20 minute read

1944–1945 Those who fared over the sea

1944–1945

Those who fared over the sea

Advertisement

While researching this book, I quickly realized that Villa Björkudden holds an astonishing amount of archived records, in places where I never imagined looking. One sheet of paper that caught my interest had the tantalizing title, ‘Record of the State Foreigners Commission’s Foreigners Camp of Baltic Refugees.’ In the document was printed ‘Tynnngö,’ the island of Björkudden, in the careful handwriting of a civil servant. It was one name in a long list, but behind these rows of letters stood the faith of tens of thousands. I had to look further into it.

The Stockholm archipelago and our Villa Björkudden bear testimony not only to the summer memories of fin de siècle bourgeoisie. They also serve as the backdrop to and testimony of one of the darkest stages of the 20th century: the WWII refugee crisis. You can find traces everywhere, even etched into the wallpapers and paneling of numerous houses; greetings from another world. Their stories are tucked away in stacks and files, meter upon meter filling the shelves of state and municipal archives. Their testimonies are also kept alive through oral accounts, the kind that all of us carry and share with our families. The kind of stories that tell us who we are and where we came from. These are the stories that complement the written reports, and offer a scope and context in the way no paperwork or government documents can.

The Great Escape.

In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution-triggered turmoil of World War I, Estonia became an independent state for the first time ever in 1920. Before this, the scenic region near the southern coastline of Finland had been subjected to numerous foreign powers: Germans, Danes, Swedes, and more hoping to establish themselves in this highly strategic Baltic location.

Estonia would only enjoy a mere 19 years of independence before foreign invaders crossed the border once again. During that time, Estonia had evolved as one of the most prosperous regions in Northern Europe. As a result of the Molotov Ribbentrop non-aggression pact between the great powers of the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, Estonia fell under harsh Soviet influence. The communist dictator Stalin then restored the now-Russian territory to its pre-World War I borders.

Baltic refugees onboard a warship in 1944. People fled in whatever vessel they could find, many in small rowboats and overloaded fishing boats. Several thousand sank during the voyage, and those who survived faced a difficult time. Photo: Lennart af Petersens. Despite declaring neutrality at the outbreak of the Second World War, Russian forces moved over the border in August 1940. The surprise attack, although anticipated, was the beginning of a brief but ruthless reign of terror. Russian officials tried to stamp out any potential resistance against the new regime. Thousands were rounded up and sent to prison camps, while some were executed straightaway. This purge continued for just over one year, and ended when German forces invaded in a surprise attack on their former ally called Operation Barbarossa. The Estonians, many of whom were of German descent, first saw the German troops as liberators but were severely mistaken. After the victory against the USSR that the Nazis were gambling for, they had an altogether different plan than the Estonians may have hoped. It was a plan of massive displacement in which more than 50% of Estonians would be moved out to be replaced by ethnic Germans; the remaining 50% would be ”Germanified.” This ”Generalplan Ost,” as it was called, managed little except murdering Estonia’s sizeable Jewish population, as so much effort had gone into the anticipated victory against the Russians. But things did not go according to plan for Nazi Germany. After the exceptionally harsh winter of 1942, it became clear that this was not a war the Germans could win. The tide turned just a few kilometers outside of Moscow and would not stop until the gates of Berlin had been smashed in.

On the Western side of the Baltic Sea, the Swedes managed to stay out of armed conflict. The government in Stockholm understood that the German breakdown on the Eastern front would bring masses of refugees attempting a risky escape over the sea. By now, the Estonian people had a clear picture of what the Soviet authorities had in store for them with ”liberation.” The Board of Civil Defense and the National Board of Health and Welfare were mobilized by the famous prince Folke Bernadotte, who would be responsible for the white bus operation later in the war. The first evacuations were organized by the Swedish state in early 1944. In a deal struck with the German occupation authorities, they bought out the Swedish-speaking minorities in Estonia. These groups had inhabited the large islands of Hiiumaa and Saaremaa (in Swedish: Dagö & Ösel) since the 12th century, and the Swedish press attentively covered their re-immigration. But with the German army’s continuing deterioration, imminent catastrophe became apparent and more Estonians decided to flee. By the

time the Red Army breached Estonian territory in late fall 1944, more than 80,000 Estonians had made their escape from the Russian forces – 32,000 of them across the water to Sweden.

