. Georg’s pale bare head shows how rarely he removed his hat, even at the summer house.

Lunch down in the family’s large sailing yacht Herminoine, 1920s. On a joyride in Herminoine. Mother Esther steers while the oldest son Carl Georg sits with his arm around his sister Ellen. Behind them, in a neat bowtie, is the youngest son Erik Wilhelm, born 1907.

Esther Steinwall, wearing her son’s summer hat, taking an afternoon coffee outside Villa Björkudden with Ellen, wearing her father Georg’s oversized KSSS-hat. The day’s delicacies were complemented with instructions to the Villa’s staff: “The whiskey should be poured into a carafe before serving, and the ladies present should be offered water now and then.”

The Steinwall family with friends, drinking port wine and cognac (a guess based on the bottles) in front of Björkudden’s main entry. On the far left, you can see the entrance to the loggia. The two men on the left are unidentified. The boy in the sailing outfit, unidentified, wears a sailor’s hat bearing a strange detail: on it, the text “SMS Germany” can be seen. This was the German Navy’s greatest pride before the First World War, and offers a foreboding premonition of what would await Europe just a few years after the photo was taken. It also shows that boys’ affinity for playing war is far from new. Beside him stands the oldest son in the family, Carl Georg, with an magnificent ‘hat-tan’ and striped summer suit. The adults to the right in the photo include Georg Steinwall and Esther enjoying the company of their guests. Of the two girls, the one in front is likely Ellen Steinwall. Of the boys in the foreground, the one to the left is the family’s youngest son Erik Vilhelm, while the one to the right is unknown.

The children, likely the Steinwall sons with friends, serve as guests aboard Herminoine. A summer photo with the family’s smaller sailboat, Iverna, which the oldest son Carl Georg was especially fond of taking out during the summers. A photo from the regatta in Sandhamn. The boats were docked with the sterns facing the beautiful beach. The gatherings were true celebrations, which can be seen in the many signal flags on the masts. 1910s.

KSSS and Sailing

Looking at photos of those who owned summer villas such as Björkudden, the elegant men in the photos often wear a white captain’s hat, often marked by a royal crown above three blue S. The Royal Swedish Sailing Company (or KSSS, abbreviated from the Swedish name), is the group behind this emblem. Its origins trace back to the 1830s when some of the city’s richest elite, in keeping with continental European trends, wanted to compete in sailing. Yacht sailing became one of our first organized sports and was seen from the beginning as exclusive and potentially dangerous, most comparable with today’s Formula 1 racing. It was during the rule of the proudly-bearded Oskar II that the sailing company gained royal association and with it, a social heyday. For a short time, the company had its clubhouse near Björkudden, on the island of Tynningö. The distinctive house with its glass sunroom on the top level is one of the island’s most notable buildings. The sailing company soon moved out to Sandhamn, and became a hub for summer parties in Stockholm’s elite circles. It was also during this time, the late 1800s, that sailing technology made significant progress and made the sport accessible, even to those who had not trained in the Navy. This broadened the membership base to include everyone who resided seasonally in the archipelago. The general improvement in Swedish living standards after the turn of the century, as well as the introduction of the motorboat laid the groundwork for even more people to make life in the archipelago a reality. KSSS led this development and has in its own way been one of the main factors in creating the ‘summer villa lifestyle’ that is so characteristic of the archipelago today. The sailing company has not ceased to be a symbol of status and an active lifestyle. The KSSS logo remains a dear accessory on everything from sweaters to cufflinks in Stockholm’s upper class, and those who want to associate with it.

The family’s small sailboat Iverna sailing past Villa Björkudden. The peninsula where the house stands is still sometimes used as a turning point in sailing competitions. Photo: Bertil Anderson, 1914.

The Family’s Fleet

Initially, the boat lines were many and the steamboat docks far more numerous than today. Up until the 1880s, most of the summer dwellers in the archipelago were far from having the means to afford their own boat. This increased gradually to become the mass of boats we see in the archipelago today, thanks to technical improvements and the creation of sailing clubs. KSSS solidified sailing as something modern. With regattas, fantastic parties and a solid brand, sailing become not just a sport but also a lifestyle. To have a captain’s hat with their club’s emblem became just as desirable and natural as wearing a summer suit. These symbols expressed both belonging and exclusivity. How this manifested within the sailing itself varied. The Steinwalls put more effort than most into the boats they owned, both personally and collectively. The drawings of several of their boats can still be found today in the Maritime Museum’s archive. The beautifully sketched vessels include a slender sailboat created for competition, and a solid motorboat, among others. The motorboat provided quick and comfortable transport for the restauranteur brothers between the city and archipelago, and can be best described a bar with a keel. The interior drawings show a beautiful panel-clad salon with stuffed seats – not entirely different from the Opera Bar’s cozy feeling. The sailboat, a slender 18-foot boat with the name Iverna, was far from the fully-equipped plastic boats seen all over the archipelago today. It was used briefly by Georg’s son who competed with it in KSSS sailing competitions. In the summers he often lent it to a neighbor at the summer house, the boat builder’s son Bertil Andersson. The most impressive of all the boats the brothers owned was of course Herminoine – an archipelago cruiser with a massive 150 square meters of sailing area. Of all the photos preserved in the Maritime Museum archive, there is one of particular interest. In this photo, we see Georg with the entire family out on a leisurely sail, fashionably dressed. Considering how few people learned to swim in Sweden, it is remarkable how relaxed people were being out at sea without any floatation devices. Life vests that could be worn during a sailing outing would not be introduced until many decades later.

Refugees from the Baltics in a small sailboat reach a warship, 1944. Photo: Lennart af Petersens.