17 minute read

1897 Stockholm, an exhibition and the summerhouses

1897

Stockholm, an exhibition and the summerhouses

Advertisement

During the latter part of the 19th century, change was stirring in Sweden’s cities. Reforms in representation and the economy combined to produce an era of economic growth that had never before been seen. This swift boost in productivity transformed Sweden from a primitive agrarian society to one of the most expansive industrial nations in the world. All in less than half a century. The prosperity created here would later create the backbone of the Swedish social welfare system, also known as ‘The Nordic Model,’ which took shape in the decades that followed. Those born in this country during the mid-19th century lived through a time of remarkable change. They started their lives in a Sweden without electricity, trains, or any large-scale industry. It was a country where church and states were the unopposed authority. By the end of their 55-year life expectancy, they could look back and see a society that had changed entirely, at a remarkable speed.

This development began with one group in particular gaining power during this time. The bourgeoisie of the towns, while lacking the noble epithets of ‘von,’ ‘count’ and ‘baron,’ had an ever-increasing affluence. This fueled the formation of an identity entirely their own, with a specific set of habits, preferences, and interests. The 19th century was indeed the century of the bourgeoisie, where men wore titles like Director, Banker, or Entrepreneur with the same gravitas as the titles of the propertied elites of old. They displayed their status in a number of ways: a yearly cycle of semi-public parties and cultural events. Property ownership moved to the cities, where status was defined by the number of rooms you could afford in your residential apartment and what part of town you chose to live in – Östermalm being the most exclusive borough for Stockholmers. Here society and progress were surrounded by a patchwork of rules written and unwritten. There also developed an increasing separation between the public and private spheres, which made for a golden age of double moral standards. In response to this new era and new demand, the modern art and gallery scene as we know it came into being. All to supply this new class, with their ”new money” and longing for an old story, with an aura of grandeur.

It is with this backdrop that you can understand the reasoning behind the summer villa. The custom of having double accommodations in Stockholm

The latrines were emptied into the lakes and seas surrounding Stockholm. In the background, you can see a glimpse of Norra Real secondary school. The wooded lake in front has completely disappeared. was nothing new for those who could afford it. Back in the 18th century, even a low-ranking clerk could afford to rent a small cottage outside the city. The opportunity to flee the reeking stench of summer and grow one’s own vegetables was attractive to many. Stockholm was one of the most polluted and smelly towns in Northern Europe, packed with tanneries and lacking a modern sewage system, making this desire all the more understandable. Few summer retreats remain from this time, Svindersvik in a fjord near city center being a lovely rococo example of an early-generation, top-notch summer villa. It was during this time that a villa became a firstclass sign of social progress.

The golden age of these summer residences would be primed with the rise of the bourgeoisie as described above, and the introduction of regular steamboat traffic between the city and the surrounding archipelago islands. Entrepreneurs who could see the writing on the wall quickly bought up large plots of land from naïve island farmers and fishermen who could not see economic value in any property not deemed fit for agricultural purposes. In fact, up until the 1950s you could buy your very own island for a few thousand Swedish crowns at Nordiska Kompaniet, a fashionable department store in town. As steamboat technology and speed improved, the villa developments rolled further out over the islands towards the open waves of the Baltic Sea. The houses were constructed almost uniformly in wood, with spacious covered verandas and gingerbread carpentry imitating the leafy crowns of the tree-planted gardens. A distinct stage from which to see and be seen.

It was from the ever-growing and increasingly unhealthy city out into the fresh air that city dwellers migrated every summer. A need that only heightened with the increase in industrial pollution. This was migration in an almost literal sense: many people packed their entire household in boxes, moving furniture from their city apartments out to their summer villas. By late spring each year, Stockholm’s waterfronts began to look like the world’s most extensive outdoor auction. Servants tirelessly loaded stacks upon stacks, piles upon piles of belongings onto steamboats that then towed out towards their destinations, followed by their owners in less-crowded boats. The season stretched from April to late September, thanks to regular boat traffic that allowed men to continue working in

the city while commuting to their summer paradises. These summer villas, or ”sommarnöjen”(eng. ‘summer delight’), developed into their own little microcosms. They were often vastly more loved by their owners than their city dwellings, which in comparison often stood out as grey, dark and dull.