Sweden Receiving the Refugees

The majority of Estonian refugees arrived in Sweden during a very short timeframe; 6000 refugees were received at the island of Gotland in the two weeks of September 1944 alone. An improvised refugee camp was hastily organized by the foreigner’s commission to meet the demand. It quickly became apparent that the 55 camps organized for the Estonian refugees were insufficient. The civil defense board managed to mass together 216 more camps in record time, just for the Estonian refugees. This quick fix involved renting hundreds of large estates, hotels, schools and summer houses and equipping them with makeshift solutions to meet basic needs. Anyplace with access to sanitary facilities and a roof would do – including Villa Björkudden.

The people who stayed here lived with the hope that they would soon return home, but this would not be the case for a long time. In the meantime, they celebrated and tended to the memory of their country. During the entire Soviet occupation of Estonia, which lasted until 1991, the Estonian minority in Sweden became a vital node for Estonian culture and debate. For many years Sweden was the country with the highest volume of publishing in the Estonian language overall. Several celebrated names in Estonian literature lived in Sweden, many of whom are yet unknown outside the Estonian community. It is a story that is major in scope, yet its proportions are hard to grasp. Villa Björkudden’s use as a refugee camp during the war offers a small window through time. A window through which to contemplate this dark maelstrom that swept through the mid-20th century world. This history which many, mainly in Sweden, had forgotten and perhaps never realized how close to home it was. Unfortunately almost all detailed documentation referring to the camp is now lost, much of it never making its way into the right file due to the chaotic circumstances. But there are still those who remember, those who were there and are still around to tell their story. People like Helga.

Helga’s Story

Helga No-u, or Helga Raukas as her maiden name was, was a little girl when she came to Sweden in 1944. Her story encapsulates so much of the hopes and hardships that awaited those who made it ashore safely to foreign Swedish soil.

She was born in a well-to-do family of the upper middle class. Her mother Elsa worked as a textile crafts teacher, her father Aleksander was Head Forest Inspector for the Northern State-Owned Forests and an accomplished leisure painter. They lived with their three children, Helga and her two younger brothers, in a four-room apartment in the suburbs of the Estonian capitol Tartu. Helga was only a small child when the Soviet occupation began, but the terror of seeing it firsthand made a stark and lasting impression on her. People around her disappeared without any given reason, and Soviet commissars were everywhere. When she was seven years old, the Soviet occupation changed to German authority. When the fighting reached Tartu, her mother took them to their grandparent’s cellars for shelter from the barrage until they could escape the city. On the roadside she could see corpses hanged for collaborating with the Russians. During the conflict her father Aleksander was designated by Soviet authorities to be sent off to Russia. During the journey, the boat was torpedoed and stranded on an island. From there he and the other survivors could make their way back to the mainland, which by then had already been captured by the Germans.

During the new occupation, Aleksander Raukas switched to a lower-profile job in the port town of Raukas on the Gulf of Riga. From there they could follow the news on the radio of how the near-victory shifted to inevitable defeat for the Germans. The family kept a map of Europe where they mapped out the frontlines with a blue woolen thread, pinned down by needles. By the summer of 1944, it was apparent to everyone that the front would collapse and the Soviet Union would soon reconquer Estonia.

Under the Bridge and Out on the Sea

By chance, Aleksander met a group of men who were building a barge for their planned escape. Through bribes involving a golden barometer, a freshwater tank and a chest of vodka, he managed to barter for the entire

family to come along. The departure was due on the 19th of September. It would be a critical moment to escape, as Tartu fell to the Red Army just three days later. The night before the planned departure, all preparations were complete. Everyone in the family had packed their bags and put on as many layers of clothing as they could. The lingering summer heat was now long gone, and they had no illusion of the discomfort they would face on a cold, windy sea in an open barge. Helga’s Grandma refused to join them. At 75 years of age she felt to elderly to face the open sea. She would stay behind to keep their belongings safe until their return. And one of the most essential preparations: the guard watching the bridge over the river where the barge was hidden had had been bribed with half a pig to look away when they passed.

