8 minute read

1898–1908 Mr Johan Sjöqvist, the builder

1898–1908

Mr Johan Sjöqvist, the builder

Advertisement

Buildings seldom move on their own, which was fortunately also the case with Villa Björkudden. So how did it come about that this prominent world fair building found its way out to an island in Stockholm’s archipelago?

The house’s first owner after the fair was a certain Per Johan Sjöqvist, a master builder from humble origins in the province of Värmland. By the time of his death, Sjöqvist would reshape the Stockholm he worked in his entire life in beyond recognition. He specialized in large, technically innovative building projects. He often worked in tandem with ”Skånska Cementgjuteriet,” known today as Skanska, a multinational building company. Anyone familiar with the buildings in Stockholm quickly realizes, after studying Mr. Sjöqvists resumé, just how much he has affected the outward appearance of the city. Ranging from breweries to opulent residential buildings and department stores, he did it all. During the time he was in business, Stockholm more than tripled in population size. Demand always vastly exceeded the supply.

Mr. Sjöqvist went to technical college in Stockholm in the 1870s, which is today called Konstfack and is one of the most prestigious art schools in the country. He managed to get an internship as a drafter, a kind of technical assistant, in the studio of Mr. Axel Kumlien. Kumlien was one of the most celebrated architects at the time, who among other things created the design for the Grand Hotel in Stockholm and many train stations around Sweden. After further apprenticeship, Sjöqvist finally managed to get the prestigious Letter of Approval from the Board of Master Builders in 1892. By then he had already made his home in the growing borough of Östermalm, which would be the place for many of his most well-known projects.

Not only did Sjöqvist build houses for others, but he also became his own most significant customer. Already by 1890, some years before he got his letter of approval, he had so many houses in Östermalm that he decided to document his properties. This photo album is still kept in the archive of the association of property owners, and was curated by the photographer Axel Lindahl. The album shows page after page of Mr. Sjöqvists impressive works in somewhat strange solidarity; an intentional choice. ”I want my buildings to stand out like monuments in a desert,” he stated in a letter

Per Johan Sjöqvist, builder who specialized in large, technically innovative projects.

A uniformly-constructed district along Strandvagen helped disguise the then-criticized stables nearby, and created a new skyline on the waterfront. to the photographer. On a majority of the houses he built for himself, he consciously let the facades testify who had created them. His monogram is scattered all around Östermalm for those who look closely. This is the same monogram you can see on the mantelpiece of the great fireplace In Villa Björkudden.

The pinnacle of his career is the palace-like residential building next to the Royal Dramatic Theater. This yellow neo-Baroque palace also stood as the entryway of Stockholm’s own Millionaires’ Mile: the Strandvägen boulevard. The house’s style, soon followed by others in the area, took clear inspiration from the Royal Drottningholm Palace outside Stockholm. Not only was it a beautiful full-service apartment building for the rich and famous, but it also improved the skyline of the prestigious Nybroviken. It kept the court stables hidden completely out of sight from bayside flâneurs. The stables were popularly described as one of Östermalm’s biggest eyesores, or as a writer in the day said: ”It made one wonder if it was a correctional facility for dilettante architects.” It was at this exclusive address that Mr. Sjöqvist himself moved in, his former apartment now used as an entire office. When he passed away in the late summer 1923, he left behind sweetening change in the city he had been so vital in forming.

The Exhibition Becomes a Summerhouse

When the Stockholm’s Fair of 1897 opened, it was during Mr. Sjöqvist’s most active years in the construction business. One of his close friends and confidants on the Board of Master Builders was responsible for the enormous building project that included the fair. Perhaps it was through him that he took notice of the impressive exhibition house, with its plaster-covered façades so resembling Sjöqvist´s own houses. After the fair had closed in the fall, there was a public auction on the buildings that were now without use. The cost of materials still exceeded the value of manual labor at this time, so there was no shortage of interest and everything was auctioned off. The building material used for the large Palace of Industries found its way to all corners of the country: the elevators ended up in a luxurious hotel in the city center; enormous wooden beams were shipped off to be reused in a paper mill. Mr. Sjöqvist claimed the elegant fair-expedition building for the price of 1500 Swedish kronor. Certainly a small sum against the original production cost of 26 058 Swedish kronor – though this came with the additional challenge of having to move the house.