Even in the summerhouse, public appearance remained a subject of utmost importance. The layout of the rooms often imitated that of city apartments, with drawing rooms, dining rooms, and salons as examples. As a compliment, there was usually a gazebo nearby, often secluded from the main house. Here, undisturbed by weather and wind and nosy servants, you could get as close to nature as possible. The sheer number of verandas, gazebos and covered patios that characterize the summer villas of this age may seem a little less odd when considering the fashion norms of the time. Starched collars, dinner jackets, and corsets were ill-fitting for the warm summer season. That and the beauty ideal of pale skin made the sun an unwanted guest. This called for the creation of shaded spaces for the tranquil enjoyment of nature from afar.

There were opportunities to push some boundaries, like fraternizing with the locals, which would have been unthinkable in any other context. At the turn of the century, the building style went from excessive gingerbread-carpentry and Swiss-style into an era of flowing Art Nouveau and nationalistic, red-painted dreams. This shift in style also signified an end to the non-relationship between the villas and their surroundings. Instead of carefully-orchestrated microcosms with sprawling gardens, a new order came into being. Increasingly, people went beyond garden boundaries or went without gardens entirely. They had the great outdoors surrounding them, and made use of it. By this time, a vast majority of the land available in the archipelago had been sold off from its former farmer owners into private hands.

After the First World War, society changed again and these monuments of bourgeoisie power scattered across Stockholm’s archipelago fell out of fashion and repair. The habits of the wealthy had changed, and so had the economy. These old houses answered poorly to the needs of the late-modern society that had grown upon the backs of industrialists. This opened the door for new inhabitants on the islands. In the time after World War

Early Nouveau styles were characterized by organically winding, billowing plantlife. Ceramic and glass shaped like fruits and blossoms. Lamp stands shaped like pine trees. Long, slender female figures can be seen in images and even ceramics and glasswork. Below: ‘Fruit’ by Alfons Mucha, 1897. II, the working class started to make its mark economically in Sweden. Around the increasingly dilapidated mansions, sports cabins and prefabricated two room-cottages were built in increasing numbers on seeded land from the old main houses, creating the landscape we see today. After a nearly eighty-year depression in the summer villa market, interest in the conservation and heritage of Stockholm’s summer houses peaked again in the 1980s. Though many villas are still in disrepair, it is because of the heritage enthusiasts that we can continue to enjoy these exquisite pieces of art along Stockholm’s waterways. They are windows to remember a Stockholm long-gone, a past that yielded the foundation of our way of life of today.

Björkudden, an ”odd bird.”

Compared to the surrounding houses of similar age, Villa Björkudden stands out from the rest in a number of ways. It lacks many of the typical hallmarks of the summer villa. Absent are the covered patios and gingerbread carpentry. The façade was once covered entirely in plaster to give the appearance of stone-and-brick construction, a far cry from the wooden architecture of the surrounding homes. The building’s exterior has an almost gothic, Dutch-renaissance style that expresses an eclectic sense of style typical of the 19th century. Even to the untrained eye, or a person unfamiliar with the history of the house, it is evident that it doesn’t fit in with the beautiful countryside setting.

Neither before nor since the industrialization of Sweden had so much armory, Oriental furniture and Flemish Renaissance carpentry been produced. During the late 19th century, an enthusiasm developed for the styles of past centuries. This use of the past would feel strange today, but was commonly seen as giving character and taste, and told of a time long gone. It was also a way of handling modernity: to dress it up in old gowns.

This trend was not only celebrated, but was also heavily criticized with the thought that you needed to understand the modern style that reflected the ‘modern man.’ Around the turn of the century, this longing for an art style that mirrored the current time birthed the Art Nouveau, or Jugendstil movement. Embracing beauty and intricate floral patterns, there was a

Fredrik Dahlberg – Architect of Details

Villa Björkudden’s architect, Fredrik Dahlberg, is little-known today despite being one of Stockholm’s most prominent architexts. During his lifetime he was able to develop his style to fit a broad range of tastes. From his first year as an architect in the 1880s until the turn of the century, the homes he designed were characterized by a New Renaissance style with Nordic influences. The apartment building he designed on Valhallavägen from 189496 could pass for a German’s prince’s castle. With the turn of the century, trends shifted away from the one he specialized in. It was the National Romantic and Art Nouveau styles that now dominated. These styles balanced historical reference with modern inspiration. Now buildings were made with genuine material – that is to say, buildings that were not covered in thick layers of plaster, which had once created a desirable appearance. Now, brick facades and granite dominated. With more villas in Lärkstaden in Stockholm, Fredrik followed suit in adapting this new style. His largest contribution to the Stockholm Exhibition in 1897 is the home we now have on Tynningö, which is something of a breaking point or milestone in his development from stylistic architecture to Art Nouveau. Throughout his life, Dahlberg was an intensely meticulous architect, with a sense for details and customers’ sometimes odd requests. The most well-known house he designed stands at Skeppsbron 44 and has a special place in Stockholm’s city landscape. The house was ordered by the wealthy director Carl Smith and given a magnificent exterior with a ships’ bow jutting out from the façade and an enormous globe on top.