But, on the night of the escape, they faced an unforeseen obstacle. The boat, which had laid hidden on land to avoid prying eyes, had dried up and couldn’t hold water. Horrified by this, several families decided to bail on the expedition and turned home. The others waited by the river for the wood to swell, risking detection. Next, the motor didn’t start. It was as if the illegally-bought gasoline was of such bad quality that the engine refused to function. Aleksander was forced to make the risky way home, breaking curfew to retrieve a flask of gasoline of pre-war quality. He successfully made his way back through the darkness, and they gave the engine another attempt – this time it worked. They were now on their way down the river, but their departure was hours behind schedule. The guard that had been bribed had now been replaced, and no one knew what awaited them downstream. ”Halt!” the words echoed through the night as the guard spotted their barge floating through the water. He quickly readied his automatic rifle and began to shoot, just as he was instructed to do. Helga still vividly remembers the bullets whizzing by before hitting the water on all sides. The barge was unharmed; maybe he consciously avoided shooting straight at them, they’ll never know. They managed to get past the first obstacle on the way to safety. But the worst was still ahead. Patrol boats would soon be on their tail, and they sped away from the coast as quickly as possible, losing their orientation in the darkness. They suddenly ran aground on the sandbanks south of the city, where they were stuck all night. Yet this might be the reason they made it in the end: the patrol boats likely tried to follow their presumed course, passing them in the darkness and out to sea. Before starting again, they had to discard much of the baggage to

Migrants, 2014. Photo: Massimo Sestini / Eyevine / IBL Bildbyrå

ease enough weight to free the hull. In the light of day, navigating with Aleksander’s land compass, they steered south of Saaremaa towards the open sea. There, the next great obstacle: a German ship convoy carrying evacuated troops lay like a long string of pearls before them. It was too late to turn back now, and they took their chances making their way between two of the ships. Nobody shot at them – by this time, they were all seeking refuge.

Further out at sea they had their final encounter with the Germans. An attack aircraft caught sight of them and came in at low altitude above them. They thought this was the end of them. But the pilot passed when he had gotten a closer look, and disappeared on the horizon. Their time wasn’t up yet. During the next day, the situation became more critical. The heavily-loaded barge had consumed more gas than anticipated on the rough sea. If they couldn’t make it to land soon, they would find themselves drifting at sea. Adding to their concerns, they could see clouds massing as a storm approached and knew that the waves would easily destroy their frail vessel. Suddenly, far away in their southern horizon, they spotted land. They found refuge on the small island of Fårö just outside Gotland in the middle of the Baltic sea, and were taken in by the islanders. The next day, the storm broke out and took the lives of thousands of refugees seeking safety in vessels as unsuitable for the sea as their own barge had been. They had been one of the lucky ones. They had arrived.

Their First Time, Camps and Transfer

After living most of her childhood years during the war, Helga couldn’t remember the appearance of a peaceful city. She marveled at all the food available, the streetlights, the shop windows – and she even got hot chocolate. It was like arriving in heaven. Starting in Gotland, they were moved to several transitional camps before ending up in one outside of Stockholm. All of the facilities they stayed in were of an improvised nature. There were over 200 camps around Sweden just for Estonians and even more for other nationalities. Authorities tried to put all capable people to work as soon as possible. Helga’s father quickly found employment as a forestry expert in The Department of Public Domains, controlling economic maps out in the field. He would hold the position until his retirement in the 1960s. In total, her family stayed at nine different locations during the first year of their escape.