Already in 1890, Mr. Sjöqvist had inherited some land on the island of Tynningö situated in the inner archipelago. The plot was on the panjandrum-peninsula of Höganäs, right in plain sight of the main waterway, or centerstage you might like to say. Since then he had been looking for a suitable house to crown it. Craftsman’s and workers were in good supply enduring the wintry author of the exhibition of works started. The plaster was removed, the underlying panel and framework were marked up before the nails were removed. Doors and windows, nails and fireplaces all was marked up and saved like a giant three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle. Finally, it was all packed in the chests and ready for shipping.

Out in the islands, preparations and landscaping were underway, and large chunks of rock had been manually cut onsite for the foundation. During the fair the house stood on a makeshift foundation of plaster imitating solid rock; this time it was done for real with granite and bricks. This also made room for food and wine cellars. Separate from the main building were planned additional houses to be built. These included a jetty and boathouse, a gazebo, a greenhouse, and lodgings for the gardener and

other staff and servants. And let’s not forget the house for the sailors of the family’s yacht. Most of these buildings still surround the house, though many with new owners as the property was sold off over the years. During the spring thaw the following year, the deconstructed house was loaded onto a barge and towed out to Tynningö.

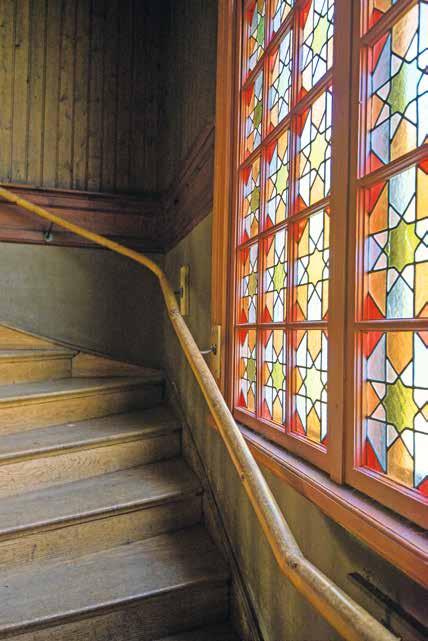

Now reconstruction could commence. The rebuilt house did not entirely cohere with its old layout. Part of the house was turned around so that the turret faced the water, maximizing the visibility of the building from the waterway. The main entrance was set on the side facing away from the water. This was a clever way to make guests approaching from the jetty walk around the house and notice the grandeur and scale of the property and gardens. New openings were made for three large loggias, or inverted balconies, that offered shade while still giving the possibility of enjoying the outdoors at a distance. The inner walls of the ground floor were wainscoted and adorned with English wallpaper. The pompous staircase

still holds some of the Stockholm Exhibition’s grandeur with a four-meter high window of stained glass. The mantelpiece in this room was adorned with its rebuilder’s monogram. The walls of the servants’ quarters and the bedrooms of the upper floor were covered in tongue-and-groove paneling. This kind of paneling was one of the biggest international exports from Sweden during this time, and you can find over ten examples of it throughout the house.

Typical of its time, the house has an distinct partition between ”upstairs” and ”downstairs,” with separate staircases and lodgings for servants and owners. This was made in order to keep services as smooth and invisible as possible, dividing the parallel worlds of the serving and the served. As one can see in the layout of the house, it would be many years before the practice of cooking became a norm in the social life of elites. When this house was built, freedom from the practical was a measurement of success.

In the drafting of the summerhouse and its additional buildings, special care and effort were taken in creating the gardens. Exotic trees and carefully-laid gravel pathways weaved smoothly through lawns and flowerbeds. Between the dwellings and the kitchen entrance, there was large garden patch with fresh flowers for house’s vases during the summer season, as well as fresh vegetables on the plates. The greenhouse supplied fresh fruits such as grapes and figs. It was no wonder they needed a full-time gardener to run it.

All this was accomplished at a remarkable speed, and the family began to spend their summers at Villa Björkudden. Its palatial setting was befitting of the entrepreneur who had created it. It was a time characterized by the lively interest for sailing that Mr. Sjöqvist and his sons had, and many tours were made out to the luxurious Sandhamn for regattas held by the Royal Swedish Yacht Club. The oldest son Arvid, who would later become a celebrated architect himself, and his twin brother Fritz made it as far as the Summar Olympics of 1912 where they competed in the 8m class and did well in fifth-place. The Sjöqvist family had Villa Björkudden for just under ten years. When the children moved out, they decided to put it up for sale. The stage was set for the new owners that bought it: the Steinwall brothers, both restaurateur legends.

Greg Steinwall and son.