But it is neither this nor the restaurant Zum

Franziskaner on the bottom floor, with its preserved interior décor designed by Dahlberg, that is the reason for the building’s renown. Above the door leading to the stairwell is a sad man’s face staring down, and below it something resembling the shape of female genitalia. The man’s face looks undeniably similar to that of Dahlberg’s customer, Carl Smith. The story that has been spun around this strange façade is one of infidelity. Carl said he had been betrayed by his wife around the time of the building’s completion, and allowed the architect to add this less-thansubtle symbol for his contempt and despair. This is how the building earned its current nickname, ‘The Cuckold of Skeppsbron,’ and Fredrik Dahlberg was written into the city’s history. Although no one has been able to confirm that the story is true, it is one of the more extreme examples of Dahlberg’s odd requests from his customers. Today the building is designated as culturally significant.

Like looking straight into a fairytale. The Stockholm Exhibition offered a playful mix of parapets and towers that led the imagination to another world. shift away from the unimaginative imitations of before. Villa Björkudden is an expression of the last quivering moment of revivalist architecture; it could even pass for some kind of stage set.

The architect behind the house, Fredrik Dahlberg, designed it as an administrative building for the Stockholm Fair of 1897. In the original plans, you can see that it was once intended to be double its current size. Yet even in its final form, it is still a grand palace. Carefully-placed plaster and paint on the façade succeeded in deceiving visitors and architectural historians alike into believing that it was permanent, brick-and-mortar construction. A modern architect true to the ideal of ”honest materials” would consequently shake their head in disbelief. This delusive, temporary architecture imitating ”real buildings” wasn’t unique to the Stockholm Fair. It was, in fact, an integral part of the World Fair concept that the Stockholm exhibitors celebrated. Due to the transient nature of this kind of architecture, very little remains today.

The Stockholm Exhibition of 1897 – the Dream for a Better World

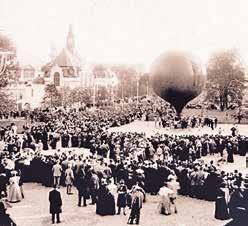

The Stockholm Exhibition of 1897, or the Inter-Nordic Art and Industries Exhibition as it was then called, was an illuminated dream of the future in plaster and wood. It was not the first or the last great exhibition in Sweden of its kind. But it came to represent, through its massive scope and reach, what a world exhibition meant to the general public. The reason is easy to see when looking at photographs from the event. Towering cupolas and minarets hearken to the saga of The Thousand and One Nights. There were hundreds of pavilions for the most fantastic things: a fairy-tale-tower built of flasks promoting Cederlunds Punch, or an enormous candle-shaped obelisk advocating the visitor to buy Liljeholmens Candles, promising 100% stearin products. Not to mention the full-scale reproduction of Stockholm’s old town, ”with scheduled scenic 16th-century brawls at 1PM every day.”

Background

Before we go on, let us deepen our context. The concept of world exhibitions traces its roots back to the French Revolution. With dreams of

liberty, equality and brotherhood, Europe’s most populated country went through a bloody revolution in the late 18th century. Out of this extreme turbulence came technical innovation at a scale never seen in France or even England, said to be the home of the Industrial Revolution. In opposition to the English, the French public committee wanted to show their citizens that the revolution project and its industrial development had a bright future ahead. This resulted in national exhibitions for the French public.