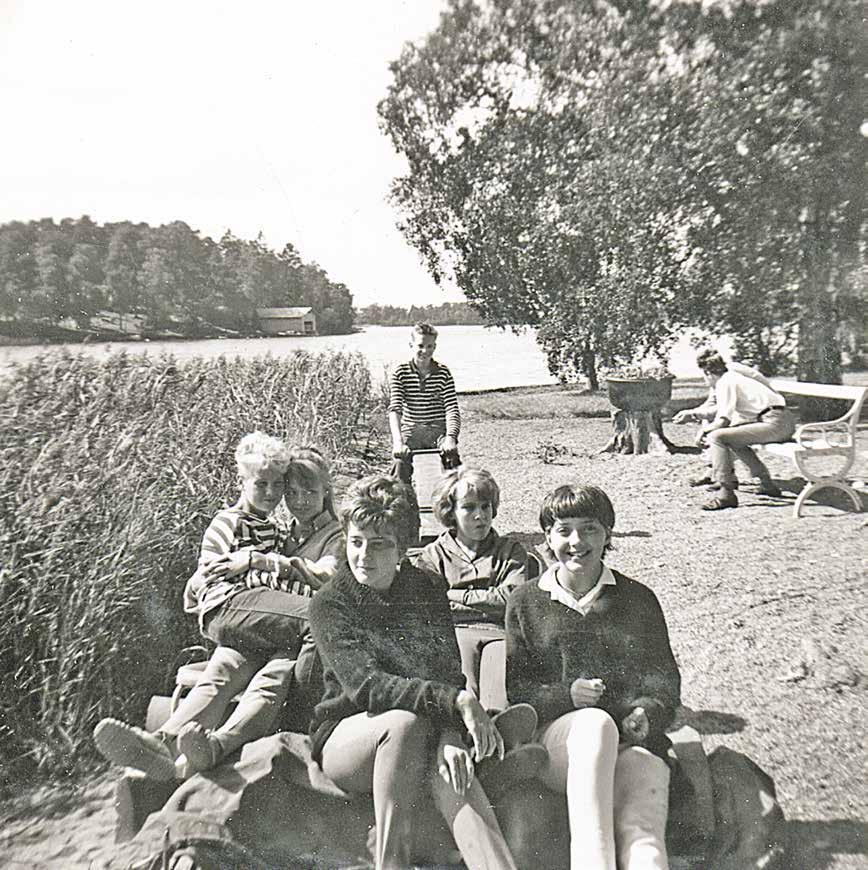

Estonian refugee camp on Tynningö, 1945. In the center, the teacher for the Estonian camp school, Ms. Siim. In the back row furthest to the left is Helga Raukas (married Nõu). In the middle row, second from the right, is Arvo Raukas, brother to Helga Raukas. Sitting second from the right is Rein Raukas, Helga Raukas’s youngest brother. Sitting furthest to the left is Ingrid Kuldevere (married Ungerson). A Palace in the Archipelago

In parallel with the family’s frequent transfers, her father spent the summers doing fieldwork away from home. Her parents’ correspondence letters serve as a complement to the memories of young Helga. In June 1945 they were transferred to a camp out in the Stockholm archipelago, but when they arrived the camp was already full. This time they were sent to a camp nearby on the island of Tynningö: Villa Björkudden. When they approached their new destination, Helga could hardly believe her eyes. It was like a magical castle surrounded by lush greenery, different in every aspect from the other camps where they had stayed.

Life in Camp

The family would spend two summer months in the ‘castle,’ as Helga still calls the house. They were housed upstairs in a large, tapestry-furnished bedroom. As she previously concluded, this was a camp much different from the others she had encountered before. It was much smaller, with only 30-40 residents compared to the hundreds that fit in the old barracks

of other places she had stayed. But the routines were just as harsh. In her letters, Helga’s mother wrote to her husband about how strict the Swedish supervisor was. They had to work all day in his private garden, and only had a break for lunch. Apart from the supervisor, contact with Swedish locals was very rare as nobody had mastered the language yet. Aside from working in the garden, the chores in camp were handed out to the adults on a rotating schedule and included assisting in the kitchen, cleaning, etc.

Helga, her brothers, and the other children at the camp went to a school supervised by an Estonian teacher, but otherwise had plenty of spare time. That summer was especially beautiful and the blooming lilac flowers have stayed in her memory. Here Helga met her first friend in Sweden; another child in the camp. Her name was Ingrid Kuldvere, and they often took evening walks along the water and speculated about what kind of life lay ahead of them. They still keep contact. It wasn’t all work at the camp, and there were many colorful personalities around. Everyone from professors to one of Estonia’s most well-renowned singers. They had even formed a puppet theater for their entertainment. Among the strange places and people Helga encountered during her first year in Sweden, Villa Björkudden with its chateau-like appearance and beautiful surroundings has kept a special place in her memory.

A group photo from the Estonian refugee camp, 1945. Sitting furthest to the left is Professor Andrus Saareste, celebrated language researcher at Tartu University. Sitting behind him is Helga Raukas (married Nõu). Sitting third from the right is Rein Raukas, and fourth from the right is Arvo Raukas. Standing third from the right is Elsa Raukas. Sitting beside Helga Raukas is Ingrid Kuldvere. Standing lowest to the right is likely Professor Evald Blumfeldt, professor at Tartu University.

After Tynningö

After August 1945, the family was transferred again to their last camp. From there the family managed to arrange accommodations in a house on Adelsö outside of Stockholm. Within a year Helga learned Swedish and later educated herself to become a primary school teacher for a steady income. She would rather have gone to art school, but her parents saw it as far too uncertain for income. They, with the trauma of losing everything they owned, lived by the motto, ”all material things perish, but the things you keep in your head persist.” In 1957 she married Enn Nou, who was also Estonian, and they moved to Uppsala. Art and literature came to play a central and vital role in their lives. Today they are both celebrated authors in Estonia, and for many years have split their time between their homes in Uppsala and Tallinn. The escape has left a significant mark in both their lives and literary work. At the beginning of the 21st-century, their daughter Lisa, who has a summer house on an island close by, brought her parents to revisit Villa Björkudden. When Helga saw it, she was shocked by how worn down the ”castle” of her childhood had become. But back then it was also one of her first reference points for Sweden and her new life. A life that has since been rich in experiences and personal fulfillment.

The Country Store Next Door

Neighboring Villa Björkudden lived the Johansson family: the father Erik, mother Ulla, and their son Göran. From 1935 and for more than 20 years, the family ran the country store that sat just across the road. There the refugees usually bought cigarettes, among other things. Many of them were skilled craftsmen, and Erik and Ulla even purchased candles that they had made. The thought was to sell them in the store, but they weren’t as sellable as they wished, and Erik and Ulla often took home the ones that had sat and collected dust for a while. The refugees were also able to take water from the drilled well across the road. They collected water in large 50-liter buckets. The capacity in Villa Björkudden’s dug well was likely not enough. Sometime the refugees also bought wood from the family, as lighting fires in the ceramic furnaces used a lot of wood. The refugees brought sauna culture with them to Sweden. Almost immediately upon arriving at Villa Björkudden, they rebuilt what had been a washroom in the bathhouse and turned it into a sauna. The construction went quickly, and soon there was constantly smoke coming from the sauna’s chimney. But it was not only Estonian refugees who reached Vaxholm and Villa Björkudden. War survivors came from Germany, many with injuries such as lost limbs. Many of them were trained cobblers and started a business where they made shoes and created prosthetic limbs. Some of the refugees later settled in Kumla and started a shoemaking business there.

1945 in the dining room of the Tynningö camp. Furthest to the right is Elsa Raukas, mother to Helga Raukas (married Nõu); second from the right is Helga Raukas. The wallpaper is still preserved today. Tynningö’s Estonian refugee camp – a castle in Helga’s eyes. All photos taken by Aleksander Raukas, father of Helga Raukas (married Nõu).

The Marionette Theater on Tynningö

Tynningö was for a short time the home of an Estonian puppet theater. In the camp’s early days, when uncertainty and idleness were contagious, the idea was formed by a group of people (Helga’s parents among them) to create a marionette theater. The father Aleksander, who in his youth studied art and painted his entire life, took part and created the the décor. The mother Elsa had been a handicrafts teacher and took care of the puppets and costumes. It started as a way to pass the time and entertain the children. Soon however, the interest grew and a small theater tour started. In the repertoire were fairytales such as Little Red Riding Hood and Hansel and Gretel. Despite several in the theater troupe, which was now 6-8 people, being funneled out of the camp into different workplaces, they were able to keep the operation running at the Tynningö camp. They also translated the pieces to Swedish and had the opportunity to perform in several schools in Stockholm. The labor board was so impressed that they suggested the troupe should have a proper theater education. This never came to fruition, however; everyone in the troupe already had an education, and the puppet theater was just a hobby for them. But the theater’s short activity left an unforgettable impression on those who witnessed the performances. Helga’s father documented it during the summer of 1945, when the entire troupe and theater was on Tynningö.

The puppet theater on Tynningö on tour in 1945, outside of Bromma Secondary School. First from the right, Helga Raukas (married Nõu) with mother Elsa Raukas. First from the left is Elmar Livet, second from the left is Rudolf Rink, officer. Caption (Right): 1945. The puppet theater at the camp. Little Red Riding Hood.