The Exhibition started in Paris, but the true beginning of the exhibition era came with The Great Exhibition of Works of the Industry of All Nations 1851 in London. The idea and execution of the exhibition was brought about by the Queen’s husband Prince Albert, to show all the progress that had made through industrialization, mainly by Great Britain. The World Exhibitions soon became a genre of entertainment in their own right. A burgeoning generation of architects, technicians and artists gathered to show the progress their countries had achieved in a time of new modernity and culture. This was a place for peaceful competition amongst nations. It was here that many of the technical inventions of the time took shape and were shown to the public. Perhaps more than anything else, it was the extravagant show of optimistic faith in human ability that marked the golden epoch of exhibitions, which lasted up to the First World War. There came several influential exhibitions after this, but the Great War had removed much of the optimism and enthusiasm that dominated the previous ones,

Stockholm’s Turn, Again

Before the Exhibition of 1897, the context was much different in Stockholm. This fair was very much a national endeavor put on by local industrialists who wanted to showcase their goods. A newfound national pride in the achievements and economic growth that the country had seen in the previous 50 years and a robust Pan-Scandinavian movement called for cross-Nordic relations. The Stockholm exhibition was a synergy between industry and culture, with powerful families standing behind financial and practical execution. Arthur Hazels, founder of the Nordic Museum and Skansen, provided the historical and national canvas. The setting of the exhibition on the island of Djurgården, most often used as a recreational park by Stockholm’s inhabitants, was consciously laid out for dual use.

The lead architect of the Exhibition, Ferdinand Boberg. Boberg was also the architect behind the NK building, Rosenbad, and Gävle fire station, among others.

Ferdinand Boberg was chosen as the lead architect, but the Exhibition area can be seen as a true collective effort with a variety of creators involved in the project. For several months, a team of eight architects and a small army of assistants worked in one of the royal palace buildings to complete the many drawings needed. Not only was there a lot of undeveloped land to use, but it also gave an excuse to clean up and provide a facelift to the sad, dilapidated park entry.

Another reason for the location of the exhibition was the nearby borough of Östermalm. During the last decade, it had transformed from its old name and identity – the poor and unattractive Ladugårdsgärdet – into the most modern, continental borough in town. Several newly-built buildings came to be rented as hotel rooms for incoming tourists. From the collective funds of industries, the state and other economic interests, the main plans for a fair were drawn up and stretched out across several acres. Several of Sweden’s leading architects were invited to participate in a prized competition to present plans for the fair, within just 30 days time. Ferdinand Boberg was appointed the head architect, but the fair can be seen as a real ”gesamtkunstwerk,” as a whole range of creators worked within the grid laid out by Mr. Boberg. At his disposal, there was a team of eight architects and a small army of assistants who worked for months to complete the many drawings and designs needed.

The Grand Opening

The day before the Exhibition opened, there stood an entire city dominated not by the church, but by the palace of industry. Its enormous dome was the most massive wooden structure constructed, with a clear reference to the Hagia Sofia Mosk in Istanbul. Around this giant of a building were scattered hundreds of pavilions, galleries and kiosks of all kinds. There were several restaurants, cafes and of course a love tunnel complete with a canal and gondoliers. In what would later become Villa Björkudden, the administrative building, were the foreign commissary, lottery girls and janitor’s offices.

The Stockholm Exhibition, through its sheer size, power of innovation, and marketing created the sheer essence of what the Exhibition meant to the Swedish public. On opening day there were representatives of both the old power and what was soon to come. The first in the form of King Oscar II, the latter in the way of August Palm, forerunner and strongman of the Social Democrats in Sweden. Although they likely didn’t speak to each other, neither regarded the other highly; yet both attended the formal opening. It bears testimony that it was an extraordinary day for everyone. After a slow start, there rose a steady volume of visitors to the temporary dream city on Djurgården. By the time the exhibition closed in August that year, they counted a staggering 1,900,000 visitors in a time when Sweden had little above 5 million inhabitants total.

After the Exhibition

The majority of the buildings used in the exhibition were deconstructed after the exhibition, and the material was used for other purposes. A few of the buildings remained in the exhibition area, while some were reused in their entirety or in smaller parts on other places around town. None larger than Villa Björkudden. But that’s not all! The exhibition came to live on in hundreds of homes around Stockholm, as a collective souvenir hunt broke out in the last days of the fair. To the despair of a few guards, the once-great area became victim to the hunt of any object that could fit in a bag. Decades later, the City Museum reclaimed such ‘souvenirs’ as donations. Memories of the radiant summer of 1897, the birth year of Villa Björkudden.

Moorish Coffee House The Machinery Hall.

The garden exhibition’s pavilion. Hot air balloon launch from the Exhibition area. (Photo: Oscar Halldin)